User login

50 years of child psychiatry, developmental-behavioral pediatrics

The 50th anniversary of Pediatric News prompts us to look back on the past 50 years in child psychiatry and developmental-behavioral pediatrics, and reflect on the evolution of the field. This includes the approach to diagnosis, the thinking about development and family, and the approach and access to treatment during this dynamic period.

While some historians identify the establishment of the first juvenile court in Chicago in 1899 and the work to help judges evaluate juvenile delinquency as the origin of child psychiatry in the United States, it was not until after World War II that the field really began to take root here, largely based on psychiatrists fleeing Europe and the seminal work of Anna Freud. Some of the earliest connections between pediatrics and child psychiatry were based on the work in England of Donald W. Winnicott, a practicing pediatrician and child psychiatrist, Albert J. Solnit, MD, at the Yale Child Study Center, and psychologically informed work of pediatrician Benjamin M. Spock, MD.

The first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) was published in 1952, based on a codification of mental disorders established by the Navy during WWII. The American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry was established in 1953, the same year that the first “tranquilizer,” chlorpromazine (Thorazine) was introduced (in France), marking the start of a revolution in psychiatric care. In 1959, the first candidates sat for a licensing examination in child psychiatry. The Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics was established as part of the American Academy of Pediatrics in 1960 to support training in this area. The AACAP established a journal in 1961. Child guidance clinics started affiliating with hospitals and universities in the 1960’s, after the Community Mental Health Act of 1963. Then, in 1965, Julius B. Richmond, MD, (a pediatrician) and Uri Bronfenbrenner, PhD, (a developmental psychologist), recognizing the importance of ecological systems to child development, were involved in the creation of Head Start, and the first Joint Commission on Mental Health for Children was established by federal legislation in 1965. The field was truly coalescing into a distinct discipline of medicine, one that bridged pediatrics, psychiatry, and neurology with nonmedical disciplines such as justice and education.

The decade between 1967 and 1977 was a period of transition from the focus on psychoanalytic concepts typical of the first half of the century to a more systematic approach to diagnosis. Children in psychiatric treatment had commonly been seen for extended individual treatments, and those with more disruptive disorders often were hospitalized for long periods. Psychoanalysis focused on the unconscious (theoretical drives and conflicts) to guide treatment. Treatment often focused on the role (causal) of parents, and family treatment was common, even on inpatient units. The second edition of the DSM (DSM-II) was published in 1968, with its first distinct section for disorders of childhood and adolescence, and an overarching focus on psychodynamics. In 1974, the decision was made to publish a new edition of the DSM that would establish a multiaxial assessment system (separating “biological” mental health problems from personality disorders, medical illnesses, and psychosocial stressors) and research-oriented diagnostic criteria that would attempt to facilitate reliable diagnoses based on common clusters of symptoms. Field trials sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health began in 1977 to establish the reliability of the new diagnoses.

The year 1977 saw the first Apple computer, the New York City blackout, the release of the first “Star Wars” movie, and also the start of a momentous decade in general and child psychiatry. The third edition of the DSM (DSM-III) was published in 1980, the beginning of a revolution in psychiatric diagnosis and treatments. It created reliable, reproducible diagnostic constructs to serve as the basis for studies on epidemiology and treatment. Implications of causality were replaced by description; for example, hyperkinetic reaction of childhood was redefined and labeled attention-deficit disorder. Recognizing the importance of research and training in this rapidly changing field, W.T. Grant Foundation funded 11 fellowship programs in 1977, and the Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics was founded in 1982 by the leaders of those programs.

In 1983, The AACAP published “Child Psychiatry: A Plan for the Coming Decades.” It was the result of 5 years’ work by 100 child psychiatrists, general psychiatrists, pediatricians, epidemiologists, nurses, leaders of the NIMH, and various child advocates. This report laid out a challenge for child psychiatry to develop research strategies that would allow evidence-based understanding and treatment of the mental illnesses of children. The established focus on individual experience and anecdotal data, particularly about social and psychodynamic influences, would shift towards a more scientific approach to diagnosis and treatment. This decade started an explosion in epidemiologic research, medication trials, and controlled studies of nonbiological treatments in child psychiatry. At the same time, the political landscape changed, and an ascendant conservatism began the process of closing publicly funded residential treatment centers that had offered care to the more chronically mentally ill and children with profound developmental disorders. This would accelerate the shift towards outpatient psychiatric care of children. Ironically, as research would accelerate in child psychiatry, access to effective treatments would become more difficult.

The decade from 1987 to 1997 was a period of dramatic growth in medication use in child psychiatry. Prozac was approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in the United States in 1988 and soon followed by other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (Zoloft in 1991 and Paxil in 1992). The journal of the AACAP began to publish more randomized controlled trials of medication treatments in children with DSM-codified diagnoses, and clinicians became more comfortable using stimulants, antidepressants, and even antipsychotic medications in the outpatient setting. This trend was enhanced by the emergence of managed care and the denial of coverage for alleged “nonbiological” diagnoses and for many psychiatric treatments. Loss of reimbursement led to a significant decline in resources, particularly inpatient child psychiatry beds and specialized clinics. This, in turn, contributed to the growing emphasis on medication treatments for children’s mental health problems. For-profit managed care companies underbid each other to provide mental health coverage and incentivized medication visits. Of note, the medical budgets, not the mental health carve outs, were billed for the medication prescribed.

The Americans with Disabilities Act was passed in 1990, increasing the funding for school-based mental health resources for children, and in 1996, Congress passed the Mental Health Parity Act, the first of several legislative attempts to ensure parity between insurance coverage for medical and psychiatric illnesses – legislation that to this day has not achieved parity of access to care. As pediatricians took on more of mental health care, a multidisciplinary team created a primary care version of DSM IV, the DSM-IV-PC, in 1995, to assist with defining levels of symptoms less than disorder to facilitate earlier intervention. A formal subspecialty of developmental-behavioral pediatrics was established in 1999 to educate leaders. Pediatric residents have had required training in developmental-behavioral pediatrics since 2008.

The year 1997 saw the first nationwide survey of parents about attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, kicking off what could be called the decade of ADHD, in which prevalence rates steadily climbed, from 5.7% in 1997 to 9.5% in 2007. The prevalence of stimulant treatment in children skyrocketed in this period. According to the NIMH, stimulants were prescribed to 4.2% of 6- to 12-year-olds in 1996, and that number grew to 5.1% in 2008. For 13- to 18-year-olds, the rate more than doubled during this time, from 2.3% in 1996 to 4.9% in 2008. The prevalence of autism also grew dramatically during this time, from 1.9 per 1,000 in 1997-1999 to 7.4 per 1,000 in 2006-2008, probably based on an evolving understanding of the disorder and this diagnosis providing special access to resources in schools.

Research during this decade became increasingly focused on imaging studies of children (and adults), as leaders in the field were trying to move from symptom clusters to anatomic and physiologic correlates of psychiatric illness. The great increase in medication use in children hit a speed bump in October 2004, when the Food and Drug Administration issued a controversial public warning about an increased risk of suicidal thoughts or behaviors in youth being treated with SSRI antidepressants. As access to child psychiatric treatment had become more difficult over the preceding decades, pediatricians had assumed much of the medication treatment of common psychiatric problems. The FDA’s black box warning complicated pediatricians’ efforts to fill this void.

The last decade has been the decade of genetics and efforts to improve access to care. It started in 2007 with the FDA expanding its SSRI warning to acknowledge that depression itself increased the risk for suicide, in an effort to not discourage needed depression treatment in young people. But studies demonstrated that the rates of diagnosing and treating depression dropped dramatically in the years following the warning: Diagnoses of depression declined by as much as 42% in children, and the rate of antidepressant treatment in adolescents dropped by as much as 32% in the 2 years following the warning (N Engl J Med. 2014 Oct 30;371(18):1666-8). There was no compensatory increase in utilization of other kinds of treatments. While suicide rates in young people had been stubbornly steady from the mid-1970’s to the mid-1990’s, they began to decline in 1996, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But that trend was broken in 2004, with a jump in attempted and completed suicides in young people. The rate stabilized later in the decade, but has never returned to the lows that were being achieved prior to the warning.

