User login

Ureter and Nerve Root Compression Secondary to Expansile Fibrous Dysplasia of the Transverse Process

Fibrous dysplasia is a developmental abnormality caused by excessive proliferation of immature spindle-cell fibrous tissues in bones. It is characterized by benign bony growths, which can lead to local swelling, bony deformities, and lytic conversion, predisposing the bone to pathologic fractures. Although this process can occur in cortical bone, it primarily affects the trabecular bone, leading to enlargement and expansion from within the medullary space. Malignant transformation to osteosarcoma or fibrosarcoma can occur, although this is exceedingly rare (<0.5%).1,2

This case report describes a patient who presented with an expansile lytic mass in a lumbar transverse process that was postoperatively identified on pathology as monostotic fibrous dysplasia. Such lesions that involve the transverse processes are rare and have been associated with pain and significant discomfort.3-5 This is the first reported case of a transverse process fibrous dysplasia causing urinary retention and neurologic symptoms simultaneously. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

History

A 52-year-old black man presented to us with 6 to 8 months of increasing right flank pain, difficulty with urination, and right lower extremity pain in the area of his anterior thigh. He also complained of “buckling” of his thigh with ambulation. On review of systems, the patient denied any fevers, chills, headache, changes in weight or vision, or hearing problems. He had no systemic symptoms except for 6 months of frequent urinary tract infections and difficulty emptying his bladder, which resulted in urinary retention. He denied any significant medical history and denied any use of alcohol or tobacco.

Physical Examination

On physical examination, the patient was a well-appearing 52-year-old man in no apparent distress. No signs of gross deformity, erythema, ecchymosis, or infection were noted upon examination of his lower extremities. His motor examination was within normal limits from L2 to S1. However, both fine and gross sensation were decreased in the L3 distribution. Sensation was intact to the remaining nerve-root distributions. The Babinski sign was negative for both lower extremities, and clonus was within physiologic limits. Examination of his gait was notable for quadriceps buckling with ambulation.

Radiographic Examination

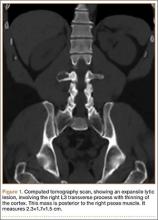

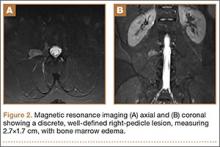

The patient initially presented to his primary care physician, who evaluated his symptoms with a computed tomography scan of his abdomen and pelvis. This showed a mass of the right L3 transverse process (Figure 1). The patient was referred to us for further management of this lesion. Dedicated magnetic resonance imaging of his lumbar spine was performed, showing an expansile, lytic, homogeneous mass in the patient’s right L3 transverse process. The mass showed a significant mass effect, compressing the exiting nerve roots and, presumably, his right ureter (Figure 2). A bone scan showed monostotic disease. The patient had failed conservative management, including physical therapy and anti-inflammatory medications. His right-sided radiculopathy was worsening, and he complained that the pain was affecting his quality of life and limiting his performance of his daily activities. A pain management specialist was requested to better manage his pain. Considering progression of his condition, surgical management was discussed, leading to a planned biopsy and resection of the mass.

Surgical Procedure

The patient was taken into the operating room and positioned prone on a Jackson table with a Wilson frame. Fluoroscopy was used to localize the right L3 transverse process. An incision was made over the right L3 transverse process and a Wiltse intramuscular approach was performed. After the right L3 transverse process was identified, the soft tissue from the transverse process was retracted in all directions, including medially up to the pedicle. The intertransverse ligament was detached from both the cephalad and caudal edges of the transverse process. We used a Woodson elevator to perform subperiosteal dissection to remove the soft tissue circumferentially. After dissection, we placed a Cobb elevator to protect the rostral and caudal soft tissue and used a high-speed burr to amputate the lytic transverse process at its base. The transverse process was removed en bloc (Figure 3) and sent for frozen pathologic evaluation (Figure 4). After the diagnosis of a benign lesion, the wound was closed in layers.

Complete resolution of both urinary and neurologic symptoms were immediately noted and up to 1 month postoperatively.

Discussion

Primary bone tumors of the spine are rare, with a reported incidence of 2.5 to 8.5 per 100,000 people per year.6 The estimated incidence of benign primary tumors involving the spine accounts for about 1% of all primary skeletal tumors and nearly 5% for malignant tumors.7-9 In contrast, secondary tumors involving the bony spinal column are relatively common. Postmortem studies indicate up to 70% of cancer patients demonstrate axial skeletal involvement.10,11 The most commonly encountered benign tumors affecting the spine include giant cell tumors, osteoid osteomas, osteoblastomas, and hemangiomas. Chordomas are frequently reported as the most common malignant primary spine neoplasms. Of all primary benign bone lesions, fibrous dysplasia accounts for approximately 1.4%.8

Primary and secondary malignant osseous tumors have a predilection for the anterior column, and primary benign lesions usually affect the posterior column.8,12-14 Because of the greater blood supply and more direct communication with the viscera via the Batson plexus, the anterior column is most likely to be seeded by metastatic disease. Similarly, hemangiomas and multiple myeloma are typically located in the anterior column, most likely because of the more abundant blood supply there. Chordomas are also found in this cancellous anterior column. Osteoid osteoma, osteoblastoma, and aneurysmal bone cysts are found within the more cortical architecture of posterior elements. The location of this patient’s lesion within the transverse process elevates confidence in the diagnosis of a benign lesion.

The conventional, isolated form of fibrous dysplasia was originally described in 1942 by Lichtenstein and Jaffe.2 They described 15 cases of benign “nonosteogenic fibromas” near the ends of long bones in young patients. Monostotic fibrous dysplasia constitutes the majority of these cases, approximately 80%.1,2,8,15 Fibrous dysplasia may also present as part of McCune-Albright syndrome, in which case it is associated with precocious puberty and café au lait spots. Less commonly, they are associated with intramuscular myxomas, as in Mazabraud syndrome. The lesions in these syndromes are typically polyostotic. In all forms, fibrous dysplasia develops from an activating mutation in the gene that encodes the alpha subunit of the G protein on chromosome 20q13, activating cyclic adenylate cyclase and slowing the differentiation of osteoblasts.3,8

With regard to presentation, fibrous dysplasia is usually asymptomatic and discovered incidentally. The literature reports that the most common presenting symptom for patients with monostotic fibrous dysplasia of the spine is back pain localized to the lesion.15 Meredith and Healey2 completed a comprehensive review of 54 cases of monostotic fibrous dysplasia involving the spine in which the majority of symptoms included back pain, neck pain, sacral region pain, pathologic fracture, painful torticollis, progressive myelopathy, paresthesias of the foot, and only 1 case of radiculopathy involving thoracic vertebra. In normal anatomy, the ureter lies within retroperitoneal fat anterior to the psoas muscle and L2-L5 transverse processes and is normally mobile.16-18 This becomes clinically significant in lean patients as the ureter becomes closer to the spine. There are several reports of iatrogenic ureter injury in lumbar disc surgery.16-18 Normal variants, including medialization towards the spine, may predispose the ureters to injury, iatrogenic, or otherwise. In fact, medialization of the ureters occurs commonly in black men and usually involves the right side, which may have occurred in this black patient.19

Fibrous dysplasia is most often diagnosed by its radiographic appearance or biopsy. However, recent data suggest that deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) analysis may soon be able to diagnose this process.20 Imaging typically reveals expansile, central lytic lesions within the medullary cavity. Pathology shows dense fibroblasts around immature woven bone, commonly referred to as “Chinese lettering.” The treatment varies from observation to en bloc surgical resection. Clinical observation is warranted for asymptomatic or incidental findings of monostotic fibrous dysplasia, as long as the risk for pathologic fracture is low.11 Bisphosphonate therapy, both oral and intravenous, offers promising outcomes for the treatment of fibrous dysplasia, with improvement in pain and function as well as in the radiographic findings.11,21 Management of monostotic fibrous dysplasia presenting as an isolated expansile mass of the transverse process in lumbar spine has rarely been described.3-5 Troop and Herring5 reported a case of monostotic fibrous dysplasia in the lumbar spine, with involvement of the vertebral body and the posterior elements. Chow and coauthors3 and Harris and colleagues4 described the involvement of the transverse process of L4. Chow and coauthors’3 treatment consisted of excision that resulted in an asymptomatic patient at 8-year follow-up, while Harris and colleagues4 chose observation. In the latter study, the patient’s lower back pain persisted at 4-year follow-up.

