User login

Chemoradiation standard of care in muscle-invasive bladder cancer

Orlando – The updated results of a large phase III trial support the use of chemoradiation with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and mitomycin C (MMC) and confirm that this treatment regimen should be a standard of care for muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC).

When comparing patients who received radiation therapy with those who received chemoradiation, there was a robust improvement in bladder cancer specific survival for the latter when adjusted for known prognostic factors (hazard ratio, 0.73; P = .043).

There was also a borderline significant improvement in metastasis-free survival (HR, 0.78) and a significant reduction in the need for salvage cystectomy in the patients treated with chemoradiation (2-year rate, chemoradiotherapy11% vs. radiation therapy:17%, HR, 0.54; P = .03).

There were no statistically significant differences between groups when it came to overall survival, but, even though overall survival did not reach significance, at 2 years, there was a hint of separation of the curves, explained study author Emma Hall, MD, from the Institute of Cancer Research, London at the 2017 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Urologic Oncology.

One of the treatment arms received a reduced rate of radiation therapy to see if that would decrease toxicity. “The radiation therapy volume modification that we used did not reduce toxicity, but there is no evidence of an increase in local failure rate, suggesting it is safe to pursue clinical trials of volume sparing radiation therapy using newer technology adaptive delivery techniques,” said Dr. Hall.

The initial findings of the BC2001 study showed that adding chemotherapy (5-FU + MMC) to radiotherapy significantly improved rates of MIBC locoregional control but that reduced high-dose volume versus standard radiotherapy did not significantly reduce late side effects.

This study was a clinical trial set up to test two different questions in the treatment of MIBC, as an alternative to cystectomy. “We wanted to see if adding synchronous chemotherapy to radiotherapy would improve locoregional recurrence control and if reducing the radiation dose to uninvolved bladder would reduce toxicity and not impact local regional recurrence control,” according to Dr. Hall.

Under the 2 x 2 partial factorial design, 458 patients were randomized to radiation therapy (n = 178) or chemoradiation (n = 182) and/or to standard radiation therapy (n = 108) or reduced high-dose volume radiation therapy (n = 111).

The primary endpoint was locoregional control, and secondary endpoints included overall survival, bladder-cancer specific survival, metastasis-free survival, and salvage cystectomy rates.

The initial patients received radiation therapy instead of chemoradiation, and there was a robust improvement in bladder cancer–specific survival when adjusted for known prognostic factors (HR, 0.73; P = .043).

The analysis, presented in 2012, showed a reduction of about one-third of locoregional recurrence. The local control rates were 54% in the radiotherapy-alone arm and 67% in the chemoradiotherapy arm.

There was no significant difference in overall survival at that time.

For the radiotherapy comparison, the rate of late toxicity was low, and much lower than was anticipated, at the outset of the trial, and there was no difference in treatment groups, said Dr. Hall.

In an updated analysis, with a median of 10 years of follow-up, 70% of the patients were now deceased. “These represent robust data, and it is unlikely we will see any changes to the data,” she noted.

The findings presented now had an additional 4 years of follow-up, and while there were additional late events, the results were basically the same.

The rate of local control now showed a 40% reduction in the risk of recurrence and 5-year local control rates of 49% in the radiotherapy arm and 63% in the chemoradiotherapy arm.

“With 10 years follow up, an improvement in locoregional control and a reduced salvage cystectomy rate is confirmed with chemoradiotherapy,” Dr. Hall concluded, “and, taken together with the good quality of life data we have, this is important for this group.”

In a discussion of the paper, Dr. Jonathan Rosenberg, MD, from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, agrees with the conclusion that the data continue to support the use of chemoradiotherapy and that 5-FU + MMC is a good option.

He noted that 5-FU + MMC is a standard of care regardless of cisplatin eligibility, but he cannot draw conclusions on dose volume. “There are also other options for chemosensitization,” he said, but it is also import to determine the best way to select patients who will derive the most benefit from chemoradiation.

“There is a high need for robust predictive biomarkers, and we need novel approaches to move beyond chemotherapy,” he said.

The study was supported by Cancer Research UK. Dr Hall has received research funding from Accuray, AstraZeneca, Aventis, and Bayer. Several co-authors also have disclosed relationships with industry. Dr. Rosenberg has disclosed multiple relationships with industry.

Orlando – The updated results of a large phase III trial support the use of chemoradiation with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and mitomycin C (MMC) and confirm that this treatment regimen should be a standard of care for muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC).

When comparing patients who received radiation therapy with those who received chemoradiation, there was a robust improvement in bladder cancer specific survival for the latter when adjusted for known prognostic factors (hazard ratio, 0.73; P = .043).

There was also a borderline significant improvement in metastasis-free survival (HR, 0.78) and a significant reduction in the need for salvage cystectomy in the patients treated with chemoradiation (2-year rate, chemoradiotherapy11% vs. radiation therapy:17%, HR, 0.54; P = .03).

There were no statistically significant differences between groups when it came to overall survival, but, even though overall survival did not reach significance, at 2 years, there was a hint of separation of the curves, explained study author Emma Hall, MD, from the Institute of Cancer Research, London at the 2017 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Urologic Oncology.

One of the treatment arms received a reduced rate of radiation therapy to see if that would decrease toxicity. “The radiation therapy volume modification that we used did not reduce toxicity, but there is no evidence of an increase in local failure rate, suggesting it is safe to pursue clinical trials of volume sparing radiation therapy using newer technology adaptive delivery techniques,” said Dr. Hall.

The initial findings of the BC2001 study showed that adding chemotherapy (5-FU + MMC) to radiotherapy significantly improved rates of MIBC locoregional control but that reduced high-dose volume versus standard radiotherapy did not significantly reduce late side effects.

This study was a clinical trial set up to test two different questions in the treatment of MIBC, as an alternative to cystectomy. “We wanted to see if adding synchronous chemotherapy to radiotherapy would improve locoregional recurrence control and if reducing the radiation dose to uninvolved bladder would reduce toxicity and not impact local regional recurrence control,” according to Dr. Hall.

Under the 2 x 2 partial factorial design, 458 patients were randomized to radiation therapy (n = 178) or chemoradiation (n = 182) and/or to standard radiation therapy (n = 108) or reduced high-dose volume radiation therapy (n = 111).

The primary endpoint was locoregional control, and secondary endpoints included overall survival, bladder-cancer specific survival, metastasis-free survival, and salvage cystectomy rates.

The initial patients received radiation therapy instead of chemoradiation, and there was a robust improvement in bladder cancer–specific survival when adjusted for known prognostic factors (HR, 0.73; P = .043).

The analysis, presented in 2012, showed a reduction of about one-third of locoregional recurrence. The local control rates were 54% in the radiotherapy-alone arm and 67% in the chemoradiotherapy arm.

There was no significant difference in overall survival at that time.

For the radiotherapy comparison, the rate of late toxicity was low, and much lower than was anticipated, at the outset of the trial, and there was no difference in treatment groups, said Dr. Hall.

In an updated analysis, with a median of 10 years of follow-up, 70% of the patients were now deceased. “These represent robust data, and it is unlikely we will see any changes to the data,” she noted.

The findings presented now had an additional 4 years of follow-up, and while there were additional late events, the results were basically the same.

The rate of local control now showed a 40% reduction in the risk of recurrence and 5-year local control rates of 49% in the radiotherapy arm and 63% in the chemoradiotherapy arm.

“With 10 years follow up, an improvement in locoregional control and a reduced salvage cystectomy rate is confirmed with chemoradiotherapy,” Dr. Hall concluded, “and, taken together with the good quality of life data we have, this is important for this group.”

In a discussion of the paper, Dr. Jonathan Rosenberg, MD, from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, agrees with the conclusion that the data continue to support the use of chemoradiotherapy and that 5-FU + MMC is a good option.

He noted that 5-FU + MMC is a standard of care regardless of cisplatin eligibility, but he cannot draw conclusions on dose volume. “There are also other options for chemosensitization,” he said, but it is also import to determine the best way to select patients who will derive the most benefit from chemoradiation.

“There is a high need for robust predictive biomarkers, and we need novel approaches to move beyond chemotherapy,” he said.

The study was supported by Cancer Research UK. Dr Hall has received research funding from Accuray, AstraZeneca, Aventis, and Bayer. Several co-authors also have disclosed relationships with industry. Dr. Rosenberg has disclosed multiple relationships with industry.

Orlando – The updated results of a large phase III trial support the use of chemoradiation with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and mitomycin C (MMC) and confirm that this treatment regimen should be a standard of care for muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC).

When comparing patients who received radiation therapy with those who received chemoradiation, there was a robust improvement in bladder cancer specific survival for the latter when adjusted for known prognostic factors (hazard ratio, 0.73; P = .043).

There was also a borderline significant improvement in metastasis-free survival (HR, 0.78) and a significant reduction in the need for salvage cystectomy in the patients treated with chemoradiation (2-year rate, chemoradiotherapy11% vs. radiation therapy:17%, HR, 0.54; P = .03).

There were no statistically significant differences between groups when it came to overall survival, but, even though overall survival did not reach significance, at 2 years, there was a hint of separation of the curves, explained study author Emma Hall, MD, from the Institute of Cancer Research, London at the 2017 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Urologic Oncology.

One of the treatment arms received a reduced rate of radiation therapy to see if that would decrease toxicity. “The radiation therapy volume modification that we used did not reduce toxicity, but there is no evidence of an increase in local failure rate, suggesting it is safe to pursue clinical trials of volume sparing radiation therapy using newer technology adaptive delivery techniques,” said Dr. Hall.

The initial findings of the BC2001 study showed that adding chemotherapy (5-FU + MMC) to radiotherapy significantly improved rates of MIBC locoregional control but that reduced high-dose volume versus standard radiotherapy did not significantly reduce late side effects.

This study was a clinical trial set up to test two different questions in the treatment of MIBC, as an alternative to cystectomy. “We wanted to see if adding synchronous chemotherapy to radiotherapy would improve locoregional recurrence control and if reducing the radiation dose to uninvolved bladder would reduce toxicity and not impact local regional recurrence control,” according to Dr. Hall.

Under the 2 x 2 partial factorial design, 458 patients were randomized to radiation therapy (n = 178) or chemoradiation (n = 182) and/or to standard radiation therapy (n = 108) or reduced high-dose volume radiation therapy (n = 111).

The primary endpoint was locoregional control, and secondary endpoints included overall survival, bladder-cancer specific survival, metastasis-free survival, and salvage cystectomy rates.

The initial patients received radiation therapy instead of chemoradiation, and there was a robust improvement in bladder cancer–specific survival when adjusted for known prognostic factors (HR, 0.73; P = .043).

The analysis, presented in 2012, showed a reduction of about one-third of locoregional recurrence. The local control rates were 54% in the radiotherapy-alone arm and 67% in the chemoradiotherapy arm.

There was no significant difference in overall survival at that time.

For the radiotherapy comparison, the rate of late toxicity was low, and much lower than was anticipated, at the outset of the trial, and there was no difference in treatment groups, said Dr. Hall.

In an updated analysis, with a median of 10 years of follow-up, 70% of the patients were now deceased. “These represent robust data, and it is unlikely we will see any changes to the data,” she noted.

The findings presented now had an additional 4 years of follow-up, and while there were additional late events, the results were basically the same.

The rate of local control now showed a 40% reduction in the risk of recurrence and 5-year local control rates of 49% in the radiotherapy arm and 63% in the chemoradiotherapy arm.

“With 10 years follow up, an improvement in locoregional control and a reduced salvage cystectomy rate is confirmed with chemoradiotherapy,” Dr. Hall concluded, “and, taken together with the good quality of life data we have, this is important for this group.”

In a discussion of the paper, Dr. Jonathan Rosenberg, MD, from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, agrees with the conclusion that the data continue to support the use of chemoradiotherapy and that 5-FU + MMC is a good option.

He noted that 5-FU + MMC is a standard of care regardless of cisplatin eligibility, but he cannot draw conclusions on dose volume. “There are also other options for chemosensitization,” he said, but it is also import to determine the best way to select patients who will derive the most benefit from chemoradiation.

“There is a high need for robust predictive biomarkers, and we need novel approaches to move beyond chemotherapy,” he said.

The study was supported by Cancer Research UK. Dr Hall has received research funding from Accuray, AstraZeneca, Aventis, and Bayer. Several co-authors also have disclosed relationships with industry. Dr. Rosenberg has disclosed multiple relationships with industry.

AT THE GENITOURINARY CANCERS SYMPOSIUM

Key clinical point: Chemoradiation with 5-FU + MMC should be a standard of care in muscle-invasive bladder cancer.

Major finding: When comparing radiation therapy versus chemoradiation, there was a robust improvement in bladder cancer specific survival when adjusted for known prognostic factors (HR, 0.73; P = .043).

