User login

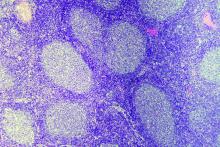

Be wary of watchful waiting in follicular lymphoma

A substantial proportion of patients with follicular lymphoma managed with watchful waiting develop organ dysfunction or transformation that may negatively impact survival outcomes, results of a retrospective study suggest.

About one-quarter of patients managed with watchful waiting developed significant organ dysfunction or transformation at first progression over 8.2 years of follow-up.

Organ dysfunction and transformation were associated with significantly worse overall survival that could not be predicted based on baseline characteristics, the study authors reported in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia.

The study confirmed certain benefits of watchful waiting, including a low risk of progression and an “excellent” rate of overall survival, the investigators said.

However, the substantial rate of organ dysfunction and transformation in a subset of patients is “clinically meaningful for informed decision making,” reported Gwynivere A. Davies, MD, of the University of Calgary (Alta.), and her coauthors.

“While consenting patients to initial [watchful waiting], patients need to be informed about the risk for these adverse events, as well as receiving education and the need for close monitoring regarding symptoms that may indicate serious progression events,” Dr. Davies and her coauthors wrote.

Alternatively, rituximab chemotherapy, with or without rituximab maintenance, might be warranted for watchful waiting patients with clear disease progression before organ dysfunction or transformation events, despite not meeting high-tumor burden therapy indications.

The retrospective study included data from the Alberta Lymphoma Database on patients with grade 1-3a follicular lymphoma aged 18-70 years who were diagnosed between 1994 and 2011. Investigators identified 238 patients initially managed with watchful waiting, with a median age of 54.1 years at diagnosis. More than 80% were advanced stage.

Only 71% of these patients progressed, with a median time to progression of about 30 months and a 10-year survival rate from diagnosis of 81.2%, investigators said. However, 58 patients (24.4%) had organ dysfunction or transformation at the time of progression.

Those adverse outcomes significantly affected overall survival. The 10-year overall survival was 65.4% for patients with transformation at progression versus 83.2% for those without (P = .0017). Likewise, 10-year overall survival was 71.5% and 82.7%, respectively, for those with organ dysfunction at progression and those without (P = .028).

Investigators also looked at a comparison group of 236 follicular lymphoma patients managed with immediate rituximab chemotherapy. They found survival outcomes in that group were similar to those in the subgroup of 56 watchful waiting patients who received primarily rituximab-containing regimens at the time of organ dysfunction or transformation.

Taken together, the findings suggest management changes may be warranted for follicular lymphoma patients managed according to a watchful waiting strategy, the investigators wrote. “Consideration should be given to implementing standardized follow-up imaging, with early initiation of rituximab-based therapy if there is evidence of progression in an attempt to prevent these potentially clinically impactful events.”

Dr. Davies reported having no financial disclosures. Study coauthors reported disclosures related to Janssen, Gilead Sciences, Lundbeck, Roche, AbbVie, Amgen, Seattle Genetics, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Servier Laboratories, and Merck.

SOURCE: Davies GA et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018 Aug 28. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2018.08.015.

A substantial proportion of patients with follicular lymphoma managed with watchful waiting develop organ dysfunction or transformation that may negatively impact survival outcomes, results of a retrospective study suggest.

About one-quarter of patients managed with watchful waiting developed significant organ dysfunction or transformation at first progression over 8.2 years of follow-up.

Organ dysfunction and transformation were associated with significantly worse overall survival that could not be predicted based on baseline characteristics, the study authors reported in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia.

The study confirmed certain benefits of watchful waiting, including a low risk of progression and an “excellent” rate of overall survival, the investigators said.

However, the substantial rate of organ dysfunction and transformation in a subset of patients is “clinically meaningful for informed decision making,” reported Gwynivere A. Davies, MD, of the University of Calgary (Alta.), and her coauthors.

“While consenting patients to initial [watchful waiting], patients need to be informed about the risk for these adverse events, as well as receiving education and the need for close monitoring regarding symptoms that may indicate serious progression events,” Dr. Davies and her coauthors wrote.

Alternatively, rituximab chemotherapy, with or without rituximab maintenance, might be warranted for watchful waiting patients with clear disease progression before organ dysfunction or transformation events, despite not meeting high-tumor burden therapy indications.

The retrospective study included data from the Alberta Lymphoma Database on patients with grade 1-3a follicular lymphoma aged 18-70 years who were diagnosed between 1994 and 2011. Investigators identified 238 patients initially managed with watchful waiting, with a median age of 54.1 years at diagnosis. More than 80% were advanced stage.

Only 71% of these patients progressed, with a median time to progression of about 30 months and a 10-year survival rate from diagnosis of 81.2%, investigators said. However, 58 patients (24.4%) had organ dysfunction or transformation at the time of progression.

Those adverse outcomes significantly affected overall survival. The 10-year overall survival was 65.4% for patients with transformation at progression versus 83.2% for those without (P = .0017). Likewise, 10-year overall survival was 71.5% and 82.7%, respectively, for those with organ dysfunction at progression and those without (P = .028).

Investigators also looked at a comparison group of 236 follicular lymphoma patients managed with immediate rituximab chemotherapy. They found survival outcomes in that group were similar to those in the subgroup of 56 watchful waiting patients who received primarily rituximab-containing regimens at the time of organ dysfunction or transformation.

Taken together, the findings suggest management changes may be warranted for follicular lymphoma patients managed according to a watchful waiting strategy, the investigators wrote. “Consideration should be given to implementing standardized follow-up imaging, with early initiation of rituximab-based therapy if there is evidence of progression in an attempt to prevent these potentially clinically impactful events.”

Dr. Davies reported having no financial disclosures. Study coauthors reported disclosures related to Janssen, Gilead Sciences, Lundbeck, Roche, AbbVie, Amgen, Seattle Genetics, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Servier Laboratories, and Merck.

SOURCE: Davies GA et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018 Aug 28. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2018.08.015.

A substantial proportion of patients with follicular lymphoma managed with watchful waiting develop organ dysfunction or transformation that may negatively impact survival outcomes, results of a retrospective study suggest.

About one-quarter of patients managed with watchful waiting developed significant organ dysfunction or transformation at first progression over 8.2 years of follow-up.

Organ dysfunction and transformation were associated with significantly worse overall survival that could not be predicted based on baseline characteristics, the study authors reported in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia.

The study confirmed certain benefits of watchful waiting, including a low risk of progression and an “excellent” rate of overall survival, the investigators said.

However, the substantial rate of organ dysfunction and transformation in a subset of patients is “clinically meaningful for informed decision making,” reported Gwynivere A. Davies, MD, of the University of Calgary (Alta.), and her coauthors.

“While consenting patients to initial [watchful waiting], patients need to be informed about the risk for these adverse events, as well as receiving education and the need for close monitoring regarding symptoms that may indicate serious progression events,” Dr. Davies and her coauthors wrote.

Alternatively, rituximab chemotherapy, with or without rituximab maintenance, might be warranted for watchful waiting patients with clear disease progression before organ dysfunction or transformation events, despite not meeting high-tumor burden therapy indications.

The retrospective study included data from the Alberta Lymphoma Database on patients with grade 1-3a follicular lymphoma aged 18-70 years who were diagnosed between 1994 and 2011. Investigators identified 238 patients initially managed with watchful waiting, with a median age of 54.1 years at diagnosis. More than 80% were advanced stage.

Only 71% of these patients progressed, with a median time to progression of about 30 months and a 10-year survival rate from diagnosis of 81.2%, investigators said. However, 58 patients (24.4%) had organ dysfunction or transformation at the time of progression.

Those adverse outcomes significantly affected overall survival. The 10-year overall survival was 65.4% for patients with transformation at progression versus 83.2% for those without (P = .0017). Likewise, 10-year overall survival was 71.5% and 82.7%, respectively, for those with organ dysfunction at progression and those without (P = .028).

Investigators also looked at a comparison group of 236 follicular lymphoma patients managed with immediate rituximab chemotherapy. They found survival outcomes in that group were similar to those in the subgroup of 56 watchful waiting patients who received primarily rituximab-containing regimens at the time of organ dysfunction or transformation.

Taken together, the findings suggest management changes may be warranted for follicular lymphoma patients managed according to a watchful waiting strategy, the investigators wrote. “Consideration should be given to implementing standardized follow-up imaging, with early initiation of rituximab-based therapy if there is evidence of progression in an attempt to prevent these potentially clinically impactful events.”

