User login

Modular Versus Nonmodular Femoral Necks for Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty

Femoral stem modularity in total hip arthroplasty (THA) has a checkered past. Developments such as the modular head–trunnion interface, which allows for placement of femoral heads of different sizes and offsets, and the modular midstem, which allows for version adjustments independent of patient anatomy (S-ROM, Depuy) and for bypassing proximal bone defects in the revision setting (Restoration Modular, Stryker; ZMR-XL, Zimmer), have proved very successful.1-10 However, even these successful advances have been associated with failures at the modular junction.11-13 Proximal femoral neck–stem modularity (PFNSM) has had mixed results, with notable failures and recalls associated with the neck–stem junction.14,15 Failures at this junction have occurred secondary to corrosion and breakage of the modular neck.16-18 Nevertheless, proximal modular stems remain available for implantation. One such system, the M/L Taper stem with Kinectiv technology (Zimmer), is an all-titanium construct that allows for adjustment of several variables (length, offset, version), providing numerous combinations beyond those of the original M/L Taper offerings. Advantages of these offerings include closer reconstruction of patient anatomy, stability improvements, and easing of the process of revision in polyethylene/femoral head exchanges or in infections in which single-staged irrigation and débridement and polyethylene/head exchange are chosen.

These theoretic advantages must be judged in the context of the possible disadvantages of the modular neck junction. The mechanical environment of the junction places it at risk for failure as well as for metallosis from fretting, crevice corrosion, and recurrent repassivation.19 Although the titanium necks are at less risk for degradation than their cobalt-chromium counterparts, they are at higher risk for breakage.13,19 For one of the surgeons in our practice, the M/L Taper stem with Kinectiv technology is the stem of choice for primary THA.

We conducted a study to determine, in the setting of primary THA, how often a neck–stem combination choice resulted in a reconstructive geometry that would not have been possible had the surgeon opted for the traditional M/L Taper stem. Every Kinectiv stem has numerous neck options with a head center position that would not be possible with the nonmodular M/L Taper. However, in a high-volume community practice, how often is a modular neck that results in an otherwise unavailable head center being used for the reconstruction?

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by our local institutional review board. The Kinectiv stem is used by 1 of the 4 high-volume joint replacement surgeons in our practice (not one of the authors). From our community practice joint registry, we identified every stem–neck combination used since the Kinectiv stem became available in 2006.20 Each case was performed using a posterior approach. A trabecular metal acetabular component (Zimmer) secured with 2 screws was used, and an M/L Taper stem with Kinectiv technology was implanted in each case.

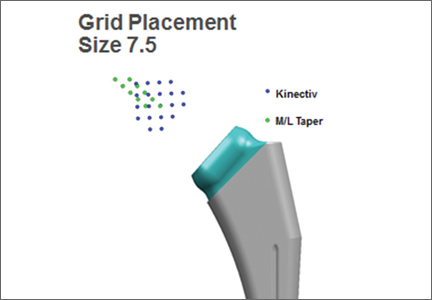

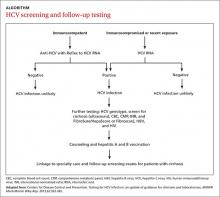

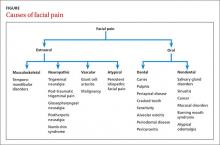

Once the neck–stem combination was determined, its position on the head centers map was compared with that of the standard M/L Taper head centers (Figures 1, 2) for each stem size as the relationship of the Kinectiv head center varies with each stem size compared with the head center of the M/L Taper stems. If the head centers were in contact on the map, the geometry was considered identical. If the head centers were not in contact, we noted where the nearest standard M/L Taper head center lay in terms of length and offset. As the head centers are laid out in regular, 4-mm increments, this estimation was relatively easy. Any anteverted or retroverted neck was considered to have no adequate substitution in the standard M/L Taper stem offerings. This initial evaluation was performed by Dr. Carothers.

We then reviewed the head center comparisons independently. For every Kinectiv head center that did not contact an M/L Taper counterpart, the difference between those head centers was reviewed. Each of us noted whether the difference between the head centers was clinically relevant, as many of the head center positions are extremely close. The head centers that were so close as to be deemed clinically irrelevant were recorded.

Results

Between January 2008 and October 2013, 463 primary THAs were performed using the M/L Taper femoral stem with Kinectiv technology. Of the neck options used, 205 (44%) had a head center identical to that of a nonmodular M/L Taper stem. In another 56 cases (12%), all 3 reviewing surgeons agreed that the M/L Taper head center was so close to the Kinectiv head center as to be clinically indistinguishable. Of these 56 cases, 54 had a head center difference of less than 1 mm in length or offset; the other 2 had a 2-mm difference in offset.

Thus, a total of 261 stems (56%) had a standard M/L Taper option that offered an identical head center or one so close as to be clinically indistinguishable. Interestingly, in the group of 202 stems that did not have an identical head center and were not clinically indistinguishable, 132 (65%) of these modular stems were within 4 mm in length and 2 mm of offset of the closest Kinectiv head center. A verted neck was used in 12 cases (11 anteverted, 1 retroverted).

Nine of the 463 cases required revision surgery, 3 for recurrent instability. In 1 of these 3 cases, the acetabulum was revised for malposition, and the neck was converted from standard offset, +0 mm length (head center identical to nonmodular stem), to extended offset, +4 mm length (2 mm shorter with 1 mm less offset than closest nonmodular head center). The second case had complete deficiency of the abductor tendons and was converted to a constrained liner, though at the time of the THA a head center identical to that of the nonmodular stem was used. The third case was revised to convert a standard offset, +0 mm length, straight neck (head center identical to nonmodular stem), to extended offset, +4 mm length, anteverted neck (anteversion making this a unique head center position). Of the other 6 cases, 1 was treated for corrosion at the head–neck junction by changing the head from cobalt-chromium to ceramic (the junction was noted to be pristine), 1 underwent revision of the acetabular component for loosening, 2 femoral stems were revised for periprosthetic femur fracture, and 2 cases underwent 2-stage revision for late infection. There were no failures secondary to metallosis at the neck–stem junction and no modular breakages. The 3 cases of recurrent instability had no dislocation episodes after revision.

Discussion

PFNSM was developed to help more closely reconstruct patient anatomy. PFNSM allows for individualization of offset, length, and version—and thus for optimization of component interaction to avoid impingement and dislocation while promoting range of motion and normal gait.21 These benefits must be judged in light of the disadvantages of proximal stem modularity, including corrosion and breakage of the modular neck.14-18

In the present study, conducted in a high-volume private practice setting, 44% of necks used in a proximally modular construct had a head center identical to that of a nonmodular alternative. In the opinion of the 3 authors (high-volume hip surgeons), an additional 12% of the modular stems had a head center so close to that of the nonmodular stem as to be clinically indistinguishable. In addition, 132 of the modular necks had a femoral head center within 4 mm in length and 2 mm of offset of the nonmodular stem. These findings call into question the theoretical benefits of regular use of this modular femoral stem for primary THA. Certainly there are extreme femoral neck–shaft angle cases in which the standard nonmodular stem may be inadequate and this proximal modularity would be helpful, but our study showed such cases are relatively less frequent. We caution against routine use of this proximal modularity in primary THA and suggest restricting it to cases in which the standard stem offerings are unacceptable. These findings are not surprising given that the standard M/L Taper stem is based on a historically successful model with neck angle and length options designed to meet the goals of restoring length, offset, range of motion, and stability. We would expect that a well-designed stem will meet these goals in the majority of cases.

Of our 463 cases with the modular neck, 9 required revision surgery. Of these 9 revisions, 2 were for recurrent dislocation in which the modular neck was revised to one that enhanced stability, and there were no further dislocations. The ability to change the geometry of the proximal femur resulted in a stability solution that avoided revision of the entire femoral component, as might otherwise be required. One case of acetabular loosening and 1 case that required placement of a constrained liner were potentially benefited by the modular neck in that the surgeries may have been expedited by being able to remove the neck to ease exposure for placement of the acetabular components. The other 5 revisions—2 for periprosthetic femur fracture, 2 two-stage revisions for infection, and 1 femoral head exchange for metallosis at the head–neck junction—saw no benefit from the modularity in the revision setting.

