User login

E/M comments may fall on deaf ears at CMS

Doctors’ dismay at the proposed flattening of evaluation and management (E/M) payments seems to be falling on deaf ears.

More than 170 medical societies and organizations expressed their concern about the new payment structure for E/M codes proposed as part of the 2019 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) in comments on the draft rule.

Yet, in the final days of the comment period, Seema Verma, administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, took to Twitter to defend her agency’s plan.

The controversial proposal would set the payment rate for a level 1 E/M office visit for a new patient at $44, down from the current $45. Payment for levels 2-5 would be $135. Currently, payments for level 2 new patient visits are set at $76, level 3 at $110, level 4 at $167, and level 5 at $211.

For E/M office visits with established patients, the proposed rate would be $24 for level 1, up from the current $22. Payment for levels 2-5 would be $93. Under the current methodology, payments for established patient level 2 visits are set at $45, level 3 at $74, level 4 at $109, and level 5 at $148.

Offsetting the changes in payment are several new proposed add-on codes, according to CMS.

Despite the lower payment for more complex patient care, Ms. Verma touted the scheme’s budget neutrality.

Ms. Verma’s tweets come as medical societies filed their formal complaints on the proposal, mirroring concerns expressed in two letters sent to the agency ahead of the comment deadline. The letters, sent at the end of August and between the two of them signed by more than 170 medical associations, aimed to preempt the comment process. They called for the E/M proposal to be rescinded, claiming that the cuts would reduce access to Medicare services by patients and hurt physicians that treat the sickest patients and those who provide comprehensive primary care because the expected lower reimbursement. One suggested that the changes exacerbate workforce shortages.

In its formal comments, the American Medical Association said that given “the groundswell of opposition from individual physicians and nearly every physician and health professional organization in the country, including the AMA, we ask that CMS set aside its proposal to restructure payment and coding for E/M office and other outpatient visits while an expert physician work group, with input from a broad spectrum of physicians and other health professionals, develops an alternative that could be implemented in 2020.”

The proposed E/M changes “are not an improvement over the current documentation requirements and payment structure. The structure is flawed, and the proposal to reduce payments when E/M services are reported with procedures fails to account for fee schedule reductions that have already been taken on these codes,” according to comments submitted by the American Academy of Dermatology Association.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology said it “supports the Agency’s proposal to reduce documentation burdens for E&M services but pairing it with reductions in payment will negatively impact patient access and should be avoided.”

ASCO also called on the agency to withdraw its proposal to consolidate E/M payments, noting that offsetting payments from add-on codes do “not appear to fully offset the direct and indirect cuts to oncology reimbursement, is ambiguous, and lacks assurances of long-term durability.”

Surgeons “cannot support the collapse of work RVU [relative value unit] values into one single rate under the [physician fee schedule] that would be paid for services using the current CPT codes for level 2 through 5 E/M visits because this single rate is a calculation of several values that were resourced-based, but in and of itself is not a resource-based value. There is no assurance that the underlying math used to derive this single value correctly reflects the resources used to deliver care across a wide spectrum of providers in America,” according to comments submitted by the American College of Surgeons.

ACS also argued that it is “not possible to fully analyze the repercussions and potential distortions to the PFS from these policies individually or taken as a whole during the 60-day comment period.” The comments noted that ACS favors documentation reduction efforts included in the proposal, but urged CMS to delay finalizing any E/M changes until more work can be done in tandem with stakeholders to craft a better solution.

The American College of Cardiology voiced support for the documentation reduction aspects of the E/M proposal but urged CMS to “not finalize any E/M payment changes for 2019. The Agency makes it clear it believes documentation proposals are intrinsically linked to the payment proposals. It is not clear to the ACC exactly why that must be the case.”

ACC also voiced concern over a provision that would halve the least-expensive procedure or the E/M visit code when a physician bills for both simultaneously. “No data are described to indicate that 50% is a correct reduction. Instead, it appears that CMS chose 50% because the reduction is equivalent to the 6.7 million RVUs needed to offset other proposed changes for compressing E/M payment into single levels and allowing use of the new add-on codes.”

A key concern for the American Academy of Family Physicians was collapsing the levels 2 through 5 E/M visits into a single payment level.

Instead, AAFP recommended that CMS work with it and other medical societies to develop new codes and values to ensure proper payment for services. Instead of a primary care add-on code, CMS should increase E/M payments by 15% for services provided “by physicians who list their primary practice designation as family medicine, internal medicine, or geriatrics,” according to the comments.

AAFP is “concerned that the changes included in the proposed rule may harm the quality and cost of care for Medicare beneficiaries,” the comment letter states, adding that it is “possible that beneficiary out-of-pocket costs would increase due to more frequent physician or clinician visits.”

The American College of Rheumatology voiced its support for the focus “on reducing physician burden by simplifying documentation requirements,” but said it had “serious concerns about the changes to evaluation and management (E/M) codes that result in cuts in reimbursement to cognitive specialists for the complex services they provide.” It added that while there is support for the documentation reduction efforts, “we are skeptical that this proposal will simplify the reporting burden on providers in the Quality Payment Program. As proposed, the new plan proposes several ‘add-on’ codes that would likely prevent reduction in audits or documentation.”

The estimated 51 hours per doctor per year of time saved “are insufficient to offset the proposed cuts to reimbursement. For example, if a physician sees around 100 patients a week, this translates to under 40 seconds per patient, which is not a benefit that outweighs the proposed reduction in reimbursement.”

The American College of Physicians voiced its opposition to the E/M proposal, noting that it “strongly believes that cognitive care of more complex patients must be appropriately recognized with higher allowed payment rates than less complex care patients.” ACP said the even with the proposed add-on codes, the proposed changes undervalue cognitive care for the most complex patients.

Doctors’ dismay at the proposed flattening of evaluation and management (E/M) payments seems to be falling on deaf ears.

More than 170 medical societies and organizations expressed their concern about the new payment structure for E/M codes proposed as part of the 2019 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) in comments on the draft rule.

Yet, in the final days of the comment period, Seema Verma, administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, took to Twitter to defend her agency’s plan.

The controversial proposal would set the payment rate for a level 1 E/M office visit for a new patient at $44, down from the current $45. Payment for levels 2-5 would be $135. Currently, payments for level 2 new patient visits are set at $76, level 3 at $110, level 4 at $167, and level 5 at $211.

For E/M office visits with established patients, the proposed rate would be $24 for level 1, up from the current $22. Payment for levels 2-5 would be $93. Under the current methodology, payments for established patient level 2 visits are set at $45, level 3 at $74, level 4 at $109, and level 5 at $148.

Offsetting the changes in payment are several new proposed add-on codes, according to CMS.

Despite the lower payment for more complex patient care, Ms. Verma touted the scheme’s budget neutrality.

Ms. Verma’s tweets come as medical societies filed their formal complaints on the proposal, mirroring concerns expressed in two letters sent to the agency ahead of the comment deadline. The letters, sent at the end of August and between the two of them signed by more than 170 medical associations, aimed to preempt the comment process. They called for the E/M proposal to be rescinded, claiming that the cuts would reduce access to Medicare services by patients and hurt physicians that treat the sickest patients and those who provide comprehensive primary care because the expected lower reimbursement. One suggested that the changes exacerbate workforce shortages.

In its formal comments, the American Medical Association said that given “the groundswell of opposition from individual physicians and nearly every physician and health professional organization in the country, including the AMA, we ask that CMS set aside its proposal to restructure payment and coding for E/M office and other outpatient visits while an expert physician work group, with input from a broad spectrum of physicians and other health professionals, develops an alternative that could be implemented in 2020.”

The proposed E/M changes “are not an improvement over the current documentation requirements and payment structure. The structure is flawed, and the proposal to reduce payments when E/M services are reported with procedures fails to account for fee schedule reductions that have already been taken on these codes,” according to comments submitted by the American Academy of Dermatology Association.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology said it “supports the Agency’s proposal to reduce documentation burdens for E&M services but pairing it with reductions in payment will negatively impact patient access and should be avoided.”

ASCO also called on the agency to withdraw its proposal to consolidate E/M payments, noting that offsetting payments from add-on codes do “not appear to fully offset the direct and indirect cuts to oncology reimbursement, is ambiguous, and lacks assurances of long-term durability.”

Surgeons “cannot support the collapse of work RVU [relative value unit] values into one single rate under the [physician fee schedule] that would be paid for services using the current CPT codes for level 2 through 5 E/M visits because this single rate is a calculation of several values that were resourced-based, but in and of itself is not a resource-based value. There is no assurance that the underlying math used to derive this single value correctly reflects the resources used to deliver care across a wide spectrum of providers in America,” according to comments submitted by the American College of Surgeons.

ACS also argued that it is “not possible to fully analyze the repercussions and potential distortions to the PFS from these policies individually or taken as a whole during the 60-day comment period.” The comments noted that ACS favors documentation reduction efforts included in the proposal, but urged CMS to delay finalizing any E/M changes until more work can be done in tandem with stakeholders to craft a better solution.

The American College of Cardiology voiced support for the documentation reduction aspects of the E/M proposal but urged CMS to “not finalize any E/M payment changes for 2019. The Agency makes it clear it believes documentation proposals are intrinsically linked to the payment proposals. It is not clear to the ACC exactly why that must be the case.”

ACC also voiced concern over a provision that would halve the least-expensive procedure or the E/M visit code when a physician bills for both simultaneously. “No data are described to indicate that 50% is a correct reduction. Instead, it appears that CMS chose 50% because the reduction is equivalent to the 6.7 million RVUs needed to offset other proposed changes for compressing E/M payment into single levels and allowing use of the new add-on codes.”

A key concern for the American Academy of Family Physicians was collapsing the levels 2 through 5 E/M visits into a single payment level.