This decade was marked by the passage of the Affordable Care Act, including – again – an unfulfilled mandate for mental health parity for any insurance plans in the marketplace. Although diagnosis is still symptom based, the effort to define psychiatric disorders based on brain anatomy, neurotransmitters, and genomics continues to intensify. There is growing evidence that psychiatric disorders are not nature or nurture, but nature and nurture. Epigenetic findings show that environment impacts gene expression and brain functioning. These findings promise to deepen our understanding of the critical role of early experiences (consider Adverse Childhood Experiences [ACE] scores) and the promise of protective relationships, in schools and parenting.

And what will come next? We believe that silos – medical, psychiatric, parenting, school, environment – will be bridged to understand the many factors that impact behavior and treatment, but the need to advocate for policies that support funding for the education and mental health care of children and the training of professionals to provide that care is never ending. As our knowledge of the genome marches forward, we may discover effective strategies for preventing the emergence of mental illness in children or create individualized treatments. We may learn more about the role of nutrition and the microbiome in health and disease, about autoimmunity and mental illness. Our focus may return to parents, not as culprits, but as the mediators of health from the prenatal period on. Technology may enable us to improve access to effective treatments, with teens monitoring their sleep and mood, and accessing therapy on their smart phones. And our understanding of development and vulnerability may help us stem the rise in autism or collaborate with educators so that education could better put every child on their healthiest possible path. We look forward to experiencing it – and writing about it – with you!

Dr. Swick is an attending psychiatrist in the division of child psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and director of the Parenting at a Challenging Time (PACT) Program at the Vernon Cancer Center at Newton Wellesley Hospital, also in Boston. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. They said they had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline Medical News. Email them at [email protected].

The 50th anniversary of Pediatric News prompts us to look back on the past 50 years in child psychiatry and developmental-behavioral pediatrics, and reflect on the evolution of the field. This includes the approach to diagnosis, the thinking about development and family, and the approach and access to treatment during this dynamic period.

While some historians identify the establishment of the first juvenile court in Chicago in 1899 and the work to help judges evaluate juvenile delinquency as the origin of child psychiatry in the United States, it was not until after World War II that the field really began to take root here, largely based on psychiatrists fleeing Europe and the seminal work of Anna Freud. Some of the earliest connections between pediatrics and child psychiatry were based on the work in England of Donald W. Winnicott, a practicing pediatrician and child psychiatrist, Albert J. Solnit, MD, at the Yale Child Study Center, and psychologically informed work of pediatrician Benjamin M. Spock, MD.

The first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) was published in 1952, based on a codification of mental disorders established by the Navy during WWII. The American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry was established in 1953, the same year that the first “tranquilizer,” chlorpromazine (Thorazine) was introduced (in France), marking the start of a revolution in psychiatric care. In 1959, the first candidates sat for a licensing examination in child psychiatry. The Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics was established as part of the American Academy of Pediatrics in 1960 to support training in this area. The AACAP established a journal in 1961. Child guidance clinics started affiliating with hospitals and universities in the 1960’s, after the Community Mental Health Act of 1963. Then, in 1965, Julius B. Richmond, MD, (a pediatrician) and Uri Bronfenbrenner, PhD, (a developmental psychologist), recognizing the importance of ecological systems to child development, were involved in the creation of Head Start, and the first Joint Commission on Mental Health for Children was established by federal legislation in 1965. The field was truly coalescing into a distinct discipline of medicine, one that bridged pediatrics, psychiatry, and neurology with nonmedical disciplines such as justice and education.

The decade between 1967 and 1977 was a period of transition from the focus on psychoanalytic concepts typical of the first half of the century to a more systematic approach to diagnosis. Children in psychiatric treatment had commonly been seen for extended individual treatments, and those with more disruptive disorders often were hospitalized for long periods. Psychoanalysis focused on the unconscious (theoretical drives and conflicts) to guide treatment. Treatment often focused on the role (causal) of parents, and family treatment was common, even on inpatient units. The second edition of the DSM (DSM-II) was published in 1968, with its first distinct section for disorders of childhood and adolescence, and an overarching focus on psychodynamics. In 1974, the decision was made to publish a new edition of the DSM that would establish a multiaxial assessment system (separating “biological” mental health problems from personality disorders, medical illnesses, and psychosocial stressors) and research-oriented diagnostic criteria that would attempt to facilitate reliable diagnoses based on common clusters of symptoms. Field trials sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health began in 1977 to establish the reliability of the new diagnoses.

The year 1977 saw the first Apple computer, the New York City blackout, the release of the first “Star Wars” movie, and also the start of a momentous decade in general and child psychiatry. The third edition of the DSM (DSM-III) was published in 1980, the beginning of a revolution in psychiatric diagnosis and treatments. It created reliable, reproducible diagnostic constructs to serve as the basis for studies on epidemiology and treatment. Implications of causality were replaced by description; for example, hyperkinetic reaction of childhood was redefined and labeled attention-deficit disorder. Recognizing the importance of research and training in this rapidly changing field, W.T. Grant Foundation funded 11 fellowship programs in 1977, and the Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics was founded in 1982 by the leaders of those programs.

In 1983, The AACAP published “Child Psychiatry: A Plan for the Coming Decades.” It was the result of 5 years’ work by 100 child psychiatrists, general psychiatrists, pediatricians, epidemiologists, nurses, leaders of the NIMH, and various child advocates. This report laid out a challenge for child psychiatry to develop research strategies that would allow evidence-based understanding and treatment of the mental illnesses of children. The established focus on individual experience and anecdotal data, particularly about social and psychodynamic influences, would shift towards a more scientific approach to diagnosis and treatment. This decade started an explosion in epidemiologic research, medication trials, and controlled studies of nonbiological treatments in child psychiatry. At the same time, the political landscape changed, and an ascendant conservatism began the process of closing publicly funded residential treatment centers that had offered care to the more chronically mentally ill and children with profound developmental disorders. This would accelerate the shift towards outpatient psychiatric care of children. Ironically, as research would accelerate in child psychiatry, access to effective treatments would become more difficult.

The decade from 1987 to 1997 was a period of dramatic growth in medication use in child psychiatry. Prozac was approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in the United States in 1988 and soon followed by other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (Zoloft in 1991 and Paxil in 1992). The journal of the AACAP began to publish more randomized controlled trials of medication treatments in children with DSM-codified diagnoses, and clinicians became more comfortable using stimulants, antidepressants, and even antipsychotic medications in the outpatient setting. This trend was enhanced by the emergence of managed care and the denial of coverage for alleged “nonbiological” diagnoses and for many psychiatric treatments. Loss of reimbursement led to a significant decline in resources, particularly inpatient child psychiatry beds and specialized clinics. This, in turn, contributed to the growing emphasis on medication treatments for children’s mental health problems. For-profit managed care companies underbid each other to provide mental health coverage and incentivized medication visits. Of note, the medical budgets, not the mental health carve outs, were billed for the medication prescribed.

The Americans with Disabilities Act was passed in 1990, increasing the funding for school-based mental health resources for children, and in 1996, Congress passed the Mental Health Parity Act, the first of several legislative attempts to ensure parity between insurance coverage for medical and psychiatric illnesses – legislation that to this day has not achieved parity of access to care. As pediatricians took on more of mental health care, a multidisciplinary team created a primary care version of DSM IV, the DSM-IV-PC, in 1995, to assist with defining levels of symptoms less than disorder to facilitate earlier intervention. A formal subspecialty of developmental-behavioral pediatrics was established in 1999 to educate leaders. Pediatric residents have had required training in developmental-behavioral pediatrics since 2008.

