User login

More pulmonary patients getting palliative care

Patients referred to palliative care are most likely to have cancer, but the proportion has gone down since 2009 as other diagnoses have increased, according to a report from the National Palliative Care Registry.

In 2015, cancer patients made up 26% of the patients referred to palliative care, compared with 35% in 2009. The situation was reversed for the next three most common diagnoses in 2015: Cardiac diagnoses rose from 5% in 2009 to 13%, pulmonary diagnoses increased from 6% to 12%, and neurologic diagnoses went from 3% to 8%, the report showed.

An increase in overall palliative care penetration was seen from 2009 to 2015, as the percentage of annual hospital admissions seen by a palliative care team increased from 2.7% to 4.8%. Over that same time period, the percentage of palliative care patients who died in the hospital decreased from 29% to 22%, according to the report.

In 2015, there were 420 palliative care programs participating in the registry, which is a joint project of the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center.

Patients referred to palliative care are most likely to have cancer, but the proportion has gone down since 2009 as other diagnoses have increased, according to a report from the National Palliative Care Registry.

In 2015, cancer patients made up 26% of the patients referred to palliative care, compared with 35% in 2009. The situation was reversed for the next three most common diagnoses in 2015: Cardiac diagnoses rose from 5% in 2009 to 13%, pulmonary diagnoses increased from 6% to 12%, and neurologic diagnoses went from 3% to 8%, the report showed.

An increase in overall palliative care penetration was seen from 2009 to 2015, as the percentage of annual hospital admissions seen by a palliative care team increased from 2.7% to 4.8%. Over that same time period, the percentage of palliative care patients who died in the hospital decreased from 29% to 22%, according to the report.

In 2015, there were 420 palliative care programs participating in the registry, which is a joint project of the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center.

Patients referred to palliative care are most likely to have cancer, but the proportion has gone down since 2009 as other diagnoses have increased, according to a report from the National Palliative Care Registry.

In 2015, cancer patients made up 26% of the patients referred to palliative care, compared with 35% in 2009. The situation was reversed for the next three most common diagnoses in 2015: Cardiac diagnoses rose from 5% in 2009 to 13%, pulmonary diagnoses increased from 6% to 12%, and neurologic diagnoses went from 3% to 8%, the report showed.

An increase in overall palliative care penetration was seen from 2009 to 2015, as the percentage of annual hospital admissions seen by a palliative care team increased from 2.7% to 4.8%. Over that same time period, the percentage of palliative care patients who died in the hospital decreased from 29% to 22%, according to the report.

In 2015, there were 420 palliative care programs participating in the registry, which is a joint project of the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center.

More neurology patients getting palliative care

Patients referred to palliative care are most likely to have cancer, but the proportion has gone down since 2009 as other diagnoses have increased, according to a report from the National Palliative Care Registry.

In 2015, cancer patients made up 26% of the patients referred to palliative care, compared with 35% in 2009. The situation was reversed for the next three most common diagnoses in 2015: Cardiac diagnoses rose from 5% in 2009 to 13%, pulmonary diagnoses increased from 6% to 12%, and neurologic diagnoses went from 3% to 8%, the report showed.

An increase in overall palliative care penetration was seen from 2009 to 2015, as the percentage of annual hospital admissions seen by a palliative care team increased from 2.7% to 4.8%. Over that same time period, the percentage of palliative care patients who died in the hospital decreased from 29% to 22%, according to the report.

In 2015, there were 420 palliative care programs participating in the registry, which is a joint project of the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center.

Patients referred to palliative care are most likely to have cancer, but the proportion has gone down since 2009 as other diagnoses have increased, according to a report from the National Palliative Care Registry.

In 2015, cancer patients made up 26% of the patients referred to palliative care, compared with 35% in 2009. The situation was reversed for the next three most common diagnoses in 2015: Cardiac diagnoses rose from 5% in 2009 to 13%, pulmonary diagnoses increased from 6% to 12%, and neurologic diagnoses went from 3% to 8%, the report showed.

An increase in overall palliative care penetration was seen from 2009 to 2015, as the percentage of annual hospital admissions seen by a palliative care team increased from 2.7% to 4.8%. Over that same time period, the percentage of palliative care patients who died in the hospital decreased from 29% to 22%, according to the report.

In 2015, there were 420 palliative care programs participating in the registry, which is a joint project of the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center.

Patients referred to palliative care are most likely to have cancer, but the proportion has gone down since 2009 as other diagnoses have increased, according to a report from the National Palliative Care Registry.

In 2015, cancer patients made up 26% of the patients referred to palliative care, compared with 35% in 2009. The situation was reversed for the next three most common diagnoses in 2015: Cardiac diagnoses rose from 5% in 2009 to 13%, pulmonary diagnoses increased from 6% to 12%, and neurologic diagnoses went from 3% to 8%, the report showed.

An increase in overall palliative care penetration was seen from 2009 to 2015, as the percentage of annual hospital admissions seen by a palliative care team increased from 2.7% to 4.8%. Over that same time period, the percentage of palliative care patients who died in the hospital decreased from 29% to 22%, according to the report.

In 2015, there were 420 palliative care programs participating in the registry, which is a joint project of the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center.

More cardiac patients getting palliative care

Patients referred to palliative care are most likely to have cancer, but the proportion has gone down since 2009 as other diagnoses have increased, according to a report from the National Palliative Care Registry.

In 2015, cancer patients made up 26% of the patients referred to palliative care, compared with 35% in 2009. The situation was reversed for the next three most common diagnoses in 2015: Cardiac diagnoses rose from 5% in 2009 to 13%, pulmonary diagnoses increased from 6% to 12%, and neurologic diagnoses went from 3% to 8%, the report showed.

An increase in overall palliative care penetration was seen from 2009 to 2015, as the percentage of annual hospital admissions seen by a palliative care team increased from 2.7% to 4.8%. Over that same time period, the percentage of palliative care patients who died in the hospital decreased from 29% to 22%, according to the report.

In 2015, there were 420 palliative care programs participating in the registry, which is a joint project of the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center.

Patients referred to palliative care are most likely to have cancer, but the proportion has gone down since 2009 as other diagnoses have increased, according to a report from the National Palliative Care Registry.

In 2015, cancer patients made up 26% of the patients referred to palliative care, compared with 35% in 2009. The situation was reversed for the next three most common diagnoses in 2015: Cardiac diagnoses rose from 5% in 2009 to 13%, pulmonary diagnoses increased from 6% to 12%, and neurologic diagnoses went from 3% to 8%, the report showed.

An increase in overall palliative care penetration was seen from 2009 to 2015, as the percentage of annual hospital admissions seen by a palliative care team increased from 2.7% to 4.8%. Over that same time period, the percentage of palliative care patients who died in the hospital decreased from 29% to 22%, according to the report.

In 2015, there were 420 palliative care programs participating in the registry, which is a joint project of the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center.

Patients referred to palliative care are most likely to have cancer, but the proportion has gone down since 2009 as other diagnoses have increased, according to a report from the National Palliative Care Registry.

In 2015, cancer patients made up 26% of the patients referred to palliative care, compared with 35% in 2009. The situation was reversed for the next three most common diagnoses in 2015: Cardiac diagnoses rose from 5% in 2009 to 13%, pulmonary diagnoses increased from 6% to 12%, and neurologic diagnoses went from 3% to 8%, the report showed.

An increase in overall palliative care penetration was seen from 2009 to 2015, as the percentage of annual hospital admissions seen by a palliative care team increased from 2.7% to 4.8%. Over that same time period, the percentage of palliative care patients who died in the hospital decreased from 29% to 22%, according to the report.

In 2015, there were 420 palliative care programs participating in the registry, which is a joint project of the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center.

Noncancer diagnoses on the rise in palliative care

Patients referred to palliative care are most likely to have cancer, but the proportion has gone down since 2009 as other diagnoses have increased, according to a report from the National Palliative Care Registry.

