User login

How effective is that face mask?

More and more, the streets of America are looking like those of Eastern countries (such as China) during previous public health crises. Americans are wearing face masks.

In addition to social distancing and hand washing, face masks are a primary defense against COVID-19. N95 face masks protect against 95% of the particles that are likely to transmit respiratory infection microbes. Last month, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended that we all use masks, in addition to social distancing, in public settings. Since there will not be a sufficient supply of N95 masks for the general public (and they are difficult to fit and wear properly), we are left with surgical masks and so-called DIY (do-it-yourself) masks. But do DIY face masks protect against COVID-19?

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine published a scientific review of fabric face masks last month.1 They found 7 studies that evaluated either the ability of the mask to protect the wearer or to prevent the spread of infectious particles from a wearer. Performance ranged from very poor to 50% filtration depending on the material used. Jayaraman2 found a filtration rate of 50% for 4 layers of polyester knitted cut-pile fabric, the best material he tested. Davies3 compared a 2-layer cotton DIY mask with a surgical face mask and found that the cotton mask was 3 times less effective. And in the only randomized trial of cotton masks, the cotton 2-layer masks performed much worse than medical masks in protecting from respiratory infection (relative risk [RR] = 13).4 A study of COVID-19-infected patients found that neither surgical nor cotton masks were effective at blocking the virus from disseminating during coughing.5

The most recent lab testing of DIY masks was done at Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, where they tested a variety of materials; the results were somewhat encouraging.6 The best homemade masks were those with “2 layers of high-quality, heavyweight ‘quilter’s cotton’ with a thread count of 180 or more, and those with especially tight weave and thicker thread such as batiks.”6 The best homemade masks achieved 79% filtration. But single-layer masks or double-layer designs of lower quality, lightweight cotton achieved as little as 1% filtration.

The bottom line: Mass production and use of N95-type masks would be most effective in preventing transmission in general public settings, but this seems unlikely. Surgical masks are next best. Well-constructed DIY masks are the last resort but can provide some protection against infection.

1. Besser R, Fischhoff B; National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Rapid Expert Consultation on the Effectiveness of Fabric Masks for the COVID-19 Pandemic (April 8, 2020). www.nap.edu/read/25776/chapter/1. Published April 8, 2020. Accessed April 28, 2020.

2. Jayaraman S. Pandemic flu—textile solutions pilot: design and development of innovative medical masks [final technical report]. Atlanta, GA: Georgia Institute of Technology; 2012.

3. Davies A, Thompson K, Giri K, et al. Testing the efficacy of homemade masks: would they protect in an influenza pandemic? Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2013;7:413-418.

4. MacIntyre CR, Seale H, Dung TC, et al. A cluster randomised trial of cloth masks compared with medical masks in healthcare workers. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006577.

5. Bae S, Kim MC, Kim JY, et al. Effectiveness of surgical and cotton masks in blocking SARS-CoV-2: a controlled comparison in 4 patients [published online ahead of print April 6, 2020]. Ann Intern Med. 2020.

6. Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center. Testing shows type of cloth used in homemade masks makes a difference, doctors say. https://newsroom.wakehealth.edu/News-Releases/2020/04/Testing-Shows-Type-of-Cloth-Used-in-Homemade-Masks-Makes-a-Difference. Published April 2, 2020. Accessed April 28, 2020.

More and more, the streets of America are looking like those of Eastern countries (such as China) during previous public health crises. Americans are wearing face masks.

In addition to social distancing and hand washing, face masks are a primary defense against COVID-19. N95 face masks protect against 95% of the particles that are likely to transmit respiratory infection microbes. Last month, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended that we all use masks, in addition to social distancing, in public settings. Since there will not be a sufficient supply of N95 masks for the general public (and they are difficult to fit and wear properly), we are left with surgical masks and so-called DIY (do-it-yourself) masks. But do DIY face masks protect against COVID-19?

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine published a scientific review of fabric face masks last month.1 They found 7 studies that evaluated either the ability of the mask to protect the wearer or to prevent the spread of infectious particles from a wearer. Performance ranged from very poor to 50% filtration depending on the material used. Jayaraman2 found a filtration rate of 50% for 4 layers of polyester knitted cut-pile fabric, the best material he tested. Davies3 compared a 2-layer cotton DIY mask with a surgical face mask and found that the cotton mask was 3 times less effective. And in the only randomized trial of cotton masks, the cotton 2-layer masks performed much worse than medical masks in protecting from respiratory infection (relative risk [RR] = 13).4 A study of COVID-19-infected patients found that neither surgical nor cotton masks were effective at blocking the virus from disseminating during coughing.5

The most recent lab testing of DIY masks was done at Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, where they tested a variety of materials; the results were somewhat encouraging.6 The best homemade masks were those with “2 layers of high-quality, heavyweight ‘quilter’s cotton’ with a thread count of 180 or more, and those with especially tight weave and thicker thread such as batiks.”6 The best homemade masks achieved 79% filtration. But single-layer masks or double-layer designs of lower quality, lightweight cotton achieved as little as 1% filtration.

The bottom line: Mass production and use of N95-type masks would be most effective in preventing transmission in general public settings, but this seems unlikely. Surgical masks are next best. Well-constructed DIY masks are the last resort but can provide some protection against infection.

More and more, the streets of America are looking like those of Eastern countries (such as China) during previous public health crises. Americans are wearing face masks.

In addition to social distancing and hand washing, face masks are a primary defense against COVID-19. N95 face masks protect against 95% of the particles that are likely to transmit respiratory infection microbes. Last month, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended that we all use masks, in addition to social distancing, in public settings. Since there will not be a sufficient supply of N95 masks for the general public (and they are difficult to fit and wear properly), we are left with surgical masks and so-called DIY (do-it-yourself) masks. But do DIY face masks protect against COVID-19?

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine published a scientific review of fabric face masks last month.1 They found 7 studies that evaluated either the ability of the mask to protect the wearer or to prevent the spread of infectious particles from a wearer. Performance ranged from very poor to 50% filtration depending on the material used. Jayaraman2 found a filtration rate of 50% for 4 layers of polyester knitted cut-pile fabric, the best material he tested. Davies3 compared a 2-layer cotton DIY mask with a surgical face mask and found that the cotton mask was 3 times less effective. And in the only randomized trial of cotton masks, the cotton 2-layer masks performed much worse than medical masks in protecting from respiratory infection (relative risk [RR] = 13).4 A study of COVID-19-infected patients found that neither surgical nor cotton masks were effective at blocking the virus from disseminating during coughing.5

The most recent lab testing of DIY masks was done at Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, where they tested a variety of materials; the results were somewhat encouraging.6 The best homemade masks were those with “2 layers of high-quality, heavyweight ‘quilter’s cotton’ with a thread count of 180 or more, and those with especially tight weave and thicker thread such as batiks.”6 The best homemade masks achieved 79% filtration. But single-layer masks or double-layer designs of lower quality, lightweight cotton achieved as little as 1% filtration.

The bottom line: Mass production and use of N95-type masks would be most effective in preventing transmission in general public settings, but this seems unlikely. Surgical masks are next best. Well-constructed DIY masks are the last resort but can provide some protection against infection.

1. Besser R, Fischhoff B; National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Rapid Expert Consultation on the Effectiveness of Fabric Masks for the COVID-19 Pandemic (April 8, 2020). www.nap.edu/read/25776/chapter/1. Published April 8, 2020. Accessed April 28, 2020.

2. Jayaraman S. Pandemic flu—textile solutions pilot: design and development of innovative medical masks [final technical report]. Atlanta, GA: Georgia Institute of Technology; 2012.

3. Davies A, Thompson K, Giri K, et al. Testing the efficacy of homemade masks: would they protect in an influenza pandemic? Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2013;7:413-418.

4. MacIntyre CR, Seale H, Dung TC, et al. A cluster randomised trial of cloth masks compared with medical masks in healthcare workers. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006577.

5. Bae S, Kim MC, Kim JY, et al. Effectiveness of surgical and cotton masks in blocking SARS-CoV-2: a controlled comparison in 4 patients [published online ahead of print April 6, 2020]. Ann Intern Med. 2020.

6. Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center. Testing shows type of cloth used in homemade masks makes a difference, doctors say. https://newsroom.wakehealth.edu/News-Releases/2020/04/Testing-Shows-Type-of-Cloth-Used-in-Homemade-Masks-Makes-a-Difference. Published April 2, 2020. Accessed April 28, 2020.

1. Besser R, Fischhoff B; National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Rapid Expert Consultation on the Effectiveness of Fabric Masks for the COVID-19 Pandemic (April 8, 2020). www.nap.edu/read/25776/chapter/1. Published April 8, 2020. Accessed April 28, 2020.

2. Jayaraman S. Pandemic flu—textile solutions pilot: design and development of innovative medical masks [final technical report]. Atlanta, GA: Georgia Institute of Technology; 2012.

3. Davies A, Thompson K, Giri K, et al. Testing the efficacy of homemade masks: would they protect in an influenza pandemic? Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2013;7:413-418.

4. MacIntyre CR, Seale H, Dung TC, et al. A cluster randomised trial of cloth masks compared with medical masks in healthcare workers. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006577.

5. Bae S, Kim MC, Kim JY, et al. Effectiveness of surgical and cotton masks in blocking SARS-CoV-2: a controlled comparison in 4 patients [published online ahead of print April 6, 2020]. Ann Intern Med. 2020.

6. Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center. Testing shows type of cloth used in homemade masks makes a difference, doctors say. https://newsroom.wakehealth.edu/News-Releases/2020/04/Testing-Shows-Type-of-Cloth-Used-in-Homemade-Masks-Makes-a-Difference. Published April 2, 2020. Accessed April 28, 2020.

Silent brain infarcts found in 3% of AFib patients, tied to cognitive decline

Patients with atrial fibrillation, even those on oral anticoagulant therapy, developed clinically silent brain infarctions at a striking rate of close to 3% per year, according to results from SWISS-AF, a prospective of study of 1,227 Swiss patients followed with serial MR brain scans over a 2 year period.

The results also showed that these brain infarctions – which occurred in 68 (5.5%) of the atrial fibrillation (AFib) patients, including 58 (85%) who did not have any strokes or transient ischemic attacks during follow-up – appeared to represent enough pathology to link with a small but statistically significant decline in three separate cognitive measures, compared with patients who did not develop brain infarctions during follow-up.

“Cognitive decline may go unrecognized for a long time in clinical practice because usually no one tests for it,” plus “the absolute declines were small and probably not appreciable” in the everyday behavior of affected patients, David Conen, MD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society, held online because of COVID-19. But “we were surprised to see a significant change after just 2 years. We expect much larger effects to develop over time,” he said during a press briefing.

Another key finding was that roughly half the patients had large cortical or noncortical infarcts, which usually have a thromboembolic cause, but the other half had small noncortical infarcts that likely have a different etiology involving the microvasculature. Causes for those small infarcts might include localized atherosclerotic disease or amyloidosis, proposed Dr. Conen, a cardiologist at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

This finding also suggests that, as a consequence, anticoagulation alone may not be enough to prevent this brain damage in Afib patients. “It calls for a more comprehensive approach to prevention,” with attention to atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk factors in AFib patients, including interventions that address hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and smoking cessation. “Anticoagulation in AFib patients is critical, but it also is not enough,” Dr. Conen said.

These data “are very important. The two pillars for taking care of AFib patients have traditionally been to manage the patient’s stroke risk and to treat symptoms. Dr. Conen’s data suggest that simply starting anticoagulation is not sufficient, and it stresses the importance of continued management of hypertension, diabetes, and other medical and social issues,” commented Fred Kusumoto, MD, director of heart rhythm services at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla.

“The risk factors associated with the development of cardiovascular disease are similar to those associated with the development of AFib and heart failure. It is important to understand the importance of managing hypertension, diabetes, and obesity; encouraging exercise and a healthy diet; and stopping smoking in all AFib patients as well as in the general population. Many clinicians have not emphasized the importance of continually addressing these behaviors,” Dr. Kusumoto said in an interview.

The SWISS-AF (Swiss Atrial Fibrillation Cohort) study enrolled 2,415 AFib patients at 14 Swiss centers during 2014-2017, and obtained both a baseline brain MR scan and baseline cognitive-test results for 1,737 patients (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Mar;73[9]:989-99). Patients retook the cognitive tests annually, and 1,227 had a second MR brain scan after 2 years in the study, the cohort that supplied the data Dr. Conen presented. At baseline, these patients averaged 71 years of age, just over a quarter were women, and 90% were on an oral anticoagulant, with 84% on an oral anticoagulant at 2-year follow-up. Treatment split roughly equally between direct-acting oral anticoagulants and vitamin K antagonists like warfarin.

Among the 68 patients with evidence for an incident brain infarct after 2 years, 59 (87%) were on treatment with an OAC, and 51 (75%) who were both on treatment with a direct-acting oral anticoagulant and developed their brain infarct without also having a stroke or transient ischemic attack, which Dr. Conen called a “silent event.” The cognitive tests that showed statistically significant declines after 2 years in the patients with silent brain infarcts compared with those without a new infarct were the Trail Making Test parts A and B, and the animal-naming verbal fluency test. The two other tests applied were the Montreal Cognitive Assessment and the Digital Symbol Substitution Test.

