User login

Concomitant emicizumab, ITI shows promise in severe hemophilia A

Concomitant emicizumab prophylaxis and immune tolerance induction (ITI) may be suitable for bleeding prevention in pediatric patients with severe hemophilia A and inhibitors, according to a retrospective analysis.

“The primary objective of this study [was] to review a case series of pediatric patients with hemophilia A and inhibitors at our institution who have received emicizumab concurrently with ITI,” wrote Glaivy Batsuli, MD, of Emory University in Atlanta, and her colleagues. The results of the study were reported in Haemophilia.

The case series included seven pediatric patients with severe hemophilia A who received concurrent emicizumab for bleeding prevention and ITI for inhibitor eradication. Data were collected from electronic medical records at a single hemophilia treatment center from Aug. 1 to Dec. 1, 2018.

The researchers included male patients from 0 to 21 years old who had titres greater than 0.6 chromogenic Bethesda units (CBU) per mL on two instances more than 2 weeks apart.

The treatment protocol, termed the “Atlanta Protocol,” used a novel dosing regimen, established using provider consensus, for the concomitant use of ITI and emicizumab.

After analysis, the researchers found that three patients attained a negative inhibitor titer of less than 0.6 CBU/mL, and two patients had a normal factor VIII recovery of greater than or equal to 66%.

In total, nine bleeding events were observed in four patients; however, no thrombotic events were reported. All patients continued on concomitant therapy at the point of data analysis.

The researchers reported that six patients used three different recombinant factor VIII products at 100 IU/kg, three times each week. The remaining patient used a plasma‐derived factor VIII product at an initial dose of 50 IU/kg, three times each week.

The small sample size, retrospective design, and short follow‐up period were key limitations of the study.

“Prospective studies will be necessary to compare treatment outcomes of ITI and emicizumab to other ITI regimens and to investigate whether emicizumab modifies the immunologic response to FVIII,” the researchers wrote.

No funding sources were reported. The authors reported financial affiliations with Bayer, Bioverativ, CSL Behring, Catalyst Biosciences, Genentech, HEMA Biologics, Novo Nordisk, Octapharma, and several others.

SOURCE: Batsuli G et al. Haemophilia. 2019 Aug 2. doi: 10.1111/hae.13819.

Concomitant emicizumab prophylaxis and immune tolerance induction (ITI) may be suitable for bleeding prevention in pediatric patients with severe hemophilia A and inhibitors, according to a retrospective analysis.

“The primary objective of this study [was] to review a case series of pediatric patients with hemophilia A and inhibitors at our institution who have received emicizumab concurrently with ITI,” wrote Glaivy Batsuli, MD, of Emory University in Atlanta, and her colleagues. The results of the study were reported in Haemophilia.

The case series included seven pediatric patients with severe hemophilia A who received concurrent emicizumab for bleeding prevention and ITI for inhibitor eradication. Data were collected from electronic medical records at a single hemophilia treatment center from Aug. 1 to Dec. 1, 2018.

The researchers included male patients from 0 to 21 years old who had titres greater than 0.6 chromogenic Bethesda units (CBU) per mL on two instances more than 2 weeks apart.

The treatment protocol, termed the “Atlanta Protocol,” used a novel dosing regimen, established using provider consensus, for the concomitant use of ITI and emicizumab.

After analysis, the researchers found that three patients attained a negative inhibitor titer of less than 0.6 CBU/mL, and two patients had a normal factor VIII recovery of greater than or equal to 66%.

In total, nine bleeding events were observed in four patients; however, no thrombotic events were reported. All patients continued on concomitant therapy at the point of data analysis.

The researchers reported that six patients used three different recombinant factor VIII products at 100 IU/kg, three times each week. The remaining patient used a plasma‐derived factor VIII product at an initial dose of 50 IU/kg, three times each week.

The small sample size, retrospective design, and short follow‐up period were key limitations of the study.

“Prospective studies will be necessary to compare treatment outcomes of ITI and emicizumab to other ITI regimens and to investigate whether emicizumab modifies the immunologic response to FVIII,” the researchers wrote.

No funding sources were reported. The authors reported financial affiliations with Bayer, Bioverativ, CSL Behring, Catalyst Biosciences, Genentech, HEMA Biologics, Novo Nordisk, Octapharma, and several others.

SOURCE: Batsuli G et al. Haemophilia. 2019 Aug 2. doi: 10.1111/hae.13819.

Concomitant emicizumab prophylaxis and immune tolerance induction (ITI) may be suitable for bleeding prevention in pediatric patients with severe hemophilia A and inhibitors, according to a retrospective analysis.

“The primary objective of this study [was] to review a case series of pediatric patients with hemophilia A and inhibitors at our institution who have received emicizumab concurrently with ITI,” wrote Glaivy Batsuli, MD, of Emory University in Atlanta, and her colleagues. The results of the study were reported in Haemophilia.

The case series included seven pediatric patients with severe hemophilia A who received concurrent emicizumab for bleeding prevention and ITI for inhibitor eradication. Data were collected from electronic medical records at a single hemophilia treatment center from Aug. 1 to Dec. 1, 2018.

The researchers included male patients from 0 to 21 years old who had titres greater than 0.6 chromogenic Bethesda units (CBU) per mL on two instances more than 2 weeks apart.

The treatment protocol, termed the “Atlanta Protocol,” used a novel dosing regimen, established using provider consensus, for the concomitant use of ITI and emicizumab.

After analysis, the researchers found that three patients attained a negative inhibitor titer of less than 0.6 CBU/mL, and two patients had a normal factor VIII recovery of greater than or equal to 66%.

In total, nine bleeding events were observed in four patients; however, no thrombotic events were reported. All patients continued on concomitant therapy at the point of data analysis.

The researchers reported that six patients used three different recombinant factor VIII products at 100 IU/kg, three times each week. The remaining patient used a plasma‐derived factor VIII product at an initial dose of 50 IU/kg, three times each week.

The small sample size, retrospective design, and short follow‐up period were key limitations of the study.

“Prospective studies will be necessary to compare treatment outcomes of ITI and emicizumab to other ITI regimens and to investigate whether emicizumab modifies the immunologic response to FVIII,” the researchers wrote.

No funding sources were reported. The authors reported financial affiliations with Bayer, Bioverativ, CSL Behring, Catalyst Biosciences, Genentech, HEMA Biologics, Novo Nordisk, Octapharma, and several others.

SOURCE: Batsuli G et al. Haemophilia. 2019 Aug 2. doi: 10.1111/hae.13819.

FROM HAEMOPHILIA

Dabrafenib plus trametinib yields long-term benefit in melanoma patients

Dabrafenib plus trametinib treatment was associated with a 5-year overall survival rate of 34% in patients with melanoma harboring a BRAF V600E or V600K mutation, according to a combined analysis of two trials.

The 5-year progression-free survival rate was 19% in the long-term, pooled analysis of the COMBI-d and COMBI-v trials, which included at total of 563 patients with previously untreated, unresectable or metastatic melanoma who received combined treatment with the BRAF inhibitor dabrafenib and the MEK inhibitor trametinib.

Previously reported 5-year progression-free survival rates for patients treated with anti–programmed death-1 checkpoint inhibitors, either nivolumab or pembrolizumab, “appear to be similar” to these results for dabrafenib plus trametinib, investigators said in a report on the analysis appearing in the New England Journal of Medicine.

To date, however, 5-year survival data have not been reported for other BRAF-targeted therapies, according to the investigators, who were led by Caroline Robert, MD, PhD, of Institut Gustave Roussy and Paris-Sud-Paris-Saclay University, Villejuif, France.

“These data will be critical to assess the potential of therapy to exert long-term disease control through analysis of survival plateaus and to understand factors predictive of long-term survival,” Dr. Robert and coauthors wrote in their report.

A total of 211 patients in the COMBI-d trial were randomly allocated to receive the combination of dabrafenib plus trametinib, while in COMBI-v, 352 received this combination therapy, according to investigators.

Notably, the survival curves for dabrafenib plus trametinib appear to plateau starting at 3 years, investigators reported. In a previously published report on pooled COMBI-d and COMBI-v data, the 3-year progression-free survival rate was 23%, and the 3-year overall survival rate was 44%.

In this more recent analysis, progression-free survival rates were 21% at 4 years and 19% at 5 years, while overall survival rates were 37% at 4 years and 34% at 5 years.

“This finding suggests stabilization of rates of progression-free survival and overall survival over time in this population,” Dr. Robert and colleagues wrote.

Survival rates were higher in patients with normal lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels at baseline, and they were especially high in those with normal LDH and three or fewer disease sites at baseline, according to the report. Specifically, the reported 5-year rates of progression-free and overall survival were 31% and 55%, respectively.

Other factors associated with prolonged progression-free survival included female sex, older age, better performance status, and BRAF V600E genotype, according to results of a multivariate analysis that investigators said confirmed findings from the previously reported 3-year data.