Dr. Davies reported having no financial disclosures. Study coauthors reported disclosures related to Janssen, Gilead Sciences, Lundbeck, Roche, AbbVie, Amgen, Seattle Genetics, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Servier Laboratories, and Merck.

SOURCE: Davies GA et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018 Aug 28. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2018.08.015.

FROM CLINICAL LYMPHOMA, MYELOMA & LEUKEMIA

Key clinical point:

Major finding: A total of 58 patients (24.4%) had organ dysfunction or transformation at the time of progression and had worse survival outcomes, compared with patients who did not experience those events.

Study details: A retrospective study including data on 238 patients with grade 1-3a follicular lymphoma aged 18-70 years who were managed with watchful waiting.

Disclosures: Study authors reported disclosures related to Janssen, Gilead Sciences, Lundbeck, Roche, AbbVie, Amgen, Seattle Genetics, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Servier Laboratories, and Merck.

Source: Davies GA et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018 Aug 28. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2018.08.015.

Disruptive physicians: Is this an HR or MEC issue?

it can greatly lower staff morale and compromise patient care. Addressing this behavior head-on is imperative, experts said, but knowing which route to take is not always clear.

Physician leaders may wonder: When is this a human resources (HR) issue and when should the medical executive committee (MEC) step in?

The answer depends on the circumstances and the employment status of the physician in question, said Mark Peters, a labor and employment attorney based in Nashville, Tenn.

“There are a couple of different considerations when deciding how, or more accurately who, should address disruptive physician behavior in the workplace,” Mr. Peters said in an interview. “The first consideration is whether the physician is employed by the health care entity or is a contractor. Typically, absent an employment relationship with the physician, human resources is not involved directly with the physician and the issue is handled through the MEC.”

However, in some cases both HR and the MEC may become involved. For instance, if the complaint is made by an employee, HR would likely get involved – regardless of whether the disruptive physician is a contractor – because employers have a legal duty to ensure a “hostile-free environment,” Mr. Peters said.

The hospital may also ask that the MEC intervene to ensure the medical staff understands all of the facts and can weigh in on whether the doctor is being treated fairly by the hospital, he said.

There are a range of advantages and disadvantages to each resolution path, said Jeffrey Moseley, a health law attorney based in Franklin, Tenn. The HR route usually means dealing with a single point person and typically the issue is resolved more swiftly. Going through the MEC, on the other hand, often takes months. The MEC path also means more people will be involved, and it’s possible the case may become more political, depending on the culture of the MEC.

“If you have to end up taking an action, the employment setting may be a quicker way to address the issue than going through the medical staff side,” Mr. Moseley said in an interview. “Most medical staffs, if they were to try to restrict or revoke privileges, they are going to have to go through a fair hearing and appeals, [which] can take 6 months easily. The downside to the employment side is you don’t get all the immunities that you get on the medical staff side.”

A disruptive physician issue handled by the MEC as a peer review matter or professional review action is protected under the Healthcare Quality Improvement Act, which shields the medical staff and/or hospital from civil damages in the event that they are sued. Additionally, information disclosed during the MEC process that is part of the peer review privilege is confidential and not necessarily discoverable by plaintiff’s attorneys in a subsequent court case.

The way the MEC handles the issue often hinges on the makeup of the committee, Mr. Moseley noted. In his experience, older medical staffs tend to be more sensitive to the accused physician and question whether the behavior is egregious. Older physicians are generally used to a more “captain of the ship” leadership style, with the doctor as the authority figure. Younger staffs are generally more sensitive to concerns about a hostile work environment and lean toward a team approach to health care.

“If your leadership on the medical staff is a [group of older doctors] versus a mix or younger docs, they might be more or less receptive to discipline [for] a behavioral issue, based on their worldview,” he said.

Disruptive behavior is best avoided by implementing sensitivity training and employing a zero tolerance policy for unprofessional behavior that applies to all staff members from the highest revenue generators to the lowest, no exceptions, Mr. Peters advised. “A top down culture that expects and requires professionalism amongst all medical staff [is key].”

it can greatly lower staff morale and compromise patient care. Addressing this behavior head-on is imperative, experts said, but knowing which route to take is not always clear.

Physician leaders may wonder: When is this a human resources (HR) issue and when should the medical executive committee (MEC) step in?

The answer depends on the circumstances and the employment status of the physician in question, said Mark Peters, a labor and employment attorney based in Nashville, Tenn.

“There are a couple of different considerations when deciding how, or more accurately who, should address disruptive physician behavior in the workplace,” Mr. Peters said in an interview. “The first consideration is whether the physician is employed by the health care entity or is a contractor. Typically, absent an employment relationship with the physician, human resources is not involved directly with the physician and the issue is handled through the MEC.”

However, in some cases both HR and the MEC may become involved. For instance, if the complaint is made by an employee, HR would likely get involved – regardless of whether the disruptive physician is a contractor – because employers have a legal duty to ensure a “hostile-free environment,” Mr. Peters said.

The hospital may also ask that the MEC intervene to ensure the medical staff understands all of the facts and can weigh in on whether the doctor is being treated fairly by the hospital, he said.

There are a range of advantages and disadvantages to each resolution path, said Jeffrey Moseley, a health law attorney based in Franklin, Tenn. The HR route usually means dealing with a single point person and typically the issue is resolved more swiftly. Going through the MEC, on the other hand, often takes months. The MEC path also means more people will be involved, and it’s possible the case may become more political, depending on the culture of the MEC.

“If you have to end up taking an action, the employment setting may be a quicker way to address the issue than going through the medical staff side,” Mr. Moseley said in an interview. “Most medical staffs, if they were to try to restrict or revoke privileges, they are going to have to go through a fair hearing and appeals, [which] can take 6 months easily. The downside to the employment side is you don’t get all the immunities that you get on the medical staff side.”

A disruptive physician issue handled by the MEC as a peer review matter or professional review action is protected under the Healthcare Quality Improvement Act, which shields the medical staff and/or hospital from civil damages in the event that they are sued. Additionally, information disclosed during the MEC process that is part of the peer review privilege is confidential and not necessarily discoverable by plaintiff’s attorneys in a subsequent court case.

The way the MEC handles the issue often hinges on the makeup of the committee, Mr. Moseley noted. In his experience, older medical staffs tend to be more sensitive to the accused physician and question whether the behavior is egregious. Older physicians are generally used to a more “captain of the ship” leadership style, with the doctor as the authority figure. Younger staffs are generally more sensitive to concerns about a hostile work environment and lean toward a team approach to health care.

“If your leadership on the medical staff is a [group of older doctors] versus a mix or younger docs, they might be more or less receptive to discipline [for] a behavioral issue, based on their worldview,” he said.

Disruptive behavior is best avoided by implementing sensitivity training and employing a zero tolerance policy for unprofessional behavior that applies to all staff members from the highest revenue generators to the lowest, no exceptions, Mr. Peters advised. “A top down culture that expects and requires professionalism amongst all medical staff [is key].”

it can greatly lower staff morale and compromise patient care. Addressing this behavior head-on is imperative, experts said, but knowing which route to take is not always clear.

Physician leaders may wonder: When is this a human resources (HR) issue and when should the medical executive committee (MEC) step in?

The answer depends on the circumstances and the employment status of the physician in question, said Mark Peters, a labor and employment attorney based in Nashville, Tenn.

“There are a couple of different considerations when deciding how, or more accurately who, should address disruptive physician behavior in the workplace,” Mr. Peters said in an interview. “The first consideration is whether the physician is employed by the health care entity or is a contractor. Typically, absent an employment relationship with the physician, human resources is not involved directly with the physician and the issue is handled through the MEC.”

However, in some cases both HR and the MEC may become involved. For instance, if the complaint is made by an employee, HR would likely get involved – regardless of whether the disruptive physician is a contractor – because employers have a legal duty to ensure a “hostile-free environment,” Mr. Peters said.

The hospital may also ask that the MEC intervene to ensure the medical staff understands all of the facts and can weigh in on whether the doctor is being treated fairly by the hospital, he said.

There are a range of advantages and disadvantages to each resolution path, said Jeffrey Moseley, a health law attorney based in Franklin, Tenn. The HR route usually means dealing with a single point person and typically the issue is resolved more swiftly. Going through the MEC, on the other hand, often takes months. The MEC path also means more people will be involved, and it’s possible the case may become more political, depending on the culture of the MEC.

