User login

MATRIX trial update: No clear winner

LONDON—The latest results* of the MATRIX trial haven’t provided any cut-and-dried answers when it comes to anticoagulation in the context of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), according to articles published in NEJM and data presented at the ESC Congress 2015.

The trial suggested that, overall, bivalirudin and heparin produce comparable results in patients undergoing PCI.

The drugs produced similar rates of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and net adverse clinical events (NACE).

In addition, among patients in the bivalirudin arm, there was no significant difference in a composite primary outcome between patients who received an additional infusion of bivalirudin after PCI and those who did not.

Results from this trial were published in NEJM alongside a related editorial. At the ESC Congress 2015, the bivalirudin dosing comparison was reported in abstract 6004.

MATRIX was sponsored by the Societa Italiana di Cardiologia Invasiva (GISE), with funding from The Medicines Company and Terumo.

The trial enrolled 7213 patients with acute coronary syndrome who were set to undergo PCI. Patients were randomized to receive bivalirudin (n=3610) or unfractionated heparin (n=3603). Patients in the bivalirudin arm were then randomized to either receive a post-PCI infusion of bivalirudin (n=1799) or not (n=1811).

Primary outcomes for the comparison between bivalirudin and heparin were the occurrence of MACE (a composite of death, myocardial infarction, or stroke) and NACE (a composite of major bleeding or a major adverse cardiovascular event).

The primary outcome for the comparison of post-PCI bivalirudin infusion with no infusion was a composite of urgent target-vessel revascularization, definite stent thrombosis, or NACE.

Heparin vs bivalirudin

There was no significant difference between the bivalirudin and heparin groups with regard to MACE—10.3% and 10.9%, respectively (P=0.44). And the same was true for NACE—11.2% and 12.4%, respectively (P=0.12).

Likewise, there was no significant difference between the bivalirudin arm and the heparin arm with regard to myocardial infarction—8.6% and 8.5%, respectively (P=0.93)—or stroke—0.4% and 0.5%, respectively (P=0.57).

However, bivalirudin was associated with a significantly lower rate of all-cause mortality than heparin—1.7% and 2.3%, respectively (P=0.04)—and a significantly lower rate of cardiac-related death—1.5% and 2.2%, respectively (P=0.03).

The rate of definite stent thrombosis was significantly higher in the bivalirudin group than the heparin group—1.0% and 0.6%, respectively (P=0.048). But there was no significant difference in the rate of definite or probable stent thrombosis—1.3% and 1.0% (P=0.27).

The rate of any bleeding was significantly lower with bivalirudin than with heparin—11.0% and 13.6%, respectively (P=0.001). And the same was true for major bleeding (BARC 3 or 5)—1.4% and 2.5%, respectively (P<0.001).

Bivalirudin duration

“Post-PCI bivalirudin did not reduce the composite outcome of ischemic and bleeding outcomes, including stent thrombosis risk, as compared to no post-PCI bivalirudin infusion,” said study investigator Marco Valgimigli, MD, PhD, of the Swiss Cardiovascular Center in Bern, Switzerland.

The proportion of patients who met the primary endpoint was 11.0% in the post-PCI infusion group and 11.9% in the no-infusion group (P=0.34).

Similarly, there was no significant difference between the infusion and no-infusion groups in the risk of definite stent thrombosis—1.3% and 0.7%, respectively (P=0.09)—or definite/probable stent thrombosis—1.5% and 1.1%, respectively (P=0.29).

And there was no significant difference in the rate of any bleeding—11.3% and 10.7%, respectively (P=0.62)—but the rate of BARC 3 or 5 bleeding was lower in the group that received the post-PCI infusion—1.0% vs 1.8% (P=0.03).

“Both treatment options are allowed per current European label and observational studies,” Dr Valgimigli said.

“Hence, I believe the option to prolong or stop bivalirudin infusion after PCI remains open for clinicians, who will have to decide based on the ischemic and bleeding risk of individual patients, as well as perhaps based on type of acute coronary syndrome, timing of loading dose, and type of oral P2Y12 inhibitors. This is in keeping with the current labeling of the drug in EU and USA.”

Cost concerns

In the NEJM editorial, Peter Berger, MD, of North Shore–Long Island Jewish Health System in Great Neck, New York, noted that bivalirudin costs more than 400 times the price of heparin.

“Many studies have shown that bivalirudin is safer than heparin—that it causes fewer bleeding complications,” Dr Berger said. “But other studies have shown that heparin is every bit as safe, especially when used in lower doses. And one recent, large study actually suggested that heparin is more effective than bivalirudin.”

Despite these conflicting results, Dr Berger said “nearly everyone” agrees that if the more expensive drug is not superior in some way, the less expensive one should be used.

“Many studies raise more questions than they answer,” he added. “It will be interesting to see whether doctors accept the results of the MATRIX trial or wait for more studies before deciding which blood thinner they prefer.” ![]()

*MATRIX investigators previously compared vascular access sites and found that radial access outperformed femoral access. These results were published earlier this year in The Lancet.

LONDON—The latest results* of the MATRIX trial haven’t provided any cut-and-dried answers when it comes to anticoagulation in the context of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), according to articles published in NEJM and data presented at the ESC Congress 2015.

The trial suggested that, overall, bivalirudin and heparin produce comparable results in patients undergoing PCI.

The drugs produced similar rates of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and net adverse clinical events (NACE).

In addition, among patients in the bivalirudin arm, there was no significant difference in a composite primary outcome between patients who received an additional infusion of bivalirudin after PCI and those who did not.

Results from this trial were published in NEJM alongside a related editorial. At the ESC Congress 2015, the bivalirudin dosing comparison was reported in abstract 6004.

MATRIX was sponsored by the Societa Italiana di Cardiologia Invasiva (GISE), with funding from The Medicines Company and Terumo.

The trial enrolled 7213 patients with acute coronary syndrome who were set to undergo PCI. Patients were randomized to receive bivalirudin (n=3610) or unfractionated heparin (n=3603). Patients in the bivalirudin arm were then randomized to either receive a post-PCI infusion of bivalirudin (n=1799) or not (n=1811).

Primary outcomes for the comparison between bivalirudin and heparin were the occurrence of MACE (a composite of death, myocardial infarction, or stroke) and NACE (a composite of major bleeding or a major adverse cardiovascular event).

The primary outcome for the comparison of post-PCI bivalirudin infusion with no infusion was a composite of urgent target-vessel revascularization, definite stent thrombosis, or NACE.

Heparin vs bivalirudin

There was no significant difference between the bivalirudin and heparin groups with regard to MACE—10.3% and 10.9%, respectively (P=0.44). And the same was true for NACE—11.2% and 12.4%, respectively (P=0.12).

Likewise, there was no significant difference between the bivalirudin arm and the heparin arm with regard to myocardial infarction—8.6% and 8.5%, respectively (P=0.93)—or stroke—0.4% and 0.5%, respectively (P=0.57).

However, bivalirudin was associated with a significantly lower rate of all-cause mortality than heparin—1.7% and 2.3%, respectively (P=0.04)—and a significantly lower rate of cardiac-related death—1.5% and 2.2%, respectively (P=0.03).

The rate of definite stent thrombosis was significantly higher in the bivalirudin group than the heparin group—1.0% and 0.6%, respectively (P=0.048). But there was no significant difference in the rate of definite or probable stent thrombosis—1.3% and 1.0% (P=0.27).

The rate of any bleeding was significantly lower with bivalirudin than with heparin—11.0% and 13.6%, respectively (P=0.001). And the same was true for major bleeding (BARC 3 or 5)—1.4% and 2.5%, respectively (P<0.001).

Bivalirudin duration

“Post-PCI bivalirudin did not reduce the composite outcome of ischemic and bleeding outcomes, including stent thrombosis risk, as compared to no post-PCI bivalirudin infusion,” said study investigator Marco Valgimigli, MD, PhD, of the Swiss Cardiovascular Center in Bern, Switzerland.

The proportion of patients who met the primary endpoint was 11.0% in the post-PCI infusion group and 11.9% in the no-infusion group (P=0.34).

Similarly, there was no significant difference between the infusion and no-infusion groups in the risk of definite stent thrombosis—1.3% and 0.7%, respectively (P=0.09)—or definite/probable stent thrombosis—1.5% and 1.1%, respectively (P=0.29).

