User login

Colorectal cancer: New observations, new implications

The incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer (CRC) have declined by 3% per year over the past 10-15 years – a remarkable achievement. The decline in incidence has been dramatic for individuals over age 50 years, who are targeted by screening. However, the reduction in CRC risk does not apply to all populations in the United States. New epidemiologic trends and observations point to patient demographics and regional variation as potential risk factors. While such observations provide what I call “blurry snapshots,” they may well have important implications for our approach to screening and prevention.

What are the reasons? There are several personal and environmental factors that could be contributing. Obesity and metabolic syndrome are risk factors for CRC and have been more commonly developing in childhood over the past 40 years. Alteration of the microbiome could also potentially predispose one to developing CRC. The use of antibiotics in childhood was more common for some of these younger generations than it was for the preceding generations, and antibiotics have been introduced into the food industry to fatten animals. The introduction of food chemicals could also either alter the microbiome and/or promote inflammation, which could lead to neoplasia. Exposure to more ambient radiation may be another risk factor.

These hypotheses are biologically plausible – but untested. Nevertheless, this observational trend does have implications for clinicians. First, studies have shown that up to 20% of CRCs before age 50 years are associated with germline mutations, while others are associated with a family history of CRC. Therefore, it is important to capture and update family history. In addition, there is evidence that individuals aged 40-49 years with rectal bleeding have a higher risk of advanced adenomas, so our threshold for performing diagnostic colonoscopy should be lowered. African Americans also have a higher risk of CRC at a younger age than do other racial groups and might benefit from early screening at age 45 years. Notably, recent recommendations from the American Cancer Society call for consideration of screening everyone at age 45 years.

There is substantial state-to-state and county-to-county variation in the incidence and mortality of CRC. While some of this variation can be explained by racial variation, smoking, obesity, and social determinants of health, there are “hot-spots” that may defy easy explanation. There has been very little research about environmental factors (air, water, and ambient radiation). Two regions at particularly high risk are the Mississippi Delta region and Appalachia – areas where water pollution could be a factor. The substantial county-to-county variation within these high-risk areas points to a potential environmental culprit, but further research is needed.

For the GI community, there are several implications to be found in these changing demographics and risks. For one, we may need to consider expanding our risk concepts to include not only genetic and personal risk factors but also environmental factors. To mitigate risk, providers and public health officials may need to then target these high-risk areas for more intensive screening efforts.

Dr. Lieberman is a professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology and hepatology at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland. He has no conflicts of interest. Dr. Lieberman made his comments during the AGA Institute Presidential Plenary at the Annual Digestive Disease Week.

The incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer (CRC) have declined by 3% per year over the past 10-15 years – a remarkable achievement. The decline in incidence has been dramatic for individuals over age 50 years, who are targeted by screening. However, the reduction in CRC risk does not apply to all populations in the United States. New epidemiologic trends and observations point to patient demographics and regional variation as potential risk factors. While such observations provide what I call “blurry snapshots,” they may well have important implications for our approach to screening and prevention.

What are the reasons? There are several personal and environmental factors that could be contributing. Obesity and metabolic syndrome are risk factors for CRC and have been more commonly developing in childhood over the past 40 years. Alteration of the microbiome could also potentially predispose one to developing CRC. The use of antibiotics in childhood was more common for some of these younger generations than it was for the preceding generations, and antibiotics have been introduced into the food industry to fatten animals. The introduction of food chemicals could also either alter the microbiome and/or promote inflammation, which could lead to neoplasia. Exposure to more ambient radiation may be another risk factor.

These hypotheses are biologically plausible – but untested. Nevertheless, this observational trend does have implications for clinicians. First, studies have shown that up to 20% of CRCs before age 50 years are associated with germline mutations, while others are associated with a family history of CRC. Therefore, it is important to capture and update family history. In addition, there is evidence that individuals aged 40-49 years with rectal bleeding have a higher risk of advanced adenomas, so our threshold for performing diagnostic colonoscopy should be lowered. African Americans also have a higher risk of CRC at a younger age than do other racial groups and might benefit from early screening at age 45 years. Notably, recent recommendations from the American Cancer Society call for consideration of screening everyone at age 45 years.

There is substantial state-to-state and county-to-county variation in the incidence and mortality of CRC. While some of this variation can be explained by racial variation, smoking, obesity, and social determinants of health, there are “hot-spots” that may defy easy explanation. There has been very little research about environmental factors (air, water, and ambient radiation). Two regions at particularly high risk are the Mississippi Delta region and Appalachia – areas where water pollution could be a factor. The substantial county-to-county variation within these high-risk areas points to a potential environmental culprit, but further research is needed.

For the GI community, there are several implications to be found in these changing demographics and risks. For one, we may need to consider expanding our risk concepts to include not only genetic and personal risk factors but also environmental factors. To mitigate risk, providers and public health officials may need to then target these high-risk areas for more intensive screening efforts.

Dr. Lieberman is a professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology and hepatology at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland. He has no conflicts of interest. Dr. Lieberman made his comments during the AGA Institute Presidential Plenary at the Annual Digestive Disease Week.

The incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer (CRC) have declined by 3% per year over the past 10-15 years – a remarkable achievement. The decline in incidence has been dramatic for individuals over age 50 years, who are targeted by screening. However, the reduction in CRC risk does not apply to all populations in the United States. New epidemiologic trends and observations point to patient demographics and regional variation as potential risk factors. While such observations provide what I call “blurry snapshots,” they may well have important implications for our approach to screening and prevention.

What are the reasons? There are several personal and environmental factors that could be contributing. Obesity and metabolic syndrome are risk factors for CRC and have been more commonly developing in childhood over the past 40 years. Alteration of the microbiome could also potentially predispose one to developing CRC. The use of antibiotics in childhood was more common for some of these younger generations than it was for the preceding generations, and antibiotics have been introduced into the food industry to fatten animals. The introduction of food chemicals could also either alter the microbiome and/or promote inflammation, which could lead to neoplasia. Exposure to more ambient radiation may be another risk factor.

These hypotheses are biologically plausible – but untested. Nevertheless, this observational trend does have implications for clinicians. First, studies have shown that up to 20% of CRCs before age 50 years are associated with germline mutations, while others are associated with a family history of CRC. Therefore, it is important to capture and update family history. In addition, there is evidence that individuals aged 40-49 years with rectal bleeding have a higher risk of advanced adenomas, so our threshold for performing diagnostic colonoscopy should be lowered. African Americans also have a higher risk of CRC at a younger age than do other racial groups and might benefit from early screening at age 45 years. Notably, recent recommendations from the American Cancer Society call for consideration of screening everyone at age 45 years.

There is substantial state-to-state and county-to-county variation in the incidence and mortality of CRC. While some of this variation can be explained by racial variation, smoking, obesity, and social determinants of health, there are “hot-spots” that may defy easy explanation. There has been very little research about environmental factors (air, water, and ambient radiation). Two regions at particularly high risk are the Mississippi Delta region and Appalachia – areas where water pollution could be a factor. The substantial county-to-county variation within these high-risk areas points to a potential environmental culprit, but further research is needed.

For the GI community, there are several implications to be found in these changing demographics and risks. For one, we may need to consider expanding our risk concepts to include not only genetic and personal risk factors but also environmental factors. To mitigate risk, providers and public health officials may need to then target these high-risk areas for more intensive screening efforts.

Dr. Lieberman is a professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology and hepatology at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland. He has no conflicts of interest. Dr. Lieberman made his comments during the AGA Institute Presidential Plenary at the Annual Digestive Disease Week.

CMS proposes site-neutral payments for hospital outpatient setting

In the proposed update to the Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) for 2019, released July 27 and scheduled to be published July 31 in the Federal Register, the CMS is proposing to apply a physician fee schedule–equivalent for the clinic visit service when provided at an off-campus, provider-based department that is paid under the OPPS.

