User login

Precision and Accuracy of Identification of Anatomical Surface Landmarks by 30 Expert Hip Arthroscopists

Take-Home Points

- Surface landmarks are routinely used for physical examination and surgical technique.

- Common surface landmarks used in establishing arthroscopic portals may be more difficult to accurately identify than previously thought.

- The greater trochanter was the surface landmark most precisely identified by expert examiners.

- Ultrasound examination identified landmarks varied from landmarks identified by palpation alone.

Anatomical surface landmarks about the hip and lower abdomen are often referenced when placing arthroscopic portals and office-based injections.1-3 However, the degree to which these landmarks can be reproducibly identified using only visual inspection and palpation is unknown.

Safe access to the hip joint and surrounding structures during hip arthroscopy has been a focus in the orthopedic literature. Authors have described anatomical relationships of recommended portals to neurovascular and other anatomical structures.4-6 This information has been reported in millimeters to centimeters of safety based on cadaver dissection studies.4-7We conducted a study to assess expert hip arthroscopists’ ability to identify, using only physical examination techniques, the anatomical structures used for reference when creating safe starting points for arthroscopic access. We hypothesized that variance in examiner-identified points would exceed safe distances from neurovascular structures for the most commonly used hip arthroscopic portals. The volunteer in this study provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this article.

Methods

In this study, we prospectively assessed 30 expert hip arthroscopic surgeons’ ability to identify commonly referenced surface landmarks on the adult male hip, using only inspection and manual palpation. Surgeons were defined as experts on the basis of their status as hip arthroscopy instructors at the Orthopaedic Learning Center (Rosemont, IL) for the Arthroscopy Association of North America and industry-sponsored hip arthroscopy education faculty (Arthrex). Five surface landmarks were selected for their relevance to publications on safe portal placement2-5: anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), tip of greater trochanter (GT), rectus origin (RO), superficial inguinal ring (SIR), and psoas tendon (PT).

A healthy adult male volunteer was placed supine on an examination table and exposed distally from the mid abdomen, with the perineum and the genital area covered bikini-style. An expert musculoskeletal ultrasonographer used a handheld musculoskeletal ultrasound transducer (Sonosite) to identify the 5 landmarks. Short- and long-axis images of each structure were obtained. The examiner applied a round (1 cm in diameter), uniquely colored adhesive label to the skin over each location. A professional photographer using a Canon digital camera and fixed mounts made precise overhead and lateral images. The positional integrity and scale of these images were confirmed with referral to constant anatomical skin features. Images were archived for analysis (Figure 1A).

After the ultrasonographer’s labels were removed, each of the 30 expert hip arthroscopic surgeons identified the structures by static physical examination (inspection and palpation only) and applied the same colored labels to the skin.

Imaging software (Adobe Photoshop Creative Suite 5.1) was used to superimpose the digital images of the examiner labels on those of the ultrasound-verified anatomical labels (Figure 1C). Measurements were then taken with digital calipers to determine average distance from ultrasound label; accuracy within 10 mm of verified ultrasound label; true average location (TAL) determined by 95% confidence interval (CI); and interobserver variability calculated by 95% prediction interval, which determined the probability of where an additional examiner data point would lie.

In the second arm of the study, examiner data were compared with previously published data on arthroscopic portal safety.

Results

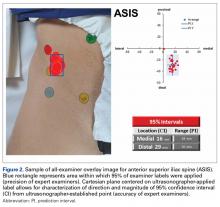

Average absolute distance from examiner labels to ultrasonographer labels was 31 mm for ASIS, 24 mm for GT, 26 mm for RO, 19 mm for SIR, and 35 mm for PT (Figure 2).

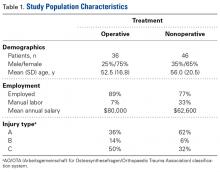

Of the 30 surgeons, 1 (3%) came within 10 mm of the ultrasound for ASIS, 1 (3%) for GT, 4 (13%) for RO, 5 (17%) for SIR, and 1 (3%) for PT (Table 1).

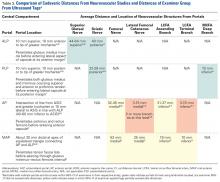

TAL as determined by CI was 16 mm medial and 29 mm inferior for ASIS; 8 mm anterior and 22 mm superior for GT; 10 mm medial and 25 mm inferior for RO; 5 mm lateral and 5 mm inferior for SIR; and 28 mm medial and 16 mm inferior for PT (Figure 3, Table 2). Interobserver variability determined by prediction interval had a range of 18 mm medial to lateral × 36 mm proximal to distal for ASIS; 33 mm anterior to posterior × 48 mm superior to inferior for GT; 41 mm medial to distal × 54 mm proximal to distal for RO; 51 mm medial to lateral × 74 mm proximal to distal for SIR; and 49 mm medial to distal × 61 mm proximal to distal for PT.

Given the difference between examiner data (direction and distance from ultrasound labels) and published data (distance to significant neurovascular structures), inaccurate identification of surface landmarks has the potential to lead to AP and MAP damage (Table 3). The examiner GT and ASIS surface landmarks used for AP overlapped directly with the safe distances for the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve and the terminal branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery.

Discussion

Others have investigated examiners’ use of palpation, compared with ultrasound, to identify common shoulder and knee structures.8-10 In a 2011 systematic review, Gilliland and colleagues11 confirmed that accuracy was improved with use of ultrasound (vs palpation) for injections in the shoulder, hip, knee, wrist, and ankle. Given the scarcity of data in this setting, we conducted the present study to assess the precision and accuracy of expert arthroscopists in identifying common surface landmarks. We hypothesized that physical examination and ultrasound examination would differ significantly in precisely and accurately identifying these landmarks.

Working with a standard awake volunteer, our test group of examiners was consistently inaccurate when they accepted ultrasonographer-placed labels as the ideal. Precision within the group, however, trended toward close agreement; examiners consistently placed labels in the same direction and approximate magnitude away from ultrasonographer labels. This suggests that a discrepancy between the ultrasonographic surface structure definitions taught to ultrasonographers and the manually identified definitions taught to surgeons for arthroscopy (training bias) can generate differences in landmark identification.

Given reported low rates of complications in the creation of standard surface anatomy portals, more data is needed to correlate whether safe distance guidelines best apply to the points identified by hip experts or the points identified by ultrasonographers. In a 2013 systematic review, Harris and colleagues8 found a 7.5% overall complication rate, with temporary neuropraxia 1 of the 2 most common complications. Whether adding ultrasound to physical examination for the creation of some or all portals will reduce the incidence of these problems is unknown. Regardless of the anatomical area referenced by experts for portal creation, the tight grouping of examiner marks in our study supports a consensus regarding the location of the landmarks studied.

In our study of the use of surface anatomical landmarks for the creation of portals, we analyzed 4 previously described locations: ALP, AP, PLP, and MAP. ALP, AP, and PLP directly reference at least 1 surface anatomical structure; AP references 2 anatomical structures (ASIS, GT); and MAP indirectly references ASIS and GT and directly references ALP and AP. In cadaveric and radiographic studies, 7 neurovascular structures have been described in proximity to ALP, AP, MAP, and PLP: superior gluteal nerve, sciatic nerve, femoral nerve, lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, lateral circumflex femoral artery, and medial circumflex femoral artery.5,6 Our results showed that use of surface anatomy in AP and MAP creation most likely places structures at risk, given the overlap of examiner CIs and the previously published cadaveric5,6 and radiographic7 data.

Hua and colleagues12 confirmed the feasibility of using ultrasound for the creation of hip arthroscopy portals. More data is needed to assess how the standard palpation-and-fluoroscopy method described by Byrd3 compares with an ultrasound-guided technique in safety and cost. However, data from our study should not be used to justify a demand for ultrasound during arthroscopy portal establishment, as limitations do not permit such a recommendation.

