User login

Major Depressive Disorder in the Primary Care Setting: Strategies to Achieve Remission and Recovery

Family physicians are on the frontline for depression care, often being the first line of defense for diagnosis and management. This 1.25-hour, CME-certified activity will provide clinicians with a comprehensive review on the following:

- Clinical factors in the primary care setting that influence treatment outcomes in major depressive disorder

- Identification and management of residual symptoms

- Tools for effective monitoring of treatment outcomes

- Nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies to treat patients to goal: remission and recovery

- Strategies to promote patient-focused, recovery-oriented care.

Family physicians are on the frontline for depression care, often being the first line of defense for diagnosis and management. This 1.25-hour, CME-certified activity will provide clinicians with a comprehensive review on the following:

- Clinical factors in the primary care setting that influence treatment outcomes in major depressive disorder

- Identification and management of residual symptoms

- Tools for effective monitoring of treatment outcomes

- Nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies to treat patients to goal: remission and recovery

- Strategies to promote patient-focused, recovery-oriented care.

Family physicians are on the frontline for depression care, often being the first line of defense for diagnosis and management. This 1.25-hour, CME-certified activity will provide clinicians with a comprehensive review on the following:

- Clinical factors in the primary care setting that influence treatment outcomes in major depressive disorder

- Identification and management of residual symptoms

- Tools for effective monitoring of treatment outcomes

- Nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies to treat patients to goal: remission and recovery

- Strategies to promote patient-focused, recovery-oriented care.

Tuberculosis testing: Which patients, which test?

› Test for latent tuberculosis (TB) infection by using a tuberculin skin test (TST) or interferon gamma release assay (IGRA) in all patients at risk for developing active TB. B

› Consider patient characteristics such as age, previous vaccination with bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG), and whether the patient will need serial testing to decide whether TST or IGRA is most appropriate for a specific patient. C

› Don’t use TST or IGRA to make or exclude a diagnosis of active TB; use cultures instead. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE 1 › Judy C is a newly employed 40-year-old health care worker who was born in China and received the bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination as a child. Her new employer requires her to undergo testing for tuberculosis (TB). Her initial tuberculin skin test (TST) is 0 mm, but on a second TST 2 weeks later, it is 8 mm. She is otherwise healthy, negative for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and has no constitutional symptoms. Does she have latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI)?

CASE 2 › A mom brings in her 3-year-old son, Patrick. She reports that a staff member at his day care center traveled outside the country for 3 months and was diagnosed with LTBI upon her return. She wants to know if her son should be tested.

More than 2 billion people—nearly one-third of the world’s population—are infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis.1 Most harbor the bacilli as LTBI, which means that while they have living TB bacilli within their bodies, these mycobacteria are kept dormant by an intact immune system. These individuals are not contagious, nor are they likely to become ill from active TB unless something adversely affects their immune system and increases the likelihood that LTBI will progress to active TB.

Two tests are available for diagnosing LTBI: the TST and the newer interferon gamma release assay (IGRA). Each test has advantages and disadvantages, and the best test to use depends on various patient-specific factors. This article describes whom you should test for LTBI, which test to use, and how to diagnose active TB.

Why test for LTBI?

LTBI is an asymptomatic infection; patients with LTBI have a 5% to 10% lifetime risk of developing active TB.2 The risk of developing active TB is approximately 5% within the first 18 months of infection, and the remaining risk is spread out over the rest of the patient’s life.2 Screening for LTBI is desirable because early diagnosis and treatment can reduce the activation risk to 1% to 2%,3 and treatment for LTBI is simpler, less costly, and less toxic than treatment for active TB.

Whom to test. Screening for LTBI should target patients for whom the benefits of treatment outweigh the cost and risks of treatment.4 A decision to screen for LTBI implies that the patient will be treated if he or she tests positive.3

The benefit of treatment increases in people who have a significant risk of progression to active TB—primarily those with recently acquired LTBI, or with co-existing conditions that increase their likelihood of progression (TABLE 1).5

All household contacts of patients with active TB and recent immigrants from countries with a high TB prevalence should be tested for LTBI.6 Those with a negative test and recent exposure should be retested in 8 to 12 weeks to allow for the delay in conversion to a positive test after recent infection.7 Health care workers and others who are potentially exposed to active TB on an ongoing basis should be tested at the time of employment, with repeat testing done periodically based on their risk of infection.8,9

Individuals with coexisting conditions should be tested for LTBI as long as the benefit of treatment outweighs the risk of drug-induced hepatitis. Because the risk of drug-induced hepatitis increases with age, the decision to test/treat is affected by age as well as the individual’s risk of progression. Patients with the highest risk conditions would benefit from testing/treating regardless of age, while treatment may not be justified in those with lower-risk conditions. A reasonable strategy is as follows:10

• high-risk conditions: test regardless of age

• moderate-risk conditions: test those <65 years

• low-risk conditions: test those <50 years.

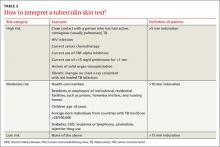

Children with LTBI are at particularly high risk of progression to active TB.5 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends assessing a child’s risk for TB at first contact with the child and once every 6 months for the first year of life. After one year, annual assessment is recommended, but specific TB testing is not required for children who don’t have risk factors.11 The AAP suggests using a TB risk assessment questionnaire that consists of 4 screening questions with follow-up questions if any of the screening questions are positive (TABLE 2).11

Use of TST is well established

To perform a TST, inject 5 tuberculin units (0.1 mL) of purified protein derivative (PPD) intradermally into the inner surface of the forearm using a 27- to 30-gauge needle. (In the United States, PPD is available as Aplisol or Tubersol.) Avoid the former practice of “control” or anergy testing with mumps or Candida antigens because this is rarely helpful in making TB treatment decisions, even in HIV-positive patients.12

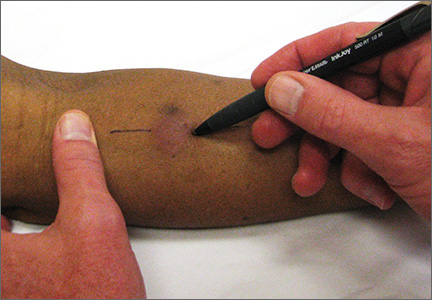

To facilitate intradermal injection, gently stretch the skin taut during injection. Raising a wheal confirms correct placement. The test should be read 48 to 72 hours after it is administered by measuring the greatest diameter of induration at the administration site. (Erythema is irrelevant to how the test is interpreted.) Induration is best read by using a ballpoint pen held at a 45-degree angle pointing toward the injection site. Roll the point of the pen over the skin with gentle pressure toward the injection site until induration causes the pen to stop rolling freely (FIGURE). The induration should be measured with a rule that has millimeter measurements and interpreted as positive or negative based on the individual’s risk factors (TABLE 3).3

Watch for these 2 factors that can affect TST results

Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG), an attenuated strain of Mycobacterium bovis, is (or has been) used as a routine childhood immunization in many parts of the world, although not in the United States.13 It is ordinarily given as a single dose shortly after birth, and has some utility in preventing serious childhood TB infection. The antigens in PPD and those in BCG are not identical, but they do overlap.

BCG administered after an individual’s first birthday resulted in false positive TSTs >10 mm in 21% of those tested more than 10 years after BCG was administered.14 However, a single BCG vaccine in infancy causes little if any change in the TST result in individuals who are older than age 10 years. When a TST is performed for appropriate reasons, a positive TST in people previously vaccinated with BCG is generally more likely to be the result of LTBI than of BCG.15 Current guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend that previous BCG status not change the cutoffs used for interpreting TST results.16

Booster phenomenon. In many adults who have undiagnosed LTBI that they acquired in the distant past, or who received BCG vaccination as a child, immunity wanes after several decades. This can result in an initial TST being negative, but because the antigens in the PPD itself stimulate antigenic memory, the next time a TST is performed, it may be positive.

