User login

Will we be wearing masks years from now?

Yesterday during an office visit I was adjusting my mask when a patient suddenly said, “What if this is the new normal? What if we still have to wear masks years from now?”

An interesting thought. That might even be the case. I mean, the COVID-19 pandemic definitely has changed our world. On the other hand, there are far worse things to have to do.

Masks, to some extent, have already become a part of our society, I see more people out and about with them than without. Like lunchboxes, they’ve transitioned from utilitarian to fashion statements. I see Darth Vader, Batman, Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and many other characters on them.

Humans have, after all, adapted to wearing all kinds of things. At some point our ancestors discovered they could walk around outside more comfortably with a covering on their feet. Then they discovered that socks prevent chafing. Now shoes and socks are worn worldwide, available for many different purposes in varied colors, styles, and cultures.

Why should masks be any different? Just because they’re new doesn’t mean they’re bad.

Obviously, I’m exaggerating. I don’t want to wear a mask full time, either. They’re hot and uncomfortable and, for people with certain respiratory issues, impossible. I live in Phoenix and I definitely don’t want to go through one of our summers wearing a face mask.

But at the same time, This makes me wonder when we’ll start to phase them out. The virus isn’t going anywhere, so the breaking point will be when there’s either an effective vaccine administered to most of the population, or enough people have had the virus that herd immunity takes effect.

Until then, I have no problem with wearing a mask and asking patients who can to please do so when they come in. I see a lot of people who are elderly and/or immune suppressed. I don’t want them to get sick. Or me. Or my family.

If wearing a mask through the Phoenix summer is a sacrifice that will lead to better health for all, it’s not a big one in the grand scheme of things.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz. He has no relevant disclosures.

Yesterday during an office visit I was adjusting my mask when a patient suddenly said, “What if this is the new normal? What if we still have to wear masks years from now?”

An interesting thought. That might even be the case. I mean, the COVID-19 pandemic definitely has changed our world. On the other hand, there are far worse things to have to do.

Masks, to some extent, have already become a part of our society, I see more people out and about with them than without. Like lunchboxes, they’ve transitioned from utilitarian to fashion statements. I see Darth Vader, Batman, Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and many other characters on them.

Humans have, after all, adapted to wearing all kinds of things. At some point our ancestors discovered they could walk around outside more comfortably with a covering on their feet. Then they discovered that socks prevent chafing. Now shoes and socks are worn worldwide, available for many different purposes in varied colors, styles, and cultures.

Why should masks be any different? Just because they’re new doesn’t mean they’re bad.

Obviously, I’m exaggerating. I don’t want to wear a mask full time, either. They’re hot and uncomfortable and, for people with certain respiratory issues, impossible. I live in Phoenix and I definitely don’t want to go through one of our summers wearing a face mask.

But at the same time, This makes me wonder when we’ll start to phase them out. The virus isn’t going anywhere, so the breaking point will be when there’s either an effective vaccine administered to most of the population, or enough people have had the virus that herd immunity takes effect.

Until then, I have no problem with wearing a mask and asking patients who can to please do so when they come in. I see a lot of people who are elderly and/or immune suppressed. I don’t want them to get sick. Or me. Or my family.

If wearing a mask through the Phoenix summer is a sacrifice that will lead to better health for all, it’s not a big one in the grand scheme of things.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz. He has no relevant disclosures.

Yesterday during an office visit I was adjusting my mask when a patient suddenly said, “What if this is the new normal? What if we still have to wear masks years from now?”

An interesting thought. That might even be the case. I mean, the COVID-19 pandemic definitely has changed our world. On the other hand, there are far worse things to have to do.

Masks, to some extent, have already become a part of our society, I see more people out and about with them than without. Like lunchboxes, they’ve transitioned from utilitarian to fashion statements. I see Darth Vader, Batman, Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and many other characters on them.

Humans have, after all, adapted to wearing all kinds of things. At some point our ancestors discovered they could walk around outside more comfortably with a covering on their feet. Then they discovered that socks prevent chafing. Now shoes and socks are worn worldwide, available for many different purposes in varied colors, styles, and cultures.

Why should masks be any different? Just because they’re new doesn’t mean they’re bad.

Obviously, I’m exaggerating. I don’t want to wear a mask full time, either. They’re hot and uncomfortable and, for people with certain respiratory issues, impossible. I live in Phoenix and I definitely don’t want to go through one of our summers wearing a face mask.