Results from several prior studies also indicated a relationship between AFib and cognitive decline, but SWISS-AF is “the largest study to rigorously examine the incidence of silent brain infarcts in AFib patients,” commented Christine M. Albert, MD, chair of cardiology at the Smidt Heart Institute of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. “Silent infarcts could be the cause, at least in part, for the cognitive decline and dementia associated with AFib,” she noted. But divining the therapeutic implications of the finding will require further investigation that looks at factors such as the impact of anticoagulant type, other treatment that addresses AFib such as ablation and rate control, the duration and type of AFib, and the prevalence of hypertension and other stroke risk factors, she said as a designated discussant for Dr. Conen’s report.

SWISS-AF received no commercial funding. Dr. Conen has been a speaker on behalf of Servier. Dr. Kusumoto had no disclosures. Dr. Albert has been a consultant to Roche Diagnostics and has received research funding from Abbott, Roche Diagnostics, and St. Jude Medical.

Patients with atrial fibrillation, even those on oral anticoagulant therapy, developed clinically silent brain infarctions at a striking rate of close to 3% per year, according to results from SWISS-AF, a prospective of study of 1,227 Swiss patients followed with serial MR brain scans over a 2 year period.

The results also showed that these brain infarctions – which occurred in 68 (5.5%) of the atrial fibrillation (AFib) patients, including 58 (85%) who did not have any strokes or transient ischemic attacks during follow-up – appeared to represent enough pathology to link with a small but statistically significant decline in three separate cognitive measures, compared with patients who did not develop brain infarctions during follow-up.

“Cognitive decline may go unrecognized for a long time in clinical practice because usually no one tests for it,” plus “the absolute declines were small and probably not appreciable” in the everyday behavior of affected patients, David Conen, MD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society, held online because of COVID-19. But “we were surprised to see a significant change after just 2 years. We expect much larger effects to develop over time,” he said during a press briefing.

Another key finding was that roughly half the patients had large cortical or noncortical infarcts, which usually have a thromboembolic cause, but the other half had small noncortical infarcts that likely have a different etiology involving the microvasculature. Causes for those small infarcts might include localized atherosclerotic disease or amyloidosis, proposed Dr. Conen, a cardiologist at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

This finding also suggests that, as a consequence, anticoagulation alone may not be enough to prevent this brain damage in Afib patients. “It calls for a more comprehensive approach to prevention,” with attention to atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk factors in AFib patients, including interventions that address hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and smoking cessation. “Anticoagulation in AFib patients is critical, but it also is not enough,” Dr. Conen said.

These data “are very important. The two pillars for taking care of AFib patients have traditionally been to manage the patient’s stroke risk and to treat symptoms. Dr. Conen’s data suggest that simply starting anticoagulation is not sufficient, and it stresses the importance of continued management of hypertension, diabetes, and other medical and social issues,” commented Fred Kusumoto, MD, director of heart rhythm services at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla.

“The risk factors associated with the development of cardiovascular disease are similar to those associated with the development of AFib and heart failure. It is important to understand the importance of managing hypertension, diabetes, and obesity; encouraging exercise and a healthy diet; and stopping smoking in all AFib patients as well as in the general population. Many clinicians have not emphasized the importance of continually addressing these behaviors,” Dr. Kusumoto said in an interview.

The SWISS-AF (Swiss Atrial Fibrillation Cohort) study enrolled 2,415 AFib patients at 14 Swiss centers during 2014-2017, and obtained both a baseline brain MR scan and baseline cognitive-test results for 1,737 patients (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Mar;73[9]:989-99). Patients retook the cognitive tests annually, and 1,227 had a second MR brain scan after 2 years in the study, the cohort that supplied the data Dr. Conen presented. At baseline, these patients averaged 71 years of age, just over a quarter were women, and 90% were on an oral anticoagulant, with 84% on an oral anticoagulant at 2-year follow-up. Treatment split roughly equally between direct-acting oral anticoagulants and vitamin K antagonists like warfarin.

Among the 68 patients with evidence for an incident brain infarct after 2 years, 59 (87%) were on treatment with an OAC, and 51 (75%) who were both on treatment with a direct-acting oral anticoagulant and developed their brain infarct without also having a stroke or transient ischemic attack, which Dr. Conen called a “silent event.” The cognitive tests that showed statistically significant declines after 2 years in the patients with silent brain infarcts compared with those without a new infarct were the Trail Making Test parts A and B, and the animal-naming verbal fluency test. The two other tests applied were the Montreal Cognitive Assessment and the Digital Symbol Substitution Test.

Results from several prior studies also indicated a relationship between AFib and cognitive decline, but SWISS-AF is “the largest study to rigorously examine the incidence of silent brain infarcts in AFib patients,” commented Christine M. Albert, MD, chair of cardiology at the Smidt Heart Institute of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. “Silent infarcts could be the cause, at least in part, for the cognitive decline and dementia associated with AFib,” she noted. But divining the therapeutic implications of the finding will require further investigation that looks at factors such as the impact of anticoagulant type, other treatment that addresses AFib such as ablation and rate control, the duration and type of AFib, and the prevalence of hypertension and other stroke risk factors, she said as a designated discussant for Dr. Conen’s report.

SWISS-AF received no commercial funding. Dr. Conen has been a speaker on behalf of Servier. Dr. Kusumoto had no disclosures. Dr. Albert has been a consultant to Roche Diagnostics and has received research funding from Abbott, Roche Diagnostics, and St. Jude Medical.

Patients with atrial fibrillation, even those on oral anticoagulant therapy, developed clinically silent brain infarctions at a striking rate of close to 3% per year, according to results from SWISS-AF, a prospective of study of 1,227 Swiss patients followed with serial MR brain scans over a 2 year period.

The results also showed that these brain infarctions – which occurred in 68 (5.5%) of the atrial fibrillation (AFib) patients, including 58 (85%) who did not have any strokes or transient ischemic attacks during follow-up – appeared to represent enough pathology to link with a small but statistically significant decline in three separate cognitive measures, compared with patients who did not develop brain infarctions during follow-up.

“Cognitive decline may go unrecognized for a long time in clinical practice because usually no one tests for it,” plus “the absolute declines were small and probably not appreciable” in the everyday behavior of affected patients, David Conen, MD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society, held online because of COVID-19. But “we were surprised to see a significant change after just 2 years. We expect much larger effects to develop over time,” he said during a press briefing.

Another key finding was that roughly half the patients had large cortical or noncortical infarcts, which usually have a thromboembolic cause, but the other half had small noncortical infarcts that likely have a different etiology involving the microvasculature. Causes for those small infarcts might include localized atherosclerotic disease or amyloidosis, proposed Dr. Conen, a cardiologist at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

This finding also suggests that, as a consequence, anticoagulation alone may not be enough to prevent this brain damage in Afib patients. “It calls for a more comprehensive approach to prevention,” with attention to atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk factors in AFib patients, including interventions that address hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and smoking cessation. “Anticoagulation in AFib patients is critical, but it also is not enough,” Dr. Conen said.

These data “are very important. The two pillars for taking care of AFib patients have traditionally been to manage the patient’s stroke risk and to treat symptoms. Dr. Conen’s data suggest that simply starting anticoagulation is not sufficient, and it stresses the importance of continued management of hypertension, diabetes, and other medical and social issues,” commented Fred Kusumoto, MD, director of heart rhythm services at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla.

“The risk factors associated with the development of cardiovascular disease are similar to those associated with the development of AFib and heart failure. It is important to understand the importance of managing hypertension, diabetes, and obesity; encouraging exercise and a healthy diet; and stopping smoking in all AFib patients as well as in the general population. Many clinicians have not emphasized the importance of continually addressing these behaviors,” Dr. Kusumoto said in an interview.

The SWISS-AF (Swiss Atrial Fibrillation Cohort) study enrolled 2,415 AFib patients at 14 Swiss centers during 2014-2017, and obtained both a baseline brain MR scan and baseline cognitive-test results for 1,737 patients (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Mar;73[9]:989-99). Patients retook the cognitive tests annually, and 1,227 had a second MR brain scan after 2 years in the study, the cohort that supplied the data Dr. Conen presented. At baseline, these patients averaged 71 years of age, just over a quarter were women, and 90% were on an oral anticoagulant, with 84% on an oral anticoagulant at 2-year follow-up. Treatment split roughly equally between direct-acting oral anticoagulants and vitamin K antagonists like warfarin.

Among the 68 patients with evidence for an incident brain infarct after 2 years, 59 (87%) were on treatment with an OAC, and 51 (75%) who were both on treatment with a direct-acting oral anticoagulant and developed their brain infarct without also having a stroke or transient ischemic attack, which Dr. Conen called a “silent event.” The cognitive tests that showed statistically significant declines after 2 years in the patients with silent brain infarcts compared with those without a new infarct were the Trail Making Test parts A and B, and the animal-naming verbal fluency test. The two other tests applied were the Montreal Cognitive Assessment and the Digital Symbol Substitution Test.

Results from several prior studies also indicated a relationship between AFib and cognitive decline, but SWISS-AF is “the largest study to rigorously examine the incidence of silent brain infarcts in AFib patients,” commented Christine M. Albert, MD, chair of cardiology at the Smidt Heart Institute of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. “Silent infarcts could be the cause, at least in part, for the cognitive decline and dementia associated with AFib,” she noted. But divining the therapeutic implications of the finding will require further investigation that looks at factors such as the impact of anticoagulant type, other treatment that addresses AFib such as ablation and rate control, the duration and type of AFib, and the prevalence of hypertension and other stroke risk factors, she said as a designated discussant for Dr. Conen’s report.

SWISS-AF received no commercial funding. Dr. Conen has been a speaker on behalf of Servier. Dr. Kusumoto had no disclosures. Dr. Albert has been a consultant to Roche Diagnostics and has received research funding from Abbott, Roche Diagnostics, and St. Jude Medical.

FROM HEART RHYTHM 2020

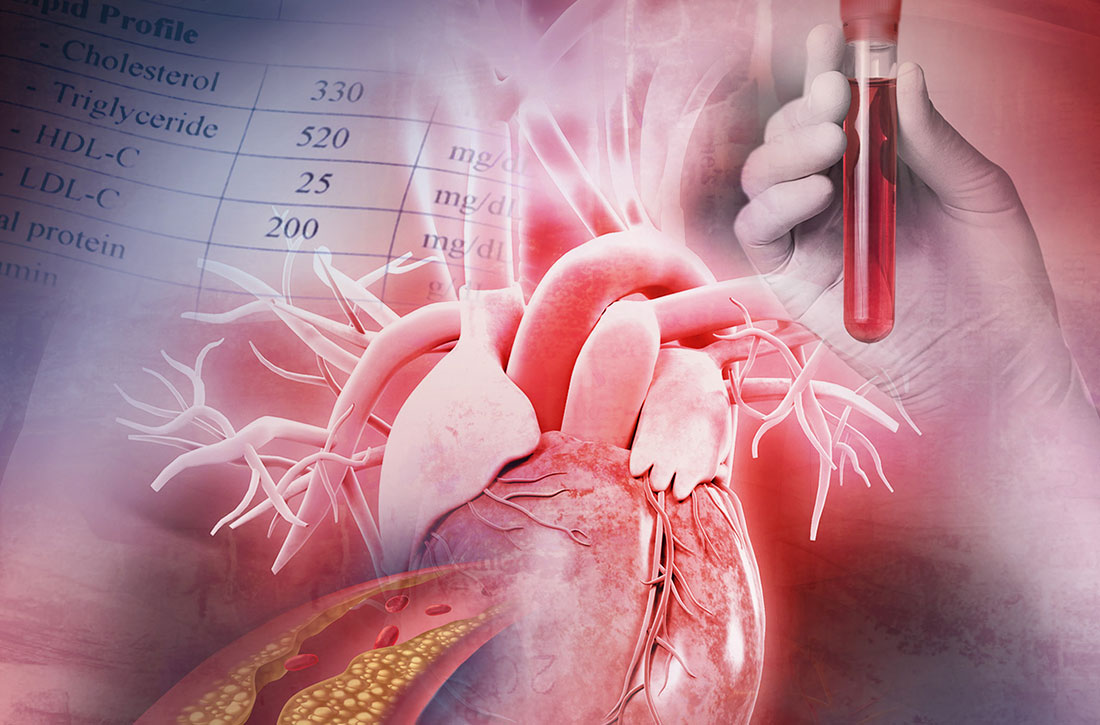

Hypertriglyceridemia: A strategic approach

CASE 1

Tyler M, age 40, otherwise healthy, and with a body mass index (BMI) of 30, presents to your office for his annual physical examination. He does not have a history of alcohol or tobacco use.

Mr. M’s obesity raises concern about metabolic syndrome, which warrants evaluation for hypertriglyceridemia (HTG). You offer him lipid testing to estimate his risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).

The only abnormal value on the lipid panel is a triglyceride (TG) level of 264 mg/dL (normal, < 175 mg/dL). Mr. M’s 10-yr ASCVD risk is determined to be < 5%.

What, if any, intervention would be triggered by the finding of moderate HTG?

CASE 2

Alicia F, age 30, with a BMI of 28 and ASCVD risk < 7.5%, comes to the clinic for evaluation of anxiety and insomnia. She reports eating a high-carbohydrate diet and drinking 3 to 5 alcoholic beverages nightly to help her sleep.

Ms. F’s daily alcohol use prompts evaluation for HTG. Results show a TG level of 1300 mg/dL and a high-density lipoprotein (HDL) level of 25 mg/dL (healthy HDL levels: adult females, ≥ 50 mg/dL; adult males, ≥ 40 mg/dL). Other test results are normal, except for elevated transaminase levels (just under twice normal).

