User login

Costs prompt changes in drug use for cancer survivors

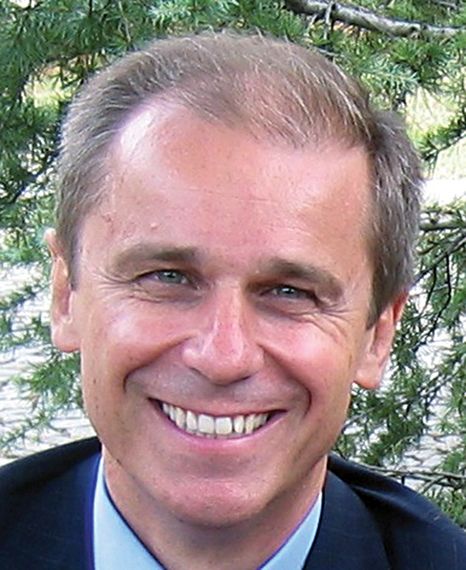

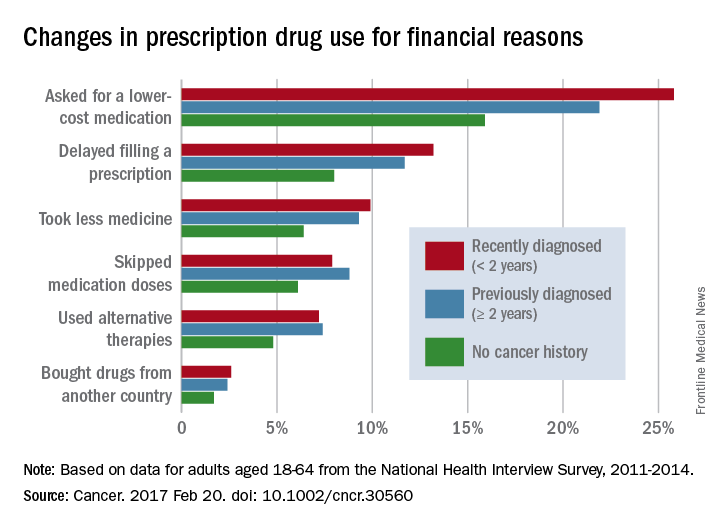

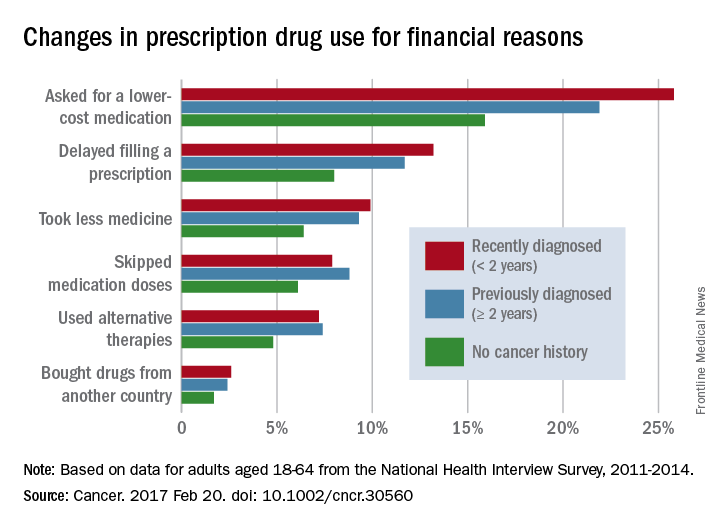

A new analysis indicates that cancer survivors may be more likely than the rest of the US population to change their prescription drug use due to financial concerns.

The study showed that cancer survivors were more likely to delay filling prescriptions, skip medication doses, request cheaper medications from their doctors, and engage in other cost-saving behaviors.

However, this was only true for non-elderly individuals.

There was no significant difference in cost-saving behaviors between elderly (age 65 and older) cancer survivors and elderly individuals in the general population.

Ahmedin Jemal, DVM, PhD, of the American Cancer Society in Atlanta, Georgia, and his colleagues reported these findings in Cancer.

The researchers used 2011-2014 data from the National Health Interview Survey, an annual household interview survey conducted by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The survey included 8931 cancer survivors and 126,287 individuals without a cancer history.

Among non-elderly adults, 31.6% of those who had been diagnosed with cancer recently and 27.9% of those who had been diagnosed at least 2 years earlier reported a change in prescription drug use for financial reasons, compared with 21.4% of individuals without a history of cancer (P<0.05).

“Specifically, non-elderly cancer survivors were more likely to skip medication, delay filling a prescription, ask their doctor for lower-cost medication, and use alternative therapies for financial reasons compared with non-elderly individuals without a cancer history,” Dr Jemal said.

On the other hand, changes in prescription drug use for financial reasons were generally similar between elderly cancer survivors and elderly individuals without a cancer history.

The proportion of elderly individuals who changed their drug use for financial reasons was 24.9% among those who had been diagnosed with cancer recently, 21.8% among those who had been diagnosed at least 2 years earlier, and 20.4% among those without a history of cancer.

The researchers said these results could be explained by uniform healthcare coverage through Medicare.

The team also said their findings may have significant policy implications.

“Healthcare reforms addressing the financial burden of cancer among survivors, including the escalating cost of prescription drugs, should consider multiple comorbid conditions and high-deductible health plans, and the working poor,” Dr Jemal said.

“Our findings also have implications for doctor and patient communication about the financial burden of cancer when making treatment decisions, especially on the use of certain drugs that cost hundreds of thousands of dollars but with very small benefit compared with alternative and more affordable drugs.” ![]()

A new analysis indicates that cancer survivors may be more likely than the rest of the US population to change their prescription drug use due to financial concerns.

The study showed that cancer survivors were more likely to delay filling prescriptions, skip medication doses, request cheaper medications from their doctors, and engage in other cost-saving behaviors.

However, this was only true for non-elderly individuals.

There was no significant difference in cost-saving behaviors between elderly (age 65 and older) cancer survivors and elderly individuals in the general population.

Ahmedin Jemal, DVM, PhD, of the American Cancer Society in Atlanta, Georgia, and his colleagues reported these findings in Cancer.

The researchers used 2011-2014 data from the National Health Interview Survey, an annual household interview survey conducted by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The survey included 8931 cancer survivors and 126,287 individuals without a cancer history.

Among non-elderly adults, 31.6% of those who had been diagnosed with cancer recently and 27.9% of those who had been diagnosed at least 2 years earlier reported a change in prescription drug use for financial reasons, compared with 21.4% of individuals without a history of cancer (P<0.05).

“Specifically, non-elderly cancer survivors were more likely to skip medication, delay filling a prescription, ask their doctor for lower-cost medication, and use alternative therapies for financial reasons compared with non-elderly individuals without a cancer history,” Dr Jemal said.

On the other hand, changes in prescription drug use for financial reasons were generally similar between elderly cancer survivors and elderly individuals without a cancer history.

The proportion of elderly individuals who changed their drug use for financial reasons was 24.9% among those who had been diagnosed with cancer recently, 21.8% among those who had been diagnosed at least 2 years earlier, and 20.4% among those without a history of cancer.

The researchers said these results could be explained by uniform healthcare coverage through Medicare.

The team also said their findings may have significant policy implications.

“Healthcare reforms addressing the financial burden of cancer among survivors, including the escalating cost of prescription drugs, should consider multiple comorbid conditions and high-deductible health plans, and the working poor,” Dr Jemal said.

“Our findings also have implications for doctor and patient communication about the financial burden of cancer when making treatment decisions, especially on the use of certain drugs that cost hundreds of thousands of dollars but with very small benefit compared with alternative and more affordable drugs.” ![]()

A new analysis indicates that cancer survivors may be more likely than the rest of the US population to change their prescription drug use due to financial concerns.

The study showed that cancer survivors were more likely to delay filling prescriptions, skip medication doses, request cheaper medications from their doctors, and engage in other cost-saving behaviors.

However, this was only true for non-elderly individuals.

There was no significant difference in cost-saving behaviors between elderly (age 65 and older) cancer survivors and elderly individuals in the general population.

Ahmedin Jemal, DVM, PhD, of the American Cancer Society in Atlanta, Georgia, and his colleagues reported these findings in Cancer.

