User login

CAR T-cell therapy elicits responses in MM

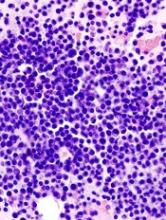

BOSTON—Early results from a phase 1 trial suggest the chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy P-BCMA-101 can produce responses in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (MM).

All 11 patients treated have experienced some clinical response, with 8 patients achieving a partial response (PR) or better.

The most common adverse events were neutropenia and thrombocytopenia. One patient was suspected to have cytokine release syndrome, but the condition resolved without use of tociluzimab or steroids.

These results were presented at the 2018 CAR-TCR Summit by Eric Ostertag, MD, PhD, chief executive officer of Poseida Therapeutics Inc., the company developing P-BCMA-101.

Dr. Ostertag presented data on 11 patients with heavily pretreated MM. They had a median of six prior therapies. Their median age was 60, and 73% were considered high risk.

Prior to receiving P-BCMA-101, patients received conditioning with fludarabine (30 mg/m2) and cyclophosphamide (300 mg/m2) for 3 days.

Patients were then treated across three dose groups with average CAR T-cell doses of 51×106 (n=3), 152×106 (n=7), and 430×106 (n=1).

As of August 10, 2018, all 11 patients were still on study.

There were no dose-limiting toxicities. Eight patients developed neutropenia, and 5 had thrombocytopenia.

Researchers suspected cytokine release syndrome in one patient, but the condition resolved without tociluzimab or steroid treatment. There was no neurotoxicity reported, and none of the patients required admission to an intensive care unit.

All patients showed improvement in biomarkers following treatment.

Ten patients were evaluable for response by International Myeloma Working Group criteria. Seven of these patients achieved at least a PR, including very good partial responses (VGPRs) and stringent complete response (CR).

The eleventh patient also responded to treatment, but this patient has oligosecretory disease and was only evaluable by PET. The patient had a near-CR by PET.

Poseida Therapeutics would not disclose additional details regarding how many patients achieved a PR, VGPR, or CR, but the company plans to release more information on response at an upcoming meeting.

“The latest data results show that P-BCMA-101 induces deep responses in a heavily pretreated population with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma, with some patients reaching VGPR and even stringent CR at early efficacy assessments,” Dr. Ostertag said.

“We believe our advantages of a purified product, where all cells express the CAR molecule, and a product with high levels of stem cell memory T cells, producing a more gradual and prolonged immune response against tumor cells, provide a significantly better therapeutic index when compared with other CAR-T therapeutics. We are also encouraged that P-BCMA-101 is demonstrating significant efficacy even at doses that have been ineffective for other anti-BCMA CAR-T therapies and that our response rates continue to improve as the dose increases.”

This study (NCT03288493) is funded by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine and Poseida Therapeutics.

BOSTON—Early results from a phase 1 trial suggest the chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy P-BCMA-101 can produce responses in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (MM).

All 11 patients treated have experienced some clinical response, with 8 patients achieving a partial response (PR) or better.

The most common adverse events were neutropenia and thrombocytopenia. One patient was suspected to have cytokine release syndrome, but the condition resolved without use of tociluzimab or steroids.

These results were presented at the 2018 CAR-TCR Summit by Eric Ostertag, MD, PhD, chief executive officer of Poseida Therapeutics Inc., the company developing P-BCMA-101.

Dr. Ostertag presented data on 11 patients with heavily pretreated MM. They had a median of six prior therapies. Their median age was 60, and 73% were considered high risk.

Prior to receiving P-BCMA-101, patients received conditioning with fludarabine (30 mg/m2) and cyclophosphamide (300 mg/m2) for 3 days.

Patients were then treated across three dose groups with average CAR T-cell doses of 51×106 (n=3), 152×106 (n=7), and 430×106 (n=1).

As of August 10, 2018, all 11 patients were still on study.

There were no dose-limiting toxicities. Eight patients developed neutropenia, and 5 had thrombocytopenia.

Researchers suspected cytokine release syndrome in one patient, but the condition resolved without tociluzimab or steroid treatment. There was no neurotoxicity reported, and none of the patients required admission to an intensive care unit.

All patients showed improvement in biomarkers following treatment.

Ten patients were evaluable for response by International Myeloma Working Group criteria. Seven of these patients achieved at least a PR, including very good partial responses (VGPRs) and stringent complete response (CR).

The eleventh patient also responded to treatment, but this patient has oligosecretory disease and was only evaluable by PET. The patient had a near-CR by PET.

Poseida Therapeutics would not disclose additional details regarding how many patients achieved a PR, VGPR, or CR, but the company plans to release more information on response at an upcoming meeting.

“The latest data results show that P-BCMA-101 induces deep responses in a heavily pretreated population with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma, with some patients reaching VGPR and even stringent CR at early efficacy assessments,” Dr. Ostertag said.

“We believe our advantages of a purified product, where all cells express the CAR molecule, and a product with high levels of stem cell memory T cells, producing a more gradual and prolonged immune response against tumor cells, provide a significantly better therapeutic index when compared with other CAR-T therapeutics. We are also encouraged that P-BCMA-101 is demonstrating significant efficacy even at doses that have been ineffective for other anti-BCMA CAR-T therapies and that our response rates continue to improve as the dose increases.”

This study (NCT03288493) is funded by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine and Poseida Therapeutics.

BOSTON—Early results from a phase 1 trial suggest the chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy P-BCMA-101 can produce responses in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (MM).

All 11 patients treated have experienced some clinical response, with 8 patients achieving a partial response (PR) or better.

The most common adverse events were neutropenia and thrombocytopenia. One patient was suspected to have cytokine release syndrome, but the condition resolved without use of tociluzimab or steroids.

These results were presented at the 2018 CAR-TCR Summit by Eric Ostertag, MD, PhD, chief executive officer of Poseida Therapeutics Inc., the company developing P-BCMA-101.

Dr. Ostertag presented data on 11 patients with heavily pretreated MM. They had a median of six prior therapies. Their median age was 60, and 73% were considered high risk.

Prior to receiving P-BCMA-101, patients received conditioning with fludarabine (30 mg/m2) and cyclophosphamide (300 mg/m2) for 3 days.

Patients were then treated across three dose groups with average CAR T-cell doses of 51×106 (n=3), 152×106 (n=7), and 430×106 (n=1).

As of August 10, 2018, all 11 patients were still on study.

There were no dose-limiting toxicities. Eight patients developed neutropenia, and 5 had thrombocytopenia.

Researchers suspected cytokine release syndrome in one patient, but the condition resolved without tociluzimab or steroid treatment. There was no neurotoxicity reported, and none of the patients required admission to an intensive care unit.

All patients showed improvement in biomarkers following treatment.

Ten patients were evaluable for response by International Myeloma Working Group criteria. Seven of these patients achieved at least a PR, including very good partial responses (VGPRs) and stringent complete response (CR).

The eleventh patient also responded to treatment, but this patient has oligosecretory disease and was only evaluable by PET. The patient had a near-CR by PET.

Poseida Therapeutics would not disclose additional details regarding how many patients achieved a PR, VGPR, or CR, but the company plans to release more information on response at an upcoming meeting.

“The latest data results show that P-BCMA-101 induces deep responses in a heavily pretreated population with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma, with some patients reaching VGPR and even stringent CR at early efficacy assessments,” Dr. Ostertag said.

“We believe our advantages of a purified product, where all cells express the CAR molecule, and a product with high levels of stem cell memory T cells, producing a more gradual and prolonged immune response against tumor cells, provide a significantly better therapeutic index when compared with other CAR-T therapeutics. We are also encouraged that P-BCMA-101 is demonstrating significant efficacy even at doses that have been ineffective for other anti-BCMA CAR-T therapies and that our response rates continue to improve as the dose increases.”

