User login

August 2015 Quiz 2

ANSWER: D

Critique

This patient has vitamin B12 deficiency, which is common in the elderly. In addition, gastrectomy can produce cobalamin deficiency due to lack of gastrin and pepsin resulting in impaired release of dietary B12 from ingested proteins. Also, the lack of intrinsic factor will result in impaired absorption of B12. B12 and folate are required to metabolize homocysteine to methionine. Therefore, with deficiency of either folate or B12, there is an increase in serum homocysteine levels. B12 is also a cofactor in the synthesis of succinyl-CoA from methylmalonyl-CoA and therefore, with B12 deficiency, methylmalonic acid levels are also elevated. Hypoglycemia would not explain this constellation of symptoms. Microscopic colitis causes diarrhea but does not cause dementia or cognitive impairment, glossitis, or taste disturbances. The dominant micronutrient deficiencies with celiac disease are iron and calcium malabsorption, and while B12 deficiency is possible with extensive disease, it is not seen as commonly, and celiac would not be the most likely etiology for her B12 deficiency.

Reference

1. Sumner, A.E., Chin, M.M., Abrahm, J.L., et al. Elevated methylmalonic acid and total homocysteine levels show high prevalence of B12 deficiency after gastric surgery. Ann. Intern. Med. 1996;124:469.

ANSWER: D

Critique

This patient has vitamin B12 deficiency, which is common in the elderly. In addition, gastrectomy can produce cobalamin deficiency due to lack of gastrin and pepsin resulting in impaired release of dietary B12 from ingested proteins. Also, the lack of intrinsic factor will result in impaired absorption of B12. B12 and folate are required to metabolize homocysteine to methionine. Therefore, with deficiency of either folate or B12, there is an increase in serum homocysteine levels. B12 is also a cofactor in the synthesis of succinyl-CoA from methylmalonyl-CoA and therefore, with B12 deficiency, methylmalonic acid levels are also elevated. Hypoglycemia would not explain this constellation of symptoms. Microscopic colitis causes diarrhea but does not cause dementia or cognitive impairment, glossitis, or taste disturbances. The dominant micronutrient deficiencies with celiac disease are iron and calcium malabsorption, and while B12 deficiency is possible with extensive disease, it is not seen as commonly, and celiac would not be the most likely etiology for her B12 deficiency.

Reference

1. Sumner, A.E., Chin, M.M., Abrahm, J.L., et al. Elevated methylmalonic acid and total homocysteine levels show high prevalence of B12 deficiency after gastric surgery. Ann. Intern. Med. 1996;124:469.

ANSWER: D

Critique

This patient has vitamin B12 deficiency, which is common in the elderly. In addition, gastrectomy can produce cobalamin deficiency due to lack of gastrin and pepsin resulting in impaired release of dietary B12 from ingested proteins. Also, the lack of intrinsic factor will result in impaired absorption of B12. B12 and folate are required to metabolize homocysteine to methionine. Therefore, with deficiency of either folate or B12, there is an increase in serum homocysteine levels. B12 is also a cofactor in the synthesis of succinyl-CoA from methylmalonyl-CoA and therefore, with B12 deficiency, methylmalonic acid levels are also elevated. Hypoglycemia would not explain this constellation of symptoms. Microscopic colitis causes diarrhea but does not cause dementia or cognitive impairment, glossitis, or taste disturbances. The dominant micronutrient deficiencies with celiac disease are iron and calcium malabsorption, and while B12 deficiency is possible with extensive disease, it is not seen as commonly, and celiac would not be the most likely etiology for her B12 deficiency.

Reference

1. Sumner, A.E., Chin, M.M., Abrahm, J.L., et al. Elevated methylmalonic acid and total homocysteine levels show high prevalence of B12 deficiency after gastric surgery. Ann. Intern. Med. 1996;124:469.

August 2015 Quiz 1

ANSWER: D

Critique

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is the correct diagnosis here even in the absence of respiratory symptoms; failure to thrive with malabsorption, elevated liver chemistries, and protein malnutrition (low serum albumin) are all suggestive of CF. Additionally, profound hypoalbuminemia and anemia have been reported with the use of soy protein-based formulas in infants with CF. Although celiac disease can have a very early onset, this may obviously only follow ingestion of gluten, so it is not a diagnostic possibility in the case of this formula-fed child. Poor feeding technique is a cause of failure to thrive in early infancy, but here we have good oral intake also suggesting an absorption issue. Giardiasis may have caused this child's symptoms, as this parasitic infection may result in malabsorption, but at this early age this is a highly unlikely explanation, especially in developed countries. Milk protein allergy-induced enteropathy is also possible in this case but is less likely with heme-negative stool and elevated liver chemistries.

Reference

1. Messick, J. A 21st century approach to cystic fibrosis: optimizing outcomes across the disease spectrum. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2010;51(Suppl 7):S1-7.

ANSWER: D

Critique

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is the correct diagnosis here even in the absence of respiratory symptoms; failure to thrive with malabsorption, elevated liver chemistries, and protein malnutrition (low serum albumin) are all suggestive of CF. Additionally, profound hypoalbuminemia and anemia have been reported with the use of soy protein-based formulas in infants with CF. Although celiac disease can have a very early onset, this may obviously only follow ingestion of gluten, so it is not a diagnostic possibility in the case of this formula-fed child. Poor feeding technique is a cause of failure to thrive in early infancy, but here we have good oral intake also suggesting an absorption issue. Giardiasis may have caused this child's symptoms, as this parasitic infection may result in malabsorption, but at this early age this is a highly unlikely explanation, especially in developed countries. Milk protein allergy-induced enteropathy is also possible in this case but is less likely with heme-negative stool and elevated liver chemistries.

Reference

1. Messick, J. A 21st century approach to cystic fibrosis: optimizing outcomes across the disease spectrum. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2010;51(Suppl 7):S1-7.

ANSWER: D

Critique

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is the correct diagnosis here even in the absence of respiratory symptoms; failure to thrive with malabsorption, elevated liver chemistries, and protein malnutrition (low serum albumin) are all suggestive of CF. Additionally, profound hypoalbuminemia and anemia have been reported with the use of soy protein-based formulas in infants with CF. Although celiac disease can have a very early onset, this may obviously only follow ingestion of gluten, so it is not a diagnostic possibility in the case of this formula-fed child. Poor feeding technique is a cause of failure to thrive in early infancy, but here we have good oral intake also suggesting an absorption issue. Giardiasis may have caused this child's symptoms, as this parasitic infection may result in malabsorption, but at this early age this is a highly unlikely explanation, especially in developed countries. Milk protein allergy-induced enteropathy is also possible in this case but is less likely with heme-negative stool and elevated liver chemistries.

Reference

1. Messick, J. A 21st century approach to cystic fibrosis: optimizing outcomes across the disease spectrum. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2010;51(Suppl 7):S1-7.

What does molecular imaging reveal about the causes of ADHD and the potential for better management?

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common pediatric psychiatric disorders, occurring in approximately 5% of children.1 The disorder persists into adulthood in about one-half of those who are affected in childhood.2 In adults and children, diagnosis continues to be based on the examiner’s subjective assessment. (Box 13-9 describes how ADHD presents a complicated, moving target for the diagnostician.)

Patients who have ADHD are rarely studied with imaging; there are no established imaging findings associated with an ADHD diagnosis. Over the past 20 years, however, significant research has shown that molecular alterations along the dopaminergic−frontostriatal pathways occur in association with the behavioral constellation of ADHD symptoms—suggesting a pathophysiologic mechanism for this disorder.

In this article, we describe molecular findings from nuclear medicine imaging in ADHD. We also summarize imaging evidence for dysfunction of the dopaminergic-frontostriatal neural circuits as central in the pathophysiology of ADHD, with special focus on the dopamine reuptake transporter (DaT). Box 210,11 reviews our key observations and looks at the future of imaging in the management of ADHD.

Dopaminergic theory of ADHD

The executive functions that are disordered in ADHD (impulse control, judgment, maintaining attention) are thought to be centered in the infraorbital, dorsolateral, and medial frontal lobes. Neurotransmitters that have been implicated in the pathophysiology of ADHD include norepinephrine12 and dopamine13; medications that selectively block reuptake of these neurotransmitters are used to treat ADHD.14,15 Only the dopamine system has been extensively evaluated with molecular imaging techniques.