“The clinic visit is the most common service billed under the OPPS and is often furnished in the physician office setting,” the CMS said in a fact sheet detailing its proposal.

According to the CMS, the average current clinical visit paid by the CMS is $116 with $23 being the average copay by the patient. If the proposal is finalized, the payment would drop to about $46 with an average patient copay of $9.

“This is intended to address concerns about recent consolidations in the market that reduce competition,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said during a July 25 press conference.

The American Hospital Association already is pushing back on this proposal.

“With today’s proposed rule, CMS has once again showed a lack of understanding about the reality in which hospitals and health systems operate daily to serve the needs of their communities,” AHA Executive Vice President Tom Nickels said in a statement. “In 2015, Congress clearly intended to provide current off-campus hospital clinics with the existing outpatient payment rate in recognition of the critical role they play in their communities. But CMS’s proposal runs counter to this and will instead impede access to care for the most vulnerable patients.”

However, Farzad Mostashari, MD, founder of the health care technology company Aledade and National Coordinator for Health IT under President Obama, suggested that this could actually be a good thing for hospitals.

“The truth is that this proposal could help hospitals be more competitive in value-based contracts/alternative-payment models, and they should embrace the changes,” he said in a tweet.

The OPPS update also includes proposals to expand the list of covered surgical procedures that can be performed in an ambulatory surgical center, a move that Ms. Verma said would “provide patients with more choices and options for lower-priced care.”

“For CY 2019, CMS is proposing to allow certain CPT codes outside of the surgical code range that directly crosswalk or are clinically similar to procedures within the CPT surgical code range to be included on the [covered procedure list] and is proposing to add certain cardiovascular codes to the ASC [covered procedure list] as a result,” the CMS fact sheet notes.

The CMS also will review all procedures added to the covered procedure list in the past 3 years to determine whether such procedures should continue to be covered.

In addition, the OPPS is seeking feedback on a number of topics.

One is related to price transparency. The agency is asking “whether providers and suppliers can and should be required to inform patients about charges and payment information for healthcare services and out-of-pocket costs, what data elements the public would find most useful, and what other charges are needed to empower patients,” according to the fact sheet.

The CMS also is seeking information about relaunching a revamped competitive acquisition program that would have private vendors administer payment arrangements for Part B drugs. The agency is soliciting feedback on ways to design a model for testing.

Finally, the agency is seeking more information on solutions to better promote interoperability.

In the proposed update to the Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) for 2019, released July 27 and scheduled to be published July 31 in the Federal Register, the CMS is proposing to apply a physician fee schedule–equivalent for the clinic visit service when provided at an off-campus, provider-based department that is paid under the OPPS.

“The clinic visit is the most common service billed under the OPPS and is often furnished in the physician office setting,” the CMS said in a fact sheet detailing its proposal.

According to the CMS, the average current clinical visit paid by the CMS is $116 with $23 being the average copay by the patient. If the proposal is finalized, the payment would drop to about $46 with an average patient copay of $9.

“This is intended to address concerns about recent consolidations in the market that reduce competition,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said during a July 25 press conference.

The American Hospital Association already is pushing back on this proposal.

“With today’s proposed rule, CMS has once again showed a lack of understanding about the reality in which hospitals and health systems operate daily to serve the needs of their communities,” AHA Executive Vice President Tom Nickels said in a statement. “In 2015, Congress clearly intended to provide current off-campus hospital clinics with the existing outpatient payment rate in recognition of the critical role they play in their communities. But CMS’s proposal runs counter to this and will instead impede access to care for the most vulnerable patients.”

However, Farzad Mostashari, MD, founder of the health care technology company Aledade and National Coordinator for Health IT under President Obama, suggested that this could actually be a good thing for hospitals.

“The truth is that this proposal could help hospitals be more competitive in value-based contracts/alternative-payment models, and they should embrace the changes,” he said in a tweet.

The OPPS update also includes proposals to expand the list of covered surgical procedures that can be performed in an ambulatory surgical center, a move that Ms. Verma said would “provide patients with more choices and options for lower-priced care.”

“For CY 2019, CMS is proposing to allow certain CPT codes outside of the surgical code range that directly crosswalk or are clinically similar to procedures within the CPT surgical code range to be included on the [covered procedure list] and is proposing to add certain cardiovascular codes to the ASC [covered procedure list] as a result,” the CMS fact sheet notes.

The CMS also will review all procedures added to the covered procedure list in the past 3 years to determine whether such procedures should continue to be covered.

In addition, the OPPS is seeking feedback on a number of topics.

One is related to price transparency. The agency is asking “whether providers and suppliers can and should be required to inform patients about charges and payment information for healthcare services and out-of-pocket costs, what data elements the public would find most useful, and what other charges are needed to empower patients,” according to the fact sheet.

The CMS also is seeking information about relaunching a revamped competitive acquisition program that would have private vendors administer payment arrangements for Part B drugs. The agency is soliciting feedback on ways to design a model for testing.

Finally, the agency is seeking more information on solutions to better promote interoperability.

In the proposed update to the Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) for 2019, released July 27 and scheduled to be published July 31 in the Federal Register, the CMS is proposing to apply a physician fee schedule–equivalent for the clinic visit service when provided at an off-campus, provider-based department that is paid under the OPPS.

“The clinic visit is the most common service billed under the OPPS and is often furnished in the physician office setting,” the CMS said in a fact sheet detailing its proposal.

According to the CMS, the average current clinical visit paid by the CMS is $116 with $23 being the average copay by the patient. If the proposal is finalized, the payment would drop to about $46 with an average patient copay of $9.

“This is intended to address concerns about recent consolidations in the market that reduce competition,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said during a July 25 press conference.

The American Hospital Association already is pushing back on this proposal.

“With today’s proposed rule, CMS has once again showed a lack of understanding about the reality in which hospitals and health systems operate daily to serve the needs of their communities,” AHA Executive Vice President Tom Nickels said in a statement. “In 2015, Congress clearly intended to provide current off-campus hospital clinics with the existing outpatient payment rate in recognition of the critical role they play in their communities. But CMS’s proposal runs counter to this and will instead impede access to care for the most vulnerable patients.”

However, Farzad Mostashari, MD, founder of the health care technology company Aledade and National Coordinator for Health IT under President Obama, suggested that this could actually be a good thing for hospitals.

“The truth is that this proposal could help hospitals be more competitive in value-based contracts/alternative-payment models, and they should embrace the changes,” he said in a tweet.

The OPPS update also includes proposals to expand the list of covered surgical procedures that can be performed in an ambulatory surgical center, a move that Ms. Verma said would “provide patients with more choices and options for lower-priced care.”

“For CY 2019, CMS is proposing to allow certain CPT codes outside of the surgical code range that directly crosswalk or are clinically similar to procedures within the CPT surgical code range to be included on the [covered procedure list] and is proposing to add certain cardiovascular codes to the ASC [covered procedure list] as a result,” the CMS fact sheet notes.

The CMS also will review all procedures added to the covered procedure list in the past 3 years to determine whether such procedures should continue to be covered.

In addition, the OPPS is seeking feedback on a number of topics.

One is related to price transparency. The agency is asking “whether providers and suppliers can and should be required to inform patients about charges and payment information for healthcare services and out-of-pocket costs, what data elements the public would find most useful, and what other charges are needed to empower patients,” according to the fact sheet.

The CMS also is seeking information about relaunching a revamped competitive acquisition program that would have private vendors administer payment arrangements for Part B drugs. The agency is soliciting feedback on ways to design a model for testing.

Finally, the agency is seeking more information on solutions to better promote interoperability.