In 2015, cancer patients made up 26% of the patients referred to palliative care, compared with 35% in 2009. The situation was reversed for the next three most common diagnoses in 2015: Cardiac diagnoses rose from 5% in 2009 to 13%, pulmonary diagnoses increased from 6% to 12%, and neurologic diagnoses went from 3% to 8%, the report showed.

Referrals by specialty were led by hospital medicine, which accounted for 48% of all patients referred to palliative care in 2015, with internal medicine/family medicine next at 14%, followed by pulmonary/critical care at 13% and oncology at 7%, the report said.

An increase in overall palliative care penetration was seen from 2009 to 2015, as the percentage of annual hospital admissions seen by a palliative care team increased from 2.7% to 4.8%. Over that same time period, the percentage of palliative care patients who died in the hospital decreased from 29% to 22%, according to the report.

In 2015, there were 420 palliative care programs participating in the registry, which is a joint project of the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center.

"But doc, isn't hospice just for cancer patients?"

"But doc, isn't hospice just for cancer patients?"

"But doc, isn't hospice just for cancer patients?"

Patients referred to palliative care are most likely to have cancer, but the proportion has gone down since 2009 as other diagnoses have increased, according to a report from the National Palliative Care Registry.

In 2015, cancer patients made up 26% of the patients referred to palliative care, compared with 35% in 2009. The situation was reversed for the next three most common diagnoses in 2015: Cardiac diagnoses rose from 5% in 2009 to 13%, pulmonary diagnoses increased from 6% to 12%, and neurologic diagnoses went from 3% to 8%, the report showed.

Referrals by specialty were led by hospital medicine, which accounted for 48% of all patients referred to palliative care in 2015, with internal medicine/family medicine next at 14%, followed by pulmonary/critical care at 13% and oncology at 7%, the report said.

An increase in overall palliative care penetration was seen from 2009 to 2015, as the percentage of annual hospital admissions seen by a palliative care team increased from 2.7% to 4.8%. Over that same time period, the percentage of palliative care patients who died in the hospital decreased from 29% to 22%, according to the report.

In 2015, there were 420 palliative care programs participating in the registry, which is a joint project of the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center.

Patients referred to palliative care are most likely to have cancer, but the proportion has gone down since 2009 as other diagnoses have increased, according to a report from the National Palliative Care Registry.

In 2015, cancer patients made up 26% of the patients referred to palliative care, compared with 35% in 2009. The situation was reversed for the next three most common diagnoses in 2015: Cardiac diagnoses rose from 5% in 2009 to 13%, pulmonary diagnoses increased from 6% to 12%, and neurologic diagnoses went from 3% to 8%, the report showed.

Referrals by specialty were led by hospital medicine, which accounted for 48% of all patients referred to palliative care in 2015, with internal medicine/family medicine next at 14%, followed by pulmonary/critical care at 13% and oncology at 7%, the report said.

An increase in overall palliative care penetration was seen from 2009 to 2015, as the percentage of annual hospital admissions seen by a palliative care team increased from 2.7% to 4.8%. Over that same time period, the percentage of palliative care patients who died in the hospital decreased from 29% to 22%, according to the report.

In 2015, there were 420 palliative care programs participating in the registry, which is a joint project of the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center.

Ankylosing spondylitis disease severity worsened by smoking

BIRMINGHAM, ENGLAND – Patients with axial spondyloarthritis who currently smoke have been found to have worse disease activity than those who do not in an early analysis of data from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register for Ankylosing Spondylitis (BSRBR-AS).

Smoking was associated with worse disease not only when comparing ever smokers with never smokers, but also when current smokers were compared to ex-smokers, and there was some evidence that the amount of smoking was important with heavier smokers having worse disease activity than light smokers.

Dr. Zhao, of Aintree University Hospital in Liverpool, England, added that, as in previous studies, these data show that “smoking is associated with worse disease activity at baseline and this needs to be accounted for in the next stage of longitudinal analysis.”

An association between smoking and worse disease activity in patients with axSpA has been reported previously, Dr. Zhao acknowledged, but this is not as clear cut as in rheumatoid arthritis where smoking is known to have a pathogenic effect. The small number of earlier studies looking at the possible effect of smoking in AS have been limited by their size and varying methodology, he added, and the studies’ researchers were not able to see if there was any potential dose effect of smoking.

The BSRBR-AS, which started recruiting patients with an Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) classification of axSpA in 2012, offers a unique opportunity to explore the association between smoking and axSpA further, he said. More than 2,500 patients are included in the register at present, none of whom should have not been treated with biologic agents at the time of recruitment.

The aim of the present analysis that looked at data on 932 patients was to quantify the effect of smoking status and quantity on several disease outcomes as measured by the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI), the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI), and the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI). Spinal pain was also assessed, by way of a visual analog scale (VAS), and quality of life was determined via the disease-specific Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life Instruments (ASQoL).

Most of the patients recruited were male (71%), and the mean age was 50 years. HLA-B27 data were available for 64% of the cohort, and 84% were positive.

Self-reported smoking status was recorded, with 19% saying they were current smokers, 37% saying they were ex-smokers, and 44% saying they had never smoked. If patients reported being ever smokers, the frequency with which they smoked (daily, weekly, monthly, once or twice, or never) was recorded, and if patients smoked daily, then the number of cigarettes smoked per day was obtained. Heavy smoking was defined as smoking 10 or more cigarettes per day and light smoking as fewer than 10 cigarettes per day. By this definition, around 37% of daily smokers were classed as heavy smokers.

In a comparison of ever smokers with never smokers, the mean BASDAI, BASFI, BASMI, spinal VAS, and ASQoL were significantly higher if patients had smoked at some point. All comparisons were adjusted for age, gender, body mass index, and HLA-B27 status.

The mean BASDAI score, for example, was more than 1 unit higher in a comparison of ever smokers with never smokers, with an adjusted regression coefficient of 1.04 and a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 0.72-1.36.

The adjusted regression coefficients for the other measures assessed were 1.34 (95% CI, 0.98-1.69) for BASFI, 0.61 (95% CI 0.36-0.87) for BASMI, 1.11 (95% CI, 0.74-1.49) for spinal VAS, and 2.71 (95% CI, 2.01–3.41) for ASQoL.

Similar findings were seen in the analysis comparing current with ex-smokers across all measures studied, and there was a trend for disease activity to be worse in heavier than in lighter smokers. The latter may not have reached significance because of the smaller number of patients (n = 172) involved in that part of the analysis. Nevertheless, these preliminary findings suggest that even being a light smoker can affect disease outcomes and so cutting down (i.e., to fewer than 10 cigarettes per day) may not be sufficient to reduce the effect that smoking has on disease activity.

“We should be actively encouraging our patients [with axSpA] to stop smoking,” Dr. Zhao concluded.

The BSRBR-AS is managed by a team of investigators based at the University of Aberdeen in collaboration with 83 centers throughout the United Kingdom. It is funded by the BSR, which in turn receives funding from the manufacturers of the biologic therapies included in this study (currently AbbVie, Pfizer, and UCB). Dr. Zhao and coauthors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

BIRMINGHAM, ENGLAND – Patients with axial spondyloarthritis who currently smoke have been found to have worse disease activity than those who do not in an early analysis of data from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register for Ankylosing Spondylitis (BSRBR-AS).

Smoking was associated with worse disease not only when comparing ever smokers with never smokers, but also when current smokers were compared to ex-smokers, and there was some evidence that the amount of smoking was important with heavier smokers having worse disease activity than light smokers.

Dr. Zhao, of Aintree University Hospital in Liverpool, England, added that, as in previous studies, these data show that “smoking is associated with worse disease activity at baseline and this needs to be accounted for in the next stage of longitudinal analysis.”

An association between smoking and worse disease activity in patients with axSpA has been reported previously, Dr. Zhao acknowledged, but this is not as clear cut as in rheumatoid arthritis where smoking is known to have a pathogenic effect. The small number of earlier studies looking at the possible effect of smoking in AS have been limited by their size and varying methodology, he added, and the studies’ researchers were not able to see if there was any potential dose effect of smoking.

