User login

Which Cognitive Domains Predict Progression From MCI to Dementia in Parkinson’s Disease?

MIAMI—Among patients with Parkinson’s disease–associated mild cognitive impairment (MCI), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) subscores in visuospatial function, attention, language, and orientation are the most useful in predicting conversion to dementia, according to research presented at the First Pan American Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders Congress. Melissa Mackenzie, of the Division of Neurology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, and colleagues conducted a study to evaluate which subscores on the cognitive assessment predict conversion to dementia in patients with Parkinson’s disease–associated MCI.

The investigators searched the Pacific Parkinson’s Research Centre Database to identify patients with a diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease who completed an itemized MoCA in the MCI range (ie, they had a corrected total score between 21 and 27) and who completed at least one other MoCA at least one year later. Patients taking potentially cognitive enhancing medications were excluded.

The researchers included in their study 529 assessments from 164 patients. They separated patients into three groups based on their last MoCA score—those who developed dementia (33 patients), those who returned to normal cognition (48 patients), and those who maintained MoCA scores in the MCI range (83 patients). In a model that predicted future MoCA score categories with 78% accuracy, the most important subscores were visuospatial, attention, language, and orientation, “but, interestingly, not delayed recall,” Dr. Mackenzie and colleagues said.

“A prevailing theory of cognitive decline in Parkinson’s disease postulates that visuospatial ‘posterior-cortical’ impairments are due to Lewy body deposition, whereas frontal executive dysfunction reflects ‘on–off’ state,” the researchers said. “Interestingly, language scores and memory function in delayed recall were the items that improved the most” in patients who reverted from MCI to normal cognition. “Whether the best approach to assess risk of conversion to dementia is to focus exclusively on these MoCA sections, or alternatively, employing multiple tests that target these cognitive domains, remains to be seen,” the researchers concluded. Patients with Parkinson’s disease–associated MCI at any time “should likely be followed more closely for cognitive decline, as they seem to be at increased risk for developing dementia, even if there is interval maintenance of MCI or return to normal cognition.”

—Jake Remaly

MIAMI—Among patients with Parkinson’s disease–associated mild cognitive impairment (MCI), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) subscores in visuospatial function, attention, language, and orientation are the most useful in predicting conversion to dementia, according to research presented at the First Pan American Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders Congress. Melissa Mackenzie, of the Division of Neurology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, and colleagues conducted a study to evaluate which subscores on the cognitive assessment predict conversion to dementia in patients with Parkinson’s disease–associated MCI.

The investigators searched the Pacific Parkinson’s Research Centre Database to identify patients with a diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease who completed an itemized MoCA in the MCI range (ie, they had a corrected total score between 21 and 27) and who completed at least one other MoCA at least one year later. Patients taking potentially cognitive enhancing medications were excluded.

The researchers included in their study 529 assessments from 164 patients. They separated patients into three groups based on their last MoCA score—those who developed dementia (33 patients), those who returned to normal cognition (48 patients), and those who maintained MoCA scores in the MCI range (83 patients). In a model that predicted future MoCA score categories with 78% accuracy, the most important subscores were visuospatial, attention, language, and orientation, “but, interestingly, not delayed recall,” Dr. Mackenzie and colleagues said.

“A prevailing theory of cognitive decline in Parkinson’s disease postulates that visuospatial ‘posterior-cortical’ impairments are due to Lewy body deposition, whereas frontal executive dysfunction reflects ‘on–off’ state,” the researchers said. “Interestingly, language scores and memory function in delayed recall were the items that improved the most” in patients who reverted from MCI to normal cognition. “Whether the best approach to assess risk of conversion to dementia is to focus exclusively on these MoCA sections, or alternatively, employing multiple tests that target these cognitive domains, remains to be seen,” the researchers concluded. Patients with Parkinson’s disease–associated MCI at any time “should likely be followed more closely for cognitive decline, as they seem to be at increased risk for developing dementia, even if there is interval maintenance of MCI or return to normal cognition.”

—Jake Remaly

MIAMI—Among patients with Parkinson’s disease–associated mild cognitive impairment (MCI), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) subscores in visuospatial function, attention, language, and orientation are the most useful in predicting conversion to dementia, according to research presented at the First Pan American Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders Congress. Melissa Mackenzie, of the Division of Neurology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, and colleagues conducted a study to evaluate which subscores on the cognitive assessment predict conversion to dementia in patients with Parkinson’s disease–associated MCI.

The investigators searched the Pacific Parkinson’s Research Centre Database to identify patients with a diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease who completed an itemized MoCA in the MCI range (ie, they had a corrected total score between 21 and 27) and who completed at least one other MoCA at least one year later. Patients taking potentially cognitive enhancing medications were excluded.

The researchers included in their study 529 assessments from 164 patients. They separated patients into three groups based on their last MoCA score—those who developed dementia (33 patients), those who returned to normal cognition (48 patients), and those who maintained MoCA scores in the MCI range (83 patients). In a model that predicted future MoCA score categories with 78% accuracy, the most important subscores were visuospatial, attention, language, and orientation, “but, interestingly, not delayed recall,” Dr. Mackenzie and colleagues said.

“A prevailing theory of cognitive decline in Parkinson’s disease postulates that visuospatial ‘posterior-cortical’ impairments are due to Lewy body deposition, whereas frontal executive dysfunction reflects ‘on–off’ state,” the researchers said. “Interestingly, language scores and memory function in delayed recall were the items that improved the most” in patients who reverted from MCI to normal cognition. “Whether the best approach to assess risk of conversion to dementia is to focus exclusively on these MoCA sections, or alternatively, employing multiple tests that target these cognitive domains, remains to be seen,” the researchers concluded. Patients with Parkinson’s disease–associated MCI at any time “should likely be followed more closely for cognitive decline, as they seem to be at increased risk for developing dementia, even if there is interval maintenance of MCI or return to normal cognition.”

—Jake Remaly

House leaders ‘came up short’ in effort to kill Obamacare

Despite days of intense negotiations and last-minute concessions to win over wavering GOP conservatives and moderates, House Republican leaders Friday failed to secure enough support to pass their plan to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act.

House Speaker Paul Ryan pulled the bill from consideration after he rushed to the White House to tell President Donald Trump that there weren’t the 216 votes necessary for passage.

“We came really close today, but we came up short,” he told reporters at a hastily called news conference.

When pressed about what happens to the federal health law, he added, “Obamacare is the law of the land. … We’re going to be living with Obamacare for the foreseeable future.”

President Trump laid the blame at the feet of Democrats, complaining that not one was willing to help Republicans on the measure, and he warned again that the Obamacare insurance markets are in serious danger. “Bad things are going to happen to Obamacare,” he told reporters at the White House. “There’s not much you can do to help it. I’ve been saying that for a year and a half. I said, look, eventually, it’s not sustainable. The insurance companies are leaving.”

But he said the collapse of the bill might allow Republicans and Democrats to work on a replacement. “I honestly believe the Democrats will come to us and say, ‘Look, let’s get together and get a great health care bill or plan that’s really great for the people of our country,’” he said.

Mr. Ryan originally had hoped to hold a floor vote on the measure Thursday – timed to coincide with the 7th anniversary of the ACA – but decided to delay that effort because GOP leaders didn’t have enough “yes” votes. The House was in session Friday, before his announcement, while members debated the bill.

House Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi (Calif.) said the speaker’s decision to pull the bill “is pretty exciting for us … a victory for the Affordable Care Act, more importantly for the American people.”

The legislation was damaged by a variety of issues raised by competing factions of the party. Many members were nervous about reports by the Congressional Budget Office showing that the bill would lead eventually to 24 million people losing insurance, while some moderate Republicans worried that ending the ACA’s Medicaid expansion would hurt low-income Americans.

At the same time, conservatives, especially the hard-right House Freedom Caucus that often has needled party leaders, complained that the bill kept too much of the ACA structure in place. They wanted a straight repeal of Obamacare, but party leaders said that couldn’t pass the Senate, where Republicans don’t have enough votes to stop a filibuster. They were hoping to use a complicated legislative strategy called budget reconciliation that would allow them to repeal parts of the ACA that only affect federal spending.

The decision came after a chaotic week of negotiations, as party leaders sought to woo more conservatives. The president lobbied 120 members through personal meetings or phone calls, according to a count provided Friday by his spokesman, Sean Spicer. “The president and the team here have left everything on the field,” Mr. Spicer said.

On Thursday evening, Mr. Trump dispatched Office of Management and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney to tell his former House GOP colleagues that the president wanted a vote on Friday. It was time to move on to other priorities, including tax reform, he told House Republicans.

“He said the president needs this, the president has said he wants a vote tomorrow, up or down. If for any reason it goes down, we’re just going to move forward with additional parts of his agenda. This is our moment in time,” Rep. Chris Collins (R-N.Y.), a loyal Trump ally, told reporters late Thursday. “If it doesn’t pass, we’re moving beyond health care. … We are done negotiating.”