Progressive enlargement, recurrence, and malignant transformation have all been described. Meredith and Healey2 reported the reappearance of monostotic fibrous dysplasia affecting C2, extending through the fusion mass to involve a previously unaffected vertebra 20 years after the original C2 posterior elements excision via posterior spinal fusion from C1 to C3. In the literature, the incidence of malignant transformation ranges from 0.4% to 4%.8 One case of malignant transformation in thoracic spine was reported by Fu and colleagues.22 Therefore, complete removal of all affected bone is recommended.1,2,4,5,15,22,23

Conclusion

We present an unusual condition with complete resolution of symptoms after surgical resection. Several points may be considered from this report. Fibrous dysplasia lesions have been found in all bones of the body, including the skull, face, and extremities; however, monostotic fibrous dysplasia involving the spine is rare.11,23,24 Furthermore, there are no other reports of these lesions causing simultaneous nerve compression and urologic symptoms. Considering anatomy, clinicians may consider lesions of the lumbar transverse process in patients presenting to orthopedic surgeons with urinary symptoms, especially when combined with neurologic symptoms. In these lesions, fibrous dysplasia should be within the differential diagnosis. Clinicians should also recognize that complete resolution of symptoms has been reported with wide resection of these lesions.

1. Leet AI, Magur E, Lee JS, Weintroub S, Robey PG, Collins MT. Fibrous dysplasia in the spine: prevalence of lesions and association with scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(3):531-537.

2. Meredith DS, Healey JH. Twenty-year follow-up of monostotic fibrous dysplasia of the second cervical vertebra: a case report and review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(13):e74.

3. Chow LT, Griffith J, Chow WH, Kumta SM. Monostotic fibrous dysplasia of the spine: report of a case involving the lumbar transverse process and review of the literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2000;120(7-8):460-464.

4. Harris WH, Dudley HR Jr, Barry RJ. The natural history of fibrous dysplasia. An orthopaedic, pathologic, and roentgenographic study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1962;44(2):207-233.

5. Troop JK, Herring JA. Monostotic fibrous dysplasia of the lumbar spine: case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Orthop. 1988;8(5):599-601.

6. Dreghorn CR, Newman RJ, Hardy GJ, Dickson RA. Primary tumors of the axial skeleton. Experience of the Leeds Regional Bone Tumor Registry. Spine. 1990;15(2):137-140.

7. Schuster JM, Grady MS. Medical management and adjuvant therapies in spinal metastatic disease. Neurosurg Focus. 2001;11(6):e3.

8. Unni K. Introduction and scope. In: Unni K, ed. Dahlin’s Bone Tumors—General Aspects and Data on 11,087 Cases. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1996:1-9.

9. Wong DA, Fornasier VL, MacNab I. Spinal metastases: the obvious, the occult, and the impostors. Spine. 1990;15(1):1-4.

10. Dagi TF, Schmidek HH. Vascular tumors of the spine. In: Sundaresan N, Schmidek HH, Schiller AL, eds. Tumors of the Spine: Diagnosis and Clinical Management. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Co; 1990:181-191.

11. DiCaprio M, Enneking W. Fibrous dysplasia. Pathophysiology, evaluation, and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(8):1848-1864.

12. Gasbarrini A, Cappuccio M, Mirabile L, et al. Spinal metastases: treatment evaluation algorithm. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2004;8(6):265-274.

13. Loblaw DA, Laperriere NJ, Mackillop WJ. A population-based study of malignant spinal cord compression in Ontario. Clin Oncol. 2003;15(4):211-217.

14. Ortiz Gómez JA. The incidence of vertebral body metastases. Int Orthop. 1995;19(5):309-311.

15. Avimadje AM, Goupille P, Zerkak D, Begnard G, Brunais-Besse J, Valat JP. Monostotic fibrous dysplasia of the lumbar spine. Joint Bone Spine. 2000;67(1):65-70.

16. Isiklar ZU, Lindsey RW, Coburn M. Ureteral injury after anterior lumbar interbody fusion. A case report. Spine. 1996;21(20):2379-2382.

17. Krone A, Heller V, Osterhage HR. Ureteral injury in lumbar disc surgery. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1985;78(3-4):108–112.

18. Cho KT, Im SH, Hong SK. Ureteral injury after inadvertent violation of the intertransverse space during posterior lumbar diskectomy: a case report. Surg Neurol. 2008;69(2):135-137.

19. Adam EJ, Desai SC, Lawton G. Racial variations in normal ureteric course. Clin Radiol. 1985;36(4):373-375.

20. Stathopoulos IP, Balanika AP, Baltas CS, et al. Fibrous dysplasia; confirmation of clinical diagnosis by DNA tests instead of biopsy. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2013;13(1):120-123.

21. Lane JM, Khan SN, O’Connor WJ, et al. Bisphosphonate therapy in fibrous dysplasia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;382:6-12.

22. Fu CJ, Hsu CY, Shih TT, Wu MZ. Monostotic fibrous dysplasia of the thoracic spine with malignant transformation. J Formos Med Assoc. 2004;103(9):711-714.

23. McCarthy EF. Fibro-osseous lesions of the maxillofacial bones. Head Neck Pathol. 2013;7(1):5-10.

24. Manjila S, Zender CA, Weaver J, Rodgers M, Cohen AR. Aneurysmal bone cyst within fibrous dysplasia of the anterior skull base: continued intracranial extension after endoscopic resections requiring craniofacial approach with free tissue transfer reconstruction [published online ahead of print February 26, 2013]. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29(7).

Fibrous dysplasia is a developmental abnormality caused by excessive proliferation of immature spindle-cell fibrous tissues in bones. It is characterized by benign bony growths, which can lead to local swelling, bony deformities, and lytic conversion, predisposing the bone to pathologic fractures. Although this process can occur in cortical bone, it primarily affects the trabecular bone, leading to enlargement and expansion from within the medullary space. Malignant transformation to osteosarcoma or fibrosarcoma can occur, although this is exceedingly rare (<0.5%).1,2

This case report describes a patient who presented with an expansile lytic mass in a lumbar transverse process that was postoperatively identified on pathology as monostotic fibrous dysplasia. Such lesions that involve the transverse processes are rare and have been associated with pain and significant discomfort.3-5 This is the first reported case of a transverse process fibrous dysplasia causing urinary retention and neurologic symptoms simultaneously. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

History

A 52-year-old black man presented to us with 6 to 8 months of increasing right flank pain, difficulty with urination, and right lower extremity pain in the area of his anterior thigh. He also complained of “buckling” of his thigh with ambulation. On review of systems, the patient denied any fevers, chills, headache, changes in weight or vision, or hearing problems. He had no systemic symptoms except for 6 months of frequent urinary tract infections and difficulty emptying his bladder, which resulted in urinary retention. He denied any significant medical history and denied any use of alcohol or tobacco.

Physical Examination

On physical examination, the patient was a well-appearing 52-year-old man in no apparent distress. No signs of gross deformity, erythema, ecchymosis, or infection were noted upon examination of his lower extremities. His motor examination was within normal limits from L2 to S1. However, both fine and gross sensation were decreased in the L3 distribution. Sensation was intact to the remaining nerve-root distributions. The Babinski sign was negative for both lower extremities, and clonus was within physiologic limits. Examination of his gait was notable for quadriceps buckling with ambulation.

Radiographic Examination

The patient initially presented to his primary care physician, who evaluated his symptoms with a computed tomography scan of his abdomen and pelvis. This showed a mass of the right L3 transverse process (Figure 1). The patient was referred to us for further management of this lesion. Dedicated magnetic resonance imaging of his lumbar spine was performed, showing an expansile, lytic, homogeneous mass in the patient’s right L3 transverse process. The mass showed a significant mass effect, compressing the exiting nerve roots and, presumably, his right ureter (Figure 2). A bone scan showed monostotic disease. The patient had failed conservative management, including physical therapy and anti-inflammatory medications. His right-sided radiculopathy was worsening, and he complained that the pain was affecting his quality of life and limiting his performance of his daily activities. A pain management specialist was requested to better manage his pain. Considering progression of his condition, surgical management was discussed, leading to a planned biopsy and resection of the mass.

Surgical Procedure

The patient was taken into the operating room and positioned prone on a Jackson table with a Wilson frame. Fluoroscopy was used to localize the right L3 transverse process. An incision was made over the right L3 transverse process and a Wiltse intramuscular approach was performed. After the right L3 transverse process was identified, the soft tissue from the transverse process was retracted in all directions, including medially up to the pedicle. The intertransverse ligament was detached from both the cephalad and caudal edges of the transverse process. We used a Woodson elevator to perform subperiosteal dissection to remove the soft tissue circumferentially. After dissection, we placed a Cobb elevator to protect the rostral and caudal soft tissue and used a high-speed burr to amputate the lytic transverse process at its base. The transverse process was removed en bloc (Figure 3) and sent for frozen pathologic evaluation (Figure 4). After the diagnosis of a benign lesion, the wound was closed in layers.