The researchers used 2011-2014 data from the National Health Interview Survey, an annual household interview survey conducted by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The survey included 8931 cancer survivors and 126,287 individuals without a cancer history.

Among non-elderly adults, 31.6% of those who had been diagnosed with cancer recently and 27.9% of those who had been diagnosed at least 2 years earlier reported a change in prescription drug use for financial reasons, compared with 21.4% of individuals without a history of cancer (P<0.05).

“Specifically, non-elderly cancer survivors were more likely to skip medication, delay filling a prescription, ask their doctor for lower-cost medication, and use alternative therapies for financial reasons compared with non-elderly individuals without a cancer history,” Dr Jemal said.

On the other hand, changes in prescription drug use for financial reasons were generally similar between elderly cancer survivors and elderly individuals without a cancer history.

The proportion of elderly individuals who changed their drug use for financial reasons was 24.9% among those who had been diagnosed with cancer recently, 21.8% among those who had been diagnosed at least 2 years earlier, and 20.4% among those without a history of cancer.

The researchers said these results could be explained by uniform healthcare coverage through Medicare.

The team also said their findings may have significant policy implications.

“Healthcare reforms addressing the financial burden of cancer among survivors, including the escalating cost of prescription drugs, should consider multiple comorbid conditions and high-deductible health plans, and the working poor,” Dr Jemal said.

“Our findings also have implications for doctor and patient communication about the financial burden of cancer when making treatment decisions, especially on the use of certain drugs that cost hundreds of thousands of dollars but with very small benefit compared with alternative and more affordable drugs.” ![]()

FDA grants priority review to ALL drug

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted priority review for inotuzumab ozogamicin as a treatment for adults with relapsed or refractory B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

The FDA grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

The agency’s goal is to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it, rather than the standard 10-month period.

The Prescription Drug User Fee Act goal date for inotuzumab ozogamicin is August 2017.

About inotuzumab ozogamicin

Inotuzumab ozogamicin is an antibody-drug conjugate that consists of a monoclonal antibody targeting CD22 and a cytotoxic agent known as calicheamicin.

The product originates from a collaboration between Pfizer and Celltech (now UCB), but Pfizer has sole responsibility for all manufacturing and clinical development activities.

The application for inotuzumab ozogamicin is supported by results from a phase 3 trial, which were published in NEJM in June 2016.

The trial enrolled 326 adult patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell ALL and compared inotuzumab ozogamicin to standard of care chemotherapy.

The rate of complete remission, including incomplete hematologic recovery, was 80.7% in the inotuzumab arm and 29.4% in the chemotherapy arm (P<0.001). The median duration of remission was 4.6 months and 3.1 months, respectively (P=0.03).

Forty-one percent of patients treated with inotuzumab and 11% of those who received chemotherapy proceeded to stem cell transplant directly after treatment (P<0.001).

The median progression-free survival was 5.0 months in the inotuzumab arm and 1.8 months in the chemotherapy arm (P<0.001).

The median overall survival was 7.7 months and 6.7 months, respectively (P=0.04). This did not meet the prespecified boundary of significance (P=0.0208).

Liver-related adverse events were more common in the inotuzumab arm than the chemotherapy arm. The most frequent of these were increased aspartate aminotransferase level (20% vs 10%), hyperbilirubinemia (15% vs 10%), and increased alanine aminotransferase level (14% vs 11%).

Veno-occlusive liver disease occurred in 11% of patients in the inotuzumab arm and 1% in the chemotherapy arm.

There were 17 deaths during treatment in the inotuzumab arm and 11 in the chemotherapy arm. Four deaths were considered related to inotuzumab, and 2 were thought to be related to chemotherapy. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted priority review for inotuzumab ozogamicin as a treatment for adults with relapsed or refractory B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

The FDA grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

The agency’s goal is to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it, rather than the standard 10-month period.

The Prescription Drug User Fee Act goal date for inotuzumab ozogamicin is August 2017.

About inotuzumab ozogamicin

Inotuzumab ozogamicin is an antibody-drug conjugate that consists of a monoclonal antibody targeting CD22 and a cytotoxic agent known as calicheamicin.

The product originates from a collaboration between Pfizer and Celltech (now UCB), but Pfizer has sole responsibility for all manufacturing and clinical development activities.

The application for inotuzumab ozogamicin is supported by results from a phase 3 trial, which were published in NEJM in June 2016.

The trial enrolled 326 adult patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell ALL and compared inotuzumab ozogamicin to standard of care chemotherapy.

The rate of complete remission, including incomplete hematologic recovery, was 80.7% in the inotuzumab arm and 29.4% in the chemotherapy arm (P<0.001). The median duration of remission was 4.6 months and 3.1 months, respectively (P=0.03).

Forty-one percent of patients treated with inotuzumab and 11% of those who received chemotherapy proceeded to stem cell transplant directly after treatment (P<0.001).

The median progression-free survival was 5.0 months in the inotuzumab arm and 1.8 months in the chemotherapy arm (P<0.001).

The median overall survival was 7.7 months and 6.7 months, respectively (P=0.04). This did not meet the prespecified boundary of significance (P=0.0208).

Liver-related adverse events were more common in the inotuzumab arm than the chemotherapy arm. The most frequent of these were increased aspartate aminotransferase level (20% vs 10%), hyperbilirubinemia (15% vs 10%), and increased alanine aminotransferase level (14% vs 11%).

Veno-occlusive liver disease occurred in 11% of patients in the inotuzumab arm and 1% in the chemotherapy arm.

There were 17 deaths during treatment in the inotuzumab arm and 11 in the chemotherapy arm. Four deaths were considered related to inotuzumab, and 2 were thought to be related to chemotherapy. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted priority review for inotuzumab ozogamicin as a treatment for adults with relapsed or refractory B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

The FDA grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

The agency’s goal is to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it, rather than the standard 10-month period.

The Prescription Drug User Fee Act goal date for inotuzumab ozogamicin is August 2017.

About inotuzumab ozogamicin

Inotuzumab ozogamicin is an antibody-drug conjugate that consists of a monoclonal antibody targeting CD22 and a cytotoxic agent known as calicheamicin.

The product originates from a collaboration between Pfizer and Celltech (now UCB), but Pfizer has sole responsibility for all manufacturing and clinical development activities.

The application for inotuzumab ozogamicin is supported by results from a phase 3 trial, which were published in NEJM in June 2016.

The trial enrolled 326 adult patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell ALL and compared inotuzumab ozogamicin to standard of care chemotherapy.

The rate of complete remission, including incomplete hematologic recovery, was 80.7% in the inotuzumab arm and 29.4% in the chemotherapy arm (P<0.001). The median duration of remission was 4.6 months and 3.1 months, respectively (P=0.03).

Forty-one percent of patients treated with inotuzumab and 11% of those who received chemotherapy proceeded to stem cell transplant directly after treatment (P<0.001).

The median progression-free survival was 5.0 months in the inotuzumab arm and 1.8 months in the chemotherapy arm (P<0.001).

The median overall survival was 7.7 months and 6.7 months, respectively (P=0.04). This did not meet the prespecified boundary of significance (P=0.0208).

Liver-related adverse events were more common in the inotuzumab arm than the chemotherapy arm. The most frequent of these were increased aspartate aminotransferase level (20% vs 10%), hyperbilirubinemia (15% vs 10%), and increased alanine aminotransferase level (14% vs 11%).

Veno-occlusive liver disease occurred in 11% of patients in the inotuzumab arm and 1% in the chemotherapy arm.

There were 17 deaths during treatment in the inotuzumab arm and 11 in the chemotherapy arm. Four deaths were considered related to inotuzumab, and 2 were thought to be related to chemotherapy. ![]()

Tumor suppressor promotes FLT3-ITD AML

New research indicates that RUNX1, a known tumor suppressor, actually cooperates with internal tandem duplications in the FLT3 receptor tyrosine kinase (FLT3-ITD) to induce acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Investigators say this discovery suggests that blocking RUNX1 activity will “greatly enhance” current therapeutic approaches using FLT3 inhibitors.

The discovery was published in The Journal of Experimental Medicine.