With diagnostic injection remaining a mainstay of differential diagnosis and treatment about the hip,1 the data presented here suggest a potential for ultrasound in enhancing outcomes. There is evidence supporting the role of image guidance in improving palpation accuracy in the area of the biceps tendon in the forearm.10 Potentially, identification and treatment of specific extra-articular structures surrounding the hip could be made safer with more routine use of ultrasound.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. The surgeons were limited to palpation and static examination of a body in its natural state. Hip arthroscopic portals typically are created under traction and after a standard perineal post is placed for hip arthroscopy. In addition, in an awake injection setting, the clinician may receive patient feedback in the form of limb movement or speech. To what degree palpation or ultrasound will be affected in these scenarios is unknown.

Another limitation is the lack of serial examination by each examiner—intrarater variability could not be gauged. In addition, with only 1 ultrasonographic examination performed, there is the potential that adding ultrasonographic examinations, or having an examiner perform serial physical examinations, could better define the precision of each component. Given the practical limitations of our volunteer’s time and the schedules of 30 expert arthroscopists, we kept the chosen study design for its single setting.

Conclusion

Visual inspection and manual palpation are standard means of identifying common surface anatomical landmarks for the creation of arthroscopy portals and the placement of injections. Our study results showed variance in landmark identification between expert examiners and an ultrasonographer. The degree of variance exceeded established neurovascular safe zones, particularly for AP and MAP. This new evidence calls for further investigation into the best, safest means of performing hip arthroscopic techniques and injection-based interventions.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):E65-E70. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Byrd JW, Potts EA, Allison RK, Jones KS. Ultrasound-guided hip injections: a comparative study with fluoroscopy-guided injections. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(1):42-46.

2. Dienst M, Seil R, Kohn DM. Safe arthroscopic access to the central compartment of the hip. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(12):1510-1514.

3. Byrd JW. Hip arthroscopy, the supine approach: technique and anatomy of the intraarticular and peripheral compartments. Tech Orthop. 2005;20(1):17-31.

4. Bond JL, Knutson ZA, Ebert A, Guanche CA. The 23-point arthroscopic examination of the hip: basic setup, portal placement, and surgical technique. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(4):416-429.

5. Roberson WJ, Kelly BT. The safe zone for hip arthroscopy: a cadaveric assessment of central, peripheral, and lateral compartment portal placement. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(9):1019-1026.

6. Byrd JW, Pappas JN, Pedley MJ. Hip arthroscopy: an anatomic study of portal placement and relationship to the extra-articular structures. Arthroscopy. 1995;11(4):418-423.

7. Watson JN, Bohnenkamp F, El-Bitar Y, Moretti V, Domb BG. Variability in locations of hip neurovascular structures and their proximity to hip arthroscopic portals. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(4):462-467.

8. Harris JD, McCormick FM, Abrams GD, et al. Complications and reoperations during and after hip arthroscopy: a systematic review of 92 studies and more than 6,000 patients. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):589-595.

9. Jacobson JA, Bedi A, Sekiya JK, Blankenbaker DG. Evaluation of the painful athletic hip: imaging options and imaging-guided injections. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(3):516-524.

10. Gazzillo GP, Finnoff JT, Hall MM, Sayeed YA, Smith J. Accuracy of palpating the long head of the biceps tendon: an ultrasonographic study. PM R. 2011;3(11):1035-1040.

11. Gilliland CA, Salazar LD, Borchers JR. Ultrasound versus anatomic guidance for intra-articular and periarticular injection: a systematic review. Phys Sportsmed. 2011;39(3):121-131.

12. Hua Y, Yang Y, Chen S, et al. Ultrasound-guided establishment of hip arthroscopy portals. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(12):1491-1495.

Take-Home Points

- Surface landmarks are routinely used for physical examination and surgical technique.

- Common surface landmarks used in establishing arthroscopic portals may be more difficult to accurately identify than previously thought.

- The greater trochanter was the surface landmark most precisely identified by expert examiners.

- Ultrasound examination identified landmarks varied from landmarks identified by palpation alone.

Anatomical surface landmarks about the hip and lower abdomen are often referenced when placing arthroscopic portals and office-based injections.1-3 However, the degree to which these landmarks can be reproducibly identified using only visual inspection and palpation is unknown.

Safe access to the hip joint and surrounding structures during hip arthroscopy has been a focus in the orthopedic literature. Authors have described anatomical relationships of recommended portals to neurovascular and other anatomical structures.4-6 This information has been reported in millimeters to centimeters of safety based on cadaver dissection studies.4-7We conducted a study to assess expert hip arthroscopists’ ability to identify, using only physical examination techniques, the anatomical structures used for reference when creating safe starting points for arthroscopic access. We hypothesized that variance in examiner-identified points would exceed safe distances from neurovascular structures for the most commonly used hip arthroscopic portals. The volunteer in this study provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this article.

Methods

In this study, we prospectively assessed 30 expert hip arthroscopic surgeons’ ability to identify commonly referenced surface landmarks on the adult male hip, using only inspection and manual palpation. Surgeons were defined as experts on the basis of their status as hip arthroscopy instructors at the Orthopaedic Learning Center (Rosemont, IL) for the Arthroscopy Association of North America and industry-sponsored hip arthroscopy education faculty (Arthrex). Five surface landmarks were selected for their relevance to publications on safe portal placement2-5: anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), tip of greater trochanter (GT), rectus origin (RO), superficial inguinal ring (SIR), and psoas tendon (PT).

A healthy adult male volunteer was placed supine on an examination table and exposed distally from the mid abdomen, with the perineum and the genital area covered bikini-style. An expert musculoskeletal ultrasonographer used a handheld musculoskeletal ultrasound transducer (Sonosite) to identify the 5 landmarks. Short- and long-axis images of each structure were obtained. The examiner applied a round (1 cm in diameter), uniquely colored adhesive label to the skin over each location. A professional photographer using a Canon digital camera and fixed mounts made precise overhead and lateral images. The positional integrity and scale of these images were confirmed with referral to constant anatomical skin features. Images were archived for analysis (Figure 1A).

After the ultrasonographer’s labels were removed, each of the 30 expert hip arthroscopic surgeons identified the structures by static physical examination (inspection and palpation only) and applied the same colored labels to the skin.

Imaging software (Adobe Photoshop Creative Suite 5.1) was used to superimpose the digital images of the examiner labels on those of the ultrasound-verified anatomical labels (Figure 1C). Measurements were then taken with digital calipers to determine average distance from ultrasound label; accuracy within 10 mm of verified ultrasound label; true average location (TAL) determined by 95% confidence interval (CI); and interobserver variability calculated by 95% prediction interval, which determined the probability of where an additional examiner data point would lie.

In the second arm of the study, examiner data were compared with previously published data on arthroscopic portal safety.

Results

Average absolute distance from examiner labels to ultrasonographer labels was 31 mm for ASIS, 24 mm for GT, 26 mm for RO, 19 mm for SIR, and 35 mm for PT (Figure 2).

Of the 30 surgeons, 1 (3%) came within 10 mm of the ultrasound for ASIS, 1 (3%) for GT, 4 (13%) for RO, 5 (17%) for SIR, and 1 (3%) for PT (Table 1).

TAL as determined by CI was 16 mm medial and 29 mm inferior for ASIS; 8 mm anterior and 22 mm superior for GT; 10 mm medial and 25 mm inferior for RO; 5 mm lateral and 5 mm inferior for SIR; and 28 mm medial and 16 mm inferior for PT (Figure 3, Table 2). Interobserver variability determined by prediction interval had a range of 18 mm medial to lateral × 36 mm proximal to distal for ASIS; 33 mm anterior to posterior × 48 mm superior to inferior for GT; 41 mm medial to distal × 54 mm proximal to distal for RO; 51 mm medial to lateral × 74 mm proximal to distal for SIR; and 49 mm medial to distal × 61 mm proximal to distal for PT.