Complete resolution of both urinary and neurologic symptoms were immediately noted and up to 1 month postoperatively.

Discussion

Primary bone tumors of the spine are rare, with a reported incidence of 2.5 to 8.5 per 100,000 people per year.6 The estimated incidence of benign primary tumors involving the spine accounts for about 1% of all primary skeletal tumors and nearly 5% for malignant tumors.7-9 In contrast, secondary tumors involving the bony spinal column are relatively common. Postmortem studies indicate up to 70% of cancer patients demonstrate axial skeletal involvement.10,11 The most commonly encountered benign tumors affecting the spine include giant cell tumors, osteoid osteomas, osteoblastomas, and hemangiomas. Chordomas are frequently reported as the most common malignant primary spine neoplasms. Of all primary benign bone lesions, fibrous dysplasia accounts for approximately 1.4%.8

Primary and secondary malignant osseous tumors have a predilection for the anterior column, and primary benign lesions usually affect the posterior column.8,12-14 Because of the greater blood supply and more direct communication with the viscera via the Batson plexus, the anterior column is most likely to be seeded by metastatic disease. Similarly, hemangiomas and multiple myeloma are typically located in the anterior column, most likely because of the more abundant blood supply there. Chordomas are also found in this cancellous anterior column. Osteoid osteoma, osteoblastoma, and aneurysmal bone cysts are found within the more cortical architecture of posterior elements. The location of this patient’s lesion within the transverse process elevates confidence in the diagnosis of a benign lesion.

The conventional, isolated form of fibrous dysplasia was originally described in 1942 by Lichtenstein and Jaffe.2 They described 15 cases of benign “nonosteogenic fibromas” near the ends of long bones in young patients. Monostotic fibrous dysplasia constitutes the majority of these cases, approximately 80%.1,2,8,15 Fibrous dysplasia may also present as part of McCune-Albright syndrome, in which case it is associated with precocious puberty and café au lait spots. Less commonly, they are associated with intramuscular myxomas, as in Mazabraud syndrome. The lesions in these syndromes are typically polyostotic. In all forms, fibrous dysplasia develops from an activating mutation in the gene that encodes the alpha subunit of the G protein on chromosome 20q13, activating cyclic adenylate cyclase and slowing the differentiation of osteoblasts.3,8

With regard to presentation, fibrous dysplasia is usually asymptomatic and discovered incidentally. The literature reports that the most common presenting symptom for patients with monostotic fibrous dysplasia of the spine is back pain localized to the lesion.15 Meredith and Healey2 completed a comprehensive review of 54 cases of monostotic fibrous dysplasia involving the spine in which the majority of symptoms included back pain, neck pain, sacral region pain, pathologic fracture, painful torticollis, progressive myelopathy, paresthesias of the foot, and only 1 case of radiculopathy involving thoracic vertebra. In normal anatomy, the ureter lies within retroperitoneal fat anterior to the psoas muscle and L2-L5 transverse processes and is normally mobile.16-18 This becomes clinically significant in lean patients as the ureter becomes closer to the spine. There are several reports of iatrogenic ureter injury in lumbar disc surgery.16-18 Normal variants, including medialization towards the spine, may predispose the ureters to injury, iatrogenic, or otherwise. In fact, medialization of the ureters occurs commonly in black men and usually involves the right side, which may have occurred in this black patient.19

Fibrous dysplasia is most often diagnosed by its radiographic appearance or biopsy. However, recent data suggest that deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) analysis may soon be able to diagnose this process.20 Imaging typically reveals expansile, central lytic lesions within the medullary cavity. Pathology shows dense fibroblasts around immature woven bone, commonly referred to as “Chinese lettering.” The treatment varies from observation to en bloc surgical resection. Clinical observation is warranted for asymptomatic or incidental findings of monostotic fibrous dysplasia, as long as the risk for pathologic fracture is low.11 Bisphosphonate therapy, both oral and intravenous, offers promising outcomes for the treatment of fibrous dysplasia, with improvement in pain and function as well as in the radiographic findings.11,21 Management of monostotic fibrous dysplasia presenting as an isolated expansile mass of the transverse process in lumbar spine has rarely been described.3-5 Troop and Herring5 reported a case of monostotic fibrous dysplasia in the lumbar spine, with involvement of the vertebral body and the posterior elements. Chow and coauthors3 and Harris and colleagues4 described the involvement of the transverse process of L4. Chow and coauthors’3 treatment consisted of excision that resulted in an asymptomatic patient at 8-year follow-up, while Harris and colleagues4 chose observation. In the latter study, the patient’s lower back pain persisted at 4-year follow-up.

Progressive enlargement, recurrence, and malignant transformation have all been described. Meredith and Healey2 reported the reappearance of monostotic fibrous dysplasia affecting C2, extending through the fusion mass to involve a previously unaffected vertebra 20 years after the original C2 posterior elements excision via posterior spinal fusion from C1 to C3. In the literature, the incidence of malignant transformation ranges from 0.4% to 4%.8 One case of malignant transformation in thoracic spine was reported by Fu and colleagues.22 Therefore, complete removal of all affected bone is recommended.1,2,4,5,15,22,23

Conclusion

We present an unusual condition with complete resolution of symptoms after surgical resection. Several points may be considered from this report. Fibrous dysplasia lesions have been found in all bones of the body, including the skull, face, and extremities; however, monostotic fibrous dysplasia involving the spine is rare.11,23,24 Furthermore, there are no other reports of these lesions causing simultaneous nerve compression and urologic symptoms. Considering anatomy, clinicians may consider lesions of the lumbar transverse process in patients presenting to orthopedic surgeons with urinary symptoms, especially when combined with neurologic symptoms. In these lesions, fibrous dysplasia should be within the differential diagnosis. Clinicians should also recognize that complete resolution of symptoms has been reported with wide resection of these lesions.

Fibrous dysplasia is a developmental abnormality caused by excessive proliferation of immature spindle-cell fibrous tissues in bones. It is characterized by benign bony growths, which can lead to local swelling, bony deformities, and lytic conversion, predisposing the bone to pathologic fractures. Although this process can occur in cortical bone, it primarily affects the trabecular bone, leading to enlargement and expansion from within the medullary space. Malignant transformation to osteosarcoma or fibrosarcoma can occur, although this is exceedingly rare (<0.5%).1,2

This case report describes a patient who presented with an expansile lytic mass in a lumbar transverse process that was postoperatively identified on pathology as monostotic fibrous dysplasia. Such lesions that involve the transverse processes are rare and have been associated with pain and significant discomfort.3-5 This is the first reported case of a transverse process fibrous dysplasia causing urinary retention and neurologic symptoms simultaneously. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

History

A 52-year-old black man presented to us with 6 to 8 months of increasing right flank pain, difficulty with urination, and right lower extremity pain in the area of his anterior thigh. He also complained of “buckling” of his thigh with ambulation. On review of systems, the patient denied any fevers, chills, headache, changes in weight or vision, or hearing problems. He had no systemic symptoms except for 6 months of frequent urinary tract infections and difficulty emptying his bladder, which resulted in urinary retention. He denied any significant medical history and denied any use of alcohol or tobacco.

Physical Examination

On physical examination, the patient was a well-appearing 52-year-old man in no apparent distress. No signs of gross deformity, erythema, ecchymosis, or infection were noted upon examination of his lower extremities. His motor examination was within normal limits from L2 to S1. However, both fine and gross sensation were decreased in the L3 distribution. Sensation was intact to the remaining nerve-root distributions. The Babinski sign was negative for both lower extremities, and clonus was within physiologic limits. Examination of his gait was notable for quadriceps buckling with ambulation.

Radiographic Examination

The patient initially presented to his primary care physician, who evaluated his symptoms with a computed tomography scan of his abdomen and pelvis. This showed a mass of the right L3 transverse process (Figure 1). The patient was referred to us for further management of this lesion. Dedicated magnetic resonance imaging of his lumbar spine was performed, showing an expansile, lytic, homogeneous mass in the patient’s right L3 transverse process. The mass showed a significant mass effect, compressing the exiting nerve roots and, presumably, his right ureter (Figure 2). A bone scan showed monostotic disease. The patient had failed conservative management, including physical therapy and anti-inflammatory medications. His right-sided radiculopathy was worsening, and he complained that the pain was affecting his quality of life and limiting his performance of his daily activities. A pain management specialist was requested to better manage his pain. Considering progression of his condition, surgical management was discussed, leading to a planned biopsy and resection of the mass.

