User login

Prescription opioid overdoses targeted in new CDC program

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has launched a program aimed at helping states combat and prevent opioid drug overdoses.

The Prescription Drug Overdose: Prevention for States program will be launching in 16 states chosen in a competitive application process. The CDC is committing $20 million in fiscal year 2015, and each state will receive $750,000 to $1 million each year for the next 4 years to advance prevention in several areas, such as enhancing prescription drug–monitoring programs, putting prevention into action in communities nationwide, and investigating the connection between prescription opioid abuse and heroin use, the CDC said in a press release.

In 2013, 16,000 people died from prescription opioid overdoses, four times more than in 1999, with prescription of opioids increasing at the same rate over the same time. Despite more opioids being prescribed, the amount of pain Americans report has not changed. In addition, heroin deaths also have spiked, with the 8,000 heroin overdose deaths nearly three times as many as in 2010.

“The prescription drug overdose epidemic requires a multifaceted approach, and states are key partners in our efforts on the front lines to prevent overdose deaths. With this funding, states can improve their ability to track the problem, work with insurers to help providers make informed prescribing decisions, and take action to combat this epidemic,” U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Sylvia M. Burwell said in the release.

Find the full CDC press release here.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has launched a program aimed at helping states combat and prevent opioid drug overdoses.

The Prescription Drug Overdose: Prevention for States program will be launching in 16 states chosen in a competitive application process. The CDC is committing $20 million in fiscal year 2015, and each state will receive $750,000 to $1 million each year for the next 4 years to advance prevention in several areas, such as enhancing prescription drug–monitoring programs, putting prevention into action in communities nationwide, and investigating the connection between prescription opioid abuse and heroin use, the CDC said in a press release.

In 2013, 16,000 people died from prescription opioid overdoses, four times more than in 1999, with prescription of opioids increasing at the same rate over the same time. Despite more opioids being prescribed, the amount of pain Americans report has not changed. In addition, heroin deaths also have spiked, with the 8,000 heroin overdose deaths nearly three times as many as in 2010.

“The prescription drug overdose epidemic requires a multifaceted approach, and states are key partners in our efforts on the front lines to prevent overdose deaths. With this funding, states can improve their ability to track the problem, work with insurers to help providers make informed prescribing decisions, and take action to combat this epidemic,” U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Sylvia M. Burwell said in the release.

Find the full CDC press release here.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has launched a program aimed at helping states combat and prevent opioid drug overdoses.

The Prescription Drug Overdose: Prevention for States program will be launching in 16 states chosen in a competitive application process. The CDC is committing $20 million in fiscal year 2015, and each state will receive $750,000 to $1 million each year for the next 4 years to advance prevention in several areas, such as enhancing prescription drug–monitoring programs, putting prevention into action in communities nationwide, and investigating the connection between prescription opioid abuse and heroin use, the CDC said in a press release.

In 2013, 16,000 people died from prescription opioid overdoses, four times more than in 1999, with prescription of opioids increasing at the same rate over the same time. Despite more opioids being prescribed, the amount of pain Americans report has not changed. In addition, heroin deaths also have spiked, with the 8,000 heroin overdose deaths nearly three times as many as in 2010.

“The prescription drug overdose epidemic requires a multifaceted approach, and states are key partners in our efforts on the front lines to prevent overdose deaths. With this funding, states can improve their ability to track the problem, work with insurers to help providers make informed prescribing decisions, and take action to combat this epidemic,” U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Sylvia M. Burwell said in the release.

Find the full CDC press release here.

HDAC inhibitor approved for MM in EU

Photo courtesy of Novartis

The European Commission has approved panobinostat (Farydak) for use in combination with other agents to treat patients with relapsed and/or refractory

multiple myeloma (MM).

The histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor is now approved, in combination with bortezomib and dexamethasone, to treat adults with MM who have received at least 2 prior treatment regimens, including bortezomib and an immunomodulatory agent (IMiD).

The approval marks the first time an HDAC inhibitor with epigenetic activity is available in the European Union (EU). The approval applies to all 28 EU member states plus Iceland, Norway, and Liechtenstein.

The European Commission approved panobinostat based on results of a subgroup analysis of 147 patients in the phase 3 PANORAMA-1 trial.

PANORAMA-1 was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 768 MM patients. The study showed that, overall, panobinostat plus bortezomib and dexamethasone increased progression-free survival (PFS) by about 4 months when compared to placebo plus bortezomib and dexamethasone.

Full results of the PANORAMA-1 study were published in The Lancet Oncology last year. Results from the substudy of 147 patients were presented at ASCO 2015.

The 147 patients had relapsed or relapsed and refractory MM and had received 2 or more prior regimens, including bortezomib and an IMiD.

The median PFS benefit in this subgroup increased by 7.8 months in the panobinostat arm compared to the placebo arm. The median PFS was 12.5 months (n=73) and 4.7 months (n=74), respectively (hazard ratio=0.47).

Common grade 3/4 non-hematologic adverse events in the panobinostat arm and placebo arm, respectively, included diarrhea (33.3% vs 15.1%), asthenia/fatigue (26.4% vs 13.7%), and peripheral neuropathy (16.7% vs 6.8%).

The most common grade 3/4 hematologic events in the panobinostat arm and placebo arm, respectively, were thrombocytopenia (68.1% vs 44.4%), lymphopenia (48.6% vs 49.3%), and neutropenia (40.3% vs 16.4%).

Cardiac events (most frequently atrial fibrillation, tachycardia, palpitation, and sinus tachycardia) were reported in 17.6% of panobinostat-treated patients and 9.8% of placebo-treated patients. Syncope was reported in 6.0% and 2.4%, respectively.

The percentage of on-treatment deaths was similar in the panobinostat and placebo arms—6.9% and 6.8%, respectively. But on-treatment deaths not due to the study indication (MM) were reported in 6.8% and 3.2% of patients, respectively.

Panobinostat in combination with bortezomib and dexamethasone is also approved in the US, Chile, and Japan for certain patients with previously treated MM. The exact indication for panobinostat varies by country. ![]()

Photo courtesy of Novartis

The European Commission has approved panobinostat (Farydak) for use in combination with other agents to treat patients with relapsed and/or refractory

multiple myeloma (MM).

The histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor is now approved, in combination with bortezomib and dexamethasone, to treat adults with MM who have received at least 2 prior treatment regimens, including bortezomib and an immunomodulatory agent (IMiD).

The approval marks the first time an HDAC inhibitor with epigenetic activity is available in the European Union (EU). The approval applies to all 28 EU member states plus Iceland, Norway, and Liechtenstein.

The European Commission approved panobinostat based on results of a subgroup analysis of 147 patients in the phase 3 PANORAMA-1 trial.

PANORAMA-1 was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 768 MM patients. The study showed that, overall, panobinostat plus bortezomib and dexamethasone increased progression-free survival (PFS) by about 4 months when compared to placebo plus bortezomib and dexamethasone.

Full results of the PANORAMA-1 study were published in The Lancet Oncology last year. Results from the substudy of 147 patients were presented at ASCO 2015.

The 147 patients had relapsed or relapsed and refractory MM and had received 2 or more prior regimens, including bortezomib and an IMiD.

The median PFS benefit in this subgroup increased by 7.8 months in the panobinostat arm compared to the placebo arm. The median PFS was 12.5 months (n=73) and 4.7 months (n=74), respectively (hazard ratio=0.47).

Common grade 3/4 non-hematologic adverse events in the panobinostat arm and placebo arm, respectively, included diarrhea (33.3% vs 15.1%), asthenia/fatigue (26.4% vs 13.7%), and peripheral neuropathy (16.7% vs 6.8%).

The most common grade 3/4 hematologic events in the panobinostat arm and placebo arm, respectively, were thrombocytopenia (68.1% vs 44.4%), lymphopenia (48.6% vs 49.3%), and neutropenia (40.3% vs 16.4%).

Cardiac events (most frequently atrial fibrillation, tachycardia, palpitation, and sinus tachycardia) were reported in 17.6% of panobinostat-treated patients and 9.8% of placebo-treated patients. Syncope was reported in 6.0% and 2.4%, respectively.

The percentage of on-treatment deaths was similar in the panobinostat and placebo arms—6.9% and 6.8%, respectively. But on-treatment deaths not due to the study indication (MM) were reported in 6.8% and 3.2% of patients, respectively.

Panobinostat in combination with bortezomib and dexamethasone is also approved in the US, Chile, and Japan for certain patients with previously treated MM. The exact indication for panobinostat varies by country. ![]()

Photo courtesy of Novartis

The European Commission has approved panobinostat (Farydak) for use in combination with other agents to treat patients with relapsed and/or refractory

multiple myeloma (MM).

The histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor is now approved, in combination with bortezomib and dexamethasone, to treat adults with MM who have received at least 2 prior treatment regimens, including bortezomib and an immunomodulatory agent (IMiD).

The approval marks the first time an HDAC inhibitor with epigenetic activity is available in the European Union (EU). The approval applies to all 28 EU member states plus Iceland, Norway, and Liechtenstein.

The European Commission approved panobinostat based on results of a subgroup analysis of 147 patients in the phase 3 PANORAMA-1 trial.

PANORAMA-1 was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 768 MM patients. The study showed that, overall, panobinostat plus bortezomib and dexamethasone increased progression-free survival (PFS) by about 4 months when compared to placebo plus bortezomib and dexamethasone.

Full results of the PANORAMA-1 study were published in The Lancet Oncology last year. Results from the substudy of 147 patients were presented at ASCO 2015.

The 147 patients had relapsed or relapsed and refractory MM and had received 2 or more prior regimens, including bortezomib and an IMiD.

The median PFS benefit in this subgroup increased by 7.8 months in the panobinostat arm compared to the placebo arm. The median PFS was 12.5 months (n=73) and 4.7 months (n=74), respectively (hazard ratio=0.47).

Common grade 3/4 non-hematologic adverse events in the panobinostat arm and placebo arm, respectively, included diarrhea (33.3% vs 15.1%), asthenia/fatigue (26.4% vs 13.7%), and peripheral neuropathy (16.7% vs 6.8%).

