User login

Upadacitinib effective against nonradiographic AxSpA

COPENHAGEN – The Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor upadacitinib (Rinvoq, AbbVie) was associated with significant improvements in disease activity, pain, function, and quality of life, compared with placebo, in patients with nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA), results of the first efficacy analysis of the phase 3, randomized SELECT-AXIS-2 trial showed.

The trial met its primary endpoint of an improvement of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society 40% (ASAS 40) response criteria in the prespecified efficacy analysis at week 14, reported Filip Van den Bosch, MD, PhD, Ghent (Belgium) University.

In all, 45% of patients randomized to receive upadacitinib achieved an ASAS 40, compared with 23% of those assigned to placebo (P < .001).

“This is the first study showing efficacy and showing that the JAK inhibitor upadacitinib might be a therapeutic option in patients with active, nonradiographic spondyloarthritis,” Van den Bosch said at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology.

Although JAK inhibitors have previously been shown to be efficacious and safe for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis, the SELECT-AXIS-2 trial is the first to evaluate a JAK inhibitor in nonradiographic axSpA, he added.

Study details

Patients 18 years and older with rheumatologist-diagnosed nr-axSpA were eligible for the study if they also met 2009 ASAS classification criteria for axSpA but not the radiologic criterion of modified New York criteria; had objective signs of active inflammation consistent with axSpA on MRI of the sacroiliac joints and/or high-sensitivity C-reactive protein above the upper limit of normal (2.87 mg/L) at screening; and had Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) and patient-assessment of total back pain scores of 4 or greater based on a 0-10 numeric rating scale at study entry.

Patients were screened with MRI imaging of the spine and x-rays of the sacroiliac joints and spine, and then randomized to receive either placebo (157 patients) or upadacitinib 15 mg daily (158 patients) for 52 weeks. At the end of 52 weeks, all patients on upadacitinib will continue on the drug at the same dose level, and those assigned to placebo will be switched over to 15 mg upadacitinib daily maintenance.

As well as meeting the primary endpoint at week 14, response rates with the JAK inhibitor were higher at all time points over this initial time period, Dr. Van den Bosch noted.

Most targets hit

Of 14 multiplicity-controlled secondary endpoints, 12 were statistically better with upadacitinib, including change from baseline in patient’s assessment of total back pain, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score, Low Disease Activity, Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life, and MRI Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada score for sacroiliac joints.

Only the BASDAI and Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesitis Score were not significantly better with the JAK inhibitor.

The safety of upadacitinib in this setting was consistent with its known safety profile, Dr. Van den Bosch said.

Approximately half of all patients in each trial arm had an adverse event. Serious adverse events were reported in four patients assigned to upadacitinib versus two on placebo, and serious adverse events requiring drug discontinuation occurred in two and four patients, respectively.

‘Important’ data

Fabian Proft, MD, head of the clinical trials unit at Charite University Hospital, Berlin, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview that the findings were not surprising.

“We know the efficacy of upadacitinib already in radiographic axial spondyloarthritis, and from all the other drugs that we also know that are effective in radiographic axial spondyloarthritis that are similarly effective in nonradiographic disease,” he said.

“I think it is really important because it is the first data on JAK inhibition also in non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis – an important step,” said Dr. Proft, who was comoderator of the oral abstract session where Van den Bosch reported the data.

The trial was supported by AbbVie. Dr. Van den Bosch disclosed speaker and consulting fees from AbbVie and others. Dr. Proft disclosed speaker and consulting fees from AbbVie as well.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COPENHAGEN – The Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor upadacitinib (Rinvoq, AbbVie) was associated with significant improvements in disease activity, pain, function, and quality of life, compared with placebo, in patients with nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA), results of the first efficacy analysis of the phase 3, randomized SELECT-AXIS-2 trial showed.

The trial met its primary endpoint of an improvement of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society 40% (ASAS 40) response criteria in the prespecified efficacy analysis at week 14, reported Filip Van den Bosch, MD, PhD, Ghent (Belgium) University.

In all, 45% of patients randomized to receive upadacitinib achieved an ASAS 40, compared with 23% of those assigned to placebo (P < .001).

“This is the first study showing efficacy and showing that the JAK inhibitor upadacitinib might be a therapeutic option in patients with active, nonradiographic spondyloarthritis,” Van den Bosch said at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology.

Although JAK inhibitors have previously been shown to be efficacious and safe for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis, the SELECT-AXIS-2 trial is the first to evaluate a JAK inhibitor in nonradiographic axSpA, he added.

Study details

Patients 18 years and older with rheumatologist-diagnosed nr-axSpA were eligible for the study if they also met 2009 ASAS classification criteria for axSpA but not the radiologic criterion of modified New York criteria; had objective signs of active inflammation consistent with axSpA on MRI of the sacroiliac joints and/or high-sensitivity C-reactive protein above the upper limit of normal (2.87 mg/L) at screening; and had Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) and patient-assessment of total back pain scores of 4 or greater based on a 0-10 numeric rating scale at study entry.

Patients were screened with MRI imaging of the spine and x-rays of the sacroiliac joints and spine, and then randomized to receive either placebo (157 patients) or upadacitinib 15 mg daily (158 patients) for 52 weeks. At the end of 52 weeks, all patients on upadacitinib will continue on the drug at the same dose level, and those assigned to placebo will be switched over to 15 mg upadacitinib daily maintenance.

As well as meeting the primary endpoint at week 14, response rates with the JAK inhibitor were higher at all time points over this initial time period, Dr. Van den Bosch noted.

Most targets hit

Of 14 multiplicity-controlled secondary endpoints, 12 were statistically better with upadacitinib, including change from baseline in patient’s assessment of total back pain, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score, Low Disease Activity, Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life, and MRI Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada score for sacroiliac joints.

Only the BASDAI and Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesitis Score were not significantly better with the JAK inhibitor.

The safety of upadacitinib in this setting was consistent with its known safety profile, Dr. Van den Bosch said.

Approximately half of all patients in each trial arm had an adverse event. Serious adverse events were reported in four patients assigned to upadacitinib versus two on placebo, and serious adverse events requiring drug discontinuation occurred in two and four patients, respectively.

‘Important’ data

Fabian Proft, MD, head of the clinical trials unit at Charite University Hospital, Berlin, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview that the findings were not surprising.

“We know the efficacy of upadacitinib already in radiographic axial spondyloarthritis, and from all the other drugs that we also know that are effective in radiographic axial spondyloarthritis that are similarly effective in nonradiographic disease,” he said.

“I think it is really important because it is the first data on JAK inhibition also in non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis – an important step,” said Dr. Proft, who was comoderator of the oral abstract session where Van den Bosch reported the data.

The trial was supported by AbbVie. Dr. Van den Bosch disclosed speaker and consulting fees from AbbVie and others. Dr. Proft disclosed speaker and consulting fees from AbbVie as well.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COPENHAGEN – The Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor upadacitinib (Rinvoq, AbbVie) was associated with significant improvements in disease activity, pain, function, and quality of life, compared with placebo, in patients with nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA), results of the first efficacy analysis of the phase 3, randomized SELECT-AXIS-2 trial showed.

The trial met its primary endpoint of an improvement of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society 40% (ASAS 40) response criteria in the prespecified efficacy analysis at week 14, reported Filip Van den Bosch, MD, PhD, Ghent (Belgium) University.

In all, 45% of patients randomized to receive upadacitinib achieved an ASAS 40, compared with 23% of those assigned to placebo (P < .001).

“This is the first study showing efficacy and showing that the JAK inhibitor upadacitinib might be a therapeutic option in patients with active, nonradiographic spondyloarthritis,” Van den Bosch said at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology.

Although JAK inhibitors have previously been shown to be efficacious and safe for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis, the SELECT-AXIS-2 trial is the first to evaluate a JAK inhibitor in nonradiographic axSpA, he added.

