User login

Ocrelizumab gets first-ever FDA approval for primary progressive MS

The humanized monoclonal antibody ocrelizumab became the first drug to receive approval from the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of primary progressive multiple sclerosis in adults, according to a March 29 announcement from the agency that also said it is approved for relapsing-remitting disease in adults.

The drug has a mechanism of action similar to rituximab (Rituxan) through its selective targeting of CD20-positive B cells, which depletes them from circulation. CD20-positive B cells are thought to be a key contributor to myelin and axonal damage.

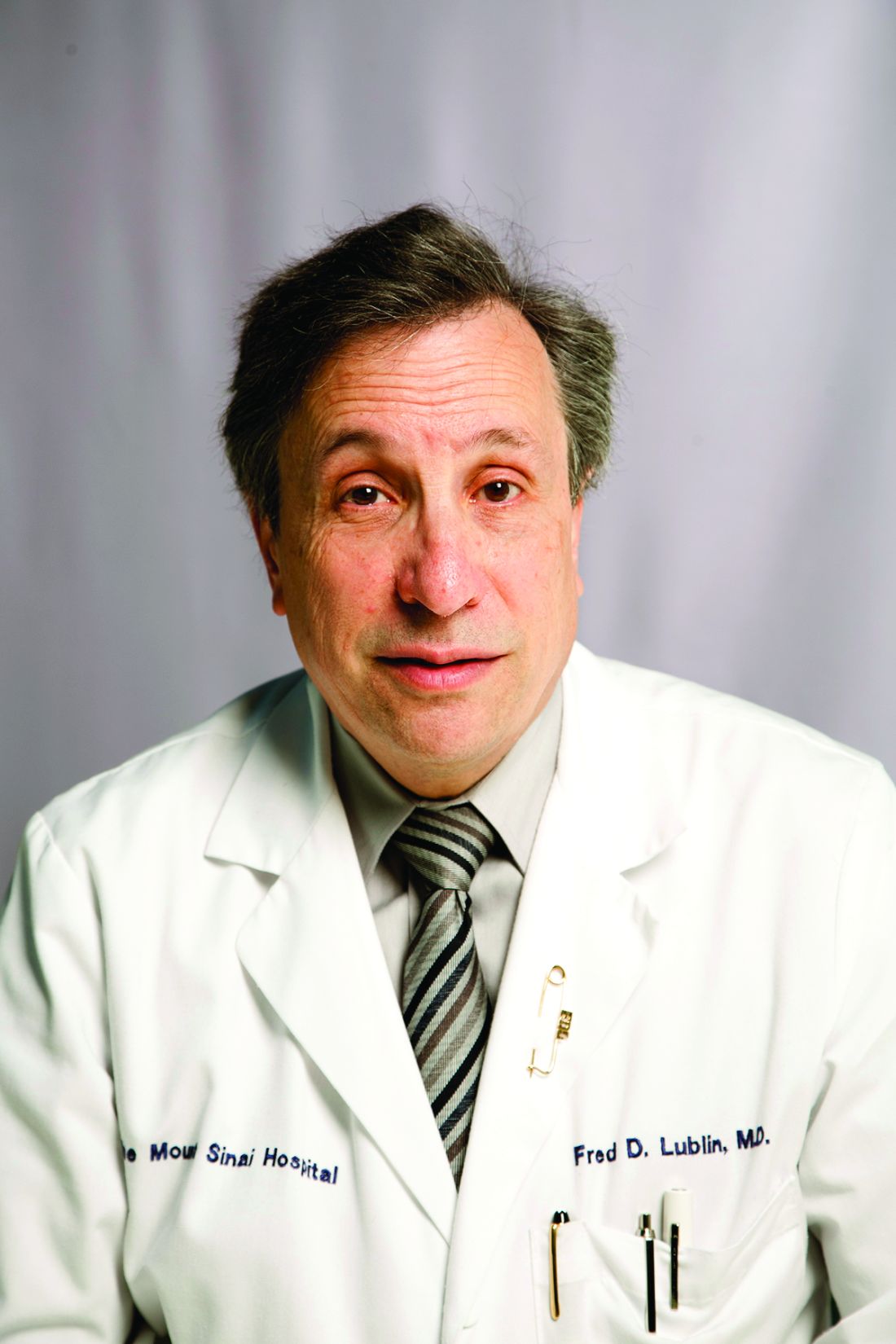

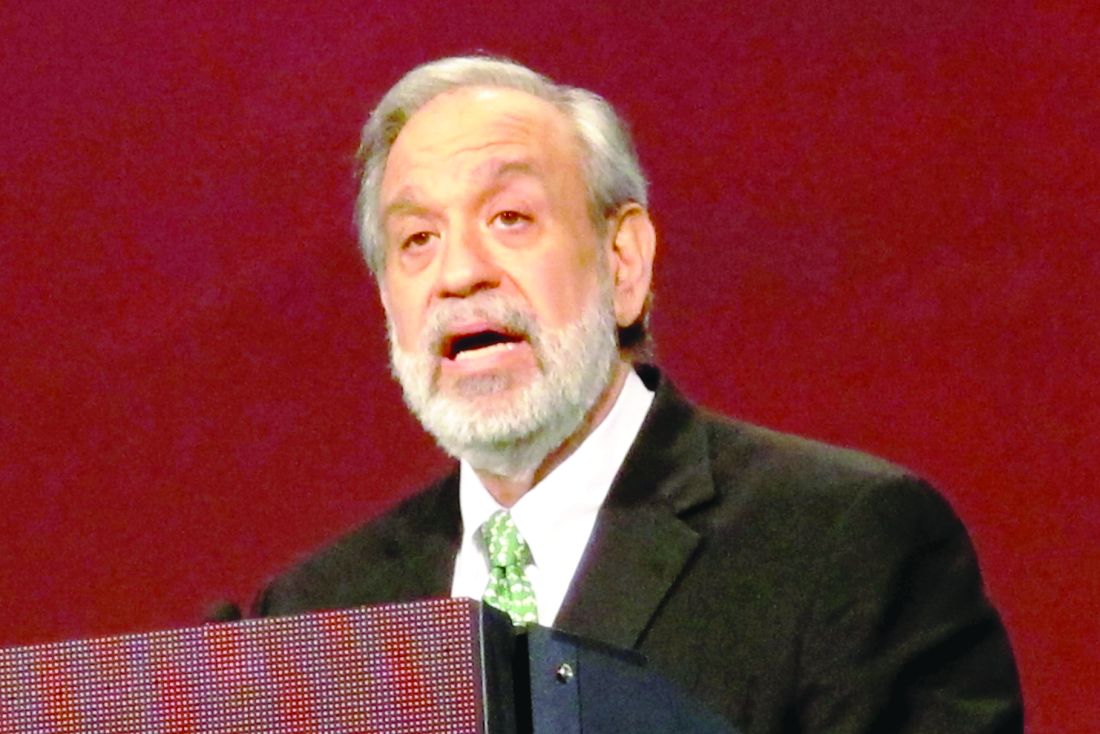

Although the effect of ocrelizumab on primary progressive MS patients was modest, its stature as the only drug approved for the indication represents “a start for being able to treat progressive MS,” Fred Lublin, MD, a member of the steering committee that designed and monitored the phase III ocrelizumab trials, said in an interview.

In the ORATORIO trial that randomized 732 patients with primary progressive MS in a 2:1 ratio to infusions of either 600 mg ocrelizumab or placebo every 24 weeks for 120 weeks, ocrelizumab reduced the risk of progression in clinical disability by 24% at 12 weeks (the primary end point), 25% at 24 weeks, and 24% at 120 weeks, compared with placebo (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jan 19;376[3]:209-20).

Over 120 weeks, the antibody also reduced the volume of hyperintense T2 lesions by 3.4%, whereas patients taking placebo experienced a 7.4% increase. The rate of whole brain volume loss was also significantly reduced from week 24 to 120 (–0.9% with ocrelizumab vs. –1.1% for placebo).

The group of patients who participated in ORATORIO was younger and had more activity on MRI, but it’s unclear if there is a progressive MS patient population who will respond best to the biologic, said Dr. Lublin, director of the Corinne Goldsmith Dickinson Center for Multiple Sclerosis at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York.

“The safety was acceptable, and so I think it will get a lot of use. There are always some who like to wait until a drug has been out for a while, but there is considerable experience with this type of drug based on off-label use of rituximab” in relapsing-remitting patients, including phase II trial data (but not phase III), he said. There’s potential for ocrelizumab to be used as a first-line treatment for relapsing-remitting disease to the same extent as natalizumab (Tysabri), he added.

In two identical phase III trials, OPERA I and OPERA II, investigators randomized 1,656 relapsing-remitting MS patients to intravenous ocrelizumab 600 mg every 24 weeks plus placebo subcutaneous injections three times weekly or to subcutaneous interferon beta-1a 44 mcg (Rebif) three times weekly plus placebo IV infusions every 24 weeks over 96 weeks (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jan 19;376[3]:221-34).

Compared with interferon beta-1a, ocrelizumab reduced the annualized relapse rate by 46% in OPERA 1 and 47% in OPERA 2. In a pooled analysis of both trials, the risk of confirmed disability progression was 40% lower for ocrelizumab at both 12 and 24 weeks. Ocrelizumab conferred a 94% and 95% reduction in the total number of T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions and a 77% and 83% reduction in the total number of new and/or enlarging hyperintense T2 lesions. An exploratory analysis also suggested that the drug reduced the rate of whole brain volume loss, compared with interferon beta-1a.

At 96 weeks, 47.9% and 47.5% of ocrelizumab patients versus 29.2% and 25.1% of interferon patients had no evidence of disease activity (NEDA) in the two studies. NEDA is a composite score defined as no relapses, no confirmed disability progression, and no new or enlarging T2 or gadolinium-enhancing T1 lesions.

Across both studies, relapses occurred in about 20% of ocrelizumab patients versus about 35% of interferon patients. About 10% of ocrelizumab patients had clinical disease progression, compared with about 15% of interferon patients. Similarly, about 10% of ocrelizumab patients developed new gadolinium-enhancing lesions, compared with about 35% in the interferon groups. New or enlarging T2 lesions were found in about 40% in the ocrelizumab groups but in more than 60% in the interferon arms.

Safety results at 24 weeks in the OPERA trials showed that infusion reactions were significantly more common with ocrelizumab than with interferon beta-1a (34% vs. 9.7%), and most of these were mild to moderate in severity. Otherwise, there were similar rates of serious adverse events, including serious infections.

In ORATORIO, infusion reaction occurred in 40% of ocrelizumab patients and 26% of placebo patients. Most of the reactions were mild to moderate in severity. Among all patients in ORATORIO, 13 malignancies occurred over 3 years, and they occurred more than twice as often in the ocrelizumab arm than in the placebo arm (2.3% vs. 0.8%). These included four breast cancers in the active arm and none in the placebo arm.

No cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) have been reported in association with ocrelizumab, although the risk of PML with long-term use is unknown.

The FDA said in its announcement that ocrelizumab should not be used in patients with hepatitis B infection or a history of life-threatening infusion-related reactions to the drug. Ocrelizumab is required to be dispensed with a patient Medication Guide that describes important information about the drug’s uses and risks. The agency also advised that vaccination with live or live attenuated vaccines is not recommended in patients receiving the drug.

Genentech says it plans to offer patient assistance programs through Genentech Access Solutions.

Dr. Lublin reported receiving fees for serving on an advisory board from Genentech/Roche and from many other companies investigating or marketing drugs for MS.

The humanized monoclonal antibody ocrelizumab became the first drug to receive approval from the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of primary progressive multiple sclerosis in adults, according to a March 29 announcement from the agency that also said it is approved for relapsing-remitting disease in adults.

The drug has a mechanism of action similar to rituximab (Rituxan) through its selective targeting of CD20-positive B cells, which depletes them from circulation. CD20-positive B cells are thought to be a key contributor to myelin and axonal damage.

Although the effect of ocrelizumab on primary progressive MS patients was modest, its stature as the only drug approved for the indication represents “a start for being able to treat progressive MS,” Fred Lublin, MD, a member of the steering committee that designed and monitored the phase III ocrelizumab trials, said in an interview.

In the ORATORIO trial that randomized 732 patients with primary progressive MS in a 2:1 ratio to infusions of either 600 mg ocrelizumab or placebo every 24 weeks for 120 weeks, ocrelizumab reduced the risk of progression in clinical disability by 24% at 12 weeks (the primary end point), 25% at 24 weeks, and 24% at 120 weeks, compared with placebo (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jan 19;376[3]:209-20).

Over 120 weeks, the antibody also reduced the volume of hyperintense T2 lesions by 3.4%, whereas patients taking placebo experienced a 7.4% increase. The rate of whole brain volume loss was also significantly reduced from week 24 to 120 (–0.9% with ocrelizumab vs. –1.1% for placebo).

The group of patients who participated in ORATORIO was younger and had more activity on MRI, but it’s unclear if there is a progressive MS patient population who will respond best to the biologic, said Dr. Lublin, director of the Corinne Goldsmith Dickinson Center for Multiple Sclerosis at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York.

“The safety was acceptable, and so I think it will get a lot of use. There are always some who like to wait until a drug has been out for a while, but there is considerable experience with this type of drug based on off-label use of rituximab” in relapsing-remitting patients, including phase II trial data (but not phase III), he said. There’s potential for ocrelizumab to be used as a first-line treatment for relapsing-remitting disease to the same extent as natalizumab (Tysabri), he added.

In two identical phase III trials, OPERA I and OPERA II, investigators randomized 1,656 relapsing-remitting MS patients to intravenous ocrelizumab 600 mg every 24 weeks plus placebo subcutaneous injections three times weekly or to subcutaneous interferon beta-1a 44 mcg (Rebif) three times weekly plus placebo IV infusions every 24 weeks over 96 weeks (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jan 19;376[3]:221-34).

Compared with interferon beta-1a, ocrelizumab reduced the annualized relapse rate by 46% in OPERA 1 and 47% in OPERA 2. In a pooled analysis of both trials, the risk of confirmed disability progression was 40% lower for ocrelizumab at both 12 and 24 weeks. Ocrelizumab conferred a 94% and 95% reduction in the total number of T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions and a 77% and 83% reduction in the total number of new and/or enlarging hyperintense T2 lesions. An exploratory analysis also suggested that the drug reduced the rate of whole brain volume loss, compared with interferon beta-1a.

At 96 weeks, 47.9% and 47.5% of ocrelizumab patients versus 29.2% and 25.1% of interferon patients had no evidence of disease activity (NEDA) in the two studies. NEDA is a composite score defined as no relapses, no confirmed disability progression, and no new or enlarging T2 or gadolinium-enhancing T1 lesions.

Across both studies, relapses occurred in about 20% of ocrelizumab patients versus about 35% of interferon patients. About 10% of ocrelizumab patients had clinical disease progression, compared with about 15% of interferon patients. Similarly, about 10% of ocrelizumab patients developed new gadolinium-enhancing lesions, compared with about 35% in the interferon groups. New or enlarging T2 lesions were found in about 40% in the ocrelizumab groups but in more than 60% in the interferon arms.

Safety results at 24 weeks in the OPERA trials showed that infusion reactions were significantly more common with ocrelizumab than with interferon beta-1a (34% vs. 9.7%), and most of these were mild to moderate in severity. Otherwise, there were similar rates of serious adverse events, including serious infections.

In ORATORIO, infusion reaction occurred in 40% of ocrelizumab patients and 26% of placebo patients. Most of the reactions were mild to moderate in severity. Among all patients in ORATORIO, 13 malignancies occurred over 3 years, and they occurred more than twice as often in the ocrelizumab arm than in the placebo arm (2.3% vs. 0.8%). These included four breast cancers in the active arm and none in the placebo arm.

No cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) have been reported in association with ocrelizumab, although the risk of PML with long-term use is unknown.

The FDA said in its announcement that ocrelizumab should not be used in patients with hepatitis B infection or a history of life-threatening infusion-related reactions to the drug. Ocrelizumab is required to be dispensed with a patient Medication Guide that describes important information about the drug’s uses and risks. The agency also advised that vaccination with live or live attenuated vaccines is not recommended in patients receiving the drug.

Genentech says it plans to offer patient assistance programs through Genentech Access Solutions.

Dr. Lublin reported receiving fees for serving on an advisory board from Genentech/Roche and from many other companies investigating or marketing drugs for MS.

The humanized monoclonal antibody ocrelizumab became the first drug to receive approval from the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of primary progressive multiple sclerosis in adults, according to a March 29 announcement from the agency that also said it is approved for relapsing-remitting disease in adults.

The drug has a mechanism of action similar to rituximab (Rituxan) through its selective targeting of CD20-positive B cells, which depletes them from circulation. CD20-positive B cells are thought to be a key contributor to myelin and axonal damage.

Although the effect of ocrelizumab on primary progressive MS patients was modest, its stature as the only drug approved for the indication represents “a start for being able to treat progressive MS,” Fred Lublin, MD, a member of the steering committee that designed and monitored the phase III ocrelizumab trials, said in an interview.

In the ORATORIO trial that randomized 732 patients with primary progressive MS in a 2:1 ratio to infusions of either 600 mg ocrelizumab or placebo every 24 weeks for 120 weeks, ocrelizumab reduced the risk of progression in clinical disability by 24% at 12 weeks (the primary end point), 25% at 24 weeks, and 24% at 120 weeks, compared with placebo (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jan 19;376[3]:209-20).

Over 120 weeks, the antibody also reduced the volume of hyperintense T2 lesions by 3.4%, whereas patients taking placebo experienced a 7.4% increase. The rate of whole brain volume loss was also significantly reduced from week 24 to 120 (–0.9% with ocrelizumab vs. –1.1% for placebo).

The group of patients who participated in ORATORIO was younger and had more activity on MRI, but it’s unclear if there is a progressive MS patient population who will respond best to the biologic, said Dr. Lublin, director of the Corinne Goldsmith Dickinson Center for Multiple Sclerosis at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York.

“The safety was acceptable, and so I think it will get a lot of use. There are always some who like to wait until a drug has been out for a while, but there is considerable experience with this type of drug based on off-label use of rituximab” in relapsing-remitting patients, including phase II trial data (but not phase III), he said. There’s potential for ocrelizumab to be used as a first-line treatment for relapsing-remitting disease to the same extent as natalizumab (Tysabri), he added.

In two identical phase III trials, OPERA I and OPERA II, investigators randomized 1,656 relapsing-remitting MS patients to intravenous ocrelizumab 600 mg every 24 weeks plus placebo subcutaneous injections three times weekly or to subcutaneous interferon beta-1a 44 mcg (Rebif) three times weekly plus placebo IV infusions every 24 weeks over 96 weeks (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jan 19;376[3]:221-34).

Compared with interferon beta-1a, ocrelizumab reduced the annualized relapse rate by 46% in OPERA 1 and 47% in OPERA 2. In a pooled analysis of both trials, the risk of confirmed disability progression was 40% lower for ocrelizumab at both 12 and 24 weeks. Ocrelizumab conferred a 94% and 95% reduction in the total number of T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions and a 77% and 83% reduction in the total number of new and/or enlarging hyperintense T2 lesions. An exploratory analysis also suggested that the drug reduced the rate of whole brain volume loss, compared with interferon beta-1a.

At 96 weeks, 47.9% and 47.5% of ocrelizumab patients versus 29.2% and 25.1% of interferon patients had no evidence of disease activity (NEDA) in the two studies. NEDA is a composite score defined as no relapses, no confirmed disability progression, and no new or enlarging T2 or gadolinium-enhancing T1 lesions.

Across both studies, relapses occurred in about 20% of ocrelizumab patients versus about 35% of interferon patients. About 10% of ocrelizumab patients had clinical disease progression, compared with about 15% of interferon patients. Similarly, about 10% of ocrelizumab patients developed new gadolinium-enhancing lesions, compared with about 35% in the interferon groups. New or enlarging T2 lesions were found in about 40% in the ocrelizumab groups but in more than 60% in the interferon arms.

Safety results at 24 weeks in the OPERA trials showed that infusion reactions were significantly more common with ocrelizumab than with interferon beta-1a (34% vs. 9.7%), and most of these were mild to moderate in severity. Otherwise, there were similar rates of serious adverse events, including serious infections.

In ORATORIO, infusion reaction occurred in 40% of ocrelizumab patients and 26% of placebo patients. Most of the reactions were mild to moderate in severity. Among all patients in ORATORIO, 13 malignancies occurred over 3 years, and they occurred more than twice as often in the ocrelizumab arm than in the placebo arm (2.3% vs. 0.8%). These included four breast cancers in the active arm and none in the placebo arm.

No cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) have been reported in association with ocrelizumab, although the risk of PML with long-term use is unknown.

The FDA said in its announcement that ocrelizumab should not be used in patients with hepatitis B infection or a history of life-threatening infusion-related reactions to the drug. Ocrelizumab is required to be dispensed with a patient Medication Guide that describes important information about the drug’s uses and risks. The agency also advised that vaccination with live or live attenuated vaccines is not recommended in patients receiving the drug.

Genentech says it plans to offer patient assistance programs through Genentech Access Solutions.

Dr. Lublin reported receiving fees for serving on an advisory board from Genentech/Roche and from many other companies investigating or marketing drugs for MS.

The role of moisturizers and lubricants in genitourinary syndrome of menopause and beyond

Can Probiotics Help Treat MS?