The BSRBR-AS, which started recruiting patients with an Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) classification of axSpA in 2012, offers a unique opportunity to explore the association between smoking and axSpA further, he said. More than 2,500 patients are included in the register at present, none of whom should have not been treated with biologic agents at the time of recruitment.

The aim of the present analysis that looked at data on 932 patients was to quantify the effect of smoking status and quantity on several disease outcomes as measured by the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI), the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI), and the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI). Spinal pain was also assessed, by way of a visual analog scale (VAS), and quality of life was determined via the disease-specific Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life Instruments (ASQoL).

Most of the patients recruited were male (71%), and the mean age was 50 years. HLA-B27 data were available for 64% of the cohort, and 84% were positive.

Self-reported smoking status was recorded, with 19% saying they were current smokers, 37% saying they were ex-smokers, and 44% saying they had never smoked. If patients reported being ever smokers, the frequency with which they smoked (daily, weekly, monthly, once or twice, or never) was recorded, and if patients smoked daily, then the number of cigarettes smoked per day was obtained. Heavy smoking was defined as smoking 10 or more cigarettes per day and light smoking as fewer than 10 cigarettes per day. By this definition, around 37% of daily smokers were classed as heavy smokers.

In a comparison of ever smokers with never smokers, the mean BASDAI, BASFI, BASMI, spinal VAS, and ASQoL were significantly higher if patients had smoked at some point. All comparisons were adjusted for age, gender, body mass index, and HLA-B27 status.

The mean BASDAI score, for example, was more than 1 unit higher in a comparison of ever smokers with never smokers, with an adjusted regression coefficient of 1.04 and a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 0.72-1.36.

The adjusted regression coefficients for the other measures assessed were 1.34 (95% CI, 0.98-1.69) for BASFI, 0.61 (95% CI 0.36-0.87) for BASMI, 1.11 (95% CI, 0.74-1.49) for spinal VAS, and 2.71 (95% CI, 2.01–3.41) for ASQoL.

Similar findings were seen in the analysis comparing current with ex-smokers across all measures studied, and there was a trend for disease activity to be worse in heavier than in lighter smokers. The latter may not have reached significance because of the smaller number of patients (n = 172) involved in that part of the analysis. Nevertheless, these preliminary findings suggest that even being a light smoker can affect disease outcomes and so cutting down (i.e., to fewer than 10 cigarettes per day) may not be sufficient to reduce the effect that smoking has on disease activity.

“We should be actively encouraging our patients [with axSpA] to stop smoking,” Dr. Zhao concluded.

The BSRBR-AS is managed by a team of investigators based at the University of Aberdeen in collaboration with 83 centers throughout the United Kingdom. It is funded by the BSR, which in turn receives funding from the manufacturers of the biologic therapies included in this study (currently AbbVie, Pfizer, and UCB). Dr. Zhao and coauthors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

BIRMINGHAM, ENGLAND – Patients with axial spondyloarthritis who currently smoke have been found to have worse disease activity than those who do not in an early analysis of data from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register for Ankylosing Spondylitis (BSRBR-AS).

Smoking was associated with worse disease not only when comparing ever smokers with never smokers, but also when current smokers were compared to ex-smokers, and there was some evidence that the amount of smoking was important with heavier smokers having worse disease activity than light smokers.

Dr. Zhao, of Aintree University Hospital in Liverpool, England, added that, as in previous studies, these data show that “smoking is associated with worse disease activity at baseline and this needs to be accounted for in the next stage of longitudinal analysis.”

An association between smoking and worse disease activity in patients with axSpA has been reported previously, Dr. Zhao acknowledged, but this is not as clear cut as in rheumatoid arthritis where smoking is known to have a pathogenic effect. The small number of earlier studies looking at the possible effect of smoking in AS have been limited by their size and varying methodology, he added, and the studies’ researchers were not able to see if there was any potential dose effect of smoking.

The BSRBR-AS, which started recruiting patients with an Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) classification of axSpA in 2012, offers a unique opportunity to explore the association between smoking and axSpA further, he said. More than 2,500 patients are included in the register at present, none of whom should have not been treated with biologic agents at the time of recruitment.

The aim of the present analysis that looked at data on 932 patients was to quantify the effect of smoking status and quantity on several disease outcomes as measured by the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI), the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI), and the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI). Spinal pain was also assessed, by way of a visual analog scale (VAS), and quality of life was determined via the disease-specific Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life Instruments (ASQoL).

Most of the patients recruited were male (71%), and the mean age was 50 years. HLA-B27 data were available for 64% of the cohort, and 84% were positive.

Self-reported smoking status was recorded, with 19% saying they were current smokers, 37% saying they were ex-smokers, and 44% saying they had never smoked. If patients reported being ever smokers, the frequency with which they smoked (daily, weekly, monthly, once or twice, or never) was recorded, and if patients smoked daily, then the number of cigarettes smoked per day was obtained. Heavy smoking was defined as smoking 10 or more cigarettes per day and light smoking as fewer than 10 cigarettes per day. By this definition, around 37% of daily smokers were classed as heavy smokers.

In a comparison of ever smokers with never smokers, the mean BASDAI, BASFI, BASMI, spinal VAS, and ASQoL were significantly higher if patients had smoked at some point. All comparisons were adjusted for age, gender, body mass index, and HLA-B27 status.

The mean BASDAI score, for example, was more than 1 unit higher in a comparison of ever smokers with never smokers, with an adjusted regression coefficient of 1.04 and a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 0.72-1.36.

The adjusted regression coefficients for the other measures assessed were 1.34 (95% CI, 0.98-1.69) for BASFI, 0.61 (95% CI 0.36-0.87) for BASMI, 1.11 (95% CI, 0.74-1.49) for spinal VAS, and 2.71 (95% CI, 2.01–3.41) for ASQoL.

Similar findings were seen in the analysis comparing current with ex-smokers across all measures studied, and there was a trend for disease activity to be worse in heavier than in lighter smokers. The latter may not have reached significance because of the smaller number of patients (n = 172) involved in that part of the analysis. Nevertheless, these preliminary findings suggest that even being a light smoker can affect disease outcomes and so cutting down (i.e., to fewer than 10 cigarettes per day) may not be sufficient to reduce the effect that smoking has on disease activity.

“We should be actively encouraging our patients [with axSpA] to stop smoking,” Dr. Zhao concluded.

The BSRBR-AS is managed by a team of investigators based at the University of Aberdeen in collaboration with 83 centers throughout the United Kingdom. It is funded by the BSR, which in turn receives funding from the manufacturers of the biologic therapies included in this study (currently AbbVie, Pfizer, and UCB). Dr. Zhao and coauthors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

AT RHEUMATOLOGY 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Mean BASDAI, BASFI, BASMI, spinal VAS, and ASQoL were all significantly higher in ever vs. never smokers.

Data source: The British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register for Ankylosing Spondylitis (BSRBR-AS).

Disclosures: The BSRBR-AS is managed by a team of investigators based at the University of Aberdeen in collaboration with 83 centers throughout the United Kingdom. It is funded by the BSR, which in turn receives funding from the manufacturers of the biologic therapies included in this study (currently AbbVie, Pfizer, and UCB). Dr. Zhao and coauthors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Survey: Botulinum toxin achieves durable improvements in hyperhidrosis

SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA – Botulinum toxin therapy achieved substantial and durable improvements in symptoms in the majority of patients with axillary hyperhidrosis, in a retrospective study presented at the annual meeting of the Australasian College of Dermatologists.

Sydney dermatologist Robert Rosen, MMed, and his associates analyzed survey data from 200 patients with primary axillary hyperhidrosis who had been treated with 100 units of botulinum toxin at a hyperhidrosis referral center between 2006 and 2016. Patients were aged 12 years or older, and had had axillary hyperhidrosis for 6 months or longer that had not responded to treatment with 20% topical aluminum chloride.

