User login

A Picture Is Worth a Thousand Words: Unconscious Bias in the Residency Application Process?

Applying for a residency program can be a stressful process for medical students. It is a combination of applying for a job in the “real world” and applying to a college or medical school. In certain fields of medicine or surgery, there may be over 600 residency applications for 40 to 80 interviewee slots. Different specialties, as well as programs within a given specialty, take a different number of residents per year. This can vary from 1 to over 20 available spots, depending on the field of medicine or surgery as well as the specific program. Orthopedic surgery residencies, for example, can match between 2 and 12 residents each year. During the 2013–2014 academic year at our institution, there were over 600 applications received for approximately 50 interview slots for a class of 5 orthopedic surgery residents. Nationally, according to publicly available 2013 National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) data, a total of 1038 applicants (833 US medical school seniors) applied for 693 spots in orthopedic surgery, of which 692 were filled, indicating that orthopedic surgery remains one of the most desired fields among medical school seniors.1 Looking at the statistics provided by the NRMP data, orthopedic applicants remain some of the most competitive, with proportionally higher board scores, publication numbers, and grades, among other factors.1

Each individual program has its own method for sifting through the applications. At some institutions, the individual “in charge” of the selection committee may look through all applications initially, narrow them down, and then distribute them to the other members of the selection committee to determine the final interviewee list. At other institutions, the initial group of applications may be divided and distributed to the committee members so that each member reviews the applications and ultimately decides upon the interview candidates.

The Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) application includes the applicant’s name, birth city, current place of residence, education history, standardized test scores, grades achieved during medical school, letters of recommendation, personal statement, extracurricular activities, volunteer activities, research experience, and languages spoken, along with several other pieces of data, all intended to be able to give the committee a better understanding of the applicant. Interestingly, however, the application also includes a photograph of the applicant.

Countless authors have demonstrated that we make assumptions and reach conclusions without even being aware that this is occurring. This is the theory of “unconscious bias.”2-5 Unconscious bias applies to how we perceive other people, and occurs when subconscious beliefs or unrecognized stereotypes about specific characteristics, including gender, ethnicity, religion, socioeconomic status, age, and sexual orientation, result in an automatic and unconscious reaction and/or behavior.6 Unconscious bias has the ability to affect everything from how health care is delivered to how employees are hired.7-12 We are all biased, and becoming aware of our biases will help us mitigate them in the workplace.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 requires that employers rely solely on job-related qualifications, and not physical characteristics, in their interviewing and hiring process. The US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), the federal agency that enforces Title VII, includes asking for photographs during the application stage on its list of prohibited practices for employers.13 It is our belief that including a photograph in the ERAS application, prior to the selection of interview candidates, may produce unconscious bias in the decision for granting (or not granting) an interview, and this component of the application should be eliminated.

Using a wide spectrum of cultural backgrounds in employers, Dion and colleagues14 demonstrated that the “what is beautiful is good” bias is present in all cultures when prospective employees are closely matched in qualification. Attractive individuals are thought to have better professional lives and stable marital relationships and personalities, according to previous studies.14 There has been much research aimed at determining if physical attractiveness is a factor in hiring, and the evidence suggests that the more attractive the applicant is, the greater the chances of being hired.15 Specifically, Watkins and Johnston15 have found that attractive people are thought to have better personalities than less attractive people, and that a photograph can influence the hiring decision process.

Bradley Ruffle at Ben-Gurion University and Ze’ev Shtudiner at Ariel University looked at what happens when job hunters include photographs with their curricula vitae (CV), as is the norm in much of Europe and Asia.16 For over 2500 job postings, they sent 2 identical résumés: one with a photograph and one without a photograph. An equal number of male and female applicants were sent to each posting, as were an equal number of attractive and plain-looking photographs; applications without photographs were also sent as a control group. For men, the results were as expected: CVs of “attractive” men were more likely to elicit a response from the employer (19.7%) compared with those of no-picture men (13.7%) and plain-looking men (9.2%). Interestingly, men who were viewed as “plain-looking” were better off not including a photograph. For the female applicants, however, the results were unexpected: CVs of women without a picture elicited the highest response rate (16.6%), while CVs of “plain-looking” women (13.6%) and of “attractive” women (12.8%) were less likely to receive a response.16

It is an unfortunate reality that personal preference, bias, and, in some cases, discriminatory hiring practices all factor into the selection process.17 This is why, as described above, the EEOC includes asking for photographs during the application stage on its list of prohibited practices for employers.13 The EEOC website also states: “If needed for identification purposes, a photograph may be obtained after an offer of employment is made and accepted.”13 In the residency application scenario, once an applicant has been granted an interview, a photograph can be taken on the day of the interview. With so many interviewees, this may help the interviewers to remember the interviewee. At this point in the process, the applicant has already been granted the interview. The bias associated with merely looking at a photograph is thus eliminated. This is in accordance with Title VII and is clearly different than including a photograph in the initial application, which directly violates Title VII.

Reviewers of applicants may have an unconscious bias due to the applicant’s attractiveness, race, sex, ethnicity, etc. Other, subtler forms of bias may also be present. Without realizing it, people may judge the quality of the photograph, or even what the applicant was wearing in the photograph. In orthopedic surgery, for example, there may be bias in the “size” of the applicant regardless of sex. Reviewers may unconsciously think how is he/she going to hold the leg, cut a rod, reduce a hip, etc. Without even realizing it, this may sway the person reviewing the application to choose one applicant over another. This may occur regardless of the applicant’s actual qualifications as based on the previously described factors, including test scores, grades during medical school, letters of recommendation, personal statement, extracurricular activities, volunteer activities, and research experience.

Unconscious bias is present in everyone. In an ideal world, one would be able to eliminate all sources of unconscious bias in the application process. Bias due to attending an Ivy League school versus a state school, bias due to where the applicant is from, bias due to who wrote the letter of recommendation, along with various other sources of unconscious bias, would be able to be eliminated. Unfortunately, this is not possible. What is possible, however, is to remove the photograph from the application process and to comply with Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

1. National Resident Matching Program, Data Release and Research Committee. Results of the 2013 NRMP Applicant Survey by Preferred Specialty and Applicant Type. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; 2013. www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/applicantresultsbyspecialty2013.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2015.

2. Santry HP, Wren SM. The role of unconscious bias in surgical safety and outcomes. Surg Clin North Am. 2012;92(1):137–151.

3. Greenwald AG, McGhee DE, Schwartz JL. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: the implicit association test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74(6):1464–1480.

4. Greenwald AG, Poehlman TA, Uhlmann EL, Banaji MR. Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: III. Meta-analysis of predictive validity. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;97(1):17–41.

5. Plessner H, Banse R. Attitude measurement using the Implicit Association Test (IAT). Z Exp Psychol. 2001;48(2):82–84.

6. Chapman EN, Kaatz A, Carnes M. Physicians and implicit bias: how doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(11):1504–1510.

7. What you don’t know: the science of unconscious bias and what to do about it in the search and recruitment process [e-learning seminar]. Association of American Medical Colleges website. https://www.aamc.org/members/leadership/catalog/178420/unconscious_bias.html. Accessed July 14, 2015.

8. Haider AH, Schneider EB, Sriram N, et al. Unconscious race and class bias: its association with decision making by trauma and acute care surgeons. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77(3):409–416.

9. Blair IV, Steiner JF, Hanratty R, et al. An investigation of associations between clinicians’ ethnic or racial bias and hypertension treatment, medication adherence and blood pressure control. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):987–995.

10. Ravenell J, Ogedegbe G. Unconscious bias and real-world hypertension outcomes: advancing disparities research. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):973–975.

11. van Ryn M, Saha S. Exploring unconscious bias in disparities research and medical education. JAMA. 2011;306(9):995–996.

12. Puhl RM, Moss-Racusin CA, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Weight stigmatization and bias reduction: perspectives of overweight and obese adults. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(2):347–358.

13. Prohibited employment policies/practices. US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission website. http://www.eeoc.gov/laws/practices/. Accessed July 14, 2015.

14. Dion K, Berscheid E, Walster E. What is beautiful is good. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1972;24(3):285–290.

15. Watkins LM, Johnston L. Screening job applicants: the impact of physical attractiveness and application quality. Int J Selection Assess. 2000;8(2):76–84.

16. Ruffle BJ, Shtudiner Z. Are good-looking people more employable? Manage Sci. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2014.1927. Published May 29, 2014. Accessed July 14, 2015.