Because methylphenidate, a potent selective dopamine reuptake inhibitor, has been shown to reduce disordered executive functional behaviors in ADHD, considerable imaging research has focused on the dopaminergic neural circuits in the frontostriatal regions of the brain. The dopaminergic theory of ADHD is based on the hypothesis that alterations in the density or function of these circuits are responsible for behaviors that constitute ADHD.

Despite decades of efforts to delineate the underlying pathophysiology and neurochemistry of ADHD, no single unifying theory accounts for all imaging findings in all patients. This might be in part because of imprecision inherent in psychiatric diagnoses that are based on subjective observations. The behavioral criteria for ADHD can manifest in several disorders. For example, anxiety-related symptoms seen in posttraumatic stress disorder, social anxiety disorder, and panic disorder also present as behaviors similar to those in ADHD diagnostic criteria.

Molecular imaging might provide a window into the underlying pathophysiology of ADHD and, by identifying objective findings, (1) allow for patient stratification based on underlying physiologic subtypes, (2) refine diagnostic criteria, and (3) predict treatment response.

Nuclear medicine findings

In general, nuclear medicine investigations of ADHD can be divided into studies of changes in regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) or glucose metabolism (rCGM) and those that have assessed the concentration of synaptic structures, using highly specific radiolabeled ligands. Both kinds of studies provide limited anatomic resolution, unless co-registered with MRI or CT scans and either single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) or positron emission tomography (PET).

Synaptic imaging using radiolabeled ligands with high biologic specificity for synaptic structures has high molecular resolution—that is, radiolabeled ligands used for selective imaging of the dopamine transporter or receptor do not identify serotonin transporters or receptors, and vice versa. (Details of SPECT and PET techniques are beyond the scope of this article but can be found in standard nuclear medicine textbooks.)

SPECT and PET of rCBF

Early investigations of rCBF in ADHD were performed using inhaled radioactive xenon-133 gas.16 Later, rCBF was assessed using fat-soluble radiolabeled ligands that rapidly distribute in the brain in proportion to blood flow by crossing the blood−brain barrier. Labeled with radioactive 99m-technetium, these ligands cross rapidly into brain cells after IV injection. Once intracellular, covalent bonds within the ligands cleave into 2 charged particles that do not easily recross the cell membrane. There is little redistribution of tracer after initial uptake.

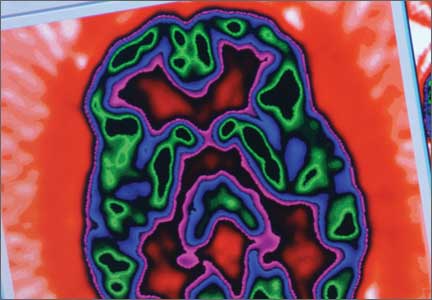

The imaging data set that results can be reconstructed as (1) surface images, on which defects indicate areas of reduced rCBF, or (2) tomographic slices on which color scales indicate relative rCBF values (Figure 1). Because of the minimal redistribution of the tracer, SPECT images obtained 1 or 2 hours after injection provide a snapshot of rCBF at the time tracer is injected. Patients can be injected under various conditions, such as at rest with eyes and ears open in a dimly lit, quiet room, and then under cognitive stress (Figure 2), such as performing a computer-based attention and impulse control task, or during stimulant treatment.

Numerous investigators have found reduced frontal or striatal rCBF, or both, in patients with ADHD, unilaterally on the right17 or left,18,19 or bilaterally.20 Additionally, with stimulant therapy, normalization of striatal and frontal rCBF has been demonstrated14,19—changes that correlate with resolution of behavioral symptoms of ADHD with stimulant treatment.21

SPECT of 32 boys with previously untreated ADHD. Kim et al21 found that the presence of reduced right or left, or both, frontal rCBF, which normalized with 8 weeks of stimulant therapy, predicted symptom improvement in 85% of patients. Absence of improvement of reduced frontal rCBF had a 75% negative predictive value for treatment response. (Additionally, hyperperfusion of the somatosensory cortex has been demonstrated in children with ADHD,16,22 suggesting increased responsiveness to extraneous environmental input.)

SPECT of 40 untreated pediatric patients compared with 17 age-matched controls. Using SPECT, Lee et al23 reported rCBF reductions in the orbitofrontal cortex and the medial temporal gyrus of participants; reductions corresponded to areas of motor and impulsivity control. The researchers also demonstrated increased rCBF in the somatosensory area.

After methylphenidate treatment, blood flow to these areas normalized, and rCBF to higher visual and superior prefrontal areas decreased. Substantial clinical improvement occurred in 64% of patients—suggesting methylphenidate treatment of ADHD works by (1) increasing function of areas of the brain that control impulses, motor activity, and attention, and (2) reducing function to sensory areas that lead to distraction by extraneous environmental sensory input.

O-15-labeled water PET of 10 adults with ADHD. Schweitzer et al24 found that participants who demonstrated improvement in behavioral symptoms with chronic stimulant therapy had reduced rCBF in the striata at baseline—again, suggesting that baseline hypometabolism in the striata is associated with ADHD.

PET of regional cerebral glucose metabolism

Cerebral metabolism requires a constant supply of glucose; regional differences in cerebral glucose metabolism can be assessed directly with positron-emitting F-18-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose. Although metabolically inert, this agent is transported intracellularly similar to glucose; once phosphorylated within brain cells, however, it can no longer undergo further metabolism or redistribution.

Studies using PET to assess rCGM were some of the earliest molecular imaging applications in ADHD. Zametkin et al25 reported low global cerebral glucose utilization in adults, but not adolescents,26 with ADHD. However, further study, with normalization of the PET data, confirmed reduced rCGM in the left prefrontal cortex in both adolescents26 and adults,27 indicating hypometabolism of cortical areas associated with impulse control and attention in ADHD. In adolescents, symptom severity was inversely related to rCBF in the left anterior frontal cortex.

Synaptic imaging

Nuclear imaging has been used to study several components of the striatal dopaminergic synapse, including:

• dopamine substrates, using fluorine- 18-labeled dopa or carbon-11-labeled dopa

• dopamine receptors, using carbon- 11-labeled raclopride or iodine-123 iodobenzamide

• the tDaT, using iodine-123 ioflupane, 99m-technetium TRODAT, or carbon-11 cocaine (Figure 3).

All of these synaptic imaging agents were used mainly as research tools until 2011, when the FDA approved the SPECT imaging agent iodine-123 ioflupane (DaTscan) for clinical use in assessment of Parkinson’s disease.28 This commercially available agent has high specificity for the DaT, with little background activity noted on SPECT imaging (Figure 4).

Dopamine transporter imaging

Because the site of action of methylphenidate is the DaT, imaging this component of the striatal dopaminergic synapse has been an area of intense investigation in ADHD. Located almost exclusively in the striata, DaT reduces synaptic concentrations of dopamine by means of reuptake channels in the cell membrane.29 By reversibly binding to, and occupying sites on, the DaT, methylphenidate impedes dopamine reuptake, which results in increased availability of dopamine at the synapse.30

By demonstrating an increase in striatal DaT density in patients with ADHD— first reported by Dougherty et al31 using iodine-123 altropane (a dopaminergic uptake inhibitor) in 6 adults with ADHD—investigators have hypothesized that excessive expression of the DaT protein in the striata, which may result from genetic or environmental factors, is a central causative agent of ADHD.32 Subsequent studies, however, have yielded contradictory findings: Hesse et al,33 using SPECT imaging, and Volkow et al,34 using carbon-11 cocaine PET imaging, found reduced DaT density in, respectively, 9 and 26 patients with ADHD.

To clarify the role of DaT levels in the etiology of ADHD and to explain discrepant results, Fusar-Poli et al35 performed a meta-analysis of 9 published papers that reported the results of DaT imaging in a total of 169 ADHD patients and 129 controls. They noted that these studies included 6 different imaging agents and protocols. Patients were stimulant therapy-naïve (n = 137) or drug-free (refrained from stimulant therapy for a time [n = 32]). The team found that the degree of elevation of the striatal DaT concentration correlated with a history of stimulant exposure, and that the drug-naïve group had a reduced DaT level.

Fusar-Poli’s hypothesis? Elevated DaT levels result from up-regulation in the presence of chronic methylphenidate therapy, which accounts for early reports that demonstrated increased striatal DaT density. Clinically, up-regulation might explain the lack of sustained relief of behavioral symptoms with stimulant therapy in 20% of patients with ADHD who showed clinical improvement initially.36

Only limited conclusions can be drawn about the role of DaT levels in ADHD, given the small number of patients studied in published reports. In addition, the Fusar-Poli meta-analysis has come under strong criticism because of methodological errors with improper patient inclusion and characterization of treatment status,37 calling into question the investigators’ conclusions.

