User login

Ketogenic diets are what’s cooking for drug-refractory epilepsy

BANGKOK – For a form of epilepsy treatment that’s been around since the 1920s, ketogenic diet therapy has lately been the focus of a surprising wealth of clinical research and development, Suvasini Sharma, MD, observed at the International Epilepsy Congress.

This high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet is now well established as a valid and effective treatment option for children and adults with drug-refractory epilepsy who aren’t candidates for surgery. That’s about a third of all epilepsy patients. And as the recently overhauled pediatric ketogenic diet therapy (KDT) best practice consensus guidelines emphasize, KDT should be strongly considered after two antiepileptic drugs have failed, and even earlier for several epilepsy syndromes, noted Dr. Sharma, a pediatric neurologist at Lady Hardinge Medical College and Kalawati Saran Children’s Hospital in New Delhi, and a coauthor of the updated guidelines.

“The consensus guidelines recommend that you start thinking about the diet early, without waiting for every drug to fail,” she said at the congress, sponsored by the International League Against Epilepsy.

Among the KDT-related topics she highlighted were the recently revised best practice consensus guidelines; an expanding role for KDT in infants, critical care settings, and in epileptic encephalopathies; mounting evidence that KDT provides additional benefits beyond seizure control; and promising new alternative diet therapies. She also described the challenges of using KDT in a low-resource nation such as India, where most of the 1.3 billion people shop in markets where food isn’t packaged with the nutritional content labels essential to traditional KDTs, and low literacy is common.

KDT best practice guidelines

The latest guidelines, which include the details of standardized KDT protocols as well as a summary of recent translational research into mechanisms of action, replace the previous 10-year-old version. Flexibility is now the watchword. While the classic KDT was started as an inpatient intervention involving several days of fasting followed by multiday gradual reintroduction of calories, that approach is now deemed optional (Epilepsia Open. 2018 May 21;3[2]:175-92).

“By and large, the trend now is going to nonfasting initiation on an outpatient basis, but with more stringent monitoring,” according to Dr. Sharma.

The guidelines note that while the research literature shows that, on average, KDT results in about a 50% chance of at least a 50% reduction in seizure frequency in patients with drug-refractory epilepsy, there are a dozen specific conditions with 70% or greater responder rates: infantile spasms, tuberous sclerosis, epilepsy with myoclonic-atonic seizures, Dravet syndrome, glucose transporter 1 deficiency syndrome (Glut 1DS), pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency (PDHD), febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES), super-refractory status epilepticus (SRSE), Ohtahara syndrome, complex I mitochondrial disorders, Angelman syndrome, and children with gastrostomy tubes. For Glut1DS and PDHD, KDTs should be considered the treatment of first choice.

Traditionally, KDTs weren’t recommended for children younger than age 2 years. There were concerns that maintaining ketosis and meeting growth requirements were contradictory goals. That’s no longer believed to be so. Indeed, current evidence shows that KDT is highly effective and well tolerated in infants with refractory epilepsy. European guidelines address patient selection, pre-KDT counseling, preferred methods of initiation and KDT discontinuation, and other key issues (Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2016 Nov;20[6]:798-809).

The guidelines recognize four major, well-studied types of KDT: the classic long-chain triglyceride-centric diet; the medium-chain triglyceride diet; the more user-friendly modified Atkins diet; and low glycemic index therapy. Except in children younger than 2 years old, who should be started on the classic KDT, the consensus panel recommended that the specific KDT selected should be based on the family and child situation and the expertise at the local KDT center. Perceived differences in efficacy between the diets aren’t supported by persuasive evidence.

KDT benefits beyond seizure control

“Most of us who work in the diet scene are aware that patients often report increased alertness, and sometimes improved cognition,” said Dr. Sharma.

That subjective experience is now supported by evidence from a randomized, controlled trial. Dutch investigators who randomized 50 drug-refractory pediatric epilepsy patients to KDT or usual care documented a positive impact of the diet therapy on cognitive activation, mood, and anxious behavior (Epilepsy Behav. 2016 Jul;60:153-7).

More recently, a systematic review showed that while subjective assessments support claims of improved alertness, attention, and global cognition in patients on KDT for refractory epilepsy, structured neuropsychologic testing confirms the enhanced alertness but without significantly improved global cognition. The investigators reported that the improvements were unrelated to decreases in medication, the type of KDT or age at its introduction, or sleep improvement. Rather, the benefits appeared to be due to a combination of seizure reduction and direct effects of KDT on cognition (Epilepsy Behav. 2018 Oct;87:69-77).

There is also encouraging preliminary evidence of a possible protective effect of KDT against sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) in a mouse model (Epilepsia. 2016 Aug;57[8]:e178-82. doi: 10.1111/epi.13444).

The use of KDT in critical care settings

Investigators from the pediatric Status Epilepticus Research Group (pSERG) reported that 10 of 14 patients with convulsive refractory status epilepticus achieved EEG seizure resolution within 7 days after starting KDT. Moreover, 11 patients were able to be weaned off their continuous infusions within 14 days of starting KDT. Treatment-emergent gastroparesis and hypertriglyceridemia occurred in three patients (Epilepsy Res. 2018 Aug;144:1-6).

“It was reasonably well tolerated, but they started it quite late – a median of 13 days after onset of refractory status epilepticus. It should come much earlier on our list of therapies. We shouldn’t be waiting 2 weeks before going to the ketogenic diet, because we can diagnose refractory status epilepticus within 48 hours after arrival in the ICU most of the time,” Dr. Sharma said.

Austrian investigators have pioneered the use of intravenous KDT as a bridge when oral therapy is temporarily impossible because of status epilepticus, surgery, or other reasons. They reported that parental KDT with fat intake of 3.5-4 g/kg per day was safe and effective in their series of 17 young children with epilepsy (Epilepsia Open. 2017 Nov 16;3[1]:30-9).

The future: nonketogenic diet therapies

KDT in its various forms is just too demanding and restrictive for some patients. Nonketotic alternatives are being explored.

Triheptanoin is a synthetic medium-chain triglyceride in the form of an edible, odorless, tasteless oil. Its mechanism of action is by anaplerosis: that is, energy generation via replenishment of the tricarboxylic acid cycle. After demonstration of neuroprotective and anticonvulsant effects in several mouse models, Australian investigators conducted a pilot study of 30- to 100-mL/day of oral triheptanoin as add-on therapy in 12 children with drug-refractory epilepsy. Eight of the 12 took triheptanoin for longer than 12 weeks, and 5 of those 8 experienced a sustained greater than 50% reduction in seizure frequency, including 1 who remained seizure free for 30 weeks. Seven children had diarrhea or other GI side effects (Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2018 Nov;22[6]:1074-80).

Parisian investigators have developed a nonketotic, palatable combination of amino acids, carbohydrates, and fatty acids with a low ratio of fat to protein-plus-carbohydrates that provided potent protection against seizures in a mouse model. This suggests that the traditional 4:1 ratio sought in KDT isn’t necessary for robust seizure reduction (Sci Rep. 2017 Jul 14;7[1]:5496).

“This is probably going to be the future of nutritional therapy in epilepsy,” Dr. Sharma predicted.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

BANGKOK – For a form of epilepsy treatment that’s been around since the 1920s, ketogenic diet therapy has lately been the focus of a surprising wealth of clinical research and development, Suvasini Sharma, MD, observed at the International Epilepsy Congress.

This high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet is now well established as a valid and effective treatment option for children and adults with drug-refractory epilepsy who aren’t candidates for surgery. That’s about a third of all epilepsy patients. And as the recently overhauled pediatric ketogenic diet therapy (KDT) best practice consensus guidelines emphasize, KDT should be strongly considered after two antiepileptic drugs have failed, and even earlier for several epilepsy syndromes, noted Dr. Sharma, a pediatric neurologist at Lady Hardinge Medical College and Kalawati Saran Children’s Hospital in New Delhi, and a coauthor of the updated guidelines.

“The consensus guidelines recommend that you start thinking about the diet early, without waiting for every drug to fail,” she said at the congress, sponsored by the International League Against Epilepsy.

