User login

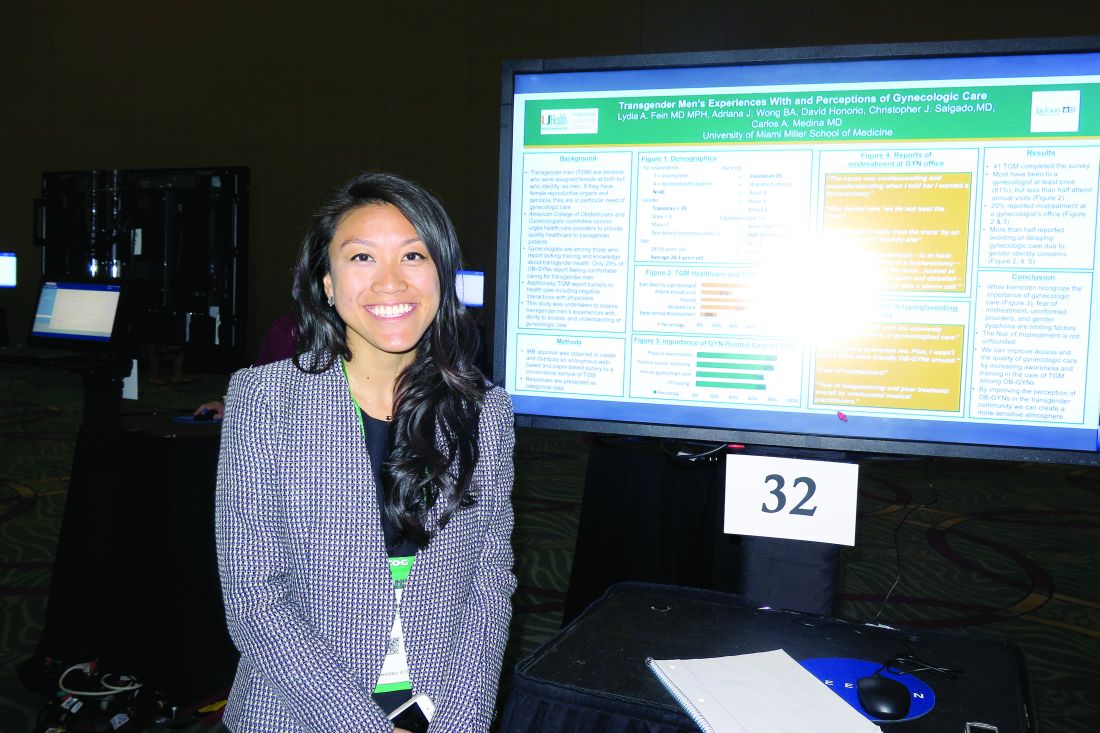

Survey highlights care gaps for transgender men

SAN DIEGO – Most transgender men have visited a gynecologist’s office at least once, but just 37% attend annual visits, results from a small survey showed.

“We’re seeing a large need and lack of access to gynecologic care,” Adriana J. Wong, the study author, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. “Some barriers that we’ve identified are fear of mistreatment, a perceived lack of informed providers, and gender dysphoria.”

In an effort to assess transgender men’s experiences with, ability to access, and understanding of gynecologic care, Ms. Wong and her associates distributed an anonymous Web-based and paper-based survey to a convenience sample of transgender men in the Miami area. The mean age of the 41 respondents was 28 years, 56% were white, 41% had a high school diploma, 27% had a college degree, and 17% had a graduate degree.

The majority of survey participants (78%) reported having been to a gynecologist, 37% attended annual visits, 78% had health insurance, 56% delayed care because of gender identity concerns, and 20% experienced mistreatment at a gynecologist’s office.

Respondents reported delaying or avoiding care because they “felt uncomfortable with the extremely gendered experience of [gynecologic] care,” “fear of mistreatment,” and “my dysphoria prevented me. Plus, I wasn’t sure if there were friendly ob.gyns. around.”

“One of the most distinctive things to me is that we had a pretty well-insured population in our sample, and they were mostly Caucasian,” said Ms. Wong, a second-year medical student at the University of Miami. “Even though almost 80% were insured, [fewer] than 40% were receiving annual visits. This is the population that would potentially have the best possibility of receiving care, but they’re not seeking it out.”

The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Most transgender men have visited a gynecologist’s office at least once, but just 37% attend annual visits, results from a small survey showed.

“We’re seeing a large need and lack of access to gynecologic care,” Adriana J. Wong, the study author, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. “Some barriers that we’ve identified are fear of mistreatment, a perceived lack of informed providers, and gender dysphoria.”

In an effort to assess transgender men’s experiences with, ability to access, and understanding of gynecologic care, Ms. Wong and her associates distributed an anonymous Web-based and paper-based survey to a convenience sample of transgender men in the Miami area. The mean age of the 41 respondents was 28 years, 56% were white, 41% had a high school diploma, 27% had a college degree, and 17% had a graduate degree.

The majority of survey participants (78%) reported having been to a gynecologist, 37% attended annual visits, 78% had health insurance, 56% delayed care because of gender identity concerns, and 20% experienced mistreatment at a gynecologist’s office.

Respondents reported delaying or avoiding care because they “felt uncomfortable with the extremely gendered experience of [gynecologic] care,” “fear of mistreatment,” and “my dysphoria prevented me. Plus, I wasn’t sure if there were friendly ob.gyns. around.”

“One of the most distinctive things to me is that we had a pretty well-insured population in our sample, and they were mostly Caucasian,” said Ms. Wong, a second-year medical student at the University of Miami. “Even though almost 80% were insured, [fewer] than 40% were receiving annual visits. This is the population that would potentially have the best possibility of receiving care, but they’re not seeking it out.”

The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Most transgender men have visited a gynecologist’s office at least once, but just 37% attend annual visits, results from a small survey showed.

“We’re seeing a large need and lack of access to gynecologic care,” Adriana J. Wong, the study author, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. “Some barriers that we’ve identified are fear of mistreatment, a perceived lack of informed providers, and gender dysphoria.”

In an effort to assess transgender men’s experiences with, ability to access, and understanding of gynecologic care, Ms. Wong and her associates distributed an anonymous Web-based and paper-based survey to a convenience sample of transgender men in the Miami area. The mean age of the 41 respondents was 28 years, 56% were white, 41% had a high school diploma, 27% had a college degree, and 17% had a graduate degree.

The majority of survey participants (78%) reported having been to a gynecologist, 37% attended annual visits, 78% had health insurance, 56% delayed care because of gender identity concerns, and 20% experienced mistreatment at a gynecologist’s office.

Respondents reported delaying or avoiding care because they “felt uncomfortable with the extremely gendered experience of [gynecologic] care,” “fear of mistreatment,” and “my dysphoria prevented me. Plus, I wasn’t sure if there were friendly ob.gyns. around.”

“One of the most distinctive things to me is that we had a pretty well-insured population in our sample, and they were mostly Caucasian,” said Ms. Wong, a second-year medical student at the University of Miami. “Even though almost 80% were insured, [fewer] than 40% were receiving annual visits. This is the population that would potentially have the best possibility of receiving care, but they’re not seeking it out.”

The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT ACOG 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Most transgender men (78%) have been to a gynecologist at least once, but just 37% attend annual visits.

Data source: Responses from a survey of 41 transgender men in the Miami area.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

It Pays to Get Screened for Colon Cancer

Although cancer death rates have been decreasing for the general population, they’ve been increasing for American Indians, according to the American Indian Cancer Foundation (AICAF). The AICAF cites a number of barriers to prevention and care, such as low awareness of risks, distrust of medical systems and research, health beliefs that may conflict with prevention practices, and low awareness of screening options.

The Northern Plains region has some of the highest rates of cancer diagnoses and death in the U.S. Colon cancer, for example, is 53% higher in Northern Plains American Indians, AICAF says. Although screening rates are improving, fewer than half of Northern Plains American Indians aged ≥ 50 years have had a colorectal cancer screening, according to the Association of American Indian Physicians.

