User login

LISTEN NOW: UCSF's Christopher Moriates, MD, discusses waste-reduction efforts in hospitals

CHRISTOPHER MORIATES, MD, assistant clinical professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, talks about the change in focus and priorities needed for medicine to make progress in waste-reduction efforts.

CHRISTOPHER MORIATES, MD, assistant clinical professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, talks about the change in focus and priorities needed for medicine to make progress in waste-reduction efforts.

CHRISTOPHER MORIATES, MD, assistant clinical professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, talks about the change in focus and priorities needed for medicine to make progress in waste-reduction efforts.

LISTEN NOW: Vladimir Cadet, MPH, discusses alarm fatigue challenges and solutions

VLADIMIR N. CADET, MPH, associate with the Applied Solutions Group at ECRI Institute in Plymouth Meeting, Pa., discusses why it can be challenging for hospitals to reduce alarm fatigue and provides strategies to address this growing problem.

VLADIMIR N. CADET, MPH, associate with the Applied Solutions Group at ECRI Institute in Plymouth Meeting, Pa., discusses why it can be challenging for hospitals to reduce alarm fatigue and provides strategies to address this growing problem.

VLADIMIR N. CADET, MPH, associate with the Applied Solutions Group at ECRI Institute in Plymouth Meeting, Pa., discusses why it can be challenging for hospitals to reduce alarm fatigue and provides strategies to address this growing problem.

From a Near-Catastrophe, I-CARE

For Robert Fogerty, MD, MPH, it’s more than just a story. It’s a nightmare that he only narrowly avoided.

Now a hospitalist at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn., Dr. Fogerty was an economics major in his senior year of college when he was diagnosed with metastatic testicular cancer. Early in the course of his treatment, amid multiple rounds of chemotherapy and before a major surgery, his insurance company informed him that his benefits had been exhausted. Even with family resources, the remaining bills would have been crippling. Luckily, he went to college in Massachusetts, where a state law allowed him to enroll in an individual insurance plan by exempting him from the normal pre-existing condition exclusion. Two years later, he got his life back in order and enrolled in medical school.

“What stuck with me is, yes, I was sick, and yes, I lost all my hair, and yes, I went to my final exams bald with my nausea medicine and my steroids in my pocket and all of those things,” he says. “But after that was all gone, after my hair grew back, and I had my last chemo and my surgery, and I was really starting to get my life back on track, the financial implications of that disease were still there. The financial impact of my illness outlasted the pathological impact of my illness, and the financial burdens could easily have been just as life-altering as a permanent disability.”

Although he was “unbelievably lucky” to escape with manageable medical bills, Dr. Fogerty says, other patients haven’t been as fortunate. That lesson is why he identifies so much with his patients. It’s why he posted his own story to the Costs of Care website, which stresses the importance of cost awareness in healthcare. And it’s why he has committed himself to helping other medical students and residents “remove the blinders” to understand healthcare’s often devastating financial impact.

“When I was going through my residency, I learned a lot about low sodium, and I learned a lot about bloodstream infections and what to do when someone can’t breathe and how to do a skin exam, and all of these things,” Dr. Fogerty says. “But all of these other components that were so devastating to me as a patient weren’t really a main portion of the education that we’re providing tomorrow’s doctors. I thought that was an opportunity to really change things."

By combining his clinical and economics expertise, Dr. Fogerty helped to develop a program called the Interactive Cost-Awareness Resident Exercise, or I-CARE. Launched in 2011, I-CARE seeks to make the abstract problem of healthcare costs—including unnecessary ones—more accessible to trainees. The concept is deceptively simple: Residents compete to see who can reach the correct diagnosis for a given case using the fewest possible resources.

By talking through each case, both trainees and faculty can discuss concepts like waste prevention and financial stewardship in a safe environment. Giving young doctors that “basic set of vocabulary,” Dr. Fogerty says, may help them engage in real decisions later on about a group or health system’s financial pressures and obligations.

The program has since spread to other medical centers, and what began as a cost-awareness exercise has blossomed into a broader discussion about minimizing the cost and burden to patients while maximizing safety and good medicine. TH

For Robert Fogerty, MD, MPH, it’s more than just a story. It’s a nightmare that he only narrowly avoided.

Now a hospitalist at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn., Dr. Fogerty was an economics major in his senior year of college when he was diagnosed with metastatic testicular cancer. Early in the course of his treatment, amid multiple rounds of chemotherapy and before a major surgery, his insurance company informed him that his benefits had been exhausted. Even with family resources, the remaining bills would have been crippling. Luckily, he went to college in Massachusetts, where a state law allowed him to enroll in an individual insurance plan by exempting him from the normal pre-existing condition exclusion. Two years later, he got his life back in order and enrolled in medical school.

“What stuck with me is, yes, I was sick, and yes, I lost all my hair, and yes, I went to my final exams bald with my nausea medicine and my steroids in my pocket and all of those things,” he says. “But after that was all gone, after my hair grew back, and I had my last chemo and my surgery, and I was really starting to get my life back on track, the financial implications of that disease were still there. The financial impact of my illness outlasted the pathological impact of my illness, and the financial burdens could easily have been just as life-altering as a permanent disability.”

Although he was “unbelievably lucky” to escape with manageable medical bills, Dr. Fogerty says, other patients haven’t been as fortunate. That lesson is why he identifies so much with his patients. It’s why he posted his own story to the Costs of Care website, which stresses the importance of cost awareness in healthcare. And it’s why he has committed himself to helping other medical students and residents “remove the blinders” to understand healthcare’s often devastating financial impact.

“When I was going through my residency, I learned a lot about low sodium, and I learned a lot about bloodstream infections and what to do when someone can’t breathe and how to do a skin exam, and all of these things,” Dr. Fogerty says. “But all of these other components that were so devastating to me as a patient weren’t really a main portion of the education that we’re providing tomorrow’s doctors. I thought that was an opportunity to really change things."

By combining his clinical and economics expertise, Dr. Fogerty helped to develop a program called the Interactive Cost-Awareness Resident Exercise, or I-CARE. Launched in 2011, I-CARE seeks to make the abstract problem of healthcare costs—including unnecessary ones—more accessible to trainees. The concept is deceptively simple: Residents compete to see who can reach the correct diagnosis for a given case using the fewest possible resources.

By talking through each case, both trainees and faculty can discuss concepts like waste prevention and financial stewardship in a safe environment. Giving young doctors that “basic set of vocabulary,” Dr. Fogerty says, may help them engage in real decisions later on about a group or health system’s financial pressures and obligations.

The program has since spread to other medical centers, and what began as a cost-awareness exercise has blossomed into a broader discussion about minimizing the cost and burden to patients while maximizing safety and good medicine. TH

For Robert Fogerty, MD, MPH, it’s more than just a story. It’s a nightmare that he only narrowly avoided.

Now a hospitalist at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn., Dr. Fogerty was an economics major in his senior year of college when he was diagnosed with metastatic testicular cancer. Early in the course of his treatment, amid multiple rounds of chemotherapy and before a major surgery, his insurance company informed him that his benefits had been exhausted. Even with family resources, the remaining bills would have been crippling. Luckily, he went to college in Massachusetts, where a state law allowed him to enroll in an individual insurance plan by exempting him from the normal pre-existing condition exclusion. Two years later, he got his life back in order and enrolled in medical school.

“What stuck with me is, yes, I was sick, and yes, I lost all my hair, and yes, I went to my final exams bald with my nausea medicine and my steroids in my pocket and all of those things,” he says. “But after that was all gone, after my hair grew back, and I had my last chemo and my surgery, and I was really starting to get my life back on track, the financial implications of that disease were still there. The financial impact of my illness outlasted the pathological impact of my illness, and the financial burdens could easily have been just as life-altering as a permanent disability.”

Although he was “unbelievably lucky” to escape with manageable medical bills, Dr. Fogerty says, other patients haven’t been as fortunate. That lesson is why he identifies so much with his patients. It’s why he posted his own story to the Costs of Care website, which stresses the importance of cost awareness in healthcare. And it’s why he has committed himself to helping other medical students and residents “remove the blinders” to understand healthcare’s often devastating financial impact.

“When I was going through my residency, I learned a lot about low sodium, and I learned a lot about bloodstream infections and what to do when someone can’t breathe and how to do a skin exam, and all of these things,” Dr. Fogerty says. “But all of these other components that were so devastating to me as a patient weren’t really a main portion of the education that we’re providing tomorrow’s doctors. I thought that was an opportunity to really change things."