What, if any, action would be prompted by the patient’s severe HTG and below-normal HDL level?

Continue to: How HTG is defined

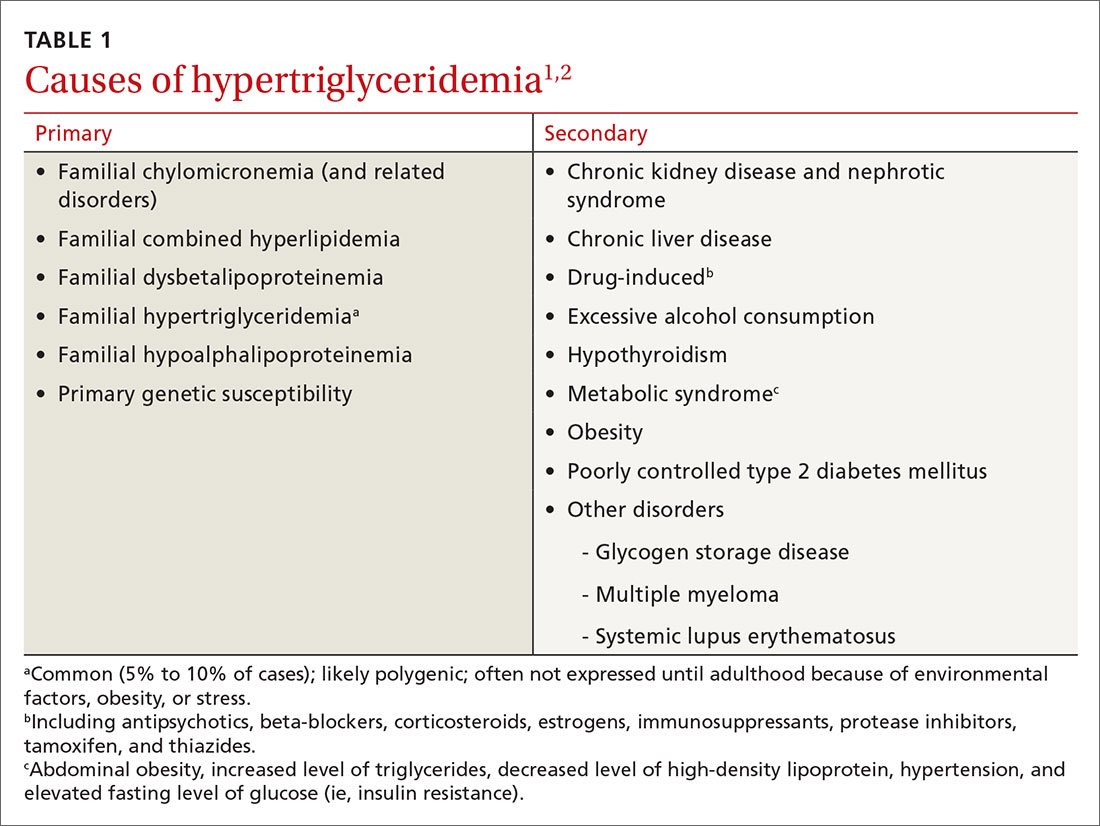

How HTG is defined: Causes, cutoffs, signs

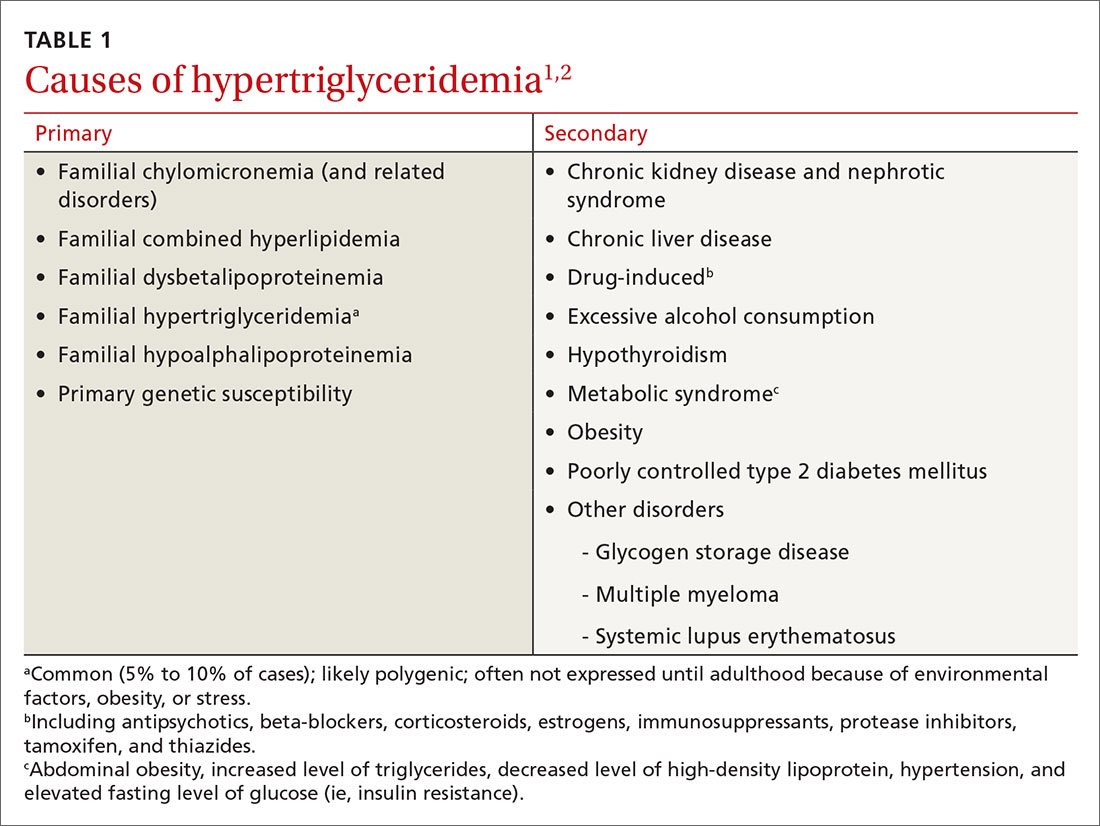

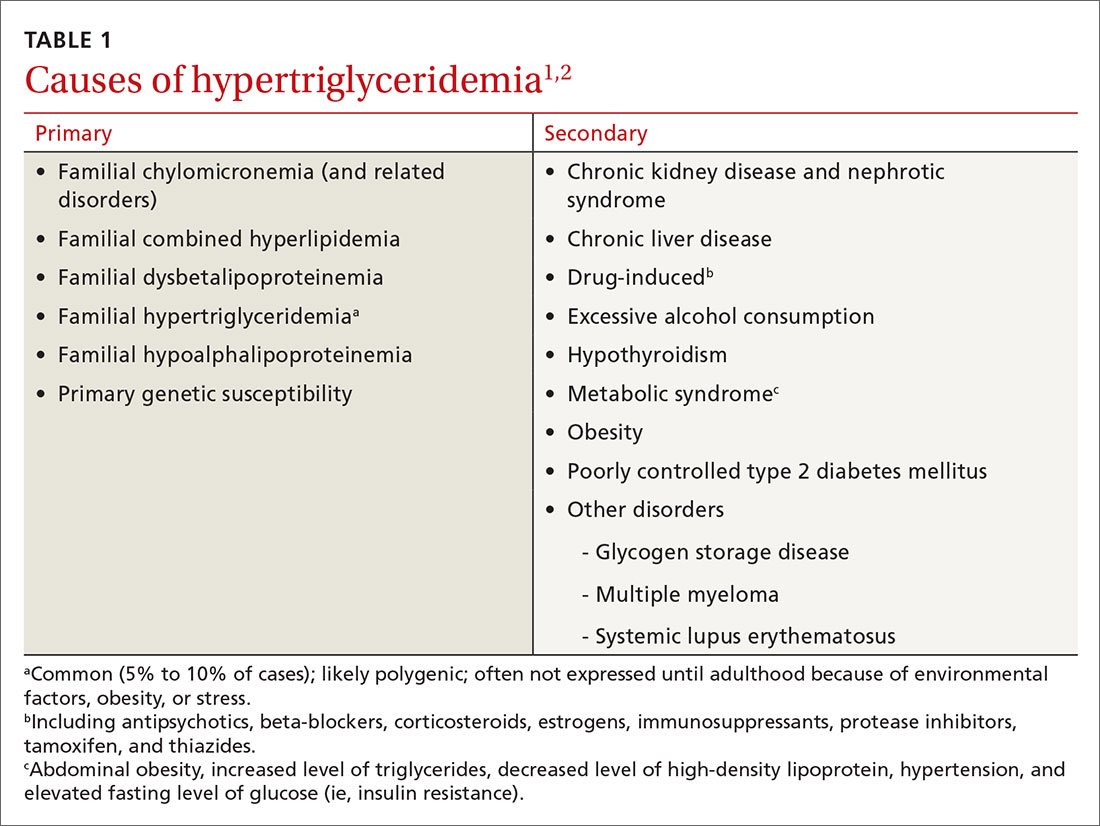

HTG is most commonly caused by obesity and a sedentary lifestyle; certain associated comorbid medical conditions can also be a precipitant (Table 11,2). Because the condition is a result of polygenic phenotypic expression, even a genetically low-risk patient can present with HTG when exposed to certain medical conditions and environmental causes.

Primary HTG (genetic or familial) is rare. Genetic testing may be considered for patients with TG > 1000 mg/dL (severely elevated TG = 500 to 1999 mg/dL, measured in fasting state*) or a family history of early ASCVD (TABLE 11,2).2,3

Typically, HTG is asymptomatic. Xanthelasmas, xanthomas, and lipemia retinalis are found in hereditary disorders of elevated TGs. Occasionally, HTG manifests as chylomicronemia syndrome, characterized by recurrent abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and, in severe HTG, pancreatitis.3

Fine points of TG measurement

Triglycerides are a component of a complete lipid profile, which also includes total cholesterol, calculated low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C), and HDL.4 As in both case vignettes, detection of HTG is often incidental, when a lipid profile is ordered to evaluate the risk of ASCVD. (Of note, for people older than 20 years, the US Preventive Services Task Force no longer addresses the question, “Which population should be screened for dyslipidemia?” Instead, current recommendations answer the question, “For which population should statin therapy be prescribed?”5)

Effect on ASCVD risk assessment. TG levels are known to vary, depending on fasting or nonfasting status, with lower levels reported when fasting. An elevated TG level can lead to inaccurate calculation of LDL when using the Friedewald formula6:

LDL = total cholesterol – (triglycerides/5) – HDL

Continue to: The purpose of testing...

The purpose of testing lipids in a fasting state (> 9 hours) is to minimize the effects of an elevated TG level on the calculated LDL. In severe HTG, beta-quantitation by ultracentrifugation and electrophoresis can be performed to determine the LDL level directly.

Advantage of nonfasting measurement. When LDL-C is not a concern, there is, in fact, value in measuring TGs in the nonfasting state. Why? Because a nonfasting TG level is a better indicator of a patient’s average TG status: Studies have found a higher ASCVD risk in the setting of an elevated postprandial TG level accompanied by a low HDL level.7

The Copenhagen City Heart Study identified postprandial HTG as an independent risk factor for atherogenicity, even in the setting of a normal fasting TG level.8 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology guidelines endorse testing the nonfasting TG level when the fasting TG level is elevated in a lipid profile; if the nonfasting TG level is > 500 mg/dL, evaluation for secondary causes is warranted9,10 (Table 11,2).

In a practical sense, therefore, offering patients nonfasting lipid testing allows more people to obtain access to timely care.

Pancreatitis. Acute pancreatitis commonly prompts an evaluation for HTG. The risk of acute pancreatitis in the general population is 0.04%, but that risk increases to 8% to 31% for a person with HTG.11 Incidence when the TG level is > 500 mg/dL is thought to be increased because chylomicrons, acting as a TG carrier in the bloodstream, are responsible for pancreatitis.3 Treating HTG can reduce both the risk and recurrence of pancreatitis12,13; given that the postprandial TG level can change rapidly from severe to very severe (> 2000 mg/dL), multiple guidelines recommend pharmacotherapy to a TG goal of < 500-1000 mg/dL.1,9,13,14

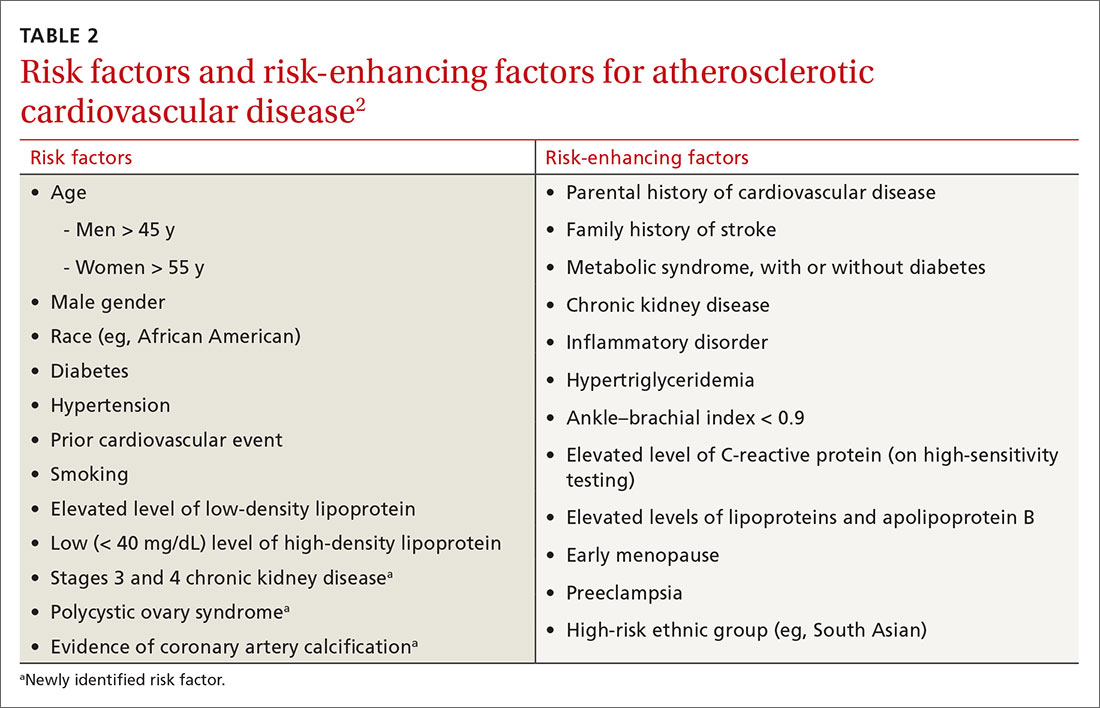

Continue to: An ASCVD risk-HTG connection?

