User login

FDA grants breakthrough therapy status to rituximab for pemphigus vulgaris

The Food and Drug Administration has granted breakthrough therapy status to rituximab (Rituxan) for treating pemphigus vulgaris, according to the manufacturer.

Rituximab, a CD20-directed cytolytic antibody approved in 1997, is currently in a phase III study evaluating its efficacy for the pemphigus indication. It is approved in the United States for treating non-Hodgkin lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, rheumatoid arthritis (with methotrexate), granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s granulomatosis), and microscopic polyangiitis (with glucocorticoids).

The patients, who were experiencing their first episode of pemphigus vulgaris, were randomized to daily oral prednisone, tapered over a 12- to 18-month period, or rituximab administered intravenously (at days 0 and 14, and months 12 and 18), plus daily oral prednisone, tapered over 3 or 6 months. At 2 years, when they were no longer on therapy, 89% of those treated with rituximab and prednisone were in complete remission, compared with 34% of those treated with prednisone alone (P less than .0001).

The breakthrough therapy process is “designed to expedite the development and review of drugs that are intended to treat a serious condition and preliminary clinical evidence indicates that the drug may demonstrate substantial improvement over available therapy on a clinically significant endpoint(s),” according to the FDA.

The study was supported by the French Ministry of Health, the French Society of Dermatology, and Roche, which owns Genentech. Genentech markets rituximab in the United States with Biogen and is conducting the phase III study.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted breakthrough therapy status to rituximab (Rituxan) for treating pemphigus vulgaris, according to the manufacturer.

Rituximab, a CD20-directed cytolytic antibody approved in 1997, is currently in a phase III study evaluating its efficacy for the pemphigus indication. It is approved in the United States for treating non-Hodgkin lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, rheumatoid arthritis (with methotrexate), granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s granulomatosis), and microscopic polyangiitis (with glucocorticoids).

The patients, who were experiencing their first episode of pemphigus vulgaris, were randomized to daily oral prednisone, tapered over a 12- to 18-month period, or rituximab administered intravenously (at days 0 and 14, and months 12 and 18), plus daily oral prednisone, tapered over 3 or 6 months. At 2 years, when they were no longer on therapy, 89% of those treated with rituximab and prednisone were in complete remission, compared with 34% of those treated with prednisone alone (P less than .0001).

The breakthrough therapy process is “designed to expedite the development and review of drugs that are intended to treat a serious condition and preliminary clinical evidence indicates that the drug may demonstrate substantial improvement over available therapy on a clinically significant endpoint(s),” according to the FDA.

The study was supported by the French Ministry of Health, the French Society of Dermatology, and Roche, which owns Genentech. Genentech markets rituximab in the United States with Biogen and is conducting the phase III study.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted breakthrough therapy status to rituximab (Rituxan) for treating pemphigus vulgaris, according to the manufacturer.

Rituximab, a CD20-directed cytolytic antibody approved in 1997, is currently in a phase III study evaluating its efficacy for the pemphigus indication. It is approved in the United States for treating non-Hodgkin lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, rheumatoid arthritis (with methotrexate), granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s granulomatosis), and microscopic polyangiitis (with glucocorticoids).

The patients, who were experiencing their first episode of pemphigus vulgaris, were randomized to daily oral prednisone, tapered over a 12- to 18-month period, or rituximab administered intravenously (at days 0 and 14, and months 12 and 18), plus daily oral prednisone, tapered over 3 or 6 months. At 2 years, when they were no longer on therapy, 89% of those treated with rituximab and prednisone were in complete remission, compared with 34% of those treated with prednisone alone (P less than .0001).

The breakthrough therapy process is “designed to expedite the development and review of drugs that are intended to treat a serious condition and preliminary clinical evidence indicates that the drug may demonstrate substantial improvement over available therapy on a clinically significant endpoint(s),” according to the FDA.

The study was supported by the French Ministry of Health, the French Society of Dermatology, and Roche, which owns Genentech. Genentech markets rituximab in the United States with Biogen and is conducting the phase III study.

A history of asthma exacerbations predicts future exacerbations

ATLANTA – Asthma exacerbations are common, severe events that can be life-threatening and can accelerate loss of lung function. That’s why it’s important to flag high-risk patients in your clinical practice, Nizar N. Jarjour, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

Each year in the United States there are 15 million clinic visits, 2 million ED visits, and 500,000 hospitalizations for severe asthma exacerbations. “These exacerbations cause a high cost on the health care system, they lead to loss of work or school, and they’re a burden to patients and certainly to their families,” said Dr. Jarjour, professor of medicine and division head of allergy, pulmonary and critical care at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Factors implicated in asthma exacerbation include air pollution, cigarette smoke, occupational exposure, stress, and allergen exposure, but 50%-85% of cases are related to viral upper respiratory infections. “Any respiratory pathogen can precipitate attacks, but rhinoviruses are the most common,” he said. “Seasonal viral [upper respiratory infections] correlate with hospital admissions for asthma, and peak in spring and fall.”

Purported ways that a viral upper respiratory infection can lead to asthma exacerbation include enhanced airway responsiveness, increased eosinophilic airway inflammation in response to antigen, enhanced lower airway neutrophilic inflammation, and direct infection of the lower airway. “There are is an accentuated eosinophilic inflammation in response to allergen challenge when somebody has a cold,” Dr. Jarjour explained. “But the viral infection can actually directly lead to eosinophilic inflammation, perhaps through TSLP [thymic stromal lymphopoietin], interleukin (IL)-25, and IL-33 simulating the ILC2 (type 2 innate lymphoid cells). So there are both accentuating response to allergens as well as direct enhancement of eosinophilic inflammation following viral infection.”

One study that examined airway lavage following experimental infection found that patients had increased numbers of neutrophils in their airway sample (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:1169-77). This means that asthma exacerbation triggers neutrophilic inflammation, which relates to the induction of cytokines and chemokines in the upper airway. “We have also demonstrated increased circulation of G-CSF [granulocyte–colony stimulating factor] and nasal IL-8 in the upper airway related to increased neutrophil recruitment,” Dr. Jarjour said.

Host factors associated with asthma exacerbations include altered innate immune response in the form of a defect in production of antiviral cytokines in response to viral infection, and a greater T helper (Th)2/Th1 ratio. Other factors include eosinophilic inflammation and greater levels of specific IgE to dust mite. Baseline data from 709 patients enrolled in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Severe Asthma Research Program III (SARP-3) showed that three top risk factors for asthma exacerbations are gastroesophageal reflux disease (relative risk (RR) 1.6), greater blood eosinophil count (RR 1.6), and obesity (RR 1.2) (Am J Resp Care Med. 2017; 195:302-13).

Risk factors for exacerbation noted in various epidemiological studies include African American and Hispanic races, poor access to medical care, inadequate chronic control, smoking, allergen sensitivity to cats and dogs, gastroesophageal reflux disease, high body mass index, sinusitis, and uncontrolled eosinophilic inflammation. Key findings from a follow-up study of SARP-3 patients include the fact that the absence of exacerbations on a 12-month recall predicted future stability.

“More importantly, participants with severe disease and two or more exacerbations at baseline had a 75% chance of having an exacerbation in the following year,” Dr. Jarjour said. “This is a call for us to pay more close attention to these patients and is an important fact to keep in mind when designing clinical trials. A history of exacerbations is the best predictor of future exacerbation.”

Dr. Jarjour disclosed that he has received research funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and consulting fees from AstraZeneca and Teva Pharmaceutical. He is a member of the American Board of Internal Medicine–Pulmonary Exam Subcommittee.

ATLANTA – Asthma exacerbations are common, severe events that can be life-threatening and can accelerate loss of lung function. That’s why it’s important to flag high-risk patients in your clinical practice, Nizar N. Jarjour, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

Each year in the United States there are 15 million clinic visits, 2 million ED visits, and 500,000 hospitalizations for severe asthma exacerbations. “These exacerbations cause a high cost on the health care system, they lead to loss of work or school, and they’re a burden to patients and certainly to their families,” said Dr. Jarjour, professor of medicine and division head of allergy, pulmonary and critical care at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Factors implicated in asthma exacerbation include air pollution, cigarette smoke, occupational exposure, stress, and allergen exposure, but 50%-85% of cases are related to viral upper respiratory infections. “Any respiratory pathogen can precipitate attacks, but rhinoviruses are the most common,” he said. “Seasonal viral [upper respiratory infections] correlate with hospital admissions for asthma, and peak in spring and fall.”

Purported ways that a viral upper respiratory infection can lead to asthma exacerbation include enhanced airway responsiveness, increased eosinophilic airway inflammation in response to antigen, enhanced lower airway neutrophilic inflammation, and direct infection of the lower airway. “There are is an accentuated eosinophilic inflammation in response to allergen challenge when somebody has a cold,” Dr. Jarjour explained. “But the viral infection can actually directly lead to eosinophilic inflammation, perhaps through TSLP [thymic stromal lymphopoietin], interleukin (IL)-25, and IL-33 simulating the ILC2 (type 2 innate lymphoid cells). So there are both accentuating response to allergens as well as direct enhancement of eosinophilic inflammation following viral infection.”

One study that examined airway lavage following experimental infection found that patients had increased numbers of neutrophils in their airway sample (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:1169-77). This means that asthma exacerbation triggers neutrophilic inflammation, which relates to the induction of cytokines and chemokines in the upper airway. “We have also demonstrated increased circulation of G-CSF [granulocyte–colony stimulating factor] and nasal IL-8 in the upper airway related to increased neutrophil recruitment,” Dr. Jarjour said.

Host factors associated with asthma exacerbations include altered innate immune response in the form of a defect in production of antiviral cytokines in response to viral infection, and a greater T helper (Th)2/Th1 ratio. Other factors include eosinophilic inflammation and greater levels of specific IgE to dust mite. Baseline data from 709 patients enrolled in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Severe Asthma Research Program III (SARP-3) showed that three top risk factors for asthma exacerbations are gastroesophageal reflux disease (relative risk (RR) 1.6), greater blood eosinophil count (RR 1.6), and obesity (RR 1.2) (Am J Resp Care Med. 2017; 195:302-13).

Risk factors for exacerbation noted in various epidemiological studies include African American and Hispanic races, poor access to medical care, inadequate chronic control, smoking, allergen sensitivity to cats and dogs, gastroesophageal reflux disease, high body mass index, sinusitis, and uncontrolled eosinophilic inflammation. Key findings from a follow-up study of SARP-3 patients include the fact that the absence of exacerbations on a 12-month recall predicted future stability.