Does the DaT level hold promise for practice? Despite a lack of clarity about the significance of DaT level in the etiology of ADHD, knowledge of a patient’s level might prove useful in predicting which patients will respond to methylphenidate. Namely, several researchers have found that:

• an elevated baseline level of DaT (before stimulant therapy) correlates with robust clinical response

• absence of an elevated baseline DaT level suggests that symptomatic improvement with stimulant therapy in unlikely.38-40

Dresel et al38 evaluated 17 drug-naïve adults, newly diagnosed with ADHD, using 99m-technetium TRODAT SPECT before and after methylphenidate therapy. They found a 15% increase in specific DaT binding in patients with ADHD, compared with controls, at baseline. After treatment, the researchers observed a 28% reduction in specific DaT binding—a significant change from baseline that correlated with behavioral response.

Study: SPECT in 18 adults with ADHD given methylphenidate. Krause39 used the same SPECT agent to study 18 adults before they received methylphenidate and 10 weeks after treatment. Participants were categorized as responders or nonresponders based on clinical assessment of ADHD symptoms after those 10 weeks. All 12 responders had an elevated striatal DaT concentration at baseline. Of the 6 nonresponders, 5 had a normal level of striatal DaT compared with age-matched controls.

Study: 22 Adult ADHD patients evaluated with 99m-technetium TRODAT SPECT. The same group of investigators40 presented imaging findings in 22 additional adult patients. Seventeen had an elevated striatal DaT level, 16 of whom responded to stimulant therapy. The remaining 5 patients had reduced striatal DaT at baseline; none had a good clinical response to methylphenidate.

The positive clinical response to methylphenidate in 67%37 and 77%40 of patients is in good agreement with results from larger studies, which reported that approximately 75% of patients with ADHD show prompt clinical improvement with stimulants.41 Improvement might be related to an increase in functioning of the frontostriatal dopaminergic circuit that is seen with stimulant therapy. Increased availability of dopamine at the synapse, resulting from stimulant blockade of the dopamine reuptake transporter, produces increased dopamine neurotransmission and increased activation of frontostriatal circuits.

In another study, rCBF in frontostriatal circuits was determined to be inversely proportional to DaT density; rCBF normalized with stimulant therapy.42

Will imaging pave the way for therapeutic stratification? Baseline determinations of striatal DaT concentration with SPECT imaging might make it possible to stratify patients with ADHD symptoms into those likely to show significant behavioral symptom response to methylphenidate and those who are not likely to respond. There might be an objective imaging finding—striatal DaT density—that allows clinicians to distinguish stimulant-responsive ADHD from stimulant-unresponsive ADHD.

Dopamine substrate imaging

Radiolabeled dopa (carbon-11 or fluorine-18) is transported into presynaptic dopaminergic neurons in the striatum, where it is decarboxylated, converted to radio-dopamine, and stored within vesicles until released in response to neuronal excitation. Semi-quantitative assessment is achieved with calculation of specific (striatal) to nonspecific (background) uptake ratios. Increased values are thought to indicate increased density of dopaminergic neurons.43

Ernst et al44 reported a 50% decrease in specific fluorine-18 dopa uptake in the left prefrontal cortex in 17 drug-naïve adults with ADHD, compared with 23 controls. The same team reported increased midbrain fluorine-18 dopa levels in 10 adolescents with ADHD—48% higher, overall, than what was seen in 10 controls.43 They hypothesized that these opposite results were the results of a reduction in the dopaminergic neuronal density in adults, which might be part of the natural history of ADHD, or a normal age-related reduction in neuronal density, or both. Increased dopa levels in the team’s adolescent group were hypothesized to reflect up-regulation in dopamine synthesis due to low synaptic dopamine concentrations that might result from increased dopamine reuptake.

Dopamine-receptor imaging

The 5 distinct dopamine receptors (D1, D2, D3, D4, and D5) can be grouped into 2 subtypes, based on their coupling with G proteins. D1 and D5 constitute a group; D2, D3, and D4, a second group.

The D1 receptor is the most common dopamine receptor in the brain and is widely distributed in the striatum and prefrontal cerebral cortex. D1 receptor knockout mice demonstrate hyperactivity and poorer performance on learning tasks and are used as an animal model for ADHD.45 D1 has been imaged using C-11 SCH 23390 PET46 in rats, but its role in ADHD has yet to be evaluated. D5 is the most recently cloned and most widely distributed of the known dopamine receptors; however, there are no imaging studies of the D5 receptor.13

D2 receptors are present in presynaptic and postsynaptic neurons47 in the neocortex, substantia nigra, nucleus accumbens, and olfactory tubercle, as well as in other structures.48 Presynaptic D2 receptors act as autoregulators, inhibiting dopaminergic synthesis, firing rate, and release.49

Using C-11 raclopride PET imaging, Lou et al50 reported high D2/3 receptor availability in adolescents who had a history of perinatal cerebral ischemia. They found that this availability is associated with an increase in the severity of ADHD symptoms. They proposed that the increase in “empty” receptor density might have been caused by perinatal ischemia-induced presynaptic dopaminergic neuronal loss or an increase in presynaptic dopamine reuptake (Figure 550). Either mechanism could result in up-regulation in postsynaptic D2/3 receptors.

Volkow et al51 reported that D2 receptor density correlated with methylphenidate-induced changes in rCBF in frontal and temporal lobes in humans. They postulated that the variable therapeutic effects of methylphenidate seen in ADHD patients might be related to variations in baseline D2 receptor availability.

Lou et al50 reported elevated D2 receptor density, demonstrated using carbon-11 raclopride, in children with ADHD, compared with normal adults.

Further support for a relationship between D2-receptor density and symptomatic improvement with methylphenidate in ADHD was presented by Ilgin et al52 using iodine-123 iodobenzamide SPECT. They found elevated D2 receptor levels in 9 drug-naïve children with ADHD, which is 20% to 60% above what is seen in unaffected children. They noted that these patients showed improvement in hyperactivity when treated with methylphenidate.

In a similar study of 20 drug-naïve adults, Volkow et al53 found that durable symptomatic improvement with methylphenidate therapy was associated with increased D2 receptor availability.

Summing up

Striatal DaT is the most likely synaptic target for stratifying patients with ADHD, now that a dopamine transporter imaging agent is available commercially. Stratification might allow for refinement in the diagnostic categorization of ADHD, with introduction of stimulant-responsive and stimulant-unresponsive subtypes that are based on DaT imaging findings.

Bottom Line

Given recent advances showing molecular alterations in the dopaminergic-frontostriatal pathway as central to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, molecular imaging might be useful as an objective study for diagnosis.

Related Resources

• Schweitzer JB, Lee DO, Hanford RB, et al. A positron emission tomography study of methylphenidate in adults with ADHD: alterations in resting blood flow and predicting treatment response. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(5):967-973.

• Raz A. Brain imaging data of ADHD. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/adhd/brain-imaging-data-adhd.

Drug Brand Names

Iodine-123 ioflupane • Methylphenidate • Ritalin DaTscan

Acknowledgment

Kylee M. L. Unsdorfer, a medical student at Northeast Ohio Medical University, helped prepare the manuscript of this article.

Disclosures

Dr. Thacker reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Binkovitz received 4 doses of ioflupane I123I (DaTscan) from General Electric for investigator-initiated research, used for animal imaging in 2012.

1. Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, et al. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):942-948.

2. Simon V, Czobor P, Bálint S, et al. Prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(3):204-211.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Berger I. Diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: much ado about something. Isr Med Assoc J. 2011;13(9):571-574.

5. Schonwald A, Lechner E. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: complexities and controversies. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18(2):189-195.

6. Rousseau C, Measham T, Bathiche-Suidan M. DSM IV, culture and child psychiatry. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;17(2):69-75.

7. Taylor-Klaus E. Bringing the ADHD debate into sharper focus: part 1. The Huffington Post. http:// www.huffingtonpost.com/elaine-taylorklaus/adhd-debate_b_4571097.html. Updated March 17, 2014. Accessed August 18, 2015.

8. Sweeney CT, Sembower MA, Ertischek MD, et al. Nonmedical use of prescription ADHD stimulants and preexisting patterns of drug abuse. J Addict Dis. 2013;32(1):1-10.

9. Hitt E. Multiple reports of ADHD drug shortages. Medscape. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/742686. Published May 13, 2011. Accessed June 4, 2015.