But at the same time, This makes me wonder when we’ll start to phase them out. The virus isn’t going anywhere, so the breaking point will be when there’s either an effective vaccine administered to most of the population, or enough people have had the virus that herd immunity takes effect.

Until then, I have no problem with wearing a mask and asking patients who can to please do so when they come in. I see a lot of people who are elderly and/or immune suppressed. I don’t want them to get sick. Or me. Or my family.

If wearing a mask through the Phoenix summer is a sacrifice that will lead to better health for all, it’s not a big one in the grand scheme of things.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz. He has no relevant disclosures.

Protective levels of vitamin D achievable in SCD with oral supplementation

Sickle cell disease is associated with worse long-term bone health than that of the general population, and SCD patients are more likely to experience vitamin D [25(OH)D] deficiency. Oral vitamin D3 supplementation can achieve protective levels in children with sickle cell disease, and a daily dose was able to achieved optimal blood levels, according to a report published online in Bone.

The researchers performed a prospective, longitudinal, single-center study of 80 children with SCD. They collected demographic, clinical, and management data, as well as 25(OH)D levels. Bone densitometries (DXA) were also collected.

Among the 80 patients were included in the analysis, there were significant differences between the means of 25(OH)D levels based on whether the patient started prophylactic treatment as an infant or not (35.7 vs. 27.9 ng/mL, respectively [P = .014]), according to the researchers.

They also found that, in multivariate analysis, an oral 800 IU daily dose of vitamin D3 was shown to be a protective factor (P = .044) in reaching optimal 25(OH)D blood levels (≥ 30 ng/mL).

Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that those patients younger than 10 years of age reached optimal levels significantly earlier than older patients when on supplementation (P = .002), as did those patients who were not being treated with hydroxyurea (P = .039), the researchers wrote.

Significant differences were seen between the mean bone mineral density in both DXAs performed when comparing suboptimal vs. optimal blood levels of 25(OH)D (0.54 g/cm2 vs. 0.64 g/cm2, respectively, P = .001), for the initial DXA, and for the most recent DXA (0.59 g/cm2 vs. 0.77 g/cm2, respectively, P = .044). “VitD3 prophylaxis is a safe practice in SCD. It is important to start this prophylactic treatment when the child is an infant. The daily regimen with 800 IU could be more effective for reaching levels ≥ 30 ng/mL, and, especially in preadolescent and adolescent patients, we should raise awareness about the importance of good bone health,” the authors concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Garrido C et al. Bone. 2020;133: doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2020.115228.

Sickle cell disease is associated with worse long-term bone health than that of the general population, and SCD patients are more likely to experience vitamin D [25(OH)D] deficiency. Oral vitamin D3 supplementation can achieve protective levels in children with sickle cell disease, and a daily dose was able to achieved optimal blood levels, according to a report published online in Bone.

The researchers performed a prospective, longitudinal, single-center study of 80 children with SCD. They collected demographic, clinical, and management data, as well as 25(OH)D levels. Bone densitometries (DXA) were also collected.

Among the 80 patients were included in the analysis, there were significant differences between the means of 25(OH)D levels based on whether the patient started prophylactic treatment as an infant or not (35.7 vs. 27.9 ng/mL, respectively [P = .014]), according to the researchers.

They also found that, in multivariate analysis, an oral 800 IU daily dose of vitamin D3 was shown to be a protective factor (P = .044) in reaching optimal 25(OH)D blood levels (≥ 30 ng/mL).

Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that those patients younger than 10 years of age reached optimal levels significantly earlier than older patients when on supplementation (P = .002), as did those patients who were not being treated with hydroxyurea (P = .039), the researchers wrote.

Significant differences were seen between the mean bone mineral density in both DXAs performed when comparing suboptimal vs. optimal blood levels of 25(OH)D (0.54 g/cm2 vs. 0.64 g/cm2, respectively, P = .001), for the initial DXA, and for the most recent DXA (0.59 g/cm2 vs. 0.77 g/cm2, respectively, P = .044). “VitD3 prophylaxis is a safe practice in SCD. It is important to start this prophylactic treatment when the child is an infant. The daily regimen with 800 IU could be more effective for reaching levels ≥ 30 ng/mL, and, especially in preadolescent and adolescent patients, we should raise awareness about the importance of good bone health,” the authors concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Garrido C et al. Bone. 2020;133: doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2020.115228.

