User login

For vertebral osteomyelitis, early switch to oral antibiotics is feasible

VIENNA – A 6-week course of antibiotics, with an early switch from intravenous to oral, appears to be a safe and appropriate option for some patients with pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis.

A single-center retrospective study of 82 such patients found two treatment failures and two deaths over 1 year (4.8% failure rate). The patients who died were very elderly with serious comorbidities. The two treatment failures occurred in patients with methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococcal infections of a central catheter.

“Only two of the failures were due to inadequate antibiotic treatment,” Adrien Lemaignen, MD, said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress. “Both patients experienced a relapse of bacteremia with the same bacteria a few days after antibiotic cessation in a context of conservative treatment of a catheter-related infection.”

Guidelines recently adopted by the Infectious Diseases Society of America inspired the study, said Dr. Lemaignen of University Hospital of Tours, France. The 2015 document calls for 6-8 weeks of antibiotics, depending upon the infective organism and whether infective endocarditis complicates management. All suggested antibiotic regimens call for initial IV therapy followed by oral, but there are no cut-and-dried recommendations about when to switch. The guideline notes one study in which patients switched to oral after about 2.7 weeks, with a 97% success rate.

Dr. Lemaignen and his colleagues set out to determine cure rates of early oral relay in 82 patients with pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis (PVO). All patients were treated at a single center from 2011 to 2016. The team defined treatment failure as death, or persistence or relapse of infection in the first year after treatment.

All patients had culture-proven PVO that also was visible on imaging. Patients were excluded if they had any brucellar, fungal, or mycobacterial coinfections, or if they had infected spinal implants.

The mean age of the patients in the cohort was 66 years; 39% had some neuropathology. The mean C-reactive protein level was 115 mg/L. More than half of the cases (56%) involved the lumbar-sacral spine; 30% were thoracic, and the remainder, cervical. About one-fifth had multiple level involvement. There was epidural inflammation in 68%, epidural abscess in 13%, and extradural abscess in 26%.

Staphylococcus aureus was the most common pathogen (34%); two infections were methicillin resistant. Other infective organisms were streptococci (27%), Gram-negative bacilli (15%), and coagulase-negative staph (12%). A few patients had enterococci (5%) or polymicrobial infections (7%).

Infective endocarditis was present in 16 patients; this was associated with enterococcal and streptococcal infections.

Treatment varied by pathogen. Patients with S. aureus received penicillin or cefazolin with an oral relay to fluoroquinolone/rifampicin or clindamycin. Those with streptococci received amoxicillin with or without an aminoglycoside, followed by oral amoxicillin or clindamycin. Those with coagulase-negative streptococci received a glycopeptide with or without blasticidin, followed by fluoroquinolone/rifampicin. Patients with enterococcal infections got a third generation cephalosporin followed by an oral third generation cephalosporin or a fluoroquinolone.

All but six patients received 6 weeks of treatment.

The mean oral relay occurred on day 12, but 30 patients (36%) were able to switch before 7 days elapsed. Thirteen patients had to stay on the IV route for their entire treatment; 25% of this group had infective endocarditis. Six patients, all of whom had motor symptoms, also needed surgery.

The median follow-up was 358 days. During this time, there were two deaths and two treatment failures.

One death was a 93-year-old who had a controlled sepsis, but died at day 79 of a massive hematemesis. The other was an 80-year-old with an amoxicillin-resistant staph infection and decompensated cirrhosis who died at day 49.

There were also two treatment failures. Both of these patients had methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staph infections of indwelling central catheters. One had a relapse 70 days after the end of IV therapy; the other relapsed on day 26 of treatment, after a 2-week course of oral antibiotics.

Not all patients were able to succeed with 6 weeks of therapy. Three needed prolonged treatment: One of these had an infected vascular prosthesis and two were immunocompromised patients who had cervical osteomyelitis with multiple abscesses.

In light of these results, Dr. Lemaignen said, “We can say confirm the safety of short IV treatment with an early oral relay in pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis under real-life conditions, with 95% success rate and good functional outcomes at 6 months.”

He had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

VIENNA – A 6-week course of antibiotics, with an early switch from intravenous to oral, appears to be a safe and appropriate option for some patients with pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis.

A single-center retrospective study of 82 such patients found two treatment failures and two deaths over 1 year (4.8% failure rate). The patients who died were very elderly with serious comorbidities. The two treatment failures occurred in patients with methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococcal infections of a central catheter.

“Only two of the failures were due to inadequate antibiotic treatment,” Adrien Lemaignen, MD, said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress. “Both patients experienced a relapse of bacteremia with the same bacteria a few days after antibiotic cessation in a context of conservative treatment of a catheter-related infection.”

Guidelines recently adopted by the Infectious Diseases Society of America inspired the study, said Dr. Lemaignen of University Hospital of Tours, France. The 2015 document calls for 6-8 weeks of antibiotics, depending upon the infective organism and whether infective endocarditis complicates management. All suggested antibiotic regimens call for initial IV therapy followed by oral, but there are no cut-and-dried recommendations about when to switch. The guideline notes one study in which patients switched to oral after about 2.7 weeks, with a 97% success rate.

Dr. Lemaignen and his colleagues set out to determine cure rates of early oral relay in 82 patients with pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis (PVO). All patients were treated at a single center from 2011 to 2016. The team defined treatment failure as death, or persistence or relapse of infection in the first year after treatment.

All patients had culture-proven PVO that also was visible on imaging. Patients were excluded if they had any brucellar, fungal, or mycobacterial coinfections, or if they had infected spinal implants.

The mean age of the patients in the cohort was 66 years; 39% had some neuropathology. The mean C-reactive protein level was 115 mg/L. More than half of the cases (56%) involved the lumbar-sacral spine; 30% were thoracic, and the remainder, cervical. About one-fifth had multiple level involvement. There was epidural inflammation in 68%, epidural abscess in 13%, and extradural abscess in 26%.

Staphylococcus aureus was the most common pathogen (34%); two infections were methicillin resistant. Other infective organisms were streptococci (27%), Gram-negative bacilli (15%), and coagulase-negative staph (12%). A few patients had enterococci (5%) or polymicrobial infections (7%).

Infective endocarditis was present in 16 patients; this was associated with enterococcal and streptococcal infections.

Treatment varied by pathogen. Patients with S. aureus received penicillin or cefazolin with an oral relay to fluoroquinolone/rifampicin or clindamycin. Those with streptococci received amoxicillin with or without an aminoglycoside, followed by oral amoxicillin or clindamycin. Those with coagulase-negative streptococci received a glycopeptide with or without blasticidin, followed by fluoroquinolone/rifampicin. Patients with enterococcal infections got a third generation cephalosporin followed by an oral third generation cephalosporin or a fluoroquinolone.

All but six patients received 6 weeks of treatment.

The mean oral relay occurred on day 12, but 30 patients (36%) were able to switch before 7 days elapsed. Thirteen patients had to stay on the IV route for their entire treatment; 25% of this group had infective endocarditis. Six patients, all of whom had motor symptoms, also needed surgery.

The median follow-up was 358 days. During this time, there were two deaths and two treatment failures.

One death was a 93-year-old who had a controlled sepsis, but died at day 79 of a massive hematemesis. The other was an 80-year-old with an amoxicillin-resistant staph infection and decompensated cirrhosis who died at day 49.

There were also two treatment failures. Both of these patients had methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staph infections of indwelling central catheters. One had a relapse 70 days after the end of IV therapy; the other relapsed on day 26 of treatment, after a 2-week course of oral antibiotics.

Not all patients were able to succeed with 6 weeks of therapy. Three needed prolonged treatment: One of these had an infected vascular prosthesis and two were immunocompromised patients who had cervical osteomyelitis with multiple abscesses.

In light of these results, Dr. Lemaignen said, “We can say confirm the safety of short IV treatment with an early oral relay in pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis under real-life conditions, with 95% success rate and good functional outcomes at 6 months.”

He had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

VIENNA – A 6-week course of antibiotics, with an early switch from intravenous to oral, appears to be a safe and appropriate option for some patients with pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis.

A single-center retrospective study of 82 such patients found two treatment failures and two deaths over 1 year (4.8% failure rate). The patients who died were very elderly with serious comorbidities. The two treatment failures occurred in patients with methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococcal infections of a central catheter.