Trump’s edict clearly irked some lawmakers, including the Freedom Caucus chairman, Rep. Mark Meadows (R-N.C), whose group of more than two dozen members represented the strongest bloc against the measure.

“Anytime you don’t have 216 votes, negotiations are not totally over,” he told reporters who had surrounded him in a Capitol basement hallway as he headed in to the party’s caucus meeting.

President Trump, Speaker Ryan, and other GOP lawmakers tweaked their initial package in a variety of ways to win over both conservatives and moderates. But every time one change was made to win votes in one camp, it repelled support in another.

The White House on Thursday accepted conservatives’ demands that the legislation strip federal guarantees of essential health benefits from insurance policies. But that was another problem for moderates, and Democrats suggested the provision would not survive in the Senate.

Republican moderates in the House – as well as the Senate – objected to the bill’s provisions that would shift Medicaid from an open-ended entitlement to a set amount of funding for states that also would give governors and state lawmakers more flexibility over the program. Moderates also were concerned that the package’s tax credits would not be generous enough to help older Americans – who could be charged five times more for coverage than would their younger counterparts – afford coverage.

The House package also lost the support of key GOP allies, including the Club for Growth and Heritage Action. Physician, patient and hospital groups also opposed it.

But Mr. Ryan’s comments made clear how difficult this decision was. “This is a disappointing day for us,” he said. “Doing big things is hard. All of us. All of us – myself included – we will need time to reflect on how we got to this moment, what we could have done to do it better.”

Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Despite days of intense negotiations and last-minute concessions to win over wavering GOP conservatives and moderates, House Republican leaders Friday failed to secure enough support to pass their plan to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act.

House Speaker Paul Ryan pulled the bill from consideration after he rushed to the White House to tell President Donald Trump that there weren’t the 216 votes necessary for passage.

“We came really close today, but we came up short,” he told reporters at a hastily called news conference.

When pressed about what happens to the federal health law, he added, “Obamacare is the law of the land. … We’re going to be living with Obamacare for the foreseeable future.”

President Trump laid the blame at the feet of Democrats, complaining that not one was willing to help Republicans on the measure, and he warned again that the Obamacare insurance markets are in serious danger. “Bad things are going to happen to Obamacare,” he told reporters at the White House. “There’s not much you can do to help it. I’ve been saying that for a year and a half. I said, look, eventually, it’s not sustainable. The insurance companies are leaving.”

But he said the collapse of the bill might allow Republicans and Democrats to work on a replacement. “I honestly believe the Democrats will come to us and say, ‘Look, let’s get together and get a great health care bill or plan that’s really great for the people of our country,’” he said.

Mr. Ryan originally had hoped to hold a floor vote on the measure Thursday – timed to coincide with the 7th anniversary of the ACA – but decided to delay that effort because GOP leaders didn’t have enough “yes” votes. The House was in session Friday, before his announcement, while members debated the bill.

House Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi (Calif.) said the speaker’s decision to pull the bill “is pretty exciting for us … a victory for the Affordable Care Act, more importantly for the American people.”

The legislation was damaged by a variety of issues raised by competing factions of the party. Many members were nervous about reports by the Congressional Budget Office showing that the bill would lead eventually to 24 million people losing insurance, while some moderate Republicans worried that ending the ACA’s Medicaid expansion would hurt low-income Americans.

At the same time, conservatives, especially the hard-right House Freedom Caucus that often has needled party leaders, complained that the bill kept too much of the ACA structure in place. They wanted a straight repeal of Obamacare, but party leaders said that couldn’t pass the Senate, where Republicans don’t have enough votes to stop a filibuster. They were hoping to use a complicated legislative strategy called budget reconciliation that would allow them to repeal parts of the ACA that only affect federal spending.

The decision came after a chaotic week of negotiations, as party leaders sought to woo more conservatives. The president lobbied 120 members through personal meetings or phone calls, according to a count provided Friday by his spokesman, Sean Spicer. “The president and the team here have left everything on the field,” Mr. Spicer said.

On Thursday evening, Mr. Trump dispatched Office of Management and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney to tell his former House GOP colleagues that the president wanted a vote on Friday. It was time to move on to other priorities, including tax reform, he told House Republicans.

“He said the president needs this, the president has said he wants a vote tomorrow, up or down. If for any reason it goes down, we’re just going to move forward with additional parts of his agenda. This is our moment in time,” Rep. Chris Collins (R-N.Y.), a loyal Trump ally, told reporters late Thursday. “If it doesn’t pass, we’re moving beyond health care. … We are done negotiating.”

Trump’s edict clearly irked some lawmakers, including the Freedom Caucus chairman, Rep. Mark Meadows (R-N.C), whose group of more than two dozen members represented the strongest bloc against the measure.

“Anytime you don’t have 216 votes, negotiations are not totally over,” he told reporters who had surrounded him in a Capitol basement hallway as he headed in to the party’s caucus meeting.

President Trump, Speaker Ryan, and other GOP lawmakers tweaked their initial package in a variety of ways to win over both conservatives and moderates. But every time one change was made to win votes in one camp, it repelled support in another.

The White House on Thursday accepted conservatives’ demands that the legislation strip federal guarantees of essential health benefits from insurance policies. But that was another problem for moderates, and Democrats suggested the provision would not survive in the Senate.

Republican moderates in the House – as well as the Senate – objected to the bill’s provisions that would shift Medicaid from an open-ended entitlement to a set amount of funding for states that also would give governors and state lawmakers more flexibility over the program. Moderates also were concerned that the package’s tax credits would not be generous enough to help older Americans – who could be charged five times more for coverage than would their younger counterparts – afford coverage.

The House package also lost the support of key GOP allies, including the Club for Growth and Heritage Action. Physician, patient and hospital groups also opposed it.

But Mr. Ryan’s comments made clear how difficult this decision was. “This is a disappointing day for us,” he said. “Doing big things is hard. All of us. All of us – myself included – we will need time to reflect on how we got to this moment, what we could have done to do it better.”

Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Despite days of intense negotiations and last-minute concessions to win over wavering GOP conservatives and moderates, House Republican leaders Friday failed to secure enough support to pass their plan to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act.

House Speaker Paul Ryan pulled the bill from consideration after he rushed to the White House to tell President Donald Trump that there weren’t the 216 votes necessary for passage.

“We came really close today, but we came up short,” he told reporters at a hastily called news conference.

When pressed about what happens to the federal health law, he added, “Obamacare is the law of the land. … We’re going to be living with Obamacare for the foreseeable future.”

President Trump laid the blame at the feet of Democrats, complaining that not one was willing to help Republicans on the measure, and he warned again that the Obamacare insurance markets are in serious danger. “Bad things are going to happen to Obamacare,” he told reporters at the White House. “There’s not much you can do to help it. I’ve been saying that for a year and a half. I said, look, eventually, it’s not sustainable. The insurance companies are leaving.”

But he said the collapse of the bill might allow Republicans and Democrats to work on a replacement. “I honestly believe the Democrats will come to us and say, ‘Look, let’s get together and get a great health care bill or plan that’s really great for the people of our country,’” he said.

Mr. Ryan originally had hoped to hold a floor vote on the measure Thursday – timed to coincide with the 7th anniversary of the ACA – but decided to delay that effort because GOP leaders didn’t have enough “yes” votes. The House was in session Friday, before his announcement, while members debated the bill.

House Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi (Calif.) said the speaker’s decision to pull the bill “is pretty exciting for us … a victory for the Affordable Care Act, more importantly for the American people.”

The legislation was damaged by a variety of issues raised by competing factions of the party. Many members were nervous about reports by the Congressional Budget Office showing that the bill would lead eventually to 24 million people losing insurance, while some moderate Republicans worried that ending the ACA’s Medicaid expansion would hurt low-income Americans.

At the same time, conservatives, especially the hard-right House Freedom Caucus that often has needled party leaders, complained that the bill kept too much of the ACA structure in place. They wanted a straight repeal of Obamacare, but party leaders said that couldn’t pass the Senate, where Republicans don’t have enough votes to stop a filibuster. They were hoping to use a complicated legislative strategy called budget reconciliation that would allow them to repeal parts of the ACA that only affect federal spending.

The decision came after a chaotic week of negotiations, as party leaders sought to woo more conservatives. The president lobbied 120 members through personal meetings or phone calls, according to a count provided Friday by his spokesman, Sean Spicer. “The president and the team here have left everything on the field,” Mr. Spicer said.

On Thursday evening, Mr. Trump dispatched Office of Management and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney to tell his former House GOP colleagues that the president wanted a vote on Friday. It was time to move on to other priorities, including tax reform, he told House Republicans.