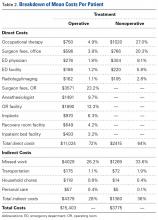

Given the difference between examiner data (direction and distance from ultrasound labels) and published data (distance to significant neurovascular structures), inaccurate identification of surface landmarks has the potential to lead to AP and MAP damage (Table 3). The examiner GT and ASIS surface landmarks used for AP overlapped directly with the safe distances for the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve and the terminal branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery.

Discussion

Others have investigated examiners’ use of palpation, compared with ultrasound, to identify common shoulder and knee structures.8-10 In a 2011 systematic review, Gilliland and colleagues11 confirmed that accuracy was improved with use of ultrasound (vs palpation) for injections in the shoulder, hip, knee, wrist, and ankle. Given the scarcity of data in this setting, we conducted the present study to assess the precision and accuracy of expert arthroscopists in identifying common surface landmarks. We hypothesized that physical examination and ultrasound examination would differ significantly in precisely and accurately identifying these landmarks.

Working with a standard awake volunteer, our test group of examiners was consistently inaccurate when they accepted ultrasonographer-placed labels as the ideal. Precision within the group, however, trended toward close agreement; examiners consistently placed labels in the same direction and approximate magnitude away from ultrasonographer labels. This suggests that a discrepancy between the ultrasonographic surface structure definitions taught to ultrasonographers and the manually identified definitions taught to surgeons for arthroscopy (training bias) can generate differences in landmark identification.

Given reported low rates of complications in the creation of standard surface anatomy portals, more data is needed to correlate whether safe distance guidelines best apply to the points identified by hip experts or the points identified by ultrasonographers. In a 2013 systematic review, Harris and colleagues8 found a 7.5% overall complication rate, with temporary neuropraxia 1 of the 2 most common complications. Whether adding ultrasound to physical examination for the creation of some or all portals will reduce the incidence of these problems is unknown. Regardless of the anatomical area referenced by experts for portal creation, the tight grouping of examiner marks in our study supports a consensus regarding the location of the landmarks studied.

In our study of the use of surface anatomical landmarks for the creation of portals, we analyzed 4 previously described locations: ALP, AP, PLP, and MAP. ALP, AP, and PLP directly reference at least 1 surface anatomical structure; AP references 2 anatomical structures (ASIS, GT); and MAP indirectly references ASIS and GT and directly references ALP and AP. In cadaveric and radiographic studies, 7 neurovascular structures have been described in proximity to ALP, AP, MAP, and PLP: superior gluteal nerve, sciatic nerve, femoral nerve, lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, lateral circumflex femoral artery, and medial circumflex femoral artery.5,6 Our results showed that use of surface anatomy in AP and MAP creation most likely places structures at risk, given the overlap of examiner CIs and the previously published cadaveric5,6 and radiographic7 data.

Hua and colleagues12 confirmed the feasibility of using ultrasound for the creation of hip arthroscopy portals. More data is needed to assess how the standard palpation-and-fluoroscopy method described by Byrd3 compares with an ultrasound-guided technique in safety and cost. However, data from our study should not be used to justify a demand for ultrasound during arthroscopy portal establishment, as limitations do not permit such a recommendation.

With diagnostic injection remaining a mainstay of differential diagnosis and treatment about the hip,1 the data presented here suggest a potential for ultrasound in enhancing outcomes. There is evidence supporting the role of image guidance in improving palpation accuracy in the area of the biceps tendon in the forearm.10 Potentially, identification and treatment of specific extra-articular structures surrounding the hip could be made safer with more routine use of ultrasound.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. The surgeons were limited to palpation and static examination of a body in its natural state. Hip arthroscopic portals typically are created under traction and after a standard perineal post is placed for hip arthroscopy. In addition, in an awake injection setting, the clinician may receive patient feedback in the form of limb movement or speech. To what degree palpation or ultrasound will be affected in these scenarios is unknown.

Another limitation is the lack of serial examination by each examiner—intrarater variability could not be gauged. In addition, with only 1 ultrasonographic examination performed, there is the potential that adding ultrasonographic examinations, or having an examiner perform serial physical examinations, could better define the precision of each component. Given the practical limitations of our volunteer’s time and the schedules of 30 expert arthroscopists, we kept the chosen study design for its single setting.

Conclusion

Visual inspection and manual palpation are standard means of identifying common surface anatomical landmarks for the creation of arthroscopy portals and the placement of injections. Our study results showed variance in landmark identification between expert examiners and an ultrasonographer. The degree of variance exceeded established neurovascular safe zones, particularly for AP and MAP. This new evidence calls for further investigation into the best, safest means of performing hip arthroscopic techniques and injection-based interventions.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):E65-E70. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

Take-Home Points

- Surface landmarks are routinely used for physical examination and surgical technique.

- Common surface landmarks used in establishing arthroscopic portals may be more difficult to accurately identify than previously thought.

- The greater trochanter was the surface landmark most precisely identified by expert examiners.

- Ultrasound examination identified landmarks varied from landmarks identified by palpation alone.

Anatomical surface landmarks about the hip and lower abdomen are often referenced when placing arthroscopic portals and office-based injections.1-3 However, the degree to which these landmarks can be reproducibly identified using only visual inspection and palpation is unknown.

Safe access to the hip joint and surrounding structures during hip arthroscopy has been a focus in the orthopedic literature. Authors have described anatomical relationships of recommended portals to neurovascular and other anatomical structures.4-6 This information has been reported in millimeters to centimeters of safety based on cadaver dissection studies.4-7We conducted a study to assess expert hip arthroscopists’ ability to identify, using only physical examination techniques, the anatomical structures used for reference when creating safe starting points for arthroscopic access. We hypothesized that variance in examiner-identified points would exceed safe distances from neurovascular structures for the most commonly used hip arthroscopic portals. The volunteer in this study provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this article.

Methods

In this study, we prospectively assessed 30 expert hip arthroscopic surgeons’ ability to identify commonly referenced surface landmarks on the adult male hip, using only inspection and manual palpation. Surgeons were defined as experts on the basis of their status as hip arthroscopy instructors at the Orthopaedic Learning Center (Rosemont, IL) for the Arthroscopy Association of North America and industry-sponsored hip arthroscopy education faculty (Arthrex). Five surface landmarks were selected for their relevance to publications on safe portal placement2-5: anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), tip of greater trochanter (GT), rectus origin (RO), superficial inguinal ring (SIR), and psoas tendon (PT).

A healthy adult male volunteer was placed supine on an examination table and exposed distally from the mid abdomen, with the perineum and the genital area covered bikini-style. An expert musculoskeletal ultrasonographer used a handheld musculoskeletal ultrasound transducer (Sonosite) to identify the 5 landmarks. Short- and long-axis images of each structure were obtained. The examiner applied a round (1 cm in diameter), uniquely colored adhesive label to the skin over each location. A professional photographer using a Canon digital camera and fixed mounts made precise overhead and lateral images. The positional integrity and scale of these images were confirmed with referral to constant anatomical skin features. Images were archived for analysis (Figure 1A).

After the ultrasonographer’s labels were removed, each of the 30 expert hip arthroscopic surgeons identified the structures by static physical examination (inspection and palpation only) and applied the same colored labels to the skin.

Imaging software (Adobe Photoshop Creative Suite 5.1) was used to superimpose the digital images of the examiner labels on those of the ultrasound-verified anatomical labels (Figure 1C). Measurements were then taken with digital calipers to determine average distance from ultrasound label; accuracy within 10 mm of verified ultrasound label; true average location (TAL) determined by 95% confidence interval (CI); and interobserver variability calculated by 95% prediction interval, which determined the probability of where an additional examiner data point would lie.

In the second arm of the study, examiner data were compared with previously published data on arthroscopic portal safety.

Results

Average absolute distance from examiner labels to ultrasonographer labels was 31 mm for ASIS, 24 mm for GT, 26 mm for RO, 19 mm for SIR, and 35 mm for PT (Figure 2).

Of the 30 surgeons, 1 (3%) came within 10 mm of the ultrasound for ASIS, 1 (3%) for GT, 4 (13%) for RO, 5 (17%) for SIR, and 1 (3%) for PT (Table 1).