“Only two of the failures were due to inadequate antibiotic treatment,” Adrien Lemaignen, MD, said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress. “Both patients experienced a relapse of bacteremia with the same bacteria a few days after antibiotic cessation in a context of conservative treatment of a catheter-related infection.”

Guidelines recently adopted by the Infectious Diseases Society of America inspired the study, said Dr. Lemaignen of University Hospital of Tours, France. The 2015 document calls for 6-8 weeks of antibiotics, depending upon the infective organism and whether infective endocarditis complicates management. All suggested antibiotic regimens call for initial IV therapy followed by oral, but there are no cut-and-dried recommendations about when to switch. The guideline notes one study in which patients switched to oral after about 2.7 weeks, with a 97% success rate.

Dr. Lemaignen and his colleagues set out to determine cure rates of early oral relay in 82 patients with pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis (PVO). All patients were treated at a single center from 2011 to 2016. The team defined treatment failure as death, or persistence or relapse of infection in the first year after treatment.

All patients had culture-proven PVO that also was visible on imaging. Patients were excluded if they had any brucellar, fungal, or mycobacterial coinfections, or if they had infected spinal implants.

The mean age of the patients in the cohort was 66 years; 39% had some neuropathology. The mean C-reactive protein level was 115 mg/L. More than half of the cases (56%) involved the lumbar-sacral spine; 30% were thoracic, and the remainder, cervical. About one-fifth had multiple level involvement. There was epidural inflammation in 68%, epidural abscess in 13%, and extradural abscess in 26%.

Staphylococcus aureus was the most common pathogen (34%); two infections were methicillin resistant. Other infective organisms were streptococci (27%), Gram-negative bacilli (15%), and coagulase-negative staph (12%). A few patients had enterococci (5%) or polymicrobial infections (7%).

Infective endocarditis was present in 16 patients; this was associated with enterococcal and streptococcal infections.

Treatment varied by pathogen. Patients with S. aureus received penicillin or cefazolin with an oral relay to fluoroquinolone/rifampicin or clindamycin. Those with streptococci received amoxicillin with or without an aminoglycoside, followed by oral amoxicillin or clindamycin. Those with coagulase-negative streptococci received a glycopeptide with or without blasticidin, followed by fluoroquinolone/rifampicin. Patients with enterococcal infections got a third generation cephalosporin followed by an oral third generation cephalosporin or a fluoroquinolone.

All but six patients received 6 weeks of treatment.

The mean oral relay occurred on day 12, but 30 patients (36%) were able to switch before 7 days elapsed. Thirteen patients had to stay on the IV route for their entire treatment; 25% of this group had infective endocarditis. Six patients, all of whom had motor symptoms, also needed surgery.

The median follow-up was 358 days. During this time, there were two deaths and two treatment failures.

One death was a 93-year-old who had a controlled sepsis, but died at day 79 of a massive hematemesis. The other was an 80-year-old with an amoxicillin-resistant staph infection and decompensated cirrhosis who died at day 49.

There were also two treatment failures. Both of these patients had methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staph infections of indwelling central catheters. One had a relapse 70 days after the end of IV therapy; the other relapsed on day 26 of treatment, after a 2-week course of oral antibiotics.

Not all patients were able to succeed with 6 weeks of therapy. Three needed prolonged treatment: One of these had an infected vascular prosthesis and two were immunocompromised patients who had cervical osteomyelitis with multiple abscesses.

In light of these results, Dr. Lemaignen said, “We can say confirm the safety of short IV treatment with an early oral relay in pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis under real-life conditions, with 95% success rate and good functional outcomes at 6 months.”

He had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

AT ECCMID 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: There were two treatment failures attributable to the antibiotic regimen, and two deaths that were not, for a total treatment success rate of 95%.

Data source: A retrospective cohort comprising 82 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Lemaignen had no financial disclosures.

Ribaxamase prevented C. difficile infections by protecting microbiome

VIENNA – An investigational beta-lactamase reduced Clostridium difficile infections by 71% in patients receiving extended antibiotic therapy for respiratory infections but not by killing the opportunistic bacteria.

Rather, ribaxamase prevented C. difficile infections (CDI) by breaking down excess therapeutic antibiotics in the gut before they could injure an otherwise healthy microbiome, John Kokai-Kun, PhD, said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress.

Ribaxamase is an oral enzyme that breaks the lactam ring in penicillins and cephalosporins. It’s formulated to release at a pH of 5.5 or higher, an environment that begins to develop in the upper small intestine near the bile duct – the same place that excess antibiotics are excreted.

“The drug is intended to be administered during, and for a short time after, intravenous administration of specific beta-lactam–containing antibiotics,” Dr. Kokai-Kun said. Ribaxamase doesn’t work on carbapenem-type antibiotics, he noted, and Synthetic Biologics is working on an effective enzyme for those as well.

In early human studies, ribaxamase was well tolerated and didn’t interfere with the pharmacokinetics of therapeutic antibiotics (Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017 Mar;61[3]:e02197-16). It’s also effective in patients who are taking a proton pump inhibitor, he said.

Dr. Kokai-Kun reported the results of a phase IIb study of 412 patients who received IV ceftriaxone for lower respiratory infections. They were assigned 1:1 to either 150 mg ribaxamase daily or placebo throughout the IV treatment and for 3 days after.

The primary endpoint was prevention of C. difficile infection. The secondary endpoint was prevention of non–C. difficile antibiotic-associated diarrhea. An exploratory endpoint examined the drug’s ability to protect the microbiome. Patients were monitored for 6 weeks after treatment stopped.

The cohort was a mean 70 years old. One-third of patients also received a macrolide during their hospitalization, and one-third were taking proton pump inhibitors. The respiratory infection cure rate was about 99% in both groups at both 72 hours and 4 weeks.

Eight patients in the placebo group (3.8%) and two in the active group (less than 1%) developed C. difficile infection. That translated to a statistically significant 71% risk reduction, with a P value of .027, Dr. Kokai-Kun said. Ribaxamase did not hit its secondary endpoint of preventing all-cause diarrhea or antibiotic-associated diarrhea that was not caused by C. difficile infection.

Although not a primary finding, ribaxamase also inhibited colonization by vancomycin-resistant enterococci, which occurred in about 70 (40%) patients in the placebo group and 40 (20%) in the ribaxamase group at both 72 hours and 4 weeks.

All patients contributed stool samples at baseline and after treatment for microbiome analysis. That portion of the study is still ongoing, Dr. Kokai-Kun said.

Synthetic Biologics sponsored the study and is developing ribaxamase. Dr. Kokai-Kun is the company’s vice president of nonclinical affairs.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

VIENNA – An investigational beta-lactamase reduced Clostridium difficile infections by 71% in patients receiving extended antibiotic therapy for respiratory infections but not by killing the opportunistic bacteria.

Rather, ribaxamase prevented C. difficile infections (CDI) by breaking down excess therapeutic antibiotics in the gut before they could injure an otherwise healthy microbiome, John Kokai-Kun, PhD, said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress.

Ribaxamase is an oral enzyme that breaks the lactam ring in penicillins and cephalosporins. It’s formulated to release at a pH of 5.5 or higher, an environment that begins to develop in the upper small intestine near the bile duct – the same place that excess antibiotics are excreted.

“The drug is intended to be administered during, and for a short time after, intravenous administration of specific beta-lactam–containing antibiotics,” Dr. Kokai-Kun said. Ribaxamase doesn’t work on carbapenem-type antibiotics, he noted, and Synthetic Biologics is working on an effective enzyme for those as well.

In early human studies, ribaxamase was well tolerated and didn’t interfere with the pharmacokinetics of therapeutic antibiotics (Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017 Mar;61[3]:e02197-16). It’s also effective in patients who are taking a proton pump inhibitor, he said.

Dr. Kokai-Kun reported the results of a phase IIb study of 412 patients who received IV ceftriaxone for lower respiratory infections. They were assigned 1:1 to either 150 mg ribaxamase daily or placebo throughout the IV treatment and for 3 days after.

The primary endpoint was prevention of C. difficile infection. The secondary endpoint was prevention of non–C. difficile antibiotic-associated diarrhea. An exploratory endpoint examined the drug’s ability to protect the microbiome. Patients were monitored for 6 weeks after treatment stopped.

The cohort was a mean 70 years old. One-third of patients also received a macrolide during their hospitalization, and one-third were taking proton pump inhibitors. The respiratory infection cure rate was about 99% in both groups at both 72 hours and 4 weeks.

