User login

What is the difference between palliative care and hospice care?

Hospice care generally falls under the category of palliative care, despite being an older subspecialty. However, the two have different indications and goals and are often provided in different settings.

ORIGINS OF PALLIATIVE CARE

Prompted by what he perceived as neglect of dying patients in the acute care setting, Dr. Balfour Mount opened the first acute inpatient palliative care unit in Royal Victoria Hospital in Montréal, Québec, in 1976.1 His purpose was to provide a crisis-intervention service for patients who were actively dying, and this continues to be the main reason for consulting palliative care services in the hospital.

Palliative care has evolved since the 1970s and is now used in a variety of situations:

- A life-limiting illness in a patient who is not terminally ill

- A life-threatening illness in a patient who has symptoms but with the potential to recover

- A chronic illness such as heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a patient who is on disease-modifying therapy but has symptoms and will eventually succumb to the illness, but is expected to live longer than someone with advanced cancer.2

PALLIATIVE CARE IN CANCER PATIENTS

In patients with advanced cancer, palliative care is utilized earlier in the course of serious and life-limiting illness and is even involved in patient care when cure is the goal. Importantly, it now includes outpatient clinics to provide patients seamless care in conjunction with their oncologist’s care.3

Because palliative care focuses on the patient’s experience of the illness (sickness) rather than on disease itself (pathology), symptom management, psychosocial support, and assistance in decision-making are foremost. Initiating palliative care early in advanced cancer improves multiple outcomes and limits overly aggressive, ineffective therapies at the end of life (eg, late chemotherapy, late referral to hospice care, death in the intensive care unit), without hastening death. In fact, it may prolong life.3,4

Palliative care is indicated in a number of situations in oncology:

- Symptomatic presentations of cancer, even when curative treatments are available

- At the time of a sentinel event such as recurrence or unanticipated hospitalization

- When palliative radiation is needed

- When changes in chemotherapy are needed because of disease progression.

Also, cancer patients may develop symptoms that require a palliative procedure such as thoracentesis for pleural effusion, paracentesis for ascites, or surgery for a fracture or spinal cord compression. A palliative care consultation is also appropriate when patients change their goals of care (ie, palliation rather than cure), and when an oncologic crisis occurs and there is a need to offer support to the family and to clarify the goals of care.

PALLIATIVE CARE IN OTHER DISEASES

For patients with illnesses other than cancer, palliative care may be helpful when disease-modifying therapy becomes burdensome or ineffective, or when patients are symptomatic despite maximum therapy. Palliative care should also be considered when goals of care need to be explored, when a second opinion is needed on goals of care, or if the primary care provider and family are at odds.

WHEN A CONSULT IS INAPPROPRIATE

Palliative care consultation is inappropriate when used in lieu of an oncology consult in advanced cancer. Palliative care specialists are not experts in cancer care, whereas oncologists are familiar with rapid advancements in cancer care, including targeted agents that may offer benefit to patients with advanced cancer.

Palliative care consultation is also inappropriate if the patient does not want to see a palliative care specialist, or if the consult is used as a way to convince a patient to change advance directives or to choose not to be resuscitated. Also, cancer patients who are asymptomatic are unlikely to benefit from palliative care initially. The decision to consult palliative care should not depend on prognosis, and palliative care is more cost-effective when utilized early rather than as a crisis intervention near the end of life.3

THE PALLIATIVE CARE EVALUATION

The initial palliative care consultation usually involves an evaluation of the patient’s symptoms and concerns. Symptoms are targeted based on the patient’s priorities and on an assessment using validated questionnaires. A validated questionnaire is a better way to comprehensively gauge symptom burden than depending on patients to volunteer symptoms.5

As the relationship develops between patient, family, and palliative care specialist and as the disease takes its course, advance directives, prognosis, and end-of-life care goals can be addressed in follow-up consultations.3 Patients want to know about their prognosis, and they usually complete advance directives based on clinical circumstances rather than viewing them as an extension of patient autonomy, as originally intended.6

REIMBURSEMENT FOR PALLIATIVE CARE

Reimbursement for palliative care is similar to that for acute care and falls within the All Patient Refined Diagnosis-Related Group, or APR-DRG, system, and palliative care has its own V code for identification. Codes are used to designate disease, stage or location of metastases, disease complications, and symptoms, as well as for the discussion of goals of care.

WHAT PALLIATIVE CARE IS NOT

Palliative care has too often been tied to end-of-life care.7 The two often appear together in titles of reports in the literature. As a result, patients and physicians may be confused and, thus, reluctant to utilize palliative care services. To avoid the confusion, certain programs have included the term “supportive” oncology care in their title. This appears to facilitate palliative care referral, but may be misleading.8

WHAT IS HOSPICE CARE?

Hospice care is a service funded and capitated under Medicare part A and is largely provided as outpatient home care for those deemed terminally ill.9 An illness must be certified as terminal by two physicians. Medicare defines terminal illness as a life expectancy of 6 months or less if the illness runs its normal course.

The philosophy of hospice care is to provide comfort through intensive nurse management and home-based follow-up. In some cases, disease-modifying therapies are continued to control symptoms—eg, continuing angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in heart failure patients. Hospice care is typically delivered at home, but it is also delivered in nursing homes, in hospital inpatient units, and at private or nonprofit hospice facilities.

Inpatient palliative care units are often mistaken for hospices. The purpose of hospice care is to provide quality of life and comfort and to avoid overly aggressive, expensive, and futile care at the end of life. The focus is on intensive, hands-on, personalized symptom care and family support at home. The goal is to provide a comfortable and dignified death among friends and family. The use of palliative radiation, transfusions, and antibiotics in hospice varies among hospice programs and is considered on a case-by-case basis.10

The Medicare per diem payment limits what hospices can afford, so they must be fiscally responsible. Hospice agencies are capitated and are responsible for providing medications and durable equipment necessary to treat symptoms related to the terminal illness. They also provide bereavement services for family members at no charge. Enrollment in hospice care can be revoked depending on circumstances and then reinstituted later as the goals of care change.

Care for nonterminal comorbid illnesses can be continued by a general practitioner or internist. This care is not covered under the Medicare hospice benefit, but it is covered under Medicare part B.

The patient and family can choose the hospice physician, who may be a family practitioner, internist, oncologist, or palliative care specialist, or may designate the hospice medical director as the hospice physician.

Criteria for hospice admission have been established for noncancer terminal illnesses and should be considered when practitioners decide to consult hospice.11–13

HOME-BASED PALLIATIVE CARE

Programs such as advanced illness management or home-based palliative care aim to improve the quality of care at home and prevent rehospitalization, particularly for patients with repeated hospitalizations.14 Home-based palliative care services are provided either by a clinician who makes home visits or by a certified home health care agency. Services are particularly useful for patients with serious illnesses who do not qualify for hospice services but are homebound. Consultations are obtained for ongoing supportive care at home, assessment for medication compliance, and disease monitoring at home. Consultations are scheduled at the time of hospital discharge.

Unlike hospice care, home-based palliative care does not include 24-hour on-call service. Comprehensive services (eg, home health aide, durable equipment, medications) are not provided as they are under hospice care: patients must qualify under Medicare stipulations for such services outside of hospice care. For example, home oxygen can only be supplied if the patient's oxygen saturation is less than 90%, while under the hospice benefit it is provided without regard to oxygen saturation and is based on symptom need. For home-based palliative care, patients must be largely homebound or unable to be seen regularly in the outpatient clinic. This type of care can be a bridge to hospice care for patients who feel they are not ready for hospice care at the time of discharge from acute care. Those who receive palliative care at home are less likely to be hospitalized at the end of life, are more likely to be transitioned to hospice at an appropriate time, and are more likely to have relief of symptoms.15

- Mount BM. The problem of caring for the dying in a general hospital; the palliative care unit as a possible solution. Can Med Assoc J 1976; 115:119–121.

- Higginson I. Palliative care: a review of past changes and future trends. J Public Health Med 1993; 15:3–8.

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:733–742.

- Zimmermann C, Riechelmann R, Krzyzanowska M, Rodin G, Tannock I. Effectiveness of specialized palliative care: a systematic review. JAMA 2008; 299:1698–1709.

- Homsi J, Walsh D, Rivera N, et al. Symptom evaluation in palliative medicine: patient report vs systematic assessment. Support Care Cancer 2006; 14:444–453.

