User login

Treatment appears feasible for acute PE

Image courtesy of the

Medical College of Georgia

New research suggests that ultrasound-facilitated, catheter-directed, low-dose thrombolysis can produce positive results in patients with acute pulmonary embolism (PE).

In the SEATTLE II study, this treatment prompted significant decreases in thrombus burden, pulmonary hypertension, and the right ventricular-to-left ventricular (RV/LV) diameter ratio.

Major bleeds occurred in 10% of patients, but there were no cases of intracranial hemorrhage.

These results were published in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

The SEATTLE II study was designed to evaluate ultrasound-facilitated, catheter-directed, low-dose thrombolysis using the EKOS EkoSonic® Endovascular System. The research was sponsored by EKOS Corporation, the company developing the system.

The trial included 150 patients diagnosed with acute massive (n=31) or submassive (n=119) PE. Patients received low-dose (24 mg) tissue plasminogen activator for 24 hours with a unilateral catheter or for 12 hours with bilateral catheters.

By 48 hours after treatment initiation, the mean RV/LV diameter ratio had significantly decreased, from 1.55 to 1.13 (P<0.0001).

The mean pulmonary artery systolic pressure decreased significantly as well, from 51.4 mm Hg to 36.9 mm Hg (P<0.0001).

And there was a significant decrease in modified Miller angiographic obstruction index score, from 22.5 to 15.8 (P<0.0001).

There were no intracranial hemorrhages and no fatal bleeding events. Major bleeds occurred in 15 patients (10%) and consisted of 1 severe bleed and 16 moderate bleeds.

Six of the major bleeds occurred in patients with comorbidities known to be associated with an increased risk of bleeding during thrombolytic therapy.

There were 3 serious adverse events that were considered potentially related to the EkoSonic Endovascular System. And 2 serious adverse events were potentially related to tissue plasminogen activator.

At 30 days post-treatment, there were 4 deaths. Three occurred in-hospital, and 1 was directly attributed to PE.

The researchers pointed out that 31 patients presented with massive PE, syncope, and hypotension. And all 31 survived the 30-day follow-up period.

“The SEATTLE II findings establish a new rationale for considering ultrasound-facilitated, catheter-directed, low-dose thrombolysis in both massive and submassive PE,” said study author Gregory Piazza, MD, of Brigham and Woman’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Without any intracranial hemorrhage and using a much-reduced lytic dose, a substantial and clinically meaningful reduction of the RV/LV ratio was achieved.” ![]()

Image courtesy of the

Medical College of Georgia

New research suggests that ultrasound-facilitated, catheter-directed, low-dose thrombolysis can produce positive results in patients with acute pulmonary embolism (PE).

In the SEATTLE II study, this treatment prompted significant decreases in thrombus burden, pulmonary hypertension, and the right ventricular-to-left ventricular (RV/LV) diameter ratio.

Major bleeds occurred in 10% of patients, but there were no cases of intracranial hemorrhage.

These results were published in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

The SEATTLE II study was designed to evaluate ultrasound-facilitated, catheter-directed, low-dose thrombolysis using the EKOS EkoSonic® Endovascular System. The research was sponsored by EKOS Corporation, the company developing the system.

The trial included 150 patients diagnosed with acute massive (n=31) or submassive (n=119) PE. Patients received low-dose (24 mg) tissue plasminogen activator for 24 hours with a unilateral catheter or for 12 hours with bilateral catheters.

By 48 hours after treatment initiation, the mean RV/LV diameter ratio had significantly decreased, from 1.55 to 1.13 (P<0.0001).

The mean pulmonary artery systolic pressure decreased significantly as well, from 51.4 mm Hg to 36.9 mm Hg (P<0.0001).

And there was a significant decrease in modified Miller angiographic obstruction index score, from 22.5 to 15.8 (P<0.0001).

There were no intracranial hemorrhages and no fatal bleeding events. Major bleeds occurred in 15 patients (10%) and consisted of 1 severe bleed and 16 moderate bleeds.

Six of the major bleeds occurred in patients with comorbidities known to be associated with an increased risk of bleeding during thrombolytic therapy.

There were 3 serious adverse events that were considered potentially related to the EkoSonic Endovascular System. And 2 serious adverse events were potentially related to tissue plasminogen activator.

At 30 days post-treatment, there were 4 deaths. Three occurred in-hospital, and 1 was directly attributed to PE.

The researchers pointed out that 31 patients presented with massive PE, syncope, and hypotension. And all 31 survived the 30-day follow-up period.

“The SEATTLE II findings establish a new rationale for considering ultrasound-facilitated, catheter-directed, low-dose thrombolysis in both massive and submassive PE,” said study author Gregory Piazza, MD, of Brigham and Woman’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Without any intracranial hemorrhage and using a much-reduced lytic dose, a substantial and clinically meaningful reduction of the RV/LV ratio was achieved.” ![]()

Image courtesy of the

Medical College of Georgia

New research suggests that ultrasound-facilitated, catheter-directed, low-dose thrombolysis can produce positive results in patients with acute pulmonary embolism (PE).

In the SEATTLE II study, this treatment prompted significant decreases in thrombus burden, pulmonary hypertension, and the right ventricular-to-left ventricular (RV/LV) diameter ratio.

Major bleeds occurred in 10% of patients, but there were no cases of intracranial hemorrhage.

These results were published in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

The SEATTLE II study was designed to evaluate ultrasound-facilitated, catheter-directed, low-dose thrombolysis using the EKOS EkoSonic® Endovascular System. The research was sponsored by EKOS Corporation, the company developing the system.

The trial included 150 patients diagnosed with acute massive (n=31) or submassive (n=119) PE. Patients received low-dose (24 mg) tissue plasminogen activator for 24 hours with a unilateral catheter or for 12 hours with bilateral catheters.

By 48 hours after treatment initiation, the mean RV/LV diameter ratio had significantly decreased, from 1.55 to 1.13 (P<0.0001).

The mean pulmonary artery systolic pressure decreased significantly as well, from 51.4 mm Hg to 36.9 mm Hg (P<0.0001).

And there was a significant decrease in modified Miller angiographic obstruction index score, from 22.5 to 15.8 (P<0.0001).

There were no intracranial hemorrhages and no fatal bleeding events. Major bleeds occurred in 15 patients (10%) and consisted of 1 severe bleed and 16 moderate bleeds.

Six of the major bleeds occurred in patients with comorbidities known to be associated with an increased risk of bleeding during thrombolytic therapy.

There were 3 serious adverse events that were considered potentially related to the EkoSonic Endovascular System. And 2 serious adverse events were potentially related to tissue plasminogen activator.

At 30 days post-treatment, there were 4 deaths. Three occurred in-hospital, and 1 was directly attributed to PE.

The researchers pointed out that 31 patients presented with massive PE, syncope, and hypotension. And all 31 survived the 30-day follow-up period.

“The SEATTLE II findings establish a new rationale for considering ultrasound-facilitated, catheter-directed, low-dose thrombolysis in both massive and submassive PE,” said study author Gregory Piazza, MD, of Brigham and Woman’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Without any intracranial hemorrhage and using a much-reduced lytic dose, a substantial and clinically meaningful reduction of the RV/LV ratio was achieved.” ![]()

Study reveals approaches to aid, prevent apoptosis

apoptosis in cancer cells

Scientists say they have gained new insight into the role Bax plays in apoptosis.

The Bax protein is known to be a key regulator of apoptosis, mediating the release of cytochrome c to the cytosol via oligomerization in the outer mitochondrial membrane before pore formation.

But the exact mechanism of Bax assembly was previously unclear.

Now, research published in Nature Communications has provided some clarity.

Katia Cosentino, PhD, of the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems in Stuttgart, Germany, and her colleagues conducted this research, examining how the mitochondrial membrane becomes permeable.

The team’s experiments on artificial membrane systems showed that Bax is initially inserted into the membrane as a single molecule.