The most common grade 3/4 hematologic events in the panobinostat arm and placebo arm, respectively, were thrombocytopenia (68.1% vs 44.4%), lymphopenia (48.6% vs 49.3%), and neutropenia (40.3% vs 16.4%).

Cardiac events (most frequently atrial fibrillation, tachycardia, palpitation, and sinus tachycardia) were reported in 17.6% of panobinostat-treated patients and 9.8% of placebo-treated patients. Syncope was reported in 6.0% and 2.4%, respectively.

The percentage of on-treatment deaths was similar in the panobinostat and placebo arms—6.9% and 6.8%, respectively. But on-treatment deaths not due to the study indication (MM) were reported in 6.8% and 3.2% of patients, respectively.

Panobinostat in combination with bortezomib and dexamethasone is also approved in the US, Chile, and Japan for certain patients with previously treated MM. The exact indication for panobinostat varies by country. ![]()

FDA expands use of antiplatelet agent

Image by Andre E.X. Brown

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the approved use of the antiplatelet agent ticagrelor (Brilinta).

The FDA first approved ticagrelor in 2011 to reduce the rate of thrombotic cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

Now, the agency has approved a 60 mg dose that can be used long-term. The 60 mg tablet is expected to be available in pharmacies by the end of this month.

The recommended dosing for ticagrelor is a loading dose of 180 mg, followed by 90 mg twice daily during the first year after the ACS event. The drug is combined with aspirin, typically at a loading dose of 325 mg, followed by a daily maintenance dose of 75-100 mg.

After 1 year, patients can now receive ticagrelor at 60 mg twice daily.

The expanded indication for ticagrelor has been approved under FDA Priority Review, a designation granted to medicines with the potential to provide significant improvements in the treatment, prevention, or diagnosis of a disease.

Ticagrelor has been approved in more than 100 countries and is included in 12 major ACS treatment guidelines globally. The drug is under development by AstraZeneca.

Trial results

The FDA’s expanded approval of ticagrelor is based on results of the PEGASUS TIMI-54 trial, a large-scale study involving more than 21,000 patients.

Investigators compared ticagrelor (at 60 mg or 90 mg) plus low-dose aspirin to placebo plus low-dose aspirin in patients who had experienced a heart attack 1 to 3 years prior to study enrollment.

The primary efficacy endpoint was a composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke. And the investigators found that patients in either ticagrelor arm were significantly less likely to achieve this endpoint.

At 3 years, the proportion of patients meeting the endpoint was 7.85% in the 90 mg group, 7.77% in the 60 mg group, and 9.04% in the placebo group (P=0.008 for 90 mg vs placebo and P=0.004 for 60 mg vs placebo).

Patients receiving ticagrelor also had a significantly higher incidence of major bleeding and dyspnea. The rate of TIMI major bleeding was 2.60% in the 90 mg group, 2.30% in the 60 mg group, and 1.06% in the placebo group (P<0.001 for each ticagrelor dose vs placebo).

The rate of dyspnea was 18.93% in the 90 mg group, 15.84% in 60 mg group, and 6.38% in the placebo group (P<0.001 for both comparisons). The rate of dyspnea leading to treatment discontinuation was 6.5% in the 90 mg group, 4.55% in the 60 mg group, and 0.79% in the placebo group (P<0.001 for both). ![]()

Image by Andre E.X. Brown

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the approved use of the antiplatelet agent ticagrelor (Brilinta).

The FDA first approved ticagrelor in 2011 to reduce the rate of thrombotic cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

Now, the agency has approved a 60 mg dose that can be used long-term. The 60 mg tablet is expected to be available in pharmacies by the end of this month.

The recommended dosing for ticagrelor is a loading dose of 180 mg, followed by 90 mg twice daily during the first year after the ACS event. The drug is combined with aspirin, typically at a loading dose of 325 mg, followed by a daily maintenance dose of 75-100 mg.

After 1 year, patients can now receive ticagrelor at 60 mg twice daily.

The expanded indication for ticagrelor has been approved under FDA Priority Review, a designation granted to medicines with the potential to provide significant improvements in the treatment, prevention, or diagnosis of a disease.

Ticagrelor has been approved in more than 100 countries and is included in 12 major ACS treatment guidelines globally. The drug is under development by AstraZeneca.

Trial results

The FDA’s expanded approval of ticagrelor is based on results of the PEGASUS TIMI-54 trial, a large-scale study involving more than 21,000 patients.

Investigators compared ticagrelor (at 60 mg or 90 mg) plus low-dose aspirin to placebo plus low-dose aspirin in patients who had experienced a heart attack 1 to 3 years prior to study enrollment.

The primary efficacy endpoint was a composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke. And the investigators found that patients in either ticagrelor arm were significantly less likely to achieve this endpoint.

At 3 years, the proportion of patients meeting the endpoint was 7.85% in the 90 mg group, 7.77% in the 60 mg group, and 9.04% in the placebo group (P=0.008 for 90 mg vs placebo and P=0.004 for 60 mg vs placebo).

Patients receiving ticagrelor also had a significantly higher incidence of major bleeding and dyspnea. The rate of TIMI major bleeding was 2.60% in the 90 mg group, 2.30% in the 60 mg group, and 1.06% in the placebo group (P<0.001 for each ticagrelor dose vs placebo).

The rate of dyspnea was 18.93% in the 90 mg group, 15.84% in 60 mg group, and 6.38% in the placebo group (P<0.001 for both comparisons). The rate of dyspnea leading to treatment discontinuation was 6.5% in the 90 mg group, 4.55% in the 60 mg group, and 0.79% in the placebo group (P<0.001 for both). ![]()

Image by Andre E.X. Brown

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the approved use of the antiplatelet agent ticagrelor (Brilinta).

The FDA first approved ticagrelor in 2011 to reduce the rate of thrombotic cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

Now, the agency has approved a 60 mg dose that can be used long-term. The 60 mg tablet is expected to be available in pharmacies by the end of this month.

The recommended dosing for ticagrelor is a loading dose of 180 mg, followed by 90 mg twice daily during the first year after the ACS event. The drug is combined with aspirin, typically at a loading dose of 325 mg, followed by a daily maintenance dose of 75-100 mg.

After 1 year, patients can now receive ticagrelor at 60 mg twice daily.

The expanded indication for ticagrelor has been approved under FDA Priority Review, a designation granted to medicines with the potential to provide significant improvements in the treatment, prevention, or diagnosis of a disease.

Ticagrelor has been approved in more than 100 countries and is included in 12 major ACS treatment guidelines globally. The drug is under development by AstraZeneca.

Trial results

The FDA’s expanded approval of ticagrelor is based on results of the PEGASUS TIMI-54 trial, a large-scale study involving more than 21,000 patients.

Investigators compared ticagrelor (at 60 mg or 90 mg) plus low-dose aspirin to placebo plus low-dose aspirin in patients who had experienced a heart attack 1 to 3 years prior to study enrollment.

The primary efficacy endpoint was a composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke. And the investigators found that patients in either ticagrelor arm were significantly less likely to achieve this endpoint.

At 3 years, the proportion of patients meeting the endpoint was 7.85% in the 90 mg group, 7.77% in the 60 mg group, and 9.04% in the placebo group (P=0.008 for 90 mg vs placebo and P=0.004 for 60 mg vs placebo).

Patients receiving ticagrelor also had a significantly higher incidence of major bleeding and dyspnea. The rate of TIMI major bleeding was 2.60% in the 90 mg group, 2.30% in the 60 mg group, and 1.06% in the placebo group (P<0.001 for each ticagrelor dose vs placebo).

The rate of dyspnea was 18.93% in the 90 mg group, 15.84% in 60 mg group, and 6.38% in the placebo group (P<0.001 for both comparisons). The rate of dyspnea leading to treatment discontinuation was 6.5% in the 90 mg group, 4.55% in the 60 mg group, and 0.79% in the placebo group (P<0.001 for both). ![]()

Fecal Microbiota Transplant for CDI

Symptomatic Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) results when C difficile, a gram‐positive bacillus that is an obligate‐anaerobe, produces cytotoxins TcdA and TcdB, causing epithelial and mucosal injury in the gastrointestinal tract.[1] Though it was first identified in 1978 as the causative agent of pseudomembranous colitis, and several effective treatments have subsequently been discovered,[2] nearly 3 decades later C difficile remains a major nosocomial pathogen. C difficile is the most frequent infectious cause of healthcare‐associated diarrhea and causes toxin mediated infection. The incidence of CDI in the United States has increased dramatically, especially in hospitals and nursing homes where there are now nearly 500,000 new cases and 30,000 deaths per year.[3, 4, 5, 6] This increased burden of disease is due both to the emergence of several strains that have led to a worldwide epidemic[7] and to a predilection for CDI in older adults, who constitute a growing proportion of hospitalized patients.[8] Ninety‐two percent of CDI‐related deaths occur in adults >65 years old,[9] and the risk of recurrent CDI is 2‐fold higher with each decade of life.[10] It is estimated that CDI is responsible for $1.5 billion in excess healthcare costs each year in the United States,[11] and that much of the additional cost and morbidity of CDI is due to recurrence, with around 83,000 cases per year.[6]