Study details

Patients 18 years and older with rheumatologist-diagnosed nr-axSpA were eligible for the study if they also met 2009 ASAS classification criteria for axSpA but not the radiologic criterion of modified New York criteria; had objective signs of active inflammation consistent with axSpA on MRI of the sacroiliac joints and/or high-sensitivity C-reactive protein above the upper limit of normal (2.87 mg/L) at screening; and had Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) and patient-assessment of total back pain scores of 4 or greater based on a 0-10 numeric rating scale at study entry.

Patients were screened with MRI imaging of the spine and x-rays of the sacroiliac joints and spine, and then randomized to receive either placebo (157 patients) or upadacitinib 15 mg daily (158 patients) for 52 weeks. At the end of 52 weeks, all patients on upadacitinib will continue on the drug at the same dose level, and those assigned to placebo will be switched over to 15 mg upadacitinib daily maintenance.

As well as meeting the primary endpoint at week 14, response rates with the JAK inhibitor were higher at all time points over this initial time period, Dr. Van den Bosch noted.

Most targets hit

Of 14 multiplicity-controlled secondary endpoints, 12 were statistically better with upadacitinib, including change from baseline in patient’s assessment of total back pain, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score, Low Disease Activity, Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life, and MRI Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada score for sacroiliac joints.

Only the BASDAI and Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesitis Score were not significantly better with the JAK inhibitor.

The safety of upadacitinib in this setting was consistent with its known safety profile, Dr. Van den Bosch said.

Approximately half of all patients in each trial arm had an adverse event. Serious adverse events were reported in four patients assigned to upadacitinib versus two on placebo, and serious adverse events requiring drug discontinuation occurred in two and four patients, respectively.

‘Important’ data

Fabian Proft, MD, head of the clinical trials unit at Charite University Hospital, Berlin, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview that the findings were not surprising.

“We know the efficacy of upadacitinib already in radiographic axial spondyloarthritis, and from all the other drugs that we also know that are effective in radiographic axial spondyloarthritis that are similarly effective in nonradiographic disease,” he said.

“I think it is really important because it is the first data on JAK inhibition also in non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis – an important step,” said Dr. Proft, who was comoderator of the oral abstract session where Van den Bosch reported the data.

The trial was supported by AbbVie. Dr. Van den Bosch disclosed speaker and consulting fees from AbbVie and others. Dr. Proft disclosed speaker and consulting fees from AbbVie as well.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT THE EULAR 2022 CONGRESS

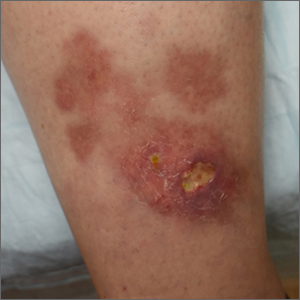

Ulcerated lower leg lesion

The patient’s atrophic plaques with a violaceous rim, indurated borders, and ulceration on the anterior pretibial surface were consistent with ulcerated necrobiosis lipoidica (NL).

NL typically manifests on the bilateral pretibial region as small papules or nodules that expand into yellow-brown atrophic, telangiectatic plaques with an elevated violaceous rim.1,2 Most lesions are asymptomatic due to nerve damage, but up to 35% of patients may experience pruritus and tenderness.2 Close monitoring of lesions is recommended due to risk of ulceration and potential for malignancy.2 Rare reports show development of squamous cell carcinoma within NL lesions.1

Women are 3 times more likely than men to have NL, with an average age of onset between 30 and 40 years.1 The exact pathogenesis of NL is unknown.2 Theories include vascular abnormalities (immunoglobulin deposition or microangiopathic changes leading to collagen degradation), abnormalities of collagen synthesis, neutrophil migration, and elevated tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels.1,3

While NL can be diagnosed clinically, a skin biopsy may be necessary in atypical lesions. The biopsy will reveal palisading granulomatous inflammation in the dermis, with multinucleated histiocytes palisading around degenerated collagen bundles.2

No treatment has proven to be effective for NL. Glucose control in patients with diabetes does not have a significant effect on the NL lesions.1-3 Corticosteroids (topical, intralesional, and systemic—depending on the severity) are considered first-line therapy.1-3 Lifestyle modifications, such as smoking cessation and trauma avoidance, are recommended to promote healing; proper wound care is important when there is ulceration.1,3 Other treatment options include oral pentoxifylline, topical retinoids or calcineurin inhibitors, and systemic immune system modulators (eg, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and cyclosporine).

Since this patient did not respond to the topical betamethasone, she was started on oral pentoxifylline 400 mg tid. Unfortunately, she had to discontinue the medication because of gastrointestinal upset and was then started on doxycycline 100 mg orally bid. She was lost to follow-up.

Photo courtesy of Cyrelle F. Finan, MD. Text courtesy of Harika Echuri, MD, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA, Cyrelle F. Finan, MD, Department of Dermatology, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Lepe K, Riley CA, Salazar FJ. Necrobiosis lipoidica. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated August 26, 2021. Accessed May 31, 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459318/

2. Tong LX, Penn L, Meehan SA, Kim RH. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt0qg3b3zw. doi: 10.5070/D32412042442

3. Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2015.03.003

The patient’s atrophic plaques with a violaceous rim, indurated borders, and ulceration on the anterior pretibial surface were consistent with ulcerated necrobiosis lipoidica (NL).

NL typically manifests on the bilateral pretibial region as small papules or nodules that expand into yellow-brown atrophic, telangiectatic plaques with an elevated violaceous rim.1,2 Most lesions are asymptomatic due to nerve damage, but up to 35% of patients may experience pruritus and tenderness.2 Close monitoring of lesions is recommended due to risk of ulceration and potential for malignancy.2 Rare reports show development of squamous cell carcinoma within NL lesions.1

Women are 3 times more likely than men to have NL, with an average age of onset between 30 and 40 years.1 The exact pathogenesis of NL is unknown.2 Theories include vascular abnormalities (immunoglobulin deposition or microangiopathic changes leading to collagen degradation), abnormalities of collagen synthesis, neutrophil migration, and elevated tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels.1,3

While NL can be diagnosed clinically, a skin biopsy may be necessary in atypical lesions. The biopsy will reveal palisading granulomatous inflammation in the dermis, with multinucleated histiocytes palisading around degenerated collagen bundles.2

No treatment has proven to be effective for NL. Glucose control in patients with diabetes does not have a significant effect on the NL lesions.1-3 Corticosteroids (topical, intralesional, and systemic—depending on the severity) are considered first-line therapy.1-3 Lifestyle modifications, such as smoking cessation and trauma avoidance, are recommended to promote healing; proper wound care is important when there is ulceration.1,3 Other treatment options include oral pentoxifylline, topical retinoids or calcineurin inhibitors, and systemic immune system modulators (eg, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and cyclosporine).

Since this patient did not respond to the topical betamethasone, she was started on oral pentoxifylline 400 mg tid. Unfortunately, she had to discontinue the medication because of gastrointestinal upset and was then started on doxycycline 100 mg orally bid. She was lost to follow-up.

Photo courtesy of Cyrelle F. Finan, MD. Text courtesy of Harika Echuri, MD, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA, Cyrelle F. Finan, MD, Department of Dermatology, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

The patient’s atrophic plaques with a violaceous rim, indurated borders, and ulceration on the anterior pretibial surface were consistent with ulcerated necrobiosis lipoidica (NL).

