User login

HM16 RIV Abstract Submission Deadline Dec. 1, 2015

Seize the opportunity to present your research, innovative ideas, and clinical stories to a national audience at HM16. Visit the submission site for full details. To ensure success, SHM strongly recommends that you complete your submission well ahead of the deadline of Wednesday, Dec. 1, 2015, at 11:30 p.m. EST. For details, visit www.hospitalmedicine2016.org.

Seize the opportunity to present your research, innovative ideas, and clinical stories to a national audience at HM16. Visit the submission site for full details. To ensure success, SHM strongly recommends that you complete your submission well ahead of the deadline of Wednesday, Dec. 1, 2015, at 11:30 p.m. EST. For details, visit www.hospitalmedicine2016.org.

Seize the opportunity to present your research, innovative ideas, and clinical stories to a national audience at HM16. Visit the submission site for full details. To ensure success, SHM strongly recommends that you complete your submission well ahead of the deadline of Wednesday, Dec. 1, 2015, at 11:30 p.m. EST. For details, visit www.hospitalmedicine2016.org.

Lupus and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma share genetic risk

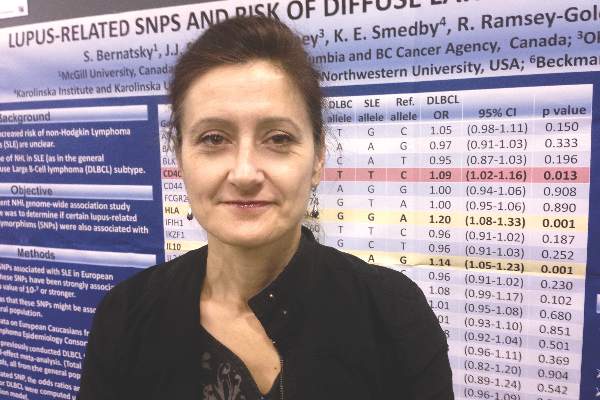

SAN FRANCISCO – Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in genes for interleukin 10 and human leukocyte antigen are significantly associated with both systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, according to a meta-analysis of data from three genome-wide association studies.

The findings add to existing data that exonerates immunosuppressive medications as the main causes of lymphoma in patients with SLE, said lead investigator Dr. Sasha Bernatsky of McGill University, Montreal, in an interview. “People with lupus may have a slight increase in risk for lymphoma because of genetic factors, which would be reassuring,” she said. “It may even mean that if you take your baseline risk of lupus and you control the inflammation, perhaps you can modify that small increase in risk of lymphoma and make it more like the risk in the general population.”

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, with an incidence of about one case in 3,000 person-years in the general population and about one case in 1,000 person-years in patients with SLE, Dr. Bernatsky noted. To look for shared genetic risk factors for both diseases, she and her colleagues analyzed pooled data from three genome-wide association studies conducted by the International Lymphoma Epidemiology Consortium. Using data from 3,857 patients with DLBCL and 7,666 controls, the investigators calculated the odds of DLBCL for each of 28 SNPs that are known genetic risk variants for SLE. “If there’s an overlap there, that might be the key,” Dr. Bernatsky said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

In fact, two SLE-related SNPs were clearly linked to an increased risk for DLBCL – rs3024505, a variant allele of the gene for interleukin 10 on chromosome 1 (odds ratio, 1.14; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.23; P = .001), and rs1270942, a variant of the gene for human leukocyte antigen on chromosome 6 (OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.08-1.33; P = .0007). Both SNPs seem plausible – interleukin 10 induces the bcl-2 protein, which prevents the spontaneous death of germinal center B cells, and some evidence has linked HLA polymorphisms to DLBCL, Dr. Bernatsky said.

The study also linked two other SLE-related SNPs to increased risk for DLBCL, although the associations were not as strong. The first was rs4810485 on the CD40 gene (OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.02-1.16; P = .013), and the second was rs2205960 on the TNFSF4 gene, which encodes a cytokine from the tumor necrosis factor–superfamily (OR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.02-1.15; P = .044). “These findings kind of make sense, because tumor necrosis factor is a very important inflammatory cytokine, and CD40 is a lymphocyte marker,” Dr. Bernatsky said. “It is possible that some genetic factor that controls their expression or function might be associated with lymphoma.”

Rheumatologists have long debated why patients with lupus are at increased risk for lymphoma, and have repeatedly asked whether immunomodulatory drugs are to blame. “We can exercise some caution, but still be aware that most people who use these drugs never end up developing cancer,” Dr. Bernatsky emphasized. In past studies, the absolute risk of lymphoma in patients with SLE remained below 1%, and those patients who did develop lymphoma often had never received drugs such as azathioprine, she noted. The exception was cyclophosphamide, which caused various severe adverse effects, including blood cancers (Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 Jan 8. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202099). “Although we need to use cyclophosphamide for very severe cases of autoimmune disease, it’s clearly a drug that we should use almost as a last resort,” she said.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research; the Fonds du recherche du Québec; Santé, the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre; and the Singer Family Fund for Lupus Research. Dr. Bernatsky and her coinvestigators had no disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in genes for interleukin 10 and human leukocyte antigen are significantly associated with both systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, according to a meta-analysis of data from three genome-wide association studies.

The findings add to existing data that exonerates immunosuppressive medications as the main causes of lymphoma in patients with SLE, said lead investigator Dr. Sasha Bernatsky of McGill University, Montreal, in an interview. “People with lupus may have a slight increase in risk for lymphoma because of genetic factors, which would be reassuring,” she said. “It may even mean that if you take your baseline risk of lupus and you control the inflammation, perhaps you can modify that small increase in risk of lymphoma and make it more like the risk in the general population.”

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, with an incidence of about one case in 3,000 person-years in the general population and about one case in 1,000 person-years in patients with SLE, Dr. Bernatsky noted. To look for shared genetic risk factors for both diseases, she and her colleagues analyzed pooled data from three genome-wide association studies conducted by the International Lymphoma Epidemiology Consortium. Using data from 3,857 patients with DLBCL and 7,666 controls, the investigators calculated the odds of DLBCL for each of 28 SNPs that are known genetic risk variants for SLE. “If there’s an overlap there, that might be the key,” Dr. Bernatsky said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

In fact, two SLE-related SNPs were clearly linked to an increased risk for DLBCL – rs3024505, a variant allele of the gene for interleukin 10 on chromosome 1 (odds ratio, 1.14; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.23; P = .001), and rs1270942, a variant of the gene for human leukocyte antigen on chromosome 6 (OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.08-1.33; P = .0007). Both SNPs seem plausible – interleukin 10 induces the bcl-2 protein, which prevents the spontaneous death of germinal center B cells, and some evidence has linked HLA polymorphisms to DLBCL, Dr. Bernatsky said.

The study also linked two other SLE-related SNPs to increased risk for DLBCL, although the associations were not as strong. The first was rs4810485 on the CD40 gene (OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.02-1.16; P = .013), and the second was rs2205960 on the TNFSF4 gene, which encodes a cytokine from the tumor necrosis factor–superfamily (OR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.02-1.15; P = .044). “These findings kind of make sense, because tumor necrosis factor is a very important inflammatory cytokine, and CD40 is a lymphocyte marker,” Dr. Bernatsky said. “It is possible that some genetic factor that controls their expression or function might be associated with lymphoma.”

Rheumatologists have long debated why patients with lupus are at increased risk for lymphoma, and have repeatedly asked whether immunomodulatory drugs are to blame. “We can exercise some caution, but still be aware that most people who use these drugs never end up developing cancer,” Dr. Bernatsky emphasized. In past studies, the absolute risk of lymphoma in patients with SLE remained below 1%, and those patients who did develop lymphoma often had never received drugs such as azathioprine, she noted. The exception was cyclophosphamide, which caused various severe adverse effects, including blood cancers (Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 Jan 8. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202099). “Although we need to use cyclophosphamide for very severe cases of autoimmune disease, it’s clearly a drug that we should use almost as a last resort,” she said.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research; the Fonds du recherche du Québec; Santé, the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre; and the Singer Family Fund for Lupus Research. Dr. Bernatsky and her coinvestigators had no disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in genes for interleukin 10 and human leukocyte antigen are significantly associated with both systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, according to a meta-analysis of data from three genome-wide association studies.