Instead, AAFP recommended that CMS work with it and other medical societies to develop new codes and values to ensure proper payment for services. Instead of a primary care add-on code, CMS should increase E/M payments by 15% for services provided “by physicians who list their primary practice designation as family medicine, internal medicine, or geriatrics,” according to the comments.

AAFP is “concerned that the changes included in the proposed rule may harm the quality and cost of care for Medicare beneficiaries,” the comment letter states, adding that it is “possible that beneficiary out-of-pocket costs would increase due to more frequent physician or clinician visits.”

The American College of Rheumatology voiced its support for the focus “on reducing physician burden by simplifying documentation requirements,” but said it had “serious concerns about the changes to evaluation and management (E/M) codes that result in cuts in reimbursement to cognitive specialists for the complex services they provide.” It added that while there is support for the documentation reduction efforts, “we are skeptical that this proposal will simplify the reporting burden on providers in the Quality Payment Program. As proposed, the new plan proposes several ‘add-on’ codes that would likely prevent reduction in audits or documentation.”

The estimated 51 hours per doctor per year of time saved “are insufficient to offset the proposed cuts to reimbursement. For example, if a physician sees around 100 patients a week, this translates to under 40 seconds per patient, which is not a benefit that outweighs the proposed reduction in reimbursement.”

The American College of Physicians voiced its opposition to the E/M proposal, noting that it “strongly believes that cognitive care of more complex patients must be appropriately recognized with higher allowed payment rates than less complex care patients.” ACP said the even with the proposed add-on codes, the proposed changes undervalue cognitive care for the most complex patients.

Doctors’ dismay at the proposed flattening of evaluation and management (E/M) payments seems to be falling on deaf ears.

More than 170 medical societies and organizations expressed their concern about the new payment structure for E/M codes proposed as part of the 2019 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) in comments on the draft rule.

Yet, in the final days of the comment period, Seema Verma, administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, took to Twitter to defend her agency’s plan.

The controversial proposal would set the payment rate for a level 1 E/M office visit for a new patient at $44, down from the current $45. Payment for levels 2-5 would be $135. Currently, payments for level 2 new patient visits are set at $76, level 3 at $110, level 4 at $167, and level 5 at $211.

For E/M office visits with established patients, the proposed rate would be $24 for level 1, up from the current $22. Payment for levels 2-5 would be $93. Under the current methodology, payments for established patient level 2 visits are set at $45, level 3 at $74, level 4 at $109, and level 5 at $148.

Offsetting the changes in payment are several new proposed add-on codes, according to CMS.

Despite the lower payment for more complex patient care, Ms. Verma touted the scheme’s budget neutrality.

Ms. Verma’s tweets come as medical societies filed their formal complaints on the proposal, mirroring concerns expressed in two letters sent to the agency ahead of the comment deadline. The letters, sent at the end of August and between the two of them signed by more than 170 medical associations, aimed to preempt the comment process. They called for the E/M proposal to be rescinded, claiming that the cuts would reduce access to Medicare services by patients and hurt physicians that treat the sickest patients and those who provide comprehensive primary care because the expected lower reimbursement. One suggested that the changes exacerbate workforce shortages.

In its formal comments, the American Medical Association said that given “the groundswell of opposition from individual physicians and nearly every physician and health professional organization in the country, including the AMA, we ask that CMS set aside its proposal to restructure payment and coding for E/M office and other outpatient visits while an expert physician work group, with input from a broad spectrum of physicians and other health professionals, develops an alternative that could be implemented in 2020.”

The proposed E/M changes “are not an improvement over the current documentation requirements and payment structure. The structure is flawed, and the proposal to reduce payments when E/M services are reported with procedures fails to account for fee schedule reductions that have already been taken on these codes,” according to comments submitted by the American Academy of Dermatology Association.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology said it “supports the Agency’s proposal to reduce documentation burdens for E&M services but pairing it with reductions in payment will negatively impact patient access and should be avoided.”

ASCO also called on the agency to withdraw its proposal to consolidate E/M payments, noting that offsetting payments from add-on codes do “not appear to fully offset the direct and indirect cuts to oncology reimbursement, is ambiguous, and lacks assurances of long-term durability.”

Surgeons “cannot support the collapse of work RVU [relative value unit] values into one single rate under the [physician fee schedule] that would be paid for services using the current CPT codes for level 2 through 5 E/M visits because this single rate is a calculation of several values that were resourced-based, but in and of itself is not a resource-based value. There is no assurance that the underlying math used to derive this single value correctly reflects the resources used to deliver care across a wide spectrum of providers in America,” according to comments submitted by the American College of Surgeons.

ACS also argued that it is “not possible to fully analyze the repercussions and potential distortions to the PFS from these policies individually or taken as a whole during the 60-day comment period.” The comments noted that ACS favors documentation reduction efforts included in the proposal, but urged CMS to delay finalizing any E/M changes until more work can be done in tandem with stakeholders to craft a better solution.

The American College of Cardiology voiced support for the documentation reduction aspects of the E/M proposal but urged CMS to “not finalize any E/M payment changes for 2019. The Agency makes it clear it believes documentation proposals are intrinsically linked to the payment proposals. It is not clear to the ACC exactly why that must be the case.”

ACC also voiced concern over a provision that would halve the least-expensive procedure or the E/M visit code when a physician bills for both simultaneously. “No data are described to indicate that 50% is a correct reduction. Instead, it appears that CMS chose 50% because the reduction is equivalent to the 6.7 million RVUs needed to offset other proposed changes for compressing E/M payment into single levels and allowing use of the new add-on codes.”

A key concern for the American Academy of Family Physicians was collapsing the levels 2 through 5 E/M visits into a single payment level.

Instead, AAFP recommended that CMS work with it and other medical societies to develop new codes and values to ensure proper payment for services. Instead of a primary care add-on code, CMS should increase E/M payments by 15% for services provided “by physicians who list their primary practice designation as family medicine, internal medicine, or geriatrics,” according to the comments.

AAFP is “concerned that the changes included in the proposed rule may harm the quality and cost of care for Medicare beneficiaries,” the comment letter states, adding that it is “possible that beneficiary out-of-pocket costs would increase due to more frequent physician or clinician visits.”

The American College of Rheumatology voiced its support for the focus “on reducing physician burden by simplifying documentation requirements,” but said it had “serious concerns about the changes to evaluation and management (E/M) codes that result in cuts in reimbursement to cognitive specialists for the complex services they provide.” It added that while there is support for the documentation reduction efforts, “we are skeptical that this proposal will simplify the reporting burden on providers in the Quality Payment Program. As proposed, the new plan proposes several ‘add-on’ codes that would likely prevent reduction in audits or documentation.”

The estimated 51 hours per doctor per year of time saved “are insufficient to offset the proposed cuts to reimbursement. For example, if a physician sees around 100 patients a week, this translates to under 40 seconds per patient, which is not a benefit that outweighs the proposed reduction in reimbursement.”

The American College of Physicians voiced its opposition to the E/M proposal, noting that it “strongly believes that cognitive care of more complex patients must be appropriately recognized with higher allowed payment rates than less complex care patients.” ACP said the even with the proposed add-on codes, the proposed changes undervalue cognitive care for the most complex patients.

The Flint Lock: A Novel Technique in Total Knee Arthroplasty Closure

ABSTRACT

Conventional interrupted sutures are traditionally used in extensor mechanism closure during total knee arthroplasty (TKA). In recent years, barbed suture has been introduced with the proposed benefits of decreased closure time and a watertight seal that is superior to interrupted sutures. Complication rates using barbed sutures and conventional interrupted sutures are similar. We propose a novel closure technique known as the Flint Lock, which is a double continuous interlocking stitch. The Flint Lock provides a quick and efficient closure to the extensor mechanism in TKA. In addition, similar to barbed suture, the Flint Lock should provide a superior watertight seal. It utilizes relatively inexpensive and readily available materials.

Continue to: In 2003, more than 400,000 total knee replacements...

In 2003, more than 400,000 total knee replacements were performed in the United States. This number is expected to increase in the coming decades to 3 million by the year 2030.1 The surgical approach to knee arthroplasty always involves a capsular incision that needs to be repaired after implantation of the components. The capsular incision repair should be strong enough to allow for immediate range of motion.

Traditionally, repair of the arthrotomy is performed using interrupted sutures. Recently, a running technique using barbed suture has been demonstrated to enable faster closure times.2-6 In addition, a running suture technique using barbed suture provides a superior watertight closure compared with an interrupted suture.7 It has been reported that the barbed suture has the same safety profile as that of interrupted sutures,2,3,4 although extensor mechanism repair failure8 and wound complications9,10 have been reported.

This study proposes a novel technique for arthrotomy closure in total knee arthroplasty (TKA). It is a double continuous interlocking stitch, termed the “Flint Lock.” Based on our clinical experience using this method, this technique has been found to be safe and effective.