“More importantly, participants with severe disease and two or more exacerbations at baseline had a 75% chance of having an exacerbation in the following year,” Dr. Jarjour said. “This is a call for us to pay more close attention to these patients and is an important fact to keep in mind when designing clinical trials. A history of exacerbations is the best predictor of future exacerbation.”

Dr. Jarjour disclosed that he has received research funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and consulting fees from AstraZeneca and Teva Pharmaceutical. He is a member of the American Board of Internal Medicine–Pulmonary Exam Subcommittee.

ATLANTA – Asthma exacerbations are common, severe events that can be life-threatening and can accelerate loss of lung function. That’s why it’s important to flag high-risk patients in your clinical practice, Nizar N. Jarjour, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

Each year in the United States there are 15 million clinic visits, 2 million ED visits, and 500,000 hospitalizations for severe asthma exacerbations. “These exacerbations cause a high cost on the health care system, they lead to loss of work or school, and they’re a burden to patients and certainly to their families,” said Dr. Jarjour, professor of medicine and division head of allergy, pulmonary and critical care at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Factors implicated in asthma exacerbation include air pollution, cigarette smoke, occupational exposure, stress, and allergen exposure, but 50%-85% of cases are related to viral upper respiratory infections. “Any respiratory pathogen can precipitate attacks, but rhinoviruses are the most common,” he said. “Seasonal viral [upper respiratory infections] correlate with hospital admissions for asthma, and peak in spring and fall.”

Purported ways that a viral upper respiratory infection can lead to asthma exacerbation include enhanced airway responsiveness, increased eosinophilic airway inflammation in response to antigen, enhanced lower airway neutrophilic inflammation, and direct infection of the lower airway. “There are is an accentuated eosinophilic inflammation in response to allergen challenge when somebody has a cold,” Dr. Jarjour explained. “But the viral infection can actually directly lead to eosinophilic inflammation, perhaps through TSLP [thymic stromal lymphopoietin], interleukin (IL)-25, and IL-33 simulating the ILC2 (type 2 innate lymphoid cells). So there are both accentuating response to allergens as well as direct enhancement of eosinophilic inflammation following viral infection.”

One study that examined airway lavage following experimental infection found that patients had increased numbers of neutrophils in their airway sample (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:1169-77). This means that asthma exacerbation triggers neutrophilic inflammation, which relates to the induction of cytokines and chemokines in the upper airway. “We have also demonstrated increased circulation of G-CSF [granulocyte–colony stimulating factor] and nasal IL-8 in the upper airway related to increased neutrophil recruitment,” Dr. Jarjour said.

Host factors associated with asthma exacerbations include altered innate immune response in the form of a defect in production of antiviral cytokines in response to viral infection, and a greater T helper (Th)2/Th1 ratio. Other factors include eosinophilic inflammation and greater levels of specific IgE to dust mite. Baseline data from 709 patients enrolled in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Severe Asthma Research Program III (SARP-3) showed that three top risk factors for asthma exacerbations are gastroesophageal reflux disease (relative risk (RR) 1.6), greater blood eosinophil count (RR 1.6), and obesity (RR 1.2) (Am J Resp Care Med. 2017; 195:302-13).

Risk factors for exacerbation noted in various epidemiological studies include African American and Hispanic races, poor access to medical care, inadequate chronic control, smoking, allergen sensitivity to cats and dogs, gastroesophageal reflux disease, high body mass index, sinusitis, and uncontrolled eosinophilic inflammation. Key findings from a follow-up study of SARP-3 patients include the fact that the absence of exacerbations on a 12-month recall predicted future stability.

“More importantly, participants with severe disease and two or more exacerbations at baseline had a 75% chance of having an exacerbation in the following year,” Dr. Jarjour said. “This is a call for us to pay more close attention to these patients and is an important fact to keep in mind when designing clinical trials. A history of exacerbations is the best predictor of future exacerbation.”

Dr. Jarjour disclosed that he has received research funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and consulting fees from AstraZeneca and Teva Pharmaceutical. He is a member of the American Board of Internal Medicine–Pulmonary Exam Subcommittee.

Smoking During Pregnancy May Damage Offspring’s Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer

Retinal nerve fiber layer defects are a defining feature of optic neuropathies and have been implicated in several neurodegenerative disorders, including multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease. Both maternal smoking during pregnancy and low birth weight have been implicated in impaired development of the retina.

The Copenhagen Child Cohort 2000 Eye Study

Mr. Ashina and colleagues sought to investigate the associations of maternal smoking during pregnancy and low birth weight with retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in preadolescent children. They examined data from a prospective, population-based, birth cohort study that included all children (n = 6,090) born in 2000 in Copenhagen. Maternal smoking data were collected through parental interviews. Birth weight, pregnancy, and medical history data were obtained from the Danish Medical Birth Registry. As a follow-up, the researchers performed eye examinations on 1,406 of these children from May 1, 2011, to October 31, 2012, when the children were age 11 or 12.

Of the 1,406 children in the study, 1,323 were included in the analysis. Mean age was 11.7. Nearly half of the children (47.8%) were boys. The mean retinal nerve fiber layer thickness was 104 mm. In 227 children whose mothers had smoked during pregnancy, the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer was 5.7 mm thinner than in children whose mothers had not smoked during pregnancy, after adjusting for age, sex, birth weight, height, body weight, Tanner stage of pubertal development, axial length, and spherical equivalent refractive error. In children with low birth weight (ie, < 2,500 g), the retinal nerve fiber layer was 3.5 mm thinner than in children with normal birth weight, after adjustment for all variables.

“The results of this study add evidence to existing recommendations to avoid smoking during pregnancy and support measures that promote maternal and fetal health,” the researchers said.

A Public Health Message

In an invited commentary that accompanied the study, Christopher Kai-Shun Leung, MD, from the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at Hong Kong Eye Hospital and Chinese University of Hong Kong in Kowloon, said that “although a difference of 5 to 6 mm in average circumpapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness is unlikely to translate into a detectable difference in visual function in children aged 12 to 13 years, the risk of subsequent development of visual impairment should not be overlooked.” Furthermore, he noted, “whether a thinner retinal nerve fiber layer in the children of mothers who smoked during pregnancy w

—Glenn S. Williams

Suggested Reading

Ashina H, Li XQ, Olsen EM, et al. Association of maternal smoking during pregnancy and birth weight with retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in children aged 11 or 12 years: The Copenhagen Child Cohort 2000 Eye Study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017 March 2 [Epub ahead of print].

Leung CK. Evaluation of retinal nerve fiber layer thinning with Fourier-domain optical coherence tomography. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017 March 2 [Epub ahead of print].

Retinal nerve fiber layer defects are a defining feature of optic neuropathies and have been implicated in several neurodegenerative disorders, including multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease. Both maternal smoking during pregnancy and low birth weight have been implicated in impaired development of the retina.

The Copenhagen Child Cohort 2000 Eye Study

Mr. Ashina and colleagues sought to investigate the associations of maternal smoking during pregnancy and low birth weight with retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in preadolescent children. They examined data from a prospective, population-based, birth cohort study that included all children (n = 6,090) born in 2000 in Copenhagen. Maternal smoking data were collected through parental interviews. Birth weight, pregnancy, and medical history data were obtained from the Danish Medical Birth Registry. As a follow-up, the researchers performed eye examinations on 1,406 of these children from May 1, 2011, to October 31, 2012, when the children were age 11 or 12.

Of the 1,406 children in the study, 1,323 were included in the analysis. Mean age was 11.7. Nearly half of the children (47.8%) were boys. The mean retinal nerve fiber layer thickness was 104 mm. In 227 children whose mothers had smoked during pregnancy, the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer was 5.7 mm thinner than in children whose mothers had not smoked during pregnancy, after adjusting for age, sex, birth weight, height, body weight, Tanner stage of pubertal development, axial length, and spherical equivalent refractive error. In children with low birth weight (ie, < 2,500 g), the retinal nerve fiber layer was 3.5 mm thinner than in children with normal birth weight, after adjustment for all variables.

“The results of this study add evidence to existing recommendations to avoid smoking during pregnancy and support measures that promote maternal and fetal health,” the researchers said.

A Public Health Message

In an invited commentary that accompanied the study, Christopher Kai-Shun Leung, MD, from the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at Hong Kong Eye Hospital and Chinese University of Hong Kong in Kowloon, said that “although a difference of 5 to 6 mm in average circumpapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness is unlikely to translate into a detectable difference in visual function in children aged 12 to 13 years, the risk of subsequent development of visual impairment should not be overlooked.” Furthermore, he noted, “whether a thinner retinal nerve fiber layer in the children of mothers who smoked during pregnancy w

—Glenn S. Williams

Suggested Reading

Ashina H, Li XQ, Olsen EM, et al. Association of maternal smoking during pregnancy and birth weight with retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in children aged 11 or 12 years: The Copenhagen Child Cohort 2000 Eye Study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017 March 2 [Epub ahead of print].

Leung CK. Evaluation of retinal nerve fiber layer thinning with Fourier-domain optical coherence tomography. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017 March 2 [Epub ahead of print].

Retinal nerve fiber layer defects are a defining feature of optic neuropathies and have been implicated in several neurodegenerative disorders, including multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease. Both maternal smoking during pregnancy and low birth weight have been implicated in impaired development of the retina.

The Copenhagen Child Cohort 2000 Eye Study

Mr. Ashina and colleagues sought to investigate the associations of maternal smoking during pregnancy and low birth weight with retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in preadolescent children. They examined data from a prospective, population-based, birth cohort study that included all children (n = 6,090) born in 2000 in Copenhagen. Maternal smoking data were collected through parental interviews. Birth weight, pregnancy, and medical history data were obtained from the Danish Medical Birth Registry. As a follow-up, the researchers performed eye examinations on 1,406 of these children from May 1, 2011, to October 31, 2012, when the children were age 11 or 12.

Of the 1,406 children in the study, 1,323 were included in the analysis. Mean age was 11.7. Nearly half of the children (47.8%) were boys. The mean retinal nerve fiber layer thickness was 104 mm. In 227 children whose mothers had smoked during pregnancy, the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer was 5.7 mm thinner than in children whose mothers had not smoked during pregnancy, after adjusting for age, sex, birth weight, height, body weight, Tanner stage of pubertal development, axial length, and spherical equivalent refractive error. In children with low birth weight (ie, < 2,500 g), the retinal nerve fiber layer was 3.5 mm thinner than in children with normal birth weight, after adjustment for all variables.

“The results of this study add evidence to existing recommendations to avoid smoking during pregnancy and support measures that promote maternal and fetal health,” the researchers said.