17. Lemay EP Jr, Clark MS, Greenberg A. What is beautiful is good because what is beautiful is desired: physical attractiveness stereotyping as projection of interpersonal goals. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2010;36(3):339–353.

Applying for a residency program can be a stressful process for medical students. It is a combination of applying for a job in the “real world” and applying to a college or medical school. In certain fields of medicine or surgery, there may be over 600 residency applications for 40 to 80 interviewee slots. Different specialties, as well as programs within a given specialty, take a different number of residents per year. This can vary from 1 to over 20 available spots, depending on the field of medicine or surgery as well as the specific program. Orthopedic surgery residencies, for example, can match between 2 and 12 residents each year. During the 2013–2014 academic year at our institution, there were over 600 applications received for approximately 50 interview slots for a class of 5 orthopedic surgery residents. Nationally, according to publicly available 2013 National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) data, a total of 1038 applicants (833 US medical school seniors) applied for 693 spots in orthopedic surgery, of which 692 were filled, indicating that orthopedic surgery remains one of the most desired fields among medical school seniors.1 Looking at the statistics provided by the NRMP data, orthopedic applicants remain some of the most competitive, with proportionally higher board scores, publication numbers, and grades, among other factors.1

Each individual program has its own method for sifting through the applications. At some institutions, the individual “in charge” of the selection committee may look through all applications initially, narrow them down, and then distribute them to the other members of the selection committee to determine the final interviewee list. At other institutions, the initial group of applications may be divided and distributed to the committee members so that each member reviews the applications and ultimately decides upon the interview candidates.

The Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) application includes the applicant’s name, birth city, current place of residence, education history, standardized test scores, grades achieved during medical school, letters of recommendation, personal statement, extracurricular activities, volunteer activities, research experience, and languages spoken, along with several other pieces of data, all intended to be able to give the committee a better understanding of the applicant. Interestingly, however, the application also includes a photograph of the applicant.

Countless authors have demonstrated that we make assumptions and reach conclusions without even being aware that this is occurring. This is the theory of “unconscious bias.”2-5 Unconscious bias applies to how we perceive other people, and occurs when subconscious beliefs or unrecognized stereotypes about specific characteristics, including gender, ethnicity, religion, socioeconomic status, age, and sexual orientation, result in an automatic and unconscious reaction and/or behavior.6 Unconscious bias has the ability to affect everything from how health care is delivered to how employees are hired.7-12 We are all biased, and becoming aware of our biases will help us mitigate them in the workplace.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 requires that employers rely solely on job-related qualifications, and not physical characteristics, in their interviewing and hiring process. The US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), the federal agency that enforces Title VII, includes asking for photographs during the application stage on its list of prohibited practices for employers.13 It is our belief that including a photograph in the ERAS application, prior to the selection of interview candidates, may produce unconscious bias in the decision for granting (or not granting) an interview, and this component of the application should be eliminated.

Using a wide spectrum of cultural backgrounds in employers, Dion and colleagues14 demonstrated that the “what is beautiful is good” bias is present in all cultures when prospective employees are closely matched in qualification. Attractive individuals are thought to have better professional lives and stable marital relationships and personalities, according to previous studies.14 There has been much research aimed at determining if physical attractiveness is a factor in hiring, and the evidence suggests that the more attractive the applicant is, the greater the chances of being hired.15 Specifically, Watkins and Johnston15 have found that attractive people are thought to have better personalities than less attractive people, and that a photograph can influence the hiring decision process.

Bradley Ruffle at Ben-Gurion University and Ze’ev Shtudiner at Ariel University looked at what happens when job hunters include photographs with their curricula vitae (CV), as is the norm in much of Europe and Asia.16 For over 2500 job postings, they sent 2 identical résumés: one with a photograph and one without a photograph. An equal number of male and female applicants were sent to each posting, as were an equal number of attractive and plain-looking photographs; applications without photographs were also sent as a control group. For men, the results were as expected: CVs of “attractive” men were more likely to elicit a response from the employer (19.7%) compared with those of no-picture men (13.7%) and plain-looking men (9.2%). Interestingly, men who were viewed as “plain-looking” were better off not including a photograph. For the female applicants, however, the results were unexpected: CVs of women without a picture elicited the highest response rate (16.6%), while CVs of “plain-looking” women (13.6%) and of “attractive” women (12.8%) were less likely to receive a response.16

It is an unfortunate reality that personal preference, bias, and, in some cases, discriminatory hiring practices all factor into the selection process.17 This is why, as described above, the EEOC includes asking for photographs during the application stage on its list of prohibited practices for employers.13 The EEOC website also states: “If needed for identification purposes, a photograph may be obtained after an offer of employment is made and accepted.”13 In the residency application scenario, once an applicant has been granted an interview, a photograph can be taken on the day of the interview. With so many interviewees, this may help the interviewers to remember the interviewee. At this point in the process, the applicant has already been granted the interview. The bias associated with merely looking at a photograph is thus eliminated. This is in accordance with Title VII and is clearly different than including a photograph in the initial application, which directly violates Title VII.

Reviewers of applicants may have an unconscious bias due to the applicant’s attractiveness, race, sex, ethnicity, etc. Other, subtler forms of bias may also be present. Without realizing it, people may judge the quality of the photograph, or even what the applicant was wearing in the photograph. In orthopedic surgery, for example, there may be bias in the “size” of the applicant regardless of sex. Reviewers may unconsciously think how is he/she going to hold the leg, cut a rod, reduce a hip, etc. Without even realizing it, this may sway the person reviewing the application to choose one applicant over another. This may occur regardless of the applicant’s actual qualifications as based on the previously described factors, including test scores, grades during medical school, letters of recommendation, personal statement, extracurricular activities, volunteer activities, and research experience.

Unconscious bias is present in everyone. In an ideal world, one would be able to eliminate all sources of unconscious bias in the application process. Bias due to attending an Ivy League school versus a state school, bias due to where the applicant is from, bias due to who wrote the letter of recommendation, along with various other sources of unconscious bias, would be able to be eliminated. Unfortunately, this is not possible. What is possible, however, is to remove the photograph from the application process and to comply with Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Applying for a residency program can be a stressful process for medical students. It is a combination of applying for a job in the “real world” and applying to a college or medical school. In certain fields of medicine or surgery, there may be over 600 residency applications for 40 to 80 interviewee slots. Different specialties, as well as programs within a given specialty, take a different number of residents per year. This can vary from 1 to over 20 available spots, depending on the field of medicine or surgery as well as the specific program. Orthopedic surgery residencies, for example, can match between 2 and 12 residents each year. During the 2013–2014 academic year at our institution, there were over 600 applications received for approximately 50 interview slots for a class of 5 orthopedic surgery residents. Nationally, according to publicly available 2013 National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) data, a total of 1038 applicants (833 US medical school seniors) applied for 693 spots in orthopedic surgery, of which 692 were filled, indicating that orthopedic surgery remains one of the most desired fields among medical school seniors.1 Looking at the statistics provided by the NRMP data, orthopedic applicants remain some of the most competitive, with proportionally higher board scores, publication numbers, and grades, among other factors.1

Each individual program has its own method for sifting through the applications. At some institutions, the individual “in charge” of the selection committee may look through all applications initially, narrow them down, and then distribute them to the other members of the selection committee to determine the final interviewee list. At other institutions, the initial group of applications may be divided and distributed to the committee members so that each member reviews the applications and ultimately decides upon the interview candidates.

The Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) application includes the applicant’s name, birth city, current place of residence, education history, standardized test scores, grades achieved during medical school, letters of recommendation, personal statement, extracurricular activities, volunteer activities, research experience, and languages spoken, along with several other pieces of data, all intended to be able to give the committee a better understanding of the applicant. Interestingly, however, the application also includes a photograph of the applicant.

Countless authors have demonstrated that we make assumptions and reach conclusions without even being aware that this is occurring. This is the theory of “unconscious bias.”2-5 Unconscious bias applies to how we perceive other people, and occurs when subconscious beliefs or unrecognized stereotypes about specific characteristics, including gender, ethnicity, religion, socioeconomic status, age, and sexual orientation, result in an automatic and unconscious reaction and/or behavior.6 Unconscious bias has the ability to affect everything from how health care is delivered to how employees are hired.7-12 We are all biased, and becoming aware of our biases will help us mitigate them in the workplace.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 requires that employers rely solely on job-related qualifications, and not physical characteristics, in their interviewing and hiring process. The US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), the federal agency that enforces Title VII, includes asking for photographs during the application stage on its list of prohibited practices for employers.13 It is our belief that including a photograph in the ERAS application, prior to the selection of interview candidates, may produce unconscious bias in the decision for granting (or not granting) an interview, and this component of the application should be eliminated.