The study was supported by GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis. Dr. Robert provided disclosures related to BMS, Pierre Fabre, Novartis, Amgen, Merck, Roche, MSD, and Sanofi.

SOURCE: Robert C et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1904059

Dabrafenib plus trametinib treatment was associated with a 5-year overall survival rate of 34% in patients with melanoma harboring a BRAF V600E or V600K mutation, according to a combined analysis of two trials.

The 5-year progression-free survival rate was 19% in the long-term, pooled analysis of the COMBI-d and COMBI-v trials, which included at total of 563 patients with previously untreated, unresectable or metastatic melanoma who received combined treatment with the BRAF inhibitor dabrafenib and the MEK inhibitor trametinib.

Previously reported 5-year progression-free survival rates for patients treated with anti–programmed death-1 checkpoint inhibitors, either nivolumab or pembrolizumab, “appear to be similar” to these results for dabrafenib plus trametinib, investigators said in a report on the analysis appearing in the New England Journal of Medicine.

To date, however, 5-year survival data have not been reported for other BRAF-targeted therapies, according to the investigators, who were led by Caroline Robert, MD, PhD, of Institut Gustave Roussy and Paris-Sud-Paris-Saclay University, Villejuif, France.

“These data will be critical to assess the potential of therapy to exert long-term disease control through analysis of survival plateaus and to understand factors predictive of long-term survival,” Dr. Robert and coauthors wrote in their report.

A total of 211 patients in the COMBI-d trial were randomly allocated to receive the combination of dabrafenib plus trametinib, while in COMBI-v, 352 received this combination therapy, according to investigators.

Notably, the survival curves for dabrafenib plus trametinib appear to plateau starting at 3 years, investigators reported. In a previously published report on pooled COMBI-d and COMBI-v data, the 3-year progression-free survival rate was 23%, and the 3-year overall survival rate was 44%.

In this more recent analysis, progression-free survival rates were 21% at 4 years and 19% at 5 years, while overall survival rates were 37% at 4 years and 34% at 5 years.

“This finding suggests stabilization of rates of progression-free survival and overall survival over time in this population,” Dr. Robert and colleagues wrote.

Survival rates were higher in patients with normal lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels at baseline, and they were especially high in those with normal LDH and three or fewer disease sites at baseline, according to the report. Specifically, the reported 5-year rates of progression-free and overall survival were 31% and 55%, respectively.

Other factors associated with prolonged progression-free survival included female sex, older age, better performance status, and BRAF V600E genotype, according to results of a multivariate analysis that investigators said confirmed findings from the previously reported 3-year data.

The study was supported by GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis. Dr. Robert provided disclosures related to BMS, Pierre Fabre, Novartis, Amgen, Merck, Roche, MSD, and Sanofi.

SOURCE: Robert C et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1904059

Dabrafenib plus trametinib treatment was associated with a 5-year overall survival rate of 34% in patients with melanoma harboring a BRAF V600E or V600K mutation, according to a combined analysis of two trials.

The 5-year progression-free survival rate was 19% in the long-term, pooled analysis of the COMBI-d and COMBI-v trials, which included at total of 563 patients with previously untreated, unresectable or metastatic melanoma who received combined treatment with the BRAF inhibitor dabrafenib and the MEK inhibitor trametinib.

Previously reported 5-year progression-free survival rates for patients treated with anti–programmed death-1 checkpoint inhibitors, either nivolumab or pembrolizumab, “appear to be similar” to these results for dabrafenib plus trametinib, investigators said in a report on the analysis appearing in the New England Journal of Medicine.

To date, however, 5-year survival data have not been reported for other BRAF-targeted therapies, according to the investigators, who were led by Caroline Robert, MD, PhD, of Institut Gustave Roussy and Paris-Sud-Paris-Saclay University, Villejuif, France.

“These data will be critical to assess the potential of therapy to exert long-term disease control through analysis of survival plateaus and to understand factors predictive of long-term survival,” Dr. Robert and coauthors wrote in their report.

A total of 211 patients in the COMBI-d trial were randomly allocated to receive the combination of dabrafenib plus trametinib, while in COMBI-v, 352 received this combination therapy, according to investigators.

Notably, the survival curves for dabrafenib plus trametinib appear to plateau starting at 3 years, investigators reported. In a previously published report on pooled COMBI-d and COMBI-v data, the 3-year progression-free survival rate was 23%, and the 3-year overall survival rate was 44%.

In this more recent analysis, progression-free survival rates were 21% at 4 years and 19% at 5 years, while overall survival rates were 37% at 4 years and 34% at 5 years.

“This finding suggests stabilization of rates of progression-free survival and overall survival over time in this population,” Dr. Robert and colleagues wrote.

Survival rates were higher in patients with normal lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels at baseline, and they were especially high in those with normal LDH and three or fewer disease sites at baseline, according to the report. Specifically, the reported 5-year rates of progression-free and overall survival were 31% and 55%, respectively.

Other factors associated with prolonged progression-free survival included female sex, older age, better performance status, and BRAF V600E genotype, according to results of a multivariate analysis that investigators said confirmed findings from the previously reported 3-year data.

The study was supported by GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis. Dr. Robert provided disclosures related to BMS, Pierre Fabre, Novartis, Amgen, Merck, Roche, MSD, and Sanofi.

SOURCE: Robert C et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1904059

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: A long-term survival benefit was seen in about a third of patients with metastatic or unresectable melanoma who underwent first-line treatment with dabrafenib and trametinib.

Major finding: The 5-year rates of progression-free survival and overall survival were 19% and 34%, respectively.

Study details: Pooled analysis including 563 patients randomly allocated to the combination treatment in two randomized trials (COMBI-d and COMBI-v).

Disclosures: The study was supported by GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis. The first author provided disclosures related to BMS, Pierre Fabre, Novartis, Amgen, Merck, Roche, MSD, and Sanofi.

Source: Robert C et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1904059

FDA approves drug combo to treat highly resistant TB

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted special approval to a new drug combo intended for the treatment of “a limited and specific population of adult patients with extensively drug resistant, treatment-intolerant or nonresponsive multidrug-resistant pulmonary” tuberculosis, according to an FDA news release.

The effectiveness of the combination treatment of pretomanid tablets with bedaquiline and linezolid was shown in a clinical study of patients with extensively drug-resistant, treatment-intolerant, or nonresponsive multidrug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis of the lungs. Of 107 infected patients who were evaluated 6 months after the end of therapy, 95 (89%) were deemed successes, which significantly exceeded the historical success rates for treatment of extensively drug-resistant TB, the FDA reported. The trial is sponsored by the Global Alliance for TB Drug Development.

The most common adverse effects reported included peripheral neuropathy, anemia, nausea, vomiting, headache, increased liver enzymes, dyspepsia, rash, visual impairment, low blood sugar, and diarrhea, according to the release.

“Multidrug-resistant TB and extensively drug-resistant TB are public health threats due to limited treatment options. New treatments are important to meet patient national and global health needs,” stated FDA Principal Deputy Commissioner Amy Abernethy, MD, PhD, in the release. She also explained that the approval marked the second time a drug was approved under the “Limited Population Pathway for Antibacterial and Antifungal Drugs, a pathway advanced by Congress to spur development of drugs targeting infections that lack effective therapies.”

In 2016, the World Health Organization reported that there were an estimated 490,000 new cases of multidrug-resistant TB worldwide, with a smaller portion of cases of extensively drug-resistant TB, according to the release, demonstrating the need for new therapeutics.

SOURCE: U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Aug. 14, 2019. News release.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted special approval to a new drug combo intended for the treatment of “a limited and specific population of adult patients with extensively drug resistant, treatment-intolerant or nonresponsive multidrug-resistant pulmonary” tuberculosis, according to an FDA news release.

The effectiveness of the combination treatment of pretomanid tablets with bedaquiline and linezolid was shown in a clinical study of patients with extensively drug-resistant, treatment-intolerant, or nonresponsive multidrug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis of the lungs. Of 107 infected patients who were evaluated 6 months after the end of therapy, 95 (89%) were deemed successes, which significantly exceeded the historical success rates for treatment of extensively drug-resistant TB, the FDA reported. The trial is sponsored by the Global Alliance for TB Drug Development.

The most common adverse effects reported included peripheral neuropathy, anemia, nausea, vomiting, headache, increased liver enzymes, dyspepsia, rash, visual impairment, low blood sugar, and diarrhea, according to the release.

“Multidrug-resistant TB and extensively drug-resistant TB are public health threats due to limited treatment options. New treatments are important to meet patient national and global health needs,” stated FDA Principal Deputy Commissioner Amy Abernethy, MD, PhD, in the release. She also explained that the approval marked the second time a drug was approved under the “Limited Population Pathway for Antibacterial and Antifungal Drugs, a pathway advanced by Congress to spur development of drugs targeting infections that lack effective therapies.”

