User login

It Started With a Bug Bite (He Thinks)

An 81-year-old man is brought in by his wife for evaluation of a very itchy rash on his bilateral lower tibial areas. He says the problem started about six months ago, after a spate of summer yardwork during which he sustained what he assumed was a bug bite. It was itchy, so he scratched it.

Of course, in the way of most itches, the scratching offered temporary relief, after which the itching resumed. The patient tried any number of OTC products, including rubbing alcohol, hydrogen peroxide, tea tree oil, several different essential oils, and triple-antibiotic cream and ointment. The worse the itching became, the more products he applied—all to no avail.

The patient describes his health as otherwise decent. He does have type 2 diabetes, which he says is in good control.

EXAMINATION

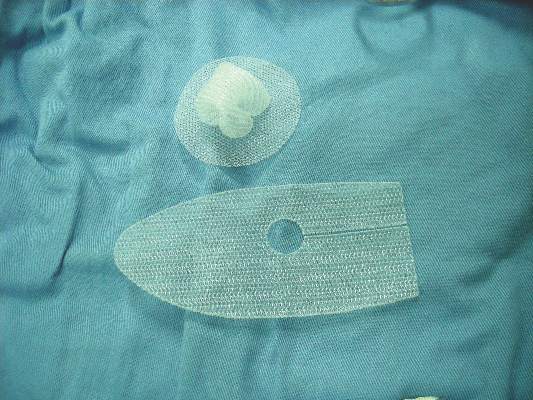

The lower anterior tibial areas of both legs are covered by a scaly red rash. The left leg is more heavily affected, and obvious edema can be seen distal to the rash on that leg. The surface scales of the rash have a polygonal look, resembling a dried lake bed or finely cracked porcelain. The edges of the cracks turn upward, resulting in a rough feel on palpation.

The patient’s skin is quite dry in general but otherwise within normal limits.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Leg skin is unique in many respects. For one thing, it’s down there, where gravity takes and often holds blood and other fluids that might not accumulate elsewhere. It’s also a long trip for blood to get out to the extremities and often a longer return trip.

Leg skin is also remarkable because it has far fewer sebaceous glands than the scalp, face, and chest, which means it tends to be quite dry. This is especially true in older patients already prone to dry skin and in those who seldom moisturize to counteract this problem (in other words, men!).

This is why most patients with asteatotic eczema (AE) are men. Also known as eczema craquele and xerotic eczema, AE is especially common in the dry winter months, when long, hot showers are so appealing, as are wearing warmer clothes and sleeping under heavy covers.

Patients with AE, including this one, often make matters worse by applying a multiplicity of contactants. The edema noted in the exam, although due to the AE, also served to worsen the condition by making the skin tighter and drier still.

At this point, the problem often starts to take on aspects of lichen simplex chronicus, in which more scratching leads to more itching (and then more scratching, and so on). Clearly, what this patient needed (and got) was a definitive diagnosis and a treatment plan dictated by that diagnosis.

AE can be a challenge to treat, but the first step is to help the patient understand the nature of the problem and his role in the solution. The patient also needs to stop applying nonprescribed/recommended contactants, which don’t help and may exacerbate the problem.

To achieve relief, the patient can soak the leg with wet compresses for 10 minutes, remove excess water, and then apply a medium-strength steroid ointment (eg, triamcinolone 0.5%) in a thin but thorough coat. The area can then be covered with an occlusive covering, such as saran wrap, taped in place. This should be left on all night. During the day, the patient should apply only petroleum jelly to the affected area.

This approach will take 90% of patients out of the crisis stage. After a week or two, attention must shift to preventing recurrence, with generous use of emollients such as petroleum jelly. The patient should also be instructed to avoid using harsh (colored, scented, high pH) soaps, switch to shorter, relatively cool showers, and stop using anything but his hand to wash with (ie, no washcloths or loofahs).

For nondiabetic patients with severe AE that persists despite these measures, an intramuscular injection of a glucocorticoid (eg, triamcinolone 40 - 60 mg) can work wonders.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Asteatotic eczema (AE), also called xerotic eczema or eczema craquele, is quite common, especially on the lower legs of older men.

• The particular rash of AE is said to resemble the cracked surface of a porcelain vessel.

• AE is often accompanied by edema distal to the rash.

• A topical steroid ointment applied to water-soaked skin, held in place overnight with an occlusive dressing, usually takes the patient out of the crisis phase.

• Prevention is then directed at avoiding drying of the affected areas.

An 81-year-old man is brought in by his wife for evaluation of a very itchy rash on his bilateral lower tibial areas. He says the problem started about six months ago, after a spate of summer yardwork during which he sustained what he assumed was a bug bite. It was itchy, so he scratched it.

Of course, in the way of most itches, the scratching offered temporary relief, after which the itching resumed. The patient tried any number of OTC products, including rubbing alcohol, hydrogen peroxide, tea tree oil, several different essential oils, and triple-antibiotic cream and ointment. The worse the itching became, the more products he applied—all to no avail.

The patient describes his health as otherwise decent. He does have type 2 diabetes, which he says is in good control.

EXAMINATION

The lower anterior tibial areas of both legs are covered by a scaly red rash. The left leg is more heavily affected, and obvious edema can be seen distal to the rash on that leg. The surface scales of the rash have a polygonal look, resembling a dried lake bed or finely cracked porcelain. The edges of the cracks turn upward, resulting in a rough feel on palpation.

The patient’s skin is quite dry in general but otherwise within normal limits.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Leg skin is unique in many respects. For one thing, it’s down there, where gravity takes and often holds blood and other fluids that might not accumulate elsewhere. It’s also a long trip for blood to get out to the extremities and often a longer return trip.

Leg skin is also remarkable because it has far fewer sebaceous glands than the scalp, face, and chest, which means it tends to be quite dry. This is especially true in older patients already prone to dry skin and in those who seldom moisturize to counteract this problem (in other words, men!).

This is why most patients with asteatotic eczema (AE) are men. Also known as eczema craquele and xerotic eczema, AE is especially common in the dry winter months, when long, hot showers are so appealing, as are wearing warmer clothes and sleeping under heavy covers.

Patients with AE, including this one, often make matters worse by applying a multiplicity of contactants. The edema noted in the exam, although due to the AE, also served to worsen the condition by making the skin tighter and drier still.

At this point, the problem often starts to take on aspects of lichen simplex chronicus, in which more scratching leads to more itching (and then more scratching, and so on). Clearly, what this patient needed (and got) was a definitive diagnosis and a treatment plan dictated by that diagnosis.

AE can be a challenge to treat, but the first step is to help the patient understand the nature of the problem and his role in the solution. The patient also needs to stop applying nonprescribed/recommended contactants, which don’t help and may exacerbate the problem.

To achieve relief, the patient can soak the leg with wet compresses for 10 minutes, remove excess water, and then apply a medium-strength steroid ointment (eg, triamcinolone 0.5%) in a thin but thorough coat. The area can then be covered with an occlusive covering, such as saran wrap, taped in place. This should be left on all night. During the day, the patient should apply only petroleum jelly to the affected area.

This approach will take 90% of patients out of the crisis stage. After a week or two, attention must shift to preventing recurrence, with generous use of emollients such as petroleum jelly. The patient should also be instructed to avoid using harsh (colored, scented, high pH) soaps, switch to shorter, relatively cool showers, and stop using anything but his hand to wash with (ie, no washcloths or loofahs).

For nondiabetic patients with severe AE that persists despite these measures, an intramuscular injection of a glucocorticoid (eg, triamcinolone 40 - 60 mg) can work wonders.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Asteatotic eczema (AE), also called xerotic eczema or eczema craquele, is quite common, especially on the lower legs of older men.

• The particular rash of AE is said to resemble the cracked surface of a porcelain vessel.

• AE is often accompanied by edema distal to the rash.

• A topical steroid ointment applied to water-soaked skin, held in place overnight with an occlusive dressing, usually takes the patient out of the crisis phase.

• Prevention is then directed at avoiding drying of the affected areas.

An 81-year-old man is brought in by his wife for evaluation of a very itchy rash on his bilateral lower tibial areas. He says the problem started about six months ago, after a spate of summer yardwork during which he sustained what he assumed was a bug bite. It was itchy, so he scratched it.

Of course, in the way of most itches, the scratching offered temporary relief, after which the itching resumed. The patient tried any number of OTC products, including rubbing alcohol, hydrogen peroxide, tea tree oil, several different essential oils, and triple-antibiotic cream and ointment. The worse the itching became, the more products he applied—all to no avail.