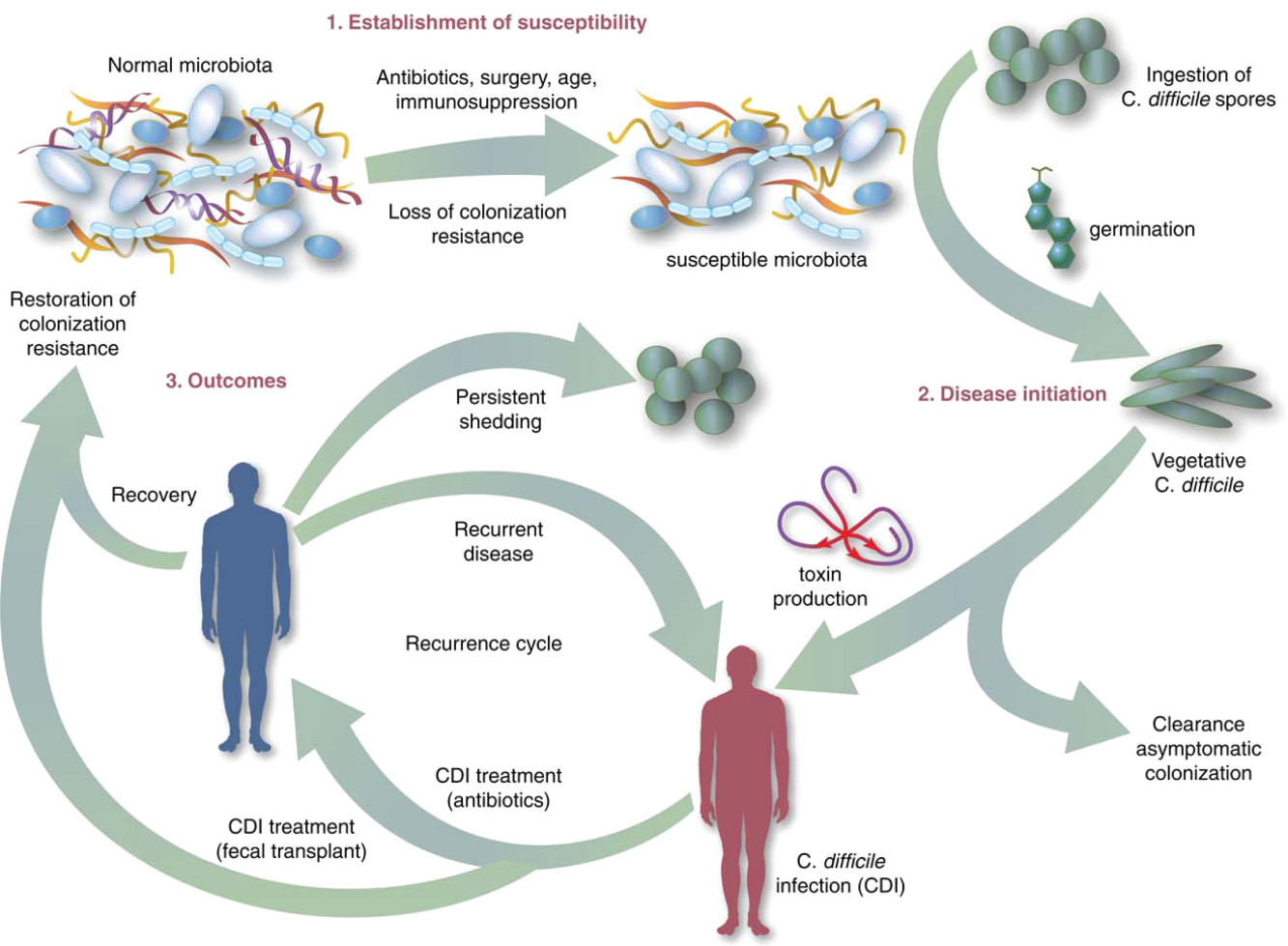

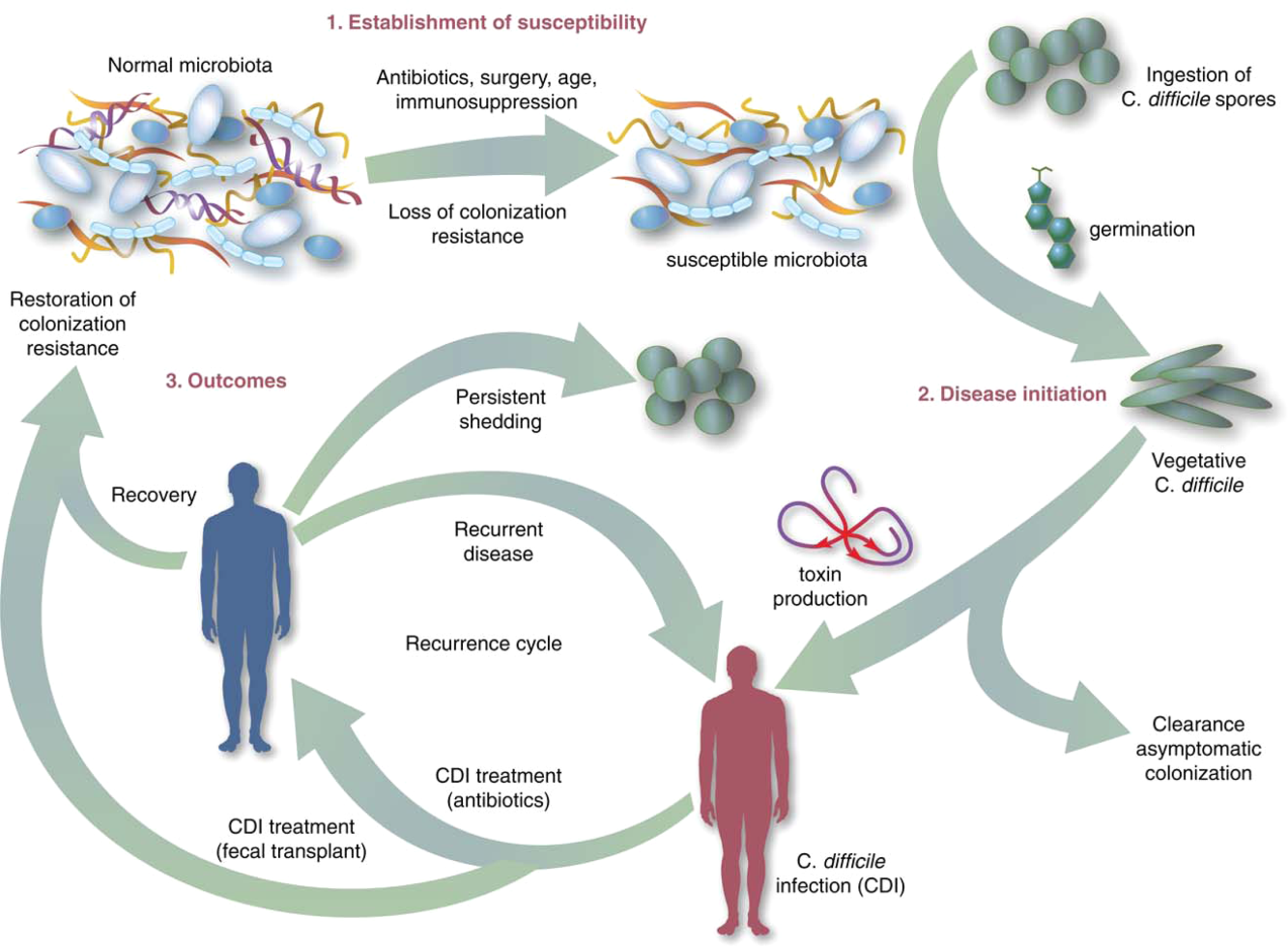

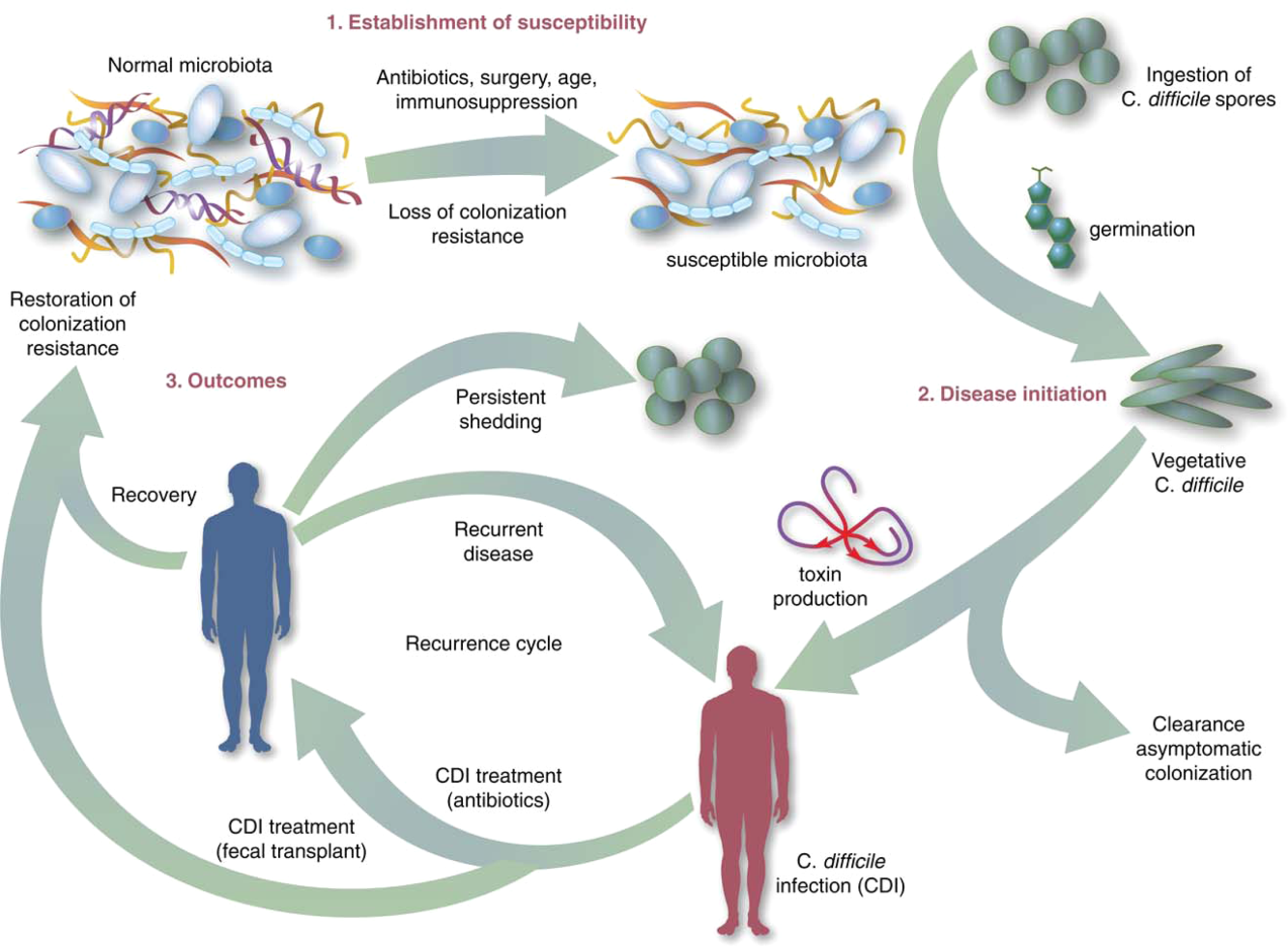

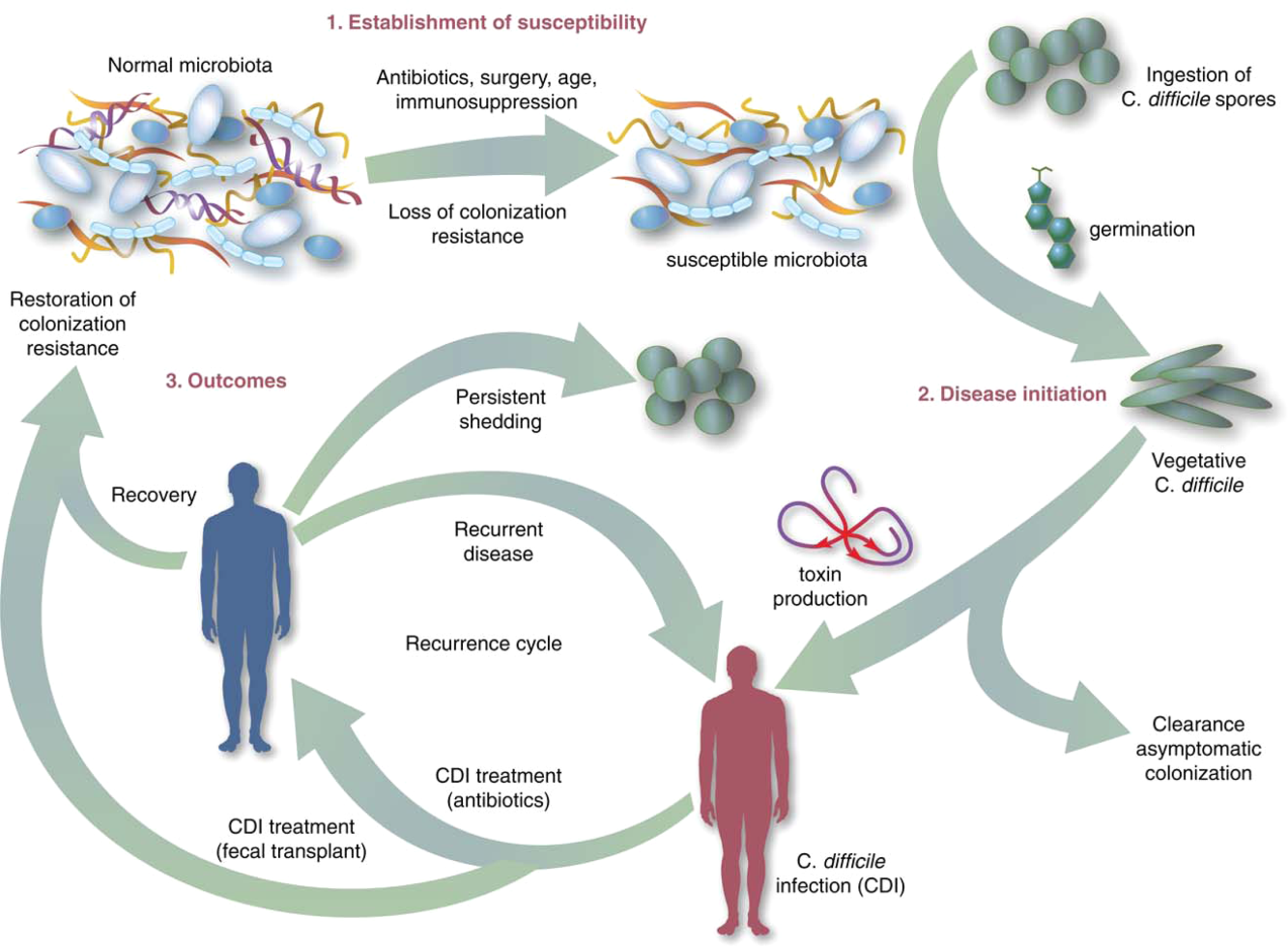

The human gut microbiota, which is a diverse ecosystem consisting of thousands of bacterial species,[12] protects against invasive pathogens such as C difficile.[13, 14] The pathogenesis of CDI requires disruption of the gut microbiota before onset of symptomatic disease,[15] and exposure to antibiotics is the most common precipitant (Figure 1).[16] Following exposure, the manifestations can vary from asymptomatic colonization, to a self‐limited diarrheal illness, to a fulminant, life‐threatening colitis.[1] Even among those who recover, recurrent disease is common.[10] A first recurrence will occur in 15% to 20% of successfully treated patients, a second recurrence will occur in 45% of those patients, and up to 5% of all patients enter a prolonged cycle of CDI with multiple recurrences.[17, 18, 19]

THE NEED FOR BETTER TREATMENT MODALITIES: RATIONALE

Conventional treatments (Table 1) utilize antibiotics with activity against C difficile,[20, 21] but these antibiotics have activity against other gut bacteria, limiting the ability of the microbiota to fully recover following CDI and predisposing patients to recurrence.[22] Traditional treatments for CDI result in a high incidence of recurrence (35%), with up to 65% of these patients who are again treated with conventional approaches developing a chronic pattern of recurrent CDI.[23] Though other factors may also explain why patients have recurrence (such as low serum antibody response to C difficile toxins,[24] use of medications such as proton pump inhibitors,[10] and the specific strain of C difficile causing infection[10, 21], restoration of the gut microbiome through fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is the treatment strategy that has garnered the most attention and has gained acceptance among practitioners in the treatment of recurrent CDI when conventional treatments have failed.[25] A review of the practices and evidence for use of FMT in the treatment of CDI in hospitalized patients is presented here, with recommendations shown in Table 2.

| Type of CDI | Associated Signs/Symptoms | Usual Treatment(s)[20] |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Primary CDI, nonsevere | Diarrhea without signs of systemic infection, WBC 15,000 cells/mL, and serum creatinine 1.5 times the premorbid level | Metronidazole 500mg by mouth 3 times daily for 1014 days OR vancomycin 125mg by mouth 4 times daily for 1014 days OR fidaxomicin 200mg by mouth twice daily for 10 daysa |

| Primary CDI, severe | Signs of systemic infection and/or WBC15,000 cells/mL, or serum creatinine 1.5 times the premorbid level | vancomycin 125mg by mouth 4 times daily for 1014 days OR fidaxomicin 200mg by mouth twice daily for 10 daysa |