NL typically manifests on the bilateral pretibial region as small papules or nodules that expand into yellow-brown atrophic, telangiectatic plaques with an elevated violaceous rim.1,2 Most lesions are asymptomatic due to nerve damage, but up to 35% of patients may experience pruritus and tenderness.2 Close monitoring of lesions is recommended due to risk of ulceration and potential for malignancy.2 Rare reports show development of squamous cell carcinoma within NL lesions.1

Women are 3 times more likely than men to have NL, with an average age of onset between 30 and 40 years.1 The exact pathogenesis of NL is unknown.2 Theories include vascular abnormalities (immunoglobulin deposition or microangiopathic changes leading to collagen degradation), abnormalities of collagen synthesis, neutrophil migration, and elevated tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels.1,3

While NL can be diagnosed clinically, a skin biopsy may be necessary in atypical lesions. The biopsy will reveal palisading granulomatous inflammation in the dermis, with multinucleated histiocytes palisading around degenerated collagen bundles.2

No treatment has proven to be effective for NL. Glucose control in patients with diabetes does not have a significant effect on the NL lesions.1-3 Corticosteroids (topical, intralesional, and systemic—depending on the severity) are considered first-line therapy.1-3 Lifestyle modifications, such as smoking cessation and trauma avoidance, are recommended to promote healing; proper wound care is important when there is ulceration.1,3 Other treatment options include oral pentoxifylline, topical retinoids or calcineurin inhibitors, and systemic immune system modulators (eg, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and cyclosporine).

Since this patient did not respond to the topical betamethasone, she was started on oral pentoxifylline 400 mg tid. Unfortunately, she had to discontinue the medication because of gastrointestinal upset and was then started on doxycycline 100 mg orally bid. She was lost to follow-up.

Photo courtesy of Cyrelle F. Finan, MD. Text courtesy of Harika Echuri, MD, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA, Cyrelle F. Finan, MD, Department of Dermatology, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Lepe K, Riley CA, Salazar FJ. Necrobiosis lipoidica. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated August 26, 2021. Accessed May 31, 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459318/

2. Tong LX, Penn L, Meehan SA, Kim RH. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt0qg3b3zw. doi: 10.5070/D32412042442

3. Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2015.03.003

1. Lepe K, Riley CA, Salazar FJ. Necrobiosis lipoidica. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated August 26, 2021. Accessed May 31, 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459318/

2. Tong LX, Penn L, Meehan SA, Kim RH. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt0qg3b3zw. doi: 10.5070/D32412042442

3. Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2015.03.003

Omega-3 supplement sweet spot found for BP reduction

A meta-analysis of 71 randomized controlled trials has found the sweet spot for omega-3 fatty acid intake for lowering blood pressure: between 2 and 3 g/day. The investigators also reported that people at higher risk for cardiovascular disease may benefit from higher daily intake of omega-3.

The study analyzed data from randomized controlled trials involving 4,973 individuals and published from 1987 to 2020. Most of the trials used a combined supplementation of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Outcomes analysis involved the impact of combined DHA-EPA at 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 grams daily on average changes in both systolic and diastolic BP and compared them with the placebo or control groups who had a combined intake of 0 g/day.

“We found a significant nonlinear dose-response relationship for both SBP and DBP models,” wrote senior author Xinzhi Li, MD, PhD, and colleagues. Dr. Li is program director of the school of pharmacy at Macau University of Science and Technology in Taipa, China.

Most of the trials included in the meta-analysis evaluated fish oil supplements, but a number also included EPA and DHA omega-3 fatty acids consumed in food.

When the investigators analyzed studies that used an average baseline SBP of greater than 130 mm Hg, they found that increasing omega-3 supplementation resulted in strong reductions in SBP and DBP, but not so with people with baseline SBP below 130 mm Hg.

Across the entire cohort, average SBP and DBP changes averaged –2.61 (95% confidence interval, –3.57 to –1.65) and –1.64 (95% CI, –2.29 to –0.99) mm Hg for people taking 2 g/d omega-3 supplements, and –2.61 (95% CI, –3.52 to –1.69) and –1.80 (95% CI, –2.38 to –1.23) for those on 3 g/d. The changes weren’t as robust in higher and lower intake groups overall.

However, the higher the BP, the more robust the reductions. For those with SBP greater than 130 mm Hg, 3 g/d resulted in an average change of –3.22 mm Hg (95% CI, –5.21 to –1.23). In the greater than 80 mm Hg DBP group, 3 g/d of omega-3 resulted in an average –3.81 mm Hg reduction (95% CI, –4.48 to –1.87). In patients with BP greater than 140/90 and hypertension, the reductions were even more pronounced. And in patients with BP greater than 130/80, omega-3 intake of 4-5 g/d had a greater impact than 2-3 g/d, although that benefit didn’t carry over in the greater than 140/90 group.

High cholesterol was also a factor in determining the benefits of omega-3 supplementation on BP, as Dr. Li and colleagues wrote that they found “an approximately linear relationship” between hyperlipidemia and SBP, “suggesting that increasing supplementation was associated with greater reductions in SBP.” Likewise, the study found stronger effects on BP in studies with an average patient age greater than 45 years.

In 2019, the Food and Drug Administration issued an update that consuming combined EPA and DHA may lower BP in the general population and reduce the risk of hypertension, but that “the evidence is inconsistent and inconclusive.”

“However, while our study may add a layer of credible evidence, it does not meet the threshold to make an authorized health claim for omega-3 fatty acids in compliance with FDA regulations,” Dr. Li said.

The study addresses shortcomings of previous studies of omega-3 and BP and by identifying the optimal dose, Marc George, MRCP, PhD, of the Institute of Cardiovascular Science, University College, London, and Ajay Gupta, MD, PhD, of the William Harvey Research Institute at Queen Mary University, London, wrote in an accompanying editorial. “More importantly, they have demonstrated a significantly stronger and increased BP-lowering effect in higher cardiovascular risk groups, such as those with hypertension or hyperlipidemia.”

They also noted that the 2.61–mm Hg reduction in SBP the study reported is “likely to be significant” on a population level. “A 2–mm Hg reduction in SBP is estimated to reduce stroke mortality by 10% and deaths from ischemic heart disease by 7%,” they wrote. “Expressed another way, an analysis in the U.S. population using 2010 data estimates that a population-wide reduction in SBP of 2 mm Hg in those aged 45- 64 years would translate to 30,045 fewer cardiovascular events ([coronary heart disease], stroke, and heart failure).”

The investigators and editorialists have no disclosures.

A meta-analysis of 71 randomized controlled trials has found the sweet spot for omega-3 fatty acid intake for lowering blood pressure: between 2 and 3 g/day. The investigators also reported that people at higher risk for cardiovascular disease may benefit from higher daily intake of omega-3.

The study analyzed data from randomized controlled trials involving 4,973 individuals and published from 1987 to 2020. Most of the trials used a combined supplementation of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Outcomes analysis involved the impact of combined DHA-EPA at 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 grams daily on average changes in both systolic and diastolic BP and compared them with the placebo or control groups who had a combined intake of 0 g/day.

“We found a significant nonlinear dose-response relationship for both SBP and DBP models,” wrote senior author Xinzhi Li, MD, PhD, and colleagues. Dr. Li is program director of the school of pharmacy at Macau University of Science and Technology in Taipa, China.

Most of the trials included in the meta-analysis evaluated fish oil supplements, but a number also included EPA and DHA omega-3 fatty acids consumed in food.

When the investigators analyzed studies that used an average baseline SBP of greater than 130 mm Hg, they found that increasing omega-3 supplementation resulted in strong reductions in SBP and DBP, but not so with people with baseline SBP below 130 mm Hg.

Across the entire cohort, average SBP and DBP changes averaged –2.61 (95% confidence interval, –3.57 to –1.65) and –1.64 (95% CI, –2.29 to –0.99) mm Hg for people taking 2 g/d omega-3 supplements, and –2.61 (95% CI, –3.52 to –1.69) and –1.80 (95% CI, –2.38 to –1.23) for those on 3 g/d. The changes weren’t as robust in higher and lower intake groups overall.