In people who will have annual TST screenings, such as health care workers or nursing home residents, a 2-step PPD can help discriminate this “booster” phenomenon from a new LTBI acquired during the first year of annual TST testing. A second TST is placed 1 to 2 weeks after the initial test, a time interval during which acquisition of LTBI would be unlikely. The result of the second test should be considered the person’s baseline for evaluation of subsequent TSTs. A subsequent TST would be considered positive if the induration is >10 mm and has increased by ≥6 mm since the previous baseline.17

IGRA offers certain benefits

IGRA uses antigens that are more specific for Mycobacterium tuberculosis than the TST, and as a result, this test is not influenced by previous BCG vaccination. It requires only one blood draw, and interpretation does not depend on the patient’s risk category or interpretation of skin induration. The primary disadvantage of IGRAs is high cost (currently $200 to $300 per test), and the need for a laboratory with adequate equipment and personnel trained in performing the test. IGRAs must be collected in special blood tubes, and the samples must be processed within 8 to 16 hours of collection, depending on the test used.5

Currently, 2 IGRAs are approved for use in the United States—the QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube (QFT-GIT) and the T-SPOT.TB assay. Both tests may produce false positives in patients infected with Mycobacterium marinum or Mycobacterium kansasii, but otherwise are highly specific for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. IGRA results may be “boosted” by recent TST (ie, a TST given within the previous 3 months may cause a false positive IGRA result), and this effect may begin as early as 3 days after a TST is administered.18 Therefore, if an IGRA is needed to clarify a TST result, it should be drawn on the day the TST is read.19

CDC guidelines (2010) recommend that IGRAs may be used in place of—but not routinely in addition to—TSTs in all cases in which TST is otherwise indicated.20 There are a few situations where one test may be preferred over the other.21

IGRA may be preferred over TST in individuals in one of 2 categories:

• those who have received BCG immunization. If a patient is unsure of their BCG status, the World Atlas of BCG Policies and Practices, available at www.bcgatlas.org,22 can aid clinicians in determining which patients likely received BCG as part of their routine childhood immunizations.

• those in groups that historically have poor rates of return for TST reading, such as individuals who are homeless or suffer from alcoholism or a substance use disorder.

Individuals in whom TST is preferred over IGRA include:

• children age <5 years, because data guiding use of IGRAs in this age group are limited.23 Both TST and IGRA may be falsely negative in children under the age of 3 months.24

• patients who require serial testing, because individuals with positive IGRAs have been shown to commonly test negative on subsequent tests, and there are limited data on interpretation and prognosis of positive IGRAs in people who require serial testing.25

Individuals in whom performing both tests simultaneously could be helpful include:

• those with an initial negative test, but with a high risk for progression to active TB or a poor outcome if the first result is falsely negative (eg, patients with HIV infection or children ages <5 years who have been exposed to a person with active TB)

• those with an initial positive test who don’t believe the test result and are reluctant to be treated for LTBI.

TST and IGRA have comparable sensitivities—around 80% to 90%, respectively—for diagnosing LTBI. IGRAs have a specificity >95% for diagnosing LTBI. While TST specificity is approximately 97% in patients not vaccinated with BCG, it can be as low as 60% in people previously vaccinated with BCG.26 IGRAs have been shown to have higher positive and negative predictive values than TSTs in high-risk patients.27 A recent study suggested that the IGRAs might have a higher rate of false-positive results compared to TSTs in a low-risk population of health care workers.28

Both the TST and IGRA have lag times of 3 to 8 weeks from the time of a new infection until the test becomes positive. It is therefore best to defer testing for LTBI infection until at least 8 weeks after a known TB exposure to decrease the likelihood of a false-negative test.3

Diagnose active TB based on symptoms, culture

The CDC reported 9412 new cases of active TB in the United States in 2014, for a rate of 3 new cases per 100,000 people.29 This is the lowest rate reported since national reporting began in 1953, when the incidence in the United States was 53 cases per 100,000.

Who should you test for active TB? The risk factors for active TB are the same as those for LTBI: recent exposure to an individual with active TB, and other disease processes or medications that compromise the immune system. Consider active TB when a patient with one of these risk factors presents with:2

• persistent fever

• weight loss

• night sweats

• cough, especially if there is any blood.

Routine laboratory and radiographic studies that should prompt you to consider TB include:2

• upper lobe infiltrates on chest x-ray

• sterile pyuria on urinalysis with a negative culture for routine pathogens

• elevated levels of C-reactive protein or an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate without another obvious cause.

Active TB typically presents as pulmonary TB, but it can also affect nearly every other body system. Other common presentations include:30

• vertebral destruction and collapse (“Pott's disease”)

• subacute meningitis

• peritonitis

• lymphadenopathy (especially in children).

Culture is the gold standard. Neither TST or IGRA should ever be relied upon to make or exclude the diagnosis of active TB, as these tests are neither sensitive nor specific for diagnosing active TB.31,32 Instead, the gold standard for the diagnosis of active TB remains a positive culture from infected tissue—commonly sputum, pleura or pleural fluid, cerebrospinal fluid, urine, or peritoneal fluid. Cultures are crucial not only to confirm the diagnosis, but to guide therapy, because of the rapidly increasing resistance to firstline antibiotics used to treat TB.33

Culture results and drug sensitivities are ordinarily not available until 2 to 6 weeks after the culture was obtained. A smear for acid-fast bacilli as well as newer rapid diagnostic tests such as nucleic acid amplification (NAA) tests are generally performed on the tissue sample submitted for culture, and these results, while less trustworthy, are generally available within 24 to 48 hours. The CDC recommends that an NAA test be performed in addition to microscopy and culture for specimens submitted for TB diagnosis.34

Since 2011, the World Health Organization has endorsed the use of a new molecular diagnostic test called Xpert MTB/RIF in settings with high prevalence of HIV infection or multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB).35 This test is able to detect M. tuberculosis as well as rifampin resistance, a surrogate for MDR-TB, within 2 hours, with sensitivity and specificity approaching that of culture.36

“Culture-negative” TB? A small but not insignificant proportion of patients will present with risk factors for, and clinical signs and symptoms of, active TB; their cultures, however, will be negative. In such cases, consultation with an infectious disease or pulmonary specialist may be warranted. If no alternative diagnosis is found, such patients are said to have “culture-negative active TB” and should be continued on anti-TB drug therapy, although the course may be shortened.37 This highlights the fact that while cultures are key to diagnosing and treating active TB, the condition is—practically speaking—a clinical diagnosis; treatment should not be withheld or stopped simply because of a negative culture or rapid diagnostic test.

CASE 1 › Based on her risk factors (being a health care worker, born in a country with a high prevalence of TB), Ms. C’s cutoff for a positive test is >10 mm, so her TST result is negative and she is not considered to have LTBI. The increase to 8 mm seen on the second TST probably represents either childhood BCG vaccination or previous infection with nontuberculous Mycobacterium.

CASE 2 › Strictly speaking, 3-year-old Patrick does not need testing, because he was exposed only to LTBI, which is not infectious. However, because children under age 5 are at particularly high risk for progressing to active TB and poor outcomes, it would be best to confirm the mother’s story with the day care center and/or health department. If it turns out that Patrick had, in fact, been exposed to active TB, much more aggressive management would be required.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jeff Hall, MD, Family Medicine Center, 3209 Colonial Drive Columbia, SC 29203; [email protected]

1. World Health Organization. Tuberculosis. World Health Organization Web site. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs104/en/. Accessed July 7, 2015.

2. Zumla A, Raviglione M, Hafner R, et al. Current concepts: tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:745-755.

3. Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. American Thoracic Society. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2000;49:1-51.

4. Hauck FR, Neese BH, Panchal AS, et al. Identification and management of latent tuberculosis infection. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79:879-886.

5. Getahun H, Matteelli A, Chaisson RE, et al. Latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2127-2135.

6. Arshad S, Bavan L, Gajari K, et al. Active screening at entry for tuberculosis among new immigrants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:1336-1345.

7. Greenaway C, Sandoe A, Vissandjee B, et al; Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health. Tuberculosis: evidence review for newly arriving immigrants and refugees. CMAJ. 2011;183:E939-E951.

8. Jensen PA, Lambert LA, Iademarco MF, et al; CDC. Guidelines for preventing the transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in health-care settings, 2005. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54:1-141.

9. Taylor Z, Nolan CM, Blumberg HM; American Thoracic Society; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Controlling tuberculosis in the United States. Recommendations from the American Thoracic Society, CDC, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54:1-81.

10. Pai M, Menzies D. Diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection (tuberculosis screening) in HIV-negative adults. UpToDate Web site. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/diagnosisof-latent-tuberculosis-infection-tuberculosis-screening-in-hivnegative-adults. Accessed July 7, 2015.

11. Pediatric Tuberculosis Collaborative Group. Targeted tuberculin skin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1175-1201.

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Anergy skin testing and tuberculosis [corrected] preventive therapy for HIV-infected persons: revised recommendations. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1997;46:1-10.

13. The role of BCG vaccine in the prevention and control of tuberculosis in the United States. A joint statement by the Advisory Council for the Elimination of Tuberculosis and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1996;45:1-18.

14. Farhat M, Greenaway C, Pai M, et al. False-positive tuberculin skin tests: what is the absolute effect of BCG and non-tuberculous mycobacteria? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10:1192-1204.

15. Wang L, Turner MO, Elwood RK, et al. A meta-analysis of the effect of Bacille Calmette Guérin vaccination on tuberculin skin test measurements. Thorax. 2002;57:804-809.

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Fact sheets: BCG vaccine. CDC Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/prevention/bcg.htm. Accessed July 16, 2015.

17. Menzies D. Interpretation of repeated tuberculin tests. Boosting, conversion, and reversion. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:15-21.

18. van Zyl-Smit RN, Zwerling A, Dheda K, et al. Within-subject variability of interferon-g assay results for tuberculosis and boosting effect of tuberculin skin testing: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8517.

19. Mazurek GH, Jereb J, Lobue P, et al; Division of Tuberculosis Elimination, National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Guidelines for using the QuantiFERON-TB Gold test for detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, United States. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54:49-55.

20. Mazurek GH, Jereb J, Vernon A, et al; IGRA Expert Committee; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Updated guidelines for using Interferon Gamma Release Assays to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection - United States, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1-25.

21. Muñoz L, Santin M. Interferon- release assays versus tuberculin skin test for targeting people for tuberculosis preventive treatment: an evidence-based review. J Infect. 2013;66:381-387.

22. Zwerling A, Behr MA, Verma A, et al. The BCG World Atlas: a database of global BCG vaccination policies and practices. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001012.

23. Mandalakas AM, Detjen AK, Hesseling AC, et al. Interferon-gamma release assays and childhood tuberculosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:1018-1032.

24. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases, Pickering L, ed. Red Book. Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 29th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2012:741.

25. Zwerling A, van den Hof S, Scholten J, et al. Interferon-gamma release assays for tuberculosis screening of healthcare workers: a systematic review. Thorax. 2012;67:62-70. 26. Pai M, Zwerling A, Menzies D. Systematic review: T-cell-based assays for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection: an update. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:177-184.

27. Diel R, Loddenkemper R, Nienhaus A. Predictive value of interferon- release assays and tuberculin skin testing for progression from latent TB infection to disease state: a meta-analysis. Chest. 2012;142:63-75.

28. Dorman SE, Belknap R, Graviss EA, et al; Tuberculosis Epidemiologic Studies Consortium. Interferon-release assays and tuberculin skin testing for diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection in healthcare workers in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:77-87.

29. Scott C, Kirking HL, Jeffries C, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Tuberculosis trends—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:265-269.

30. Golden MP, Vikram HR. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:1761-1768.

31. Rangaka MX, Wilkinson KA, Glynn JR, et al. Predictive value of interferon-release assays for incident active tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:45-55.

32. Metcalfe JZ, Everett CK, Steingart KR, et al. Interferon-release assays for active pulmonary tuberculosis diagnosis in adults in low- and middle-income countries: systematic review and metaanalysis. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:S1120-S1129.

33. Keshavjee S, Farmer PE. Tuberculosis, drug resistance, and the history of modern medicine. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:931-936.

34. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Updated guidelines for the use of nucleic acid amplification tests in the diagnosis of tuberculosis. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:7-10.

35. World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2014. World Health Organization Web site. Available at: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/. Accessed July 17, 2015.

36. Steingart KR, Schiller I, Horne DJ, et al. Xpert® MTB/RIF assay for pulmonary tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD009593.

37. Hall J, Elliott C. Tuberculosis: Which drug regimen and when. J Fam Practice. 2015;64:27-33.

› Test for latent tuberculosis (TB) infection by using a tuberculin skin test (TST) or interferon gamma release assay (IGRA) in all patients at risk for developing active TB. B

› Consider patient characteristics such as age, previous vaccination with bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG), and whether the patient will need serial testing to decide whether TST or IGRA is most appropriate for a specific patient. C

› Don’t use TST or IGRA to make or exclude a diagnosis of active TB; use cultures instead. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE 1 › Judy C is a newly employed 40-year-old health care worker who was born in China and received the bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination as a child. Her new employer requires her to undergo testing for tuberculosis (TB). Her initial tuberculin skin test (TST) is 0 mm, but on a second TST 2 weeks later, it is 8 mm. She is otherwise healthy, negative for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and has no constitutional symptoms. Does she have latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI)?

CASE 2 › A mom brings in her 3-year-old son, Patrick. She reports that a staff member at his day care center traveled outside the country for 3 months and was diagnosed with LTBI upon her return. She wants to know if her son should be tested.

More than 2 billion people—nearly one-third of the world’s population—are infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis.1 Most harbor the bacilli as LTBI, which means that while they have living TB bacilli within their bodies, these mycobacteria are kept dormant by an intact immune system. These individuals are not contagious, nor are they likely to become ill from active TB unless something adversely affects their immune system and increases the likelihood that LTBI will progress to active TB.

Two tests are available for diagnosing LTBI: the TST and the newer interferon gamma release assay (IGRA). Each test has advantages and disadvantages, and the best test to use depends on various patient-specific factors. This article describes whom you should test for LTBI, which test to use, and how to diagnose active TB.

Why test for LTBI?

LTBI is an asymptomatic infection; patients with LTBI have a 5% to 10% lifetime risk of developing active TB.2 The risk of developing active TB is approximately 5% within the first 18 months of infection, and the remaining risk is spread out over the rest of the patient’s life.2 Screening for LTBI is desirable because early diagnosis and treatment can reduce the activation risk to 1% to 2%,3 and treatment for LTBI is simpler, less costly, and less toxic than treatment for active TB.