Eight patients in the placebo group (3.8%) and two in the active group (less than 1%) developed C. difficile infection. That translated to a statistically significant 71% risk reduction, with a P value of .027, Dr. Kokai-Kun said. Ribaxamase did not hit its secondary endpoint of preventing all-cause diarrhea or antibiotic-associated diarrhea that was not caused by C. difficile infection.

Although not a primary finding, ribaxamase also inhibited colonization by vancomycin-resistant enterococci, which occurred in about 70 (40%) patients in the placebo group and 40 (20%) in the ribaxamase group at both 72 hours and 4 weeks.

All patients contributed stool samples at baseline and after treatment for microbiome analysis. That portion of the study is still ongoing, Dr. Kokai-Kun said.

Synthetic Biologics sponsored the study and is developing ribaxamase. Dr. Kokai-Kun is the company’s vice president of nonclinical affairs.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

VIENNA – An investigational beta-lactamase reduced Clostridium difficile infections by 71% in patients receiving extended antibiotic therapy for respiratory infections but not by killing the opportunistic bacteria.

Rather, ribaxamase prevented C. difficile infections (CDI) by breaking down excess therapeutic antibiotics in the gut before they could injure an otherwise healthy microbiome, John Kokai-Kun, PhD, said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress.

Ribaxamase is an oral enzyme that breaks the lactam ring in penicillins and cephalosporins. It’s formulated to release at a pH of 5.5 or higher, an environment that begins to develop in the upper small intestine near the bile duct – the same place that excess antibiotics are excreted.

“The drug is intended to be administered during, and for a short time after, intravenous administration of specific beta-lactam–containing antibiotics,” Dr. Kokai-Kun said. Ribaxamase doesn’t work on carbapenem-type antibiotics, he noted, and Synthetic Biologics is working on an effective enzyme for those as well.

In early human studies, ribaxamase was well tolerated and didn’t interfere with the pharmacokinetics of therapeutic antibiotics (Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017 Mar;61[3]:e02197-16). It’s also effective in patients who are taking a proton pump inhibitor, he said.

Dr. Kokai-Kun reported the results of a phase IIb study of 412 patients who received IV ceftriaxone for lower respiratory infections. They were assigned 1:1 to either 150 mg ribaxamase daily or placebo throughout the IV treatment and for 3 days after.

The primary endpoint was prevention of C. difficile infection. The secondary endpoint was prevention of non–C. difficile antibiotic-associated diarrhea. An exploratory endpoint examined the drug’s ability to protect the microbiome. Patients were monitored for 6 weeks after treatment stopped.

The cohort was a mean 70 years old. One-third of patients also received a macrolide during their hospitalization, and one-third were taking proton pump inhibitors. The respiratory infection cure rate was about 99% in both groups at both 72 hours and 4 weeks.

Eight patients in the placebo group (3.8%) and two in the active group (less than 1%) developed C. difficile infection. That translated to a statistically significant 71% risk reduction, with a P value of .027, Dr. Kokai-Kun said. Ribaxamase did not hit its secondary endpoint of preventing all-cause diarrhea or antibiotic-associated diarrhea that was not caused by C. difficile infection.

Although not a primary finding, ribaxamase also inhibited colonization by vancomycin-resistant enterococci, which occurred in about 70 (40%) patients in the placebo group and 40 (20%) in the ribaxamase group at both 72 hours and 4 weeks.

All patients contributed stool samples at baseline and after treatment for microbiome analysis. That portion of the study is still ongoing, Dr. Kokai-Kun said.

Synthetic Biologics sponsored the study and is developing ribaxamase. Dr. Kokai-Kun is the company’s vice president of nonclinical affairs.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

AT ECCMID 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Ribaxamase reduced C. difficile infections by 71%, relative to a placebo.

Data source: The study randomized 412 patients to either placebo or ribaxamase in addition to their therapeutic antibiotics.

Disclosures: Synthetic Biologics sponsored the study and is developing ribaxamase. Dr. Kokai-Kun is the company’s vice president of nonclinical affairs.

Topical imiquimod boosted response to intradermal hepatitis B vaccine

VIENNA – Topical imiquimod appeared to enhance the immunogenicity of an intradermal hepatitis B vaccine in patients on renal replacement therapy.

Patients on hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis who got the combination developed significantly higher seroprotection and antibody levels than those who got either the typical intramuscular vaccination or an intradermal vaccination on unprepared skin, Ivan Fan-Ngai Hung, MD, said at the European Conference on Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. By 1 year, the protection and titers did begin to fall, but they still remained significantly higher than in the two comparator groups, said Dr. Hung, a clinical professor at the University of Hong Kong.

Dr. Hung and his colleagues have been investigating imiquimod’s immunogenicity-boosting potential for several years. Their initial murine work with an H1N1 influenza virus appeared in 2014 (Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2014 Apr;21[4]: 570-9). The investigators intraperitoneally immunized mice with a monovalent A(H1N1) vaccine combined with imiquimod (VIC) then intranasally inoculated them with a lethal dose of the virus. When compared with mice who received only vaccine, only imiquimod, or only placebo, the VIC group showed significantly greater and significantly longer survival. Virus-specific serum immunoglobulin M, IgG, and neutralizing antibodies were all significantly higher.

The investigators theorized that imiquimod, a Toll-like receptor 7 agonist, plays several key roles in boosting immune response, including inducing the differentiation and migration of dendritic cells, enhancing B cell differentiation, and increasing long-term B cell memory.

Within the past 2 years, the group has advanced to human influenza trials in healthy young adults and elders with comorbidities.

Both studies employed a 5% imiquimod cream delivering 250 mg of the drug. It was applied at the injection site 5 minutes before vaccination. In the elder study, 90% of the 91 subjects who got the combination achieved seroconversion, compared with 13% of those who got an intramuscular injection and 39% of those who got an intradermal injection plus placebo cream. The geometric mean titers went up faster and stayed elevated longer. The better immunogenicity was associated with fewer hospitalizations for influenza or pneumonia (Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59[9]:1246-55).

The immunogenicity findings were similar in the study of 160 healthy young people. This study had a surprising twist too, Dr. Hung said in his talk. Not only did the combination significantly improve immunogenicity against the vaccine influenza strains, it increased immunogenicity against the nonvaccine strains, especially the antigenically drifted H3N2 strain of 2015, which was not included in the 2013-2014 recommended vaccine (Lancet Inf Dis. 2016 Feb;16(2):209-18).

The study Dr. Hung presented in Vienna was an interim analysis of the first to apply this technique to a hepatitis B vaccine. It enrolled 69 patients (51 on peritoneal dialysis and 18 on hemodialysis). They were a mean 65 years old. All received 10 mcg of the Sci-B-Vac at baseline, 1 month, and 6 months. Vaccine was delivered in a trineedle unit designed for shallow intradermal penetration (MicronJet600; NanoPass Technologies) Group IQ received topical imiquimod along with the intradermal vaccine. Group ID received a placebo cream and the intradermal vaccine. Group IM received a placebo cream and an intramuscular vaccination.

Anti–hepatitis B titers were measured at baseline and at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. The primary outcome was seroprotection at 1 month. The secondary outcomes were seroprotection at 3, 6, and 12 months; anti–hepatitis B antibody titer; and safety.

By 1 month, seroprotection was already significantly higher in the IQ group than in the ID and IM groups (60% vs. 50% and 38%, respectively).

By 3 months, the seroprotection rate in group IQ had risen to 85%. It remained elevated there at 6 months then tailed off to about 70% by 12 months. The ID and IM groups followed this same rising and falling curve but remained significantly lower at all time points. At 12 months, seroprotection was similar in both these groups – about 40%.

The anti–hepatitis B antibody titers told a similar story. Titers in the IQ group rose more rapidly and sharply, to 544 mIU/mL at 6 months and 566 mIU/mL at 12 months. The ID group also experienced a strong response, rising to 489 mIU/mL at 6 months. However, by 12 months, titer levels had dropped to 170 mIU/mL.

Titers in the IM group barely moved at all during the entire follow-up period, never rising above 21 mIU/mL.

There were no differences in systemic reactions among the three groups, but those who got the intradermal vaccines reported slightly more swelling and induration at the injection site.

“Since this is an interim analysis, we cannot determine long-term protection or antibody titers,” Dr. Hung cautioned. “However, we are starting a similar study in elderly patients and also one for those who are on low-dose immunosuppressants. We believe this regimen will also work for them.”