This study had several limitations. First, as it was primarily an evaluation of use of a modular femoral system, there was no attempt to account for the fact that acetabular component orientation can affect stability and, thus, the perceived need for additional offset or changes in version. The habit of all 3 of the reviewing surgeons is to consider the position of the acetabular component and to reposition the component, if necessary, to achieve appropriate stability. Therefore, the need for the modularity may be even less than suggested by this study. In addition, the idea that (in 12 cases) no standard stem option would be acceptable because of the use of a verted neck ignores the possibility that cup repositioning could have obviated the need for additional version. Furthermore, use of a 36-mm head results in an additional 3.5 mm of offset in the polyethylene liner, and this study did not account for the option of increasing head size—and for the potential increase in stability from a larger head and the increased offset gained from the liner.

A second limitation is that a significant number of Kinectiv stems (132) had a head center within 4 mm in length and 2 mm of offset of the nearest M/L Taper stem. We carefully template every primary THA to determine the plan that will optimize component size and position and restore length and offset. More options for achieving these goals are available when templating with the intention of using the Kinectiv modular neck. The neck cut and position of the stem proximally or distally in the proximal femur may not need to be so exact, as the additional options may be able to accommodate minor inaccuracies. Thus, the reported percentage of clinically indistinguishable head centers (12%) may underestimate the actual number of modular stems that could have been replaced with a nonmodular stem.

Third, this study did not evaluate the effect of the modular junction on ease of irrigation and débridement with head/neck and polyethylene exchange in cases of infection, or on ease of head/neck and polyethylene exchange for revision. In addition, the study did not evaluate other cases of instability involving a nonmodular stem that otherwise could have been solved with simple revision of the head/neck combination, avoiding revision of the entire stem and/or the acetabular component. We reported revisions for infection and for instability, but comprehensive assessment and comparison were beyond the scope of this study. Certainly ease of revision of the head and neck is a factor that could favor use of the modularity.

Fourth, this was not a clinical outcome study comparing 2 different femoral stems. We sought only to determine how often a modular neck was chosen that resulted in a head center that would have been unavailable to the non-modular stem suggesting that the patient was receiving a reconstructive benefit in exchange for the modularity. However, 2 recent reports have noted no clinical benefit at 2-year follow-up with use of the modular neck compared with the nonmodular stem.22,23

Though the M/L Taper with Kinectiv technology has, thus far, performed well, PFNSM should be used with caution in light of recently reported failures at the neck–stem junction.14,16-18 Our study results suggest that most (≥56%) of the modular stems used could have been reconstructed as acceptably with a nonmodular stem, and therefore a reconstructive benefit was not realized in trade for the potential risks of proximal modularity. Only 2 of the 9 revision cases saw a clear advantage in being able to change the modular neck geometry in the revision setting. Given the recently reported failures and the high-profile recall of a modular stem,14 we recommend restricting the modular stem to cases that cannot be adequately reconstructed with the nonmodular option.

1. Barrack RL. Modularity of prosthetic implants. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1994;2(1):16-25.

2. Cameron HU. Modularity in primary total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11(3):332-334.

3. Hozack WJ, Mesa JJ, Rothman RF. Head–neck modularity for total hip arthroplasty. Is it necessary? J Arthroplasty. 1996;11(4):397-399.

4. Holt GE, Christie MJ, Schwartz HS. Trabecular metal endoprosthetic limb salvage reconstruction of the lower limb. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(7):1079-1089.

5. Sporer SM, Obar RJ, Bernini PM. Primary total hip arthroplasty using a modular proximally coated prosthesis in patients older than 70: two to eight year results. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19(2):197-203.

6. Spitzer AI. The S-ROM cementless femoral stem: history and literature review. Orthopedics. 2005;28(9 suppl):s1117-s1124.

7. Mumme T, Müller-Rath R, Andereya S, Wirtz DC. Uncemented femoral revision arthroplasty using the modular revision prosthesis MRP-TITAN revision stem. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2007;19(1):56-77.

8. Wirtz DC, Heller KD, Holzwarth U, et al. A modular femoral implant for uncemented stem revision in THR. Int Orthop. 2000;24(3):134-138.

9. Lakstein D, Backstein D, Safir O, Kosashvili Y, Gross AE. Revision total hip arthroplasty with a porous-coated modular stem: 5 to 10 years follow-up. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(5):1310-1315.

10. Bolognesi MP, Pietrobon R, Clifford PE, Vail TP. Comparison of a hydroxyapatite-coated sleeve and a porous-coated sleeve with a modular revision hip stem. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(12):2720-2725.

11. Huot Carlson JC, Van Citters DW, Currier JH, Bryant AM, Mayor MB, Collier JP. Femoral stem fracture and in vivo corrosion of retrieved modular femoral hips. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(7):1389-1396.e1.

12. Gilbert JL, Mehta M, Pinder B. Fretting crevice corrosion of stainless steel stem–CoCr femoral head connections: comparisons of materials, initial moisture, and offset length. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2009;88(1):162-173.

13. Kop AM, Keogh C, Swarts E. Proximal component modularity in THA—at what cost? An implant retrieval study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(7):1885-1894.

14. Cooper HJ, Urban RM, Wixson RL, Meneghini RM, Jacobs JJ. Adverse local tissue reaction arising from corrosion at the femoral neck–body junction in a dual-taper stem with a cobalt-chromium modular neck. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(10):865-872.

15. Vundelinckx BJ, Verhelst LA, De Schepper J. Taper corrosion in modular hip prostheses: analysis of serum metal ions in 19 patients. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(7):1218-1223.

16. Kouzelis A, Georgiou CS, Megas P. Dissociation of modular total hip arthroplasty at the neck–stem interface without dislocation. J Orthop Traumatol. 2012;13(4):221-224.

17. Sotereanos NG, Sauber TJ, Tupis TT. Modular femoral neck fracture after primary total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(1):196.e7-e9.

18. Wodecki P, Sabbah D, Kermarrec G, Semaan I. New type of hip arthroplasty failure related to modular femoral components: breakage at the neck–stem junction. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2013;99(6):741-744.

19. Dorn U, Neumann D, Frank M. Corrosion behavior of tantalum-coated cobalt-chromium modular necks compared to titanium modular necks in a simulator test. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(4):831-835.

20. Carothers JT, White RE, Tripuraneni KR, Hattab MW, Archibeck MJ. Lessons learned from managing a prospective, private practice joint replacement registry: a 25-year experience. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(2):537-543.

21. Archibeck MJ, Cummins T, Carothers J, Junick DW, White RE Jr. A comparison of two implant systems in restoration of hip geometry in arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 2011;469(2):443-446.

22. Duwelius PJ, Hartzband MA, Burkhart R, et al. Clinical results of a modular neck hip system: hitting the “bull’s-eye” more accurately. Am J Orthop. 2010;39(10 suppl):2-6.

23. Duwelius PJ, Burkhart B, Carnahan C, et al. Modular versus nonmodular neck femoral implants in primary total hip arthroplasty: which is better? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(4):1240-1245.

Femoral stem modularity in total hip arthroplasty (THA) has a checkered past. Developments such as the modular head–trunnion interface, which allows for placement of femoral heads of different sizes and offsets, and the modular midstem, which allows for version adjustments independent of patient anatomy (S-ROM, Depuy) and for bypassing proximal bone defects in the revision setting (Restoration Modular, Stryker; ZMR-XL, Zimmer), have proved very successful.1-10 However, even these successful advances have been associated with failures at the modular junction.11-13 Proximal femoral neck–stem modularity (PFNSM) has had mixed results, with notable failures and recalls associated with the neck–stem junction.14,15 Failures at this junction have occurred secondary to corrosion and breakage of the modular neck.16-18 Nevertheless, proximal modular stems remain available for implantation. One such system, the M/L Taper stem with Kinectiv technology (Zimmer), is an all-titanium construct that allows for adjustment of several variables (length, offset, version), providing numerous combinations beyond those of the original M/L Taper offerings. Advantages of these offerings include closer reconstruction of patient anatomy, stability improvements, and easing of the process of revision in polyethylene/femoral head exchanges or in infections in which single-staged irrigation and débridement and polyethylene/head exchange are chosen.