ORLANDO—Probiotic treatment is associated with the induction of an anti-inflammatory peripheral immune profile in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), and discontinuing probiotics is associated with a decrease in immune regulatory cells, according to pilot study results presented at the ACTRIMS 2017 Forum. The results suggest that probiotics may be applicable as a therapy for MS. More studies, including controlled clinical trials, are needed to guide treatment decisions, said Howard L. Weiner, MD, Director of the MS Program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Newton, Massachusetts, and Robert L. Kroc Professor of Neurology at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

The gut microbiome can modulate neuroimmune function, and studies have found that patients with MS have alterations in the gut microbiome, compared with healthy controls. These findings have led researchers to ask, “Can you treat MS by modulating the microbiome?” Dr. Weiner said. One way to modulate the microbiome is with probiotics, which can be taken as an oral, nontoxic treatment in combination with current therapies. He and his research colleagues conducted a pilot study to investigate the effect of probiotics in patients with MS. “We did not feel that we could do a clinically related study,” he said. Instead, the investigators focused on what happens to the gut microbiome and immune profiles in the blood of patients who receive probiotics.

Two Months of Treatment

The study included nine patients with MS and 13 controls. The investigators gave study participants the probiotic VSL#3. Some formulations of VSL#3 are available in stores. The company that markets the probiotic, Sigma-Tau HealthScience USA, based in Gaithersburg, Maryland, requires a prescription for VSL#3 DS, the double-strength formulation used in the study.

Prior studies of the probiotic have found that VSL#3 provides benefit in animal models of diabetes, colitis, and allergy. Kigerl et al reported that, in mice with spinal cord injury, dysbiosis induced by antibiotics exacerbates neurologic impairment and spinal cord pathology, whereas feeding mice VSL#3 enriched with lactic-acid-producing bacteria triggers a protective immune response, confers neuroprotection, and improves walking. In addition, some doctors prescribe VSL#3 to patients with ulcerative colitis, irritable bowel syndrome, and pouchitis, Dr. Weiner said.

In the pilot study, participants took VSL#3 DS sachets twice daily for two months. Researchers took blood and stool samples from participants before administering the probiotic, at discontinuation of therapy, and three months thereafter.

VSL#3 had no effect on alpha or phylogenetic diversity, but did change the gut microbiome composition. Researchers observed an increase in the relative abundance of specific organisms contained in the probiotic. Methanogens, which are increased in MS, decreased when patients received the probiotic. Administration of VSL#3 also was associated with a decrease in proinflammatory monocytes and decreased expression of activation markers on monocytes and dendritic cells.

When patients stopped probiotic treatment, the numbers of CD39 and IL10 T regulatory cells decreased, and proinflammatory monocytes increased. “We did see changes when you stop treatment, almost as if there is a rebound,” he said. “We are seeing an immune effect in the blood.”

The treatment was well tolerated. “I myself took some,” Dr. Weiner said. “It tastes a little chalky, but otherwise it is fine.” Some patients said they felt better after taking the probiotic. The study was not placebo-controlled, however. Future randomized clinical studies will include MRI scans, he said.

What should neurologists tell patients who want to take a probiotic and ask which probiotic they should take? “We are all asked those questions,” Dr. Weiner said. “I tell them, we really don’t know, but if you would like to take a probiotic, that is fine. But we have no particular recommendations at this time. We need a lot of science before we know what we are doing, as far as treatment, in this regard.”

Changes in the Gut Microbiome in MS

Prior to conducting the pilot study, Sushrut Jangi, MD, research fellow at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Dr. Weiner, and colleagues studied the gut microbiome in 60 patients with MS and 43 healthy controls. They found that patients with MS had increases in Methanobrevibacter and Akkermansia and decreases in Butyricimonas, compared with controls. Methanobrevibacter produces methane, and in another cohort, the researchers detected more methane in the breath of patients with MS than in controls.

In addition, Prevotella and Sutterella were increased, and Sarcina was decreased in patients with MS who were treated with disease-modifying therapy, compared with untreated patients with MS. “It gives us a whole series of targets to try to understand,” he said. The gut microbiome alterations in patients with MS correlated with variations in the expression of genes in circulating T cells and monocytes that have been implicated in MS pathogenesis.

How Are the Gut Microbiome and MS Related?

The nature of the relationship between the gut microbiome and MS is unclear. One possibility is that “the gut could be the key to MS,” Dr. Weiner said. An organism in the gut may trigger MS, and that organism potentially could be altered or used in vaccinations to treat or prevent the disease. Alternatively, the gut microbiome might relate to MS susceptibility. Environmental factors, including diet and antibiotics, could affect the microbiome and MS risk. It is also possible that MS disease-modifying therapies act in part through the gut, Dr. Weiner said.

Various treatments targeting the microbiome are under investigation. For example, researchers are asking whether a particular bacteria or fecal microbiome transplants might help treat MS. “I am very interested in the concept of oral tolerance, where we trigger immune responses in the mucosa,” said Dr. Weiner. “We are beginning a trial of anti-CD3 [monoclonal antibodies], which will be given mucosally to stimulate the gut immune response.”

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Jangi S, Gandhi R, Cox LM, et al. Alterations of the human gut microbiome in multiple sclerosis. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12015.

Kigerl KA, Hall JC, Wang L, et al. Gut dysbiosis impairs recovery after spinal cord injury. J Exp Med. 2016;213(12):2603-2620.

Kouchaki E, Tamtaji OR, Salami M, et al. Clinical and metabolic response to probiotic supplementation in patients with multiple sclerosis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 2016 Sep 16 [Epub ahead of print].

Miyake S, Kim S, Suda W, et al. Dysbiosis in the gut microbiota of patients with multiple sclerosis, with a striking depletion of species belonging to Clostridia XIVa and IV clusters. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0137429.

Tremlett H, Waubant E. The multiple sclerosis microbiome? Ann Transl Med. 2017;5(3):53.

ORLANDO—Probiotic treatment is associated with the induction of an anti-inflammatory peripheral immune profile in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), and discontinuing probiotics is associated with a decrease in immune regulatory cells, according to pilot study results presented at the ACTRIMS 2017 Forum. The results suggest that probiotics may be applicable as a therapy for MS. More studies, including controlled clinical trials, are needed to guide treatment decisions, said Howard L. Weiner, MD, Director of the MS Program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Newton, Massachusetts, and Robert L. Kroc Professor of Neurology at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

The gut microbiome can modulate neuroimmune function, and studies have found that patients with MS have alterations in the gut microbiome, compared with healthy controls. These findings have led researchers to ask, “Can you treat MS by modulating the microbiome?” Dr. Weiner said. One way to modulate the microbiome is with probiotics, which can be taken as an oral, nontoxic treatment in combination with current therapies. He and his research colleagues conducted a pilot study to investigate the effect of probiotics in patients with MS. “We did not feel that we could do a clinically related study,” he said. Instead, the investigators focused on what happens to the gut microbiome and immune profiles in the blood of patients who receive probiotics.

Two Months of Treatment

The study included nine patients with MS and 13 controls. The investigators gave study participants the probiotic VSL#3. Some formulations of VSL#3 are available in stores. The company that markets the probiotic, Sigma-Tau HealthScience USA, based in Gaithersburg, Maryland, requires a prescription for VSL#3 DS, the double-strength formulation used in the study.

Prior studies of the probiotic have found that VSL#3 provides benefit in animal models of diabetes, colitis, and allergy. Kigerl et al reported that, in mice with spinal cord injury, dysbiosis induced by antibiotics exacerbates neurologic impairment and spinal cord pathology, whereas feeding mice VSL#3 enriched with lactic-acid-producing bacteria triggers a protective immune response, confers neuroprotection, and improves walking. In addition, some doctors prescribe VSL#3 to patients with ulcerative colitis, irritable bowel syndrome, and pouchitis, Dr. Weiner said.

In the pilot study, participants took VSL#3 DS sachets twice daily for two months. Researchers took blood and stool samples from participants before administering the probiotic, at discontinuation of therapy, and three months thereafter.

VSL#3 had no effect on alpha or phylogenetic diversity, but did change the gut microbiome composition. Researchers observed an increase in the relative abundance of specific organisms contained in the probiotic. Methanogens, which are increased in MS, decreased when patients received the probiotic. Administration of VSL#3 also was associated with a decrease in proinflammatory monocytes and decreased expression of activation markers on monocytes and dendritic cells.

When patients stopped probiotic treatment, the numbers of CD39 and IL10 T regulatory cells decreased, and proinflammatory monocytes increased. “We did see changes when you stop treatment, almost as if there is a rebound,” he said. “We are seeing an immune effect in the blood.”

The treatment was well tolerated. “I myself took some,” Dr. Weiner said. “It tastes a little chalky, but otherwise it is fine.” Some patients said they felt better after taking the probiotic. The study was not placebo-controlled, however. Future randomized clinical studies will include MRI scans, he said.

What should neurologists tell patients who want to take a probiotic and ask which probiotic they should take? “We are all asked those questions,” Dr. Weiner said. “I tell them, we really don’t know, but if you would like to take a probiotic, that is fine. But we have no particular recommendations at this time. We need a lot of science before we know what we are doing, as far as treatment, in this regard.”

Changes in the Gut Microbiome in MS

Prior to conducting the pilot study, Sushrut Jangi, MD, research fellow at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Dr. Weiner, and colleagues studied the gut microbiome in 60 patients with MS and 43 healthy controls. They found that patients with MS had increases in Methanobrevibacter and Akkermansia and decreases in Butyricimonas, compared with controls. Methanobrevibacter produces methane, and in another cohort, the researchers detected more methane in the breath of patients with MS than in controls.

In addition, Prevotella and Sutterella were increased, and Sarcina was decreased in patients with MS who were treated with disease-modifying therapy, compared with untreated patients with MS. “It gives us a whole series of targets to try to understand,” he said. The gut microbiome alterations in patients with MS correlated with variations in the expression of genes in circulating T cells and monocytes that have been implicated in MS pathogenesis.

How Are the Gut Microbiome and MS Related?

The nature of the relationship between the gut microbiome and MS is unclear. One possibility is that “the gut could be the key to MS,” Dr. Weiner said. An organism in the gut may trigger MS, and that organism potentially could be altered or used in vaccinations to treat or prevent the disease. Alternatively, the gut microbiome might relate to MS susceptibility. Environmental factors, including diet and antibiotics, could affect the microbiome and MS risk. It is also possible that MS disease-modifying therapies act in part through the gut, Dr. Weiner said.

Various treatments targeting the microbiome are under investigation. For example, researchers are asking whether a particular bacteria or fecal microbiome transplants might help treat MS. “I am very interested in the concept of oral tolerance, where we trigger immune responses in the mucosa,” said Dr. Weiner. “We are beginning a trial of anti-CD3 [monoclonal antibodies], which will be given mucosally to stimulate the gut immune response.”