In 2016, the World Health Organization reported that there were an estimated 490,000 new cases of multidrug-resistant TB worldwide, with a smaller portion of cases of extensively drug-resistant TB, according to the release, demonstrating the need for new therapeutics.

SOURCE: U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Aug. 14, 2019. News release.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted special approval to a new drug combo intended for the treatment of “a limited and specific population of adult patients with extensively drug resistant, treatment-intolerant or nonresponsive multidrug-resistant pulmonary” tuberculosis, according to an FDA news release.

The effectiveness of the combination treatment of pretomanid tablets with bedaquiline and linezolid was shown in a clinical study of patients with extensively drug-resistant, treatment-intolerant, or nonresponsive multidrug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis of the lungs. Of 107 infected patients who were evaluated 6 months after the end of therapy, 95 (89%) were deemed successes, which significantly exceeded the historical success rates for treatment of extensively drug-resistant TB, the FDA reported. The trial is sponsored by the Global Alliance for TB Drug Development.

The most common adverse effects reported included peripheral neuropathy, anemia, nausea, vomiting, headache, increased liver enzymes, dyspepsia, rash, visual impairment, low blood sugar, and diarrhea, according to the release.

“Multidrug-resistant TB and extensively drug-resistant TB are public health threats due to limited treatment options. New treatments are important to meet patient national and global health needs,” stated FDA Principal Deputy Commissioner Amy Abernethy, MD, PhD, in the release. She also explained that the approval marked the second time a drug was approved under the “Limited Population Pathway for Antibacterial and Antifungal Drugs, a pathway advanced by Congress to spur development of drugs targeting infections that lack effective therapies.”

In 2016, the World Health Organization reported that there were an estimated 490,000 new cases of multidrug-resistant TB worldwide, with a smaller portion of cases of extensively drug-resistant TB, according to the release, demonstrating the need for new therapeutics.

SOURCE: U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Aug. 14, 2019. News release.

NEWS FROM THE FDA

Pigmented Mass on the Shoulder

The Diagnosis: Pigmented Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans

Pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (PDFSP), also known as Bednar tumor, is an uncommon variant of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). Pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans constitutes 1% to 5% of all DFSP cases and most commonly is seen in nonwhite adults in the fourth decade of life, with occasional cases seen in pediatric patients, including some congenital cases. Typical sites of involvement include the shoulders, trunk, arms, legs, head, and neck.1,2 It also has been reported at sites of prior immunization, trauma, and insect bites.3

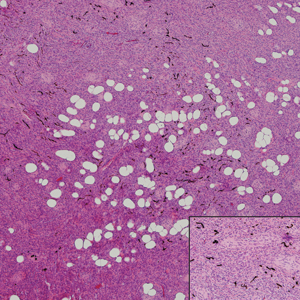

Histopathologic examination of our patient's shoulder nodule revealed an infiltrative neoplasm in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue composed of spindled cells with a storiform pattern and foci of scattered elongated dendritic pigmented cells. A narrow grenz zone separated the tumor from the epidermis, and characteristic honeycomb infiltration by tumor cells was noted in the subcutaneous fat. The nuclei were bland and monomorphous with areas of neuroid differentiation containing whorls and nerve cord-like structures (quiz image). The tumor cells were diffusely CD34 and vimentin positive, while S-100, SOX-10, neurofilament, smooth muscle actin, desmin, epithelial membrane antigen, and cytokeratins were negative. The immunophenotype excluded the possibility of neurogenic, pericytic, myofibroblastic, and myoid differentiation.

Wang and Yang4 previously reported a case of PDFSP with prominent meningothelial-like whorls focally resembling extracranial meningioma; however, the tumor cells were CD34 positive and epithelial membrane antigen negative, weighing against a diagnosis of meningioma. Most cases of PDFSP demonstrate the COL1A1-PDGFB (collagen type I α; 1/platelet-derived growth factor B-chain) fusion protein caused by the translocation t(17;22)(q22;q13), as in classic DFSP.5

Cellular blue nevus (CBN) is a benign melanocytic neoplasm that can present at any age and often occurs on the buttocks and in the sacrococcygeal region. Clinically, CBN presents as a firm, bluish black to bluish gray, dome-shaped nodule. The size varies from a few millimeters to several centimeters.6,7 Histologically, CBN is located completely in the dermis, extending along the adnexae into the subcutaneous tissue with a dumbbell-shaped outline (Figure 1).6-8 The tumor demonstrates oval epithelioid melanocytes with vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli. Immunohistochemically, tumor cells stain positively for melanocytic markers such as S-100, SOX-10, MART-1, and human melanoma black 45. CD34 expression rarely is reported in a subset of CBN.9

Pigmented neurofibroma is a rare variant of neurofibroma that produces melanin pigment and has a strong association with neurofibromatosis.10 It occurs most frequently in dark-skinned populations (Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI). The most common location is the head and neck region.11,12 Histologically, pigmented neurofibroma resembles a diffuse neurofibroma admixed with melanin-producing cells (Figure 2).12 Immunostaining shows positivity for S-100 in both pigmented and Schwann cells; however, the pigmented cells stain positively for human melanoma black 45, Melan-A, and tyrosinase.10 CD34 can be fingerprint positive in neurofibroma, but a distinction from DFSP can be made by S-100 and SOX-10 immunostaining.13

Desmoplastic melanoma (DM) is an uncommon variant of malignant melanoma and has a higher tendency for persistent local growth and less frequent metastases than other variants of melanoma. It has a predilection for chronically sun-exposed areas such as the head and neck and occurs later in life. Clinically, DM appears as nonspecific, often amelanotic nodules or plaques or as scarlike lesions.14 Histologically, DM can be classified as mixed or pure based on the degree of desmoplasia and cellularity. A paucicellular proliferation of malignant spindled melanocytes within a densely fibrotic stroma with lymphoid nodules in the dermis is characteristic (Figure 3); perineural involvement is common.14,15 The most reliable confirmative stains are S-100 and SOX-10.16

Cutaneous meningioma is a rare tumor and could be subtyped into 3 groups. Type I is primary cutaneous meningioma and usually is present at birth on the scalp and paravertebral regions with a relatively good prognosis. Type II is ectopic soft-tissue meningioma that extends into the skin from around the sensory organs on the face. Type III is local invasion or true metastasis from a central nervous system meningioma. Types II and III develop later in life and the prognosis is poor.17,18 Clinically, lesions present as firm subcutaneous nodules or swellings. Cutaneous meningioma has several histopathologic variants. The classic presentation reveals concentric wrapping of tumor cells with round-oval nuclei containing delicate chromatin. Psammoma bodies are a common finding (Figure 4). Immunohistochemically, tumor cells are diffusely positive for epithelial membrane antigen and vimentin.18,19

- Amonkar GP, Rupani A, Shah A, et al. Bednar tumor: an uncommon entity. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2016;3:36-38.

- El Hachem M, Diociaiuti A, Latella E, et al. Congenital myxoid and pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a case report. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:E74-E77.

- Anon-Requena MJ, Pico-Valimana M, Munoz-Arias G. Bednar tumor (pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans). Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:618-620.

- Wang J, Yang W. Pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with prominent meningothelial-like whorls. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 1):65-69.

- Zardawi IM, Kattampallil J, Rode J. An unusual pigmented skin tumour. Bednar tumour, dorsum of left foot (pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans). Pathology. 2004;36:358-361.

- Sugianto JZ, Ralston JS, Metcalf JS, et al. Blue nevus and "malignant blue nevus": a concise review. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2016;33:219-224.

- Zembowicz A. Blue nevi and related tumors. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:401-415.

- Zembowicz A, Granter SR, McKee PH, et al. Amelanotic cellular blue nevus: a hypopigmented variant of the cellular blue nevus: clinicopathologic analysis of 20 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1493-1500.

- Smith K, Germain M, Williams J, et al. CD34-positive cellular blue nevi. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:145-150.

- Inaba M, Yamamoto T, Minami R, et al. Pigmented neurofibroma: report of two cases and literature review. Pathol Int. 2001;51:565-569.

- Fetsch JF, Michal M, Miettinen M. Pigmented (melanotic) neurofibroma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 19 lesions from 17 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:331-343.

- Motoi T, Ishida T, Kawato A, et al. Pigmented neurofibroma: review of Japanese patients with an analysis of melanogenesis demonstrating coexpression of c-met protooncogene and microphthalmia-associated transcription factor. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:871-877.

- Yeh I, McCalmont TH. Distinguishing neurofibroma from desmoplastic melanoma: the value of the CD34 fingerprint. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:625-630.

- Chen LL, Jaimes N, Barker CA, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:825-833.

- Busam KJ. Desmoplastic melanoma. Clin Lab Med. 2011;31:321-330.

