User login

Findings may help advance treatment of malaria

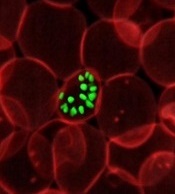

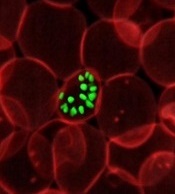

infecting a red blood cell

Image courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

Researchers have found that a screening model can classify antimalarial drugs and reveal drug targets for Plasmodium falciparum, according to a paper published in Scientific Reports.

The team performed chemogenomic profiling of P falciparum for the first time.

They used a collection of malaria parasite mutants that each had altered metabolism linked to a defect in a single P falciparum gene.

They then screened 53 drugs and compounds against 71 of these P falciparum piggyBac single-insertion mutant parasites.

Computational analysis of the response patterns linked the different antimalarial drug candidates and metabolic inhibitors to the specific gene defect.

This revealed new insights into the drugs’ mechanism of action and uncovered 6 new genes that were involved in P falciparum’s response to artemisinin but were associated with increased susceptibility to the drugs tested.

“That represents 6 new targets potentially as effective as artemisinin for killing the malaria parasite,” said study author Dennis Kyle, PhD, of the University of South Florida in Tampa.

“There is definitely a sense of urgency for discovering new antimalarial drugs that may replace artemisinin, or work better with artemisinin, to prevent or delay drug resistance.”

P falciparum, which is becoming increasingly resistant to artemisinin, causes three-quarters of all malaria cases in Africa and 95% of malaria deaths worldwide. ![]()

infecting a red blood cell

Image courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

Researchers have found that a screening model can classify antimalarial drugs and reveal drug targets for Plasmodium falciparum, according to a paper published in Scientific Reports.

The team performed chemogenomic profiling of P falciparum for the first time.

They used a collection of malaria parasite mutants that each had altered metabolism linked to a defect in a single P falciparum gene.

They then screened 53 drugs and compounds against 71 of these P falciparum piggyBac single-insertion mutant parasites.

Computational analysis of the response patterns linked the different antimalarial drug candidates and metabolic inhibitors to the specific gene defect.

This revealed new insights into the drugs’ mechanism of action and uncovered 6 new genes that were involved in P falciparum’s response to artemisinin but were associated with increased susceptibility to the drugs tested.

“That represents 6 new targets potentially as effective as artemisinin for killing the malaria parasite,” said study author Dennis Kyle, PhD, of the University of South Florida in Tampa.

“There is definitely a sense of urgency for discovering new antimalarial drugs that may replace artemisinin, or work better with artemisinin, to prevent or delay drug resistance.”

P falciparum, which is becoming increasingly resistant to artemisinin, causes three-quarters of all malaria cases in Africa and 95% of malaria deaths worldwide. ![]()

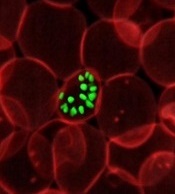

infecting a red blood cell

Image courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

Researchers have found that a screening model can classify antimalarial drugs and reveal drug targets for Plasmodium falciparum, according to a paper published in Scientific Reports.

The team performed chemogenomic profiling of P falciparum for the first time.

They used a collection of malaria parasite mutants that each had altered metabolism linked to a defect in a single P falciparum gene.

They then screened 53 drugs and compounds against 71 of these P falciparum piggyBac single-insertion mutant parasites.

Computational analysis of the response patterns linked the different antimalarial drug candidates and metabolic inhibitors to the specific gene defect.

This revealed new insights into the drugs’ mechanism of action and uncovered 6 new genes that were involved in P falciparum’s response to artemisinin but were associated with increased susceptibility to the drugs tested.

“That represents 6 new targets potentially as effective as artemisinin for killing the malaria parasite,” said study author Dennis Kyle, PhD, of the University of South Florida in Tampa.

“There is definitely a sense of urgency for discovering new antimalarial drugs that may replace artemisinin, or work better with artemisinin, to prevent or delay drug resistance.”

P falciparum, which is becoming increasingly resistant to artemisinin, causes three-quarters of all malaria cases in Africa and 95% of malaria deaths worldwide. ![]()

Managing Patients With Alopecia

What does the patient need to know at the first visit?

When I communicate with alopecia patients at the first visit, I make sure they know that I’m there to help them—that I won’t minimize their concerns and that I understand how important their condition is to them. Alopecia can be frustrating for both the patient and the physician, and there often is a confounding background of psychosocial stress and/or a history of physicians who have dismissed the patient’s concerns about his or her hair loss as trivial. Establishing an effective doctor-patient relationship is key in treating alopecia. Physicians sometimes may be left feeling like the patient wants to keep them in the room until his or her hair regrows, but in reality you simply need to reassure the patient that you are comfortable with the evaluation and treatment of alopecia and that several steps will be required but you will get started today.

How do you use punch biopsies to determine the best treatment options?

My most important tips regarding alopecia diagnosis relate to scalp biopsies, which usually are required in distinguishing chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus from other scarring alopecias. First, an absorbable gelatin compressed sponge is your best friend. A small strip inserted into the punch biopsy wound results in prompt hemostasis without the need for sutures, and the resulting scar often looks as good or better than that produced by suturing. Next, don’t biopsy the active advancing borders of an alopecia patch, as the findings usually are nonspecific. Instead, biopsy a well-established portion that has been present for at least 4 to 6 months but is still active. In inconclusive cases, a biopsy of a scarred area stained with Verhoeff elastic stain can demonstrate characteristic patterns of elastic tissue loss and often establish a diagnosis. It is important to distinguish chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus from other forms of scarring alopecia, as it is more likely to respond to antimalarials.

What are your go-to treatments? Are your recommendations anecdotal or evidence based?

There isn’t an extensive arsenal of evidence-based therapy for refractory scarring alopecia, but that doesn’t mean we don’t have effective therapies; it simply means that our treatments are based on experience without accompanying randomized controlled trials. We need to produce more evidence, but patients with severe disease still need to be treated in the meantime. It’s important to remember that therapeutic complacency can result in permanent irreversible scarring. The presence of easily extractable anagen hairs is a sign of active disease. This simple test is helpful to monitor therapeutic progress.

Topical and intralesional corticosteroids can be extremely useful and often are underused. In general, the risk of scarring and atrophy from untreated disease is much greater than that from the corticosteroid. On the scalp, atrophy often presents as erythema, which should not be confused with erythema related to active disease. Dermoscopy is useful to demonstrate that the redness represents dermal atrophy with prominence of the subpapillary plexus of vessels.

When systemic therapy is required, antimalarials, retinoids, dapsone, thalidomide, sulfasalazine, mycophenolate mofetil, and methotrexate have all been used successfully in the setting of cutaneous lupus erythematosus, while topical tazarotene and topical calcineurin inhibitors are generally disappointing.

For the treatment of lichen planopilaris, intralesional corticosteroids, oral retinoids, and excimer laser can be effective. In contrast, antimalarials usually are not effective in preventing disease progression. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ agonist pioglitazone can be effective, but reported results vary widely. In my experience, mycophenolate mofetil is generally reliable in patients with refractory disease. Dutasteride can be effective as a first-line therapy in the setting of frontal fibrosing alopecia, although some of the noted improvement may relate to the nonscarring portion of the disease in patients with a background of pattern alopecia.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

Again, the key to treatment compliance is to establish an effective doctor-patient relationship. Whenever possible, begin with adequately potent therapy to give patients an early response. Don’t hesitate to use prednisone initially for inflammatory scarring alopecia. Patients need to see signs of progress in order to stay compliant with treatment, and long trials of ineffective therapies destroy trust. Adequate doses of intralesional or oral corticosteroids often are appropriate to ensure an early response with subsequent transition to steroid-sparing agents.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

Try to find out why—often it’s simply fear of side effects. Patient education is key, and it can help tremendously to share with them the number of patients you have treated safely with the medication in question and assure them that you know how to monitor for the important side effects.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

It is helpful to keep a handy list of patient advocacy Web sites. Well-established support groups such as the National Alopecia Areata Foundation (https://www.naaf.org) and the Cicatricial Alopecia Research Foundation (http://www.carfintl.org) provide excellent information for patients and help to support research to improve outcomes for these difficult disorders.

