User login

Credit cards FAQ

After my last column on credit cards, I was (as usual) inundated with questions, comments, and requests for copies of the letter we give to patients explaining our credit card policy.

at www.mdedge.com/edermatologynews. If you have a question not addressed here, feel free to ask, either on the website or via email ([email protected]).

How do you safeguard the credit information you keep on file?

The same way we do medical information; it’s all covered by the same HIPAA rules. If you have an EHR, it can go in the chart with everything else; if not, I suggest a separate portable file that can be locked up each night.

How do you keep the info current, as cards do expire?

We check expiration dates at each visit, and ask for a new number or date if the card has expired or is close.

Don’t your patients object to signing, in effect, a blank check?

They’re not “signing a blank check.” All credit card contracts give cardholders the right to challenge any charge against their account.

There were some initial objections, mostly from devotees of the financial “old school.” But when we explain that we’re doing nothing different than a hotel does at each check-in, and that it will work to their advantage as well, by decreasing the bills they will receive and the checks they must write, most come around.

How do you handle patients who refuse to hand over a number, particularly those who say they have no credit cards?

We used to let refusers slide, but now we’ve made the policy mandatory. Patients who refuse without a good reason are asked, like any patient who refuses to cooperate with any standard office policy, to go elsewhere. Life’s too short. And “I don’t have any credit cards” does not count as a good reason. Nearly everyone has credit cards in this day and age. For the occasional patient who does not have a credit card, my office manager does have authority to make exceptions on a case-by-case basis, however.

One cosmetic surgeon I know asks “no credit card” patients to pay a lawyer-style “retainer,” which is held in escrow, and used to pay receivable amounts as they come due. When presented with that alternative, he told me, most of them suddenly remember that they do have a credit card after all.

What’s the difference between this and “balance billing”?

All the difference in the world. “Balance billing” is billing patients for the difference between your normal fee and the insurer’s authorized payment. If your office has contracted to accept that particular insurance, you can’t do that; but you can bill for the portion of the insurer-determined payment not paid by the insurer. (Many contracts stipulate that you must do so.) For example, your normal fee is $200; the insurer approves $100, and pays 80% of that. The other $20 is the patient’s responsibility, and that is what you charge to the credit card – instead of sending out a statement for that amount.

Since we instituted this policy, one patient has called to ask if it is legal, and one insurance company has inquired about it. How do you respond to such queries?

Of course it’s legal; you are entitled to collect what is owed to you. Ask those patients if they question the legality every time they check into a hotel or rent a car.

We have had no inquiries from insurers, but my response would be that it’s none of their business. Again, you have every right to bill for the patient-owed portion of your fees – in fact, Medicare and many private insurers consider it an illegal “inducement” if you don’t – and third parties have no right to dictate how you can or cannot collect it.

In the past, another popular practice management columnist advised against adopting this policy.

Despite multiple requests from me and others, that columnist – who owns a medical billing company – has never, to my knowledge, offered a single convincing argument in support of that position.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

After my last column on credit cards, I was (as usual) inundated with questions, comments, and requests for copies of the letter we give to patients explaining our credit card policy.

at www.mdedge.com/edermatologynews. If you have a question not addressed here, feel free to ask, either on the website or via email ([email protected]).

How do you safeguard the credit information you keep on file?

The same way we do medical information; it’s all covered by the same HIPAA rules. If you have an EHR, it can go in the chart with everything else; if not, I suggest a separate portable file that can be locked up each night.

How do you keep the info current, as cards do expire?

We check expiration dates at each visit, and ask for a new number or date if the card has expired or is close.

Don’t your patients object to signing, in effect, a blank check?

They’re not “signing a blank check.” All credit card contracts give cardholders the right to challenge any charge against their account.

There were some initial objections, mostly from devotees of the financial “old school.” But when we explain that we’re doing nothing different than a hotel does at each check-in, and that it will work to their advantage as well, by decreasing the bills they will receive and the checks they must write, most come around.

How do you handle patients who refuse to hand over a number, particularly those who say they have no credit cards?

We used to let refusers slide, but now we’ve made the policy mandatory. Patients who refuse without a good reason are asked, like any patient who refuses to cooperate with any standard office policy, to go elsewhere. Life’s too short. And “I don’t have any credit cards” does not count as a good reason. Nearly everyone has credit cards in this day and age. For the occasional patient who does not have a credit card, my office manager does have authority to make exceptions on a case-by-case basis, however.

One cosmetic surgeon I know asks “no credit card” patients to pay a lawyer-style “retainer,” which is held in escrow, and used to pay receivable amounts as they come due. When presented with that alternative, he told me, most of them suddenly remember that they do have a credit card after all.

What’s the difference between this and “balance billing”?

All the difference in the world. “Balance billing” is billing patients for the difference between your normal fee and the insurer’s authorized payment. If your office has contracted to accept that particular insurance, you can’t do that; but you can bill for the portion of the insurer-determined payment not paid by the insurer. (Many contracts stipulate that you must do so.) For example, your normal fee is $200; the insurer approves $100, and pays 80% of that. The other $20 is the patient’s responsibility, and that is what you charge to the credit card – instead of sending out a statement for that amount.

Since we instituted this policy, one patient has called to ask if it is legal, and one insurance company has inquired about it. How do you respond to such queries?

Of course it’s legal; you are entitled to collect what is owed to you. Ask those patients if they question the legality every time they check into a hotel or rent a car.

We have had no inquiries from insurers, but my response would be that it’s none of their business. Again, you have every right to bill for the patient-owed portion of your fees – in fact, Medicare and many private insurers consider it an illegal “inducement” if you don’t – and third parties have no right to dictate how you can or cannot collect it.

In the past, another popular practice management columnist advised against adopting this policy.

Despite multiple requests from me and others, that columnist – who owns a medical billing company – has never, to my knowledge, offered a single convincing argument in support of that position.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

After my last column on credit cards, I was (as usual) inundated with questions, comments, and requests for copies of the letter we give to patients explaining our credit card policy.

at www.mdedge.com/edermatologynews. If you have a question not addressed here, feel free to ask, either on the website or via email ([email protected]).

How do you safeguard the credit information you keep on file?

The same way we do medical information; it’s all covered by the same HIPAA rules. If you have an EHR, it can go in the chart with everything else; if not, I suggest a separate portable file that can be locked up each night.

How do you keep the info current, as cards do expire?

We check expiration dates at each visit, and ask for a new number or date if the card has expired or is close.

Don’t your patients object to signing, in effect, a blank check?

They’re not “signing a blank check.” All credit card contracts give cardholders the right to challenge any charge against their account.

There were some initial objections, mostly from devotees of the financial “old school.” But when we explain that we’re doing nothing different than a hotel does at each check-in, and that it will work to their advantage as well, by decreasing the bills they will receive and the checks they must write, most come around.

How do you handle patients who refuse to hand over a number, particularly those who say they have no credit cards?

We used to let refusers slide, but now we’ve made the policy mandatory. Patients who refuse without a good reason are asked, like any patient who refuses to cooperate with any standard office policy, to go elsewhere. Life’s too short. And “I don’t have any credit cards” does not count as a good reason. Nearly everyone has credit cards in this day and age. For the occasional patient who does not have a credit card, my office manager does have authority to make exceptions on a case-by-case basis, however.

One cosmetic surgeon I know asks “no credit card” patients to pay a lawyer-style “retainer,” which is held in escrow, and used to pay receivable amounts as they come due. When presented with that alternative, he told me, most of them suddenly remember that they do have a credit card after all.

What’s the difference between this and “balance billing”?