Surgical Procedure

The patient was taken into the operating room and positioned prone on a Jackson table with a Wilson frame. Fluoroscopy was used to localize the right L3 transverse process. An incision was made over the right L3 transverse process and a Wiltse intramuscular approach was performed. After the right L3 transverse process was identified, the soft tissue from the transverse process was retracted in all directions, including medially up to the pedicle. The intertransverse ligament was detached from both the cephalad and caudal edges of the transverse process. We used a Woodson elevator to perform subperiosteal dissection to remove the soft tissue circumferentially. After dissection, we placed a Cobb elevator to protect the rostral and caudal soft tissue and used a high-speed burr to amputate the lytic transverse process at its base. The transverse process was removed en bloc (Figure 3) and sent for frozen pathologic evaluation (Figure 4). After the diagnosis of a benign lesion, the wound was closed in layers.

Complete resolution of both urinary and neurologic symptoms were immediately noted and up to 1 month postoperatively.

Discussion

Primary bone tumors of the spine are rare, with a reported incidence of 2.5 to 8.5 per 100,000 people per year.6 The estimated incidence of benign primary tumors involving the spine accounts for about 1% of all primary skeletal tumors and nearly 5% for malignant tumors.7-9 In contrast, secondary tumors involving the bony spinal column are relatively common. Postmortem studies indicate up to 70% of cancer patients demonstrate axial skeletal involvement.10,11 The most commonly encountered benign tumors affecting the spine include giant cell tumors, osteoid osteomas, osteoblastomas, and hemangiomas. Chordomas are frequently reported as the most common malignant primary spine neoplasms. Of all primary benign bone lesions, fibrous dysplasia accounts for approximately 1.4%.8

Primary and secondary malignant osseous tumors have a predilection for the anterior column, and primary benign lesions usually affect the posterior column.8,12-14 Because of the greater blood supply and more direct communication with the viscera via the Batson plexus, the anterior column is most likely to be seeded by metastatic disease. Similarly, hemangiomas and multiple myeloma are typically located in the anterior column, most likely because of the more abundant blood supply there. Chordomas are also found in this cancellous anterior column. Osteoid osteoma, osteoblastoma, and aneurysmal bone cysts are found within the more cortical architecture of posterior elements. The location of this patient’s lesion within the transverse process elevates confidence in the diagnosis of a benign lesion.

The conventional, isolated form of fibrous dysplasia was originally described in 1942 by Lichtenstein and Jaffe.2 They described 15 cases of benign “nonosteogenic fibromas” near the ends of long bones in young patients. Monostotic fibrous dysplasia constitutes the majority of these cases, approximately 80%.1,2,8,15 Fibrous dysplasia may also present as part of McCune-Albright syndrome, in which case it is associated with precocious puberty and café au lait spots. Less commonly, they are associated with intramuscular myxomas, as in Mazabraud syndrome. The lesions in these syndromes are typically polyostotic. In all forms, fibrous dysplasia develops from an activating mutation in the gene that encodes the alpha subunit of the G protein on chromosome 20q13, activating cyclic adenylate cyclase and slowing the differentiation of osteoblasts.3,8

With regard to presentation, fibrous dysplasia is usually asymptomatic and discovered incidentally. The literature reports that the most common presenting symptom for patients with monostotic fibrous dysplasia of the spine is back pain localized to the lesion.15 Meredith and Healey2 completed a comprehensive review of 54 cases of monostotic fibrous dysplasia involving the spine in which the majority of symptoms included back pain, neck pain, sacral region pain, pathologic fracture, painful torticollis, progressive myelopathy, paresthesias of the foot, and only 1 case of radiculopathy involving thoracic vertebra. In normal anatomy, the ureter lies within retroperitoneal fat anterior to the psoas muscle and L2-L5 transverse processes and is normally mobile.16-18 This becomes clinically significant in lean patients as the ureter becomes closer to the spine. There are several reports of iatrogenic ureter injury in lumbar disc surgery.16-18 Normal variants, including medialization towards the spine, may predispose the ureters to injury, iatrogenic, or otherwise. In fact, medialization of the ureters occurs commonly in black men and usually involves the right side, which may have occurred in this black patient.19

Fibrous dysplasia is most often diagnosed by its radiographic appearance or biopsy. However, recent data suggest that deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) analysis may soon be able to diagnose this process.20 Imaging typically reveals expansile, central lytic lesions within the medullary cavity. Pathology shows dense fibroblasts around immature woven bone, commonly referred to as “Chinese lettering.” The treatment varies from observation to en bloc surgical resection. Clinical observation is warranted for asymptomatic or incidental findings of monostotic fibrous dysplasia, as long as the risk for pathologic fracture is low.11 Bisphosphonate therapy, both oral and intravenous, offers promising outcomes for the treatment of fibrous dysplasia, with improvement in pain and function as well as in the radiographic findings.11,21 Management of monostotic fibrous dysplasia presenting as an isolated expansile mass of the transverse process in lumbar spine has rarely been described.3-5 Troop and Herring5 reported a case of monostotic fibrous dysplasia in the lumbar spine, with involvement of the vertebral body and the posterior elements. Chow and coauthors3 and Harris and colleagues4 described the involvement of the transverse process of L4. Chow and coauthors’3 treatment consisted of excision that resulted in an asymptomatic patient at 8-year follow-up, while Harris and colleagues4 chose observation. In the latter study, the patient’s lower back pain persisted at 4-year follow-up.

Progressive enlargement, recurrence, and malignant transformation have all been described. Meredith and Healey2 reported the reappearance of monostotic fibrous dysplasia affecting C2, extending through the fusion mass to involve a previously unaffected vertebra 20 years after the original C2 posterior elements excision via posterior spinal fusion from C1 to C3. In the literature, the incidence of malignant transformation ranges from 0.4% to 4%.8 One case of malignant transformation in thoracic spine was reported by Fu and colleagues.22 Therefore, complete removal of all affected bone is recommended.1,2,4,5,15,22,23

Conclusion

We present an unusual condition with complete resolution of symptoms after surgical resection. Several points may be considered from this report. Fibrous dysplasia lesions have been found in all bones of the body, including the skull, face, and extremities; however, monostotic fibrous dysplasia involving the spine is rare.11,23,24 Furthermore, there are no other reports of these lesions causing simultaneous nerve compression and urologic symptoms. Considering anatomy, clinicians may consider lesions of the lumbar transverse process in patients presenting to orthopedic surgeons with urinary symptoms, especially when combined with neurologic symptoms. In these lesions, fibrous dysplasia should be within the differential diagnosis. Clinicians should also recognize that complete resolution of symptoms has been reported with wide resection of these lesions.

1. Leet AI, Magur E, Lee JS, Weintroub S, Robey PG, Collins MT. Fibrous dysplasia in the spine: prevalence of lesions and association with scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(3):531-537.

2. Meredith DS, Healey JH. Twenty-year follow-up of monostotic fibrous dysplasia of the second cervical vertebra: a case report and review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(13):e74.

3. Chow LT, Griffith J, Chow WH, Kumta SM. Monostotic fibrous dysplasia of the spine: report of a case involving the lumbar transverse process and review of the literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2000;120(7-8):460-464.

4. Harris WH, Dudley HR Jr, Barry RJ. The natural history of fibrous dysplasia. An orthopaedic, pathologic, and roentgenographic study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1962;44(2):207-233.

5. Troop JK, Herring JA. Monostotic fibrous dysplasia of the lumbar spine: case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Orthop. 1988;8(5):599-601.

6. Dreghorn CR, Newman RJ, Hardy GJ, Dickson RA. Primary tumors of the axial skeleton. Experience of the Leeds Regional Bone Tumor Registry. Spine. 1990;15(2):137-140.

7. Schuster JM, Grady MS. Medical management and adjuvant therapies in spinal metastatic disease. Neurosurg Focus. 2001;11(6):e3.

8. Unni K. Introduction and scope. In: Unni K, ed. Dahlin’s Bone Tumors—General Aspects and Data on 11,087 Cases. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1996:1-9.

9. Wong DA, Fornasier VL, MacNab I. Spinal metastases: the obvious, the occult, and the impostors. Spine. 1990;15(1):1-4.

10. Dagi TF, Schmidek HH. Vascular tumors of the spine. In: Sundaresan N, Schmidek HH, Schiller AL, eds. Tumors of the Spine: Diagnosis and Clinical Management. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Co; 1990:181-191.