These theoretic advantages must be judged in the context of the possible disadvantages of the modular neck junction. The mechanical environment of the junction places it at risk for failure as well as for metallosis from fretting, crevice corrosion, and recurrent repassivation.19 Although the titanium necks are at less risk for degradation than their cobalt-chromium counterparts, they are at higher risk for breakage.13,19 For one of the surgeons in our practice, the M/L Taper stem with Kinectiv technology is the stem of choice for primary THA.

We conducted a study to determine, in the setting of primary THA, how often a neck–stem combination choice resulted in a reconstructive geometry that would not have been possible had the surgeon opted for the traditional M/L Taper stem. Every Kinectiv stem has numerous neck options with a head center position that would not be possible with the nonmodular M/L Taper. However, in a high-volume community practice, how often is a modular neck that results in an otherwise unavailable head center being used for the reconstruction?

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by our local institutional review board. The Kinectiv stem is used by 1 of the 4 high-volume joint replacement surgeons in our practice (not one of the authors). From our community practice joint registry, we identified every stem–neck combination used since the Kinectiv stem became available in 2006.20 Each case was performed using a posterior approach. A trabecular metal acetabular component (Zimmer) secured with 2 screws was used, and an M/L Taper stem with Kinectiv technology was implanted in each case.

Once the neck–stem combination was determined, its position on the head centers map was compared with that of the standard M/L Taper head centers (Figures 1, 2) for each stem size as the relationship of the Kinectiv head center varies with each stem size compared with the head center of the M/L Taper stems. If the head centers were in contact on the map, the geometry was considered identical. If the head centers were not in contact, we noted where the nearest standard M/L Taper head center lay in terms of length and offset. As the head centers are laid out in regular, 4-mm increments, this estimation was relatively easy. Any anteverted or retroverted neck was considered to have no adequate substitution in the standard M/L Taper stem offerings. This initial evaluation was performed by Dr. Carothers.

We then reviewed the head center comparisons independently. For every Kinectiv head center that did not contact an M/L Taper counterpart, the difference between those head centers was reviewed. Each of us noted whether the difference between the head centers was clinically relevant, as many of the head center positions are extremely close. The head centers that were so close as to be deemed clinically irrelevant were recorded.

Results

Between January 2008 and October 2013, 463 primary THAs were performed using the M/L Taper femoral stem with Kinectiv technology. Of the neck options used, 205 (44%) had a head center identical to that of a nonmodular M/L Taper stem. In another 56 cases (12%), all 3 reviewing surgeons agreed that the M/L Taper head center was so close to the Kinectiv head center as to be clinically indistinguishable. Of these 56 cases, 54 had a head center difference of less than 1 mm in length or offset; the other 2 had a 2-mm difference in offset.

Thus, a total of 261 stems (56%) had a standard M/L Taper option that offered an identical head center or one so close as to be clinically indistinguishable. Interestingly, in the group of 202 stems that did not have an identical head center and were not clinically indistinguishable, 132 (65%) of these modular stems were within 4 mm in length and 2 mm of offset of the closest Kinectiv head center. A verted neck was used in 12 cases (11 anteverted, 1 retroverted).

Nine of the 463 cases required revision surgery, 3 for recurrent instability. In 1 of these 3 cases, the acetabulum was revised for malposition, and the neck was converted from standard offset, +0 mm length (head center identical to nonmodular stem), to extended offset, +4 mm length (2 mm shorter with 1 mm less offset than closest nonmodular head center). The second case had complete deficiency of the abductor tendons and was converted to a constrained liner, though at the time of the THA a head center identical to that of the nonmodular stem was used. The third case was revised to convert a standard offset, +0 mm length, straight neck (head center identical to nonmodular stem), to extended offset, +4 mm length, anteverted neck (anteversion making this a unique head center position). Of the other 6 cases, 1 was treated for corrosion at the head–neck junction by changing the head from cobalt-chromium to ceramic (the junction was noted to be pristine), 1 underwent revision of the acetabular component for loosening, 2 femoral stems were revised for periprosthetic femur fracture, and 2 cases underwent 2-stage revision for late infection. There were no failures secondary to metallosis at the neck–stem junction and no modular breakages. The 3 cases of recurrent instability had no dislocation episodes after revision.

Discussion

PFNSM was developed to help more closely reconstruct patient anatomy. PFNSM allows for individualization of offset, length, and version—and thus for optimization of component interaction to avoid impingement and dislocation while promoting range of motion and normal gait.21 These benefits must be judged in light of the disadvantages of proximal stem modularity, including corrosion and breakage of the modular neck.14-18

In the present study, conducted in a high-volume private practice setting, 44% of necks used in a proximally modular construct had a head center identical to that of a nonmodular alternative. In the opinion of the 3 authors (high-volume hip surgeons), an additional 12% of the modular stems had a head center so close to that of the nonmodular stem as to be clinically indistinguishable. In addition, 132 of the modular necks had a femoral head center within 4 mm in length and 2 mm of offset of the nonmodular stem. These findings call into question the theoretical benefits of regular use of this modular femoral stem for primary THA. Certainly there are extreme femoral neck–shaft angle cases in which the standard nonmodular stem may be inadequate and this proximal modularity would be helpful, but our study showed such cases are relatively less frequent. We caution against routine use of this proximal modularity in primary THA and suggest restricting it to cases in which the standard stem offerings are unacceptable. These findings are not surprising given that the standard M/L Taper stem is based on a historically successful model with neck angle and length options designed to meet the goals of restoring length, offset, range of motion, and stability. We would expect that a well-designed stem will meet these goals in the majority of cases.

Of our 463 cases with the modular neck, 9 required revision surgery. Of these 9 revisions, 2 were for recurrent dislocation in which the modular neck was revised to one that enhanced stability, and there were no further dislocations. The ability to change the geometry of the proximal femur resulted in a stability solution that avoided revision of the entire femoral component, as might otherwise be required. One case of acetabular loosening and 1 case that required placement of a constrained liner were potentially benefited by the modular neck in that the surgeries may have been expedited by being able to remove the neck to ease exposure for placement of the acetabular components. The other 5 revisions—2 for periprosthetic femur fracture, 2 two-stage revisions for infection, and 1 femoral head exchange for metallosis at the head–neck junction—saw no benefit from the modularity in the revision setting.

This study had several limitations. First, as it was primarily an evaluation of use of a modular femoral system, there was no attempt to account for the fact that acetabular component orientation can affect stability and, thus, the perceived need for additional offset or changes in version. The habit of all 3 of the reviewing surgeons is to consider the position of the acetabular component and to reposition the component, if necessary, to achieve appropriate stability. Therefore, the need for the modularity may be even less than suggested by this study. In addition, the idea that (in 12 cases) no standard stem option would be acceptable because of the use of a verted neck ignores the possibility that cup repositioning could have obviated the need for additional version. Furthermore, use of a 36-mm head results in an additional 3.5 mm of offset in the polyethylene liner, and this study did not account for the option of increasing head size—and for the potential increase in stability from a larger head and the increased offset gained from the liner.

A second limitation is that a significant number of Kinectiv stems (132) had a head center within 4 mm in length and 2 mm of offset of the nearest M/L Taper stem. We carefully template every primary THA to determine the plan that will optimize component size and position and restore length and offset. More options for achieving these goals are available when templating with the intention of using the Kinectiv modular neck. The neck cut and position of the stem proximally or distally in the proximal femur may not need to be so exact, as the additional options may be able to accommodate minor inaccuracies. Thus, the reported percentage of clinically indistinguishable head centers (12%) may underestimate the actual number of modular stems that could have been replaced with a nonmodular stem.

Third, this study did not evaluate the effect of the modular junction on ease of irrigation and débridement with head/neck and polyethylene exchange in cases of infection, or on ease of head/neck and polyethylene exchange for revision. In addition, the study did not evaluate other cases of instability involving a nonmodular stem that otherwise could have been solved with simple revision of the head/neck combination, avoiding revision of the entire stem and/or the acetabular component. We reported revisions for infection and for instability, but comprehensive assessment and comparison were beyond the scope of this study. Certainly ease of revision of the head and neck is a factor that could favor use of the modularity.

