User login

Management of Proximal Biceps Pathology in Overhead Athletes: What Is the Role of Biceps Tenodesis?

Take Home Points

- Outcomes after SLAP repair remain guarded.

- Physical examination is key in determining proper management of biceps pathology.

- When performing SLAP repair, knotless technology may prevent future cartilage or rotator cuff injury.

- Revision of SLAP repair is best handled with biceps tenodesis.

- Subpectoral biceps tenodesis avoids residual groove pain.

In recent decades, the long head of the biceps (LHB) tendon has been recognized as a pain generator in the shoulder of throwing athletes. The LHB muscle and its role in glenohumeral kinematics remains largely in question. The LHB tendon varies in size but most commonly is 5 mm to 6mm in diameter and about 9 cm in length, inserting on the superior labrum and supraglenoid tubercle after traveling through the bicipital groove.1 The many conditions that can develop along the course of the biceps tendon include overall biceps tendonitis, biceps tendon subluxation or instability, and injuries to the superior anterior to posterior area of the labrum.

These injuries can occur in young overhead athletes as well as manual laborers and older overhead recreational athletes. Pitching is the most common activity that leads to proximal biceps tendon disorders. The 6 phases of the pitch are linked in a kinetic chain that generates energy that is then translated to high velocity. The amount of force that is exerted on the shoulder during pitching and especially after ball release is impressive, and the athlete’s shoulder changes in many ways as it adapts to the motion.2-5 The late-cocking and deceleration phases are most commonly associated with proximal biceps pathology and the “peel-back” phenomenon. Other common activities that lead to biceps tendon issues in a young population are volleyball, baseball, tennis, softball, swimming, and cricket. Shoulder arthroscopies performed in older patients show degenerative biceps and labrum tears, which should be treated appropriately but perhaps different from how they are treated in overhead athletes.6-8 Further, many professional athletes have asymptomatic superior labrum anterior-posterior (SLAP) tears.9

Mechanism of Injury

Overhead throwing is commonly thought to be the mechanism by which lesions are created in the biceps–labrum complex (BLC). Pitching in particular generates incredible force and torque within the shoulder. In professional pitchers, the resulting throwing speed creates forces regularly in excess of 1000 N.3 These forces effect internal compensatory changes and internal derangement of the BLC. These changes often involve internal rotation deficits and alterations in the rotator cuff, which may contribute to glenohumeral instability and altered joint kinematics.10

Repetitive overhead activity is largely considered the mechanism of injury in this population, though more specific mechanisms have been described, including the peel-back mechanism11 and the posterior superior glenoid impingement. There is little evidence that preventive programs have any effect on decreasing the incidence of SLAP tears in overhead athletes.

Preoperative Evaluation

Preoperative evaluation is arguably the most important step in treating a patient with persistent or recurrent symptoms consistent with a SLAP tear. Evaluation includes thorough history, physical examination, and review of any prior injuries or surgical procedures. The physical examination should focus on maneuvers that define where the problem is occurring. Although SLAP tears are most common in this population, disorders of the biceps tendon within the groove, including inflammation and instability, should be ruled out with physical examination and advanced imaging. Palpation for groove tenderness, impingement-type complaints, internal rotation loss, and SLAP provocative testing are crucial in the diagnosis.12,13 The cause of symptoms may be multifactorial and include the often encountered concomitant pathology of rotator cuff tears, internal impingement, and instability.

Standard radiographs (Grashey anteroposterior, scapular/lateral, axillary lateral) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with or without arthrography can be helpful in identifying and characterizing most SLAP tears as well as failed SLAP tear repairs. However, MRI is often positive for SLAP tears in asymptomatic patients, and diagnosing SLAP tears with MRI is often a challenge.14 MRI can help in determining concomitant pathology, including rotator cuff injury and cysts causing nerve compression. Correlation with clinical examination and patient history is most crucial. Conservative treatment (rest, activity modification, use of oral anti-inflammatory medications) typically is attempted and coordinated with respect to the athlete’s season of play.15,16

Classification

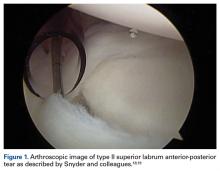

In overhead throwing athletes, SLAP tears typically are associated with anterior shoulder pain. Associated shoulder instability and significant glenohumeral dysfunction are not uncommon in athletes with lesions of the BLC. In 1985, Andrews and colleagues17 were the first to describe SLAP tears in overhead athletes (73 patients). Later, Snyder and colleagues18,19 further classified these lesions into 4 types based on tear stability and location, and they coined the acronym SLAP (Figure 1).

Type I lesions typically are described as fraying at the inner margin of the labrum and are common in throwers, even asymptomatic throwers. Type II lesions, separations of the biceps and labrum from the superior glenoid (≥5 mm of excursion), are the most commonly occurring and treated variant in throwing athletes.20-22 Intraoperative evaluation for a peel-back lesion (placing the arm in abduction with external rotation), rather than for a sulcus of 1 mm to 2 mm, may confirm a type II SLAP tear.20,23,24 It is often important to consider the direction of tear propagation as well. Type III lesions include those with an intact BLC (but with a bucket-handle tear of the superior labral complex and an intact biceps tendon), whereas type IV lesions involve additional extension of the tear into the biceps tendon.18,19The classification systems are well defined. Nevertheless, management of SLAP lesions remains controversial.

Options for Surgical Treatment

SLAP Tear Repair—Outcomes

The incidence of SLAP tear repairs has increased dramatically in recent years.6,25 There are various SLAP tear repair methods, but the most common consists of repairing the labrum and biceps anchor. Management of type II SLAP lesions remains controversial. Several prospective studies have found overall improvement after SLAP tear repair.26-31 Other series have reported less encouraging outcomes, including dissatisfaction with persistent pain and inability to return to throwing.28,32 A 2010 systematic review found that the percentage of patients who returned to their preinjury level of play was only 64%, and outcomes for overhead throwing athletes were even worse—only 22% to 60% of these patients returned to their previous level.33 The right surgery for SLAP tears in this population continues to be an area of uncertainty for many surgeons.

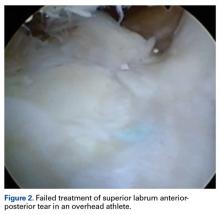

Failed SLAP tear repairs (poor outcomes) have become common in overhead throwing athletes. The reasons for these failed repairs are unclear, but several possible explanations have been offered. One is that labral repair may result in permanent alterations in pitching biomechanics, which may lead to an inability to regain velocity and command.3 Another is that the athlete’s shoulder may remain unstable even after repair.10Hardware complications are a significant concern in this high-level population. Suture anchor pullout or iatrogenic cartilage damage may occur during instrumentation or as a result of suture anchor reactive changes. In addition, there are several reports of glenoid osteochondrolysis (Figure 2) caused by prominent hardware or prominent knots.34-39

Stiffness after SLAP tear repair is a significant problem, with most patients taking up to 6 months to regain full motion.26,48 Overtensioning of the labrum and the glenohumeral ligaments may be the cause, and the solution may be to place anchors posterior (vs anterior) to the biceps insertion. In a large prospective military study, mean forward flexion and external rotation were reduced at final follow-up.31 These outcomes are less acceptable to overhead throwing athletes, who rely on motion for high-end throwing activities.

Primary Biceps Tenodesis—Outcomes

A 2015 database study found a 1.7-fold increase in biceps tenodesis over the preceding 5 years.49 However, relatively few procedures included in the study were performed in patients age younger than 30 years. For many older non-overhead throwers with type II tears, SLAP tear repair has become less popular as a treatment option.32 There is a dearth of knowledge about the outcomes of subpectoral biceps tenodesis as a primary treatment for biceps tendonitis and an associated SLAP tear. Although type I tears historically have been treated with débridement, débridement is seldom used for concomitant biceps tendonitis. It should be coupled with careful clinical examination.

In recent years, biceps tenodesis has been proposed as an alternative to repair for SLAP tears, particularly in older patients.24,44 For obvious reasons, however, there has been some trepidation about performing biceps tenodesis in throwing athletes. Some authors have proposed biceps tenodesis as primary treatment for isolated SLAP tears. Boileau and colleagues44 compared the outcomes of treatment of isolated type II SLAP lesions in 25 consecutive patients. For 10 patients, repair involved suture anchors; for the other 15, arthroscopic biceps tenodesis was performed with an absorbable interference screw. Six of the 10 suture anchor patients were disappointed with their outcome (persistent pain or inability to return to sport), whereas 14 of the 15 biceps tenodesis patients were satisfied. The authors concluded that arthroscopic biceps tenodesis is an effective alternative to repair for type II SLAP lesions, though their study was not isolated to overhead athletes (tenodesis group mean age, 52 years).