10. Rubia K, Alegria AA, Cubillo AI, et al. Effects of stimulants on brain function in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;76(8):616-628.

11. Cortese S, Kelly C, Chabernaud C, et al. Toward systems neuroscience of ADHD: a meta-analysis of 55 fMRI studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(10):1038-1055.

12. Garnock-Jones KP, Keating GM. Atomoxetine: a review of its use in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Paediatr Drugs. 2009;11(3):203-226.

13. Wu J, Xiao H, Sun H, et al. Role of dopamine receptors in ADHD: a systematic meta-analysis. Mol Neurobiol. 2012; 45(3):605-620.

14. Del Campo N, Chamberlain SR, Sahakian BJ, et al. The roles of dopamine and noradrenaline in the pathophysiology and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69(12):e145-e157.

15. Berridge CW, Devilbiss DM. Psychostimulants as cognitive enhancers: the prefrontal cortex, catecholamines, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69(12):e101-e111.

16. Lou HC, Henriksen L, Bruhn P. Focal cerebral hypoperfusion in children with dysphasia and/or attention deficit disorder. Arch Neurol. 1984;41(8):825-829.

17. Gustafsson P, Thernlund G, Ryding E, et al. Associations between cerebral blood-flow measured by single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), electro-encephalogram (EEG), behaviour symptoms, cognition and neurological soft signs in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Acta Paediatr. 2000;89(7):830-835.

18. Sieg KG, Gaffney GR, Preston DF, et al. SPECT brain imaging abnormalities in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Clin Nucl Med. 1995;20(1):55-60.

19. Spalletta G, Pasini A, Pau F, et al. Prefrontal blood flow dysregulation in drug naive ADHD children without structural abnormalities. J Neural Transm. 2001;108(10):1203-1216.

20. Amen DG, Carmichael BD. High-resolution brain SPECT imaging in ADHD. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1997;9(2):81-86.

21. Kim BN, Lee JS, Cho SC, et al. Methylphenidate increased regional cerebral blood flow in subjects with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Yonsei Med J. 2001;42(1):19-29.

22. Lou HC, Henriksen L, Bruhn P, et al. Striatal dysfunction in attention deficit and hyperkinetic disorder. Arch Neurol. 1989;46(1):48-52.

23. Lee JS, Kim BN, Kang E, et al. Regional cerebral blood flow in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: comparison before and after methylphenidate treatment. Hum Brain Mapp. 2005;24(3):157-164.

24. Schweitzer JB, Lee DO, Hanford RB, et al. A positron emission tomography study of methylphenidate in adults with ADHD: alterations in resting blood flow and predicting treatment response. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(5):967-973.

25. Zametkin AJ, Nordahl TE, Gross M, et al. Cerebral glucose metabolism in adults with hyperactivity of childhood onset. N Engl J Med. 1990;323(20):1361-1366.

26. Zametkin AJ, Liebenauer LL, Fitzgerald GA, et al. Brain metabolism in teenagers with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(5):333-340.

27. Ernst M, Zametkin AJ, Matochik JA, et al. Effects of intravenous dextroamphetamine on brain metabolism in adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Preliminary findings. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1994;30(2):219-225.

28. Janssen M. Dopamine transporter (DaT) SPECT imaging. MI Gateway. 2012;6(1):1-3. http://interactive.snm.org/ docs/MI_Gateway_Newsletter_2012-1%20Dopamine%20 Transporter%20SPECT%20Imaging.pdf. Accessed August 18, 2015.

29. Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, et al. Dopamine transporter occupancies in the human brain induced by therapeutic doses of oral methylphenidate. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(10):1325-1331.

30. Volkow ND, Wang G, Fowler JS, et al. Therapeutic doses of oral methylphenidate significantly increase extracellular dopamine in the human brain. J Neurosci. 2001;21(2):RC121.

31. Dougherty DD, Bonab AA, Spencer TJ, et al. Dopamine transporter density in patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet. 1999;354(9196):2132-2133.

32. Li JJ, Lee SS. Interaction of dopamine transporter gene and observed parenting behaviors on attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder: a structural equation modeling approach. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2013;42(2):174-186.

33. Hesse S, Ballaschke O, Barthel H, et al. Dopamine transporter imaging in adult patients with attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2009;171(2):120-128.

34. Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Kollins SH, et al. Evaluating dopamine reward pathway in ADHD: clinical implications. JAMA. 2009;302(10):1084-1091.

35. Fusar-Poli P, Rubia K, Rossi G, et al. Striatal dopamine transporter alterations in ADHD: pathophysiology or adaptation to psychostimulants? A meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(3):264-272.

36. Wang GJ, Volkow ND, Wigal T, et al. Long-term stimulant treatment affects brain dopamine transporter level in patients with attention deficit hyperactive disorder. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63023.

37. Spencer TJ, Madras BK, Fischman AJ, et al. Striatal dopamine transporter binding in adults with ADHD. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(6):665; author reply 666.

38. Dresel S, Krause J, Krause KH, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: binding of [99mTc]TRODAT-1 to the dopamine transporter before and after methylphenidate treatment. Eur J Nucl Med. 2000;27(10):1518-1524.

39. Krause J, la Fougere C, Krause KH, et al. Influence of striatal dopamine transporter availability on the response to methylphenidate in adult patients with ADHD. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;255(6):428-431.

40. la Fougère C, Krause J, Krause KH, et al. Value of 99mTc-TRODAT-1 SPECT to predict clinical response to methylphenidate treatment in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Nucl Med Commun. 2006;27(9):733-737.

41. MTA Cooperative Group. National Institute of Mental Health Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD follow-up: 24-month outcomes of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2004;113(4):754-761.

42. da Silva N Jr, Szobot CM, Anselmi CE, et al. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: is there a correlation between dopamine transporter density and cerebral blood flow? Clin Nucl Med. 2011;36(8):656-660.

43. Ernst M, Zametkin AJ, Matochik JA, et al. High midbrain [18F]DOPA accumulation in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(8):1209-1215.

44. Ernst M, Zametkin AJ, Matochik JA, et al. DOPA decarboxylase activity in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder adults. A [fluorine-18]fluorodopa positron emission tomographic study. J Neurosci. 1998;18(15):5901-5907.

45. Xu M, Moratalla R, Gold LH, et al. Dopamine D1 receptor mutant mice are deficient in striatal expression of dynorphin and in dopamine-mediated behavioral responses. Cell. 1994;79(4):729-742.

46. Goodwin RJ, Mackay CL, Nilsson A, et al. Qualitative and quantitative MALDI imaging of the positron emission tomography ligands raclopride (a D2 dopamine antagonist) and SCH 23390 (a D1 dopamine antagonist) in rat brain tissue sections using a solvent-free dry matrix application method. Anal Chem. 2011;83(24):9694-9701.

47. Negyessy L, Goldman-Rakic PS. Subcellular localization of the dopamine D2 receptor and coexistence with the calcium-binding protein neuronal calcium sensor-1 in the primate prefrontal cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2005;488(4):464-475.

48. Boyson SJ, McGonigle P, Molinoff PB. Quantitative autoradiographic localization of the D1 and D2 subtypes of dopamine receptors in rat brain. J Neurosci. 1986;6(11):3177-3188.

49. Doi M, Yujnovsky I, Hirayama J, et al. Impaired light masking in dopamine D2 receptor-null mice. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(6):732-734.

50. Lou HC, Rosa P, Pryds O, et al. ADHD: increased dopamine receptor availability linked to attention deficit and low neonatal cerebral blood flow. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2004;46(3):179-183.

51. Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, et al. Effects of methylphenidate on regional brain glucose metabolism in humans: relationship to dopamine D2 receptors. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(1):50-55.

52. Ilgin N, Senol S, Gucuyener K, et al. Is increased D2 receptor availability associated with response to stimulant medication in ADHD. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001;43(11):755-760.

53. Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Tomasi D, et al. Methylphenidate-elicited dopamine increases in ventral striatum are associated with long-term symptom improvement in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Neurosci. 2012;32(3):841-849.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common pediatric psychiatric disorders, occurring in approximately 5% of children.1 The disorder persists into adulthood in about one-half of those who are affected in childhood.2 In adults and children, diagnosis continues to be based on the examiner’s subjective assessment. (Box 13-9 describes how ADHD presents a complicated, moving target for the diagnostician.)