What does the patient need to know at the first visit?

When I communicate with alopecia patients at the first visit, I make sure they know that I’m there to help them—that I won’t minimize their concerns and that I understand how important their condition is to them. Alopecia can be frustrating for both the patient and the physician, and there often is a confounding background of psychosocial stress and/or a history of physicians who have dismissed the patient’s concerns about his or her hair loss as trivial. Establishing an effective doctor-patient relationship is key in treating alopecia. Physicians sometimes may be left feeling like the patient wants to keep them in the room until his or her hair regrows, but in reality you simply need to reassure the patient that you are comfortable with the evaluation and treatment of alopecia and that several steps will be required but you will get started today.

How do you use punch biopsies to determine the best treatment options?

My most important tips regarding alopecia diagnosis relate to scalp biopsies, which usually are required in distinguishing chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus from other scarring alopecias. First, an absorbable gelatin compressed sponge is your best friend. A small strip inserted into the punch biopsy wound results in prompt hemostasis without the need for sutures, and the resulting scar often looks as good or better than that produced by suturing. Next, don’t biopsy the active advancing borders of an alopecia patch, as the findings usually are nonspecific. Instead, biopsy a well-established portion that has been present for at least 4 to 6 months but is still active. In inconclusive cases, a biopsy of a scarred area stained with Verhoeff elastic stain can demonstrate characteristic patterns of elastic tissue loss and often establish a diagnosis. It is important to distinguish chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus from other forms of scarring alopecia, as it is more likely to respond to antimalarials.

What are your go-to treatments? Are your recommendations anecdotal or evidence based?

There isn’t an extensive arsenal of evidence-based therapy for refractory scarring alopecia, but that doesn’t mean we don’t have effective therapies; it simply means that our treatments are based on experience without accompanying randomized controlled trials. We need to produce more evidence, but patients with severe disease still need to be treated in the meantime. It’s important to remember that therapeutic complacency can result in permanent irreversible scarring. The presence of easily extractable anagen hairs is a sign of active disease. This simple test is helpful to monitor therapeutic progress.

Topical and intralesional corticosteroids can be extremely useful and often are underused. In general, the risk of scarring and atrophy from untreated disease is much greater than that from the corticosteroid. On the scalp, atrophy often presents as erythema, which should not be confused with erythema related to active disease. Dermoscopy is useful to demonstrate that the redness represents dermal atrophy with prominence of the subpapillary plexus of vessels.

When systemic therapy is required, antimalarials, retinoids, dapsone, thalidomide, sulfasalazine, mycophenolate mofetil, and methotrexate have all been used successfully in the setting of cutaneous lupus erythematosus, while topical tazarotene and topical calcineurin inhibitors are generally disappointing.

For the treatment of lichen planopilaris, intralesional corticosteroids, oral retinoids, and excimer laser can be effective. In contrast, antimalarials usually are not effective in preventing disease progression. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ agonist pioglitazone can be effective, but reported results vary widely. In my experience, mycophenolate mofetil is generally reliable in patients with refractory disease. Dutasteride can be effective as a first-line therapy in the setting of frontal fibrosing alopecia, although some of the noted improvement may relate to the nonscarring portion of the disease in patients with a background of pattern alopecia.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

Again, the key to treatment compliance is to establish an effective doctor-patient relationship. Whenever possible, begin with adequately potent therapy to give patients an early response. Don’t hesitate to use prednisone initially for inflammatory scarring alopecia. Patients need to see signs of progress in order to stay compliant with treatment, and long trials of ineffective therapies destroy trust. Adequate doses of intralesional or oral corticosteroids often are appropriate to ensure an early response with subsequent transition to steroid-sparing agents.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

Try to find out why—often it’s simply fear of side effects. Patient education is key, and it can help tremendously to share with them the number of patients you have treated safely with the medication in question and assure them that you know how to monitor for the important side effects.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

It is helpful to keep a handy list of patient advocacy Web sites. Well-established support groups such as the National Alopecia Areata Foundation (https://www.naaf.org) and the Cicatricial Alopecia Research Foundation (http://www.carfintl.org) provide excellent information for patients and help to support research to improve outcomes for these difficult disorders.

What does the patient need to know at the first visit?

When I communicate with alopecia patients at the first visit, I make sure they know that I’m there to help them—that I won’t minimize their concerns and that I understand how important their condition is to them. Alopecia can be frustrating for both the patient and the physician, and there often is a confounding background of psychosocial stress and/or a history of physicians who have dismissed the patient’s concerns about his or her hair loss as trivial. Establishing an effective doctor-patient relationship is key in treating alopecia. Physicians sometimes may be left feeling like the patient wants to keep them in the room until his or her hair regrows, but in reality you simply need to reassure the patient that you are comfortable with the evaluation and treatment of alopecia and that several steps will be required but you will get started today.

How do you use punch biopsies to determine the best treatment options?

My most important tips regarding alopecia diagnosis relate to scalp biopsies, which usually are required in distinguishing chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus from other scarring alopecias. First, an absorbable gelatin compressed sponge is your best friend. A small strip inserted into the punch biopsy wound results in prompt hemostasis without the need for sutures, and the resulting scar often looks as good or better than that produced by suturing. Next, don’t biopsy the active advancing borders of an alopecia patch, as the findings usually are nonspecific. Instead, biopsy a well-established portion that has been present for at least 4 to 6 months but is still active. In inconclusive cases, a biopsy of a scarred area stained with Verhoeff elastic stain can demonstrate characteristic patterns of elastic tissue loss and often establish a diagnosis. It is important to distinguish chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus from other forms of scarring alopecia, as it is more likely to respond to antimalarials.

What are your go-to treatments? Are your recommendations anecdotal or evidence based?

There isn’t an extensive arsenal of evidence-based therapy for refractory scarring alopecia, but that doesn’t mean we don’t have effective therapies; it simply means that our treatments are based on experience without accompanying randomized controlled trials. We need to produce more evidence, but patients with severe disease still need to be treated in the meantime. It’s important to remember that therapeutic complacency can result in permanent irreversible scarring. The presence of easily extractable anagen hairs is a sign of active disease. This simple test is helpful to monitor therapeutic progress.

Topical and intralesional corticosteroids can be extremely useful and often are underused. In general, the risk of scarring and atrophy from untreated disease is much greater than that from the corticosteroid. On the scalp, atrophy often presents as erythema, which should not be confused with erythema related to active disease. Dermoscopy is useful to demonstrate that the redness represents dermal atrophy with prominence of the subpapillary plexus of vessels.

When systemic therapy is required, antimalarials, retinoids, dapsone, thalidomide, sulfasalazine, mycophenolate mofetil, and methotrexate have all been used successfully in the setting of cutaneous lupus erythematosus, while topical tazarotene and topical calcineurin inhibitors are generally disappointing.

For the treatment of lichen planopilaris, intralesional corticosteroids, oral retinoids, and excimer laser can be effective. In contrast, antimalarials usually are not effective in preventing disease progression. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ agonist pioglitazone can be effective, but reported results vary widely. In my experience, mycophenolate mofetil is generally reliable in patients with refractory disease. Dutasteride can be effective as a first-line therapy in the setting of frontal fibrosing alopecia, although some of the noted improvement may relate to the nonscarring portion of the disease in patients with a background of pattern alopecia.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

Again, the key to treatment compliance is to establish an effective doctor-patient relationship. Whenever possible, begin with adequately potent therapy to give patients an early response. Don’t hesitate to use prednisone initially for inflammatory scarring alopecia. Patients need to see signs of progress in order to stay compliant with treatment, and long trials of ineffective therapies destroy trust. Adequate doses of intralesional or oral corticosteroids often are appropriate to ensure an early response with subsequent transition to steroid-sparing agents.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

Try to find out why—often it’s simply fear of side effects. Patient education is key, and it can help tremendously to share with them the number of patients you have treated safely with the medication in question and assure them that you know how to monitor for the important side effects.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

It is helpful to keep a handy list of patient advocacy Web sites. Well-established support groups such as the National Alopecia Areata Foundation (https://www.naaf.org) and the Cicatricial Alopecia Research Foundation (http://www.carfintl.org) provide excellent information for patients and help to support research to improve outcomes for these difficult disorders.