In a 2014 series of cases, Ek and colleagues50 reported good outcomes of SLAP tear repair and biceps tenodesis. Again, though, tenodesis was used in older patients, and repair in younger, more active patients, with no high-level athletes in either group. There was no difference in return to sport between groups. In a study of patients who underwent primary biceps tenodesis, Gupta and colleagues51 found 80% excellent outcomes (improved shoulder outcome scores) in select SLAP tear patients, including 8 athletes, 88% of whom were overhead athletes. Gottschalk and colleagues52 reported on differences in prospectively collected outcome data (age, sex, SLAP lesion type II or IV) for primary biceps tenodesis in a series of 33 patients. Twenty-six of the 29 patients who completed follow-up returned to their previous level of activity. These studies suggest that primary biceps tenodesis may be an alternative with lower failure rates in the treatment of SLAP tears in middle-aged patients, and in overhead athletes, though additional specific studies are needed to focus on overhead athletes on a larger scale.

Revision SLAP Tear Repair Versus Biceps Tenodesis

Failed arthroscopic SLAP tear repairs, which are increasingly common, present a unique treatment challenge. In a 2013 prospective cohort series, Gupta and colleagues46 found excellent clinical outcomes of subpectoral biceps tenodesis for failed type II SLAP tears. The authors reported a postoperative SANE (Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation) score of 70.4%, an SST (Simple Shoulder Test) score of 9.33, and an ASES (American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons) score of 77.96, along with reasonable health-related quality-of-life scores. Werner and colleagues53 evaluated 2-year outcomes of biceps tenodesis performed after SLAP tear repair in 24 patients and found a return to almost normal range of motion as well as good clinical outcome scores. Significantly worse outcomes were found for patients with open worker’s compensation claims.

McCormick and colleagues26 prospectively evaluated the efficacy of biceps tenodesis for failed type II SLAP tear repair in 46 patients. Improvement was noted across all outcome assessments during follow-up (mean, 3.6 years). From these findings, we might conclude that biceps tenodesis is a more predictable option for failed SLAP tear repair, and that it has a relatively low complication rate. However, most investigators have used a heterogeneous patient population, as opposed to overhead athletes specifically. To our knowledge, no one has evaluated the specific population of overhead throwers with failed SLAP tear repairs. In addition, no one has conducted randomized controlled trials comparing débridement, biceps tenodesis, and repair for failed SLAP tear repairs.

Postoperative Considerations

When overhead athletes and their surgeons are considering surgical options, they must take rehabilitation and return to play into account. Many surgeons think the possible marginal clinical benefit of SLAP tear repair may not be worth the protracted rehabilitation. In most practices, rehabilitation after biceps tenodesis is less involved. Discussing the advantages and disadvantages of these 2 procedures can be helpful in decision making.

Dein and colleagues54 reported the case of a middle-aged pitcher who sustained a fracture after biceps tenodesis with an interference screw. Cases like this are concerning. Surgeons should consider altering the rehabilitation regimen when planning postoperative care in cases of biceps tenodesis in throwers. Other reported complications of open tenodesis are deep infection, thrombosis, postoperative stiffness, and nerve injury.55-58

Consequences for Overhead Throwers

The unknown role of the BLC leaves surgeons wary when considering biceps tenodesis for elite athletes. Some have postulated that removing the intra-articular portion of the LHB may cause microinstability and alter joint kinematics.10,59-61 Others have suggested the biceps is desynchronized from the other musculature and is not functionally important.62 Disruption of one portion of the superior labrum may result in instability on the opposite side of the glenoid.10,61 Biomechanical studies, both cadaveric and in vivo, have tried to create proper loads to the LHB and evaluate the kinematics of the shoulder before and after biceps tenodesis and SLAP tear repair.59,60 Using a cadaveric model, Strauss and colleagues63 found that type II SLAP lesions resulted in increased glenohumeral translation compared with baseline. Biceps tenodesis did not restore normal translation, but this did not negatively affect stability in the presence of a SLAP lesion. The consensus is that the role of the biceps is controversial at best.

Several studies have used electromyography (EMG) to evaluate LHB functioning. In 2014, Chalmers and colleagues59 used surface EMG and motion analysis to evaluate 18 pitchers: 6 underwent SLAP tear repair, 5 underwent biceps tenodesis, and 7 were uninjured controls. There were no significant differences in the activity of the LHB muscle, the short head of the biceps muscle, the deltoid, the infraspinatus, or the latissimus among the 3 groups. Motion analysis showed that the normal pattern of muscular activation within the LHB muscle was more closely restored by biceps tenodesis than by SLAP tear repair. In addition, thoracic rotation patterns were significantly more altered in the SLAP tear repair patients than in the uninjured controls. As the authors noted, given the low frequency with which biceps tenodesis is performed in overhead athletes, it is unlikely that larger scale studies will be conducted without a multicenter effort.

Recommendations and Our Preferred Technique

Which surgical option is best for treating symptomatic SLAP lesions in overhead athletes remains unclear. Many athletes struggle to return to high-level play after SLAP tear repair. Whether the same is true after biceps tenodesis is yet to be determined because of the low frequency with which biceps tenodesis is performed in high-level overhead athletes. The options for fixation, technique, and fixation location are equally broad. In this section, we outline our general line of thinking for cases of proximal biceps pathology.

In each case, we perform glenohumeral arthroscopy to evaluate the BLC and identify any other pathology. For overhead athletes who are younger than 30 years and lack bicipital groove pain or signs of gross tendinopathy, we favor arthroscopic SLAP tear repair. Repair is usually performed through an anterior working portal for suture passage and a Wilmington portal for anchor placement. We use knotless technology to achieve stable fixation and stay posterior to the biceps anchor insertion.

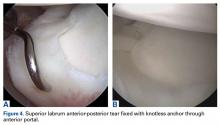

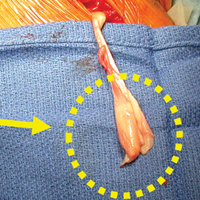

For the prevention of any potential pain from the bicipital groove in carefully selected patients—recreational overhead athletes and patients who want a less involved surgical recovery—we favor open subpectoral biceps tenodesis rather than arthroscopic tenodesis. The outcomes of biceps tenodesis are consistent, according to the literature.47,57,64 Moreover, the open approach is favored for the incidence of postoperative stiffness in the arthroscopic population.65 Tendons can be fixed with multiple procedures, including soft-tissue tenodesis, interference screw fixation, and surface anchors. We favor using a tenodesis screw in the subpectoral location, as outlined by Mazzocca and colleagues.64Our algorithm for SLAP lesions is evolving with our understanding of this complex disease process. For young overhead throwers with type II SLAP lesions, we favor arthroscopic SLAP tear repair with knotless technology. For older recreational overhead athletes, we favor biceps tenodesis in the subpectoral region after diagnostic arthroscopy plus biceps tenotomy with or without additional SLAP tear fixation, depending on the stability of the biceps anchor (Figures 4A, 4B).

Conclusion

Overhead athletes who present with symptomatic SLAP lesions often provide a treatment dilemma. Although SLAP tear repair historically has been standard treatment, biceps tenodesis represents a consistent surgical option with low complication rates and low revision rates. It is likely that, as additional data on glenohumeral kinematics and outcomes in young athletes become available, improved decision-making algorithms will follow.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):E71-E78. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Elser F, Braun S, Dewing CB, Giphart JE, Millett PJ. Anatomy, function, injuries, and treatment of the long head of the biceps brachii tendon. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(4):581-592.

2. Fedoriw WW, Ramkumar P, McCulloch PC, Lintner DM. Return to play after treatment of superior labral tears in professional baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(5):1155-1160.

3. Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, Dillman CJ, Escamilla RF. Kinetics of baseball pitching with implications about injury mechanisms. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(2):233-239.

4. Aydin N, Sirin E, Arya A. Superior labrum anterior to posterior lesions of the shoulder: diagnosis and arthroscopic management. World J Orthop. 2014;5(3):344-350.

5. Barber A, Field LD, Ryu R. Biceps tendon and superior labrum injuries: decision-marking. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(8):1844-1855.

6. Onyekwelu I, Khatib O, Zuckerman JD, Rokito AS, Kwon YW. The rising incidence of arthroscopic superior labrum anterior and posterior (SLAP) repairs. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(6):728-731.

7. Patterson BM, Creighton RA, Spang JT, Roberson JR, Kamath GV. Surgical trends in the treatment of superior labrum anterior and posterior lesions of the shoulder: analysis of data from the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery Certification Examination Database. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(8):1904-1910.