Patients who have ADHD are rarely studied with imaging; there are no established imaging findings associated with an ADHD diagnosis. Over the past 20 years, however, significant research has shown that molecular alterations along the dopaminergic−frontostriatal pathways occur in association with the behavioral constellation of ADHD symptoms—suggesting a pathophysiologic mechanism for this disorder.

In this article, we describe molecular findings from nuclear medicine imaging in ADHD. We also summarize imaging evidence for dysfunction of the dopaminergic-frontostriatal neural circuits as central in the pathophysiology of ADHD, with special focus on the dopamine reuptake transporter (DaT). Box 210,11 reviews our key observations and looks at the future of imaging in the management of ADHD.

Dopaminergic theory of ADHD

The executive functions that are disordered in ADHD (impulse control, judgment, maintaining attention) are thought to be centered in the infraorbital, dorsolateral, and medial frontal lobes. Neurotransmitters that have been implicated in the pathophysiology of ADHD include norepinephrine12 and dopamine13; medications that selectively block reuptake of these neurotransmitters are used to treat ADHD.14,15 Only the dopamine system has been extensively evaluated with molecular imaging techniques.

Because methylphenidate, a potent selective dopamine reuptake inhibitor, has been shown to reduce disordered executive functional behaviors in ADHD, considerable imaging research has focused on the dopaminergic neural circuits in the frontostriatal regions of the brain. The dopaminergic theory of ADHD is based on the hypothesis that alterations in the density or function of these circuits are responsible for behaviors that constitute ADHD.

Despite decades of efforts to delineate the underlying pathophysiology and neurochemistry of ADHD, no single unifying theory accounts for all imaging findings in all patients. This might be in part because of imprecision inherent in psychiatric diagnoses that are based on subjective observations. The behavioral criteria for ADHD can manifest in several disorders. For example, anxiety-related symptoms seen in posttraumatic stress disorder, social anxiety disorder, and panic disorder also present as behaviors similar to those in ADHD diagnostic criteria.

Molecular imaging might provide a window into the underlying pathophysiology of ADHD and, by identifying objective findings, (1) allow for patient stratification based on underlying physiologic subtypes, (2) refine diagnostic criteria, and (3) predict treatment response.

Nuclear medicine findings

In general, nuclear medicine investigations of ADHD can be divided into studies of changes in regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) or glucose metabolism (rCGM) and those that have assessed the concentration of synaptic structures, using highly specific radiolabeled ligands. Both kinds of studies provide limited anatomic resolution, unless co-registered with MRI or CT scans and either single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) or positron emission tomography (PET).

Synaptic imaging using radiolabeled ligands with high biologic specificity for synaptic structures has high molecular resolution—that is, radiolabeled ligands used for selective imaging of the dopamine transporter or receptor do not identify serotonin transporters or receptors, and vice versa. (Details of SPECT and PET techniques are beyond the scope of this article but can be found in standard nuclear medicine textbooks.)

SPECT and PET of rCBF

Early investigations of rCBF in ADHD were performed using inhaled radioactive xenon-133 gas.16 Later, rCBF was assessed using fat-soluble radiolabeled ligands that rapidly distribute in the brain in proportion to blood flow by crossing the blood−brain barrier. Labeled with radioactive 99m-technetium, these ligands cross rapidly into brain cells after IV injection. Once intracellular, covalent bonds within the ligands cleave into 2 charged particles that do not easily recross the cell membrane. There is little redistribution of tracer after initial uptake.

The imaging data set that results can be reconstructed as (1) surface images, on which defects indicate areas of reduced rCBF, or (2) tomographic slices on which color scales indicate relative rCBF values (Figure 1). Because of the minimal redistribution of the tracer, SPECT images obtained 1 or 2 hours after injection provide a snapshot of rCBF at the time tracer is injected. Patients can be injected under various conditions, such as at rest with eyes and ears open in a dimly lit, quiet room, and then under cognitive stress (Figure 2), such as performing a computer-based attention and impulse control task, or during stimulant treatment.

Numerous investigators have found reduced frontal or striatal rCBF, or both, in patients with ADHD, unilaterally on the right17 or left,18,19 or bilaterally.20 Additionally, with stimulant therapy, normalization of striatal and frontal rCBF has been demonstrated14,19—changes that correlate with resolution of behavioral symptoms of ADHD with stimulant treatment.21

SPECT of 32 boys with previously untreated ADHD. Kim et al21 found that the presence of reduced right or left, or both, frontal rCBF, which normalized with 8 weeks of stimulant therapy, predicted symptom improvement in 85% of patients. Absence of improvement of reduced frontal rCBF had a 75% negative predictive value for treatment response. (Additionally, hyperperfusion of the somatosensory cortex has been demonstrated in children with ADHD,16,22 suggesting increased responsiveness to extraneous environmental input.)

SPECT of 40 untreated pediatric patients compared with 17 age-matched controls. Using SPECT, Lee et al23 reported rCBF reductions in the orbitofrontal cortex and the medial temporal gyrus of participants; reductions corresponded to areas of motor and impulsivity control. The researchers also demonstrated increased rCBF in the somatosensory area.

After methylphenidate treatment, blood flow to these areas normalized, and rCBF to higher visual and superior prefrontal areas decreased. Substantial clinical improvement occurred in 64% of patients—suggesting methylphenidate treatment of ADHD works by (1) increasing function of areas of the brain that control impulses, motor activity, and attention, and (2) reducing function to sensory areas that lead to distraction by extraneous environmental sensory input.

O-15-labeled water PET of 10 adults with ADHD. Schweitzer et al24 found that participants who demonstrated improvement in behavioral symptoms with chronic stimulant therapy had reduced rCBF in the striata at baseline—again, suggesting that baseline hypometabolism in the striata is associated with ADHD.

PET of regional cerebral glucose metabolism

Cerebral metabolism requires a constant supply of glucose; regional differences in cerebral glucose metabolism can be assessed directly with positron-emitting F-18-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose. Although metabolically inert, this agent is transported intracellularly similar to glucose; once phosphorylated within brain cells, however, it can no longer undergo further metabolism or redistribution.

Studies using PET to assess rCGM were some of the earliest molecular imaging applications in ADHD. Zametkin et al25 reported low global cerebral glucose utilization in adults, but not adolescents,26 with ADHD. However, further study, with normalization of the PET data, confirmed reduced rCGM in the left prefrontal cortex in both adolescents26 and adults,27 indicating hypometabolism of cortical areas associated with impulse control and attention in ADHD. In adolescents, symptom severity was inversely related to rCBF in the left anterior frontal cortex.

Synaptic imaging

Nuclear imaging has been used to study several components of the striatal dopaminergic synapse, including:

• dopamine substrates, using fluorine- 18-labeled dopa or carbon-11-labeled dopa

• dopamine receptors, using carbon- 11-labeled raclopride or iodine-123 iodobenzamide

• the tDaT, using iodine-123 ioflupane, 99m-technetium TRODAT, or carbon-11 cocaine (Figure 3).

All of these synaptic imaging agents were used mainly as research tools until 2011, when the FDA approved the SPECT imaging agent iodine-123 ioflupane (DaTscan) for clinical use in assessment of Parkinson’s disease.28 This commercially available agent has high specificity for the DaT, with little background activity noted on SPECT imaging (Figure 4).

Dopamine transporter imaging

Because the site of action of methylphenidate is the DaT, imaging this component of the striatal dopaminergic synapse has been an area of intense investigation in ADHD. Located almost exclusively in the striata, DaT reduces synaptic concentrations of dopamine by means of reuptake channels in the cell membrane.29 By reversibly binding to, and occupying sites on, the DaT, methylphenidate impedes dopamine reuptake, which results in increased availability of dopamine at the synapse.30

By demonstrating an increase in striatal DaT density in patients with ADHD— first reported by Dougherty et al31 using iodine-123 altropane (a dopaminergic uptake inhibitor) in 6 adults with ADHD—investigators have hypothesized that excessive expression of the DaT protein in the striata, which may result from genetic or environmental factors, is a central causative agent of ADHD.32 Subsequent studies, however, have yielded contradictory findings: Hesse et al,33 using SPECT imaging, and Volkow et al,34 using carbon-11 cocaine PET imaging, found reduced DaT density in, respectively, 9 and 26 patients with ADHD.

To clarify the role of DaT levels in the etiology of ADHD and to explain discrepant results, Fusar-Poli et al35 performed a meta-analysis of 9 published papers that reported the results of DaT imaging in a total of 169 ADHD patients and 129 controls. They noted that these studies included 6 different imaging agents and protocols. Patients were stimulant therapy-naïve (n = 137) or drug-free (refrained from stimulant therapy for a time [n = 32]). The team found that the degree of elevation of the striatal DaT concentration correlated with a history of stimulant exposure, and that the drug-naïve group had a reduced DaT level.