11. DiCaprio M, Enneking W. Fibrous dysplasia. Pathophysiology, evaluation, and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(8):1848-1864.

12. Gasbarrini A, Cappuccio M, Mirabile L, et al. Spinal metastases: treatment evaluation algorithm. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2004;8(6):265-274.

13. Loblaw DA, Laperriere NJ, Mackillop WJ. A population-based study of malignant spinal cord compression in Ontario. Clin Oncol. 2003;15(4):211-217.

14. Ortiz Gómez JA. The incidence of vertebral body metastases. Int Orthop. 1995;19(5):309-311.

15. Avimadje AM, Goupille P, Zerkak D, Begnard G, Brunais-Besse J, Valat JP. Monostotic fibrous dysplasia of the lumbar spine. Joint Bone Spine. 2000;67(1):65-70.

16. Isiklar ZU, Lindsey RW, Coburn M. Ureteral injury after anterior lumbar interbody fusion. A case report. Spine. 1996;21(20):2379-2382.

17. Krone A, Heller V, Osterhage HR. Ureteral injury in lumbar disc surgery. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1985;78(3-4):108–112.

18. Cho KT, Im SH, Hong SK. Ureteral injury after inadvertent violation of the intertransverse space during posterior lumbar diskectomy: a case report. Surg Neurol. 2008;69(2):135-137.

19. Adam EJ, Desai SC, Lawton G. Racial variations in normal ureteric course. Clin Radiol. 1985;36(4):373-375.

20. Stathopoulos IP, Balanika AP, Baltas CS, et al. Fibrous dysplasia; confirmation of clinical diagnosis by DNA tests instead of biopsy. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2013;13(1):120-123.

21. Lane JM, Khan SN, O’Connor WJ, et al. Bisphosphonate therapy in fibrous dysplasia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;382:6-12.

22. Fu CJ, Hsu CY, Shih TT, Wu MZ. Monostotic fibrous dysplasia of the thoracic spine with malignant transformation. J Formos Med Assoc. 2004;103(9):711-714.

23. McCarthy EF. Fibro-osseous lesions of the maxillofacial bones. Head Neck Pathol. 2013;7(1):5-10.

24. Manjila S, Zender CA, Weaver J, Rodgers M, Cohen AR. Aneurysmal bone cyst within fibrous dysplasia of the anterior skull base: continued intracranial extension after endoscopic resections requiring craniofacial approach with free tissue transfer reconstruction [published online ahead of print February 26, 2013]. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29(7).

1. Leet AI, Magur E, Lee JS, Weintroub S, Robey PG, Collins MT. Fibrous dysplasia in the spine: prevalence of lesions and association with scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(3):531-537.

2. Meredith DS, Healey JH. Twenty-year follow-up of monostotic fibrous dysplasia of the second cervical vertebra: a case report and review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(13):e74.

3. Chow LT, Griffith J, Chow WH, Kumta SM. Monostotic fibrous dysplasia of the spine: report of a case involving the lumbar transverse process and review of the literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2000;120(7-8):460-464.

4. Harris WH, Dudley HR Jr, Barry RJ. The natural history of fibrous dysplasia. An orthopaedic, pathologic, and roentgenographic study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1962;44(2):207-233.

5. Troop JK, Herring JA. Monostotic fibrous dysplasia of the lumbar spine: case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Orthop. 1988;8(5):599-601.

6. Dreghorn CR, Newman RJ, Hardy GJ, Dickson RA. Primary tumors of the axial skeleton. Experience of the Leeds Regional Bone Tumor Registry. Spine. 1990;15(2):137-140.

7. Schuster JM, Grady MS. Medical management and adjuvant therapies in spinal metastatic disease. Neurosurg Focus. 2001;11(6):e3.

8. Unni K. Introduction and scope. In: Unni K, ed. Dahlin’s Bone Tumors—General Aspects and Data on 11,087 Cases. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1996:1-9.

9. Wong DA, Fornasier VL, MacNab I. Spinal metastases: the obvious, the occult, and the impostors. Spine. 1990;15(1):1-4.

10. Dagi TF, Schmidek HH. Vascular tumors of the spine. In: Sundaresan N, Schmidek HH, Schiller AL, eds. Tumors of the Spine: Diagnosis and Clinical Management. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Co; 1990:181-191.

11. DiCaprio M, Enneking W. Fibrous dysplasia. Pathophysiology, evaluation, and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(8):1848-1864.

12. Gasbarrini A, Cappuccio M, Mirabile L, et al. Spinal metastases: treatment evaluation algorithm. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2004;8(6):265-274.

13. Loblaw DA, Laperriere NJ, Mackillop WJ. A population-based study of malignant spinal cord compression in Ontario. Clin Oncol. 2003;15(4):211-217.

14. Ortiz Gómez JA. The incidence of vertebral body metastases. Int Orthop. 1995;19(5):309-311.

15. Avimadje AM, Goupille P, Zerkak D, Begnard G, Brunais-Besse J, Valat JP. Monostotic fibrous dysplasia of the lumbar spine. Joint Bone Spine. 2000;67(1):65-70.

16. Isiklar ZU, Lindsey RW, Coburn M. Ureteral injury after anterior lumbar interbody fusion. A case report. Spine. 1996;21(20):2379-2382.

17. Krone A, Heller V, Osterhage HR. Ureteral injury in lumbar disc surgery. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1985;78(3-4):108–112.

18. Cho KT, Im SH, Hong SK. Ureteral injury after inadvertent violation of the intertransverse space during posterior lumbar diskectomy: a case report. Surg Neurol. 2008;69(2):135-137.

19. Adam EJ, Desai SC, Lawton G. Racial variations in normal ureteric course. Clin Radiol. 1985;36(4):373-375.

20. Stathopoulos IP, Balanika AP, Baltas CS, et al. Fibrous dysplasia; confirmation of clinical diagnosis by DNA tests instead of biopsy. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2013;13(1):120-123.

21. Lane JM, Khan SN, O’Connor WJ, et al. Bisphosphonate therapy in fibrous dysplasia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;382:6-12.

22. Fu CJ, Hsu CY, Shih TT, Wu MZ. Monostotic fibrous dysplasia of the thoracic spine with malignant transformation. J Formos Med Assoc. 2004;103(9):711-714.

23. McCarthy EF. Fibro-osseous lesions of the maxillofacial bones. Head Neck Pathol. 2013;7(1):5-10.

24. Manjila S, Zender CA, Weaver J, Rodgers M, Cohen AR. Aneurysmal bone cyst within fibrous dysplasia of the anterior skull base: continued intracranial extension after endoscopic resections requiring craniofacial approach with free tissue transfer reconstruction [published online ahead of print February 26, 2013]. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29(7).

Fludarabine added to interferon hints at benefits for breakthrough MS

Relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS) patients who experienced breakthrough disease despite treatment with interferon beta-1a required less acute corticosteroids during relapses and had better responses on several MRI outcomes with the addition of fludarabine, compared with monthly methylprednisolone, in a small, prospective, randomized, open-label study.

Investigators led by Dr. Steven J. Greenberg of AbbVie, North Chicago, chose to test fludarabine in the proof-of-concept, pilot study because of its immunosuppressive properties and effectiveness in treating disorders involving immune dysregulation, most notably lymphoproliferative disorders and hematologic malignancies.

Fludarabine is a purine nucleoside analog prodrug that upon phosphorylation is toxic to dividing and quiescent lymphocytes and monocytes, according to the researchers, and exerts its effects through DNA synthesis interference and apoptosis. Methylprednisolone was used as an add-on comparator because of its common use in multiple sclerosis.

In addition to weekly intramuscular interferon beta-1a (Avonex), all 18 patients in the study initially received IV methylprednisolone 1 g once daily for 3 consecutive days, and then 1 week later were randomized to receive fludarabine 25 mg/m2 IV once daily for 5 consecutive days per 4-week cycle for 3 consecutive cycles or methylprednisolone 1 g IV 1 day per 4-week cycle for 3 consecutive cycles (Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2016 Jan 21. doi: 10.1177/1756285615626049).

Treatment-emergent adverse events occurred with similar frequency in each group over 12 months of follow-up, with infection being the most common AE (three with fludarabine and two with methylprednisolone). Grade 3 or grade 2 leukopenia that had not normalized within 28 days after treatment occurred in three fludarabine patients and one methylprednisolone patient, and took significantly longer resolve for those taking fludarabine (3.75 months vs. 0.17 months).