However, the higher the BP, the more robust the reductions. For those with SBP greater than 130 mm Hg, 3 g/d resulted in an average change of –3.22 mm Hg (95% CI, –5.21 to –1.23). In the greater than 80 mm Hg DBP group, 3 g/d of omega-3 resulted in an average –3.81 mm Hg reduction (95% CI, –4.48 to –1.87). In patients with BP greater than 140/90 and hypertension, the reductions were even more pronounced. And in patients with BP greater than 130/80, omega-3 intake of 4-5 g/d had a greater impact than 2-3 g/d, although that benefit didn’t carry over in the greater than 140/90 group.

High cholesterol was also a factor in determining the benefits of omega-3 supplementation on BP, as Dr. Li and colleagues wrote that they found “an approximately linear relationship” between hyperlipidemia and SBP, “suggesting that increasing supplementation was associated with greater reductions in SBP.” Likewise, the study found stronger effects on BP in studies with an average patient age greater than 45 years.

In 2019, the Food and Drug Administration issued an update that consuming combined EPA and DHA may lower BP in the general population and reduce the risk of hypertension, but that “the evidence is inconsistent and inconclusive.”

“However, while our study may add a layer of credible evidence, it does not meet the threshold to make an authorized health claim for omega-3 fatty acids in compliance with FDA regulations,” Dr. Li said.

The study addresses shortcomings of previous studies of omega-3 and BP and by identifying the optimal dose, Marc George, MRCP, PhD, of the Institute of Cardiovascular Science, University College, London, and Ajay Gupta, MD, PhD, of the William Harvey Research Institute at Queen Mary University, London, wrote in an accompanying editorial. “More importantly, they have demonstrated a significantly stronger and increased BP-lowering effect in higher cardiovascular risk groups, such as those with hypertension or hyperlipidemia.”

They also noted that the 2.61–mm Hg reduction in SBP the study reported is “likely to be significant” on a population level. “A 2–mm Hg reduction in SBP is estimated to reduce stroke mortality by 10% and deaths from ischemic heart disease by 7%,” they wrote. “Expressed another way, an analysis in the U.S. population using 2010 data estimates that a population-wide reduction in SBP of 2 mm Hg in those aged 45- 64 years would translate to 30,045 fewer cardiovascular events ([coronary heart disease], stroke, and heart failure).”

The investigators and editorialists have no disclosures.

A meta-analysis of 71 randomized controlled trials has found the sweet spot for omega-3 fatty acid intake for lowering blood pressure: between 2 and 3 g/day. The investigators also reported that people at higher risk for cardiovascular disease may benefit from higher daily intake of omega-3.

The study analyzed data from randomized controlled trials involving 4,973 individuals and published from 1987 to 2020. Most of the trials used a combined supplementation of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Outcomes analysis involved the impact of combined DHA-EPA at 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 grams daily on average changes in both systolic and diastolic BP and compared them with the placebo or control groups who had a combined intake of 0 g/day.

“We found a significant nonlinear dose-response relationship for both SBP and DBP models,” wrote senior author Xinzhi Li, MD, PhD, and colleagues. Dr. Li is program director of the school of pharmacy at Macau University of Science and Technology in Taipa, China.

Most of the trials included in the meta-analysis evaluated fish oil supplements, but a number also included EPA and DHA omega-3 fatty acids consumed in food.

When the investigators analyzed studies that used an average baseline SBP of greater than 130 mm Hg, they found that increasing omega-3 supplementation resulted in strong reductions in SBP and DBP, but not so with people with baseline SBP below 130 mm Hg.

Across the entire cohort, average SBP and DBP changes averaged –2.61 (95% confidence interval, –3.57 to –1.65) and –1.64 (95% CI, –2.29 to –0.99) mm Hg for people taking 2 g/d omega-3 supplements, and –2.61 (95% CI, –3.52 to –1.69) and –1.80 (95% CI, –2.38 to –1.23) for those on 3 g/d. The changes weren’t as robust in higher and lower intake groups overall.

However, the higher the BP, the more robust the reductions. For those with SBP greater than 130 mm Hg, 3 g/d resulted in an average change of –3.22 mm Hg (95% CI, –5.21 to –1.23). In the greater than 80 mm Hg DBP group, 3 g/d of omega-3 resulted in an average –3.81 mm Hg reduction (95% CI, –4.48 to –1.87). In patients with BP greater than 140/90 and hypertension, the reductions were even more pronounced. And in patients with BP greater than 130/80, omega-3 intake of 4-5 g/d had a greater impact than 2-3 g/d, although that benefit didn’t carry over in the greater than 140/90 group.

High cholesterol was also a factor in determining the benefits of omega-3 supplementation on BP, as Dr. Li and colleagues wrote that they found “an approximately linear relationship” between hyperlipidemia and SBP, “suggesting that increasing supplementation was associated with greater reductions in SBP.” Likewise, the study found stronger effects on BP in studies with an average patient age greater than 45 years.

In 2019, the Food and Drug Administration issued an update that consuming combined EPA and DHA may lower BP in the general population and reduce the risk of hypertension, but that “the evidence is inconsistent and inconclusive.”

“However, while our study may add a layer of credible evidence, it does not meet the threshold to make an authorized health claim for omega-3 fatty acids in compliance with FDA regulations,” Dr. Li said.

The study addresses shortcomings of previous studies of omega-3 and BP and by identifying the optimal dose, Marc George, MRCP, PhD, of the Institute of Cardiovascular Science, University College, London, and Ajay Gupta, MD, PhD, of the William Harvey Research Institute at Queen Mary University, London, wrote in an accompanying editorial. “More importantly, they have demonstrated a significantly stronger and increased BP-lowering effect in higher cardiovascular risk groups, such as those with hypertension or hyperlipidemia.”

They also noted that the 2.61–mm Hg reduction in SBP the study reported is “likely to be significant” on a population level. “A 2–mm Hg reduction in SBP is estimated to reduce stroke mortality by 10% and deaths from ischemic heart disease by 7%,” they wrote. “Expressed another way, an analysis in the U.S. population using 2010 data estimates that a population-wide reduction in SBP of 2 mm Hg in those aged 45- 64 years would translate to 30,045 fewer cardiovascular events ([coronary heart disease], stroke, and heart failure).”

The investigators and editorialists have no disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION

ADA prioritizes heart failure in patients with diabetes

All U.S. patients with diabetes should undergo annual biomarker testing to allow for early diagnosis of progressive but presymptomatic heart failure, and treatment with an agent from the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor class should expand among such patients to include everyone with stage B heart failure (“pre–heart failure”) or more advanced stages.

That’s a recommendation from an American Diabetes Association consensus report published June 1 in Diabetes Care.

The report notes that until now, “implementation of available strategies to detect asymptomatic heart failure [in patients with diabetes] has been suboptimal.” The remedy for this is that, “among individuals with diabetes, measurement of a natriuretic peptide or high-sensitivity cardiac troponin is recommended on at least a yearly basis to identify the earliest heart failure stages and to implement strategies to prevent transition to symptomatic heart failure.”

Written by a 10-member panel, chaired by Rodica Pop-Busui, MD, PhD, and endorsed by the American College of Cardiology, the document also set threshold for levels of these biomarkers that are diagnostic for a more advanced stage (stage B) of heart failure in patients with diabetes but without heart failure symptoms:

- A B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) level of ≥50 pg/mL;

- An N-terminal pro-BNP level of ≥125 pg/mL; or

- Any high sensitivity cardiac troponin value that’s above the usual upper reference limit set at >99th percentile.

‘Inexpensive’ biomarker testing

“Addition of relatively inexpensive biomarker testing as part of the standard of care may help to refine heart failure risk prediction in individuals with diabetes,” the report says.

“Substantial data indicate the ability of these biomarkers to identify those in stage A or B [heart failure] at highest risk of progressing to symptomatic heart failure or death,” and this identification is useful because “the risk in such individuals may be lowered through targeted intervention or multidisciplinary care.”