- Schleich C, Ferringer T. Desmoplastic melanoma. Cutis. 2015;96:306, 313-314, 335.

- Lopez DA, Silvers DN, Helwig EB. Cutaneous meningiomas--a clinicopathologic study. Cancer. 1974;34:728-744.

- Miedema JR, Zedek D. Cutaneous meningioma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:208-211.

- Bhanusali DG, Heath C, Gur D, et al. Metastatic meningioma of the scalp. Cutis. 2018;101:386-389.

The Diagnosis: Pigmented Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans

Pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (PDFSP), also known as Bednar tumor, is an uncommon variant of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). Pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans constitutes 1% to 5% of all DFSP cases and most commonly is seen in nonwhite adults in the fourth decade of life, with occasional cases seen in pediatric patients, including some congenital cases. Typical sites of involvement include the shoulders, trunk, arms, legs, head, and neck.1,2 It also has been reported at sites of prior immunization, trauma, and insect bites.3

Histopathologic examination of our patient's shoulder nodule revealed an infiltrative neoplasm in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue composed of spindled cells with a storiform pattern and foci of scattered elongated dendritic pigmented cells. A narrow grenz zone separated the tumor from the epidermis, and characteristic honeycomb infiltration by tumor cells was noted in the subcutaneous fat. The nuclei were bland and monomorphous with areas of neuroid differentiation containing whorls and nerve cord-like structures (quiz image). The tumor cells were diffusely CD34 and vimentin positive, while S-100, SOX-10, neurofilament, smooth muscle actin, desmin, epithelial membrane antigen, and cytokeratins were negative. The immunophenotype excluded the possibility of neurogenic, pericytic, myofibroblastic, and myoid differentiation.

Wang and Yang4 previously reported a case of PDFSP with prominent meningothelial-like whorls focally resembling extracranial meningioma; however, the tumor cells were CD34 positive and epithelial membrane antigen negative, weighing against a diagnosis of meningioma. Most cases of PDFSP demonstrate the COL1A1-PDGFB (collagen type I α; 1/platelet-derived growth factor B-chain) fusion protein caused by the translocation t(17;22)(q22;q13), as in classic DFSP.5

Cellular blue nevus (CBN) is a benign melanocytic neoplasm that can present at any age and often occurs on the buttocks and in the sacrococcygeal region. Clinically, CBN presents as a firm, bluish black to bluish gray, dome-shaped nodule. The size varies from a few millimeters to several centimeters.6,7 Histologically, CBN is located completely in the dermis, extending along the adnexae into the subcutaneous tissue with a dumbbell-shaped outline (Figure 1).6-8 The tumor demonstrates oval epithelioid melanocytes with vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli. Immunohistochemically, tumor cells stain positively for melanocytic markers such as S-100, SOX-10, MART-1, and human melanoma black 45. CD34 expression rarely is reported in a subset of CBN.9

Pigmented neurofibroma is a rare variant of neurofibroma that produces melanin pigment and has a strong association with neurofibromatosis.10 It occurs most frequently in dark-skinned populations (Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI). The most common location is the head and neck region.11,12 Histologically, pigmented neurofibroma resembles a diffuse neurofibroma admixed with melanin-producing cells (Figure 2).12 Immunostaining shows positivity for S-100 in both pigmented and Schwann cells; however, the pigmented cells stain positively for human melanoma black 45, Melan-A, and tyrosinase.10 CD34 can be fingerprint positive in neurofibroma, but a distinction from DFSP can be made by S-100 and SOX-10 immunostaining.13

Desmoplastic melanoma (DM) is an uncommon variant of malignant melanoma and has a higher tendency for persistent local growth and less frequent metastases than other variants of melanoma. It has a predilection for chronically sun-exposed areas such as the head and neck and occurs later in life. Clinically, DM appears as nonspecific, often amelanotic nodules or plaques or as scarlike lesions.14 Histologically, DM can be classified as mixed or pure based on the degree of desmoplasia and cellularity. A paucicellular proliferation of malignant spindled melanocytes within a densely fibrotic stroma with lymphoid nodules in the dermis is characteristic (Figure 3); perineural involvement is common.14,15 The most reliable confirmative stains are S-100 and SOX-10.16

Cutaneous meningioma is a rare tumor and could be subtyped into 3 groups. Type I is primary cutaneous meningioma and usually is present at birth on the scalp and paravertebral regions with a relatively good prognosis. Type II is ectopic soft-tissue meningioma that extends into the skin from around the sensory organs on the face. Type III is local invasion or true metastasis from a central nervous system meningioma. Types II and III develop later in life and the prognosis is poor.17,18 Clinically, lesions present as firm subcutaneous nodules or swellings. Cutaneous meningioma has several histopathologic variants. The classic presentation reveals concentric wrapping of tumor cells with round-oval nuclei containing delicate chromatin. Psammoma bodies are a common finding (Figure 4). Immunohistochemically, tumor cells are diffusely positive for epithelial membrane antigen and vimentin.18,19

The Diagnosis: Pigmented Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans

Pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (PDFSP), also known as Bednar tumor, is an uncommon variant of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). Pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans constitutes 1% to 5% of all DFSP cases and most commonly is seen in nonwhite adults in the fourth decade of life, with occasional cases seen in pediatric patients, including some congenital cases. Typical sites of involvement include the shoulders, trunk, arms, legs, head, and neck.1,2 It also has been reported at sites of prior immunization, trauma, and insect bites.3

Histopathologic examination of our patient's shoulder nodule revealed an infiltrative neoplasm in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue composed of spindled cells with a storiform pattern and foci of scattered elongated dendritic pigmented cells. A narrow grenz zone separated the tumor from the epidermis, and characteristic honeycomb infiltration by tumor cells was noted in the subcutaneous fat. The nuclei were bland and monomorphous with areas of neuroid differentiation containing whorls and nerve cord-like structures (quiz image). The tumor cells were diffusely CD34 and vimentin positive, while S-100, SOX-10, neurofilament, smooth muscle actin, desmin, epithelial membrane antigen, and cytokeratins were negative. The immunophenotype excluded the possibility of neurogenic, pericytic, myofibroblastic, and myoid differentiation.

Wang and Yang4 previously reported a case of PDFSP with prominent meningothelial-like whorls focally resembling extracranial meningioma; however, the tumor cells were CD34 positive and epithelial membrane antigen negative, weighing against a diagnosis of meningioma. Most cases of PDFSP demonstrate the COL1A1-PDGFB (collagen type I α; 1/platelet-derived growth factor B-chain) fusion protein caused by the translocation t(17;22)(q22;q13), as in classic DFSP.5

Cellular blue nevus (CBN) is a benign melanocytic neoplasm that can present at any age and often occurs on the buttocks and in the sacrococcygeal region. Clinically, CBN presents as a firm, bluish black to bluish gray, dome-shaped nodule. The size varies from a few millimeters to several centimeters.6,7 Histologically, CBN is located completely in the dermis, extending along the adnexae into the subcutaneous tissue with a dumbbell-shaped outline (Figure 1).6-8 The tumor demonstrates oval epithelioid melanocytes with vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli. Immunohistochemically, tumor cells stain positively for melanocytic markers such as S-100, SOX-10, MART-1, and human melanoma black 45. CD34 expression rarely is reported in a subset of CBN.9

Pigmented neurofibroma is a rare variant of neurofibroma that produces melanin pigment and has a strong association with neurofibromatosis.10 It occurs most frequently in dark-skinned populations (Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI). The most common location is the head and neck region.11,12 Histologically, pigmented neurofibroma resembles a diffuse neurofibroma admixed with melanin-producing cells (Figure 2).12 Immunostaining shows positivity for S-100 in both pigmented and Schwann cells; however, the pigmented cells stain positively for human melanoma black 45, Melan-A, and tyrosinase.10 CD34 can be fingerprint positive in neurofibroma, but a distinction from DFSP can be made by S-100 and SOX-10 immunostaining.13

Desmoplastic melanoma (DM) is an uncommon variant of malignant melanoma and has a higher tendency for persistent local growth and less frequent metastases than other variants of melanoma. It has a predilection for chronically sun-exposed areas such as the head and neck and occurs later in life. Clinically, DM appears as nonspecific, often amelanotic nodules or plaques or as scarlike lesions.14 Histologically, DM can be classified as mixed or pure based on the degree of desmoplasia and cellularity. A paucicellular proliferation of malignant spindled melanocytes within a densely fibrotic stroma with lymphoid nodules in the dermis is characteristic (Figure 3); perineural involvement is common.14,15 The most reliable confirmative stains are S-100 and SOX-10.16

Cutaneous meningioma is a rare tumor and could be subtyped into 3 groups. Type I is primary cutaneous meningioma and usually is present at birth on the scalp and paravertebral regions with a relatively good prognosis. Type II is ectopic soft-tissue meningioma that extends into the skin from around the sensory organs on the face. Type III is local invasion or true metastasis from a central nervous system meningioma. Types II and III develop later in life and the prognosis is poor.17,18 Clinically, lesions present as firm subcutaneous nodules or swellings. Cutaneous meningioma has several histopathologic variants. The classic presentation reveals concentric wrapping of tumor cells with round-oval nuclei containing delicate chromatin. Psammoma bodies are a common finding (Figure 4). Immunohistochemically, tumor cells are diffusely positive for epithelial membrane antigen and vimentin.18,19

- Amonkar GP, Rupani A, Shah A, et al. Bednar tumor: an uncommon entity. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2016;3:36-38.

