User login

Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Pulmonary Disease

Nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease is a broad term for a group of pulmonary disorders caused and characterized by exposure to environmental mycobacteria other than those belonging to the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and Mycobacterium leprae. Mycobacteria are aerobic, nonmotile organisms that appear positive with acid-fast alcohol stains. Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are ubiquitous in the environment and have been recovered from domestic and natural water sources, soil, and food products, and from around livestock, cattle, and wildlife.1-3 To date, no evidence exists of human-to-human or animal-to-human transmission of NTM in the general population. Infections in humans are usually acquired from environmental exposures, although the specific source of infection cannot always be identified. Similarly, the mode of infection with NTM has not been established with certainty, but it is highly likely that the organism is implanted, ingested, aspirated, or inhaled. Aerosolization of droplets associated with use of bathroom showerheads and municipal water sources and soil contamination are some of the factors associated with the transmission of infection. Proven routes of transmission include showerheads and potting soil dust.2,3

NTM pulmonary disease occurs in individuals with or without comorbid conditions such as bronchiectasis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pulmonary fibrosis, or structural lung diseases. Slender, middle-aged or elderly white females with marfanoid body habitus, with or without apparent immune or genetic disorders, showing impaired airway and mucus clearance present with this infection as a form of underlying bronchiectasis (Lady Windermere syndrome). It is unclear why NTM infections and escalation to clinical disease occur in certain individuals. Many risk factors, including inherited and acquired defects of host immune response (eg, cystic fibrosis trait and α1 antitrypsin deficiency), have been associated with increased susceptibility to NTM infections.4

NTM infection can lead to chronic symptoms, frequent exacerbations, progressive functional and structural lung destruction, and impaired quality of life, and is associated with an increased risk of hospitalization and higher 5-year all-cause mortality. As such, NTM disease is drawing increasing attention at the clinical, academic, and research levels.5 This case-based review outlines the clinical features of NTM infection, with a focus on the challenges in diagnosis, treatment, and management of NTM pulmonary disease. The cases use Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), a slow-growing mycobacteria (SGM), and Mycobacterium abscessus, a rapidly growing mycobacteria (RGM), as prototypes in a non–cystic fibrosis, non-HIV clinical setting.

Epidemiology

Of the almost 200 isolated species of NTM, the most prevalent pathogens for respiratory disease in the United States are MAC, Mycobacterium kansasii, and M. abscessus. MAC accounts for more than 80% of cases of NTM respiratory disease in the United States.6 The prevalence of NTM disease is increasing at a rate of about 8% each year, with 75,000 to 105,000 patients diagnosed with NTM lung disease in the United States annually. NTM infections in the United States are increasing among patients aged 65 years and older, a population that is expected to nearly double by 2030.7,8

Isolation and prevalence of many NTM species are higher in certain geographic areas of the United States, especially in the southeast. The US coastal regions have a higher prevalence of NTM pulmonary disease, and account for 70% of NTM cases in the United States each year. Half of patients diagnosed with NTM lung disease reside in 7 states: Florida, New York, Texas, California, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Ohio, with 1 in 7 residing in Florida. Three parishes in Louisiana are among the top 10 counties with the highest prevalence in United States. The prevalence of NTM infection–associated hospitalizations is increasing worldwide as well. Co-infection with tuberculosis and multiple NTMs in individual patients has been observed clinically and documented in patients with and without HIV.9,10

It is not clear why the prevalence of NTM pulmonary disease is increasing, but there may be several contributing factors: (1) an increased awareness and identification of NTM infection sources in the environment; (2) an expanding cohort of immunocompromised individuals with exogenous or endogenous immune deficiencies; (3) availability of improved diagnostic techniques, such as use of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), DNA probes, and gene sequencing; and (4) an increased awareness of the morbidity and mortality associated with NTM pulmonary disease. However, it is important to recognize that to best understand the clinical relevance of epidemiologic studies based on laboratory diagnosis and identification, the findings must be evaluated by correlating them with the microbiological and other clinical criteria established by the American Thoracic Society (ATS)/Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines.11