The findings add to existing data that exonerates immunosuppressive medications as the main causes of lymphoma in patients with SLE, said lead investigator Dr. Sasha Bernatsky of McGill University, Montreal, in an interview. “People with lupus may have a slight increase in risk for lymphoma because of genetic factors, which would be reassuring,” she said. “It may even mean that if you take your baseline risk of lupus and you control the inflammation, perhaps you can modify that small increase in risk of lymphoma and make it more like the risk in the general population.”

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, with an incidence of about one case in 3,000 person-years in the general population and about one case in 1,000 person-years in patients with SLE, Dr. Bernatsky noted. To look for shared genetic risk factors for both diseases, she and her colleagues analyzed pooled data from three genome-wide association studies conducted by the International Lymphoma Epidemiology Consortium. Using data from 3,857 patients with DLBCL and 7,666 controls, the investigators calculated the odds of DLBCL for each of 28 SNPs that are known genetic risk variants for SLE. “If there’s an overlap there, that might be the key,” Dr. Bernatsky said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

In fact, two SLE-related SNPs were clearly linked to an increased risk for DLBCL – rs3024505, a variant allele of the gene for interleukin 10 on chromosome 1 (odds ratio, 1.14; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.23; P = .001), and rs1270942, a variant of the gene for human leukocyte antigen on chromosome 6 (OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.08-1.33; P = .0007). Both SNPs seem plausible – interleukin 10 induces the bcl-2 protein, which prevents the spontaneous death of germinal center B cells, and some evidence has linked HLA polymorphisms to DLBCL, Dr. Bernatsky said.

The study also linked two other SLE-related SNPs to increased risk for DLBCL, although the associations were not as strong. The first was rs4810485 on the CD40 gene (OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.02-1.16; P = .013), and the second was rs2205960 on the TNFSF4 gene, which encodes a cytokine from the tumor necrosis factor–superfamily (OR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.02-1.15; P = .044). “These findings kind of make sense, because tumor necrosis factor is a very important inflammatory cytokine, and CD40 is a lymphocyte marker,” Dr. Bernatsky said. “It is possible that some genetic factor that controls their expression or function might be associated with lymphoma.”

Rheumatologists have long debated why patients with lupus are at increased risk for lymphoma, and have repeatedly asked whether immunomodulatory drugs are to blame. “We can exercise some caution, but still be aware that most people who use these drugs never end up developing cancer,” Dr. Bernatsky emphasized. In past studies, the absolute risk of lymphoma in patients with SLE remained below 1%, and those patients who did develop lymphoma often had never received drugs such as azathioprine, she noted. The exception was cyclophosphamide, which caused various severe adverse effects, including blood cancers (Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 Jan 8. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202099). “Although we need to use cyclophosphamide for very severe cases of autoimmune disease, it’s clearly a drug that we should use almost as a last resort,” she said.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research; the Fonds du recherche du Québec; Santé, the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre; and the Singer Family Fund for Lupus Research. Dr. Bernatsky and her coinvestigators had no disclosures.

AT THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Two genetic risk variants for systemic lupus erythematosus also were clearly linked to risk of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Major finding: The single-nucleotide polymorphisms were rs3024505 on chromosome 1 (OR, 1.14; P = .001), and rs1270942 on chromosome 6 (OR, 1.2; P = .0007).

Data source: A fixed-effect meta-analysis of 28 SLE-related SNPs from 3,857 patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and 7,666 controls.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research; the Fonds du recherche du Québec; Santé, the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre; and the Singer Family Fund for Lupus Research. Dr. Bernatsky and her coinvestigators had no disclosures.

Sessile Pink Plaque on the Lower Back

The Diagnosis: Eccrine Poroma

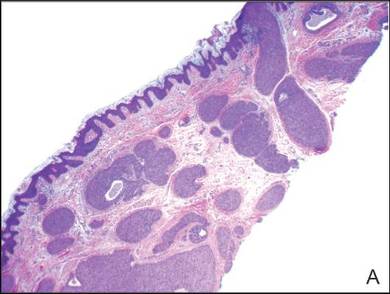

A shave biopsy of the lesion was performed for definitive diagnosis and demonstrated a well-circumscribed tumor with cords and broad columns composed of uniform basaloid cells extending into the dermis and in areas connecting to the overlying epidermis (Figure). There also were small ducts and cysts admixed in the tumor columns that were embedded in a tumor stroma rich in blood vessels. A diagnosis of eccrine poroma was made based on these characteristic histologic features.

|

Biopsy revealed a basaloid tumor originating from the epidermis and extending into the dermis (A)(H&E, original magnification ×4). On higher magnification, ducts were evident amongst the tumor cells and a vascular rich stroma was revealed (B)(H&E, original magnification ×10). |

First described by Pinkus et al1 in 1956, eccrine poroma is a benign neoplasm of cells from the intraepidermal ductal portion of the eccrine sweat gland. Eccrine poroma (along with hidroacanthoma simplex, dermal duct tumor, and poroid hidradenoma) is one of the poroid neoplasms, which account for approximately 10% of all primary sweat gland tumors.2 Eccrine poroma usually is seen in patients over 40 years of age without any predilection for race or sex.

Characteristically, eccrine poromas clinically manifest as solitary, firm, sharply demarcated papules or nodules that may be sessile or pedunculated and rarely exceed 2 cm in diameter. This entity classically presents on acral, non–hair-bearing areas (eg, palms and soles). Eccrine poromas have a wide range of clinical appearances that can lead to broad differential diagnoses3 and have been described as flesh-colored,3 pink to red,4 purple,5 and pigmented3,4 papules or nodules depending on features such as blood vessel proliferation and pigment deposition.

Eccrine poromas also have been reported on hair-bearing areas of the body, including the head,3 neck,3,6 chest,4,6 hip,7 and pubic area,8 despite the paucity of eccrine glands in these areas on the body. These findings suggest that these neoplasms may not be purely eccrine in origin. The wide range of clinical presentations of eccrine poromas has prompted investigation into further classification and delineation of this neoplasm.3 The occurrence of eccrine poromas on areas of the skin known to have few eccrine glands suggests that eccrine poromas may not be purely comprised of eccrine ducts and instead may be of apocrine origin.3,9,10 Histologic features of eccrine poromas that suggest apocrine origination include sebaceous and follicular differentiation (eg, folliculocentric distribution), the association with the follicular infundibulum, and the presence of follicular germ cells.3,9,10 Thus, apocrine gland involvement in eccrine poromas may account for their appearance in anatomic areas that do not have high concentrations of eccrine glands, such as the trunk and pubic area.

Based on these findings, eccrine poromas may therefore be of eccrine and/or apocrine origin; however, the nomenclature of this neoplasm remains confusing and possibly misleading, as the term eccrine poroma continues to be accepted even in instances in which the differentiation appears to be largely apocrine. The terms poroma and eccrine poroma often are used interchangeably, which contributes to the confusion by failing to acknowledge the possibility of apocrine influence and possibly causing the clinician to exclude eccrine poromas from the differential diagnosis in areas that do not have high concentrations of eccrine glands.

Because of their high degree of clinical variability, characteristic acral location, and misleading nomenclature, eccrine poromas often are mistakenly confused with a long list of other cutaneous neoplasms, including hemangiomas, pyogenic granulomas, melanocytic nevi, warts, cysts, and other adnexal neoplasms.3 In our case, the lesion was abnormally large and was clinically concerning for an unusual sebaceous nevus. Its location on the lower back is not commonly noted and should remind the clinician of the possibility of apocrine differentiation. Clinicians should be aware of the wide phenotypic diversity of eccrine poromas, and therefore they should consider this diagnosis in their differential diagnosis for solitary papules or nodules occurring in any anatomic area.

- Pinkus H, Rogin JR, Goldman P. Eccrine poroma: tumors exhibiting features of the epidermal sweat duct unit. Arch Dermatol. 1956;74:511-521.

- Pylyser K, Dewolf-Peeters C, Marlen K. The histology of eccrine poromas: a study of 14 cases. Dermatologica. 1983;167:243-249.