Among the KDT-related topics she highlighted were the recently revised best practice consensus guidelines; an expanding role for KDT in infants, critical care settings, and in epileptic encephalopathies; mounting evidence that KDT provides additional benefits beyond seizure control; and promising new alternative diet therapies. She also described the challenges of using KDT in a low-resource nation such as India, where most of the 1.3 billion people shop in markets where food isn’t packaged with the nutritional content labels essential to traditional KDTs, and low literacy is common.

KDT best practice guidelines

The latest guidelines, which include the details of standardized KDT protocols as well as a summary of recent translational research into mechanisms of action, replace the previous 10-year-old version. Flexibility is now the watchword. While the classic KDT was started as an inpatient intervention involving several days of fasting followed by multiday gradual reintroduction of calories, that approach is now deemed optional (Epilepsia Open. 2018 May 21;3[2]:175-92).

“By and large, the trend now is going to nonfasting initiation on an outpatient basis, but with more stringent monitoring,” according to Dr. Sharma.

The guidelines note that while the research literature shows that, on average, KDT results in about a 50% chance of at least a 50% reduction in seizure frequency in patients with drug-refractory epilepsy, there are a dozen specific conditions with 70% or greater responder rates: infantile spasms, tuberous sclerosis, epilepsy with myoclonic-atonic seizures, Dravet syndrome, glucose transporter 1 deficiency syndrome (Glut 1DS), pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency (PDHD), febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES), super-refractory status epilepticus (SRSE), Ohtahara syndrome, complex I mitochondrial disorders, Angelman syndrome, and children with gastrostomy tubes. For Glut1DS and PDHD, KDTs should be considered the treatment of first choice.

Traditionally, KDTs weren’t recommended for children younger than age 2 years. There were concerns that maintaining ketosis and meeting growth requirements were contradictory goals. That’s no longer believed to be so. Indeed, current evidence shows that KDT is highly effective and well tolerated in infants with refractory epilepsy. European guidelines address patient selection, pre-KDT counseling, preferred methods of initiation and KDT discontinuation, and other key issues (Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2016 Nov;20[6]:798-809).

The guidelines recognize four major, well-studied types of KDT: the classic long-chain triglyceride-centric diet; the medium-chain triglyceride diet; the more user-friendly modified Atkins diet; and low glycemic index therapy. Except in children younger than 2 years old, who should be started on the classic KDT, the consensus panel recommended that the specific KDT selected should be based on the family and child situation and the expertise at the local KDT center. Perceived differences in efficacy between the diets aren’t supported by persuasive evidence.

KDT benefits beyond seizure control

“Most of us who work in the diet scene are aware that patients often report increased alertness, and sometimes improved cognition,” said Dr. Sharma.

That subjective experience is now supported by evidence from a randomized, controlled trial. Dutch investigators who randomized 50 drug-refractory pediatric epilepsy patients to KDT or usual care documented a positive impact of the diet therapy on cognitive activation, mood, and anxious behavior (Epilepsy Behav. 2016 Jul;60:153-7).

More recently, a systematic review showed that while subjective assessments support claims of improved alertness, attention, and global cognition in patients on KDT for refractory epilepsy, structured neuropsychologic testing confirms the enhanced alertness but without significantly improved global cognition. The investigators reported that the improvements were unrelated to decreases in medication, the type of KDT or age at its introduction, or sleep improvement. Rather, the benefits appeared to be due to a combination of seizure reduction and direct effects of KDT on cognition (Epilepsy Behav. 2018 Oct;87:69-77).

There is also encouraging preliminary evidence of a possible protective effect of KDT against sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) in a mouse model (Epilepsia. 2016 Aug;57[8]:e178-82. doi: 10.1111/epi.13444).

The use of KDT in critical care settings

Investigators from the pediatric Status Epilepticus Research Group (pSERG) reported that 10 of 14 patients with convulsive refractory status epilepticus achieved EEG seizure resolution within 7 days after starting KDT. Moreover, 11 patients were able to be weaned off their continuous infusions within 14 days of starting KDT. Treatment-emergent gastroparesis and hypertriglyceridemia occurred in three patients (Epilepsy Res. 2018 Aug;144:1-6).

“It was reasonably well tolerated, but they started it quite late – a median of 13 days after onset of refractory status epilepticus. It should come much earlier on our list of therapies. We shouldn’t be waiting 2 weeks before going to the ketogenic diet, because we can diagnose refractory status epilepticus within 48 hours after arrival in the ICU most of the time,” Dr. Sharma said.

Austrian investigators have pioneered the use of intravenous KDT as a bridge when oral therapy is temporarily impossible because of status epilepticus, surgery, or other reasons. They reported that parental KDT with fat intake of 3.5-4 g/kg per day was safe and effective in their series of 17 young children with epilepsy (Epilepsia Open. 2017 Nov 16;3[1]:30-9).

The future: nonketogenic diet therapies

KDT in its various forms is just too demanding and restrictive for some patients. Nonketotic alternatives are being explored.

Triheptanoin is a synthetic medium-chain triglyceride in the form of an edible, odorless, tasteless oil. Its mechanism of action is by anaplerosis: that is, energy generation via replenishment of the tricarboxylic acid cycle. After demonstration of neuroprotective and anticonvulsant effects in several mouse models, Australian investigators conducted a pilot study of 30- to 100-mL/day of oral triheptanoin as add-on therapy in 12 children with drug-refractory epilepsy. Eight of the 12 took triheptanoin for longer than 12 weeks, and 5 of those 8 experienced a sustained greater than 50% reduction in seizure frequency, including 1 who remained seizure free for 30 weeks. Seven children had diarrhea or other GI side effects (Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2018 Nov;22[6]:1074-80).

Parisian investigators have developed a nonketotic, palatable combination of amino acids, carbohydrates, and fatty acids with a low ratio of fat to protein-plus-carbohydrates that provided potent protection against seizures in a mouse model. This suggests that the traditional 4:1 ratio sought in KDT isn’t necessary for robust seizure reduction (Sci Rep. 2017 Jul 14;7[1]:5496).

“This is probably going to be the future of nutritional therapy in epilepsy,” Dr. Sharma predicted.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

BANGKOK – For a form of epilepsy treatment that’s been around since the 1920s, ketogenic diet therapy has lately been the focus of a surprising wealth of clinical research and development, Suvasini Sharma, MD, observed at the International Epilepsy Congress.

This high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet is now well established as a valid and effective treatment option for children and adults with drug-refractory epilepsy who aren’t candidates for surgery. That’s about a third of all epilepsy patients. And as the recently overhauled pediatric ketogenic diet therapy (KDT) best practice consensus guidelines emphasize, KDT should be strongly considered after two antiepileptic drugs have failed, and even earlier for several epilepsy syndromes, noted Dr. Sharma, a pediatric neurologist at Lady Hardinge Medical College and Kalawati Saran Children’s Hospital in New Delhi, and a coauthor of the updated guidelines.

“The consensus guidelines recommend that you start thinking about the diet early, without waiting for every drug to fail,” she said at the congress, sponsored by the International League Against Epilepsy.

Among the KDT-related topics she highlighted were the recently revised best practice consensus guidelines; an expanding role for KDT in infants, critical care settings, and in epileptic encephalopathies; mounting evidence that KDT provides additional benefits beyond seizure control; and promising new alternative diet therapies. She also described the challenges of using KDT in a low-resource nation such as India, where most of the 1.3 billion people shop in markets where food isn’t packaged with the nutritional content labels essential to traditional KDTs, and low literacy is common.

KDT best practice guidelines

The latest guidelines, which include the details of standardized KDT protocols as well as a summary of recent translational research into mechanisms of action, replace the previous 10-year-old version. Flexibility is now the watchword. While the classic KDT was started as an inpatient intervention involving several days of fasting followed by multiday gradual reintroduction of calories, that approach is now deemed optional (Epilepsia Open. 2018 May 21;3[2]:175-92).

“By and large, the trend now is going to nonfasting initiation on an outpatient basis, but with more stringent monitoring,” according to Dr. Sharma.