Dr. Hung has been on advisory boards for Pfizer and Gilead Sciences.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

VIENNA – Topical imiquimod appeared to enhance the immunogenicity of an intradermal hepatitis B vaccine in patients on renal replacement therapy.

Patients on hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis who got the combination developed significantly higher seroprotection and antibody levels than those who got either the typical intramuscular vaccination or an intradermal vaccination on unprepared skin, Ivan Fan-Ngai Hung, MD, said at the European Conference on Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. By 1 year, the protection and titers did begin to fall, but they still remained significantly higher than in the two comparator groups, said Dr. Hung, a clinical professor at the University of Hong Kong.

Dr. Hung and his colleagues have been investigating imiquimod’s immunogenicity-boosting potential for several years. Their initial murine work with an H1N1 influenza virus appeared in 2014 (Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2014 Apr;21[4]: 570-9). The investigators intraperitoneally immunized mice with a monovalent A(H1N1) vaccine combined with imiquimod (VIC) then intranasally inoculated them with a lethal dose of the virus. When compared with mice who received only vaccine, only imiquimod, or only placebo, the VIC group showed significantly greater and significantly longer survival. Virus-specific serum immunoglobulin M, IgG, and neutralizing antibodies were all significantly higher.

The investigators theorized that imiquimod, a Toll-like receptor 7 agonist, plays several key roles in boosting immune response, including inducing the differentiation and migration of dendritic cells, enhancing B cell differentiation, and increasing long-term B cell memory.

Within the past 2 years, the group has advanced to human influenza trials in healthy young adults and elders with comorbidities.

Both studies employed a 5% imiquimod cream delivering 250 mg of the drug. It was applied at the injection site 5 minutes before vaccination. In the elder study, 90% of the 91 subjects who got the combination achieved seroconversion, compared with 13% of those who got an intramuscular injection and 39% of those who got an intradermal injection plus placebo cream. The geometric mean titers went up faster and stayed elevated longer. The better immunogenicity was associated with fewer hospitalizations for influenza or pneumonia (Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59[9]:1246-55).

The immunogenicity findings were similar in the study of 160 healthy young people. This study had a surprising twist too, Dr. Hung said in his talk. Not only did the combination significantly improve immunogenicity against the vaccine influenza strains, it increased immunogenicity against the nonvaccine strains, especially the antigenically drifted H3N2 strain of 2015, which was not included in the 2013-2014 recommended vaccine (Lancet Inf Dis. 2016 Feb;16(2):209-18).

The study Dr. Hung presented in Vienna was an interim analysis of the first to apply this technique to a hepatitis B vaccine. It enrolled 69 patients (51 on peritoneal dialysis and 18 on hemodialysis). They were a mean 65 years old. All received 10 mcg of the Sci-B-Vac at baseline, 1 month, and 6 months. Vaccine was delivered in a trineedle unit designed for shallow intradermal penetration (MicronJet600; NanoPass Technologies) Group IQ received topical imiquimod along with the intradermal vaccine. Group ID received a placebo cream and the intradermal vaccine. Group IM received a placebo cream and an intramuscular vaccination.

Anti–hepatitis B titers were measured at baseline and at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. The primary outcome was seroprotection at 1 month. The secondary outcomes were seroprotection at 3, 6, and 12 months; anti–hepatitis B antibody titer; and safety.

By 1 month, seroprotection was already significantly higher in the IQ group than in the ID and IM groups (60% vs. 50% and 38%, respectively).

By 3 months, the seroprotection rate in group IQ had risen to 85%. It remained elevated there at 6 months then tailed off to about 70% by 12 months. The ID and IM groups followed this same rising and falling curve but remained significantly lower at all time points. At 12 months, seroprotection was similar in both these groups – about 40%.

The anti–hepatitis B antibody titers told a similar story. Titers in the IQ group rose more rapidly and sharply, to 544 mIU/mL at 6 months and 566 mIU/mL at 12 months. The ID group also experienced a strong response, rising to 489 mIU/mL at 6 months. However, by 12 months, titer levels had dropped to 170 mIU/mL.

Titers in the IM group barely moved at all during the entire follow-up period, never rising above 21 mIU/mL.

There were no differences in systemic reactions among the three groups, but those who got the intradermal vaccines reported slightly more swelling and induration at the injection site.

“Since this is an interim analysis, we cannot determine long-term protection or antibody titers,” Dr. Hung cautioned. “However, we are starting a similar study in elderly patients and also one for those who are on low-dose immunosuppressants. We believe this regimen will also work for them.”

Dr. Hung has been on advisory boards for Pfizer and Gilead Sciences.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

VIENNA – Topical imiquimod appeared to enhance the immunogenicity of an intradermal hepatitis B vaccine in patients on renal replacement therapy.

Patients on hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis who got the combination developed significantly higher seroprotection and antibody levels than those who got either the typical intramuscular vaccination or an intradermal vaccination on unprepared skin, Ivan Fan-Ngai Hung, MD, said at the European Conference on Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. By 1 year, the protection and titers did begin to fall, but they still remained significantly higher than in the two comparator groups, said Dr. Hung, a clinical professor at the University of Hong Kong.

Dr. Hung and his colleagues have been investigating imiquimod’s immunogenicity-boosting potential for several years. Their initial murine work with an H1N1 influenza virus appeared in 2014 (Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2014 Apr;21[4]: 570-9). The investigators intraperitoneally immunized mice with a monovalent A(H1N1) vaccine combined with imiquimod (VIC) then intranasally inoculated them with a lethal dose of the virus. When compared with mice who received only vaccine, only imiquimod, or only placebo, the VIC group showed significantly greater and significantly longer survival. Virus-specific serum immunoglobulin M, IgG, and neutralizing antibodies were all significantly higher.

The investigators theorized that imiquimod, a Toll-like receptor 7 agonist, plays several key roles in boosting immune response, including inducing the differentiation and migration of dendritic cells, enhancing B cell differentiation, and increasing long-term B cell memory.

Within the past 2 years, the group has advanced to human influenza trials in healthy young adults and elders with comorbidities.

Both studies employed a 5% imiquimod cream delivering 250 mg of the drug. It was applied at the injection site 5 minutes before vaccination. In the elder study, 90% of the 91 subjects who got the combination achieved seroconversion, compared with 13% of those who got an intramuscular injection and 39% of those who got an intradermal injection plus placebo cream. The geometric mean titers went up faster and stayed elevated longer. The better immunogenicity was associated with fewer hospitalizations for influenza or pneumonia (Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59[9]:1246-55).

The immunogenicity findings were similar in the study of 160 healthy young people. This study had a surprising twist too, Dr. Hung said in his talk. Not only did the combination significantly improve immunogenicity against the vaccine influenza strains, it increased immunogenicity against the nonvaccine strains, especially the antigenically drifted H3N2 strain of 2015, which was not included in the 2013-2014 recommended vaccine (Lancet Inf Dis. 2016 Feb;16(2):209-18).

The study Dr. Hung presented in Vienna was an interim analysis of the first to apply this technique to a hepatitis B vaccine. It enrolled 69 patients (51 on peritoneal dialysis and 18 on hemodialysis). They were a mean 65 years old. All received 10 mcg of the Sci-B-Vac at baseline, 1 month, and 6 months. Vaccine was delivered in a trineedle unit designed for shallow intradermal penetration (MicronJet600; NanoPass Technologies) Group IQ received topical imiquimod along with the intradermal vaccine. Group ID received a placebo cream and the intradermal vaccine. Group IM received a placebo cream and an intramuscular vaccination.

Anti–hepatitis B titers were measured at baseline and at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. The primary outcome was seroprotection at 1 month. The secondary outcomes were seroprotection at 3, 6, and 12 months; anti–hepatitis B antibody titer; and safety.

By 1 month, seroprotection was already significantly higher in the IQ group than in the ID and IM groups (60% vs. 50% and 38%, respectively).

By 3 months, the seroprotection rate in group IQ had risen to 85%. It remained elevated there at 6 months then tailed off to about 70% by 12 months. The ID and IM groups followed this same rising and falling curve but remained significantly lower at all time points. At 12 months, seroprotection was similar in both these groups – about 40%.

The anti–hepatitis B antibody titers told a similar story. Titers in the IQ group rose more rapidly and sharply, to 544 mIU/mL at 6 months and 566 mIU/mL at 12 months. The ID group also experienced a strong response, rising to 489 mIU/mL at 6 months. However, by 12 months, titer levels had dropped to 170 mIU/mL.