AAGL 2015: Conference social highlights

Tune in daily for social media coverage of AAGL 2015 from OBG Management and ObGyn News. Share your thoughts with us, and we may highlight them below. Thank you for your social contributions!

|

|

Tune in daily for social media coverage of AAGL 2015 from OBG Management and ObGyn News. Share your thoughts with us, and we may highlight them below. Thank you for your social contributions!

|

|

Tune in daily for social media coverage of AAGL 2015 from OBG Management and ObGyn News. Share your thoughts with us, and we may highlight them below. Thank you for your social contributions!

|

|

Iron deficiency may explain persistent hypothyroidism symptoms

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. – Between 30% and 50% of hypothyroid patients with persistent symptoms despite adequate levothyroxine therapy may have covert iron deficiency, findings from a small study suggest.

The findings cast “a dark shadow of doubt on the validity of the studies on the effect of T3 therapy in these patients,” Dr. Esa Soppi reported in a poster at the International Thyroid Congress.

Study subjects were women with a history of overt hypothyroidism who had persistent symptoms after appropriate and ongoing treatment with L-T4. L-T4 dosing was adjusted as necessary to achieve a thyroid-stimulating hormone concentration of 1-2 mU/L, and diabetes, B12-vitamin deficiency, celiac disease, hypercalcemia, and vitamin D deficiency were ruled out as causes for the persistent symptoms.

Further, none of the patients had anemia, and red cell indices were within the reference range.

Five of the women had serum ferritin of less than 15 mcg/L, and two of those had serum iron, transferrin, or soluble transferrin receptor concentration or transferrin saturation out of range, suggesting iron deficiency. The remaining 20 women had a serum ferritin concentration between 15 mcg/L and 60 mcg/L, Dr. Soppi of Eira Hospital, Helsinki, noted at the meeting held by the American Thyroid Association, Asia-Oceania Thyroid Association , European Thyroid Association, and Latin American Thyroid Society.

Four of the five women with serum ferritin less than 15 mcg/L, and 14 of the 20 with less than 15-60 mcg/L became symptom free when treated with oral iron substitution therapy for 6-12 months, Dr. Soppi said.

“All patients were advised to take their thyroxine dose at the fasting state in the morning and start breakfast 30 minutes later. The interval between the iron and thyroxine was at least 4 hours. The response was observed at a serum ferritin concentration approaching 70-100 mcg/L,” Dr. Soppi wrote, noting that in one patient – a 28-year-old woman with type 1 diabetes and hypothyroidism – all symptoms of fatigue, failure to thrive, and lethargy experienced before the start of the iron therapy disappeared after about 4 months of oral iron therapy at a dose of 100 mg twice daily.

However, another patient – an 18-year-old woman with hypothyroidism after total thyroidectomy performed because of a suspected thyroid malignancy – was found to have no malignancy; disabling tiredness, and failure to thrive emerged after the thyroidectomy and persisted despite iron therapy given at 100 mg twice daily.

“Iron deficiency is as common as hypothyroidism and its symptoms resemble those of hypothyroidism. However, the diagnosis of iron deficiency without anemia is extremely challenging since all indicators of iron status may be ‘normal.’ A clinical suspicion is key to diagnosis of covert iron deficiency,” Dr. Soppi wrote, noting that the serum ferritin concentration may be helpful, and restoration of ferritin above 100 mcg/L seems to ameliorate symptoms in about two-thirds of patients, and that it is not currently known why some iron-deficient patients fail to respond to restoration of their functional iron stores.

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. – Between 30% and 50% of hypothyroid patients with persistent symptoms despite adequate levothyroxine therapy may have covert iron deficiency, findings from a small study suggest.

The findings cast “a dark shadow of doubt on the validity of the studies on the effect of T3 therapy in these patients,” Dr. Esa Soppi reported in a poster at the International Thyroid Congress.

Study subjects were women with a history of overt hypothyroidism who had persistent symptoms after appropriate and ongoing treatment with L-T4. L-T4 dosing was adjusted as necessary to achieve a thyroid-stimulating hormone concentration of 1-2 mU/L, and diabetes, B12-vitamin deficiency, celiac disease, hypercalcemia, and vitamin D deficiency were ruled out as causes for the persistent symptoms.

Further, none of the patients had anemia, and red cell indices were within the reference range.

Five of the women had serum ferritin of less than 15 mcg/L, and two of those had serum iron, transferrin, or soluble transferrin receptor concentration or transferrin saturation out of range, suggesting iron deficiency. The remaining 20 women had a serum ferritin concentration between 15 mcg/L and 60 mcg/L, Dr. Soppi of Eira Hospital, Helsinki, noted at the meeting held by the American Thyroid Association, Asia-Oceania Thyroid Association , European Thyroid Association, and Latin American Thyroid Society.

Four of the five women with serum ferritin less than 15 mcg/L, and 14 of the 20 with less than 15-60 mcg/L became symptom free when treated with oral iron substitution therapy for 6-12 months, Dr. Soppi said.

“All patients were advised to take their thyroxine dose at the fasting state in the morning and start breakfast 30 minutes later. The interval between the iron and thyroxine was at least 4 hours. The response was observed at a serum ferritin concentration approaching 70-100 mcg/L,” Dr. Soppi wrote, noting that in one patient – a 28-year-old woman with type 1 diabetes and hypothyroidism – all symptoms of fatigue, failure to thrive, and lethargy experienced before the start of the iron therapy disappeared after about 4 months of oral iron therapy at a dose of 100 mg twice daily.

However, another patient – an 18-year-old woman with hypothyroidism after total thyroidectomy performed because of a suspected thyroid malignancy – was found to have no malignancy; disabling tiredness, and failure to thrive emerged after the thyroidectomy and persisted despite iron therapy given at 100 mg twice daily.

“Iron deficiency is as common as hypothyroidism and its symptoms resemble those of hypothyroidism. However, the diagnosis of iron deficiency without anemia is extremely challenging since all indicators of iron status may be ‘normal.’ A clinical suspicion is key to diagnosis of covert iron deficiency,” Dr. Soppi wrote, noting that the serum ferritin concentration may be helpful, and restoration of ferritin above 100 mcg/L seems to ameliorate symptoms in about two-thirds of patients, and that it is not currently known why some iron-deficient patients fail to respond to restoration of their functional iron stores.

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. – Between 30% and 50% of hypothyroid patients with persistent symptoms despite adequate levothyroxine therapy may have covert iron deficiency, findings from a small study suggest.

The findings cast “a dark shadow of doubt on the validity of the studies on the effect of T3 therapy in these patients,” Dr. Esa Soppi reported in a poster at the International Thyroid Congress.

Study subjects were women with a history of overt hypothyroidism who had persistent symptoms after appropriate and ongoing treatment with L-T4. L-T4 dosing was adjusted as necessary to achieve a thyroid-stimulating hormone concentration of 1-2 mU/L, and diabetes, B12-vitamin deficiency, celiac disease, hypercalcemia, and vitamin D deficiency were ruled out as causes for the persistent symptoms.

Further, none of the patients had anemia, and red cell indices were within the reference range.

Five of the women had serum ferritin of less than 15 mcg/L, and two of those had serum iron, transferrin, or soluble transferrin receptor concentration or transferrin saturation out of range, suggesting iron deficiency. The remaining 20 women had a serum ferritin concentration between 15 mcg/L and 60 mcg/L, Dr. Soppi of Eira Hospital, Helsinki, noted at the meeting held by the American Thyroid Association, Asia-Oceania Thyroid Association , European Thyroid Association, and Latin American Thyroid Society.

Four of the five women with serum ferritin less than 15 mcg/L, and 14 of the 20 with less than 15-60 mcg/L became symptom free when treated with oral iron substitution therapy for 6-12 months, Dr. Soppi said.