The guidelines note that while the research literature shows that, on average, KDT results in about a 50% chance of at least a 50% reduction in seizure frequency in patients with drug-refractory epilepsy, there are a dozen specific conditions with 70% or greater responder rates: infantile spasms, tuberous sclerosis, epilepsy with myoclonic-atonic seizures, Dravet syndrome, glucose transporter 1 deficiency syndrome (Glut 1DS), pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency (PDHD), febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES), super-refractory status epilepticus (SRSE), Ohtahara syndrome, complex I mitochondrial disorders, Angelman syndrome, and children with gastrostomy tubes. For Glut1DS and PDHD, KDTs should be considered the treatment of first choice.

Traditionally, KDTs weren’t recommended for children younger than age 2 years. There were concerns that maintaining ketosis and meeting growth requirements were contradictory goals. That’s no longer believed to be so. Indeed, current evidence shows that KDT is highly effective and well tolerated in infants with refractory epilepsy. European guidelines address patient selection, pre-KDT counseling, preferred methods of initiation and KDT discontinuation, and other key issues (Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2016 Nov;20[6]:798-809).

The guidelines recognize four major, well-studied types of KDT: the classic long-chain triglyceride-centric diet; the medium-chain triglyceride diet; the more user-friendly modified Atkins diet; and low glycemic index therapy. Except in children younger than 2 years old, who should be started on the classic KDT, the consensus panel recommended that the specific KDT selected should be based on the family and child situation and the expertise at the local KDT center. Perceived differences in efficacy between the diets aren’t supported by persuasive evidence.

KDT benefits beyond seizure control

“Most of us who work in the diet scene are aware that patients often report increased alertness, and sometimes improved cognition,” said Dr. Sharma.

That subjective experience is now supported by evidence from a randomized, controlled trial. Dutch investigators who randomized 50 drug-refractory pediatric epilepsy patients to KDT or usual care documented a positive impact of the diet therapy on cognitive activation, mood, and anxious behavior (Epilepsy Behav. 2016 Jul;60:153-7).

More recently, a systematic review showed that while subjective assessments support claims of improved alertness, attention, and global cognition in patients on KDT for refractory epilepsy, structured neuropsychologic testing confirms the enhanced alertness but without significantly improved global cognition. The investigators reported that the improvements were unrelated to decreases in medication, the type of KDT or age at its introduction, or sleep improvement. Rather, the benefits appeared to be due to a combination of seizure reduction and direct effects of KDT on cognition (Epilepsy Behav. 2018 Oct;87:69-77).

There is also encouraging preliminary evidence of a possible protective effect of KDT against sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) in a mouse model (Epilepsia. 2016 Aug;57[8]:e178-82. doi: 10.1111/epi.13444).

The use of KDT in critical care settings

Investigators from the pediatric Status Epilepticus Research Group (pSERG) reported that 10 of 14 patients with convulsive refractory status epilepticus achieved EEG seizure resolution within 7 days after starting KDT. Moreover, 11 patients were able to be weaned off their continuous infusions within 14 days of starting KDT. Treatment-emergent gastroparesis and hypertriglyceridemia occurred in three patients (Epilepsy Res. 2018 Aug;144:1-6).

“It was reasonably well tolerated, but they started it quite late – a median of 13 days after onset of refractory status epilepticus. It should come much earlier on our list of therapies. We shouldn’t be waiting 2 weeks before going to the ketogenic diet, because we can diagnose refractory status epilepticus within 48 hours after arrival in the ICU most of the time,” Dr. Sharma said.

Austrian investigators have pioneered the use of intravenous KDT as a bridge when oral therapy is temporarily impossible because of status epilepticus, surgery, or other reasons. They reported that parental KDT with fat intake of 3.5-4 g/kg per day was safe and effective in their series of 17 young children with epilepsy (Epilepsia Open. 2017 Nov 16;3[1]:30-9).

The future: nonketogenic diet therapies

KDT in its various forms is just too demanding and restrictive for some patients. Nonketotic alternatives are being explored.

Triheptanoin is a synthetic medium-chain triglyceride in the form of an edible, odorless, tasteless oil. Its mechanism of action is by anaplerosis: that is, energy generation via replenishment of the tricarboxylic acid cycle. After demonstration of neuroprotective and anticonvulsant effects in several mouse models, Australian investigators conducted a pilot study of 30- to 100-mL/day of oral triheptanoin as add-on therapy in 12 children with drug-refractory epilepsy. Eight of the 12 took triheptanoin for longer than 12 weeks, and 5 of those 8 experienced a sustained greater than 50% reduction in seizure frequency, including 1 who remained seizure free for 30 weeks. Seven children had diarrhea or other GI side effects (Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2018 Nov;22[6]:1074-80).

Parisian investigators have developed a nonketotic, palatable combination of amino acids, carbohydrates, and fatty acids with a low ratio of fat to protein-plus-carbohydrates that provided potent protection against seizures in a mouse model. This suggests that the traditional 4:1 ratio sought in KDT isn’t necessary for robust seizure reduction (Sci Rep. 2017 Jul 14;7[1]:5496).

“This is probably going to be the future of nutritional therapy in epilepsy,” Dr. Sharma predicted.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

REPORTING FROM IEC 2019

Asthma hospitalization in kids linked with doubled migraine incidence

when compared with a similar pediatric population without asthma. The finding is based on an analysis of more than 11 million U.S. pediatric hospitalizations over the course of a decade.

Among children and adolescents aged 3-21 years who were hospitalized for asthma, migraine rates were significantly higher among girls, adolescents, and whites, compared with boys, children aged 12 years or younger, and nonwhites, respectively, in a trio of adjusted analyses, Riddhiben S. Patel, MD, and associates reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

“Our hope is that, by establishing an association between childhood asthma and migraine, [these children] may be more easily screened for, diagnosed, and treated early by providers,” wrote Dr. Patel, a pediatric neurologist and headache specialist at the University of Mississippi, Jackson, and associates.

Their analysis used administrative billing data collected by the Kids’ Inpatient Database, maintained by the U.S. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. The project includes a representative national sample of about 3 million pediatric hospital discharges every 3 years. The study used data from 11,483,103 hospitalizations of children and adolescents aged 3-21 years during 2003, 2006, 2009, and 2012, and found an overall hospitalization rate of 0.8% billed for migraine. For patients also hospitalized with a billing code for asthma, the rate jumped to 1.36%, a 120% statistically significant relative increase in migraine hospitalizations after adjustment for baseline demographic differences, the researchers said.

Among the children and adolescents hospitalized with an asthma billing code, the relative rate of also having a billing code for migraine after adjustment was a statistically significant 80% higher in girls, compared with boys, a statistically significant 7% higher in adolescents, compared with children 12 years or younger, and was significantly reduced by a relative 45% rate in nonwhites, compared with whites.

The mechanisms behind these associations are not known, but could involve mast-cell degranulation, autonomic dysfunction, or shared genetic or environmental etiologic factors, the authors said.

Dr. Patel reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Patel RS et al. Headache. 2019 June;59[S1]:1-208, Abstract P78.

when compared with a similar pediatric population without asthma. The finding is based on an analysis of more than 11 million U.S. pediatric hospitalizations over the course of a decade.

Among children and adolescents aged 3-21 years who were hospitalized for asthma, migraine rates were significantly higher among girls, adolescents, and whites, compared with boys, children aged 12 years or younger, and nonwhites, respectively, in a trio of adjusted analyses, Riddhiben S. Patel, MD, and associates reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

“Our hope is that, by establishing an association between childhood asthma and migraine, [these children] may be more easily screened for, diagnosed, and treated early by providers,” wrote Dr. Patel, a pediatric neurologist and headache specialist at the University of Mississippi, Jackson, and associates.

Their analysis used administrative billing data collected by the Kids’ Inpatient Database, maintained by the U.S. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. The project includes a representative national sample of about 3 million pediatric hospital discharges every 3 years. The study used data from 11,483,103 hospitalizations of children and adolescents aged 3-21 years during 2003, 2006, 2009, and 2012, and found an overall hospitalization rate of 0.8% billed for migraine. For patients also hospitalized with a billing code for asthma, the rate jumped to 1.36%, a 120% statistically significant relative increase in migraine hospitalizations after adjustment for baseline demographic differences, the researchers said.