Titers in the IM group barely moved at all during the entire follow-up period, never rising above 21 mIU/mL.

There were no differences in systemic reactions among the three groups, but those who got the intradermal vaccines reported slightly more swelling and induration at the injection site.

“Since this is an interim analysis, we cannot determine long-term protection or antibody titers,” Dr. Hung cautioned. “However, we are starting a similar study in elderly patients and also one for those who are on low-dose immunosuppressants. We believe this regimen will also work for them.”

Dr. Hung has been on advisory boards for Pfizer and Gilead Sciences.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

AT ECCMID 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: By 1 month, seroprotection was significantly higher in the imiquimod group than in those who got an intradermal vaccination without imiquimod and those who had an intramuscular injection only (60% vs. 50% and 38%, respectively).

Data source: The four-armed randomized study comprised 69 patients on hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis.

Disclosures: Dr. Hung has served on advisory boards for Pfizer and Gilead Sciences.

Lung cancer metastatic sites differ by histology, tumor factors

GENEVA – A review of data on more than 75,000 patients with lung cancer has revealed distinct patterns of metastasis according to subtype, a finding that could help in surveillance, treatment planning, and prophylaxis, an investigator contends.

Patients with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) had significantly higher rates of liver metastases than patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), while patients with NSCLC had significantly higher rates of metastases to bone, reported Mohamed Hendawi, MD, a visiting scholar at the Ohio State University Medical Center in Columbus.

“Predictors for liver metastasis were small cell and adenocarcinoma histology, lower and upper lobe locations, and high grade tumors. Predictors for metastasis to brain were advanced age at diagnosis, adenocarcinoma and small-cell histology, lower lobe [and] main bronchus locations, and high grade tumors,” he wrote in a scientific poster presented at the European Lung Cancer Conference.

Dr. Hendawi drew records on all patients with metastatic lung cancer included in the 2010-2013 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. He used univariate and multivariate logistic regression models to evaluate predictors of metastasis.

The data set included a total of 76,254 patients with metastatic lung cancer, of which 17% were SCLC and 83% were NSCLC tumors. In 54% of patients, the primary tumor was in the right lung; in 38%, it was in the left lung; and, in 8% of patients, the primary tumor was bilateral.

The rates of metastases to bone were high in both major lung cancer types but, as noted before, were significantly higher in patients with NSCLC: 37% compared with 34% for patients with SCLC (P less than .001).

In contrast, the incidence of liver metastases in SCLC was more than double that of NSCLC: 46% vs. 20%, respectively (P less than .001). There were slightly, but significantly, fewer cases of brain metastases at the time of diagnosis among patients with SCLC: 25% vs. 26% (P = .003).

Histologic subtypes significantly associated with both brain and liver metastases were, in descending order, adenocarcinomas, small cell, and squamous cell cancers.

Although carcinoid lung cancers accounted for only 2.1% of all tumors, they were associated with a high rate of metastasis to brain at diagnosis (44.8%).

As noted, independent risk factors for liver metastasis were small cell and adenocarcinoma histologies (P less than .001), tumors in the upper lobe (P = .028), and high-grade tumor (P less than .001).

Independent predictors for brain metastases were advanced age at diagnosis (P less than .001), adenocarcinoma and small-cell histologies (P less than .001), lower lobe or main bronchus locations (P = .004), and higher-grade tumors (P less than .001).

In a poster discussion session, Paolo Boffetta, MD, MPH, from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, the invited discussant, commented that, while he thought that the data were interesting, “the main issue I had with this poster is that it’s limited to patients with metastasis, so we cannot really evaluate the risk of metastasis according to the different histological types and the absolute risk of developing metastases in one or the other organ but only the relative risk of developing metastasis in one organ versus the other having one or the other histology.”

“So, we really don’t know whether the risk is increased in one group or decreased in the other one that generates these differences,” he said.

The study did not receive outside support. Dr. Hendawi declared no conflicts of interest.

GENEVA – A review of data on more than 75,000 patients with lung cancer has revealed distinct patterns of metastasis according to subtype, a finding that could help in surveillance, treatment planning, and prophylaxis, an investigator contends.

Patients with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) had significantly higher rates of liver metastases than patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), while patients with NSCLC had significantly higher rates of metastases to bone, reported Mohamed Hendawi, MD, a visiting scholar at the Ohio State University Medical Center in Columbus.

“Predictors for liver metastasis were small cell and adenocarcinoma histology, lower and upper lobe locations, and high grade tumors. Predictors for metastasis to brain were advanced age at diagnosis, adenocarcinoma and small-cell histology, lower lobe [and] main bronchus locations, and high grade tumors,” he wrote in a scientific poster presented at the European Lung Cancer Conference.

Dr. Hendawi drew records on all patients with metastatic lung cancer included in the 2010-2013 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. He used univariate and multivariate logistic regression models to evaluate predictors of metastasis.

The data set included a total of 76,254 patients with metastatic lung cancer, of which 17% were SCLC and 83% were NSCLC tumors. In 54% of patients, the primary tumor was in the right lung; in 38%, it was in the left lung; and, in 8% of patients, the primary tumor was bilateral.

The rates of metastases to bone were high in both major lung cancer types but, as noted before, were significantly higher in patients with NSCLC: 37% compared with 34% for patients with SCLC (P less than .001).

In contrast, the incidence of liver metastases in SCLC was more than double that of NSCLC: 46% vs. 20%, respectively (P less than .001). There were slightly, but significantly, fewer cases of brain metastases at the time of diagnosis among patients with SCLC: 25% vs. 26% (P = .003).

Histologic subtypes significantly associated with both brain and liver metastases were, in descending order, adenocarcinomas, small cell, and squamous cell cancers.

Although carcinoid lung cancers accounted for only 2.1% of all tumors, they were associated with a high rate of metastasis to brain at diagnosis (44.8%).

As noted, independent risk factors for liver metastasis were small cell and adenocarcinoma histologies (P less than .001), tumors in the upper lobe (P = .028), and high-grade tumor (P less than .001).

Independent predictors for brain metastases were advanced age at diagnosis (P less than .001), adenocarcinoma and small-cell histologies (P less than .001), lower lobe or main bronchus locations (P = .004), and higher-grade tumors (P less than .001).

In a poster discussion session, Paolo Boffetta, MD, MPH, from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, the invited discussant, commented that, while he thought that the data were interesting, “the main issue I had with this poster is that it’s limited to patients with metastasis, so we cannot really evaluate the risk of metastasis according to the different histological types and the absolute risk of developing metastases in one or the other organ but only the relative risk of developing metastasis in one organ versus the other having one or the other histology.”

“So, we really don’t know whether the risk is increased in one group or decreased in the other one that generates these differences,” he said.

The study did not receive outside support. Dr. Hendawi declared no conflicts of interest.

GENEVA – A review of data on more than 75,000 patients with lung cancer has revealed distinct patterns of metastasis according to subtype, a finding that could help in surveillance, treatment planning, and prophylaxis, an investigator contends.

Patients with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) had significantly higher rates of liver metastases than patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), while patients with NSCLC had significantly higher rates of metastases to bone, reported Mohamed Hendawi, MD, a visiting scholar at the Ohio State University Medical Center in Columbus.

“Predictors for liver metastasis were small cell and adenocarcinoma histology, lower and upper lobe locations, and high grade tumors. Predictors for metastasis to brain were advanced age at diagnosis, adenocarcinoma and small-cell histology, lower lobe [and] main bronchus locations, and high grade tumors,” he wrote in a scientific poster presented at the European Lung Cancer Conference.

Dr. Hendawi drew records on all patients with metastatic lung cancer included in the 2010-2013 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. He used univariate and multivariate logistic regression models to evaluate predictors of metastasis.

The data set included a total of 76,254 patients with metastatic lung cancer, of which 17% were SCLC and 83% were NSCLC tumors. In 54% of patients, the primary tumor was in the right lung; in 38%, it was in the left lung; and, in 8% of patients, the primary tumor was bilateral.

The rates of metastases to bone were high in both major lung cancer types but, as noted before, were significantly higher in patients with NSCLC: 37% compared with 34% for patients with SCLC (P less than .001).