And there was no significant difference in the rate of any bleeding—11.3% and 10.7%, respectively (P=0.62)—but the rate of BARC 3 or 5 bleeding was lower in the group that received the post-PCI infusion—1.0% vs 1.8% (P=0.03).

“Both treatment options are allowed per current European label and observational studies,” Dr Valgimigli said.

“Hence, I believe the option to prolong or stop bivalirudin infusion after PCI remains open for clinicians, who will have to decide based on the ischemic and bleeding risk of individual patients, as well as perhaps based on type of acute coronary syndrome, timing of loading dose, and type of oral P2Y12 inhibitors. This is in keeping with the current labeling of the drug in EU and USA.”

Cost concerns

In the NEJM editorial, Peter Berger, MD, of North Shore–Long Island Jewish Health System in Great Neck, New York, noted that bivalirudin costs more than 400 times the price of heparin.

“Many studies have shown that bivalirudin is safer than heparin—that it causes fewer bleeding complications,” Dr Berger said. “But other studies have shown that heparin is every bit as safe, especially when used in lower doses. And one recent, large study actually suggested that heparin is more effective than bivalirudin.”

Despite these conflicting results, Dr Berger said “nearly everyone” agrees that if the more expensive drug is not superior in some way, the less expensive one should be used.

“Many studies raise more questions than they answer,” he added. “It will be interesting to see whether doctors accept the results of the MATRIX trial or wait for more studies before deciding which blood thinner they prefer.” ![]()

*MATRIX investigators previously compared vascular access sites and found that radial access outperformed femoral access. These results were published earlier this year in The Lancet.

LONDON—The latest results* of the MATRIX trial haven’t provided any cut-and-dried answers when it comes to anticoagulation in the context of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), according to articles published in NEJM and data presented at the ESC Congress 2015.

The trial suggested that, overall, bivalirudin and heparin produce comparable results in patients undergoing PCI.

The drugs produced similar rates of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and net adverse clinical events (NACE).

In addition, among patients in the bivalirudin arm, there was no significant difference in a composite primary outcome between patients who received an additional infusion of bivalirudin after PCI and those who did not.

Results from this trial were published in NEJM alongside a related editorial. At the ESC Congress 2015, the bivalirudin dosing comparison was reported in abstract 6004.

MATRIX was sponsored by the Societa Italiana di Cardiologia Invasiva (GISE), with funding from The Medicines Company and Terumo.

The trial enrolled 7213 patients with acute coronary syndrome who were set to undergo PCI. Patients were randomized to receive bivalirudin (n=3610) or unfractionated heparin (n=3603). Patients in the bivalirudin arm were then randomized to either receive a post-PCI infusion of bivalirudin (n=1799) or not (n=1811).

Primary outcomes for the comparison between bivalirudin and heparin were the occurrence of MACE (a composite of death, myocardial infarction, or stroke) and NACE (a composite of major bleeding or a major adverse cardiovascular event).

The primary outcome for the comparison of post-PCI bivalirudin infusion with no infusion was a composite of urgent target-vessel revascularization, definite stent thrombosis, or NACE.

Heparin vs bivalirudin

There was no significant difference between the bivalirudin and heparin groups with regard to MACE—10.3% and 10.9%, respectively (P=0.44). And the same was true for NACE—11.2% and 12.4%, respectively (P=0.12).

Likewise, there was no significant difference between the bivalirudin arm and the heparin arm with regard to myocardial infarction—8.6% and 8.5%, respectively (P=0.93)—or stroke—0.4% and 0.5%, respectively (P=0.57).

However, bivalirudin was associated with a significantly lower rate of all-cause mortality than heparin—1.7% and 2.3%, respectively (P=0.04)—and a significantly lower rate of cardiac-related death—1.5% and 2.2%, respectively (P=0.03).

The rate of definite stent thrombosis was significantly higher in the bivalirudin group than the heparin group—1.0% and 0.6%, respectively (P=0.048). But there was no significant difference in the rate of definite or probable stent thrombosis—1.3% and 1.0% (P=0.27).

The rate of any bleeding was significantly lower with bivalirudin than with heparin—11.0% and 13.6%, respectively (P=0.001). And the same was true for major bleeding (BARC 3 or 5)—1.4% and 2.5%, respectively (P<0.001).

Bivalirudin duration

“Post-PCI bivalirudin did not reduce the composite outcome of ischemic and bleeding outcomes, including stent thrombosis risk, as compared to no post-PCI bivalirudin infusion,” said study investigator Marco Valgimigli, MD, PhD, of the Swiss Cardiovascular Center in Bern, Switzerland.

The proportion of patients who met the primary endpoint was 11.0% in the post-PCI infusion group and 11.9% in the no-infusion group (P=0.34).

Similarly, there was no significant difference between the infusion and no-infusion groups in the risk of definite stent thrombosis—1.3% and 0.7%, respectively (P=0.09)—or definite/probable stent thrombosis—1.5% and 1.1%, respectively (P=0.29).

And there was no significant difference in the rate of any bleeding—11.3% and 10.7%, respectively (P=0.62)—but the rate of BARC 3 or 5 bleeding was lower in the group that received the post-PCI infusion—1.0% vs 1.8% (P=0.03).

“Both treatment options are allowed per current European label and observational studies,” Dr Valgimigli said.

“Hence, I believe the option to prolong or stop bivalirudin infusion after PCI remains open for clinicians, who will have to decide based on the ischemic and bleeding risk of individual patients, as well as perhaps based on type of acute coronary syndrome, timing of loading dose, and type of oral P2Y12 inhibitors. This is in keeping with the current labeling of the drug in EU and USA.”

Cost concerns

In the NEJM editorial, Peter Berger, MD, of North Shore–Long Island Jewish Health System in Great Neck, New York, noted that bivalirudin costs more than 400 times the price of heparin.

“Many studies have shown that bivalirudin is safer than heparin—that it causes fewer bleeding complications,” Dr Berger said. “But other studies have shown that heparin is every bit as safe, especially when used in lower doses. And one recent, large study actually suggested that heparin is more effective than bivalirudin.”

Despite these conflicting results, Dr Berger said “nearly everyone” agrees that if the more expensive drug is not superior in some way, the less expensive one should be used.

“Many studies raise more questions than they answer,” he added. “It will be interesting to see whether doctors accept the results of the MATRIX trial or wait for more studies before deciding which blood thinner they prefer.” ![]()

*MATRIX investigators previously compared vascular access sites and found that radial access outperformed femoral access. These results were published earlier this year in The Lancet.

FDA approves drug to prevent delayed CINV in adults

Photo by Rhoda Baer

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved rolapitant (Varubi) for use in adult cancer patients receiving initial and repeat courses of emetogenic chemotherapy.

Rolapitant is to be used in combination with other antiemetic agents to prevent delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV).

Tesaro, Inc., the company developing rolapitant, plans to launch the drug in the fourth quarter of this year.

Rolapitant is a selective and competitive antagonist of human substance P/neurokinin 1 (NK-1) receptors, with a plasma half-life of approximately 7 days. Activation of NK-1 receptors plays a central role in CINV, particularly in the delayed phase (the 25- to 120-hour period after chemotherapy administration).

Rolapitant comes in tablet form. The recommended dose is 180 mg, given approximately 1 to 2 hours prior to chemotherapy administration in combination with a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone. No dosage adjustment is required for dexamethasone when administering rolapitant.

Rolapitant inhibits the CYP2D6 enzyme, so it is contraindicated with the use of thioridazine, a drug metabolized by the CYP2D6 enzyme. Use of these drugs together may increase the amount of thioridazine in the blood and cause an abnormal heart rhythm that can be serious.

Rolapitant clinical trials

Results from three phase 3 trials suggested that rolapitant (at 180 mg) in combination with a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone was more effective than the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone on their own (active control).

The 3-drug combination demonstrated a significant reduction in episodes of vomiting or use of rescue medication during the 25- to 120-hour period following administration of highly emetogenic and moderately emetogenic chemotherapy regimens.

In addition, patients who received rolapitant reported experiencing less nausea that interfered with normal daily life and fewer episodes of vomiting or retching over multiple cycles of chemotherapy.

Highly emetogenic chemotherapy

The clinical profile of rolapitant in cisplatin-based, highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC) was confirmed in two phase 3 studies: HEC1 and HEC2. Results from these trials were recently published in The Lancet Oncology.

Both trials met their primary endpoint of complete response (CR) and demonstrated statistical superiority of the rolapitant combination compared to active control.