“All patients were advised to take their thyroxine dose at the fasting state in the morning and start breakfast 30 minutes later. The interval between the iron and thyroxine was at least 4 hours. The response was observed at a serum ferritin concentration approaching 70-100 mcg/L,” Dr. Soppi wrote, noting that in one patient – a 28-year-old woman with type 1 diabetes and hypothyroidism – all symptoms of fatigue, failure to thrive, and lethargy experienced before the start of the iron therapy disappeared after about 4 months of oral iron therapy at a dose of 100 mg twice daily.

However, another patient – an 18-year-old woman with hypothyroidism after total thyroidectomy performed because of a suspected thyroid malignancy – was found to have no malignancy; disabling tiredness, and failure to thrive emerged after the thyroidectomy and persisted despite iron therapy given at 100 mg twice daily.

“Iron deficiency is as common as hypothyroidism and its symptoms resemble those of hypothyroidism. However, the diagnosis of iron deficiency without anemia is extremely challenging since all indicators of iron status may be ‘normal.’ A clinical suspicion is key to diagnosis of covert iron deficiency,” Dr. Soppi wrote, noting that the serum ferritin concentration may be helpful, and restoration of ferritin above 100 mcg/L seems to ameliorate symptoms in about two-thirds of patients, and that it is not currently known why some iron-deficient patients fail to respond to restoration of their functional iron stores.

AT THE INTERNATIONAL THYROID CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Between 30% and 50% of hypothyroid patients with persistent symptoms despite adequate levothyroxine therapy may have covert iron deficiency, findings from a small study suggest.

Major finding: Four of five women with serum ferritin less than 15 mcg/L, and 14 of 20 with less than 15-60 mcg/L became symptom free when treated with oral iron substitution therapy for 6-12 months.

Data source: A prospective study of 25 women.

Disclosures: Dr. Soppi reported having no disclosures.

ACS: Watchful waiting for some rectal cancers almost ready for ‘prime time’

CHICAGO – Watchful waiting with careful surveillance may become an option for the majority of locally advanced rectal cancer patients who have a complete clinical response to neoadjuvant therapy, according to a review of 442 rectal cancer patients at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

Seventy-three of those patients had a complete clinical response to neoadjuvant therapy and opted for watchful waiting instead of surgery after weighing the risks and benefits – including about a 25% chance of local recurrence – with their doctors.

At 4 years’ follow-up, 54 (74%) remained cancer free. Nineteen patients had local tumor recurrence, generally within 13 months. Two of those patients had successful local excisions, and the remaining 17 had salvage total mesorectal excisions (TME).

There were no statistically significant differences in 4-year disease-specific and overall survival among the 73 patients and 72 other patients who opted for TME after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and were found to have had pathologic complete responses.

“In our cohort, watch and wait was safe. It’s an effective treatment strategy achieving a high rate of rectal preservation in tumors that respond to neoadjuvant therapy. I don’t think the rectum needs to come out in everybody,” said investigator Dr. J. Joshua Smith, a surgical oncologist at Sloan Kettering.

Several studies have reported similar results similar to the Sloan Kettering study, but other investigations have been retrospective, so optimal patient selection, assessment of response, surveillance protocols, and other matters remain uncertain. Sloan Kettering and about 20 other cancer centers in United States – all members of the Rectal Cancer Consortium – recently launched a randomized clinical trial to get a better handle on those issues.

Locally advanced rectal cancer patients will be randomized to either chemoradiation for 5.5 weeks followed by folinic acid, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) or capecitabine and oxaliplatin (CapeOX) over about 16 weeks, or FOLFOX/CapeOX first and chemoradiation second. Those who have a significant clinical response will then undergo watchful waiting; those who do not will have TME.

About 50 patients have enrolled in the phase II trial so far; the investigators are looking for more than 200.

“I think ‘prime time for watchful waiting’ is around the corner, but not yet here. It must be preceded by a prospective trial.” Meanwhile, “how we define complete clinical response is important” when considering watchful waiting, Dr. Smith said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons..

At Sloan Kettering, where watchful waiting has become more popular in recent years, complete clinical response means no tumor or lymph nodes on imaging, and, on digital rectal exam (DRE) and proctoscopy, normal flat mucosa, smooth induration, no mass, no nodules, no ulcerations, and no luminal narrowing; a pale scar and telangiectasias are okay.

In the first year, surveillance includes DRE and endoscopy every 3 months and imaging every 6 months. In the second year, DRE and endoscopy come every 4 months, and imaging again every 6 months. From years 3 to 5, DRE and endoscopy are done every 6 months, and imaging every 6-12 months. After 5 years, surveillance is by yearly DRE and endoscopy.

When discussing the option with patients, they need to know – besides the risk of recurrence – that watchful waiting is currently not standard medical management; surveillance must be frequent; they are at risk for a more extensive salvage TME than they might have had otherwise; and the approach might compromise the chance of a cure, Dr. Smith said.

Dr. Smith said he has no relevant disclosures.

CHICAGO – Watchful waiting with careful surveillance may become an option for the majority of locally advanced rectal cancer patients who have a complete clinical response to neoadjuvant therapy, according to a review of 442 rectal cancer patients at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

Seventy-three of those patients had a complete clinical response to neoadjuvant therapy and opted for watchful waiting instead of surgery after weighing the risks and benefits – including about a 25% chance of local recurrence – with their doctors.

At 4 years’ follow-up, 54 (74%) remained cancer free. Nineteen patients had local tumor recurrence, generally within 13 months. Two of those patients had successful local excisions, and the remaining 17 had salvage total mesorectal excisions (TME).

There were no statistically significant differences in 4-year disease-specific and overall survival among the 73 patients and 72 other patients who opted for TME after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and were found to have had pathologic complete responses.

“In our cohort, watch and wait was safe. It’s an effective treatment strategy achieving a high rate of rectal preservation in tumors that respond to neoadjuvant therapy. I don’t think the rectum needs to come out in everybody,” said investigator Dr. J. Joshua Smith, a surgical oncologist at Sloan Kettering.

Several studies have reported similar results similar to the Sloan Kettering study, but other investigations have been retrospective, so optimal patient selection, assessment of response, surveillance protocols, and other matters remain uncertain. Sloan Kettering and about 20 other cancer centers in United States – all members of the Rectal Cancer Consortium – recently launched a randomized clinical trial to get a better handle on those issues.

Locally advanced rectal cancer patients will be randomized to either chemoradiation for 5.5 weeks followed by folinic acid, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) or capecitabine and oxaliplatin (CapeOX) over about 16 weeks, or FOLFOX/CapeOX first and chemoradiation second. Those who have a significant clinical response will then undergo watchful waiting; those who do not will have TME.

About 50 patients have enrolled in the phase II trial so far; the investigators are looking for more than 200.

“I think ‘prime time for watchful waiting’ is around the corner, but not yet here. It must be preceded by a prospective trial.” Meanwhile, “how we define complete clinical response is important” when considering watchful waiting, Dr. Smith said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons..

At Sloan Kettering, where watchful waiting has become more popular in recent years, complete clinical response means no tumor or lymph nodes on imaging, and, on digital rectal exam (DRE) and proctoscopy, normal flat mucosa, smooth induration, no mass, no nodules, no ulcerations, and no luminal narrowing; a pale scar and telangiectasias are okay.

In the first year, surveillance includes DRE and endoscopy every 3 months and imaging every 6 months. In the second year, DRE and endoscopy come every 4 months, and imaging again every 6 months. From years 3 to 5, DRE and endoscopy are done every 6 months, and imaging every 6-12 months. After 5 years, surveillance is by yearly DRE and endoscopy.

When discussing the option with patients, they need to know – besides the risk of recurrence – that watchful waiting is currently not standard medical management; surveillance must be frequent; they are at risk for a more extensive salvage TME than they might have had otherwise; and the approach might compromise the chance of a cure, Dr. Smith said.

Dr. Smith said he has no relevant disclosures.

CHICAGO – Watchful waiting with careful surveillance may become an option for the majority of locally advanced rectal cancer patients who have a complete clinical response to neoadjuvant therapy, according to a review of 442 rectal cancer patients at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

Seventy-three of those patients had a complete clinical response to neoadjuvant therapy and opted for watchful waiting instead of surgery after weighing the risks and benefits – including about a 25% chance of local recurrence – with their doctors.