This study (NCT03288493) is funded by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine and Poseida Therapeutics.

Risk factors for postop cardiac events differ between vascular and general surgery

Predictive risk factors for cardiac events (CEs) after general and vascular surgery differed significantly, according to a large retrospective study. However, there was no significant difference seen in the overall incidence of CEs between the two types of surgery, reported Derrick Acheampong, MD, and his colleagues at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

They performed a retrospective data analysis of 8,441 adult patients at their large urban teaching hospital; these patients had undergone general or vascular surgery during 2013-2016 and, in the analysis, were grouped by whether they experienced postoperative CEs.

Univariate and multivariate analyses identified predictors of postoperative CE and the association of CEs with adverse postoperative outcomes. CEs were defined as myocardial infarction or cardiac arrest within the 30-day postoperative period.

A total of 157 patients (1.9%) experienced CEs after major general and vascular surgery, with no significant difference in incidence between the two types of surgery (P = .44), according to their report, published online in the Annals of Medicine and Surgery. CE-associated mortality among this group was high, at 55.4%.

The occurrence of a CE following surgery in both groups was significantly associated with increased mortality, as well as pulmonary, renal, and neurological complications, in addition to systemic sepsis, postoperative red blood cell transfusion, unplanned return to the operating room, and prolonged hospitalization, according to the researchers.

However, predictors of CEs risk between vascular and general surgery were significantly different.

For general surgery, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) status greater than 3, dependent functional status, acute renal failure or dialysis, weight loss, creatinine greater than 1.2 mg/dL, international normalized ratio (INR) greater than 1.5, and partial thromboplastin time (PTT) less than 35 seconds were all unique independent predictors of postoperative CEs.

For vascular surgery, the unique significant predictors of postoperative CEs were age greater than 65 years, emergency surgery, diabetes, congestive heart failure, systemic sepsis, and operative time greater than 240 minutes.

The only common predictive risk factors for postoperative CEs for the two forms of surgery were hematocrit less than 34% and ventilator dependence.

“The present study corroborates reported studies that recommend separate predictive CE risk indices and risk stratification among different surgical specialties. Predictors for CE greatly differed between general and vascular surgery patients in our patient population,” the authors stated.

They concluded with the hope that their study “provides useful information to surgeons and allows for the necessary resources to be focused on identified at-risk patients to improve surgical outcomes.”

Dr. Acheampong and his colleagues reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Acheampong D et al. Ann Med Surg. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2018.08.001.

Predictive risk factors for cardiac events (CEs) after general and vascular surgery differed significantly, according to a large retrospective study. However, there was no significant difference seen in the overall incidence of CEs between the two types of surgery, reported Derrick Acheampong, MD, and his colleagues at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

They performed a retrospective data analysis of 8,441 adult patients at their large urban teaching hospital; these patients had undergone general or vascular surgery during 2013-2016 and, in the analysis, were grouped by whether they experienced postoperative CEs.

Univariate and multivariate analyses identified predictors of postoperative CE and the association of CEs with adverse postoperative outcomes. CEs were defined as myocardial infarction or cardiac arrest within the 30-day postoperative period.

A total of 157 patients (1.9%) experienced CEs after major general and vascular surgery, with no significant difference in incidence between the two types of surgery (P = .44), according to their report, published online in the Annals of Medicine and Surgery. CE-associated mortality among this group was high, at 55.4%.

The occurrence of a CE following surgery in both groups was significantly associated with increased mortality, as well as pulmonary, renal, and neurological complications, in addition to systemic sepsis, postoperative red blood cell transfusion, unplanned return to the operating room, and prolonged hospitalization, according to the researchers.

However, predictors of CEs risk between vascular and general surgery were significantly different.

For general surgery, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) status greater than 3, dependent functional status, acute renal failure or dialysis, weight loss, creatinine greater than 1.2 mg/dL, international normalized ratio (INR) greater than 1.5, and partial thromboplastin time (PTT) less than 35 seconds were all unique independent predictors of postoperative CEs.

For vascular surgery, the unique significant predictors of postoperative CEs were age greater than 65 years, emergency surgery, diabetes, congestive heart failure, systemic sepsis, and operative time greater than 240 minutes.

The only common predictive risk factors for postoperative CEs for the two forms of surgery were hematocrit less than 34% and ventilator dependence.

“The present study corroborates reported studies that recommend separate predictive CE risk indices and risk stratification among different surgical specialties. Predictors for CE greatly differed between general and vascular surgery patients in our patient population,” the authors stated.

They concluded with the hope that their study “provides useful information to surgeons and allows for the necessary resources to be focused on identified at-risk patients to improve surgical outcomes.”

Dr. Acheampong and his colleagues reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Acheampong D et al. Ann Med Surg. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2018.08.001.

Predictive risk factors for cardiac events (CEs) after general and vascular surgery differed significantly, according to a large retrospective study. However, there was no significant difference seen in the overall incidence of CEs between the two types of surgery, reported Derrick Acheampong, MD, and his colleagues at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

They performed a retrospective data analysis of 8,441 adult patients at their large urban teaching hospital; these patients had undergone general or vascular surgery during 2013-2016 and, in the analysis, were grouped by whether they experienced postoperative CEs.

Univariate and multivariate analyses identified predictors of postoperative CE and the association of CEs with adverse postoperative outcomes. CEs were defined as myocardial infarction or cardiac arrest within the 30-day postoperative period.

A total of 157 patients (1.9%) experienced CEs after major general and vascular surgery, with no significant difference in incidence between the two types of surgery (P = .44), according to their report, published online in the Annals of Medicine and Surgery. CE-associated mortality among this group was high, at 55.4%.

The occurrence of a CE following surgery in both groups was significantly associated with increased mortality, as well as pulmonary, renal, and neurological complications, in addition to systemic sepsis, postoperative red blood cell transfusion, unplanned return to the operating room, and prolonged hospitalization, according to the researchers.

However, predictors of CEs risk between vascular and general surgery were significantly different.

For general surgery, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) status greater than 3, dependent functional status, acute renal failure or dialysis, weight loss, creatinine greater than 1.2 mg/dL, international normalized ratio (INR) greater than 1.5, and partial thromboplastin time (PTT) less than 35 seconds were all unique independent predictors of postoperative CEs.

For vascular surgery, the unique significant predictors of postoperative CEs were age greater than 65 years, emergency surgery, diabetes, congestive heart failure, systemic sepsis, and operative time greater than 240 minutes.

The only common predictive risk factors for postoperative CEs for the two forms of surgery were hematocrit less than 34% and ventilator dependence.

“The present study corroborates reported studies that recommend separate predictive CE risk indices and risk stratification among different surgical specialties. Predictors for CE greatly differed between general and vascular surgery patients in our patient population,” the authors stated.

They concluded with the hope that their study “provides useful information to surgeons and allows for the necessary resources to be focused on identified at-risk patients to improve surgical outcomes.”

Dr. Acheampong and his colleagues reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Acheampong D et al. Ann Med Surg. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2018.08.001.

FROM ANNALS OF MEDICINE AND SURGERY

Key clinical point: There was a significant difference in predictive risk factors for postoperative cardiac events between vascular and general surgery.

Major finding: The 1.9% incidence of cardiac events following general or vascular surgery was associated with a mortality rate of 55%.

Study details: Retrospective study of 8,441 patients who underwent vascular or general surgery during 2013-2015.

Disclosures: The authors reported having no disclosures.

Source: Acheampong D et al. Ann Med Surg. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2018.08.001.