“If you have to end up taking an action, the employment setting may be a quicker way to address the issue than going through the medical staff side,” Mr. Moseley said in an interview. “Most medical staffs, if they were to try to restrict or revoke privileges, they are going to have to go through a fair hearing and appeals, [which] can take 6 months easily. The downside to the employment side is you don’t get all the immunities that you get on the medical staff side.”

A disruptive physician issue handled by the MEC as a peer review matter or professional review action is protected under the Healthcare Quality Improvement Act, which shields the medical staff and/or hospital from civil damages in the event that they are sued. Additionally, information disclosed during the MEC process that is part of the peer review privilege is confidential and not necessarily discoverable by plaintiff’s attorneys in a subsequent court case.

The way the MEC handles the issue often hinges on the makeup of the committee, Mr. Moseley noted. In his experience, older medical staffs tend to be more sensitive to the accused physician and question whether the behavior is egregious. Older physicians are generally used to a more “captain of the ship” leadership style, with the doctor as the authority figure. Younger staffs are generally more sensitive to concerns about a hostile work environment and lean toward a team approach to health care.

“If your leadership on the medical staff is a [group of older doctors] versus a mix or younger docs, they might be more or less receptive to discipline [for] a behavioral issue, based on their worldview,” he said.

Disruptive behavior is best avoided by implementing sensitivity training and employing a zero tolerance policy for unprofessional behavior that applies to all staff members from the highest revenue generators to the lowest, no exceptions, Mr. Peters advised. “A top down culture that expects and requires professionalism amongst all medical staff [is key].”

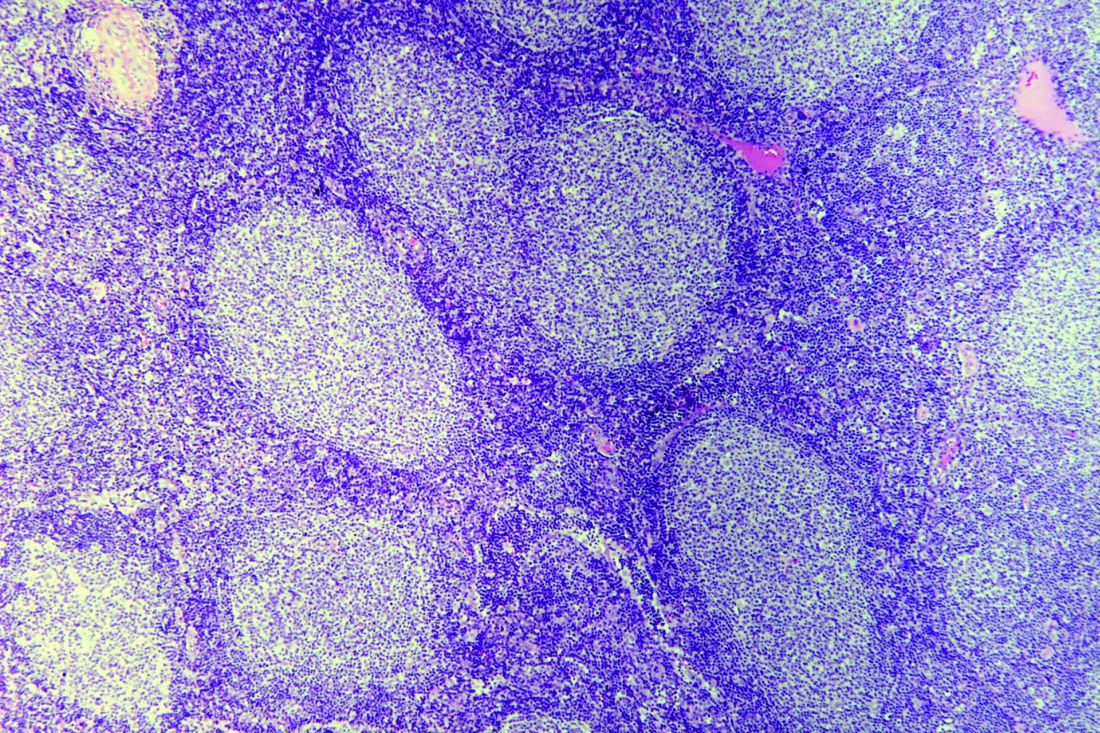

Pruritus linked to wide variety of cancers

A wide variety of hematologic, dermatologic, and solid organ malignancies are associated with pruritus, a large, single-center, retrospective study suggests.

Blacks with pruritus had a higher odds ratio of hematologic malignancies, among others, while whites had higher likelihood of liver, gastrointestinal, respiratory and gynecologic cancers, results of the study show.

The results by race help address a gap in the literature, according to Shawn G. Kwatra, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his coinvestigators.

“Little is known about the association between pruritus and malignancy among different ethnic groups,” Dr. Kwatra and his coauthors wrote in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The study shows a stronger association with more types of malignancies than has been reported previously, according to the investigators.

“The main difference is that prior studies focused on diagnosis of malignancy after the onset of pruritus, while our study includes malignancies diagnosed on or after pruritus onset,” they wrote.

Retrospective data for the study, which came from the Johns Hopkins Health System, included 16,925 patients aged 18 years or older who presented with itching or pruritus between April 4, 2013 and Dec. 31, 2017.

Of those 16,925 patients, 2,903 were also diagnosed with a concomitant malignancy during that time period. Compared with patients with no itching diagnosis during that time period, the pruritus patients more likely to have a concomitant malignancy, with an OR of 5.76 (95% confidence interval, 5.53-6.00), Dr. Kwatra and his colleagues found.

Malignancies most strongly associated with pruritus included those of the skin, liver, gallbladder and biliary tract, and hematopoietic system.

Among hematologic malignancies, pruritus was most strongly linked to myeloid leukemia and primary cutaneous lymphoma, while among skin cancers, squamous cell carcinoma was most strongly linked.

Whites had higher odds of any malignancy versus blacks, according to investigators, with ORs of 6.12 (95% CI, 5.81-6.46) and 5.61 (95% CI, 5.21-6.04), respectively.

Blacks with pruritus had higher ORs for hematologic and soft tissue malignancies including those of the muscle, fat, and peripheral nerve, investigators said, while whites had higher ORs for skin and liver malignancies.

The investigators also looked at the prevalence of skin eruptions in patients with pruritus and malignancy. “Eruption is variable by malignancy type and points to differing underlying mechanisms of pruritus,” they reported.

The highest rates of skin eruption were in patients with myeloid leukemia at 66%, followed by bone cancers at 58%, lymphocytic leukemia at 57%, multiple myeloma at 53%, and bronchus at 53%. The lowest rates of skin eruption were in patients with gallbladder and biliary tract, colon, pancreas, and liver malignancies.

Dr. Kwatra reported that he is an advisory board member for Menlo Therapeutics and Trevi Therapeutics.

SOURCE: Kwatra SG et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Sep 11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.044.

A wide variety of hematologic, dermatologic, and solid organ malignancies are associated with pruritus, a large, single-center, retrospective study suggests.

Blacks with pruritus had a higher odds ratio of hematologic malignancies, among others, while whites had higher likelihood of liver, gastrointestinal, respiratory and gynecologic cancers, results of the study show.

The results by race help address a gap in the literature, according to Shawn G. Kwatra, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his coinvestigators.

“Little is known about the association between pruritus and malignancy among different ethnic groups,” Dr. Kwatra and his coauthors wrote in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The study shows a stronger association with more types of malignancies than has been reported previously, according to the investigators.

“The main difference is that prior studies focused on diagnosis of malignancy after the onset of pruritus, while our study includes malignancies diagnosed on or after pruritus onset,” they wrote.

Retrospective data for the study, which came from the Johns Hopkins Health System, included 16,925 patients aged 18 years or older who presented with itching or pruritus between April 4, 2013 and Dec. 31, 2017.

Of those 16,925 patients, 2,903 were also diagnosed with a concomitant malignancy during that time period. Compared with patients with no itching diagnosis during that time period, the pruritus patients more likely to have a concomitant malignancy, with an OR of 5.76 (95% confidence interval, 5.53-6.00), Dr. Kwatra and his colleagues found.

Malignancies most strongly associated with pruritus included those of the skin, liver, gallbladder and biliary tract, and hematopoietic system.

Among hematologic malignancies, pruritus was most strongly linked to myeloid leukemia and primary cutaneous lymphoma, while among skin cancers, squamous cell carcinoma was most strongly linked.

