User login

Screen all infants exposed to Zika for eye abnormalities, study suggests

CNS abnormalities associated with antenatal Zika virus infection correlate strongly with opthalmic abnormalities, but there were cases of eye abnormalities in the absence of CNS abnormalities, which suggests a need for universal eye screening in endemic areas, according to a study published in Pediatrics.

Irena Tsui, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, and her associates examined 224 infants suspected of antenatal Zika virus infection for eye abnormalities between Jan. 2, 2016, and Feb. 28, 2017. They found that 40% had CNS abnormalities and 25% of all infants had eye abnormalities; of those 90 infants with CNS abnormalities, 54% had eye abnormalities, which makes for an odds ratio of 14.9 (P less than .0001). However, among the 134 infants without CNS abnormalities, 4% had eye abnormalities.

The study also investigated the existence of eye abnormalities among infants did not laboratory-confirmed diagnosis of Zika virus infection. To do so, they performed reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing on 189 infants. They found eye abnormalities among 22% of the 156 RT-PCR–positive infants and 38% of the 68 RT-PCR–unconfirmed infants. Among the 52% of infants with eye abnormalities who were reexamined, there were no signs of worsening, ongoing activity, or regression in their lesions.

The guidelines in Brazil, where the study was performed, recommend eye examinations only for infants with microcephaly, and the United States currently recommends it only at the discretion of the health care provider. The study investigators think that

“The early identification of eye abnormalities enables low-vision interventions to improve visual function with important repercussions for neurocognitive development,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Tsui I et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Oct;142(4):e20181104.

CNS abnormalities associated with antenatal Zika virus infection correlate strongly with opthalmic abnormalities, but there were cases of eye abnormalities in the absence of CNS abnormalities, which suggests a need for universal eye screening in endemic areas, according to a study published in Pediatrics.

Irena Tsui, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, and her associates examined 224 infants suspected of antenatal Zika virus infection for eye abnormalities between Jan. 2, 2016, and Feb. 28, 2017. They found that 40% had CNS abnormalities and 25% of all infants had eye abnormalities; of those 90 infants with CNS abnormalities, 54% had eye abnormalities, which makes for an odds ratio of 14.9 (P less than .0001). However, among the 134 infants without CNS abnormalities, 4% had eye abnormalities.

The study also investigated the existence of eye abnormalities among infants did not laboratory-confirmed diagnosis of Zika virus infection. To do so, they performed reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing on 189 infants. They found eye abnormalities among 22% of the 156 RT-PCR–positive infants and 38% of the 68 RT-PCR–unconfirmed infants. Among the 52% of infants with eye abnormalities who were reexamined, there were no signs of worsening, ongoing activity, or regression in their lesions.

The guidelines in Brazil, where the study was performed, recommend eye examinations only for infants with microcephaly, and the United States currently recommends it only at the discretion of the health care provider. The study investigators think that

“The early identification of eye abnormalities enables low-vision interventions to improve visual function with important repercussions for neurocognitive development,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Tsui I et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Oct;142(4):e20181104.

CNS abnormalities associated with antenatal Zika virus infection correlate strongly with opthalmic abnormalities, but there were cases of eye abnormalities in the absence of CNS abnormalities, which suggests a need for universal eye screening in endemic areas, according to a study published in Pediatrics.

Irena Tsui, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, and her associates examined 224 infants suspected of antenatal Zika virus infection for eye abnormalities between Jan. 2, 2016, and Feb. 28, 2017. They found that 40% had CNS abnormalities and 25% of all infants had eye abnormalities; of those 90 infants with CNS abnormalities, 54% had eye abnormalities, which makes for an odds ratio of 14.9 (P less than .0001). However, among the 134 infants without CNS abnormalities, 4% had eye abnormalities.

The study also investigated the existence of eye abnormalities among infants did not laboratory-confirmed diagnosis of Zika virus infection. To do so, they performed reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing on 189 infants. They found eye abnormalities among 22% of the 156 RT-PCR–positive infants and 38% of the 68 RT-PCR–unconfirmed infants. Among the 52% of infants with eye abnormalities who were reexamined, there were no signs of worsening, ongoing activity, or regression in their lesions.

The guidelines in Brazil, where the study was performed, recommend eye examinations only for infants with microcephaly, and the United States currently recommends it only at the discretion of the health care provider. The study investigators think that

“The early identification of eye abnormalities enables low-vision interventions to improve visual function with important repercussions for neurocognitive development,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Tsui I et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Oct;142(4):e20181104.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Think DEB, not BMS, with high bleeding risk

PARIS – Treatment with a drug-eluting balloon rather than bare-metal stent provided superior outcomes in patients at high bleeding risk with large-vessel coronary lesions, according to the results of the randomized DEBUT study.

“PCI with a drug-eluting balloon, with the possibility of bailout stenting if needed, is a safe and efficient novel option in patients with high bleeding risk,” Tuomas T. Rissanen, MD, PhD, said in presenting the results of the trial at the annual meeting of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

“The major advantage of the drug-eluting balloon–only strategy is that DAPT [dual-antiplatelet therapy] duration is short – usually 1 month – and positive remodeling of the treated vessel may occur because there is no metallic material present,” added Dr. Rissanen, head of the Heart Center at the University of Eastern Finland in Joensuu.

DEBUT (Drug-Eluting Balloon in Stable and Unstable Angina in a Randomized Controlled Noninferiority Trial) was a five-center, single-blind Finnish study in which patients at elevated bleeding risk – most often because they required oral anticoagulation and were over age 80 – were randomized to a paclitaxel-coated drug-eluting balloon (DEB) applied for a minimum of 30 seconds or a bare-metal stent (BMS). They were placed on DAPT for 1 month if they had stable coronary artery disease and 6 months after an acute coronary syndrome.

Participants had to have a target vessel diameter amenable for PCI with a DEB: that is, 2.5-4.0 mm. Patients with in-stent restenosis, an unprotected left main lesion, ST-elevation MI, chronic total occlusion, a dissection sufficient to reduce flow, greater than 30% recoil after predilation, or a bifurcation lesion requiring side branch stenting were excluded.

The impetus for the DEBUT trial was a recognition that, while the use of DEBs is recommended for treatment of in-stent restenosis by European Society of Cardiology guidelines, until DEBUT there were no high-quality randomized trial data regarding the use of such devices in de novo coronary lesions, the cardiologist noted.

The study results were unequivocal. Indeed, DEBUT, planned for 530 patients, was halted after enrollment of only 208 because an interim analysis showed clear superiority for the DEB strategy.

To wit, the primary endpoint – a composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, or target lesion revascularization at 9 months post PCI – occurred in 1.9% of the DEB group, compared with 12.4% of BMS recipients. This absolute 10.5% difference in risk translated to an 85% relative risk reduction.

Target lesion revascularization, a major secondary outcome, occurred in none of the DEB group and 4.8% of the BMS group. Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 2 bleeding rates were similar at 11%-12% in the two groups.

Four percent of the DEB group required bailout stenting.

“Importantly, at 9 months, there were two definite stent thrombosis cases in the BMS group and no vessel closures in the DEB group,” Dr. Rissanen observed.

Discussant Antonio Colombo, MD, said, “I think a strategy with a drug-eluting balloon makes sense.”

Even though the 2-year results of the LEADERS FREE trial have shown that the BioFreedom polymer-free drug-coated stent proved safer and more effective than a BMS in high–bleeding risk patients with 1 month of DAPT (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Jan 17;69[2]:162-71), not all PCI centers have access to the BioFreedom stent.

“Why do you need to place a stent in everyone? If you have a good result with the DEB, there is no reason to. Maybe you should use fractional flow reserve [FFR] to give reassurance that the result is really good, but I am in favor of this strategy. I think if you find a small dissection, and the residual lumen is large, it’s okay. It will usually heal. I think a dissection is problematic when the residual lumen is not large,” said Dr. Colombo, chief of invasive cardiology at San Raffaele Hospital in Milan.

There is a practical problem with the DEB-only strategy, however: “Many operators are uncomfortable in not using a stent in a large vessel, even when they have a good result,” he noted.

His fellow discussant Marc Bosiers, MD, said interventional cardiologists need to get over that hangup, which isn’t evidence based.

“We have the same experience in the periphery: We leave arteries as is after DEB therapy with only small Type A, B, and even C dissections, and we have fantastic results. We have total vessel remodeling. In many cases we see the patients back after 6 months or a year and do follow-up angiography, and you’ll be surprised at what you see with DEB alone,” according to Dr. Bosiers, head of the department of vascular surgery at St. Blasius Hospital in Dendermonde, Belgium.