Continue to: Mycobacterium avium Complex

Mycobacterium avium Complex

Case Patient 1

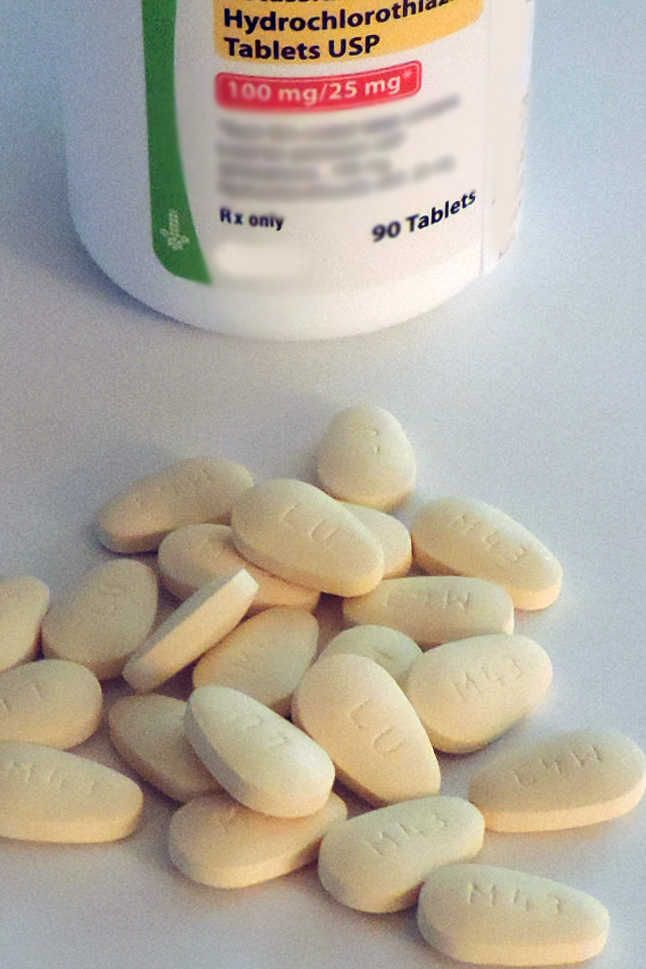

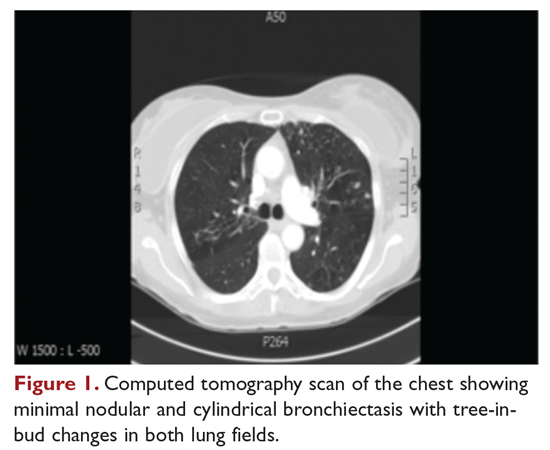

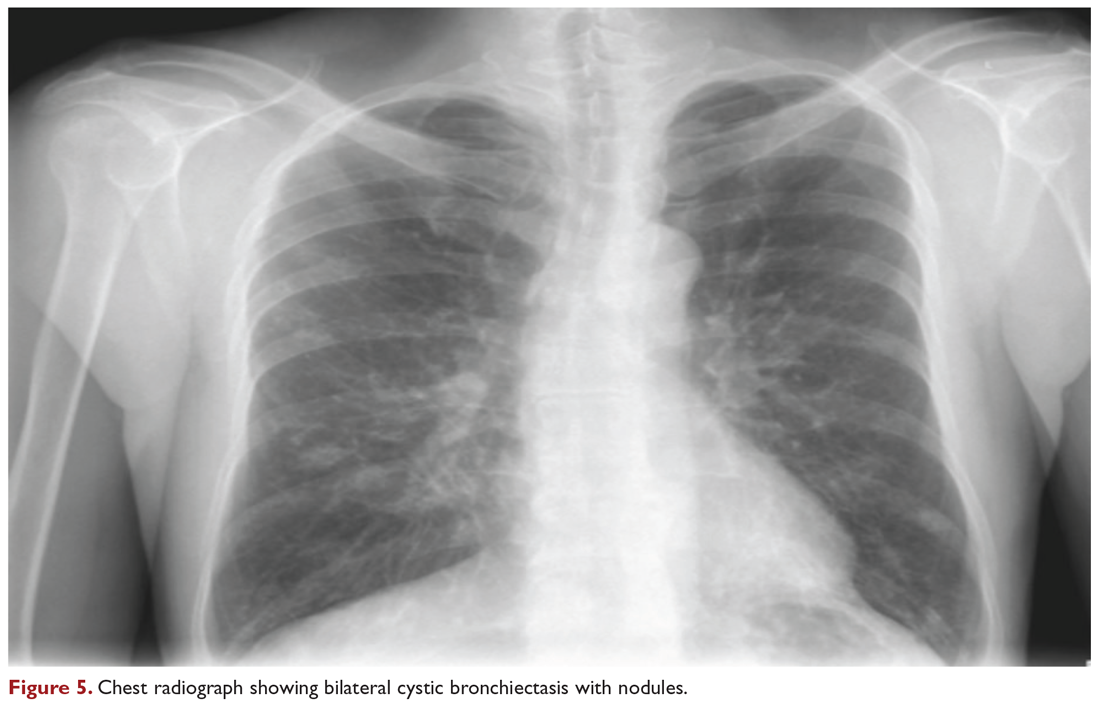

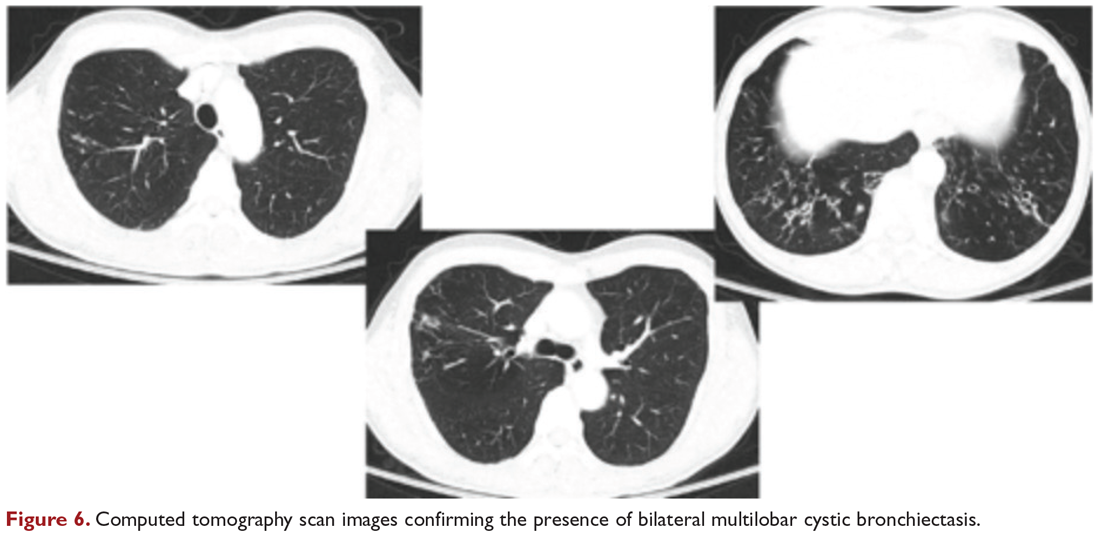

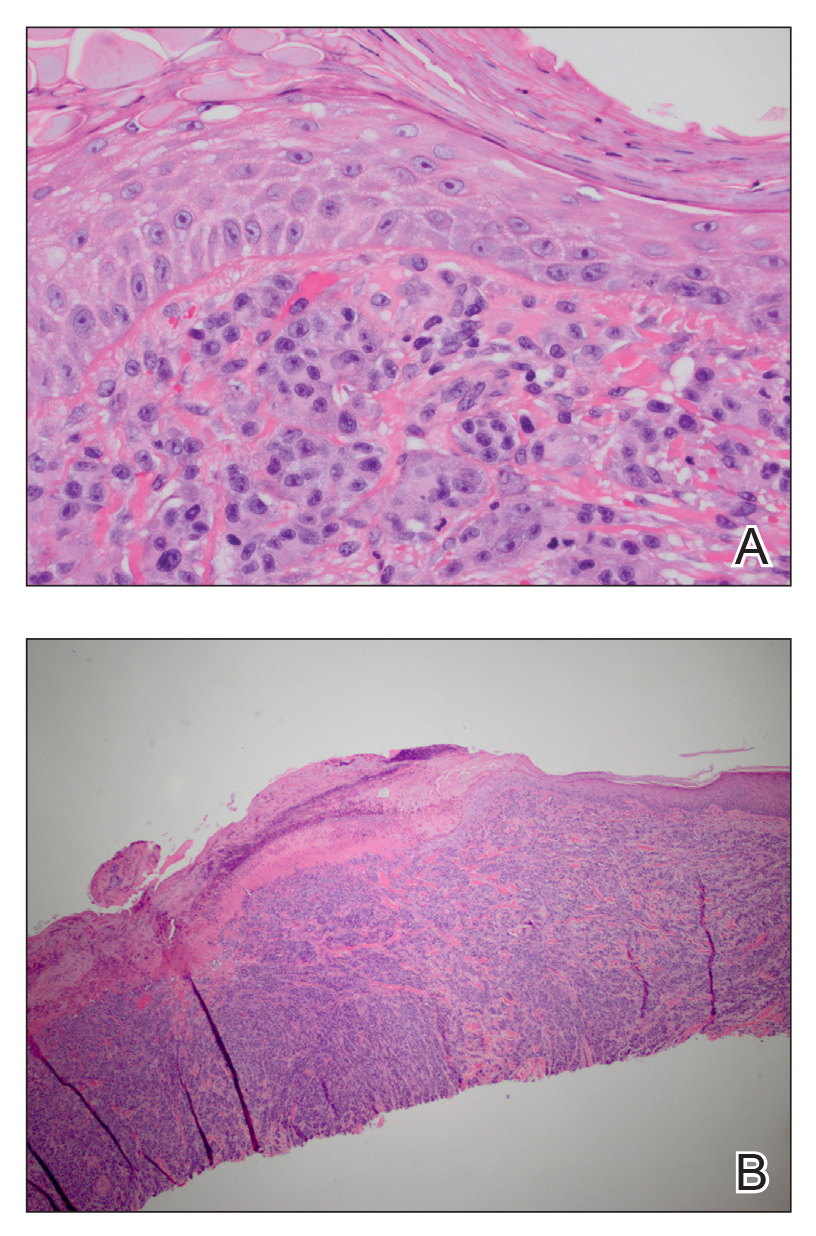

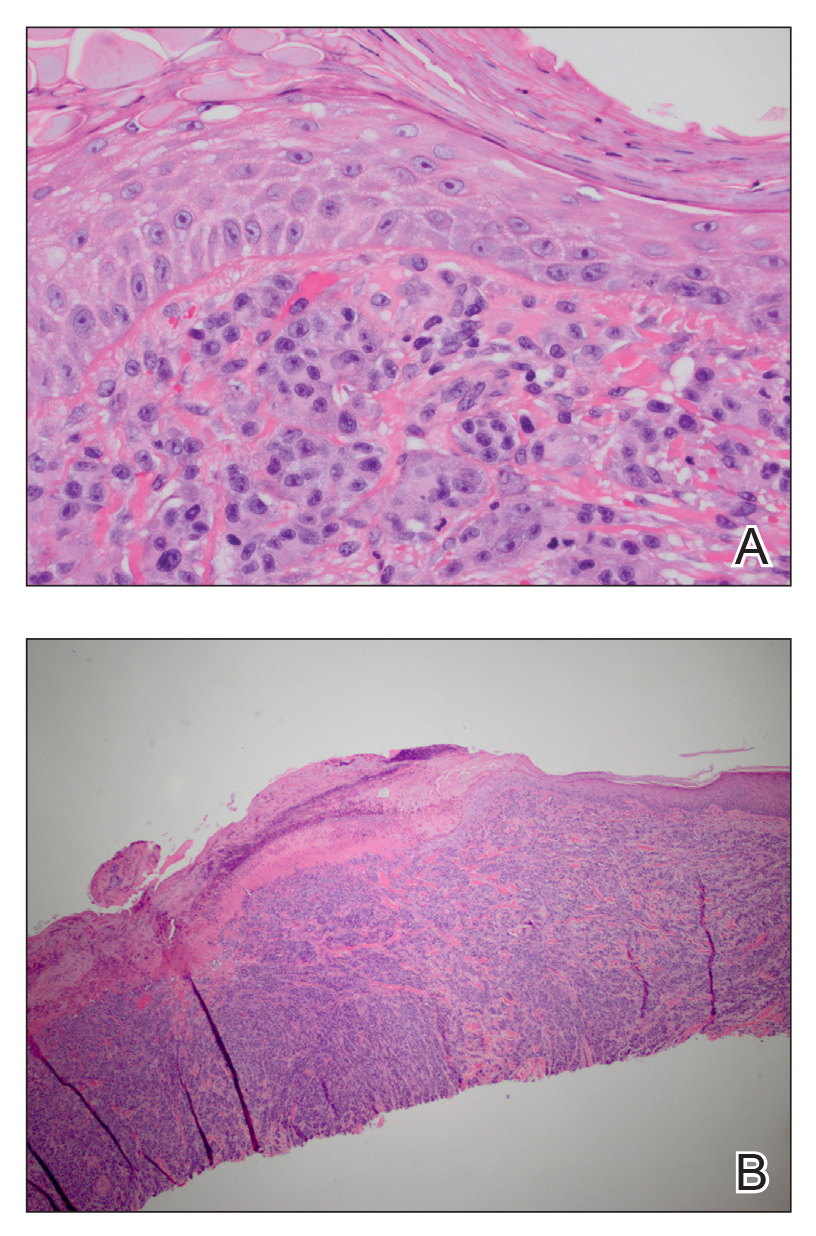

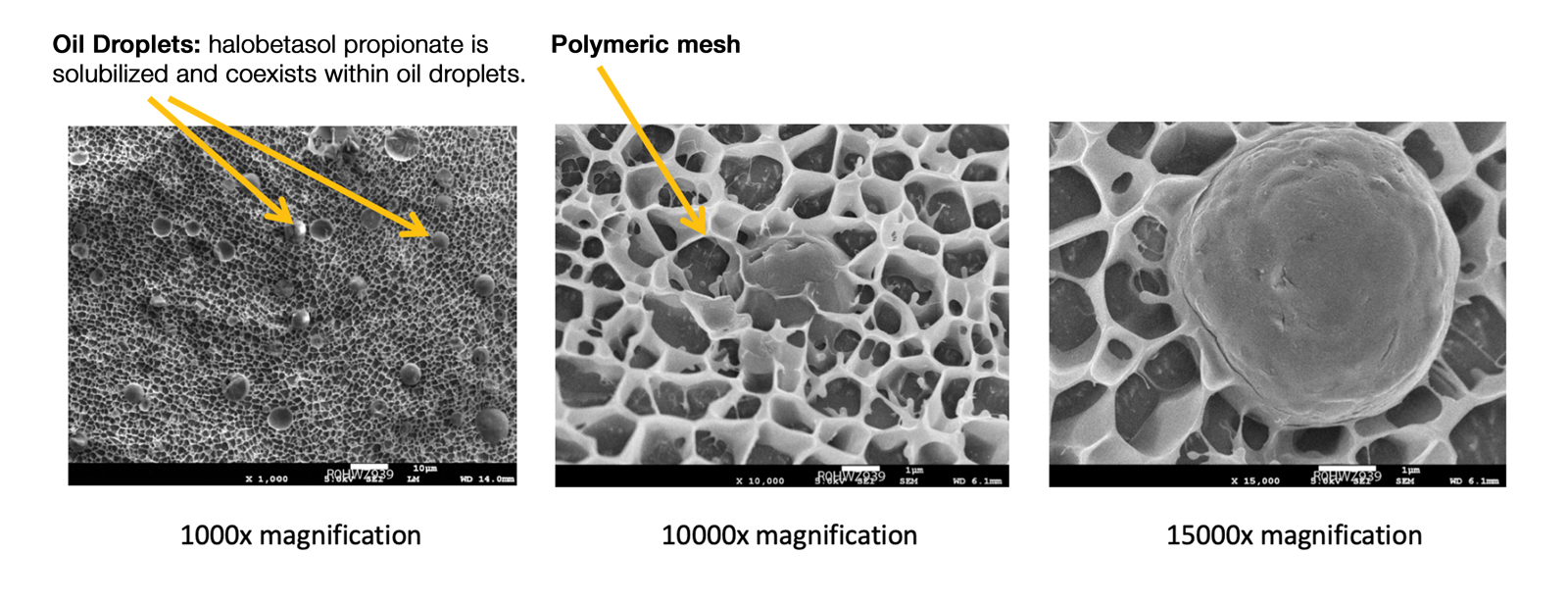

A 48-year-old woman who has never smoked and has no past medical problems, except seasonal allergic rhinitis and “colds and flu-like illness” once or twice a year, is evaluated for a chronic lingering cough with occasional sputum production. The patient denies any other chronic symptoms and is otherwise active. Physical examination reveals no specific findings except mild pectus excavatum and mild scoliosis. Body mass index is 22 kg/m2. Chest radiograph shows nonspecific increased markings in the lower zones. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest reveals minimal nodular and cylindrical bronchiectasis in both lungs (Figure 1). No previous radiographs are available for comparison. The patient is HIV-negative. Sputum tests reveal normal flora, and both fungus and acid-fast bacilli smear are negative. Culture for mycobacteria shows scanty growth of MAC in 1 specimen.

What is the clinical presentation of MAC pulmonary disease?

Among NTM, MAC is the most common cause of pulmonary disease worldwide.6 MAC primarily includes 2 species: M. avium and Mycobacterium intracellulare. M. avium is the more important pathogen in disseminated disease, whereas M. intracellulare is the more common respiratory pathogen.11 These organisms are genetically similar and generally not differentiated in the clinical microbiology laboratory, although there are isolated reports in the literature suggesting differences in prevalence, presentation, and prognosis in M. avium infection versus M. intracellulare infection.12

Three major disease syndromes are produced by MAC in humans: pulmonary disease, usually in adults whose systemic immunity is intact; disseminated disease, usually in patients with advanced HIV infection; and cervical lymphadenitis.13 Pulmonary disease caused by MAC may take on 1 of several clinically different forms, including asymptomatic “colonization” or persistent minimal infection without obvious clinical significance; endobronchial involvement; progressive pulmonary disease with radiographic and clinical deterioration and nodular bronchiectasis or cavitary lung disease; hypersensitivity pneumonitis; or persistent, overwhelming mycobacterial growth with symptomatic manifestations, often in a lung with underlying damage due to either chronic obstructive lung disease or pulmonary fibrosis (Table 1).14

Cavitary Disease

The traditionally recognized presentation of MAC lung disease has been apical cavitary lung disease in men in their late 40s and early 50s who have a history of cigarette smoking, and frequently, excessive alcohol use. If left untreated, or in the case of erratic treatment or macrolide drug resistance, this form of disease is generally progressive within a relatively short time and can result in extensive cavitary lung destruction and progressive respiratory failure.15

Nodular Bronchiectasis

The more common presentation of MAC lung disease, which is outlined in the case described here, is interstitial nodular infiltrates, frequently involving the right middle lobe or lingula and predominantly occurring in postmenopausal, nonsmoking white women. This is sometimes labelled “Lady Windermere syndrome.” These patients with M. avium infection appear to have similar clinical characteristics and body types, including lean build, scoliosis, pectus excavatum, and mitral valve prolapse.16,17 The mechanism by which this body morphotype predisposes to pulmonary mycobacterial infection is not defined, but ineffective mucociliary clearance is a possible explanation. Evidence suggests that some patients may be predisposed to NTM lung disease because of preexisting bronchiectasis. Some potential etiologies of bronchiectasis in this population include chronic sinusitis, gastroesophageal reflux with chronic aspiration, α1 antitrypsin deficiency, and cystic fibrosis genetic traits and mutations.18 Risk factors for increased morbidity and mortality include the development of cavitary disease, age, weight loss, lower body mass index, and other comorbid conditions.

This form of disease, termed nodular bronchiectasis, tends to have a much slower progression than cavitary disease, such that long-term follow-up (months to years) may be necessary to demonstrate clinical or radiographic changes.11 The radiographic term “tree-in-bud” has been used to describe what may reflect inflammatory changes, including bronchiolitis. High-resolution CT scans of the chest are especially helpful for diagnosing this pattern of MAC lung disease, as bronchiectasis and small nodules may not be easily discernible on plain chest radiograph. The nodular/bronchiectasis radiographic pattern can also be seen with other NTM pathogens, including M. abscessus, Mycobacterium simiae, and M. kansasii. Solitary nodules and dense consolidation have also been described. Pleural effusions are uncommon, but reactive pleural thickening is frequently seen. Co-pathogens may be isolated from culture, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and, occasionally, other NTM such as M. abscessus or Mycobacterium chelonae.19-21

Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis, initially described in patients who were exposed to hot tubs, mimics allergic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, with respiratory symptoms and culture/tissue identification of MAC or sometimes other NTM. It is unclear whether hypersensitivity pneumonitis is an inflammatory process, an infection, or both, and opinion regarding the need for specific antibiotic treatment is divided.11,22 However, avoidance of exposure is prudent and recommended.

Disseminated Disease

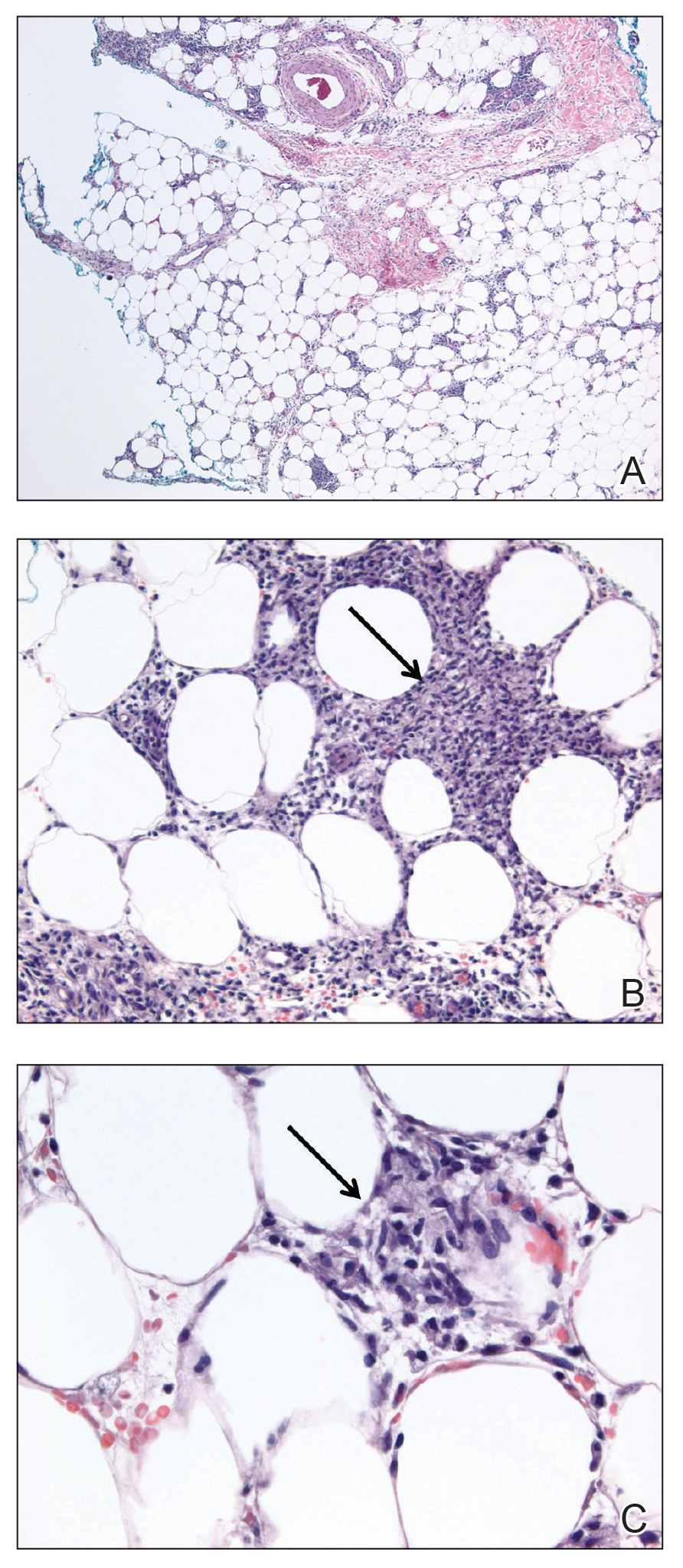

Disseminated NTM disease is associated with very low CD4+ lymphocyte counts and is seen in approximately 5% of patients with HIV infection.23-25 Although disseminated NTM disease is rarely seen in immunosuppressed patients without HIV infection, it has been reported in patients who have undergone renal or cardiac transplant, patients on long-term corticosteroid therapy, and those with leukemia or lymphoma. More than 90% of infections are caused by MAC; other potential pathogens include M. kansasii, M. chelonae, M. abscessus, and Mycobacterium haemophilum. Although seen less frequently since the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy, disseminated infection can develop progressively from an apparently indolent or localized infection or a respiratory or gastrointestinal source. Signs and symptoms of disseminated infection (specifically MAC-associated disease) are nonspecific and include fever, night sweats, weight loss, and abdominal tenderness. Disseminated MAC disease occurs primarily in patients with more advanced HIV disease (CD4+ count typically < 50 cells/μL). Clinically, disseminated MAC manifests as intermittent or persistent fever, constitutional symptoms with organomegaly and organ-specific abnormalities (eg, anemia, neutropenia from bone marrow involvement, adenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly), and elevations of liver enzymes or lung infiltrates from pulmonary involvement.