Whom to test. Screening for LTBI should target patients for whom the benefits of treatment outweigh the cost and risks of treatment.4 A decision to screen for LTBI implies that the patient will be treated if he or she tests positive.3

The benefit of treatment increases in people who have a significant risk of progression to active TB—primarily those with recently acquired LTBI, or with co-existing conditions that increase their likelihood of progression (TABLE 1).5

All household contacts of patients with active TB and recent immigrants from countries with a high TB prevalence should be tested for LTBI.6 Those with a negative test and recent exposure should be retested in 8 to 12 weeks to allow for the delay in conversion to a positive test after recent infection.7 Health care workers and others who are potentially exposed to active TB on an ongoing basis should be tested at the time of employment, with repeat testing done periodically based on their risk of infection.8,9

Individuals with coexisting conditions should be tested for LTBI as long as the benefit of treatment outweighs the risk of drug-induced hepatitis. Because the risk of drug-induced hepatitis increases with age, the decision to test/treat is affected by age as well as the individual’s risk of progression. Patients with the highest risk conditions would benefit from testing/treating regardless of age, while treatment may not be justified in those with lower-risk conditions. A reasonable strategy is as follows:10

• high-risk conditions: test regardless of age

• moderate-risk conditions: test those <65 years

• low-risk conditions: test those <50 years.

Children with LTBI are at particularly high risk of progression to active TB.5 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends assessing a child’s risk for TB at first contact with the child and once every 6 months for the first year of life. After one year, annual assessment is recommended, but specific TB testing is not required for children who don’t have risk factors.11 The AAP suggests using a TB risk assessment questionnaire that consists of 4 screening questions with follow-up questions if any of the screening questions are positive (TABLE 2).11

Use of TST is well established

To perform a TST, inject 5 tuberculin units (0.1 mL) of purified protein derivative (PPD) intradermally into the inner surface of the forearm using a 27- to 30-gauge needle. (In the United States, PPD is available as Aplisol or Tubersol.) Avoid the former practice of “control” or anergy testing with mumps or Candida antigens because this is rarely helpful in making TB treatment decisions, even in HIV-positive patients.12

To facilitate intradermal injection, gently stretch the skin taut during injection. Raising a wheal confirms correct placement. The test should be read 48 to 72 hours after it is administered by measuring the greatest diameter of induration at the administration site. (Erythema is irrelevant to how the test is interpreted.) Induration is best read by using a ballpoint pen held at a 45-degree angle pointing toward the injection site. Roll the point of the pen over the skin with gentle pressure toward the injection site until induration causes the pen to stop rolling freely (FIGURE). The induration should be measured with a rule that has millimeter measurements and interpreted as positive or negative based on the individual’s risk factors (TABLE 3).3

Watch for these 2 factors that can affect TST results

Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG), an attenuated strain of Mycobacterium bovis, is (or has been) used as a routine childhood immunization in many parts of the world, although not in the United States.13 It is ordinarily given as a single dose shortly after birth, and has some utility in preventing serious childhood TB infection. The antigens in PPD and those in BCG are not identical, but they do overlap.

BCG administered after an individual’s first birthday resulted in false positive TSTs >10 mm in 21% of those tested more than 10 years after BCG was administered.14 However, a single BCG vaccine in infancy causes little if any change in the TST result in individuals who are older than age 10 years. When a TST is performed for appropriate reasons, a positive TST in people previously vaccinated with BCG is generally more likely to be the result of LTBI than of BCG.15 Current guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend that previous BCG status not change the cutoffs used for interpreting TST results.16

Booster phenomenon. In many adults who have undiagnosed LTBI that they acquired in the distant past, or who received BCG vaccination as a child, immunity wanes after several decades. This can result in an initial TST being negative, but because the antigens in the PPD itself stimulate antigenic memory, the next time a TST is performed, it may be positive.

In people who will have annual TST screenings, such as health care workers or nursing home residents, a 2-step PPD can help discriminate this “booster” phenomenon from a new LTBI acquired during the first year of annual TST testing. A second TST is placed 1 to 2 weeks after the initial test, a time interval during which acquisition of LTBI would be unlikely. The result of the second test should be considered the person’s baseline for evaluation of subsequent TSTs. A subsequent TST would be considered positive if the induration is >10 mm and has increased by ≥6 mm since the previous baseline.17

IGRA offers certain benefits

IGRA uses antigens that are more specific for Mycobacterium tuberculosis than the TST, and as a result, this test is not influenced by previous BCG vaccination. It requires only one blood draw, and interpretation does not depend on the patient’s risk category or interpretation of skin induration. The primary disadvantage of IGRAs is high cost (currently $200 to $300 per test), and the need for a laboratory with adequate equipment and personnel trained in performing the test. IGRAs must be collected in special blood tubes, and the samples must be processed within 8 to 16 hours of collection, depending on the test used.5

Currently, 2 IGRAs are approved for use in the United States—the QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube (QFT-GIT) and the T-SPOT.TB assay. Both tests may produce false positives in patients infected with Mycobacterium marinum or Mycobacterium kansasii, but otherwise are highly specific for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. IGRA results may be “boosted” by recent TST (ie, a TST given within the previous 3 months may cause a false positive IGRA result), and this effect may begin as early as 3 days after a TST is administered.18 Therefore, if an IGRA is needed to clarify a TST result, it should be drawn on the day the TST is read.19

CDC guidelines (2010) recommend that IGRAs may be used in place of—but not routinely in addition to—TSTs in all cases in which TST is otherwise indicated.20 There are a few situations where one test may be preferred over the other.21

IGRA may be preferred over TST in individuals in one of 2 categories:

• those who have received BCG immunization. If a patient is unsure of their BCG status, the World Atlas of BCG Policies and Practices, available at www.bcgatlas.org,22 can aid clinicians in determining which patients likely received BCG as part of their routine childhood immunizations.

• those in groups that historically have poor rates of return for TST reading, such as individuals who are homeless or suffer from alcoholism or a substance use disorder.

Individuals in whom TST is preferred over IGRA include:

• children age <5 years, because data guiding use of IGRAs in this age group are limited.23 Both TST and IGRA may be falsely negative in children under the age of 3 months.24

• patients who require serial testing, because individuals with positive IGRAs have been shown to commonly test negative on subsequent tests, and there are limited data on interpretation and prognosis of positive IGRAs in people who require serial testing.25

Individuals in whom performing both tests simultaneously could be helpful include:

• those with an initial negative test, but with a high risk for progression to active TB or a poor outcome if the first result is falsely negative (eg, patients with HIV infection or children ages <5 years who have been exposed to a person with active TB)

• those with an initial positive test who don’t believe the test result and are reluctant to be treated for LTBI.

TST and IGRA have comparable sensitivities—around 80% to 90%, respectively—for diagnosing LTBI. IGRAs have a specificity >95% for diagnosing LTBI. While TST specificity is approximately 97% in patients not vaccinated with BCG, it can be as low as 60% in people previously vaccinated with BCG.26 IGRAs have been shown to have higher positive and negative predictive values than TSTs in high-risk patients.27 A recent study suggested that the IGRAs might have a higher rate of false-positive results compared to TSTs in a low-risk population of health care workers.28

Both the TST and IGRA have lag times of 3 to 8 weeks from the time of a new infection until the test becomes positive. It is therefore best to defer testing for LTBI infection until at least 8 weeks after a known TB exposure to decrease the likelihood of a false-negative test.3

Diagnose active TB based on symptoms, culture

The CDC reported 9412 new cases of active TB in the United States in 2014, for a rate of 3 new cases per 100,000 people.29 This is the lowest rate reported since national reporting began in 1953, when the incidence in the United States was 53 cases per 100,000.

Who should you test for active TB? The risk factors for active TB are the same as those for LTBI: recent exposure to an individual with active TB, and other disease processes or medications that compromise the immune system. Consider active TB when a patient with one of these risk factors presents with:2

• persistent fever

• weight loss

• night sweats

• cough, especially if there is any blood.

Routine laboratory and radiographic studies that should prompt you to consider TB include:2

• upper lobe infiltrates on chest x-ray

• sterile pyuria on urinalysis with a negative culture for routine pathogens

• elevated levels of C-reactive protein or an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate without another obvious cause.