8. Walton DM, Sadi J. Identifying SLAP lesions: a meta-analysis of clinical tests and exercise in clinical reasoning. Phys Ther Sport. 2008;9(4):167-176.

9. Lesniak BP, Baraga MG, Jose J, Smith MK, Cunningham S, Kaplan LD. Glenohumeral findings on magnetic resonance imaging correlate with innings pitched in asymptomatic pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(9):2022-2027.

10. Mihata T, McGarry MH, Tibone JE, Fitzpatrick MJ, Kinoshita M, Lee TQ. Biomechanical assessment of type II superior labral anterior-posterior (SLAP) lesions associated with anterior shoulder capsular laxity as seen in throwers: a cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(8):1604-1610.

11. Burkhart SS, Morgan CD, Kibler WB. The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology. Part II: evaluation and treatment of SLAP lesions in throwers. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(5):531-539.

12. Meserve BB, Cleland JA, Boucher TR. A meta-analysis examining clinical test utility for assessing superior labral anterior posterior lesions. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(11):2252-2258.

13. Pandya NK, Colton A, Webner D, Sennett B, Huffman GR. Physical examination and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of superior labrum anterior-posterior lesions of the shoulder: a sensitivity analysis. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(3):311-317.

14. Amin MF, Youssef AO. The diagnostic value of magnetic resonance arthrography of the shoulder in detection and grading of SLAP lesions: comparison with arthroscopic findings. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81(9):2343-2347.

15. Cook C, Beaty S, Kissenberth MJ, Siffri P, Pill SG, Hawkins RJ. Diagnostic accuracy of five orthopedic clinical tests for diagnosis of superior labrum anterior posterior (SLAP) lesions. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(1):13-22.

16. Edwards SL, Lee JA, Bell JE, et al. Nonoperative treatment of superior labrum anterior posterior tears: improvements in pain, function, and quality of life. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(7):1456-1461.

17. Andrews JR, Carson WG Jr, McLeod WD. Glenoid labrum tears related to the long head of the biceps. Am J Sports Med. 1985;13(5):337-341.

18. Snyder SJ, Karzel RP, Del Pizzo W, Ferkel RD, Friedman MJ. SLAP lesions of the shoulder. Arthroscopy. 1990;6(4):274-279.

19. Snyder SJ, Banas MP, Karzel RP. An analysis of 140 injuries to the superior glenoid labrum. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1995;4(4):243-248.

20. Morgan CD, Burkhart SS, Palmeri M, Gillespie M. Type II SLAP lesions: three subtypes and their relationships to superior instability and rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 1998;14(6):553-565.

21. Weber SC, Martin DF, Seiler JG 3rd, Harrast JJ. Superior labrum anterior and posterior lesions of the shoulder: incidence rates, complications, and outcomes as reported by American Board of Orthopedic Surgery. Part II candidates. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(7):1538-1543.

22. Keener JD, Brophy RH. Superior labral tears of the shoulder: pathogenesis, evaluation, and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17(10):627-637.

23. Chen CH, Hsu KY, Chen WJ, Shih CH. Incidence and severity of biceps long head tendon lesion in patients with complete rotator cuff tears. J Trauma. 2005;58(6):1189-1193.

24. Nho SJ, Strauss EJ, Lenart BA, et al. Long head of the biceps tendinopathy: diagnosis and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(11):645-656.

25. Zhang AL, Kreulen C, Ngo SS, Hame SL, Wang JC, Gamradt SC. Demographic trends in arthroscopic SLAP repair in the United States. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(5):1144-1147.

26. McCormick F, Bhatia S, Chalmers P, Gupta A, Verma N, Romeo AA. The management of type II superior labral anterior to posterior injuries. Orthop Clin North Am. 2014;45(1):121-128.

27. Brockmeier SF, Voos JE, Williams RJ 3rd, Altchek DW, Cordasco FA, Allen AA; Hospital for Special Surgery Sports Medicine and Shoulder Service. Outcomes after arthroscopic repair of type-II SLAP lesions. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(7):1595-1603.

28. Boileau P, Parratte S, Chuinard C, Roussanne Y, Shia D, Bicknell R. Arthroscopic treatment of isolated type II SLAP lesions: biceps tenodesis as an alternative to reinsertion. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(5):929-936.

29. Denard PJ, Lädermann A, Burkhart SS. Long-term outcome after arthroscopic repair of type II SLAP lesions: results according to age and workers’ compensation status. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(4):451-457.

30. Friel NA, Karas V, Slabaugh MA, Cole BJ. Outcomes of type II superior labrum, anterior to posterior (SLAP) repair: prospective evaluation at a minimum two-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(6):859-867.

31. Provencher MT, McCormick F, Dewing C, McIntire S, Solomon D. A prospective analysis of 179 type 2 superior labrum anterior and posterior repairs: outcomes and factors associated with success and failure. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(4):880-886.

32. Gupta AK, Chalmers PN, Klosterman EL, et al. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis for bicipital tendonitis with SLAP tear. Orthopedics. 2015;38(1):e48-e53.

33. Gorantla K, Gill C, Wright RW. The outcome of type II SLAP repair: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(4):537-545.

34. Katz LM, Hsu S, Miller SL, et al. Poor outcomes after SLAP repair: descriptive analysis and prognosis. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(8):849-855.

35. Park MJ, Hsu JE, Harper C, Sennett BJ, Huffman GR. Poly-L/D-lactic acid anchors are associated with reoperation and failure of SLAP repairs. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(10):1335-1340.

36. Sassmannshausen G, Sukay M, Mair SD. Broken or dislodged poly-L-lactic acid bioabsorbable tacks in patients after SLAP lesion surgery. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(6):615-619.

37. Uggen C, Wei A, Glousman RE, et al. Biomechanical comparison of knotless anchor repair versus simple suture repair for type II SLAP lesions. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(10):1085-1092.

38. Weber SC. Surgical management of the failed SLAP repair. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2010;18(3):162-166.

39. Wilkerson JP, Zvijac JE, Uribe JW, Schürhoff MR, Green JB. Failure of polymerized lactic acid tacks in shoulder surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(2):117-121.

40. Weber S. Surgical management of the failed SLAP lesion. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(suppl):e8-e9.

41. Schrøder CP, Skare O, Gjengedal E, Uppheim G, Reikerås O, Brox JI. Long-term results after SLAP repair: a 5-year follow-up study of 107 patients with comparison of patients aged over and under 40 years. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(11):1601-1607.

42. Mazzocca AD, Cote MP, Arciero CL, Romeo AA, Arciero RA. Clinical outcomes after subpectoral biceps tenodesis with an interference screw. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(10):1922-1929.

43. Mazzocca AD, McCarthy MB, Ledgard FA, et al. Histomorphologic changes of the long head of the biceps tendon in common shoulder pathologies. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(6):972-981.

44. Boileau P, Parratte S, Chuinard C, Roussanne Y, Shia D, Bicknell R. Arthroscopic treatment of isolated type II SLAP lesions: biceps tenodesis as an alternative to reinsertion. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(5):929-936.

45. Boileau P, Krishnan SG, Coste JS, Walch G. Arthroscopic biceps tenodesis: a new technique using bioabsorbable interference screw fixation. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(9):1002-1012.

46. Gupta AK, Bruce B, Klosterman EL, McCormick F, Harris J, Romeo AA. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis for failed type II SLAP repair. Orthopedics. 2013;36(6):e723-e728.

47. Provencher MT, LeClere LE, Romeo AA. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2008;16(3):170-176.

48. McCarty LP 3rd, Buss DD, Datta MW, Freehill MQ, Giveans MR. Complications observed following labral or rotator cuff repair with use of poly-L-lactic acid implants. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(6):507-511.

49. Werner BC, Brockmeier SF, Gwathmey FW. Trends in long head biceps tenodesis. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(3):570-578.

50. Ek ET, Shi LL, Tompson JD, Freehill MT, Warner JJ. Surgical treatment of isolated type II superior labrum anterior-posterior (SLAP) lesions: repair versus biceps tenodesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(7):1059-1065.

51. Gupta AK, Chalmers PN, Klosterman EL, et al. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis for bicipital tendonitis with SLAP tear. Orthopedics. 2015;38(1):e48-e53.

52. Gottschalk MB, Karas SG, Ghattas TN, Burdette R. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis for the treatment of type II and IV superior labral anterior and posterior lesions. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(9):2128-2135.

53. Werner BC, Pehlivan HC, Hart JM, et al. Biceps tenodesis is a viable option for salvage of failed SLAP repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(8):e179-e184.

54. Dein EJ, Huri G, Gordon JC, McFarland EG. A humerus fracture in a baseball pitcher after biceps tenodesis [published correction appears in Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(6):NP39]. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(4):877-879.