TAL as determined by CI was 16 mm medial and 29 mm inferior for ASIS; 8 mm anterior and 22 mm superior for GT; 10 mm medial and 25 mm inferior for RO; 5 mm lateral and 5 mm inferior for SIR; and 28 mm medial and 16 mm inferior for PT (Figure 3, Table 2). Interobserver variability determined by prediction interval had a range of 18 mm medial to lateral × 36 mm proximal to distal for ASIS; 33 mm anterior to posterior × 48 mm superior to inferior for GT; 41 mm medial to distal × 54 mm proximal to distal for RO; 51 mm medial to lateral × 74 mm proximal to distal for SIR; and 49 mm medial to distal × 61 mm proximal to distal for PT.

Given the difference between examiner data (direction and distance from ultrasound labels) and published data (distance to significant neurovascular structures), inaccurate identification of surface landmarks has the potential to lead to AP and MAP damage (Table 3). The examiner GT and ASIS surface landmarks used for AP overlapped directly with the safe distances for the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve and the terminal branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery.

Discussion

Others have investigated examiners’ use of palpation, compared with ultrasound, to identify common shoulder and knee structures.8-10 In a 2011 systematic review, Gilliland and colleagues11 confirmed that accuracy was improved with use of ultrasound (vs palpation) for injections in the shoulder, hip, knee, wrist, and ankle. Given the scarcity of data in this setting, we conducted the present study to assess the precision and accuracy of expert arthroscopists in identifying common surface landmarks. We hypothesized that physical examination and ultrasound examination would differ significantly in precisely and accurately identifying these landmarks.

Working with a standard awake volunteer, our test group of examiners was consistently inaccurate when they accepted ultrasonographer-placed labels as the ideal. Precision within the group, however, trended toward close agreement; examiners consistently placed labels in the same direction and approximate magnitude away from ultrasonographer labels. This suggests that a discrepancy between the ultrasonographic surface structure definitions taught to ultrasonographers and the manually identified definitions taught to surgeons for arthroscopy (training bias) can generate differences in landmark identification.

Given reported low rates of complications in the creation of standard surface anatomy portals, more data is needed to correlate whether safe distance guidelines best apply to the points identified by hip experts or the points identified by ultrasonographers. In a 2013 systematic review, Harris and colleagues8 found a 7.5% overall complication rate, with temporary neuropraxia 1 of the 2 most common complications. Whether adding ultrasound to physical examination for the creation of some or all portals will reduce the incidence of these problems is unknown. Regardless of the anatomical area referenced by experts for portal creation, the tight grouping of examiner marks in our study supports a consensus regarding the location of the landmarks studied.

In our study of the use of surface anatomical landmarks for the creation of portals, we analyzed 4 previously described locations: ALP, AP, PLP, and MAP. ALP, AP, and PLP directly reference at least 1 surface anatomical structure; AP references 2 anatomical structures (ASIS, GT); and MAP indirectly references ASIS and GT and directly references ALP and AP. In cadaveric and radiographic studies, 7 neurovascular structures have been described in proximity to ALP, AP, MAP, and PLP: superior gluteal nerve, sciatic nerve, femoral nerve, lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, lateral circumflex femoral artery, and medial circumflex femoral artery.5,6 Our results showed that use of surface anatomy in AP and MAP creation most likely places structures at risk, given the overlap of examiner CIs and the previously published cadaveric5,6 and radiographic7 data.

Hua and colleagues12 confirmed the feasibility of using ultrasound for the creation of hip arthroscopy portals. More data is needed to assess how the standard palpation-and-fluoroscopy method described by Byrd3 compares with an ultrasound-guided technique in safety and cost. However, data from our study should not be used to justify a demand for ultrasound during arthroscopy portal establishment, as limitations do not permit such a recommendation.

With diagnostic injection remaining a mainstay of differential diagnosis and treatment about the hip,1 the data presented here suggest a potential for ultrasound in enhancing outcomes. There is evidence supporting the role of image guidance in improving palpation accuracy in the area of the biceps tendon in the forearm.10 Potentially, identification and treatment of specific extra-articular structures surrounding the hip could be made safer with more routine use of ultrasound.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. The surgeons were limited to palpation and static examination of a body in its natural state. Hip arthroscopic portals typically are created under traction and after a standard perineal post is placed for hip arthroscopy. In addition, in an awake injection setting, the clinician may receive patient feedback in the form of limb movement or speech. To what degree palpation or ultrasound will be affected in these scenarios is unknown.

Another limitation is the lack of serial examination by each examiner—intrarater variability could not be gauged. In addition, with only 1 ultrasonographic examination performed, there is the potential that adding ultrasonographic examinations, or having an examiner perform serial physical examinations, could better define the precision of each component. Given the practical limitations of our volunteer’s time and the schedules of 30 expert arthroscopists, we kept the chosen study design for its single setting.

Conclusion

Visual inspection and manual palpation are standard means of identifying common surface anatomical landmarks for the creation of arthroscopy portals and the placement of injections. Our study results showed variance in landmark identification between expert examiners and an ultrasonographer. The degree of variance exceeded established neurovascular safe zones, particularly for AP and MAP. This new evidence calls for further investigation into the best, safest means of performing hip arthroscopic techniques and injection-based interventions.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):E65-E70. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Byrd JW, Potts EA, Allison RK, Jones KS. Ultrasound-guided hip injections: a comparative study with fluoroscopy-guided injections. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(1):42-46.

2. Dienst M, Seil R, Kohn DM. Safe arthroscopic access to the central compartment of the hip. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(12):1510-1514.

3. Byrd JW. Hip arthroscopy, the supine approach: technique and anatomy of the intraarticular and peripheral compartments. Tech Orthop. 2005;20(1):17-31.

4. Bond JL, Knutson ZA, Ebert A, Guanche CA. The 23-point arthroscopic examination of the hip: basic setup, portal placement, and surgical technique. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(4):416-429.

5. Roberson WJ, Kelly BT. The safe zone for hip arthroscopy: a cadaveric assessment of central, peripheral, and lateral compartment portal placement. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(9):1019-1026.

6. Byrd JW, Pappas JN, Pedley MJ. Hip arthroscopy: an anatomic study of portal placement and relationship to the extra-articular structures. Arthroscopy. 1995;11(4):418-423.

7. Watson JN, Bohnenkamp F, El-Bitar Y, Moretti V, Domb BG. Variability in locations of hip neurovascular structures and their proximity to hip arthroscopic portals. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(4):462-467.

8. Harris JD, McCormick FM, Abrams GD, et al. Complications and reoperations during and after hip arthroscopy: a systematic review of 92 studies and more than 6,000 patients. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):589-595.

9. Jacobson JA, Bedi A, Sekiya JK, Blankenbaker DG. Evaluation of the painful athletic hip: imaging options and imaging-guided injections. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(3):516-524.

10. Gazzillo GP, Finnoff JT, Hall MM, Sayeed YA, Smith J. Accuracy of palpating the long head of the biceps tendon: an ultrasonographic study. PM R. 2011;3(11):1035-1040.

11. Gilliland CA, Salazar LD, Borchers JR. Ultrasound versus anatomic guidance for intra-articular and periarticular injection: a systematic review. Phys Sportsmed. 2011;39(3):121-131.

12. Hua Y, Yang Y, Chen S, et al. Ultrasound-guided establishment of hip arthroscopy portals. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(12):1491-1495.

1. Byrd JW, Potts EA, Allison RK, Jones KS. Ultrasound-guided hip injections: a comparative study with fluoroscopy-guided injections. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(1):42-46.

2. Dienst M, Seil R, Kohn DM. Safe arthroscopic access to the central compartment of the hip. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(12):1510-1514.

3. Byrd JW. Hip arthroscopy, the supine approach: technique and anatomy of the intraarticular and peripheral compartments. Tech Orthop. 2005;20(1):17-31.

4. Bond JL, Knutson ZA, Ebert A, Guanche CA. The 23-point arthroscopic examination of the hip: basic setup, portal placement, and surgical technique. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(4):416-429.