Alzheimer’s trial design problem throws a wrench in promising BAN2401 results

CHICAGO – BAN2401, a monoclonal antibody that targets soluble amyloid-beta oligomers, slowed cognitive decline by up to 47% while clearing brain amyloid in 81% of patients with mild cognitive impairment and very mild Alzheimer’s disease, a phase 2 study has shown.

At the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, Eisai, which is developing the antibody along with Biogen, touted it the study results as an important step forward in a field desperate for success. But questions remain, especially about the unequal distribution of apolipoprotein E4 (APOE4)-positive patients across the six treatment groups: BAN2401 2.5 mg/kg biweekly, 5 mg/kg monthly, 5 mg/kg biweekly, 10 mg/kg monthly, and 10 mg/kg biweekly, or placebo. This troubled some researchers, who said the mix could have biased cognitive results in the antibody’s favor. APOE4 carriers comprised about 70%-80% of every unsuccessful treatment arm in the trial, and 29% of the arm that conferred significant cognitive benefits.

“This is a big confound,” Keith Fargo, PhD, director of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, said when he saw the numbers. “An important point is that, according to the trial sponsors, for a period of time a regulatory body requested that people with the APOE4 Alzheimer’s risk gene not be included in the highest dose group, for safety reasons. Because of this, the people in the highest-dose group are different from people in the other groups on an important dimension; they were much less likely to have the APOE4 gene, which is known to be a major risk factor for cognitive decline. So it is plausible that the people on the highest dose declined differently due to genetic differences rather than due to being on the highest dose. A planned subgroup analysis will shed more light on this, and whether it reduces confidence in the overall findings. We eagerly await the results of this analysis.”

The decision to restructure the randomization was not Eisai’s, according to David Knopman, MD, chair of the Alzheimer’s Association Medical and Scientific Advisory Council.

“European regulators did not allow randomization of [some] APOE4 carriers to the highest dose,” he said in an interview. “I ultimately don’t know what it would do to the results, except make them even more difficult to justify as sufficient for registration. In general, in symptomatic Alzheimer’s dementia patients, APOE4 carriage has no substantial impact on rate of decline, but whether [APOE4] status interacted with the treatment is of course completely unknown. Bottom line: Just another feature that makes this a phase 2 study that needs to be followed by a phase 3 study with a simple design using the high dose.”

Alzheimer’s researcher Michael S. Wolfe, PhD, was more candid.

“Regardless of who made the decision and why, the data is what it is, and the question remains,” said Dr. Wolfe, the Mathias P. Mertes Professor of Medicinal Chemistry at the University of Kansas, Lawrence. “Given the numbers of E4-positive vs. E4-negative for each treatment group, the interpretation of the results is now seriously thrown into question. The one group that showed a clear slowing of cognitive decline versus placebo (10 mg/kg biweekly) also has far fewer E4-positive vs. E4-negative. This difference in proportion of E4-positive could be a major factor in the apparent reduced rate of cognitive decline and confounds the ability to tell if the 10-mg/kg biweekly dose is effective. In contrast, the 10-mg/kg monthly dose group has an E4-positive/-negative ratio more comparable to that of placebo, and the effect of the drug on cognitive decline under this dosing regimen is not clearly distinguishable from that seen with placebo.”

Additionally, BAN2401 failed to meet its 12-month prespecified primary cognitive endpoints, a conclusion determined by a complex Bayesian analysis that strove to predict an 80% probability of reaching at least a 25% cognitive benefit. In December, the company announced that the study hit just a 64% probability. But because Eisai felt the numbers were moving in the right direction, it continued with the additional 6 months of treatment, as allowed for in the study design, and then reanalyzed results with a simpler and more straightforward method. This analysis concluded that 10 mg/kg infused biweekly conferred a 30% slowing of decline on the Alzheimer’s Disease Composite Score (ADCOMS), a new tool developed and promoted by Eisai, and a 47% slowing of decline on the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive subscale (ADAS-Cog). It also cleared brain amyloid in 81% of subjects and sent cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers in the right direction. CSF amyloid levels went up – to be expected if the antibody was clearing it from the brain – and CSF total tau went down, an indication of decreased neuronal injury.

Inquiries to Eisai to clarify these issues had not been returned at press time.

This is a developing story.

CHICAGO – BAN2401, a monoclonal antibody that targets soluble amyloid-beta oligomers, slowed cognitive decline by up to 47% while clearing brain amyloid in 81% of patients with mild cognitive impairment and very mild Alzheimer’s disease, a phase 2 study has shown.

At the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, Eisai, which is developing the antibody along with Biogen, touted it the study results as an important step forward in a field desperate for success. But questions remain, especially about the unequal distribution of apolipoprotein E4 (APOE4)-positive patients across the six treatment groups: BAN2401 2.5 mg/kg biweekly, 5 mg/kg monthly, 5 mg/kg biweekly, 10 mg/kg monthly, and 10 mg/kg biweekly, or placebo. This troubled some researchers, who said the mix could have biased cognitive results in the antibody’s favor. APOE4 carriers comprised about 70%-80% of every unsuccessful treatment arm in the trial, and 29% of the arm that conferred significant cognitive benefits.

“This is a big confound,” Keith Fargo, PhD, director of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, said when he saw the numbers. “An important point is that, according to the trial sponsors, for a period of time a regulatory body requested that people with the APOE4 Alzheimer’s risk gene not be included in the highest dose group, for safety reasons. Because of this, the people in the highest-dose group are different from people in the other groups on an important dimension; they were much less likely to have the APOE4 gene, which is known to be a major risk factor for cognitive decline. So it is plausible that the people on the highest dose declined differently due to genetic differences rather than due to being on the highest dose. A planned subgroup analysis will shed more light on this, and whether it reduces confidence in the overall findings. We eagerly await the results of this analysis.”

The decision to restructure the randomization was not Eisai’s, according to David Knopman, MD, chair of the Alzheimer’s Association Medical and Scientific Advisory Council.

“European regulators did not allow randomization of [some] APOE4 carriers to the highest dose,” he said in an interview. “I ultimately don’t know what it would do to the results, except make them even more difficult to justify as sufficient for registration. In general, in symptomatic Alzheimer’s dementia patients, APOE4 carriage has no substantial impact on rate of decline, but whether [APOE4] status interacted with the treatment is of course completely unknown. Bottom line: Just another feature that makes this a phase 2 study that needs to be followed by a phase 3 study with a simple design using the high dose.”

Alzheimer’s researcher Michael S. Wolfe, PhD, was more candid.

“Regardless of who made the decision and why, the data is what it is, and the question remains,” said Dr. Wolfe, the Mathias P. Mertes Professor of Medicinal Chemistry at the University of Kansas, Lawrence. “Given the numbers of E4-positive vs. E4-negative for each treatment group, the interpretation of the results is now seriously thrown into question. The one group that showed a clear slowing of cognitive decline versus placebo (10 mg/kg biweekly) also has far fewer E4-positive vs. E4-negative. This difference in proportion of E4-positive could be a major factor in the apparent reduced rate of cognitive decline and confounds the ability to tell if the 10-mg/kg biweekly dose is effective. In contrast, the 10-mg/kg monthly dose group has an E4-positive/-negative ratio more comparable to that of placebo, and the effect of the drug on cognitive decline under this dosing regimen is not clearly distinguishable from that seen with placebo.”

Additionally, BAN2401 failed to meet its 12-month prespecified primary cognitive endpoints, a conclusion determined by a complex Bayesian analysis that strove to predict an 80% probability of reaching at least a 25% cognitive benefit. In December, the company announced that the study hit just a 64% probability. But because Eisai felt the numbers were moving in the right direction, it continued with the additional 6 months of treatment, as allowed for in the study design, and then reanalyzed results with a simpler and more straightforward method. This analysis concluded that 10 mg/kg infused biweekly conferred a 30% slowing of decline on the Alzheimer’s Disease Composite Score (ADCOMS), a new tool developed and promoted by Eisai, and a 47% slowing of decline on the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive subscale (ADAS-Cog). It also cleared brain amyloid in 81% of subjects and sent cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers in the right direction. CSF amyloid levels went up – to be expected if the antibody was clearing it from the brain – and CSF total tau went down, an indication of decreased neuronal injury.

Inquiries to Eisai to clarify these issues had not been returned at press time.

This is a developing story.

CHICAGO – BAN2401, a monoclonal antibody that targets soluble amyloid-beta oligomers, slowed cognitive decline by up to 47% while clearing brain amyloid in 81% of patients with mild cognitive impairment and very mild Alzheimer’s disease, a phase 2 study has shown.

At the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, Eisai, which is developing the antibody along with Biogen, touted it the study results as an important step forward in a field desperate for success. But questions remain, especially about the unequal distribution of apolipoprotein E4 (APOE4)-positive patients across the six treatment groups: BAN2401 2.5 mg/kg biweekly, 5 mg/kg monthly, 5 mg/kg biweekly, 10 mg/kg monthly, and 10 mg/kg biweekly, or placebo. This troubled some researchers, who said the mix could have biased cognitive results in the antibody’s favor. APOE4 carriers comprised about 70%-80% of every unsuccessful treatment arm in the trial, and 29% of the arm that conferred significant cognitive benefits.

“This is a big confound,” Keith Fargo, PhD, director of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, said when he saw the numbers. “An important point is that, according to the trial sponsors, for a period of time a regulatory body requested that people with the APOE4 Alzheimer’s risk gene not be included in the highest dose group, for safety reasons. Because of this, the people in the highest-dose group are different from people in the other groups on an important dimension; they were much less likely to have the APOE4 gene, which is known to be a major risk factor for cognitive decline. So it is plausible that the people on the highest dose declined differently due to genetic differences rather than due to being on the highest dose. A planned subgroup analysis will shed more light on this, and whether it reduces confidence in the overall findings. We eagerly await the results of this analysis.”

The decision to restructure the randomization was not Eisai’s, according to David Knopman, MD, chair of the Alzheimer’s Association Medical and Scientific Advisory Council.

“European regulators did not allow randomization of [some] APOE4 carriers to the highest dose,” he said in an interview. “I ultimately don’t know what it would do to the results, except make them even more difficult to justify as sufficient for registration. In general, in symptomatic Alzheimer’s dementia patients, APOE4 carriage has no substantial impact on rate of decline, but whether [APOE4] status interacted with the treatment is of course completely unknown. Bottom line: Just another feature that makes this a phase 2 study that needs to be followed by a phase 3 study with a simple design using the high dose.”

Alzheimer’s researcher Michael S. Wolfe, PhD, was more candid.

“Regardless of who made the decision and why, the data is what it is, and the question remains,” said Dr. Wolfe, the Mathias P. Mertes Professor of Medicinal Chemistry at the University of Kansas, Lawrence. “Given the numbers of E4-positive vs. E4-negative for each treatment group, the interpretation of the results is now seriously thrown into question. The one group that showed a clear slowing of cognitive decline versus placebo (10 mg/kg biweekly) also has far fewer E4-positive vs. E4-negative. This difference in proportion of E4-positive could be a major factor in the apparent reduced rate of cognitive decline and confounds the ability to tell if the 10-mg/kg biweekly dose is effective. In contrast, the 10-mg/kg monthly dose group has an E4-positive/-negative ratio more comparable to that of placebo, and the effect of the drug on cognitive decline under this dosing regimen is not clearly distinguishable from that seen with placebo.”

Additionally, BAN2401 failed to meet its 12-month prespecified primary cognitive endpoints, a conclusion determined by a complex Bayesian analysis that strove to predict an 80% probability of reaching at least a 25% cognitive benefit. In December, the company announced that the study hit just a 64% probability. But because Eisai felt the numbers were moving in the right direction, it continued with the additional 6 months of treatment, as allowed for in the study design, and then reanalyzed results with a simpler and more straightforward method. This analysis concluded that 10 mg/kg infused biweekly conferred a 30% slowing of decline on the Alzheimer’s Disease Composite Score (ADCOMS), a new tool developed and promoted by Eisai, and a 47% slowing of decline on the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive subscale (ADAS-Cog). It also cleared brain amyloid in 81% of subjects and sent cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers in the right direction. CSF amyloid levels went up – to be expected if the antibody was clearing it from the brain – and CSF total tau went down, an indication of decreased neuronal injury.

Inquiries to Eisai to clarify these issues had not been returned at press time.

This is a developing story.

REPORTING FROM AAIC 2018

Ten tips for managing patients with both heart failure and COPD

Patients with both are prone to hospital readmissions that detract from quality of life and dramatically drive up care costs.

Because the two chronic diseases spring from the same root cause and share overlapping symptoms, strategies that improve clinical outcomes in one can also benefit the other, Ravi Kalhan, MD, and R. Kannan Mutharasan, MD, wrote in CHEST Journal (doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.06.001).

“Both conditions are characterized by periods of clinical stability punctuated by episodes of exacerbation and are typified by gradual functional decline,” wrote the colleagues, both of Northwestern University, Chicago. “From a patient perspective, both conditions lead to highly overlapping patterns of symptoms, involve complicated medication regimens, and have courses highly sensitive to adherence and lifestyle modification. Therefore, disease management strategies for both conditions can be synergistic.”

The team came up with a “Top 10 list” of practical tips for reducing readmissions in patients with this challenging combination.

Diagnose accurately

An acute hospitalization is often the first time these patients pop up on the radar. This is a great time to employ spirometry to accurately diagnose COPD. It’s also appropriate to conduct a chest CT and check right heart size, diameter of the pulmonary artery, and the presence of coronary calcification. The authors noted that relatively little is known about the course of patients with combined asthma and HF in contrast to COPD and HF.

Detect admissions for exacerbations early

Check soon to find out if this is a readmission, get an acute plan going, and don’t wait to implement multidisciplinary interventions. “First, specialist involvement can occur more rapidly, allowing for faster identification of any root causes driving the HF or COPD syndromes, and allowing for more rapid institution of treatment plans to control the acute exacerbation. Second, early identification during hospitalization allows time to deploy multidisciplinary interventions, such as disease management education, social work evaluation, follow-up appointment scheduling, and coordination of home services. These interventions are less effective, and are often not implemented, if initiated toward the end of hospitalization.”

Use specialist management in the hospital

Get experts on board fast. An integrated team means a coordinated treatment plan that’s easier to follow and more effective therapeutically. Specialist care may impact rates of readmission: weight loss with diuretics; discharge doses of guideline-directed medical therapy for heart failure; and higher rates of discharge on long-acting beta-agonists, long-acting muscarinic antagonists, inhaled corticosteroids, and home supplemental oxygen.

Modify the underlying disease substrate

Heart failure is more likely to arise from a correctable pathophysiology, so find it early and treat it thoroughly – especially in younger patients. Ischemic heart disease, valvular heart disease, systemic hypertension, and pulmonary hypertension all have potential to make the HF syndrome more tractable.

Apply and intensify evidence-based therapies

Start in the hospital if possible; if not, begin upon discharge. “The order of application of these therapies can be bewildering, as many strategies for initiation and up-titration of these medications are reasonable. Not only are there long-term outcome benefits for these therapies, evidence suggests early initiation of HF therapies can reduce 30-day readmissions.”

Activate the patient and develop critical health behaviors

Medical regimens for these diseases can be complex, and they must be supported by patient engagement. “Many strategies for engaging patients in care have been tested, including teaching to goal, motivational interviewing, and teach-back methods of activation and engagement. Often these methods are time intensive. Because physician time is increasingly constrained, a team approach is particularly useful.”

Set up feedback loops

“Course correction should the patient decompensate is critically important to maintaining outpatient success. Feedback loops can allow for clinical stabilization before rehospitalization is necessary.” Self-monitoring with individually set benchmarks is critical.

Arrange an early follow-up appointment prior to discharge

About half of Medicare patients with these conditions are readmitted before they’ve even had a postdischarge follow-up appointment. Ideally this should occur within 7 days. The purpose of early follow-up is to identify and address gaps in the discharge plan of care, revise the discharge plan of care to adapt to the outpatient environment, and reinforce critical health behaviors.

Consider and address other comorbidities

Comorbidities are the rule rather than the exception and contribute to many readmissions. Get primary care on the team and enlist their help in managing these issues before they lead to an exacerbation. “Meticulous control – even perfect control were it possible – of cardiopulmonary disease would still leave patients vulnerable to significant risk of readmission from other causes.”

Consider ancillary supportive services at home

Patients may be overwhelmed by the complexity of postdischarge care. Home health assistance can help in getting patients to physical therapy, continuing patient education, and providing a home clinical assessment.

Neither of the authors had any financial disclosures.

Patients with both are prone to hospital readmissions that detract from quality of life and dramatically drive up care costs.

Because the two chronic diseases spring from the same root cause and share overlapping symptoms, strategies that improve clinical outcomes in one can also benefit the other, Ravi Kalhan, MD, and R. Kannan Mutharasan, MD, wrote in CHEST Journal (doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.06.001).

“Both conditions are characterized by periods of clinical stability punctuated by episodes of exacerbation and are typified by gradual functional decline,” wrote the colleagues, both of Northwestern University, Chicago. “From a patient perspective, both conditions lead to highly overlapping patterns of symptoms, involve complicated medication regimens, and have courses highly sensitive to adherence and lifestyle modification. Therefore, disease management strategies for both conditions can be synergistic.”

The team came up with a “Top 10 list” of practical tips for reducing readmissions in patients with this challenging combination.

Diagnose accurately

An acute hospitalization is often the first time these patients pop up on the radar. This is a great time to employ spirometry to accurately diagnose COPD. It’s also appropriate to conduct a chest CT and check right heart size, diameter of the pulmonary artery, and the presence of coronary calcification. The authors noted that relatively little is known about the course of patients with combined asthma and HF in contrast to COPD and HF.

Detect admissions for exacerbations early

Check soon to find out if this is a readmission, get an acute plan going, and don’t wait to implement multidisciplinary interventions. “First, specialist involvement can occur more rapidly, allowing for faster identification of any root causes driving the HF or COPD syndromes, and allowing for more rapid institution of treatment plans to control the acute exacerbation. Second, early identification during hospitalization allows time to deploy multidisciplinary interventions, such as disease management education, social work evaluation, follow-up appointment scheduling, and coordination of home services. These interventions are less effective, and are often not implemented, if initiated toward the end of hospitalization.”

Use specialist management in the hospital

Get experts on board fast. An integrated team means a coordinated treatment plan that’s easier to follow and more effective therapeutically. Specialist care may impact rates of readmission: weight loss with diuretics; discharge doses of guideline-directed medical therapy for heart failure; and higher rates of discharge on long-acting beta-agonists, long-acting muscarinic antagonists, inhaled corticosteroids, and home supplemental oxygen.

Modify the underlying disease substrate

Heart failure is more likely to arise from a correctable pathophysiology, so find it early and treat it thoroughly – especially in younger patients. Ischemic heart disease, valvular heart disease, systemic hypertension, and pulmonary hypertension all have potential to make the HF syndrome more tractable.

Apply and intensify evidence-based therapies

Start in the hospital if possible; if not, begin upon discharge. “The order of application of these therapies can be bewildering, as many strategies for initiation and up-titration of these medications are reasonable. Not only are there long-term outcome benefits for these therapies, evidence suggests early initiation of HF therapies can reduce 30-day readmissions.”

Activate the patient and develop critical health behaviors

Medical regimens for these diseases can be complex, and they must be supported by patient engagement. “Many strategies for engaging patients in care have been tested, including teaching to goal, motivational interviewing, and teach-back methods of activation and engagement. Often these methods are time intensive. Because physician time is increasingly constrained, a team approach is particularly useful.”

Set up feedback loops

“Course correction should the patient decompensate is critically important to maintaining outpatient success. Feedback loops can allow for clinical stabilization before rehospitalization is necessary.” Self-monitoring with individually set benchmarks is critical.

Arrange an early follow-up appointment prior to discharge

About half of Medicare patients with these conditions are readmitted before they’ve even had a postdischarge follow-up appointment. Ideally this should occur within 7 days. The purpose of early follow-up is to identify and address gaps in the discharge plan of care, revise the discharge plan of care to adapt to the outpatient environment, and reinforce critical health behaviors.

Consider and address other comorbidities

Comorbidities are the rule rather than the exception and contribute to many readmissions. Get primary care on the team and enlist their help in managing these issues before they lead to an exacerbation. “Meticulous control – even perfect control were it possible – of cardiopulmonary disease would still leave patients vulnerable to significant risk of readmission from other causes.”

Consider ancillary supportive services at home

Patients may be overwhelmed by the complexity of postdischarge care. Home health assistance can help in getting patients to physical therapy, continuing patient education, and providing a home clinical assessment.

Neither of the authors had any financial disclosures.

Patients with both are prone to hospital readmissions that detract from quality of life and dramatically drive up care costs.

Because the two chronic diseases spring from the same root cause and share overlapping symptoms, strategies that improve clinical outcomes in one can also benefit the other, Ravi Kalhan, MD, and R. Kannan Mutharasan, MD, wrote in CHEST Journal (doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.06.001).

“Both conditions are characterized by periods of clinical stability punctuated by episodes of exacerbation and are typified by gradual functional decline,” wrote the colleagues, both of Northwestern University, Chicago. “From a patient perspective, both conditions lead to highly overlapping patterns of symptoms, involve complicated medication regimens, and have courses highly sensitive to adherence and lifestyle modification. Therefore, disease management strategies for both conditions can be synergistic.”

The team came up with a “Top 10 list” of practical tips for reducing readmissions in patients with this challenging combination.

Diagnose accurately

An acute hospitalization is often the first time these patients pop up on the radar. This is a great time to employ spirometry to accurately diagnose COPD. It’s also appropriate to conduct a chest CT and check right heart size, diameter of the pulmonary artery, and the presence of coronary calcification. The authors noted that relatively little is known about the course of patients with combined asthma and HF in contrast to COPD and HF.

Detect admissions for exacerbations early

Check soon to find out if this is a readmission, get an acute plan going, and don’t wait to implement multidisciplinary interventions. “First, specialist involvement can occur more rapidly, allowing for faster identification of any root causes driving the HF or COPD syndromes, and allowing for more rapid institution of treatment plans to control the acute exacerbation. Second, early identification during hospitalization allows time to deploy multidisciplinary interventions, such as disease management education, social work evaluation, follow-up appointment scheduling, and coordination of home services. These interventions are less effective, and are often not implemented, if initiated toward the end of hospitalization.”

Use specialist management in the hospital

Get experts on board fast. An integrated team means a coordinated treatment plan that’s easier to follow and more effective therapeutically. Specialist care may impact rates of readmission: weight loss with diuretics; discharge doses of guideline-directed medical therapy for heart failure; and higher rates of discharge on long-acting beta-agonists, long-acting muscarinic antagonists, inhaled corticosteroids, and home supplemental oxygen.

Modify the underlying disease substrate

Heart failure is more likely to arise from a correctable pathophysiology, so find it early and treat it thoroughly – especially in younger patients. Ischemic heart disease, valvular heart disease, systemic hypertension, and pulmonary hypertension all have potential to make the HF syndrome more tractable.

Apply and intensify evidence-based therapies

Start in the hospital if possible; if not, begin upon discharge. “The order of application of these therapies can be bewildering, as many strategies for initiation and up-titration of these medications are reasonable. Not only are there long-term outcome benefits for these therapies, evidence suggests early initiation of HF therapies can reduce 30-day readmissions.”

Activate the patient and develop critical health behaviors

Medical regimens for these diseases can be complex, and they must be supported by patient engagement. “Many strategies for engaging patients in care have been tested, including teaching to goal, motivational interviewing, and teach-back methods of activation and engagement. Often these methods are time intensive. Because physician time is increasingly constrained, a team approach is particularly useful.”

Set up feedback loops

“Course correction should the patient decompensate is critically important to maintaining outpatient success. Feedback loops can allow for clinical stabilization before rehospitalization is necessary.” Self-monitoring with individually set benchmarks is critical.

Arrange an early follow-up appointment prior to discharge

About half of Medicare patients with these conditions are readmitted before they’ve even had a postdischarge follow-up appointment. Ideally this should occur within 7 days. The purpose of early follow-up is to identify and address gaps in the discharge plan of care, revise the discharge plan of care to adapt to the outpatient environment, and reinforce critical health behaviors.

Consider and address other comorbidities

Comorbidities are the rule rather than the exception and contribute to many readmissions. Get primary care on the team and enlist their help in managing these issues before they lead to an exacerbation. “Meticulous control – even perfect control were it possible – of cardiopulmonary disease would still leave patients vulnerable to significant risk of readmission from other causes.”

Consider ancillary supportive services at home

Patients may be overwhelmed by the complexity of postdischarge care. Home health assistance can help in getting patients to physical therapy, continuing patient education, and providing a home clinical assessment.

Neither of the authors had any financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM CHEST JOURNAL

‘Can’t believe we won! (The AGA Shark Tank)’: Building sustainable careers in clinical and translational GI research

Tell us about your recent experience at the AGA Tech Summit.

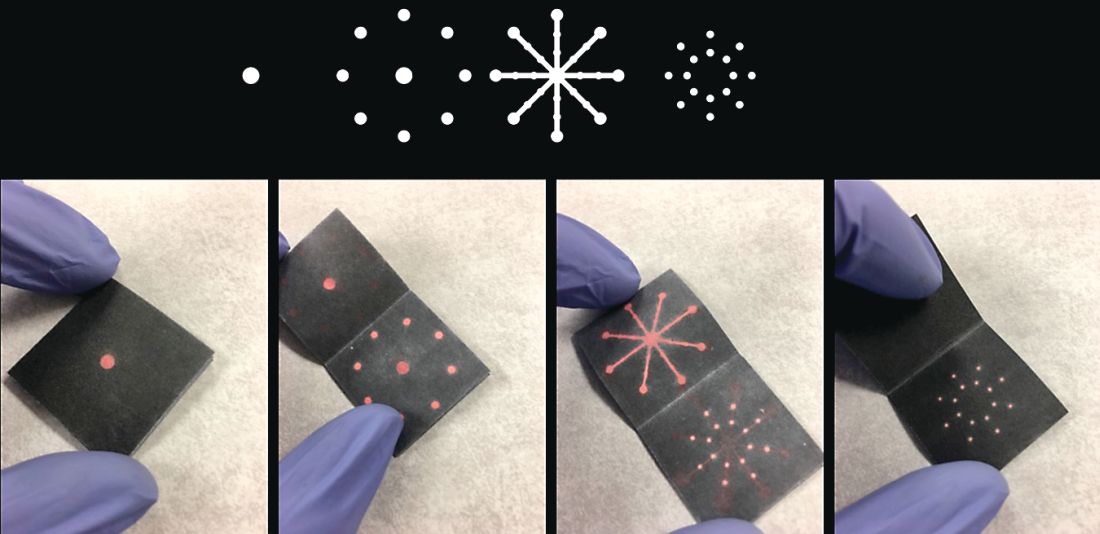

We attended our first AGA Tech Summit in Boston on March 21-23, flying between New England Nor’easter snowstorms this year. We had been selected as one of the five Shark Tank competition finalists after submitting our application and a video of our technology. We pitched a rapid paper diagnostic that we are developing to detect a multiplex of gastrointestinal pathogens. These pathogens cause infectious diarrhea and are detected from stool in 15 minutes without any instruments or electric power at the point of care (See Figure 1).

The goal is for the test to aid in diagnosis and treatment for patients in real time instead of sending stool samples to the laboratory, which could take days for the return of results. Our idea was the first to be pitched (by Dr. Kim) and it was nerve-racking to be the first presenter and watch others pitch after us. So, we were delightfully surprised that both the “sharks” and the audience picked our technology as the winner!

What led you to go into the innovation industry?

My collaborator, Dr. Henderson, had a dream to create diagnostic products that can be used in real time to diagnose and treat patients with diarrhea during the clinician-patient encounter. The product would be low cost and be run without an electrical power source, making it useful for resource-limited settings. The product would be especially helpful in rural, outbreak, and global settings where mortality from diarrhea is the highest. Approximately 525,000 children a year die of diarrheal diseases, and the elderly and immunocompromised also are significantly affected.

To realize our dream, we invented this technology through a public-private partnership called a Clinical Cooperative Research and Development Agreement between the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health, and GoDx Inc. GoDx, Inc. is a start-up company that Dr. Kim incorporated to develop and commercialize global health technologies into products. Through this partnership, we co-invented the technology, which we patented as a joint invention. We have also obtained IRB approval of a clinical protocol to test our “Stool Tool” on patient samples. Dr. Henderson is the principal investigator of this NIH clinical protocol. Last year, GoDx, Inc. was awarded a Phase 1 Small Business Innovation Research grant by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), NIH. They were recently awarded a $1.93 million Phase 2 SBIR grant from the NCATS to further develop the product; we will serve as co-PIs.

What do you enjoy most about the innovation industry?

What we enjoy the most about developing innovative products is the potential to help millions of people. It’s exhilarating to think that the discoveries we make in the lab can turn into innovative and useful new products that help save lives and improve health.

What are important factors for success in the innovation industry?

The first step is having the personal drive and vision toward an innovation. As clinicians and scientists our patients, families, and life experiences give us the drive on a daily basis as we strive to improve patient outcomes through more efficient, patient centered, less costly methods. The next step is having the training to know how to innovate. Dr. Henderson was part of a cohort trained in clinical and translational team science.1 Dr. Kim left the NIH to join his first startup company called Dxterity Diagnostics to learn product development and commercialization firsthand before starting GoDx.

A purposeful long-term commitment to innovation is the cornerstone of success in the implementation science space.2,3 Finding other innovators in your scientific space with similar values and dedication is priceless. An important aspect for someone with an innovative idea for a product is to talk to a patent lawyer or a licensing officer at the technology transfer office to discuss filing a patent. Next steps would be to find or form a company to license the technology, and develop and commercialize the product.

What are the biggest challenges to getting a new product on the market?

One of the biggest challenges for getting a new product to the market is building something that people want to buy. “Technology is the easy part” is a common mantra among bioentrepreneurs. Another mantra is “The market kills innovation.” To address this, GoDx applied for and was awarded a grant supplement to their NCATS Phase 1 SBIR grantto participate in the NIH Innovation Corps (I-Corps) program. As part of the I-Corps program GoDX conducted more than 100 interviews with potential customers and stakeholders for our product. This allowed GoDx to focus their business canvas (an evolving sketch of a business plan) and make key pivots in their customer segments and our technology in order to better achieve a “product-market” fit. While GoDx had thought of the idea from reading journals, when they met real customers and potential strategic partners, GoDx gained a real understanding of who the customers would be and the unmet needs they have. Through the coaching in this I-Corps course and the interviews, GoDx was able to develop a realistic go-to-market strategy. We highly recommend physician entrepreneurs to take part in I-Corps or other Lean Startup courses.

We are so thankful that our innovation was selected as the AGA Shark Tank winner! It garnered us lot of publicity and interest from potential investors and accelerators, and we highly recommend the AGA Tech Summit to all AGA members and GI health professionals who are interested in innovation in the GI space.4 The AGA Tech Summit is an excellent meeting that covers significant practical aspects of innovating technologies in health care including raising capital, patents, commercialization, regulatory approvals, reimbursement, and adoption. The AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology is an excellent support group that can provide guidance on the different aspects of innovation and commercialization. See you in San Francisco at the 2019 AGA Tech Summit, April 10-12!

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R44TR001912 and the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

1. Robinson GF et al. Development, implementation, and evaluation of an interprofessional course in translational research. Clin Transl Sci. 2013;6(1):50-6.

2. Nearing KA et al. Solving the puzzle of recruitment and retention: strategies for building a robust clinical and translational research workforce. Clin Transl Sci. 2015 Oct;8(5):563-7.

3. Manson SM et al. Vision, identity, and career in the clinical and translational sciences: Building upon the formative years. Clin Transl Sci. 2015 Oct;8(5):568-72.

4. Nimgaonkar A, Yock PG, Brinton TJ, et al. Gastroenterology and biodesign: contributing to the future of our specialty. Gastroenterology. 2013 Feb;144(2):258-62.

Dr. Kim is CEO of GoDx. Dr. Henderson is Investigator & Chief, Digestive Disorder Unit, Biobehavioral Branch, National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health.

Tell us about your recent experience at the AGA Tech Summit.

We attended our first AGA Tech Summit in Boston on March 21-23, flying between New England Nor’easter snowstorms this year. We had been selected as one of the five Shark Tank competition finalists after submitting our application and a video of our technology. We pitched a rapid paper diagnostic that we are developing to detect a multiplex of gastrointestinal pathogens. These pathogens cause infectious diarrhea and are detected from stool in 15 minutes without any instruments or electric power at the point of care (See Figure 1).

The goal is for the test to aid in diagnosis and treatment for patients in real time instead of sending stool samples to the laboratory, which could take days for the return of results. Our idea was the first to be pitched (by Dr. Kim) and it was nerve-racking to be the first presenter and watch others pitch after us. So, we were delightfully surprised that both the “sharks” and the audience picked our technology as the winner!

What led you to go into the innovation industry?

My collaborator, Dr. Henderson, had a dream to create diagnostic products that can be used in real time to diagnose and treat patients with diarrhea during the clinician-patient encounter. The product would be low cost and be run without an electrical power source, making it useful for resource-limited settings. The product would be especially helpful in rural, outbreak, and global settings where mortality from diarrhea is the highest. Approximately 525,000 children a year die of diarrheal diseases, and the elderly and immunocompromised also are significantly affected.

To realize our dream, we invented this technology through a public-private partnership called a Clinical Cooperative Research and Development Agreement between the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health, and GoDx Inc. GoDx, Inc. is a start-up company that Dr. Kim incorporated to develop and commercialize global health technologies into products. Through this partnership, we co-invented the technology, which we patented as a joint invention. We have also obtained IRB approval of a clinical protocol to test our “Stool Tool” on patient samples. Dr. Henderson is the principal investigator of this NIH clinical protocol. Last year, GoDx, Inc. was awarded a Phase 1 Small Business Innovation Research grant by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), NIH. They were recently awarded a $1.93 million Phase 2 SBIR grant from the NCATS to further develop the product; we will serve as co-PIs.

What do you enjoy most about the innovation industry?

What we enjoy the most about developing innovative products is the potential to help millions of people. It’s exhilarating to think that the discoveries we make in the lab can turn into innovative and useful new products that help save lives and improve health.

What are important factors for success in the innovation industry?

The first step is having the personal drive and vision toward an innovation. As clinicians and scientists our patients, families, and life experiences give us the drive on a daily basis as we strive to improve patient outcomes through more efficient, patient centered, less costly methods. The next step is having the training to know how to innovate. Dr. Henderson was part of a cohort trained in clinical and translational team science.1 Dr. Kim left the NIH to join his first startup company called Dxterity Diagnostics to learn product development and commercialization firsthand before starting GoDx.

A purposeful long-term commitment to innovation is the cornerstone of success in the implementation science space.2,3 Finding other innovators in your scientific space with similar values and dedication is priceless. An important aspect for someone with an innovative idea for a product is to talk to a patent lawyer or a licensing officer at the technology transfer office to discuss filing a patent. Next steps would be to find or form a company to license the technology, and develop and commercialize the product.

What are the biggest challenges to getting a new product on the market?

One of the biggest challenges for getting a new product to the market is building something that people want to buy. “Technology is the easy part” is a common mantra among bioentrepreneurs. Another mantra is “The market kills innovation.” To address this, GoDx applied for and was awarded a grant supplement to their NCATS Phase 1 SBIR grantto participate in the NIH Innovation Corps (I-Corps) program. As part of the I-Corps program GoDX conducted more than 100 interviews with potential customers and stakeholders for our product. This allowed GoDx to focus their business canvas (an evolving sketch of a business plan) and make key pivots in their customer segments and our technology in order to better achieve a “product-market” fit. While GoDx had thought of the idea from reading journals, when they met real customers and potential strategic partners, GoDx gained a real understanding of who the customers would be and the unmet needs they have. Through the coaching in this I-Corps course and the interviews, GoDx was able to develop a realistic go-to-market strategy. We highly recommend physician entrepreneurs to take part in I-Corps or other Lean Startup courses.

We are so thankful that our innovation was selected as the AGA Shark Tank winner! It garnered us lot of publicity and interest from potential investors and accelerators, and we highly recommend the AGA Tech Summit to all AGA members and GI health professionals who are interested in innovation in the GI space.4 The AGA Tech Summit is an excellent meeting that covers significant practical aspects of innovating technologies in health care including raising capital, patents, commercialization, regulatory approvals, reimbursement, and adoption. The AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology is an excellent support group that can provide guidance on the different aspects of innovation and commercialization. See you in San Francisco at the 2019 AGA Tech Summit, April 10-12!

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R44TR001912 and the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

1. Robinson GF et al. Development, implementation, and evaluation of an interprofessional course in translational research. Clin Transl Sci. 2013;6(1):50-6.

2. Nearing KA et al. Solving the puzzle of recruitment and retention: strategies for building a robust clinical and translational research workforce. Clin Transl Sci. 2015 Oct;8(5):563-7.

3. Manson SM et al. Vision, identity, and career in the clinical and translational sciences: Building upon the formative years. Clin Transl Sci. 2015 Oct;8(5):568-72.

4. Nimgaonkar A, Yock PG, Brinton TJ, et al. Gastroenterology and biodesign: contributing to the future of our specialty. Gastroenterology. 2013 Feb;144(2):258-62.

Dr. Kim is CEO of GoDx. Dr. Henderson is Investigator & Chief, Digestive Disorder Unit, Biobehavioral Branch, National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health.

Tell us about your recent experience at the AGA Tech Summit.

We attended our first AGA Tech Summit in Boston on March 21-23, flying between New England Nor’easter snowstorms this year. We had been selected as one of the five Shark Tank competition finalists after submitting our application and a video of our technology. We pitched a rapid paper diagnostic that we are developing to detect a multiplex of gastrointestinal pathogens. These pathogens cause infectious diarrhea and are detected from stool in 15 minutes without any instruments or electric power at the point of care (See Figure 1).

The goal is for the test to aid in diagnosis and treatment for patients in real time instead of sending stool samples to the laboratory, which could take days for the return of results. Our idea was the first to be pitched (by Dr. Kim) and it was nerve-racking to be the first presenter and watch others pitch after us. So, we were delightfully surprised that both the “sharks” and the audience picked our technology as the winner!

What led you to go into the innovation industry?

My collaborator, Dr. Henderson, had a dream to create diagnostic products that can be used in real time to diagnose and treat patients with diarrhea during the clinician-patient encounter. The product would be low cost and be run without an electrical power source, making it useful for resource-limited settings. The product would be especially helpful in rural, outbreak, and global settings where mortality from diarrhea is the highest. Approximately 525,000 children a year die of diarrheal diseases, and the elderly and immunocompromised also are significantly affected.

To realize our dream, we invented this technology through a public-private partnership called a Clinical Cooperative Research and Development Agreement between the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health, and GoDx Inc. GoDx, Inc. is a start-up company that Dr. Kim incorporated to develop and commercialize global health technologies into products. Through this partnership, we co-invented the technology, which we patented as a joint invention. We have also obtained IRB approval of a clinical protocol to test our “Stool Tool” on patient samples. Dr. Henderson is the principal investigator of this NIH clinical protocol. Last year, GoDx, Inc. was awarded a Phase 1 Small Business Innovation Research grant by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), NIH. They were recently awarded a $1.93 million Phase 2 SBIR grant from the NCATS to further develop the product; we will serve as co-PIs.

What do you enjoy most about the innovation industry?

What we enjoy the most about developing innovative products is the potential to help millions of people. It’s exhilarating to think that the discoveries we make in the lab can turn into innovative and useful new products that help save lives and improve health.

What are important factors for success in the innovation industry?

The first step is having the personal drive and vision toward an innovation. As clinicians and scientists our patients, families, and life experiences give us the drive on a daily basis as we strive to improve patient outcomes through more efficient, patient centered, less costly methods. The next step is having the training to know how to innovate. Dr. Henderson was part of a cohort trained in clinical and translational team science.1 Dr. Kim left the NIH to join his first startup company called Dxterity Diagnostics to learn product development and commercialization firsthand before starting GoDx.

A purposeful long-term commitment to innovation is the cornerstone of success in the implementation science space.2,3 Finding other innovators in your scientific space with similar values and dedication is priceless. An important aspect for someone with an innovative idea for a product is to talk to a patent lawyer or a licensing officer at the technology transfer office to discuss filing a patent. Next steps would be to find or form a company to license the technology, and develop and commercialize the product.

What are the biggest challenges to getting a new product on the market?

One of the biggest challenges for getting a new product to the market is building something that people want to buy. “Technology is the easy part” is a common mantra among bioentrepreneurs. Another mantra is “The market kills innovation.” To address this, GoDx applied for and was awarded a grant supplement to their NCATS Phase 1 SBIR grantto participate in the NIH Innovation Corps (I-Corps) program. As part of the I-Corps program GoDX conducted more than 100 interviews with potential customers and stakeholders for our product. This allowed GoDx to focus their business canvas (an evolving sketch of a business plan) and make key pivots in their customer segments and our technology in order to better achieve a “product-market” fit. While GoDx had thought of the idea from reading journals, when they met real customers and potential strategic partners, GoDx gained a real understanding of who the customers would be and the unmet needs they have. Through the coaching in this I-Corps course and the interviews, GoDx was able to develop a realistic go-to-market strategy. We highly recommend physician entrepreneurs to take part in I-Corps or other Lean Startup courses.

We are so thankful that our innovation was selected as the AGA Shark Tank winner! It garnered us lot of publicity and interest from potential investors and accelerators, and we highly recommend the AGA Tech Summit to all AGA members and GI health professionals who are interested in innovation in the GI space.4 The AGA Tech Summit is an excellent meeting that covers significant practical aspects of innovating technologies in health care including raising capital, patents, commercialization, regulatory approvals, reimbursement, and adoption. The AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology is an excellent support group that can provide guidance on the different aspects of innovation and commercialization. See you in San Francisco at the 2019 AGA Tech Summit, April 10-12!

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R44TR001912 and the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

1. Robinson GF et al. Development, implementation, and evaluation of an interprofessional course in translational research. Clin Transl Sci. 2013;6(1):50-6.

2. Nearing KA et al. Solving the puzzle of recruitment and retention: strategies for building a robust clinical and translational research workforce. Clin Transl Sci. 2015 Oct;8(5):563-7.

3. Manson SM et al. Vision, identity, and career in the clinical and translational sciences: Building upon the formative years. Clin Transl Sci. 2015 Oct;8(5):568-72.

4. Nimgaonkar A, Yock PG, Brinton TJ, et al. Gastroenterology and biodesign: contributing to the future of our specialty. Gastroenterology. 2013 Feb;144(2):258-62.

Dr. Kim is CEO of GoDx. Dr. Henderson is Investigator & Chief, Digestive Disorder Unit, Biobehavioral Branch, National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health.

Calendar

For more information about upcoming events and award deadlines, please visit http://www.gastro.org/education and http://www.gastro.org/research-funding.

UPCOMING EVENTS

Aug. 15-16; Sept. 19-20; Oct. 10-11, 2018

Two-Day, In-Depth Coding and Billing Seminar

Become a certified GI coder with a two-day, in-depth training course provided by McVey Associates, Inc.

Baltimore, MD (8/15-8/16); Atlanta, GA (9/19-9/20); Las Vegas, NV (10/10-10/11)

Aug. 18-19, 2018

James W. Freston Conference: Obesity and Metabolic Disease — Integrating New Paradigms in Pathophysiology to Advance Treatment

Collaborate with researchers and clinicians to help advance obesity treatment and enhance the continuum of obesity care.

Arlington, VA

Sept. 28, 2018

Partners in Value

Join leaders from AGA, DHPA, and GI trailblazers from across the country for an in-depth look at how your practice can develop and implement strategies to thrive in the changing business of health care, and address the demands of value-based care.

Dallas, TX

Feb. 7–9, 2019

Crohn’s & Colitis Congress™

Expand your knowledge, network with IBD leaders, spark innovative research and get inspired to improve patient care.

Las Vegas, NV

AWARDS APPLICATION DEADLINES

AGA-Allergan Foundation Pilot Research Award in Irritable Bowel Syndrome

This award provides $30,000 for one year to an investigator at any career stage researching the pathophysiology and/or treatment of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Application Deadline: Sept. 7, 2018

AGA-Allergan Foundation Pilot Research Award in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

This award provides $30,000 for one year to an investigator at any career stage researching the pathophysiology and/or treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

Application Deadline: Sept. 7, 2018

AGA-Boston Scientific Technology and Innovation Pilot Research Award

This award provides $30,000 for one year to early career and established investigators working in gastroenterology, hepatology or related areas focused on endoscopic technology and innovation.

Application Deadline: Sept. 7, 2018

AGA-Pfizer Young Investigator Pilot Research Award in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

This award provides $30,000 for one year to recipients at any career stage researching new directions focused on improving the diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Application Deadline: Sept. 7, 2018

AGA-Rome Foundation Functional GI and Motility Disorders Pilot Research Award

This one-year, $30,000 research grant is offered to a recipient at any career stage to support pilot research projects pertaining to functional GI and motility disorders. This award is jointly sponsored by AGA and the Rome Foundation.

Application Deadline: Sept. 7, 2018

AGA-Medtronic Research and Development Pilot Award in Technology

This research initiative grant for $30,000 for 1 year is offered to investigators to support the research and development of novel devices or technologies that will potentially impact the diagnosis or treatment of digestive disease.

Application Deadline: Sept. 7, 2018

AGA-Elsevier Pilot Research Award