TECHNIQUE

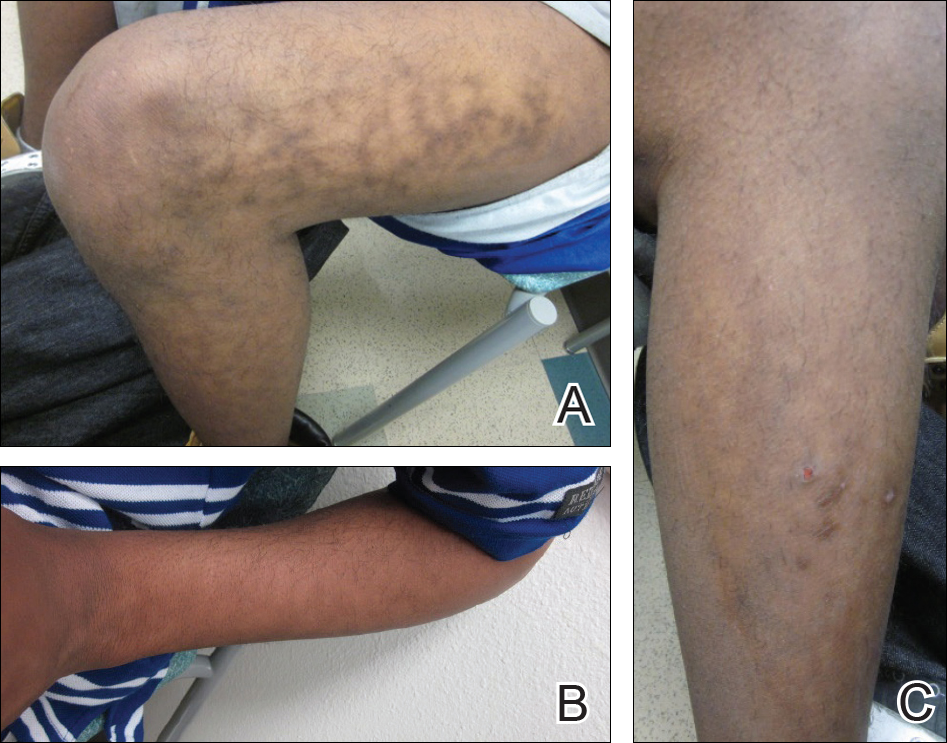

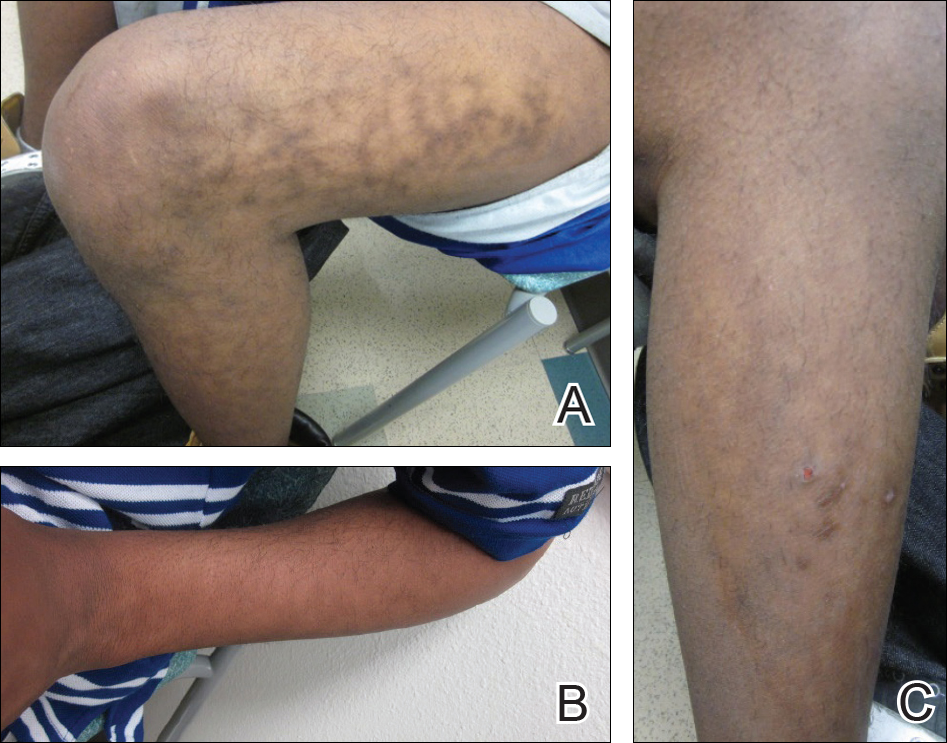

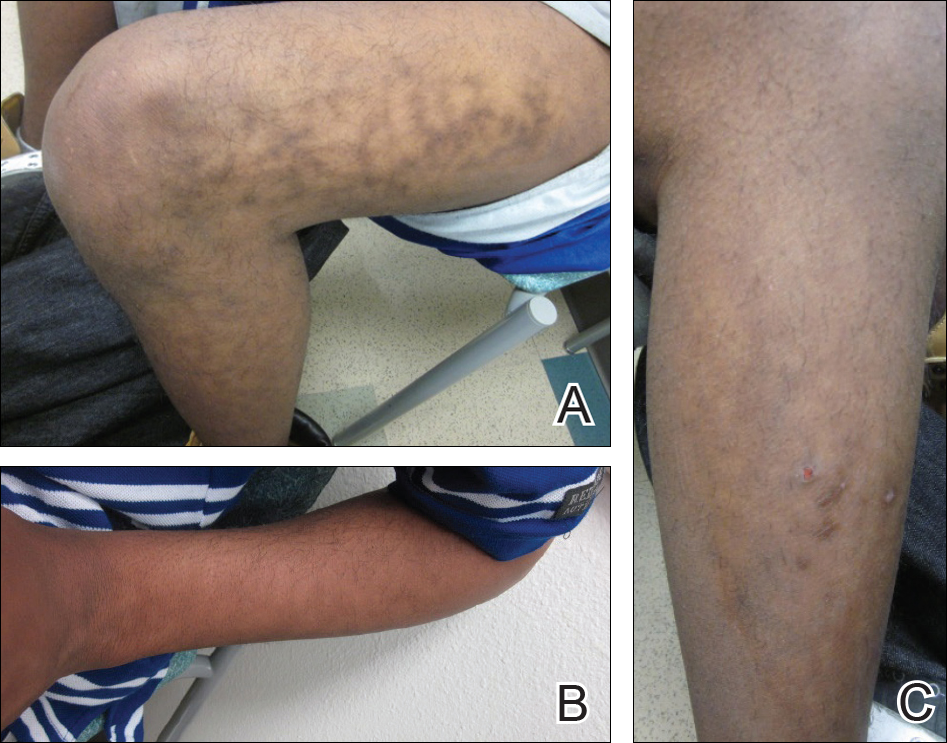

The Flint Lock was developed for closure in TKA, which was performed through a standard medial parapatellar approach. Before creating the arthrotomy, a horizontal line is drawn along the medial side of the patella to ensure anatomic alignment of the extensor mechanism during closure of the capsule.

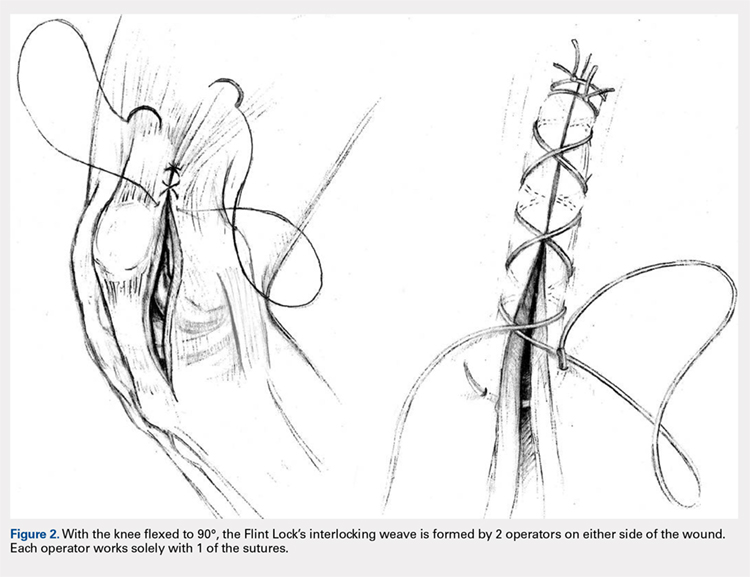

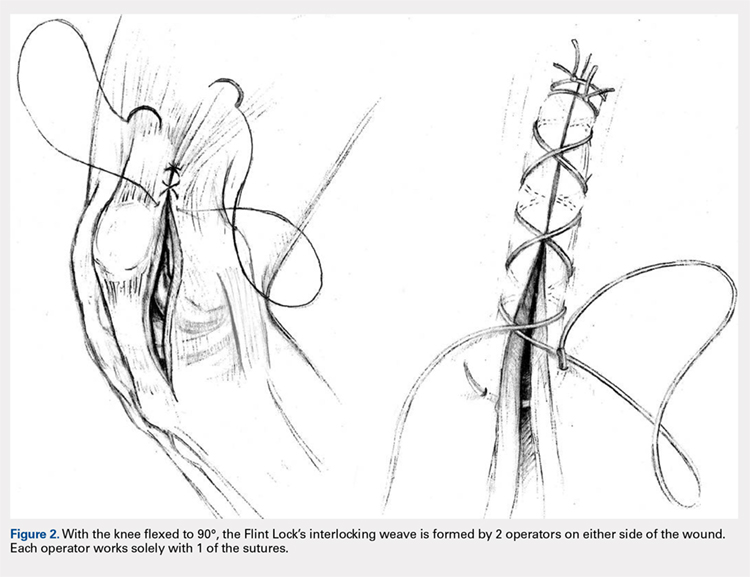

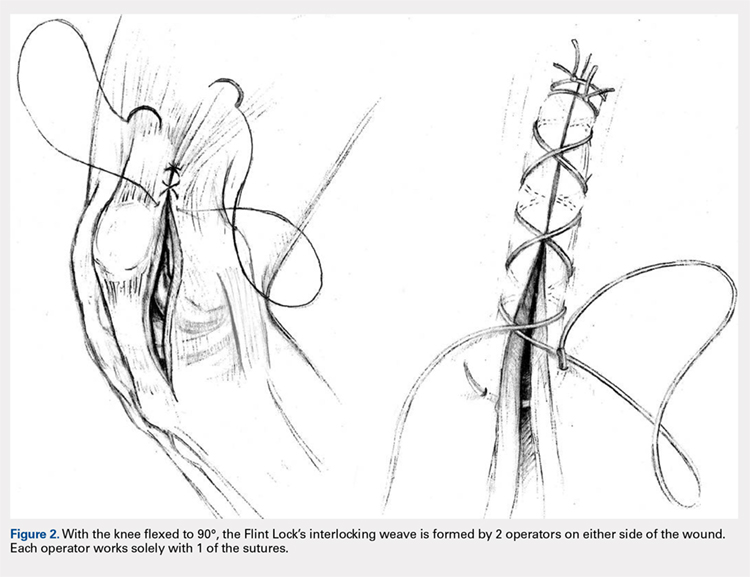

The Flint Lock is performed by 2 people working simultaneously. Closure begins at the proximal end of the arthrotomy using 2 No. 1 Vicryl (Ethicon) sutures. Each suture is thrown a single time at the most proximal extent of the arthrotomy with the knee in 30° to 40° of flexion. These sutures are tied off independently from each other (Figure 1). At this point, the knee is flexed to 90° and the sutures are thrown alternately, with the first operator passing medial to lateral through the capsule and the second operator passing lateral to medial. While 1 operator is passing a suture, the other operator holds the other suture tight to maintain tension on the closure. The alternating throws create an interlocking weave as the pattern is repeated and progressively moves distally (Figure 2). This technique results in 2 continuous sutures running in opposing directions. Each No. 1 Vicryl suture is specific to each operator. Therefore, each operator uses the same suture for the entirety of the closure.