5. Roberson WJ, Kelly BT. The safe zone for hip arthroscopy: a cadaveric assessment of central, peripheral, and lateral compartment portal placement. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(9):1019-1026.

6. Byrd JW, Pappas JN, Pedley MJ. Hip arthroscopy: an anatomic study of portal placement and relationship to the extra-articular structures. Arthroscopy. 1995;11(4):418-423.

7. Watson JN, Bohnenkamp F, El-Bitar Y, Moretti V, Domb BG. Variability in locations of hip neurovascular structures and their proximity to hip arthroscopic portals. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(4):462-467.

8. Harris JD, McCormick FM, Abrams GD, et al. Complications and reoperations during and after hip arthroscopy: a systematic review of 92 studies and more than 6,000 patients. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):589-595.

9. Jacobson JA, Bedi A, Sekiya JK, Blankenbaker DG. Evaluation of the painful athletic hip: imaging options and imaging-guided injections. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(3):516-524.

10. Gazzillo GP, Finnoff JT, Hall MM, Sayeed YA, Smith J. Accuracy of palpating the long head of the biceps tendon: an ultrasonographic study. PM R. 2011;3(11):1035-1040.

11. Gilliland CA, Salazar LD, Borchers JR. Ultrasound versus anatomic guidance for intra-articular and periarticular injection: a systematic review. Phys Sportsmed. 2011;39(3):121-131.

12. Hua Y, Yang Y, Chen S, et al. Ultrasound-guided establishment of hip arthroscopy portals. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(12):1491-1495.

Gluten-free diets related to high levels of arsenic, mercury

Individuals who adopt a gluten-free diet are putting themselves at risk for uncommonly high levels of arsenic and mercury, according to the findings of a recent study published in Epidemiology.

“Despite [less than] 1% of Americans having diagnosed celiac disease, an estimated 25% of American consumers reported consuming gluten-free food in 2015, a 67% increase from 2013,” wrote the authors of the study, led by Maria Argos, PhD, of the University of Illinois at Chicago. “Despite such a dramatic shift in the diet of many Americans, little is known about how gluten-free diets might affect exposure to toxic metals found in certain foods,” they noted.

Dr. Argos and her colleagues analyzed data collected from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), which included self-reported questionnaires in which subjects indicated what type of diet they were on, if any. Data on those who indicated that they followed a gluten-free diet were analyzed to determine if their urinary and blood biomarkers indicated any exposure to toxic metals. A total of 7,471 subjects from the NHANES were included in the analysis.

“We accounted for the complex sampling design of NHANES [by] using Taylor series linearization and sampling weights, per the NHANES analytic guidelines, to ensure unbiased and nationally representative estimates,” the authors explained.

A total of 73 subjects identified themselves as following a gluten-free diet. Within this group, the mean total arsenic level in urine was found to be 12.1 mcg/L, compared to 7.8 mcg/L for the other 7,398 subjects. Levels of dimethylarsinic acid averaged 5.3 mcg/L for those who were gluten-free, but only 3.7 for everyone else, while cadmium and lead levels were also slightly higher for gluten-free individuals: 0.18 mcg/L vs. 0.16 mcg/L, and 0.40 mcg/L vs. 0.37 mcg/L, respectively.

Blood analyses showed that total mercury levels were also substantially higher in the gluten-free group, at a mean of 1.3 mcg/L compared to 0.8 mcg/L. While cadmium levels were the same between the two – both showed a mean level of 0.29 mcg/L – lead measured 1.1 mcg/dL and inorganic mercury measured 0.30 mcg/L, compared to 0.96 mcg/L and 0.28 mcg/L in everyone else, respectively.

Geometric mean ratios showed that total arsenic, total arsenic 1, and total mercury levels had the largest disparity between the two groups. Total arsenic registered a 1.5 (95% CI, 1.2-2.0), total mercury a 1.7 (95% CI, 1.1-2.4), and total arsenic 1 a 1.9 (95% CI 1.3-2.6), meaning the gluten-free group had nearly double the risk for higher levels than those on other diets.

“These findings may have important health implications since the health effects of low-level arsenic and mercury exposure from food sources are uncertain but may increase the risk for cancer and other chronic diseases,” Dr. Argos and her coauthors concluded, adding that “future studies are needed to more fully examine exposure to toxic metals from consuming gluten-free foods.”

The study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Argos and her coauthors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

Individuals who adopt a gluten-free diet are putting themselves at risk for uncommonly high levels of arsenic and mercury, according to the findings of a recent study published in Epidemiology.

“Despite [less than] 1% of Americans having diagnosed celiac disease, an estimated 25% of American consumers reported consuming gluten-free food in 2015, a 67% increase from 2013,” wrote the authors of the study, led by Maria Argos, PhD, of the University of Illinois at Chicago. “Despite such a dramatic shift in the diet of many Americans, little is known about how gluten-free diets might affect exposure to toxic metals found in certain foods,” they noted.

Dr. Argos and her colleagues analyzed data collected from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), which included self-reported questionnaires in which subjects indicated what type of diet they were on, if any. Data on those who indicated that they followed a gluten-free diet were analyzed to determine if their urinary and blood biomarkers indicated any exposure to toxic metals. A total of 7,471 subjects from the NHANES were included in the analysis.

“We accounted for the complex sampling design of NHANES [by] using Taylor series linearization and sampling weights, per the NHANES analytic guidelines, to ensure unbiased and nationally representative estimates,” the authors explained.

A total of 73 subjects identified themselves as following a gluten-free diet. Within this group, the mean total arsenic level in urine was found to be 12.1 mcg/L, compared to 7.8 mcg/L for the other 7,398 subjects. Levels of dimethylarsinic acid averaged 5.3 mcg/L for those who were gluten-free, but only 3.7 for everyone else, while cadmium and lead levels were also slightly higher for gluten-free individuals: 0.18 mcg/L vs. 0.16 mcg/L, and 0.40 mcg/L vs. 0.37 mcg/L, respectively.

Blood analyses showed that total mercury levels were also substantially higher in the gluten-free group, at a mean of 1.3 mcg/L compared to 0.8 mcg/L. While cadmium levels were the same between the two – both showed a mean level of 0.29 mcg/L – lead measured 1.1 mcg/dL and inorganic mercury measured 0.30 mcg/L, compared to 0.96 mcg/L and 0.28 mcg/L in everyone else, respectively.

Geometric mean ratios showed that total arsenic, total arsenic 1, and total mercury levels had the largest disparity between the two groups. Total arsenic registered a 1.5 (95% CI, 1.2-2.0), total mercury a 1.7 (95% CI, 1.1-2.4), and total arsenic 1 a 1.9 (95% CI 1.3-2.6), meaning the gluten-free group had nearly double the risk for higher levels than those on other diets.

“These findings may have important health implications since the health effects of low-level arsenic and mercury exposure from food sources are uncertain but may increase the risk for cancer and other chronic diseases,” Dr. Argos and her coauthors concluded, adding that “future studies are needed to more fully examine exposure to toxic metals from consuming gluten-free foods.”

The study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Argos and her coauthors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

Individuals who adopt a gluten-free diet are putting themselves at risk for uncommonly high levels of arsenic and mercury, according to the findings of a recent study published in Epidemiology.

“Despite [less than] 1% of Americans having diagnosed celiac disease, an estimated 25% of American consumers reported consuming gluten-free food in 2015, a 67% increase from 2013,” wrote the authors of the study, led by Maria Argos, PhD, of the University of Illinois at Chicago. “Despite such a dramatic shift in the diet of many Americans, little is known about how gluten-free diets might affect exposure to toxic metals found in certain foods,” they noted.

Dr. Argos and her colleagues analyzed data collected from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), which included self-reported questionnaires in which subjects indicated what type of diet they were on, if any. Data on those who indicated that they followed a gluten-free diet were analyzed to determine if their urinary and blood biomarkers indicated any exposure to toxic metals. A total of 7,471 subjects from the NHANES were included in the analysis.