Fourth, this was not a clinical outcome study comparing 2 different femoral stems. We sought only to determine how often a modular neck was chosen that resulted in a head center that would have been unavailable to the non-modular stem suggesting that the patient was receiving a reconstructive benefit in exchange for the modularity. However, 2 recent reports have noted no clinical benefit at 2-year follow-up with use of the modular neck compared with the nonmodular stem.22,23

Though the M/L Taper with Kinectiv technology has, thus far, performed well, PFNSM should be used with caution in light of recently reported failures at the neck–stem junction.14,16-18 Our study results suggest that most (≥56%) of the modular stems used could have been reconstructed as acceptably with a nonmodular stem, and therefore a reconstructive benefit was not realized in trade for the potential risks of proximal modularity. Only 2 of the 9 revision cases saw a clear advantage in being able to change the modular neck geometry in the revision setting. Given the recently reported failures and the high-profile recall of a modular stem,14 we recommend restricting the modular stem to cases that cannot be adequately reconstructed with the nonmodular option.

Femoral stem modularity in total hip arthroplasty (THA) has a checkered past. Developments such as the modular head–trunnion interface, which allows for placement of femoral heads of different sizes and offsets, and the modular midstem, which allows for version adjustments independent of patient anatomy (S-ROM, Depuy) and for bypassing proximal bone defects in the revision setting (Restoration Modular, Stryker; ZMR-XL, Zimmer), have proved very successful.1-10 However, even these successful advances have been associated with failures at the modular junction.11-13 Proximal femoral neck–stem modularity (PFNSM) has had mixed results, with notable failures and recalls associated with the neck–stem junction.14,15 Failures at this junction have occurred secondary to corrosion and breakage of the modular neck.16-18 Nevertheless, proximal modular stems remain available for implantation. One such system, the M/L Taper stem with Kinectiv technology (Zimmer), is an all-titanium construct that allows for adjustment of several variables (length, offset, version), providing numerous combinations beyond those of the original M/L Taper offerings. Advantages of these offerings include closer reconstruction of patient anatomy, stability improvements, and easing of the process of revision in polyethylene/femoral head exchanges or in infections in which single-staged irrigation and débridement and polyethylene/head exchange are chosen.

These theoretic advantages must be judged in the context of the possible disadvantages of the modular neck junction. The mechanical environment of the junction places it at risk for failure as well as for metallosis from fretting, crevice corrosion, and recurrent repassivation.19 Although the titanium necks are at less risk for degradation than their cobalt-chromium counterparts, they are at higher risk for breakage.13,19 For one of the surgeons in our practice, the M/L Taper stem with Kinectiv technology is the stem of choice for primary THA.

We conducted a study to determine, in the setting of primary THA, how often a neck–stem combination choice resulted in a reconstructive geometry that would not have been possible had the surgeon opted for the traditional M/L Taper stem. Every Kinectiv stem has numerous neck options with a head center position that would not be possible with the nonmodular M/L Taper. However, in a high-volume community practice, how often is a modular neck that results in an otherwise unavailable head center being used for the reconstruction?

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by our local institutional review board. The Kinectiv stem is used by 1 of the 4 high-volume joint replacement surgeons in our practice (not one of the authors). From our community practice joint registry, we identified every stem–neck combination used since the Kinectiv stem became available in 2006.20 Each case was performed using a posterior approach. A trabecular metal acetabular component (Zimmer) secured with 2 screws was used, and an M/L Taper stem with Kinectiv technology was implanted in each case.

Once the neck–stem combination was determined, its position on the head centers map was compared with that of the standard M/L Taper head centers (Figures 1, 2) for each stem size as the relationship of the Kinectiv head center varies with each stem size compared with the head center of the M/L Taper stems. If the head centers were in contact on the map, the geometry was considered identical. If the head centers were not in contact, we noted where the nearest standard M/L Taper head center lay in terms of length and offset. As the head centers are laid out in regular, 4-mm increments, this estimation was relatively easy. Any anteverted or retroverted neck was considered to have no adequate substitution in the standard M/L Taper stem offerings. This initial evaluation was performed by Dr. Carothers.

We then reviewed the head center comparisons independently. For every Kinectiv head center that did not contact an M/L Taper counterpart, the difference between those head centers was reviewed. Each of us noted whether the difference between the head centers was clinically relevant, as many of the head center positions are extremely close. The head centers that were so close as to be deemed clinically irrelevant were recorded.

Results

Between January 2008 and October 2013, 463 primary THAs were performed using the M/L Taper femoral stem with Kinectiv technology. Of the neck options used, 205 (44%) had a head center identical to that of a nonmodular M/L Taper stem. In another 56 cases (12%), all 3 reviewing surgeons agreed that the M/L Taper head center was so close to the Kinectiv head center as to be clinically indistinguishable. Of these 56 cases, 54 had a head center difference of less than 1 mm in length or offset; the other 2 had a 2-mm difference in offset.

Thus, a total of 261 stems (56%) had a standard M/L Taper option that offered an identical head center or one so close as to be clinically indistinguishable. Interestingly, in the group of 202 stems that did not have an identical head center and were not clinically indistinguishable, 132 (65%) of these modular stems were within 4 mm in length and 2 mm of offset of the closest Kinectiv head center. A verted neck was used in 12 cases (11 anteverted, 1 retroverted).

Nine of the 463 cases required revision surgery, 3 for recurrent instability. In 1 of these 3 cases, the acetabulum was revised for malposition, and the neck was converted from standard offset, +0 mm length (head center identical to nonmodular stem), to extended offset, +4 mm length (2 mm shorter with 1 mm less offset than closest nonmodular head center). The second case had complete deficiency of the abductor tendons and was converted to a constrained liner, though at the time of the THA a head center identical to that of the nonmodular stem was used. The third case was revised to convert a standard offset, +0 mm length, straight neck (head center identical to nonmodular stem), to extended offset, +4 mm length, anteverted neck (anteversion making this a unique head center position). Of the other 6 cases, 1 was treated for corrosion at the head–neck junction by changing the head from cobalt-chromium to ceramic (the junction was noted to be pristine), 1 underwent revision of the acetabular component for loosening, 2 femoral stems were revised for periprosthetic femur fracture, and 2 cases underwent 2-stage revision for late infection. There were no failures secondary to metallosis at the neck–stem junction and no modular breakages. The 3 cases of recurrent instability had no dislocation episodes after revision.

Discussion

PFNSM was developed to help more closely reconstruct patient anatomy. PFNSM allows for individualization of offset, length, and version—and thus for optimization of component interaction to avoid impingement and dislocation while promoting range of motion and normal gait.21 These benefits must be judged in light of the disadvantages of proximal stem modularity, including corrosion and breakage of the modular neck.14-18

In the present study, conducted in a high-volume private practice setting, 44% of necks used in a proximally modular construct had a head center identical to that of a nonmodular alternative. In the opinion of the 3 authors (high-volume hip surgeons), an additional 12% of the modular stems had a head center so close to that of the nonmodular stem as to be clinically indistinguishable. In addition, 132 of the modular necks had a femoral head center within 4 mm in length and 2 mm of offset of the nonmodular stem. These findings call into question the theoretical benefits of regular use of this modular femoral stem for primary THA. Certainly there are extreme femoral neck–shaft angle cases in which the standard nonmodular stem may be inadequate and this proximal modularity would be helpful, but our study showed such cases are relatively less frequent. We caution against routine use of this proximal modularity in primary THA and suggest restricting it to cases in which the standard stem offerings are unacceptable. These findings are not surprising given that the standard M/L Taper stem is based on a historically successful model with neck angle and length options designed to meet the goals of restoring length, offset, range of motion, and stability. We would expect that a well-designed stem will meet these goals in the majority of cases.

Of our 463 cases with the modular neck, 9 required revision surgery. Of these 9 revisions, 2 were for recurrent dislocation in which the modular neck was revised to one that enhanced stability, and there were no further dislocations. The ability to change the geometry of the proximal femur resulted in a stability solution that avoided revision of the entire femoral component, as might otherwise be required. One case of acetabular loosening and 1 case that required placement of a constrained liner were potentially benefited by the modular neck in that the surgeries may have been expedited by being able to remove the neck to ease exposure for placement of the acetabular components. The other 5 revisions—2 for periprosthetic femur fracture, 2 two-stage revisions for infection, and 1 femoral head exchange for metallosis at the head–neck junction—saw no benefit from the modularity in the revision setting.