- Moore TO, Orman HL, Orman SK, et al. Poromas of the head and neck. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:48-52.

- Agarwal S, Kumar B, Sharma N. Nodule on the chest. eccrine poroma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:639.

- Ackerman AB, Abenoza P. Neoplasms With Eccrine Differentiation. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febinger; 1990:113-185.

- Okun M, Ansell H. Eccrine poroma. report of three cases, two with an unusual location. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:561-566.

- Sarma DP, Zaman SU, Santos EE, et al. Poroma of the hip and buttock. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:10.

- Altamura D, Piccolo D, Lozzi GP, et al. Eccrine poroma in an unusual site: a clinical and dermoscopic simulator of amelanotic melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:539-541.

- Groben PA, Hitchcock MG, Leshin B, et al. Apocrine poroma, a distinctive case in a patient with nevoid BCC. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;21:31-33.

- Harvell JD, Kerschmann RL, LeBoit PE. Eccrine or apocrine poroma? six poromas with divergent adnexal differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:1-9.

The Diagnosis: Eccrine Poroma

A shave biopsy of the lesion was performed for definitive diagnosis and demonstrated a well-circumscribed tumor with cords and broad columns composed of uniform basaloid cells extending into the dermis and in areas connecting to the overlying epidermis (Figure). There also were small ducts and cysts admixed in the tumor columns that were embedded in a tumor stroma rich in blood vessels. A diagnosis of eccrine poroma was made based on these characteristic histologic features.

|

Biopsy revealed a basaloid tumor originating from the epidermis and extending into the dermis (A)(H&E, original magnification ×4). On higher magnification, ducts were evident amongst the tumor cells and a vascular rich stroma was revealed (B)(H&E, original magnification ×10). |

First described by Pinkus et al1 in 1956, eccrine poroma is a benign neoplasm of cells from the intraepidermal ductal portion of the eccrine sweat gland. Eccrine poroma (along with hidroacanthoma simplex, dermal duct tumor, and poroid hidradenoma) is one of the poroid neoplasms, which account for approximately 10% of all primary sweat gland tumors.2 Eccrine poroma usually is seen in patients over 40 years of age without any predilection for race or sex.

Characteristically, eccrine poromas clinically manifest as solitary, firm, sharply demarcated papules or nodules that may be sessile or pedunculated and rarely exceed 2 cm in diameter. This entity classically presents on acral, non–hair-bearing areas (eg, palms and soles). Eccrine poromas have a wide range of clinical appearances that can lead to broad differential diagnoses3 and have been described as flesh-colored,3 pink to red,4 purple,5 and pigmented3,4 papules or nodules depending on features such as blood vessel proliferation and pigment deposition.

Eccrine poromas also have been reported on hair-bearing areas of the body, including the head,3 neck,3,6 chest,4,6 hip,7 and pubic area,8 despite the paucity of eccrine glands in these areas on the body. These findings suggest that these neoplasms may not be purely eccrine in origin. The wide range of clinical presentations of eccrine poromas has prompted investigation into further classification and delineation of this neoplasm.3 The occurrence of eccrine poromas on areas of the skin known to have few eccrine glands suggests that eccrine poromas may not be purely comprised of eccrine ducts and instead may be of apocrine origin.3,9,10 Histologic features of eccrine poromas that suggest apocrine origination include sebaceous and follicular differentiation (eg, folliculocentric distribution), the association with the follicular infundibulum, and the presence of follicular germ cells.3,9,10 Thus, apocrine gland involvement in eccrine poromas may account for their appearance in anatomic areas that do not have high concentrations of eccrine glands, such as the trunk and pubic area.

Based on these findings, eccrine poromas may therefore be of eccrine and/or apocrine origin; however, the nomenclature of this neoplasm remains confusing and possibly misleading, as the term eccrine poroma continues to be accepted even in instances in which the differentiation appears to be largely apocrine. The terms poroma and eccrine poroma often are used interchangeably, which contributes to the confusion by failing to acknowledge the possibility of apocrine influence and possibly causing the clinician to exclude eccrine poromas from the differential diagnosis in areas that do not have high concentrations of eccrine glands.

Because of their high degree of clinical variability, characteristic acral location, and misleading nomenclature, eccrine poromas often are mistakenly confused with a long list of other cutaneous neoplasms, including hemangiomas, pyogenic granulomas, melanocytic nevi, warts, cysts, and other adnexal neoplasms.3 In our case, the lesion was abnormally large and was clinically concerning for an unusual sebaceous nevus. Its location on the lower back is not commonly noted and should remind the clinician of the possibility of apocrine differentiation. Clinicians should be aware of the wide phenotypic diversity of eccrine poromas, and therefore they should consider this diagnosis in their differential diagnosis for solitary papules or nodules occurring in any anatomic area.

The Diagnosis: Eccrine Poroma

A shave biopsy of the lesion was performed for definitive diagnosis and demonstrated a well-circumscribed tumor with cords and broad columns composed of uniform basaloid cells extending into the dermis and in areas connecting to the overlying epidermis (Figure). There also were small ducts and cysts admixed in the tumor columns that were embedded in a tumor stroma rich in blood vessels. A diagnosis of eccrine poroma was made based on these characteristic histologic features.

|

Biopsy revealed a basaloid tumor originating from the epidermis and extending into the dermis (A)(H&E, original magnification ×4). On higher magnification, ducts were evident amongst the tumor cells and a vascular rich stroma was revealed (B)(H&E, original magnification ×10). |

First described by Pinkus et al1 in 1956, eccrine poroma is a benign neoplasm of cells from the intraepidermal ductal portion of the eccrine sweat gland. Eccrine poroma (along with hidroacanthoma simplex, dermal duct tumor, and poroid hidradenoma) is one of the poroid neoplasms, which account for approximately 10% of all primary sweat gland tumors.2 Eccrine poroma usually is seen in patients over 40 years of age without any predilection for race or sex.

Characteristically, eccrine poromas clinically manifest as solitary, firm, sharply demarcated papules or nodules that may be sessile or pedunculated and rarely exceed 2 cm in diameter. This entity classically presents on acral, non–hair-bearing areas (eg, palms and soles). Eccrine poromas have a wide range of clinical appearances that can lead to broad differential diagnoses3 and have been described as flesh-colored,3 pink to red,4 purple,5 and pigmented3,4 papules or nodules depending on features such as blood vessel proliferation and pigment deposition.

Eccrine poromas also have been reported on hair-bearing areas of the body, including the head,3 neck,3,6 chest,4,6 hip,7 and pubic area,8 despite the paucity of eccrine glands in these areas on the body. These findings suggest that these neoplasms may not be purely eccrine in origin. The wide range of clinical presentations of eccrine poromas has prompted investigation into further classification and delineation of this neoplasm.3 The occurrence of eccrine poromas on areas of the skin known to have few eccrine glands suggests that eccrine poromas may not be purely comprised of eccrine ducts and instead may be of apocrine origin.3,9,10 Histologic features of eccrine poromas that suggest apocrine origination include sebaceous and follicular differentiation (eg, folliculocentric distribution), the association with the follicular infundibulum, and the presence of follicular germ cells.3,9,10 Thus, apocrine gland involvement in eccrine poromas may account for their appearance in anatomic areas that do not have high concentrations of eccrine glands, such as the trunk and pubic area.

Based on these findings, eccrine poromas may therefore be of eccrine and/or apocrine origin; however, the nomenclature of this neoplasm remains confusing and possibly misleading, as the term eccrine poroma continues to be accepted even in instances in which the differentiation appears to be largely apocrine. The terms poroma and eccrine poroma often are used interchangeably, which contributes to the confusion by failing to acknowledge the possibility of apocrine influence and possibly causing the clinician to exclude eccrine poromas from the differential diagnosis in areas that do not have high concentrations of eccrine glands.