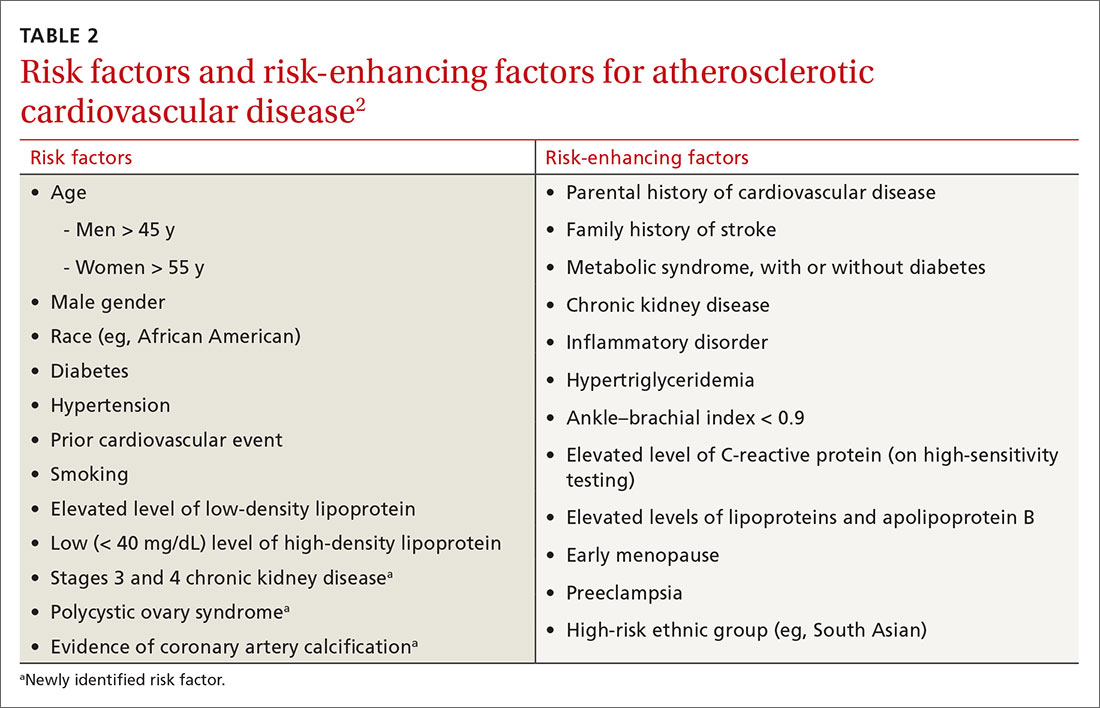

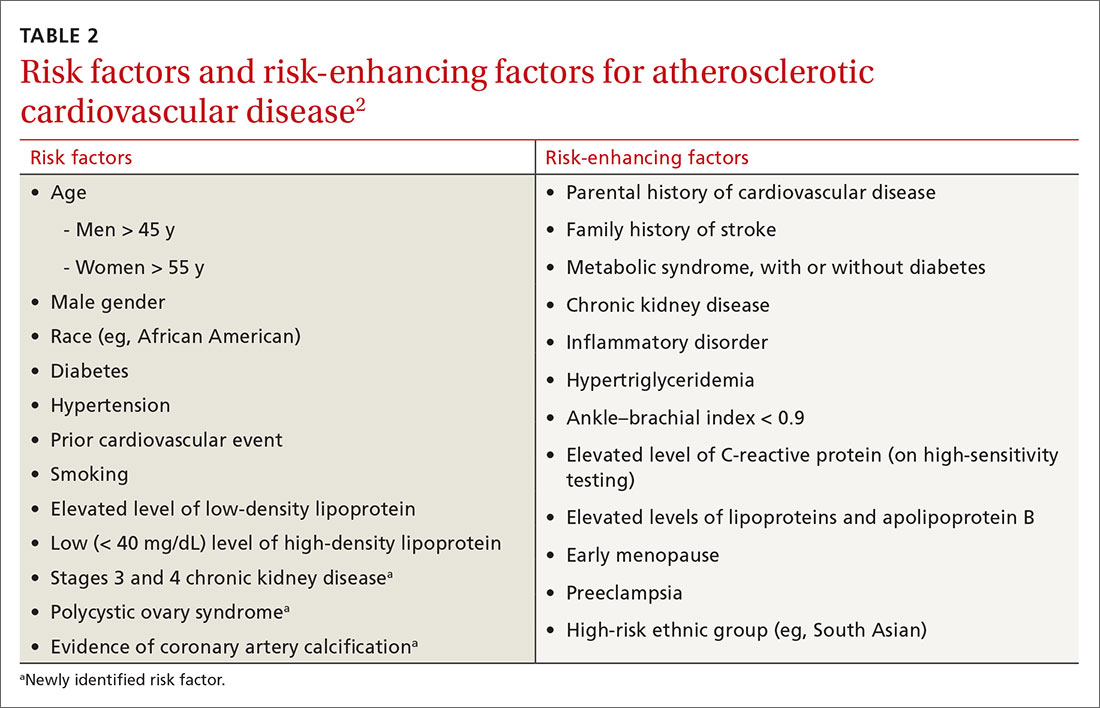

An ASCVD risk–HTG connection? In the population already at higher risk of ASCVD (> 7.5%), HTG is recognized as a risk-enhancing factor because of its atherogenic potential (Table 22); however, there is insufficient evidence that TGs have a role as an independent risk factor for ASCVD. In a population-based study of 58,000 people, 40 to 65 years of age, conducted at Copenhagen [Denmark] University Hospital, investigators found that those who did not meet criteria for statin treatment and who had a TG level > 264 mg/dL had a 10-year risk of a major adverse cardiovascular event similar to that of people who did meet criteria for statin therapy.15

The FIELD (Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes) and AIM-HIGH (Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome with Low HDL/High Triglycerides and Impact on Global Health Outcomes) studies, among others, have failed to show a significant reduction in coronary events by treating HTG.10

That said, it’s worth considering the findings of other trials:

- In the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 (Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 22) trial, an overall 28% reduction in endpoint events (myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome) was seen with high-intensity statin therapy, compared to moderate-intensity therapy.10 However, there was a sizeable residual risk identified that was theorized by investigators to be associated with high non-HDL lipoproteins, including TGs.

- A 2016 study in Israel, in which 22 years of data on 15,355 patients with established ASCVD were studied, revealed that elevated TGs are associated with an increased long-term mortality risk that is independent of the HDL level.16

- A cross-sectional study, nested in the prospective Copenhagen City Heart Study, demonstrated that HTG is associated with an increase in ischemic stroke events.17

Treatment

Therapeutic lifestyle changes

Changes in lifestyle are the foundation of management of, and recommended first-line treatment for, all patients with HTG. Patients with a moderately elevated TG level (175-499 mg/dL, measured in a fasting or nonfasting state) can be treated with therapeutic lifestyle changes alone1,2; a trial of 3 to 6 months (see specific interventions below) is recommended before considering adding medications.10

Weight loss. There is a strong association between BMI > 30 and HTG. Visceral adiposity is a much more significant risk than subcutaneous adipose tissue. Although weight loss to an ideal range is recommended, even a 10% to 15% reduction in an obese patient can reduce the TG level by 20%. A combination of moderate-intensity exercise and healthy eating habits appears to assist best with this intervention.18

Continue to: Exercise

Exercise. Thirty minutes a day of moderate-intensity exercise is associated with a significant drop in postprandial TG. This benefit can last as long as 3 days, suggesting a goal of at least 3 days a week of an active lifestyle. Such a program can include intermittent aerobics or mild resistance exercise.19

Healthy eating habits. The difference between a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet and a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet is less important than the overall benefit of weight loss from either of these diets. Complex carbohydrates are recommended over simple carbohydrates. A low-carbohydrate diet in a patient with diabetes has been demonstrated to improve the TG level, irrespective of weight change.

A Mediterranean diet can reduce the TG level by 10% to 15%, and is recommended over a low-fat diet.14 (This diet generally includes a high intake of extra virgin olive oil; leafy green vegetables, fruits, cereals, nuts, and legumes; moderate intake of fish and other meat, dairy products, and red wine; and low intake of eggs and sugars.) The American Heart Association recommends 2 servings of fatty fish a week for its omega-3 oil benefit of reducing ASCVD risk. Working with a registered dietician to assist with lipid lowering can produce better results than physician-only instruction on healthy eating.9

Alcohol consumption. Complete cessation or moderation of alcohol consumption (1 drink a day/women and 2 drinks a day/men*) is recommended to improve HTG. Among secondary factors, alcohol is commonly the cause of an unusually high elevation of the TG level.14

Smoking cessation. Smoking increases the postprandial TG level.10 Complete cessation for just 1 year can reduce a person’s ASCVD risk by approximately 50%. However, in a clinical trial,22 smoking cessation did not significantly decrease the TG level—possibly because of the counterbalancing effect of weight gain following cessation.