At 4 years’ follow-up, 54 (74%) remained cancer free. Nineteen patients had local tumor recurrence, generally within 13 months. Two of those patients had successful local excisions, and the remaining 17 had salvage total mesorectal excisions (TME).

There were no statistically significant differences in 4-year disease-specific and overall survival among the 73 patients and 72 other patients who opted for TME after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and were found to have had pathologic complete responses.

“In our cohort, watch and wait was safe. It’s an effective treatment strategy achieving a high rate of rectal preservation in tumors that respond to neoadjuvant therapy. I don’t think the rectum needs to come out in everybody,” said investigator Dr. J. Joshua Smith, a surgical oncologist at Sloan Kettering.

Several studies have reported similar results similar to the Sloan Kettering study, but other investigations have been retrospective, so optimal patient selection, assessment of response, surveillance protocols, and other matters remain uncertain. Sloan Kettering and about 20 other cancer centers in United States – all members of the Rectal Cancer Consortium – recently launched a randomized clinical trial to get a better handle on those issues.

Locally advanced rectal cancer patients will be randomized to either chemoradiation for 5.5 weeks followed by folinic acid, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) or capecitabine and oxaliplatin (CapeOX) over about 16 weeks, or FOLFOX/CapeOX first and chemoradiation second. Those who have a significant clinical response will then undergo watchful waiting; those who do not will have TME.

About 50 patients have enrolled in the phase II trial so far; the investigators are looking for more than 200.

“I think ‘prime time for watchful waiting’ is around the corner, but not yet here. It must be preceded by a prospective trial.” Meanwhile, “how we define complete clinical response is important” when considering watchful waiting, Dr. Smith said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons..

At Sloan Kettering, where watchful waiting has become more popular in recent years, complete clinical response means no tumor or lymph nodes on imaging, and, on digital rectal exam (DRE) and proctoscopy, normal flat mucosa, smooth induration, no mass, no nodules, no ulcerations, and no luminal narrowing; a pale scar and telangiectasias are okay.

In the first year, surveillance includes DRE and endoscopy every 3 months and imaging every 6 months. In the second year, DRE and endoscopy come every 4 months, and imaging again every 6 months. From years 3 to 5, DRE and endoscopy are done every 6 months, and imaging every 6-12 months. After 5 years, surveillance is by yearly DRE and endoscopy.

When discussing the option with patients, they need to know – besides the risk of recurrence – that watchful waiting is currently not standard medical management; surveillance must be frequent; they are at risk for a more extensive salvage TME than they might have had otherwise; and the approach might compromise the chance of a cure, Dr. Smith said.

Dr. Smith said he has no relevant disclosures.

AT THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Organ preservation seems to be a valid option when locally advanced rectal cancers respond completely to neoadjuvant therapy.

Major finding: Almost three-quarters of 73 patients who opted for watchful waiting after complete clinical responses to neodjuvant therapy remained cancer free at 4 years.

Data source: Review of 442 patients at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Disclosures: The presenting investigator has no relevant financial disclosures.

Status Report From the American Acne & Rosacea Society on Medical Management of Acne in Adult Women, Part 2: Topical Therapies

It seems intuitive that clinicians in dermatology would automatically recognize the importance of proper selection and integration of skin care products and techniques in the management of acne vulgaris (AV). However, an understanding of the fundamental importance of skin care in AV management and the scientific basis for maintaining epidermal barrier (EpB) function and repair cannot be assumed. In fact, there is limited scientific information about EpB dysfunction and AV or the adjunctive benefits of specific skin care products. However, some data have emerged that can be successfully applied by clinicians.1-9

In part 2 of this series, emphasis is placed on skin care and topical therapies for the treatment of AV in adult women. In addition to the plethora of cleanser and moisturizer formulations that exist in the marketplace, there are many over-the-counter (OTC) products marketed to treat AV that contain benzoyl peroxide (BP) and salicylic acid. Importantly, women tend to be selective about what they use to cleanse and moisturize their skin, and use of OTC products to treat AV is common among adult women.10,11

A thorough discussion of EpB impairment, related inflammatory cascades, and potential relevance to AV are beyond the scope of this article. In short, appropriate skin care products can reduce the inflammation and sensitivity associated with increased transepidermal water loss and reduced stratum corneum hydration and can mitigate EpB impairments induced by certain acne medications or vehicles.1,12 Available data support the adjunctive benefit of proper skin care in the management of AV by mitigating cutaneous irritation and potentially contributing to a reduction in AV lesions.2-4,7,13 Use of a formulation that also provides broad-spectrum photoprotection also is helpful.3,4

Another challenge is the myriad of cosmeceuticals that are heavily marketed to adult women with AV.13,14 Unfortunately, the scientific evidence supporting these products for treatment of AV is limited, resulting in the clinician’s inability to make specific recommendations. The core message is to incorporate skin care products that can reduce EpB impairment and mitigate cutaneous irritation associated with some AV therapies.1-4,7-9,12

OTC Topical Therapies

The marketplace is replete with several OTC products for treatment of AV, most of which contain BP and salicylic acid.15,16 There is a lack of efficacy data for OTC products for AV, including cleansers and topical medications, although some may be beneficial for milder cases. A variety of formulations are available to choose from, usually without the advice of a clinician. Additionally, heavy marketing is directed at adult women with AV, which may promote the use of therapies that may not be optimal for their respective AV severity or may cause facial skin irritation. Self-treatment may also cause delay in seeking dermatologic care, increasing the risk of persistent or permanent sequelae. Delay in adequate treatment is a major risk factor for the development of acne scars.17

Prescription Topical Therapies

Despite the high prevalence of AV in adult women, there is a paucity of studies evaluating topical therapies for AV in this subset.18-24 Reports in the literature on AV in adult women have focused on systemic hormonal agents (eg, oral contraceptives, spironolactone); however, more recent reports have addressed the use of topical therapies in this subpopulation.11,25-30 Published data on topical formulations are predominantly post hoc analyses from pivotal randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that included adolescents and adults of both genders with facial AV located above the jawline and predominantly moderate in severity.11,26,28,30 Participants in all of these studies presented with non-nodular, mixed inflammatory, and comedonal facial AV above the jawline, with inclusion criteria that required a minimum of 20 comedonal lesions and 20 papulopustular lesions at baseline. An important differentiating factor among these various post hoc analyses evaluating adult women versus adolescent girls with AV are the ages used to separate adults from adolescents. A dividing line of 18 years and older was used in some reports (eg, adapalene gel 0.3%, dapsone gel 5%), while other reports used 25 years and older to separate adolescent girls from adult women (ie, clindamycin phosphate [CP] 1.2%– BP 3.75% gel, adapalene 0.1%–BP 2.5% gel).11,26,28,30

Importantly, these studies included adult women with AV who presented with mixed comedonal and inflammatory AV (mixed pattern AV) similar to adolescents. None of the studies included women with a U-shaped AV pattern or lower facial AV characterized by deep inflammatory lesions that are often tender and few in number. Unfortunately, there is a lack of data evaluating topical therapies for these patterns of AV in adult women, including AV below the jawline and on the trunk. Although mixed pattern AV has been reported to affect 75% to 90% of adult women with AV, epidemiologic data quantifying the clinical AV patterns affecting adult women are limited.11,22,29,31,32 More well-designed studies are needed.

The treatment of AV in adult women may incorporate any of the topical therapies used to treat AV in adolescents, especially as studies encompass both the adolescent and adult age ranges. This is especially true with mixed pattern AV, which is the predominant presentation in participants enrolled in clinical trials with topical therapies, especially of moderate severity.

Herein we provide a summary of the topical therapies that have been evaluated by post hoc analyses of data from pivotal studies in adult women with AV.

Adapalene Gel 0.3%

Adapalene exhibits retinoid activity with efficacy in reducing inflammatory and comedonal AV lesions shown with both 0.1% and 0.3% concentrations.33-35 Post hoc analyses of 2 pivotal RCTs of patients with facial AV showed that adapalene gel 0.3% once daily (n=74; mean age, 27.2 years) was superior to vehicle once daily (n=43; mean age, 25.2 years) in both mean and median percentage reductions of comedonal, inflammatory, and total lesions in women 18 years and older who were treated for 12 weeks; the difference in mean percentage lesion reduction from vehicle for total AV lesions was statistically significant at 12 weeks (P=.045).26 Adapalene gel 0.3% produced a favorable skin tolerability profile similar to adapalene gel 0.1%, with the most common adverse reactions being discomfort and dryness.