Sickle cell disease is associated with worse long-term bone health than that of the general population, and SCD patients are more likely to experience vitamin D [25(OH)D] deficiency. Oral vitamin D3 supplementation can achieve protective levels in children with sickle cell disease, and a daily dose was able to achieved optimal blood levels, according to a report published online in Bone.

The researchers performed a prospective, longitudinal, single-center study of 80 children with SCD. They collected demographic, clinical, and management data, as well as 25(OH)D levels. Bone densitometries (DXA) were also collected.

Among the 80 patients were included in the analysis, there were significant differences between the means of 25(OH)D levels based on whether the patient started prophylactic treatment as an infant or not (35.7 vs. 27.9 ng/mL, respectively [P = .014]), according to the researchers.

They also found that, in multivariate analysis, an oral 800 IU daily dose of vitamin D3 was shown to be a protective factor (P = .044) in reaching optimal 25(OH)D blood levels (≥ 30 ng/mL).

Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that those patients younger than 10 years of age reached optimal levels significantly earlier than older patients when on supplementation (P = .002), as did those patients who were not being treated with hydroxyurea (P = .039), the researchers wrote.

Significant differences were seen between the mean bone mineral density in both DXAs performed when comparing suboptimal vs. optimal blood levels of 25(OH)D (0.54 g/cm2 vs. 0.64 g/cm2, respectively, P = .001), for the initial DXA, and for the most recent DXA (0.59 g/cm2 vs. 0.77 g/cm2, respectively, P = .044). “VitD3 prophylaxis is a safe practice in SCD. It is important to start this prophylactic treatment when the child is an infant. The daily regimen with 800 IU could be more effective for reaching levels ≥ 30 ng/mL, and, especially in preadolescent and adolescent patients, we should raise awareness about the importance of good bone health,” the authors concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Garrido C et al. Bone. 2020;133: doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2020.115228.

FROM BONE

One strikeout, one hit against low-grade serous carcinomas

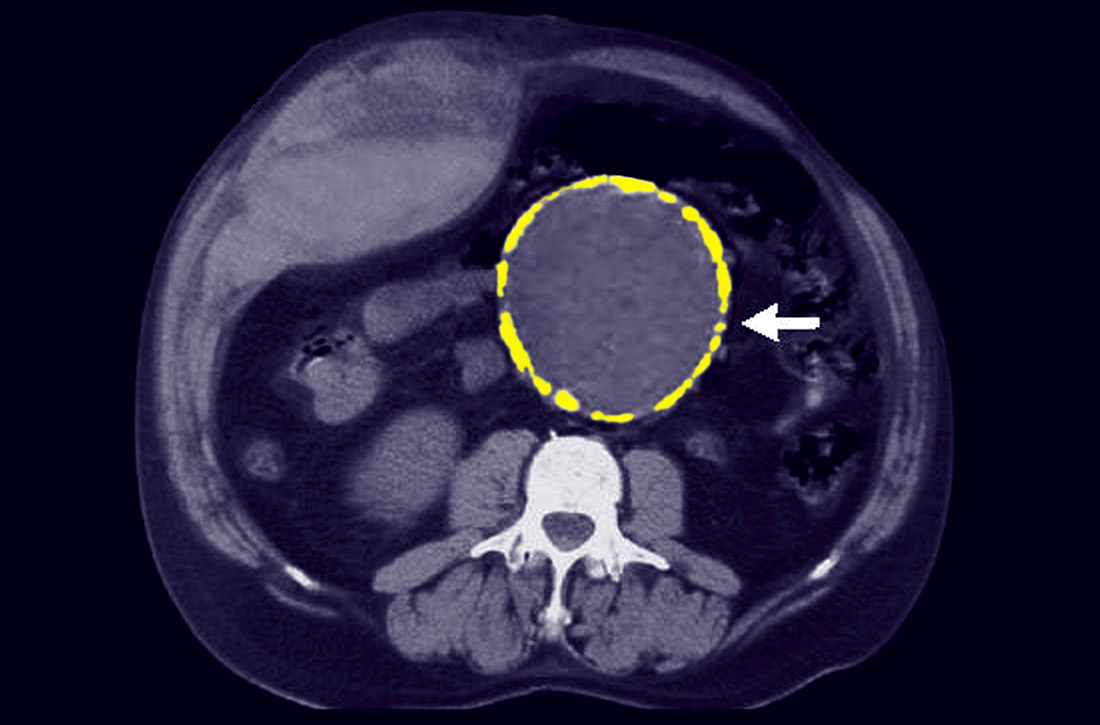

Two MEK inhibitors were tested against recurrent low-grade serous carcinomas of the ovaries, fallopian tubes, or peritoneum, but only one inhibitor offered clinical benefit over standard care, investigators from two randomized trials reported.