Of these patients, 96% reported at least moderate satisfaction with the results of their treatment with botulinum toxin, with a mean satisfaction rating of 3.41 on a four-point scale that ranged from 1 (slight improvement) to 4 (complete abolition of signs and symptoms).

Durability of effect increased with successive treatments, according to 42% of the patients. There was no change in durability among 44% of the survey respondents, and 14% reported a shortened durability with successive treatments.

More than 80% of patients reported life-changing or substantial improvements in their quality of life after treatment with botulinum toxin, 14% reported some improvement, and 3% reported no improvement.

Only 6.5% of patients reported compensatory sweating elsewhere on the body, a rate similar to that of 5% reported in other studies, Dr. Rosen pointed out. This was in contrast to the 85%-90% rate of compensatory hyperhidrosis after surgical sympathectomy reported in other studies.

“That’s a big procedure and if you have compensatory hyperhidrosis elsewhere, you wouldn’t be terribly satisfied,” he said.

Dr. Rosen and his associates also looked at prognostic factors that might predict response to botulinum toxin. “People who did better with durability were those people who had sweating elsewhere, so they had more than one site of primary hyperhidrosis,” or they had failed other treatments, he said at the meeting.

In an interview, Dr. Rosen said that any treatment with a success rate greater than 90% was extraordinary. “It’s something that we as dermatologists can do where we have a lot of patient gratitude and satisfaction,” he noted. “Before we had this therapy, our other therapies were not great and people were quite desperate and had surgery, and the problem with surgery … is that they got compensatory hyperhidrosis elsewhere.”

Dr. Rosen, of Southern Suburbs Dermatology in Sydney, disclosed serving as a consultant for Allergan and Galderma unrelated to this research. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA – Botulinum toxin therapy achieved substantial and durable improvements in symptoms in the majority of patients with axillary hyperhidrosis, in a retrospective study presented at the annual meeting of the Australasian College of Dermatologists.

Sydney dermatologist Robert Rosen, MMed, and his associates analyzed survey data from 200 patients with primary axillary hyperhidrosis who had been treated with 100 units of botulinum toxin at a hyperhidrosis referral center between 2006 and 2016. Patients were aged 12 years or older, and had had axillary hyperhidrosis for 6 months or longer that had not responded to treatment with 20% topical aluminum chloride.

Of these patients, 96% reported at least moderate satisfaction with the results of their treatment with botulinum toxin, with a mean satisfaction rating of 3.41 on a four-point scale that ranged from 1 (slight improvement) to 4 (complete abolition of signs and symptoms).

Durability of effect increased with successive treatments, according to 42% of the patients. There was no change in durability among 44% of the survey respondents, and 14% reported a shortened durability with successive treatments.

More than 80% of patients reported life-changing or substantial improvements in their quality of life after treatment with botulinum toxin, 14% reported some improvement, and 3% reported no improvement.

Only 6.5% of patients reported compensatory sweating elsewhere on the body, a rate similar to that of 5% reported in other studies, Dr. Rosen pointed out. This was in contrast to the 85%-90% rate of compensatory hyperhidrosis after surgical sympathectomy reported in other studies.

“That’s a big procedure and if you have compensatory hyperhidrosis elsewhere, you wouldn’t be terribly satisfied,” he said.

Dr. Rosen and his associates also looked at prognostic factors that might predict response to botulinum toxin. “People who did better with durability were those people who had sweating elsewhere, so they had more than one site of primary hyperhidrosis,” or they had failed other treatments, he said at the meeting.

In an interview, Dr. Rosen said that any treatment with a success rate greater than 90% was extraordinary. “It’s something that we as dermatologists can do where we have a lot of patient gratitude and satisfaction,” he noted. “Before we had this therapy, our other therapies were not great and people were quite desperate and had surgery, and the problem with surgery … is that they got compensatory hyperhidrosis elsewhere.”

Dr. Rosen, of Southern Suburbs Dermatology in Sydney, disclosed serving as a consultant for Allergan and Galderma unrelated to this research. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA – Botulinum toxin therapy achieved substantial and durable improvements in symptoms in the majority of patients with axillary hyperhidrosis, in a retrospective study presented at the annual meeting of the Australasian College of Dermatologists.

Sydney dermatologist Robert Rosen, MMed, and his associates analyzed survey data from 200 patients with primary axillary hyperhidrosis who had been treated with 100 units of botulinum toxin at a hyperhidrosis referral center between 2006 and 2016. Patients were aged 12 years or older, and had had axillary hyperhidrosis for 6 months or longer that had not responded to treatment with 20% topical aluminum chloride.

Of these patients, 96% reported at least moderate satisfaction with the results of their treatment with botulinum toxin, with a mean satisfaction rating of 3.41 on a four-point scale that ranged from 1 (slight improvement) to 4 (complete abolition of signs and symptoms).

Durability of effect increased with successive treatments, according to 42% of the patients. There was no change in durability among 44% of the survey respondents, and 14% reported a shortened durability with successive treatments.

More than 80% of patients reported life-changing or substantial improvements in their quality of life after treatment with botulinum toxin, 14% reported some improvement, and 3% reported no improvement.

Only 6.5% of patients reported compensatory sweating elsewhere on the body, a rate similar to that of 5% reported in other studies, Dr. Rosen pointed out. This was in contrast to the 85%-90% rate of compensatory hyperhidrosis after surgical sympathectomy reported in other studies.

“That’s a big procedure and if you have compensatory hyperhidrosis elsewhere, you wouldn’t be terribly satisfied,” he said.

Dr. Rosen and his associates also looked at prognostic factors that might predict response to botulinum toxin. “People who did better with durability were those people who had sweating elsewhere, so they had more than one site of primary hyperhidrosis,” or they had failed other treatments, he said at the meeting.

In an interview, Dr. Rosen said that any treatment with a success rate greater than 90% was extraordinary. “It’s something that we as dermatologists can do where we have a lot of patient gratitude and satisfaction,” he noted. “Before we had this therapy, our other therapies were not great and people were quite desperate and had surgery, and the problem with surgery … is that they got compensatory hyperhidrosis elsewhere.”

Dr. Rosen, of Southern Suburbs Dermatology in Sydney, disclosed serving as a consultant for Allergan and Galderma unrelated to this research. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

AT ACDASM 2017

Key clinical point: Botulinum toxin therapy achieves substantial and durable improvements in axillary hyperhidrosis symptoms in a majority of patients with hyperhidrosis.

Major finding: Almost all patients (96%) reported moderate improvement or better with botulinum toxin treatment of primary axillary hyperhidrosis.

Data source: A retrospective review of 200 patients with primary axillary hyperhidrosis, treated over a decade.

Disclosures: Dr. Rosen declared consultancies with Allergan and Galderma unrelated to this research. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

Peripheral Exudative Hemorrhagic Chorioretinopathy in Patients With Nonexudative Age-Related Macular Degeneration

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a common condition that affects the elderly white population. About 6.5% of Americans have been diagnosed with AMD, and 0.8% have received an end-stage AMD diagnosis.1 Exudative AMD is typically more visually debilitating and comprises between 10% and 15% of all AMD cases, with conversion from dry to wet about 10%.1

A thorough examination of the posterior pole is of utmost importance in patients with dry AMD in order to ensure there is no conversion to the exudative form. However, it also is imperative to perform a peripheral evaluation in these patients due to the incidence of peripheral choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM) and its potential visual significance.

Case Report 1

An 80-year-old white male with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) without retinopathy, dry AMD, and epiretinal membranes (ERM) in both eyes presented to the eye clinic for a 6-month follow-up. On examination, he had visual acuity (VA) of 20/25 in both eyes and reported no ocular problems. The intraocular pressures were 17 mm Hg in the right eye and 20 mm Hg in the left eye. Slit-lamp examination of the anterior segment of both eyes was significant for 2+ nuclear sclerotic cataracts.