Data source: A long-term phase III randomized trial that included 458 patients with MIBC.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Cancer Research UK. Dr. Hall has received research funding from Accuray, AstraZeneca, Aventis , and Bayer. Several coauthors also have disclosed relationships with industry. Dr. Rosenberg has disclosed multiple relationships with industry.

Hyperkalemia in Adults: Review of a Common Electrolyte Imbalance

CE/CME No: CR-1703

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Describe the pathophysiology and causes of hyperkalemia.

• Identify patients who are susceptible to hyperkalemia.

• Recognize the clinical sequelae of hyperkalemia.

• Formulate assessment and treatment plans for patients with hyperkalemia.

FACULTY

Melanie Douglas is a Physician Assistant in the Medicine Department at NYU Langone Medical Center in New York, New York. Denise Rizzolo is a Clinical Assistant Professor in the PA Program at Pace University in New York, New York, and Research Director in the Program of PA Studies at Kean University in Union, New Jersey. Danielle Kruger is an Academic Coordinator and Associate Professor in the PA Program at St. John’s University in Queens, New York. The authors have no financial relationships to disclose.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid for one year from the issue date of March 2017.

Article begins on next page >>

Hyperkalemia is a common electrolyte disorder associated with life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias. Prompt recognition and appropriate treatment are essential in preventing serious cardiac complications. Although clinical manifestations of hyperkalemia are usually nonspecific or absent, laboratory testing and electrocardiography performed by the astute clinician aware of predisposing risk factors can help direct management.

Potassium is contained mostly in intracellular fluid; only about 2% is found in the extracellular space.1 The average total body potassium is about 50 mEq per kg of body weight (eg, a 70-kg individual has a total body potassium of approximately 3,500 mEq).2 Levels are tightly regulated by alterations in excretion in the distal renal tubule in response to potassium load and balance, and potassium distribution is influenced by insulin, aldosterone, catecholamines, and acid-base status.2 Movement of potassium across cell membranes is driven by the sodium-potassium adenosine triphosphatase (Na-K-ATPase) pump.3 In this article, we use the common serum potassium reference range of 3.5 to 5.0 mEq/L and define hyperkalemia as a serum potassium concentration greater than 5.5 mEq/L.4

Hyperkalemia can lead to life-threatening complications of cardiac arrhythmias, asystole, hypotension, flaccid paralysis, tetany, dyspnea, and altered mental status.5 Among patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), hyperkalemia is thought to contribute to 2% to 5% of deaths.6 A retrospective study found that patients with serum potassium levels exceeding 6.0 mEq/L on ICU admission had a significantly higher death rate within 30 days than patients who were normokalemic on presentation.7

RISK FACTORS

It is estimated that more than 35% of patients age 70 and older have chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 3 or higher.8 Hyperkalemia is closely associated with CKD, increasing linearly in relation to the degree of renal impairment.8 As such, the prevalence of hyperkalemia in older adults is high, and it will increase overall as the US population ages. In a retrospective analysis of veterans older than 65 with CKD stage 3 or higher, the prevalence of hyperkalemia was 2.5%.9 Use of certain medications is also associated with hyperkalemia. Another retrospective study analyzed records obtained from 70,873 patients with CKD (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) hospitalized in the Veterans Health Administration system. It found that patients treated with renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) blockers, such as ACE inhibitors (ACEis) or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs), had a higher incidence of hyperkalemia (potassium level ≥ 5.5 mEq/L) than patients not treated with these medications (8.22 vs 1.77 events per 100 patient-months).9,10

POTASSIUM HOMEOSTASIS

Tight control over extracellular potassium is maintained in part by the Na-K-ATPase pump, which uses adenosine triphosphatase to move potassium and sodium ions in opposite directions across cell membranes.3 Specifically, three sodium ions are pumped out of the cell for every two potassium ions pumped in, resulting in a potassium gradient that is partially responsible for maintaining a resting membrane potential. This resting membrane potential, which determines myocardial, skeletal muscle, and nerve cell excitability and signaling, is highly sensitive to changes in the extracellular potassium level.4 Even small extracellular imbalances can induce cell depolarization and evoke an action potential. Increased extracellular potassium concentration decreases the resting membrane potential of the myocardium, shortens repolarization time, and decreases the rate of myocardial cell conduction, and also slows down neuromuscular conduction.11,12

Renal tubular function plays a significant role in potassium homeostasis, with approximately 90% of dietary potassium intake ex