The year 1997 saw the first nationwide survey of parents about attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, kicking off what could be called the decade of ADHD, in which prevalence rates steadily climbed, from 5.7% in 1997 to 9.5% in 2007. The prevalence of stimulant treatment in children skyrocketed in this period. According to the NIMH, stimulants were prescribed to 4.2% of 6- to 12-year-olds in 1996, and that number grew to 5.1% in 2008. For 13- to 18-year-olds, the rate more than doubled during this time, from 2.3% in 1996 to 4.9% in 2008. The prevalence of autism also grew dramatically during this time, from 1.9 per 1,000 in 1997-1999 to 7.4 per 1,000 in 2006-2008, probably based on an evolving understanding of the disorder and this diagnosis providing special access to resources in schools.

Research during this decade became increasingly focused on imaging studies of children (and adults), as leaders in the field were trying to move from symptom clusters to anatomic and physiologic correlates of psychiatric illness. The great increase in medication use in children hit a speed bump in October 2004, when the Food and Drug Administration issued a controversial public warning about an increased risk of suicidal thoughts or behaviors in youth being treated with SSRI antidepressants. As access to child psychiatric treatment had become more difficult over the preceding decades, pediatricians had assumed much of the medication treatment of common psychiatric problems. The FDA’s black box warning complicated pediatricians’ efforts to fill this void.

The last decade has been the decade of genetics and efforts to improve access to care. It started in 2007 with the FDA expanding its SSRI warning to acknowledge that depression itself increased the risk for suicide, in an effort to not discourage needed depression treatment in young people. But studies demonstrated that the rates of diagnosing and treating depression dropped dramatically in the years following the warning: Diagnoses of depression declined by as much as 42% in children, and the rate of antidepressant treatment in adolescents dropped by as much as 32% in the 2 years following the warning (N Engl J Med. 2014 Oct 30;371(18):1666-8). There was no compensatory increase in utilization of other kinds of treatments. While suicide rates in young people had been stubbornly steady from the mid-1970’s to the mid-1990’s, they began to decline in 1996, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But that trend was broken in 2004, with a jump in attempted and completed suicides in young people. The rate stabilized later in the decade, but has never returned to the lows that were being achieved prior to the warning.

This decade was marked by the passage of the Affordable Care Act, including – again – an unfulfilled mandate for mental health parity for any insurance plans in the marketplace. Although diagnosis is still symptom based, the effort to define psychiatric disorders based on brain anatomy, neurotransmitters, and genomics continues to intensify. There is growing evidence that psychiatric disorders are not nature or nurture, but nature and nurture. Epigenetic findings show that environment impacts gene expression and brain functioning. These findings promise to deepen our understanding of the critical role of early experiences (consider Adverse Childhood Experiences [ACE] scores) and the promise of protective relationships, in schools and parenting.

And what will come next? We believe that silos – medical, psychiatric, parenting, school, environment – will be bridged to understand the many factors that impact behavior and treatment, but the need to advocate for policies that support funding for the education and mental health care of children and the training of professionals to provide that care is never ending. As our knowledge of the genome marches forward, we may discover effective strategies for preventing the emergence of mental illness in children or create individualized treatments. We may learn more about the role of nutrition and the microbiome in health and disease, about autoimmunity and mental illness. Our focus may return to parents, not as culprits, but as the mediators of health from the prenatal period on. Technology may enable us to improve access to effective treatments, with teens monitoring their sleep and mood, and accessing therapy on their smart phones. And our understanding of development and vulnerability may help us stem the rise in autism or collaborate with educators so that education could better put every child on their healthiest possible path. We look forward to experiencing it – and writing about it – with you!

Dr. Swick is an attending psychiatrist in the division of child psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and director of the Parenting at a Challenging Time (PACT) Program at the Vernon Cancer Center at Newton Wellesley Hospital, also in Boston. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. They said they had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline Medical News. Email them at [email protected].

The 50th anniversary of Pediatric News prompts us to look back on the past 50 years in child psychiatry and developmental-behavioral pediatrics, and reflect on the evolution of the field. This includes the approach to diagnosis, the thinking about development and family, and the approach and access to treatment during this dynamic period.

While some historians identify the establishment of the first juvenile court in Chicago in 1899 and the work to help judges evaluate juvenile delinquency as the origin of child psychiatry in the United States, it was not until after World War II that the field really began to take root here, largely based on psychiatrists fleeing Europe and the seminal work of Anna Freud. Some of the earliest connections between pediatrics and child psychiatry were based on the work in England of Donald W. Winnicott, a practicing pediatrician and child psychiatrist, Albert J. Solnit, MD, at the Yale Child Study Center, and psychologically informed work of pediatrician Benjamin M. Spock, MD.

The first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) was published in 1952, based on a codification of mental disorders established by the Navy during WWII. The American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry was established in 1953, the same year that the first “tranquilizer,” chlorpromazine (Thorazine) was introduced (in France), marking the start of a revolution in psychiatric care. In 1959, the first candidates sat for a licensing examination in child psychiatry. The Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics was established as part of the American Academy of Pediatrics in 1960 to support training in this area. The AACAP established a journal in 1961. Child guidance clinics started affiliating with hospitals and universities in the 1960’s, after the Community Mental Health Act of 1963. Then, in 1965, Julius B. Richmond, MD, (a pediatrician) and Uri Bronfenbrenner, PhD, (a developmental psychologist), recognizing the importance of ecological systems to child development, were involved in the creation of Head Start, and the first Joint Commission on Mental Health for Children was established by federal legislation in 1965. The field was truly coalescing into a distinct discipline of medicine, one that bridged pediatrics, psychiatry, and neurology with nonmedical disciplines such as justice and education.

The decade between 1967 and 1977 was a period of transition from the focus on psychoanalytic concepts typical of the first half of the century to a more systematic approach to diagnosis. Children in psychiatric treatment had commonly been seen for extended individual treatments, and those with more disruptive disorders often were hospitalized for long periods. Psychoanalysis focused on the unconscious (theoretical drives and conflicts) to guide treatment. Treatment often focused on the role (causal) of parents, and family treatment was common, even on inpatient units. The second edition of the DSM (DSM-II) was published in 1968, with its first distinct section for disorders of childhood and adolescence, and an overarching focus on psychodynamics. In 1974, the decision was made to publish a new edition of the DSM that would establish a multiaxial assessment system (separating “biological” mental health problems from personality disorders, medical illnesses, and psychosocial stressors) and research-oriented diagnostic criteria that would attempt to facilitate reliable diagnoses based on common clusters of symptoms. Field trials sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health began in 1977 to establish the reliability of the new diagnoses.

The year 1977 saw the first Apple computer, the New York City blackout, the release of the first “Star Wars” movie, and also the start of a momentous decade in general and child psychiatry. The third edition of the DSM (DSM-III) was published in 1980, the beginning of a revolution in psychiatric diagnosis and treatments. It created reliable, reproducible diagnostic constructs to serve as the basis for studies on epidemiology and treatment. Implications of causality were replaced by description; for example, hyperkinetic reaction of childhood was redefined and labeled attention-deficit disorder. Recognizing the importance of research and training in this rapidly changing field, W.T. Grant Foundation funded 11 fellowship programs in 1977, and the Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics was founded in 1982 by the leaders of those programs.