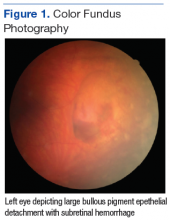

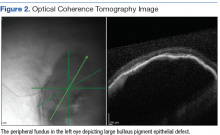

On dilated fundus exam, there were macular drusen and ERM in both eyes; peripherally in the right eye, there was cobblestone degeneration and pigmentary changes. Peripherally in the left eye, there was a large retinal pigment epithelial detachment (PED) with subretinal hemorrhage in the inferior temporal quadrant (Figure 1) along with cobblestone degeneration and pigmentary changes. Peripheral optical coherence tomography (OCT) in the left eye showed a large PED in the location of the hemorrhage (Figure 2).

Case Report 2

An 88-year-old white male presented to the eye clinic reporting blurred vision at distance and dry eyes. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for vascular and heart disease, treated with warfarin. The patient also had insulin controlled DM, with no prior history of retinopathy. His past ocular history included hard drusen in the macula, peripheral drusen, pavingstone degeneration, and a fibrotic scar temporally in the right eye.

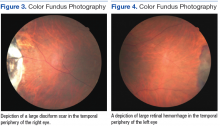

At his annual eye examination, the patient’s vision was correctable to 20/25 in both eyes. His anterior segment slit-lamp exam was remarkable for posterior chamber intraocular lenses, clear and centered in each eye. His posterior pole exam was remarkable for small hard drusen at the macula in both eyes. Peripherally in the right eye, there was a large disciform fibrotic scar temporally (Figure 3) as well as cobblestone degeneration and peripheral drusen. The left eye revealed a large disciform hemorrhage temporally (Figure 4) with cobblestone degeneration and peripheral drusen.

Both patients currently are being closely monitored for any encroachment of the peripheral lesions into the posterior poles.

Discussion

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR), also referred to in the literature as eccentric disciform CNVM, peripheral CNVM, and peripheral age-related degeneration, is a rare condition more prevalent in elderly white females.2-4 Mean age ranges from 70 to 82 years, with bilateral involvement ranging from 18% to 37%.2-4 The mid-periphery or periphery is the most common location for these lesions, more specifically, in the inferior temporal quadrant.2,3,5,6

Age-related macular degeneration is not pathognomonic for PEHCR. Mantel and colleagues reported that 68.9% of the patients in their study had AMD.3 Visual acuity ranges from 20/20 to light perception, dependent upon ocular comorbidities.2,3 As reported by Mantel and colleagues, patients with symptomatic PEHCR commonly experience visual loss, floaters, photopsias, metamorphopsia, and scotoma.3

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is a hemorrhagic or exudative process that can occur either as an isolated lesion or as multiple lesions that consist of a PED along with hemorrhage, subretinal fluid and/or fibrotic scarring.2-5 Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is not visually significant unless a vitreous hemorrhage is evident or the blood and/or fluid extends to the macular region.2,5

The exact etiology of peripheral CNVM remains unknown; however, ischemia, mechanical forces, and defects in Bruch’s membrane all have been speculated as causative factors.2,3,6 Others have hypothesized that PEHCR is a form of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy.3,7,8 A rupture in Bruch’s membrane with a vascular complex contributes to the pathophysiology and histology of this condition.3,6

Given the propensity for cardiovascular diseases, such as DM and hypertension, to lead to retinal ischemia, it is important to take a good case history.2,4,6 Additionally, anticoagulants have been shown to exacerbate bleeding.2,5 Due to PEHCR’s location in the periphery, as well as its appearance as an elevated dark mass, it is important to differentiate these lesions from a choroidal melanoma.2,6 Recognition of PEHCR can save the patient from unnecessary treatment with radiation or enucleation.

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is a self-limiting condition that generally requires close observation only. Long-term follow-up studies show resolution, regression, or stability of the peripheral lesions.4,5,8 If a hemorrhage is present, the blood will resolve and leave a disciform scar with pigmentary changes.2-4 In cases where vision is threatened, CNVM has been treated with photocoagulation, cryopexy, and more recently, intravitreal anti-VEGF injections.4,5,9,10 Given that VEGF is more prevalent in the presence of a choroidal neovascular complex, the goal of anti-VEGF therapy is to prevent the growth of and further damage from these abnormal blood vessels.5

Conclusion

The authors have described 2 cases of asymptomatic PEHCR in elderly white males who are both currently being observed closely. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is an uncommon finding; therefore, knowledge of this condition also may be rare. Through this article and these cases, the importance of routine peripheral fundus examination to detect PEHCR should be stressed. It also is important to include PEHCR as a differential diagnosis when evaluating a peripheral dark elevated lesion to distinguish from peripheral melanomas and avoid unnecessary treatments. If identified, these lesions often require close observation only, and a retina referral is warranted if there is macular involvement or a rapidly progressive lesion.5

1. Pron G. Optical coherence tomography monitoring strategies for A-VEGF–treated age-related macular degeneration: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2014;14(10):1–64.

2. Annesley WH Jr. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1980;78:321-364.

3. Mantel I, Uffer S, Zografos L. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: a clinical angiographic, and histologic study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(6):932-938.

4. Pinarci EY, Kilic I, Bayar SA, Sizmaz S, Akkoyun I, Yilmaz G. Clinical characteristics of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy and its response to bevacizumab therapy. Eye (Lond). 2013;27(1):111-112.

5. Seibel I, Hager A, Duncker T, et al. Anti-VEGF therapy in symptomatic peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR) involving the macula. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;254(4):653-659.

6. Collaer N, James C. Peripheral exudative and hemorrhagic chorio-retinopathy…the peripheral form of age-related macular degeneration? Report on 2 cases. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol. 2007;(305):23-26.

7. Goldman DR, Freund KB, McCannel CA, Sarraf D. Peripheral polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy as a cause of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: A report of 10 eyes. Retina. 2013;33(1):48-55.

8. Mashayekhi A, Shields CL, Shields JA. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: a variant of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy? J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2013;8(3):264-267.

9. Takayama K, Enoki T, Kojima T, Ishikawa S, Takeuchi M. Treatment of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy by intravitreal injections of ranibizumab. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:865-869.

10. Barkmeier AJ, Kadikoy H, Holz ER, Carvounis PE. Regression of serous macular detachment due to peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy following intravitreal bevacizumab. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2011;21(4):506-508.

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a common condition that affects the elderly white population. About 6.5% of Americans have been diagnosed with AMD, and 0.8% have received an end-stage AMD diagnosis.1 Exudative AMD is typically more visually debilitating and comprises between 10% and 15% of all AMD cases, with conversion from dry to wet about 10%.1

A thorough examination of the posterior pole is of utmost importance in patients with dry AMD in order to ensure there is no conversion to the exudative form. However, it also is imperative to perform a peripheral evaluation in these patients due to the incidence of peripheral choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM) and its potential visual significance.

Case Report 1

An 80-year-old white male with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) without retinopathy, dry AMD, and epiretinal membranes (ERM) in both eyes presented to the eye clinic for a 6-month follow-up. On examination, he had visual acuity (VA) of 20/25 in both eyes and reported no ocular problems. The intraocular pressures were 17 mm Hg in the right eye and 20 mm Hg in the left eye. Slit-lamp examination of the anterior segment of both eyes was significant for 2+ nuclear sclerotic cataracts.

On dilated fundus exam, there were macular drusen and ERM in both eyes; peripherally in the right eye, there was cobblestone degeneration and pigmentary changes. Peripherally in the left eye, there was a large retinal pigment epithelial detachment (PED) with subretinal hemorrhage in the inferior temporal quadrant (Figure 1) along with cobblestone degeneration and pigmentary changes. Peripheral optical coherence tomography (OCT) in the left eye showed a large PED in the location of the hemorrhage (Figure 2).

Case Report 2

An 88-year-old white male presented to the eye clinic reporting blurred vision at distance and dry eyes. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for vascular and heart disease, treated with warfarin. The patient also had insulin controlled DM, with no prior history of retinopathy. His past ocular history included hard drusen in the macula, peripheral drusen, pavingstone degeneration, and a fibrotic scar temporally in the right eye.