Using a wide spectrum of cultural backgrounds in employers, Dion and colleagues14 demonstrated that the “what is beautiful is good” bias is present in all cultures when prospective employees are closely matched in qualification. Attractive individuals are thought to have better professional lives and stable marital relationships and personalities, according to previous studies.14 There has been much research aimed at determining if physical attractiveness is a factor in hiring, and the evidence suggests that the more attractive the applicant is, the greater the chances of being hired.15 Specifically, Watkins and Johnston15 have found that attractive people are thought to have better personalities than less attractive people, and that a photograph can influence the hiring decision process.

Bradley Ruffle at Ben-Gurion University and Ze’ev Shtudiner at Ariel University looked at what happens when job hunters include photographs with their curricula vitae (CV), as is the norm in much of Europe and Asia.16 For over 2500 job postings, they sent 2 identical résumés: one with a photograph and one without a photograph. An equal number of male and female applicants were sent to each posting, as were an equal number of attractive and plain-looking photographs; applications without photographs were also sent as a control group. For men, the results were as expected: CVs of “attractive” men were more likely to elicit a response from the employer (19.7%) compared with those of no-picture men (13.7%) and plain-looking men (9.2%). Interestingly, men who were viewed as “plain-looking” were better off not including a photograph. For the female applicants, however, the results were unexpected: CVs of women without a picture elicited the highest response rate (16.6%), while CVs of “plain-looking” women (13.6%) and of “attractive” women (12.8%) were less likely to receive a response.16

It is an unfortunate reality that personal preference, bias, and, in some cases, discriminatory hiring practices all factor into the selection process.17 This is why, as described above, the EEOC includes asking for photographs during the application stage on its list of prohibited practices for employers.13 The EEOC website also states: “If needed for identification purposes, a photograph may be obtained after an offer of employment is made and accepted.”13 In the residency application scenario, once an applicant has been granted an interview, a photograph can be taken on the day of the interview. With so many interviewees, this may help the interviewers to remember the interviewee. At this point in the process, the applicant has already been granted the interview. The bias associated with merely looking at a photograph is thus eliminated. This is in accordance with Title VII and is clearly different than including a photograph in the initial application, which directly violates Title VII.

Reviewers of applicants may have an unconscious bias due to the applicant’s attractiveness, race, sex, ethnicity, etc. Other, subtler forms of bias may also be present. Without realizing it, people may judge the quality of the photograph, or even what the applicant was wearing in the photograph. In orthopedic surgery, for example, there may be bias in the “size” of the applicant regardless of sex. Reviewers may unconsciously think how is he/she going to hold the leg, cut a rod, reduce a hip, etc. Without even realizing it, this may sway the person reviewing the application to choose one applicant over another. This may occur regardless of the applicant’s actual qualifications as based on the previously described factors, including test scores, grades during medical school, letters of recommendation, personal statement, extracurricular activities, volunteer activities, and research experience.

Unconscious bias is present in everyone. In an ideal world, one would be able to eliminate all sources of unconscious bias in the application process. Bias due to attending an Ivy League school versus a state school, bias due to where the applicant is from, bias due to who wrote the letter of recommendation, along with various other sources of unconscious bias, would be able to be eliminated. Unfortunately, this is not possible. What is possible, however, is to remove the photograph from the application process and to comply with Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

1. National Resident Matching Program, Data Release and Research Committee. Results of the 2013 NRMP Applicant Survey by Preferred Specialty and Applicant Type. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; 2013. www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/applicantresultsbyspecialty2013.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2015.

2. Santry HP, Wren SM. The role of unconscious bias in surgical safety and outcomes. Surg Clin North Am. 2012;92(1):137–151.

3. Greenwald AG, McGhee DE, Schwartz JL. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: the implicit association test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74(6):1464–1480.

4. Greenwald AG, Poehlman TA, Uhlmann EL, Banaji MR. Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: III. Meta-analysis of predictive validity. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;97(1):17–41.

5. Plessner H, Banse R. Attitude measurement using the Implicit Association Test (IAT). Z Exp Psychol. 2001;48(2):82–84.

6. Chapman EN, Kaatz A, Carnes M. Physicians and implicit bias: how doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(11):1504–1510.

7. What you don’t know: the science of unconscious bias and what to do about it in the search and recruitment process [e-learning seminar]. Association of American Medical Colleges website. https://www.aamc.org/members/leadership/catalog/178420/unconscious_bias.html. Accessed July 14, 2015.

8. Haider AH, Schneider EB, Sriram N, et al. Unconscious race and class bias: its association with decision making by trauma and acute care surgeons. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77(3):409–416.

9. Blair IV, Steiner JF, Hanratty R, et al. An investigation of associations between clinicians’ ethnic or racial bias and hypertension treatment, medication adherence and blood pressure control. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):987–995.

10. Ravenell J, Ogedegbe G. Unconscious bias and real-world hypertension outcomes: advancing disparities research. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):973–975.

11. van Ryn M, Saha S. Exploring unconscious bias in disparities research and medical education. JAMA. 2011;306(9):995–996.

12. Puhl RM, Moss-Racusin CA, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Weight stigmatization and bias reduction: perspectives of overweight and obese adults. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(2):347–358.

13. Prohibited employment policies/practices. US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission website. http://www.eeoc.gov/laws/practices/. Accessed July 14, 2015.

14. Dion K, Berscheid E, Walster E. What is beautiful is good. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1972;24(3):285–290.

15. Watkins LM, Johnston L. Screening job applicants: the impact of physical attractiveness and application quality. Int J Selection Assess. 2000;8(2):76–84.

16. Ruffle BJ, Shtudiner Z. Are good-looking people more employable? Manage Sci. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2014.1927. Published May 29, 2014. Accessed July 14, 2015.

17. Lemay EP Jr, Clark MS, Greenberg A. What is beautiful is good because what is beautiful is desired: physical attractiveness stereotyping as projection of interpersonal goals. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2010;36(3):339–353.

1. National Resident Matching Program, Data Release and Research Committee. Results of the 2013 NRMP Applicant Survey by Preferred Specialty and Applicant Type. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; 2013. www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/applicantresultsbyspecialty2013.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2015.

2. Santry HP, Wren SM. The role of unconscious bias in surgical safety and outcomes. Surg Clin North Am. 2012;92(1):137–151.

3. Greenwald AG, McGhee DE, Schwartz JL. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: the implicit association test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74(6):1464–1480.

4. Greenwald AG, Poehlman TA, Uhlmann EL, Banaji MR. Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: III. Meta-analysis of predictive validity. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;97(1):17–41.

5. Plessner H, Banse R. Attitude measurement using the Implicit Association Test (IAT). Z Exp Psychol. 2001;48(2):82–84.

6. Chapman EN, Kaatz A, Carnes M. Physicians and implicit bias: how doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(11):1504–1510.

7. What you don’t know: the science of unconscious bias and what to do about it in the search and recruitment process [e-learning seminar]. Association of American Medical Colleges website. https://www.aamc.org/members/leadership/catalog/178420/unconscious_bias.html. Accessed July 14, 2015.

8. Haider AH, Schneider EB, Sriram N, et al. Unconscious race and class bias: its association with decision making by trauma and acute care surgeons. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77(3):409–416.

9. Blair IV, Steiner JF, Hanratty R, et al. An investigation of associations between clinicians’ ethnic or racial bias and hypertension treatment, medication adherence and blood pressure control. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):987–995.

10. Ravenell J, Ogedegbe G. Unconscious bias and real-world hypertension outcomes: advancing disparities research. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):973–975.

11. van Ryn M, Saha S. Exploring unconscious bias in disparities research and medical education. JAMA. 2011;306(9):995–996.

12. Puhl RM, Moss-Racusin CA, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Weight stigmatization and bias reduction: perspectives of overweight and obese adults. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(2):347–358.

13. Prohibited employment policies/practices. US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission website. http://www.eeoc.gov/laws/practices/. Accessed July 14, 2015.

14. Dion K, Berscheid E, Walster E. What is beautiful is good. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1972;24(3):285–290.