By combining his clinical and economics expertise, Dr. Fogerty helped to develop a program called the Interactive Cost-Awareness Resident Exercise, or I-CARE. Launched in 2011, I-CARE seeks to make the abstract problem of healthcare costs—including unnecessary ones—more accessible to trainees. The concept is deceptively simple: Residents compete to see who can reach the correct diagnosis for a given case using the fewest possible resources.

By talking through each case, both trainees and faculty can discuss concepts like waste prevention and financial stewardship in a safe environment. Giving young doctors that “basic set of vocabulary,” Dr. Fogerty says, may help them engage in real decisions later on about a group or health system’s financial pressures and obligations.

The program has since spread to other medical centers, and what began as a cost-awareness exercise has blossomed into a broader discussion about minimizing the cost and burden to patients while maximizing safety and good medicine. TH

Listen Now: Hospital Medicine Goes Global

As the hospital medicine specialty matures in the U.S., HM is establishing itself globally. Two American hospitalists who have moved to Doha, Qatar to build a hospital medicine program at Hamid General Hospital talk about their experiences, how they decided to practice overseas, and what they see as an opportunity for HM globally.

As the hospital medicine specialty matures in the U.S., HM is establishing itself globally. Two American hospitalists who have moved to Doha, Qatar to build a hospital medicine program at Hamid General Hospital talk about their experiences, how they decided to practice overseas, and what they see as an opportunity for HM globally.

As the hospital medicine specialty matures in the U.S., HM is establishing itself globally. Two American hospitalists who have moved to Doha, Qatar to build a hospital medicine program at Hamid General Hospital talk about their experiences, how they decided to practice overseas, and what they see as an opportunity for HM globally.

Hand eczema linked to anxiety, not depression

Adults with chronic hand eczema showed significantly higher levels of anxiety but no difference in depression, compared with healthy controls, based on data from a review of 71 patients. The patients were assessed for anxiety and depression with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and also for compulsive behavior with the Leyton Trait Scale.

Overall quality of life was evaluated according to the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), and the average score in the patient population was 11.11.

Patients with hand dermatitis had significantly higher scores on the HADS-Anxiety subscale compared to healthy controls, but there was no significant difference in HADS-Depression subscale scores between the groups, noted lead author Dr. Anargyros Kouris of Andreas Sygros Hospital, Athens, and colleagues.

“Hand eczema treatment should address the severity of skin lesions as well as the psychological impact of hand eczema,” the researchers concluded (Contact Dermatitis 2015 June [doi: 10.1111/cod.12366]).

Find the full article online here.

Adults with chronic hand eczema showed significantly higher levels of anxiety but no difference in depression, compared with healthy controls, based on data from a review of 71 patients. The patients were assessed for anxiety and depression with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and also for compulsive behavior with the Leyton Trait Scale.

Overall quality of life was evaluated according to the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), and the average score in the patient population was 11.11.

Patients with hand dermatitis had significantly higher scores on the HADS-Anxiety subscale compared to healthy controls, but there was no significant difference in HADS-Depression subscale scores between the groups, noted lead author Dr. Anargyros Kouris of Andreas Sygros Hospital, Athens, and colleagues.

“Hand eczema treatment should address the severity of skin lesions as well as the psychological impact of hand eczema,” the researchers concluded (Contact Dermatitis 2015 June [doi: 10.1111/cod.12366]).

Find the full article online here.

Adults with chronic hand eczema showed significantly higher levels of anxiety but no difference in depression, compared with healthy controls, based on data from a review of 71 patients. The patients were assessed for anxiety and depression with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and also for compulsive behavior with the Leyton Trait Scale.

Overall quality of life was evaluated according to the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), and the average score in the patient population was 11.11.

Patients with hand dermatitis had significantly higher scores on the HADS-Anxiety subscale compared to healthy controls, but there was no significant difference in HADS-Depression subscale scores between the groups, noted lead author Dr. Anargyros Kouris of Andreas Sygros Hospital, Athens, and colleagues.

“Hand eczema treatment should address the severity of skin lesions as well as the psychological impact of hand eczema,” the researchers concluded (Contact Dermatitis 2015 June [doi: 10.1111/cod.12366]).

Find the full article online here.

FROM CONTACT DERMATITIS

Fragile Drug Development Process

We are currently in the midst of a new wave of drug developments and approvals for psoriasis; however, we recently have been reminded of the tenuous nature of bringing a new drug to market. Last month, Amgen Inc announced it was pulling out of the long-running collaboration on the high-profile IL-17 program after evaluating the likely commercial impact it would face in light of the suicidal thoughts some patients reported during the studies.

Brodalumab had successfully completed 3 phase 3 studies in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis known as the AMAGINE program. Top-line results from AMAGINE-1 comparing brodalumab with placebo were released in May 2014. Top-line results from AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 comparing brodalumab with ustekinumab and placebo were announced in November 2014. AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 are identical in design. “During our preparation process for regulatory submissions, we came to believe that labeling requirements likely would limit the appropriate patient population for brodalumab,” said Amgen Executive Vice President of Research and Development Sean Harper in a statement. AstraZeneca must now decide whether to pursue brodalumab independently.

Once the exact data are publicly released, we will be able to better evaluate the issues of suicidal ideation involved.

What’s the issue?

Brodalumab was eagerly anticipated in the dermatology community. In an instant, the drug’s future is in doubt, which once again demonstrates the fragility of the drug development process. How will this recent announcement affect your use of new biologics?

We are currently in the midst of a new wave of drug developments and approvals for psoriasis; however, we recently have been reminded of the tenuous nature of bringing a new drug to market. Last month, Amgen Inc announced it was pulling out of the long-running collaboration on the high-profile IL-17 program after evaluating the likely commercial impact it would face in light of the suicidal thoughts some patients reported during the studies.

Brodalumab had successfully completed 3 phase 3 studies in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis known as the AMAGINE program. Top-line results from AMAGINE-1 comparing brodalumab with placebo were released in May 2014. Top-line results from AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 comparing brodalumab with ustekinumab and placebo were announced in November 2014. AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 are identical in design. “During our preparation process for regulatory submissions, we came to believe that labeling requirements likely would limit the appropriate patient population for brodalumab,” said Amgen Executive Vice President of Research and Development Sean Harper in a statement. AstraZeneca must now decide whether to pursue brodalumab independently.

Once the exact data are publicly released, we will be able to better evaluate the issues of suicidal ideation involved.

What’s the issue?

Brodalumab was eagerly anticipated in the dermatology community. In an instant, the drug’s future is in doubt, which once again demonstrates the fragility of the drug development process. How will this recent announcement affect your use of new biologics?

We are currently in the midst of a new wave of drug developments and approvals for psoriasis; however, we recently have been reminded of the tenuous nature of bringing a new drug to market. Last month, Amgen Inc announced it was pulling out of the long-running collaboration on the high-profile IL-17 program after evaluating the likely commercial impact it would face in light of the suicidal thoughts some patients reported during the studies.

Brodalumab had successfully completed 3 phase 3 studies in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis known as the AMAGINE program. Top-line results from AMAGINE-1 comparing brodalumab with placebo were released in May 2014. Top-line results from AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 comparing brodalumab with ustekinumab and placebo were announced in November 2014. AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 are identical in design. “During our preparation process for regulatory submissions, we came to believe that labeling requirements likely would limit the appropriate patient population for brodalumab,” said Amgen Executive Vice President of Research and Development Sean Harper in a statement. AstraZeneca must now decide whether to pursue brodalumab independently.

Once the exact data are publicly released, we will be able to better evaluate the issues of suicidal ideation involved.

What’s the issue?

Brodalumab was eagerly anticipated in the dermatology community. In an instant, the drug’s future is in doubt, which once again demonstrates the fragility of the drug development process. How will this recent announcement affect your use of new biologics?