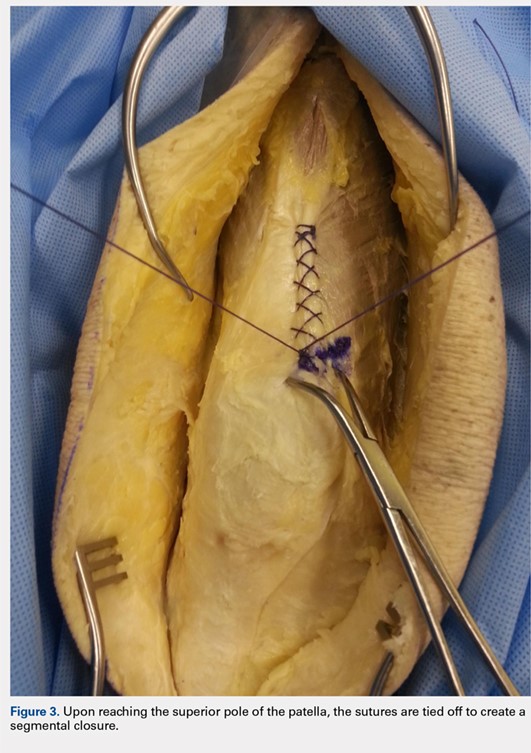

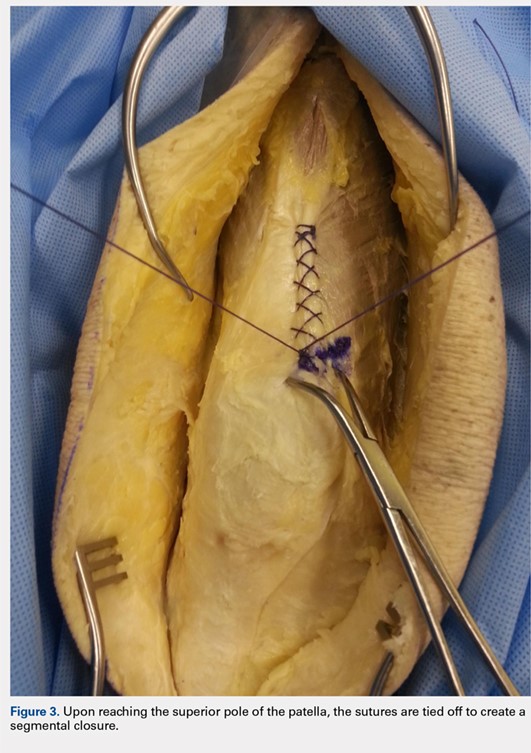

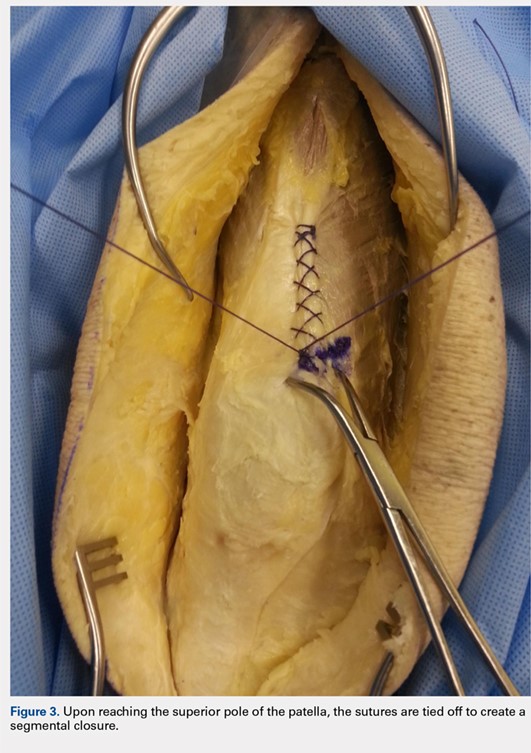

When the superior pole of the patella is reached, the 2 sutures are tied together, thus creating a segmental closure (Figure 3). Following this tie off, the closure is continued in a similar manner until the inferior pole of the patella is reached. The sutures are then tied off to each other again, creating another segmental closure (Figure 4). The remainder of the arthrotomy is closed continuing the Flint Lock technique, and the 2 sutures are tied off to each other at the distal end of the arthrotomy and cut (Figure 5).

Continue to: The superficial layers are closed at the surgeon’s discretion...

The superficial layers are closed at the surgeon’s discretion. The authors prefer interrupted 2-0 Vicryl sutures followed by a running 3-0 Monocryl (Ethicon) suture in the subcutaneous layer. Dermabond (Ethicon) skin glue and an Aquacel Ag (ConvaTec) dressing are applied, followed by a compressive bandage.

DISCUSSION

The importance of a strong, tight closure of the arthrotomy in TKA is critical to the success of the procedure. Nevertheless, there are multiple methods to achieve closure. The Flint Lock technique is a novel method that employs basic concepts of surgical technique in an original manner. The continuous nature of the closure should provide a tighter seal, leading to less wound drainage. Persistent wound drainage has been associated with deep wound infections following total joint arthroplasty.11,12 In addition, the double suture provides a safeguard to a single suture rupture, while the segmental quality protects against complete arthrotomy failure.

A potential downside of this technique is that it requires 2 individuals operating 2 needles simultaneously. This presents a potential for a sharp injury to the operators; however, this has not occurred in our experience. A comparable risk with interrupted sutures is probably present because there are often multiple sutures utilized during closure via the interrupted technique.

In 2015, the cost of a single No. 1 barbed suture was $13.14 at our institution, whereas the cost of 2 No. 1 Vicryl sutures was $3.66. Although pricing differs across hospitals, the Vicryl sutures are probably less costly compared with the barbed sutures.

Our experience with the Flint Lock technique has been favorable thus far, with no incidences of postoperative drainage, infection, or extensor mechanism failure. Our current use has been in closure of the knee, but it could be considered in closure of long incisions about the hip as well. A more in-depth analysis of relevant factors, such as time for closure, mechanical strength, cost savings, and clinical outcomes, is needed to further evaluate this method of closure. In addition, biomechanical analysis of the technique would aid in its evaluation. Future studies are needed to analyze these factors to verify the benefits and viability of the Flint Lock technique.

1. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780-785. doi:10.2106/JBJS.F.00222.

2. Eickmann T, Quane E. Total knee arthroplasty closure with barbed sutures. J Knee Surg. 2010;23(3):163-167. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1268692.

3. Gililland JM, Anderson LA, Sun G, Erickson JA, Peters CL. Perioperative closure-related complication rates and cost analysis of barbed suture for closure in TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(1):125-129. doi:10.1007/s11999-011-2104-7.

4. Ting NT, Moric MM, Della Valle CJ, Levine BR. Use of knotless suture for closure of total hip and knee arthroplasties: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(10):1783-1788. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2012.05.022.

5. Stephens S, Politi J, Taylor BC. Evaluation of primary total knee arthroplasty incision closure with use of continuous bidirectional barbed suture. Surg Technol Int. 2011;21:199-203.

6. Levine BR, Ting N, Della Valle CJ. Use of a barbed suture in the closure of hip and knee arthroplasty wounds. Orthopedics. 2011;34(9):e473-e475. doi:10.3928/01477447-20110714-35.

7. Nett M, Avelar R, Sheehan M, Cushner F. Water-tight knee arthrotomy closure: comparison of a novel single bidirectional barbed self-retaining running suture versus conventional interrupted sutures. J Knee Surg. 2011;24(1):55-59. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1275400.

8. Wright RC, Gillis CT, Yacoubian SV, Raven RB 3rd, Falkinstein Y, Yacoubian SV. Extensor mechanism repair failure with use of birectional barbed suture in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(7):1413.e1-e4. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2011.08.013.

9. Campbell AL, Patrick DA Jr, Liabaud B, Geller JA. Superficial wound closure complications with barbed sutures following knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(5):966-969. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2013.09.045.

10. Smith EL, DiSegna ST, Shukla PY, Matzkin EG. Barbed versus traditional sutures: closure time, cost, and wound related outcomes in total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(2):283-287. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2013.05.031.

11. Saleh K, Olson M, Resig S, et al. Predictors of wound infection in hip and knee joint replacement: results from a 20 year surveillance program. J Orthop Res. 2002;20(3):506-515. doi:10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00153-X.

12. Weiss AP, Krackow KA. Persistent wound drainage after primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1993;8(3):285-289. doi:10.1016/S0883-5403(06)80091-4.