15. Watkins LM, Johnston L. Screening job applicants: the impact of physical attractiveness and application quality. Int J Selection Assess. 2000;8(2):76–84.

16. Ruffle BJ, Shtudiner Z. Are good-looking people more employable? Manage Sci. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2014.1927. Published May 29, 2014. Accessed July 14, 2015.

17. Lemay EP Jr, Clark MS, Greenberg A. What is beautiful is good because what is beautiful is desired: physical attractiveness stereotyping as projection of interpersonal goals. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2010;36(3):339–353.

Osteochondroma With Contiguous Bronchogenic Cyst of the Scapula

Osteochondromas are common benign bone tumors composed of a bony protrusion with an overlying cartilage cap.1 This lesion constitutes 24% to 40% of all benign bone tumors, and the great majority arise from the metaphyseal region of long bones.2 The scapula accounts for only 3% to 5% of all osteochondromas; however, this lesion is the most common benign bone tumor to involve the scapula.3

In contrast, cutaneous bronchogenic cyst of the scapula is an exceedingly rare pathology. The bronchogenic cyst is a congenital cystic mass lined by tracheobronchial structures and respiratory epithelium.4 These are most commonly located in the thorax, although numerous remote locations have also been described, including cutaneous cysts.5 The overall incidence of bronchogenic cysts is thought to be 1 in 42,000 to 1 in 68,000.6 There are only 15 case reports of cutaneous bronchogenic cysts in the scapular region.7

We report the case of a novel dual lesion of both an osteochondroma and a contiguous cutaneous bronchogenic cyst in the scapula. The patient’s guardian provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

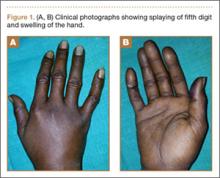

A 12-month-old boy presented to our clinic with the complaint of a mass over the left scapula. The mass was first noted incidentally several weeks earlier during bathing. Examination revealed a firm, subcutaneous, nontender mass measuring 1×2 cm located over the spine of the scapula. There were no overlying skin changes, and there was normal function of the ipsilateral upper extremity. Anteroposterior and lateral chest radiographs revealed no abnormality. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed an exostosis projecting from the scapular spine measuring 2×6×7 mm with an adjacent cystic mass measuring 5×8×9 mm that was thought to represent bursitis (Figure 1). The decision was made to observe the mass.

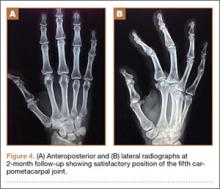

The patient returned to clinic at age 31 months with a new complaint of scant drainage of serous fluid from a pinprick-sized hole located just superolateral to the scapular mass. The child’s mother reported daily manual expression of fluid from the mass via the hole, without which the mass would enlarge. There were no local or systemic signs of infection. A repeat MRI again revealed an exostosis with an adjacent cystic mass with interval enlargement of the cyst (Figure 2). At age 4.5 years, the decision was made to proceed with excision of the osteochondroma and adjacent cystic mass.

The mass was approached via a 2-cm incision designed to excise the tract to the skin. Dissection revealed a sinus tract connecting to a well-defined cystic sac. This sac was attached to the underlying exostosis. The exostosis and attached cyst were excised en bloc. The cyst was opened, revealing foul-smelling, cloudy white fluid that was sent for culture; the specimen was sent for pathology.

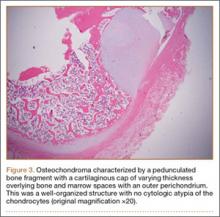

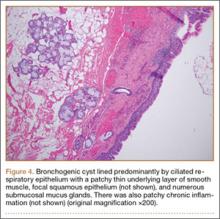

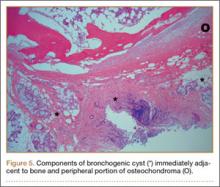

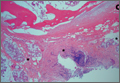

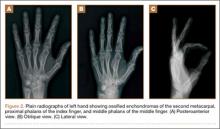

The fluid culture grew mixed flora, with no Staphylococcus aureus, group A streptococcus, or Pseudomonas aeruginosa identified. The pathologic examination identified bone with a cartilaginous cap, consistent with osteochondroma (Figure 3), as well as a cyst lined by respiratory epithelium with patchy areas of squamous epithelium and surrounding mucus glands, consistent with bronchogenic cyst (Figure 4). Figure 5 shows the contiguous nature of the 2 lesions.

The postoperative course was uneventful. The patient returned to full use of the left upper extremity and had resolution of all drainage.

Discussion

Osteochondromas are thought to arise from aberrant growth of the epiphyseal growth plate cartilage. A small portion of the physis herniates past the groove of Ranvier and grows parallel to the normal physis with medullary continuity. This can occur idiopathically or, more rarely, secondary to an identified injury to the growth plate.1

The formation of bronchogenic cysts is most often attributed to anomalous budding of the ventral foregut during fetal development,4 hence the alternative designation of these cysts as foregut cysts. An extrathoracic location of the cyst has been postulated to stem from 2 possible events: a preexisting cyst may migrate out of the thorax prior to closure of the sternal plates, or sternal plate closure may itself pinch off the cyst.8,9 An alternative explanation is in situ metaplastic development of respiratory epithelium.10 When located near the skin, these cysts often drain clear fluid.11

Scapular osteochondromas are known to cause various pathologies of the shoulder girdle, including snapping scapula syndrome, chest wall deformity, shoulder impingement, and bursa formation.12-17 This case, however, is the first known finding of a scapular osteochondroma with a contiguous cutaneous bronchogenic cyst. A putative explanation for their co-occurrence is that local disturbances caused by one lesion stimulated the formation of the second. The direct connection between the bronchogenic cyst and the bone, as has been reported in 3 cases,7,9,18 seems to favor this explanation. Definitive conclusions regarding any causal relationship are beyond the scope of this single case report.

Definitive management of bronchogenic cysts is complete excision, although the diagnosis is often not made until histopathologic examination has been completed.19 Osteochondromas are managed with observation unless they are symptomatic.2 Malignant degeneration is a rare but documented occurrence in both lesions.2,20

Conclusion

In approaching the pediatric patient with a cystic mass over the scapula, a cutaneous bronchogenic cyst may be included in the differential diagnosis. This lesion can occur in isolation or can be found with another pathology, such as osteochondroma, as reported here.

1. Milgram JW. The origins of osteochondromas and enchondromas. A histopathologic study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;174:264-284.

2. Dahlin DC. Osteochondroma (osteocartilaginous exostosis). In: Dahlin DC. Bone Tumors. Springfield, IL: Thomas; 1978: 17-27.

3. Samilson RL, Morris JM, Thompson RW. Tumors of the scapula. A review of the literature and an analysis of 31 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1968;58:105-115.

4. Rodgers BM, Harman PK, Johnson AM. Bronchopulmonary foregut malformations. The spectrum of anomalies. Ann Surg. 1986;203(5):517-524.

5. Zvulunov A, Amichai B, Grunwald MH, Avinoach I, Halevy S. Cutaneous bronchogenic cyst: delineation of a poorly recognized lesion. Pediatr Dermatol. 1998;15(4):277-281.

6. Sanli A, Onen A, Ceylan E, Yilmaz E, Silistreli E, Açikel U. A case of a bronchogenic cyst in a rare location. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77(3):1093-1094.

7. Al-Balushi Z, Ehsan MT, Al Sajee D, Al Riyami M. Scapular bronchogenic cyst: a case report and literature review. Oman Med J. 2012;27(2):161-163.

8. Miller OF 3rd, Tyler W. Cutaneous bronchogenic cyst with papilloma and sinus presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11(2 Pt 2):367-371.

9. Fraga S, Helwig EB, Rosen SH. Bronchogenic cyst in the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Am J Clin Pathol. 1971;56(2):230-238.

10. Van der Putte SC, Toonstra J. Cutaneous ‘bronchogenic’ cyst. J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12(5):404-409.

11. Schouten van der Velden AP, Severijnen RS, Wobbes T. A bronchogenic cyst under the scapula with a fistula on the back. Pediatr Surg Int. 2006;22(10):857-860.

12. Lu MT, Abboud JA. Subacromial osteochondroma. Orthopedics. 2011;34(9):581-583.

13. Lazar MA, Kwon YW, Rokito AS. Snapping scapula syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(9):2251-2262.

14. Okada K, Terada K, Sashi R, Hoshi N. Large bursa formation associated with osteochondroma of the scapula: a case report and review of the literature. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1999;29(7):356-360.