| Primary CDI, complicated | Signs of systemic infection including hypotension, ileus, or megacolon | vancomycin 500mg by mouth 4 times daily AND vancomycin 500mg by rectum 4 times daily AND intravenous metronidazole 500mg 3 times daily |

| Recurrent CDI | Return of symptoms with positive Clostridium difficile testing within 8 weeks of onset, but after initial symptoms resolved with treatment | First recurrence: same as initial treatment, based on severity. Second recurrence: Start treatment based on severity, followed by a vancomycin pulsed and/or tapered regimen over 6 or more weeks |

| Type of CDI | Recommendation on Use of FMT |

|---|---|

| |

| Primary CDI, nonsevere | Insufficient data on safety/efficacy to make a recommendation; effective conventional treatments exist |

| Primary CDI, severe | Not recommended due to insufficient data on safety/efficacy with documented adverse events |

| Primary CDI, complicated | Not recommended due to insufficient data on safety/efficacy with documented adverse events |

| Recurrent CDI (usually second recurrence) | Recommended based on data from case reports, systematic reviews, and 2 randomized, controlled clinical trials demonstrating safety and efficacy |

OVERVIEW OF FMT

FMT is not new to modern times, as there are reports of its use in ancient China for various purposes.[26] It was first described as a treatment for pseudomembranous colitis in the 1950s,[27] and in the past several years the use of FMT for CDI has increasingly gained acceptance as a safe and effective treatment. The optimal protocol for FMT is unknown; there are numerous published methods of stool preparation, infusion, and recipient and donor preparation. Diluents include tap water, normal saline, or even yogurt.[23, 28, 29] Sites of instillation of the stool include the stomach, small intestine, and large intestine.[23, 29, 30] Methods of recipient preparation for the infusion include cessation of antibiotic therapy for 24 to 48 hours prior to FMT, a bowel preparation or lavage, and use of antimotility agents, such as loperamide, to aid in retention of transplanted stool.[28] Donors may include friends or family members of the patients or 1 or more universal donors for an entire center. In both cases, screening for blood‐borne and fecal pathogens is performed before one can donate stool, though the tests performed vary between centers. FMT has been performed in both inpatient and outpatient settings, and a published study that instructed patients on self‐administration of fecal enema at home also demonstrated success.[30]

Although there are numerous variables to consider in designing a protocol, as discussed further below, it is encouraging that FMT appears to be highly effective regardless of the specific details of the protocol.[28] If the first procedure fails, evidence suggests a second or third treatment can be quite effective.[28] In a recent advance, successful FMT via administration of frozen stool oral capsules has been demonstrated,[31] which potentially removes many system‐ and patient‐level barriers to receipt of this treatment.