The patient describes his health as otherwise decent. He does have type 2 diabetes, which he says is in good control.

EXAMINATION

The lower anterior tibial areas of both legs are covered by a scaly red rash. The left leg is more heavily affected, and obvious edema can be seen distal to the rash on that leg. The surface scales of the rash have a polygonal look, resembling a dried lake bed or finely cracked porcelain. The edges of the cracks turn upward, resulting in a rough feel on palpation.

The patient’s skin is quite dry in general but otherwise within normal limits.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Leg skin is unique in many respects. For one thing, it’s down there, where gravity takes and often holds blood and other fluids that might not accumulate elsewhere. It’s also a long trip for blood to get out to the extremities and often a longer return trip.

Leg skin is also remarkable because it has far fewer sebaceous glands than the scalp, face, and chest, which means it tends to be quite dry. This is especially true in older patients already prone to dry skin and in those who seldom moisturize to counteract this problem (in other words, men!).

This is why most patients with asteatotic eczema (AE) are men. Also known as eczema craquele and xerotic eczema, AE is especially common in the dry winter months, when long, hot showers are so appealing, as are wearing warmer clothes and sleeping under heavy covers.

Patients with AE, including this one, often make matters worse by applying a multiplicity of contactants. The edema noted in the exam, although due to the AE, also served to worsen the condition by making the skin tighter and drier still.

At this point, the problem often starts to take on aspects of lichen simplex chronicus, in which more scratching leads to more itching (and then more scratching, and so on). Clearly, what this patient needed (and got) was a definitive diagnosis and a treatment plan dictated by that diagnosis.

AE can be a challenge to treat, but the first step is to help the patient understand the nature of the problem and his role in the solution. The patient also needs to stop applying nonprescribed/recommended contactants, which don’t help and may exacerbate the problem.

To achieve relief, the patient can soak the leg with wet compresses for 10 minutes, remove excess water, and then apply a medium-strength steroid ointment (eg, triamcinolone 0.5%) in a thin but thorough coat. The area can then be covered with an occlusive covering, such as saran wrap, taped in place. This should be left on all night. During the day, the patient should apply only petroleum jelly to the affected area.

This approach will take 90% of patients out of the crisis stage. After a week or two, attention must shift to preventing recurrence, with generous use of emollients such as petroleum jelly. The patient should also be instructed to avoid using harsh (colored, scented, high pH) soaps, switch to shorter, relatively cool showers, and stop using anything but his hand to wash with (ie, no washcloths or loofahs).

For nondiabetic patients with severe AE that persists despite these measures, an intramuscular injection of a glucocorticoid (eg, triamcinolone 40 - 60 mg) can work wonders.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Asteatotic eczema (AE), also called xerotic eczema or eczema craquele, is quite common, especially on the lower legs of older men.

• The particular rash of AE is said to resemble the cracked surface of a porcelain vessel.

• AE is often accompanied by edema distal to the rash.

• A topical steroid ointment applied to water-soaked skin, held in place overnight with an occlusive dressing, usually takes the patient out of the crisis phase.

• Prevention is then directed at avoiding drying of the affected areas.

Consensus document issued on hematology research priorities for Europe

A consensus document that summarizes the status of basic, translational, and clinical hematology research and identifies areas of unmet scientific and medical needs in Europe has been published in the February 2016 issue of Haematologica.

“For the first time, hematologists in Europe came together to develop a road map to guide hematology research in Europe,” Professor Andreas Engert, chair of the European Hematology Association’s Research Roadmap Task Force, said in a written statement. “Hematology ... must focus and collaborate to be efficient and remain successful in improving patient outcomes.”

Some 300 experts from over 20 countries in Europe helped to draft the road map. A wide variety of stakeholders, such as national hematology societies, patient organizations, hematology trial groups, and other European organizations, were consulted to comment on the final draft.

“The document reflects the views of the hematological research community in Europe, Professor Tony Green, president of the European Hematology Association (EHA), noted in the statement. “This is crucial if we want to convince policy makers to support the realization of this important research.”

“With an aging population, the slow recovery from the financial and Euro crises, costly medical breakthroughs and innovations – quite a few of which involve hematology researchers, Europe faces increased health expenditures while budgets are limited,” Professor Ulrich Jäger, chair of the EHA European Affairs Committee, said in the statement. “So it is our responsibility to provide the policy makers with the information and evidence they need to decide where their support impacts knowledge and health most efficiently, to the benefit of patients and society. ... Now it is up to the policy makers in the EU to deliver, too.”

You may find the full article in Haematologica 2016 Jan. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.136739.

In a time of restricted federal budgets, research funding becomes somewhat of a luxury. Yet, research and innovation are the primary movers of change and progress, both of which are needed to drive growth to ease budget restrictions. In order to ensure that precious resources are allocated to the most promising endeavors, federal governments establish bureaucracies charged with the task of allocating funding to the “best” proposals. Unfortunately, the task of defining “best” is imprecise and largely subjective.

To address this systemic deficiency and to improve the efficient allocation of resources, the scientific community often provides guidance to funding agencies to help choose among competing proposals. In 2015, the American Society of Hematology (ASH) announced its “Agenda for Hematology Research.” The agenda included recommendations to prioritize funding to projects in the following domains: genomic profiling and chemical biology, immunologic treatments of hematologic malignancies, genome editing and gene therapy, stem cell biology and regenerative medicine, epigenetic mechanisms, and venous thromboembolic disease.

|

Dr. Matt Kalyacio |

More recently, the European Hematology Association has published its Roadmap for European Hematology Research. Ostensibly similar to the ASH Agenda, the EHA document is a much more detailed policy statement that calls out the most promising research opportunities across the nine major components of hematology: normal hematopoiesis, malignant lymphoid disorders, malignant myeloid disease, anemias and related diseases, platelet disorders, blood coagulation and hemostatic disorders, transfusion medicine, infections in hematology, and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and other cell based therapies.

I find the two documents complementary in that the ASH Agenda is more accessible to grant reviewers and funding agencies, while the EHA Roadmap seems more directed to the scientific community. Whether a grant writer or a grant reviewer, these documents should help researchers focus their applications on preferred projects and help reviewers prioritize proposals.

While laudable in their goals globally, such consensus documents place much faith in the knowable future and less in the unknowable, disruptive future. Researchers with innovative ideas that do not fall into the prioritizations set forth by the community at large might find themselves struggling for resources. This unintended consequence of consensus building risks the loss of inspired science on the altar of groupthink. The “moonshot” championed by Vice-President Biden will be more likely to succeed when consensus science allows for novel approaches that have yet to be revealed.

Dr. Matt Kalaycio is the editor-in-chief of Hematology News and chairs the department of hematologic oncology and blood disorders at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute, Cleveland. Leave your comments on our website or write to Dr. Kalaycio at [email protected].

In a time of restricted federal budgets, research funding becomes somewhat of a luxury. Yet, research and innovation are the primary movers of change and progress, both of which are needed to drive growth to ease budget restrictions. In order to ensure that precious resources are allocated to the most promising endeavors, federal governments establish bureaucracies charged with the task of allocating funding to the “best” proposals. Unfortunately, the task of defining “best” is imprecise and largely subjective.

To address this systemic deficiency and to improve the efficient allocation of resources, the scientific community often provides guidance to funding agencies to help choose among competing proposals. In 2015, the American Society of Hematology (ASH) announced its “Agenda for Hematology Research.” The agenda included recommendations to prioritize funding to projects in the following domains: genomic profiling and chemical biology, immunologic treatments of hematologic malignancies, genome editing and gene therapy, stem cell biology and regenerative medicine, epigenetic mechanisms, and venous thromboembolic disease.

|

Dr. Matt Kalyacio |

More recently, the European Hematology Association has published its Roadmap for European Hematology Research. Ostensibly similar to the ASH Agenda, the EHA document is a much more detailed policy statement that calls out the most promising research opportunities across the nine major components of hematology: normal hematopoiesis, malignant lymphoid disorders, malignant myeloid disease, anemias and related diseases, platelet disorders, blood coagulation and hemostatic disorders, transfusion medicine, infections in hematology, and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and other cell based therapies.

I find the two documents complementary in that the ASH Agenda is more accessible to grant reviewers and funding agencies, while the EHA Roadmap seems more directed to the scientific community. Whether a grant writer or a grant reviewer, these documents should help researchers focus their applications on preferred projects and help reviewers prioritize proposals.

