User login

Safe, effective backup for U.S. MMR vaccine exists

Antibodies against measles, mumps, and rubella persisted for up to 2 years after vaccination of children 12-15 months with the MMR vaccine approved in the United States and a similar one approved in Europe, both of which are manufactured without human serum albumin, Andrea A. Berry, MD, at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, and her associates said.

In 752 children aged a mean 12 months who received either the United States MMR vaccine and the European one, seropositivity for measles, mumps, and rubella persisted for up to 2 years with both vaccines. Both vaccines also were well tolerated.

Because there is only one MMR vaccine licensed in the United States, interruption to this single supply line could present a public health risk, Dr. Berry and her associates said. As both the vaccines used in this study do not contain human serum albumin, the theoretical risk of microbial contamination is reduced, compared with previous formulations of MMR.

Read more at Human Vaccines Immunotherapeutics. (2017. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1309486).

Antibodies against measles, mumps, and rubella persisted for up to 2 years after vaccination of children 12-15 months with the MMR vaccine approved in the United States and a similar one approved in Europe, both of which are manufactured without human serum albumin, Andrea A. Berry, MD, at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, and her associates said.

In 752 children aged a mean 12 months who received either the United States MMR vaccine and the European one, seropositivity for measles, mumps, and rubella persisted for up to 2 years with both vaccines. Both vaccines also were well tolerated.

Because there is only one MMR vaccine licensed in the United States, interruption to this single supply line could present a public health risk, Dr. Berry and her associates said. As both the vaccines used in this study do not contain human serum albumin, the theoretical risk of microbial contamination is reduced, compared with previous formulations of MMR.

Read more at Human Vaccines Immunotherapeutics. (2017. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1309486).

Antibodies against measles, mumps, and rubella persisted for up to 2 years after vaccination of children 12-15 months with the MMR vaccine approved in the United States and a similar one approved in Europe, both of which are manufactured without human serum albumin, Andrea A. Berry, MD, at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, and her associates said.

In 752 children aged a mean 12 months who received either the United States MMR vaccine and the European one, seropositivity for measles, mumps, and rubella persisted for up to 2 years with both vaccines. Both vaccines also were well tolerated.

Because there is only one MMR vaccine licensed in the United States, interruption to this single supply line could present a public health risk, Dr. Berry and her associates said. As both the vaccines used in this study do not contain human serum albumin, the theoretical risk of microbial contamination is reduced, compared with previous formulations of MMR.

Read more at Human Vaccines Immunotherapeutics. (2017. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1309486).

FROM HUMAN VACCINES & IMMUNOTHERAPEUTICS

Acquired Epidermodysplasia Verruciformis Occurring in a Renal Transplant Recipient

Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EDV) is a rare disorder occurring in patients with depressed cellular immunity, particularly individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Rare cases of acquired EDV have been reported in stem cell or solid organ transplant recipients. Weakened cellular immunity predisposes the patient to human papillomavirus (HPV) infections, with 92% of renal transplant recipients developing warts within 5 years posttransplantation.1 Specific EDV-HPV subtypes have been isolated from lesions in several immunosuppressed individuals, with HPV-5 and HPV-8 being the most commonly isolated subtypes.2,3 Herein, we present the clinical findings of a renal transplant recipient who presented for evaluation of multiple skin lesions characteristic of EDV 5 years following transplantation and initiation of immunosuppressive therapy. Additionally, we review the current diagnostic findings, management, and treatment of acquired EDV.

A 44-year-old white woman presented for evaluation of several pruritic cutaneous lesions that had developed on the chest and neck of 1 month’s duration. The patient had been on the immunosuppressant medications cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil for more than 5 years following renal transplantation 7 years prior to the current presentation. She also was on low-dose prednisone for chronic systemic lupus erythematosus. Her family history was negative for any pertinent skin conditions.