Because of their high degree of clinical variability, characteristic acral location, and misleading nomenclature, eccrine poromas often are mistakenly confused with a long list of other cutaneous neoplasms, including hemangiomas, pyogenic granulomas, melanocytic nevi, warts, cysts, and other adnexal neoplasms.3 In our case, the lesion was abnormally large and was clinically concerning for an unusual sebaceous nevus. Its location on the lower back is not commonly noted and should remind the clinician of the possibility of apocrine differentiation. Clinicians should be aware of the wide phenotypic diversity of eccrine poromas, and therefore they should consider this diagnosis in their differential diagnosis for solitary papules or nodules occurring in any anatomic area.

- Pinkus H, Rogin JR, Goldman P. Eccrine poroma: tumors exhibiting features of the epidermal sweat duct unit. Arch Dermatol. 1956;74:511-521.

- Pylyser K, Dewolf-Peeters C, Marlen K. The histology of eccrine poromas: a study of 14 cases. Dermatologica. 1983;167:243-249.

- Moore TO, Orman HL, Orman SK, et al. Poromas of the head and neck. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:48-52.

- Agarwal S, Kumar B, Sharma N. Nodule on the chest. eccrine poroma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:639.

- Ackerman AB, Abenoza P. Neoplasms With Eccrine Differentiation. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febinger; 1990:113-185.

- Okun M, Ansell H. Eccrine poroma. report of three cases, two with an unusual location. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:561-566.

- Sarma DP, Zaman SU, Santos EE, et al. Poroma of the hip and buttock. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:10.

- Altamura D, Piccolo D, Lozzi GP, et al. Eccrine poroma in an unusual site: a clinical and dermoscopic simulator of amelanotic melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:539-541.

- Groben PA, Hitchcock MG, Leshin B, et al. Apocrine poroma, a distinctive case in a patient with nevoid BCC. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;21:31-33.

- Harvell JD, Kerschmann RL, LeBoit PE. Eccrine or apocrine poroma? six poromas with divergent adnexal differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:1-9.

- Pinkus H, Rogin JR, Goldman P. Eccrine poroma: tumors exhibiting features of the epidermal sweat duct unit. Arch Dermatol. 1956;74:511-521.

- Pylyser K, Dewolf-Peeters C, Marlen K. The histology of eccrine poromas: a study of 14 cases. Dermatologica. 1983;167:243-249.

- Moore TO, Orman HL, Orman SK, et al. Poromas of the head and neck. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:48-52.

- Agarwal S, Kumar B, Sharma N. Nodule on the chest. eccrine poroma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:639.

- Ackerman AB, Abenoza P. Neoplasms With Eccrine Differentiation. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febinger; 1990:113-185.

- Okun M, Ansell H. Eccrine poroma. report of three cases, two with an unusual location. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:561-566.

- Sarma DP, Zaman SU, Santos EE, et al. Poroma of the hip and buttock. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:10.

- Altamura D, Piccolo D, Lozzi GP, et al. Eccrine poroma in an unusual site: a clinical and dermoscopic simulator of amelanotic melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:539-541.

- Groben PA, Hitchcock MG, Leshin B, et al. Apocrine poroma, a distinctive case in a patient with nevoid BCC. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;21:31-33.

- Harvell JD, Kerschmann RL, LeBoit PE. Eccrine or apocrine poroma? six poromas with divergent adnexal differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:1-9.

A 47-year-old man presented with an asymptomatic, 2.5×1.5-cm, sessile pink plaque with a coalescing papular texture on the lower back of 30 years’ duration. The patient reported that 2 papillated papules with peripheral rims of dark crust had developed in the center of the lesion over the past 6 months. His personal and family histories were unremarkable.

AHA: Mixed results for mitral valve replacement vs. repair

Patients undergoing mitral valve replacement had a lower risk of regurgitation and heart failure–related adverse events at 2 years than those undergoing valve repair, according to the results of a trial presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The results of the trial appear to associate mitral valve replacement with clinical advantages over mitral valve repair after 2 years of follow-up. However, replacement held no significant advantages over repair in the primary endpoint of left ventricular end-systolic volume index (LVESVI) or in overall survival, said Dr. Daniel Goldstein of the department of cardiothoracic surgery at Montefiore Medical Center, New York.

In the trial conducted by the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network (CTSN), 251 patients with chronic severe ischemic mitral regurgitation were randomly assigned to undergo surgical repair of the mitral valve or to receive a mitral valve replacement with a prosthetic and procedure selected at the discretion of the surgeon.

In addition to the primary endpoint of LVESVI, the two approaches were also compared for survival, regurgitation recurrence, and heart failure events.

At 2 years, the mean change from baseline in LVESVI, a measure of remodeling, did not differ significantly between the repair and replacement arms (–9.0 vs. –6.5 mL/m2, respectively). In addition, although the 2-year mortality rate was numerically lower in the repair arm relative to the replacement arm (19% vs. 23.2%, respectively), it was also not statistically different (P = .39).

However, the rate of recurrence of moderate or severe mitral regurgitation favored replacement over repair and was significant (3.8% vs. 58.8%, respectively; P less than .001). In addition, the rate of cardiovascular readmissions was significantly lower in the replacement group (P = .01).

For those in the repair group, there were significant trends for more serious adverse events related to heart failure (P = .05) and for a lower quality of life improvement (P = .07) on the Minnesota Living With Heart Failure questionnaire. There were no significant differences in rates of all serious adverse events or overall readmissions.

All of the differences between groups observed at 2 years amplify differences previously reported after 12 months (N Engl J Med. 2014 Jan 2;370[1]:23-32). For example, the difference in the rate of moderate to severe regurgitation favoring replacement over repair was already significant at that time (2.3% vs. 32.6%, respectively; P less than .001), even though the mortality rates were then, as now, numerically lower in the repair group versus the replacement group (14.3% vs. 17.6%, respectively; P = .45).

Dr. Goldstein reported no relevant financial relationships.

Patients undergoing mitral valve replacement had a lower risk of regurgitation and heart failure–related adverse events at 2 years than those undergoing valve repair, according to the results of a trial presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The results of the trial appear to associate mitral valve replacement with clinical advantages over mitral valve repair after 2 years of follow-up. However, replacement held no significant advantages over repair in the primary endpoint of left ventricular end-systolic volume index (LVESVI) or in overall survival, said Dr. Daniel Goldstein of the department of cardiothoracic surgery at Montefiore Medical Center, New York.

In the trial conducted by the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network (CTSN), 251 patients with chronic severe ischemic mitral regurgitation were randomly assigned to undergo surgical repair of the mitral valve or to receive a mitral valve replacement with a prosthetic and procedure selected at the discretion of the surgeon.

In addition to the primary endpoint of LVESVI, the two approaches were also compared for survival, regurgitation recurrence, and heart failure events.

At 2 years, the mean change from baseline in LVESVI, a measure of remodeling, did not differ significantly between the repair and replacement arms (–9.0 vs. –6.5 mL/m2, respectively). In addition, although the 2-year mortality rate was numerically lower in the repair arm relative to the replacement arm (19% vs. 23.2%, respectively), it was also not statistically different (P = .39).

However, the rate of recurrence of moderate or severe mitral regurgitation favored replacement over repair and was significant (3.8% vs. 58.8%, respectively; P less than .001). In addition, the rate of cardiovascular readmissions was significantly lower in the replacement group (P = .01).

For those in the repair group, there were significant trends for more serious adverse events related to heart failure (P = .05) and for a lower quality of life improvement (P = .07) on the Minnesota Living With Heart Failure questionnaire. There were no significant differences in rates of all serious adverse events or overall readmissions.

All of the differences between groups observed at 2 years amplify differences previously reported after 12 months (N Engl J Med. 2014 Jan 2;370[1]:23-32). For example, the difference in the rate of moderate to severe regurgitation favoring replacement over repair was already significant at that time (2.3% vs. 32.6%, respectively; P less than .001), even though the mortality rates were then, as now, numerically lower in the repair group versus the replacement group (14.3% vs. 17.6%, respectively; P = .45).

Dr. Goldstein reported no relevant financial relationships.

Patients undergoing mitral valve replacement had a lower risk of regurgitation and heart failure–related adverse events at 2 years than those undergoing valve repair, according to the results of a trial presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The results of the trial appear to associate mitral valve replacement with clinical advantages over mitral valve repair after 2 years of follow-up. However, replacement held no significant advantages over repair in the primary endpoint of left ventricular end-systolic volume index (LVESVI) or in overall survival, said Dr. Daniel Goldstein of the department of cardiothoracic surgery at Montefiore Medical Center, New York.