While laudable in their goals globally, such consensus documents place much faith in the knowable future and less in the unknowable, disruptive future. Researchers with innovative ideas that do not fall into the prioritizations set forth by the community at large might find themselves struggling for resources. This unintended consequence of consensus building risks the loss of inspired science on the altar of groupthink. The “moonshot” championed by Vice-President Biden will be more likely to succeed when consensus science allows for novel approaches that have yet to be revealed.

Dr. Matt Kalaycio is the editor-in-chief of Hematology News and chairs the department of hematologic oncology and blood disorders at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute, Cleveland. Leave your comments on our website or write to Dr. Kalaycio at [email protected].

In a time of restricted federal budgets, research funding becomes somewhat of a luxury. Yet, research and innovation are the primary movers of change and progress, both of which are needed to drive growth to ease budget restrictions. In order to ensure that precious resources are allocated to the most promising endeavors, federal governments establish bureaucracies charged with the task of allocating funding to the “best” proposals. Unfortunately, the task of defining “best” is imprecise and largely subjective.

To address this systemic deficiency and to improve the efficient allocation of resources, the scientific community often provides guidance to funding agencies to help choose among competing proposals. In 2015, the American Society of Hematology (ASH) announced its “Agenda for Hematology Research.” The agenda included recommendations to prioritize funding to projects in the following domains: genomic profiling and chemical biology, immunologic treatments of hematologic malignancies, genome editing and gene therapy, stem cell biology and regenerative medicine, epigenetic mechanisms, and venous thromboembolic disease.

|

Dr. Matt Kalyacio |

More recently, the European Hematology Association has published its Roadmap for European Hematology Research. Ostensibly similar to the ASH Agenda, the EHA document is a much more detailed policy statement that calls out the most promising research opportunities across the nine major components of hematology: normal hematopoiesis, malignant lymphoid disorders, malignant myeloid disease, anemias and related diseases, platelet disorders, blood coagulation and hemostatic disorders, transfusion medicine, infections in hematology, and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and other cell based therapies.

I find the two documents complementary in that the ASH Agenda is more accessible to grant reviewers and funding agencies, while the EHA Roadmap seems more directed to the scientific community. Whether a grant writer or a grant reviewer, these documents should help researchers focus their applications on preferred projects and help reviewers prioritize proposals.

While laudable in their goals globally, such consensus documents place much faith in the knowable future and less in the unknowable, disruptive future. Researchers with innovative ideas that do not fall into the prioritizations set forth by the community at large might find themselves struggling for resources. This unintended consequence of consensus building risks the loss of inspired science on the altar of groupthink. The “moonshot” championed by Vice-President Biden will be more likely to succeed when consensus science allows for novel approaches that have yet to be revealed.

Dr. Matt Kalaycio is the editor-in-chief of Hematology News and chairs the department of hematologic oncology and blood disorders at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute, Cleveland. Leave your comments on our website or write to Dr. Kalaycio at [email protected].

A consensus document that summarizes the status of basic, translational, and clinical hematology research and identifies areas of unmet scientific and medical needs in Europe has been published in the February 2016 issue of Haematologica.

“For the first time, hematologists in Europe came together to develop a road map to guide hematology research in Europe,” Professor Andreas Engert, chair of the European Hematology Association’s Research Roadmap Task Force, said in a written statement. “Hematology ... must focus and collaborate to be efficient and remain successful in improving patient outcomes.”

Some 300 experts from over 20 countries in Europe helped to draft the road map. A wide variety of stakeholders, such as national hematology societies, patient organizations, hematology trial groups, and other European organizations, were consulted to comment on the final draft.

“The document reflects the views of the hematological research community in Europe, Professor Tony Green, president of the European Hematology Association (EHA), noted in the statement. “This is crucial if we want to convince policy makers to support the realization of this important research.”

“With an aging population, the slow recovery from the financial and Euro crises, costly medical breakthroughs and innovations – quite a few of which involve hematology researchers, Europe faces increased health expenditures while budgets are limited,” Professor Ulrich Jäger, chair of the EHA European Affairs Committee, said in the statement. “So it is our responsibility to provide the policy makers with the information and evidence they need to decide where their support impacts knowledge and health most efficiently, to the benefit of patients and society. ... Now it is up to the policy makers in the EU to deliver, too.”

You may find the full article in Haematologica 2016 Jan. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.136739.

A consensus document that summarizes the status of basic, translational, and clinical hematology research and identifies areas of unmet scientific and medical needs in Europe has been published in the February 2016 issue of Haematologica.

“For the first time, hematologists in Europe came together to develop a road map to guide hematology research in Europe,” Professor Andreas Engert, chair of the European Hematology Association’s Research Roadmap Task Force, said in a written statement. “Hematology ... must focus and collaborate to be efficient and remain successful in improving patient outcomes.”

Some 300 experts from over 20 countries in Europe helped to draft the road map. A wide variety of stakeholders, such as national hematology societies, patient organizations, hematology trial groups, and other European organizations, were consulted to comment on the final draft.

“The document reflects the views of the hematological research community in Europe, Professor Tony Green, president of the European Hematology Association (EHA), noted in the statement. “This is crucial if we want to convince policy makers to support the realization of this important research.”

“With an aging population, the slow recovery from the financial and Euro crises, costly medical breakthroughs and innovations – quite a few of which involve hematology researchers, Europe faces increased health expenditures while budgets are limited,” Professor Ulrich Jäger, chair of the EHA European Affairs Committee, said in the statement. “So it is our responsibility to provide the policy makers with the information and evidence they need to decide where their support impacts knowledge and health most efficiently, to the benefit of patients and society. ... Now it is up to the policy makers in the EU to deliver, too.”

You may find the full article in Haematologica 2016 Jan. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.136739.

Cyclical hypofractionated radiotherapy technique for palliative treatment of locally advanced head and neck cancer: institutional experience and review of palliative regimens

Background Effective palliation in patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer is important. Cyclical hypofractionated radiotherapy (Quad Shot) is a short-course palliative regimen with good patient compliance, low rates of acute toxicity, and delayed late fibrosis.

Objective To review use of the Quad Shot technique at our institution in order to quantify the palliative response in locally advanced head and neck cancer.

Methods The medical records of 70 patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma who had been treated with the Quad Shot technique were analyzed retrospectively (36 had been treated with intensity-modulated radiation therapy and 34 with 3-D conformal radiotherapy). They had received cyclical hypofractionated radiotherapy administrated as 14.8 Gy in 4 fractions over 2 days, twice daily, repeated every 3 weeks for a total of 3 cycles. The total prescribed dose was 44.4 Gy. Primary endpoints were improvement in pain using a verbal numeric pain rating scale (range 1-10, 10 being severe pain) and dysphagia using the Food Intake Level Scale, and the secondary endpoints included overall survival (OS), local regional recurrence-free survival (LRRFS), progression-free survival (PFS) and time to progression.

Results Pain response occurred in 61% of the patients. The mean pain scores decreased significantly from pre to post treatment (5.81 to 2.55, P = .009). The mean initial dysphagia score improved from 2.20 to 4.77 55 (P = .045). 26% of patients developed mucositis (≤ grade 2), with 9% developing grade 3-level mucositis. 12 patients had tumor recurrence. The estimated 1-year PFS was 20.7%. The median survival was 3.85 months with an estimated 1-year OS of 22.6%. Pain response (hazard ratio [HR], 2.69; 95% confidence index [CI], I.552-1.77) and completion of all 3 cycles (HR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.003-2.907) were predictive for improved OS.

Limitations This study is a retrospective analysis.

Conclusion Quad Shot is an appropriate palliative regimen for locally advanced head and neck cancer.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Background Effective palliation in patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer is important. Cyclical hypofractionated radiotherapy (Quad Shot) is a short-course palliative regimen with good patient compliance, low rates of acute toxicity, and delayed late fibrosis.

Objective To review use of the Quad Shot technique at our institution in order to quantify the palliative response in locally advanced head and neck cancer.

Methods The medical records of 70 patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma who had been treated with the Quad Shot technique were analyzed retrospectively (36 had been treated with intensity-modulated radiation therapy and 34 with 3-D conformal radiotherapy). They had received cyclical hypofractionated radiotherapy administrated as 14.8 Gy in 4 fractions over 2 days, twice daily, repeated every 3 weeks for a total of 3 cycles. The total prescribed dose was 44.4 Gy. Primary endpoints were improvement in pain using a verbal numeric pain rating scale (range 1-10, 10 being severe pain) and dysphagia using the Food Intake Level Scale, and the secondary endpoints included overall survival (OS), local regional recurrence-free survival (LRRFS), progression-free survival (PFS) and time to progression.