In HEC1, 264 patients received the rolapitant combination, and 262 received active control. The proportion of patients achieving a CR was 72.7% and 58.4%, respectively (P<0.001).

In HEC2, 271 patients received the rolapitant combination, and 273 received active control. The proportion of patients achieving a CR was 70.1% and 61.9%, respectively (P=0.043).

The most common adverse events (≥3%) were neutropenia (9% rolapitant and 8% control), hiccups (5% and 4%), and abdominal pain (3% and 2%).

Moderately emetogenic chemotherapy

Researchers conducted another phase 3 trial to compare the rolapitant combination with active control in 1332 patients receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy regimens. Results from this trial were recently published in The Lancet Oncology.

This trial met its primary endpoint of CR and demonstrated statistical superiority of the rolapitant combination compared to active control. The proportion of patients achieving a CR was 71.3% and 61.6%, respectively (P<0.001).

The most common adverse events (≥3%) were decreased appetite (9% rolapitant and 7% control), neutropenia (7% and 6%), dizziness (6% and 4%), dyspepsia (4% and 2%), urinary tract infection (4% and 3%), stomatitis (4% and 2%), and anemia (3% and 2%).

The full prescribing information for rolapitant is available at www.varubirx.com. ![]()

Photo by Rhoda Baer

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved rolapitant (Varubi) for use in adult cancer patients receiving initial and repeat courses of emetogenic chemotherapy.

Rolapitant is to be used in combination with other antiemetic agents to prevent delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV).

Tesaro, Inc., the company developing rolapitant, plans to launch the drug in the fourth quarter of this year.

Rolapitant is a selective and competitive antagonist of human substance P/neurokinin 1 (NK-1) receptors, with a plasma half-life of approximately 7 days. Activation of NK-1 receptors plays a central role in CINV, particularly in the delayed phase (the 25- to 120-hour period after chemotherapy administration).

Rolapitant comes in tablet form. The recommended dose is 180 mg, given approximately 1 to 2 hours prior to chemotherapy administration in combination with a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone. No dosage adjustment is required for dexamethasone when administering rolapitant.

Rolapitant inhibits the CYP2D6 enzyme, so it is contraindicated with the use of thioridazine, a drug metabolized by the CYP2D6 enzyme. Use of these drugs together may increase the amount of thioridazine in the blood and cause an abnormal heart rhythm that can be serious.

Rolapitant clinical trials

Results from three phase 3 trials suggested that rolapitant (at 180 mg) in combination with a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone was more effective than the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone on their own (active control).

The 3-drug combination demonstrated a significant reduction in episodes of vomiting or use of rescue medication during the 25- to 120-hour period following administration of highly emetogenic and moderately emetogenic chemotherapy regimens.

In addition, patients who received rolapitant reported experiencing less nausea that interfered with normal daily life and fewer episodes of vomiting or retching over multiple cycles of chemotherapy.

Highly emetogenic chemotherapy

The clinical profile of rolapitant in cisplatin-based, highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC) was confirmed in two phase 3 studies: HEC1 and HEC2. Results from these trials were recently published in The Lancet Oncology.

Both trials met their primary endpoint of complete response (CR) and demonstrated statistical superiority of the rolapitant combination compared to active control.

In HEC1, 264 patients received the rolapitant combination, and 262 received active control. The proportion of patients achieving a CR was 72.7% and 58.4%, respectively (P<0.001).

In HEC2, 271 patients received the rolapitant combination, and 273 received active control. The proportion of patients achieving a CR was 70.1% and 61.9%, respectively (P=0.043).

The most common adverse events (≥3%) were neutropenia (9% rolapitant and 8% control), hiccups (5% and 4%), and abdominal pain (3% and 2%).

Moderately emetogenic chemotherapy

Researchers conducted another phase 3 trial to compare the rolapitant combination with active control in 1332 patients receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy regimens. Results from this trial were recently published in The Lancet Oncology.

This trial met its primary endpoint of CR and demonstrated statistical superiority of the rolapitant combination compared to active control. The proportion of patients achieving a CR was 71.3% and 61.6%, respectively (P<0.001).

The most common adverse events (≥3%) were decreased appetite (9% rolapitant and 7% control), neutropenia (7% and 6%), dizziness (6% and 4%), dyspepsia (4% and 2%), urinary tract infection (4% and 3%), stomatitis (4% and 2%), and anemia (3% and 2%).

The full prescribing information for rolapitant is available at www.varubirx.com. ![]()

Photo by Rhoda Baer

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved rolapitant (Varubi) for use in adult cancer patients receiving initial and repeat courses of emetogenic chemotherapy.

Rolapitant is to be used in combination with other antiemetic agents to prevent delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV).

Tesaro, Inc., the company developing rolapitant, plans to launch the drug in the fourth quarter of this year.

Rolapitant is a selective and competitive antagonist of human substance P/neurokinin 1 (NK-1) receptors, with a plasma half-life of approximately 7 days. Activation of NK-1 receptors plays a central role in CINV, particularly in the delayed phase (the 25- to 120-hour period after chemotherapy administration).

Rolapitant comes in tablet form. The recommended dose is 180 mg, given approximately 1 to 2 hours prior to chemotherapy administration in combination with a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone. No dosage adjustment is required for dexamethasone when administering rolapitant.

Rolapitant inhibits the CYP2D6 enzyme, so it is contraindicated with the use of thioridazine, a drug metabolized by the CYP2D6 enzyme. Use of these drugs together may increase the amount of thioridazine in the blood and cause an abnormal heart rhythm that can be serious.

Rolapitant clinical trials

Results from three phase 3 trials suggested that rolapitant (at 180 mg) in combination with a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone was more effective than the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone on their own (active control).

The 3-drug combination demonstrated a significant reduction in episodes of vomiting or use of rescue medication during the 25- to 120-hour period following administration of highly emetogenic and moderately emetogenic chemotherapy regimens.

In addition, patients who received rolapitant reported experiencing less nausea that interfered with normal daily life and fewer episodes of vomiting or retching over multiple cycles of chemotherapy.

Highly emetogenic chemotherapy

The clinical profile of rolapitant in cisplatin-based, highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC) was confirmed in two phase 3 studies: HEC1 and HEC2. Results from these trials were recently published in The Lancet Oncology.

Both trials met their primary endpoint of complete response (CR) and demonstrated statistical superiority of the rolapitant combination compared to active control.

In HEC1, 264 patients received the rolapitant combination, and 262 received active control. The proportion of patients achieving a CR was 72.7% and 58.4%, respectively (P<0.001).

In HEC2, 271 patients received the rolapitant combination, and 273 received active control. The proportion of patients achieving a CR was 70.1% and 61.9%, respectively (P=0.043).

The most common adverse events (≥3%) were neutropenia (9% rolapitant and 8% control), hiccups (5% and 4%), and abdominal pain (3% and 2%).

Moderately emetogenic chemotherapy

Researchers conducted another phase 3 trial to compare the rolapitant combination with active control in 1332 patients receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy regimens. Results from this trial were recently published in The Lancet Oncology.

This trial met its primary endpoint of CR and demonstrated statistical superiority of the rolapitant combination compared to active control. The proportion of patients achieving a CR was 71.3% and 61.6%, respectively (P<0.001).

The most common adverse events (≥3%) were decreased appetite (9% rolapitant and 7% control), neutropenia (7% and 6%), dizziness (6% and 4%), dyspepsia (4% and 2%), urinary tract infection (4% and 3%), stomatitis (4% and 2%), and anemia (3% and 2%).

The full prescribing information for rolapitant is available at www.varubirx.com. ![]()

Eltrombopag approved to treat SAA in EU

The European Commission has approved eltrombopag (Revolade) for the treatment of adults with severe aplastic anemia (SAA) who were either refractory to prior immunosuppressive therapy or heavily pretreated and are unsuitable for hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

Eltrombopag is the first therapy approved in the European Union (EU) for this patient population.

The approval applies to all 28 EU member states plus Iceland, Norway, and Liechtenstein.

Trials of eltrombopag in SAA

The European Commission’s approval is based primarily on results of a phase 2 pilot study (NCT00922883) conducted by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute at the National Institutes of Health.

Results from the ongoing study were published in NEJM in 2012 and Blood in 2013. The trial has enrolled 43 patients with SAA who had an insufficient response to at least 1 prior immunosuppressive therapy and who had a platelet count of 30 x 109/L or less.