Dr. Rissanen said that, for their next research project, he and his coinvestigators plan to mount a multicenter randomized trial of DEB versus a drug-eluting stent rather than a BMS in high–bleeding risk patients with de novo coronary lesions. And they’re considering ditching the 1 month of DAPT in the DEB patients.

“What is this 1-month DAPT for DEB based on, anyway? I don’t think we need it at all. We could use single-antiplatelet therapy or only the loading dose of the second agent,” he asserted.

But, as one of the discussants responded, that may well be true, and perhaps in the future a course of post-DEB therapy with a single antiplatelet agent or a direct-acting oral anticoagulant will be the routine strategy, but before clinical practice is revised such novel proposals will need to be well-grounded in proof of safety and efficacy. Dr. Rissanen reported having no financial conflicts regarding the DEBUT study, conducted free of commercial support.

PARIS – Treatment with a drug-eluting balloon rather than bare-metal stent provided superior outcomes in patients at high bleeding risk with large-vessel coronary lesions, according to the results of the randomized DEBUT study.

“PCI with a drug-eluting balloon, with the possibility of bailout stenting if needed, is a safe and efficient novel option in patients with high bleeding risk,” Tuomas T. Rissanen, MD, PhD, said in presenting the results of the trial at the annual meeting of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

“The major advantage of the drug-eluting balloon–only strategy is that DAPT [dual-antiplatelet therapy] duration is short – usually 1 month – and positive remodeling of the treated vessel may occur because there is no metallic material present,” added Dr. Rissanen, head of the Heart Center at the University of Eastern Finland in Joensuu.

DEBUT (Drug-Eluting Balloon in Stable and Unstable Angina in a Randomized Controlled Noninferiority Trial) was a five-center, single-blind Finnish study in which patients at elevated bleeding risk – most often because they required oral anticoagulation and were over age 80 – were randomized to a paclitaxel-coated drug-eluting balloon (DEB) applied for a minimum of 30 seconds or a bare-metal stent (BMS). They were placed on DAPT for 1 month if they had stable coronary artery disease and 6 months after an acute coronary syndrome.

Participants had to have a target vessel diameter amenable for PCI with a DEB: that is, 2.5-4.0 mm. Patients with in-stent restenosis, an unprotected left main lesion, ST-elevation MI, chronic total occlusion, a dissection sufficient to reduce flow, greater than 30% recoil after predilation, or a bifurcation lesion requiring side branch stenting were excluded.

The impetus for the DEBUT trial was a recognition that, while the use of DEBs is recommended for treatment of in-stent restenosis by European Society of Cardiology guidelines, until DEBUT there were no high-quality randomized trial data regarding the use of such devices in de novo coronary lesions, the cardiologist noted.

The study results were unequivocal. Indeed, DEBUT, planned for 530 patients, was halted after enrollment of only 208 because an interim analysis showed clear superiority for the DEB strategy.

To wit, the primary endpoint – a composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, or target lesion revascularization at 9 months post PCI – occurred in 1.9% of the DEB group, compared with 12.4% of BMS recipients. This absolute 10.5% difference in risk translated to an 85% relative risk reduction.

Target lesion revascularization, a major secondary outcome, occurred in none of the DEB group and 4.8% of the BMS group. Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 2 bleeding rates were similar at 11%-12% in the two groups.

Four percent of the DEB group required bailout stenting.

“Importantly, at 9 months, there were two definite stent thrombosis cases in the BMS group and no vessel closures in the DEB group,” Dr. Rissanen observed.

Discussant Antonio Colombo, MD, said, “I think a strategy with a drug-eluting balloon makes sense.”

Even though the 2-year results of the LEADERS FREE trial have shown that the BioFreedom polymer-free drug-coated stent proved safer and more effective than a BMS in high–bleeding risk patients with 1 month of DAPT (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Jan 17;69[2]:162-71), not all PCI centers have access to the BioFreedom stent.

“Why do you need to place a stent in everyone? If you have a good result with the DEB, there is no reason to. Maybe you should use fractional flow reserve [FFR] to give reassurance that the result is really good, but I am in favor of this strategy. I think if you find a small dissection, and the residual lumen is large, it’s okay. It will usually heal. I think a dissection is problematic when the residual lumen is not large,” said Dr. Colombo, chief of invasive cardiology at San Raffaele Hospital in Milan.

There is a practical problem with the DEB-only strategy, however: “Many operators are uncomfortable in not using a stent in a large vessel, even when they have a good result,” he noted.

His fellow discussant Marc Bosiers, MD, said interventional cardiologists need to get over that hangup, which isn’t evidence based.

“We have the same experience in the periphery: We leave arteries as is after DEB therapy with only small Type A, B, and even C dissections, and we have fantastic results. We have total vessel remodeling. In many cases we see the patients back after 6 months or a year and do follow-up angiography, and you’ll be surprised at what you see with DEB alone,” according to Dr. Bosiers, head of the department of vascular surgery at St. Blasius Hospital in Dendermonde, Belgium.

Dr. Rissanen said that, for their next research project, he and his coinvestigators plan to mount a multicenter randomized trial of DEB versus a drug-eluting stent rather than a BMS in high–bleeding risk patients with de novo coronary lesions. And they’re considering ditching the 1 month of DAPT in the DEB patients.

“What is this 1-month DAPT for DEB based on, anyway? I don’t think we need it at all. We could use single-antiplatelet therapy or only the loading dose of the second agent,” he asserted.

But, as one of the discussants responded, that may well be true, and perhaps in the future a course of post-DEB therapy with a single antiplatelet agent or a direct-acting oral anticoagulant will be the routine strategy, but before clinical practice is revised such novel proposals will need to be well-grounded in proof of safety and efficacy. Dr. Rissanen reported having no financial conflicts regarding the DEBUT study, conducted free of commercial support.

PARIS – Treatment with a drug-eluting balloon rather than bare-metal stent provided superior outcomes in patients at high bleeding risk with large-vessel coronary lesions, according to the results of the randomized DEBUT study.

“PCI with a drug-eluting balloon, with the possibility of bailout stenting if needed, is a safe and efficient novel option in patients with high bleeding risk,” Tuomas T. Rissanen, MD, PhD, said in presenting the results of the trial at the annual meeting of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

“The major advantage of the drug-eluting balloon–only strategy is that DAPT [dual-antiplatelet therapy] duration is short – usually 1 month – and positive remodeling of the treated vessel may occur because there is no metallic material present,” added Dr. Rissanen, head of the Heart Center at the University of Eastern Finland in Joensuu.

DEBUT (Drug-Eluting Balloon in Stable and Unstable Angina in a Randomized Controlled Noninferiority Trial) was a five-center, single-blind Finnish study in which patients at elevated bleeding risk – most often because they required oral anticoagulation and were over age 80 – were randomized to a paclitaxel-coated drug-eluting balloon (DEB) applied for a minimum of 30 seconds or a bare-metal stent (BMS). They were placed on DAPT for 1 month if they had stable coronary artery disease and 6 months after an acute coronary syndrome.

Participants had to have a target vessel diameter amenable for PCI with a DEB: that is, 2.5-4.0 mm. Patients with in-stent restenosis, an unprotected left main lesion, ST-elevation MI, chronic total occlusion, a dissection sufficient to reduce flow, greater than 30% recoil after predilation, or a bifurcation lesion requiring side branch stenting were excluded.

The impetus for the DEBUT trial was a recognition that, while the use of DEBs is recommended for treatment of in-stent restenosis by European Society of Cardiology guidelines, until DEBUT there were no high-quality randomized trial data regarding the use of such devices in de novo coronary lesions, the cardiologist noted.

The study results were unequivocal. Indeed, DEBUT, planned for 530 patients, was halted after enrollment of only 208 because an interim analysis showed clear superiority for the DEB strategy.

To wit, the primary endpoint – a composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, or target lesion revascularization at 9 months post PCI – occurred in 1.9% of the DEB group, compared with 12.4% of BMS recipients. This absolute 10.5% difference in risk translated to an 85% relative risk reduction.

Target lesion revascularization, a major secondary outcome, occurred in none of the DEB group and 4.8% of the BMS group. Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 2 bleeding rates were similar at 11%-12% in the two groups.

Four percent of the DEB group required bailout stenting.

“Importantly, at 9 months, there were two definite stent thrombosis cases in the BMS group and no vessel closures in the DEB group,” Dr. Rissanen observed.

Discussant Antonio Colombo, MD, said, “I think a strategy with a drug-eluting balloon makes sense.”