CLINICAL EVIDENCE FOR EFFICACY OF FMT IN TREATMENT OF CDI

Recurrent CDI

The clinical evidence for FMT is most robust for recurrent CDI, consisting of case reports or case series, recently aggregated by 2 large systematic reviews, as well as several clinical trials.[23, 29] Gough et al. published the larger of the 2 reviews with data from 317 patients treated via FMT for recurrent CDI,[23] including FMT via retention enema (35%), colonoscopic infusion (42%), and gastric infusion (23%). Though the authors noted differences in resolution proportions among routes of infusion, types of donors, and types of infusates, it is not possible to draw definite conclusions form these data given their anecdotal nature. Regardless of the specific protocol's details, 92% of patients in the review had resolution of recurrent CDI overall after 1 or more treatments, with 89% improving after only 1 treatment. Another systematic review of FMT, both for CDI and non‐CDI indications, reinforced its efficacy in CDI and overall benign safety profile.[32] Other individual case series and reports of FMT for CDI not included in these reviews have been published; they too demonstrate an excellent resolution rate.[33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38] As with any case reports/series, generalizing from these data to arrive at conclusions about the safety and efficacy of FMT for CDI is limited by potential confounding and publication bias; thus, there emerged a need for high‐quality prospective trials.

The first randomized, controlled clinical trial (RCT) of FMT for recurrent CDI was reported in 2013.[39] Three treatment groups were compared: vancomycin for 5 days followed by FMT (n=16), vancomycin alone for 14 days (n=13), or vancomycin for 14 days with bowel lavage (n=13). Despite a strict definition of cure (absence of diarrhea or persistent diarrhea from another cause with 3 consecutive negative stool tests for C difficile toxin), the study was stopped early after an interim analysis due to resolution of CDI in 94% of patients in the FMT arm (81% after just 1 infusion) versus 23% to 31% in the others. Off‐protocol FMT was offered to the patients in the other 2 groups and 83% of them were also cured.

Youngster et al. conducted a pilot RCT with 10 patients in each group, where patients were randomized to receive FMT via either colonoscopy or nasogastric tube from a frozen fecal suspension, and no difference in efficacy was seen between administration routes, with an overall cure rate of 90%.[40] Subsequently, Youngster et al. conducted an open‐label noncomparative study with frozen fecal capsules for FMT in 20 patients with recurrent CDI.[31] Resolution occurred in 14 (70%) patients after a single treatment, and 4 of the 6 nonresponders had resolution upon retreatment for an overall efficacy of 90%.

Finally, Cammarota et al. conducted an open‐label RCT on FMT for recurrent CDI,[41] comparing FMT to a standard course of vancomycin for 10 days, followed by pulsed dosing every 2 to 3 days for 3 weeks. The study was stopped after a 1‐year interim analysis as 18 of 20 patients (90%) treated by FMT exhibited resolution of CDI‐associated diarrhea compared to only 5 of 19 patients (26%) in the vancomycin‐treated group (P0.001).

Primary and Severe CDI

There are few data on the use of FMT for primary, nonrecurrent CDI aside from a few case reports, which are included in the data presented above. A mathematical model of CDI in an intensive care unit assessed the role of FMT on primary CDI,[42] and predicted a decreased median incidence of recurrent CDI in patients treated with FMT for primary CDI. In addition to the general limitations inherent in any mathematical model, the study had specific assumptions for model parameters that limited generalizability, such as lack of incorporation of known risk factors for CDI and assumed immediate, persistent disruption of the microbiota after any antimicrobial exposure until FMT occurred.[43]

Lagier et al.[44] conducted a nonrandomized, open‐label, before and after prospective study comparing mortality between 2 intervention periods: conventional antibiotic treatment for CDI versus early FMT via nasogastric infusion. This shift happened due to clinical need, as their hospital in Marseille developed a ribotype 027 outbreak with a dramatic global mortality rate (50.8%). Mortality in the FMT group was significantly less (64.4% vs 18.8%, P0.01). This was an older cohort (mean age 84 years), suggesting that in an epidemic setting with a high mortality rate, early FMT may be beneficial, but one cannot extrapolate these data to support a position of early FMT for primary CDI in a nonepidemic setting.

Similarly, the evidence for use of FMT in severe CDI (defined in Table 1) consists of published case reports, which suggest efficacy.[45, 46, 47, 48] Similarly, the study by Lagier et al.[44] does not provide data on severity classification, but had a high mortality rate and found a benefit of FMT versus conventional therapy, suggesting that at least some patients presented with severe CDI and benefited. However, 1 documented death (discussed further below) following FMT for severe CDI highlights the need for caution before this treatment is used in that setting.[49]

Patient and Provider Perceptions Regarding Acceptability of FMT as a Treatment Option for CDI

A commonly cited reason for a limited role of FMT is the aesthetics of the treatment. However, few studies exist on the perceptions of patients and providers regarding FMT. Zipursky et al. surveyed 192 outpatients on their attitudes toward FMT using hypothetical case scenarios.[50] Only 1 patient had a history of CDI. The results were largely positive, with 81% of respondents agreeing to FMT for CDI. However, the need to handle stool and the nasogastric route of administration were identified as the most unappealing aspects of FMT. More respondents (90%, P=0.002) agreed to FMT when offered as a pill.

The same group of investigators undertook an electronic survey to examine physician attitudes toward FMT,[51] and found that 83 of 135 physicians (65%) in their sample had not offered or referred a patient for FMT. Frequent reasons for this included institutional barriers, concern that patients would find it too unappealing, and uncertainty regarding indications for FMT. Only 8% of physicians believed that patients would choose FMT if given the option. As the role of FMT in CDI continues to grow, it is likely that patient and provider perceptions and attitudes regarding this treatment will evolve to better align.

SAFETY OF FMT

Short‐term Complications

Serious adverse effects directly attributable to FMT in patients with normal immune function are uncommon. Symptoms of an irritable bowel (constipation, diarrhea, cramping, bloating) shortly after FMT are observed and usually last less than 48 hours.[23] A recent case series of immunocompromised patients (excluding those with inflammatory bowel disease [IBD]) treated for CDI with FMT did not find many adverse events in this group.[35] However, patients with IBD may have a different risk profile; the same case series noted adverse events occurred in 14% of IBD patients, who experienced disease flare requiring hospitalization in some cases.[35] No cases of septicemia or other infections were observed in this series. An increased risk of IBD flare, fever, and elevation in inflammatory markers following FMT has also been observed in other studies.[52, 53, 54] However, the interaction between IBD and the microbiome is complex, and a recent RCT for patients with ulcerative colitis (without CDI) treated via FMT did not show any significant adverse events.[55] FMT side effects may vary by the administration method and may be related to complications of the method itself rather than FMT (for example, misplacement of a nasogastric tube, perforation risk with colonoscopy).

Deaths following FMT are rare and often are not directly attributed to FMT. One reported death occurred as a result of aspiration pneumonia during sedation for colonoscopy for FMT.[35] In another case, a patient with severe CDI was treated with FMT, did not achieve cure, and developed toxic megacolon and shock, dying shortly after. The authors speculate that withdrawal of antibiotics with activity against CDI following FMT contributed to the outcome, rather than FMT itself.[49] FMT is largely untested in patients with severe CDI,[45, 46, 47, 48] and this fatal case of toxic megacolon warrants caution.

Long‐term Complications

The long‐term safety of FMT is unknown. There is an incomplete understanding of the interaction between the gut microbiome and the host, but this is a complex system, and associations with disease processes have been demonstrated. The gut microbiome may be associated with colon cancer, diabetes, obesity, and atopic disorders.[56] The role of FMT in contributing to these conditions is unknown. It is also not known whether targeted screening/selection of stool for infusion can mitigate these potential risks.

In the only study to capture long‐term outcomes after FMT, 77 patients were followed for 3 to 68 months (mean 17 months).[57] New conditions such as ovarian cancer, myocardial infarction, autoimmune disease, and stroke were observed. Although it is not possible to establish causality from this study or infer an increased risk of these conditions from FMT, the results underscore the need for long‐term follow‐up after FMT.

Regulatory Status

The increased use of FMT for CDI and interest in non‐CDI indications led the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2013 to publish an initial guidance statement regulating stool as a biologic agent.[58] However, subsequently, the United States Department of Health and Human Services' FDA issued guidance stating that it would exercise enforcement discretion for physicians administering FMT to treat patients with C difficile infections; thus, an investigational new drug approval is not required, but appropriate informed consent from the patient indicating that FMT is an investigational therapy is needed. Revision to this guidance is in progress.[59]

Future Directions

Expansion of the indications for FMT and use of synthetic and/or frozen stool are directions currently under active exploration. There are a number of clinical trials studying FMT for CDI underway that are not yet completed,[60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65] and these may shed light on the safety and efficacy of FMT for primary CDI, severe CDI, and FMT as a preemptive therapy for high‐risk patients on antibiotics. Frozen stool preparations, often from a known set of prescreened donors and recently in capsule form, have been used for FMT and are gaining popularity.[31, 33] A synthetic intestinal microbiota suspension for use in FMT is currently being tested.[62] There also exists a nonprofit organization, OpenBiome (

CONCLUSIONS

Based on several prospective trials and observational data, FMT appears to be a safe and effective treatment for recurrent CDI that is superior to conventional approaches. Despite recent pivotal advances in the field of FMT, there remain many unanswered questions, and further research is needed to examine the optimal parameters, indications, and outcomes with FMT.

Disclosures

K.R. is supported by grants from the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (grant number AG‐024824) and the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research (grant number 2UL1TR000433). N.S. is supported by a VA MERIT award. The contents of this article do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , . Emergence of Clostridium difficile‐associated disease in North America and Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:2–18.

- , , , , . Antibiotic‐associated pseudomembranous colitis due to toxin‐producing clostridia. N Engl J Med. 1978;298(10):531–534.

- , , ,, et al. Clostridium difficile infection in Ohio hospitals and nursing homes during 2006. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30(6):526–533.

- , , , , . Attributable burden of hospital‐onset Clostridium difficile infection: a propensity score matching study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(6):588–596.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs. Making health care safer. Stopping C. difficile infections. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/VitalSigns/Hai/StoppingCdifficile. Accessed January 15, 2015.

