User login

Antiplatelet drug appears effective for women

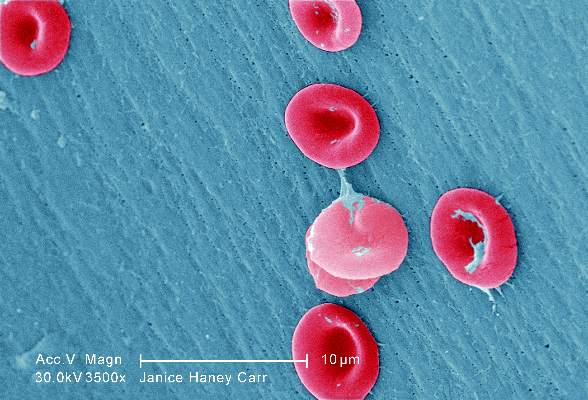

while another doctor looks on

Photo courtesy of NCI

An analysis of data from the CHAMPION PHOENIX trial suggests cangrelor is more effective than clopidogrel for preventing complications in women undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Rates of severe bleeding did not differ significantly between the treatment arms, but women who received cangrelor had a higher rate of moderate bleeding than those who received clopidogrel.

Researchers relayed these results in Circulation.

The CHAMPION PHOENIX trial was funded by The Medicines Company, which manufactures cangrelor.

For this phase 3 trial, researchers compared the safety and efficacy of clopidogrel and cangrelor in 11,145 patients who were undergoing elective or urgent PCI.

In the initial analysis of trial data, cangrelor reduced the overall odds of complications from PCI, which included death, myocardial infarction, ischemia-driven revascularization, and stent thrombosis.

But cangrelor also resulted in significantly higher rates of major and minor bleeding when compared to clopidogrel. The rates of severe bleeding were similar between the treatment arms.

With the current analysis, researchers wanted to determine if the effects of cangrelor and clopidogrel differed between men and women.

“In the past, questions have been raised about the safety and efficacy of blood thinners in women,” said study author Michelle O’Donoghue, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

“This study provides important reassurance, overall, that [cangrelor] appears to offer as much benefit for women as it does for men.”

The primary efficacy endpoint was the composite of death, myocardial infarction, ischemia-driven revascularization, and stent thrombosis at 48 hours. The primary safety endpoint was GUSTO severe bleeding at 48 hours.

Sex differences

Of the 11,451 patients in this trial, 3051 (28%) were female. These patients were more likely than males to be older and to have a history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, prior stroke, or transient ischemic attack.

Women were more likely than men to be enrolled with stable angina or non ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction was more common in men.

The women were less likely to have a prior history of myocardial infarction or coronary revascularization, and they had lower baseline hemoglobin and hematocrit levels than men.

Men were more likely than women to receive aspirin, but there was no difference between the sexes when it came to the choice of clopidogrel loading dose and the use of unfractionated heparin and bivalirudin. The median duration of PCI was longer in men than women, but the choice of access site was similar.

When the researchers adjusted for potentially confounding factors, they found that being female was independently associated with higher odds of the primary efficacy outcome (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]=1.30) and GUSTO moderate or severe bleeding (aOR=2.70).

Efficacy and safety

For women, cangrelor was associated with a significant decrease in the odds of achieving the primary efficacy endpoint. Men were less likely to achieve the endpoint when on cangrelor as well, but the difference between the cangrelor and clopidogrel arms was not statistically significant for men.

The percentage of women who met criteria for the primary efficacy endpoint was 4.8% in the cangrelor arm and 6.9% in the clopidogrel arm (aOR=0.65, P=0.01). The percentage of men who did so was 4.7% in the cangrelor arm and 5.5% in the clopidogrel arm (aOR=0.86, P=0.14, P interaction=0.23).

Cangrelor was associated with a significantly lower risk of stent thrombosis at 48 hours for women but not men.

For women, the incidence of stent thrombosis was 0.8% in the cangrelor arm and 1.9% in the clopidogrel arm (aOR=0.39, P=0.01). For men, the rates were 0.9% and 1.1%, respectively (aOR=0.84, P=0.44, P interaction=0.11).

There was no significant difference in severe bleeding between the treatment arms for men or women, but women had a significantly higher risk of moderate bleeding if they received cangrelor.

For women, the rate of severe bleeding was 0.3% in the cangrelor arm and 0.2% in the clopidogrel arm (aOR=2.37, P=0.30). For men, the rates were 0.1% in both arms (aOR=2.04, P=0.41, P interaction=0.88 ).

For women, the rate of moderate bleeding was 0.9% in the cangrelor arm and 0.3% in the clopidogrel arm (aOR=3.63, P=0.02). For men, the rates were 0.2% in both arms (aOR=0.81, P=0.68, P interaction=0.04). ![]()

while another doctor looks on

Photo courtesy of NCI

An analysis of data from the CHAMPION PHOENIX trial suggests cangrelor is more effective than clopidogrel for preventing complications in women undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Rates of severe bleeding did not differ significantly between the treatment arms, but women who received cangrelor had a higher rate of moderate bleeding than those who received clopidogrel.

Researchers relayed these results in Circulation.

The CHAMPION PHOENIX trial was funded by The Medicines Company, which manufactures cangrelor.

For this phase 3 trial, researchers compared the safety and efficacy of clopidogrel and cangrelor in 11,145 patients who were undergoing elective or urgent PCI.

In the initial analysis of trial data, cangrelor reduced the overall odds of complications from PCI, which included death, myocardial infarction, ischemia-driven revascularization, and stent thrombosis.

But cangrelor also resulted in significantly higher rates of major and minor bleeding when compared to clopidogrel. The rates of severe bleeding were similar between the treatment arms.

With the current analysis, researchers wanted to determine if the effects of cangrelor and clopidogrel differed between men and women.

“In the past, questions have been raised about the safety and efficacy of blood thinners in women,” said study author Michelle O’Donoghue, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

“This study provides important reassurance, overall, that [cangrelor] appears to offer as much benefit for women as it does for men.”

The primary efficacy endpoint was the composite of death, myocardial infarction, ischemia-driven revascularization, and stent thrombosis at 48 hours. The primary safety endpoint was GUSTO severe bleeding at 48 hours.

Sex differences

Of the 11,451 patients in this trial, 3051 (28%) were female. These patients were more likely than males to be older and to have a history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, prior stroke, or transient ischemic attack.

Women were more likely than men to be enrolled with stable angina or non ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction was more common in men.

The women were less likely to have a prior history of myocardial infarction or coronary revascularization, and they had lower baseline hemoglobin and hematocrit levels than men.

Men were more likely than women to receive aspirin, but there was no difference between the sexes when it came to the choice of clopidogrel loading dose and the use of unfractionated heparin and bivalirudin. The median duration of PCI was longer in men than women, but the choice of access site was similar.

When the researchers adjusted for potentially confounding factors, they found that being female was independently associated with higher odds of the primary efficacy outcome (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]=1.30) and GUSTO moderate or severe bleeding (aOR=2.70).

Efficacy and safety

For women, cangrelor was associated with a significant decrease in the odds of achieving the primary efficacy endpoint. Men were less likely to achieve the endpoint when on cangrelor as well, but the difference between the cangrelor and clopidogrel arms was not statistically significant for men.

The percentage of women who met criteria for the primary efficacy endpoint was 4.8% in the cangrelor arm and 6.9% in the clopidogrel arm (aOR=0.65, P=0.01). The percentage of men who did so was 4.7% in the cangrelor arm and 5.5% in the clopidogrel arm (aOR=0.86, P=0.14, P interaction=0.23).

Cangrelor was associated with a significantly lower risk of stent thrombosis at 48 hours for women but not men.

For women, the incidence of stent thrombosis was 0.8% in the cangrelor arm and 1.9% in the clopidogrel arm (aOR=0.39, P=0.01). For men, the rates were 0.9% and 1.1%, respectively (aOR=0.84, P=0.44, P interaction=0.11).

There was no significant difference in severe bleeding between the treatment arms for men or women, but women had a significantly higher risk of moderate bleeding if they received cangrelor.