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Jangi S, Gandhi R, Cox LM, et al. Alterations of the human gut microbiome in multiple sclerosis. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12015.

Kigerl KA, Hall JC, Wang L, et al. Gut dysbiosis impairs recovery after spinal cord injury. J Exp Med. 2016;213(12):2603-2620.

Kouchaki E, Tamtaji OR, Salami M, et al. Clinical and metabolic response to probiotic supplementation in patients with multiple sclerosis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 2016 Sep 16 [Epub ahead of print].

Miyake S, Kim S, Suda W, et al. Dysbiosis in the gut microbiota of patients with multiple sclerosis, with a striking depletion of species belonging to Clostridia XIVa and IV clusters. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0137429.

Tremlett H, Waubant E. The multiple sclerosis microbiome? Ann Transl Med. 2017;5(3):53.

ORLANDO—Probiotic treatment is associated with the induction of an anti-inflammatory peripheral immune profile in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), and discontinuing probiotics is associated with a decrease in immune regulatory cells, according to pilot study results presented at the ACTRIMS 2017 Forum. The results suggest that probiotics may be applicable as a therapy for MS. More studies, including controlled clinical trials, are needed to guide treatment decisions, said Howard L. Weiner, MD, Director of the MS Program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Newton, Massachusetts, and Robert L. Kroc Professor of Neurology at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

The gut microbiome can modulate neuroimmune function, and studies have found that patients with MS have alterations in the gut microbiome, compared with healthy controls. These findings have led researchers to ask, “Can you treat MS by modulating the microbiome?” Dr. Weiner said. One way to modulate the microbiome is with probiotics, which can be taken as an oral, nontoxic treatment in combination with current therapies. He and his research colleagues conducted a pilot study to investigate the effect of probiotics in patients with MS. “We did not feel that we could do a clinically related study,” he said. Instead, the investigators focused on what happens to the gut microbiome and immune profiles in the blood of patients who receive probiotics.

Two Months of Treatment

The study included nine patients with MS and 13 controls. The investigators gave study participants the probiotic VSL#3. Some formulations of VSL#3 are available in stores. The company that markets the probiotic, Sigma-Tau HealthScience USA, based in Gaithersburg, Maryland, requires a prescription for VSL#3 DS, the double-strength formulation used in the study.

Prior studies of the probiotic have found that VSL#3 provides benefit in animal models of diabetes, colitis, and allergy. Kigerl et al reported that, in mice with spinal cord injury, dysbiosis induced by antibiotics exacerbates neurologic impairment and spinal cord pathology, whereas feeding mice VSL#3 enriched with lactic-acid-producing bacteria triggers a protective immune response, confers neuroprotection, and improves walking. In addition, some doctors prescribe VSL#3 to patients with ulcerative colitis, irritable bowel syndrome, and pouchitis, Dr. Weiner said.

In the pilot study, participants took VSL#3 DS sachets twice daily for two months. Researchers took blood and stool samples from participants before administering the probiotic, at discontinuation of therapy, and three months thereafter.

VSL#3 had no effect on alpha or phylogenetic diversity, but did change the gut microbiome composition. Researchers observed an increase in the relative abundance of specific organisms contained in the probiotic. Methanogens, which are increased in MS, decreased when patients received the probiotic. Administration of VSL#3 also was associated with a decrease in proinflammatory monocytes and decreased expression of activation markers on monocytes and dendritic cells.

When patients stopped probiotic treatment, the numbers of CD39 and IL10 T regulatory cells decreased, and proinflammatory monocytes increased. “We did see changes when you stop treatment, almost as if there is a rebound,” he said. “We are seeing an immune effect in the blood.”

The treatment was well tolerated. “I myself took some,” Dr. Weiner said. “It tastes a little chalky, but otherwise it is fine.” Some patients said they felt better after taking the probiotic. The study was not placebo-controlled, however. Future randomized clinical studies will include MRI scans, he said.

What should neurologists tell patients who want to take a probiotic and ask which probiotic they should take? “We are all asked those questions,” Dr. Weiner said. “I tell them, we really don’t know, but if you would like to take a probiotic, that is fine. But we have no particular recommendations at this time. We need a lot of science before we know what we are doing, as far as treatment, in this regard.”

Changes in the Gut Microbiome in MS

Prior to conducting the pilot study, Sushrut Jangi, MD, research fellow at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Dr. Weiner, and colleagues studied the gut microbiome in 60 patients with MS and 43 healthy controls. They found that patients with MS had increases in Methanobrevibacter and Akkermansia and decreases in Butyricimonas, compared with controls. Methanobrevibacter produces methane, and in another cohort, the researchers detected more methane in the breath of patients with MS than in controls.

In addition, Prevotella and Sutterella were increased, and Sarcina was decreased in patients with MS who were treated with disease-modifying therapy, compared with untreated patients with MS. “It gives us a whole series of targets to try to understand,” he said. The gut microbiome alterations in patients with MS correlated with variations in the expression of genes in circulating T cells and monocytes that have been implicated in MS pathogenesis.

How Are the Gut Microbiome and MS Related?

The nature of the relationship between the gut microbiome and MS is unclear. One possibility is that “the gut could be the key to MS,” Dr. Weiner said. An organism in the gut may trigger MS, and that organism potentially could be altered or used in vaccinations to treat or prevent the disease. Alternatively, the gut microbiome might relate to MS susceptibility. Environmental factors, including diet and antibiotics, could affect the microbiome and MS risk. It is also possible that MS disease-modifying therapies act in part through the gut, Dr. Weiner said.

Various treatments targeting the microbiome are under investigation. For example, researchers are asking whether a particular bacteria or fecal microbiome transplants might help treat MS. “I am very interested in the concept of oral tolerance, where we trigger immune responses in the mucosa,” said Dr. Weiner. “We are beginning a trial of anti-CD3 [monoclonal antibodies], which will be given mucosally to stimulate the gut immune response.”

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Jangi S, Gandhi R, Cox LM, et al. Alterations of the human gut microbiome in multiple sclerosis. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12015.

Kigerl KA, Hall JC, Wang L, et al. Gut dysbiosis impairs recovery after spinal cord injury. J Exp Med. 2016;213(12):2603-2620.

Kouchaki E, Tamtaji OR, Salami M, et al. Clinical and metabolic response to probiotic supplementation in patients with multiple sclerosis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 2016 Sep 16 [Epub ahead of print].

Miyake S, Kim S, Suda W, et al. Dysbiosis in the gut microbiota of patients with multiple sclerosis, with a striking depletion of species belonging to Clostridia XIVa and IV clusters. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0137429.

Tremlett H, Waubant E. The multiple sclerosis microbiome? Ann Transl Med. 2017;5(3):53.