At baseline, the median platelet count was 20 x 109/L, hemoglobin was 8.4 g/dL, the absolute neutrophil count was 0.58 x 109/L, and absolute reticulocyte count was 24.3 x 109/L.

Patients had a median age of 45 (range, 17 to 77), and 56% were male. The majority of patients (84%) had received at least 2 prior immunosuppressive therapies.

Patients received eltrombopag at an initial dose of 50 mg once daily for 2 weeks. The dose increased over 2-week periods to a maximum of 150 mg once daily.

The study’s primary endpoint was hematologic response, which was initially assessed after 12 weeks of treatment. Treatment was discontinued after 16 weeks in patients who did not exhibit a hematologic response.

Forty percent of patients (n=17) experienced a hematologic response in at least 1 lineage—platelets, red blood cells (RBCs), or white blood cells—after week 12.

In the extension phase of the study, 8 patients achieved a multilineage response. Four of these patients subsequently tapered off treatment and maintained the response. The median follow-up was 8.1 months (range, 7.2 to 10.6 months).

Ninety-one percent of patients were platelet-transfusion-dependent at baseline. Patients who responded to eltrombopag did not require platelet transfusions for a median of 200 days (range, 8 to 1096 days).

Eighty-six percent of patients were RBC-transfusion-dependent at baseline. Patients who responded to eltrombopag did not require RBC transfusions for a median of 208 days (range, 15 to 1082 days).

The most common adverse events (≥20%) associated with eltrombopag were nausea (33%), fatigue (28%), cough (23%), diarrhea (21%), and headache (21%).

Patients were also evaluated for cytogenetic abnormalities. Eight patients had a new cytogenetic abnormality after treatment, including 5 patients who had complex changes in chromosome 7.

Patients who develop new cytogenetic abnormalities while on eltrombopag may need to be taken off treatment.

About eltrombopag

Eltrombopag is already approved to treat SAA in the US and Canada. The drug recently gained approval in the US to treat children age 1 and older who have chronic immune thrombocytopenia and have had an insufficient response to corticosteroids, immunoglobulins, or splenectomy.

Eltrombopag is approved in more than 100 countries to treat adults with chronic immune thrombocytopenia who have had an inadequate response to or are intolerant of other treatments.

The drug is approved in more than 45 countries for the treatment of thrombocytopenia in patients with chronic hepatitis C to allow them to initiate and maintain interferon-based therapy.

Eltrombopag is marketed under the brand name Promacta in the US and Revolade in most other countries. For more details on the drug, see the European Medicines Agency’s Summary of Product Characteristics. ![]()

The European Commission has approved eltrombopag (Revolade) for the treatment of adults with severe aplastic anemia (SAA) who were either refractory to prior immunosuppressive therapy or heavily pretreated and are unsuitable for hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

Eltrombopag is the first therapy approved in the European Union (EU) for this patient population.

The approval applies to all 28 EU member states plus Iceland, Norway, and Liechtenstein.

Trials of eltrombopag in SAA

The European Commission’s approval is based primarily on results of a phase 2 pilot study (NCT00922883) conducted by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute at the National Institutes of Health.

Results from the ongoing study were published in NEJM in 2012 and Blood in 2013. The trial has enrolled 43 patients with SAA who had an insufficient response to at least 1 prior immunosuppressive therapy and who had a platelet count of 30 x 109/L or less.

At baseline, the median platelet count was 20 x 109/L, hemoglobin was 8.4 g/dL, the absolute neutrophil count was 0.58 x 109/L, and absolute reticulocyte count was 24.3 x 109/L.

Patients had a median age of 45 (range, 17 to 77), and 56% were male. The majority of patients (84%) had received at least 2 prior immunosuppressive therapies.

Patients received eltrombopag at an initial dose of 50 mg once daily for 2 weeks. The dose increased over 2-week periods to a maximum of 150 mg once daily.

The study’s primary endpoint was hematologic response, which was initially assessed after 12 weeks of treatment. Treatment was discontinued after 16 weeks in patients who did not exhibit a hematologic response.

Forty percent of patients (n=17) experienced a hematologic response in at least 1 lineage—platelets, red blood cells (RBCs), or white blood cells—after week 12.

In the extension phase of the study, 8 patients achieved a multilineage response. Four of these patients subsequently tapered off treatment and maintained the response. The median follow-up was 8.1 months (range, 7.2 to 10.6 months).

Ninety-one percent of patients were platelet-transfusion-dependent at baseline. Patients who responded to eltrombopag did not require platelet transfusions for a median of 200 days (range, 8 to 1096 days).

Eighty-six percent of patients were RBC-transfusion-dependent at baseline. Patients who responded to eltrombopag did not require RBC transfusions for a median of 208 days (range, 15 to 1082 days).

The most common adverse events (≥20%) associated with eltrombopag were nausea (33%), fatigue (28%), cough (23%), diarrhea (21%), and headache (21%).

Patients were also evaluated for cytogenetic abnormalities. Eight patients had a new cytogenetic abnormality after treatment, including 5 patients who had complex changes in chromosome 7.

Patients who develop new cytogenetic abnormalities while on eltrombopag may need to be taken off treatment.

About eltrombopag

Eltrombopag is already approved to treat SAA in the US and Canada. The drug recently gained approval in the US to treat children age 1 and older who have chronic immune thrombocytopenia and have had an insufficient response to corticosteroids, immunoglobulins, or splenectomy.

Eltrombopag is approved in more than 100 countries to treat adults with chronic immune thrombocytopenia who have had an inadequate response to or are intolerant of other treatments.

The drug is approved in more than 45 countries for the treatment of thrombocytopenia in patients with chronic hepatitis C to allow them to initiate and maintain interferon-based therapy.

Eltrombopag is marketed under the brand name Promacta in the US and Revolade in most other countries. For more details on the drug, see the European Medicines Agency’s Summary of Product Characteristics. ![]()

The European Commission has approved eltrombopag (Revolade) for the treatment of adults with severe aplastic anemia (SAA) who were either refractory to prior immunosuppressive therapy or heavily pretreated and are unsuitable for hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

Eltrombopag is the first therapy approved in the European Union (EU) for this patient population.

The approval applies to all 28 EU member states plus Iceland, Norway, and Liechtenstein.

Trials of eltrombopag in SAA

The European Commission’s approval is based primarily on results of a phase 2 pilot study (NCT00922883) conducted by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute at the National Institutes of Health.

Results from the ongoing study were published in NEJM in 2012 and Blood in 2013. The trial has enrolled 43 patients with SAA who had an insufficient response to at least 1 prior immunosuppressive therapy and who had a platelet count of 30 x 109/L or less.

At baseline, the median platelet count was 20 x 109/L, hemoglobin was 8.4 g/dL, the absolute neutrophil count was 0.58 x 109/L, and absolute reticulocyte count was 24.3 x 109/L.

Patients had a median age of 45 (range, 17 to 77), and 56% were male. The majority of patients (84%) had received at least 2 prior immunosuppressive therapies.

Patients received eltrombopag at an initial dose of 50 mg once daily for 2 weeks. The dose increased over 2-week periods to a maximum of 150 mg once daily.

The study’s primary endpoint was hematologic response, which was initially assessed after 12 weeks of treatment. Treatment was discontinued after 16 weeks in patients who did not exhibit a hematologic response.

Forty percent of patients (n=17) experienced a hematologic response in at least 1 lineage—platelets, red blood cells (RBCs), or white blood cells—after week 12.

In the extension phase of the study, 8 patients achieved a multilineage response. Four of these patients subsequently tapered off treatment and maintained the response. The median follow-up was 8.1 months (range, 7.2 to 10.6 months).

Ninety-one percent of patients were platelet-transfusion-dependent at baseline. Patients who responded to eltrombopag did not require platelet transfusions for a median of 200 days (range, 8 to 1096 days).

Eighty-six percent of patients were RBC-transfusion-dependent at baseline. Patients who responded to eltrombopag did not require RBC transfusions for a median of 208 days (range, 15 to 1082 days).

The most common adverse events (≥20%) associated with eltrombopag were nausea (33%), fatigue (28%), cough (23%), diarrhea (21%), and headache (21%).

Patients were also evaluated for cytogenetic abnormalities. Eight patients had a new cytogenetic abnormality after treatment, including 5 patients who had complex changes in chromosome 7.