For women, the rate of severe bleeding was 0.3% in the cangrelor arm and 0.2% in the clopidogrel arm (aOR=2.37, P=0.30). For men, the rates were 0.1% in both arms (aOR=2.04, P=0.41, P interaction=0.88 ).

For women, the rate of moderate bleeding was 0.9% in the cangrelor arm and 0.3% in the clopidogrel arm (aOR=3.63, P=0.02). For men, the rates were 0.2% in both arms (aOR=0.81, P=0.68, P interaction=0.04). ![]()

while another doctor looks on

Photo courtesy of NCI

An analysis of data from the CHAMPION PHOENIX trial suggests cangrelor is more effective than clopidogrel for preventing complications in women undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Rates of severe bleeding did not differ significantly between the treatment arms, but women who received cangrelor had a higher rate of moderate bleeding than those who received clopidogrel.

Researchers relayed these results in Circulation.

The CHAMPION PHOENIX trial was funded by The Medicines Company, which manufactures cangrelor.

For this phase 3 trial, researchers compared the safety and efficacy of clopidogrel and cangrelor in 11,145 patients who were undergoing elective or urgent PCI.

In the initial analysis of trial data, cangrelor reduced the overall odds of complications from PCI, which included death, myocardial infarction, ischemia-driven revascularization, and stent thrombosis.

But cangrelor also resulted in significantly higher rates of major and minor bleeding when compared to clopidogrel. The rates of severe bleeding were similar between the treatment arms.

With the current analysis, researchers wanted to determine if the effects of cangrelor and clopidogrel differed between men and women.

“In the past, questions have been raised about the safety and efficacy of blood thinners in women,” said study author Michelle O’Donoghue, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

“This study provides important reassurance, overall, that [cangrelor] appears to offer as much benefit for women as it does for men.”

The primary efficacy endpoint was the composite of death, myocardial infarction, ischemia-driven revascularization, and stent thrombosis at 48 hours. The primary safety endpoint was GUSTO severe bleeding at 48 hours.

Sex differences

Of the 11,451 patients in this trial, 3051 (28%) were female. These patients were more likely than males to be older and to have a history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, prior stroke, or transient ischemic attack.

Women were more likely than men to be enrolled with stable angina or non ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction was more common in men.

The women were less likely to have a prior history of myocardial infarction or coronary revascularization, and they had lower baseline hemoglobin and hematocrit levels than men.

Men were more likely than women to receive aspirin, but there was no difference between the sexes when it came to the choice of clopidogrel loading dose and the use of unfractionated heparin and bivalirudin. The median duration of PCI was longer in men than women, but the choice of access site was similar.

When the researchers adjusted for potentially confounding factors, they found that being female was independently associated with higher odds of the primary efficacy outcome (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]=1.30) and GUSTO moderate or severe bleeding (aOR=2.70).

Efficacy and safety

For women, cangrelor was associated with a significant decrease in the odds of achieving the primary efficacy endpoint. Men were less likely to achieve the endpoint when on cangrelor as well, but the difference between the cangrelor and clopidogrel arms was not statistically significant for men.

The percentage of women who met criteria for the primary efficacy endpoint was 4.8% in the cangrelor arm and 6.9% in the clopidogrel arm (aOR=0.65, P=0.01). The percentage of men who did so was 4.7% in the cangrelor arm and 5.5% in the clopidogrel arm (aOR=0.86, P=0.14, P interaction=0.23).

Cangrelor was associated with a significantly lower risk of stent thrombosis at 48 hours for women but not men.

For women, the incidence of stent thrombosis was 0.8% in the cangrelor arm and 1.9% in the clopidogrel arm (aOR=0.39, P=0.01). For men, the rates were 0.9% and 1.1%, respectively (aOR=0.84, P=0.44, P interaction=0.11).

There was no significant difference in severe bleeding between the treatment arms for men or women, but women had a significantly higher risk of moderate bleeding if they received cangrelor.

For women, the rate of severe bleeding was 0.3% in the cangrelor arm and 0.2% in the clopidogrel arm (aOR=2.37, P=0.30). For men, the rates were 0.1% in both arms (aOR=2.04, P=0.41, P interaction=0.88 ).

For women, the rate of moderate bleeding was 0.9% in the cangrelor arm and 0.3% in the clopidogrel arm (aOR=3.63, P=0.02). For men, the rates were 0.2% in both arms (aOR=0.81, P=0.68, P interaction=0.04). ![]()

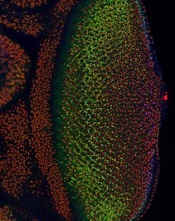

New insight into CLL development

Photo by Graham Colm

New research indicates that chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) can develop during nearly any stage of B-cell maturation.

However, CLL that arises from more progressive maturation stages responds better to therapy.

The study also suggests that most methylation events that were previously thought to be tumor-specific are normally present in non-malignant B cells.

These findings were published in Nature Genetics.

Christoph Plass, PhD, of the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) in Heidelberg, and his colleagues conducted this study to determine which development stage of B cells marks the origin of B-cell CLL.

The team took blood samples from 268 CLL patients, separated the blood cells using specific B-cell maturation markers and analyzed the methylation patterns of each individual maturation stage.

The investigators were surprised to find that CLL can develop from almost all maturation stages. They also found that maturation was associated with “increasingly favorable clinical outcomes.”

In addition, methylation patterns that were previously regarded as cancer-specific actually reflect the characteristic patterns of the development stages at the moment of cancerous transformation.

The investigators found that the cell “freezes” this methylation pattern, and this is followed by only a few changes that are truly cancer-specific.

The team said they used advanced bioinformatic methods to calculate the small percentage of cancer-specific methylation patterns from the wealth of maturation-related variations.

“Up until recently, it was technically impossible to study the various maturation stages in such detail as we have done,” Dr Plass said. “It took the advanced sequencing technology and the powerful bioinformatic methods that we have available now to make such a detailed comparison possible.”

The investigators said their findings differ from those of prior studies because, with the current study, they compared CLL cells with the whole pool of B-cell maturation stages.

“All differences found were attributed to cancer,” Dr Plass said, adding that some previous works on the cancer epigenome will need to be re-interpreted in the light of the current results.

Next, Dr Plass and his colleagues want to examine other cancer types to determine whether methylation patterns that are thought to be cancer-specific also arise from the normal cellular maturation program. In particular, they plan to study other hematologic malignancies and prostate cancer. ![]()

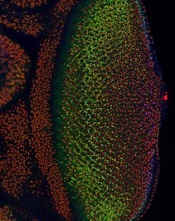

Photo by Graham Colm

New research indicates that chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) can develop during nearly any stage of B-cell maturation.

However, CLL that arises from more progressive maturation stages responds better to therapy.

The study also suggests that most methylation events that were previously thought to be tumor-specific are normally present in non-malignant B cells.

These findings were published in Nature Genetics.

Christoph Plass, PhD, of the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) in Heidelberg, and his colleagues conducted this study to determine which development stage of B cells marks the origin of B-cell CLL.

The team took blood samples from 268 CLL patients, separated the blood cells using specific B-cell maturation markers and analyzed the methylation patterns of each individual maturation stage.

The investigators were surprised to find that CLL can develop from almost all maturation stages. They also found that maturation was associated with “increasingly favorable clinical outcomes.”

In addition, methylation patterns that were previously regarded as cancer-specific actually reflect the characteristic patterns of the development stages at the moment of cancerous transformation.

The investigators found that the cell “freezes” this methylation pattern, and this is followed by only a few changes that are truly cancer-specific.

The team said they used advanced bioinformatic methods to calculate the small percentage of cancer-specific methylation patterns from the wealth of maturation-related variations.

“Up until recently, it was technically impossible to study the various maturation stages in such detail as we have done,” Dr Plass said. “It took the advanced sequencing technology and the powerful bioinformatic methods that we have available now to make such a detailed comparison possible.”