In 1983, The AACAP published “Child Psychiatry: A Plan for the Coming Decades.” It was the result of 5 years’ work by 100 child psychiatrists, general psychiatrists, pediatricians, epidemiologists, nurses, leaders of the NIMH, and various child advocates. This report laid out a challenge for child psychiatry to develop research strategies that would allow evidence-based understanding and treatment of the mental illnesses of children. The established focus on individual experience and anecdotal data, particularly about social and psychodynamic influences, would shift towards a more scientific approach to diagnosis and treatment. This decade started an explosion in epidemiologic research, medication trials, and controlled studies of nonbiological treatments in child psychiatry. At the same time, the political landscape changed, and an ascendant conservatism began the process of closing publicly funded residential treatment centers that had offered care to the more chronically mentally ill and children with profound developmental disorders. This would accelerate the shift towards outpatient psychiatric care of children. Ironically, as research would accelerate in child psychiatry, access to effective treatments would become more difficult.

The decade from 1987 to 1997 was a period of dramatic growth in medication use in child psychiatry. Prozac was approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in the United States in 1988 and soon followed by other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (Zoloft in 1991 and Paxil in 1992). The journal of the AACAP began to publish more randomized controlled trials of medication treatments in children with DSM-codified diagnoses, and clinicians became more comfortable using stimulants, antidepressants, and even antipsychotic medications in the outpatient setting. This trend was enhanced by the emergence of managed care and the denial of coverage for alleged “nonbiological” diagnoses and for many psychiatric treatments. Loss of reimbursement led to a significant decline in resources, particularly inpatient child psychiatry beds and specialized clinics. This, in turn, contributed to the growing emphasis on medication treatments for children’s mental health problems. For-profit managed care companies underbid each other to provide mental health coverage and incentivized medication visits. Of note, the medical budgets, not the mental health carve outs, were billed for the medication prescribed.

The Americans with Disabilities Act was passed in 1990, increasing the funding for school-based mental health resources for children, and in 1996, Congress passed the Mental Health Parity Act, the first of several legislative attempts to ensure parity between insurance coverage for medical and psychiatric illnesses – legislation that to this day has not achieved parity of access to care. As pediatricians took on more of mental health care, a multidisciplinary team created a primary care version of DSM IV, the DSM-IV-PC, in 1995, to assist with defining levels of symptoms less than disorder to facilitate earlier intervention. A formal subspecialty of developmental-behavioral pediatrics was established in 1999 to educate leaders. Pediatric residents have had required training in developmental-behavioral pediatrics since 2008.

The year 1997 saw the first nationwide survey of parents about attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, kicking off what could be called the decade of ADHD, in which prevalence rates steadily climbed, from 5.7% in 1997 to 9.5% in 2007. The prevalence of stimulant treatment in children skyrocketed in this period. According to the NIMH, stimulants were prescribed to 4.2% of 6- to 12-year-olds in 1996, and that number grew to 5.1% in 2008. For 13- to 18-year-olds, the rate more than doubled during this time, from 2.3% in 1996 to 4.9% in 2008. The prevalence of autism also grew dramatically during this time, from 1.9 per 1,000 in 1997-1999 to 7.4 per 1,000 in 2006-2008, probably based on an evolving understanding of the disorder and this diagnosis providing special access to resources in schools.

Research during this decade became increasingly focused on imaging studies of children (and adults), as leaders in the field were trying to move from symptom clusters to anatomic and physiologic correlates of psychiatric illness. The great increase in medication use in children hit a speed bump in October 2004, when the Food and Drug Administration issued a controversial public warning about an increased risk of suicidal thoughts or behaviors in youth being treated with SSRI antidepressants. As access to child psychiatric treatment had become more difficult over the preceding decades, pediatricians had assumed much of the medication treatment of common psychiatric problems. The FDA’s black box warning complicated pediatricians’ efforts to fill this void.

The last decade has been the decade of genetics and efforts to improve access to care. It started in 2007 with the FDA expanding its SSRI warning to acknowledge that depression itself increased the risk for suicide, in an effort to not discourage needed depression treatment in young people. But studies demonstrated that the rates of diagnosing and treating depression dropped dramatically in the years following the warning: Diagnoses of depression declined by as much as 42% in children, and the rate of antidepressant treatment in adolescents dropped by as much as 32% in the 2 years following the warning (N Engl J Med. 2014 Oct 30;371(18):1666-8). There was no compensatory increase in utilization of other kinds of treatments. While suicide rates in young people had been stubbornly steady from the mid-1970’s to the mid-1990’s, they began to decline in 1996, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But that trend was broken in 2004, with a jump in attempted and completed suicides in young people. The rate stabilized later in the decade, but has never returned to the lows that were being achieved prior to the warning.

This decade was marked by the passage of the Affordable Care Act, including – again – an unfulfilled mandate for mental health parity for any insurance plans in the marketplace. Although diagnosis is still symptom based, the effort to define psychiatric disorders based on brain anatomy, neurotransmitters, and genomics continues to intensify. There is growing evidence that psychiatric disorders are not nature or nurture, but nature and nurture. Epigenetic findings show that environment impacts gene expression and brain functioning. These findings promise to deepen our understanding of the critical role of early experiences (consider Adverse Childhood Experiences [ACE] scores) and the promise of protective relationships, in schools and parenting.

And what will come next? We believe that silos – medical, psychiatric, parenting, school, environment – will be bridged to understand the many factors that impact behavior and treatment, but the need to advocate for policies that support funding for the education and mental health care of children and the training of professionals to provide that care is never ending. As our knowledge of the genome marches forward, we may discover effective strategies for preventing the emergence of mental illness in children or create individualized treatments. We may learn more about the role of nutrition and the microbiome in health and disease, about autoimmunity and mental illness. Our focus may return to parents, not as culprits, but as the mediators of health from the prenatal period on. Technology may enable us to improve access to effective treatments, with teens monitoring their sleep and mood, and accessing therapy on their smart phones. And our understanding of development and vulnerability may help us stem the rise in autism or collaborate with educators so that education could better put every child on their healthiest possible path. We look forward to experiencing it – and writing about it – with you!

Dr. Swick is an attending psychiatrist in the division of child psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and director of the Parenting at a Challenging Time (PACT) Program at the Vernon Cancer Center at Newton Wellesley Hospital, also in Boston. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. They said they had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline Medical News. Email them at [email protected].

Ublituximab was safe, highly active in rituximab-pretreated B-cell NHL, CLL

The investigational anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody ublituximab is safe and has good antitumor activity in patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (B-NHL) or chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who have previously received the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab, results from a phase I/II trial suggest.

Ublituximab is engineered to have a low fucose content. This feature gives it enhanced antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity relative to other anti-CD20 antibodies, especially against tumors having low expression of that protein, as may occur in the development of rituximab resistance.

In the trial, nearly half of the 35 patients studied had a complete or partial response to ublituximab, including nearly one-third of those whose disease was refractory to rituximab (Rituxan) (Br J Haematol. 2017 Apr;177[2]:243-53). The main adverse events were infusion-related reactions, fatigue, pyrexia, and diarrhea, but almost all were lower grade.

“Ublituximab was well tolerated and efficacious in a heterogeneous and highly rituximab–pretreated patient population,” said the investigators, who were led by Ahmed Sawas, MD, at the Center for Lymphoid Malignancies, Columbia University Medical Center, N.Y.

The observed response rate is much the same as those seen with two other anti-CD20 antibodies – obinutuzumab (Gazyva)and ofatumumab (Arzerra)– in similar patient populations, and ublituximab may have advantages in terms of fewer higher-grade infusion-related reactions and shorter infusion time.

“Enhanced anti-CD20 [monoclonal antibodies] that are well tolerated and active in rituximab-resistant disease can provide meaningful clinical benefit to patients with limited treatment options,” the investigators noted.

The trial enrolled 27 patients with B-NHL and 8 patients with CLL (or small lymphocytic lymphoma) who had rituximab-refractory disease (defined by progression on or within 6 months of receiving that agent) or rituximab-relapsed disease (defined by progression more than 6 months after receiving it). They had received a median of three prior therapies.