Patients who develop new cytogenetic abnormalities while on eltrombopag may need to be taken off treatment.

About eltrombopag

Eltrombopag is already approved to treat SAA in the US and Canada. The drug recently gained approval in the US to treat children age 1 and older who have chronic immune thrombocytopenia and have had an insufficient response to corticosteroids, immunoglobulins, or splenectomy.

Eltrombopag is approved in more than 100 countries to treat adults with chronic immune thrombocytopenia who have had an inadequate response to or are intolerant of other treatments.

The drug is approved in more than 45 countries for the treatment of thrombocytopenia in patients with chronic hepatitis C to allow them to initiate and maintain interferon-based therapy.

Eltrombopag is marketed under the brand name Promacta in the US and Revolade in most other countries. For more details on the drug, see the European Medicines Agency’s Summary of Product Characteristics. ![]()

Liraglutide Produces Clinically Significant Weight Loss in Nondiabetic Patients, But At What Cost?

Study Overview

Objective. To evaluate the efficacy of liraglutide for weight loss in a group of nondiabetic patients with obesity.

Design. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial.

Setting and participants. This trial took place across 27 countries in Europe, North America, South America, Asia, Africa and Australia. It was funded by NovoNordisk, the pharmaceutical company that manufactures liraglutide. Participants were 18 years or older, with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 (or 27 kg/m2 with hypertension or dyslipidemia). Patients with diabetes, those on medications known to induce weight gain (or loss), those with history of bariatric surgery, and those with psychiatric illness were excluded from participating. Patients with prediabetes were not excluded.

Intervention. Participants were randomized (2:1 in favor of study drug) to liraglutide or placebo, stratified according to BMI category and pre-diabetes status. They were started at a 0.6–mg dose of medication and up-titrated as tolerated to a dose of 3.0 mg over several weeks. All received counseling on behavioral changes to promote weight loss. Participants were then followed for 56 weeks. A small subgroup in the liraglutide arm was randomly assigned to switch to placebo after 12 weeks on medication to examine for durability of effect of medication, and to evaluate for safety issues that might occur on drug discontinuation.

Main outcome measures. This study focused on 3 primary outcomes: individual-level weight change from baseline, group-level percentage of participants achieving at least 5% weight loss, and percentage of participants with at least 10% weight loss, all assessed at 56 weeks.

Secondary outcomes included change in BMI, waist circumference, markers of glycemia (hemoglobin A1c, insulin level), markers of cardiometabolic health (blood pressure, lipids, CRP), and health-related quality of life (using several validated survey measures). Adverse events were also assessed.

The investigators used an intention-to-treat analysis, comparing outcomes among all patients who were randomized and received at least 1 dose of liraglutide or placebo. For patients with missing values (eg, due to dropout), outcome values were imputed using the last-observation-carried-forward method. A multivariable analysis of covariance model was used to analyze changes in the primary outcomes and included a covariate for the baseline measure of the outcome in question. Sensitivity analyses were conducted in which the investigators used different imputation techniques (multiple imputation, repeated measures) to account for missing data.

Results. The trial enrolled 3731 participants, 2487 of whom were randomized to receive liraglutide and 1244 of whom received placebo. The groups were similar on measured baseline characteristics, with a mean age of 45 years, mostly female participants (78.7% in liraglutide arm, 78.1% in placebo), and the vast majority of participants identified as “white” race/ethnicity (84.7% in liraglutide, 85.3% in placebo). Mean baseline BMI was 38.3 kg/m2 in both groups. Although overweight patients with BMI 27 kg/m2 or greater were included, they represented a small fraction of all participants (2.7% in liraglutide group and 3.5% in placebo group). Furthermore, although patients with overt diabetes were excluded from participating, over half of the participants qualified as having prediabetes (61.4% in liraglutide group, 60.9% in placebo group). Just over one-third (34.2% of liraglutide group, 35.9% placebo) had hypertension diagnosed at baseline. Study withdrawal was relatively substantial in both groups – 71.9% remained enrolled at 56 weeks in the liraglutide group, and 64.4% remained in the placebo arm. The investigators note that withdrawal due to adverse events was more common in the liraglutide group (9.9% of withdrawals vs. 3.8% in placebo), while other reasons for withdrawing (ineffective therapy, withdrawal of consent) were more common among placebo participants.

Liraglutide participants lost significantly more weight than placebo participants at 56 weeks (mean [SD] 8.0 [6.7] kg vs. 2.6 [5.7] kg). Similarly, more patients in the liraglutide group achieved at least 5% weight loss (63% vs. 27%), and 10% weight loss (33.1% vs. 10.6%) than those taking placebo. When subgroups of patients were examined according to baseline BMI, the investigators suggested that liraglutide appeared to be more effective at promoting weight loss among patients starting below 40 kg/m2.

Hemoglobin A1c dropped significantly more (–0.23 points, P < 0.001) among liraglutide participants than among placebo participants. Similarly, fasting insulin levels dropped by 8% more (P < 0.001) in the liraglutide group at 56 weeks. In keeping with the greater weight loss, markers of cardiometabolic health also improved to a greater extent among liraglutide participants, with larger decreases in blood pressure (SBP –2.8 mm Hg lower in liraglutide, P < 0.001), and LDL (–2.4% difference, P = 0.002), and a larger increase in HDL (1.9% difference, P = 0.001). By week 56, 14% of prediabetic patients in the placebo arm had received a new diagnosis of diabetes, compared to just 4% in the liraglutide group (P < 0.001).

Quality of life scores were higher for liraglutide participants on all included measures except those related to side effects of treatment, where placebo participants reported lower levels of side effects. The most common side effects reported by liraglutide participants related to GI upset, including nausea (40%), diarrhea (21%), and vomiting (16%). More serious events, including cholelithiasis (0.8%), cholecystitis (0.5%), and pancreatitis (0.2%), were also reported. Somewhat surprisingly, although liraglutide is also used to improve glycemic control in diabetics, rates of reported spontaneous hypoglycemia were fairly low in the liraglutide group (1.3% vs. 1.0% in placebo).

Conclusion. Liraglutide given at a dose of 3.0 mg daily, along with lifestyle advice, produces clinically significant weight loss and improvement in glycemic and cardiometabolic parameters that is sustained after 1 full year of treatment.

Commentary

Over the past few years, the FDA has approved a growing list of medications for the treatment of obesity [1,2]. Unlike the prior mainstay for prescription weight management, phentermine, which can only be used for a few months at a time due to concerns about abuse, many of these newer medications are approved for long-term use, aligning well with the growing recognition of obesity as a chronic illness. Interestingly, most of the drugs that have emerged onto the market do not represent novel compounds, but rather are existing drugs that have been repurposed and repackaged for the indication of weight management. These “recycled” medications include Qsymia (a mix of phentermine and topiramate) [1], Contrave (naltrexone and buproprion) [2], and now, Saxenda (liraglutide, also marketed as Victoza for treatment of type 2 diabetes). Liraglutide is a glucagon-like-peptide 1 (GLP-1) analogue, meaning it has an effect similar to that of GLP-1, a gut hormone that stimulates insulin secretion, inhibits pancreatic beta cell apoptosis, inhibits gastric emptying, and decreases appetite by acting on the brain’s satiety centers [3]. For several years, endocrinologists and some internists have been using liraglutide (Victoza) to help with glycemic control in diabetics, with the known benefit that, unlike some other diabetes medications, it tends to promote modest weight loss [4].

In this large multicenter trial, Pi-Sunyer et al evaluated the efficacy of liraglutide at a 3.0 mg daily dose (almost twice the dose used for diabetes) for weight management. The trial utilized a strong study design, with double blinding, randomization of a subgroup for early discontinuation (to evaluate for weight regain and stopping-related side effects), and, importantly, the intervention for both groups also included a behavior change component (albeit one of relatively low intensity, based on the limited description). Patients were followed for 56 weeks on the medication, making the “intervention” phase of the study longer than what has been done in many diet trials. Testing for a long-lasting impact on weight, and at the same time attempting to quantify risks associated with longer-term use of a medication, was an important contribution for this study given that liraglutide is being marketed for long-term use.