A Public Health Message

In an invited commentary that accompanied the study, Christopher Kai-Shun Leung, MD, from the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at Hong Kong Eye Hospital and Chinese University of Hong Kong in Kowloon, said that “although a difference of 5 to 6 mm in average circumpapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness is unlikely to translate into a detectable difference in visual function in children aged 12 to 13 years, the risk of subsequent development of visual impairment should not be overlooked.” Furthermore, he noted, “whether a thinner retinal nerve fiber layer in the children of mothers who smoked during pregnancy w

—Glenn S. Williams

Suggested Reading

Ashina H, Li XQ, Olsen EM, et al. Association of maternal smoking during pregnancy and birth weight with retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in children aged 11 or 12 years: The Copenhagen Child Cohort 2000 Eye Study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017 March 2 [Epub ahead of print].

Leung CK. Evaluation of retinal nerve fiber layer thinning with Fourier-domain optical coherence tomography. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017 March 2 [Epub ahead of print].

Treating polycystic ovary syndrome: Start using dual medical therapy

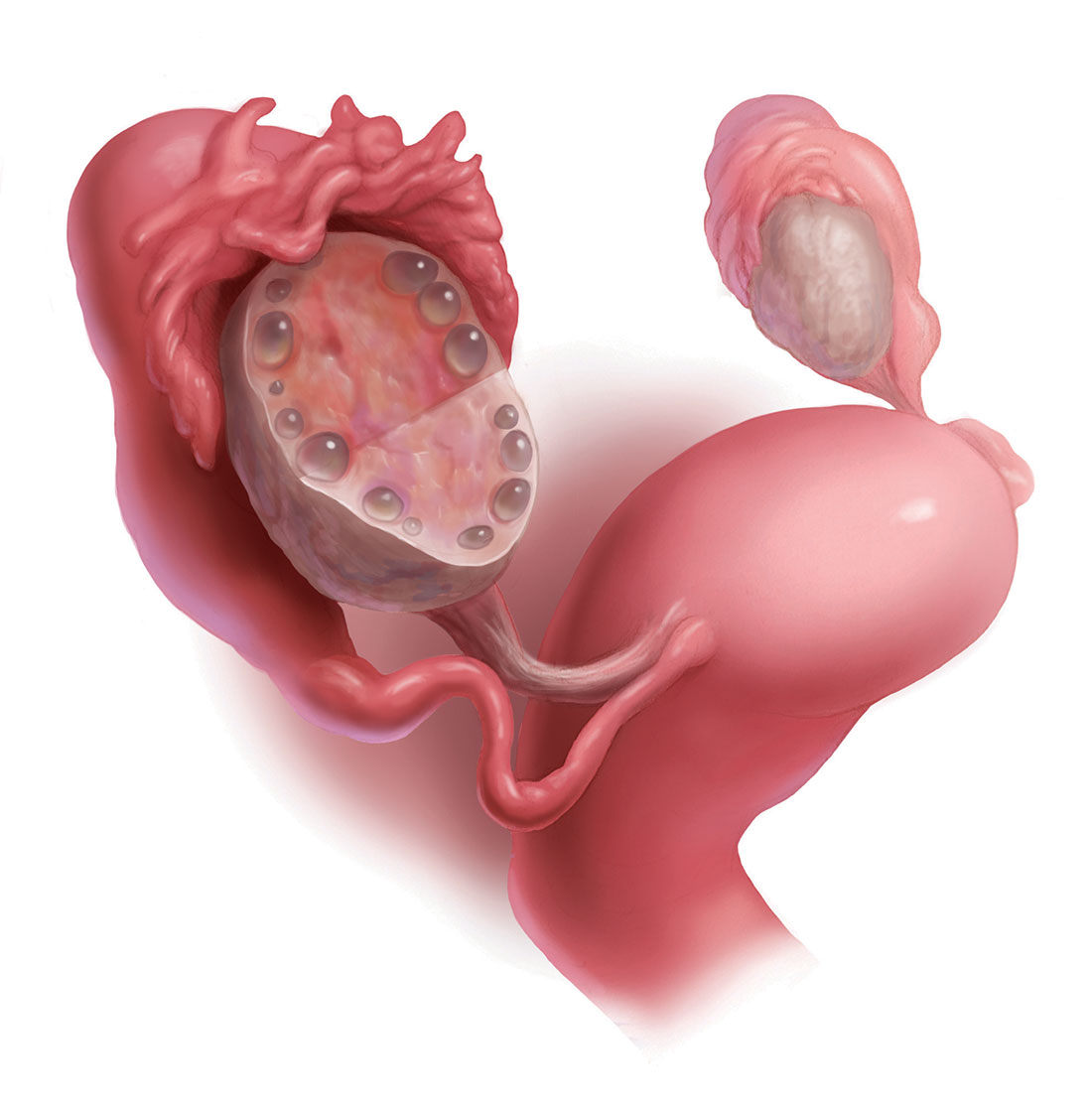

Using the Rotterdam criteria, the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is made in the presence of 2 of the following 3 criteria1:

- oligo-ovulation or anovulation

- hyperandrogenism manifested by the presence of either hirsutism or elevated hormone levels (including serum testosterone androstenedione and/or dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate)