55. Nho SJ, Reiff SN, Verma NN, Slabaugh MA, Mazzocca AD, Romeo AA. Complications associated with subpectoral biceps tenodesis: low rates of incidence following surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(5):764-768.

56. Osbahr DC, Diamond AB, Speer KP. The cosmetic appearance of the biceps muscle after long-head tenotomy versus tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(5):483-487.

57. Romeo AA, Mazzocca AD, Tauro JC. Arthroscopic biceps tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(2):206-213.

58. Ma H, Van Heest A, Glisson C, Patel S. Musculocutaneous nerve entrapment: an unusual complication after biceps tenodesis. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(12):2467-2469.

59. Chalmers PN, Trombley R, Cip J, et al. Postoperative restoration of upper extremity motion and neuromuscular control during the overhand pitch: evaluation of tenodesis and repair for superior labral anterior-posterior tears. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(12):2825-2836.

60. Giphart JE, Elser F, Dewing CB, Torry MR, Millett PJ. The long head of the biceps tendon has minimal effect on in vivo glenohumeral kinematics: a biplane fluoroscopy study. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(1):202-212.

61. Grossman MG, Tibone JE, McGarry MH, Schneider DJ, Veneziani S, Lee TQ. A cadaveric model of the throwing shoulder: a possible etiology of superior labrum anterior-to-posterior lesions. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(4):824-831.

62. Hawkes DH, Alizadehkhaiyat O, Fisher AC, Kemp GJ, Roebuck MM, Frostick SP. Normal shoulder muscular activation and co-ordination during a shoulder elevation task based on activities of daily living: an electromyographic study. J Orthop Res. 2012;30(1):53-60.

63. Strauss EJ, Salata MJ, Sershon RA, et al. Role of the superior labrum after biceps tenodesis in glenohumeral stability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(4):485-491.

64. Mazzocca AD, Bicos J, Santangelo S, Romeo AA, Arciero RA. The biomechanical evaluation of four fixation techniques for proximal biceps tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(11):1296-1306.

65. Werner BC, Pehlivan HC, Hart JM, et al. Increased incidence of postoperative stiffness after arthroscopic compared with open biceps tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(9):1075-1084.

66. Denard PJ, Dai X, Hanypsiak BT, Burkhart SS. Anatomy of the biceps tendon: implications for restoring physiological length–tension relation during biceps tenodesis with interference screw fixation. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(10):1352-1358.

67. Mazzocca AD, Rios CG, Romeo AA, Arciero RA. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis with interference screw fixation. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(7):896.

Take Home Points

- Outcomes after SLAP repair remain guarded.

- Physical examination is key in determining proper management of biceps pathology.

- When performing SLAP repair, knotless technology may prevent future cartilage or rotator cuff injury.

- Revision of SLAP repair is best handled with biceps tenodesis.

- Subpectoral biceps tenodesis avoids residual groove pain.

In recent decades, the long head of the biceps (LHB) tendon has been recognized as a pain generator in the shoulder of throwing athletes. The LHB muscle and its role in glenohumeral kinematics remains largely in question. The LHB tendon varies in size but most commonly is 5 mm to 6mm in diameter and about 9 cm in length, inserting on the superior labrum and supraglenoid tubercle after traveling through the bicipital groove.1 The many conditions that can develop along the course of the biceps tendon include overall biceps tendonitis, biceps tendon subluxation or instability, and injuries to the superior anterior to posterior area of the labrum.

These injuries can occur in young overhead athletes as well as manual laborers and older overhead recreational athletes. Pitching is the most common activity that leads to proximal biceps tendon disorders. The 6 phases of the pitch are linked in a kinetic chain that generates energy that is then translated to high velocity. The amount of force that is exerted on the shoulder during pitching and especially after ball release is impressive, and the athlete’s shoulder changes in many ways as it adapts to the motion.2-5 The late-cocking and deceleration phases are most commonly associated with proximal biceps pathology and the “peel-back” phenomenon. Other common activities that lead to biceps tendon issues in a young population are volleyball, baseball, tennis, softball, swimming, and cricket. Shoulder arthroscopies performed in older patients show degenerative biceps and labrum tears, which should be treated appropriately but perhaps different from how they are treated in overhead athletes.6-8 Further, many professional athletes have asymptomatic superior labrum anterior-posterior (SLAP) tears.9

Mechanism of Injury

Overhead throwing is commonly thought to be the mechanism by which lesions are created in the biceps–labrum complex (BLC). Pitching in particular generates incredible force and torque within the shoulder. In professional pitchers, the resulting throwing speed creates forces regularly in excess of 1000 N.3 These forces effect internal compensatory changes and internal derangement of the BLC. These changes often involve internal rotation deficits and alterations in the rotator cuff, which may contribute to glenohumeral instability and altered joint kinematics.10

Repetitive overhead activity is largely considered the mechanism of injury in this population, though more specific mechanisms have been described, including the peel-back mechanism11 and the posterior superior glenoid impingement. There is little evidence that preventive programs have any effect on decreasing the incidence of SLAP tears in overhead athletes.

Preoperative Evaluation

Preoperative evaluation is arguably the most important step in treating a patient with persistent or recurrent symptoms consistent with a SLAP tear. Evaluation includes thorough history, physical examination, and review of any prior injuries or surgical procedures. The physical examination should focus on maneuvers that define where the problem is occurring. Although SLAP tears are most common in this population, disorders of the biceps tendon within the groove, including inflammation and instability, should be ruled out with physical examination and advanced imaging. Palpation for groove tenderness, impingement-type complaints, internal rotation loss, and SLAP provocative testing are crucial in the diagnosis.12,13 The cause of symptoms may be multifactorial and include the often encountered concomitant pathology of rotator cuff tears, internal impingement, and instability.

Standard radiographs (Grashey anteroposterior, scapular/lateral, axillary lateral) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with or without arthrography can be helpful in identifying and characterizing most SLAP tears as well as failed SLAP tear repairs. However, MRI is often positive for SLAP tears in asymptomatic patients, and diagnosing SLAP tears with MRI is often a challenge.14 MRI can help in determining concomitant pathology, including rotator cuff injury and cysts causing nerve compression. Correlation with clinical examination and patient history is most crucial. Conservative treatment (rest, activity modification, use of oral anti-inflammatory medications) typically is attempted and coordinated with respect to the athlete’s season of play.15,16

Classification

In overhead throwing athletes, SLAP tears typically are associated with anterior shoulder pain. Associated shoulder instability and significant glenohumeral dysfunction are not uncommon in athletes with lesions of the BLC. In 1985, Andrews and colleagues17 were the first to describe SLAP tears in overhead athletes (73 patients). Later, Snyder and colleagues18,19 further classified these lesions into 4 types based on tear stability and location, and they coined the acronym SLAP (Figure 1).

Type I lesions typically are described as fraying at the inner margin of the labrum and are common in throwers, even asymptomatic throwers. Type II lesions, separations of the biceps and labrum from the superior glenoid (≥5 mm of excursion), are the most commonly occurring and treated variant in throwing athletes.20-22 Intraoperative evaluation for a peel-back lesion (placing the arm in abduction with external rotation), rather than for a sulcus of 1 mm to 2 mm, may confirm a type II SLAP tear.20,23,24 It is often important to consider the direction of tear propagation as well. Type III lesions include those with an intact BLC (but with a bucket-handle tear of the superior labral complex and an intact biceps tendon), whereas type IV lesions involve additional extension of the tear into the biceps tendon.18,19The classification systems are well defined. Nevertheless, management of SLAP lesions remains controversial.

Options for Surgical Treatment

SLAP Tear Repair—Outcomes

The incidence of SLAP tear repairs has increased dramatically in recent years.6,25 There are various SLAP tear repair methods, but the most common consists of repairing the labrum and biceps anchor. Management of type II SLAP lesions remains controversial. Several prospective studies have found overall improvement after SLAP tear repair.26-31 Other series have reported less encouraging outcomes, including dissatisfaction with persistent pain and inability to return to throwing.28,32 A 2010 systematic review found that the percentage of patients who returned to their preinjury level of play was only 64%, and outcomes for overhead throwing athletes were even worse—only 22% to 60% of these patients returned to their previous level.33 The right surgery for SLAP tears in this population continues to be an area of uncertainty for many surgeons.