- El Hachem M, Diociaiuti A, Latella E, et al. Congenital myxoid and pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a case report. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:E74-E77.

- Anon-Requena MJ, Pico-Valimana M, Munoz-Arias G. Bednar tumor (pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans). Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:618-620.

- Wang J, Yang W. Pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with prominent meningothelial-like whorls. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 1):65-69.

- Zardawi IM, Kattampallil J, Rode J. An unusual pigmented skin tumour. Bednar tumour, dorsum of left foot (pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans). Pathology. 2004;36:358-361.

- Sugianto JZ, Ralston JS, Metcalf JS, et al. Blue nevus and "malignant blue nevus": a concise review. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2016;33:219-224.

- Zembowicz A. Blue nevi and related tumors. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:401-415.

- Zembowicz A, Granter SR, McKee PH, et al. Amelanotic cellular blue nevus: a hypopigmented variant of the cellular blue nevus: clinicopathologic analysis of 20 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1493-1500.

- Smith K, Germain M, Williams J, et al. CD34-positive cellular blue nevi. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:145-150.

- Inaba M, Yamamoto T, Minami R, et al. Pigmented neurofibroma: report of two cases and literature review. Pathol Int. 2001;51:565-569.

- Fetsch JF, Michal M, Miettinen M. Pigmented (melanotic) neurofibroma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 19 lesions from 17 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:331-343.

- Motoi T, Ishida T, Kawato A, et al. Pigmented neurofibroma: review of Japanese patients with an analysis of melanogenesis demonstrating coexpression of c-met protooncogene and microphthalmia-associated transcription factor. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:871-877.

- Yeh I, McCalmont TH. Distinguishing neurofibroma from desmoplastic melanoma: the value of the CD34 fingerprint. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:625-630.

- Chen LL, Jaimes N, Barker CA, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:825-833.

- Busam KJ. Desmoplastic melanoma. Clin Lab Med. 2011;31:321-330.

- Schleich C, Ferringer T. Desmoplastic melanoma. Cutis. 2015;96:306, 313-314, 335.

- Lopez DA, Silvers DN, Helwig EB. Cutaneous meningiomas--a clinicopathologic study. Cancer. 1974;34:728-744.

- Miedema JR, Zedek D. Cutaneous meningioma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:208-211.

- Bhanusali DG, Heath C, Gur D, et al. Metastatic meningioma of the scalp. Cutis. 2018;101:386-389.

- Amonkar GP, Rupani A, Shah A, et al. Bednar tumor: an uncommon entity. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2016;3:36-38.

- El Hachem M, Diociaiuti A, Latella E, et al. Congenital myxoid and pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a case report. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:E74-E77.

- Anon-Requena MJ, Pico-Valimana M, Munoz-Arias G. Bednar tumor (pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans). Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:618-620.

- Wang J, Yang W. Pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with prominent meningothelial-like whorls. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 1):65-69.

- Zardawi IM, Kattampallil J, Rode J. An unusual pigmented skin tumour. Bednar tumour, dorsum of left foot (pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans). Pathology. 2004;36:358-361.

- Sugianto JZ, Ralston JS, Metcalf JS, et al. Blue nevus and "malignant blue nevus": a concise review. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2016;33:219-224.

- Zembowicz A. Blue nevi and related tumors. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:401-415.

- Zembowicz A, Granter SR, McKee PH, et al. Amelanotic cellular blue nevus: a hypopigmented variant of the cellular blue nevus: clinicopathologic analysis of 20 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1493-1500.

- Smith K, Germain M, Williams J, et al. CD34-positive cellular blue nevi. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:145-150.

- Inaba M, Yamamoto T, Minami R, et al. Pigmented neurofibroma: report of two cases and literature review. Pathol Int. 2001;51:565-569.

- Fetsch JF, Michal M, Miettinen M. Pigmented (melanotic) neurofibroma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 19 lesions from 17 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:331-343.

- Motoi T, Ishida T, Kawato A, et al. Pigmented neurofibroma: review of Japanese patients with an analysis of melanogenesis demonstrating coexpression of c-met protooncogene and microphthalmia-associated transcription factor. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:871-877.

- Yeh I, McCalmont TH. Distinguishing neurofibroma from desmoplastic melanoma: the value of the CD34 fingerprint. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:625-630.

- Chen LL, Jaimes N, Barker CA, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:825-833.

- Busam KJ. Desmoplastic melanoma. Clin Lab Med. 2011;31:321-330.

- Schleich C, Ferringer T. Desmoplastic melanoma. Cutis. 2015;96:306, 313-314, 335.

- Lopez DA, Silvers DN, Helwig EB. Cutaneous meningiomas--a clinicopathologic study. Cancer. 1974;34:728-744.

- Miedema JR, Zedek D. Cutaneous meningioma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:208-211.

- Bhanusali DG, Heath C, Gur D, et al. Metastatic meningioma of the scalp. Cutis. 2018;101:386-389.

A 37-year-old woman presented with an asymptomatic, indurated, pigmented, subcutaneous nodule on the right shoulder of more than 3 years' duration. The lesion had gradually increased in size with no associated symptoms. The patient had a history of endometrial adenocarcinoma and papillary thyroid carcinoma, which had been treated by hysterectomy-oophorectomy and right thyroidectomy, respectively. She had no other notable systemic abnormalities, and there was no family history of genetic disease or cancer. Physical examination demonstrated a 1.2×1.8-cm nontender, pigmented, subcutaneous nodule with a rough surface and indistinct borders. An excisional biopsy was performed.

Self-reported adherence fails to line up with objective measures in hemophilia

Considerable differences may exist between objective and subjective measures of adherence to prophylaxis in patients with hemophilia, according to a cross-sectional study.

The results highlight the effect of social desirability bias in self-reported measures of adherence and differences in conceptual understanding of adherence between hemophilia experts and patients.

Vanessa Giroto Guedes, MPH, of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and colleagues studied 29 male patients with hemophilia who received prophylactic treatment between August 2015 and January 2016. The study was conducted at two hemophilia treatment centers in São Paulo.

Self-perceived adherence, measured using the estimated number of clotting factor concentrate doses missed over the previous dispensing interval, was compared with an objective estimate of adherence, measured using the number of vials returned by study participants. The findings were published in Haemophilia.

Patient interviews were conducted during regularly scheduled visits to the treatment facility. The team collected self-perceived adherence data using a 5-point Likert scale, scored from very poor to very good adherence.

After analysis, the researchers found no significant correlation between the objective categorization of adherence and self-perceived extent of adherence (correlation coefficient, 0.10; 95% confidence interval, –0.28 to 0.46; P = .61).

Additionally, there was no significant correlation between the categorization of adherence measured using the proportion of missed doses evaluated objectively and using participants’ self‐reports (correlation coefficient, 0.32; 95% CI, –0.01 to 0.59; P = .11).

“Participants’ self-reported perception of adherence was almost three times more likely to be rated as very good or good than it was for the objective assessment of adherence to be classified as adherent or suboptimally adherent,” the researchers wrote.

No funding sources were reported. One coauthor reported providing consultancy services for manufacturers of therapies for hemophilia. The others reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Guedes VG et al. Haemophilia. 2019 Jul 19. doi: 10.1111/hae.13811.

Considerable differences may exist between objective and subjective measures of adherence to prophylaxis in patients with hemophilia, according to a cross-sectional study.

The results highlight the effect of social desirability bias in self-reported measures of adherence and differences in conceptual understanding of adherence between hemophilia experts and patients.

Vanessa Giroto Guedes, MPH, of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and colleagues studied 29 male patients with hemophilia who received prophylactic treatment between August 2015 and January 2016. The study was conducted at two hemophilia treatment centers in São Paulo.

Self-perceived adherence, measured using the estimated number of clotting factor concentrate doses missed over the previous dispensing interval, was compared with an objective estimate of adherence, measured using the number of vials returned by study participants. The findings were published in Haemophilia.

Patient interviews were conducted during regularly scheduled visits to the treatment facility. The team collected self-perceived adherence data using a 5-point Likert scale, scored from very poor to very good adherence.