Continue to: Medical therapy

Medical therapy

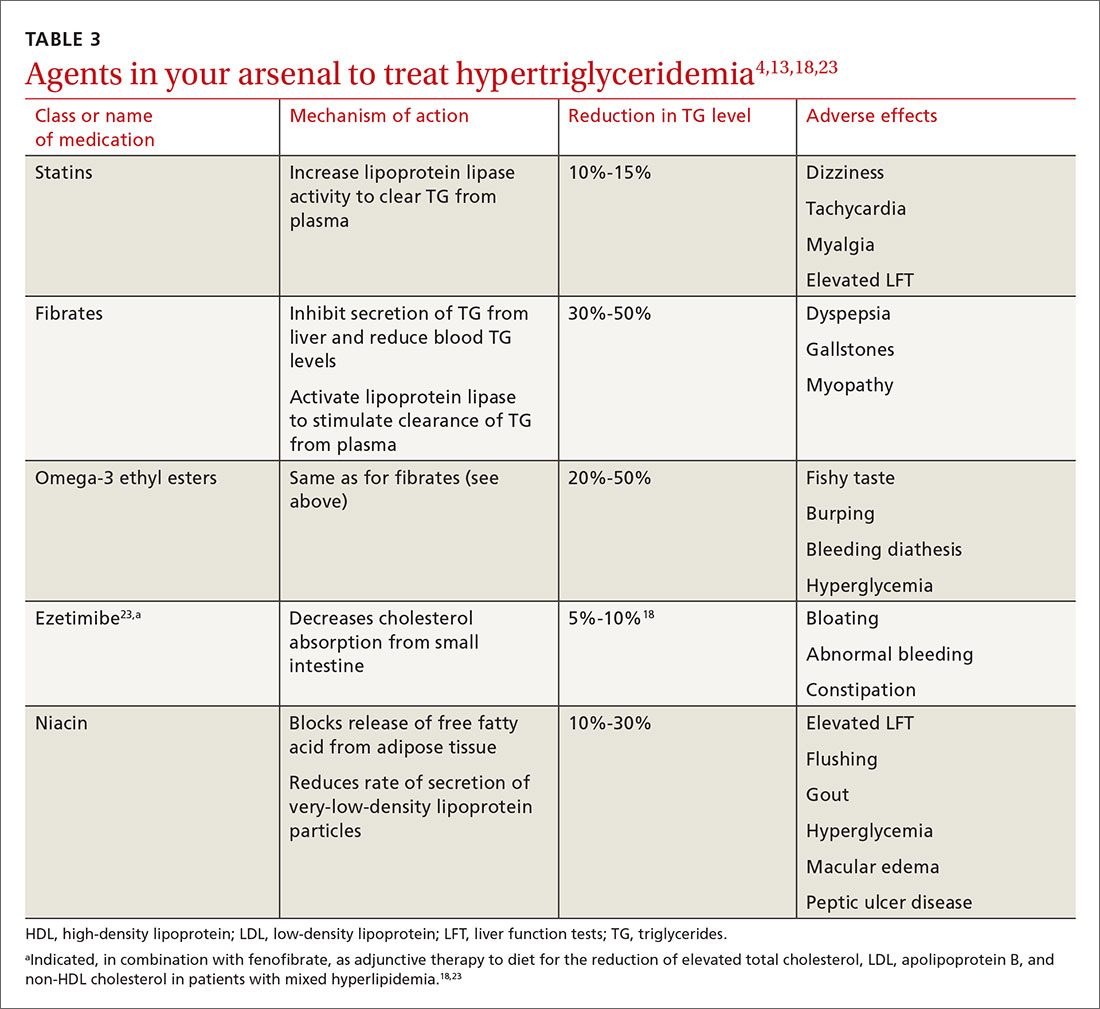

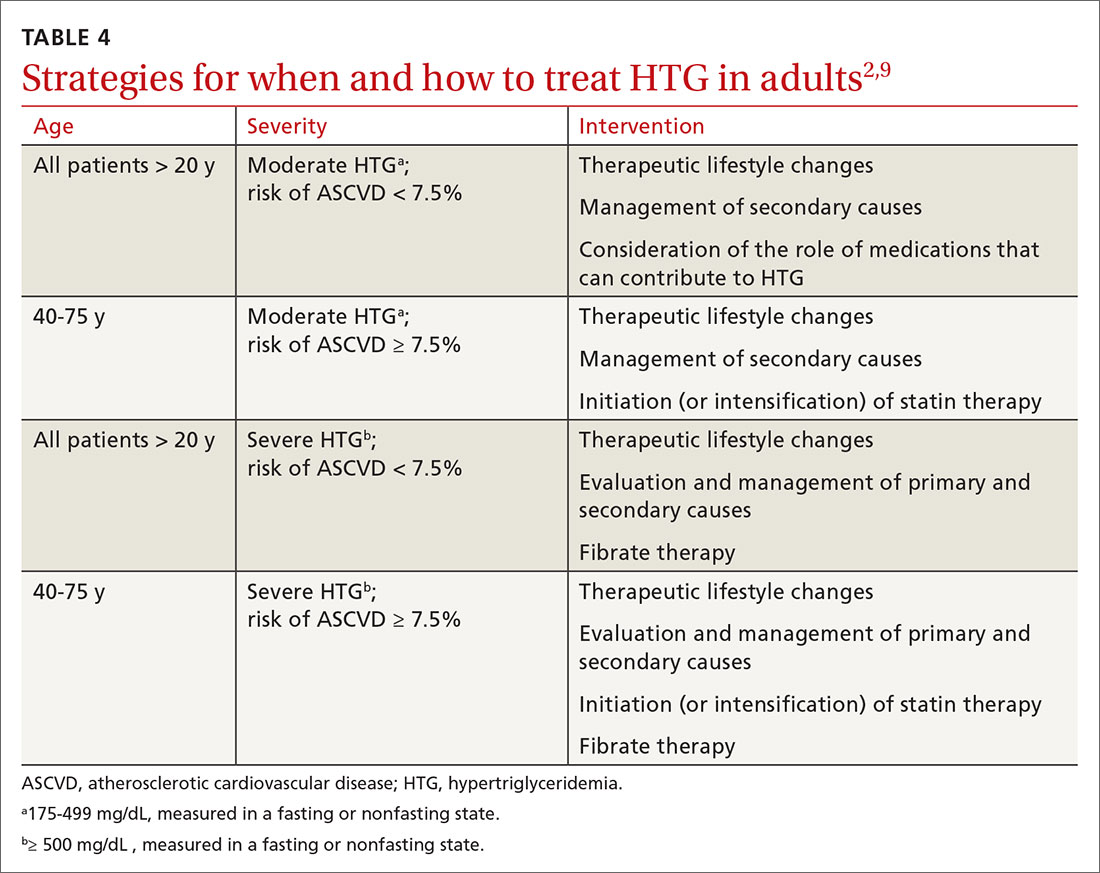

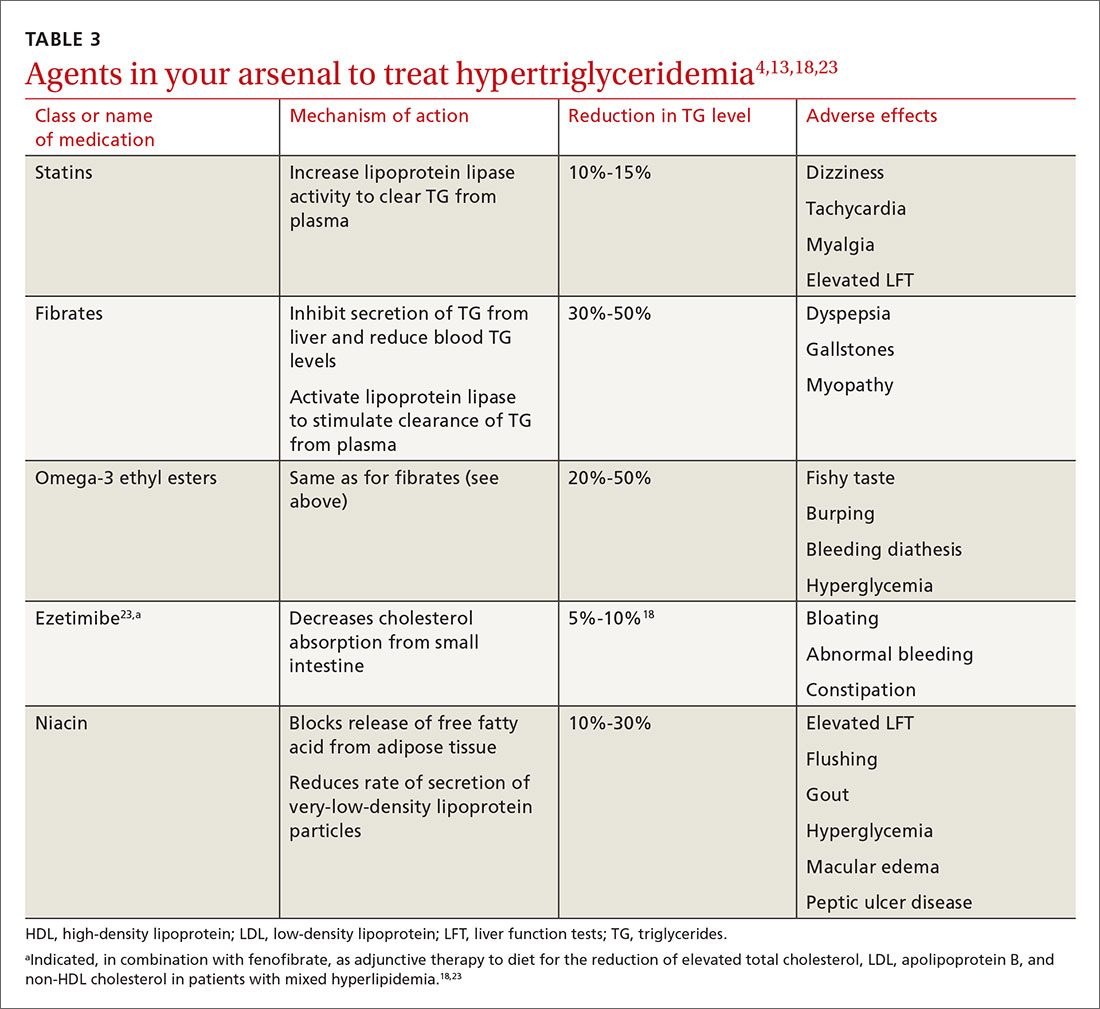

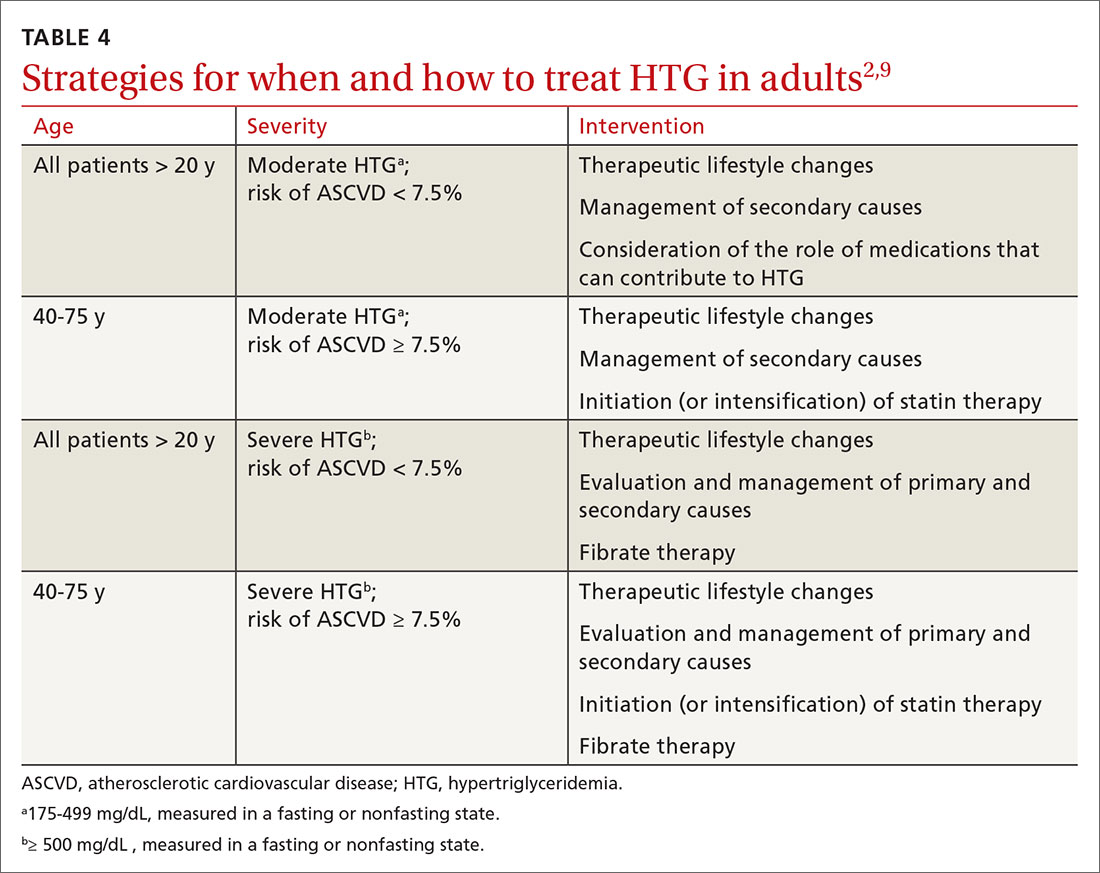

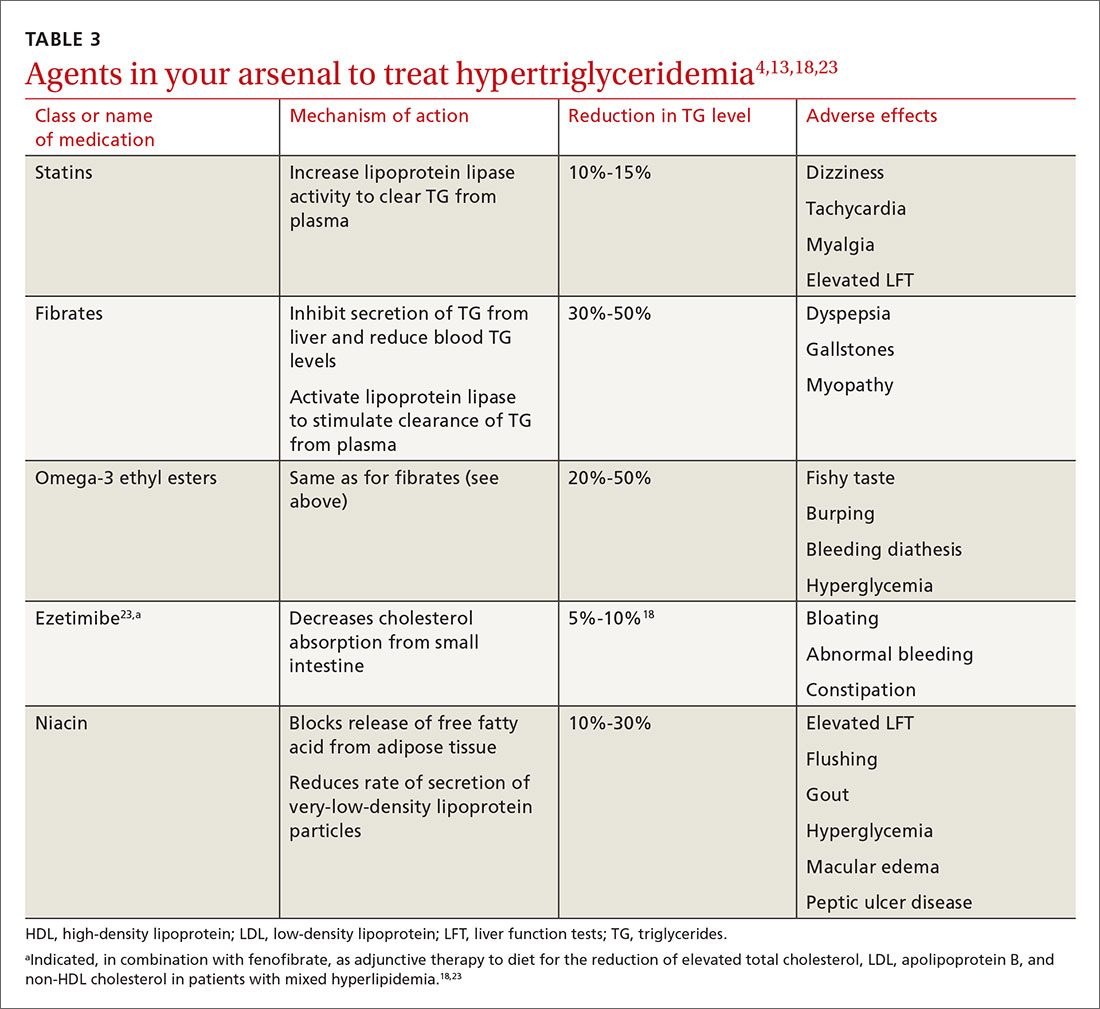

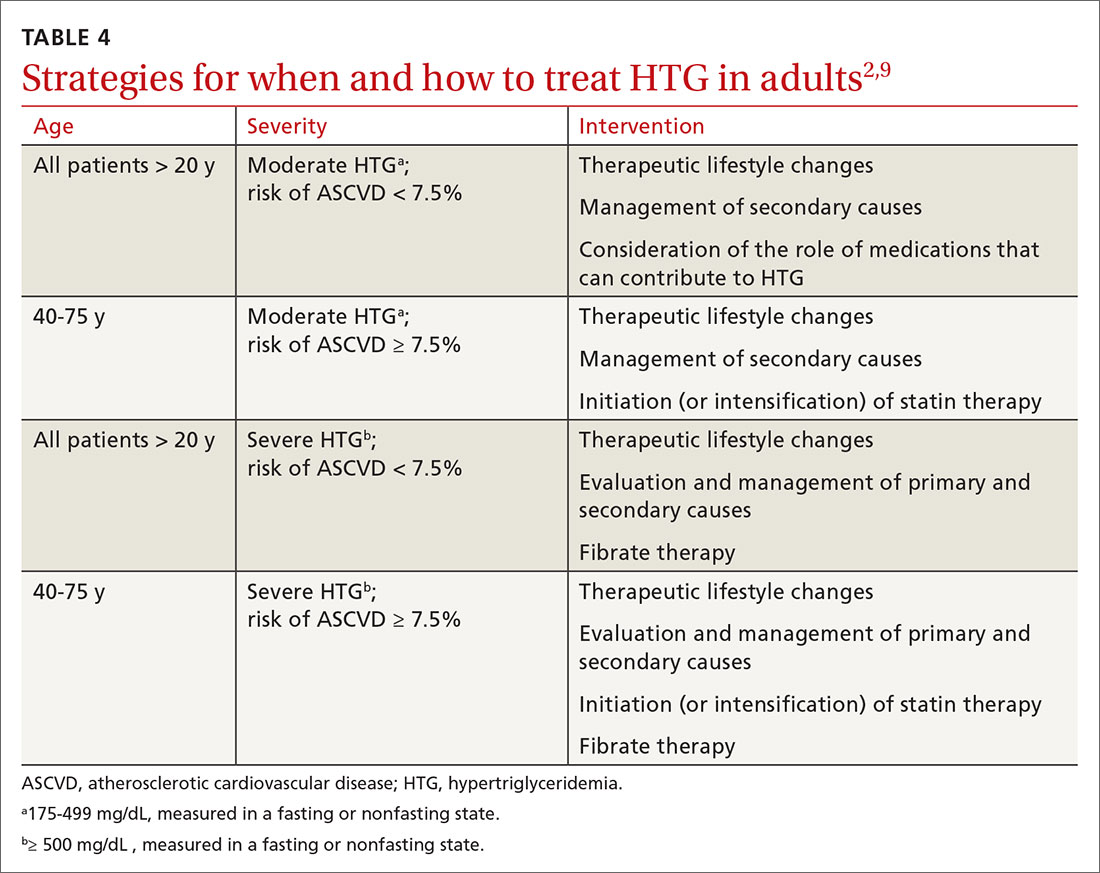

In addition to lifestyle modification, medications are recommended to reduce atherogenic potential in patients with moderate or severe HTG and an ASCVD risk > 7.5% (Table 34,13,18,23 and Table 42,9). Before initiating medical therapy, we recommend that you engage in shared decision-making with patients to (1) delineate treatment goals and (2) describe the risks and benefits of medications for HTG.2

Statins. These agents are recommended first-line therapy for reducing ASCVD risk.2 If the TG level remains elevated (> 500 mg/dL) after statin therapy is maximized, an additional agent can be added—ie, a fibrate or fish oil (see below).

Fibrates. If a fibrate is used as an add-on to a statin, fenofibrate is preferred over gemfibrozil because it presents less risk of the severe myopathy that can develop when taken with a statin.13 Despite the effectiveness of fibrates in reducing the TG level, these drugs have not been shown to reduce overall mortality.24 The evidence on improved cardiovascular outcomes is subgroup-specific (ie, prevention of a second myocardial infarction in the setting of optimal statin use and elevated non-HDL lipoproteins).12 A study demonstrated that gemfibrozil reduced the incidence of transient ischemic attack and stroke in a subgroup of male US veterans who had coronary artery disease and a low HDL level.25

Fish oil. The omega-3 ethyl esters eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), available as EPA alone or in combination with DHA, do not interact with statins and are tolerated well. They reduce hypertriglyceridemia by 20% to 50%.13

Eicosapentaenoic acid, EPA plus DHA, and icosapent ethyl, an ethyl ester product containing EPA without DHA, are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for HTG > 500 mg/dL, at a dosage of 2000 mg twice daily. In the REDUCE-IT trial, adding icosapent ethyl, 2 g twice daily, to a statin in patients with HTG was associated with fewer ischemic events, compared to placebo.23,26

Continue to: Fish oil formulations...

Fish oil formulations can inhibit platelet aggregation and increase bleeding time in otherwise healthy people; however, such episodes are minor and nonfatal. Patients on anticoagulation or an antiplatelet medication should be monitored periodically for bleeding events, although recommendations on how to monitor aren’t specified in a recent advisory by the American Heart Association.23

DHA was thought to increase the LDL-C levels and, by doing so, potentially counterbalance benefit,23,27 but most studies have failed to reproduce this effect.28 Instead, studies have shown minimal elevation of LDL-C when DHA is used to treat HTG.23,27

Niacin. At a dosage of 500-2000 mg/dL, niacin lowers the TG level by 10% to 30%. It also increases HDL by 10% to 40% and lowers LDL by 5% to 20%.13

Considerations in pancreatitis. For management of recurrent pancreatitis in patients with HTG, lifestyle modification remains the mainstay of treatment. When medication is considered for persistent severe HTG, fibrates have evidence of primary and secondary prevention of pancreatitis.

CASE 1

Recommendation for Mr. M: Therapeutic lifestyle changes to address moderate HTG.

Continue to: Because Mr. M's...

Because Mr. M’s 10-yr ASCVD risk is < 5%, statin therapy is not indicated for risk reduction. With a fasting TG value < 500 mg/dL, he is not considered at increased risk of pancreatitis.

CASE 2

Recommendations for Ms. F:

- Therapeutic lifestyle changes to address severe HTG. Ms. F agrees to wean off alcohol; add relaxation exercises before bedtime; do aerobic exercise 30 minutes a day, 3 times a week; decrease dietary carbohydrates daily by cutting portion size in half; and increase intake of fresh vegetables and lean protein.

- Treatment with fenofibrate to reduce the risk of pancreatitis. Ms. F begins a trial. Six months into treatment, she has reduced her BMI to 24 and the TG level has fallen to < 500 mg/dL. Ms. F also reports that she is sleeping well, believes that she is able to manage her infrequent anxiety, and is now in a routine that feels sustainable.

You congratulate Ms. F on her success and support her decision to undertake a trial of discontinuing fenofibrate, after shared decision-making about the risks and potential benefits of doing so.

Summing up: Management of HTG

Keep these treatment strategy highlights in mind:

- Lifestyle modification with a low-fat, low-carbohydrate diet, avoidance of alcohol, and moderate-intensity exercise is the mainstay of HTG management.

- The latest evidence supports that (1) HTG is a risk-enhancing factor for ASCVD and (2) statin therapy is recommended for patients who have HTG and an ASCVD risk > 7.5%.

- When the TG level remains elevated despite statin therapy and lifestyle changes, an omega-3 ethyl ester can be used as an adjunct for additional atherogenic risk reduction.

- For severe HTG, a regimen of therapeutic lifestyle changes plus a fibrate is recommended to reduce the risk and recurrence of pancreatitis.1,24

* In comparison, a normal level of triglycerides is < 175 mg/dL; a moderately elevated level, measured in a fasting or nonfasting state, 175-499 mg/dL; and a very severely elevated level, ≥ 2000 mg/dL.2

CORRESPONDENCE

Ashwini Kamath Mulki, MD, Family Health Center, 1730 Chew Street, Allentown, PA 18104; [email protected].

1. Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, et al. Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2969-2989.

2. Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:e285-e350.

3. Brahm A, Hegele RA. Hypertriglyceridemia. Nutrients. 2013;5:981-1001.

4. Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001;285:2486-2497.

5. US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: preventive medication. November 13, 2016. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/statin-use-in-adults-preventive-medication. Accessed April 24, 2020.

6. Fukuyama N, Homma K, Wakana N, et al. Validation of the Friedewald equation for evaluation of plasma LDL-cholesterol. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2007;43:1-5.

7. Scherer DJ, Nicholls SJ. Lowering triglycerides to modify cardiovascular risk: Will icosapent deliver? Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2015;11:203.

8. Nordestgaard BG, Benn M, Schnohr P, et al. Nonfasting triglycerides and risk of myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, and death in men and women. JAMA. 2007;298:299-308.

9. Jellinger PS. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology Management of Dyslipidemia and Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Clinical Practice Guidelines. Diabetes Spectr. 2018;31:234-245.

10. Malhotra G, Sethi A, Arora R. Hypertriglyceridemia and cardiovascular outcomes. Am J Therapeut. 2016;23:e862-e870.

11. Carr RA, Rejowski BJ, Cote GA, et al. Systematic review of hypertriglyceridemia-induced acute pancreatitis: a more virulent etiology? Pancreatology. 2016;16:469-476.

12. Charlesworth A, Steger A, Crook MA. Acute pancreatitis associated with severe hypertriglyceridemia; a retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2015;23(pt A):23-27.

13. Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, et al. Treatment options for hypertriglyceridemia: from risk reduction to pancreatitis. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;28:423-437.

14. Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2935-2959. [Erratum. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:3026.]

15. Madsen CM, Varbo A, Nordestgaard BG. Unmet need for primary prevention in individuals with hypertriglyceridaemia not eligible for statin therapy according to European Society of Cardiology/European Atherosclerosis Society guidelines: a contemporary population-based study. Euro Heart J. 2017;39:610-619.

16. Klempfner R, Erez A, Sagit B-Z, et al. Elevated triglyceride level is independently associated with increased all-cause mortality in patients with established coronary heart disease: twenty-two-year follow-up of the Bezafibrate Infarction Prevention Study and Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9:100-108.

17. Freiberg JJ, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Jensen JS, et al. Nonfasting triglycerides and risk of ischemic stroke in the general population. JAMA. 2008;300:2142-2152.

18. Miller M, Stone NJ, Ballantyne C, et al; ; ; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease. Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2011;123:2292-2333.

19. Graham TE. Exercise, postprandial triacylglyceridemia, and cardiovascular disease risk. Can J Appl Physiol. 2004;29:781-799.

20. Meng Y, Bai H, Wang S, et al. Efficacy of low carbohydrate diet for type 2 diabetes mellitus management: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;131:124-131.

21. What is a standard drink? National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Web site. www.niaaa.nih.gov/what-standard-drink. Accessed April 24, 2020.

22. Gepner AD, Piper ME, Johnson HM, et al. Effects of smoking and smoking cessation on lipids and lipoproteins: outcomes from a randomized clinical trial. Am Heart J. 2011;161:145-151.

23. Skulas-Ray AC, Wilson PWF, Harris WS, et al; American Heart Association Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Council on Clinical Cardiology. Omega-3 fatty acids for the management of hypertriglyceridemia: a science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;140:e673-e691.

24. Jakob T, Nordmann AJ, Schandelmaier S, et al. Fibrates for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease events. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11:CD009753.

25. Lisak M, Demarin V, Trkanjec Z, et al. Hypertriglyceridemia as a possible independent risk factor for stroke. Acta Clin Croat. 2013;52:458-463.

26. Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, et al; REDUCE-IT Investigators. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:11-22.

27. Barter P, Ginsberg HN. Effectiveness of combined statin plus omega-3 fatty acid therapy for mixed dyslipidemia. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:1040-1045.

28. Bays H, Ballantyne C, Kastelein J, et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid ethyl ester (AMR101) therapy in patients with very high triglyceride levels (from the Multi-center, plAcebo-controlled, Randomized, double-blINd, 12-week study with an open-label Extension [MARINE] Trial). Am J Cardiol. 2011;108:682-690.

CASE 1

Tyler M, age 40, otherwise healthy, and with a body mass index (BMI) of 30, presents to your office for his annual physical examination. He does not have a history of alcohol or tobacco use.

Mr. M’s obesity raises concern about metabolic syndrome, which warrants evaluation for hypertriglyceridemia (HTG). You offer him lipid testing to estimate his risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).

The only abnormal value on the lipid panel is a triglyceride (TG) level of 264 mg/dL (normal, < 175 mg/dL). Mr. M’s 10-yr ASCVD risk is determined to be < 5%.