Results Pain response occurred in 61% of the patients. The mean pain scores decreased significantly from pre to post treatment (5.81 to 2.55, P = .009). The mean initial dysphagia score improved from 2.20 to 4.77 55 (P = .045). 26% of patients developed mucositis (≤ grade 2), with 9% developing grade 3-level mucositis. 12 patients had tumor recurrence. The estimated 1-year PFS was 20.7%. The median survival was 3.85 months with an estimated 1-year OS of 22.6%. Pain response (hazard ratio [HR], 2.69; 95% confidence index [CI], I.552-1.77) and completion of all 3 cycles (HR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.003-2.907) were predictive for improved OS.

Limitations This study is a retrospective analysis.

Conclusion Quad Shot is an appropriate palliative regimen for locally advanced head and neck cancer.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Background Effective palliation in patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer is important. Cyclical hypofractionated radiotherapy (Quad Shot) is a short-course palliative regimen with good patient compliance, low rates of acute toxicity, and delayed late fibrosis.

Objective To review use of the Quad Shot technique at our institution in order to quantify the palliative response in locally advanced head and neck cancer.

Methods The medical records of 70 patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma who had been treated with the Quad Shot technique were analyzed retrospectively (36 had been treated with intensity-modulated radiation therapy and 34 with 3-D conformal radiotherapy). They had received cyclical hypofractionated radiotherapy administrated as 14.8 Gy in 4 fractions over 2 days, twice daily, repeated every 3 weeks for a total of 3 cycles. The total prescribed dose was 44.4 Gy. Primary endpoints were improvement in pain using a verbal numeric pain rating scale (range 1-10, 10 being severe pain) and dysphagia using the Food Intake Level Scale, and the secondary endpoints included overall survival (OS), local regional recurrence-free survival (LRRFS), progression-free survival (PFS) and time to progression.

Results Pain response occurred in 61% of the patients. The mean pain scores decreased significantly from pre to post treatment (5.81 to 2.55, P = .009). The mean initial dysphagia score improved from 2.20 to 4.77 55 (P = .045). 26% of patients developed mucositis (≤ grade 2), with 9% developing grade 3-level mucositis. 12 patients had tumor recurrence. The estimated 1-year PFS was 20.7%. The median survival was 3.85 months with an estimated 1-year OS of 22.6%. Pain response (hazard ratio [HR], 2.69; 95% confidence index [CI], I.552-1.77) and completion of all 3 cycles (HR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.003-2.907) were predictive for improved OS.

Limitations This study is a retrospective analysis.

Conclusion Quad Shot is an appropriate palliative regimen for locally advanced head and neck cancer.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Warfarin is best for anticoagulation in prosthetic heart valve pregnancies

SNOWMASS, COLO. – How would you manage anticoagulation in a newly pregnant 23-year-old with a mechanical heart valve who has been on warfarin at 3 mg/day?

A) Weight-adjusted low-molecular-weight heparin during the first trimester, then warfarin in the second and third until switching to unfractionated heparin for delivery.

B) Low-molecular-weight heparin throughout pregnancy.

C) Warfarin throughout pregnancy.

D) Unfractionated heparin in the first trimester, warfarin in the second and third until returning to unfractionated heparin peridelivery.

The correct answer, according to both the ACC/AHA guidelines (Circulation. 2014 Jun 10;129[23]:e521-643) and European Society of Cardiology guidelines (Eur Heart J. 2011 Dec;32[24]:3147-97), is C in women who are on 5 mg/day of warfarin or less.

“Oral anticoagulants throughout pregnancy are much better for the mother, and this is where the guidelines have moved,” Dr. Carole A. Warnes said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

Both sets of guidelines give a class I recommendation to warfarin during the second and third trimesters, because the risk of warfarin embryopathy is confined to weeks 6-12. During the first trimester, warfarin at 5 mg/day or less gets a class IIa rating – making it preferable to unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin – because heparin is a far less effective anticoagulant. Plus, multiple small studies indicate the risk of embryopathy is low – roughly 1%-2% – when the mother is on warfarin at 5 mg/day or less.

In a woman on more than 5 mg/day of warfarin, the risk of warfarin embryopathy is about 6%, so the guidelines recommend replacing the drug with heparin during weeks 6-12.

“It’s not a walk in the park,” said Dr. Warnes, director of the Snowmass conference and professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

The major concern in using heparin for anticoagulation in pregnancy is valve thrombosis. It doubles the risk.

“Pregnancy is the most prothrombotic state there is,” she said. “It’s not like managing a patient through a hip replacement or prostate surgery. Women with a mechanical prosthetic valve should be managed by a heart valve team with expertise in treatment during pregnancy.”

The alternatives to warfarin are adjusted-dose unfractionated heparin, which must be given in a continuous intravenous infusion with meticulous monitoring of activated partial thromboplastin time, or twice-daily low-molecular-weight heparin with dose adjustment by weight and maintenance of a target anti–Factor Xa level of 1.0-1.2 IU/mL.

“If you use low-molecular-weight heparin, you’re going to be seeing that patient every week to monitor anti–Factor Xa 4-6 hours post injection. You’ll find it’s not that easy to stay in the sweet spot, with excellent anticoagulation without an increased risk of maternal thromboembolism, or at the other extreme, fetal bleeding. What might look initially as a relatively easy strategy with a lot of appeal turns out to entail considerable risk,” Dr. Warnes said.

This was underscored in a cautionary report by highly experienced University of Toronto investigators. In their series of 23 pregnancies in 17 women with mechanical heart valves on low-molecular-weight heparin throughout pregnancy with careful monitoring, there was one maternal thromboembolic event resulting in maternal and fetal death despite a documented therapeutic anti–Factor Xa level (Am J Cardiol. 2009 Nov 1;104[9]:1259-63).

Although warfarin is clearly the better anticoagulant for the mother, the fetus pays the price. This was highlighted in a recent report from the ESC Registry of Pregnancy and Cardiac Disease (ROPAC) that compared pregnancy outcomes in 212 patients with a mechanical heart valve, 134 with a tissue valve, and 2,620 women without a prosthetic heart valve. Use of warfarin or another vitamin K antagonist in the first trimester was associated with a higher rate of miscarriage than heparin – 28.6% vs. 9.2% – as well as a 7.1% incidence of late fetal death, compared with just 0.7% with heparin.

On the other hand, the mechanical valve thrombosis rate was 4.7%, with half of those serious events occurring during the first trimester in patients after they’d been switched to heparin (Circulation. 2015 Jul 14;132[2]:132-42).

Hemorrhagic events occurred in 23.1% of mothers with a mechanical heart valve, 5.1% of those with a bioprosthetic valve, and 4.9% of patients without a prosthetic valve. A point worth incorporating into prepregnancy patient counseling, Dr. Warnes noted, is that only 58% of ROPAC participants with a mechanical heart valve had an uncomplicated pregnancy with a live birth, in contrast to 79% of those with a tissue valve and 78% of controls.

Because warfarin crosses the placenta, and it takes about a week for the fetus to eliminate the drug following maternal discontinuation, the guidelines recommend stopping warfarin at about week 36 and changing to a continuous infusion of dose-adjusted unfractionated heparin peridelivery. The heparin should be stopped for as short a time as possible before delivery and resumed 6-12 hours post delivery in order to protect against valve thrombosis.

Of course, opting for a bioprosthetic rather than a mechanical heart valve avoids all these difficult anticoagulation-related issues. But it poses a different serious problem: The younger the patient at the time of tissue valve implantation, the greater the risk of rapid calcification and structural valve deterioration. Indeed, among patients who are age 16-39 when they receive a bioprosthetic valve, the rate of structural valve deterioration is 50% at 10 years and 90% at 15 years.

“There is no ideal valve prosthesis. If you elect a tissue prosthesis, you have to discuss the risk of reoperation in that young woman,” Dr. Warnes advised.

Recent data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons database indicate the mortality associated with redo elective aortic valve replacement in a 35-year-old woman with no comorbidities averages 1.63%, with a 2% mortality rate for redo mitral valve replacement.

Dr. Warnes reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – How would you manage anticoagulation in a newly pregnant 23-year-old with a mechanical heart valve who has been on warfarin at 3 mg/day?