Failed SLAP tear repairs (poor outcomes) have become common in overhead throwing athletes. The reasons for these failed repairs are unclear, but several possible explanations have been offered. One is that labral repair may result in permanent alterations in pitching biomechanics, which may lead to an inability to regain velocity and command.3 Another is that the athlete’s shoulder may remain unstable even after repair.10Hardware complications are a significant concern in this high-level population. Suture anchor pullout or iatrogenic cartilage damage may occur during instrumentation or as a result of suture anchor reactive changes. In addition, there are several reports of glenoid osteochondrolysis (Figure 2) caused by prominent hardware or prominent knots.34-39

Stiffness after SLAP tear repair is a significant problem, with most patients taking up to 6 months to regain full motion.26,48 Overtensioning of the labrum and the glenohumeral ligaments may be the cause, and the solution may be to place anchors posterior (vs anterior) to the biceps insertion. In a large prospective military study, mean forward flexion and external rotation were reduced at final follow-up.31 These outcomes are less acceptable to overhead throwing athletes, who rely on motion for high-end throwing activities.

Primary Biceps Tenodesis—Outcomes

A 2015 database study found a 1.7-fold increase in biceps tenodesis over the preceding 5 years.49 However, relatively few procedures included in the study were performed in patients age younger than 30 years. For many older non-overhead throwers with type II tears, SLAP tear repair has become less popular as a treatment option.32 There is a dearth of knowledge about the outcomes of subpectoral biceps tenodesis as a primary treatment for biceps tendonitis and an associated SLAP tear. Although type I tears historically have been treated with débridement, débridement is seldom used for concomitant biceps tendonitis. It should be coupled with careful clinical examination.

In recent years, biceps tenodesis has been proposed as an alternative to repair for SLAP tears, particularly in older patients.24,44 For obvious reasons, however, there has been some trepidation about performing biceps tenodesis in throwing athletes. Some authors have proposed biceps tenodesis as primary treatment for isolated SLAP tears. Boileau and colleagues44 compared the outcomes of treatment of isolated type II SLAP lesions in 25 consecutive patients. For 10 patients, repair involved suture anchors; for the other 15, arthroscopic biceps tenodesis was performed with an absorbable interference screw. Six of the 10 suture anchor patients were disappointed with their outcome (persistent pain or inability to return to sport), whereas 14 of the 15 biceps tenodesis patients were satisfied. The authors concluded that arthroscopic biceps tenodesis is an effective alternative to repair for type II SLAP lesions, though their study was not isolated to overhead athletes (tenodesis group mean age, 52 years).

In a 2014 series of cases, Ek and colleagues50 reported good outcomes of SLAP tear repair and biceps tenodesis. Again, though, tenodesis was used in older patients, and repair in younger, more active patients, with no high-level athletes in either group. There was no difference in return to sport between groups. In a study of patients who underwent primary biceps tenodesis, Gupta and colleagues51 found 80% excellent outcomes (improved shoulder outcome scores) in select SLAP tear patients, including 8 athletes, 88% of whom were overhead athletes. Gottschalk and colleagues52 reported on differences in prospectively collected outcome data (age, sex, SLAP lesion type II or IV) for primary biceps tenodesis in a series of 33 patients. Twenty-six of the 29 patients who completed follow-up returned to their previous level of activity. These studies suggest that primary biceps tenodesis may be an alternative with lower failure rates in the treatment of SLAP tears in middle-aged patients, and in overhead athletes, though additional specific studies are needed to focus on overhead athletes on a larger scale.

Revision SLAP Tear Repair Versus Biceps Tenodesis

Failed arthroscopic SLAP tear repairs, which are increasingly common, present a unique treatment challenge. In a 2013 prospective cohort series, Gupta and colleagues46 found excellent clinical outcomes of subpectoral biceps tenodesis for failed type II SLAP tears. The authors reported a postoperative SANE (Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation) score of 70.4%, an SST (Simple Shoulder Test) score of 9.33, and an ASES (American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons) score of 77.96, along with reasonable health-related quality-of-life scores. Werner and colleagues53 evaluated 2-year outcomes of biceps tenodesis performed after SLAP tear repair in 24 patients and found a return to almost normal range of motion as well as good clinical outcome scores. Significantly worse outcomes were found for patients with open worker’s compensation claims.

McCormick and colleagues26 prospectively evaluated the efficacy of biceps tenodesis for failed type II SLAP tear repair in 46 patients. Improvement was noted across all outcome assessments during follow-up (mean, 3.6 years). From these findings, we might conclude that biceps tenodesis is a more predictable option for failed SLAP tear repair, and that it has a relatively low complication rate. However, most investigators have used a heterogeneous patient population, as opposed to overhead athletes specifically. To our knowledge, no one has evaluated the specific population of overhead throwers with failed SLAP tear repairs. In addition, no one has conducted randomized controlled trials comparing débridement, biceps tenodesis, and repair for failed SLAP tear repairs.

Postoperative Considerations

When overhead athletes and their surgeons are considering surgical options, they must take rehabilitation and return to play into account. Many surgeons think the possible marginal clinical benefit of SLAP tear repair may not be worth the protracted rehabilitation. In most practices, rehabilitation after biceps tenodesis is less involved. Discussing the advantages and disadvantages of these 2 procedures can be helpful in decision making.

Dein and colleagues54 reported the case of a middle-aged pitcher who sustained a fracture after biceps tenodesis with an interference screw. Cases like this are concerning. Surgeons should consider altering the rehabilitation regimen when planning postoperative care in cases of biceps tenodesis in throwers. Other reported complications of open tenodesis are deep infection, thrombosis, postoperative stiffness, and nerve injury.55-58

Consequences for Overhead Throwers

The unknown role of the BLC leaves surgeons wary when considering biceps tenodesis for elite athletes. Some have postulated that removing the intra-articular portion of the LHB may cause microinstability and alter joint kinematics.10,59-61 Others have suggested the biceps is desynchronized from the other musculature and is not functionally important.62 Disruption of one portion of the superior labrum may result in instability on the opposite side of the glenoid.10,61 Biomechanical studies, both cadaveric and in vivo, have tried to create proper loads to the LHB and evaluate the kinematics of the shoulder before and after biceps tenodesis and SLAP tear repair.59,60 Using a cadaveric model, Strauss and colleagues63 found that type II SLAP lesions resulted in increased glenohumeral translation compared with baseline. Biceps tenodesis did not restore normal translation, but this did not negatively affect stability in the presence of a SLAP lesion. The consensus is that the role of the biceps is controversial at best.

Several studies have used electromyography (EMG) to evaluate LHB functioning. In 2014, Chalmers and colleagues59 used surface EMG and motion analysis to evaluate 18 pitchers: 6 underwent SLAP tear repair, 5 underwent biceps tenodesis, and 7 were uninjured controls. There were no significant differences in the activity of the LHB muscle, the short head of the biceps muscle, the deltoid, the infraspinatus, or the latissimus among the 3 groups. Motion analysis showed that the normal pattern of muscular activation within the LHB muscle was more closely restored by biceps tenodesis than by SLAP tear repair. In addition, thoracic rotation patterns were significantly more altered in the SLAP tear repair patients than in the uninjured controls. As the authors noted, given the low frequency with which biceps tenodesis is performed in overhead athletes, it is unlikely that larger scale studies will be conducted without a multicenter effort.

Recommendations and Our Preferred Technique

Which surgical option is best for treating symptomatic SLAP lesions in overhead athletes remains unclear. Many athletes struggle to return to high-level play after SLAP tear repair. Whether the same is true after biceps tenodesis is yet to be determined because of the low frequency with which biceps tenodesis is performed in high-level overhead athletes. The options for fixation, technique, and fixation location are equally broad. In this section, we outline our general line of thinking for cases of proximal biceps pathology.

In each case, we perform glenohumeral arthroscopy to evaluate the BLC and identify any other pathology. For overhead athletes who are younger than 30 years and lack bicipital groove pain or signs of gross tendinopathy, we favor arthroscopic SLAP tear repair. Repair is usually performed through an anterior working portal for suture passage and a Wilmington portal for anchor placement. We use knotless technology to achieve stable fixation and stay posterior to the biceps anchor insertion.

For the prevention of any potential pain from the bicipital groove in carefully selected patients—recreational overhead athletes and patients who want a less involved surgical recovery—we favor open subpectoral biceps tenodesis rather than arthroscopic tenodesis. The outcomes of biceps tenodesis are consistent, according to the literature.47,57,64 Moreover, the open approach is favored for the incidence of postoperative stiffness in the arthroscopic population.65 Tendons can be fixed with multiple procedures, including soft-tissue tenodesis, interference screw fixation, and surface anchors. We favor using a tenodesis screw in the subpectoral location, as outlined by Mazzocca and colleagues.64Our algorithm for SLAP lesions is evolving with our understanding of this complex disease process. For young overhead throwers with type II SLAP lesions, we favor arthroscopic SLAP tear repair with knotless technology. For older recreational overhead athletes, we favor biceps tenodesis in the subpectoral region after diagnostic arthroscopy plus biceps tenotomy with or without additional SLAP tear fixation, depending on the stability of the biceps anchor (Figures 4A, 4B).