At his annual eye examination, the patient’s vision was correctable to 20/25 in both eyes. His anterior segment slit-lamp exam was remarkable for posterior chamber intraocular lenses, clear and centered in each eye. His posterior pole exam was remarkable for small hard drusen at the macula in both eyes. Peripherally in the right eye, there was a large disciform fibrotic scar temporally (Figure 3) as well as cobblestone degeneration and peripheral drusen. The left eye revealed a large disciform hemorrhage temporally (Figure 4) with cobblestone degeneration and peripheral drusen.

Both patients currently are being closely monitored for any encroachment of the peripheral lesions into the posterior poles.

Discussion

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR), also referred to in the literature as eccentric disciform CNVM, peripheral CNVM, and peripheral age-related degeneration, is a rare condition more prevalent in elderly white females.2-4 Mean age ranges from 70 to 82 years, with bilateral involvement ranging from 18% to 37%.2-4 The mid-periphery or periphery is the most common location for these lesions, more specifically, in the inferior temporal quadrant.2,3,5,6

Age-related macular degeneration is not pathognomonic for PEHCR. Mantel and colleagues reported that 68.9% of the patients in their study had AMD.3 Visual acuity ranges from 20/20 to light perception, dependent upon ocular comorbidities.2,3 As reported by Mantel and colleagues, patients with symptomatic PEHCR commonly experience visual loss, floaters, photopsias, metamorphopsia, and scotoma.3

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is a hemorrhagic or exudative process that can occur either as an isolated lesion or as multiple lesions that consist of a PED along with hemorrhage, subretinal fluid and/or fibrotic scarring.2-5 Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is not visually significant unless a vitreous hemorrhage is evident or the blood and/or fluid extends to the macular region.2,5

The exact etiology of peripheral CNVM remains unknown; however, ischemia, mechanical forces, and defects in Bruch’s membrane all have been speculated as causative factors.2,3,6 Others have hypothesized that PEHCR is a form of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy.3,7,8 A rupture in Bruch’s membrane with a vascular complex contributes to the pathophysiology and histology of this condition.3,6

Given the propensity for cardiovascular diseases, such as DM and hypertension, to lead to retinal ischemia, it is important to take a good case history.2,4,6 Additionally, anticoagulants have been shown to exacerbate bleeding.2,5 Due to PEHCR’s location in the periphery, as well as its appearance as an elevated dark mass, it is important to differentiate these lesions from a choroidal melanoma.2,6 Recognition of PEHCR can save the patient from unnecessary treatment with radiation or enucleation.

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is a self-limiting condition that generally requires close observation only. Long-term follow-up studies show resolution, regression, or stability of the peripheral lesions.4,5,8 If a hemorrhage is present, the blood will resolve and leave a disciform scar with pigmentary changes.2-4 In cases where vision is threatened, CNVM has been treated with photocoagulation, cryopexy, and more recently, intravitreal anti-VEGF injections.4,5,9,10 Given that VEGF is more prevalent in the presence of a choroidal neovascular complex, the goal of anti-VEGF therapy is to prevent the growth of and further damage from these abnormal blood vessels.5

Conclusion

The authors have described 2 cases of asymptomatic PEHCR in elderly white males who are both currently being observed closely. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is an uncommon finding; therefore, knowledge of this condition also may be rare. Through this article and these cases, the importance of routine peripheral fundus examination to detect PEHCR should be stressed. It also is important to include PEHCR as a differential diagnosis when evaluating a peripheral dark elevated lesion to distinguish from peripheral melanomas and avoid unnecessary treatments. If identified, these lesions often require close observation only, and a retina referral is warranted if there is macular involvement or a rapidly progressive lesion.5

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a common condition that affects the elderly white population. About 6.5% of Americans have been diagnosed with AMD, and 0.8% have received an end-stage AMD diagnosis.1 Exudative AMD is typically more visually debilitating and comprises between 10% and 15% of all AMD cases, with conversion from dry to wet about 10%.1

A thorough examination of the posterior pole is of utmost importance in patients with dry AMD in order to ensure there is no conversion to the exudative form. However, it also is imperative to perform a peripheral evaluation in these patients due to the incidence of peripheral choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM) and its potential visual significance.

Case Report 1

An 80-year-old white male with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) without retinopathy, dry AMD, and epiretinal membranes (ERM) in both eyes presented to the eye clinic for a 6-month follow-up. On examination, he had visual acuity (VA) of 20/25 in both eyes and reported no ocular problems. The intraocular pressures were 17 mm Hg in the right eye and 20 mm Hg in the left eye. Slit-lamp examination of the anterior segment of both eyes was significant for 2+ nuclear sclerotic cataracts.

On dilated fundus exam, there were macular drusen and ERM in both eyes; peripherally in the right eye, there was cobblestone degeneration and pigmentary changes. Peripherally in the left eye, there was a large retinal pigment epithelial detachment (PED) with subretinal hemorrhage in the inferior temporal quadrant (Figure 1) along with cobblestone degeneration and pigmentary changes. Peripheral optical coherence tomography (OCT) in the left eye showed a large PED in the location of the hemorrhage (Figure 2).

Case Report 2

An 88-year-old white male presented to the eye clinic reporting blurred vision at distance and dry eyes. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for vascular and heart disease, treated with warfarin. The patient also had insulin controlled DM, with no prior history of retinopathy. His past ocular history included hard drusen in the macula, peripheral drusen, pavingstone degeneration, and a fibrotic scar temporally in the right eye.

At his annual eye examination, the patient’s vision was correctable to 20/25 in both eyes. His anterior segment slit-lamp exam was remarkable for posterior chamber intraocular lenses, clear and centered in each eye. His posterior pole exam was remarkable for small hard drusen at the macula in both eyes. Peripherally in the right eye, there was a large disciform fibrotic scar temporally (Figure 3) as well as cobblestone degeneration and peripheral drusen. The left eye revealed a large disciform hemorrhage temporally (Figure 4) with cobblestone degeneration and peripheral drusen.

Both patients currently are being closely monitored for any encroachment of the peripheral lesions into the posterior poles.

Discussion

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR), also referred to in the literature as eccentric disciform CNVM, peripheral CNVM, and peripheral age-related degeneration, is a rare condition more prevalent in elderly white females.2-4 Mean age ranges from 70 to 82 years, with bilateral involvement ranging from 18% to 37%.2-4 The mid-periphery or periphery is the most common location for these lesions, more specifically, in the inferior temporal quadrant.2,3,5,6

Age-related macular degeneration is not pathognomonic for PEHCR. Mantel and colleagues reported that 68.9% of the patients in their study had AMD.3 Visual acuity ranges from 20/20 to light perception, dependent upon ocular comorbidities.2,3 As reported by Mantel and colleagues, patients with symptomatic PEHCR commonly experience visual loss, floaters, photopsias, metamorphopsia, and scotoma.3

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is a hemorrhagic or exudative process that can occur either as an isolated lesion or as multiple lesions that consist of a PED along with hemorrhage, subretinal fluid and/or fibrotic scarring.2-5 Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is not visually significant unless a vitreous hemorrhage is evident or the blood and/or fluid extends to the macular region.2,5

The exact etiology of peripheral CNVM remains unknown; however, ischemia, mechanical forces, and defects in Bruch’s membrane all have been speculated as causative factors.2,3,6 Others have hypothesized that PEHCR is a form of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy.3,7,8 A rupture in Bruch’s membrane with a vascular complex contributes to the pathophysiology and histology of this condition.3,6

Given the propensity for cardiovascular diseases, such as DM and hypertension, to lead to retinal ischemia, it is important to take a good case history.2,4,6 Additionally, anticoagulants have been shown to exacerbate bleeding.2,5 Due to PEHCR’s location in the periphery, as well as its appearance as an elevated dark mass, it is important to differentiate these lesions from a choroidal melanoma.2,6 Recognition of PEHCR can save the patient from unnecessary treatment with radiation or enucleation.