Extramammary Paget Disease

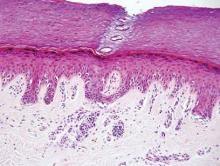

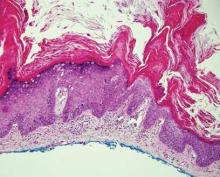

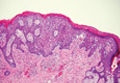

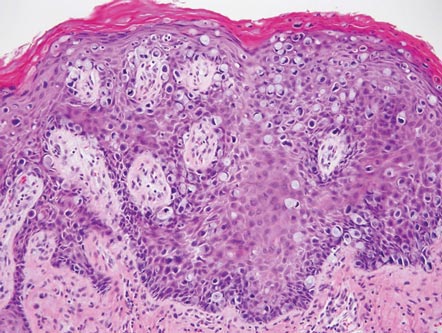

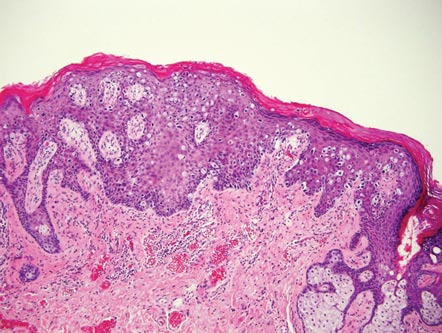

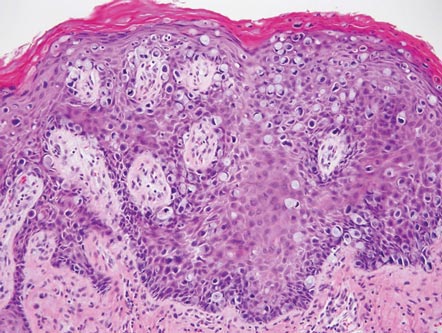

Extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is an uncommon condition that usually presents in apocrine sweat gland–rich areas, most commonly the vulva followed by the perianal region. Lesions clinically present as erythematous, well-demarcated plaques that may become ulcerated, erosive, scaly, or eczematous. Extramammary Paget disease has a female predominance and usually occurs in the sixth to eighth decades of life.1 Histologically, EMPD displays intraepidermal spread of large cells with plentiful amphophilic cytoplasm and large nuclei (Figure 1). These atypical cells may be seen “spit out” whole into the stratum corneum rather than keratinizing into parakeratotic cells (Figure 2). Frequently, the cytoplasm of these tumor cells is positive on mucicarmine staining, which indicates the presence of mucin, giving the cytoplasm a bluish gray color on hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections. Typically, EMPD cells can be found alone or in nests throughout the epithelium. The basal layer of the epithelium will appear crushed but not infiltrated by these atypical cells in some areas.2 Extramammary Paget disease is epithelial membrane antigen and cytokeratin 7 positive, unlike other conditions in the differential diagnosis such as benign acral nevus, Bowen disease, mycosis fungoides, and superficial spreading melanoma in situ, with the rare exception of cytokeratin 7 positivity in Bowen disease.3

|

|

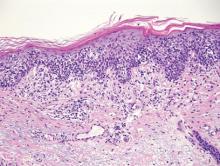

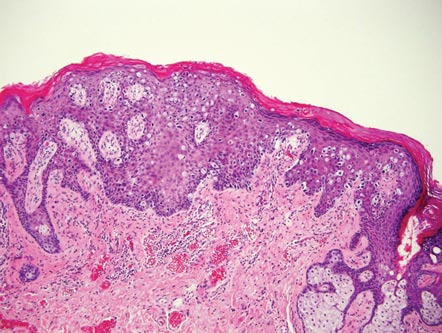

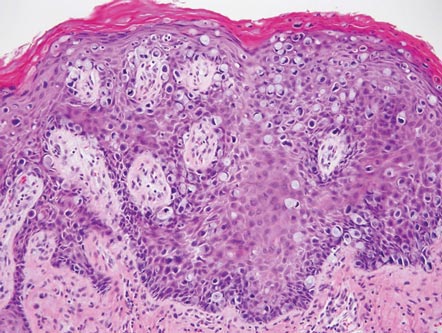

Benign acral nevi, similar to melanoma in situ, can have melanocytes scattered above the basal layer, but they usually appear in the lower half of the epidermis without cytologic atypia.4 When present, these pagetoid cells are most often limited to the center of a well-delineated lesion. The compact thick stratum corneum characteristic of acral skin also is helpful in distinguishing a benign acral nevus from EMPD, which does not involve acral sites (Figure 3).2

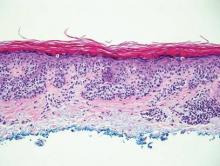

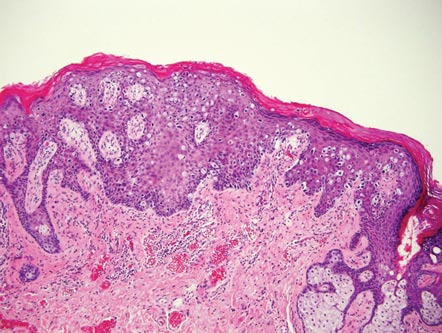

Bowen disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ) may have pagetoid spread (or buckshot scatter) through the epidermis similar to EMPD and melanoma in situ. However, in Bowen disease the malignant cells are keratinocytes that keratinize and become incorporated into the stratum corneum as parakeratotic nuclei rather than intact “spit out” cells, as seen in melanoma in situ and EMPD. Usually the pagetoid spread is only focal in Bowen disease with other areas of more characteristic full-thickness keratinocyte atypia (Figure 4).2

Mycosis fungoides displays atypical lymphocytes with large dark nuclei and minimal to no cytoplasm scattered throughout the epidermis. The atypical cells have irregular nuclear contours and often a clear perinuclear space (Figure 5). These cells tend to line up along the dermoepidermal junction and form intraepidermal clusters known as Pautrier microabscesses. Papillary dermal fibroplasia also is usually present in mycosis fungoides.2

Similar to EMPD, superficial spreading melanoma in situ shows single or nested atypical cells scattered throughout all levels of the epithelium and may be “spit out” whole into the stratum corneum rather than keratinizing into parakeratotic cells. However, in melanoma, nests of atypical melanocytes predominate and involve the basal layer (Figure 6), whereas clusters of cells in EMPD typically are located superficial to the basal layer. The cells of melanoma also lack the amphophilic mucinous cytoplasm of EMPD.1

1. Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. London, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2011.

2. Ferringer T, Elston D, eds. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. London, England: Elsevier; 2014.

3. Sah SP, Kelly PJ, McManus DT, et al. Diffuse CK7, CAM5.2 and BerEP4 positivity in pagetoid squamous cell carcinoma in situ (pagetoid Bowen’s disease) of the perianal region: a mimic of extramammary Paget’s disease. Histopathology. 2013;62:511-514.

4. LeBoit PE. A diagnosis for maniacs. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:556-558.

Extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is an uncommon condition that usually presents in apocrine sweat gland–rich areas, most commonly the vulva followed by the perianal region. Lesions clinically present as erythematous, well-demarcated plaques that may become ulcerated, erosive, scaly, or eczematous. Extramammary Paget disease has a female predominance and usually occurs in the sixth to eighth decades of life.1 Histologically, EMPD displays intraepidermal spread of large cells with plentiful amphophilic cytoplasm and large nuclei (Figure 1). These atypical cells may be seen “spit out” whole into the stratum corneum rather than keratinizing into parakeratotic cells (Figure 2). Frequently, the cytoplasm of these tumor cells is positive on mucicarmine staining, which indicates the presence of mucin, giving the cytoplasm a bluish gray color on hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections. Typically, EMPD cells can be found alone or in nests throughout the epithelium. The basal layer of the epithelium will appear crushed but not infiltrated by these atypical cells in some areas.2 Extramammary Paget disease is epithelial membrane antigen and cytokeratin 7 positive, unlike other conditions in the differential diagnosis such as benign acral nevus, Bowen disease, mycosis fungoides, and superficial spreading melanoma in situ, with the rare exception of cytokeratin 7 positivity in Bowen disease.3

|

|

Benign acral nevi, similar to melanoma in situ, can have melanocytes scattered above the basal layer, but they usually appear in the lower half of the epidermis without cytologic atypia.4 When present, these pagetoid cells are most often limited to the center of a well-delineated lesion. The compact thick stratum corneum characteristic of acral skin also is helpful in distinguishing a benign acral nevus from EMPD, which does not involve acral sites (Figure 3).2

Bowen disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ) may have pagetoid spread (or buckshot scatter) through the epidermis similar to EMPD and melanoma in situ. However, in Bowen disease the malignant cells are keratinocytes that keratinize and become incorporated into the stratum corneum as parakeratotic nuclei rather than intact “spit out” cells, as seen in melanoma in situ and EMPD. Usually the pagetoid spread is only focal in Bowen disease with other areas of more characteristic full-thickness keratinocyte atypia (Figure 4).2