15. Tomo H, Ito Y, Aono M, Takaoka K. Chest wall deformity associated with osteochondroma of the scapula: a case report and review of the literature. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(1):103-106.

16. Jacobi CA, Gellert K, Zieren J. Rapid development of subscapular exostosis bursata. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;6(2):164-166.

17. Van Riet RP, Van Glabbeek F. Arthroscopic resection of a symptomatic snapping subscapular osteochondroma. Acta Orthop Belg. 2007;73(2):252-254.

18. Das K, Jackson PB, D’Cruz AJ. Periscapular bronchogenic cyst. Indian J Pediatr. 70(2):181-182.

19. Suen HC, Mathisen DJ, Grillo HC, et al. Surgical management and radiological characteristics of bronchogenic cysts. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993;55(2):476-481.

20. Tanita M, Kikuchi-Numagami K, Ogoshi K, et al. Malignant melanoma arising from cutaneous bronchogenic cyst of the scapular area. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl case reports):S19-S21.

Osteochondromas are common benign bone tumors composed of a bony protrusion with an overlying cartilage cap.1 This lesion constitutes 24% to 40% of all benign bone tumors, and the great majority arise from the metaphyseal region of long bones.2 The scapula accounts for only 3% to 5% of all osteochondromas; however, this lesion is the most common benign bone tumor to involve the scapula.3

In contrast, cutaneous bronchogenic cyst of the scapula is an exceedingly rare pathology. The bronchogenic cyst is a congenital cystic mass lined by tracheobronchial structures and respiratory epithelium.4 These are most commonly located in the thorax, although numerous remote locations have also been described, including cutaneous cysts.5 The overall incidence of bronchogenic cysts is thought to be 1 in 42,000 to 1 in 68,000.6 There are only 15 case reports of cutaneous bronchogenic cysts in the scapular region.7

We report the case of a novel dual lesion of both an osteochondroma and a contiguous cutaneous bronchogenic cyst in the scapula. The patient’s guardian provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 12-month-old boy presented to our clinic with the complaint of a mass over the left scapula. The mass was first noted incidentally several weeks earlier during bathing. Examination revealed a firm, subcutaneous, nontender mass measuring 1×2 cm located over the spine of the scapula. There were no overlying skin changes, and there was normal function of the ipsilateral upper extremity. Anteroposterior and lateral chest radiographs revealed no abnormality. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed an exostosis projecting from the scapular spine measuring 2×6×7 mm with an adjacent cystic mass measuring 5×8×9 mm that was thought to represent bursitis (Figure 1). The decision was made to observe the mass.

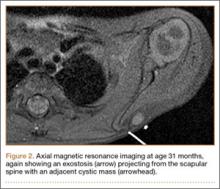

The patient returned to clinic at age 31 months with a new complaint of scant drainage of serous fluid from a pinprick-sized hole located just superolateral to the scapular mass. The child’s mother reported daily manual expression of fluid from the mass via the hole, without which the mass would enlarge. There were no local or systemic signs of infection. A repeat MRI again revealed an exostosis with an adjacent cystic mass with interval enlargement of the cyst (Figure 2). At age 4.5 years, the decision was made to proceed with excision of the osteochondroma and adjacent cystic mass.

The mass was approached via a 2-cm incision designed to excise the tract to the skin. Dissection revealed a sinus tract connecting to a well-defined cystic sac. This sac was attached to the underlying exostosis. The exostosis and attached cyst were excised en bloc. The cyst was opened, revealing foul-smelling, cloudy white fluid that was sent for culture; the specimen was sent for pathology.

The fluid culture grew mixed flora, with no Staphylococcus aureus, group A streptococcus, or Pseudomonas aeruginosa identified. The pathologic examination identified bone with a cartilaginous cap, consistent with osteochondroma (Figure 3), as well as a cyst lined by respiratory epithelium with patchy areas of squamous epithelium and surrounding mucus glands, consistent with bronchogenic cyst (Figure 4). Figure 5 shows the contiguous nature of the 2 lesions.

The postoperative course was uneventful. The patient returned to full use of the left upper extremity and had resolution of all drainage.

Discussion

Osteochondromas are thought to arise from aberrant growth of the epiphyseal growth plate cartilage. A small portion of the physis herniates past the groove of Ranvier and grows parallel to the normal physis with medullary continuity. This can occur idiopathically or, more rarely, secondary to an identified injury to the growth plate.1

The formation of bronchogenic cysts is most often attributed to anomalous budding of the ventral foregut during fetal development,4 hence the alternative designation of these cysts as foregut cysts. An extrathoracic location of the cyst has been postulated to stem from 2 possible events: a preexisting cyst may migrate out of the thorax prior to closure of the sternal plates, or sternal plate closure may itself pinch off the cyst.8,9 An alternative explanation is in situ metaplastic development of respiratory epithelium.10 When located near the skin, these cysts often drain clear fluid.11

Scapular osteochondromas are known to cause various pathologies of the shoulder girdle, including snapping scapula syndrome, chest wall deformity, shoulder impingement, and bursa formation.12-17 This case, however, is the first known finding of a scapular osteochondroma with a contiguous cutaneous bronchogenic cyst. A putative explanation for their co-occurrence is that local disturbances caused by one lesion stimulated the formation of the second. The direct connection between the bronchogenic cyst and the bone, as has been reported in 3 cases,7,9,18 seems to favor this explanation. Definitive conclusions regarding any causal relationship are beyond the scope of this single case report.

Definitive management of bronchogenic cysts is complete excision, although the diagnosis is often not made until histopathologic examination has been completed.19 Osteochondromas are managed with observation unless they are symptomatic.2 Malignant degeneration is a rare but documented occurrence in both lesions.2,20

Conclusion

In approaching the pediatric patient with a cystic mass over the scapula, a cutaneous bronchogenic cyst may be included in the differential diagnosis. This lesion can occur in isolation or can be found with another pathology, such as osteochondroma, as reported here.

Osteochondromas are common benign bone tumors composed of a bony protrusion with an overlying cartilage cap.1 This lesion constitutes 24% to 40% of all benign bone tumors, and the great majority arise from the metaphyseal region of long bones.2 The scapula accounts for only 3% to 5% of all osteochondromas; however, this lesion is the most common benign bone tumor to involve the scapula.3

In contrast, cutaneous bronchogenic cyst of the scapula is an exceedingly rare pathology. The bronchogenic cyst is a congenital cystic mass lined by tracheobronchial structures and respiratory epithelium.4 These are most commonly located in the thorax, although numerous remote locations have also been described, including cutaneous cysts.5 The overall incidence of bronchogenic cysts is thought to be 1 in 42,000 to 1 in 68,000.6 There are only 15 case reports of cutaneous bronchogenic cysts in the scapular region.7

We report the case of a novel dual lesion of both an osteochondroma and a contiguous cutaneous bronchogenic cyst in the scapula. The patient’s guardian provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 12-month-old boy presented to our clinic with the complaint of a mass over the left scapula. The mass was first noted incidentally several weeks earlier during bathing. Examination revealed a firm, subcutaneous, nontender mass measuring 1×2 cm located over the spine of the scapula. There were no overlying skin changes, and there was normal function of the ipsilateral upper extremity. Anteroposterior and lateral chest radiographs revealed no abnormality. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed an exostosis projecting from the scapular spine measuring 2×6×7 mm with an adjacent cystic mass measuring 5×8×9 mm that was thought to represent bursitis (Figure 1). The decision was made to observe the mass.

The patient returned to clinic at age 31 months with a new complaint of scant drainage of serous fluid from a pinprick-sized hole located just superolateral to the scapular mass. The child’s mother reported daily manual expression of fluid from the mass via the hole, without which the mass would enlarge. There were no local or systemic signs of infection. A repeat MRI again revealed an exostosis with an adjacent cystic mass with interval enlargement of the cyst (Figure 2). At age 4.5 years, the decision was made to proceed with excision of the osteochondroma and adjacent cystic mass.

The mass was approached via a 2-cm incision designed to excise the tract to the skin. Dissection revealed a sinus tract connecting to a well-defined cystic sac. This sac was attached to the underlying exostosis. The exostosis and attached cyst were excised en bloc. The cyst was opened, revealing foul-smelling, cloudy white fluid that was sent for culture; the specimen was sent for pathology.