- Tang ST, Liu TW, Lai MS, Liu LN, Chen CH, Koong SL. Congruence of knowledge, experiences, and p for disclosure of diagnosis and prognosis between terminally-ill cancer patients and their family caregivers in Taiwan. Cancer Invest 2006; 24:360–366.

- Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, Ahles T. Oncologists’ perspectives on concurrent palliative care in a National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center. Palliat Support Care 2013; 11:415–423.

- Fadul N, Elsayem A, Palmer JL, et al. Supportive versus palliative care: what’s in a name: a survey of medical oncologists and midlevel providers at a comprehensive cancer center. Cancer 2009; 115:2013–2021.

- Rinaldo MJ. Medicare to cover hospice services. J Med Soc NJ 1982; 79:1015–1016.

- Enck RE. Palliative radiation therapy in hospice care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2002; 19:151–152.

- Luchins DJ, Hanrahan P, Murphy K. Criteria for enrolling dementia patients in hospice. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997; 45:1054–1059.

- Fox E, Landrum-McNiff K, Zhong Z, Dawson NV, Wu AW, Lynn J. Evaluation of prognostic criteria for determining hospice eligibility in patients with advanced lung, heart, or liver disease. JAMA 1999; 282:1638–1645.

- Stuart B. The NHO medical guidelines for non-cancer disease and local medical review policy: hospice access for patients with diseases other than cancer. Hosp J 1999; 14:139–154.

- McKinney M. Beyond hospice. New models of care focus on advanced illnesses. Mod Healthc 2013; 43:14–15.

- Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, McCrone P, Higginson IJ. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 6:CD007760.

Hospice care generally falls under the category of palliative care, despite being an older subspecialty. However, the two have different indications and goals and are often provided in different settings.

ORIGINS OF PALLIATIVE CARE

Prompted by what he perceived as neglect of dying patients in the acute care setting, Dr. Balfour Mount opened the first acute inpatient palliative care unit in Royal Victoria Hospital in Montréal, Québec, in 1976.1 His purpose was to provide a crisis-intervention service for patients who were actively dying, and this continues to be the main reason for consulting palliative care services in the hospital.

Palliative care has evolved since the 1970s and is now used in a variety of situations:

- A life-limiting illness in a patient who is not terminally ill

- A life-threatening illness in a patient who has symptoms but with the potential to recover

- A chronic illness such as heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a patient who is on disease-modifying therapy but has symptoms and will eventually succumb to the illness, but is expected to live longer than someone with advanced cancer.2

PALLIATIVE CARE IN CANCER PATIENTS

In patients with advanced cancer, palliative care is utilized earlier in the course of serious and life-limiting illness and is even involved in patient care when cure is the goal. Importantly, it now includes outpatient clinics to provide patients seamless care in conjunction with their oncologist’s care.3

Because palliative care focuses on the patient’s experience of the illness (sickness) rather than on disease itself (pathology), symptom management, psychosocial support, and assistance in decision-making are foremost. Initiating palliative care early in advanced cancer improves multiple outcomes and limits overly aggressive, ineffective therapies at the end of life (eg, late chemotherapy, late referral to hospice care, death in the intensive care unit), without hastening death. In fact, it may prolong life.3,4

Palliative care is indicated in a number of situations in oncology:

- Symptomatic presentations of cancer, even when curative treatments are available

- At the time of a sentinel event such as recurrence or unanticipated hospitalization

- When palliative radiation is needed

- When changes in chemotherapy are needed because of disease progression.

Also, cancer patients may develop symptoms that require a palliative procedure such as thoracentesis for pleural effusion, paracentesis for ascites, or surgery for a fracture or spinal cord compression. A palliative care consultation is also appropriate when patients change their goals of care (ie, palliation rather than cure), and when an oncologic crisis occurs and there is a need to offer support to the family and to clarify the goals of care.

PALLIATIVE CARE IN OTHER DISEASES

For patients with illnesses other than cancer, palliative care may be helpful when disease-modifying therapy becomes burdensome or ineffective, or when patients are symptomatic despite maximum therapy. Palliative care should also be considered when goals of care need to be explored, when a second opinion is needed on goals of care, or if the primary care provider and family are at odds.

WHEN A CONSULT IS INAPPROPRIATE

Palliative care consultation is inappropriate when used in lieu of an oncology consult in advanced cancer. Palliative care specialists are not experts in cancer care, whereas oncologists are familiar with rapid advancements in cancer care, including targeted agents that may offer benefit to patients with advanced cancer.

Palliative care consultation is also inappropriate if the patient does not want to see a palliative care specialist, or if the consult is used as a way to convince a patient to change advance directives or to choose not to be resuscitated. Also, cancer patients who are asymptomatic are unlikely to benefit from palliative care initially. The decision to consult palliative care should not depend on prognosis, and palliative care is more cost-effective when utilized early rather than as a crisis intervention near the end of life.3

THE PALLIATIVE CARE EVALUATION

The initial palliative care consultation usually involves an evaluation of the patient’s symptoms and concerns. Symptoms are targeted based on the patient’s priorities and on an assessment using validated questionnaires. A validated questionnaire is a better way to comprehensively gauge symptom burden than depending on patients to volunteer symptoms.5

As the relationship develops between patient, family, and palliative care specialist and as the disease takes its course, advance directives, prognosis, and end-of-life care goals can be addressed in follow-up consultations.3 Patients want to know about their prognosis, and they usually complete advance directives based on clinical circumstances rather than viewing them as an extension of patient autonomy, as originally intended.6

REIMBURSEMENT FOR PALLIATIVE CARE

Reimbursement for palliative care is similar to that for acute care and falls within the All Patient Refined Diagnosis-Related Group, or APR-DRG, system, and palliative care has its own V code for identification. Codes are used to designate disease, stage or location of metastases, disease complications, and symptoms, as well as for the discussion of goals of care.

WHAT PALLIATIVE CARE IS NOT

Palliative care has too often been tied to end-of-life care.7 The two often appear together in titles of reports in the literature. As a result, patients and physicians may be confused and, thus, reluctant to utilize palliative care services. To avoid the confusion, certain programs have included the term “supportive” oncology care in their title. This appears to facilitate palliative care referral, but may be misleading.8

WHAT IS HOSPICE CARE?

Hospice care is a service funded and capitated under Medicare part A and is largely provided as outpatient home care for those deemed terminally ill.9 An illness must be certified as terminal by two physicians. Medicare defines terminal illness as a life expectancy of 6 months or less if the illness runs its normal course.

The philosophy of hospice care is to provide comfort through intensive nurse management and home-based follow-up. In some cases, disease-modifying therapies are continued to control symptoms—eg, continuing angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in heart failure patients. Hospice care is typically delivered at home, but it is also delivered in nursing homes, in hospital inpatient units, and at private or nonprofit hospice facilities.

Inpatient palliative care units are often mistaken for hospices. The purpose of hospice care is to provide quality of life and comfort and to avoid overly aggressive, expensive, and futile care at the end of life. The focus is on intensive, hands-on, personalized symptom care and family support at home. The goal is to provide a comfortable and dignified death among friends and family. The use of palliative radiation, transfusions, and antibiotics in hospice varies among hospice programs and is considered on a case-by-case basis.10

The Medicare per diem payment limits what hospices can afford, so they must be fiscally responsible. Hospice agencies are capitated and are responsible for providing medications and durable equipment necessary to treat symptoms related to the terminal illness. They also provide bereavement services for family members at no charge. Enrollment in hospice care can be revoked depending on circumstances and then reinstituted later as the goals of care change.

Care for nonterminal comorbid illnesses can be continued by a general practitioner or internist. This care is not covered under the Medicare hospice benefit, but it is covered under Medicare part B.

The patient and family can choose the hospice physician, who may be a family practitioner, internist, oncologist, or palliative care specialist, or may designate the hospice medical director as the hospice physician.

Criteria for hospice admission have been established for noncancer terminal illnesses and should be considered when practitioners decide to consult hospice.11–13

HOME-BASED PALLIATIVE CARE

Programs such as advanced illness management or home-based palliative care aim to improve the quality of care at home and prevent rehospitalization, particularly for patients with repeated hospitalizations.14 Home-based palliative care services are provided either by a clinician who makes home visits or by a certified home health care agency. Services are particularly useful for patients with serious illnesses who do not qualify for hospice services but are homebound. Consultations are obtained for ongoing supportive care at home, assessment for medication compliance, and disease monitoring at home. Consultations are scheduled at the time of hospital discharge.