Trametinib improved progression-free survival (PFS) when compared with standard care, while binimetinib conferred no PFS benefit.

In a phase 2/3 trial, the median PFS was 13 months for patients treated with trametinib and 7.2 months for patients who received an aromatase inhibitor or chemotherapy (P < .0001).

“Our findings suggest that trametinib represents a new standard-of-care treatment option for women with recurrent low-grade serous carcinoma,” said investigator David M. Gershenson, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

In contrast, in the phase 3 MILO/ENGOT-ov11 trial, there was no significant difference in PFS between patients treated with binimetinib and those who received physician’s choice of chemotherapy. The median PFS was 11.2 months with binimetinib and 14.1 months with chemotherapy (P = .752).

“Although this study did not meet its primary endpoint, binimetinib showed activity in low-grade serous ovarian cancer across the efficacy endpoints evaluated, with a response rate of 24% and a median PFS of 11.2 months on updated analysis. Chemotherapy responses were better than predicted, based on historical retrospective data,” said investigator Rachel N. Grisham, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

The binimetinib trial and the trametinib trial were both discussed during a webinar on rare tumors covering research slated for presentation at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer. The meeting was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Chemoresistant cancers

Low-grade serous ovarian or peritoneal cancers are rare, accounting for only 5% to 10% of all serous cancers, Dr. Gershenson noted.

“[Low-grade serous cancers are] characterized by alterations in the MAP kinase pathway, as well as relative chemoresistance, and prolonged overall survival compared to high-grade serous cancers. Because of this subtype’s relative chemoresistance, the search for novel therapeutics has predominated over the last decade or so,” he said.

MEK inhibitors interfere with the MEK1 and MEK2 enzymes in the MAPK pathway. Alterations in MAPK, especially in KRAS and BRAF proteins, are found in 30%-60% of low-grade serous carcinomas, providing the rationale for MEK inhibitors in these rare malignancies.

Trametinib study

In a phase 2/3 study, Dr. Gershenson and colleagues enrolled 260 patients with recurrent, low-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary or peritoneum. Patients were randomized to receive either trametinib at 2 mg daily continuously until progression (n = 130) or standard care (n = 130).

Standard care consisted of one of the following: letrozole at 2.5 mg daily; pegylated liposomal doxorubicin at 40-50 mg IV every 28 days; weekly paclitaxel at 80 mg/m2 for 3 out of 4 weeks; tamoxifen at 20 mg twice daily; or topotecan at 4 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 every 28 days. Patients randomized to standard care could be crossed over to trametinib at progression.

All patients had at least one prior line of platinum-based chemotherapy, and nearly half had three or more prior lines of therapy. The median age was 56.6 years in the trametinib arm and 55.3 years in the control arm.

At a median follow-up of 31.4 months, median PFS, the primary endpoint, was 13 months with trametinib vs. 7.2 months with standard care. The hazard ratio (HR) for progression on trametinib was 0.48 (P < .0001).

The overall response rates were 26.2% in the trametinib arm and 6.2% in the standard care arm. The odds ratio for response on trametinib was 5.4 (P < .0001).

For 88 patients who crossed over to trametinib, the median PFS was 10.8 months, and the overall response rate was 15%.

Trametinib was also associated with a significantly longer response duration, at a median of 13.6 months, compared with 5.9 months for standard care (P value not shown).

The median overall survival was 37 months with trametinib and 29.2 months with standard care, with an HR favoring trametinib of 0.75, although this just missed statistical significance (P = .054). Dr. Gershenson pointed out that the overall survival in the standard care arm included patients who had been crossed over to trametinib.

Grade 3 or greater adverse events included hematologic toxicities in 13.4% of patients on trametinib and 9.4% on standard care; gastrointestinal toxicity in 27.6% and 29%, respectively; skin toxicities in 15% and 3.9%, respectively; and vascular toxicities in 18.9% and 8.6%, respectively.