Fusar-Poli’s hypothesis? Elevated DaT levels result from up-regulation in the presence of chronic methylphenidate therapy, which accounts for early reports that demonstrated increased striatal DaT density. Clinically, up-regulation might explain the lack of sustained relief of behavioral symptoms with stimulant therapy in 20% of patients with ADHD who showed clinical improvement initially.36

Only limited conclusions can be drawn about the role of DaT levels in ADHD, given the small number of patients studied in published reports. In addition, the Fusar-Poli meta-analysis has come under strong criticism because of methodological errors with improper patient inclusion and characterization of treatment status,37 calling into question the investigators’ conclusions.

Does the DaT level hold promise for practice? Despite a lack of clarity about the significance of DaT level in the etiology of ADHD, knowledge of a patient’s level might prove useful in predicting which patients will respond to methylphenidate. Namely, several researchers have found that:

• an elevated baseline level of DaT (before stimulant therapy) correlates with robust clinical response

• absence of an elevated baseline DaT level suggests that symptomatic improvement with stimulant therapy in unlikely.38-40

Dresel et al38 evaluated 17 drug-naïve adults, newly diagnosed with ADHD, using 99m-technetium TRODAT SPECT before and after methylphenidate therapy. They found a 15% increase in specific DaT binding in patients with ADHD, compared with controls, at baseline. After treatment, the researchers observed a 28% reduction in specific DaT binding—a significant change from baseline that correlated with behavioral response.

Study: SPECT in 18 adults with ADHD given methylphenidate. Krause39 used the same SPECT agent to study 18 adults before they received methylphenidate and 10 weeks after treatment. Participants were categorized as responders or nonresponders based on clinical assessment of ADHD symptoms after those 10 weeks. All 12 responders had an elevated striatal DaT concentration at baseline. Of the 6 nonresponders, 5 had a normal level of striatal DaT compared with age-matched controls.

Study: 22 Adult ADHD patients evaluated with 99m-technetium TRODAT SPECT. The same group of investigators40 presented imaging findings in 22 additional adult patients. Seventeen had an elevated striatal DaT level, 16 of whom responded to stimulant therapy. The remaining 5 patients had reduced striatal DaT at baseline; none had a good clinical response to methylphenidate.

The positive clinical response to methylphenidate in 67%37 and 77%40 of patients is in good agreement with results from larger studies, which reported that approximately 75% of patients with ADHD show prompt clinical improvement with stimulants.41 Improvement might be related to an increase in functioning of the frontostriatal dopaminergic circuit that is seen with stimulant therapy. Increased availability of dopamine at the synapse, resulting from stimulant blockade of the dopamine reuptake transporter, produces increased dopamine neurotransmission and increased activation of frontostriatal circuits.

In another study, rCBF in frontostriatal circuits was determined to be inversely proportional to DaT density; rCBF normalized with stimulant therapy.42

Will imaging pave the way for therapeutic stratification? Baseline determinations of striatal DaT concentration with SPECT imaging might make it possible to stratify patients with ADHD symptoms into those likely to show significant behavioral symptom response to methylphenidate and those who are not likely to respond. There might be an objective imaging finding—striatal DaT density—that allows clinicians to distinguish stimulant-responsive ADHD from stimulant-unresponsive ADHD.

Dopamine substrate imaging

Radiolabeled dopa (carbon-11 or fluorine-18) is transported into presynaptic dopaminergic neurons in the striatum, where it is decarboxylated, converted to radio-dopamine, and stored within vesicles until released in response to neuronal excitation. Semi-quantitative assessment is achieved with calculation of specific (striatal) to nonspecific (background) uptake ratios. Increased values are thought to indicate increased density of dopaminergic neurons.43

Ernst et al44 reported a 50% decrease in specific fluorine-18 dopa uptake in the left prefrontal cortex in 17 drug-naïve adults with ADHD, compared with 23 controls. The same team reported increased midbrain fluorine-18 dopa levels in 10 adolescents with ADHD—48% higher, overall, than what was seen in 10 controls.43 They hypothesized that these opposite results were the results of a reduction in the dopaminergic neuronal density in adults, which might be part of the natural history of ADHD, or a normal age-related reduction in neuronal density, or both. Increased dopa levels in the team’s adolescent group were hypothesized to reflect up-regulation in dopamine synthesis due to low synaptic dopamine concentrations that might result from increased dopamine reuptake.

Dopamine-receptor imaging

The 5 distinct dopamine receptors (D1, D2, D3, D4, and D5) can be grouped into 2 subtypes, based on their coupling with G proteins. D1 and D5 constitute a group; D2, D3, and D4, a second group.

The D1 receptor is the most common dopamine receptor in the brain and is widely distributed in the striatum and prefrontal cerebral cortex. D1 receptor knockout mice demonstrate hyperactivity and poorer performance on learning tasks and are used as an animal model for ADHD.45 D1 has been imaged using C-11 SCH 23390 PET46 in rats, but its role in ADHD has yet to be evaluated. D5 is the most recently cloned and most widely distributed of the known dopamine receptors; however, there are no imaging studies of the D5 receptor.13

D2 receptors are present in presynaptic and postsynaptic neurons47 in the neocortex, substantia nigra, nucleus accumbens, and olfactory tubercle, as well as in other structures.48 Presynaptic D2 receptors act as autoregulators, inhibiting dopaminergic synthesis, firing rate, and release.49

Using C-11 raclopride PET imaging, Lou et al50 reported high D2/3 receptor availability in adolescents who had a history of perinatal cerebral ischemia. They found that this availability is associated with an increase in the severity of ADHD symptoms. They proposed that the increase in “empty” receptor density might have been caused by perinatal ischemia-induced presynaptic dopaminergic neuronal loss or an increase in presynaptic dopamine reuptake (Figure 550). Either mechanism could result in up-regulation in postsynaptic D2/3 receptors.

Volkow et al51 reported that D2 receptor density correlated with methylphenidate-induced changes in rCBF in frontal and temporal lobes in humans. They postulated that the variable therapeutic effects of methylphenidate seen in ADHD patients might be related to variations in baseline D2 receptor availability.

Lou et al50 reported elevated D2 receptor density, demonstrated using carbon-11 raclopride, in children with ADHD, compared with normal adults.

Further support for a relationship between D2-receptor density and symptomatic improvement with methylphenidate in ADHD was presented by Ilgin et al52 using iodine-123 iodobenzamide SPECT. They found elevated D2 receptor levels in 9 drug-naïve children with ADHD, which is 20% to 60% above what is seen in unaffected children. They noted that these patients showed improvement in hyperactivity when treated with methylphenidate.

In a similar study of 20 drug-naïve adults, Volkow et al53 found that durable symptomatic improvement with methylphenidate therapy was associated with increased D2 receptor availability.

Summing up

Striatal DaT is the most likely synaptic target for stratifying patients with ADHD, now that a dopamine transporter imaging agent is available commercially. Stratification might allow for refinement in the diagnostic categorization of ADHD, with introduction of stimulant-responsive and stimulant-unresponsive subtypes that are based on DaT imaging findings.

Bottom Line

Given recent advances showing molecular alterations in the dopaminergic-frontostriatal pathway as central to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, molecular imaging might be useful as an objective study for diagnosis.

Related Resources

• Schweitzer JB, Lee DO, Hanford RB, et al. A positron emission tomography study of methylphenidate in adults with ADHD: alterations in resting blood flow and predicting treatment response. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(5):967-973.

• Raz A. Brain imaging data of ADHD. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/adhd/brain-imaging-data-adhd.

Drug Brand Names

Iodine-123 ioflupane • Methylphenidate • Ritalin DaTscan

Acknowledgment

Kylee M. L. Unsdorfer, a medical student at Northeast Ohio Medical University, helped prepare the manuscript of this article.

Disclosures

Dr. Thacker reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Binkovitz received 4 doses of ioflupane I123I (DaTscan) from General Electric for investigator-initiated research, used for animal imaging in 2012.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common pediatric psychiatric disorders, occurring in approximately 5% of children.1 The disorder persists into adulthood in about one-half of those who are affected in childhood.2 In adults and children, diagnosis continues to be based on the examiner’s subjective assessment. (Box 13-9 describes how ADHD presents a complicated, moving target for the diagnostician.)