The cancer mortality rates are the result of a “complex set of factors” that the AICAF is beginning to address with a comprehensive set of approaches. For instance, in addition to educating the public, AICAF, in partnership with the Minnesota Department of Health and Get Your Rear in Gear Colon Cancer Coalition is putting money where its mouth is, with the “Refer-a-Relative” program.

“We are all related,” the campaign says: “Help your community and end colon cancer!” Refer-a-Relative encourages Native Americans in the Minneapolis-St. Paul metropolitan area to get screened, and then to refer up to 5 relatives aged ≥ 50 years for screening. Patients receive a $20 gift card for completing screening, and $10 for each relative who completes screening. The relatives receive a $20 gift card and can refer more people.

The screening project is 1 branch of the AICAF’s interest in innovating clinical systems at IHS, Tribal, and Urban (ITU) clinics. Much of the work is based on the Improving Northern Plains American Indian Colorectal Cancer Screening (INPACS) project with ITU clinics. The AICAF invites interested ITU clinics to join the Clinical Cancer Screening Network. For more information, infographics, and other patient education materials, visit www.americanindiancancer.org.

Although cancer death rates have been decreasing for the general population, they’ve been increasing for American Indians, according to the American Indian Cancer Foundation (AICAF). The AICAF cites a number of barriers to prevention and care, such as low awareness of risks, distrust of medical systems and research, health beliefs that may conflict with prevention practices, and low awareness of screening options.

The Northern Plains region has some of the highest rates of cancer diagnoses and death in the U.S. Colon cancer, for example, is 53% higher in Northern Plains American Indians, AICAF says. Although screening rates are improving, fewer than half of Northern Plains American Indians aged ≥ 50 years have had a colorectal cancer screening, according to the Association of American Indian Physicians.

The cancer mortality rates are the result of a “complex set of factors” that the AICAF is beginning to address with a comprehensive set of approaches. For instance, in addition to educating the public, AICAF, in partnership with the Minnesota Department of Health and Get Your Rear in Gear Colon Cancer Coalition is putting money where its mouth is, with the “Refer-a-Relative” program.

“We are all related,” the campaign says: “Help your community and end colon cancer!” Refer-a-Relative encourages Native Americans in the Minneapolis-St. Paul metropolitan area to get screened, and then to refer up to 5 relatives aged ≥ 50 years for screening. Patients receive a $20 gift card for completing screening, and $10 for each relative who completes screening. The relatives receive a $20 gift card and can refer more people.

The screening project is 1 branch of the AICAF’s interest in innovating clinical systems at IHS, Tribal, and Urban (ITU) clinics. Much of the work is based on the Improving Northern Plains American Indian Colorectal Cancer Screening (INPACS) project with ITU clinics. The AICAF invites interested ITU clinics to join the Clinical Cancer Screening Network. For more information, infographics, and other patient education materials, visit www.americanindiancancer.org.

Although cancer death rates have been decreasing for the general population, they’ve been increasing for American Indians, according to the American Indian Cancer Foundation (AICAF). The AICAF cites a number of barriers to prevention and care, such as low awareness of risks, distrust of medical systems and research, health beliefs that may conflict with prevention practices, and low awareness of screening options.

The Northern Plains region has some of the highest rates of cancer diagnoses and death in the U.S. Colon cancer, for example, is 53% higher in Northern Plains American Indians, AICAF says. Although screening rates are improving, fewer than half of Northern Plains American Indians aged ≥ 50 years have had a colorectal cancer screening, according to the Association of American Indian Physicians.

The cancer mortality rates are the result of a “complex set of factors” that the AICAF is beginning to address with a comprehensive set of approaches. For instance, in addition to educating the public, AICAF, in partnership with the Minnesota Department of Health and Get Your Rear in Gear Colon Cancer Coalition is putting money where its mouth is, with the “Refer-a-Relative” program.

“We are all related,” the campaign says: “Help your community and end colon cancer!” Refer-a-Relative encourages Native Americans in the Minneapolis-St. Paul metropolitan area to get screened, and then to refer up to 5 relatives aged ≥ 50 years for screening. Patients receive a $20 gift card for completing screening, and $10 for each relative who completes screening. The relatives receive a $20 gift card and can refer more people.

The screening project is 1 branch of the AICAF’s interest in innovating clinical systems at IHS, Tribal, and Urban (ITU) clinics. Much of the work is based on the Improving Northern Plains American Indian Colorectal Cancer Screening (INPACS) project with ITU clinics. The AICAF invites interested ITU clinics to join the Clinical Cancer Screening Network. For more information, infographics, and other patient education materials, visit www.americanindiancancer.org.

HL survivors should be screened for CAD after chest irradiation

VIENNA, AUSTRIA—Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) survivors who received chest irradiation should be screened for coronary artery disease (CAD), according to researchers.

The team evaluated HL survivors who underwent mediastinal irradiation 20 years prior to study initiation.

These individuals were more likely to have CAD and to have more severe CAD than matched control subjects.

The researchers presented these findings at ICNC 2017, the International Conference on Nuclear Cardiology and Cardiac CT (abstract P118).

“Patients with Hodgkin lymphoma receive high-dose mediastinal irradiation at a young age as part of their treatment,” said Alexander van Rosendael, MD, of Leiden University Medical Centre in the Netherlands.

“There is an ongoing debate about whether to screen patients who get chest irradiation for coronary artery disease.”

Therefore, Dr van Rosendael and his colleagues assessed the extent, severity, and location of CAD in HL survivors who had received chest irradiation.

The study included 79 patients who had been free of HL for at least 10 years and had received mediastinal irradiation 20 years ago, plus 273 control subjects without HL or irradiation.

CAD was assessed using coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA). To assess differences in CAD between patients and controls, they were matched in a 1:3 fashion by age, gender, diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, family history of CAD, and smoking status.

Patients were 45 years old, on average, and the presence of cardiovascular risk factors was low overall.

Forty-two percent of patients had no atherosclerosis on coronary CTA, compared to 64% of controls (P<0.001).

Regarding the extent and severity of CAD, HL patients had significantly more multi-vessel CAD than controls. Ten percent of patients had 2-vessel disease, and 24% had 3-vessel disease, compared to 6% and 9% of controls, respectively (P=0.001).

The segment involvement score (which measures overall coronary plaque distribution) and the segment stenosis score (which measures overall coronary plaque extent and severity) were significantly higher for patients than for controls (P<0.001 and P=0.034, respectively).

Regarding the location of CAD, patients had significantly more coronary plaques in the left main (17% vs 6%, P=0.004), proximal left anterior descending (30% vs 16%, P=0.004), proximal right coronary artery (25% vs 10%, P<0.001), and proximal left circumflex (14% vs 6%, P=0.022), but not in non-proximal coronary segments.

Patients had about a 4-fold higher risk of proximal plaque and about 3-fold higher risk of proximal obstructive stenosis compared to controls (odds ratios, 4.1 and 2.9, respectively; P values, <0.001 and 0.025, respectively).

“Hodgkin patients who have chest irradiation have much more CAD than people of the same age who did not have irradiation,” Dr van Rosendael said.

“The CAD occurred at a young age—patients were 45 years old, on average—and was probably caused by the irradiation. The CTA was done about 20 years after chest irradiation, so there was time for CAD to develop.”

“What was remarkable was that irradiated patients had all the features of high-risk CAD, including high stenosis severity, proximal location, and extensive disease. We know that the proximal location of the disease is much riskier, and this may explain why Hodgkin patients have such poor cardiovascular outcomes when they get older.”

Dr van Rosendael explained that irradiation of the chest can cause inflammation of the coronary arteries, making patients more vulnerable to developing CAD. But it is not known why the CAD in irradiated patients tends to be proximally located.

He said the finding of more, and more severe, CAD in irradiated patients supports the argument for screening.

“When you see CAD in patients who received chest irradiation, it is high-risk CAD,” he said. “Such patients should be screened at regular intervals after irradiation so that CAD can be spotted early and early treatment can be initiated.”