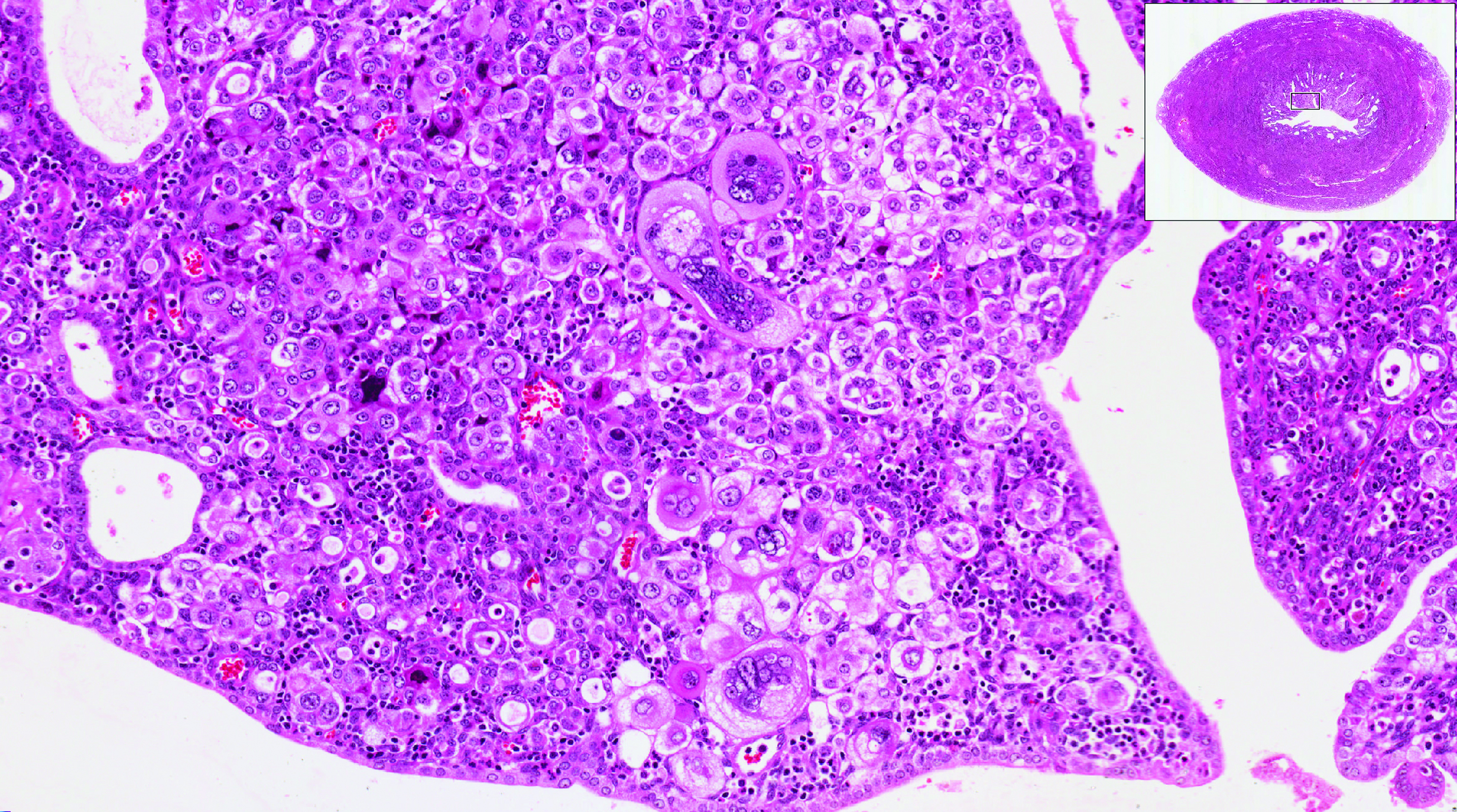

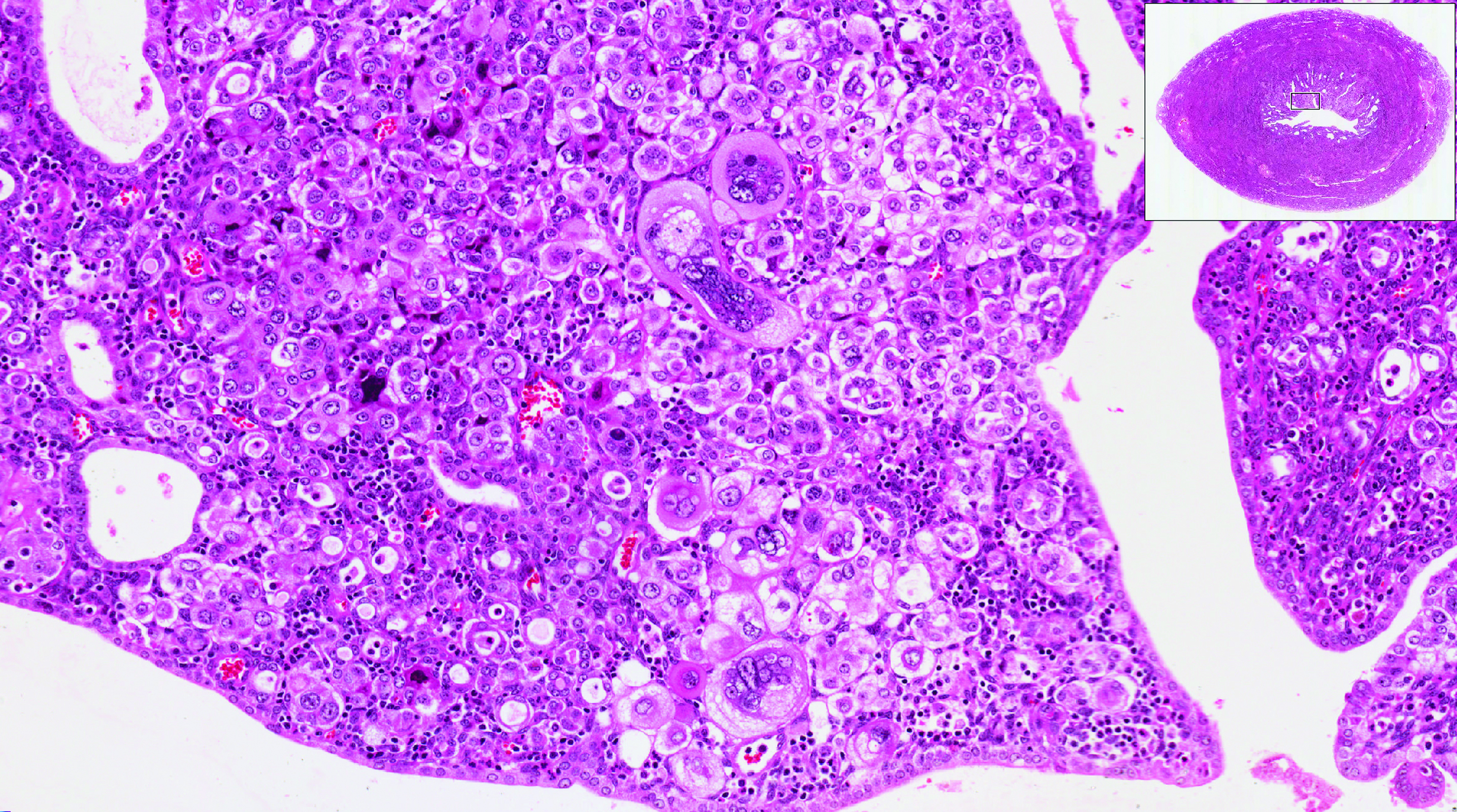

2017 Update on abnormal uterine bleeding

Two issues of emerging importance are being addressed in the literature: caring for patients with obesity and the concept of delivering value-based care. Value-based care does not mean providing the cheapest care; “value” places importance on quality as well as cost. In this Update, we present 3 practices that the evidence says will deliver value:

- endometrial biopsy in all obese women. Although performing more endometrial biopsies in younger women with a body mass index (BMI) in the obese range will not be less expensive initially, the procedure’s value likely will be in early diagnosis, which hopefully will translate to eventual health care system savings.

- use of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) in obese patients experiencing abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB). This practice appears to add value in the context of AUB.

- performance of routine diagnostic hysteroscopy in the office setting. We should reconsider our current habits and traditions of performing routine diagnostic hysteroscopy in the operating room (OR) as we move toward providing value-based care.

Read about obesity as a risk factor for endometrial hyperplasia

Endometrial sampling and obesity: Forget the "age 45" rule

Wise MR, Gill P, Lensen S, Thompson JM, Farquhar CM. Body mass index trumps age in decision for endometrial biopsy: cohort study of symptomatic premenopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(5):598.e1-e8.

How do we bring more value to our patients with AUB? We are well aware that heavy menstrual bleeding places a burden on many women; AUB affects 30% of those of reproductive age. The condition often results in lost workdays and diminished quality of life. It also is associated with significant cost expenditures for hygiene products. It is important not only to bring value to women with heavy menstrual bleeding but also to consider our increasingly expensive health care system.

Obesity is a significant problem that likely will increase the number of women presenting with AUB to ObGyns. Recent studies from New Zealand--which has 33% of its population classified as obese--have provided valuable information.1

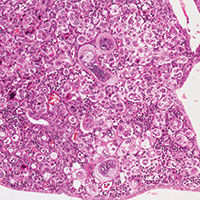

Obesity is a risk factor for endometrial hyperplasia

In a large retrospective cohort study, Wise and colleagues analyzed data from 916 premenopausal women referred for AUB who had an endometrial biopsy from 2008 to 2014. The setting was a single large urban secondary women's health service in New Zealand. This study challenges the concept of age-related biopsy guidelines.

Of the 916 women, half were obese. Almost 5% of the women had complex endometrial hyperplasia with atypia or cancer. This incidence had risen from 3% in the years 1995 to 1997, likely due to the rising incidence of obesity. Women with a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 were 4 times more likely to develop complex hyperplasia or cancer than normal-weight women.

Other factors associated with an increased risk for complex hyperplasia or cancer were nulliparity (odds ratio [OR], 2.51; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.25-5.05), anemia (OR, 2.38; 95% CI, 1.25-4.56), and a thickened endometrium on ultrasonography (defined as >12 mm; OR, 4.04; 95% CI, 1.69-9.65). Age was not a significant risk factor in this group.

Read about using LNG-IUD to treat AUB in obese women

Small study shows LNG-IUD is effective for treating heavy menstrual bleeding in obese patients

Shaw V, Vandal AC, Coomarasamy C, Ekeroma AJ. The effectiveness of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system in obese women with heavy menstrual bleeding. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;56(6):619-623.

In another recent study from New Zealand, researchers set out to assess the efficacy of the LNG-IUD for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding in obese women. This study is important because there are very few studies of the LNG-IUD in the obese population, and none that have studied quality-of-life measures.

Shaw and colleagues conducted the prospective observational study at a tertiary teaching hospital. Twenty obese (BMI >30 kg/m2) women with heavy menstrual bleeding agreed to treatment with an LNG-IUD, and 14 completed the study (2 had a device expulsion, 1 had a device removed for pain, and 1 had a device removed for infection; 2 were lost to follow-up). The women were aged 27 to 52 years (median, 40.5 years), and their BMI ranged from 30 to 68 kg/m2 (median, 40.6 kg/m2). At recruitment, 6 months, and 12 months, participants completed the Menstrual Impact Questionnaire and the Pictorial Bleeding Assessment Chart--2 validated tools.

Compared with baseline Pictorial Bleeding Assessment scores, the authors found the LNG-IUD to be effective in 73.2% (95% CI, 55.3%-83.9%) of women at 6 months and in 92.8% (95% CI, 80.0%-97.4%) of women at 12 months. Taking into consideration device failures, including removed and expelled LNG-IUDs (which occurred in 4 women, or 20%, in the intent-to-treat analysis), the actual efficacy rate was 67%. Similarly, there was significant improvement at 6 and 12 months in Menstrual Impact Questionnaire scores for social activities, work performance, tiredness, productivity, hygiene, and depression.

Read about doing more diagnostic hysteroscopy in the office

Is it time to abandon diagnostic hysteroscopy in the OR?

Leung S, Leyland N, Murji A. Decreasing diagnostic hysteroscopy performed in the operating room: a quality improvement initiative. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2016;38(4):351-356.

Diagnostic hysteroscopy: Are we stuck in the 1990s? Why are we still performing so many diagnostic hysteroscopies in the OR, thus subjecting our patients to general anesthesia and using our precious OR time? That is the question asked by a group of researchers in Canada.

According to data from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care, diagnostic hysteroscopy was performed 10,027 times in the 2013-2014 fiscal year. Ontario researchers designed and implemented a quality improvement initiative at their institution and successfully decreased the number of diagnostic hysteroscopies performed in their hospital by 70% from their baseline 12-month period. The improvements resulted in a savings of 78 hours of case costing, or $126,984. When these data are extrapolated to the Ontario population (in which more than 10,000 diagnostic hysteroscopies were performed), potentially 7,000 women could avoid the risk of general anesthesia and the health care system could save $11 million.

Re-education protocol was key to reducing OR procedures

How did the researchers accomplish their results? The multifaceted intervention had 3 key components:

Staff education and review. Many surgeons were performing diagnostic hysteroscopy in the OR because that is how they were trained, and they were unaware of less invasive options. An awareness campaign was conducted by e-mail, during staff meetings, and at rounds.

Accessible sonohysterography. This diagnostic modality was made more accessible to referring physicians in a timely manner.

Initiation of an operative hysteroscopy education program. To allow more surgeons greater comfort with office hysteroscopy, the authors instituted didactic sessions, dry and wet lab simulations, and mentorship.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD obesity update 2014. http://www.oecd.org/health/Obesity-Update-2014.pdf. Published June 2014. Accessed March 10, 2017.

Two issues of emerging importance are being addressed in the literature: caring for patients with obesity and the concept of delivering value-based care. Value-based care does not mean providing the cheapest care; “value” places importance on quality as well as cost. In this Update, we present 3 practices that the evidence says will deliver value:

- endometrial biopsy in all obese women. Although performing more endometrial biopsies in younger women with a body mass index (BMI) in the obese range will not be less expensive initially, the procedure’s value likely will be in early diagnosis, which hopefully will translate to eventual health care system savings.

- use of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) in obese patients experiencing abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB). This practice appears to add value in the context of AUB.

- performance of routine diagnostic hysteroscopy in the office setting. We should reconsider our current habits and traditions of performing routine diagnostic hysteroscopy in the operating room (OR) as we move toward providing value-based care.

Read about obesity as a risk factor for endometrial hyperplasia

Endometrial sampling and obesity: Forget the "age 45" rule

Wise MR, Gill P, Lensen S, Thompson JM, Farquhar CM. Body mass index trumps age in decision for endometrial biopsy: cohort study of symptomatic premenopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(5):598.e1-e8.