Over 12 months of follow-up, fludarabine-treated patients experienced numerically, but not significantly, fewer mean relapses (0.5 vs. 0.8) and longer median time to relapse (10.5 months vs. 8.5 months). However, fludarabine led to significantly fewer mean cycles of corticosteroids (0.5 vs. 0.8).

Expanded Disability Status Scale scores declined from baseline to 12 months by a mean of –0.2 in the fludarabine group but increased in the methylprednisolone group by 0.5. Both groups achieved slight improvements in MS Functional Composite scores.

Fludarabine-treated patients had significant declines from baseline to 12 months in gadolinium-positive lesion volume (–98.3%) and number (–93.3%), but no significant differences were recorded in either group for changes in FLAIR lesion volume, T1-hypointense lesion volume or number, or brain parenchymal fraction.

Two outlier patients in the fludarabine group who had 21 and 17 gadolinium-positive lesions, respectively, at baseline were examined in separate analyses and results for the fludarabine group were analyzed both with and without them. None of the results appreciably changed when they were included or excluded, except for gadolinium-positive lesion volume and number, which were not significantly changed without the two patients. The two outlier patients had 100% mean reductions in gadolinium-positive lesion number and volume and a 19.4% mean reduction in FLAIR lesion volume.

The investigators cautioned that “the long-term safety of repetitive use has not been established by this study, which is a critical consideration for a chronic disease like MS. We emphasize that our results should be considered preliminary and would await confirmation in a larger-scale trial.”

This study was supported in part by an investigator-initiated study grant provided by Biogen. Berlex Laboratories provided fludarabine. Dr. Greenberg is an employee of AbbVie, and two coauthors reported financial ties to companies marketing MS drugs.

Relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS) patients who experienced breakthrough disease despite treatment with interferon beta-1a required less acute corticosteroids during relapses and had better responses on several MRI outcomes with the addition of fludarabine, compared with monthly methylprednisolone, in a small, prospective, randomized, open-label study.

Investigators led by Dr. Steven J. Greenberg of AbbVie, North Chicago, chose to test fludarabine in the proof-of-concept, pilot study because of its immunosuppressive properties and effectiveness in treating disorders involving immune dysregulation, most notably lymphoproliferative disorders and hematologic malignancies.

Fludarabine is a purine nucleoside analog prodrug that upon phosphorylation is toxic to dividing and quiescent lymphocytes and monocytes, according to the researchers, and exerts its effects through DNA synthesis interference and apoptosis. Methylprednisolone was used as an add-on comparator because of its common use in multiple sclerosis.

In addition to weekly intramuscular interferon beta-1a (Avonex), all 18 patients in the study initially received IV methylprednisolone 1 g once daily for 3 consecutive days, and then 1 week later were randomized to receive fludarabine 25 mg/m2 IV once daily for 5 consecutive days per 4-week cycle for 3 consecutive cycles or methylprednisolone 1 g IV 1 day per 4-week cycle for 3 consecutive cycles (Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2016 Jan 21. doi: 10.1177/1756285615626049).

Treatment-emergent adverse events occurred with similar frequency in each group over 12 months of follow-up, with infection being the most common AE (three with fludarabine and two with methylprednisolone). Grade 3 or grade 2 leukopenia that had not normalized within 28 days after treatment occurred in three fludarabine patients and one methylprednisolone patient, and took significantly longer resolve for those taking fludarabine (3.75 months vs. 0.17 months).

Over 12 months of follow-up, fludarabine-treated patients experienced numerically, but not significantly, fewer mean relapses (0.5 vs. 0.8) and longer median time to relapse (10.5 months vs. 8.5 months). However, fludarabine led to significantly fewer mean cycles of corticosteroids (0.5 vs. 0.8).

Expanded Disability Status Scale scores declined from baseline to 12 months by a mean of –0.2 in the fludarabine group but increased in the methylprednisolone group by 0.5. Both groups achieved slight improvements in MS Functional Composite scores.

Fludarabine-treated patients had significant declines from baseline to 12 months in gadolinium-positive lesion volume (–98.3%) and number (–93.3%), but no significant differences were recorded in either group for changes in FLAIR lesion volume, T1-hypointense lesion volume or number, or brain parenchymal fraction.

Two outlier patients in the fludarabine group who had 21 and 17 gadolinium-positive lesions, respectively, at baseline were examined in separate analyses and results for the fludarabine group were analyzed both with and without them. None of the results appreciably changed when they were included or excluded, except for gadolinium-positive lesion volume and number, which were not significantly changed without the two patients. The two outlier patients had 100% mean reductions in gadolinium-positive lesion number and volume and a 19.4% mean reduction in FLAIR lesion volume.

The investigators cautioned that “the long-term safety of repetitive use has not been established by this study, which is a critical consideration for a chronic disease like MS. We emphasize that our results should be considered preliminary and would await confirmation in a larger-scale trial.”

This study was supported in part by an investigator-initiated study grant provided by Biogen. Berlex Laboratories provided fludarabine. Dr. Greenberg is an employee of AbbVie, and two coauthors reported financial ties to companies marketing MS drugs.

Relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS) patients who experienced breakthrough disease despite treatment with interferon beta-1a required less acute corticosteroids during relapses and had better responses on several MRI outcomes with the addition of fludarabine, compared with monthly methylprednisolone, in a small, prospective, randomized, open-label study.

Investigators led by Dr. Steven J. Greenberg of AbbVie, North Chicago, chose to test fludarabine in the proof-of-concept, pilot study because of its immunosuppressive properties and effectiveness in treating disorders involving immune dysregulation, most notably lymphoproliferative disorders and hematologic malignancies.

Fludarabine is a purine nucleoside analog prodrug that upon phosphorylation is toxic to dividing and quiescent lymphocytes and monocytes, according to the researchers, and exerts its effects through DNA synthesis interference and apoptosis. Methylprednisolone was used as an add-on comparator because of its common use in multiple sclerosis.

In addition to weekly intramuscular interferon beta-1a (Avonex), all 18 patients in the study initially received IV methylprednisolone 1 g once daily for 3 consecutive days, and then 1 week later were randomized to receive fludarabine 25 mg/m2 IV once daily for 5 consecutive days per 4-week cycle for 3 consecutive cycles or methylprednisolone 1 g IV 1 day per 4-week cycle for 3 consecutive cycles (Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2016 Jan 21. doi: 10.1177/1756285615626049).

Treatment-emergent adverse events occurred with similar frequency in each group over 12 months of follow-up, with infection being the most common AE (three with fludarabine and two with methylprednisolone). Grade 3 or grade 2 leukopenia that had not normalized within 28 days after treatment occurred in three fludarabine patients and one methylprednisolone patient, and took significantly longer resolve for those taking fludarabine (3.75 months vs. 0.17 months).

Over 12 months of follow-up, fludarabine-treated patients experienced numerically, but not significantly, fewer mean relapses (0.5 vs. 0.8) and longer median time to relapse (10.5 months vs. 8.5 months). However, fludarabine led to significantly fewer mean cycles of corticosteroids (0.5 vs. 0.8).

Expanded Disability Status Scale scores declined from baseline to 12 months by a mean of –0.2 in the fludarabine group but increased in the methylprednisolone group by 0.5. Both groups achieved slight improvements in MS Functional Composite scores.

Fludarabine-treated patients had significant declines from baseline to 12 months in gadolinium-positive lesion volume (–98.3%) and number (–93.3%), but no significant differences were recorded in either group for changes in FLAIR lesion volume, T1-hypointense lesion volume or number, or brain parenchymal fraction.

Two outlier patients in the fludarabine group who had 21 and 17 gadolinium-positive lesions, respectively, at baseline were examined in separate analyses and results for the fludarabine group were analyzed both with and without them. None of the results appreciably changed when they were included or excluded, except for gadolinium-positive lesion volume and number, which were not significantly changed without the two patients. The two outlier patients had 100% mean reductions in gadolinium-positive lesion number and volume and a 19.4% mean reduction in FLAIR lesion volume.

The investigators cautioned that “the long-term safety of repetitive use has not been established by this study, which is a critical consideration for a chronic disease like MS. We emphasize that our results should be considered preliminary and would await confirmation in a larger-scale trial.”

This study was supported in part by an investigator-initiated study grant provided by Biogen. Berlex Laboratories provided fludarabine. Dr. Greenberg is an employee of AbbVie, and two coauthors reported financial ties to companies marketing MS drugs.