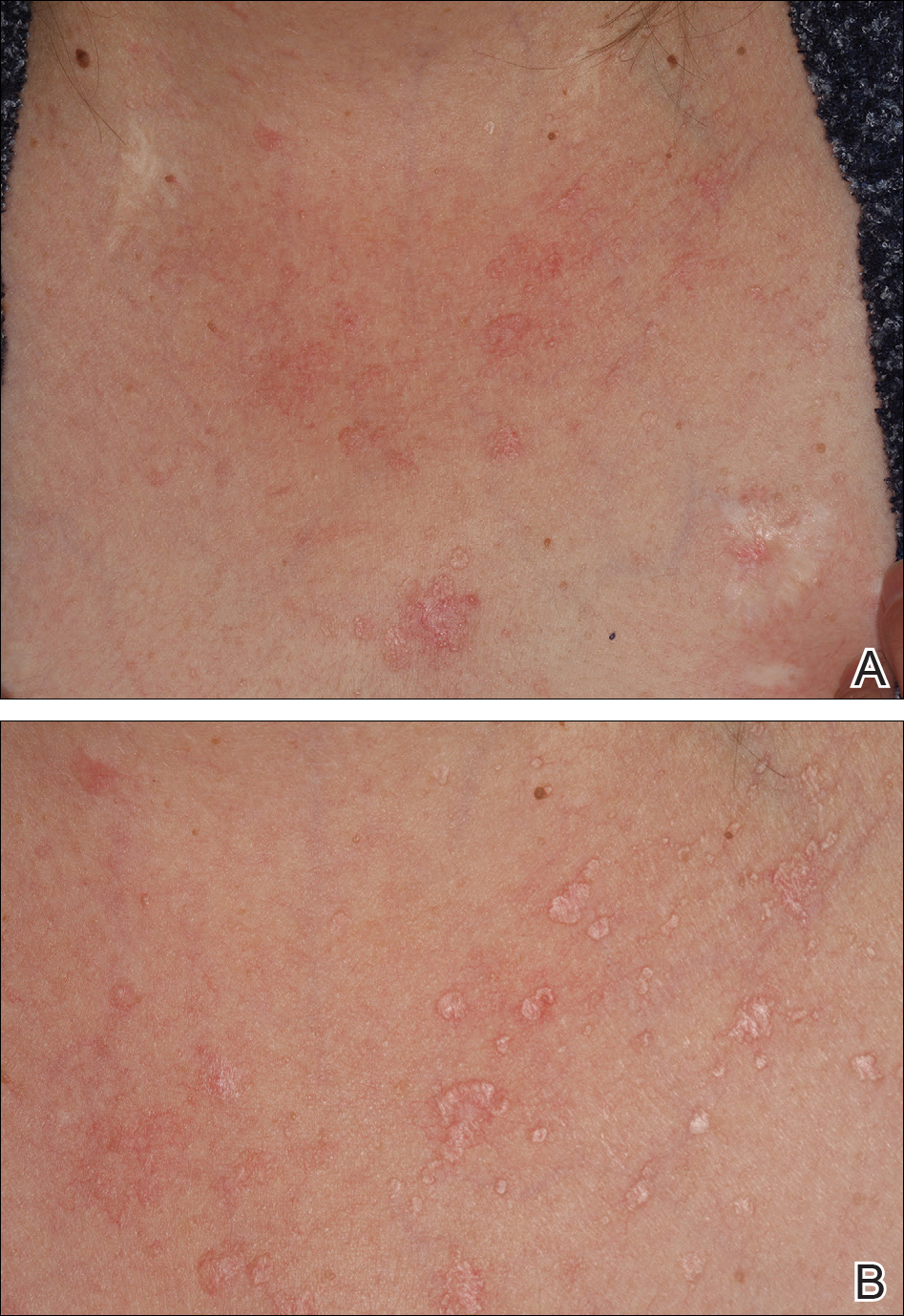

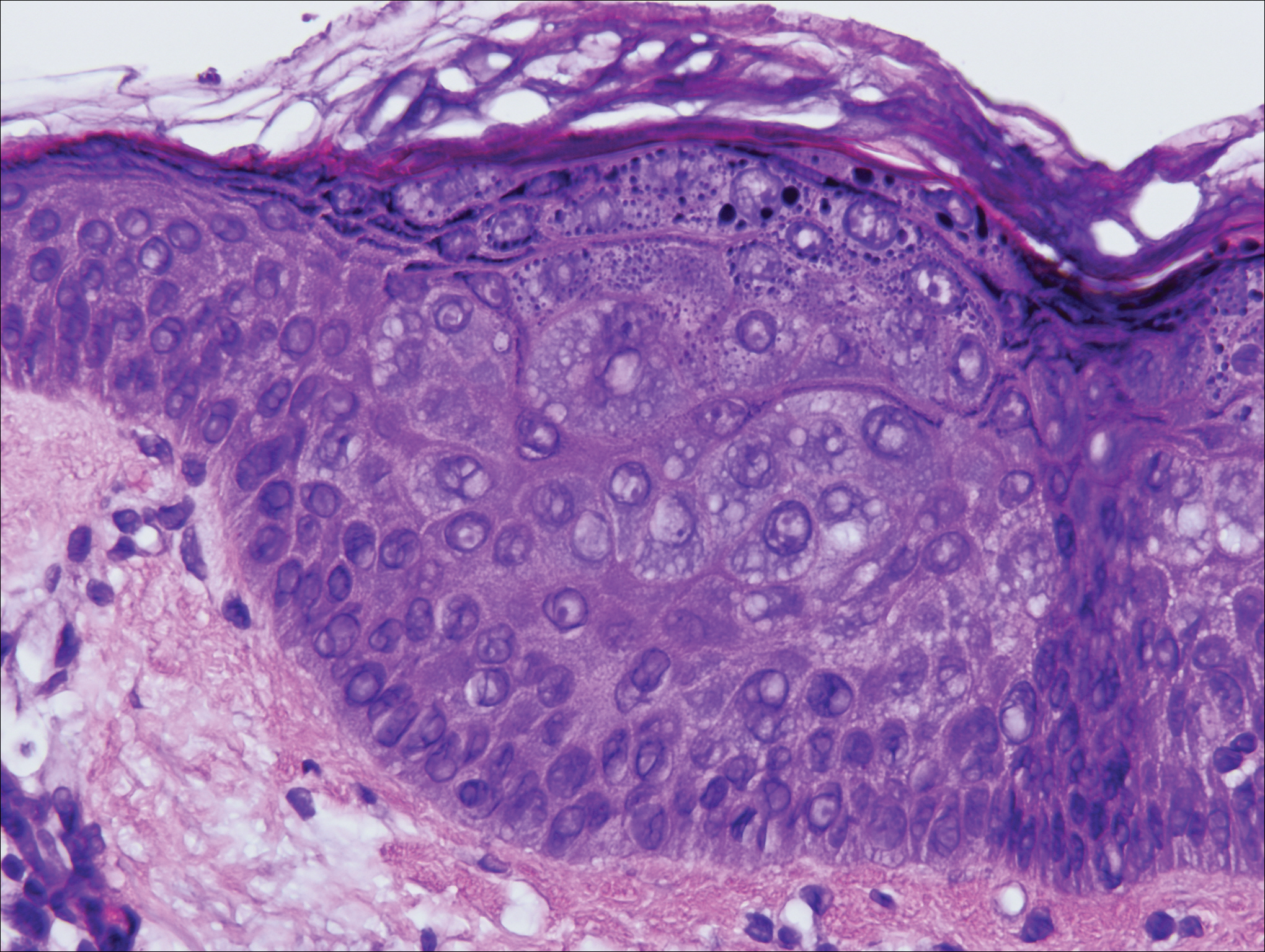

On physical examination the patient exhibited several grouped 0.5-cm, shiny, pink lichenoid macules located on the upper mid chest, anterior neck, and left leg clinically resembling the lesions of pityriasis versicolor (Figure 1). A shave biopsy was taken from one of the newest lesions on the left leg. Histopathology revealed viral epidermal cytopathic changes, blue cytoplasm, and coarse hypergranulosis characteristic of EDV (Figure 2). A diagnosis of acquired EDV was made based on the clinical and histopathologic findings.

The patient’s skin lesions became more widespread despite several different treatment regimens, including cryosurgery; tazarotene cream 0.05% nightly; imiquimod cream 5% once weekly; and intermittent short courses of 5-fluorouracil cream 5%, which provided the best response. At her most recent clinic visit 8 years after initial presentation, she continued to have more widespread lesions on the trunk, arms, and legs, but no evidence of malignant transformation.

Comment

Epidermodysplasia verruciformis was first recognized as an inherited condition, most commonly inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion; however, X-linked recessive cases have been reported.4,5 Patients with the inherited forms of this condition are prone to recurrent HPV infections secondary to a missense mutation in the epidermodysplasia verruciformis 1 and 2 genes, EVER1 and EVER2, on the EV1 locus located on chromosome 17q25.6 Because of this mutation, the patient’s cellular immunity becomes weakened. Cellular presentation of the EDV-HPV antigen to T lymphocytes becomes impaired, thereby inhibiting the body’s ability to successfully clear itself of the virus.5,6 The most commonly isolated EDV-HPV subtypes are HPV-5 and HPV-8, but HPV types 9, 12, 14, 15, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, and 50 also have been associated with EDV.1,3,7

Patients who have suppressed cellular immunity, such as transplant recipients on long-term immunosuppressant medications and individuals with HIV, graft-vs-host disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, and hematologic malignancies, are susceptible to EDV, as well as patients with atopic dermatitis being treated with topical calcineurin inhibitors.2,3,8-15 These patients acquire depressed cellular immunity and become increasingly susceptible to infections with the EDV-HPV subtypes. When clinical and histopathologic findings are consistent with EDV, a diagnosis of acquired EDV is given, which was further confirmed in a study conducted by Harwood et al.16 They found immunocompromised patients carry more EDV-HPV subtypes in skin lesions analyzed by polymerase chain reaction than immunocompetent individuals.16 Additionally, there is a positive correlation between the length of immunosuppression and the development of HPV lesions, with a majority of patients developing lesions within 5 years following initial immunosuppression.1,7,10,17

Epidermodysplasia verruciformis commonly presents with multiple hypopigmented to red macules that may coalesce into patches with a fine scale, clinically resembling the lesions of pityriasis versicolor.2,3,8-15 Epidermodysplasia verruciformis also may present as multiple flesh-colored, flat-topped, verrucous papules that clinically resemble the lesions of verruca plana on sun-exposed areas such as the face, arms, and legs.9 The characteristic histopathologic findings are enlarged keratinocytes with perinuclear halos and blue-gray cytoplasm as well as hypergranulosis.18 Immunocompromised hosts infected with EDV-HPV histologically tend to display more severe dysplasia than immunocompetent individuals.19 The differential diagnosis includes pityriasis versicolor, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and verruca plana. Tissue cultures and potassium hydroxide scrapings for microorganisms should be negative.

The specific EDV-HPV strains 5, 8, and 41 carry the highest oncogenic potential, with more than 60% of inherited EDV patients developing SCC by the fourth and fifth decades of life.16 Unlike inherited EDV, the clinical course of acquired EDV is less well known; however, UV light is thought to act synergistically with the EDV-HPV in oncogenic transformation of the lesions, as most of the SCCs develop on sun-exposed areas, and darker-skinned patients seem to have a decreased risk for malignant transformation of EDV lesions.4,9,20,21 Preventative measures such as strict sun protection and annual surveillance of lesions can help to prevent oncogenic progression of the lesions; however, several single- and multiple-agent regimens have been used in the treatment of EDV with variable results. Topical imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, tretinoin, and tazarotene have been used with variable success. Acitretin alone and in combination with interferon alfa-2a also has been used.22,23 Highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV has effectively decreased the number of lesions in a subset of patients.24 We (anecdotal) and others25 also have had success using photodynamic therapy. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in patients with EDV can be managed by excision or by Mohs micrographic surgery.

Conclusion

We report a rare case of acquired EDV in a solid organ transplant recipient. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis can be acquired in immunosuppressed patients such as ours, and these patients should be followed closely due to the potential for malignant transformation. More studies regarding the anticipated clinical course of skin lesions in patients with acquired EDV are needed to better predict the time frame for malignant transformation.

- Dyall-Smith D, Trowell H, Dyall-Smith ML. Benign human papillomavirus infection in renal transplant recipients. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:785-789.

- Lutzner MA, Orth G, Dutronquay V, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus type 5 DNA in skin cancers of an immunosuppressed renal allograft recipient. Lancet. 1983;2:422-424.

- Lutzner M, Croissant O, Ducasse MF, et al. A potentially oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV-5) found in two renal allograft recipients. J Invest Dermatol. 1980;75:353-356.

- Androphy EJ, Dvoretzky I, Lowy DR. X-linked inheritance of epidermodysplasia verruciformis. genetic and virologic studies of a kindred. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:864-868.

- Lutzner MA. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis. an autosomal recessive disease characterized by viral warts and skin cancer. a model for viral oncogenesis. Bull Cancer. 1978;65:169-182.

- Ramoz N, Rueda LA, Bouadjar B, et al. Mutations in two adjacent novel genes are associated with epidermodysplasia verruciformis. Nat Genet. 2002;32:579-581.

- Rüdlinger R, Smith IW, Bunney MH, et al. Human papillomavirus infections in a group of renal transplant recipients. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115:681-692.

- Kawai K, Egawa N, Kiyono T, et al. Epidermodysplasia-verruciformis-like eruption associated with gamma-papillomavirus infection in a patient with adult T-cell leukemia. Dermatology. 2009;219:274-278.

- Barr BB, Benton EC, McLaren K, et al. Human papilloma virus infection and skin cancer in renal allograft recipients. Lancet. 1989;1:124-129.

- Tanigaki T, Kanda R, Sato K. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis (L-L, 1922) in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol Res. 1986;278:247-248.

- Holmes C, Chong AH, Tabrizi SN, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis-like syndrome in association with systemic lupus erythematosus. Australas J Dermatol. 2009;50:44-47.

- Gross G, Ellinger K, Roussaki A, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis in a patient with Hodgkin’s disease: characterization of a new papillomavirus type and interferon treatment. J Invest Dermatol. 1988;91:43-48.