Even though the 2-year results of the LEADERS FREE trial have shown that the BioFreedom polymer-free drug-coated stent proved safer and more effective than a BMS in high–bleeding risk patients with 1 month of DAPT (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Jan 17;69[2]:162-71), not all PCI centers have access to the BioFreedom stent.

“Why do you need to place a stent in everyone? If you have a good result with the DEB, there is no reason to. Maybe you should use fractional flow reserve [FFR] to give reassurance that the result is really good, but I am in favor of this strategy. I think if you find a small dissection, and the residual lumen is large, it’s okay. It will usually heal. I think a dissection is problematic when the residual lumen is not large,” said Dr. Colombo, chief of invasive cardiology at San Raffaele Hospital in Milan.

There is a practical problem with the DEB-only strategy, however: “Many operators are uncomfortable in not using a stent in a large vessel, even when they have a good result,” he noted.

His fellow discussant Marc Bosiers, MD, said interventional cardiologists need to get over that hangup, which isn’t evidence based.

“We have the same experience in the periphery: We leave arteries as is after DEB therapy with only small Type A, B, and even C dissections, and we have fantastic results. We have total vessel remodeling. In many cases we see the patients back after 6 months or a year and do follow-up angiography, and you’ll be surprised at what you see with DEB alone,” according to Dr. Bosiers, head of the department of vascular surgery at St. Blasius Hospital in Dendermonde, Belgium.

Dr. Rissanen said that, for their next research project, he and his coinvestigators plan to mount a multicenter randomized trial of DEB versus a drug-eluting stent rather than a BMS in high–bleeding risk patients with de novo coronary lesions. And they’re considering ditching the 1 month of DAPT in the DEB patients.

“What is this 1-month DAPT for DEB based on, anyway? I don’t think we need it at all. We could use single-antiplatelet therapy or only the loading dose of the second agent,” he asserted.

But, as one of the discussants responded, that may well be true, and perhaps in the future a course of post-DEB therapy with a single antiplatelet agent or a direct-acting oral anticoagulant will be the routine strategy, but before clinical practice is revised such novel proposals will need to be well-grounded in proof of safety and efficacy. Dr. Rissanen reported having no financial conflicts regarding the DEBUT study, conducted free of commercial support.

REPORTING FROM EUROPCR 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The 9-month MACE rate was 1.9% in the drug-eluting balloon group versus 12.4% with a bare-metal stent.

Study details: This prospective, multicenter, single-blind trial randomized 208 high–bleeding risk patients with de novo lesions in large coronary vessels to PCI with a drug-eluting balloon-only or a bare-metal stent.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding the DEBUT study, conducted free of commercial support.

Psoriatic arthritis activity spikes briefly postpartum

Disease activity for women with psoriatic arthritis seeking pregnancy was relatively stable through 1 year after delivery, but there was a significant jump at 6 months postpartum follow-up, based on data from a prospective study of more than 100 patients.

Previous research has described rheumatoid arthritis remission during pregnancy, but the symptoms of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) before, during, and after pregnancy have not been well studied, wrote Kristin Ursin, MD, of Trondheim (Norway) University Hospital, and her colleagues.

In a study published in Arthritis Care & Research, the investigators reviewed data from 108 pregnancies in 103 women with PsA who were diagnosed between January 2006 and October 2017.

The participants were enrolled in a Norwegian nationwide registry that followed women with inflammatory diseases from preconception through 1 year after delivery. Disease activity was measured using the DAS28-CRP (28-Joint Disease Activity Score with C-reactive Protein). Participants were assessed at seven time points: before pregnancy, during each trimester, and at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months after delivery.

Although approximately 75% of the women had stable disease activity throughout the study period, activity spiked at 6 months after delivery; DAS28-CRP scores at 6 months post partum were significantly higher than scores at 6 weeks post partum (2.71 vs. 2.45, respectively; P = .016).

The researchers conducted an additional analysis of the potential role of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor use and found that women taking a TNFi had significantly lower disease activity during pregnancy, compared with women not taking a TNFi; mean DAS28-CRP scores at 6 months post partum for these groups were 2.22 and 2.72, respectively (P = .043).

The study was limited by the use of DAS28-CRP as the main measure of disease activity; the index does not include potentially affected distal interphalangeal joints. In addition, not all the participants were assessed at each of the seven time points. However, the results suggest that most pregnant women with PsA experience low levels of disease activity, the researchers said. “Future research on pregnancy in women with PsA should include extended joint count (66/68 joints), and assessment of dactylitis, entheses, axial skeleton, and psoriasis,” they added.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The study was funded by the department of rheumatology at Trondheim University Hospital and the Research Fund of the Norwegian organization for people with rheumatic disease.

SOURCE: Ursin K et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2018 Sep 7. doi: 10.1002/acr.23747.

Disease activity for women with psoriatic arthritis seeking pregnancy was relatively stable through 1 year after delivery, but there was a significant jump at 6 months postpartum follow-up, based on data from a prospective study of more than 100 patients.

Previous research has described rheumatoid arthritis remission during pregnancy, but the symptoms of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) before, during, and after pregnancy have not been well studied, wrote Kristin Ursin, MD, of Trondheim (Norway) University Hospital, and her colleagues.

In a study published in Arthritis Care & Research, the investigators reviewed data from 108 pregnancies in 103 women with PsA who were diagnosed between January 2006 and October 2017.

The participants were enrolled in a Norwegian nationwide registry that followed women with inflammatory diseases from preconception through 1 year after delivery. Disease activity was measured using the DAS28-CRP (28-Joint Disease Activity Score with C-reactive Protein). Participants were assessed at seven time points: before pregnancy, during each trimester, and at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months after delivery.

Although approximately 75% of the women had stable disease activity throughout the study period, activity spiked at 6 months after delivery; DAS28-CRP scores at 6 months post partum were significantly higher than scores at 6 weeks post partum (2.71 vs. 2.45, respectively; P = .016).

The researchers conducted an additional analysis of the potential role of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor use and found that women taking a TNFi had significantly lower disease activity during pregnancy, compared with women not taking a TNFi; mean DAS28-CRP scores at 6 months post partum for these groups were 2.22 and 2.72, respectively (P = .043).

The study was limited by the use of DAS28-CRP as the main measure of disease activity; the index does not include potentially affected distal interphalangeal joints. In addition, not all the participants were assessed at each of the seven time points. However, the results suggest that most pregnant women with PsA experience low levels of disease activity, the researchers said. “Future research on pregnancy in women with PsA should include extended joint count (66/68 joints), and assessment of dactylitis, entheses, axial skeleton, and psoriasis,” they added.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The study was funded by the department of rheumatology at Trondheim University Hospital and the Research Fund of the Norwegian organization for people with rheumatic disease.

SOURCE: Ursin K et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2018 Sep 7. doi: 10.1002/acr.23747.

Disease activity for women with psoriatic arthritis seeking pregnancy was relatively stable through 1 year after delivery, but there was a significant jump at 6 months postpartum follow-up, based on data from a prospective study of more than 100 patients.

Previous research has described rheumatoid arthritis remission during pregnancy, but the symptoms of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) before, during, and after pregnancy have not been well studied, wrote Kristin Ursin, MD, of Trondheim (Norway) University Hospital, and her colleagues.

In a study published in Arthritis Care & Research, the investigators reviewed data from 108 pregnancies in 103 women with PsA who were diagnosed between January 2006 and October 2017.

The participants were enrolled in a Norwegian nationwide registry that followed women with inflammatory diseases from preconception through 1 year after delivery. Disease activity was measured using the DAS28-CRP (28-Joint Disease Activity Score with C-reactive Protein). Participants were assessed at seven time points: before pregnancy, during each trimester, and at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months after delivery.

Although approximately 75% of the women had stable disease activity throughout the study period, activity spiked at 6 months after delivery; DAS28-CRP scores at 6 months post partum were significantly higher than scores at 6 weeks post partum (2.71 vs. 2.45, respectively; P = .016).

The researchers conducted an additional analysis of the potential role of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor use and found that women taking a TNFi had significantly lower disease activity during pregnancy, compared with women not taking a TNFi; mean DAS28-CRP scores at 6 months post partum for these groups were 2.22 and 2.72, respectively (P = .043).

The study was limited by the use of DAS28-CRP as the main measure of disease activity; the index does not include potentially affected distal interphalangeal joints. In addition, not all the participants were assessed at each of the seven time points. However, the results suggest that most pregnant women with PsA experience low levels of disease activity, the researchers said. “Future research on pregnancy in women with PsA should include extended joint count (66/68 joints), and assessment of dactylitis, entheses, axial skeleton, and psoriasis,” they added.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The study was funded by the department of rheumatology at Trondheim University Hospital and the Research Fund of the Norwegian organization for people with rheumatic disease.