Among the children and adolescents hospitalized with an asthma billing code, the relative rate of also having a billing code for migraine after adjustment was a statistically significant 80% higher in girls, compared with boys, a statistically significant 7% higher in adolescents, compared with children 12 years or younger, and was significantly reduced by a relative 45% rate in nonwhites, compared with whites.

The mechanisms behind these associations are not known, but could involve mast-cell degranulation, autonomic dysfunction, or shared genetic or environmental etiologic factors, the authors said.

Dr. Patel reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Patel RS et al. Headache. 2019 June;59[S1]:1-208, Abstract P78.

when compared with a similar pediatric population without asthma. The finding is based on an analysis of more than 11 million U.S. pediatric hospitalizations over the course of a decade.

Among children and adolescents aged 3-21 years who were hospitalized for asthma, migraine rates were significantly higher among girls, adolescents, and whites, compared with boys, children aged 12 years or younger, and nonwhites, respectively, in a trio of adjusted analyses, Riddhiben S. Patel, MD, and associates reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

“Our hope is that, by establishing an association between childhood asthma and migraine, [these children] may be more easily screened for, diagnosed, and treated early by providers,” wrote Dr. Patel, a pediatric neurologist and headache specialist at the University of Mississippi, Jackson, and associates.

Their analysis used administrative billing data collected by the Kids’ Inpatient Database, maintained by the U.S. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. The project includes a representative national sample of about 3 million pediatric hospital discharges every 3 years. The study used data from 11,483,103 hospitalizations of children and adolescents aged 3-21 years during 2003, 2006, 2009, and 2012, and found an overall hospitalization rate of 0.8% billed for migraine. For patients also hospitalized with a billing code for asthma, the rate jumped to 1.36%, a 120% statistically significant relative increase in migraine hospitalizations after adjustment for baseline demographic differences, the researchers said.

Among the children and adolescents hospitalized with an asthma billing code, the relative rate of also having a billing code for migraine after adjustment was a statistically significant 80% higher in girls, compared with boys, a statistically significant 7% higher in adolescents, compared with children 12 years or younger, and was significantly reduced by a relative 45% rate in nonwhites, compared with whites.

The mechanisms behind these associations are not known, but could involve mast-cell degranulation, autonomic dysfunction, or shared genetic or environmental etiologic factors, the authors said.

Dr. Patel reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Patel RS et al. Headache. 2019 June;59[S1]:1-208, Abstract P78.

REPORTING FROM AHS 2019

Criteria found largely interchangeable for classifying radiographic axSpA

, according to a comparative study first presented at the 2019 European League Against Rheumatism and now published.

“The major finding is that patients classified with one set of the criteria are essentially the same as those classified with the other,” according to Anne Boel, a researcher in the department of rheumatology at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center, and first author of the study.

The study addresses a controversy that has persisted since the introduction of ASAS criteria for defining axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) with definite structural changes on conventional radiographs. It was unclear whether this ASAS diagnosis, called radiographic axSpA (r-axSpA), was the same as ankylosing spondylitis (AS) as defined by the older modified New York (mNY) criteria.

In this study, patients from eight cohorts were evaluated with the two classification sets. In addition to having radiographic sacroiliitis, all patients had to have back pain for at least 3 months, which is also mandatory for both classification sets.

Of the 3,434 fulfilling the ASAS criteria for r-axSpA, 96% fulfilled the mNY criteria for AS. Of the 3,882 meeting the mNY criteria for AS, 93% fulfilled the ASAS criteria for r-axSpA.

On the basis of this level of agreement, the authors called the terms r-axSpA and AS “interchangeable.” In the small proportion of cases when there was disagreement, the reason was considered to be minor and not to alter the conclusion that the disease entities are the same.

“Patients cannot be classified according to the ASAS criteria if they first develop back pain at age 45 years or older, so this is one difference between the two criteria sets that would affect classification,” Ms. Boel explained in an interview.

When tallied, 7% of the 4,041 patients with axSpA with radiographic sacroiliitis evaluated met only the mNY criteria, 3% met only the ASAS criteria, 89% met both sets of criteria, and 1% met neither, according to the published data.

Of those who met the mNY criteria but not the ASAS criteria, 99.7% would have potentially fulfilled the ASAS criteria for r-axSpA except for older age at onset. The remainder was attributed to an absence of inflammatory back pain or another spondyloarthritis feature.

Of the 3,434 patients fulfilling the ASAS criteria, 90% fulfilled the mNY criteria because of the presence of inflammatory back pain. Most of those without inflammatory back pain had a mobility restriction and so still met the mNY criteria. A small proportion without inflammatory back pain or mobility restriction fulfilled the ASAS criteria because of other SpA features.

The study resolves a persistent debate over whether AS patients identified by mNY criteria are the same as r-axSpA identified by ASAS criteria, according to the authors, reiterating that these data show that they can be considered the same disease.

This finding is particularly relevant when evaluating studies that have classified patients by either the mNY or the ASAS criteria.

This finding “has important implications for the axSpA research field,” the authors concluded. “Acknowledging that both criteria sets identify the same patients implies that older literature on AS and newer literature on r-axSpA can be directly compared.”

The study had no specific funding source. Ms. Boel reported having no potential conflicts of interest. Coauthors reported ties with pharmaceutical companies outside of this study.

SOURCE: Boel A et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Jul 30. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215707.

, according to a comparative study first presented at the 2019 European League Against Rheumatism and now published.

“The major finding is that patients classified with one set of the criteria are essentially the same as those classified with the other,” according to Anne Boel, a researcher in the department of rheumatology at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center, and first author of the study.

The study addresses a controversy that has persisted since the introduction of ASAS criteria for defining axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) with definite structural changes on conventional radiographs. It was unclear whether this ASAS diagnosis, called radiographic axSpA (r-axSpA), was the same as ankylosing spondylitis (AS) as defined by the older modified New York (mNY) criteria.

In this study, patients from eight cohorts were evaluated with the two classification sets. In addition to having radiographic sacroiliitis, all patients had to have back pain for at least 3 months, which is also mandatory for both classification sets.

Of the 3,434 fulfilling the ASAS criteria for r-axSpA, 96% fulfilled the mNY criteria for AS. Of the 3,882 meeting the mNY criteria for AS, 93% fulfilled the ASAS criteria for r-axSpA.

On the basis of this level of agreement, the authors called the terms r-axSpA and AS “interchangeable.” In the small proportion of cases when there was disagreement, the reason was considered to be minor and not to alter the conclusion that the disease entities are the same.

“Patients cannot be classified according to the ASAS criteria if they first develop back pain at age 45 years or older, so this is one difference between the two criteria sets that would affect classification,” Ms. Boel explained in an interview.

When tallied, 7% of the 4,041 patients with axSpA with radiographic sacroiliitis evaluated met only the mNY criteria, 3% met only the ASAS criteria, 89% met both sets of criteria, and 1% met neither, according to the published data.

Of those who met the mNY criteria but not the ASAS criteria, 99.7% would have potentially fulfilled the ASAS criteria for r-axSpA except for older age at onset. The remainder was attributed to an absence of inflammatory back pain or another spondyloarthritis feature.

Of the 3,434 patients fulfilling the ASAS criteria, 90% fulfilled the mNY criteria because of the presence of inflammatory back pain. Most of those without inflammatory back pain had a mobility restriction and so still met the mNY criteria. A small proportion without inflammatory back pain or mobility restriction fulfilled the ASAS criteria because of other SpA features.

The study resolves a persistent debate over whether AS patients identified by mNY criteria are the same as r-axSpA identified by ASAS criteria, according to the authors, reiterating that these data show that they can be considered the same disease.

This finding is particularly relevant when evaluating studies that have classified patients by either the mNY or the ASAS criteria.

This finding “has important implications for the axSpA research field,” the authors concluded. “Acknowledging that both criteria sets identify the same patients implies that older literature on AS and newer literature on r-axSpA can be directly compared.”

The study had no specific funding source. Ms. Boel reported having no potential conflicts of interest. Coauthors reported ties with pharmaceutical companies outside of this study.

SOURCE: Boel A et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Jul 30. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215707.

, according to a comparative study first presented at the 2019 European League Against Rheumatism and now published.