ABSTRACT

Conventional interrupted sutures are traditionally used in extensor mechanism closure during total knee arthroplasty (TKA). In recent years, barbed suture has been introduced with the proposed benefits of decreased closure time and a watertight seal that is superior to interrupted sutures. Complication rates using barbed sutures and conventional interrupted sutures are similar. We propose a novel closure technique known as the Flint Lock, which is a double continuous interlocking stitch. The Flint Lock provides a quick and efficient closure to the extensor mechanism in TKA. In addition, similar to barbed suture, the Flint Lock should provide a superior watertight seal. It utilizes relatively inexpensive and readily available materials.

Continue to: In 2003, more than 400,000 total knee replacements...

In 2003, more than 400,000 total knee replacements were performed in the United States. This number is expected to increase in the coming decades to 3 million by the year 2030.1 The surgical approach to knee arthroplasty always involves a capsular incision that needs to be repaired after implantation of the components. The capsular incision repair should be strong enough to allow for immediate range of motion.

Traditionally, repair of the arthrotomy is performed using interrupted sutures. Recently, a running technique using barbed suture has been demonstrated to enable faster closure times.2-6 In addition, a running suture technique using barbed suture provides a superior watertight closure compared with an interrupted suture.7 It has been reported that the barbed suture has the same safety profile as that of interrupted sutures,2,3,4 although extensor mechanism repair failure8 and wound complications9,10 have been reported.

This study proposes a novel technique for arthrotomy closure in total knee arthroplasty (TKA). It is a double continuous interlocking stitch, termed the “Flint Lock.” Based on our clinical experience using this method, this technique has been found to be safe and effective.

TECHNIQUE

The Flint Lock was developed for closure in TKA, which was performed through a standard medial parapatellar approach. Before creating the arthrotomy, a horizontal line is drawn along the medial side of the patella to ensure anatomic alignment of the extensor mechanism during closure of the capsule.

The Flint Lock is performed by 2 people working simultaneously. Closure begins at the proximal end of the arthrotomy using 2 No. 1 Vicryl (Ethicon) sutures. Each suture is thrown a single time at the most proximal extent of the arthrotomy with the knee in 30° to 40° of flexion. These sutures are tied off independently from each other (Figure 1). At this point, the knee is flexed to 90° and the sutures are thrown alternately, with the first operator passing medial to lateral through the capsule and the second operator passing lateral to medial. While 1 operator is passing a suture, the other operator holds the other suture tight to maintain tension on the closure. The alternating throws create an interlocking weave as the pattern is repeated and progressively moves distally (Figure 2). This technique results in 2 continuous sutures running in opposing directions. Each No. 1 Vicryl suture is specific to each operator. Therefore, each operator uses the same suture for the entirety of the closure.

When the superior pole of the patella is reached, the 2 sutures are tied together, thus creating a segmental closure (Figure 3). Following this tie off, the closure is continued in a similar manner until the inferior pole of the patella is reached. The sutures are then tied off to each other again, creating another segmental closure (Figure 4). The remainder of the arthrotomy is closed continuing the Flint Lock technique, and the 2 sutures are tied off to each other at the distal end of the arthrotomy and cut (Figure 5).

Continue to: The superficial layers are closed at the surgeon’s discretion...

The superficial layers are closed at the surgeon’s discretion. The authors prefer interrupted 2-0 Vicryl sutures followed by a running 3-0 Monocryl (Ethicon) suture in the subcutaneous layer. Dermabond (Ethicon) skin glue and an Aquacel Ag (ConvaTec) dressing are applied, followed by a compressive bandage.

DISCUSSION

The importance of a strong, tight closure of the arthrotomy in TKA is critical to the success of the procedure. Nevertheless, there are multiple methods to achieve closure. The Flint Lock technique is a novel method that employs basic concepts of surgical technique in an original manner. The continuous nature of the closure should provide a tighter seal, leading to less wound drainage. Persistent wound drainage has been associated with deep wound infections following total joint arthroplasty.11,12 In addition, the double suture provides a safeguard to a single suture rupture, while the segmental quality protects against complete arthrotomy failure.

A potential downside of this technique is that it requires 2 individuals operating 2 needles simultaneously. This presents a potential for a sharp injury to the operators; however, this has not occurred in our experience. A comparable risk with interrupted sutures is probably present because there are often multiple sutures utilized during closure via the interrupted technique.

In 2015, the cost of a single No. 1 barbed suture was $13.14 at our institution, whereas the cost of 2 No. 1 Vicryl sutures was $3.66. Although pricing differs across hospitals, the Vicryl sutures are probably less costly compared with the barbed sutures.

Our experience with the Flint Lock technique has been favorable thus far, with no incidences of postoperative drainage, infection, or extensor mechanism failure. Our current use has been in closure of the knee, but it could be considered in closure of long incisions about the hip as well. A more in-depth analysis of relevant factors, such as time for closure, mechanical strength, cost savings, and clinical outcomes, is needed to further evaluate this method of closure. In addition, biomechanical analysis of the technique would aid in its evaluation. Future studies are needed to analyze these factors to verify the benefits and viability of the Flint Lock technique.

ABSTRACT

Conventional interrupted sutures are traditionally used in extensor mechanism closure during total knee arthroplasty (TKA). In recent years, barbed suture has been introduced with the proposed benefits of decreased closure time and a watertight seal that is superior to interrupted sutures. Complication rates using barbed sutures and conventional interrupted sutures are similar. We propose a novel closure technique known as the Flint Lock, which is a double continuous interlocking stitch. The Flint Lock provides a quick and efficient closure to the extensor mechanism in TKA. In addition, similar to barbed suture, the Flint Lock should provide a superior watertight seal. It utilizes relatively inexpensive and readily available materials.

Continue to: In 2003, more than 400,000 total knee replacements...

In 2003, more than 400,000 total knee replacements were performed in the United States. This number is expected to increase in the coming decades to 3 million by the year 2030.1 The surgical approach to knee arthroplasty always involves a capsular incision that needs to be repaired after implantation of the components. The capsular incision repair should be strong enough to allow for immediate range of motion.

Traditionally, repair of the arthrotomy is performed using interrupted sutures. Recently, a running technique using barbed suture has been demonstrated to enable faster closure times.2-6 In addition, a running suture technique using barbed suture provides a superior watertight closure compared with an interrupted suture.7 It has been reported that the barbed suture has the same safety profile as that of interrupted sutures,2,3,4 although extensor mechanism repair failure8 and wound complications9,10 have been reported.

This study proposes a novel technique for arthrotomy closure in total knee arthroplasty (TKA). It is a double continuous interlocking stitch, termed the “Flint Lock.” Based on our clinical experience using this method, this technique has been found to be safe and effective.

TECHNIQUE

The Flint Lock was developed for closure in TKA, which was performed through a standard medial parapatellar approach. Before creating the arthrotomy, a horizontal line is drawn along the medial side of the patella to ensure anatomic alignment of the extensor mechanism during closure of the capsule.

The Flint Lock is performed by 2 people working simultaneously. Closure begins at the proximal end of the arthrotomy using 2 No. 1 Vicryl (Ethicon) sutures. Each suture is thrown a single time at the most proximal extent of the arthrotomy with the knee in 30° to 40° of flexion. These sutures are tied off independently from each other (Figure 1). At this point, the knee is flexed to 90° and the sutures are thrown alternately, with the first operator passing medial to lateral through the capsule and the second operator passing lateral to medial. While 1 operator is passing a suture, the other operator holds the other suture tight to maintain tension on the closure. The alternating throws create an interlocking weave as the pattern is repeated and progressively moves distally (Figure 2). This technique results in 2 continuous sutures running in opposing directions. Each No. 1 Vicryl suture is specific to each operator. Therefore, each operator uses the same suture for the entirety of the closure.

When the superior pole of the patella is reached, the 2 sutures are tied together, thus creating a segmental closure (Figure 3). Following this tie off, the closure is continued in a similar manner until the inferior pole of the patella is reached. The sutures are then tied off to each other again, creating another segmental closure (Figure 4). The remainder of the arthrotomy is closed continuing the Flint Lock technique, and the 2 sutures are tied off to each other at the distal end of the arthrotomy and cut (Figure 5).

Continue to: The superficial layers are closed at the surgeon’s discretion...

The superficial layers are closed at the surgeon’s discretion. The authors prefer interrupted 2-0 Vicryl sutures followed by a running 3-0 Monocryl (Ethicon) suture in the subcutaneous layer. Dermabond (Ethicon) skin glue and an Aquacel Ag (ConvaTec) dressing are applied, followed by a compressive bandage.

DISCUSSION

The importance of a strong, tight closure of the arthrotomy in TKA is critical to the success of the procedure. Nevertheless, there are multiple methods to achieve closure. The Flint Lock technique is a novel method that employs basic concepts of surgical technique in an original manner. The continuous nature of the closure should provide a tighter seal, leading to less wound drainage. Persistent wound drainage has been associated with deep wound infections following total joint arthroplasty.11,12 In addition, the double suture provides a safeguard to a single suture rupture, while the segmental quality protects against complete arthrotomy failure.

A potential downside of this technique is that it requires 2 individuals operating 2 needles simultaneously. This presents a potential for a sharp injury to the operators; however, this has not occurred in our experience. A comparable risk with interrupted sutures is probably present because there are often multiple sutures utilized during closure via the interrupted technique.

In 2015, the cost of a single No. 1 barbed suture was $13.14 at our institution, whereas the cost of 2 No. 1 Vicryl sutures was $3.66. Although pricing differs across hospitals, the Vicryl sutures are probably less costly compared with the barbed sutures.

Our experience with the Flint Lock technique has been favorable thus far, with no incidences of postoperative drainage, infection, or extensor mechanism failure. Our current use has been in closure of the knee, but it could be considered in closure of long incisions about the hip as well. A more in-depth analysis of relevant factors, such as time for closure, mechanical strength, cost savings, and clinical outcomes, is needed to further evaluate this method of closure. In addition, biomechanical analysis of the technique would aid in its evaluation. Future studies are needed to analyze these factors to verify the benefits and viability of the Flint Lock technique.

1. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780-785. doi:10.2106/JBJS.F.00222.

2. Eickmann T, Quane E. Total knee arthroplasty closure with barbed sutures. J Knee Surg. 2010;23(3):163-167. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1268692.

3. Gililland JM, Anderson LA, Sun G, Erickson JA, Peters CL. Perioperative closure-related complication rates and cost analysis of barbed suture for closure in TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(1):125-129. doi:10.1007/s11999-011-2104-7.

4. Ting NT, Moric MM, Della Valle CJ, Levine BR. Use of knotless suture for closure of total hip and knee arthroplasties: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(10):1783-1788. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2012.05.022.

5. Stephens S, Politi J, Taylor BC. Evaluation of primary total knee arthroplasty incision closure with use of continuous bidirectional barbed suture. Surg Technol Int. 2011;21:199-203.

6. Levine BR, Ting N, Della Valle CJ. Use of a barbed suture in the closure of hip and knee arthroplasty wounds. Orthopedics. 2011;34(9):e473-e475. doi:10.3928/01477447-20110714-35.

7. Nett M, Avelar R, Sheehan M, Cushner F. Water-tight knee arthrotomy closure: comparison of a novel single bidirectional barbed self-retaining running suture versus conventional interrupted sutures. J Knee Surg. 2011;24(1):55-59. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1275400.

8. Wright RC, Gillis CT, Yacoubian SV, Raven RB 3rd, Falkinstein Y, Yacoubian SV. Extensor mechanism repair failure with use of birectional barbed suture in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(7):1413.e1-e4. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2011.08.013.

9. Campbell AL, Patrick DA Jr, Liabaud B, Geller JA. Superficial wound closure complications with barbed sutures following knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(5):966-969. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2013.09.045.

10. Smith EL, DiSegna ST, Shukla PY, Matzkin EG. Barbed versus traditional sutures: closure time, cost, and wound related outcomes in total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(2):283-287. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2013.05.031.

11. Saleh K, Olson M, Resig S, et al. Predictors of wound infection in hip and knee joint replacement: results from a 20 year surveillance program. J Orthop Res. 2002;20(3):506-515. doi:10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00153-X.

12. Weiss AP, Krackow KA. Persistent wound drainage after primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1993;8(3):285-289. doi:10.1016/S0883-5403(06)80091-4.

1. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780-785. doi:10.2106/JBJS.F.00222.

2. Eickmann T, Quane E. Total knee arthroplasty closure with barbed sutures. J Knee Surg. 2010;23(3):163-167. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1268692.

3. Gililland JM, Anderson LA, Sun G, Erickson JA, Peters CL. Perioperative closure-related complication rates and cost analysis of barbed suture for closure in TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(1):125-129. doi:10.1007/s11999-011-2104-7.

4. Ting NT, Moric MM, Della Valle CJ, Levine BR. Use of knotless suture for closure of total hip and knee arthroplasties: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(10):1783-1788. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2012.05.022.

5. Stephens S, Politi J, Taylor BC. Evaluation of primary total knee arthroplasty incision closure with use of continuous bidirectional barbed suture. Surg Technol Int. 2011;21:199-203.

6. Levine BR, Ting N, Della Valle CJ. Use of a barbed suture in the closure of hip and knee arthroplasty wounds. Orthopedics. 2011;34(9):e473-e475. doi:10.3928/01477447-20110714-35.

7. Nett M, Avelar R, Sheehan M, Cushner F. Water-tight knee arthrotomy closure: comparison of a novel single bidirectional barbed self-retaining running suture versus conventional interrupted sutures. J Knee Surg. 2011;24(1):55-59. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1275400.

8. Wright RC, Gillis CT, Yacoubian SV, Raven RB 3rd, Falkinstein Y, Yacoubian SV. Extensor mechanism repair failure with use of birectional barbed suture in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(7):1413.e1-e4. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2011.08.013.

9. Campbell AL, Patrick DA Jr, Liabaud B, Geller JA. Superficial wound closure complications with barbed sutures following knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(5):966-969. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2013.09.045.

10. Smith EL, DiSegna ST, Shukla PY, Matzkin EG. Barbed versus traditional sutures: closure time, cost, and wound related outcomes in total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(2):283-287. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2013.05.031.

11. Saleh K, Olson M, Resig S, et al. Predictors of wound infection in hip and knee joint replacement: results from a 20 year surveillance program. J Orthop Res. 2002;20(3):506-515. doi:10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00153-X.

12. Weiss AP, Krackow KA. Persistent wound drainage after primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1993;8(3):285-289. doi:10.1016/S0883-5403(06)80091-4.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- The Flint Lock is a novel technique in TKA closure.

- Its continuous nature provides a tight seal with extensor mechanism closure.

- The utilization of a segmental closure with double suture provides a safeguard for suture failure.

- The suture used in the technique is less expensive than barbed suture.

- Future investigation is warranted to further validate the use of the Flint Lock.

The Effect of Insurance Type on Patient Access to Ankle Fracture Care Under the Affordable Care Act

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study is to assess the effect of insurance type (Medicaid, Medicare, private insurance) on the ability for patients with operative ankle fractures to access orthopedic traumatologists. The research team called 245 board-certified orthopedic surgeons specializing in orthopedic trauma within 8 representative states. The caller requested an appointment for their fictitious mother in order to be evaluated for an ankle fracture which was previously evaluated by her primary care physician and believed to require surgery. Each office was called 3 times to assess the response for each insurance type. For each call, information was documented regarding whether the patient was able to receive an appointment and the barriers the patient confronted to receive an appointment. Overall, 35.7% of offices scheduled an appointment for a patient with Medicaid, in comparison to 81.4%and 88.6% for Medicare and BlueCross, respectively (P < .0001). Medicaid patients confronted more barriers for receiving appointments. There was no statistically significant difference in access for Medicaid patients in states that had expanded Medicaid eligibility vs states that had not expanded Medicaid. Medicaid reimbursement for open reduction and internal fixation of an ankle fracture did not significantly correlate with appointment success rates or wait times. Despite the passage of the Affordable Care Act, patients with Medicaid have reduced access to orthopedic surgeons and more complex barriers to receiving appointments. A more robust strategy for increasing care-access for patients with Medicaid would be more equitable.

Continue to: In 2010, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act...

In 2010, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) expanded the eligibility criteria for Medicaid to all individuals with an income up to 138% of the poverty level.1 A Supreme Court ruling stated that the decision to expand Medicaid was to be decided by individual states.2 Currently, 31 states have chosen to expand Medicaid eligibility to their residents.2 This expansion has allowed an additional 11.7 million people to enroll in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program by May 2015.3-5

Even with the passage of the PPACA, Medicaid patients seeking specialty orthopedic care have experienced more barriers to accessing care than Medicare or commercially-insured patients.2,6-10 One major cited reason is Medicaid’s low reimbursement, which may discourage physicians from open panel participation in Medicaid.11,12

A common fundamental teaching for orthopedic traumatologists is the notion that they should be available to treat all injuries regardless of the patient’s ability to pay.13 This has resulted in both trauma centers and trauma surgeons becoming financially challenged due to the higher proportion of Medicaid and uninsured trauma patients and lower Medicaid reimbursement levels.14,15

This study focuses on the effect of different types of insurance (Medicaid, Medicare, or commercial insurance) on the ability of patients to obtain care for operative ankle fractures. The purpose of this study is to evaluate, in the context of the PPACA, patient access to orthopedic surgeons for operative ankle fractures based on insurance-type. We hypothesized that patients with Medicaid would face a greater volume of obstacles when seeking appointments for an ankle fracture, even after the PPACA.

Continue to: MATERIALS AND METHODS...

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study population included board-certified orthopedic surgeons who belonged to the Orthopaedic Trauma Association (OTA) from 8 representative states; 4 states with expanded Medicaid eligibility (California, Massachusetts, New York, Ohio) and 4 states without expanded Medicaid eligibility (Florida, North Carolina, Georgia, Texas). These states were selected due to their ability to represent diverse healthcare marketplaces throughout the country. Using the OTA website’s “Find a Surgeon” search tool,16 we created a list of surgeons for each state and matched each surgeon with a random number. The list of surgeons was ordered according to the value of the surgeon’s associated random number, and surgeons were called in ascending order. We excluded disconnected or inaccurate numbers from the calling list. Surgeons who did not manage ankle fractures were removed from the dataset. Approximately 30 orthopedic trauma surgeons per state were contacted.

Each office was called to make an appointment for the caller’s mother. Every surgeon’s office was specifically asked if the surgeon would accept the patient to be evaluated for an ankle fracture that occurred out-of-state. The caller had a standardized protocol to limit intra- and inter-office variations (Appendix). The scenario involved a request to be evaluated for an unstable ankle fracture, with the patient having Medicaid, Medicare, or BlueCross insurance. The scenario required 3 separate calls to the same surgeon in order to obtain data regarding each insurance-type. The calls were separated by at least 1 week to avoid caller recognition by the surgeon’s office.

Appendix

Scenario

1. Date of Birth: Medicaid–2/07/55; BlueCross PPO–2/09/55; Medicare–7/31/45.

2. Ankle fracture evaluated by primary care physician 1 or 2 days ago

3. Not seen previously by your clinic or hospital, she would be a new patient

4. Asked how early she could be scheduled for an appointment

5. Script:

“I’m calling for my mother who injured her ankle a few days ago. Her family doctor took an X-ray and believes she has a fracture and needs surgery. Is Dr. X accepting new patients for evaluation and treatment of ankle fractures?” If YES →

“I was wondering if you take Medicaid/Medicare/BlueCross plan?” If YES →

“When is your soonest available appointment?”