SOURCE: Ursin K et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2018 Sep 7. doi: 10.1002/acr.23747.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Key clinical point: Disease activity for pregnant women with PsA decreased during pregnancy, increased significantly by 6 months post partum, and returned to baseline by 12 months post partum.

Major finding: The average DAS28-CRP was 2.71 at 6 months vs. 2.45 at 6 weeks (P = .016).

Study details: The data come from 108 women with 103 pregnancies who were part of a national registry in Norway.

Disclosures: The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The study was funded by the department of rheumatology at Trondheim University Hospital and the Research Fund of the Norwegian organization for people with rheumatic disease.

Source: Ursin K et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2018 Sep 7. doi: 10.1002/acr.23747.

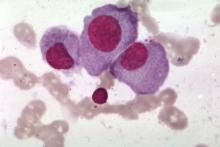

Novel AKT inhibitor active against MM cells

A novel inhibitor of AKT pathway signaling showed significant cytotoxic activity in mouse models and in human cells isolated from patients with primary or relapsed multiple myeloma (MM), investigators reported.

The experimental agent, labeled HS1793, is a derivative of the naturally occurring antioxidant compound resveratrol. In preclinical studies, HS1793 was shown to offer “great promise in eliminating MM cells and improving therapeutic responses in primary and relapsed/refractory MM patients,” according to Jin Han, MD, PhD, of Inje University in Busan, South Korea, and colleagues.

In a series of experiments, described in the journal Cancer Letters, the investigators demonstrated that HS1793 decreased AKT signaling to induce mitochondria-mediated cell death in multiple myeloma cells, and was cytotoxic and specific for myeloma cells in a mouse model of human metastatic myeloma, and in samples of human multiple myeloma cells.

When activated, AKT promotes oncogenesis by in turn activating other downstream pathways involved in proliferation or survival of malignant cells.

“AKT is frequently activated in MM cells and the incidence of AKT activation correlates positively with disease activity,” the authors noted.

They first screened 400 compounds, and narrowed in on resveratrol analogs, eventually choosing HS1793 as the most promising candidate.

This first experiment found evidence that suggested that the compound inhibits AKT activation by interfering with the interaction between AKT and its promoter HSP90.

They then showed in human MM cell lines that the antimyeloma action of HS1793 appeared to be from a dose-dependent effect that allowed for mitochondria-mediated programmed cell death.

In a separate series of experiments, they found that the inhibition by HS1793 of AKT/HSP90 interaction results in cell death by suppressing nuclear factor kappa–B (NF-KB) pathway signaling. The investigators had previously reported that a different compound, an inhibitor of spindle protein kinesin, induced MM cell death via inhibition of NF-KB signaling.

Next, the investigators showed that HS1793-induced cell death was caused by the direct inhibition of AKT that in turn suppressed NF-KB activation.

Finally, they showed in a mouse model of multiple myeloma metastatic to bone that HS1793 “dramatically decreased” lytic skull and femur lesions in treated mice, compared with mice treated with a vehicle placebo, and increased survival of the mice that received the AKT inhibitor.

They also showed that HS1793 was cytotoxic to multiple myeloma cells but not to normal plasma cells isolated from patients with MM.

“Given that HS1793 treatment specifically induced the death of primary and relapsed MM cells, HS1793 offers excellent translational potential as a novel MM therapy,” they wrote.

The study was supported by grants from the Korean government. The researchers reported having no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Song IS et al. Cancer Lett. 2018;432:205-15.

A novel inhibitor of AKT pathway signaling showed significant cytotoxic activity in mouse models and in human cells isolated from patients with primary or relapsed multiple myeloma (MM), investigators reported.

The experimental agent, labeled HS1793, is a derivative of the naturally occurring antioxidant compound resveratrol. In preclinical studies, HS1793 was shown to offer “great promise in eliminating MM cells and improving therapeutic responses in primary and relapsed/refractory MM patients,” according to Jin Han, MD, PhD, of Inje University in Busan, South Korea, and colleagues.

In a series of experiments, described in the journal Cancer Letters, the investigators demonstrated that HS1793 decreased AKT signaling to induce mitochondria-mediated cell death in multiple myeloma cells, and was cytotoxic and specific for myeloma cells in a mouse model of human metastatic myeloma, and in samples of human multiple myeloma cells.

When activated, AKT promotes oncogenesis by in turn activating other downstream pathways involved in proliferation or survival of malignant cells.

“AKT is frequently activated in MM cells and the incidence of AKT activation correlates positively with disease activity,” the authors noted.

They first screened 400 compounds, and narrowed in on resveratrol analogs, eventually choosing HS1793 as the most promising candidate.

This first experiment found evidence that suggested that the compound inhibits AKT activation by interfering with the interaction between AKT and its promoter HSP90.

They then showed in human MM cell lines that the antimyeloma action of HS1793 appeared to be from a dose-dependent effect that allowed for mitochondria-mediated programmed cell death.

In a separate series of experiments, they found that the inhibition by HS1793 of AKT/HSP90 interaction results in cell death by suppressing nuclear factor kappa–B (NF-KB) pathway signaling. The investigators had previously reported that a different compound, an inhibitor of spindle protein kinesin, induced MM cell death via inhibition of NF-KB signaling.

Next, the investigators showed that HS1793-induced cell death was caused by the direct inhibition of AKT that in turn suppressed NF-KB activation.

Finally, they showed in a mouse model of multiple myeloma metastatic to bone that HS1793 “dramatically decreased” lytic skull and femur lesions in treated mice, compared with mice treated with a vehicle placebo, and increased survival of the mice that received the AKT inhibitor.

They also showed that HS1793 was cytotoxic to multiple myeloma cells but not to normal plasma cells isolated from patients with MM.

“Given that HS1793 treatment specifically induced the death of primary and relapsed MM cells, HS1793 offers excellent translational potential as a novel MM therapy,” they wrote.

The study was supported by grants from the Korean government. The researchers reported having no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Song IS et al. Cancer Lett. 2018;432:205-15.

A novel inhibitor of AKT pathway signaling showed significant cytotoxic activity in mouse models and in human cells isolated from patients with primary or relapsed multiple myeloma (MM), investigators reported.

The experimental agent, labeled HS1793, is a derivative of the naturally occurring antioxidant compound resveratrol. In preclinical studies, HS1793 was shown to offer “great promise in eliminating MM cells and improving therapeutic responses in primary and relapsed/refractory MM patients,” according to Jin Han, MD, PhD, of Inje University in Busan, South Korea, and colleagues.

In a series of experiments, described in the journal Cancer Letters, the investigators demonstrated that HS1793 decreased AKT signaling to induce mitochondria-mediated cell death in multiple myeloma cells, and was cytotoxic and specific for myeloma cells in a mouse model of human metastatic myeloma, and in samples of human multiple myeloma cells.

When activated, AKT promotes oncogenesis by in turn activating other downstream pathways involved in proliferation or survival of malignant cells.

“AKT is frequently activated in MM cells and the incidence of AKT activation correlates positively with disease activity,” the authors noted.

They first screened 400 compounds, and narrowed in on resveratrol analogs, eventually choosing HS1793 as the most promising candidate.

This first experiment found evidence that suggested that the compound inhibits AKT activation by interfering with the interaction between AKT and its promoter HSP90.

They then showed in human MM cell lines that the antimyeloma action of HS1793 appeared to be from a dose-dependent effect that allowed for mitochondria-mediated programmed cell death.

In a separate series of experiments, they found that the inhibition by HS1793 of AKT/HSP90 interaction results in cell death by suppressing nuclear factor kappa–B (NF-KB) pathway signaling. The investigators had previously reported that a different compound, an inhibitor of spindle protein kinesin, induced MM cell death via inhibition of NF-KB signaling.

Next, the investigators showed that HS1793-induced cell death was caused by the direct inhibition of AKT that in turn suppressed NF-KB activation.

Finally, they showed in a mouse model of multiple myeloma metastatic to bone that HS1793 “dramatically decreased” lytic skull and femur lesions in treated mice, compared with mice treated with a vehicle placebo, and increased survival of the mice that received the AKT inhibitor.

They also showed that HS1793 was cytotoxic to multiple myeloma cells but not to normal plasma cells isolated from patients with MM.