A) Weight-adjusted low-molecular-weight heparin during the first trimester, then warfarin in the second and third until switching to unfractionated heparin for delivery.

B) Low-molecular-weight heparin throughout pregnancy.

C) Warfarin throughout pregnancy.

D) Unfractionated heparin in the first trimester, warfarin in the second and third until returning to unfractionated heparin peridelivery.

The correct answer, according to both the ACC/AHA guidelines (Circulation. 2014 Jun 10;129[23]:e521-643) and European Society of Cardiology guidelines (Eur Heart J. 2011 Dec;32[24]:3147-97), is C in women who are on 5 mg/day of warfarin or less.

“Oral anticoagulants throughout pregnancy are much better for the mother, and this is where the guidelines have moved,” Dr. Carole A. Warnes said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

Both sets of guidelines give a class I recommendation to warfarin during the second and third trimesters, because the risk of warfarin embryopathy is confined to weeks 6-12. During the first trimester, warfarin at 5 mg/day or less gets a class IIa rating – making it preferable to unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin – because heparin is a far less effective anticoagulant. Plus, multiple small studies indicate the risk of embryopathy is low – roughly 1%-2% – when the mother is on warfarin at 5 mg/day or less.

In a woman on more than 5 mg/day of warfarin, the risk of warfarin embryopathy is about 6%, so the guidelines recommend replacing the drug with heparin during weeks 6-12.

“It’s not a walk in the park,” said Dr. Warnes, director of the Snowmass conference and professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

The major concern in using heparin for anticoagulation in pregnancy is valve thrombosis. It doubles the risk.

“Pregnancy is the most prothrombotic state there is,” she said. “It’s not like managing a patient through a hip replacement or prostate surgery. Women with a mechanical prosthetic valve should be managed by a heart valve team with expertise in treatment during pregnancy.”

The alternatives to warfarin are adjusted-dose unfractionated heparin, which must be given in a continuous intravenous infusion with meticulous monitoring of activated partial thromboplastin time, or twice-daily low-molecular-weight heparin with dose adjustment by weight and maintenance of a target anti–Factor Xa level of 1.0-1.2 IU/mL.

“If you use low-molecular-weight heparin, you’re going to be seeing that patient every week to monitor anti–Factor Xa 4-6 hours post injection. You’ll find it’s not that easy to stay in the sweet spot, with excellent anticoagulation without an increased risk of maternal thromboembolism, or at the other extreme, fetal bleeding. What might look initially as a relatively easy strategy with a lot of appeal turns out to entail considerable risk,” Dr. Warnes said.

This was underscored in a cautionary report by highly experienced University of Toronto investigators. In their series of 23 pregnancies in 17 women with mechanical heart valves on low-molecular-weight heparin throughout pregnancy with careful monitoring, there was one maternal thromboembolic event resulting in maternal and fetal death despite a documented therapeutic anti–Factor Xa level (Am J Cardiol. 2009 Nov 1;104[9]:1259-63).

Although warfarin is clearly the better anticoagulant for the mother, the fetus pays the price. This was highlighted in a recent report from the ESC Registry of Pregnancy and Cardiac Disease (ROPAC) that compared pregnancy outcomes in 212 patients with a mechanical heart valve, 134 with a tissue valve, and 2,620 women without a prosthetic heart valve. Use of warfarin or another vitamin K antagonist in the first trimester was associated with a higher rate of miscarriage than heparin – 28.6% vs. 9.2% – as well as a 7.1% incidence of late fetal death, compared with just 0.7% with heparin.

On the other hand, the mechanical valve thrombosis rate was 4.7%, with half of those serious events occurring during the first trimester in patients after they’d been switched to heparin (Circulation. 2015 Jul 14;132[2]:132-42).

Hemorrhagic events occurred in 23.1% of mothers with a mechanical heart valve, 5.1% of those with a bioprosthetic valve, and 4.9% of patients without a prosthetic valve. A point worth incorporating into prepregnancy patient counseling, Dr. Warnes noted, is that only 58% of ROPAC participants with a mechanical heart valve had an uncomplicated pregnancy with a live birth, in contrast to 79% of those with a tissue valve and 78% of controls.

Because warfarin crosses the placenta, and it takes about a week for the fetus to eliminate the drug following maternal discontinuation, the guidelines recommend stopping warfarin at about week 36 and changing to a continuous infusion of dose-adjusted unfractionated heparin peridelivery. The heparin should be stopped for as short a time as possible before delivery and resumed 6-12 hours post delivery in order to protect against valve thrombosis.

Of course, opting for a bioprosthetic rather than a mechanical heart valve avoids all these difficult anticoagulation-related issues. But it poses a different serious problem: The younger the patient at the time of tissue valve implantation, the greater the risk of rapid calcification and structural valve deterioration. Indeed, among patients who are age 16-39 when they receive a bioprosthetic valve, the rate of structural valve deterioration is 50% at 10 years and 90% at 15 years.

“There is no ideal valve prosthesis. If you elect a tissue prosthesis, you have to discuss the risk of reoperation in that young woman,” Dr. Warnes advised.

Recent data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons database indicate the mortality associated with redo elective aortic valve replacement in a 35-year-old woman with no comorbidities averages 1.63%, with a 2% mortality rate for redo mitral valve replacement.

Dr. Warnes reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – How would you manage anticoagulation in a newly pregnant 23-year-old with a mechanical heart valve who has been on warfarin at 3 mg/day?

A) Weight-adjusted low-molecular-weight heparin during the first trimester, then warfarin in the second and third until switching to unfractionated heparin for delivery.

B) Low-molecular-weight heparin throughout pregnancy.

C) Warfarin throughout pregnancy.

D) Unfractionated heparin in the first trimester, warfarin in the second and third until returning to unfractionated heparin peridelivery.

The correct answer, according to both the ACC/AHA guidelines (Circulation. 2014 Jun 10;129[23]:e521-643) and European Society of Cardiology guidelines (Eur Heart J. 2011 Dec;32[24]:3147-97), is C in women who are on 5 mg/day of warfarin or less.

“Oral anticoagulants throughout pregnancy are much better for the mother, and this is where the guidelines have moved,” Dr. Carole A. Warnes said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

Both sets of guidelines give a class I recommendation to warfarin during the second and third trimesters, because the risk of warfarin embryopathy is confined to weeks 6-12. During the first trimester, warfarin at 5 mg/day or less gets a class IIa rating – making it preferable to unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin – because heparin is a far less effective anticoagulant. Plus, multiple small studies indicate the risk of embryopathy is low – roughly 1%-2% – when the mother is on warfarin at 5 mg/day or less.

In a woman on more than 5 mg/day of warfarin, the risk of warfarin embryopathy is about 6%, so the guidelines recommend replacing the drug with heparin during weeks 6-12.

“It’s not a walk in the park,” said Dr. Warnes, director of the Snowmass conference and professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

The major concern in using heparin for anticoagulation in pregnancy is valve thrombosis. It doubles the risk.

“Pregnancy is the most prothrombotic state there is,” she said. “It’s not like managing a patient through a hip replacement or prostate surgery. Women with a mechanical prosthetic valve should be managed by a heart valve team with expertise in treatment during pregnancy.”

The alternatives to warfarin are adjusted-dose unfractionated heparin, which must be given in a continuous intravenous infusion with meticulous monitoring of activated partial thromboplastin time, or twice-daily low-molecular-weight heparin with dose adjustment by weight and maintenance of a target anti–Factor Xa level of 1.0-1.2 IU/mL.

“If you use low-molecular-weight heparin, you’re going to be seeing that patient every week to monitor anti–Factor Xa 4-6 hours post injection. You’ll find it’s not that easy to stay in the sweet spot, with excellent anticoagulation without an increased risk of maternal thromboembolism, or at the other extreme, fetal bleeding. What might look initially as a relatively easy strategy with a lot of appeal turns out to entail considerable risk,” Dr. Warnes said.

This was underscored in a cautionary report by highly experienced University of Toronto investigators. In their series of 23 pregnancies in 17 women with mechanical heart valves on low-molecular-weight heparin throughout pregnancy with careful monitoring, there was one maternal thromboembolic event resulting in maternal and fetal death despite a documented therapeutic anti–Factor Xa level (Am J Cardiol. 2009 Nov 1;104[9]:1259-63).