How do we bring more value to our patients with AUB? We are well aware that heavy menstrual bleeding places a burden on many women; AUB affects 30% of those of reproductive age. The condition often results in lost workdays and diminished quality of life. It also is associated with significant cost expenditures for hygiene products. It is important not only to bring value to women with heavy menstrual bleeding but also to consider our increasingly expensive health care system.

Obesity is a significant problem that likely will increase the number of women presenting with AUB to ObGyns. Recent studies from New Zealand--which has 33% of its population classified as obese--have provided valuable information.1

Obesity is a risk factor for endometrial hyperplasia

In a large retrospective cohort study, Wise and colleagues analyzed data from 916 premenopausal women referred for AUB who had an endometrial biopsy from 2008 to 2014. The setting was a single large urban secondary women's health service in New Zealand. This study challenges the concept of age-related biopsy guidelines.

Of the 916 women, half were obese. Almost 5% of the women had complex endometrial hyperplasia with atypia or cancer. This incidence had risen from 3% in the years 1995 to 1997, likely due to the rising incidence of obesity. Women with a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 were 4 times more likely to develop complex hyperplasia or cancer than normal-weight women.

Other factors associated with an increased risk for complex hyperplasia or cancer were nulliparity (odds ratio [OR], 2.51; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.25-5.05), anemia (OR, 2.38; 95% CI, 1.25-4.56), and a thickened endometrium on ultrasonography (defined as >12 mm; OR, 4.04; 95% CI, 1.69-9.65). Age was not a significant risk factor in this group.

Read about using LNG-IUD to treat AUB in obese women

Small study shows LNG-IUD is effective for treating heavy menstrual bleeding in obese patients

Shaw V, Vandal AC, Coomarasamy C, Ekeroma AJ. The effectiveness of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system in obese women with heavy menstrual bleeding. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;56(6):619-623.

In another recent study from New Zealand, researchers set out to assess the efficacy of the LNG-IUD for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding in obese women. This study is important because there are very few studies of the LNG-IUD in the obese population, and none that have studied quality-of-life measures.

Shaw and colleagues conducted the prospective observational study at a tertiary teaching hospital. Twenty obese (BMI >30 kg/m2) women with heavy menstrual bleeding agreed to treatment with an LNG-IUD, and 14 completed the study (2 had a device expulsion, 1 had a device removed for pain, and 1 had a device removed for infection; 2 were lost to follow-up). The women were aged 27 to 52 years (median, 40.5 years), and their BMI ranged from 30 to 68 kg/m2 (median, 40.6 kg/m2). At recruitment, 6 months, and 12 months, participants completed the Menstrual Impact Questionnaire and the Pictorial Bleeding Assessment Chart--2 validated tools.

Compared with baseline Pictorial Bleeding Assessment scores, the authors found the LNG-IUD to be effective in 73.2% (95% CI, 55.3%-83.9%) of women at 6 months and in 92.8% (95% CI, 80.0%-97.4%) of women at 12 months. Taking into consideration device failures, including removed and expelled LNG-IUDs (which occurred in 4 women, or 20%, in the intent-to-treat analysis), the actual efficacy rate was 67%. Similarly, there was significant improvement at 6 and 12 months in Menstrual Impact Questionnaire scores for social activities, work performance, tiredness, productivity, hygiene, and depression.

Read about doing more diagnostic hysteroscopy in the office

Is it time to abandon diagnostic hysteroscopy in the OR?

Leung S, Leyland N, Murji A. Decreasing diagnostic hysteroscopy performed in the operating room: a quality improvement initiative. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2016;38(4):351-356.

Diagnostic hysteroscopy: Are we stuck in the 1990s? Why are we still performing so many diagnostic hysteroscopies in the OR, thus subjecting our patients to general anesthesia and using our precious OR time? That is the question asked by a group of researchers in Canada.

According to data from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care, diagnostic hysteroscopy was performed 10,027 times in the 2013-2014 fiscal year. Ontario researchers designed and implemented a quality improvement initiative at their institution and successfully decreased the number of diagnostic hysteroscopies performed in their hospital by 70% from their baseline 12-month period. The improvements resulted in a savings of 78 hours of case costing, or $126,984. When these data are extrapolated to the Ontario population (in which more than 10,000 diagnostic hysteroscopies were performed), potentially 7,000 women could avoid the risk of general anesthesia and the health care system could save $11 million.

Re-education protocol was key to reducing OR procedures

How did the researchers accomplish their results? The multifaceted intervention had 3 key components:

Staff education and review. Many surgeons were performing diagnostic hysteroscopy in the OR because that is how they were trained, and they were unaware of less invasive options. An awareness campaign was conducted by e-mail, during staff meetings, and at rounds.

Accessible sonohysterography. This diagnostic modality was made more accessible to referring physicians in a timely manner.

Initiation of an operative hysteroscopy education program. To allow more surgeons greater comfort with office hysteroscopy, the authors instituted didactic sessions, dry and wet lab simulations, and mentorship.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Two issues of emerging importance are being addressed in the literature: caring for patients with obesity and the concept of delivering value-based care. Value-based care does not mean providing the cheapest care; “value” places importance on quality as well as cost. In this Update, we present 3 practices that the evidence says will deliver value:

- endometrial biopsy in all obese women. Although performing more endometrial biopsies in younger women with a body mass index (BMI) in the obese range will not be less expensive initially, the procedure’s value likely will be in early diagnosis, which hopefully will translate to eventual health care system savings.

- use of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) in obese patients experiencing abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB). This practice appears to add value in the context of AUB.

- performance of routine diagnostic hysteroscopy in the office setting. We should reconsider our current habits and traditions of performing routine diagnostic hysteroscopy in the operating room (OR) as we move toward providing value-based care.

Read about obesity as a risk factor for endometrial hyperplasia

Endometrial sampling and obesity: Forget the "age 45" rule

Wise MR, Gill P, Lensen S, Thompson JM, Farquhar CM. Body mass index trumps age in decision for endometrial biopsy: cohort study of symptomatic premenopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(5):598.e1-e8.

How do we bring more value to our patients with AUB? We are well aware that heavy menstrual bleeding places a burden on many women; AUB affects 30% of those of reproductive age. The condition often results in lost workdays and diminished quality of life. It also is associated with significant cost expenditures for hygiene products. It is important not only to bring value to women with heavy menstrual bleeding but also to consider our increasingly expensive health care system.

Obesity is a significant problem that likely will increase the number of women presenting with AUB to ObGyns. Recent studies from New Zealand--which has 33% of its population classified as obese--have provided valuable information.1

Obesity is a risk factor for endometrial hyperplasia

In a large retrospective cohort study, Wise and colleagues analyzed data from 916 premenopausal women referred for AUB who had an endometrial biopsy from 2008 to 2014. The setting was a single large urban secondary women's health service in New Zealand. This study challenges the concept of age-related biopsy guidelines.

Of the 916 women, half were obese. Almost 5% of the women had complex endometrial hyperplasia with atypia or cancer. This incidence had risen from 3% in the years 1995 to 1997, likely due to the rising incidence of obesity. Women with a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 were 4 times more likely to develop complex hyperplasia or cancer than normal-weight women.

Other factors associated with an increased risk for complex hyperplasia or cancer were nulliparity (odds ratio [OR], 2.51; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.25-5.05), anemia (OR, 2.38; 95% CI, 1.25-4.56), and a thickened endometrium on ultrasonography (defined as >12 mm; OR, 4.04; 95% CI, 1.69-9.65). Age was not a significant risk factor in this group.

Read about using LNG-IUD to treat AUB in obese women

Small study shows LNG-IUD is effective for treating heavy menstrual bleeding in obese patients

Shaw V, Vandal AC, Coomarasamy C, Ekeroma AJ. The effectiveness of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system in obese women with heavy menstrual bleeding. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;56(6):619-623.

In another recent study from New Zealand, researchers set out to assess the efficacy of the LNG-IUD for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding in obese women. This study is important because there are very few studies of the LNG-IUD in the obese population, and none that have studied quality-of-life measures.

Shaw and colleagues conducted the prospective observational study at a tertiary teaching hospital. Twenty obese (BMI >30 kg/m2) women with heavy menstrual bleeding agreed to treatment with an LNG-IUD, and 14 completed the study (2 had a device expulsion, 1 had a device removed for pain, and 1 had a device removed for infection; 2 were lost to follow-up). The women were aged 27 to 52 years (median, 40.5 years), and their BMI ranged from 30 to 68 kg/m2 (median, 40.6 kg/m2). At recruitment, 6 months, and 12 months, participants completed the Menstrual Impact Questionnaire and the Pictorial Bleeding Assessment Chart--2 validated tools.

Compared with baseline Pictorial Bleeding Assessment scores, the authors found the LNG-IUD to be effective in 73.2% (95% CI, 55.3%-83.9%) of women at 6 months and in 92.8% (95% CI, 80.0%-97.4%) of women at 12 months. Taking into consideration device failures, including removed and expelled LNG-IUDs (which occurred in 4 women, or 20%, in the intent-to-treat analysis), the actual efficacy rate was 67%. Similarly, there was significant improvement at 6 and 12 months in Menstrual Impact Questionnaire scores for social activities, work performance, tiredness, productivity, hygiene, and depression.

Read about doing more diagnostic hysteroscopy in the office

Is it time to abandon diagnostic hysteroscopy in the OR?

Leung S, Leyland N, Murji A. Decreasing diagnostic hysteroscopy performed in the operating room: a quality improvement initiative. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2016;38(4):351-356.

Diagnostic hysteroscopy: Are we stuck in the 1990s? Why are we still performing so many diagnostic hysteroscopies in the OR, thus subjecting our patients to general anesthesia and using our precious OR time? That is the question asked by a group of researchers in Canada.

According to data from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care, diagnostic hysteroscopy was performed 10,027 times in the 2013-2014 fiscal year. Ontario researchers designed and implemented a quality improvement initiative at their institution and successfully decreased the number of diagnostic hysteroscopies performed in their hospital by 70% from their baseline 12-month period. The improvements resulted in a savings of 78 hours of case costing, or $126,984. When these data are extrapolated to the Ontario population (in which more than 10,000 diagnostic hysteroscopies were performed), potentially 7,000 women could avoid the risk of general anesthesia and the health care system could save $11 million.

Re-education protocol was key to reducing OR procedures

How did the researchers accomplish their results? The multifaceted intervention had 3 key components:

Staff education and review. Many surgeons were performing diagnostic hysteroscopy in the OR because that is how they were trained, and they were unaware of less invasive options. An awareness campaign was conducted by e-mail, during staff meetings, and at rounds.

Accessible sonohysterography. This diagnostic modality was made more accessible to referring physicians in a timely manner.