Whites had higher odds of any malignancy versus blacks, according to investigators, with ORs of 6.12 (95% CI, 5.81-6.46) and 5.61 (95% CI, 5.21-6.04), respectively.

Blacks with pruritus had higher ORs for hematologic and soft tissue malignancies including those of the muscle, fat, and peripheral nerve, investigators said, while whites had higher ORs for skin and liver malignancies.

The investigators also looked at the prevalence of skin eruptions in patients with pruritus and malignancy. “Eruption is variable by malignancy type and points to differing underlying mechanisms of pruritus,” they reported.

The highest rates of skin eruption were in patients with myeloid leukemia at 66%, followed by bone cancers at 58%, lymphocytic leukemia at 57%, multiple myeloma at 53%, and bronchus at 53%. The lowest rates of skin eruption were in patients with gallbladder and biliary tract, colon, pancreas, and liver malignancies.

Dr. Kwatra reported that he is an advisory board member for Menlo Therapeutics and Trevi Therapeutics.

SOURCE: Kwatra SG et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Sep 11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.044.

A wide variety of hematologic, dermatologic, and solid organ malignancies are associated with pruritus, a large, single-center, retrospective study suggests.

Blacks with pruritus had a higher odds ratio of hematologic malignancies, among others, while whites had higher likelihood of liver, gastrointestinal, respiratory and gynecologic cancers, results of the study show.

The results by race help address a gap in the literature, according to Shawn G. Kwatra, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his coinvestigators.

“Little is known about the association between pruritus and malignancy among different ethnic groups,” Dr. Kwatra and his coauthors wrote in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The study shows a stronger association with more types of malignancies than has been reported previously, according to the investigators.

“The main difference is that prior studies focused on diagnosis of malignancy after the onset of pruritus, while our study includes malignancies diagnosed on or after pruritus onset,” they wrote.

Retrospective data for the study, which came from the Johns Hopkins Health System, included 16,925 patients aged 18 years or older who presented with itching or pruritus between April 4, 2013 and Dec. 31, 2017.

Of those 16,925 patients, 2,903 were also diagnosed with a concomitant malignancy during that time period. Compared with patients with no itching diagnosis during that time period, the pruritus patients more likely to have a concomitant malignancy, with an OR of 5.76 (95% confidence interval, 5.53-6.00), Dr. Kwatra and his colleagues found.

Malignancies most strongly associated with pruritus included those of the skin, liver, gallbladder and biliary tract, and hematopoietic system.

Among hematologic malignancies, pruritus was most strongly linked to myeloid leukemia and primary cutaneous lymphoma, while among skin cancers, squamous cell carcinoma was most strongly linked.

Whites had higher odds of any malignancy versus blacks, according to investigators, with ORs of 6.12 (95% CI, 5.81-6.46) and 5.61 (95% CI, 5.21-6.04), respectively.

Blacks with pruritus had higher ORs for hematologic and soft tissue malignancies including those of the muscle, fat, and peripheral nerve, investigators said, while whites had higher ORs for skin and liver malignancies.

The investigators also looked at the prevalence of skin eruptions in patients with pruritus and malignancy. “Eruption is variable by malignancy type and points to differing underlying mechanisms of pruritus,” they reported.

The highest rates of skin eruption were in patients with myeloid leukemia at 66%, followed by bone cancers at 58%, lymphocytic leukemia at 57%, multiple myeloma at 53%, and bronchus at 53%. The lowest rates of skin eruption were in patients with gallbladder and biliary tract, colon, pancreas, and liver malignancies.

Dr. Kwatra reported that he is an advisory board member for Menlo Therapeutics and Trevi Therapeutics.

SOURCE: Kwatra SG et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Sep 11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.044.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Blacks with pruritus had higher odds ratios for hematologic and soft tissue malignancies, while whites had higher ORs for skin and liver malignancies.

Study details: A retrospective study of 16,925 adults with itching or pruritus seen at a tertiary care center.

Disclosures: Dr. Kwatra reported serving as an advisory board member for Menlo Therapeutics and Trevi Therapeutics.

Source: Kwatra SG et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Sep 11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.044.

Repeat MRI not useful in suspected axial spondyloarthritis

Patients with chronic back pain suspected of having axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) should not undergo follow-up MRI of the sacroiliac joint (MRI-SI) within a year if they had a negative baseline MRI-SI, according to investigators.

It is very unlikely that a follow-up MRI-SI will yield new results, reported Pauline A. Bakker, MD, of the department of rheumatology at Leiden University Medical Centre, the Netherlands, and her colleagues.

Since gender and HLA-B27 status were closely associated with MRI-SI positivity, these factors should be considered when deciding to repeat an MRI-SI.

“Over the last decade, MRI rapidly gained ground and proved to be an important imaging technique in the diagnostic process of [nonradiographic] axial spondyloarthritis,” the investigators wrote in Arthritis and Rheumatology. “It has been shown that MRI can detect the early inflammatory stages of sacroiliitis months to years before structural damage can be detected on a conventional radiograph.”

Although MRI represents a diagnostic leap forward, questions of clinical application remain. “For example… if an MRI is completely normal and there is still a clinical suspicion of axSpA, should the MRI be repeated? And if so, after what period of follow-up? Or does this not contribute to the diagnostic process?”

To answer these questions, the investigators observed the “evolution of MRI lesions over a 3-month and 1-year time frame” in patients with early chronic back pain and suspected axSpA.

The prospective study involved 188 patients from the Spondyloarthritis Caught Early (SPACE) cohort. The authors commented that this is “an ideal cohort… since it includes a population of patients with back pain of short duration referred to rheumatologists with a suspicion of SpA [but without the mandatory presence of a single or multiple SpA features].”

Enrolled patients had chronic back pain lasting between 3 months and 2 years, with onset beginning between 16 and 45 years of age. Each underwent physical examination (including evaluation of other SpA features), MRI and radiographs of the sacroiliac joints, and HLA-B27 testing. If patients fulfilled axSpA criteria or had possible axSpA (at least one SpA feature), then they proceeded into the follow-up phase of the study, which included repeat MRI-SI at 3 months and 1 year.

Among enrolled patients, slightly more than one-third were male, almost half were HLA-B27 positive, and about three-quarters had Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society–defined inflammatory back pain. Mean age was 31 years; 31 (16.5%) patients were MRI-SI positive.

Of patients that were MRI-SI positive at baseline, 11.1% and 37.9% had a negative MRI-SI at 3 months and 1 year, respectively. The authors noted that this change “was partly induced by the start of anti-TNF [tumor necrosis factor] therapy.” In patients who were MRI-SI negative at baseline, 4.3% and 7.2% were positive at 3 months and 1 year, respectively.

“A very small percentage of patients become positive… which indicates that the usefulness of repeating an MRI-SI in the diagnostic process after 3 months or 1 year is very limited,” the authors wrote.

Gender and HLA-B27 status were independently associated with a positive MRI-SI at any point in time. About 43% of HLA-B27-positive men had a positive MRI-SI, compared with just 7% of HLA-B27-negative women. The investigators advised that these associations be considered when deciding upon repeat MRI-SI.

“If a clinical suspicion [of axSpA] remains [for example, a patient develops other SpA features] it might be worthwhile to consider redoing an MRI in HLA-B27 positive patients,” the investigators wrote. “Likewise, there is a statistically significant difference between male and female patients with a negative baseline MRI, namely that in male patients more often a positive MRI at follow-up is seen [difference: 12% in men, 3% in women].”

The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bakker PA et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018 Sep 11. doi: 10.1002/art.40718.

Patients with chronic back pain suspected of having axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) should not undergo follow-up MRI of the sacroiliac joint (MRI-SI) within a year if they had a negative baseline MRI-SI, according to investigators.

It is very unlikely that a follow-up MRI-SI will yield new results, reported Pauline A. Bakker, MD, of the department of rheumatology at Leiden University Medical Centre, the Netherlands, and her colleagues.

Since gender and HLA-B27 status were closely associated with MRI-SI positivity, these factors should be considered when deciding to repeat an MRI-SI.

“Over the last decade, MRI rapidly gained ground and proved to be an important imaging technique in the diagnostic process of [nonradiographic] axial spondyloarthritis,” the investigators wrote in Arthritis and Rheumatology. “It has been shown that MRI can detect the early inflammatory stages of sacroiliitis months to years before structural damage can be detected on a conventional radiograph.”