This study had several limitations. First, as it was primarily an evaluation of use of a modular femoral system, there was no attempt to account for the fact that acetabular component orientation can affect stability and, thus, the perceived need for additional offset or changes in version. The habit of all 3 of the reviewing surgeons is to consider the position of the acetabular component and to reposition the component, if necessary, to achieve appropriate stability. Therefore, the need for the modularity may be even less than suggested by this study. In addition, the idea that (in 12 cases) no standard stem option would be acceptable because of the use of a verted neck ignores the possibility that cup repositioning could have obviated the need for additional version. Furthermore, use of a 36-mm head results in an additional 3.5 mm of offset in the polyethylene liner, and this study did not account for the option of increasing head size—and for the potential increase in stability from a larger head and the increased offset gained from the liner.

A second limitation is that a significant number of Kinectiv stems (132) had a head center within 4 mm in length and 2 mm of offset of the nearest M/L Taper stem. We carefully template every primary THA to determine the plan that will optimize component size and position and restore length and offset. More options for achieving these goals are available when templating with the intention of using the Kinectiv modular neck. The neck cut and position of the stem proximally or distally in the proximal femur may not need to be so exact, as the additional options may be able to accommodate minor inaccuracies. Thus, the reported percentage of clinically indistinguishable head centers (12%) may underestimate the actual number of modular stems that could have been replaced with a nonmodular stem.

Third, this study did not evaluate the effect of the modular junction on ease of irrigation and débridement with head/neck and polyethylene exchange in cases of infection, or on ease of head/neck and polyethylene exchange for revision. In addition, the study did not evaluate other cases of instability involving a nonmodular stem that otherwise could have been solved with simple revision of the head/neck combination, avoiding revision of the entire stem and/or the acetabular component. We reported revisions for infection and for instability, but comprehensive assessment and comparison were beyond the scope of this study. Certainly ease of revision of the head and neck is a factor that could favor use of the modularity.

Fourth, this was not a clinical outcome study comparing 2 different femoral stems. We sought only to determine how often a modular neck was chosen that resulted in a head center that would have been unavailable to the non-modular stem suggesting that the patient was receiving a reconstructive benefit in exchange for the modularity. However, 2 recent reports have noted no clinical benefit at 2-year follow-up with use of the modular neck compared with the nonmodular stem.22,23

Though the M/L Taper with Kinectiv technology has, thus far, performed well, PFNSM should be used with caution in light of recently reported failures at the neck–stem junction.14,16-18 Our study results suggest that most (≥56%) of the modular stems used could have been reconstructed as acceptably with a nonmodular stem, and therefore a reconstructive benefit was not realized in trade for the potential risks of proximal modularity. Only 2 of the 9 revision cases saw a clear advantage in being able to change the modular neck geometry in the revision setting. Given the recently reported failures and the high-profile recall of a modular stem,14 we recommend restricting the modular stem to cases that cannot be adequately reconstructed with the nonmodular option.

1. Barrack RL. Modularity of prosthetic implants. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1994;2(1):16-25.

2. Cameron HU. Modularity in primary total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11(3):332-334.

3. Hozack WJ, Mesa JJ, Rothman RF. Head–neck modularity for total hip arthroplasty. Is it necessary? J Arthroplasty. 1996;11(4):397-399.

4. Holt GE, Christie MJ, Schwartz HS. Trabecular metal endoprosthetic limb salvage reconstruction of the lower limb. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(7):1079-1089.

5. Sporer SM, Obar RJ, Bernini PM. Primary total hip arthroplasty using a modular proximally coated prosthesis in patients older than 70: two to eight year results. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19(2):197-203.

6. Spitzer AI. The S-ROM cementless femoral stem: history and literature review. Orthopedics. 2005;28(9 suppl):s1117-s1124.

7. Mumme T, Müller-Rath R, Andereya S, Wirtz DC. Uncemented femoral revision arthroplasty using the modular revision prosthesis MRP-TITAN revision stem. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2007;19(1):56-77.

8. Wirtz DC, Heller KD, Holzwarth U, et al. A modular femoral implant for uncemented stem revision in THR. Int Orthop. 2000;24(3):134-138.

9. Lakstein D, Backstein D, Safir O, Kosashvili Y, Gross AE. Revision total hip arthroplasty with a porous-coated modular stem: 5 to 10 years follow-up. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(5):1310-1315.

10. Bolognesi MP, Pietrobon R, Clifford PE, Vail TP. Comparison of a hydroxyapatite-coated sleeve and a porous-coated sleeve with a modular revision hip stem. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(12):2720-2725.

11. Huot Carlson JC, Van Citters DW, Currier JH, Bryant AM, Mayor MB, Collier JP. Femoral stem fracture and in vivo corrosion of retrieved modular femoral hips. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(7):1389-1396.e1.

12. Gilbert JL, Mehta M, Pinder B. Fretting crevice corrosion of stainless steel stem–CoCr femoral head connections: comparisons of materials, initial moisture, and offset length. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2009;88(1):162-173.

13. Kop AM, Keogh C, Swarts E. Proximal component modularity in THA—at what cost? An implant retrieval study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(7):1885-1894.

14. Cooper HJ, Urban RM, Wixson RL, Meneghini RM, Jacobs JJ. Adverse local tissue reaction arising from corrosion at the femoral neck–body junction in a dual-taper stem with a cobalt-chromium modular neck. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(10):865-872.

15. Vundelinckx BJ, Verhelst LA, De Schepper J. Taper corrosion in modular hip prostheses: analysis of serum metal ions in 19 patients. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(7):1218-1223.

16. Kouzelis A, Georgiou CS, Megas P. Dissociation of modular total hip arthroplasty at the neck–stem interface without dislocation. J Orthop Traumatol. 2012;13(4):221-224.

17. Sotereanos NG, Sauber TJ, Tupis TT. Modular femoral neck fracture after primary total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(1):196.e7-e9.

18. Wodecki P, Sabbah D, Kermarrec G, Semaan I. New type of hip arthroplasty failure related to modular femoral components: breakage at the neck–stem junction. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2013;99(6):741-744.

19. Dorn U, Neumann D, Frank M. Corrosion behavior of tantalum-coated cobalt-chromium modular necks compared to titanium modular necks in a simulator test. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(4):831-835.

20. Carothers JT, White RE, Tripuraneni KR, Hattab MW, Archibeck MJ. Lessons learned from managing a prospective, private practice joint replacement registry: a 25-year experience. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(2):537-543.

21. Archibeck MJ, Cummins T, Carothers J, Junick DW, White RE Jr. A comparison of two implant systems in restoration of hip geometry in arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 2011;469(2):443-446.

22. Duwelius PJ, Hartzband MA, Burkhart R, et al. Clinical results of a modular neck hip system: hitting the “bull’s-eye” more accurately. Am J Orthop. 2010;39(10 suppl):2-6.

23. Duwelius PJ, Burkhart B, Carnahan C, et al. Modular versus nonmodular neck femoral implants in primary total hip arthroplasty: which is better? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(4):1240-1245.

1. Barrack RL. Modularity of prosthetic implants. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1994;2(1):16-25.

2. Cameron HU. Modularity in primary total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11(3):332-334.

3. Hozack WJ, Mesa JJ, Rothman RF. Head–neck modularity for total hip arthroplasty. Is it necessary? J Arthroplasty. 1996;11(4):397-399.

4. Holt GE, Christie MJ, Schwartz HS. Trabecular metal endoprosthetic limb salvage reconstruction of the lower limb. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(7):1079-1089.

5. Sporer SM, Obar RJ, Bernini PM. Primary total hip arthroplasty using a modular proximally coated prosthesis in patients older than 70: two to eight year results. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19(2):197-203.

6. Spitzer AI. The S-ROM cementless femoral stem: history and literature review. Orthopedics. 2005;28(9 suppl):s1117-s1124.

7. Mumme T, Müller-Rath R, Andereya S, Wirtz DC. Uncemented femoral revision arthroplasty using the modular revision prosthesis MRP-TITAN revision stem. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2007;19(1):56-77.

8. Wirtz DC, Heller KD, Holzwarth U, et al. A modular femoral implant for uncemented stem revision in THR. Int Orthop. 2000;24(3):134-138.

9. Lakstein D, Backstein D, Safir O, Kosashvili Y, Gross AE. Revision total hip arthroplasty with a porous-coated modular stem: 5 to 10 years follow-up. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(5):1310-1315.