The investigators said their findings differ from those of prior studies because, with the current study, they compared CLL cells with the whole pool of B-cell maturation stages.

“All differences found were attributed to cancer,” Dr Plass said, adding that some previous works on the cancer epigenome will need to be re-interpreted in the light of the current results.

Next, Dr Plass and his colleagues want to examine other cancer types to determine whether methylation patterns that are thought to be cancer-specific also arise from the normal cellular maturation program. In particular, they plan to study other hematologic malignancies and prostate cancer. ![]()

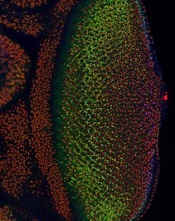

Photo by Graham Colm

New research indicates that chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) can develop during nearly any stage of B-cell maturation.

However, CLL that arises from more progressive maturation stages responds better to therapy.

The study also suggests that most methylation events that were previously thought to be tumor-specific are normally present in non-malignant B cells.

These findings were published in Nature Genetics.

Christoph Plass, PhD, of the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) in Heidelberg, and his colleagues conducted this study to determine which development stage of B cells marks the origin of B-cell CLL.

The team took blood samples from 268 CLL patients, separated the blood cells using specific B-cell maturation markers and analyzed the methylation patterns of each individual maturation stage.

The investigators were surprised to find that CLL can develop from almost all maturation stages. They also found that maturation was associated with “increasingly favorable clinical outcomes.”

In addition, methylation patterns that were previously regarded as cancer-specific actually reflect the characteristic patterns of the development stages at the moment of cancerous transformation.

The investigators found that the cell “freezes” this methylation pattern, and this is followed by only a few changes that are truly cancer-specific.

The team said they used advanced bioinformatic methods to calculate the small percentage of cancer-specific methylation patterns from the wealth of maturation-related variations.

“Up until recently, it was technically impossible to study the various maturation stages in such detail as we have done,” Dr Plass said. “It took the advanced sequencing technology and the powerful bioinformatic methods that we have available now to make such a detailed comparison possible.”

The investigators said their findings differ from those of prior studies because, with the current study, they compared CLL cells with the whole pool of B-cell maturation stages.

“All differences found were attributed to cancer,” Dr Plass said, adding that some previous works on the cancer epigenome will need to be re-interpreted in the light of the current results.

Next, Dr Plass and his colleagues want to examine other cancer types to determine whether methylation patterns that are thought to be cancer-specific also arise from the normal cellular maturation program. In particular, they plan to study other hematologic malignancies and prostate cancer. ![]()

VIDEO: Preventing healthcare acquired infections after CT surgery

PHOENIX – More and more attention is being paid to preventing healthcare acquired infections (HAIs) in the hospital setting, and the role of HAIs in cardiothoracic surgery is a particlularly important area of focus.

“The good news is that cardiothoracic surgeons are really good at preventing infections. There’s been a lot of pressure over the past many years to report infections after cardiothoracic surgery, and so they’ve gotten a lot of things right,” Dr. Emily Landon said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

“However, patients that undergo cardiothoracic surgery are still at risk of the infections that plague everyone in hospitals ... all of these are a problem based on whatever the hospital’s current situation is.”

Dr. Landon, who is the medical director of antimicrobial stewardship and infection control at University of Chicago Medicine, Chicago, discussed how cardiothroacic surgeons can maintain their own good outcomes and how they can have a postive impact outside the OR on protecting their patients after surgery.

Dr. Landon reported having no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

PHOENIX – More and more attention is being paid to preventing healthcare acquired infections (HAIs) in the hospital setting, and the role of HAIs in cardiothoracic surgery is a particlularly important area of focus.

“The good news is that cardiothoracic surgeons are really good at preventing infections. There’s been a lot of pressure over the past many years to report infections after cardiothoracic surgery, and so they’ve gotten a lot of things right,” Dr. Emily Landon said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

“However, patients that undergo cardiothoracic surgery are still at risk of the infections that plague everyone in hospitals ... all of these are a problem based on whatever the hospital’s current situation is.”

Dr. Landon, who is the medical director of antimicrobial stewardship and infection control at University of Chicago Medicine, Chicago, discussed how cardiothroacic surgeons can maintain their own good outcomes and how they can have a postive impact outside the OR on protecting their patients after surgery.

Dr. Landon reported having no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

PHOENIX – More and more attention is being paid to preventing healthcare acquired infections (HAIs) in the hospital setting, and the role of HAIs in cardiothoracic surgery is a particlularly important area of focus.

“The good news is that cardiothoracic surgeons are really good at preventing infections. There’s been a lot of pressure over the past many years to report infections after cardiothoracic surgery, and so they’ve gotten a lot of things right,” Dr. Emily Landon said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

“However, patients that undergo cardiothoracic surgery are still at risk of the infections that plague everyone in hospitals ... all of these are a problem based on whatever the hospital’s current situation is.”

Dr. Landon, who is the medical director of antimicrobial stewardship and infection control at University of Chicago Medicine, Chicago, discussed how cardiothroacic surgeons can maintain their own good outcomes and how they can have a postive impact outside the OR on protecting their patients after surgery.

Dr. Landon reported having no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE STS ANNUAL MEETING

Proper hydroxyurea dose tied to better survival in sickle cell anemia

Adults with sickle cell disease who received recommended doses of hydroxyurea had higher fetal hemoglobin (HbF) levels, less organ dysfunction, and improved survival, compared with those who did receive recommended hydroxyurea doses, according to researchers.

“Our data suggest that even moderate increases, and not necessarily maximum HbF induction, may improve survival in patients with sickle cell anemia,” wrote Dr. Courtney D. Fitzhugh, assistant clinical investigator in the Laboratory of Sickle Mortality Prevention at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Md., and her colleagues (PLoS One. 2015 Nov 17; doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0141706).

From 2001 to 2010, 383 patients with sickle cell disease underwent data clinical, laboratory, and echocardiographic evaluations every 2 years during a median follow-up of 2.6 years (range, 0.1-11.7).

In total, 59 patients died, and the median age at death was 46 years for men and 44.5 for women. Deceased subjects had lower fetal hemoglobin (P = .0044), were less likely to have taken hydroxyurea (56% vs. 68%, P = .040), and had a smaller proportion who were prescribed hydroxyurea within the recommended dose range (29% vs. 46%, P = .0039). Study participants who received a dose between 15 and 35 mg/kg/day more likely survived than those who never took hydroxyurea (P = .005). To assess the impact of hydroxyurea-induced HbF on organ injury, the study compared laboratory values from the highest and lowest HbF quartiles. For the lowest HbF quartile, alkaline phosphatase, a marker of organ damage, was consistently lower. “Because organ dysfunction may limit dosing, and hydroxyurea may not reverse severe tissue injury, we recommend treatment before organ damage occurs,” the researchers wrote.

Dr. Fitzhugh reported having no disclosures.

Adults with sickle cell disease who received recommended doses of hydroxyurea had higher fetal hemoglobin (HbF) levels, less organ dysfunction, and improved survival, compared with those who did receive recommended hydroxyurea doses, according to researchers.

“Our data suggest that even moderate increases, and not necessarily maximum HbF induction, may improve survival in patients with sickle cell anemia,” wrote Dr. Courtney D. Fitzhugh, assistant clinical investigator in the Laboratory of Sickle Mortality Prevention at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Md., and her colleagues (PLoS One. 2015 Nov 17; doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0141706).

From 2001 to 2010, 383 patients with sickle cell disease underwent data clinical, laboratory, and echocardiographic evaluations every 2 years during a median follow-up of 2.6 years (range, 0.1-11.7).

In total, 59 patients died, and the median age at death was 46 years for men and 44.5 for women. Deceased subjects had lower fetal hemoglobin (P = .0044), were less likely to have taken hydroxyurea (56% vs. 68%, P = .040), and had a smaller proportion who were prescribed hydroxyurea within the recommended dose range (29% vs. 46%, P = .0039). Study participants who received a dose between 15 and 35 mg/kg/day more likely survived than those who never took hydroxyurea (P = .005). To assess the impact of hydroxyurea-induced HbF on organ injury, the study compared laboratory values from the highest and lowest HbF quartiles. For the lowest HbF quartile, alkaline phosphatase, a marker of organ damage, was consistently lower. “Because organ dysfunction may limit dosing, and hydroxyurea may not reverse severe tissue injury, we recommend treatment before organ damage occurs,” the researchers wrote.