In contrast, the incidence of liver metastases in SCLC was more than double that of NSCLC: 46% vs. 20%, respectively (P less than .001). There were slightly, but significantly, fewer cases of brain metastases at the time of diagnosis among patients with SCLC: 25% vs. 26% (P = .003).

Histologic subtypes significantly associated with both brain and liver metastases were, in descending order, adenocarcinomas, small cell, and squamous cell cancers.

Although carcinoid lung cancers accounted for only 2.1% of all tumors, they were associated with a high rate of metastasis to brain at diagnosis (44.8%).

As noted, independent risk factors for liver metastasis were small cell and adenocarcinoma histologies (P less than .001), tumors in the upper lobe (P = .028), and high-grade tumor (P less than .001).

Independent predictors for brain metastases were advanced age at diagnosis (P less than .001), adenocarcinoma and small-cell histologies (P less than .001), lower lobe or main bronchus locations (P = .004), and higher-grade tumors (P less than .001).

In a poster discussion session, Paolo Boffetta, MD, MPH, from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, the invited discussant, commented that, while he thought that the data were interesting, “the main issue I had with this poster is that it’s limited to patients with metastasis, so we cannot really evaluate the risk of metastasis according to the different histological types and the absolute risk of developing metastases in one or the other organ but only the relative risk of developing metastasis in one organ versus the other having one or the other histology.”

“So, we really don’t know whether the risk is increased in one group or decreased in the other one that generates these differences,” he said.

The study did not receive outside support. Dr. Hendawi declared no conflicts of interest.

FROM ELCC

Key clinical point: Lung cancers tend to metastasize to different organs based on histology and other clinical factors.

Major finding: The incidence of metastasis to bone was higher in patients with NSCLC than SCLC, while liver metastases were more than twice as high among patients with SCLC.

Data source: Review of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data on 76,254 patients with metastatic lung cancer.

Disclosures: The study did not receive outside support. Dr. Hendawi declared no conflicts of interest.

Molecular tests for GAS pharyngitis could spur overuse of antibiotics

SAN FRANCISCO – The diagnosis of pharyngitis due to infection by group A streptococcus (GAS) based on the detection of nucleic acid is fast and accurate. But this benefit brings the possibility of overuse of antibiotics, with treatment offered to those who, in the era of growth-based detection of the bacteria, would not have received treatment, according to Robert R. Tanz, MD.

Dr. Tanz, professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago, delivered this cautionary note at the meeting of the Pediatrics Academics Societies.

“The short turnaround time, high sensitivity, and high specificity of newer molecular tests for GAS will make their use increasingly common. Many of the additional patients identified by molecular testing may not have an illness attributable to GAS. The increase in positive tests will probably be associated with increased antibiotic prescribing. This may not be beneficial, especially in areas with low rates of acute rheumatic fever,” said Dr. Tanz, who practices at Ann & Robert Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

Nowadays, diagnosis of GAS at Ann & Robert Lurie Children’s Hospital uses the Illumigene system. Its use has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for diagnosis without the need for backup culture of throat swabs. Results are available in about 1 hour.

Dr. Tanz and his colleagues took a retrospective look at patient records during 2013, when testing was still growth-based, and in 2014 and 2015, after the hospital had shifted to the molecular analysis of throat swabs. The aim was to determine the proportion of tests positive for GAS prior to and after the switch.

The positive detection rate of 9.6% (96 of 997 samples) in 2013 climbed to 17% (152 of 894) in 2014 and 16% (138 of 859) in 2015. The difference was highly significant (P less than .00001).

Sore throats increase in the colder months when people tend to be indoors more often, and this seasonality was evident in 2013. However, detection was more consistent throughout the 12 months in 2014 (2013 vs 2014, P less than .000001) and 2015 (2013 vs 2015, P less than .00001). The detection rates in 2014 and 2015 were similar (P equal to .59), according to Dr. Tanz.

The new era of molecular testing circumvents what is known as the spectrum effect, in which culture-based tests are more often positive in patients with symptoms that are consistent with the infection, he said. In contrast, molecular tests can increase the identification of the target bacterium, here GAS, in patients who have sore throat caused by a viral infection.

Preliminary results presented by Dr. Tanz indicated a significantly greater detection of GAS in children not displaying symptoms of infection. In decades past, these children would not have been treated.

“The increase in positive tests for group A strep is likely associated with increased antibiotic prescribing. This may or may not represent a benefit to patients, as the additional identified patients may not have an illness actually attributable to group A strep,” said Dr. Tanz.

“Our findings support rigorous selectivity in choosing which patients to test, specifically excluding those with overt viral symptoms, as recommended in the guidelines from the [Infectious Diseases Society of America], [American Academy of Pediatrics], and other groups,” he said, adding that clinician guidance on the use of molecular diagnostic tests for pharyngitis caused by group A strep is a prudent step.

Features suggestive of GAS may include sudden onset of sore throat, age 5-15 years, fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, tonsillopharyngeal inflammation and patchy tonsillopharyngeal exudates, palatal petechiae, tender nodes, and scarlatiniform rash. Viral pharyngitis features include conjunctivitis, coryza, cough, diarrhea, discrete ulcerative stomatitis, viral exanthema, and hoarseness, according to the 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of American guidelines (Clin Infect Dis. 2012. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis629).

For most people, a sore throat is more of a temporary inconvenience rather than a looming health threat, but GAS easily spreads from person to person and can lead to the more serious condition of acute rheumatic fever, Dr. Tanz said. Hence the concern with diagnosing the cause of sore throat and, when the cause is bacterial, alleviating the infection using antibiotics.

The study was conducted at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago and was not funded. Dr. Tanz reported having received support from Meridian Bioscience, manufacturer of the Illumigene Group A Streptococcus assay. Meridian Bioscience did not support this study.

SAN FRANCISCO – The diagnosis of pharyngitis due to infection by group A streptococcus (GAS) based on the detection of nucleic acid is fast and accurate. But this benefit brings the possibility of overuse of antibiotics, with treatment offered to those who, in the era of growth-based detection of the bacteria, would not have received treatment, according to Robert R. Tanz, MD.

Dr. Tanz, professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago, delivered this cautionary note at the meeting of the Pediatrics Academics Societies.

“The short turnaround time, high sensitivity, and high specificity of newer molecular tests for GAS will make their use increasingly common. Many of the additional patients identified by molecular testing may not have an illness attributable to GAS. The increase in positive tests will probably be associated with increased antibiotic prescribing. This may not be beneficial, especially in areas with low rates of acute rheumatic fever,” said Dr. Tanz, who practices at Ann & Robert Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

Nowadays, diagnosis of GAS at Ann & Robert Lurie Children’s Hospital uses the Illumigene system. Its use has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for diagnosis without the need for backup culture of throat swabs. Results are available in about 1 hour.

Dr. Tanz and his colleagues took a retrospective look at patient records during 2013, when testing was still growth-based, and in 2014 and 2015, after the hospital had shifted to the molecular analysis of throat swabs. The aim was to determine the proportion of tests positive for GAS prior to and after the switch.

The positive detection rate of 9.6% (96 of 997 samples) in 2013 climbed to 17% (152 of 894) in 2014 and 16% (138 of 859) in 2015. The difference was highly significant (P less than .00001).

Sore throats increase in the colder months when people tend to be indoors more often, and this seasonality was evident in 2013. However, detection was more consistent throughout the 12 months in 2014 (2013 vs 2014, P less than .000001) and 2015 (2013 vs 2015, P less than .00001). The detection rates in 2014 and 2015 were similar (P equal to .59), according to Dr. Tanz.

The new era of molecular testing circumvents what is known as the spectrum effect, in which culture-based tests are more often positive in patients with symptoms that are consistent with the infection, he said. In contrast, molecular tests can increase the identification of the target bacterium, here GAS, in patients who have sore throat caused by a viral infection.

Preliminary results presented by Dr. Tanz indicated a significantly greater detection of GAS in children not displaying symptoms of infection. In decades past, these children would not have been treated.

“The increase in positive tests for group A strep is likely associated with increased antibiotic prescribing. This may or may not represent a benefit to patients, as the additional identified patients may not have an illness actually attributable to group A strep,” said Dr. Tanz.

“Our findings support rigorous selectivity in choosing which patients to test, specifically excluding those with overt viral symptoms, as recommended in the guidelines from the [Infectious Diseases Society of America], [American Academy of Pediatrics], and other groups,” he said, adding that clinician guidance on the use of molecular diagnostic tests for pharyngitis caused by group A strep is a prudent step.

Features suggestive of GAS may include sudden onset of sore throat, age 5-15 years, fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, tonsillopharyngeal inflammation and patchy tonsillopharyngeal exudates, palatal petechiae, tender nodes, and scarlatiniform rash. Viral pharyngitis features include conjunctivitis, coryza, cough, diarrhea, discrete ulcerative stomatitis, viral exanthema, and hoarseness, according to the 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of American guidelines (Clin Infect Dis. 2012. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis629).

For most people, a sore throat is more of a temporary inconvenience rather than a looming health threat, but GAS easily spreads from person to person and can lead to the more serious condition of acute rheumatic fever, Dr. Tanz said. Hence the concern with diagnosing the cause of sore throat and, when the cause is bacterial, alleviating the infection using antibiotics.

The study was conducted at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago and was not funded. Dr. Tanz reported having received support from Meridian Bioscience, manufacturer of the Illumigene Group A Streptococcus assay. Meridian Bioscience did not support this study.

SAN FRANCISCO – The diagnosis of pharyngitis due to infection by group A streptococcus (GAS) based on the detection of nucleic acid is fast and accurate. But this benefit brings the possibility of overuse of antibiotics, with treatment offered to those who, in the era of growth-based detection of the bacteria, would not have received treatment, according to Robert R. Tanz, MD.

Dr. Tanz, professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago, delivered this cautionary note at the meeting of the Pediatrics Academics Societies.

“The short turnaround time, high sensitivity, and high specificity of newer molecular tests for GAS will make their use increasingly common. Many of the additional patients identified by molecular testing may not have an illness attributable to GAS. The increase in positive tests will probably be associated with increased antibiotic prescribing. This may not be beneficial, especially in areas with low rates of acute rheumatic fever,” said Dr. Tanz, who practices at Ann & Robert Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

Nowadays, diagnosis of GAS at Ann & Robert Lurie Children’s Hospital uses the Illumigene system. Its use has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for diagnosis without the need for backup culture of throat swabs. Results are available in about 1 hour.

Dr. Tanz and his colleagues took a retrospective look at patient records during 2013, when testing was still growth-based, and in 2014 and 2015, after the hospital had shifted to the molecular analysis of throat swabs. The aim was to determine the proportion of tests positive for GAS prior to and after the switch.

The positive detection rate of 9.6% (96 of 997 samples) in 2013 climbed to 17% (152 of 894) in 2014 and 16% (138 of 859) in 2015. The difference was highly significant (P less than .00001).

Sore throats increase in the colder months when people tend to be indoors more often, and this seasonality was evident in 2013. However, detection was more consistent throughout the 12 months in 2014 (2013 vs 2014, P less than .000001) and 2015 (2013 vs 2015, P less than .00001). The detection rates in 2014 and 2015 were similar (P equal to .59), according to Dr. Tanz.

The new era of molecular testing circumvents what is known as the spectrum effect, in which culture-based tests are more often positive in patients with symptoms that are consistent with the infection, he said. In contrast, molecular tests can increase the identification of the target bacterium, here GAS, in patients who have sore throat caused by a viral infection.

Preliminary results presented by Dr. Tanz indicated a significantly greater detection of GAS in children not displaying symptoms of infection. In decades past, these children would not have been treated.

“The increase in positive tests for group A strep is likely associated with increased antibiotic prescribing. This may or may not represent a benefit to patients, as the additional identified patients may not have an illness actually attributable to group A strep,” said Dr. Tanz.

“Our findings support rigorous selectivity in choosing which patients to test, specifically excluding those with overt viral symptoms, as recommended in the guidelines from the [Infectious Diseases Society of America], [American Academy of Pediatrics], and other groups,” he said, adding that clinician guidance on the use of molecular diagnostic tests for pharyngitis caused by group A strep is a prudent step.

Features suggestive of GAS may include sudden onset of sore throat, age 5-15 years, fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, tonsillopharyngeal inflammation and patchy tonsillopharyngeal exudates, palatal petechiae, tender nodes, and scarlatiniform rash. Viral pharyngitis features include conjunctivitis, coryza, cough, diarrhea, discrete ulcerative stomatitis, viral exanthema, and hoarseness, according to the 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of American guidelines (Clin Infect Dis. 2012. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis629).

For most people, a sore throat is more of a temporary inconvenience rather than a looming health threat, but GAS easily spreads from person to person and can lead to the more serious condition of acute rheumatic fever, Dr. Tanz said. Hence the concern with diagnosing the cause of sore throat and, when the cause is bacterial, alleviating the infection using antibiotics.

The study was conducted at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago and was not funded. Dr. Tanz reported having received support from Meridian Bioscience, manufacturer of the Illumigene Group A Streptococcus assay. Meridian Bioscience did not support this study.

Key clinical point: The increased molecular-based detection of group A streptococci could led to antibiotic overuse, with prescriptions for patients who do not have bacterial infections.

Major finding: In the most recent year of culture-based testing at Lurie Children’s Hospital, the detection rate of group A streptococci was 9.6%; detection rates were 17.0% and 16.1% in the next 2 years when molecular-based analysis was implemented.

Data source: Quality assessment study involving a retrospective review of hospital electronic medical records.

Disclosures: The study was conducted at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago and was not funded. Dr. Tanz reported having received support from Meridian Bioscience, manufacturer of the Illumigene Group A Streptococcus assay. Meridian Bioscience did not support this study.

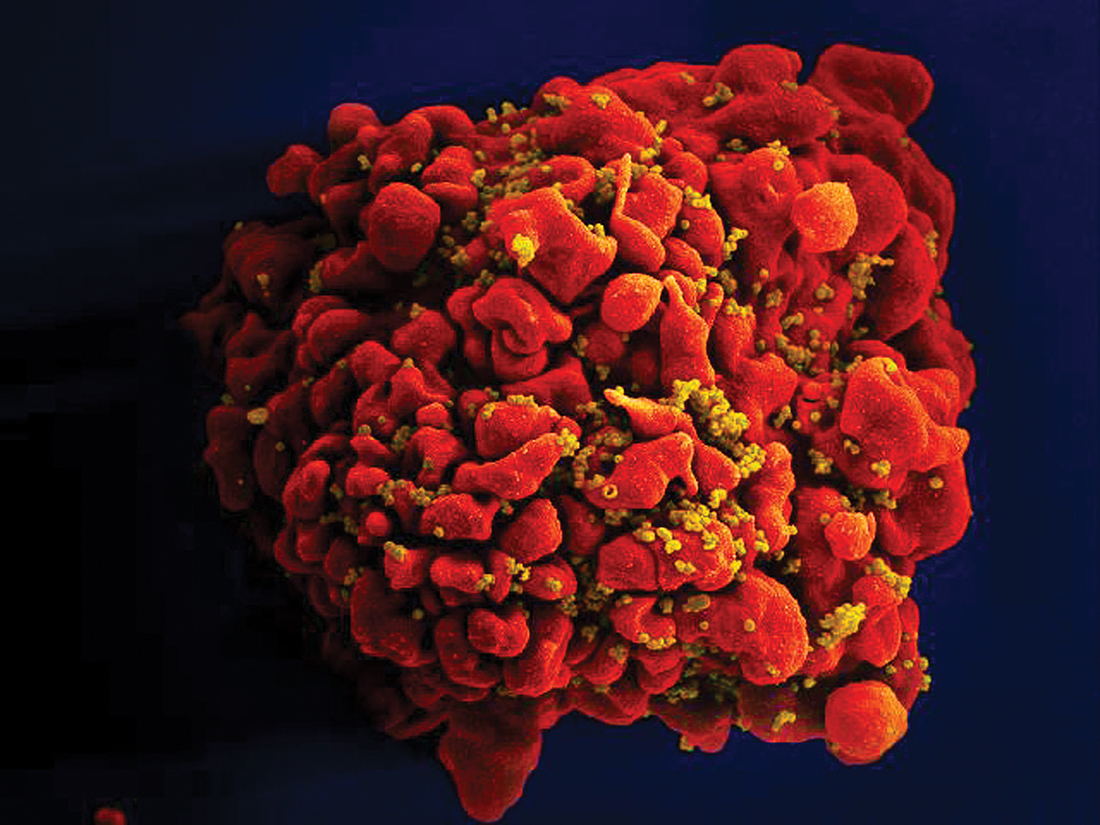

Survival in the first 3 years of ART continues to improve

Mortality continues to decline for patients in the first 3 years of combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) for HIV-1 infection, according to an analysis of 18 different cohorts from 1996 to 2013.

The Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration (ART-CC) combined data from participating cohorts from Europe and North America. Patients were at least 16 years of age, naive to ART, and starting treatment with three or more antiretroviral drugs between 1996 and 2010. Of 88,504 patients, 2% died in the first year of ART, and 3% died in the second or third year of ART.

Where the ART-CC previously reported that mortality within 1 year of starting ART had not improved from 1998 to 2003, the current analysis found lower mortality in the first year for patients starting ART in the years 2008 to 2010, compared with patients starting ART in the years 2000 to 2003 (hazard ratio, 0.71; 95% confidence interval, 0.61-0.83).

All-cause mortality also was decreased in the second and third years of ART for those respective calendar periods (HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.49-0.67).

“Patients who started ART during 2008-2010 whose CD4 counts exceeded 350 cells per microL 1 year after ART initiation have estimated life expectancy approaching that of the general population,” Dr. Trickey and his colleagues said.

The authors speculate that the improvements in mortality may result from better ART regimens and improved adherence. Declines in all-cause mortality may reflect better management of comorbidities.

Given the high effectiveness of ART today, for further improvement “lifestyle issues that affect adherence to ART and non-AIDS mortality, and diagnosis and treatment of comorbidities in people living with HIV will need to be addressed,” Dr. Trickey and his coauthors concluded.

The study received funding from the United Kingdom Medical Research Council, the United Kingdom Department for International Development, and the European Union European & Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP2) program. Dr. Trickey reported no conflicts of interest. Some members of the writing committee received fees from various drug companies for work unrelated to this study.

This article was updated on 5/18/17.

Mortality continues to decline for patients in the first 3 years of combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) for HIV-1 infection, according to an analysis of 18 different cohorts from 1996 to 2013.

The Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration (ART-CC) combined data from participating cohorts from Europe and North America. Patients were at least 16 years of age, naive to ART, and starting treatment with three or more antiretroviral drugs between 1996 and 2010. Of 88,504 patients, 2% died in the first year of ART, and 3% died in the second or third year of ART.

Where the ART-CC previously reported that mortality within 1 year of starting ART had not improved from 1998 to 2003, the current analysis found lower mortality in the first year for patients starting ART in the years 2008 to 2010, compared with patients starting ART in the years 2000 to 2003 (hazard ratio, 0.71; 95% confidence interval, 0.61-0.83).

All-cause mortality also was decreased in the second and third years of ART for those respective calendar periods (HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.49-0.67).

“Patients who started ART during 2008-2010 whose CD4 counts exceeded 350 cells per microL 1 year after ART initiation have estimated life expectancy approaching that of the general population,” Dr. Trickey and his colleagues said.

The authors speculate that the improvements in mortality may result from better ART regimens and improved adherence. Declines in all-cause mortality may reflect better management of comorbidities.

Given the high effectiveness of ART today, for further improvement “lifestyle issues that affect adherence to ART and non-AIDS mortality, and diagnosis and treatment of comorbidities in people living with HIV will need to be addressed,” Dr. Trickey and his coauthors concluded.

The study received funding from the United Kingdom Medical Research Council, the United Kingdom Department for International Development, and the European Union European & Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP2) program. Dr. Trickey reported no conflicts of interest. Some members of the writing committee received fees from various drug companies for work unrelated to this study.

This article was updated on 5/18/17.

Mortality continues to decline for patients in the first 3 years of combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) for HIV-1 infection, according to an analysis of 18 different cohorts from 1996 to 2013.

The Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration (ART-CC) combined data from participating cohorts from Europe and North America. Patients were at least 16 years of age, naive to ART, and starting treatment with three or more antiretroviral drugs between 1996 and 2010. Of 88,504 patients, 2% died in the first year of ART, and 3% died in the second or third year of ART.

Where the ART-CC previously reported that mortality within 1 year of starting ART had not improved from 1998 to 2003, the current analysis found lower mortality in the first year for patients starting ART in the years 2008 to 2010, compared with patients starting ART in the years 2000 to 2003 (hazard ratio, 0.71; 95% confidence interval, 0.61-0.83).

All-cause mortality also was decreased in the second and third years of ART for those respective calendar periods (HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.49-0.67).

“Patients who started ART during 2008-2010 whose CD4 counts exceeded 350 cells per microL 1 year after ART initiation have estimated life expectancy approaching that of the general population,” Dr. Trickey and his colleagues said.

The authors speculate that the improvements in mortality may result from better ART regimens and improved adherence. Declines in all-cause mortality may reflect better management of comorbidities.

Given the high effectiveness of ART today, for further improvement “lifestyle issues that affect adherence to ART and non-AIDS mortality, and diagnosis and treatment of comorbidities in people living with HIV will need to be addressed,” Dr. Trickey and his coauthors concluded.

The study received funding from the United Kingdom Medical Research Council, the United Kingdom Department for International Development, and the European Union European & Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP2) program. Dr. Trickey reported no conflicts of interest. Some members of the writing committee received fees from various drug companies for work unrelated to this study.

This article was updated on 5/18/17.

FROM THE LANCET HIV

Key clinical point: Mortality continues to decline for patients in the first 3 years of taking ART for HIV-1 infection.

Major finding: The current analysis found lower mortality in the first year for patients starting ART in the years 2008 to 2010, compared with patients starting ART in the years 2000 to 2003 (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.61-0.83).

Data source: An analysis of 18 different cohorts in Europe and North America from 1996 to 2013.

Disclosures: The study received funding from the United Kingdom Medical Research Council, the United Kingdom Department for International Development, and the European Union European & Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP2) program. Some members of the writing committee received fees from various drug companies for work unrelated to this study.

Children exposed to violence show accelerated cellular aging

SAN FRANCISCO – Children exposed to high levels of urban violence demonstrate accelerated cellular aging beyond their chronologic years, Vasiliki Michopoulos, PhD, reported at the annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

This fast-running cellular biologic clock is not a good thing. Neither is their blunted heart rate variability in response to stress, an indicator of autonomic dysfunction that constitutes a cardiovascular risk factor, she added.

Accelerated cellular aging as measured by DNA methylation in blood or saliva samples has become a red hot research area. Investigators have shown that a person’s DNA methylation age, also known as epigenetic age, predicts all-cause mortality risk in later life. In adults, accelerated cellular aging as reflected in a 5-year discrepancy between DNA methylation age and chronologic age is predictive of an adjusted 16% increased mortality risk independent of social class, education level, lifestyle factors, and chronic diseases, including diabetes and cardiovascular disease (Genome Biol. 2015 Jan 30;16:25).

Lifetime exposure to stress has been convincingly shown to accelerate epigenetic aging, as reflected by DNA methylation level. But, prior to Dr. Michopoulos’s study, it wasn’t known if exposure to violence during childhood influences epigenetic aging or if perhaps only later-life trauma is relevant.

To address this question, she and her coinvestigators recruited 101 African American children aged 6-11 years and their mothers. Of note, medical attention wasn’t being sought for the children. Rather, their mothers were approached regarding study participation while attending primary care clinics at Atlanta’s Grady Memorial Hospital. Children were not eligible to participate if they had been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, bipolar disorder, cognitive impairment, or a psychotic disorder.

The children had been exposed to a lot of violence, both witnessed and directly experienced, as reflected in their mean total score of 18.9 on the Violence Exposure Scale for Children-Revised (VEX-R). More than 80% of the children had witnessed an assault and 30% a murder. Stabbings, shootings, drug trafficking, and arrests were other common exposures.

One-quarter of the children showed accelerated cellular aging. They had experienced twice as much violence exposure as reflected in their VEX-R scores, compared with children whose epigenetic and chronologic ages were the same.

The children with accelerated cellular aging also demonstrated decreased heart rate variability in response to a standardized stressor, which involved a startle experience in a darkened room. Their heart rate in the stressor situation shot up on average by 17 bpm less than the children whose cellular age as measured by DNA methylation matched their chronologic age.

“Our data suggest that DNA methylation may serve as a biomarker by which to identify at-risk individuals who may benefit from interventions that decrease risk for cardiometabolic disorders in adulthood,” Dr. Michopoulos said. “It’ll be really interesting to see, as these kids grow up and develop, whether their phenotype stays static, reverses, or changes completely.”