“We accounted for the complex sampling design of NHANES [by] using Taylor series linearization and sampling weights, per the NHANES analytic guidelines, to ensure unbiased and nationally representative estimates,” the authors explained.

A total of 73 subjects identified themselves as following a gluten-free diet. Within this group, the mean total arsenic level in urine was found to be 12.1 mcg/L, compared to 7.8 mcg/L for the other 7,398 subjects. Levels of dimethylarsinic acid averaged 5.3 mcg/L for those who were gluten-free, but only 3.7 for everyone else, while cadmium and lead levels were also slightly higher for gluten-free individuals: 0.18 mcg/L vs. 0.16 mcg/L, and 0.40 mcg/L vs. 0.37 mcg/L, respectively.

Blood analyses showed that total mercury levels were also substantially higher in the gluten-free group, at a mean of 1.3 mcg/L compared to 0.8 mcg/L. While cadmium levels were the same between the two – both showed a mean level of 0.29 mcg/L – lead measured 1.1 mcg/dL and inorganic mercury measured 0.30 mcg/L, compared to 0.96 mcg/L and 0.28 mcg/L in everyone else, respectively.

Geometric mean ratios showed that total arsenic, total arsenic 1, and total mercury levels had the largest disparity between the two groups. Total arsenic registered a 1.5 (95% CI, 1.2-2.0), total mercury a 1.7 (95% CI, 1.1-2.4), and total arsenic 1 a 1.9 (95% CI 1.3-2.6), meaning the gluten-free group had nearly double the risk for higher levels than those on other diets.

“These findings may have important health implications since the health effects of low-level arsenic and mercury exposure from food sources are uncertain but may increase the risk for cancer and other chronic diseases,” Dr. Argos and her coauthors concluded, adding that “future studies are needed to more fully examine exposure to toxic metals from consuming gluten-free foods.”

The study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Argos and her coauthors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

FROM EPIDEMIOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Total arsenic and mercury levels were higher in those that self-reported being on gluten-free diet than in those who weren’t: 12.1 mcg/L vs. 7.8 mcg/L for arsenic and 1.3 mcg/L vs. 0.8 mcg/L for mercury.

Data source: Retrospective analysis of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey during 2009-2014.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health funded the study. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

Cooperation must overcome polarization

Each profession has its own core set of knowledge, skills, and values. For physicians, the core set of knowledge is anatomy, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Skills include taking a history, the physical exam, and surgical procedures. The core values traditionally have been compassion and altruism. For modern medical practice, I urge adding cooperation as a core value. Medical school and the apprenticeship of residency are designed to teach, role model, foster, develop, and groom these core competencies.

Getting into medical school is highly competitive. Medical training uses methods that are very different than those used to train elite Olympic and professional athletes. Some competitiveness persists in medical school, but in general the faculty emphasizes cooperation rather than competition. The metric is not whether one student or resident is better than another. Gold and silver medals are not awarded. It is about whether each physician-to-be has passed the milestones needed to practice medicine.

But American health care is threatened by the continued polarization of our government and our society. For years both Cleveland Clinic and Dana Farber have held annual fundraising events at Mar-a-Lago. In February 2017, because of that location’s association with President Trump, some people associated with the organizations advocated boycotting those important fund-raisers. These past few months, it seems every action and every purchase has become a political statement. One restaurant mentioned immigrants on its receipt. The action went viral and caused other people to advocate boycotting the restaurant or not tipping the wait staff (“The new political battleground: Your restaurant receipt,” The Washington Post, by Maura Judkis, Feb. 14, 2017).

Secondary boycotts are an ethical quandary. In labor disputes, organized unions can go on strike. In the 1970s, Japanese cars were not welcome in the employee parking lot of a Ford assembly plant. People do vote with their pocketbook. But in labor disputes, there are legal restrictions on secondary boycotts against other companies. People do need to get along with their neighbors and so do businesses. Politics is the art of encouraging cooperation on one project amongst people who disagree about the goals of many other proposed projects. The Preamble to the United States Constitution enumerates the benefits of cooperation.

In any large-scale human endeavor, conflicts arise that may limit cooperation. Accommodating conscientious objection is the safety valve that permits cooperation when dealing with contested government endeavors such as war, abortion, and physician-assisted suicide. It is meant as a last ditch effort to maintain cohesion of both societal and individual moral integrity. But if every proposed action is met with votes divided along party lines, conscientious objection loses its moral high ground.

Judge Neil Gorsuch, the nominee for the U.S. Supreme Court, has a record of supporting religious freedom in Yellowbear v. Lambert (10th Cir. 2014). He would likely support conscientious objection in relation to assisted dying by physicians, contrary to the arguments made recently by bioethicists Julian Savulescu and Udo Schuklenk. In related news, the liberty of physicians to address gun safety was affirmed when a Florida appeals court upheld the overturning of the state’s Privacy of Firearm Owners Act.

Summing up a tumultuous month of medical ethics, I leave you with the words of Voltaire: “Cherish those who seek the truth but beware of those who find it.”

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

Each profession has its own core set of knowledge, skills, and values. For physicians, the core set of knowledge is anatomy, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Skills include taking a history, the physical exam, and surgical procedures. The core values traditionally have been compassion and altruism. For modern medical practice, I urge adding cooperation as a core value. Medical school and the apprenticeship of residency are designed to teach, role model, foster, develop, and groom these core competencies.

Getting into medical school is highly competitive. Medical training uses methods that are very different than those used to train elite Olympic and professional athletes. Some competitiveness persists in medical school, but in general the faculty emphasizes cooperation rather than competition. The metric is not whether one student or resident is better than another. Gold and silver medals are not awarded. It is about whether each physician-to-be has passed the milestones needed to practice medicine.

But American health care is threatened by the continued polarization of our government and our society. For years both Cleveland Clinic and Dana Farber have held annual fundraising events at Mar-a-Lago. In February 2017, because of that location’s association with President Trump, some people associated with the organizations advocated boycotting those important fund-raisers. These past few months, it seems every action and every purchase has become a political statement. One restaurant mentioned immigrants on its receipt. The action went viral and caused other people to advocate boycotting the restaurant or not tipping the wait staff (“The new political battleground: Your restaurant receipt,” The Washington Post, by Maura Judkis, Feb. 14, 2017).

Secondary boycotts are an ethical quandary. In labor disputes, organized unions can go on strike. In the 1970s, Japanese cars were not welcome in the employee parking lot of a Ford assembly plant. People do vote with their pocketbook. But in labor disputes, there are legal restrictions on secondary boycotts against other companies. People do need to get along with their neighbors and so do businesses. Politics is the art of encouraging cooperation on one project amongst people who disagree about the goals of many other proposed projects. The Preamble to the United States Constitution enumerates the benefits of cooperation.

In any large-scale human endeavor, conflicts arise that may limit cooperation. Accommodating conscientious objection is the safety valve that permits cooperation when dealing with contested government endeavors such as war, abortion, and physician-assisted suicide. It is meant as a last ditch effort to maintain cohesion of both societal and individual moral integrity. But if every proposed action is met with votes divided along party lines, conscientious objection loses its moral high ground.

Judge Neil Gorsuch, the nominee for the U.S. Supreme Court, has a record of supporting religious freedom in Yellowbear v. Lambert (10th Cir. 2014). He would likely support conscientious objection in relation to assisted dying by physicians, contrary to the arguments made recently by bioethicists Julian Savulescu and Udo Schuklenk. In related news, the liberty of physicians to address gun safety was affirmed when a Florida appeals court upheld the overturning of the state’s Privacy of Firearm Owners Act.

Summing up a tumultuous month of medical ethics, I leave you with the words of Voltaire: “Cherish those who seek the truth but beware of those who find it.”

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

Each profession has its own core set of knowledge, skills, and values. For physicians, the core set of knowledge is anatomy, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Skills include taking a history, the physical exam, and surgical procedures. The core values traditionally have been compassion and altruism. For modern medical practice, I urge adding cooperation as a core value. Medical school and the apprenticeship of residency are designed to teach, role model, foster, develop, and groom these core competencies.