“The major finding is that patients classified with one set of the criteria are essentially the same as those classified with the other,” according to Anne Boel, a researcher in the department of rheumatology at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center, and first author of the study.

The study addresses a controversy that has persisted since the introduction of ASAS criteria for defining axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) with definite structural changes on conventional radiographs. It was unclear whether this ASAS diagnosis, called radiographic axSpA (r-axSpA), was the same as ankylosing spondylitis (AS) as defined by the older modified New York (mNY) criteria.

In this study, patients from eight cohorts were evaluated with the two classification sets. In addition to having radiographic sacroiliitis, all patients had to have back pain for at least 3 months, which is also mandatory for both classification sets.

Of the 3,434 fulfilling the ASAS criteria for r-axSpA, 96% fulfilled the mNY criteria for AS. Of the 3,882 meeting the mNY criteria for AS, 93% fulfilled the ASAS criteria for r-axSpA.

On the basis of this level of agreement, the authors called the terms r-axSpA and AS “interchangeable.” In the small proportion of cases when there was disagreement, the reason was considered to be minor and not to alter the conclusion that the disease entities are the same.

“Patients cannot be classified according to the ASAS criteria if they first develop back pain at age 45 years or older, so this is one difference between the two criteria sets that would affect classification,” Ms. Boel explained in an interview.

When tallied, 7% of the 4,041 patients with axSpA with radiographic sacroiliitis evaluated met only the mNY criteria, 3% met only the ASAS criteria, 89% met both sets of criteria, and 1% met neither, according to the published data.

Of those who met the mNY criteria but not the ASAS criteria, 99.7% would have potentially fulfilled the ASAS criteria for r-axSpA except for older age at onset. The remainder was attributed to an absence of inflammatory back pain or another spondyloarthritis feature.

Of the 3,434 patients fulfilling the ASAS criteria, 90% fulfilled the mNY criteria because of the presence of inflammatory back pain. Most of those without inflammatory back pain had a mobility restriction and so still met the mNY criteria. A small proportion without inflammatory back pain or mobility restriction fulfilled the ASAS criteria because of other SpA features.

The study resolves a persistent debate over whether AS patients identified by mNY criteria are the same as r-axSpA identified by ASAS criteria, according to the authors, reiterating that these data show that they can be considered the same disease.

This finding is particularly relevant when evaluating studies that have classified patients by either the mNY or the ASAS criteria.

This finding “has important implications for the axSpA research field,” the authors concluded. “Acknowledging that both criteria sets identify the same patients implies that older literature on AS and newer literature on r-axSpA can be directly compared.”

The study had no specific funding source. Ms. Boel reported having no potential conflicts of interest. Coauthors reported ties with pharmaceutical companies outside of this study.

SOURCE: Boel A et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Jul 30. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215707.

FROM ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES

Fatal Drug-Resistant Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillus fumigatus in a 56-Year-Old Immunosuppressed Man (FULL)

Historically, aspergillosis in patients with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has carried a high mortality rate. However, recent data demonstrate a dramatic improvement in outcomes for patients with HSCT: 90-day survival increased from 22% before 2000 to 45% over the past 15 years.1 Improved outcomes coincide with changes in transplant immunosuppression practices, use of cross-sectional imaging for early disease identification, galactomannan screening, and the development of novel treatment options.

Voriconazole is an azole drug that blocks the synthesis of ergosterol, a vital component of the cellular membrane of fungi. Voriconazole was approved in 2002 after a clinical trial demonstrated an improvement in 50% of patients with invasive aspergillosis in the voriconazole arm vs 30% in the amphotericin B arm at 12 weeks.2 Amphotericin B is a polyene antifungal drug that binds with ergosterol, creating leaks in the cell membrane that lead to cellular demise. Voriconazole quickly became the first-line therapy for invasive aspergillosis and is recommended by both the Infectious Disease Society of American (IDSA) and the European Conference on Infections in Leukemia.3

Case Presentation

A 55-year-old man with high-risk chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) underwent a 10 of 10 human leukocyte antigen allele and antigen-matched peripheral blood allogeneic HSCT with a myeloablative-conditioning regimen of busulfan and cyclophosphamide, along with prophylactic voriconazole, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, and acyclovir. After successful engraftment (without significant neutropenia), his posttransplant course was complicated by grade 2 graft vs host disease (GVHD) of the skin, eyes, and liver, which responded well to steroids and tacrolimus. Voriconazole was continued for 5 months until immunosuppression was minimized (tacrolimus 1 mg twice daily). Two months later, the patient’s GVHD worsened, necessitating treatment at an outside hospital with high-dose prednisone (2 mg/kg/d) and cyclosporine (300 mg twice daily). Voriconazole prophylaxis was not reinitiated at that time.

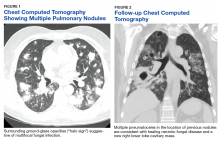

One year later, at a routine follow-up appointment, the patient endorsed several weeks of malaise, weight loss, and nonproductive cough. The patient’s immunosuppression recently had been reduced to 1 mg/kg/d of prednisone and 100 mg of cyclosporine twice daily. A chest X-ray demonstrated multiple pulmonary nodules; follow-up chest computed tomography (CT) confirmed multiple nodular infiltrates with surrounding ground-glass opacities suspicious with a fungal infection (Figure 1).

Treatment with oral voriconazole (300 mg twice daily) was initiated for probable pulmonary aspergillosis. Cyclosporine (150 mg twice daily) and prednisone (1 mg/kg/d) were continued throughout treatment out of concern for hepatic GVHD. The patient’s symptoms improved over the next 10 days, and follow-up chest imaging demonstrated improvement.

Two weeks after initiation of voriconazole treatment, the patient developed a new productive cough and dyspnea, associated with fevers and chills. Repeat imaging revealed right lower-lobe pneumonia. The serum voriconazole trough level was checked and was 3.1 mg/L, suggesting therapeutic dosing. The patient subsequently developed acute respiratory distress syndrome and required intubation and mechanical ventilation. Repeat BAL sampling demonstrated multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli, a BAL galactomannan level of 2.0 ODI, and negative fungal cultures. The patient’s hospital course was complicated by profound hypoxemia, requiring prone positioning and neuromuscular blockade. He was treated with meropenem and voriconazole. His immunosuppression was reduced, but he rapidly developed acute liver injury from hepatic GVHD that resolved after reinitiation of cyclosporine and prednisone at 0.75 mg/kg/d.

The patient improved over the next 3 weeks and was successfully extubated. Repeat chest CT imaging demonstrated numerous pneumatoceles in the location of previous nodules, consistent with healing necrotic fungal disease, and a new right lower-lobe cavitary mass (Figure 2). Two days after transferring out of the intensive care unit, the patient again developed hypoxemia and fevers to 39° C. Bronchoscopy with BAL of the right lower lobe revealed positive A fumigatus and Rhizopus sp polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays, although fungal cultures were positive only for A fumigatus. Liposomal amphotericin B (5 mg/kg) was added to voriconazole therapy to treat mucormycosis and to provide a second active agent against A fumigatus.

Unfortunately, the patient’s clinical status continued to deteriorate with signs of progressive respiratory failure and infection despite empiric, broad-spectrum antibiotics and dual antifungal therapy. His serum voriconazole level continued to be therapeutic at 1.9 mg/L. The patient declined reintubation and invasive mechanical ventilation, and he ultimately transitioned to comfort measures and died with his family at the bedside.

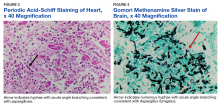

Autopsy demonstrated widely disseminated Aspergillus infection as the cause of death, with evidence of myocardial, neural, and vascular invasion of A fumigatus (Figures 3 and 4).

Discussion

This case of fatal, progressive, invasive, pulmonary aspergillosis demonstrates several important factors in the treatment of patients with this disease. Treatment failure usually relates to any of 4 possible factors: host immune status, severity or burden of disease, appropriate dosing of antifungal agents, and drug resistance. This patient’s immune system was heavily suppressed for a prolonged period. Attempts at reducing immunosuppression to the minimal required dosage to prevent a GVHD flare were unsuccessful and became an unmodifiable risk factor, a major contributor to his demise.