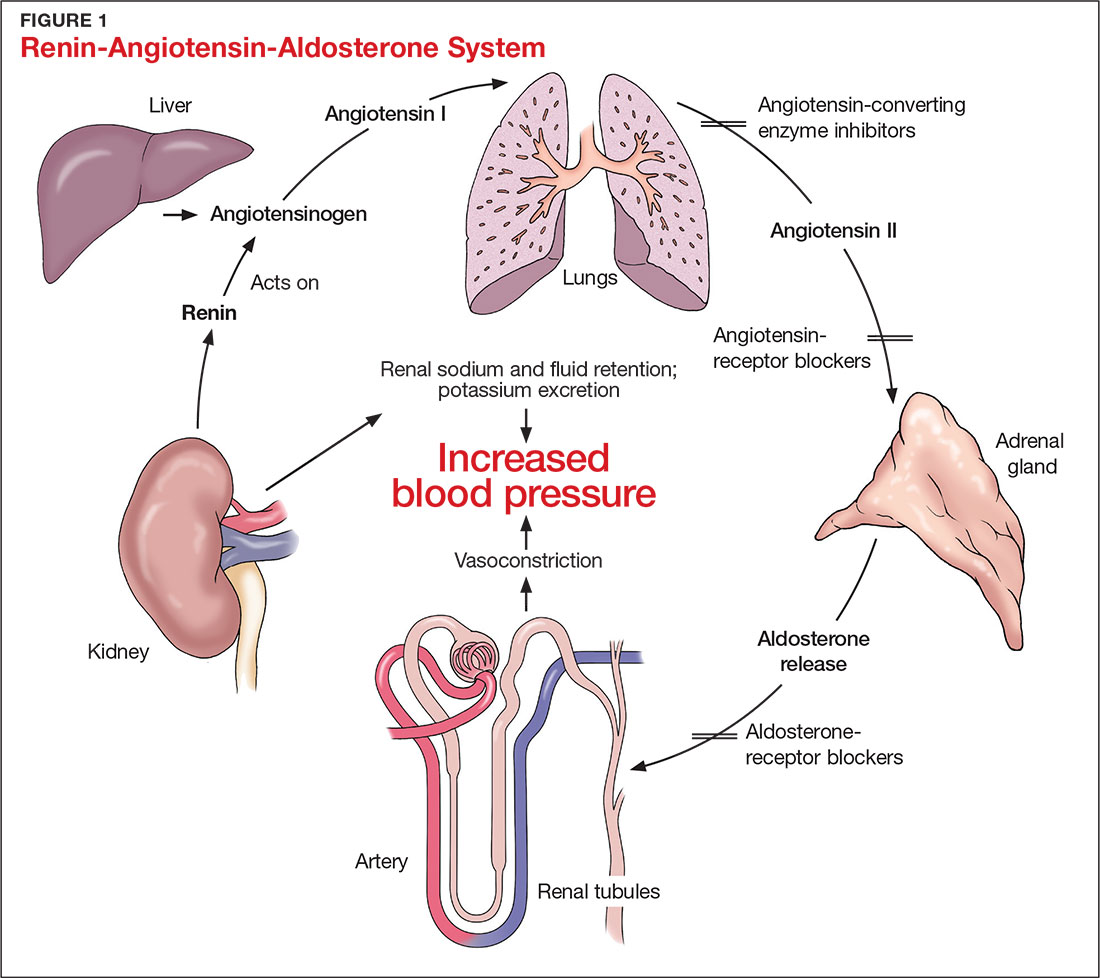

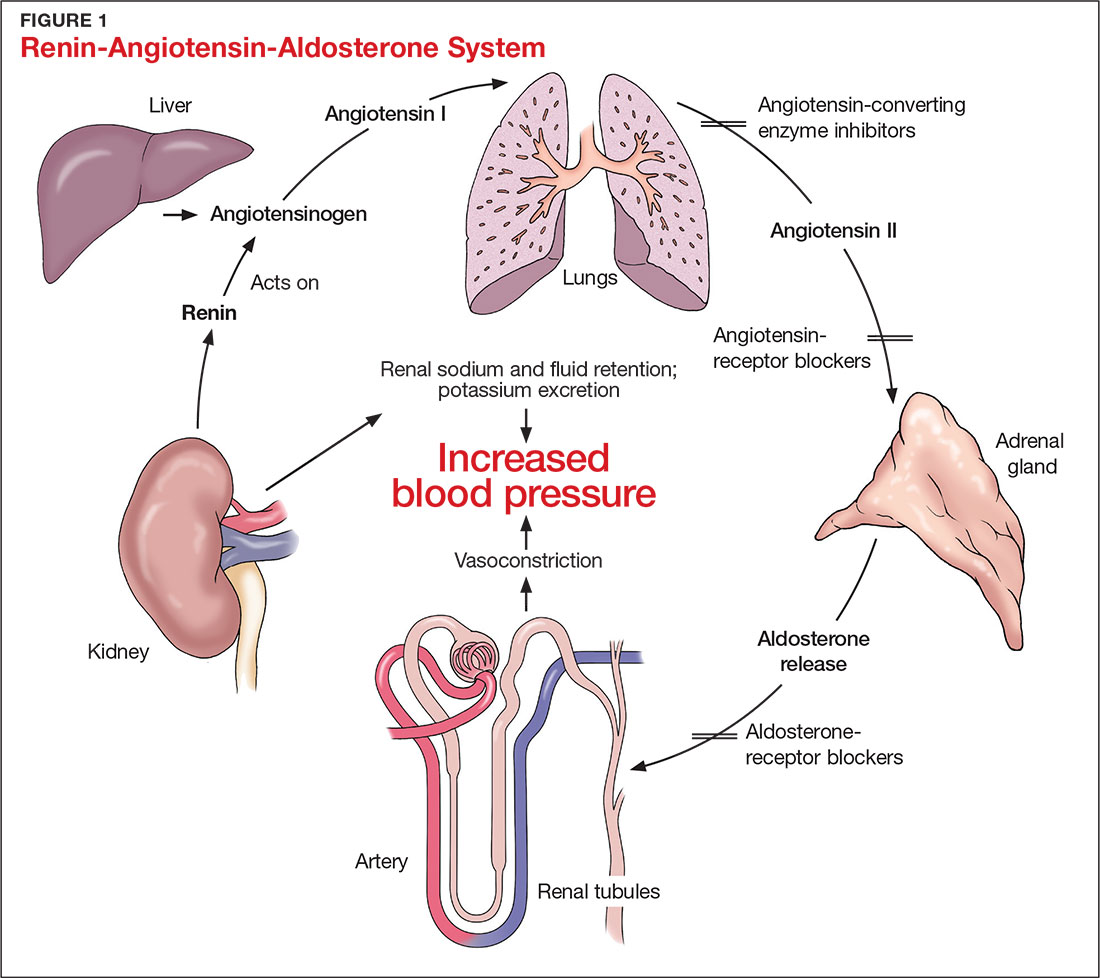

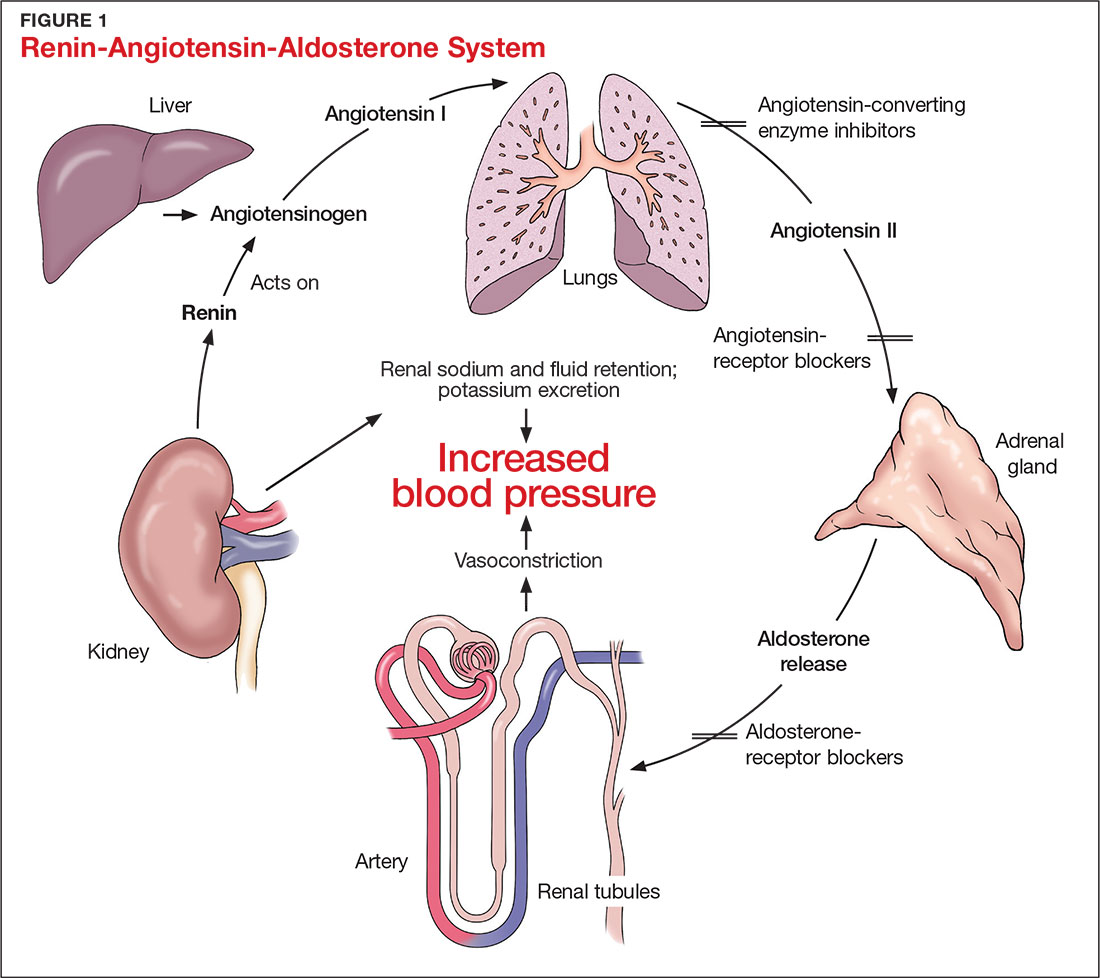

The RAAS is a signal transduction pathway that regulates potassium excretion by the kidneys. Renin is secreted by the kidney in response to low renal perfusion, catecholamines, ß-adrenergic stimulation, potassium and sodium levels, and other factors. Secretion of renin triggers a signaling cascade that eventually results in the release of aldosterone from the adrenal cortex.5 Aldosterone binds to a receptor in the kidney’s collecting ducts where it increases potassium excretion by stimulating sodium reabsorption and fluid retention (see Figure 1).5

CAUSES OF HYPERKALEMIA

The pathophysiology of hyperkalemia generally involves either decreased renal excretion or shifts in extracellular potassium. Causes of hyperkalemia are listed in the Table. Potassium excretion can be disrupted in acute kidney injury (AKI), sepsis, cardiac ischemia, heart failure, diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), insulin deficiency, tumor lysis syndrome (TLS), sickle cell disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, renal transplant, hepatorenal syndrome, adrenal insufficiency, and obstructive uropathy.15 In addition, certain medications can impair potassium excretion (eg, RAAS blockers, potassium-sparing diuretics in patients with CKD, digoxin toxicity).16 The following sections highlight the pathophysiology and manifestations of more common causes of hyperkalemia.

Renal impairment

Hyperkalemia may be a manifestation of worsening renal function. Potassium excretion is reduced in CKD, and CKD is the most common cause of hyperkalemia due to lower GFR.8,17 Patients with lower GFR tend to be older and male, and frequently have comorbid conditions such as type 2 diabetes, chronic liver disease, and heart failure.17

In CKD, decreased delivery of sodium to the distal tubules and reduced filtration capacity of the kidney diminishes the collecting duct’s ability to excrete potassium in exchange for sodium.2 Metabolic acidosis, which often contributes to AKI or CKD, causes potassium to shift from the intracellular to the extracellular compartment.4 Renal impairment may present clinically with dehydration, oliguria, nausea, vomiting, constipation, altered mental status, or weakness.

Hyperglycemia

Insulin and catecholamines (eg, epinephrine and norepinephrine) drive potassium into cells. Insulin increases potassium uptake into liver and muscle cells.13 A decrease in insulin levels, as may occur in type 2 diabetes or DKA, can cause a buildup of extracellular potassium.4 Also, serum hypertonicity from hyperglycemia results in water movement from the intracellular to the extracellular compartment; this raises the intracellular concentration of potassium, further promoting its movement to the extracellular space.4,14 Patients with hyperglycemia may present with dizziness, polyuria, polydipsia, nausea, vomiting, altered mental status, or fatigue.

Rhabdomyolysis

Rhabdomyolysis is a rapid breakdown of skeletal muscle that results in leakage of cellular contents into the extracellular space.4,18 Causes of rhabdomyolysis include use of medications such as statins, illicit drugs (eg, cocaine), or alcohol; rigorous exercise; and trauma.19

Muscle cell contents that are released into the circulation include potassium and other electrolytes, enzymes (eg, lactate dehydrogenase, aspartate transaminase, aldolase), and myoglobin.19 In rhabdomyolysis, myoglobin accumulation and hypovolemia lead to AKI and hyperkalemia.19 Patients may present with myalgias, extremity paresthesias, generalized weakness, nausea, altered mental status, fever, or darkened urine.18,19

Adrenal insufficiency

During critical illness such as sepsis, adrenal insufficiency can result from destruction of the adrenal glands, leading to hypoaldosteronism.20 Reduced aldosterone in adrenal insufficiency enables sodium and water to be eliminated from the body more easily, but as a result, less potassium gets excreted through the renal system and more is driven into the plasma.15

Acute adrenal insufficiency may manifest with hypotension, nausea, vomiting, or altered mental status, and labwork may reveal hyperkalemia as well as hypoglycemia or hyponatremia. Additionally, long-term glucocorticoid therapy can suppress the hypothalamic-pituitary axis and cause adrenal atrophy; rapid discontinuation of steroids can lead to adrenal insufficiency and hyperkalemia.21

Medications

RAAS blockers reduce CKD progression in patients with an eGFR of 29 mL/min/1.73 m2 or greater.22 Nonetheless, prescribing two or more drugs from the ACEi or ARB classes is not recommended. The Veterans Administration Nephron-Diabetes Trial (VA-NEPHRON-D) was terminated early because patients with stage 3 CKD due to diabetes who received dual ACEi/ARB therapy had higher rates of hyperkalemia but no slowing of CKD.22

Within the RAAS cascade, ACEis block the formation of angiotensin II and ARBs prevent angiotensin II from binding to the adrenal receptor. This impairs renal excretion of potassium and potentially contributes to hyperkalemia.5 Nonetheless, when patients on ACEis or ARBs develop hyperkalemia, aldosterone concentrations usually decrease due to preexisting illnesses (eg, diabetes, heart failure, CKD, AKI) or drug effects (eg, potassium-sparing diuretics, ß-blockers, digoxin).5 Ultimately, a combination of factors resulting from ACEi or ARB therapy causes reductions in renal perfusion and predisposes patients to hyperkalemia.5

NSAIDs may lead to hyperkalemia, as they interfere with prostaglandin release, decrease renal perfusion, and reduce renin and aldosterone levels.22 ß-blockers and tacrolimus inhibit renin release, leading to decreased aldosterone levels.5 Potassium-sparing diuretics block the interaction of aldosterone with the aldosterone receptor in the nephron.5 Digoxin decreases the activity of Na-K-ATPase, diminishing potassium uptake by cells.9 Potassium supplements, often prescribed for patients on diuretics, may contribute to hyperkalemia in patients with CKD. In the hospital setting, potassium tablets or IV formulations are utilized to correct hypokalemia. Especially in patients with CKD, clinicians should prescribe these agents with caution to avoid inducing hyperkalemia. Salt substitutes, which commonly contain potassium chloride, may be appealing to patients concerned about their sodium intake. However, consumption of these substitutes may contribute to hyperkalemia, especially in patients with CKD, heart failure, or type 2 diabetes.23

Tumor lysis syndrome

TLS involves rapid release of electrolytes and other intracellular contents into the extracellular space during the lysis of tumor cells.24 Nucleic acids within DNA strands break down and build up extracellularly, leading to hyperuricemia and often AKI. Potassium and other electrolytes released into the plasma during cell lysis can usually be removed by a healthy renal system. In TLS, however, AKI due to uric acid nephropathy prevents kidneys from removing the excess electrolytes from the bloodstream.24 Patients with rapidly growing hematologic tumors undergoing chemotherapy are especially at risk.

Pseudohyperkalemia

Pseudohyperkalemia is a transiently elevated serum potassium level that erroneously represents the true serum potassium level. It results from hemolysis due to mechanical trauma during the blood draw (eg, a tourniquet tied too tightly or use of a small-bore needle) or during specimen handling afterwards.25 Furthermore, leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, and polycythemia make red blood cells more fragile, increasing the chance of hemolysis and potassium leakage.26 Blood transfusion also can lead to pseudohyperkalemia. When blood is stored, potassium leakage from the cells and cell lysis, along with diminished Na-K-ATPase activity, lead to a buildup of potassium in the medium surrounding the stored red blood cells.27,28 The rise in serum potassium levels post-transfusion is usually transient, as the blood cells redistribute the potassium load once they become metabolically active.27,29

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Clinical manifestations of mild to moderate hyperkalemia (serum potassium > 5.5 mEq/L but < 6.5 mEq/L) include fatigue, generalized weakness, nausea, vomiting, constipation, and diarrhea.15 In many patients, mild to moderate hyperkalemia may not be associated with any acute symptoms and vital signs may be normal.13 Severe hyperkalemia (serum potassium > 6.5 mEq/L) may present clinically with acute extremity paresthesias, muscle weakness and paralysis, heart palpitations, dyspnea, altered mental status, cardiac arrhythmias, and cardiac arrest.30,31 Irregular heart rhythm, decreased deep tendon reflexes, or decreased strength may be revealed on physical exam.3 Individuals with ESRD on hemodialysis seem to tolerate higher levels of potassium than the general population without displaying clinical symptoms. However, these individuals are still susceptible to the cardiac effects of hyperkalemia.32

INITIAL ASSESSMENT

In assessing hyperkalemia, the clinician must perform a focused history and physical exam and review the patient’s medication list, including supplements and dietary habits that impact potassium intake. Potassium-rich foods include meat, fish, milk, almonds, spinach, cantaloupe, bananas, oranges, mushrooms, and potatoes.33 Hyperkalemia may present in association with various medical emergencies. The clinician should have an index of suspicion, depending on the patient’s overall medical profile and presentation, for emergencies such as cardiac ischemia, sepsis, adrenal crisis, DKA, TLS, and digoxin overdose.

The clinician must identify whether an elevated potassium level requires emergent therapy; assessment of vital signs is paramount in determining this. Orthostatic hypotension and tachycardia may hint that the patient is volume depleted. The patient should be examined for signs of hemodynamic shock with the CAB sequence: circulation, airway, breathing.34 Symptoms such as chest pain, shortness of breath, muscle weakness, paralysis, and altered mental status suggest that an expedited evaluation is warranted.