In the trial conducted by the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network (CTSN), 251 patients with chronic severe ischemic mitral regurgitation were randomly assigned to undergo surgical repair of the mitral valve or to receive a mitral valve replacement with a prosthetic and procedure selected at the discretion of the surgeon.

In addition to the primary endpoint of LVESVI, the two approaches were also compared for survival, regurgitation recurrence, and heart failure events.

At 2 years, the mean change from baseline in LVESVI, a measure of remodeling, did not differ significantly between the repair and replacement arms (–9.0 vs. –6.5 mL/m2, respectively). In addition, although the 2-year mortality rate was numerically lower in the repair arm relative to the replacement arm (19% vs. 23.2%, respectively), it was also not statistically different (P = .39).

However, the rate of recurrence of moderate or severe mitral regurgitation favored replacement over repair and was significant (3.8% vs. 58.8%, respectively; P less than .001). In addition, the rate of cardiovascular readmissions was significantly lower in the replacement group (P = .01).

For those in the repair group, there were significant trends for more serious adverse events related to heart failure (P = .05) and for a lower quality of life improvement (P = .07) on the Minnesota Living With Heart Failure questionnaire. There were no significant differences in rates of all serious adverse events or overall readmissions.

All of the differences between groups observed at 2 years amplify differences previously reported after 12 months (N Engl J Med. 2014 Jan 2;370[1]:23-32). For example, the difference in the rate of moderate to severe regurgitation favoring replacement over repair was already significant at that time (2.3% vs. 32.6%, respectively; P less than .001), even though the mortality rates were then, as now, numerically lower in the repair group versus the replacement group (14.3% vs. 17.6%, respectively; P = .45).

Dr. Goldstein reported no relevant financial relationships.

FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Mitral valve replacement reduced regurgitation better than valve repair, but it didn’t significantly improve left ventricular function or survival.

Major finding: In patients with severe ischemic mitral regurgitation, regurgitation occurred more frequently after mitral valve repair than after valve replacement (58.8% vs. 3.8%; P less than .001), but left ventricular end-systolic volume indexes and survival rates were not significantly different.

Data source: A randomized, multicenter trial with 251 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Goldstein reported no relevant financial relationships.

Younger AF Patients at Higher Risk of Dementia

NEW YORK - Atrial fibrillation (AF) is associated with an increased risk of dementia, especially in younger individuals, according to results from the Rotterdam Study.

"When we started this study, we hypothesized that the hazard of atrial fibrillation would be higher with longer exposure, but to find such a strong exposure-time association in younger participants was striking," said Dr. Frank J. Wolters from Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

"It emphasizes that prevention of dementia doesn't start when people report to their physician with mild memory complaints, but years, if not decades before, by identifying those at risk and optimizing preventive strategies," he said by email.

An earlier report from the Rotterdam Study showed that AF is more prevalent in people with dementia, but the cross-sectional design did not allow conclusions regarding a causal relationship.

Dr. Wolters's team investigated the association between AF and dementia during a follow up of 20 years of nearly 6,200 participants in the Rotterdam Study.

About 5% of the participants had AF at baseline, and 15.3% of these individuals developed dementia during more than 81,000 person-years of follow-up.

Another 11.7% developed AF later, and 15.0% developed dementia during more than 79,000 person-years, the researchers report in JAMA Neurology, online September 21.

People who had AF at the start of the study had a 34% increased risk of dementia (compared with those who did not have prevalent AF), and people who developed AF during follow-up had a 23% increased risk of dementia (compared with those who did not have incident AF).

The association between AF and dementia was strongest in persons younger than the median age (67 years), and in these younger participants, the risk of dementia was higher with increasing duration of AF.

"As we found atrial fibrillation to increase the risk of dementia independent of clinical stroke, either chronic hypoperfusion or more acutely silent infarcts or perhaps cortical microinfarcts could account for the increased risk of dementia," Dr. Wolters said.

"A few observational studies have suggested beneficialeffect of treatment of atrial fibrillation on the risk of dementia, but more evidence on treatment efficacy is sorely needed. This includes insight into whether optimal treatment consists of anticoagulation, heart rhythm, or rate control," he noted.

"With regard to treatment of atrial fibrillation, until further evidence on efficacy becomes available, it is worth realizing that optimal adherence to current guidelines may contribute to prevention of cognitive decline in addition to prevention of stroke," Dr. Wolters added. "Although we found the strongest associations between atrial fibrillation and dementia for younger people, the need to determine treatment efficacy is just as profound in the elderly."

Dr. Sanjay Dixit, director of cardiac electrophysiology at Philadelphia VA Medical Center in Pennsylvania, said by email, "Although the association between AF and dementia has been shown, it's difficult to establish cause and effect. As I point out in my previous review, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is considered to be a major contributor to the development of neurocognitive decline and dementia. OSA is very common in the AF population and many consider this to be (a) risk factor in the development of AF. So the question remains whether AF is the cause of dementia or other co-morbidities such as OSA that frequently co-exist in the AF population."

"Look for AF in patients with dementia and also caution patients with AF of the possibility of developing this condition in the future," Dr. Dixit advised. "Since catheter ablation therapy has been shown to have better outcomes for long-term control of AF than drugs, physicians should discuss this with patients and consider referring them to cardiac electrophysiologists early in the course of the disease."

Dr. T. Jared Bunch, director of heart rhythm services for Intermountain Healthcare, Murray, Utah, said by email, "It is great to see another confirmatory study that found essentially the same thing we did 5 years ago. These data in aggregate make the likelihood of the association much more compelling."

"What is interesting in our subsequent work is the patients more sensitive to poor warfarin management (low times in therapeutic range) were at the highest relative risk of dementia compared to older patients," Dr. Bunch explained. "Now we all need to start to unravel the mechanisms behind it and find avenues of preventative treatment. The choice and manner of anticoagulant treatment is one and allowing faster heart rates is another."

Dr. Shih-An Chen and Dr. Tzu-Fan Chao from Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan, who recently reported on the independent association between AF and dementia, struck a more cautious note.

"Only when a lower risk of dementia can be achieved by AF ablation in the prospective and randomized trial can we conclude that AF is the direct cause of dementia," they said in a joint email. "It should also be noted that the development of dementia is multifactorial, and AF only represents one of them."

NEW YORK - Atrial fibrillation (AF) is associated with an increased risk of dementia, especially in younger individuals, according to results from the Rotterdam Study.

"When we started this study, we hypothesized that the hazard of atrial fibrillation would be higher with longer exposure, but to find such a strong exposure-time association in younger participants was striking," said Dr. Frank J. Wolters from Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

"It emphasizes that prevention of dementia doesn't start when people report to their physician with mild memory complaints, but years, if not decades before, by identifying those at risk and optimizing preventive strategies," he said by email.

An earlier report from the Rotterdam Study showed that AF is more prevalent in people with dementia, but the cross-sectional design did not allow conclusions regarding a causal relationship.

Dr. Wolters's team investigated the association between AF and dementia during a follow up of 20 years of nearly 6,200 participants in the Rotterdam Study.

About 5% of the participants had AF at baseline, and 15.3% of these individuals developed dementia during more than 81,000 person-years of follow-up.

Another 11.7% developed AF later, and 15.0% developed dementia during more than 79,000 person-years, the researchers report in JAMA Neurology, online September 21.

People who had AF at the start of the study had a 34% increased risk of dementia (compared with those who did not have prevalent AF), and people who developed AF during follow-up had a 23% increased risk of dementia (compared with those who did not have incident AF).

The association between AF and dementia was strongest in persons younger than the median age (67 years), and in these younger participants, the risk of dementia was higher with increasing duration of AF.

"As we found atrial fibrillation to increase the risk of dementia independent of clinical stroke, either chronic hypoperfusion or more acutely silent infarcts or perhaps cortical microinfarcts could account for the increased risk of dementia," Dr. Wolters said.