- Fernandez KH, Rady P, Tyring S, et al. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis in a child with atopic dermatitis [published online September 3, 2012]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:400-402.

- Hultgren TL, Srinivasan SK, DiMaio DJ. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis occurring in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus: a case report. Cutis. 2007;79:307-311.

- Kunishige JH, Hymes SR, Madkan V, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis in the setting of graft-versus-host disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(5 suppl):S78-S80.

- Harwood CA, Surentheran T, McGregor JM, et al. Human papillomavirus infection and non-melanoma skin cancer in immunosuppressed and immunocompetent individuals. J Med Virol. 2000;61:289-297.

- Moloney FJ, Keane S, O’Kelly P, et al. The impact of skin disease following renal transplantation on quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:574-578.

- Tanigaki T, Endo H. A case of epidermodysplasia verruciformis (Lewandowsky-Lutz, 1922) with skin cancer: histopathology of malignant cutaneous changes. Dermatologica. 1984;169:97-101.

- Morrison C, Eliezri Y, Magro C, et al. The histologic spectrum of epidermodysplasia verruciformis in transplant and AIDS patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:480-489.

- Majewski S, Jabło´nska S. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis as a model of human papillomavirus-induced genetic cancer of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1312-1318.

- Jacyk WK, De Villiers EM. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis in Africans. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:806-810.

- Gubinelli E, Posteraro P, Cocuroccia B, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis with multiple mucosal carcinomas treated with pegylated interferon alfa and acitretin. J Dermatolog Treat. 2003;14:184-188.

- Anadolu R, Oskay T, Erdem C, et al. Treatment of epidermodysplasia verruciformis with a combination of acitretin and interferon alfa-2a. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:296-299.

- Haas N, Fuchs PG, Hermes B, et al. Remission of epidermodysplasia verruciformis-like skin eruption after highly active antiretroviral therapy in a human immunodeficiency virus-positive patient. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:669-670.

- Karrer S, Szeimies RM, Abels C, et al. Epidermo-dysplasia verruciformis treated using topical 5-aminolaevulinic acid photodynamic therapy. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:935-938.

Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EDV) is a rare disorder occurring in patients with depressed cellular immunity, particularly individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Rare cases of acquired EDV have been reported in stem cell or solid organ transplant recipients. Weakened cellular immunity predisposes the patient to human papillomavirus (HPV) infections, with 92% of renal transplant recipients developing warts within 5 years posttransplantation.1 Specific EDV-HPV subtypes have been isolated from lesions in several immunosuppressed individuals, with HPV-5 and HPV-8 being the most commonly isolated subtypes.2,3 Herein, we present the clinical findings of a renal transplant recipient who presented for evaluation of multiple skin lesions characteristic of EDV 5 years following transplantation and initiation of immunosuppressive therapy. Additionally, we review the current diagnostic findings, management, and treatment of acquired EDV.

A 44-year-old white woman presented for evaluation of several pruritic cutaneous lesions that had developed on the chest and neck of 1 month’s duration. The patient had been on the immunosuppressant medications cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil for more than 5 years following renal transplantation 7 years prior to the current presentation. She also was on low-dose prednisone for chronic systemic lupus erythematosus. Her family history was negative for any pertinent skin conditions.

On physical examination the patient exhibited several grouped 0.5-cm, shiny, pink lichenoid macules located on the upper mid chest, anterior neck, and left leg clinically resembling the lesions of pityriasis versicolor (Figure 1). A shave biopsy was taken from one of the newest lesions on the left leg. Histopathology revealed viral epidermal cytopathic changes, blue cytoplasm, and coarse hypergranulosis characteristic of EDV (Figure 2). A diagnosis of acquired EDV was made based on the clinical and histopathologic findings.

The patient’s skin lesions became more widespread despite several different treatment regimens, including cryosurgery; tazarotene cream 0.05% nightly; imiquimod cream 5% once weekly; and intermittent short courses of 5-fluorouracil cream 5%, which provided the best response. At her most recent clinic visit 8 years after initial presentation, she continued to have more widespread lesions on the trunk, arms, and legs, but no evidence of malignant transformation.

Comment

Epidermodysplasia verruciformis was first recognized as an inherited condition, most commonly inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion; however, X-linked recessive cases have been reported.4,5 Patients with the inherited forms of this condition are prone to recurrent HPV infections secondary to a missense mutation in the epidermodysplasia verruciformis 1 and 2 genes, EVER1 and EVER2, on the EV1 locus located on chromosome 17q25.6 Because of this mutation, the patient’s cellular immunity becomes weakened. Cellular presentation of the EDV-HPV antigen to T lymphocytes becomes impaired, thereby inhibiting the body’s ability to successfully clear itself of the virus.5,6 The most commonly isolated EDV-HPV subtypes are HPV-5 and HPV-8, but HPV types 9, 12, 14, 15, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, and 50 also have been associated with EDV.1,3,7

Patients who have suppressed cellular immunity, such as transplant recipients on long-term immunosuppressant medications and individuals with HIV, graft-vs-host disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, and hematologic malignancies, are susceptible to EDV, as well as patients with atopic dermatitis being treated with topical calcineurin inhibitors.2,3,8-15 These patients acquire depressed cellular immunity and become increasingly susceptible to infections with the EDV-HPV subtypes. When clinical and histopathologic findings are consistent with EDV, a diagnosis of acquired EDV is given, which was further confirmed in a study conducted by Harwood et al.16 They found immunocompromised patients carry more EDV-HPV subtypes in skin lesions analyzed by polymerase chain reaction than immunocompetent individuals.16 Additionally, there is a positive correlation between the length of immunosuppression and the development of HPV lesions, with a majority of patients developing lesions within 5 years following initial immunosuppression.1,7,10,17

Epidermodysplasia verruciformis commonly presents with multiple hypopigmented to red macules that may coalesce into patches with a fine scale, clinically resembling the lesions of pityriasis versicolor.2,3,8-15 Epidermodysplasia verruciformis also may present as multiple flesh-colored, flat-topped, verrucous papules that clinically resemble the lesions of verruca plana on sun-exposed areas such as the face, arms, and legs.9 The characteristic histopathologic findings are enlarged keratinocytes with perinuclear halos and blue-gray cytoplasm as well as hypergranulosis.18 Immunocompromised hosts infected with EDV-HPV histologically tend to display more severe dysplasia than immunocompetent individuals.19 The differential diagnosis includes pityriasis versicolor, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and verruca plana. Tissue cultures and potassium hydroxide scrapings for microorganisms should be negative.

The specific EDV-HPV strains 5, 8, and 41 carry the highest oncogenic potential, with more than 60% of inherited EDV patients developing SCC by the fourth and fifth decades of life.16 Unlike inherited EDV, the clinical course of acquired EDV is less well known; however, UV light is thought to act synergistically with the EDV-HPV in oncogenic transformation of the lesions, as most of the SCCs develop on sun-exposed areas, and darker-skinned patients seem to have a decreased risk for malignant transformation of EDV lesions.4,9,20,21 Preventative measures such as strict sun protection and annual surveillance of lesions can help to prevent oncogenic progression of the lesions; however, several single- and multiple-agent regimens have been used in the treatment of EDV with variable results. Topical imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, tretinoin, and tazarotene have been used with variable success. Acitretin alone and in combination with interferon alfa-2a also has been used.22,23 Highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV has effectively decreased the number of lesions in a subset of patients.24 We (anecdotal) and others25 also have had success using photodynamic therapy. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in patients with EDV can be managed by excision or by Mohs micrographic surgery.

Conclusion

We report a rare case of acquired EDV in a solid organ transplant recipient. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis can be acquired in immunosuppressed patients such as ours, and these patients should be followed closely due to the potential for malignant transformation. More studies regarding the anticipated clinical course of skin lesions in patients with acquired EDV are needed to better predict the time frame for malignant transformation.

Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EDV) is a rare disorder occurring in patients with depressed cellular immunity, particularly individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Rare cases of acquired EDV have been reported in stem cell or solid organ transplant recipients. Weakened cellular immunity predisposes the patient to human papillomavirus (HPV) infections, with 92% of renal transplant recipients developing warts within 5 years posttransplantation.1 Specific EDV-HPV subtypes have been isolated from lesions in several immunosuppressed individuals, with HPV-5 and HPV-8 being the most commonly isolated subtypes.2,3 Herein, we present the clinical findings of a renal transplant recipient who presented for evaluation of multiple skin lesions characteristic of EDV 5 years following transplantation and initiation of immunosuppressive therapy. Additionally, we review the current diagnostic findings, management, and treatment of acquired EDV.

A 44-year-old white woman presented for evaluation of several pruritic cutaneous lesions that had developed on the chest and neck of 1 month’s duration. The patient had been on the immunosuppressant medications cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil for more than 5 years following renal transplantation 7 years prior to the current presentation. She also was on low-dose prednisone for chronic systemic lupus erythematosus. Her family history was negative for any pertinent skin conditions.