Although warfarin is clearly the better anticoagulant for the mother, the fetus pays the price. This was highlighted in a recent report from the ESC Registry of Pregnancy and Cardiac Disease (ROPAC) that compared pregnancy outcomes in 212 patients with a mechanical heart valve, 134 with a tissue valve, and 2,620 women without a prosthetic heart valve. Use of warfarin or another vitamin K antagonist in the first trimester was associated with a higher rate of miscarriage than heparin – 28.6% vs. 9.2% – as well as a 7.1% incidence of late fetal death, compared with just 0.7% with heparin.

On the other hand, the mechanical valve thrombosis rate was 4.7%, with half of those serious events occurring during the first trimester in patients after they’d been switched to heparin (Circulation. 2015 Jul 14;132[2]:132-42).

Hemorrhagic events occurred in 23.1% of mothers with a mechanical heart valve, 5.1% of those with a bioprosthetic valve, and 4.9% of patients without a prosthetic valve. A point worth incorporating into prepregnancy patient counseling, Dr. Warnes noted, is that only 58% of ROPAC participants with a mechanical heart valve had an uncomplicated pregnancy with a live birth, in contrast to 79% of those with a tissue valve and 78% of controls.

Because warfarin crosses the placenta, and it takes about a week for the fetus to eliminate the drug following maternal discontinuation, the guidelines recommend stopping warfarin at about week 36 and changing to a continuous infusion of dose-adjusted unfractionated heparin peridelivery. The heparin should be stopped for as short a time as possible before delivery and resumed 6-12 hours post delivery in order to protect against valve thrombosis.

Of course, opting for a bioprosthetic rather than a mechanical heart valve avoids all these difficult anticoagulation-related issues. But it poses a different serious problem: The younger the patient at the time of tissue valve implantation, the greater the risk of rapid calcification and structural valve deterioration. Indeed, among patients who are age 16-39 when they receive a bioprosthetic valve, the rate of structural valve deterioration is 50% at 10 years and 90% at 15 years.

“There is no ideal valve prosthesis. If you elect a tissue prosthesis, you have to discuss the risk of reoperation in that young woman,” Dr. Warnes advised.

Recent data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons database indicate the mortality associated with redo elective aortic valve replacement in a 35-year-old woman with no comorbidities averages 1.63%, with a 2% mortality rate for redo mitral valve replacement.

Dr. Warnes reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

Migraines more severe in PNES patients than in epilepsy patients

Psychogenic nonepileptic seizure (PNES) patients reported having more frequent and longer-lasting migraines than patients diagnosed with epilepsy, in an observational study conducted in the United States.

Researchers questioned 29 patients with epilepsy and 43 PNES patients about their migraines and seizures through the use of standardized questionnaires and a standardized interview. All study participants were found in a clinician database of patients who had been evaluated in the Mayo Clinic epilepsy monitoring unit between 2008 and 2014. Their ages ranged from 20 years to 82 years. Patients who were diagnosed with both PNES and epilepsy were excluded from the research project.

PNES patients reported having significantly more migraine attacks and longer-duration migraines (when untreated) than patients with epilepsy. Specifically, on average, PNES patients said they experienced 6.5 migraine attacks per month and migraines with a length of 39.5 hours, whereas patients with epilepsy said they had, on average, 3.8 migraine attacks per month and migraines lasting 27.3 hours. Another significant difference between the two groups of patients occurred in the numbers of nonvisual migraine aura symptoms reported. While 22 of the PNES patients (78.6%) reported experiencing such symptoms, 7 of the epilepsy patients (46.7%) reported having nonvisual aura symptoms (P = .033).

“Our study adds to the existing literature [on the relationship between PNES and migraine] by detailing specific migraine characteristics in patients with PNES,” wrote Morgan A. Shepard and colleagues. The researchers noted that PNES patients could have overreported the severity of their migraine symptoms and that a high level of somatization has been found in patients with PNES.

The results of this research project “justify the need for clinicians to assess PNES patients for the presence of migraine and when present, to treat them appropriately for migraine,” according to the researchers.

The study’s authors did not report any conflicts of interest.

Read the study in Seizure (doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2015.12.006).

Psychogenic nonepileptic seizure (PNES) patients reported having more frequent and longer-lasting migraines than patients diagnosed with epilepsy, in an observational study conducted in the United States.

Researchers questioned 29 patients with epilepsy and 43 PNES patients about their migraines and seizures through the use of standardized questionnaires and a standardized interview. All study participants were found in a clinician database of patients who had been evaluated in the Mayo Clinic epilepsy monitoring unit between 2008 and 2014. Their ages ranged from 20 years to 82 years. Patients who were diagnosed with both PNES and epilepsy were excluded from the research project.

PNES patients reported having significantly more migraine attacks and longer-duration migraines (when untreated) than patients with epilepsy. Specifically, on average, PNES patients said they experienced 6.5 migraine attacks per month and migraines with a length of 39.5 hours, whereas patients with epilepsy said they had, on average, 3.8 migraine attacks per month and migraines lasting 27.3 hours. Another significant difference between the two groups of patients occurred in the numbers of nonvisual migraine aura symptoms reported. While 22 of the PNES patients (78.6%) reported experiencing such symptoms, 7 of the epilepsy patients (46.7%) reported having nonvisual aura symptoms (P = .033).

“Our study adds to the existing literature [on the relationship between PNES and migraine] by detailing specific migraine characteristics in patients with PNES,” wrote Morgan A. Shepard and colleagues. The researchers noted that PNES patients could have overreported the severity of their migraine symptoms and that a high level of somatization has been found in patients with PNES.

The results of this research project “justify the need for clinicians to assess PNES patients for the presence of migraine and when present, to treat them appropriately for migraine,” according to the researchers.

The study’s authors did not report any conflicts of interest.

Read the study in Seizure (doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2015.12.006).

Psychogenic nonepileptic seizure (PNES) patients reported having more frequent and longer-lasting migraines than patients diagnosed with epilepsy, in an observational study conducted in the United States.

Researchers questioned 29 patients with epilepsy and 43 PNES patients about their migraines and seizures through the use of standardized questionnaires and a standardized interview. All study participants were found in a clinician database of patients who had been evaluated in the Mayo Clinic epilepsy monitoring unit between 2008 and 2014. Their ages ranged from 20 years to 82 years. Patients who were diagnosed with both PNES and epilepsy were excluded from the research project.

PNES patients reported having significantly more migraine attacks and longer-duration migraines (when untreated) than patients with epilepsy. Specifically, on average, PNES patients said they experienced 6.5 migraine attacks per month and migraines with a length of 39.5 hours, whereas patients with epilepsy said they had, on average, 3.8 migraine attacks per month and migraines lasting 27.3 hours. Another significant difference between the two groups of patients occurred in the numbers of nonvisual migraine aura symptoms reported. While 22 of the PNES patients (78.6%) reported experiencing such symptoms, 7 of the epilepsy patients (46.7%) reported having nonvisual aura symptoms (P = .033).

“Our study adds to the existing literature [on the relationship between PNES and migraine] by detailing specific migraine characteristics in patients with PNES,” wrote Morgan A. Shepard and colleagues. The researchers noted that PNES patients could have overreported the severity of their migraine symptoms and that a high level of somatization has been found in patients with PNES.

The results of this research project “justify the need for clinicians to assess PNES patients for the presence of migraine and when present, to treat them appropriately for migraine,” according to the researchers.

The study’s authors did not report any conflicts of interest.

Read the study in Seizure (doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2015.12.006).

FROM SEIZURE

Cariprazine for schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder

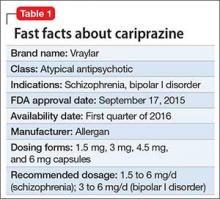

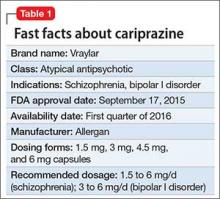

Cariprazine is a newly approved (September 2015) dopamine D3/D2 receptor partial agonist with higher affinity for the D3 receptor than for D2. The drug is FDA-indicated for treating schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder (BD I)1,2 (Table 1). In clinical trials, cariprazine alleviated symptoms of schizophrenia and mixed and manic symptoms of BD I, with minimal effect on metabolic parameters, the prolactin level, and cardiac conduction.

Clinical implications

Despite numerous developments in pharmacotherapeutics, people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder continue to struggle with residual symptoms or endure treatments that produce adverse effects (AEs). In particular, metabolic issues, sedation, and cognitive impairment plague many current treatment options for these disorders.