Pantothenic acid enhances doxycycline’s antiacne effects

PARIS – in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, Maria A. Santos, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

The beauty of this treatment strategy is that it enables acne patients to obtain the therapeutic benefits of oral antibiotic therapy while minimizing exposure in accord with the current push to curb the growing problem of antibiotic resistance. Indeed, adjunctive oral pantothenic acid (also known as vitamin B5) appears to offer a solution to the high rate of clinical deterioration that often follows antibiotic discontinuation, observed Dr. Santos, a dermatologist at University of Santo Tomas Hospital in Manila.

“The use of pantothenic acid as an adjunct may enhance acne therapy and possibly prolong control despite antibiotic discontinuation,” she said.

Dr. Santos reported on 40 patients aged 16-45 years with moderate to severe acne who were randomized to 2 g/day of pantothenic acid or placebo for 16 weeks on top of 6 weeks of oral doxycycline at 100 mg once daily, plus ongoing topical adapalene and benzoyl peroxide gel.

After 8 weeks – that is, 2 weeks after everyone completed 6 weeks on doxycycline – the mean reduction in noninflammatory and total lesion counts was virtually identical in the two groups. For example, there was a 57.7% decrease in total lesion count compared with baseline in the pantothenic acid group and a 55% reduction in placebo-treated controls. Thereafter, however, the response curves diverged. Backsliding occurred in the control group such that their mean reduction in total lesions was 48.4% at 14 weeks and 40.4% at 16 weeks, compared with baseline. In contrast, patients on daily pantothenic acid had a 78.7% reduction in total lesion count at 14 weeks and an 80% decrease from baseline at 16 weeks.

Similarly, at 16 weeks, the mean reduction in noninflammatory lesions was 49% in the pantothenic acid group versus 19.2% in controls, compared with 34%-36% reductions at 10 weeks, even though all patients remained on topical adapalene and benzoyl peroxide throughout.

Mean reduction in inflammatory lesions followed the same trend; however, the numeric advantage in the pantothenic acid group didn’t achieve statistical significance.

Median Dermatology Life Quality Index scores improved over the course of the study in both groups, although significantly more patients in the pantothenic acid group achieved at least a 4-point improvement over baseline, which is considered the minimum clinically important difference. Moreover, while modified Global Severity Scores and subjective self-assessment scores improved in both groups, from week 12 onwards, the improvements were significantly greater in the pantothenic acid group.

Receiving adjunctive pantothenic acid for 10 weeks was safe. Adverse events were the same in both study arms, consisting chiefly of mild erythema, scaling, dryness, and nausea during the initial weeks on doxycycline.

Pantothenic acid is a water-soluble essential nutrient. Dr. Santos said that while the precise mechanism of the benefit seen in this randomized trial isn’t known, other investigators have generated evidence suggestive of enhanced epidermal barrier function through normalization of keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation in acne patients, coupled with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects.

Dr. Santos reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, conducted free of commercial support.

PARIS – in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, Maria A. Santos, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

The beauty of this treatment strategy is that it enables acne patients to obtain the therapeutic benefits of oral antibiotic therapy while minimizing exposure in accord with the current push to curb the growing problem of antibiotic resistance. Indeed, adjunctive oral pantothenic acid (also known as vitamin B5) appears to offer a solution to the high rate of clinical deterioration that often follows antibiotic discontinuation, observed Dr. Santos, a dermatologist at University of Santo Tomas Hospital in Manila.

“The use of pantothenic acid as an adjunct may enhance acne therapy and possibly prolong control despite antibiotic discontinuation,” she said.

Dr. Santos reported on 40 patients aged 16-45 years with moderate to severe acne who were randomized to 2 g/day of pantothenic acid or placebo for 16 weeks on top of 6 weeks of oral doxycycline at 100 mg once daily, plus ongoing topical adapalene and benzoyl peroxide gel.

After 8 weeks – that is, 2 weeks after everyone completed 6 weeks on doxycycline – the mean reduction in noninflammatory and total lesion counts was virtually identical in the two groups. For example, there was a 57.7% decrease in total lesion count compared with baseline in the pantothenic acid group and a 55% reduction in placebo-treated controls. Thereafter, however, the response curves diverged. Backsliding occurred in the control group such that their mean reduction in total lesions was 48.4% at 14 weeks and 40.4% at 16 weeks, compared with baseline. In contrast, patients on daily pantothenic acid had a 78.7% reduction in total lesion count at 14 weeks and an 80% decrease from baseline at 16 weeks.

Similarly, at 16 weeks, the mean reduction in noninflammatory lesions was 49% in the pantothenic acid group versus 19.2% in controls, compared with 34%-36% reductions at 10 weeks, even though all patients remained on topical adapalene and benzoyl peroxide throughout.

Mean reduction in inflammatory lesions followed the same trend; however, the numeric advantage in the pantothenic acid group didn’t achieve statistical significance.

Median Dermatology Life Quality Index scores improved over the course of the study in both groups, although significantly more patients in the pantothenic acid group achieved at least a 4-point improvement over baseline, which is considered the minimum clinically important difference. Moreover, while modified Global Severity Scores and subjective self-assessment scores improved in both groups, from week 12 onwards, the improvements were significantly greater in the pantothenic acid group.

Receiving adjunctive pantothenic acid for 10 weeks was safe. Adverse events were the same in both study arms, consisting chiefly of mild erythema, scaling, dryness, and nausea during the initial weeks on doxycycline.

Pantothenic acid is a water-soluble essential nutrient. Dr. Santos said that while the precise mechanism of the benefit seen in this randomized trial isn’t known, other investigators have generated evidence suggestive of enhanced epidermal barrier function through normalization of keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation in acne patients, coupled with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects.

Dr. Santos reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, conducted free of commercial support.

PARIS – in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, Maria A. Santos, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

The beauty of this treatment strategy is that it enables acne patients to obtain the therapeutic benefits of oral antibiotic therapy while minimizing exposure in accord with the current push to curb the growing problem of antibiotic resistance. Indeed, adjunctive oral pantothenic acid (also known as vitamin B5) appears to offer a solution to the high rate of clinical deterioration that often follows antibiotic discontinuation, observed Dr. Santos, a dermatologist at University of Santo Tomas Hospital in Manila.

“The use of pantothenic acid as an adjunct may enhance acne therapy and possibly prolong control despite antibiotic discontinuation,” she said.

Dr. Santos reported on 40 patients aged 16-45 years with moderate to severe acne who were randomized to 2 g/day of pantothenic acid or placebo for 16 weeks on top of 6 weeks of oral doxycycline at 100 mg once daily, plus ongoing topical adapalene and benzoyl peroxide gel.

After 8 weeks – that is, 2 weeks after everyone completed 6 weeks on doxycycline – the mean reduction in noninflammatory and total lesion counts was virtually identical in the two groups. For example, there was a 57.7% decrease in total lesion count compared with baseline in the pantothenic acid group and a 55% reduction in placebo-treated controls. Thereafter, however, the response curves diverged. Backsliding occurred in the control group such that their mean reduction in total lesions was 48.4% at 14 weeks and 40.4% at 16 weeks, compared with baseline. In contrast, patients on daily pantothenic acid had a 78.7% reduction in total lesion count at 14 weeks and an 80% decrease from baseline at 16 weeks.

Similarly, at 16 weeks, the mean reduction in noninflammatory lesions was 49% in the pantothenic acid group versus 19.2% in controls, compared with 34%-36% reductions at 10 weeks, even though all patients remained on topical adapalene and benzoyl peroxide throughout.

Mean reduction in inflammatory lesions followed the same trend; however, the numeric advantage in the pantothenic acid group didn’t achieve statistical significance.