It is “impossible to understate the importance of early recognition of heart failure” in patients with heart failure, the authors declare. However, the report also cautions that, “using biomarkers to identify and in turn reduce risk for heart failure should always be done within the context of a thoughtful clinical evaluation, supported by all information available.”

The report, written during March 2021 – March 2022, cites the high prevalence and increasing incidence of heart failure in patients with diabetes as the rationale for the new recommendations.

For a person with diabetes who receives a heart failure diagnosis, the report details several management steps, starting with an evaluation for obstructive coronary artery disease, given the strong link between diabetes and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

It highlights the importance of interventions that involve nutrition, smoking avoidance, minimized alcohol intake, exercise, weight loss, and relevant social determinants of health, but focuses in greater detail on a range of pharmacologic interventions. These include treatment of hypertension for people with early-stage heart failure with an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker, a thiazide-type diuretic, and a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, such as spironolactone or the newer, nonsteroidal agent finerenone for patients with diabetic kidney disease.

Dr. Busui of the division of metabolism, endocrinology, and diabetes at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues cite recent recommendations for using guidelines-directed medical therapy to treat patients with more advanced, symptomatic stages of heart failure, including heart failure with reduced or with preserved ejection fraction.

‘Prioritize’ the SGLT2-inhibitor class

The consensus report also summarizes the roles for agents in the various classes of antidiabetes drugs now available, with particular emphasis on the role for the SGLT2-inhibitor class.

SGLT2 inhibitors “are recommended for all individuals with [diabetes and] heart failure,” it says. “This consensus recommends prioritizing the use of SGLT2 inhibitors in individuals with stage B heart failure, and that SGLT2 inhibitors be an expected element of care in all individuals with diabetes and symptomatic heart failure.”

Other agents for glycemic control that receive endorsement from the report are those in the glucagonlike peptide 1 receptor agonist class. “Despite the lack of conclusive evidence of direct heart failure risk reduction” with this class, it gets a “should be considered” designation, based on its positive effects on weight loss, blood pressure, and atherothrombotic disease.

Similar acknowledgment of potential benefit in a “should be considered” role goes to metformin. But the report turned a thumb down for both the class of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors and the thiazolidinedione class, and said that agents from the insulin and sulfonylurea classes should be used “judiciously.”

The report did not identify any commercial funding. Several of the writing committee members listed personal commercial disclosures.

All U.S. patients with diabetes should undergo annual biomarker testing to allow for early diagnosis of progressive but presymptomatic heart failure, and treatment with an agent from the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor class should expand among such patients to include everyone with stage B heart failure (“pre–heart failure”) or more advanced stages.

That’s a recommendation from an American Diabetes Association consensus report published June 1 in Diabetes Care.

The report notes that until now, “implementation of available strategies to detect asymptomatic heart failure [in patients with diabetes] has been suboptimal.” The remedy for this is that, “among individuals with diabetes, measurement of a natriuretic peptide or high-sensitivity cardiac troponin is recommended on at least a yearly basis to identify the earliest heart failure stages and to implement strategies to prevent transition to symptomatic heart failure.”

Written by a 10-member panel, chaired by Rodica Pop-Busui, MD, PhD, and endorsed by the American College of Cardiology, the document also set threshold for levels of these biomarkers that are diagnostic for a more advanced stage (stage B) of heart failure in patients with diabetes but without heart failure symptoms:

- A B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) level of ≥50 pg/mL;

- An N-terminal pro-BNP level of ≥125 pg/mL; or

- Any high sensitivity cardiac troponin value that’s above the usual upper reference limit set at >99th percentile.

‘Inexpensive’ biomarker testing

“Addition of relatively inexpensive biomarker testing as part of the standard of care may help to refine heart failure risk prediction in individuals with diabetes,” the report says.

“Substantial data indicate the ability of these biomarkers to identify those in stage A or B [heart failure] at highest risk of progressing to symptomatic heart failure or death,” and this identification is useful because “the risk in such individuals may be lowered through targeted intervention or multidisciplinary care.”

It is “impossible to understate the importance of early recognition of heart failure” in patients with heart failure, the authors declare. However, the report also cautions that, “using biomarkers to identify and in turn reduce risk for heart failure should always be done within the context of a thoughtful clinical evaluation, supported by all information available.”

The report, written during March 2021 – March 2022, cites the high prevalence and increasing incidence of heart failure in patients with diabetes as the rationale for the new recommendations.

For a person with diabetes who receives a heart failure diagnosis, the report details several management steps, starting with an evaluation for obstructive coronary artery disease, given the strong link between diabetes and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

It highlights the importance of interventions that involve nutrition, smoking avoidance, minimized alcohol intake, exercise, weight loss, and relevant social determinants of health, but focuses in greater detail on a range of pharmacologic interventions. These include treatment of hypertension for people with early-stage heart failure with an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker, a thiazide-type diuretic, and a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, such as spironolactone or the newer, nonsteroidal agent finerenone for patients with diabetic kidney disease.

Dr. Busui of the division of metabolism, endocrinology, and diabetes at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues cite recent recommendations for using guidelines-directed medical therapy to treat patients with more advanced, symptomatic stages of heart failure, including heart failure with reduced or with preserved ejection fraction.

‘Prioritize’ the SGLT2-inhibitor class

The consensus report also summarizes the roles for agents in the various classes of antidiabetes drugs now available, with particular emphasis on the role for the SGLT2-inhibitor class.

SGLT2 inhibitors “are recommended for all individuals with [diabetes and] heart failure,” it says. “This consensus recommends prioritizing the use of SGLT2 inhibitors in individuals with stage B heart failure, and that SGLT2 inhibitors be an expected element of care in all individuals with diabetes and symptomatic heart failure.”

Other agents for glycemic control that receive endorsement from the report are those in the glucagonlike peptide 1 receptor agonist class. “Despite the lack of conclusive evidence of direct heart failure risk reduction” with this class, it gets a “should be considered” designation, based on its positive effects on weight loss, blood pressure, and atherothrombotic disease.

Similar acknowledgment of potential benefit in a “should be considered” role goes to metformin. But the report turned a thumb down for both the class of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors and the thiazolidinedione class, and said that agents from the insulin and sulfonylurea classes should be used “judiciously.”

The report did not identify any commercial funding. Several of the writing committee members listed personal commercial disclosures.

All U.S. patients with diabetes should undergo annual biomarker testing to allow for early diagnosis of progressive but presymptomatic heart failure, and treatment with an agent from the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor class should expand among such patients to include everyone with stage B heart failure (“pre–heart failure”) or more advanced stages.

That’s a recommendation from an American Diabetes Association consensus report published June 1 in Diabetes Care.

The report notes that until now, “implementation of available strategies to detect asymptomatic heart failure [in patients with diabetes] has been suboptimal.” The remedy for this is that, “among individuals with diabetes, measurement of a natriuretic peptide or high-sensitivity cardiac troponin is recommended on at least a yearly basis to identify the earliest heart failure stages and to implement strategies to prevent transition to symptomatic heart failure.”

Written by a 10-member panel, chaired by Rodica Pop-Busui, MD, PhD, and endorsed by the American College of Cardiology, the document also set threshold for levels of these biomarkers that are diagnostic for a more advanced stage (stage B) of heart failure in patients with diabetes but without heart failure symptoms:

- A B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) level of ≥50 pg/mL;

- An N-terminal pro-BNP level of ≥125 pg/mL; or

- Any high sensitivity cardiac troponin value that’s above the usual upper reference limit set at >99th percentile.

‘Inexpensive’ biomarker testing

“Addition of relatively inexpensive biomarker testing as part of the standard of care may help to refine heart failure risk prediction in individuals with diabetes,” the report says.

“Substantial data indicate the ability of these biomarkers to identify those in stage A or B [heart failure] at highest risk of progressing to symptomatic heart failure or death,” and this identification is useful because “the risk in such individuals may be lowered through targeted intervention or multidisciplinary care.”