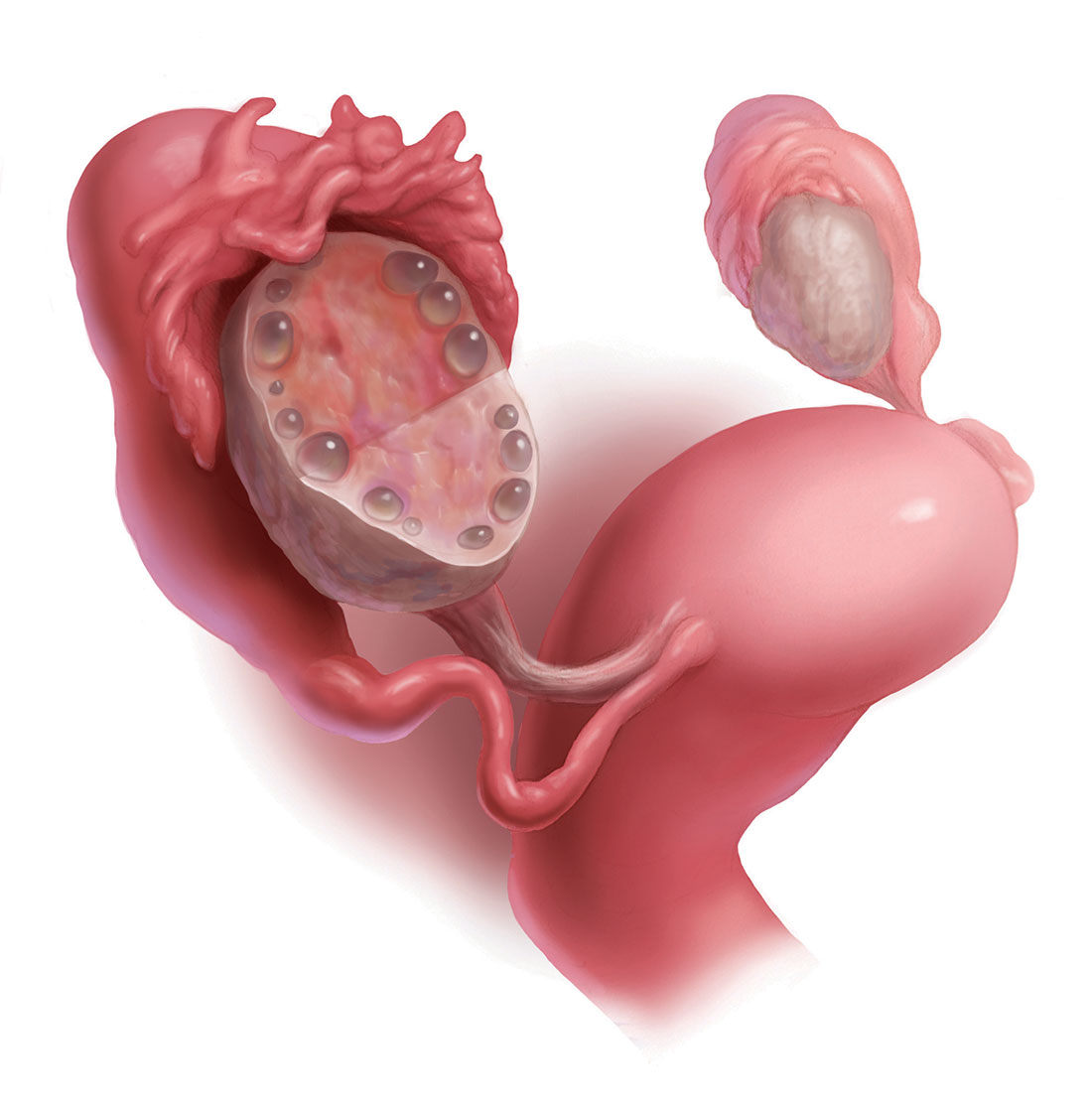

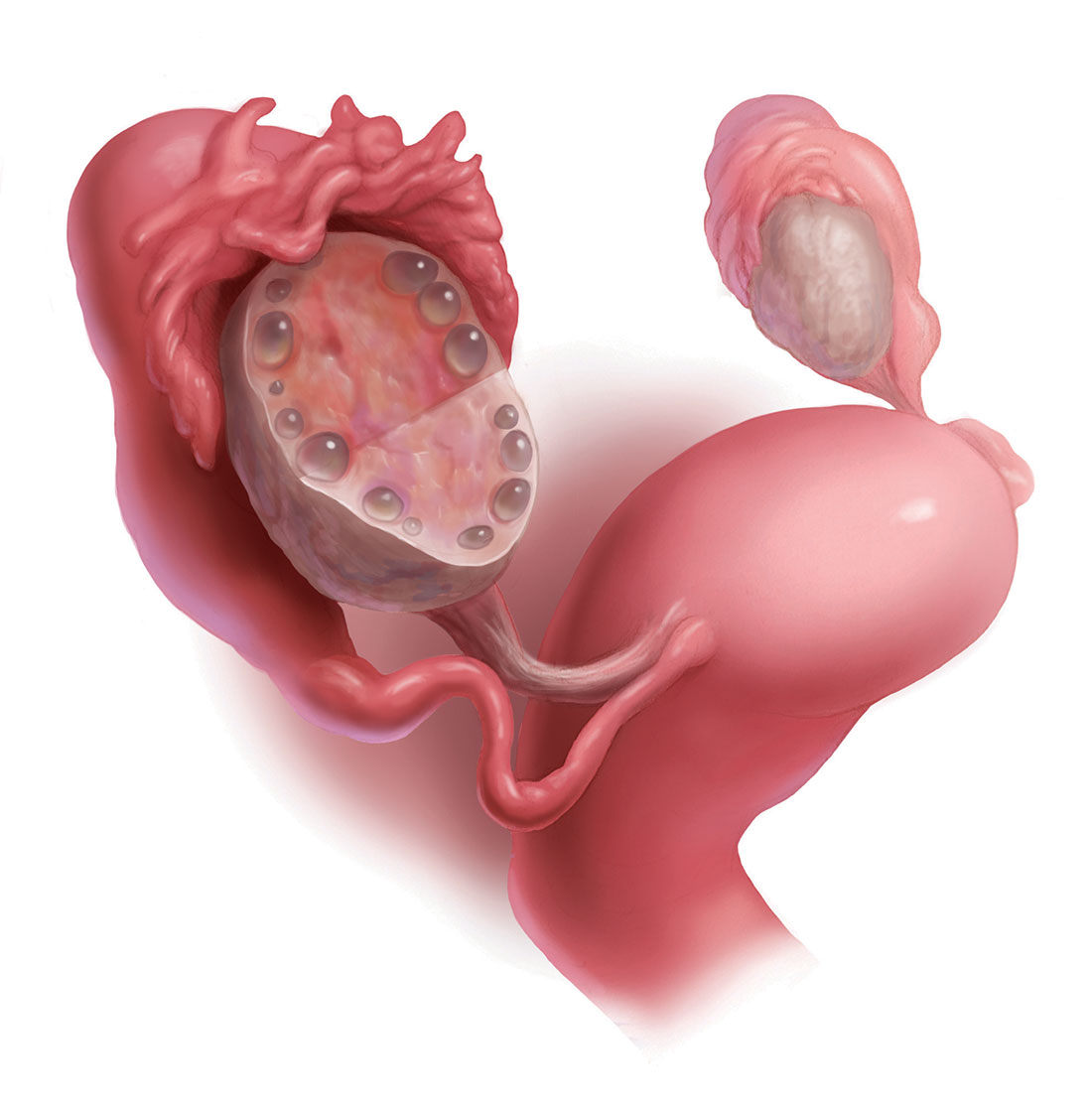

- ultrasonography evidence of multifollicular ovaries (≥12 follicles with a diameter of 2 mm to 9 mm in one or both ovaries; FIGURE) or ovarian stromal volume of 10 mL or more.

Among reproductive-age women, the prevalence of PCOS has been reported to range from 8% to 13% for different populations.2 Most clinicians initiate treatment for PCOS with oral estrogen−progestin (OEP) monotherapy. OEP treatment has many beneficial hormonal effects, including:

- a resulting decrease in pituitary luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion, which decreases ovarian androgen production

- an increase in liver production of sex hormone−binding globulin (SHBG), which decreases free testosterone levels

- protection against the development of endometrial hyperplasia

- induction of regular uterine withdrawal bleeding.

However, OEP therapy neither improves metabolic indices (insulin sensitivity and visceral fat secretion of adipokines) nor blocks androgen action in the skin.

Dual medical treatment for PCOS can address the issues that monotherapy cannot and, along with providing guidance on improving diet and exercise, many experts support the initial therapy of PCOS with dual medical therapy (OEP plus metformin or spironolactone).

Advantages of OEP plus metformin

For many women with PCOS, the syndrome is characterized by abnormalities in both the reproductive (increase in LH secretion) and metabolic (insulin resistance and increased adipokines) systems. OEP monotherapy does not improve the metabolic abnormalities of PCOS. Combination treatment with both OEP plus metformin, along with diet and exercise, can best treat these combined abnormalities.

Data support dual therapy with metformin. In one small, randomized trial in women with PCOS, OEP plus metformin (1,500 mg daily) resulted in a greater reduction in serum androstenedione and a greater increase in SHBG than OEP monotherapy.3 In addition, weight loss and a reduction in waist-to-hip ratio only occurred in the OEP plus metformin group.3 In another small randomized study in women with PCOS, OEP plus metformin (1,500 mg daily) resulted in a greater decrease in free androgen index than OEP monotherapy.4

In my clinical opinion, women who may best benefit from OEP plus metformin therapy have one of the following factors indicating the presence of insulin resistance5:

- body mass index >30 kg/m2

- waist-to-hip ratio ≥0.85

- waist circumference >35 in (89 cm)

- acanthosis nigricans

- personal history of gestational diabetes

- family history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in a first-degree relative

- diagnosis of the metabolic syndrome.

My preferred treatment approach

Metformin is a low cost and safe treatment for metabolic dysfunction due to insulin resistance and excess adipokines. I often start PCOS treatment for my patients with an OEP plus metformin extended release (XR) 750 mg with dinner. If the patient tolerates this dose, I increase the dose to metformin XR 1,500 mg with dinner.

Adverse effects. The most common side effects of metformin are gastrointestinal, including abdominal discomfort, flatulence, borborygmi, diarrhea, and nausea. Metformin reduces serum vitamin B12 levels by 5% to 10%; therefore, ensuring adequate vitamin B12 intake (2.6 µg daily) is helpful.6 Although metformin does reduce vitamin B12 levels, there is no strong relationship between metformin and anemia or peripheral neuropathy.7 Lactic acidosis is a rare complication of metformin.

Beneficial effects. In the treatment of PCOS, metformin may have many beneficial effects, including8:

- decrease in insulin resistance

- decrease in harmful adipokines

- reduction in visceral fat

- reduction in the incidence of T2DM.

- oral norethindrone acetate 5 mg daily (which can lower luteinizing hormone levels and block ovulation) plus metformin

- norethindrone acetate 5 mg plus spironolactone

- levonorgestrel-intrauterine device plus metformin or spironolactone.

OEP plus spironolactone

Many women with PCOS have increased LH secretion and increased androgen activity in the skin due to increased 5-alpha reductase enzyme activity, which catalyzes the conversion of testosterone to the powerful intracellular androgen dihydrotestosterone.9 Women with PCOS may present with a chief problem report of hirsutism, acne, or female androgenetic alopecia. OEP plus spironolactone may be an optimal initial treatment for women with a dominant dermatologic manifestation of PCOS. OEP treatment results in a decrease in pituitary LH secretion and ovarian androgen production. Spironolactone adds to this therapeutic effect by blocking androgen action in the skin.

The data on dual therapy with spironolactone. Many dermatologists recommend spironolactone in combination with cosmetic measures for the treatment of acne, but there are only a few randomized trials that demonstrate its efficacy.10 In one trial spironolactone was demonstrated to be superior to placebo for the treatment of inflammatory acne.10 Authors of multiple randomized trials report that the antiandrogens, spironolactone, or finasteride are superior to metformin to treat hirsutism.11 In addition, a few small trials report that spironolactone plus OEP is superior to either OEP or metformin monotherapy for hirsutism.11 Clinical trials of spironolactone for hirsutism have been rated as “low quality” and additional controlled trials of OEP monotherapy versus OEP plus spironolactone are warranted.12

My preferred treatment approach

Spironolactone is effective in the treatment of hirsutism at doses ranging from 50 mg to 200 mg daily. I routinely use a dose of spironolactone 100 mg daily because this dose is near of the top of the dose-response curve and has few adverse effects (such as intermittent uterine bleeding or spotting). With spironolactone monotherapy at a dose of 200 mg, irregular uterine bleeding or spotting is common, but concomitant treatment with an OEP tends to minimize this side effect. In my practice I rarely have patients report irregular uterine bleeding or spotting with the combination treatment of an OEP and spironolactone 100 mg daily.

Contraindications. Spironolactone should not be given to women with renal insufficiency because it can cause hyperkalemia. However, it is not necessary to check potassium levels in young women taking spironolactone with normal creatinine levels.13

Triple therapy: OEP plus metformin plus spironolactone

Some experts strongly recommend the initial treatment of PCOS in adolescents and young women with triple therapy: OEP plus an insulin sensitizer plus an antiandrogen.14 This recommendation is based in part on the observation that OEP monotherapy may be associated with an increase in circulating adipokines and visceral fat mass as determined by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.15 By contrast, triple treatment with an OEP plus metformin plus an antiandrogen is associated with a decrease in circulating adipokines and visceral fat mass.

What is the best progestin for PCOS?

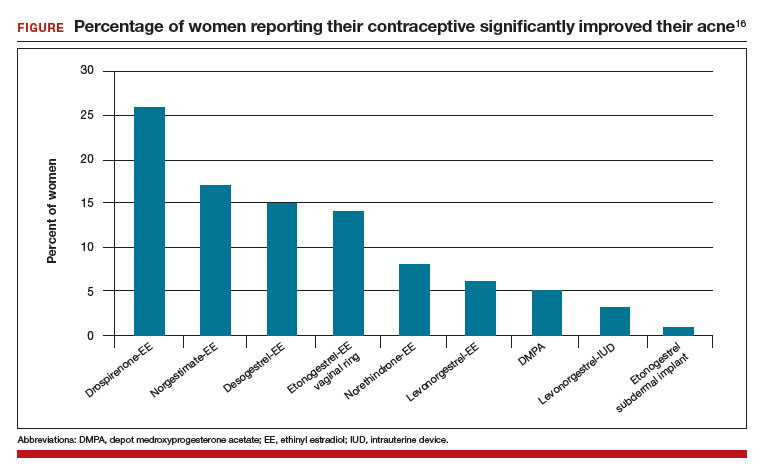

Any OEP is better than no OEP, regardless of the progestin used to treat the PCOS because ethinyl estradiol plus any synthetic progestin suppresses pituitary secretion of LH and decreases ovarian androgen production. However, for the treatment of acne, using a progestin that is less androgenic may be beneficial.16