Median Dermatology Life Quality Index scores improved over the course of the study in both groups, although significantly more patients in the pantothenic acid group achieved at least a 4-point improvement over baseline, which is considered the minimum clinically important difference. Moreover, while modified Global Severity Scores and subjective self-assessment scores improved in both groups, from week 12 onwards, the improvements were significantly greater in the pantothenic acid group.

Receiving adjunctive pantothenic acid for 10 weeks was safe. Adverse events were the same in both study arms, consisting chiefly of mild erythema, scaling, dryness, and nausea during the initial weeks on doxycycline.

Pantothenic acid is a water-soluble essential nutrient. Dr. Santos said that while the precise mechanism of the benefit seen in this randomized trial isn’t known, other investigators have generated evidence suggestive of enhanced epidermal barrier function through normalization of keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation in acne patients, coupled with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects.

Dr. Santos reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, conducted free of commercial support.

REPORTING FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Oral pantothenic acid at 2 g/day appears to be a safe and effective adjunct to oral doxycycline for moderate to severe acne.

Major finding: Acne patients on oral pantothenic acid had a mean 80% reduction in total lesion count 10 weeks after completing 6 weeks on oral doxycycline, a rate twice that of placebo-treated controls.

Study details: This 16-week, prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study included 40 patients with moderate to severe acne.

Disclosures: Dr. Santos reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, conducted free of commercial support.

FDA attacks antibiotic resistance with new strategy

WASHINGTON – A strategy combining stewardship and science is needed to help combat antimicrobial resistance, and updated plans from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration include four key components to address all aspects of product development and use, FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, said in a press briefing in Washington on Sept. 14.

“The FDA plays a unique role in advancing human and animal health” that provides a unique vantage point for coordinating all aspects of product development and application, he said.

The FDA’s comprehensive approach to the challenge of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) includes:

- Facilitating product development.

- Promoting antimicrobial stewardship.

- Supporting the development of new tools for surveillance.

- Advancing scientific initiatives, including research for the development of alternative treatments.

The FDA’s product development plan to combat AMR includes the creation of incentives for companies to develop new antibiotic products and create a robust pipeline, which is a challenge because of the lack of immediate economic gain, Dr. Gottlieb said.

“It necessary to change the perception that the costs and risks of antibiotic innovation are too high relative to their expected gains,” he emphasized.

Strategies to incentivize companies include fast track designation, priority review, and breakthrough therapy designation. In addition, the Limited Population Pathway for Antibacterial and Antifungal Drugs (LPAD) is designed to promote development of antimicrobial drugs for limited and underserved populations, Dr. Gottlieb said. The FDA plan also calls for pursuing reimbursement options with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Promoting antimicrobial stewardship remains an ongoing element of the FDA’s plan to reduce AMR. In conjunction with the release of the FDA’s updated approach to AMR, the FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine CVM released a 5-year action plan to promote and support antimicrobial stewardship in not only the agricultural arena, but in companion animals as well.

The FDA plans to bring all antimicrobials of medical importance that are approved for use in animals under the oversight of CVM, which will pursue the improve labeling on antimicrobial drugs used in the feed and water of food-producing animals, including defining durations of use, Dr. Gottlieb noted.

Supporting the development and improvement of surveillance tools is “essential to understanding the drivers of resistance in human and veterinary settings and formulating appropriate responses” to outbreaks, Dr. Gottlieb said.

To help meet this goal, the FDA will expand sampling via the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS) database, he said. Other surveillance goals include supporting genomics research and expanding AMR monitoring to include pathogens associated with animal feed and companion animals, he added.

As part of the final component of the FDA’s AMR strategy to advance scientific initiatives, the FDA has released a new Request for Information “to obtain additional, external input on how best to develop an annual list of regulatory science initiatives specific for antimicrobial products,” Dr. Gottlieb announced. The FDA intends to use the information gained from clinicians and others in its creation of guidance documents and recommendations to streamline the antibiotic development process. He also cited the FDA’s ongoing support of partnerships with public and private organizations such as the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative, which focuses on drug development for severe bacterial infections with current unmet medical need.

“We need to harness science and policy to help our public health systems and researchers become nimbler in the battle against drug-resistant pathogens,” Dr. Gottlieb concluded.

In a panel discussion following the briefing, several experts offered perspective on the FDA’s goals and on the challenges of AMR.

William Flynn, DVM, deputy director of science policy for the Center of Veterinary Medicine, noted some goals for reducing the use of antibiotics in the veterinary arena.

“We are trying to focus on the driver: What are the disease conditions that drive use of the product,” he said. Ideally, better management of disease conditions can reduce reliance on antibiotics, he added.

Also in the panel discussion, Steven Gitterman, MD, deputy director of the division of microbiology devices at the Center for Devices and Radiological Health, emphasized the value of sustainable trial databases so AMR research can continue on an ongoing basis. Finally, Carolyn Wilson, PhD, associate director of research at the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, noted that the FDA’s research and development efforts include antibiotic alternatives, including live biotherapeutic products, fecal microbiota transplantation, and bacteriophage therapy.

Visit www.fda.gov for a transcript of Dr. Gottlieb’s talk, and for the updated FDA website page with more details on the agency’s plans to combat antimicrobial resistance.

Dr. Gottlieb and the panelists had no financial conflicts to disclose.

WASHINGTON – A strategy combining stewardship and science is needed to help combat antimicrobial resistance, and updated plans from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration include four key components to address all aspects of product development and use, FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, said in a press briefing in Washington on Sept. 14.

“The FDA plays a unique role in advancing human and animal health” that provides a unique vantage point for coordinating all aspects of product development and application, he said.

The FDA’s comprehensive approach to the challenge of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) includes:

- Facilitating product development.

- Promoting antimicrobial stewardship.

- Supporting the development of new tools for surveillance.

- Advancing scientific initiatives, including research for the development of alternative treatments.

The FDA’s product development plan to combat AMR includes the creation of incentives for companies to develop new antibiotic products and create a robust pipeline, which is a challenge because of the lack of immediate economic gain, Dr. Gottlieb said.

“It necessary to change the perception that the costs and risks of antibiotic innovation are too high relative to their expected gains,” he emphasized.

Strategies to incentivize companies include fast track designation, priority review, and breakthrough therapy designation. In addition, the Limited Population Pathway for Antibacterial and Antifungal Drugs (LPAD) is designed to promote development of antimicrobial drugs for limited and underserved populations, Dr. Gottlieb said. The FDA plan also calls for pursuing reimbursement options with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Promoting antimicrobial stewardship remains an ongoing element of the FDA’s plan to reduce AMR. In conjunction with the release of the FDA’s updated approach to AMR, the FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine CVM released a 5-year action plan to promote and support antimicrobial stewardship in not only the agricultural arena, but in companion animals as well.

The FDA plans to bring all antimicrobials of medical importance that are approved for use in animals under the oversight of CVM, which will pursue the improve labeling on antimicrobial drugs used in the feed and water of food-producing animals, including defining durations of use, Dr. Gottlieb noted.

Supporting the development and improvement of surveillance tools is “essential to understanding the drivers of resistance in human and veterinary settings and formulating appropriate responses” to outbreaks, Dr. Gottlieb said.

To help meet this goal, the FDA will expand sampling via the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS) database, he said. Other surveillance goals include supporting genomics research and expanding AMR monitoring to include pathogens associated with animal feed and companion animals, he added.

As part of the final component of the FDA’s AMR strategy to advance scientific initiatives, the FDA has released a new Request for Information “to obtain additional, external input on how best to develop an annual list of regulatory science initiatives specific for antimicrobial products,” Dr. Gottlieb announced. The FDA intends to use the information gained from clinicians and others in its creation of guidance documents and recommendations to streamline the antibiotic development process. He also cited the FDA’s ongoing support of partnerships with public and private organizations such as the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative, which focuses on drug development for severe bacterial infections with current unmet medical need.