Mycosis fungoides displays atypical lymphocytes with large dark nuclei and minimal to no cytoplasm scattered throughout the epidermis. The atypical cells have irregular nuclear contours and often a clear perinuclear space (Figure 5). These cells tend to line up along the dermoepidermal junction and form intraepidermal clusters known as Pautrier microabscesses. Papillary dermal fibroplasia also is usually present in mycosis fungoides.2

Similar to EMPD, superficial spreading melanoma in situ shows single or nested atypical cells scattered throughout all levels of the epithelium and may be “spit out” whole into the stratum corneum rather than keratinizing into parakeratotic cells. However, in melanoma, nests of atypical melanocytes predominate and involve the basal layer (Figure 6), whereas clusters of cells in EMPD typically are located superficial to the basal layer. The cells of melanoma also lack the amphophilic mucinous cytoplasm of EMPD.1

Extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is an uncommon condition that usually presents in apocrine sweat gland–rich areas, most commonly the vulva followed by the perianal region. Lesions clinically present as erythematous, well-demarcated plaques that may become ulcerated, erosive, scaly, or eczematous. Extramammary Paget disease has a female predominance and usually occurs in the sixth to eighth decades of life.1 Histologically, EMPD displays intraepidermal spread of large cells with plentiful amphophilic cytoplasm and large nuclei (Figure 1). These atypical cells may be seen “spit out” whole into the stratum corneum rather than keratinizing into parakeratotic cells (Figure 2). Frequently, the cytoplasm of these tumor cells is positive on mucicarmine staining, which indicates the presence of mucin, giving the cytoplasm a bluish gray color on hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections. Typically, EMPD cells can be found alone or in nests throughout the epithelium. The basal layer of the epithelium will appear crushed but not infiltrated by these atypical cells in some areas.2 Extramammary Paget disease is epithelial membrane antigen and cytokeratin 7 positive, unlike other conditions in the differential diagnosis such as benign acral nevus, Bowen disease, mycosis fungoides, and superficial spreading melanoma in situ, with the rare exception of cytokeratin 7 positivity in Bowen disease.3

|

|

Benign acral nevi, similar to melanoma in situ, can have melanocytes scattered above the basal layer, but they usually appear in the lower half of the epidermis without cytologic atypia.4 When present, these pagetoid cells are most often limited to the center of a well-delineated lesion. The compact thick stratum corneum characteristic of acral skin also is helpful in distinguishing a benign acral nevus from EMPD, which does not involve acral sites (Figure 3).2

Bowen disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ) may have pagetoid spread (or buckshot scatter) through the epidermis similar to EMPD and melanoma in situ. However, in Bowen disease the malignant cells are keratinocytes that keratinize and become incorporated into the stratum corneum as parakeratotic nuclei rather than intact “spit out” cells, as seen in melanoma in situ and EMPD. Usually the pagetoid spread is only focal in Bowen disease with other areas of more characteristic full-thickness keratinocyte atypia (Figure 4).2

Mycosis fungoides displays atypical lymphocytes with large dark nuclei and minimal to no cytoplasm scattered throughout the epidermis. The atypical cells have irregular nuclear contours and often a clear perinuclear space (Figure 5). These cells tend to line up along the dermoepidermal junction and form intraepidermal clusters known as Pautrier microabscesses. Papillary dermal fibroplasia also is usually present in mycosis fungoides.2

Similar to EMPD, superficial spreading melanoma in situ shows single or nested atypical cells scattered throughout all levels of the epithelium and may be “spit out” whole into the stratum corneum rather than keratinizing into parakeratotic cells. However, in melanoma, nests of atypical melanocytes predominate and involve the basal layer (Figure 6), whereas clusters of cells in EMPD typically are located superficial to the basal layer. The cells of melanoma also lack the amphophilic mucinous cytoplasm of EMPD.1

1. Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. London, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2011.

2. Ferringer T, Elston D, eds. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. London, England: Elsevier; 2014.

3. Sah SP, Kelly PJ, McManus DT, et al. Diffuse CK7, CAM5.2 and BerEP4 positivity in pagetoid squamous cell carcinoma in situ (pagetoid Bowen’s disease) of the perianal region: a mimic of extramammary Paget’s disease. Histopathology. 2013;62:511-514.

4. LeBoit PE. A diagnosis for maniacs. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:556-558.

1. Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. London, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2011.

2. Ferringer T, Elston D, eds. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. London, England: Elsevier; 2014.

3. Sah SP, Kelly PJ, McManus DT, et al. Diffuse CK7, CAM5.2 and BerEP4 positivity in pagetoid squamous cell carcinoma in situ (pagetoid Bowen’s disease) of the perianal region: a mimic of extramammary Paget’s disease. Histopathology. 2013;62:511-514.

4. LeBoit PE. A diagnosis for maniacs. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:556-558.

Doing much with less

Nepal – a peaceful, small country lying amidst the Himalayas – was struck by an enormous 7.8-magnitude earthquake on April 25, 2015. Over 8,000 people lost their lives; tens of thousands were injured. The earthquake launched an avalanche on Mt. Everest, killing at least 19, with many more reported missing. The villages were wiped away. The capital, Kathmandu, famous for its brick-and-timber attached houses, was in rubble.

I was born and raised in Nepal, and I earned my medical degree there before I moved to the United States for further studies. I was in Nepal weeks before the earthquake, and it was heart wrenching to later see all those familiar places turned into debris. The first few hours of this news were terrifying, as I struggled to track down my family members from afar. When I learned everyone was safe, I didn’t know if I should be thankful or feel unfortunate that I wasn’t there with them. Within hours, Nepal was all over the news, and the world responded. The next few days were worse, with continuous aftershocks. My family members, along with the rest of Nepal, spent days and nights in open tents, cold and soaked in heavy rains.

Weeks before the earthquake I was there – visiting hospitals, teaching medical students, and analyzing the health care scenario. In Nepal, the family treatment budget is limited, and the physician decides which test/procedure will provide maximum information for management. Health care facilities, sanitation, and hygiene are very poor and are beyond the means of most Nepalese people. Mortality for those under 5 years of age is 51 per 1,000, and the chances of dying while giving birth are 1 in 80.

I revisited “clinical decision making” as obtaining labs and imaging was out of reach, and I realized how many unnecessary medical tests and procedures are done in the United States. I learned how to make a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine with a bottle of water, a piece of tubing, oxygen, and medical tape. In my 14-day trip, I witnessed purulent fluid being drained from spinal taps, constant seizures that refused to go away in spite of antiseizure medications, and children left to die as the family could not afford to pay for medical treatment.

In the days after the earthquake, I kept in constant touch with my family and friends from the medical community. Nepalese doctors worked endlessly, operating in paddy fields under the open sky with minimal medical supplies. People dug with bare hands to get trapped neighbors out. Time has elapsed since then, but life will not be the same again for these people. The strength and perseverance that the medical community showed was commendable. They showed the world, with so little, so much can be done. If only we here in the United States could embrace this.

Dr. Rajbhandari is a fellow in hospital medicine at Cleveland Clinic Children’s Hospital. Email her at [email protected].

Nepal – a peaceful, small country lying amidst the Himalayas – was struck by an enormous 7.8-magnitude earthquake on April 25, 2015. Over 8,000 people lost their lives; tens of thousands were injured. The earthquake launched an avalanche on Mt. Everest, killing at least 19, with many more reported missing. The villages were wiped away. The capital, Kathmandu, famous for its brick-and-timber attached houses, was in rubble.

I was born and raised in Nepal, and I earned my medical degree there before I moved to the United States for further studies. I was in Nepal weeks before the earthquake, and it was heart wrenching to later see all those familiar places turned into debris. The first few hours of this news were terrifying, as I struggled to track down my family members from afar. When I learned everyone was safe, I didn’t know if I should be thankful or feel unfortunate that I wasn’t there with them. Within hours, Nepal was all over the news, and the world responded. The next few days were worse, with continuous aftershocks. My family members, along with the rest of Nepal, spent days and nights in open tents, cold and soaked in heavy rains.

Weeks before the earthquake I was there – visiting hospitals, teaching medical students, and analyzing the health care scenario. In Nepal, the family treatment budget is limited, and the physician decides which test/procedure will provide maximum information for management. Health care facilities, sanitation, and hygiene are very poor and are beyond the means of most Nepalese people. Mortality for those under 5 years of age is 51 per 1,000, and the chances of dying while giving birth are 1 in 80.