Although MRI represents a diagnostic leap forward, questions of clinical application remain. “For example… if an MRI is completely normal and there is still a clinical suspicion of axSpA, should the MRI be repeated? And if so, after what period of follow-up? Or does this not contribute to the diagnostic process?”

To answer these questions, the investigators observed the “evolution of MRI lesions over a 3-month and 1-year time frame” in patients with early chronic back pain and suspected axSpA.

The prospective study involved 188 patients from the Spondyloarthritis Caught Early (SPACE) cohort. The authors commented that this is “an ideal cohort… since it includes a population of patients with back pain of short duration referred to rheumatologists with a suspicion of SpA [but without the mandatory presence of a single or multiple SpA features].”

Enrolled patients had chronic back pain lasting between 3 months and 2 years, with onset beginning between 16 and 45 years of age. Each underwent physical examination (including evaluation of other SpA features), MRI and radiographs of the sacroiliac joints, and HLA-B27 testing. If patients fulfilled axSpA criteria or had possible axSpA (at least one SpA feature), then they proceeded into the follow-up phase of the study, which included repeat MRI-SI at 3 months and 1 year.

Among enrolled patients, slightly more than one-third were male, almost half were HLA-B27 positive, and about three-quarters had Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society–defined inflammatory back pain. Mean age was 31 years; 31 (16.5%) patients were MRI-SI positive.

Of patients that were MRI-SI positive at baseline, 11.1% and 37.9% had a negative MRI-SI at 3 months and 1 year, respectively. The authors noted that this change “was partly induced by the start of anti-TNF [tumor necrosis factor] therapy.” In patients who were MRI-SI negative at baseline, 4.3% and 7.2% were positive at 3 months and 1 year, respectively.

“A very small percentage of patients become positive… which indicates that the usefulness of repeating an MRI-SI in the diagnostic process after 3 months or 1 year is very limited,” the authors wrote.

Gender and HLA-B27 status were independently associated with a positive MRI-SI at any point in time. About 43% of HLA-B27-positive men had a positive MRI-SI, compared with just 7% of HLA-B27-negative women. The investigators advised that these associations be considered when deciding upon repeat MRI-SI.

“If a clinical suspicion [of axSpA] remains [for example, a patient develops other SpA features] it might be worthwhile to consider redoing an MRI in HLA-B27 positive patients,” the investigators wrote. “Likewise, there is a statistically significant difference between male and female patients with a negative baseline MRI, namely that in male patients more often a positive MRI at follow-up is seen [difference: 12% in men, 3% in women].”

The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bakker PA et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018 Sep 11. doi: 10.1002/art.40718.

Patients with chronic back pain suspected of having axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) should not undergo follow-up MRI of the sacroiliac joint (MRI-SI) within a year if they had a negative baseline MRI-SI, according to investigators.

It is very unlikely that a follow-up MRI-SI will yield new results, reported Pauline A. Bakker, MD, of the department of rheumatology at Leiden University Medical Centre, the Netherlands, and her colleagues.

Since gender and HLA-B27 status were closely associated with MRI-SI positivity, these factors should be considered when deciding to repeat an MRI-SI.

“Over the last decade, MRI rapidly gained ground and proved to be an important imaging technique in the diagnostic process of [nonradiographic] axial spondyloarthritis,” the investigators wrote in Arthritis and Rheumatology. “It has been shown that MRI can detect the early inflammatory stages of sacroiliitis months to years before structural damage can be detected on a conventional radiograph.”

Although MRI represents a diagnostic leap forward, questions of clinical application remain. “For example… if an MRI is completely normal and there is still a clinical suspicion of axSpA, should the MRI be repeated? And if so, after what period of follow-up? Or does this not contribute to the diagnostic process?”

To answer these questions, the investigators observed the “evolution of MRI lesions over a 3-month and 1-year time frame” in patients with early chronic back pain and suspected axSpA.

The prospective study involved 188 patients from the Spondyloarthritis Caught Early (SPACE) cohort. The authors commented that this is “an ideal cohort… since it includes a population of patients with back pain of short duration referred to rheumatologists with a suspicion of SpA [but without the mandatory presence of a single or multiple SpA features].”

Enrolled patients had chronic back pain lasting between 3 months and 2 years, with onset beginning between 16 and 45 years of age. Each underwent physical examination (including evaluation of other SpA features), MRI and radiographs of the sacroiliac joints, and HLA-B27 testing. If patients fulfilled axSpA criteria or had possible axSpA (at least one SpA feature), then they proceeded into the follow-up phase of the study, which included repeat MRI-SI at 3 months and 1 year.

Among enrolled patients, slightly more than one-third were male, almost half were HLA-B27 positive, and about three-quarters had Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society–defined inflammatory back pain. Mean age was 31 years; 31 (16.5%) patients were MRI-SI positive.

Of patients that were MRI-SI positive at baseline, 11.1% and 37.9% had a negative MRI-SI at 3 months and 1 year, respectively. The authors noted that this change “was partly induced by the start of anti-TNF [tumor necrosis factor] therapy.” In patients who were MRI-SI negative at baseline, 4.3% and 7.2% were positive at 3 months and 1 year, respectively.

“A very small percentage of patients become positive… which indicates that the usefulness of repeating an MRI-SI in the diagnostic process after 3 months or 1 year is very limited,” the authors wrote.

Gender and HLA-B27 status were independently associated with a positive MRI-SI at any point in time. About 43% of HLA-B27-positive men had a positive MRI-SI, compared with just 7% of HLA-B27-negative women. The investigators advised that these associations be considered when deciding upon repeat MRI-SI.

“If a clinical suspicion [of axSpA] remains [for example, a patient develops other SpA features] it might be worthwhile to consider redoing an MRI in HLA-B27 positive patients,” the investigators wrote. “Likewise, there is a statistically significant difference between male and female patients with a negative baseline MRI, namely that in male patients more often a positive MRI at follow-up is seen [difference: 12% in men, 3% in women].”

The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bakker PA et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018 Sep 11. doi: 10.1002/art.40718.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In patients who had a negative baseline MRI of the sacroiliac joints, the maximum likelihood of a follow-up MRI being positive was 7%.

Study details: A prospective study involving 188 patients (from the Spondyloarthritis Caught Early cohort) with early chronic back pain suspected of axial spondyloarthritis.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Bakker PA et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018 Sep 11. doi: 10.1002/art.40718.

Natural history is comparable for astrovirus, sapovirus, norovirus

ATLANTA – Astrovirus and sapovirus in children visiting the ED with acute gastroenteritis have a similar natural history, which is also similar to that of norovirus, according to findings from a prospective cohort study.

Thanks to the increased use of molecular diagnostic testing, astrovirus and sapovirus (AsV and SaV) recently gained new appreciation as a cause of gastroenteritis, but little is known about their natural history.

The current findings from the Alberta Provincial Pediatric Enteric Infection Team (APPETITE) study provide some longitudinal insight regarding that history, Gillian A. M. Tarr, PhD, of the University of Calgary (Alta.), and her colleagues noted in a poster presentation at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The investigators tested rectal swabs and stool samples from 2,590 children under age 18 years who had experienced at least three episodes of diarrhea and/or vomiting in 24 hours. AsV was detected in 84 children (3.2%), SaV was detected in 229 (8.8%), and norovirus (NoV) was detected in 655 (25%). After excluding those with coinfection, a total of 54, 144, and 478 children with AsV, SaV, and NoV, respectively, were included.

Vomiting occurred in 83%, 92%, and 98%; diarrhea occurred in 94%, 79% and 75%; and blood was present in the stool in 4.0%, 7.0%, and 3.5%, of those with AsV, SaV, and NoV, respectively, they reported.

The median maximal vomiting episodes per day was slightly lower for AsV versus SaV and NoV (about 3 vs. 5 and 7, respectively); the median maximal diarrhea episodes was slightly higher for AsV (about 5 vs. 4 for both SaV and NoV).

Vomiting duration was similar for AsV and SaV (about 3 days) and slightly longer than for NoV (about 2 days); median diarrhea duration was about 5 days for all three viruses.

“Most AsV cases present with both vomiting and diarrhea; most SaV cases present with vomiting and only approximately half with diarrhea,” the investigators wrote.

APPETITE study participants were enrolled from the EDs of two large children’s hospitals from December 2014 to May 2018. All were tested for 18 enteric pathogens and information on patient symptoms, medications, and potential exposures at enrollment and at 14 days was provided by patients and parents/guardians.