Once inserted, one Bax molecule will join up with a second Bax molecule to form a stable complex, the Bax dimers. From these dimers, larger complexes are formed.

“Surprisingly, Bax complexes have no standard size, but we observed a mixture of different-sized Bax species, and these species are mostly based on dimer units,” Dr Cosentino said.

She and her colleagues noted that these Bax complexes form the pores through which cytochrome c exits the mitochondrial membrane.

But the process of pore formation is finely controlled by other proteins. Some (such as cBid) enable the assembly of Bax elements, while others (such as Bcl-xL) induce their dismantling.

“The differing size of the Bax complexes in the pore formation is likely part of the reason why earlier investigations on pore formation conveyed contradictory results,” Dr Cosentino said.

She and her colleagues believe that, based on these findings, they can make some initial recommendations for medical intervention in the apoptotic process.

They think that, to promote apoptosis, it should be enough to initiate the first step of activating Bax proteins because the subsequent steps of self-organization will then happen automatically.

Conversely, the team’s findings suggest apoptosis can be prevented when drugs force the dismantling of the Bax dimers into their individual elements. ![]()

apoptosis in cancer cells

Scientists say they have gained new insight into the role Bax plays in apoptosis.

The Bax protein is known to be a key regulator of apoptosis, mediating the release of cytochrome c to the cytosol via oligomerization in the outer mitochondrial membrane before pore formation.

But the exact mechanism of Bax assembly was previously unclear.

Now, research published in Nature Communications has provided some clarity.

Katia Cosentino, PhD, of the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems in Stuttgart, Germany, and her colleagues conducted this research, examining how the mitochondrial membrane becomes permeable.

The team’s experiments on artificial membrane systems showed that Bax is initially inserted into the membrane as a single molecule.

Once inserted, one Bax molecule will join up with a second Bax molecule to form a stable complex, the Bax dimers. From these dimers, larger complexes are formed.

“Surprisingly, Bax complexes have no standard size, but we observed a mixture of different-sized Bax species, and these species are mostly based on dimer units,” Dr Cosentino said.

She and her colleagues noted that these Bax complexes form the pores through which cytochrome c exits the mitochondrial membrane.

But the process of pore formation is finely controlled by other proteins. Some (such as cBid) enable the assembly of Bax elements, while others (such as Bcl-xL) induce their dismantling.

“The differing size of the Bax complexes in the pore formation is likely part of the reason why earlier investigations on pore formation conveyed contradictory results,” Dr Cosentino said.

She and her colleagues believe that, based on these findings, they can make some initial recommendations for medical intervention in the apoptotic process.

They think that, to promote apoptosis, it should be enough to initiate the first step of activating Bax proteins because the subsequent steps of self-organization will then happen automatically.

Conversely, the team’s findings suggest apoptosis can be prevented when drugs force the dismantling of the Bax dimers into their individual elements. ![]()

apoptosis in cancer cells

Scientists say they have gained new insight into the role Bax plays in apoptosis.

The Bax protein is known to be a key regulator of apoptosis, mediating the release of cytochrome c to the cytosol via oligomerization in the outer mitochondrial membrane before pore formation.

But the exact mechanism of Bax assembly was previously unclear.

Now, research published in Nature Communications has provided some clarity.

Katia Cosentino, PhD, of the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems in Stuttgart, Germany, and her colleagues conducted this research, examining how the mitochondrial membrane becomes permeable.

The team’s experiments on artificial membrane systems showed that Bax is initially inserted into the membrane as a single molecule.

Once inserted, one Bax molecule will join up with a second Bax molecule to form a stable complex, the Bax dimers. From these dimers, larger complexes are formed.

“Surprisingly, Bax complexes have no standard size, but we observed a mixture of different-sized Bax species, and these species are mostly based on dimer units,” Dr Cosentino said.

She and her colleagues noted that these Bax complexes form the pores through which cytochrome c exits the mitochondrial membrane.

But the process of pore formation is finely controlled by other proteins. Some (such as cBid) enable the assembly of Bax elements, while others (such as Bcl-xL) induce their dismantling.

“The differing size of the Bax complexes in the pore formation is likely part of the reason why earlier investigations on pore formation conveyed contradictory results,” Dr Cosentino said.

She and her colleagues believe that, based on these findings, they can make some initial recommendations for medical intervention in the apoptotic process.

They think that, to promote apoptosis, it should be enough to initiate the first step of activating Bax proteins because the subsequent steps of self-organization will then happen automatically.

Conversely, the team’s findings suggest apoptosis can be prevented when drugs force the dismantling of the Bax dimers into their individual elements. ![]()

New proteasome inhibitor exhibits activity against MM

A novel, cancer-selective proteasome inhibitor has shown early promise for treating multiple myeloma (MM) and breast cancer, according to researchers.

The drug, known as VR23, is a quinoline-sulfonyl hybrid proteasome inhibitor.

In preclinical experiments, VR23 preferentially targeted MM cells and breast cancer cells, demonstrated synergy with bortezomib or paclitaxel, and shrank both MM and breast cancer tumors in mice.

Hoyun Lee, PhD, of the Advanced Medical Research Institute of Canada (AMRIC) in Sudbury, Ontario, and his colleagues described these experiments in Cancer Research.

The team noted that VR23 is structurally distinct from other known proteasome inhibitors, and it “potently inhibits” the activities of trypsin-like proteasomes, chymotrypsin-like proteasomes, and caspase-like proteasomes.

In several experiments, VR23 proved active against breast cancer.

In experiments with MM cell lines, VR23 exhibited activity as a single agent and demonstrated synergy with bortezomib. VR23 proved more effective against bortezomib-resistant cells than bortezomib-naïve cells.

When the researchers introduced treatments to bortezomib-naïve RPMI-8226 cells, they found the cell growth rate was 79.3% with VR23, 12.5% with bortezomib, and 1.6% with both drugs. In bortezomib-resistant RPMI-8226 cells, the cell growth rate was 47% with VR23, 109.7% with bortezomib, and -8.6% with both drugs.

In KAS6/1 cells, the cell growth rate was 65% with VR23, 92% with bortezomib, and 26.5% with both drugs. In bortezomib-resistant ANBL6 cells, the cell growth rate was 94% with VR23, 102.9% with bortezomib, and 48.9% with both drugs.

The researchers also tested VR23 in mice engrafted with RPMI-8226 MM cells. At 24 days after treatment, the tumor volume for VR23-treated mice was 19.1% that of placebo-treated mice.

The team noted that VR23 selectively killed cancer cells via apoptosis. Cancer cells exposed to the drug underwent an abnormal centrosome amplification cycle caused by the accumulation of ubiquitinated cyclin E.

Dr Lee and his colleagues are now planning to work with the US National Cancer Institute to test VR23 in additional cancers. The team is hoping to progress to clinical trials with the drug in the next 3 years.

AMRIC has applied for international intellectual property protection for VR23 and licensed commercial rights to Ramsey Lake Pharmaceutical Corporation (www.ramseylakepharma.com), an operation of AMRIC. ![]()

A novel, cancer-selective proteasome inhibitor has shown early promise for treating multiple myeloma (MM) and breast cancer, according to researchers.

The drug, known as VR23, is a quinoline-sulfonyl hybrid proteasome inhibitor.

In preclinical experiments, VR23 preferentially targeted MM cells and breast cancer cells, demonstrated synergy with bortezomib or paclitaxel, and shrank both MM and breast cancer tumors in mice.

Hoyun Lee, PhD, of the Advanced Medical Research Institute of Canada (AMRIC) in Sudbury, Ontario, and his colleagues described these experiments in Cancer Research.

The team noted that VR23 is structurally distinct from other known proteasome inhibitors, and it “potently inhibits” the activities of trypsin-like proteasomes, chymotrypsin-like proteasomes, and caspase-like proteasomes.

In several experiments, VR23 proved active against breast cancer.