The research began when investigators noticed that many AML patients with FLT3-ITD also showed increased levels of RUNX1.

“This was unexpected because up to 20% of AML patients carry mutations that inactivate RUNX1, which is generally considered to be a tumor suppressor that prevents the formation of leukemias,” said study author Carol Stocking, PhD, of Heinrich-Pette-Institute-Leibniz Institute for Experimental Virology in Hamburg, Germany.

To investigate this finding, she and her colleagues injected mice with human AML cells expressing FLT3-ITD. The team found that reducing RUNX1 levels attenuated the cells’ ability to form tumors, but elevated RUNX1 levels worked with FLT3-ITD to induce AML.

Mouse hematopoietic stem cells expressing FLT3-ITD were highly proliferative, and co-expression of RUNX1 blocked their differentiation, allowing them to give rise to AML.

Mutant FLT3 appears to stabilize and activate RUNX1 by promoting the transcription factor’s phosphorylation. Active RUNX1 then blocks differentiation, at least in part, by upregulation of another transcription factor, Hhex.

The investigators found that hematopoietic stem cells expressing both Hhex and FLT3-ITD gave rise to AML.

RUNX1 may therefore suppress the initiation of AML but, after being activated by mutant FLT3, block differentiation and promote tumor development.

“Therapies that can reverse this differentiation block may offer significant therapeutic efficacy in AML patients with FLT3 mutations,” Dr Stocking said. “Ablating RUNX1 is toxic to leukemic cells but not to normal hematopoietic stem cells, so inhibiting RUNX1 may be a promising target in combination with FLT3 inhibitors.” ![]()

New research indicates that RUNX1, a known tumor suppressor, actually cooperates with internal tandem duplications in the FLT3 receptor tyrosine kinase (FLT3-ITD) to induce acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Investigators say this discovery suggests that blocking RUNX1 activity will “greatly enhance” current therapeutic approaches using FLT3 inhibitors.

The discovery was published in The Journal of Experimental Medicine.

The research began when investigators noticed that many AML patients with FLT3-ITD also showed increased levels of RUNX1.

“This was unexpected because up to 20% of AML patients carry mutations that inactivate RUNX1, which is generally considered to be a tumor suppressor that prevents the formation of leukemias,” said study author Carol Stocking, PhD, of Heinrich-Pette-Institute-Leibniz Institute for Experimental Virology in Hamburg, Germany.

To investigate this finding, she and her colleagues injected mice with human AML cells expressing FLT3-ITD. The team found that reducing RUNX1 levels attenuated the cells’ ability to form tumors, but elevated RUNX1 levels worked with FLT3-ITD to induce AML.

Mouse hematopoietic stem cells expressing FLT3-ITD were highly proliferative, and co-expression of RUNX1 blocked their differentiation, allowing them to give rise to AML.

Mutant FLT3 appears to stabilize and activate RUNX1 by promoting the transcription factor’s phosphorylation. Active RUNX1 then blocks differentiation, at least in part, by upregulation of another transcription factor, Hhex.

The investigators found that hematopoietic stem cells expressing both Hhex and FLT3-ITD gave rise to AML.

RUNX1 may therefore suppress the initiation of AML but, after being activated by mutant FLT3, block differentiation and promote tumor development.

“Therapies that can reverse this differentiation block may offer significant therapeutic efficacy in AML patients with FLT3 mutations,” Dr Stocking said. “Ablating RUNX1 is toxic to leukemic cells but not to normal hematopoietic stem cells, so inhibiting RUNX1 may be a promising target in combination with FLT3 inhibitors.” ![]()

New research indicates that RUNX1, a known tumor suppressor, actually cooperates with internal tandem duplications in the FLT3 receptor tyrosine kinase (FLT3-ITD) to induce acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Investigators say this discovery suggests that blocking RUNX1 activity will “greatly enhance” current therapeutic approaches using FLT3 inhibitors.

The discovery was published in The Journal of Experimental Medicine.

The research began when investigators noticed that many AML patients with FLT3-ITD also showed increased levels of RUNX1.

“This was unexpected because up to 20% of AML patients carry mutations that inactivate RUNX1, which is generally considered to be a tumor suppressor that prevents the formation of leukemias,” said study author Carol Stocking, PhD, of Heinrich-Pette-Institute-Leibniz Institute for Experimental Virology in Hamburg, Germany.

To investigate this finding, she and her colleagues injected mice with human AML cells expressing FLT3-ITD. The team found that reducing RUNX1 levels attenuated the cells’ ability to form tumors, but elevated RUNX1 levels worked with FLT3-ITD to induce AML.

Mouse hematopoietic stem cells expressing FLT3-ITD were highly proliferative, and co-expression of RUNX1 blocked their differentiation, allowing them to give rise to AML.

Mutant FLT3 appears to stabilize and activate RUNX1 by promoting the transcription factor’s phosphorylation. Active RUNX1 then blocks differentiation, at least in part, by upregulation of another transcription factor, Hhex.

The investigators found that hematopoietic stem cells expressing both Hhex and FLT3-ITD gave rise to AML.

RUNX1 may therefore suppress the initiation of AML but, after being activated by mutant FLT3, block differentiation and promote tumor development.

“Therapies that can reverse this differentiation block may offer significant therapeutic efficacy in AML patients with FLT3 mutations,” Dr Stocking said. “Ablating RUNX1 is toxic to leukemic cells but not to normal hematopoietic stem cells, so inhibiting RUNX1 may be a promising target in combination with FLT3 inhibitors.” ![]()

Immunotherapy receives fast track designation

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to CMD-003 (baltaleucel-T) for patients with relapsed/refractory lymphoma and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

CMD-003 consists of patient-derived T cells that have been activated to kill malignant cells expressing antigens associated with EBV.

The T cells specifically target 4 EBV epitopes—LMP1, LMP2, EBNA, and BARF1.

CMD-003 is being developed by Cell Medica and the Baylor College of Medicine with funding provided, in part, by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas.

About fast track designation

The FDA’s fast track program is designed to facilitate the development and expedite the review of products intended to treat or prevent serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical need.

Through the FDA’s fast track program, a product may be eligible for priority review. In addition, the company developing the product may be allowed to submit sections of the biologic license application or new drug application on a rolling basis as data become available.

Fast track designation also provides the company with opportunities for more frequent meetings and written communications with the FDA.

CMD-003-related research

CMD-003 is currently under investigation in the phase 2 CITADEL trial for patients with extranodal natural killer T-cell lymphoma and the phase 2 CIVIC trial for patients with EBV-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease.

Researchers have not published results from any trials of CMD-003, but they have published results with EBV-specific T-cell products related to CMD-003.

In one study, published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2014, researchers administered cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) in 50 patients with EBV-associated Hodgkin or non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Twenty-nine of the patients were in remission when they received CTL infusions, but they were at a high risk of relapse. The remaining 21 patients had relapsed or refractory disease at the time of CTL infusion.

Twenty-seven of the patients who received CTLs as an adjuvant treatment remained in remission at 3.1 years after treatment.

Their 2-year event-free survival rate was 82%. None of the patients died of lymphoma, but 9 died from complications associated with the chemotherapy and radiation they had received.

Of the 21 patients with relapsed or refractory disease, 13 responded to CTL infusions, and 11 patients achieved a complete response. In this group, the 2-year event-free survival rate was about 50%.

The researchers said there were no toxicities that were definitively related to CTL infusion.

One patient had central nervous system deterioration 2 weeks after infusion. This was attributed to disease progression but could possibly have been treatment-related.

Another patient developed respiratory complications about 4 weeks after a second CTL infusion that may have been treatment-related. However, the researchers attributed it to an intercurrent infection, and the patient made a complete recovery.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to CMD-003 (baltaleucel-T) for patients with relapsed/refractory lymphoma and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

CMD-003 consists of patient-derived T cells that have been activated to kill malignant cells expressing antigens associated with EBV.

The T cells specifically target 4 EBV epitopes—LMP1, LMP2, EBNA, and BARF1.

CMD-003 is being developed by Cell Medica and the Baylor College of Medicine with funding provided, in part, by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas.