Active TB typically presents as pulmonary TB, but it can also affect nearly every other body system. Other common presentations include:30

• vertebral destruction and collapse (“Pott's disease”)

• subacute meningitis

• peritonitis

• lymphadenopathy (especially in children).

Culture is the gold standard. Neither TST or IGRA should ever be relied upon to make or exclude the diagnosis of active TB, as these tests are neither sensitive nor specific for diagnosing active TB.31,32 Instead, the gold standard for the diagnosis of active TB remains a positive culture from infected tissue—commonly sputum, pleura or pleural fluid, cerebrospinal fluid, urine, or peritoneal fluid. Cultures are crucial not only to confirm the diagnosis, but to guide therapy, because of the rapidly increasing resistance to firstline antibiotics used to treat TB.33

Culture results and drug sensitivities are ordinarily not available until 2 to 6 weeks after the culture was obtained. A smear for acid-fast bacilli as well as newer rapid diagnostic tests such as nucleic acid amplification (NAA) tests are generally performed on the tissue sample submitted for culture, and these results, while less trustworthy, are generally available within 24 to 48 hours. The CDC recommends that an NAA test be performed in addition to microscopy and culture for specimens submitted for TB diagnosis.34

Since 2011, the World Health Organization has endorsed the use of a new molecular diagnostic test called Xpert MTB/RIF in settings with high prevalence of HIV infection or multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB).35 This test is able to detect M. tuberculosis as well as rifampin resistance, a surrogate for MDR-TB, within 2 hours, with sensitivity and specificity approaching that of culture.36

“Culture-negative” TB? A small but not insignificant proportion of patients will present with risk factors for, and clinical signs and symptoms of, active TB; their cultures, however, will be negative. In such cases, consultation with an infectious disease or pulmonary specialist may be warranted. If no alternative diagnosis is found, such patients are said to have “culture-negative active TB” and should be continued on anti-TB drug therapy, although the course may be shortened.37 This highlights the fact that while cultures are key to diagnosing and treating active TB, the condition is—practically speaking—a clinical diagnosis; treatment should not be withheld or stopped simply because of a negative culture or rapid diagnostic test.

CASE 1 › Based on her risk factors (being a health care worker, born in a country with a high prevalence of TB), Ms. C’s cutoff for a positive test is >10 mm, so her TST result is negative and she is not considered to have LTBI. The increase to 8 mm seen on the second TST probably represents either childhood BCG vaccination or previous infection with nontuberculous Mycobacterium.

CASE 2 › Strictly speaking, 3-year-old Patrick does not need testing, because he was exposed only to LTBI, which is not infectious. However, because children under age 5 are at particularly high risk for progressing to active TB and poor outcomes, it would be best to confirm the mother’s story with the day care center and/or health department. If it turns out that Patrick had, in fact, been exposed to active TB, much more aggressive management would be required.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jeff Hall, MD, Family Medicine Center, 3209 Colonial Drive Columbia, SC 29203; [email protected]

› Test for latent tuberculosis (TB) infection by using a tuberculin skin test (TST) or interferon gamma release assay (IGRA) in all patients at risk for developing active TB. B

› Consider patient characteristics such as age, previous vaccination with bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG), and whether the patient will need serial testing to decide whether TST or IGRA is most appropriate for a specific patient. C

› Don’t use TST or IGRA to make or exclude a diagnosis of active TB; use cultures instead. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE 1 › Judy C is a newly employed 40-year-old health care worker who was born in China and received the bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination as a child. Her new employer requires her to undergo testing for tuberculosis (TB). Her initial tuberculin skin test (TST) is 0 mm, but on a second TST 2 weeks later, it is 8 mm. She is otherwise healthy, negative for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and has no constitutional symptoms. Does she have latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI)?

CASE 2 › A mom brings in her 3-year-old son, Patrick. She reports that a staff member at his day care center traveled outside the country for 3 months and was diagnosed with LTBI upon her return. She wants to know if her son should be tested.

More than 2 billion people—nearly one-third of the world’s population—are infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis.1 Most harbor the bacilli as LTBI, which means that while they have living TB bacilli within their bodies, these mycobacteria are kept dormant by an intact immune system. These individuals are not contagious, nor are they likely to become ill from active TB unless something adversely affects their immune system and increases the likelihood that LTBI will progress to active TB.

Two tests are available for diagnosing LTBI: the TST and the newer interferon gamma release assay (IGRA). Each test has advantages and disadvantages, and the best test to use depends on various patient-specific factors. This article describes whom you should test for LTBI, which test to use, and how to diagnose active TB.

Why test for LTBI?

LTBI is an asymptomatic infection; patients with LTBI have a 5% to 10% lifetime risk of developing active TB.2 The risk of developing active TB is approximately 5% within the first 18 months of infection, and the remaining risk is spread out over the rest of the patient’s life.2 Screening for LTBI is desirable because early diagnosis and treatment can reduce the activation risk to 1% to 2%,3 and treatment for LTBI is simpler, less costly, and less toxic than treatment for active TB.

Whom to test. Screening for LTBI should target patients for whom the benefits of treatment outweigh the cost and risks of treatment.4 A decision to screen for LTBI implies that the patient will be treated if he or she tests positive.3

The benefit of treatment increases in people who have a significant risk of progression to active TB—primarily those with recently acquired LTBI, or with co-existing conditions that increase their likelihood of progression (TABLE 1).5

All household contacts of patients with active TB and recent immigrants from countries with a high TB prevalence should be tested for LTBI.6 Those with a negative test and recent exposure should be retested in 8 to 12 weeks to allow for the delay in conversion to a positive test after recent infection.7 Health care workers and others who are potentially exposed to active TB on an ongoing basis should be tested at the time of employment, with repeat testing done periodically based on their risk of infection.8,9

Individuals with coexisting conditions should be tested for LTBI as long as the benefit of treatment outweighs the risk of drug-induced hepatitis. Because the risk of drug-induced hepatitis increases with age, the decision to test/treat is affected by age as well as the individual’s risk of progression. Patients with the highest risk conditions would benefit from testing/treating regardless of age, while treatment may not be justified in those with lower-risk conditions. A reasonable strategy is as follows:10

• high-risk conditions: test regardless of age

• moderate-risk conditions: test those <65 years

• low-risk conditions: test those <50 years.

Children with LTBI are at particularly high risk of progression to active TB.5 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends assessing a child’s risk for TB at first contact with the child and once every 6 months for the first year of life. After one year, annual assessment is recommended, but specific TB testing is not required for children who don’t have risk factors.11 The AAP suggests using a TB risk assessment questionnaire that consists of 4 screening questions with follow-up questions if any of the screening questions are positive (TABLE 2).11

Use of TST is well established

To perform a TST, inject 5 tuberculin units (0.1 mL) of purified protein derivative (PPD) intradermally into the inner surface of the forearm using a 27- to 30-gauge needle. (In the United States, PPD is available as Aplisol or Tubersol.) Avoid the former practice of “control” or anergy testing with mumps or Candida antigens because this is rarely helpful in making TB treatment decisions, even in HIV-positive patients.12

To facilitate intradermal injection, gently stretch the skin taut during injection. Raising a wheal confirms correct placement. The test should be read 48 to 72 hours after it is administered by measuring the greatest diameter of induration at the administration site. (Erythema is irrelevant to how the test is interpreted.) Induration is best read by using a ballpoint pen held at a 45-degree angle pointing toward the injection site. Roll the point of the pen over the skin with gentle pressure toward the injection site until induration causes the pen to stop rolling freely (FIGURE). The induration should be measured with a rule that has millimeter measurements and interpreted as positive or negative based on the individual’s risk factors (TABLE 3).3

Watch for these 2 factors that can affect TST results

Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG), an attenuated strain of Mycobacterium bovis, is (or has been) used as a routine childhood immunization in many parts of the world, although not in the United States.13 It is ordinarily given as a single dose shortly after birth, and has some utility in preventing serious childhood TB infection. The antigens in PPD and those in BCG are not identical, but they do overlap.