The fluid culture grew mixed flora, with no Staphylococcus aureus, group A streptococcus, or Pseudomonas aeruginosa identified. The pathologic examination identified bone with a cartilaginous cap, consistent with osteochondroma (Figure 3), as well as a cyst lined by respiratory epithelium with patchy areas of squamous epithelium and surrounding mucus glands, consistent with bronchogenic cyst (Figure 4). Figure 5 shows the contiguous nature of the 2 lesions.

The postoperative course was uneventful. The patient returned to full use of the left upper extremity and had resolution of all drainage.

Discussion

Osteochondromas are thought to arise from aberrant growth of the epiphyseal growth plate cartilage. A small portion of the physis herniates past the groove of Ranvier and grows parallel to the normal physis with medullary continuity. This can occur idiopathically or, more rarely, secondary to an identified injury to the growth plate.1

The formation of bronchogenic cysts is most often attributed to anomalous budding of the ventral foregut during fetal development,4 hence the alternative designation of these cysts as foregut cysts. An extrathoracic location of the cyst has been postulated to stem from 2 possible events: a preexisting cyst may migrate out of the thorax prior to closure of the sternal plates, or sternal plate closure may itself pinch off the cyst.8,9 An alternative explanation is in situ metaplastic development of respiratory epithelium.10 When located near the skin, these cysts often drain clear fluid.11

Scapular osteochondromas are known to cause various pathologies of the shoulder girdle, including snapping scapula syndrome, chest wall deformity, shoulder impingement, and bursa formation.12-17 This case, however, is the first known finding of a scapular osteochondroma with a contiguous cutaneous bronchogenic cyst. A putative explanation for their co-occurrence is that local disturbances caused by one lesion stimulated the formation of the second. The direct connection between the bronchogenic cyst and the bone, as has been reported in 3 cases,7,9,18 seems to favor this explanation. Definitive conclusions regarding any causal relationship are beyond the scope of this single case report.

Definitive management of bronchogenic cysts is complete excision, although the diagnosis is often not made until histopathologic examination has been completed.19 Osteochondromas are managed with observation unless they are symptomatic.2 Malignant degeneration is a rare but documented occurrence in both lesions.2,20

Conclusion

In approaching the pediatric patient with a cystic mass over the scapula, a cutaneous bronchogenic cyst may be included in the differential diagnosis. This lesion can occur in isolation or can be found with another pathology, such as osteochondroma, as reported here.

1. Milgram JW. The origins of osteochondromas and enchondromas. A histopathologic study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;174:264-284.

2. Dahlin DC. Osteochondroma (osteocartilaginous exostosis). In: Dahlin DC. Bone Tumors. Springfield, IL: Thomas; 1978: 17-27.

3. Samilson RL, Morris JM, Thompson RW. Tumors of the scapula. A review of the literature and an analysis of 31 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1968;58:105-115.

4. Rodgers BM, Harman PK, Johnson AM. Bronchopulmonary foregut malformations. The spectrum of anomalies. Ann Surg. 1986;203(5):517-524.

5. Zvulunov A, Amichai B, Grunwald MH, Avinoach I, Halevy S. Cutaneous bronchogenic cyst: delineation of a poorly recognized lesion. Pediatr Dermatol. 1998;15(4):277-281.

6. Sanli A, Onen A, Ceylan E, Yilmaz E, Silistreli E, Açikel U. A case of a bronchogenic cyst in a rare location. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77(3):1093-1094.

7. Al-Balushi Z, Ehsan MT, Al Sajee D, Al Riyami M. Scapular bronchogenic cyst: a case report and literature review. Oman Med J. 2012;27(2):161-163.

8. Miller OF 3rd, Tyler W. Cutaneous bronchogenic cyst with papilloma and sinus presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11(2 Pt 2):367-371.

9. Fraga S, Helwig EB, Rosen SH. Bronchogenic cyst in the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Am J Clin Pathol. 1971;56(2):230-238.

10. Van der Putte SC, Toonstra J. Cutaneous ‘bronchogenic’ cyst. J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12(5):404-409.

11. Schouten van der Velden AP, Severijnen RS, Wobbes T. A bronchogenic cyst under the scapula with a fistula on the back. Pediatr Surg Int. 2006;22(10):857-860.

12. Lu MT, Abboud JA. Subacromial osteochondroma. Orthopedics. 2011;34(9):581-583.

13. Lazar MA, Kwon YW, Rokito AS. Snapping scapula syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(9):2251-2262.

14. Okada K, Terada K, Sashi R, Hoshi N. Large bursa formation associated with osteochondroma of the scapula: a case report and review of the literature. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1999;29(7):356-360.

15. Tomo H, Ito Y, Aono M, Takaoka K. Chest wall deformity associated with osteochondroma of the scapula: a case report and review of the literature. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(1):103-106.

16. Jacobi CA, Gellert K, Zieren J. Rapid development of subscapular exostosis bursata. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;6(2):164-166.

17. Van Riet RP, Van Glabbeek F. Arthroscopic resection of a symptomatic snapping subscapular osteochondroma. Acta Orthop Belg. 2007;73(2):252-254.

18. Das K, Jackson PB, D’Cruz AJ. Periscapular bronchogenic cyst. Indian J Pediatr. 70(2):181-182.

19. Suen HC, Mathisen DJ, Grillo HC, et al. Surgical management and radiological characteristics of bronchogenic cysts. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993;55(2):476-481.

20. Tanita M, Kikuchi-Numagami K, Ogoshi K, et al. Malignant melanoma arising from cutaneous bronchogenic cyst of the scapular area. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl case reports):S19-S21.

1. Milgram JW. The origins of osteochondromas and enchondromas. A histopathologic study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;174:264-284.

2. Dahlin DC. Osteochondroma (osteocartilaginous exostosis). In: Dahlin DC. Bone Tumors. Springfield, IL: Thomas; 1978: 17-27.

3. Samilson RL, Morris JM, Thompson RW. Tumors of the scapula. A review of the literature and an analysis of 31 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1968;58:105-115.

4. Rodgers BM, Harman PK, Johnson AM. Bronchopulmonary foregut malformations. The spectrum of anomalies. Ann Surg. 1986;203(5):517-524.

5. Zvulunov A, Amichai B, Grunwald MH, Avinoach I, Halevy S. Cutaneous bronchogenic cyst: delineation of a poorly recognized lesion. Pediatr Dermatol. 1998;15(4):277-281.

6. Sanli A, Onen A, Ceylan E, Yilmaz E, Silistreli E, Açikel U. A case of a bronchogenic cyst in a rare location. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77(3):1093-1094.

7. Al-Balushi Z, Ehsan MT, Al Sajee D, Al Riyami M. Scapular bronchogenic cyst: a case report and literature review. Oman Med J. 2012;27(2):161-163.

8. Miller OF 3rd, Tyler W. Cutaneous bronchogenic cyst with papilloma and sinus presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11(2 Pt 2):367-371.

9. Fraga S, Helwig EB, Rosen SH. Bronchogenic cyst in the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Am J Clin Pathol. 1971;56(2):230-238.

10. Van der Putte SC, Toonstra J. Cutaneous ‘bronchogenic’ cyst. J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12(5):404-409.

11. Schouten van der Velden AP, Severijnen RS, Wobbes T. A bronchogenic cyst under the scapula with a fistula on the back. Pediatr Surg Int. 2006;22(10):857-860.

12. Lu MT, Abboud JA. Subacromial osteochondroma. Orthopedics. 2011;34(9):581-583.

13. Lazar MA, Kwon YW, Rokito AS. Snapping scapula syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(9):2251-2262.

14. Okada K, Terada K, Sashi R, Hoshi N. Large bursa formation associated with osteochondroma of the scapula: a case report and review of the literature. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1999;29(7):356-360.

15. Tomo H, Ito Y, Aono M, Takaoka K. Chest wall deformity associated with osteochondroma of the scapula: a case report and review of the literature. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(1):103-106.

16. Jacobi CA, Gellert K, Zieren J. Rapid development of subscapular exostosis bursata. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;6(2):164-166.

17. Van Riet RP, Van Glabbeek F. Arthroscopic resection of a symptomatic snapping subscapular osteochondroma. Acta Orthop Belg. 2007;73(2):252-254.

18. Das K, Jackson PB, D’Cruz AJ. Periscapular bronchogenic cyst. Indian J Pediatr. 70(2):181-182.

19. Suen HC, Mathisen DJ, Grillo HC, et al. Surgical management and radiological characteristics of bronchogenic cysts. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993;55(2):476-481.