Continue to: What are the criteria for diagnosing NTM pulmonary disease?

What are the criteria for diagnosing NTM pulmonary disease?

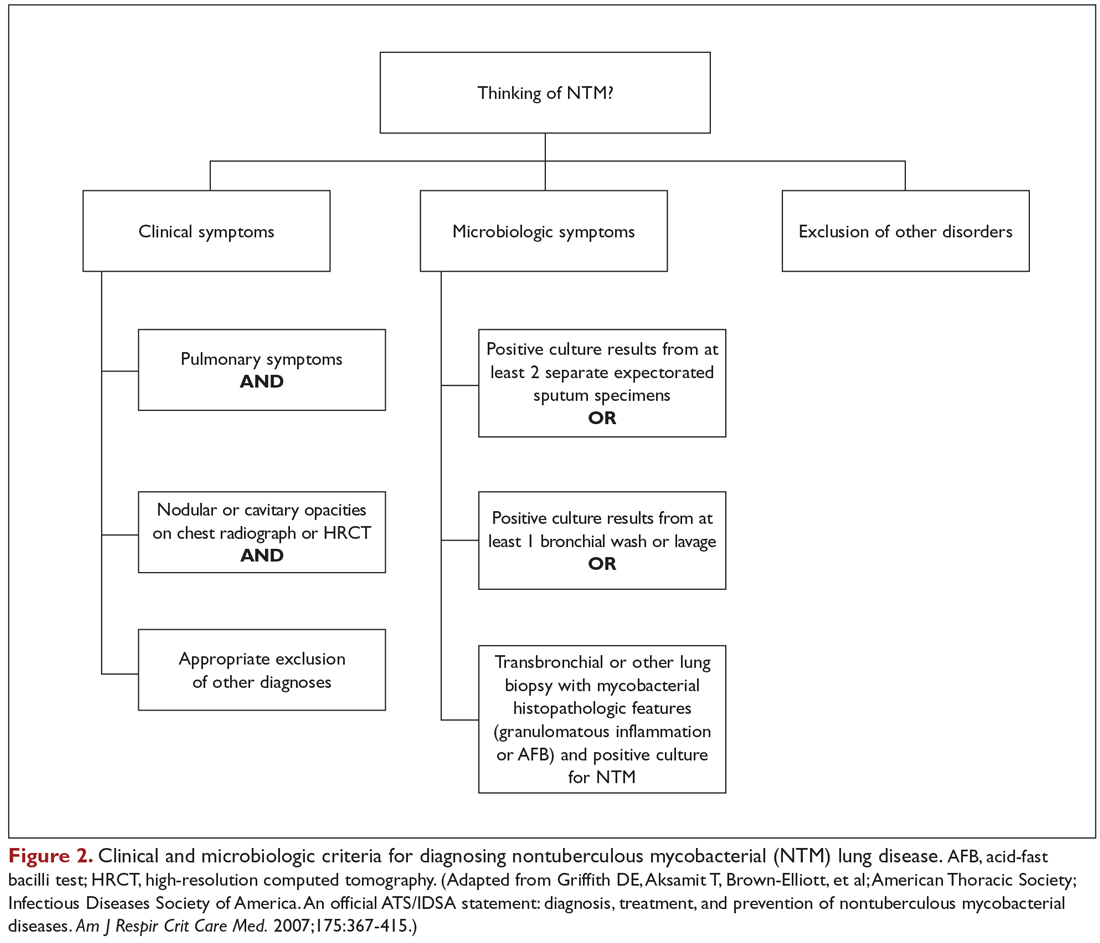

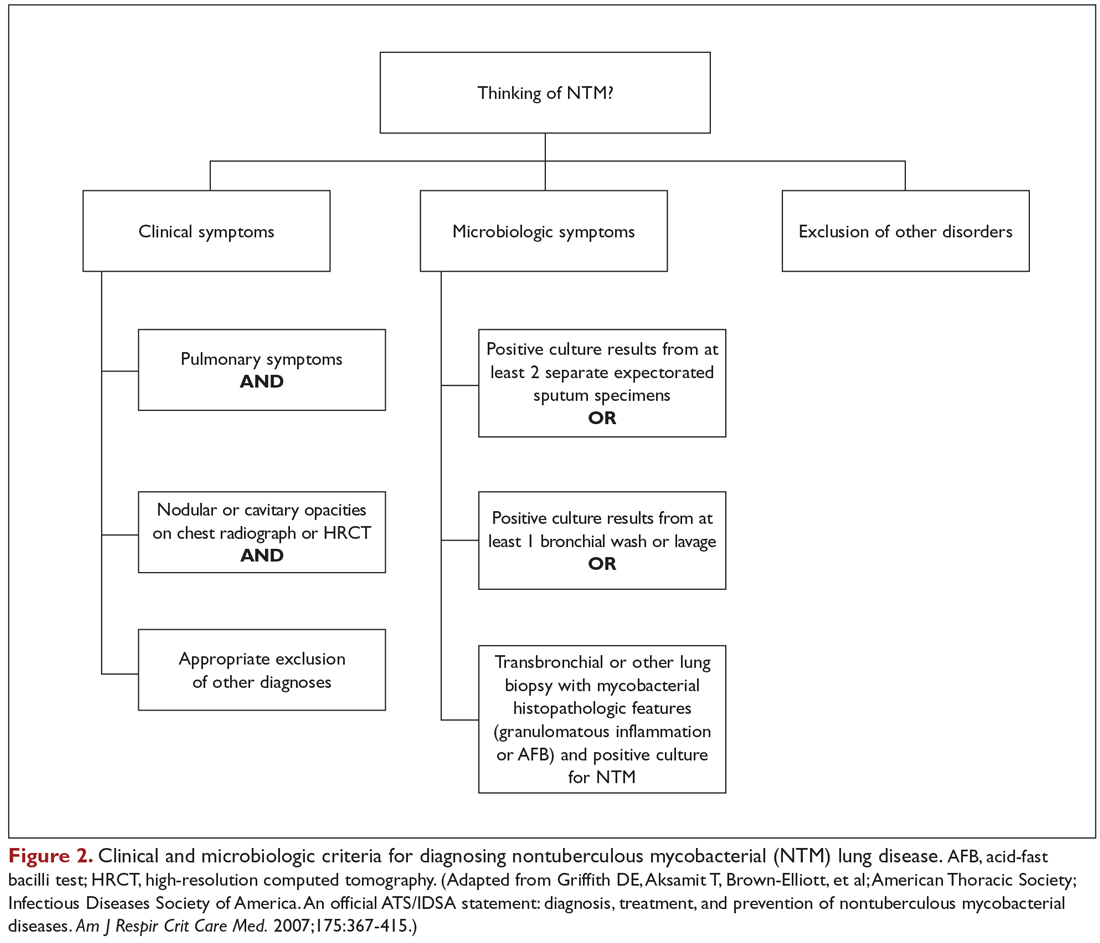

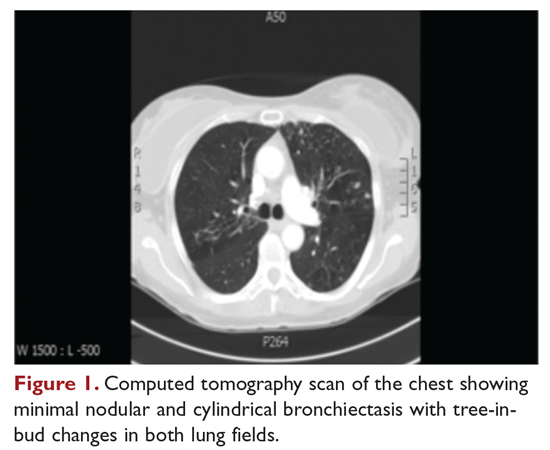

The diagnosis of NTM disease is based on clinical, radiologic, and mycobacterial correlation with good communication between the experts in this field. The ATS/IDSA criteria for diagnosing NTM lung disease are shown in Figure 2. These criteria best apply to MAC, M. kansasii, and M. abscessus, but are also clinically applied to other NTM respiratory pathogens. The diagnosis of MAC infection is most readily established by culture of blood, bone marrow, respiratory secretions/fluid, or tissue specimens from suspected sites of involvement. Due to erratic shedding of MAC into the respiratory secretions in patients with nodular bronchiectasis, as compared to those with the cavitary form of the disease, sputum may be intermittently positive, with variable colony counts and polyclonal infections.12 Prior to the advent of high-resolution CT, isolation of MAC organisms from the sputum of such patients was frequently dismissed as colonization.

Mycobacterial Testing

Because of the nonspecific symptoms and lack of diagnostic specificity of chest imaging, the diagnosis of NTM lung disease requires microbiologic confirmation. Specimens sent to the laboratory for identification of NTM must be handled with care to prevent contamination and false-positive results. Transport media and preservatives should be avoided, and transportation of the specimens should be prompt. These measures will prevent bacterial overgrowth. Furthermore, the yield of NTM may be affected if the patient has used antibiotics, such as macrolides and fluoroquinolones, prior to obtaining the specimen.

NTM should be identified at the species and subspecies level, although this is not practical in community practice settings. The preferred staining procedure in the laboratory is the fluorochrome method. Some species require special growth conditions and/or lower incubation temperatures, and other identification methods may have to be employed, such as DNA probes, polymerase chain reaction genotyping, nucleic acid sequence determination, and high-performance liquid chromatography. As a gold standard, clinical specimens for mycobacterial cultures should be inoculated onto 1 or more solid media (eg, Middlebrook 7H11 media and/or Lowenstein-Jensen media, the former of which is the preferred medium for NTM) and into a liquid medium (eg, BACTEC 12B broth or Mycobacteria growth indicator tube broth). Growth of visible colonies on solid media typically requires 2 to 4 weeks, but liquid media (eg, the radiometric BACTEC system), used as a supplementary and not as an exclusive test, usually produce results within 10 to 14 days. Furthermore, even after initial growth, identification of specific isolates based on the growth characteristics on solid media requires additional time. Use of specific nucleic acid probes for MAC and M. kansasii and HPLC testing of mycolic acid patterns in acid-fast bacilli smear–positive specimens can reduce the turnaround time of specific identification of a primary culture–positive sample. However, HPLC is not sufficient for definitive identification of many NTM species, including the RGM. Other newer techniques, including 16S ribosomal DNA sequencing and polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis, also allow NTM to be identified and speciated more reliably and rapidly from clinical specimens.

Cost and other practical considerations limit widespread adoption of these techniques. However, the recognition that M. abscessus can be separated into more than 1 subspecies, and that there are important prognostic implications of that separation, lends urgency to the broader adoption of newer molecular techniques in the mycobacteriology laboratory. Susceptibility testing is based on the broth microdilution method; RGM usually grow within 7 days of subculture, and the laboratory time to culture is a helpful hint, although not necessarily specific. Recognizing the morphology of mycobacterial colony growth may also be helpful in identification.

Are skin tests helpful in diagnosing NTM infection?

Tuberculin skin testing remains a nonspecific marker of mycobacterial infection and does not help in further elucidating NTM infection. However, epidemiologic and laboratory studies with well-characterized antigens have shown that dual skin testing with tuberculosis- versus NTM-derived tuberculin can discriminate between prior NTM and prior tuberculosis disease. Species-specific skin test antigens are not commercially available and are not helpful in the diagnosis of NTM disease because of cross-reactivity of M. tuberculosis and some NTM. However, increased prevalence of NTM sensitization based on purified protein derivative testing has been noted in a recent survey, which is consistent with an observed increase in the rates of NTM infections, specifically MAC, in the United States.26,27

Interferon-gamma release assays (IGRAs) are now being used as an alternative to tuberculin skin testing to diagnose M. tuberculosis infection. Certain NTM species also contain gene sequences that encode for ESAT-6 or CFP-10 antigens used in the IGRAs, and hence, yield a positive IGRA test. These include M. marinum, M. szulgai, and M. kansasii.28,29 However, MAC organisms do not produce positive results on assays that use these antigens.

Continue to: What is the approach to management of NTM pulmonary disease?

What is the approach to management of NTM pulmonary disease?

The correlation of symptoms with radiographic and microbiologic evidence is essential to categorize the disease and determine the need for therapy. Making the diagnosis of NTM lung disease does not necessitate the institution of therapy. The decision to treat should be weighed against potential risks and benefits to the individual patient based on symptomatic, radiographic, and microbiologic criteria, as well as underlying systemic or pulmonary immune status. In the absence of evidence of clinical, radiologic, or mycobacterial progression of disease, pursuing airway clearance therapy and clinical surveillance without initiating specific anti-MAC therapy is a reasonable option.11 Identifying the sustained presence of NTM infection, especially MAC, in a patient with underlying clinical and radiographic evidence of bronchiectasis is of value in determining comprehensive treatment and management strategies. Close observation is indicated if the decision not to treat is made. If treatment is initiated, comprehensive management includes long-term follow-up with periodic bacteriologic surveillance, watching for drug toxicity and drug-drug interactions, ensuring adherence and compliance to treatment, and managing comorbidity.

The Bronchiectasis Severity Index is a useful clinical predictive tool that identifies patients at risk of future mortality, hospitalization, and exacerbations and can be used to evaluate the need for specific treatment.30 The index is based on dyspnea score, lung function tests, colonization of pathogens, and extent of disease.