Binimetinib study

The phase 3 MILO/ENGOT-ov11 study enrolled 341 patients with low-grade serous carcinomas of the ovaries, fallopian tubes, or peritoneum. Patients were randomized on a 2:1 basis to receive either binimetinib at 45 mg twice daily (n = 228) or physician’s choice of chemotherapy (n = 113). Chemotherapy consisted of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin at 40 mg/m2 on day 1 of each 28-day cycle; paclitaxel at 80 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 of each 28-day cycle; or topotecan at 1.25 mg/m2 IV on days 1-5 of each 21-day cycle.

The efficacy analysis included 227 patients assigned to binimetinib and 106 assigned to chemotherapy.

A planned interim analysis was performed in 2016 after the first 303 patients were enrolled. At that time, the median PFS by blinded central review was 9.1 months in the binimetinib arm and 10.6 months in the physician’s choice arm (HR, 1.21; P = .807), so the trial was halted early for futility. Patients on active treatment at the time could continue until progression and were followed by local radiology.

At the interim analysis, secondary endpoints were also similar between the arms. The overall response rate was 16% in the binimetinib arm and 13% in the chemotherapy arm.

The most common grade 3 or greater adverse events with binimetinib were blood creatinine phosphokinase increase (26%) and vomiting (10%).

Dr. Grisham also reported updated follow-up results through January 2019.

The median PFS in the updated analysis was 11.2 months with the MEK inhibitor and 14.1 months with chemotherapy, a difference that was not statistically significant (HR, 1.12; P = .752). Updated overall response rates were the same in both arms, at 24%.

A post hoc molecular analysis of 215 patients suggested a possible association between KRAS mutation and response to binimetinib.

Two MEKs, one ‘meh’

Discussant Jubilee Brown, MD, of the Levine Cancer Institute at Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C., said that “with a 2% to 5% chance of response in patients with low-grade serous ovarian cancer, there is a low bar for any compound to demonstrate success.”

Regarding the MILO/ENGOT-ov11 trial, she noted that “this study did not meet its primary endpoint, but perhaps the endpoint is not reflective of the importance of the study.”

A different outcome might have occurred had investigators stratified patients by KRAS status upfront, comparing patients with KRAS mutations treated with binimetinib to KRAS wild-type patients treated with either a MEK inhibitor or physician’s choice of care, Dr. Brown said.

She agreed with the assertion by Dr. Gershenson and colleagues that improved PFS qualifies trametinib to be considered a new option for standard care, ”especially in a rare tumor setting with limited options. This is a huge win for patients.”

The trametinib study was sponsored by NRG Oncology and the UK National Cancer Research Institute. Dr. Gershenson disclosed relationships with NRG Oncology, Genentech, Novartis, Elsevier, and UpToDate, as well as stock in several companies.

The binimetinib study was sponsored by Pfizer. Dr. Grisham disclosed relationships with Clovis, Regeneron, Mateon, Amgen, Abbvie, OncLive, PRIME, MCM, and Medscape. MDedge News and Medscape are owned by the same parent organization.

Dr. Brown disclosed consulting for Biodesix, Caris, Clovis, Genentech, Invitae, Janssen, Olympus, OncLive, and Tempus.

SOURCE: Gershenson DM et al. SGO 2020, Abstract 42; Grisham RN et al. SGO 2020, Abstract 41.

Two MEK inhibitors were tested against recurrent low-grade serous carcinomas of the ovaries, fallopian tubes, or peritoneum, but only one inhibitor offered clinical benefit over standard care, investigators from two randomized trials reported.

Trametinib improved progression-free survival (PFS) when compared with standard care, while binimetinib conferred no PFS benefit.

In a phase 2/3 trial, the median PFS was 13 months for patients treated with trametinib and 7.2 months for patients who received an aromatase inhibitor or chemotherapy (P < .0001).

“Our findings suggest that trametinib represents a new standard-of-care treatment option for women with recurrent low-grade serous carcinoma,” said investigator David M. Gershenson, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

In contrast, in the phase 3 MILO/ENGOT-ov11 trial, there was no significant difference in PFS between patients treated with binimetinib and those who received physician’s choice of chemotherapy. The median PFS was 11.2 months with binimetinib and 14.1 months with chemotherapy (P = .752).