FROM THERAPEUTIC ADVANCES IN NEUROLOGICAL DISORDERS

Key clinical point: Preliminary evidence suggests that fludarabine added to interferon beta-1a for breakthrough disease in relapsing-remitting MS patients may be a safe and well-tolerated adjunct with some hints of ability to reduce disease activity.

Major finding: Fludarabine-treated patients had significant declines from baseline to 12 months in gadolinium-positive lesion volume (–98.3%) and number (–93.3%), but no significant differences were recorded in either group for changes in FLAIR lesion volume, T1-hypointense lesion volume or number, or brain parenchymal fraction.

Data source: A prospective, randomized, open-label study of 18 relapsing-remitting MS patients.

Disclosures: This study was supported in part by an investigator-initiated study grant provided by Biogen. Berlex Laboratories provided fludarabine. Dr. Greenberg is an employee of AbbVie, and two coauthors reported financial ties to companies marketing MS drugs.

Thyroid nodule: not as clear-cut as it seems

Benign etiologies and primary thyroid cancers are the most common causes of incidental thyroid nodules. Clinically evident metastases to the thyroid gland are not common and account for 2%-3% of thyroid cancers, though the incidence of thyroid metastases reaches 24% in autopsy studies.1 The most common clinically detected thyroid metastases originate from renal cell carcinoma (RCC; 48.1%).2 We report here a rare case of a man with clear-cell RCC with late recurrence in the thyroid gland as a solitary metastasis, 13 years after the primary diagnosis.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Benign etiologies and primary thyroid cancers are the most common causes of incidental thyroid nodules. Clinically evident metastases to the thyroid gland are not common and account for 2%-3% of thyroid cancers, though the incidence of thyroid metastases reaches 24% in autopsy studies.1 The most common clinically detected thyroid metastases originate from renal cell carcinoma (RCC; 48.1%).2 We report here a rare case of a man with clear-cell RCC with late recurrence in the thyroid gland as a solitary metastasis, 13 years after the primary diagnosis.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Benign etiologies and primary thyroid cancers are the most common causes of incidental thyroid nodules. Clinically evident metastases to the thyroid gland are not common and account for 2%-3% of thyroid cancers, though the incidence of thyroid metastases reaches 24% in autopsy studies.1 The most common clinically detected thyroid metastases originate from renal cell carcinoma (RCC; 48.1%).2 We report here a rare case of a man with clear-cell RCC with late recurrence in the thyroid gland as a solitary metastasis, 13 years after the primary diagnosis.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Cryolipolysis and Delayed Posttreatment Pain

Cryolipolysis is a popular noninvasive treatment for areas of excess adipose deposition, such as in the abdomen and flanks. During the 60-minute procedure, a uniquely shaped treatment applicator is applied to the area with suction, causing cold exposure–induced crystallization of adipocytes through apoptosis. Overall, cryolipolysis treatment has a good safety profile and is well tolerated by patients without the need for anesthesia. A rare side effect of cryolipolysis is paradoxical adipose hyperplasia, which has been reported to be more common in men. Another rare adverse effect is the development of substantial posttreatment pain. Most patients usually experience minimal posttreatment discomfort and the phenomenon of delayed posttreatment pain rarely has been reported in the literature.

An online article published in Dermatologic Surgery in November evaluated posttreatment pain. Keaney et al performed a retrospective review that looked at the incidence of posttreatment pain after cryolipolysis as well as any correlating factors among patients that experience this pain.

In this retrospective chart review, 125 patients who received 554 consecutive cryolipolysis procedures over 1 year were evaluated for at least 2 of the following symptoms: (1) neuropathic symptoms (ie, stabbing, burning, shooting pain within treatment area), (2) increased pain at night that disturbed sleep, and (3) discomfort not alleviated by analgesic medication (ie, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, narcotics). In these patients, 114 treatments were performed on 27 men and 440 treatments on 98 women; 36.6% of treatments were performed on the lower abdomen, 34.7% on the flanks, 11.9% on the upper abdomen, 9.4% on the back, 6.0% on the thighs, and 1.4% on the chest. A small cryolipolysis applicator was used for 95% of the treatments and a large applicator for 5% of the treatments.

Of 125 patients, 19 (15.2%) developed delayed postcryolipolysis pain and all were female patients. These patients received a total of 75 treatments (3.9 treatments per patient). All but 1 patient developed pain on the abdomen. One patient had pain on the flanks only. Three patients had pain at multiple sites (eg, abdomen and flanks, abdomen and thighs). Younger women (average age, 39 years) were more likely to have posttreatment pain. The number of treatments did not correlate with the development of pain. The average onset of pain was 3 days, with an average resolution time of 11 days (range, 2–60 days). Three patients underwent a second cryolipolysis treatment in the same area, which induced delayed pain again. Six patients underwent treatments on other body regions and did not develop pain.

Although postcryolipolysis pain is self-limiting and self-resolving, it can still be debilitating in some cases. Keaney et al managed the posttreatment discomfort with compression garments, lidocaine 5% transdermal patches, low-dose gabapentin, and/or acetaminophen with codeine. Low-dose oral gabapentin appears to have a good effect in pain treatment for these patients, which had a complete response in 14 patients as the sole treatment. Interestingly, 2 other large patient series were reported, with 518 patients in one study (Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1209-1216) and 528 treatments in another study (Aesthetic Surg J. 2013;33:835-846); there were only 3 reports of mild to moderate pain.

What’s the issue?

Delayed posttreatment pain seems to be a common phenomenon, affecting primarily younger women who have had cryolipolysis of the abdominal region. It is reassuring that this pain is self-limiting and that it is responsive to oral gabapentin treatment. However, it is important to discuss this possible not-so-rare side effect with patients considering this treatment. Do you discuss delayed posttreatment pain with your cryolipolysis patients?

Cryolipolysis is a popular noninvasive treatment for areas of excess adipose deposition, such as in the abdomen and flanks. During the 60-minute procedure, a uniquely shaped treatment applicator is applied to the area with suction, causing cold exposure–induced crystallization of adipocytes through apoptosis. Overall, cryolipolysis treatment has a good safety profile and is well tolerated by patients without the need for anesthesia. A rare side effect of cryolipolysis is paradoxical adipose hyperplasia, which has been reported to be more common in men. Another rare adverse effect is the development of substantial posttreatment pain. Most patients usually experience minimal posttreatment discomfort and the phenomenon of delayed posttreatment pain rarely has been reported in the literature.

An online article published in Dermatologic Surgery in November evaluated posttreatment pain. Keaney et al performed a retrospective review that looked at the incidence of posttreatment pain after cryolipolysis as well as any correlating factors among patients that experience this pain.

In this retrospective chart review, 125 patients who received 554 consecutive cryolipolysis procedures over 1 year were evaluated for at least 2 of the following symptoms: (1) neuropathic symptoms (ie, stabbing, burning, shooting pain within treatment area), (2) increased pain at night that disturbed sleep, and (3) discomfort not alleviated by analgesic medication (ie, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, narcotics). In these patients, 114 treatments were performed on 27 men and 440 treatments on 98 women; 36.6% of treatments were performed on the lower abdomen, 34.7% on the flanks, 11.9% on the upper abdomen, 9.4% on the back, 6.0% on the thighs, and 1.4% on the chest. A small cryolipolysis applicator was used for 95% of the treatments and a large applicator for 5% of the treatments.

Of 125 patients, 19 (15.2%) developed delayed postcryolipolysis pain and all were female patients. These patients received a total of 75 treatments (3.9 treatments per patient). All but 1 patient developed pain on the abdomen. One patient had pain on the flanks only. Three patients had pain at multiple sites (eg, abdomen and flanks, abdomen and thighs). Younger women (average age, 39 years) were more likely to have posttreatment pain. The number of treatments did not correlate with the development of pain. The average onset of pain was 3 days, with an average resolution time of 11 days (range, 2–60 days). Three patients underwent a second cryolipolysis treatment in the same area, which induced delayed pain again. Six patients underwent treatments on other body regions and did not develop pain.

Although postcryolipolysis pain is self-limiting and self-resolving, it can still be debilitating in some cases. Keaney et al managed the posttreatment discomfort with compression garments, lidocaine 5% transdermal patches, low-dose gabapentin, and/or acetaminophen with codeine. Low-dose oral gabapentin appears to have a good effect in pain treatment for these patients, which had a complete response in 14 patients as the sole treatment. Interestingly, 2 other large patient series were reported, with 518 patients in one study (Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1209-1216) and 528 treatments in another study (Aesthetic Surg J. 2013;33:835-846); there were only 3 reports of mild to moderate pain.

What’s the issue?