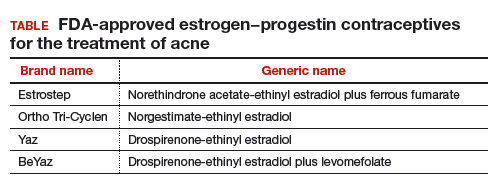

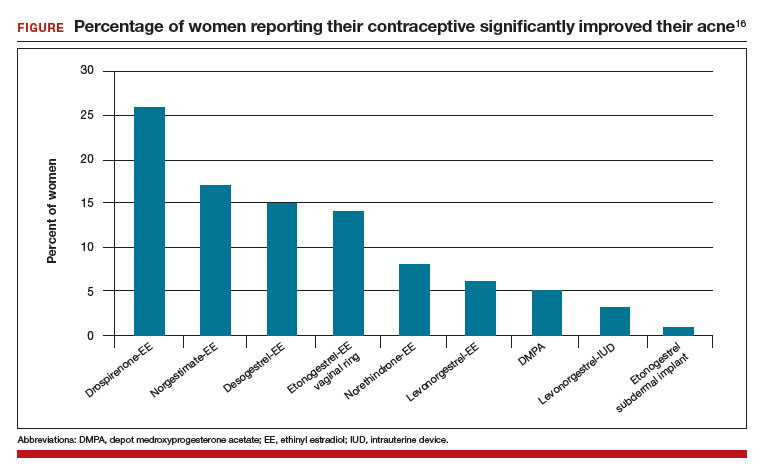

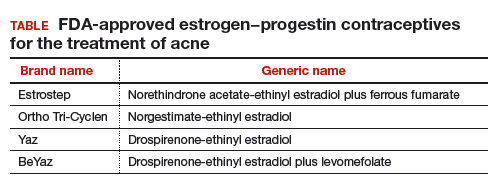

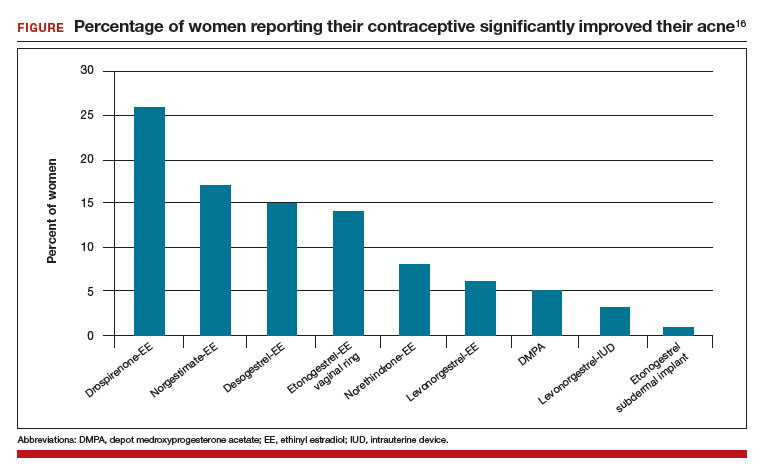

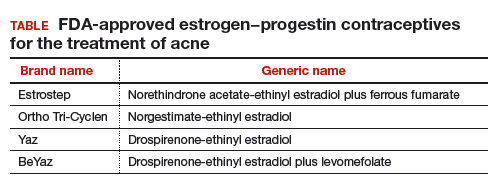

In one study, 2,147 consecutive women who were taking a contraceptive and presented for treatment of acne were asked if their contraceptive had a positive impact on their acne. The percentage of women reporting that their contraceptive significantly improved their acne ranged from 26% for those taking drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol (EE) to 1% for those taking the etonogestrel subdermal implant (FIGURE).16 The US Food and Drug Administration has approved 4 OEP contraceptives for the treatment of acne (TABLE). The OEPs with drospirenone, norgestimate, desogestrel, or norethindrone acetate may be optimal choices for the treatment of acne caused by PCOS.

The bottom line

PCOS is a common endocrine disorder treated primarily by obstetricians-gynecologists. Among adolescents and young women with PCOS chief problem reports include irregular menses, hirsutism, obesity, acne, and infertility. Among mid-life women the presentation of PCOS often evolves into chronic medical problems, including obesity, metabolic syndrome, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, T2DM, cardiovascular disease, and endometrial cancer.17–19 To optimally treat the multiple pathophysiologic disorders manifested in PCOS, I recommend initial dual medical therapy with an OEP plus metformin or an OEP plus spironolactone.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Hum Reprod. 2004;19(1):41-47.

- Bozdag G, Mumusoglu S, Zengin D, Karabulut E, Yildiz BO. The prevalence and phenotypic features of polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(12):2841-2855.

- Elter K, Imir G, Durmusoglu F. Clinical, endocrine and metabolic effects of metformin added to ethinyl estradiol-cyproterone acetate in non-obese women with polycystic ovarian syndrome: a randomized controlled study. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(7):1729-1737.

- Cibula D, Fanta M, Vrbikova J, et al. The effect of combination therapy with metformin and combined oral contraceptives (COC) versus COC alone on insulin sensitivity, hyperandrogenism, SHBG and lipids in PCOS patients. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(1):180-184.

- Grundy SM, Brewer HB, Cleeman JI, Smith SC Jr, Lenfant C; American Heart Association; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 2004;109(3):433-438.

- Niafar M, Hai F, Porhomayon J, Nader ND. The role of metformin on vitamin B12 deficiency: a meta-analysis review. Intern Emerg Med. 2015;10(1):93-102.

- de Groot-Kamphuis DM, van Dijk PR, Groenier KH, Houweling St, Bilo HJ, Kleefstra N. Vitamin B12 deficiency and the lack of its consequences in type 2 diabetes patients using metformin. Neth J Med. 2013;71(7):386-390.

- Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Christakou CD, Kandaraki E, Economou FN. Metformin: an old medication of new fashion: evolving new molecular mechanisms and clinical implications in polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162(2):193-212.

- Skalba P, Dabkowska-Huc A, Kazimierczak W, Samojedny A, Samojedny MP, Chelmicki Z. Content of 5-alph-reductase (type 1 and type 2) mRNA in dermal papillae from the lower abdominal region in women with hirsutism. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31(4):564-570.

- Layton AM, Eady EA, Whitehouse H, Del Rosso JQ, Fedorowicz Z, van Zuuren EJ. Oral spironolactone for acne vulgaris in adult females: a hybrid systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18(2):169-191.

- Swiglo BA, Cosma M, Flynn DN, et al. Clinical review: antiandrogens for the treatment of hirsutism: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(4):1153-1160.

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z. Interventions for hirsutism excluding laser and photoepilation therapy alone: abridged Cochrane systematic review including GRADE assessments. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175(1):45-61.

- Plovanich M, Weng QY, Mostaghimi A. Low usefulness of potassium monitoring among healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(9):941-944.

- Ibanez L, de Zegher F. Low-dose combination of flutamide, metformin and an oral contraceptive for non-obese, young women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(1):57-60.

- Ibanez L, de Zegher F. Ethinyl estradiol-drospirenone, flutamide-metformin or both for adolescents and women with hyperinsulinemic hyperandrogenism: opposite effects on adipocytokines and body adiposity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(4):1592-1597.

- Lortscher D, Admani S, Stur N, Eichenfield LF. Hormonal contraceptives and acne: a retrospective analysis of 2147 patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(6):670-674.

- Wang ET, Calderon-Margalit R, Cedars MI, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome and risk for long-term diabetes and dyslipidemia. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(1):6-13.

- Joham AE, Raniasinha S, Zoungas S, Moran L, Teede HJ. Gestational diabetes and type 2 diabetes in reproductive aged women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(3):e447-e452.

- Gottschau M, Kjaer SK, Jensen A, Munk C, Mellemkjaer L. Risk of cancer among women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a Danish cohort study. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(1):99-103.

Using the Rotterdam criteria, the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is made in the presence of 2 of the following 3 criteria1:

- oligo-ovulation or anovulation

- hyperandrogenism manifested by the presence of either hirsutism or elevated hormone levels (including serum testosterone androstenedione and/or dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate)

- ultrasonography evidence of multifollicular ovaries (≥12 follicles with a diameter of 2 mm to 9 mm in one or both ovaries; FIGURE) or ovarian stromal volume of 10 mL or more.

Among reproductive-age women, the prevalence of PCOS has been reported to range from 8% to 13% for different populations.2 Most clinicians initiate treatment for PCOS with oral estrogen−progestin (OEP) monotherapy. OEP treatment has many beneficial hormonal effects, including:

- a resulting decrease in pituitary luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion, which decreases ovarian androgen production

- an increase in liver production of sex hormone−binding globulin (SHBG), which decreases free testosterone levels

- protection against the development of endometrial hyperplasia

- induction of regular uterine withdrawal bleeding.

However, OEP therapy neither improves metabolic indices (insulin sensitivity and visceral fat secretion of adipokines) nor blocks androgen action in the skin.

Dual medical treatment for PCOS can address the issues that monotherapy cannot and, along with providing guidance on improving diet and exercise, many experts support the initial therapy of PCOS with dual medical therapy (OEP plus metformin or spironolactone).

Advantages of OEP plus metformin

For many women with PCOS, the syndrome is characterized by abnormalities in both the reproductive (increase in LH secretion) and metabolic (insulin resistance and increased adipokines) systems. OEP monotherapy does not improve the metabolic abnormalities of PCOS. Combination treatment with both OEP plus metformin, along with diet and exercise, can best treat these combined abnormalities.

Data support dual therapy with metformin. In one small, randomized trial in women with PCOS, OEP plus metformin (1,500 mg daily) resulted in a greater reduction in serum androstenedione and a greater increase in SHBG than OEP monotherapy.3 In addition, weight loss and a reduction in waist-to-hip ratio only occurred in the OEP plus metformin group.3 In another small randomized study in women with PCOS, OEP plus metformin (1,500 mg daily) resulted in a greater decrease in free androgen index than OEP monotherapy.4

In my clinical opinion, women who may best benefit from OEP plus metformin therapy have one of the following factors indicating the presence of insulin resistance5:

- body mass index >30 kg/m2

- waist-to-hip ratio ≥0.85

- waist circumference >35 in (89 cm)

- acanthosis nigricans

- personal history of gestational diabetes

- family history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in a first-degree relative

- diagnosis of the metabolic syndrome.

My preferred treatment approach

Metformin is a low cost and safe treatment for metabolic dysfunction due to insulin resistance and excess adipokines. I often start PCOS treatment for my patients with an OEP plus metformin extended release (XR) 750 mg with dinner. If the patient tolerates this dose, I increase the dose to metformin XR 1,500 mg with dinner.

Adverse effects. The most common side effects of metformin are gastrointestinal, including abdominal discomfort, flatulence, borborygmi, diarrhea, and nausea. Metformin reduces serum vitamin B12 levels by 5% to 10%; therefore, ensuring adequate vitamin B12 intake (2.6 µg daily) is helpful.6 Although metformin does reduce vitamin B12 levels, there is no strong relationship between metformin and anemia or peripheral neuropathy.7 Lactic acidosis is a rare complication of metformin.

Beneficial effects. In the treatment of PCOS, metformin may have many beneficial effects, including8:

- decrease in insulin resistance

- decrease in harmful adipokines

- reduction in visceral fat

- reduction in the incidence of T2DM.