“These patients are around 45 years old, and they are almost all asymptomatic. If you see a severe left main stenosis by screening with CTA (which occurred in 4%), then you can start statin therapy and perform revascularization, which may improve outcome. We know such treatment reduces the risk of events in non-irradiated patients, so it seems likely that it would benefit Hodgkin patients.” ![]()

VIENNA, AUSTRIA—Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) survivors who received chest irradiation should be screened for coronary artery disease (CAD), according to researchers.

The team evaluated HL survivors who underwent mediastinal irradiation 20 years prior to study initiation.

These individuals were more likely to have CAD and to have more severe CAD than matched control subjects.

The researchers presented these findings at ICNC 2017, the International Conference on Nuclear Cardiology and Cardiac CT (abstract P118).

“Patients with Hodgkin lymphoma receive high-dose mediastinal irradiation at a young age as part of their treatment,” said Alexander van Rosendael, MD, of Leiden University Medical Centre in the Netherlands.

“There is an ongoing debate about whether to screen patients who get chest irradiation for coronary artery disease.”

Therefore, Dr van Rosendael and his colleagues assessed the extent, severity, and location of CAD in HL survivors who had received chest irradiation.

The study included 79 patients who had been free of HL for at least 10 years and had received mediastinal irradiation 20 years ago, plus 273 control subjects without HL or irradiation.

CAD was assessed using coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA). To assess differences in CAD between patients and controls, they were matched in a 1:3 fashion by age, gender, diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, family history of CAD, and smoking status.

Patients were 45 years old, on average, and the presence of cardiovascular risk factors was low overall.

Forty-two percent of patients had no atherosclerosis on coronary CTA, compared to 64% of controls (P<0.001).

Regarding the extent and severity of CAD, HL patients had significantly more multi-vessel CAD than controls. Ten percent of patients had 2-vessel disease, and 24% had 3-vessel disease, compared to 6% and 9% of controls, respectively (P=0.001).

The segment involvement score (which measures overall coronary plaque distribution) and the segment stenosis score (which measures overall coronary plaque extent and severity) were significantly higher for patients than for controls (P<0.001 and P=0.034, respectively).

Regarding the location of CAD, patients had significantly more coronary plaques in the left main (17% vs 6%, P=0.004), proximal left anterior descending (30% vs 16%, P=0.004), proximal right coronary artery (25% vs 10%, P<0.001), and proximal left circumflex (14% vs 6%, P=0.022), but not in non-proximal coronary segments.

Patients had about a 4-fold higher risk of proximal plaque and about 3-fold higher risk of proximal obstructive stenosis compared to controls (odds ratios, 4.1 and 2.9, respectively; P values, <0.001 and 0.025, respectively).

“Hodgkin patients who have chest irradiation have much more CAD than people of the same age who did not have irradiation,” Dr van Rosendael said.

“The CAD occurred at a young age—patients were 45 years old, on average—and was probably caused by the irradiation. The CTA was done about 20 years after chest irradiation, so there was time for CAD to develop.”

“What was remarkable was that irradiated patients had all the features of high-risk CAD, including high stenosis severity, proximal location, and extensive disease. We know that the proximal location of the disease is much riskier, and this may explain why Hodgkin patients have such poor cardiovascular outcomes when they get older.”

Dr van Rosendael explained that irradiation of the chest can cause inflammation of the coronary arteries, making patients more vulnerable to developing CAD. But it is not known why the CAD in irradiated patients tends to be proximally located.

He said the finding of more, and more severe, CAD in irradiated patients supports the argument for screening.

“When you see CAD in patients who received chest irradiation, it is high-risk CAD,” he said. “Such patients should be screened at regular intervals after irradiation so that CAD can be spotted early and early treatment can be initiated.”

“These patients are around 45 years old, and they are almost all asymptomatic. If you see a severe left main stenosis by screening with CTA (which occurred in 4%), then you can start statin therapy and perform revascularization, which may improve outcome. We know such treatment reduces the risk of events in non-irradiated patients, so it seems likely that it would benefit Hodgkin patients.” ![]()

VIENNA, AUSTRIA—Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) survivors who received chest irradiation should be screened for coronary artery disease (CAD), according to researchers.

The team evaluated HL survivors who underwent mediastinal irradiation 20 years prior to study initiation.

These individuals were more likely to have CAD and to have more severe CAD than matched control subjects.

The researchers presented these findings at ICNC 2017, the International Conference on Nuclear Cardiology and Cardiac CT (abstract P118).

“Patients with Hodgkin lymphoma receive high-dose mediastinal irradiation at a young age as part of their treatment,” said Alexander van Rosendael, MD, of Leiden University Medical Centre in the Netherlands.

“There is an ongoing debate about whether to screen patients who get chest irradiation for coronary artery disease.”

Therefore, Dr van Rosendael and his colleagues assessed the extent, severity, and location of CAD in HL survivors who had received chest irradiation.

The study included 79 patients who had been free of HL for at least 10 years and had received mediastinal irradiation 20 years ago, plus 273 control subjects without HL or irradiation.

CAD was assessed using coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA). To assess differences in CAD between patients and controls, they were matched in a 1:3 fashion by age, gender, diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, family history of CAD, and smoking status.

Patients were 45 years old, on average, and the presence of cardiovascular risk factors was low overall.

Forty-two percent of patients had no atherosclerosis on coronary CTA, compared to 64% of controls (P<0.001).

Regarding the extent and severity of CAD, HL patients had significantly more multi-vessel CAD than controls. Ten percent of patients had 2-vessel disease, and 24% had 3-vessel disease, compared to 6% and 9% of controls, respectively (P=0.001).

The segment involvement score (which measures overall coronary plaque distribution) and the segment stenosis score (which measures overall coronary plaque extent and severity) were significantly higher for patients than for controls (P<0.001 and P=0.034, respectively).

Regarding the location of CAD, patients had significantly more coronary plaques in the left main (17% vs 6%, P=0.004), proximal left anterior descending (30% vs 16%, P=0.004), proximal right coronary artery (25% vs 10%, P<0.001), and proximal left circumflex (14% vs 6%, P=0.022), but not in non-proximal coronary segments.

Patients had about a 4-fold higher risk of proximal plaque and about 3-fold higher risk of proximal obstructive stenosis compared to controls (odds ratios, 4.1 and 2.9, respectively; P values, <0.001 and 0.025, respectively).

“Hodgkin patients who have chest irradiation have much more CAD than people of the same age who did not have irradiation,” Dr van Rosendael said.

“The CAD occurred at a young age—patients were 45 years old, on average—and was probably caused by the irradiation. The CTA was done about 20 years after chest irradiation, so there was time for CAD to develop.”

“What was remarkable was that irradiated patients had all the features of high-risk CAD, including high stenosis severity, proximal location, and extensive disease. We know that the proximal location of the disease is much riskier, and this may explain why Hodgkin patients have such poor cardiovascular outcomes when they get older.”

Dr van Rosendael explained that irradiation of the chest can cause inflammation of the coronary arteries, making patients more vulnerable to developing CAD. But it is not known why the CAD in irradiated patients tends to be proximally located.

He said the finding of more, and more severe, CAD in irradiated patients supports the argument for screening.

“When you see CAD in patients who received chest irradiation, it is high-risk CAD,” he said. “Such patients should be screened at regular intervals after irradiation so that CAD can be spotted early and early treatment can be initiated.”

“These patients are around 45 years old, and they are almost all asymptomatic. If you see a severe left main stenosis by screening with CTA (which occurred in 4%), then you can start statin therapy and perform revascularization, which may improve outcome. We know such treatment reduces the risk of events in non-irradiated patients, so it seems likely that it would benefit Hodgkin patients.” ![]()

Compound inhibits translation program to treat MM

A new compound has shown promise for treating multiple myeloma (MM) by inhibiting the oncogenic MYC-driven translation program supporting the disease, according to researchers.