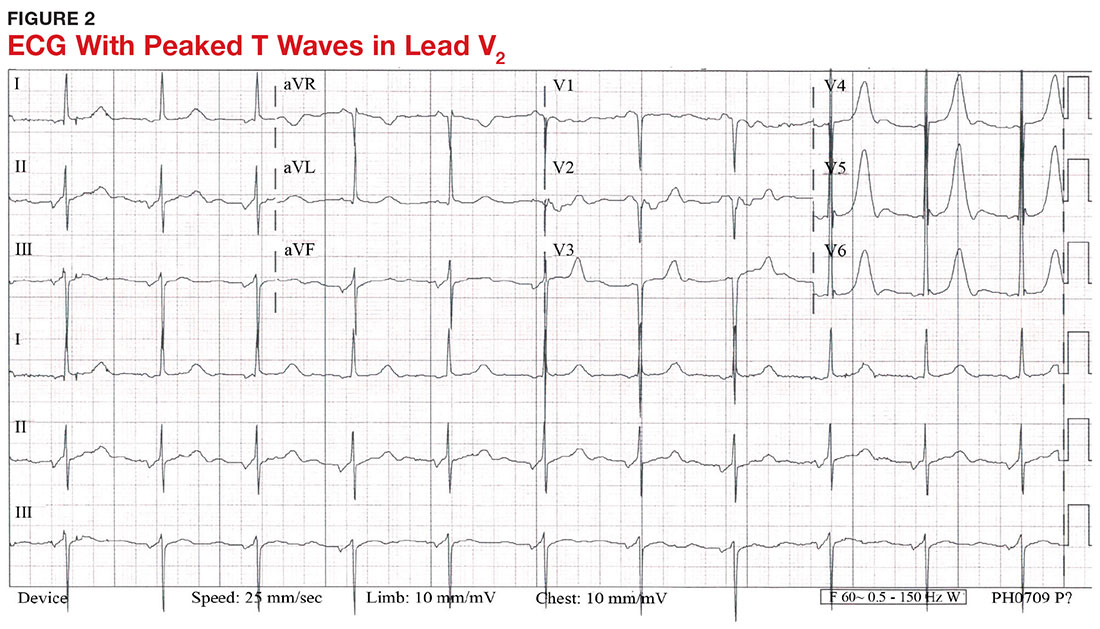

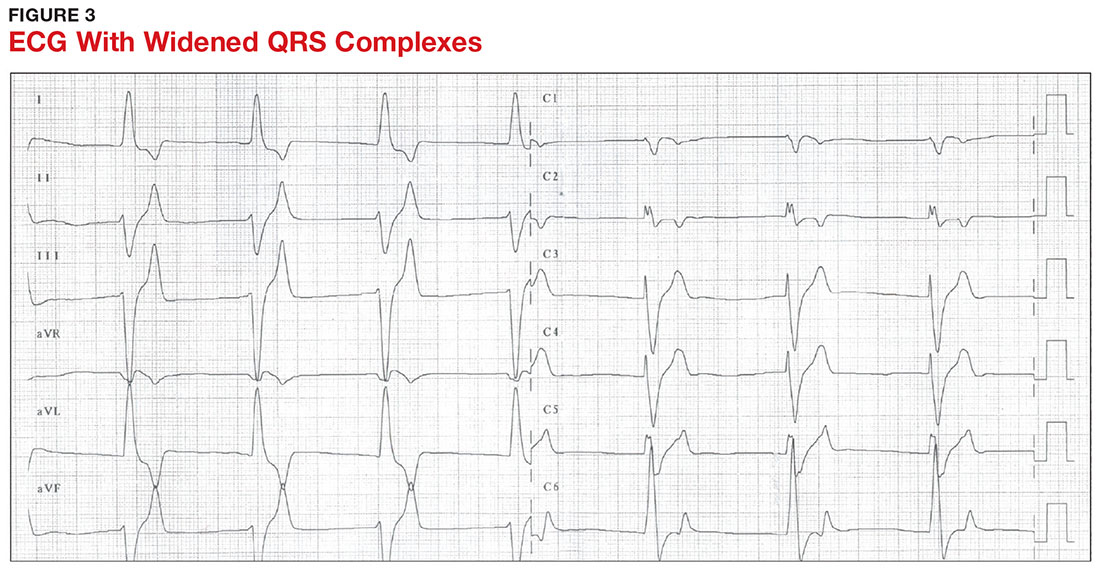

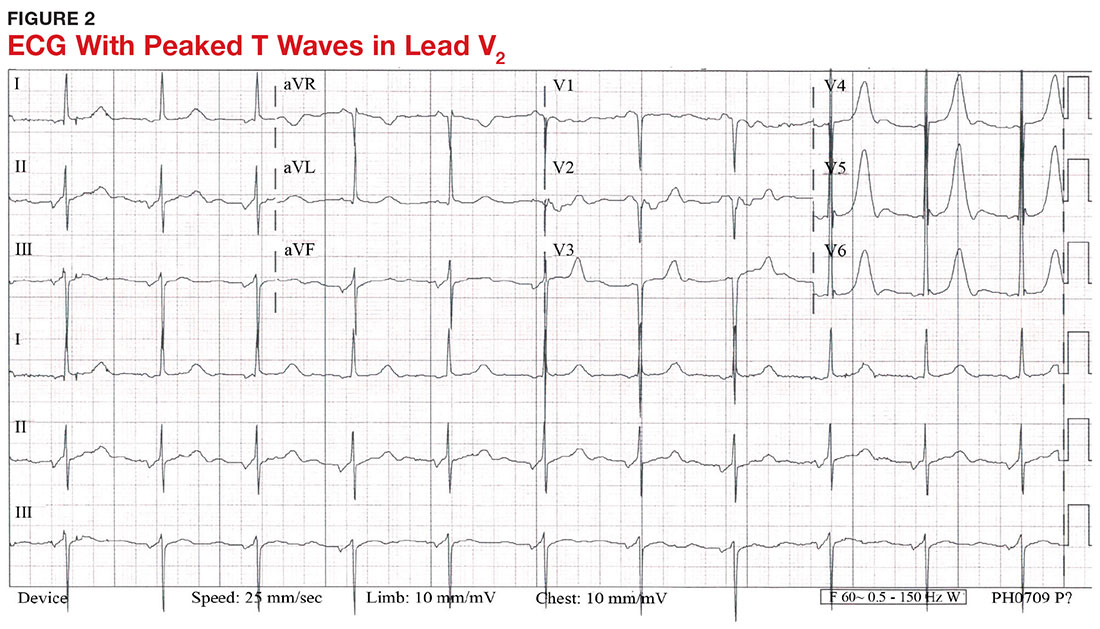

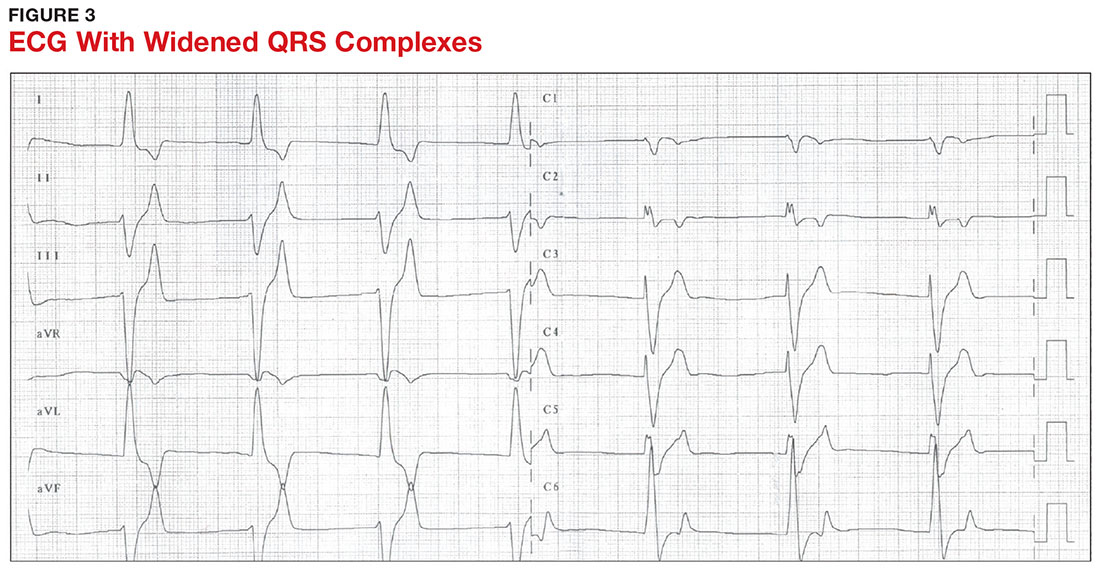

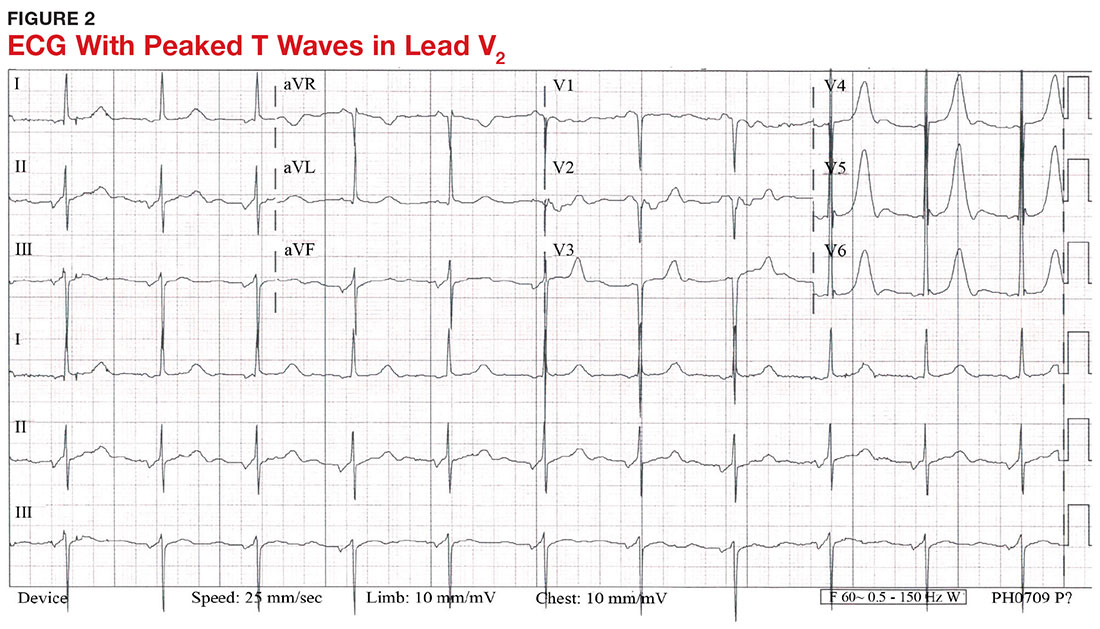

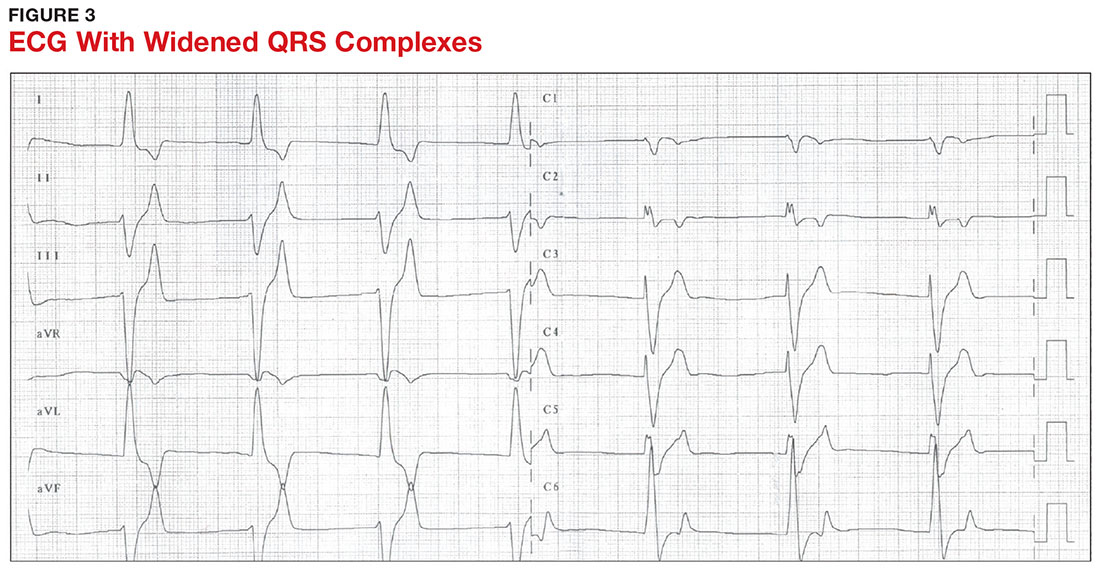

With a serum potassium level > 5.5 mEq/L, urgent electrocardiography should be performed.26 ECG findings observed with serum potassium levels of 5.5-6.5 mEq/L usually include peaked T-waves and prolonged PR intervals (see Figure 2). With potassium levels > 6.5 mEq/L consistent with further cardiac destabilization, the P-wave flattens then disappears, the QRS complex broadens, and sinus bradycardia or ectopic beats may occur.12,26 ST depression, T-wave inversion, or ST elevation also may be seen.12 With serum potassium levels > 7.5 mEq/L, progressive widening of the QRS complex to a sine-wave with bundle branch blocks or fascicular blocks may occur (see Figure 3).26 Without prompt intervention, ventricular fibrillation may ensue.26

An extensive laboratory workup may be necessary to investigate the etiology; this includes a complete blood count, metabolic panel, liver function tests, cardiac enzymes, blood gas analysis, serum/urine osmolality, urinalysis, urine electrolytes, and toxicology screen.13,26 Arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis may show metabolic acidosis with AKI or DKA, or an elevated lactate may occur with sepsis. In patients with hyperglycemia, besides checking for acidosis, obtaining blood/urine ketone levels and a metabolic panel with anion gap to evaluate for DKA is useful.35