“He said the president needs this, the president has said he wants a vote tomorrow, up or down. If for any reason it goes down, we’re just going to move forward with additional parts of his agenda. This is our moment in time,” Rep. Chris Collins (R-N.Y.), a loyal Trump ally, told reporters late Thursday. “If it doesn’t pass, we’re moving beyond health care. … We are done negotiating.”

Trump’s edict clearly irked some lawmakers, including the Freedom Caucus chairman, Rep. Mark Meadows (R-N.C), whose group of more than two dozen members represented the strongest bloc against the measure.

“Anytime you don’t have 216 votes, negotiations are not totally over,” he told reporters who had surrounded him in a Capitol basement hallway as he headed in to the party’s caucus meeting.

President Trump, Speaker Ryan, and other GOP lawmakers tweaked their initial package in a variety of ways to win over both conservatives and moderates. But every time one change was made to win votes in one camp, it repelled support in another.

The White House on Thursday accepted conservatives’ demands that the legislation strip federal guarantees of essential health benefits from insurance policies. But that was another problem for moderates, and Democrats suggested the provision would not survive in the Senate.

Republican moderates in the House – as well as the Senate – objected to the bill’s provisions that would shift Medicaid from an open-ended entitlement to a set amount of funding for states that also would give governors and state lawmakers more flexibility over the program. Moderates also were concerned that the package’s tax credits would not be generous enough to help older Americans – who could be charged five times more for coverage than would their younger counterparts – afford coverage.

The House package also lost the support of key GOP allies, including the Club for Growth and Heritage Action. Physician, patient and hospital groups also opposed it.

But Mr. Ryan’s comments made clear how difficult this decision was. “This is a disappointing day for us,” he said. “Doing big things is hard. All of us. All of us – myself included – we will need time to reflect on how we got to this moment, what we could have done to do it better.”

Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

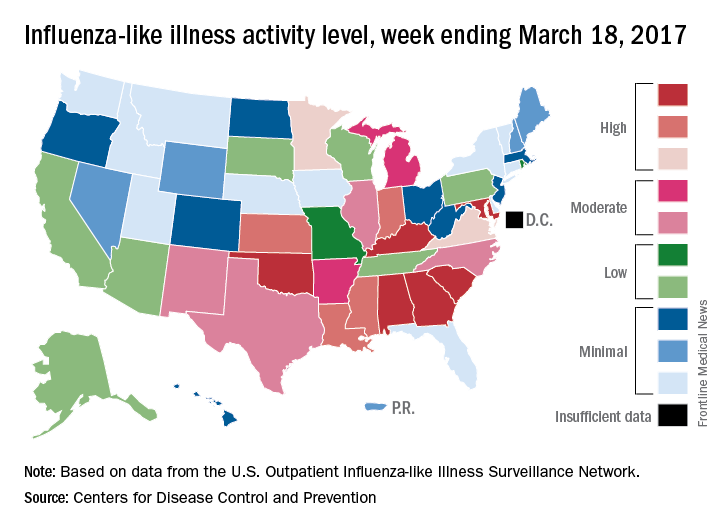

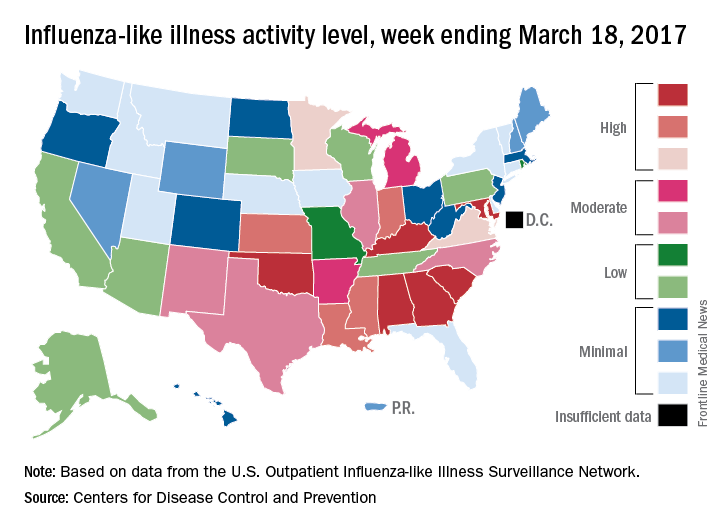

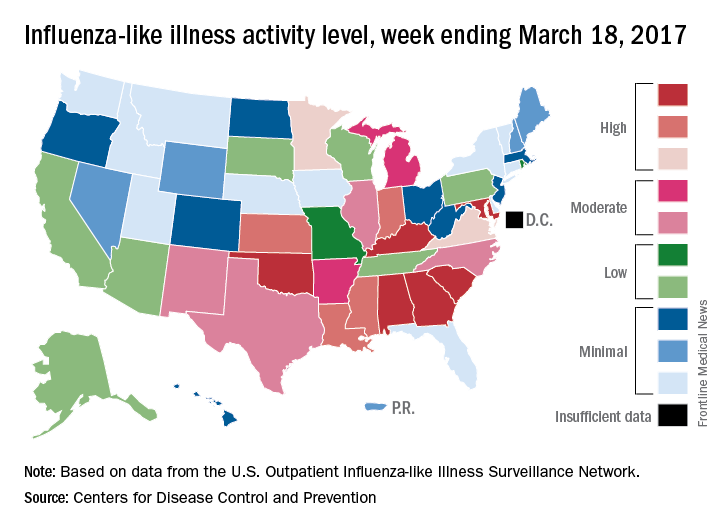

2016-2017 flu season continues to wind down

Influenza activity took another healthy step down as outpatient visits continued to drop, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was down to 3.2% for the week ending March 18, 2017, the CDC reported, compared with 3.6% the week before. (The figure of 3.7% previously reported for last week has been adjusted this week, so the halt in the decline in outpatient visits was actually more of a slowdown.) The national baseline for outpatient ILI visits is 2.2%.

Two flu-related pediatric deaths were reported during the week of March 18, but both occurred earlier: one during the week ending Feb. 18 and the other in the week ending Feb. 25, the CDC reported. The total number of pediatric flu deaths reported is now 55 for the 2016-2017 season.

Influenza activity took another healthy step down as outpatient visits continued to drop, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was down to 3.2% for the week ending March 18, 2017, the CDC reported, compared with 3.6% the week before. (The figure of 3.7% previously reported for last week has been adjusted this week, so the halt in the decline in outpatient visits was actually more of a slowdown.) The national baseline for outpatient ILI visits is 2.2%.

Two flu-related pediatric deaths were reported during the week of March 18, but both occurred earlier: one during the week ending Feb. 18 and the other in the week ending Feb. 25, the CDC reported. The total number of pediatric flu deaths reported is now 55 for the 2016-2017 season.

Influenza activity took another healthy step down as outpatient visits continued to drop, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was down to 3.2% for the week ending March 18, 2017, the CDC reported, compared with 3.6% the week before. (The figure of 3.7% previously reported for last week has been adjusted this week, so the halt in the decline in outpatient visits was actually more of a slowdown.) The national baseline for outpatient ILI visits is 2.2%.

Two flu-related pediatric deaths were reported during the week of March 18, but both occurred earlier: one during the week ending Feb. 18 and the other in the week ending Feb. 25, the CDC reported. The total number of pediatric flu deaths reported is now 55 for the 2016-2017 season.

SPECT reveals perfusion problems in antiphospholipid syndrome

MELBOURNE – SPECT imaging can identify abnormalities in brain perfusion in patients with multiple antiphospholipid antibodies and neuropsychiatric symptoms, but without a history of thrombosis, according to a study presented at an international congress on systemic lupus erythematosus.

The retrospective study by researchers from National Taiwan University Hospital addresses the challenge posed by patients who have antiphospholipid antibodies and neuropsychiatric symptoms but do not meet the full criteria for antiphospholipid syndrome because of a lack of a history of thromboembolism. Current antiphospholipid syndrome classification criteria are based on thrombosis or pregnancy loss, with a third category of noncriteria manifestations that include a range of neuropsychiatric symptoms, said presenter Ting-Syuan Lin, MD, of the Yun-Lin Branch of National Taiwan University Hospital.

“Some physicians may not give the patient early treatment because they do not fill the criteria,” Dr. Lin said in an interview. “But if we have SPECT image to document the abnormality, then the physician can have more confidence to give them early treatment.”

Dr. Lin and his colleagues looked at the brain SPECT images of 54 patients with a history of positive antiphospholipid antibodies and neuropsychiatric symptoms, but who had no history of thromboembolism or other lupus-related antibodies such as antibodies to double-stranded DNA. When the researchers looked simply at mean brain perfusion according to the number of antiphospholipid antibodies each patient had, they found no significant differences between the groups, including a control group of six patients without antiphospholipid antibodies.

But when they examined heterogeneity of brain perfusion, they saw significantly greater heterogeneity (P = .01) in patients with four antiphospholipid antibodies compared with patients who had no antibodies.