About fast track designation

The FDA’s fast track program is designed to facilitate the development and expedite the review of products intended to treat or prevent serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical need.

Through the FDA’s fast track program, a product may be eligible for priority review. In addition, the company developing the product may be allowed to submit sections of the biologic license application or new drug application on a rolling basis as data become available.

Fast track designation also provides the company with opportunities for more frequent meetings and written communications with the FDA.

CMD-003-related research

CMD-003 is currently under investigation in the phase 2 CITADEL trial for patients with extranodal natural killer T-cell lymphoma and the phase 2 CIVIC trial for patients with EBV-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease.

Researchers have not published results from any trials of CMD-003, but they have published results with EBV-specific T-cell products related to CMD-003.

In one study, published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2014, researchers administered cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) in 50 patients with EBV-associated Hodgkin or non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Twenty-nine of the patients were in remission when they received CTL infusions, but they were at a high risk of relapse. The remaining 21 patients had relapsed or refractory disease at the time of CTL infusion.

Twenty-seven of the patients who received CTLs as an adjuvant treatment remained in remission at 3.1 years after treatment.

Their 2-year event-free survival rate was 82%. None of the patients died of lymphoma, but 9 died from complications associated with the chemotherapy and radiation they had received.

Of the 21 patients with relapsed or refractory disease, 13 responded to CTL infusions, and 11 patients achieved a complete response. In this group, the 2-year event-free survival rate was about 50%.

The researchers said there were no toxicities that were definitively related to CTL infusion.

One patient had central nervous system deterioration 2 weeks after infusion. This was attributed to disease progression but could possibly have been treatment-related.

Another patient developed respiratory complications about 4 weeks after a second CTL infusion that may have been treatment-related. However, the researchers attributed it to an intercurrent infection, and the patient made a complete recovery.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to CMD-003 (baltaleucel-T) for patients with relapsed/refractory lymphoma and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

CMD-003 consists of patient-derived T cells that have been activated to kill malignant cells expressing antigens associated with EBV.

The T cells specifically target 4 EBV epitopes—LMP1, LMP2, EBNA, and BARF1.

CMD-003 is being developed by Cell Medica and the Baylor College of Medicine with funding provided, in part, by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas.

About fast track designation

The FDA’s fast track program is designed to facilitate the development and expedite the review of products intended to treat or prevent serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical need.

Through the FDA’s fast track program, a product may be eligible for priority review. In addition, the company developing the product may be allowed to submit sections of the biologic license application or new drug application on a rolling basis as data become available.

Fast track designation also provides the company with opportunities for more frequent meetings and written communications with the FDA.

CMD-003-related research

CMD-003 is currently under investigation in the phase 2 CITADEL trial for patients with extranodal natural killer T-cell lymphoma and the phase 2 CIVIC trial for patients with EBV-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease.

Researchers have not published results from any trials of CMD-003, but they have published results with EBV-specific T-cell products related to CMD-003.

In one study, published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2014, researchers administered cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) in 50 patients with EBV-associated Hodgkin or non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Twenty-nine of the patients were in remission when they received CTL infusions, but they were at a high risk of relapse. The remaining 21 patients had relapsed or refractory disease at the time of CTL infusion.

Twenty-seven of the patients who received CTLs as an adjuvant treatment remained in remission at 3.1 years after treatment.

Their 2-year event-free survival rate was 82%. None of the patients died of lymphoma, but 9 died from complications associated with the chemotherapy and radiation they had received.

Of the 21 patients with relapsed or refractory disease, 13 responded to CTL infusions, and 11 patients achieved a complete response. In this group, the 2-year event-free survival rate was about 50%.

The researchers said there were no toxicities that were definitively related to CTL infusion.

One patient had central nervous system deterioration 2 weeks after infusion. This was attributed to disease progression but could possibly have been treatment-related.

Another patient developed respiratory complications about 4 weeks after a second CTL infusion that may have been treatment-related. However, the researchers attributed it to an intercurrent infection, and the patient made a complete recovery.

Three signs predict hypercalcemic crisis in hyperparathyroid patients

LAS VEGAS – A triad of signs – elevated serum calcium, elevated parathyroid hormone, and a history of kidney stones – can predict hypercalcemic crisis among patients with hyperparathyroidism, a study showed.

Patients who present with the trifecta should be considered for expedited parathyroidectomy, Andrew Lowell said at the Association for Academic Surgery/Society of University Surgeons Academic Surgical Congress.

The model was based on a retrospective analysis of 183 patients with hyperparathyroidism who were hospitalized and treated for hypercalcemia. These were divided into two groups: those who developed a hypercalcemic crisis (29) and those who did not (154).

There were no significant differences in age, sex, alcohol or tobacco use, body mass index, or Charlson comorbidity score. However, those who developed a crisis were significantly more likely to have had kidney stones (31% vs. 14%). Their preoperative serum calcium level was also significantly higher (median, 13.8 vs. 12.4 mg/dL), and they had significantly higher parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels (median, 318 vs. 160 pg/mL). Their preoperative vitamin D level was also significantly lower (median, 16 vs. 26 ng/mL).

Parathyroidectomy was equally effective in both groups, but twice as many patients with crisis needed a multigland resection (24% vs. 12%).

Mr. Lowell conducted a univariate, and then a multivariate, analysis to determine independent risk factors for hypercalcemic crisis. This revealed that a higher preoperative calcium level, an elevated PTH level, and a history of kidney stones were significantly associated with crisis.

Hypercalcemia developed in:

• 91% of those with a serum calcium higher than 13.25 mg/dL and 6% of those with a lower serum calcium level.

• 60% of those with a PTH of 394 pg/mL or higher and 19% of those with a PTH less than 394 pg/mL.

• 31% of those with a history of kidney stones and 14% of those without such a history.

The investigators created a decision tree that begins with a calcium level greater than 13.25 mg/dL, a PTH level higher than 394 pg/mL, and a Charlson comorbidity index of 4 or greater. The model carried an overall predictive accuracy of 90% and a positive predictive value of 76%, Mr. Lowell said.

Session moderator Benjamin Poulose, MD, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., said the model looks very good on paper, but might be challenging to implement when assessing emergent patients.

Mr. Lowell suggested that it would be better employed in an outpatient setting.

“I think this would be more useful in the situation of a physician who knows that patient’s comorbidities, in the context of counseling, to determine” the need for and timing of surgery, he said.

He had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

LAS VEGAS – A triad of signs – elevated serum calcium, elevated parathyroid hormone, and a history of kidney stones – can predict hypercalcemic crisis among patients with hyperparathyroidism, a study showed.

Patients who present with the trifecta should be considered for expedited parathyroidectomy, Andrew Lowell said at the Association for Academic Surgery/Society of University Surgeons Academic Surgical Congress.

The model was based on a retrospective analysis of 183 patients with hyperparathyroidism who were hospitalized and treated for hypercalcemia. These were divided into two groups: those who developed a hypercalcemic crisis (29) and those who did not (154).

There were no significant differences in age, sex, alcohol or tobacco use, body mass index, or Charlson comorbidity score. However, those who developed a crisis were significantly more likely to have had kidney stones (31% vs. 14%). Their preoperative serum calcium level was also significantly higher (median, 13.8 vs. 12.4 mg/dL), and they had significantly higher parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels (median, 318 vs. 160 pg/mL). Their preoperative vitamin D level was also significantly lower (median, 16 vs. 26 ng/mL).

Parathyroidectomy was equally effective in both groups, but twice as many patients with crisis needed a multigland resection (24% vs. 12%).

Mr. Lowell conducted a univariate, and then a multivariate, analysis to determine independent risk factors for hypercalcemic crisis. This revealed that a higher preoperative calcium level, an elevated PTH level, and a history of kidney stones were significantly associated with crisis.

Hypercalcemia developed in:

• 91% of those with a serum calcium higher than 13.25 mg/dL and 6% of those with a lower serum calcium level.

• 60% of those with a PTH of 394 pg/mL or higher and 19% of those with a PTH less than 394 pg/mL.

• 31% of those with a history of kidney stones and 14% of those without such a history.