After a year on liraglutide, participants in that group had lost around 12 lb more, on average, than those using placebo, and had achieved greater improvements cardiometabolic risk markers, with a much lower risk of developing diabetes. While these findings are promising from a clinical standpoint, it is not clear whether the moderate health impacts of this drug will be sufficient to outweigh several issues that may impede its widespread use in practice. The rate of GI side effects (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea) in liraglutide participants was fairly high, and it is worth considering whether the side effects themselves could have been driving some of the weight loss observed in that group. Furthermore, the out of pocket cost of this medication, when used for weight loss in nondiabetics, is likely to be around $1000 per month. For most patients, this high price will prohibit longer-term use of liraglutide. Even in the setting of a trial where participants faced no out of pocket costs, almost one-third in the liraglutide arm did not complete a year of treatment. On a related note, the primary analysis for this trial used a “last observation carried forward” approach—somewhat concerning given that patients are likely to regain weight after stopping any weight loss intervention, pharmaceutical or otherwise. The authors do report that a range of sensitivity analyses with varying imputation techniques were conducted and did not change the main conclusions of the trial.

Despite the promising findings from this trial, several important clinical questions remain. What is the durability of health effects for patients who discontinue the medication after a year? What safety concerns may arise in those who can afford to continue using liraglutide at this higher dose for several years? A 2-year follow-up study on participants from the current trial has been completed and those results are expected soon, which may help to shed light on some of these issues [5]. Cost-effectiveness evaluations, and head-to-head comparisons of liraglutide with lower cost weight management options would also be very helpful for clinicians presenting a range of treatment options to patients with obesity.

Applications for Clinical Practice

Liraglutide at a daily dose of 3.0 mg represents a new option for treatment of patients with obesity. It should be used in conjunction with behavioral interventions that promote a more healthful diet and increased physical activity, and may result in clinically meaningful weight loss and decreased risk of diabetes. On the other hand, the medication is costly and associated with some unpleasant GI side effects, both important factors that may limit patients’ ability to use it in the long-term. More studies are needed to establish durability of effects and safety beyond a year and that offer direct comparisons with other evidence-based weight loss tools, pharmaceutical and otherwise.

—Kristina Lewis, MD, MPH

1. Bray GA, Ryan DH. Update on obesity pharmacotherapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2014;1311:1–13.

2. Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Naltrexone extended-release plus bupropion extended-release for treatment of obesity. JAMA 2015;313:1213–4.

3. de Mello AH, Pra M, Cardoso LC, de Bona Schraiber R, Rezin GT. Incretin-based therapies for obesity treatment. Metabolism 23 May 2015.

4. Prasad-Reddy L, Isaacs D. A clinical review of GLP-1 receptor agonists: efficacy and safety in diabetes and beyond. Drugs Context 2015;4:212283.

5. Siraj ES, Williams KJ. Another agent for obesity—will this time be different? N Engl J Med 2015;373:82–3.

Study Overview

Objective. To evaluate the efficacy of liraglutide for weight loss in a group of nondiabetic patients with obesity.

Design. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial.

Setting and participants. This trial took place across 27 countries in Europe, North America, South America, Asia, Africa and Australia. It was funded by NovoNordisk, the pharmaceutical company that manufactures liraglutide. Participants were 18 years or older, with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 (or 27 kg/m2 with hypertension or dyslipidemia). Patients with diabetes, those on medications known to induce weight gain (or loss), those with history of bariatric surgery, and those with psychiatric illness were excluded from participating. Patients with prediabetes were not excluded.

Intervention. Participants were randomized (2:1 in favor of study drug) to liraglutide or placebo, stratified according to BMI category and pre-diabetes status. They were started at a 0.6–mg dose of medication and up-titrated as tolerated to a dose of 3.0 mg over several weeks. All received counseling on behavioral changes to promote weight loss. Participants were then followed for 56 weeks. A small subgroup in the liraglutide arm was randomly assigned to switch to placebo after 12 weeks on medication to examine for durability of effect of medication, and to evaluate for safety issues that might occur on drug discontinuation.

Main outcome measures. This study focused on 3 primary outcomes: individual-level weight change from baseline, group-level percentage of participants achieving at least 5% weight loss, and percentage of participants with at least 10% weight loss, all assessed at 56 weeks.

Secondary outcomes included change in BMI, waist circumference, markers of glycemia (hemoglobin A1c, insulin level), markers of cardiometabolic health (blood pressure, lipids, CRP), and health-related quality of life (using several validated survey measures). Adverse events were also assessed.

The investigators used an intention-to-treat analysis, comparing outcomes among all patients who were randomized and received at least 1 dose of liraglutide or placebo. For patients with missing values (eg, due to dropout), outcome values were imputed using the last-observation-carried-forward method. A multivariable analysis of covariance model was used to analyze changes in the primary outcomes and included a covariate for the baseline measure of the outcome in question. Sensitivity analyses were conducted in which the investigators used different imputation techniques (multiple imputation, repeated measures) to account for missing data.

Results. The trial enrolled 3731 participants, 2487 of whom were randomized to receive liraglutide and 1244 of whom received placebo. The groups were similar on measured baseline characteristics, with a mean age of 45 years, mostly female participants (78.7% in liraglutide arm, 78.1% in placebo), and the vast majority of participants identified as “white” race/ethnicity (84.7% in liraglutide, 85.3% in placebo). Mean baseline BMI was 38.3 kg/m2 in both groups. Although overweight patients with BMI 27 kg/m2 or greater were included, they represented a small fraction of all participants (2.7% in liraglutide group and 3.5% in placebo group). Furthermore, although patients with overt diabetes were excluded from participating, over half of the participants qualified as having prediabetes (61.4% in liraglutide group, 60.9% in placebo group). Just over one-third (34.2% of liraglutide group, 35.9% placebo) had hypertension diagnosed at baseline. Study withdrawal was relatively substantial in both groups – 71.9% remained enrolled at 56 weeks in the liraglutide group, and 64.4% remained in the placebo arm. The investigators note that withdrawal due to adverse events was more common in the liraglutide group (9.9% of withdrawals vs. 3.8% in placebo), while other reasons for withdrawing (ineffective therapy, withdrawal of consent) were more common among placebo participants.

Liraglutide participants lost significantly more weight than placebo participants at 56 weeks (mean [SD] 8.0 [6.7] kg vs. 2.6 [5.7] kg). Similarly, more patients in the liraglutide group achieved at least 5% weight loss (63% vs. 27%), and 10% weight loss (33.1% vs. 10.6%) than those taking placebo. When subgroups of patients were examined according to baseline BMI, the investigators suggested that liraglutide appeared to be more effective at promoting weight loss among patients starting below 40 kg/m2.

Hemoglobin A1c dropped significantly more (–0.23 points, P < 0.001) among liraglutide participants than among placebo participants. Similarly, fasting insulin levels dropped by 8% more (P < 0.001) in the liraglutide group at 56 weeks. In keeping with the greater weight loss, markers of cardiometabolic health also improved to a greater extent among liraglutide participants, with larger decreases in blood pressure (SBP –2.8 mm Hg lower in liraglutide, P < 0.001), and LDL (–2.4% difference, P = 0.002), and a larger increase in HDL (1.9% difference, P = 0.001). By week 56, 14% of prediabetic patients in the placebo arm had received a new diagnosis of diabetes, compared to just 4% in the liraglutide group (P < 0.001).

Quality of life scores were higher for liraglutide participants on all included measures except those related to side effects of treatment, where placebo participants reported lower levels of side effects. The most common side effects reported by liraglutide participants related to GI upset, including nausea (40%), diarrhea (21%), and vomiting (16%). More serious events, including cholelithiasis (0.8%), cholecystitis (0.5%), and pancreatitis (0.2%), were also reported. Somewhat surprisingly, although liraglutide is also used to improve glycemic control in diabetics, rates of reported spontaneous hypoglycemia were fairly low in the liraglutide group (1.3% vs. 1.0% in placebo).

Conclusion. Liraglutide given at a dose of 3.0 mg daily, along with lifestyle advice, produces clinically significant weight loss and improvement in glycemic and cardiometabolic parameters that is sustained after 1 full year of treatment.