Dr. Fitzhugh reported having no disclosures.

Adults with sickle cell disease who received recommended doses of hydroxyurea had higher fetal hemoglobin (HbF) levels, less organ dysfunction, and improved survival, compared with those who did receive recommended hydroxyurea doses, according to researchers.

“Our data suggest that even moderate increases, and not necessarily maximum HbF induction, may improve survival in patients with sickle cell anemia,” wrote Dr. Courtney D. Fitzhugh, assistant clinical investigator in the Laboratory of Sickle Mortality Prevention at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Md., and her colleagues (PLoS One. 2015 Nov 17; doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0141706).

From 2001 to 2010, 383 patients with sickle cell disease underwent data clinical, laboratory, and echocardiographic evaluations every 2 years during a median follow-up of 2.6 years (range, 0.1-11.7).

In total, 59 patients died, and the median age at death was 46 years for men and 44.5 for women. Deceased subjects had lower fetal hemoglobin (P = .0044), were less likely to have taken hydroxyurea (56% vs. 68%, P = .040), and had a smaller proportion who were prescribed hydroxyurea within the recommended dose range (29% vs. 46%, P = .0039). Study participants who received a dose between 15 and 35 mg/kg/day more likely survived than those who never took hydroxyurea (P = .005). To assess the impact of hydroxyurea-induced HbF on organ injury, the study compared laboratory values from the highest and lowest HbF quartiles. For the lowest HbF quartile, alkaline phosphatase, a marker of organ damage, was consistently lower. “Because organ dysfunction may limit dosing, and hydroxyurea may not reverse severe tissue injury, we recommend treatment before organ damage occurs,” the researchers wrote.

Dr. Fitzhugh reported having no disclosures.

FROM PLOS ONE

Key clinical point: Proper hydroxyurea dose in adults with sickle cell anemia was linked to higher fetal hemoglobin levels, less organ dysfunction, and improved survival.

Major finding: Patients in the highest fetal hemoglobin quartiles had higher rates of survival, and 75% of patients in the highest quartile received recommended hydroxyurea doses, compared with 18% in the lowest quartile.

Data source: From 2001 to 2010, 383 patients with sickle cell disease underwent data clinical, laboratory, and echocardiographic evaluations at enrollment and every two years subsequently.

Disclosures: Dr. Fitzhugh reported having no disclosures.

Fruit fly findings may have implications for leukemia, other cancers

Image courtesy of

Northwestern University

In studying the fruit fly equivalent of an oncogene implicated in human leukemias, researchers have gained insight into how developing cells switch to a specialized state and how that process might go awry in cancers.

The team found that levels of the protein Yan start fluctuating wildly when a cell is switching from a stem-like state to a more specialized state. If the levels of Yan don’t or can’t fluctuate, the cell doesn’t differentiate.

The Yan protein is called Tel-1 in humans, and the gene that produces the Tel-1 protein, the Tel-1 oncogene, is frequently mutated in human leukemias.

Richard W. Carthew, PhD, of Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, and his colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in eLife.

The researchers studied cell behavior in the eye of Drosophila melanogaster, the common fruit fly, which has many of the same oncogenes as humans.

The team was surprised to discover that fluctuating levels of Yan were needed for cell differentiation.

“This mad fluctuation, or noise, happens at the time of cell transition,” Dr Carthew explained. “For the first time, we see there is a brief time period as the developing cell goes from point A to point B. The noise is a state of ‘in between’ and is important for cells to switch to a more specialized state. This limbo might be where normal cells take a cancerous path.”

He noted that it takes 15 to 20 hours for a fruit fly cell to transition from an unspecialized to a specialized state. The researchers found the Yan protein is “noisy,” or fluctuating, for 6 to 8 of those hours.

The team also found that a molecular signal received by the cell receptor EGFR is important for turning the noise off. If that signal is not received, the cell remains in an uncontrolled state.

The EGFR protein that turns off the noise in flies is called Her-2 in humans, and the Her-2 oncogene is known to play an important role in breast cancer.

“On the surface, flies and humans are very different, but we share a remarkable amount of infrastructure,” Dr Carthew noted. “We can use fruit fly genetics to understand how humans work and how things go wrong in cancer and other diseases.” ![]()

Image courtesy of

Northwestern University

In studying the fruit fly equivalent of an oncogene implicated in human leukemias, researchers have gained insight into how developing cells switch to a specialized state and how that process might go awry in cancers.

The team found that levels of the protein Yan start fluctuating wildly when a cell is switching from a stem-like state to a more specialized state. If the levels of Yan don’t or can’t fluctuate, the cell doesn’t differentiate.

The Yan protein is called Tel-1 in humans, and the gene that produces the Tel-1 protein, the Tel-1 oncogene, is frequently mutated in human leukemias.

Richard W. Carthew, PhD, of Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, and his colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in eLife.

The researchers studied cell behavior in the eye of Drosophila melanogaster, the common fruit fly, which has many of the same oncogenes as humans.

The team was surprised to discover that fluctuating levels of Yan were needed for cell differentiation.

“This mad fluctuation, or noise, happens at the time of cell transition,” Dr Carthew explained. “For the first time, we see there is a brief time period as the developing cell goes from point A to point B. The noise is a state of ‘in between’ and is important for cells to switch to a more specialized state. This limbo might be where normal cells take a cancerous path.”

He noted that it takes 15 to 20 hours for a fruit fly cell to transition from an unspecialized to a specialized state. The researchers found the Yan protein is “noisy,” or fluctuating, for 6 to 8 of those hours.

The team also found that a molecular signal received by the cell receptor EGFR is important for turning the noise off. If that signal is not received, the cell remains in an uncontrolled state.

The EGFR protein that turns off the noise in flies is called Her-2 in humans, and the Her-2 oncogene is known to play an important role in breast cancer.

“On the surface, flies and humans are very different, but we share a remarkable amount of infrastructure,” Dr Carthew noted. “We can use fruit fly genetics to understand how humans work and how things go wrong in cancer and other diseases.” ![]()

Image courtesy of

Northwestern University

In studying the fruit fly equivalent of an oncogene implicated in human leukemias, researchers have gained insight into how developing cells switch to a specialized state and how that process might go awry in cancers.

The team found that levels of the protein Yan start fluctuating wildly when a cell is switching from a stem-like state to a more specialized state. If the levels of Yan don’t or can’t fluctuate, the cell doesn’t differentiate.

The Yan protein is called Tel-1 in humans, and the gene that produces the Tel-1 protein, the Tel-1 oncogene, is frequently mutated in human leukemias.

Richard W. Carthew, PhD, of Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, and his colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in eLife.

The researchers studied cell behavior in the eye of Drosophila melanogaster, the common fruit fly, which has many of the same oncogenes as humans.

The team was surprised to discover that fluctuating levels of Yan were needed for cell differentiation.

“This mad fluctuation, or noise, happens at the time of cell transition,” Dr Carthew explained. “For the first time, we see there is a brief time period as the developing cell goes from point A to point B. The noise is a state of ‘in between’ and is important for cells to switch to a more specialized state. This limbo might be where normal cells take a cancerous path.”

He noted that it takes 15 to 20 hours for a fruit fly cell to transition from an unspecialized to a specialized state. The researchers found the Yan protein is “noisy,” or fluctuating, for 6 to 8 of those hours.

The team also found that a molecular signal received by the cell receptor EGFR is important for turning the noise off. If that signal is not received, the cell remains in an uncontrolled state.

The EGFR protein that turns off the noise in flies is called Her-2 in humans, and the Her-2 oncogene is known to play an important role in breast cancer.