“Although this study did not meet its primary endpoint, binimetinib showed activity in low-grade serous ovarian cancer across the efficacy endpoints evaluated, with a response rate of 24% and a median PFS of 11.2 months on updated analysis. Chemotherapy responses were better than predicted, based on historical retrospective data,” said investigator Rachel N. Grisham, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

The binimetinib trial and the trametinib trial were both discussed during a webinar on rare tumors covering research slated for presentation at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer. The meeting was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Chemoresistant cancers

Low-grade serous ovarian or peritoneal cancers are rare, accounting for only 5% to 10% of all serous cancers, Dr. Gershenson noted.

“[Low-grade serous cancers are] characterized by alterations in the MAP kinase pathway, as well as relative chemoresistance, and prolonged overall survival compared to high-grade serous cancers. Because of this subtype’s relative chemoresistance, the search for novel therapeutics has predominated over the last decade or so,” he said.

MEK inhibitors interfere with the MEK1 and MEK2 enzymes in the MAPK pathway. Alterations in MAPK, especially in KRAS and BRAF proteins, are found in 30%-60% of low-grade serous carcinomas, providing the rationale for MEK inhibitors in these rare malignancies.

Trametinib study

In a phase 2/3 study, Dr. Gershenson and colleagues enrolled 260 patients with recurrent, low-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary or peritoneum. Patients were randomized to receive either trametinib at 2 mg daily continuously until progression (n = 130) or standard care (n = 130).

Standard care consisted of one of the following: letrozole at 2.5 mg daily; pegylated liposomal doxorubicin at 40-50 mg IV every 28 days; weekly paclitaxel at 80 mg/m2 for 3 out of 4 weeks; tamoxifen at 20 mg twice daily; or topotecan at 4 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 every 28 days. Patients randomized to standard care could be crossed over to trametinib at progression.

All patients had at least one prior line of platinum-based chemotherapy, and nearly half had three or more prior lines of therapy. The median age was 56.6 years in the trametinib arm and 55.3 years in the control arm.

At a median follow-up of 31.4 months, median PFS, the primary endpoint, was 13 months with trametinib vs. 7.2 months with standard care. The hazard ratio (HR) for progression on trametinib was 0.48 (P < .0001).

The overall response rates were 26.2% in the trametinib arm and 6.2% in the standard care arm. The odds ratio for response on trametinib was 5.4 (P < .0001).

For 88 patients who crossed over to trametinib, the median PFS was 10.8 months, and the overall response rate was 15%.

Trametinib was also associated with a significantly longer response duration, at a median of 13.6 months, compared with 5.9 months for standard care (P value not shown).

The median overall survival was 37 months with trametinib and 29.2 months with standard care, with an HR favoring trametinib of 0.75, although this just missed statistical significance (P = .054). Dr. Gershenson pointed out that the overall survival in the standard care arm included patients who had been crossed over to trametinib.

Grade 3 or greater adverse events included hematologic toxicities in 13.4% of patients on trametinib and 9.4% on standard care; gastrointestinal toxicity in 27.6% and 29%, respectively; skin toxicities in 15% and 3.9%, respectively; and vascular toxicities in 18.9% and 8.6%, respectively.

Binimetinib study

The phase 3 MILO/ENGOT-ov11 study enrolled 341 patients with low-grade serous carcinomas of the ovaries, fallopian tubes, or peritoneum. Patients were randomized on a 2:1 basis to receive either binimetinib at 45 mg twice daily (n = 228) or physician’s choice of chemotherapy (n = 113). Chemotherapy consisted of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin at 40 mg/m2 on day 1 of each 28-day cycle; paclitaxel at 80 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 of each 28-day cycle; or topotecan at 1.25 mg/m2 IV on days 1-5 of each 21-day cycle.

The efficacy analysis included 227 patients assigned to binimetinib and 106 assigned to chemotherapy.

A planned interim analysis was performed in 2016 after the first 303 patients were enrolled. At that time, the median PFS by blinded central review was 9.1 months in the binimetinib arm and 10.6 months in the physician’s choice arm (HR, 1.21; P = .807), so the trial was halted early for futility. Patients on active treatment at the time could continue until progression and were followed by local radiology.

At the interim analysis, secondary endpoints were also similar between the arms. The overall response rate was 16% in the binimetinib arm and 13% in the chemotherapy arm.

The most common grade 3 or greater adverse events with binimetinib were blood creatinine phosphokinase increase (26%) and vomiting (10%).

Dr. Grisham also reported updated follow-up results through January 2019.

The median PFS in the updated analysis was 11.2 months with the MEK inhibitor and 14.1 months with chemotherapy, a difference that was not statistically significant (HR, 1.12; P = .752). Updated overall response rates were the same in both arms, at 24%.