Unlike hospice care, home-based palliative care does not include 24-hour on-call service. Comprehensive services (eg, home health aide, durable equipment, medications) are not provided as they are under hospice care: patients must qualify under Medicare stipulations for such services outside of hospice care. For example, home oxygen can only be supplied if the patient's oxygen saturation is less than 90%, while under the hospice benefit it is provided without regard to oxygen saturation and is based on symptom need. For home-based palliative care, patients must be largely homebound or unable to be seen regularly in the outpatient clinic. This type of care can be a bridge to hospice care for patients who feel they are not ready for hospice care at the time of discharge from acute care. Those who receive palliative care at home are less likely to be hospitalized at the end of life, are more likely to be transitioned to hospice at an appropriate time, and are more likely to have relief of symptoms.15

Hospice care generally falls under the category of palliative care, despite being an older subspecialty. However, the two have different indications and goals and are often provided in different settings.

ORIGINS OF PALLIATIVE CARE

Prompted by what he perceived as neglect of dying patients in the acute care setting, Dr. Balfour Mount opened the first acute inpatient palliative care unit in Royal Victoria Hospital in Montréal, Québec, in 1976.1 His purpose was to provide a crisis-intervention service for patients who were actively dying, and this continues to be the main reason for consulting palliative care services in the hospital.

Palliative care has evolved since the 1970s and is now used in a variety of situations:

- A life-limiting illness in a patient who is not terminally ill

- A life-threatening illness in a patient who has symptoms but with the potential to recover

- A chronic illness such as heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a patient who is on disease-modifying therapy but has symptoms and will eventually succumb to the illness, but is expected to live longer than someone with advanced cancer.2

PALLIATIVE CARE IN CANCER PATIENTS

In patients with advanced cancer, palliative care is utilized earlier in the course of serious and life-limiting illness and is even involved in patient care when cure is the goal. Importantly, it now includes outpatient clinics to provide patients seamless care in conjunction with their oncologist’s care.3

Because palliative care focuses on the patient’s experience of the illness (sickness) rather than on disease itself (pathology), symptom management, psychosocial support, and assistance in decision-making are foremost. Initiating palliative care early in advanced cancer improves multiple outcomes and limits overly aggressive, ineffective therapies at the end of life (eg, late chemotherapy, late referral to hospice care, death in the intensive care unit), without hastening death. In fact, it may prolong life.3,4

Palliative care is indicated in a number of situations in oncology:

- Symptomatic presentations of cancer, even when curative treatments are available

- At the time of a sentinel event such as recurrence or unanticipated hospitalization

- When palliative radiation is needed

- When changes in chemotherapy are needed because of disease progression.

Also, cancer patients may develop symptoms that require a palliative procedure such as thoracentesis for pleural effusion, paracentesis for ascites, or surgery for a fracture or spinal cord compression. A palliative care consultation is also appropriate when patients change their goals of care (ie, palliation rather than cure), and when an oncologic crisis occurs and there is a need to offer support to the family and to clarify the goals of care.

PALLIATIVE CARE IN OTHER DISEASES

For patients with illnesses other than cancer, palliative care may be helpful when disease-modifying therapy becomes burdensome or ineffective, or when patients are symptomatic despite maximum therapy. Palliative care should also be considered when goals of care need to be explored, when a second opinion is needed on goals of care, or if the primary care provider and family are at odds.

WHEN A CONSULT IS INAPPROPRIATE

Palliative care consultation is inappropriate when used in lieu of an oncology consult in advanced cancer. Palliative care specialists are not experts in cancer care, whereas oncologists are familiar with rapid advancements in cancer care, including targeted agents that may offer benefit to patients with advanced cancer.

Palliative care consultation is also inappropriate if the patient does not want to see a palliative care specialist, or if the consult is used as a way to convince a patient to change advance directives or to choose not to be resuscitated. Also, cancer patients who are asymptomatic are unlikely to benefit from palliative care initially. The decision to consult palliative care should not depend on prognosis, and palliative care is more cost-effective when utilized early rather than as a crisis intervention near the end of life.3

THE PALLIATIVE CARE EVALUATION

The initial palliative care consultation usually involves an evaluation of the patient’s symptoms and concerns. Symptoms are targeted based on the patient’s priorities and on an assessment using validated questionnaires. A validated questionnaire is a better way to comprehensively gauge symptom burden than depending on patients to volunteer symptoms.5

As the relationship develops between patient, family, and palliative care specialist and as the disease takes its course, advance directives, prognosis, and end-of-life care goals can be addressed in follow-up consultations.3 Patients want to know about their prognosis, and they usually complete advance directives based on clinical circumstances rather than viewing them as an extension of patient autonomy, as originally intended.6

REIMBURSEMENT FOR PALLIATIVE CARE

Reimbursement for palliative care is similar to that for acute care and falls within the All Patient Refined Diagnosis-Related Group, or APR-DRG, system, and palliative care has its own V code for identification. Codes are used to designate disease, stage or location of metastases, disease complications, and symptoms, as well as for the discussion of goals of care.

WHAT PALLIATIVE CARE IS NOT

Palliative care has too often been tied to end-of-life care.7 The two often appear together in titles of reports in the literature. As a result, patients and physicians may be confused and, thus, reluctant to utilize palliative care services. To avoid the confusion, certain programs have included the term “supportive” oncology care in their title. This appears to facilitate palliative care referral, but may be misleading.8

WHAT IS HOSPICE CARE?

Hospice care is a service funded and capitated under Medicare part A and is largely provided as outpatient home care for those deemed terminally ill.9 An illness must be certified as terminal by two physicians. Medicare defines terminal illness as a life expectancy of 6 months or less if the illness runs its normal course.

The philosophy of hospice care is to provide comfort through intensive nurse management and home-based follow-up. In some cases, disease-modifying therapies are continued to control symptoms—eg, continuing angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in heart failure patients. Hospice care is typically delivered at home, but it is also delivered in nursing homes, in hospital inpatient units, and at private or nonprofit hospice facilities.

Inpatient palliative care units are often mistaken for hospices. The purpose of hospice care is to provide quality of life and comfort and to avoid overly aggressive, expensive, and futile care at the end of life. The focus is on intensive, hands-on, personalized symptom care and family support at home. The goal is to provide a comfortable and dignified death among friends and family. The use of palliative radiation, transfusions, and antibiotics in hospice varies among hospice programs and is considered on a case-by-case basis.10

The Medicare per diem payment limits what hospices can afford, so they must be fiscally responsible. Hospice agencies are capitated and are responsible for providing medications and durable equipment necessary to treat symptoms related to the terminal illness. They also provide bereavement services for family members at no charge. Enrollment in hospice care can be revoked depending on circumstances and then reinstituted later as the goals of care change.

Care for nonterminal comorbid illnesses can be continued by a general practitioner or internist. This care is not covered under the Medicare hospice benefit, but it is covered under Medicare part B.

The patient and family can choose the hospice physician, who may be a family practitioner, internist, oncologist, or palliative care specialist, or may designate the hospice medical director as the hospice physician.

Criteria for hospice admission have been established for noncancer terminal illnesses and should be considered when practitioners decide to consult hospice.11–13

HOME-BASED PALLIATIVE CARE

Programs such as advanced illness management or home-based palliative care aim to improve the quality of care at home and prevent rehospitalization, particularly for patients with repeated hospitalizations.14 Home-based palliative care services are provided either by a clinician who makes home visits or by a certified home health care agency. Services are particularly useful for patients with serious illnesses who do not qualify for hospice services but are homebound. Consultations are obtained for ongoing supportive care at home, assessment for medication compliance, and disease monitoring at home. Consultations are scheduled at the time of hospital discharge.