Commentary

Over the past few years, the FDA has approved a growing list of medications for the treatment of obesity [1,2]. Unlike the prior mainstay for prescription weight management, phentermine, which can only be used for a few months at a time due to concerns about abuse, many of these newer medications are approved for long-term use, aligning well with the growing recognition of obesity as a chronic illness. Interestingly, most of the drugs that have emerged onto the market do not represent novel compounds, but rather are existing drugs that have been repurposed and repackaged for the indication of weight management. These “recycled” medications include Qsymia (a mix of phentermine and topiramate) [1], Contrave (naltrexone and buproprion) [2], and now, Saxenda (liraglutide, also marketed as Victoza for treatment of type 2 diabetes). Liraglutide is a glucagon-like-peptide 1 (GLP-1) analogue, meaning it has an effect similar to that of GLP-1, a gut hormone that stimulates insulin secretion, inhibits pancreatic beta cell apoptosis, inhibits gastric emptying, and decreases appetite by acting on the brain’s satiety centers [3]. For several years, endocrinologists and some internists have been using liraglutide (Victoza) to help with glycemic control in diabetics, with the known benefit that, unlike some other diabetes medications, it tends to promote modest weight loss [4].

In this large multicenter trial, Pi-Sunyer et al evaluated the efficacy of liraglutide at a 3.0 mg daily dose (almost twice the dose used for diabetes) for weight management. The trial utilized a strong study design, with double blinding, randomization of a subgroup for early discontinuation (to evaluate for weight regain and stopping-related side effects), and, importantly, the intervention for both groups also included a behavior change component (albeit one of relatively low intensity, based on the limited description). Patients were followed for 56 weeks on the medication, making the “intervention” phase of the study longer than what has been done in many diet trials. Testing for a long-lasting impact on weight, and at the same time attempting to quantify risks associated with longer-term use of a medication, was an important contribution for this study given that liraglutide is being marketed for long-term use.

After a year on liraglutide, participants in that group had lost around 12 lb more, on average, than those using placebo, and had achieved greater improvements cardiometabolic risk markers, with a much lower risk of developing diabetes. While these findings are promising from a clinical standpoint, it is not clear whether the moderate health impacts of this drug will be sufficient to outweigh several issues that may impede its widespread use in practice. The rate of GI side effects (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea) in liraglutide participants was fairly high, and it is worth considering whether the side effects themselves could have been driving some of the weight loss observed in that group. Furthermore, the out of pocket cost of this medication, when used for weight loss in nondiabetics, is likely to be around $1000 per month. For most patients, this high price will prohibit longer-term use of liraglutide. Even in the setting of a trial where participants faced no out of pocket costs, almost one-third in the liraglutide arm did not complete a year of treatment. On a related note, the primary analysis for this trial used a “last observation carried forward” approach—somewhat concerning given that patients are likely to regain weight after stopping any weight loss intervention, pharmaceutical or otherwise. The authors do report that a range of sensitivity analyses with varying imputation techniques were conducted and did not change the main conclusions of the trial.

Despite the promising findings from this trial, several important clinical questions remain. What is the durability of health effects for patients who discontinue the medication after a year? What safety concerns may arise in those who can afford to continue using liraglutide at this higher dose for several years? A 2-year follow-up study on participants from the current trial has been completed and those results are expected soon, which may help to shed light on some of these issues [5]. Cost-effectiveness evaluations, and head-to-head comparisons of liraglutide with lower cost weight management options would also be very helpful for clinicians presenting a range of treatment options to patients with obesity.

Applications for Clinical Practice

Liraglutide at a daily dose of 3.0 mg represents a new option for treatment of patients with obesity. It should be used in conjunction with behavioral interventions that promote a more healthful diet and increased physical activity, and may result in clinically meaningful weight loss and decreased risk of diabetes. On the other hand, the medication is costly and associated with some unpleasant GI side effects, both important factors that may limit patients’ ability to use it in the long-term. More studies are needed to establish durability of effects and safety beyond a year and that offer direct comparisons with other evidence-based weight loss tools, pharmaceutical and otherwise.

—Kristina Lewis, MD, MPH

Study Overview

Objective. To evaluate the efficacy of liraglutide for weight loss in a group of nondiabetic patients with obesity.

Design. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial.

Setting and participants. This trial took place across 27 countries in Europe, North America, South America, Asia, Africa and Australia. It was funded by NovoNordisk, the pharmaceutical company that manufactures liraglutide. Participants were 18 years or older, with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 (or 27 kg/m2 with hypertension or dyslipidemia). Patients with diabetes, those on medications known to induce weight gain (or loss), those with history of bariatric surgery, and those with psychiatric illness were excluded from participating. Patients with prediabetes were not excluded.

Intervention. Participants were randomized (2:1 in favor of study drug) to liraglutide or placebo, stratified according to BMI category and pre-diabetes status. They were started at a 0.6–mg dose of medication and up-titrated as tolerated to a dose of 3.0 mg over several weeks. All received counseling on behavioral changes to promote weight loss. Participants were then followed for 56 weeks. A small subgroup in the liraglutide arm was randomly assigned to switch to placebo after 12 weeks on medication to examine for durability of effect of medication, and to evaluate for safety issues that might occur on drug discontinuation.

Main outcome measures. This study focused on 3 primary outcomes: individual-level weight change from baseline, group-level percentage of participants achieving at least 5% weight loss, and percentage of participants with at least 10% weight loss, all assessed at 56 weeks.

Secondary outcomes included change in BMI, waist circumference, markers of glycemia (hemoglobin A1c, insulin level), markers of cardiometabolic health (blood pressure, lipids, CRP), and health-related quality of life (using several validated survey measures). Adverse events were also assessed.

The investigators used an intention-to-treat analysis, comparing outcomes among all patients who were randomized and received at least 1 dose of liraglutide or placebo. For patients with missing values (eg, due to dropout), outcome values were imputed using the last-observation-carried-forward method. A multivariable analysis of covariance model was used to analyze changes in the primary outcomes and included a covariate for the baseline measure of the outcome in question. Sensitivity analyses were conducted in which the investigators used different imputation techniques (multiple imputation, repeated measures) to account for missing data.

Results. The trial enrolled 3731 participants, 2487 of whom were randomized to receive liraglutide and 1244 of whom received placebo. The groups were similar on measured baseline characteristics, with a mean age of 45 years, mostly female participants (78.7% in liraglutide arm, 78.1% in placebo), and the vast majority of participants identified as “white” race/ethnicity (84.7% in liraglutide, 85.3% in placebo). Mean baseline BMI was 38.3 kg/m2 in both groups. Although overweight patients with BMI 27 kg/m2 or greater were included, they represented a small fraction of all participants (2.7% in liraglutide group and 3.5% in placebo group). Furthermore, although patients with overt diabetes were excluded from participating, over half of the participants qualified as having prediabetes (61.4% in liraglutide group, 60.9% in placebo group). Just over one-third (34.2% of liraglutide group, 35.9% placebo) had hypertension diagnosed at baseline. Study withdrawal was relatively substantial in both groups – 71.9% remained enrolled at 56 weeks in the liraglutide group, and 64.4% remained in the placebo arm. The investigators note that withdrawal due to adverse events was more common in the liraglutide group (9.9% of withdrawals vs. 3.8% in placebo), while other reasons for withdrawing (ineffective therapy, withdrawal of consent) were more common among placebo participants.

Liraglutide participants lost significantly more weight than placebo participants at 56 weeks (mean [SD] 8.0 [6.7] kg vs. 2.6 [5.7] kg). Similarly, more patients in the liraglutide group achieved at least 5% weight loss (63% vs. 27%), and 10% weight loss (33.1% vs. 10.6%) than those taking placebo. When subgroups of patients were examined according to baseline BMI, the investigators suggested that liraglutide appeared to be more effective at promoting weight loss among patients starting below 40 kg/m2.

Hemoglobin A1c dropped significantly more (–0.23 points, P < 0.001) among liraglutide participants than among placebo participants. Similarly, fasting insulin levels dropped by 8% more (P < 0.001) in the liraglutide group at 56 weeks. In keeping with the greater weight loss, markers of cardiometabolic health also improved to a greater extent among liraglutide participants, with larger decreases in blood pressure (SBP –2.8 mm Hg lower in liraglutide, P < 0.001), and LDL (–2.4% difference, P = 0.002), and a larger increase in HDL (1.9% difference, P = 0.001). By week 56, 14% of prediabetic patients in the placebo arm had received a new diagnosis of diabetes, compared to just 4% in the liraglutide group (P < 0.001).

Quality of life scores were higher for liraglutide participants on all included measures except those related to side effects of treatment, where placebo participants reported lower levels of side effects. The most common side effects reported by liraglutide participants related to GI upset, including nausea (40%), diarrhea (21%), and vomiting (16%). More serious events, including cholelithiasis (0.8%), cholecystitis (0.5%), and pancreatitis (0.2%), were also reported. Somewhat surprisingly, although liraglutide is also used to improve glycemic control in diabetics, rates of reported spontaneous hypoglycemia were fairly low in the liraglutide group (1.3% vs. 1.0% in placebo).

