User login

Troublesome Foreign Bodies

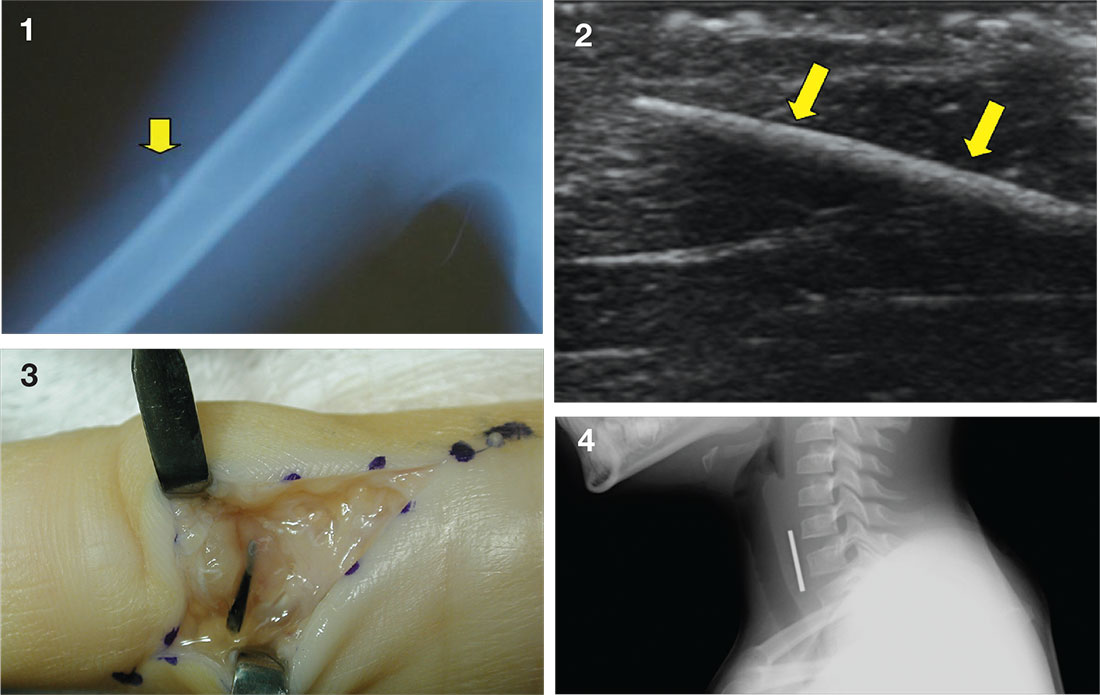

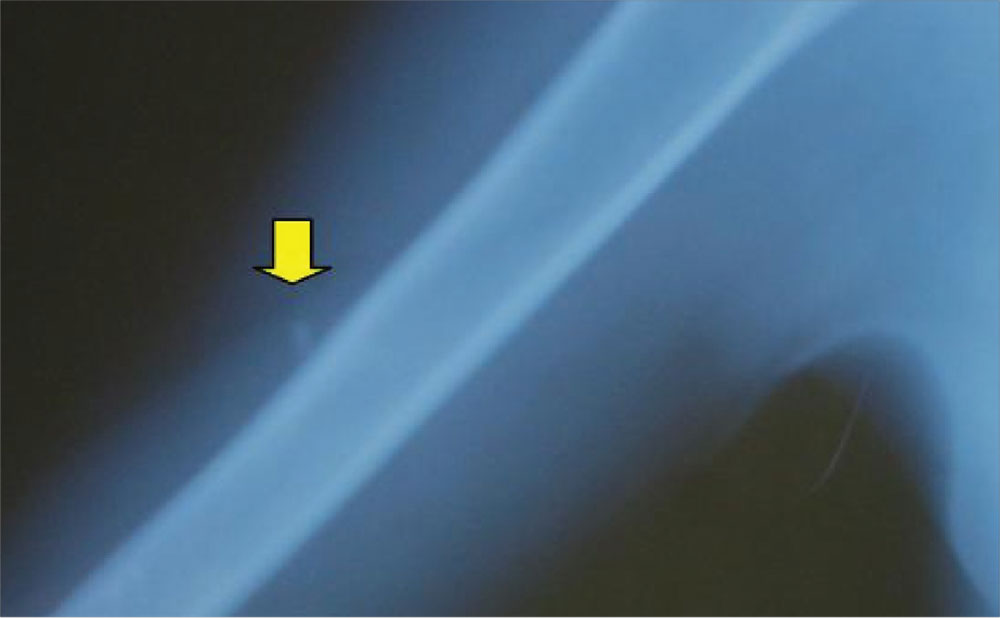

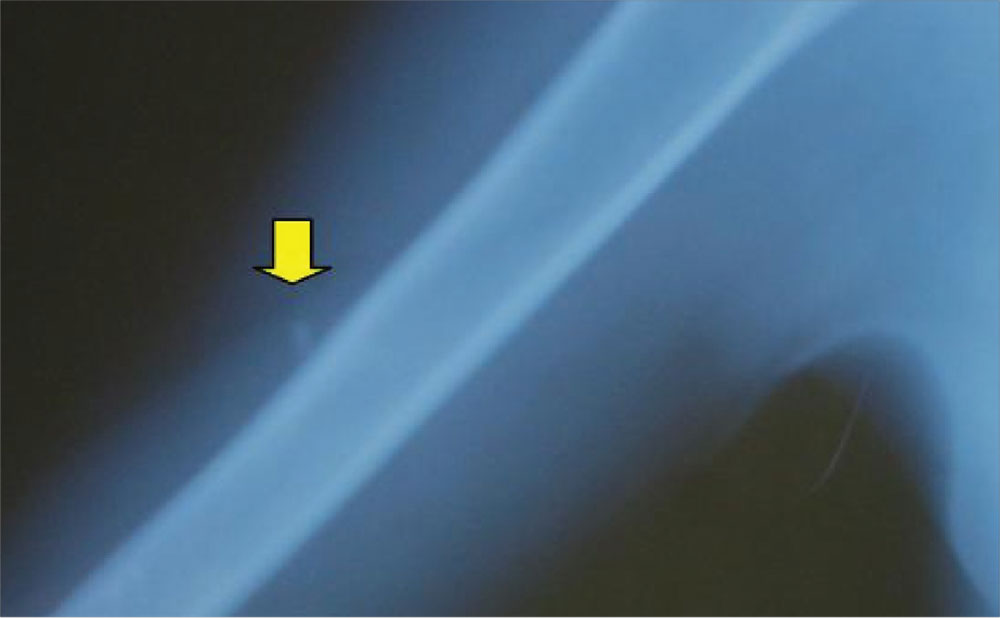

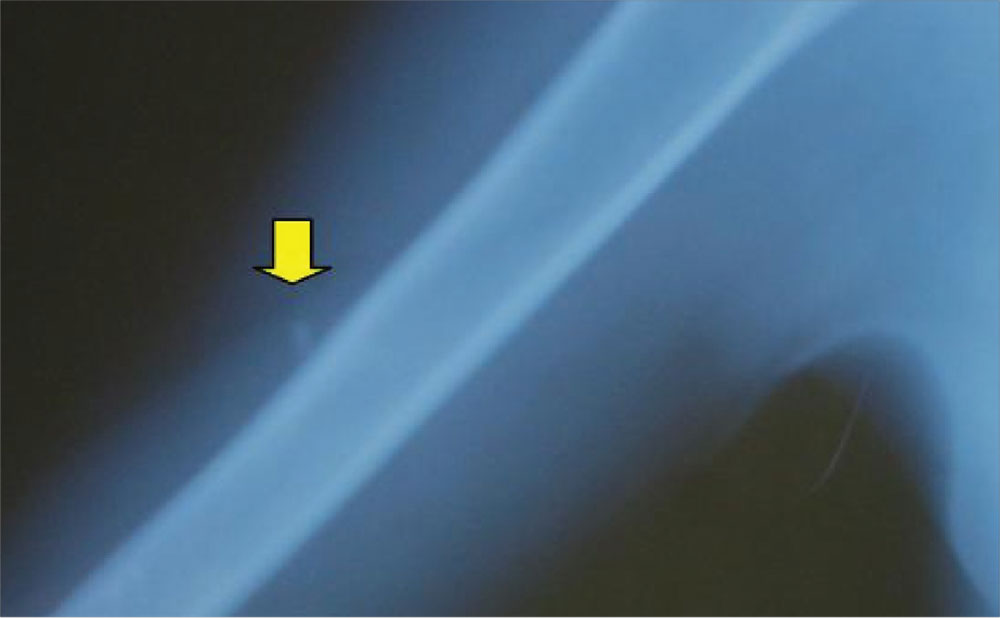

Case a. A 30-month-old boy, who is in obvious distress with a barking cough and croup-like symptoms but no fever, is brought by his mother for examination. History is unremarkable except for a recent choking episode. A radiograph is ordered.