"A few observational studies have suggested beneficialeffect of treatment of atrial fibrillation on the risk of dementia, but more evidence on treatment efficacy is sorely needed. This includes insight into whether optimal treatment consists of anticoagulation, heart rhythm, or rate control," he noted.

"With regard to treatment of atrial fibrillation, until further evidence on efficacy becomes available, it is worth realizing that optimal adherence to current guidelines may contribute to prevention of cognitive decline in addition to prevention of stroke," Dr. Wolters added. "Although we found the strongest associations between atrial fibrillation and dementia for younger people, the need to determine treatment efficacy is just as profound in the elderly."

Dr. Sanjay Dixit, director of cardiac electrophysiology at Philadelphia VA Medical Center in Pennsylvania, said by email, "Although the association between AF and dementia has been shown, it's difficult to establish cause and effect. As I point out in my previous review, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is considered to be a major contributor to the development of neurocognitive decline and dementia. OSA is very common in the AF population and many consider this to be (a) risk factor in the development of AF. So the question remains whether AF is the cause of dementia or other co-morbidities such as OSA that frequently co-exist in the AF population."

"Look for AF in patients with dementia and also caution patients with AF of the possibility of developing this condition in the future," Dr. Dixit advised. "Since catheter ablation therapy has been shown to have better outcomes for long-term control of AF than drugs, physicians should discuss this with patients and consider referring them to cardiac electrophysiologists early in the course of the disease."

Dr. T. Jared Bunch, director of heart rhythm services for Intermountain Healthcare, Murray, Utah, said by email, "It is great to see another confirmatory study that found essentially the same thing we did 5 years ago. These data in aggregate make the likelihood of the association much more compelling."

"What is interesting in our subsequent work is the patients more sensitive to poor warfarin management (low times in therapeutic range) were at the highest relative risk of dementia compared to older patients," Dr. Bunch explained. "Now we all need to start to unravel the mechanisms behind it and find avenues of preventative treatment. The choice and manner of anticoagulant treatment is one and allowing faster heart rates is another."

Dr. Shih-An Chen and Dr. Tzu-Fan Chao from Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan, who recently reported on the independent association between AF and dementia, struck a more cautious note.

"Only when a lower risk of dementia can be achieved by AF ablation in the prospective and randomized trial can we conclude that AF is the direct cause of dementia," they said in a joint email. "It should also be noted that the development of dementia is multifactorial, and AF only represents one of them."

NEW YORK - Atrial fibrillation (AF) is associated with an increased risk of dementia, especially in younger individuals, according to results from the Rotterdam Study.

"When we started this study, we hypothesized that the hazard of atrial fibrillation would be higher with longer exposure, but to find such a strong exposure-time association in younger participants was striking," said Dr. Frank J. Wolters from Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

"It emphasizes that prevention of dementia doesn't start when people report to their physician with mild memory complaints, but years, if not decades before, by identifying those at risk and optimizing preventive strategies," he said by email.

An earlier report from the Rotterdam Study showed that AF is more prevalent in people with dementia, but the cross-sectional design did not allow conclusions regarding a causal relationship.

Dr. Wolters's team investigated the association between AF and dementia during a follow up of 20 years of nearly 6,200 participants in the Rotterdam Study.

About 5% of the participants had AF at baseline, and 15.3% of these individuals developed dementia during more than 81,000 person-years of follow-up.

Another 11.7% developed AF later, and 15.0% developed dementia during more than 79,000 person-years, the researchers report in JAMA Neurology, online September 21.

People who had AF at the start of the study had a 34% increased risk of dementia (compared with those who did not have prevalent AF), and people who developed AF during follow-up had a 23% increased risk of dementia (compared with those who did not have incident AF).

The association between AF and dementia was strongest in persons younger than the median age (67 years), and in these younger participants, the risk of dementia was higher with increasing duration of AF.

"As we found atrial fibrillation to increase the risk of dementia independent of clinical stroke, either chronic hypoperfusion or more acutely silent infarcts or perhaps cortical microinfarcts could account for the increased risk of dementia," Dr. Wolters said.

"A few observational studies have suggested beneficialeffect of treatment of atrial fibrillation on the risk of dementia, but more evidence on treatment efficacy is sorely needed. This includes insight into whether optimal treatment consists of anticoagulation, heart rhythm, or rate control," he noted.

"With regard to treatment of atrial fibrillation, until further evidence on efficacy becomes available, it is worth realizing that optimal adherence to current guidelines may contribute to prevention of cognitive decline in addition to prevention of stroke," Dr. Wolters added. "Although we found the strongest associations between atrial fibrillation and dementia for younger people, the need to determine treatment efficacy is just as profound in the elderly."

Dr. Sanjay Dixit, director of cardiac electrophysiology at Philadelphia VA Medical Center in Pennsylvania, said by email, "Although the association between AF and dementia has been shown, it's difficult to establish cause and effect. As I point out in my previous review, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is considered to be a major contributor to the development of neurocognitive decline and dementia. OSA is very common in the AF population and many consider this to be (a) risk factor in the development of AF. So the question remains whether AF is the cause of dementia or other co-morbidities such as OSA that frequently co-exist in the AF population."

"Look for AF in patients with dementia and also caution patients with AF of the possibility of developing this condition in the future," Dr. Dixit advised. "Since catheter ablation therapy has been shown to have better outcomes for long-term control of AF than drugs, physicians should discuss this with patients and consider referring them to cardiac electrophysiologists early in the course of the disease."

Dr. T. Jared Bunch, director of heart rhythm services for Intermountain Healthcare, Murray, Utah, said by email, "It is great to see another confirmatory study that found essentially the same thing we did 5 years ago. These data in aggregate make the likelihood of the association much more compelling."

"What is interesting in our subsequent work is the patients more sensitive to poor warfarin management (low times in therapeutic range) were at the highest relative risk of dementia compared to older patients," Dr. Bunch explained. "Now we all need to start to unravel the mechanisms behind it and find avenues of preventative treatment. The choice and manner of anticoagulant treatment is one and allowing faster heart rates is another."

Dr. Shih-An Chen and Dr. Tzu-Fan Chao from Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan, who recently reported on the independent association between AF and dementia, struck a more cautious note.

"Only when a lower risk of dementia can be achieved by AF ablation in the prospective and randomized trial can we conclude that AF is the direct cause of dementia," they said in a joint email. "It should also be noted that the development of dementia is multifactorial, and AF only represents one of them."

Highlights From the 2015 ECTRIMS Annual Meeting

Click here to download the PDF.

Click here to download the PDF.

Click here to download the PDF.

Donor CAR T cells treat aggressive ALL in infant

person treated with UCART19

Photo courtesy of GOSH

A hospital in the UK has reported success with the first-in-human use of an allogeneic chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell treatment.

The therapy, UCART19, helped treat an aggressive case of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in an infant named Layla Richards.

Chemotherapy, a first transplant, and blinatumomab all failed to treat Layla’s disease. But UCART19 provided a bridge to a second transplant, and Layla

is now free of leukemia.

“We have only used this treatment on one very strong little girl, and we have to be cautious about claiming that this will be a suitable treatment option for all children,” said Waseem Qasim, MBBS, PhD, a professor at University College London’s Institute of Child Health and a consultant immunologist at Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) in London, where Layla was treated.

“But this is a landmark in the use of new gene-engineering technology, and the effects for this child have been staggering. If replicated, it could represent a huge step forward in treating leukemia and other cancers.”

Layla’s history

Layla was born in June 2014 and, at 14 weeks old, was diagnosed with CD19+ ALL (t[11;19] rearrangement). Doctors at GOSH described her leukemia as “one of the most aggressive forms of the disease we have ever seen.”

Layla underwent several rounds of chemotherapy at GOSH and then received a transplant from a mismatched, unrelated donor. Seven weeks later, her leukemia had returned.

A second round of chemotherapy wasn’t an option, so Layla went on to receive blinatumomab. This, too, ultimately failed.

Layla’s family was unwilling to accept palliative care, so her doctors mentioned the possibility of using UCART19.

“The approach was looking incredibly successful in laboratory studies, and so when I heard there were no options left for treating this child’s disease, I thought, ‘Why don’t we use the new UCART19 cells?’” Dr Qasim said.

