User login

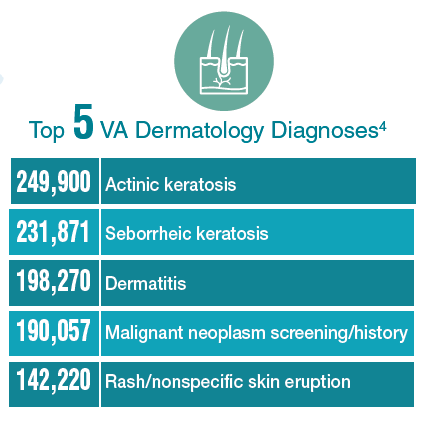

Federal Health Care Data Trends: Dermatology

There is significant variation among the civilian, active-duty, and veteran populations in regard to dermatologic conditions. Civilians most frequently visit a specialist with complaints of eczema, dermatitis, acne, and other benign conditions. Among active-duty service members, infections and allergic bite reactions are the most common reasons for a trip to a health care facility. In contrast, veterans are more likely to be diagnosed with precancerous skin conditions or to receive a screening for malignant skin cancers.

Click here to continue reading.

There is significant variation among the civilian, active-duty, and veteran populations in regard to dermatologic conditions. Civilians most frequently visit a specialist with complaints of eczema, dermatitis, acne, and other benign conditions. Among active-duty service members, infections and allergic bite reactions are the most common reasons for a trip to a health care facility. In contrast, veterans are more likely to be diagnosed with precancerous skin conditions or to receive a screening for malignant skin cancers.

Click here to continue reading.

There is significant variation among the civilian, active-duty, and veteran populations in regard to dermatologic conditions. Civilians most frequently visit a specialist with complaints of eczema, dermatitis, acne, and other benign conditions. Among active-duty service members, infections and allergic bite reactions are the most common reasons for a trip to a health care facility. In contrast, veterans are more likely to be diagnosed with precancerous skin conditions or to receive a screening for malignant skin cancers.

Click here to continue reading.

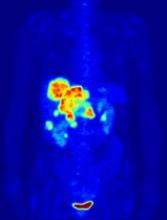

PET-guided treatment didn’t improve outcomes

In the PETAL trial, treatment intensification based on results of an interim positron emission tomography (PET) scan did not improve survival outcomes for patients with aggressive lymphomas.

PET-positive patients did not benefit by switching from R-CHOP to a more intensive chemotherapy regimen.

PET-negative patients did not benefit from 2 additional cycles of rituximab after R-CHOP.

These results were published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

PETAL was a randomized trial of patients with newly diagnosed T- or B-cell lymphomas.

Patients received 2 cycles of CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone)—plus rituximab (R-CHOP) in CD20-positive lymphomas—followed by a PET scan.

PET-positive patients were randomized to receive 6 additional cycles of R-CHOP or 6 blocks of an intensive protocol used to treat Burkitt lymphoma. This protocol consisted of high-dose methotrexate, cytarabine, hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide, split-dose doxorubicin and etoposide, vincristine, vindesine, and dexamethasone.

PET-negative patients with CD20-positive lymphomas were randomized to receive 4 additional cycles of R-CHOP or 4 additional cycles of R-CHOP followed by 2 more doses of rituximab.

Among patients with T-cell lymphomas, only PET-positive individuals underwent randomization. PET-negative patients received CHOP. Patients with CD20-positive T-cell lymphomas also received rituximab.

PET-positive results

Of the PET-positive patients (108/862), 52 were randomized to receive 6 additional cycles of R-CHOP, and 56 were randomized to 6 cycles of the Burkitt protocol.

In general, survival rates were similar regardless of treatment. The 2-year overall survival (OS) rate was 63.6% for patients who received R-CHOP and 55.4% for those who received the more intensive protocol.

Two-year progression-free survival (PFS) rates were 49.4% and 43.1%, respectively. Two-year event-free survival (EFS) rates were 42.0% and 31.6%, respectively.

Among patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), the OS rate was 64.8% for patients who received R-CHOP and 47.1% for those on the Burkitt protocol. PFS rates were 55.5% and 41.4%, respectively.

There was a significant difference in EFS rates among the DLBCL patients—52.4% in the R-CHOP arm and 28.3% in the intensive arm (P=0.0186).

Among T-cell lymphoma patients, the OS rate was 22.2% in the R-CHOP arm and 30.0% in the intensive arm. The PFS rates were 12.7% and 30%, respectively. The EFS rates were the same as the PFS rates.

Overall, patients who received the Burkitt protocol had significantly higher rates of grade 3/4 hematologic toxicities, infection, and mucositis.

PET-negative results

Of 754 PET-negative patients, 697 had CD20-positive lymphomas, and 255 of those patients (all with B-cell lymphomas) underwent randomization.

There were 129 patients who were randomized to receive 6 cycles of R-CHOP (2 before and 4 after randomization) and 126 who were randomized to receive 6 cycles of R-CHOP plus 2 additional cycles of rituximab.

Again, survival rates were similar regardless of treatment.

The 2-year OS was 88.2% for patients who received only R-CHOP and 87.2% for those with additional rituximab exposure. PFS rates were 82.0% and 77.5%, respectively. EFS rates were 76.4% and 73.5%, respectively.

In the DLBCL patients, the OS rate was 88.5% in the R-CHOP arm and 85.8% in the intensive arm. PFS rates were 82.3% and 77.7%, respectively. EFS rates were 72.6% and 78.9%, respectively.

As increasing the dose of rituximab did not improve outcomes, the investigators concluded that 6 cycles of R-CHOP should be the standard of care for these patients.

The team also said interim PET scanning is “a powerful tool” for identifying chemotherapy-resistant lymphomas, and PET-positive patients may be candidates for immunologic treatment approaches.

In the PETAL trial, treatment intensification based on results of an interim positron emission tomography (PET) scan did not improve survival outcomes for patients with aggressive lymphomas.

PET-positive patients did not benefit by switching from R-CHOP to a more intensive chemotherapy regimen.

PET-negative patients did not benefit from 2 additional cycles of rituximab after R-CHOP.

These results were published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

PETAL was a randomized trial of patients with newly diagnosed T- or B-cell lymphomas.

Patients received 2 cycles of CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone)—plus rituximab (R-CHOP) in CD20-positive lymphomas—followed by a PET scan.

PET-positive patients were randomized to receive 6 additional cycles of R-CHOP or 6 blocks of an intensive protocol used to treat Burkitt lymphoma. This protocol consisted of high-dose methotrexate, cytarabine, hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide, split-dose doxorubicin and etoposide, vincristine, vindesine, and dexamethasone.

PET-negative patients with CD20-positive lymphomas were randomized to receive 4 additional cycles of R-CHOP or 4 additional cycles of R-CHOP followed by 2 more doses of rituximab.

Among patients with T-cell lymphomas, only PET-positive individuals underwent randomization. PET-negative patients received CHOP. Patients with CD20-positive T-cell lymphomas also received rituximab.

PET-positive results

Of the PET-positive patients (108/862), 52 were randomized to receive 6 additional cycles of R-CHOP, and 56 were randomized to 6 cycles of the Burkitt protocol.

In general, survival rates were similar regardless of treatment. The 2-year overall survival (OS) rate was 63.6% for patients who received R-CHOP and 55.4% for those who received the more intensive protocol.

Two-year progression-free survival (PFS) rates were 49.4% and 43.1%, respectively. Two-year event-free survival (EFS) rates were 42.0% and 31.6%, respectively.

Among patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), the OS rate was 64.8% for patients who received R-CHOP and 47.1% for those on the Burkitt protocol. PFS rates were 55.5% and 41.4%, respectively.

There was a significant difference in EFS rates among the DLBCL patients—52.4% in the R-CHOP arm and 28.3% in the intensive arm (P=0.0186).

Among T-cell lymphoma patients, the OS rate was 22.2% in the R-CHOP arm and 30.0% in the intensive arm. The PFS rates were 12.7% and 30%, respectively. The EFS rates were the same as the PFS rates.

Overall, patients who received the Burkitt protocol had significantly higher rates of grade 3/4 hematologic toxicities, infection, and mucositis.