The risks of continuous high-dose immunosuppression in steroid-refractory GVHD is well understood and has been previously demonstrated to have up to 50% 4-year nonrelapse mortality, mainly due to overwhelming bacterial, viral, and fungal infections.4 All attempts should be made to cease or reduce immunosuppression in the setting of a severe infection, although this is sometimes impossible as in this case.

The patient’s disease burden was significant as evidenced by the bilateral, multifocal pulmonary nodules seen on chest imaging and the disseminated disease found at postmortem examination. His initial improvement in symptoms with voriconazole and the evolution of his images (with many of his initial pulmonary nodules becoming pneumatoceles) suggested a temporary positive immune response. The authors believe that the Rhizopus in his sputum represents noninvasive colonization of one of his pneumatoceles, because postmortem examination failed to reveal Rhizopus at any other location.

Voriconazole has excellent pulmonary and central nervous system penetration: In this patient serum levels were well within the therapeutic range. His peculiar drug resistance pattern (sensitivity to azoles and resistance to amphotericin) is unusual. Azole resistance in leukemia and patients with HSCT is more common than is amphotericin resistance, with current estimates of azole resistance close to 5%, ranging between 1% and 30%.5,6 Widespread use of antifungal prophylaxis with azoles likely selects for azole resistance.6

Despite this concern of azole resistance, current IDSA guidelines recommend against routine susceptibility testing of Aspergillus to azole therapy because of the current lack of consensus between the European Committee on Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing and Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute on break points for resistance patterns.3,7 This is an area of emerging research, and proposed cut points for declaration of resistance do exist in the literature even if not globally agreed on.8

Combination antifungal therapy is an option for treatment in cases of possible drug resistance. Nonetheless, a recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial comparing voriconazole monotherapy with the combination of voriconazole and anidulafungin failed to demonstrate an overall mortality benefit in the primary analysis, although secondary analysis showed a mortality benefit with combination therapy in patients at highest risk for death.9

Despite the lack of unified standards with susceptibility testing, it may be reasonable to perform such tests in patients with demonstrating progressive disease. In this patient’s case, amphotericin B was added to treat the Rhizopus species found in his sputum, and while not the combination studied in the previously mentioned study, the drug should have provided an additional active agent for Aspergillus should this patient have had azole resistance.

Surprisingly, subsequent testing demonstrated the Aspergillus species to be resistant to amphotericin B. De novo amphotericin B-resistant A fumigates is extremely rare, with an expected incidence of 1% or less.10 The authors believe the patient may have demonstrated induction of amphotericin-B resistance through activation of fungal stress pathways by prior treatment with voriconazole. This has been demonstrated in vitro and should be considered should combination salvage therapy be required for the treatment of a refractory Aspergillus infection especially if patients have received prior treatment with voriconazole.11

Conclusion

This fatal case of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis illustrates the importance of considering the 4 main causes of treatment failure in an infection. Although the patient had a high burden of disease with a rare resistance pattern, he was treated with appropriate and well-dosed therapy. Ultimately, his unmodifiable immunosuppression was likely the driving factor leading to treatment failure and death. The indication for and number of bone marrow transplants continues to increase, thus exposure to and treatment of invasive fungal infections will increase accordingly. As such, providers should ensure that all causes of treatment failure are considered and addressed.

1. Upton A, Kirby KA, Carpenter P, Boeckh M, Marr KA. Invasive aspergillosis following hematopoietic cell transplantation: outcomes and prognostic factors associated with mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(4):531-540.

2. Herbrecht R, Denning DW, Patterson TF, et al; Invasive Fungal Infections Group of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Global Aspergillus Study Group. Voriconazole versus amphotericin B for primary therapy of invasive aspergillosis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(6):408-415.

3. Patterson TF, Thompson GR III, Denning DW, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aspergillosis: 2016 update by the Infectious Disease Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(4):e1-e60.

4. García-Cadenas I, Rivera I, Martino R, et al. Patterns of infection and infection-related mortality in patients with steroid-refractory acute graft versus host disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017;52(1):107-113.

5. Vermeulen E, Maertens J, De Bel A, et al. Nationwide surveillance of azole resistance in Aspergillus diseases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(8):4569-4576.

6. Wiederhold NP, Patterson TF. Emergence of azole resistance in Aspergillus. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36(5):673-680.

7. Cuenca-Estrella M, Moore CB, Barchiesi F, et al; AFST Subcommittee of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Multicenter evaluation of the reproducibility of the proposed antifungal susceptibility testing method for fermentative yeasts of the Antifungal Susceptibility Testing Subcommittee of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AFST-EUCAST). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9(6):467-474.

8. Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Ghannoum MA, et al; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Antifungal Testing Subcommittee. Wild-type MIC distribution and epidemiological cutoff values for Aspergillus fumigatus and three triazoles as determined by Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute for broth microdilution methods. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(10):3142-3146.

9. Marr KA, Schlamm HT, Herbrecht R, et al. Combination antifungal therapy for invasive aspergillosis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(2):81-89.

10. Tashiro M, Izumikawa K, Minematsu A, et al. Antifungal susceptibilities of Aspergillus fumigatus clinical isolates obtained in Nagasaki, Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(1):584-587.

11. Rajendran R, Mowat E, Jones B, Williams C, Ramage G. Prior in vitro exposure to voriconazole confers resistance to amphotericin B in Aspergillus fumigatus biofilms. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2015;46(3):342-345.

Historically, aspergillosis in patients with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has carried a high mortality rate. However, recent data demonstrate a dramatic improvement in outcomes for patients with HSCT: 90-day survival increased from 22% before 2000 to 45% over the past 15 years.1 Improved outcomes coincide with changes in transplant immunosuppression practices, use of cross-sectional imaging for early disease identification, galactomannan screening, and the development of novel treatment options.

Voriconazole is an azole drug that blocks the synthesis of ergosterol, a vital component of the cellular membrane of fungi. Voriconazole was approved in 2002 after a clinical trial demonstrated an improvement in 50% of patients with invasive aspergillosis in the voriconazole arm vs 30% in the amphotericin B arm at 12 weeks.2 Amphotericin B is a polyene antifungal drug that binds with ergosterol, creating leaks in the cell membrane that lead to cellular demise. Voriconazole quickly became the first-line therapy for invasive aspergillosis and is recommended by both the Infectious Disease Society of American (IDSA) and the European Conference on Infections in Leukemia.3

Case Presentation

A 55-year-old man with high-risk chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) underwent a 10 of 10 human leukocyte antigen allele and antigen-matched peripheral blood allogeneic HSCT with a myeloablative-conditioning regimen of busulfan and cyclophosphamide, along with prophylactic voriconazole, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, and acyclovir. After successful engraftment (without significant neutropenia), his posttransplant course was complicated by grade 2 graft vs host disease (GVHD) of the skin, eyes, and liver, which responded well to steroids and tacrolimus. Voriconazole was continued for 5 months until immunosuppression was minimized (tacrolimus 1 mg twice daily). Two months later, the patient’s GVHD worsened, necessitating treatment at an outside hospital with high-dose prednisone (2 mg/kg/d) and cyclosporine (300 mg twice daily). Voriconazole prophylaxis was not reinitiated at that time.

One year later, at a routine follow-up appointment, the patient endorsed several weeks of malaise, weight loss, and nonproductive cough. The patient’s immunosuppression recently had been reduced to 1 mg/kg/d of prednisone and 100 mg of cyclosporine twice daily. A chest X-ray demonstrated multiple pulmonary nodules; follow-up chest computed tomography (CT) confirmed multiple nodular infiltrates with surrounding ground-glass opacities suspicious with a fungal infection (Figure 1).

Treatment with oral voriconazole (300 mg twice daily) was initiated for probable pulmonary aspergillosis. Cyclosporine (150 mg twice daily) and prednisone (1 mg/kg/d) were continued throughout treatment out of concern for hepatic GVHD. The patient’s symptoms improved over the next 10 days, and follow-up chest imaging demonstrated improvement.