Case 1 Continued

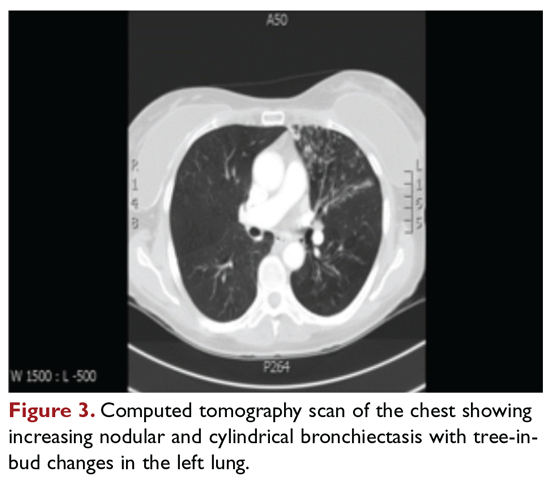

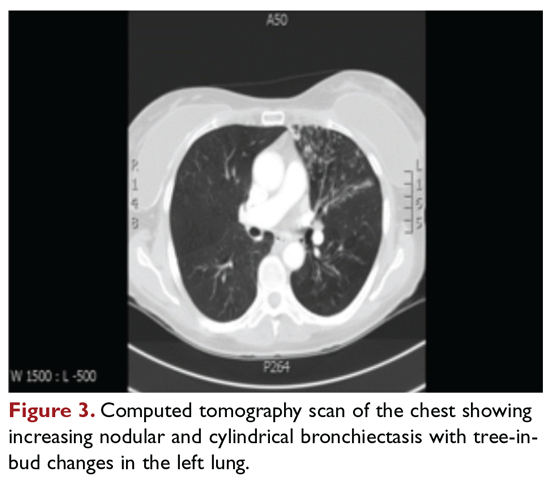

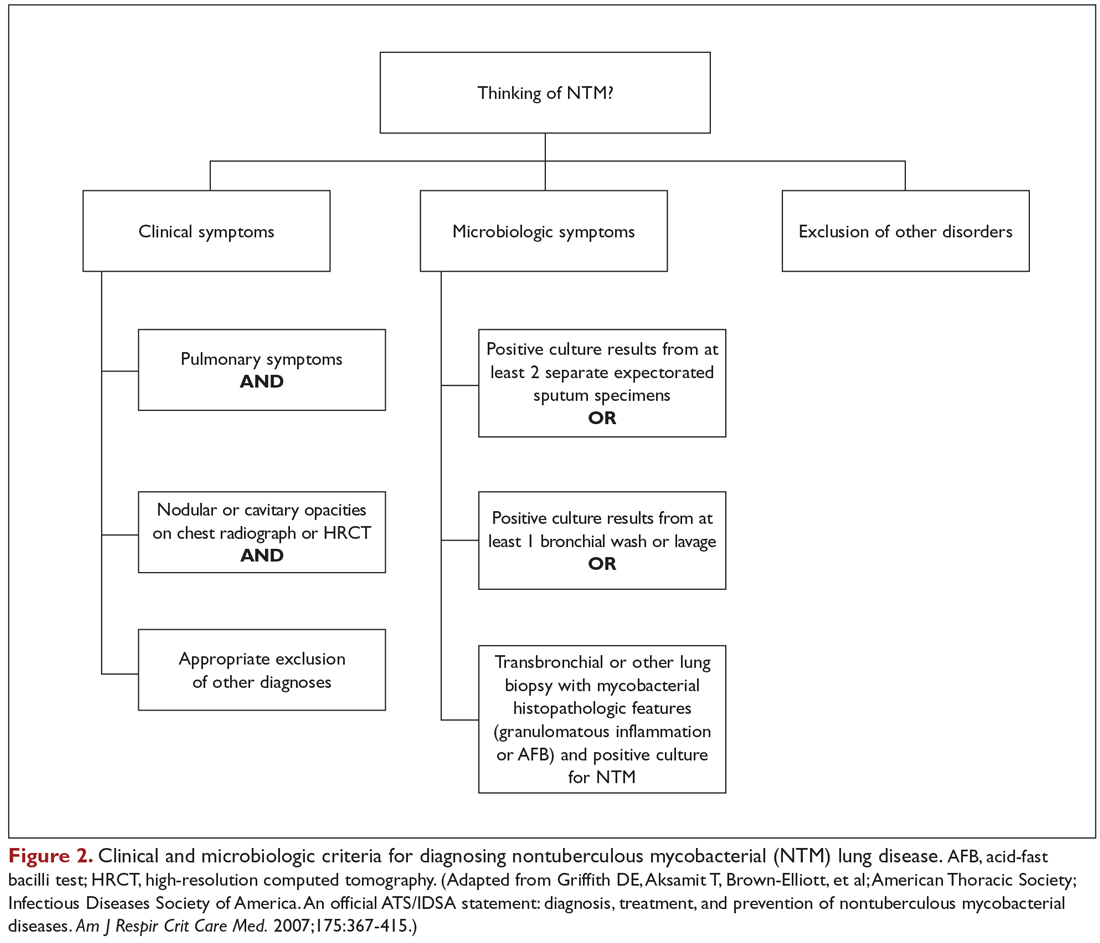

After approximately 2 months of observation and symptomatic treatment, without specific antibiotic therapy, the patient’s symptoms continue. She now develops intermittent hemoptysis. Repeat sputum studies reveal moderate growth of M. avium. A follow-up CT scan shows progression of disease, with an increase in the tree-in-bud pattern (Figure 3).

What treatment protocols are recommended for MAC pulmonary disease?

As per the ATS/IDSA statement, macrolides are the mainstay of treatment for pulmonary MAC disease.11 Macrolides achieve an increased concentration in the lung, and when used for treatment of pulmonary MAC disease, there is a strong correlation between in vitro susceptibility, in vivo (clinical) response, and the immunomodulating effects of macrolides.31,32 Macrolide-containing regimens have demonstrated efficacy in patients with MAC pulmonary disease33,34; however, macrolide monotherapy should be avoided to prevent the development of resistance.

At the outset, it is critical to establish the objective criteria for determining response and to ensure that the patient understands the goals of the treatment and expectations of the treatment plan. Moreover, experts suggest that due to the possibility of drug intolerance, side effects, and the need for prolonged therapy, a “step ladder” ramping up approach to treatment could be adopted, with gradual introduction of therapy within a short time period; this approach may improve compliance and adherence to treatment.11 If this approach is used, the doses may have to be divided. Patients who are unable to tolerate daily medications, even with dosage adjustment, should be tried on an intermittent treatment regimen. Older female patients frequently require gradual introduction of medications (ie, 1 medication added to the regimen every 1 to 2 weeks) to evaluate tolerance to each medication and medication dose.11 Commonly encountered adverse effects of NTM treatment include intolerance to clarithromycin due to gastrointestinal problems, low body mass index, or age older than 70 years.

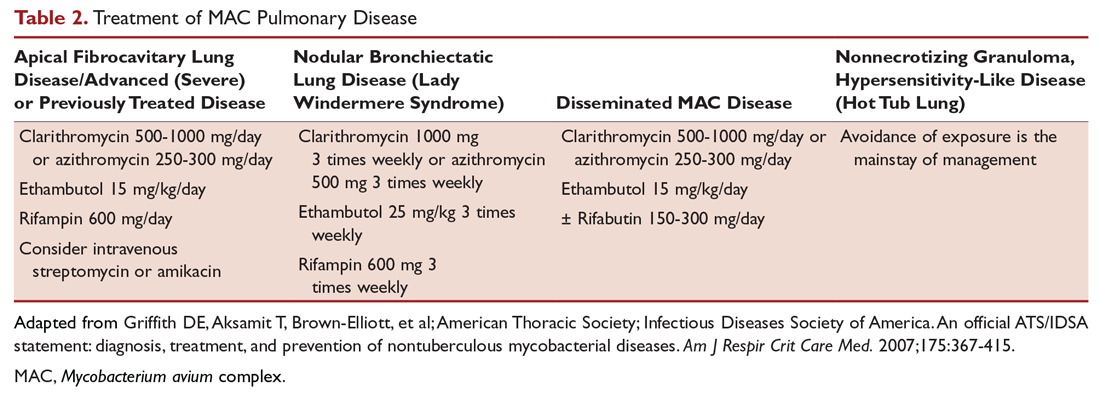

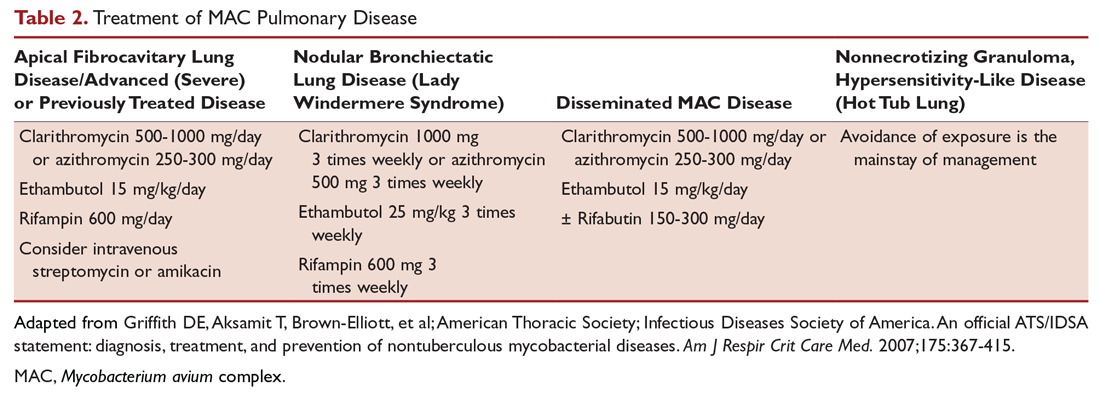

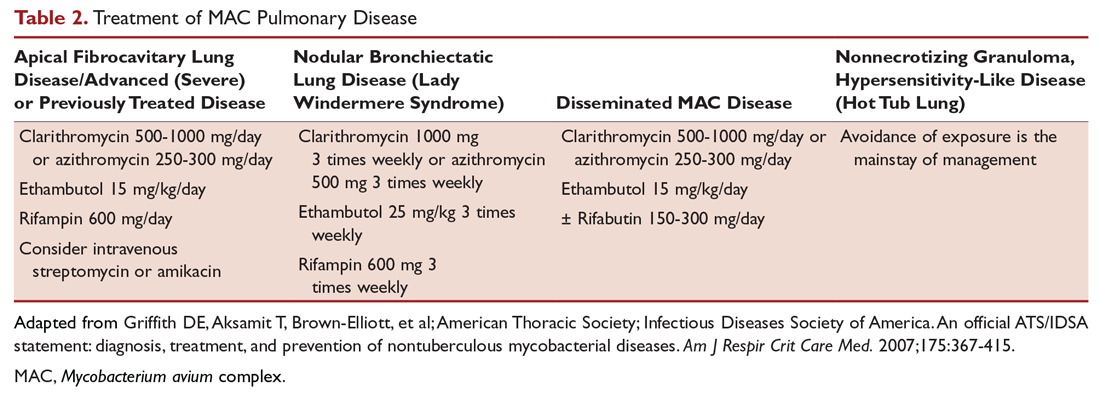

After determining that the patient requires therapy, the standard recommended treatment for MAC pulmonary disease includes the following: for most patients with nodular/bronchiectasis disease, a thrice-weekly regimen of clarithromycin (1000 mg) or azithromycin (500 mg), rifampin (600 mg), and ethambutol (25 mg/kg) is recommended. For patients with cavitary MAC pulmonary disease or severe nodular/bronchiectasis disease, the guidelines recommend a daily regimen of clarithromycin (500-1000 mg) or azithromycin (250 mg), rifampin (600 mg) or rifabutin (150–300 mg), and ethambutol (15 mg/kg), with consideration of intravenous (IV) amikacin 3 times/week early in therapy (Table 2).11

The treatment of MAC hypersensitivity-like disease speaks to the controversy of whether this is an inflammatory process, infectious process, or a combination of inflammation and infection. Avoidance of exposure is the mainstay of management. In some cases, steroids are used with or without a short course of anti-MAC therapy (ie, clarithromycin or azithromycin with rifampin and ethambutol).

Prophylaxis for disseminated MAC disease should be given to adults with HIV infection who have a CD4+ count less than 50 cells/μL. Azithromycin 1200 mg/week or clarithromycin 1000 mg/day has proven efficacy, and rifabutin 300 mg/day is also effective but less well tolerated. Rifabutin is more active in vitro against MAC than rifampin, and is used in HIV-positive patients because of drug-drug interaction between antiretroviral drugs and rifampin.