- oral norethindrone acetate 5 mg daily (which can lower luteinizing hormone levels and block ovulation) plus metformin

- norethindrone acetate 5 mg plus spironolactone

- levonorgestrel-intrauterine device plus metformin or spironolactone.

OEP plus spironolactone

Many women with PCOS have increased LH secretion and increased androgen activity in the skin due to increased 5-alpha reductase enzyme activity, which catalyzes the conversion of testosterone to the powerful intracellular androgen dihydrotestosterone.9 Women with PCOS may present with a chief problem report of hirsutism, acne, or female androgenetic alopecia. OEP plus spironolactone may be an optimal initial treatment for women with a dominant dermatologic manifestation of PCOS. OEP treatment results in a decrease in pituitary LH secretion and ovarian androgen production. Spironolactone adds to this therapeutic effect by blocking androgen action in the skin.

The data on dual therapy with spironolactone. Many dermatologists recommend spironolactone in combination with cosmetic measures for the treatment of acne, but there are only a few randomized trials that demonstrate its efficacy.10 In one trial spironolactone was demonstrated to be superior to placebo for the treatment of inflammatory acne.10 Authors of multiple randomized trials report that the antiandrogens, spironolactone, or finasteride are superior to metformin to treat hirsutism.11 In addition, a few small trials report that spironolactone plus OEP is superior to either OEP or metformin monotherapy for hirsutism.11 Clinical trials of spironolactone for hirsutism have been rated as “low quality” and additional controlled trials of OEP monotherapy versus OEP plus spironolactone are warranted.12

My preferred treatment approach

Spironolactone is effective in the treatment of hirsutism at doses ranging from 50 mg to 200 mg daily. I routinely use a dose of spironolactone 100 mg daily because this dose is near of the top of the dose-response curve and has few adverse effects (such as intermittent uterine bleeding or spotting). With spironolactone monotherapy at a dose of 200 mg, irregular uterine bleeding or spotting is common, but concomitant treatment with an OEP tends to minimize this side effect. In my practice I rarely have patients report irregular uterine bleeding or spotting with the combination treatment of an OEP and spironolactone 100 mg daily.

Contraindications. Spironolactone should not be given to women with renal insufficiency because it can cause hyperkalemia. However, it is not necessary to check potassium levels in young women taking spironolactone with normal creatinine levels.13

Triple therapy: OEP plus metformin plus spironolactone

Some experts strongly recommend the initial treatment of PCOS in adolescents and young women with triple therapy: OEP plus an insulin sensitizer plus an antiandrogen.14 This recommendation is based in part on the observation that OEP monotherapy may be associated with an increase in circulating adipokines and visceral fat mass as determined by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.15 By contrast, triple treatment with an OEP plus metformin plus an antiandrogen is associated with a decrease in circulating adipokines and visceral fat mass.

What is the best progestin for PCOS?

Any OEP is better than no OEP, regardless of the progestin used to treat the PCOS because ethinyl estradiol plus any synthetic progestin suppresses pituitary secretion of LH and decreases ovarian androgen production. However, for the treatment of acne, using a progestin that is less androgenic may be beneficial.16

In one study, 2,147 consecutive women who were taking a contraceptive and presented for treatment of acne were asked if their contraceptive had a positive impact on their acne. The percentage of women reporting that their contraceptive significantly improved their acne ranged from 26% for those taking drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol (EE) to 1% for those taking the etonogestrel subdermal implant (FIGURE).16 The US Food and Drug Administration has approved 4 OEP contraceptives for the treatment of acne (TABLE). The OEPs with drospirenone, norgestimate, desogestrel, or norethindrone acetate may be optimal choices for the treatment of acne caused by PCOS.

The bottom line

PCOS is a common endocrine disorder treated primarily by obstetricians-gynecologists. Among adolescents and young women with PCOS chief problem reports include irregular menses, hirsutism, obesity, acne, and infertility. Among mid-life women the presentation of PCOS often evolves into chronic medical problems, including obesity, metabolic syndrome, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, T2DM, cardiovascular disease, and endometrial cancer.17–19 To optimally treat the multiple pathophysiologic disorders manifested in PCOS, I recommend initial dual medical therapy with an OEP plus metformin or an OEP plus spironolactone.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Using the Rotterdam criteria, the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is made in the presence of 2 of the following 3 criteria1:

- oligo-ovulation or anovulation

- hyperandrogenism manifested by the presence of either hirsutism or elevated hormone levels (including serum testosterone androstenedione and/or dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate)

- ultrasonography evidence of multifollicular ovaries (≥12 follicles with a diameter of 2 mm to 9 mm in one or both ovaries; FIGURE) or ovarian stromal volume of 10 mL or more.

Among reproductive-age women, the prevalence of PCOS has been reported to range from 8% to 13% for different populations.2 Most clinicians initiate treatment for PCOS with oral estrogen−progestin (OEP) monotherapy. OEP treatment has many beneficial hormonal effects, including:

- a resulting decrease in pituitary luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion, which decreases ovarian androgen production

- an increase in liver production of sex hormone−binding globulin (SHBG), which decreases free testosterone levels

- protection against the development of endometrial hyperplasia

- induction of regular uterine withdrawal bleeding.

However, OEP therapy neither improves metabolic indices (insulin sensitivity and visceral fat secretion of adipokines) nor blocks androgen action in the skin.

Dual medical treatment for PCOS can address the issues that monotherapy cannot and, along with providing guidance on improving diet and exercise, many experts support the initial therapy of PCOS with dual medical therapy (OEP plus metformin or spironolactone).

Advantages of OEP plus metformin

For many women with PCOS, the syndrome is characterized by abnormalities in both the reproductive (increase in LH secretion) and metabolic (insulin resistance and increased adipokines) systems. OEP monotherapy does not improve the metabolic abnormalities of PCOS. Combination treatment with both OEP plus metformin, along with diet and exercise, can best treat these combined abnormalities.

Data support dual therapy with metformin. In one small, randomized trial in women with PCOS, OEP plus metformin (1,500 mg daily) resulted in a greater reduction in serum androstenedione and a greater increase in SHBG than OEP monotherapy.3 In addition, weight loss and a reduction in waist-to-hip ratio only occurred in the OEP plus metformin group.3 In another small randomized study in women with PCOS, OEP plus metformin (1,500 mg daily) resulted in a greater decrease in free androgen index than OEP monotherapy.4

In my clinical opinion, women who may best benefit from OEP plus metformin therapy have one of the following factors indicating the presence of insulin resistance5:

- body mass index >30 kg/m2

- waist-to-hip ratio ≥0.85

- waist circumference >35 in (89 cm)

- acanthosis nigricans

- personal history of gestational diabetes

- family history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in a first-degree relative

- diagnosis of the metabolic syndrome.

My preferred treatment approach

Metformin is a low cost and safe treatment for metabolic dysfunction due to insulin resistance and excess adipokines. I often start PCOS treatment for my patients with an OEP plus metformin extended release (XR) 750 mg with dinner. If the patient tolerates this dose, I increase the dose to metformin XR 1,500 mg with dinner.

Adverse effects. The most common side effects of metformin are gastrointestinal, including abdominal discomfort, flatulence, borborygmi, diarrhea, and nausea. Metformin reduces serum vitamin B12 levels by 5% to 10%; therefore, ensuring adequate vitamin B12 intake (2.6 µg daily) is helpful.6 Although metformin does reduce vitamin B12 levels, there is no strong relationship between metformin and anemia or peripheral neuropathy.7 Lactic acidosis is a rare complication of metformin.

Beneficial effects. In the treatment of PCOS, metformin may have many beneficial effects, including8:

- decrease in insulin resistance

- decrease in harmful adipokines

- reduction in visceral fat

- reduction in the incidence of T2DM.

- oral norethindrone acetate 5 mg daily (which can lower luteinizing hormone levels and block ovulation) plus metformin

- norethindrone acetate 5 mg plus spironolactone

- levonorgestrel-intrauterine device plus metformin or spironolactone.

OEP plus spironolactone

Many women with PCOS have increased LH secretion and increased androgen activity in the skin due to increased 5-alpha reductase enzyme activity, which catalyzes the conversion of testosterone to the powerful intracellular androgen dihydrotestosterone.9 Women with PCOS may present with a chief problem report of hirsutism, acne, or female androgenetic alopecia. OEP plus spironolactone may be an optimal initial treatment for women with a dominant dermatologic manifestation of PCOS. OEP treatment results in a decrease in pituitary LH secretion and ovarian androgen production. Spironolactone adds to this therapeutic effect by blocking androgen action in the skin.

The data on dual therapy with spironolactone. Many dermatologists recommend spironolactone in combination with cosmetic measures for the treatment of acne, but there are only a few randomized trials that demonstrate its efficacy.10 In one trial spironolactone was demonstrated to be superior to placebo for the treatment of inflammatory acne.10 Authors of multiple randomized trials report that the antiandrogens, spironolactone, or finasteride are superior to metformin to treat hirsutism.11 In addition, a few small trials report that spironolactone plus OEP is superior to either OEP or metformin monotherapy for hirsutism.11 Clinical trials of spironolactone for hirsutism have been rated as “low quality” and additional controlled trials of OEP monotherapy versus OEP plus spironolactone are warranted.12

My preferred treatment approach

Spironolactone is effective in the treatment of hirsutism at doses ranging from 50 mg to 200 mg daily. I routinely use a dose of spironolactone 100 mg daily because this dose is near of the top of the dose-response curve and has few adverse effects (such as intermittent uterine bleeding or spotting). With spironolactone monotherapy at a dose of 200 mg, irregular uterine bleeding or spotting is common, but concomitant treatment with an OEP tends to minimize this side effect. In my practice I rarely have patients report irregular uterine bleeding or spotting with the combination treatment of an OEP and spironolactone 100 mg daily.

Contraindications. Spironolactone should not be given to women with renal insufficiency because it can cause hyperkalemia. However, it is not necessary to check potassium levels in young women taking spironolactone with normal creatinine levels.13

Triple therapy: OEP plus metformin plus spironolactone

Some experts strongly recommend the initial treatment of PCOS in adolescents and young women with triple therapy: OEP plus an insulin sensitizer plus an antiandrogen.14 This recommendation is based in part on the observation that OEP monotherapy may be associated with an increase in circulating adipokines and visceral fat mass as determined by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.15 By contrast, triple treatment with an OEP plus metformin plus an antiandrogen is associated with a decrease in circulating adipokines and visceral fat mass.

What is the best progestin for PCOS?