Two weeks after initiation of voriconazole treatment, the patient developed a new productive cough and dyspnea, associated with fevers and chills. Repeat imaging revealed right lower-lobe pneumonia. The serum voriconazole trough level was checked and was 3.1 mg/L, suggesting therapeutic dosing. The patient subsequently developed acute respiratory distress syndrome and required intubation and mechanical ventilation. Repeat BAL sampling demonstrated multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli, a BAL galactomannan level of 2.0 ODI, and negative fungal cultures. The patient’s hospital course was complicated by profound hypoxemia, requiring prone positioning and neuromuscular blockade. He was treated with meropenem and voriconazole. His immunosuppression was reduced, but he rapidly developed acute liver injury from hepatic GVHD that resolved after reinitiation of cyclosporine and prednisone at 0.75 mg/kg/d.

The patient improved over the next 3 weeks and was successfully extubated. Repeat chest CT imaging demonstrated numerous pneumatoceles in the location of previous nodules, consistent with healing necrotic fungal disease, and a new right lower-lobe cavitary mass (Figure 2). Two days after transferring out of the intensive care unit, the patient again developed hypoxemia and fevers to 39° C. Bronchoscopy with BAL of the right lower lobe revealed positive A fumigatus and Rhizopus sp polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays, although fungal cultures were positive only for A fumigatus. Liposomal amphotericin B (5 mg/kg) was added to voriconazole therapy to treat mucormycosis and to provide a second active agent against A fumigatus.

Unfortunately, the patient’s clinical status continued to deteriorate with signs of progressive respiratory failure and infection despite empiric, broad-spectrum antibiotics and dual antifungal therapy. His serum voriconazole level continued to be therapeutic at 1.9 mg/L. The patient declined reintubation and invasive mechanical ventilation, and he ultimately transitioned to comfort measures and died with his family at the bedside.

Autopsy demonstrated widely disseminated Aspergillus infection as the cause of death, with evidence of myocardial, neural, and vascular invasion of A fumigatus (Figures 3 and 4).

Discussion

This case of fatal, progressive, invasive, pulmonary aspergillosis demonstrates several important factors in the treatment of patients with this disease. Treatment failure usually relates to any of 4 possible factors: host immune status, severity or burden of disease, appropriate dosing of antifungal agents, and drug resistance. This patient’s immune system was heavily suppressed for a prolonged period. Attempts at reducing immunosuppression to the minimal required dosage to prevent a GVHD flare were unsuccessful and became an unmodifiable risk factor, a major contributor to his demise.

The risks of continuous high-dose immunosuppression in steroid-refractory GVHD is well understood and has been previously demonstrated to have up to 50% 4-year nonrelapse mortality, mainly due to overwhelming bacterial, viral, and fungal infections.4 All attempts should be made to cease or reduce immunosuppression in the setting of a severe infection, although this is sometimes impossible as in this case.

The patient’s disease burden was significant as evidenced by the bilateral, multifocal pulmonary nodules seen on chest imaging and the disseminated disease found at postmortem examination. His initial improvement in symptoms with voriconazole and the evolution of his images (with many of his initial pulmonary nodules becoming pneumatoceles) suggested a temporary positive immune response. The authors believe that the Rhizopus in his sputum represents noninvasive colonization of one of his pneumatoceles, because postmortem examination failed to reveal Rhizopus at any other location.

Voriconazole has excellent pulmonary and central nervous system penetration: In this patient serum levels were well within the therapeutic range. His peculiar drug resistance pattern (sensitivity to azoles and resistance to amphotericin) is unusual. Azole resistance in leukemia and patients with HSCT is more common than is amphotericin resistance, with current estimates of azole resistance close to 5%, ranging between 1% and 30%.5,6 Widespread use of antifungal prophylaxis with azoles likely selects for azole resistance.6

Despite this concern of azole resistance, current IDSA guidelines recommend against routine susceptibility testing of Aspergillus to azole therapy because of the current lack of consensus between the European Committee on Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing and Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute on break points for resistance patterns.3,7 This is an area of emerging research, and proposed cut points for declaration of resistance do exist in the literature even if not globally agreed on.8

Combination antifungal therapy is an option for treatment in cases of possible drug resistance. Nonetheless, a recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial comparing voriconazole monotherapy with the combination of voriconazole and anidulafungin failed to demonstrate an overall mortality benefit in the primary analysis, although secondary analysis showed a mortality benefit with combination therapy in patients at highest risk for death.9

Despite the lack of unified standards with susceptibility testing, it may be reasonable to perform such tests in patients with demonstrating progressive disease. In this patient’s case, amphotericin B was added to treat the Rhizopus species found in his sputum, and while not the combination studied in the previously mentioned study, the drug should have provided an additional active agent for Aspergillus should this patient have had azole resistance.

Surprisingly, subsequent testing demonstrated the Aspergillus species to be resistant to amphotericin B. De novo amphotericin B-resistant A fumigates is extremely rare, with an expected incidence of 1% or less.10 The authors believe the patient may have demonstrated induction of amphotericin-B resistance through activation of fungal stress pathways by prior treatment with voriconazole. This has been demonstrated in vitro and should be considered should combination salvage therapy be required for the treatment of a refractory Aspergillus infection especially if patients have received prior treatment with voriconazole.11

Conclusion

This fatal case of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis illustrates the importance of considering the 4 main causes of treatment failure in an infection. Although the patient had a high burden of disease with a rare resistance pattern, he was treated with appropriate and well-dosed therapy. Ultimately, his unmodifiable immunosuppression was likely the driving factor leading to treatment failure and death. The indication for and number of bone marrow transplants continues to increase, thus exposure to and treatment of invasive fungal infections will increase accordingly. As such, providers should ensure that all causes of treatment failure are considered and addressed.

Historically, aspergillosis in patients with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has carried a high mortality rate. However, recent data demonstrate a dramatic improvement in outcomes for patients with HSCT: 90-day survival increased from 22% before 2000 to 45% over the past 15 years.1 Improved outcomes coincide with changes in transplant immunosuppression practices, use of cross-sectional imaging for early disease identification, galactomannan screening, and the development of novel treatment options.

Voriconazole is an azole drug that blocks the synthesis of ergosterol, a vital component of the cellular membrane of fungi. Voriconazole was approved in 2002 after a clinical trial demonstrated an improvement in 50% of patients with invasive aspergillosis in the voriconazole arm vs 30% in the amphotericin B arm at 12 weeks.2 Amphotericin B is a polyene antifungal drug that binds with ergosterol, creating leaks in the cell membrane that lead to cellular demise. Voriconazole quickly became the first-line therapy for invasive aspergillosis and is recommended by both the Infectious Disease Society of American (IDSA) and the European Conference on Infections in Leukemia.3

Case Presentation

A 55-year-old man with high-risk chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) underwent a 10 of 10 human leukocyte antigen allele and antigen-matched peripheral blood allogeneic HSCT with a myeloablative-conditioning regimen of busulfan and cyclophosphamide, along with prophylactic voriconazole, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, and acyclovir. After successful engraftment (without significant neutropenia), his posttransplant course was complicated by grade 2 graft vs host disease (GVHD) of the skin, eyes, and liver, which responded well to steroids and tacrolimus. Voriconazole was continued for 5 months until immunosuppression was minimized (tacrolimus 1 mg twice daily). Two months later, the patient’s GVHD worsened, necessitating treatment at an outside hospital with high-dose prednisone (2 mg/kg/d) and cyclosporine (300 mg twice daily). Voriconazole prophylaxis was not reinitiated at that time.

One year later, at a routine follow-up appointment, the patient endorsed several weeks of malaise, weight loss, and nonproductive cough. The patient’s immunosuppression recently had been reduced to 1 mg/kg/d of prednisone and 100 mg of cyclosporine twice daily. A chest X-ray demonstrated multiple pulmonary nodules; follow-up chest computed tomography (CT) confirmed multiple nodular infiltrates with surrounding ground-glass opacities suspicious with a fungal infection (Figure 1).

Treatment with oral voriconazole (300 mg twice daily) was initiated for probable pulmonary aspergillosis. Cyclosporine (150 mg twice daily) and prednisone (1 mg/kg/d) were continued throughout treatment out of concern for hepatic GVHD. The patient’s symptoms improved over the next 10 days, and follow-up chest imaging demonstrated improvement.