Initiation of an operative hysteroscopy education program. To allow more surgeons greater comfort with office hysteroscopy, the authors instituted didactic sessions, dry and wet lab simulations, and mentorship.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD obesity update 2014. http://www.oecd.org/health/Obesity-Update-2014.pdf. Published June 2014. Accessed March 10, 2017.

- The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD obesity update 2014. http://www.oecd.org/health/Obesity-Update-2014.pdf. Published June 2014. Accessed March 10, 2017.

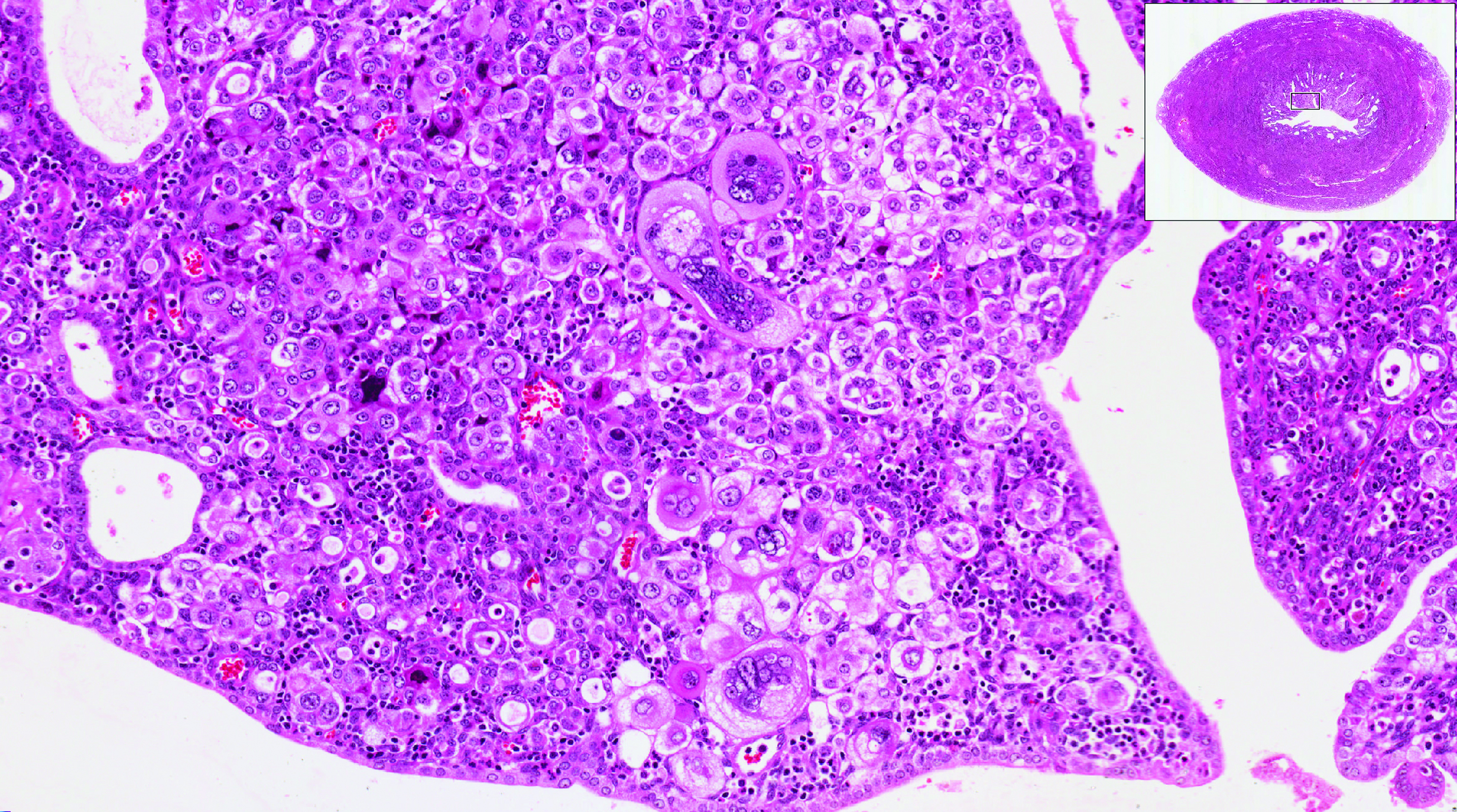

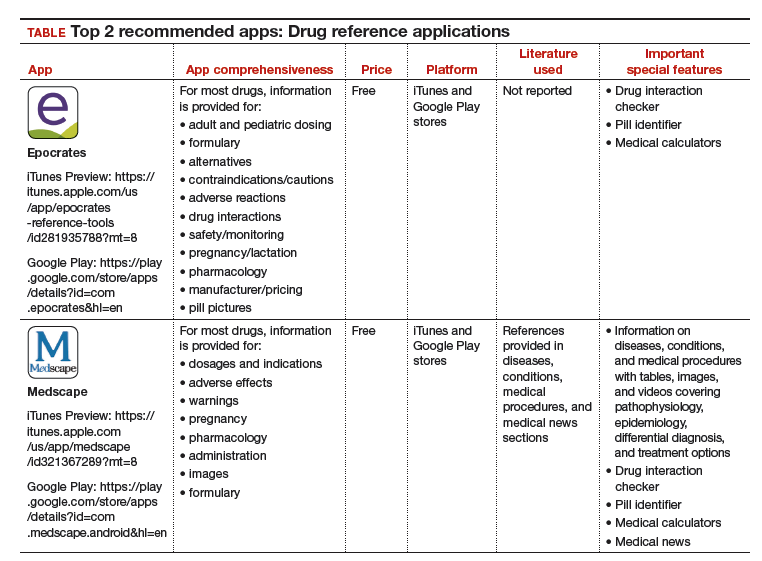

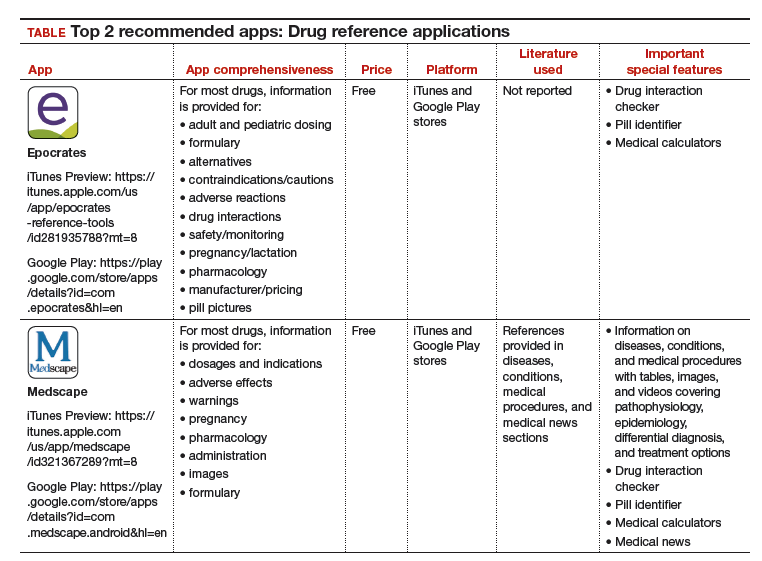

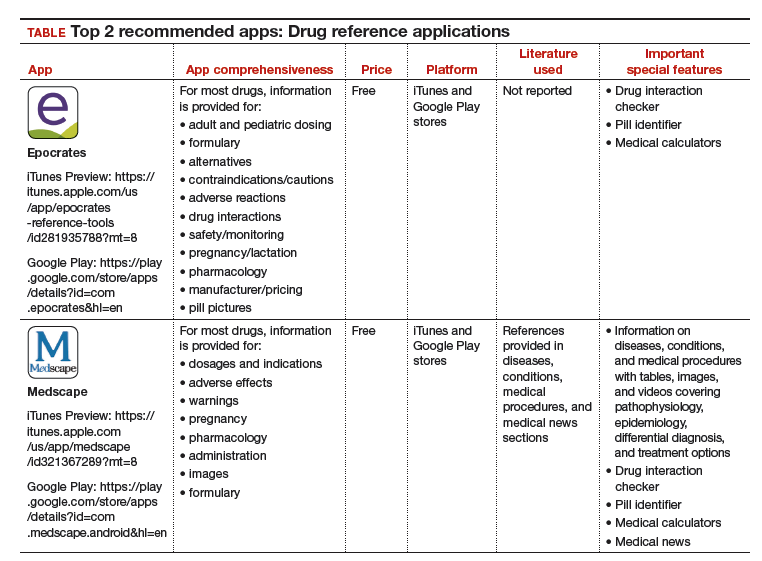

Two free, comprehensive drug reference apps for your practice

I understand that you as an ObGyn do not have the time or bandwidth to “vet” the available mobile apps for your practice. However, that does not mean you need to forgo using apps that could make your clinical life a little easier if possible. In this continuation of my “APP review” series, I focus on drug reference apps, which generally include the names of drugs, their indications, dosages, pharmacology, drug-drug interactions, contraindications, cost, and identifying characteristics.1 Drug reference apps, along with medical calculator and disease diagnosis apps, are reported as most useful by health care professionals and medical or nursing students.1 Drug reference apps are particularly popular among residents and medical students as the apps allow for rapid decision making.2

I have selected 2 drug reference apps—Epocrates and Medscape—to report here as both of these apps are free and are the only apps that appear in independent comprehensive studies.1,3 I particularly like Epocrates’ pill identification function for those patients who have forgotten the name of the medication they use but have the actual pill with them. I find Medscape’s additional information on diseases, conditions, and medical procedures especially useful for the times I have forgotten the condition that the medication is indicated for.

The recommended apps are listed in the TABLE alphabetically and are detailed with a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature use, and important special features).4 Visit the OBG Management website to download the apps featured.

Watch for my next column in which I will recommend, according to APPLI, the top apps for patients to use to track their menstrual cycles.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Mosa AS, Yoo I, Sheets L. A systematic review of health care apps for smartphones. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:67.

- Payne KB, Wharrad H, Watts K. Smartphone and medical related app use among medical students and junior doctors in the United Kingdom (UK): a regional survey. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:121.

- Aungst TD. Medical applications for pharmacists using mobile devices. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(7-8):1088-1095.

- Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(6):1478-1483.

I understand that you as an ObGyn do not have the time or bandwidth to “vet” the available mobile apps for your practice. However, that does not mean you need to forgo using apps that could make your clinical life a little easier if possible. In this continuation of my “APP review” series, I focus on drug reference apps, which generally include the names of drugs, their indications, dosages, pharmacology, drug-drug interactions, contraindications, cost, and identifying characteristics.1 Drug reference apps, along with medical calculator and disease diagnosis apps, are reported as most useful by health care professionals and medical or nursing students.1 Drug reference apps are particularly popular among residents and medical students as the apps allow for rapid decision making.2

I have selected 2 drug reference apps—Epocrates and Medscape—to report here as both of these apps are free and are the only apps that appear in independent comprehensive studies.1,3 I particularly like Epocrates’ pill identification function for those patients who have forgotten the name of the medication they use but have the actual pill with them. I find Medscape’s additional information on diseases, conditions, and medical procedures especially useful for the times I have forgotten the condition that the medication is indicated for.