Any OEP is better than no OEP, regardless of the progestin used to treat the PCOS because ethinyl estradiol plus any synthetic progestin suppresses pituitary secretion of LH and decreases ovarian androgen production. However, for the treatment of acne, using a progestin that is less androgenic may be beneficial.16

In one study, 2,147 consecutive women who were taking a contraceptive and presented for treatment of acne were asked if their contraceptive had a positive impact on their acne. The percentage of women reporting that their contraceptive significantly improved their acne ranged from 26% for those taking drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol (EE) to 1% for those taking the etonogestrel subdermal implant (FIGURE).16 The US Food and Drug Administration has approved 4 OEP contraceptives for the treatment of acne (TABLE). The OEPs with drospirenone, norgestimate, desogestrel, or norethindrone acetate may be optimal choices for the treatment of acne caused by PCOS.

The bottom line

PCOS is a common endocrine disorder treated primarily by obstetricians-gynecologists. Among adolescents and young women with PCOS chief problem reports include irregular menses, hirsutism, obesity, acne, and infertility. Among mid-life women the presentation of PCOS often evolves into chronic medical problems, including obesity, metabolic syndrome, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, T2DM, cardiovascular disease, and endometrial cancer.17–19 To optimally treat the multiple pathophysiologic disorders manifested in PCOS, I recommend initial dual medical therapy with an OEP plus metformin or an OEP plus spironolactone.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Hum Reprod. 2004;19(1):41-47.

- Bozdag G, Mumusoglu S, Zengin D, Karabulut E, Yildiz BO. The prevalence and phenotypic features of polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(12):2841-2855.

- Elter K, Imir G, Durmusoglu F. Clinical, endocrine and metabolic effects of metformin added to ethinyl estradiol-cyproterone acetate in non-obese women with polycystic ovarian syndrome: a randomized controlled study. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(7):1729-1737.

- Cibula D, Fanta M, Vrbikova J, et al. The effect of combination therapy with metformin and combined oral contraceptives (COC) versus COC alone on insulin sensitivity, hyperandrogenism, SHBG and lipids in PCOS patients. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(1):180-184.

- Grundy SM, Brewer HB, Cleeman JI, Smith SC Jr, Lenfant C; American Heart Association; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 2004;109(3):433-438.

- Niafar M, Hai F, Porhomayon J, Nader ND. The role of metformin on vitamin B12 deficiency: a meta-analysis review. Intern Emerg Med. 2015;10(1):93-102.

- de Groot-Kamphuis DM, van Dijk PR, Groenier KH, Houweling St, Bilo HJ, Kleefstra N. Vitamin B12 deficiency and the lack of its consequences in type 2 diabetes patients using metformin. Neth J Med. 2013;71(7):386-390.

- Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Christakou CD, Kandaraki E, Economou FN. Metformin: an old medication of new fashion: evolving new molecular mechanisms and clinical implications in polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162(2):193-212.

- Skalba P, Dabkowska-Huc A, Kazimierczak W, Samojedny A, Samojedny MP, Chelmicki Z. Content of 5-alph-reductase (type 1 and type 2) mRNA in dermal papillae from the lower abdominal region in women with hirsutism. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31(4):564-570.

- Layton AM, Eady EA, Whitehouse H, Del Rosso JQ, Fedorowicz Z, van Zuuren EJ. Oral spironolactone for acne vulgaris in adult females: a hybrid systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18(2):169-191.

- Swiglo BA, Cosma M, Flynn DN, et al. Clinical review: antiandrogens for the treatment of hirsutism: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(4):1153-1160.

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z. Interventions for hirsutism excluding laser and photoepilation therapy alone: abridged Cochrane systematic review including GRADE assessments. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175(1):45-61.

- Plovanich M, Weng QY, Mostaghimi A. Low usefulness of potassium monitoring among healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(9):941-944.

- Ibanez L, de Zegher F. Low-dose combination of flutamide, metformin and an oral contraceptive for non-obese, young women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(1):57-60.

- Ibanez L, de Zegher F. Ethinyl estradiol-drospirenone, flutamide-metformin or both for adolescents and women with hyperinsulinemic hyperandrogenism: opposite effects on adipocytokines and body adiposity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(4):1592-1597.

- Lortscher D, Admani S, Stur N, Eichenfield LF. Hormonal contraceptives and acne: a retrospective analysis of 2147 patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(6):670-674.

- Wang ET, Calderon-Margalit R, Cedars MI, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome and risk for long-term diabetes and dyslipidemia. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(1):6-13.

- Joham AE, Raniasinha S, Zoungas S, Moran L, Teede HJ. Gestational diabetes and type 2 diabetes in reproductive aged women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(3):e447-e452.

- Gottschau M, Kjaer SK, Jensen A, Munk C, Mellemkjaer L. Risk of cancer among women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a Danish cohort study. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(1):99-103.

- Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Hum Reprod. 2004;19(1):41-47.

- Bozdag G, Mumusoglu S, Zengin D, Karabulut E, Yildiz BO. The prevalence and phenotypic features of polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(12):2841-2855.

- Elter K, Imir G, Durmusoglu F. Clinical, endocrine and metabolic effects of metformin added to ethinyl estradiol-cyproterone acetate in non-obese women with polycystic ovarian syndrome: a randomized controlled study. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(7):1729-1737.

- Cibula D, Fanta M, Vrbikova J, et al. The effect of combination therapy with metformin and combined oral contraceptives (COC) versus COC alone on insulin sensitivity, hyperandrogenism, SHBG and lipids in PCOS patients. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(1):180-184.

- Grundy SM, Brewer HB, Cleeman JI, Smith SC Jr, Lenfant C; American Heart Association; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 2004;109(3):433-438.

- Niafar M, Hai F, Porhomayon J, Nader ND. The role of metformin on vitamin B12 deficiency: a meta-analysis review. Intern Emerg Med. 2015;10(1):93-102.

- de Groot-Kamphuis DM, van Dijk PR, Groenier KH, Houweling St, Bilo HJ, Kleefstra N. Vitamin B12 deficiency and the lack of its consequences in type 2 diabetes patients using metformin. Neth J Med. 2013;71(7):386-390.

- Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Christakou CD, Kandaraki E, Economou FN. Metformin: an old medication of new fashion: evolving new molecular mechanisms and clinical implications in polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162(2):193-212.

- Skalba P, Dabkowska-Huc A, Kazimierczak W, Samojedny A, Samojedny MP, Chelmicki Z. Content of 5-alph-reductase (type 1 and type 2) mRNA in dermal papillae from the lower abdominal region in women with hirsutism. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31(4):564-570.

- Layton AM, Eady EA, Whitehouse H, Del Rosso JQ, Fedorowicz Z, van Zuuren EJ. Oral spironolactone for acne vulgaris in adult females: a hybrid systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18(2):169-191.

- Swiglo BA, Cosma M, Flynn DN, et al. Clinical review: antiandrogens for the treatment of hirsutism: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(4):1153-1160.

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z. Interventions for hirsutism excluding laser and photoepilation therapy alone: abridged Cochrane systematic review including GRADE assessments. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175(1):45-61.

- Plovanich M, Weng QY, Mostaghimi A. Low usefulness of potassium monitoring among healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(9):941-944.

- Ibanez L, de Zegher F. Low-dose combination of flutamide, metformin and an oral contraceptive for non-obese, young women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(1):57-60.

- Ibanez L, de Zegher F. Ethinyl estradiol-drospirenone, flutamide-metformin or both for adolescents and women with hyperinsulinemic hyperandrogenism: opposite effects on adipocytokines and body adiposity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(4):1592-1597.

- Lortscher D, Admani S, Stur N, Eichenfield LF. Hormonal contraceptives and acne: a retrospective analysis of 2147 patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(6):670-674.

- Wang ET, Calderon-Margalit R, Cedars MI, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome and risk for long-term diabetes and dyslipidemia. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(1):6-13.

- Joham AE, Raniasinha S, Zoungas S, Moran L, Teede HJ. Gestational diabetes and type 2 diabetes in reproductive aged women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(3):e447-e452.

- Gottschau M, Kjaer SK, Jensen A, Munk C, Mellemkjaer L. Risk of cancer among women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a Danish cohort study. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(1):99-103.

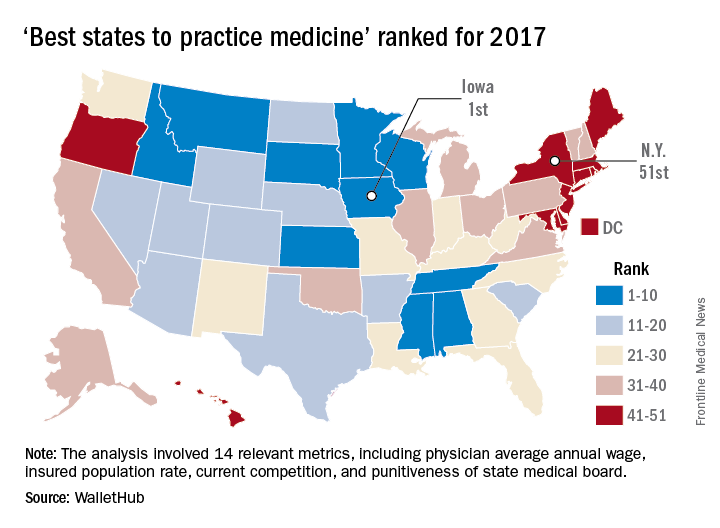

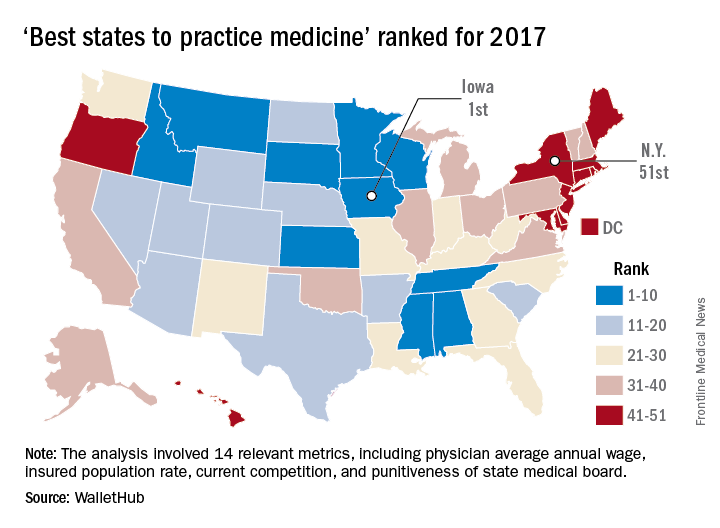

Moving or starting a practice? Consider Iowa

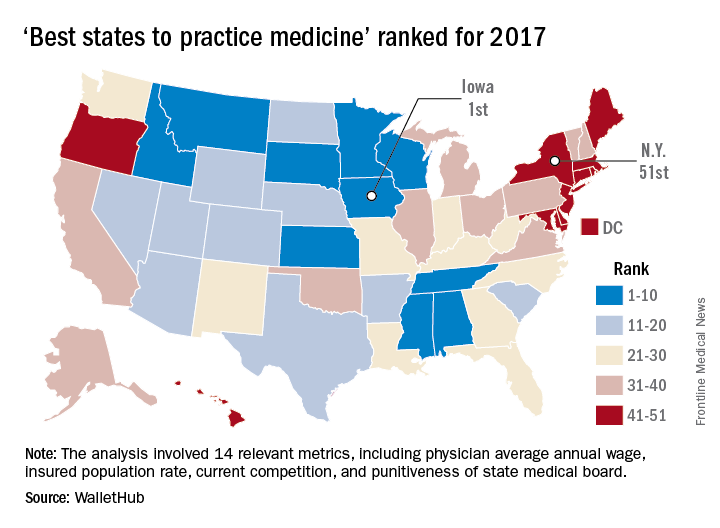

The federal government may or may not believe in global warming, but when it comes to states’ medical practice climates, Iowa trumps them all, according to the personal finance website WalletHub.