The compound is CMLD01059, a derivative of natural products called rocaglates that are known to interfere with translation.

CMLD010509 induced apoptosis in MM cells in culture and exhibited anti-myeloma activity in 3 different mouse models.

In addition, the compound was well-tolerated by the mice and spared normal cells in culture.

Salomon Manier, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts, and his colleagues reported these results in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers found that CMLD01059 treatment significantly reduced the levels of 54 proteins in MM cell lines, including 5 known drivers of tumor progression—MYC, MDM2, CCND1, MAF, and MCL-1.

Further investigation confirmed that CMLD010509 inhibits the translation of oncoproteins that support the proliferation and survival of MM cells.

The researchers also found that CMLD010509 triggered a “strong” and “rapid” apoptotic response in MM cells (NCI-H929 and MM1S).

So the team tested the anti-myeloma activity of CMLD010509 in mouse models.

In one model (mice injected with MM1S cells), CMLD010509 “caused a marked reduction in tumor burden,” according to the researchers.

The median survival was 47 days in CMLD010509-treated mice, compared to 35 days in control mice (P<0.001).

The researchers also noted that 4 weeks of CMLD010509 treatment was well-tolerated in the mice, who maintained their weight and normal complete blood counts.

In another MM model (mice injected with KMS-11 cells), the mice received CMLD010509 or vehicle control twice a week for 4 weeks and were sacrificed at the end of treatment.

Immunohistochemistry studies conducted on bone marrow samples revealed a decrease in CD138+ plasma cells, depletion of MYC, and inhibition of proliferation in the CMLD010509-treated mice.

For the last model, the researchers injected transplantable mouse MM cells into C57BL/6 mice. The team noted that these cells are driven by plasma cell-specific MYC overexpression (Vk*Myc cells).

The mice received CMLD010509 or vehicle control twice a week starting 1 week after cell inoculation.

The researchers said CMLD010509 was well-tolerated, and they observed a “robust” decrease of M-spike in the treated mice that was associated with a significant improvement in survival.

The median survival was 39 days in the control mice, but it had not been reached by 90 days in the treated mice (P=0.0019).

The researchers said these results support targeting translation with rocaglates to treat MM. ![]()

A new compound has shown promise for treating multiple myeloma (MM) by inhibiting the oncogenic MYC-driven translation program supporting the disease, according to researchers.

The compound is CMLD01059, a derivative of natural products called rocaglates that are known to interfere with translation.

CMLD010509 induced apoptosis in MM cells in culture and exhibited anti-myeloma activity in 3 different mouse models.

In addition, the compound was well-tolerated by the mice and spared normal cells in culture.

Salomon Manier, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts, and his colleagues reported these results in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers found that CMLD01059 treatment significantly reduced the levels of 54 proteins in MM cell lines, including 5 known drivers of tumor progression—MYC, MDM2, CCND1, MAF, and MCL-1.

Further investigation confirmed that CMLD010509 inhibits the translation of oncoproteins that support the proliferation and survival of MM cells.

The researchers also found that CMLD010509 triggered a “strong” and “rapid” apoptotic response in MM cells (NCI-H929 and MM1S).

So the team tested the anti-myeloma activity of CMLD010509 in mouse models.

In one model (mice injected with MM1S cells), CMLD010509 “caused a marked reduction in tumor burden,” according to the researchers.

The median survival was 47 days in CMLD010509-treated mice, compared to 35 days in control mice (P<0.001).

The researchers also noted that 4 weeks of CMLD010509 treatment was well-tolerated in the mice, who maintained their weight and normal complete blood counts.

In another MM model (mice injected with KMS-11 cells), the mice received CMLD010509 or vehicle control twice a week for 4 weeks and were sacrificed at the end of treatment.

Immunohistochemistry studies conducted on bone marrow samples revealed a decrease in CD138+ plasma cells, depletion of MYC, and inhibition of proliferation in the CMLD010509-treated mice.

For the last model, the researchers injected transplantable mouse MM cells into C57BL/6 mice. The team noted that these cells are driven by plasma cell-specific MYC overexpression (Vk*Myc cells).

The mice received CMLD010509 or vehicle control twice a week starting 1 week after cell inoculation.

The researchers said CMLD010509 was well-tolerated, and they observed a “robust” decrease of M-spike in the treated mice that was associated with a significant improvement in survival.

The median survival was 39 days in the control mice, but it had not been reached by 90 days in the treated mice (P=0.0019).

The researchers said these results support targeting translation with rocaglates to treat MM. ![]()

A new compound has shown promise for treating multiple myeloma (MM) by inhibiting the oncogenic MYC-driven translation program supporting the disease, according to researchers.

The compound is CMLD01059, a derivative of natural products called rocaglates that are known to interfere with translation.

CMLD010509 induced apoptosis in MM cells in culture and exhibited anti-myeloma activity in 3 different mouse models.

In addition, the compound was well-tolerated by the mice and spared normal cells in culture.

Salomon Manier, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts, and his colleagues reported these results in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers found that CMLD01059 treatment significantly reduced the levels of 54 proteins in MM cell lines, including 5 known drivers of tumor progression—MYC, MDM2, CCND1, MAF, and MCL-1.

Further investigation confirmed that CMLD010509 inhibits the translation of oncoproteins that support the proliferation and survival of MM cells.

The researchers also found that CMLD010509 triggered a “strong” and “rapid” apoptotic response in MM cells (NCI-H929 and MM1S).

So the team tested the anti-myeloma activity of CMLD010509 in mouse models.

In one model (mice injected with MM1S cells), CMLD010509 “caused a marked reduction in tumor burden,” according to the researchers.

The median survival was 47 days in CMLD010509-treated mice, compared to 35 days in control mice (P<0.001).

The researchers also noted that 4 weeks of CMLD010509 treatment was well-tolerated in the mice, who maintained their weight and normal complete blood counts.

In another MM model (mice injected with KMS-11 cells), the mice received CMLD010509 or vehicle control twice a week for 4 weeks and were sacrificed at the end of treatment.

Immunohistochemistry studies conducted on bone marrow samples revealed a decrease in CD138+ plasma cells, depletion of MYC, and inhibition of proliferation in the CMLD010509-treated mice.

For the last model, the researchers injected transplantable mouse MM cells into C57BL/6 mice. The team noted that these cells are driven by plasma cell-specific MYC overexpression (Vk*Myc cells).

The mice received CMLD010509 or vehicle control twice a week starting 1 week after cell inoculation.

The researchers said CMLD010509 was well-tolerated, and they observed a “robust” decrease of M-spike in the treated mice that was associated with a significant improvement in survival.

The median survival was 39 days in the control mice, but it had not been reached by 90 days in the treated mice (P=0.0019).

The researchers said these results support targeting translation with rocaglates to treat MM. ![]()

EMA recommends drug receive orphan designation for PNH

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has recommended orphan drug designation for the complement C3 inhibitor APL-2 as a treatment for paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH).

APL-2 is a synthetic cyclic peptide conjugated to a polyethylene glycol polymer that binds specifically to C3 and C3b, blocking all 3 pathways of complement activation (classical, lectin, and alternative).

This comprehensive inhibition of complement-mediated pathology may have the potential to control symptoms and modify underlying disease in patients with PNH, according to Apellis Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing APL-2.

APL-2 has been evaluated in a pair of phase 1 studies of healthy volunteers. Results from these studies were presented at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 1251).

Now, Apellis is evaluating APL-2 in PNH patients in a pair of phase 1b trials.

In PADDOCK (NCT02588833), researchers are assessing the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and preliminary efficacy of multiple doses of APL-2 administered by daily subcutaneous injection in patients with PNH who have not received the standard of care in the past.

In PHAROAH (NCT02264639), researchers are assessing the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of single and multiple doses of APL-2 administered by subcutaneous injection as an add-on to the standard of care in patients with PNH.

About orphan designation

Orphan designation provides regulatory and financial incentives for companies to develop and market therapies that treat life-threatening or chronically debilitating conditions affecting no more than 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union, and where no satisfactory treatment is available.