The patients were treated on an open-label basis with ublituximab at various doses as induction therapy (3-4 weekly infusions during cycles 1 and 2) and then as maintenance therapy (monthly during cycles 3-5, then once every 3 months for up to 2 years). All patients received an oral antihistamine and steroids before infusions.

By the end of the trial, 60% of patients had discontinued treatment because of progression; 23% had discontinued because of adverse events, physician decision, or other reasons; and the remaining 17% had received all planned treatment, Dr. Sawas and his coinvestigators reported.

None of the patients experienced dose-limiting toxicities or unexpected adverse events. The rate of any-grade adverse events was 100%, and the rate specifically of grade 3/4 adverse events was 49%. The rate of serious adverse events (most commonly pneumonia) was 37%.

The leading nonhematologic adverse events were infusion-related reactions (40%; grade 3/4, 0%), fatigue (37%; grade 3/4, 3%), pyrexia (29%; grade 3/4, 0%), and diarrhea (26%; grade 3/4, 0%).

The leading hematologic adverse events were neutropenia (14%; grade 3/4, 14%), with no associated infections; anemia (11%; grade 3/4, 6%); and thrombocytopenia (6%; grade 3/4, 6%), with no associated bleeding.

The overall response rate was 45% (44% in the B-NHL cohort and 50% in the CLL cohort); the majority of responses were partial responses. Notably, the rate was 31% among the subset of patients who had rituximab-refractory disease.

The median duration of response to ublituximab was 9.2 months, and the median progression-free survival was 7.7 months.

“Anti-CD20 therapy has demonstrated the greatest benefit in combination, traditionally with multidrug chemotherapy–based regimens,” the investigators noted. “While the introduction of novel targeted therapies has shifted the treatment paradigm of CLL and indolent lymphoma, the activity of these agents is likely to be potentiated by the addition of an anti-CD20 [monoclonal antibody], given their different mechanisms of action.”

In fact, several multidrug, non–chemotherapy-based regimens are showing promising efficacy and milder toxicity in early trials, they pointed out. “In similar fashion, ublituximab is being evaluated for the treatment of NHL or CLL in combination with other agents,” such as the immunomodulator lenalidomide (Revlimid) and the Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib (Imbruvica).

TG Therapeutics funded the trial. Dr. Sawas disclosed that he receives research funds from TG Therapeutics.

The investigational anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody ublituximab is safe and has good antitumor activity in patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (B-NHL) or chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who have previously received the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab, results from a phase I/II trial suggest.

Ublituximab is engineered to have a low fucose content. This feature gives it enhanced antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity relative to other anti-CD20 antibodies, especially against tumors having low expression of that protein, as may occur in the development of rituximab resistance.

In the trial, nearly half of the 35 patients studied had a complete or partial response to ublituximab, including nearly one-third of those whose disease was refractory to rituximab (Rituxan) (Br J Haematol. 2017 Apr;177[2]:243-53). The main adverse events were infusion-related reactions, fatigue, pyrexia, and diarrhea, but almost all were lower grade.

“Ublituximab was well tolerated and efficacious in a heterogeneous and highly rituximab–pretreated patient population,” said the investigators, who were led by Ahmed Sawas, MD, at the Center for Lymphoid Malignancies, Columbia University Medical Center, N.Y.

The observed response rate is much the same as those seen with two other anti-CD20 antibodies – obinutuzumab (Gazyva)and ofatumumab (Arzerra)– in similar patient populations, and ublituximab may have advantages in terms of fewer higher-grade infusion-related reactions and shorter infusion time.

“Enhanced anti-CD20 [monoclonal antibodies] that are well tolerated and active in rituximab-resistant disease can provide meaningful clinical benefit to patients with limited treatment options,” the investigators noted.

The trial enrolled 27 patients with B-NHL and 8 patients with CLL (or small lymphocytic lymphoma) who had rituximab-refractory disease (defined by progression on or within 6 months of receiving that agent) or rituximab-relapsed disease (defined by progression more than 6 months after receiving it). They had received a median of three prior therapies.

The patients were treated on an open-label basis with ublituximab at various doses as induction therapy (3-4 weekly infusions during cycles 1 and 2) and then as maintenance therapy (monthly during cycles 3-5, then once every 3 months for up to 2 years). All patients received an oral antihistamine and steroids before infusions.

By the end of the trial, 60% of patients had discontinued treatment because of progression; 23% had discontinued because of adverse events, physician decision, or other reasons; and the remaining 17% had received all planned treatment, Dr. Sawas and his coinvestigators reported.

None of the patients experienced dose-limiting toxicities or unexpected adverse events. The rate of any-grade adverse events was 100%, and the rate specifically of grade 3/4 adverse events was 49%. The rate of serious adverse events (most commonly pneumonia) was 37%.

The leading nonhematologic adverse events were infusion-related reactions (40%; grade 3/4, 0%), fatigue (37%; grade 3/4, 3%), pyrexia (29%; grade 3/4, 0%), and diarrhea (26%; grade 3/4, 0%).

The leading hematologic adverse events were neutropenia (14%; grade 3/4, 14%), with no associated infections; anemia (11%; grade 3/4, 6%); and thrombocytopenia (6%; grade 3/4, 6%), with no associated bleeding.

The overall response rate was 45% (44% in the B-NHL cohort and 50% in the CLL cohort); the majority of responses were partial responses. Notably, the rate was 31% among the subset of patients who had rituximab-refractory disease.

The median duration of response to ublituximab was 9.2 months, and the median progression-free survival was 7.7 months.

“Anti-CD20 therapy has demonstrated the greatest benefit in combination, traditionally with multidrug chemotherapy–based regimens,” the investigators noted. “While the introduction of novel targeted therapies has shifted the treatment paradigm of CLL and indolent lymphoma, the activity of these agents is likely to be potentiated by the addition of an anti-CD20 [monoclonal antibody], given their different mechanisms of action.”

In fact, several multidrug, non–chemotherapy-based regimens are showing promising efficacy and milder toxicity in early trials, they pointed out. “In similar fashion, ublituximab is being evaluated for the treatment of NHL or CLL in combination with other agents,” such as the immunomodulator lenalidomide (Revlimid) and the Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib (Imbruvica).

TG Therapeutics funded the trial. Dr. Sawas disclosed that he receives research funds from TG Therapeutics.

The investigational anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody ublituximab is safe and has good antitumor activity in patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (B-NHL) or chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who have previously received the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab, results from a phase I/II trial suggest.

Ublituximab is engineered to have a low fucose content. This feature gives it enhanced antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity relative to other anti-CD20 antibodies, especially against tumors having low expression of that protein, as may occur in the development of rituximab resistance.

In the trial, nearly half of the 35 patients studied had a complete or partial response to ublituximab, including nearly one-third of those whose disease was refractory to rituximab (Rituxan) (Br J Haematol. 2017 Apr;177[2]:243-53). The main adverse events were infusion-related reactions, fatigue, pyrexia, and diarrhea, but almost all were lower grade.

“Ublituximab was well tolerated and efficacious in a heterogeneous and highly rituximab–pretreated patient population,” said the investigators, who were led by Ahmed Sawas, MD, at the Center for Lymphoid Malignancies, Columbia University Medical Center, N.Y.

The observed response rate is much the same as those seen with two other anti-CD20 antibodies – obinutuzumab (Gazyva)and ofatumumab (Arzerra)– in similar patient populations, and ublituximab may have advantages in terms of fewer higher-grade infusion-related reactions and shorter infusion time.

“Enhanced anti-CD20 [monoclonal antibodies] that are well tolerated and active in rituximab-resistant disease can provide meaningful clinical benefit to patients with limited treatment options,” the investigators noted.