The patients enrolled in the study presented with a range of neuropsychiatric symptoms. The most common was headache (56.7%), followed by dizziness (41.7%), depression (28.3%), psychosis (15%), vertigo (8.3%), and seizures (6.7%). The mean age of the patients was 38 years, and 52 of the patients were women.

One of the patients – a 39-year-old woman with more than four antiphospholipid antibodies – had a normal CT scan but showed significant heterogeneity in brain perfusion on the SPECT imaging. She experienced a stroke 1 year after the study.

Commenting on the presentation, session cochair Timothy Godfrey, MBBS, of St. Vincent’s Hospital in Melbourne, said neuropsychiatric lupus was particularly problematic, especially when patients had normal imaging.

“You’re wondering is the patient just depressed or is there some other explanation, or do they truly have a manifestation of lupus which may require immunosuppression or anticoagulation?” he said in an interview.

This study “is highlighting the fact that maybe we do need to do these tests when the MRI is normal, particularly in people that have documented abnormalities in their blood test.”

Dr. Lin said the next phase of the study would look at whether treatment was associated with changes in brain perfusion on SPECT, and whether the abnormality of the SPECT imaging correlated with clinical outcomes.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

MELBOURNE – SPECT imaging can identify abnormalities in brain perfusion in patients with multiple antiphospholipid antibodies and neuropsychiatric symptoms, but without a history of thrombosis, according to a study presented at an international congress on systemic lupus erythematosus.

The retrospective study by researchers from National Taiwan University Hospital addresses the challenge posed by patients who have antiphospholipid antibodies and neuropsychiatric symptoms but do not meet the full criteria for antiphospholipid syndrome because of a lack of a history of thromboembolism. Current antiphospholipid syndrome classification criteria are based on thrombosis or pregnancy loss, with a third category of noncriteria manifestations that include a range of neuropsychiatric symptoms, said presenter Ting-Syuan Lin, MD, of the Yun-Lin Branch of National Taiwan University Hospital.

“Some physicians may not give the patient early treatment because they do not fill the criteria,” Dr. Lin said in an interview. “But if we have SPECT image to document the abnormality, then the physician can have more confidence to give them early treatment.”

Dr. Lin and his colleagues looked at the brain SPECT images of 54 patients with a history of positive antiphospholipid antibodies and neuropsychiatric symptoms, but who had no history of thromboembolism or other lupus-related antibodies such as antibodies to double-stranded DNA. When the researchers looked simply at mean brain perfusion according to the number of antiphospholipid antibodies each patient had, they found no significant differences between the groups, including a control group of six patients without antiphospholipid antibodies.

But when they examined heterogeneity of brain perfusion, they saw significantly greater heterogeneity (P = .01) in patients with four antiphospholipid antibodies compared with patients who had no antibodies.

The patients enrolled in the study presented with a range of neuropsychiatric symptoms. The most common was headache (56.7%), followed by dizziness (41.7%), depression (28.3%), psychosis (15%), vertigo (8.3%), and seizures (6.7%). The mean age of the patients was 38 years, and 52 of the patients were women.

One of the patients – a 39-year-old woman with more than four antiphospholipid antibodies – had a normal CT scan but showed significant heterogeneity in brain perfusion on the SPECT imaging. She experienced a stroke 1 year after the study.

Commenting on the presentation, session cochair Timothy Godfrey, MBBS, of St. Vincent’s Hospital in Melbourne, said neuropsychiatric lupus was particularly problematic, especially when patients had normal imaging.

“You’re wondering is the patient just depressed or is there some other explanation, or do they truly have a manifestation of lupus which may require immunosuppression or anticoagulation?” he said in an interview.

This study “is highlighting the fact that maybe we do need to do these tests when the MRI is normal, particularly in people that have documented abnormalities in their blood test.”

Dr. Lin said the next phase of the study would look at whether treatment was associated with changes in brain perfusion on SPECT, and whether the abnormality of the SPECT imaging correlated with clinical outcomes.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

MELBOURNE – SPECT imaging can identify abnormalities in brain perfusion in patients with multiple antiphospholipid antibodies and neuropsychiatric symptoms, but without a history of thrombosis, according to a study presented at an international congress on systemic lupus erythematosus.

The retrospective study by researchers from National Taiwan University Hospital addresses the challenge posed by patients who have antiphospholipid antibodies and neuropsychiatric symptoms but do not meet the full criteria for antiphospholipid syndrome because of a lack of a history of thromboembolism. Current antiphospholipid syndrome classification criteria are based on thrombosis or pregnancy loss, with a third category of noncriteria manifestations that include a range of neuropsychiatric symptoms, said presenter Ting-Syuan Lin, MD, of the Yun-Lin Branch of National Taiwan University Hospital.

“Some physicians may not give the patient early treatment because they do not fill the criteria,” Dr. Lin said in an interview. “But if we have SPECT image to document the abnormality, then the physician can have more confidence to give them early treatment.”

Dr. Lin and his colleagues looked at the brain SPECT images of 54 patients with a history of positive antiphospholipid antibodies and neuropsychiatric symptoms, but who had no history of thromboembolism or other lupus-related antibodies such as antibodies to double-stranded DNA. When the researchers looked simply at mean brain perfusion according to the number of antiphospholipid antibodies each patient had, they found no significant differences between the groups, including a control group of six patients without antiphospholipid antibodies.

But when they examined heterogeneity of brain perfusion, they saw significantly greater heterogeneity (P = .01) in patients with four antiphospholipid antibodies compared with patients who had no antibodies.

The patients enrolled in the study presented with a range of neuropsychiatric symptoms. The most common was headache (56.7%), followed by dizziness (41.7%), depression (28.3%), psychosis (15%), vertigo (8.3%), and seizures (6.7%). The mean age of the patients was 38 years, and 52 of the patients were women.

One of the patients – a 39-year-old woman with more than four antiphospholipid antibodies – had a normal CT scan but showed significant heterogeneity in brain perfusion on the SPECT imaging. She experienced a stroke 1 year after the study.

Commenting on the presentation, session cochair Timothy Godfrey, MBBS, of St. Vincent’s Hospital in Melbourne, said neuropsychiatric lupus was particularly problematic, especially when patients had normal imaging.

“You’re wondering is the patient just depressed or is there some other explanation, or do they truly have a manifestation of lupus which may require immunosuppression or anticoagulation?” he said in an interview.

This study “is highlighting the fact that maybe we do need to do these tests when the MRI is normal, particularly in people that have documented abnormalities in their blood test.”

Dr. Lin said the next phase of the study would look at whether treatment was associated with changes in brain perfusion on SPECT, and whether the abnormality of the SPECT imaging correlated with clinical outcomes.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

AT LUPUS 2017

Key clinical point: SPECT may be worthwhile in patients who don’t meet antiphospholipid syndrome criteria but have aPL antibodies, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and no thrombosis history.

Major finding: Patients with four antiphospholipid antibodies have significantly greater heterogeneity in brain perfusion on SPECT imaging than do patients with no antiphospholipid antibodies.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study in 54 patients with antiphospholipid syndrome.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest were declared.

Oral agent found promising for subset of chronic rhinosinusitis patients

ATLANTA – The use of dexpramipexole by patients with chronic rhinosinusitis was well tolerated and showed robust and tissue eosinophil–lowering activity, according to results from a small study.

Dexpramipexole is an investigational oral agent that has been studied in previous clinical trials for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Calman Prussin, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. The drug did not meet the clinical endpoint for ALS patients, but its investigators noted that it lowered eosinophil counts by about 50%. “It was a serendipitous finding,” said Dr. Prussin, senior director of clinical and translational medicine for Pittsburgh-based Knopp Biosciences. “We do not have a mechanism of action, but we think it’s working on progenitor cells in the bone marrow.”

In all, 16 of the 20 patients completed the trial. Dr. Prussin and his associates found that the baseline eosinophil count fell from 0.525 x 109/L to 0.031 x 109/L at 6 months, a reduction of 94% (P less than.001). “I don’t think any of us expected to see this,” he said, noting that the drug’s maximal eosinophil-lowering effect was maximal after 2 months. No reduction in total polyp score was observed.

Biopsies conducted in 12 of the patients revealed that polyp tissue eosinophilia was reduced from a mean of 233 to 5 eosinophils/high-powered field, a drop of 97% (P = .001). No serious drug-related adverse effects occurred. The most common adverse event was infection (50%), followed by respiratory symptoms (35%) and gastrointestinal disorders (20%).

Knopp Biosciences funded the study. Dr. Prussin is an employee of the company.

ATLANTA – The use of dexpramipexole by patients with chronic rhinosinusitis was well tolerated and showed robust and tissue eosinophil–lowering activity, according to results from a small study.