“We need to harness science and policy to help our public health systems and researchers become nimbler in the battle against drug-resistant pathogens,” Dr. Gottlieb concluded.

In a panel discussion following the briefing, several experts offered perspective on the FDA’s goals and on the challenges of AMR.

William Flynn, DVM, deputy director of science policy for the Center of Veterinary Medicine, noted some goals for reducing the use of antibiotics in the veterinary arena.

“We are trying to focus on the driver: What are the disease conditions that drive use of the product,” he said. Ideally, better management of disease conditions can reduce reliance on antibiotics, he added.

Also in the panel discussion, Steven Gitterman, MD, deputy director of the division of microbiology devices at the Center for Devices and Radiological Health, emphasized the value of sustainable trial databases so AMR research can continue on an ongoing basis. Finally, Carolyn Wilson, PhD, associate director of research at the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, noted that the FDA’s research and development efforts include antibiotic alternatives, including live biotherapeutic products, fecal microbiota transplantation, and bacteriophage therapy.

Visit www.fda.gov for a transcript of Dr. Gottlieb’s talk, and for the updated FDA website page with more details on the agency’s plans to combat antimicrobial resistance.

Dr. Gottlieb and the panelists had no financial conflicts to disclose.

WASHINGTON – A strategy combining stewardship and science is needed to help combat antimicrobial resistance, and updated plans from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration include four key components to address all aspects of product development and use, FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, said in a press briefing in Washington on Sept. 14.

“The FDA plays a unique role in advancing human and animal health” that provides a unique vantage point for coordinating all aspects of product development and application, he said.

The FDA’s comprehensive approach to the challenge of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) includes:

- Facilitating product development.

- Promoting antimicrobial stewardship.

- Supporting the development of new tools for surveillance.

- Advancing scientific initiatives, including research for the development of alternative treatments.

The FDA’s product development plan to combat AMR includes the creation of incentives for companies to develop new antibiotic products and create a robust pipeline, which is a challenge because of the lack of immediate economic gain, Dr. Gottlieb said.

“It necessary to change the perception that the costs and risks of antibiotic innovation are too high relative to their expected gains,” he emphasized.

Strategies to incentivize companies include fast track designation, priority review, and breakthrough therapy designation. In addition, the Limited Population Pathway for Antibacterial and Antifungal Drugs (LPAD) is designed to promote development of antimicrobial drugs for limited and underserved populations, Dr. Gottlieb said. The FDA plan also calls for pursuing reimbursement options with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Promoting antimicrobial stewardship remains an ongoing element of the FDA’s plan to reduce AMR. In conjunction with the release of the FDA’s updated approach to AMR, the FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine CVM released a 5-year action plan to promote and support antimicrobial stewardship in not only the agricultural arena, but in companion animals as well.

The FDA plans to bring all antimicrobials of medical importance that are approved for use in animals under the oversight of CVM, which will pursue the improve labeling on antimicrobial drugs used in the feed and water of food-producing animals, including defining durations of use, Dr. Gottlieb noted.

Supporting the development and improvement of surveillance tools is “essential to understanding the drivers of resistance in human and veterinary settings and formulating appropriate responses” to outbreaks, Dr. Gottlieb said.

To help meet this goal, the FDA will expand sampling via the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS) database, he said. Other surveillance goals include supporting genomics research and expanding AMR monitoring to include pathogens associated with animal feed and companion animals, he added.

As part of the final component of the FDA’s AMR strategy to advance scientific initiatives, the FDA has released a new Request for Information “to obtain additional, external input on how best to develop an annual list of regulatory science initiatives specific for antimicrobial products,” Dr. Gottlieb announced. The FDA intends to use the information gained from clinicians and others in its creation of guidance documents and recommendations to streamline the antibiotic development process. He also cited the FDA’s ongoing support of partnerships with public and private organizations such as the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative, which focuses on drug development for severe bacterial infections with current unmet medical need.

“We need to harness science and policy to help our public health systems and researchers become nimbler in the battle against drug-resistant pathogens,” Dr. Gottlieb concluded.

In a panel discussion following the briefing, several experts offered perspective on the FDA’s goals and on the challenges of AMR.

William Flynn, DVM, deputy director of science policy for the Center of Veterinary Medicine, noted some goals for reducing the use of antibiotics in the veterinary arena.

“We are trying to focus on the driver: What are the disease conditions that drive use of the product,” he said. Ideally, better management of disease conditions can reduce reliance on antibiotics, he added.

Also in the panel discussion, Steven Gitterman, MD, deputy director of the division of microbiology devices at the Center for Devices and Radiological Health, emphasized the value of sustainable trial databases so AMR research can continue on an ongoing basis. Finally, Carolyn Wilson, PhD, associate director of research at the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, noted that the FDA’s research and development efforts include antibiotic alternatives, including live biotherapeutic products, fecal microbiota transplantation, and bacteriophage therapy.

Visit www.fda.gov for a transcript of Dr. Gottlieb’s talk, and for the updated FDA website page with more details on the agency’s plans to combat antimicrobial resistance.

Dr. Gottlieb and the panelists had no financial conflicts to disclose.

What is the Relation Between PTSD and Medical Conditions?

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) develops after exposure to a traumatic event, which can involve witnessing the traumatic event or directly experiencing the trauma.1 The prevalence of PTSD in the general population is approximately 7% to 8%.1 However, not everyone who experiences trauma develops PTSD since the majority of men and women experience at least 1 traumatic event in their lifetimes but do not develop PTSD.1

In order to be diagnosed with PTSD, a patient must meet several criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5).2 The patient is required to have exposure to trauma, begin having a certain number of prespecified symptoms, and these symptoms must persist for at least a month.2 Symptoms of PTSD include re-experiencing the traumatic event, avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma, negative cognitions and mood, and hyperarousal.3,4 The hyperarousal that is associated with PTSD has been theorized to be either a result of the trauma experienced or exacerbation of a pre-existing tendency.5 This can manifest in various ways, such as hypervigilance, exaggerated startle response, trouble sleeping, problems concentrating, or irritability.3,5 These symptoms can cause individuals with PTSD to have elevated levels of stress and to experience difficulties with completing everyday tasks.6

PTSD and Inflimmation-Related Medical Conditions

Posttraumatic stress disorder has been linked to various physical health problems. Studies have found that PTSD is often comorbid with cardiovascular, autoimmune, musculoskeletal, digestive, chronic pain and respiratory disorders.3,7-11 Inflammation may be a contributing factor in the associations between PTSD and these conditions.12-16 Studies have found that increases in pro-inflammatory cytokines and interferons are associated with PTSD, as well as changes in immune-related blood cells.12-16

Considering that PTSD has been linked to many medical conditions that have inflammatory components, especially cardiovascular disease, inflammatory markers may be early indicators of PTSD.12-16 Additionally, inflammatory markers such as cytokines and interferons can be targeted through medications, and potentially influence symptoms.13 However, the relation between PTSD and inflammation remains unclear. Associations between PTSD and inflammation-related medical conditions may be due to confounding variables, such as sociodemographic characteristics and health behaviors. Moreover, the list of inflammation-related medical conditions is long and there is no universal agreement of what conditions are related to inflammation.

We recently conducted an epidemiological study using a representative sample of residents living in New York City and found significant associations between PTSD and some inflammation-related medical conditions.8 We found that participants who had PTSD were more than 4 times more likely to report having had a heart attack or emphysema than were those without PTSD. In addition, participants with PTSD were 2 times more likely to report having hypercholesterolemia, insulin resistance, and angina than were those without PTSD. However, we also found that participants who had PTSD were less likely to develop other inflammation-related conditions like hypertension, type 1 diabetes mellitus, asthma, coronary heart disease, stroke, osteoporosis, and failing kidney.