- , , , et al. Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):825–834.

- , , , et al. Emergence and global spread of epidemic healthcare‐associated Clostridium difficile. Nat Genet. 2013;45(1):109–113.

- , , , et al. Effect of age on treatment outcomes in Clostridium difficile infection. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(2):222–230.

- , , . Current status of Clostridium difficile infection epidemiology. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(suppl 2):S65–S70.

- , , , . Risk factors for recurrence, complications and mortality in Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e98400.

- , , , et al. Health care‐associated infections: a meta‐analysis of costs and financial impact on the US health care system. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(22):2039–2046.

- , , , et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature. 2012;486(7402):222–227.

- , , . Colonization resistance of the digestive tract in conventional and antibiotic‐treated mice. Epidemiol Infect. 1971;69(03):405–411.

- , . Colonization resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38(3):409.

- , . Role of the intestinal microbiota in resistance to colonization by Clostridium difficile. Gastroenterol. 2014;146(6):1547–1553.

- , , , et al. Antibiotic‐induced shifts in the mouse gut microbiome and metabolome increase susceptibility to Clostridium difficile infection. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3114.

- . Fecal bacteriotherapy for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Anaerobe. 2009;15(6):285–289.

- , . Treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile diarrhea. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;2(3):203–208.

- , , , , , . Bacteriotherapy using fecal flora: toying with human motions. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38(6):475–483.

- , , , et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the infectious diseases society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(5):431–455.

- , , , et al. Fidaxomicin Versus Vancomycin for Clostridium difficile Infection: meta‐analysis of pivotal randomized controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(suppl 2):S93–S103.

- , , , et al. Decreased diversity of the fecal microbiome in recurrent Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhea. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(3):435–438.

- , , . Systematic review of intestinal microbiota transplantation (fecal bacteriotherapy) for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(10):994–1002.

- , , , . Association between antibody response to toxin A and protection against recurrent Clostridium difficile diarrhoea. Lancet. 2001;357(9251):189–193.

- , , , , . Treatment approaches including fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (RCDI) among infectious disease physicians. Anaerobe. 2013;24:20–24.

- , , , , . Should we standardize the 1,700‐year‐old fecal microbiota transplantation? Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(11):1755.

- , , , . Fecal enema as an adjunct in the treatment of pseudomembranous enterocolitis. Surgery. 1958;44(5):854–859.

- , , , et al. Treating Clostridium difficile infection with fecal microbiota transplantation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(12):1044–1049.

- , , , . Fecal microbiota transplantation for Clostridium difficile infection: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(4):500–508.

- , , . Success of self‐administered home fecal transplantation for chronic Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(5):471–473.

- , , , , , . Oral, Capsulized, frozen fecal microbiota transplantation for relapsing Clostridium difficile infection. JAMA. 2014;312(17):1772–1778.

- , , , et al. Systematic review: faecal microbiota transplantation therapy for digestive and nondigestive disorders in adults and children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39(10):1003–1032.

- , , , . Standardized frozen preparation for transplantation of fecal microbiota for recurrent Clostridium difficile Infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(5):761–767.

- , , , . Fecal transplant via retention enema for refractory or recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(2):191–193.

- , , , et al. Fecal microbiota transplant for treatment of Clostridium difficile infection in immunocompromised patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(7):1065–1071.

- , , , et al. Efficacy of combined jejunal and colonic fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(9):1572–1576.

- , , , . Fecal microbiota transplantation for refractory Clostridium difficile colitis in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(2):477–480.

- , , , , . Faecal microbiota transplantation and bacteriotherapy for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a retrospective evaluation of 31 patients. Scand J Infect Dis. 2014;46(2):89–97.

- , , , et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(5):407–415.

- , , , et al. Fecal microbiota transplant for relapsing Clostridium difficile infection using a frozen inoculum from unrelated donors: a randomized, open‐label, controlled pilot study. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(11):1515–1522.

- , , , et al. Randomised clinical trial: faecal microbiota transplantation by colonoscopy vs. vancomycin for the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41(9):835–843.

- , , , , . A mathematical model to evaluate the routine use of fecal microbiota transplantation to prevent incident and recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;35(1):18–27.

- , , . Commentary: fecal microbiota therapy: ready for prime time? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(1):28–30.

- , , , et al. Dramatic reduction in Clostridium difficile ribotype 027‐associated mortality with early fecal transplantation by the nasogastric route: a preliminary report. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34(8):1597–1601.

- , , , , , . Fecal microbiota transplantation for fulminant Clostridium difficile infection in an allogeneic stem cell transplant patient. Transplant Infect Dis. 2012;14(6):E161–E165.

- , , , , , . Faecal microbiota transplantation for severe Clostridium difficile infection in the intensive care unit. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25(2):255–257.

- , , , . Successful colonoscopic fecal transplant for severe acute Clostridium difficile pseudomembranous colitis. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2011;77(1):40–42.

- , , . Successful treatment of fulminant Clostridium difficile infection with fecal bacteriotherapy. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(8):632–633.

- , , , . Tempered enthusiasm for fecal transplant. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):319.

- , , , , . Patient attitudes toward the use of fecal microbiota transplantation in the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(12):1652–1658.

- , , , , . Physician attitudes toward the use of fecal microbiota transplantation for the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28(6):319–324.

- , , . Transient flare of ulcerative colitis after fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(8):1036–1038.

- , , , et al. Temporal Bacterial Community Dynamics Vary Among Ulcerative Colitis Patients After Fecal Microbiota Transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(10):1620–1630.

- , , , et al. Alteration of intestinal dysbiosis by fecal microbiota transplantation does not induce remission in patients with chronic active ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(10):2155–2165.

- , , , et al. Findings from a randomized controlled trial of fecal transplantation for patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterol. 2015;149(1):110–118.e4.

- , , , . Gut microbiota in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2010;90(3):859–904.

- , , , et al. Long‐term follow‐up of colonoscopic fecal microbiota transplant for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(7):1079–1087.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: enforcement policy regarding investigational new drug requirements for use of fecal microbiota for transplantation to treat Clostridium difficile infection not responsive to standard therapies. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/biologicsbloodvaccines/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/vaccines/ucm361379.htm. Accessed July 1, 2014.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Draft guidance for industry: enforcement policy regarding investigational new drug requirements for use of fecal microbiota for transplantation to treat Clostridium difficile infection not responsive to standard therapies. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/biologicsbloodvaccines/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/vaccines/ucm387023.htm. Accessed July 1, 2014.

- University Health Network Toronto. Oral vancomycin followed by fecal transplant versus tapering oral vancomycin. Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine; 2000. NLM identifier: NCT01226992. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01226992. Accessed July 1, 2014.

- Tel‐Aviv Sourasky Medical Center. Transplantation of fecal microbiota for Clostridium difficile infection. Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine; 2000. NLM identifier: NCT01958463. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01958463. Accessed July 1, 2014.

- Rebiotix Inc. Microbiota restoration therapy for recurrent Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhea (PUNCH CD). Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine; 2000. NLM identifier: NCT01925417. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01925417. Accessed July 1, 2014.

- Hadassah Medical Organization. Efficacy and safety of fecal microbiota transplantation for severe Clostridium difficile‐associated colitis. Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine; 2000. NLM identifier: NCT01959048. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01959048. Accessed July 1, 2014.

- University Hospital Tuebingen. Fecal microbiota transplantation in recurrent or refractory Clostridium difficile colitis (TOCSIN). Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine; 2000. NLM identifier: NCT01942447. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01942447. Accessed July 1, 2014.

- Duke University. Stool transplants to treat refractory Clostridium difficile colitis. Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine; 2000. NLM identifier: NCT02127398. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02127398. Accessed July 1, 2014.

Symptomatic Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) results when C difficile, a gram‐positive bacillus that is an obligate‐anaerobe, produces cytotoxins TcdA and TcdB, causing epithelial and mucosal injury in the gastrointestinal tract.[1] Though it was first identified in 1978 as the causative agent of pseudomembranous colitis, and several effective treatments have subsequently been discovered,[2] nearly 3 decades later C difficile remains a major nosocomial pathogen. C difficile is the most frequent infectious cause of healthcare‐associated diarrhea and causes toxin mediated infection. The incidence of CDI in the United States has increased dramatically, especially in hospitals and nursing homes where there are now nearly 500,000 new cases and 30,000 deaths per year.[3, 4, 5, 6] This increased burden of disease is due both to the emergence of several strains that have led to a worldwide epidemic[7] and to a predilection for CDI in older adults, who constitute a growing proportion of hospitalized patients.[8] Ninety‐two percent of CDI‐related deaths occur in adults >65 years old,[9] and the risk of recurrent CDI is 2‐fold higher with each decade of life.[10] It is estimated that CDI is responsible for $1.5 billion in excess healthcare costs each year in the United States,[11] and that much of the additional cost and morbidity of CDI is due to recurrence, with around 83,000 cases per year.[6]

The human gut microbiota, which is a diverse ecosystem consisting of thousands of bacterial species,[12] protects against invasive pathogens such as C difficile.[13, 14] The pathogenesis of CDI requires disruption of the gut microbiota before onset of symptomatic disease,[15] and exposure to antibiotics is the most common precipitant (Figure 1).[16] Following exposure, the manifestations can vary from asymptomatic colonization, to a self‐limited diarrheal illness, to a fulminant, life‐threatening colitis.[1] Even among those who recover, recurrent disease is common.[10] A first recurrence will occur in 15% to 20% of successfully treated patients, a second recurrence will occur in 45% of those patients, and up to 5% of all patients enter a prolonged cycle of CDI with multiple recurrences.[17, 18, 19]