I revisited “clinical decision making” as obtaining labs and imaging was out of reach, and I realized how many unnecessary medical tests and procedures are done in the United States. I learned how to make a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine with a bottle of water, a piece of tubing, oxygen, and medical tape. In my 14-day trip, I witnessed purulent fluid being drained from spinal taps, constant seizures that refused to go away in spite of antiseizure medications, and children left to die as the family could not afford to pay for medical treatment.

In the days after the earthquake, I kept in constant touch with my family and friends from the medical community. Nepalese doctors worked endlessly, operating in paddy fields under the open sky with minimal medical supplies. People dug with bare hands to get trapped neighbors out. Time has elapsed since then, but life will not be the same again for these people. The strength and perseverance that the medical community showed was commendable. They showed the world, with so little, so much can be done. If only we here in the United States could embrace this.

Dr. Rajbhandari is a fellow in hospital medicine at Cleveland Clinic Children’s Hospital. Email her at [email protected].

Nepal – a peaceful, small country lying amidst the Himalayas – was struck by an enormous 7.8-magnitude earthquake on April 25, 2015. Over 8,000 people lost their lives; tens of thousands were injured. The earthquake launched an avalanche on Mt. Everest, killing at least 19, with many more reported missing. The villages were wiped away. The capital, Kathmandu, famous for its brick-and-timber attached houses, was in rubble.

I was born and raised in Nepal, and I earned my medical degree there before I moved to the United States for further studies. I was in Nepal weeks before the earthquake, and it was heart wrenching to later see all those familiar places turned into debris. The first few hours of this news were terrifying, as I struggled to track down my family members from afar. When I learned everyone was safe, I didn’t know if I should be thankful or feel unfortunate that I wasn’t there with them. Within hours, Nepal was all over the news, and the world responded. The next few days were worse, with continuous aftershocks. My family members, along with the rest of Nepal, spent days and nights in open tents, cold and soaked in heavy rains.

Weeks before the earthquake I was there – visiting hospitals, teaching medical students, and analyzing the health care scenario. In Nepal, the family treatment budget is limited, and the physician decides which test/procedure will provide maximum information for management. Health care facilities, sanitation, and hygiene are very poor and are beyond the means of most Nepalese people. Mortality for those under 5 years of age is 51 per 1,000, and the chances of dying while giving birth are 1 in 80.

I revisited “clinical decision making” as obtaining labs and imaging was out of reach, and I realized how many unnecessary medical tests and procedures are done in the United States. I learned how to make a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine with a bottle of water, a piece of tubing, oxygen, and medical tape. In my 14-day trip, I witnessed purulent fluid being drained from spinal taps, constant seizures that refused to go away in spite of antiseizure medications, and children left to die as the family could not afford to pay for medical treatment.

In the days after the earthquake, I kept in constant touch with my family and friends from the medical community. Nepalese doctors worked endlessly, operating in paddy fields under the open sky with minimal medical supplies. People dug with bare hands to get trapped neighbors out. Time has elapsed since then, but life will not be the same again for these people. The strength and perseverance that the medical community showed was commendable. They showed the world, with so little, so much can be done. If only we here in the United States could embrace this.

Dr. Rajbhandari is a fellow in hospital medicine at Cleveland Clinic Children’s Hospital. Email her at [email protected].

Outcomes and Medication Use in a Longitudinal Cohort of Type 2 Diabetes Patients, 2006 to 2012

From the Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC.

Abstract

- Objective: To assess outcomes and pharmacotherapy in a cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes in a university-based family medicine teaching practice.

- Methods: We used ICD-9-CM codes to identify a cohort of patients with diabetes seen in 2006 and 2012. A total of 891 patients were identified who made follow-up visits in both years. We collected data on patient characteristics, pharmacotherapy, and outcomes for glycemia, blood pressure (BP), and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. We determined type and number of medications taken to achieve target outcomes.

- Results: A1C remained constant between 2006 and 2012 (7.6% to 7.7%) along with BMI (34.7 kg/m2 to 34.1 kg/m2), while mean LDL cholesterol significantly decreased from 109 mg/dL in 2006 to 98.8 mg/dL in 2012. The number of patients achieving a goal LDL < 100 mg/dL increased from 43.5 % in 2006 to 58.6% in 2012. The largest group with controlled A1C (< 7 %) were taking metformin with a sulfonylurea, DPP-4 inhibitor, glitazone or an injectable GLP-agonist. The majority achieved an LDL goal of < 100 mg/dl. The majority of hypertensive regimens included use of an ACE inhibitor or ARB with overall BP control achieved in at least 45% of patients.

- Conclusion: Multiple medications are necessary to achieve control among patients with type 2 diabetes over time and this cannot be attributed to an increase in BMI. Overall control for A1C and BP can be sustained and significantly decreased for LDL cholesterol using multiple medications, with the primary agent for LDL reduction being a statin.

Diabetes is an illness that affects an estimated 25.8 million Americans and is quickly becoming a worldwide epidemic [1,2]. Diabetes is a significant cause of both microvascular and macrovascular sequelae, but its frequent association with the comorbid conditions of hypertension and dyslipidemia further increases the risk of heart disease, stroke, peripheral vascular complications, and renal impairment [3–5]. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) publishes consensus guidelines annually to guide management for patients with diabetes. From 2006 to 2012, the accepted standard of medical care included achieving a hemoglobin A1C (A1C) measurement of < 7%, a low-density lipoprotein (LDL) level of < 100 mg/dL, and a blood pressure (BP) of < 130/80 mm Hg [6,7]. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) recently reported that the goal of simultaneous control of A1C, LDL and BP is met in only about 19% of diabetes patients [8]. Target glycemic control is relaxed to an A1C < 8% in some patients with multiple comorbidities, limited life span, or risk for hypoglycemia; and in 2013 the BP goal was modified to < 140/80 based on clinical trial evidence [9].

In combination with lifestyle modification, pharmacotherapy is a critical component of chronic disease management. Initial pharmacotherapy treatment recommendations include metformin for diabetes, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) for hypertension, and a statin for dyslipidemia [6,7,9]. In patients who already have a diagnosis of diabetes, achieving control becomes more difficult to accomplish with lifestyle alone, and the benefit of lifestyle intervention on all-cause mortality as well as cardiovascular and microvascular events remains a debated issue [10]. The need for pharmacologic agents in most patients with diabetes is inevitable. Metformin is the agent of choice for initial treatment with drug therapy, with the option of adding a variety of other oral or injectable medications based on clinician decision-making [7]. In this study, we reviewed data from a longitudinal cohort of type 2 diabetes patients and compared medication use and outcomes at 2 different time-points (2006 and 2012) to see how medical management and outcome measures changed over time.

Methods

Setting

Data were obtained from an academic family medicine clinic in the southeastern United States. Approximately 56,000 patient visits to this clinic are conducted annually. Family medicine residents in training, fellows, faculty physicians, physician assistants, a nutritionist, and diabetes educators care for patients seen in this practice.

Data Collection

A cohort of patients was identified using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification codes for type 2 diabetes. The cohort comprised patients with diabetes in 2006 and 2012 who made follow-up visits in both years.

The data from both time-points were obtained from electronic medical record (EMR) data capture and structured chart review. Two reviewers reviewed 10% of the charts for accuracy after the data was pre-populated from the EMR. The following data were obtained: demographic variables (patient age, gender, and race), height, weight, insurance, smoking status, A1C, LDL, and BP measurements, pharmacotherapy for glycemia, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, and number of medications needed for control. For variables that had multiple measures, we calculated an average for the year.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed to compute means, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentages for demographic variables and for glycemia, BP, LDL includ-ing patient characteristics, diabetes outcomes, and pharmacotherapy medication variables. Paired t tests were used to assess for a difference at the level of the patient in the means of the A1C, BP, and LDL between the 2 study time-points (2-sided alpha = 0.05). The non-parametric McNemar test was used to assess for differences in the proportions of patients at the identified goal for A1C, LDL, and BP for 2006 and 2012.

Results

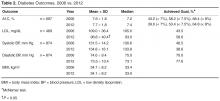

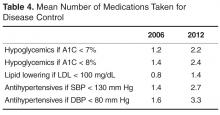

The number of visits per patient was 5.9 in 2006 and 5.3 in 2012. A1C remained constant between 2006 and 2012 (mean 7.6% vs. 7.7%, ± 1.8) along with body mass index (BMI), while mean LDL cholesterol significantly decreased from 109 ± 36.4 mg/dL in 2006 to 98.8 ± 40.4 mg/dL in 2012 (Table 2). Mean systolic BP marginally increased over the 6-year period from 131.5 ± 14.2 to 134.8 ± 16.1 mm Hg with diastolic BP remaining constant.

The percentage of patients achieving the less stringent A1C goal of < 8% comprised over 50% of the population at both time points; however, compared with 2006, in 2012 there was a lower percentage of patients at the more stringent A1C target of < 7% (43.2% vs. 39.6%). The percentage of patients achieving goal for systolic BP was significantly decreased to 38.6% in 2012 versus 46.5% in 2006 (Table 2). However, the proportion of patients with controlled diastolic BP rose significantly from 70% to 77.6%. The number of patients achieving goal LDL (< 100 mg/dL) increased from 43.5% in 2006 to 58.6% in 2012.

Table 3 shows number of patients at LDL goal of < 100 mg/dL by lipid-lowering agent. There was a large portion (n = 303 or 34%) of the 891 patients that did not have LDL values available in both 2006 and 2012. A total of 89 patients were taking no medications for LDL, with 64% achieving controlled levels. The large majority of patients were controlled on a single statin drug (n = 195, 59%) while those requiring more than a statin drug for control comprised 53% of patients (n = 92).

Table 3 shows achievement of BP < 130/80 by anti-hypertensive regimen. The majority of the hypertensive regimens included the use of an ACEI or an ARB, with overall BP control achieved in at least 45% of patients. The highest BP control (49%) was achieved in the diuretic and CCB–containing regimens without an ACEI or ARB, represented by a smaller group of patients (n = 65). There were 32 patients whose hypertension was controlled without antihypertensive therapy. Ninety-three percent of the cohort had data for evaluation in both years.

Discussion

Despite the availability of evidence-based guidelines and vast knowledge about microvascular and macrovascular complications due to diabetes, clinical goals for diabetes outcomes are not being routinely achieved in practice. More work is needed to achieve national standards of care. NHANES data from 2007 to 2010 revealed that 52.5% of patients with diabetes achieved an A1C of < 7% while 51.1% had a BP < 130/80 and 56.2% had an LDL < 100 mg/dL [8].

Improvement in LDL cholesterol was seen in the current study, and A1C remained constant during the 6-year time period. While mean A1C, BP, and LDL measurements were close to ADA target goals, a smaller proportion of patients were controlled in 2012 compared with 2006. Hoerger and colleagues [11] found using NHANES data 1999 to 2004 that mean A1C levels significantly declined over time, with 55.7% (up from 36.9%) achieving an A1C of < 7% by 2004 [11]. In our sample of patient with diabetes, only 39.6% were at A1C goal in 2012; 8.2% (61/742) achieved control with no medications.

Metformin is first-line therapy according to ADA recommendations. Most regimens in our study included this drug, with a large percentage of patients with controlled A1C taking this very affordable agent [12]. The combination regimens with metformin plus another oral therapy or 2 oral drugs with insulin resulted in a higher percentage of patients controlled compared to metformin or insulin monotherapy. From our previous chart review [13] of the entire practice of patients with diabetes (n = 1398) from 2006, A1C control was similarly achieved in patients taking insulin (31% vs. 33%) or insulin combinations (19% vs. 20%) from 2006 to 2012, respectively.

For LDL cholesterol control, 9.7% (57/588) of the cohort used no medications to reach goal. Statin use predominated, with 60% of the cohort reaching goal with a single statin agent. Approximately one-third (175/588) of evaluable patients were on more than 1 cholesterol medication, and about half of these (53%) reached goal. Over the 6-year period, atorvastatin become available generically, which may have impacted the number of patients able to use this statin. Compared with a recent literature review over a 12-year period of LDL attainment in primary care [14], the results of our study show equivalent or better LDL goal achievement among patient with diabetes.

The majority of the patients received an ACEI or ARB. There were a comparable number of patients controlled with ACEI or ARB with a diuretic, versus an ACEI or ARB with a diuretic and CCB. Large-scale clinical trials have shown that using an ACEI or ARB in combination with a CCB is superior to a hydrochlorathiazide-based combination for reducing risk of major cardiovascular events [15]. The Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial showed that serious adverse events attributed to antihypertensive treatment occurred more frequently in the intensive therapy group (< 120/80) than in the standard therapy (< 140/80) group [16]. The stringent systolic BP goal in accord was accomplished using 3.4 medications. Aggressive lowering of BP may be dangerous in patients with diabetes and there is no benefit found in many large-scale studies [17]. The 2013 ADA goal for BP is now < 140/80 mm Hg, and while our data show that a significant increase in BP was seen over a 6-year period, the number of medications needed to control BP will likely be lower with the new ADA target and potentially safer.

In our cohort, over the 6-year period there was an increase in the number of medications needed to achieve glycemic, BP, and LDL goals. During this time, there were no major changes in the way the patients received care in the clinic environment. We cannot comment on whether lifestyle changes or diabetes education may have impacted the need for increased medication use. Limitations to this study include the unavailability of A1C (17%) and LDL (34%) data at both time points for every patient, inability to verify insurance data for the 2012 time period, and that the data are from a single practice. We also were unable to determine the duration of diabetes diagnosis due to a change in electronic medical record systems and lack of full documentation by providers.

These findings suggest that as patients live longer with type 2 diabetes, they will need increasing numbers of medications to achieve standard of care goals. Research has shown that there are challenges in implementing diabetes guidelines in primary care, including potential inaccuracies contained in electronic patient health information, inadequate coordination among health care providers, physician lack of awareness of guidelines, and clinical inertia [18]. As shown in the current study and other research, intensification of traditional therapies for glycemic control can sustain target outcomes without the risk of significant weight gain [19].

The chronic condition of diabetes is associated with medical complications as well as challenges for providing optimal care, despite advances in pharmacotherapy. As more medications are added to a patient’s regimen, adherence can become challenging. The cost of medications also warrants consideration. Research is needed to understand the impact on quality of life, cost of care, and outcomes of these regimens as well as whether lifestyle modifications can impact the number of medications needed by individual patients. The current study indicates that overall outcome control for A1C and BP can be sustained and significantly decreased for LDL cholesterol using multiple medications with the primary agent being a statin drug.

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank Drs. Elizabeth Strachan and Madhavi Peechara for their past contributions and diligence in the original chart review.

Corresponding author: Julienne K. Kirk, PharmD, CDE, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Medical Center Blvd., Winston-Salem, NC 27157-1084, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

Author contributions: conception and design, JKK, KL, RWL; analysis and interpretation of data, JKK, SWD, KL, CAH, RWL; drafting of article, JKK, KL, RWL; critical revision of the article, JKK, KL, CAH; provision of study materials or patients, JKK, SWD; statistical expertise, SWD; administrative or technical support, CAH; collection and assembly of data, JKK, KL, CAH.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes fact sheet: national estimates and general information on diabetes and prediabetes in the United States, 2011. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011.

2. Narayan KM, Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, et al. Lifetime risk for diabetes mellitus in the United States. JAMA 2003;290:1884–90.

3. McWilliams JM, Meara E, Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ. Differences in control of cardiovascular disease and diabetes by race, ethnicity, and education: U.S. trends from 1999 to 2006 and effects of Medicare coverage. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:505–15.

4. Vouri SM, Shaw RF, Waterbury NV, et al. Prevalence of achievement of A1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol (ABC) goal in veterans with diabetes. Manag Care Pharm 2011;17:304–12.

5. Kirk JK, Bell RA, Bertoni AG, et al. Ethnic disparities: control of glycemia, blood pressure, and LDL cholesterol among US adults with type 2 diabetes. Ann Pharmacother 2005;39:1489–501.

6. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes–2006. Diabetes Care 2006;29(Suppl 1):S4–S42.

7. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes–2012. Diabetes Care 2012;35(Suppl 1):S11–S63.

8. Casagrande SS, Fradkin JE, Saydah SH, et al. The prevalence of meeting A1C, blood pressure, and LDL goals among people with diabetes, 1988-2010. Diabetes Care 2013;36:2271–9.

9. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes–2013. Diabetes Care 2013;36(Suppl 1):S11–S66.

10. Schellenberg ES, Dryden DM, Vandermeer B, et al. Lifestyle intervention for patients with and at risk for type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Inten Med 2013;159:543–51.

11. Hoerger TJ, Segel JE, Gregg EW, Saaddine JB. Is glycemic control improving in US adults? Diabetes Care 2008;31:81–6.

12. Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach. Diabetes Care 2012;35:1364–79.

