User login

Avapritinib produces durable responses in SM

STOCKHOLM—The KIT/PDGFRA inhibitor avapritinib has produced durable responses in patients with systemic mastocytosis (SM).

In the phase 1 EXPLORER trial, avapritinib produced an overall response rate of 83%.

Responses have lasted up to 22 months, and 79% of responders remained on avapritinib as of the data cutoff.

The most common treatment-related adverse events (AEs) were periorbital edema, anemia, nausea, and fatigue.

These data were presented in a poster (abstract PF612) at the 23rd Congress of the European Hematology Association (EHA).

The trial was sponsored by Blueprint Medicines Corporation.

As of the data cutoff (April 30, 2018), 52 patients had been treated with avapritinib in the dose-escalation and expansion portions of the EXPLORER trial.

This included 25 patients with aggressive SM (ASM), 15 with advanced SM and an associated hematologic neoplasm (SM-AHN), 5 with mast cell leukemia (MCL), 5 pending central pathology diagnosis, and 2 with smoldering SM.

Thirty-five patients (67%) were previously treated, including 10 (19%) who previously received midostaurin. The patients’ median age was 63 (range, 34-83), and 52% were male.

Treatment

Thirty-two patients were treated in the dose-escalation portion of the study and received avapritinib at doses ranging from 30 mg to 400 mg daily. The 35 patients in the expansion portion received avapritinib at 300 mg daily.

Among all 52 enrolled patients, 42 remained on treatment as of the data cutoff date. Four patients discontinued treatment with avapritinib due to AEs. Three of these were treatment-related, and 1 was unrelated.

Three patients discontinued treatment due to clinical progression as determined by the investigator. None of the patients had documented disease progression by IWG-MRT-ECNM criteria.

Two patients discontinued due to investigator decision, and 1 withdrew consent.

Safety

All 52 patients were evaluable for safety.

Treatment-related AEs included periorbital edema (62%), anemia (33%), nausea (33%), fatigue (31%), peripheral edema (27%), diarrhea (25%), hair color changes (23%), thrombocytopenia (19%), cognitive effects (19%), vomiting (19%), and dizziness (12%).

Grade 3 or higher AEs, regardless of drug relationship, included thrombocytopenia (17%), anemia (15%), fatigue (6%), vomiting (6%), periorbital edema (4%), nausea (4%), diarrhea (2%), hair color changes (2%), and cognitive effects (2%).

Efficacy

As of the data cutoff, 23 patients were evaluable for response by IWG-MRT-ECNM criteria. This included 8 patients with ASM, 10 with SM-AHN, and 5 with MCL.

The overall response rate was 83% (n=19). All responses observed in the dose-escalation portion of the trial have been confirmed, and all responses in the dose-expansion portion of the trial are pending confirmation.

Four patients (17%) had a confirmed complete response with a full (n=1) or partial (n=3) recovery of peripheral blood counts. All of these responses occurred in patients with ASM.

Twelve patients (52%) had a partial response (7 confirmed, 5 pending confirmation). This included 6 patients with SM-AHN, 4 with MCL, and 2 with ASM.

Three patients (13%) had clinical improvement (2 confirmed, 1 pending confirmation), and 4 had stable disease. None of the patients progressed.

The duration of response ranged from 8 months to 22 months, and 79% of responders (15/19) remained on treatment at the data cutoff.

“As a clinician treating patients with this devastating and sometimes fatal rare disease, I’m excited to see that most patients with advanced systemic mastocytosis respond to treatment with avapritinib, and these responses deepen over time and are durable,” said study investigator Michael W. Deininger, MD, PhD, of Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

“These data further support avapritinib’s unique approach of selectively targeting D816V mutant KIT, the disease driver in most patients with systemic mastocytosis. If these results are confirmed in the planned phase 2 trial, avapritinib has the potential to become a new standard of care for patients with advanced forms of the disease.”

STOCKHOLM—The KIT/PDGFRA inhibitor avapritinib has produced durable responses in patients with systemic mastocytosis (SM).

In the phase 1 EXPLORER trial, avapritinib produced an overall response rate of 83%.

Responses have lasted up to 22 months, and 79% of responders remained on avapritinib as of the data cutoff.

The most common treatment-related adverse events (AEs) were periorbital edema, anemia, nausea, and fatigue.

These data were presented in a poster (abstract PF612) at the 23rd Congress of the European Hematology Association (EHA).

The trial was sponsored by Blueprint Medicines Corporation.

As of the data cutoff (April 30, 2018), 52 patients had been treated with avapritinib in the dose-escalation and expansion portions of the EXPLORER trial.

This included 25 patients with aggressive SM (ASM), 15 with advanced SM and an associated hematologic neoplasm (SM-AHN), 5 with mast cell leukemia (MCL), 5 pending central pathology diagnosis, and 2 with smoldering SM.

Thirty-five patients (67%) were previously treated, including 10 (19%) who previously received midostaurin. The patients’ median age was 63 (range, 34-83), and 52% were male.

Treatment

Thirty-two patients were treated in the dose-escalation portion of the study and received avapritinib at doses ranging from 30 mg to 400 mg daily. The 35 patients in the expansion portion received avapritinib at 300 mg daily.

Among all 52 enrolled patients, 42 remained on treatment as of the data cutoff date. Four patients discontinued treatment with avapritinib due to AEs. Three of these were treatment-related, and 1 was unrelated.

Three patients discontinued treatment due to clinical progression as determined by the investigator. None of the patients had documented disease progression by IWG-MRT-ECNM criteria.

Two patients discontinued due to investigator decision, and 1 withdrew consent.

Safety

All 52 patients were evaluable for safety.

Treatment-related AEs included periorbital edema (62%), anemia (33%), nausea (33%), fatigue (31%), peripheral edema (27%), diarrhea (25%), hair color changes (23%), thrombocytopenia (19%), cognitive effects (19%), vomiting (19%), and dizziness (12%).

Grade 3 or higher AEs, regardless of drug relationship, included thrombocytopenia (17%), anemia (15%), fatigue (6%), vomiting (6%), periorbital edema (4%), nausea (4%), diarrhea (2%), hair color changes (2%), and cognitive effects (2%).

Efficacy

As of the data cutoff, 23 patients were evaluable for response by IWG-MRT-ECNM criteria. This included 8 patients with ASM, 10 with SM-AHN, and 5 with MCL.

The overall response rate was 83% (n=19). All responses observed in the dose-escalation portion of the trial have been confirmed, and all responses in the dose-expansion portion of the trial are pending confirmation.

Four patients (17%) had a confirmed complete response with a full (n=1) or partial (n=3) recovery of peripheral blood counts. All of these responses occurred in patients with ASM.

Twelve patients (52%) had a partial response (7 confirmed, 5 pending confirmation). This included 6 patients with SM-AHN, 4 with MCL, and 2 with ASM.

Three patients (13%) had clinical improvement (2 confirmed, 1 pending confirmation), and 4 had stable disease. None of the patients progressed.

The duration of response ranged from 8 months to 22 months, and 79% of responders (15/19) remained on treatment at the data cutoff.

“As a clinician treating patients with this devastating and sometimes fatal rare disease, I’m excited to see that most patients with advanced systemic mastocytosis respond to treatment with avapritinib, and these responses deepen over time and are durable,” said study investigator Michael W. Deininger, MD, PhD, of Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

“These data further support avapritinib’s unique approach of selectively targeting D816V mutant KIT, the disease driver in most patients with systemic mastocytosis. If these results are confirmed in the planned phase 2 trial, avapritinib has the potential to become a new standard of care for patients with advanced forms of the disease.”

STOCKHOLM—The KIT/PDGFRA inhibitor avapritinib has produced durable responses in patients with systemic mastocytosis (SM).

In the phase 1 EXPLORER trial, avapritinib produced an overall response rate of 83%.

Responses have lasted up to 22 months, and 79% of responders remained on avapritinib as of the data cutoff.

The most common treatment-related adverse events (AEs) were periorbital edema, anemia, nausea, and fatigue.

These data were presented in a poster (abstract PF612) at the 23rd Congress of the European Hematology Association (EHA).

The trial was sponsored by Blueprint Medicines Corporation.

As of the data cutoff (April 30, 2018), 52 patients had been treated with avapritinib in the dose-escalation and expansion portions of the EXPLORER trial.