Unlike hospice care, home-based palliative care does not include 24-hour on-call service. Comprehensive services (eg, home health aide, durable equipment, medications) are not provided as they are under hospice care: patients must qualify under Medicare stipulations for such services outside of hospice care. For example, home oxygen can only be supplied if the patient's oxygen saturation is less than 90%, while under the hospice benefit it is provided without regard to oxygen saturation and is based on symptom need. For home-based palliative care, patients must be largely homebound or unable to be seen regularly in the outpatient clinic. This type of care can be a bridge to hospice care for patients who feel they are not ready for hospice care at the time of discharge from acute care. Those who receive palliative care at home are less likely to be hospitalized at the end of life, are more likely to be transitioned to hospice at an appropriate time, and are more likely to have relief of symptoms.15

- Mount BM. The problem of caring for the dying in a general hospital; the palliative care unit as a possible solution. Can Med Assoc J 1976; 115:119–121.

- Higginson I. Palliative care: a review of past changes and future trends. J Public Health Med 1993; 15:3–8.

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:733–742.

- Zimmermann C, Riechelmann R, Krzyzanowska M, Rodin G, Tannock I. Effectiveness of specialized palliative care: a systematic review. JAMA 2008; 299:1698–1709.

- Homsi J, Walsh D, Rivera N, et al. Symptom evaluation in palliative medicine: patient report vs systematic assessment. Support Care Cancer 2006; 14:444–453.

- Tang ST, Liu TW, Lai MS, Liu LN, Chen CH, Koong SL. Congruence of knowledge, experiences, and p for disclosure of diagnosis and prognosis between terminally-ill cancer patients and their family caregivers in Taiwan. Cancer Invest 2006; 24:360–366.

- Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, Ahles T. Oncologists’ perspectives on concurrent palliative care in a National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center. Palliat Support Care 2013; 11:415–423.

- Fadul N, Elsayem A, Palmer JL, et al. Supportive versus palliative care: what’s in a name: a survey of medical oncologists and midlevel providers at a comprehensive cancer center. Cancer 2009; 115:2013–2021.

- Rinaldo MJ. Medicare to cover hospice services. J Med Soc NJ 1982; 79:1015–1016.

- Enck RE. Palliative radiation therapy in hospice care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2002; 19:151–152.

- Luchins DJ, Hanrahan P, Murphy K. Criteria for enrolling dementia patients in hospice. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997; 45:1054–1059.

- Fox E, Landrum-McNiff K, Zhong Z, Dawson NV, Wu AW, Lynn J. Evaluation of prognostic criteria for determining hospice eligibility in patients with advanced lung, heart, or liver disease. JAMA 1999; 282:1638–1645.

- Stuart B. The NHO medical guidelines for non-cancer disease and local medical review policy: hospice access for patients with diseases other than cancer. Hosp J 1999; 14:139–154.

- McKinney M. Beyond hospice. New models of care focus on advanced illnesses. Mod Healthc 2013; 43:14–15.

- Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, McCrone P, Higginson IJ. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 6:CD007760.

- Mount BM. The problem of caring for the dying in a general hospital; the palliative care unit as a possible solution. Can Med Assoc J 1976; 115:119–121.

- Higginson I. Palliative care: a review of past changes and future trends. J Public Health Med 1993; 15:3–8.

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:733–742.

- Zimmermann C, Riechelmann R, Krzyzanowska M, Rodin G, Tannock I. Effectiveness of specialized palliative care: a systematic review. JAMA 2008; 299:1698–1709.

- Homsi J, Walsh D, Rivera N, et al. Symptom evaluation in palliative medicine: patient report vs systematic assessment. Support Care Cancer 2006; 14:444–453.

- Tang ST, Liu TW, Lai MS, Liu LN, Chen CH, Koong SL. Congruence of knowledge, experiences, and p for disclosure of diagnosis and prognosis between terminally-ill cancer patients and their family caregivers in Taiwan. Cancer Invest 2006; 24:360–366.

- Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, Ahles T. Oncologists’ perspectives on concurrent palliative care in a National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center. Palliat Support Care 2013; 11:415–423.

- Fadul N, Elsayem A, Palmer JL, et al. Supportive versus palliative care: what’s in a name: a survey of medical oncologists and midlevel providers at a comprehensive cancer center. Cancer 2009; 115:2013–2021.

- Rinaldo MJ. Medicare to cover hospice services. J Med Soc NJ 1982; 79:1015–1016.

- Enck RE. Palliative radiation therapy in hospice care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2002; 19:151–152.

- Luchins DJ, Hanrahan P, Murphy K. Criteria for enrolling dementia patients in hospice. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997; 45:1054–1059.

- Fox E, Landrum-McNiff K, Zhong Z, Dawson NV, Wu AW, Lynn J. Evaluation of prognostic criteria for determining hospice eligibility in patients with advanced lung, heart, or liver disease. JAMA 1999; 282:1638–1645.

- Stuart B. The NHO medical guidelines for non-cancer disease and local medical review policy: hospice access for patients with diseases other than cancer. Hosp J 1999; 14:139–154.

- McKinney M. Beyond hospice. New models of care focus on advanced illnesses. Mod Healthc 2013; 43:14–15.

- Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, McCrone P, Higginson IJ. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 6:CD007760.

Occult satellite metastasis of an auricular melanoma

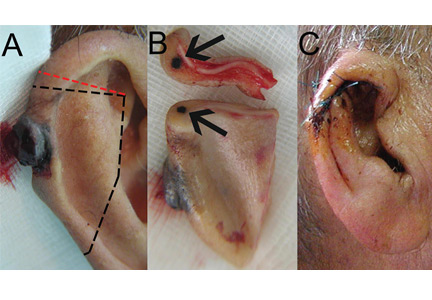

A 90-year-old man presented to our clinic with a dark, exophytic, hemorrhagic mass on the helix of his right auricle (Figure 1A). He had first noticed the lesion 6 months before.

Evaluation of the lesion with the standard ABCDE criteria (Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color variation, Diameter > 6 mm, Evolution/elevation) raised our suspicion of melanoma.1 We performed a wide, full-thickness, auricular wedge resection, which revealed a second dark lesion in the subcutaneous tissue of the upper border of the resected specimen. The rest of the second lesion was evident on the corresponding location of the edge of the remaining auricle (Figure 1B). Thus, we excised an additional strip of auricular tissue. The aesthetic result of the auricular reconstruction was quite good (Figure 1C).

Histopathologic study confirmed cutaneous melanoma and showed the second lesion to be a satellite melanoma metastasis (Figure 2). The patient refused to undergo staging investigations for lymph node and distant metastases. He died 1 year later of ischemic stroke.

IN-TRANSIT AND SATELLITE METASTASES

Melanoma is highly metastatic. In addition to regional lymph node and distant metastases, patients may develop in-transit metastases and satellite metastases.

In-transit metastases grow more than 2 cm away from the primary tumor but not beyond the regional lymph node basin. Satellite lesions are found within 2 cm of the primary melanoma.

As seen in our patient, satellite metastases are not always cutaneous and evident. This is also true of in-transit melanoma lesions. They can also be located in subcutaneous tissue, making them difficult to detect. The presence of satellite lesions is a sign of aggressive disease and requires a thorough evaluation for metastases.2

- Thomas L, Tranchand P, Berard F, Secchi T, Colin C, Moulin G. Semiological value of ABCDE criteria in the diagnosis of cutaneous pigmented tumors. Dermatology 1998; 197:11–17.

- Homsi J, Kashani-Sabet M, Messina JL, Daud A. Cutaneous melanoma: prognostic factors. Cancer Control 2005; 12:223–229.

A 90-year-old man presented to our clinic with a dark, exophytic, hemorrhagic mass on the helix of his right auricle (Figure 1A). He had first noticed the lesion 6 months before.

Evaluation of the lesion with the standard ABCDE criteria (Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color variation, Diameter > 6 mm, Evolution/elevation) raised our suspicion of melanoma.1 We performed a wide, full-thickness, auricular wedge resection, which revealed a second dark lesion in the subcutaneous tissue of the upper border of the resected specimen. The rest of the second lesion was evident on the corresponding location of the edge of the remaining auricle (Figure 1B). Thus, we excised an additional strip of auricular tissue. The aesthetic result of the auricular reconstruction was quite good (Figure 1C).

Histopathologic study confirmed cutaneous melanoma and showed the second lesion to be a satellite melanoma metastasis (Figure 2). The patient refused to undergo staging investigations for lymph node and distant metastases. He died 1 year later of ischemic stroke.

IN-TRANSIT AND SATELLITE METASTASES

Melanoma is highly metastatic. In addition to regional lymph node and distant metastases, patients may develop in-transit metastases and satellite metastases.