Two weeks after initiation of voriconazole treatment, the patient developed a new productive cough and dyspnea, associated with fevers and chills. Repeat imaging revealed right lower-lobe pneumonia. The serum voriconazole trough level was checked and was 3.1 mg/L, suggesting therapeutic dosing. The patient subsequently developed acute respiratory distress syndrome and required intubation and mechanical ventilation. Repeat BAL sampling demonstrated multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli, a BAL galactomannan level of 2.0 ODI, and negative fungal cultures. The patient’s hospital course was complicated by profound hypoxemia, requiring prone positioning and neuromuscular blockade. He was treated with meropenem and voriconazole. His immunosuppression was reduced, but he rapidly developed acute liver injury from hepatic GVHD that resolved after reinitiation of cyclosporine and prednisone at 0.75 mg/kg/d.

The patient improved over the next 3 weeks and was successfully extubated. Repeat chest CT imaging demonstrated numerous pneumatoceles in the location of previous nodules, consistent with healing necrotic fungal disease, and a new right lower-lobe cavitary mass (Figure 2). Two days after transferring out of the intensive care unit, the patient again developed hypoxemia and fevers to 39° C. Bronchoscopy with BAL of the right lower lobe revealed positive A fumigatus and Rhizopus sp polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays, although fungal cultures were positive only for A fumigatus. Liposomal amphotericin B (5 mg/kg) was added to voriconazole therapy to treat mucormycosis and to provide a second active agent against A fumigatus.

Unfortunately, the patient’s clinical status continued to deteriorate with signs of progressive respiratory failure and infection despite empiric, broad-spectrum antibiotics and dual antifungal therapy. His serum voriconazole level continued to be therapeutic at 1.9 mg/L. The patient declined reintubation and invasive mechanical ventilation, and he ultimately transitioned to comfort measures and died with his family at the bedside.

Autopsy demonstrated widely disseminated Aspergillus infection as the cause of death, with evidence of myocardial, neural, and vascular invasion of A fumigatus (Figures 3 and 4).

Discussion

This case of fatal, progressive, invasive, pulmonary aspergillosis demonstrates several important factors in the treatment of patients with this disease. Treatment failure usually relates to any of 4 possible factors: host immune status, severity or burden of disease, appropriate dosing of antifungal agents, and drug resistance. This patient’s immune system was heavily suppressed for a prolonged period. Attempts at reducing immunosuppression to the minimal required dosage to prevent a GVHD flare were unsuccessful and became an unmodifiable risk factor, a major contributor to his demise.

The risks of continuous high-dose immunosuppression in steroid-refractory GVHD is well understood and has been previously demonstrated to have up to 50% 4-year nonrelapse mortality, mainly due to overwhelming bacterial, viral, and fungal infections.4 All attempts should be made to cease or reduce immunosuppression in the setting of a severe infection, although this is sometimes impossible as in this case.

The patient’s disease burden was significant as evidenced by the bilateral, multifocal pulmonary nodules seen on chest imaging and the disseminated disease found at postmortem examination. His initial improvement in symptoms with voriconazole and the evolution of his images (with many of his initial pulmonary nodules becoming pneumatoceles) suggested a temporary positive immune response. The authors believe that the Rhizopus in his sputum represents noninvasive colonization of one of his pneumatoceles, because postmortem examination failed to reveal Rhizopus at any other location.

Voriconazole has excellent pulmonary and central nervous system penetration: In this patient serum levels were well within the therapeutic range. His peculiar drug resistance pattern (sensitivity to azoles and resistance to amphotericin) is unusual. Azole resistance in leukemia and patients with HSCT is more common than is amphotericin resistance, with current estimates of azole resistance close to 5%, ranging between 1% and 30%.5,6 Widespread use of antifungal prophylaxis with azoles likely selects for azole resistance.6

Despite this concern of azole resistance, current IDSA guidelines recommend against routine susceptibility testing of Aspergillus to azole therapy because of the current lack of consensus between the European Committee on Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing and Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute on break points for resistance patterns.3,7 This is an area of emerging research, and proposed cut points for declaration of resistance do exist in the literature even if not globally agreed on.8

Combination antifungal therapy is an option for treatment in cases of possible drug resistance. Nonetheless, a recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial comparing voriconazole monotherapy with the combination of voriconazole and anidulafungin failed to demonstrate an overall mortality benefit in the primary analysis, although secondary analysis showed a mortality benefit with combination therapy in patients at highest risk for death.9

Despite the lack of unified standards with susceptibility testing, it may be reasonable to perform such tests in patients with demonstrating progressive disease. In this patient’s case, amphotericin B was added to treat the Rhizopus species found in his sputum, and while not the combination studied in the previously mentioned study, the drug should have provided an additional active agent for Aspergillus should this patient have had azole resistance.

Surprisingly, subsequent testing demonstrated the Aspergillus species to be resistant to amphotericin B. De novo amphotericin B-resistant A fumigates is extremely rare, with an expected incidence of 1% or less.10 The authors believe the patient may have demonstrated induction of amphotericin-B resistance through activation of fungal stress pathways by prior treatment with voriconazole. This has been demonstrated in vitro and should be considered should combination salvage therapy be required for the treatment of a refractory Aspergillus infection especially if patients have received prior treatment with voriconazole.11

Conclusion

This fatal case of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis illustrates the importance of considering the 4 main causes of treatment failure in an infection. Although the patient had a high burden of disease with a rare resistance pattern, he was treated with appropriate and well-dosed therapy. Ultimately, his unmodifiable immunosuppression was likely the driving factor leading to treatment failure and death. The indication for and number of bone marrow transplants continues to increase, thus exposure to and treatment of invasive fungal infections will increase accordingly. As such, providers should ensure that all causes of treatment failure are considered and addressed.

1. Upton A, Kirby KA, Carpenter P, Boeckh M, Marr KA. Invasive aspergillosis following hematopoietic cell transplantation: outcomes and prognostic factors associated with mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(4):531-540.

2. Herbrecht R, Denning DW, Patterson TF, et al; Invasive Fungal Infections Group of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Global Aspergillus Study Group. Voriconazole versus amphotericin B for primary therapy of invasive aspergillosis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(6):408-415.

3. Patterson TF, Thompson GR III, Denning DW, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aspergillosis: 2016 update by the Infectious Disease Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(4):e1-e60.

4. García-Cadenas I, Rivera I, Martino R, et al. Patterns of infection and infection-related mortality in patients with steroid-refractory acute graft versus host disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017;52(1):107-113.

5. Vermeulen E, Maertens J, De Bel A, et al. Nationwide surveillance of azole resistance in Aspergillus diseases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(8):4569-4576.

6. Wiederhold NP, Patterson TF. Emergence of azole resistance in Aspergillus. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36(5):673-680.

7. Cuenca-Estrella M, Moore CB, Barchiesi F, et al; AFST Subcommittee of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Multicenter evaluation of the reproducibility of the proposed antifungal susceptibility testing method for fermentative yeasts of the Antifungal Susceptibility Testing Subcommittee of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AFST-EUCAST). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9(6):467-474.

8. Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Ghannoum MA, et al; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Antifungal Testing Subcommittee. Wild-type MIC distribution and epidemiological cutoff values for Aspergillus fumigatus and three triazoles as determined by Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute for broth microdilution methods. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(10):3142-3146.

9. Marr KA, Schlamm HT, Herbrecht R, et al. Combination antifungal therapy for invasive aspergillosis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(2):81-89.

10. Tashiro M, Izumikawa K, Minematsu A, et al. Antifungal susceptibilities of Aspergillus fumigatus clinical isolates obtained in Nagasaki, Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(1):584-587.

11. Rajendran R, Mowat E, Jones B, Williams C, Ramage G. Prior in vitro exposure to voriconazole confers resistance to amphotericin B in Aspergillus fumigatus biofilms. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2015;46(3):342-345.

1. Upton A, Kirby KA, Carpenter P, Boeckh M, Marr KA. Invasive aspergillosis following hematopoietic cell transplantation: outcomes and prognostic factors associated with mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(4):531-540.