10. Bolognesi MP, Pietrobon R, Clifford PE, Vail TP. Comparison of a hydroxyapatite-coated sleeve and a porous-coated sleeve with a modular revision hip stem. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(12):2720-2725.

11. Huot Carlson JC, Van Citters DW, Currier JH, Bryant AM, Mayor MB, Collier JP. Femoral stem fracture and in vivo corrosion of retrieved modular femoral hips. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(7):1389-1396.e1.

12. Gilbert JL, Mehta M, Pinder B. Fretting crevice corrosion of stainless steel stem–CoCr femoral head connections: comparisons of materials, initial moisture, and offset length. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2009;88(1):162-173.

13. Kop AM, Keogh C, Swarts E. Proximal component modularity in THA—at what cost? An implant retrieval study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(7):1885-1894.

14. Cooper HJ, Urban RM, Wixson RL, Meneghini RM, Jacobs JJ. Adverse local tissue reaction arising from corrosion at the femoral neck–body junction in a dual-taper stem with a cobalt-chromium modular neck. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(10):865-872.

15. Vundelinckx BJ, Verhelst LA, De Schepper J. Taper corrosion in modular hip prostheses: analysis of serum metal ions in 19 patients. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(7):1218-1223.

16. Kouzelis A, Georgiou CS, Megas P. Dissociation of modular total hip arthroplasty at the neck–stem interface without dislocation. J Orthop Traumatol. 2012;13(4):221-224.

17. Sotereanos NG, Sauber TJ, Tupis TT. Modular femoral neck fracture after primary total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(1):196.e7-e9.

18. Wodecki P, Sabbah D, Kermarrec G, Semaan I. New type of hip arthroplasty failure related to modular femoral components: breakage at the neck–stem junction. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2013;99(6):741-744.

19. Dorn U, Neumann D, Frank M. Corrosion behavior of tantalum-coated cobalt-chromium modular necks compared to titanium modular necks in a simulator test. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(4):831-835.

20. Carothers JT, White RE, Tripuraneni KR, Hattab MW, Archibeck MJ. Lessons learned from managing a prospective, private practice joint replacement registry: a 25-year experience. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(2):537-543.

21. Archibeck MJ, Cummins T, Carothers J, Junick DW, White RE Jr. A comparison of two implant systems in restoration of hip geometry in arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 2011;469(2):443-446.

22. Duwelius PJ, Hartzband MA, Burkhart R, et al. Clinical results of a modular neck hip system: hitting the “bull’s-eye” more accurately. Am J Orthop. 2010;39(10 suppl):2-6.

23. Duwelius PJ, Burkhart B, Carnahan C, et al. Modular versus nonmodular neck femoral implants in primary total hip arthroplasty: which is better? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(4):1240-1245.

Radiographically Silent Loosening of the Acetabular Component in Hip Arthroplasty

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is an excellent option for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the hip. In numerous studies, modern implants have shown survivorship of more than 90% at 10 years.1,2 Polyethylene wear and subsequent osteolysis are major obstacles to the long-term success of THA.3-5 Polyethylene wear particles are phagocytized by macrophages, inducing an inflammatory response that can ultimately lead to osteolysis of the bony architecture surrounding the bone–implant interface.6,7 As modern implants often rely on direct implant-to-bone ingrowth to maintain fixation, wear at this junction can lead to aseptic component loosening and ultimately require revision surgery.8-10 Osteolysis can be diagnosed with plain radiography or computed tomography (CT).11 CT is more sensitive than plain radiography for the diagnosis of osteolysis and is better able to determine the size and location of osteolytic lesions.12,13

Although diagnosis of osteolysis is well defined in the literature, what is more challenging is radiographic diagnosis of a loose acetabular component.11 The most commonly described criteria for loosening are presence of a complete radiolucent line of more than 2 mm in width at the bone–implant interface and any progressive tilting or migration of the component.14,15 CT-based criteria for component loosening remain largely undefined, though Egawa and colleagues16 showed that acetabular osteolysis involving less than 40% of the total cup surface is not associated with component loosening. Although a patient may show signs of osteolysis on postoperative imaging, this finding does not necessitate immediate revision surgery.17 Osteolysis may be monitored clinically and followed radiographically to determine when intervention is necessary.13

The goals of revision surgery are to eliminate the wear generator and bone-graft lytic lesions where needed to help maintain the bone–implant interface.17 The timing of such surgery is important, as the surgeon must balance the risk for gross component migration against the morbidity and mortality associated with acetabular component revision.18 This is in contrast to the settings of infection, periprosthetic fracture, recurrent instability, and component fracture/loosening, in which revision is urgently indicated and the case cannot be managed conservatively.

We conducted a study to determine the incidence of loose acetabular components without radiographic or clinical findings that would necessitate urgent revision THA. Radiographically silent loosening (RSL) was defined as an acetabular component that was loose at time of revision surgery but that did not show frank signs of loosening on either plain radiography or CT. Although these patients make up a small minority of the revision population, knowing the incidence of RSL can help raise surgeon awareness of this potentially dangerous situation. We further sought to determine whether patients with RSL present with different demographic characteristics or clinical symptoms than patients with stable acetabular components.

Materials and Methods

In this retrospective, case–control, institutional review board–approved study, we evaluated patients who had undergone revision THA and had preoperative plain radiographs and CT images. We identified patients by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD‑9) codes (00.70, 00.71, 00.72, 00.73, 80.05, 81.53, 84.56, 84.57) and searched for those cases treated between 2000 and 2012.

Inclusion criteria were confirmed revision THA and confirmed plain radiography and CT of the THA performed before revision. When osteolysis was diagnosed by plain radiography, CT was ordered to determine the extent of bony lesions or to evaluate for eccentric head position or component malposition. Last, all patients included in the study had a detailed operative report clearly indicating acetabular component stability at time of revision. Acetabular component stability at time of surgery was determined according to the criteria defined by Berger and colleagues.19 Cups were evaluated for gross motion during both hip dislocation and during edge loading of the component after thorough scar and capsular débridement.

Patients who did not have CT performed before revision surgery were excluded from the study. These patients had been diagnosed by clinical history and/or plain radiography. Cases revised for periprosthetic infection or periprosthetic fracture were also excluded. Patients with metal-on-metal bearings were excluded, as were any cases revised from hemiarthroplasty to THA, as well as cases revised for recurrent dislocations or component malposition.

All plain radiographs and CT images were evaluated by the orthopedic surgeon who performed the revision and by a radiologist. Images were inspected for signs of gross component migration, tilting, and concentric lucency of the bone–implant interface. Patients with imaging that showed signs of component movement or migration (as seen by the attending surgeon or the radiologist) were excluded. Patients with radiographic evidence of femoral stem loosening were also excluded, as they had an indication to undergo revision arthroplasty. The remaining patients were then stratified into 2 groups: those with stable acetabular components at time of revision and those with loose acetabular components. Stable acetabular shells showed no gross motion of the implant with dislocation, edge loading with an impactor, or pulling with a Kocher clamp after débridement and screw removal.15,19 The 2 groups were then compared with respect to age, sex, and most common presenting symptoms and diagnoses. Fischer exact test and Student t test were used to statistically compare the groups.

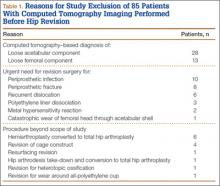

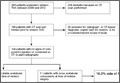

Results

Overall, 393 patients underwent revision arthroplasty for the diagnoses (ICD-9 codes) indicated (Figure). One hundred eighty-nine patients (48.1%) had CT performed before revision. Of these 189 patients, 85 were excluded for diagnoses that were evident on either plain radiography or CT, that necessitated urgent revision, or for procedures beyond the scope of the study (Table 1). CT showed a loose cup in 28 patients; 6 of these cups were also seen on CT. Thirteen patients were diagnosed with a loose femoral stem, 10 with a periprosthetic infection, and 8 with a periprosthetic fracture.