Dexpramipexole is an investigational oral agent that has been studied in previous clinical trials for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Calman Prussin, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. The drug did not meet the clinical endpoint for ALS patients, but its investigators noted that it lowered eosinophil counts by about 50%. “It was a serendipitous finding,” said Dr. Prussin, senior director of clinical and translational medicine for Pittsburgh-based Knopp Biosciences. “We do not have a mechanism of action, but we think it’s working on progenitor cells in the bone marrow.”

In all, 16 of the 20 patients completed the trial. Dr. Prussin and his associates found that the baseline eosinophil count fell from 0.525 x 109/L to 0.031 x 109/L at 6 months, a reduction of 94% (P less than.001). “I don’t think any of us expected to see this,” he said, noting that the drug’s maximal eosinophil-lowering effect was maximal after 2 months. No reduction in total polyp score was observed.

Biopsies conducted in 12 of the patients revealed that polyp tissue eosinophilia was reduced from a mean of 233 to 5 eosinophils/high-powered field, a drop of 97% (P = .001). No serious drug-related adverse effects occurred. The most common adverse event was infection (50%), followed by respiratory symptoms (35%) and gastrointestinal disorders (20%).

Knopp Biosciences funded the study. Dr. Prussin is an employee of the company.

ATLANTA – The use of dexpramipexole by patients with chronic rhinosinusitis was well tolerated and showed robust and tissue eosinophil–lowering activity, according to results from a small study.

Dexpramipexole is an investigational oral agent that has been studied in previous clinical trials for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Calman Prussin, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. The drug did not meet the clinical endpoint for ALS patients, but its investigators noted that it lowered eosinophil counts by about 50%. “It was a serendipitous finding,” said Dr. Prussin, senior director of clinical and translational medicine for Pittsburgh-based Knopp Biosciences. “We do not have a mechanism of action, but we think it’s working on progenitor cells in the bone marrow.”

In all, 16 of the 20 patients completed the trial. Dr. Prussin and his associates found that the baseline eosinophil count fell from 0.525 x 109/L to 0.031 x 109/L at 6 months, a reduction of 94% (P less than.001). “I don’t think any of us expected to see this,” he said, noting that the drug’s maximal eosinophil-lowering effect was maximal after 2 months. No reduction in total polyp score was observed.

Biopsies conducted in 12 of the patients revealed that polyp tissue eosinophilia was reduced from a mean of 233 to 5 eosinophils/high-powered field, a drop of 97% (P = .001). No serious drug-related adverse effects occurred. The most common adverse event was infection (50%), followed by respiratory symptoms (35%) and gastrointestinal disorders (20%).

Knopp Biosciences funded the study. Dr. Prussin is an employee of the company.

AT THE 2017 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The baseline eosinophil count fell from 0.525 x 109/L to 0.031 x 109/L at 6 months, a reduction of 94% (P less than .001).

Data source: Results from a open-label trial in 16 chronic rhinosinusitis patients who received dexpramipexole 150 mg b.i.d. for 6 months.

Disclosures: Knopp Biosciences funded the study. Dr. Prussin is an employee of the company.

Freezing of Gait May Be Associated With Anxiety and Depression in Parkinson’s Disease

MIAMI—Freezing of gait in Parkinson's disease may be associated with higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms, as well as recurrent falls and lower quality of life, according to research presented at the First Pan American Parkinson's Disease and Movement Disorders Congress.

"Our data suggest that people with Parkinson's disease and freezing of gait have advanced disease, functional limitations, lower balance confidence, and a higher level of anxiety and depressive symptoms, which may negatively impact their quality of life," said Milla Pimenta, a medical student at the Bahiana School of Medicine and Public Health in Brazil, and colleagues. "Future prospective studies should elucidate whether the treatment of anxiety can contribute to reduce the frequency or severity of freezing of gait episodes."

To identify the association between freezing of gait and symptoms of anxiety and depression, the researchers recruited consecutive patients with idiopathic Parkinson's disease and independent walking ability from the Movement Disorders Clinic at the State of Bahia Health Attention Center for the Elderly in Brazil. They excluded patients with other neurologic conditions or comorbidities that affect balance.

The investigators assessed patients' demographics, Parkinson's disease severity and symptoms, medication, disability, freezing, anxiety, depression, self-efficacy, and quality of life.

A total of 78 people with Parkinson's disease (mean age, 70.5; mean Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale motor score, 32; Hoehn and Yahr stages between 1.5 and 4) were included in the study.

Twenty-seven participants (35%) were identified as having freezing of gait (ie, they scored at least 1 point on item 3 of the Freezing of Gait Questionnaire).

Patients with freezing of gait had higher Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale scores and lower Activities-Specific Balance Confidence Scale scores, compared with patients without freezing.

Patients with freezing of gait were more likely to have had recurrent falls in the previous year. In addition, patients with freezing had longer median disease duration (nine years versus four years) and received a higher median levodopa equivalent dose (800 mg/day vs 532 mg/day) than patients without freezing. Quality of life, as assessed by the eight-item Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire, was worse in patients with freezing of gait (40.6 vs 25).

—Jake Remaly

MIAMI—Freezing of gait in Parkinson's disease may be associated with higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms, as well as recurrent falls and lower quality of life, according to research presented at the First Pan American Parkinson's Disease and Movement Disorders Congress.

"Our data suggest that people with Parkinson's disease and freezing of gait have advanced disease, functional limitations, lower balance confidence, and a higher level of anxiety and depressive symptoms, which may negatively impact their quality of life," said Milla Pimenta, a medical student at the Bahiana School of Medicine and Public Health in Brazil, and colleagues. "Future prospective studies should elucidate whether the treatment of anxiety can contribute to reduce the frequency or severity of freezing of gait episodes."

To identify the association between freezing of gait and symptoms of anxiety and depression, the researchers recruited consecutive patients with idiopathic Parkinson's disease and independent walking ability from the Movement Disorders Clinic at the State of Bahia Health Attention Center for the Elderly in Brazil. They excluded patients with other neurologic conditions or comorbidities that affect balance.

The investigators assessed patients' demographics, Parkinson's disease severity and symptoms, medication, disability, freezing, anxiety, depression, self-efficacy, and quality of life.

A total of 78 people with Parkinson's disease (mean age, 70.5; mean Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale motor score, 32; Hoehn and Yahr stages between 1.5 and 4) were included in the study.

Twenty-seven participants (35%) were identified as having freezing of gait (ie, they scored at least 1 point on item 3 of the Freezing of Gait Questionnaire).

Patients with freezing of gait had higher Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale scores and lower Activities-Specific Balance Confidence Scale scores, compared with patients without freezing.

Patients with freezing of gait were more likely to have had recurrent falls in the previous year. In addition, patients with freezing had longer median disease duration (nine years versus four years) and received a higher median levodopa equivalent dose (800 mg/day vs 532 mg/day) than patients without freezing. Quality of life, as assessed by the eight-item Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire, was worse in patients with freezing of gait (40.6 vs 25).

—Jake Remaly

MIAMI—Freezing of gait in Parkinson's disease may be associated with higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms, as well as recurrent falls and lower quality of life, according to research presented at the First Pan American Parkinson's Disease and Movement Disorders Congress.

"Our data suggest that people with Parkinson's disease and freezing of gait have advanced disease, functional limitations, lower balance confidence, and a higher level of anxiety and depressive symptoms, which may negatively impact their quality of life," said Milla Pimenta, a medical student at the Bahiana School of Medicine and Public Health in Brazil, and colleagues. "Future prospective studies should elucidate whether the treatment of anxiety can contribute to reduce the frequency or severity of freezing of gait episodes."

To identify the association between freezing of gait and symptoms of anxiety and depression, the researchers recruited consecutive patients with idiopathic Parkinson's disease and independent walking ability from the Movement Disorders Clinic at the State of Bahia Health Attention Center for the Elderly in Brazil. They excluded patients with other neurologic conditions or comorbidities that affect balance.

The investigators assessed patients' demographics, Parkinson's disease severity and symptoms, medication, disability, freezing, anxiety, depression, self-efficacy, and quality of life.

A total of 78 people with Parkinson's disease (mean age, 70.5; mean Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale motor score, 32; Hoehn and Yahr stages between 1.5 and 4) were included in the study.

Twenty-seven participants (35%) were identified as having freezing of gait (ie, they scored at least 1 point on item 3 of the Freezing of Gait Questionnaire).

Patients with freezing of gait had higher Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale scores and lower Activities-Specific Balance Confidence Scale scores, compared with patients without freezing.

Patients with freezing of gait were more likely to have had recurrent falls in the previous year. In addition, patients with freezing had longer median disease duration (nine years versus four years) and received a higher median levodopa equivalent dose (800 mg/day vs 532 mg/day) than patients without freezing. Quality of life, as assessed by the eight-item Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire, was worse in patients with freezing of gait (40.6 vs 25).