“On the surface, flies and humans are very different, but we share a remarkable amount of infrastructure,” Dr Carthew noted. “We can use fruit fly genetics to understand how humans work and how things go wrong in cancer and other diseases.” ![]()

Simple change increases forced-air warming use in trauma

SAN ANTONIO – A month-long quality improvement project to increase the use of forced-air warming blankets reduced mean hypothermia times in trauma patients at Parkland Memorial Hospital, Dallas, from 229 to 154 minutes.

All it took to get doctors, nurses, and staff to use the forced-air warming blankets more often was a reminder that hypothermia is an independent predictor of death in trauma, and data showing that Parkland, a Level 1 trauma center, used forced-air warming in just 11% of its hypothermic trauma patients. Meetings to get those points across were held in December 2014.

Forced-air warming jumped to 70% of hypothermic patients over the next 4 months in 2015 (P equal to or less than .0001), leading to the 33% drop in rewarming times (P = .009). The improvement came without any shift in the use of the rewarming methods trauma teams were in the habit of using: warm blankets, room air, and IV fluids.

Investigator Dr. Frank Zhao thinks it’s something all trauma centers can and should do. “There’s no reason that we shouldn’t recommend this be part of the rewarming protocol in every trauma center. It took about a month to roll this out so everyone was on the same page and was easily achieved,” said Dr. Zhao, formerly a Parkland surgery resident but now a trauma and surgical critical care fellow at the Oregon Health and Sciences University in Portland.

The blankets are an almost universal presence in operating rooms to keep core temperatures at least 36 degrees Celsius, but “from what I’ve seen at multiple institutions, the Bair Hugger is probably one of the least used warming methods” in trauma. “They’re recommended for trauma rewarming, but we [didn’t] use them very often.” Staff were not in the habit, he said at the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma scientific assembly.

From July to November 2014, before the intervention, 15.2% (114) of Levels 1 and 2 trauma patients arrived at Parkland hypothermic, versus 20.9% (82) during the colder period of January-April 2015. Almost 80% of the trauma patients over that time were male, and the average patient age was about 40 years.

The investigators have no disclosures, and there was no outside funding for the project.

SAN ANTONIO – A month-long quality improvement project to increase the use of forced-air warming blankets reduced mean hypothermia times in trauma patients at Parkland Memorial Hospital, Dallas, from 229 to 154 minutes.

All it took to get doctors, nurses, and staff to use the forced-air warming blankets more often was a reminder that hypothermia is an independent predictor of death in trauma, and data showing that Parkland, a Level 1 trauma center, used forced-air warming in just 11% of its hypothermic trauma patients. Meetings to get those points across were held in December 2014.

Forced-air warming jumped to 70% of hypothermic patients over the next 4 months in 2015 (P equal to or less than .0001), leading to the 33% drop in rewarming times (P = .009). The improvement came without any shift in the use of the rewarming methods trauma teams were in the habit of using: warm blankets, room air, and IV fluids.

Investigator Dr. Frank Zhao thinks it’s something all trauma centers can and should do. “There’s no reason that we shouldn’t recommend this be part of the rewarming protocol in every trauma center. It took about a month to roll this out so everyone was on the same page and was easily achieved,” said Dr. Zhao, formerly a Parkland surgery resident but now a trauma and surgical critical care fellow at the Oregon Health and Sciences University in Portland.

The blankets are an almost universal presence in operating rooms to keep core temperatures at least 36 degrees Celsius, but “from what I’ve seen at multiple institutions, the Bair Hugger is probably one of the least used warming methods” in trauma. “They’re recommended for trauma rewarming, but we [didn’t] use them very often.” Staff were not in the habit, he said at the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma scientific assembly.

From July to November 2014, before the intervention, 15.2% (114) of Levels 1 and 2 trauma patients arrived at Parkland hypothermic, versus 20.9% (82) during the colder period of January-April 2015. Almost 80% of the trauma patients over that time were male, and the average patient age was about 40 years.

The investigators have no disclosures, and there was no outside funding for the project.

SAN ANTONIO – A month-long quality improvement project to increase the use of forced-air warming blankets reduced mean hypothermia times in trauma patients at Parkland Memorial Hospital, Dallas, from 229 to 154 minutes.

All it took to get doctors, nurses, and staff to use the forced-air warming blankets more often was a reminder that hypothermia is an independent predictor of death in trauma, and data showing that Parkland, a Level 1 trauma center, used forced-air warming in just 11% of its hypothermic trauma patients. Meetings to get those points across were held in December 2014.

Forced-air warming jumped to 70% of hypothermic patients over the next 4 months in 2015 (P equal to or less than .0001), leading to the 33% drop in rewarming times (P = .009). The improvement came without any shift in the use of the rewarming methods trauma teams were in the habit of using: warm blankets, room air, and IV fluids.

Investigator Dr. Frank Zhao thinks it’s something all trauma centers can and should do. “There’s no reason that we shouldn’t recommend this be part of the rewarming protocol in every trauma center. It took about a month to roll this out so everyone was on the same page and was easily achieved,” said Dr. Zhao, formerly a Parkland surgery resident but now a trauma and surgical critical care fellow at the Oregon Health and Sciences University in Portland.

The blankets are an almost universal presence in operating rooms to keep core temperatures at least 36 degrees Celsius, but “from what I’ve seen at multiple institutions, the Bair Hugger is probably one of the least used warming methods” in trauma. “They’re recommended for trauma rewarming, but we [didn’t] use them very often.” Staff were not in the habit, he said at the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma scientific assembly.

From July to November 2014, before the intervention, 15.2% (114) of Levels 1 and 2 trauma patients arrived at Parkland hypothermic, versus 20.9% (82) during the colder period of January-April 2015. Almost 80% of the trauma patients over that time were male, and the average patient age was about 40 years.

The investigators have no disclosures, and there was no outside funding for the project.

AT THE EAST SCIENTIFIC ASSEMBLY

Key clinical point: It can take as little as a month to make forced-air warming blankets a routine part of hypothermia care in trauma.

Major finding: A month-long quality improvement project to increase the use of forced-air warming blankets reduced mean hypothermia times at a Level 1 trauma center from 229 to 154 minutes.

Data source: The project involved 196 hypothermic trauma patients

Disclosures: The investigators have no disclosures, and there was no outside funding for the project.

Minimal residual disease a powerful prognostic factor in AML

The presence of minimal residual disease predicts relapse in patients with NMP1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia and is superior to currently used molecular genetic markers in determining whether these patients should be considered for stem cell transplantation, a new study has found.

At 3 years, patients with minimal residual disease (MRD) had a significantly greater risk of relapse than those with no MRD (82% vs. 30%; univariate hazard ratio, 4.80; P less than .001) and a lower rate of survival (24% vs. 75%; univariate HR, 4.38; P less than .001), Adam Ivey of King’s College London reported (N Engl J Med. 2016; doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1507471).

In an editorial that accompanied the study Dr. Michael J. Burke from the Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin in Milwaukee wrote, “Time will tell, but this moment may prove to be a pivotal one in the assessment of minimal residual disease to assign treatment in patients with AML” (N Engl J Med. 2016; doi:10.1056/NEJMe1515525).

In adult AML, assessment of MRD has taken a back seat to analyses of cytogenetic and molecular lesions in determining a patient’s risk and treatment strategy. Typically, allogeneic stem cell transplantation is used for patients with high-risk features such as chromosome 3, 5, or 7 abnormalities or the FLT3-internal tandem duplication (ITD) mutation, while chemotherapy alone is used for low-risk disease.

The role of transplantation is unclear, however, for cytogenetically standard-risk patients, which includes those with a mutation in the gene encoding nucleophosmin (NPM1).

To address this issue, the investigators used a reverse-transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction assay to evaluate 2,569 bone marrow and peripheral-blood samples from 346 patients with NPM1 mutations who had completed two cycles of induction chemotherapy in the U.K. National Cancer Research Institute AML17 trial.

MRD, defined as persistence of NPM1-mutated transcripts in peripheral blood, was present in 15% of patients after the second chemotherapy cycle.