Delayed posttreatment pain seems to be a common phenomenon, affecting primarily younger women who have had cryolipolysis of the abdominal region. It is reassuring that this pain is self-limiting and that it is responsive to oral gabapentin treatment. However, it is important to discuss this possible not-so-rare side effect with patients considering this treatment. Do you discuss delayed posttreatment pain with your cryolipolysis patients?

Cryolipolysis is a popular noninvasive treatment for areas of excess adipose deposition, such as in the abdomen and flanks. During the 60-minute procedure, a uniquely shaped treatment applicator is applied to the area with suction, causing cold exposure–induced crystallization of adipocytes through apoptosis. Overall, cryolipolysis treatment has a good safety profile and is well tolerated by patients without the need for anesthesia. A rare side effect of cryolipolysis is paradoxical adipose hyperplasia, which has been reported to be more common in men. Another rare adverse effect is the development of substantial posttreatment pain. Most patients usually experience minimal posttreatment discomfort and the phenomenon of delayed posttreatment pain rarely has been reported in the literature.

An online article published in Dermatologic Surgery in November evaluated posttreatment pain. Keaney et al performed a retrospective review that looked at the incidence of posttreatment pain after cryolipolysis as well as any correlating factors among patients that experience this pain.

In this retrospective chart review, 125 patients who received 554 consecutive cryolipolysis procedures over 1 year were evaluated for at least 2 of the following symptoms: (1) neuropathic symptoms (ie, stabbing, burning, shooting pain within treatment area), (2) increased pain at night that disturbed sleep, and (3) discomfort not alleviated by analgesic medication (ie, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, narcotics). In these patients, 114 treatments were performed on 27 men and 440 treatments on 98 women; 36.6% of treatments were performed on the lower abdomen, 34.7% on the flanks, 11.9% on the upper abdomen, 9.4% on the back, 6.0% on the thighs, and 1.4% on the chest. A small cryolipolysis applicator was used for 95% of the treatments and a large applicator for 5% of the treatments.

Of 125 patients, 19 (15.2%) developed delayed postcryolipolysis pain and all were female patients. These patients received a total of 75 treatments (3.9 treatments per patient). All but 1 patient developed pain on the abdomen. One patient had pain on the flanks only. Three patients had pain at multiple sites (eg, abdomen and flanks, abdomen and thighs). Younger women (average age, 39 years) were more likely to have posttreatment pain. The number of treatments did not correlate with the development of pain. The average onset of pain was 3 days, with an average resolution time of 11 days (range, 2–60 days). Three patients underwent a second cryolipolysis treatment in the same area, which induced delayed pain again. Six patients underwent treatments on other body regions and did not develop pain.

Although postcryolipolysis pain is self-limiting and self-resolving, it can still be debilitating in some cases. Keaney et al managed the posttreatment discomfort with compression garments, lidocaine 5% transdermal patches, low-dose gabapentin, and/or acetaminophen with codeine. Low-dose oral gabapentin appears to have a good effect in pain treatment for these patients, which had a complete response in 14 patients as the sole treatment. Interestingly, 2 other large patient series were reported, with 518 patients in one study (Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1209-1216) and 528 treatments in another study (Aesthetic Surg J. 2013;33:835-846); there were only 3 reports of mild to moderate pain.

What’s the issue?

Delayed posttreatment pain seems to be a common phenomenon, affecting primarily younger women who have had cryolipolysis of the abdominal region. It is reassuring that this pain is self-limiting and that it is responsive to oral gabapentin treatment. However, it is important to discuss this possible not-so-rare side effect with patients considering this treatment. Do you discuss delayed posttreatment pain with your cryolipolysis patients?

Impact of surgery for stage IA non-small-cell lung cancer on patient quality of life

Background There is a paucity of literature comparing quality of life (QoL) before and after surgery in stage IA lung cancer, where surgical resection is the recommended curative treatment.

Objective To assess the impact of surgery on physical and mental health-related QoL in patients with stage IA lung cancer treated with surgical resection.

Methods Participants in the I-ELCAP cohort who were diagnosed with their first primary pathologic stage IA non-small-cell lung cancer, underwent surgery, and provided follow-up information on QoL 1 year later were included in the present analysis (N = 107). QoL information was collected using the SF-12 (12-item Short Form Health Survey), which generates 2 component scores related to mental health and physical health.

Results Statistical analyses indicated that physical health QoL was significantly worsened from before surgery to after surgery, whereas mental health QoL marginally improved from before to after surgery. Physical health QoL worsened for women from baseline to follow-up, but not for men. Only lobectomy (not limited resection) had an impact on QoL from before to after surgery.

Limitations Results are considered preliminary given the small sample size and multiple comparisons.

Conclusions The current study findings have implications for lung cancer health care professionals in regard to how they can most effectively present the possible impact of surgery on quality of life to this subset of patients in which disease has not yet significantly progressed.

Funding/sponsorship Gift from Sonia Lasry Gardner, in memory of her father, Moise Lasry.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Background There is a paucity of literature comparing quality of life (QoL) before and after surgery in stage IA lung cancer, where surgical resection is the recommended curative treatment.

Objective To assess the impact of surgery on physical and mental health-related QoL in patients with stage IA lung cancer treated with surgical resection.

Methods Participants in the I-ELCAP cohort who were diagnosed with their first primary pathologic stage IA non-small-cell lung cancer, underwent surgery, and provided follow-up information on QoL 1 year later were included in the present analysis (N = 107). QoL information was collected using the SF-12 (12-item Short Form Health Survey), which generates 2 component scores related to mental health and physical health.

Results Statistical analyses indicated that physical health QoL was significantly worsened from before surgery to after surgery, whereas mental health QoL marginally improved from before to after surgery. Physical health QoL worsened for women from baseline to follow-up, but not for men. Only lobectomy (not limited resection) had an impact on QoL from before to after surgery.

Limitations Results are considered preliminary given the small sample size and multiple comparisons.

Conclusions The current study findings have implications for lung cancer health care professionals in regard to how they can most effectively present the possible impact of surgery on quality of life to this subset of patients in which disease has not yet significantly progressed.

Funding/sponsorship Gift from Sonia Lasry Gardner, in memory of her father, Moise Lasry.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Background There is a paucity of literature comparing quality of life (QoL) before and after surgery in stage IA lung cancer, where surgical resection is the recommended curative treatment.

Objective To assess the impact of surgery on physical and mental health-related QoL in patients with stage IA lung cancer treated with surgical resection.

Methods Participants in the I-ELCAP cohort who were diagnosed with their first primary pathologic stage IA non-small-cell lung cancer, underwent surgery, and provided follow-up information on QoL 1 year later were included in the present analysis (N = 107). QoL information was collected using the SF-12 (12-item Short Form Health Survey), which generates 2 component scores related to mental health and physical health.

Results Statistical analyses indicated that physical health QoL was significantly worsened from before surgery to after surgery, whereas mental health QoL marginally improved from before to after surgery. Physical health QoL worsened for women from baseline to follow-up, but not for men. Only lobectomy (not limited resection) had an impact on QoL from before to after surgery.

Limitations Results are considered preliminary given the small sample size and multiple comparisons.

Conclusions The current study findings have implications for lung cancer health care professionals in regard to how they can most effectively present the possible impact of surgery on quality of life to this subset of patients in which disease has not yet significantly progressed.

Funding/sponsorship Gift from Sonia Lasry Gardner, in memory of her father, Moise Lasry.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Chlorthalidone controls blood pressure longer than HCTZ

Low-dose chlorthalidone is significantly better at reducing blood pressure over a 24-hour period than is the most commonly prescribed formulation of hydrochlorothiazide for essential hypertension, findings from a randomized, controlled trial published Jan. 25 suggest.

Standard HCTZ at 12.5 mg was seen reducing blood pressure during daytime or office hours, resulting in undetected or masked hypertension during nighttime and early-morning hours, investigators found.

However, both 6.25 mg chlorthalidone and an extended-release preparation of 12.5 mg HCTZ were shown to be effective at sustaining a smooth, 24-hour control as measured by ambulatory blood pressure monitoring.

For their research, Dr. Anil K. Pareek of Ipca Laboratories in Mumbai, India, and his colleagues randomized 54 patients aged 65 years and younger with stage 1 hypertension and no comorbidities to chlorthalidone, 6.25 mg (16 patients); HCTZ 12.5 mg (18); or HCTZ-controlled release 12.5 mg (20) for 12 weeks.

For the cohort as a whole, patients’ mean in-office blood pressure was 149/93 mm Hg. At both 4 and 12 weeks, all three study arms saw significant reductions in office BP (P less than .01).