After analysis, the researchers found no significant correlation between the objective categorization of adherence and self-perceived extent of adherence (correlation coefficient, 0.10; 95% confidence interval, –0.28 to 0.46; P = .61).

Additionally, there was no significant correlation between the categorization of adherence measured using the proportion of missed doses evaluated objectively and using participants’ self‐reports (correlation coefficient, 0.32; 95% CI, –0.01 to 0.59; P = .11).

“Participants’ self-reported perception of adherence was almost three times more likely to be rated as very good or good than it was for the objective assessment of adherence to be classified as adherent or suboptimally adherent,” the researchers wrote.

No funding sources were reported. One coauthor reported providing consultancy services for manufacturers of therapies for hemophilia. The others reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Guedes VG et al. Haemophilia. 2019 Jul 19. doi: 10.1111/hae.13811.

Considerable differences may exist between objective and subjective measures of adherence to prophylaxis in patients with hemophilia, according to a cross-sectional study.

The results highlight the effect of social desirability bias in self-reported measures of adherence and differences in conceptual understanding of adherence between hemophilia experts and patients.

Vanessa Giroto Guedes, MPH, of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and colleagues studied 29 male patients with hemophilia who received prophylactic treatment between August 2015 and January 2016. The study was conducted at two hemophilia treatment centers in São Paulo.

Self-perceived adherence, measured using the estimated number of clotting factor concentrate doses missed over the previous dispensing interval, was compared with an objective estimate of adherence, measured using the number of vials returned by study participants. The findings were published in Haemophilia.

Patient interviews were conducted during regularly scheduled visits to the treatment facility. The team collected self-perceived adherence data using a 5-point Likert scale, scored from very poor to very good adherence.

After analysis, the researchers found no significant correlation between the objective categorization of adherence and self-perceived extent of adherence (correlation coefficient, 0.10; 95% confidence interval, –0.28 to 0.46; P = .61).

Additionally, there was no significant correlation between the categorization of adherence measured using the proportion of missed doses evaluated objectively and using participants’ self‐reports (correlation coefficient, 0.32; 95% CI, –0.01 to 0.59; P = .11).

“Participants’ self-reported perception of adherence was almost three times more likely to be rated as very good or good than it was for the objective assessment of adherence to be classified as adherent or suboptimally adherent,” the researchers wrote.

No funding sources were reported. One coauthor reported providing consultancy services for manufacturers of therapies for hemophilia. The others reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Guedes VG et al. Haemophilia. 2019 Jul 19. doi: 10.1111/hae.13811.

FROM HAEMOPHILIA

Drug-inducible gene therapy unlocks IL-12 for glioblastoma

For patients with recurrent, high-grade glioblastoma, localized, drug-inducible gene therapy could unlock the anticancer potential of interleukin-12, based on a phase 1 trial.

In 31 patients who had their tumors excised, intraoperative site injection with an IL-12 vector followed by postoperative administration of veledimex, an oral activator of the transgene, increased IL-12 levels in the brain and appeared to improve overall survival, reported E. Antonio Chiocca, MD, PhD, Harvey W. Cushing Professor of Neurosurgery at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues. Although some serious adverse events were encountered, the investigators noted that these were less common with lower doses of veledimex and were reversible upon discontinuation. These findings mark a turning point in IL-12 cancer research, which previously encountered prohibitive safety obstacles.

“There was interest in the use of recombinant IL-12 in humans with cancer, and clinical trials of systemic IL-12 were undertaken but had to be stopped because the cytokine, administered as a recombinant soluble protein, was poorly tolerated,” the investigators wrote in Science Translational Medicine.

To overcome this issue, a novel treatment approach was developed. “With the objective of minimizing systemic toxicity, a ligand-inducible expression switch [RheoSwitch Therapeutic System] was developed to locally control production of IL-12 in the tumor microenvironment. In this system, transcription of the IL-12 transgene occurs only in the presence of the activator ligand, veledimex,” they noted.

The primary aim of the study was to evaluate safety and determine the optimal dose of veledimex; four dose levels were tested: 10, 20, 30, and 40 mg. Survival outcomes also were reported.

The protocol-defined maximum tolerated dose was not reached; however, the 20-mg dose was chosen, based on observed tolerability. At this dose level, the most common grade 3 or higher adverse events were lymphopenia (20.3%), thrombocytopenia (13.3%), and hyponatremia (13.3%). Specifically for grade 3 or higher neurologic adverse events, headache was most common, occurring in 13.3% of patients. Grade 2 cytokine release syndrome occurred in about one-fourth of patients (26.7%), whereas grade 3 cytokine release syndrome occurred about half as frequently (13.3%). All adverse events, including cytokine release syndrome, were reversible upon discontinuation of veledimex.

After a mean follow-up of 13.1 months, the median overall survival among patients receiving the 20-mg dose was 12.7 months. The investigators pointed out that this compared favorably with historical controls, who had a weighted median overall survival of 8.1 months. Those who received 30- or 40-mg doses had the poorest survival, which the investigators attributed to intolerability and other subgroup factors.

Data analysis also revealed a negative correlation between dexamethasone use and survival. Among patients in the 20-mg veledimex group who received 20 mg or less of dexamethasone during active veledimex dosing, median overall survival was extended to 17.8 months. The investigators speculated that this was because of reduced immune suppression, although dexamethasone could have induced cytochrome P450 3A4, which may have increased elimination of veledimex.

“In summary, this phase 1 trial reports the use of a transcriptional switch to safely control dosing of [IL-12], highlighting that this can be accomplished across the [blood-brain barrier] to remodel the tumor microenvironment with an influx of activated immune cells,” the investigators wrote.

They noted that this strategy could potentially be applied to other types of cancer, particularly those that are immunologically cold. “These data contribute to our understanding of IL-12 as a ‘master regulator’ of the immune system and highlight that even the transient production of this cytokine may function as a match to turn tumors from cold to hot.”

The study was funded by Ziopharm Oncology and the National Institutes of Health. The investigators reported additional relationships with Advantagene, Stemgen, Sigilon Therapeutics, and others.

SOURCE: Chiocca EA et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Aug 14. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw5680.

For patients with recurrent, high-grade glioblastoma, localized, drug-inducible gene therapy could unlock the anticancer potential of interleukin-12, based on a phase 1 trial.

In 31 patients who had their tumors excised, intraoperative site injection with an IL-12 vector followed by postoperative administration of veledimex, an oral activator of the transgene, increased IL-12 levels in the brain and appeared to improve overall survival, reported E. Antonio Chiocca, MD, PhD, Harvey W. Cushing Professor of Neurosurgery at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues. Although some serious adverse events were encountered, the investigators noted that these were less common with lower doses of veledimex and were reversible upon discontinuation. These findings mark a turning point in IL-12 cancer research, which previously encountered prohibitive safety obstacles.

“There was interest in the use of recombinant IL-12 in humans with cancer, and clinical trials of systemic IL-12 were undertaken but had to be stopped because the cytokine, administered as a recombinant soluble protein, was poorly tolerated,” the investigators wrote in Science Translational Medicine.

To overcome this issue, a novel treatment approach was developed. “With the objective of minimizing systemic toxicity, a ligand-inducible expression switch [RheoSwitch Therapeutic System] was developed to locally control production of IL-12 in the tumor microenvironment. In this system, transcription of the IL-12 transgene occurs only in the presence of the activator ligand, veledimex,” they noted.

The primary aim of the study was to evaluate safety and determine the optimal dose of veledimex; four dose levels were tested: 10, 20, 30, and 40 mg. Survival outcomes also were reported.

The protocol-defined maximum tolerated dose was not reached; however, the 20-mg dose was chosen, based on observed tolerability. At this dose level, the most common grade 3 or higher adverse events were lymphopenia (20.3%), thrombocytopenia (13.3%), and hyponatremia (13.3%). Specifically for grade 3 or higher neurologic adverse events, headache was most common, occurring in 13.3% of patients. Grade 2 cytokine release syndrome occurred in about one-fourth of patients (26.7%), whereas grade 3 cytokine release syndrome occurred about half as frequently (13.3%). All adverse events, including cytokine release syndrome, were reversible upon discontinuation of veledimex.

After a mean follow-up of 13.1 months, the median overall survival among patients receiving the 20-mg dose was 12.7 months. The investigators pointed out that this compared favorably with historical controls, who had a weighted median overall survival of 8.1 months. Those who received 30- or 40-mg doses had the poorest survival, which the investigators attributed to intolerability and other subgroup factors.

Data analysis also revealed a negative correlation between dexamethasone use and survival. Among patients in the 20-mg veledimex group who received 20 mg or less of dexamethasone during active veledimex dosing, median overall survival was extended to 17.8 months. The investigators speculated that this was because of reduced immune suppression, although dexamethasone could have induced cytochrome P450 3A4, which may have increased elimination of veledimex.