Continue to: Case 1 Continued

Case 1 Continued

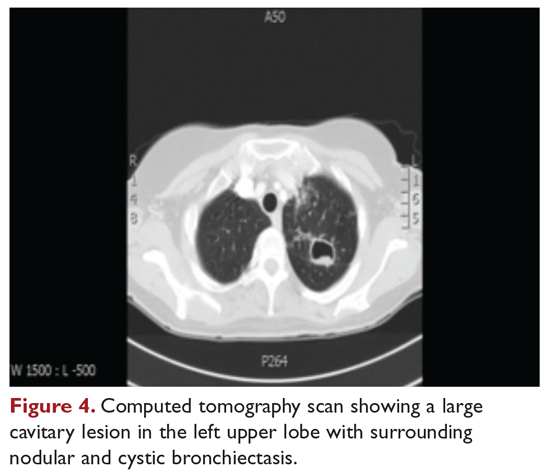

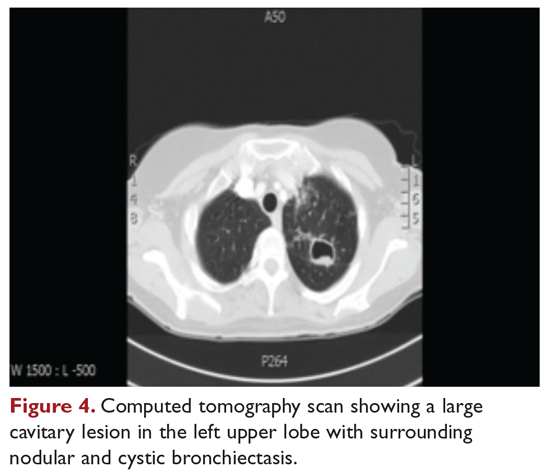

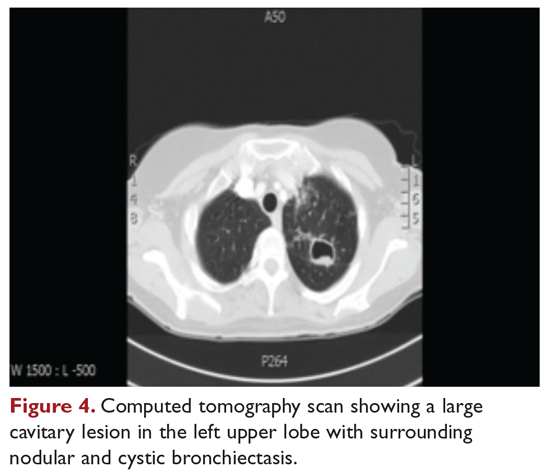

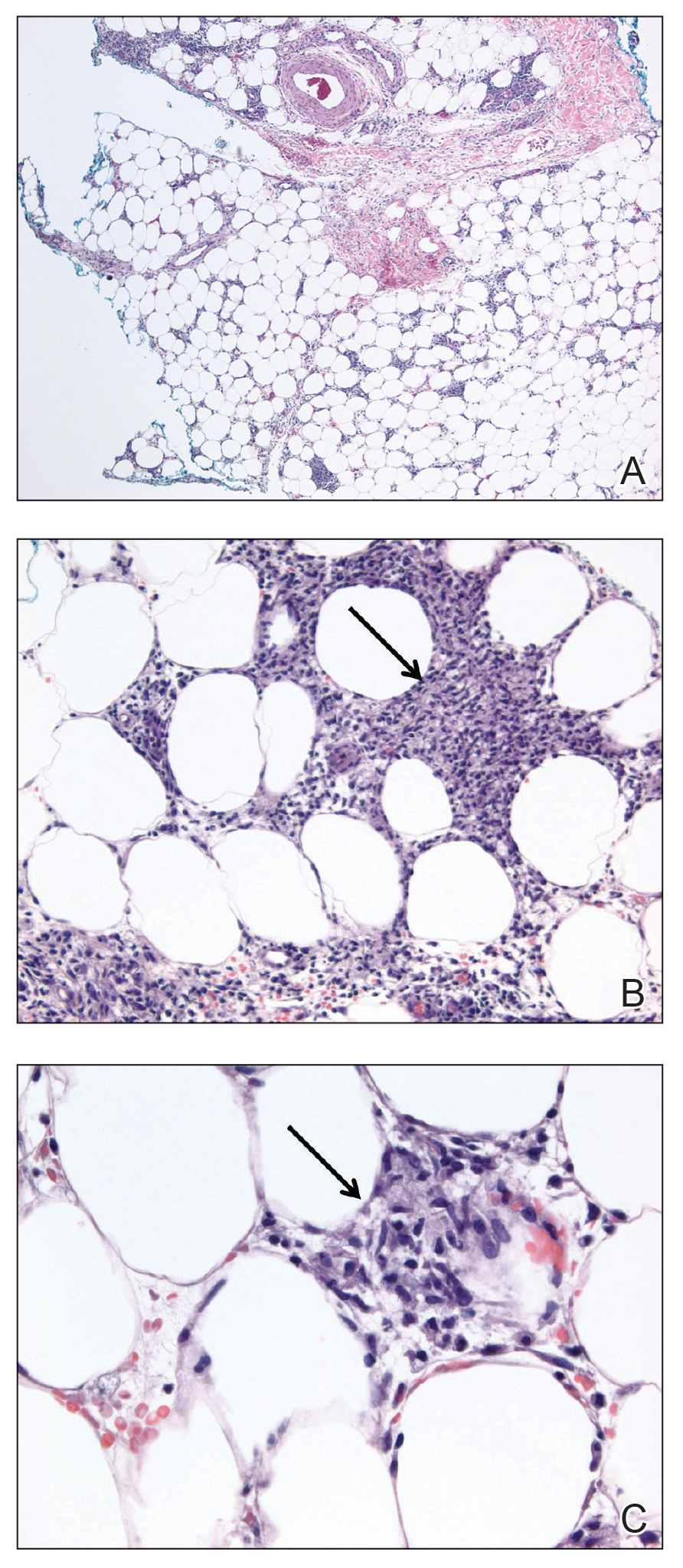

The patient is treated with clarithromycin, rifampin, and ethambutol for 1 year, with sputum conversion after 9 months. In the latter part of her treatment, she experiences decreased visual acuity. Treatment is discontinued prematurely after 1 year due to drug toxicity and continued intolerance to drug therapy. The patient remains asymptomatic for 8 months, and then begins to experience mild to moderate hemoptysis, with increasing cough and sputum production associated with postural changes during exercise. Physical examination overall remains unchanged. Three sputum results reveal heavy growth of MAC, and a CT scan of the chest shows a cavitary lesion in the left upper lobe along with the nodular bronchiectasis (Figure 4).

What are the management options at this stage?

Based on this patient’s continued symptoms, progression of radiologic abnormalities, and current culture growth, she requires re-treatment. With the adverse effects associated with ethambutol during the first round of therapy, the drug regimen needs to be modified. Several considerations are relevant at this stage. Relapse rates range from 20% to 30% after treatment with a macrolide-based therapy.11,34 Obtaining a culture-sensitivity profile is imperative in these cases. Of note, treatment should not be discontinued altogether, but instead the toxic agent should be removed from the treatment regimen. Continuing treatment with a 2-drug regimen of clarithromycin and rifampin may be considered in this patient. Re-infection with multiple genotypes may also occur after successful drug therapy, but this is primarily seen in MAC patients with nodular bronchiectasis.34,35 Patients in whom previous therapy has failed, even those with macrolide-susceptible MAC isolates, are less likely to respond to subsequent therapy. Data suggest that intermittent medication dosing is not effective for patients with severe or cavitary disease or in those in whom previous therapy has failed.36 In this case, treatment should include a daily 3-drug therapy, with an injectable thrice-weekly aminoglycoside. Other agents such as linezolid and clofazimine may have to be tried. Cycloserine, ethionamide, and other agents are sometimes used, but their efficacy is unproven and doubtful. Pyrazinamide and isoniazid have no activity against MAC.

Treatment Failure and Drug Resistance

Treatment failure is considered to have occurred if patients have not had a response (microbiologic, clinical, or radiographic) after 6 months of appropriate therapy or had not achieved conversion of sputum to culture-negative after 12 months of appropriate therapy.11 This occurs in about 40% of patients. Multiple factors can interfere with the successful treatment of MAC pulmonary disease, including medication nonadherence, medication side effects or intolerance, lack of response to a medication regimen, or the emergence of a macrolide-resistant or multidrug-resistant strain. Inducible macrolide resistance remains a potential factor.34-36 A number of characteristics of NTM contribute to the poor response to currently used antibiotics: the organisms have a lipid outer membrane and prefer to adhere to surfaces and form biofilms, which makes them relatively impermeable to antibiotics.37 Also, NTM replicate in phagocytic cells, allowing them to subvert normal cellular defense mechanisms. Furthermore, NTM can display colony variants, whereby single colony isolates switch between antibiotic-susceptible and -resistant variants. These factors have also impeded in development of new antibiotics for NTM infection.37

Recent limited approval of amikacin liposomal inhalation suspension (ALIS) for treatment failure and refractory MAC infection in combination with guideline-based antimicrobial therapy (GBT) is a promising addition to the available treatment armamentarium. In a multinational trial, the addition of ALIS to GBT for treatment-refractory MAC lung disease achieved significantly greater culture conversion rates by month 6 than GBT alone, with comparable rates of serious adverse events.38

Is therapeutic drug monitoring recommended during treatment of MAC pulmonary disease?

Treatment failure may also be drug-related, including poor drug penetration into the damaged lung tissue or drug-drug interactions leading to suboptimal drug levels. Peak serum concentrations have been found to be below target ranges in approximately 50% of patients using a macrolide and ethambutol. Concurrent use of rifampin decreases the peak serum concentration of macrolides and quinolones, with acceptable target levels seen in only 18% to 57% of cases. Whether this alters patient outcomes is not clear.39-42 Factors identified as contributing to the poor response to therapy include poor compliance, cavitary disease, previous treatment for MAC pulmonary disease, and a history of chronic obstructive lung disease. Studies by Koh and colleagues40 and van Ingen and colleagues41 with pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics data showed that, in patients on MAC treatment with both clarithromycin and rifampicin, plasma levels of clarithromycin were lower than the recommended minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC) against MAC for that drug. The studies also showed that rifampicin lowered clarithromycin concentrations more than did rifabutin, with the AUC/MIC ratio being suboptimal in nearly half the cases. However, low plasma clarithromycin concentrations did not have any correlation with treatment outcomes, as the peak plasma drug concentrations and the peak plasma drug concentration/MIC ratios did not differ between patients with unfavorable treatment outcomes and those with favorable outcomes. This is further compounded by the fact that macrolides achieve higher levels in lung tissue than in plasma, and hence the significance of low plasma levels is unclear; however, it is postulated that achieving higher drug levels could, in fact, lead to better clinical outcomes. Pending specific well-designed, prospective randomized controlled trials, routine therapeutic drug monitoring is not currently recommended, although some referral centers do this as their practice pattern.

Is surgery an option in this case?

The overall 5-year mortality for MAC pulmonary disease was approximately 28% in a retrospective analysis, with patients with cavitary disease at increased risk for death at 5 years.42 As such, surgery is an option in selected cases as part of adjunctive therapy along with anti-MAC therapy based on mycobacterial sensitivity. Surgery is used as either a curative approach or a “debulking” measure.11 When present, clearly localized disease, especially in the upper lobe, lends itself best to surgical intervention. Surgical resection of a solitary pulmonary nodule due to MAC, in addition to concomitant medical treatment, is recommended. Surgical intervention should be considered early in the course of the disease because it may provide a cure without prolonged treatment and its associated problems, and this approach may lead to early sputum conversion. Surgery should also be considered in patients with macrolide-resistant or multidrug-resistant MAC infection or in those who cannot tolerate the side effects of therapy, provided that the disease is focal and limited. Patients with poor preoperative lung function have poorer outcomes than those with good lung function, and postoperative complications arising from treatment, especially with a right-sided pneumonectomy, tend to occur more frequently in these patients. Thoracic surgery for NTM pulmonary disease must be considered cautiously, as this is associated with significant morbidity and mortality and is best performed at specialized centers that have expertise and experience in this field.43

Continue to: Mycobacterium abscessus Complex

Mycobacterium abscessus Complex

Case Patient 2

A 64-year-old man who is an ex-smoker presents with chronic cough, mild shortness of breath on exertion, low-grade fever, and unintentional weight loss of 10 lb. Physical exam is unremarkable. The patient was diagnosed with immunoglobulin deficiency (low IgM and low IgG4) in 2002, and has been on replacement therapy since then. He also has had multiple episodes of NTM infection, with MAC and M. kansasii infections diagnosed in 2012-2014, which required 18 months of multi-drug antibiotic treatment that resulted in sputum conversion. Pulmonary function testing done on this visit in 2017 shows mild obstructive impairment.