Orphan designation provides a 10-year period of marketing exclusivity if the drug receives regulatory approval. The designation also provides incentives for companies seeking protocol assistance from the EMA during the product development phase and direct access to the centralized authorization procedure.

The EMA adopts an opinion on the granting of orphan drug designation, and that opinion is submitted to the European Commission for a final decision. The European Commission typically makes a decision within 30 days. ![]()

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has recommended orphan drug designation for the complement C3 inhibitor APL-2 as a treatment for paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH).

APL-2 is a synthetic cyclic peptide conjugated to a polyethylene glycol polymer that binds specifically to C3 and C3b, blocking all 3 pathways of complement activation (classical, lectin, and alternative).

This comprehensive inhibition of complement-mediated pathology may have the potential to control symptoms and modify underlying disease in patients with PNH, according to Apellis Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing APL-2.

APL-2 has been evaluated in a pair of phase 1 studies of healthy volunteers. Results from these studies were presented at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 1251).

Now, Apellis is evaluating APL-2 in PNH patients in a pair of phase 1b trials.

In PADDOCK (NCT02588833), researchers are assessing the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and preliminary efficacy of multiple doses of APL-2 administered by daily subcutaneous injection in patients with PNH who have not received the standard of care in the past.

In PHAROAH (NCT02264639), researchers are assessing the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of single and multiple doses of APL-2 administered by subcutaneous injection as an add-on to the standard of care in patients with PNH.

About orphan designation

Orphan designation provides regulatory and financial incentives for companies to develop and market therapies that treat life-threatening or chronically debilitating conditions affecting no more than 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union, and where no satisfactory treatment is available.

Orphan designation provides a 10-year period of marketing exclusivity if the drug receives regulatory approval. The designation also provides incentives for companies seeking protocol assistance from the EMA during the product development phase and direct access to the centralized authorization procedure.

The EMA adopts an opinion on the granting of orphan drug designation, and that opinion is submitted to the European Commission for a final decision. The European Commission typically makes a decision within 30 days. ![]()

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has recommended orphan drug designation for the complement C3 inhibitor APL-2 as a treatment for paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH).

APL-2 is a synthetic cyclic peptide conjugated to a polyethylene glycol polymer that binds specifically to C3 and C3b, blocking all 3 pathways of complement activation (classical, lectin, and alternative).

This comprehensive inhibition of complement-mediated pathology may have the potential to control symptoms and modify underlying disease in patients with PNH, according to Apellis Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing APL-2.

APL-2 has been evaluated in a pair of phase 1 studies of healthy volunteers. Results from these studies were presented at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 1251).

Now, Apellis is evaluating APL-2 in PNH patients in a pair of phase 1b trials.

In PADDOCK (NCT02588833), researchers are assessing the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and preliminary efficacy of multiple doses of APL-2 administered by daily subcutaneous injection in patients with PNH who have not received the standard of care in the past.

In PHAROAH (NCT02264639), researchers are assessing the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of single and multiple doses of APL-2 administered by subcutaneous injection as an add-on to the standard of care in patients with PNH.

About orphan designation

Orphan designation provides regulatory and financial incentives for companies to develop and market therapies that treat life-threatening or chronically debilitating conditions affecting no more than 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union, and where no satisfactory treatment is available.

Orphan designation provides a 10-year period of marketing exclusivity if the drug receives regulatory approval. The designation also provides incentives for companies seeking protocol assistance from the EMA during the product development phase and direct access to the centralized authorization procedure.

The EMA adopts an opinion on the granting of orphan drug designation, and that opinion is submitted to the European Commission for a final decision. The European Commission typically makes a decision within 30 days. ![]()

Dry spots on lower legs

The FP made the presumptive diagnosis of nummular eczema, but recognized that a fungal infection and psoriasis were part of the differential diagnosis. He performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, which was negative for hyphae and fungal elements. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation here: http://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/100603/dermatology/koh-preparation.) In order to explore whether this might be a case of guttate psoriasis, the FP asked about any preceding strep pharyngitis or other respiratory infections. The patient, however, had not had any preceding infections. The FP also checked her nails, scalp, and umbilicus for other signs of psoriasis, but found none. The FP was now confident in making a clinical diagnosis of nummular eczema (also known as nummular dermatitis).

Nummular eczema is a type of eczema characterized by circular or oval-shaped scaling plaques with well-defined borders. (“Nummus” is Latin for “coin.”) Nummular eczema produces multiple lesions that are most commonly found on the dorsa of the hands, arms, and legs.

Patients who have a history of atopic dermatitis are more likely to get nummular eczema even after they outgrow the atopic dermatitis. The 2 conditions involve problems with the barrier function of the skin, and emollients are helpful for the prevention and treatment of both.

In this case, the FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to be applied twice daily until the lesions resolved. At a one-month follow-up appointment, the patient indicated that her legs were now smooth and she was happy that she could shave them again. The FP told her that it would be a good idea to use emollients after bathing to keep the skin moist in order to prevent future episodes of nummular eczema.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Wah Y, Usatine R. Eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP made the presumptive diagnosis of nummular eczema, but recognized that a fungal infection and psoriasis were part of the differential diagnosis. He performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, which was negative for hyphae and fungal elements. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation here: http://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/100603/dermatology/koh-preparation.) In order to explore whether this might be a case of guttate psoriasis, the FP asked about any preceding strep pharyngitis or other respiratory infections. The patient, however, had not had any preceding infections. The FP also checked her nails, scalp, and umbilicus for other signs of psoriasis, but found none. The FP was now confident in making a clinical diagnosis of nummular eczema (also known as nummular dermatitis).

Nummular eczema is a type of eczema characterized by circular or oval-shaped scaling plaques with well-defined borders. (“Nummus” is Latin for “coin.”) Nummular eczema produces multiple lesions that are most commonly found on the dorsa of the hands, arms, and legs.

Patients who have a history of atopic dermatitis are more likely to get nummular eczema even after they outgrow the atopic dermatitis. The 2 conditions involve problems with the barrier function of the skin, and emollients are helpful for the prevention and treatment of both.

In this case, the FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to be applied twice daily until the lesions resolved. At a one-month follow-up appointment, the patient indicated that her legs were now smooth and she was happy that she could shave them again. The FP told her that it would be a good idea to use emollients after bathing to keep the skin moist in order to prevent future episodes of nummular eczema.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Wah Y, Usatine R. Eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP made the presumptive diagnosis of nummular eczema, but recognized that a fungal infection and psoriasis were part of the differential diagnosis. He performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, which was negative for hyphae and fungal elements. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation here: http://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/100603/dermatology/koh-preparation.) In order to explore whether this might be a case of guttate psoriasis, the FP asked about any preceding strep pharyngitis or other respiratory infections. The patient, however, had not had any preceding infections. The FP also checked her nails, scalp, and umbilicus for other signs of psoriasis, but found none. The FP was now confident in making a clinical diagnosis of nummular eczema (also known as nummular dermatitis).

Nummular eczema is a type of eczema characterized by circular or oval-shaped scaling plaques with well-defined borders. (“Nummus” is Latin for “coin.”) Nummular eczema produces multiple lesions that are most commonly found on the dorsa of the hands, arms, and legs.

Patients who have a history of atopic dermatitis are more likely to get nummular eczema even after they outgrow the atopic dermatitis. The 2 conditions involve problems with the barrier function of the skin, and emollients are helpful for the prevention and treatment of both.

In this case, the FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to be applied twice daily until the lesions resolved. At a one-month follow-up appointment, the patient indicated that her legs were now smooth and she was happy that she could shave them again. The FP told her that it would be a good idea to use emollients after bathing to keep the skin moist in order to prevent future episodes of nummular eczema.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Wah Y, Usatine R. Eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Boy’s Dark Side Comes Out

ANSWER

The correct answer is Becker nevus (BN; choice “c”).