Together, these associations suggest there is a strong link between PTSD and certain medical conditions, but the link may not be solely based on inflammation.8 Moreover, positive associations between PTSD and hypertension, asthma, and coronary heart disease disappeared when depression was controlled for. This finding points to depression as a major factor, consistent with previous findings that depression is associated with the development of various medical conditions and may be a stronger factor than PTSD.8

Nonetheless, findings concerning the increased risk for heart problems among adults with PTSD are striking and important given that heart disease is one of the main causes of death in the United States.9 Specifically, well over half a million people in the United States die of heart disease annually as the leading cause of death.17 Heart disease has been one of the top 2 leading causes of death for Americans since 1975.18

In the veteran population, heart disease has also been found to be a leading cause of death, accounting for 20 percent of all deaths in veterans from 1993 to 2002.19 Posttraumatic stress disorder has been linked to a 55% increase in the chance of developing heart disease or dying from a heart-related medical problem.9 For example, data from the World Trade Center Registry showed that on average adults who developed PTSD from the 9/11 terrorist attack had a heightened risk for heart disease for 3 years after the event.9 Other studies of the U.S. veteran population have shown that veterans with PTSD are more likely to experience heart failure, myocardial infarction, and cardiac arrhythmia than other veterans.10,20

Veteran-Specific Issues

In the US veteran population, there is a higher prevalence of PTSD and physical health conditions when compared with the general population.21,21 The prevalence of combat-related PTSD in veterans ranges from 2% to 17%, compared with a 7% to 8% prevalence of PTSD in the general population.1,22 In a study of veterans who were seen in patient-aligned care teams (PACTs) > 1 year, 9.3% were diagnosed with PTSD and many of those with PTSD also had other medical conditions.21 It was found that 43% of veterans seen by PACTs with chronic pain had PTSD, 33% with hypertension had PTSD, and 32% with diabetes mellitus had PTSD.21 In another study of combat veterans it was found that those who were trauma-exposed had more physical health problems, regardless of the amount of time spent in combat.19 Consequentially, veterans with PTSD have been found to make more frequent visits to primary care and specialty medical care clinics. 21

Integrated healthcare has been a main service model for the Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) and several programs have been created to integrate mental health and primary care. For example, the VA primary care-mental health integration (PCMHI) program places mental health services within primary care services.21 Assessments of this program have demonstrated that it improves the screening of psychological disorders and preventive care of patients who have psychological disorders.21 Specifically, it has been found that contact with PCMHI diminishes risks for poor outcomes among psychiatric patients.21 Another program called SCAN-ECHO, provides specialized training for VA general practitioners on treating specific health conditions through a specialty care team and video conferencing.23 This VA program allows for patients in more remote locations to receive specialty care from generalists.23 While there has not yet been a focus in SCAN-ECHO on PTSD, this may be considered in the future as a way to better train primary care and mental health providers about PTSD and common comorbid medical conditions.

Through their professional experiences, VA practitioners have knowledge of the link between PTSD and various medical conditions. The VA has already implemented screening for PTSD in primary care clinics, but it is important for mental health providers and medical practitioners to continue educating themselves about medical comorbidities and the possible exacerbation of medical conditions due to PTSD.21 Some physical manifestations of PTSD symptoms, such as sleep disturbances, avoidance of crowds, or hypervigilance, can affect overall health. Hypervigilance can result in over-activation of stress pathways, which puts patients with PTSD at a heighted risk for medical conditions.11 Additionally, some of the cognitive symptoms of PTSD, such as sleep problems, may worsen current health problems. Therefore, further collaboration between primary care physicians and mental health providers is beneficial in treating clients that have PTSD.

Conclusion

Posttraumatic stress disorder is a prevalent condition among veterans that is often comorbid with other medical conditions, which may have important implications for VA healthcare teams.3 It can manifest both psychologically and physiologically, and can greatly affect a patient’s quality of life.3 Veterans with PTSD may be at increased risk for certain medical conditions, such as cardiovascular disease.9,10,20 However, preventive screenings for medical conditions linked to PTSD and regular health assessments may reduce these risks.21 The VA’s infrastructure of integrated medical and mental healthcare can help provide comprehensive care to the many veterans who have both PTSD and serious medical conditions.21 While the relation between PTSD and inflammation remains unclear, it is clear that many people with PTSD have medical conditions that may be affected by PTSD symptoms.

1. US Department of Veteran Affairs. How common is PTSD? https://www.ptsd.va.gov/public/PTSD-overview/basics/how-common-is-ptsd.asp. Updated October 3, 2016. Accessed September 14, 2018.

2. Pai A, Suris AM, North CS. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the DSM-5: controversy, change, and conceptual considerations. Behav Sci (Basel). 2017;7(1):pii E7.

3. Gupta MA. Review of somatic symptoms in post-traumatic stress disorder. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2013;25(1):86-99.

4. Tsai J, Harpaz-Rotem I, Armour C, Southwick SM, Krystal JH, Pietrzak RH. Dimensional structure of DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(5):546-553.

5. Schalinski I, Elbert TR, Schauer M. Cardiac defense in response to imminent threat in women with multiple trauma and severe PTSD. Psychophysiology. 2013;50(7):691-700.

6. National Institute of Mental Health. Post-traumatic stress disorder. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd/index.shtml. Updated February 2016. Accessed September 14, 2018.

7. Sledjeski EM, Speisman B, Dierker LC. Does number of lifetime traumas explain the relationship between PTSD and chronic medical conditions? Answers from the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication (NCS-R). J Behav Med. 2008;31(4):341-349.

8. Tsai J, Shen J. Exploring the link between posttraumatic stress disorder and inflammation-related medical conditions: an epidemiological examination. Psychiatr Q. 2017;88(4):909-916.

9. Tulloch H, Greenman PS, Tassé V. Post-traumatic stress disorder among cardiac patients: Prevalence, risk factors, and considerations for assessment and treatment. Behav Sci (Basel). 2014;5(1):27-40.

10. Britvić D, Antičević V, Kaliterna M, et al. Comorbidities with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among combat veterans: 15 years postwar analysis. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2015;15(2):81-92.

11. Pacella ML, Hruska B, Delahanty DL. The physical health consequences of PTSD and PTSD symptoms: a meta-analytic review. J Anxiety Disord. 2013;27(1):33-46.

12. Brouwers C, Wolf J, von Känel R. Inflammatory markers in PTSD. In: Martin CR, Preedy VR, Patel VB, eds. Comprehensive Guide to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Zürich, Switzerland: Springer; 2016:979-993.

13. Passos IC, Vasconcelos-Moreno MP, Costa LG, et al. Inflammatory markers in post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(11):1002-1012.

14. von Känel R, Begré S, Abbas CC, Saner H, Gander ML, Schmid JP. Inflammatory biomarkers in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder caused by myocardial infarction and the role of depressive symptoms. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2010;17(1):39-46.

15. Spitzer C, Barnow S, Völzke H, et al. Association of posttraumatic stress disorder with low-grade elevation of C-reactive protein: evidence from the general population. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(1):15-21.

16. Gola H, Engler H, Sommershof A, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder is associated with an enhanced spontaneous production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by peripheral blood mononuclear cells. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:40.

17. Sidney S, Sorel ME, Quesenberry CP, et al. Comparative trends in heart disease, stroke, and all-cause mortality in the United States and a large integrated healthcare delivery system. Am J Med. 2018;131(7):829-836.e1.

18. US Department of Health and Human Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2016: with chartbook on long-term trends in health. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus16.pdf. Published May 2017. Accessed September 14, 2018.

19. Weiner J, Richmond TS, Conigliaro J, Wiebe DJ. Military veteran mortality following a survived suicide attempt. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:374.