In-transit metastases grow more than 2 cm away from the primary tumor but not beyond the regional lymph node basin. Satellite lesions are found within 2 cm of the primary melanoma.

As seen in our patient, satellite metastases are not always cutaneous and evident. This is also true of in-transit melanoma lesions. They can also be located in subcutaneous tissue, making them difficult to detect. The presence of satellite lesions is a sign of aggressive disease and requires a thorough evaluation for metastases.2

A 90-year-old man presented to our clinic with a dark, exophytic, hemorrhagic mass on the helix of his right auricle (Figure 1A). He had first noticed the lesion 6 months before.

Evaluation of the lesion with the standard ABCDE criteria (Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color variation, Diameter > 6 mm, Evolution/elevation) raised our suspicion of melanoma.1 We performed a wide, full-thickness, auricular wedge resection, which revealed a second dark lesion in the subcutaneous tissue of the upper border of the resected specimen. The rest of the second lesion was evident on the corresponding location of the edge of the remaining auricle (Figure 1B). Thus, we excised an additional strip of auricular tissue. The aesthetic result of the auricular reconstruction was quite good (Figure 1C).

Histopathologic study confirmed cutaneous melanoma and showed the second lesion to be a satellite melanoma metastasis (Figure 2). The patient refused to undergo staging investigations for lymph node and distant metastases. He died 1 year later of ischemic stroke.

IN-TRANSIT AND SATELLITE METASTASES

Melanoma is highly metastatic. In addition to regional lymph node and distant metastases, patients may develop in-transit metastases and satellite metastases.

In-transit metastases grow more than 2 cm away from the primary tumor but not beyond the regional lymph node basin. Satellite lesions are found within 2 cm of the primary melanoma.

As seen in our patient, satellite metastases are not always cutaneous and evident. This is also true of in-transit melanoma lesions. They can also be located in subcutaneous tissue, making them difficult to detect. The presence of satellite lesions is a sign of aggressive disease and requires a thorough evaluation for metastases.2

- Thomas L, Tranchand P, Berard F, Secchi T, Colin C, Moulin G. Semiological value of ABCDE criteria in the diagnosis of cutaneous pigmented tumors. Dermatology 1998; 197:11–17.

- Homsi J, Kashani-Sabet M, Messina JL, Daud A. Cutaneous melanoma: prognostic factors. Cancer Control 2005; 12:223–229.

- Thomas L, Tranchand P, Berard F, Secchi T, Colin C, Moulin G. Semiological value of ABCDE criteria in the diagnosis of cutaneous pigmented tumors. Dermatology 1998; 197:11–17.

- Homsi J, Kashani-Sabet M, Messina JL, Daud A. Cutaneous melanoma: prognostic factors. Cancer Control 2005; 12:223–229.

2015 Update on Parkinson disease

This has been a boom year for Parkinson disease, with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approving two new therapies, and with others in the pipeline.

This article details clinical signs of Parkinson disease, discusses functional imaging, provides an update on current thinking on disease pathogenesis, and gives an overview of managing parkinsonian symptoms and dyskinesias.

DIAGNOSIS REMAINS CLINICAL

Although a better understanding of Parkinson disease has been gained in recent years, with the recognition of several premotor features and potential biomarkers, its diagnosis is still primarily based on clinical motor findings. The four cardinal motor features have the mnemonic TRAP:

- Tremor at rest can be subtle, involving just the thumb, best observed when the patient is sitting with the hand resting on the lap; or it can be obvious, involving the entire hand, arm, feet, lips, and chin.

- Rigidity can be felt rather than seen, by slowly passively rotating the patient’s wrist or elbow and feeling resistance. The right and left sides often differ.

- Akinesia or bradykinesia (slowness or lack of movement) can be observed by having the patient walk down a hallway. One may observe reduced arm swing and hesitation in initiating movement.

- Postural instability usually develops later rather than sooner in the disease progression. The patient may need to hold onto someone to maintain balance when getting up or walking.

At least two features must be present to make the diagnosis of parkinsonism. One feature must be tremor or rigidity.

Although the criteria for parkinsonism appear simple, the diagnosis of Parkinson disease is not always clear-cut. For example, shaking can be secondary to a dopamine receptor-blocking medication, to anxiety, or to essential tremor; rigidity and slowness may be due to arthritis; and postural instability can result from a neuropathy. Moreover, other neurodegenerative parkinsonian disorders may respond to levodopa (at least initially) and may present with levodopa-induced dyskinesias. Robust response to levodopa and the occurrence of dyskinesias are two additional features that strongly suggest the diagnosis of Parkinson disease.

Supporting parkinsonian features include stooped posture, masked facies, micrographia (small handwriting), drooling, speech changes (eg, hypophonia or soft speech, stuttering, slurring, monotonic speech), and a shuffling, festinating gait (quick short steps as if falling forward).

PARKINSON MIMICS

Parkinsonism is a broader term than Parkinson disease or idiopathic Parkinson disease. It is characterized by akinetic rigidity and impaired motor activity that leads to reduced function and falls; behavioral changes also may occur.

In the United States, Parkinson disease is the most common cause of parkinsonism. Other nonneurodegenerative causes are drug-induced parkinsonism (due to dopamine receptor antagonists such as antipsychotic or antiemetic drugs), stroke (in the basal ganglia or frontal lobe), and normal-pressure hydrocephalus (causing lower-body parkinsonism). Mimics of parkinsonism include essential tremor and psychogenic parkinsonism.

Parkinsonism can also be caused by Parkinson-plus disorders, ie, neurodegenerative conditions characterized by parkinsonism along with additional signs and symptoms, as listed below. Parkinson-plus disorders include progressive supranuclear palsy, multiple system atrophy, corticobasal degeneration, and Lewy body disease.

Clinical features that suggest a diagnosis other than Parkinson disease include1:

- Poor response to adequate dosages of levodopa

- Early onset of postural instability and falls

- Axial rigidity (eg, stiff neck) more than appendicular rigidity

- Early dementia

- Supranuclear gaze palsy

- Unusual movements besides tremor, eg, limb dystonia, myoclonus, limb levitation or alien limb syndrome

- Profound autonomic dysfunction

- Psychotic symptoms before taking levodopa or dopaminergic medication.

The precise diagnosis of Parkinson-plus disorders is not critical, as the treatment is generally the same for all of them: ie, levodopa (if it shows some efficacy and is well tolerated), with additional symptomatic treatment for features such as depression, cognitive impairment, and autonomic dysfunction, and supportive therapy including physical, occupational, speech, and swallowing therapy.

IMAGING MAY ASSIST IN THE DIAGNOSIS

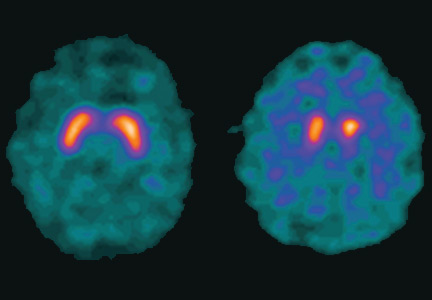

Dopamine transporter single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) is a functional imaging technique that supposedly reflects dopamine uptake by surviving presynaptic dopaminergic neurons in the striate bodies of the basal ganglia. Normal uptake shows distinct cashew-shaped enhancement bilaterally. In Parkinson disease, the enhanced areas are smaller and asymmetric, first with diminution of the tail (representing the putamen), then later involving the head (representing the caudate) along with the other striate bodies (Figure 1).

Dopamine transporter SPECT does not distinguish one neurodegenerative parkinsonian disorder from another. Therefore, it should not be used to distinguish Parkinson disease from other Parkinson-plus syndromes. But it does distinguish neurodegenerative parkinsonian disorders from nonneurodegenerative conditions and mimics, which have a normal result on dopamine transporter SPECT (Table 1).

SLOWING DISEASE PROGRESSION

Current treatments for Parkinson disease can significantly improve symptoms but, unfortunately, do not cure the disease or slow its progression. Testing whether agents modify the disease course is particularly difficult with Parkinson disease, because it affects individuals differently, has a wide spectrum of symptoms, has a long time course, and lacks definitive markers to monitor progression. Some agents have shown promise:

Caffeine. People who drink coffee are less likely to develop Parkinson disease, with the risk declining with the number of cups per day.2 For those who have the disease, drinking coffee is associated with reduced symptoms.