This included 25 patients with aggressive SM (ASM), 15 with advanced SM and an associated hematologic neoplasm (SM-AHN), 5 with mast cell leukemia (MCL), 5 pending central pathology diagnosis, and 2 with smoldering SM.

Thirty-five patients (67%) were previously treated, including 10 (19%) who previously received midostaurin. The patients’ median age was 63 (range, 34-83), and 52% were male.

Treatment

Thirty-two patients were treated in the dose-escalation portion of the study and received avapritinib at doses ranging from 30 mg to 400 mg daily. The 35 patients in the expansion portion received avapritinib at 300 mg daily.

Among all 52 enrolled patients, 42 remained on treatment as of the data cutoff date. Four patients discontinued treatment with avapritinib due to AEs. Three of these were treatment-related, and 1 was unrelated.

Three patients discontinued treatment due to clinical progression as determined by the investigator. None of the patients had documented disease progression by IWG-MRT-ECNM criteria.

Two patients discontinued due to investigator decision, and 1 withdrew consent.

Safety

All 52 patients were evaluable for safety.

Treatment-related AEs included periorbital edema (62%), anemia (33%), nausea (33%), fatigue (31%), peripheral edema (27%), diarrhea (25%), hair color changes (23%), thrombocytopenia (19%), cognitive effects (19%), vomiting (19%), and dizziness (12%).

Grade 3 or higher AEs, regardless of drug relationship, included thrombocytopenia (17%), anemia (15%), fatigue (6%), vomiting (6%), periorbital edema (4%), nausea (4%), diarrhea (2%), hair color changes (2%), and cognitive effects (2%).

Efficacy

As of the data cutoff, 23 patients were evaluable for response by IWG-MRT-ECNM criteria. This included 8 patients with ASM, 10 with SM-AHN, and 5 with MCL.

The overall response rate was 83% (n=19). All responses observed in the dose-escalation portion of the trial have been confirmed, and all responses in the dose-expansion portion of the trial are pending confirmation.

Four patients (17%) had a confirmed complete response with a full (n=1) or partial (n=3) recovery of peripheral blood counts. All of these responses occurred in patients with ASM.

Twelve patients (52%) had a partial response (7 confirmed, 5 pending confirmation). This included 6 patients with SM-AHN, 4 with MCL, and 2 with ASM.

Three patients (13%) had clinical improvement (2 confirmed, 1 pending confirmation), and 4 had stable disease. None of the patients progressed.

The duration of response ranged from 8 months to 22 months, and 79% of responders (15/19) remained on treatment at the data cutoff.

“As a clinician treating patients with this devastating and sometimes fatal rare disease, I’m excited to see that most patients with advanced systemic mastocytosis respond to treatment with avapritinib, and these responses deepen over time and are durable,” said study investigator Michael W. Deininger, MD, PhD, of Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

“These data further support avapritinib’s unique approach of selectively targeting D816V mutant KIT, the disease driver in most patients with systemic mastocytosis. If these results are confirmed in the planned phase 2 trial, avapritinib has the potential to become a new standard of care for patients with advanced forms of the disease.”

Urge expectant parents to have prenatal pediatrician visit

All parents-to-be, especially first-time parents, should visit a pediatrician during the third trimester of pregnancy to establish a relationship, according to an updated clinical report on the prenatal visit issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The report was published online June 25 and in the July issue of Pediatrics.

“It’s a chance to talk about how to keep a baby safe and thriving physically, but also ways to build strong parent-child bonds that promote resilience and help a child stay emotionally healthy,” Michael Yogman, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in a statement. Dr. Yogman was the lead author of the report and chair of the AAP Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health.

A comprehensive prenatal visit gives pediatricians the opportunity to meet four objectives: build a trusting relationship with parents, gather information about family history, provide advice and guidance on infant care and safety, and identify risk factors for psychosocial issues such as perinatal depression, according to the report in Pediatrics.

The prenatal visit allows families and clinicians to learn whether their philosophies align to start a relationship that may last for many years and this visit can include extended family members such as grandparents. In addition, pediatricians can use the prenatal visit as an opportunity to learn more about family history including past pregnancies, failed and successful, as well as pregnancy complications, chronic medical conditions in family members that may affect the home environment, and plans for child care if parents will be working outside the home.

The report also emphasizes “positive parenting” and the role of pediatricians at a prenatal visit in offering support and guidance to help prepare parents for infant care. This guidance may include advice on feeding, sleeping, diapering, and bathing, as well as acknowledging cultural practices.

The authors noted that a prime opporunity to schedule the prenatal visit is when an expectant parent seeking information about insurance, practice hours, and whether the practice is taking new patients.

The AAP advises clinicians to encourage same sex parents, parents expecting via surrogate, and parents who are adopting to schedule a prenatal visit to identify particular concerns they may have.

“This is the only routine child wellness visit recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics that doesn’t actually require a child in the room,” coauthor Arthur Lavin, MD, also of Harvard Medical School, said in a statement.

The prenatal visit “gives parents an opportunity to really focus on any questions and concerns they may have. They can talk with a pediatrician before the fatigue of new parenthood sets in and there’s an adorably distracting little human in their arms who may be crying, spitting up, or in immediate need of feeding or a diaper change,” Dr. Lavin said.

“At its heart and soul,” Dr. Lavin noted, “this visit is about laying a foundation for a trusting, supportive relationship between the family and their pediatrician, who will work together to keep the child healthy for the next 18 or 20 years.”

The report recommends the Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents, Fourth Edition, as a resource for clinicians. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Yogman M et al. Pediatrics. 2018; doi: 10.1542/peds. 2018-1218

All parents-to-be, especially first-time parents, should visit a pediatrician during the third trimester of pregnancy to establish a relationship, according to an updated clinical report on the prenatal visit issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The report was published online June 25 and in the July issue of Pediatrics.

“It’s a chance to talk about how to keep a baby safe and thriving physically, but also ways to build strong parent-child bonds that promote resilience and help a child stay emotionally healthy,” Michael Yogman, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in a statement. Dr. Yogman was the lead author of the report and chair of the AAP Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health.

A comprehensive prenatal visit gives pediatricians the opportunity to meet four objectives: build a trusting relationship with parents, gather information about family history, provide advice and guidance on infant care and safety, and identify risk factors for psychosocial issues such as perinatal depression, according to the report in Pediatrics.

The prenatal visit allows families and clinicians to learn whether their philosophies align to start a relationship that may last for many years and this visit can include extended family members such as grandparents. In addition, pediatricians can use the prenatal visit as an opportunity to learn more about family history including past pregnancies, failed and successful, as well as pregnancy complications, chronic medical conditions in family members that may affect the home environment, and plans for child care if parents will be working outside the home.

The report also emphasizes “positive parenting” and the role of pediatricians at a prenatal visit in offering support and guidance to help prepare parents for infant care. This guidance may include advice on feeding, sleeping, diapering, and bathing, as well as acknowledging cultural practices.

The authors noted that a prime opporunity to schedule the prenatal visit is when an expectant parent seeking information about insurance, practice hours, and whether the practice is taking new patients.

The AAP advises clinicians to encourage same sex parents, parents expecting via surrogate, and parents who are adopting to schedule a prenatal visit to identify particular concerns they may have.

“This is the only routine child wellness visit recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics that doesn’t actually require a child in the room,” coauthor Arthur Lavin, MD, also of Harvard Medical School, said in a statement.

The prenatal visit “gives parents an opportunity to really focus on any questions and concerns they may have. They can talk with a pediatrician before the fatigue of new parenthood sets in and there’s an adorably distracting little human in their arms who may be crying, spitting up, or in immediate need of feeding or a diaper change,” Dr. Lavin said.

“At its heart and soul,” Dr. Lavin noted, “this visit is about laying a foundation for a trusting, supportive relationship between the family and their pediatrician, who will work together to keep the child healthy for the next 18 or 20 years.”

The report recommends the Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents, Fourth Edition, as a resource for clinicians. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Yogman M et al. Pediatrics. 2018; doi: 10.1542/peds. 2018-1218

All parents-to-be, especially first-time parents, should visit a pediatrician during the third trimester of pregnancy to establish a relationship, according to an updated clinical report on the prenatal visit issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The report was published online June 25 and in the July issue of Pediatrics.