13. Kirk JK, Strachan E, Martin CL, et al. Patient characteristics and process of care measures as predictors of glycemic control. J Clin Outcomes Manag 2010;17:27–30.

14. Chopra I, Kamal KM, Candrilli SD. Variations in blood pressure and lipid goal attainment in primary care. Curr Med Res Opin 2013;29:1115–25.

15. Jamerson K, Weber MA, Bakris GL, et al. Benazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med 2008;359:2417–28.

16. Grossman E. Blood pressure: the lower, the better. The con side. Diabetes Care 2011;34:S308–12.

17. Cushman WC, Evans GW, Byington RP, et al. Effects of intensive blood pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1575–85.

18. Appiah B, Hong Y, Ory MG, et al. Challenges and opportunities for implementing diabetes self-management guidelines. J Am Board Fam Med 2013;26:90–2.

19. Best JD, Drury PL, Davis TME, et al. Glycemic control over 4 years in 4,900 people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012;35:1165–70.

From the Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC.

Abstract

- Objective: To assess outcomes and pharmacotherapy in a cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes in a university-based family medicine teaching practice.

- Methods: We used ICD-9-CM codes to identify a cohort of patients with diabetes seen in 2006 and 2012. A total of 891 patients were identified who made follow-up visits in both years. We collected data on patient characteristics, pharmacotherapy, and outcomes for glycemia, blood pressure (BP), and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. We determined type and number of medications taken to achieve target outcomes.

- Results: A1C remained constant between 2006 and 2012 (7.6% to 7.7%) along with BMI (34.7 kg/m2 to 34.1 kg/m2), while mean LDL cholesterol significantly decreased from 109 mg/dL in 2006 to 98.8 mg/dL in 2012. The number of patients achieving a goal LDL < 100 mg/dL increased from 43.5 % in 2006 to 58.6% in 2012. The largest group with controlled A1C (< 7 %) were taking metformin with a sulfonylurea, DPP-4 inhibitor, glitazone or an injectable GLP-agonist. The majority achieved an LDL goal of < 100 mg/dl. The majority of hypertensive regimens included use of an ACE inhibitor or ARB with overall BP control achieved in at least 45% of patients.

- Conclusion: Multiple medications are necessary to achieve control among patients with type 2 diabetes over time and this cannot be attributed to an increase in BMI. Overall control for A1C and BP can be sustained and significantly decreased for LDL cholesterol using multiple medications, with the primary agent for LDL reduction being a statin.

Diabetes is an illness that affects an estimated 25.8 million Americans and is quickly becoming a worldwide epidemic [1,2]. Diabetes is a significant cause of both microvascular and macrovascular sequelae, but its frequent association with the comorbid conditions of hypertension and dyslipidemia further increases the risk of heart disease, stroke, peripheral vascular complications, and renal impairment [3–5]. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) publishes consensus guidelines annually to guide management for patients with diabetes. From 2006 to 2012, the accepted standard of medical care included achieving a hemoglobin A1C (A1C) measurement of < 7%, a low-density lipoprotein (LDL) level of < 100 mg/dL, and a blood pressure (BP) of < 130/80 mm Hg [6,7]. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) recently reported that the goal of simultaneous control of A1C, LDL and BP is met in only about 19% of diabetes patients [8]. Target glycemic control is relaxed to an A1C < 8% in some patients with multiple comorbidities, limited life span, or risk for hypoglycemia; and in 2013 the BP goal was modified to < 140/80 based on clinical trial evidence [9].

In combination with lifestyle modification, pharmacotherapy is a critical component of chronic disease management. Initial pharmacotherapy treatment recommendations include metformin for diabetes, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) for hypertension, and a statin for dyslipidemia [6,7,9]. In patients who already have a diagnosis of diabetes, achieving control becomes more difficult to accomplish with lifestyle alone, and the benefit of lifestyle intervention on all-cause mortality as well as cardiovascular and microvascular events remains a debated issue [10]. The need for pharmacologic agents in most patients with diabetes is inevitable. Metformin is the agent of choice for initial treatment with drug therapy, with the option of adding a variety of other oral or injectable medications based on clinician decision-making [7]. In this study, we reviewed data from a longitudinal cohort of type 2 diabetes patients and compared medication use and outcomes at 2 different time-points (2006 and 2012) to see how medical management and outcome measures changed over time.

Methods

Setting

Data were obtained from an academic family medicine clinic in the southeastern United States. Approximately 56,000 patient visits to this clinic are conducted annually. Family medicine residents in training, fellows, faculty physicians, physician assistants, a nutritionist, and diabetes educators care for patients seen in this practice.

Data Collection

A cohort of patients was identified using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification codes for type 2 diabetes. The cohort comprised patients with diabetes in 2006 and 2012 who made follow-up visits in both years.

The data from both time-points were obtained from electronic medical record (EMR) data capture and structured chart review. Two reviewers reviewed 10% of the charts for accuracy after the data was pre-populated from the EMR. The following data were obtained: demographic variables (patient age, gender, and race), height, weight, insurance, smoking status, A1C, LDL, and BP measurements, pharmacotherapy for glycemia, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, and number of medications needed for control. For variables that had multiple measures, we calculated an average for the year.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed to compute means, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentages for demographic variables and for glycemia, BP, LDL includ-ing patient characteristics, diabetes outcomes, and pharmacotherapy medication variables. Paired t tests were used to assess for a difference at the level of the patient in the means of the A1C, BP, and LDL between the 2 study time-points (2-sided alpha = 0.05). The non-parametric McNemar test was used to assess for differences in the proportions of patients at the identified goal for A1C, LDL, and BP for 2006 and 2012.

Results

The number of visits per patient was 5.9 in 2006 and 5.3 in 2012. A1C remained constant between 2006 and 2012 (mean 7.6% vs. 7.7%, ± 1.8) along with body mass index (BMI), while mean LDL cholesterol significantly decreased from 109 ± 36.4 mg/dL in 2006 to 98.8 ± 40.4 mg/dL in 2012 (Table 2). Mean systolic BP marginally increased over the 6-year period from 131.5 ± 14.2 to 134.8 ± 16.1 mm Hg with diastolic BP remaining constant.

The percentage of patients achieving the less stringent A1C goal of < 8% comprised over 50% of the population at both time points; however, compared with 2006, in 2012 there was a lower percentage of patients at the more stringent A1C target of < 7% (43.2% vs. 39.6%). The percentage of patients achieving goal for systolic BP was significantly decreased to 38.6% in 2012 versus 46.5% in 2006 (Table 2). However, the proportion of patients with controlled diastolic BP rose significantly from 70% to 77.6%. The number of patients achieving goal LDL (< 100 mg/dL) increased from 43.5% in 2006 to 58.6% in 2012.

Table 3 shows number of patients at LDL goal of < 100 mg/dL by lipid-lowering agent. There was a large portion (n = 303 or 34%) of the 891 patients that did not have LDL values available in both 2006 and 2012. A total of 89 patients were taking no medications for LDL, with 64% achieving controlled levels. The large majority of patients were controlled on a single statin drug (n = 195, 59%) while those requiring more than a statin drug for control comprised 53% of patients (n = 92).

Table 3 shows achievement of BP < 130/80 by anti-hypertensive regimen. The majority of the hypertensive regimens included the use of an ACEI or an ARB, with overall BP control achieved in at least 45% of patients. The highest BP control (49%) was achieved in the diuretic and CCB–containing regimens without an ACEI or ARB, represented by a smaller group of patients (n = 65). There were 32 patients whose hypertension was controlled without antihypertensive therapy. Ninety-three percent of the cohort had data for evaluation in both years.

Discussion

Despite the availability of evidence-based guidelines and vast knowledge about microvascular and macrovascular complications due to diabetes, clinical goals for diabetes outcomes are not being routinely achieved in practice. More work is needed to achieve national standards of care. NHANES data from 2007 to 2010 revealed that 52.5% of patients with diabetes achieved an A1C of < 7% while 51.1% had a BP < 130/80 and 56.2% had an LDL < 100 mg/dL [8].

Improvement in LDL cholesterol was seen in the current study, and A1C remained constant during the 6-year time period. While mean A1C, BP, and LDL measurements were close to ADA target goals, a smaller proportion of patients were controlled in 2012 compared with 2006. Hoerger and colleagues [11] found using NHANES data 1999 to 2004 that mean A1C levels significantly declined over time, with 55.7% (up from 36.9%) achieving an A1C of < 7% by 2004 [11]. In our sample of patient with diabetes, only 39.6% were at A1C goal in 2012; 8.2% (61/742) achieved control with no medications.