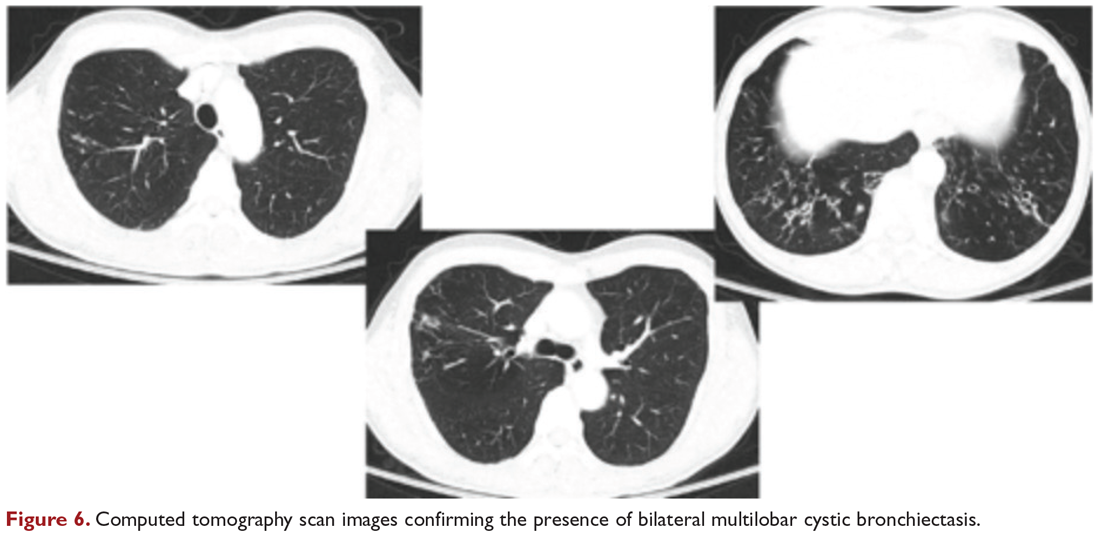

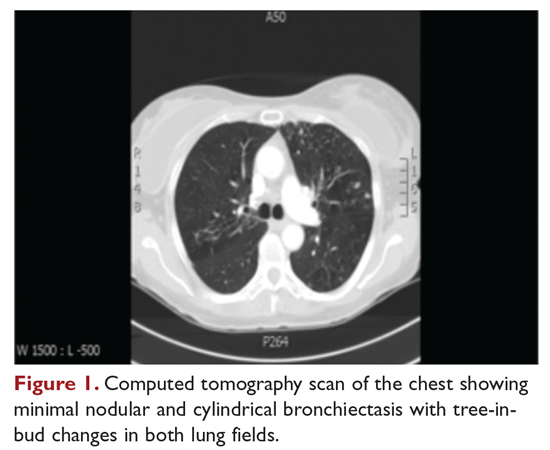

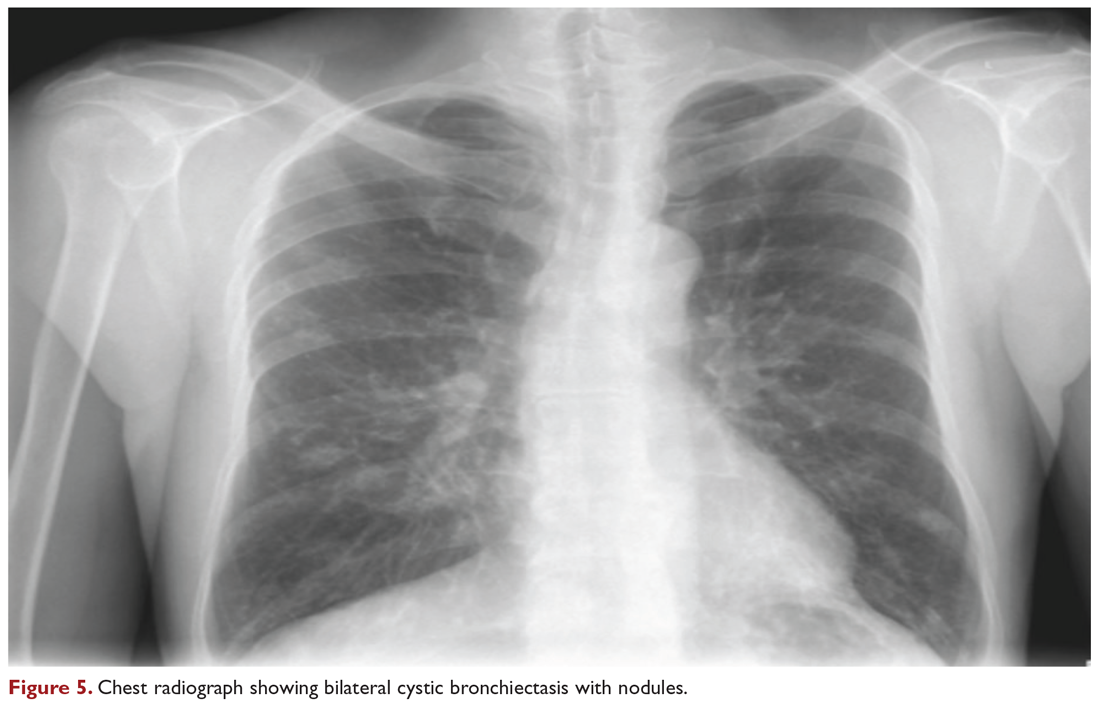

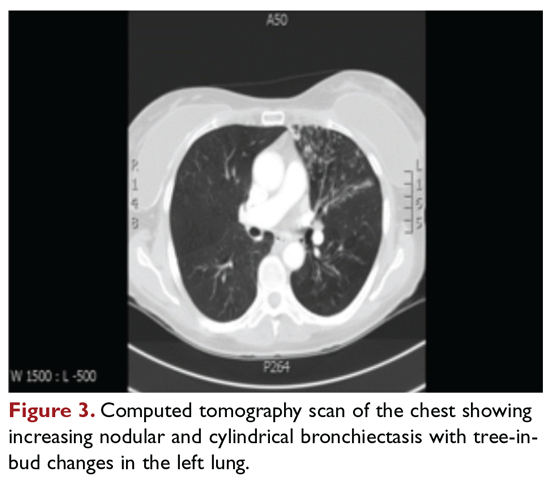

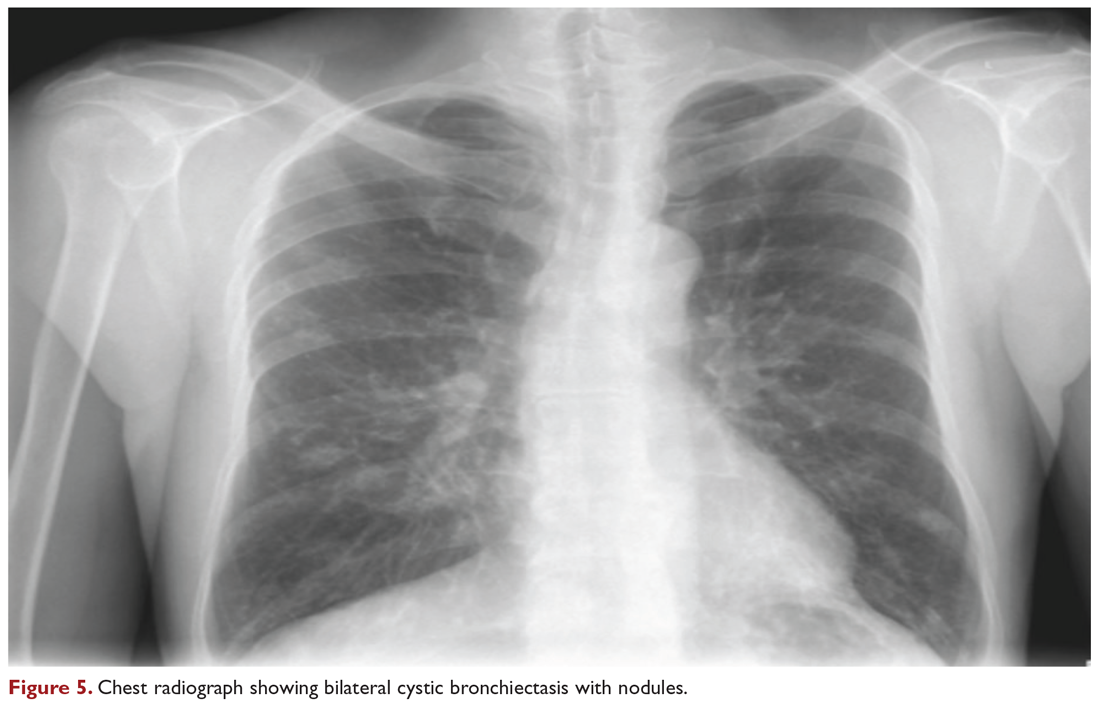

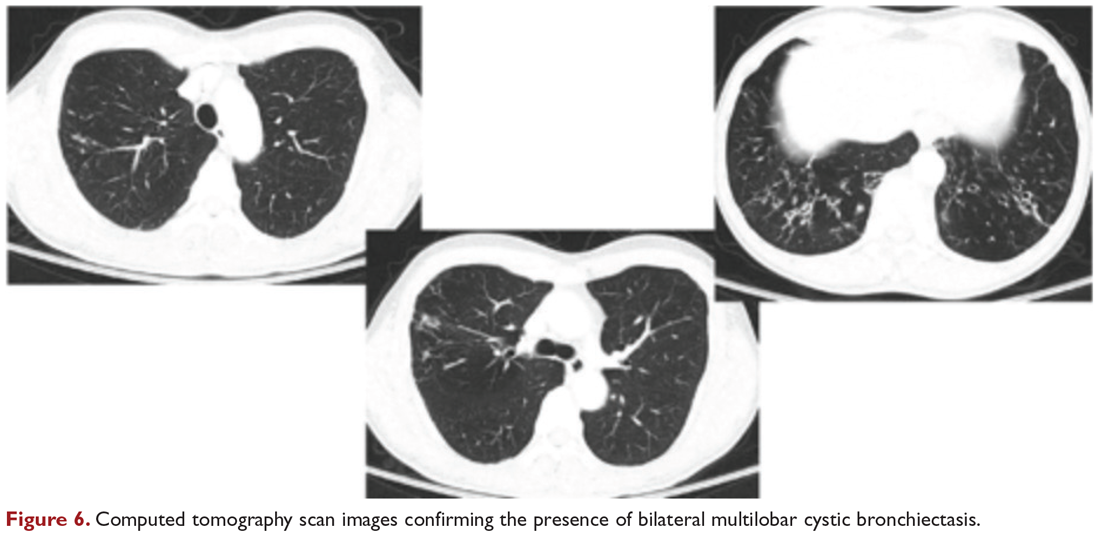

Chest radiograph and CT scan show bilateral bronchiectasis (Figure 5 and Figure 6).

The results of serial sputum microbiology testing performed over the course of 6 months are outlined below:

- 5/2017 (bronchoalveolar lavage): 2+; M. abscessus

- 9/2017 × 2: smear (–); group IV RGM

- 11/2017: smear (–); M. abscessus (> 50 CFU)

- 12/2017: smear (–); M. abscessus (> 50 CFU)

What are the clinical considerations in this patient with multiple NTM infections?

M. abscessus complex was originally described in soft tissue abscesses and skin infections possibly resulting from soil or water contamination. Subspeciation of M. abscessus complex during laboratory testing is critical to facilitate selection of a specific therapeutic approach; treatment decisions are impacted by the presence of an active erm gene and in vitro macrolide sensitivity, which differ between subspecies. The most acceptable classification outlines 3 species in the M. abscessus complex: Mycobacterium abscessus subsp abscessus, Mycobacterium abscessus subsp bolletii (both with an active erm gene responsible for macrolide resistance), and Mycobacterium abscessus subsp massiliense (with an inactive erm gene and therefore susceptible to macrolides).44

RGM typically manifest in skin, soft tissue, and bone, and can cause soft tissue, surgical wound, and catheter-related infections. Although the role of RGM as pulmonary pathogens is unclear, underlying diseases associated with RGM include previously treated mycobacterial disease, coexistent pulmonary diseases with or without MAC, cystic fibrosis, malignancies, and gastroesophageal disorders. M. abscessus is the third most commonly identified respiratory NTM and accounts for the majority (80%) of RGM respiratory isolates. Other NTM reported to cause both lung disease and skin, bone, and joint infections include Mycobacterium simiae, Mycobacterium xenopi, and Mycobacterium malmoense. Ocular granulomatous diseases, such as chorioretinitis and keratitis, have been reported with both RGM and Runyon group III SGM, such as MAC or M. szulgai, following trauma or refractive surgery. These can mimic fungal, herpetic, or amebic keratitis. The pulmonary syndromes associated with multiple culture positivity are seen in elderly women with bronchiectasis or cavitary lung disease and/or associated with gastrointestinal symptoms of acid reflux, with or without achalasia and concomitant lipoid interstitial pneumonia.45

Generally, pulmonary disease progresses slowly, but lung disease attributed to RGM can result in respiratory failure. Thus, RGM should be recognized as a possible cause of chronic mycobacterial lung disease, especially in immunocompromised patients, and respiratory isolates should be assessed carefully. Identification and drug susceptibility testing are essential before initiation of treatment for RGM.

What is the approach to management of M. abscessus pulmonary disease in a patient without cystic fibrosis?

The management of M. abscessus pulmonary infection as a subset of RGM requires a considered step-wise approach. The criteria for diagnosis and threshold for starting treatment are the same as those used in the management of MAC pulmonary disease,11 but the treatment of M. abscessus pulmonary infection is more complex and has lower rates of success and cure. Also, antibiotic treatment presents challenges related to rapid identification of the causative organism, nomenclature, resistance patterns, and tolerance of treatment and side effects. If a source such as catheter, access port, or any surgical site is identified, prompt removal and clearance of the infected site are strongly advised

In the absence of any controlled clinical trials, treatment of RGM is based on in vitro susceptibility testing and expert opinion. As in MAC pulmonary disease, macrolides are the mainstay of treatment, with an induction phase of intravenous antibiotics. Treatment may include a combination of injectable aminoglycosides, imipenem, or cefoxitin and oral drugs such as a macrolide (eg, clarithromycin, azithromycin), doxycycline, fluoroquinolones, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, or linezolid. While antibiotic treatment of M. abscessus pulmonary disease is based on in vitro sensitivity pattern to a greater degree than is treatment of MAC pulmonary disease, this approach has significant practical limitations and hence variable applicability. The final choice of antibiotics is best based on the extended susceptibility results, if available. The presence of an active erm gene on a prolonged growth specimen in M. abscessus subsp abscessus and M. abscessus subsp bolletii precludes the use of a macrolide. In such cases, amikacin, especially in an intravenous form, is the mainstay of treatment based on MIC. Recently, there has been a resurgence in interest in the use of clofazimine in combination with amikacin when treatment is not successful in patients with M. abscessus subsp abscessus or M. bolletii with an active erm gene.45,46 When localized abscess formation is noted, surgery may be the best option, with emphasis on removal of implants and catheters if implicated in RGM infection.

Attention must also be given to confounding pulmonary and associated comorbidities. This includes management of bronchiectasis with appropriately aggressive airway clearance techniques; anti-reflux measures for prevention of micro-aspiration; and management of other comorbid pulmonary conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pulmonary fibrosis, and sarcoidosis, if applicable. These interventions play a critical role in clearing the M. abscessus infection, preventing progression of disease, and reducing morbidity. The role of immunomodulatory therapy needs to be considered on a regular, ongoing basis. Identification of genetic factors and correction of immune deficiencies may help in managing the infection.

Case Patient 2 Conclusion

The treatment regimen adopted in this case includes a 3-month course of daily intravenous amikacin and imipenem with oral azithromycin, followed by a continuation phase of azithromycin with clofazimine and linezolid. Airway clearance techniques such as Vest/Acapella/CPT are intensified and monthly intravenous immunoglobulin therapy is continued. The patient responds to treatment, with resolution of his clinical symptoms and reduction in the colony count of M. abscessus in the sputum.

Summary

NTM are ubiquitous in the environment, and NTM infection has variable manifestations, especially in patients with no recognizable immune impairments. Underlying comorbid conditions with bronchiectasis complicate its management. Treatment strategies must be individualized based on degree of involvement, associated comorbidities, immune deficiencies, goals of therapy, outcome-based risk-benefit ratio assessment, and patient engagement and expectations. In diffuse pulmonary disease, drug treatment remains difficult due to poor match of in vitro and in vivo culture sensitivity, side effects of medications, and high failure rates. When a localized resectable foci of infection is identified, especially in RGM disease, surgical treatment may be the best approach in selected patients, but it must be performed in centers with expertise and experience in this field.

1. Johnson MM, Odell JA. Nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary infections. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6:210-220.

2. Falkinham JO III. Environmental sources of NTM. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:35-41.

3. Falkinham JO III, Current epidemiological trends in NTM. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2016;3:161-167.

4. Honda JR, Knight V, Chan ED. Pathogenesis and risk factors for nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:1-11.

5. Marras TK, Mirsaeidi M, Chou E, et al. Health care utilization and expenditures following diagnosis of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease in the United States. Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24:964-974.

6. Prevots DR, Shaw PA, Strickland D, et al. Nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease prevalence at four integrated healthcare delivery systems. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:970-976.

7. Winthrop KL, McNelley E, Kendall B, et al. Pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease prevalence and clinical features: an emerging public health disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:977-982.

8. Adjemian, Olivier KN, Seitz AE, J et al. Prevalence of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease in US Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185;881-886.

9. Ringshausen FC, Apel RM, Bange FC, et al. Burden and trends of hospitalizations associated with pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial infections in Germany, 2005-2011. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:231.

10. Aliyu G, El-Kamary SS, Abimiku A, et al. Prevalence of non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections among tuberculosis suspects in Nigeria. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63170.

11. Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott, et al; American Thoracic Society; Infectious Diseases Society of America. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-415.

12. Wallace RJ Jr, Zhang Y, Brown BA, et al. Polyclonal Mycobacterium avium complex infections in patients with nodular bronchiectasis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:1235-1244.

13. Gordin FM, Horsburgh CR Jr. Mycobacterium avium complex. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2015.

14. Chitty S, Ali J. Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary disease in immune competent patients. South Med J. 2005;98:646-52.

15. Ramirez J, Mason C, Ali J, Lopez FA. MAC pulmonary disease: management options in HIV-negative patients. J La State Med Soc. 2008;160:248-254.

16. Iseman MD, Buschman DL, Ackerson LM. Pectus excavatum and scoliosis. Thoracic anomalies associated with pulmonary disease caused by Mycobacterium avium complex. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:914-916.

17. Kim RD, Greenburg DE, Ehrmantraut ME, et al. Pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease: prospective study of a distinct preexisting syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:1066-1074.

18. Ziedalski TM, Kao PN, Henig NR, et al. Prospective analysis of cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator mutations in adults with bronchiectasis or pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial infection. Chest. 2006;130:995-1002.

19. Koh WJ, Lee KS, Kwon OJ, et al. Bilateral bronchiectasis and bronchiolitis at thin-section CT: diagnostic implications in nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary infection. Radiology. 2005;235:282-288.

20. Swensen SJ, Hartman TE, Williams DE. Computed tomographic diagnosis of Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex in patients with bronchiectasis. Chest. 1994;105:49-52.

21. Huang JH, Kao PN, Adi V, Ruoss SJ. Mycobacterium avium intracellulare pulmonary infection in HIV-negative patients without preexisting lung disease: diagnostic and management limitations. Chest. 1999;115:1033-1040.