A post hoc molecular analysis of 215 patients suggested a possible association between KRAS mutation and response to binimetinib.

Two MEKs, one ‘meh’

Discussant Jubilee Brown, MD, of the Levine Cancer Institute at Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C., said that “with a 2% to 5% chance of response in patients with low-grade serous ovarian cancer, there is a low bar for any compound to demonstrate success.”

Regarding the MILO/ENGOT-ov11 trial, she noted that “this study did not meet its primary endpoint, but perhaps the endpoint is not reflective of the importance of the study.”

A different outcome might have occurred had investigators stratified patients by KRAS status upfront, comparing patients with KRAS mutations treated with binimetinib to KRAS wild-type patients treated with either a MEK inhibitor or physician’s choice of care, Dr. Brown said.

She agreed with the assertion by Dr. Gershenson and colleagues that improved PFS qualifies trametinib to be considered a new option for standard care, ”especially in a rare tumor setting with limited options. This is a huge win for patients.”

The trametinib study was sponsored by NRG Oncology and the UK National Cancer Research Institute. Dr. Gershenson disclosed relationships with NRG Oncology, Genentech, Novartis, Elsevier, and UpToDate, as well as stock in several companies.

The binimetinib study was sponsored by Pfizer. Dr. Grisham disclosed relationships with Clovis, Regeneron, Mateon, Amgen, Abbvie, OncLive, PRIME, MCM, and Medscape. MDedge News and Medscape are owned by the same parent organization.

Dr. Brown disclosed consulting for Biodesix, Caris, Clovis, Genentech, Invitae, Janssen, Olympus, OncLive, and Tempus.

SOURCE: Gershenson DM et al. SGO 2020, Abstract 42; Grisham RN et al. SGO 2020, Abstract 41.

Two MEK inhibitors were tested against recurrent low-grade serous carcinomas of the ovaries, fallopian tubes, or peritoneum, but only one inhibitor offered clinical benefit over standard care, investigators from two randomized trials reported.

Trametinib improved progression-free survival (PFS) when compared with standard care, while binimetinib conferred no PFS benefit.

In a phase 2/3 trial, the median PFS was 13 months for patients treated with trametinib and 7.2 months for patients who received an aromatase inhibitor or chemotherapy (P < .0001).

“Our findings suggest that trametinib represents a new standard-of-care treatment option for women with recurrent low-grade serous carcinoma,” said investigator David M. Gershenson, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

In contrast, in the phase 3 MILO/ENGOT-ov11 trial, there was no significant difference in PFS between patients treated with binimetinib and those who received physician’s choice of chemotherapy. The median PFS was 11.2 months with binimetinib and 14.1 months with chemotherapy (P = .752).

“Although this study did not meet its primary endpoint, binimetinib showed activity in low-grade serous ovarian cancer across the efficacy endpoints evaluated, with a response rate of 24% and a median PFS of 11.2 months on updated analysis. Chemotherapy responses were better than predicted, based on historical retrospective data,” said investigator Rachel N. Grisham, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

The binimetinib trial and the trametinib trial were both discussed during a webinar on rare tumors covering research slated for presentation at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer. The meeting was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Chemoresistant cancers

Low-grade serous ovarian or peritoneal cancers are rare, accounting for only 5% to 10% of all serous cancers, Dr. Gershenson noted.

“[Low-grade serous cancers are] characterized by alterations in the MAP kinase pathway, as well as relative chemoresistance, and prolonged overall survival compared to high-grade serous cancers. Because of this subtype’s relative chemoresistance, the search for novel therapeutics has predominated over the last decade or so,” he said.

MEK inhibitors interfere with the MEK1 and MEK2 enzymes in the MAPK pathway. Alterations in MAPK, especially in KRAS and BRAF proteins, are found in 30%-60% of low-grade serous carcinomas, providing the rationale for MEK inhibitors in these rare malignancies.

Trametinib study

In a phase 2/3 study, Dr. Gershenson and colleagues enrolled 260 patients with recurrent, low-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary or peritoneum. Patients were randomized to receive either trametinib at 2 mg daily continuously until progression (n = 130) or standard care (n = 130).