Getting into medical school is highly competitive. Medical training uses methods that are very different than those used to train elite Olympic and professional athletes. Some competitiveness persists in medical school, but in general the faculty emphasizes cooperation rather than competition. The metric is not whether one student or resident is better than another. Gold and silver medals are not awarded. It is about whether each physician-to-be has passed the milestones needed to practice medicine.

But American health care is threatened by the continued polarization of our government and our society. For years both Cleveland Clinic and Dana Farber have held annual fundraising events at Mar-a-Lago. In February 2017, because of that location’s association with President Trump, some people associated with the organizations advocated boycotting those important fund-raisers. These past few months, it seems every action and every purchase has become a political statement. One restaurant mentioned immigrants on its receipt. The action went viral and caused other people to advocate boycotting the restaurant or not tipping the wait staff (“The new political battleground: Your restaurant receipt,” The Washington Post, by Maura Judkis, Feb. 14, 2017).

Secondary boycotts are an ethical quandary. In labor disputes, organized unions can go on strike. In the 1970s, Japanese cars were not welcome in the employee parking lot of a Ford assembly plant. People do vote with their pocketbook. But in labor disputes, there are legal restrictions on secondary boycotts against other companies. People do need to get along with their neighbors and so do businesses. Politics is the art of encouraging cooperation on one project amongst people who disagree about the goals of many other proposed projects. The Preamble to the United States Constitution enumerates the benefits of cooperation.

In any large-scale human endeavor, conflicts arise that may limit cooperation. Accommodating conscientious objection is the safety valve that permits cooperation when dealing with contested government endeavors such as war, abortion, and physician-assisted suicide. It is meant as a last ditch effort to maintain cohesion of both societal and individual moral integrity. But if every proposed action is met with votes divided along party lines, conscientious objection loses its moral high ground.

Judge Neil Gorsuch, the nominee for the U.S. Supreme Court, has a record of supporting religious freedom in Yellowbear v. Lambert (10th Cir. 2014). He would likely support conscientious objection in relation to assisted dying by physicians, contrary to the arguments made recently by bioethicists Julian Savulescu and Udo Schuklenk. In related news, the liberty of physicians to address gun safety was affirmed when a Florida appeals court upheld the overturning of the state’s Privacy of Firearm Owners Act.

Summing up a tumultuous month of medical ethics, I leave you with the words of Voltaire: “Cherish those who seek the truth but beware of those who find it.”

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

DoD Rolls Out EHR Genesis at Fairchild Air Force Base

After years of preparation, a new electronic health record (EHR) system is now live at Fairchild Air Force Base in Washington. According to DoD officials, the system remains on schedule for the next step in the rollout later this year and the eventual completion in 2022. “This is just the first step in implementing what will be the largest integrated inpatient and outpatient electronic health record in the United States,” said VADM Raquel Bono, director of the Defense Health Agency.

Home to the 92nd Medical Group, Fairchild has a number of outpatient clinics and a pharmacy. According to Col Margaret Carey, the 92nd Medical Group commander, Genesis is being used by all the medical personnel at Fairchild.

For many years, the VA and DoD discussed possibly developing a single EHR across both systems before rejecting the idea for being too costly and complicated. Instead the 2 agencies looked to make their systems interoperable and to improve data sharing across the systems. The 2 agencies developed the Joint Legacy Viewer system to improve data sharing. The Joint Legacy Viewer is a clinical application that provides an integrated, read-only display of health data from DoD, VA, private sector partners, and the current military medical record system in a common data viewer.

The DoD originally awarded the $4.3 billion contract to Leidos in 2014 to develop Genesis, but the system was delayed to address cyber-security concerns. The concerns also caused DoD to reduce a larger rollout to focus initially on Fairchild.

“I can report firsthand from the command center that everything is going as expected,” reported Stacy Cummings, program executive officer for Defense Healthcare Management Systems. “Initial feedback from [health care] providers is positive.”

According to Dr. Paul Cordts, director, functional champion for the MHS at the Defense Health Agency, the biggest change that Genesis will bring is offering open medical notes to patients to “empower our patients to know what medical data are in the medical records and to use that data to improve their health and their health care over time.” Patients will be able to access data through a patient portal.

“This EHR is built to enable a team approach to providing health services to patients,” said U.S. Air Force Surgeon General Lt Gen Mark Ediger, MD. “In medicine today we really leverage a number of different skill sets on a health care team… That’s why in the Air Force we are piloting the addition of a health coaching capability here at Fairchild to leverage capabilities that are in MHS, so that health coaches can interact with patients between visits to work on things like tobacco cessation and weight loss, exercise plans and things of that nature.”

After years of preparation, a new electronic health record (EHR) system is now live at Fairchild Air Force Base in Washington. According to DoD officials, the system remains on schedule for the next step in the rollout later this year and the eventual completion in 2022. “This is just the first step in implementing what will be the largest integrated inpatient and outpatient electronic health record in the United States,” said VADM Raquel Bono, director of the Defense Health Agency.

Home to the 92nd Medical Group, Fairchild has a number of outpatient clinics and a pharmacy. According to Col Margaret Carey, the 92nd Medical Group commander, Genesis is being used by all the medical personnel at Fairchild.

For many years, the VA and DoD discussed possibly developing a single EHR across both systems before rejecting the idea for being too costly and complicated. Instead the 2 agencies looked to make their systems interoperable and to improve data sharing across the systems. The 2 agencies developed the Joint Legacy Viewer system to improve data sharing. The Joint Legacy Viewer is a clinical application that provides an integrated, read-only display of health data from DoD, VA, private sector partners, and the current military medical record system in a common data viewer.

The DoD originally awarded the $4.3 billion contract to Leidos in 2014 to develop Genesis, but the system was delayed to address cyber-security concerns. The concerns also caused DoD to reduce a larger rollout to focus initially on Fairchild.

“I can report firsthand from the command center that everything is going as expected,” reported Stacy Cummings, program executive officer for Defense Healthcare Management Systems. “Initial feedback from [health care] providers is positive.”

According to Dr. Paul Cordts, director, functional champion for the MHS at the Defense Health Agency, the biggest change that Genesis will bring is offering open medical notes to patients to “empower our patients to know what medical data are in the medical records and to use that data to improve their health and their health care over time.” Patients will be able to access data through a patient portal.

“This EHR is built to enable a team approach to providing health services to patients,” said U.S. Air Force Surgeon General Lt Gen Mark Ediger, MD. “In medicine today we really leverage a number of different skill sets on a health care team… That’s why in the Air Force we are piloting the addition of a health coaching capability here at Fairchild to leverage capabilities that are in MHS, so that health coaches can interact with patients between visits to work on things like tobacco cessation and weight loss, exercise plans and things of that nature.”

After years of preparation, a new electronic health record (EHR) system is now live at Fairchild Air Force Base in Washington. According to DoD officials, the system remains on schedule for the next step in the rollout later this year and the eventual completion in 2022. “This is just the first step in implementing what will be the largest integrated inpatient and outpatient electronic health record in the United States,” said VADM Raquel Bono, director of the Defense Health Agency.

Home to the 92nd Medical Group, Fairchild has a number of outpatient clinics and a pharmacy. According to Col Margaret Carey, the 92nd Medical Group commander, Genesis is being used by all the medical personnel at Fairchild.

For many years, the VA and DoD discussed possibly developing a single EHR across both systems before rejecting the idea for being too costly and complicated. Instead the 2 agencies looked to make their systems interoperable and to improve data sharing across the systems. The 2 agencies developed the Joint Legacy Viewer system to improve data sharing. The Joint Legacy Viewer is a clinical application that provides an integrated, read-only display of health data from DoD, VA, private sector partners, and the current military medical record system in a common data viewer.

The DoD originally awarded the $4.3 billion contract to Leidos in 2014 to develop Genesis, but the system was delayed to address cyber-security concerns. The concerns also caused DoD to reduce a larger rollout to focus initially on Fairchild.