Because the lesion was not congenital, a number of possibilities, including congenital melanocytic nevus (choice “a”), were ruled out. Another differential item that was eliminated was nevus spilus (choice “b”), a tan congenital nevus covered with darker, punctate macules that usually manifest on extremities. These have little, if any, malignant potential.

And while BN is not associated with malignancy, it is possible for it to co-exist with melanoma (choice “d”). Therefore, atypical BN cases may need to be followed or serially biopsied.

DISCUSSION

BN is unusual but not rare. Also referred to as Becker melanosis, the condition affects approximately 0.5% of the population. It primarily manifests in young men during early puberty, although women can develop BN.

Histologic signs of BN include epidermal thickening, elongation of rete ridges, and increased bundles of smooth muscle in the dermis.

Androgen causation is strongly indicated by the condition’s predominance in males and onset at puberty, as well as its associated hypertrichosis and increased density of androgen receptors in affected areas. Variations of the condition can involve the legs, arms, or face. It is possible for BN to manifest without additional hair growth. Hypoplasia of ipsilateral pectoral structures (or the ipsilateral breast in women) has also been reported.

Several types of lasers can be used to lighten the hyperpigmentation and remove hairs. This treatment modality yields variable results.

ANSWER

The correct answer is Becker nevus (BN; choice “c”).

Because the lesion was not congenital, a number of possibilities, including congenital melanocytic nevus (choice “a”), were ruled out. Another differential item that was eliminated was nevus spilus (choice “b”), a tan congenital nevus covered with darker, punctate macules that usually manifest on extremities. These have little, if any, malignant potential.

And while BN is not associated with malignancy, it is possible for it to co-exist with melanoma (choice “d”). Therefore, atypical BN cases may need to be followed or serially biopsied.

DISCUSSION

BN is unusual but not rare. Also referred to as Becker melanosis, the condition affects approximately 0.5% of the population. It primarily manifests in young men during early puberty, although women can develop BN.

Histologic signs of BN include epidermal thickening, elongation of rete ridges, and increased bundles of smooth muscle in the dermis.

Androgen causation is strongly indicated by the condition’s predominance in males and onset at puberty, as well as its associated hypertrichosis and increased density of androgen receptors in affected areas. Variations of the condition can involve the legs, arms, or face. It is possible for BN to manifest without additional hair growth. Hypoplasia of ipsilateral pectoral structures (or the ipsilateral breast in women) has also been reported.

Several types of lasers can be used to lighten the hyperpigmentation and remove hairs. This treatment modality yields variable results.

ANSWER

The correct answer is Becker nevus (BN; choice “c”).

Because the lesion was not congenital, a number of possibilities, including congenital melanocytic nevus (choice “a”), were ruled out. Another differential item that was eliminated was nevus spilus (choice “b”), a tan congenital nevus covered with darker, punctate macules that usually manifest on extremities. These have little, if any, malignant potential.

And while BN is not associated with malignancy, it is possible for it to co-exist with melanoma (choice “d”). Therefore, atypical BN cases may need to be followed or serially biopsied.

DISCUSSION

BN is unusual but not rare. Also referred to as Becker melanosis, the condition affects approximately 0.5% of the population. It primarily manifests in young men during early puberty, although women can develop BN.

Histologic signs of BN include epidermal thickening, elongation of rete ridges, and increased bundles of smooth muscle in the dermis.

Androgen causation is strongly indicated by the condition’s predominance in males and onset at puberty, as well as its associated hypertrichosis and increased density of androgen receptors in affected areas. Variations of the condition can involve the legs, arms, or face. It is possible for BN to manifest without additional hair growth. Hypoplasia of ipsilateral pectoral structures (or the ipsilateral breast in women) has also been reported.

Several types of lasers can be used to lighten the hyperpigmentation and remove hairs. This treatment modality yields variable results.

This 14-year-old boy’s family is alarmed by a darkening patch of skin on the right side of his chest and shoulder, which first appeared two years ago. Over the span of a few months, dark hairs grew on the hyperpigmented area.

The family’s primary care provider assured them that it was likely benign, but the lack of a specific diagnosis left them concerned. They requested referral to dermatology.

A large portion of the patient’s right anterior chest and shoulder is completely covered by uniformly hyperpigmented, hypertrichotic skin, which feels a bit thicker than the unaffected skin. The lesion’s borders are quite irregular and uneven; beyond them, no hairs can be seen. The problem is confined to the chest and shoulder; although the medial border extends to the sternal area, the lower edge stops short of the pectoral area.

The patient denies any symptoms and claims to be healthy in all other respects. There is no family history of similar problems.

Alpha blockers may facilitate the expulsion of larger ureteric stones

CLINICAL QUESTION: Are alpha blockers efficacious in patients with ureteric stones?

STUDY DESIGN: Systematic review & meta-analysis.

SETTING: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs); most conducted in Europe and Asia.

SYNOPSIS: Fifty-five unique RCTs (5,990 subjects) examining alpha blockers as the main treatment of ureteric stones versus placebo or control were included regardless of language and publication status.

Treatment with alpha blockers resulted in a 49% greater likelihood of stone passage (RR, 1.49; CI, 1.39-1.61) with a number needed to treat of four. A priori subgroup analysis revealed treatment was only beneficial in patients with larger stones (5mm or greater) independent of stone location or type of alpha blocker.

Secondary outcomes included reduced time to stone passage, fewer episodes of pain, decreased risk of surgical intervention, and lower risk of hospital admission with alpha blocker treatment without an increase in serious adverse events.

The meta-analysis was limited by the overall lack of methodological rigor of and clinical heterogeneity between the pooled studies.

BOTTOM LINE: Based on available evidence, it is reasonable to utilize an alpha blocker as medical expulsive therapy in patients with larger ureteric stones.

CITATIONS: Hollingsworth JM, Canales BK, Rogers MA, et al. Alpha blockers for treatment of ureteric stones: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2016;355:i6112.

Dr. Ecker is the assistant director of education, Division of Hospital Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora.

CLINICAL QUESTION: Are alpha blockers efficacious in patients with ureteric stones?

STUDY DESIGN: Systematic review & meta-analysis.

SETTING: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs); most conducted in Europe and Asia.

SYNOPSIS: Fifty-five unique RCTs (5,990 subjects) examining alpha blockers as the main treatment of ureteric stones versus placebo or control were included regardless of language and publication status.

Treatment with alpha blockers resulted in a 49% greater likelihood of stone passage (RR, 1.49; CI, 1.39-1.61) with a number needed to treat of four. A priori subgroup analysis revealed treatment was only beneficial in patients with larger stones (5mm or greater) independent of stone location or type of alpha blocker.

Secondary outcomes included reduced time to stone passage, fewer episodes of pain, decreased risk of surgical intervention, and lower risk of hospital admission with alpha blocker treatment without an increase in serious adverse events.

The meta-analysis was limited by the overall lack of methodological rigor of and clinical heterogeneity between the pooled studies.

BOTTOM LINE: Based on available evidence, it is reasonable to utilize an alpha blocker as medical expulsive therapy in patients with larger ureteric stones.

CITATIONS: Hollingsworth JM, Canales BK, Rogers MA, et al. Alpha blockers for treatment of ureteric stones: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2016;355:i6112.

Dr. Ecker is the assistant director of education, Division of Hospital Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora.

CLINICAL QUESTION: Are alpha blockers efficacious in patients with ureteric stones?

STUDY DESIGN: Systematic review & meta-analysis.

SETTING: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs); most conducted in Europe and Asia.

SYNOPSIS: Fifty-five unique RCTs (5,990 subjects) examining alpha blockers as the main treatment of ureteric stones versus placebo or control were included regardless of language and publication status.

Treatment with alpha blockers resulted in a 49% greater likelihood of stone passage (RR, 1.49; CI, 1.39-1.61) with a number needed to treat of four. A priori subgroup analysis revealed treatment was only beneficial in patients with larger stones (5mm or greater) independent of stone location or type of alpha blocker.