20. Tanita M, Kikuchi-Numagami K, Ogoshi K, et al. Malignant melanoma arising from cutaneous bronchogenic cyst of the scapular area. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl case reports):S19-S21.

A Rare Cause of Postoperative Abdominal Pain in a Spinal Fusion Patient

Posterior spinal fusion for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis is a relatively common procedure. However, intestinal obstruction is a possible complication in the case of an asthenic adolescent with weight loss after surgery. We present the case of a 12-year-old girl who underwent an uncomplicated posterior spinal fusion with instrumentation for scoliosis and who developed nausea, emesis, and abdominal pain. We also discuss the origins, epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of superior mesenteric artery syndrome (SMAS), a rare condition. The patient’s parents provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

The patient was a 12-year-old girl with juvenile idiopathic scoliosis. She was seen by a pediatric orthopedist at age 8 after her primary care physician noticed a curve in her back during her physical examination. Given her age and primary curve of 25º, magnetic resonance imaging was ordered, which was negative for syrinx, tethered cord, or bony abnormalities. An underarm thoracolumbosacral orthosis (Boston Brace) was prescribed to be worn 23 hours/day. There was inconsistent follow-up over the next 4 years, and her curve progressed to 55º (right thoracic) and 47º in the lumbar spine (Figures 1, 2). Given the magnitude of the curves, surgical intervention was recommended, because bracing would no longer be beneficial.

The patient was healthy and appeared vibrant with no medical issues. She weighed 49 kg and her height was 162 cm (body mass index [BMI], 18.6; normal). She underwent segmental posterior spinal instrumentation, and a fusion was performed from T4 to L4 using a cobalt chrome rod. Postoperatively, there were no problems. Her diet was slowly advanced from clear liquids to regular food over 3 days. She was discharged on postoperative day 4. She had no abdominal distention, pain, or nausea. The family was instructed about pain medication (oxycodone liquid, 5 mg every 4 hours as needed) and how to prevent and treat constipation.

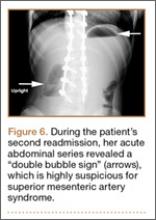

Three days after discharge, her mother called to inquire about positioning because the patient was uncomfortable owing to back pain. There were no abdominal complaints, and she was taking her pain medicine every 4 hours. She was instructed to lie in a comfortable position and to ambulate several times daily. The patient took little food or fluids because of a lack of appetite and back pain. On postoperative day 8, she presented to the emergency department with complaints of generalized abdominal pain and 1 day’s emesis. The patient had not had a bowel movement postoperatively. An acute abdominal series (AAS) was obtained (Figure 3), which noted a nonobstructive bowel gas pattern, with some increased colonic fecal retention. The patient was given intravenous (IV) fluids and an IV anti-emetic, and was admitted for observation. The pediatric surgical team evaluated her and concluded her symptoms resulted from constipation. Her symptoms improved over 2 to 3 days, and she had several bowel movements on day 2 after taking polyethylene glycol, sennosides, and bisacodyl suppositories. At discharge, she was noted to be passing gas, and her abdominal examination revealed no tenderness or guarding. She had mild distention, but it had improved from the previous day. She ate breakfast and ambulated several times. She had no complaints of abdominal pain and was released home with her parents. Staff reiterated instructions regarding constipation, diet, and follow-up. Her discharge weight was 48 kg (down 1 kg) and her BMI was 17.2 (down 1.4; underweight). Her height was now 165 cm (up 3 cm). Postoperative radiographs noted stable fixation with corrected curves (Figures 4, 5).

At home, the patient ate little but continued to drink fluids. On postdischarge day 3, she developed nausea, bilious emesis, and generalized abdominal pain. She returned to the emergency department. At this point, the patient weighed 44.5 kg (down 6.6 kg since the initial surgery) and her BMI was 16.1 (down 2.5; underweight). She was admitted, and IV fluids were initiated. She had more than 1300 mL of bilious emesis. A nasogastric (NG) tube was inserted. Initial laboratory findings were unremarkable other than an increase in serum lipase of 261 U/L. Her amylase level was within normal limits. An AAS was again completed and showed a distended stomach and loop of small bowel below the liver with an air fluid level. There were also distended loops of bowel in the pelvis (Figure 6).

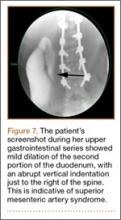

A pediatric surgical consultant examined her the next morning. An upper gastrointestinal series (UGI) was obtained and showed air fluid levels in the stomach with prompt gastric emptying into a normal caliber duodenal bulb. However, with supine positioning, there was significant dilatation of the second portion of the duodenum with abrupt vertical cutoff just to the right of the spine, compatible with SMAS (Figure 7). There was reflux of contrast material into the stomach from the duodenum, with no passage of barium into the distal duodenum. After the UGI, a nasojejunal (NJ) feeding tube was placed. The tip was left at the beginning of the fourth part of the duodenum. Repeated attempts to pass the NJ feeding tube beyond the fourth part of the duodenum were unsuccessful because of massive gastric distention. The patient was taken to the operating room for placement of a Stamm gastrostomy feeding tube with insertion of a transgastric jejunal (G-J) feeding tube under fluoroscopy (Figure 5). The patient had the G-J feeding tube in place for 6 weeks to augment her enteral nutrition. As she gained weight, her duodenal emptying improved. She gradually transitioned to normal oral intake. She has done well since the G-J feeding tube was removed.

Discussion

Von Rokitansky first described SMAS in the mid-1800s.1 The exact pathology was further defined 60 years later when vascular involvement was determined to be the definitive mechanism of obstruction.2-4 Superior mesenteric artery syndrome is caused by the superior mesenteric vessels compressing the third portion of the duodenum, resulting in an extrinsic obstruction. This syndrome is also commonly called Wilkie disease, after Dr. David Wilkie, who first published in 1927 results of a comprehensive series of 75 patients.1 The syndrome is also known as arteriomesenteric duodenal compression, aortomesenteric syndrome, chronic duodenal ileus, megaduodenum, and cast syndrome.1,4,5 The term cast syndrome was derived from events in 1878, when Willet applied a body cast to a scoliosis patient who died after what was termed “fatal vomiting.”3

Epidemiology, Incidence, and Prevalence

While not unheard of, SMAS is an uncommon disorder. There have been only 400 documented reports in the English-language literature since 1980.5-8 Studies have stated that the incidence of the affected population is less than 0.4%.5,7,9,10 However, SMAS has been reported to have a mortality rate as high as 33% because of the uncommon nature of the disease and prolonged duration between onset of symptoms and diagnosis.7,9,11,12 The incidence of SMAS is higher after surgical procedures to correct spinal deformities, with rates between 0.5% and 4.7%.10,12,13 Females are affected more frequently than males (3:2 ratio).1,9,14 One large study with 80 patients that spanned 10 years reported that female incidence was 66%, and another study with 75 patients also observed that two-thirds of the patients were women.1,7 This syndrome commonly affects patients who are tall and thin with an asthenic body habitus.1,6,11,12 Superior mesenteric artery syndrome develops more commonly in younger patients. Previous studies noted that two-thirds of patients were between ages 10 and 39 years.1,8 However, given the right set of medical conditions, it can occur in patients of any age.2,9,15,16 In young, thin patients with scoliosis, the risk of developing SMAS after spinal fusion with instrumentation increases, given their already low weight coupled with the surgical intervention at the height of their longitudinal growth spurt.1,11,12

Other patients also at increased risk for developing SMAS include those with anorexia nervosa, psychiatric/emotional disorders, or drug addiction. It can also be found in persons on prolonged bedrest, those who have increased their activity and lost weight volitionally, or patients with illness or injuries, such as burns, trauma, or significant postoperative complications that decrease caloric intake and keep them in a supine position.2,6,17 The syndrome can be acute or chronic in its presentation.