In experiments with MM cell lines, VR23 exhibited activity as a single agent and demonstrated synergy with bortezomib. VR23 proved more effective against bortezomib-resistant cells than bortezomib-naïve cells.

When the researchers introduced treatments to bortezomib-naïve RPMI-8226 cells, they found the cell growth rate was 79.3% with VR23, 12.5% with bortezomib, and 1.6% with both drugs. In bortezomib-resistant RPMI-8226 cells, the cell growth rate was 47% with VR23, 109.7% with bortezomib, and -8.6% with both drugs.

In KAS6/1 cells, the cell growth rate was 65% with VR23, 92% with bortezomib, and 26.5% with both drugs. In bortezomib-resistant ANBL6 cells, the cell growth rate was 94% with VR23, 102.9% with bortezomib, and 48.9% with both drugs.

The researchers also tested VR23 in mice engrafted with RPMI-8226 MM cells. At 24 days after treatment, the tumor volume for VR23-treated mice was 19.1% that of placebo-treated mice.

The team noted that VR23 selectively killed cancer cells via apoptosis. Cancer cells exposed to the drug underwent an abnormal centrosome amplification cycle caused by the accumulation of ubiquitinated cyclin E.

Dr Lee and his colleagues are now planning to work with the US National Cancer Institute to test VR23 in additional cancers. The team is hoping to progress to clinical trials with the drug in the next 3 years.

AMRIC has applied for international intellectual property protection for VR23 and licensed commercial rights to Ramsey Lake Pharmaceutical Corporation (www.ramseylakepharma.com), an operation of AMRIC. ![]()

A novel, cancer-selective proteasome inhibitor has shown early promise for treating multiple myeloma (MM) and breast cancer, according to researchers.

The drug, known as VR23, is a quinoline-sulfonyl hybrid proteasome inhibitor.

In preclinical experiments, VR23 preferentially targeted MM cells and breast cancer cells, demonstrated synergy with bortezomib or paclitaxel, and shrank both MM and breast cancer tumors in mice.

Hoyun Lee, PhD, of the Advanced Medical Research Institute of Canada (AMRIC) in Sudbury, Ontario, and his colleagues described these experiments in Cancer Research.

The team noted that VR23 is structurally distinct from other known proteasome inhibitors, and it “potently inhibits” the activities of trypsin-like proteasomes, chymotrypsin-like proteasomes, and caspase-like proteasomes.

In several experiments, VR23 proved active against breast cancer.

In experiments with MM cell lines, VR23 exhibited activity as a single agent and demonstrated synergy with bortezomib. VR23 proved more effective against bortezomib-resistant cells than bortezomib-naïve cells.

When the researchers introduced treatments to bortezomib-naïve RPMI-8226 cells, they found the cell growth rate was 79.3% with VR23, 12.5% with bortezomib, and 1.6% with both drugs. In bortezomib-resistant RPMI-8226 cells, the cell growth rate was 47% with VR23, 109.7% with bortezomib, and -8.6% with both drugs.

In KAS6/1 cells, the cell growth rate was 65% with VR23, 92% with bortezomib, and 26.5% with both drugs. In bortezomib-resistant ANBL6 cells, the cell growth rate was 94% with VR23, 102.9% with bortezomib, and 48.9% with both drugs.

The researchers also tested VR23 in mice engrafted with RPMI-8226 MM cells. At 24 days after treatment, the tumor volume for VR23-treated mice was 19.1% that of placebo-treated mice.

The team noted that VR23 selectively killed cancer cells via apoptosis. Cancer cells exposed to the drug underwent an abnormal centrosome amplification cycle caused by the accumulation of ubiquitinated cyclin E.

Dr Lee and his colleagues are now planning to work with the US National Cancer Institute to test VR23 in additional cancers. The team is hoping to progress to clinical trials with the drug in the next 3 years.

AMRIC has applied for international intellectual property protection for VR23 and licensed commercial rights to Ramsey Lake Pharmaceutical Corporation (www.ramseylakepharma.com), an operation of AMRIC. ![]()

Corticosteroids Show Benefit in Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Clinical question: Does corticosteroid treatment shorten systemic illness in patients admitted to the hospital for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)?

Background: Pneumonia is the third-leading cause of death worldwide. Studies have yielded conflicting data about the benefit of adding systemic corticosteroids for treatment of CAP.

Study design: Double-blind, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: Seven tertiary-care hospitals in Switzerland.

Synopsis: A group of 784 patients hospitalized for CAP were randomized to receive either oral prednisone 50 mg daily for seven days or placebo, with the primary endpoint being time to stable vital signs. The intention-to-treat analysis found that the median time to clinical stability was 1.4 days earlier in the prednisone group (hazard ratio 1.33; 95% CI, 1.15–1.50, P <0.0001) and that length of stay and IV antibiotics were reduced by one day; this effect was valid across all PSI classes and was not dependent on age. Pneumonia-associated complications in the two groups did not differ at 30 days, though the prednisone group had a higher incidence of hyperglycemia requiring insulin. Because all study locations were in a single, fairly homogenous northern European country, care should be taken when hospitalists apply these findings to their patient population, and the risks of hyperglycemia requiring insulin should be taken into consideration.

Bottom line: Systemic steroids may reduce the time to clinical stability in patients with CAP.

Citation: Blum CA, Nigro N, Briel M, et al. Adjunct prednisone therapy for patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9977):1511–1518.

Clinical question: Does corticosteroid treatment shorten systemic illness in patients admitted to the hospital for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)?

Background: Pneumonia is the third-leading cause of death worldwide. Studies have yielded conflicting data about the benefit of adding systemic corticosteroids for treatment of CAP.

Study design: Double-blind, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: Seven tertiary-care hospitals in Switzerland.

Synopsis: A group of 784 patients hospitalized for CAP were randomized to receive either oral prednisone 50 mg daily for seven days or placebo, with the primary endpoint being time to stable vital signs. The intention-to-treat analysis found that the median time to clinical stability was 1.4 days earlier in the prednisone group (hazard ratio 1.33; 95% CI, 1.15–1.50, P <0.0001) and that length of stay and IV antibiotics were reduced by one day; this effect was valid across all PSI classes and was not dependent on age. Pneumonia-associated complications in the two groups did not differ at 30 days, though the prednisone group had a higher incidence of hyperglycemia requiring insulin. Because all study locations were in a single, fairly homogenous northern European country, care should be taken when hospitalists apply these findings to their patient population, and the risks of hyperglycemia requiring insulin should be taken into consideration.

Bottom line: Systemic steroids may reduce the time to clinical stability in patients with CAP.

Citation: Blum CA, Nigro N, Briel M, et al. Adjunct prednisone therapy for patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9977):1511–1518.

Clinical question: Does corticosteroid treatment shorten systemic illness in patients admitted to the hospital for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)?

Background: Pneumonia is the third-leading cause of death worldwide. Studies have yielded conflicting data about the benefit of adding systemic corticosteroids for treatment of CAP.

Study design: Double-blind, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: Seven tertiary-care hospitals in Switzerland.

Synopsis: A group of 784 patients hospitalized for CAP were randomized to receive either oral prednisone 50 mg daily for seven days or placebo, with the primary endpoint being time to stable vital signs. The intention-to-treat analysis found that the median time to clinical stability was 1.4 days earlier in the prednisone group (hazard ratio 1.33; 95% CI, 1.15–1.50, P <0.0001) and that length of stay and IV antibiotics were reduced by one day; this effect was valid across all PSI classes and was not dependent on age. Pneumonia-associated complications in the two groups did not differ at 30 days, though the prednisone group had a higher incidence of hyperglycemia requiring insulin. Because all study locations were in a single, fairly homogenous northern European country, care should be taken when hospitalists apply these findings to their patient population, and the risks of hyperglycemia requiring insulin should be taken into consideration.

Bottom line: Systemic steroids may reduce the time to clinical stability in patients with CAP.