The trial enrolled 27 patients with B-NHL and 8 patients with CLL (or small lymphocytic lymphoma) who had rituximab-refractory disease (defined by progression on or within 6 months of receiving that agent) or rituximab-relapsed disease (defined by progression more than 6 months after receiving it). They had received a median of three prior therapies.

The patients were treated on an open-label basis with ublituximab at various doses as induction therapy (3-4 weekly infusions during cycles 1 and 2) and then as maintenance therapy (monthly during cycles 3-5, then once every 3 months for up to 2 years). All patients received an oral antihistamine and steroids before infusions.

By the end of the trial, 60% of patients had discontinued treatment because of progression; 23% had discontinued because of adverse events, physician decision, or other reasons; and the remaining 17% had received all planned treatment, Dr. Sawas and his coinvestigators reported.

None of the patients experienced dose-limiting toxicities or unexpected adverse events. The rate of any-grade adverse events was 100%, and the rate specifically of grade 3/4 adverse events was 49%. The rate of serious adverse events (most commonly pneumonia) was 37%.

The leading nonhematologic adverse events were infusion-related reactions (40%; grade 3/4, 0%), fatigue (37%; grade 3/4, 3%), pyrexia (29%; grade 3/4, 0%), and diarrhea (26%; grade 3/4, 0%).

The leading hematologic adverse events were neutropenia (14%; grade 3/4, 14%), with no associated infections; anemia (11%; grade 3/4, 6%); and thrombocytopenia (6%; grade 3/4, 6%), with no associated bleeding.

The overall response rate was 45% (44% in the B-NHL cohort and 50% in the CLL cohort); the majority of responses were partial responses. Notably, the rate was 31% among the subset of patients who had rituximab-refractory disease.

The median duration of response to ublituximab was 9.2 months, and the median progression-free survival was 7.7 months.

“Anti-CD20 therapy has demonstrated the greatest benefit in combination, traditionally with multidrug chemotherapy–based regimens,” the investigators noted. “While the introduction of novel targeted therapies has shifted the treatment paradigm of CLL and indolent lymphoma, the activity of these agents is likely to be potentiated by the addition of an anti-CD20 [monoclonal antibody], given their different mechanisms of action.”

In fact, several multidrug, non–chemotherapy-based regimens are showing promising efficacy and milder toxicity in early trials, they pointed out. “In similar fashion, ublituximab is being evaluated for the treatment of NHL or CLL in combination with other agents,” such as the immunomodulator lenalidomide (Revlimid) and the Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib (Imbruvica).

TG Therapeutics funded the trial. Dr. Sawas disclosed that he receives research funds from TG Therapeutics.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The overall response rate was 45%. There were no dose-limiting toxicities; main adverse events of any grade were infusion-related reactions (40%), fatigue (37%), pyrexia (29%), and diarrhea (26%).

Data source: A phase I/II trial among 35 patients with B-NHL or CLL who had previously received rituximab.

Disclosures: TG Therapeutics funded the trial. Dr. Sawas disclosed that he receives research funds from TG Therapeutics.

Sleep-Disordered Breathing in the Active-Duty Military Population and Its Civilian Care Cost

Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) is a continuum of symptoms that range from primary snoring with upper airway resistance to frank obstruction seen in obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). This disease spectrum has been reported to affect 10% to 17% of men and 3% to 9% of women in the general population.1 The specific incidence of OSA has been estimated to be about 2% to 4% of the general adult population.2,3 Sleep-disordered breathing often leads to poor sleep quality, which has been associated with many medical comorbidities, including vascular disease, hypertension, major cardiac events, cardiomyopathies, impaired concentration, reduced psychomotor vigilance and cognition, and daytime somnolence.1,2,4-6 Furthermore, there is evidence that the prevalence of SDB continues to grow among the general population.1 However, the prevalence of SDB in various populations (eg, pediatric vs adult, varying body mass index, country of origin) varies widely due to the multifactorial nature of the risk factors and the difficulty in diagnosing SDB.

Some of the more intuitive medical sequelae of SDB are daytime somnolence and subsequent impaired concentration for those with disrupted sleep patterns. Medical literature has paid specific attention to cohorts of personnel who may be at heightened risk from impaired concentration or inability to focus. These populations include but are not limited to sleep-deprived resident physicians, firefighters, truck drivers, and heavy-machine operators.7,8

Military service members represent a distinct cohort that often is relied on to maintain vigilance even in austere environments. Concentration is paramount in order to perform combat operations or tasks that involve operating heavy machinery, such as nuclear submarines, aircraft, or tanks. Given the myriad of unique operational demands on service members, SDB can have detrimental consequences on an individual’s health and his or her military readiness and training. Ultimately, SDB may degrade a unit’s effectiveness and perhaps the country’s military capability.

Active-duty military service members seem to be more susceptible to clinically relevant sleep conditions. In the military, causes of disruptions in normal sleep patterns are multifactorial. Medical literature focuses on circadian disruptions due to shift work and frequent travel, frequent alternating use of caffeine and sedatives, exposure to combat/trauma, and chronic sleep deprivation.9-11 Studies have been published that focus on service members who have returned from combat deployment.10,12,13 However, these studies do not explore the overall burden of disease, and there are no specific data to suggest the prevalence, annual incidence, or associated costs.

To quantify this disease burden in the military, this study focused on the subset of sleep disorders that impact respiration during sleep and determined the prevalence and annual incidence for the entire active-duty population. Additionally, the authors fill a void in the literature by determining the financial burden of SDB on civilian care expenditures.

Methods

This study was a retrospective review of administrative military health care data spanning fiscal years (FYs) 2009 to 2013 (October 1, 2008 to September 30, 2013). The study protocol was approved by the Naval Medical Center Portsmouth Institutional Review Board, and approval was given to waive informed consent. The Health Analysis Department at the Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Center (NMCPHC) obtained and analyzed data from the Military Health System (MHS) Management Analysis and Reporting Tool (M2). The M2 system is an ad hoc query tool used for viewing population, clinical, and financial MHS data, including care received within military treatment facilities (MTFs) and care purchased through TRICARE at civilian facilities. Both inpatient and outpatient health care records were included.

The population included all active-duty service members and guard/reserve members on active duty within all military services, including air force, army, coast guard, and navy branches, between FY 2009 and FY 2013. The authors identified service members with SDB as those with at least 1 ICD-9 diagnosis code related to SDB: obstructive sleep apnea (327.23); sleep-related hypoventilation/hypoxemia (327.26); and other organic sleep disorder (327.80).

Due to the transient nature of the military population, a monthly average over the 5 years of the study determined the overall number of service members eligible for care (1,717,227 service members).

Data Analysis

Prevalence of diagnosed SDB per FY was calculated as the number of service members who received at least 1 SDB diagnostic code between October 1, 2008 and September 30, 2013, over the average total active-duty population. Incidence per year was calculated as the number of new cases per FY, using 2009 as the baseline. Data were stratified by demographic and enrollment information for diagnosed service members and analyzed using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC) software.

Direct costs associated with SDB treatment fall into 2 categories for service members: (1) care delivered by civilian providers, calculated based on the amount TRICARE paid for the service, using insurance claim data; and (2) care received at MTFs by military providers. Costs for care at MTFs cannot be calculated, as the total cost amount for a single record is not directly attributed to SDB diagnosis.

Results

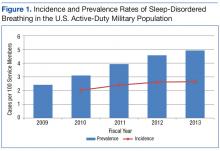

A total of 197,183 service members were diagnosed with SDB from FY 2009 to FY 2013. Both the annual incidence and prevalence of SDB for the active-duty military population showed upward trends for each of the years evaluated (Figure 1).

Notably, 72% of service members seen for SDB ranged in age from 25 to 44 years (Table).