20. Roy SS, Foraker RE, Girton RA, Mansfield AJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder and incident heart failure among a community-based sample of US veterans. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(4):757-763.

21. Trivedi RB, Post EP, Sun H, et al. Prevalence, comorbidity, and prognosis of mental health among US veterans. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):2564-2569.

22. Richardson LK, Frueh BC, Acierno R. Prevalence estimates of combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder: a critical review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44(1):4-19.

23. US Department of Veterans Affairs. In the spotlight: VA uses technology to provide rural veterans greater access to specialty care services. https://www.patientcare.va.gov/In_the_Spotlight.asp. Updated June 3, 2015. Accessed September 14, 2018.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) develops after exposure to a traumatic event, which can involve witnessing the traumatic event or directly experiencing the trauma.1 The prevalence of PTSD in the general population is approximately 7% to 8%.1 However, not everyone who experiences trauma develops PTSD since the majority of men and women experience at least 1 traumatic event in their lifetimes but do not develop PTSD.1

In order to be diagnosed with PTSD, a patient must meet several criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5).2 The patient is required to have exposure to trauma, begin having a certain number of prespecified symptoms, and these symptoms must persist for at least a month.2 Symptoms of PTSD include re-experiencing the traumatic event, avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma, negative cognitions and mood, and hyperarousal.3,4 The hyperarousal that is associated with PTSD has been theorized to be either a result of the trauma experienced or exacerbation of a pre-existing tendency.5 This can manifest in various ways, such as hypervigilance, exaggerated startle response, trouble sleeping, problems concentrating, or irritability.3,5 These symptoms can cause individuals with PTSD to have elevated levels of stress and to experience difficulties with completing everyday tasks.6

PTSD and Inflimmation-Related Medical Conditions

Posttraumatic stress disorder has been linked to various physical health problems. Studies have found that PTSD is often comorbid with cardiovascular, autoimmune, musculoskeletal, digestive, chronic pain and respiratory disorders.3,7-11 Inflammation may be a contributing factor in the associations between PTSD and these conditions.12-16 Studies have found that increases in pro-inflammatory cytokines and interferons are associated with PTSD, as well as changes in immune-related blood cells.12-16

Considering that PTSD has been linked to many medical conditions that have inflammatory components, especially cardiovascular disease, inflammatory markers may be early indicators of PTSD.12-16 Additionally, inflammatory markers such as cytokines and interferons can be targeted through medications, and potentially influence symptoms.13 However, the relation between PTSD and inflammation remains unclear. Associations between PTSD and inflammation-related medical conditions may be due to confounding variables, such as sociodemographic characteristics and health behaviors. Moreover, the list of inflammation-related medical conditions is long and there is no universal agreement of what conditions are related to inflammation.

We recently conducted an epidemiological study using a representative sample of residents living in New York City and found significant associations between PTSD and some inflammation-related medical conditions.8 We found that participants who had PTSD were more than 4 times more likely to report having had a heart attack or emphysema than were those without PTSD. In addition, participants with PTSD were 2 times more likely to report having hypercholesterolemia, insulin resistance, and angina than were those without PTSD. However, we also found that participants who had PTSD were less likely to develop other inflammation-related conditions like hypertension, type 1 diabetes mellitus, asthma, coronary heart disease, stroke, osteoporosis, and failing kidney.

Together, these associations suggest there is a strong link between PTSD and certain medical conditions, but the link may not be solely based on inflammation.8 Moreover, positive associations between PTSD and hypertension, asthma, and coronary heart disease disappeared when depression was controlled for. This finding points to depression as a major factor, consistent with previous findings that depression is associated with the development of various medical conditions and may be a stronger factor than PTSD.8

Nonetheless, findings concerning the increased risk for heart problems among adults with PTSD are striking and important given that heart disease is one of the main causes of death in the United States.9 Specifically, well over half a million people in the United States die of heart disease annually as the leading cause of death.17 Heart disease has been one of the top 2 leading causes of death for Americans since 1975.18

In the veteran population, heart disease has also been found to be a leading cause of death, accounting for 20 percent of all deaths in veterans from 1993 to 2002.19 Posttraumatic stress disorder has been linked to a 55% increase in the chance of developing heart disease or dying from a heart-related medical problem.9 For example, data from the World Trade Center Registry showed that on average adults who developed PTSD from the 9/11 terrorist attack had a heightened risk for heart disease for 3 years after the event.9 Other studies of the U.S. veteran population have shown that veterans with PTSD are more likely to experience heart failure, myocardial infarction, and cardiac arrhythmia than other veterans.10,20

Veteran-Specific Issues

In the US veteran population, there is a higher prevalence of PTSD and physical health conditions when compared with the general population.21,21 The prevalence of combat-related PTSD in veterans ranges from 2% to 17%, compared with a 7% to 8% prevalence of PTSD in the general population.1,22 In a study of veterans who were seen in patient-aligned care teams (PACTs) > 1 year, 9.3% were diagnosed with PTSD and many of those with PTSD also had other medical conditions.21 It was found that 43% of veterans seen by PACTs with chronic pain had PTSD, 33% with hypertension had PTSD, and 32% with diabetes mellitus had PTSD.21 In another study of combat veterans it was found that those who were trauma-exposed had more physical health problems, regardless of the amount of time spent in combat.19 Consequentially, veterans with PTSD have been found to make more frequent visits to primary care and specialty medical care clinics. 21

Integrated healthcare has been a main service model for the Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) and several programs have been created to integrate mental health and primary care. For example, the VA primary care-mental health integration (PCMHI) program places mental health services within primary care services.21 Assessments of this program have demonstrated that it improves the screening of psychological disorders and preventive care of patients who have psychological disorders.21 Specifically, it has been found that contact with PCMHI diminishes risks for poor outcomes among psychiatric patients.21 Another program called SCAN-ECHO, provides specialized training for VA general practitioners on treating specific health conditions through a specialty care team and video conferencing.23 This VA program allows for patients in more remote locations to receive specialty care from generalists.23 While there has not yet been a focus in SCAN-ECHO on PTSD, this may be considered in the future as a way to better train primary care and mental health providers about PTSD and common comorbid medical conditions.

Through their professional experiences, VA practitioners have knowledge of the link between PTSD and various medical conditions. The VA has already implemented screening for PTSD in primary care clinics, but it is important for mental health providers and medical practitioners to continue educating themselves about medical comorbidities and the possible exacerbation of medical conditions due to PTSD.21 Some physical manifestations of PTSD symptoms, such as sleep disturbances, avoidance of crowds, or hypervigilance, can affect overall health. Hypervigilance can result in over-activation of stress pathways, which puts patients with PTSD at a heighted risk for medical conditions.11 Additionally, some of the cognitive symptoms of PTSD, such as sleep problems, may worsen current health problems. Therefore, further collaboration between primary care physicians and mental health providers is beneficial in treating clients that have PTSD.