On physical examination the patient exhibited several grouped 0.5-cm, shiny, pink lichenoid macules located on the upper mid chest, anterior neck, and left leg clinically resembling the lesions of pityriasis versicolor (Figure 1). A shave biopsy was taken from one of the newest lesions on the left leg. Histopathology revealed viral epidermal cytopathic changes, blue cytoplasm, and coarse hypergranulosis characteristic of EDV (Figure 2). A diagnosis of acquired EDV was made based on the clinical and histopathologic findings.

The patient’s skin lesions became more widespread despite several different treatment regimens, including cryosurgery; tazarotene cream 0.05% nightly; imiquimod cream 5% once weekly; and intermittent short courses of 5-fluorouracil cream 5%, which provided the best response. At her most recent clinic visit 8 years after initial presentation, she continued to have more widespread lesions on the trunk, arms, and legs, but no evidence of malignant transformation.

Comment

Epidermodysplasia verruciformis was first recognized as an inherited condition, most commonly inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion; however, X-linked recessive cases have been reported.4,5 Patients with the inherited forms of this condition are prone to recurrent HPV infections secondary to a missense mutation in the epidermodysplasia verruciformis 1 and 2 genes, EVER1 and EVER2, on the EV1 locus located on chromosome 17q25.6 Because of this mutation, the patient’s cellular immunity becomes weakened. Cellular presentation of the EDV-HPV antigen to T lymphocytes becomes impaired, thereby inhibiting the body’s ability to successfully clear itself of the virus.5,6 The most commonly isolated EDV-HPV subtypes are HPV-5 and HPV-8, but HPV types 9, 12, 14, 15, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, and 50 also have been associated with EDV.1,3,7

Patients who have suppressed cellular immunity, such as transplant recipients on long-term immunosuppressant medications and individuals with HIV, graft-vs-host disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, and hematologic malignancies, are susceptible to EDV, as well as patients with atopic dermatitis being treated with topical calcineurin inhibitors.2,3,8-15 These patients acquire depressed cellular immunity and become increasingly susceptible to infections with the EDV-HPV subtypes. When clinical and histopathologic findings are consistent with EDV, a diagnosis of acquired EDV is given, which was further confirmed in a study conducted by Harwood et al.16 They found immunocompromised patients carry more EDV-HPV subtypes in skin lesions analyzed by polymerase chain reaction than immunocompetent individuals.16 Additionally, there is a positive correlation between the length of immunosuppression and the development of HPV lesions, with a majority of patients developing lesions within 5 years following initial immunosuppression.1,7,10,17

Epidermodysplasia verruciformis commonly presents with multiple hypopigmented to red macules that may coalesce into patches with a fine scale, clinically resembling the lesions of pityriasis versicolor.2,3,8-15 Epidermodysplasia verruciformis also may present as multiple flesh-colored, flat-topped, verrucous papules that clinically resemble the lesions of verruca plana on sun-exposed areas such as the face, arms, and legs.9 The characteristic histopathologic findings are enlarged keratinocytes with perinuclear halos and blue-gray cytoplasm as well as hypergranulosis.18 Immunocompromised hosts infected with EDV-HPV histologically tend to display more severe dysplasia than immunocompetent individuals.19 The differential diagnosis includes pityriasis versicolor, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and verruca plana. Tissue cultures and potassium hydroxide scrapings for microorganisms should be negative.

The specific EDV-HPV strains 5, 8, and 41 carry the highest oncogenic potential, with more than 60% of inherited EDV patients developing SCC by the fourth and fifth decades of life.16 Unlike inherited EDV, the clinical course of acquired EDV is less well known; however, UV light is thought to act synergistically with the EDV-HPV in oncogenic transformation of the lesions, as most of the SCCs develop on sun-exposed areas, and darker-skinned patients seem to have a decreased risk for malignant transformation of EDV lesions.4,9,20,21 Preventative measures such as strict sun protection and annual surveillance of lesions can help to prevent oncogenic progression of the lesions; however, several single- and multiple-agent regimens have been used in the treatment of EDV with variable results. Topical imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, tretinoin, and tazarotene have been used with variable success. Acitretin alone and in combination with interferon alfa-2a also has been used.22,23 Highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV has effectively decreased the number of lesions in a subset of patients.24 We (anecdotal) and others25 also have had success using photodynamic therapy. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in patients with EDV can be managed by excision or by Mohs micrographic surgery.

Conclusion

We report a rare case of acquired EDV in a solid organ transplant recipient. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis can be acquired in immunosuppressed patients such as ours, and these patients should be followed closely due to the potential for malignant transformation. More studies regarding the anticipated clinical course of skin lesions in patients with acquired EDV are needed to better predict the time frame for malignant transformation.

- Dyall-Smith D, Trowell H, Dyall-Smith ML. Benign human papillomavirus infection in renal transplant recipients. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:785-789.

- Lutzner MA, Orth G, Dutronquay V, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus type 5 DNA in skin cancers of an immunosuppressed renal allograft recipient. Lancet. 1983;2:422-424.

- Lutzner M, Croissant O, Ducasse MF, et al. A potentially oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV-5) found in two renal allograft recipients. J Invest Dermatol. 1980;75:353-356.

- Androphy EJ, Dvoretzky I, Lowy DR. X-linked inheritance of epidermodysplasia verruciformis. genetic and virologic studies of a kindred. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:864-868.

- Lutzner MA. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis. an autosomal recessive disease characterized by viral warts and skin cancer. a model for viral oncogenesis. Bull Cancer. 1978;65:169-182.

- Ramoz N, Rueda LA, Bouadjar B, et al. Mutations in two adjacent novel genes are associated with epidermodysplasia verruciformis. Nat Genet. 2002;32:579-581.

- Rüdlinger R, Smith IW, Bunney MH, et al. Human papillomavirus infections in a group of renal transplant recipients. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115:681-692.

- Kawai K, Egawa N, Kiyono T, et al. Epidermodysplasia-verruciformis-like eruption associated with gamma-papillomavirus infection in a patient with adult T-cell leukemia. Dermatology. 2009;219:274-278.

- Barr BB, Benton EC, McLaren K, et al. Human papilloma virus infection and skin cancer in renal allograft recipients. Lancet. 1989;1:124-129.

- Tanigaki T, Kanda R, Sato K. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis (L-L, 1922) in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol Res. 1986;278:247-248.

- Holmes C, Chong AH, Tabrizi SN, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis-like syndrome in association with systemic lupus erythematosus. Australas J Dermatol. 2009;50:44-47.

- Gross G, Ellinger K, Roussaki A, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis in a patient with Hodgkin’s disease: characterization of a new papillomavirus type and interferon treatment. J Invest Dermatol. 1988;91:43-48.

- Fernandez KH, Rady P, Tyring S, et al. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis in a child with atopic dermatitis [published online September 3, 2012]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:400-402.

- Hultgren TL, Srinivasan SK, DiMaio DJ. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis occurring in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus: a case report. Cutis. 2007;79:307-311.

- Kunishige JH, Hymes SR, Madkan V, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis in the setting of graft-versus-host disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(5 suppl):S78-S80.

- Harwood CA, Surentheran T, McGregor JM, et al. Human papillomavirus infection and non-melanoma skin cancer in immunosuppressed and immunocompetent individuals. J Med Virol. 2000;61:289-297.

- Moloney FJ, Keane S, O’Kelly P, et al. The impact of skin disease following renal transplantation on quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:574-578.

- Tanigaki T, Endo H. A case of epidermodysplasia verruciformis (Lewandowsky-Lutz, 1922) with skin cancer: histopathology of malignant cutaneous changes. Dermatologica. 1984;169:97-101.

- Morrison C, Eliezri Y, Magro C, et al. The histologic spectrum of epidermodysplasia verruciformis in transplant and AIDS patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:480-489.

- Majewski S, Jabło´nska S. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis as a model of human papillomavirus-induced genetic cancer of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1312-1318.

- Jacyk WK, De Villiers EM. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis in Africans. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:806-810.

- Gubinelli E, Posteraro P, Cocuroccia B, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis with multiple mucosal carcinomas treated with pegylated interferon alfa and acitretin. J Dermatolog Treat. 2003;14:184-188.

- Anadolu R, Oskay T, Erdem C, et al. Treatment of epidermodysplasia verruciformis with a combination of acitretin and interferon alfa-2a. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:296-299.

- Haas N, Fuchs PG, Hermes B, et al. Remission of epidermodysplasia verruciformis-like skin eruption after highly active antiretroviral therapy in a human immunodeficiency virus-positive patient. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:669-670.

- Karrer S, Szeimies RM, Abels C, et al. Epidermo-dysplasia verruciformis treated using topical 5-aminolaevulinic acid photodynamic therapy. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:935-938.

- Dyall-Smith D, Trowell H, Dyall-Smith ML. Benign human papillomavirus infection in renal transplant recipients. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:785-789.

- Lutzner MA, Orth G, Dutronquay V, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus type 5 DNA in skin cancers of an immunosuppressed renal allograft recipient. Lancet. 1983;2:422-424.

- Lutzner M, Croissant O, Ducasse MF, et al. A potentially oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV-5) found in two renal allograft recipients. J Invest Dermatol. 1980;75:353-356.