All the difference in the world. “Balance billing” is billing patients for the difference between your normal fee and the insurer’s authorized payment. If your office has contracted to accept that particular insurance, you can’t do that; but you can bill for the portion of the insurer-determined payment not paid by the insurer. (Many contracts stipulate that you must do so.) For example, your normal fee is $200; the insurer approves $100, and pays 80% of that. The other $20 is the patient’s responsibility, and that is what you charge to the credit card – instead of sending out a statement for that amount.

Since we instituted this policy, one patient has called to ask if it is legal, and one insurance company has inquired about it. How do you respond to such queries?

Of course it’s legal; you are entitled to collect what is owed to you. Ask those patients if they question the legality every time they check into a hotel or rent a car.

We have had no inquiries from insurers, but my response would be that it’s none of their business. Again, you have every right to bill for the patient-owed portion of your fees – in fact, Medicare and many private insurers consider it an illegal “inducement” if you don’t – and third parties have no right to dictate how you can or cannot collect it.

In the past, another popular practice management columnist advised against adopting this policy.

Despite multiple requests from me and others, that columnist – who owns a medical billing company – has never, to my knowledge, offered a single convincing argument in support of that position.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

Pediatric inpatient seizures treated quickly with new intervention

TORONTO – Researchers at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital in San Francisco implemented a novel intervention that leveraged existing in-room technology to expedite antiepileptic drug administration to inpatients having a seizure.

With the quality initiative, they were able to decrease median time from seizure onset to benzodiazepine (BZD) administration from 7 minutes (preintervention) to 2 minutes (post intervention) and reduce the median time from order to administration of second-phase non-BZDs from 28 minutes to 11 minutes.

“Leveraging existing patient room technology to mobilize pharmacy to the bedside expedited non-BZD administration by 60%,” reported principal investigator Arpi Bekmezian, MD, a pediatric hospitalist and medical director of quality and safety at Benioff Children’s Hospital. She presented the findings at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

“Furthermore, the rapid-response seizure rescue process may have created an increased sense of urgency helping to expedite initial BZD administration by 70%. ... This may have prevented the need for second-phase therapy and progression to status epilepticus, potentially minimizing the risk of neuronal injury, and all without the additional resources of a Code team.”

Early and rapid escalation of treatment is critical to prevent neuronal injury in patients with status epilepticus. Guidelines recommend initial antiepileptic therapy at 5 minutes, with rapid escalation to second-phase therapy if the seizure persists.

Preintervention baseline data from UCSF Benioff Children’s indicated a 7-minute lag time from seizure onset to BZD therapy and a 28-minute lag from order to administration of non-BZDs (phenobarbital, phenytoin, levetiracetam, valproic acid). Other studies have shown significantly greater delays to antiepileptic treatment.

“That was just too long, and it matched our clinical experience of being at the bedside of a seizing patient and wondering why the medication was taking so long to arrive from the pharmacy.”

The researchers set out to reduce time to BZD administration from 7 minutes to 5 minutes or less and to reduce time to second-phase non-BZD administration to less than 10 minutes. To accomplish this, a multidisciplinary team that included leadership from physicians, pharmacy, and nursing defined primary and secondary drivers of efficiency, with interventions targeting both team communication and medication delivery.

The intervention period lasted 16 months, during which time there were 61 seizure events requiring urgent antiepileptic treatment. Complete data were available for 57 seizures.

Among the interventions they implemented was to stock all medication-dispensing stations with intranasal/buccal BZD available on “nursing override” for easy access and administration.

Because non-BZDs require pharmacy compounding, and the main pharmacy receives many STAT orders with competing priorities, they developed a hospitalwide “seizure rescue” (SR) process by using patient-room staff terminals to activate a dedicated individual from the pharmacy, who would then report to the bedside with a backpack stocked with non-BZDs ready to compound. Nurses were trained to press the SR button for any seizure that may require urgent therapy.

“We didn’t want nurses to waste time on the phone [calling pharmacy], and we considered calling a Code, but we couldn’t really justify the resource utilization as most of these patients didn’t have respiratory compromise, and they didn’t need the whole Code team,” said Dr. Bekmezian. She noted that her hospital strongly discourages bedside compounding by nursing staff.

Instead, they realized they could easily reprogram the patient-room electronic staff terminals to have a dedicated SR button that would directly alert a dedicated pharmacist carrying the SR phone. The pharmacist could then swipe and confirm that they received the alert and let the nurse know they were on the way, “and this would free up the nurse to go ahead and obtain the benzodiazepines and administer them as pharmacy made their way to the room.”

“To our knowledge, this is the first study to report expediting antiepileptic drug delivery to patients in the hospital,” said Dr. Bekmezian. She noted that less than 50% of cases actually required pharmacist response, “but the pharmacy staff chose to be activated earlier in the management algorithm to avoid delays in treatment.”

UCSF Children’s Hospital San Francisco campus is a 183-bed, tertiary care, teaching children’s hospital that has pediatric, neonatal, and cardiac intensive care units and set-down units. They provide liver, bone marrow, kidney, and cardiac transplantation and have more than 10,000 annual admissions.

The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bekmezian A et al. PAS 2018. Abstract 3545.3.

TORONTO – Researchers at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital in San Francisco implemented a novel intervention that leveraged existing in-room technology to expedite antiepileptic drug administration to inpatients having a seizure.

With the quality initiative, they were able to decrease median time from seizure onset to benzodiazepine (BZD) administration from 7 minutes (preintervention) to 2 minutes (post intervention) and reduce the median time from order to administration of second-phase non-BZDs from 28 minutes to 11 minutes.

“Leveraging existing patient room technology to mobilize pharmacy to the bedside expedited non-BZD administration by 60%,” reported principal investigator Arpi Bekmezian, MD, a pediatric hospitalist and medical director of quality and safety at Benioff Children’s Hospital. She presented the findings at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

“Furthermore, the rapid-response seizure rescue process may have created an increased sense of urgency helping to expedite initial BZD administration by 70%. ... This may have prevented the need for second-phase therapy and progression to status epilepticus, potentially minimizing the risk of neuronal injury, and all without the additional resources of a Code team.”

Early and rapid escalation of treatment is critical to prevent neuronal injury in patients with status epilepticus. Guidelines recommend initial antiepileptic therapy at 5 minutes, with rapid escalation to second-phase therapy if the seizure persists.

Preintervention baseline data from UCSF Benioff Children’s indicated a 7-minute lag time from seizure onset to BZD therapy and a 28-minute lag from order to administration of non-BZDs (phenobarbital, phenytoin, levetiracetam, valproic acid). Other studies have shown significantly greater delays to antiepileptic treatment.

“That was just too long, and it matched our clinical experience of being at the bedside of a seizing patient and wondering why the medication was taking so long to arrive from the pharmacy.”

The researchers set out to reduce time to BZD administration from 7 minutes to 5 minutes or less and to reduce time to second-phase non-BZD administration to less than 10 minutes. To accomplish this, a multidisciplinary team that included leadership from physicians, pharmacy, and nursing defined primary and secondary drivers of efficiency, with interventions targeting both team communication and medication delivery.

The intervention period lasted 16 months, during which time there were 61 seizure events requiring urgent antiepileptic treatment. Complete data were available for 57 seizures.

Among the interventions they implemented was to stock all medication-dispensing stations with intranasal/buccal BZD available on “nursing override” for easy access and administration.

Because non-BZDs require pharmacy compounding, and the main pharmacy receives many STAT orders with competing priorities, they developed a hospitalwide “seizure rescue” (SR) process by using patient-room staff terminals to activate a dedicated individual from the pharmacy, who would then report to the bedside with a backpack stocked with non-BZDs ready to compound. Nurses were trained to press the SR button for any seizure that may require urgent therapy.

“We didn’t want nurses to waste time on the phone [calling pharmacy], and we considered calling a Code, but we couldn’t really justify the resource utilization as most of these patients didn’t have respiratory compromise, and they didn’t need the whole Code team,” said Dr. Bekmezian. She noted that her hospital strongly discourages bedside compounding by nursing staff.