—Jake Remaly

Advanced CLL treatment approach depends on comorbidity burden

ORLANDO – The choice of first-line therapy in symptomatic chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients depends largely on comorbidity burden, Andrew D. Zelenetz, MD, PhD, said at the annual conference of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

“This is a disease of elderly patients. Frequently they have comorbidities,” he said. Categorizing these patients as having a low or high comorbidity burden can be done with the Cumulative Index Rating Scale score, which involves scoring of all organ systems on a 0-5 scale representing “not affected” to “extremely disabled.”

“We use this to determine first-line therapy,” said Dr. Zelenetz of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York. Dr. Zelenetz is chair of the NCCN Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Guidelines panel.

Patients with a score of greater than 12 on the 0- to 56-point scale, are “no-go” patients with respect to therapy, and are typically treated only with palliative approaches. Those with a score of 7-12 (“slow-go” patients) have a significant comorbidity burden, but can undergo treatment, thought typically to be at reduced intensity. Those with a score of 0-6 are “go-go” patients with respect to treatment, as they are physically fit, have excellent renal function, and have no significant comorbidities, he said.

Treatment options for ‘go-go’ CLL patients

Among the treatment options for the latter is FCR–the combination of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab, which was shown in the phase III CLL10 trial of patients with advanced CLL to be associated with improved complete response rates compared with the popular regimen of bendamustine and rituximab (BR), both overall and in patients under age 65. In older patients, the advantage disappeared, Dr. Zelenetz said.

FCR was also associated with improved outcomes vs. BR in patients with del(11q).

The primary endpoint of the study was progression-free survival, which favored FCR (median of 55.2 vs. 41.7 months; hazard ratio, 1.643), he said, noting that no difference was seen between the two regimens in terms of overall survival.

In a recent publication, MD Anderson Cancer Center reported its experience with its first 300 CLL patients treated with FCR. With long-term follow-up of at least 9-10 years (median of 12.8 years), patients in this trial have done extremely well.

“But interestingly, when you stratify these patients by whether they have IGHV [immunoglobulin heavy chain variable] mutated or unmutated [disease], the IGHV mutated patients have something that looks a whole lot like a survival plateau, and that survival plateau is not trivial – it’s about 60%,” he said. “So there is a group of patients with CLL who are, in fact, curable with conventional chemoimmunotherapy.

“This is an appropriate treatment for a young, fit, ‘go-go’ patient, and it has a big implication,” he said. That is, patients who are young and fit require IGHV mutation testing, as “you will absolutely choose FCR chemotherapy for the fit, young patients who has IGHV mutated disease.

“In that setting IGHV testing is now mandatory,” he stressed, noting that the benefits in this population extend to overall survival as well as progression-free survival.

Dr. Zelenetz also emphasized the need for increasing the single dose of rituximab from 375 mg/m2 during cycle 1 to 500 mg/m2 during cycles 2-6 in those receiving FCR, as this is often forgotten.

The data demonstrating the efficacy of FCR were based on this approach, he said.

Fludarabine is to be given at a dose of 25 mg/m2, and cyclophosphamide at a dose of 250 mg/m2 – both for 2-4 days during cycle 1 and for 1-3 days during cycles 2-6.

Treatment options for ‘slow-go’ CLL patients

In “slow-go” patients, an interesting approach is to use new anti-CD20 antibodies such as ofatumumab and obinutuzumab, which have features that are distinct from rituximab.

Both have been studied in CLL. The CLL11 trial compared chlorambucil, rituximab+chlorambucil, and obinutuzumab+chlorambucil, and the latest analysis showed substantial improvement in progression-free survival with obinutuzumab+chlorambucil vs. the other two regimens (26.7 months vs. 11.1 and 16.3 months, respectively), Dr. Zelenetz said, noting that rituximab+chlorambucil was also superior to chlorambucil alone, but that only the obinutuzumab regimen had an overall survival advantage vs. chlorambucil alone.

An updated analysis to be reported soon will show emerging evidence of a survival advantage of obinutuzumab+chlorambucil vs. rituximab+chlorambucil, he said.

“This suggests that obinutuzumab is a far better antibody,” he added, noting that the reasons for that are under debate, “but the way it’s given, it works better in CLL, and that, I think is unequivocal.”

A similar study looking at chlorambucil with and without ofatumumab in “slow-go” patients also demonstrated an improvement in PFS with ofatumumab, but showed “no difference whatsoever in overall survival.”

“This is actually very similar to the rituximab result, and I actually call this the ‘death of ofatumumab’ study, because clearly obinutuzumab in CLL is, I think, a superior anti-CD20 antibody,” Dr. Zelenetz said.

Studies in which obinutuzumab is substituted for rituximab in the FCR combination are currently underway as are a number of other studies of obinutuzumab, he noted.

Another treatment option in the up-front setting is ibrutinib, which was shown to be effective in the RESONATE 2 trial .

“But notice, a very, very small [complete response rate]. CRs are very difficult to achieve with ibrutinib alone, so this drug is given continuously, lifelong,” Dr. Zelenetz said, noting that it was, however, associated with an overall survival advantage vs. chlorambucil.

“Should this be the standard of care? I think it is in patients who have del(17p) or mutation of TP53. Outside of that setting, I’m still concerned about the cost of long-term tolerability of the agent,” he said.

Future of first-line CLL treatment

Avoidance of long-term therapy and conventional chemotherapy in patients with CLL is a goal, he added, noting that new understanding from studies in patients in the relapsed/refractory CLL setting – such as recent findings from a phase Ib study of venetoclax plus rituximab, which demonstrated potentially durable responses after treatment discontinuation in minimal residual disease (MRD)–negative patients – are providing insights into achieving MRD negativity that could be applied in the front line treatment setting.

“We’re still trying to figure out how to best use this. We want to try to use some of this knowledge about achievement of MRD negativity in the up-front setting so we don’t have to give patients long-term therapy, and we would like to avoid conventional chemotherapy,” he said. “So I’m hoping we’re going to be able to replace chronic long-term therapy of CLL with a defined course of treatment with high levels of MRD negativity.”

Dr. Zelenetz reported receiving consulting fees, honoraria, and/or grant/research support from Acerta Pharma, Amgen Inc., BeiGene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene Corporation, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Janssen Pharmaceutica Products, MEI Pharma, NanoString Technologies, Pharmacyclics, Portola Pharmaceuticals, Roche Laboratories, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America.

ORLANDO – The choice of first-line therapy in symptomatic chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients depends largely on comorbidity burden, Andrew D. Zelenetz, MD, PhD, said at the annual conference of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

“This is a disease of elderly patients. Frequently they have comorbidities,” he said. Categorizing these patients as having a low or high comorbidity burden can be done with the Cumulative Index Rating Scale score, which involves scoring of all organ systems on a 0-5 scale representing “not affected” to “extremely disabled.”

“We use this to determine first-line therapy,” said Dr. Zelenetz of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York. Dr. Zelenetz is chair of the NCCN Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Guidelines panel.

Patients with a score of greater than 12 on the 0- to 56-point scale, are “no-go” patients with respect to therapy, and are typically treated only with palliative approaches. Those with a score of 7-12 (“slow-go” patients) have a significant comorbidity burden, but can undergo treatment, thought typically to be at reduced intensity. Those with a score of 0-6 are “go-go” patients with respect to treatment, as they are physically fit, have excellent renal function, and have no significant comorbidities, he said.

Treatment options for ‘go-go’ CLL patients

Among the treatment options for the latter is FCR–the combination of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab, which was shown in the phase III CLL10 trial of patients with advanced CLL to be associated with improved complete response rates compared with the popular regimen of bendamustine and rituximab (BR), both overall and in patients under age 65. In older patients, the advantage disappeared, Dr. Zelenetz said.

FCR was also associated with improved outcomes vs. BR in patients with del(11q).

The primary endpoint of the study was progression-free survival, which favored FCR (median of 55.2 vs. 41.7 months; hazard ratio, 1.643), he said, noting that no difference was seen between the two regimens in terms of overall survival.

In a recent publication, MD Anderson Cancer Center reported its experience with its first 300 CLL patients treated with FCR. With long-term follow-up of at least 9-10 years (median of 12.8 years), patients in this trial have done extremely well.

“But interestingly, when you stratify these patients by whether they have IGHV [immunoglobulin heavy chain variable] mutated or unmutated [disease], the IGHV mutated patients have something that looks a whole lot like a survival plateau, and that survival plateau is not trivial – it’s about 60%,” he said. “So there is a group of patients with CLL who are, in fact, curable with conventional chemoimmunotherapy.

“This is an appropriate treatment for a young, fit, ‘go-go’ patient, and it has a big implication,” he said. That is, patients who are young and fit require IGHV mutation testing, as “you will absolutely choose FCR chemotherapy for the fit, young patients who has IGHV mutated disease.

“In that setting IGHV testing is now mandatory,” he stressed, noting that the benefits in this population extend to overall survival as well as progression-free survival.