“Given that HS1793 treatment specifically induced the death of primary and relapsed MM cells, HS1793 offers excellent translational potential as a novel MM therapy,” they wrote.

The study was supported by grants from the Korean government. The researchers reported having no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Song IS et al. Cancer Lett. 2018;432:205-15.

FROM CANCER LETTERS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: HS1793 showed significant multiple myeloma cytotoxicity in mouse models and in human cells isolated from patients with primary or relapsed/refractory myeloma.

Study details: Preclinical investigations in cell lines, murine models, and isolated human multiple myeloma cells.

Disclosures: The study was supported by grants from the Korean government. The researchers reported having no potential conflicts of interest.

Source: Song IS et al. Cancer Lett. 2018:432:205-15.

MDS posttransplant gene sequencing prognostic for progression

For patients with myelodysplastic syndrome, gene sequencing of bone marrow samples early after bone marrow transplant with curative intent may provide important prognostic information.

Among 86 patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), higher maximum variant allele frequency of residual disease–associated mutations at 30 days posttransplantation was significantly associated with disease progression and lower rates of progression-free survival (PFS) at 1 year, reported Eric J. Duncavage, MD, from Washington University in St. Louis, and his colleagues.

“Although this exploratory study has limitations, our results suggest that sequencing-based detection of tumor cells and measurable residual disease after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation has prognostic significance for patients with MDS,” they wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Risk of progression was significantly higher among patients who had undergone reduced-intensity conditioning prior to hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCT) than among patients who had undergone myeloablative conditioning regimens.

To get a better handle on the significance of molecular predictors of disease progression after HSCT, the authors used enhanced exome sequencing to evaluate paired samples of bone marrow and control DNA from normal skin, and error-corrected sequencing to identify somatic single-nucleotide variant mutations in posttransplant samples.

They detected at least one validated somatic mutation in the pretransplant samples from 86 of 90 patients. Of the 86 patients, 32 had at least one mutation with a maximum variant allele frequency of at least 0.5% detected 30 days after transplantation. The frequency is equivalent to 1 heterozygous mutant cell per 100 cells, the authors explained.

Patients who experienced disease progression had mutations with a median maximum variant allele frequency of 0.9%, compared with 0% for patients who did not have progression (P less than .001).

In all, 53.1% of patients with one or more mutations with a variant allele frequency of at least 0.5% at 30 days had disease progression within a year, compared with 13% of patients who did not have the mutations, even after adjustment for the type of conditioning regimen. The hazard ratio (HR) for disease progression in the patients with mutations was 3.86 (P less than .001).

The association between the presence of one or more mutations with a variant allele frequency of at least 0.5% with increased risk of disease progression was also seen at 100 days, even after adjustment for conditioning regimen (66.7% vs. 0%; HR, 6.52; P less than .001). In multivariable analysis controlling for prognostic scores, maximum variant allele frequency at 30 days, TP53 mutation status and conditioning regimen, the presence of a mutation with at least 0.5% variant allele frequency was associated with a more than fourfold risk of progression, including when the revised International Prognostic Scoring System score and conditioning regimen were considered as covariates. (HR, 4.48; P less than .001),

A separate multivariable analysis of PFS controlling for maximum variant allele frequency at day 30, conditioning regimen, age at transplantation, and type of MDS showed that mutations were associated with a more than twofold risk of progression or death (HR, 2.39; P = .002).

This analysis also showed that secondary acute myeloid leukemia was associated with worse PFS, compared with primary MDS (HR, 2.24; P = .001).

The investigators acknowledged that the high-coverage exome sequencing technique used for the study is not routinely available in the clinic. To control for this, they also looked at their data using a subset of genes that are usually included in gene sequencing panels for MDS and AML.

“Although we identified fewer patients with mutations with the use of this approach than with enhanced exome sequencing, the prognostic value of detection of measurable residual disease was still highly clinically significant,” they wrote.

The study was supported by grants from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, Edward P. Evans Foundation, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Gabrielle’s Angel Foundation, and the Lottie Caroline Hardy Trust. Dr. Duncavage disclosed personal fees from AbbVie and Cofactor Genomics. The majority of coauthors reported nothing to disclose.

SOURCE: Duncavage EJ et al. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1028-41.

For patients with myelodysplastic syndrome, gene sequencing of bone marrow samples early after bone marrow transplant with curative intent may provide important prognostic information.

Among 86 patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), higher maximum variant allele frequency of residual disease–associated mutations at 30 days posttransplantation was significantly associated with disease progression and lower rates of progression-free survival (PFS) at 1 year, reported Eric J. Duncavage, MD, from Washington University in St. Louis, and his colleagues.

“Although this exploratory study has limitations, our results suggest that sequencing-based detection of tumor cells and measurable residual disease after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation has prognostic significance for patients with MDS,” they wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Risk of progression was significantly higher among patients who had undergone reduced-intensity conditioning prior to hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCT) than among patients who had undergone myeloablative conditioning regimens.

To get a better handle on the significance of molecular predictors of disease progression after HSCT, the authors used enhanced exome sequencing to evaluate paired samples of bone marrow and control DNA from normal skin, and error-corrected sequencing to identify somatic single-nucleotide variant mutations in posttransplant samples.

They detected at least one validated somatic mutation in the pretransplant samples from 86 of 90 patients. Of the 86 patients, 32 had at least one mutation with a maximum variant allele frequency of at least 0.5% detected 30 days after transplantation. The frequency is equivalent to 1 heterozygous mutant cell per 100 cells, the authors explained.

Patients who experienced disease progression had mutations with a median maximum variant allele frequency of 0.9%, compared with 0% for patients who did not have progression (P less than .001).

In all, 53.1% of patients with one or more mutations with a variant allele frequency of at least 0.5% at 30 days had disease progression within a year, compared with 13% of patients who did not have the mutations, even after adjustment for the type of conditioning regimen. The hazard ratio (HR) for disease progression in the patients with mutations was 3.86 (P less than .001).

The association between the presence of one or more mutations with a variant allele frequency of at least 0.5% with increased risk of disease progression was also seen at 100 days, even after adjustment for conditioning regimen (66.7% vs. 0%; HR, 6.52; P less than .001). In multivariable analysis controlling for prognostic scores, maximum variant allele frequency at 30 days, TP53 mutation status and conditioning regimen, the presence of a mutation with at least 0.5% variant allele frequency was associated with a more than fourfold risk of progression, including when the revised International Prognostic Scoring System score and conditioning regimen were considered as covariates. (HR, 4.48; P less than .001),

A separate multivariable analysis of PFS controlling for maximum variant allele frequency at day 30, conditioning regimen, age at transplantation, and type of MDS showed that mutations were associated with a more than twofold risk of progression or death (HR, 2.39; P = .002).

This analysis also showed that secondary acute myeloid leukemia was associated with worse PFS, compared with primary MDS (HR, 2.24; P = .001).

The investigators acknowledged that the high-coverage exome sequencing technique used for the study is not routinely available in the clinic. To control for this, they also looked at their data using a subset of genes that are usually included in gene sequencing panels for MDS and AML.

“Although we identified fewer patients with mutations with the use of this approach than with enhanced exome sequencing, the prognostic value of detection of measurable residual disease was still highly clinically significant,” they wrote.

The study was supported by grants from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, Edward P. Evans Foundation, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Gabrielle’s Angel Foundation, and the Lottie Caroline Hardy Trust. Dr. Duncavage disclosed personal fees from AbbVie and Cofactor Genomics. The majority of coauthors reported nothing to disclose.

SOURCE: Duncavage EJ et al. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1028-41.

For patients with myelodysplastic syndrome, gene sequencing of bone marrow samples early after bone marrow transplant with curative intent may provide important prognostic information.

Among 86 patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), higher maximum variant allele frequency of residual disease–associated mutations at 30 days posttransplantation was significantly associated with disease progression and lower rates of progression-free survival (PFS) at 1 year, reported Eric J. Duncavage, MD, from Washington University in St. Louis, and his colleagues.

“Although this exploratory study has limitations, our results suggest that sequencing-based detection of tumor cells and measurable residual disease after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation has prognostic significance for patients with MDS,” they wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Risk of progression was significantly higher among patients who had undergone reduced-intensity conditioning prior to hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCT) than among patients who had undergone myeloablative conditioning regimens.

To get a better handle on the significance of molecular predictors of disease progression after HSCT, the authors used enhanced exome sequencing to evaluate paired samples of bone marrow and control DNA from normal skin, and error-corrected sequencing to identify somatic single-nucleotide variant mutations in posttransplant samples.