- Androphy EJ, Dvoretzky I, Lowy DR. X-linked inheritance of epidermodysplasia verruciformis. genetic and virologic studies of a kindred. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:864-868.

- Lutzner MA. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis. an autosomal recessive disease characterized by viral warts and skin cancer. a model for viral oncogenesis. Bull Cancer. 1978;65:169-182.

- Ramoz N, Rueda LA, Bouadjar B, et al. Mutations in two adjacent novel genes are associated with epidermodysplasia verruciformis. Nat Genet. 2002;32:579-581.

- Rüdlinger R, Smith IW, Bunney MH, et al. Human papillomavirus infections in a group of renal transplant recipients. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115:681-692.

- Kawai K, Egawa N, Kiyono T, et al. Epidermodysplasia-verruciformis-like eruption associated with gamma-papillomavirus infection in a patient with adult T-cell leukemia. Dermatology. 2009;219:274-278.

- Barr BB, Benton EC, McLaren K, et al. Human papilloma virus infection and skin cancer in renal allograft recipients. Lancet. 1989;1:124-129.

- Tanigaki T, Kanda R, Sato K. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis (L-L, 1922) in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol Res. 1986;278:247-248.

- Holmes C, Chong AH, Tabrizi SN, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis-like syndrome in association with systemic lupus erythematosus. Australas J Dermatol. 2009;50:44-47.

- Gross G, Ellinger K, Roussaki A, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis in a patient with Hodgkin’s disease: characterization of a new papillomavirus type and interferon treatment. J Invest Dermatol. 1988;91:43-48.

- Fernandez KH, Rady P, Tyring S, et al. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis in a child with atopic dermatitis [published online September 3, 2012]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:400-402.

- Hultgren TL, Srinivasan SK, DiMaio DJ. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis occurring in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus: a case report. Cutis. 2007;79:307-311.

- Kunishige JH, Hymes SR, Madkan V, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis in the setting of graft-versus-host disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(5 suppl):S78-S80.

- Harwood CA, Surentheran T, McGregor JM, et al. Human papillomavirus infection and non-melanoma skin cancer in immunosuppressed and immunocompetent individuals. J Med Virol. 2000;61:289-297.

- Moloney FJ, Keane S, O’Kelly P, et al. The impact of skin disease following renal transplantation on quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:574-578.

- Tanigaki T, Endo H. A case of epidermodysplasia verruciformis (Lewandowsky-Lutz, 1922) with skin cancer: histopathology of malignant cutaneous changes. Dermatologica. 1984;169:97-101.

- Morrison C, Eliezri Y, Magro C, et al. The histologic spectrum of epidermodysplasia verruciformis in transplant and AIDS patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:480-489.

- Majewski S, Jabło´nska S. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis as a model of human papillomavirus-induced genetic cancer of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1312-1318.

- Jacyk WK, De Villiers EM. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis in Africans. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:806-810.

- Gubinelli E, Posteraro P, Cocuroccia B, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis with multiple mucosal carcinomas treated with pegylated interferon alfa and acitretin. J Dermatolog Treat. 2003;14:184-188.

- Anadolu R, Oskay T, Erdem C, et al. Treatment of epidermodysplasia verruciformis with a combination of acitretin and interferon alfa-2a. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:296-299.

- Haas N, Fuchs PG, Hermes B, et al. Remission of epidermodysplasia verruciformis-like skin eruption after highly active antiretroviral therapy in a human immunodeficiency virus-positive patient. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:669-670.

- Karrer S, Szeimies RM, Abels C, et al. Epidermo-dysplasia verruciformis treated using topical 5-aminolaevulinic acid photodynamic therapy. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:935-938.

Practice Points

- Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EDV) is a rare complication of iatrogenic immuno-suppression in the setting of solid organ transplantation.

- Patients with EDV should be counseled to avoid exposure to UV radiation to reduce the risk formalignant transformation.

Do you have to MIPS in 2017? CMS has a tool for that

Want to know if Medicare’s Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) is in your future?

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services launched a Web tool on May 9. To see if you must participate in MIPS in 2017, just enter your national provider identifier. The agency is also in the process of mailing letters to update physicians on their status. The Web tool can be found at the CMS website.

Physicians who bill Medicare Part B more than $30,000 and see more than 100 Medicare patients must participate in MIPS this year. That threshold will be determined by means of claims submitted Sept. 1, 2015, through Aug. 31, 2016, and Sept. 1, 2016, through Aug. 31, 2017.

Those who don’t meet those criteria but want to participate may do so, but they won’t receive either a bonus or a penalty.

Under the MIPS “pick your pace” option, physicians who meet the threshold but are not ready to participate for either the 90-day period or the full year can report on one measure for 2017. Data on the lone measure need to be submitted to CMS no later than March 31, 2018.

Data need only be submitted for one patient, and, in 2017, all forms of submission – via registry, electronic health record, administrative claims, or attestation – are acceptable, though options may vary based on the performance option selected. Doing this minimum effort will result in no adjustment to Medicare payments in 2019.

Submitting no data at all for 2017, however, will mean a 4% Medicare pay cut in 2019.

To do the bare minimum to avoid any penalty, select a single data measurement from one of three categories: quality measures, improvement activity, or, in the case of Advancing Care Information, four or five base measures, depending on which certified EHR is being used.

There are 271 quality measures from which to choose, as well as 92 improvement activities. Improvement activities focus on care coordination, patient engagement, and patient safety.

For each measure, there is a downloadable spreadsheet that gives detailed information about the measure and how to meet it. The spreadsheet can also be used by physicians to track the data that are collected for submission.

Physicians who are new to Medicare in 2017 do not have to participate in MIPS in 2017.

Another way to be exempt from MIPS is to participate in the Advanced Alternative Payment Model track of the QPP. Doctors participating in APMs will have the opportunity to earn higher payment bonuses but will have to assume more risk and could see payment reductions if quality and value thresholds are not met.

Want to know if Medicare’s Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) is in your future?

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services launched a Web tool on May 9. To see if you must participate in MIPS in 2017, just enter your national provider identifier. The agency is also in the process of mailing letters to update physicians on their status. The Web tool can be found at the CMS website.

Physicians who bill Medicare Part B more than $30,000 and see more than 100 Medicare patients must participate in MIPS this year. That threshold will be determined by means of claims submitted Sept. 1, 2015, through Aug. 31, 2016, and Sept. 1, 2016, through Aug. 31, 2017.

Those who don’t meet those criteria but want to participate may do so, but they won’t receive either a bonus or a penalty.

Under the MIPS “pick your pace” option, physicians who meet the threshold but are not ready to participate for either the 90-day period or the full year can report on one measure for 2017. Data on the lone measure need to be submitted to CMS no later than March 31, 2018.

Data need only be submitted for one patient, and, in 2017, all forms of submission – via registry, electronic health record, administrative claims, or attestation – are acceptable, though options may vary based on the performance option selected. Doing this minimum effort will result in no adjustment to Medicare payments in 2019.

Submitting no data at all for 2017, however, will mean a 4% Medicare pay cut in 2019.

To do the bare minimum to avoid any penalty, select a single data measurement from one of three categories: quality measures, improvement activity, or, in the case of Advancing Care Information, four or five base measures, depending on which certified EHR is being used.

There are 271 quality measures from which to choose, as well as 92 improvement activities. Improvement activities focus on care coordination, patient engagement, and patient safety.

For each measure, there is a downloadable spreadsheet that gives detailed information about the measure and how to meet it. The spreadsheet can also be used by physicians to track the data that are collected for submission.

Physicians who are new to Medicare in 2017 do not have to participate in MIPS in 2017.

Another way to be exempt from MIPS is to participate in the Advanced Alternative Payment Model track of the QPP. Doctors participating in APMs will have the opportunity to earn higher payment bonuses but will have to assume more risk and could see payment reductions if quality and value thresholds are not met.

Want to know if Medicare’s Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) is in your future?

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services launched a Web tool on May 9. To see if you must participate in MIPS in 2017, just enter your national provider identifier. The agency is also in the process of mailing letters to update physicians on their status. The Web tool can be found at the CMS website.

Physicians who bill Medicare Part B more than $30,000 and see more than 100 Medicare patients must participate in MIPS this year. That threshold will be determined by means of claims submitted Sept. 1, 2015, through Aug. 31, 2016, and Sept. 1, 2016, through Aug. 31, 2017.

Those who don’t meet those criteria but want to participate may do so, but they won’t receive either a bonus or a penalty.

Under the MIPS “pick your pace” option, physicians who meet the threshold but are not ready to participate for either the 90-day period or the full year can report on one measure for 2017. Data on the lone measure need to be submitted to CMS no later than March 31, 2018.

Data need only be submitted for one patient, and, in 2017, all forms of submission – via registry, electronic health record, administrative claims, or attestation – are acceptable, though options may vary based on the performance option selected. Doing this minimum effort will result in no adjustment to Medicare payments in 2019.

Submitting no data at all for 2017, however, will mean a 4% Medicare pay cut in 2019.