PET-negative results

Of 754 PET-negative patients, 697 had CD20-positive lymphomas, and 255 of those patients (all with B-cell lymphomas) underwent randomization.

There were 129 patients who were randomized to receive 6 cycles of R-CHOP (2 before and 4 after randomization) and 126 who were randomized to receive 6 cycles of R-CHOP plus 2 additional cycles of rituximab.

Again, survival rates were similar regardless of treatment.

The 2-year OS was 88.2% for patients who received only R-CHOP and 87.2% for those with additional rituximab exposure. PFS rates were 82.0% and 77.5%, respectively. EFS rates were 76.4% and 73.5%, respectively.

In the DLBCL patients, the OS rate was 88.5% in the R-CHOP arm and 85.8% in the intensive arm. PFS rates were 82.3% and 77.7%, respectively. EFS rates were 72.6% and 78.9%, respectively.

As increasing the dose of rituximab did not improve outcomes, the investigators concluded that 6 cycles of R-CHOP should be the standard of care for these patients.

The team also said interim PET scanning is “a powerful tool” for identifying chemotherapy-resistant lymphomas, and PET-positive patients may be candidates for immunologic treatment approaches.

In the PETAL trial, treatment intensification based on results of an interim positron emission tomography (PET) scan did not improve survival outcomes for patients with aggressive lymphomas.

PET-positive patients did not benefit by switching from R-CHOP to a more intensive chemotherapy regimen.

PET-negative patients did not benefit from 2 additional cycles of rituximab after R-CHOP.

These results were published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

PETAL was a randomized trial of patients with newly diagnosed T- or B-cell lymphomas.

Patients received 2 cycles of CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone)—plus rituximab (R-CHOP) in CD20-positive lymphomas—followed by a PET scan.

PET-positive patients were randomized to receive 6 additional cycles of R-CHOP or 6 blocks of an intensive protocol used to treat Burkitt lymphoma. This protocol consisted of high-dose methotrexate, cytarabine, hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide, split-dose doxorubicin and etoposide, vincristine, vindesine, and dexamethasone.

PET-negative patients with CD20-positive lymphomas were randomized to receive 4 additional cycles of R-CHOP or 4 additional cycles of R-CHOP followed by 2 more doses of rituximab.

Among patients with T-cell lymphomas, only PET-positive individuals underwent randomization. PET-negative patients received CHOP. Patients with CD20-positive T-cell lymphomas also received rituximab.

PET-positive results

Of the PET-positive patients (108/862), 52 were randomized to receive 6 additional cycles of R-CHOP, and 56 were randomized to 6 cycles of the Burkitt protocol.

In general, survival rates were similar regardless of treatment. The 2-year overall survival (OS) rate was 63.6% for patients who received R-CHOP and 55.4% for those who received the more intensive protocol.

Two-year progression-free survival (PFS) rates were 49.4% and 43.1%, respectively. Two-year event-free survival (EFS) rates were 42.0% and 31.6%, respectively.

Among patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), the OS rate was 64.8% for patients who received R-CHOP and 47.1% for those on the Burkitt protocol. PFS rates were 55.5% and 41.4%, respectively.

There was a significant difference in EFS rates among the DLBCL patients—52.4% in the R-CHOP arm and 28.3% in the intensive arm (P=0.0186).

Among T-cell lymphoma patients, the OS rate was 22.2% in the R-CHOP arm and 30.0% in the intensive arm. The PFS rates were 12.7% and 30%, respectively. The EFS rates were the same as the PFS rates.

Overall, patients who received the Burkitt protocol had significantly higher rates of grade 3/4 hematologic toxicities, infection, and mucositis.

PET-negative results

Of 754 PET-negative patients, 697 had CD20-positive lymphomas, and 255 of those patients (all with B-cell lymphomas) underwent randomization.

There were 129 patients who were randomized to receive 6 cycles of R-CHOP (2 before and 4 after randomization) and 126 who were randomized to receive 6 cycles of R-CHOP plus 2 additional cycles of rituximab.

Again, survival rates were similar regardless of treatment.

The 2-year OS was 88.2% for patients who received only R-CHOP and 87.2% for those with additional rituximab exposure. PFS rates were 82.0% and 77.5%, respectively. EFS rates were 76.4% and 73.5%, respectively.

In the DLBCL patients, the OS rate was 88.5% in the R-CHOP arm and 85.8% in the intensive arm. PFS rates were 82.3% and 77.7%, respectively. EFS rates were 72.6% and 78.9%, respectively.

As increasing the dose of rituximab did not improve outcomes, the investigators concluded that 6 cycles of R-CHOP should be the standard of care for these patients.

The team also said interim PET scanning is “a powerful tool” for identifying chemotherapy-resistant lymphomas, and PET-positive patients may be candidates for immunologic treatment approaches.

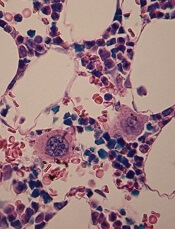

Turbulence aids platelet production

Turbulence promotes large-scale production of functional platelets from human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), according to research published in Cell.

Exposure to turbulent energy in a bioreactor stimulated hiPSC-derived megakaryocytes to produce 100 billion platelets.

Transfusion of these platelets in 2 animal models promoted blood clotting and prevented bleeding just as well as platelets from human donors.

“The discovery of turbulent energy provides a new physical mechanism and ex vivo production strategy for the generation of platelets that should impact clinical-scale cell therapies for regenerative medicine,” said study author Koji Eto, MD, PhD, of Kyoto University in Japan.

Previous attempts to generate platelets from hiPSC-derived megakaryocytes failed to achieve a scale suitable for clinical manufacturing.

While searching for a solution to this problem, Dr Eto and his colleagues noticed that hiPSC-derived megakaryocytes produced more platelets when being rotated in a flask than under static conditions in a petri dish.

This observation suggested that physical stress from horizontal shaking under liquid conditions enhances platelet generation.

Following up on this discovery, the researchers tested a rocking-bag-based bioreactor followed by a new microfluidic system with a flow chamber and multiple pillars, but these devices generated fewer than 20 platelets per hiPSC-derived megakaryocyte.

To examine the ideal physical conditions for generating platelets, Dr Eto and his team conducted live-imaging studies of mouse bone marrow.

These experiments revealed that megakaryocytes release platelets only when they are exposed to turbulent blood flow. In support of this idea, simulations confirmed that the bioreactor and microfluidic system the researchers previously tested lacked sufficient turbulent energy.

“The discovery of the crucial role of turbulence in platelet production significantly extends past research showing that shear stress from blood flow is also a key physical factor in this process,” Dr Eto said.

“Our findings also show that iPS cells are not the end-all be-all for producing platelets. Understanding fluid dynamics in addition to iPS cell technology was necessary for our discovery.”

After testing various devices, the researchers discovered that large-scale production of high-quality platelets was possible using a bioreactor called VerMES. This system consists of 2 oval-shaped, horizontally oriented mixing blades that generate relatively high levels of turbulence by moving up and down in a cylinder.

With the optimal level of turbulent energy and shear stress created by the blade motion, the hiPSC-derived megakaryocytes generated 100 billion platelets—enough to satisfy clinical requirements.

Transfusion experiments in 2 animal models of thrombocytopenia showed that these platelets perform similarly to platelets from human donors. Both types of platelets promoted blood clotting and reduced bleeding times to a comparable extent after ear vein incisions in rabbits and tail artery punctures in mice.

Dr Eto and his team are taking this work further by designing automated protocols, lowering manufacturing costs, and optimizing platelet yields. They are also developing universal platelets lacking human leukocyte antigens in order to reduce the risk of immune-mediated transfusion reactions.

“We expect clinical trials to begin within a year or two,” Dr Eto said. “We believe these findings will be a last scientific step to receiving permission for clinical trials using our platelets.”

Turbulence promotes large-scale production of functional platelets from human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), according to research published in Cell.

Exposure to turbulent energy in a bioreactor stimulated hiPSC-derived megakaryocytes to produce 100 billion platelets.