“It’s a chance to talk about how to keep a baby safe and thriving physically, but also ways to build strong parent-child bonds that promote resilience and help a child stay emotionally healthy,” Michael Yogman, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in a statement. Dr. Yogman was the lead author of the report and chair of the AAP Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health.

A comprehensive prenatal visit gives pediatricians the opportunity to meet four objectives: build a trusting relationship with parents, gather information about family history, provide advice and guidance on infant care and safety, and identify risk factors for psychosocial issues such as perinatal depression, according to the report in Pediatrics.

The prenatal visit allows families and clinicians to learn whether their philosophies align to start a relationship that may last for many years and this visit can include extended family members such as grandparents. In addition, pediatricians can use the prenatal visit as an opportunity to learn more about family history including past pregnancies, failed and successful, as well as pregnancy complications, chronic medical conditions in family members that may affect the home environment, and plans for child care if parents will be working outside the home.

The report also emphasizes “positive parenting” and the role of pediatricians at a prenatal visit in offering support and guidance to help prepare parents for infant care. This guidance may include advice on feeding, sleeping, diapering, and bathing, as well as acknowledging cultural practices.

The authors noted that a prime opporunity to schedule the prenatal visit is when an expectant parent seeking information about insurance, practice hours, and whether the practice is taking new patients.

The AAP advises clinicians to encourage same sex parents, parents expecting via surrogate, and parents who are adopting to schedule a prenatal visit to identify particular concerns they may have.

“This is the only routine child wellness visit recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics that doesn’t actually require a child in the room,” coauthor Arthur Lavin, MD, also of Harvard Medical School, said in a statement.

The prenatal visit “gives parents an opportunity to really focus on any questions and concerns they may have. They can talk with a pediatrician before the fatigue of new parenthood sets in and there’s an adorably distracting little human in their arms who may be crying, spitting up, or in immediate need of feeding or a diaper change,” Dr. Lavin said.

“At its heart and soul,” Dr. Lavin noted, “this visit is about laying a foundation for a trusting, supportive relationship between the family and their pediatrician, who will work together to keep the child healthy for the next 18 or 20 years.”

The report recommends the Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents, Fourth Edition, as a resource for clinicians. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Yogman M et al. Pediatrics. 2018; doi: 10.1542/peds. 2018-1218

FROM PEDIATRICS

Buprenorphine endangers lives and health of children

Eleven children died from exposure to buprenorphine – a drug used to treat opioid exposure – from 2007 to 2016, mostly very young children who accidentally ingested the drug.

Four deaths, however, were teens who took buprenorphine recreationally or used it in a suicide attempt, according to a new database review by Sara Post, MS, of the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, and her associates.

“In 2016, the American Academy of Pediatrics issued a statement advocating for increased access to buprenorphine for opioid-addicted adolescents in primary care settings,” the authors noted. “This recommendation is warranted because of the high and increasing prevalence of opioid dependence among adolescents. However, caution should be used, because increased prescriptions among adolescents could lead to increased diversion and abuse and increased access to younger children in the home. Therefore, patient education for adolescents should include information about the dangers of misusing and/or abusing prescription drugs and the proper storage of medications.”

The deaths comprise a small fraction of the 11,275 children aged 19 years and younger whose buprenorphine ingestions were reported to a poison control center during that time, the investigators said. Nevertheless, almost half (45%) of the exposed children were admitted to a health care facility – with 22% needing treatment in a critical care unit.

The rate of exposures was highest during the years when only tablet formulations were available and fell after film was introduced, wrote Ms. Post, a medical student at the Northeast Ohio Medical University in Rootstown, and her colleagues. But after 2013, the rate held steady, at about 38 exposures per 1 million children per year.

Childproof packaging for all buprenorphine formulations could help protect younger children, and education could help protect older ones, she and her coinvestigators said. Manufacturers should use unit-dose packaging for all buprenorphine products to help prevent unintentional exposure among young children. Health care providers should inform caregivers of young children about the dangers of buprenorphine exposure and provide instructions on proper storage and disposal of medications. Adolescents should receive information regarding the risks of substance abuse and misuse.”

Ms. Post and her colleagues analyzed calls to poison control centers affiliated with the National Poison Data System from 2007 to 2016. During that time, the centers received 11,275 calls about buprenorphine exposure among children and adolescents 19 years and younger.

The mean age of exposure in children was about 4 years; children younger than 6 years comprised 86% of the exposures (9,709).

The investigators noted temporal trends in exposure rates in this group. From 2007 to 2013, the rate increased by 215%, peaking at 20 per 1 million in 2010. A decline followed, with exposure dropping to 12 per 1 million in 2013, before rising again to 13 in 2016.

The increase “was likely attributable to the increasing number of buprenorphine prescriptions dispensed since the Food and Drug Administration approved its use as a treatment of opioid dependence in 2002,” Ms. Post and her colleagues wrote.

The transient decrease may have been related to a shift in adult prescribing patterns, as the drug was prescribed less often to those in their 20s and gradually given more often to people aged 40-59 years.

The decrease also was probably related to the packaging shift from tablet to film. “In 2013, the leading brand-name tablets were voluntarily withdrawn from the U.S. market because of potential risk of unintentional pediatric exposures,” the team wrote. Unfortunately, the film packaging didn’t completely deter some children; from 2013 to 2016, there was a 30% increase in the frequency of exposures to buprenorphine film.

The bulk of exposures were unintentional (98%) and involved ingestion of a single buprenorphine product. However, the authors noted, even a single adult therapeutic dose can be extremely dangerous to a small child.

“Therapeutic doses of buprenorphine-naloxone for pediatric patients are 2 to 6 mcg/kg, so ingestion of a single 2-mg sublingual tablet in a 10-kg child can result in more than a 30-fold overdose. This is particularly dangerous, because children exposed to buprenorphine do not display the ‘ceiling effect’ reported in adults, in which escalating doses do not lead to additional increases in respiratory depression,” Ms. Post and her coauthors said.

This was reflected in the serious clinical effects experienced: respiratory depression, bradycardia, coma, cyanosis, respiratory arrest, seizure, and cardiac arrest. These youngest children experienced the most serious outcomes, with half requiring a hospital admittance and 21% experiencing a serious medical outcome. Seven died, six of whom were 2 years or younger.

There were 315 (3%) exposures in children aged 6-12 years; most of these (83%) were either unintentional or therapeutic errors (18%). About 30% of the group required hospital admission and about 12% experienced a serious medical outcome. There were no fatalities among this group, the investigators noted.

Among adolescents aged 13-19 years, there were 1,251 (11%) exposures and four deaths. The bulk of these (77%) was intentional, with suspected suicide accounting for 12%, and 30% involving more than one substance. The exposure rate followed the same general trends, rising to a peak of about 6 per 1 million in 2010 and the falling and leveling off at about 3 per 1 million in 2016, they said.

About 22% of teen exposures required hospital admission, with 11% needing treatment in a critical care unit. The four deaths, one of which was a suicide, all involved multiple substances (benzodiazepines, alcohol, and marijuana).

Ms. Post received a research stipend from the National Student Injury Research Training Program while she worked on the study. The coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Post et al. Pediatrics. 2018;142:e20173652.

Eleven children died from exposure to buprenorphine – a drug used to treat opioid exposure – from 2007 to 2016, mostly very young children who accidentally ingested the drug.

Four deaths, however, were teens who took buprenorphine recreationally or used it in a suicide attempt, according to a new database review by Sara Post, MS, of the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, and her associates.

“In 2016, the American Academy of Pediatrics issued a statement advocating for increased access to buprenorphine for opioid-addicted adolescents in primary care settings,” the authors noted. “This recommendation is warranted because of the high and increasing prevalence of opioid dependence among adolescents. However, caution should be used, because increased prescriptions among adolescents could lead to increased diversion and abuse and increased access to younger children in the home. Therefore, patient education for adolescents should include information about the dangers of misusing and/or abusing prescription drugs and the proper storage of medications.”

The deaths comprise a small fraction of the 11,275 children aged 19 years and younger whose buprenorphine ingestions were reported to a poison control center during that time, the investigators said. Nevertheless, almost half (45%) of the exposed children were admitted to a health care facility – with 22% needing treatment in a critical care unit.