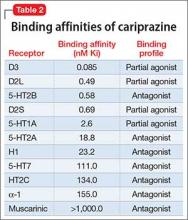

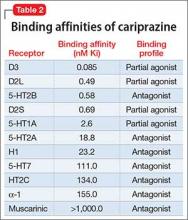

Receptor blocking. As a dopamine D3-preferring D3/D2 partial agonist, cariprazine offers an alternative to antipsychotics that preferentially modulate D2 receptors. First-generation (typical) antipsychotics block D2 receptors; atypical antipsychotics block D2 receptors and 5-HT2A receptors. Dopamine partial agonists aripiprazole and brexpiprazole are D2-preferring, with minimal D3 effects. In contrast, cariprazine has a 6-fold to 8-fold higher affinity for D3 receptors than for D2 receptors, and has specificity for the D3 receptor that is 3 to 10 times higher than what aripiprazole has for the D3 receptor3-5 (Table 2).

Use in schizophrenia. Recommended dosage range is 1.5 to 6 mg/d. In Phase-III clinical trials, dosages of 3 to 9 mg/d produced significant improvement on the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS) and on the Clinical Global Impression scale. Higher dosages (6 to 9 mg/d) showed early separation from placebo—by the end of Week 1—but carried a dosage-related risk of AEs, leading the FDA to recommend 6 mg/d as the maximum dosage.1,6-8

Use in manic or mixed episodes of BD I. Recommended dosage range is 3 to 6 mg/d. In clinical trials, dosages in the range of 3 to 12 mg/d were effective for acute manic or mixed symptoms; significant improvement in the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) score was seen as early as Day 4. Dosages >6 mg/d yielded no additional benefit and were associated with increased risk of AEs.9-12

Pharmacologic profile, adverse effects. Cariprazine has a pharmacologic profile consistent with the generally favorable metabolic profile and lack of anticholinergic effects seen in clinical trials. In short- and long-term trials, the drug had minimal effects on prolactin, blood pressure, and cardiac conduction.13

Across clinical trials for both disorders, akathisia and parkinsonism were among more common AEs of cariprazine. Both AEs were usually mild, resulting in relatively few premature discontinuations from trials. Parkinsonism appeared somewhat dosage-related; akathisia had no clear relationship to dosage.

How it works

The theory behind the use of partial agonists, including cariprazine, is that these agents restore homeostatic balance to neurochemical circuits by:

- decreasing the effects of endogenous neurotransmitters (dopamine tone) in regions of the brain where their transmission is excessive, such as mesolimbic regions in schizophrenia or mania

- simultaneously increasing neurotransmission in regions where transmission of endogenous neurotransmitters is low, such as the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia

- exerting little effect in regions where neurotransmitter activity is normal, such as the pituitary gland.

- simultaneously

Cariprazine has higher binding affinity for dopamine D3 receptors (Ki 0.085 nM) than for D2L receptors (Ki 0.49 nM) and D2S receptors (Ki 0.69 nM). The drug also has strong affinity for serotonin receptor 5-HT2B; moderate affinity for 5-HT1A; and lower affinity for 5-HT2A, histamine H1, and 5-HT7 receptors. Cariprazine has little or no affinity for adrenergic or cholinergic receptors.14In patients with schizophrenia, as measured on PET scanning, a dosage of 1.5 mg/d yielded 69% to 75% D2/D3 receptor occupancy. A dosage of 3 mg/d yielded >90% occupancy.

Search for an understanding of action continues. The relative contribution of D3 partial agonism, compared with D2 partial agonism, is a subject of ongoing basic scientific and clinical research. D3 is an autoreceptor that (1) controls phasic, but not tonic, activity of dopamine nerve cells and (2) mediates behavioral abnormalities induced by glutamate and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists.5,12 In animal studies, D3-preferring agents have been shown to exert pro-cognitive effects and improve anhedonic symptoms.

Pharmacokinetics

Cariprazine is a once-daily medication with a relatively long half-life that can be taken with or without food. Dosages of 3 to 12 mg/d yield a fairly linear, dose-proportional increase in plasma concentration. The peak serum concentration for cariprazine is 3 to 4 hours under fasting conditions; taking the drug with food causes a slight delay in absorption but does not have a significant effect on the area under the curve. Mean half-life for cariprazine is 2 to 5 days over a dosage range of 1.5 to 12.5 mg/d in otherwise healthy adults with schizophrenia.1

Cariprazine is metabolized primarily by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4. It is a weak inhibitor of CYP2D6 and CYP3A4.1 Hepatic metabolism of cariprazine produces 2 active metabolites: desmethyl-cariprazine (DCAR) and didesmethyl-cariprazine (DDCAR), both of which are equipotent to cariprazine. After multiple dose administration, mean cariprazine and DCAR levels reach steady state in 1 to 2 weeks; DDCAR, in 4 to 8 weeks. The systemic exposure and serum levels of DDCAR are roughly 3-fold greater than cariprazine because of the longer elimination half-life of DDCAR.1

Efficacy in schizophrenia

The efficacy of cariprazine in schizophrenia was established by 3 six-week, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Two trials were fixed-dosage; a third used 2 flexible dosage ranges. The primary efficacy measure was change from baseline in the total score of the PANSS at the end of Week 6, compared with placebo. In all trials, patients were adults (age 18 to 60) who met DSM-IV-TR criteria for schizophrenia and had a PANSS score between 80 and 120 at screening and baseline.

Study 1 (n = 711) compared dosages of 1.5 mg/d, 3 mg/d, and 4.5 mg/d with placebo.7 All cariprazine dosages and an active control (risperdone) were superior to placebo in reducing symptoms of schizophrenia, as measured by the PANSS. The placebo-subtracted differences on PANSS score at 6 weeks for dosages of 1.5 mg/d, 3 mg/d, and 4.5 mg/d were –7.6, –8.8, –10.4, respectively (significant at 95% CI).

Study 2 (n = 151) compared 3 mg/d and 6 mg/d dosages of cariprazine with placebo.1 Both dosages and an active control (aripiprazole) were superior to placebo in reducing PANSS scores. Placebo-subtracted differences on PANSS score at 6 weeks for dosages of 3 mg/d and 6 mg/day were –6.0, –8.8, respectively (significant at 95% CI).

Study 3 (n = 147) was a fixed-flexible dosage trial comparing cariprazine, 3 to 6 mg/d and 6 to 9 mg/d dosage ranges, to placebo.8 Both ranges were superior to placebo in reducing symptoms on PANSS. Placebo-subtracted differences from placebo on PANSS at 6 weeks for cariprazine 3 to 6 or 6 to 9 mg/d were –6.8, –9.9, respectively (significant at 95% CI).

These trials established the efficacy of cariprazine for acute schizophrenia at dosages ranging from 1.5 to 9 mg/d. Although there was a modest trend toward higher efficacy at higher dosages, there was a dose-related increase in certain adverse reactions (extrapyramidal symptoms [EPS]) at dosages >6 mg/d.1

Efficacy in bipolar disorder

The efficacy of cariprazine for acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes of BD I was established in 3 randomized, placebo-controlled, flexibly dosed 3-week trials. In all trials, patients were adults (age 18 to 65) who met DSM-IV-TR criteria for BD I with manic or mixed episodes and with or without psychotic features (YMRS score, ≥20). The primary efficacy measure in the 3 trials was a change from baseline in the total YMRS score at the end of Week 3, compared with placebo.

Study 1 (n = 492) compared 2 flexibly dosed ranges of cariprazine (3 to 6 mg/d and 6 to 12 mg/d) with placebo.10 Both dosage ranges were superior to placebo in reducing mixed and manic symptoms, as measured by reduction in the total YMRS score. Placebo-subtracted differences in YMRS scores from placebo at Week 3 for cariprazine 3 to 6 mg/d and 6 to 12 mg/d were –6.1, –5.9, respectively (significant at 95% CI). The higher range offered no additional advantage over the lower range.

Study 2 (n = 235) compared flexibly dosed cariprazine, 3 to 12 mg/d, to placebo.11 Cariprazine was superior to placebo in reducing bipolar symptoms as measured by the YMRS. The difference between cariprazine 3 to 12 mg/d and placebo on the YMRS score at Week 3 was –6.1 (significant at 95% CI).

Study 3 (n = 310) compared flexibly dosed cariprazine, 3 to 12 mg/d, with placebo.15 Again, cariprazine was superior to placebo in reducing the YMRS score at Week 3: difference, –4.3 (significant at 95% CI).