The investigators created a decision tree that begins with a calcium level greater than 13.25 mg/dL, a PTH level higher than 394 pg/mL, and a Charlson comorbidity index of 4 or greater. The model carried an overall predictive accuracy of 90% and a positive predictive value of 76%, Mr. Lowell said.

Session moderator Benjamin Poulose, MD, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., said the model looks very good on paper, but might be challenging to implement when assessing emergent patients.

Mr. Lowell suggested that it would be better employed in an outpatient setting.

“I think this would be more useful in the situation of a physician who knows that patient’s comorbidities, in the context of counseling, to determine” the need for and timing of surgery, he said.

He had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

LAS VEGAS – A triad of signs – elevated serum calcium, elevated parathyroid hormone, and a history of kidney stones – can predict hypercalcemic crisis among patients with hyperparathyroidism, a study showed.

Patients who present with the trifecta should be considered for expedited parathyroidectomy, Andrew Lowell said at the Association for Academic Surgery/Society of University Surgeons Academic Surgical Congress.

The model was based on a retrospective analysis of 183 patients with hyperparathyroidism who were hospitalized and treated for hypercalcemia. These were divided into two groups: those who developed a hypercalcemic crisis (29) and those who did not (154).

There were no significant differences in age, sex, alcohol or tobacco use, body mass index, or Charlson comorbidity score. However, those who developed a crisis were significantly more likely to have had kidney stones (31% vs. 14%). Their preoperative serum calcium level was also significantly higher (median, 13.8 vs. 12.4 mg/dL), and they had significantly higher parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels (median, 318 vs. 160 pg/mL). Their preoperative vitamin D level was also significantly lower (median, 16 vs. 26 ng/mL).

Parathyroidectomy was equally effective in both groups, but twice as many patients with crisis needed a multigland resection (24% vs. 12%).

Mr. Lowell conducted a univariate, and then a multivariate, analysis to determine independent risk factors for hypercalcemic crisis. This revealed that a higher preoperative calcium level, an elevated PTH level, and a history of kidney stones were significantly associated with crisis.

Hypercalcemia developed in:

• 91% of those with a serum calcium higher than 13.25 mg/dL and 6% of those with a lower serum calcium level.

• 60% of those with a PTH of 394 pg/mL or higher and 19% of those with a PTH less than 394 pg/mL.

• 31% of those with a history of kidney stones and 14% of those without such a history.

The investigators created a decision tree that begins with a calcium level greater than 13.25 mg/dL, a PTH level higher than 394 pg/mL, and a Charlson comorbidity index of 4 or greater. The model carried an overall predictive accuracy of 90% and a positive predictive value of 76%, Mr. Lowell said.

Session moderator Benjamin Poulose, MD, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., said the model looks very good on paper, but might be challenging to implement when assessing emergent patients.

Mr. Lowell suggested that it would be better employed in an outpatient setting.

“I think this would be more useful in the situation of a physician who knows that patient’s comorbidities, in the context of counseling, to determine” the need for and timing of surgery, he said.

He had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

AT THE ACADEMIC SURGICAL CONGRESS

Key clinical point: .

Major finding: A model based on the biomarkers and comorbidity status had a predictive accuracy of 90% and a positive predictive value of 76%.

Data source: A study cohort consisting of 183 patients.

Disclosures: Mr. Lowell had no relevant financial disclosures.

Methotrexate prolonged efficacy of steroid injections in oligoarticular JIA

Oral methotrexate prolonged and slightly boosted the efficacy of intra-articular corticosteroid injections in children with oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis without causing serious adverse effects, based on the results of a first-in-kind multicenter, randomized, open-label trial.

“This combination could be considered as reference treatment in everyday clinical practice for pediatricians, particularly in children with higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate,” Angelo Ravelli, MD, of Istituto Giannini Gaslini, Genoa, Italy, and his associates wrote in The Lancet. The regimen also could take center stage in treat-to-target strategies for children with chronic arthritis, they said (Lancet. 2017 Feb 2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[17]30065-X).

For the study, they randomly assigned 207 children and adolescents with oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis to receive intra-articular injections with triamcinolone hexacetonide or methylprednisolone acetate, either alone or with 15 mg/m2 oral methotrexate at a maximum dose of 20 mg. The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients with remission of all injected joints at 12 months.

Methotrexate missed this endpoint – 12-month remission rates were 34% in the injection-only group and 39% in the dual therapy group (P = .48). However, methotrexate seemed to prolong the time to arthritis flare. The median time to flare was 10.1 months (95% confidence interval, 7.6 to more than 16 months) when patients received injections plus methotrexate, and only 6 months (95% CI, 4.6-8.2 months) when they received injections only (hazard ratio, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.46-0.97; P = .03).

Consequently, the dual therapy group had a higher rate of remission at 6 months (67%; 95% CI, 56%-75%) than did the injection-only group (49%; 95% CI, 39%-58%). Cumulative remission rates at 12 months also were higher for dual therapy (46%), compared with injections only (35%).

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate predicted arthritis flare, but did not seem to affect the chances of methotrexate being effective, the researchers said. After controlling for erythrocyte sedimentation rate, methotrexate decreased the 12-month risk of flare by 47%, “although the statistical effect was marginal,” they noted (adjusted odds ratio, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.27-1.01; P = .05).

These findings support those of noncontrolled studies and can inform strategies for initial treatment of oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis because study participants had short disease durations, the researchers said. But they emphasized that the cohort excluded patients with monoarthritis of the knee, for whom they use only local injections, adding methotrexate if patients relapse soon after the knee is injected or if arthritis spreads to other joints within 6-12 months.

Rates of new-onset uveitis were less than 10% and did not significantly differ between arms. Methotrexate most frequently caused nausea, vomiting, or constipation, but eight patients developed elevated liver enzymes. One patient stopped methotrexate as a result, and five interrupted treatment or had dose reductions. Another patient stopped treatment because of gastrointestinal discomfort, but no there were no serious adverse effects of any type, the researchers said. They will follow the cohort for up to 2 years to evaluate longer-term safety, they added.

The Italian Agency of Drug Evaluation funded the study. Dr. Ravelli disclosed personal fees from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Johnson & Johnson. Several coinvestigators also disclosed ties to a number of pharmaceutical companies.

These outcomes [of adding methotrexate to intra-articular corticosteroids] seem of substantial benefit for the individual patient [with juvenile idiopathic arthritis]. However, we need to know more about the pathogenesis of this disease and to develop more robust and validated biomarkers to predict an individual’s disease course and response to therapy. Both oral and subcutaneous methotrexate are associated with nausea or intolerance symptoms in up to 40% of patients, which often causes noncompliance in children and adolescents. Therefore, knowledge of who will benefit most from early methotrexate therapy is important.

Nico M. Wulffraat, MD, is with the department of pediatric rheumatology at University Medical Center Utrecht (the Netherlands). He disclosed unrestricted grants from AbbVie, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and Sobi. These comments are from his editorial accompanying Dr. Ravelli and his colleagues’ report (Lancet. 2017 Feb 2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[17]30180-0).

These outcomes [of adding methotrexate to intra-articular corticosteroids] seem of substantial benefit for the individual patient [with juvenile idiopathic arthritis]. However, we need to know more about the pathogenesis of this disease and to develop more robust and validated biomarkers to predict an individual’s disease course and response to therapy. Both oral and subcutaneous methotrexate are associated with nausea or intolerance symptoms in up to 40% of patients, which often causes noncompliance in children and adolescents. Therefore, knowledge of who will benefit most from early methotrexate therapy is important.

Nico M. Wulffraat, MD, is with the department of pediatric rheumatology at University Medical Center Utrecht (the Netherlands). He disclosed unrestricted grants from AbbVie, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and Sobi. These comments are from his editorial accompanying Dr. Ravelli and his colleagues’ report (Lancet. 2017 Feb 2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[17]30180-0).

These outcomes [of adding methotrexate to intra-articular corticosteroids] seem of substantial benefit for the individual patient [with juvenile idiopathic arthritis]. However, we need to know more about the pathogenesis of this disease and to develop more robust and validated biomarkers to predict an individual’s disease course and response to therapy. Both oral and subcutaneous methotrexate are associated with nausea or intolerance symptoms in up to 40% of patients, which often causes noncompliance in children and adolescents. Therefore, knowledge of who will benefit most from early methotrexate therapy is important.