Citation: Blum CA, Nigro N, Briel M, et al. Adjunct prednisone therapy for patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9977):1511–1518.

Infection, Acute Kidney Injury Raise 30-Day Readmission Risk for Sepsis Survivors

Nearly one-third of hospitalized patients who survive severe sepsis or septic shock require readmission within 30 days, according to a new report in the Journal of Hospital Medicine. Between 660,000 and 750,000 sepsis hospitalizations occur annually, with the direct costs surpassing $24 billion, the paper notes.

The study, which examined 1697 sepsis survivors from 2008 to 2012, links several clinical factors with increased 30-day readmission risk, including infection with Bacteroides spp and extended-spectrum beta-lactamases organisms and puts sepsis survivors with mild-to-moderate acute kidney injury (AKI) at nearly double the risk of readmission.

Study lead author Marya Zilberberg, MD, MPH, notes that efforts to reduce AKI in sepsis survivors might affect patient outcomes but that more research needs to be done to help decrease readmission rates.

“The hypothesis that reducing the occurrence of AKI would in turn reduce the risk of a 30-day hospitalization needs to be validated,” Dr. Zilberberg writes in an email to The Hospitalist. “Furthermore, it is a difficult goal among the critically ill. So, what this means to me is … this quality metric may be yet another that is putting the cart (the metric) before the horse (evidence to support its use).”

Dr. Zilberberg, founder and president of EviMed Research Group, LLC, an evidence-based medicine and outcomes research firm based in Goshen, Mass., says the study’s results were not completely unexpected as resistant infections are associated with worsening of all outcomes, and “we just showed that 30-day readmission was not immune to that,” she notes.

“We are not sure what effective strategies [there] may be to achieve this goal,” she notes. “In general, delivery of best-known care is the best that can be done. The most that can be said from our study is that antimicrobial resistance is bad even vis-à-vis this outcome, so reducing the burden of antimicrobial resistance, in addition to AKI prevention, is a strategy that might impact this outcome, along with many others.”

Visit our website for more information on sepsis and HM.

Nearly one-third of hospitalized patients who survive severe sepsis or septic shock require readmission within 30 days, according to a new report in the Journal of Hospital Medicine. Between 660,000 and 750,000 sepsis hospitalizations occur annually, with the direct costs surpassing $24 billion, the paper notes.

The study, which examined 1697 sepsis survivors from 2008 to 2012, links several clinical factors with increased 30-day readmission risk, including infection with Bacteroides spp and extended-spectrum beta-lactamases organisms and puts sepsis survivors with mild-to-moderate acute kidney injury (AKI) at nearly double the risk of readmission.

Study lead author Marya Zilberberg, MD, MPH, notes that efforts to reduce AKI in sepsis survivors might affect patient outcomes but that more research needs to be done to help decrease readmission rates.

“The hypothesis that reducing the occurrence of AKI would in turn reduce the risk of a 30-day hospitalization needs to be validated,” Dr. Zilberberg writes in an email to The Hospitalist. “Furthermore, it is a difficult goal among the critically ill. So, what this means to me is … this quality metric may be yet another that is putting the cart (the metric) before the horse (evidence to support its use).”

Dr. Zilberberg, founder and president of EviMed Research Group, LLC, an evidence-based medicine and outcomes research firm based in Goshen, Mass., says the study’s results were not completely unexpected as resistant infections are associated with worsening of all outcomes, and “we just showed that 30-day readmission was not immune to that,” she notes.

“We are not sure what effective strategies [there] may be to achieve this goal,” she notes. “In general, delivery of best-known care is the best that can be done. The most that can be said from our study is that antimicrobial resistance is bad even vis-à-vis this outcome, so reducing the burden of antimicrobial resistance, in addition to AKI prevention, is a strategy that might impact this outcome, along with many others.”

Visit our website for more information on sepsis and HM.

Nearly one-third of hospitalized patients who survive severe sepsis or septic shock require readmission within 30 days, according to a new report in the Journal of Hospital Medicine. Between 660,000 and 750,000 sepsis hospitalizations occur annually, with the direct costs surpassing $24 billion, the paper notes.

The study, which examined 1697 sepsis survivors from 2008 to 2012, links several clinical factors with increased 30-day readmission risk, including infection with Bacteroides spp and extended-spectrum beta-lactamases organisms and puts sepsis survivors with mild-to-moderate acute kidney injury (AKI) at nearly double the risk of readmission.

Study lead author Marya Zilberberg, MD, MPH, notes that efforts to reduce AKI in sepsis survivors might affect patient outcomes but that more research needs to be done to help decrease readmission rates.

“The hypothesis that reducing the occurrence of AKI would in turn reduce the risk of a 30-day hospitalization needs to be validated,” Dr. Zilberberg writes in an email to The Hospitalist. “Furthermore, it is a difficult goal among the critically ill. So, what this means to me is … this quality metric may be yet another that is putting the cart (the metric) before the horse (evidence to support its use).”

Dr. Zilberberg, founder and president of EviMed Research Group, LLC, an evidence-based medicine and outcomes research firm based in Goshen, Mass., says the study’s results were not completely unexpected as resistant infections are associated with worsening of all outcomes, and “we just showed that 30-day readmission was not immune to that,” she notes.

“We are not sure what effective strategies [there] may be to achieve this goal,” she notes. “In general, delivery of best-known care is the best that can be done. The most that can be said from our study is that antimicrobial resistance is bad even vis-à-vis this outcome, so reducing the burden of antimicrobial resistance, in addition to AKI prevention, is a strategy that might impact this outcome, along with many others.”

Visit our website for more information on sepsis and HM.

Is Your Electronic Health Record Putting You at Risk for a Documentation Audit?

A group of 3 busy orthopedists attended coding education each year and did their best to accurately code and document their services. As a risk-reduction strategy, the group engaged our firm to conduct an audit to determine whether they were documenting their services properly and to provide feedback about how they could improve.

What we found was shocking to the surgeons, but all too common, as we review thousands of orthopedic visit notes every year: The same examination had been documented for all visits, with physicians stating in their notes that the examination was medically necessary. In addition, their documentation supported Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 99214 at every visit, with visit frequencies of 2 weeks to 4 months.

The culprit of all this sameness? The practice’s electronic health record (EHR).

“Practices with EHRs often have a large volume of visit notes that look almost identical for a patient who is seen for multiple visits,” explains Mary LeGrand, RN, MA, CCS-P, CPC, KarenZupko & Associates consultant and coding educator. “And that is putting physicians at higher risk of being audited or of not passing an audit.”

According to LeGrand, this is because physicians are using the practice’s EHR to “pull forward” the patient’s previous visit note for the current visit, but failing to customize it for the current visit. The unintended consequence of this workflow efficiency is twofold:

1. It creates documentation that looks strikingly similar to, if not exactly like, the patient’s last billed visit note. This is often referred to as note “cloning.”

2. It creates documentation that includes a lot of unnecessary detail that, even if delivered and documented, doesn’t match the medical necessity of the visit, based on the history of present illness statements.

Both of these things can come back to bite you.

Zero in on the Risk

If your practice has an EHR, it is important that you evaluate whether certain workflow efficiency features are putting the practice at risk. You do not necessarily need to dump the EHR, but you may need to take action to reduce the risk of using these features.

In a pre-EHR practice, physicians began each visit with a blank piece of paper or dictated the entire visit. Then along came EHR vendors who, in an effort to make things easier and more efficient, created visit templates and the ability to “pull forward” the last visit note and use it as a basis for the current visit. The intention was always that physicians would modify it based on the current visit. But the reality is that physicians are busy, editing is time-consuming, and the unintended consequence is cloning.

“If you pull in unnecessary history or exam information from a previous visit that’s not relevant to the current visit, you can get dinged in an audit for not customizing the note to the patient’s specific presenting complaint,” LeGrand explains, “or, for attempting to bill a higher-level code by unintentionally padding the note with irrelevant information. What is documented for ‘reference’ has to be separated from what can be used to select the level of service.”