These trials establish the efficacy of cariprazine in treating acute mania or mixed BD I episodes at dosages ranging from 3 to 12 mg/d. Dosages >6 mg/d did not offer additional benefit over lower dosages, and resulted in a dosage-related increase in EPS at dosages >6 mg/d.16

Tolerability

Cariprazine generally was well tolerated in short-term trials for schizophrenia and BD I. The only treatment-emergent adverse event reported for at least 1 treatment group in all trials at a rate of ≥10%, and at least twice the rate seen with placebo was akathisia. Adverse events reported at a lower rate than placebo included EPS (particularly parkinsonism), restlessness, headache, insomnia, fatigue, and gastrointestinal distress. The discontinuation rate due to AEs for treatment groups and placebo-treated patients generally was similar. In schizophrenia Study 3, for example, the discontinuation rate due to AEs was 13% for placebo; 14% for cariprazine, 3 to 6 mg/d; and 13% for cariprazine, 6 to 9 mg/d.1 48-Week open-label safety study. Patients with schizophrenia received open-label cariprazine for as long as 48 weeks.7 Serious adverse events were reported in 12.9%, including 1 death (suicide); exacerbation of symptoms of schizophrenia (4.3%); and psychosis (2.2%). Treatment-emergent adverse events reported in at least 10% of patients included akathisia (14.0%), insomnia (14.0%), and weight gain (11.8%). The mean change in laboratory values, blood pressure, pulse rate, and electrocardiographic parameters was clinically insignificant.

Other studies. In a 16-week, open-label extension study of patients with BD I, the major tolerability issue was akathisia. This AE developed in 37% of patients and led to a 5% withdrawal rate.12

In short- and long-term studies for either indication, the effect of the drug on metabolic parameters appears to be small. In studies with active controls, potentially significant weight gain (>7%) was greater for aripiprazole and risperidone than for cariprazine.6,7 The effect on the prolactin level was minimal. There do not appear to be clinically meaningful changes in laboratory values, vital signs, or QT interval.

Unique clinical issues

Preferential binding. Cariprazine is the third dopamine partial agonist approved for use in the United States; unlike the other 2—aripiprazole and brexpiprazole—cariprazine shows preference for D3 receptors over D2 receptors. The exact clinical impact of a preference for D3 and the drug’s partial agonism of 5-HT1A has not been fully elucidated.

EPS, including akathisia and parkinsonism, were among common adverse events. Both were usually mild, with 0.5% of schizophrenia patients and 2% of BD I patients dropping out of trials because of any type of EPS-related AEs.

Why Rx? On a practical medical level, reasons to prescribe cariprazine likely include:

- minimal effect on prolactin

- relative lack of effect on metabolic parameters, including weight (cariprazine showed less weight gain than risperidone or aripiprazole control arms in trials).

Dosing

The recommended dosage of cariprazine for schizophrenia ranges from 1.5 to 6 mg/d. The recommended starting dosage is 1.5 mg/d, which can be increased to 3 mg on Day 2, with further upward dosage adjustments of 1.5 to 3 mg/d, based on clinical response and tolerability.1

The recommended dosages of cariprazine for mixed and manic episodes of BD I range from 3 to 6 mg/d. The recommended starting dosage is 1.5 mg/d, which can be increased to 3 mg on Day 2, with further upward dosage adjustments of 1.5 to 3 mg/d, based on clinical response and tolerability.1

Other key aspects of dosing to keep in mind:

- Because of the long half-life and 2 equipotent active metabolites of cariprazine, any changes made to the dosage will not be reflected fully in the serum level for 2 weeks.

- Administering the drug with food slightly delays, but does not affect, the extent of absorption.

- Because the drug is metabolized primarily by CYP3A4, dosage adjustment is required in the presence of a CYP3A4 inhibitor; the recommended starting dosage of cariprazine is 1.5 mg every other day with a maximum dosage of 3 mg/d when it is administered concomitantly with a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor.

- Because data are not available regarding concomitant use of cariprazine with a strong CYP3A4 inducer, this practice is not recommended.1

- Because the drug is metabolized primarily by CYP3A4, dosage adjustment is required in the presence of a CYP3A4 Because data are not available regarding concomitant use of cariprazine with a strong CYP3A4

Contraindications

Cariprazine carries a FDA black-box warning of increased mortality in older patients who have dementia-related psychosis, as other atypical antipsychotics do. Clinical trials produced few data about the use of cariprazine in geriatric patients; no data exist about use in the pediatric population.1

Metabolic, prolactin, and cardiac concerns about cariprazine appeared favorably minor in Phase-III and long-term safety trials. Concomitant use of cariprazine with any strong inducer of CYP3A4 has not been studied, and is not recommended. Dosage reduction is recommended when using cariprazine concomitantly with a CYP3A4 inhibitor.1

In conclusion

The puzzle in neuropsychiatry has always been to find ways to produce different effects in different brain regions—with a single drug. Cariprazine’s particular binding profile—higher affinity and higher selectivity for D3 receptors than for D2 receptors compared with either aripiprazole or brexpiprazole—may secure a role for it in managing psychosis and mood disorders.

1. Vraylar [package insert]. Parsippany, NJ: Actavis Pharma, Inc.; 2015.

2. McCormack PL, Cariprazine: first global approval. Drugs. 2015;75(17):2035-2043.

3. Kiss B, Horváth A, Némethy Z, et al. Cariprazine (RGH-188), a dopamine D(3) receptor-preferring, D(3)/D(2) dopamine receptor antagonist-partial agonist antipsychotic candidate: in vitro and neurochemical profile. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;333(1):328-340.

4. Potkin, S, Keator, D, Mukherjee J, et al. P. 1. E 028 dopamine D3 and D2 receptor occupancy of cariprazine in schizophrenic patients. Eur Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;19(suppl 3):S316.

5. Veselinovicˇ T, Paulzen M, Gründer G. Cariprazine, a new, orally active dopamine D2/3 receptor partial agonist for the treatment of schizophrenia, bipolar mania and depression. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13(11):1141-1159.

6. Cutler A, Mokliatchouk O, Laszlovszky I, et al. Cariprazine in acute schizophrenia: a fixed-dose phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled trial. Abstract presented at: 166th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; May 18-22, 2013; San Francisco, CA.

7. Durgam S, Starace A, Li D, et al. An evaluation of the safety and efficacy of cariprazine in patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: a phase II, randomized clinical trial. Schizophr Res. 2014;152(2-3):450-457.

8. Kane JM, Zukin S, Wang Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of cariprazine in acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: results from an international, phase III clinical trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;35(4):367-373.

9. Bose A, Starace A, Lu, K, et al. Cariprazine in the treatment of acute mania in bipolar disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. Poster presented at: 16th Annual Meeting of the College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists; April 21-24, 2013; Colorado Springs, CO.

10. Calabrese JR, Keck PE Jr, Starace A, et al. Efficacy and safety of low- and high-dose cariprazine in acute and mixed mania associated with bipolar I disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(3):284-292.

11. Durgam S, Starace A, Li D, et al. The efficacy and tolerability of cariprazine in acute mania associated with bipolar I disorder: a phase II trial. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17(1):63-75.

12. Ketter, T. A phase III, open-label, 16-week study of flexibly dosed cariprazine in 402 patients with bipolar I disorder. Presented at: 53rd Annual Meeting of the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit; May 28-31, 2013; Hollywood, FL.

13. Bose A, Li D, Migliore R. The efficacy and safety of the novel antipsychotic cariprazine in the acute exacerbation of schizophrenia. Poster presented at: 50th Annual Meeting of the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit; June 14-17, 2010; Boca Raton, FL.

14. Citrome L. Cariprazine: chemistry, pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, and metabolism, clinical efficacy, safety, and tolerability. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2013;9(2):193-206.

15. Sachs GS, Greenberg WM, Starace A, et al. Cariprazine in the treatment of acute mania in bipolar I disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. J Affect Disord. 2015;174:296-302.

16. Vieta E, Durgam S, Lu K, et al. Effect of cariprazine across the symptoms of mania in bipolar I disorder: analyses of pooled data from phase II/III trials. Eur Neuropsycholpharmacol. 2015;25(11):1882-1891.

Cariprazine is a newly approved (September 2015) dopamine D3/D2 receptor partial agonist with higher affinity for the D3 receptor than for D2. The drug is FDA-indicated for treating schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder (BD I)1,2 (Table 1). In clinical trials, cariprazine alleviated symptoms of schizophrenia and mixed and manic symptoms of BD I, with minimal effect on metabolic parameters, the prolactin level, and cardiac conduction.

Clinical implications