BCG administered after an individual’s first birthday resulted in false positive TSTs >10 mm in 21% of those tested more than 10 years after BCG was administered.14 However, a single BCG vaccine in infancy causes little if any change in the TST result in individuals who are older than age 10 years. When a TST is performed for appropriate reasons, a positive TST in people previously vaccinated with BCG is generally more likely to be the result of LTBI than of BCG.15 Current guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend that previous BCG status not change the cutoffs used for interpreting TST results.16

Booster phenomenon. In many adults who have undiagnosed LTBI that they acquired in the distant past, or who received BCG vaccination as a child, immunity wanes after several decades. This can result in an initial TST being negative, but because the antigens in the PPD itself stimulate antigenic memory, the next time a TST is performed, it may be positive.

In people who will have annual TST screenings, such as health care workers or nursing home residents, a 2-step PPD can help discriminate this “booster” phenomenon from a new LTBI acquired during the first year of annual TST testing. A second TST is placed 1 to 2 weeks after the initial test, a time interval during which acquisition of LTBI would be unlikely. The result of the second test should be considered the person’s baseline for evaluation of subsequent TSTs. A subsequent TST would be considered positive if the induration is >10 mm and has increased by ≥6 mm since the previous baseline.17

IGRA offers certain benefits

IGRA uses antigens that are more specific for Mycobacterium tuberculosis than the TST, and as a result, this test is not influenced by previous BCG vaccination. It requires only one blood draw, and interpretation does not depend on the patient’s risk category or interpretation of skin induration. The primary disadvantage of IGRAs is high cost (currently $200 to $300 per test), and the need for a laboratory with adequate equipment and personnel trained in performing the test. IGRAs must be collected in special blood tubes, and the samples must be processed within 8 to 16 hours of collection, depending on the test used.5

Currently, 2 IGRAs are approved for use in the United States—the QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube (QFT-GIT) and the T-SPOT.TB assay. Both tests may produce false positives in patients infected with Mycobacterium marinum or Mycobacterium kansasii, but otherwise are highly specific for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. IGRA results may be “boosted” by recent TST (ie, a TST given within the previous 3 months may cause a false positive IGRA result), and this effect may begin as early as 3 days after a TST is administered.18 Therefore, if an IGRA is needed to clarify a TST result, it should be drawn on the day the TST is read.19

CDC guidelines (2010) recommend that IGRAs may be used in place of—but not routinely in addition to—TSTs in all cases in which TST is otherwise indicated.20 There are a few situations where one test may be preferred over the other.21

IGRA may be preferred over TST in individuals in one of 2 categories:

• those who have received BCG immunization. If a patient is unsure of their BCG status, the World Atlas of BCG Policies and Practices, available at www.bcgatlas.org,22 can aid clinicians in determining which patients likely received BCG as part of their routine childhood immunizations.

• those in groups that historically have poor rates of return for TST reading, such as individuals who are homeless or suffer from alcoholism or a substance use disorder.

Individuals in whom TST is preferred over IGRA include:

• children age <5 years, because data guiding use of IGRAs in this age group are limited.23 Both TST and IGRA may be falsely negative in children under the age of 3 months.24

• patients who require serial testing, because individuals with positive IGRAs have been shown to commonly test negative on subsequent tests, and there are limited data on interpretation and prognosis of positive IGRAs in people who require serial testing.25

Individuals in whom performing both tests simultaneously could be helpful include:

• those with an initial negative test, but with a high risk for progression to active TB or a poor outcome if the first result is falsely negative (eg, patients with HIV infection or children ages <5 years who have been exposed to a person with active TB)

• those with an initial positive test who don’t believe the test result and are reluctant to be treated for LTBI.

TST and IGRA have comparable sensitivities—around 80% to 90%, respectively—for diagnosing LTBI. IGRAs have a specificity >95% for diagnosing LTBI. While TST specificity is approximately 97% in patients not vaccinated with BCG, it can be as low as 60% in people previously vaccinated with BCG.26 IGRAs have been shown to have higher positive and negative predictive values than TSTs in high-risk patients.27 A recent study suggested that the IGRAs might have a higher rate of false-positive results compared to TSTs in a low-risk population of health care workers.28

Both the TST and IGRA have lag times of 3 to 8 weeks from the time of a new infection until the test becomes positive. It is therefore best to defer testing for LTBI infection until at least 8 weeks after a known TB exposure to decrease the likelihood of a false-negative test.3

Diagnose active TB based on symptoms, culture

The CDC reported 9412 new cases of active TB in the United States in 2014, for a rate of 3 new cases per 100,000 people.29 This is the lowest rate reported since national reporting began in 1953, when the incidence in the United States was 53 cases per 100,000.

Who should you test for active TB? The risk factors for active TB are the same as those for LTBI: recent exposure to an individual with active TB, and other disease processes or medications that compromise the immune system. Consider active TB when a patient with one of these risk factors presents with:2

• persistent fever

• weight loss

• night sweats

• cough, especially if there is any blood.

Routine laboratory and radiographic studies that should prompt you to consider TB include:2

• upper lobe infiltrates on chest x-ray

• sterile pyuria on urinalysis with a negative culture for routine pathogens

• elevated levels of C-reactive protein or an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate without another obvious cause.

Active TB typically presents as pulmonary TB, but it can also affect nearly every other body system. Other common presentations include:30

• vertebral destruction and collapse (“Pott's disease”)

• subacute meningitis

• peritonitis

• lymphadenopathy (especially in children).

Culture is the gold standard. Neither TST or IGRA should ever be relied upon to make or exclude the diagnosis of active TB, as these tests are neither sensitive nor specific for diagnosing active TB.31,32 Instead, the gold standard for the diagnosis of active TB remains a positive culture from infected tissue—commonly sputum, pleura or pleural fluid, cerebrospinal fluid, urine, or peritoneal fluid. Cultures are crucial not only to confirm the diagnosis, but to guide therapy, because of the rapidly increasing resistance to firstline antibiotics used to treat TB.33

Culture results and drug sensitivities are ordinarily not available until 2 to 6 weeks after the culture was obtained. A smear for acid-fast bacilli as well as newer rapid diagnostic tests such as nucleic acid amplification (NAA) tests are generally performed on the tissue sample submitted for culture, and these results, while less trustworthy, are generally available within 24 to 48 hours. The CDC recommends that an NAA test be performed in addition to microscopy and culture for specimens submitted for TB diagnosis.34

Since 2011, the World Health Organization has endorsed the use of a new molecular diagnostic test called Xpert MTB/RIF in settings with high prevalence of HIV infection or multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB).35 This test is able to detect M. tuberculosis as well as rifampin resistance, a surrogate for MDR-TB, within 2 hours, with sensitivity and specificity approaching that of culture.36

“Culture-negative” TB? A small but not insignificant proportion of patients will present with risk factors for, and clinical signs and symptoms of, active TB; their cultures, however, will be negative. In such cases, consultation with an infectious disease or pulmonary specialist may be warranted. If no alternative diagnosis is found, such patients are said to have “culture-negative active TB” and should be continued on anti-TB drug therapy, although the course may be shortened.37 This highlights the fact that while cultures are key to diagnosing and treating active TB, the condition is—practically speaking—a clinical diagnosis; treatment should not be withheld or stopped simply because of a negative culture or rapid diagnostic test.

CASE 1 › Based on her risk factors (being a health care worker, born in a country with a high prevalence of TB), Ms. C’s cutoff for a positive test is >10 mm, so her TST result is negative and she is not considered to have LTBI. The increase to 8 mm seen on the second TST probably represents either childhood BCG vaccination or previous infection with nontuberculous Mycobacterium.