“We compared the natural histories of AsV and SaV to that of NoV, and found that all are comparable. These data provide a clearer picture than previously available of the duration and intensity of cardinal gastroenteritis symptoms associated with AsV and SaV infections,” they concluded.

Dr. Tarr reported having no financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – Astrovirus and sapovirus in children visiting the ED with acute gastroenteritis have a similar natural history, which is also similar to that of norovirus, according to findings from a prospective cohort study.

Thanks to the increased use of molecular diagnostic testing, astrovirus and sapovirus (AsV and SaV) recently gained new appreciation as a cause of gastroenteritis, but little is known about their natural history.

The current findings from the Alberta Provincial Pediatric Enteric Infection Team (APPETITE) study provide some longitudinal insight regarding that history, Gillian A. M. Tarr, PhD, of the University of Calgary (Alta.), and her colleagues noted in a poster presentation at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The investigators tested rectal swabs and stool samples from 2,590 children under age 18 years who had experienced at least three episodes of diarrhea and/or vomiting in 24 hours. AsV was detected in 84 children (3.2%), SaV was detected in 229 (8.8%), and norovirus (NoV) was detected in 655 (25%). After excluding those with coinfection, a total of 54, 144, and 478 children with AsV, SaV, and NoV, respectively, were included.

Vomiting occurred in 83%, 92%, and 98%; diarrhea occurred in 94%, 79% and 75%; and blood was present in the stool in 4.0%, 7.0%, and 3.5%, of those with AsV, SaV, and NoV, respectively, they reported.

The median maximal vomiting episodes per day was slightly lower for AsV versus SaV and NoV (about 3 vs. 5 and 7, respectively); the median maximal diarrhea episodes was slightly higher for AsV (about 5 vs. 4 for both SaV and NoV).

Vomiting duration was similar for AsV and SaV (about 3 days) and slightly longer than for NoV (about 2 days); median diarrhea duration was about 5 days for all three viruses.

“Most AsV cases present with both vomiting and diarrhea; most SaV cases present with vomiting and only approximately half with diarrhea,” the investigators wrote.

APPETITE study participants were enrolled from the EDs of two large children’s hospitals from December 2014 to May 2018. All were tested for 18 enteric pathogens and information on patient symptoms, medications, and potential exposures at enrollment and at 14 days was provided by patients and parents/guardians.

“We compared the natural histories of AsV and SaV to that of NoV, and found that all are comparable. These data provide a clearer picture than previously available of the duration and intensity of cardinal gastroenteritis symptoms associated with AsV and SaV infections,” they concluded.

Dr. Tarr reported having no financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – Astrovirus and sapovirus in children visiting the ED with acute gastroenteritis have a similar natural history, which is also similar to that of norovirus, according to findings from a prospective cohort study.

Thanks to the increased use of molecular diagnostic testing, astrovirus and sapovirus (AsV and SaV) recently gained new appreciation as a cause of gastroenteritis, but little is known about their natural history.

The current findings from the Alberta Provincial Pediatric Enteric Infection Team (APPETITE) study provide some longitudinal insight regarding that history, Gillian A. M. Tarr, PhD, of the University of Calgary (Alta.), and her colleagues noted in a poster presentation at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The investigators tested rectal swabs and stool samples from 2,590 children under age 18 years who had experienced at least three episodes of diarrhea and/or vomiting in 24 hours. AsV was detected in 84 children (3.2%), SaV was detected in 229 (8.8%), and norovirus (NoV) was detected in 655 (25%). After excluding those with coinfection, a total of 54, 144, and 478 children with AsV, SaV, and NoV, respectively, were included.

Vomiting occurred in 83%, 92%, and 98%; diarrhea occurred in 94%, 79% and 75%; and blood was present in the stool in 4.0%, 7.0%, and 3.5%, of those with AsV, SaV, and NoV, respectively, they reported.

The median maximal vomiting episodes per day was slightly lower for AsV versus SaV and NoV (about 3 vs. 5 and 7, respectively); the median maximal diarrhea episodes was slightly higher for AsV (about 5 vs. 4 for both SaV and NoV).

Vomiting duration was similar for AsV and SaV (about 3 days) and slightly longer than for NoV (about 2 days); median diarrhea duration was about 5 days for all three viruses.

“Most AsV cases present with both vomiting and diarrhea; most SaV cases present with vomiting and only approximately half with diarrhea,” the investigators wrote.

APPETITE study participants were enrolled from the EDs of two large children’s hospitals from December 2014 to May 2018. All were tested for 18 enteric pathogens and information on patient symptoms, medications, and potential exposures at enrollment and at 14 days was provided by patients and parents/guardians.

“We compared the natural histories of AsV and SaV to that of NoV, and found that all are comparable. These data provide a clearer picture than previously available of the duration and intensity of cardinal gastroenteritis symptoms associated with AsV and SaV infections,” they concluded.

Dr. Tarr reported having no financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM ICEID 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Vomiting lasted about 3 days for astrovirus and sapovirus and 2 days for norovirus; diarrhea lasted about 5 days for all three viruses.

Study details: A prospective cohort study of 2,590 children.

Disclosures: Dr. Tarr reported having no financial disclosures.

Noninvasive fat removal devices continue to gain popularity

SAN DIEGO – Noninvasive fat removal, such as laser treatment and cryolipolysis, is here to stay.

That’s what Mathew M. Avram, MD, JD, told attendees at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium.

“It does not compare to liposuction, but many patients prefer these devices because there’s less downtime,” he said. “They don’t want pain. They don’t want time away from work.”

In the decade or so since the inception of the noninvasive body contouring field, noninvasive and minimally invasive devices have become far more popular than traditional liposuction, said Dr. Avram, director of laser, cosmetics, and dermatologic surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. “It’s not even close. Among American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [ASDS] members, for every 1 liposuction, there are over 10 noninvasive body sculpting treatments.”

There were 408,000 body-sculpting procedures performed in 2017. More than half of those (208,000) were cryolipolysis, followed by use of radiofrequency (89,000), deoxycholic acid (46,000), laser lipolysis (25,000), “other” procedures (25,000), and tumescent liposuction (15,000), according to data from the ASDS.

“Each treatment has improved in efficacy with time,” Dr. Avram said.

Devices currently cleared by the Food and Drug Administration for the noninvasive removal of fat include ultrasound, lasers, low-level laser therapy, cryolipolysis, and radiofrequency. One of the most common is low-level laser therapy.

“There are several different devices on the market, but there’s no good histology to confirm mechanism of action, so you question what the efficacy is,” said Dr. Avram, who is also the immediate past president of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery.

SculpSure

In the traditional laser domain, the one most commonly used for fat removal is SculpSure, an FDA-cleared hyperthermic 1,060-nm diode laser. It features four flat, nonsuction applicators, a contact cooling system, and it enables the user to treat more than one area in a 25-minute session. There is minimal absorption by melanin.

“You shouldn’t treat over tattoos, however, because if there’s black ink, the tattoo will absorb the wavelength,” Dr. Avram said. “It’s safe in all skin types and there are a variety of different configurations you can use to treat the desired area.”

Initially there is a 4-minute warm-up cycle to achieve the target temperature. Over the next 21 minutes, 1,060-nm energy is delivered via proprietary modulation, alternating between heat and cooling.

“There is definitely some pain with this device,” he said. “Whether or not it’s a relevant endpoint is not known at this point. But typically, if you’re destroying fat with heat there should be some pain. It’s relieved by a period of cooling. A submental fat treatment is now available. I have not personally used it, but it’s the same technology.”

CoolSculpting

Another popular technology is cryolipolysis (CoolSculpting), which was developed at Massachusetts General Hospital by R. Rox Anderson, MD, and Dieter Manstein, MD, PhD.

It’s FDA cleared for noninvasive fat removal and there have been more than 6 million cryolipolysis treatments performed around the world. The purported mechanism of action is selective crystallization of lipids and fat cells at temperatures below freezing. An inflammatory process results in fat reduction over 2-4 months.

“When it first started, cryolipolysis was designed to treat local areas like love handles in males,” Dr. Avram said. “Over time, applicators have been designed to treat different areas, most recently, one for the posterior upper arms and above the knees. There is now a larger, faster CoolSculpting applicator which results in a 35-minute treatment. It’s a little larger, there’s a little less pain, a lower temperature, and it’s a little bit more effective. This has been helpful in our practice in terms of getting more treatment cycles in a visit.”