What, if any, intervention would be triggered by the finding of moderate HTG?

CASE 2

Alicia F, age 30, with a BMI of 28 and ASCVD risk < 7.5%, comes to the clinic for evaluation of anxiety and insomnia. She reports eating a high-carbohydrate diet and drinking 3 to 5 alcoholic beverages nightly to help her sleep.

Ms. F’s daily alcohol use prompts evaluation for HTG. Results show a TG level of 1300 mg/dL and a high-density lipoprotein (HDL) level of 25 mg/dL (healthy HDL levels: adult females, ≥ 50 mg/dL; adult males, ≥ 40 mg/dL). Other test results are normal, except for elevated transaminase levels (just under twice normal).

What, if any, action would be prompted by the patient’s severe HTG and below-normal HDL level?

Continue to: How HTG is defined

How HTG is defined: Causes, cutoffs, signs

HTG is most commonly caused by obesity and a sedentary lifestyle; certain associated comorbid medical conditions can also be a precipitant (Table 11,2). Because the condition is a result of polygenic phenotypic expression, even a genetically low-risk patient can present with HTG when exposed to certain medical conditions and environmental causes.

Primary HTG (genetic or familial) is rare. Genetic testing may be considered for patients with TG > 1000 mg/dL (severely elevated TG = 500 to 1999 mg/dL, measured in fasting state*) or a family history of early ASCVD (TABLE 11,2).2,3

Typically, HTG is asymptomatic. Xanthelasmas, xanthomas, and lipemia retinalis are found in hereditary disorders of elevated TGs. Occasionally, HTG manifests as chylomicronemia syndrome, characterized by recurrent abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and, in severe HTG, pancreatitis.3

Fine points of TG measurement

Triglycerides are a component of a complete lipid profile, which also includes total cholesterol, calculated low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C), and HDL.4 As in both case vignettes, detection of HTG is often incidental, when a lipid profile is ordered to evaluate the risk of ASCVD. (Of note, for people older than 20 years, the US Preventive Services Task Force no longer addresses the question, “Which population should be screened for dyslipidemia?” Instead, current recommendations answer the question, “For which population should statin therapy be prescribed?”5)

Effect on ASCVD risk assessment. TG levels are known to vary, depending on fasting or nonfasting status, with lower levels reported when fasting. An elevated TG level can lead to inaccurate calculation of LDL when using the Friedewald formula6:

LDL = total cholesterol – (triglycerides/5) – HDL

Continue to: The purpose of testing...

The purpose of testing lipids in a fasting state (> 9 hours) is to minimize the effects of an elevated TG level on the calculated LDL. In severe HTG, beta-quantitation by ultracentrifugation and electrophoresis can be performed to determine the LDL level directly.

Advantage of nonfasting measurement. When LDL-C is not a concern, there is, in fact, value in measuring TGs in the nonfasting state. Why? Because a nonfasting TG level is a better indicator of a patient’s average TG status: Studies have found a higher ASCVD risk in the setting of an elevated postprandial TG level accompanied by a low HDL level.7

The Copenhagen City Heart Study identified postprandial HTG as an independent risk factor for atherogenicity, even in the setting of a normal fasting TG level.8 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology guidelines endorse testing the nonfasting TG level when the fasting TG level is elevated in a lipid profile; if the nonfasting TG level is > 500 mg/dL, evaluation for secondary causes is warranted9,10 (Table 11,2).

In a practical sense, therefore, offering patients nonfasting lipid testing allows more people to obtain access to timely care.

Pancreatitis. Acute pancreatitis commonly prompts an evaluation for HTG. The risk of acute pancreatitis in the general population is 0.04%, but that risk increases to 8% to 31% for a person with HTG.11 Incidence when the TG level is > 500 mg/dL is thought to be increased because chylomicrons, acting as a TG carrier in the bloodstream, are responsible for pancreatitis.3 Treating HTG can reduce both the risk and recurrence of pancreatitis12,13; given that the postprandial TG level can change rapidly from severe to very severe (> 2000 mg/dL), multiple guidelines recommend pharmacotherapy to a TG goal of < 500-1000 mg/dL.1,9,13,14

Continue to: An ASCVD risk-HTG connection?

An ASCVD risk–HTG connection? In the population already at higher risk of ASCVD (> 7.5%), HTG is recognized as a risk-enhancing factor because of its atherogenic potential (Table 22); however, there is insufficient evidence that TGs have a role as an independent risk factor for ASCVD. In a population-based study of 58,000 people, 40 to 65 years of age, conducted at Copenhagen [Denmark] University Hospital, investigators found that those who did not meet criteria for statin treatment and who had a TG level > 264 mg/dL had a 10-year risk of a major adverse cardiovascular event similar to that of people who did meet criteria for statin therapy.15

The FIELD (Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes) and AIM-HIGH (Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome with Low HDL/High Triglycerides and Impact on Global Health Outcomes) studies, among others, have failed to show a significant reduction in coronary events by treating HTG.10

That said, it’s worth considering the findings of other trials:

- In the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 (Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 22) trial, an overall 28% reduction in endpoint events (myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome) was seen with high-intensity statin therapy, compared to moderate-intensity therapy.10 However, there was a sizeable residual risk identified that was theorized by investigators to be associated with high non-HDL lipoproteins, including TGs.

- A 2016 study in Israel, in which 22 years of data on 15,355 patients with established ASCVD were studied, revealed that elevated TGs are associated with an increased long-term mortality risk that is independent of the HDL level.16

- A cross-sectional study, nested in the prospective Copenhagen City Heart Study, demonstrated that HTG is associated with an increase in ischemic stroke events.17

Treatment

Therapeutic lifestyle changes

Changes in lifestyle are the foundation of management of, and recommended first-line treatment for, all patients with HTG. Patients with a moderately elevated TG level (175-499 mg/dL, measured in a fasting or nonfasting state) can be treated with therapeutic lifestyle changes alone1,2; a trial of 3 to 6 months (see specific interventions below) is recommended before considering adding medications.10

Weight loss. There is a strong association between BMI > 30 and HTG. Visceral adiposity is a much more significant risk than subcutaneous adipose tissue. Although weight loss to an ideal range is recommended, even a 10% to 15% reduction in an obese patient can reduce the TG level by 20%. A combination of moderate-intensity exercise and healthy eating habits appears to assist best with this intervention.18

Continue to: Exercise

Exercise. Thirty minutes a day of moderate-intensity exercise is associated with a significant drop in postprandial TG. This benefit can last as long as 3 days, suggesting a goal of at least 3 days a week of an active lifestyle. Such a program can include intermittent aerobics or mild resistance exercise.19

Healthy eating habits. The difference between a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet and a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet is less important than the overall benefit of weight loss from either of these diets. Complex carbohydrates are recommended over simple carbohydrates. A low-carbohydrate diet in a patient with diabetes has been demonstrated to improve the TG level, irrespective of weight change.

A Mediterranean diet can reduce the TG level by 10% to 15%, and is recommended over a low-fat diet.14 (This diet generally includes a high intake of extra virgin olive oil; leafy green vegetables, fruits, cereals, nuts, and legumes; moderate intake of fish and other meat, dairy products, and red wine; and low intake of eggs and sugars.) The American Heart Association recommends 2 servings of fatty fish a week for its omega-3 oil benefit of reducing ASCVD risk. Working with a registered dietician to assist with lipid lowering can produce better results than physician-only instruction on healthy eating.9

Alcohol consumption. Complete cessation or moderation of alcohol consumption (1 drink a day/women and 2 drinks a day/men*) is recommended to improve HTG. Among secondary factors, alcohol is commonly the cause of an unusually high elevation of the TG level.14

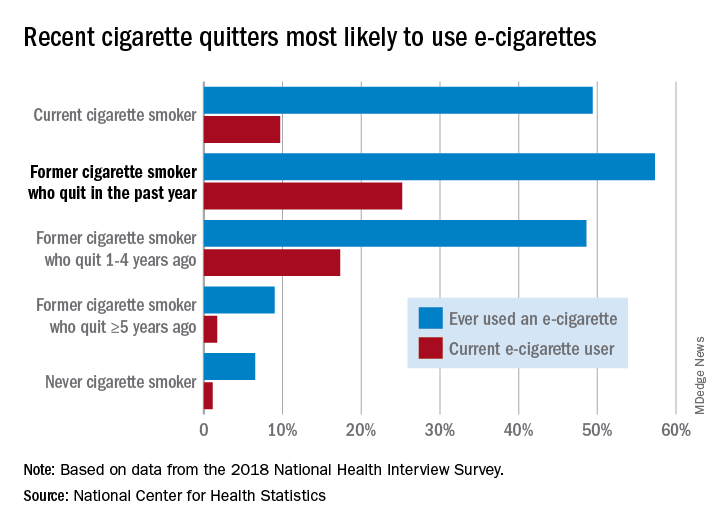

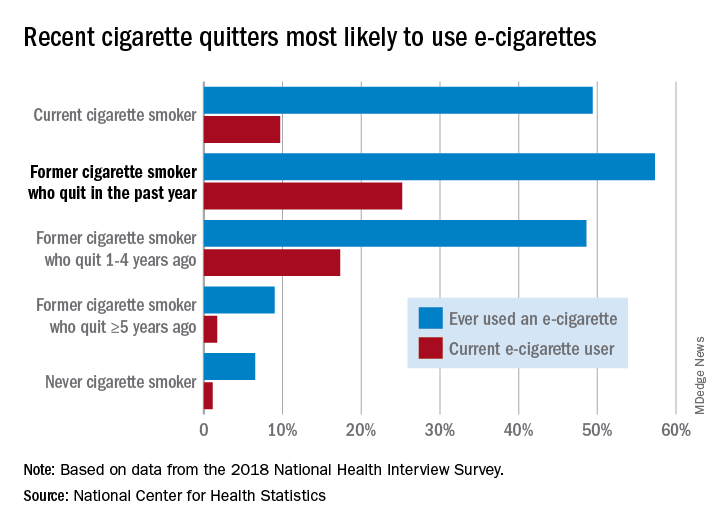

Smoking cessation. Smoking increases the postprandial TG level.10 Complete cessation for just 1 year can reduce a person’s ASCVD risk by approximately 50%. However, in a clinical trial,22 smoking cessation did not significantly decrease the TG level—possibly because of the counterbalancing effect of weight gain following cessation.

Continue to: Medical therapy

Medical therapy

In addition to lifestyle modification, medications are recommended to reduce atherogenic potential in patients with moderate or severe HTG and an ASCVD risk > 7.5% (Table 34,13,18,23 and Table 42,9). Before initiating medical therapy, we recommend that you engage in shared decision-making with patients to (1) delineate treatment goals and (2) describe the risks and benefits of medications for HTG.2

Statins. These agents are recommended first-line therapy for reducing ASCVD risk.2 If the TG level remains elevated (> 500 mg/dL) after statin therapy is maximized, an additional agent can be added—ie, a fibrate or fish oil (see below).

Fibrates. If a fibrate is used as an add-on to a statin, fenofibrate is preferred over gemfibrozil because it presents less risk of the severe myopathy that can develop when taken with a statin.13 Despite the effectiveness of fibrates in reducing the TG level, these drugs have not been shown to reduce overall mortality.24 The evidence on improved cardiovascular outcomes is subgroup-specific (ie, prevention of a second myocardial infarction in the setting of optimal statin use and elevated non-HDL lipoproteins).12 A study demonstrated that gemfibrozil reduced the incidence of transient ischemic attack and stroke in a subgroup of male US veterans who had coronary artery disease and a low HDL level.25

Fish oil. The omega-3 ethyl esters eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), available as EPA alone or in combination with DHA, do not interact with statins and are tolerated well. They reduce hypertriglyceridemia by 20% to 50%.13

Eicosapentaenoic acid, EPA plus DHA, and icosapent ethyl, an ethyl ester product containing EPA without DHA, are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for HTG > 500 mg/dL, at a dosage of 2000 mg twice daily. In the REDUCE-IT trial, adding icosapent ethyl, 2 g twice daily, to a statin in patients with HTG was associated with fewer ischemic events, compared to placebo.23,26

Continue to: Fish oil formulations...

Fish oil formulations can inhibit platelet aggregation and increase bleeding time in otherwise healthy people; however, such episodes are minor and nonfatal. Patients on anticoagulation or an antiplatelet medication should be monitored periodically for bleeding events, although recommendations on how to monitor aren’t specified in a recent advisory by the American Heart Association.23

DHA was thought to increase the LDL-C levels and, by doing so, potentially counterbalance benefit,23,27 but most studies have failed to reproduce this effect.28 Instead, studies have shown minimal elevation of LDL-C when DHA is used to treat HTG.23,27

Niacin. At a dosage of 500-2000 mg/dL, niacin lowers the TG level by 10% to 30%. It also increases HDL by 10% to 40% and lowers LDL by 5% to 20%.13

Considerations in pancreatitis. For management of recurrent pancreatitis in patients with HTG, lifestyle modification remains the mainstay of treatment. When medication is considered for persistent severe HTG, fibrates have evidence of primary and secondary prevention of pancreatitis.

CASE 1

Recommendation for Mr. M: Therapeutic lifestyle changes to address moderate HTG.

Continue to: Because Mr. M's...

Because Mr. M’s 10-yr ASCVD risk is < 5%, statin therapy is not indicated for risk reduction. With a fasting TG value < 500 mg/dL, he is not considered at increased risk of pancreatitis.