Patients who have ADHD are rarely studied with imaging; there are no established imaging findings associated with an ADHD diagnosis. Over the past 20 years, however, significant research has shown that molecular alterations along the dopaminergic−frontostriatal pathways occur in association with the behavioral constellation of ADHD symptoms—suggesting a pathophysiologic mechanism for this disorder.

In this article, we describe molecular findings from nuclear medicine imaging in ADHD. We also summarize imaging evidence for dysfunction of the dopaminergic-frontostriatal neural circuits as central in the pathophysiology of ADHD, with special focus on the dopamine reuptake transporter (DaT). Box 210,11 reviews our key observations and looks at the future of imaging in the management of ADHD.

Dopaminergic theory of ADHD

The executive functions that are disordered in ADHD (impulse control, judgment, maintaining attention) are thought to be centered in the infraorbital, dorsolateral, and medial frontal lobes. Neurotransmitters that have been implicated in the pathophysiology of ADHD include norepinephrine12 and dopamine13; medications that selectively block reuptake of these neurotransmitters are used to treat ADHD.14,15 Only the dopamine system has been extensively evaluated with molecular imaging techniques.

Because methylphenidate, a potent selective dopamine reuptake inhibitor, has been shown to reduce disordered executive functional behaviors in ADHD, considerable imaging research has focused on the dopaminergic neural circuits in the frontostriatal regions of the brain. The dopaminergic theory of ADHD is based on the hypothesis that alterations in the density or function of these circuits are responsible for behaviors that constitute ADHD.

Despite decades of efforts to delineate the underlying pathophysiology and neurochemistry of ADHD, no single unifying theory accounts for all imaging findings in all patients. This might be in part because of imprecision inherent in psychiatric diagnoses that are based on subjective observations. The behavioral criteria for ADHD can manifest in several disorders. For example, anxiety-related symptoms seen in posttraumatic stress disorder, social anxiety disorder, and panic disorder also present as behaviors similar to those in ADHD diagnostic criteria.

Molecular imaging might provide a window into the underlying pathophysiology of ADHD and, by identifying objective findings, (1) allow for patient stratification based on underlying physiologic subtypes, (2) refine diagnostic criteria, and (3) predict treatment response.

Nuclear medicine findings

In general, nuclear medicine investigations of ADHD can be divided into studies of changes in regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) or glucose metabolism (rCGM) and those that have assessed the concentration of synaptic structures, using highly specific radiolabeled ligands. Both kinds of studies provide limited anatomic resolution, unless co-registered with MRI or CT scans and either single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) or positron emission tomography (PET).

Synaptic imaging using radiolabeled ligands with high biologic specificity for synaptic structures has high molecular resolution—that is, radiolabeled ligands used for selective imaging of the dopamine transporter or receptor do not identify serotonin transporters or receptors, and vice versa. (Details of SPECT and PET techniques are beyond the scope of this article but can be found in standard nuclear medicine textbooks.)

SPECT and PET of rCBF

Early investigations of rCBF in ADHD were performed using inhaled radioactive xenon-133 gas.16 Later, rCBF was assessed using fat-soluble radiolabeled ligands that rapidly distribute in the brain in proportion to blood flow by crossing the blood−brain barrier. Labeled with radioactive 99m-technetium, these ligands cross rapidly into brain cells after IV injection. Once intracellular, covalent bonds within the ligands cleave into 2 charged particles that do not easily recross the cell membrane. There is little redistribution of tracer after initial uptake.

The imaging data set that results can be reconstructed as (1) surface images, on which defects indicate areas of reduced rCBF, or (2) tomographic slices on which color scales indicate relative rCBF values (Figure 1). Because of the minimal redistribution of the tracer, SPECT images obtained 1 or 2 hours after injection provide a snapshot of rCBF at the time tracer is injected. Patients can be injected under various conditions, such as at rest with eyes and ears open in a dimly lit, quiet room, and then under cognitive stress (Figure 2), such as performing a computer-based attention and impulse control task, or during stimulant treatment.

Numerous investigators have found reduced frontal or striatal rCBF, or both, in patients with ADHD, unilaterally on the right17 or left,18,19 or bilaterally.20 Additionally, with stimulant therapy, normalization of striatal and frontal rCBF has been demonstrated14,19—changes that correlate with resolution of behavioral symptoms of ADHD with stimulant treatment.21

SPECT of 32 boys with previously untreated ADHD. Kim et al21 found that the presence of reduced right or left, or both, frontal rCBF, which normalized with 8 weeks of stimulant therapy, predicted symptom improvement in 85% of patients. Absence of improvement of reduced frontal rCBF had a 75% negative predictive value for treatment response. (Additionally, hyperperfusion of the somatosensory cortex has been demonstrated in children with ADHD,16,22 suggesting increased responsiveness to extraneous environmental input.)

SPECT of 40 untreated pediatric patients compared with 17 age-matched controls. Using SPECT, Lee et al23 reported rCBF reductions in the orbitofrontal cortex and the medial temporal gyrus of participants; reductions corresponded to areas of motor and impulsivity control. The researchers also demonstrated increased rCBF in the somatosensory area.

After methylphenidate treatment, blood flow to these areas normalized, and rCBF to higher visual and superior prefrontal areas decreased. Substantial clinical improvement occurred in 64% of patients—suggesting methylphenidate treatment of ADHD works by (1) increasing function of areas of the brain that control impulses, motor activity, and attention, and (2) reducing function to sensory areas that lead to distraction by extraneous environmental sensory input.

O-15-labeled water PET of 10 adults with ADHD. Schweitzer et al24 found that participants who demonstrated improvement in behavioral symptoms with chronic stimulant therapy had reduced rCBF in the striata at baseline—again, suggesting that baseline hypometabolism in the striata is associated with ADHD.

PET of regional cerebral glucose metabolism

Cerebral metabolism requires a constant supply of glucose; regional differences in cerebral glucose metabolism can be assessed directly with positron-emitting F-18-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose. Although metabolically inert, this agent is transported intracellularly similar to glucose; once phosphorylated within brain cells, however, it can no longer undergo further metabolism or redistribution.

Studies using PET to assess rCGM were some of the earliest molecular imaging applications in ADHD. Zametkin et al25 reported low global cerebral glucose utilization in adults, but not adolescents,26 with ADHD. However, further study, with normalization of the PET data, confirmed reduced rCGM in the left prefrontal cortex in both adolescents26 and adults,27 indicating hypometabolism of cortical areas associated with impulse control and attention in ADHD. In adolescents, symptom severity was inversely related to rCBF in the left anterior frontal cortex.

Synaptic imaging

Nuclear imaging has been used to study several components of the striatal dopaminergic synapse, including:

• dopamine substrates, using fluorine- 18-labeled dopa or carbon-11-labeled dopa

• dopamine receptors, using carbon- 11-labeled raclopride or iodine-123 iodobenzamide

• the tDaT, using iodine-123 ioflupane, 99m-technetium TRODAT, or carbon-11 cocaine (Figure 3).

All of these synaptic imaging agents were used mainly as research tools until 2011, when the FDA approved the SPECT imaging agent iodine-123 ioflupane (DaTscan) for clinical use in assessment of Parkinson’s disease.28 This commercially available agent has high specificity for the DaT, with little background activity noted on SPECT imaging (Figure 4).

Dopamine transporter imaging

Because the site of action of methylphenidate is the DaT, imaging this component of the striatal dopaminergic synapse has been an area of intense investigation in ADHD. Located almost exclusively in the striata, DaT reduces synaptic concentrations of dopamine by means of reuptake channels in the cell membrane.29 By reversibly binding to, and occupying sites on, the DaT, methylphenidate impedes dopamine reuptake, which results in increased availability of dopamine at the synapse.30

By demonstrating an increase in striatal DaT density in patients with ADHD— first reported by Dougherty et al31 using iodine-123 altropane (a dopaminergic uptake inhibitor) in 6 adults with ADHD—investigators have hypothesized that excessive expression of the DaT protein in the striata, which may result from genetic or environmental factors, is a central causative agent of ADHD.32 Subsequent studies, however, have yielded contradictory findings: Hesse et al,33 using SPECT imaging, and Volkow et al,34 using carbon-11 cocaine PET imaging, found reduced DaT density in, respectively, 9 and 26 patients with ADHD.