Nico M. Wulffraat, MD, is with the department of pediatric rheumatology at University Medical Center Utrecht (the Netherlands). He disclosed unrestricted grants from AbbVie, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and Sobi. These comments are from his editorial accompanying Dr. Ravelli and his colleagues’ report (Lancet. 2017 Feb 2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[17]30180-0).

Oral methotrexate prolonged and slightly boosted the efficacy of intra-articular corticosteroid injections in children with oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis without causing serious adverse effects, based on the results of a first-in-kind multicenter, randomized, open-label trial.

“This combination could be considered as reference treatment in everyday clinical practice for pediatricians, particularly in children with higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate,” Angelo Ravelli, MD, of Istituto Giannini Gaslini, Genoa, Italy, and his associates wrote in The Lancet. The regimen also could take center stage in treat-to-target strategies for children with chronic arthritis, they said (Lancet. 2017 Feb 2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[17]30065-X).

For the study, they randomly assigned 207 children and adolescents with oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis to receive intra-articular injections with triamcinolone hexacetonide or methylprednisolone acetate, either alone or with 15 mg/m2 oral methotrexate at a maximum dose of 20 mg. The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients with remission of all injected joints at 12 months.

Methotrexate missed this endpoint – 12-month remission rates were 34% in the injection-only group and 39% in the dual therapy group (P = .48). However, methotrexate seemed to prolong the time to arthritis flare. The median time to flare was 10.1 months (95% confidence interval, 7.6 to more than 16 months) when patients received injections plus methotrexate, and only 6 months (95% CI, 4.6-8.2 months) when they received injections only (hazard ratio, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.46-0.97; P = .03).

Consequently, the dual therapy group had a higher rate of remission at 6 months (67%; 95% CI, 56%-75%) than did the injection-only group (49%; 95% CI, 39%-58%). Cumulative remission rates at 12 months also were higher for dual therapy (46%), compared with injections only (35%).

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate predicted arthritis flare, but did not seem to affect the chances of methotrexate being effective, the researchers said. After controlling for erythrocyte sedimentation rate, methotrexate decreased the 12-month risk of flare by 47%, “although the statistical effect was marginal,” they noted (adjusted odds ratio, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.27-1.01; P = .05).

These findings support those of noncontrolled studies and can inform strategies for initial treatment of oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis because study participants had short disease durations, the researchers said. But they emphasized that the cohort excluded patients with monoarthritis of the knee, for whom they use only local injections, adding methotrexate if patients relapse soon after the knee is injected or if arthritis spreads to other joints within 6-12 months.

Rates of new-onset uveitis were less than 10% and did not significantly differ between arms. Methotrexate most frequently caused nausea, vomiting, or constipation, but eight patients developed elevated liver enzymes. One patient stopped methotrexate as a result, and five interrupted treatment or had dose reductions. Another patient stopped treatment because of gastrointestinal discomfort, but no there were no serious adverse effects of any type, the researchers said. They will follow the cohort for up to 2 years to evaluate longer-term safety, they added.

The Italian Agency of Drug Evaluation funded the study. Dr. Ravelli disclosed personal fees from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Johnson & Johnson. Several coinvestigators also disclosed ties to a number of pharmaceutical companies.

Oral methotrexate prolonged and slightly boosted the efficacy of intra-articular corticosteroid injections in children with oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis without causing serious adverse effects, based on the results of a first-in-kind multicenter, randomized, open-label trial.

“This combination could be considered as reference treatment in everyday clinical practice for pediatricians, particularly in children with higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate,” Angelo Ravelli, MD, of Istituto Giannini Gaslini, Genoa, Italy, and his associates wrote in The Lancet. The regimen also could take center stage in treat-to-target strategies for children with chronic arthritis, they said (Lancet. 2017 Feb 2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[17]30065-X).

For the study, they randomly assigned 207 children and adolescents with oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis to receive intra-articular injections with triamcinolone hexacetonide or methylprednisolone acetate, either alone or with 15 mg/m2 oral methotrexate at a maximum dose of 20 mg. The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients with remission of all injected joints at 12 months.

Methotrexate missed this endpoint – 12-month remission rates were 34% in the injection-only group and 39% in the dual therapy group (P = .48). However, methotrexate seemed to prolong the time to arthritis flare. The median time to flare was 10.1 months (95% confidence interval, 7.6 to more than 16 months) when patients received injections plus methotrexate, and only 6 months (95% CI, 4.6-8.2 months) when they received injections only (hazard ratio, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.46-0.97; P = .03).

Consequently, the dual therapy group had a higher rate of remission at 6 months (67%; 95% CI, 56%-75%) than did the injection-only group (49%; 95% CI, 39%-58%). Cumulative remission rates at 12 months also were higher for dual therapy (46%), compared with injections only (35%).

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate predicted arthritis flare, but did not seem to affect the chances of methotrexate being effective, the researchers said. After controlling for erythrocyte sedimentation rate, methotrexate decreased the 12-month risk of flare by 47%, “although the statistical effect was marginal,” they noted (adjusted odds ratio, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.27-1.01; P = .05).

These findings support those of noncontrolled studies and can inform strategies for initial treatment of oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis because study participants had short disease durations, the researchers said. But they emphasized that the cohort excluded patients with monoarthritis of the knee, for whom they use only local injections, adding methotrexate if patients relapse soon after the knee is injected or if arthritis spreads to other joints within 6-12 months.

Rates of new-onset uveitis were less than 10% and did not significantly differ between arms. Methotrexate most frequently caused nausea, vomiting, or constipation, but eight patients developed elevated liver enzymes. One patient stopped methotrexate as a result, and five interrupted treatment or had dose reductions. Another patient stopped treatment because of gastrointestinal discomfort, but no there were no serious adverse effects of any type, the researchers said. They will follow the cohort for up to 2 years to evaluate longer-term safety, they added.

The Italian Agency of Drug Evaluation funded the study. Dr. Ravelli disclosed personal fees from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Johnson & Johnson. Several coinvestigators also disclosed ties to a number of pharmaceutical companies.

FROM THE LANCET

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The primary endpoint, remission of arthritis in all injected joints at 12 months, occurred in 34% of patients who received intra-articular corticosteroids only and in 39% of those who also received oral methotrexate (P = .48). Median time to arthritis flare was 10.1 months with dual therapy and 6 months with injections only (HR, 0.67; P = .03).

Data source: A multicenter, open-label, randomized trial of 207 children younger than 18 years with oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Disclosures: The Italian Agency of Drug Evaluation funded the study. Dr. Ravelli disclosed personal fees from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Johnson & Johnson. Several coinvestigators also disclosed ties to a number of pharmaceutical companies.

Mentally ill? Go directly to jail

In the course of researching our book, “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care,” I came to a few very important conclusions. Involuntary commitment can be traumatizing to patients, and it should be done as a last resort when patients are dangerous (generally to themselves, but sometimes toward others) or tormented, and when they can’t be persuaded to get voluntary care. That may sound obvious, but in practice, it doesn’t always work that way. Furthermore, if there is no choice but to hold people against their will, there should be no use of physical force unless it is absolutely necessary to maintain safety, and patients should be treated with kindness and respect. It’s what we’d all want if we were the patient, and it’s not what all patients get.

Knowing that, you can imagine my shock when I saw reporter Mike Anderson’s article “Jail cells await mentally ill in Rapid City” in the Feb. 8, 2017, edition of the Rapid City Journal. Mr. Anderson noted that the Rapid City Regional Hospital was changing its policy on psychiatric admissions. The South Dakota city of 60,000 has a 44-bed psychiatric hospital located 1.5 miles from the main hospital. It is the only inpatient facility for at least 250 miles and serves a total population of approximately 250,000 people. If the unit is full – either because all beds are full or because staffing and acuity issues limit capacity – its policy always has been to admit overflow psychiatric patients to medical beds.