Exercise improves Parkinson disease and may prevent it, and some studies suggest that it can delay its progression.3 Exercise has been shown in an animal model to reduce the vulnerability of dopamine neurons to the toxic agent 6-hydroxydopamine.4 Functional magnetic resonance imaging studies have shown blood flow patterns before and after exercise that are similar to those seen in patients with and without Parkinson medication.3

Rasagiline, a monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitor used for symptomatic treatment of Parkinson disease, had conflicting results in a neuroprotective clinical trial. Patients who received rasagiline 1 mg daily—but not those who received 2 mg daily—at the beginning of the trial had better Parkinson motor scores compared with patients who received rasagiline 9 months later.5

Inosine is a urate precursor that elevates urate levels in serum and the central nervous system. For unknown reasons, patients with Parkinson disease tend to have a low uric acid level, and higher levels are associated with milder disease. It is hoped that raising the uric acid level to a “pre-gout level” may slow the progression of Parkinson disease.

Isradipine, a calcium channel blocker, was found in an epidemiologic study of elderly patients to be associated with reduced likelihood of developing Parkinson disease.6 The drug is now undergoing clinical trials.

Smoking. Although cigarette smokers have long been recognized as having a very low risk of developing Parkinson disease, smoking is not recommended.

Agents found ineffective. Agents that have been tested and found ineffective in modifying the course of Parkinson disease include vitamin E, coenzyme Q10, riluzole, GPI-1485, pramipexole, cogane, CEP-1347, TCH-346, and creatine.

NOT JUST DOPAMINE—OR TREMORS

Dopamine deficiency is central to the current understanding of the pathogenesis of Parkinson disease and the focus of treatment efforts, but if dopamine deficiency were the only problem, replacing it should completely ameliorate all parkinsonian features. Other neurotransmitters also play roles: norepinephrine is implicated in orthostatic symptoms and apathy, acetylcholine in cognitive behaviors, glutamate in dyskinesias, and serotonin in depression, anxiety, and sleep abnormalities.

The most recognized area of involvement in the brain has traditionally been the substantia nigra in the midbrain. However, current thinking is that the disease starts lower in the caudal area of the brainstem (along with the olfactory tubercle), moves through the pons to the midbrain, then spreads across the cerebrum with extensive neocortical involvement.

Early premotor indicators are now recognized to occur 15 to 20 years before a tremor appears. The first signs are often hyposmia (diminished sense of smell, reflecting involvement of the olfactory tubercle) and constipation (reflecting involvement of the medulla and the vagus nucleus). With pons involvement, the patient can develop rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder, depression, or anxiety. Only then does the disease spread to the midbrain and cause resting tremor, rigidity, and bradykinesia.7

Identifying the preclinical stages and starting disease-modifying treatments before the onset of motor symptoms may one day prove important, but at this point, the premotor symptoms (anosmia, constipation, depression) are too nonspecific to be useful, and such treatments have not yet been identified.

TREATMENT: LEVODOPA STILL PRIMARY

When to start drug treatment depends primarily on how much the symptoms bother the patient. Regardless of the clinician’s (or patient’s) belief in the benefits of delaying symptomatic treatment, it is universally considered necessary to start medication when gait problems develop because of the danger of a fall and resulting disability.

Carbidopa-levodopa combination therapy remains the most effective treatment; if it is not effective, another diagnosis may need to be considered. Carbidopa-levodopa improves tremor, rigidity, and bradykinesia, particularly in the early stages of Parkinson disease. It is well tolerated, has rapid onset, reduces the risk of death, and is the least expensive of the medications for Parkinson disease.

Immediate-release and continued-release formulations are available, as well as one that dissolves rapidly on the tongue and can be taken without water. An oral extended-release carbidopa-levodopa formulation (Rytary) was approved by the FDA in January 2015. Tablets are filled with drug-containing microbeads that dissolve at different rates to achieve therapeutic levodopa levels as quickly as the immediate-release formulation and maintain them for an extended time.8

The development of dyskinesias is the major psychological drawback of levodopa, occurring in 80% of patients after 5 to 10 years of treatment. Although many patients fear this side effect, most patients who develop it find it preferable to the rigidity and bradykinesia of Parkinson disease. In most cases, bothersome dyskinesias can be controlled by adjusting medications.9,10

Dopamine agonists include pramipexole, ropinirole, and rotigotine. They are available in generic form as three-times-daily dosing; once-daily dosing is also available, but not as a generic formulation. Dopamine agonists have the advantage of potentially improving depression and delaying the onset of dyskinesias.

However, dopamine agonists have a number of disadvantages compared with levodopa: they have a longer titration period, are less effective, and are less well tolerated, especially in the elderly. Side effects occur more frequently than with levodopa and include general and peripheral edema, hallucinations, nausea, lightheadedness, and sleepiness.11,12 These drugs are also associated with “sleep attacks” (sudden falling asleep while active, such as while driving or eating) and with compulsive and impulsive behaviors such as hypersexuality, buying, binge eating, and gambling. Although these behaviors occur in fewer than 10% of patients, they can be devastating, leading to marital, financial, and legal problems. A bothersome clinical state termed dopamine agonist withdrawal syndrome is characterized by anxiety, depression, jitteriness, and palpitations when dopamine agonists are tapered or discontinued because of a side effect.13

MAO-B inhibitors delay the breakdown of dopamine, allowing it to “stay” in the brain for a longer period of time. Rasagiline for early monotherapy has the advantages of once-daily dosing, no titration, and excellent tolerability, even in the elderly. Potential drug interactions should be considered when using this drug. Early warnings about interactions with tyramine-rich foods were lifted after trials showed that this was not a problem.14

Amantadine is an N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist often used in early Parkinson disease and for treatment of dyskinesias and fatigue. It is the only drug that is intrinsically antidyskinetic and also improves Parkinson symptoms.15 Side effects include leg swelling, livedo reticularis, and neuropsychiatric and anticholinergic effects.

Anticholinergic agents (eg, trihexyphenidyl) improve tremor but are not as useful for bradykinesia or rigidity, and often have anticholinergic effects such as mental dullness, dry mouth, dry eye, and urinary hesitancy, especially in the elderly, so they have a limited role in Parkinson treatment.

MOTOR COMPLICATIONS: FLUCTUATIONS AND DYSKINESIAS

Motor fluctuations are changes between the akinetic and mobile phases of Parkinson disease, or the off-periods and on-periods of drug treatment. A patient who is “off” is generally rigid and feels that the medication is not working. A patient who is “on” feels loose and mobile and that the medication is working. Variants of motor fluctuations include:

- End-of-dose deterioration

- Delayed onset of response (more than half an hour after taking medication)

- Drug-resistant offs—medication has become ineffective

- Random oscillation—on-off phenomenon

- Freezing—unpredictable inability to start or finish a movement.

Dyskinesias are abnormal involuntary movements such as writhing and twisting. They are associated with dopaminergic therapy at peak dose, when the drug starts to turn on or wear off (termed diphasic dyskinesias).16

The storage hypothesis provides a plausible explanation for the development of motor complications as the disease progresses. Although the half-life of levodopa is only 60 to 90 minutes, it is effective in early disease when given three times a day. It is believed that at this stage of the disease, enough dopaminergic neurons survive to “store” dopamine and release it as needed. As the disease progresses and dopaminergic neurons die, storage capacity diminishes, and the clinical effect slowly starts to approximate the pharmacokinetic profile of the drug. Upon taking the medication, the patient gets a surge of drug, causing dyskinesias, followed later by rigidity as the effect wears off since there are fewer surviving dopaminergic cells to store dopamine.

MANAGING DYSKINESIAS

Patients with dyskinesias should first be asked if they are bothered by them; not all patients are troubled by dyskinesias. If the movements only bother others (eg, family members), then education is often the only treatment needed. If the patient is uncomfortable, the following measures can be tried:

- Taking lower, more frequent doses of levodopa (however, risk of wearing off becomes a problem)

- Adding a dopamine agonist or MAO-B inhibitor while lowering the levodopa dose (however, MAO-B inhibitors pose a risk of side effects in elderly patients)

- Adding clozapine (periodic laboratory testing is required to monitor blood levels and liver and kidney function)

- Adding amantadine (however, this poses a risk of cognitive side effects).