Patients with MRD were significantly more likely than those without MRD to have a high U.K. Medical Research Council clinical risk score and to carry the FLT3-ITD mutation.

On univariate analysis, the risk of relapse was significantly higher with the presence of MRD in peripheral blood, an increased white cell count, and with the DNMT3A and FLT3-ITD mutations.

Only the presence of MRD and an elevated white cell count significantly predicted survival, Mr. Ivey reported.

“We could find no specific molecular subgroup consisting of 10 patients or more that had a rate of survival less than 52%; in contrast, the rate in the group with the presence of minimal residual disease was 24%,” he observed.

In multivariate analysis, the presence of MRD was the only significant prognostic factor for relapse (HR, 5.09; P less than .001) or death (HR, 4.84; P less than .001).

The results were validated in an independent cohort of 91 AML17 study patients. It confirmed that MRD in peripheral blood predicts worse outcome at 2 years than the absence of MRD, with a cumulative incidence of relapse of 70% vs. 31% (P = .001) and overall survival rates of 40% vs. 87% (P = .001), reported the investigators, including senior author Professor David Grimwade, also from King’s College London.

The clinical implications of these results “are substantive” because NPM-1 mutated AML is the most common subtype of AML and because of the uncertainty over the best treatment strategy for patients typically classified as standard risk, editorialist Dr. Burke observed.

“Now with the ability to reclassify standard-risk or low-risk patients as high-risk on the basis of the persistent expression of mutant NPM1 transcripts, it may be possible that stem-cell transplantation is a better approach in patients who otherwise would be treated with chemotherapy alone and that transplantation may be avoidable in high-risk patients who have no evidence of minimal residual disease,” he wrote. “Such predictions will need to be tested prospectively.”

The presence of MRD is also known to be an important independent prognostic factor in acute lymphoblastic leukemia, but since AML has a greater molecular heterogeneity, routine MRD assessment has not been as quickly adopted in AML, Dr. Burke noted.

The Children’s Oncology Group, however, recently adopted MRD assessment by flow cytometry to further stratify children with newly diagnosed AML after first induction therapy into low-risk or high-risk groups.

The study was supported by grants from Bloodwise and the National Institute for Health Research. Mr. Ivey and Dr. Burke reported having no disclosures.

The presence of minimal residual disease predicts relapse in patients with NMP1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia and is superior to currently used molecular genetic markers in determining whether these patients should be considered for stem cell transplantation, a new study has found.

At 3 years, patients with minimal residual disease (MRD) had a significantly greater risk of relapse than those with no MRD (82% vs. 30%; univariate hazard ratio, 4.80; P less than .001) and a lower rate of survival (24% vs. 75%; univariate HR, 4.38; P less than .001), Adam Ivey of King’s College London reported (N Engl J Med. 2016; doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1507471).

In an editorial that accompanied the study Dr. Michael J. Burke from the Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin in Milwaukee wrote, “Time will tell, but this moment may prove to be a pivotal one in the assessment of minimal residual disease to assign treatment in patients with AML” (N Engl J Med. 2016; doi:10.1056/NEJMe1515525).

In adult AML, assessment of MRD has taken a back seat to analyses of cytogenetic and molecular lesions in determining a patient’s risk and treatment strategy. Typically, allogeneic stem cell transplantation is used for patients with high-risk features such as chromosome 3, 5, or 7 abnormalities or the FLT3-internal tandem duplication (ITD) mutation, while chemotherapy alone is used for low-risk disease.

The role of transplantation is unclear, however, for cytogenetically standard-risk patients, which includes those with a mutation in the gene encoding nucleophosmin (NPM1).

To address this issue, the investigators used a reverse-transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction assay to evaluate 2,569 bone marrow and peripheral-blood samples from 346 patients with NPM1 mutations who had completed two cycles of induction chemotherapy in the U.K. National Cancer Research Institute AML17 trial.

MRD, defined as persistence of NPM1-mutated transcripts in peripheral blood, was present in 15% of patients after the second chemotherapy cycle.

Patients with MRD were significantly more likely than those without MRD to have a high U.K. Medical Research Council clinical risk score and to carry the FLT3-ITD mutation.

On univariate analysis, the risk of relapse was significantly higher with the presence of MRD in peripheral blood, an increased white cell count, and with the DNMT3A and FLT3-ITD mutations.

Only the presence of MRD and an elevated white cell count significantly predicted survival, Mr. Ivey reported.

“We could find no specific molecular subgroup consisting of 10 patients or more that had a rate of survival less than 52%; in contrast, the rate in the group with the presence of minimal residual disease was 24%,” he observed.

In multivariate analysis, the presence of MRD was the only significant prognostic factor for relapse (HR, 5.09; P less than .001) or death (HR, 4.84; P less than .001).

The results were validated in an independent cohort of 91 AML17 study patients. It confirmed that MRD in peripheral blood predicts worse outcome at 2 years than the absence of MRD, with a cumulative incidence of relapse of 70% vs. 31% (P = .001) and overall survival rates of 40% vs. 87% (P = .001), reported the investigators, including senior author Professor David Grimwade, also from King’s College London.

The clinical implications of these results “are substantive” because NPM-1 mutated AML is the most common subtype of AML and because of the uncertainty over the best treatment strategy for patients typically classified as standard risk, editorialist Dr. Burke observed.

“Now with the ability to reclassify standard-risk or low-risk patients as high-risk on the basis of the persistent expression of mutant NPM1 transcripts, it may be possible that stem-cell transplantation is a better approach in patients who otherwise would be treated with chemotherapy alone and that transplantation may be avoidable in high-risk patients who have no evidence of minimal residual disease,” he wrote. “Such predictions will need to be tested prospectively.”

The presence of MRD is also known to be an important independent prognostic factor in acute lymphoblastic leukemia, but since AML has a greater molecular heterogeneity, routine MRD assessment has not been as quickly adopted in AML, Dr. Burke noted.

The Children’s Oncology Group, however, recently adopted MRD assessment by flow cytometry to further stratify children with newly diagnosed AML after first induction therapy into low-risk or high-risk groups.

The study was supported by grants from Bloodwise and the National Institute for Health Research. Mr. Ivey and Dr. Burke reported having no disclosures.

The presence of minimal residual disease predicts relapse in patients with NMP1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia and is superior to currently used molecular genetic markers in determining whether these patients should be considered for stem cell transplantation, a new study has found.

At 3 years, patients with minimal residual disease (MRD) had a significantly greater risk of relapse than those with no MRD (82% vs. 30%; univariate hazard ratio, 4.80; P less than .001) and a lower rate of survival (24% vs. 75%; univariate HR, 4.38; P less than .001), Adam Ivey of King’s College London reported (N Engl J Med. 2016; doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1507471).

In an editorial that accompanied the study Dr. Michael J. Burke from the Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin in Milwaukee wrote, “Time will tell, but this moment may prove to be a pivotal one in the assessment of minimal residual disease to assign treatment in patients with AML” (N Engl J Med. 2016; doi:10.1056/NEJMe1515525).

In adult AML, assessment of MRD has taken a back seat to analyses of cytogenetic and molecular lesions in determining a patient’s risk and treatment strategy. Typically, allogeneic stem cell transplantation is used for patients with high-risk features such as chromosome 3, 5, or 7 abnormalities or the FLT3-internal tandem duplication (ITD) mutation, while chemotherapy alone is used for low-risk disease.

The role of transplantation is unclear, however, for cytogenetically standard-risk patients, which includes those with a mutation in the gene encoding nucleophosmin (NPM1).

To address this issue, the investigators used a reverse-transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction assay to evaluate 2,569 bone marrow and peripheral-blood samples from 346 patients with NPM1 mutations who had completed two cycles of induction chemotherapy in the U.K. National Cancer Research Institute AML17 trial.

MRD, defined as persistence of NPM1-mutated transcripts in peripheral blood, was present in 15% of patients after the second chemotherapy cycle.

Patients with MRD were significantly more likely than those without MRD to have a high U.K. Medical Research Council clinical risk score and to carry the FLT3-ITD mutation.