Instead, they realized they could easily reprogram the patient-room electronic staff terminals to have a dedicated SR button that would directly alert a dedicated pharmacist carrying the SR phone. The pharmacist could then swipe and confirm that they received the alert and let the nurse know they were on the way, “and this would free up the nurse to go ahead and obtain the benzodiazepines and administer them as pharmacy made their way to the room.”

“To our knowledge, this is the first study to report expediting antiepileptic drug delivery to patients in the hospital,” said Dr. Bekmezian. She noted that less than 50% of cases actually required pharmacist response, “but the pharmacy staff chose to be activated earlier in the management algorithm to avoid delays in treatment.”

UCSF Children’s Hospital San Francisco campus is a 183-bed, tertiary care, teaching children’s hospital that has pediatric, neonatal, and cardiac intensive care units and set-down units. They provide liver, bone marrow, kidney, and cardiac transplantation and have more than 10,000 annual admissions.

The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bekmezian A et al. PAS 2018. Abstract 3545.3.

TORONTO – Researchers at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital in San Francisco implemented a novel intervention that leveraged existing in-room technology to expedite antiepileptic drug administration to inpatients having a seizure.

With the quality initiative, they were able to decrease median time from seizure onset to benzodiazepine (BZD) administration from 7 minutes (preintervention) to 2 minutes (post intervention) and reduce the median time from order to administration of second-phase non-BZDs from 28 minutes to 11 minutes.

“Leveraging existing patient room technology to mobilize pharmacy to the bedside expedited non-BZD administration by 60%,” reported principal investigator Arpi Bekmezian, MD, a pediatric hospitalist and medical director of quality and safety at Benioff Children’s Hospital. She presented the findings at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

“Furthermore, the rapid-response seizure rescue process may have created an increased sense of urgency helping to expedite initial BZD administration by 70%. ... This may have prevented the need for second-phase therapy and progression to status epilepticus, potentially minimizing the risk of neuronal injury, and all without the additional resources of a Code team.”

Early and rapid escalation of treatment is critical to prevent neuronal injury in patients with status epilepticus. Guidelines recommend initial antiepileptic therapy at 5 minutes, with rapid escalation to second-phase therapy if the seizure persists.

Preintervention baseline data from UCSF Benioff Children’s indicated a 7-minute lag time from seizure onset to BZD therapy and a 28-minute lag from order to administration of non-BZDs (phenobarbital, phenytoin, levetiracetam, valproic acid). Other studies have shown significantly greater delays to antiepileptic treatment.

“That was just too long, and it matched our clinical experience of being at the bedside of a seizing patient and wondering why the medication was taking so long to arrive from the pharmacy.”

The researchers set out to reduce time to BZD administration from 7 minutes to 5 minutes or less and to reduce time to second-phase non-BZD administration to less than 10 minutes. To accomplish this, a multidisciplinary team that included leadership from physicians, pharmacy, and nursing defined primary and secondary drivers of efficiency, with interventions targeting both team communication and medication delivery.

The intervention period lasted 16 months, during which time there were 61 seizure events requiring urgent antiepileptic treatment. Complete data were available for 57 seizures.

Among the interventions they implemented was to stock all medication-dispensing stations with intranasal/buccal BZD available on “nursing override” for easy access and administration.

Because non-BZDs require pharmacy compounding, and the main pharmacy receives many STAT orders with competing priorities, they developed a hospitalwide “seizure rescue” (SR) process by using patient-room staff terminals to activate a dedicated individual from the pharmacy, who would then report to the bedside with a backpack stocked with non-BZDs ready to compound. Nurses were trained to press the SR button for any seizure that may require urgent therapy.

“We didn’t want nurses to waste time on the phone [calling pharmacy], and we considered calling a Code, but we couldn’t really justify the resource utilization as most of these patients didn’t have respiratory compromise, and they didn’t need the whole Code team,” said Dr. Bekmezian. She noted that her hospital strongly discourages bedside compounding by nursing staff.

Instead, they realized they could easily reprogram the patient-room electronic staff terminals to have a dedicated SR button that would directly alert a dedicated pharmacist carrying the SR phone. The pharmacist could then swipe and confirm that they received the alert and let the nurse know they were on the way, “and this would free up the nurse to go ahead and obtain the benzodiazepines and administer them as pharmacy made their way to the room.”

“To our knowledge, this is the first study to report expediting antiepileptic drug delivery to patients in the hospital,” said Dr. Bekmezian. She noted that less than 50% of cases actually required pharmacist response, “but the pharmacy staff chose to be activated earlier in the management algorithm to avoid delays in treatment.”

UCSF Children’s Hospital San Francisco campus is a 183-bed, tertiary care, teaching children’s hospital that has pediatric, neonatal, and cardiac intensive care units and set-down units. They provide liver, bone marrow, kidney, and cardiac transplantation and have more than 10,000 annual admissions.

The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bekmezian A et al. PAS 2018. Abstract 3545.3.

AT PAS 2018

Key clinical point: An intervention to speed delivery of antiepileptic drugs significantly reduced time to treatment.

Major finding: Median time from seizure onset to benzodiazepine (BZD) administration fell from 7 minutes preintervention to 2 minutes post intervention, and median time from order to administration of non-BZDs dropped from 28 minutes to 11 minutes.

Study details: A prospective, multicenter study of 57 seizure events during a 16-month period.

Disclosures: The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Bekmezian A et al. PAS 2018. Abstract 3545.3.

CDC releases website for ME/CFS information

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has released a website for health care providers about myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).

The website is designed to help clinicians by offering information about how they can better assess and help their patients manage the illness. The website includes information about the presentation and clinical course of ME/CFS, diagnosis, clinical care, understanding historical case definitions and criteria, and free continuing education.

The website’s resource section includes the National Academy of Medicine report published in 2015, as well as primers and clinical practice guidelines.

Currently, it is estimated that 836,000 to 2.5 million Americans have ME/CFS. Roughly 90% of people who have ME/CFS have not been diagnosed.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has released a website for health care providers about myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).

The website is designed to help clinicians by offering information about how they can better assess and help their patients manage the illness. The website includes information about the presentation and clinical course of ME/CFS, diagnosis, clinical care, understanding historical case definitions and criteria, and free continuing education.

The website’s resource section includes the National Academy of Medicine report published in 2015, as well as primers and clinical practice guidelines.

Currently, it is estimated that 836,000 to 2.5 million Americans have ME/CFS. Roughly 90% of people who have ME/CFS have not been diagnosed.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has released a website for health care providers about myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).

The website is designed to help clinicians by offering information about how they can better assess and help their patients manage the illness. The website includes information about the presentation and clinical course of ME/CFS, diagnosis, clinical care, understanding historical case definitions and criteria, and free continuing education.

The website’s resource section includes the National Academy of Medicine report published in 2015, as well as primers and clinical practice guidelines.

Currently, it is estimated that 836,000 to 2.5 million Americans have ME/CFS. Roughly 90% of people who have ME/CFS have not been diagnosed.

FDA grants accelerated approval to ipilimumab/nivolumab combo for CRC

The Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approval to ipilimumab (Yervoy) for the treatment of colorectal cancer (CRC) in patients aged 12 years and older, in combination with nivolumab (Opdivo). Specifically, this indication is for microsatellite instability–high or mismatch repair deficient metastatic CRC that has progressed after treatment with a fluoropyrimidine, oxaliplatin, or irinotecan, the FDA said in a press announcement.

This new use has been added to the nivolumab labeling; nivolumab received an accelerated approval of its own on July 31, 2017, as a single-agent treatment for these kinds of CRCs.