Dr. Zelenetz also emphasized the need for increasing the single dose of rituximab from 375 mg/m2 during cycle 1 to 500 mg/m2 during cycles 2-6 in those receiving FCR, as this is often forgotten.

The data demonstrating the efficacy of FCR were based on this approach, he said.

Fludarabine is to be given at a dose of 25 mg/m2, and cyclophosphamide at a dose of 250 mg/m2 – both for 2-4 days during cycle 1 and for 1-3 days during cycles 2-6.

Treatment options for ‘slow-go’ CLL patients

In “slow-go” patients, an interesting approach is to use new anti-CD20 antibodies such as ofatumumab and obinutuzumab, which have features that are distinct from rituximab.

Both have been studied in CLL. The CLL11 trial compared chlorambucil, rituximab+chlorambucil, and obinutuzumab+chlorambucil, and the latest analysis showed substantial improvement in progression-free survival with obinutuzumab+chlorambucil vs. the other two regimens (26.7 months vs. 11.1 and 16.3 months, respectively), Dr. Zelenetz said, noting that rituximab+chlorambucil was also superior to chlorambucil alone, but that only the obinutuzumab regimen had an overall survival advantage vs. chlorambucil alone.

An updated analysis to be reported soon will show emerging evidence of a survival advantage of obinutuzumab+chlorambucil vs. rituximab+chlorambucil, he said.

“This suggests that obinutuzumab is a far better antibody,” he added, noting that the reasons for that are under debate, “but the way it’s given, it works better in CLL, and that, I think is unequivocal.”

A similar study looking at chlorambucil with and without ofatumumab in “slow-go” patients also demonstrated an improvement in PFS with ofatumumab, but showed “no difference whatsoever in overall survival.”

“This is actually very similar to the rituximab result, and I actually call this the ‘death of ofatumumab’ study, because clearly obinutuzumab in CLL is, I think, a superior anti-CD20 antibody,” Dr. Zelenetz said.

Studies in which obinutuzumab is substituted for rituximab in the FCR combination are currently underway as are a number of other studies of obinutuzumab, he noted.

Another treatment option in the up-front setting is ibrutinib, which was shown to be effective in the RESONATE 2 trial .

“But notice, a very, very small [complete response rate]. CRs are very difficult to achieve with ibrutinib alone, so this drug is given continuously, lifelong,” Dr. Zelenetz said, noting that it was, however, associated with an overall survival advantage vs. chlorambucil.

“Should this be the standard of care? I think it is in patients who have del(17p) or mutation of TP53. Outside of that setting, I’m still concerned about the cost of long-term tolerability of the agent,” he said.

Future of first-line CLL treatment

Avoidance of long-term therapy and conventional chemotherapy in patients with CLL is a goal, he added, noting that new understanding from studies in patients in the relapsed/refractory CLL setting – such as recent findings from a phase Ib study of venetoclax plus rituximab, which demonstrated potentially durable responses after treatment discontinuation in minimal residual disease (MRD)–negative patients – are providing insights into achieving MRD negativity that could be applied in the front line treatment setting.

“We’re still trying to figure out how to best use this. We want to try to use some of this knowledge about achievement of MRD negativity in the up-front setting so we don’t have to give patients long-term therapy, and we would like to avoid conventional chemotherapy,” he said. “So I’m hoping we’re going to be able to replace chronic long-term therapy of CLL with a defined course of treatment with high levels of MRD negativity.”

Dr. Zelenetz reported receiving consulting fees, honoraria, and/or grant/research support from Acerta Pharma, Amgen Inc., BeiGene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene Corporation, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Janssen Pharmaceutica Products, MEI Pharma, NanoString Technologies, Pharmacyclics, Portola Pharmaceuticals, Roche Laboratories, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America.

ORLANDO – The choice of first-line therapy in symptomatic chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients depends largely on comorbidity burden, Andrew D. Zelenetz, MD, PhD, said at the annual conference of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

“This is a disease of elderly patients. Frequently they have comorbidities,” he said. Categorizing these patients as having a low or high comorbidity burden can be done with the Cumulative Index Rating Scale score, which involves scoring of all organ systems on a 0-5 scale representing “not affected” to “extremely disabled.”

“We use this to determine first-line therapy,” said Dr. Zelenetz of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York. Dr. Zelenetz is chair of the NCCN Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Guidelines panel.

Patients with a score of greater than 12 on the 0- to 56-point scale, are “no-go” patients with respect to therapy, and are typically treated only with palliative approaches. Those with a score of 7-12 (“slow-go” patients) have a significant comorbidity burden, but can undergo treatment, thought typically to be at reduced intensity. Those with a score of 0-6 are “go-go” patients with respect to treatment, as they are physically fit, have excellent renal function, and have no significant comorbidities, he said.

Treatment options for ‘go-go’ CLL patients

Among the treatment options for the latter is FCR–the combination of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab, which was shown in the phase III CLL10 trial of patients with advanced CLL to be associated with improved complete response rates compared with the popular regimen of bendamustine and rituximab (BR), both overall and in patients under age 65. In older patients, the advantage disappeared, Dr. Zelenetz said.

FCR was also associated with improved outcomes vs. BR in patients with del(11q).

The primary endpoint of the study was progression-free survival, which favored FCR (median of 55.2 vs. 41.7 months; hazard ratio, 1.643), he said, noting that no difference was seen between the two regimens in terms of overall survival.

In a recent publication, MD Anderson Cancer Center reported its experience with its first 300 CLL patients treated with FCR. With long-term follow-up of at least 9-10 years (median of 12.8 years), patients in this trial have done extremely well.

“But interestingly, when you stratify these patients by whether they have IGHV [immunoglobulin heavy chain variable] mutated or unmutated [disease], the IGHV mutated patients have something that looks a whole lot like a survival plateau, and that survival plateau is not trivial – it’s about 60%,” he said. “So there is a group of patients with CLL who are, in fact, curable with conventional chemoimmunotherapy.

“This is an appropriate treatment for a young, fit, ‘go-go’ patient, and it has a big implication,” he said. That is, patients who are young and fit require IGHV mutation testing, as “you will absolutely choose FCR chemotherapy for the fit, young patients who has IGHV mutated disease.

“In that setting IGHV testing is now mandatory,” he stressed, noting that the benefits in this population extend to overall survival as well as progression-free survival.

Dr. Zelenetz also emphasized the need for increasing the single dose of rituximab from 375 mg/m2 during cycle 1 to 500 mg/m2 during cycles 2-6 in those receiving FCR, as this is often forgotten.

The data demonstrating the efficacy of FCR were based on this approach, he said.

Fludarabine is to be given at a dose of 25 mg/m2, and cyclophosphamide at a dose of 250 mg/m2 – both for 2-4 days during cycle 1 and for 1-3 days during cycles 2-6.

Treatment options for ‘slow-go’ CLL patients

In “slow-go” patients, an interesting approach is to use new anti-CD20 antibodies such as ofatumumab and obinutuzumab, which have features that are distinct from rituximab.

Both have been studied in CLL. The CLL11 trial compared chlorambucil, rituximab+chlorambucil, and obinutuzumab+chlorambucil, and the latest analysis showed substantial improvement in progression-free survival with obinutuzumab+chlorambucil vs. the other two regimens (26.7 months vs. 11.1 and 16.3 months, respectively), Dr. Zelenetz said, noting that rituximab+chlorambucil was also superior to chlorambucil alone, but that only the obinutuzumab regimen had an overall survival advantage vs. chlorambucil alone.

An updated analysis to be reported soon will show emerging evidence of a survival advantage of obinutuzumab+chlorambucil vs. rituximab+chlorambucil, he said.

“This suggests that obinutuzumab is a far better antibody,” he added, noting that the reasons for that are under debate, “but the way it’s given, it works better in CLL, and that, I think is unequivocal.”

A similar study looking at chlorambucil with and without ofatumumab in “slow-go” patients also demonstrated an improvement in PFS with ofatumumab, but showed “no difference whatsoever in overall survival.”

“This is actually very similar to the rituximab result, and I actually call this the ‘death of ofatumumab’ study, because clearly obinutuzumab in CLL is, I think, a superior anti-CD20 antibody,” Dr. Zelenetz said.

Studies in which obinutuzumab is substituted for rituximab in the FCR combination are currently underway as are a number of other studies of obinutuzumab, he noted.

Another treatment option in the up-front setting is ibrutinib, which was shown to be effective in the RESONATE 2 trial .

“But notice, a very, very small [complete response rate]. CRs are very difficult to achieve with ibrutinib alone, so this drug is given continuously, lifelong,” Dr. Zelenetz said, noting that it was, however, associated with an overall survival advantage vs. chlorambucil.

“Should this be the standard of care? I think it is in patients who have del(17p) or mutation of TP53. Outside of that setting, I’m still concerned about the cost of long-term tolerability of the agent,” he said.