On univariate analysis, the risk of relapse was significantly higher with the presence of MRD in peripheral blood, an increased white cell count, and with the DNMT3A and FLT3-ITD mutations.

Only the presence of MRD and an elevated white cell count significantly predicted survival, Mr. Ivey reported.

“We could find no specific molecular subgroup consisting of 10 patients or more that had a rate of survival less than 52%; in contrast, the rate in the group with the presence of minimal residual disease was 24%,” he observed.

In multivariate analysis, the presence of MRD was the only significant prognostic factor for relapse (HR, 5.09; P less than .001) or death (HR, 4.84; P less than .001).

The results were validated in an independent cohort of 91 AML17 study patients. It confirmed that MRD in peripheral blood predicts worse outcome at 2 years than the absence of MRD, with a cumulative incidence of relapse of 70% vs. 31% (P = .001) and overall survival rates of 40% vs. 87% (P = .001), reported the investigators, including senior author Professor David Grimwade, also from King’s College London.

The clinical implications of these results “are substantive” because NPM-1 mutated AML is the most common subtype of AML and because of the uncertainty over the best treatment strategy for patients typically classified as standard risk, editorialist Dr. Burke observed.

“Now with the ability to reclassify standard-risk or low-risk patients as high-risk on the basis of the persistent expression of mutant NPM1 transcripts, it may be possible that stem-cell transplantation is a better approach in patients who otherwise would be treated with chemotherapy alone and that transplantation may be avoidable in high-risk patients who have no evidence of minimal residual disease,” he wrote. “Such predictions will need to be tested prospectively.”

The presence of MRD is also known to be an important independent prognostic factor in acute lymphoblastic leukemia, but since AML has a greater molecular heterogeneity, routine MRD assessment has not been as quickly adopted in AML, Dr. Burke noted.

The Children’s Oncology Group, however, recently adopted MRD assessment by flow cytometry to further stratify children with newly diagnosed AML after first induction therapy into low-risk or high-risk groups.

The study was supported by grants from Bloodwise and the National Institute for Health Research. Mr. Ivey and Dr. Burke reported having no disclosures.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: The presence of minimal residual disease provides powerful prognostic information independent of other risk factors in patients with NPM1-mutated AML.

Major finding: Minimal residual disease was associated with a significantly greater risk of relapse than absence of MRD (82% vs. 30%; hazard ratio, 4.80; P less than .001) and a lower rate of survival (24% vs. 75%; HR, 4.38, P less than .001).

Data source: Analysis of 346 patients with NPM1-mutated AML.

Disclosures: The study was supported by grants from Bloodwise and the National Institute for Health Research. Mr. Ivey and Dr. Burke reported having no disclosures.

Baux cut-points predict geriatric burn outcomes

SAN ANTONIO – Geriatric burn patients have less than a 50% chance of returning home with a Baux score of about 85, and the risk of death begins to climb steadily after a score 93, approaching 50% at 110 points and almost 100% at 130 points, according to a review of 8,001 elderly patients in the National Burn Repository.

The investigators are developing the findings into a decision-making tool to help counsel families and caregivers about their options when elderly loved ones are seriously burned.

“There’s just not a lot of data out there on prognosis after burn injury in the geriatric population. We thought a simple decision aid for discussion with key stakeholders would provide significant assistance,” said investigator Dr. Erica Hodgman, a surgery research resident at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

The hope is that families and caregivers will be able to better judge if the patient would want to press on with treatment given the odds of returning home, being discharged to a skilled nursing or rehab facility, or dying. “I think it will help people” feel less guilty if they decide to withdraw care or not send patients far away to a burn center, she said at the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma scientific assembly.

The Baux score, a well-known metric in the burn community, adds the patient’s age to the percentage of surface area burned, so a 70 year old patient burned over 23% of their body, for instance, would have a score of 93. A modified Baux score adds points for inhalation injuries, but because the data didn’t include inhalation injury severity, the investigators found it more useful to stick with the original formula.

They queried the repository for patients 65 years or older with second- or third-degree burns from 2002-2011. They excluded patients with a length of stay of a day or less, along with elective admissions, non-burn injuries, and transfers to other burn centers. Next, they calculated Baux scores for each of their 8,001 subjects and noted if the patients were discharged home or to an alternate facility, or if he or she died.

Most patients had moderate scores of 70-100, and almost half were sent home. Of the 1,509 that died in hospital, 264 (17.5%) had care withdraw at a median of 3 days, but a range of 0-231 days. Flames were the most common cause of injury, followed by scalding.

A receiver operating curve analysis found that a Baux score at or below 86.15 predicted discharge home (AUC 0.698, 75.28% sensitivity, 54.64% specificity); a score above 77.12 predicted discharge to an alternate setting (AUC 0.539, 74.91% sensitivity, 34.38% specificity); and a score above 93.3 predicted mortality (AUC 0.779, 57.46% sensitivity, 87.08% specificity).

Dr. Hodgman said she thinks the cut-points will remain useful even as burn care improves with new grafting techniques that require smaller donor sites. Such innovation will apply mostly to moderately injured patients; for the more severely injured, the predictive power of the findings should still hold.

The investigators have no disclosures.

SAN ANTONIO – Geriatric burn patients have less than a 50% chance of returning home with a Baux score of about 85, and the risk of death begins to climb steadily after a score 93, approaching 50% at 110 points and almost 100% at 130 points, according to a review of 8,001 elderly patients in the National Burn Repository.

The investigators are developing the findings into a decision-making tool to help counsel families and caregivers about their options when elderly loved ones are seriously burned.

“There’s just not a lot of data out there on prognosis after burn injury in the geriatric population. We thought a simple decision aid for discussion with key stakeholders would provide significant assistance,” said investigator Dr. Erica Hodgman, a surgery research resident at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

The hope is that families and caregivers will be able to better judge if the patient would want to press on with treatment given the odds of returning home, being discharged to a skilled nursing or rehab facility, or dying. “I think it will help people” feel less guilty if they decide to withdraw care or not send patients far away to a burn center, she said at the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma scientific assembly.

The Baux score, a well-known metric in the burn community, adds the patient’s age to the percentage of surface area burned, so a 70 year old patient burned over 23% of their body, for instance, would have a score of 93. A modified Baux score adds points for inhalation injuries, but because the data didn’t include inhalation injury severity, the investigators found it more useful to stick with the original formula.

They queried the repository for patients 65 years or older with second- or third-degree burns from 2002-2011. They excluded patients with a length of stay of a day or less, along with elective admissions, non-burn injuries, and transfers to other burn centers. Next, they calculated Baux scores for each of their 8,001 subjects and noted if the patients were discharged home or to an alternate facility, or if he or she died.

Most patients had moderate scores of 70-100, and almost half were sent home. Of the 1,509 that died in hospital, 264 (17.5%) had care withdraw at a median of 3 days, but a range of 0-231 days. Flames were the most common cause of injury, followed by scalding.

A receiver operating curve analysis found that a Baux score at or below 86.15 predicted discharge home (AUC 0.698, 75.28% sensitivity, 54.64% specificity); a score above 77.12 predicted discharge to an alternate setting (AUC 0.539, 74.91% sensitivity, 34.38% specificity); and a score above 93.3 predicted mortality (AUC 0.779, 57.46% sensitivity, 87.08% specificity).

Dr. Hodgman said she thinks the cut-points will remain useful even as burn care improves with new grafting techniques that require smaller donor sites. Such innovation will apply mostly to moderately injured patients; for the more severely injured, the predictive power of the findings should still hold.

The investigators have no disclosures.

SAN ANTONIO – Geriatric burn patients have less than a 50% chance of returning home with a Baux score of about 85, and the risk of death begins to climb steadily after a score 93, approaching 50% at 110 points and almost 100% at 130 points, according to a review of 8,001 elderly patients in the National Burn Repository.

The investigators are developing the findings into a decision-making tool to help counsel families and caregivers about their options when elderly loved ones are seriously burned.