Effective Feb. 1, 2017, we will no longer admit behavioral health patients who do not have acute medical needs to the main hospital when the Behavioral Health facility is at capacity. In these instances, we will expect the County to take custody of patients who are subject to the involuntary mental commitment process, pending an opening at the Behavioral Health unit. It is simply no longer feasible for us to care for behavioral health patients who do not have acute medical needs outside of the Behavioral Health facility. Unless we hear differently, we will contact the Sheriff’s Office to take custody of involuntarily detained persons when the Behavioral Health facility is at capacity.

Also, by way of information, we will no longer admit patients to the Behavioral Health facility who have neurodevelopmental/cognitive disorders such as dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, or Autism Spectrum Disorders. We believe it is in the best interest of all patients to limit the conditions which are appropriate for treatment in our facility.

In other words, if there are no open beds in a psychiatric facility, patients would be transported from the emergency deparment to the Pennington County Jail. The fate of patients with psychiatric issues and dementia or autism was not at all clear.

I spoke with Stephen Manlove, MD, DFAPA. Dr. Manlove has a psychiatric outpatient practice but worked for the Rapid City Regional Hospital for 26 years. He left this past September because he felt the facility had lost sight of its mission to give psychiatric patients excellent care. He also works two mornings a week providing psychiatric treatment at the local jail, a 600-bed facility where 1 in 6 inmates is on psychotropic medications, and an average of 25 inmates at any given time suffer from severe and persistent mental disorders.

“This is obviously a complicated story,” Dr. Manlove noted. “The hospital gave the jail only a few days’ notice. The hospital doesn’t seem to want to invest in this population. They are investing millions of dollars in other projects but can’t find the money to fund psychiatry. Surprisingly, the medical community seems to have accepted this.”

Dr. Manlove noted that the jail is not equipped to offer comprehensive psychiatric treatment, and that inmates are held in cinder block cells with very limited medical supervision.

Kevin Thom, the Pennington County sheriff, was quick to say, “We shouldn’t be criminalizing mental health problems.” While he noted that local statute allows for patients to be held in a jail cell for up to 24 hours if a hospital bed is not available, he commented on the inappropriateness of this and on the brief notice his office was given: “There was no time to figure out a process or alternatives. It’s frustrating.”

Dr. Manlove said he believes that a few patients may have been taken to the jail since the new policy was instituted, but the jail has turned some away. Sheriff Thom said his office had been called to transport a patient and had refused.

I asked what happens when a voluntary patient needs a bed and there is no room. Dr. Manlove replied: “If they are not considered acutely dangerous, I assume they will be told to go to another hospital. If they are acutely dangerous to themselves or others, then a mental health hold would be placed, and they would be sent to jail.”

Of note, the closest hospital with a psychiatric unit is 253 miles away, in Casper, Wyo.

One reason for limiting the type of patients the psychiatric facility will admit may have to do with an effort by the hospital to lower its use of seclusion and restraint. In an article in the Rapid City Journal on Feb. 19, 2017, reporter Chris Huber noted that between July 2015 and July 2016, Rapid City Behavioral Health had seclusion rates 300 times higher than the national average, a fact the hospital attributes to the high acuity needs of autistic patients. Rather than improving its ability to treat these patients, the facility has decided not to accept them.

In June 2016, the Boston Globe Spotlight team began a series called “The Desperate and the Dead” as a way to highlight deficiencies in the Massachusetts public mental health system. The first article was a sensationalized piece about psychiatric patients who kill their family members. The backlash to the stigmatization of psychiatric patients as murderers was huge; a Facebook page set up to accept comments soon had more than 1,300 members, and the entrance to the Globe was blocked by 150 protesters. The response to the Rapid City hospital’s decision to jail people with psychiatric disorders who have committed no crime has been surprisingly quiet; there have been no stories of protests or advocacy outrage. In this egregious stigmatization of those with psychiatric disorders, I had to wonder what they do when the medical beds overflow: Do they send those patients to jail? Of course not. And why would anyone think this is okay?

We know that involuntary care can be traumatizing and that psychiatric care can feel demeaning. On the one hand, there is a call to pass laws to make it easier to treat patients involuntarily. In our polarized world with rising suicide rates, should we be doing everything possible to engage patients in voluntary care? How do we reconcile the fact that a hospital administration can decide that if distressed people seek care, having broken no law, they can be sent to jail? And finally, since suicide rates among physicians remain so high, I’d like to ask this: Would you go to a hospital for treatment if you knew you might end up desperate and alone, receiving no treatment, in a jail cell?

My thanks to Mr. Anderson of the Rapid City Journal, Dr. Manlove, and Sheriff Thom for their help with this article.

Dr. Miller wrote “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” with Annette Hanson, MD (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

In the course of researching our book, “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care,” I came to a few very important conclusions. Involuntary commitment can be traumatizing to patients, and it should be done as a last resort when patients are dangerous (generally to themselves, but sometimes toward others) or tormented, and when they can’t be persuaded to get voluntary care. That may sound obvious, but in practice, it doesn’t always work that way. Furthermore, if there is no choice but to hold people against their will, there should be no use of physical force unless it is absolutely necessary to maintain safety, and patients should be treated with kindness and respect. It’s what we’d all want if we were the patient, and it’s not what all patients get.

Knowing that, you can imagine my shock when I saw reporter Mike Anderson’s article “Jail cells await mentally ill in Rapid City” in the Feb. 8, 2017, edition of the Rapid City Journal. Mr. Anderson noted that the Rapid City Regional Hospital was changing its policy on psychiatric admissions. The South Dakota city of 60,000 has a 44-bed psychiatric hospital located 1.5 miles from the main hospital. It is the only inpatient facility for at least 250 miles and serves a total population of approximately 250,000 people. If the unit is full – either because all beds are full or because staffing and acuity issues limit capacity – its policy always has been to admit overflow psychiatric patients to medical beds.

Effective Feb. 1, 2017, we will no longer admit behavioral health patients who do not have acute medical needs to the main hospital when the Behavioral Health facility is at capacity. In these instances, we will expect the County to take custody of patients who are subject to the involuntary mental commitment process, pending an opening at the Behavioral Health unit. It is simply no longer feasible for us to care for behavioral health patients who do not have acute medical needs outside of the Behavioral Health facility. Unless we hear differently, we will contact the Sheriff’s Office to take custody of involuntarily detained persons when the Behavioral Health facility is at capacity.

Also, by way of information, we will no longer admit patients to the Behavioral Health facility who have neurodevelopmental/cognitive disorders such as dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, or Autism Spectrum Disorders. We believe it is in the best interest of all patients to limit the conditions which are appropriate for treatment in our facility.

In other words, if there are no open beds in a psychiatric facility, patients would be transported from the emergency deparment to the Pennington County Jail. The fate of patients with psychiatric issues and dementia or autism was not at all clear.

I spoke with Stephen Manlove, MD, DFAPA. Dr. Manlove has a psychiatric outpatient practice but worked for the Rapid City Regional Hospital for 26 years. He left this past September because he felt the facility had lost sight of its mission to give psychiatric patients excellent care. He also works two mornings a week providing psychiatric treatment at the local jail, a 600-bed facility where 1 in 6 inmates is on psychotropic medications, and an average of 25 inmates at any given time suffer from severe and persistent mental disorders.

“This is obviously a complicated story,” Dr. Manlove noted. “The hospital gave the jail only a few days’ notice. The hospital doesn’t seem to want to invest in this population. They are investing millions of dollars in other projects but can’t find the money to fund psychiatry. Surprisingly, the medical community seems to have accepted this.”

Dr. Manlove noted that the jail is not equipped to offer comprehensive psychiatric treatment, and that inmates are held in cinder block cells with very limited medical supervision.

Kevin Thom, the Pennington County sheriff, was quick to say, “We shouldn’t be criminalizing mental health problems.” While he noted that local statute allows for patients to be held in a jail cell for up to 24 hours if a hospital bed is not available, he commented on the inappropriateness of this and on the brief notice his office was given: “There was no time to figure out a process or alternatives. It’s frustrating.”

Dr. Manlove said he believes that a few patients may have been taken to the jail since the new policy was instituted, but the jail has turned some away. Sheriff Thom said his office had been called to transport a patient and had refused.

I asked what happens when a voluntary patient needs a bed and there is no room. Dr. Manlove replied: “If they are not considered acutely dangerous, I assume they will be told to go to another hospital. If they are acutely dangerous to themselves or others, then a mental health hold would be placed, and they would be sent to jail.”