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is a self-limiting condition that generally requires close observation only. Long-term follow-up studies show resolution, regression, or stability of the peripheral lesions.4,5,8 If a hemorrhage is present, the blood will resolve and leave a disciform scar with pigmentary changes.2-4 In cases where vision is threatened, CNVM has been treated with photocoagulation, cryopexy, and more recently, intravitreal anti-VEGF injections.4,5,9,10 Given that VEGF is more prevalent in the presence of a choroidal neovascular complex, the goal of anti-VEGF therapy is to prevent the growth of and further damage from these abnormal blood vessels.5

Conclusion

The authors have described 2 cases of asymptomatic PEHCR in elderly white males who are both currently being observed closely. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is an uncommon finding; therefore, knowledge of this condition also may be rare. Through this article and these cases, the importance of routine peripheral fundus examination to detect PEHCR should be stressed. It also is important to include PEHCR as a differential diagnosis when evaluating a peripheral dark elevated lesion to distinguish from peripheral melanomas and avoid unnecessary treatments. If identified, these lesions often require close observation only, and a retina referral is warranted if there is macular involvement or a rapidly progressive lesion.5

1. Pron G. Optical coherence tomography monitoring strategies for A-VEGF–treated age-related macular degeneration: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2014;14(10):1–64.

2. Annesley WH Jr. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1980;78:321-364.

3. Mantel I, Uffer S, Zografos L. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: a clinical angiographic, and histologic study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(6):932-938.

4. Pinarci EY, Kilic I, Bayar SA, Sizmaz S, Akkoyun I, Yilmaz G. Clinical characteristics of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy and its response to bevacizumab therapy. Eye (Lond). 2013;27(1):111-112.

5. Seibel I, Hager A, Duncker T, et al. Anti-VEGF therapy in symptomatic peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR) involving the macula. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;254(4):653-659.

6. Collaer N, James C. Peripheral exudative and hemorrhagic chorio-retinopathy…the peripheral form of age-related macular degeneration? Report on 2 cases. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol. 2007;(305):23-26.

7. Goldman DR, Freund KB, McCannel CA, Sarraf D. Peripheral polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy as a cause of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: A report of 10 eyes. Retina. 2013;33(1):48-55.

8. Mashayekhi A, Shields CL, Shields JA. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: a variant of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy? J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2013;8(3):264-267.

9. Takayama K, Enoki T, Kojima T, Ishikawa S, Takeuchi M. Treatment of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy by intravitreal injections of ranibizumab. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:865-869.

10. Barkmeier AJ, Kadikoy H, Holz ER, Carvounis PE. Regression of serous macular detachment due to peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy following intravitreal bevacizumab. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2011;21(4):506-508.

1. Pron G. Optical coherence tomography monitoring strategies for A-VEGF–treated age-related macular degeneration: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2014;14(10):1–64.

2. Annesley WH Jr. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1980;78:321-364.

3. Mantel I, Uffer S, Zografos L. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: a clinical angiographic, and histologic study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(6):932-938.

4. Pinarci EY, Kilic I, Bayar SA, Sizmaz S, Akkoyun I, Yilmaz G. Clinical characteristics of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy and its response to bevacizumab therapy. Eye (Lond). 2013;27(1):111-112.

5. Seibel I, Hager A, Duncker T, et al. Anti-VEGF therapy in symptomatic peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR) involving the macula. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;254(4):653-659.

6. Collaer N, James C. Peripheral exudative and hemorrhagic chorio-retinopathy…the peripheral form of age-related macular degeneration? Report on 2 cases. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol. 2007;(305):23-26.

7. Goldman DR, Freund KB, McCannel CA, Sarraf D. Peripheral polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy as a cause of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: A report of 10 eyes. Retina. 2013;33(1):48-55.

8. Mashayekhi A, Shields CL, Shields JA. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: a variant of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy? J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2013;8(3):264-267.

9. Takayama K, Enoki T, Kojima T, Ishikawa S, Takeuchi M. Treatment of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy by intravitreal injections of ranibizumab. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:865-869.

10. Barkmeier AJ, Kadikoy H, Holz ER, Carvounis PE. Regression of serous macular detachment due to peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy following intravitreal bevacizumab. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2011;21(4):506-508.

Iron-transporting molecule could treat anemia, iron overload

Researchers say they have identified a small molecule that can transport iron when typical transport routes are mutated or absent.

The molecule, hinokitiol, was able to move iron into or out of cells by wrapping around iron atoms and shuttling them across the membrane layer.

Hinokitiol promoted gut iron absorption in rats and mice deficient in iron transport complexes, and it promoted hemoglobin production in zebrafish that otherwise couldn’t transport iron effectively.

The researchers believe these findings, published in Science, may lead to new treatments for disorders associated with iron metabolism, such as anemias and hemochromatosis.

“The long-term therapeutic implications of our work with hinokitiol points to potentially using this chemical to correct anemias caused by genetic deficiencies of iron transporters required for normal red cell formation,” said study author Barry Paw, MD, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

“At the same time, hinokitiol has the potential to correct iron-overload syndromes, such as hemochromatosis. More extensive clinical trials are necessary to work out the full potential of hinokitiol and to identify potential toxicities that we have not identified using preclinical models.”

Dr Paw and his colleagues discovered the potential of hinokitiol when screening for a molecule that could restore growth to yeast lacking an iron transporter complex. Hinokitiol is a natural product originally isolated from the Taiwanese hinoki tree.

The researchers found that hinokitiol could transport iron across the yeast cellular membrane in mutant yeasts lacking their major iron uptake transporters. Three hinokitiol molecules can wrap around an iron atom and transport it directly across the membrane where the missing protein should be.

The team also tested hinokitiol in mice, rats, and zebrafish that were missing iron-transport proteins.

Orally administered hinokitiol restored iron uptake in the guts of ferroportin-deficient mice and DMT1-deficient rats, and adding hinokitiol to a tank housing DMT1- and mitoferrin-deficient zebrafish prompted hemoglobin production in the fish.

The researchers also found that hinokitiol restored iron transport in human cells taken from the lining of the gut.

“We found that hinokitiol can restore iron transport within cells, out of cells, or both,” Dr Paw said. “It can also promote iron gut absorption and the creation of hemoglobin in some of our models. These findings suggest that small molecules like hinokitiol that can mimic the biological function of a missing protein may have potential for treating human diseases.” ![]()

Researchers say they have identified a small molecule that can transport iron when typical transport routes are mutated or absent.

The molecule, hinokitiol, was able to move iron into or out of cells by wrapping around iron atoms and shuttling them across the membrane layer.

Hinokitiol promoted gut iron absorption in rats and mice deficient in iron transport complexes, and it promoted hemoglobin production in zebrafish that otherwise couldn’t transport iron effectively.

The researchers believe these findings, published in Science, may lead to new treatments for disorders associated with iron metabolism, such as anemias and hemochromatosis.

“The long-term therapeutic implications of our work with hinokitiol points to potentially using this chemical to correct anemias caused by genetic deficiencies of iron transporters required for normal red cell formation,” said study author Barry Paw, MD, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

“At the same time, hinokitiol has the potential to correct iron-overload syndromes, such as hemochromatosis. More extensive clinical trials are necessary to work out the full potential of hinokitiol and to identify potential toxicities that we have not identified using preclinical models.”

Dr Paw and his colleagues discovered the potential of hinokitiol when screening for a molecule that could restore growth to yeast lacking an iron transporter complex. Hinokitiol is a natural product originally isolated from the Taiwanese hinoki tree.

The researchers found that hinokitiol could transport iron across the yeast cellular membrane in mutant yeasts lacking their major iron uptake transporters. Three hinokitiol molecules can wrap around an iron atom and transport it directly across the membrane where the missing protein should be.

The team also tested hinokitiol in mice, rats, and zebrafish that were missing iron-transport proteins.