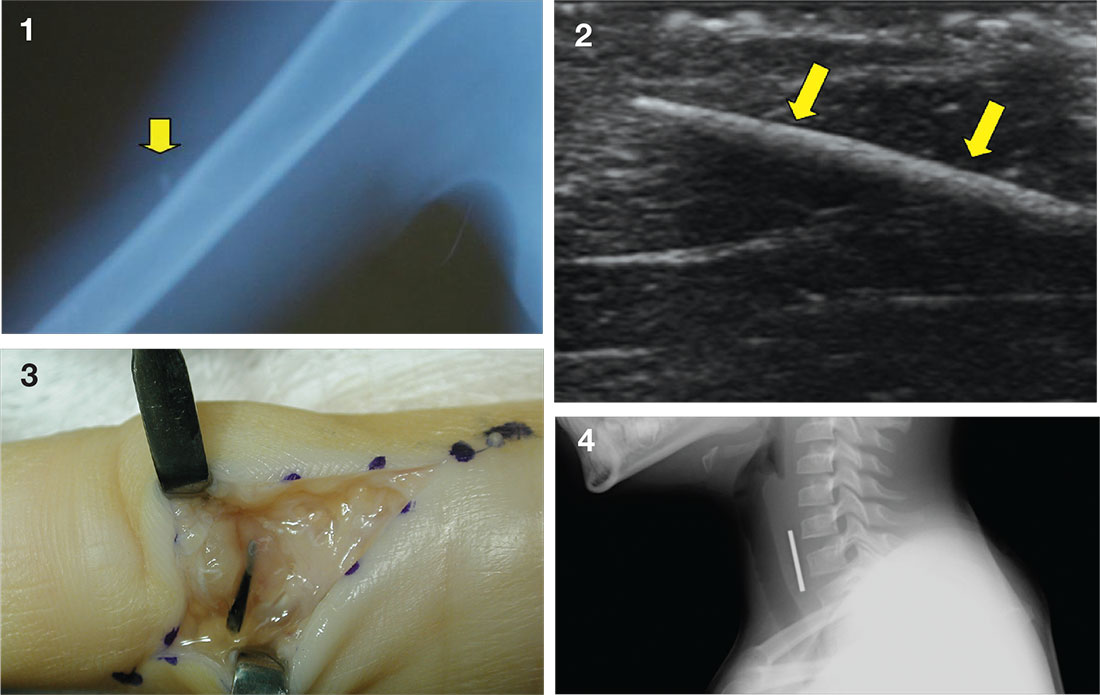

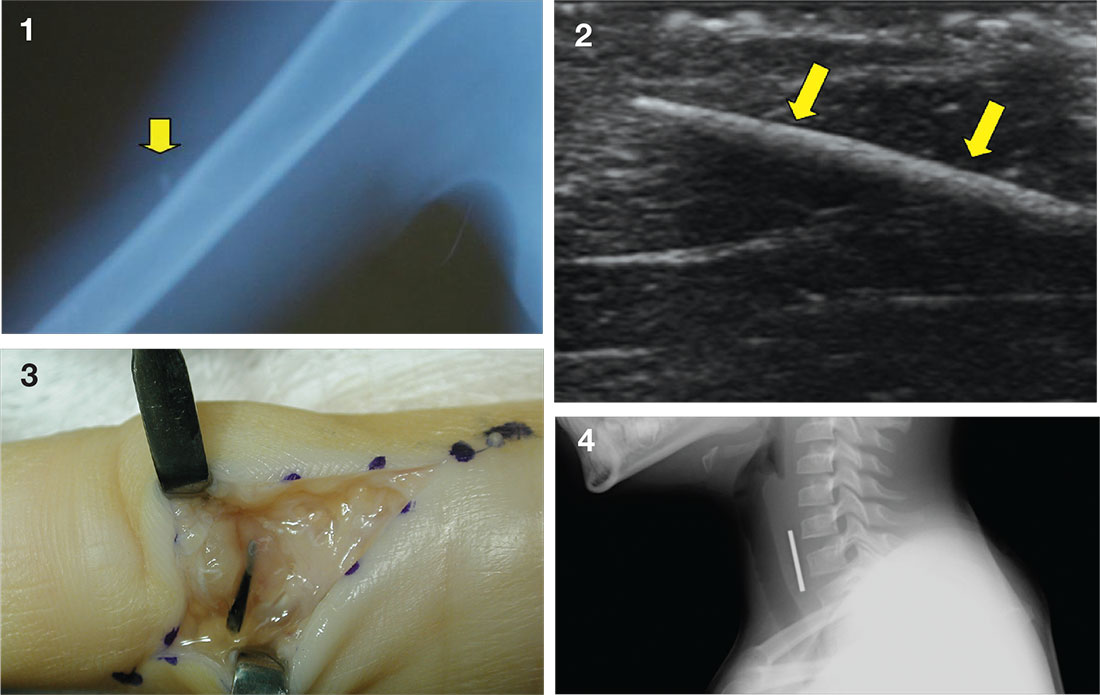

Case b. A 13-year-old girl presents to urgent care with a laceration that occurred when she fell through a glass door. You note a 2-cm linear laceration, and radiography shows what appears to be a residual piece of glass at or near the site of the laceration.

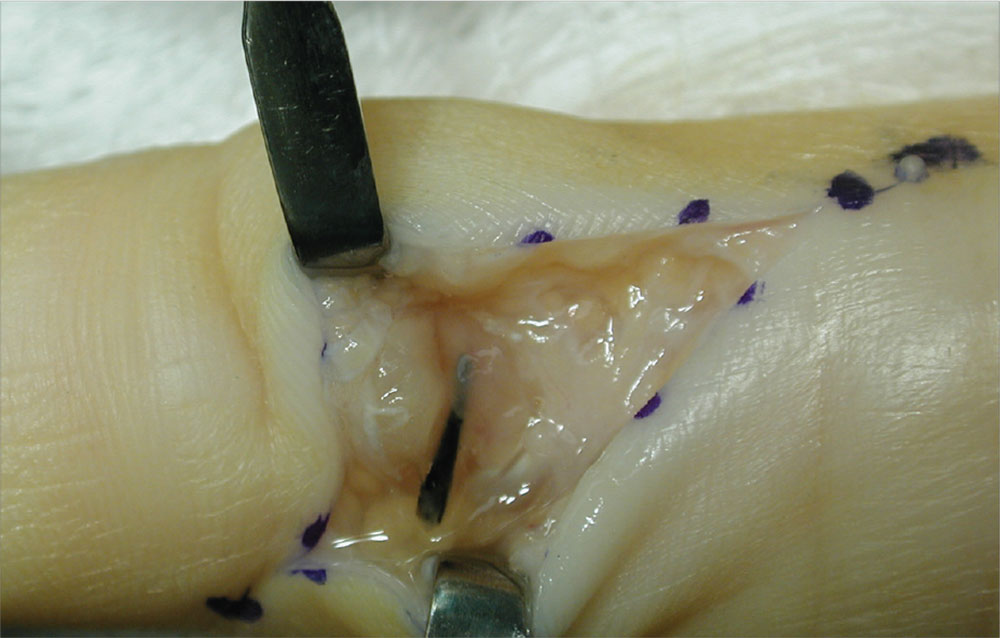

Case c. This patient was punctured by a sago palm thorn, but believes that she removed the entire thorn at the time of injury. A small puncture wound is seen on physical exam, and x-rays are unremarkable. The patient is placed on a 10-day course of oral cephalexin. At follow-up, she has swelling in an adjacent finger.

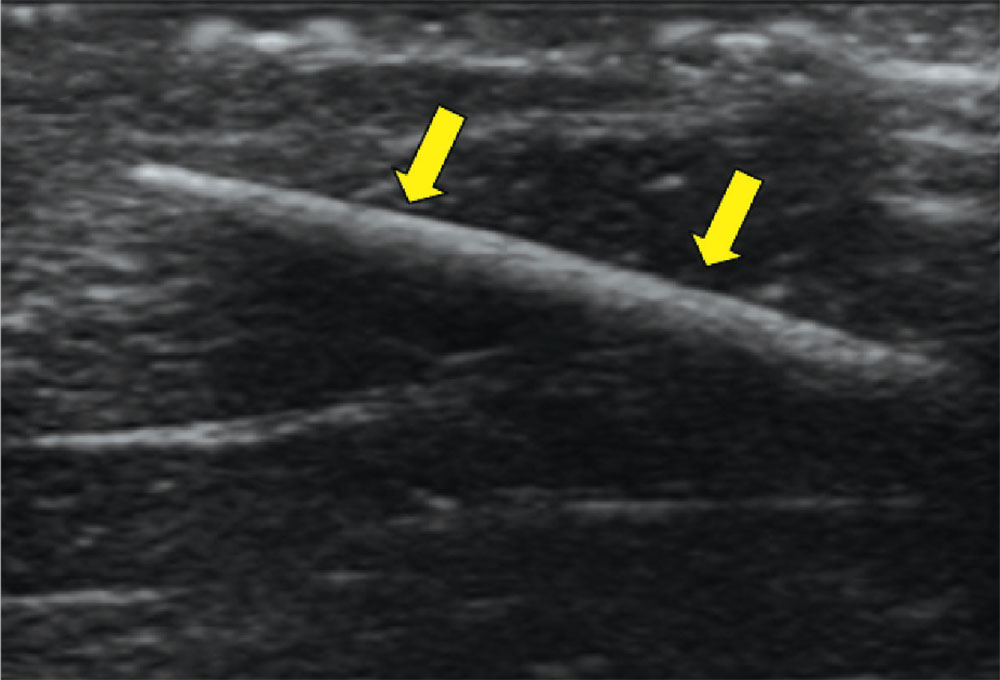

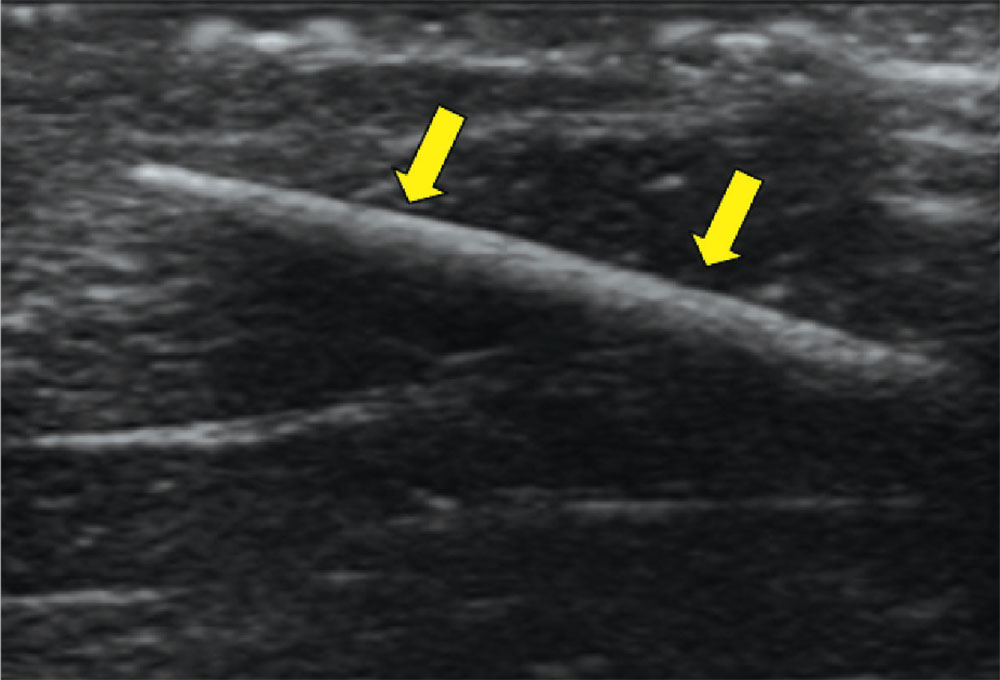

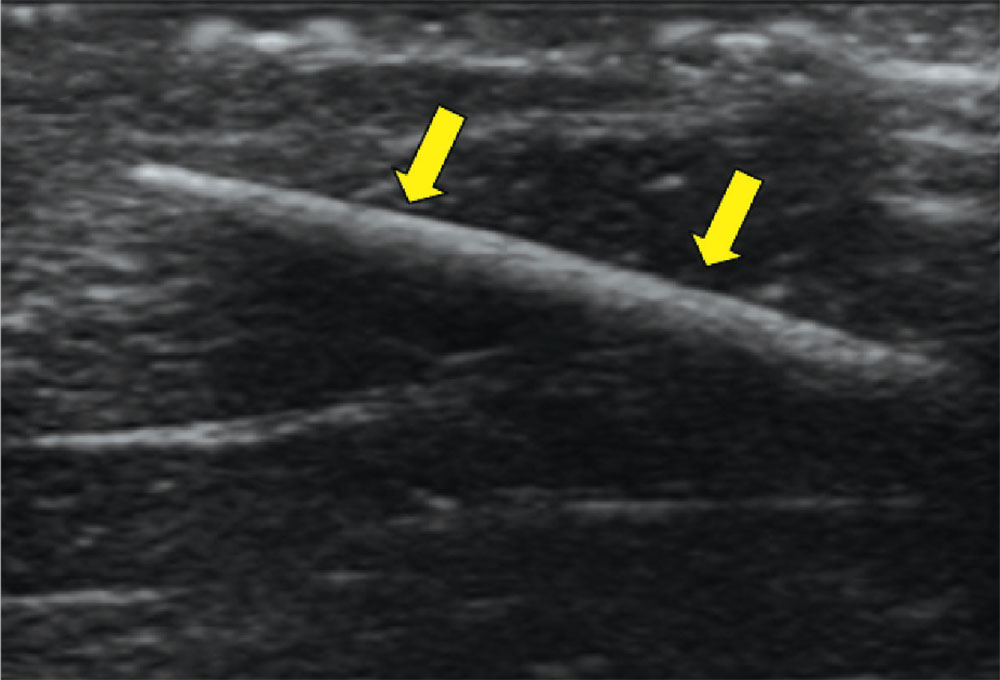

Case d. A 2-year-old boy complains of pain after stepping on a toothpick. His father suspects that part of the toothpick remains embedded. Examination reveals a plantar puncture wound but no sign of a foreign body. Radiography shows no deformity. An ultrasound is ordered and reveals a toothpick segment.

Case a. A 30-month-old boy, who is in obvious distress with a barking cough and croup-like symptoms but no fever, is brought by his mother for examination. History is unremarkable except for a recent choking episode. A radiograph is ordered.

Complete obstruction should be treated with back blows in a child aged less than 1 year and abdominal thrusts in an older child. In a more stable child, provide supplemental oxygen and consult a physician skilled in laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy for removal of the foreign body. Esophageal foreign bodies may also cause stridor. In these cases the child will often complain of dysphagia or avoid swallowing.

While some objects, such as coins, can be visualized on plain imaging, a negative film does not rule out a foreign body and a specialist should be consulted for endoscopy. A coin in the trachea will be seen on its edge in an anteroposterior view. In the esophagus, it will generally appear as a full circle (en face) in an anteroposterior oblique view. For the lateral view, it is just the opposite, as seen in the case figure.

For more information, see “Differential Diagnosis of Stridor in Children.” Emergency Medicine. 2009 September;41(9):10-11.

Case b. A 13-year-old girl presents to urgent care with a laceration that occurred when she fell through a glass door. You note a 2-cm linear laceration, and radiography shows what appears to be a residual piece of glass at or near the site of the laceration.

You anesthetize the area and begin dissection in an attempt to locate the glass fragment, which goes on for 20 minutes without success. The child and her mother are becoming anxious. You call for the portable ultrasound system, and using its high-frequency transducer, quickly locate the foreign body. After additional anesthesia is applied, the splinter is easily removed under ultrasound guidance and the patient is discharged.

For more information, see “Capturing Elusive Foreign Bodies With Ultrasound.” Emergency Medicine. 2009 June;41(6):36-42.

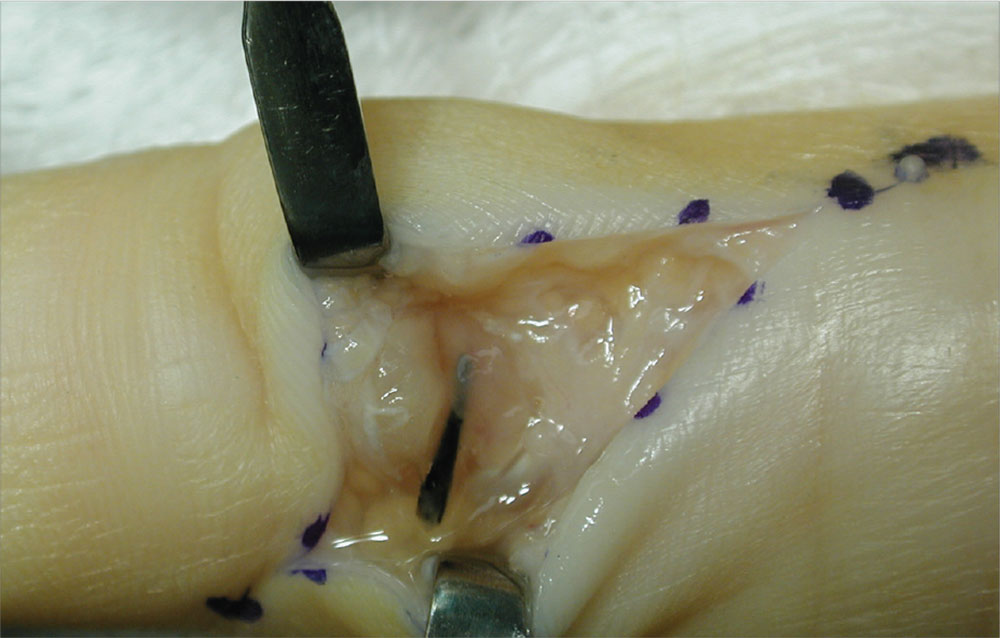

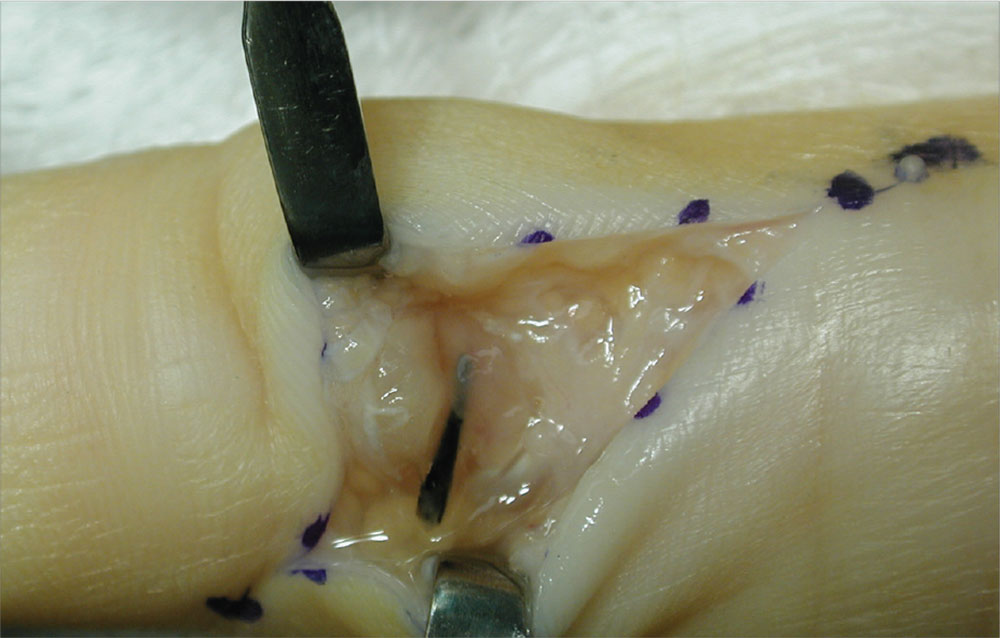

Case c. This patient was punctured by a sago palm thorn, but believes that she removed the entire thorn at the time of injury. A small puncture wound is seen on physical exam, and x-rays are unremarkable. The patient is placed on a 10-day course of oral cephalexin. At follow-up, she has swelling in an adjacent finger.

The palmar puncture wound site was surgically explored, and no foreign body fragments were found. In addition, the tendons, retracted and delivered through the skin incision, appeared normal.

Histopathology of a specimen intraoperatively biopsied from the flexor tendon sheath showed some refractile foreign material consistent with plant material. After surgery, swelling persisted, and the patient developed limited motion at the extremes of active flexion and extension.

After 2 months, the decision was made to re-explore the palmar puncture site and flexor tendon and obtain tissue specimens for culture, including atypical mycobacterial and fungal cultures. During the second surgery, the palmar site and flexor tendon still appeared unremarkable. As there was some swelling in the long finger, the flexor tendon sheath was explored distally through a separate incision over the middle phalanx. A transversely oriented fragment of the sago palm thorn was found within the flexor tendon sheath. Flexor tendon sheath material was cultured and subsequently found to be negative.

For more information, see “Distal Migration of a Foreign Body (Sago Palm Thorn Fragment) Within the Long-Finger Flexor Tendon Sheath.” Am J Orthop. 2008;37(4):208-209.

Case d. A 2-year-old boy complains of pain after stepping on a toothpick. His father suspects that part of the toothpick remains embedded. Examination reveals a plantar puncture wound but no sign of a foreign body. Radiography shows no deformity. An ultrasound is ordered and reveals a toothpick segment.

With local anesthesia and ultrasound guidance, the splinter is easily removed and the patient is discharged.

For more information, see “Capturing Elusive Foreign Bodies With Ultrasound.” Emergency Medicine. 2009 June;41(6):36-42.

Case a. A 30-month-old boy, who is in obvious distress with a barking cough and croup-like symptoms but no fever, is brought by his mother for examination. History is unremarkable except for a recent choking episode. A radiograph is ordered.

Case b. A 13-year-old girl presents to urgent care with a laceration that occurred when she fell through a glass door. You note a 2-cm linear laceration, and radiography shows what appears to be a residual piece of glass at or near the site of the laceration.

Case c. This patient was punctured by a sago palm thorn, but believes that she removed the entire thorn at the time of injury. A small puncture wound is seen on physical exam, and x-rays are unremarkable. The patient is placed on a 10-day course of oral cephalexin. At follow-up, she has swelling in an adjacent finger.

Case d. A 2-year-old boy complains of pain after stepping on a toothpick. His father suspects that part of the toothpick remains embedded. Examination reveals a plantar puncture wound but no sign of a foreign body. Radiography shows no deformity. An ultrasound is ordered and reveals a toothpick segment.

Case a. A 30-month-old boy, who is in obvious distress with a barking cough and croup-like symptoms but no fever, is brought by his mother for examination. History is unremarkable except for a recent choking episode. A radiograph is ordered.

Complete obstruction should be treated with back blows in a child aged less than 1 year and abdominal thrusts in an older child. In a more stable child, provide supplemental oxygen and consult a physician skilled in laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy for removal of the foreign body. Esophageal foreign bodies may also cause stridor. In these cases the child will often complain of dysphagia or avoid swallowing.

While some objects, such as coins, can be visualized on plain imaging, a negative film does not rule out a foreign body and a specialist should be consulted for endoscopy. A coin in the trachea will be seen on its edge in an anteroposterior view. In the esophagus, it will generally appear as a full circle (en face) in an anteroposterior oblique view. For the lateral view, it is just the opposite, as seen in the case figure.

For more information, see “Differential Diagnosis of Stridor in Children.” Emergency Medicine. 2009 September;41(9):10-11.

Case b. A 13-year-old girl presents to urgent care with a laceration that occurred when she fell through a glass door. You note a 2-cm linear laceration, and radiography shows what appears to be a residual piece of glass at or near the site of the laceration.

You anesthetize the area and begin dissection in an attempt to locate the glass fragment, which goes on for 20 minutes without success. The child and her mother are becoming anxious. You call for the portable ultrasound system, and using its high-frequency transducer, quickly locate the foreign body. After additional anesthesia is applied, the splinter is easily removed under ultrasound guidance and the patient is discharged.

For more information, see “Capturing Elusive Foreign Bodies With Ultrasound.” Emergency Medicine. 2009 June;41(6):36-42.

Case c. This patient was punctured by a sago palm thorn, but believes that she removed the entire thorn at the time of injury. A small puncture wound is seen on physical exam, and x-rays are unremarkable. The patient is placed on a 10-day course of oral cephalexin. At follow-up, she has swelling in an adjacent finger.

The palmar puncture wound site was surgically explored, and no foreign body fragments were found. In addition, the tendons, retracted and delivered through the skin incision, appeared normal.

Histopathology of a specimen intraoperatively biopsied from the flexor tendon sheath showed some refractile foreign material consistent with plant material. After surgery, swelling persisted, and the patient developed limited motion at the extremes of active flexion and extension.

After 2 months, the decision was made to re-explore the palmar puncture site and flexor tendon and obtain tissue specimens for culture, including atypical mycobacterial and fungal cultures. During the second surgery, the palmar site and flexor tendon still appeared unremarkable. As there was some swelling in the long finger, the flexor tendon sheath was explored distally through a separate incision over the middle phalanx. A transversely oriented fragment of the sago palm thorn was found within the flexor tendon sheath. Flexor tendon sheath material was cultured and subsequently found to be negative.

For more information, see “Distal Migration of a Foreign Body (Sago Palm Thorn Fragment) Within the Long-Finger Flexor Tendon Sheath.” Am J Orthop. 2008;37(4):208-209.

Case d. A 2-year-old boy complains of pain after stepping on a toothpick. His father suspects that part of the toothpick remains embedded. Examination reveals a plantar puncture wound but no sign of a foreign body. Radiography shows no deformity. An ultrasound is ordered and reveals a toothpick segment.

With local anesthesia and ultrasound guidance, the splinter is easily removed and the patient is discharged.

For more information, see “Capturing Elusive Foreign Bodies With Ultrasound.” Emergency Medicine. 2009 June;41(6):36-42.

Case a. A 30-month-old boy, who is in obvious distress with a barking cough and croup-like symptoms but no fever, is brought by his mother for examination. History is unremarkable except for a recent choking episode. A radiograph is ordered.

Case b. A 13-year-old girl presents to urgent care with a laceration that occurred when she fell through a glass door. You note a 2-cm linear laceration, and radiography shows what appears to be a residual piece of glass at or near the site of the laceration.

Case c. This patient was punctured by a sago palm thorn, but believes that she removed the entire thorn at the time of injury. A small puncture wound is seen on physical exam, and x-rays are unremarkable. The patient is placed on a 10-day course of oral cephalexin. At follow-up, she has swelling in an adjacent finger.

Case d. A 2-year-old boy complains of pain after stepping on a toothpick. His father suspects that part of the toothpick remains embedded. Examination reveals a plantar puncture wound but no sign of a foreign body. Radiography shows no deformity. An ultrasound is ordered and reveals a toothpick segment.

Case a. A 30-month-old boy, who is in obvious distress with a barking cough and croup-like symptoms but no fever, is brought by his mother for examination. History is unremarkable except for a recent choking episode. A radiograph is ordered.

Complete obstruction should be treated with back blows in a child aged less than 1 year and abdominal thrusts in an older child. In a more stable child, provide supplemental oxygen and consult a physician skilled in laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy for removal of the foreign body. Esophageal foreign bodies may also cause stridor. In these cases the child will often complain of dysphagia or avoid swallowing.

While some objects, such as coins, can be visualized on plain imaging, a negative film does not rule out a foreign body and a specialist should be consulted for endoscopy. A coin in the trachea will be seen on its edge in an anteroposterior view. In the esophagus, it will generally appear as a full circle (en face) in an anteroposterior oblique view. For the lateral view, it is just the opposite, as seen in the case figure.

For more information, see “Differential Diagnosis of Stridor in Children.” Emergency Medicine. 2009 September;41(9):10-11.

Case b. A 13-year-old girl presents to urgent care with a laceration that occurred when she fell through a glass door. You note a 2-cm linear laceration, and radiography shows what appears to be a residual piece of glass at or near the site of the laceration.

You anesthetize the area and begin dissection in an attempt to locate the glass fragment, which goes on for 20 minutes without success. The child and her mother are becoming anxious. You call for the portable ultrasound system, and using its high-frequency transducer, quickly locate the foreign body. After additional anesthesia is applied, the splinter is easily removed under ultrasound guidance and the patient is discharged.

For more information, see “Capturing Elusive Foreign Bodies With Ultrasound.” Emergency Medicine. 2009 June;41(6):36-42.

Case c. This patient was punctured by a sago palm thorn, but believes that she removed the entire thorn at the time of injury. A small puncture wound is seen on physical exam, and x-rays are unremarkable. The patient is placed on a 10-day course of oral cephalexin. At follow-up, she has swelling in an adjacent finger.

The palmar puncture wound site was surgically explored, and no foreign body fragments were found. In addition, the tendons, retracted and delivered through the skin incision, appeared normal.

Histopathology of a specimen intraoperatively biopsied from the flexor tendon sheath showed some refractile foreign material consistent with plant material. After surgery, swelling persisted, and the patient developed limited motion at the extremes of active flexion and extension.

After 2 months, the decision was made to re-explore the palmar puncture site and flexor tendon and obtain tissue specimens for culture, including atypical mycobacterial and fungal cultures. During the second surgery, the palmar site and flexor tendon still appeared unremarkable. As there was some swelling in the long finger, the flexor tendon sheath was explored distally through a separate incision over the middle phalanx. A transversely oriented fragment of the sago palm thorn was found within the flexor tendon sheath. Flexor tendon sheath material was cultured and subsequently found to be negative.

For more information, see “Distal Migration of a Foreign Body (Sago Palm Thorn Fragment) Within the Long-Finger Flexor Tendon Sheath.” Am J Orthop. 2008;37(4):208-209.

Case d. A 2-year-old boy complains of pain after stepping on a toothpick. His father suspects that part of the toothpick remains embedded. Examination reveals a plantar puncture wound but no sign of a foreign body. Radiography shows no deformity. An ultrasound is ordered and reveals a toothpick segment.

With local anesthesia and ultrasound guidance, the splinter is easily removed and the patient is discharged.

For more information, see “Capturing Elusive Foreign Bodies With Ultrasound.” Emergency Medicine. 2009 June;41(6):36-42.

Study: Most oncologists don’t discuss exercise with patients

Results of a small, single-center study suggest oncologists may not provide cancer patients with adequate guidance on exercise.

A majority of the patients and oncologists surveyed for this study placed importance on exercise during cancer care, but most of the oncologists failed to give patients recommendations on exercise.

“Our results indicate that exercise is perceived as important to patients with cancer, both from a patient and physician perspective,” said study author Agnes Smaradottir, MD, of Gundersen Health System in La Crosse, Wisconsin.

“However, physicians are reluctant to consistently include [physical activity] recommendations in their patient discussions.”

Dr Smaradottir and her colleagues reported these findings in JNCCN.

The researchers surveyed 20 cancer patients and 9 oncologists for this study.

The patients’ mean age was 64. Ten patients had stage I-III non-metastatic cancer after adjuvant therapy, and 10 had stage IV metastatic disease and were undergoing palliative treatment. Most patients had solid tumor malignancies, but 1 had chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

The oncologists’ mean age was 45, 56% were male, and they had a mean of 12 years of practice. Most (89%) said they exercise on a regular basis.

Discussions

Nineteen (95%) of the patients surveyed felt they benefited from exercise during treatment, but only 3 of the patients recalled being instructed to exercise.

Exercise was felt to be an equally important part of treatment and well-being for patients with early stage cancer treated with curative intent as well as patients receiving palliative therapy.

Although all the oncologists noted that exercise can benefit cancer patients, only 1 of the 9 surveyed documented discussion of exercise in patient charts.

Preferences and concerns

More than 80% of the patients said they would prefer a home-based exercise regimen that could be performed in alignment with their personal schedules and symptoms.

Patients also noted a preference that exercise recommendations come from their oncologists, as they have an established relationship and feel their oncologists best understand the complexities of their personalized treatment plans.

The oncologists, on the other hand, wanted to refer patients to specialist care for exercise recommendations. Reasons for this included the oncologists’ mounting clinic schedules and a lack of education about appropriate physical activity recommendations for patients.

The oncologists also expressed concern about asking patients to be more physically active during chemotherapy and radiation and expressed trepidation about prescribing exercise to frail patients with limited mobility.

“We were surprised by the gap in expectations regarding exercise recommendation between patients and providers,” Dr Smaradottir said. “Many providers, ourselves included, thought patients would prefer to be referred to an exercise center, but they clearly preferred to have a home-based program recommended by their oncologist.”

“Our findings highlight the value of examining both patient and provider attitudes and behavioral intentions. While we uncovered barriers to exercise recommendations, questions remain on how to bridge the gap between patient and provider preferences.” ![]()

Results of a small, single-center study suggest oncologists may not provide cancer patients with adequate guidance on exercise.

A majority of the patients and oncologists surveyed for this study placed importance on exercise during cancer care, but most of the oncologists failed to give patients recommendations on exercise.

“Our results indicate that exercise is perceived as important to patients with cancer, both from a patient and physician perspective,” said study author Agnes Smaradottir, MD, of Gundersen Health System in La Crosse, Wisconsin.

“However, physicians are reluctant to consistently include [physical activity] recommendations in their patient discussions.”

Dr Smaradottir and her colleagues reported these findings in JNCCN.

The researchers surveyed 20 cancer patients and 9 oncologists for this study.

The patients’ mean age was 64. Ten patients had stage I-III non-metastatic cancer after adjuvant therapy, and 10 had stage IV metastatic disease and were undergoing palliative treatment. Most patients had solid tumor malignancies, but 1 had chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

The oncologists’ mean age was 45, 56% were male, and they had a mean of 12 years of practice. Most (89%) said they exercise on a regular basis.

Discussions

Nineteen (95%) of the patients surveyed felt they benefited from exercise during treatment, but only 3 of the patients recalled being instructed to exercise.

Exercise was felt to be an equally important part of treatment and well-being for patients with early stage cancer treated with curative intent as well as patients receiving palliative therapy.

Although all the oncologists noted that exercise can benefit cancer patients, only 1 of the 9 surveyed documented discussion of exercise in patient charts.

Preferences and concerns

More than 80% of the patients said they would prefer a home-based exercise regimen that could be performed in alignment with their personal schedules and symptoms.

Patients also noted a preference that exercise recommendations come from their oncologists, as they have an established relationship and feel their oncologists best understand the complexities of their personalized treatment plans.

The oncologists, on the other hand, wanted to refer patients to specialist care for exercise recommendations. Reasons for this included the oncologists’ mounting clinic schedules and a lack of education about appropriate physical activity recommendations for patients.

The oncologists also expressed concern about asking patients to be more physically active during chemotherapy and radiation and expressed trepidation about prescribing exercise to frail patients with limited mobility.

“We were surprised by the gap in expectations regarding exercise recommendation between patients and providers,” Dr Smaradottir said. “Many providers, ourselves included, thought patients would prefer to be referred to an exercise center, but they clearly preferred to have a home-based program recommended by their oncologist.”

“Our findings highlight the value of examining both patient and provider attitudes and behavioral intentions. While we uncovered barriers to exercise recommendations, questions remain on how to bridge the gap between patient and provider preferences.” ![]()

Results of a small, single-center study suggest oncologists may not provide cancer patients with adequate guidance on exercise.

A majority of the patients and oncologists surveyed for this study placed importance on exercise during cancer care, but most of the oncologists failed to give patients recommendations on exercise.

“Our results indicate that exercise is perceived as important to patients with cancer, both from a patient and physician perspective,” said study author Agnes Smaradottir, MD, of Gundersen Health System in La Crosse, Wisconsin.

“However, physicians are reluctant to consistently include [physical activity] recommendations in their patient discussions.”

Dr Smaradottir and her colleagues reported these findings in JNCCN.

The researchers surveyed 20 cancer patients and 9 oncologists for this study.

The patients’ mean age was 64. Ten patients had stage I-III non-metastatic cancer after adjuvant therapy, and 10 had stage IV metastatic disease and were undergoing palliative treatment. Most patients had solid tumor malignancies, but 1 had chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

The oncologists’ mean age was 45, 56% were male, and they had a mean of 12 years of practice. Most (89%) said they exercise on a regular basis.

Discussions

Nineteen (95%) of the patients surveyed felt they benefited from exercise during treatment, but only 3 of the patients recalled being instructed to exercise.

Exercise was felt to be an equally important part of treatment and well-being for patients with early stage cancer treated with curative intent as well as patients receiving palliative therapy.

Although all the oncologists noted that exercise can benefit cancer patients, only 1 of the 9 surveyed documented discussion of exercise in patient charts.

Preferences and concerns

More than 80% of the patients said they would prefer a home-based exercise regimen that could be performed in alignment with their personal schedules and symptoms.

Patients also noted a preference that exercise recommendations come from their oncologists, as they have an established relationship and feel their oncologists best understand the complexities of their personalized treatment plans.

The oncologists, on the other hand, wanted to refer patients to specialist care for exercise recommendations. Reasons for this included the oncologists’ mounting clinic schedules and a lack of education about appropriate physical activity recommendations for patients.

The oncologists also expressed concern about asking patients to be more physically active during chemotherapy and radiation and expressed trepidation about prescribing exercise to frail patients with limited mobility.

“We were surprised by the gap in expectations regarding exercise recommendation between patients and providers,” Dr Smaradottir said. “Many providers, ourselves included, thought patients would prefer to be referred to an exercise center, but they clearly preferred to have a home-based program recommended by their oncologist.”

“Our findings highlight the value of examining both patient and provider attitudes and behavioral intentions. While we uncovered barriers to exercise recommendations, questions remain on how to bridge the gap between patient and provider preferences.” ![]()

System monitors and maintains drug levels in the body

New technology could make it easier to ensure patients receive the correct dose of chemotherapy and other drugs, according to research published in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

Researchers developed a closed-loop system that was able to continuously regulate drug levels in rabbits and rats.

“This is the first time anyone has been able to continuously control the drug levels in the body in real time,” said study author H. Tom Soh, PhD, of Stanford University in California.

“This is a novel concept with big implications because we believe we can adapt our technology to control the levels of a wide range of drugs.”

The researchers’ system has 3 basic components: a real-time biosensor to continuously monitor drug levels in the bloodstream, a control system to calculate the right dose, and a programmable pump that delivers just enough medicine to maintain a desired dose.

The sensor contains aptamers that are specially designed to bind a drug of interest. When the drug is present in the bloodstream, the aptamer changes shape, which an electric sensor detects. The more drug, the more aptamers change shape.

That information, captured every few seconds, is routed through software that controls the pump to deliver additional drugs as needed.

Researchers tested the technology by administering the chemotherapy drug doxorubicin to rabbits and rats.

Despite physiological and metabolic differences among individual animals, the team was able to keep a constant dosage in all the animals, something not possible with current drug delivery methods.

The researchers also tested for acute drug-drug interactions and found the system was able to stabilize drug levels to moderate what might otherwise be a dangerous spike or dip.

Dr Soh and his colleagues believe this technology could be particularly useful in treating pediatric cancer patients, who are notoriously difficult to dose because a child’s metabolism is usually different from an adult’s.

The team plans to miniaturize the system so it can be implanted or worn by the patient.

At present, the technology is an external apparatus, like a smart IV drip. The biosensor is a device about the size of a microscope slide.

The current setup might be suitable for a chemotherapy drug but not for continual use.

The researchers are also adapting the system with different aptamers so it can sense and regulate the levels of other biomolecules in the body. ![]()

New technology could make it easier to ensure patients receive the correct dose of chemotherapy and other drugs, according to research published in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

Researchers developed a closed-loop system that was able to continuously regulate drug levels in rabbits and rats.

“This is the first time anyone has been able to continuously control the drug levels in the body in real time,” said study author H. Tom Soh, PhD, of Stanford University in California.

“This is a novel concept with big implications because we believe we can adapt our technology to control the levels of a wide range of drugs.”

The researchers’ system has 3 basic components: a real-time biosensor to continuously monitor drug levels in the bloodstream, a control system to calculate the right dose, and a programmable pump that delivers just enough medicine to maintain a desired dose.

The sensor contains aptamers that are specially designed to bind a drug of interest. When the drug is present in the bloodstream, the aptamer changes shape, which an electric sensor detects. The more drug, the more aptamers change shape.

That information, captured every few seconds, is routed through software that controls the pump to deliver additional drugs as needed.

Researchers tested the technology by administering the chemotherapy drug doxorubicin to rabbits and rats.

Despite physiological and metabolic differences among individual animals, the team was able to keep a constant dosage in all the animals, something not possible with current drug delivery methods.

The researchers also tested for acute drug-drug interactions and found the system was able to stabilize drug levels to moderate what might otherwise be a dangerous spike or dip.

Dr Soh and his colleagues believe this technology could be particularly useful in treating pediatric cancer patients, who are notoriously difficult to dose because a child’s metabolism is usually different from an adult’s.

The team plans to miniaturize the system so it can be implanted or worn by the patient.

At present, the technology is an external apparatus, like a smart IV drip. The biosensor is a device about the size of a microscope slide.

The current setup might be suitable for a chemotherapy drug but not for continual use.

The researchers are also adapting the system with different aptamers so it can sense and regulate the levels of other biomolecules in the body. ![]()

New technology could make it easier to ensure patients receive the correct dose of chemotherapy and other drugs, according to research published in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

Researchers developed a closed-loop system that was able to continuously regulate drug levels in rabbits and rats.

“This is the first time anyone has been able to continuously control the drug levels in the body in real time,” said study author H. Tom Soh, PhD, of Stanford University in California.

“This is a novel concept with big implications because we believe we can adapt our technology to control the levels of a wide range of drugs.”

The researchers’ system has 3 basic components: a real-time biosensor to continuously monitor drug levels in the bloodstream, a control system to calculate the right dose, and a programmable pump that delivers just enough medicine to maintain a desired dose.

The sensor contains aptamers that are specially designed to bind a drug of interest. When the drug is present in the bloodstream, the aptamer changes shape, which an electric sensor detects. The more drug, the more aptamers change shape.

That information, captured every few seconds, is routed through software that controls the pump to deliver additional drugs as needed.

Researchers tested the technology by administering the chemotherapy drug doxorubicin to rabbits and rats.

Despite physiological and metabolic differences among individual animals, the team was able to keep a constant dosage in all the animals, something not possible with current drug delivery methods.

The researchers also tested for acute drug-drug interactions and found the system was able to stabilize drug levels to moderate what might otherwise be a dangerous spike or dip.

Dr Soh and his colleagues believe this technology could be particularly useful in treating pediatric cancer patients, who are notoriously difficult to dose because a child’s metabolism is usually different from an adult’s.

The team plans to miniaturize the system so it can be implanted or worn by the patient.

At present, the technology is an external apparatus, like a smart IV drip. The biosensor is a device about the size of a microscope slide.

The current setup might be suitable for a chemotherapy drug but not for continual use.

The researchers are also adapting the system with different aptamers so it can sense and regulate the levels of other biomolecules in the body. ![]()

Tattoo artist survey finds almost half agree to tattoo skin with lesions

The importance of educating tattoo artists on identifying and being careful around skin with melanocytic nevi and other lesions was highlighted by the results of a survey of tattoo artists, according to a study from the University of Pittsburgh.

“While most of those surveyed reported deliberately avoiding nevi, a similar proportion reported either tattooing over them or simply deferring to the client’s preference,” wrote Westley S. Mori and his associates in the department of dermatology at the University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. “This is concerning because few clients specifically ask tattoo artists to avoid skin lesions,” they added.

They surveyed 42 tattoo artists in July and August 2016 regarding their encounters with clients with skin lesions and their personal knowledge or experiences they may have had with skin cancer. Of those surveyed, 23 (55%) said they had declined to tattoo skin with a rash or lesion (JAMA Dermatology. 2017;153[4]:328-30).When asked about their reasoning for declining a client’s request, 21 (50%) of respondents said they did so because of a poor cosmetic outcome, while the next highest answer, a concern of potential skin cancer, was only cited by 12 (29%).

Most (74%) said there was no official store policy about tattooing over moles or other skin lesions. When asked about their approaches to tattooing skin with moles or other lesions, many said they choose to tattoo around the lesion (41%), tattoo over the lesion (19%), or defer to the client’s preferences (24%). However, with regards to deferring to a client, 29 artists (69%) reported never being asked to avoid a lesion.

Investigators noted that 12 respondents reported that they had identified a possible cancerous lesion on a client, followed by the same number of respondents reporting having recommended that a client see a dermatologist.

Tattoo artists who had seen a dermatologist for a skin examination were significantly more likely to refuse to tattoo a client with a lesion (P = .01) and recommend that the client see a dermatologist (P less than .001) when they had a lesion. Based on this response, the authors said that they believed that educating both clients and tattoo artists may be the best way to get tattoo artists to engage clients. “Our study highlights an opportunity for dermatologists to educate tattoo artists about skin cancer, particularly melanoma, to help reduce the incidence of skin cancers hidden in tattoos and to encourage appropriate referral to dermatologists for suspicious lesions on clients,” they concluded.

“When you perform a total body skin examination, it’s a little difficult to kind of tease out if a lesion looks suspicious or not if it’s surrounded by ink,” Mr. Mori, a medical student at the university, said in an interview. “Tattoos are becoming more and more common, especially among younger people, and incidence of melanoma has increased in younger populations as well. ... It is very concerning that skin cancers could be hidden in tattoos.”

In fact, Mr. Mori pointed out, there are opportunities for dermatologists to reach out to the tattoo artist community and start the communication process. “Tattoo artists have national conferences where they get together and discuss the state of the industry, and that represents one opportunity where dermatologists could talk about the effects of skin cancer,” he said.

The study was funded by the University of Pittsburgh. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

The importance of educating tattoo artists on identifying and being careful around skin with melanocytic nevi and other lesions was highlighted by the results of a survey of tattoo artists, according to a study from the University of Pittsburgh.

“While most of those surveyed reported deliberately avoiding nevi, a similar proportion reported either tattooing over them or simply deferring to the client’s preference,” wrote Westley S. Mori and his associates in the department of dermatology at the University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. “This is concerning because few clients specifically ask tattoo artists to avoid skin lesions,” they added.

They surveyed 42 tattoo artists in July and August 2016 regarding their encounters with clients with skin lesions and their personal knowledge or experiences they may have had with skin cancer. Of those surveyed, 23 (55%) said they had declined to tattoo skin with a rash or lesion (JAMA Dermatology. 2017;153[4]:328-30).When asked about their reasoning for declining a client’s request, 21 (50%) of respondents said they did so because of a poor cosmetic outcome, while the next highest answer, a concern of potential skin cancer, was only cited by 12 (29%).

Most (74%) said there was no official store policy about tattooing over moles or other skin lesions. When asked about their approaches to tattooing skin with moles or other lesions, many said they choose to tattoo around the lesion (41%), tattoo over the lesion (19%), or defer to the client’s preferences (24%). However, with regards to deferring to a client, 29 artists (69%) reported never being asked to avoid a lesion.

Investigators noted that 12 respondents reported that they had identified a possible cancerous lesion on a client, followed by the same number of respondents reporting having recommended that a client see a dermatologist.

Tattoo artists who had seen a dermatologist for a skin examination were significantly more likely to refuse to tattoo a client with a lesion (P = .01) and recommend that the client see a dermatologist (P less than .001) when they had a lesion. Based on this response, the authors said that they believed that educating both clients and tattoo artists may be the best way to get tattoo artists to engage clients. “Our study highlights an opportunity for dermatologists to educate tattoo artists about skin cancer, particularly melanoma, to help reduce the incidence of skin cancers hidden in tattoos and to encourage appropriate referral to dermatologists for suspicious lesions on clients,” they concluded.

“When you perform a total body skin examination, it’s a little difficult to kind of tease out if a lesion looks suspicious or not if it’s surrounded by ink,” Mr. Mori, a medical student at the university, said in an interview. “Tattoos are becoming more and more common, especially among younger people, and incidence of melanoma has increased in younger populations as well. ... It is very concerning that skin cancers could be hidden in tattoos.”

In fact, Mr. Mori pointed out, there are opportunities for dermatologists to reach out to the tattoo artist community and start the communication process. “Tattoo artists have national conferences where they get together and discuss the state of the industry, and that represents one opportunity where dermatologists could talk about the effects of skin cancer,” he said.

The study was funded by the University of Pittsburgh. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

The importance of educating tattoo artists on identifying and being careful around skin with melanocytic nevi and other lesions was highlighted by the results of a survey of tattoo artists, according to a study from the University of Pittsburgh.

“While most of those surveyed reported deliberately avoiding nevi, a similar proportion reported either tattooing over them or simply deferring to the client’s preference,” wrote Westley S. Mori and his associates in the department of dermatology at the University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. “This is concerning because few clients specifically ask tattoo artists to avoid skin lesions,” they added.

They surveyed 42 tattoo artists in July and August 2016 regarding their encounters with clients with skin lesions and their personal knowledge or experiences they may have had with skin cancer. Of those surveyed, 23 (55%) said they had declined to tattoo skin with a rash or lesion (JAMA Dermatology. 2017;153[4]:328-30).When asked about their reasoning for declining a client’s request, 21 (50%) of respondents said they did so because of a poor cosmetic outcome, while the next highest answer, a concern of potential skin cancer, was only cited by 12 (29%).

Most (74%) said there was no official store policy about tattooing over moles or other skin lesions. When asked about their approaches to tattooing skin with moles or other lesions, many said they choose to tattoo around the lesion (41%), tattoo over the lesion (19%), or defer to the client’s preferences (24%). However, with regards to deferring to a client, 29 artists (69%) reported never being asked to avoid a lesion.

Investigators noted that 12 respondents reported that they had identified a possible cancerous lesion on a client, followed by the same number of respondents reporting having recommended that a client see a dermatologist.

Tattoo artists who had seen a dermatologist for a skin examination were significantly more likely to refuse to tattoo a client with a lesion (P = .01) and recommend that the client see a dermatologist (P less than .001) when they had a lesion. Based on this response, the authors said that they believed that educating both clients and tattoo artists may be the best way to get tattoo artists to engage clients. “Our study highlights an opportunity for dermatologists to educate tattoo artists about skin cancer, particularly melanoma, to help reduce the incidence of skin cancers hidden in tattoos and to encourage appropriate referral to dermatologists for suspicious lesions on clients,” they concluded.

“When you perform a total body skin examination, it’s a little difficult to kind of tease out if a lesion looks suspicious or not if it’s surrounded by ink,” Mr. Mori, a medical student at the university, said in an interview. “Tattoos are becoming more and more common, especially among younger people, and incidence of melanoma has increased in younger populations as well. ... It is very concerning that skin cancers could be hidden in tattoos.”

In fact, Mr. Mori pointed out, there are opportunities for dermatologists to reach out to the tattoo artist community and start the communication process. “Tattoo artists have national conferences where they get together and discuss the state of the industry, and that represents one opportunity where dermatologists could talk about the effects of skin cancer,” he said.

The study was funded by the University of Pittsburgh. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

Key clinical point: Dermatologists can educate tattoo artists about avoiding tattoos around moles and other skin lesions.

Major finding: Of 42 tattoo artists who were surveyed, 19 (45%) reported never declining a client’s request to tattoo skin with a lesion, and 31 (74%) reporting having no official store policy on tattooing over lesions.

Data source: An anonymous survey of 42 tattoo artists conducted in July and August 2016.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the University of Pittsburgh. Investigators reported no relevant disclosures.

VAM 2017 Features Alliances and Teamwork

This year’s Vascular Annual Meeting could be subtitled: “The Year of Inter-Society Collaboration.”

Last year, joint sessions with specialty societies that have overlapping interests proved so popular that the number of such sessions was expanded for 2017.

“These sessions provide a multidisciplinary perspective on our common problems, and showcase the SVS’ leadership role in vascular disease diagnosis and management,” said Dr. Ron Dalman, chair of the SVS VAM Program Committee.

“While our specialty encompasses broad expertise across the spectrum of vascular disease, as SVS members we also are interested in what we can learn from others. We want to advance the field, share information and hear how other perspectives may contribute to improved patient care.”

Dr. Kellie Brown, chair of the SVS Postgraduate Education Committee, agreed. “Collaboration helps us have a broader impact on disease management,” she said.

Seven societies are working with SVS members on eight joint programs, nearly double the number in 2016. They are: American Podiatric Medical Association, American Venous Forum, European Society for Vascular Surgery, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, Society for Vascular Medicine, Society for Vascular Nursing and the Society for Vascular Ultrasound.

Here are the 2017 joint sessions:

Wednesday, May 31Postgraduate course2 – 5 p.m.The APMA returns with another joint postgraduate course, “Advances in Wound Care and Limb Management.”

Friday, June 2Concurrent Sessions3:30 – 5 p.m.C5: SVS/ESVS: “Joint Debate Session”C6: SVS/STS: “Sharing Common Ground for Cardiovascular Problems”C7: SVS/AVF: “How and When to Treat Deep Venous Obstructions”

Saturday, June 3Concurrent Sessions10:30 a.m. – 12 p.m.C12: SVS/SVM: “Medical Management of Vascular Disease”C13: SVS/SVN: “Building the Vascular Team – Evolving Collaboration of Surgeons and Nurses”C14: SVS/SVU: “Organization, Operation and Management of a Vascular Laboratory”1:30 – 5:15 p.m. SVS/STS Summit: “Advances and Controversies in the Management of Complex Thoracoabdominal Aneurysmal Disease and Type B Aortic Dissection.” STS is co-sponsoring the session. Moderators for the thoracoabdominal portion are Dr. Jason T. Lee (SVS) and Dr. Wilson Szeto (STS); moderators for the portion on Type B aortic dissection are Dr. Matthew Eagleton (SVS) and Dr. Michael Fischbein (STS).

This year’s Vascular Annual Meeting could be subtitled: “The Year of Inter-Society Collaboration.”

Last year, joint sessions with specialty societies that have overlapping interests proved so popular that the number of such sessions was expanded for 2017.

“These sessions provide a multidisciplinary perspective on our common problems, and showcase the SVS’ leadership role in vascular disease diagnosis and management,” said Dr. Ron Dalman, chair of the SVS VAM Program Committee.

“While our specialty encompasses broad expertise across the spectrum of vascular disease, as SVS members we also are interested in what we can learn from others. We want to advance the field, share information and hear how other perspectives may contribute to improved patient care.”

Dr. Kellie Brown, chair of the SVS Postgraduate Education Committee, agreed. “Collaboration helps us have a broader impact on disease management,” she said.

Seven societies are working with SVS members on eight joint programs, nearly double the number in 2016. They are: American Podiatric Medical Association, American Venous Forum, European Society for Vascular Surgery, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, Society for Vascular Medicine, Society for Vascular Nursing and the Society for Vascular Ultrasound.

Here are the 2017 joint sessions:

Wednesday, May 31Postgraduate course2 – 5 p.m.The APMA returns with another joint postgraduate course, “Advances in Wound Care and Limb Management.”

Friday, June 2Concurrent Sessions3:30 – 5 p.m.C5: SVS/ESVS: “Joint Debate Session”C6: SVS/STS: “Sharing Common Ground for Cardiovascular Problems”C7: SVS/AVF: “How and When to Treat Deep Venous Obstructions”

Saturday, June 3Concurrent Sessions10:30 a.m. – 12 p.m.C12: SVS/SVM: “Medical Management of Vascular Disease”C13: SVS/SVN: “Building the Vascular Team – Evolving Collaboration of Surgeons and Nurses”C14: SVS/SVU: “Organization, Operation and Management of a Vascular Laboratory”1:30 – 5:15 p.m. SVS/STS Summit: “Advances and Controversies in the Management of Complex Thoracoabdominal Aneurysmal Disease and Type B Aortic Dissection.” STS is co-sponsoring the session. Moderators for the thoracoabdominal portion are Dr. Jason T. Lee (SVS) and Dr. Wilson Szeto (STS); moderators for the portion on Type B aortic dissection are Dr. Matthew Eagleton (SVS) and Dr. Michael Fischbein (STS).

This year’s Vascular Annual Meeting could be subtitled: “The Year of Inter-Society Collaboration.”

Last year, joint sessions with specialty societies that have overlapping interests proved so popular that the number of such sessions was expanded for 2017.

“These sessions provide a multidisciplinary perspective on our common problems, and showcase the SVS’ leadership role in vascular disease diagnosis and management,” said Dr. Ron Dalman, chair of the SVS VAM Program Committee.

“While our specialty encompasses broad expertise across the spectrum of vascular disease, as SVS members we also are interested in what we can learn from others. We want to advance the field, share information and hear how other perspectives may contribute to improved patient care.”

Dr. Kellie Brown, chair of the SVS Postgraduate Education Committee, agreed. “Collaboration helps us have a broader impact on disease management,” she said.

Seven societies are working with SVS members on eight joint programs, nearly double the number in 2016. They are: American Podiatric Medical Association, American Venous Forum, European Society for Vascular Surgery, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, Society for Vascular Medicine, Society for Vascular Nursing and the Society for Vascular Ultrasound.

Here are the 2017 joint sessions:

Wednesday, May 31Postgraduate course2 – 5 p.m.The APMA returns with another joint postgraduate course, “Advances in Wound Care and Limb Management.”

Friday, June 2Concurrent Sessions3:30 – 5 p.m.C5: SVS/ESVS: “Joint Debate Session”C6: SVS/STS: “Sharing Common Ground for Cardiovascular Problems”C7: SVS/AVF: “How and When to Treat Deep Venous Obstructions”

Saturday, June 3Concurrent Sessions10:30 a.m. – 12 p.m.C12: SVS/SVM: “Medical Management of Vascular Disease”C13: SVS/SVN: “Building the Vascular Team – Evolving Collaboration of Surgeons and Nurses”C14: SVS/SVU: “Organization, Operation and Management of a Vascular Laboratory”1:30 – 5:15 p.m. SVS/STS Summit: “Advances and Controversies in the Management of Complex Thoracoabdominal Aneurysmal Disease and Type B Aortic Dissection.” STS is co-sponsoring the session. Moderators for the thoracoabdominal portion are Dr. Jason T. Lee (SVS) and Dr. Wilson Szeto (STS); moderators for the portion on Type B aortic dissection are Dr. Matthew Eagleton (SVS) and Dr. Michael Fischbein (STS).

Schizophrenia researchers seek elusive ‘quantum leap’

Mental health researchers like to say a half-century has passed since the last major advance in schizophrenia treatment came along. Gavin P. Reynolds, PhD, a schizophrenia researcher, says that’s wrong. In fact, he says, “it’s more like 60-plus!”

Yes, there have been advances in drug treatment since the early 1950s, when chlorpromazine (Thorazine) was introduced. Available are new types of antipsychotics, a whole bunch in fact, and they’ve helped many patients. “But these have been incremental, rather than the much-needed quantum leap,” said Dr. Reynolds in an interview. “We still need improved treatments. About one-third of patients do not respond to standard drug treatment. And of those who do respond, the negative symptoms and cognitive problems caused by schizophrenia may still be very limiting.”

That’s quite optimistic. The “revolution” hasn’t yet jumped from medical journals and clinical trials to prescription pads and drugstore shelves, and it’s not likely to do so any time soon. “This isn’t around the corner,” said Joshua T. Kantrowitz, MD, also a schizophrenia researcher. “But I can imagine a day where someone with schizophrenia will undergo a full genetic scan or a specific type of MRI or EEG, and we’ll then be able to recommend the drug they’d be able to use.” And he believes that a glutamate-based medication will be among the available options.

Thorazine: A pioneer with major limits

Like every person, each illness has a history. But schizophrenia’s past is fuzzier than that of many diseases, and this lack of clarity continues into the present as researchers try to understand exactly what it is – a single disorder? a collection of conditions? – and what it isn’t.

“Schizophrenia is a serious mental illness with a remarkably short recorded history. Unlike depression and mania, which are recognizable in ancient texts, schizophrenia-like disorder appeared rather suddenly in the early 19th century,” wrote R. Walter Heinrichs, PhD, a psychologist at Toronto’s York University (J Hist Behav Sci. 2003 Fall;39[4]:349-63). “This could mean that the illness is a recent disease that was largely unknown in earlier times. But perhaps schizophrenia existed, embedded and disguised within more general concepts of madness, and within the arcane languages and cultures of remote times,” he wrote.

As Dr. Heinrichs noted, schizophrenia’s history has spawned at least three theories: It’s a fairly new disease that just popped up in recent centuries. It has been around a long time but just didn’t get identified. It’s not a real disease but a product of modern thought.

Psychiatrists and researchers have rejected the latter possibility and its implications that psychotherapy could be the best treatment. Instead, they have tried to adjust the workings of the schizophrenic brain via medication.

The main breakthrough came in the 1950s through the development of the antipsychotic chlorpromazine. Its success “was instrumental in the reintegration of psychiatry with the other medical disciplines,” wrote Thomas A. Ban, MD, an emeritus professor at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. “It turned psychiatrists from caregivers to full-fledged physicians who can help their patients and not only listen to their problems” (Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007 Aug; 3[4]:495-500).

Since chlorpromazine, however, medical treatment for schizophrenia has barely evolved, said Dr. Reynolds, professor emeritus at Queen’s University Belfast (Northern Ireland) and honorary professor at Sheffield (England) Hallam University. “The two most important developments have been the introduction of clozapine (Clozaril) for patients who don’t respond to other treatments and aripiprazole (Abilify), which has a somewhat different pharmacological action from other antipsychotics and thereby avoids some of the side effects.”

Negative symptoms fail to crumble

But, he said, side effects such as severe weight gain still can hamper the use of antipsychotics. And antipsychotics don’t fare well at treating the negative symptoms of schizophrenia.

As one overview puts it, “negative symptoms, e.g., social withdrawal, reduced initiative, anhedonia, and affective flattening, are notoriously difficult to treat.” Nonmedical treatments have shown some promise, the overview authors write: “Some positive findings have been reported, with the most robust improvements observed for social skills training. Although cognitive-behavior therapy shows significant effects for negative symptoms as a secondary outcome measure, there is a lack of data to allow for definite conclusions of its effectiveness for patients with predominant negative symptoms.”

As for medications, “antipsychotics have been shown to improve negative symptoms, but this seems to be limited to secondary negative symptoms in acute patients. It has also been suggested that antipsychotics may aggravate negative symptoms” (Schizophr Res. 2016 Jun 9. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.05.015).

Looking to dopamine... and beyond

One solution to the vexing schizophrenia treatment gap is to develop a new medication that does a better job of adjusting the brain’s processing of dopamine.

Some researchers have found evidence that dopamine levels rise in the brains of people with schizophrenia, potentially explaining why chlorpromazine – which blocks receptors that process dopamine – is so effective. There also are signs that genes linked to dopamine play a role in schizophrenia.

But chlorpromazine is not effective enough to help many patients. Some gain no benefit, while others only see improvement in positive schizophrenia symptoms, those that are considered to be brought on – added – such as hallucinations and delusions.

And chlorpromazine isn’t believed to improve cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia like disorganized thoughts and concentration difficulties.

Atypical antipsychotics like clozapine (Clozaril) and risperidone (Risperdal), add the blocking of serotonin receptors to their dopamine focus. But they have serious limitations just like chlorpromazine.

The conclusion to take from the failure of dopamine-based drugs to fully combat schizophrenia, Dr. Kantrowitz and a colleague wrote, is that “dopaminergic dysfunction appears to account for only a part of schizophrenia’s symptomatic and neurocognitive profile.” Something else must be going on.

Enter the neurotransmitter known as glutamate.

The angel dust connection

Children who grew up in the 1970s and 1980s were flooded plenty of media messages about the dangers of illegal drugs. But one drug, “angel dust,” also known as phencyclidine or PCP, stood apart from the rest.

Using PCP, television shows and films suggested, led to consequences that could be deadly in ways that were entirely unlike the usual causes of death by drug use – a car accident, say, or a heroin overdose. Taking PCP, it seemed, was tied to crazed misadventure.

Consider a 1982 TV movie, “Desperate Lives,” starring a young actress named Helen Hunt. In a startling scene, she takes the drug and promptly jumps through a second-story window before screeching and cutting herself with jagged glass. The portrayal of PCP users as vividly unhinged – detached from reality and willing to hurt themselves or others – reflected a real phenomenon. As scientists had discovered, angel dust could made people act as if they were psychotic.

In the 1960s, “people started observing that drugs like PCP and ketamine produced schizophrenia-like symptoms,” Dr. Kantrowitz said. “But these observations were mostly ignored until the 1980s and 1990s.”

That’s when scientists started looking into the connections between these drugs and the psychotic states that they could induce. “These drugs can mimic, in animals and humans, the negative and cognitive symptoms as well as the positive symptoms of schizophrenia,” Dr. Reynolds said. “Combined with postmortem evidence of changes in various indicators of glutamate neurotransmission in the brain, these findings provide the basis for the glutamate hypothesis.”

The hypothesis theorizes that disruptions in the brain’s processing of glutamate are crucial to schizophrenia. Specifically, scientists believe the key lies in the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor in nerve cells.

“Glutamatergic models are based upon the observation that the psychotomimetic agents such as phencyclidine and ketamine induce psychotic symptoms and neurocognitive disturbances similar to those of schizophrenia by blocking neurotransmission at N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-type glutamate receptors,” writes Daniel C. Javitt, MD, professor of psychiatry and director of schizophrenia research at the Nathan Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research at Columbia University. “Because glutamate/NMDA receptors are located throughout the brain, glutamatergic models predict widespread cortical dysfunction with particular involvement of NMDA receptors throughout the brain.

“Further, NMDA receptors are located on brain circuits that regulate dopamine release, suggesting that dopaminergic deficits in schizophrenia may also be secondary to underlying glutamatergic dysfunction.” (Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2010;47[1]:4-16).

There’s even more to the story, said Dr. Reynolds, who cautions that the term “glutamate hypothesis” is misleading, because it misses the whole picture.

“The original research identifying the importance of the NMDA receptor highlighted how these receptors were actually on GABA neurons, reflecting the close interaction and interdependence of the two transmitter systems,” he said. (GABA receptors respond to the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid, or GABA.)

“Subsequently, it has been established that there is a dysfunction, if not a deficit, of a subgroup of GABA neurons in schizophrenia,” Dr. Reynolds said, “and these neurons, which are important in the control of glutamate neuronal activity, are also a focus of current research.”

Challenges on the drug development front

Earlier findings linking glutamate to schizophrenia “have been strengthened by recent large genetic studies identifying that variability in some genes involved in glutamate’s action is a risk factor for schizophrenia,” Dr. Reynolds said, “while in animal models, some drugs influencing glutamate transmission have shown promise as potential treatments.”

But glutamate-based drugs for schizophrenia remain elusive. “It is disappointing that the new antipsychotic drugs becoming available now are still all variations on the dopamine antagonist or partial agonist theme, even if they have some advantages in terms of side effects and evidence that they may have some limited effects on negative or cognitive symptoms,” Dr. Reynolds said. “Several drugs addressing glutamate systems – indirectly modulating the NMDA receptor or synaptic glutamate – have been developed that had good potential but have failed in clinical trials. Nevertheless, this strategy is still being pursued by the pharma industry.”

Dr. Reynolds points to drug development challenges on several fronts. For one, research subjects don’t necessarily represent patients who’d benefit the most from treatment.

“Drug treatments are likely to be most effective, and most important, in the early stages of the disease,” he said. “However, drug trials are almost inevitably undertaken on subjects who may have had many years of treatment prior to the trial without, perhaps, always responding very well.”

Another challenge: The tight interconnectedness of neural systems linked to schizophrenia. Tinkering with something in one part of the brain may lead to something going wrong somewhere else. “Glutamate and GABA neurons are ubiquitous throughout the brain,” Dr. Reynolds said, “and targeting systems particularly affected in schizophrenia is difficult without influencing other neuronal systems, potentially leading to further side effects.”

Targets offer hope for new medications

The challenges are significant, but the latest schizophrenia research also is opening up opportunities for new medications.

The GABA connection, for example, is a fertile field for researchers. “One interesting and novel approach that seems promising is the development of a drug that modulates ion channels in GABA/parvalbumin neurons, thereby potentially restoring their function,” Dr. Reynolds said. “We are still years away from availability of these new treatments, however.”

But what if drugs targeted specific types of schizophrenia just like antibiotics aim to treat different types of bacterial infections?

Dr. Tamminga is pushing researchers to focus on how disruptions in glutamate processing affect specific parts of the brain and specific brain functions. “Some people want to have a single glutamate defect throughout the whole brain,” she said. But she notes that “the glutamate system is prominent in every brain region,” suggesting that a global problem would entirely incapacitate schizophrenia patients.