The recommended apps are listed in the TABLE alphabetically and are detailed with a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature use, and important special features).4 Visit the OBG Management website to download the apps featured.

Watch for my next column in which I will recommend, according to APPLI, the top apps for patients to use to track their menstrual cycles.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

I understand that you as an ObGyn do not have the time or bandwidth to “vet” the available mobile apps for your practice. However, that does not mean you need to forgo using apps that could make your clinical life a little easier if possible. In this continuation of my “APP review” series, I focus on drug reference apps, which generally include the names of drugs, their indications, dosages, pharmacology, drug-drug interactions, contraindications, cost, and identifying characteristics.1 Drug reference apps, along with medical calculator and disease diagnosis apps, are reported as most useful by health care professionals and medical or nursing students.1 Drug reference apps are particularly popular among residents and medical students as the apps allow for rapid decision making.2

I have selected 2 drug reference apps—Epocrates and Medscape—to report here as both of these apps are free and are the only apps that appear in independent comprehensive studies.1,3 I particularly like Epocrates’ pill identification function for those patients who have forgotten the name of the medication they use but have the actual pill with them. I find Medscape’s additional information on diseases, conditions, and medical procedures especially useful for the times I have forgotten the condition that the medication is indicated for.

The recommended apps are listed in the TABLE alphabetically and are detailed with a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature use, and important special features).4 Visit the OBG Management website to download the apps featured.

Watch for my next column in which I will recommend, according to APPLI, the top apps for patients to use to track their menstrual cycles.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Mosa AS, Yoo I, Sheets L. A systematic review of health care apps for smartphones. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:67.

- Payne KB, Wharrad H, Watts K. Smartphone and medical related app use among medical students and junior doctors in the United Kingdom (UK): a regional survey. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:121.

- Aungst TD. Medical applications for pharmacists using mobile devices. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(7-8):1088-1095.

- Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(6):1478-1483.

- Mosa AS, Yoo I, Sheets L. A systematic review of health care apps for smartphones. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:67.

- Payne KB, Wharrad H, Watts K. Smartphone and medical related app use among medical students and junior doctors in the United Kingdom (UK): a regional survey. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:121.

- Aungst TD. Medical applications for pharmacists using mobile devices. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(7-8):1088-1095.

- Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(6):1478-1483.

Venetoclax produces durable effects in relapsed/refractory CLL

ORLANDO – In patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), the results with venetoclax continue to be encouraging, and recent findings from a multicenter phase Ib study hint that venetoclax may also provide durable responses – even with treatment discontinuation.

Venetoclax is an orally bioavailable selective BCL2 inhibitor that is typically given in an open-ended fashion. Toxicity – including tumor lysis syndrome – is always a concern, however, and the issue of whether open-ended administration is necessary is an important question, Andrew D. Zelenetz, MD, PhD, said at the annual conference of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

In one phase II multicenter study of venetoclax monotherapy in 107 patients with relapsed/refractory CLL with del(17p) at 31 centers in the United States, Canada, and Europe, the overall response rate was 79.4% based on an independent review committee assessment, (Lancet Oncol. 2016[17]:768-78).

Treatment included once-daily venetoclax beginning with a dose of 20 mg that was ramped up to 50, 100, 200, and 400 mg over 4-5 weeks, followed by daily 400 mg continuous dosing until disease progression or discontinuation for another reason.

Notably, 18 of 85 patients from the study who achieved an objective response were minimal residual disease (MRD)–negative in peripheral blood samples – an outcome that has not been seen with tyrosine kinase inhibitors, noted Dr. Zelenetz of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York.

The durability of venetoclax’s activity in the study was 84.7% at 12 months in all responders; 100% in those who achieved complete response, complete response with incomplete recovery of blood counts, or nodular partial remission; and 94.4% in the MRD-negative patients.

The authors concluded that venetoclax monotherapy is active and well tolerated in patients with relapsed or refractory del(17p) chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and that given the distinct mechanism of action of this new therapeutic option for these very poor-prognosis patients, it deserves further investigation as part of a combination or as part of sequential treatment with other novel targeted agents.

The finding that patients on venetoclax can achieve MRD negativity also raised the question of whether treatment can be stopped, Dr. Zelenetz said.

“Because who wants to be on a drug forever? Nobody,” he added.

This question was explored in a study published in February by Seymour et al., which provided early evidence that stopping treatment may indeed be feasible in some patients (Lancet Oncol. 2017;18[2]:230-40).

Venetoclax in this study was given in a dose-escalating fashion to target doses of 200-600 mg daily, in 49 patients with relapsed or refractory “moderately heavily pretreated” CLL. Rituximab was added at a dose of 375 mg/m2 in month 1 and 500 mg/m2 in months 2-6.

Patients had the option of stopping treatment if they achieved a complete response.

The overall response rate was 86%, including a complete response in 51% of patients. Two-year estimates for progression-free survival and ongoing response were 82% and 89% respectively.

MRD negativity was attained in 80% of complete responders and 57% of patients overall. Thirteen responders discontinued all treatment, and at the time of publication, 11 MRD-negative responders who discontinued therapy remained progression free off therapy. Two MRD-positive patients who achieved complete response and discontinued therapy progressed after 2 years, but were able to recapture response once they restarted the drug.

“So it’s really quite interesting. We might have durable responses after discontinuation of this drug in an MRD-negative state,” Dr. Zelenetz said.

Of note, the latest update to the NCCN guidelines for the treatment of CLL/SLL (small lymphocytic lymphoma) included the addition of “+/– rituximab” as part of the “suggested treatment regimen” of venetoclax in the relapsed/refractory disease setting. This recommendation is category 2A, meaning it is based on lower level evidence with uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Venetoclax: adverse events of special interest

In these studies, venetoclax was considered well tolerated, but attention to adverse events and their prevention and management – particularly with respect to tumor lysis syndrome – is essential, Dr. Zelenetz said.

In the phase II study by Stilgenbauer et al., adverse events of special interest included grade 3/4 neutropenia, which occurred in 40% of patients. This was manageable with dose interruptions (five patients) or reductions (four patients), or with granulocyte–colony stimulating factor and antibiotics (six patients, including one who received only antibiotics). None of the patients permanently discontinued treatment.

Infections occurred in 72% of patients, and grade 3 or greater infections occurred in 20% of patients. The most common overall were upper respiratory infections (15%), nasopharyngitis (14%), and urinary tract infections (9%).

Serious infections occurring in two or more patients were pneumonia, lower respiratory tract infection, and upper respiratory tract infection. One patient died from septic shock, 10 had infections leading to venetoclax interruption, and 2 had infections leading to dose reduction.

No mandated infection prophylaxis was used in this study.

Serious adverse events occurred in 59 patients (55%). The most common, occurring in at least 5% of patients, were pyrexia, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, pneumonia, and febrile neutropenia. Thirteen had adverse events leading to dose reductions, most commonly due to neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and febrile neutropenia.

Laboratory-confirmed tumor lysis syndrome was reported in five patients during the ramp-up period, including four who developed the syndrome within the first 2 days of treatment. All cases resolved without clinical sequelae. Treatment was continued without interruption in three patients with tumor lysis syndrome, who received only electrolyte management, and two patients had a 1-day treatment interruption. Both resumed dosing the next day.

In the phase Ib study by Seymour et al., common grade 1-2 toxicities included upper respiratory tract infections, diarrhea, and nausea occurring in 57%, 55%, and 53% of patients, respectively. Grade 3-4 adverse events occurred in 76% of 49 patients, and most often included neutropenia (12% of patients), thrombocytopenia (16%), anemia (14%), febrile neutropenia (12%), and leukopenia (12%). The most common serious adverse events were pyrexia (12%), febrile neutropenia (10%), lower respiratory tract infection (6%), and pneumonia (6%). Clinical tumor lysis syndrome occurred in two patients who initiated venetoclax at 50 mg, one of whom died as a result.

After enhancement of tumor lysis syndrome prophylaxis measures and reduction of the starting dose of venetoclax to 20 mg, no additional cases occurred, the authors reported.

Mitigating tumor lysis syndrome risk

General measures for mitigating the risk of tumor lysis syndrome include identification of patients at increased risk, initiation of prophylaxis with hydration and a uric acid reducing agent, and initiation of venetoclax at a 20 mg dose for 1 week, with gradual step-wise ramp-up over 5 weeks to the target dose, Dr. Zelenetz noted.

As reported by Stilgenbauer, et al., patients with a nodal mass less than 5 cm and absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) of 25,000 or less are considered at low risk for tumor lysis syndrome, those with a nodal mass of 5 cm to less than 10 cm or ALC greater than 25,000 are at medium risk, and those with a nodal mass of 10 cm or greater or nodal mass of 5 cm or greater and ALC of greater than 25,000 are considered to be at high risk.

High-risk patients in the study received inpatient venetoclax dosing and monitoring at 4, 8, 12, and 24 hours with 20 mg and 50 mg dosing, as well as outpatient intravenous hydration at 100 mg if there was no indication to hospitalize, and post-dose 8-24 hour laboratory monitoring at 100 mg and above.

Medium-risk patients received IV hydration at 20 and 50 mg dosing, inpatient care if creatinine clearance was less than 80 mL/min or if there was a high tumor burden, and postdose 8- and 24-hour laboratory monitoring after the initial dose and at dose escalations. Low-risk patients received outpatient dosing at all dose levels in the absence of an indication to hospitalize, and postdose 8- and 24-hour laboratory monitoring after the initial dose and at dose increases.

“Unfortunately, the dose-limiting toxicity of venetoclax is fatal tumor lysis,” Dr. Zelenetz said, adding that by increasing the dose slowly over time according to current treatment recommendations – from 20 mg, to 50, 100, 200, and 400 mg at weekly intervals, this complication can be avoided.

Dr. Zelenetz reported receiving consulting fees, honoraria, and/or grant/research support from Genentech, the maker of venetoclax (Venclexta), and a wide variety of other drug companies.

ORLANDO – In patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), the results with venetoclax continue to be encouraging, and recent findings from a multicenter phase Ib study hint that venetoclax may also provide durable responses – even with treatment discontinuation.

Venetoclax is an orally bioavailable selective BCL2 inhibitor that is typically given in an open-ended fashion. Toxicity – including tumor lysis syndrome – is always a concern, however, and the issue of whether open-ended administration is necessary is an important question, Andrew D. Zelenetz, MD, PhD, said at the annual conference of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.