CASE 2

Recommendations for Ms. F:

- Therapeutic lifestyle changes to address severe HTG. Ms. F agrees to wean off alcohol; add relaxation exercises before bedtime; do aerobic exercise 30 minutes a day, 3 times a week; decrease dietary carbohydrates daily by cutting portion size in half; and increase intake of fresh vegetables and lean protein.

- Treatment with fenofibrate to reduce the risk of pancreatitis. Ms. F begins a trial. Six months into treatment, she has reduced her BMI to 24 and the TG level has fallen to < 500 mg/dL. Ms. F also reports that she is sleeping well, believes that she is able to manage her infrequent anxiety, and is now in a routine that feels sustainable.

You congratulate Ms. F on her success and support her decision to undertake a trial of discontinuing fenofibrate, after shared decision-making about the risks and potential benefits of doing so.

Summing up: Management of HTG

Keep these treatment strategy highlights in mind:

- Lifestyle modification with a low-fat, low-carbohydrate diet, avoidance of alcohol, and moderate-intensity exercise is the mainstay of HTG management.

- The latest evidence supports that (1) HTG is a risk-enhancing factor for ASCVD and (2) statin therapy is recommended for patients who have HTG and an ASCVD risk > 7.5%.

- When the TG level remains elevated despite statin therapy and lifestyle changes, an omega-3 ethyl ester can be used as an adjunct for additional atherogenic risk reduction.

- For severe HTG, a regimen of therapeutic lifestyle changes plus a fibrate is recommended to reduce the risk and recurrence of pancreatitis.1,24

* In comparison, a normal level of triglycerides is < 175 mg/dL; a moderately elevated level, measured in a fasting or nonfasting state, 175-499 mg/dL; and a very severely elevated level, ≥ 2000 mg/dL.2

CORRESPONDENCE

Ashwini Kamath Mulki, MD, Family Health Center, 1730 Chew Street, Allentown, PA 18104; [email protected].

CASE 1

Tyler M, age 40, otherwise healthy, and with a body mass index (BMI) of 30, presents to your office for his annual physical examination. He does not have a history of alcohol or tobacco use.

Mr. M’s obesity raises concern about metabolic syndrome, which warrants evaluation for hypertriglyceridemia (HTG). You offer him lipid testing to estimate his risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).

The only abnormal value on the lipid panel is a triglyceride (TG) level of 264 mg/dL (normal, < 175 mg/dL). Mr. M’s 10-yr ASCVD risk is determined to be < 5%.

What, if any, intervention would be triggered by the finding of moderate HTG?

CASE 2

Alicia F, age 30, with a BMI of 28 and ASCVD risk < 7.5%, comes to the clinic for evaluation of anxiety and insomnia. She reports eating a high-carbohydrate diet and drinking 3 to 5 alcoholic beverages nightly to help her sleep.

Ms. F’s daily alcohol use prompts evaluation for HTG. Results show a TG level of 1300 mg/dL and a high-density lipoprotein (HDL) level of 25 mg/dL (healthy HDL levels: adult females, ≥ 50 mg/dL; adult males, ≥ 40 mg/dL). Other test results are normal, except for elevated transaminase levels (just under twice normal).

What, if any, action would be prompted by the patient’s severe HTG and below-normal HDL level?

Continue to: How HTG is defined

How HTG is defined: Causes, cutoffs, signs

HTG is most commonly caused by obesity and a sedentary lifestyle; certain associated comorbid medical conditions can also be a precipitant (Table 11,2). Because the condition is a result of polygenic phenotypic expression, even a genetically low-risk patient can present with HTG when exposed to certain medical conditions and environmental causes.

Primary HTG (genetic or familial) is rare. Genetic testing may be considered for patients with TG > 1000 mg/dL (severely elevated TG = 500 to 1999 mg/dL, measured in fasting state*) or a family history of early ASCVD (TABLE 11,2).2,3

Typically, HTG is asymptomatic. Xanthelasmas, xanthomas, and lipemia retinalis are found in hereditary disorders of elevated TGs. Occasionally, HTG manifests as chylomicronemia syndrome, characterized by recurrent abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and, in severe HTG, pancreatitis.3

Fine points of TG measurement

Triglycerides are a component of a complete lipid profile, which also includes total cholesterol, calculated low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C), and HDL.4 As in both case vignettes, detection of HTG is often incidental, when a lipid profile is ordered to evaluate the risk of ASCVD. (Of note, for people older than 20 years, the US Preventive Services Task Force no longer addresses the question, “Which population should be screened for dyslipidemia?” Instead, current recommendations answer the question, “For which population should statin therapy be prescribed?”5)

Effect on ASCVD risk assessment. TG levels are known to vary, depending on fasting or nonfasting status, with lower levels reported when fasting. An elevated TG level can lead to inaccurate calculation of LDL when using the Friedewald formula6:

LDL = total cholesterol – (triglycerides/5) – HDL

Continue to: The purpose of testing...

The purpose of testing lipids in a fasting state (> 9 hours) is to minimize the effects of an elevated TG level on the calculated LDL. In severe HTG, beta-quantitation by ultracentrifugation and electrophoresis can be performed to determine the LDL level directly.

Advantage of nonfasting measurement. When LDL-C is not a concern, there is, in fact, value in measuring TGs in the nonfasting state. Why? Because a nonfasting TG level is a better indicator of a patient’s average TG status: Studies have found a higher ASCVD risk in the setting of an elevated postprandial TG level accompanied by a low HDL level.7

The Copenhagen City Heart Study identified postprandial HTG as an independent risk factor for atherogenicity, even in the setting of a normal fasting TG level.8 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology guidelines endorse testing the nonfasting TG level when the fasting TG level is elevated in a lipid profile; if the nonfasting TG level is > 500 mg/dL, evaluation for secondary causes is warranted9,10 (Table 11,2).

In a practical sense, therefore, offering patients nonfasting lipid testing allows more people to obtain access to timely care.

Pancreatitis. Acute pancreatitis commonly prompts an evaluation for HTG. The risk of acute pancreatitis in the general population is 0.04%, but that risk increases to 8% to 31% for a person with HTG.11 Incidence when the TG level is > 500 mg/dL is thought to be increased because chylomicrons, acting as a TG carrier in the bloodstream, are responsible for pancreatitis.3 Treating HTG can reduce both the risk and recurrence of pancreatitis12,13; given that the postprandial TG level can change rapidly from severe to very severe (> 2000 mg/dL), multiple guidelines recommend pharmacotherapy to a TG goal of < 500-1000 mg/dL.1,9,13,14

Continue to: An ASCVD risk-HTG connection?

An ASCVD risk–HTG connection? In the population already at higher risk of ASCVD (> 7.5%), HTG is recognized as a risk-enhancing factor because of its atherogenic potential (Table 22); however, there is insufficient evidence that TGs have a role as an independent risk factor for ASCVD. In a population-based study of 58,000 people, 40 to 65 years of age, conducted at Copenhagen [Denmark] University Hospital, investigators found that those who did not meet criteria for statin treatment and who had a TG level > 264 mg/dL had a 10-year risk of a major adverse cardiovascular event similar to that of people who did meet criteria for statin therapy.15

The FIELD (Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes) and AIM-HIGH (Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome with Low HDL/High Triglycerides and Impact on Global Health Outcomes) studies, among others, have failed to show a significant reduction in coronary events by treating HTG.10

That said, it’s worth considering the findings of other trials:

- In the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 (Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 22) trial, an overall 28% reduction in endpoint events (myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome) was seen with high-intensity statin therapy, compared to moderate-intensity therapy.10 However, there was a sizeable residual risk identified that was theorized by investigators to be associated with high non-HDL lipoproteins, including TGs.

- A 2016 study in Israel, in which 22 years of data on 15,355 patients with established ASCVD were studied, revealed that elevated TGs are associated with an increased long-term mortality risk that is independent of the HDL level.16

- A cross-sectional study, nested in the prospective Copenhagen City Heart Study, demonstrated that HTG is associated with an increase in ischemic stroke events.17

Treatment

Therapeutic lifestyle changes

Changes in lifestyle are the foundation of management of, and recommended first-line treatment for, all patients with HTG. Patients with a moderately elevated TG level (175-499 mg/dL, measured in a fasting or nonfasting state) can be treated with therapeutic lifestyle changes alone1,2; a trial of 3 to 6 months (see specific interventions below) is recommended before considering adding medications.10

Weight loss. There is a strong association between BMI > 30 and HTG. Visceral adiposity is a much more significant risk than subcutaneous adipose tissue. Although weight loss to an ideal range is recommended, even a 10% to 15% reduction in an obese patient can reduce the TG level by 20%. A combination of moderate-intensity exercise and healthy eating habits appears to assist best with this intervention.18

Continue to: Exercise

Exercise. Thirty minutes a day of moderate-intensity exercise is associated with a significant drop in postprandial TG. This benefit can last as long as 3 days, suggesting a goal of at least 3 days a week of an active lifestyle. Such a program can include intermittent aerobics or mild resistance exercise.19

Healthy eating habits. The difference between a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet and a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet is less important than the overall benefit of weight loss from either of these diets. Complex carbohydrates are recommended over simple carbohydrates. A low-carbohydrate diet in a patient with diabetes has been demonstrated to improve the TG level, irrespective of weight change.

A Mediterranean diet can reduce the TG level by 10% to 15%, and is recommended over a low-fat diet.14 (This diet generally includes a high intake of extra virgin olive oil; leafy green vegetables, fruits, cereals, nuts, and legumes; moderate intake of fish and other meat, dairy products, and red wine; and low intake of eggs and sugars.) The American Heart Association recommends 2 servings of fatty fish a week for its omega-3 oil benefit of reducing ASCVD risk. Working with a registered dietician to assist with lipid lowering can produce better results than physician-only instruction on healthy eating.9

Alcohol consumption. Complete cessation or moderation of alcohol consumption (1 drink a day/women and 2 drinks a day/men*) is recommended to improve HTG. Among secondary factors, alcohol is commonly the cause of an unusually high elevation of the TG level.14

Smoking cessation. Smoking increases the postprandial TG level.10 Complete cessation for just 1 year can reduce a person’s ASCVD risk by approximately 50%. However, in a clinical trial,22 smoking cessation did not significantly decrease the TG level—possibly because of the counterbalancing effect of weight gain following cessation.

Continue to: Medical therapy

Medical therapy

In addition to lifestyle modification, medications are recommended to reduce atherogenic potential in patients with moderate or severe HTG and an ASCVD risk > 7.5% (Table 34,13,18,23 and Table 42,9). Before initiating medical therapy, we recommend that you engage in shared decision-making with patients to (1) delineate treatment goals and (2) describe the risks and benefits of medications for HTG.2

Statins. These agents are recommended first-line therapy for reducing ASCVD risk.2 If the TG level remains elevated (> 500 mg/dL) after statin therapy is maximized, an additional agent can be added—ie, a fibrate or fish oil (see below).

Fibrates. If a fibrate is used as an add-on to a statin, fenofibrate is preferred over gemfibrozil because it presents less risk of the severe myopathy that can develop when taken with a statin.13 Despite the effectiveness of fibrates in reducing the TG level, these drugs have not been shown to reduce overall mortality.24 The evidence on improved cardiovascular outcomes is subgroup-specific (ie, prevention of a second myocardial infarction in the setting of optimal statin use and elevated non-HDL lipoproteins).12 A study demonstrated that gemfibrozil reduced the incidence of transient ischemic attack and stroke in a subgroup of male US veterans who had coronary artery disease and a low HDL level.25

Fish oil. The omega-3 ethyl esters eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), available as EPA alone or in combination with DHA, do not interact with statins and are tolerated well. They reduce hypertriglyceridemia by 20% to 50%.13

Eicosapentaenoic acid, EPA plus DHA, and icosapent ethyl, an ethyl ester product containing EPA without DHA, are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for HTG > 500 mg/dL, at a dosage of 2000 mg twice daily. In the REDUCE-IT trial, adding icosapent ethyl, 2 g twice daily, to a statin in patients with HTG was associated with fewer ischemic events, compared to placebo.23,26

Continue to: Fish oil formulations...

Fish oil formulations can inhibit platelet aggregation and increase bleeding time in otherwise healthy people; however, such episodes are minor and nonfatal. Patients on anticoagulation or an antiplatelet medication should be monitored periodically for bleeding events, although recommendations on how to monitor aren’t specified in a recent advisory by the American Heart Association.23

DHA was thought to increase the LDL-C levels and, by doing so, potentially counterbalance benefit,23,27 but most studies have failed to reproduce this effect.28 Instead, studies have shown minimal elevation of LDL-C when DHA is used to treat HTG.23,27

Niacin. At a dosage of 500-2000 mg/dL, niacin lowers the TG level by 10% to 30%. It also increases HDL by 10% to 40% and lowers LDL by 5% to 20%.13

Considerations in pancreatitis. For management of recurrent pancreatitis in patients with HTG, lifestyle modification remains the mainstay of treatment. When medication is considered for persistent severe HTG, fibrates have evidence of primary and secondary prevention of pancreatitis.

CASE 1

Recommendation for Mr. M: Therapeutic lifestyle changes to address moderate HTG.

Continue to: Because Mr. M's...

Because Mr. M’s 10-yr ASCVD risk is < 5%, statin therapy is not indicated for risk reduction. With a fasting TG value < 500 mg/dL, he is not considered at increased risk of pancreatitis.

CASE 2