It is “impossible to understate the importance of early recognition of heart failure” in patients with heart failure, the authors declare. However, the report also cautions that, “using biomarkers to identify and in turn reduce risk for heart failure should always be done within the context of a thoughtful clinical evaluation, supported by all information available.”

The report, written during March 2021 – March 2022, cites the high prevalence and increasing incidence of heart failure in patients with diabetes as the rationale for the new recommendations.

For a person with diabetes who receives a heart failure diagnosis, the report details several management steps, starting with an evaluation for obstructive coronary artery disease, given the strong link between diabetes and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

It highlights the importance of interventions that involve nutrition, smoking avoidance, minimized alcohol intake, exercise, weight loss, and relevant social determinants of health, but focuses in greater detail on a range of pharmacologic interventions. These include treatment of hypertension for people with early-stage heart failure with an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker, a thiazide-type diuretic, and a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, such as spironolactone or the newer, nonsteroidal agent finerenone for patients with diabetic kidney disease.

Dr. Busui of the division of metabolism, endocrinology, and diabetes at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues cite recent recommendations for using guidelines-directed medical therapy to treat patients with more advanced, symptomatic stages of heart failure, including heart failure with reduced or with preserved ejection fraction.

‘Prioritize’ the SGLT2-inhibitor class

The consensus report also summarizes the roles for agents in the various classes of antidiabetes drugs now available, with particular emphasis on the role for the SGLT2-inhibitor class.

SGLT2 inhibitors “are recommended for all individuals with [diabetes and] heart failure,” it says. “This consensus recommends prioritizing the use of SGLT2 inhibitors in individuals with stage B heart failure, and that SGLT2 inhibitors be an expected element of care in all individuals with diabetes and symptomatic heart failure.”

Other agents for glycemic control that receive endorsement from the report are those in the glucagonlike peptide 1 receptor agonist class. “Despite the lack of conclusive evidence of direct heart failure risk reduction” with this class, it gets a “should be considered” designation, based on its positive effects on weight loss, blood pressure, and atherothrombotic disease.

Similar acknowledgment of potential benefit in a “should be considered” role goes to metformin. But the report turned a thumb down for both the class of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors and the thiazolidinedione class, and said that agents from the insulin and sulfonylurea classes should be used “judiciously.”

The report did not identify any commercial funding. Several of the writing committee members listed personal commercial disclosures.

FROM DIABETES CARE

Early metformin minimizes antipsychotic-induced weight gain

MAR DEL PLATA, ARGENTINA – , according to a new evidence-based Irish guideline for the management of this common complication in adults with psychoses who are taking medications.

The document was discussed during one of the sessions of the XXXV Argentine Congress of Psychiatry of the Association of Argentine Psychiatrists. The document also was presented by one of its authors at the European Congress on Obesity 2022.

The guideline encourages psychiatrists not to underestimate the adverse metabolic effects of their treatments and encourages them to contemplate and carry out this prevention and management strategy, commented María Delia Michat, PhD, professor of clinical psychiatry and psychopharmacology at the APSA Postgraduate Training Institute, Buenos Aires.

“Although it is always good to work as a team, it is usually we psychiatrists who coordinate the pharmacological treatment of our patients, and we have to know how to manage drugs that can prevent cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Michat said in an interview.

“The new guideline is helpful because it protocolizes the use of metformin, which is the cheapest drug and has the most evidence for antipsychotic-induced weight gain,” she added.

Avoiding metabolic syndrome

In patients with schizophrenia, obesity rates are 40% higher than in the general population, and 80% of patients develop weight gain after their first treatment, noted Dr. Michat. “Right away, weight gain is seen in the first month. And it is a serious problem, because patients with schizophrenia, major depression, or bipolar disorder already have an increased risk of premature mortality, especially from cardiovascular diseases, and they have an increased risk of metabolic syndrome. And we sometimes give drugs that further increase that risk,” she said.

Being overweight is a major criterion for defining metabolic syndrome. Dr. Michat noted that, among the antipsychotic drugs that increase weight the most are clozapine, olanzapine, chlorpromazine, quetiapine, and risperidone, in addition to other psychoactive drugs, such as valproic acid, lithium, mirtazapine, and tricyclic antidepressants.

Several clinical trials, such as a pioneering Chinese study from 2008, have shown the potential of metformin to mitigate the weight gain induced by this type of drug.

However, Dr. Michat noted that so far the major guidelines (for example, the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments [CANMAT]/International Society for Bipolar Disorders [ISBD] for bipolar disorder and the American Psychiatric Association [APA] for schizophrenia) “say very little” on how to address this complication. They propose what she defined as a “problematic” order of action in which the initial emphasis is on promoting lifestyle changes, which are difficult for these patients to carry out, as well as general proposals for changing medication (which is not simple to implement when the patient’s condition is stabilized) and eventual consultation with a clinician to start therapy with metformin or other drugs, such as liraglutide, semaglutide, and topiramate.

The new clinical practice guideline, which was published in Evidence-Based Mental Health (of the BMJ journal group), was written by a multidisciplinary team of pharmacists, psychiatrists, and mental health nurses from Ireland. It aims to fill that gap. The investigators reviewed 1,270 scientific articles and analyzed 26 of them in depth, including seven randomized clinical trials and a 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis. The authors made a “strong” recommendation, for which there was moderate-quality evidence, that for patients for whom a lifestyle intervention is unacceptable or inappropriate the use of metformin is an “alternative first-line intervention” for antipsychotic drug–induced weight gain.

Likewise, as a strong recommendation with moderate-quality evidence, the guidance encourages the use of metformin when nonpharmacologic intervention does not seem to be effective.

The guideline also says it is preferable to start metformin early for patients who gain more than 7% of their baseline weight within the first month of antipsychotic treatment. It also endorses metformin when weight gain is established.

Other recommendations include evaluating baseline kidney function before starting metformin treatment and suggest a dose adjustment when the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. The guidance says the use of metformin is contraindicated for patients in whom eGFR is <30 mL/min per 1.73 m2. The proposed starting dosage is 500 mg twice per day with meals, with increments of 500 mg every 1-2 weeks until reaching a target dose of 2,000 mg/day. The guidance recommends that consideration always be given to individual tolerability and efficacy.

Treatment goals should be personalized and agreed upon with patients. In the case of early intervention, the guideline proposes initially stabilizing the weight gained or, if possible, reverse excess weight. When weight gain is established, the goal would be to lose at least 5% of the weight within the next 6 months.

The authors also recommend monitoring kidney function annually, as well as vitamin B12 levels and individual tolerability and compliance. Gastrointestinal adverse effects can be managed by dose reduction or slower dose titration. The risk of lactic acidosis, which affects 4.3 per 100,000 person-years among those taking metformin, can be attenuated by adjusting the dose according to kidney function or avoiding prescribing it to patients who have a history of alcohol abuse or who are receiving treatment that may interact with the drug.

Validating pharmacologic management

The lead author of the new guideline, Ita Fitzgerald, a teacher in clinical pharmacy and senior pharmacist at St. Patrick’s Mental Health Services in Dublin, pointed out that there is a bias toward not using drugs for weight management and shifting the responsibility onto the patients themselves, something that is very often out of their control.

“The purpose of the guideline was to decide on a range of criteria to maximize the use of metformin, to recognize that for many people, pharmacological management is a valid and important option that could and should be more widely used and to provide precise and practical guidance to physicians to facilitate a more widespread use,” Ms. Fitzgerald said in an interview.

According to Fitzgerald, who is pursuing her doctorate at University College Cork (Ireland), one of the most outstanding results of the work is that it highlights that the main benefit of metformin is to flatten rather than reverse antipsychotic-induced weight gain and that indicating it late can nullify that effect.