Postprocedurally, massage may improve clinical results by mobilizing lipid crystals created from treatment.

Extracorporeal shock wave therapy

Another modality to consider is extracorporeal shock wave therapy, which is the application of mechanically generated external sound waves. “It’s not the same as ultrasound or focused ultrasound, and it’s FDA cleared for the treatment of cellulite,” Dr. Avram said.

EmSculpt

A newer innovation, known as High Intensity Focused Electromagnetic (HIFEM) technology (EmSculpt), induces 20,000 forced muscle contractions per session, which leads to supramaximal contractions that can’t be achieved through normal voluntary muscle action.

“The idea is that you’re getting hypertrophy of the muscle to get volumetric growth,” he said. “There’s believed to be a cascaded apoptotic effect, inducing apoptosis and fat disruption.”

Dr. Avram added that HIFEM is nonionizing, nonradiating, nonthermal, and it does not affect sensory nerves. “It’s designed to only stimulate motor neurons. Time will tell in terms of what the ultimate results are with that device.”

truSculpt

Some clinicians are using monopolar radiofrequency with truSculpt, the proprietary delivery of deep radiofrequency energy. This device increases fat temperature between 6 and 10 degrees Celsius with dual frequency at 1 and 2 MHz.

Published data show that 45 degrees Celsius sustained for 3 minutes resulted in a 60% loss of adipose tissue viability (Lasers Surg Med. 2009;41:745-50; Lasers Surg Med. 2010;42:361-70).

“The heat delivery induces cell apoptosis, leading to the removal of those cells by natural healing processes,” said Dr. Avram, who added that he has not used the device. “We need more clinical data to assess this as well.”

Selective photothermolysis

Another technology being evaluated for fat removal is selective photothermolysis, a concept developed at Massachusetts General Hospital in 1983. It extends the theory of selective photothermolysis to target the lipids that make up subcutaneous fat.

“The theory is that you must select a wavelength well absorbed by the target chromophore with a pulse duration shorter than the target’s thermal relaxation time,” Dr. Avram explained. “This produces selective, localized heating with focal destruction of the target with minimal damage to the surrounding tissue. It requires a deeply penetrating wavelength.”

Lipids are a tempting target “because they heat quickly and easily and they do not lose their heat easily to surrounding structures. You want to target fat selectively and confine thermal damage effectively,” he said.

Nearly 10 years ago, Dr. Avram and his associates evaluated the effects of noninvasive 1,210-nm laser exposure on the adipose tissue of 24 patients with skin types 1-5 (Laser Surg Med. 2009;41:401-7).

“The laser pulses were painful, which limited the efficacy,” he said.

The contact cooling device failed in some subjects, and two patients had bulla, but no scarring. Histologic evidence of laser-induced fat damage was observed in 89% of test sites at 4-7 weeks, but dermal damage was also seen.

“This was the first study to show histologic evidence of laser-induced damage to subcutaneous fat,” Dr. Avram said.

Development of selective photothermolysis technology fell off the wayside after the Great Recession of 2008, but it is still being evaluated at Massachusetts General Hospital and other centers.

To optimize the technology, Dr. Avram said that longer pulse durations may target larger volumes of fat. “Cooling is essential to protect the epidermis, as well as to control pain.”

Injectables

Injectables provide a new, minimally invasive means to achieve noninvasive fat removal, Dr. Avram noted.

“Many injectables of questionable efficacy and safety had been available internationally for years,” he said, but none had FDA clearance until 2015, when the agency gave ATX-101 (Kybella) the nod.

ATX-101 is a nonanimal-derived formulation of deoxycholic acid that causes preferential adipocytolysis. Data from a phase 3 trial presented at the 2014 American Society of Plastic Surgery and the American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery meetings showed a statistically significant reduction in submental fat among subjects who received ATX-101, compared with placebo. It requires an average of 2-4 treatments.

“In my experience, it tends not to require that many, but based on MRI, as well as clinician and patient-reported outcomes, there are significant improvements in the visual impact of chin fat,” Dr. Avram said.

Most adverse events are mild to moderate in severity, primarily bruising, pain, and a sensation of numbness to the anesthesia. “They decrease in incidence and severity over successive treatments, and they infrequently lead to discontinuation of treatment,” he said.

For submental fat, clinicians can combine cryolipolysis and deoxycholic acid. “Here, the idea is to assess the amount of fat targeted for treatment,” Dr. Avram said. “If the fat fills the cryolipolysis cup, use cryolipolysis alone. If the fat does not fill the cup, inject deoxycholic acid for a more targeted treatment. If there is residual fat after cryolipolysis, consider treating more focally with deoxycholic acid.”

Both treatments can produce temporary marginal mandibular nerve injury. “It’s not common, but that’s something to include in your consent forms,” he said.

Dr. Avram reported that he has received consulting fees from Allergan, Merz Pharma, Sciton, Soliton, and Zalea. He also reported having ownership and/or shareholder interest in Cytrellis Biosystems, Invasix, and Zalea.

[email protected]

SAN DIEGO – Noninvasive fat removal, such as laser treatment and cryolipolysis, is here to stay.

That’s what Mathew M. Avram, MD, JD, told attendees at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium.

“It does not compare to liposuction, but many patients prefer these devices because there’s less downtime,” he said. “They don’t want pain. They don’t want time away from work.”

In the decade or so since the inception of the noninvasive body contouring field, noninvasive and minimally invasive devices have become far more popular than traditional liposuction, said Dr. Avram, director of laser, cosmetics, and dermatologic surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. “It’s not even close. Among American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [ASDS] members, for every 1 liposuction, there are over 10 noninvasive body sculpting treatments.”

There were 408,000 body-sculpting procedures performed in 2017. More than half of those (208,000) were cryolipolysis, followed by use of radiofrequency (89,000), deoxycholic acid (46,000), laser lipolysis (25,000), “other” procedures (25,000), and tumescent liposuction (15,000), according to data from the ASDS.

“Each treatment has improved in efficacy with time,” Dr. Avram said.

Devices currently cleared by the Food and Drug Administration for the noninvasive removal of fat include ultrasound, lasers, low-level laser therapy, cryolipolysis, and radiofrequency. One of the most common is low-level laser therapy.

“There are several different devices on the market, but there’s no good histology to confirm mechanism of action, so you question what the efficacy is,” said Dr. Avram, who is also the immediate past president of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery.

SculpSure

In the traditional laser domain, the one most commonly used for fat removal is SculpSure, an FDA-cleared hyperthermic 1,060-nm diode laser. It features four flat, nonsuction applicators, a contact cooling system, and it enables the user to treat more than one area in a 25-minute session. There is minimal absorption by melanin.

“You shouldn’t treat over tattoos, however, because if there’s black ink, the tattoo will absorb the wavelength,” Dr. Avram said. “It’s safe in all skin types and there are a variety of different configurations you can use to treat the desired area.”

Initially there is a 4-minute warm-up cycle to achieve the target temperature. Over the next 21 minutes, 1,060-nm energy is delivered via proprietary modulation, alternating between heat and cooling.

“There is definitely some pain with this device,” he said. “Whether or not it’s a relevant endpoint is not known at this point. But typically, if you’re destroying fat with heat there should be some pain. It’s relieved by a period of cooling. A submental fat treatment is now available. I have not personally used it, but it’s the same technology.”

CoolSculpting

Another popular technology is cryolipolysis (CoolSculpting), which was developed at Massachusetts General Hospital by R. Rox Anderson, MD, and Dieter Manstein, MD, PhD.

It’s FDA cleared for noninvasive fat removal and there have been more than 6 million cryolipolysis treatments performed around the world. The purported mechanism of action is selective crystallization of lipids and fat cells at temperatures below freezing. An inflammatory process results in fat reduction over 2-4 months.

“When it first started, cryolipolysis was designed to treat local areas like love handles in males,” Dr. Avram said. “Over time, applicators have been designed to treat different areas, most recently, one for the posterior upper arms and above the knees. There is now a larger, faster CoolSculpting applicator which results in a 35-minute treatment. It’s a little larger, there’s a little less pain, a lower temperature, and it’s a little bit more effective. This has been helpful in our practice in terms of getting more treatment cycles in a visit.”

Postprocedurally, massage may improve clinical results by mobilizing lipid crystals created from treatment.