Secondary outcomes included reduced time to stone passage, fewer episodes of pain, decreased risk of surgical intervention, and lower risk of hospital admission with alpha blocker treatment without an increase in serious adverse events.

The meta-analysis was limited by the overall lack of methodological rigor of and clinical heterogeneity between the pooled studies.

BOTTOM LINE: Based on available evidence, it is reasonable to utilize an alpha blocker as medical expulsive therapy in patients with larger ureteric stones.

CITATIONS: Hollingsworth JM, Canales BK, Rogers MA, et al. Alpha blockers for treatment of ureteric stones: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2016;355:i6112.

Dr. Ecker is the assistant director of education, Division of Hospital Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora.

Interventions, especially those that are organization-directed, reduce burnout in physicians

CLINICAL QUESTION: How efficacious are interventions to reduce burnout in physicians?

BACKGROUND: Burnout is characterized by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a diminished sense of personal accomplishment. It is driven by workplace stressors and affects nearly half of physicians practicing in the U.S.

SETTING: Randomized controlled trials and controlled before-after studies in primary, secondary, or intensive care settings; most conducted in North America and Europe.

SYNOPSIS: Twenty independent comparisons from 19 studies (1,550 physicians of any specialty including trainees) were included. All reported burnout outcomes after either physician- or organization-directed interventions designed to relieve stress and/or improve physician performance. Most physician-directed interventions utilized mindfulness-based stress reduction techniques or other educational interventions. Most organizational-directed interventions introduced reductions in workload or schedule changes.

Interventions were associated with small, significant reductions in burnout (standardized mean difference, –0.29; CI –0.42 to –0.16). A pre-specified subgroup analysis revealed organization-directed interventions had significantly improved effects, compared with physician-directed ones.

The generalizability of this meta-analysis is limited as the included studies significantly differed in their methodologies.

BOTTOM LINE: Burnout intervention programs for physicians are associated with small benefits, and the increased efficacy of organization-directed interventions suggest burnout is a problem of the health care system, rather than of individuals.

CITATIONS: Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):195-205.

Dr. Ecker is the assistant director of education, Division of Hospital Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora.

CLINICAL QUESTION: How efficacious are interventions to reduce burnout in physicians?

BACKGROUND: Burnout is characterized by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a diminished sense of personal accomplishment. It is driven by workplace stressors and affects nearly half of physicians practicing in the U.S.

SETTING: Randomized controlled trials and controlled before-after studies in primary, secondary, or intensive care settings; most conducted in North America and Europe.

SYNOPSIS: Twenty independent comparisons from 19 studies (1,550 physicians of any specialty including trainees) were included. All reported burnout outcomes after either physician- or organization-directed interventions designed to relieve stress and/or improve physician performance. Most physician-directed interventions utilized mindfulness-based stress reduction techniques or other educational interventions. Most organizational-directed interventions introduced reductions in workload or schedule changes.

Interventions were associated with small, significant reductions in burnout (standardized mean difference, –0.29; CI –0.42 to –0.16). A pre-specified subgroup analysis revealed organization-directed interventions had significantly improved effects, compared with physician-directed ones.

The generalizability of this meta-analysis is limited as the included studies significantly differed in their methodologies.

BOTTOM LINE: Burnout intervention programs for physicians are associated with small benefits, and the increased efficacy of organization-directed interventions suggest burnout is a problem of the health care system, rather than of individuals.

CITATIONS: Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):195-205.

Dr. Ecker is the assistant director of education, Division of Hospital Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora.

CLINICAL QUESTION: How efficacious are interventions to reduce burnout in physicians?

BACKGROUND: Burnout is characterized by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a diminished sense of personal accomplishment. It is driven by workplace stressors and affects nearly half of physicians practicing in the U.S.

SETTING: Randomized controlled trials and controlled before-after studies in primary, secondary, or intensive care settings; most conducted in North America and Europe.

SYNOPSIS: Twenty independent comparisons from 19 studies (1,550 physicians of any specialty including trainees) were included. All reported burnout outcomes after either physician- or organization-directed interventions designed to relieve stress and/or improve physician performance. Most physician-directed interventions utilized mindfulness-based stress reduction techniques or other educational interventions. Most organizational-directed interventions introduced reductions in workload or schedule changes.

Interventions were associated with small, significant reductions in burnout (standardized mean difference, –0.29; CI –0.42 to –0.16). A pre-specified subgroup analysis revealed organization-directed interventions had significantly improved effects, compared with physician-directed ones.

The generalizability of this meta-analysis is limited as the included studies significantly differed in their methodologies.

BOTTOM LINE: Burnout intervention programs for physicians are associated with small benefits, and the increased efficacy of organization-directed interventions suggest burnout is a problem of the health care system, rather than of individuals.

CITATIONS: Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):195-205.

Dr. Ecker is the assistant director of education, Division of Hospital Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora.

Deep infiltrating endometriosis lesions harbor cancer-driver mutations

Deep infiltrating endometriosis lesions were found to harbor several genetic mutations, including well-known cancer-driver mutations in the ARID1A, PIK3CA, KRAS, and PPP2R1A genes, investigators reported in the May 11 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

This finding was possible only through the use of a combination of next-generation sequencing tools, together with highly sensitive digital genomic assays. A finding of cancer-related mutations in noncancerous lesions – and, “in particular, in nonovarian deep infiltrating lesions that rarely (if ever) transform into cancer” – was very “surprising” and raises new questions about the pathobiology of endometriosis, said Michael S. Anglesio, PhD, of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and his associates.

All three subtypes of endometriosis exhibit “benign clinical behavior and normal-appearing histologic features,” and are considered to be nonmalignant inflammatory lesions, Dr. Anglesio and his associates said. However, they also “recapitulate some features of malignant neoplasms, including local invasion and resistance to apoptosis,” the investigators noted.

To further explore whether deep infiltrating endometriosis lesions harbor somatic mutations, they performed a series of genetic analyses on samples obtained from three independent cohorts of 27 affected patients in New York, Japan, and Vancouver. Whole-exome sequencing of lesions and adjacent normal tissue from 24 women revealed 80 different somatic mutations in 19 (79%) of the lesions.

The number of mutations per lesion varied widely, from 0 to 17, with a mean of 3.3 mutations per lesion. Five of these lesions harbored mutations in the cancer-driver genes ARID1A, PIK3CA, KRAS, or PPP2R1A.

In targeted-sequencing analyses of samples from three more patients, more activating mutations in the KRAS gene were found in two (66%). One woman had two different activating KRAS mutations, and the other had the same KRAS mutation in three separate lesions.

A further analysis of samples from an additional 12 patients showed KRAS mutations in 3 (25%) of them.

The data indicate that these mutations were very unlikely to have arisen by chance alone. In addition, “because cancer-driver mutations were present only in the epithelium but not the stroma of the same endometriosis lesion, we can assume that the observed mutations provide some key selective advantage to endometriotic epithelial cells,” Dr. Anglesio and his associates said (N Engl J Med. 2017 May 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614814).

Their findings are consistent with those of recent studies of other organ systems, which reported cancer-driver mutations in benign lesions and in normal tissues from skin, neuronal, and ovarian samples, they added.

“Our findings challenge the current understanding of this invasive subtype of endometriosis and open the discussion on whether deep infiltrating endometriosis can be considered as a benign neoplasm,” the investigators wrote.

This study was sponsored by 27 nonindustry sources, including the Johns Hopkins University, the Virginia and D.K. Ludwig Fund for Cancer Research, the Ephraim and Wilma Shaw Roseman Foundation, the Endometriosis Foundation of America, and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Anglesio reported having no relevant financial disclosures; some of his associates reported ties to several industry sources.

The variable patterns of somatic mutations discovered by Anglesio et al. are “intriguing” and raise many questions.

Do specific mutations in deep infiltrating endometriosis lesions contribute to the severity and progression of the disorder? Are such mutations to be found in other types of lesions? In endometrial precursor cells? Do specific mutations account for different presentations in different patients?