The date of each phone call and date of appointment, if provided, were recorded. If the office did not give an appointment, we asked for reasons why. If an appointment was denied for a patient with Medicaid, we asked for a referral to another office that accepted Medicaid. We considered barriers to obtaining an initial appointment, such as requiring a referral from a primary care physician (PCP), as an unsuccessful attempt at making an appointment. We determined the waiting period for an appointment by calculating the time between the date of the call and the date of the appointment. Appointments were not scheduled to ensure that actual patients were not disadvantaged. For both appointment success rates and waiting periods, we stratified the data into 2 groups: states with expanded Medicaid eligibility (California, Massachusetts, New York, Ohio) and states without expanded Medicaid eligibility (Florida, North Carolina, Georgia, Texas).

We obtained Medicaid reimbursement rates for open reduction and internal fixation of an ankle fracture by querying each state’s reimbursement rate using Current Procedural Terminology code 27822.

Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze acceptance rate differences based on the patient’s type of insurance. To compare the waiting periods for an appointment, we used an independent samples t-test after applying natural log-transformation, as the data was not normally distributed. We performed logistic regression analysis to detect whether reimbursement was a significant predictor of successfully making an appointment for patients, and a linear regression analysis was used to evaluate whether reimbursement predicted waiting periods. Unless otherwise stated, all statistical testing was performed two-tailed at an alpha-level of 0.05.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yale University School of Medicine (HIC No. 1363).

Continue to: RESULTS...

RESULTS

In total, 350 offices were contacted across 8 states (4 states with and 4 states without expanded Medicaid eligibility) of which we identified 245 orthopedic surgeons who would surgically treat ankle fractures. The 245 surgeons’ offices were called 3 times for each separate insurance-type.

Table 1. Appointment Success Rate

| Medicaid | Medicare | Private |

All states |

|

| |

Yes (%) | 100 (35.7) | 228 (81.4) | 248 (88.6) |

No (%) | 180 (64.3) | 52 (18.60 | 32 (11.4) |

P-valuea |

| 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

States with expanded Medicaid eligibility |

|

|

|

Yes (%) | 55 (39.6) | 116 (83.5) | 124 (89.2) |

No (%) | 84 (60.4) | 23 (16.5) | 15 (10.8) |

P-valuea |

| 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

States without expanded Medicaid eligibility |

|

|

|

Yes (%) | 45 (31.9) | 112 (79.4) | 124 (87.9) |

No (%) | 96 (68.1) | 29 (20.6) | 17 (12.1) |

P-valuea |

| 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

aComparison to Medicaid.

The overall rate of successfully being offered an appointment with Medicaid was 35.7%, 81.4% for Medicare, and 88.6% for BlueCross (Table 1). For states with expanded Medicaid eligibility, the success rate for obtaining an appointment was 39.6%, 83.5%, and 89.2% for Medicaid, Medicare, and BlueCross, respectively. For states without expanded Medicaid eligibility, the success rate for obtaining an appointment was 31.9% for Medicaid, 79.4% for Medicare, and 87.9% for BlueCross. In all cases, the success rate for obtaining an appointment was significantly lower for Medicaid, compared to Medicare (P < .0001) or BlueCross (P < .0001). Medicaid appointment success rate was 39.6% in expanded states vs 31.9% in non-expanded states, however, the difference was not statistically significant (Table 2).

Table 2. Medicaid Appointment Success Rate in Expanded Vs Non-Expanded States

| Expanded states | Non-expanded states | P-value |

Yes (%) | 55 (39.6) | 45 (31.9) | .181 |

No (%) | 84 (60.4) | 96 (68.1) |

|

In 43.7% of occasions, patients with Medicaid did not have their insurance accepted, compared to 7.3% for Medicare and 0% for BlueCross. The majority of offices which did not accept Medicaid were not able to refer patients to another surgeon who would accept Medicaid. The requirement to have a primary care referral was the second most common reason for Medicaid patients not obtaining an appointment. No Medicare (10.4% vs 0.0%, P < .0001) or BlueCross (10.4% vs 0.0%, P < .0001) patients experienced this requirement (Table 3). There was no difference found between the percent of Medicaid patients who were required to have referrals in states with and without expanded Medicaid eligibility (Table 4).

Table 3. Referral Rate

| Medicaid | Medicare | Private |

All states |

|

|

|

Yes (%) | 29 (10.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

No (%) | 251 (89.6) | 280 (100) | 280 (100) |

P-valuea |

| 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

States with expanded Medicaid eligibility |

|

|

|

Yes (%) | 12 (8.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

No (%) | 127 (91.4) | 139 (100) | 139 (100) |

P-valuea |

| 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

States without expanded Medicaid eligibility |

|

|

|

Yes (%) | 17 (12.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

No (%) | 124 (87.9) | 141 (100) | 141 (100) |

P-valuea |

| 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

aComparison to Medicaid.

Table 4. Medicaid Referral Rates in Expanded Vs Non-Expanded States

| Expanded states | Non-expanded states | P-value |

Yes (%) | 12 (9.7) | 17 (14.0) | .35 |

No (%) | 127 (91.4) | 124 (87.9) |

|

Reimbursements for ankle fracture varied across states (Table 5). For Medicaid, Georgia paid the highest reimbursement ($1049.95) and Florida paid the lowest ($469.44). Logistic and linear regression analysis did not demonstrate a significant relationship between reimbursement and appointment success rate or waiting periods.

Table 5. Medicaid Reimbursements for Ankle Fracture Repair (CPT and HCPCS 27822) in 2014

State | Medicaid reimbursement |

Californiaa | $785.55 |

Texas | $678.95 |

Florida | $469.44 |

Ohioa | $617.08 |

New Yorka | $500.02 |

North Carolina | $621.63 |

Massachusettsa | $627.94 |

Georgia | $1,049.95 |

Average | $668.82 |

aStates with expanded Medicaid eligibility.

Abbreviations: CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; HCPCS, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System.

Waiting periods (Table 6) varied significantly by the type of insurance (7.3 days for Medicaid, 6.0 days for Medicare, and 6.0 days for BlueCross; P = .002). For states with expanded Medicaid eligibility, waiting periods varied significantly by insurance (7.7 days for Medicaid, 6.2 days for Medicare, P = .003; and 6.1 days for BlueCross, P = .01). Waiting periods did not vary significantly for states without expanded Medicaid. Additionally, waiting periods did not differ significantly when comparing between states with and without Medicaid expansion.

Table 6. Waiting Period (Days) by Insurance Type.

| Medicaid | Medicare | Private |

Comparison by Insurance Type |

|

|

|

All states |

|

|

|

Waiting period | 7.3 | 6.0 | 6.0 |

P-value |

| 0.002 | 0.002 |

States with expanded Medicaid eligibility |

|

|

|

Waiting period | 7.7 | 6.2 | 6.1 |

P-value |

| 0.003 | 0.01 |

States without expanded Medicaid eligibility |

|

|

|

Waiting period | 6.9 | 5.9 | 5.9 |

P-value |

| 0.15 | 0.15 |

Comparison by Medicaid Expansion |

|

|

|

States with expanded Medicaid eligibility | 7.7 | 6.2 | 6.1 |

States without expanded Medicaid eligibility | 6.9 | 5.9 | 5.9 |

P-value | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.07 |

Continue to: DISCUSSION...

DISCUSSION

This study assessed how insurance type (Medicaid, Medicare, and BlueCross) affects patient access to orthopedic trauma surgeons in 8 geographically representative states. We selected unstable ankle fractures as they are basic fractures treated by nearly all trauma surgeons and should often be surgically treated to prevent serious long-term consequences. Our hypothesis stated that despite the passage of the PPACA, patients with Medicaid would have reduced access to care. As the PPACA has changed the healthcare marketplace by increasing the number of Medicaid enrollees, it is important to ensure that patient access to care improves.

This nationwide survey of orthopedic trauma surgeons demonstrates that Medicaid patients experience added barriers to care that ultimately results in lower rates of successfully obtaining care. This is consistent with other investigations which have assessed Medicaid patient healthcare access.6,8,10,17-19 This study did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference between Medicaid patients’ ability to obtain appointments in states with expanded Medicaid eligibility vs in states without expanded Medicaid eligibility (39.6% vs 31.9%, P < .18); this has been demonstrated in the literature.6

A barrier that was unique to Medicaid patients was the requirement to have a PCP referral (Table 3). A PCP referral was not a barrier to receiving an appointment for patients with Medicare or BlueCross. One reason to explain why Medicaid patients may be required to have PCP referrals is due to their increased medical complexity, extra documentation requirements, and low reimbursement.4 Patients who have obtained a PCP referral may be characterized as being more medically compliant.

It is important to note that the Medicaid policies for 4 states included in this study (Massachusetts, North Carolina, Texas, and New York) required a PCP referral in order to see a specialist. However, we found that many orthopedic trauma practices in these states scheduled appointments for Medicaid patients without a PCP referral, suggesting that the decision depended on individual policy. In addition, the majority of offices within these states cited that they simply did not accept Medicaid as an insurance policy, and not that they required a referral.

Our regression analysis did not find a significant relationship between being able to successfully obtain an appointment to be evaluated for an ankle fracture and reimbursement rates for Medicaid. Although studies have stressed the importance of Medicaid reimbursements on physician participation, this result is consistent with previous studies regarding carpal tunnel release and total ankle replacements.17,19 Long20 suggested that although reimbursements may help, additional strategies for promoting Medicaid acceptance may be needed, including: lowering the costs of participating in Medicaid by simplifying administrative processes, speeding up reimbursement, and reducing the costs associated with caring for those patients.

Continue to: Previous studies have demonstrated...