These approvals were based on the overall response rate in the nonrandomized CheckMate 142 trial. In the multiple parallel-cohort, open-label study, 82 patients received 1 mg/kg of IV ipilimumab and 3 mg/kg of IV nivolumab every 3 weeks for four doses, followed by 3 mg/kg of IV nivolumab alone every 2 weeks until either radiographic progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Their overall response rate was 46%, and 89% of those responding had response durations greater than 6 months. These rates were higher than those observed in a separate cohort of 58 patients who received only nivolumab: 28% and 67%, respectively.

The most common adverse events were fatigue, diarrhea, pyrexia, musculoskeletal pain, abdominal pain, pruritus, nausea, rash, dyspnea, decreased appetite, and vomiting.

Full prescribing information for ipilimumab and nivolumab can be found on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approval to ipilimumab (Yervoy) for the treatment of colorectal cancer (CRC) in patients aged 12 years and older, in combination with nivolumab (Opdivo). Specifically, this indication is for microsatellite instability–high or mismatch repair deficient metastatic CRC that has progressed after treatment with a fluoropyrimidine, oxaliplatin, or irinotecan, the FDA said in a press announcement.

This new use has been added to the nivolumab labeling; nivolumab received an accelerated approval of its own on July 31, 2017, as a single-agent treatment for these kinds of CRCs.

These approvals were based on the overall response rate in the nonrandomized CheckMate 142 trial. In the multiple parallel-cohort, open-label study, 82 patients received 1 mg/kg of IV ipilimumab and 3 mg/kg of IV nivolumab every 3 weeks for four doses, followed by 3 mg/kg of IV nivolumab alone every 2 weeks until either radiographic progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Their overall response rate was 46%, and 89% of those responding had response durations greater than 6 months. These rates were higher than those observed in a separate cohort of 58 patients who received only nivolumab: 28% and 67%, respectively.

The most common adverse events were fatigue, diarrhea, pyrexia, musculoskeletal pain, abdominal pain, pruritus, nausea, rash, dyspnea, decreased appetite, and vomiting.

Full prescribing information for ipilimumab and nivolumab can be found on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approval to ipilimumab (Yervoy) for the treatment of colorectal cancer (CRC) in patients aged 12 years and older, in combination with nivolumab (Opdivo). Specifically, this indication is for microsatellite instability–high or mismatch repair deficient metastatic CRC that has progressed after treatment with a fluoropyrimidine, oxaliplatin, or irinotecan, the FDA said in a press announcement.

This new use has been added to the nivolumab labeling; nivolumab received an accelerated approval of its own on July 31, 2017, as a single-agent treatment for these kinds of CRCs.

These approvals were based on the overall response rate in the nonrandomized CheckMate 142 trial. In the multiple parallel-cohort, open-label study, 82 patients received 1 mg/kg of IV ipilimumab and 3 mg/kg of IV nivolumab every 3 weeks for four doses, followed by 3 mg/kg of IV nivolumab alone every 2 weeks until either radiographic progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Their overall response rate was 46%, and 89% of those responding had response durations greater than 6 months. These rates were higher than those observed in a separate cohort of 58 patients who received only nivolumab: 28% and 67%, respectively.

The most common adverse events were fatigue, diarrhea, pyrexia, musculoskeletal pain, abdominal pain, pruritus, nausea, rash, dyspnea, decreased appetite, and vomiting.

Full prescribing information for ipilimumab and nivolumab can be found on the FDA website.

Prenatal depression tracked through multiple generations shows increase

Rebecca M. Pearson, PhD, and her associates reported in JAMA Network Open.

The findings come from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC), which prospectively followed women who became pregnant between 1990 and 1992 (G0) in a region in southwest England.

In the current analysis, the researchers examined 180 daughters of the original participants, or the female partners of male children (G1). They were recruited during a pregnancy that occurred between June 6, 2012, and Dec. 31, 2016, and had to have completed the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) at 18 weeks of the pregnancy. They were compared to G0 mothers who had become pregnant in the same age range as the G1 subjects (age 19-24 years). Because the G1 participants had all been born in the county of Avon, the G0 subjects were also restricted to 2,390 women who were born there, which represented about 50% of the G0 sample.

Seventeen percent of the G0 women had high depression scores (EPDS greater than or equal to 13) at 18 weeks, compared with 25% of the G1 women. After adjustment for age, body mass index, smoking, parity, and education, the risk ratio for prenatal depression in the later generation of women was 1.77 (95% confidence interval, 1.27-2.46).

There was a strong association between prenatal depression in G1 women and their mothers: Fifty-four percent of women whose mothers had experienced prenatal depression also were positive for prenatal depression, compared with 16% of women whose mothers did not have prenatal depression (RR, 3.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.65-6.67).

An increased incidence of prenatal depression has major implications for service providers and public health efforts. The authors of the study call for more research to confirm this increase and identify potential causes.

The study is the first multigenerational cohort look at prenatal depression, but was limited by the much smaller size of the G1 group. The study also may not be generalizable to older women or ethnic groups other than white European individuals, and selection bias is possible.

The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children was supported by the UK Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust, and the University of Bristol. This current study received support from the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at the University Hospitals Bristol National Health Service Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol, the National Institutes of Health, and the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme. Dr. Pearson reported no relevant financial disclosures; a number of the other researchers reported support from a variety of grants.

SOURCE: RM Pearson RM et al. JAMA Network Open. 2018;1(3):e180725.

Rebecca M. Pearson, PhD, and her associates reported in JAMA Network Open.

The findings come from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC), which prospectively followed women who became pregnant between 1990 and 1992 (G0) in a region in southwest England.

In the current analysis, the researchers examined 180 daughters of the original participants, or the female partners of male children (G1). They were recruited during a pregnancy that occurred between June 6, 2012, and Dec. 31, 2016, and had to have completed the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) at 18 weeks of the pregnancy. They were compared to G0 mothers who had become pregnant in the same age range as the G1 subjects (age 19-24 years). Because the G1 participants had all been born in the county of Avon, the G0 subjects were also restricted to 2,390 women who were born there, which represented about 50% of the G0 sample.

Seventeen percent of the G0 women had high depression scores (EPDS greater than or equal to 13) at 18 weeks, compared with 25% of the G1 women. After adjustment for age, body mass index, smoking, parity, and education, the risk ratio for prenatal depression in the later generation of women was 1.77 (95% confidence interval, 1.27-2.46).

There was a strong association between prenatal depression in G1 women and their mothers: Fifty-four percent of women whose mothers had experienced prenatal depression also were positive for prenatal depression, compared with 16% of women whose mothers did not have prenatal depression (RR, 3.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.65-6.67).

An increased incidence of prenatal depression has major implications for service providers and public health efforts. The authors of the study call for more research to confirm this increase and identify potential causes.

The study is the first multigenerational cohort look at prenatal depression, but was limited by the much smaller size of the G1 group. The study also may not be generalizable to older women or ethnic groups other than white European individuals, and selection bias is possible.

The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children was supported by the UK Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust, and the University of Bristol. This current study received support from the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at the University Hospitals Bristol National Health Service Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol, the National Institutes of Health, and the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme. Dr. Pearson reported no relevant financial disclosures; a number of the other researchers reported support from a variety of grants.

SOURCE: RM Pearson RM et al. JAMA Network Open. 2018;1(3):e180725.

Rebecca M. Pearson, PhD, and her associates reported in JAMA Network Open.

The findings come from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC), which prospectively followed women who became pregnant between 1990 and 1992 (G0) in a region in southwest England.

In the current analysis, the researchers examined 180 daughters of the original participants, or the female partners of male children (G1). They were recruited during a pregnancy that occurred between June 6, 2012, and Dec. 31, 2016, and had to have completed the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) at 18 weeks of the pregnancy. They were compared to G0 mothers who had become pregnant in the same age range as the G1 subjects (age 19-24 years). Because the G1 participants had all been born in the county of Avon, the G0 subjects were also restricted to 2,390 women who were born there, which represented about 50% of the G0 sample.

Seventeen percent of the G0 women had high depression scores (EPDS greater than or equal to 13) at 18 weeks, compared with 25% of the G1 women. After adjustment for age, body mass index, smoking, parity, and education, the risk ratio for prenatal depression in the later generation of women was 1.77 (95% confidence interval, 1.27-2.46).

There was a strong association between prenatal depression in G1 women and their mothers: Fifty-four percent of women whose mothers had experienced prenatal depression also were positive for prenatal depression, compared with 16% of women whose mothers did not have prenatal depression (RR, 3.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.65-6.67).

An increased incidence of prenatal depression has major implications for service providers and public health efforts. The authors of the study call for more research to confirm this increase and identify potential causes.

The study is the first multigenerational cohort look at prenatal depression, but was limited by the much smaller size of the G1 group. The study also may not be generalizable to older women or ethnic groups other than white European individuals, and selection bias is possible.

The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children was supported by the UK Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust, and the University of Bristol. This current study received support from the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at the University Hospitals Bristol National Health Service Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol, the National Institutes of Health, and the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme. Dr. Pearson reported no relevant financial disclosures; a number of the other researchers reported support from a variety of grants.

SOURCE: RM Pearson RM et al. JAMA Network Open. 2018;1(3):e180725.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Key clinical point: The frequency of prenatal depression increased from one generation to the next in English women.

Major finding: The second generation of mothers had a higher risk of prenatal depression (risk ratio, 1.77).

Study details: Prospective study of 2,390 first-generation mothers and 180 second-generation mothers.

Disclosures: The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children was supported by the UK Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust, and the University of Bristol. This current study received support from the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at the University Hospitals Bristol National Health Service Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol, the National Institutes of Health, and the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme. Dr. Pearson reported no relevant financial disclosures; a number of the other researchers reported support from a variety of grants.

Source: RM Pearson RM et al. JAMA Network Open. 2018;1(3):e180725.

Mosaic HIV-1 vaccine stimulates broad antigenicity, enters phase 2b human efficacy trial

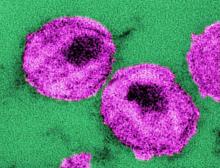

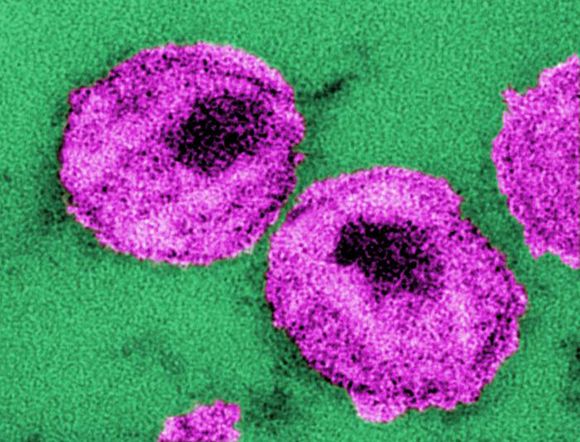

A mosaic adenovirus human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) vaccine induced robust immune responses in humans and rhesus monkeys, and significantly protected the monkeys against repetitive simian/HIV (SHIV) mosaic challenges in rhesus monkeys. This vaccine concept is currently being evaluated in a phase 2b clinical efficacy study in sub-Saharan Africa, according to a report published online in The Lancet.

Because a mosaic combination of antigens can induce an immunogenic response to a broad geographic range of viral subtypes, such a vaccine can offer the theoretical possibility of developing a global HIV-1 vaccine, according to Dan H. Barouch, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his colleagues.

The researchers conducted a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2a trial (APPROACH) with 393 healthy, HIV-1-uninfected participants (aged 18-50 years) who were considered at low risk for HIV-1 infection and were recruited from 12 clinics in East Africa, South Africa, Thailand, and the United States. Participants were primed at weeks 0 and 12 with Ad26.Mos.HIV (5 × 1010 viral particles per 0.5 mL) expressing mosaic HIV-1 envelope (Env)/Gag/Pol antigens and given boosters at weeks 24 and 48 with Ad26.Mos.HIV or modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA; 108 plaque-forming units per 0.5 mL) vectors with or without adjuvanted Env gp140 protein. The placebo group received 0.9% saline.

Eligible participants were randomly assigned to one of eight study groups: Ad26/Ad26 plus high-dose gp140; Ad26/Ad26 plus low-dose gp140; Ad26/Ad26; Ad26/MVA plus high-dose gp140; Ad26/MVA plus low-dose gp140; Ad26/MVA; Ad26/high-dose gp140; and placebo. “Overall, no substantial differences in safety or tolerability of any of the seven active vaccine groups were observed,” according to Dr. Barouch and his colleagues.

In addition, the researchers vaccinated 72 Indian-origin rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) using a study design that was similar to that of the human APPROACH clinical study.

The mosaic HIV-1 vaccine “induced robust humoral and cellular immune responses in both humans and rhesus monkeys,” which were similar in both species in “magnitude, durability, and phenotype,” the investigators reported. In addition, the vaccine “provided 67% protection against acquisition of six intrarectal SHIV challenges in rhesus monkeys.”

Based on these results, the mosaic Ad26/Ad26 plus gp140 HIV-1 vaccine sufficiently met “pre-established safety and immunogenicity criteria to advance into a phase 2b clinical efficacy study in sub-Saharan Africa, which is now underway (NCT03060629),” according to the authors.

“Previous HIV-1 vaccine candidates have typically been limited to specific regions of the world. Optimized mosaic antigens offer the theoretical possibility of developing a global HIV-1 vaccine,” Dr. Barouch and his colleagues concluded.

This study was funded in part by Janssen Vaccines & Prevention BV and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Barouch has received grant funding from Janssen Vaccines & Prevention BV and is a co-inventor on HIV-1 vaccine antigen patents that have been licensed to Janssen Vaccines & Prevention.

SOURCE: Barouch DH et al., The Lancet. 2018 July 6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31364-3.

A mosaic adenovirus human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) vaccine induced robust immune responses in humans and rhesus monkeys, and significantly protected the monkeys against repetitive simian/HIV (SHIV) mosaic challenges in rhesus monkeys. This vaccine concept is currently being evaluated in a phase 2b clinical efficacy study in sub-Saharan Africa, according to a report published online in The Lancet.

Because a mosaic combination of antigens can induce an immunogenic response to a broad geographic range of viral subtypes, such a vaccine can offer the theoretical possibility of developing a global HIV-1 vaccine, according to Dan H. Barouch, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his colleagues.

The researchers conducted a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2a trial (APPROACH) with 393 healthy, HIV-1-uninfected participants (aged 18-50 years) who were considered at low risk for HIV-1 infection and were recruited from 12 clinics in East Africa, South Africa, Thailand, and the United States. Participants were primed at weeks 0 and 12 with Ad26.Mos.HIV (5 × 1010 viral particles per 0.5 mL) expressing mosaic HIV-1 envelope (Env)/Gag/Pol antigens and given boosters at weeks 24 and 48 with Ad26.Mos.HIV or modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA; 108 plaque-forming units per 0.5 mL) vectors with or without adjuvanted Env gp140 protein. The placebo group received 0.9% saline.

Eligible participants were randomly assigned to one of eight study groups: Ad26/Ad26 plus high-dose gp140; Ad26/Ad26 plus low-dose gp140; Ad26/Ad26; Ad26/MVA plus high-dose gp140; Ad26/MVA plus low-dose gp140; Ad26/MVA; Ad26/high-dose gp140; and placebo. “Overall, no substantial differences in safety or tolerability of any of the seven active vaccine groups were observed,” according to Dr. Barouch and his colleagues.

In addition, the researchers vaccinated 72 Indian-origin rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) using a study design that was similar to that of the human APPROACH clinical study.

The mosaic HIV-1 vaccine “induced robust humoral and cellular immune responses in both humans and rhesus monkeys,” which were similar in both species in “magnitude, durability, and phenotype,” the investigators reported. In addition, the vaccine “provided 67% protection against acquisition of six intrarectal SHIV challenges in rhesus monkeys.”

Based on these results, the mosaic Ad26/Ad26 plus gp140 HIV-1 vaccine sufficiently met “pre-established safety and immunogenicity criteria to advance into a phase 2b clinical efficacy study in sub-Saharan Africa, which is now underway (NCT03060629),” according to the authors.

“Previous HIV-1 vaccine candidates have typically been limited to specific regions of the world. Optimized mosaic antigens offer the theoretical possibility of developing a global HIV-1 vaccine,” Dr. Barouch and his colleagues concluded.

This study was funded in part by Janssen Vaccines & Prevention BV and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Barouch has received grant funding from Janssen Vaccines & Prevention BV and is a co-inventor on HIV-1 vaccine antigen patents that have been licensed to Janssen Vaccines & Prevention.

SOURCE: Barouch DH et al., The Lancet. 2018 July 6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31364-3.

A mosaic adenovirus human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) vaccine induced robust immune responses in humans and rhesus monkeys, and significantly protected the monkeys against repetitive simian/HIV (SHIV) mosaic challenges in rhesus monkeys. This vaccine concept is currently being evaluated in a phase 2b clinical efficacy study in sub-Saharan Africa, according to a report published online in The Lancet.

Because a mosaic combination of antigens can induce an immunogenic response to a broad geographic range of viral subtypes, such a vaccine can offer the theoretical possibility of developing a global HIV-1 vaccine, according to Dan H. Barouch, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his colleagues.

The researchers conducted a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2a trial (APPROACH) with 393 healthy, HIV-1-uninfected participants (aged 18-50 years) who were considered at low risk for HIV-1 infection and were recruited from 12 clinics in East Africa, South Africa, Thailand, and the United States. Participants were primed at weeks 0 and 12 with Ad26.Mos.HIV (5 × 1010 viral particles per 0.5 mL) expressing mosaic HIV-1 envelope (Env)/Gag/Pol antigens and given boosters at weeks 24 and 48 with Ad26.Mos.HIV or modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA; 108 plaque-forming units per 0.5 mL) vectors with or without adjuvanted Env gp140 protein. The placebo group received 0.9% saline.

Eligible participants were randomly assigned to one of eight study groups: Ad26/Ad26 plus high-dose gp140; Ad26/Ad26 plus low-dose gp140; Ad26/Ad26; Ad26/MVA plus high-dose gp140; Ad26/MVA plus low-dose gp140; Ad26/MVA; Ad26/high-dose gp140; and placebo. “Overall, no substantial differences in safety or tolerability of any of the seven active vaccine groups were observed,” according to Dr. Barouch and his colleagues.

In addition, the researchers vaccinated 72 Indian-origin rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) using a study design that was similar to that of the human APPROACH clinical study.

The mosaic HIV-1 vaccine “induced robust humoral and cellular immune responses in both humans and rhesus monkeys,” which were similar in both species in “magnitude, durability, and phenotype,” the investigators reported. In addition, the vaccine “provided 67% protection against acquisition of six intrarectal SHIV challenges in rhesus monkeys.”

Based on these results, the mosaic Ad26/Ad26 plus gp140 HIV-1 vaccine sufficiently met “pre-established safety and immunogenicity criteria to advance into a phase 2b clinical efficacy study in sub-Saharan Africa, which is now underway (NCT03060629),” according to the authors.

“Previous HIV-1 vaccine candidates have typically been limited to specific regions of the world. Optimized mosaic antigens offer the theoretical possibility of developing a global HIV-1 vaccine,” Dr. Barouch and his colleagues concluded.

This study was funded in part by Janssen Vaccines & Prevention BV and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Barouch has received grant funding from Janssen Vaccines & Prevention BV and is a co-inventor on HIV-1 vaccine antigen patents that have been licensed to Janssen Vaccines & Prevention.

SOURCE: Barouch DH et al., The Lancet. 2018 July 6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31364-3.

FROM THE LANCET

Promising phase 3 results for ixazomib in multiple myeloma

who had responded to high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplant.

The drug’s sponsor, Takeda, announced that the oral proteasome inhibitor had met the primary endpoint – progression-free survival versus placebo – in the randomized, phase 3 TOURMALINE-MM3 study. They also reported that adverse events were consistent with previously reported results for single-agent use of ixazomib and that there were no new safety signals.

Full study results will be presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology. Company officials plan to submit the trial data to the Food and Drug Administration and regulatory agencies around the world to gain approval of ixazomib as a single-agent maintenance therapy, according to a Takeda announcement.

The TOURMALINE-MM3 study is a double-blind study of 656 patients with multiple myeloma who have had complete response, very good partial response, or partial response to induction therapy followed by high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplant. In addition to progression-free survival, the trial assessed overall survival.

who had responded to high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplant.

The drug’s sponsor, Takeda, announced that the oral proteasome inhibitor had met the primary endpoint – progression-free survival versus placebo – in the randomized, phase 3 TOURMALINE-MM3 study. They also reported that adverse events were consistent with previously reported results for single-agent use of ixazomib and that there were no new safety signals.

Full study results will be presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology. Company officials plan to submit the trial data to the Food and Drug Administration and regulatory agencies around the world to gain approval of ixazomib as a single-agent maintenance therapy, according to a Takeda announcement.

The TOURMALINE-MM3 study is a double-blind study of 656 patients with multiple myeloma who have had complete response, very good partial response, or partial response to induction therapy followed by high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplant. In addition to progression-free survival, the trial assessed overall survival.

who had responded to high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplant.

The drug’s sponsor, Takeda, announced that the oral proteasome inhibitor had met the primary endpoint – progression-free survival versus placebo – in the randomized, phase 3 TOURMALINE-MM3 study. They also reported that adverse events were consistent with previously reported results for single-agent use of ixazomib and that there were no new safety signals.

Full study results will be presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology. Company officials plan to submit the trial data to the Food and Drug Administration and regulatory agencies around the world to gain approval of ixazomib as a single-agent maintenance therapy, according to a Takeda announcement.

The TOURMALINE-MM3 study is a double-blind study of 656 patients with multiple myeloma who have had complete response, very good partial response, or partial response to induction therapy followed by high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplant. In addition to progression-free survival, the trial assessed overall survival.

Benefits, drawbacks when hospitalists expand roles

Hospitalists can’t ‘fill all the cracks’ in primary care

As vice chair of the hospital medicine service at Northwell Health, Nick Fitterman, MD, FACP, SFHM, oversees 16 HM groups at 15 hospitals in New York. He says the duties of his hospitalist staff, like those of most U.S. hospitalists, are similar to what they have traditionally been – clinical care on the wards, teaching, comanagement of surgery, quality improvement, committee work, and research. But he has noticed a trend of late: rapid expansion of the hospitalist’s role.

Speaking at an education session at HM18 in Orlando, Dr. Fitterman said the role of the hospitalist is growing to include tasks that might not be as common, but are becoming more familiar all the time: working at infusion centers, caring for patients in skilled nursing facilities, specializing in electronic health record use, colocating in psychiatric hospitals, even being deployed to natural disasters. His list went on, and it was much longer than the list of traditional hospitalist responsibilities.

“Where do we draw the line and say, ‘Wait a minute, our primary site is going to suffer if we continue to get spread this thin. Can we really do it all?” Dr. Fitterman said. As the number of hats hospitalists wear grows ever bigger, he said more thought must be placed into how expansion happens.

The preop clinic

Efren Manjarrez, MD, SFHM, former chief of hospital medicine at the University of Miami, told a cautionary tale about a preoperative clinic staffed by hospitalists that appeared to provide a financial benefit to a hospital – helping to avoid costly last-minute cancellations of surgeries – but that ultimately was shuttered. The hospital, he said, loses $8,000-$10,000 for each case that gets canceled on the same day.

“Think about that just for a minute,” Dr. Manjarrez said. “If 100 cases are canceled during the year at the last minute, that’s a lot of money.”

A preoperative clinic seemed like a worthwhile role for hospitalists – the program was started in Miami by the same doctor who initiated a similar program at Cleveland Clinic. “Surgical cases are what support the hospital [financially], and we’re here to help them along,” Dr. Manjarrez said. “The purpose of hospitalists is to make sure that patients are medically optimized.”

The preop program concept, used in U.S. medicine since the 1990s, was originally started by anesthesiologists, but they may not always be the best fit to staff such programs.

“Anesthesiologists do not manage all beta blockers,” Dr. Manjarrez said. “They don’t manage ACE inhibitors by mouth. They don’t manage all oral diabetes agents, and they sure as heck don’t manage pills that are anticoagulants. That’s the domain of internal medicine. And as patients have become more complex, that’s where hospitalists who [work in] preop clinics have stepped in.”

Studies have found that hospitalists staffing preop clinics have improved quality metrics and some clinical outcomes, including lowering cancellation rates and more appropriate use of beta blockers, he said.

In the Miami program described by Dr. Manjarrez, hospitalists in the preop clinic at first saw only patients who’d been financially cleared as able to pay. But ultimately, a tiered system was developed, and hospitalists saw only patients who were higher risk – those with COPD or stroke patients, for example – without regard to ability to pay.

“The hospital would have to make up any financial deficit at the very end,” Dr. Manjarrez said. This meant there were no longer efficient 5-minute encounters with patients. Instead, visits lasted about 45 minutes, so fewer patients were seen.

The program was successful, in that the same-day cancellation rate for surgeries dropped to less than 0.1% – fewer than 1 in 1,000 – with the preop clinic up and running, Dr. Manjarrez. Still, the hospital decided to end the program. “The hospital no longer wanted to reimburse us,” he said.

A takeaway from this experience for Dr. Manjarrez was that hospitalists need to do a better job of showing the financial benefits in their expanding roles, if they want them to endure.

“At the end of the day, hospitalists do provide value in preoperative clinics,” he said. “But unfortunately, we’re not doing a great job of publishing our data and showing our value.”

At-home care

At Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, hospitalists have demonstrated good results with a program to provide care at home rather than in the hospital.

David Levine, MD, MPH, MA, clinician and investigator at Brigham and Women’s and an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School, said that the structure of inpatient care has generally not changed much over decades, despite advances in technology.

“We round on them once a day – if they’re lucky, twice,” he said. “The medicines have changed and imaging has changed, but we really haven’t changed the structure of how we take care of acutely ill adults for almost a hundred years.”

Hospitalizing patients brings unintended consequences. Twenty percent of older adults will become delirious during their stay, 1 out of 3 will lose a level of functional status in the hospital that they’ll never regain, and 1 out of 10 hospitalized patients will experience an adverse event, like an infection or a medication error.

Brigham and Women’s program of at-home care involves “admitting” patients to their homes after being treated in the emergency department. The goal is to reduce costs by 20%, while maintaining quality and safety and improving patients’ quality of life and experience.

Researchers are studying their results. They randomized patients, after the ED determined they required admission, either to admission to the hospital or to their home. The decision on whether to admit was made before the study investigators became involved with the patients, Dr. Levine said.

The program is also intended to improve access to hospitals. Brigham and Women’s is often over 100% capacity in the general medical ward.

Patients in the study needed to live within a 5-mile radius of either Brigham and Women’s Hospital, or Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital, a nearby community hospital. A physician and a registered nurse form the core team; they assess patient needs and ratchet care either up or down, perhaps adding a home health aide or social worker.

The home care team takes advantage of technology: Portable equipment allows a basic metabolic panel to be performed on the spot – for example, a hemoglobin and hematocrit can be produced within 2 minutes. Also, portable ultrasounds and x-rays are used. Doctors keep a “tackle box” of urgent medications such as antibiotics and diuretics.

“We showed a direct cost reduction taking care of patients at home,” Dr. Levine said. There was also a reduction in utilization of care, and an increase in patient activity, with patients taking about 1,800 steps at home, compared with 180 in the hospital. There were no significant changes in safety, quality, or patient experience, he said.

Postdischarge clinics

Lauren Doctoroff, MD, FHM – a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconness Medical Center in Boston and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School – explained another hospitalist-staffed project meant to improve access to care: her center’s postdischarge clinic, which was started in 2009 but is no longer operating.

The clinic tackled the problem of what to do with patients when you discharge them, Dr. Doctoroff said, and its goal was to foster more cooperation between hospitalists and the faculty primary care practice, as well as to improve postdischarge access for patients from that practice.

A dedicated group of hospitalists staffed the clinics, handling medication reconciliation, symptom management, pending tests, and other services the patients were supposed to be getting after discharge, Dr. Doctoroff said.

“We greatly improved access so that when you came to see us you generally saw a hospitalist a week before you would have seen your primary care doctor,” she said. “And that was mostly because we created open access in a clinic that did not have open access. So if a doctor discharging a patient really thought that the patient needed to be seen after discharge, they would often see us.”

Hospitalists considering starting such a clinic have several key questions to consider, Dr. Doctoroff said.

“You need to focus on who the patient population is, the clinic structure, how you plan to staff the clinic, and what your outcomes are – mainly how you will measure performance,” she said.

Dr. Doctoroff said hospitalists are good for this role because “we’re very comfortable with patients who are complicated, and we are very adept at accessing information from the hospitalization. I think, as a hospitalist who spent 5 years seeing patients in a discharge clinic, it greatly enhances my understanding of patients and their challenges at discharge.”

The clinic was closed, she said, in part because it was largely an extension of primary care, and the patient volume wasn’t big enough to justify continuing it.

“Postdischarge clinics are, in a very narrow sense, a bit of a Band-Aid for a really dysfunctional primary care system,” Dr. Doctoroff said. “Ideally, if all you’re doing is providing a postdischarge physician visit, then you really want primary care to be able to do that in order to reengage with their patient. I think this is because postdischarge clinics are construed in a very narrow way to address the simple need to see a patient after discharge. And this may lead to the failure of these clinics, or make them easy to replace. Also, often what patients really need is more than just a physician visit, so a discharge clinic may need to be designed to provide an enhanced array of services.”

Dr. Fitterman said that these stories show that not all role expansion in hospital medicine is good role expansion. The experiences described by Dr. Manjarrez, Dr. Levine, and Dr. Doctoroff demonstrate the challenges hospitalists face as they attempt expansions into new roles, he said.

“We can’t be expected to fill all the cracks in primary care,” Dr. Fitterman said. “As a country we need to really prop up primary care. This all can’t come under the roof of hospital medicine. We need to be part of a patient-centered medical home – but we are not the patient-centered medical home.”

He said the experience with the preop clinic described by Dr. Manjarrez also shows the need for buy-in from hospital or health system administration.

“While most of us are employed by hospitals and want to help meet their needs, we have to be more cautious. We have to look, I think, with a more critical eye, for the value; it may not always be in the dollars coming back in,” he said. “It might be in cost avoidance, such as reducing readmissions, or reducing same-day cancellations in an OR. Unless the C-suite appreciates that value, such programs will be short-lived.”

Hospitalists can’t ‘fill all the cracks’ in primary care

Hospitalists can’t ‘fill all the cracks’ in primary care

As vice chair of the hospital medicine service at Northwell Health, Nick Fitterman, MD, FACP, SFHM, oversees 16 HM groups at 15 hospitals in New York. He says the duties of his hospitalist staff, like those of most U.S. hospitalists, are similar to what they have traditionally been – clinical care on the wards, teaching, comanagement of surgery, quality improvement, committee work, and research. But he has noticed a trend of late: rapid expansion of the hospitalist’s role.

Speaking at an education session at HM18 in Orlando, Dr. Fitterman said the role of the hospitalist is growing to include tasks that might not be as common, but are becoming more familiar all the time: working at infusion centers, caring for patients in skilled nursing facilities, specializing in electronic health record use, colocating in psychiatric hospitals, even being deployed to natural disasters. His list went on, and it was much longer than the list of traditional hospitalist responsibilities.

“Where do we draw the line and say, ‘Wait a minute, our primary site is going to suffer if we continue to get spread this thin. Can we really do it all?” Dr. Fitterman said. As the number of hats hospitalists wear grows ever bigger, he said more thought must be placed into how expansion happens.

The preop clinic

Efren Manjarrez, MD, SFHM, former chief of hospital medicine at the University of Miami, told a cautionary tale about a preoperative clinic staffed by hospitalists that appeared to provide a financial benefit to a hospital – helping to avoid costly last-minute cancellations of surgeries – but that ultimately was shuttered. The hospital, he said, loses $8,000-$10,000 for each case that gets canceled on the same day.

“Think about that just for a minute,” Dr. Manjarrez said. “If 100 cases are canceled during the year at the last minute, that’s a lot of money.”

A preoperative clinic seemed like a worthwhile role for hospitalists – the program was started in Miami by the same doctor who initiated a similar program at Cleveland Clinic. “Surgical cases are what support the hospital [financially], and we’re here to help them along,” Dr. Manjarrez said. “The purpose of hospitalists is to make sure that patients are medically optimized.”

The preop program concept, used in U.S. medicine since the 1990s, was originally started by anesthesiologists, but they may not always be the best fit to staff such programs.

“Anesthesiologists do not manage all beta blockers,” Dr. Manjarrez said. “They don’t manage ACE inhibitors by mouth. They don’t manage all oral diabetes agents, and they sure as heck don’t manage pills that are anticoagulants. That’s the domain of internal medicine. And as patients have become more complex, that’s where hospitalists who [work in] preop clinics have stepped in.”

Studies have found that hospitalists staffing preop clinics have improved quality metrics and some clinical outcomes, including lowering cancellation rates and more appropriate use of beta blockers, he said.

In the Miami program described by Dr. Manjarrez, hospitalists in the preop clinic at first saw only patients who’d been financially cleared as able to pay. But ultimately, a tiered system was developed, and hospitalists saw only patients who were higher risk – those with COPD or stroke patients, for example – without regard to ability to pay.

“The hospital would have to make up any financial deficit at the very end,” Dr. Manjarrez said. This meant there were no longer efficient 5-minute encounters with patients. Instead, visits lasted about 45 minutes, so fewer patients were seen.

The program was successful, in that the same-day cancellation rate for surgeries dropped to less than 0.1% – fewer than 1 in 1,000 – with the preop clinic up and running, Dr. Manjarrez. Still, the hospital decided to end the program. “The hospital no longer wanted to reimburse us,” he said.

A takeaway from this experience for Dr. Manjarrez was that hospitalists need to do a better job of showing the financial benefits in their expanding roles, if they want them to endure.

“At the end of the day, hospitalists do provide value in preoperative clinics,” he said. “But unfortunately, we’re not doing a great job of publishing our data and showing our value.”

At-home care

At Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, hospitalists have demonstrated good results with a program to provide care at home rather than in the hospital.

David Levine, MD, MPH, MA, clinician and investigator at Brigham and Women’s and an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School, said that the structure of inpatient care has generally not changed much over decades, despite advances in technology.

“We round on them once a day – if they’re lucky, twice,” he said. “The medicines have changed and imaging has changed, but we really haven’t changed the structure of how we take care of acutely ill adults for almost a hundred years.”

Hospitalizing patients brings unintended consequences. Twenty percent of older adults will become delirious during their stay, 1 out of 3 will lose a level of functional status in the hospital that they’ll never regain, and 1 out of 10 hospitalized patients will experience an adverse event, like an infection or a medication error.

Brigham and Women’s program of at-home care involves “admitting” patients to their homes after being treated in the emergency department. The goal is to reduce costs by 20%, while maintaining quality and safety and improving patients’ quality of life and experience.

Researchers are studying their results. They randomized patients, after the ED determined they required admission, either to admission to the hospital or to their home. The decision on whether to admit was made before the study investigators became involved with the patients, Dr. Levine said.

The program is also intended to improve access to hospitals. Brigham and Women’s is often over 100% capacity in the general medical ward.

Patients in the study needed to live within a 5-mile radius of either Brigham and Women’s Hospital, or Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital, a nearby community hospital. A physician and a registered nurse form the core team; they assess patient needs and ratchet care either up or down, perhaps adding a home health aide or social worker.

The home care team takes advantage of technology: Portable equipment allows a basic metabolic panel to be performed on the spot – for example, a hemoglobin and hematocrit can be produced within 2 minutes. Also, portable ultrasounds and x-rays are used. Doctors keep a “tackle box” of urgent medications such as antibiotics and diuretics.

“We showed a direct cost reduction taking care of patients at home,” Dr. Levine said. There was also a reduction in utilization of care, and an increase in patient activity, with patients taking about 1,800 steps at home, compared with 180 in the hospital. There were no significant changes in safety, quality, or patient experience, he said.

Postdischarge clinics

Lauren Doctoroff, MD, FHM – a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconness Medical Center in Boston and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School – explained another hospitalist-staffed project meant to improve access to care: her center’s postdischarge clinic, which was started in 2009 but is no longer operating.

The clinic tackled the problem of what to do with patients when you discharge them, Dr. Doctoroff said, and its goal was to foster more cooperation between hospitalists and the faculty primary care practice, as well as to improve postdischarge access for patients from that practice.

A dedicated group of hospitalists staffed the clinics, handling medication reconciliation, symptom management, pending tests, and other services the patients were supposed to be getting after discharge, Dr. Doctoroff said.

“We greatly improved access so that when you came to see us you generally saw a hospitalist a week before you would have seen your primary care doctor,” she said. “And that was mostly because we created open access in a clinic that did not have open access. So if a doctor discharging a patient really thought that the patient needed to be seen after discharge, they would often see us.”

Hospitalists considering starting such a clinic have several key questions to consider, Dr. Doctoroff said.

“You need to focus on who the patient population is, the clinic structure, how you plan to staff the clinic, and what your outcomes are – mainly how you will measure performance,” she said.

Dr. Doctoroff said hospitalists are good for this role because “we’re very comfortable with patients who are complicated, and we are very adept at accessing information from the hospitalization. I think, as a hospitalist who spent 5 years seeing patients in a discharge clinic, it greatly enhances my understanding of patients and their challenges at discharge.”

The clinic was closed, she said, in part because it was largely an extension of primary care, and the patient volume wasn’t big enough to justify continuing it.

“Postdischarge clinics are, in a very narrow sense, a bit of a Band-Aid for a really dysfunctional primary care system,” Dr. Doctoroff said. “Ideally, if all you’re doing is providing a postdischarge physician visit, then you really want primary care to be able to do that in order to reengage with their patient. I think this is because postdischarge clinics are construed in a very narrow way to address the simple need to see a patient after discharge. And this may lead to the failure of these clinics, or make them easy to replace. Also, often what patients really need is more than just a physician visit, so a discharge clinic may need to be designed to provide an enhanced array of services.”