The rate of exposures was highest during the years when only tablet formulations were available and fell after film was introduced, wrote Ms. Post, a medical student at the Northeast Ohio Medical University in Rootstown, and her colleagues. But after 2013, the rate held steady, at about 38 exposures per 1 million children per year.

Childproof packaging for all buprenorphine formulations could help protect younger children, and education could help protect older ones, she and her coinvestigators said. Manufacturers should use unit-dose packaging for all buprenorphine products to help prevent unintentional exposure among young children. Health care providers should inform caregivers of young children about the dangers of buprenorphine exposure and provide instructions on proper storage and disposal of medications. Adolescents should receive information regarding the risks of substance abuse and misuse.”

Ms. Post and her colleagues analyzed calls to poison control centers affiliated with the National Poison Data System from 2007 to 2016. During that time, the centers received 11,275 calls about buprenorphine exposure among children and adolescents 19 years and younger.

The mean age of exposure in children was about 4 years; children younger than 6 years comprised 86% of the exposures (9,709).

The investigators noted temporal trends in exposure rates in this group. From 2007 to 2013, the rate increased by 215%, peaking at 20 per 1 million in 2010. A decline followed, with exposure dropping to 12 per 1 million in 2013, before rising again to 13 in 2016.

The increase “was likely attributable to the increasing number of buprenorphine prescriptions dispensed since the Food and Drug Administration approved its use as a treatment of opioid dependence in 2002,” Ms. Post and her colleagues wrote.

The transient decrease may have been related to a shift in adult prescribing patterns, as the drug was prescribed less often to those in their 20s and gradually given more often to people aged 40-59 years.

The decrease also was probably related to the packaging shift from tablet to film. “In 2013, the leading brand-name tablets were voluntarily withdrawn from the U.S. market because of potential risk of unintentional pediatric exposures,” the team wrote. Unfortunately, the film packaging didn’t completely deter some children; from 2013 to 2016, there was a 30% increase in the frequency of exposures to buprenorphine film.

The bulk of exposures were unintentional (98%) and involved ingestion of a single buprenorphine product. However, the authors noted, even a single adult therapeutic dose can be extremely dangerous to a small child.

“Therapeutic doses of buprenorphine-naloxone for pediatric patients are 2 to 6 mcg/kg, so ingestion of a single 2-mg sublingual tablet in a 10-kg child can result in more than a 30-fold overdose. This is particularly dangerous, because children exposed to buprenorphine do not display the ‘ceiling effect’ reported in adults, in which escalating doses do not lead to additional increases in respiratory depression,” Ms. Post and her coauthors said.

This was reflected in the serious clinical effects experienced: respiratory depression, bradycardia, coma, cyanosis, respiratory arrest, seizure, and cardiac arrest. These youngest children experienced the most serious outcomes, with half requiring a hospital admittance and 21% experiencing a serious medical outcome. Seven died, six of whom were 2 years or younger.

There were 315 (3%) exposures in children aged 6-12 years; most of these (83%) were either unintentional or therapeutic errors (18%). About 30% of the group required hospital admission and about 12% experienced a serious medical outcome. There were no fatalities among this group, the investigators noted.

Among adolescents aged 13-19 years, there were 1,251 (11%) exposures and four deaths. The bulk of these (77%) was intentional, with suspected suicide accounting for 12%, and 30% involving more than one substance. The exposure rate followed the same general trends, rising to a peak of about 6 per 1 million in 2010 and the falling and leveling off at about 3 per 1 million in 2016, they said.

About 22% of teen exposures required hospital admission, with 11% needing treatment in a critical care unit. The four deaths, one of which was a suicide, all involved multiple substances (benzodiazepines, alcohol, and marijuana).

Ms. Post received a research stipend from the National Student Injury Research Training Program while she worked on the study. The coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Post et al. Pediatrics. 2018;142:e20173652.

Eleven children died from exposure to buprenorphine – a drug used to treat opioid exposure – from 2007 to 2016, mostly very young children who accidentally ingested the drug.

Four deaths, however, were teens who took buprenorphine recreationally or used it in a suicide attempt, according to a new database review by Sara Post, MS, of the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, and her associates.

“In 2016, the American Academy of Pediatrics issued a statement advocating for increased access to buprenorphine for opioid-addicted adolescents in primary care settings,” the authors noted. “This recommendation is warranted because of the high and increasing prevalence of opioid dependence among adolescents. However, caution should be used, because increased prescriptions among adolescents could lead to increased diversion and abuse and increased access to younger children in the home. Therefore, patient education for adolescents should include information about the dangers of misusing and/or abusing prescription drugs and the proper storage of medications.”

The deaths comprise a small fraction of the 11,275 children aged 19 years and younger whose buprenorphine ingestions were reported to a poison control center during that time, the investigators said. Nevertheless, almost half (45%) of the exposed children were admitted to a health care facility – with 22% needing treatment in a critical care unit.

The rate of exposures was highest during the years when only tablet formulations were available and fell after film was introduced, wrote Ms. Post, a medical student at the Northeast Ohio Medical University in Rootstown, and her colleagues. But after 2013, the rate held steady, at about 38 exposures per 1 million children per year.

Childproof packaging for all buprenorphine formulations could help protect younger children, and education could help protect older ones, she and her coinvestigators said. Manufacturers should use unit-dose packaging for all buprenorphine products to help prevent unintentional exposure among young children. Health care providers should inform caregivers of young children about the dangers of buprenorphine exposure and provide instructions on proper storage and disposal of medications. Adolescents should receive information regarding the risks of substance abuse and misuse.”

Ms. Post and her colleagues analyzed calls to poison control centers affiliated with the National Poison Data System from 2007 to 2016. During that time, the centers received 11,275 calls about buprenorphine exposure among children and adolescents 19 years and younger.

The mean age of exposure in children was about 4 years; children younger than 6 years comprised 86% of the exposures (9,709).

The investigators noted temporal trends in exposure rates in this group. From 2007 to 2013, the rate increased by 215%, peaking at 20 per 1 million in 2010. A decline followed, with exposure dropping to 12 per 1 million in 2013, before rising again to 13 in 2016.

The increase “was likely attributable to the increasing number of buprenorphine prescriptions dispensed since the Food and Drug Administration approved its use as a treatment of opioid dependence in 2002,” Ms. Post and her colleagues wrote.

The transient decrease may have been related to a shift in adult prescribing patterns, as the drug was prescribed less often to those in their 20s and gradually given more often to people aged 40-59 years.

The decrease also was probably related to the packaging shift from tablet to film. “In 2013, the leading brand-name tablets were voluntarily withdrawn from the U.S. market because of potential risk of unintentional pediatric exposures,” the team wrote. Unfortunately, the film packaging didn’t completely deter some children; from 2013 to 2016, there was a 30% increase in the frequency of exposures to buprenorphine film.

The bulk of exposures were unintentional (98%) and involved ingestion of a single buprenorphine product. However, the authors noted, even a single adult therapeutic dose can be extremely dangerous to a small child.

“Therapeutic doses of buprenorphine-naloxone for pediatric patients are 2 to 6 mcg/kg, so ingestion of a single 2-mg sublingual tablet in a 10-kg child can result in more than a 30-fold overdose. This is particularly dangerous, because children exposed to buprenorphine do not display the ‘ceiling effect’ reported in adults, in which escalating doses do not lead to additional increases in respiratory depression,” Ms. Post and her coauthors said.

This was reflected in the serious clinical effects experienced: respiratory depression, bradycardia, coma, cyanosis, respiratory arrest, seizure, and cardiac arrest. These youngest children experienced the most serious outcomes, with half requiring a hospital admittance and 21% experiencing a serious medical outcome. Seven died, six of whom were 2 years or younger.

There were 315 (3%) exposures in children aged 6-12 years; most of these (83%) were either unintentional or therapeutic errors (18%). About 30% of the group required hospital admission and about 12% experienced a serious medical outcome. There were no fatalities among this group, the investigators noted.

Among adolescents aged 13-19 years, there were 1,251 (11%) exposures and four deaths. The bulk of these (77%) was intentional, with suspected suicide accounting for 12%, and 30% involving more than one substance. The exposure rate followed the same general trends, rising to a peak of about 6 per 1 million in 2010 and the falling and leveling off at about 3 per 1 million in 2016, they said.