Previous studies have demonstrated that more physicians may accept Medicaid if reimbursements increased.4,12 Given the high percentage of trauma patients with Medicaid as their primary insurance or whom are emergently enrolled in Medicaid by hospital systems, it is concerning that the PPACA is reducing payments under the Medicare and Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital programs which provide hospitals for uncompensated care given to low-income and uninsured patients.21 Trauma centers generally operate at a deficit due to the higher proportion of Medicaid and uninsured patients.14 This is currently worsened by additional federal funding cuts for supporting trauma service’s humane mission.21

This study has several limitations. While the study evaluated access to care in 8 representative states, a thorough nationwide survey would be more representative. Some results may have become statistically significant if we had performed the study with a larger sample size. In addition, we were unable to control for many factors which could impact appointment wait times, such as physician call schedules and vacations. Socioeconomic factors can influence a patient’s ability to attend an appointment, such as transportation costs, time off from work, and childcare availability. In addition, this study did not assess access for the uninsured, who are predominantly the working poor who cannot afford health insurance, even with federal and state subsidies.

The authors apologize for inconveniencing these offices, however, data collection could not be achieved in a better manner. We hope that the value of this study compensates any inconvenience.

CONCLUSION

Overall, our results demonstrate that despite the ratification of the PPACA, Medicaid patients are confronted with more barriers to accessing care by comparison to patients with Medicare and BlueCross insurance. Medicaid patients have worse baseline health22 and are at an increased risk of complications. These disparities are thought to be due to decreased healthcare access,23,24 as well as socioeconomic challenges. Interventions, such as increasing Medicaid’s reimbursement levels, reducing burdensome administrative responsibilities, and establishing partnerships between trauma centers and trauma surgeons, may enable underinsured patients to be appropriately cared for.

This paper will be judged for the Resident Writer’s Award.

1. Blumenthal D, Collins SR. Health care coverage under the affordable care act--a progress report. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(3):275-281. doi:10.1056/NEJMhpr1405667.

2. Sommers BD. Health care reform's unfinished work--remaining barriers to coverage and access. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(25):2395-2397. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1509462.

3. US Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicaid & CHIP: February 2015 monthly applications, eligibility determinations and enrollment report. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/downloads/medicaid-and-chip-february-2015-application-eligibility-and-enrollment-data.pdf. Published May 1, 2015. Accessed May 2015.

4. Iglehart JK, Sommers BD. Medicaid at 50--from welfare program to nation's largest health insurer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(22):2152-2159. doi:10.1056/NEJMhpr1500791.

5. Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid moving forward. http://kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/the-medicaid-program-at-a-glance-update/. Updated 2014. Accessed October 10, 2014.

6. Kim CY, Wiznia DH, Hsiang WR, Pelker RR. The effect of insurance type on patient access to knee arthroplasty and revision under the affordable care act. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(9):1498-1501. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2015.03.015.

7. Draeger RW, Patterson BM, Olsson EC, Schaffer A, Patterson JM. The influence of patient insurance status on access to outpatient orthopedic care for flexor tendon lacerations. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(3):527-533. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.10.031.

8. Patterson BM, Spang JT, Draeger RW, Olsson EC, Creighton RA, Kamath GV. Access to outpatient care for adult rotator cuff patients with private insurance versus Medicaid in North Carolina. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(12):1623-1627. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.07.051.

9. Patterson BM, Draeger RW, Olsson EC, Spang JT, Lin FC, Kamath GV. A regional assessment of medicaid access to outpatient orthopaedic care: the influence of population density and proximity to academic medical centers on patient access. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(18):e156. doi:10.2106/JBJS.M.01188.

10. Schwarzkopf R, Phan D, Hoang M, Ross S, Mukamel D. Do patients with income-based insurance have access to total joint arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(6):1083-1086. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2013.11.022.

11. Decker SL. In 2011 nearly one-third of physicians said they would not accept new Medicaid patients, but rising fees may help. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(8):1673-1679 doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0294.

12. Perloff JD, Kletke P, Fossett JW. Which physicians limit their Medicaid participation, and why. Health Serv Res. 1995;30(1):7-26.

13. Althausen PL. Building a successful trauma practice in a community setting. J Orthop Trauma. 2011;25 Suppl 3:S113-S117. doi:10.1097/BOT.0b013e318237bcce.

14. Greenberg S, Mir HR, Jahangir AA, Mehta S, Sethi MK. Impacting policy change for orthopaedic trauma. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28 Suppl 10:S14-S16. doi:10.1097/BOT.0000000000000216.

15. Wiznia DH, Averbukh L, Kim CY, Goel A, Leslie MP. Motorcycle helmets: The economic burden of an incomplete helmet law to medical care in the state of Connecticut. Conn Med. 2015;79(8):453-459.

16. Orthopaedic Trauma Association. Find a surgeon. https://online.ota.org/otassa/otacenssafindasurgeon.query_page. Updated 2015. Accessed July, 2015.

17. Kim CY, Wiznia DH, Roth AS, Walls RJ, Pelker RR. Survey of patient insurance status on access to specialty foot and ankle care under the affordable care act. Foot Ankle Int. 2016;37(7):776-781. doi:1071100716642015.

18. Patterson BM, Draeger RW, Olsson EC, Spang JT, Lin FC, Kamath GV. A regional assessment of Medicaid access to outpatient orthopaedic care: the influence of population density and proximity to academic medical centers on patient access. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(18):e156. doi:10.2106/JBJS.M.01188.

19. Kim CY, Wiznia DH, Wang Y, et al. The effect of insurance type on patient access to carpal tunnel release under the affordable care act. J Hand Surg Am. 2016;41(4):503-509.e1. doi:S0363-5023(16)00104-0.

20. Long SK. Physicians may need more than higher reimbursements to expand Medicaid participation: findings from Washington state. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(9):1560-1567. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1010.

21. Issar NM, Jahangir AA. The affordable care act and orthopaedic trauma. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28 Suppl 10:S5-S7. doi:10.1097/BOT.0000000000000211.

22. Hahn B, Flood AB. No insurance, public insurance, and private insurance: do these options contribute to differences in general health? J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1995;6(1):41-59.

23. Hinman A, Bozic KJ. Impact of payer type on resource utilization, outcomes and access to care in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(6 Suppl 1):9-14. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2008.05.010.

24. Schoenfeld AJ, Tipirneni R, Nelson JH, Carpenter JE, Iwashyna TJ. The influence of race and ethnicity on complications and mortality after orthopedic surgery: A systematic review of the literature. Med Care. 2014;52(9):842-851. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000177.

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study is to assess the effect of insurance type (Medicaid, Medicare, private insurance) on the ability for patients with operative ankle fractures to access orthopedic traumatologists. The research team called 245 board-certified orthopedic surgeons specializing in orthopedic trauma within 8 representative states. The caller requested an appointment for their fictitious mother in order to be evaluated for an ankle fracture which was previously evaluated by her primary care physician and believed to require surgery. Each office was called 3 times to assess the response for each insurance type. For each call, information was documented regarding whether the patient was able to receive an appointment and the barriers the patient confronted to receive an appointment. Overall, 35.7% of offices scheduled an appointment for a patient with Medicaid, in comparison to 81.4%and 88.6% for Medicare and BlueCross, respectively (P < .0001). Medicaid patients confronted more barriers for receiving appointments. There was no statistically significant difference in access for Medicaid patients in states that had expanded Medicaid eligibility vs states that had not expanded Medicaid. Medicaid reimbursement for open reduction and internal fixation of an ankle fracture did not significantly correlate with appointment success rates or wait times. Despite the passage of the Affordable Care Act, patients with Medicaid have reduced access to orthopedic surgeons and more complex barriers to receiving appointments. A more robust strategy for increasing care-access for patients with Medicaid would be more equitable.

Continue to: In 2010, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act...

In 2010, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) expanded the eligibility criteria for Medicaid to all individuals with an income up to 138% of the poverty level.1 A Supreme Court ruling stated that the decision to expand Medicaid was to be decided by individual states.2 Currently, 31 states have chosen to expand Medicaid eligibility to their residents.2 This expansion has allowed an additional 11.7 million people to enroll in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program by May 2015.3-5

Even with the passage of the PPACA, Medicaid patients seeking specialty orthopedic care have experienced more barriers to accessing care than Medicare or commercially-insured patients.2,6-10 One major cited reason is Medicaid’s low reimbursement, which may discourage physicians from open panel participation in Medicaid.11,12

A common fundamental teaching for orthopedic traumatologists is the notion that they should be available to treat all injuries regardless of the patient’s ability to pay.13 This has resulted in both trauma centers and trauma surgeons becoming financially challenged due to the higher proportion of Medicaid and uninsured trauma patients and lower Medicaid reimbursement levels.14,15

This study focuses on the effect of different types of insurance (Medicaid, Medicare, or commercial insurance) on the ability of patients to obtain care for operative ankle fractures. The purpose of this study is to evaluate, in the context of the PPACA, patient access to orthopedic surgeons for operative ankle fractures based on insurance-type. We hypothesized that patients with Medicaid would face a greater volume of obstacles when seeking appointments for an ankle fracture, even after the PPACA.

Continue to: MATERIALS AND METHODS...

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study population included board-certified orthopedic surgeons who belonged to the Orthopaedic Trauma Association (OTA) from 8 representative states; 4 states with expanded Medicaid eligibility (California, Massachusetts, New York, Ohio) and 4 states without expanded Medicaid eligibility (Florida, North Carolina, Georgia, Texas). These states were selected due to their ability to represent diverse healthcare marketplaces throughout the country. Using the OTA website’s “Find a Surgeon” search tool,16 we created a list of surgeons for each state and matched each surgeon with a random number. The list of surgeons was ordered according to the value of the surgeon’s associated random number, and surgeons were called in ascending order. We excluded disconnected or inaccurate numbers from the calling list. Surgeons who did not manage ankle fractures were removed from the dataset. Approximately 30 orthopedic trauma surgeons per state were contacted.