Metformin is first-line therapy according to ADA recommendations. Most regimens in our study included this drug, with a large percentage of patients with controlled A1C taking this very affordable agent [12]. The combination regimens with metformin plus another oral therapy or 2 oral drugs with insulin resulted in a higher percentage of patients controlled compared to metformin or insulin monotherapy. From our previous chart review [13] of the entire practice of patients with diabetes (n = 1398) from 2006, A1C control was similarly achieved in patients taking insulin (31% vs. 33%) or insulin combinations (19% vs. 20%) from 2006 to 2012, respectively.

For LDL cholesterol control, 9.7% (57/588) of the cohort used no medications to reach goal. Statin use predominated, with 60% of the cohort reaching goal with a single statin agent. Approximately one-third (175/588) of evaluable patients were on more than 1 cholesterol medication, and about half of these (53%) reached goal. Over the 6-year period, atorvastatin become available generically, which may have impacted the number of patients able to use this statin. Compared with a recent literature review over a 12-year period of LDL attainment in primary care [14], the results of our study show equivalent or better LDL goal achievement among patient with diabetes.

The majority of the patients received an ACEI or ARB. There were a comparable number of patients controlled with ACEI or ARB with a diuretic, versus an ACEI or ARB with a diuretic and CCB. Large-scale clinical trials have shown that using an ACEI or ARB in combination with a CCB is superior to a hydrochlorathiazide-based combination for reducing risk of major cardiovascular events [15]. The Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial showed that serious adverse events attributed to antihypertensive treatment occurred more frequently in the intensive therapy group (< 120/80) than in the standard therapy (< 140/80) group [16]. The stringent systolic BP goal in accord was accomplished using 3.4 medications. Aggressive lowering of BP may be dangerous in patients with diabetes and there is no benefit found in many large-scale studies [17]. The 2013 ADA goal for BP is now < 140/80 mm Hg, and while our data show that a significant increase in BP was seen over a 6-year period, the number of medications needed to control BP will likely be lower with the new ADA target and potentially safer.

In our cohort, over the 6-year period there was an increase in the number of medications needed to achieve glycemic, BP, and LDL goals. During this time, there were no major changes in the way the patients received care in the clinic environment. We cannot comment on whether lifestyle changes or diabetes education may have impacted the need for increased medication use. Limitations to this study include the unavailability of A1C (17%) and LDL (34%) data at both time points for every patient, inability to verify insurance data for the 2012 time period, and that the data are from a single practice. We also were unable to determine the duration of diabetes diagnosis due to a change in electronic medical record systems and lack of full documentation by providers.

These findings suggest that as patients live longer with type 2 diabetes, they will need increasing numbers of medications to achieve standard of care goals. Research has shown that there are challenges in implementing diabetes guidelines in primary care, including potential inaccuracies contained in electronic patient health information, inadequate coordination among health care providers, physician lack of awareness of guidelines, and clinical inertia [18]. As shown in the current study and other research, intensification of traditional therapies for glycemic control can sustain target outcomes without the risk of significant weight gain [19].

The chronic condition of diabetes is associated with medical complications as well as challenges for providing optimal care, despite advances in pharmacotherapy. As more medications are added to a patient’s regimen, adherence can become challenging. The cost of medications also warrants consideration. Research is needed to understand the impact on quality of life, cost of care, and outcomes of these regimens as well as whether lifestyle modifications can impact the number of medications needed by individual patients. The current study indicates that overall outcome control for A1C and BP can be sustained and significantly decreased for LDL cholesterol using multiple medications with the primary agent being a statin drug.

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank Drs. Elizabeth Strachan and Madhavi Peechara for their past contributions and diligence in the original chart review.

Corresponding author: Julienne K. Kirk, PharmD, CDE, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Medical Center Blvd., Winston-Salem, NC 27157-1084, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

Author contributions: conception and design, JKK, KL, RWL; analysis and interpretation of data, JKK, SWD, KL, CAH, RWL; drafting of article, JKK, KL, RWL; critical revision of the article, JKK, KL, CAH; provision of study materials or patients, JKK, SWD; statistical expertise, SWD; administrative or technical support, CAH; collection and assembly of data, JKK, KL, CAH.

From the Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC.

Abstract

- Objective: To assess outcomes and pharmacotherapy in a cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes in a university-based family medicine teaching practice.

- Methods: We used ICD-9-CM codes to identify a cohort of patients with diabetes seen in 2006 and 2012. A total of 891 patients were identified who made follow-up visits in both years. We collected data on patient characteristics, pharmacotherapy, and outcomes for glycemia, blood pressure (BP), and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. We determined type and number of medications taken to achieve target outcomes.

- Results: A1C remained constant between 2006 and 2012 (7.6% to 7.7%) along with BMI (34.7 kg/m2 to 34.1 kg/m2), while mean LDL cholesterol significantly decreased from 109 mg/dL in 2006 to 98.8 mg/dL in 2012. The number of patients achieving a goal LDL < 100 mg/dL increased from 43.5 % in 2006 to 58.6% in 2012. The largest group with controlled A1C (< 7 %) were taking metformin with a sulfonylurea, DPP-4 inhibitor, glitazone or an injectable GLP-agonist. The majority achieved an LDL goal of < 100 mg/dl. The majority of hypertensive regimens included use of an ACE inhibitor or ARB with overall BP control achieved in at least 45% of patients.

- Conclusion: Multiple medications are necessary to achieve control among patients with type 2 diabetes over time and this cannot be attributed to an increase in BMI. Overall control for A1C and BP can be sustained and significantly decreased for LDL cholesterol using multiple medications, with the primary agent for LDL reduction being a statin.

Diabetes is an illness that affects an estimated 25.8 million Americans and is quickly becoming a worldwide epidemic [1,2]. Diabetes is a significant cause of both microvascular and macrovascular sequelae, but its frequent association with the comorbid conditions of hypertension and dyslipidemia further increases the risk of heart disease, stroke, peripheral vascular complications, and renal impairment [3–5]. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) publishes consensus guidelines annually to guide management for patients with diabetes. From 2006 to 2012, the accepted standard of medical care included achieving a hemoglobin A1C (A1C) measurement of < 7%, a low-density lipoprotein (LDL) level of < 100 mg/dL, and a blood pressure (BP) of < 130/80 mm Hg [6,7]. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) recently reported that the goal of simultaneous control of A1C, LDL and BP is met in only about 19% of diabetes patients [8]. Target glycemic control is relaxed to an A1C < 8% in some patients with multiple comorbidities, limited life span, or risk for hypoglycemia; and in 2013 the BP goal was modified to < 140/80 based on clinical trial evidence [9].

In combination with lifestyle modification, pharmacotherapy is a critical component of chronic disease management. Initial pharmacotherapy treatment recommendations include metformin for diabetes, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) for hypertension, and a statin for dyslipidemia [6,7,9]. In patients who already have a diagnosis of diabetes, achieving control becomes more difficult to accomplish with lifestyle alone, and the benefit of lifestyle intervention on all-cause mortality as well as cardiovascular and microvascular events remains a debated issue [10]. The need for pharmacologic agents in most patients with diabetes is inevitable. Metformin is the agent of choice for initial treatment with drug therapy, with the option of adding a variety of other oral or injectable medications based on clinician decision-making [7]. In this study, we reviewed data from a longitudinal cohort of type 2 diabetes patients and compared medication use and outcomes at 2 different time-points (2006 and 2012) to see how medical management and outcome measures changed over time.

Methods

Setting

Data were obtained from an academic family medicine clinic in the southeastern United States. Approximately 56,000 patient visits to this clinic are conducted annually. Family medicine residents in training, fellows, faculty physicians, physician assistants, a nutritionist, and diabetes educators care for patients seen in this practice.

Data Collection

A cohort of patients was identified using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification codes for type 2 diabetes. The cohort comprised patients with diabetes in 2006 and 2012 who made follow-up visits in both years.

The data from both time-points were obtained from electronic medical record (EMR) data capture and structured chart review. Two reviewers reviewed 10% of the charts for accuracy after the data was pre-populated from the EMR. The following data were obtained: demographic variables (patient age, gender, and race), height, weight, insurance, smoking status, A1C, LDL, and BP measurements, pharmacotherapy for glycemia, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, and number of medications needed for control. For variables that had multiple measures, we calculated an average for the year.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Statistical Analysis