When assessing a patient with an elevated creatinine, the GFR at the time of evaluation should be compared with the patient’s baseline GFR to determine chronicity and duration of his/her kidney disease.36 Obtaining a urinalysis and urine electrolytes in addition to the basic metabolic panel can help narrow the etiology.36 A Foley catheter should be placed in cases of urinary retention because without intervention, urinary obstruction may lead to AKI and hyperkalemia. Myoglobinuria on urinalysis and an elevated creatine kinase are diagnostic markers of rhabdomyolysis.18

TLS should be considered in patients who recently received chemotherapy, especially those with proliferative hematologic malignancies, such as acute lymphoblastic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, and Burkitt lymphoma.24 In TLS, bloodwork often reveals hyperkalemia along with AKI, an elevated uric acid level, hyperphosphatemia, and hypocalcemia.24

Patients presenting with hyperkalemia, hypotension, hypoglycemia, and hyponatremia may have adrenal insufficiency.20 If insufficiency is suspected, a cortisol level may be checked during morning hours; a low level is often suggestive of this diagnosis.37 Treatment includes daily doses of steroids, and consultation with an endocrinologist is recommended.37

If an elevated potassium level is not accompanied by renal dysfunction, electrolyte imbalances, ECG changes, or inciting medications, pseudohyperkalemia should be considered.38 A repeat lab sample should be checked. Consider obtaining an ABG analysis, as the shorter time interval between drawing the blood sample and the sample analysis reportedly increases the reliability of the resulting potassium level.38

THERAPY

Emergent

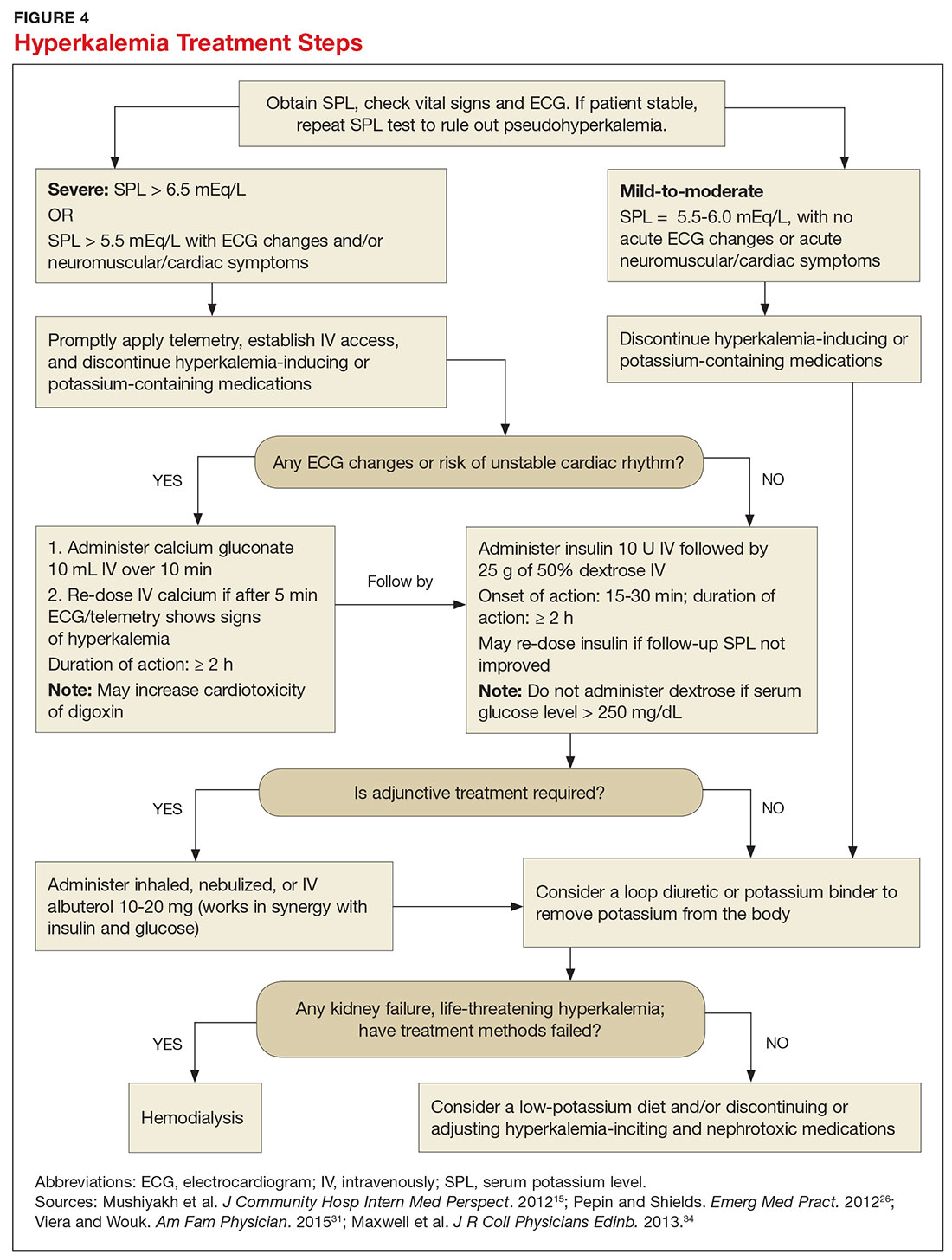

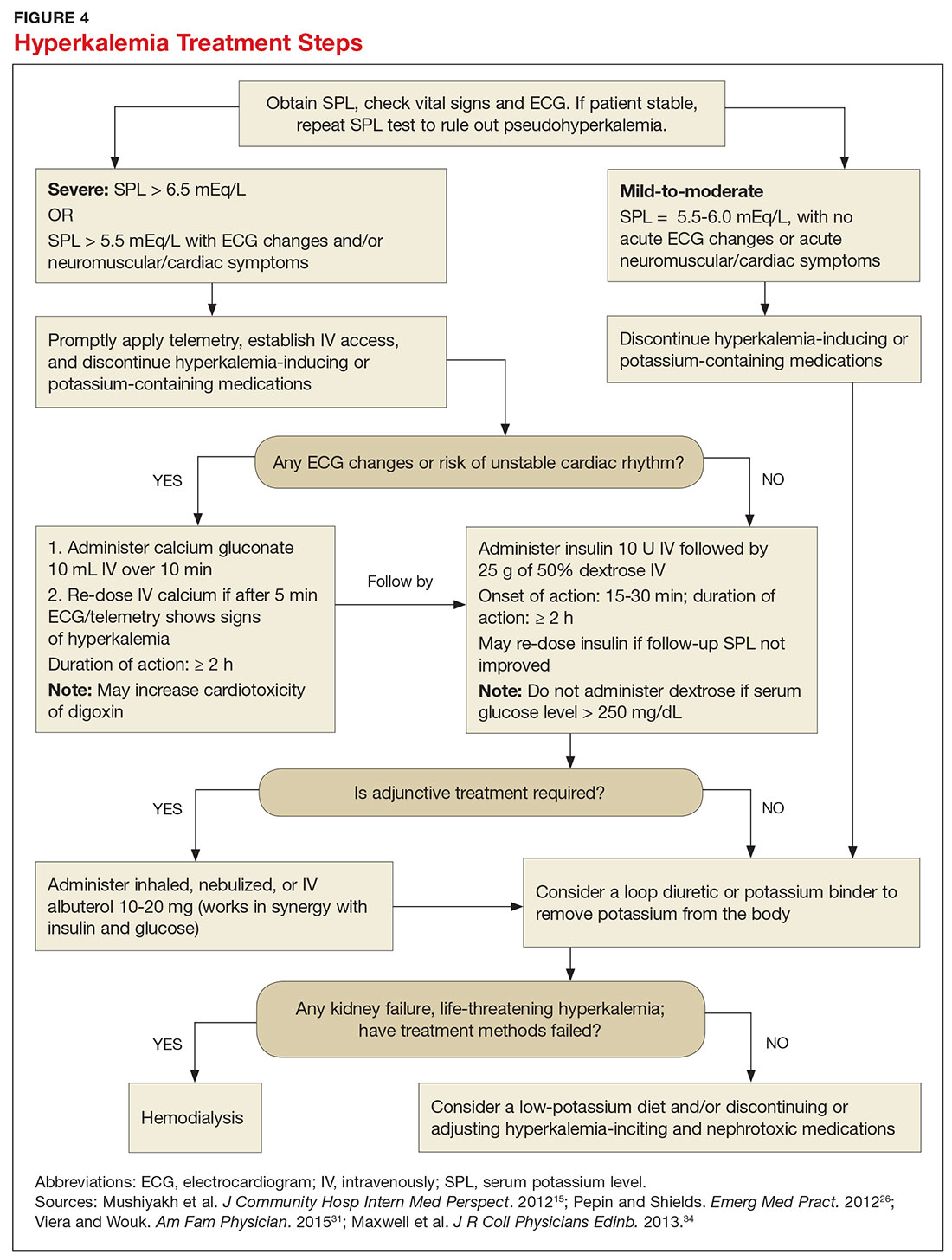

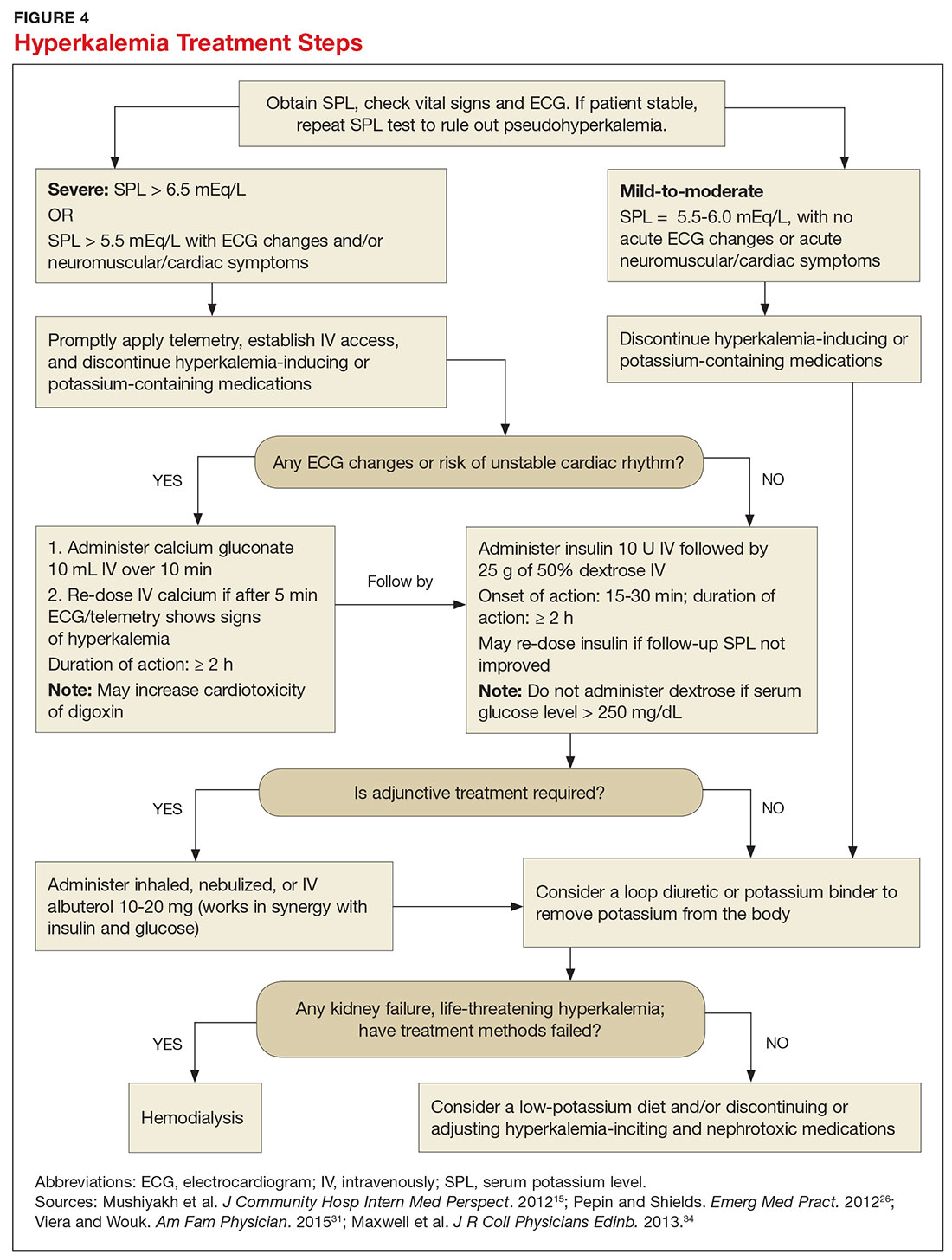

Emergent treatment is needed for severe hyperkalemia (see Figure 4). Any hyperkalemia-inciting medications or potassium supplements should be immediately discontinued.39 IV access and cardiac telemetry monitoring should be promptly applied.26

In cases of severe hyperkalemia that involve cardiac arrhythmias, manifestations on ECG, or risk for arrhythmias, calcium gluconate (10 mL IV over 10 min) should be urgently administered, followed by IV insulin in conjunction with dextrose.26 Calcium chloride should be utilized for hyperkalemia in the context of the advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) protocol for cardiac arrest.26 The patient should remain on cardiac telemetry during this treatment to monitor for ventricular fibrillation or other arrhythmias.15 IV calcium does not lower serum potassium but rather antagonizes the effects of potassium on the cardiac cell membranes, helping to prevent or terminate arrhythmias.15,34 It should be noted, however, that firstline treatment for patients who develop hyperkalemia in the setting of digoxin toxicity involves administration of digoxin-specific antibody, while calcium infusion may be utilized later.34 Alternatively, if the patient is dialysis-dependent with ESRD, dialysis may be considered as a prompt initial treatment, with nephrologist consultation.