They detected at least one validated somatic mutation in the pretransplant samples from 86 of 90 patients. Of the 86 patients, 32 had at least one mutation with a maximum variant allele frequency of at least 0.5% detected 30 days after transplantation. The frequency is equivalent to 1 heterozygous mutant cell per 100 cells, the authors explained.

Patients who experienced disease progression had mutations with a median maximum variant allele frequency of 0.9%, compared with 0% for patients who did not have progression (P less than .001).

In all, 53.1% of patients with one or more mutations with a variant allele frequency of at least 0.5% at 30 days had disease progression within a year, compared with 13% of patients who did not have the mutations, even after adjustment for the type of conditioning regimen. The hazard ratio (HR) for disease progression in the patients with mutations was 3.86 (P less than .001).

The association between the presence of one or more mutations with a variant allele frequency of at least 0.5% with increased risk of disease progression was also seen at 100 days, even after adjustment for conditioning regimen (66.7% vs. 0%; HR, 6.52; P less than .001). In multivariable analysis controlling for prognostic scores, maximum variant allele frequency at 30 days, TP53 mutation status and conditioning regimen, the presence of a mutation with at least 0.5% variant allele frequency was associated with a more than fourfold risk of progression, including when the revised International Prognostic Scoring System score and conditioning regimen were considered as covariates. (HR, 4.48; P less than .001),

A separate multivariable analysis of PFS controlling for maximum variant allele frequency at day 30, conditioning regimen, age at transplantation, and type of MDS showed that mutations were associated with a more than twofold risk of progression or death (HR, 2.39; P = .002).

This analysis also showed that secondary acute myeloid leukemia was associated with worse PFS, compared with primary MDS (HR, 2.24; P = .001).

The investigators acknowledged that the high-coverage exome sequencing technique used for the study is not routinely available in the clinic. To control for this, they also looked at their data using a subset of genes that are usually included in gene sequencing panels for MDS and AML.

“Although we identified fewer patients with mutations with the use of this approach than with enhanced exome sequencing, the prognostic value of detection of measurable residual disease was still highly clinically significant,” they wrote.

The study was supported by grants from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, Edward P. Evans Foundation, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Gabrielle’s Angel Foundation, and the Lottie Caroline Hardy Trust. Dr. Duncavage disclosed personal fees from AbbVie and Cofactor Genomics. The majority of coauthors reported nothing to disclose.

SOURCE: Duncavage EJ et al. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1028-41.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)–associated mutations present 30 days after stem cell transplant may be predict disease progression and survival.

Major finding: Higher maximum variant allele frequency of residual disease–associated mutations at 30 days posttransplantation was significantly associated with disease progression and lower rates of progression-free survival at 1 year.

Study details: Exploratory study of mutations pre- and posttransplant in 90 patients with primary or therapy-related MDS or secondary acute myeloid leukemia.

Disclosures: The study was supported by grants from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, Edward P. Evans Foundation, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Gabrielle’s Angel Foundation, and the Lottie Caroline Hardy Trust. Dr. Duncavage disclosed personal fees from AbbVie and Cofactor Genomics. The majority of the coauthors reported nothing to disclose.

Source: Duncavage EJ et al. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1028-41.

ICYMI: Fingolimod effective in pediatric relapsing multiple sclerosis

Fingolimod reduced the rate of relapse as well as the deposition of lesions on MRI better than interferon beta-1a did over 2 years in pediatric patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis, according to the results of the PARADIGMS trial, published online Sept. 12 in the New England Journal of Medicine (2018; 379:1017-27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800149). More serious adverse events were seen in fingolimod-treated patients.

We covered the story before it was published in the journal. Find our conference coverage at the links below.

Fingolimod reduced the rate of relapse as well as the deposition of lesions on MRI better than interferon beta-1a did over 2 years in pediatric patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis, according to the results of the PARADIGMS trial, published online Sept. 12 in the New England Journal of Medicine (2018; 379:1017-27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800149). More serious adverse events were seen in fingolimod-treated patients.

We covered the story before it was published in the journal. Find our conference coverage at the links below.

Fingolimod reduced the rate of relapse as well as the deposition of lesions on MRI better than interferon beta-1a did over 2 years in pediatric patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis, according to the results of the PARADIGMS trial, published online Sept. 12 in the New England Journal of Medicine (2018; 379:1017-27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800149). More serious adverse events were seen in fingolimod-treated patients.

We covered the story before it was published in the journal. Find our conference coverage at the links below.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Burnout may jeopardize patient care

because of depersonalization of care, according to recent research published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“The primary conclusion of this review is that physician burnout might jeopardize patient care,” Maria Panagioti, PhD, from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research and the NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre at the University of Manchester (United Kingdom) and her colleagues wrote in their study. “Physician wellness and quality of patient care are critical [as are] complementary dimensions of health care organization efficiency.”

Dr. Panagioti and her colleagues performed a search of the MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsycInfo databases and found 47 eligible studies on the topics of physician burnout and patient care, which altogether included data from a pooled cohort of 42,473 physicians. The physicians were median 38 years old, with 44.7% of studies looking at physicians in residency or early career (up to 5 years post residency) and 55.3% of studies examining experienced physicians. The meta-analysis also evaluated physicians in a hospital setting (63.8%), primary care (13.8%), and across various different health care settings (8.5%).

The researchers found physicians with burnout were significantly associated with higher rates of patient safety issues (odds ratio, 1.96; 95% confidence interval, 1.59-2.40), reduced patient satisfaction (OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.42-3.68), and lower quality of care (OR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.87-2.85). System-reported instances of patient safety issues and low professionalism were not statistically significant, but the subgroup differences did reach statistical significance (Cohen Q, 8.14; P = .007). Among residents and physicians in their early career, there was a greater association between burnout and low professionalism (OR, 3.39; 95% CI, 2.38-4.40), compared with physicians in the middle or later in their career (OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.46-2.01; Cohen Q, 7.27; P = .003).

“Investments in organizational strategies to jointly monitor and improve physician wellness and patient care outcomes are needed,” Dr. Panagioti and her colleagues wrote in the study. “Interventions aimed at improving the culture of health care organizations, as well as interventions focused on individual physicians but supported and funded by health care organizations, are beneficial.”

Researchers noted the study quality was low to moderate. Variation in outcomes across studies, heterogeneity among studies, potential selection bias by excluding gray literature, and the inability to establish causal links from findings because of the cross-sectional nature of the studies analyzed were potential limitations in the study, they reported.

The study was funded by the United Kingdom NIHR School for Primary Care Research and the NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Panagioti M et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Sept 4. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713.

Because of a lack of funding for research into burnout and the immediate need for change based on the effect it has on patient care seen in Pangioti et al., the question of how to address physician burnout should be answered with quality improvement programs aimed at making immediate changes in health care settings, Mark Linzer, MD, wrote in a related editorial.

“Resonating with these concepts, I propose that, for the burnout prevention and wellness field, we encourage quality improvement projects of high standards: multiple sites, concurrent control groups, longitudinal design, and blinding when feasible, with assessment of outcomes and costs,” he wrote. “These studies can point us toward what we will evaluate in larger trials and allow a place for the rapidly developing information base to be viewed and thus become part of the developing science of work conditions, burnout reduction, and the anticipated result on quality and safety.”

There are research questions that have yet to be answered on this topic, he added, such as to what extent do factors like workflow redesign, use and upkeep of electronic medical records, and chaotic workplaces affect burnout. Further, regulatory environments may play a role, and it is still not known whether reducing burnout among physicians will also reduce burnout among staff. Future studies should also look at how burnout affects trainees and female physicians, he suggested.

“The link between burnout and adverse patient outcomes is stronger, thanks to the work of Panagioti and colleagues,” Dr. Linzer said. “With close to half of U.S. physicians experiencing symptoms of burnout, more work is needed to understand how to reduce it and what we can expect from doing so.”

Dr. Linzer is from the Hennepin Healthcare Systems in Minneapolis. These comments summarize his editorial regarding the findings of Pangioti et al. He reported support for Wellness Champion training by the American College of Physicians and the Association of Chiefs and Leaders in General Internal Medicine and that he has received support for American Medical Association research projects.

Because of a lack of funding for research into burnout and the immediate need for change based on the effect it has on patient care seen in Pangioti et al., the question of how to address physician burnout should be answered with quality improvement programs aimed at making immediate changes in health care settings, Mark Linzer, MD, wrote in a related editorial.