Anatomy and Physiology

The superior mesenteric artery (SMA) comes off the right anterolateral portion of the abdominal aorta, which is just anterior to the L1 vertebra. It passes over the third part of the duodenum, generally at the L2 level (Figure 8A). The duodenum passes across the aorta at the level of the L3 vertebral body and is suspended between the aorta and the SMA by the ligament of Treitz (Figure 8B).3 The angle between the aorta and SMA (aortomesenteric angle) typically ranges from 25º to 60º with an average of 45º (Figure 8A). The distance between the aorta and SMA at the level of the duodenum is called the aortomesenteric distance, and it normally measures from 10 mm to 28 mm. Obstruction is usually observed at 2 mm to 8 mm (Figure 8C).1,3

Compression and outlet obstruction from narrowing of the SMA aortomesenteric angle can be caused by a multitude of problems.3,5,9,17 In chronic conditions, narrowing of the aorto-mesenteric angle could be the result of a shortened ligament, or a low origin of the SMA on the aorta, or a high insertion of the duodenum at the ligament of Treitz. Postoperatively, any change in anatomy caused by adhesions could result in compression as well. Most commonly, however, in those with significant weight loss, such as postoperative spinal fusion patients, there is loss of retroperitoneal fat, which normally acts as a cushion around the duodenum. This allows the SMA to move posteriorly obstructing the duodenum. Lying in a recumbent position along with weight loss also puts patients at risk after surgery.3,5,9,17 SMAS should be distinguished from other conditions that can cause duodenal obstruction, such as duodenal hematomas and congenital webs.

Symptoms and Patient Presentation

Whether SMAS is acute or chronic, most patients with SMAS present in a similar fashion. Almost all patients with acute SMAS complain of abdominal pain, nausea, and emesis (usually bilious) that usually occur after eating. Early satiety is commonly observed, resulting from delayed gastric emptying. Abdominal pain may improve when patients lie prone and are in the knee-chest, or lateral decubitus, position. These patients frequently have upper abdominal distention because of massive retention of gastric contents.4,6,16,18,19 Most spinal fusion patients present with these symptoms 7 to 10 days after surgery.11-13

Diagnosis

Our first diagnostic tool is a comprehensive history and physical examination. Once that is complete, many radiologic tests can be used to confirm the anatomic abnormality. The first test ordered is a simple AAS, which may show a “double bubble sign” (Figure 6), indicative of duodenal obstruction.4 There are several other tests, and each facility and surgeon has a preference as to which is considered the “gold standard.” Upper gastrointestinal (GI) barium studies are the simplest and most reliable. The barium test shows foregut anatomy and, to some extent, function. In SMAS patients, one should see duodenal dilatation and failure of the contrast to flow past the third section of the duodenum, along with an abrupt termination of the barium column as the duodenum crosses the vertebrae. This is the traditional method of diagnosis. There is minimal radiation, and the cost is less than that of many other tests, but it can be uncomfortable for the patient.1-4

At some institutions, an upper GI barium study is combined with angiography, which can be used to measure aortomesenteric angle and distance.1,3 Other practitioners prefer computed tomography (CT) with 3-dimensional reconstruction, which allows for measurement of the aortomesenteric angle and distance. In 1 study, CT was found to have an extremely high sensitivity and specificity for these measurements.10 CT angiography also identifies the obstruction with increased sensitivity, but it is rarely necessary and provides more radiation exposure and increased cost.1,6,14,19 Abdominal ultrasound has been used to measure the angle of the SMA and the aortomesenteric distance. When combined with endoscopy, this offers an alternative way to diagnose SMAS and decreases radiation exposure. However, it may require sedation or anesthesia.7,15,17 Overall, 3 criteria are used to define whether a patient has SMAS: duodenal dilatation, an aortomesenteric angle that is less than 25º, and an SMA that is shown to be compressing the third part of the duodenum.5

Treatment

Conservative treatment of SMAS usually starts by removing any precipitating factors present, such as a splint or cast that was applied for scoliosis, or ending activity associated with significant weight loss. Medical management consists of IV hydration, anti-emetics, oral feeding restriction, posture therapy, and placement of an NG tube for decompression. In most cases, patients will need to have an NJ feeding tube passed distal to the site of obstruction. This provides access for enteral feeding, and patients will gradually gain weight, repleting their retroperitoneal fat stores, which pushes the SMA forward and relieves the pressure on the duodenum. Electrolyte balance should be closely monitored along with weight gain. A nutritionist is often consulted to prevent underfeeding, which can produce a slow return to weight gain, poor wound healing, and loss of lean body muscle mass; or overfeeding, which can result in hyperglycemia and respiratory failure. Once patients are stable on enteral feedings, they can begin a slow return to oral intake.2-4,7,12 Total parental nutrition may be needed in some cases, but the risks associated with IV feeding usually outweigh the benefits.4 Almost all cases of acute SMAS can be successfully treated medically if diagnosed in a timely manner and supportive treatment begins promptly.7

Surgical intervention is rarely necessary for acute SMAS, but when conservative measures fail (after a 4- to 6-week trial), or in the presence of peptic ulcer disease or pancreatitis, this may become an appropriate option. In our patient, multiple attempts at passing an NJ feeding tube were unsuccessful, and she needed an operative procedure for insertion of a G-J feeding tube.

Further surgical intervention is usually reserved for those patients with long-standing SMAS for whom medical management has failed or other issues, such as pancreatitis, colitis, or megaduodenum, have arisen. Many operations are described in the literature. A duodenojejunostomy to bypass the site of the obstruction is one option. Another is duodenal derotation (Strong procedure) to alter the aortomesenteric angle and place the third and fourth duodenal portions to the right of the SMA. Other procedures include a Roux-en-Y duodenojejunostomy and duodenal uncrossing. A lateral duodenojejunostomy between the second portion of the duodenum and the jejunum is considered the simplest surgical technique. It achieves successful outcomes in 90% of cases.2-5,14 With regards to SMAS and scoliosis, it is extremely rare that this kind of surgical intervention would be necessary.

Conclusion

When planning operative spinal correction in scoliosis patients (especially females) who have a low BMI at the time of surgery and who have increased thoracic stiffness, be alert for signs and symptoms of SMAS. This rare complication can develop, and timely diagnosis and medical management will decrease morbidity and shorten the length of time needed for nutritional rehabilitation.

1. Lee TH, Lee JS, Jo Y, et al. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome: where do we stand today? J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16(12):2203-2211.

2. Chan DK, Mak KS, Cheah YL. Successful nutritional therapy for superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Singapore Med J. 2012;53(11):e233-e236.

3. Beltrán OD, Martinez AV, Manrique Mdel C, Rodriguez JS, Febres EL, Peña SR. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome in a patient with Charcot Marie Tooth disease. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;3(12):197-200.

4. Verhoef PA, Rampal A. Unique challenges for appropriate management of a 16-year-old girl with superior mesenteric artery syndrome as a result of anorexia nervosa: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:127.

5. Kingham TP, Shen R, Ren C. Laparoscopic treatment of superior mesenteric artery syndrome. JSLS. 2004;8(4):376-379.

6. Schauer SG, Thompson AJ, Bebarta VS. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome in a young military basic trainee. Mil Med. 2013;178(3):e398-e399.

7. Karrer FM, Jones SA, Vargas JH. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Treatment and management. Medscape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/932220. Updated July 27, 2015. Accessed August 3, 2015.

8. Arthurs OJ, Mehta U, Set PA. Nutcracker and SMA syndromes: What is the normal SMA angle in children? Eur J Radiol. 2012;81(8):e854-e861.

9. Capitano S, Donatelli G, Boccoli G. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome--Believe in it! Report of a case. Case Rep Surg. 2012;2012(10):282646.

10. Sabbagh C, Santin E, Potier A, Regimbeau JM. The superior mesenteric artery syndrome: a rare etiology for proximal obstructive syndrome. J Visc Surg. 2012;149(6):428-429.

11. Shah MA, Albright MB, Vogt MT, Moreland MS. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome in scoliosis surgery: weight percentile for height as an indicator of risk. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23(5):665-668.

12. Tsirikos AI, Anakwe RE, Baker AD. Late presentation of superior mesenteric artery syndrome following scoliosis surgery: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2(9):9.

13. Hod-Feins R, Copeliovitch L, Abu-Kishk I, et al. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome after scoliosis repair surgery: a case study and reassessment of the syndrome’s pathogenesis. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2007;16(5):345-349.

14. Kennedy KV, Yela R, Achalandabaso Mdel M, Martín-Pérez E. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2013;105(4):236-238.

15. Agrawal S, Patel H. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Surgery. 2013;153(4):601-602.

16. Felton BM, White JM, Racine MA. An uncommon case of abdominal pain: superior mesenteric artery syndrome. West J Emerg Med. 2012;13(6):501-502.

17. Kothari TH, Machnicki S, Kurtz L. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25(11):599-600.