Administration of 10 U of regular insulin plus 25 g of 50% dextrose via IV will shift potassium intracellularly (see Figure 4). The dextrose will offset the resultant hypoglycemia.31,34 Of note, this treatment is often firstline for moderate to severe hyperkalemia in patients with a stable cardiac rhythm and ECG. Blood glucose should be monitored with a fingerstick within 30 to 60 minutes of infusion and every hour thereafter for up to six hours following insulin administration.34 Potassium levels should be checked every one to two hours after this treatment step until the serum potassium level stabilizes. Thereafter, recheck the levels every four to six hours to gauge whether further treatment is needed.34

Adjunctive

After performing firstline treatment strategies for severe hyperkalemia, there are alternate therapies to consider that can help lower total body potassium. Nebulized albuterol may be used, which pushes potassium into cells; this works in synergy with insulin and glucose.26,33 Sodium bicarbonate may be effective in cases in which the ABG analysis or labs show metabolic acidosis, as this infusion shifts potassium into cells by increasing the blood pH.33

In patients with dehydration, sepsis, TLS, or rhabdomyolysis, administration of IV fluids to maintain appropriate vascular volume is important. However, excessive fluid resuscitation can result in fluid overload, inducing complications such as respiratory failure and worsened renal function.40 A Foley catheter may be placed for strict intake and output monitoring.

The patient’s volume status must be carefully assessed. Hyperkalemia may present in association with heart failure exacerbation or ascites, which are usually hypervolemic states. Loop diuretics may be used to compensate for volume overload and to help remove potassium from the body, but these medications are contraindicated in anuric patients.13,41

Removing total body potassium

After emergent therapy is carried out, potassium may need to be removed from the body through diuresis, hemodialysis, or potassium binders. Loop diuretics or potassium binders may be used to treat mild to moderate hyperkalemia or to continue to stabilize the potassium level after emergent therapy is carried out. If severe hyperkalemia persists with kidney injury or with absence of urine output, hemodialysis is the therapy of choice.13

The potassium binder sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS) exchanges sodium for potassium in the intestine.42 This agent is contraindicated if the patient has intestinal obstruction. SPS’s slow onset of action (two to six hours) makes it ineffective as firstline therapy for severe hyperkalemia.3 In addition, SPS has serious but rare adverse effects, more commonly seen in patients who have uremia after kidney transplant or who have had recent abdominal surgery, bowel injury, or intestinal perforation.41 Adverse effects of SPS include aspiration pneumonitis, upper gastrointestinal injury, colonic necrosis, and rectal stenosis.41 However, there have been documented events of colonic necrosis due to SPS in patients without ESRD who have not had abdominal surgery.43,44 In 2009, the FDA advised against concomitant administration of sorbitol with SPS. However, this drug preparation continues to be the only one stocked by many hospital pharmacies.44 Because SPS has potentially harmful adverse effects and generally is not effective in promptly lowering serum potassium, it is prudent for clinicians to implement other management strategies first.44

MONITORING AT-RISK PATIENTS

Patients with a GFR < 45 mL/min/1.73 m2 and a baseline serum potassium level > 4.5 mEq/L are at risk for hyperkalemia while taking an ACEi or an ARB and should be advised to adhere to a potassium-restrictive diet with frequent laboratory checkups.22 Depending on the serum potassium and GFR levels at checkups, these medication doses may need to be reduced or discontinued altogether.

NEW DRUG DEVELOPMENTS

A potassium binder approved for daily use would benefit patients on aggressive heart failure medication regimens, as hyperkalemia commonly occurs with these regimens. As discussed, the widely available potassium binder SPS has been associated with severe gastrointestinal adverse effects, limiting its potential for routine use.44,45 In clinical trials, new potassium binders patiromer and zirconium cyclosilicate (ZS-9) have demonstrated an ability to maintain normokalemia over weeks of therapy with acceptable adverse effect profiles.45 In 2015, patiromer was approved by the FDA as therapy for hyperkalemia.46 An in-depth discussion, which is outside the scope of this article, will be presented by experts in the April 2017 edition of Renal Consult.

CONCLUSION

The best treatment for hyperkalemia is prevention through close surveillance of at-risk patients. Clinicians should be aware of predisposing risk factors for hyperkalemia, as it can have an insidious onset, with symptoms manifesting only when this electrolyte imbalance becomes life-threatening. It is particularly important to recognize when this condition mandates emergent treatment so that critical cardiac arrhythmias can be prevented.26

1. An JN, Lee JP, Jeon HJ, et al. Severe hyperkalemia requiring hospitalization: predictors of mortality. Crit Care. 2012; 16(6):R225.

2. Palmer BF, Clegg DJ. Physiology and pathophysiology of potassium homeostasis. Adv Physiol Educ. 2016;40(4):480-490.

3. Medford-Davis L, Rafique Z. Derangements of potassium. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2014;32(2):329-347.

4. Eleftheriadis T, Leivaditis K, Antoniadi G, Liakopoulos V. Differential diagnosis of hyperkalemia: an update to a complex problem. Hippokratia. 2012;16(4):294-302.

5. Raebel M. Hyperkalemia associated with use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers. Cardiovasc Ther. 2012;30(3):156-166.

6. Korgaonkar S, Tilea A, Gillespie BW, et al. Serum potassium and outcomes in CKD: insights from the RRI-CKD Cohort Study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(5):762-769.

7. McMahon GM, Mendu ML, Gibbons FK, Christopher KB. Association between hyperkalemia at critical care initiation and mortality. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(11):1834-1842.

8. Drawz PE, Babineau DC, Rahman M. Metabolic complications in elderly adults with chronic kidney disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(2):310-315.

9. Sarafidis PA, Georgianos PI, Bakris GL. Advances in treatment of hyperkalemia in chronic kidney disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015;16(14):2205-2215.

10. Einhorn LM, Zhan M, Hsu VD, et al. The frequency of hyperkalemia and its significance in chronic kidney disease. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(12):1156-1162.

11. Khanagavi J, Gupta T, Aronow WS, et al. Hyperkalemia among hospitalized patients and association between duration of hyperkalemia and outcomes. Arch Med Sci. 2014;10(2):251-257.

12. Berkova M, Berka Z, Topinkova E. Arrhythmias and ECG changes in life threatening hyperkalemia in older patients treated by potassium sparing drugs. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2014;158(1):84-91.

13. Lehnhardt A, Kemper MJ. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of hyperkalemia. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26(3):377-384.

14. Palmer BF. A physiologic-based approach to the evaluation of a patient with hyperkalemia. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56(2):387-393.

15. Mushiyakh Y, Dangaria H, Qavi S, et al. Treatment and pathogenesis of acute hyperkalemia. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2012;1(4):7372.

16. Elliott MJ, Ronksley PE, Clase CM, et al. Management of patients with acute hyperkalemia. CMAJ. 2010;182(15):1631-1635.

17. Wiebe N, Klarenbach SW, Allan GM, et al. Potentially preventable hospitalization as a complication of CKD: a cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64(2):230-238.

18. Zutt R, van der Kooi AJ, Linthorst GE, et al. Rhabdomyolysis: review of the literature. Neuromuscul Disord. 2014;24(8):651-659.

19. Zimmerman JL, Shen MC. Rhabdomyolysis. Chest. 2013; 144(3):1058-1065.

20. Khardori R, Castillo D. Endocrine and metabolic changes during sepsis: an update. Med Clin North Am. 2012;96(6):1095-1105.

21. Raff H, Sharma ST, Nieman LK. Physiological basis for the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of adrenal disorders: Cushing’s syndrome, adrenal insufficiency, and congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Compr Physiol. 2014;4(20):739-769.

22. Lazich I, Bakris GL. Prediction and management of hyperkalemia across the spectrum of chronic kidney disease. Semin Nephrol. 2014;34(3):333-339.

23. Ayach T, Nappo R, Paugh-Miller J, Ross E. Life-threatening hyperkalemia in a patient with normal renal function. Clin Kidney J. 2014;7(1):49-52.

24. Wilson FP, Berns JS. Tumor lysis syndrome: new challenges and recent advances. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2014;21(1):18-26.

25. Asiryatham JR, Moses V, Bjornson L. Errors in potassium measurement: a laboratory perspective for the clinician. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5(4):255-259.

26. Pepin J, Shields C. Advances in diagnosis and management of hypokalemic and hyperkalemic emergencies. Emerg Med Pract. 2012;14(2):1-17.

27. Vraets A, Lin Y, Callum JL. Transfusion-associated hyperkalemia. Transfus Med Rev. 2011;25(3):184-196.

28. Aboudara MC, Hurst FP, Abbott KC, Perkins RM. Hyperkalemia after packed red blood cell transfusion in trauma patients. J Trauma. 2008;64(2 suppl):S86-S91.

29. Olson J, Talekar M, Sachdev M, et al. Potassium changes associated with blood transfusion in pediatric patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139(6):800-805.

30. Chon S, Kwak YH, Hwang SS, et al. Severe hyperkalemia can be detected immediately by quantitative electrocardiography and clinical history in patients with symptomatic or extreme bradycardia: a retrospective cross-sectional study. J Crit Care. 2013;28(6):1112.e7-1112.e13.

31. Viera AJ, Wouk N. Potassium disorders: hypokalemia and hyperkalemia. Am Fam Physician. 2015;92(6):487-495.

32. Sanghavi S, Whitling S, Uribarri J. Potassium balance in dialysis patients. Semin Dial. 2013;26(5):597-603.

33. Crawford AH. Hyperkalemia: Recognition and management of a critical electrolyte disturbance. J Infus Nurs. 2014;37(3):167-175.

34. Maxwell AP, Linden K, O’Donnell S, et al. Management of hyperkalemia. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2013;43(3):246-251.

35. Seth P, Kaur H, Kaur M. Clinical profile of diabetic ketoacidosis: a prospective study in a tertiary care hospital. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(6):OC01-OC04.

36. Rahman M, Shad F, Smith M. Acute kidney injury: a guide to diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86(7): 631-639.

37. Puar TH, Stikkelbroeck NM, Smans LC, et al. Adrenal crisis: still a deadly event in the 21st century. Am J Med. 2016;129(3):339.e1-9.

38. Liamis G, Liberopoulos E, Barkas F, Elisaf M. Spurious electrolyte disorders: a diagnostic challenge for clinicians. Am J Nephrol. 2013;38(1):50-57.

39. Kovesdy CP. Management of hyperkalemia: an update for the internist. Am J Med. 2015;128(12):1281-1287.

40. Labib M, Khalid R, Khan A, Khan S. Volume management in the critically ill patient with acute kidney injury. Crit Care Res Pract. 2013;2013:792830.

41. Watson M, Abbott KC, Yuan CM. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t: potassium binding resins in hyperkalemia. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(10):1723-1726.

42. Nguyen T, Ondrik D, Zhufyak O, et al. Hyperkalemia and potential pitfalls of sodium polystyrene sulfonate. JAAPA. 2015; 28(3):41-45.

43. McGowan CE, Saha S, Resnick MB, Moss SF. Intestinal necrosis due to sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate) in sorbitol. South Med J. 2009;102(5):493-497.

44. Sterns RH, Rojas M, Bernstein P, Chennupati S. Ion-exchange resins for the treatment of hyperkalemia: are they safe and effective? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:733-735.

45. Pitt B, Bakris GL. New potassium binders for the treatment of hyperkalemia: current data and opportunities for the future. Hypertension. 2015;66(4):731-738.