THE NEED FOR BETTER TREATMENT MODALITIES: RATIONALE

Conventional treatments (Table 1) utilize antibiotics with activity against C difficile,[20, 21] but these antibiotics have activity against other gut bacteria, limiting the ability of the microbiota to fully recover following CDI and predisposing patients to recurrence.[22] Traditional treatments for CDI result in a high incidence of recurrence (35%), with up to 65% of these patients who are again treated with conventional approaches developing a chronic pattern of recurrent CDI.[23] Though other factors may also explain why patients have recurrence (such as low serum antibody response to C difficile toxins,[24] use of medications such as proton pump inhibitors,[10] and the specific strain of C difficile causing infection[10, 21], restoration of the gut microbiome through fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is the treatment strategy that has garnered the most attention and has gained acceptance among practitioners in the treatment of recurrent CDI when conventional treatments have failed.[25] A review of the practices and evidence for use of FMT in the treatment of CDI in hospitalized patients is presented here, with recommendations shown in Table 2.

| Type of CDI | Associated Signs/Symptoms | Usual Treatment(s)[20] |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Primary CDI, nonsevere | Diarrhea without signs of systemic infection, WBC 15,000 cells/mL, and serum creatinine 1.5 times the premorbid level | Metronidazole 500mg by mouth 3 times daily for 1014 days OR vancomycin 125mg by mouth 4 times daily for 1014 days OR fidaxomicin 200mg by mouth twice daily for 10 daysa |

| Primary CDI, severe | Signs of systemic infection and/or WBC15,000 cells/mL, or serum creatinine 1.5 times the premorbid level | vancomycin 125mg by mouth 4 times daily for 1014 days OR fidaxomicin 200mg by mouth twice daily for 10 daysa |

| Primary CDI, complicated | Signs of systemic infection including hypotension, ileus, or megacolon | vancomycin 500mg by mouth 4 times daily AND vancomycin 500mg by rectum 4 times daily AND intravenous metronidazole 500mg 3 times daily |

| Recurrent CDI | Return of symptoms with positive Clostridium difficile testing within 8 weeks of onset, but after initial symptoms resolved with treatment | First recurrence: same as initial treatment, based on severity. Second recurrence: Start treatment based on severity, followed by a vancomycin pulsed and/or tapered regimen over 6 or more weeks |

| Type of CDI | Recommendation on Use of FMT |

|---|---|

| |

| Primary CDI, nonsevere | Insufficient data on safety/efficacy to make a recommendation; effective conventional treatments exist |

| Primary CDI, severe | Not recommended due to insufficient data on safety/efficacy with documented adverse events |

| Primary CDI, complicated | Not recommended due to insufficient data on safety/efficacy with documented adverse events |

| Recurrent CDI (usually second recurrence) | Recommended based on data from case reports, systematic reviews, and 2 randomized, controlled clinical trials demonstrating safety and efficacy |

OVERVIEW OF FMT

FMT is not new to modern times, as there are reports of its use in ancient China for various purposes.[26] It was first described as a treatment for pseudomembranous colitis in the 1950s,[27] and in the past several years the use of FMT for CDI has increasingly gained acceptance as a safe and effective treatment. The optimal protocol for FMT is unknown; there are numerous published methods of stool preparation, infusion, and recipient and donor preparation. Diluents include tap water, normal saline, or even yogurt.[23, 28, 29] Sites of instillation of the stool include the stomach, small intestine, and large intestine.[23, 29, 30] Methods of recipient preparation for the infusion include cessation of antibiotic therapy for 24 to 48 hours prior to FMT, a bowel preparation or lavage, and use of antimotility agents, such as loperamide, to aid in retention of transplanted stool.[28] Donors may include friends or family members of the patients or 1 or more universal donors for an entire center. In both cases, screening for blood‐borne and fecal pathogens is performed before one can donate stool, though the tests performed vary between centers. FMT has been performed in both inpatient and outpatient settings, and a published study that instructed patients on self‐administration of fecal enema at home also demonstrated success.[30]

Although there are numerous variables to consider in designing a protocol, as discussed further below, it is encouraging that FMT appears to be highly effective regardless of the specific details of the protocol.[28] If the first procedure fails, evidence suggests a second or third treatment can be quite effective.[28] In a recent advance, successful FMT via administration of frozen stool oral capsules has been demonstrated,[31] which potentially removes many system‐ and patient‐level barriers to receipt of this treatment.

CLINICAL EVIDENCE FOR EFFICACY OF FMT IN TREATMENT OF CDI

Recurrent CDI

The clinical evidence for FMT is most robust for recurrent CDI, consisting of case reports or case series, recently aggregated by 2 large systematic reviews, as well as several clinical trials.[23, 29] Gough et al. published the larger of the 2 reviews with data from 317 patients treated via FMT for recurrent CDI,[23] including FMT via retention enema (35%), colonoscopic infusion (42%), and gastric infusion (23%). Though the authors noted differences in resolution proportions among routes of infusion, types of donors, and types of infusates, it is not possible to draw definite conclusions form these data given their anecdotal nature. Regardless of the specific protocol's details, 92% of patients in the review had resolution of recurrent CDI overall after 1 or more treatments, with 89% improving after only 1 treatment. Another systematic review of FMT, both for CDI and non‐CDI indications, reinforced its efficacy in CDI and overall benign safety profile.[32] Other individual case series and reports of FMT for CDI not included in these reviews have been published; they too demonstrate an excellent resolution rate.[33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38] As with any case reports/series, generalizing from these data to arrive at conclusions about the safety and efficacy of FMT for CDI is limited by potential confounding and publication bias; thus, there emerged a need for high‐quality prospective trials.

The first randomized, controlled clinical trial (RCT) of FMT for recurrent CDI was reported in 2013.[39] Three treatment groups were compared: vancomycin for 5 days followed by FMT (n=16), vancomycin alone for 14 days (n=13), or vancomycin for 14 days with bowel lavage (n=13). Despite a strict definition of cure (absence of diarrhea or persistent diarrhea from another cause with 3 consecutive negative stool tests for C difficile toxin), the study was stopped early after an interim analysis due to resolution of CDI in 94% of patients in the FMT arm (81% after just 1 infusion) versus 23% to 31% in the others. Off‐protocol FMT was offered to the patients in the other 2 groups and 83% of them were also cured.

Youngster et al. conducted a pilot RCT with 10 patients in each group, where patients were randomized to receive FMT via either colonoscopy or nasogastric tube from a frozen fecal suspension, and no difference in efficacy was seen between administration routes, with an overall cure rate of 90%.[40] Subsequently, Youngster et al. conducted an open‐label noncomparative study with frozen fecal capsules for FMT in 20 patients with recurrent CDI.[31] Resolution occurred in 14 (70%) patients after a single treatment, and 4 of the 6 nonresponders had resolution upon retreatment for an overall efficacy of 90%.

Finally, Cammarota et al. conducted an open‐label RCT on FMT for recurrent CDI,[41] comparing FMT to a standard course of vancomycin for 10 days, followed by pulsed dosing every 2 to 3 days for 3 weeks. The study was stopped after a 1‐year interim analysis as 18 of 20 patients (90%) treated by FMT exhibited resolution of CDI‐associated diarrhea compared to only 5 of 19 patients (26%) in the vancomycin‐treated group (P0.001).

Primary and Severe CDI

There are few data on the use of FMT for primary, nonrecurrent CDI aside from a few case reports, which are included in the data presented above. A mathematical model of CDI in an intensive care unit assessed the role of FMT on primary CDI,[42] and predicted a decreased median incidence of recurrent CDI in patients treated with FMT for primary CDI. In addition to the general limitations inherent in any mathematical model, the study had specific assumptions for model parameters that limited generalizability, such as lack of incorporation of known risk factors for CDI and assumed immediate, persistent disruption of the microbiota after any antimicrobial exposure until FMT occurred.[43]

Lagier et al.[44] conducted a nonrandomized, open‐label, before and after prospective study comparing mortality between 2 intervention periods: conventional antibiotic treatment for CDI versus early FMT via nasogastric infusion. This shift happened due to clinical need, as their hospital in Marseille developed a ribotype 027 outbreak with a dramatic global mortality rate (50.8%). Mortality in the FMT group was significantly less (64.4% vs 18.8%, P0.01). This was an older cohort (mean age 84 years), suggesting that in an epidemic setting with a high mortality rate, early FMT may be beneficial, but one cannot extrapolate these data to support a position of early FMT for primary CDI in a nonepidemic setting.

Similarly, the evidence for use of FMT in severe CDI (defined in Table 1) consists of published case reports, which suggest efficacy.[45, 46, 47, 48] Similarly, the study by Lagier et al.[44] does not provide data on severity classification, but had a high mortality rate and found a benefit of FMT versus conventional therapy, suggesting that at least some patients presented with severe CDI and benefited. However, 1 documented death (discussed further below) following FMT for severe CDI highlights the need for caution before this treatment is used in that setting.[49]

Patient and Provider Perceptions Regarding Acceptability of FMT as a Treatment Option for CDI

A commonly cited reason for a limited role of FMT is the aesthetics of the treatment. However, few studies exist on the perceptions of patients and providers regarding FMT. Zipursky et al. surveyed 192 outpatients on their attitudes toward FMT using hypothetical case scenarios.[50] Only 1 patient had a history of CDI. The results were largely positive, with 81% of respondents agreeing to FMT for CDI. However, the need to handle stool and the nasogastric route of administration were identified as the most unappealing aspects of FMT. More respondents (90%, P=0.002) agreed to FMT when offered as a pill.

The same group of investigators undertook an electronic survey to examine physician attitudes toward FMT,[51] and found that 83 of 135 physicians (65%) in their sample had not offered or referred a patient for FMT. Frequent reasons for this included institutional barriers, concern that patients would find it too unappealing, and uncertainty regarding indications for FMT. Only 8% of physicians believed that patients would choose FMT if given the option. As the role of FMT in CDI continues to grow, it is likely that patient and provider perceptions and attitudes regarding this treatment will evolve to better align.