“In all the recommendations, we try very hard to shift the focus from metformin’s role as a weight reversal agent to one as a weight management agent that should be used early in treatment, which is when most weight gain occurs. If metformin succeeds in flattening that increase, that’s a huge potential benefit for an inexpensive and easily accessible drug. When people have already established weight gain, metformin may not be enough and alternative treatments should be used,” she said.

In addition to its effects on weight, metformin has many other potential health benefits. Of particular importance is that it reduces hyperphagia-mediated antipsychotic-induced weight gain, Ms. Fitzgerald pointed out.

“This is subjectively very important for patients and provides a more positive experience when taking antipsychotics. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain is one of the main reasons for premature discontinuation or incomplete adherence to these drugs and therefore needs to be addressed proactively,” she concluded.

Ms. Fitzgerald and Dr. Michat have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com. This article was translated from the Medscape Spanish edition.

MAR DEL PLATA, ARGENTINA – , according to a new evidence-based Irish guideline for the management of this common complication in adults with psychoses who are taking medications.

The document was discussed during one of the sessions of the XXXV Argentine Congress of Psychiatry of the Association of Argentine Psychiatrists. The document also was presented by one of its authors at the European Congress on Obesity 2022.

The guideline encourages psychiatrists not to underestimate the adverse metabolic effects of their treatments and encourages them to contemplate and carry out this prevention and management strategy, commented María Delia Michat, PhD, professor of clinical psychiatry and psychopharmacology at the APSA Postgraduate Training Institute, Buenos Aires.

“Although it is always good to work as a team, it is usually we psychiatrists who coordinate the pharmacological treatment of our patients, and we have to know how to manage drugs that can prevent cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Michat said in an interview.

“The new guideline is helpful because it protocolizes the use of metformin, which is the cheapest drug and has the most evidence for antipsychotic-induced weight gain,” she added.

Avoiding metabolic syndrome

In patients with schizophrenia, obesity rates are 40% higher than in the general population, and 80% of patients develop weight gain after their first treatment, noted Dr. Michat. “Right away, weight gain is seen in the first month. And it is a serious problem, because patients with schizophrenia, major depression, or bipolar disorder already have an increased risk of premature mortality, especially from cardiovascular diseases, and they have an increased risk of metabolic syndrome. And we sometimes give drugs that further increase that risk,” she said.

Being overweight is a major criterion for defining metabolic syndrome. Dr. Michat noted that, among the antipsychotic drugs that increase weight the most are clozapine, olanzapine, chlorpromazine, quetiapine, and risperidone, in addition to other psychoactive drugs, such as valproic acid, lithium, mirtazapine, and tricyclic antidepressants.

Several clinical trials, such as a pioneering Chinese study from 2008, have shown the potential of metformin to mitigate the weight gain induced by this type of drug.

However, Dr. Michat noted that so far the major guidelines (for example, the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments [CANMAT]/International Society for Bipolar Disorders [ISBD] for bipolar disorder and the American Psychiatric Association [APA] for schizophrenia) “say very little” on how to address this complication. They propose what she defined as a “problematic” order of action in which the initial emphasis is on promoting lifestyle changes, which are difficult for these patients to carry out, as well as general proposals for changing medication (which is not simple to implement when the patient’s condition is stabilized) and eventual consultation with a clinician to start therapy with metformin or other drugs, such as liraglutide, semaglutide, and topiramate.

The new clinical practice guideline, which was published in Evidence-Based Mental Health (of the BMJ journal group), was written by a multidisciplinary team of pharmacists, psychiatrists, and mental health nurses from Ireland. It aims to fill that gap. The investigators reviewed 1,270 scientific articles and analyzed 26 of them in depth, including seven randomized clinical trials and a 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis. The authors made a “strong” recommendation, for which there was moderate-quality evidence, that for patients for whom a lifestyle intervention is unacceptable or inappropriate the use of metformin is an “alternative first-line intervention” for antipsychotic drug–induced weight gain.

Likewise, as a strong recommendation with moderate-quality evidence, the guidance encourages the use of metformin when nonpharmacologic intervention does not seem to be effective.

The guideline also says it is preferable to start metformin early for patients who gain more than 7% of their baseline weight within the first month of antipsychotic treatment. It also endorses metformin when weight gain is established.

Other recommendations include evaluating baseline kidney function before starting metformin treatment and suggest a dose adjustment when the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. The guidance says the use of metformin is contraindicated for patients in whom eGFR is <30 mL/min per 1.73 m2. The proposed starting dosage is 500 mg twice per day with meals, with increments of 500 mg every 1-2 weeks until reaching a target dose of 2,000 mg/day. The guidance recommends that consideration always be given to individual tolerability and efficacy.

Treatment goals should be personalized and agreed upon with patients. In the case of early intervention, the guideline proposes initially stabilizing the weight gained or, if possible, reverse excess weight. When weight gain is established, the goal would be to lose at least 5% of the weight within the next 6 months.

The authors also recommend monitoring kidney function annually, as well as vitamin B12 levels and individual tolerability and compliance. Gastrointestinal adverse effects can be managed by dose reduction or slower dose titration. The risk of lactic acidosis, which affects 4.3 per 100,000 person-years among those taking metformin, can be attenuated by adjusting the dose according to kidney function or avoiding prescribing it to patients who have a history of alcohol abuse or who are receiving treatment that may interact with the drug.

Validating pharmacologic management

The lead author of the new guideline, Ita Fitzgerald, a teacher in clinical pharmacy and senior pharmacist at St. Patrick’s Mental Health Services in Dublin, pointed out that there is a bias toward not using drugs for weight management and shifting the responsibility onto the patients themselves, something that is very often out of their control.

“The purpose of the guideline was to decide on a range of criteria to maximize the use of metformin, to recognize that for many people, pharmacological management is a valid and important option that could and should be more widely used and to provide precise and practical guidance to physicians to facilitate a more widespread use,” Ms. Fitzgerald said in an interview.

According to Fitzgerald, who is pursuing her doctorate at University College Cork (Ireland), one of the most outstanding results of the work is that it highlights that the main benefit of metformin is to flatten rather than reverse antipsychotic-induced weight gain and that indicating it late can nullify that effect.

“In all the recommendations, we try very hard to shift the focus from metformin’s role as a weight reversal agent to one as a weight management agent that should be used early in treatment, which is when most weight gain occurs. If metformin succeeds in flattening that increase, that’s a huge potential benefit for an inexpensive and easily accessible drug. When people have already established weight gain, metformin may not be enough and alternative treatments should be used,” she said.

In addition to its effects on weight, metformin has many other potential health benefits. Of particular importance is that it reduces hyperphagia-mediated antipsychotic-induced weight gain, Ms. Fitzgerald pointed out.

“This is subjectively very important for patients and provides a more positive experience when taking antipsychotics. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain is one of the main reasons for premature discontinuation or incomplete adherence to these drugs and therefore needs to be addressed proactively,” she concluded.

Ms. Fitzgerald and Dr. Michat have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com. This article was translated from the Medscape Spanish edition.

MAR DEL PLATA, ARGENTINA – , according to a new evidence-based Irish guideline for the management of this common complication in adults with psychoses who are taking medications.

The document was discussed during one of the sessions of the XXXV Argentine Congress of Psychiatry of the Association of Argentine Psychiatrists. The document also was presented by one of its authors at the European Congress on Obesity 2022.

The guideline encourages psychiatrists not to underestimate the adverse metabolic effects of their treatments and encourages them to contemplate and carry out this prevention and management strategy, commented María Delia Michat, PhD, professor of clinical psychiatry and psychopharmacology at the APSA Postgraduate Training Institute, Buenos Aires.

“Although it is always good to work as a team, it is usually we psychiatrists who coordinate the pharmacological treatment of our patients, and we have to know how to manage drugs that can prevent cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Michat said in an interview.

“The new guideline is helpful because it protocolizes the use of metformin, which is the cheapest drug and has the most evidence for antipsychotic-induced weight gain,” she added.