CASE 2 › Strictly speaking, 3-year-old Patrick does not need testing, because he was exposed only to LTBI, which is not infectious. However, because children under age 5 are at particularly high risk for progressing to active TB and poor outcomes, it would be best to confirm the mother’s story with the day care center and/or health department. If it turns out that Patrick had, in fact, been exposed to active TB, much more aggressive management would be required.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jeff Hall, MD, Family Medicine Center, 3209 Colonial Drive Columbia, SC 29203; [email protected]

1. World Health Organization. Tuberculosis. World Health Organization Web site. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs104/en/. Accessed July 7, 2015.

2. Zumla A, Raviglione M, Hafner R, et al. Current concepts: tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:745-755.

3. Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. American Thoracic Society. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2000;49:1-51.

4. Hauck FR, Neese BH, Panchal AS, et al. Identification and management of latent tuberculosis infection. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79:879-886.

5. Getahun H, Matteelli A, Chaisson RE, et al. Latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2127-2135.

6. Arshad S, Bavan L, Gajari K, et al. Active screening at entry for tuberculosis among new immigrants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:1336-1345.

7. Greenaway C, Sandoe A, Vissandjee B, et al; Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health. Tuberculosis: evidence review for newly arriving immigrants and refugees. CMAJ. 2011;183:E939-E951.

8. Jensen PA, Lambert LA, Iademarco MF, et al; CDC. Guidelines for preventing the transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in health-care settings, 2005. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54:1-141.

9. Taylor Z, Nolan CM, Blumberg HM; American Thoracic Society; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Controlling tuberculosis in the United States. Recommendations from the American Thoracic Society, CDC, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54:1-81.

10. Pai M, Menzies D. Diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection (tuberculosis screening) in HIV-negative adults. UpToDate Web site. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/diagnosisof-latent-tuberculosis-infection-tuberculosis-screening-in-hivnegative-adults. Accessed July 7, 2015.

11. Pediatric Tuberculosis Collaborative Group. Targeted tuberculin skin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1175-1201.

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Anergy skin testing and tuberculosis [corrected] preventive therapy for HIV-infected persons: revised recommendations. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1997;46:1-10.

13. The role of BCG vaccine in the prevention and control of tuberculosis in the United States. A joint statement by the Advisory Council for the Elimination of Tuberculosis and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1996;45:1-18.

14. Farhat M, Greenaway C, Pai M, et al. False-positive tuberculin skin tests: what is the absolute effect of BCG and non-tuberculous mycobacteria? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10:1192-1204.

15. Wang L, Turner MO, Elwood RK, et al. A meta-analysis of the effect of Bacille Calmette Guérin vaccination on tuberculin skin test measurements. Thorax. 2002;57:804-809.

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Fact sheets: BCG vaccine. CDC Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/prevention/bcg.htm. Accessed July 16, 2015.

17. Menzies D. Interpretation of repeated tuberculin tests. Boosting, conversion, and reversion. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:15-21.

18. van Zyl-Smit RN, Zwerling A, Dheda K, et al. Within-subject variability of interferon-g assay results for tuberculosis and boosting effect of tuberculin skin testing: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8517.

19. Mazurek GH, Jereb J, Lobue P, et al; Division of Tuberculosis Elimination, National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Guidelines for using the QuantiFERON-TB Gold test for detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, United States. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54:49-55.

20. Mazurek GH, Jereb J, Vernon A, et al; IGRA Expert Committee; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Updated guidelines for using Interferon Gamma Release Assays to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection - United States, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1-25.

21. Muñoz L, Santin M. Interferon- release assays versus tuberculin skin test for targeting people for tuberculosis preventive treatment: an evidence-based review. J Infect. 2013;66:381-387.

22. Zwerling A, Behr MA, Verma A, et al. The BCG World Atlas: a database of global BCG vaccination policies and practices. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001012.

23. Mandalakas AM, Detjen AK, Hesseling AC, et al. Interferon-gamma release assays and childhood tuberculosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:1018-1032.

24. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases, Pickering L, ed. Red Book. Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 29th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2012:741.

25. Zwerling A, van den Hof S, Scholten J, et al. Interferon-gamma release assays for tuberculosis screening of healthcare workers: a systematic review. Thorax. 2012;67:62-70. 26. Pai M, Zwerling A, Menzies D. Systematic review: T-cell-based assays for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection: an update. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:177-184.

27. Diel R, Loddenkemper R, Nienhaus A. Predictive value of interferon- release assays and tuberculin skin testing for progression from latent TB infection to disease state: a meta-analysis. Chest. 2012;142:63-75.

28. Dorman SE, Belknap R, Graviss EA, et al; Tuberculosis Epidemiologic Studies Consortium. Interferon-release assays and tuberculin skin testing for diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection in healthcare workers in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:77-87.

29. Scott C, Kirking HL, Jeffries C, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Tuberculosis trends—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:265-269.

30. Golden MP, Vikram HR. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:1761-1768.

31. Rangaka MX, Wilkinson KA, Glynn JR, et al. Predictive value of interferon-release assays for incident active tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:45-55.

32. Metcalfe JZ, Everett CK, Steingart KR, et al. Interferon-release assays for active pulmonary tuberculosis diagnosis in adults in low- and middle-income countries: systematic review and metaanalysis. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:S1120-S1129.

33. Keshavjee S, Farmer PE. Tuberculosis, drug resistance, and the history of modern medicine. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:931-936.

34. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Updated guidelines for the use of nucleic acid amplification tests in the diagnosis of tuberculosis. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:7-10.

35. World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2014. World Health Organization Web site. Available at: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/. Accessed July 17, 2015.

36. Steingart KR, Schiller I, Horne DJ, et al. Xpert® MTB/RIF assay for pulmonary tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD009593.

37. Hall J, Elliott C. Tuberculosis: Which drug regimen and when. J Fam Practice. 2015;64:27-33.

1. World Health Organization. Tuberculosis. World Health Organization Web site. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs104/en/. Accessed July 7, 2015.

2. Zumla A, Raviglione M, Hafner R, et al. Current concepts: tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:745-755.

3. Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. American Thoracic Society. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2000;49:1-51.

4. Hauck FR, Neese BH, Panchal AS, et al. Identification and management of latent tuberculosis infection. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79:879-886.

5. Getahun H, Matteelli A, Chaisson RE, et al. Latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2127-2135.

6. Arshad S, Bavan L, Gajari K, et al. Active screening at entry for tuberculosis among new immigrants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:1336-1345.

7. Greenaway C, Sandoe A, Vissandjee B, et al; Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health. Tuberculosis: evidence review for newly arriving immigrants and refugees. CMAJ. 2011;183:E939-E951.

8. Jensen PA, Lambert LA, Iademarco MF, et al; CDC. Guidelines for preventing the transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in health-care settings, 2005. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54:1-141.

9. Taylor Z, Nolan CM, Blumberg HM; American Thoracic Society; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Controlling tuberculosis in the United States. Recommendations from the American Thoracic Society, CDC, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54:1-81.

10. Pai M, Menzies D. Diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection (tuberculosis screening) in HIV-negative adults. UpToDate Web site. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/diagnosisof-latent-tuberculosis-infection-tuberculosis-screening-in-hivnegative-adults. Accessed July 7, 2015.

11. Pediatric Tuberculosis Collaborative Group. Targeted tuberculin skin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1175-1201.

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Anergy skin testing and tuberculosis [corrected] preventive therapy for HIV-infected persons: revised recommendations. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1997;46:1-10.

13. The role of BCG vaccine in the prevention and control of tuberculosis in the United States. A joint statement by the Advisory Council for the Elimination of Tuberculosis and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1996;45:1-18.