Transfusion of these platelets in 2 animal models promoted blood clotting and prevented bleeding just as well as platelets from human donors.

“The discovery of turbulent energy provides a new physical mechanism and ex vivo production strategy for the generation of platelets that should impact clinical-scale cell therapies for regenerative medicine,” said study author Koji Eto, MD, PhD, of Kyoto University in Japan.

Previous attempts to generate platelets from hiPSC-derived megakaryocytes failed to achieve a scale suitable for clinical manufacturing.

While searching for a solution to this problem, Dr Eto and his colleagues noticed that hiPSC-derived megakaryocytes produced more platelets when being rotated in a flask than under static conditions in a petri dish.

This observation suggested that physical stress from horizontal shaking under liquid conditions enhances platelet generation.

Following up on this discovery, the researchers tested a rocking-bag-based bioreactor followed by a new microfluidic system with a flow chamber and multiple pillars, but these devices generated fewer than 20 platelets per hiPSC-derived megakaryocyte.

To examine the ideal physical conditions for generating platelets, Dr Eto and his team conducted live-imaging studies of mouse bone marrow.

These experiments revealed that megakaryocytes release platelets only when they are exposed to turbulent blood flow. In support of this idea, simulations confirmed that the bioreactor and microfluidic system the researchers previously tested lacked sufficient turbulent energy.

“The discovery of the crucial role of turbulence in platelet production significantly extends past research showing that shear stress from blood flow is also a key physical factor in this process,” Dr Eto said.

“Our findings also show that iPS cells are not the end-all be-all for producing platelets. Understanding fluid dynamics in addition to iPS cell technology was necessary for our discovery.”

After testing various devices, the researchers discovered that large-scale production of high-quality platelets was possible using a bioreactor called VerMES. This system consists of 2 oval-shaped, horizontally oriented mixing blades that generate relatively high levels of turbulence by moving up and down in a cylinder.

With the optimal level of turbulent energy and shear stress created by the blade motion, the hiPSC-derived megakaryocytes generated 100 billion platelets—enough to satisfy clinical requirements.

Transfusion experiments in 2 animal models of thrombocytopenia showed that these platelets perform similarly to platelets from human donors. Both types of platelets promoted blood clotting and reduced bleeding times to a comparable extent after ear vein incisions in rabbits and tail artery punctures in mice.

Dr Eto and his team are taking this work further by designing automated protocols, lowering manufacturing costs, and optimizing platelet yields. They are also developing universal platelets lacking human leukocyte antigens in order to reduce the risk of immune-mediated transfusion reactions.

“We expect clinical trials to begin within a year or two,” Dr Eto said. “We believe these findings will be a last scientific step to receiving permission for clinical trials using our platelets.”

Turbulence promotes large-scale production of functional platelets from human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), according to research published in Cell.

Exposure to turbulent energy in a bioreactor stimulated hiPSC-derived megakaryocytes to produce 100 billion platelets.

Transfusion of these platelets in 2 animal models promoted blood clotting and prevented bleeding just as well as platelets from human donors.

“The discovery of turbulent energy provides a new physical mechanism and ex vivo production strategy for the generation of platelets that should impact clinical-scale cell therapies for regenerative medicine,” said study author Koji Eto, MD, PhD, of Kyoto University in Japan.

Previous attempts to generate platelets from hiPSC-derived megakaryocytes failed to achieve a scale suitable for clinical manufacturing.

While searching for a solution to this problem, Dr Eto and his colleagues noticed that hiPSC-derived megakaryocytes produced more platelets when being rotated in a flask than under static conditions in a petri dish.

This observation suggested that physical stress from horizontal shaking under liquid conditions enhances platelet generation.

Following up on this discovery, the researchers tested a rocking-bag-based bioreactor followed by a new microfluidic system with a flow chamber and multiple pillars, but these devices generated fewer than 20 platelets per hiPSC-derived megakaryocyte.

To examine the ideal physical conditions for generating platelets, Dr Eto and his team conducted live-imaging studies of mouse bone marrow.

These experiments revealed that megakaryocytes release platelets only when they are exposed to turbulent blood flow. In support of this idea, simulations confirmed that the bioreactor and microfluidic system the researchers previously tested lacked sufficient turbulent energy.

“The discovery of the crucial role of turbulence in platelet production significantly extends past research showing that shear stress from blood flow is also a key physical factor in this process,” Dr Eto said.

“Our findings also show that iPS cells are not the end-all be-all for producing platelets. Understanding fluid dynamics in addition to iPS cell technology was necessary for our discovery.”

After testing various devices, the researchers discovered that large-scale production of high-quality platelets was possible using a bioreactor called VerMES. This system consists of 2 oval-shaped, horizontally oriented mixing blades that generate relatively high levels of turbulence by moving up and down in a cylinder.

With the optimal level of turbulent energy and shear stress created by the blade motion, the hiPSC-derived megakaryocytes generated 100 billion platelets—enough to satisfy clinical requirements.

Transfusion experiments in 2 animal models of thrombocytopenia showed that these platelets perform similarly to platelets from human donors. Both types of platelets promoted blood clotting and reduced bleeding times to a comparable extent after ear vein incisions in rabbits and tail artery punctures in mice.

Dr Eto and his team are taking this work further by designing automated protocols, lowering manufacturing costs, and optimizing platelet yields. They are also developing universal platelets lacking human leukocyte antigens in order to reduce the risk of immune-mediated transfusion reactions.

“We expect clinical trials to begin within a year or two,” Dr Eto said. “We believe these findings will be a last scientific step to receiving permission for clinical trials using our platelets.”

Mutations linked to higher risk of SNs in CCSs

New research has shown that childhood cancer survivors (CCSs) with certain germline mutations have higher relative rates (RRs) of secondary neoplasms (SNs) later in life.

Mutation carriers had significantly higher rates of breast cancer and sarcoma if they had received radiation to treat their initial cancer.

Among CCSs who did not receive radiation, the mutations were associated with increased rates of any SN, breast cancer, nonmelanoma skin cancer, and 2 or more histologically distinct SNs.

These findings were reported in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Researchers sequenced samples from 3006 CCSs who were at least 5 years from their initial cancer diagnosis as well as 341 samples from cancer-free control subjects.

All subjects were participants in the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study, a retrospective study with prospective clinical follow-up.

Thirty-five percent of the CCSs had survived leukemia, and 19% had survived lymphoma.

The CCS’s median age at childhood cancer diagnosis was 7.1 years, and the median follow-up was 28 years. The controls had a median age of 36.4 at follow-up.

Results

There were 1120 SNs diagnosed in 439 CCSs (14.6%). Ninety-one CCSs developed 2 or more histologically distinct SNs. The median time to SN diagnosis was 25.6 years

Non-melanoma skin cancer (580 in 159 CCSs), meningiomas (233 in 102 CCSs), thyroid cancer (67 in 67 CCSs), and breast cancer (60 in 53 CCSs) were among the SNs reported.

There were 15 neoplasms recorded in the control group—14 cases of non-melanoma skin cancer and 1 meningioma.

Pathogenic or likely pathogenic (P/LP) mutations in 32 genes were reported in 175 CCSs. The prevalence in CCSs (5.8%) was nearly 10-fold higher than in controls (0.6%).

The most commonly mutated genes in CCSs were RB1 (n=43), NF1 (n=22), BRCA2 (n=14), BRCA1 (n=12), and TP53 (n=10).

In a multivariable analysis adjusted for sex, age at primary cancer diagnosis, and treatment, P/LP mutation carriers had a significantly higher rate of any SN (RR=1.8).

The rate of subsequent breast cancer was significantly increased among females with a P/LP mutation (RR= 9.4), recipients of chest radiation (RR=7.9), and those with higher anthracycline exposure (RR=2.4).

The rate of subsequent sarcoma was significantly increased for mutation carriers (RR=10.9) and CCSs with greater exposure to alkylating agents (RR=3.8).

Among irradiated CCSs, P/LP mutations were associated with significantly increased rates of breast cancer (RR=13.9) and sarcoma (RR=10.6)

Among non-irradiated CCSs, P/LP mutations were associated with significantly increased rates of any SN (RR=4.7), breast cancer (RR=7.7), nonmelanoma skin cancer (RR=11.0), and 2 or more histologically distinct SNs (RR=18.6).