Conclusion

Overhead athletes who present with symptomatic SLAP lesions often provide a treatment dilemma. Although SLAP tear repair historically has been standard treatment, biceps tenodesis represents a consistent surgical option with low complication rates and low revision rates. It is likely that, as additional data on glenohumeral kinematics and outcomes in young athletes become available, improved decision-making algorithms will follow.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):E71-E78. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

Take Home Points

- Outcomes after SLAP repair remain guarded.

- Physical examination is key in determining proper management of biceps pathology.

- When performing SLAP repair, knotless technology may prevent future cartilage or rotator cuff injury.

- Revision of SLAP repair is best handled with biceps tenodesis.

- Subpectoral biceps tenodesis avoids residual groove pain.

In recent decades, the long head of the biceps (LHB) tendon has been recognized as a pain generator in the shoulder of throwing athletes. The LHB muscle and its role in glenohumeral kinematics remains largely in question. The LHB tendon varies in size but most commonly is 5 mm to 6mm in diameter and about 9 cm in length, inserting on the superior labrum and supraglenoid tubercle after traveling through the bicipital groove.1 The many conditions that can develop along the course of the biceps tendon include overall biceps tendonitis, biceps tendon subluxation or instability, and injuries to the superior anterior to posterior area of the labrum.

These injuries can occur in young overhead athletes as well as manual laborers and older overhead recreational athletes. Pitching is the most common activity that leads to proximal biceps tendon disorders. The 6 phases of the pitch are linked in a kinetic chain that generates energy that is then translated to high velocity. The amount of force that is exerted on the shoulder during pitching and especially after ball release is impressive, and the athlete’s shoulder changes in many ways as it adapts to the motion.2-5 The late-cocking and deceleration phases are most commonly associated with proximal biceps pathology and the “peel-back” phenomenon. Other common activities that lead to biceps tendon issues in a young population are volleyball, baseball, tennis, softball, swimming, and cricket. Shoulder arthroscopies performed in older patients show degenerative biceps and labrum tears, which should be treated appropriately but perhaps different from how they are treated in overhead athletes.6-8 Further, many professional athletes have asymptomatic superior labrum anterior-posterior (SLAP) tears.9

Mechanism of Injury

Overhead throwing is commonly thought to be the mechanism by which lesions are created in the biceps–labrum complex (BLC). Pitching in particular generates incredible force and torque within the shoulder. In professional pitchers, the resulting throwing speed creates forces regularly in excess of 1000 N.3 These forces effect internal compensatory changes and internal derangement of the BLC. These changes often involve internal rotation deficits and alterations in the rotator cuff, which may contribute to glenohumeral instability and altered joint kinematics.10

Repetitive overhead activity is largely considered the mechanism of injury in this population, though more specific mechanisms have been described, including the peel-back mechanism11 and the posterior superior glenoid impingement. There is little evidence that preventive programs have any effect on decreasing the incidence of SLAP tears in overhead athletes.

Preoperative Evaluation

Preoperative evaluation is arguably the most important step in treating a patient with persistent or recurrent symptoms consistent with a SLAP tear. Evaluation includes thorough history, physical examination, and review of any prior injuries or surgical procedures. The physical examination should focus on maneuvers that define where the problem is occurring. Although SLAP tears are most common in this population, disorders of the biceps tendon within the groove, including inflammation and instability, should be ruled out with physical examination and advanced imaging. Palpation for groove tenderness, impingement-type complaints, internal rotation loss, and SLAP provocative testing are crucial in the diagnosis.12,13 The cause of symptoms may be multifactorial and include the often encountered concomitant pathology of rotator cuff tears, internal impingement, and instability.

Standard radiographs (Grashey anteroposterior, scapular/lateral, axillary lateral) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with or without arthrography can be helpful in identifying and characterizing most SLAP tears as well as failed SLAP tear repairs. However, MRI is often positive for SLAP tears in asymptomatic patients, and diagnosing SLAP tears with MRI is often a challenge.14 MRI can help in determining concomitant pathology, including rotator cuff injury and cysts causing nerve compression. Correlation with clinical examination and patient history is most crucial. Conservative treatment (rest, activity modification, use of oral anti-inflammatory medications) typically is attempted and coordinated with respect to the athlete’s season of play.15,16

Classification

In overhead throwing athletes, SLAP tears typically are associated with anterior shoulder pain. Associated shoulder instability and significant glenohumeral dysfunction are not uncommon in athletes with lesions of the BLC. In 1985, Andrews and colleagues17 were the first to describe SLAP tears in overhead athletes (73 patients). Later, Snyder and colleagues18,19 further classified these lesions into 4 types based on tear stability and location, and they coined the acronym SLAP (Figure 1).

Type I lesions typically are described as fraying at the inner margin of the labrum and are common in throwers, even asymptomatic throwers. Type II lesions, separations of the biceps and labrum from the superior glenoid (≥5 mm of excursion), are the most commonly occurring and treated variant in throwing athletes.20-22 Intraoperative evaluation for a peel-back lesion (placing the arm in abduction with external rotation), rather than for a sulcus of 1 mm to 2 mm, may confirm a type II SLAP tear.20,23,24 It is often important to consider the direction of tear propagation as well. Type III lesions include those with an intact BLC (but with a bucket-handle tear of the superior labral complex and an intact biceps tendon), whereas type IV lesions involve additional extension of the tear into the biceps tendon.18,19The classification systems are well defined. Nevertheless, management of SLAP lesions remains controversial.

Options for Surgical Treatment

SLAP Tear Repair—Outcomes

The incidence of SLAP tear repairs has increased dramatically in recent years.6,25 There are various SLAP tear repair methods, but the most common consists of repairing the labrum and biceps anchor. Management of type II SLAP lesions remains controversial. Several prospective studies have found overall improvement after SLAP tear repair.26-31 Other series have reported less encouraging outcomes, including dissatisfaction with persistent pain and inability to return to throwing.28,32 A 2010 systematic review found that the percentage of patients who returned to their preinjury level of play was only 64%, and outcomes for overhead throwing athletes were even worse—only 22% to 60% of these patients returned to their previous level.33 The right surgery for SLAP tears in this population continues to be an area of uncertainty for many surgeons.

Failed SLAP tear repairs (poor outcomes) have become common in overhead throwing athletes. The reasons for these failed repairs are unclear, but several possible explanations have been offered. One is that labral repair may result in permanent alterations in pitching biomechanics, which may lead to an inability to regain velocity and command.3 Another is that the athlete’s shoulder may remain unstable even after repair.10Hardware complications are a significant concern in this high-level population. Suture anchor pullout or iatrogenic cartilage damage may occur during instrumentation or as a result of suture anchor reactive changes. In addition, there are several reports of glenoid osteochondrolysis (Figure 2) caused by prominent hardware or prominent knots.34-39

Stiffness after SLAP tear repair is a significant problem, with most patients taking up to 6 months to regain full motion.26,48 Overtensioning of the labrum and the glenohumeral ligaments may be the cause, and the solution may be to place anchors posterior (vs anterior) to the biceps insertion. In a large prospective military study, mean forward flexion and external rotation were reduced at final follow-up.31 These outcomes are less acceptable to overhead throwing athletes, who rely on motion for high-end throwing activities.

Primary Biceps Tenodesis—Outcomes

A 2015 database study found a 1.7-fold increase in biceps tenodesis over the preceding 5 years.49 However, relatively few procedures included in the study were performed in patients age younger than 30 years. For many older non-overhead throwers with type II tears, SLAP tear repair has become less popular as a treatment option.32 There is a dearth of knowledge about the outcomes of subpectoral biceps tenodesis as a primary treatment for biceps tendonitis and an associated SLAP tear. Although type I tears historically have been treated with débridement, débridement is seldom used for concomitant biceps tendonitis. It should be coupled with careful clinical examination.

In recent years, biceps tenodesis has been proposed as an alternative to repair for SLAP tears, particularly in older patients.24,44 For obvious reasons, however, there has been some trepidation about performing biceps tenodesis in throwing athletes. Some authors have proposed biceps tenodesis as primary treatment for isolated SLAP tears. Boileau and colleagues44 compared the outcomes of treatment of isolated type II SLAP lesions in 25 consecutive patients. For 10 patients, repair involved suture anchors; for the other 15, arthroscopic biceps tenodesis was performed with an absorbable interference screw. Six of the 10 suture anchor patients were disappointed with their outcome (persistent pain or inability to return to sport), whereas 14 of the 15 biceps tenodesis patients were satisfied. The authors concluded that arthroscopic biceps tenodesis is an effective alternative to repair for type II SLAP lesions, though their study was not isolated to overhead athletes (tenodesis group mean age, 52 years).