“Resonating with these concepts, I propose that, for the burnout prevention and wellness field, we encourage quality improvement projects of high standards: multiple sites, concurrent control groups, longitudinal design, and blinding when feasible, with assessment of outcomes and costs,” he wrote. “These studies can point us toward what we will evaluate in larger trials and allow a place for the rapidly developing information base to be viewed and thus become part of the developing science of work conditions, burnout reduction, and the anticipated result on quality and safety.”

There are research questions that have yet to be answered on this topic, he added, such as to what extent do factors like workflow redesign, use and upkeep of electronic medical records, and chaotic workplaces affect burnout. Further, regulatory environments may play a role, and it is still not known whether reducing burnout among physicians will also reduce burnout among staff. Future studies should also look at how burnout affects trainees and female physicians, he suggested.

“The link between burnout and adverse patient outcomes is stronger, thanks to the work of Panagioti and colleagues,” Dr. Linzer said. “With close to half of U.S. physicians experiencing symptoms of burnout, more work is needed to understand how to reduce it and what we can expect from doing so.”

Dr. Linzer is from the Hennepin Healthcare Systems in Minneapolis. These comments summarize his editorial regarding the findings of Pangioti et al. He reported support for Wellness Champion training by the American College of Physicians and the Association of Chiefs and Leaders in General Internal Medicine and that he has received support for American Medical Association research projects.

Because of a lack of funding for research into burnout and the immediate need for change based on the effect it has on patient care seen in Pangioti et al., the question of how to address physician burnout should be answered with quality improvement programs aimed at making immediate changes in health care settings, Mark Linzer, MD, wrote in a related editorial.

“Resonating with these concepts, I propose that, for the burnout prevention and wellness field, we encourage quality improvement projects of high standards: multiple sites, concurrent control groups, longitudinal design, and blinding when feasible, with assessment of outcomes and costs,” he wrote. “These studies can point us toward what we will evaluate in larger trials and allow a place for the rapidly developing information base to be viewed and thus become part of the developing science of work conditions, burnout reduction, and the anticipated result on quality and safety.”

There are research questions that have yet to be answered on this topic, he added, such as to what extent do factors like workflow redesign, use and upkeep of electronic medical records, and chaotic workplaces affect burnout. Further, regulatory environments may play a role, and it is still not known whether reducing burnout among physicians will also reduce burnout among staff. Future studies should also look at how burnout affects trainees and female physicians, he suggested.

“The link between burnout and adverse patient outcomes is stronger, thanks to the work of Panagioti and colleagues,” Dr. Linzer said. “With close to half of U.S. physicians experiencing symptoms of burnout, more work is needed to understand how to reduce it and what we can expect from doing so.”

Dr. Linzer is from the Hennepin Healthcare Systems in Minneapolis. These comments summarize his editorial regarding the findings of Pangioti et al. He reported support for Wellness Champion training by the American College of Physicians and the Association of Chiefs and Leaders in General Internal Medicine and that he has received support for American Medical Association research projects.

because of depersonalization of care, according to recent research published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“The primary conclusion of this review is that physician burnout might jeopardize patient care,” Maria Panagioti, PhD, from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research and the NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre at the University of Manchester (United Kingdom) and her colleagues wrote in their study. “Physician wellness and quality of patient care are critical [as are] complementary dimensions of health care organization efficiency.”

Dr. Panagioti and her colleagues performed a search of the MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsycInfo databases and found 47 eligible studies on the topics of physician burnout and patient care, which altogether included data from a pooled cohort of 42,473 physicians. The physicians were median 38 years old, with 44.7% of studies looking at physicians in residency or early career (up to 5 years post residency) and 55.3% of studies examining experienced physicians. The meta-analysis also evaluated physicians in a hospital setting (63.8%), primary care (13.8%), and across various different health care settings (8.5%).

The researchers found physicians with burnout were significantly associated with higher rates of patient safety issues (odds ratio, 1.96; 95% confidence interval, 1.59-2.40), reduced patient satisfaction (OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.42-3.68), and lower quality of care (OR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.87-2.85). System-reported instances of patient safety issues and low professionalism were not statistically significant, but the subgroup differences did reach statistical significance (Cohen Q, 8.14; P = .007). Among residents and physicians in their early career, there was a greater association between burnout and low professionalism (OR, 3.39; 95% CI, 2.38-4.40), compared with physicians in the middle or later in their career (OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.46-2.01; Cohen Q, 7.27; P = .003).

“Investments in organizational strategies to jointly monitor and improve physician wellness and patient care outcomes are needed,” Dr. Panagioti and her colleagues wrote in the study. “Interventions aimed at improving the culture of health care organizations, as well as interventions focused on individual physicians but supported and funded by health care organizations, are beneficial.”

Researchers noted the study quality was low to moderate. Variation in outcomes across studies, heterogeneity among studies, potential selection bias by excluding gray literature, and the inability to establish causal links from findings because of the cross-sectional nature of the studies analyzed were potential limitations in the study, they reported.

The study was funded by the United Kingdom NIHR School for Primary Care Research and the NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Panagioti M et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Sept 4. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713.

because of depersonalization of care, according to recent research published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“The primary conclusion of this review is that physician burnout might jeopardize patient care,” Maria Panagioti, PhD, from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research and the NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre at the University of Manchester (United Kingdom) and her colleagues wrote in their study. “Physician wellness and quality of patient care are critical [as are] complementary dimensions of health care organization efficiency.”

Dr. Panagioti and her colleagues performed a search of the MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsycInfo databases and found 47 eligible studies on the topics of physician burnout and patient care, which altogether included data from a pooled cohort of 42,473 physicians. The physicians were median 38 years old, with 44.7% of studies looking at physicians in residency or early career (up to 5 years post residency) and 55.3% of studies examining experienced physicians. The meta-analysis also evaluated physicians in a hospital setting (63.8%), primary care (13.8%), and across various different health care settings (8.5%).

The researchers found physicians with burnout were significantly associated with higher rates of patient safety issues (odds ratio, 1.96; 95% confidence interval, 1.59-2.40), reduced patient satisfaction (OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.42-3.68), and lower quality of care (OR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.87-2.85). System-reported instances of patient safety issues and low professionalism were not statistically significant, but the subgroup differences did reach statistical significance (Cohen Q, 8.14; P = .007). Among residents and physicians in their early career, there was a greater association between burnout and low professionalism (OR, 3.39; 95% CI, 2.38-4.40), compared with physicians in the middle or later in their career (OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.46-2.01; Cohen Q, 7.27; P = .003).

“Investments in organizational strategies to jointly monitor and improve physician wellness and patient care outcomes are needed,” Dr. Panagioti and her colleagues wrote in the study. “Interventions aimed at improving the culture of health care organizations, as well as interventions focused on individual physicians but supported and funded by health care organizations, are beneficial.”

Researchers noted the study quality was low to moderate. Variation in outcomes across studies, heterogeneity among studies, potential selection bias by excluding gray literature, and the inability to establish causal links from findings because of the cross-sectional nature of the studies analyzed were potential limitations in the study, they reported.

The study was funded by the United Kingdom NIHR School for Primary Care Research and the NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Panagioti M et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Sept 4. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Burnout among physicians was associated with lower quality of care because of unprofessionalism, reduced patient satisfaction, and an increased risk of patient safety issues.

Major finding: Physicians with burnout were significantly associated with higher rates of patient safety issues (odds ratio, 1.96; 95% confidence interval, 1.59-2.40), reduced patient satisfaction (OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.42-3.68), and lower quality of care (OR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.87-2.85).

Study details: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 42,473 physicians from 47 different studies.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the United Kingdom National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research and the NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Source: Panagioti M et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Sept 4. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713.