To clarify the role of DaT levels in the etiology of ADHD and to explain discrepant results, Fusar-Poli et al35 performed a meta-analysis of 9 published papers that reported the results of DaT imaging in a total of 169 ADHD patients and 129 controls. They noted that these studies included 6 different imaging agents and protocols. Patients were stimulant therapy-naïve (n = 137) or drug-free (refrained from stimulant therapy for a time [n = 32]). The team found that the degree of elevation of the striatal DaT concentration correlated with a history of stimulant exposure, and that the drug-naïve group had a reduced DaT level.

Fusar-Poli’s hypothesis? Elevated DaT levels result from up-regulation in the presence of chronic methylphenidate therapy, which accounts for early reports that demonstrated increased striatal DaT density. Clinically, up-regulation might explain the lack of sustained relief of behavioral symptoms with stimulant therapy in 20% of patients with ADHD who showed clinical improvement initially.36

Only limited conclusions can be drawn about the role of DaT levels in ADHD, given the small number of patients studied in published reports. In addition, the Fusar-Poli meta-analysis has come under strong criticism because of methodological errors with improper patient inclusion and characterization of treatment status,37 calling into question the investigators’ conclusions.

Does the DaT level hold promise for practice? Despite a lack of clarity about the significance of DaT level in the etiology of ADHD, knowledge of a patient’s level might prove useful in predicting which patients will respond to methylphenidate. Namely, several researchers have found that:

• an elevated baseline level of DaT (before stimulant therapy) correlates with robust clinical response

• absence of an elevated baseline DaT level suggests that symptomatic improvement with stimulant therapy in unlikely.38-40

Dresel et al38 evaluated 17 drug-naïve adults, newly diagnosed with ADHD, using 99m-technetium TRODAT SPECT before and after methylphenidate therapy. They found a 15% increase in specific DaT binding in patients with ADHD, compared with controls, at baseline. After treatment, the researchers observed a 28% reduction in specific DaT binding—a significant change from baseline that correlated with behavioral response.

Study: SPECT in 18 adults with ADHD given methylphenidate. Krause39 used the same SPECT agent to study 18 adults before they received methylphenidate and 10 weeks after treatment. Participants were categorized as responders or nonresponders based on clinical assessment of ADHD symptoms after those 10 weeks. All 12 responders had an elevated striatal DaT concentration at baseline. Of the 6 nonresponders, 5 had a normal level of striatal DaT compared with age-matched controls.

Study: 22 Adult ADHD patients evaluated with 99m-technetium TRODAT SPECT. The same group of investigators40 presented imaging findings in 22 additional adult patients. Seventeen had an elevated striatal DaT level, 16 of whom responded to stimulant therapy. The remaining 5 patients had reduced striatal DaT at baseline; none had a good clinical response to methylphenidate.

The positive clinical response to methylphenidate in 67%37 and 77%40 of patients is in good agreement with results from larger studies, which reported that approximately 75% of patients with ADHD show prompt clinical improvement with stimulants.41 Improvement might be related to an increase in functioning of the frontostriatal dopaminergic circuit that is seen with stimulant therapy. Increased availability of dopamine at the synapse, resulting from stimulant blockade of the dopamine reuptake transporter, produces increased dopamine neurotransmission and increased activation of frontostriatal circuits.

In another study, rCBF in frontostriatal circuits was determined to be inversely proportional to DaT density; rCBF normalized with stimulant therapy.42

Will imaging pave the way for therapeutic stratification? Baseline determinations of striatal DaT concentration with SPECT imaging might make it possible to stratify patients with ADHD symptoms into those likely to show significant behavioral symptom response to methylphenidate and those who are not likely to respond. There might be an objective imaging finding—striatal DaT density—that allows clinicians to distinguish stimulant-responsive ADHD from stimulant-unresponsive ADHD.

Dopamine substrate imaging

Radiolabeled dopa (carbon-11 or fluorine-18) is transported into presynaptic dopaminergic neurons in the striatum, where it is decarboxylated, converted to radio-dopamine, and stored within vesicles until released in response to neuronal excitation. Semi-quantitative assessment is achieved with calculation of specific (striatal) to nonspecific (background) uptake ratios. Increased values are thought to indicate increased density of dopaminergic neurons.43

Ernst et al44 reported a 50% decrease in specific fluorine-18 dopa uptake in the left prefrontal cortex in 17 drug-naïve adults with ADHD, compared with 23 controls. The same team reported increased midbrain fluorine-18 dopa levels in 10 adolescents with ADHD—48% higher, overall, than what was seen in 10 controls.43 They hypothesized that these opposite results were the results of a reduction in the dopaminergic neuronal density in adults, which might be part of the natural history of ADHD, or a normal age-related reduction in neuronal density, or both. Increased dopa levels in the team’s adolescent group were hypothesized to reflect up-regulation in dopamine synthesis due to low synaptic dopamine concentrations that might result from increased dopamine reuptake.

Dopamine-receptor imaging

The 5 distinct dopamine receptors (D1, D2, D3, D4, and D5) can be grouped into 2 subtypes, based on their coupling with G proteins. D1 and D5 constitute a group; D2, D3, and D4, a second group.

The D1 receptor is the most common dopamine receptor in the brain and is widely distributed in the striatum and prefrontal cerebral cortex. D1 receptor knockout mice demonstrate hyperactivity and poorer performance on learning tasks and are used as an animal model for ADHD.45 D1 has been imaged using C-11 SCH 23390 PET46 in rats, but its role in ADHD has yet to be evaluated. D5 is the most recently cloned and most widely distributed of the known dopamine receptors; however, there are no imaging studies of the D5 receptor.13

D2 receptors are present in presynaptic and postsynaptic neurons47 in the neocortex, substantia nigra, nucleus accumbens, and olfactory tubercle, as well as in other structures.48 Presynaptic D2 receptors act as autoregulators, inhibiting dopaminergic synthesis, firing rate, and release.49

Using C-11 raclopride PET imaging, Lou et al50 reported high D2/3 receptor availability in adolescents who had a history of perinatal cerebral ischemia. They found that this availability is associated with an increase in the severity of ADHD symptoms. They proposed that the increase in “empty” receptor density might have been caused by perinatal ischemia-induced presynaptic dopaminergic neuronal loss or an increase in presynaptic dopamine reuptake (Figure 550). Either mechanism could result in up-regulation in postsynaptic D2/3 receptors.

Volkow et al51 reported that D2 receptor density correlated with methylphenidate-induced changes in rCBF in frontal and temporal lobes in humans. They postulated that the variable therapeutic effects of methylphenidate seen in ADHD patients might be related to variations in baseline D2 receptor availability.

Lou et al50 reported elevated D2 receptor density, demonstrated using carbon-11 raclopride, in children with ADHD, compared with normal adults.

Further support for a relationship between D2-receptor density and symptomatic improvement with methylphenidate in ADHD was presented by Ilgin et al52 using iodine-123 iodobenzamide SPECT. They found elevated D2 receptor levels in 9 drug-naïve children with ADHD, which is 20% to 60% above what is seen in unaffected children. They noted that these patients showed improvement in hyperactivity when treated with methylphenidate.

In a similar study of 20 drug-naïve adults, Volkow et al53 found that durable symptomatic improvement with methylphenidate therapy was associated with increased D2 receptor availability.

Summing up

Striatal DaT is the most likely synaptic target for stratifying patients with ADHD, now that a dopamine transporter imaging agent is available commercially. Stratification might allow for refinement in the diagnostic categorization of ADHD, with introduction of stimulant-responsive and stimulant-unresponsive subtypes that are based on DaT imaging findings.

Bottom Line

Given recent advances showing molecular alterations in the dopaminergic-frontostriatal pathway as central to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, molecular imaging might be useful as an objective study for diagnosis.

Related Resources

• Schweitzer JB, Lee DO, Hanford RB, et al. A positron emission tomography study of methylphenidate in adults with ADHD: alterations in resting blood flow and predicting treatment response. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(5):967-973.

• Raz A. Brain imaging data of ADHD. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/adhd/brain-imaging-data-adhd.

Drug Brand Names

Iodine-123 ioflupane • Methylphenidate • Ritalin DaTscan

Acknowledgment

Kylee M. L. Unsdorfer, a medical student at Northeast Ohio Medical University, helped prepare the manuscript of this article.

Disclosures

Dr. Thacker reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Binkovitz received 4 doses of ioflupane I123I (DaTscan) from General Electric for investigator-initiated research, used for animal imaging in 2012.

1. Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, et al. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):942-948.

2. Simon V, Czobor P, Bálint S, et al. Prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(3):204-211.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Berger I. Diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: much ado about something. Isr Med Assoc J. 2011;13(9):571-574.