Avoiding metabolic syndrome

In patients with schizophrenia, obesity rates are 40% higher than in the general population, and 80% of patients develop weight gain after their first treatment, noted Dr. Michat. “Right away, weight gain is seen in the first month. And it is a serious problem, because patients with schizophrenia, major depression, or bipolar disorder already have an increased risk of premature mortality, especially from cardiovascular diseases, and they have an increased risk of metabolic syndrome. And we sometimes give drugs that further increase that risk,” she said.

Being overweight is a major criterion for defining metabolic syndrome. Dr. Michat noted that, among the antipsychotic drugs that increase weight the most are clozapine, olanzapine, chlorpromazine, quetiapine, and risperidone, in addition to other psychoactive drugs, such as valproic acid, lithium, mirtazapine, and tricyclic antidepressants.

Several clinical trials, such as a pioneering Chinese study from 2008, have shown the potential of metformin to mitigate the weight gain induced by this type of drug.

However, Dr. Michat noted that so far the major guidelines (for example, the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments [CANMAT]/International Society for Bipolar Disorders [ISBD] for bipolar disorder and the American Psychiatric Association [APA] for schizophrenia) “say very little” on how to address this complication. They propose what she defined as a “problematic” order of action in which the initial emphasis is on promoting lifestyle changes, which are difficult for these patients to carry out, as well as general proposals for changing medication (which is not simple to implement when the patient’s condition is stabilized) and eventual consultation with a clinician to start therapy with metformin or other drugs, such as liraglutide, semaglutide, and topiramate.

The new clinical practice guideline, which was published in Evidence-Based Mental Health (of the BMJ journal group), was written by a multidisciplinary team of pharmacists, psychiatrists, and mental health nurses from Ireland. It aims to fill that gap. The investigators reviewed 1,270 scientific articles and analyzed 26 of them in depth, including seven randomized clinical trials and a 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis. The authors made a “strong” recommendation, for which there was moderate-quality evidence, that for patients for whom a lifestyle intervention is unacceptable or inappropriate the use of metformin is an “alternative first-line intervention” for antipsychotic drug–induced weight gain.

Likewise, as a strong recommendation with moderate-quality evidence, the guidance encourages the use of metformin when nonpharmacologic intervention does not seem to be effective.

The guideline also says it is preferable to start metformin early for patients who gain more than 7% of their baseline weight within the first month of antipsychotic treatment. It also endorses metformin when weight gain is established.

Other recommendations include evaluating baseline kidney function before starting metformin treatment and suggest a dose adjustment when the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. The guidance says the use of metformin is contraindicated for patients in whom eGFR is <30 mL/min per 1.73 m2. The proposed starting dosage is 500 mg twice per day with meals, with increments of 500 mg every 1-2 weeks until reaching a target dose of 2,000 mg/day. The guidance recommends that consideration always be given to individual tolerability and efficacy.

Treatment goals should be personalized and agreed upon with patients. In the case of early intervention, the guideline proposes initially stabilizing the weight gained or, if possible, reverse excess weight. When weight gain is established, the goal would be to lose at least 5% of the weight within the next 6 months.

The authors also recommend monitoring kidney function annually, as well as vitamin B12 levels and individual tolerability and compliance. Gastrointestinal adverse effects can be managed by dose reduction or slower dose titration. The risk of lactic acidosis, which affects 4.3 per 100,000 person-years among those taking metformin, can be attenuated by adjusting the dose according to kidney function or avoiding prescribing it to patients who have a history of alcohol abuse or who are receiving treatment that may interact with the drug.

Validating pharmacologic management

The lead author of the new guideline, Ita Fitzgerald, a teacher in clinical pharmacy and senior pharmacist at St. Patrick’s Mental Health Services in Dublin, pointed out that there is a bias toward not using drugs for weight management and shifting the responsibility onto the patients themselves, something that is very often out of their control.

“The purpose of the guideline was to decide on a range of criteria to maximize the use of metformin, to recognize that for many people, pharmacological management is a valid and important option that could and should be more widely used and to provide precise and practical guidance to physicians to facilitate a more widespread use,” Ms. Fitzgerald said in an interview.

According to Fitzgerald, who is pursuing her doctorate at University College Cork (Ireland), one of the most outstanding results of the work is that it highlights that the main benefit of metformin is to flatten rather than reverse antipsychotic-induced weight gain and that indicating it late can nullify that effect.

“In all the recommendations, we try very hard to shift the focus from metformin’s role as a weight reversal agent to one as a weight management agent that should be used early in treatment, which is when most weight gain occurs. If metformin succeeds in flattening that increase, that’s a huge potential benefit for an inexpensive and easily accessible drug. When people have already established weight gain, metformin may not be enough and alternative treatments should be used,” she said.

In addition to its effects on weight, metformin has many other potential health benefits. Of particular importance is that it reduces hyperphagia-mediated antipsychotic-induced weight gain, Ms. Fitzgerald pointed out.

“This is subjectively very important for patients and provides a more positive experience when taking antipsychotics. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain is one of the main reasons for premature discontinuation or incomplete adherence to these drugs and therefore needs to be addressed proactively,” she concluded.

Ms. Fitzgerald and Dr. Michat have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com. This article was translated from the Medscape Spanish edition.

Confronting endoscopic infection control

The reprocessing of endoscopes following gastrointestinal endoscopy is highly effective for mitigating the risk of exogenous infections, yet challenges in duodenoscope reprocessing continue to persist. While several enhanced reprocessing measures have been developed to reduce duodenoscope-related infection risks, the effectiveness of these enhanced measures is largely unclear.

Rahul A. Shimpi, MD, and Joshua P. Spaete, MD, from Duke University, Durham, N.C., wrote in a paper in Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy that novel disposable duodenoscope technologies offer promise for reducing infection risk and overcoming current reprocessing challenges. The paper notes that, despite this promise, there is a need to better define the usability, costs, and environmental impact of these disposable technologies.

Current challenges in endoscope reprocessing

According to the authors, the reprocessing of gastrointestinal endoscopes involves several sequential steps that require a “meticulous” attention to detail “to ensure the adequacy of reprocessing.” Human factors/errors are a major contributor to suboptimal reprocessing quality, and these errors are often related to varying adherence to current reprocessing protocols among centers and reprocessing staff members.

Despite these challenges, infectious complications associated with gastrointestinal endoscopy are rare, particularly in relation to end-viewing endoscopes. Many high-profile infectious outbreaks associated with duodenoscopes have been reported in recent years, however, which has heightened the awareness and corresponding concern with endoscope reprocessing. Many of these infectious outbreaks, the authors said, have involved multidrug-resistant organisms.

The complex elevator mechanism, which the authors noted “is relatively inaccessible during the precleaning and manual cleaning steps in reprocessing,” represents a paramount challenge in the reprocessing of duodenoscopes. The challenge related to this mechanism potentially contributes to greater biofilm formation and contamination. Other factors implicated in the transmission of duodenoscope-associated infections from patient to patient include other design issues, human errors in reprocessing, endoscope damage and channel defects, and storage and environmental factors.

“Given the reprocessing challenges posed by duodenoscopes, in 2015 the Food and Drug Administration issued a recommendation that one or more supplemental measures be implemented by facilities as a means to decrease the infectious risk posed by duodenoscopes,” the authors noted, including ethylene oxide (EtO) sterilization, liquid chemical sterilization, and repeat high-level disinfection (HLD). They added, however, that a recent U.S. multisociety reprocessing guideline “does not recommend repeat high-level disinfection over single high-level disinfection, and recommends use of EtO sterilization only for duodenoscopes in infectious outbreak settings.”

New sterilization technologies

Liquid chemical sterilization may be a promising alternative to EtO sterilization because it features a shorter disinfection cycle time and less endoscope wear or damage. However, clinical data for the effectiveness of LCS in endoscope reprocessing remains very limited.