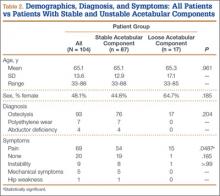

One hundred four patients (54 men, 50 women) met the study inclusion criteria. Mean age was 65.1 years. Of these 104 patients, 87 (83.7%) had a stable acetabular shell at time of revision surgery; the other 17 (16.3%) were diagnosed with RSL of the acetabular shell. Osteolysis was the most common diagnosis (89.4%) in the overall population, and pain was the most common complaint at time of presentation (66.6%). Lack of symptoms was the second most common presentation at time of revision (19.2%) (Table 2). Patients without symptoms underwent revision surgery because of concern about impending compromise of the bone–implant interface and progressive osteolysis.

The 2 groups (stable vs unstable acetabular shells) were not significantly different with respect to age (P = .961) or sex distribution (P = .185). All patients in the RSL group were diagnosed with osteolysis radiographically, and 15 (88%) of 17 patients presented with pain as the primary complaint, compared with only 54 (62%) of 87 patients in the group with stable shells. Patients with RSL were significantly more likely to present with pain as the primary complaint (P = .0487). Nineteen patients in the stable implant group and only 1 patient in the RSL group were asymptomatic, but this was not statistically significant (P = .185) when compared against all other diagnoses.

Discussion

We defined RSL as an acetabular component that was loose at time of revision surgery but that did not show frank signs of loosening on either plain radiography or CT. Patients with RSL and the surgeons who treat them are in a difficult position. In the setting of osteolysis, patients can be treated with serial radiographic imaging and clinical monitoring to determine if and when revision arthroplasty should be performed.17 However, given the complexity and risks associated with revision THA, surgeons should be aware that the acetabular shell may necessitate revision even if it does not appear to be frankly unstable on radiographic imaging.18

Of the 393 patients who underwent revision THA at our institution, 48.1% were evaluated with CT. Eighty-five of the 189 patients who underwent CT were diagnosed with radiographic loosening, or were diagnosed as needing urgent revision THA in the setting of loose components, periprosthetic infection, periprosthetic fracture, or catastrophic implant failure. Of the remaining 104 patients, 17 (16.3%) met the diagnosis of RSL of the acetabular component. The most common complaint was pain, and the most common diagnoses were osteolysis and polyethylene wear. Age and sex were not associated with increased likelihood of RSL.

Our study has several limitations. We defined the radiographic diagnosis of loose acetabular components as components showing frank migration, tilting, or a 2-mm concentric lucency on plain radiography or CT. Although these are common definitions of loose acetabular components, more sensitive radiographic measures have been described.16 We also excluded patients with recurrent dislocations and metal-on-metal prostheses, as these cases increase the metal artifact on CT and limit the ability to evaluate the bone–implant interface. Metal artifact remains an ongoing challenge to use of CT for post-THA imaging. However, tailored imaging protocols are helping to eliminate metal artifact. Bone scan was not used to evaluate for possible component loosening. Although sensitivity and specificity are about 67% and 76%, respectively,20 Temmerman and colleagues21 also found poor intraobserver reliability (0.53) for bone scans in the setting of uncemented acetabular components. Last, our study did not evaluate the bony ingrowth patterns that corresponded to stable or unstable fixation and did not evaluate the volumetric size or anatomical location of the osteolytic lesions on CT. Careful assessment of these variables is clinically relevant when trying to determine if revision arthroplasty is warranted.

Although we used relatively simple radiographic criteria to define loose components, more sensitive and specific techniques have been described for both plain radiography and CT. Moore and colleagues22 described 5 radiographic signs of bony ingrowth; when 3 or more were present, sensitivity was 89.6% and specificity 76.9%. Mehin and colleagues23 suggested that osteolysis involving more than 50% of the circumference of the shell on a standard pelvic radiograph might require revision arthroplasty. However, more recent studies have found that anteroposterior and lateral radiographs are less able to evaluate the anterior and posterior rims of the bone–implant interface, and it is this ingrowth area that may be the most crucial for stable osseointegration.12,16

CT has expanded our ability to evaluate the bone–implant interface in 3 dimensions. Egawa and colleagues16 described using CT to evaluate the surface area involved with osteolysis and found that less than 40% involvement of the surface area generally corresponded to well-fixed components. Furthermore, they found that osteolysis generally creates lesions inferior and superior to the acetabular component and less often involves the anterior and posterior rims, which may be more important for stable fixation. The authors noted that volumetric analysis and CT were not as cost-effective as plain radiography and were more time- and skill-intensive.

Osteolysis itself remains a common indication for revision THA. However, the most appropriate procedure remains controversial. Mallory and colleagues24 recommended explanting all acetabular shells in the setting of revision arthroplasty. They indicated that full assessment of the bony pelvis and any lytic defects was possible only with the wide exposure gained by acetabular component removal. More recent studies have begun to justify isolated component revision in the setting of well-fixed acetabular shells. Studies by Maloney and colleagues,10 Park and colleagues,15 and Beaulé and colleagues25 have shown excellent outcomes with retention of well-fixed acetabular shells and removal of the wear generator in the setting of osteolysis. Haidukewych17 wrote that the goals in addressing osteolysis in revision THA are to eliminate the wear generator, débride osteolytic lesions, and restore bone stock. Surgeons should weigh the benefits of component retention and isolated liner exchange against the morbidity associated with explantation and preparation for implanting a new component. Good outcomes have been achieved with isolated component exchange, but surgeons should be aware that instability remains the most common complication after isolated liner exchange.8

The majority of our patients with RSL presented with complaints of pain and the diagnosis of osteolysis. One patient who had the diagnosis but was clinically asymptomatic was found to have a loose acetabular shell at time of revision surgery. Given the increased morbidity associated with acetabular component revision, this patient’s condition represents a dangerous combination of RSL and clinically asymptomatic component loosening. By raising awareness about RSL and its incidence, we should be able to increase our ability to detect RSL. A surgeon who detects RSL before gross migration or movement of the acetabular component may be better able to plan for revision arthroplasty before a catastrophic event that may necessitate a larger, more complex procedure. With the number of patients who require revision THA continuing to rise, surgeons should be aware of the incidence of RSL and the potential of RSL to affect patient care and potential surgical options.

1. Milošev I, Kovač S, Trebše R, Levašič V, Pišot V. Comparison of ten-year survivorship of hip prostheses with use of conventional polyethylene, metal-on-metal, or ceramic-on-ceramic bearings. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(19):1756-1763.

2. D’Antonio JA, Capello WN, Naughton M. Ceramic bearings for total hip arthroplasty have high survivorship at 10 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(2):373-381.

3. Dowd JE, Sychterz CJ, Young AM, Engh CA. Characterization of long-term femoral-head-penetration rates. Association with and prediction of osteolysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(8):1102-1107.

4. Orishimo KF, Claus AM, Sychterz CJ, Engh CA. Relationship between polyethylene wear and osteolysis in hips with a second-generation porous-coated cementless cup after seven years of follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(6):1095-1099.

5. Harris WH. Wear and periprosthetic osteolysis: the problem. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(393):66-70.

6. Holt G, Murnaghan C, Reilly J, Meek RM. The biology of aseptic osteolysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;(460):240-252.

7. Catelas I, Jacobs JJ. Biologic activity of wear particles. Instr Course Lect. 2010;59:3-16.

8. Paprosky WG, Nourbash P, Gill P. Treatment of progressive periacetabular osteolysis: cup revision versus liner exchange and bone grafting. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; February 4-8, 1999; Anaheim, CA.

9. Engh CA Jr, Claus AM, Hopper RH Jr, Engh CA. Long-term results using the anatomic medullary locking hip prosthesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(393):137-146.

10. Maloney WJ, Peters P, Engh CA, Chandler H. Severe osteolysis of the pelvic in association with acetabular replacement without cement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75(11):1627-1635.

11. Claus AM, Engh CA Jr, Sychterz CJ, Xenos JS, Orishimo KF, Engh CA Sr. Radiographic definition of pelvic osteolysis following total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(8):1519-1526.

12. Puri L, Wixson RL, Stern SH, Kohli J, Hendrix RW, Stulberg SD. Use of helical computed tomography for the assessment of acetabular osteolysis after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(4):609-614.

13. Stulberg SD, Wixson RL, Adams AD, Hendrix RW, Bernfield JB. Monitoring pelvic osteolysis following total hip replacement surgery: an algorithm for surveillance. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(suppl 2):116-122.