Of note, the closest hospital with a psychiatric unit is 253 miles away, in Casper, Wyo.

One reason for limiting the type of patients the psychiatric facility will admit may have to do with an effort by the hospital to lower its use of seclusion and restraint. In an article in the Rapid City Journal on Feb. 19, 2017, reporter Chris Huber noted that between July 2015 and July 2016, Rapid City Behavioral Health had seclusion rates 300 times higher than the national average, a fact the hospital attributes to the high acuity needs of autistic patients. Rather than improving its ability to treat these patients, the facility has decided not to accept them.

In June 2016, the Boston Globe Spotlight team began a series called “The Desperate and the Dead” as a way to highlight deficiencies in the Massachusetts public mental health system. The first article was a sensationalized piece about psychiatric patients who kill their family members. The backlash to the stigmatization of psychiatric patients as murderers was huge; a Facebook page set up to accept comments soon had more than 1,300 members, and the entrance to the Globe was blocked by 150 protesters. The response to the Rapid City hospital’s decision to jail people with psychiatric disorders who have committed no crime has been surprisingly quiet; there have been no stories of protests or advocacy outrage. In this egregious stigmatization of those with psychiatric disorders, I had to wonder what they do when the medical beds overflow: Do they send those patients to jail? Of course not. And why would anyone think this is okay?

We know that involuntary care can be traumatizing and that psychiatric care can feel demeaning. On the one hand, there is a call to pass laws to make it easier to treat patients involuntarily. In our polarized world with rising suicide rates, should we be doing everything possible to engage patients in voluntary care? How do we reconcile the fact that a hospital administration can decide that if distressed people seek care, having broken no law, they can be sent to jail? And finally, since suicide rates among physicians remain so high, I’d like to ask this: Would you go to a hospital for treatment if you knew you might end up desperate and alone, receiving no treatment, in a jail cell?

My thanks to Mr. Anderson of the Rapid City Journal, Dr. Manlove, and Sheriff Thom for their help with this article.

Dr. Miller wrote “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” with Annette Hanson, MD (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

In the course of researching our book, “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care,” I came to a few very important conclusions. Involuntary commitment can be traumatizing to patients, and it should be done as a last resort when patients are dangerous (generally to themselves, but sometimes toward others) or tormented, and when they can’t be persuaded to get voluntary care. That may sound obvious, but in practice, it doesn’t always work that way. Furthermore, if there is no choice but to hold people against their will, there should be no use of physical force unless it is absolutely necessary to maintain safety, and patients should be treated with kindness and respect. It’s what we’d all want if we were the patient, and it’s not what all patients get.

Knowing that, you can imagine my shock when I saw reporter Mike Anderson’s article “Jail cells await mentally ill in Rapid City” in the Feb. 8, 2017, edition of the Rapid City Journal. Mr. Anderson noted that the Rapid City Regional Hospital was changing its policy on psychiatric admissions. The South Dakota city of 60,000 has a 44-bed psychiatric hospital located 1.5 miles from the main hospital. It is the only inpatient facility for at least 250 miles and serves a total population of approximately 250,000 people. If the unit is full – either because all beds are full or because staffing and acuity issues limit capacity – its policy always has been to admit overflow psychiatric patients to medical beds.

Effective Feb. 1, 2017, we will no longer admit behavioral health patients who do not have acute medical needs to the main hospital when the Behavioral Health facility is at capacity. In these instances, we will expect the County to take custody of patients who are subject to the involuntary mental commitment process, pending an opening at the Behavioral Health unit. It is simply no longer feasible for us to care for behavioral health patients who do not have acute medical needs outside of the Behavioral Health facility. Unless we hear differently, we will contact the Sheriff’s Office to take custody of involuntarily detained persons when the Behavioral Health facility is at capacity.

Also, by way of information, we will no longer admit patients to the Behavioral Health facility who have neurodevelopmental/cognitive disorders such as dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, or Autism Spectrum Disorders. We believe it is in the best interest of all patients to limit the conditions which are appropriate for treatment in our facility.

In other words, if there are no open beds in a psychiatric facility, patients would be transported from the emergency deparment to the Pennington County Jail. The fate of patients with psychiatric issues and dementia or autism was not at all clear.

I spoke with Stephen Manlove, MD, DFAPA. Dr. Manlove has a psychiatric outpatient practice but worked for the Rapid City Regional Hospital for 26 years. He left this past September because he felt the facility had lost sight of its mission to give psychiatric patients excellent care. He also works two mornings a week providing psychiatric treatment at the local jail, a 600-bed facility where 1 in 6 inmates is on psychotropic medications, and an average of 25 inmates at any given time suffer from severe and persistent mental disorders.

“This is obviously a complicated story,” Dr. Manlove noted. “The hospital gave the jail only a few days’ notice. The hospital doesn’t seem to want to invest in this population. They are investing millions of dollars in other projects but can’t find the money to fund psychiatry. Surprisingly, the medical community seems to have accepted this.”

Dr. Manlove noted that the jail is not equipped to offer comprehensive psychiatric treatment, and that inmates are held in cinder block cells with very limited medical supervision.

Kevin Thom, the Pennington County sheriff, was quick to say, “We shouldn’t be criminalizing mental health problems.” While he noted that local statute allows for patients to be held in a jail cell for up to 24 hours if a hospital bed is not available, he commented on the inappropriateness of this and on the brief notice his office was given: “There was no time to figure out a process or alternatives. It’s frustrating.”

Dr. Manlove said he believes that a few patients may have been taken to the jail since the new policy was instituted, but the jail has turned some away. Sheriff Thom said his office had been called to transport a patient and had refused.

I asked what happens when a voluntary patient needs a bed and there is no room. Dr. Manlove replied: “If they are not considered acutely dangerous, I assume they will be told to go to another hospital. If they are acutely dangerous to themselves or others, then a mental health hold would be placed, and they would be sent to jail.”

Of note, the closest hospital with a psychiatric unit is 253 miles away, in Casper, Wyo.

One reason for limiting the type of patients the psychiatric facility will admit may have to do with an effort by the hospital to lower its use of seclusion and restraint. In an article in the Rapid City Journal on Feb. 19, 2017, reporter Chris Huber noted that between July 2015 and July 2016, Rapid City Behavioral Health had seclusion rates 300 times higher than the national average, a fact the hospital attributes to the high acuity needs of autistic patients. Rather than improving its ability to treat these patients, the facility has decided not to accept them.

In June 2016, the Boston Globe Spotlight team began a series called “The Desperate and the Dead” as a way to highlight deficiencies in the Massachusetts public mental health system. The first article was a sensationalized piece about psychiatric patients who kill their family members. The backlash to the stigmatization of psychiatric patients as murderers was huge; a Facebook page set up to accept comments soon had more than 1,300 members, and the entrance to the Globe was blocked by 150 protesters. The response to the Rapid City hospital’s decision to jail people with psychiatric disorders who have committed no crime has been surprisingly quiet; there have been no stories of protests or advocacy outrage. In this egregious stigmatization of those with psychiatric disorders, I had to wonder what they do when the medical beds overflow: Do they send those patients to jail? Of course not. And why would anyone think this is okay?

We know that involuntary care can be traumatizing and that psychiatric care can feel demeaning. On the one hand, there is a call to pass laws to make it easier to treat patients involuntarily. In our polarized world with rising suicide rates, should we be doing everything possible to engage patients in voluntary care? How do we reconcile the fact that a hospital administration can decide that if distressed people seek care, having broken no law, they can be sent to jail? And finally, since suicide rates among physicians remain so high, I’d like to ask this: Would you go to a hospital for treatment if you knew you might end up desperate and alone, receiving no treatment, in a jail cell?

My thanks to Mr. Anderson of the Rapid City Journal, Dr. Manlove, and Sheriff Thom for their help with this article.

Dr. Miller wrote “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” with Annette Hanson, MD (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

ERCP testing guidelines accurate, but could be improved

Though current American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guidelines for whether a patient suspected of choledocholithiasis should undergo endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) are accurate, more restrictive criteria would improve specificity and positive predictive value, researchers have determined.