“In summary, this phase 1 trial reports the use of a transcriptional switch to safely control dosing of [IL-12], highlighting that this can be accomplished across the [blood-brain barrier] to remodel the tumor microenvironment with an influx of activated immune cells,” the investigators wrote.

They noted that this strategy could potentially be applied to other types of cancer, particularly those that are immunologically cold. “These data contribute to our understanding of IL-12 as a ‘master regulator’ of the immune system and highlight that even the transient production of this cytokine may function as a match to turn tumors from cold to hot.”

The study was funded by Ziopharm Oncology and the National Institutes of Health. The investigators reported additional relationships with Advantagene, Stemgen, Sigilon Therapeutics, and others.

SOURCE: Chiocca EA et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Aug 14. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw5680.

For patients with recurrent, high-grade glioblastoma, localized, drug-inducible gene therapy could unlock the anticancer potential of interleukin-12, based on a phase 1 trial.

In 31 patients who had their tumors excised, intraoperative site injection with an IL-12 vector followed by postoperative administration of veledimex, an oral activator of the transgene, increased IL-12 levels in the brain and appeared to improve overall survival, reported E. Antonio Chiocca, MD, PhD, Harvey W. Cushing Professor of Neurosurgery at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues. Although some serious adverse events were encountered, the investigators noted that these were less common with lower doses of veledimex and were reversible upon discontinuation. These findings mark a turning point in IL-12 cancer research, which previously encountered prohibitive safety obstacles.

“There was interest in the use of recombinant IL-12 in humans with cancer, and clinical trials of systemic IL-12 were undertaken but had to be stopped because the cytokine, administered as a recombinant soluble protein, was poorly tolerated,” the investigators wrote in Science Translational Medicine.

To overcome this issue, a novel treatment approach was developed. “With the objective of minimizing systemic toxicity, a ligand-inducible expression switch [RheoSwitch Therapeutic System] was developed to locally control production of IL-12 in the tumor microenvironment. In this system, transcription of the IL-12 transgene occurs only in the presence of the activator ligand, veledimex,” they noted.

The primary aim of the study was to evaluate safety and determine the optimal dose of veledimex; four dose levels were tested: 10, 20, 30, and 40 mg. Survival outcomes also were reported.

The protocol-defined maximum tolerated dose was not reached; however, the 20-mg dose was chosen, based on observed tolerability. At this dose level, the most common grade 3 or higher adverse events were lymphopenia (20.3%), thrombocytopenia (13.3%), and hyponatremia (13.3%). Specifically for grade 3 or higher neurologic adverse events, headache was most common, occurring in 13.3% of patients. Grade 2 cytokine release syndrome occurred in about one-fourth of patients (26.7%), whereas grade 3 cytokine release syndrome occurred about half as frequently (13.3%). All adverse events, including cytokine release syndrome, were reversible upon discontinuation of veledimex.

After a mean follow-up of 13.1 months, the median overall survival among patients receiving the 20-mg dose was 12.7 months. The investigators pointed out that this compared favorably with historical controls, who had a weighted median overall survival of 8.1 months. Those who received 30- or 40-mg doses had the poorest survival, which the investigators attributed to intolerability and other subgroup factors.

Data analysis also revealed a negative correlation between dexamethasone use and survival. Among patients in the 20-mg veledimex group who received 20 mg or less of dexamethasone during active veledimex dosing, median overall survival was extended to 17.8 months. The investigators speculated that this was because of reduced immune suppression, although dexamethasone could have induced cytochrome P450 3A4, which may have increased elimination of veledimex.

“In summary, this phase 1 trial reports the use of a transcriptional switch to safely control dosing of [IL-12], highlighting that this can be accomplished across the [blood-brain barrier] to remodel the tumor microenvironment with an influx of activated immune cells,” the investigators wrote.

They noted that this strategy could potentially be applied to other types of cancer, particularly those that are immunologically cold. “These data contribute to our understanding of IL-12 as a ‘master regulator’ of the immune system and highlight that even the transient production of this cytokine may function as a match to turn tumors from cold to hot.”

The study was funded by Ziopharm Oncology and the National Institutes of Health. The investigators reported additional relationships with Advantagene, Stemgen, Sigilon Therapeutics, and others.

SOURCE: Chiocca EA et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Aug 14. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw5680.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: For patients with recurrent, high-grade glioblastoma, localized, drug-inducible gene therapy could unlock the anticancer potential of interleukin-12.

Major finding: After 13.1 months of follow-up, median overall survival was 12.7 months, compared with a weighted median overall survival among historical controls of 8.1 months.

Study details: A phase 1 trial involving 31 patients with recurrent glioblastoma.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Ziopharm Oncology and the National Institutes of Health. The investigators reported additional relationships with Advantagene, Stemgen, Sigilon Therapeutics, and others.

Source: Chiocca EA et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Aug 14. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw5680.

Possible role of enterovirus infection in acute flaccid myelitis cases detected

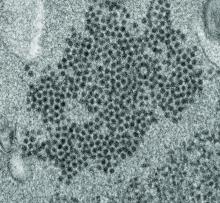

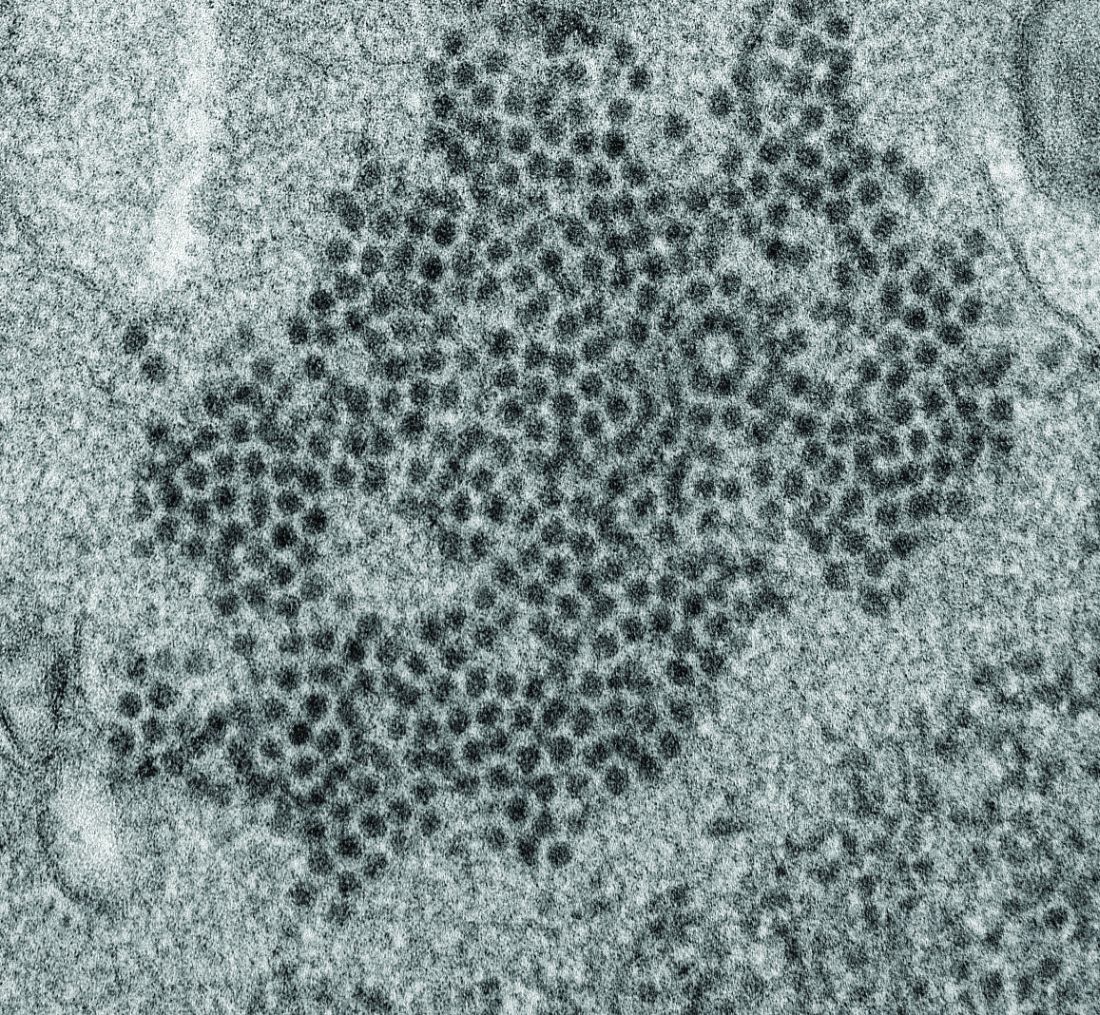

High levels of enterovirus (EV) peptides were found in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum samples of individuals with acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) that were not present in a variety of control individuals, according to the results of a small study of patients with and without AFM published online in mBio.