SAFETY OF FMT

Short‐term Complications

Serious adverse effects directly attributable to FMT in patients with normal immune function are uncommon. Symptoms of an irritable bowel (constipation, diarrhea, cramping, bloating) shortly after FMT are observed and usually last less than 48 hours.[23] A recent case series of immunocompromised patients (excluding those with inflammatory bowel disease [IBD]) treated for CDI with FMT did not find many adverse events in this group.[35] However, patients with IBD may have a different risk profile; the same case series noted adverse events occurred in 14% of IBD patients, who experienced disease flare requiring hospitalization in some cases.[35] No cases of septicemia or other infections were observed in this series. An increased risk of IBD flare, fever, and elevation in inflammatory markers following FMT has also been observed in other studies.[52, 53, 54] However, the interaction between IBD and the microbiome is complex, and a recent RCT for patients with ulcerative colitis (without CDI) treated via FMT did not show any significant adverse events.[55] FMT side effects may vary by the administration method and may be related to complications of the method itself rather than FMT (for example, misplacement of a nasogastric tube, perforation risk with colonoscopy).

Deaths following FMT are rare and often are not directly attributed to FMT. One reported death occurred as a result of aspiration pneumonia during sedation for colonoscopy for FMT.[35] In another case, a patient with severe CDI was treated with FMT, did not achieve cure, and developed toxic megacolon and shock, dying shortly after. The authors speculate that withdrawal of antibiotics with activity against CDI following FMT contributed to the outcome, rather than FMT itself.[49] FMT is largely untested in patients with severe CDI,[45, 46, 47, 48] and this fatal case of toxic megacolon warrants caution.

Long‐term Complications

The long‐term safety of FMT is unknown. There is an incomplete understanding of the interaction between the gut microbiome and the host, but this is a complex system, and associations with disease processes have been demonstrated. The gut microbiome may be associated with colon cancer, diabetes, obesity, and atopic disorders.[56] The role of FMT in contributing to these conditions is unknown. It is also not known whether targeted screening/selection of stool for infusion can mitigate these potential risks.

In the only study to capture long‐term outcomes after FMT, 77 patients were followed for 3 to 68 months (mean 17 months).[57] New conditions such as ovarian cancer, myocardial infarction, autoimmune disease, and stroke were observed. Although it is not possible to establish causality from this study or infer an increased risk of these conditions from FMT, the results underscore the need for long‐term follow‐up after FMT.

Regulatory Status

The increased use of FMT for CDI and interest in non‐CDI indications led the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2013 to publish an initial guidance statement regulating stool as a biologic agent.[58] However, subsequently, the United States Department of Health and Human Services' FDA issued guidance stating that it would exercise enforcement discretion for physicians administering FMT to treat patients with C difficile infections; thus, an investigational new drug approval is not required, but appropriate informed consent from the patient indicating that FMT is an investigational therapy is needed. Revision to this guidance is in progress.[59]

Future Directions

Expansion of the indications for FMT and use of synthetic and/or frozen stool are directions currently under active exploration. There are a number of clinical trials studying FMT for CDI underway that are not yet completed,[60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65] and these may shed light on the safety and efficacy of FMT for primary CDI, severe CDI, and FMT as a preemptive therapy for high‐risk patients on antibiotics. Frozen stool preparations, often from a known set of prescreened donors and recently in capsule form, have been used for FMT and are gaining popularity.[31, 33] A synthetic intestinal microbiota suspension for use in FMT is currently being tested.[62] There also exists a nonprofit organization, OpenBiome (

CONCLUSIONS

Based on several prospective trials and observational data, FMT appears to be a safe and effective treatment for recurrent CDI that is superior to conventional approaches. Despite recent pivotal advances in the field of FMT, there remain many unanswered questions, and further research is needed to examine the optimal parameters, indications, and outcomes with FMT.

Disclosures

K.R. is supported by grants from the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (grant number AG‐024824) and the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research (grant number 2UL1TR000433). N.S. is supported by a VA MERIT award. The contents of this article do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Symptomatic Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) results when C difficile, a gram‐positive bacillus that is an obligate‐anaerobe, produces cytotoxins TcdA and TcdB, causing epithelial and mucosal injury in the gastrointestinal tract.[1] Though it was first identified in 1978 as the causative agent of pseudomembranous colitis, and several effective treatments have subsequently been discovered,[2] nearly 3 decades later C difficile remains a major nosocomial pathogen. C difficile is the most frequent infectious cause of healthcare‐associated diarrhea and causes toxin mediated infection. The incidence of CDI in the United States has increased dramatically, especially in hospitals and nursing homes where there are now nearly 500,000 new cases and 30,000 deaths per year.[3, 4, 5, 6] This increased burden of disease is due both to the emergence of several strains that have led to a worldwide epidemic[7] and to a predilection for CDI in older adults, who constitute a growing proportion of hospitalized patients.[8] Ninety‐two percent of CDI‐related deaths occur in adults >65 years old,[9] and the risk of recurrent CDI is 2‐fold higher with each decade of life.[10] It is estimated that CDI is responsible for $1.5 billion in excess healthcare costs each year in the United States,[11] and that much of the additional cost and morbidity of CDI is due to recurrence, with around 83,000 cases per year.[6]

The human gut microbiota, which is a diverse ecosystem consisting of thousands of bacterial species,[12] protects against invasive pathogens such as C difficile.[13, 14] The pathogenesis of CDI requires disruption of the gut microbiota before onset of symptomatic disease,[15] and exposure to antibiotics is the most common precipitant (Figure 1).[16] Following exposure, the manifestations can vary from asymptomatic colonization, to a self‐limited diarrheal illness, to a fulminant, life‐threatening colitis.[1] Even among those who recover, recurrent disease is common.[10] A first recurrence will occur in 15% to 20% of successfully treated patients, a second recurrence will occur in 45% of those patients, and up to 5% of all patients enter a prolonged cycle of CDI with multiple recurrences.[17, 18, 19]

THE NEED FOR BETTER TREATMENT MODALITIES: RATIONALE

Conventional treatments (Table 1) utilize antibiotics with activity against C difficile,[20, 21] but these antibiotics have activity against other gut bacteria, limiting the ability of the microbiota to fully recover following CDI and predisposing patients to recurrence.[22] Traditional treatments for CDI result in a high incidence of recurrence (35%), with up to 65% of these patients who are again treated with conventional approaches developing a chronic pattern of recurrent CDI.[23] Though other factors may also explain why patients have recurrence (such as low serum antibody response to C difficile toxins,[24] use of medications such as proton pump inhibitors,[10] and the specific strain of C difficile causing infection[10, 21], restoration of the gut microbiome through fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is the treatment strategy that has garnered the most attention and has gained acceptance among practitioners in the treatment of recurrent CDI when conventional treatments have failed.[25] A review of the practices and evidence for use of FMT in the treatment of CDI in hospitalized patients is presented here, with recommendations shown in Table 2.

| Type of CDI | Associated Signs/Symptoms | Usual Treatment(s)[20] |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Primary CDI, nonsevere | Diarrhea without signs of systemic infection, WBC 15,000 cells/mL, and serum creatinine 1.5 times the premorbid level | Metronidazole 500mg by mouth 3 times daily for 1014 days OR vancomycin 125mg by mouth 4 times daily for 1014 days OR fidaxomicin 200mg by mouth twice daily for 10 daysa |

| Primary CDI, severe | Signs of systemic infection and/or WBC15,000 cells/mL, or serum creatinine 1.5 times the premorbid level | vancomycin 125mg by mouth 4 times daily for 1014 days OR fidaxomicin 200mg by mouth twice daily for 10 daysa |

| Primary CDI, complicated | Signs of systemic infection including hypotension, ileus, or megacolon | vancomycin 500mg by mouth 4 times daily AND vancomycin 500mg by rectum 4 times daily AND intravenous metronidazole 500mg 3 times daily |

| Recurrent CDI | Return of symptoms with positive Clostridium difficile testing within 8 weeks of onset, but after initial symptoms resolved with treatment | First recurrence: same as initial treatment, based on severity. Second recurrence: Start treatment based on severity, followed by a vancomycin pulsed and/or tapered regimen over 6 or more weeks |

| Type of CDI | Recommendation on Use of FMT |

|---|---|

| |

| Primary CDI, nonsevere | Insufficient data on safety/efficacy to make a recommendation; effective conventional treatments exist |

| Primary CDI, severe | Not recommended due to insufficient data on safety/efficacy with documented adverse events |

| Primary CDI, complicated | Not recommended due to insufficient data on safety/efficacy with documented adverse events |

| Recurrent CDI (usually second recurrence) | Recommended based on data from case reports, systematic reviews, and 2 randomized, controlled clinical trials demonstrating safety and efficacy |

OVERVIEW OF FMT

FMT is not new to modern times, as there are reports of its use in ancient China for various purposes.[26] It was first described as a treatment for pseudomembranous colitis in the 1950s,[27] and in the past several years the use of FMT for CDI has increasingly gained acceptance as a safe and effective treatment. The optimal protocol for FMT is unknown; there are numerous published methods of stool preparation, infusion, and recipient and donor preparation. Diluents include tap water, normal saline, or even yogurt.[23, 28, 29] Sites of instillation of the stool include the stomach, small intestine, and large intestine.[23, 29, 30] Methods of recipient preparation for the infusion include cessation of antibiotic therapy for 24 to 48 hours prior to FMT, a bowel preparation or lavage, and use of antimotility agents, such as loperamide, to aid in retention of transplanted stool.[28] Donors may include friends or family members of the patients or 1 or more universal donors for an entire center. In both cases, screening for blood‐borne and fecal pathogens is performed before one can donate stool, though the tests performed vary between centers. FMT has been performed in both inpatient and outpatient settings, and a published study that instructed patients on self‐administration of fecal enema at home also demonstrated success.[30]

Although there are numerous variables to consider in designing a protocol, as discussed further below, it is encouraging that FMT appears to be highly effective regardless of the specific details of the protocol.[28] If the first procedure fails, evidence suggests a second or third treatment can be quite effective.[28] In a recent advance, successful FMT via administration of frozen stool oral capsules has been demonstrated,[31] which potentially removes many system‐ and patient‐level barriers to receipt of this treatment.

CLINICAL EVIDENCE FOR EFFICACY OF FMT IN TREATMENT OF CDI

Recurrent CDI