Conclusion

Posttraumatic stress disorder is a prevalent condition among veterans that is often comorbid with other medical conditions, which may have important implications for VA healthcare teams.3 It can manifest both psychologically and physiologically, and can greatly affect a patient’s quality of life.3 Veterans with PTSD may be at increased risk for certain medical conditions, such as cardiovascular disease.9,10,20 However, preventive screenings for medical conditions linked to PTSD and regular health assessments may reduce these risks.21 The VA’s infrastructure of integrated medical and mental healthcare can help provide comprehensive care to the many veterans who have both PTSD and serious medical conditions.21 While the relation between PTSD and inflammation remains unclear, it is clear that many people with PTSD have medical conditions that may be affected by PTSD symptoms.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) develops after exposure to a traumatic event, which can involve witnessing the traumatic event or directly experiencing the trauma.1 The prevalence of PTSD in the general population is approximately 7% to 8%.1 However, not everyone who experiences trauma develops PTSD since the majority of men and women experience at least 1 traumatic event in their lifetimes but do not develop PTSD.1

In order to be diagnosed with PTSD, a patient must meet several criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5).2 The patient is required to have exposure to trauma, begin having a certain number of prespecified symptoms, and these symptoms must persist for at least a month.2 Symptoms of PTSD include re-experiencing the traumatic event, avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma, negative cognitions and mood, and hyperarousal.3,4 The hyperarousal that is associated with PTSD has been theorized to be either a result of the trauma experienced or exacerbation of a pre-existing tendency.5 This can manifest in various ways, such as hypervigilance, exaggerated startle response, trouble sleeping, problems concentrating, or irritability.3,5 These symptoms can cause individuals with PTSD to have elevated levels of stress and to experience difficulties with completing everyday tasks.6

PTSD and Inflimmation-Related Medical Conditions

Posttraumatic stress disorder has been linked to various physical health problems. Studies have found that PTSD is often comorbid with cardiovascular, autoimmune, musculoskeletal, digestive, chronic pain and respiratory disorders.3,7-11 Inflammation may be a contributing factor in the associations between PTSD and these conditions.12-16 Studies have found that increases in pro-inflammatory cytokines and interferons are associated with PTSD, as well as changes in immune-related blood cells.12-16

Considering that PTSD has been linked to many medical conditions that have inflammatory components, especially cardiovascular disease, inflammatory markers may be early indicators of PTSD.12-16 Additionally, inflammatory markers such as cytokines and interferons can be targeted through medications, and potentially influence symptoms.13 However, the relation between PTSD and inflammation remains unclear. Associations between PTSD and inflammation-related medical conditions may be due to confounding variables, such as sociodemographic characteristics and health behaviors. Moreover, the list of inflammation-related medical conditions is long and there is no universal agreement of what conditions are related to inflammation.

We recently conducted an epidemiological study using a representative sample of residents living in New York City and found significant associations between PTSD and some inflammation-related medical conditions.8 We found that participants who had PTSD were more than 4 times more likely to report having had a heart attack or emphysema than were those without PTSD. In addition, participants with PTSD were 2 times more likely to report having hypercholesterolemia, insulin resistance, and angina than were those without PTSD. However, we also found that participants who had PTSD were less likely to develop other inflammation-related conditions like hypertension, type 1 diabetes mellitus, asthma, coronary heart disease, stroke, osteoporosis, and failing kidney.

Together, these associations suggest there is a strong link between PTSD and certain medical conditions, but the link may not be solely based on inflammation.8 Moreover, positive associations between PTSD and hypertension, asthma, and coronary heart disease disappeared when depression was controlled for. This finding points to depression as a major factor, consistent with previous findings that depression is associated with the development of various medical conditions and may be a stronger factor than PTSD.8

Nonetheless, findings concerning the increased risk for heart problems among adults with PTSD are striking and important given that heart disease is one of the main causes of death in the United States.9 Specifically, well over half a million people in the United States die of heart disease annually as the leading cause of death.17 Heart disease has been one of the top 2 leading causes of death for Americans since 1975.18

In the veteran population, heart disease has also been found to be a leading cause of death, accounting for 20 percent of all deaths in veterans from 1993 to 2002.19 Posttraumatic stress disorder has been linked to a 55% increase in the chance of developing heart disease or dying from a heart-related medical problem.9 For example, data from the World Trade Center Registry showed that on average adults who developed PTSD from the 9/11 terrorist attack had a heightened risk for heart disease for 3 years after the event.9 Other studies of the U.S. veteran population have shown that veterans with PTSD are more likely to experience heart failure, myocardial infarction, and cardiac arrhythmia than other veterans.10,20

Veteran-Specific Issues

In the US veteran population, there is a higher prevalence of PTSD and physical health conditions when compared with the general population.21,21 The prevalence of combat-related PTSD in veterans ranges from 2% to 17%, compared with a 7% to 8% prevalence of PTSD in the general population.1,22 In a study of veterans who were seen in patient-aligned care teams (PACTs) > 1 year, 9.3% were diagnosed with PTSD and many of those with PTSD also had other medical conditions.21 It was found that 43% of veterans seen by PACTs with chronic pain had PTSD, 33% with hypertension had PTSD, and 32% with diabetes mellitus had PTSD.21 In another study of combat veterans it was found that those who were trauma-exposed had more physical health problems, regardless of the amount of time spent in combat.19 Consequentially, veterans with PTSD have been found to make more frequent visits to primary care and specialty medical care clinics. 21

Integrated healthcare has been a main service model for the Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) and several programs have been created to integrate mental health and primary care. For example, the VA primary care-mental health integration (PCMHI) program places mental health services within primary care services.21 Assessments of this program have demonstrated that it improves the screening of psychological disorders and preventive care of patients who have psychological disorders.21 Specifically, it has been found that contact with PCMHI diminishes risks for poor outcomes among psychiatric patients.21 Another program called SCAN-ECHO, provides specialized training for VA general practitioners on treating specific health conditions through a specialty care team and video conferencing.23 This VA program allows for patients in more remote locations to receive specialty care from generalists.23 While there has not yet been a focus in SCAN-ECHO on PTSD, this may be considered in the future as a way to better train primary care and mental health providers about PTSD and common comorbid medical conditions.

Through their professional experiences, VA practitioners have knowledge of the link between PTSD and various medical conditions. The VA has already implemented screening for PTSD in primary care clinics, but it is important for mental health providers and medical practitioners to continue educating themselves about medical comorbidities and the possible exacerbation of medical conditions due to PTSD.21 Some physical manifestations of PTSD symptoms, such as sleep disturbances, avoidance of crowds, or hypervigilance, can affect overall health. Hypervigilance can result in over-activation of stress pathways, which puts patients with PTSD at a heighted risk for medical conditions.11 Additionally, some of the cognitive symptoms of PTSD, such as sleep problems, may worsen current health problems. Therefore, further collaboration between primary care physicians and mental health providers is beneficial in treating clients that have PTSD.

Conclusion

Posttraumatic stress disorder is a prevalent condition among veterans that is often comorbid with other medical conditions, which may have important implications for VA healthcare teams.3 It can manifest both psychologically and physiologically, and can greatly affect a patient’s quality of life.3 Veterans with PTSD may be at increased risk for certain medical conditions, such as cardiovascular disease.9,10,20 However, preventive screenings for medical conditions linked to PTSD and regular health assessments may reduce these risks.21 The VA’s infrastructure of integrated medical and mental healthcare can help provide comprehensive care to the many veterans who have both PTSD and serious medical conditions.21 While the relation between PTSD and inflammation remains unclear, it is clear that many people with PTSD have medical conditions that may be affected by PTSD symptoms.

1. US Department of Veteran Affairs. How common is PTSD? https://www.ptsd.va.gov/public/PTSD-overview/basics/how-common-is-ptsd.asp. Updated October 3, 2016. Accessed September 14, 2018.

2. Pai A, Suris AM, North CS. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the DSM-5: controversy, change, and conceptual considerations. Behav Sci (Basel). 2017;7(1):pii E7.

3. Gupta MA. Review of somatic symptoms in post-traumatic stress disorder. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2013;25(1):86-99.

4. Tsai J, Harpaz-Rotem I, Armour C, Southwick SM, Krystal JH, Pietrzak RH. Dimensional structure of DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(5):546-553.

5. Schalinski I, Elbert TR, Schauer M. Cardiac defense in response to imminent threat in women with multiple trauma and severe PTSD. Psychophysiology. 2013;50(7):691-700.