Deep-brain-stimulation surgery is appropriate for select patients who are generally physically healthy, cognitively intact, and emotionally stable, with a strong family support system, but who are bothered by symptoms of parkinsonism (such as tremors), motor fluctuations, or dyskinesias.17

Infusion pump. In January 2015, the FDA approved a new system that continuously delivers levodopa-carbidopa in a 4:1 ratio in gel suspension for 16 hours directly into the small intestine, minimizing motor fluctuations. The patient changes the cartridge daily and turns it off at bedtime.

*Dr. Fernandez has received research support from AbbVie, Acadia, Auspex, Biotie Therapies, Civitas, Kyowa/ProStrakan, Michael J. Fox Foundation, Movement Disorders Society, NIH/NINDS, Parkinson Study Group, Rhythm, Synosia, and Teva. He also has received honoraria from Carling Communications, International Parkinson and Movement Disorders Society, The Ohio State University, and PRIME Education, Inc as a speaker in CME events. He has received honoraria from Biogen, GE Health Care, Lundbeck, Merz Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer as a consultant. He has received royalty payments from Demos Publishing for serving as a book author/editor. Cleveland Clinic has contracts with AbbVie and Merz Pharmaceuticals for Dr. Fernandez’s role as a member of the Global Steering Committee for LCIG studies and as a consultant or speaker, and as Head Principal Investigator for the Xeomin Registry Study. Dr. Fernandez has received a stipend from International Parkinson and Movement Disorders Society for serving as medical editor of the Movement Disorders Society website.

- Wenning GK, Ben-Shlomo Y, Hughes A, Daniel SE, Lees A, Quinn NP. What clinical features are most useful to distinguish definite multiple system atrophy from Parkinson’s disease? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000; 68:434–440.

- Hernán MA, Takkouche B, Caamaño-Isoma F, et al. A meta-analysis of coffee drinking, cigarette smoking, and risk of Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol 2002; 52:276–84.

- Ridgel A, Thota A, Vitek JL, Alberts JL. Forced, not voluntary, exercise improves motor function in Parkinson’s disease patients. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2009; 23:600–608.

- Smith AD, Zigmond MJ. Can the brain be protected through exercise? Lessons from an animal model of parkinsonism. Exp Neurol 2003; 184:31–39.

- Olanow CW, Rascol O, Hauser R, et al, for the ADAGIO Study Investigators. A double-blind, delayed-start trial of rasagiline in Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:1268–1278.

- Pasternak B, Svanström H, Nielsen NM, Fugger L, Melbye M, Hviid A. Use of calcium channel blockers and Parkinson’s disease. Am J Epidemiol 2012; 175:627-635.

- Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rüb U, de Vos RAI, Jansen Steur ENH, Braak E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 2003; 24:197–211.

- Hauser RA, Ellenbogen AL, Metman LV, et al. Crossover comparison of IPX066 and a standard levodopa formulation in advanced Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2011; 26:2246–2252.

- Hely MA, Morris JG, Reid WG, Trafficante R. Sydney Multicenter Study of Parkinson’s disease: non-L-dopa-responsive problems dominate at 15 years. Mov Disord 2005; 20:190–199.

- Hung SW, Adeli GM, Arenovich T, Fox SH, Lang AE. Patient perception of dyskinesia in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010; 81:1112–1115.

- Rascol O, Brooks DJ, Korczyn AD, De Deyn PP, Clarke CE, Lang AE. A five-year study of the incidence of dyskinesia in patients with early Parkinson’s disease who were treated with ropinirole or levodopa. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:1484–1491.

- Parkinson Study Group. Pramipexole vs levodopa as initial treatment for Parkinson disease: a randomized controlled trial. Parkinson Study Group. JAMA 2000; 284:1931–1938.

- Nirenberg MJ. Dopamine agonist withdrawal syndrome: implications for patient care. Drugs Aging 2013; 30:587–592.

- Teva Neuroscience, Inc. Azilect prescribing information. https://www.azilect.com/Content/pdf/azi-40850-azilect-electronic-pi.pdf. Accessed June 29, 2015.

- Snow BJ, Macdonald L, Mcauley D, Wallis W. The effect of amantadine on levodopa-induced dyskinesias in Parkinson’s disease: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin Neuropharmacol 2000; 23:82–85.

- Adler CH, Ahlskog JE, eds. Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders: Diagnosis and Treatment Guidelines for the Practicing Physician. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2000.

- Machado A, Fernandez HH, Deogaonkar M. Deep brain stimulation: what can patients expect from it? Cleve Clin J Med 2012; 79:113–120.

This has been a boom year for Parkinson disease, with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approving two new therapies, and with others in the pipeline.

This article details clinical signs of Parkinson disease, discusses functional imaging, provides an update on current thinking on disease pathogenesis, and gives an overview of managing parkinsonian symptoms and dyskinesias.

DIAGNOSIS REMAINS CLINICAL

Although a better understanding of Parkinson disease has been gained in recent years, with the recognition of several premotor features and potential biomarkers, its diagnosis is still primarily based on clinical motor findings. The four cardinal motor features have the mnemonic TRAP:

- Tremor at rest can be subtle, involving just the thumb, best observed when the patient is sitting with the hand resting on the lap; or it can be obvious, involving the entire hand, arm, feet, lips, and chin.

- Rigidity can be felt rather than seen, by slowly passively rotating the patient’s wrist or elbow and feeling resistance. The right and left sides often differ.

- Akinesia or bradykinesia (slowness or lack of movement) can be observed by having the patient walk down a hallway. One may observe reduced arm swing and hesitation in initiating movement.

- Postural instability usually develops later rather than sooner in the disease progression. The patient may need to hold onto someone to maintain balance when getting up or walking.

At least two features must be present to make the diagnosis of parkinsonism. One feature must be tremor or rigidity.

Although the criteria for parkinsonism appear simple, the diagnosis of Parkinson disease is not always clear-cut. For example, shaking can be secondary to a dopamine receptor-blocking medication, to anxiety, or to essential tremor; rigidity and slowness may be due to arthritis; and postural instability can result from a neuropathy. Moreover, other neurodegenerative parkinsonian disorders may respond to levodopa (at least initially) and may present with levodopa-induced dyskinesias. Robust response to levodopa and the occurrence of dyskinesias are two additional features that strongly suggest the diagnosis of Parkinson disease.

Supporting parkinsonian features include stooped posture, masked facies, micrographia (small handwriting), drooling, speech changes (eg, hypophonia or soft speech, stuttering, slurring, monotonic speech), and a shuffling, festinating gait (quick short steps as if falling forward).

PARKINSON MIMICS

Parkinsonism is a broader term than Parkinson disease or idiopathic Parkinson disease. It is characterized by akinetic rigidity and impaired motor activity that leads to reduced function and falls; behavioral changes also may occur.

In the United States, Parkinson disease is the most common cause of parkinsonism. Other nonneurodegenerative causes are drug-induced parkinsonism (due to dopamine receptor antagonists such as antipsychotic or antiemetic drugs), stroke (in the basal ganglia or frontal lobe), and normal-pressure hydrocephalus (causing lower-body parkinsonism). Mimics of parkinsonism include essential tremor and psychogenic parkinsonism.

Parkinsonism can also be caused by Parkinson-plus disorders, ie, neurodegenerative conditions characterized by parkinsonism along with additional signs and symptoms, as listed below. Parkinson-plus disorders include progressive supranuclear palsy, multiple system atrophy, corticobasal degeneration, and Lewy body disease.

Clinical features that suggest a diagnosis other than Parkinson disease include1:

- Poor response to adequate dosages of levodopa

- Early onset of postural instability and falls

- Axial rigidity (eg, stiff neck) more than appendicular rigidity

- Early dementia

- Supranuclear gaze palsy

- Unusual movements besides tremor, eg, limb dystonia, myoclonus, limb levitation or alien limb syndrome

- Profound autonomic dysfunction

- Psychotic symptoms before taking levodopa or dopaminergic medication.

The precise diagnosis of Parkinson-plus disorders is not critical, as the treatment is generally the same for all of them: ie, levodopa (if it shows some efficacy and is well tolerated), with additional symptomatic treatment for features such as depression, cognitive impairment, and autonomic dysfunction, and supportive therapy including physical, occupational, speech, and swallowing therapy.