About 22% of teen exposures required hospital admission, with 11% needing treatment in a critical care unit. The four deaths, one of which was a suicide, all involved multiple substances (benzodiazepines, alcohol, and marijuana).

Ms. Post received a research stipend from the National Student Injury Research Training Program while she worked on the study. The coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Post et al. Pediatrics. 2018;142:e20173652.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Buprenorphine ingestion remains a threat to children, especially those younger than 6 years.

Major finding: From 2007 to 2016, 11,275 exposures were reported; 11 children died.

Study details: The database review looked at records from the National Poison Data System.

Disclosures: Ms. Post received a research stipend from the National Student Injury Research Training Program while she worked on the study. The coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Post et al. Pediatrics. 2018;142:e20173652.

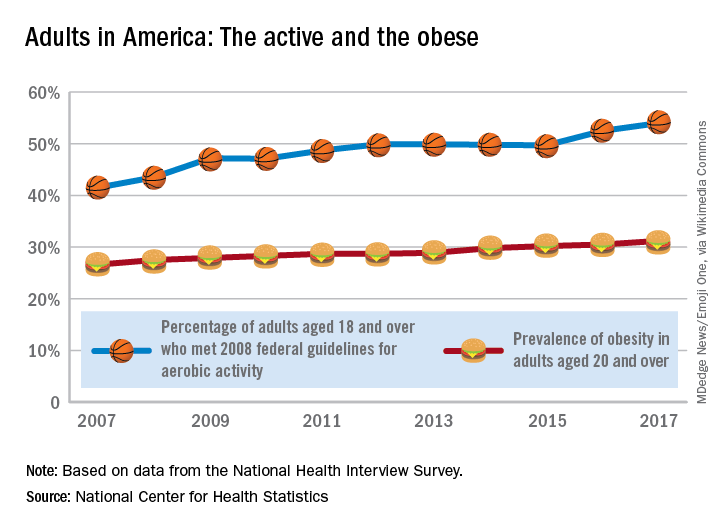

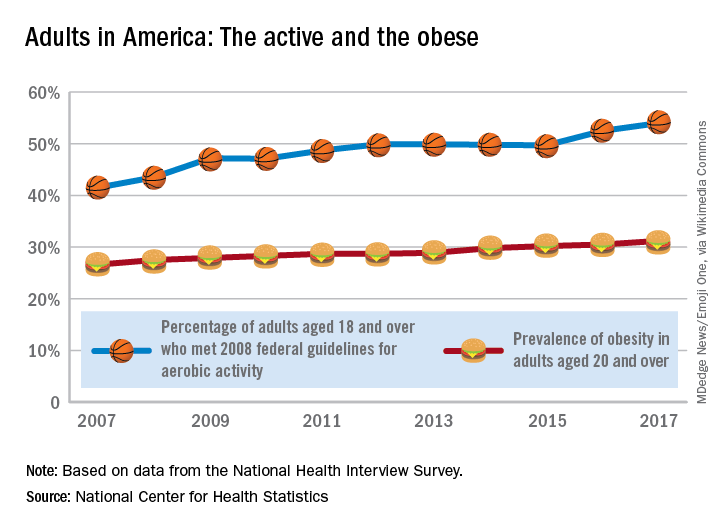

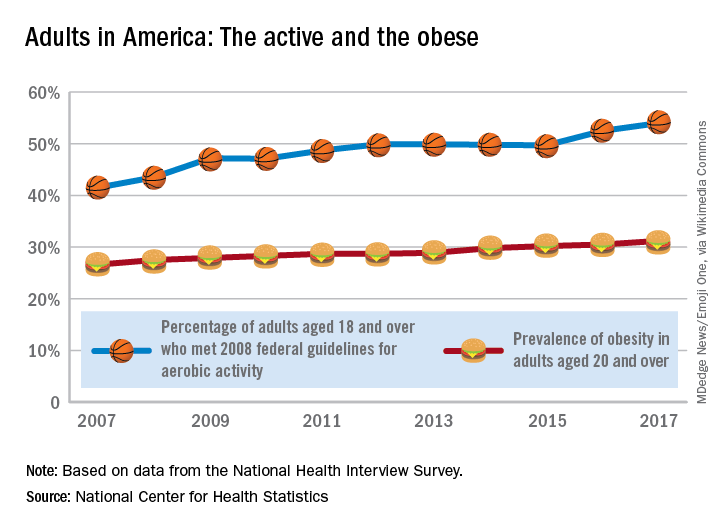

Obesity didn’t just happen overnight

Is it possible to get more exercise and still gain weight? In America it is.

The steady increase in obesity prevalence among adults in the United States has been exceeded over the last decade by the percentage of adults who are getting the recommended amount of exercise, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

The 2008 guideline, “Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans” recommends that “adults perform at least 150 minutes a week of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity, 75 minutes a week of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity aerobic activity, performed in episodes of at least 10 minutes and preferably should be spread throughout the week,” the NCHS noted.

Is it possible to get more exercise and still gain weight? In America it is.

The steady increase in obesity prevalence among adults in the United States has been exceeded over the last decade by the percentage of adults who are getting the recommended amount of exercise, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

The 2008 guideline, “Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans” recommends that “adults perform at least 150 minutes a week of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity, 75 minutes a week of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity aerobic activity, performed in episodes of at least 10 minutes and preferably should be spread throughout the week,” the NCHS noted.

Is it possible to get more exercise and still gain weight? In America it is.

The steady increase in obesity prevalence among adults in the United States has been exceeded over the last decade by the percentage of adults who are getting the recommended amount of exercise, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

The 2008 guideline, “Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans” recommends that “adults perform at least 150 minutes a week of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity, 75 minutes a week of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity aerobic activity, performed in episodes of at least 10 minutes and preferably should be spread throughout the week,” the NCHS noted.

Trump administration proposes changes to HHS, FDA

The Trump administration seeks to reorganize several federal agencies as part of a sweeping reform proposal, issued June 21.

“Government in the 21st century is fundamentally a services business, and modern information technology should be at the heart of the U.S. government service delivery model,” according to the administration’s reform proposal. “And yet, today’s Executive branch is still aligned to the stove-piped organizational constructs of the 20th century, which in many cases have grown inefficient and out of date. Consequently, the public and our workforce are frustrated with government’s ability to deliver its mission in an effective, efficient, and secure way.”

Under the proposal, nutrition assistance programs currently run out of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) would move to the Department of Health and Human Services, which would be rebranded the Department of Health and Public Welfare.

Moving these programs “would allow for better and easier coordination across programs that serve similar populations, ensuring consistent policies and a single point of administration for the major public assistance programs,” according to the proposal. “This single point of administration would lead to reduced duplication in state reporting requirements and other administrative burdens, and a more streamlined process for issuing guidance, writing regulations, and approving waivers.”

Food oversight functions would move from the Food and Drug Administration to the USDA; FDA would be rebranded the Federal Drug Administration and focus on drugs, devices, biologics, tobacco, dietary supplements, and cosmetics.

The administration also proposed to created a Council on Public Assistance comprised of “all federal agencies that administer public benefits, with a statutory authority to set cross-cutting program policies, including uniform work requirements.”

Other functions of the council would include approving service plans and waivers by states under Welfare-to-Work projects; resolving disputes when multiple agencies disagree on a particular policy; and recommending policy changes to eliminate barriers at the federal, state, and local level to getting welfare beneficiaries to work.

The proposal also calls for a restructuring of the National Institutes of Health “to ensure operations are effective and efficient,” with no detail provided. It would also place the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality under the auspices of NIH.

The Strategic National Stockpile would be managed by the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response “to consolidate strategic decision making around the development and procurement of medical countermeasures, and streamline operational decisions during responses to public health and other emergencies to improve responsiveness.”

The Trump administration seeks to reorganize several federal agencies as part of a sweeping reform proposal, issued June 21.

“Government in the 21st century is fundamentally a services business, and modern information technology should be at the heart of the U.S. government service delivery model,” according to the administration’s reform proposal. “And yet, today’s Executive branch is still aligned to the stove-piped organizational constructs of the 20th century, which in many cases have grown inefficient and out of date. Consequently, the public and our workforce are frustrated with government’s ability to deliver its mission in an effective, efficient, and secure way.”