Orally administered hinokitiol restored iron uptake in the guts of ferroportin-deficient mice and DMT1-deficient rats, and adding hinokitiol to a tank housing DMT1- and mitoferrin-deficient zebrafish prompted hemoglobin production in the fish.

The researchers also found that hinokitiol restored iron transport in human cells taken from the lining of the gut.

“We found that hinokitiol can restore iron transport within cells, out of cells, or both,” Dr Paw said. “It can also promote iron gut absorption and the creation of hemoglobin in some of our models. These findings suggest that small molecules like hinokitiol that can mimic the biological function of a missing protein may have potential for treating human diseases.” ![]()

Researchers say they have identified a small molecule that can transport iron when typical transport routes are mutated or absent.

The molecule, hinokitiol, was able to move iron into or out of cells by wrapping around iron atoms and shuttling them across the membrane layer.

Hinokitiol promoted gut iron absorption in rats and mice deficient in iron transport complexes, and it promoted hemoglobin production in zebrafish that otherwise couldn’t transport iron effectively.

The researchers believe these findings, published in Science, may lead to new treatments for disorders associated with iron metabolism, such as anemias and hemochromatosis.

“The long-term therapeutic implications of our work with hinokitiol points to potentially using this chemical to correct anemias caused by genetic deficiencies of iron transporters required for normal red cell formation,” said study author Barry Paw, MD, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

“At the same time, hinokitiol has the potential to correct iron-overload syndromes, such as hemochromatosis. More extensive clinical trials are necessary to work out the full potential of hinokitiol and to identify potential toxicities that we have not identified using preclinical models.”

Dr Paw and his colleagues discovered the potential of hinokitiol when screening for a molecule that could restore growth to yeast lacking an iron transporter complex. Hinokitiol is a natural product originally isolated from the Taiwanese hinoki tree.

The researchers found that hinokitiol could transport iron across the yeast cellular membrane in mutant yeasts lacking their major iron uptake transporters. Three hinokitiol molecules can wrap around an iron atom and transport it directly across the membrane where the missing protein should be.

The team also tested hinokitiol in mice, rats, and zebrafish that were missing iron-transport proteins.

Orally administered hinokitiol restored iron uptake in the guts of ferroportin-deficient mice and DMT1-deficient rats, and adding hinokitiol to a tank housing DMT1- and mitoferrin-deficient zebrafish prompted hemoglobin production in the fish.

The researchers also found that hinokitiol restored iron transport in human cells taken from the lining of the gut.

“We found that hinokitiol can restore iron transport within cells, out of cells, or both,” Dr Paw said. “It can also promote iron gut absorption and the creation of hemoglobin in some of our models. These findings suggest that small molecules like hinokitiol that can mimic the biological function of a missing protein may have potential for treating human diseases.” ![]()

Videos reduce need for anesthesia in kids undergoing radiotherapy

VIENNA, AUSTRIA—Children with cancer may not require general anesthesia prior to radiotherapy if they can watch videos during their treatment, according to research presented at the ESTRO 36 conference (abstract OC-0546).

Allowing children to watch videos during radiotherapy reduced but did not completely eliminate the use of anesthesia in this small study.

The use of videos proved less traumatic than anesthesia for children and their families, as well as making each treatment quicker and more cost-effective, according to study investigator Catia Aguas, of the Cliniques Universitaires Saint Luc in Brussels, Belgium.

“Being treated with radiotherapy means coming in for a treatment every weekday for 4 to 6 weeks,” Aguas noted. “The children need to remain motionless during treatment, and, on the whole, that means a general anesthesia. That, in turn, means they have to keep their stomach empty for 6 hours before the treatment.”

“We wanted to see if installing a projector and letting children watch a video of their choice would allow them to keep still enough that we would not need to give them anesthesia.”

The study included 12 children, ages 1.5 to 6 years, who were treated with radiotherapy using a Tomotherapy® treatment unit at the university hospital. Six children were treated before a video projector was installed in 2014, and 6 were treated after.

Before the video was available, general anesthesia was needed for 83.3% of children’s treatments. Once the projector was installed, anesthesia was needed in 33.3% of treatments.

“Radiotherapy can be very scary for children,” Aguas noted. “It’s a huge room full of machines and strange noises, and the worst part is that they’re in the room alone during their treatment. Before their radiotherapy treatment, they have already been through a series of tests and treatments, some of them painful, so when they arrive for radiotherapy, they don’t really feel very safe or confident.”

“Since we started using videos, children are a lot less anxious. Now they know that they’re going to watch a movie of their choice, they’re more relaxed, and, once the movie starts, it’s as though they travel to another world. Sponge Bob, Cars, and Barbie have been popular movie choices with our patients.”

The research also showed that treatments that used to take 1 hour or more now take around 15 to 20 minutes. This is partly because of the time saved by not having to prepare and administer anesthesia, but it is also because the children who know they are going to watch videos are more cooperative.

“Now, in our clinic, video has almost completely replaced anesthesia, resulting in reduced treatment times and reduction of stress for the young patients and their families,” Aguas said.

She also noted that the projector was inexpensive and simple to install.

“In radiotherapy, everything is usually very expensive, but, in this case, it was not,” Aguas said. “We bought a projector, and, with the help of college students, we created a support to fix the device to the patient couch. Using video is saving money and resources by reducing the need for anesthesia.”

Aguas and her colleagues continue to study children who have been treated since the projector was installed, and the team is extending the project to include adult patients who are claustrophobic or anxious. ![]()

VIENNA, AUSTRIA—Children with cancer may not require general anesthesia prior to radiotherapy if they can watch videos during their treatment, according to research presented at the ESTRO 36 conference (abstract OC-0546).

Allowing children to watch videos during radiotherapy reduced but did not completely eliminate the use of anesthesia in this small study.

The use of videos proved less traumatic than anesthesia for children and their families, as well as making each treatment quicker and more cost-effective, according to study investigator Catia Aguas, of the Cliniques Universitaires Saint Luc in Brussels, Belgium.

“Being treated with radiotherapy means coming in for a treatment every weekday for 4 to 6 weeks,” Aguas noted. “The children need to remain motionless during treatment, and, on the whole, that means a general anesthesia. That, in turn, means they have to keep their stomach empty for 6 hours before the treatment.”

“We wanted to see if installing a projector and letting children watch a video of their choice would allow them to keep still enough that we would not need to give them anesthesia.”

The study included 12 children, ages 1.5 to 6 years, who were treated with radiotherapy using a Tomotherapy® treatment unit at the university hospital. Six children were treated before a video projector was installed in 2014, and 6 were treated after.

Before the video was available, general anesthesia was needed for 83.3% of children’s treatments. Once the projector was installed, anesthesia was needed in 33.3% of treatments.

“Radiotherapy can be very scary for children,” Aguas noted. “It’s a huge room full of machines and strange noises, and the worst part is that they’re in the room alone during their treatment. Before their radiotherapy treatment, they have already been through a series of tests and treatments, some of them painful, so when they arrive for radiotherapy, they don’t really feel very safe or confident.”

“Since we started using videos, children are a lot less anxious. Now they know that they’re going to watch a movie of their choice, they’re more relaxed, and, once the movie starts, it’s as though they travel to another world. Sponge Bob, Cars, and Barbie have been popular movie choices with our patients.”

The research also showed that treatments that used to take 1 hour or more now take around 15 to 20 minutes. This is partly because of the time saved by not having to prepare and administer anesthesia, but it is also because the children who know they are going to watch videos are more cooperative.

“Now, in our clinic, video has almost completely replaced anesthesia, resulting in reduced treatment times and reduction of stress for the young patients and their families,” Aguas said.

She also noted that the projector was inexpensive and simple to install.

“In radiotherapy, everything is usually very expensive, but, in this case, it was not,” Aguas said. “We bought a projector, and, with the help of college students, we created a support to fix the device to the patient couch. Using video is saving money and resources by reducing the need for anesthesia.”

Aguas and her colleagues continue to study children who have been treated since the projector was installed, and the team is extending the project to include adult patients who are claustrophobic or anxious. ![]()