In a 2014 series of cases, Ek and colleagues50 reported good outcomes of SLAP tear repair and biceps tenodesis. Again, though, tenodesis was used in older patients, and repair in younger, more active patients, with no high-level athletes in either group. There was no difference in return to sport between groups. In a study of patients who underwent primary biceps tenodesis, Gupta and colleagues51 found 80% excellent outcomes (improved shoulder outcome scores) in select SLAP tear patients, including 8 athletes, 88% of whom were overhead athletes. Gottschalk and colleagues52 reported on differences in prospectively collected outcome data (age, sex, SLAP lesion type II or IV) for primary biceps tenodesis in a series of 33 patients. Twenty-six of the 29 patients who completed follow-up returned to their previous level of activity. These studies suggest that primary biceps tenodesis may be an alternative with lower failure rates in the treatment of SLAP tears in middle-aged patients, and in overhead athletes, though additional specific studies are needed to focus on overhead athletes on a larger scale.

Revision SLAP Tear Repair Versus Biceps Tenodesis

Failed arthroscopic SLAP tear repairs, which are increasingly common, present a unique treatment challenge. In a 2013 prospective cohort series, Gupta and colleagues46 found excellent clinical outcomes of subpectoral biceps tenodesis for failed type II SLAP tears. The authors reported a postoperative SANE (Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation) score of 70.4%, an SST (Simple Shoulder Test) score of 9.33, and an ASES (American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons) score of 77.96, along with reasonable health-related quality-of-life scores. Werner and colleagues53 evaluated 2-year outcomes of biceps tenodesis performed after SLAP tear repair in 24 patients and found a return to almost normal range of motion as well as good clinical outcome scores. Significantly worse outcomes were found for patients with open worker’s compensation claims.

McCormick and colleagues26 prospectively evaluated the efficacy of biceps tenodesis for failed type II SLAP tear repair in 46 patients. Improvement was noted across all outcome assessments during follow-up (mean, 3.6 years). From these findings, we might conclude that biceps tenodesis is a more predictable option for failed SLAP tear repair, and that it has a relatively low complication rate. However, most investigators have used a heterogeneous patient population, as opposed to overhead athletes specifically. To our knowledge, no one has evaluated the specific population of overhead throwers with failed SLAP tear repairs. In addition, no one has conducted randomized controlled trials comparing débridement, biceps tenodesis, and repair for failed SLAP tear repairs.

Postoperative Considerations

When overhead athletes and their surgeons are considering surgical options, they must take rehabilitation and return to play into account. Many surgeons think the possible marginal clinical benefit of SLAP tear repair may not be worth the protracted rehabilitation. In most practices, rehabilitation after biceps tenodesis is less involved. Discussing the advantages and disadvantages of these 2 procedures can be helpful in decision making.

Dein and colleagues54 reported the case of a middle-aged pitcher who sustained a fracture after biceps tenodesis with an interference screw. Cases like this are concerning. Surgeons should consider altering the rehabilitation regimen when planning postoperative care in cases of biceps tenodesis in throwers. Other reported complications of open tenodesis are deep infection, thrombosis, postoperative stiffness, and nerve injury.55-58

Consequences for Overhead Throwers

The unknown role of the BLC leaves surgeons wary when considering biceps tenodesis for elite athletes. Some have postulated that removing the intra-articular portion of the LHB may cause microinstability and alter joint kinematics.10,59-61 Others have suggested the biceps is desynchronized from the other musculature and is not functionally important.62 Disruption of one portion of the superior labrum may result in instability on the opposite side of the glenoid.10,61 Biomechanical studies, both cadaveric and in vivo, have tried to create proper loads to the LHB and evaluate the kinematics of the shoulder before and after biceps tenodesis and SLAP tear repair.59,60 Using a cadaveric model, Strauss and colleagues63 found that type II SLAP lesions resulted in increased glenohumeral translation compared with baseline. Biceps tenodesis did not restore normal translation, but this did not negatively affect stability in the presence of a SLAP lesion. The consensus is that the role of the biceps is controversial at best.

Several studies have used electromyography (EMG) to evaluate LHB functioning. In 2014, Chalmers and colleagues59 used surface EMG and motion analysis to evaluate 18 pitchers: 6 underwent SLAP tear repair, 5 underwent biceps tenodesis, and 7 were uninjured controls. There were no significant differences in the activity of the LHB muscle, the short head of the biceps muscle, the deltoid, the infraspinatus, or the latissimus among the 3 groups. Motion analysis showed that the normal pattern of muscular activation within the LHB muscle was more closely restored by biceps tenodesis than by SLAP tear repair. In addition, thoracic rotation patterns were significantly more altered in the SLAP tear repair patients than in the uninjured controls. As the authors noted, given the low frequency with which biceps tenodesis is performed in overhead athletes, it is unlikely that larger scale studies will be conducted without a multicenter effort.

Recommendations and Our Preferred Technique

Which surgical option is best for treating symptomatic SLAP lesions in overhead athletes remains unclear. Many athletes struggle to return to high-level play after SLAP tear repair. Whether the same is true after biceps tenodesis is yet to be determined because of the low frequency with which biceps tenodesis is performed in high-level overhead athletes. The options for fixation, technique, and fixation location are equally broad. In this section, we outline our general line of thinking for cases of proximal biceps pathology.

In each case, we perform glenohumeral arthroscopy to evaluate the BLC and identify any other pathology. For overhead athletes who are younger than 30 years and lack bicipital groove pain or signs of gross tendinopathy, we favor arthroscopic SLAP tear repair. Repair is usually performed through an anterior working portal for suture passage and a Wilmington portal for anchor placement. We use knotless technology to achieve stable fixation and stay posterior to the biceps anchor insertion.

For the prevention of any potential pain from the bicipital groove in carefully selected patients—recreational overhead athletes and patients who want a less involved surgical recovery—we favor open subpectoral biceps tenodesis rather than arthroscopic tenodesis. The outcomes of biceps tenodesis are consistent, according to the literature.47,57,64 Moreover, the open approach is favored for the incidence of postoperative stiffness in the arthroscopic population.65 Tendons can be fixed with multiple procedures, including soft-tissue tenodesis, interference screw fixation, and surface anchors. We favor using a tenodesis screw in the subpectoral location, as outlined by Mazzocca and colleagues.64Our algorithm for SLAP lesions is evolving with our understanding of this complex disease process. For young overhead throwers with type II SLAP lesions, we favor arthroscopic SLAP tear repair with knotless technology. For older recreational overhead athletes, we favor biceps tenodesis in the subpectoral region after diagnostic arthroscopy plus biceps tenotomy with or without additional SLAP tear fixation, depending on the stability of the biceps anchor (Figures 4A, 4B).

Conclusion

Overhead athletes who present with symptomatic SLAP lesions often provide a treatment dilemma. Although SLAP tear repair historically has been standard treatment, biceps tenodesis represents a consistent surgical option with low complication rates and low revision rates. It is likely that, as additional data on glenohumeral kinematics and outcomes in young athletes become available, improved decision-making algorithms will follow.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):E71-E78. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Elser F, Braun S, Dewing CB, Giphart JE, Millett PJ. Anatomy, function, injuries, and treatment of the long head of the biceps brachii tendon. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(4):581-592.

2. Fedoriw WW, Ramkumar P, McCulloch PC, Lintner DM. Return to play after treatment of superior labral tears in professional baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(5):1155-1160.

3. Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, Dillman CJ, Escamilla RF. Kinetics of baseball pitching with implications about injury mechanisms. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(2):233-239.

4. Aydin N, Sirin E, Arya A. Superior labrum anterior to posterior lesions of the shoulder: diagnosis and arthroscopic management. World J Orthop. 2014;5(3):344-350.

5. Barber A, Field LD, Ryu R. Biceps tendon and superior labrum injuries: decision-marking. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(8):1844-1855.

6. Onyekwelu I, Khatib O, Zuckerman JD, Rokito AS, Kwon YW. The rising incidence of arthroscopic superior labrum anterior and posterior (SLAP) repairs. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(6):728-731.

7. Patterson BM, Creighton RA, Spang JT, Roberson JR, Kamath GV. Surgical trends in the treatment of superior labrum anterior and posterior lesions of the shoulder: analysis of data from the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery Certification Examination Database. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(8):1904-1910.