In 2018, CSF samples from AFM patients were investigated by viral-capture high-throughput sequencing. These CSF and serum samples, as well as those from multiple controls, were tested for antibodies to human EVs using peptide microarrays, according to Nischay Mishra, PhD, of Columbia University, New York, and colleagues.

Although EV RNA was confirmed in CSF from only 1 adult AFM case and 1 non-AFM case, antibodies to EV peptides were present in 11 of 14 AFM patients (79%), which was a significantly higher rate than in control groups, including non-AFM patients (1 of 5, or 20%), children with Kawasaki disease (0 of 10), and adults with non-AFM CNS diseases (2 of 11, 18%), according to the authors.

In addition, 6 of 14 (43%) CSF samples and 8 of 11 (73%) serum samples from AFM patients were immunoreactive to an EV-D68–specific peptide, whereas samples from the three control groups were not immunoreactive in either CSF or sera. Previous studies have suggested that infection with EV-D68 and EV-A71 may contribute to AFM.

“There have been 570 confirmed cases since CDC began tracking AFM in August 2014. AFM outbreaks were reported to the CDC in 2014, 2016, and 2018. AFM affects the spinal cord and is characterized by the sudden onset of muscle weakness in one or more limbs. Spikes in AFM cases, primarily in children, have coincided in time and location with outbreaks of EV-D68 and a related enterovirus, EV-A71,” according to an NIH media advisory discussing the article.

In particular, as the study authors point out, a potential link to EV-D68 has also been based on the presence of viral RNA in some respiratory and stool specimens and the observation that EV-D68 infection can result in spinal cord infection.

“While other etiologies of AFM continue to be investigated, our study provides further evidence that EV infection may be a factor in AFM. In the absence of direct detection of a pathogen, antibody evidence of pathogen exposure within the CNS can be an important indicator of the underlying cause of disease,” Dr. Mishra and his colleagues added.

“These initial results may provide avenues to further explore how exposure to EV may contribute to AFM as well as the development of diagnostic tools and treatments,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported that they had no competing financial interests.

SOURCE: Mishra N et al. mBio. 2019 Aug;10(4):e01903-19.

High levels of enterovirus (EV) peptides were found in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum samples of individuals with acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) that were not present in a variety of control individuals, according to the results of a small study of patients with and without AFM published online in mBio.

In 2018, CSF samples from AFM patients were investigated by viral-capture high-throughput sequencing. These CSF and serum samples, as well as those from multiple controls, were tested for antibodies to human EVs using peptide microarrays, according to Nischay Mishra, PhD, of Columbia University, New York, and colleagues.

Although EV RNA was confirmed in CSF from only 1 adult AFM case and 1 non-AFM case, antibodies to EV peptides were present in 11 of 14 AFM patients (79%), which was a significantly higher rate than in control groups, including non-AFM patients (1 of 5, or 20%), children with Kawasaki disease (0 of 10), and adults with non-AFM CNS diseases (2 of 11, 18%), according to the authors.

In addition, 6 of 14 (43%) CSF samples and 8 of 11 (73%) serum samples from AFM patients were immunoreactive to an EV-D68–specific peptide, whereas samples from the three control groups were not immunoreactive in either CSF or sera. Previous studies have suggested that infection with EV-D68 and EV-A71 may contribute to AFM.

“There have been 570 confirmed cases since CDC began tracking AFM in August 2014. AFM outbreaks were reported to the CDC in 2014, 2016, and 2018. AFM affects the spinal cord and is characterized by the sudden onset of muscle weakness in one or more limbs. Spikes in AFM cases, primarily in children, have coincided in time and location with outbreaks of EV-D68 and a related enterovirus, EV-A71,” according to an NIH media advisory discussing the article.

In particular, as the study authors point out, a potential link to EV-D68 has also been based on the presence of viral RNA in some respiratory and stool specimens and the observation that EV-D68 infection can result in spinal cord infection.

“While other etiologies of AFM continue to be investigated, our study provides further evidence that EV infection may be a factor in AFM. In the absence of direct detection of a pathogen, antibody evidence of pathogen exposure within the CNS can be an important indicator of the underlying cause of disease,” Dr. Mishra and his colleagues added.

“These initial results may provide avenues to further explore how exposure to EV may contribute to AFM as well as the development of diagnostic tools and treatments,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported that they had no competing financial interests.

SOURCE: Mishra N et al. mBio. 2019 Aug;10(4):e01903-19.

High levels of enterovirus (EV) peptides were found in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum samples of individuals with acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) that were not present in a variety of control individuals, according to the results of a small study of patients with and without AFM published online in mBio.

In 2018, CSF samples from AFM patients were investigated by viral-capture high-throughput sequencing. These CSF and serum samples, as well as those from multiple controls, were tested for antibodies to human EVs using peptide microarrays, according to Nischay Mishra, PhD, of Columbia University, New York, and colleagues.

Although EV RNA was confirmed in CSF from only 1 adult AFM case and 1 non-AFM case, antibodies to EV peptides were present in 11 of 14 AFM patients (79%), which was a significantly higher rate than in control groups, including non-AFM patients (1 of 5, or 20%), children with Kawasaki disease (0 of 10), and adults with non-AFM CNS diseases (2 of 11, 18%), according to the authors.

In addition, 6 of 14 (43%) CSF samples and 8 of 11 (73%) serum samples from AFM patients were immunoreactive to an EV-D68–specific peptide, whereas samples from the three control groups were not immunoreactive in either CSF or sera. Previous studies have suggested that infection with EV-D68 and EV-A71 may contribute to AFM.

“There have been 570 confirmed cases since CDC began tracking AFM in August 2014. AFM outbreaks were reported to the CDC in 2014, 2016, and 2018. AFM affects the spinal cord and is characterized by the sudden onset of muscle weakness in one or more limbs. Spikes in AFM cases, primarily in children, have coincided in time and location with outbreaks of EV-D68 and a related enterovirus, EV-A71,” according to an NIH media advisory discussing the article.

In particular, as the study authors point out, a potential link to EV-D68 has also been based on the presence of viral RNA in some respiratory and stool specimens and the observation that EV-D68 infection can result in spinal cord infection.

“While other etiologies of AFM continue to be investigated, our study provides further evidence that EV infection may be a factor in AFM. In the absence of direct detection of a pathogen, antibody evidence of pathogen exposure within the CNS can be an important indicator of the underlying cause of disease,” Dr. Mishra and his colleagues added.

“These initial results may provide avenues to further explore how exposure to EV may contribute to AFM as well as the development of diagnostic tools and treatments,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported that they had no competing financial interests.

SOURCE: Mishra N et al. mBio. 2019 Aug;10(4):e01903-19.

FROM MBIO

Key clinical point:

Major finding: EV peptide antibodies were present in 11 of 14 AFM patients (79%), significantly higher than in controls.

Study details: A peptide microarray analysis was performed on CSF and sera from 14 AFM patients, as well as three control groups of 5 pediatric and adult patients with a non-AFM CNS diseases, 10 children with Kawasaki disease, and 10 adult patients with non-AFM CNS diseases.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported that they had no conflicts.

Source: Mishra N et al. mBio. 2019 Aug;10(4):e01903-19.

Low benefits spur alternative drug cost proposals

It’s no secret that cancer drugs are among the most expensive medical treatments in the United States, and now, new research reveals some high-priced cancer drugs may yield little benefit for patients.

A recent analysis of 71 oncology indications approved by the Food and Drug Administration between 2011 and 2017 found that overall survival gains were marginal for drugs approved by the FDA based on overall survival (OS) data. The majority of the 71 indications (75%) demonstrated no statistically significant improvement in patient-reported outcomes (PROs), according to the study (JAMA Oncol. 2019 Jul 3 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1760).

More than half of the indications evaluated demonstrated neither an OS benefit nor a PRO improvement post approval, the study found.

While the researchers did not analyze cost, a number of the cancer drugs that demonstrated little benefit come with a high price tag. Cabozantinib (Cabometyx) for example, approved for the treatment of medullary thyroid carcinoma and advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) during the study period, did not demonstrate an overall survival benefit post approval, findings showed. Cabometyx, approved based on survival data, had a 2016 wholesale acquisition cost of $13,750 for a 1-month supply. Olaparib (Lynparza) meanwhile, approved for the treatment of advanced ovarian cancer during the study period, also showed no overall survival benefit post approval. The 2017 wholesale acquisition cost for olaparib was $13,482 for a 30-day supply.

Investigators noted in the study that evaluation of OS can be challenging or unfeasible in some instances and is complicated by factors such as use of crossover trial design.

The findings emphasize the need for a sharper eye on how regulatory authorities approve drugs, said Chadi Nabhan, MD, senior author of the study and chief medical officer at Aptitude Health based in Chicago.