To do the bare minimum to avoid any penalty, select a single data measurement from one of three categories: quality measures, improvement activity, or, in the case of Advancing Care Information, four or five base measures, depending on which certified EHR is being used.

There are 271 quality measures from which to choose, as well as 92 improvement activities. Improvement activities focus on care coordination, patient engagement, and patient safety.

For each measure, there is a downloadable spreadsheet that gives detailed information about the measure and how to meet it. The spreadsheet can also be used by physicians to track the data that are collected for submission.

Physicians who are new to Medicare in 2017 do not have to participate in MIPS in 2017.

Another way to be exempt from MIPS is to participate in the Advanced Alternative Payment Model track of the QPP. Doctors participating in APMs will have the opportunity to earn higher payment bonuses but will have to assume more risk and could see payment reductions if quality and value thresholds are not met.

PPIs triple heart failure hospitalization risk in atrial fib patients

PARIS – Unwarranted prescriptions for proton pump inhibitors tripled the rate at which patients with atrial fibrillation needed hospitalization for a first episode of acute heart failure, in a retrospective study of 172 patients at a single center in Portugal.

About a third of the atrial fibrillation patients received a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) without a clear indication, and the PPI recipients developed heart failure at 2.9 times the rate as patients not on a PPI, a statistically significant difference, João B. Augusto, MD, reported at a meeting held by the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Dr. Augusto believes that these patients largely had no need for PPI treatment, and the drug may have cut iron and vitamin B12 absorption by lowering gastric acid, resulting in deficiencies that produced anemia, and following that, heart failure, he suggested.

The study focused on 423 patients admitted to Fernando da Fonseca Hospital during January 2014–June 2015 with a primary or secondary diagnosis of atrial fibrillation. He excluded 101 patients with a history of heart failure, 109 patients on antiplatelet therapy, and 33 patients with a clear need for PPI treatment because of a gastrointestinal condition. Another 11 patients were lost to follow-up, leaving 172 patients followed for 1 year.

At the time of their initial hospitalization, 53 patients (31%) received a prescription for a PPI despite having no gastrointestinal diagnosis, likely a prophylactic step for patients receiving an oral anticoagulant, Dr. Augusto said. The patients averaged 69 years old, and nearly two-thirds were men.

During 1-year follow-up, the incidence of hospitalization for acute heart failure was 8% in the patients not on a PPI and 23% among those on a PPI, a statistically significant difference. In a regression analysis that controlled for age and chronic kidney disease, the incidence of acute heart failure was 2.9 times more common among patients on a PPI, Dr. Augusto said. He and his associates used these findings to educate their hospital’s staff to not needlessly prescribe a PPI to atrial fibrillation patients.

Dr. Augusto had no disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PARIS – Unwarranted prescriptions for proton pump inhibitors tripled the rate at which patients with atrial fibrillation needed hospitalization for a first episode of acute heart failure, in a retrospective study of 172 patients at a single center in Portugal.

About a third of the atrial fibrillation patients received a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) without a clear indication, and the PPI recipients developed heart failure at 2.9 times the rate as patients not on a PPI, a statistically significant difference, João B. Augusto, MD, reported at a meeting held by the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Dr. Augusto believes that these patients largely had no need for PPI treatment, and the drug may have cut iron and vitamin B12 absorption by lowering gastric acid, resulting in deficiencies that produced anemia, and following that, heart failure, he suggested.

The study focused on 423 patients admitted to Fernando da Fonseca Hospital during January 2014–June 2015 with a primary or secondary diagnosis of atrial fibrillation. He excluded 101 patients with a history of heart failure, 109 patients on antiplatelet therapy, and 33 patients with a clear need for PPI treatment because of a gastrointestinal condition. Another 11 patients were lost to follow-up, leaving 172 patients followed for 1 year.

At the time of their initial hospitalization, 53 patients (31%) received a prescription for a PPI despite having no gastrointestinal diagnosis, likely a prophylactic step for patients receiving an oral anticoagulant, Dr. Augusto said. The patients averaged 69 years old, and nearly two-thirds were men.

During 1-year follow-up, the incidence of hospitalization for acute heart failure was 8% in the patients not on a PPI and 23% among those on a PPI, a statistically significant difference. In a regression analysis that controlled for age and chronic kidney disease, the incidence of acute heart failure was 2.9 times more common among patients on a PPI, Dr. Augusto said. He and his associates used these findings to educate their hospital’s staff to not needlessly prescribe a PPI to atrial fibrillation patients.

Dr. Augusto had no disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PARIS – Unwarranted prescriptions for proton pump inhibitors tripled the rate at which patients with atrial fibrillation needed hospitalization for a first episode of acute heart failure, in a retrospective study of 172 patients at a single center in Portugal.

About a third of the atrial fibrillation patients received a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) without a clear indication, and the PPI recipients developed heart failure at 2.9 times the rate as patients not on a PPI, a statistically significant difference, João B. Augusto, MD, reported at a meeting held by the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Dr. Augusto believes that these patients largely had no need for PPI treatment, and the drug may have cut iron and vitamin B12 absorption by lowering gastric acid, resulting in deficiencies that produced anemia, and following that, heart failure, he suggested.

The study focused on 423 patients admitted to Fernando da Fonseca Hospital during January 2014–June 2015 with a primary or secondary diagnosis of atrial fibrillation. He excluded 101 patients with a history of heart failure, 109 patients on antiplatelet therapy, and 33 patients with a clear need for PPI treatment because of a gastrointestinal condition. Another 11 patients were lost to follow-up, leaving 172 patients followed for 1 year.

At the time of their initial hospitalization, 53 patients (31%) received a prescription for a PPI despite having no gastrointestinal diagnosis, likely a prophylactic step for patients receiving an oral anticoagulant, Dr. Augusto said. The patients averaged 69 years old, and nearly two-thirds were men.

During 1-year follow-up, the incidence of hospitalization for acute heart failure was 8% in the patients not on a PPI and 23% among those on a PPI, a statistically significant difference. In a regression analysis that controlled for age and chronic kidney disease, the incidence of acute heart failure was 2.9 times more common among patients on a PPI, Dr. Augusto said. He and his associates used these findings to educate their hospital’s staff to not needlessly prescribe a PPI to atrial fibrillation patients.

Dr. Augusto had no disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT HEART FAILURE 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Atrial fibrillation patients had a 2.9 times higher acute heart failure rate on a proton pump inhibitor, compared with no PPI.

Data source: Retrospective review of 172 atrial fibrillation patients seen during 2014-2015 at a single center in Portugal.

Disclosures: Dr. Augusto had no disclosures.

Misoprostol effective in healing aspirin-induced small bowel bleeding

CHICAGO – , a small study showed.

Compared with placebo, it was superior in healing small bowel ulcers. A total of 12 patients who received misoprostol had complete healing at 8 weeks, compared with 4 in the placebo group (P = .017).

“Among patients with overt bleeding or anemia from small bowel lesions who receive continuous aspirin therapy, misoprostol is superior to placebo in achieving complete mucosal healing,” said lead author Francis Chan, MD, professor of gastroenterology and hepatology at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, who presented the findings at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

Millions of individuals use low-dose aspirin daily to lower their risk of stroke and cardiovascular events, but they face a risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. In fact, Dr. Chan pointed out, continuous aspirin use has been associated with a threefold risk of a lower GI bleed.

“But to date, there is no effective pharmacological treatment for small bowel ulcers that are associated with use of low-dose aspirin,” he said.

Misoprostol is a synthetic prostaglandin E1 analog that is indicated for reducing the risk of NSAID–induced gastric ulcers in individuals who are at high risk of complications from gastric ulcers. In their study, Dr. Chan and his colleagues assessed the efficacy of misoprostol for healing small bowel ulcers in patients with GI bleeding who were using continuous aspirin therapy.

The primary endpoint was complete mucosal healing in 8 weeks, and secondary endpoints included changes in the number of GI erosions.

The double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial included 35 patients assigned to misoprostol and 37 to placebo. All patients were on regular aspirin (at least 160 mg/day) for established cardiothrombotic diseases and had either overt bleeding of the small bowel or anemia. No bleeding source was identified on gastroscopy and colonoscopy. They had a score of 3 (more than four erosions) or 4 (large erosion or ulcer) that was confirmed by capsule endoscopy.

Those randomized to the active therapy arm received 200 mg misoprostol four times daily, and all patients continued aspirin 80 mg/day for the duration of the trial. During the study period, concomitant NSAIDs, proton pump inhibitors, sucralfate, rebamipide, antibiotics, corticosteroids, or iron supplement was prohibited.

A follow-up capsule endoscopy was performed at 8 weeks to assess mucosal healing, and all images were evaluated by a blinded panel.

The intention-to-treat population included all patients who took at least one dose of the study drug and returned for follow-up capsule endoscopy (n = 72).

In this population, 33% of patients in the misoprostol group and 10.5% on placebo had complete mucosal healing at 8 weeks.

“For the secondary endpoint of changes in small bowel erosions, there was a significant difference between the misoprostol group and placebo group with a P value of .025,” said Dr. Chan.