22. Cappelluti E, Fraire AE, Schaefer OP. A case of “hot tub lung” due to Mycobacterium avium complex in an immunocompetent host. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:845-848.

23. Nightingale SD, Byrd LT, Southern PM, et al. Incidence of Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex bacteremia in human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients. J Infect Dis. 1992;165:1082-1085.

24. Horsburgh CR Jr, Selik RM. The epidemiology of disseminated tuberculous mycobacterial infection in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;139:4-7.

25. Chin DP, Hopewell PC, Yajko DM, et al. Mycobacterium avium complex in the respiratory or gastrointestinal tract and the risk of M. avium complex bacteremia in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:289-295.

26. Khan K, Wang J, Marras TK. Nontuberculous mycobacterial sensitization in the United States: national trends over three decades. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:306-313.

27. Lillo M, Orengo S, Cernoch P, Harris RL. Pulmonary and disseminated infection due to Mycobacterium kansasii: a decade of experience. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12:760-767.

28. Andersen P, Munk ME, Pollock JM, Doherty TM. Specific immune-based diagnosis of tuberculosis. Lancet. 2000;356:1099-1104.

29. Arend SM, van Meijgaarden KE, de Boer K, et al. Tuberculin skin testing and in vitro T cell responses to ESAT-6 and culture filtrate protein 10 after infection with Mycobacterium marinum or M. kansasii. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:1797-1807.

30. James D, Chalmers JD, Goeminne P, et al. The Bronchiectasis Severity Index: an international derivation and validation study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:576-585.

31. Heifets L. MIC as a quantitative measurement of the susceptibility of Mycobacterium avium strains to seven antituberculosis drugs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:1131-1136.

32. Horsburgh CR Jr, Mason UG 3rd, Heifits LB, et al. Response to therapy of pulmonary Mycobacterium avium intracellulare infection correlates with results of in vitro susceptibility testing. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;135:418-421.

33. Rubin BK, Henke MO. Immunomodulatory activity and effectiveness of macrolides in chronic airway disease. Chest. 2004;125(2 Suppl):70S-78S.

34. Wallace RJ Jr, Brown BA, Griffith DE, et al. Clarithromycin regimens for pulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex. The first 50 patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:1766-1772.

35. Griffith DE, Brown-Elliott BA, Langsjoen B, et al. Clinical and molecular analysis of macrolide resistance in Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:928-934.

36. Lam PK, Griffith DE, Aksamit TR, et al. Factors related to response to intermittent treatment of Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:1283-1289.

37. Falkinham J III. Challenges of NTM drug development. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1613.

38. Griffith DE, Eagle G, Thomson R, et al. Amikacin liposome inhalation suspension for treatment-refractory lung disease caused by Mycobacterium avium complex (CONVERT). A prospective, open-label, randomized study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198:1559-1569.

39. Schluger NW. Treatment of pulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex infections: do drug levels matter? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:710-711.

40. Van Ingen J, Egelund EF, Levin A, et al. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of pulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex disease treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:559-565.

41. Koh WJ, Jeong BH, Jeon K, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring in the treatment of Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:797-802.

42. Ito Y, Hirai T, Maekawa K, et al. Predictors of 5-year mortality in pulmonary MAC disease. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:408-414.

43. Yuji S, Yutsuki N, Keiichiso T, et al. Surgery for Mycobacterium avium lung disease in the clarithromycin era. Eur J Cardiothor Surg. 2002;21:314-318.

44. Tortoli E, Kohl TA, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. Emended description of Mycobacterium abscessus, Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. abscessus and Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. bolletii and designation of Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. massiliense comb. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2016; 66:4471-4479.

45. Griffith DE, Girard WM, Wallace RJ Jr. Clinical features of pulmonary disease caused by rapidly growing mycobacteria. An analysis of 154 patients. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147:1271-1278.

46. Koh WJ, Jeong BH, Kim SY, et al. Mycobacterial characteristics and treatment outcomes in Mycobacterium abscessus lung disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:309-316.

Nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease is a broad term for a group of pulmonary disorders caused and characterized by exposure to environmental mycobacteria other than those belonging to the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and Mycobacterium leprae. Mycobacteria are aerobic, nonmotile organisms that appear positive with acid-fast alcohol stains. Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are ubiquitous in the environment and have been recovered from domestic and natural water sources, soil, and food products, and from around livestock, cattle, and wildlife.1-3 To date, no evidence exists of human-to-human or animal-to-human transmission of NTM in the general population. Infections in humans are usually acquired from environmental exposures, although the specific source of infection cannot always be identified. Similarly, the mode of infection with NTM has not been established with certainty, but it is highly likely that the organism is implanted, ingested, aspirated, or inhaled. Aerosolization of droplets associated with use of bathroom showerheads and municipal water sources and soil contamination are some of the factors associated with the transmission of infection. Proven routes of transmission include showerheads and potting soil dust.2,3

NTM pulmonary disease occurs in individuals with or without comorbid conditions such as bronchiectasis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pulmonary fibrosis, or structural lung diseases. Slender, middle-aged or elderly white females with marfanoid body habitus, with or without apparent immune or genetic disorders, showing impaired airway and mucus clearance present with this infection as a form of underlying bronchiectasis (Lady Windermere syndrome). It is unclear why NTM infections and escalation to clinical disease occur in certain individuals. Many risk factors, including inherited and acquired defects of host immune response (eg, cystic fibrosis trait and α1 antitrypsin deficiency), have been associated with increased susceptibility to NTM infections.4

NTM infection can lead to chronic symptoms, frequent exacerbations, progressive functional and structural lung destruction, and impaired quality of life, and is associated with an increased risk of hospitalization and higher 5-year all-cause mortality. As such, NTM disease is drawing increasing attention at the clinical, academic, and research levels.5 This case-based review outlines the clinical features of NTM infection, with a focus on the challenges in diagnosis, treatment, and management of NTM pulmonary disease. The cases use Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), a slow-growing mycobacteria (SGM), and Mycobacterium abscessus, a rapidly growing mycobacteria (RGM), as prototypes in a non–cystic fibrosis, non-HIV clinical setting.

Epidemiology

Of the almost 200 isolated species of NTM, the most prevalent pathogens for respiratory disease in the United States are MAC, Mycobacterium kansasii, and M. abscessus. MAC accounts for more than 80% of cases of NTM respiratory disease in the United States.6 The prevalence of NTM disease is increasing at a rate of about 8% each year, with 75,000 to 105,000 patients diagnosed with NTM lung disease in the United States annually. NTM infections in the United States are increasing among patients aged 65 years and older, a population that is expected to nearly double by 2030.7,8

Isolation and prevalence of many NTM species are higher in certain geographic areas of the United States, especially in the southeast. The US coastal regions have a higher prevalence of NTM pulmonary disease, and account for 70% of NTM cases in the United States each year. Half of patients diagnosed with NTM lung disease reside in 7 states: Florida, New York, Texas, California, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Ohio, with 1 in 7 residing in Florida. Three parishes in Louisiana are among the top 10 counties with the highest prevalence in United States. The prevalence of NTM infection–associated hospitalizations is increasing worldwide as well. Co-infection with tuberculosis and multiple NTMs in individual patients has been observed clinically and documented in patients with and without HIV.9,10

It is not clear why the prevalence of NTM pulmonary disease is increasing, but there may be several contributing factors: (1) an increased awareness and identification of NTM infection sources in the environment; (2) an expanding cohort of immunocompromised individuals with exogenous or endogenous immune deficiencies; (3) availability of improved diagnostic techniques, such as use of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), DNA probes, and gene sequencing; and (4) an increased awareness of the morbidity and mortality associated with NTM pulmonary disease. However, it is important to recognize that to best understand the clinical relevance of epidemiologic studies based on laboratory diagnosis and identification, the findings must be evaluated by correlating them with the microbiological and other clinical criteria established by the American Thoracic Society (ATS)/Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines.11

Continue to: Mycobacterium avium Complex

Mycobacterium avium Complex

Case Patient 1

A 48-year-old woman who has never smoked and has no past medical problems, except seasonal allergic rhinitis and “colds and flu-like illness” once or twice a year, is evaluated for a chronic lingering cough with occasional sputum production. The patient denies any other chronic symptoms and is otherwise active. Physical examination reveals no specific findings except mild pectus excavatum and mild scoliosis. Body mass index is 22 kg/m2. Chest radiograph shows nonspecific increased markings in the lower zones. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest reveals minimal nodular and cylindrical bronchiectasis in both lungs (Figure 1). No previous radiographs are available for comparison. The patient is HIV-negative. Sputum tests reveal normal flora, and both fungus and acid-fast bacilli smear are negative. Culture for mycobacteria shows scanty growth of MAC in 1 specimen.

What is the clinical presentation of MAC pulmonary disease?

Among NTM, MAC is the most common cause of pulmonary disease worldwide.6 MAC primarily includes 2 species: M. avium and Mycobacterium intracellulare. M. avium is the more important pathogen in disseminated disease, whereas M. intracellulare is the more common respiratory pathogen.11 These organisms are genetically similar and generally not differentiated in the clinical microbiology laboratory, although there are isolated reports in the literature suggesting differences in prevalence, presentation, and prognosis in M. avium infection versus M. intracellulare infection.12

Three major disease syndromes are produced by MAC in humans: pulmonary disease, usually in adults whose systemic immunity is intact; disseminated disease, usually in patients with advanced HIV infection; and cervical lymphadenitis.13 Pulmonary disease caused by MAC may take on 1 of several clinically different forms, including asymptomatic “colonization” or persistent minimal infection without obvious clinical significance; endobronchial involvement; progressive pulmonary disease with radiographic and clinical deterioration and nodular bronchiectasis or cavitary lung disease; hypersensitivity pneumonitis; or persistent, overwhelming mycobacterial growth with symptomatic manifestations, often in a lung with underlying damage due to either chronic obstructive lung disease or pulmonary fibrosis (Table 1).14

Cavitary Disease

The traditionally recognized presentation of MAC lung disease has been apical cavitary lung disease in men in their late 40s and early 50s who have a history of cigarette smoking, and frequently, excessive alcohol use. If left untreated, or in the case of erratic treatment or macrolide drug resistance, this form of disease is generally progressive within a relatively short time and can result in extensive cavitary lung destruction and progressive respiratory failure.15

Nodular Bronchiectasis

The more common presentation of MAC lung disease, which is outlined in the case described here, is interstitial nodular infiltrates, frequently involving the right middle lobe or lingula and predominantly occurring in postmenopausal, nonsmoking white women. This is sometimes labelled “Lady Windermere syndrome.” These patients with M. avium infection appear to have similar clinical characteristics and body types, including lean build, scoliosis, pectus excavatum, and mitral valve prolapse.16,17 The mechanism by which this body morphotype predisposes to pulmonary mycobacterial infection is not defined, but ineffective mucociliary clearance is a possible explanation. Evidence suggests that some patients may be predisposed to NTM lung disease because of preexisting bronchiectasis. Some potential etiologies of bronchiectasis in this population include chronic sinusitis, gastroesophageal reflux with chronic aspiration, α1 antitrypsin deficiency, and cystic fibrosis genetic traits and mutations.18 Risk factors for increased morbidity and mortality include the development of cavitary disease, age, weight loss, lower body mass index, and other comorbid conditions.

This form of disease, termed nodular bronchiectasis, tends to have a much slower progression than cavitary disease, such that long-term follow-up (months to years) may be necessary to demonstrate clinical or radiographic changes.11 The radiographic term “tree-in-bud” has been used to describe what may reflect inflammatory changes, including bronchiolitis. High-resolution CT scans of the chest are especially helpful for diagnosing this pattern of MAC lung disease, as bronchiectasis and small nodules may not be easily discernible on plain chest radiograph. The nodular/bronchiectasis radiographic pattern can also be seen with other NTM pathogens, including M. abscessus, Mycobacterium simiae, and M. kansasii. Solitary nodules and dense consolidation have also been described. Pleural effusions are uncommon, but reactive pleural thickening is frequently seen. Co-pathogens may be isolated from culture, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and, occasionally, other NTM such as M. abscessus or Mycobacterium chelonae.19-21

Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis, initially described in patients who were exposed to hot tubs, mimics allergic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, with respiratory symptoms and culture/tissue identification of MAC or sometimes other NTM. It is unclear whether hypersensitivity pneumonitis is an inflammatory process, an infection, or both, and opinion regarding the need for specific antibiotic treatment is divided.11,22 However, avoidance of exposure is prudent and recommended.

Disseminated Disease

Disseminated NTM disease is associated with very low CD4+ lymphocyte counts and is seen in approximately 5% of patients with HIV infection.23-25 Although disseminated NTM disease is rarely seen in immunosuppressed patients without HIV infection, it has been reported in patients who have undergone renal or cardiac transplant, patients on long-term corticosteroid therapy, and those with leukemia or lymphoma. More than 90% of infections are caused by MAC; other potential pathogens include M. kansasii, M. chelonae, M. abscessus, and Mycobacterium haemophilum. Although seen less frequently since the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy, disseminated infection can develop progressively from an apparently indolent or localized infection or a respiratory or gastrointestinal source. Signs and symptoms of disseminated infection (specifically MAC-associated disease) are nonspecific and include fever, night sweats, weight loss, and abdominal tenderness. Disseminated MAC disease occurs primarily in patients with more advanced HIV disease (CD4+ count typically < 50 cells/μL). Clinically, disseminated MAC manifests as intermittent or persistent fever, constitutional symptoms with organomegaly and organ-specific abnormalities (eg, anemia, neutropenia from bone marrow involvement, adenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly), and elevations of liver enzymes or lung infiltrates from pulmonary involvement.

Continue to: What are the criteria for diagnosing NTM pulmonary disease?

What are the criteria for diagnosing NTM pulmonary disease?

The diagnosis of NTM disease is based on clinical, radiologic, and mycobacterial correlation with good communication between the experts in this field. The ATS/IDSA criteria for diagnosing NTM lung disease are shown in Figure 2. These criteria best apply to MAC, M. kansasii, and M. abscessus, but are also clinically applied to other NTM respiratory pathogens. The diagnosis of MAC infection is most readily established by culture of blood, bone marrow, respiratory secretions/fluid, or tissue specimens from suspected sites of involvement. Due to erratic shedding of MAC into the respiratory secretions in patients with nodular bronchiectasis, as compared to those with the cavitary form of the disease, sputum may be intermittently positive, with variable colony counts and polyclonal infections.12 Prior to the advent of high-resolution CT, isolation of MAC organisms from the sputum of such patients was frequently dismissed as colonization.

Mycobacterial Testing

Because of the nonspecific symptoms and lack of diagnostic specificity of chest imaging, the diagnosis of NTM lung disease requires microbiologic confirmation. Specimens sent to the laboratory for identification of NTM must be handled with care to prevent contamination and false-positive results. Transport media and preservatives should be avoided, and transportation of the specimens should be prompt. These measures will prevent bacterial overgrowth. Furthermore, the yield of NTM may be affected if the patient has used antibiotics, such as macrolides and fluoroquinolones, prior to obtaining the specimen.