Your first documentation risk-reduction strategy is to review notes and look for signs of cloning.

LeGrand explains that a practice may be predisposed to cloning simply because of the way the EHR templates and workflow were set up when the system was implemented. “But,” she says, “‘the EHR made me do it’ defense won’t hold water, because it’s still the physician’s responsibility to customize or remove the information from templates and make the note unique to the visit.”

Yes, physician time is precious. But the reality is that the onus is on the physician to integrate EHR features with clinic workflow and to follow documentation rules.

The second documentation risk-reduction strategy is to make sure the level of evaluation and management (E/M) service billed is supported by medical necessity, not only by documentation artifacts that were relevant to the patient in the past but irrelevant to his or her current presenting complaint or condition.

“Medicare won’t pay for services that aren’t supported by medical necessity,” says LeGrand, “and you can’t achieve medical necessity by simply documenting additional E/M elements.”

This has always been the rule, LeGrand says. “But with the increased use of EHRs, and templates that automatically document visit elements and drive visits to a higher level of service, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS] and private payers have added scrutiny to medical necessity reviews. They want to validate that higher-level visits billed indeed required a higher level of history and/or exam.”

To do this, the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) has supplemented its audit team with registered nurses. “The nurses assist certified coders by determining whether medical necessity has been met,” explains LeGrand.

Look at a patient who presents with toe pain. You take a detailed family history, conduct a review of systems (ROS), bill a high-level code, and document all the elements to support it. LeGrand explains, “There is no medical necessity to support doing an eye exam for a patient with toe pain in the absence of any other medical history, or performing a ROS to correlate an eye exam with toe pain. So, even if you do it and document it, the higher-level code won’t pass muster in an audit because the information documented is not medically necessary.”

According to LeGrand, the extent of the history and examination should be based on the presenting problem and the patient’s condition. “If an ankle sprain patient returns 2 weeks after the initial evaluation of the injury with a negative medical or surgical history, and the patient has been treated conservatively, it’s probably not necessary to conduct a ROS that includes 10 organ systems,” she says. “If your standard of care is to perform this level of service, no one will fault you for your care delivery; however, if you also choose a level of service based on this system review, without relevance to the presenting problem, and you bill a higher level of service than is supported by the nature of the presenting problem or the plan of care, the documentation probably won’t hold up in an audit where medical necessity is valued into the equation.”

On the other hand, LeGrand adds, if a patient presents to the emergency department after an automobile accident with an open fracture and other injuries, and the surgeon performs a complete ROS, the medical necessity would most likely be supported as the surgeon is preparing the patient for surgery.

Based on LeGrand’s work with practices, this distinction about medical necessity is news to many nonclinical billing staff. “They confuse medical necessity with medical decision-making, an E/M code documentation component, and incorrectly bill for a high-level visit because medical decision-making elements meet the documentation requirements—yet the code is not supported by medical necessity of the presenting problem.”

Talk with your billing team to make sure all staff members understand this critical difference. They must comprehend that the medically necessary level of service is determined by a number of clinical factors, not medical decision-making. Describe some of these clinical factors, which include, but are not limited to, chief complaint, clinical judgment, standards of practice, acute exacerbations/onsets of medical conditions or injuries, and comorbidities.

EHR Dos and Don’ts

LeGrand recommends the following best practices for using EHR documentation features:

1. DON’T simply cut and paste from a previous note. “This is what leads to verbose notes that have little to do with the patient you are documenting,” she says. “If you don’t cut and paste, you’ll avoid the root cause of this risk.”

2. DON’T pull forward information from previous visit notes that have nothing to do with the nature of the patient’s problem. “We understand that this takes extra time because physicians must review the previous note,” LeGrand says. “So if you don’t have time to review the past note, just don’t pull it forward. Start fresh with a new drop-down menu and select elements pertinent to the current visit. Or, dictate or type a note relevant to the current condition and presenting problems.”

How you choose to work this into your process will vary depending on which EHR system you use. “One surgeon I work with dictates everything because the drop-down menus and templates are cumbersome,” LeGrand says. “Some groups find it faster to use the EHR templates that they have customized. Others find their EHR’s point-and-click features most efficient for customizing quickly.”

3. DO customize your EHR visit templates if the use of templates is critical to your efficiency. “This is the most overlooked step in the EHR implementation process because it takes a fair amount of time to do,” LeGrand says. She suggests avoiding the use of multisystem examination templates created for medicine specialties altogether, and insists, “Don’t assume ‘that is how the vendor built it so we have to use it.’ Customize a template for each of your visit types so you can document in the EHR in the same fashion as when you used a paper system. Doing so will save you loads of documentation time.”

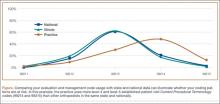

4. DO review your E/M code distribution. Generate a CPT frequency report for each physician and for the practice as a whole. Compare the data with state and national usage in orthopedics as a baseline. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeon’s Code-X tool enables easy comparison of your practice’s E/M code usage with state and national data for orthopedics. Simply generate a CPT frequency report from your practice management system and enter the E/M data. Line graphs are automatically generated, making trends and patterns easy to see (Figure).

“Identify your outliers, pull charts randomly, and review the notes,” recommends LeGrand. “Make sure there is medical necessity for the level of code that’s been billed and that documentation supports it.”

You may be surprised to find you are an outlier on inpatient hospital codes, or your distribution of level-2 or -3 codes varies from your practice, state, or national data. Orthopedic surgeons don’t typically report high volumes of CPT codes 99204, 99205 or 99215, but if your practice does and you are an outlier, best to pay attention before someone else does.

5. DO select auditors with the right skill sets. Evaluating medical necessity in the note requires a clinical background. “If internal documentation reviews are conducted by the billing team, that’s fine,” LeGrand advises. “Just add a physician assistant or nurse to your internal review team. They can provide clinical oversight and review the note when necessary for medical necessity.”

If you are contracting with external auditors or consultants, verify auditor credentials and skill sets to ensure they can abstract and incorporate medical necessity into the review. “Auditors must be able to do more than count elements,” LeGrand says. “They must have clinical knowledge, and expertise in orthopedics is critical. This knowledge should be used to verify that medical necessity is present in every note.” LeGrand is quick to point out that not every note will be at risk, based on the amount of work performed and documented and the level of service billed. “But medical necessity must always be present.”

The addition of nurses to the OIG’s audit team is a big change and will refine the auditing process by adding more clinical scrutiny. The EHR documentation features are intended to improve efficiency, but only a clinician can determine and document unique visit elements and medical necessity.

Address these intersections of risk by ensuring your documentation meets medical necessity as well as E/M documentation elements. Conduct internal audits bi-annually to verify that E/M usage patterns align with peers and physician documentation is appropriate. And be sure there is clinical expertise on your audit team, whether it is internal or external. CMS now has it, and your practice should too. ◾

A group of 3 busy orthopedists attended coding education each year and did their best to accurately code and document their services. As a risk-reduction strategy, the group engaged our firm to conduct an audit to determine whether they were documenting their services properly and to provide feedback about how they could improve.

What we found was shocking to the surgeons, but all too common, as we review thousands of orthopedic visit notes every year: The same examination had been documented for all visits, with physicians stating in their notes that the examination was medically necessary. In addition, their documentation supported Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 99214 at every visit, with visit frequencies of 2 weeks to 4 months.

The culprit of all this sameness? The practice’s electronic health record (EHR).

“Practices with EHRs often have a large volume of visit notes that look almost identical for a patient who is seen for multiple visits,” explains Mary LeGrand, RN, MA, CCS-P, CPC, KarenZupko & Associates consultant and coding educator. “And that is putting physicians at higher risk of being audited or of not passing an audit.”

According to LeGrand, this is because physicians are using the practice’s EHR to “pull forward” the patient’s previous visit note for the current visit, but failing to customize it for the current visit. The unintended consequence of this workflow efficiency is twofold:

1. It creates documentation that looks strikingly similar to, if not exactly like, the patient’s last billed visit note. This is often referred to as note “cloning.”