“The treatment was highly experimental, and we had to get special permissions, but she appeared ideally suited for this type of approach.”

UCART19 treatment

Before Layla received UCART19, investigators from GOSH, University College London, and the biotech company Cellectis had been developing off-the-shelf banks of the cells for use in clinical trials.

UCART19 consists of donor T cells modified using transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALEN). Like some other CAR T-cell products, UCART19 is designed to target CD19+ cancer cells.

But UCART19 cells are also programmed to be insensitive to alemtuzumab. That way, a patient can receive the drug to prevent rejection of HLA-mismatched cells.

Before receiving UCART19, Layla was given vincristine, dexamethasone, and asparaginase, followed by fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and alemtuzumab. She then received a single dose (4.5 x 106/kg) of UCART19.

After this, Layla spent several months in isolation to protect her from infections while her immune system was extremely weak. Within weeks of receiving UCART19, Layla demonstrated an immune response in the form of a rash.

The rash worsened, but, aside from that, Layla appeared to be well. To date, she has shown no signs of cytokine release syndrome.

She did, however, show signs of molecular and cytogenetic remission. Once she was deemed leukemia-free, Layla underwent a second transplant. One month later, she was well enough to go home. Today, Layla is still free of ALL.

More details on Layla’s story and UCART19 are scheduled to be presented at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 2046). Clinical trials of UCART19 (funded by Cellectis) are set to begin early next year. ![]()

person treated with UCART19

Photo courtesy of GOSH

A hospital in the UK has reported success with the first-in-human use of an allogeneic chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell treatment.

The therapy, UCART19, helped treat an aggressive case of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in an infant named Layla Richards.

Chemotherapy, a first transplant, and blinatumomab all failed to treat Layla’s disease. But UCART19 provided a bridge to a second transplant, and Layla

is now free of leukemia.

“We have only used this treatment on one very strong little girl, and we have to be cautious about claiming that this will be a suitable treatment option for all children,” said Waseem Qasim, MBBS, PhD, a professor at University College London’s Institute of Child Health and a consultant immunologist at Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) in London, where Layla was treated.

“But this is a landmark in the use of new gene-engineering technology, and the effects for this child have been staggering. If replicated, it could represent a huge step forward in treating leukemia and other cancers.”

Layla’s history

Layla was born in June 2014 and, at 14 weeks old, was diagnosed with CD19+ ALL (t[11;19] rearrangement). Doctors at GOSH described her leukemia as “one of the most aggressive forms of the disease we have ever seen.”

Layla underwent several rounds of chemotherapy at GOSH and then received a transplant from a mismatched, unrelated donor. Seven weeks later, her leukemia had returned.

A second round of chemotherapy wasn’t an option, so Layla went on to receive blinatumomab. This, too, ultimately failed.

Layla’s family was unwilling to accept palliative care, so her doctors mentioned the possibility of using UCART19.

“The approach was looking incredibly successful in laboratory studies, and so when I heard there were no options left for treating this child’s disease, I thought, ‘Why don’t we use the new UCART19 cells?’” Dr Qasim said.

“The treatment was highly experimental, and we had to get special permissions, but she appeared ideally suited for this type of approach.”

UCART19 treatment

Before Layla received UCART19, investigators from GOSH, University College London, and the biotech company Cellectis had been developing off-the-shelf banks of the cells for use in clinical trials.

UCART19 consists of donor T cells modified using transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALEN). Like some other CAR T-cell products, UCART19 is designed to target CD19+ cancer cells.

But UCART19 cells are also programmed to be insensitive to alemtuzumab. That way, a patient can receive the drug to prevent rejection of HLA-mismatched cells.

Before receiving UCART19, Layla was given vincristine, dexamethasone, and asparaginase, followed by fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and alemtuzumab. She then received a single dose (4.5 x 106/kg) of UCART19.

After this, Layla spent several months in isolation to protect her from infections while her immune system was extremely weak. Within weeks of receiving UCART19, Layla demonstrated an immune response in the form of a rash.

The rash worsened, but, aside from that, Layla appeared to be well. To date, she has shown no signs of cytokine release syndrome.

She did, however, show signs of molecular and cytogenetic remission. Once she was deemed leukemia-free, Layla underwent a second transplant. One month later, she was well enough to go home. Today, Layla is still free of ALL.

More details on Layla’s story and UCART19 are scheduled to be presented at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 2046). Clinical trials of UCART19 (funded by Cellectis) are set to begin early next year. ![]()

person treated with UCART19

Photo courtesy of GOSH

A hospital in the UK has reported success with the first-in-human use of an allogeneic chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell treatment.

The therapy, UCART19, helped treat an aggressive case of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in an infant named Layla Richards.

Chemotherapy, a first transplant, and blinatumomab all failed to treat Layla’s disease. But UCART19 provided a bridge to a second transplant, and Layla

is now free of leukemia.

“We have only used this treatment on one very strong little girl, and we have to be cautious about claiming that this will be a suitable treatment option for all children,” said Waseem Qasim, MBBS, PhD, a professor at University College London’s Institute of Child Health and a consultant immunologist at Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) in London, where Layla was treated.

“But this is a landmark in the use of new gene-engineering technology, and the effects for this child have been staggering. If replicated, it could represent a huge step forward in treating leukemia and other cancers.”

Layla’s history

Layla was born in June 2014 and, at 14 weeks old, was diagnosed with CD19+ ALL (t[11;19] rearrangement). Doctors at GOSH described her leukemia as “one of the most aggressive forms of the disease we have ever seen.”

Layla underwent several rounds of chemotherapy at GOSH and then received a transplant from a mismatched, unrelated donor. Seven weeks later, her leukemia had returned.

A second round of chemotherapy wasn’t an option, so Layla went on to receive blinatumomab. This, too, ultimately failed.

Layla’s family was unwilling to accept palliative care, so her doctors mentioned the possibility of using UCART19.

“The approach was looking incredibly successful in laboratory studies, and so when I heard there were no options left for treating this child’s disease, I thought, ‘Why don’t we use the new UCART19 cells?’” Dr Qasim said.

“The treatment was highly experimental, and we had to get special permissions, but she appeared ideally suited for this type of approach.”

UCART19 treatment

Before Layla received UCART19, investigators from GOSH, University College London, and the biotech company Cellectis had been developing off-the-shelf banks of the cells for use in clinical trials.

UCART19 consists of donor T cells modified using transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALEN). Like some other CAR T-cell products, UCART19 is designed to target CD19+ cancer cells.

But UCART19 cells are also programmed to be insensitive to alemtuzumab. That way, a patient can receive the drug to prevent rejection of HLA-mismatched cells.

Before receiving UCART19, Layla was given vincristine, dexamethasone, and asparaginase, followed by fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and alemtuzumab. She then received a single dose (4.5 x 106/kg) of UCART19.

After this, Layla spent several months in isolation to protect her from infections while her immune system was extremely weak. Within weeks of receiving UCART19, Layla demonstrated an immune response in the form of a rash.

The rash worsened, but, aside from that, Layla appeared to be well. To date, she has shown no signs of cytokine release syndrome.

She did, however, show signs of molecular and cytogenetic remission. Once she was deemed leukemia-free, Layla underwent a second transplant. One month later, she was well enough to go home. Today, Layla is still free of ALL.

More details on Layla’s story and UCART19 are scheduled to be presented at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 2046). Clinical trials of UCART19 (funded by Cellectis) are set to begin early next year. ![]()

Study challenges ‘textbook’ view of hematopoiesis

University Health Network

Results of a study published in Science challenge traditional ideas about how blood is made.

The findings suggest hematopoiesis does not occur through a gradual process consisting of multipotent, oligopotent, and unilineage progenitor stages.

Rather, hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) mature into different types of blood cells quickly, and the process differs between early human development (fetal liver HSCs) and adulthood (HSCs from bone marrow).

The research indicates “that the whole classic ‘textbook’ view we thought we knew doesn’t actually even exist,” said study investigator John Dick, PhD, of Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

He and his colleagues mapped the lineage potential of nearly 3000 single cells from 33 different populations of HSCs obtained from human blood samples taken at various life stages and ages.