The study was supported by a competitive grant from the Research Grant Council of Hong Kong. Dr. Chan reported relationships with AstraZeneca, Eisai, Pfizer, and Takeda.

CHICAGO – , a small study showed.

Compared with placebo, it was superior in healing small bowel ulcers. A total of 12 patients who received misoprostol had complete healing at 8 weeks, compared with 4 in the placebo group (P = .017).

“Among patients with overt bleeding or anemia from small bowel lesions who receive continuous aspirin therapy, misoprostol is superior to placebo in achieving complete mucosal healing,” said lead author Francis Chan, MD, professor of gastroenterology and hepatology at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, who presented the findings at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

Millions of individuals use low-dose aspirin daily to lower their risk of stroke and cardiovascular events, but they face a risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. In fact, Dr. Chan pointed out, continuous aspirin use has been associated with a threefold risk of a lower GI bleed.

“But to date, there is no effective pharmacological treatment for small bowel ulcers that are associated with use of low-dose aspirin,” he said.

Misoprostol is a synthetic prostaglandin E1 analog that is indicated for reducing the risk of NSAID–induced gastric ulcers in individuals who are at high risk of complications from gastric ulcers. In their study, Dr. Chan and his colleagues assessed the efficacy of misoprostol for healing small bowel ulcers in patients with GI bleeding who were using continuous aspirin therapy.

The primary endpoint was complete mucosal healing in 8 weeks, and secondary endpoints included changes in the number of GI erosions.

The double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial included 35 patients assigned to misoprostol and 37 to placebo. All patients were on regular aspirin (at least 160 mg/day) for established cardiothrombotic diseases and had either overt bleeding of the small bowel or anemia. No bleeding source was identified on gastroscopy and colonoscopy. They had a score of 3 (more than four erosions) or 4 (large erosion or ulcer) that was confirmed by capsule endoscopy.

Those randomized to the active therapy arm received 200 mg misoprostol four times daily, and all patients continued aspirin 80 mg/day for the duration of the trial. During the study period, concomitant NSAIDs, proton pump inhibitors, sucralfate, rebamipide, antibiotics, corticosteroids, or iron supplement was prohibited.

A follow-up capsule endoscopy was performed at 8 weeks to assess mucosal healing, and all images were evaluated by a blinded panel.

The intention-to-treat population included all patients who took at least one dose of the study drug and returned for follow-up capsule endoscopy (n = 72).

In this population, 33% of patients in the misoprostol group and 10.5% on placebo had complete mucosal healing at 8 weeks.

“For the secondary endpoint of changes in small bowel erosions, there was a significant difference between the misoprostol group and placebo group with a P value of .025,” said Dr. Chan.

The study was supported by a competitive grant from the Research Grant Council of Hong Kong. Dr. Chan reported relationships with AstraZeneca, Eisai, Pfizer, and Takeda.

CHICAGO – , a small study showed.

Compared with placebo, it was superior in healing small bowel ulcers. A total of 12 patients who received misoprostol had complete healing at 8 weeks, compared with 4 in the placebo group (P = .017).

“Among patients with overt bleeding or anemia from small bowel lesions who receive continuous aspirin therapy, misoprostol is superior to placebo in achieving complete mucosal healing,” said lead author Francis Chan, MD, professor of gastroenterology and hepatology at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, who presented the findings at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

Millions of individuals use low-dose aspirin daily to lower their risk of stroke and cardiovascular events, but they face a risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. In fact, Dr. Chan pointed out, continuous aspirin use has been associated with a threefold risk of a lower GI bleed.

“But to date, there is no effective pharmacological treatment for small bowel ulcers that are associated with use of low-dose aspirin,” he said.

Misoprostol is a synthetic prostaglandin E1 analog that is indicated for reducing the risk of NSAID–induced gastric ulcers in individuals who are at high risk of complications from gastric ulcers. In their study, Dr. Chan and his colleagues assessed the efficacy of misoprostol for healing small bowel ulcers in patients with GI bleeding who were using continuous aspirin therapy.

The primary endpoint was complete mucosal healing in 8 weeks, and secondary endpoints included changes in the number of GI erosions.

The double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial included 35 patients assigned to misoprostol and 37 to placebo. All patients were on regular aspirin (at least 160 mg/day) for established cardiothrombotic diseases and had either overt bleeding of the small bowel or anemia. No bleeding source was identified on gastroscopy and colonoscopy. They had a score of 3 (more than four erosions) or 4 (large erosion or ulcer) that was confirmed by capsule endoscopy.

Those randomized to the active therapy arm received 200 mg misoprostol four times daily, and all patients continued aspirin 80 mg/day for the duration of the trial. During the study period, concomitant NSAIDs, proton pump inhibitors, sucralfate, rebamipide, antibiotics, corticosteroids, or iron supplement was prohibited.

A follow-up capsule endoscopy was performed at 8 weeks to assess mucosal healing, and all images were evaluated by a blinded panel.

The intention-to-treat population included all patients who took at least one dose of the study drug and returned for follow-up capsule endoscopy (n = 72).

In this population, 33% of patients in the misoprostol group and 10.5% on placebo had complete mucosal healing at 8 weeks.

“For the secondary endpoint of changes in small bowel erosions, there was a significant difference between the misoprostol group and placebo group with a P value of .025,” said Dr. Chan.

The study was supported by a competitive grant from the Research Grant Council of Hong Kong. Dr. Chan reported relationships with AstraZeneca, Eisai, Pfizer, and Takeda.

AT DDW

Key clinical point: Misoprostol was more effective than placebo in healing small bowel ulcers in patients who used daily low-dose aspirin.

Major finding: 33% of patients in the misoprostol group and 10.5% on placebo had complete mucosal healing at 8 weeks.

Data source: An 8-week, double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial of 72 patients that assessed misoprostol vs. placebo for healing small bowel ulcers.

Disclosures: The study was supported by a competitive grant from the Research Grant Council of Hong Kong. Dr. Chan reported relationships with AstraZeneca, Eisai, Pfizer, and Takeda.

Determining patients’ decisional capacity

Question: Mrs. Wong, age 80 years, has vascular dementia, and for the last 2 years has lived in a nursing home. She is forgetful and disoriented to time, person, and place, and totally dependent on others for all of her daily living needs. But she remains verbal and recognizes family members.

Recently, her glomerular filtration rate declined to less than 10% normal, and she has developed symptoms of uremia, i.e., nausea, vomiting, and intractable hiccups. The nephrologist has diagnosed end-stage renal failure and recommends hemodialysis, which will improve her renal symptoms and may extend her life by 1-2 years. But it will do nothing for her underlying dementia, which is progressive and irreversible.

Should she undergo hemodialysis? Choose the best single answer:

A. Mrs. Wong definitely lacks the capacity to decide whether to undergo hemodialysis.

B. A court-appointed guardian should make the decision.

C. Hemodialysis is futile and is medically contraindicated, inhumane, and unethical.

D. Hemodialysis is a life-extending form of comfort care, and therefore cannot be withheld.

E. The choice is hers if she understands the procedure and the consequences of her decision.

Answer: E. The terms competence and capacity are often used interchangeably in the health care context, although there are distinctions. Technically, a patient remains competent until a court says otherwise. On the other hand, the determination of medical decision-making capacity can be made by the attending physician and does not ordinarily require a court hearing.

Medical capacity can be determined by the use of the four-point test, which asks whether:

1. The patient understands the nature of the intervention.

2. The patient understands the consequences of the decision (especially refusal of treatment).

3. The patient is able to communicate his/her wishes.

4. Those wishes are compatible with the patient’s known values.

Courts tend to rule in favor of a finding of capacity. In one case, the court found no evidence that the patient’s “forgetfulness and confusion cause, or relate in any way to, impairment of her ability to understand that, in rejecting the amputation, she is, in effect, choosing death over life.”1

In another, the court opined, “However humble the background, sad and deprived the way of life, each individual should have the choice as to what is done to his body, if he is capable of understanding the consequences. This patient, although suffering from an organic brain disease, in the court’s opinion understands the consequences of his refusal. … I find that he has sufficient capacity and competence to consent to or refuse the proposed surgery.”2

Sometimes capacity is truly lacking. In a Tennessee case, Mary Northern, an elderly woman, refused amputation, denying that gangrene had caused her feet to be “dead, black, shriveled, rotting, and stinking.”3 Instead, she believed that they were merely blackened by soot or dust.

The court declared her incompetent, because she was “incapable of recognizing facts which would be obvious to a person of normal perception.” The court said that if she had acknowledged that her legs were gangrenous but refused amputation because she preferred death to the loss of her feet, she would have been considered competent to refuse surgery.

When the patient lacks capacity, a surrogate steps in. This may be a person previously designated by the patient as having durable power of attorney for health care decisions, and he/she is obligated to give voice to what the patient would have wanted. This is called substituted judgment.

Often, no surrogate has been formally mentioned, and a family member assumes the role; rarely, a court-appointed guardian takes over. When there is no knowledge of the patient’s wishes, the decision is then made in the patient’s best interests.