Advantages of topical retinoid therapy in adult women with facial AV are reduction in postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and therapeutic modulation of chronic photodamage (eg, fine lines, rough texture, dyschromia).29,36,37 Disadvantages include signs and symptoms of cutaneous irritation, although this tends to occur less frequently on facial skin with adapalene gel 0.3% as compared to other topical retinoids that exhibit comparable efficacy.33-37 Topical retinoid therapy on the anterior neck and upper chest should be used cautiously, as these anatomic sites appear to be more prone to cutaneous irritation.

Dapsone Gel 5%

Dapsone is a sulfone antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory agent that has been shown to be effective, safe, and well tolerated in the treatment of AV in a topical 5% formulation.38,39 A post hoc analysis of pivotal 12-week trial data suggested that dapsone gel 5% twice daily produced greater AV reductions in females compared to males; no gender differences were noted in adverse effects, which were low in frequency.39 A separate subgroup analysis compared outcomes among adult women (≥18 years of age; n=434) and adolescent girls (12–17 years of age; n=347) treated with dapsone gel 5%.11 The proportion with no or minimal acne based on the Global Acne Assessment Score at week 12 was greater in adult women (53.5%) versus adolescent girls (45.3%, P=.022), with significantly greater percentage reductions in both noninflammatory (P<.0001) and total lesion counts (P=.0008) observed in the adult group. Percentage reductions in inflammatory lesions were similar in both groups. No major safety or tolerability issues or new safety signals were noted. Advantages of dapsone gel 5% are highly favorable tolerability and the perception of decreased oily skin in some participants.38,39

Clindamycin Phosphate 1.2%–Benzoyl Peroxide 3.75% Gel

The combination formulation of CP 1.2%– BP 3.75% gel applied once daily has been shown to be effective, well tolerated, and safe for the treatment of facial AV, with a gender analysis noting an apparent greater efficacy in females.40,41 A post hoc analysis from the 12-week pivotal study data in adult women aged 25 years and older showed a mean percentage change from baseline in inflammatory and noninflammatory lesion counts and the percentage of participants who achieved a 2-grade improvement by global assessment to be 68.7%, 60.4%, and 52.7% in actively treated participants (n=29), respectively, which was significantly superior to vehicle applied once daily (n=43; P=.019, P=.020, and P=.074, respectively).42 No relevant differences in tolerability were noted among treatment groups, and no participants discontinued therapy due to adverse events. Advantages of CP 1.2%–BP 3.75% gel are highly favorable skin tolerability and the perception of decreased oily skin in some participants.41-43

Adapalene 0.1%–Benzoyl Peroxide 2.5% Gel

A meta-analysis of pooled data from 3 RCTs evaluated use of adapalene 0.1%–BP 2.5% gel applied once daily in adult women aged 25 years and older with facial AV (n=130) versus vehicle gel applied once daily (n=124).30 The percentage of participants who achieved investigator global assessment ratings of clear or almost clear was 39.2% in actively treated participants versus 18.5% with vehicle (P<.001), and median percentage lesion reduction was approximately 30% greater in those treated with adapalene 0.1%–BP 2.5% gel versus vehicle gel. Tolerability and safety were favorable.

Other Agents

Topical azelaic acid (20% cream formulation, 15% gel formulation) has been suggested as a treatment option for adult women with AV, including patients with darker skin who are more prone to persistent hyperpigmentation.29

Conclusion

Proper skin care is an important component in the management of AV in adult women. Data for topical therapies in this subpopulation are limited; however, post hoc analyses provide some information regarding their efficacy in treating mixed pattern AV. More well-designed studies are needed to better evaluate the use of topical agents in adult women with AV. Although most topical AV therapies appear to be safe for use during pregnancy when properly used and limited to facial application, their use in women of childbearing potential and during pregnancy warrants individual consideration; topical retinoids are best avoided during pregnancy, especially tazarotene, which is rated category X.44 In part 3 of this series, oral therapies used to treat AV in adult women will be discussed.

1. Thiboutot D, Del Rosso JQ. Acne vulgaris and the epidermal barrier: is acne vulgaris associated with inherent epidermal abnormalities that cause impairment of barrier functions? do any topical acne therapies alter the structural and/or functional integrity of the epidermal barrier? J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:18-24.

2. Subramanyan K. Role of mild cleansing in the management of patient skin. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17(suppl 1):26-34.

3. Del Rosso JQ, Gold M, Rueda MJ, et al. Efficacy, safety, and subject satisfaction of a specified skin care regimen to cleanse, medicate, moisturize, and protect the skin of patients under treatment for acne vulgaris. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:22-30.

4. Del Rosso JQ, Brandt S. The role of skin care as an integral component in the management of acne vulgaris: part 2: tolerability and performance of a designated skin care regimen using a foam wash and moisturizer SPF 30 in patients with acne vulgaris undergoing active treatment. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:28-36.

5. Draelos ZD. Facial cosmetics for acne patients. Cosmetics in Dermatology. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone Inc; 1995:22-23.

6. Leyden JJ, Del Rosso JQ, Baum EW. The use of isotretinoin in the treatment of acne vulgaris: clinical considerations and future directions. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7(suppl 2):S3-S21.

7. Hayashi N, Kawashima M. Study of the usefulness of moisturizers on adherence of acne patients treated with adapalene. J Dermatol. 2014;41:592-597.

8. Isoda K, Seki T, Inoue Y, et al. Efficacy of the combined use of a facial cleanser and moisturizers for the care of mild acne patients with sensitive skin. J Dermatol. 2015;42:181-188.

9. Hensley D, Meckfessel MH. Tolerability of a skin care regimen formulated for acne-prone skin in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:501-505.

10. Tanghetti EA, Kawata AK, Daniels SR, et al. Understanding the burden of adult female acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:22-30.

11. Del Rosso JQ, Kircik L, Gallagher CJ. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of dapsone 5% gel in adult versus adolescent females with acne vulgaris. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:31-37.

12. Del Rosso JQ, Levin J. The clinical relevance of maintaining the functional integrity of the stratum corneum in both healthy and disease-affected skin. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:22-42.

13. Levin J, Momin SB. How much do we really know about our favorite cosmeceutical ingredients? J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:22-41.

14. Draelos ZD. Acne. In: Draelos ZD, ed. Cosmeceuticals. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders-Elsevier; 2009:175-180.

15. Kircik LH, Gwazdauskas J, Butners V, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy, tolerability, and safety of an over-the-counter acne regimen containing benzoyl peroxide and salicylic acid in subjects with acne. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:259-264.

16. Decker A, Graber EM. Over-the-counter acne treatments: a review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:32-40.

17. Layton AM, Henderson C, Cunliffe WJ. A clinical evaluation of acne scarring and its incidence. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:303-308.

18. Perkins AC, Maglione J, Hillebrand GG, et al. Acne vulgaris in women: prevalence across the life span. J Womens Health. 2012;21:223-230.

19. Poli F, Dreno B, Verschoore M. An epidemiological study of acne in female adults: results of a survey conducted in France. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:541-545.

20. Collier CN, Harper JC, Cafardi JA, et al. The prevalence of acne in adults 20 years and older. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:56-59.

21. Capitanio B, Sinagra JL, Bordignon V, et al. Underestimated clinical features of postadolescent acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:782-788.

22. Holzmann R, Shakery K. Postadolescent acne in females. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2014;27(suppl 1):3-8.

23. Williams C, Layton AM. Persistent acne in women: implications for the patient and for therapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:281-290.

24. Rendon MI, Rodriguez DA, Kawata AK, et al. Acne treatment patterns, expectations, and satisfaction among adult females of different races/ethnicities. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:231-238.

25. Villasenor J, Berson DS, Kroshinsky D. Treatment guidelines in adult women. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:198-207.