The team’s discoveries build on research published in Science in 2011. In that paper, Dr Dick and his colleagues described isolating an HSC in its purest form—as a single cell capable of regenerating the entire blood system.

“Four years ago, when we isolated the pure stem cell, we realized we had also uncovered populations of stem-cell like ‘daughter’ cells that we thought at the time were other types of stem cells,” Dr Dick said.

“When we burrowed further to study these ‘daughters,’ we discovered they were actually already mature blood lineages. In other words, lineages that had broken off almost immediately from the stem cell compartment and had not developed downstream through the slow, gradual ‘textbook’ process.”

“So in human blood formation, everything begins with the stem cell, which is the executive decision-maker quickly driving the process that replenishes blood at a daily rate that exceeds 300 billion cells.”

The investigators believe this work could help advance the manufacture of blood cells in the lab, and it should aid the study of blood disorders.

“Our discovery means we will be able to understand far better a wide variety of human blood disorders and diseases—from anemia . . . to leukemia,” Dr Dick said. “Think of it as moving from the old world of black-and-white television into the new world of high-definition.” ![]()

University Health Network

Results of a study published in Science challenge traditional ideas about how blood is made.

The findings suggest hematopoiesis does not occur through a gradual process consisting of multipotent, oligopotent, and unilineage progenitor stages.

Rather, hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) mature into different types of blood cells quickly, and the process differs between early human development (fetal liver HSCs) and adulthood (HSCs from bone marrow).

The research indicates “that the whole classic ‘textbook’ view we thought we knew doesn’t actually even exist,” said study investigator John Dick, PhD, of Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

He and his colleagues mapped the lineage potential of nearly 3000 single cells from 33 different populations of HSCs obtained from human blood samples taken at various life stages and ages.

The team’s discoveries build on research published in Science in 2011. In that paper, Dr Dick and his colleagues described isolating an HSC in its purest form—as a single cell capable of regenerating the entire blood system.

“Four years ago, when we isolated the pure stem cell, we realized we had also uncovered populations of stem-cell like ‘daughter’ cells that we thought at the time were other types of stem cells,” Dr Dick said.

“When we burrowed further to study these ‘daughters,’ we discovered they were actually already mature blood lineages. In other words, lineages that had broken off almost immediately from the stem cell compartment and had not developed downstream through the slow, gradual ‘textbook’ process.”

“So in human blood formation, everything begins with the stem cell, which is the executive decision-maker quickly driving the process that replenishes blood at a daily rate that exceeds 300 billion cells.”

The investigators believe this work could help advance the manufacture of blood cells in the lab, and it should aid the study of blood disorders.

“Our discovery means we will be able to understand far better a wide variety of human blood disorders and diseases—from anemia . . . to leukemia,” Dr Dick said. “Think of it as moving from the old world of black-and-white television into the new world of high-definition.” ![]()

University Health Network

Results of a study published in Science challenge traditional ideas about how blood is made.

The findings suggest hematopoiesis does not occur through a gradual process consisting of multipotent, oligopotent, and unilineage progenitor stages.

Rather, hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) mature into different types of blood cells quickly, and the process differs between early human development (fetal liver HSCs) and adulthood (HSCs from bone marrow).

The research indicates “that the whole classic ‘textbook’ view we thought we knew doesn’t actually even exist,” said study investigator John Dick, PhD, of Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

He and his colleagues mapped the lineage potential of nearly 3000 single cells from 33 different populations of HSCs obtained from human blood samples taken at various life stages and ages.

The team’s discoveries build on research published in Science in 2011. In that paper, Dr Dick and his colleagues described isolating an HSC in its purest form—as a single cell capable of regenerating the entire blood system.

“Four years ago, when we isolated the pure stem cell, we realized we had also uncovered populations of stem-cell like ‘daughter’ cells that we thought at the time were other types of stem cells,” Dr Dick said.

“When we burrowed further to study these ‘daughters,’ we discovered they were actually already mature blood lineages. In other words, lineages that had broken off almost immediately from the stem cell compartment and had not developed downstream through the slow, gradual ‘textbook’ process.”

“So in human blood formation, everything begins with the stem cell, which is the executive decision-maker quickly driving the process that replenishes blood at a daily rate that exceeds 300 billion cells.”

The investigators believe this work could help advance the manufacture of blood cells in the lab, and it should aid the study of blood disorders.

“Our discovery means we will be able to understand far better a wide variety of human blood disorders and diseases—from anemia . . . to leukemia,” Dr Dick said. “Think of it as moving from the old world of black-and-white television into the new world of high-definition.” ![]()

Jury still out on cannabinoid therapy for rheumatic diseases

Only four short-term, randomized trials have addressed the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of cannabinoids for treating rheumatic diseases, and all have methodologic weaknesses and a high risk of bias, according to a qualitative review of data published since 1946.

“There is low-quality evidence suggesting that cannabinoids may be associated with improvements in pain and sleep quality in rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia. Clinical positive effects for the studies assessed in this review must be balanced by the reported adverse events,” wrote Dr. Mary-Ann Fitzcharles of McGill University, Montreal, and her colleagues (Arthritis Care Res. 2015 Nov 9. doi: 10.1002/acr.22727).

The four randomized clinical trials, ranging in duration from 2 to 8 weeks, included one with 58 rheumatoid arthritis patients, two with a total of 71 fibromyalgia patients, and one with 74 osteoarthritis patients. Three trials met their respective primary endpoints and found a statistically significant effect of cannabinoids on pain (in two studies), sleep (in two studies), and improved quality of life (in one study). The investigators noted a high incidence (generally observed in 25%-50% of subjects) of mild to moderate side effects (dizziness, drowsiness, nausea, dry mouth) and many methodologic weaknesses in the evaluated data. The study that tested a fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitor in osteoarthritis patients was stopped early due to futility. The other three completed studies were associated with an overall high risk of bias.

One of the two fibromyalgia studies was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted in 2008 that assessed nabilone in 40 fibromyalgia patients. Nabilone treatment led to significant decreases in the visual analog scale for pain (–2.04, P less than .02) at 4 weeks. A second fibromyalgia trial from 2010 compared amitriptyline to nabilone in 31 subjects and found the latter agent to be superior on the primary endpoint of difference in score on the Insomnia Severity Index (difference = 3.2; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-5.3). A 2006 rheumatoid arthritis trial found that cannabis-based Sativex demonstrated a clinically meaningful advantage over placebo for the primary endpoint of morning pain on movement (difference of –0.95, 95% CI, –1.83 to –0.02; P = .044). No trials assessed herbal cannabis.

“It is not currently possible to recommend this category of treatments as therapy for patients with rheumatic diseases. Any conclusions based on these studies remain tenuous and call for larger, well controlled clinical trials to better understand potential benefits and risks as pertaining to rheumatic conditions,” Dr. Fitzcharles and her coauthors wrote.

No relevant financial disclosures were reported.

Only four short-term, randomized trials have addressed the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of cannabinoids for treating rheumatic diseases, and all have methodologic weaknesses and a high risk of bias, according to a qualitative review of data published since 1946.

“There is low-quality evidence suggesting that cannabinoids may be associated with improvements in pain and sleep quality in rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia. Clinical positive effects for the studies assessed in this review must be balanced by the reported adverse events,” wrote Dr. Mary-Ann Fitzcharles of McGill University, Montreal, and her colleagues (Arthritis Care Res. 2015 Nov 9. doi: 10.1002/acr.22727).

The four randomized clinical trials, ranging in duration from 2 to 8 weeks, included one with 58 rheumatoid arthritis patients, two with a total of 71 fibromyalgia patients, and one with 74 osteoarthritis patients. Three trials met their respective primary endpoints and found a statistically significant effect of cannabinoids on pain (in two studies), sleep (in two studies), and improved quality of life (in one study). The investigators noted a high incidence (generally observed in 25%-50% of subjects) of mild to moderate side effects (dizziness, drowsiness, nausea, dry mouth) and many methodologic weaknesses in the evaluated data. The study that tested a fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitor in osteoarthritis patients was stopped early due to futility. The other three completed studies were associated with an overall high risk of bias.