46. Epstein M, Pitt B. Recent advances in pharmacological treatments of hyperkalemia: focus on patiromer. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2016;17(10):1435-1448.

CE/CME No: CR-1703

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Describe the pathophysiology and causes of hyperkalemia.

• Identify patients who are susceptible to hyperkalemia.

• Recognize the clinical sequelae of hyperkalemia.

• Formulate assessment and treatment plans for patients with hyperkalemia.

FACULTY

Melanie Douglas is a Physician Assistant in the Medicine Department at NYU Langone Medical Center in New York, New York. Denise Rizzolo is a Clinical Assistant Professor in the PA Program at Pace University in New York, New York, and Research Director in the Program of PA Studies at Kean University in Union, New Jersey. Danielle Kruger is an Academic Coordinator and Associate Professor in the PA Program at St. John’s University in Queens, New York. The authors have no financial relationships to disclose.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid for one year from the issue date of March 2017.

Article begins on next page >>

Hyperkalemia is a common electrolyte disorder associated with life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias. Prompt recognition and appropriate treatment are essential in preventing serious cardiac complications. Although clinical manifestations of hyperkalemia are usually nonspecific or absent, laboratory testing and electrocardiography performed by the astute clinician aware of predisposing risk factors can help direct management.

Potassium is contained mostly in intracellular fluid; only about 2% is found in the extracellular space.1 The average total body potassium is about 50 mEq per kg of body weight (eg, a 70-kg individual has a total body potassium of approximately 3,500 mEq).2 Levels are tightly regulated by alterations in excretion in the distal renal tubule in response to potassium load and balance, and potassium distribution is influenced by insulin, aldosterone, catecholamines, and acid-base status.2 Movement of potassium across cell membranes is driven by the sodium-potassium adenosine triphosphatase (Na-K-ATPase) pump.3 In this article, we use the common serum potassium reference range of 3.5 to 5.0 mEq/L and define hyperkalemia as a serum potassium concentration greater than 5.5 mEq/L.4

Hyperkalemia can lead to life-threatening complications of cardiac arrhythmias, asystole, hypotension, flaccid paralysis, tetany, dyspnea, and altered mental status.5 Among patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), hyperkalemia is thought to contribute to 2% to 5% of deaths.6 A retrospective study found that patients with serum potassium levels exceeding 6.0 mEq/L on ICU admission had a significantly higher death rate within 30 days than patients who were normokalemic on presentation.7

RISK FACTORS

It is estimated that more than 35% of patients age 70 and older have chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 3 or higher.8 Hyperkalemia is closely associated with CKD, increasing linearly in relation to the degree of renal impairment.8 As such, the prevalence of hyperkalemia in older adults is high, and it will increase overall as the US population ages. In a retrospective analysis of veterans older than 65 with CKD stage 3 or higher, the prevalence of hyperkalemia was 2.5%.9 Use of certain medications is also associated with hyperkalemia. Another retrospective study analyzed records obtained from 70,873 patients with CKD (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) hospitalized in the Veterans Health Administration system. It found that patients treated with renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) blockers, such as ACE inhibitors (ACEis) or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs), had a higher incidence of hyperkalemia (potassium level ≥ 5.5 mEq/L) than patients not treated with these medications (8.22 vs 1.77 events per 100 patient-months).9,10

POTASSIUM HOMEOSTASIS

Tight control over extracellular potassium is maintained in part by the Na-K-ATPase pump, which uses adenosine triphosphatase to move potassium and sodium ions in opposite directions across cell membranes.3 Specifically, three sodium ions are pumped out of the cell for every two potassium ions pumped in, resulting in a potassium gradient that is partially responsible for maintaining a resting membrane potential. This resting membrane potential, which determines myocardial, skeletal muscle, and nerve cell excitability and signaling, is highly sensitive to changes in the extracellular potassium level.4 Even small extracellular imbalances can induce cell depolarization and evoke an action potential. Increased extracellular potassium concentration decreases the resting membrane potential of the myocardium, shortens repolarization time, and decreases the rate of myocardial cell conduction, and also slows down neuromuscular conduction.11,12

Renal tubular function plays a significant role in potassium homeostasis, with approximately 90% of dietary potassium intake ex

The RAAS is a signal transduction pathway that regulates potassium excretion by the kidneys. Renin is secreted by the kidney in response to low renal perfusion, catecholamines, ß-adrenergic stimulation, potassium and sodium levels, and other factors. Secretion of renin triggers a signaling cascade that eventually results in the release of aldosterone from the adrenal cortex.5 Aldosterone binds to a receptor in the kidney’s collecting ducts where it increases potassium excretion by stimulating sodium reabsorption and fluid retention (see Figure 1).5

CAUSES OF HYPERKALEMIA

The pathophysiology of hyperkalemia generally involves either decreased renal excretion or shifts in extracellular potassium. Causes of hyperkalemia are listed in the Table. Potassium excretion can be disrupted in acute kidney injury (AKI), sepsis, cardiac ischemia, heart failure, diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), insulin deficiency, tumor lysis syndrome (TLS), sickle cell disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, renal transplant, hepatorenal syndrome, adrenal insufficiency, and obstructive uropathy.15 In addition, certain medications can impair potassium excretion (eg, RAAS blockers, potassium-sparing diuretics in patients with CKD, digoxin toxicity).16 The following sections highlight the pathophysiology and manifestations of more common causes of hyperkalemia.

Renal impairment

Hyperkalemia may be a manifestation of worsening renal function. Potassium excretion is reduced in CKD, and CKD is the most common cause of hyperkalemia due to lower GFR.8,17 Patients with lower GFR tend to be older and male, and frequently have comorbid conditions such as type 2 diabetes, chronic liver disease, and heart failure.17

In CKD, decreased delivery of sodium to the distal tubules and reduced filtration capacity of the kidney diminishes the collecting duct’s ability to excrete potassium in exchange for sodium.2 Metabolic acidosis, which often contributes to AKI or CKD, causes potassium to shift from the intracellular to the extracellular compartment.4 Renal impairment may present clinically with dehydration, oliguria, nausea, vomiting, constipation, altered mental status, or weakness.

Hyperglycemia

Insulin and catecholamines (eg, epinephrine and norepinephrine) drive potassium into cells. Insulin increases potassium uptake into liver and muscle cells.13 A decrease in insulin levels, as may occur in type 2 diabetes or DKA, can cause a buildup of extracellular potassium.4 Also, serum hypertonicity from hyperglycemia results in water movement from the intracellular to the extracellular compartment; this raises the intracellular concentration of potassium, further promoting its movement to the extracellular space.4,14 Patients with hyperglycemia may present with dizziness, polyuria, polydipsia, nausea, vomiting, altered mental status, or fatigue.

Rhabdomyolysis

Rhabdomyolysis is a rapid breakdown of skeletal muscle that results in leakage of cellular contents into the extracellular space.4,18 Causes of rhabdomyolysis include use of medications such as statins, illicit drugs (eg, cocaine), or alcohol; rigorous exercise; and trauma.19

Muscle cell contents that are released into the circulation include potassium and other electrolytes, enzymes (eg, lactate dehydrogenase, aspartate transaminase, aldolase), and myoglobin.19 In rhabdomyolysis, myoglobin accumulation and hypovolemia lead to AKI and hyperkalemia.19 Patients may present with myalgias, extremity paresthesias, generalized weakness, nausea, altered mental status, fever, or darkened urine.18,19

Adrenal insufficiency

During critical illness such as sepsis, adrenal insufficiency can result from destruction of the adrenal glands, leading to hypoaldosteronism.20 Reduced aldosterone in adrenal insufficiency enables sodium and water to be eliminated from the body more easily, but as a result, less potassium gets excreted through the renal system and more is driven into the plasma.15

Acute adrenal insufficiency may manifest with hypotension, nausea, vomiting, or altered mental status, and labwork may reveal hyperkalemia as well as hypoglycemia or hyponatremia. Additionally, long-term glucocorticoid therapy can suppress the hypothalamic-pituitary axis and cause adrenal atrophy; rapid discontinuation of steroids can lead to adrenal insufficiency and hyperkalemia.21

Medications

RAAS blockers reduce CKD progression in patients with an eGFR of 29 mL/min/1.73 m2 or greater.22 Nonetheless, prescribing two or more drugs from the ACEi or ARB classes is not recommended. The Veterans Administration Nephron-Diabetes Trial (VA-NEPHRON-D) was terminated early because patients with stage 3 CKD due to diabetes who received dual ACEi/ARB therapy had higher rates of hyperkalemia but no slowing of CKD.22

Within the RAAS cascade, ACEis block the formation of angiotensin II and ARBs prevent angiotensin II from binding to the adrenal receptor. This impairs renal excretion of potassium and potentially contributes to hyperkalemia.5 Nonetheless, when patients on ACEis or ARBs develop hyperkalemia, aldosterone concentrations usually decrease due to preexisting illnesses (eg, diabetes, heart failure, CKD, AKI) or drug effects (eg, potassium-sparing diuretics, ß-blockers, digoxin).5 Ultimately, a combination of factors resulting from ACEi or ARB therapy causes reductions in renal perfusion and predisposes patients to hyperkalemia.5

NSAIDs may lead to hyperkalemia, as they interfere with prostaglandin release, decrease renal perfusion, and reduce renin and aldosterone levels.22 ß-blockers and tacrolimus inhibit renin release, leading to decreased aldosterone levels.5 Potassium-sparing diuretics block the interaction of aldosterone with the aldosterone receptor in the nephron.5 Digoxin decreases the activity of Na-K-ATPase, diminishing potassium uptake by cells.9 Potassium supplements, often prescribed for patients on diuretics, may contribute to hyperkalemia in patients with CKD. In the hospital setting, potassium tablets or IV formulations are utilized to correct hypokalemia. Especially in patients with CKD, clinicians should prescribe these agents with caution to avoid inducing hyperkalemia. Salt substitutes, which commonly contain potassium chloride, may be appealing to patients concerned about their sodium intake. However, consumption of these substitutes may contribute to hyperkalemia, especially in patients with CKD, heart failure, or type 2 diabetes.23

Tumor lysis syndrome

TLS involves rapid release of electrolytes and other intracellular contents into the extracellular space during the lysis of tumor cells.24 Nucleic acids within DNA strands break down and build up extracellularly, leading to hyperuricemia and often AKI. Potassium and other electrolytes released into the plasma during cell lysis can usually be removed by a healthy renal system. In TLS, however, AKI due to uric acid nephropathy prevents kidneys from removing the excess electrolytes from the bloodstream.24 Patients with rapidly growing hematologic tumors undergoing chemotherapy are especially at risk.

Pseudohyperkalemia

Pseudohyperkalemia is a transiently elevated serum potassium level that erroneously represents the true serum potassium level. It results from hemolysis due to mechanical trauma during the blood draw (eg, a tourniquet tied too tightly or use of a small-bore needle) or during specimen handling afterwards.25 Furthermore, leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, and polycythemia make red blood cells more fragile, increasing the chance of hemolysis and potassium leakage.26 Blood transfusion also can lead to pseudohyperkalemia. When blood is stored, potassium leakage from the cells and cell lysis, along with diminished Na-K-ATPase activity, lead to a buildup of potassium in the medium surrounding the stored red blood cells.27,28 The rise in serum potassium levels post-transfusion is usually transient, as the blood cells redistribute the potassium load once they become metabolically active.27,29

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Clinical manifestations of mild to moderate hyperkalemia (serum potassium > 5.5 mEq/L but < 6.5 mEq/L) include fatigue, generalized weakness, nausea, vomiting, constipation, and diarrhea.15 In many patients, mild to moderate hyperkalemia may not be associated with any acute symptoms and vital signs may be normal.13 Severe hyperkalemia (serum potassium > 6.5 mEq/L) may present clinically with acute extremity paresthesias, muscle weakness and paralysis, heart palpitations, dyspnea, altered mental status, cardiac arrhythmias, and cardiac arrest.30,31 Irregular heart rhythm, decreased deep tendon reflexes, or decreased strength may be revealed on physical exam.3 Individuals with ESRD on hemodialysis seem to tolerate higher levels of potassium than the general population without displaying clinical symptoms. However, these individuals are still susceptible to the cardiac effects of hyperkalemia.32

INITIAL ASSESSMENT

In assessing hyperkalemia, the clinician must perform a focused history and physical exam and review the patient’s medication list, including supplements and dietary habits that impact potassium intake. Potassium-rich foods include meat, fish, milk, almonds, spinach, cantaloupe, bananas, oranges, mushrooms, and potatoes.33 Hyperkalemia may present in association with various medical emergencies. The clinician should have an index of suspicion, depending on the patient’s overall medical profile and presentation, for emergencies such as cardiac ischemia, sepsis, adrenal crisis, DKA, TLS, and digoxin overdose.