That a surrogate can make life and death decisions was first enunciated in the seminal case of Karen Ann Quinlan, where the New Jersey Supreme Court famously wrote, “The sad truth, however, is that she is grossly incompetent, and we cannot discern her supposed choice based on the testimony of her previous conversations with friends, where such testimony is without sufficient probative weight. Nevertheless, we have concluded that Karen’s right of privacy may be asserted on her behalf by her guardian under the peculiar circumstances here present.”4

The U.S. Supreme Court in Cruzan v. Director Missouri Department of Health has similarly held that an “incompetent person is not able to make an informed and voluntary choice to exercise a hypothetical right to refuse treatment or any other right. Such a ‘right’ must be exercised for her, if at all, by some sort of surrogate.”5 The court also opined that a state – in this case, Missouri – may apply a clear and convincing evidentiary standard in proceedings where a guardian seeks to discontinue nutrition and hydration.

Clear and convincing evidence is said to exist where there is a finding of high probability, based on evidence “so clear as to leave no substantial doubt” and “sufficiently strong to command the unhesitating assent of every reasonable mind.”

However, where a patient’s wishes are not clear and convincing, a court will be reluctant to order cessation of treatment, as in the landmark case of Wendland v. Wendland, where the California Supreme Court unanimously disallowed the discontinuation of a patient’s tube feedings.6

The patient, Robert Wendland, had regained consciousness after 14 months in a coma, but was left hemiparetic and incontinent, and could not feed by mouth or dress, bathe, and communicate consistently. He did not have an advance directive, but had made statements to the effect he would not want to live in a vegetative state.

His wife, Rose, refused to authorize reinsertion of his dislodged feeding tube, believing that Robert would not have wanted it replaced. The patient’s daughter and brother, as well as the hospital’s ethics committee, county ombudsman, and a court-appointed counsel, all agreed with the decision.

But the patient’s mother, Florence, went to court to block the action. The court determined that Robert’s statements were not clear and convincing, because they did not address his current condition, were not sufficiently specific, and were not necessarily intended to direct his medical care. Further, the patient’s spouse had failed to provide sufficient evidence that her decision was in her husband’s best interests.

Issues surrounding treatment at the end of life can be difficult and elusive. Even where there is an advance medical directive, statements made by patients in the document do not always comport with their eventual treatment decisions.

In a telling study, the authors found that only two-thirds of the time were decisions consistent.7 One-third of patients changed their preferences in the face of actual illness, usually in favor of treatments rejected in advance. Surrogate agreement was only 58%, and surrogates tended to overestimate their loved one’s desire for treatment.

The designation of who may be the legitimate alternative decision maker is another contentious issue, with laws varying widely from state to state.8

All of this may have in part prompted Singapore’s newly enacted Mental Capacity Act,9 which permits a surrogate to make wide-ranging decisions on behalf of an incapacitated person, to specifically exclude decisions regarding life-sustaining treatment and any measure that the physician “reasonably believes is necessary to prevent a serious deterioration” in the patient’s condition.

The decisional responsibility resides in the treating physician, who is obligated by law to make an effort to assist the patient to come to a decision, failing which it is made in the patient’s best interests.

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

References

1. Lane v. Candura, 6 Mass. App. 377 (1978).

2. Matter of Roosevelt Hospital, N.Y.L.J. 13 Jan 1977 p. 7 (Sup. Ct., New York Co.).

3. State Dept Human Resources v. Northern, 563 SW 2d 197 (Tenn. Ct. App., 1978).

4. In the matter of Karen Quinlan, 355 A.2d 647 (N.J., 1976).

5. Cruzan v. Director Missouri Department of Health, 110 S. Ct. 2841 (1990).

6. Wendland v. Wendland, 28 P.3d 151 (Cal., 2001).

7. J Clin Ethics. 1998 Fall;9(3):258-62.

8. N Engl J Med. 2017 Apr 13;376(15):1478-82.

9. Singapore’s Mental Capacity Act (Chapter 177A).

Question: Mrs. Wong, age 80 years, has vascular dementia, and for the last 2 years has lived in a nursing home. She is forgetful and disoriented to time, person, and place, and totally dependent on others for all of her daily living needs. But she remains verbal and recognizes family members.

Recently, her glomerular filtration rate declined to less than 10% normal, and she has developed symptoms of uremia, i.e., nausea, vomiting, and intractable hiccups. The nephrologist has diagnosed end-stage renal failure and recommends hemodialysis, which will improve her renal symptoms and may extend her life by 1-2 years. But it will do nothing for her underlying dementia, which is progressive and irreversible.

Should she undergo hemodialysis? Choose the best single answer:

A. Mrs. Wong definitely lacks the capacity to decide whether to undergo hemodialysis.

B. A court-appointed guardian should make the decision.

C. Hemodialysis is futile and is medically contraindicated, inhumane, and unethical.

D. Hemodialysis is a life-extending form of comfort care, and therefore cannot be withheld.

E. The choice is hers if she understands the procedure and the consequences of her decision.

Answer: E. The terms competence and capacity are often used interchangeably in the health care context, although there are distinctions. Technically, a patient remains competent until a court says otherwise. On the other hand, the determination of medical decision-making capacity can be made by the attending physician and does not ordinarily require a court hearing.

Medical capacity can be determined by the use of the four-point test, which asks whether:

1. The patient understands the nature of the intervention.

2. The patient understands the consequences of the decision (especially refusal of treatment).

3. The patient is able to communicate his/her wishes.

4. Those wishes are compatible with the patient’s known values.

Courts tend to rule in favor of a finding of capacity. In one case, the court found no evidence that the patient’s “forgetfulness and confusion cause, or relate in any way to, impairment of her ability to understand that, in rejecting the amputation, she is, in effect, choosing death over life.”1

In another, the court opined, “However humble the background, sad and deprived the way of life, each individual should have the choice as to what is done to his body, if he is capable of understanding the consequences. This patient, although suffering from an organic brain disease, in the court’s opinion understands the consequences of his refusal. … I find that he has sufficient capacity and competence to consent to or refuse the proposed surgery.”2

Sometimes capacity is truly lacking. In a Tennessee case, Mary Northern, an elderly woman, refused amputation, denying that gangrene had caused her feet to be “dead, black, shriveled, rotting, and stinking.”3 Instead, she believed that they were merely blackened by soot or dust.

The court declared her incompetent, because she was “incapable of recognizing facts which would be obvious to a person of normal perception.” The court said that if she had acknowledged that her legs were gangrenous but refused amputation because she preferred death to the loss of her feet, she would have been considered competent to refuse surgery.

When the patient lacks capacity, a surrogate steps in. This may be a person previously designated by the patient as having durable power of attorney for health care decisions, and he/she is obligated to give voice to what the patient would have wanted. This is called substituted judgment.

Often, no surrogate has been formally mentioned, and a family member assumes the role; rarely, a court-appointed guardian takes over. When there is no knowledge of the patient’s wishes, the decision is then made in the patient’s best interests.

That a surrogate can make life and death decisions was first enunciated in the seminal case of Karen Ann Quinlan, where the New Jersey Supreme Court famously wrote, “The sad truth, however, is that she is grossly incompetent, and we cannot discern her supposed choice based on the testimony of her previous conversations with friends, where such testimony is without sufficient probative weight. Nevertheless, we have concluded that Karen’s right of privacy may be asserted on her behalf by her guardian under the peculiar circumstances here present.”4

The U.S. Supreme Court in Cruzan v. Director Missouri Department of Health has similarly held that an “incompetent person is not able to make an informed and voluntary choice to exercise a hypothetical right to refuse treatment or any other right. Such a ‘right’ must be exercised for her, if at all, by some sort of surrogate.”5 The court also opined that a state – in this case, Missouri – may apply a clear and convincing evidentiary standard in proceedings where a guardian seeks to discontinue nutrition and hydration.

Clear and convincing evidence is said to exist where there is a finding of high probability, based on evidence “so clear as to leave no substantial doubt” and “sufficiently strong to command the unhesitating assent of every reasonable mind.”

However, where a patient’s wishes are not clear and convincing, a court will be reluctant to order cessation of treatment, as in the landmark case of Wendland v. Wendland, where the California Supreme Court unanimously disallowed the discontinuation of a patient’s tube feedings.6

The patient, Robert Wendland, had regained consciousness after 14 months in a coma, but was left hemiparetic and incontinent, and could not feed by mouth or dress, bathe, and communicate consistently. He did not have an advance directive, but had made statements to the effect he would not want to live in a vegetative state.

His wife, Rose, refused to authorize reinsertion of his dislodged feeding tube, believing that Robert would not have wanted it replaced. The patient’s daughter and brother, as well as the hospital’s ethics committee, county ombudsman, and a court-appointed counsel, all agreed with the decision.

But the patient’s mother, Florence, went to court to block the action. The court determined that Robert’s statements were not clear and convincing, because they did not address his current condition, were not sufficiently specific, and were not necessarily intended to direct his medical care. Further, the patient’s spouse had failed to provide sufficient evidence that her decision was in her husband’s best interests.

Issues surrounding treatment at the end of life can be difficult and elusive. Even where there is an advance medical directive, statements made by patients in the document do not always comport with their eventual treatment decisions.