Extracorporeal shock wave therapy

Another modality to consider is extracorporeal shock wave therapy, which is the application of mechanically generated external sound waves. “It’s not the same as ultrasound or focused ultrasound, and it’s FDA cleared for the treatment of cellulite,” Dr. Avram said.

EmSculpt

A newer innovation, known as High Intensity Focused Electromagnetic (HIFEM) technology (EmSculpt), induces 20,000 forced muscle contractions per session, which leads to supramaximal contractions that can’t be achieved through normal voluntary muscle action.

“The idea is that you’re getting hypertrophy of the muscle to get volumetric growth,” he said. “There’s believed to be a cascaded apoptotic effect, inducing apoptosis and fat disruption.”

Dr. Avram added that HIFEM is nonionizing, nonradiating, nonthermal, and it does not affect sensory nerves. “It’s designed to only stimulate motor neurons. Time will tell in terms of what the ultimate results are with that device.”

truSculpt

Some clinicians are using monopolar radiofrequency with truSculpt, the proprietary delivery of deep radiofrequency energy. This device increases fat temperature between 6 and 10 degrees Celsius with dual frequency at 1 and 2 MHz.

Published data show that 45 degrees Celsius sustained for 3 minutes resulted in a 60% loss of adipose tissue viability (Lasers Surg Med. 2009;41:745-50; Lasers Surg Med. 2010;42:361-70).

“The heat delivery induces cell apoptosis, leading to the removal of those cells by natural healing processes,” said Dr. Avram, who added that he has not used the device. “We need more clinical data to assess this as well.”

Selective photothermolysis

Another technology being evaluated for fat removal is selective photothermolysis, a concept developed at Massachusetts General Hospital in 1983. It extends the theory of selective photothermolysis to target the lipids that make up subcutaneous fat.

“The theory is that you must select a wavelength well absorbed by the target chromophore with a pulse duration shorter than the target’s thermal relaxation time,” Dr. Avram explained. “This produces selective, localized heating with focal destruction of the target with minimal damage to the surrounding tissue. It requires a deeply penetrating wavelength.”

Lipids are a tempting target “because they heat quickly and easily and they do not lose their heat easily to surrounding structures. You want to target fat selectively and confine thermal damage effectively,” he said.

Nearly 10 years ago, Dr. Avram and his associates evaluated the effects of noninvasive 1,210-nm laser exposure on the adipose tissue of 24 patients with skin types 1-5 (Laser Surg Med. 2009;41:401-7).

“The laser pulses were painful, which limited the efficacy,” he said.

The contact cooling device failed in some subjects, and two patients had bulla, but no scarring. Histologic evidence of laser-induced fat damage was observed in 89% of test sites at 4-7 weeks, but dermal damage was also seen.

“This was the first study to show histologic evidence of laser-induced damage to subcutaneous fat,” Dr. Avram said.

Development of selective photothermolysis technology fell off the wayside after the Great Recession of 2008, but it is still being evaluated at Massachusetts General Hospital and other centers.

To optimize the technology, Dr. Avram said that longer pulse durations may target larger volumes of fat. “Cooling is essential to protect the epidermis, as well as to control pain.”

Injectables

Injectables provide a new, minimally invasive means to achieve noninvasive fat removal, Dr. Avram noted.

“Many injectables of questionable efficacy and safety had been available internationally for years,” he said, but none had FDA clearance until 2015, when the agency gave ATX-101 (Kybella) the nod.

ATX-101 is a nonanimal-derived formulation of deoxycholic acid that causes preferential adipocytolysis. Data from a phase 3 trial presented at the 2014 American Society of Plastic Surgery and the American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery meetings showed a statistically significant reduction in submental fat among subjects who received ATX-101, compared with placebo. It requires an average of 2-4 treatments.

“In my experience, it tends not to require that many, but based on MRI, as well as clinician and patient-reported outcomes, there are significant improvements in the visual impact of chin fat,” Dr. Avram said.

Most adverse events are mild to moderate in severity, primarily bruising, pain, and a sensation of numbness to the anesthesia. “They decrease in incidence and severity over successive treatments, and they infrequently lead to discontinuation of treatment,” he said.

For submental fat, clinicians can combine cryolipolysis and deoxycholic acid. “Here, the idea is to assess the amount of fat targeted for treatment,” Dr. Avram said. “If the fat fills the cryolipolysis cup, use cryolipolysis alone. If the fat does not fill the cup, inject deoxycholic acid for a more targeted treatment. If there is residual fat after cryolipolysis, consider treating more focally with deoxycholic acid.”

Both treatments can produce temporary marginal mandibular nerve injury. “It’s not common, but that’s something to include in your consent forms,” he said.

Dr. Avram reported that he has received consulting fees from Allergan, Merz Pharma, Sciton, Soliton, and Zalea. He also reported having ownership and/or shareholder interest in Cytrellis Biosystems, Invasix, and Zalea.

[email protected]

SAN DIEGO – Noninvasive fat removal, such as laser treatment and cryolipolysis, is here to stay.

That’s what Mathew M. Avram, MD, JD, told attendees at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium.

“It does not compare to liposuction, but many patients prefer these devices because there’s less downtime,” he said. “They don’t want pain. They don’t want time away from work.”

In the decade or so since the inception of the noninvasive body contouring field, noninvasive and minimally invasive devices have become far more popular than traditional liposuction, said Dr. Avram, director of laser, cosmetics, and dermatologic surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. “It’s not even close. Among American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [ASDS] members, for every 1 liposuction, there are over 10 noninvasive body sculpting treatments.”

There were 408,000 body-sculpting procedures performed in 2017. More than half of those (208,000) were cryolipolysis, followed by use of radiofrequency (89,000), deoxycholic acid (46,000), laser lipolysis (25,000), “other” procedures (25,000), and tumescent liposuction (15,000), according to data from the ASDS.

“Each treatment has improved in efficacy with time,” Dr. Avram said.

Devices currently cleared by the Food and Drug Administration for the noninvasive removal of fat include ultrasound, lasers, low-level laser therapy, cryolipolysis, and radiofrequency. One of the most common is low-level laser therapy.

“There are several different devices on the market, but there’s no good histology to confirm mechanism of action, so you question what the efficacy is,” said Dr. Avram, who is also the immediate past president of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery.

SculpSure

In the traditional laser domain, the one most commonly used for fat removal is SculpSure, an FDA-cleared hyperthermic 1,060-nm diode laser. It features four flat, nonsuction applicators, a contact cooling system, and it enables the user to treat more than one area in a 25-minute session. There is minimal absorption by melanin.

“You shouldn’t treat over tattoos, however, because if there’s black ink, the tattoo will absorb the wavelength,” Dr. Avram said. “It’s safe in all skin types and there are a variety of different configurations you can use to treat the desired area.”

Initially there is a 4-minute warm-up cycle to achieve the target temperature. Over the next 21 minutes, 1,060-nm energy is delivered via proprietary modulation, alternating between heat and cooling.

“There is definitely some pain with this device,” he said. “Whether or not it’s a relevant endpoint is not known at this point. But typically, if you’re destroying fat with heat there should be some pain. It’s relieved by a period of cooling. A submental fat treatment is now available. I have not personally used it, but it’s the same technology.”

CoolSculpting

Another popular technology is cryolipolysis (CoolSculpting), which was developed at Massachusetts General Hospital by R. Rox Anderson, MD, and Dieter Manstein, MD, PhD.

It’s FDA cleared for noninvasive fat removal and there have been more than 6 million cryolipolysis treatments performed around the world. The purported mechanism of action is selective crystallization of lipids and fat cells at temperatures below freezing. An inflammatory process results in fat reduction over 2-4 months.

“When it first started, cryolipolysis was designed to treat local areas like love handles in males,” Dr. Avram said. “Over time, applicators have been designed to treat different areas, most recently, one for the posterior upper arms and above the knees. There is now a larger, faster CoolSculpting applicator which results in a 35-minute treatment. It’s a little larger, there’s a little less pain, a lower temperature, and it’s a little bit more effective. This has been helpful in our practice in terms of getting more treatment cycles in a visit.”

Postprocedurally, massage may improve clinical results by mobilizing lipid crystals created from treatment.

Extracorporeal shock wave therapy

Another modality to consider is extracorporeal shock wave therapy, which is the application of mechanically generated external sound waves. “It’s not the same as ultrasound or focused ultrasound, and it’s FDA cleared for the treatment of cellulite,” Dr. Avram said.

EmSculpt