Under the proposal, nutrition assistance programs currently run out of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) would move to the Department of Health and Human Services, which would be rebranded the Department of Health and Public Welfare.

Moving these programs “would allow for better and easier coordination across programs that serve similar populations, ensuring consistent policies and a single point of administration for the major public assistance programs,” according to the proposal. “This single point of administration would lead to reduced duplication in state reporting requirements and other administrative burdens, and a more streamlined process for issuing guidance, writing regulations, and approving waivers.”

Food oversight functions would move from the Food and Drug Administration to the USDA; FDA would be rebranded the Federal Drug Administration and focus on drugs, devices, biologics, tobacco, dietary supplements, and cosmetics.

The administration also proposed to created a Council on Public Assistance comprised of “all federal agencies that administer public benefits, with a statutory authority to set cross-cutting program policies, including uniform work requirements.”

Other functions of the council would include approving service plans and waivers by states under Welfare-to-Work projects; resolving disputes when multiple agencies disagree on a particular policy; and recommending policy changes to eliminate barriers at the federal, state, and local level to getting welfare beneficiaries to work.

The proposal also calls for a restructuring of the National Institutes of Health “to ensure operations are effective and efficient,” with no detail provided. It would also place the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality under the auspices of NIH.

The Strategic National Stockpile would be managed by the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response “to consolidate strategic decision making around the development and procurement of medical countermeasures, and streamline operational decisions during responses to public health and other emergencies to improve responsiveness.”

The Trump administration seeks to reorganize several federal agencies as part of a sweeping reform proposal, issued June 21.

“Government in the 21st century is fundamentally a services business, and modern information technology should be at the heart of the U.S. government service delivery model,” according to the administration’s reform proposal. “And yet, today’s Executive branch is still aligned to the stove-piped organizational constructs of the 20th century, which in many cases have grown inefficient and out of date. Consequently, the public and our workforce are frustrated with government’s ability to deliver its mission in an effective, efficient, and secure way.”

Under the proposal, nutrition assistance programs currently run out of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) would move to the Department of Health and Human Services, which would be rebranded the Department of Health and Public Welfare.

Moving these programs “would allow for better and easier coordination across programs that serve similar populations, ensuring consistent policies and a single point of administration for the major public assistance programs,” according to the proposal. “This single point of administration would lead to reduced duplication in state reporting requirements and other administrative burdens, and a more streamlined process for issuing guidance, writing regulations, and approving waivers.”

Food oversight functions would move from the Food and Drug Administration to the USDA; FDA would be rebranded the Federal Drug Administration and focus on drugs, devices, biologics, tobacco, dietary supplements, and cosmetics.

The administration also proposed to created a Council on Public Assistance comprised of “all federal agencies that administer public benefits, with a statutory authority to set cross-cutting program policies, including uniform work requirements.”

Other functions of the council would include approving service plans and waivers by states under Welfare-to-Work projects; resolving disputes when multiple agencies disagree on a particular policy; and recommending policy changes to eliminate barriers at the federal, state, and local level to getting welfare beneficiaries to work.

The proposal also calls for a restructuring of the National Institutes of Health “to ensure operations are effective and efficient,” with no detail provided. It would also place the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality under the auspices of NIH.

The Strategic National Stockpile would be managed by the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response “to consolidate strategic decision making around the development and procurement of medical countermeasures, and streamline operational decisions during responses to public health and other emergencies to improve responsiveness.”

Research provides more evidence of a maternal diabetes/autism link

ORLANDO – Longer-term data are providing more evidence of a possible link between maternal diabetes and autism spectrum disorder in their children.

Anny Xiang, PhD, and coathors with Kaiser Permanente of Southern California sought to further understand the possible effect of maternal T1D on offspring’s development of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) by expanding the cohort and timeline of their earlier work (JAMA. 2015;313(14):1425-1434).

Across the cohort, 1.3% of children were diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The rate was barely different, at 1.5%, for those whose mothers developed gestational diabetes after 26 weeks. But rates of ASD were higher – 3.1%, 2.5%, 2.1% – among those whose mothers had T1D, T2D, and gestational diabetes that developed at 26 weeks or earlier, respectively. The findings were adjusted for co-founders such as birth year, age at delivery, eduction level and income, Dr. Xiang said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Compared to offspring of mothers without diabetes, ASD was more common in the children of mothers with T1D (adjusted HR=2.36, 95% CI, 1.36-4.12) mothers with type 2 diabetes (AHR= 1.45, 95% CI, 1.24-1.70) and gestational diabetes mellitus that developed by 26 weeks gestation (1.30, 95% CI, 1.12-1.51).

The numbers remained similar after they were adjusted for smoking during pregnancy and prepregnancy BMI, statistics which were available for about 36% of the subjects, according to the findings which were published simultaneously in JAMA (June 23, 2018. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.7614).

Possible explanations for the link between ASD and maternal diabetes include maternal glycemic control, prematurity, and levels of neonatal hypoglycemia, Dr. Xiang said.

The results do not take into account any paternal risks for offspring developing ASD, which also includes diabetes, Dr. Xiang said, noting that two previous studies linked diabetes in fathers to ASD, although to a lesser extent than diabetes in mothers. (Epidemiology. 2010 Nov;21(6):805-8; Pediatrics. 2009 Aug;124(2):687-94)

The study also doesn’t take breastfeeding into account, Dr. Xiang noted. A 2016 study found that women with T2D were less likely to breastfeed (J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29(15):2513-8), and some research has suggested that breastfeeding may be protective against the development of ASD in children (Nutrition 2012;28(7-8):e27-32).

In addition, the study doesn’t track maternal glucose levels over time.

Session co-chair Peter Damm, MD, professor of obstetrics at the University of Copenhagen, said in an interview that he is impressed by the study. He cautioned, however, that it does not prove a connection.“This not a proof, but it seems likely, or like a possibility,” he said.

One possible explanation for a diabetes/ASD connection is the fact that the fetal brain is evolving throughout pregnancy unlike other body organs, which simply grow after developing in the first trimester, he said. As a result, glucose levels may affect the brain’s development in a unique way compared to other organs.

He also noted that the impact may be reduced when pregnancy is further along, potentially explaining why researchers didn’t connect late-developing gestational diabetes to ASD.

There’s still a “low risk” of ASD even in children born to mothers with diabetes, he said. “You shouldn’t scare anyone with this.”

The study was funded in part by Kaiser Permanente Southern California Direct Community Benefit funds. The study authors and Dr. Damm report no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Xiang A, et al. ADA 2018 Abstract OR-117.

ORLANDO – Longer-term data are providing more evidence of a possible link between maternal diabetes and autism spectrum disorder in their children.

Anny Xiang, PhD, and coathors with Kaiser Permanente of Southern California sought to further understand the possible effect of maternal T1D on offspring’s development of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) by expanding the cohort and timeline of their earlier work (JAMA. 2015;313(14):1425-1434).

Across the cohort, 1.3% of children were diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The rate was barely different, at 1.5%, for those whose mothers developed gestational diabetes after 26 weeks. But rates of ASD were higher – 3.1%, 2.5%, 2.1% – among those whose mothers had T1D, T2D, and gestational diabetes that developed at 26 weeks or earlier, respectively. The findings were adjusted for co-founders such as birth year, age at delivery, eduction level and income, Dr. Xiang said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Compared to offspring of mothers without diabetes, ASD was more common in the children of mothers with T1D (adjusted HR=2.36, 95% CI, 1.36-4.12) mothers with type 2 diabetes (AHR= 1.45, 95% CI, 1.24-1.70) and gestational diabetes mellitus that developed by 26 weeks gestation (1.30, 95% CI, 1.12-1.51).

The numbers remained similar after they were adjusted for smoking during pregnancy and prepregnancy BMI, statistics which were available for about 36% of the subjects, according to the findings which were published simultaneously in JAMA (June 23, 2018. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.7614).

Possible explanations for the link between ASD and maternal diabetes include maternal glycemic control, prematurity, and levels of neonatal hypoglycemia, Dr. Xiang said.

The results do not take into account any paternal risks for offspring developing ASD, which also includes diabetes, Dr. Xiang said, noting that two previous studies linked diabetes in fathers to ASD, although to a lesser extent than diabetes in mothers. (Epidemiology. 2010 Nov;21(6):805-8; Pediatrics. 2009 Aug;124(2):687-94)

The study also doesn’t take breastfeeding into account, Dr. Xiang noted. A 2016 study found that women with T2D were less likely to breastfeed (J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29(15):2513-8), and some research has suggested that breastfeeding may be protective against the development of ASD in children (Nutrition 2012;28(7-8):e27-32).

In addition, the study doesn’t track maternal glucose levels over time.

Session co-chair Peter Damm, MD, professor of obstetrics at the University of Copenhagen, said in an interview that he is impressed by the study. He cautioned, however, that it does not prove a connection.“This not a proof, but it seems likely, or like a possibility,” he said.

One possible explanation for a diabetes/ASD connection is the fact that the fetal brain is evolving throughout pregnancy unlike other body organs, which simply grow after developing in the first trimester, he said. As a result, glucose levels may affect the brain’s development in a unique way compared to other organs.

He also noted that the impact may be reduced when pregnancy is further along, potentially explaining why researchers didn’t connect late-developing gestational diabetes to ASD.

There’s still a “low risk” of ASD even in children born to mothers with diabetes, he said. “You shouldn’t scare anyone with this.”

The study was funded in part by Kaiser Permanente Southern California Direct Community Benefit funds. The study authors and Dr. Damm report no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Xiang A, et al. ADA 2018 Abstract OR-117.

ORLANDO – Longer-term data are providing more evidence of a possible link between maternal diabetes and autism spectrum disorder in their children.

Anny Xiang, PhD, and coathors with Kaiser Permanente of Southern California sought to further understand the possible effect of maternal T1D on offspring’s development of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) by expanding the cohort and timeline of their earlier work (JAMA. 2015;313(14):1425-1434).

Across the cohort, 1.3% of children were diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The rate was barely different, at 1.5%, for those whose mothers developed gestational diabetes after 26 weeks. But rates of ASD were higher – 3.1%, 2.5%, 2.1% – among those whose mothers had T1D, T2D, and gestational diabetes that developed at 26 weeks or earlier, respectively. The findings were adjusted for co-founders such as birth year, age at delivery, eduction level and income, Dr. Xiang said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Compared to offspring of mothers without diabetes, ASD was more common in the children of mothers with T1D (adjusted HR=2.36, 95% CI, 1.36-4.12) mothers with type 2 diabetes (AHR= 1.45, 95% CI, 1.24-1.70) and gestational diabetes mellitus that developed by 26 weeks gestation (1.30, 95% CI, 1.12-1.51).

The numbers remained similar after they were adjusted for smoking during pregnancy and prepregnancy BMI, statistics which were available for about 36% of the subjects, according to the findings which were published simultaneously in JAMA (June 23, 2018. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.7614).

Possible explanations for the link between ASD and maternal diabetes include maternal glycemic control, prematurity, and levels of neonatal hypoglycemia, Dr. Xiang said.

The results do not take into account any paternal risks for offspring developing ASD, which also includes diabetes, Dr. Xiang said, noting that two previous studies linked diabetes in fathers to ASD, although to a lesser extent than diabetes in mothers. (Epidemiology. 2010 Nov;21(6):805-8; Pediatrics. 2009 Aug;124(2):687-94)

The study also doesn’t take breastfeeding into account, Dr. Xiang noted. A 2016 study found that women with T2D were less likely to breastfeed (J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29(15):2513-8), and some research has suggested that breastfeeding may be protective against the development of ASD in children (Nutrition 2012;28(7-8):e27-32).

In addition, the study doesn’t track maternal glucose levels over time.

Session co-chair Peter Damm, MD, professor of obstetrics at the University of Copenhagen, said in an interview that he is impressed by the study. He cautioned, however, that it does not prove a connection.“This not a proof, but it seems likely, or like a possibility,” he said.

One possible explanation for a diabetes/ASD connection is the fact that the fetal brain is evolving throughout pregnancy unlike other body organs, which simply grow after developing in the first trimester, he said. As a result, glucose levels may affect the brain’s development in a unique way compared to other organs.

He also noted that the impact may be reduced when pregnancy is further along, potentially explaining why researchers didn’t connect late-developing gestational diabetes to ASD.

There’s still a “low risk” of ASD even in children born to mothers with diabetes, he said. “You shouldn’t scare anyone with this.”

The study was funded in part by Kaiser Permanente Southern California Direct Community Benefit funds. The study authors and Dr. Damm report no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Xiang A, et al. ADA 2018 Abstract OR-117.

REPORTING FROM ADA 2018

Key clinical point: Children of mothers with various forms of diabetes – including type 1 diabetes (T1D) – could be at higher risk of autism.

Major finding: Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) was more common in the children of mothers with T1D (adjusted HR=2.36, 95% CI, 1.36-4.12) type 2 diabetes (AHR= 1.45, 95% CI, 1.24-1.70) and gestational diabetes that developed by 26 weeks gestation (1.30, 95% CI, 1.12-1.51).

Study details: Retrospective analysis of 419,425 children born at Kaiser Permanente Southern California hospitals from 1995-2012 (51% boys).

Disclosures: The study was funded in part by Kaiser Permanente Southern California Direct Community Benefit funds. The study authors report no relevant disclosures.

Source: Xiang A, et al. ADA 2018 Abstract OR-117.

Eversense CGM shown safe, accurate for 180 days in adolescents

ORLANDO – The Eversense continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) system, recently approved for use in adults with diabetes, also provides safe, durable, and accurate monitoring in the pediatric population, according to findings from a prospective single-arm study of 30 children and 6 adults.

Study subjects, who were all over age 11 years, with an average of 14 years, had the fully implantable sensor inserted at day 0 and removed at day 180, and the mean absolute relative difference (MARD) between sensor and true laboratory glucose values showed high device accuracy, Ronnie Aronson, MD, reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“Anything under 10% is considered good, and ours was 9.4% – and it didn’t deteriorate throughout the duration, so at 180 days it was still at 9.4%; every accuracy measure we looked at showed similar high levels of accuracy,” Dr. Aronson, founder and chief medical officer of LMC Diabetes & Endocrinology in Ontario, Canada said in a video interview.

The sensor, which is roughly 1.5 cm long, is coated with a material that fluoresces when exposed to glucose; the sensor uses the amount of light emitted to calculate blood glucose levels. Patients use an adhesive patch, changed daily, to attach a “smart” transmitter that overlies the area where the sensor is implanted. This rechargeable transmitter sends blood glucose levels to the mobile app every 5 minutes, and also powers the sensor. The Food and Drug Administration approved it for use in adults on June 21.

The system was highly rated by study participants, he said. “What makes it stand out is that it’s implanted, it’s there for at least 180 days, it’s accurate for 180 days,” the transmitter can be taken on and off, and the results can be seen very easily on a smart phone or Apple Watch.

Dr. Aronson said he also hopes to study the device in younger patients and for longer durations.

Dr. Aronson is an advisor for Novo Nordisk and Sanofi. He also receives research support from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Valeant, Janssen, and Senseonics.

SOURCE: Aronson R et al. ADA 2018 Abstract 13-OR.

ORLANDO – The Eversense continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) system, recently approved for use in adults with diabetes, also provides safe, durable, and accurate monitoring in the pediatric population, according to findings from a prospective single-arm study of 30 children and 6 adults.

Study subjects, who were all over age 11 years, with an average of 14 years, had the fully implantable sensor inserted at day 0 and removed at day 180, and the mean absolute relative difference (MARD) between sensor and true laboratory glucose values showed high device accuracy, Ronnie Aronson, MD, reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“Anything under 10% is considered good, and ours was 9.4% – and it didn’t deteriorate throughout the duration, so at 180 days it was still at 9.4%; every accuracy measure we looked at showed similar high levels of accuracy,” Dr. Aronson, founder and chief medical officer of LMC Diabetes & Endocrinology in Ontario, Canada said in a video interview.

The sensor, which is roughly 1.5 cm long, is coated with a material that fluoresces when exposed to glucose; the sensor uses the amount of light emitted to calculate blood glucose levels. Patients use an adhesive patch, changed daily, to attach a “smart” transmitter that overlies the area where the sensor is implanted. This rechargeable transmitter sends blood glucose levels to the mobile app every 5 minutes, and also powers the sensor. The Food and Drug Administration approved it for use in adults on June 21.

The system was highly rated by study participants, he said. “What makes it stand out is that it’s implanted, it’s there for at least 180 days, it’s accurate for 180 days,” the transmitter can be taken on and off, and the results can be seen very easily on a smart phone or Apple Watch.

Dr. Aronson said he also hopes to study the device in younger patients and for longer durations.

Dr. Aronson is an advisor for Novo Nordisk and Sanofi. He also receives research support from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Valeant, Janssen, and Senseonics.

SOURCE: Aronson R et al. ADA 2018 Abstract 13-OR.

ORLANDO – The Eversense continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) system, recently approved for use in adults with diabetes, also provides safe, durable, and accurate monitoring in the pediatric population, according to findings from a prospective single-arm study of 30 children and 6 adults.

Study subjects, who were all over age 11 years, with an average of 14 years, had the fully implantable sensor inserted at day 0 and removed at day 180, and the mean absolute relative difference (MARD) between sensor and true laboratory glucose values showed high device accuracy, Ronnie Aronson, MD, reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“Anything under 10% is considered good, and ours was 9.4% – and it didn’t deteriorate throughout the duration, so at 180 days it was still at 9.4%; every accuracy measure we looked at showed similar high levels of accuracy,” Dr. Aronson, founder and chief medical officer of LMC Diabetes & Endocrinology in Ontario, Canada said in a video interview.

The sensor, which is roughly 1.5 cm long, is coated with a material that fluoresces when exposed to glucose; the sensor uses the amount of light emitted to calculate blood glucose levels. Patients use an adhesive patch, changed daily, to attach a “smart” transmitter that overlies the area where the sensor is implanted. This rechargeable transmitter sends blood glucose levels to the mobile app every 5 minutes, and also powers the sensor. The Food and Drug Administration approved it for use in adults on June 21.

The system was highly rated by study participants, he said. “What makes it stand out is that it’s implanted, it’s there for at least 180 days, it’s accurate for 180 days,” the transmitter can be taken on and off, and the results can be seen very easily on a smart phone or Apple Watch.

Dr. Aronson said he also hopes to study the device in younger patients and for longer durations.

Dr. Aronson is an advisor for Novo Nordisk and Sanofi. He also receives research support from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Valeant, Janssen, and Senseonics.

SOURCE: Aronson R et al. ADA 2018 Abstract 13-OR.

REPORTING FROM ADA 2018

Key clinical point: The Eversense fully implantable continuous glucose monitoring device is safe and accurate in adolescents.

Major finding: The MARD between sensor and true laboratory glucose values showed high device accuracy, at 9.4% over 180 days.

Study details: A prospective single-arm study of 30 children and 6 adults.

Disclosures: Dr. Aronson is an advisor for Novo Nordisk and Sanofi. He also receives research support from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Valeant, Janssen, and Senseonics.

Source: Aronson R et al. ADA Abstract 13-OR.

Switch back to human insulin a viable money saver

ORLANDO – It’s safe to switch many Medicare beneficiaries with type 2 diabetes to human insulins to save money on analogues, according to a review of 14,635 members of CareMore, a Medicare Advantage company based in Cerritos, Calif.

The company noticed that it’s spending on analogue insulins had ballooned to over $3 million a month by the end of 2014, in the wake of a more than 300% price increase in analogue insulins in recent years, while copays on analogues rose from nothing to $37.50. In 2015, it launched a program to switch type 2 patients to less costly human insulins. Physicians were counseled to stop secretagogues and move patients to premixed insulins at 80% of their former total daily analogue dose, two-thirds at breakfast, and one-third a dinner, with appropriate follow-up.

Analogue insulins fell from 90% of all insulins dispensed to 30%, with a corresponding rise in human insulin prescriptions. Total plan spending on analogues fell to about a half million dollars a month by the end of 2016. Spending on human insulins rose to just under a million dollars. The risk of patients falling into the Medicare Part D coverage gap – where they assume a greater proportion of their drug costs – was reduced by 55% (P less than .001).

“A lot of money was saved as a result of this intervention,” said lead investigator Jin Luo, MD, an internist and health services researcher at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Mean hemoglobin A1c rose 0.14 % from a baseline of 8.46% in 2014 (P less than 0.01), “but we do not believe that this is clinically important because this value falls within the biological within-subject variation of most modern HbA1c assays,” he said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Meanwhile, there was no statistically significant change in the rate of hospitalizations or emergency department visits for hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia.

“Patients with type 2 diabetes and their clinical providers should strongly consider human insulin as a clinically viable and cost effective option,” Dr. Luo said.

“My personal clinical opinion is that if I have a patient who is really hard to control, and after four or five different regimens, we finally settle on an analogue regimen that [keeps] them under control” and out of the hospital, “I’m not going to switch them just because a health plan tells me I should. They are just too brittle, and I’m not comfortable doing that. Whereas if I have a patient who’d be fine with either option, and I’m not really worried about hypoglycemia, I’ll switch them,” he said.

There was no industry funding. Dr. Luo is a consultant for Alosa Health and Health Action International.

SOURCE: Luo J et al. 2018 American Diabetes Association scientific session abstract 4-OR

ORLANDO – It’s safe to switch many Medicare beneficiaries with type 2 diabetes to human insulins to save money on analogues, according to a review of 14,635 members of CareMore, a Medicare Advantage company based in Cerritos, Calif.

The company noticed that it’s spending on analogue insulins had ballooned to over $3 million a month by the end of 2014, in the wake of a more than 300% price increase in analogue insulins in recent years, while copays on analogues rose from nothing to $37.50. In 2015, it launched a program to switch type 2 patients to less costly human insulins. Physicians were counseled to stop secretagogues and move patients to premixed insulins at 80% of their former total daily analogue dose, two-thirds at breakfast, and one-third a dinner, with appropriate follow-up.

Analogue insulins fell from 90% of all insulins dispensed to 30%, with a corresponding rise in human insulin prescriptions. Total plan spending on analogues fell to about a half million dollars a month by the end of 2016. Spending on human insulins rose to just under a million dollars. The risk of patients falling into the Medicare Part D coverage gap – where they assume a greater proportion of their drug costs – was reduced by 55% (P less than .001).

“A lot of money was saved as a result of this intervention,” said lead investigator Jin Luo, MD, an internist and health services researcher at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Mean hemoglobin A1c rose 0.14 % from a baseline of 8.46% in 2014 (P less than 0.01), “but we do not believe that this is clinically important because this value falls within the biological within-subject variation of most modern HbA1c assays,” he said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Meanwhile, there was no statistically significant change in the rate of hospitalizations or emergency department visits for hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia.

“Patients with type 2 diabetes and their clinical providers should strongly consider human insulin as a clinically viable and cost effective option,” Dr. Luo said.

“My personal clinical opinion is that if I have a patient who is really hard to control, and after four or five different regimens, we finally settle on an analogue regimen that [keeps] them under control” and out of the hospital, “I’m not going to switch them just because a health plan tells me I should. They are just too brittle, and I’m not comfortable doing that. Whereas if I have a patient who’d be fine with either option, and I’m not really worried about hypoglycemia, I’ll switch them,” he said.

There was no industry funding. Dr. Luo is a consultant for Alosa Health and Health Action International.

SOURCE: Luo J et al. 2018 American Diabetes Association scientific session abstract 4-OR

ORLANDO – It’s safe to switch many Medicare beneficiaries with type 2 diabetes to human insulins to save money on analogues, according to a review of 14,635 members of CareMore, a Medicare Advantage company based in Cerritos, Calif.

The company noticed that it’s spending on analogue insulins had ballooned to over $3 million a month by the end of 2014, in the wake of a more than 300% price increase in analogue insulins in recent years, while copays on analogues rose from nothing to $37.50. In 2015, it launched a program to switch type 2 patients to less costly human insulins. Physicians were counseled to stop secretagogues and move patients to premixed insulins at 80% of their former total daily analogue dose, two-thirds at breakfast, and one-third a dinner, with appropriate follow-up.