The Hawkeye State came out on top of WalletHub’s list of the Best States to Practice Medicine for 2017 with 68.7 out of a possible 100 points, while New York finished 51st (Washington, D.C., was 50th) with 28.5 points. Minnesota is the second-best state for physicians, followed by Idaho, Wisconsin, and Kansas. The rest of the bottom five included New Jersey at 49th, Maryland at 48th, and Rhode Island at 47th, WalletHub reported.

WalletHub compared the 50 states and Washington using 14 different metrics across two broad categories: “opportunity and competition” (70 points) and “medical environment” (30 points). Metrics included physicians’ average annual wage (adjusted for cost of living), hospitals per capita, quality of public hospital system, and annual malpractice liability insurance rate.

The federal government may or may not believe in global warming, but when it comes to states’ medical practice climates, Iowa trumps them all, according to the personal finance website WalletHub.

The Hawkeye State came out on top of WalletHub’s list of the Best States to Practice Medicine for 2017 with 68.7 out of a possible 100 points, while New York finished 51st (Washington, D.C., was 50th) with 28.5 points. Minnesota is the second-best state for physicians, followed by Idaho, Wisconsin, and Kansas. The rest of the bottom five included New Jersey at 49th, Maryland at 48th, and Rhode Island at 47th, WalletHub reported.

WalletHub compared the 50 states and Washington using 14 different metrics across two broad categories: “opportunity and competition” (70 points) and “medical environment” (30 points). Metrics included physicians’ average annual wage (adjusted for cost of living), hospitals per capita, quality of public hospital system, and annual malpractice liability insurance rate.

The federal government may or may not believe in global warming, but when it comes to states’ medical practice climates, Iowa trumps them all, according to the personal finance website WalletHub.

The Hawkeye State came out on top of WalletHub’s list of the Best States to Practice Medicine for 2017 with 68.7 out of a possible 100 points, while New York finished 51st (Washington, D.C., was 50th) with 28.5 points. Minnesota is the second-best state for physicians, followed by Idaho, Wisconsin, and Kansas. The rest of the bottom five included New Jersey at 49th, Maryland at 48th, and Rhode Island at 47th, WalletHub reported.

WalletHub compared the 50 states and Washington using 14 different metrics across two broad categories: “opportunity and competition” (70 points) and “medical environment” (30 points). Metrics included physicians’ average annual wage (adjusted for cost of living), hospitals per capita, quality of public hospital system, and annual malpractice liability insurance rate.

Vascular involvement may signify worse outcomes in lupus nephritis

MELBOURNE – Vascular involvement in patients with lupus nephritis is associated with poorer outcomes and could be a trigger for a more aggressive treatment approach, according to observational study results reported at an international congress on systemic lupus erythematosus.

Manish Rathi, MD, a nephrologist at the Postgraduate Institution of Medical Education & Research in Chandigarh, India, reported the results of a 5-year prospective cohort study in 241 patients with biopsy-proven lupus nephritis.

Researchers found that patients with vascular involvement had significantly higher serum creatinine at baseline than did those without it. At follow-up, they also had significantly higher proteinuria and serum creatinine, as well as significantly lower serum albumin.

This group was also less likely to achieve complete remission, compared with patients without vascular involvement (38.2% vs. 61.9%; P = .006), and had treatment-refractory disease almost twice as often (26.3% vs. 14.3%; P = .02).

Overall, vascular involvement was seen in 32.3% of patients, with the most common form being arteriosclerosis (22.8%), followed by vascular thrombotic microangiopathy (11.2%), asymptomatic vascular immune deposits (5.3%), vasculopathy (2%), and vasculitis (0.8%).

Three-quarters of all patients had nephrotic syndrome, and 41.9% were identified as Class IV, 18.7% as Class V, 10.4% as Class III, and 3.7% as Class II.

When researchers examined the presentation and outcomes among these subgroups, they found that patients with vascular thrombotic microangiopathy had a significantly higher serum creatinine and were less likely to respond to treatment, compared with patients without vascular thrombotic microangiopathy (60% vs. 79.1%).

Similarly, patients with arteriosclerosis had significantly lower incidence of complete remission, compared with those without arteriosclerosis (37.7% vs. 58.8%) although they had significantly higher rates of partial remission (35.8% vs. 19.4%).

“Lupus patients, if they had involvement of vascular compartment, they had more severe presentation at the time of presentation as well as poorer outcomes despite giving the standard therapy,” Dr. Rathi said.

In an interview, Dr. Rathi said the results had already influenced their own treatment approach with these patients.

“What we have started doing now is – if there is vascular involvement, particularly the thrombotic microangiopathy – we treat them as severe lupus nephritis [patients], so even if their class of lupus nephritis is less severe, we’ll be treating them as severe,” he said.

Commenting on the presentation, Frederic Houssiau, MD, PhD, a professor of rheumatology at the Cliniques Universitaires Saint-Luc in Brussels, said he agreed that vascular involvement was neglected in the current classification of lupus nephritis and that it should be taken into account.

“Maybe we should not only consider the class but also look in more detail to the pathophysiological findings,” Dr. Houssiau said in an interview. “When you have a lot of inflammation in the vessels, for instance, maybe we should use cyclophosphamide.”

No conflicts of interest were disclosed.

MELBOURNE – Vascular involvement in patients with lupus nephritis is associated with poorer outcomes and could be a trigger for a more aggressive treatment approach, according to observational study results reported at an international congress on systemic lupus erythematosus.

Manish Rathi, MD, a nephrologist at the Postgraduate Institution of Medical Education & Research in Chandigarh, India, reported the results of a 5-year prospective cohort study in 241 patients with biopsy-proven lupus nephritis.

Researchers found that patients with vascular involvement had significantly higher serum creatinine at baseline than did those without it. At follow-up, they also had significantly higher proteinuria and serum creatinine, as well as significantly lower serum albumin.

This group was also less likely to achieve complete remission, compared with patients without vascular involvement (38.2% vs. 61.9%; P = .006), and had treatment-refractory disease almost twice as often (26.3% vs. 14.3%; P = .02).

Overall, vascular involvement was seen in 32.3% of patients, with the most common form being arteriosclerosis (22.8%), followed by vascular thrombotic microangiopathy (11.2%), asymptomatic vascular immune deposits (5.3%), vasculopathy (2%), and vasculitis (0.8%).

Three-quarters of all patients had nephrotic syndrome, and 41.9% were identified as Class IV, 18.7% as Class V, 10.4% as Class III, and 3.7% as Class II.

When researchers examined the presentation and outcomes among these subgroups, they found that patients with vascular thrombotic microangiopathy had a significantly higher serum creatinine and were less likely to respond to treatment, compared with patients without vascular thrombotic microangiopathy (60% vs. 79.1%).

Similarly, patients with arteriosclerosis had significantly lower incidence of complete remission, compared with those without arteriosclerosis (37.7% vs. 58.8%) although they had significantly higher rates of partial remission (35.8% vs. 19.4%).

“Lupus patients, if they had involvement of vascular compartment, they had more severe presentation at the time of presentation as well as poorer outcomes despite giving the standard therapy,” Dr. Rathi said.

In an interview, Dr. Rathi said the results had already influenced their own treatment approach with these patients.

“What we have started doing now is – if there is vascular involvement, particularly the thrombotic microangiopathy – we treat them as severe lupus nephritis [patients], so even if their class of lupus nephritis is less severe, we’ll be treating them as severe,” he said.

Commenting on the presentation, Frederic Houssiau, MD, PhD, a professor of rheumatology at the Cliniques Universitaires Saint-Luc in Brussels, said he agreed that vascular involvement was neglected in the current classification of lupus nephritis and that it should be taken into account.

“Maybe we should not only consider the class but also look in more detail to the pathophysiological findings,” Dr. Houssiau said in an interview. “When you have a lot of inflammation in the vessels, for instance, maybe we should use cyclophosphamide.”

No conflicts of interest were disclosed.

MELBOURNE – Vascular involvement in patients with lupus nephritis is associated with poorer outcomes and could be a trigger for a more aggressive treatment approach, according to observational study results reported at an international congress on systemic lupus erythematosus.

Manish Rathi, MD, a nephrologist at the Postgraduate Institution of Medical Education & Research in Chandigarh, India, reported the results of a 5-year prospective cohort study in 241 patients with biopsy-proven lupus nephritis.

Researchers found that patients with vascular involvement had significantly higher serum creatinine at baseline than did those without it. At follow-up, they also had significantly higher proteinuria and serum creatinine, as well as significantly lower serum albumin.

This group was also less likely to achieve complete remission, compared with patients without vascular involvement (38.2% vs. 61.9%; P = .006), and had treatment-refractory disease almost twice as often (26.3% vs. 14.3%; P = .02).

Overall, vascular involvement was seen in 32.3% of patients, with the most common form being arteriosclerosis (22.8%), followed by vascular thrombotic microangiopathy (11.2%), asymptomatic vascular immune deposits (5.3%), vasculopathy (2%), and vasculitis (0.8%).

Three-quarters of all patients had nephrotic syndrome, and 41.9% were identified as Class IV, 18.7% as Class V, 10.4% as Class III, and 3.7% as Class II.

When researchers examined the presentation and outcomes among these subgroups, they found that patients with vascular thrombotic microangiopathy had a significantly higher serum creatinine and were less likely to respond to treatment, compared with patients without vascular thrombotic microangiopathy (60% vs. 79.1%).