NTM should be identified at the species and subspecies level, although this is not practical in community practice settings. The preferred staining procedure in the laboratory is the fluorochrome method. Some species require special growth conditions and/or lower incubation temperatures, and other identification methods may have to be employed, such as DNA probes, polymerase chain reaction genotyping, nucleic acid sequence determination, and high-performance liquid chromatography. As a gold standard, clinical specimens for mycobacterial cultures should be inoculated onto 1 or more solid media (eg, Middlebrook 7H11 media and/or Lowenstein-Jensen media, the former of which is the preferred medium for NTM) and into a liquid medium (eg, BACTEC 12B broth or Mycobacteria growth indicator tube broth). Growth of visible colonies on solid media typically requires 2 to 4 weeks, but liquid media (eg, the radiometric BACTEC system), used as a supplementary and not as an exclusive test, usually produce results within 10 to 14 days. Furthermore, even after initial growth, identification of specific isolates based on the growth characteristics on solid media requires additional time. Use of specific nucleic acid probes for MAC and M. kansasii and HPLC testing of mycolic acid patterns in acid-fast bacilli smear–positive specimens can reduce the turnaround time of specific identification of a primary culture–positive sample. However, HPLC is not sufficient for definitive identification of many NTM species, including the RGM. Other newer techniques, including 16S ribosomal DNA sequencing and polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis, also allow NTM to be identified and speciated more reliably and rapidly from clinical specimens.

Cost and other practical considerations limit widespread adoption of these techniques. However, the recognition that M. abscessus can be separated into more than 1 subspecies, and that there are important prognostic implications of that separation, lends urgency to the broader adoption of newer molecular techniques in the mycobacteriology laboratory. Susceptibility testing is based on the broth microdilution method; RGM usually grow within 7 days of subculture, and the laboratory time to culture is a helpful hint, although not necessarily specific. Recognizing the morphology of mycobacterial colony growth may also be helpful in identification.

Are skin tests helpful in diagnosing NTM infection?

Tuberculin skin testing remains a nonspecific marker of mycobacterial infection and does not help in further elucidating NTM infection. However, epidemiologic and laboratory studies with well-characterized antigens have shown that dual skin testing with tuberculosis- versus NTM-derived tuberculin can discriminate between prior NTM and prior tuberculosis disease. Species-specific skin test antigens are not commercially available and are not helpful in the diagnosis of NTM disease because of cross-reactivity of M. tuberculosis and some NTM. However, increased prevalence of NTM sensitization based on purified protein derivative testing has been noted in a recent survey, which is consistent with an observed increase in the rates of NTM infections, specifically MAC, in the United States.26,27

Interferon-gamma release assays (IGRAs) are now being used as an alternative to tuberculin skin testing to diagnose M. tuberculosis infection. Certain NTM species also contain gene sequences that encode for ESAT-6 or CFP-10 antigens used in the IGRAs, and hence, yield a positive IGRA test. These include M. marinum, M. szulgai, and M. kansasii.28,29 However, MAC organisms do not produce positive results on assays that use these antigens.

Continue to: What is the approach to management of NTM pulmonary disease?

What is the approach to management of NTM pulmonary disease?

The correlation of symptoms with radiographic and microbiologic evidence is essential to categorize the disease and determine the need for therapy. Making the diagnosis of NTM lung disease does not necessitate the institution of therapy. The decision to treat should be weighed against potential risks and benefits to the individual patient based on symptomatic, radiographic, and microbiologic criteria, as well as underlying systemic or pulmonary immune status. In the absence of evidence of clinical, radiologic, or mycobacterial progression of disease, pursuing airway clearance therapy and clinical surveillance without initiating specific anti-MAC therapy is a reasonable option.11 Identifying the sustained presence of NTM infection, especially MAC, in a patient with underlying clinical and radiographic evidence of bronchiectasis is of value in determining comprehensive treatment and management strategies. Close observation is indicated if the decision not to treat is made. If treatment is initiated, comprehensive management includes long-term follow-up with periodic bacteriologic surveillance, watching for drug toxicity and drug-drug interactions, ensuring adherence and compliance to treatment, and managing comorbidity.

The Bronchiectasis Severity Index is a useful clinical predictive tool that identifies patients at risk of future mortality, hospitalization, and exacerbations and can be used to evaluate the need for specific treatment.30 The index is based on dyspnea score, lung function tests, colonization of pathogens, and extent of disease.

Case 1 Continued

After approximately 2 months of observation and symptomatic treatment, without specific antibiotic therapy, the patient’s symptoms continue. She now develops intermittent hemoptysis. Repeat sputum studies reveal moderate growth of M. avium. A follow-up CT scan shows progression of disease, with an increase in the tree-in-bud pattern (Figure 3).

What treatment protocols are recommended for MAC pulmonary disease?

As per the ATS/IDSA statement, macrolides are the mainstay of treatment for pulmonary MAC disease.11 Macrolides achieve an increased concentration in the lung, and when used for treatment of pulmonary MAC disease, there is a strong correlation between in vitro susceptibility, in vivo (clinical) response, and the immunomodulating effects of macrolides.31,32 Macrolide-containing regimens have demonstrated efficacy in patients with MAC pulmonary disease33,34; however, macrolide monotherapy should be avoided to prevent the development of resistance.

At the outset, it is critical to establish the objective criteria for determining response and to ensure that the patient understands the goals of the treatment and expectations of the treatment plan. Moreover, experts suggest that due to the possibility of drug intolerance, side effects, and the need for prolonged therapy, a “step ladder” ramping up approach to treatment could be adopted, with gradual introduction of therapy within a short time period; this approach may improve compliance and adherence to treatment.11 If this approach is used, the doses may have to be divided. Patients who are unable to tolerate daily medications, even with dosage adjustment, should be tried on an intermittent treatment regimen. Older female patients frequently require gradual introduction of medications (ie, 1 medication added to the regimen every 1 to 2 weeks) to evaluate tolerance to each medication and medication dose.11 Commonly encountered adverse effects of NTM treatment include intolerance to clarithromycin due to gastrointestinal problems, low body mass index, or age older than 70 years.

After determining that the patient requires therapy, the standard recommended treatment for MAC pulmonary disease includes the following: for most patients with nodular/bronchiectasis disease, a thrice-weekly regimen of clarithromycin (1000 mg) or azithromycin (500 mg), rifampin (600 mg), and ethambutol (25 mg/kg) is recommended. For patients with cavitary MAC pulmonary disease or severe nodular/bronchiectasis disease, the guidelines recommend a daily regimen of clarithromycin (500-1000 mg) or azithromycin (250 mg), rifampin (600 mg) or rifabutin (150–300 mg), and ethambutol (15 mg/kg), with consideration of intravenous (IV) amikacin 3 times/week early in therapy (Table 2).11

The treatment of MAC hypersensitivity-like disease speaks to the controversy of whether this is an inflammatory process, infectious process, or a combination of inflammation and infection. Avoidance of exposure is the mainstay of management. In some cases, steroids are used with or without a short course of anti-MAC therapy (ie, clarithromycin or azithromycin with rifampin and ethambutol).

Prophylaxis for disseminated MAC disease should be given to adults with HIV infection who have a CD4+ count less than 50 cells/μL. Azithromycin 1200 mg/week or clarithromycin 1000 mg/day has proven efficacy, and rifabutin 300 mg/day is also effective but less well tolerated. Rifabutin is more active in vitro against MAC than rifampin, and is used in HIV-positive patients because of drug-drug interaction between antiretroviral drugs and rifampin.

Continue to: Case 1 Continued

Case 1 Continued

The patient is treated with clarithromycin, rifampin, and ethambutol for 1 year, with sputum conversion after 9 months. In the latter part of her treatment, she experiences decreased visual acuity. Treatment is discontinued prematurely after 1 year due to drug toxicity and continued intolerance to drug therapy. The patient remains asymptomatic for 8 months, and then begins to experience mild to moderate hemoptysis, with increasing cough and sputum production associated with postural changes during exercise. Physical examination overall remains unchanged. Three sputum results reveal heavy growth of MAC, and a CT scan of the chest shows a cavitary lesion in the left upper lobe along with the nodular bronchiectasis (Figure 4).

What are the management options at this stage?

Based on this patient’s continued symptoms, progression of radiologic abnormalities, and current culture growth, she requires re-treatment. With the adverse effects associated with ethambutol during the first round of therapy, the drug regimen needs to be modified. Several considerations are relevant at this stage. Relapse rates range from 20% to 30% after treatment with a macrolide-based therapy.11,34 Obtaining a culture-sensitivity profile is imperative in these cases. Of note, treatment should not be discontinued altogether, but instead the toxic agent should be removed from the treatment regimen. Continuing treatment with a 2-drug regimen of clarithromycin and rifampin may be considered in this patient. Re-infection with multiple genotypes may also occur after successful drug therapy, but this is primarily seen in MAC patients with nodular bronchiectasis.34,35 Patients in whom previous therapy has failed, even those with macrolide-susceptible MAC isolates, are less likely to respond to subsequent therapy. Data suggest that intermittent medication dosing is not effective for patients with severe or cavitary disease or in those in whom previous therapy has failed.36 In this case, treatment should include a daily 3-drug therapy, with an injectable thrice-weekly aminoglycoside. Other agents such as linezolid and clofazimine may have to be tried. Cycloserine, ethionamide, and other agents are sometimes used, but their efficacy is unproven and doubtful. Pyrazinamide and isoniazid have no activity against MAC.

Treatment Failure and Drug Resistance

Treatment failure is considered to have occurred if patients have not had a response (microbiologic, clinical, or radiographic) after 6 months of appropriate therapy or had not achieved conversion of sputum to culture-negative after 12 months of appropriate therapy.11 This occurs in about 40% of patients. Multiple factors can interfere with the successful treatment of MAC pulmonary disease, including medication nonadherence, medication side effects or intolerance, lack of response to a medication regimen, or the emergence of a macrolide-resistant or multidrug-resistant strain. Inducible macrolide resistance remains a potential factor.34-36 A number of characteristics of NTM contribute to the poor response to currently used antibiotics: the organisms have a lipid outer membrane and prefer to adhere to surfaces and form biofilms, which makes them relatively impermeable to antibiotics.37 Also, NTM replicate in phagocytic cells, allowing them to subvert normal cellular defense mechanisms. Furthermore, NTM can display colony variants, whereby single colony isolates switch between antibiotic-susceptible and -resistant variants. These factors have also impeded in development of new antibiotics for NTM infection.37

Recent limited approval of amikacin liposomal inhalation suspension (ALIS) for treatment failure and refractory MAC infection in combination with guideline-based antimicrobial therapy (GBT) is a promising addition to the available treatment armamentarium. In a multinational trial, the addition of ALIS to GBT for treatment-refractory MAC lung disease achieved significantly greater culture conversion rates by month 6 than GBT alone, with comparable rates of serious adverse events.38

Is therapeutic drug monitoring recommended during treatment of MAC pulmonary disease?

Treatment failure may also be drug-related, including poor drug penetration into the damaged lung tissue or drug-drug interactions leading to suboptimal drug levels. Peak serum concentrations have been found to be below target ranges in approximately 50% of patients using a macrolide and ethambutol. Concurrent use of rifampin decreases the peak serum concentration of macrolides and quinolones, with acceptable target levels seen in only 18% to 57% of cases. Whether this alters patient outcomes is not clear.39-42 Factors identified as contributing to the poor response to therapy include poor compliance, cavitary disease, previous treatment for MAC pulmonary disease, and a history of chronic obstructive lung disease. Studies by Koh and colleagues40 and van Ingen and colleagues41 with pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics data showed that, in patients on MAC treatment with both clarithromycin and rifampicin, plasma levels of clarithromycin were lower than the recommended minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC) against MAC for that drug. The studies also showed that rifampicin lowered clarithromycin concentrations more than did rifabutin, with the AUC/MIC ratio being suboptimal in nearly half the cases. However, low plasma clarithromycin concentrations did not have any correlation with treatment outcomes, as the peak plasma drug concentrations and the peak plasma drug concentration/MIC ratios did not differ between patients with unfavorable treatment outcomes and those with favorable outcomes. This is further compounded by the fact that macrolides achieve higher levels in lung tissue than in plasma, and hence the significance of low plasma levels is unclear; however, it is postulated that achieving higher drug levels could, in fact, lead to better clinical outcomes. Pending specific well-designed, prospective randomized controlled trials, routine therapeutic drug monitoring is not currently recommended, although some referral centers do this as their practice pattern.

Is surgery an option in this case?

The overall 5-year mortality for MAC pulmonary disease was approximately 28% in a retrospective analysis, with patients with cavitary disease at increased risk for death at 5 years.42 As such, surgery is an option in selected cases as part of adjunctive therapy along with anti-MAC therapy based on mycobacterial sensitivity. Surgery is used as either a curative approach or a “debulking” measure.11 When present, clearly localized disease, especially in the upper lobe, lends itself best to surgical intervention. Surgical resection of a solitary pulmonary nodule due to MAC, in addition to concomitant medical treatment, is recommended. Surgical intervention should be considered early in the course of the disease because it may provide a cure without prolonged treatment and its associated problems, and this approach may lead to early sputum conversion. Surgery should also be considered in patients with macrolide-resistant or multidrug-resistant MAC infection or in those who cannot tolerate the side effects of therapy, provided that the disease is focal and limited. Patients with poor preoperative lung function have poorer outcomes than those with good lung function, and postoperative complications arising from treatment, especially with a right-sided pneumonectomy, tend to occur more frequently in these patients. Thoracic surgery for NTM pulmonary disease must be considered cautiously, as this is associated with significant morbidity and mortality and is best performed at specialized centers that have expertise and experience in this field.43

Continue to: Mycobacterium abscessus Complex

Mycobacterium abscessus Complex

Case Patient 2

A 64-year-old man who is an ex-smoker presents with chronic cough, mild shortness of breath on exertion, low-grade fever, and unintentional weight loss of 10 lb. Physical exam is unremarkable. The patient was diagnosed with immunoglobulin deficiency (low IgM and low IgG4) in 2002, and has been on replacement therapy since then. He also has had multiple episodes of NTM infection, with MAC and M. kansasii infections diagnosed in 2012-2014, which required 18 months of multi-drug antibiotic treatment that resulted in sputum conversion. Pulmonary function testing done on this visit in 2017 shows mild obstructive impairment.

Chest radiograph and CT scan show bilateral bronchiectasis (Figure 5 and Figure 6).

The results of serial sputum microbiology testing performed over the course of 6 months are outlined below:

- 5/2017 (bronchoalveolar lavage): 2+; M. abscessus

- 9/2017 × 2: smear (–); group IV RGM