“I can report firsthand from the command center that everything is going as expected,” reported Stacy Cummings, program executive officer for Defense Healthcare Management Systems. “Initial feedback from [health care] providers is positive.”

According to Dr. Paul Cordts, director, functional champion for the MHS at the Defense Health Agency, the biggest change that Genesis will bring is offering open medical notes to patients to “empower our patients to know what medical data are in the medical records and to use that data to improve their health and their health care over time.” Patients will be able to access data through a patient portal.

“This EHR is built to enable a team approach to providing health services to patients,” said U.S. Air Force Surgeon General Lt Gen Mark Ediger, MD. “In medicine today we really leverage a number of different skill sets on a health care team… That’s why in the Air Force we are piloting the addition of a health coaching capability here at Fairchild to leverage capabilities that are in MHS, so that health coaches can interact with patients between visits to work on things like tobacco cessation and weight loss, exercise plans and things of that nature.”

NIOSH Guide Promotes Holistic View of Worker Health

Stress levels, access to sick leave (or lack thereof), hazardous conditions, and interactions with coworkers have a ripple effect on the lives of workers, their families, and their communities. A safe workplace that supports the well-being of workers can have far-reaching benefits. That’s the premise and promise of Fundamentals of Total Worker Health Approaches: Essential Elements for Advancing Worker Safety, Health, and Well-Being, created by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

The workbook provides a “user-friendly entry point” into total worker health with examples and tips, such as, “design programs with a long-term outlook to ensure sustainability. Short-term approaches have short-term value.” It also includes a self-assessment tool and resources to develop an action plan and measure progress specific to the organization. A new conceptual model—a “hierarchy of controls”—lists ways to minimize or eliminate exposure to hazards in the workplace, from least effective (eg, providing personal protective equipment) to most effective (eg, physically removing the hazard).

Each workplace is unique, NIOSH says, and because the experiences of people who manage and work in them differ, the workbook is not intended as a one-size-fits-all tool. But it can be used to provide a “snapshot” of where the organization is on the path to total worker health.

Stress levels, access to sick leave (or lack thereof), hazardous conditions, and interactions with coworkers have a ripple effect on the lives of workers, their families, and their communities. A safe workplace that supports the well-being of workers can have far-reaching benefits. That’s the premise and promise of Fundamentals of Total Worker Health Approaches: Essential Elements for Advancing Worker Safety, Health, and Well-Being, created by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

The workbook provides a “user-friendly entry point” into total worker health with examples and tips, such as, “design programs with a long-term outlook to ensure sustainability. Short-term approaches have short-term value.” It also includes a self-assessment tool and resources to develop an action plan and measure progress specific to the organization. A new conceptual model—a “hierarchy of controls”—lists ways to minimize or eliminate exposure to hazards in the workplace, from least effective (eg, providing personal protective equipment) to most effective (eg, physically removing the hazard).

Each workplace is unique, NIOSH says, and because the experiences of people who manage and work in them differ, the workbook is not intended as a one-size-fits-all tool. But it can be used to provide a “snapshot” of where the organization is on the path to total worker health.

Stress levels, access to sick leave (or lack thereof), hazardous conditions, and interactions with coworkers have a ripple effect on the lives of workers, their families, and their communities. A safe workplace that supports the well-being of workers can have far-reaching benefits. That’s the premise and promise of Fundamentals of Total Worker Health Approaches: Essential Elements for Advancing Worker Safety, Health, and Well-Being, created by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

The workbook provides a “user-friendly entry point” into total worker health with examples and tips, such as, “design programs with a long-term outlook to ensure sustainability. Short-term approaches have short-term value.” It also includes a self-assessment tool and resources to develop an action plan and measure progress specific to the organization. A new conceptual model—a “hierarchy of controls”—lists ways to minimize or eliminate exposure to hazards in the workplace, from least effective (eg, providing personal protective equipment) to most effective (eg, physically removing the hazard).

Each workplace is unique, NIOSH says, and because the experiences of people who manage and work in them differ, the workbook is not intended as a one-size-fits-all tool. But it can be used to provide a “snapshot” of where the organization is on the path to total worker health.

Adrenal “incidentalomas”

Appeals court strikes down doctor gun gag law

An appeals court has struck down a Florida law that banned physicians from asking patients about firearms, ruling that the so-called gun gag law violates doctors’ First Amendment rights.

The decision by the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals enables Florida physicians to once again query patients and families about gun ownership and record firearm information in their records. The court, however, left intact a provision that allows patients to refuse answering such questions and upheld another rule that physicians cannot discriminate against patients based on firearm status.

”While the chapter does not wish to impinge on the rights of gun owners, it has fought this legislation in the legislature and in the courts because it is essential that physicians and patients have the right to an open dialogue, free from government restrictions,” Dr. Goldman said in a statement. “[The] ruling is a victory for patients and the profession.”

Florida Gov. Rick Scott (R) did not respond to a request for comment.

The Florida Firearms Owners’ Privacy Act (FOPA) was enacted in 2011 after complaints from patients that physicians were inquiring about firearms in the home and in some cases, refusing to provide care if patients declined to answer. The law barred physicians from asking about firearms and from recording information about firearms in patient records. The statute also precluded doctors from unnecessarily harassing patients about firearm ownership during an examination and prevented physicians from discriminating against patients based solely on firearm ownership. Violations of the law could result in a $10,000 fine per offense, a letter of reprimand, probation, suspension, compulsory remedial education, or permanent license revocation.

Shortly after the law passed, the ACP Florida Chapter sued the state; the suit was joined by the American Academy of Family Physicians Florida Chapter, the American Academy of Pediatrics Florida chapter, and a group of physicians. The plaintiffs argued that doctors routinely ask patients about potential health and safety risks, including firearms, to assess safety risks, educate patients and parents, and encourage gun safety. The gag law violated doctors’ free speech protections, according to the plaintiffs. The state argued that FOPA ensures patient privacy and protects gun owners’ right to own and bear arms from private encumbrances. A district court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs.

In the ruling, judges for the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals wrote that the right to own and possess firearms does not preclude questions about, commentary on, or criticism for the exercise of that right.

“As the district court aptly noted, there is no actual conflict between the First Amendment rights of doctors and medical professionals and the Second Amendment rights of patients that justifies FOPA’s speaker-focused and content-based restrictions on speech,” judges wrote. “Even if there were some possible conflict between the First Amendment rights of doctors and medical professionals and the Second Amendment rights of patients, the record-keeping, inquiry, and anti-harassment provisions do not advance [the legislative goals] in a permissible way.”

“The legislature has every right to regulate any profession to protect the public from discrimination and abuse,” Ms. Hammer said in an interview. “Doctors are businessmen, not gods. This activist decision attempts to use the First Amendment as a sword to terrorize the Second Amendment and completely disregards the rights and the will of the elected representatives of the people of Florida.”

The American Medical Association called the court ruling a clear victory against censorship of private medical discussions between patients and physicians.

“The court agreed that in the fields of medicine and public health, information saves lives,” according to an AMA statement. “Studies show that patients who received physician counseling on firearm safety are more likely to adopt one or more safe gun-storage practices. … Counseling patients we care for makes a difference in preventing gun-related injuries and deaths.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

An appeals court has struck down a Florida law that banned physicians from asking patients about firearms, ruling that the so-called gun gag law violates doctors’ First Amendment rights.

The decision by the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals enables Florida physicians to once again query patients and families about gun ownership and record firearm information in their records. The court, however, left intact a provision that allows patients to refuse answering such questions and upheld another rule that physicians cannot discriminate against patients based on firearm status.

”While the chapter does not wish to impinge on the rights of gun owners, it has fought this legislation in the legislature and in the courts because it is essential that physicians and patients have the right to an open dialogue, free from government restrictions,” Dr. Goldman said in a statement. “[The] ruling is a victory for patients and the profession.”

Florida Gov. Rick Scott (R) did not respond to a request for comment.