2. It creates documentation that includes a lot of unnecessary detail that, even if delivered and documented, doesn’t match the medical necessity of the visit, based on the history of present illness statements.

Both of these things can come back to bite you.

Zero in on the Risk

If your practice has an EHR, it is important that you evaluate whether certain workflow efficiency features are putting the practice at risk. You do not necessarily need to dump the EHR, but you may need to take action to reduce the risk of using these features.

In a pre-EHR practice, physicians began each visit with a blank piece of paper or dictated the entire visit. Then along came EHR vendors who, in an effort to make things easier and more efficient, created visit templates and the ability to “pull forward” the last visit note and use it as a basis for the current visit. The intention was always that physicians would modify it based on the current visit. But the reality is that physicians are busy, editing is time-consuming, and the unintended consequence is cloning.

“If you pull in unnecessary history or exam information from a previous visit that’s not relevant to the current visit, you can get dinged in an audit for not customizing the note to the patient’s specific presenting complaint,” LeGrand explains, “or, for attempting to bill a higher-level code by unintentionally padding the note with irrelevant information. What is documented for ‘reference’ has to be separated from what can be used to select the level of service.”

Your first documentation risk-reduction strategy is to review notes and look for signs of cloning.

LeGrand explains that a practice may be predisposed to cloning simply because of the way the EHR templates and workflow were set up when the system was implemented. “But,” she says, “‘the EHR made me do it’ defense won’t hold water, because it’s still the physician’s responsibility to customize or remove the information from templates and make the note unique to the visit.”

Yes, physician time is precious. But the reality is that the onus is on the physician to integrate EHR features with clinic workflow and to follow documentation rules.

The second documentation risk-reduction strategy is to make sure the level of evaluation and management (E/M) service billed is supported by medical necessity, not only by documentation artifacts that were relevant to the patient in the past but irrelevant to his or her current presenting complaint or condition.

“Medicare won’t pay for services that aren’t supported by medical necessity,” says LeGrand, “and you can’t achieve medical necessity by simply documenting additional E/M elements.”

This has always been the rule, LeGrand says. “But with the increased use of EHRs, and templates that automatically document visit elements and drive visits to a higher level of service, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS] and private payers have added scrutiny to medical necessity reviews. They want to validate that higher-level visits billed indeed required a higher level of history and/or exam.”

To do this, the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) has supplemented its audit team with registered nurses. “The nurses assist certified coders by determining whether medical necessity has been met,” explains LeGrand.

Look at a patient who presents with toe pain. You take a detailed family history, conduct a review of systems (ROS), bill a high-level code, and document all the elements to support it. LeGrand explains, “There is no medical necessity to support doing an eye exam for a patient with toe pain in the absence of any other medical history, or performing a ROS to correlate an eye exam with toe pain. So, even if you do it and document it, the higher-level code won’t pass muster in an audit because the information documented is not medically necessary.”

According to LeGrand, the extent of the history and examination should be based on the presenting problem and the patient’s condition. “If an ankle sprain patient returns 2 weeks after the initial evaluation of the injury with a negative medical or surgical history, and the patient has been treated conservatively, it’s probably not necessary to conduct a ROS that includes 10 organ systems,” she says. “If your standard of care is to perform this level of service, no one will fault you for your care delivery; however, if you also choose a level of service based on this system review, without relevance to the presenting problem, and you bill a higher level of service than is supported by the nature of the presenting problem or the plan of care, the documentation probably won’t hold up in an audit where medical necessity is valued into the equation.”

On the other hand, LeGrand adds, if a patient presents to the emergency department after an automobile accident with an open fracture and other injuries, and the surgeon performs a complete ROS, the medical necessity would most likely be supported as the surgeon is preparing the patient for surgery.

Based on LeGrand’s work with practices, this distinction about medical necessity is news to many nonclinical billing staff. “They confuse medical necessity with medical decision-making, an E/M code documentation component, and incorrectly bill for a high-level visit because medical decision-making elements meet the documentation requirements—yet the code is not supported by medical necessity of the presenting problem.”

Talk with your billing team to make sure all staff members understand this critical difference. They must comprehend that the medically necessary level of service is determined by a number of clinical factors, not medical decision-making. Describe some of these clinical factors, which include, but are not limited to, chief complaint, clinical judgment, standards of practice, acute exacerbations/onsets of medical conditions or injuries, and comorbidities.

EHR Dos and Don’ts

LeGrand recommends the following best practices for using EHR documentation features:

1. DON’T simply cut and paste from a previous note. “This is what leads to verbose notes that have little to do with the patient you are documenting,” she says. “If you don’t cut and paste, you’ll avoid the root cause of this risk.”

2. DON’T pull forward information from previous visit notes that have nothing to do with the nature of the patient’s problem. “We understand that this takes extra time because physicians must review the previous note,” LeGrand says. “So if you don’t have time to review the past note, just don’t pull it forward. Start fresh with a new drop-down menu and select elements pertinent to the current visit. Or, dictate or type a note relevant to the current condition and presenting problems.”

How you choose to work this into your process will vary depending on which EHR system you use. “One surgeon I work with dictates everything because the drop-down menus and templates are cumbersome,” LeGrand says. “Some groups find it faster to use the EHR templates that they have customized. Others find their EHR’s point-and-click features most efficient for customizing quickly.”

3. DO customize your EHR visit templates if the use of templates is critical to your efficiency. “This is the most overlooked step in the EHR implementation process because it takes a fair amount of time to do,” LeGrand says. She suggests avoiding the use of multisystem examination templates created for medicine specialties altogether, and insists, “Don’t assume ‘that is how the vendor built it so we have to use it.’ Customize a template for each of your visit types so you can document in the EHR in the same fashion as when you used a paper system. Doing so will save you loads of documentation time.”

4. DO review your E/M code distribution. Generate a CPT frequency report for each physician and for the practice as a whole. Compare the data with state and national usage in orthopedics as a baseline. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeon’s Code-X tool enables easy comparison of your practice’s E/M code usage with state and national data for orthopedics. Simply generate a CPT frequency report from your practice management system and enter the E/M data. Line graphs are automatically generated, making trends and patterns easy to see (Figure).

“Identify your outliers, pull charts randomly, and review the notes,” recommends LeGrand. “Make sure there is medical necessity for the level of code that’s been billed and that documentation supports it.”

You may be surprised to find you are an outlier on inpatient hospital codes, or your distribution of level-2 or -3 codes varies from your practice, state, or national data. Orthopedic surgeons don’t typically report high volumes of CPT codes 99204, 99205 or 99215, but if your practice does and you are an outlier, best to pay attention before someone else does.

5. DO select auditors with the right skill sets. Evaluating medical necessity in the note requires a clinical background. “If internal documentation reviews are conducted by the billing team, that’s fine,” LeGrand advises. “Just add a physician assistant or nurse to your internal review team. They can provide clinical oversight and review the note when necessary for medical necessity.”

If you are contracting with external auditors or consultants, verify auditor credentials and skill sets to ensure they can abstract and incorporate medical necessity into the review. “Auditors must be able to do more than count elements,” LeGrand says. “They must have clinical knowledge, and expertise in orthopedics is critical. This knowledge should be used to verify that medical necessity is present in every note.” LeGrand is quick to point out that not every note will be at risk, based on the amount of work performed and documented and the level of service billed. “But medical necessity must always be present.”

The addition of nurses to the OIG’s audit team is a big change and will refine the auditing process by adding more clinical scrutiny. The EHR documentation features are intended to improve efficiency, but only a clinician can determine and document unique visit elements and medical necessity.