Future of first-line CLL treatment

Avoidance of long-term therapy and conventional chemotherapy in patients with CLL is a goal, he added, noting that new understanding from studies in patients in the relapsed/refractory CLL setting – such as recent findings from a phase Ib study of venetoclax plus rituximab, which demonstrated potentially durable responses after treatment discontinuation in minimal residual disease (MRD)–negative patients – are providing insights into achieving MRD negativity that could be applied in the front line treatment setting.

“We’re still trying to figure out how to best use this. We want to try to use some of this knowledge about achievement of MRD negativity in the up-front setting so we don’t have to give patients long-term therapy, and we would like to avoid conventional chemotherapy,” he said. “So I’m hoping we’re going to be able to replace chronic long-term therapy of CLL with a defined course of treatment with high levels of MRD negativity.”

Dr. Zelenetz reported receiving consulting fees, honoraria, and/or grant/research support from Acerta Pharma, Amgen Inc., BeiGene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene Corporation, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Janssen Pharmaceutica Products, MEI Pharma, NanoString Technologies, Pharmacyclics, Portola Pharmaceuticals, Roche Laboratories, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE NCCN ANNUAL CONFERENCE

Is your patient’s valproic acid dosage too low or high? Adjust it with this equation

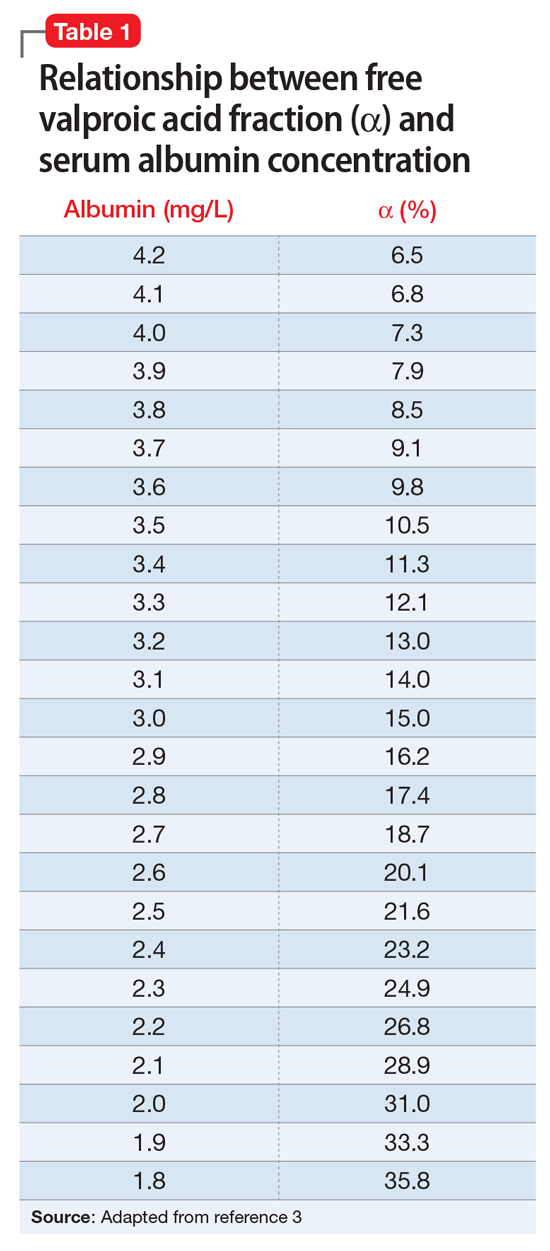

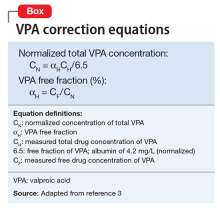

Valproic acid (VPA) often is used to treat mania in bipolar disorder, and it has a therapeutic range of 50 to 125 µg/mL of total serum concentration.1 VPA binds highly to albumin, resulting in free drug concentrations (5 to 15 mg/L) that are responsible for its therapeutic effect.2 Monitoring total VPA levels in patients with hypoalbuminemia could reveal seemingly subtherapeutic VPA levels, which could lead to unnecessary dosage adjustments or drug toxicity. Hermida et al3 devised a correction equation to normalize total VPA serum concentrations <75 µg/mL in patients with hypoalbuminemia (Table 1, Box).

We present a case employing this equation in a patient

Case

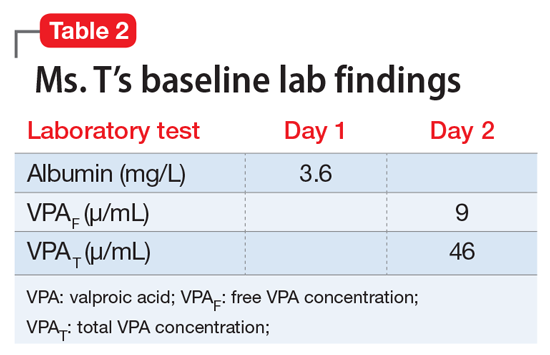

Ms. T, age 75, is admitted to the hospital with delusional, paranoid, assaultive, and combative behavior. By applying Ms. T’s baseline lab findings (Table 2) to the equation, a normalized total VPA level and estimated free VPA level of 70 µg/mL and 7 µg/mL, respectively, can be approximated. These estimates fall within the therapeutic range and are validated by the measured free VPA level of 9 µg/mL.

VPA serum levels should be assessed 2 to 4 days after initiation or dosage adjustments.1 Also, consider patient-specific goals and intended clinical effect when adjusting VPA dosage. In practice settings, where free VPA levels are not routinely monitored or are cost prohibitive, this equation can guide clinical decision-making.3

1. Depakote [divalproex sodium]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc; 2016.

2. DeVane CL. Pharmacokinetics, drug interactions, and tolerability of valproate. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2003;37(suppl 2):25-42.

3. Hermida J, Tutor JC. A theoretical method for normalizing total serum valproic acid concentration in hypoalbuminemic patients. J Pharmacol Sci. 2005;97(4):489-493.

Valproic acid (VPA) often is used to treat mania in bipolar disorder, and it has a therapeutic range of 50 to 125 µg/mL of total serum concentration.1 VPA binds highly to albumin, resulting in free drug concentrations (5 to 15 mg/L) that are responsible for its therapeutic effect.2 Monitoring total VPA levels in patients with hypoalbuminemia could reveal seemingly subtherapeutic VPA levels, which could lead to unnecessary dosage adjustments or drug toxicity. Hermida et al3 devised a correction equation to normalize total VPA serum concentrations <75 µg/mL in patients with hypoalbuminemia (Table 1, Box).

We present a case employing this equation in a patient

Case

Ms. T, age 75, is admitted to the hospital with delusional, paranoid, assaultive, and combative behavior. By applying Ms. T’s baseline lab findings (Table 2) to the equation, a normalized total VPA level and estimated free VPA level of 70 µg/mL and 7 µg/mL, respectively, can be approximated. These estimates fall within the therapeutic range and are validated by the measured free VPA level of 9 µg/mL.

VPA serum levels should be assessed 2 to 4 days after initiation or dosage adjustments.1 Also, consider patient-specific goals and intended clinical effect when adjusting VPA dosage. In practice settings, where free VPA levels are not routinely monitored or are cost prohibitive, this equation can guide clinical decision-making.3

Valproic acid (VPA) often is used to treat mania in bipolar disorder, and it has a therapeutic range of 50 to 125 µg/mL of total serum concentration.1 VPA binds highly to albumin, resulting in free drug concentrations (5 to 15 mg/L) that are responsible for its therapeutic effect.2 Monitoring total VPA levels in patients with hypoalbuminemia could reveal seemingly subtherapeutic VPA levels, which could lead to unnecessary dosage adjustments or drug toxicity. Hermida et al3 devised a correction equation to normalize total VPA serum concentrations <75 µg/mL in patients with hypoalbuminemia (Table 1, Box).

We present a case employing this equation in a patient

Case

Ms. T, age 75, is admitted to the hospital with delusional, paranoid, assaultive, and combative behavior. By applying Ms. T’s baseline lab findings (Table 2) to the equation, a normalized total VPA level and estimated free VPA level of 70 µg/mL and 7 µg/mL, respectively, can be approximated. These estimates fall within the therapeutic range and are validated by the measured free VPA level of 9 µg/mL.

VPA serum levels should be assessed 2 to 4 days after initiation or dosage adjustments.1 Also, consider patient-specific goals and intended clinical effect when adjusting VPA dosage. In practice settings, where free VPA levels are not routinely monitored or are cost prohibitive, this equation can guide clinical decision-making.3

1. Depakote [divalproex sodium]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc; 2016.

2. DeVane CL. Pharmacokinetics, drug interactions, and tolerability of valproate. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2003;37(suppl 2):25-42.

3. Hermida J, Tutor JC. A theoretical method for normalizing total serum valproic acid concentration in hypoalbuminemic patients. J Pharmacol Sci. 2005;97(4):489-493.