Discussion

This study shows that the prevalence and incidence of SDB in the active-duty population are less than those reported for the civilian populace as a whole but are still greater than expected for an otherwise healthy and young population. Furthermore, the burden of disease and the cost to diagnose and treat have steadily increased for each of the past 5 fiscal years that were assessed.

The data show an upward trend in the incidence and prevalence of SDB in the military from FY 2009 to FY 2013 for reasons that are not clear but likely with many confounding contributions. As the spectrum of SDB has become better defined and the detrimental sequelae are better understood, it is likely that both service members and health care providers are more aware of the symptoms and more importantly, the potential for interventions that improve quality of life. It is also important to note that the U.S. military is a very transient organization with a nearly constant turnover between new enlistees/officers and those leaving the service or retiring after 20 years of service. Thus, despite an annual incidence of nearly 3% throughout the years evaluated, the annual increase in prevalence is not necessarily commensurate.

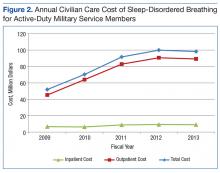

The FY 2013 prevalence (4.2%) and civilian care costs ($98,259,519) present traditional indications of the disease burden. Both metrics represent a sizable and increasing disease burden for the military. It is also important to note that these costs reflect only the short-term expenses for initial diagnosis and therapy. These costs in no way reflect the care for the long-term medical sequelae that have been recently linked to uncontrolled SDB/OSA, such as heart and vascular diseases, hypertension, and increased stroke risk. Additional costs will continue to grow.

Perhaps the most validated predictive factor for diagnosis of SDB or OSA is body habitus as measured by body mass index (BMI). In particular, nearly 60% to 90% of patients with OSA are obese.2 Weight gain seems to increase the OSA severity, whereas losing weight decreases it.14-16 Although the U.S. military employs height and weight standards that preclude those with persistently overweight or obese BMIs from continued service, these standards often are not rigid, and there are overweight or even obese active-duty members. Interestingly, despite a population that essentially controls for the most predictive risk factor, the prevalence of SDB is still approximately 1 in 20 (4.9%) in FY 2013.

Given the significant burden of disease represented by the incidence, prevalence, and cost data determined in this study and the growing recognition of long-term complications from poorly controlled SDB, it has become evident that more efficacious interventions are needed. Modern treatments for SDB can be classified as surgical or nonsurgical but with no single modality fitting the need for all patients secondary to poor adherence and/or limited efficacy.17-20 However, to mitigate the impact on military readiness and taxpayer-funded health care costs, it may be appropriate to begin exploring therapeutic options beyond the current standard of care. For example, an invasive and costly onetime surgical intervention using an implantable device to stimulate the hypoglossal nerve to open a person’s airway during inspiration is being investigated in a younger, nonobese cohort of patients.21 Further research is warranted into this specific model of therapeutic intervention and others for service members.

Limitations

Limitations in this study include possible reporting errors due to improper or insufficient medical coding as well as data entry errors at the clinic that may exist within medical billing databases. Therefore, the results of this analysis may be over- or underrepresented. The increase in incidence and prevalence may not necessarily reflect an increasing number of people who have the disease. The increase could be a result of better SDB detection practices or incentives to be diagnosed with SDB (VA disability claims upon retirement). The assumption is made that procedures corresponding with SDB diagnoses are directly related to SDB, and any costs incurred from those procedures are due to SDB.

It is important to note variability between services and institutions within the DoD in the diagnosis and treatment of SDB. Specifically, some institutions use ambulatory polysomnograms, or studies done at home, and autotitration of continuous positive airway pressure, whereas others require more costly hospital-based studies and laboratory titration. Another confounder in the cost data is the number of diagnoses and treatment deferred to the network as a result of the relatively small number of sleep-trained physicians within the military.

Conclusion

As the field of sleep medicine continues to develop its literature, it is becoming clearer that the detrimental sequelae of SDB are varied and pose significant short- and long-term risks. Active-duty service members represent a subset of the population with consequences that are potentially graver than those of civilians, especially when they are expected to operate complicated machinery or to make rapid and critical decisions in battle.

The prevalence and incidence of SDB increased each year during a 5-year review and currently affects 1 in 20 service members. Furthermore, the cost of civilian care for this disease process was nearly $100 million in FY 2012 to FY 2013, suggesting a growing financial burden for taxpayers. Further research is warranted to fully appreciate the impact of SDB on both service members and the U.S. military.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the U.S. Navy and specifically the support within the Department of Otolaryngology at the Naval Medical Center Portsmouth for the time and effort allotted for completion of this study. This research was supported in part by an appointment to the Postgraduate Research Participation Program at the Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Center (NMCPHC) administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and NMCPHC.

1. Peppard PE, Young T, Barnet JH, Palta M, Hagen EW, Hla KM. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177(9):1006-1014.

2. Young T, Peppard PE, Gottlieb DJ. Epidemiology of obstructive sleep apnea: a population health perspective. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(9):1217-1239.

3. Ram S, Seirawan H, Kumar SK, Clark GT. Prevalence and impact of sleep disorders and sleep habits in the United States. Sleep Breath. 2010;14(1):63-70.

4. Kim H, Dinges DF, Young T. Sleep-disordered breathing and psychomotor vigilance in a community-based sample. Sleep. 2007;30(10):1309-1316.

5. Yaffe K, Falvey CM, Hoang T. Connections between sleep and cognition in older adults. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(10):1017-1028.

6. Gilat H, Vinker S, Buda I, Soudry E, Shani M, Bachar G. Obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular comorbidities: a large epidemiologic study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93(9):e45.

7. Li X, Sundquist K, Sundquist J. Socioeconomic status and occupation as risk factors for obstructive sleep apnea in Sweden: a population-based study. Sleep Med. 2008;9(2):129-136.

8. Barger LK, Rajaratnam SM, Wang W, et al. Common sleep disorders increase risk of motor vehicle crashes and adverse health outcomes in firefighters. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11(3):233-240.

9. Mysliwiec V, Gill J, Lee H, et al. Sleep disorders in US military personnel: a high rate of comorbid insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2013;144(2):549-557.

10. Mysliwiec V, McGraw L, Pierce R, Smith P, Trapp B, Roth BJ. Sleep disorders and associated medical comorbidities in active duty military personnel. Sleep. 2013;36(2):167-174.

11. Capaldi VF 2nd, Guerrero ML, Killgore WD. Sleep disruptions among returning combat veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan. Mil Med. 2011;176(8):879-888.

12. Collen J, Orr N, Lettieri CJ, Carter K, Holley AB. Sleep disturbances among soldiers with combat-related traumatic brain injury. Chest. 2012;142(3):622-630.

13. Peterson AL, Goodie JL, Satterfield WA, Brim WL. Sleep disturbance during military deployment. Mil Med. 2008;173(3):230-235.

14. Dixon JB, Schachter LM, O’Brien PE. Polysomnography before and after weight loss in obese patients with severe sleep apnea. Int J Obes (Lond). 2005;29(9):1048-1054.

15. Loube DI, Loube AA, Erman MK. Continuous positive airway pressure treatment results in weight less in obese and overweight patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Am Diet Assoc. 1997;97(8):896-897.

16. Loube DI, Loube AA, Mitler MM. Weight loss for obstructive sleep apnea: the optimal therapy for obese patients. J Am Diet Assoc. 1994;94(11):1291-1295.

17. Malhotra A, Orr JE, Owens RL. On the cutting edge of obstructive sleep apnoea: where next? Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3(5):397-403.

18. Mysliwiec V, Capaldi VF, 2nd, Gill J, et al. Adherence to positive airway pressure therapy in U.S. military personnel with sleep apnea improves sleepiness, sleep quality, and depressive symptoms. Mil Med. 2015;180(4):475-482.