Address these intersections of risk by ensuring your documentation meets medical necessity as well as E/M documentation elements. Conduct internal audits bi-annually to verify that E/M usage patterns align with peers and physician documentation is appropriate. And be sure there is clinical expertise on your audit team, whether it is internal or external. CMS now has it, and your practice should too. ◾

A group of 3 busy orthopedists attended coding education each year and did their best to accurately code and document their services. As a risk-reduction strategy, the group engaged our firm to conduct an audit to determine whether they were documenting their services properly and to provide feedback about how they could improve.

What we found was shocking to the surgeons, but all too common, as we review thousands of orthopedic visit notes every year: The same examination had been documented for all visits, with physicians stating in their notes that the examination was medically necessary. In addition, their documentation supported Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 99214 at every visit, with visit frequencies of 2 weeks to 4 months.

The culprit of all this sameness? The practice’s electronic health record (EHR).

“Practices with EHRs often have a large volume of visit notes that look almost identical for a patient who is seen for multiple visits,” explains Mary LeGrand, RN, MA, CCS-P, CPC, KarenZupko & Associates consultant and coding educator. “And that is putting physicians at higher risk of being audited or of not passing an audit.”

According to LeGrand, this is because physicians are using the practice’s EHR to “pull forward” the patient’s previous visit note for the current visit, but failing to customize it for the current visit. The unintended consequence of this workflow efficiency is twofold:

1. It creates documentation that looks strikingly similar to, if not exactly like, the patient’s last billed visit note. This is often referred to as note “cloning.”

2. It creates documentation that includes a lot of unnecessary detail that, even if delivered and documented, doesn’t match the medical necessity of the visit, based on the history of present illness statements.

Both of these things can come back to bite you.

Zero in on the Risk

If your practice has an EHR, it is important that you evaluate whether certain workflow efficiency features are putting the practice at risk. You do not necessarily need to dump the EHR, but you may need to take action to reduce the risk of using these features.

In a pre-EHR practice, physicians began each visit with a blank piece of paper or dictated the entire visit. Then along came EHR vendors who, in an effort to make things easier and more efficient, created visit templates and the ability to “pull forward” the last visit note and use it as a basis for the current visit. The intention was always that physicians would modify it based on the current visit. But the reality is that physicians are busy, editing is time-consuming, and the unintended consequence is cloning.

“If you pull in unnecessary history or exam information from a previous visit that’s not relevant to the current visit, you can get dinged in an audit for not customizing the note to the patient’s specific presenting complaint,” LeGrand explains, “or, for attempting to bill a higher-level code by unintentionally padding the note with irrelevant information. What is documented for ‘reference’ has to be separated from what can be used to select the level of service.”

Your first documentation risk-reduction strategy is to review notes and look for signs of cloning.

LeGrand explains that a practice may be predisposed to cloning simply because of the way the EHR templates and workflow were set up when the system was implemented. “But,” she says, “‘the EHR made me do it’ defense won’t hold water, because it’s still the physician’s responsibility to customize or remove the information from templates and make the note unique to the visit.”

Yes, physician time is precious. But the reality is that the onus is on the physician to integrate EHR features with clinic workflow and to follow documentation rules.

The second documentation risk-reduction strategy is to make sure the level of evaluation and management (E/M) service billed is supported by medical necessity, not only by documentation artifacts that were relevant to the patient in the past but irrelevant to his or her current presenting complaint or condition.

“Medicare won’t pay for services that aren’t supported by medical necessity,” says LeGrand, “and you can’t achieve medical necessity by simply documenting additional E/M elements.”

This has always been the rule, LeGrand says. “But with the increased use of EHRs, and templates that automatically document visit elements and drive visits to a higher level of service, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS] and private payers have added scrutiny to medical necessity reviews. They want to validate that higher-level visits billed indeed required a higher level of history and/or exam.”

To do this, the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) has supplemented its audit team with registered nurses. “The nurses assist certified coders by determining whether medical necessity has been met,” explains LeGrand.

Look at a patient who presents with toe pain. You take a detailed family history, conduct a review of systems (ROS), bill a high-level code, and document all the elements to support it. LeGrand explains, “There is no medical necessity to support doing an eye exam for a patient with toe pain in the absence of any other medical history, or performing a ROS to correlate an eye exam with toe pain. So, even if you do it and document it, the higher-level code won’t pass muster in an audit because the information documented is not medically necessary.”

According to LeGrand, the extent of the history and examination should be based on the presenting problem and the patient’s condition. “If an ankle sprain patient returns 2 weeks after the initial evaluation of the injury with a negative medical or surgical history, and the patient has been treated conservatively, it’s probably not necessary to conduct a ROS that includes 10 organ systems,” she says. “If your standard of care is to perform this level of service, no one will fault you for your care delivery; however, if you also choose a level of service based on this system review, without relevance to the presenting problem, and you bill a higher level of service than is supported by the nature of the presenting problem or the plan of care, the documentation probably won’t hold up in an audit where medical necessity is valued into the equation.”

On the other hand, LeGrand adds, if a patient presents to the emergency department after an automobile accident with an open fracture and other injuries, and the surgeon performs a complete ROS, the medical necessity would most likely be supported as the surgeon is preparing the patient for surgery.

Based on LeGrand’s work with practices, this distinction about medical necessity is news to many nonclinical billing staff. “They confuse medical necessity with medical decision-making, an E/M code documentation component, and incorrectly bill for a high-level visit because medical decision-making elements meet the documentation requirements—yet the code is not supported by medical necessity of the presenting problem.”

Talk with your billing team to make sure all staff members understand this critical difference. They must comprehend that the medically necessary level of service is determined by a number of clinical factors, not medical decision-making. Describe some of these clinical factors, which include, but are not limited to, chief complaint, clinical judgment, standards of practice, acute exacerbations/onsets of medical conditions or injuries, and comorbidities.

EHR Dos and Don’ts

LeGrand recommends the following best practices for using EHR documentation features:

1. DON’T simply cut and paste from a previous note. “This is what leads to verbose notes that have little to do with the patient you are documenting,” she says. “If you don’t cut and paste, you’ll avoid the root cause of this risk.”

2. DON’T pull forward information from previous visit notes that have nothing to do with the nature of the patient’s problem. “We understand that this takes extra time because physicians must review the previous note,” LeGrand says. “So if you don’t have time to review the past note, just don’t pull it forward. Start fresh with a new drop-down menu and select elements pertinent to the current visit. Or, dictate or type a note relevant to the current condition and presenting problems.”

How you choose to work this into your process will vary depending on which EHR system you use. “One surgeon I work with dictates everything because the drop-down menus and templates are cumbersome,” LeGrand says. “Some groups find it faster to use the EHR templates that they have customized. Others find their EHR’s point-and-click features most efficient for customizing quickly.”

3. DO customize your EHR visit templates if the use of templates is critical to your efficiency. “This is the most overlooked step in the EHR implementation process because it takes a fair amount of time to do,” LeGrand says. She suggests avoiding the use of multisystem examination templates created for medicine specialties altogether, and insists, “Don’t assume ‘that is how the vendor built it so we have to use it.’ Customize a template for each of your visit types so you can document in the EHR in the same fashion as when you used a paper system. Doing so will save you loads of documentation time.”

4. DO review your E/M code distribution. Generate a CPT frequency report for each physician and for the practice as a whole. Compare the data with state and national usage in orthopedics as a baseline. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeon’s Code-X tool enables easy comparison of your practice’s E/M code usage with state and national data for orthopedics. Simply generate a CPT frequency report from your practice management system and enter the E/M data. Line graphs are automatically generated, making trends and patterns easy to see (Figure).

“Identify your outliers, pull charts randomly, and review the notes,” recommends LeGrand. “Make sure there is medical necessity for the level of code that’s been billed and that documentation supports it.”

You may be surprised to find you are an outlier on inpatient hospital codes, or your distribution of level-2 or -3 codes varies from your practice, state, or national data. Orthopedic surgeons don’t typically report high volumes of CPT codes 99204, 99205 or 99215, but if your practice does and you are an outlier, best to pay attention before someone else does.