Exploring these questions will not be straightforward because of the difficulties in obtaining sufficient endometriotic tissue for genetic studies. Not only is it hard to get samples from peritoneal lesions, but the mutations occur in only one cell type – epithelium – which is even harder to isolate from mixed tissue samples.

Grant W. Montgomery, PhD, is at the Institute for Molecular Bioscience at the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, and reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Linda C. Giudice, MD, PhD, is in the department of ob.gyn. and reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Francisco, and reported ties to AbbVie and Bayer. Dr. Montgomery and Dr. Giudice made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Anglesio’s report (N Engl J Med. 2017 May 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1701700).

The variable patterns of somatic mutations discovered by Anglesio et al. are “intriguing” and raise many questions.

Do specific mutations in deep infiltrating endometriosis lesions contribute to the severity and progression of the disorder? Are such mutations to be found in other types of lesions? In endometrial precursor cells? Do specific mutations account for different presentations in different patients?

Exploring these questions will not be straightforward because of the difficulties in obtaining sufficient endometriotic tissue for genetic studies. Not only is it hard to get samples from peritoneal lesions, but the mutations occur in only one cell type – epithelium – which is even harder to isolate from mixed tissue samples.

Grant W. Montgomery, PhD, is at the Institute for Molecular Bioscience at the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, and reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Linda C. Giudice, MD, PhD, is in the department of ob.gyn. and reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Francisco, and reported ties to AbbVie and Bayer. Dr. Montgomery and Dr. Giudice made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Anglesio’s report (N Engl J Med. 2017 May 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1701700).

The variable patterns of somatic mutations discovered by Anglesio et al. are “intriguing” and raise many questions.

Do specific mutations in deep infiltrating endometriosis lesions contribute to the severity and progression of the disorder? Are such mutations to be found in other types of lesions? In endometrial precursor cells? Do specific mutations account for different presentations in different patients?

Exploring these questions will not be straightforward because of the difficulties in obtaining sufficient endometriotic tissue for genetic studies. Not only is it hard to get samples from peritoneal lesions, but the mutations occur in only one cell type – epithelium – which is even harder to isolate from mixed tissue samples.

Grant W. Montgomery, PhD, is at the Institute for Molecular Bioscience at the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, and reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Linda C. Giudice, MD, PhD, is in the department of ob.gyn. and reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Francisco, and reported ties to AbbVie and Bayer. Dr. Montgomery and Dr. Giudice made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Anglesio’s report (N Engl J Med. 2017 May 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1701700).

Deep infiltrating endometriosis lesions were found to harbor several genetic mutations, including well-known cancer-driver mutations in the ARID1A, PIK3CA, KRAS, and PPP2R1A genes, investigators reported in the May 11 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

This finding was possible only through the use of a combination of next-generation sequencing tools, together with highly sensitive digital genomic assays. A finding of cancer-related mutations in noncancerous lesions – and, “in particular, in nonovarian deep infiltrating lesions that rarely (if ever) transform into cancer” – was very “surprising” and raises new questions about the pathobiology of endometriosis, said Michael S. Anglesio, PhD, of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and his associates.

All three subtypes of endometriosis exhibit “benign clinical behavior and normal-appearing histologic features,” and are considered to be nonmalignant inflammatory lesions, Dr. Anglesio and his associates said. However, they also “recapitulate some features of malignant neoplasms, including local invasion and resistance to apoptosis,” the investigators noted.

To further explore whether deep infiltrating endometriosis lesions harbor somatic mutations, they performed a series of genetic analyses on samples obtained from three independent cohorts of 27 affected patients in New York, Japan, and Vancouver. Whole-exome sequencing of lesions and adjacent normal tissue from 24 women revealed 80 different somatic mutations in 19 (79%) of the lesions.

The number of mutations per lesion varied widely, from 0 to 17, with a mean of 3.3 mutations per lesion. Five of these lesions harbored mutations in the cancer-driver genes ARID1A, PIK3CA, KRAS, or PPP2R1A.

In targeted-sequencing analyses of samples from three more patients, more activating mutations in the KRAS gene were found in two (66%). One woman had two different activating KRAS mutations, and the other had the same KRAS mutation in three separate lesions.

A further analysis of samples from an additional 12 patients showed KRAS mutations in 3 (25%) of them.

The data indicate that these mutations were very unlikely to have arisen by chance alone. In addition, “because cancer-driver mutations were present only in the epithelium but not the stroma of the same endometriosis lesion, we can assume that the observed mutations provide some key selective advantage to endometriotic epithelial cells,” Dr. Anglesio and his associates said (N Engl J Med. 2017 May 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614814).

Their findings are consistent with those of recent studies of other organ systems, which reported cancer-driver mutations in benign lesions and in normal tissues from skin, neuronal, and ovarian samples, they added.

“Our findings challenge the current understanding of this invasive subtype of endometriosis and open the discussion on whether deep infiltrating endometriosis can be considered as a benign neoplasm,” the investigators wrote.

This study was sponsored by 27 nonindustry sources, including the Johns Hopkins University, the Virginia and D.K. Ludwig Fund for Cancer Research, the Ephraim and Wilma Shaw Roseman Foundation, the Endometriosis Foundation of America, and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Anglesio reported having no relevant financial disclosures; some of his associates reported ties to several industry sources.

Deep infiltrating endometriosis lesions were found to harbor several genetic mutations, including well-known cancer-driver mutations in the ARID1A, PIK3CA, KRAS, and PPP2R1A genes, investigators reported in the May 11 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

This finding was possible only through the use of a combination of next-generation sequencing tools, together with highly sensitive digital genomic assays. A finding of cancer-related mutations in noncancerous lesions – and, “in particular, in nonovarian deep infiltrating lesions that rarely (if ever) transform into cancer” – was very “surprising” and raises new questions about the pathobiology of endometriosis, said Michael S. Anglesio, PhD, of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and his associates.

All three subtypes of endometriosis exhibit “benign clinical behavior and normal-appearing histologic features,” and are considered to be nonmalignant inflammatory lesions, Dr. Anglesio and his associates said. However, they also “recapitulate some features of malignant neoplasms, including local invasion and resistance to apoptosis,” the investigators noted.

To further explore whether deep infiltrating endometriosis lesions harbor somatic mutations, they performed a series of genetic analyses on samples obtained from three independent cohorts of 27 affected patients in New York, Japan, and Vancouver. Whole-exome sequencing of lesions and adjacent normal tissue from 24 women revealed 80 different somatic mutations in 19 (79%) of the lesions.

The number of mutations per lesion varied widely, from 0 to 17, with a mean of 3.3 mutations per lesion. Five of these lesions harbored mutations in the cancer-driver genes ARID1A, PIK3CA, KRAS, or PPP2R1A.

In targeted-sequencing analyses of samples from three more patients, more activating mutations in the KRAS gene were found in two (66%). One woman had two different activating KRAS mutations, and the other had the same KRAS mutation in three separate lesions.

A further analysis of samples from an additional 12 patients showed KRAS mutations in 3 (25%) of them.

The data indicate that these mutations were very unlikely to have arisen by chance alone. In addition, “because cancer-driver mutations were present only in the epithelium but not the stroma of the same endometriosis lesion, we can assume that the observed mutations provide some key selective advantage to endometriotic epithelial cells,” Dr. Anglesio and his associates said (N Engl J Med. 2017 May 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614814).

Their findings are consistent with those of recent studies of other organ systems, which reported cancer-driver mutations in benign lesions and in normal tissues from skin, neuronal, and ovarian samples, they added.

“Our findings challenge the current understanding of this invasive subtype of endometriosis and open the discussion on whether deep infiltrating endometriosis can be considered as a benign neoplasm,” the investigators wrote.

This study was sponsored by 27 nonindustry sources, including the Johns Hopkins University, the Virginia and D.K. Ludwig Fund for Cancer Research, the Ephraim and Wilma Shaw Roseman Foundation, the Endometriosis Foundation of America, and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Anglesio reported having no relevant financial disclosures; some of his associates reported ties to several industry sources.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE