User login

Characterizing Counterfeit Dermatologic Devices Sold on Popular E-commerce Websites

To the Editor:

Approved medical devices on the market are substantial capital investments for practitioners. E-commerce websites, such as Alibaba.com (https://www.alibaba.com/) and DHgate.com (https://www.dhgate.com/), sell sham medical devices at a fraction of the cost of authentic products, with sellers often echoing the same treatment claims as legitimate devices that have been cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

In dermatology, devices claiming to perform cryolipolysis, laser skin resurfacing, radiofrequency skin tightening, and more exist on e-commerce websites. These counterfeit medical devices might differ from legitimate devices in ways that affect patient safety and treatment efficacy.1,2 The degree of difference between counterfeit and legitimate devices remains unknown, and potential harm from so-called knockoff devices needs to be critically examined by providers.

In this exploratory study, we characterize counterfeit listings of devices commonly used in dermatology. Using the trademark name of devices as the key terms, we searched Alibaba.com and DHgate.com for listings of counterfeit products. We recorded the total number of listings; the listing name, catalog number, and unit price; and claims of FDA certification. Characteristics of counterfeit listings were summarized using standard descriptive statistics in Microsoft Excel. Continuous variables were summarized with means and ranges.

Six medical devices that had been cleared by the FDA between 2002 and 2012 for use in dermatology were explored, including systems for picosecond and fractionated lasers, monopolar and bipolar radiofrequency skin tightening, cryolipolysis, and nonablative radiofrequency skin resurfacing. Our search of these 6 representative dermatologic devices revealed 47,055 counterfeit product listings on Alibaba.com and DHgate.com. Upon searching these popular e-commerce websites using the device name as the search term, the number of listings varied considerably between the 2 e-commerce websites for the same device and from device to device on the same e-commerce website. On Alibaba.com, the greatest number of listings resulted for picosecond laser (23,622 listings), fractionated laser (15,269), and radiofrequency skin tightening devices (3555); cryolipolysis and nonablative radiofrequency resurfacing devices had notably fewer listings (35 and 38, respectively). On DHGate.com, a similar trend was noted with the most numerous listings for picosecond and fractionated laser systems (2429 and 1345, respectively).

Among the first 10 listings of products on Alibaba.com and DHgate.com for these 6 devices, 10.7% (11 of 103) had advertised claims of FDA clearance on the listing page. Of 103 counterfeit products, China was the country of origin for 100; South Korea for 2; and Thailand for 1. Unit pricing was heterogeneous between the 2 e-commerce websites for the counterfeit listings; pricing for duplicate fractionated laser systems was particularly dissimilar, with an average price on Alibab.com of US $8105.80 and an average price on DHgate.com of US $3409.14. Even on the same e-commerce website, the range of unit pricing differed greatly for dermatologic devices. For example, among the first 10 listings on Alibaba.com for a fractionated laser system, the price ranged from US $2300 to US $32,000.

Counterfeit medical devices are on the rise in dermatology.1,3 Although devices such as radiofrequency and laser systems had thousands of knockoff listings on 2 e-commerce websites, other devices, such as cryolipolysis and body contouring systems, had fewer listings, suggesting heterogeneity in the prevalence of different counterfeit dermatologic devices on the market.

The varied pricing of the top 10 listings for each product and spurious claims of FDA clearance for some listings highlight the lack of regulatory authority over consistent product information on e-commerce websites. Furthermore, differences between characteristics of counterfeit device listings can impede efforts to trace suppliers and increase the opacity of counterfeit purchasing.

Three criteria have been proposed for a device to be considered counterfeit3:

• The device has no proven safety or efficacy among consumers. For example, the substantial threat of copycat devices in dermatology has been demonstrated by reports of burns caused by fake cryolipolysis devices.2

• The device violates patent rights or copy trademarks. Due to the regional nature of intellectual property rights, country-specific filings of patents and trademarks are required if protections are sought internationally. In this study, counterfeit devices originated in China, South Korea, and Thailand, where patent and trademark protections for the original devices do not extend.

• The device is falsely claimed to have been cleared by the FDA or other clinical regulatory authorities. Legitimate medical devices are subject to rounds of safety and compatibility testing using standards set by regulatory bodies, such as the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, the International Organization of Standardization, and the International Electrotechnical Commission. Compliance with these safety standards is lost, however, among unregulated internet sales of medical devices. Our search revealed that 10.7% of the top 10 counterfeit device listings for each product explicitly mentioned FDA clearance in the product description. Among the thousands of listings on e-commerce sites, even a fraction that make spurious FDA-clearance claims can mislead consumers.

The issue of counterfeit medical devices has not gone unrecognized globally. In 2013, the World Health Organization created the Global Surveillance and Monitoring System to unify international efforts for reporting substandard, unlicensed, or falsified medical products.4 Although universal monitoring systems can improve detection of counterfeit products, we highlight the alarming continuing ease of purchasing counterfeit dermatologic devices through e-commerce websites. Due to the widespread nature of counterfeiting across all domains of medicine, the onus of curbing counterfeit dermatologic devices might be on dermatology providers to recognize and report such occurrences.

This exploration of counterfeit dermatologic devices revealed a lack of consistency throughout product listings on 2 popular e-commerce websites, Alibaba.com and DHgate.com. Given the alarming availability of these devices on the internet, practitioners should approach the purchase of any device with concern about counterfeiting. Future avenues of study might explore the prevalence of counterfeit devices used in dermatology practices and offer insight on regulation and consumer safety efforts.

- Wang JV, Zachary CB, Saedi N. Counterfeit esthetic devices and patient safety in dermatology. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:396-397. doi:10.1111/jocd.12526

- Biesman BS, Patel N. Physician alert: beware of counterfeit medical devices. Lasers Surg Med. 2014;46:528‐530. doi:10.1002/lsm.22275

- Stevens WG, Spring MA, Macias LH. Counterfeit medical devices: the money you save up front will cost you big in the end. Aesthet Surg J. 2014;34:786‐788. doi:10.1177/1090820X14529960

- Pisani E. WHO Global Surveillance and Monitoring System for Substandard and Falsified Medical Products. World Health Organization; 2017. Accessed November 21, 2021. https://www.who.int/medicines/regulation/ssffc/publications/GSMSreport_EN.pdf?ua=1

To the Editor:

Approved medical devices on the market are substantial capital investments for practitioners. E-commerce websites, such as Alibaba.com (https://www.alibaba.com/) and DHgate.com (https://www.dhgate.com/), sell sham medical devices at a fraction of the cost of authentic products, with sellers often echoing the same treatment claims as legitimate devices that have been cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

In dermatology, devices claiming to perform cryolipolysis, laser skin resurfacing, radiofrequency skin tightening, and more exist on e-commerce websites. These counterfeit medical devices might differ from legitimate devices in ways that affect patient safety and treatment efficacy.1,2 The degree of difference between counterfeit and legitimate devices remains unknown, and potential harm from so-called knockoff devices needs to be critically examined by providers.

In this exploratory study, we characterize counterfeit listings of devices commonly used in dermatology. Using the trademark name of devices as the key terms, we searched Alibaba.com and DHgate.com for listings of counterfeit products. We recorded the total number of listings; the listing name, catalog number, and unit price; and claims of FDA certification. Characteristics of counterfeit listings were summarized using standard descriptive statistics in Microsoft Excel. Continuous variables were summarized with means and ranges.

Six medical devices that had been cleared by the FDA between 2002 and 2012 for use in dermatology were explored, including systems for picosecond and fractionated lasers, monopolar and bipolar radiofrequency skin tightening, cryolipolysis, and nonablative radiofrequency skin resurfacing. Our search of these 6 representative dermatologic devices revealed 47,055 counterfeit product listings on Alibaba.com and DHgate.com. Upon searching these popular e-commerce websites using the device name as the search term, the number of listings varied considerably between the 2 e-commerce websites for the same device and from device to device on the same e-commerce website. On Alibaba.com, the greatest number of listings resulted for picosecond laser (23,622 listings), fractionated laser (15,269), and radiofrequency skin tightening devices (3555); cryolipolysis and nonablative radiofrequency resurfacing devices had notably fewer listings (35 and 38, respectively). On DHGate.com, a similar trend was noted with the most numerous listings for picosecond and fractionated laser systems (2429 and 1345, respectively).

Among the first 10 listings of products on Alibaba.com and DHgate.com for these 6 devices, 10.7% (11 of 103) had advertised claims of FDA clearance on the listing page. Of 103 counterfeit products, China was the country of origin for 100; South Korea for 2; and Thailand for 1. Unit pricing was heterogeneous between the 2 e-commerce websites for the counterfeit listings; pricing for duplicate fractionated laser systems was particularly dissimilar, with an average price on Alibab.com of US $8105.80 and an average price on DHgate.com of US $3409.14. Even on the same e-commerce website, the range of unit pricing differed greatly for dermatologic devices. For example, among the first 10 listings on Alibaba.com for a fractionated laser system, the price ranged from US $2300 to US $32,000.

Counterfeit medical devices are on the rise in dermatology.1,3 Although devices such as radiofrequency and laser systems had thousands of knockoff listings on 2 e-commerce websites, other devices, such as cryolipolysis and body contouring systems, had fewer listings, suggesting heterogeneity in the prevalence of different counterfeit dermatologic devices on the market.

The varied pricing of the top 10 listings for each product and spurious claims of FDA clearance for some listings highlight the lack of regulatory authority over consistent product information on e-commerce websites. Furthermore, differences between characteristics of counterfeit device listings can impede efforts to trace suppliers and increase the opacity of counterfeit purchasing.

Three criteria have been proposed for a device to be considered counterfeit3:

• The device has no proven safety or efficacy among consumers. For example, the substantial threat of copycat devices in dermatology has been demonstrated by reports of burns caused by fake cryolipolysis devices.2

• The device violates patent rights or copy trademarks. Due to the regional nature of intellectual property rights, country-specific filings of patents and trademarks are required if protections are sought internationally. In this study, counterfeit devices originated in China, South Korea, and Thailand, where patent and trademark protections for the original devices do not extend.

• The device is falsely claimed to have been cleared by the FDA or other clinical regulatory authorities. Legitimate medical devices are subject to rounds of safety and compatibility testing using standards set by regulatory bodies, such as the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, the International Organization of Standardization, and the International Electrotechnical Commission. Compliance with these safety standards is lost, however, among unregulated internet sales of medical devices. Our search revealed that 10.7% of the top 10 counterfeit device listings for each product explicitly mentioned FDA clearance in the product description. Among the thousands of listings on e-commerce sites, even a fraction that make spurious FDA-clearance claims can mislead consumers.

The issue of counterfeit medical devices has not gone unrecognized globally. In 2013, the World Health Organization created the Global Surveillance and Monitoring System to unify international efforts for reporting substandard, unlicensed, or falsified medical products.4 Although universal monitoring systems can improve detection of counterfeit products, we highlight the alarming continuing ease of purchasing counterfeit dermatologic devices through e-commerce websites. Due to the widespread nature of counterfeiting across all domains of medicine, the onus of curbing counterfeit dermatologic devices might be on dermatology providers to recognize and report such occurrences.

This exploration of counterfeit dermatologic devices revealed a lack of consistency throughout product listings on 2 popular e-commerce websites, Alibaba.com and DHgate.com. Given the alarming availability of these devices on the internet, practitioners should approach the purchase of any device with concern about counterfeiting. Future avenues of study might explore the prevalence of counterfeit devices used in dermatology practices and offer insight on regulation and consumer safety efforts.

To the Editor:

Approved medical devices on the market are substantial capital investments for practitioners. E-commerce websites, such as Alibaba.com (https://www.alibaba.com/) and DHgate.com (https://www.dhgate.com/), sell sham medical devices at a fraction of the cost of authentic products, with sellers often echoing the same treatment claims as legitimate devices that have been cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

In dermatology, devices claiming to perform cryolipolysis, laser skin resurfacing, radiofrequency skin tightening, and more exist on e-commerce websites. These counterfeit medical devices might differ from legitimate devices in ways that affect patient safety and treatment efficacy.1,2 The degree of difference between counterfeit and legitimate devices remains unknown, and potential harm from so-called knockoff devices needs to be critically examined by providers.

In this exploratory study, we characterize counterfeit listings of devices commonly used in dermatology. Using the trademark name of devices as the key terms, we searched Alibaba.com and DHgate.com for listings of counterfeit products. We recorded the total number of listings; the listing name, catalog number, and unit price; and claims of FDA certification. Characteristics of counterfeit listings were summarized using standard descriptive statistics in Microsoft Excel. Continuous variables were summarized with means and ranges.

Six medical devices that had been cleared by the FDA between 2002 and 2012 for use in dermatology were explored, including systems for picosecond and fractionated lasers, monopolar and bipolar radiofrequency skin tightening, cryolipolysis, and nonablative radiofrequency skin resurfacing. Our search of these 6 representative dermatologic devices revealed 47,055 counterfeit product listings on Alibaba.com and DHgate.com. Upon searching these popular e-commerce websites using the device name as the search term, the number of listings varied considerably between the 2 e-commerce websites for the same device and from device to device on the same e-commerce website. On Alibaba.com, the greatest number of listings resulted for picosecond laser (23,622 listings), fractionated laser (15,269), and radiofrequency skin tightening devices (3555); cryolipolysis and nonablative radiofrequency resurfacing devices had notably fewer listings (35 and 38, respectively). On DHGate.com, a similar trend was noted with the most numerous listings for picosecond and fractionated laser systems (2429 and 1345, respectively).

Among the first 10 listings of products on Alibaba.com and DHgate.com for these 6 devices, 10.7% (11 of 103) had advertised claims of FDA clearance on the listing page. Of 103 counterfeit products, China was the country of origin for 100; South Korea for 2; and Thailand for 1. Unit pricing was heterogeneous between the 2 e-commerce websites for the counterfeit listings; pricing for duplicate fractionated laser systems was particularly dissimilar, with an average price on Alibab.com of US $8105.80 and an average price on DHgate.com of US $3409.14. Even on the same e-commerce website, the range of unit pricing differed greatly for dermatologic devices. For example, among the first 10 listings on Alibaba.com for a fractionated laser system, the price ranged from US $2300 to US $32,000.

Counterfeit medical devices are on the rise in dermatology.1,3 Although devices such as radiofrequency and laser systems had thousands of knockoff listings on 2 e-commerce websites, other devices, such as cryolipolysis and body contouring systems, had fewer listings, suggesting heterogeneity in the prevalence of different counterfeit dermatologic devices on the market.

The varied pricing of the top 10 listings for each product and spurious claims of FDA clearance for some listings highlight the lack of regulatory authority over consistent product information on e-commerce websites. Furthermore, differences between characteristics of counterfeit device listings can impede efforts to trace suppliers and increase the opacity of counterfeit purchasing.

Three criteria have been proposed for a device to be considered counterfeit3:

• The device has no proven safety or efficacy among consumers. For example, the substantial threat of copycat devices in dermatology has been demonstrated by reports of burns caused by fake cryolipolysis devices.2

• The device violates patent rights or copy trademarks. Due to the regional nature of intellectual property rights, country-specific filings of patents and trademarks are required if protections are sought internationally. In this study, counterfeit devices originated in China, South Korea, and Thailand, where patent and trademark protections for the original devices do not extend.

• The device is falsely claimed to have been cleared by the FDA or other clinical regulatory authorities. Legitimate medical devices are subject to rounds of safety and compatibility testing using standards set by regulatory bodies, such as the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, the International Organization of Standardization, and the International Electrotechnical Commission. Compliance with these safety standards is lost, however, among unregulated internet sales of medical devices. Our search revealed that 10.7% of the top 10 counterfeit device listings for each product explicitly mentioned FDA clearance in the product description. Among the thousands of listings on e-commerce sites, even a fraction that make spurious FDA-clearance claims can mislead consumers.

The issue of counterfeit medical devices has not gone unrecognized globally. In 2013, the World Health Organization created the Global Surveillance and Monitoring System to unify international efforts for reporting substandard, unlicensed, or falsified medical products.4 Although universal monitoring systems can improve detection of counterfeit products, we highlight the alarming continuing ease of purchasing counterfeit dermatologic devices through e-commerce websites. Due to the widespread nature of counterfeiting across all domains of medicine, the onus of curbing counterfeit dermatologic devices might be on dermatology providers to recognize and report such occurrences.

This exploration of counterfeit dermatologic devices revealed a lack of consistency throughout product listings on 2 popular e-commerce websites, Alibaba.com and DHgate.com. Given the alarming availability of these devices on the internet, practitioners should approach the purchase of any device with concern about counterfeiting. Future avenues of study might explore the prevalence of counterfeit devices used in dermatology practices and offer insight on regulation and consumer safety efforts.

- Wang JV, Zachary CB, Saedi N. Counterfeit esthetic devices and patient safety in dermatology. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:396-397. doi:10.1111/jocd.12526

- Biesman BS, Patel N. Physician alert: beware of counterfeit medical devices. Lasers Surg Med. 2014;46:528‐530. doi:10.1002/lsm.22275

- Stevens WG, Spring MA, Macias LH. Counterfeit medical devices: the money you save up front will cost you big in the end. Aesthet Surg J. 2014;34:786‐788. doi:10.1177/1090820X14529960

- Pisani E. WHO Global Surveillance and Monitoring System for Substandard and Falsified Medical Products. World Health Organization; 2017. Accessed November 21, 2021. https://www.who.int/medicines/regulation/ssffc/publications/GSMSreport_EN.pdf?ua=1

- Wang JV, Zachary CB, Saedi N. Counterfeit esthetic devices and patient safety in dermatology. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:396-397. doi:10.1111/jocd.12526

- Biesman BS, Patel N. Physician alert: beware of counterfeit medical devices. Lasers Surg Med. 2014;46:528‐530. doi:10.1002/lsm.22275

- Stevens WG, Spring MA, Macias LH. Counterfeit medical devices: the money you save up front will cost you big in the end. Aesthet Surg J. 2014;34:786‐788. doi:10.1177/1090820X14529960

- Pisani E. WHO Global Surveillance and Monitoring System for Substandard and Falsified Medical Products. World Health Organization; 2017. Accessed November 21, 2021. https://www.who.int/medicines/regulation/ssffc/publications/GSMSreport_EN.pdf?ua=1

Practice Points

- Among thousands of counterfeit dermatologic listings, there is great heterogeneity in the number of listings per different subtypes of dermatologic devices, device descriptions, and unit pricing, along with false claims of US Food and Drug Administration clearance.

- Given the prevalence of counterfeit medical devices readily available for purchase online, dermatology practitioners should be wary of the authenticity of any medical device purchased for clinical use.

Risk Stratification for Cellulitis Versus Noncellulitic Conditions of the Lower Extremity: A Retrospective Review of the NEW HAvUN Criteria

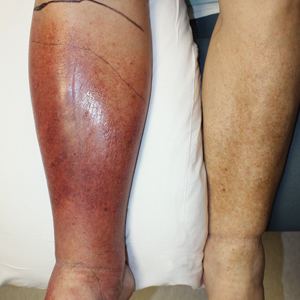

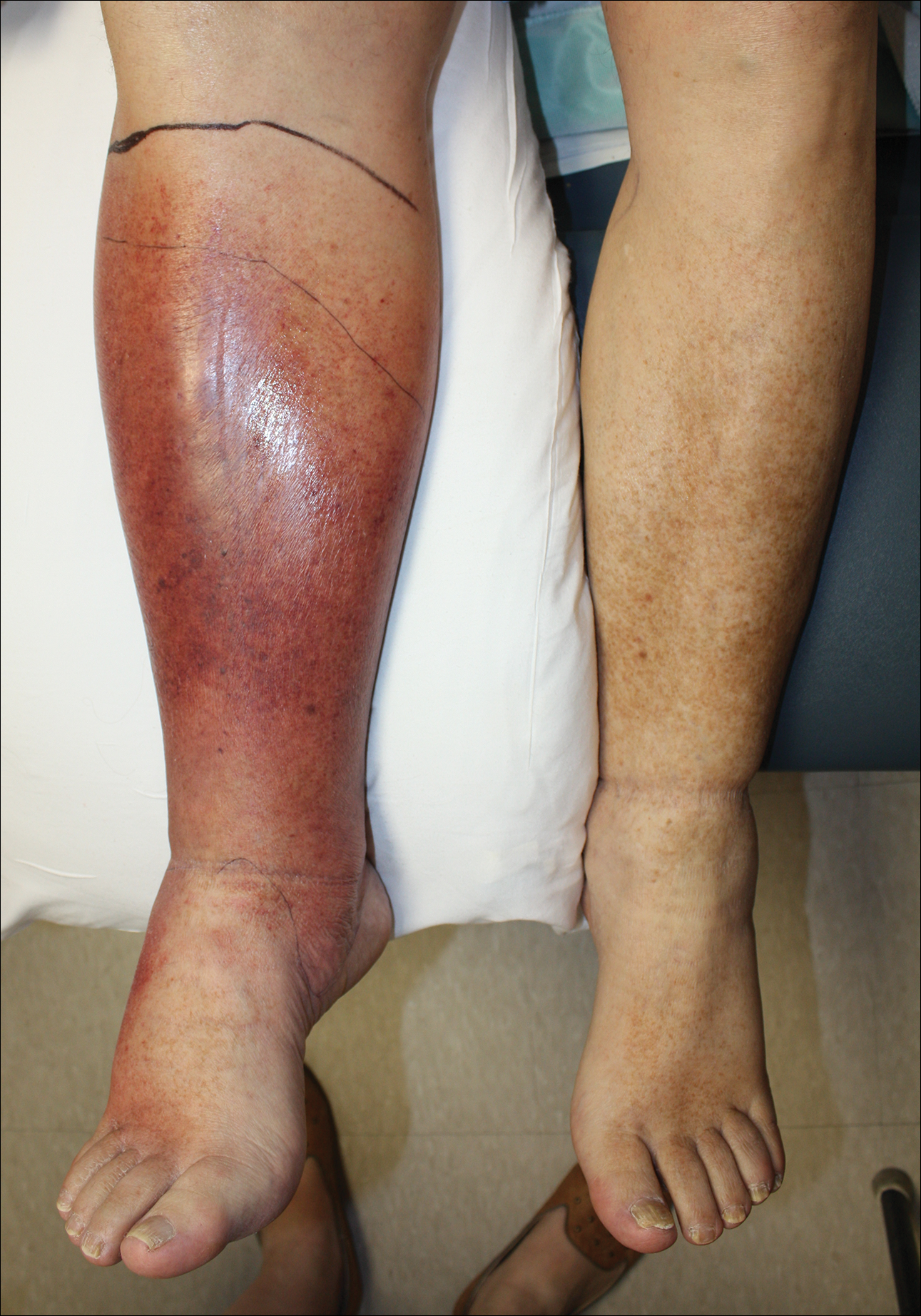

Cellulitis is defined as an acute or subacute, bacterial-induced inflammation of subcutaneous tissue that can extend superficially. The inciting incident often is assumed to be invasion of bacteria through loose connective tissue.1 Although cellulitis is bacterial in origin, it often is difficult to culture the offending microorganism from biopsy sites, swabs, or blood. Erythema, fever, induration, and tenderness are largely seen as clinical manifestations. Moderate and severe cases may be accompanied by fever, malaise, and leukocytosis. The lower extremity is the most common location of involvement (Figure 1), and usually a wound, ulcer, or interdigital superficial infection can be identified and implicated as the source of entry.

Effective treatment of cellulitis is necessary because complications such as abscesses, underlying fascia or muscle involvement, and septicemia can develop, leading to poor outcomes. Antibiotics should be administered intravenously in patients with suspected fascial involvement, septicemia, or dermal necrosis, or in those with an immunological comorbidity.2

The differential diagnosis of lower extremity cellulitis is wide due to the existence of several mimicking dermatologic conditions. These so-called pseudocellulitis conditions include stasis dermatitis, venous ulceration, acute lipodermatosclerosis, pigmented purpura, vasculopathy, contact dermatitis, adverse medication reaction, and arthropod bite. Stasis dermatitis and lipodermatosclerosis, both arising from venous insufficiency, are by far 2 of the most common skin conditions that imitate cellulitis.

Stasis dermatitis is a common condition in the United States and Europe, usually manifesting as a pigmented purpuric dermatosis on anterior tibial surfaces, around the ankle, or overlying dependent varicosities. Skin changes can include hyperpigmentation, edema, mild scaling, eczematous patches, and even ulceration.3

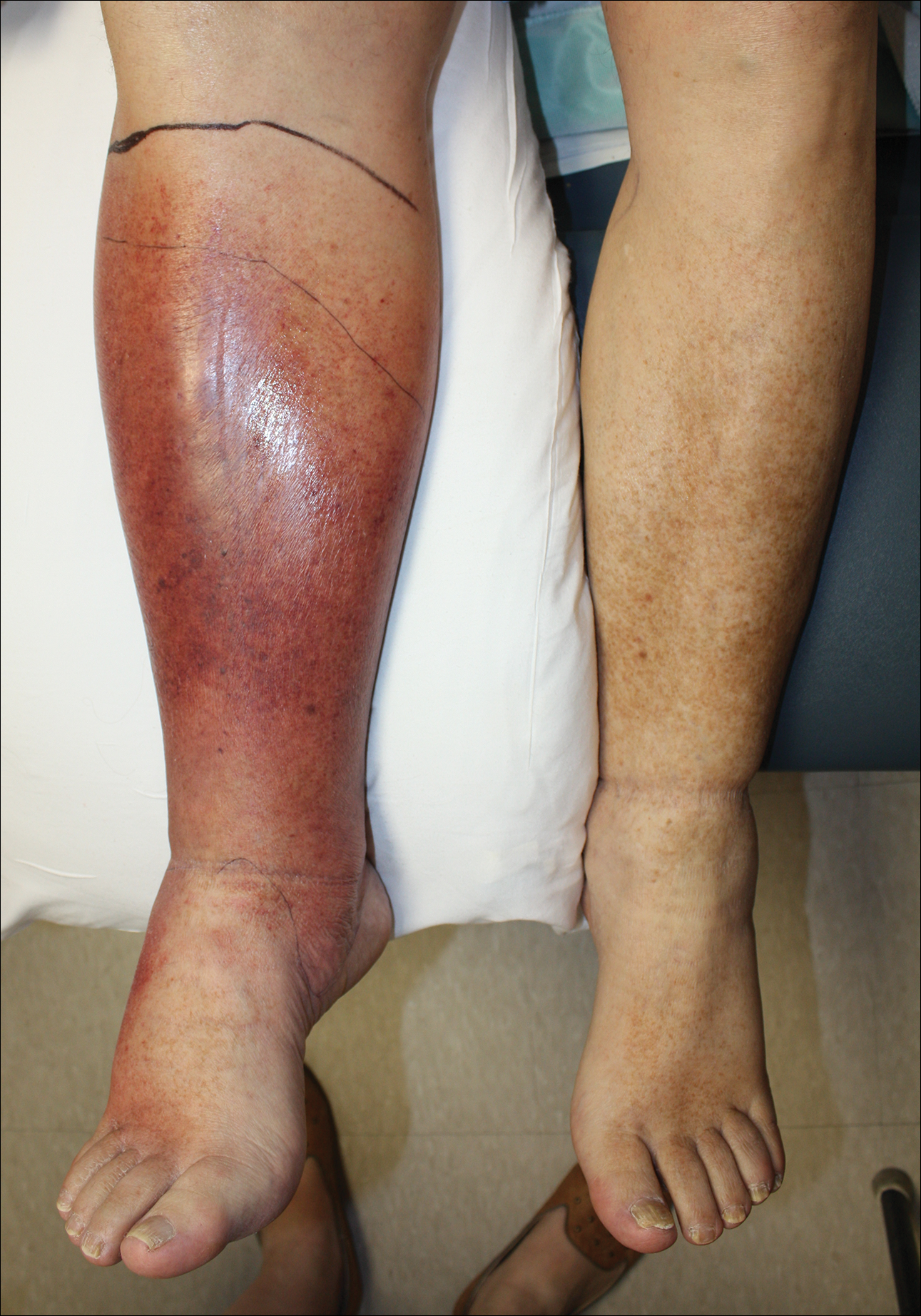

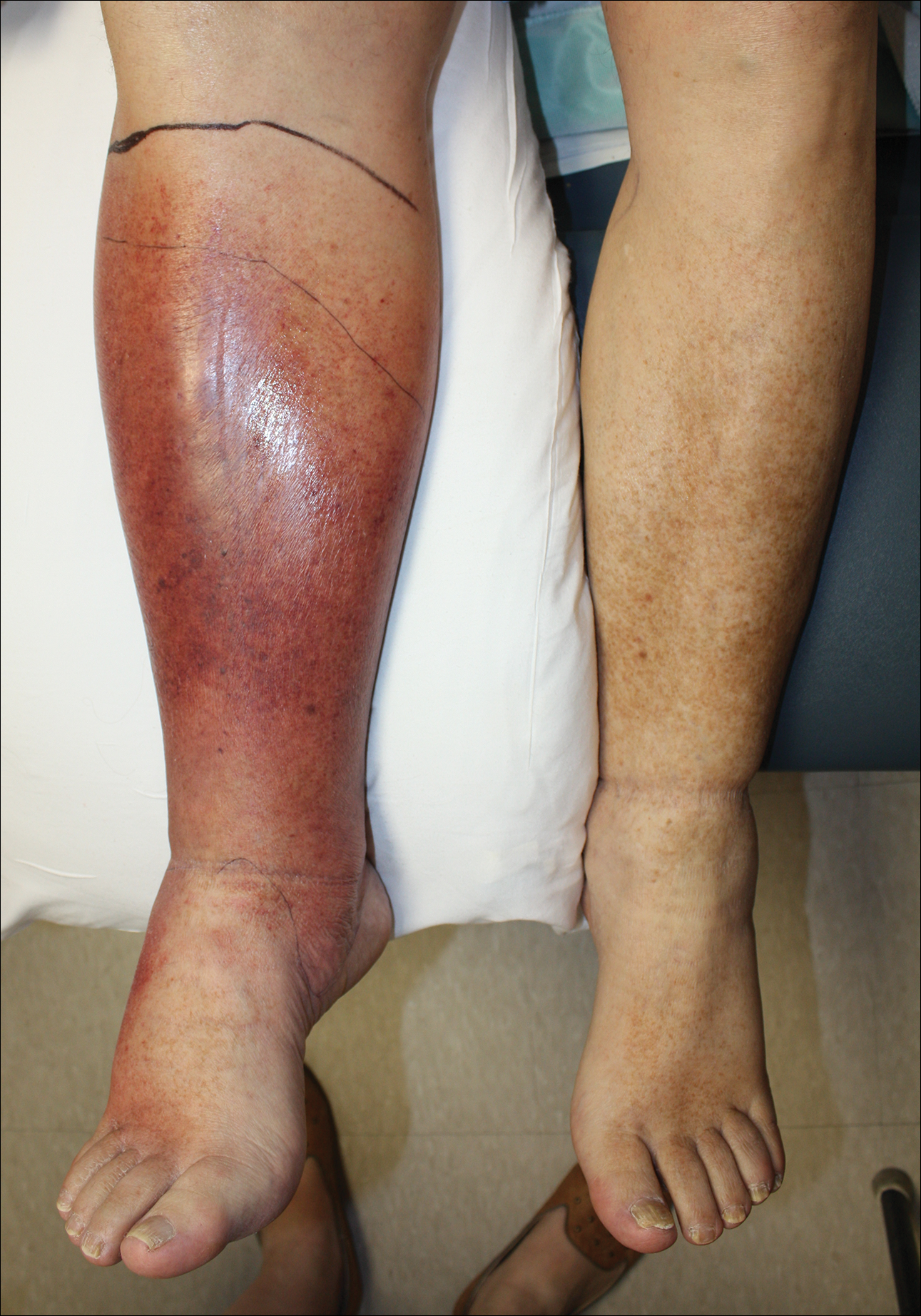

Lipodermatosclerosis is a disorder of progressive fibrosis of subcutaneous fat. It is more common in middle-aged women who have a high body mass index and a venous abnormality.4 This form of panniculitis typically affects the lower extremities bilaterally, manifesting as erythematous and indurated skin changes, sometimes described as inverted champagne bottles (Figure 2). At times, there can be accompanying painful ulceration on the erythematous areas, features that closely resemble cellulitis.5,6 Lipodermatosclerosis is commonly misdiagnosed as cellulitis, leading to inappropriate prescription of antibiotics.7

Distinguishing cellulitis from noncellulitic conditions of the lower extremity is paramount to effective patient management in the emergent setting. With a reported incidence of 24.6 per 100 person-years, cellulitis constitutes 1% to 14% of emergency department visits and 4% to 7% of hospital admissions.Therefore, prompt appropriate diagnosis and treatment can avoid life-threatening complications associated with infection such as sepsis, abscess, lymphangitis, and necrotizing fasciitis.8-11

It is estimated that 10% to 20% of patients who have been given a diagnosis of cellulitis do not actually have the disease.2,12 This discrepancy consumes a remarkable amount of hospital resources and can lead to inappropriate or excessive use of antibiotics.13 Although the true incidence of adverse antibiotic reactions is unknown, it is estimated that they are the cause of 3% to 6% of acute hospital admissions and occur in 10% to 15% of inpatients admitted for other primary reasons.14 These findings illustrate the potential for an increased risk for morbidity and increased length of stay for patients beginning an antibiotic regimen, especially when the agents are administered unnecessarily. In addition, inappropriate antibiotic use contributes to antibiotic resistance, which continues to be a major problem, especially in hospitalized patients.

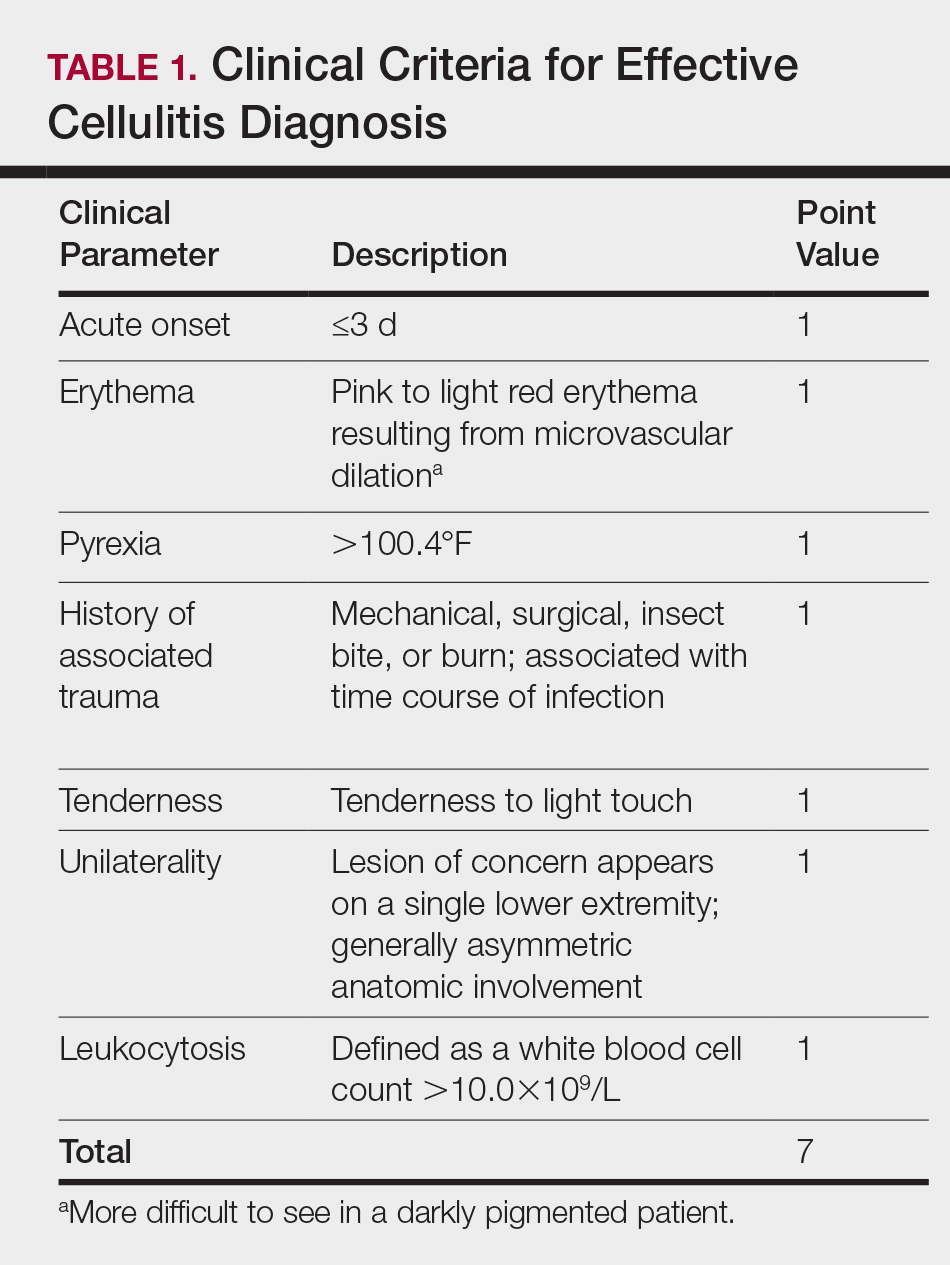

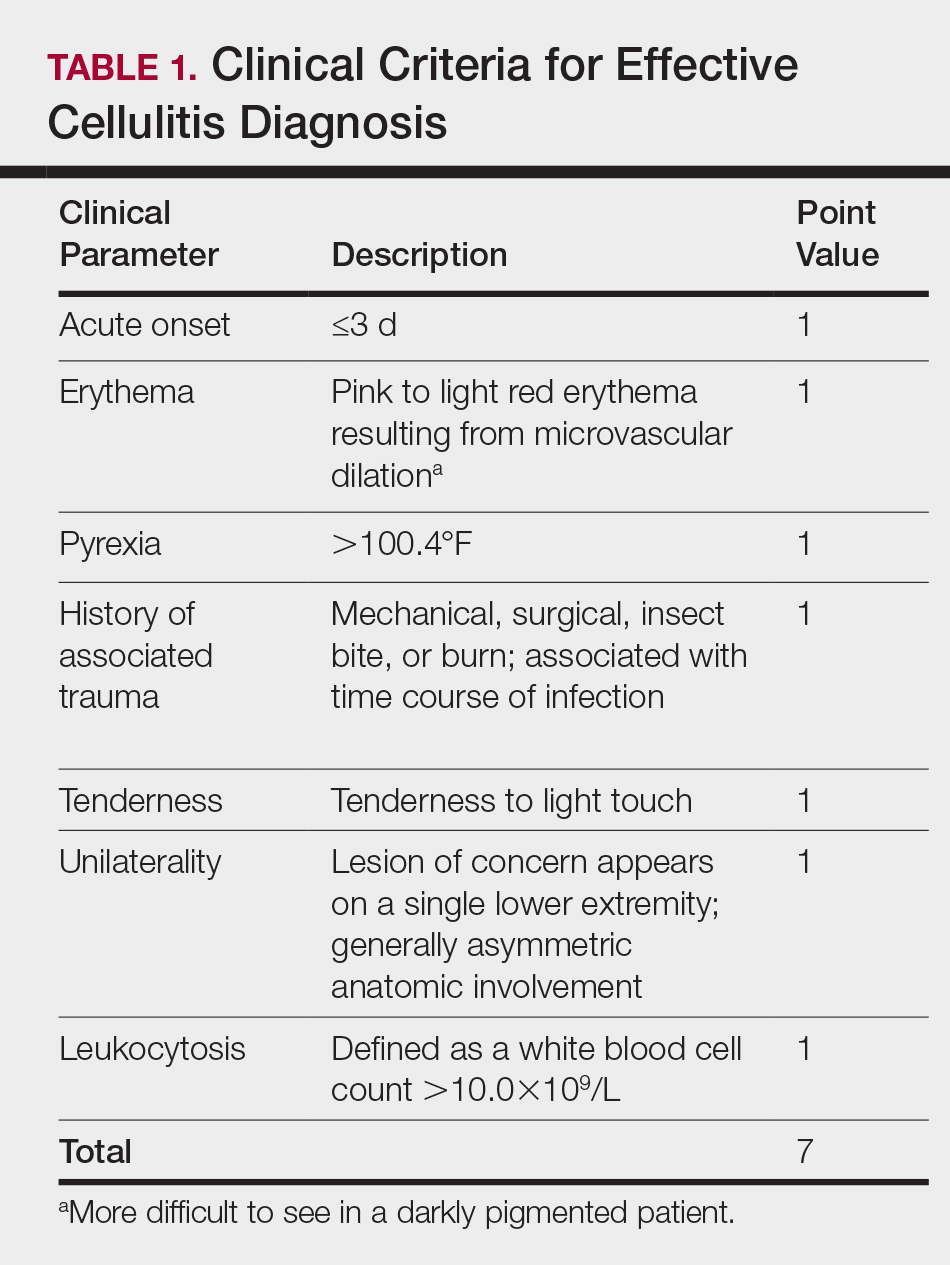

There is a lack of consensus in the literature about methods to risk stratify patients who present with acute dermatologic conditions that include and resemble cellulitis. We sought to identify clinical features based on available clinical literature-derived variables. We tested our scheme in a series of patients with a known diagnosis of cellulitis or other dermatologic pathology of the lower extremity to assess the validity of the following 7 clinical criteria: acute onset, erythema, pyrexia, history of associated trauma, tenderness, unilaterality, and leukocytosis.

Materials and Methods

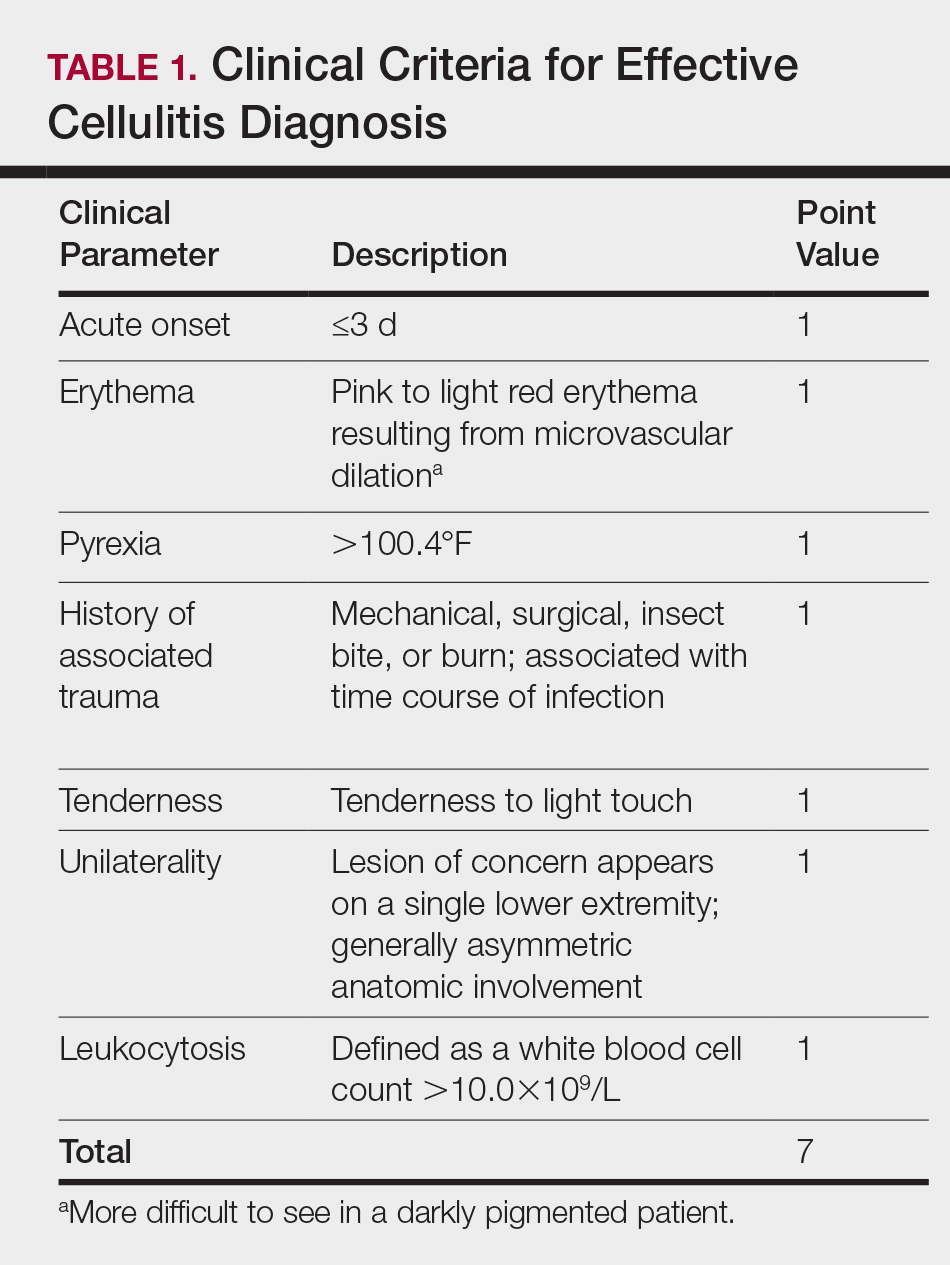

This retrospective chart review was approved by the Yale University (New Haven, Connecticut) institutional review board (HIC#1409014533). Final diagnosis, demographic data, clinical manifestations, and relevant diagnostic laboratory values of 57 patients were obtained from a database in the dermatology department’s consultation log and electronic medical record database (December 2011 to December 2014). The presence of each clinical symptom—acute onset, erythema, pyrexia, history of associated trauma, tenderness, unilaterality, and leukocytosis—was assigned a score equal to 1; values were tallied to achieve a final score for each patient (Table 1). Patients who were seen initially as a consultation for possible cellulitis but given a final diagnosis of stasis dermatitis or lipodermatosclerosis were included (Table 2).

Clinical Criteria

The clinical criteria were developed based largely on clinical experience and relevant secondary literature.15-17 At the patient encounter, presence of each of the variables (Table 1) was assessed according to the following definitions:

- acute onset: within the prior 72 hours and more indicative of an acute infective process than a gradual and chronic consequence of venous stasis

- erythema: a subjective clinical marker for inflammation that can be associated with cellulitis, though darker, erythematous-appearing discolorations also can be seen in patients with chronic venous hypertension or valvular incompetence4,15

- pyrexia: body temperature greater than 100.4°F

- history of associated trauma: encompassing mechanical wounds, surgical incisions, burns, and insect bites that correlate closely to the time course of symptomatic development

- tenderness: tenderness to light touch, which may be more common in patients afflicted with cellulitis than in those with venous insufficiency

- unilaterality: a helpful distinguishing feature that points the diagnosis away from a dermatitislike clinical picture, especially because bilateral cellulitis is rare and regarded as a diagnostic pitfall18

- leukocytosis: white blood cell count greater than 10.0×109/L and is reasonably considered a cardinal metric of inflammatory processes, though it can be confounded by immunocompromise (low count) or steroid use (high count)

Statistical Analysis

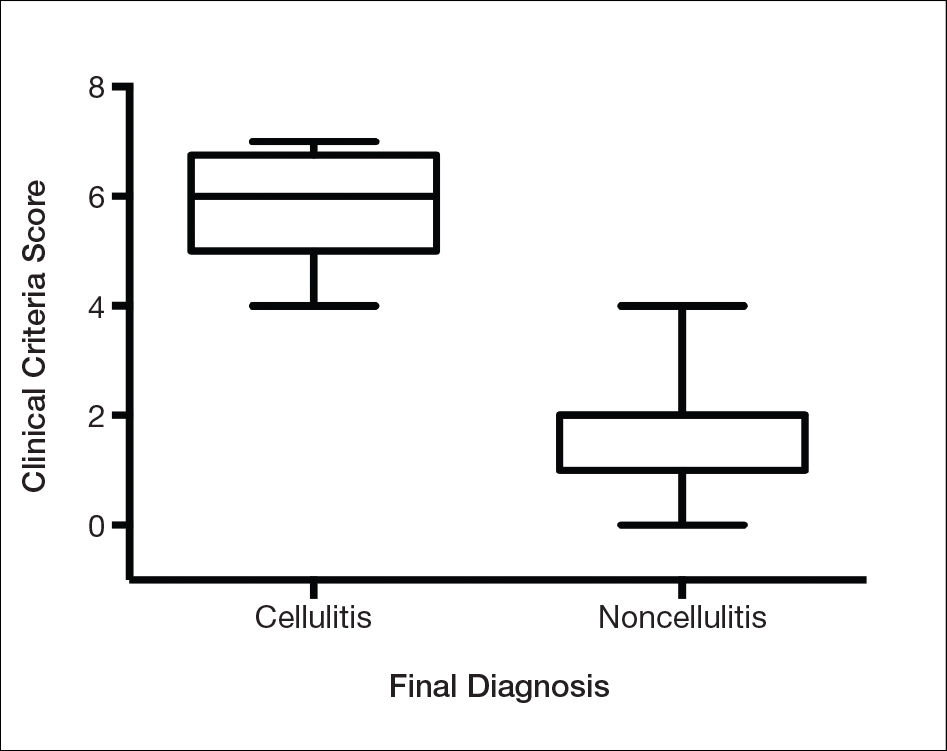

Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated and χ2 analysis was performed for each presenting symptom using JMP 10.0 analytical software (SAS Institute Inc). Each patient was rated separately by means of the clinical feature–based scoring system for the calculation of a total score. After application of the score to the patient population, receiver operating characteristic curves were constructed to identify the optimal score threshold for discriminating cellulitis from dermatitis in this group. For each clinical feature, P<.05 was considered significant.

Results

Our cohort included 32 male and 25 female patients with a mean age of 63 and 61 years, respectively. The final clinical diagnosis of cellulitis was made in 20 patients (35%). An established diagnosis of cellulitis was assigned based on a dermatology evaluation located within our electronic medical record database (Table 2).

Each clinical parameter was evaluated separately for each patient; combined results are summarized in Table 3. Acute onset (≤3 days) was a clinical characteristic seen in 80% (16/20) of cellulitis cases and 22% (8/37) of noncellulitis cases (OR, 14.5; P<.001). Erythema had similar significance (OR, 10.3; prevalence, 95% [19/20] vs 65% [24/37]; P=.012). Pyrexia possessed an OR of 99.2 for cellulitis and was seen in 85% (17/20) of cellulitis cases and only 5% (2/37) of noncellulitis cases (P<.001).

A history of associated trauma had an OR of 36.0 for cellulitis, with 50% (10/20) and 3% (1/37) prevalence in cellulitis cases and noncellulitis cases, respectively (P<.001). Tenderness, documented in 90% (18/20) of cellulitis cases and 43% (16/37) of noncellulitis cases, had an OR of 11.8 (P<.001).

Unilaterality had 100% (20/20) prevalence in our cellulitis cohort and was the only characteristic within the algorithm that yielded an incalculable OR. Noncellulitis or stasis dermatitis of the lower extremity exhibited a unilateral lesion in 11 cases (30%), of which 1 case resulted from a unilateral tibial fracture. Leukocytosis was seen in 65% (13/20) of cellulitis cases and 8% (3/37) of noncellulitis cases, with an OR for cellulitis of 21.0 (P<.001).

All parameters were significant by χ2 analysis (Table 3).

Comment

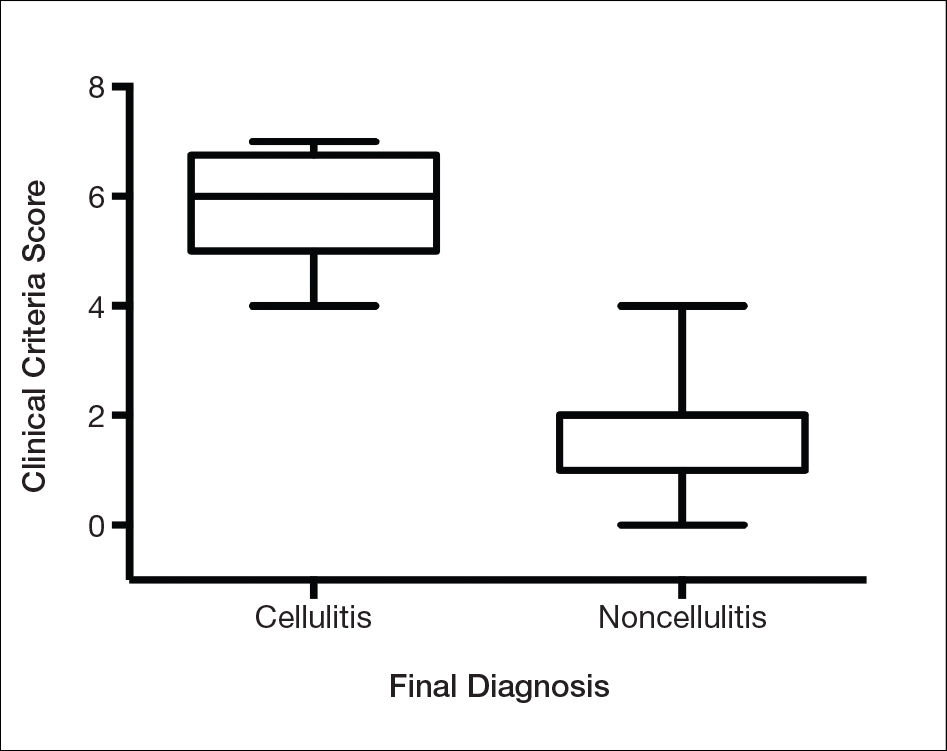

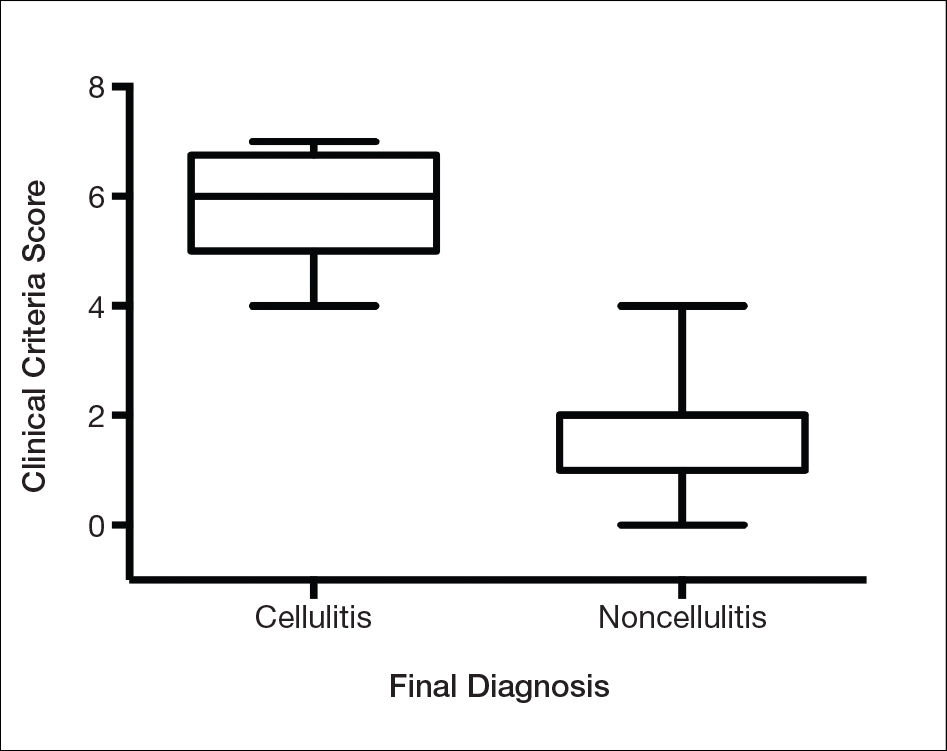

We found that testing positive for 4 of 7 clinical criteria for assessing cellulitis was highly specific (95%) and sensitive (100%) for a diagnosis of cellulitis among its range of mimics (Figure 3). These cellulitis criteria can be remembered, with some modification, using NEW HAvUN as a mnemonic device (New onset,

Consistent with the literature, pyrexia, history of associated trauma, and unilaterality also were predictors of cellulitis diagnosis. Unilaterality often is used as a diagnostic tool by dermatologist consultants when a patient lacks other criteria for cellulitis, so these findings are intuitive and consistent with our institutional experience. Interestingly, leukocytosis was seen in only 65% of cellulitis cases and 8% of noncellulitis cases and therefore might not serve as a sensitive independent predictor of a diagnosis of cellulitis, emphasizing the importance of the multifactorial scoring system we have put forward. Additionally, acuity of onset, erythema, and tenderness are not independently associated with cellulitis when assessing a patient because several of those findings are present in other dermatologic conditions of the lower extremity; when combined with the other criteria, however, these 3 findings can play a role in diagnosis.

Effective cellulitis diagnosis provides well-recognized challenges in the acute medical setting because many clinical mimics exist. The estimated rate of misdiagnosed cellulitis is certainly well-established: 30% to 75% in independent and multi-institutional studies. These studies also revealed that patients admitted for bilateral “cellulitis” overwhelmingly tended to be stasis clinical pictures.13,19

Cost implications from inappropriate diagnosis largely regard inappropriate antibiotic use and the potential for microbial resistance, with associated costs estimated to be more than $50 billion (2004 dollars).20,21 The true cost burden is extremely difficult to model or predict due to remarkable variations in the institutional misdiagnosis rate, prescribing pattern, and antibiotic cost and could represent avenues of further study. Misappropriation of antibiotics includes not only a monetary cost that encompasses all aspects of acute treatment and hospitalization but also an unquantifiable cost: human lives associated with the consequences of antibiotic resistance.

Conclusion

There is a lack of consensus or criteria for differentiating cellulitis from its most common clinical counterparts. Here, we propose a convenient clinical correlation system that we hope will lead to more efficient allocation of clinical resources, including antibiotics and hospital admissions, while lowering the incidence of adverse events and leading to better patient outcomes. We recognize that the small sample size of our study may limit broad application of these criteria, though we anticipate that further prospective studies can improve the diagnostic relevance and risk-assessment power of the NEW HAvUN criteria put forth here for assessing cellulitis in the acute medical setting.

Acknowledgement—Author H.H.E. recognizes the loving memory of Nadia Ezaldein for her profound influence on and motivation behind this research.

- Lep

pard BJ, Seal DV, Colman G, et al. The value of bacteriology and serology in the diagnosis of cellulitis and erysipelas. Br J Dermatol. 1985;112:559-567. - Hep

burn MJ, Dooley DP, Skidmore PJ, et al. Comparison of short-course (5 days) and standard (10 days) treatment for uncomplicated cellulitis. Arch Int Med. 2004;164:1669-1674. - Bergan JJ, Schmid-Schönbein GW, Smith PD, et al. Chronic venous disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:488-498.

- Bruc

e AJ, Bennett DD, Lohse CM, et al. Lipodermatosclerosis: review of cases evaluated at Mayo Clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:187-192. - Heym

ann WR. Lipodermatosclerosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:1022-1023. - Vesi

ć S, Vuković J, Medenica LJ, et al. Acute lipodermatosclerosis: an open clinical trial of stanozolol in patients unable to sustain compression therapy. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:1. - Keller

EC, Tomecki KJ, Alraies MC. Distinguishing cellulitis from its mimics. Cleve Clin J Med. 2012;79:547-552. - Dong SL, Kelly KD, Oland RC, et al. ED management of cellulitis: a review of five urban centers. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19:535-540.

- Ellis Simonsen SM, van Orman ER, Hatch BE, et al. Cellulitis incidence in a defined population. Epidemiol Infect. 2006;134:293-299.

- Manfredi R, Calza L, Chiodo F. Epidemiology and microbiology of cellulitis and bacterial soft tissue infection during HIV disease: a 10-year survey. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:168-172.

- Pascarella L, Schonbein GW, Bergan JJ. Microcirculation and venous ulcers: a review. Ann Vasc Surg. 2005;19:921-927.

- Hepburn MJ, Dooley DP, Ellis MW. Alternative diagnoses that often mimic cellulitis. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:2471.

- David CV, Chira S, Eells SJ, et al. Diagnostic accuracy in patients admitted to hospitals with cellulitis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:1.

- Hay RJ, Adriaans BM. Bacterial infections. In: Thong BY, Tan TC. Epidemiology and risk factors for drug allergy. 8th ed. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;71:684-700.

- Hay RJ, Adriaans BM. Bacterial infections. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2004:1345-1426.

- Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology In General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2003.

- Sommer LL, Reboli AC, Heymann WR. Bacterial infections. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, et al. Dermatology. Vol 4. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1462-1502.

- Cox NH. Management of lower leg cellulitis. Clin Med. 2002;2:23-27.

- Strazzula L, Cotliar J, Fox LP, et al. Inpatient dermatology consultation aids diagnosis of cellulitis among hospitalized patients: a multi-institutional analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:70-75.

- Pinder R, Sallis A, Berry D, et al. Behaviour change and antibiotic prescribing in healthcare settings: literature review and behavioural analysis. London, UK: Public Health England; February 2015. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/

uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/405031

/Behaviour_Change_for_Antibiotic_Prescribing_-_FINAL.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2018. - Smith R, Coast J. The true cost of antimicrobial resistance. BMJ. 2013;346:f1493.

Cellulitis is defined as an acute or subacute, bacterial-induced inflammation of subcutaneous tissue that can extend superficially. The inciting incident often is assumed to be invasion of bacteria through loose connective tissue.1 Although cellulitis is bacterial in origin, it often is difficult to culture the offending microorganism from biopsy sites, swabs, or blood. Erythema, fever, induration, and tenderness are largely seen as clinical manifestations. Moderate and severe cases may be accompanied by fever, malaise, and leukocytosis. The lower extremity is the most common location of involvement (Figure 1), and usually a wound, ulcer, or interdigital superficial infection can be identified and implicated as the source of entry.

Effective treatment of cellulitis is necessary because complications such as abscesses, underlying fascia or muscle involvement, and septicemia can develop, leading to poor outcomes. Antibiotics should be administered intravenously in patients with suspected fascial involvement, septicemia, or dermal necrosis, or in those with an immunological comorbidity.2

The differential diagnosis of lower extremity cellulitis is wide due to the existence of several mimicking dermatologic conditions. These so-called pseudocellulitis conditions include stasis dermatitis, venous ulceration, acute lipodermatosclerosis, pigmented purpura, vasculopathy, contact dermatitis, adverse medication reaction, and arthropod bite. Stasis dermatitis and lipodermatosclerosis, both arising from venous insufficiency, are by far 2 of the most common skin conditions that imitate cellulitis.

Stasis dermatitis is a common condition in the United States and Europe, usually manifesting as a pigmented purpuric dermatosis on anterior tibial surfaces, around the ankle, or overlying dependent varicosities. Skin changes can include hyperpigmentation, edema, mild scaling, eczematous patches, and even ulceration.3

Lipodermatosclerosis is a disorder of progressive fibrosis of subcutaneous fat. It is more common in middle-aged women who have a high body mass index and a venous abnormality.4 This form of panniculitis typically affects the lower extremities bilaterally, manifesting as erythematous and indurated skin changes, sometimes described as inverted champagne bottles (Figure 2). At times, there can be accompanying painful ulceration on the erythematous areas, features that closely resemble cellulitis.5,6 Lipodermatosclerosis is commonly misdiagnosed as cellulitis, leading to inappropriate prescription of antibiotics.7

Distinguishing cellulitis from noncellulitic conditions of the lower extremity is paramount to effective patient management in the emergent setting. With a reported incidence of 24.6 per 100 person-years, cellulitis constitutes 1% to 14% of emergency department visits and 4% to 7% of hospital admissions.Therefore, prompt appropriate diagnosis and treatment can avoid life-threatening complications associated with infection such as sepsis, abscess, lymphangitis, and necrotizing fasciitis.8-11

It is estimated that 10% to 20% of patients who have been given a diagnosis of cellulitis do not actually have the disease.2,12 This discrepancy consumes a remarkable amount of hospital resources and can lead to inappropriate or excessive use of antibiotics.13 Although the true incidence of adverse antibiotic reactions is unknown, it is estimated that they are the cause of 3% to 6% of acute hospital admissions and occur in 10% to 15% of inpatients admitted for other primary reasons.14 These findings illustrate the potential for an increased risk for morbidity and increased length of stay for patients beginning an antibiotic regimen, especially when the agents are administered unnecessarily. In addition, inappropriate antibiotic use contributes to antibiotic resistance, which continues to be a major problem, especially in hospitalized patients.

There is a lack of consensus in the literature about methods to risk stratify patients who present with acute dermatologic conditions that include and resemble cellulitis. We sought to identify clinical features based on available clinical literature-derived variables. We tested our scheme in a series of patients with a known diagnosis of cellulitis or other dermatologic pathology of the lower extremity to assess the validity of the following 7 clinical criteria: acute onset, erythema, pyrexia, history of associated trauma, tenderness, unilaterality, and leukocytosis.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective chart review was approved by the Yale University (New Haven, Connecticut) institutional review board (HIC#1409014533). Final diagnosis, demographic data, clinical manifestations, and relevant diagnostic laboratory values of 57 patients were obtained from a database in the dermatology department’s consultation log and electronic medical record database (December 2011 to December 2014). The presence of each clinical symptom—acute onset, erythema, pyrexia, history of associated trauma, tenderness, unilaterality, and leukocytosis—was assigned a score equal to 1; values were tallied to achieve a final score for each patient (Table 1). Patients who were seen initially as a consultation for possible cellulitis but given a final diagnosis of stasis dermatitis or lipodermatosclerosis were included (Table 2).

Clinical Criteria

The clinical criteria were developed based largely on clinical experience and relevant secondary literature.15-17 At the patient encounter, presence of each of the variables (Table 1) was assessed according to the following definitions:

- acute onset: within the prior 72 hours and more indicative of an acute infective process than a gradual and chronic consequence of venous stasis

- erythema: a subjective clinical marker for inflammation that can be associated with cellulitis, though darker, erythematous-appearing discolorations also can be seen in patients with chronic venous hypertension or valvular incompetence4,15

- pyrexia: body temperature greater than 100.4°F

- history of associated trauma: encompassing mechanical wounds, surgical incisions, burns, and insect bites that correlate closely to the time course of symptomatic development

- tenderness: tenderness to light touch, which may be more common in patients afflicted with cellulitis than in those with venous insufficiency

- unilaterality: a helpful distinguishing feature that points the diagnosis away from a dermatitislike clinical picture, especially because bilateral cellulitis is rare and regarded as a diagnostic pitfall18

- leukocytosis: white blood cell count greater than 10.0×109/L and is reasonably considered a cardinal metric of inflammatory processes, though it can be confounded by immunocompromise (low count) or steroid use (high count)

Statistical Analysis

Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated and χ2 analysis was performed for each presenting symptom using JMP 10.0 analytical software (SAS Institute Inc). Each patient was rated separately by means of the clinical feature–based scoring system for the calculation of a total score. After application of the score to the patient population, receiver operating characteristic curves were constructed to identify the optimal score threshold for discriminating cellulitis from dermatitis in this group. For each clinical feature, P<.05 was considered significant.

Results

Our cohort included 32 male and 25 female patients with a mean age of 63 and 61 years, respectively. The final clinical diagnosis of cellulitis was made in 20 patients (35%). An established diagnosis of cellulitis was assigned based on a dermatology evaluation located within our electronic medical record database (Table 2).

Each clinical parameter was evaluated separately for each patient; combined results are summarized in Table 3. Acute onset (≤3 days) was a clinical characteristic seen in 80% (16/20) of cellulitis cases and 22% (8/37) of noncellulitis cases (OR, 14.5; P<.001). Erythema had similar significance (OR, 10.3; prevalence, 95% [19/20] vs 65% [24/37]; P=.012). Pyrexia possessed an OR of 99.2 for cellulitis and was seen in 85% (17/20) of cellulitis cases and only 5% (2/37) of noncellulitis cases (P<.001).

A history of associated trauma had an OR of 36.0 for cellulitis, with 50% (10/20) and 3% (1/37) prevalence in cellulitis cases and noncellulitis cases, respectively (P<.001). Tenderness, documented in 90% (18/20) of cellulitis cases and 43% (16/37) of noncellulitis cases, had an OR of 11.8 (P<.001).

Unilaterality had 100% (20/20) prevalence in our cellulitis cohort and was the only characteristic within the algorithm that yielded an incalculable OR. Noncellulitis or stasis dermatitis of the lower extremity exhibited a unilateral lesion in 11 cases (30%), of which 1 case resulted from a unilateral tibial fracture. Leukocytosis was seen in 65% (13/20) of cellulitis cases and 8% (3/37) of noncellulitis cases, with an OR for cellulitis of 21.0 (P<.001).

All parameters were significant by χ2 analysis (Table 3).

Comment

We found that testing positive for 4 of 7 clinical criteria for assessing cellulitis was highly specific (95%) and sensitive (100%) for a diagnosis of cellulitis among its range of mimics (Figure 3). These cellulitis criteria can be remembered, with some modification, using NEW HAvUN as a mnemonic device (New onset,

Consistent with the literature, pyrexia, history of associated trauma, and unilaterality also were predictors of cellulitis diagnosis. Unilaterality often is used as a diagnostic tool by dermatologist consultants when a patient lacks other criteria for cellulitis, so these findings are intuitive and consistent with our institutional experience. Interestingly, leukocytosis was seen in only 65% of cellulitis cases and 8% of noncellulitis cases and therefore might not serve as a sensitive independent predictor of a diagnosis of cellulitis, emphasizing the importance of the multifactorial scoring system we have put forward. Additionally, acuity of onset, erythema, and tenderness are not independently associated with cellulitis when assessing a patient because several of those findings are present in other dermatologic conditions of the lower extremity; when combined with the other criteria, however, these 3 findings can play a role in diagnosis.

Effective cellulitis diagnosis provides well-recognized challenges in the acute medical setting because many clinical mimics exist. The estimated rate of misdiagnosed cellulitis is certainly well-established: 30% to 75% in independent and multi-institutional studies. These studies also revealed that patients admitted for bilateral “cellulitis” overwhelmingly tended to be stasis clinical pictures.13,19

Cost implications from inappropriate diagnosis largely regard inappropriate antibiotic use and the potential for microbial resistance, with associated costs estimated to be more than $50 billion (2004 dollars).20,21 The true cost burden is extremely difficult to model or predict due to remarkable variations in the institutional misdiagnosis rate, prescribing pattern, and antibiotic cost and could represent avenues of further study. Misappropriation of antibiotics includes not only a monetary cost that encompasses all aspects of acute treatment and hospitalization but also an unquantifiable cost: human lives associated with the consequences of antibiotic resistance.

Conclusion

There is a lack of consensus or criteria for differentiating cellulitis from its most common clinical counterparts. Here, we propose a convenient clinical correlation system that we hope will lead to more efficient allocation of clinical resources, including antibiotics and hospital admissions, while lowering the incidence of adverse events and leading to better patient outcomes. We recognize that the small sample size of our study may limit broad application of these criteria, though we anticipate that further prospective studies can improve the diagnostic relevance and risk-assessment power of the NEW HAvUN criteria put forth here for assessing cellulitis in the acute medical setting.

Acknowledgement—Author H.H.E. recognizes the loving memory of Nadia Ezaldein for her profound influence on and motivation behind this research.

Cellulitis is defined as an acute or subacute, bacterial-induced inflammation of subcutaneous tissue that can extend superficially. The inciting incident often is assumed to be invasion of bacteria through loose connective tissue.1 Although cellulitis is bacterial in origin, it often is difficult to culture the offending microorganism from biopsy sites, swabs, or blood. Erythema, fever, induration, and tenderness are largely seen as clinical manifestations. Moderate and severe cases may be accompanied by fever, malaise, and leukocytosis. The lower extremity is the most common location of involvement (Figure 1), and usually a wound, ulcer, or interdigital superficial infection can be identified and implicated as the source of entry.

Effective treatment of cellulitis is necessary because complications such as abscesses, underlying fascia or muscle involvement, and septicemia can develop, leading to poor outcomes. Antibiotics should be administered intravenously in patients with suspected fascial involvement, septicemia, or dermal necrosis, or in those with an immunological comorbidity.2

The differential diagnosis of lower extremity cellulitis is wide due to the existence of several mimicking dermatologic conditions. These so-called pseudocellulitis conditions include stasis dermatitis, venous ulceration, acute lipodermatosclerosis, pigmented purpura, vasculopathy, contact dermatitis, adverse medication reaction, and arthropod bite. Stasis dermatitis and lipodermatosclerosis, both arising from venous insufficiency, are by far 2 of the most common skin conditions that imitate cellulitis.

Stasis dermatitis is a common condition in the United States and Europe, usually manifesting as a pigmented purpuric dermatosis on anterior tibial surfaces, around the ankle, or overlying dependent varicosities. Skin changes can include hyperpigmentation, edema, mild scaling, eczematous patches, and even ulceration.3

Lipodermatosclerosis is a disorder of progressive fibrosis of subcutaneous fat. It is more common in middle-aged women who have a high body mass index and a venous abnormality.4 This form of panniculitis typically affects the lower extremities bilaterally, manifesting as erythematous and indurated skin changes, sometimes described as inverted champagne bottles (Figure 2). At times, there can be accompanying painful ulceration on the erythematous areas, features that closely resemble cellulitis.5,6 Lipodermatosclerosis is commonly misdiagnosed as cellulitis, leading to inappropriate prescription of antibiotics.7

Distinguishing cellulitis from noncellulitic conditions of the lower extremity is paramount to effective patient management in the emergent setting. With a reported incidence of 24.6 per 100 person-years, cellulitis constitutes 1% to 14% of emergency department visits and 4% to 7% of hospital admissions.Therefore, prompt appropriate diagnosis and treatment can avoid life-threatening complications associated with infection such as sepsis, abscess, lymphangitis, and necrotizing fasciitis.8-11

It is estimated that 10% to 20% of patients who have been given a diagnosis of cellulitis do not actually have the disease.2,12 This discrepancy consumes a remarkable amount of hospital resources and can lead to inappropriate or excessive use of antibiotics.13 Although the true incidence of adverse antibiotic reactions is unknown, it is estimated that they are the cause of 3% to 6% of acute hospital admissions and occur in 10% to 15% of inpatients admitted for other primary reasons.14 These findings illustrate the potential for an increased risk for morbidity and increased length of stay for patients beginning an antibiotic regimen, especially when the agents are administered unnecessarily. In addition, inappropriate antibiotic use contributes to antibiotic resistance, which continues to be a major problem, especially in hospitalized patients.

There is a lack of consensus in the literature about methods to risk stratify patients who present with acute dermatologic conditions that include and resemble cellulitis. We sought to identify clinical features based on available clinical literature-derived variables. We tested our scheme in a series of patients with a known diagnosis of cellulitis or other dermatologic pathology of the lower extremity to assess the validity of the following 7 clinical criteria: acute onset, erythema, pyrexia, history of associated trauma, tenderness, unilaterality, and leukocytosis.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective chart review was approved by the Yale University (New Haven, Connecticut) institutional review board (HIC#1409014533). Final diagnosis, demographic data, clinical manifestations, and relevant diagnostic laboratory values of 57 patients were obtained from a database in the dermatology department’s consultation log and electronic medical record database (December 2011 to December 2014). The presence of each clinical symptom—acute onset, erythema, pyrexia, history of associated trauma, tenderness, unilaterality, and leukocytosis—was assigned a score equal to 1; values were tallied to achieve a final score for each patient (Table 1). Patients who were seen initially as a consultation for possible cellulitis but given a final diagnosis of stasis dermatitis or lipodermatosclerosis were included (Table 2).

Clinical Criteria

The clinical criteria were developed based largely on clinical experience and relevant secondary literature.15-17 At the patient encounter, presence of each of the variables (Table 1) was assessed according to the following definitions:

- acute onset: within the prior 72 hours and more indicative of an acute infective process than a gradual and chronic consequence of venous stasis

- erythema: a subjective clinical marker for inflammation that can be associated with cellulitis, though darker, erythematous-appearing discolorations also can be seen in patients with chronic venous hypertension or valvular incompetence4,15

- pyrexia: body temperature greater than 100.4°F

- history of associated trauma: encompassing mechanical wounds, surgical incisions, burns, and insect bites that correlate closely to the time course of symptomatic development

- tenderness: tenderness to light touch, which may be more common in patients afflicted with cellulitis than in those with venous insufficiency

- unilaterality: a helpful distinguishing feature that points the diagnosis away from a dermatitislike clinical picture, especially because bilateral cellulitis is rare and regarded as a diagnostic pitfall18

- leukocytosis: white blood cell count greater than 10.0×109/L and is reasonably considered a cardinal metric of inflammatory processes, though it can be confounded by immunocompromise (low count) or steroid use (high count)

Statistical Analysis

Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated and χ2 analysis was performed for each presenting symptom using JMP 10.0 analytical software (SAS Institute Inc). Each patient was rated separately by means of the clinical feature–based scoring system for the calculation of a total score. After application of the score to the patient population, receiver operating characteristic curves were constructed to identify the optimal score threshold for discriminating cellulitis from dermatitis in this group. For each clinical feature, P<.05 was considered significant.

Results

Our cohort included 32 male and 25 female patients with a mean age of 63 and 61 years, respectively. The final clinical diagnosis of cellulitis was made in 20 patients (35%). An established diagnosis of cellulitis was assigned based on a dermatology evaluation located within our electronic medical record database (Table 2).

Each clinical parameter was evaluated separately for each patient; combined results are summarized in Table 3. Acute onset (≤3 days) was a clinical characteristic seen in 80% (16/20) of cellulitis cases and 22% (8/37) of noncellulitis cases (OR, 14.5; P<.001). Erythema had similar significance (OR, 10.3; prevalence, 95% [19/20] vs 65% [24/37]; P=.012). Pyrexia possessed an OR of 99.2 for cellulitis and was seen in 85% (17/20) of cellulitis cases and only 5% (2/37) of noncellulitis cases (P<.001).

A history of associated trauma had an OR of 36.0 for cellulitis, with 50% (10/20) and 3% (1/37) prevalence in cellulitis cases and noncellulitis cases, respectively (P<.001). Tenderness, documented in 90% (18/20) of cellulitis cases and 43% (16/37) of noncellulitis cases, had an OR of 11.8 (P<.001).

Unilaterality had 100% (20/20) prevalence in our cellulitis cohort and was the only characteristic within the algorithm that yielded an incalculable OR. Noncellulitis or stasis dermatitis of the lower extremity exhibited a unilateral lesion in 11 cases (30%), of which 1 case resulted from a unilateral tibial fracture. Leukocytosis was seen in 65% (13/20) of cellulitis cases and 8% (3/37) of noncellulitis cases, with an OR for cellulitis of 21.0 (P<.001).

All parameters were significant by χ2 analysis (Table 3).

Comment

We found that testing positive for 4 of 7 clinical criteria for assessing cellulitis was highly specific (95%) and sensitive (100%) for a diagnosis of cellulitis among its range of mimics (Figure 3). These cellulitis criteria can be remembered, with some modification, using NEW HAvUN as a mnemonic device (New onset,

Consistent with the literature, pyrexia, history of associated trauma, and unilaterality also were predictors of cellulitis diagnosis. Unilaterality often is used as a diagnostic tool by dermatologist consultants when a patient lacks other criteria for cellulitis, so these findings are intuitive and consistent with our institutional experience. Interestingly, leukocytosis was seen in only 65% of cellulitis cases and 8% of noncellulitis cases and therefore might not serve as a sensitive independent predictor of a diagnosis of cellulitis, emphasizing the importance of the multifactorial scoring system we have put forward. Additionally, acuity of onset, erythema, and tenderness are not independently associated with cellulitis when assessing a patient because several of those findings are present in other dermatologic conditions of the lower extremity; when combined with the other criteria, however, these 3 findings can play a role in diagnosis.

Effective cellulitis diagnosis provides well-recognized challenges in the acute medical setting because many clinical mimics exist. The estimated rate of misdiagnosed cellulitis is certainly well-established: 30% to 75% in independent and multi-institutional studies. These studies also revealed that patients admitted for bilateral “cellulitis” overwhelmingly tended to be stasis clinical pictures.13,19

Cost implications from inappropriate diagnosis largely regard inappropriate antibiotic use and the potential for microbial resistance, with associated costs estimated to be more than $50 billion (2004 dollars).20,21 The true cost burden is extremely difficult to model or predict due to remarkable variations in the institutional misdiagnosis rate, prescribing pattern, and antibiotic cost and could represent avenues of further study. Misappropriation of antibiotics includes not only a monetary cost that encompasses all aspects of acute treatment and hospitalization but also an unquantifiable cost: human lives associated with the consequences of antibiotic resistance.

Conclusion

There is a lack of consensus or criteria for differentiating cellulitis from its most common clinical counterparts. Here, we propose a convenient clinical correlation system that we hope will lead to more efficient allocation of clinical resources, including antibiotics and hospital admissions, while lowering the incidence of adverse events and leading to better patient outcomes. We recognize that the small sample size of our study may limit broad application of these criteria, though we anticipate that further prospective studies can improve the diagnostic relevance and risk-assessment power of the NEW HAvUN criteria put forth here for assessing cellulitis in the acute medical setting.

Acknowledgement—Author H.H.E. recognizes the loving memory of Nadia Ezaldein for her profound influence on and motivation behind this research.

- Lep

pard BJ, Seal DV, Colman G, et al. The value of bacteriology and serology in the diagnosis of cellulitis and erysipelas. Br J Dermatol. 1985;112:559-567. - Hep

burn MJ, Dooley DP, Skidmore PJ, et al. Comparison of short-course (5 days) and standard (10 days) treatment for uncomplicated cellulitis. Arch Int Med. 2004;164:1669-1674. - Bergan JJ, Schmid-Schönbein GW, Smith PD, et al. Chronic venous disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:488-498.

- Bruc

e AJ, Bennett DD, Lohse CM, et al. Lipodermatosclerosis: review of cases evaluated at Mayo Clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:187-192. - Heym

ann WR. Lipodermatosclerosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:1022-1023. - Vesi

ć S, Vuković J, Medenica LJ, et al. Acute lipodermatosclerosis: an open clinical trial of stanozolol in patients unable to sustain compression therapy. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:1. - Keller

EC, Tomecki KJ, Alraies MC. Distinguishing cellulitis from its mimics. Cleve Clin J Med. 2012;79:547-552. - Dong SL, Kelly KD, Oland RC, et al. ED management of cellulitis: a review of five urban centers. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19:535-540.

- Ellis Simonsen SM, van Orman ER, Hatch BE, et al. Cellulitis incidence in a defined population. Epidemiol Infect. 2006;134:293-299.

- Manfredi R, Calza L, Chiodo F. Epidemiology and microbiology of cellulitis and bacterial soft tissue infection during HIV disease: a 10-year survey. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:168-172.

- Pascarella L, Schonbein GW, Bergan JJ. Microcirculation and venous ulcers: a review. Ann Vasc Surg. 2005;19:921-927.

- Hepburn MJ, Dooley DP, Ellis MW. Alternative diagnoses that often mimic cellulitis. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:2471.

- David CV, Chira S, Eells SJ, et al. Diagnostic accuracy in patients admitted to hospitals with cellulitis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:1.

- Hay RJ, Adriaans BM. Bacterial infections. In: Thong BY, Tan TC. Epidemiology and risk factors for drug allergy. 8th ed. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;71:684-700.

- Hay RJ, Adriaans BM. Bacterial infections. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2004:1345-1426.

- Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology In General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2003.

- Sommer LL, Reboli AC, Heymann WR. Bacterial infections. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, et al. Dermatology. Vol 4. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1462-1502.

- Cox NH. Management of lower leg cellulitis. Clin Med. 2002;2:23-27.

- Strazzula L, Cotliar J, Fox LP, et al. Inpatient dermatology consultation aids diagnosis of cellulitis among hospitalized patients: a multi-institutional analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:70-75.

- Pinder R, Sallis A, Berry D, et al. Behaviour change and antibiotic prescribing in healthcare settings: literature review and behavioural analysis. London, UK: Public Health England; February 2015. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/

uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/405031

/Behaviour_Change_for_Antibiotic_Prescribing_-_FINAL.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2018. - Smith R, Coast J. The true cost of antimicrobial resistance. BMJ. 2013;346:f1493.

- Lep

pard BJ, Seal DV, Colman G, et al. The value of bacteriology and serology in the diagnosis of cellulitis and erysipelas. Br J Dermatol. 1985;112:559-567. - Hep

burn MJ, Dooley DP, Skidmore PJ, et al. Comparison of short-course (5 days) and standard (10 days) treatment for uncomplicated cellulitis. Arch Int Med. 2004;164:1669-1674. - Bergan JJ, Schmid-Schönbein GW, Smith PD, et al. Chronic venous disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:488-498.

- Bruc

e AJ, Bennett DD, Lohse CM, et al. Lipodermatosclerosis: review of cases evaluated at Mayo Clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:187-192. - Heym

ann WR. Lipodermatosclerosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:1022-1023. - Vesi

ć S, Vuković J, Medenica LJ, et al. Acute lipodermatosclerosis: an open clinical trial of stanozolol in patients unable to sustain compression therapy. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:1. - Keller

EC, Tomecki KJ, Alraies MC. Distinguishing cellulitis from its mimics. Cleve Clin J Med. 2012;79:547-552. - Dong SL, Kelly KD, Oland RC, et al. ED management of cellulitis: a review of five urban centers. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19:535-540.

- Ellis Simonsen SM, van Orman ER, Hatch BE, et al. Cellulitis incidence in a defined population. Epidemiol Infect. 2006;134:293-299.

- Manfredi R, Calza L, Chiodo F. Epidemiology and microbiology of cellulitis and bacterial soft tissue infection during HIV disease: a 10-year survey. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:168-172.

- Pascarella L, Schonbein GW, Bergan JJ. Microcirculation and venous ulcers: a review. Ann Vasc Surg. 2005;19:921-927.

- Hepburn MJ, Dooley DP, Ellis MW. Alternative diagnoses that often mimic cellulitis. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:2471.

- David CV, Chira S, Eells SJ, et al. Diagnostic accuracy in patients admitted to hospitals with cellulitis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:1.

- Hay RJ, Adriaans BM. Bacterial infections. In: Thong BY, Tan TC. Epidemiology and risk factors for drug allergy. 8th ed. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;71:684-700.

- Hay RJ, Adriaans BM. Bacterial infections. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2004:1345-1426.

- Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology In General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2003.

- Sommer LL, Reboli AC, Heymann WR. Bacterial infections. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, et al. Dermatology. Vol 4. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1462-1502.

- Cox NH. Management of lower leg cellulitis. Clin Med. 2002;2:23-27.

- Strazzula L, Cotliar J, Fox LP, et al. Inpatient dermatology consultation aids diagnosis of cellulitis among hospitalized patients: a multi-institutional analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:70-75.

- Pinder R, Sallis A, Berry D, et al. Behaviour change and antibiotic prescribing in healthcare settings: literature review and behavioural analysis. London, UK: Public Health England; February 2015. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/

uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/405031

/Behaviour_Change_for_Antibiotic_Prescribing_-_FINAL.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2018. - Smith R, Coast J. The true cost of antimicrobial resistance. BMJ. 2013;346:f1493.

Practice Points

- Distinguishing cellulitis from noncellulitic conditions of the lower extremity is paramount to effective patient management in the emergent setting, given that misdiagnosis consumes hospital resources and can lead to inappropriate or excessive use of antibiotics.

- We evaluated the specificity and sensitivity of the following 7 clinical criteria: acute onset, erythema, pyrexia, history of associated trauma, tenderness, unilaterality, and leukocytosis.