Conclusion. Liraglutide given at a dose of 3.0 mg daily, along with lifestyle advice, produces clinically significant weight loss and improvement in glycemic and cardiometabolic parameters that is sustained after 1 full year of treatment.

Commentary

Over the past few years, the FDA has approved a growing list of medications for the treatment of obesity [1,2]. Unlike the prior mainstay for prescription weight management, phentermine, which can only be used for a few months at a time due to concerns about abuse, many of these newer medications are approved for long-term use, aligning well with the growing recognition of obesity as a chronic illness. Interestingly, most of the drugs that have emerged onto the market do not represent novel compounds, but rather are existing drugs that have been repurposed and repackaged for the indication of weight management. These “recycled” medications include Qsymia (a mix of phentermine and topiramate) [1], Contrave (naltrexone and buproprion) [2], and now, Saxenda (liraglutide, also marketed as Victoza for treatment of type 2 diabetes). Liraglutide is a glucagon-like-peptide 1 (GLP-1) analogue, meaning it has an effect similar to that of GLP-1, a gut hormone that stimulates insulin secretion, inhibits pancreatic beta cell apoptosis, inhibits gastric emptying, and decreases appetite by acting on the brain’s satiety centers [3]. For several years, endocrinologists and some internists have been using liraglutide (Victoza) to help with glycemic control in diabetics, with the known benefit that, unlike some other diabetes medications, it tends to promote modest weight loss [4].

In this large multicenter trial, Pi-Sunyer et al evaluated the efficacy of liraglutide at a 3.0 mg daily dose (almost twice the dose used for diabetes) for weight management. The trial utilized a strong study design, with double blinding, randomization of a subgroup for early discontinuation (to evaluate for weight regain and stopping-related side effects), and, importantly, the intervention for both groups also included a behavior change component (albeit one of relatively low intensity, based on the limited description). Patients were followed for 56 weeks on the medication, making the “intervention” phase of the study longer than what has been done in many diet trials. Testing for a long-lasting impact on weight, and at the same time attempting to quantify risks associated with longer-term use of a medication, was an important contribution for this study given that liraglutide is being marketed for long-term use.

After a year on liraglutide, participants in that group had lost around 12 lb more, on average, than those using placebo, and had achieved greater improvements cardiometabolic risk markers, with a much lower risk of developing diabetes. While these findings are promising from a clinical standpoint, it is not clear whether the moderate health impacts of this drug will be sufficient to outweigh several issues that may impede its widespread use in practice. The rate of GI side effects (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea) in liraglutide participants was fairly high, and it is worth considering whether the side effects themselves could have been driving some of the weight loss observed in that group. Furthermore, the out of pocket cost of this medication, when used for weight loss in nondiabetics, is likely to be around $1000 per month. For most patients, this high price will prohibit longer-term use of liraglutide. Even in the setting of a trial where participants faced no out of pocket costs, almost one-third in the liraglutide arm did not complete a year of treatment. On a related note, the primary analysis for this trial used a “last observation carried forward” approach—somewhat concerning given that patients are likely to regain weight after stopping any weight loss intervention, pharmaceutical or otherwise. The authors do report that a range of sensitivity analyses with varying imputation techniques were conducted and did not change the main conclusions of the trial.

Despite the promising findings from this trial, several important clinical questions remain. What is the durability of health effects for patients who discontinue the medication after a year? What safety concerns may arise in those who can afford to continue using liraglutide at this higher dose for several years? A 2-year follow-up study on participants from the current trial has been completed and those results are expected soon, which may help to shed light on some of these issues [5]. Cost-effectiveness evaluations, and head-to-head comparisons of liraglutide with lower cost weight management options would also be very helpful for clinicians presenting a range of treatment options to patients with obesity.

Applications for Clinical Practice

Liraglutide at a daily dose of 3.0 mg represents a new option for treatment of patients with obesity. It should be used in conjunction with behavioral interventions that promote a more healthful diet and increased physical activity, and may result in clinically meaningful weight loss and decreased risk of diabetes. On the other hand, the medication is costly and associated with some unpleasant GI side effects, both important factors that may limit patients’ ability to use it in the long-term. More studies are needed to establish durability of effects and safety beyond a year and that offer direct comparisons with other evidence-based weight loss tools, pharmaceutical and otherwise.

—Kristina Lewis, MD, MPH

1. Bray GA, Ryan DH. Update on obesity pharmacotherapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2014;1311:1–13.

2. Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Naltrexone extended-release plus bupropion extended-release for treatment of obesity. JAMA 2015;313:1213–4.

3. de Mello AH, Pra M, Cardoso LC, de Bona Schraiber R, Rezin GT. Incretin-based therapies for obesity treatment. Metabolism 23 May 2015.

4. Prasad-Reddy L, Isaacs D. A clinical review of GLP-1 receptor agonists: efficacy and safety in diabetes and beyond. Drugs Context 2015;4:212283.

5. Siraj ES, Williams KJ. Another agent for obesity—will this time be different? N Engl J Med 2015;373:82–3.

1. Bray GA, Ryan DH. Update on obesity pharmacotherapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2014;1311:1–13.

2. Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Naltrexone extended-release plus bupropion extended-release for treatment of obesity. JAMA 2015;313:1213–4.

3. de Mello AH, Pra M, Cardoso LC, de Bona Schraiber R, Rezin GT. Incretin-based therapies for obesity treatment. Metabolism 23 May 2015.

4. Prasad-Reddy L, Isaacs D. A clinical review of GLP-1 receptor agonists: efficacy and safety in diabetes and beyond. Drugs Context 2015;4:212283.

5. Siraj ES, Williams KJ. Another agent for obesity—will this time be different? N Engl J Med 2015;373:82–3.

A Multipronged Approach to Decrease the Risk of Clostridium difficile Infection at a Community Hospital and Long-Term Care Facility

From Sharp HealthCare, San Diego, CA.

Abstract

- Objective: To examine the relationship between the rate of Clostridium difficile infections (CDI) and implementation of 3 interventions aimed at preserving the fecal microbiome: (1) reduction of antimicrobial pressure; (2) reduction in intensity of gastrointestinal prophylaxis with proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs); and (3) expansion of probiotic therapy.

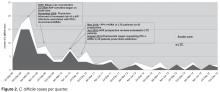

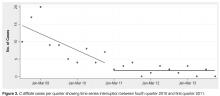

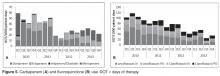

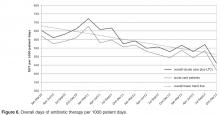

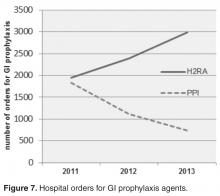

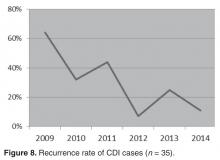

- Methods: We conducted a retrospective analysis of all inpatients with CDI between January 2009 and December 2013 receiving care at our community hospital and associated long-term care (LTC) facility. We used interrupted time series analysis to assess CDI rates during the implementation phase (2008–2010) and the postimplementation phase (2011–2013).

- Results: A reduction in the rate of health care facility–associated CDIs was seen. The mean number of cases per 10,000 patient days fell from 11.9 to 3.6 in acute care and 6.1 to 1.1 in LTC. Recurrence rates decreased from 64% in 2009 to 16% by 2014. The likelihood of CDI recurring was 3 times higher in those exposed to PPI and 0.35 times less likely in those who received probiotics with their initial CDI therapy.

- Conclusion: The risk of CDI incidence and recurrence was significantly reduced in our inpatients, with recurrent CDI associated with PPI use, multiple antibiotic courses, and lack of probiotics. We attribute our success to the combined effect of intensified antibiotic stewardship, reduced PPI use, and expanded probiotic use.

Clostridium difficile is classified as an urgent public health threat by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [1]. A recent study by the CDC found that it caused more than 400,000 infections in the United States in 2011, leading to over 29,000 deaths [2]. The costs of treating CDI are substantial and recurrences are common. While rates for many health care–associated infections are declining, C. difficile infection (CDI) rates remain at historically high levels [1] with the elderly at greatest risk for infection and mortality from the illness [3].