14. Massin P, Schmidt L, Engh CA. Evaluation of cementless acetabular component migration. An experimental study. J Arthroplasty. 1989;4(3):245-251.

15. Park KS, Yoon TR, Song EK, Lee KB. Results of isolated femoral component revision with well-fixed acetabular implant retention. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(8):1188-1195.

16. Egawa H, Ho H, Hopper RH Jr, Engh CA Jr, Engh CA. Computed tomography assessment of pelvic osteolysis and cup–lesion interface involvement with a press-fit porous-coated acetabular cup. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(2):233-239.

17. Haidukewych GJ. Osteolysis in the well-fixed socket: cup retention or revision? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(12):65-69.

18. Stulberg BN, Della Valle AG. What are the guidelines for the surgical and nonsurgical treatment of periprosthetic osteolysis? J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(suppl 1):S20-S25.

19. Berger RA, Quigley LR, Jacobs JJ, Sheinkop MB, Rosenberg AG, Galante JO. The fate of stable cemented acetabular components retained during revision of a femoral component of a total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81(12):1682-1691.

20. Temmerman OP, Raijmakers PG, Deville WL, Berkhof J, Hooft L, Heyligers IC. The use of plain radiography, subtraction arthrography, nuclear arthrography, and bone scintigraphy in the diagnosis of a loose acetabular component of a total hip prosthesis: a systematic review. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(6):818-827.

21. Temmerman OP, Raijmakers PG, David EF, et al. A comparison of radiographic and scintigraphic techniques to assess aseptic loosening of the acetabular component in a total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(11):2456-2463.

22. Moore MS, McAuley JP, Young AM, Engh CA Sr. Radiographic signs of osseointegration in porous-coated acetabular components. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;(444):176-183.

23. Mehin R, Yuan X, Haydon C, et al. Retroacetabular osteolysis: when to operate? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(428):247-255.

24. Mallory TH, Lombardi AV Jr, Fada RA, Adams JB, Kefauver CA, Eberle RW. Noncemented acetabular component removal in the presence of osteolysis: the affirmative. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;(381):120-128.

25. Beaulé PE, Le Duff MJ, Dorey FJ, Amstutz HC. Fate of cementless acetabular components retained during revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(12):2288-2293.

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is an excellent option for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the hip. In numerous studies, modern implants have shown survivorship of more than 90% at 10 years.1,2 Polyethylene wear and subsequent osteolysis are major obstacles to the long-term success of THA.3-5 Polyethylene wear particles are phagocytized by macrophages, inducing an inflammatory response that can ultimately lead to osteolysis of the bony architecture surrounding the bone–implant interface.6,7 As modern implants often rely on direct implant-to-bone ingrowth to maintain fixation, wear at this junction can lead to aseptic component loosening and ultimately require revision surgery.8-10 Osteolysis can be diagnosed with plain radiography or computed tomography (CT).11 CT is more sensitive than plain radiography for the diagnosis of osteolysis and is better able to determine the size and location of osteolytic lesions.12,13

Although diagnosis of osteolysis is well defined in the literature, what is more challenging is radiographic diagnosis of a loose acetabular component.11 The most commonly described criteria for loosening are presence of a complete radiolucent line of more than 2 mm in width at the bone–implant interface and any progressive tilting or migration of the component.14,15 CT-based criteria for component loosening remain largely undefined, though Egawa and colleagues16 showed that acetabular osteolysis involving less than 40% of the total cup surface is not associated with component loosening. Although a patient may show signs of osteolysis on postoperative imaging, this finding does not necessitate immediate revision surgery.17 Osteolysis may be monitored clinically and followed radiographically to determine when intervention is necessary.13

The goals of revision surgery are to eliminate the wear generator and bone-graft lytic lesions where needed to help maintain the bone–implant interface.17 The timing of such surgery is important, as the surgeon must balance the risk for gross component migration against the morbidity and mortality associated with acetabular component revision.18 This is in contrast to the settings of infection, periprosthetic fracture, recurrent instability, and component fracture/loosening, in which revision is urgently indicated and the case cannot be managed conservatively.

We conducted a study to determine the incidence of loose acetabular components without radiographic or clinical findings that would necessitate urgent revision THA. Radiographically silent loosening (RSL) was defined as an acetabular component that was loose at time of revision surgery but that did not show frank signs of loosening on either plain radiography or CT. Although these patients make up a small minority of the revision population, knowing the incidence of RSL can help raise surgeon awareness of this potentially dangerous situation. We further sought to determine whether patients with RSL present with different demographic characteristics or clinical symptoms than patients with stable acetabular components.

Materials and Methods

In this retrospective, case–control, institutional review board–approved study, we evaluated patients who had undergone revision THA and had preoperative plain radiographs and CT images. We identified patients by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD‑9) codes (00.70, 00.71, 00.72, 00.73, 80.05, 81.53, 84.56, 84.57) and searched for those cases treated between 2000 and 2012.

Inclusion criteria were confirmed revision THA and confirmed plain radiography and CT of the THA performed before revision. When osteolysis was diagnosed by plain radiography, CT was ordered to determine the extent of bony lesions or to evaluate for eccentric head position or component malposition. Last, all patients included in the study had a detailed operative report clearly indicating acetabular component stability at time of revision. Acetabular component stability at time of surgery was determined according to the criteria defined by Berger and colleagues.19 Cups were evaluated for gross motion during both hip dislocation and during edge loading of the component after thorough scar and capsular débridement.

Patients who did not have CT performed before revision surgery were excluded from the study. These patients had been diagnosed by clinical history and/or plain radiography. Cases revised for periprosthetic infection or periprosthetic fracture were also excluded. Patients with metal-on-metal bearings were excluded, as were any cases revised from hemiarthroplasty to THA, as well as cases revised for recurrent dislocations or component malposition.

All plain radiographs and CT images were evaluated by the orthopedic surgeon who performed the revision and by a radiologist. Images were inspected for signs of gross component migration, tilting, and concentric lucency of the bone–implant interface. Patients with imaging that showed signs of component movement or migration (as seen by the attending surgeon or the radiologist) were excluded. Patients with radiographic evidence of femoral stem loosening were also excluded, as they had an indication to undergo revision arthroplasty. The remaining patients were then stratified into 2 groups: those with stable acetabular components at time of revision and those with loose acetabular components. Stable acetabular shells showed no gross motion of the implant with dislocation, edge loading with an impactor, or pulling with a Kocher clamp after débridement and screw removal.15,19 The 2 groups were then compared with respect to age, sex, and most common presenting symptoms and diagnoses. Fischer exact test and Student t test were used to statistically compare the groups.

Results

Overall, 393 patients underwent revision arthroplasty for the diagnoses (ICD-9 codes) indicated (Figure). One hundred eighty-nine patients (48.1%) had CT performed before revision. Of these 189 patients, 85 were excluded for diagnoses that were evident on either plain radiography or CT, that necessitated urgent revision, or for procedures beyond the scope of the study (Table 1). CT showed a loose cup in 28 patients; 6 of these cups were also seen on CT. Thirteen patients were diagnosed with a loose femoral stem, 10 with a periprosthetic infection, and 8 with a periprosthetic fracture.

One hundred four patients (54 men, 50 women) met the study inclusion criteria. Mean age was 65.1 years. Of these 104 patients, 87 (83.7%) had a stable acetabular shell at time of revision surgery; the other 17 (16.3%) were diagnosed with RSL of the acetabular shell. Osteolysis was the most common diagnosis (89.4%) in the overall population, and pain was the most common complaint at time of presentation (66.6%). Lack of symptoms was the second most common presentation at time of revision (19.2%) (Table 2). Patients without symptoms underwent revision surgery because of concern about impending compromise of the bone–implant interface and progressive osteolysis.

The 2 groups (stable vs unstable acetabular shells) were not significantly different with respect to age (P = .961) or sex distribution (P = .185). All patients in the RSL group were diagnosed with osteolysis radiographically, and 15 (88%) of 17 patients presented with pain as the primary complaint, compared with only 54 (62%) of 87 patients in the group with stable shells. Patients with RSL were significantly more likely to present with pain as the primary complaint (P = .0487). Nineteen patients in the stable implant group and only 1 patient in the RSL group were asymptomatic, but this was not statistically significant (P = .185) when compared against all other diagnoses.

Discussion