IMAGING MAY ASSIST IN THE DIAGNOSIS

Dopamine transporter single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) is a functional imaging technique that supposedly reflects dopamine uptake by surviving presynaptic dopaminergic neurons in the striate bodies of the basal ganglia. Normal uptake shows distinct cashew-shaped enhancement bilaterally. In Parkinson disease, the enhanced areas are smaller and asymmetric, first with diminution of the tail (representing the putamen), then later involving the head (representing the caudate) along with the other striate bodies (Figure 1).

Dopamine transporter SPECT does not distinguish one neurodegenerative parkinsonian disorder from another. Therefore, it should not be used to distinguish Parkinson disease from other Parkinson-plus syndromes. But it does distinguish neurodegenerative parkinsonian disorders from nonneurodegenerative conditions and mimics, which have a normal result on dopamine transporter SPECT (Table 1).

SLOWING DISEASE PROGRESSION

Current treatments for Parkinson disease can significantly improve symptoms but, unfortunately, do not cure the disease or slow its progression. Testing whether agents modify the disease course is particularly difficult with Parkinson disease, because it affects individuals differently, has a wide spectrum of symptoms, has a long time course, and lacks definitive markers to monitor progression. Some agents have shown promise:

Caffeine. People who drink coffee are less likely to develop Parkinson disease, with the risk declining with the number of cups per day.2 For those who have the disease, drinking coffee is associated with reduced symptoms.

Exercise improves Parkinson disease and may prevent it, and some studies suggest that it can delay its progression.3 Exercise has been shown in an animal model to reduce the vulnerability of dopamine neurons to the toxic agent 6-hydroxydopamine.4 Functional magnetic resonance imaging studies have shown blood flow patterns before and after exercise that are similar to those seen in patients with and without Parkinson medication.3

Rasagiline, a monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitor used for symptomatic treatment of Parkinson disease, had conflicting results in a neuroprotective clinical trial. Patients who received rasagiline 1 mg daily—but not those who received 2 mg daily—at the beginning of the trial had better Parkinson motor scores compared with patients who received rasagiline 9 months later.5

Inosine is a urate precursor that elevates urate levels in serum and the central nervous system. For unknown reasons, patients with Parkinson disease tend to have a low uric acid level, and higher levels are associated with milder disease. It is hoped that raising the uric acid level to a “pre-gout level” may slow the progression of Parkinson disease.

Isradipine, a calcium channel blocker, was found in an epidemiologic study of elderly patients to be associated with reduced likelihood of developing Parkinson disease.6 The drug is now undergoing clinical trials.

Smoking. Although cigarette smokers have long been recognized as having a very low risk of developing Parkinson disease, smoking is not recommended.

Agents found ineffective. Agents that have been tested and found ineffective in modifying the course of Parkinson disease include vitamin E, coenzyme Q10, riluzole, GPI-1485, pramipexole, cogane, CEP-1347, TCH-346, and creatine.

NOT JUST DOPAMINE—OR TREMORS

Dopamine deficiency is central to the current understanding of the pathogenesis of Parkinson disease and the focus of treatment efforts, but if dopamine deficiency were the only problem, replacing it should completely ameliorate all parkinsonian features. Other neurotransmitters also play roles: norepinephrine is implicated in orthostatic symptoms and apathy, acetylcholine in cognitive behaviors, glutamate in dyskinesias, and serotonin in depression, anxiety, and sleep abnormalities.

The most recognized area of involvement in the brain has traditionally been the substantia nigra in the midbrain. However, current thinking is that the disease starts lower in the caudal area of the brainstem (along with the olfactory tubercle), moves through the pons to the midbrain, then spreads across the cerebrum with extensive neocortical involvement.

Early premotor indicators are now recognized to occur 15 to 20 years before a tremor appears. The first signs are often hyposmia (diminished sense of smell, reflecting involvement of the olfactory tubercle) and constipation (reflecting involvement of the medulla and the vagus nucleus). With pons involvement, the patient can develop rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder, depression, or anxiety. Only then does the disease spread to the midbrain and cause resting tremor, rigidity, and bradykinesia.7

Identifying the preclinical stages and starting disease-modifying treatments before the onset of motor symptoms may one day prove important, but at this point, the premotor symptoms (anosmia, constipation, depression) are too nonspecific to be useful, and such treatments have not yet been identified.

TREATMENT: LEVODOPA STILL PRIMARY

When to start drug treatment depends primarily on how much the symptoms bother the patient. Regardless of the clinician’s (or patient’s) belief in the benefits of delaying symptomatic treatment, it is universally considered necessary to start medication when gait problems develop because of the danger of a fall and resulting disability.

Carbidopa-levodopa combination therapy remains the most effective treatment; if it is not effective, another diagnosis may need to be considered. Carbidopa-levodopa improves tremor, rigidity, and bradykinesia, particularly in the early stages of Parkinson disease. It is well tolerated, has rapid onset, reduces the risk of death, and is the least expensive of the medications for Parkinson disease.

Immediate-release and continued-release formulations are available, as well as one that dissolves rapidly on the tongue and can be taken without water. An oral extended-release carbidopa-levodopa formulation (Rytary) was approved by the FDA in January 2015. Tablets are filled with drug-containing microbeads that dissolve at different rates to achieve therapeutic levodopa levels as quickly as the immediate-release formulation and maintain them for an extended time.8

The development of dyskinesias is the major psychological drawback of levodopa, occurring in 80% of patients after 5 to 10 years of treatment. Although many patients fear this side effect, most patients who develop it find it preferable to the rigidity and bradykinesia of Parkinson disease. In most cases, bothersome dyskinesias can be controlled by adjusting medications.9,10

Dopamine agonists include pramipexole, ropinirole, and rotigotine. They are available in generic form as three-times-daily dosing; once-daily dosing is also available, but not as a generic formulation. Dopamine agonists have the advantage of potentially improving depression and delaying the onset of dyskinesias.

However, dopamine agonists have a number of disadvantages compared with levodopa: they have a longer titration period, are less effective, and are less well tolerated, especially in the elderly. Side effects occur more frequently than with levodopa and include general and peripheral edema, hallucinations, nausea, lightheadedness, and sleepiness.11,12 These drugs are also associated with “sleep attacks” (sudden falling asleep while active, such as while driving or eating) and with compulsive and impulsive behaviors such as hypersexuality, buying, binge eating, and gambling. Although these behaviors occur in fewer than 10% of patients, they can be devastating, leading to marital, financial, and legal problems. A bothersome clinical state termed dopamine agonist withdrawal syndrome is characterized by anxiety, depression, jitteriness, and palpitations when dopamine agonists are tapered or discontinued because of a side effect.13

MAO-B inhibitors delay the breakdown of dopamine, allowing it to “stay” in the brain for a longer period of time. Rasagiline for early monotherapy has the advantages of once-daily dosing, no titration, and excellent tolerability, even in the elderly. Potential drug interactions should be considered when using this drug. Early warnings about interactions with tyramine-rich foods were lifted after trials showed that this was not a problem.14

Amantadine is an N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist often used in early Parkinson disease and for treatment of dyskinesias and fatigue. It is the only drug that is intrinsically antidyskinetic and also improves Parkinson symptoms.15 Side effects include leg swelling, livedo reticularis, and neuropsychiatric and anticholinergic effects.

Anticholinergic agents (eg, trihexyphenidyl) improve tremor but are not as useful for bradykinesia or rigidity, and often have anticholinergic effects such as mental dullness, dry mouth, dry eye, and urinary hesitancy, especially in the elderly, so they have a limited role in Parkinson treatment.

MOTOR COMPLICATIONS: FLUCTUATIONS AND DYSKINESIAS

Motor fluctuations are changes between the akinetic and mobile phases of Parkinson disease, or the off-periods and on-periods of drug treatment. A patient who is “off” is generally rigid and feels that the medication is not working. A patient who is “on” feels loose and mobile and that the medication is working. Variants of motor fluctuations include:

- End-of-dose deterioration

- Delayed onset of response (more than half an hour after taking medication)

- Drug-resistant offs—medication has become ineffective

- Random oscillation—on-off phenomenon

- Freezing—unpredictable inability to start or finish a movement.

Dyskinesias are abnormal involuntary movements such as writhing and twisting. They are associated with dopaminergic therapy at peak dose, when the drug starts to turn on or wear off (termed diphasic dyskinesias).16