14. Farhat M, Greenaway C, Pai M, et al. False-positive tuberculin skin tests: what is the absolute effect of BCG and non-tuberculous mycobacteria? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10:1192-1204.

15. Wang L, Turner MO, Elwood RK, et al. A meta-analysis of the effect of Bacille Calmette Guérin vaccination on tuberculin skin test measurements. Thorax. 2002;57:804-809.

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Fact sheets: BCG vaccine. CDC Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/prevention/bcg.htm. Accessed July 16, 2015.

17. Menzies D. Interpretation of repeated tuberculin tests. Boosting, conversion, and reversion. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:15-21.

18. van Zyl-Smit RN, Zwerling A, Dheda K, et al. Within-subject variability of interferon-g assay results for tuberculosis and boosting effect of tuberculin skin testing: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8517.

19. Mazurek GH, Jereb J, Lobue P, et al; Division of Tuberculosis Elimination, National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Guidelines for using the QuantiFERON-TB Gold test for detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, United States. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54:49-55.

20. Mazurek GH, Jereb J, Vernon A, et al; IGRA Expert Committee; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Updated guidelines for using Interferon Gamma Release Assays to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection - United States, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1-25.

21. Muñoz L, Santin M. Interferon- release assays versus tuberculin skin test for targeting people for tuberculosis preventive treatment: an evidence-based review. J Infect. 2013;66:381-387.

22. Zwerling A, Behr MA, Verma A, et al. The BCG World Atlas: a database of global BCG vaccination policies and practices. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001012.

23. Mandalakas AM, Detjen AK, Hesseling AC, et al. Interferon-gamma release assays and childhood tuberculosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:1018-1032.

24. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases, Pickering L, ed. Red Book. Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 29th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2012:741.

25. Zwerling A, van den Hof S, Scholten J, et al. Interferon-gamma release assays for tuberculosis screening of healthcare workers: a systematic review. Thorax. 2012;67:62-70. 26. Pai M, Zwerling A, Menzies D. Systematic review: T-cell-based assays for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection: an update. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:177-184.

27. Diel R, Loddenkemper R, Nienhaus A. Predictive value of interferon- release assays and tuberculin skin testing for progression from latent TB infection to disease state: a meta-analysis. Chest. 2012;142:63-75.

28. Dorman SE, Belknap R, Graviss EA, et al; Tuberculosis Epidemiologic Studies Consortium. Interferon-release assays and tuberculin skin testing for diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection in healthcare workers in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:77-87.

29. Scott C, Kirking HL, Jeffries C, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Tuberculosis trends—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:265-269.

30. Golden MP, Vikram HR. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:1761-1768.

31. Rangaka MX, Wilkinson KA, Glynn JR, et al. Predictive value of interferon-release assays for incident active tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:45-55.

32. Metcalfe JZ, Everett CK, Steingart KR, et al. Interferon-release assays for active pulmonary tuberculosis diagnosis in adults in low- and middle-income countries: systematic review and metaanalysis. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:S1120-S1129.

33. Keshavjee S, Farmer PE. Tuberculosis, drug resistance, and the history of modern medicine. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:931-936.

34. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Updated guidelines for the use of nucleic acid amplification tests in the diagnosis of tuberculosis. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:7-10.

35. World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2014. World Health Organization Web site. Available at: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/. Accessed July 17, 2015.

36. Steingart KR, Schiller I, Horne DJ, et al. Xpert® MTB/RIF assay for pulmonary tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD009593.

37. Hall J, Elliott C. Tuberculosis: Which drug regimen and when. J Fam Practice. 2015;64:27-33.

A Prescription for Trouble

ANSWER

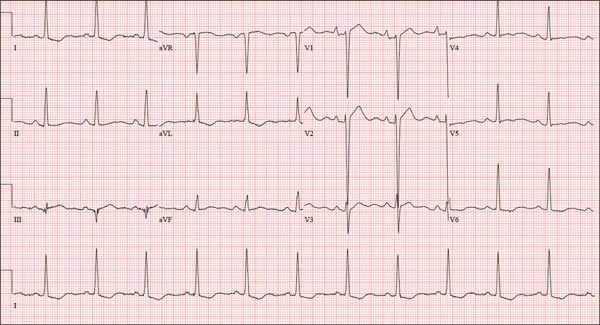

The correct interpretation includes normal sinus rhythm, right atrial enlargement, left ventricular hypertrophy, and a prolonged QT interval. Normal sinus rhythm is indicated by a P for every QRS and a QRS for every P, with a constant PR interval (see rhythm strip of lead I).

Right atrial enlargement is evidenced by the tall P waves in leads II, III, aVF, and V1. Note that there is no biphasic P wave in lead V1, so there is no evidence of accompanying left atrial enlargement.

High-voltage limb leads (sum of R in lead I and S in lead III ≥ 25 mm) or precordial leads (sum of S in V1 and R in V5 or V6 ≥ 35 mm) are indicative of left ventricular hypertrophy.

The QTc interval of 653 ms with a normal sinus rate is worrisome for prolonged QT syndrome. A review of the history shows the patient to be taking two drugs (lithium, azithromycin) known to prolong the QT interval. Although it is not known whether this patient has inherent QT prolongation, use of these types of agents should be avoided.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation includes normal sinus rhythm, right atrial enlargement, left ventricular hypertrophy, and a prolonged QT interval. Normal sinus rhythm is indicated by a P for every QRS and a QRS for every P, with a constant PR interval (see rhythm strip of lead I).

Right atrial enlargement is evidenced by the tall P waves in leads II, III, aVF, and V1. Note that there is no biphasic P wave in lead V1, so there is no evidence of accompanying left atrial enlargement.

High-voltage limb leads (sum of R in lead I and S in lead III ≥ 25 mm) or precordial leads (sum of S in V1 and R in V5 or V6 ≥ 35 mm) are indicative of left ventricular hypertrophy.

The QTc interval of 653 ms with a normal sinus rate is worrisome for prolonged QT syndrome. A review of the history shows the patient to be taking two drugs (lithium, azithromycin) known to prolong the QT interval. Although it is not known whether this patient has inherent QT prolongation, use of these types of agents should be avoided.

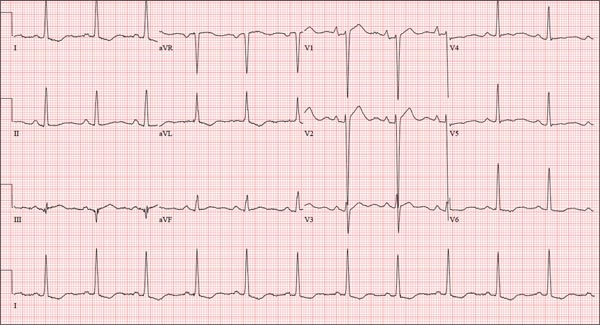

ANSWER

The correct interpretation includes normal sinus rhythm, right atrial enlargement, left ventricular hypertrophy, and a prolonged QT interval. Normal sinus rhythm is indicated by a P for every QRS and a QRS for every P, with a constant PR interval (see rhythm strip of lead I).

Right atrial enlargement is evidenced by the tall P waves in leads II, III, aVF, and V1. Note that there is no biphasic P wave in lead V1, so there is no evidence of accompanying left atrial enlargement.

High-voltage limb leads (sum of R in lead I and S in lead III ≥ 25 mm) or precordial leads (sum of S in V1 and R in V5 or V6 ≥ 35 mm) are indicative of left ventricular hypertrophy.

The QTc interval of 653 ms with a normal sinus rate is worrisome for prolonged QT syndrome. A review of the history shows the patient to be taking two drugs (lithium, azithromycin) known to prolong the QT interval. Although it is not known whether this patient has inherent QT prolongation, use of these types of agents should be avoided.