The researchers said the higher risk of SNs in CCSs with P/LP mutations suggests all CCSs should be referred for genetic counseling.

New research has shown that childhood cancer survivors (CCSs) with certain germline mutations have higher relative rates (RRs) of secondary neoplasms (SNs) later in life.

Mutation carriers had significantly higher rates of breast cancer and sarcoma if they had received radiation to treat their initial cancer.

Among CCSs who did not receive radiation, the mutations were associated with increased rates of any SN, breast cancer, nonmelanoma skin cancer, and 2 or more histologically distinct SNs.

These findings were reported in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Researchers sequenced samples from 3006 CCSs who were at least 5 years from their initial cancer diagnosis as well as 341 samples from cancer-free control subjects.

All subjects were participants in the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study, a retrospective study with prospective clinical follow-up.

Thirty-five percent of the CCSs had survived leukemia, and 19% had survived lymphoma.

The CCS’s median age at childhood cancer diagnosis was 7.1 years, and the median follow-up was 28 years. The controls had a median age of 36.4 at follow-up.

Results

There were 1120 SNs diagnosed in 439 CCSs (14.6%). Ninety-one CCSs developed 2 or more histologically distinct SNs. The median time to SN diagnosis was 25.6 years

Non-melanoma skin cancer (580 in 159 CCSs), meningiomas (233 in 102 CCSs), thyroid cancer (67 in 67 CCSs), and breast cancer (60 in 53 CCSs) were among the SNs reported.

There were 15 neoplasms recorded in the control group—14 cases of non-melanoma skin cancer and 1 meningioma.

Pathogenic or likely pathogenic (P/LP) mutations in 32 genes were reported in 175 CCSs. The prevalence in CCSs (5.8%) was nearly 10-fold higher than in controls (0.6%).

The most commonly mutated genes in CCSs were RB1 (n=43), NF1 (n=22), BRCA2 (n=14), BRCA1 (n=12), and TP53 (n=10).

In a multivariable analysis adjusted for sex, age at primary cancer diagnosis, and treatment, P/LP mutation carriers had a significantly higher rate of any SN (RR=1.8).

The rate of subsequent breast cancer was significantly increased among females with a P/LP mutation (RR= 9.4), recipients of chest radiation (RR=7.9), and those with higher anthracycline exposure (RR=2.4).

The rate of subsequent sarcoma was significantly increased for mutation carriers (RR=10.9) and CCSs with greater exposure to alkylating agents (RR=3.8).

Among irradiated CCSs, P/LP mutations were associated with significantly increased rates of breast cancer (RR=13.9) and sarcoma (RR=10.6)

Among non-irradiated CCSs, P/LP mutations were associated with significantly increased rates of any SN (RR=4.7), breast cancer (RR=7.7), nonmelanoma skin cancer (RR=11.0), and 2 or more histologically distinct SNs (RR=18.6).

The researchers said the higher risk of SNs in CCSs with P/LP mutations suggests all CCSs should be referred for genetic counseling.

New research has shown that childhood cancer survivors (CCSs) with certain germline mutations have higher relative rates (RRs) of secondary neoplasms (SNs) later in life.

Mutation carriers had significantly higher rates of breast cancer and sarcoma if they had received radiation to treat their initial cancer.

Among CCSs who did not receive radiation, the mutations were associated with increased rates of any SN, breast cancer, nonmelanoma skin cancer, and 2 or more histologically distinct SNs.

These findings were reported in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Researchers sequenced samples from 3006 CCSs who were at least 5 years from their initial cancer diagnosis as well as 341 samples from cancer-free control subjects.

All subjects were participants in the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study, a retrospective study with prospective clinical follow-up.

Thirty-five percent of the CCSs had survived leukemia, and 19% had survived lymphoma.

The CCS’s median age at childhood cancer diagnosis was 7.1 years, and the median follow-up was 28 years. The controls had a median age of 36.4 at follow-up.

Results

There were 1120 SNs diagnosed in 439 CCSs (14.6%). Ninety-one CCSs developed 2 or more histologically distinct SNs. The median time to SN diagnosis was 25.6 years

Non-melanoma skin cancer (580 in 159 CCSs), meningiomas (233 in 102 CCSs), thyroid cancer (67 in 67 CCSs), and breast cancer (60 in 53 CCSs) were among the SNs reported.

There were 15 neoplasms recorded in the control group—14 cases of non-melanoma skin cancer and 1 meningioma.

Pathogenic or likely pathogenic (P/LP) mutations in 32 genes were reported in 175 CCSs. The prevalence in CCSs (5.8%) was nearly 10-fold higher than in controls (0.6%).

The most commonly mutated genes in CCSs were RB1 (n=43), NF1 (n=22), BRCA2 (n=14), BRCA1 (n=12), and TP53 (n=10).

In a multivariable analysis adjusted for sex, age at primary cancer diagnosis, and treatment, P/LP mutation carriers had a significantly higher rate of any SN (RR=1.8).

The rate of subsequent breast cancer was significantly increased among females with a P/LP mutation (RR= 9.4), recipients of chest radiation (RR=7.9), and those with higher anthracycline exposure (RR=2.4).

The rate of subsequent sarcoma was significantly increased for mutation carriers (RR=10.9) and CCSs with greater exposure to alkylating agents (RR=3.8).

Among irradiated CCSs, P/LP mutations were associated with significantly increased rates of breast cancer (RR=13.9) and sarcoma (RR=10.6)

Among non-irradiated CCSs, P/LP mutations were associated with significantly increased rates of any SN (RR=4.7), breast cancer (RR=7.7), nonmelanoma skin cancer (RR=11.0), and 2 or more histologically distinct SNs (RR=18.6).

The researchers said the higher risk of SNs in CCSs with P/LP mutations suggests all CCSs should be referred for genetic counseling.

From the Editors: The Value of Community

I was recently reminded of the importance of face-to-face meetings to gain understanding and to learn from the experiences of others. In this case, the lesson was delivered in the idyllic setting of Sunriver, Oregon, where the Oregon and Washington chapters of the American College of Surgeons held their annual meeting. I always come away from this meeting energized and inspired by the shared experiences of young and old, urban and rural. This meeting exceeded all expectations in the quality of the presentations but also, more importantly, in the quality of the exchange of ideas and viewpoints among surgeons across the full spectrum of practice types, geographical locations, and generations.

Community and rural surgeons were both well represented at this meeting, perhaps because our Oregon chapter president, Keith Thomas, is a rural surgeon; he had invited rural surgeon extraordinaire Tyler Hughes to be the keynote speaker; and the overarching theme of the meeting was “The Right Care in the Right Place.” The program featured controversial topics that were presented in a way that respected all views and shed more light than heat on the subject: a debate about whether (and which) cancers needed to be referred to tertiary centers, an exploration of how surgical care for all might be improved by regionalization in a matrix that could allow all patients to access timely and appropriate care, and even a discussion of a strategy through which we might build consensus for the prevention of firearm injuries and deaths while avoiding the “demonization of the enemy” that currently occurs whenever the subject is mentioned.

The residents’ and fellows’ presentations have evolved over the past few decades to include a broader range of research topics than those in prior meetings. This year, trainees gave papers not only on the treatment of specific surgical conditions or basic science studies but also on quality improvement, patient safety, ethics, end-of-life care, and cutting-edge technologies. Those who presented their research displayed the very best attributes of the millennial generation: creativity, altruism, and a commitment to make our shared future world a better, safer, more humane place. They fielded questions from the audience like “old pros,” demonstrating an impressive understanding of their subjects as well as a passion for their work.

Although the accelerating demands on our lives have led some to question whether the time required to attend a chapter meeting is worth the money and effort, I would argue that it is crucial to our future to do so. As surgical practice becomes more specialized and “siloed,” it is critical that we reaffirm what unites us rather than focus on what separates us. It is easy to attribute ill motives and malevolent characteristics to someone who sees things differently than you do. Is much more difficult to do so when you spend time with that person and learn about him or her as an individual. Local ACS chapter meetings accomplish that and more. Older surgeons nearing retirement and worried about the future of their communities can meet and mingle with residents and fellows who might become future partners. Former colleagues from medical school or residency who have pursued different practice paths can reacquaint themselves with one another, relive the good (and perhaps bad) old times, and share a chuckle or two. Surgeons who practice in the “ivory tower” can gain appreciation for the challenges of practicing in a resource-limited facility. Those from competing institutions or practices can learn that the “other” is facing the same issues and that common strategies for success might be found. We can all gain a greater understanding that the other person’s problems aren’t that different or less complex than ours.

In addition to providing a stimulating program, a successful chapter meeting requires skillful planning and execution by an experienced chapter manager. Our Oregon chapter is fortunate to have Harvey Gail, an outstanding manager who takes care of those essential tasks that make the meeting run smoothly so that we can focus on the substance of the meeting itself.

Attending a chapter meeting requires a relatively short time commitment of three days away from home – including a weekend – and a tank of gas. Some have suggested that holding the meeting in the largest city in the region would lessen travel time demands for many, but doing so would mean losing the low-key setting that creates the perfect atmosphere for developing professional and personal relationships and building a true community. The future survival of our profession depends on finding better, novel solutions to our common problems; we can accomplish that only by sharing our diverse perspectives and identifying solutions that meet all of our needs and those of our patients.

To those of you who rarely (or never) have attended a chapter meeting, you need to go. You’ll be surprised at how much you can learn from your fellow surgeons, who, I guarantee, are more like you than they are different.

Dr. Deveney is a professor of surgery and the vice chair of education in the department of surgery at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. She is the coeditor of ACS Surgery News.

I was recently reminded of the importance of face-to-face meetings to gain understanding and to learn from the experiences of others. In this case, the lesson was delivered in the idyllic setting of Sunriver, Oregon, where the Oregon and Washington chapters of the American College of Surgeons held their annual meeting. I always come away from this meeting energized and inspired by the shared experiences of young and old, urban and rural. This meeting exceeded all expectations in the quality of the presentations but also, more importantly, in the quality of the exchange of ideas and viewpoints among surgeons across the full spectrum of practice types, geographical locations, and generations.

Community and rural surgeons were both well represented at this meeting, perhaps because our Oregon chapter president, Keith Thomas, is a rural surgeon; he had invited rural surgeon extraordinaire Tyler Hughes to be the keynote speaker; and the overarching theme of the meeting was “The Right Care in the Right Place.” The program featured controversial topics that were presented in a way that respected all views and shed more light than heat on the subject: a debate about whether (and which) cancers needed to be referred to tertiary centers, an exploration of how surgical care for all might be improved by regionalization in a matrix that could allow all patients to access timely and appropriate care, and even a discussion of a strategy through which we might build consensus for the prevention of firearm injuries and deaths while avoiding the “demonization of the enemy” that currently occurs whenever the subject is mentioned.

The residents’ and fellows’ presentations have evolved over the past few decades to include a broader range of research topics than those in prior meetings. This year, trainees gave papers not only on the treatment of specific surgical conditions or basic science studies but also on quality improvement, patient safety, ethics, end-of-life care, and cutting-edge technologies. Those who presented their research displayed the very best attributes of the millennial generation: creativity, altruism, and a commitment to make our shared future world a better, safer, more humane place. They fielded questions from the audience like “old pros,” demonstrating an impressive understanding of their subjects as well as a passion for their work.

Although the accelerating demands on our lives have led some to question whether the time required to attend a chapter meeting is worth the money and effort, I would argue that it is crucial to our future to do so. As surgical practice becomes more specialized and “siloed,” it is critical that we reaffirm what unites us rather than focus on what separates us. It is easy to attribute ill motives and malevolent characteristics to someone who sees things differently than you do. Is much more difficult to do so when you spend time with that person and learn about him or her as an individual. Local ACS chapter meetings accomplish that and more. Older surgeons nearing retirement and worried about the future of their communities can meet and mingle with residents and fellows who might become future partners. Former colleagues from medical school or residency who have pursued different practice paths can reacquaint themselves with one another, relive the good (and perhaps bad) old times, and share a chuckle or two. Surgeons who practice in the “ivory tower” can gain appreciation for the challenges of practicing in a resource-limited facility. Those from competing institutions or practices can learn that the “other” is facing the same issues and that common strategies for success might be found. We can all gain a greater understanding that the other person’s problems aren’t that different or less complex than ours.

In addition to providing a stimulating program, a successful chapter meeting requires skillful planning and execution by an experienced chapter manager. Our Oregon chapter is fortunate to have Harvey Gail, an outstanding manager who takes care of those essential tasks that make the meeting run smoothly so that we can focus on the substance of the meeting itself.

Attending a chapter meeting requires a relatively short time commitment of three days away from home – including a weekend – and a tank of gas. Some have suggested that holding the meeting in the largest city in the region would lessen travel time demands for many, but doing so would mean losing the low-key setting that creates the perfect atmosphere for developing professional and personal relationships and building a true community. The future survival of our profession depends on finding better, novel solutions to our common problems; we can accomplish that only by sharing our diverse perspectives and identifying solutions that meet all of our needs and those of our patients.

To those of you who rarely (or never) have attended a chapter meeting, you need to go. You’ll be surprised at how much you can learn from your fellow surgeons, who, I guarantee, are more like you than they are different.

Dr. Deveney is a professor of surgery and the vice chair of education in the department of surgery at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. She is the coeditor of ACS Surgery News.

I was recently reminded of the importance of face-to-face meetings to gain understanding and to learn from the experiences of others. In this case, the lesson was delivered in the idyllic setting of Sunriver, Oregon, where the Oregon and Washington chapters of the American College of Surgeons held their annual meeting. I always come away from this meeting energized and inspired by the shared experiences of young and old, urban and rural. This meeting exceeded all expectations in the quality of the presentations but also, more importantly, in the quality of the exchange of ideas and viewpoints among surgeons across the full spectrum of practice types, geographical locations, and generations.

Community and rural surgeons were both well represented at this meeting, perhaps because our Oregon chapter president, Keith Thomas, is a rural surgeon; he had invited rural surgeon extraordinaire Tyler Hughes to be the keynote speaker; and the overarching theme of the meeting was “The Right Care in the Right Place.” The program featured controversial topics that were presented in a way that respected all views and shed more light than heat on the subject: a debate about whether (and which) cancers needed to be referred to tertiary centers, an exploration of how surgical care for all might be improved by regionalization in a matrix that could allow all patients to access timely and appropriate care, and even a discussion of a strategy through which we might build consensus for the prevention of firearm injuries and deaths while avoiding the “demonization of the enemy” that currently occurs whenever the subject is mentioned.

The residents’ and fellows’ presentations have evolved over the past few decades to include a broader range of research topics than those in prior meetings. This year, trainees gave papers not only on the treatment of specific surgical conditions or basic science studies but also on quality improvement, patient safety, ethics, end-of-life care, and cutting-edge technologies. Those who presented their research displayed the very best attributes of the millennial generation: creativity, altruism, and a commitment to make our shared future world a better, safer, more humane place. They fielded questions from the audience like “old pros,” demonstrating an impressive understanding of their subjects as well as a passion for their work.

Although the accelerating demands on our lives have led some to question whether the time required to attend a chapter meeting is worth the money and effort, I would argue that it is crucial to our future to do so. As surgical practice becomes more specialized and “siloed,” it is critical that we reaffirm what unites us rather than focus on what separates us. It is easy to attribute ill motives and malevolent characteristics to someone who sees things differently than you do. Is much more difficult to do so when you spend time with that person and learn about him or her as an individual. Local ACS chapter meetings accomplish that and more. Older surgeons nearing retirement and worried about the future of their communities can meet and mingle with residents and fellows who might become future partners. Former colleagues from medical school or residency who have pursued different practice paths can reacquaint themselves with one another, relive the good (and perhaps bad) old times, and share a chuckle or two. Surgeons who practice in the “ivory tower” can gain appreciation for the challenges of practicing in a resource-limited facility. Those from competing institutions or practices can learn that the “other” is facing the same issues and that common strategies for success might be found. We can all gain a greater understanding that the other person’s problems aren’t that different or less complex than ours.

In addition to providing a stimulating program, a successful chapter meeting requires skillful planning and execution by an experienced chapter manager. Our Oregon chapter is fortunate to have Harvey Gail, an outstanding manager who takes care of those essential tasks that make the meeting run smoothly so that we can focus on the substance of the meeting itself.

Attending a chapter meeting requires a relatively short time commitment of three days away from home – including a weekend – and a tank of gas. Some have suggested that holding the meeting in the largest city in the region would lessen travel time demands for many, but doing so would mean losing the low-key setting that creates the perfect atmosphere for developing professional and personal relationships and building a true community. The future survival of our profession depends on finding better, novel solutions to our common problems; we can accomplish that only by sharing our diverse perspectives and identifying solutions that meet all of our needs and those of our patients.

To those of you who rarely (or never) have attended a chapter meeting, you need to go. You’ll be surprised at how much you can learn from your fellow surgeons, who, I guarantee, are more like you than they are different.

Dr. Deveney is a professor of surgery and the vice chair of education in the department of surgery at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. She is the coeditor of ACS Surgery News.

Members in the news

Stephanie J. Drew, DMD, FACS, was elected president of the American College of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (ACOMS) at its Annual Scientific Conference in April. She is the 26th president of ACOMS and the first woman elected to the position.

Dr. Drew, associate professor of surgery, division of oral and maxillofacial surgery, department of surgery, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, has been at the forefront of using computer planning technology to help treat patients, as well as to teach residents and practicing physicians. Her goal as ACOMS president is to bring the latest technological advances in surgical education to the members of the organization. Dr. Drew has been actively involved in the committees of ACOMS and served as the chairperson of their Committee on Continuing Education for two years. She also co-chaired the organization’s Annual Scientific Conference in 2016.

ACOMS immediate past-president R. Bryan Bell, MD, DDS, FACS, said that in selecting Dr. Drew, “We have chosen a proven leader who exemplifies the surgical excellence, academic citizenship, and collegiality ACOMS emphasizes.”

Read more about Dr. Drew at bit.ly/2KBppvK.

The board of directors of the Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), Portland, has unanimously elected Danny Jacobs, MD, MPH, FACS, as the next president of the university. Dr. Jacobs, presently executive vice-president, provost, and dean of the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) School of Medicine, Galveston, will begin his presidency at OHSU August 1. He will be OHSU’s fifth president.

“I believe strongly in the values rooted in public academic health centers like OHSU. I believe in OHSU’s mission to serve all Oregonians and its strong commitment to innovation and adaptation to meet the needs of the community,” Dr. Jacobs said.

At UTMB, Dr. Jacobs is the chief academic officer, responsible for approximately 3,800 employees and trainees for its schools of Medicine, Nursing, Health Professions, and Biomedical Sciences. Dr. Jacobs’ faculty appointments at UTMB include professorships in the Institute for Translational Sciences, as well as the department of surgery and the department of preventive medicine and community health. He also oversees the institution’s research programs.

Read more about Dr. Jacobs at bit.ly/2rxGqyX.

Giuliano Testa, MD, FACS, was recently recognized on the annual TIME 100 list, which honors the most influential people of 2018, for his role in a groundbreaking uterine transplant clinical trial. A woman receiving the transplant gave birth to the first baby born via uterus transplant in the U.S.

Dr. Testa is the surgical director of living donor liver transplantation at Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, TX, where he specializes in living donor liver transplantation for both adult and pediatric patients. In 2016, Dr. Testa and a team of experts at Baylor successfully performed the uterus transplant, which has only been attempted by a handful of teams in the world.

The patient, who was born without a uterus, gave birth to a baby boy in November 2017. Hers was the first functioning transplanted uterus in the U.S. Although she chose to remain anonymous, the woman wrote on TIME’s website (ti.me/2LcZBXE) that Dr. Testa was “a pillar of strength and assurance” during her experience. “It has been the honor of my life to be a small part of his miracle.”

Stephanie J. Drew, DMD, FACS, was elected president of the American College of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (ACOMS) at its Annual Scientific Conference in April. She is the 26th president of ACOMS and the first woman elected to the position.

Dr. Drew, associate professor of surgery, division of oral and maxillofacial surgery, department of surgery, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, has been at the forefront of using computer planning technology to help treat patients, as well as to teach residents and practicing physicians. Her goal as ACOMS president is to bring the latest technological advances in surgical education to the members of the organization. Dr. Drew has been actively involved in the committees of ACOMS and served as the chairperson of their Committee on Continuing Education for two years. She also co-chaired the organization’s Annual Scientific Conference in 2016.

ACOMS immediate past-president R. Bryan Bell, MD, DDS, FACS, said that in selecting Dr. Drew, “We have chosen a proven leader who exemplifies the surgical excellence, academic citizenship, and collegiality ACOMS emphasizes.”

Read more about Dr. Drew at bit.ly/2KBppvK.

The board of directors of the Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), Portland, has unanimously elected Danny Jacobs, MD, MPH, FACS, as the next president of the university. Dr. Jacobs, presently executive vice-president, provost, and dean of the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) School of Medicine, Galveston, will begin his presidency at OHSU August 1. He will be OHSU’s fifth president.

“I believe strongly in the values rooted in public academic health centers like OHSU. I believe in OHSU’s mission to serve all Oregonians and its strong commitment to innovation and adaptation to meet the needs of the community,” Dr. Jacobs said.

At UTMB, Dr. Jacobs is the chief academic officer, responsible for approximately 3,800 employees and trainees for its schools of Medicine, Nursing, Health Professions, and Biomedical Sciences. Dr. Jacobs’ faculty appointments at UTMB include professorships in the Institute for Translational Sciences, as well as the department of surgery and the department of preventive medicine and community health. He also oversees the institution’s research programs.

Read more about Dr. Jacobs at bit.ly/2rxGqyX.

Giuliano Testa, MD, FACS, was recently recognized on the annual TIME 100 list, which honors the most influential people of 2018, for his role in a groundbreaking uterine transplant clinical trial. A woman receiving the transplant gave birth to the first baby born via uterus transplant in the U.S.

Dr. Testa is the surgical director of living donor liver transplantation at Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, TX, where he specializes in living donor liver transplantation for both adult and pediatric patients. In 2016, Dr. Testa and a team of experts at Baylor successfully performed the uterus transplant, which has only been attempted by a handful of teams in the world.

The patient, who was born without a uterus, gave birth to a baby boy in November 2017. Hers was the first functioning transplanted uterus in the U.S. Although she chose to remain anonymous, the woman wrote on TIME’s website (ti.me/2LcZBXE) that Dr. Testa was “a pillar of strength and assurance” during her experience. “It has been the honor of my life to be a small part of his miracle.”

Stephanie J. Drew, DMD, FACS, was elected president of the American College of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (ACOMS) at its Annual Scientific Conference in April. She is the 26th president of ACOMS and the first woman elected to the position.

Dr. Drew, associate professor of surgery, division of oral and maxillofacial surgery, department of surgery, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, has been at the forefront of using computer planning technology to help treat patients, as well as to teach residents and practicing physicians. Her goal as ACOMS president is to bring the latest technological advances in surgical education to the members of the organization. Dr. Drew has been actively involved in the committees of ACOMS and served as the chairperson of their Committee on Continuing Education for two years. She also co-chaired the organization’s Annual Scientific Conference in 2016.

ACOMS immediate past-president R. Bryan Bell, MD, DDS, FACS, said that in selecting Dr. Drew, “We have chosen a proven leader who exemplifies the surgical excellence, academic citizenship, and collegiality ACOMS emphasizes.”

Read more about Dr. Drew at bit.ly/2KBppvK.

The board of directors of the Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), Portland, has unanimously elected Danny Jacobs, MD, MPH, FACS, as the next president of the university. Dr. Jacobs, presently executive vice-president, provost, and dean of the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) School of Medicine, Galveston, will begin his presidency at OHSU August 1. He will be OHSU’s fifth president.

“I believe strongly in the values rooted in public academic health centers like OHSU. I believe in OHSU’s mission to serve all Oregonians and its strong commitment to innovation and adaptation to meet the needs of the community,” Dr. Jacobs said.

At UTMB, Dr. Jacobs is the chief academic officer, responsible for approximately 3,800 employees and trainees for its schools of Medicine, Nursing, Health Professions, and Biomedical Sciences. Dr. Jacobs’ faculty appointments at UTMB include professorships in the Institute for Translational Sciences, as well as the department of surgery and the department of preventive medicine and community health. He also oversees the institution’s research programs.

Read more about Dr. Jacobs at bit.ly/2rxGqyX.

Giuliano Testa, MD, FACS, was recently recognized on the annual TIME 100 list, which honors the most influential people of 2018, for his role in a groundbreaking uterine transplant clinical trial. A woman receiving the transplant gave birth to the first baby born via uterus transplant in the U.S.

Dr. Testa is the surgical director of living donor liver transplantation at Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, TX, where he specializes in living donor liver transplantation for both adult and pediatric patients. In 2016, Dr. Testa and a team of experts at Baylor successfully performed the uterus transplant, which has only been attempted by a handful of teams in the world.

The patient, who was born without a uterus, gave birth to a baby boy in November 2017. Hers was the first functioning transplanted uterus in the U.S. Although she chose to remain anonymous, the woman wrote on TIME’s website (ti.me/2LcZBXE) that Dr. Testa was “a pillar of strength and assurance” during her experience. “It has been the honor of my life to be a small part of his miracle.”

Information every surgeon should know about the ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC

Measuring success when it comes to political action, particularly in the current climate, can be challenging. Just as the American College of Surgeons (ACS) strives to represent all of surgery and focuses on an extensive list of priorities, the American College of Surgeons Professional Association Political Action Committee (ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC) works to maintain relationships with numerous lawmakers to ensure the College’s advocacy and health policy agenda remains at the forefront.

Leading up to the November midterm elections, every surgeon should be familiar with some basic facts about ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC fundraising and disbursement efforts.

Fundraising and disbursements

Fundraising is on par with the 2016 election cycle, a record year for “hard” dollars, or personal funds used to support candidates. SurgeonsPAC supports both Democrat and Republican candidates running in U.S. House and Senate races across the nation. SurgeonsPAC has a track record of balanced giving, contributing to candidates and incumbents of both parties who are willing to champion issues of importance to surgeons and surgical patients. All 2017‒2018 election cycle disbursements can be viewed at www.surgeonspac.org/disbursements. Legally, SurgeonsPAC cannot earmark contributions for a particular candidate or based on a single issue.

From January 1, 2017, through May 31, 2018, the ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC reported more than $805,000 in receipts from more than 1,500 College members and staff, and disbursed more than $558,900 to more than 115 congressional candidates, leadership PACs, and political campaign committees. Of the amount given, in line with congressional party ratios, 59 percent was given to Republicans and 41 percent to Democrats.

In addition to raising funds to elect and reelect congressional candidates, SurgeonsPAC hosted several health care industry events in the ACS Washington Office for key members of Congress and political campaign committees, collaborated with other medical community PACs to host fundraising events and physician candidate meet and greets, participated in party committee briefings and additional engagement opportunities, and increased in-district check deliveries and targeted donor events.

To learn more about SurgeonsPAC fundraising or disbursements, visit SurgeonsPAC.org (login required using facs.org username and password) or contact Katie Oehmen, Manager, ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC and Grassroots at 202-672-1503 or [email protected]. For more information about the College’s legislative priorities, visit SurgeonsVoice.org.

Contributions to ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC are not deductible as charitable contributions for federal income tax purposes. Contributions are voluntary, and all members of ACSPA have the right to refuse to contribute without reprisal. Federal law prohibits ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC from accepting contributions from foreign nations. By law, if your contributions are made using a personal check or credit card, ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC may only use your contribution to support candidates in federal elections. All corporate contributions to ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC will be used for educational and administrative fees of ACSPA and other activities permissible under federal law. Federal law requires ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC to use its best efforts to collect and report the name, mailing address, occupation, and the name of the employer of individuals whose contributions exceed $200 in a calendar year. ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC is a program of the ACSPA, which is exempt from federal income tax under section 501c (6) of the Internal Revenue Code.

Measuring success when it comes to political action, particularly in the current climate, can be challenging. Just as the American College of Surgeons (ACS) strives to represent all of surgery and focuses on an extensive list of priorities, the American College of Surgeons Professional Association Political Action Committee (ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC) works to maintain relationships with numerous lawmakers to ensure the College’s advocacy and health policy agenda remains at the forefront.

Leading up to the November midterm elections, every surgeon should be familiar with some basic facts about ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC fundraising and disbursement efforts.

Fundraising and disbursements

Fundraising is on par with the 2016 election cycle, a record year for “hard” dollars, or personal funds used to support candidates. SurgeonsPAC supports both Democrat and Republican candidates running in U.S. House and Senate races across the nation. SurgeonsPAC has a track record of balanced giving, contributing to candidates and incumbents of both parties who are willing to champion issues of importance to surgeons and surgical patients. All 2017‒2018 election cycle disbursements can be viewed at www.surgeonspac.org/disbursements. Legally, SurgeonsPAC cannot earmark contributions for a particular candidate or based on a single issue.

From January 1, 2017, through May 31, 2018, the ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC reported more than $805,000 in receipts from more than 1,500 College members and staff, and disbursed more than $558,900 to more than 115 congressional candidates, leadership PACs, and political campaign committees. Of the amount given, in line with congressional party ratios, 59 percent was given to Republicans and 41 percent to Democrats.

In addition to raising funds to elect and reelect congressional candidates, SurgeonsPAC hosted several health care industry events in the ACS Washington Office for key members of Congress and political campaign committees, collaborated with other medical community PACs to host fundraising events and physician candidate meet and greets, participated in party committee briefings and additional engagement opportunities, and increased in-district check deliveries and targeted donor events.

To learn more about SurgeonsPAC fundraising or disbursements, visit SurgeonsPAC.org (login required using facs.org username and password) or contact Katie Oehmen, Manager, ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC and Grassroots at 202-672-1503 or [email protected]. For more information about the College’s legislative priorities, visit SurgeonsVoice.org.

Contributions to ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC are not deductible as charitable contributions for federal income tax purposes. Contributions are voluntary, and all members of ACSPA have the right to refuse to contribute without reprisal. Federal law prohibits ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC from accepting contributions from foreign nations. By law, if your contributions are made using a personal check or credit card, ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC may only use your contribution to support candidates in federal elections. All corporate contributions to ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC will be used for educational and administrative fees of ACSPA and other activities permissible under federal law. Federal law requires ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC to use its best efforts to collect and report the name, mailing address, occupation, and the name of the employer of individuals whose contributions exceed $200 in a calendar year. ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC is a program of the ACSPA, which is exempt from federal income tax under section 501c (6) of the Internal Revenue Code.

Measuring success when it comes to political action, particularly in the current climate, can be challenging. Just as the American College of Surgeons (ACS) strives to represent all of surgery and focuses on an extensive list of priorities, the American College of Surgeons Professional Association Political Action Committee (ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC) works to maintain relationships with numerous lawmakers to ensure the College’s advocacy and health policy agenda remains at the forefront.

Leading up to the November midterm elections, every surgeon should be familiar with some basic facts about ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC fundraising and disbursement efforts.

Fundraising and disbursements

Fundraising is on par with the 2016 election cycle, a record year for “hard” dollars, or personal funds used to support candidates. SurgeonsPAC supports both Democrat and Republican candidates running in U.S. House and Senate races across the nation. SurgeonsPAC has a track record of balanced giving, contributing to candidates and incumbents of both parties who are willing to champion issues of importance to surgeons and surgical patients. All 2017‒2018 election cycle disbursements can be viewed at www.surgeonspac.org/disbursements. Legally, SurgeonsPAC cannot earmark contributions for a particular candidate or based on a single issue.

From January 1, 2017, through May 31, 2018, the ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC reported more than $805,000 in receipts from more than 1,500 College members and staff, and disbursed more than $558,900 to more than 115 congressional candidates, leadership PACs, and political campaign committees. Of the amount given, in line with congressional party ratios, 59 percent was given to Republicans and 41 percent to Democrats.

In addition to raising funds to elect and reelect congressional candidates, SurgeonsPAC hosted several health care industry events in the ACS Washington Office for key members of Congress and political campaign committees, collaborated with other medical community PACs to host fundraising events and physician candidate meet and greets, participated in party committee briefings and additional engagement opportunities, and increased in-district check deliveries and targeted donor events.

To learn more about SurgeonsPAC fundraising or disbursements, visit SurgeonsPAC.org (login required using facs.org username and password) or contact Katie Oehmen, Manager, ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC and Grassroots at 202-672-1503 or [email protected]. For more information about the College’s legislative priorities, visit SurgeonsVoice.org.

Contributions to ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC are not deductible as charitable contributions for federal income tax purposes. Contributions are voluntary, and all members of ACSPA have the right to refuse to contribute without reprisal. Federal law prohibits ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC from accepting contributions from foreign nations. By law, if your contributions are made using a personal check or credit card, ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC may only use your contribution to support candidates in federal elections. All corporate contributions to ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC will be used for educational and administrative fees of ACSPA and other activities permissible under federal law. Federal law requires ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC to use its best efforts to collect and report the name, mailing address, occupation, and the name of the employer of individuals whose contributions exceed $200 in a calendar year. ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC is a program of the ACSPA, which is exempt from federal income tax under section 501c (6) of the Internal Revenue Code.

Register for ACS Comprehensive General Surgery Review Course, July 26–29

The 2018 American College of Surgeons (ACS) Comprehensive General Surgery Review Course, July 26–29 in Chicago, IL, is an intensive three-and-a-half-day review course that will cover essential content areas in general surgery, including alimentary tract, endocrine and soft tissue, oncology, skin and breast, surgical critical care, trauma, and vascular operations, as well as perioperative care.

Course Chair John A. Weigelt, MD, DVM, MMA, FACS, and a distinguished faculty will use didactic and case-based formats to present a comprehensive and practical review. Dr. Weigelt recently retired from the Medical College of Wisconsin, where he was the Milt & Lidy Lunda/Charles Aprahamian Professor of Trauma Surgery, as well as professor and chief, division of trauma and critical care. He is joining the University of South Dakota and the Sanford Health System, Sioux Falls, this summer as professor of surgery. Dr. Weigelt is Medical Director of the ACS Surgical Education and Self-Assessment Program (also known as SESAP®).

The course offers a pragmatic review designed to focus on practice issues and will offer several special features, such as self-assessment materials, including pre- and posttests. It may be helpful in preparing for examinations. Self-assessment credit will be available.

The ACS is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) to provide Continuing Medical Education for physicians.

The ACS designates this live activity for a maximum of 28 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Register today at bit.ly/2s19VtX. Space is limited and registration will be accepted on a first-come, first-served basis. For more information and registration, visit the Comprehensive General Surgery Review Course web page at facs.org/gsreviewcourse or e-mail [email protected] or [email protected].

The 2018 American College of Surgeons (ACS) Comprehensive General Surgery Review Course, July 26–29 in Chicago, IL, is an intensive three-and-a-half-day review course that will cover essential content areas in general surgery, including alimentary tract, endocrine and soft tissue, oncology, skin and breast, surgical critical care, trauma, and vascular operations, as well as perioperative care.

Course Chair John A. Weigelt, MD, DVM, MMA, FACS, and a distinguished faculty will use didactic and case-based formats to present a comprehensive and practical review. Dr. Weigelt recently retired from the Medical College of Wisconsin, where he was the Milt & Lidy Lunda/Charles Aprahamian Professor of Trauma Surgery, as well as professor and chief, division of trauma and critical care. He is joining the University of South Dakota and the Sanford Health System, Sioux Falls, this summer as professor of surgery. Dr. Weigelt is Medical Director of the ACS Surgical Education and Self-Assessment Program (also known as SESAP®).

The course offers a pragmatic review designed to focus on practice issues and will offer several special features, such as self-assessment materials, including pre- and posttests. It may be helpful in preparing for examinations. Self-assessment credit will be available.

The ACS is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) to provide Continuing Medical Education for physicians.

The ACS designates this live activity for a maximum of 28 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Register today at bit.ly/2s19VtX. Space is limited and registration will be accepted on a first-come, first-served basis. For more information and registration, visit the Comprehensive General Surgery Review Course web page at facs.org/gsreviewcourse or e-mail [email protected] or [email protected].

The 2018 American College of Surgeons (ACS) Comprehensive General Surgery Review Course, July 26–29 in Chicago, IL, is an intensive three-and-a-half-day review course that will cover essential content areas in general surgery, including alimentary tract, endocrine and soft tissue, oncology, skin and breast, surgical critical care, trauma, and vascular operations, as well as perioperative care.

Course Chair John A. Weigelt, MD, DVM, MMA, FACS, and a distinguished faculty will use didactic and case-based formats to present a comprehensive and practical review. Dr. Weigelt recently retired from the Medical College of Wisconsin, where he was the Milt & Lidy Lunda/Charles Aprahamian Professor of Trauma Surgery, as well as professor and chief, division of trauma and critical care. He is joining the University of South Dakota and the Sanford Health System, Sioux Falls, this summer as professor of surgery. Dr. Weigelt is Medical Director of the ACS Surgical Education and Self-Assessment Program (also known as SESAP®).

The course offers a pragmatic review designed to focus on practice issues and will offer several special features, such as self-assessment materials, including pre- and posttests. It may be helpful in preparing for examinations. Self-assessment credit will be available.

The ACS is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) to provide Continuing Medical Education for physicians.

The ACS designates this live activity for a maximum of 28 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Register today at bit.ly/2s19VtX. Space is limited and registration will be accepted on a first-come, first-served basis. For more information and registration, visit the Comprehensive General Surgery Review Course web page at facs.org/gsreviewcourse or e-mail [email protected] or [email protected].

NAPRC awards first accreditation to John Muir Health Rectal Cancer Program

The National Accreditation Program for Rectal Cancer (NAPRC), which the American College of Surgeons (ACS) launched in 2017, has awarded its first accreditation to the John Muir Health Rectal Cancer Program, Walnut Creek and Concord, CA. To earn the voluntary accreditation, the John Muir Health Rectal Cancer Program met 19 standards, including the establishment of a rectal cancer multidisciplin

Thirteen of those standards address clinical services that the program was required to provide, including carcinoembryonic antigen testing, magnetic resonance imagining, and computed tomography imaging for cancer staging, and ensuring a process whereby the patient starts treatment within a defined time frame. One of the most important clinical standards requires all rectal cancer patients to be present at both pre- and post-treatment RC-MDT meetings.

“When a cancer center achieves this type of specialized accreditation, it means that their rectal cancer patients will receive streamlined, modern evaluation and treatment for the disease. Compliance with our standards will assure optimal care for these patients,” said David P. Winchester, MD, FACS, Medical Director, ACS Cancer Programs.

“We have come a long way in the treatment of rectal cancer, but it remains a very complex disease that can be challenging to treat,” said Samuel Oommen, MD, FACS, a colorectal surgeon and medical director of the gastrointestinal oncology program at John Muir Health.

“This accreditation demonstrates to patients that we have an innovative program that is at the forefront of rectal cancer care by following rigorous standards and best practices. Achieving this designation is a recognition of the work done by a dedicated multidisciplinary team providing high quality, patient-centered care to provide superior oncological outcomes while preserving quality of life,” Dr. Oommen said.

The NAPRC was developed through a collaboration between the Optimizing the Surgical Treatment of Rectal Cancer Consortium and the ACS Commission on Cancer. It is based on successful international models that emphasize program structure, patient care processes, performance improvement, and performance measures. Its goal is to ensure that rectal cancer patients receive appropriate care using a multidisciplinary approach.

For more information about the program and instructions on how to apply for accreditation, visit the NAPRC website at facs.org/naprc, or contact [email protected].