“There’s just not a lot of data out there on prognosis after burn injury in the geriatric population. We thought a simple decision aid for discussion with key stakeholders would provide significant assistance,” said investigator Dr. Erica Hodgman, a surgery research resident at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

The hope is that families and caregivers will be able to better judge if the patient would want to press on with treatment given the odds of returning home, being discharged to a skilled nursing or rehab facility, or dying. “I think it will help people” feel less guilty if they decide to withdraw care or not send patients far away to a burn center, she said at the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma scientific assembly.

The Baux score, a well-known metric in the burn community, adds the patient’s age to the percentage of surface area burned, so a 70 year old patient burned over 23% of their body, for instance, would have a score of 93. A modified Baux score adds points for inhalation injuries, but because the data didn’t include inhalation injury severity, the investigators found it more useful to stick with the original formula.

They queried the repository for patients 65 years or older with second- or third-degree burns from 2002-2011. They excluded patients with a length of stay of a day or less, along with elective admissions, non-burn injuries, and transfers to other burn centers. Next, they calculated Baux scores for each of their 8,001 subjects and noted if the patients were discharged home or to an alternate facility, or if he or she died.

Most patients had moderate scores of 70-100, and almost half were sent home. Of the 1,509 that died in hospital, 264 (17.5%) had care withdraw at a median of 3 days, but a range of 0-231 days. Flames were the most common cause of injury, followed by scalding.

A receiver operating curve analysis found that a Baux score at or below 86.15 predicted discharge home (AUC 0.698, 75.28% sensitivity, 54.64% specificity); a score above 77.12 predicted discharge to an alternate setting (AUC 0.539, 74.91% sensitivity, 34.38% specificity); and a score above 93.3 predicted mortality (AUC 0.779, 57.46% sensitivity, 87.08% specificity).

Dr. Hodgman said she thinks the cut-points will remain useful even as burn care improves with new grafting techniques that require smaller donor sites. Such innovation will apply mostly to moderately injured patients; for the more severely injured, the predictive power of the findings should still hold.

The investigators have no disclosures.

AT THE EAST SCIENTIFIC ASSEMBLY

Key clinical point: Baux score cut-points help counsel families about their options when an elderly family member is seriously burned.

Major finding: Geriatric burn patients have less than a 50% chance of returning home with a Baux score of about 85, and the risk of death begins to climb steadily after a score 93.

Data source: Review of 8,001 patients over 65 years old in the National Burn Repository

Disclosures: The investigators have no disclosures.

Health IT Chief, Hospital Medicine ‘Godfather’ Headline SHM Annual Meeting Keynotes

Health information technology (IT) will take center stage early and often at this year’s annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Karen DeSalvo, MD, MPH, MSc, acting assistant secretary for health in the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) and the national coordinator for health information technology, will deliver the keynote address. She is scheduled to give her talk an hour into the first day of programming.

Another highly anticipated talk will be delivered by Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of California at San Francisco, the “godfather” of hospital medicine, and the field’s most well-known practitioner. Dr. Wachter will give his 12th straight meeting-closing talk at noon Wednesday.

Dr. DeSalvo, an internist by training, was the chief of general internal medicine at Tulane University for about 10 years. She also started at Charity Hospital in New Orleans, site of one of the earliest hospital medicine programs.

She says her speech will take a broad look at information technology as a tool for advancing good health, with attention to the role that hospitals and hospitalists play. She also plans to touch on the successes in U.S. healthcare in recent years, including expanded coverage, quality and safety improvements, and the rapid rate of adoption of electronic health records (EHRs), especially in the hospital. She says the hospital setting is “most ripe” for health IT advancement because it is the site of “the most rich data about the patient’s care and care experience and health … and there is the best interoperability right now between hospital systems and the best opportunity to make that more seamless.”

The future, she says, will be about “much more than the electronic health record.”

“I want to talk a bit about what’s happening on the pioneering edge in health IT, ranging anywhere from apps to consumer interface with digital health records to some really on-the-edge things like using telehealth and hologram technology for remote patient care,” she explains.

Dr. DeSalvo also plans to underscore health IT’s key role in HHS’s push for delivery system reform: changing the way care is paid for and delivered and the way information is delivered. HHS’s goal is for 50% of payments to be in the form of alternative or value-based payment models by 2018. Without health IT advancements, that won’t be possible, she says.

Health IT policy at HHS, she notes, has centered largely on “freeing the data” so that information is no longer trapped within a particular EHR system. A rule taking effect in 2018 will require that EHRs be built so that apps can be overlaid onto the data, allowing easier access and the ability to tailor data to an individual’s needs.

“It’s going to get to be more like the way we do our banking or call for transportation with a smartphone or have an interface for our travel arrangements,” she says. “That’s the way that the health IT world is evolving.”

She says hospitalists are “pioneering, early adopters who are by nature very innovative” and are ideal for helping refine health IT. But she also recognizes that the bumps along the way can cause technology to be seen as a hurdle. That’s why HHS policy has focused on making data more readily available, smoothing out clunkiness, making EHR vendors become more transparent about their products, and aligning documentation requirements with real patient outcomes so that unnecessary requirements can be eliminated.

Good systems have been developed, but improvements are needed, she acknowledges.

“We’re working with an intense sense of urgency at HHS because we know that is a source of frustration to doctors on the frontlines,” Dr. DeSalvo says. “We not only hear it all the time when we’re out speaking with folks, but some of us still practice and will shortly be practicing again, so it’s very real to us to know that this has to get better. What we don’t want is for people to be frustrated with the technology. We want it to lift them up and help make their practice better. We also want it to be an enabler for consumers.”

Dr. Wachter has an easy way to remember how many annual meeting lectures he’s given: The 10th was the one where he dressed up as Elton John, sang, and played the piano on stage. That was in Las Vegas, of course.

This year? Don’t expect the piano, or singing for that matter. His HM16 theme will be more sober, one of caution and the importance of perspective.

The early title, he tells The Hospitalist, is “Why Culture Is Key to Improvement … And Why Hospitalists Are the Key to Hospital Culture.” The title might change, and the precise direction and details of his talk are still in flux, he says.

But the thrust will be a concern that, with a blizzard of quality improvement (QI) projects and process analyses being taken on by hospitalists, hospitalists are not immune to the burnout we’re seeing throughout medicine. A bad vibe is creeping in, he fears, and unless there’s more awareness of, and attention to, the culture itself—and not just a grim soldiering on from one initiative to another—the field will suffer.

“There’s a risk that we’ll lose sight of the people and culture within the organization,” Dr. Wachter says. “Even good people are beginning to say, ‘I just can’t do another QI project; I just can’t do another thing.’”

He wants hospitalists to think “more deeply” about the issues of culture, how the workforce is being managed, and “that we’re focusing on the right things in the right way.”

He hopes to call on hospitalists and hospitalist leaders to continue to recognize “the importance of the human spirit in all of this.”

So how worried is he?

“It won’t be a downer,” he says. “I still think we’re in great shape, but I am a bit worried, in part, because of our successes. We grew so fast, and we became so important to our organizations. We have to be sure we’re taking care of ourselves.”

So many hospitalists now have leadership roles. That’s a good thing, he adds, “but it does mean that as people are beginning to be burned out or organizations are struggling with dealing with initiative fatigue, we’re the first ones that are going to feel that because we are disproportionately involved.” TH

Thomas R. Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

Health information technology (IT) will take center stage early and often at this year’s annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Karen DeSalvo, MD, MPH, MSc, acting assistant secretary for health in the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) and the national coordinator for health information technology, will deliver the keynote address. She is scheduled to give her talk an hour into the first day of programming.

Another highly anticipated talk will be delivered by Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of California at San Francisco, the “godfather” of hospital medicine, and the field’s most well-known practitioner. Dr. Wachter will give his 12th straight meeting-closing talk at noon Wednesday.

Dr. DeSalvo, an internist by training, was the chief of general internal medicine at Tulane University for about 10 years. She also started at Charity Hospital in New Orleans, site of one of the earliest hospital medicine programs.