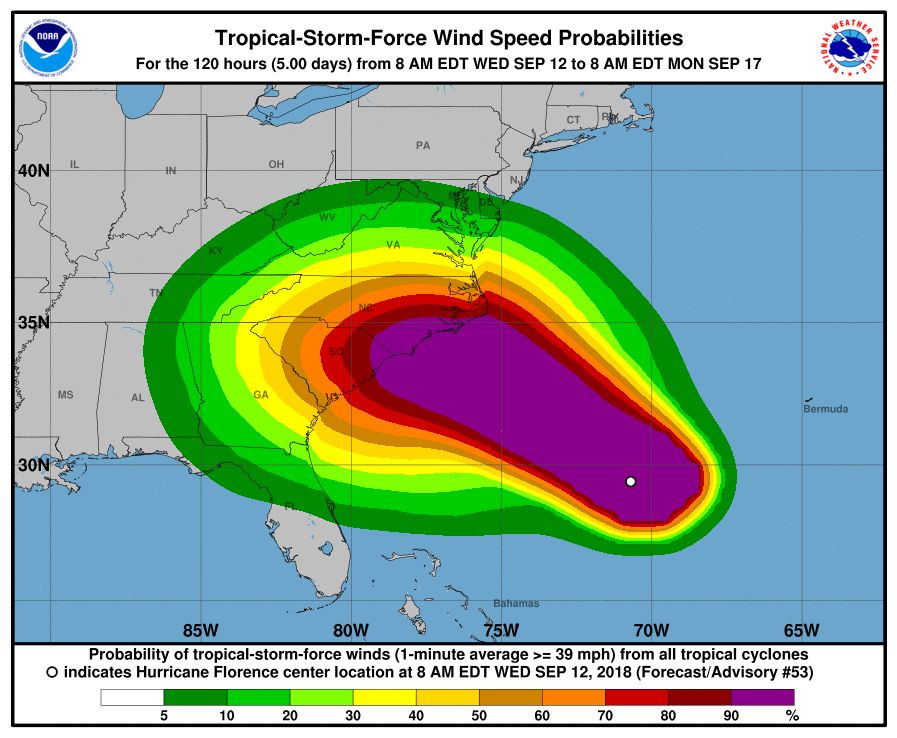

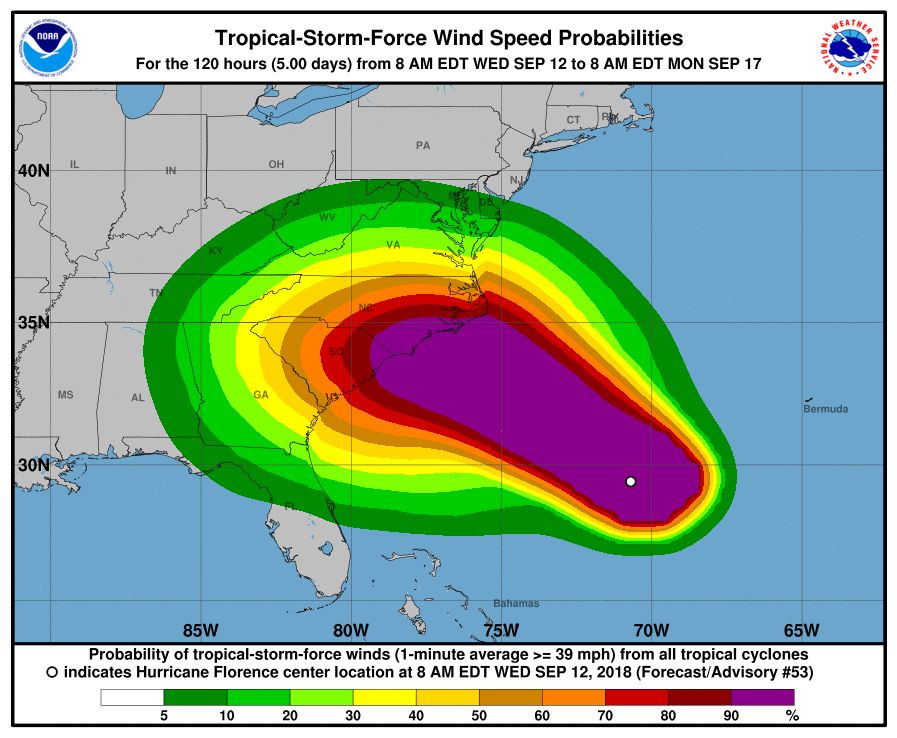

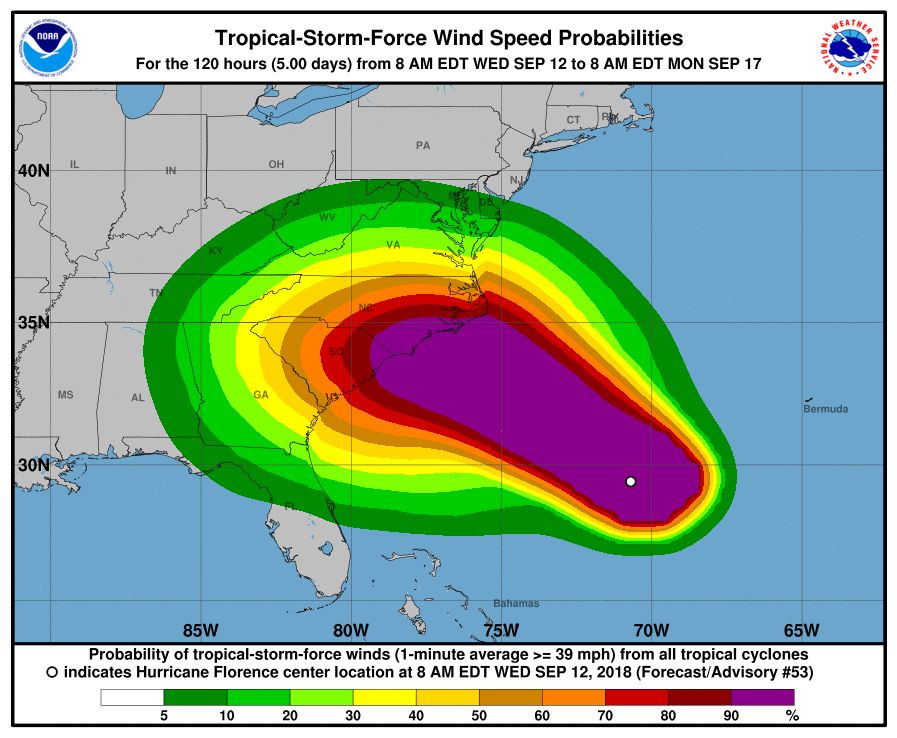

CDC opens Emergency Operations Center in advance of Hurricane Florence

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is activating its Emergency Operations Center (EOC) in advance of the landfall of Hurricane Florence, according to a CDC media statement.

Activation of the center will allow for 24/7 management of all CDC activities before, during, and after the landfall of Hurricane Florence, including deployment of personnel and resources.

All CDC staff should be ready to provide infectious disease outbreak surveillance, public health messages, water/food safety evaluations, mold prevention and treatment, industrial contamination containment, and standing water control. The CDC is also sharing messages with the public on how to protect themselves from threats before, during, and after landfall, such as drowning and floodwater safety, carbon monoxide poisoning, downed power lines, unsafe food and water, and mold.

The EOC is the CDC’s command center for the coordination and monitoring of CDC activity with all other U.S. federal, state, and local agencies. The EOC also works with the Secretary of Health & Human Services Secretary’s Operations Center to ensure awareness and a coordinated public health and medical response, according to the statement.

Additional resources for interested parties can be found on the CDC website.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is activating its Emergency Operations Center (EOC) in advance of the landfall of Hurricane Florence, according to a CDC media statement.

Activation of the center will allow for 24/7 management of all CDC activities before, during, and after the landfall of Hurricane Florence, including deployment of personnel and resources.

All CDC staff should be ready to provide infectious disease outbreak surveillance, public health messages, water/food safety evaluations, mold prevention and treatment, industrial contamination containment, and standing water control. The CDC is also sharing messages with the public on how to protect themselves from threats before, during, and after landfall, such as drowning and floodwater safety, carbon monoxide poisoning, downed power lines, unsafe food and water, and mold.

The EOC is the CDC’s command center for the coordination and monitoring of CDC activity with all other U.S. federal, state, and local agencies. The EOC also works with the Secretary of Health & Human Services Secretary’s Operations Center to ensure awareness and a coordinated public health and medical response, according to the statement.

Additional resources for interested parties can be found on the CDC website.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is activating its Emergency Operations Center (EOC) in advance of the landfall of Hurricane Florence, according to a CDC media statement.

Activation of the center will allow for 24/7 management of all CDC activities before, during, and after the landfall of Hurricane Florence, including deployment of personnel and resources.

All CDC staff should be ready to provide infectious disease outbreak surveillance, public health messages, water/food safety evaluations, mold prevention and treatment, industrial contamination containment, and standing water control. The CDC is also sharing messages with the public on how to protect themselves from threats before, during, and after landfall, such as drowning and floodwater safety, carbon monoxide poisoning, downed power lines, unsafe food and water, and mold.

The EOC is the CDC’s command center for the coordination and monitoring of CDC activity with all other U.S. federal, state, and local agencies. The EOC also works with the Secretary of Health & Human Services Secretary’s Operations Center to ensure awareness and a coordinated public health and medical response, according to the statement.

Additional resources for interested parties can be found on the CDC website.

October 2018