5. DO select auditors with the right skill sets. Evaluating medical necessity in the note requires a clinical background. “If internal documentation reviews are conducted by the billing team, that’s fine,” LeGrand advises. “Just add a physician assistant or nurse to your internal review team. They can provide clinical oversight and review the note when necessary for medical necessity.”

If you are contracting with external auditors or consultants, verify auditor credentials and skill sets to ensure they can abstract and incorporate medical necessity into the review. “Auditors must be able to do more than count elements,” LeGrand says. “They must have clinical knowledge, and expertise in orthopedics is critical. This knowledge should be used to verify that medical necessity is present in every note.” LeGrand is quick to point out that not every note will be at risk, based on the amount of work performed and documented and the level of service billed. “But medical necessity must always be present.”

The addition of nurses to the OIG’s audit team is a big change and will refine the auditing process by adding more clinical scrutiny. The EHR documentation features are intended to improve efficiency, but only a clinician can determine and document unique visit elements and medical necessity.

Address these intersections of risk by ensuring your documentation meets medical necessity as well as E/M documentation elements. Conduct internal audits bi-annually to verify that E/M usage patterns align with peers and physician documentation is appropriate. And be sure there is clinical expertise on your audit team, whether it is internal or external. CMS now has it, and your practice should too. ◾

Cementing Multihole, Metal, Modular Acetabular Shells Into Cages in Revision Total Hip Arthroplasty

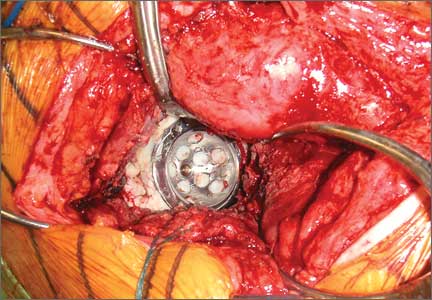

Although the number of total hip arthroplasties (THAs) being performed in the United States is increasing, revision THAs are more common.1 Many acetabular revisions can be successfully performed with standard or jumbo cementless acetabular cups, but major osseous deficiencies typically require reconstruction with a cage or cup/cage that bridges gaps in the pelvis and obtains fixation of the arthroplasty components.2,3 Cages and rings have been combined with all-polyethylene acetabular components (ie, all-polyethylene cups, or APCs) to reconstruct pelvic bone defects, but complications, including APC dissociation (Figure 1) and postoperative instability, can occur despite stable fixation of cage to pelvis.4 The incidence of dislocations with pelvic reconstruction rings using APCs has been reported to be 11%.4 If an APC has to be replaced because of wear, then major surgery may be required to extract the worn cup and cement a new cup in its place.

In this article, we describe a technique in which a metal, multihole acetabular shell is cemented into the cage or ring construct, avoiding some of the complications associated with traditional techniques by permitting use of a variety of liners.

Materials and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the cases of all of Dr. Bolanos’ patients who underwent acetabular revision THA with cage reconstruction between February 1, 1998 and October 9, 2006. During this period, we were cementing a modular metal shell into the cage instead of an APC or polyethylene liner. All patients who underwent revision THA with cage reconstruction during the study period were included. Bone defects were treated with structural or morselized bone allograft. Every reconstruction involved use of an antiprotrusio cage or ring secured to the pelvis with screws, and a multihole acetabular shell cemented into place with a polyethylene liner applied. Elevated rims, lateralized liners, and constrained liners were used as needed to optimize stability. Femoral components were retained. Cage size was based on matching the osseous deficiencies. Shell size was determined by the inner diameter of the corresponding cage. Liner size was based on matching the shell and femoral head. During this period, none of the patients had other reconstructive techniques, such as trabecular metal augmentation, in combination with a modular acetabular shell, cup/cage reconstruction, or custom triflange components.

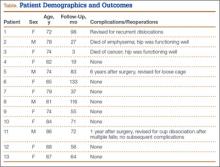

Patients engaged in protected weight-bearing ambulation for 3 months after surgery and were then permitted full, unrestricted activity. The primary outcome was mechanical failure of the reconstruction, or reoperation (Table). All reconstructions in this series consisted of acetabular revisions for aseptic loosening.

Surgical Technique

Six consecutive cases of pelvic discontinuity and 7 cases of segmental acetabular bone loss required use of cages or rings. Reconstruction cages were used to secure fixation to the ilium and ischium. With the technique described in this article, we used screws with rounded, prominent heads rather than flat heads between the cup and the cage or ring (Synthes, 6.5 mm) to ensure adequate cement mantle. The rounded screw heads were left prominent to approximate the function of cement pegs found on APCs. Screws were placed into the anterior, superior, medial, and posterior aspects of the cage to ensure adequate cement mantle between cup and cage. This was confirmed with trial placement of the cup into the cage before cementation and observation of the uniformity of the space between cup and cage. Trial placement also confirmed that the screws did not interfere with appropriate positioning of the cup. A multihole, metal acetabular cup was then cemented in the cage or ring such that cement extruded around the shell and into the holes of the cup and the cage, securing the cup to the cage. Use of a multihole, metal shell resulted in excellent cement fixation because the multiple holes created multiple circumferential cement pegs. Various liner options could then be used to optimize stability of the reconstruction. In some cases, excessive cement extruded into the interior aspect of the shell and hardened before curettage. If the excess cement could interfere with complete seating/locking of the liner, then a high-speed burr was used to easily remove cement (Figure 2). Polyethylene liners were then inserted into the shell. Femoral reconstruction was then performed, if needed, and stability of the arthroplasty checked. This technique allows the surgeon to then select from a variety of polyethylene liners as needed to optimize stability. Liners with elevated rims, lateralized liners, and constrained liners could be interchangeable options with this technique.

Results

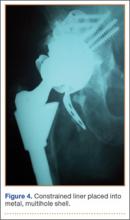

Thirteen patients with major osseous deficiencies of the pelvis were treated using this technique. At mean follow-up of 64.2 months (range, 3-133 months), 10 of the 13 patients had favorable outcomes without further surgery. One patient developed recurrent aseptic loosening that required re-revision, another patient developed recurrent instability that required acetabular liner and femoral head exchange, and a third patient with poor balance fell multiple times. This patient’s ninth fall resulted in dissociation of the acetabular shell from the cage (Figure 3), treated with placement of another cemented multihole metal shell with a standard liner. As dislocations recurred, the liner was changed to a constrained liner (Figure 4). The patient did not have any further dislocations or other hip-related problems. Integrity of cemented shell-cage fixation was maintained in 12 of the 13 patients at final follow-up.

Discussion

We have described a novel technique that facilitates reconstruction of major osseous deficiencies of the pelvis. The technique involves cementation of a multihole, metal acetabular shell into a cage or ring, permitting use of modular liners. The modularity in this approach to major hip reconstruction provides stability-optimization options that are not available with APCs. So far, the technique has demonstrated more advantages than disadvantages, so the indications for its use would be whenever a cage is used for pelvic reconstruction. Traditional techniques involve cementing an APC into the cage or ring. Use of multihole, metal shells for this purpose has several theoretical advantages. Multiple holes and the textured surface allow more interdigitation of cement with cup than APCs do; this interdigitation may improve the durability of the cemented interface. Cement also extrudes through the holes of the cage to secure the cup to the pelvis, as is done with cementation of APCs. Introduction of trabecular metal shells may also provide an even more secure bond to the shell, compared with APCs, though durability of a cemented trabecular metal interface has not been established. In addition, mechanical alignment guides cannot fasten as securely onto some APCs.

Nonmodular, cemented, metal-backed acetabular components, which were commonly used in hip arthroplasties at one time, were abandoned because of their relatively high loosening rate and because of advantages noted with modular components.5 The nonmodular components had been developed because of their theoretical advantages of improved distribution of forces into the cement mantle.5,6 However, those models had a relatively smooth metallic surface, which probably did not bond as well to cement as the shells used with the technique described in this article.