The clinician must identify whether an elevated potassium level requires emergent therapy; assessment of vital signs is paramount in determining this. Orthostatic hypotension and tachycardia may hint that the patient is volume depleted. The patient should be examined for signs of hemodynamic shock with the CAB sequence: circulation, airway, breathing.34 Symptoms such as chest pain, shortness of breath, muscle weakness, paralysis, and altered mental status suggest that an expedited evaluation is warranted.

With a serum potassium level > 5.5 mEq/L, urgent electrocardiography should be performed.26 ECG findings observed with serum potassium levels of 5.5-6.5 mEq/L usually include peaked T-waves and prolonged PR intervals (see Figure 2). With potassium levels > 6.5 mEq/L consistent with further cardiac destabilization, the P-wave flattens then disappears, the QRS complex broadens, and sinus bradycardia or ectopic beats may occur.12,26 ST depression, T-wave inversion, or ST elevation also may be seen.12 With serum potassium levels > 7.5 mEq/L, progressive widening of the QRS complex to a sine-wave with bundle branch blocks or fascicular blocks may occur (see Figure 3).26 Without prompt intervention, ventricular fibrillation may ensue.26

An extensive laboratory workup may be necessary to investigate the etiology; this includes a complete blood count, metabolic panel, liver function tests, cardiac enzymes, blood gas analysis, serum/urine osmolality, urinalysis, urine electrolytes, and toxicology screen.13,26 Arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis may show metabolic acidosis with AKI or DKA, or an elevated lactate may occur with sepsis. In patients with hyperglycemia, besides checking for acidosis, obtaining blood/urine ketone levels and a metabolic panel with anion gap to evaluate for DKA is useful.35

When assessing a patient with an elevated creatinine, the GFR at the time of evaluation should be compared with the patient’s baseline GFR to determine chronicity and duration of his/her kidney disease.36 Obtaining a urinalysis and urine electrolytes in addition to the basic metabolic panel can help narrow the etiology.36 A Foley catheter should be placed in cases of urinary retention because without intervention, urinary obstruction may lead to AKI and hyperkalemia. Myoglobinuria on urinalysis and an elevated creatine kinase are diagnostic markers of rhabdomyolysis.18

TLS should be considered in patients who recently received chemotherapy, especially those with proliferative hematologic malignancies, such as acute lymphoblastic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, and Burkitt lymphoma.24 In TLS, bloodwork often reveals hyperkalemia along with AKI, an elevated uric acid level, hyperphosphatemia, and hypocalcemia.24

Patients presenting with hyperkalemia, hypotension, hypoglycemia, and hyponatremia may have adrenal insufficiency.20 If insufficiency is suspected, a cortisol level may be checked during morning hours; a low level is often suggestive of this diagnosis.37 Treatment includes daily doses of steroids, and consultation with an endocrinologist is recommended.37

If an elevated potassium level is not accompanied by renal dysfunction, electrolyte imbalances, ECG changes, or inciting medications, pseudohyperkalemia should be considered.38 A repeat lab sample should be checked. Consider obtaining an ABG analysis, as the shorter time interval between drawing the blood sample and the sample analysis reportedly increases the reliability of the resulting potassium level.38

THERAPY

Emergent

Emergent treatment is needed for severe hyperkalemia (see Figure 4). Any hyperkalemia-inciting medications or potassium supplements should be immediately discontinued.39 IV access and cardiac telemetry monitoring should be promptly applied.26

In cases of severe hyperkalemia that involve cardiac arrhythmias, manifestations on ECG, or risk for arrhythmias, calcium gluconate (10 mL IV over 10 min) should be urgently administered, followed by IV insulin in conjunction with dextrose.26 Calcium chloride should be utilized for hyperkalemia in the context of the advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) protocol for cardiac arrest.26 The patient should remain on cardiac telemetry during this treatment to monitor for ventricular fibrillation or other arrhythmias.15 IV calcium does not lower serum potassium but rather antagonizes the effects of potassium on the cardiac cell membranes, helping to prevent or terminate arrhythmias.15,34 It should be noted, however, that firstline treatment for patients who develop hyperkalemia in the setting of digoxin toxicity involves administration of digoxin-specific antibody, while calcium infusion may be utilized later.34 Alternatively, if the patient is dialysis-dependent with ESRD, dialysis may be considered as a prompt initial treatment, with nephrologist consultation.

Administration of 10 U of regular insulin plus 25 g of 50% dextrose via IV will shift potassium intracellularly (see Figure 4). The dextrose will offset the resultant hypoglycemia.31,34 Of note, this treatment is often firstline for moderate to severe hyperkalemia in patients with a stable cardiac rhythm and ECG. Blood glucose should be monitored with a fingerstick within 30 to 60 minutes of infusion and every hour thereafter for up to six hours following insulin administration.34 Potassium levels should be checked every one to two hours after this treatment step until the serum potassium level stabilizes. Thereafter, recheck the levels every four to six hours to gauge whether further treatment is needed.34

Adjunctive

After performing firstline treatment strategies for severe hyperkalemia, there are alternate therapies to consider that can help lower total body potassium. Nebulized albuterol may be used, which pushes potassium into cells; this works in synergy with insulin and glucose.26,33 Sodium bicarbonate may be effective in cases in which the ABG analysis or labs show metabolic acidosis, as this infusion shifts potassium into cells by increasing the blood pH.33

In patients with dehydration, sepsis, TLS, or rhabdomyolysis, administration of IV fluids to maintain appropriate vascular volume is important. However, excessive fluid resuscitation can result in fluid overload, inducing complications such as respiratory failure and worsened renal function.40 A Foley catheter may be placed for strict intake and output monitoring.

The patient’s volume status must be carefully assessed. Hyperkalemia may present in association with heart failure exacerbation or ascites, which are usually hypervolemic states. Loop diuretics may be used to compensate for volume overload and to help remove potassium from the body, but these medications are contraindicated in anuric patients.13,41

Removing total body potassium

After emergent therapy is carried out, potassium may need to be removed from the body through diuresis, hemodialysis, or potassium binders. Loop diuretics or potassium binders may be used to treat mild to moderate hyperkalemia or to continue to stabilize the potassium level after emergent therapy is carried out. If severe hyperkalemia persists with kidney injury or with absence of urine output, hemodialysis is the therapy of choice.13

The potassium binder sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS) exchanges sodium for potassium in the intestine.42 This agent is contraindicated if the patient has intestinal obstruction. SPS’s slow onset of action (two to six hours) makes it ineffective as firstline therapy for severe hyperkalemia.3 In addition, SPS has serious but rare adverse effects, more commonly seen in patients who have uremia after kidney transplant or who have had recent abdominal surgery, bowel injury, or intestinal perforation.41 Adverse effects of SPS include aspiration pneumonitis, upper gastrointestinal injury, colonic necrosis, and rectal stenosis.41 However, there have been documented events of colonic necrosis due to SPS in patients without ESRD who have not had abdominal surgery.43,44 In 2009, the FDA advised against concomitant administration of sorbitol with SPS. However, this drug preparation continues to be the only one stocked by many hospital pharmacies.44 Because SPS has potentially harmful adverse effects and generally is not effective in promptly lowering serum potassium, it is prudent for clinicians to implement other management strategies first.44

MONITORING AT-RISK PATIENTS

Patients with a GFR < 45 mL/min/1.73 m2 and a baseline serum potassium level > 4.5 mEq/L are at risk for hyperkalemia while taking an ACEi or an ARB and should be advised to adhere to a potassium-restrictive diet with frequent laboratory checkups.22 Depending on the serum potassium and GFR levels at checkups, these medication doses may need to be reduced or discontinued altogether.

NEW DRUG DEVELOPMENTS

A potassium binder approved for daily use would benefit patients on aggressive heart failure medication regimens, as hyperkalemia commonly occurs with these regimens. As discussed, the widely available potassium binder SPS has been associated with severe gastrointestinal adverse effects, limiting its potential for routine use.44,45 In clinical trials, new potassium binders patiromer and zirconium cyclosilicate (ZS-9) have demonstrated an ability to maintain normokalemia over weeks of therapy with acceptable adverse effect profiles.45 In 2015, patiromer was approved by the FDA as therapy for hyperkalemia.46 An in-depth discussion, which is outside the scope of this article, will be presented by experts in the April 2017 edition of Renal Consult.

CONCLUSION

The best treatment for hyperkalemia is prevention through close surveillance of at-risk patients. Clinicians should be aware of predisposing risk factors for hyperkalemia, as it can have an insidious onset, with symptoms manifesting only when this electrolyte imbalance becomes life-threatening. It is particularly important to recognize when this condition mandates emergent treatment so that critical cardiac arrhythmias can be prevented.26

CE/CME No: CR-1703

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Describe the pathophysiology and causes of hyperkalemia.

• Identify patients who are susceptible to hyperkalemia.

• Recognize the clinical sequelae of hyperkalemia.

• Formulate assessment and treatment plans for patients with hyperkalemia.

FACULTY

Melanie Douglas is a Physician Assistant in the Medicine Department at NYU Langone Medical Center in New York, New York. Denise Rizzolo is a Clinical Assistant Professor in the PA Program at Pace University in New York, New York, and Research Director in the Program of PA Studies at Kean University in Union, New Jersey. Danielle Kruger is an Academic Coordinator and Associate Professor in the PA Program at St. John’s University in Queens, New York. The authors have no financial relationships to disclose.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid for one year from the issue date of March 2017.

Article begins on next page >>

Hyperkalemia is a common electrolyte disorder associated with life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias. Prompt recognition and appropriate treatment are essential in preventing serious cardiac complications. Although clinical manifestations of hyperkalemia are usually nonspecific or absent, laboratory testing and electrocardiography performed by the astute clinician aware of predisposing risk factors can help direct management.

Potassium is contained mostly in intracellular fluid; only about 2% is found in the extracellular space.1 The average total body potassium is about 50 mEq per kg of body weight (eg, a 70-kg individual has a total body potassium of approximately 3,500 mEq).2 Levels are tightly regulated by alterations in excretion in the distal renal tubule in response to potassium load and balance, and potassium distribution is influenced by insulin, aldosterone, catecholamines, and acid-base status.2 Movement of potassium across cell membranes is driven by the sodium-potassium adenosine triphosphatase (Na-K-ATPase) pump.3 In this article, we use the common serum potassium reference range of 3.5 to 5.0 mEq/L and define hyperkalemia as a serum potassium concentration greater than 5.5 mEq/L.4

Hyperkalemia can lead to life-threatening complications of cardiac arrhythmias, asystole, hypotension, flaccid paralysis, tetany, dyspnea, and altered mental status.5 Among patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), hyperkalemia is thought to contribute to 2% to 5% of deaths.6 A retrospective study found that patients with serum potassium levels exceeding 6.0 mEq/L on ICU admission had a significantly higher death rate within 30 days than patients who were normokalemic on presentation.7

RISK FACTORS

It is estimated that more than 35% of patients age 70 and older have chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 3 or higher.8 Hyperkalemia is closely associated with CKD, increasing linearly in relation to the degree of renal impairment.8 As such, the prevalence of hyperkalemia in older adults is high, and it will increase overall as the US population ages. In a retrospective analysis of veterans older than 65 with CKD stage 3 or higher, the prevalence of hyperkalemia was 2.5%.9 Use of certain medications is also associated with hyperkalemia. Another retrospective study analyzed records obtained from 70,873 patients with CKD (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) hospitalized in the Veterans Health Administration system. It found that patients treated with renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) blockers, such as ACE inhibitors (ACEis) or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs), had a higher incidence of hyperkalemia (potassium level ≥ 5.5 mEq/L) than patients not treated with these medications (8.22 vs 1.77 events per 100 patient-months).9,10

POTASSIUM HOMEOSTASIS

Tight control over extracellular potassium is maintained in part by the Na-K-ATPase pump, which uses adenosine triphosphatase to move potassium and sodium ions in opposite directions across cell membranes.3 Specifically, three sodium ions are pumped out of the cell for every two potassium ions pumped in, resulting in a potassium gradient that is partially responsible for maintaining a resting membrane potential. This resting membrane potential, which determines myocardial, skeletal muscle, and nerve cell excitability and signaling, is highly sensitive to changes in the extracellular potassium level.4 Even small extracellular imbalances can induce cell depolarization and evoke an action potential. Increased extracellular potassium concentration decreases the resting membrane potential of the myocardium, shortens repolarization time, and decreases the rate of myocardial cell conduction, and also slows down neuromuscular conduction.11,12

Renal tubular function plays a significant role in potassium homeostasis, with approximately 90% of dietary potassium intake ex