8. Walton DM, Sadi J. Identifying SLAP lesions: a meta-analysis of clinical tests and exercise in clinical reasoning. Phys Ther Sport. 2008;9(4):167-176.

9. Lesniak BP, Baraga MG, Jose J, Smith MK, Cunningham S, Kaplan LD. Glenohumeral findings on magnetic resonance imaging correlate with innings pitched in asymptomatic pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(9):2022-2027.

10. Mihata T, McGarry MH, Tibone JE, Fitzpatrick MJ, Kinoshita M, Lee TQ. Biomechanical assessment of type II superior labral anterior-posterior (SLAP) lesions associated with anterior shoulder capsular laxity as seen in throwers: a cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(8):1604-1610.

11. Burkhart SS, Morgan CD, Kibler WB. The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology. Part II: evaluation and treatment of SLAP lesions in throwers. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(5):531-539.

12. Meserve BB, Cleland JA, Boucher TR. A meta-analysis examining clinical test utility for assessing superior labral anterior posterior lesions. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(11):2252-2258.

13. Pandya NK, Colton A, Webner D, Sennett B, Huffman GR. Physical examination and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of superior labrum anterior-posterior lesions of the shoulder: a sensitivity analysis. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(3):311-317.

14. Amin MF, Youssef AO. The diagnostic value of magnetic resonance arthrography of the shoulder in detection and grading of SLAP lesions: comparison with arthroscopic findings. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81(9):2343-2347.

15. Cook C, Beaty S, Kissenberth MJ, Siffri P, Pill SG, Hawkins RJ. Diagnostic accuracy of five orthopedic clinical tests for diagnosis of superior labrum anterior posterior (SLAP) lesions. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(1):13-22.

16. Edwards SL, Lee JA, Bell JE, et al. Nonoperative treatment of superior labrum anterior posterior tears: improvements in pain, function, and quality of life. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(7):1456-1461.

17. Andrews JR, Carson WG Jr, McLeod WD. Glenoid labrum tears related to the long head of the biceps. Am J Sports Med. 1985;13(5):337-341.

18. Snyder SJ, Karzel RP, Del Pizzo W, Ferkel RD, Friedman MJ. SLAP lesions of the shoulder. Arthroscopy. 1990;6(4):274-279.

19. Snyder SJ, Banas MP, Karzel RP. An analysis of 140 injuries to the superior glenoid labrum. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1995;4(4):243-248.

20. Morgan CD, Burkhart SS, Palmeri M, Gillespie M. Type II SLAP lesions: three subtypes and their relationships to superior instability and rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 1998;14(6):553-565.

21. Weber SC, Martin DF, Seiler JG 3rd, Harrast JJ. Superior labrum anterior and posterior lesions of the shoulder: incidence rates, complications, and outcomes as reported by American Board of Orthopedic Surgery. Part II candidates. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(7):1538-1543.

22. Keener JD, Brophy RH. Superior labral tears of the shoulder: pathogenesis, evaluation, and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17(10):627-637.

23. Chen CH, Hsu KY, Chen WJ, Shih CH. Incidence and severity of biceps long head tendon lesion in patients with complete rotator cuff tears. J Trauma. 2005;58(6):1189-1193.

24. Nho SJ, Strauss EJ, Lenart BA, et al. Long head of the biceps tendinopathy: diagnosis and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(11):645-656.

25. Zhang AL, Kreulen C, Ngo SS, Hame SL, Wang JC, Gamradt SC. Demographic trends in arthroscopic SLAP repair in the United States. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(5):1144-1147.

26. McCormick F, Bhatia S, Chalmers P, Gupta A, Verma N, Romeo AA. The management of type II superior labral anterior to posterior injuries. Orthop Clin North Am. 2014;45(1):121-128.

27. Brockmeier SF, Voos JE, Williams RJ 3rd, Altchek DW, Cordasco FA, Allen AA; Hospital for Special Surgery Sports Medicine and Shoulder Service. Outcomes after arthroscopic repair of type-II SLAP lesions. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(7):1595-1603.

28. Boileau P, Parratte S, Chuinard C, Roussanne Y, Shia D, Bicknell R. Arthroscopic treatment of isolated type II SLAP lesions: biceps tenodesis as an alternative to reinsertion. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(5):929-936.

29. Denard PJ, Lädermann A, Burkhart SS. Long-term outcome after arthroscopic repair of type II SLAP lesions: results according to age and workers’ compensation status. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(4):451-457.

30. Friel NA, Karas V, Slabaugh MA, Cole BJ. Outcomes of type II superior labrum, anterior to posterior (SLAP) repair: prospective evaluation at a minimum two-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(6):859-867.

31. Provencher MT, McCormick F, Dewing C, McIntire S, Solomon D. A prospective analysis of 179 type 2 superior labrum anterior and posterior repairs: outcomes and factors associated with success and failure. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(4):880-886.

32. Gupta AK, Chalmers PN, Klosterman EL, et al. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis for bicipital tendonitis with SLAP tear. Orthopedics. 2015;38(1):e48-e53.

33. Gorantla K, Gill C, Wright RW. The outcome of type II SLAP repair: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(4):537-545.

34. Katz LM, Hsu S, Miller SL, et al. Poor outcomes after SLAP repair: descriptive analysis and prognosis. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(8):849-855.

35. Park MJ, Hsu JE, Harper C, Sennett BJ, Huffman GR. Poly-L/D-lactic acid anchors are associated with reoperation and failure of SLAP repairs. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(10):1335-1340.

36. Sassmannshausen G, Sukay M, Mair SD. Broken or dislodged poly-L-lactic acid bioabsorbable tacks in patients after SLAP lesion surgery. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(6):615-619.

37. Uggen C, Wei A, Glousman RE, et al. Biomechanical comparison of knotless anchor repair versus simple suture repair for type II SLAP lesions. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(10):1085-1092.

38. Weber SC. Surgical management of the failed SLAP repair. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2010;18(3):162-166.

39. Wilkerson JP, Zvijac JE, Uribe JW, Schürhoff MR, Green JB. Failure of polymerized lactic acid tacks in shoulder surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(2):117-121.

40. Weber S. Surgical management of the failed SLAP lesion. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(suppl):e8-e9.

41. Schrøder CP, Skare O, Gjengedal E, Uppheim G, Reikerås O, Brox JI. Long-term results after SLAP repair: a 5-year follow-up study of 107 patients with comparison of patients aged over and under 40 years. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(11):1601-1607.

42. Mazzocca AD, Cote MP, Arciero CL, Romeo AA, Arciero RA. Clinical outcomes after subpectoral biceps tenodesis with an interference screw. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(10):1922-1929.

43. Mazzocca AD, McCarthy MB, Ledgard FA, et al. Histomorphologic changes of the long head of the biceps tendon in common shoulder pathologies. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(6):972-981.

44. Boileau P, Parratte S, Chuinard C, Roussanne Y, Shia D, Bicknell R. Arthroscopic treatment of isolated type II SLAP lesions: biceps tenodesis as an alternative to reinsertion. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(5):929-936.

45. Boileau P, Krishnan SG, Coste JS, Walch G. Arthroscopic biceps tenodesis: a new technique using bioabsorbable interference screw fixation. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(9):1002-1012.

46. Gupta AK, Bruce B, Klosterman EL, McCormick F, Harris J, Romeo AA. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis for failed type II SLAP repair. Orthopedics. 2013;36(6):e723-e728.

47. Provencher MT, LeClere LE, Romeo AA. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2008;16(3):170-176.

48. McCarty LP 3rd, Buss DD, Datta MW, Freehill MQ, Giveans MR. Complications observed following labral or rotator cuff repair with use of poly-L-lactic acid implants. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(6):507-511.

49. Werner BC, Brockmeier SF, Gwathmey FW. Trends in long head biceps tenodesis. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(3):570-578.

50. Ek ET, Shi LL, Tompson JD, Freehill MT, Warner JJ. Surgical treatment of isolated type II superior labrum anterior-posterior (SLAP) lesions: repair versus biceps tenodesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(7):1059-1065.

51. Gupta AK, Chalmers PN, Klosterman EL, et al. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis for bicipital tendonitis with SLAP tear. Orthopedics. 2015;38(1):e48-e53.

52. Gottschalk MB, Karas SG, Ghattas TN, Burdette R. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis for the treatment of type II and IV superior labral anterior and posterior lesions. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(9):2128-2135.

53. Werner BC, Pehlivan HC, Hart JM, et al. Biceps tenodesis is a viable option for salvage of failed SLAP repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(8):e179-e184.

54. Dein EJ, Huri G, Gordon JC, McFarland EG. A humerus fracture in a baseball pitcher after biceps tenodesis [published correction appears in Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(6):NP39]. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(4):877-879.