Standard care consisted of one of the following: letrozole at 2.5 mg daily; pegylated liposomal doxorubicin at 40-50 mg IV every 28 days; weekly paclitaxel at 80 mg/m2 for 3 out of 4 weeks; tamoxifen at 20 mg twice daily; or topotecan at 4 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 every 28 days. Patients randomized to standard care could be crossed over to trametinib at progression.

All patients had at least one prior line of platinum-based chemotherapy, and nearly half had three or more prior lines of therapy. The median age was 56.6 years in the trametinib arm and 55.3 years in the control arm.

At a median follow-up of 31.4 months, median PFS, the primary endpoint, was 13 months with trametinib vs. 7.2 months with standard care. The hazard ratio (HR) for progression on trametinib was 0.48 (P < .0001).

The overall response rates were 26.2% in the trametinib arm and 6.2% in the standard care arm. The odds ratio for response on trametinib was 5.4 (P < .0001).

For 88 patients who crossed over to trametinib, the median PFS was 10.8 months, and the overall response rate was 15%.

Trametinib was also associated with a significantly longer response duration, at a median of 13.6 months, compared with 5.9 months for standard care (P value not shown).

The median overall survival was 37 months with trametinib and 29.2 months with standard care, with an HR favoring trametinib of 0.75, although this just missed statistical significance (P = .054). Dr. Gershenson pointed out that the overall survival in the standard care arm included patients who had been crossed over to trametinib.

Grade 3 or greater adverse events included hematologic toxicities in 13.4% of patients on trametinib and 9.4% on standard care; gastrointestinal toxicity in 27.6% and 29%, respectively; skin toxicities in 15% and 3.9%, respectively; and vascular toxicities in 18.9% and 8.6%, respectively.

Binimetinib study

The phase 3 MILO/ENGOT-ov11 study enrolled 341 patients with low-grade serous carcinomas of the ovaries, fallopian tubes, or peritoneum. Patients were randomized on a 2:1 basis to receive either binimetinib at 45 mg twice daily (n = 228) or physician’s choice of chemotherapy (n = 113). Chemotherapy consisted of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin at 40 mg/m2 on day 1 of each 28-day cycle; paclitaxel at 80 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 of each 28-day cycle; or topotecan at 1.25 mg/m2 IV on days 1-5 of each 21-day cycle.

The efficacy analysis included 227 patients assigned to binimetinib and 106 assigned to chemotherapy.

A planned interim analysis was performed in 2016 after the first 303 patients were enrolled. At that time, the median PFS by blinded central review was 9.1 months in the binimetinib arm and 10.6 months in the physician’s choice arm (HR, 1.21; P = .807), so the trial was halted early for futility. Patients on active treatment at the time could continue until progression and were followed by local radiology.

At the interim analysis, secondary endpoints were also similar between the arms. The overall response rate was 16% in the binimetinib arm and 13% in the chemotherapy arm.

The most common grade 3 or greater adverse events with binimetinib were blood creatinine phosphokinase increase (26%) and vomiting (10%).

Dr. Grisham also reported updated follow-up results through January 2019.

The median PFS in the updated analysis was 11.2 months with the MEK inhibitor and 14.1 months with chemotherapy, a difference that was not statistically significant (HR, 1.12; P = .752). Updated overall response rates were the same in both arms, at 24%.

A post hoc molecular analysis of 215 patients suggested a possible association between KRAS mutation and response to binimetinib.

Two MEKs, one ‘meh’

Discussant Jubilee Brown, MD, of the Levine Cancer Institute at Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C., said that “with a 2% to 5% chance of response in patients with low-grade serous ovarian cancer, there is a low bar for any compound to demonstrate success.”

Regarding the MILO/ENGOT-ov11 trial, she noted that “this study did not meet its primary endpoint, but perhaps the endpoint is not reflective of the importance of the study.”

A different outcome might have occurred had investigators stratified patients by KRAS status upfront, comparing patients with KRAS mutations treated with binimetinib to KRAS wild-type patients treated with either a MEK inhibitor or physician’s choice of care, Dr. Brown said.

She agreed with the assertion by Dr. Gershenson and colleagues that improved PFS qualifies trametinib to be considered a new option for standard care, ”especially in a rare tumor setting with limited options. This is a huge win for patients.”

The trametinib study was sponsored by NRG Oncology and the UK National Cancer Research Institute. Dr. Gershenson disclosed relationships with NRG Oncology, Genentech, Novartis, Elsevier, and UpToDate, as well as stock in several companies.

The binimetinib study was sponsored by Pfizer. Dr. