User login

Smartphone apps may aid home rheumatoid arthritis monitoring

BIRMINGHAM, ENGLAND – Researchers in the United Kingdom are looking at how smartphone technology can help to improve how patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) monitor their disease at home and between clinic visits.

As part of the Remote Monitoring of Rheumatoid Arthritis (REMORA) study, a team led by Will Dixon, MD, at the University of Manchester (England), has developed an app that links directly into electronic patient records to help collect information from patients between their regular clinic visits for both self-monitoring and research purposes.

“REMORA is motivated by the need to learn about what happens to patients in between clinic visits, and that’s both for clinical care and for research but also to have the opportunity to support self-management, so we’ve designed the study to meet those three needs,” Dr. Dixon, professor and chair of digital epidemiology in Manchester University’s division of musculoskeletal and dermatological sciences, said in an interview at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

Dr. Dixon explained that when patients are seen every few months they might forget or underplay events that could have significance for their clinical care. Use of the beta version of the app between clinic consultations in the study proved there was recall error.

“In the consultation, we’d ask people how they’d been doing before looking at the graphs in the app, and even people who had said they’d been absolutely fine since they’d last been seen, even in the previous month of beta-testing, have signs that they could have been [having] pain flares,” Dr. Dixon said. This sort of prospective data collection by the app could enable discussion of any irregularities even if more stoic patients reported having no problems.

The responses showed that there were some similarities in the information that clinicians and researchers and patients want to record, but also some key differences.

All groups wanted the app to be able to collect information about possible changes in disease activity (indicated by levels of pain, joint swelling, or disease flares) and the impact that these had on physical and emotional well-being.

Patients were open to regular monitoring, if not too burdensome, but would prefer to note things down “when something happened.” On the other hand, clinicians and researchers wanted regularity and consistency in the monitoring, although they saw the benefit of a more “ad hoc” approach.

Clinicians and researchers felt no need to “reinvent the wheel” and indicated that existing validated tools could be used to collect the information. Conversely, patients preferred a more pictorial or free-text approach, although were aware of some standardized tools in common use.

Daily, weekly, and monthly question sets were developed, with a diary that uses emojis to indicate how people using the app are feeling and a free-text area to allow them to note down any significant health events or thoughts.

Pilot testing of the app has been done in one hospital so far, but it was so well received that patients did not want to have to stop using it at the end of the study, Dr. Austin said in an interview.

Linking into the patient records is a unique approach, and if it proves successful in RA, it could be rolled out across the country’s National Health Service (NHS) and perhaps even into other chronic conditions where self-monitoring is needed.

“We all know we have a limited time in our consultations, so we need to develop a system whereby a clinician, in the 15 minutes they have got for a follow-up appointment, can set somebody up with an ‘app prescription,’ ” Dr. Dixon said. “We’re looking to really develop a blueprint for how apps can successfully connect into the NHS,” Dr. Dixon said. At present, however, the next step is to try to scale up the app for use in several hospitals within an area rather than roll it out nationally, he said.

Using built-in accelerometer for research

Another approach to harnessing smartphone technology is being taken by researchers at the University of Southampton (England), where engineering postgraduate student Jimmy Caroupapoulle and his collaborators are working on an app that continually uses the built-in sensors in a phone to detect movements, and thus how physically active someone is.

“What we are trying to achieve is to develop an application that can just run in the background so people do not have to do too much,” Mr. Caroupapoulle explained in an interview around his poster presentation.

Using the app, called RApp, patients will be able to answer daily questions based on existing tools (RAPID3 and MDHAQ) to record their levels of pain, joint inflammation, and physical activity. The latter would be recorded via the phone’s onboard accelerometer to give a more objective view of whether the patient is moving around, as well as the patient’s speed in getting up from a seated position. The app collects data using the 28-joint Disease Activity Score so an indication of the severity of joint pain or inflammation can be assessed.

The aim is to give the patients the power to monitor themselves but also to facilitate discussion with their physicians. Data from the app will be integrated into an online portal so that patients and their doctors can see the information provided.

So far, 5 patients with RA have tested the application and the next stage is to release the application to a wider group, perhaps 20 patients, Mr. Caroupapoulle said.

“There are lots of apps out there, but this is something that looks at the quality of movement.” consultant rheumatologist Christopher Edwards, MD, a member of the team behind the RApp, said in an interview.

As opposed to pedometers or other devices that monitor physical activity to varying degrees of accuracy, RApp looks at how people accelerate as they stand up or move, which can be important for those with arthritis, and how that relates to their disease activity, said Dr. Edwards, professor of rheumatology at the University of Southampton.

“You can’t guarantee that someone always had their phone in their hand or in their bag,” Dr. Edwards said, “so what you want to do is get a sample from time during the day that gives you an overall representation, even if that is a very short period, just once during the day, then we’ll see if that makes a difference over time and whether that correlates with someone’s disease activity.”

The REMORA study is sponsored by Arthritis Research UK and the National Institute of Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care Greater Manchester. RApp is being developed without commercial funding. Dr. Austin, Dr. Dixon, Mr. Caroupapoulle, and Dr. Edwards stated they had no conflicts of interest.

BIRMINGHAM, ENGLAND – Researchers in the United Kingdom are looking at how smartphone technology can help to improve how patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) monitor their disease at home and between clinic visits.

As part of the Remote Monitoring of Rheumatoid Arthritis (REMORA) study, a team led by Will Dixon, MD, at the University of Manchester (England), has developed an app that links directly into electronic patient records to help collect information from patients between their regular clinic visits for both self-monitoring and research purposes.

“REMORA is motivated by the need to learn about what happens to patients in between clinic visits, and that’s both for clinical care and for research but also to have the opportunity to support self-management, so we’ve designed the study to meet those three needs,” Dr. Dixon, professor and chair of digital epidemiology in Manchester University’s division of musculoskeletal and dermatological sciences, said in an interview at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

Dr. Dixon explained that when patients are seen every few months they might forget or underplay events that could have significance for their clinical care. Use of the beta version of the app between clinic consultations in the study proved there was recall error.

“In the consultation, we’d ask people how they’d been doing before looking at the graphs in the app, and even people who had said they’d been absolutely fine since they’d last been seen, even in the previous month of beta-testing, have signs that they could have been [having] pain flares,” Dr. Dixon said. This sort of prospective data collection by the app could enable discussion of any irregularities even if more stoic patients reported having no problems.

The responses showed that there were some similarities in the information that clinicians and researchers and patients want to record, but also some key differences.

All groups wanted the app to be able to collect information about possible changes in disease activity (indicated by levels of pain, joint swelling, or disease flares) and the impact that these had on physical and emotional well-being.

Patients were open to regular monitoring, if not too burdensome, but would prefer to note things down “when something happened.” On the other hand, clinicians and researchers wanted regularity and consistency in the monitoring, although they saw the benefit of a more “ad hoc” approach.

Clinicians and researchers felt no need to “reinvent the wheel” and indicated that existing validated tools could be used to collect the information. Conversely, patients preferred a more pictorial or free-text approach, although were aware of some standardized tools in common use.

Daily, weekly, and monthly question sets were developed, with a diary that uses emojis to indicate how people using the app are feeling and a free-text area to allow them to note down any significant health events or thoughts.

Pilot testing of the app has been done in one hospital so far, but it was so well received that patients did not want to have to stop using it at the end of the study, Dr. Austin said in an interview.

Linking into the patient records is a unique approach, and if it proves successful in RA, it could be rolled out across the country’s National Health Service (NHS) and perhaps even into other chronic conditions where self-monitoring is needed.

“We all know we have a limited time in our consultations, so we need to develop a system whereby a clinician, in the 15 minutes they have got for a follow-up appointment, can set somebody up with an ‘app prescription,’ ” Dr. Dixon said. “We’re looking to really develop a blueprint for how apps can successfully connect into the NHS,” Dr. Dixon said. At present, however, the next step is to try to scale up the app for use in several hospitals within an area rather than roll it out nationally, he said.

Using built-in accelerometer for research

Another approach to harnessing smartphone technology is being taken by researchers at the University of Southampton (England), where engineering postgraduate student Jimmy Caroupapoulle and his collaborators are working on an app that continually uses the built-in sensors in a phone to detect movements, and thus how physically active someone is.

“What we are trying to achieve is to develop an application that can just run in the background so people do not have to do too much,” Mr. Caroupapoulle explained in an interview around his poster presentation.

Using the app, called RApp, patients will be able to answer daily questions based on existing tools (RAPID3 and MDHAQ) to record their levels of pain, joint inflammation, and physical activity. The latter would be recorded via the phone’s onboard accelerometer to give a more objective view of whether the patient is moving around, as well as the patient’s speed in getting up from a seated position. The app collects data using the 28-joint Disease Activity Score so an indication of the severity of joint pain or inflammation can be assessed.

The aim is to give the patients the power to monitor themselves but also to facilitate discussion with their physicians. Data from the app will be integrated into an online portal so that patients and their doctors can see the information provided.

So far, 5 patients with RA have tested the application and the next stage is to release the application to a wider group, perhaps 20 patients, Mr. Caroupapoulle said.

“There are lots of apps out there, but this is something that looks at the quality of movement.” consultant rheumatologist Christopher Edwards, MD, a member of the team behind the RApp, said in an interview.

As opposed to pedometers or other devices that monitor physical activity to varying degrees of accuracy, RApp looks at how people accelerate as they stand up or move, which can be important for those with arthritis, and how that relates to their disease activity, said Dr. Edwards, professor of rheumatology at the University of Southampton.

“You can’t guarantee that someone always had their phone in their hand or in their bag,” Dr. Edwards said, “so what you want to do is get a sample from time during the day that gives you an overall representation, even if that is a very short period, just once during the day, then we’ll see if that makes a difference over time and whether that correlates with someone’s disease activity.”

The REMORA study is sponsored by Arthritis Research UK and the National Institute of Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care Greater Manchester. RApp is being developed without commercial funding. Dr. Austin, Dr. Dixon, Mr. Caroupapoulle, and Dr. Edwards stated they had no conflicts of interest.

BIRMINGHAM, ENGLAND – Researchers in the United Kingdom are looking at how smartphone technology can help to improve how patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) monitor their disease at home and between clinic visits.

As part of the Remote Monitoring of Rheumatoid Arthritis (REMORA) study, a team led by Will Dixon, MD, at the University of Manchester (England), has developed an app that links directly into electronic patient records to help collect information from patients between their regular clinic visits for both self-monitoring and research purposes.

“REMORA is motivated by the need to learn about what happens to patients in between clinic visits, and that’s both for clinical care and for research but also to have the opportunity to support self-management, so we’ve designed the study to meet those three needs,” Dr. Dixon, professor and chair of digital epidemiology in Manchester University’s division of musculoskeletal and dermatological sciences, said in an interview at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

Dr. Dixon explained that when patients are seen every few months they might forget or underplay events that could have significance for their clinical care. Use of the beta version of the app between clinic consultations in the study proved there was recall error.

“In the consultation, we’d ask people how they’d been doing before looking at the graphs in the app, and even people who had said they’d been absolutely fine since they’d last been seen, even in the previous month of beta-testing, have signs that they could have been [having] pain flares,” Dr. Dixon said. This sort of prospective data collection by the app could enable discussion of any irregularities even if more stoic patients reported having no problems.

The responses showed that there were some similarities in the information that clinicians and researchers and patients want to record, but also some key differences.

All groups wanted the app to be able to collect information about possible changes in disease activity (indicated by levels of pain, joint swelling, or disease flares) and the impact that these had on physical and emotional well-being.

Patients were open to regular monitoring, if not too burdensome, but would prefer to note things down “when something happened.” On the other hand, clinicians and researchers wanted regularity and consistency in the monitoring, although they saw the benefit of a more “ad hoc” approach.

Clinicians and researchers felt no need to “reinvent the wheel” and indicated that existing validated tools could be used to collect the information. Conversely, patients preferred a more pictorial or free-text approach, although were aware of some standardized tools in common use.

Daily, weekly, and monthly question sets were developed, with a diary that uses emojis to indicate how people using the app are feeling and a free-text area to allow them to note down any significant health events or thoughts.

Pilot testing of the app has been done in one hospital so far, but it was so well received that patients did not want to have to stop using it at the end of the study, Dr. Austin said in an interview.

Linking into the patient records is a unique approach, and if it proves successful in RA, it could be rolled out across the country’s National Health Service (NHS) and perhaps even into other chronic conditions where self-monitoring is needed.

“We all know we have a limited time in our consultations, so we need to develop a system whereby a clinician, in the 15 minutes they have got for a follow-up appointment, can set somebody up with an ‘app prescription,’ ” Dr. Dixon said. “We’re looking to really develop a blueprint for how apps can successfully connect into the NHS,” Dr. Dixon said. At present, however, the next step is to try to scale up the app for use in several hospitals within an area rather than roll it out nationally, he said.

Using built-in accelerometer for research

Another approach to harnessing smartphone technology is being taken by researchers at the University of Southampton (England), where engineering postgraduate student Jimmy Caroupapoulle and his collaborators are working on an app that continually uses the built-in sensors in a phone to detect movements, and thus how physically active someone is.

“What we are trying to achieve is to develop an application that can just run in the background so people do not have to do too much,” Mr. Caroupapoulle explained in an interview around his poster presentation.

Using the app, called RApp, patients will be able to answer daily questions based on existing tools (RAPID3 and MDHAQ) to record their levels of pain, joint inflammation, and physical activity. The latter would be recorded via the phone’s onboard accelerometer to give a more objective view of whether the patient is moving around, as well as the patient’s speed in getting up from a seated position. The app collects data using the 28-joint Disease Activity Score so an indication of the severity of joint pain or inflammation can be assessed.

The aim is to give the patients the power to monitor themselves but also to facilitate discussion with their physicians. Data from the app will be integrated into an online portal so that patients and their doctors can see the information provided.

So far, 5 patients with RA have tested the application and the next stage is to release the application to a wider group, perhaps 20 patients, Mr. Caroupapoulle said.

“There are lots of apps out there, but this is something that looks at the quality of movement.” consultant rheumatologist Christopher Edwards, MD, a member of the team behind the RApp, said in an interview.

As opposed to pedometers or other devices that monitor physical activity to varying degrees of accuracy, RApp looks at how people accelerate as they stand up or move, which can be important for those with arthritis, and how that relates to their disease activity, said Dr. Edwards, professor of rheumatology at the University of Southampton.

“You can’t guarantee that someone always had their phone in their hand or in their bag,” Dr. Edwards said, “so what you want to do is get a sample from time during the day that gives you an overall representation, even if that is a very short period, just once during the day, then we’ll see if that makes a difference over time and whether that correlates with someone’s disease activity.”

The REMORA study is sponsored by Arthritis Research UK and the National Institute of Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care Greater Manchester. RApp is being developed without commercial funding. Dr. Austin, Dr. Dixon, Mr. Caroupapoulle, and Dr. Edwards stated they had no conflicts of interest.

Confronting the open chest – Samuel J. Meltzer and the first AATS annual meeting

In retrospect, the founding of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery (AATS) in 1917 may seem surprisingly optimistic, given the status of cardiothoracic surgery as a discipline at that time. While important strides had been made in dealing with open chest wounds, to the modern eye, the field in the second decade of the 20th century seems more characterized by what was not yet possible rather than by what was.

One of the most critical issues holding back the development of cardiothoracic surgery in this early period was the problem of acute pneumothorax that occurred whenever the chest was opened.

As Willy Meyer (1858-1932), second president of the AATS, described the problem at the first AATS annual meeting in 1917: “What is it that happens when the thorax is opened, let us say [for example] by a stab wound in an intercostal space in an affray on the street? Immediately air rushes into the pleural cavity and this normal atmospheric pressure, being greater than the normal pressure within ... the lung contracts to a very small organ around its hilum. Air fills the space formerly occupied by the lung. This condition, with its immediate clinical pathologic consequences, is called ‘acute pneumothorax.’ It has been the stumbling block for almost a century to the proper development of the surgery of the chest. … Carbonic acid is retained in the blood … The accumulation of CO, with its deleterious effect increases, finally ending in the patient’s death.”

But in the first decade of the 20th century, two major and competing techniques evolved to solve the problem, each one represented by the first and second presidents of the fledgling AATS. For a short period of time a controversy seemed to separate the two men, but their views were expressly reconciled at the first annual meeting of the AATS.

The Meltzer/Auer technique was significantly improved upon by the addition of a carbon dioxide absorption method and the creation of a closed circuit apparatus by Dennis Jackson, MD (1878-1980) in 1915. “This fulfilled the criteria of oxygen supply, carbon dioxide absorption, and ether regulation with a hand bag-breather. With this apparatus, respiration could be maintained with the open thorax,” said pioneering thoracic surgeon Rudolf Nissen, MD, and Roger H.L. Wilson, MD, in their Pages in the History of Chest Surgery (Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1960).

However, insufflation was not universally applauded when it was first introduced. It was considered a poor second by many who instead embraced the alternate method of preventing chest collapse – the differential pressure–maintaining Sauerbruch chamber. The Sauerbruch chamber was developed by Ernst Ferdinand Sauerbruch (1875-1951) and first reported in 1904 in his paper, “The pathology of open pneumothorax and the bases of my methods for its elimination.”

As described by Nissen and Wilson, “He transformed the operating room into a kind of extended or enlarged pleural cavity, lowering the atmospheric pressure by vacuum. The head of the patient was outside the operating room, tightly sealed at the neck. This ‘pneumatic chamber’ solved in an ideal way the problem of negative pleural pressure.”

Sauerbruch was aware of the Meltzer/Auer technique, but specifically rejected it, and his powerful influence in Germany helped to prevent it from being adopted there.

Among the earliest and most vocal advocates of using the Sauerbruch negative pressure chamber approach in the United States was Dr. Meyer. Both he and Dr. Meltzer addressed the issue and the controversy at the first meeting of the AATS in 1917.

“You probably remember the little battle between differential pressure and intratracheal insufflation. It occurred only 8 years ago; but it seems now like history. When I presented my paper on intratracheal insufflation at the New York Academy of Medicine, my views were opposed, in the interest of conservatism in surgery, by three able surgeons,” Dr. Meltzer said in his address.

“Now, these same surgeons are among the principal founders of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, and my being the first presiding officer of the Association is due exclusively to their generous spirit and not to any merits of mine. This is my little story of how the introduction of a stomach tube carried a mere medical man into the presidential chair of a national surgical association.”

Dr. Meyer, one of the three surgeons mentioned by Dr. Meltzer, responded shortly thereafter in his own speech at the meeting: “Dr. Meltzer mentioned in his inaugural address today that, in the discussion following his presentation of the matter before the New York Academy of Medicine his views were opposed, in the interest of conservatism in surgery, by three surgeons.

“Inasmuch as I was one of the three, I would, in explanation, here state that ... at that very time it was reported to me that Dr. Meltzer had stated that in his opinion thoracic operations on human beings could be done in a much simpler way than by working in the negative chamber; that a catheter in the trachea and bellows was all that was needed. He, a physiologist who had always done scientific surgical work on animals, certainly found these paraphernalia sufficient. I personally had meanwhile seen and learned to admire the absolutely reliable working of the mechanism of the chamber, without the possibility of doing the slightest harm to the patient.

“In my remarks on that memorable evening at the New York Academy of Medicine, I therefore tried to impress upon my colleagues the great importance of absolute safety. I stated that no matter what apparatus we might use in thoracic surgery on the usually much run down human being, it must be so constructed that it could not possibly do harm to the patient. I further stated that I would be only too happy to personally use intratracheal insufflation as soon as it was sufficiently perfected to render it safe under all conditions. … I want to lay stress upon the statement that I for my part have never been in opposition, but rather in full accord with his splendid discovery. The fact is that I personally have been among the very first in New York to use intratracheal insufflation in thoracic operations upon the human subject,” said Dr. Meyer.

“But, please bear in mind … that only the use of the differential pressure method – no matter what the apparatus – enables the surgeon to work in the thorax with the same equanimity and tranquility as in the abdomen,” he summarized.

So by the early years of the founding of the AATS, no matter the barriers that remained, the fact that thoracic surgery had reached the same level of confidence in terms of attempting operations as had already existed for the abdomen permitted the fledgling association to move forward with a confidence and optimism that had not existed before, when opening the chest in the operating room was generally considered deadly.

Sources

Meltzer, S. J., 1917. First President’s Address. http://t.aats.org/annualmeeting/Program-Books/50th-Anniversary-Book/First-Presidents-Address.cgi

Meyer, W., 1917. Surgery Within the Past Fourteen Years. http://t.aats.org/annualmeeting/Program-Books/50th-Anniversary-Book/A-Review-of-the-Evolution-of-Thoracic-Surgery-Within-the-Pas.cgi

Nissen, R., Wilson, R.H.L. Pages in the History of Chest Surgery. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1960.

In retrospect, the founding of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery (AATS) in 1917 may seem surprisingly optimistic, given the status of cardiothoracic surgery as a discipline at that time. While important strides had been made in dealing with open chest wounds, to the modern eye, the field in the second decade of the 20th century seems more characterized by what was not yet possible rather than by what was.

One of the most critical issues holding back the development of cardiothoracic surgery in this early period was the problem of acute pneumothorax that occurred whenever the chest was opened.

As Willy Meyer (1858-1932), second president of the AATS, described the problem at the first AATS annual meeting in 1917: “What is it that happens when the thorax is opened, let us say [for example] by a stab wound in an intercostal space in an affray on the street? Immediately air rushes into the pleural cavity and this normal atmospheric pressure, being greater than the normal pressure within ... the lung contracts to a very small organ around its hilum. Air fills the space formerly occupied by the lung. This condition, with its immediate clinical pathologic consequences, is called ‘acute pneumothorax.’ It has been the stumbling block for almost a century to the proper development of the surgery of the chest. … Carbonic acid is retained in the blood … The accumulation of CO, with its deleterious effect increases, finally ending in the patient’s death.”

But in the first decade of the 20th century, two major and competing techniques evolved to solve the problem, each one represented by the first and second presidents of the fledgling AATS. For a short period of time a controversy seemed to separate the two men, but their views were expressly reconciled at the first annual meeting of the AATS.

The Meltzer/Auer technique was significantly improved upon by the addition of a carbon dioxide absorption method and the creation of a closed circuit apparatus by Dennis Jackson, MD (1878-1980) in 1915. “This fulfilled the criteria of oxygen supply, carbon dioxide absorption, and ether regulation with a hand bag-breather. With this apparatus, respiration could be maintained with the open thorax,” said pioneering thoracic surgeon Rudolf Nissen, MD, and Roger H.L. Wilson, MD, in their Pages in the History of Chest Surgery (Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1960).

However, insufflation was not universally applauded when it was first introduced. It was considered a poor second by many who instead embraced the alternate method of preventing chest collapse – the differential pressure–maintaining Sauerbruch chamber. The Sauerbruch chamber was developed by Ernst Ferdinand Sauerbruch (1875-1951) and first reported in 1904 in his paper, “The pathology of open pneumothorax and the bases of my methods for its elimination.”

As described by Nissen and Wilson, “He transformed the operating room into a kind of extended or enlarged pleural cavity, lowering the atmospheric pressure by vacuum. The head of the patient was outside the operating room, tightly sealed at the neck. This ‘pneumatic chamber’ solved in an ideal way the problem of negative pleural pressure.”

Sauerbruch was aware of the Meltzer/Auer technique, but specifically rejected it, and his powerful influence in Germany helped to prevent it from being adopted there.

Among the earliest and most vocal advocates of using the Sauerbruch negative pressure chamber approach in the United States was Dr. Meyer. Both he and Dr. Meltzer addressed the issue and the controversy at the first meeting of the AATS in 1917.

“You probably remember the little battle between differential pressure and intratracheal insufflation. It occurred only 8 years ago; but it seems now like history. When I presented my paper on intratracheal insufflation at the New York Academy of Medicine, my views were opposed, in the interest of conservatism in surgery, by three able surgeons,” Dr. Meltzer said in his address.

“Now, these same surgeons are among the principal founders of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, and my being the first presiding officer of the Association is due exclusively to their generous spirit and not to any merits of mine. This is my little story of how the introduction of a stomach tube carried a mere medical man into the presidential chair of a national surgical association.”

Dr. Meyer, one of the three surgeons mentioned by Dr. Meltzer, responded shortly thereafter in his own speech at the meeting: “Dr. Meltzer mentioned in his inaugural address today that, in the discussion following his presentation of the matter before the New York Academy of Medicine his views were opposed, in the interest of conservatism in surgery, by three surgeons.

“Inasmuch as I was one of the three, I would, in explanation, here state that ... at that very time it was reported to me that Dr. Meltzer had stated that in his opinion thoracic operations on human beings could be done in a much simpler way than by working in the negative chamber; that a catheter in the trachea and bellows was all that was needed. He, a physiologist who had always done scientific surgical work on animals, certainly found these paraphernalia sufficient. I personally had meanwhile seen and learned to admire the absolutely reliable working of the mechanism of the chamber, without the possibility of doing the slightest harm to the patient.

“In my remarks on that memorable evening at the New York Academy of Medicine, I therefore tried to impress upon my colleagues the great importance of absolute safety. I stated that no matter what apparatus we might use in thoracic surgery on the usually much run down human being, it must be so constructed that it could not possibly do harm to the patient. I further stated that I would be only too happy to personally use intratracheal insufflation as soon as it was sufficiently perfected to render it safe under all conditions. … I want to lay stress upon the statement that I for my part have never been in opposition, but rather in full accord with his splendid discovery. The fact is that I personally have been among the very first in New York to use intratracheal insufflation in thoracic operations upon the human subject,” said Dr. Meyer.

“But, please bear in mind … that only the use of the differential pressure method – no matter what the apparatus – enables the surgeon to work in the thorax with the same equanimity and tranquility as in the abdomen,” he summarized.

So by the early years of the founding of the AATS, no matter the barriers that remained, the fact that thoracic surgery had reached the same level of confidence in terms of attempting operations as had already existed for the abdomen permitted the fledgling association to move forward with a confidence and optimism that had not existed before, when opening the chest in the operating room was generally considered deadly.

Sources

Meltzer, S. J., 1917. First President’s Address. http://t.aats.org/annualmeeting/Program-Books/50th-Anniversary-Book/First-Presidents-Address.cgi

Meyer, W., 1917. Surgery Within the Past Fourteen Years. http://t.aats.org/annualmeeting/Program-Books/50th-Anniversary-Book/A-Review-of-the-Evolution-of-Thoracic-Surgery-Within-the-Pas.cgi

Nissen, R., Wilson, R.H.L. Pages in the History of Chest Surgery. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1960.

In retrospect, the founding of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery (AATS) in 1917 may seem surprisingly optimistic, given the status of cardiothoracic surgery as a discipline at that time. While important strides had been made in dealing with open chest wounds, to the modern eye, the field in the second decade of the 20th century seems more characterized by what was not yet possible rather than by what was.

One of the most critical issues holding back the development of cardiothoracic surgery in this early period was the problem of acute pneumothorax that occurred whenever the chest was opened.

As Willy Meyer (1858-1932), second president of the AATS, described the problem at the first AATS annual meeting in 1917: “What is it that happens when the thorax is opened, let us say [for example] by a stab wound in an intercostal space in an affray on the street? Immediately air rushes into the pleural cavity and this normal atmospheric pressure, being greater than the normal pressure within ... the lung contracts to a very small organ around its hilum. Air fills the space formerly occupied by the lung. This condition, with its immediate clinical pathologic consequences, is called ‘acute pneumothorax.’ It has been the stumbling block for almost a century to the proper development of the surgery of the chest. … Carbonic acid is retained in the blood … The accumulation of CO, with its deleterious effect increases, finally ending in the patient’s death.”

But in the first decade of the 20th century, two major and competing techniques evolved to solve the problem, each one represented by the first and second presidents of the fledgling AATS. For a short period of time a controversy seemed to separate the two men, but their views were expressly reconciled at the first annual meeting of the AATS.

The Meltzer/Auer technique was significantly improved upon by the addition of a carbon dioxide absorption method and the creation of a closed circuit apparatus by Dennis Jackson, MD (1878-1980) in 1915. “This fulfilled the criteria of oxygen supply, carbon dioxide absorption, and ether regulation with a hand bag-breather. With this apparatus, respiration could be maintained with the open thorax,” said pioneering thoracic surgeon Rudolf Nissen, MD, and Roger H.L. Wilson, MD, in their Pages in the History of Chest Surgery (Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1960).

However, insufflation was not universally applauded when it was first introduced. It was considered a poor second by many who instead embraced the alternate method of preventing chest collapse – the differential pressure–maintaining Sauerbruch chamber. The Sauerbruch chamber was developed by Ernst Ferdinand Sauerbruch (1875-1951) and first reported in 1904 in his paper, “The pathology of open pneumothorax and the bases of my methods for its elimination.”

As described by Nissen and Wilson, “He transformed the operating room into a kind of extended or enlarged pleural cavity, lowering the atmospheric pressure by vacuum. The head of the patient was outside the operating room, tightly sealed at the neck. This ‘pneumatic chamber’ solved in an ideal way the problem of negative pleural pressure.”

Sauerbruch was aware of the Meltzer/Auer technique, but specifically rejected it, and his powerful influence in Germany helped to prevent it from being adopted there.

Among the earliest and most vocal advocates of using the Sauerbruch negative pressure chamber approach in the United States was Dr. Meyer. Both he and Dr. Meltzer addressed the issue and the controversy at the first meeting of the AATS in 1917.

“You probably remember the little battle between differential pressure and intratracheal insufflation. It occurred only 8 years ago; but it seems now like history. When I presented my paper on intratracheal insufflation at the New York Academy of Medicine, my views were opposed, in the interest of conservatism in surgery, by three able surgeons,” Dr. Meltzer said in his address.

“Now, these same surgeons are among the principal founders of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, and my being the first presiding officer of the Association is due exclusively to their generous spirit and not to any merits of mine. This is my little story of how the introduction of a stomach tube carried a mere medical man into the presidential chair of a national surgical association.”

Dr. Meyer, one of the three surgeons mentioned by Dr. Meltzer, responded shortly thereafter in his own speech at the meeting: “Dr. Meltzer mentioned in his inaugural address today that, in the discussion following his presentation of the matter before the New York Academy of Medicine his views were opposed, in the interest of conservatism in surgery, by three surgeons.

“Inasmuch as I was one of the three, I would, in explanation, here state that ... at that very time it was reported to me that Dr. Meltzer had stated that in his opinion thoracic operations on human beings could be done in a much simpler way than by working in the negative chamber; that a catheter in the trachea and bellows was all that was needed. He, a physiologist who had always done scientific surgical work on animals, certainly found these paraphernalia sufficient. I personally had meanwhile seen and learned to admire the absolutely reliable working of the mechanism of the chamber, without the possibility of doing the slightest harm to the patient.

“In my remarks on that memorable evening at the New York Academy of Medicine, I therefore tried to impress upon my colleagues the great importance of absolute safety. I stated that no matter what apparatus we might use in thoracic surgery on the usually much run down human being, it must be so constructed that it could not possibly do harm to the patient. I further stated that I would be only too happy to personally use intratracheal insufflation as soon as it was sufficiently perfected to render it safe under all conditions. … I want to lay stress upon the statement that I for my part have never been in opposition, but rather in full accord with his splendid discovery. The fact is that I personally have been among the very first in New York to use intratracheal insufflation in thoracic operations upon the human subject,” said Dr. Meyer.

“But, please bear in mind … that only the use of the differential pressure method – no matter what the apparatus – enables the surgeon to work in the thorax with the same equanimity and tranquility as in the abdomen,” he summarized.

So by the early years of the founding of the AATS, no matter the barriers that remained, the fact that thoracic surgery had reached the same level of confidence in terms of attempting operations as had already existed for the abdomen permitted the fledgling association to move forward with a confidence and optimism that had not existed before, when opening the chest in the operating room was generally considered deadly.

Sources

Meltzer, S. J., 1917. First President’s Address. http://t.aats.org/annualmeeting/Program-Books/50th-Anniversary-Book/First-Presidents-Address.cgi

Meyer, W., 1917. Surgery Within the Past Fourteen Years. http://t.aats.org/annualmeeting/Program-Books/50th-Anniversary-Book/A-Review-of-the-Evolution-of-Thoracic-Surgery-Within-the-Pas.cgi

Nissen, R., Wilson, R.H.L. Pages in the History of Chest Surgery. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1960.

Corticosteroids effective just hours before preterm delivery

Antenatal corticosteroids may significantly decrease neonatal mortality and morbidity even when they are given just hours before preterm delivery, according to a report published online May 15 in JAMA Pediatrics.

In women at risk of preterm delivery, antenatal corticosteroids given between 1 and 7 days before birth reduce infant mortality by an estimated 31%, respiratory distress syndrome by 34%, intraventricular hemorrhage by 46%, and necrotizing enterocolitis by 54%. But until now their effect when given less than 24 hours before preterm birth has been described as “suboptimal,” “partial,” or “incomplete,” said Mikael Norman, MD, PhD, of Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden, and his associates.

“Our findings challenge current thinking about the optimal timing” of antenatal corticosteroids and encourage “a more proactive management of women at risk for imminent preterm birth, which may help reduce infant mortality and severe neonatal brain injury,” the investigators said.

To further examine this issue, they assessed the effects of antenatal corticosteroids when given at different intervals before preterm birth, using data from a prospective cohort study of perinatal intensive care. That study involved 10,329 very preterm births throughout 11 countries in Europe during a 1-year period.

For their analysis, Dr. Norman and his associates focused on 4,594 singleton births at 24-31 weeks’ gestation. They classified the timing of antenatal corticosteroids into four categories: no injections (662 infants, or 14.4% of the study population), first injection at less than 24 hours before birth (1,111 infants, or 24.2%), first injection at the recommended 1-7 days before birth (1,871 infants, or 40.7%), and first injection more than 7 days before birth (950 infants, or 20.7%).

Receiving antenatal corticosteroids at any interval before preterm birth was associated with lower infant mortality, a lower rate of severe neonatal morbidity, and a lower rate of severe neonatal brain injury, compared with not receiving any antenatal corticosteroids. The largest reduction in risk (more than 50%) occurred at the recommended interval of 1-7 days before birth. However, receiving the treatment less than 24 hours before birth also significantly reduced these risks (JAMA Pediatr. 2017 May 15. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0602).

Using their findings on treatment intervals and effectiveness, the investigators created a simulation model for the 661 infants in this cohort who did not receive any antenatal corticosteroids. Their model predicted that if these infants had received treatment at least 3 hours before delivery, overall mortality would have decreased by 26%. If they had received treatment 3-5 hours before delivery, mortality would have decreased by 37%, and if they had received treatment at 6-12 hours before delivery it would have decreased by 51%.

At the other end of the timing spectrum, infant mortality increased 40% when corticosteroids were given more than 7 days before delivery, compared with when they were given within the recommended 1-7 days. This represents a substantial number of infants – approximately 20% of the study cohort.

The study was supported by the European Union, the French Institute of Public Health, the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education, the Karolinska Institutet, and other nonindustry sources. Dr. Norman and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Antenatal corticosteroids may significantly decrease neonatal mortality and morbidity even when they are given just hours before preterm delivery, according to a report published online May 15 in JAMA Pediatrics.

In women at risk of preterm delivery, antenatal corticosteroids given between 1 and 7 days before birth reduce infant mortality by an estimated 31%, respiratory distress syndrome by 34%, intraventricular hemorrhage by 46%, and necrotizing enterocolitis by 54%. But until now their effect when given less than 24 hours before preterm birth has been described as “suboptimal,” “partial,” or “incomplete,” said Mikael Norman, MD, PhD, of Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden, and his associates.

“Our findings challenge current thinking about the optimal timing” of antenatal corticosteroids and encourage “a more proactive management of women at risk for imminent preterm birth, which may help reduce infant mortality and severe neonatal brain injury,” the investigators said.

To further examine this issue, they assessed the effects of antenatal corticosteroids when given at different intervals before preterm birth, using data from a prospective cohort study of perinatal intensive care. That study involved 10,329 very preterm births throughout 11 countries in Europe during a 1-year period.

For their analysis, Dr. Norman and his associates focused on 4,594 singleton births at 24-31 weeks’ gestation. They classified the timing of antenatal corticosteroids into four categories: no injections (662 infants, or 14.4% of the study population), first injection at less than 24 hours before birth (1,111 infants, or 24.2%), first injection at the recommended 1-7 days before birth (1,871 infants, or 40.7%), and first injection more than 7 days before birth (950 infants, or 20.7%).

Receiving antenatal corticosteroids at any interval before preterm birth was associated with lower infant mortality, a lower rate of severe neonatal morbidity, and a lower rate of severe neonatal brain injury, compared with not receiving any antenatal corticosteroids. The largest reduction in risk (more than 50%) occurred at the recommended interval of 1-7 days before birth. However, receiving the treatment less than 24 hours before birth also significantly reduced these risks (JAMA Pediatr. 2017 May 15. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0602).

Using their findings on treatment intervals and effectiveness, the investigators created a simulation model for the 661 infants in this cohort who did not receive any antenatal corticosteroids. Their model predicted that if these infants had received treatment at least 3 hours before delivery, overall mortality would have decreased by 26%. If they had received treatment 3-5 hours before delivery, mortality would have decreased by 37%, and if they had received treatment at 6-12 hours before delivery it would have decreased by 51%.

At the other end of the timing spectrum, infant mortality increased 40% when corticosteroids were given more than 7 days before delivery, compared with when they were given within the recommended 1-7 days. This represents a substantial number of infants – approximately 20% of the study cohort.

The study was supported by the European Union, the French Institute of Public Health, the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education, the Karolinska Institutet, and other nonindustry sources. Dr. Norman and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Antenatal corticosteroids may significantly decrease neonatal mortality and morbidity even when they are given just hours before preterm delivery, according to a report published online May 15 in JAMA Pediatrics.

In women at risk of preterm delivery, antenatal corticosteroids given between 1 and 7 days before birth reduce infant mortality by an estimated 31%, respiratory distress syndrome by 34%, intraventricular hemorrhage by 46%, and necrotizing enterocolitis by 54%. But until now their effect when given less than 24 hours before preterm birth has been described as “suboptimal,” “partial,” or “incomplete,” said Mikael Norman, MD, PhD, of Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden, and his associates.

“Our findings challenge current thinking about the optimal timing” of antenatal corticosteroids and encourage “a more proactive management of women at risk for imminent preterm birth, which may help reduce infant mortality and severe neonatal brain injury,” the investigators said.

To further examine this issue, they assessed the effects of antenatal corticosteroids when given at different intervals before preterm birth, using data from a prospective cohort study of perinatal intensive care. That study involved 10,329 very preterm births throughout 11 countries in Europe during a 1-year period.

For their analysis, Dr. Norman and his associates focused on 4,594 singleton births at 24-31 weeks’ gestation. They classified the timing of antenatal corticosteroids into four categories: no injections (662 infants, or 14.4% of the study population), first injection at less than 24 hours before birth (1,111 infants, or 24.2%), first injection at the recommended 1-7 days before birth (1,871 infants, or 40.7%), and first injection more than 7 days before birth (950 infants, or 20.7%).

Receiving antenatal corticosteroids at any interval before preterm birth was associated with lower infant mortality, a lower rate of severe neonatal morbidity, and a lower rate of severe neonatal brain injury, compared with not receiving any antenatal corticosteroids. The largest reduction in risk (more than 50%) occurred at the recommended interval of 1-7 days before birth. However, receiving the treatment less than 24 hours before birth also significantly reduced these risks (JAMA Pediatr. 2017 May 15. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0602).

Using their findings on treatment intervals and effectiveness, the investigators created a simulation model for the 661 infants in this cohort who did not receive any antenatal corticosteroids. Their model predicted that if these infants had received treatment at least 3 hours before delivery, overall mortality would have decreased by 26%. If they had received treatment 3-5 hours before delivery, mortality would have decreased by 37%, and if they had received treatment at 6-12 hours before delivery it would have decreased by 51%.

At the other end of the timing spectrum, infant mortality increased 40% when corticosteroids were given more than 7 days before delivery, compared with when they were given within the recommended 1-7 days. This represents a substantial number of infants – approximately 20% of the study cohort.

The study was supported by the European Union, the French Institute of Public Health, the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education, the Karolinska Institutet, and other nonindustry sources. Dr. Norman and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: A simulation model predicted that if untreated infants had received antenatal corticosteroids 6-12 hours before delivery, overall mortality would have decreased by 51%.

Data source: A secondary analysis of data from a population-based cohort study of perinatal intensive care across Europe, involving 4,594 preterm singleton births.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the European Union, the French Institute of Public Health, the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education, the Karolinska Institutet, and other nonindustry sources. Dr. Norman and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

One-third of drug postmarket studies go unpublished

More than one-third of postmarket studies following drug approval that should be published are not, according to new research.

Investigators examined a Food and Drug Administration internal database to identify all postmarket drug studies between 2009 and 2013 identified by the agency as completed, with a follow-up search to find if/where the results of the studies were published.

“As of July 2016, 183 of the 288 postmarket studies (63.5%) meeting inclusion criteria were published in either the scientific literature or on the ClinicalTrials.gov website,” Marisa Cruz, MD, medical officer in the Food and Drug Administration’s Office of Public Health Strategy and Analysis, and her colleagues wrote in a researcher letter published online May 15 in JAMA Internal Medicine (doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1313).

More studies were published in journals (175) than in the agency’s clinical trial registry (87), and the 183 interventional clinical trials had a higher overall publication rate (87.4%) than the other 105 studies combined (21.9%).

Of the 69 interventional clinical trials that were focused on efficacy, 86.2% were categorized as having results that were favorable to the trial sponsor. However, the 57 interventional clinical trials with positive results were no more likely to be published than the 12 trials with negative results, Dr. Cruz and colleagues noted.

The findings are consistent with previous research, the researchers noted, with the analysis demonstrating “that postmarket study results are not consistently disseminated, either through journal publication or trial registries.”

“Despite calls for data sharing and publication of all clinical trial results, publication rates for completed postmarket studies required by the FDA remain relatively low,” the researchers wrote.

While the FDA could publish the data itself, “this approach would likely require new regulations,” the authors noted. “Alternatively, increased sponsor commitment to submitting to journals and to publish all clinical trial results on trial registries, regardless of whether publication is legally required, may serve to promote dissemination of scientific knowledge.”

The researchers reported no conflicts of interest.

More than one-third of postmarket studies following drug approval that should be published are not, according to new research.

Investigators examined a Food and Drug Administration internal database to identify all postmarket drug studies between 2009 and 2013 identified by the agency as completed, with a follow-up search to find if/where the results of the studies were published.

“As of July 2016, 183 of the 288 postmarket studies (63.5%) meeting inclusion criteria were published in either the scientific literature or on the ClinicalTrials.gov website,” Marisa Cruz, MD, medical officer in the Food and Drug Administration’s Office of Public Health Strategy and Analysis, and her colleagues wrote in a researcher letter published online May 15 in JAMA Internal Medicine (doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1313).

More studies were published in journals (175) than in the agency’s clinical trial registry (87), and the 183 interventional clinical trials had a higher overall publication rate (87.4%) than the other 105 studies combined (21.9%).

Of the 69 interventional clinical trials that were focused on efficacy, 86.2% were categorized as having results that were favorable to the trial sponsor. However, the 57 interventional clinical trials with positive results were no more likely to be published than the 12 trials with negative results, Dr. Cruz and colleagues noted.

The findings are consistent with previous research, the researchers noted, with the analysis demonstrating “that postmarket study results are not consistently disseminated, either through journal publication or trial registries.”

“Despite calls for data sharing and publication of all clinical trial results, publication rates for completed postmarket studies required by the FDA remain relatively low,” the researchers wrote.

While the FDA could publish the data itself, “this approach would likely require new regulations,” the authors noted. “Alternatively, increased sponsor commitment to submitting to journals and to publish all clinical trial results on trial registries, regardless of whether publication is legally required, may serve to promote dissemination of scientific knowledge.”

The researchers reported no conflicts of interest.

More than one-third of postmarket studies following drug approval that should be published are not, according to new research.

Investigators examined a Food and Drug Administration internal database to identify all postmarket drug studies between 2009 and 2013 identified by the agency as completed, with a follow-up search to find if/where the results of the studies were published.

“As of July 2016, 183 of the 288 postmarket studies (63.5%) meeting inclusion criteria were published in either the scientific literature or on the ClinicalTrials.gov website,” Marisa Cruz, MD, medical officer in the Food and Drug Administration’s Office of Public Health Strategy and Analysis, and her colleagues wrote in a researcher letter published online May 15 in JAMA Internal Medicine (doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1313).

More studies were published in journals (175) than in the agency’s clinical trial registry (87), and the 183 interventional clinical trials had a higher overall publication rate (87.4%) than the other 105 studies combined (21.9%).

Of the 69 interventional clinical trials that were focused on efficacy, 86.2% were categorized as having results that were favorable to the trial sponsor. However, the 57 interventional clinical trials with positive results were no more likely to be published than the 12 trials with negative results, Dr. Cruz and colleagues noted.

The findings are consistent with previous research, the researchers noted, with the analysis demonstrating “that postmarket study results are not consistently disseminated, either through journal publication or trial registries.”

“Despite calls for data sharing and publication of all clinical trial results, publication rates for completed postmarket studies required by the FDA remain relatively low,” the researchers wrote.

While the FDA could publish the data itself, “this approach would likely require new regulations,” the authors noted. “Alternatively, increased sponsor commitment to submitting to journals and to publish all clinical trial results on trial registries, regardless of whether publication is legally required, may serve to promote dissemination of scientific knowledge.”

The researchers reported no conflicts of interest.

Value-based care didn’t trigger spikes in patient dismissals

Fears that the transition to value-based care could lead to doctors dismissing patients from their practice who could adversely affect their reimbursement didn’t come to fruition in a recent federal value-based initiative.

“Patient dismissal could be an unintended consequence of this shift as clinicians face (or perceive they face) pressure to limit their panel to patients for whom they can readily demonstrate value in order to maximize revenue,” Ann S. O’Malley, MD, senior fellow at Mathematica Policy Research, and her colleagues wrote in a research letter published online May 15 in JAMA Internal Medicine (doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1309).

“A similar portion and distribution of CPC and comparison practices reported ever dismissing patients in the past 2 years,” 89% and 92%, respectively, the researchers reported.

CPC and comparison practices “dismissed patients for similar reasons,” Dr. O’Malley and colleagues added, noting the exception that more comparison practices reported dismissing patients for violating bill payment policies than CPC practices did – 43% vs. 35%, respectively.

Other reasons for dismissing patients included patients being extremely disruptive and/or behaving inappropriately toward clinicians or staff, patients violating chronic pain/controlled substances policies, patients repeatedly missing appointments, patients not following recommended lifestyle changes, and patients making frequent emergency department visits and/or frequent self-referrals to specialists.

Practices participating in the CPC initiative were also asked if participation in the value-based payment model would make them more or less likely to dismiss patients.

“According to most CPC practices, the initiative had no effect or made them less likely to dismiss patients,” the researchers found.

The CMS Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation funded the study. The study authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Fears that the transition to value-based care could lead to doctors dismissing patients from their practice who could adversely affect their reimbursement didn’t come to fruition in a recent federal value-based initiative.

“Patient dismissal could be an unintended consequence of this shift as clinicians face (or perceive they face) pressure to limit their panel to patients for whom they can readily demonstrate value in order to maximize revenue,” Ann S. O’Malley, MD, senior fellow at Mathematica Policy Research, and her colleagues wrote in a research letter published online May 15 in JAMA Internal Medicine (doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1309).

“A similar portion and distribution of CPC and comparison practices reported ever dismissing patients in the past 2 years,” 89% and 92%, respectively, the researchers reported.

CPC and comparison practices “dismissed patients for similar reasons,” Dr. O’Malley and colleagues added, noting the exception that more comparison practices reported dismissing patients for violating bill payment policies than CPC practices did – 43% vs. 35%, respectively.

Other reasons for dismissing patients included patients being extremely disruptive and/or behaving inappropriately toward clinicians or staff, patients violating chronic pain/controlled substances policies, patients repeatedly missing appointments, patients not following recommended lifestyle changes, and patients making frequent emergency department visits and/or frequent self-referrals to specialists.

Practices participating in the CPC initiative were also asked if participation in the value-based payment model would make them more or less likely to dismiss patients.

“According to most CPC practices, the initiative had no effect or made them less likely to dismiss patients,” the researchers found.

The CMS Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation funded the study. The study authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Fears that the transition to value-based care could lead to doctors dismissing patients from their practice who could adversely affect their reimbursement didn’t come to fruition in a recent federal value-based initiative.

“Patient dismissal could be an unintended consequence of this shift as clinicians face (or perceive they face) pressure to limit their panel to patients for whom they can readily demonstrate value in order to maximize revenue,” Ann S. O’Malley, MD, senior fellow at Mathematica Policy Research, and her colleagues wrote in a research letter published online May 15 in JAMA Internal Medicine (doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1309).

“A similar portion and distribution of CPC and comparison practices reported ever dismissing patients in the past 2 years,” 89% and 92%, respectively, the researchers reported.

CPC and comparison practices “dismissed patients for similar reasons,” Dr. O’Malley and colleagues added, noting the exception that more comparison practices reported dismissing patients for violating bill payment policies than CPC practices did – 43% vs. 35%, respectively.

Other reasons for dismissing patients included patients being extremely disruptive and/or behaving inappropriately toward clinicians or staff, patients violating chronic pain/controlled substances policies, patients repeatedly missing appointments, patients not following recommended lifestyle changes, and patients making frequent emergency department visits and/or frequent self-referrals to specialists.

Practices participating in the CPC initiative were also asked if participation in the value-based payment model would make them more or less likely to dismiss patients.

“According to most CPC practices, the initiative had no effect or made them less likely to dismiss patients,” the researchers found.

The CMS Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation funded the study. The study authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Pediatric Dermatology Consult - May 2017

BY LAWRENCE F. EICHENFIELD, MD, and JENNA BOROK

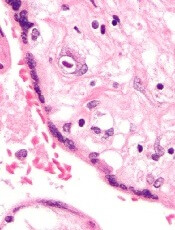

Nevus sebaceous (NS) is considered a subtype of an epidermal nevus, a benign hamartoma that includes an excess or deficiency of structural elements of the skin, such as epidermis, sebaceous, and apocrine glands.1

Nevus sebaceous, also known as nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn, was first described in 1895 by Josef Jadassohn as a nevoid growth composed predominantly of sebaceous glands.2 Sebaceous glands are found everywhere on the body where hair is found and are located adjacent to hair follicles with ducts, through which sebum flows.3

NS clinically appears as a waxy, yellowish-orange to pink, hairless plaque, ranging from 1 cm to over 10 cm in size and usually located on the scalp, face, neck, or trunk.1 When the lesions are linear, they typically follow Blaschko lines.1 The lesions change over time. An infant’s lesion will be slightly raised and can be hardly noticeable. If the lesion is located on the scalp, it will remain hairless. During later childhood, the nevus may thicken. The lesions may become thicker and verrucous during adolescence.

Histologically, NS are benign hamartomas with epidermal, follicular, sebaceous, and apocrine elements.4 The malformation is primarily within the individual folliculosebaceous units.1 An infantile lesion will deviate little from normal skin as the follicular units are so small.1 During childhood, microscopically, it is easier to see misshapen follicles and thickened epidermis.1 During adolescence, the histological pattern is similar to that of an epidermal nevi, which includes acanthosis and fibroplasia of the papillary dermis.

There are now several lines of evidence showing that nevus sebaceous is caused by genetic postzygotic mosaic mutations in the mitogen–activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, which specifically activate ras mutations including H ras and K ras genes.5-7 Since NS is caused by a somatic mosaicism mutation, there are a several syndromic findings associated with NS depending on the timing of the mutations during development and whether single versus multiple tissues are affected.8 Specifically, NS has been associated with Schimmelpenning-Feuerstein-Mims syndrome that includes NS, and skeletal, ocular, and neurologic abnormalities.1,7 A study found that cutaneous skeletal hypophosphatemia syndrome, manifested as NS and vitamin D–resistant rickets, has identical ras mutations in both skin and bone tissues, providing further support that these syndromic findings are a result of a multilineage somatic ras mutation.8

Diagnosis

NS is typically diagnosed clinically, based on the presence of a circumscribed, thin, yellow-orange, oval, round, or linear plaque, usually on the scalp or face. During infancy or the first stage, the lesions remain stable. In the second stage, during puberty, the lesions thicken and become verrucous or nodular because of changes in sebaceous gland activity that are driven by hormones. In the third stage of their natural course, benign and malignant epithelial neoplasms can develop, including trichoblastoma, syringocystadenoma papilliferum, sebaceous epithelioma, basal cell carcinoma, and trichilemmoma.9

The associated syndrome, nevus sebaceous syndrome, also known as Schimmelpenning syndrome, has more extensive cutaneous lesions along Blaschko lines and presents with CNS, ocular, or skeletal defects. The CNS abnormalities include mental retardation, seizures, and hemimegalencephaly.1 Therefore, a thorough neurologic and ophthalmologic examination should be performed in patients with suspected nevus sebaceous syndrome.

Aplasia cutis congenita is the absence of the skin at birth that presents with an erosion or deep ulceration to a scar or a defect that is covered with an epidermal membrane.1 Some aplasia cutis may present as a smooth, hairless surface at birth, making differentiation from nevus sebaceous difficult. The pinkish, orange to yellow hue of NS may help differentiate these entities. Juvenile xanthogranuloma is a fairly common histiocytosis and is the most common histiocytic disease of childhood.1 It is a benign proliferation of dermal dendrocytes, and it presents in infants as many red to yellow papules or a few nodules on the head and neck. Many lesions even remain undetected.1

Syringocystadenoma papilliferum is a benign neoplasm with apocrine differentiation and presents as a papule or plaque on the head and neck. It can be associated with nevus sebaceous.1

Treatment

The definitive treatment is an excision. The necessity and timing of excision of these lesions is still under debate.9 Secondary neoplasms do arise from the nevus sebaceous, although the incidence is low pre puberty.1 It has been estimated that 16% of cases develop benign tumors and that 8% of cases develop malignant tumors.9 The majority of malignant lesions are basal cell carcinomas, and a large recent study found that only 1% of patients had malignancies.10 While most of these tumors develop in adulthood, there have been reports of malignancies in children.10

An additional reason to excise NS is that, over time, they grow more verrucous, become inflamed, bleed with trauma, and may be unappealing cosmetically.1 Some experts recommend earlier excision in childhood, especially with larger lesions or facial lesions where minimizing deformity is important and with the possibility of less noticeable scarring.9 The prophylactic removal of NS remains controversial, and there is a lack of consensus among experts about the timing of excision. It is recommended that each lesion be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Ms. Borok is a medical student at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Eichenfield and Ms. Borok said they had no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. “Dermatology.” 3rd ed. (St Louis, Mo: Elsevier, 2012).

2. Arch Dermatol Res. 1895. doi: 10.1007/BF01842810.

3. J Invest Dermatol. 2004 Jul;123(1):1-12.

4. J Cutan Pathol. 1984;11(5):396-414.

5. J Invest Dermatol. 2013 Mar;133(3):827-30.

6. J Invest Dermatol. 2013 Mar;133(3):597-600.

7. Nat Genet. 2012 Jun 10;44(7):783-7.

8. JAAD. 2016 Aug;75(2):420-7.

9. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012 Jan-Feb;29(1):15-23.

10. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009 Nov-Dec;26(6):676-81.

BY LAWRENCE F. EICHENFIELD, MD, and JENNA BOROK

Nevus sebaceous (NS) is considered a subtype of an epidermal nevus, a benign hamartoma that includes an excess or deficiency of structural elements of the skin, such as epidermis, sebaceous, and apocrine glands.1

Nevus sebaceous, also known as nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn, was first described in 1895 by Josef Jadassohn as a nevoid growth composed predominantly of sebaceous glands.2 Sebaceous glands are found everywhere on the body where hair is found and are located adjacent to hair follicles with ducts, through which sebum flows.3

NS clinically appears as a waxy, yellowish-orange to pink, hairless plaque, ranging from 1 cm to over 10 cm in size and usually located on the scalp, face, neck, or trunk.1 When the lesions are linear, they typically follow Blaschko lines.1 The lesions change over time. An infant’s lesion will be slightly raised and can be hardly noticeable. If the lesion is located on the scalp, it will remain hairless. During later childhood, the nevus may thicken. The lesions may become thicker and verrucous during adolescence.

Histologically, NS are benign hamartomas with epidermal, follicular, sebaceous, and apocrine elements.4 The malformation is primarily within the individual folliculosebaceous units.1 An infantile lesion will deviate little from normal skin as the follicular units are so small.1 During childhood, microscopically, it is easier to see misshapen follicles and thickened epidermis.1 During adolescence, the histological pattern is similar to that of an epidermal nevi, which includes acanthosis and fibroplasia of the papillary dermis.

There are now several lines of evidence showing that nevus sebaceous is caused by genetic postzygotic mosaic mutations in the mitogen–activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, which specifically activate ras mutations including H ras and K ras genes.5-7 Since NS is caused by a somatic mosaicism mutation, there are a several syndromic findings associated with NS depending on the timing of the mutations during development and whether single versus multiple tissues are affected.8 Specifically, NS has been associated with Schimmelpenning-Feuerstein-Mims syndrome that includes NS, and skeletal, ocular, and neurologic abnormalities.1,7 A study found that cutaneous skeletal hypophosphatemia syndrome, manifested as NS and vitamin D–resistant rickets, has identical ras mutations in both skin and bone tissues, providing further support that these syndromic findings are a result of a multilineage somatic ras mutation.8

Diagnosis

NS is typically diagnosed clinically, based on the presence of a circumscribed, thin, yellow-orange, oval, round, or linear plaque, usually on the scalp or face. During infancy or the first stage, the lesions remain stable. In the second stage, during puberty, the lesions thicken and become verrucous or nodular because of changes in sebaceous gland activity that are driven by hormones. In the third stage of their natural course, benign and malignant epithelial neoplasms can develop, including trichoblastoma, syringocystadenoma papilliferum, sebaceous epithelioma, basal cell carcinoma, and trichilemmoma.9

The associated syndrome, nevus sebaceous syndrome, also known as Schimmelpenning syndrome, has more extensive cutaneous lesions along Blaschko lines and presents with CNS, ocular, or skeletal defects. The CNS abnormalities include mental retardation, seizures, and hemimegalencephaly.1 Therefore, a thorough neurologic and ophthalmologic examination should be performed in patients with suspected nevus sebaceous syndrome.

Aplasia cutis congenita is the absence of the skin at birth that presents with an erosion or deep ulceration to a scar or a defect that is covered with an epidermal membrane.1 Some aplasia cutis may present as a smooth, hairless surface at birth, making differentiation from nevus sebaceous difficult. The pinkish, orange to yellow hue of NS may help differentiate these entities. Juvenile xanthogranuloma is a fairly common histiocytosis and is the most common histiocytic disease of childhood.1 It is a benign proliferation of dermal dendrocytes, and it presents in infants as many red to yellow papules or a few nodules on the head and neck. Many lesions even remain undetected.1

Syringocystadenoma papilliferum is a benign neoplasm with apocrine differentiation and presents as a papule or plaque on the head and neck. It can be associated with nevus sebaceous.1

Treatment

The definitive treatment is an excision. The necessity and timing of excision of these lesions is still under debate.9 Secondary neoplasms do arise from the nevus sebaceous, although the incidence is low pre puberty.1 It has been estimated that 16% of cases develop benign tumors and that 8% of cases develop malignant tumors.9 The majority of malignant lesions are basal cell carcinomas, and a large recent study found that only 1% of patients had malignancies.10 While most of these tumors develop in adulthood, there have been reports of malignancies in children.10

An additional reason to excise NS is that, over time, they grow more verrucous, become inflamed, bleed with trauma, and may be unappealing cosmetically.1 Some experts recommend earlier excision in childhood, especially with larger lesions or facial lesions where minimizing deformity is important and with the possibility of less noticeable scarring.9 The prophylactic removal of NS remains controversial, and there is a lack of consensus among experts about the timing of excision. It is recommended that each lesion be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.