26. Berson D, Alexis A. Adapalene 0.3% for the treatment of acne in women. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:32-35.

27. Del Rosso JQ. Topical therapy for acne in women: is there a role for clindamycin phosphate–benzoyl peroxide gel? Cutis. 2014;94:177-182.

28. Zeichner JA. The efficacy and tolerability of a fixed combination (1.2%) and benzoyl peroxide (3.75%) aqueous gel in adult females with facial acne vulgaris. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:21-25.

29. Fisk WA, Lev-Tov HA, Sivamani RK. Epidemiology and management of acne in adult women. Curr Derm Rep. 2014;3:29-39.

30. Stein-Gold L. Adapalene 0.1%-benzoyl peroxide 2.5% gel in adult female acne. Poster presented at: Winter Clinical Dermatology Conference; January 16–21, 2015; Maui, Hawaii.

31. Dréno B, Thiboutot D, Layton AM, et al. Large-scale international study enhances understanding of an emerging acne population: adult females. J Euro Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1096-1106.

32. Dréno B, Layton AM, Zouboulis CC, et al. Adult female acne: a new paradigm. J Euro Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1063-1070.

33. Shalita A, Weiss JS, Chalker DK, et al. A comparison of the efficacy and safety of adapalene gel 0.1% and tretinoin gel 0.025% in the treatment of acne vulgaris: a multicenter trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:482-485.

34. Pariser DM, Thiboutot DM, Clark SD, et al. The efficacy and safety of adapalene gel 0.3% in the treatment of acne vulgaris: a randomized, multicenter, investigator-blinded, controlled comparison study versus adapalene gel 0.1% and vehicle. Cutis. 2005;76:145-151.

35. Thiboutot D, Pariser DM, Egan N, et al. Adapalene gel 0.3% for the treatment of acne vulgaris: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, controlled, phase III trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:242-250.

36. Tanghetti E, Dhawan S, Green L, et al. Randomized comparison of the safety and efficacy of tazarotene 0.1% cream and adapalene 0.3% gel in the treatment of patients with at least moderate facial acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:549-558.

37. Hui AM, Shalita AR. Topical retinoids. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:86-94.

38. Draelos Z, Carter E, Maloney JM, et al. Two randomized studies demonstrate the efficacy and safety of dapsone gel 5% for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:439.e1-439.e10.

39. Tanghetti E, Harper JC, Oefelein MG. The efficacy and tolerability of dapsone 5% gel in female vs male patients with facial acne vulgaris: gender as a clinically relevant outcome variable. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:1417-1421.

40. Pariser DM, Rich P, Cook-Bolden FE, et al. An aqueous gel fixed combination of clindamycin phosphate 1.2% and benzoyl peroxide 3.75% for the once-daily treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:1083-1089.

41. Harper JC. The efficacy and tolerability of a fixed combination clindamycin (1.2%) and benzoyl peroxide (3.75%) aqueous gel in patients with facial acne vulgaris: gender as a clinically relevant outcome variable. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:381-384.

42. Zeichner JA. The efficacy and tolerability of a fixed combination clindamycin (1.2%) and benzoyl peroxide (3.75%) aqueous gel in adult female patients with facial acne vulgaris. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:21-25.

43. Coley MK, Berson DS, Callendar VD. Overview of treatment principles for skin of color. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:70-85.

44. Ebede TL, Berson DS. Acne in pregnancy. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:177-181.

It seems intuitive that clinicians in dermatology would automatically recognize the importance of proper selection and integration of skin care products and techniques in the management of acne vulgaris (AV). However, an understanding of the fundamental importance of skin care in AV management and the scientific basis for maintaining epidermal barrier (EpB) function and repair cannot be assumed. In fact, there is limited scientific information about EpB dysfunction and AV or the adjunctive benefits of specific skin care products. However, some data have emerged that can be successfully applied by clinicians.1-9

In part 2 of this series, emphasis is placed on skin care and topical therapies for the treatment of AV in adult women. In addition to the plethora of cleanser and moisturizer formulations that exist in the marketplace, there are many over-the-counter (OTC) products marketed to treat AV that contain benzoyl peroxide (BP) and salicylic acid. Importantly, women tend to be selective about what they use to cleanse and moisturize their skin, and use of OTC products to treat AV is common among adult women.10,11

A thorough discussion of EpB impairment, related inflammatory cascades, and potential relevance to AV are beyond the scope of this article. In short, appropriate skin care products can reduce the inflammation and sensitivity associated with increased transepidermal water loss and reduced stratum corneum hydration and can mitigate EpB impairments induced by certain acne medications or vehicles.1,12 Available data support the adjunctive benefit of proper skin care in the management of AV by mitigating cutaneous irritation and potentially contributing to a reduction in AV lesions.2-4,7,13 Use of a formulation that also provides broad-spectrum photoprotection also is helpful.3,4

Another challenge is the myriad of cosmeceuticals that are heavily marketed to adult women with AV.13,14 Unfortunately, the scientific evidence supporting these products for treatment of AV is limited, resulting in the clinician’s inability to make specific recommendations. The core message is to incorporate skin care products that can reduce EpB impairment and mitigate cutaneous irritation associated with some AV therapies.1-4,7-9,12

OTC Topical Therapies

The marketplace is replete with several OTC products for treatment of AV, most of which contain BP and salicylic acid.15,16 There is a lack of efficacy data for OTC products for AV, including cleansers and topical medications, although some may be beneficial for milder cases. A variety of formulations are available to choose from, usually without the advice of a clinician. Additionally, heavy marketing is directed at adult women with AV, which may promote the use of therapies that may not be optimal for their respective AV severity or may cause facial skin irritation. Self-treatment may also cause delay in seeking dermatologic care, increasing the risk of persistent or permanent sequelae. Delay in adequate treatment is a major risk factor for the development of acne scars.17

Prescription Topical Therapies

Despite the high prevalence of AV in adult women, there is a paucity of studies evaluating topical therapies for AV in this subset.18-24 Reports in the literature on AV in adult women have focused on systemic hormonal agents (eg, oral contraceptives, spironolactone); however, more recent reports have addressed the use of topical therapies in this subpopulation.11,25-30 Published data on topical formulations are predominantly post hoc analyses from pivotal randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that included adolescents and adults of both genders with facial AV located above the jawline and predominantly moderate in severity.11,26,28,30 Participants in all of these studies presented with non-nodular, mixed inflammatory, and comedonal facial AV above the jawline, with inclusion criteria that required a minimum of 20 comedonal lesions and 20 papulopustular lesions at baseline. An important differentiating factor among these various post hoc analyses evaluating adult women versus adolescent girls with AV are the ages used to separate adults from adolescents. A dividing line of 18 years and older was used in some reports (eg, adapalene gel 0.3%, dapsone gel 5%), while other reports used 25 years and older to separate adolescent girls from adult women (ie, clindamycin phosphate [CP] 1.2%– BP 3.75% gel, adapalene 0.1%–BP 2.5% gel).11,26,28,30

Importantly, these studies included adult women with AV who presented with mixed comedonal and inflammatory AV (mixed pattern AV) similar to adolescents. None of the studies included women with a U-shaped AV pattern or lower facial AV characterized by deep inflammatory lesions that are often tender and few in number. Unfortunately, there is a lack of data evaluating topical therapies for these patterns of AV in adult women, including AV below the jawline and on the trunk. Although mixed pattern AV has been reported to affect 75% to 90% of adult women with AV, epidemiologic data quantifying the clinical AV patterns affecting adult women are limited.11,22,29,31,32 More well-designed studies are needed.

The treatment of AV in adult women may incorporate any of the topical therapies used to treat AV in adolescents, especially as studies encompass both the adolescent and adult age ranges. This is especially true with mixed pattern AV, which is the predominant presentation in participants enrolled in clinical trials with topical therapies, especially of moderate severity.

Herein we provide a summary of the topical therapies that have been evaluated by post hoc analyses of data from pivotal studies in adult women with AV.