In fact, “while people with schizophrenia do have glutamate-mediated troubles with their condition, with their memory, they don’t have glutamate problems with their motor system or sensory system,” she said. “There’s very little evidence for a generalized brain defect. We ought to be taking another tack: We need to figure out pathophysiology by region and brain function.”

Dr. Kantrowitz also is working on developing biomarkers. He said he’s collaborating with colleagues to follow directives by the National Institute on Mental Health to develop schizophrenia biomarkers in early-stage studies.

“It’s a way to assess how well a specific drug is hitting its target,” he said. “Once you’ve developed a good understanding of how well they’re hitting their target, then you can more finely tune doses before you put the drugs in thousands of people.”

The research may shed light on a question that continues to divide schizophrenia researchers: Is the disease one single condition or multiple disorders masquerading as one?

“I think that eventually, once we get better at genetics and looking at schizophrenia, we’ll realize it’s not one thing, that it’s many different things,” Dr. Kantrowitz said. “The brain is a very complex organ, and there are lots of different areas of things that can go wrong to produce similar symptoms that are grouped together as schizophrenia.”

It’s possible, he believes, that one group of schizophrenia patients, maybe 10 percent, will respond to a glutamate-based treatment. An additional 10 percent, perhaps will require something else.

“We’re not good enough to discern these things yet,” he said. “But eventually we’ll get to more targeted treatment.”

And then we’ll finally get to reset the clock marking the time – now almost 70 years – since the last major milestone in schizophrenia treatment.

Dr. Reynolds reported that over the past 3 years, he has received honoraria for lectures, advisory board membership, travel support and/or research support from Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Sunovion, and Sumitomo. Dr. Kantrowitz reported having received consulting payments within the last 24 months from Vindico Medical Education, Annenberg Center for Health Sciences at Eisenhower, Health Advances, SlingShot, Strategic Edge Communications, Havas Life, and Cowen and Company. He has conducted clinical research supported by the NIMH, the Stanley Foundation, Merck, Roche-Genentech, Forum, Sunovion, Novartis, Lundbeck, Alkermes, NeuroRx, Pfizer, and Lilly. He owns a small number of shares of common stock in GlaxoSmithKline.

Dr. Tamminga reported no relevant disclosures.

Lessons from the latest research

One major thrust of research is to understand exactly how the glutamate system works and what goes wrong in schizophrenia patients. Here are some questions and answers from recent research:

Question: If NMDA receptors are crucial to glutamate, would an NMDA receptor channel blocker help improve symptoms in schizophrenia patients? What about memantine (Namenda), an Alzheimer’s disease medication that treats the cognitive problems caused by dementia?

Answer: A 2017 systematic review of 10 studies (including two case reports) found “unclear results”: “memantine therapy in schizophrenic patients seems to improve mainly negative symptoms while positive symptoms and cognitive symptoms did not improve significantly.”

The researchers add that the “use of memantine should be considered in patients with prevalent negative symptoms and cognitive impairment, even if further trials are required. Memantine could be a new opportunity to treat young patients in order to prevent further cognitive decline that will lead to global impairment” (J Amino Acids. 2017;2017:7021071).

The review did not include a 2017 double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 46 adult male patients (average age around 45 years) comparing the antipsychotic risperidone with risperidone plus memantine. The researchers found no difference in positive symptom improvement between the two groups, but the combination treatment group showed significant improvement in cognitive function (at 6 weeks and study completion at 12 weeks) and negative symptoms (at 12 weeks) (Psychiatry Res. 2017 Jan;247:291-5).

Q: We know that the cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia are difficult to treat. What hope does the glutamate system hold in this area?

A: A 2017 systematic review of 44 studies says “memory, working memory and executive functions appear to be most influenced by the glutamatergic pathway.” But there’s some added complexity: “evidence from the literature suggests that presynaptic components synthesis and uptake of glutamate is involved in memory, while postsynaptic signaling appears to be involved in working memory.”

In the big picture, the review says, “the glutamatergic system appears to contribute to the cognitive deficits in schizophrenia, whereby different parts of the pathway are associated with different cognitive domains” (Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017 Apr 13;77:369-87).

Q: Could imaging via proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy prove a link between schizophrenia and certain kinds of glutamate activity in the brain, giving mental health professionals a tool to identify at-risk people who are most likely to develop psychosis?

A: A 2016 meta-analysis examined 59 studies and reported that “schizophrenia is associated with elevations in glutamatergic metabolites across several brain regions. This finding supports the hypothesis that schizophrenia is associated with excess glutamatergic neurotransmission in several limbic areas and further indicates that compounds that reduce glutamatergic transmission may have therapeutic potential” (JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Jul 1;73[7]:665-74).

A review published in 2016 examined 11 proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies in search of signs that the state of the glutamate system could predict future psychosis.

Researchers found that six studies reported “significant alterations in glutamate metabolites across different cerebral areas (frontal lobe, thalamus, and the associative striatum)” in at-risk patients. “A longitudinal analysis in two of these trials confirmed an association between these abnormalities and worsening of symptoms and final transition to psychosis.”

But the other five studies analyzed in the review “found no significant differences across these same areas” (Schizophr Res. 2016 Mar;171[1-3]:166-75).

Mental health researchers like to say a half-century has passed since the last major advance in schizophrenia treatment came along. Gavin P. Reynolds, PhD, a schizophrenia researcher, says that’s wrong. In fact, he says, “it’s more like 60-plus!”

Yes, there have been advances in drug treatment since the early 1950s, when chlorpromazine (Thorazine) was introduced. Available are new types of antipsychotics, a whole bunch in fact, and they’ve helped many patients. “But these have been incremental, rather than the much-needed quantum leap,” said Dr. Reynolds in an interview. “We still need improved treatments. About one-third of patients do not respond to standard drug treatment. And of those who do respond, the negative symptoms and cognitive problems caused by schizophrenia may still be very limiting.”

That’s quite optimistic. The “revolution” hasn’t yet jumped from medical journals and clinical trials to prescription pads and drugstore shelves, and it’s not likely to do so any time soon. “This isn’t around the corner,” said Joshua T. Kantrowitz, MD, also a schizophrenia researcher. “But I can imagine a day where someone with schizophrenia will undergo a full genetic scan or a specific type of MRI or EEG, and we’ll then be able to recommend the drug they’d be able to use.” And he believes that a glutamate-based medication will be among the available options.

Thorazine: A pioneer with major limits

Like every person, each illness has a history. But schizophrenia’s past is fuzzier than that of many diseases, and this lack of clarity continues into the present as researchers try to understand exactly what it is – a single disorder? a collection of conditions? – and what it isn’t.

“Schizophrenia is a serious mental illness with a remarkably short recorded history. Unlike depression and mania, which are recognizable in ancient texts, schizophrenia-like disorder appeared rather suddenly in the early 19th century,” wrote R. Walter Heinrichs, PhD, a psychologist at Toronto’s York University (J Hist Behav Sci. 2003 Fall;39[4]:349-63). “This could mean that the illness is a recent disease that was largely unknown in earlier times. But perhaps schizophrenia existed, embedded and disguised within more general concepts of madness, and within the arcane languages and cultures of remote times,” he wrote.

As Dr. Heinrichs noted, schizophrenia’s history has spawned at least three theories: It’s a fairly new disease that just popped up in recent centuries. It has been around a long time but just didn’t get identified. It’s not a real disease but a product of modern thought.

Psychiatrists and researchers have rejected the latter possibility and its implications that psychotherapy could be the best treatment. Instead, they have tried to adjust the workings of the schizophrenic brain via medication.

The main breakthrough came in the 1950s through the development of the antipsychotic chlorpromazine. Its success “was instrumental in the reintegration of psychiatry with the other medical disciplines,” wrote Thomas A. Ban, MD, an emeritus professor at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. “It turned psychiatrists from caregivers to full-fledged physicians who can help their patients and not only listen to their problems” (Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007 Aug; 3[4]:495-500).

Since chlorpromazine, however, medical treatment for schizophrenia has barely evolved, said Dr. Reynolds, professor emeritus at Queen’s University Belfast (Northern Ireland) and honorary professor at Sheffield (England) Hallam University. “The two most important developments have been the introduction of clozapine (Clozaril) for patients who don’t respond to other treatments and aripiprazole (Abilify), which has a somewhat different pharmacological action from other antipsychotics and thereby avoids some of the side effects.”

Negative symptoms fail to crumble

But, he said, side effects such as severe weight gain still can hamper the use of antipsychotics. And antipsychotics don’t fare well at treating the negative symptoms of schizophrenia.

As one overview puts it, “negative symptoms, e.g., social withdrawal, reduced initiative, anhedonia, and affective flattening, are notoriously difficult to treat.” Nonmedical treatments have shown some promise, the overview authors write: “Some positive findings have been reported, with the most robust improvements observed for social skills training. Although cognitive-behavior therapy shows significant effects for negative symptoms as a secondary outcome measure, there is a lack of data to allow for definite conclusions of its effectiveness for patients with predominant negative symptoms.”

As for medications, “antipsychotics have been shown to improve negative symptoms, but this seems to be limited to secondary negative symptoms in acute patients. It has also been suggested that antipsychotics may aggravate negative symptoms” (Schizophr Res. 2016 Jun 9. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.05.015).

Looking to dopamine... and beyond

One solution to the vexing schizophrenia treatment gap is to develop a new medication that does a better job of adjusting the brain’s processing of dopamine.

Some researchers have found evidence that dopamine levels rise in the brains of people with schizophrenia, potentially explaining why chlorpromazine – which blocks receptors that process dopamine – is so effective. There also are signs that genes linked to dopamine play a role in schizophrenia.

But chlorpromazine is not effective enough to help many patients. Some gain no benefit, while others only see improvement in positive schizophrenia symptoms, those that are considered to be brought on – added – such as hallucinations and delusions.

And chlorpromazine isn’t believed to improve cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia like disorganized thoughts and concentration difficulties.

Atypical antipsychotics like clozapine (Clozaril) and risperidone (Risperdal), add the blocking of serotonin receptors to their dopamine focus. But they have serious limitations just like chlorpromazine.

The conclusion to take from the failure of dopamine-based drugs to fully combat schizophrenia, Dr. Kantrowitz and a colleague wrote, is that “dopaminergic dysfunction appears to account for only a part of schizophrenia’s symptomatic and neurocognitive profile.” Something else must be going on.

Enter the neurotransmitter known as glutamate.

The angel dust connection

Children who grew up in the 1970s and 1980s were flooded plenty of media messages about the dangers of illegal drugs. But one drug, “angel dust,” also known as phencyclidine or PCP, stood apart from the rest.

Using PCP, television shows and films suggested, led to consequences that could be deadly in ways that were entirely unlike the usual causes of death by drug use – a car accident, say, or a heroin overdose. Taking PCP, it seemed, was tied to crazed misadventure.

Consider a 1982 TV movie, “Desperate Lives,” starring a young actress named Helen Hunt. In a startling scene, she takes the drug and promptly jumps through a second-story window before screeching and cutting herself with jagged glass. The portrayal of PCP users as vividly unhinged – detached from reality and willing to hurt themselves or others – reflected a real phenomenon. As scientists had discovered, angel dust could made people act as if they were psychotic.