19. Salepci B, Caglayan B, Kiral N, et al. CPAP adherence of patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Respir Care. 2013;58(9):1467-1473.

20. Weaver TE, Grunstein RR. Adherence to continuous positive airway pressure therapy: the challenge to effective treatment. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(2):173-178.

21. Pietzsch JB, Liu S, Garner AM, Kezirian EJ, Strollo PJ. Long-term cost-effectiveness of upper airway stimulation for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: a model-based projection based on the STAR trial. Sleep. 2015;38(5):735-744.

Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) is a continuum of symptoms that range from primary snoring with upper airway resistance to frank obstruction seen in obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). This disease spectrum has been reported to affect 10% to 17% of men and 3% to 9% of women in the general population.1 The specific incidence of OSA has been estimated to be about 2% to 4% of the general adult population.2,3 Sleep-disordered breathing often leads to poor sleep quality, which has been associated with many medical comorbidities, including vascular disease, hypertension, major cardiac events, cardiomyopathies, impaired concentration, reduced psychomotor vigilance and cognition, and daytime somnolence.1,2,4-6 Furthermore, there is evidence that the prevalence of SDB continues to grow among the general population.1 However, the prevalence of SDB in various populations (eg, pediatric vs adult, varying body mass index, country of origin) varies widely due to the multifactorial nature of the risk factors and the difficulty in diagnosing SDB.

Some of the more intuitive medical sequelae of SDB are daytime somnolence and subsequent impaired concentration for those with disrupted sleep patterns. Medical literature has paid specific attention to cohorts of personnel who may be at heightened risk from impaired concentration or inability to focus. These populations include but are not limited to sleep-deprived resident physicians, firefighters, truck drivers, and heavy-machine operators.7,8

Military service members represent a distinct cohort that often is relied on to maintain vigilance even in austere environments. Concentration is paramount in order to perform combat operations or tasks that involve operating heavy machinery, such as nuclear submarines, aircraft, or tanks. Given the myriad of unique operational demands on service members, SDB can have detrimental consequences on an individual’s health and his or her military readiness and training. Ultimately, SDB may degrade a unit’s effectiveness and perhaps the country’s military capability.

Active-duty military service members seem to be more susceptible to clinically relevant sleep conditions. In the military, causes of disruptions in normal sleep patterns are multifactorial. Medical literature focuses on circadian disruptions due to shift work and frequent travel, frequent alternating use of caffeine and sedatives, exposure to combat/trauma, and chronic sleep deprivation.9-11 Studies have been published that focus on service members who have returned from combat deployment.10,12,13 However, these studies do not explore the overall burden of disease, and there are no specific data to suggest the prevalence, annual incidence, or associated costs.

To quantify this disease burden in the military, this study focused on the subset of sleep disorders that impact respiration during sleep and determined the prevalence and annual incidence for the entire active-duty population. Additionally, the authors fill a void in the literature by determining the financial burden of SDB on civilian care expenditures.

Methods

This study was a retrospective review of administrative military health care data spanning fiscal years (FYs) 2009 to 2013 (October 1, 2008 to September 30, 2013). The study protocol was approved by the Naval Medical Center Portsmouth Institutional Review Board, and approval was given to waive informed consent. The Health Analysis Department at the Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Center (NMCPHC) obtained and analyzed data from the Military Health System (MHS) Management Analysis and Reporting Tool (M2). The M2 system is an ad hoc query tool used for viewing population, clinical, and financial MHS data, including care received within military treatment facilities (MTFs) and care purchased through TRICARE at civilian facilities. Both inpatient and outpatient health care records were included.

The population included all active-duty service members and guard/reserve members on active duty within all military services, including air force, army, coast guard, and navy branches, between FY 2009 and FY 2013. The authors identified service members with SDB as those with at least 1 ICD-9 diagnosis code related to SDB: obstructive sleep apnea (327.23); sleep-related hypoventilation/hypoxemia (327.26); and other organic sleep disorder (327.80).

Due to the transient nature of the military population, a monthly average over the 5 years of the study determined the overall number of service members eligible for care (1,717,227 service members).

Data Analysis

Prevalence of diagnosed SDB per FY was calculated as the number of service members who received at least 1 SDB diagnostic code between October 1, 2008 and September 30, 2013, over the average total active-duty population. Incidence per year was calculated as the number of new cases per FY, using 2009 as the baseline. Data were stratified by demographic and enrollment information for diagnosed service members and analyzed using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC) software.

Direct costs associated with SDB treatment fall into 2 categories for service members: (1) care delivered by civilian providers, calculated based on the amount TRICARE paid for the service, using insurance claim data; and (2) care received at MTFs by military providers. Costs for care at MTFs cannot be calculated, as the total cost amount for a single record is not directly attributed to SDB diagnosis.

Results

A total of 197,183 service members were diagnosed with SDB from FY 2009 to FY 2013. Both the annual incidence and prevalence of SDB for the active-duty military population showed upward trends for each of the years evaluated (Figure 1).

Notably, 72% of service members seen for SDB ranged in age from 25 to 44 years (Table).

Discussion

This study shows that the prevalence and incidence of SDB in the active-duty population are less than those reported for the civilian populace as a whole but are still greater than expected for an otherwise healthy and young population. Furthermore, the burden of disease and the cost to diagnose and treat have steadily increased for each of the past 5 fiscal years that were assessed.

The data show an upward trend in the incidence and prevalence of SDB in the military from FY 2009 to FY 2013 for reasons that are not clear but likely with many confounding contributions. As the spectrum of SDB has become better defined and the detrimental sequelae are better understood, it is likely that both service members and health care providers are more aware of the symptoms and more importantly, the potential for interventions that improve quality of life. It is also important to note that the U.S. military is a very transient organization with a nearly constant turnover between new enlistees/officers and those leaving the service or retiring after 20 years of service. Thus, despite an annual incidence of nearly 3% throughout the years evaluated, the annual increase in prevalence is not necessarily commensurate.

The FY 2013 prevalence (4.2%) and civilian care costs ($98,259,519) present traditional indications of the disease burden. Both metrics represent a sizable and increasing disease burden for the military. It is also important to note that these costs reflect only the short-term expenses for initial diagnosis and therapy. These costs in no way reflect the care for the long-term medical sequelae that have been recently linked to uncontrolled SDB/OSA, such as heart and vascular diseases, hypertension, and increased stroke risk. Additional costs will continue to grow.

Perhaps the most validated predictive factor for diagnosis of SDB or OSA is body habitus as measured by body mass index (BMI). In particular, nearly 60% to 90% of patients with OSA are obese.2 Weight gain seems to increase the OSA severity, whereas losing weight decreases it.14-16 Although the U.S. military employs height and weight standards that preclude those with persistently overweight or obese BMIs from continued service, these standards often are not rigid, and there are overweight or even obese active-duty members. Interestingly, despite a population that essentially controls for the most predictive risk factor, the prevalence of SDB is still approximately 1 in 20 (4.9%) in FY 2013.

Given the significant burden of disease represented by the incidence, prevalence, and cost data determined in this study and the growing recognition of long-term complications from poorly controlled SDB, it has become evident that more efficacious interventions are needed. Modern treatments for SDB can be classified as surgical or nonsurgical but with no single modality fitting the need for all patients secondary to poor adherence and/or limited efficacy.17-20 However, to mitigate the impact on military readiness and taxpayer-funded health care costs, it may be appropriate to begin exploring therapeutic options beyond the current standard of care. For example, an invasive and costly onetime surgical intervention using an implantable device to stimulate the hypoglossal nerve to open a person’s airway during inspiration is being investigated in a younger, nonobese cohort of patients.21 Further research is warranted into this specific model of therapeutic intervention and others for service members.

Limitations