Adapalene Gel 0.3%

Adapalene exhibits retinoid activity with efficacy in reducing inflammatory and comedonal AV lesions shown with both 0.1% and 0.3% concentrations.33-35 Post hoc analyses of 2 pivotal RCTs of patients with facial AV showed that adapalene gel 0.3% once daily (n=74; mean age, 27.2 years) was superior to vehicle once daily (n=43; mean age, 25.2 years) in both mean and median percentage reductions of comedonal, inflammatory, and total lesions in women 18 years and older who were treated for 12 weeks; the difference in mean percentage lesion reduction from vehicle for total AV lesions was statistically significant at 12 weeks (P=.045).26 Adapalene gel 0.3% produced a favorable skin tolerability profile similar to adapalene gel 0.1%, with the most common adverse reactions being discomfort and dryness.

Advantages of topical retinoid therapy in adult women with facial AV are reduction in postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and therapeutic modulation of chronic photodamage (eg, fine lines, rough texture, dyschromia).29,36,37 Disadvantages include signs and symptoms of cutaneous irritation, although this tends to occur less frequently on facial skin with adapalene gel 0.3% as compared to other topical retinoids that exhibit comparable efficacy.33-37 Topical retinoid therapy on the anterior neck and upper chest should be used cautiously, as these anatomic sites appear to be more prone to cutaneous irritation.

Dapsone Gel 5%

Dapsone is a sulfone antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory agent that has been shown to be effective, safe, and well tolerated in the treatment of AV in a topical 5% formulation.38,39 A post hoc analysis of pivotal 12-week trial data suggested that dapsone gel 5% twice daily produced greater AV reductions in females compared to males; no gender differences were noted in adverse effects, which were low in frequency.39 A separate subgroup analysis compared outcomes among adult women (≥18 years of age; n=434) and adolescent girls (12–17 years of age; n=347) treated with dapsone gel 5%.11 The proportion with no or minimal acne based on the Global Acne Assessment Score at week 12 was greater in adult women (53.5%) versus adolescent girls (45.3%, P=.022), with significantly greater percentage reductions in both noninflammatory (P<.0001) and total lesion counts (P=.0008) observed in the adult group. Percentage reductions in inflammatory lesions were similar in both groups. No major safety or tolerability issues or new safety signals were noted. Advantages of dapsone gel 5% are highly favorable tolerability and the perception of decreased oily skin in some participants.38,39

Clindamycin Phosphate 1.2%–Benzoyl Peroxide 3.75% Gel

The combination formulation of CP 1.2%– BP 3.75% gel applied once daily has been shown to be effective, well tolerated, and safe for the treatment of facial AV, with a gender analysis noting an apparent greater efficacy in females.40,41 A post hoc analysis from the 12-week pivotal study data in adult women aged 25 years and older showed a mean percentage change from baseline in inflammatory and noninflammatory lesion counts and the percentage of participants who achieved a 2-grade improvement by global assessment to be 68.7%, 60.4%, and 52.7% in actively treated participants (n=29), respectively, which was significantly superior to vehicle applied once daily (n=43; P=.019, P=.020, and P=.074, respectively).42 No relevant differences in tolerability were noted among treatment groups, and no participants discontinued therapy due to adverse events. Advantages of CP 1.2%–BP 3.75% gel are highly favorable skin tolerability and the perception of decreased oily skin in some participants.41-43

Adapalene 0.1%–Benzoyl Peroxide 2.5% Gel

A meta-analysis of pooled data from 3 RCTs evaluated use of adapalene 0.1%–BP 2.5% gel applied once daily in adult women aged 25 years and older with facial AV (n=130) versus vehicle gel applied once daily (n=124).30 The percentage of participants who achieved investigator global assessment ratings of clear or almost clear was 39.2% in actively treated participants versus 18.5% with vehicle (P<.001), and median percentage lesion reduction was approximately 30% greater in those treated with adapalene 0.1%–BP 2.5% gel versus vehicle gel. Tolerability and safety were favorable.

Other Agents

Topical azelaic acid (20% cream formulation, 15% gel formulation) has been suggested as a treatment option for adult women with AV, including patients with darker skin who are more prone to persistent hyperpigmentation.29

Conclusion

Proper skin care is an important component in the management of AV in adult women. Data for topical therapies in this subpopulation are limited; however, post hoc analyses provide some information regarding their efficacy in treating mixed pattern AV. More well-designed studies are needed to better evaluate the use of topical agents in adult women with AV. Although most topical AV therapies appear to be safe for use during pregnancy when properly used and limited to facial application, their use in women of childbearing potential and during pregnancy warrants individual consideration; topical retinoids are best avoided during pregnancy, especially tazarotene, which is rated category X.44 In part 3 of this series, oral therapies used to treat AV in adult women will be discussed.

It seems intuitive that clinicians in dermatology would automatically recognize the importance of proper selection and integration of skin care products and techniques in the management of acne vulgaris (AV). However, an understanding of the fundamental importance of skin care in AV management and the scientific basis for maintaining epidermal barrier (EpB) function and repair cannot be assumed. In fact, there is limited scientific information about EpB dysfunction and AV or the adjunctive benefits of specific skin care products. However, some data have emerged that can be successfully applied by clinicians.1-9

In part 2 of this series, emphasis is placed on skin care and topical therapies for the treatment of AV in adult women. In addition to the plethora of cleanser and moisturizer formulations that exist in the marketplace, there are many over-the-counter (OTC) products marketed to treat AV that contain benzoyl peroxide (BP) and salicylic acid. Importantly, women tend to be selective about what they use to cleanse and moisturize their skin, and use of OTC products to treat AV is common among adult women.10,11

A thorough discussion of EpB impairment, related inflammatory cascades, and potential relevance to AV are beyond the scope of this article. In short, appropriate skin care products can reduce the inflammation and sensitivity associated with increased transepidermal water loss and reduced stratum corneum hydration and can mitigate EpB impairments induced by certain acne medications or vehicles.1,12 Available data support the adjunctive benefit of proper skin care in the management of AV by mitigating cutaneous irritation and potentially contributing to a reduction in AV lesions.2-4,7,13 Use of a formulation that also provides broad-spectrum photoprotection also is helpful.3,4

Another challenge is the myriad of cosmeceuticals that are heavily marketed to adult women with AV.13,14 Unfortunately, the scientific evidence supporting these products for treatment of AV is limited, resulting in the clinician’s inability to make specific recommendations. The core message is to incorporate skin care products that can reduce EpB impairment and mitigate cutaneous irritation associated with some AV therapies.1-4,7-9,12

OTC Topical Therapies

The marketplace is replete with several OTC products for treatment of AV, most of which contain BP and salicylic acid.15,16 There is a lack of efficacy data for OTC products for AV, including cleansers and topical medications, although some may be beneficial for milder cases. A variety of formulations are available to choose from, usually without the advice of a clinician. Additionally, heavy marketing is directed at adult women with AV, which may promote the use of therapies that may not be optimal for their respective AV severity or may cause facial skin irritation. Self-treatment may also cause delay in seeking dermatologic care, increasing the risk of persistent or permanent sequelae. Delay in adequate treatment is a major risk factor for the development of acne scars.17

Prescription Topical Therapies

Despite the high prevalence of AV in adult women, there is a paucity of studies evaluating topical therapies for AV in this subset.18-24 Reports in the literature on AV in adult women have focused on systemic hormonal agents (eg, oral contraceptives, spironolactone); however, more recent reports have addressed the use of topical therapies in this subpopulation.11,25-30 Published data on topical formulations are predominantly post hoc analyses from pivotal randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that included adolescents and adults of both genders with facial AV located above the jawline and predominantly moderate in severity.11,26,28,30 Participants in all of these studies presented with non-nodular, mixed inflammatory, and comedonal facial AV above the jawline, with inclusion criteria that required a minimum of 20 comedonal lesions and 20 papulopustular lesions at baseline. An important differentiating factor among these various post hoc analyses evaluating adult women versus adolescent girls with AV are the ages used to separate adults from adolescents. A dividing line of 18 years and older was used in some reports (eg, adapalene gel 0.3%, dapsone gel 5%), while other reports used 25 years and older to separate adolescent girls from adult women (ie, clindamycin phosphate [CP] 1.2%– BP 3.75% gel, adapalene 0.1%–BP 2.5% gel).11,26,28,30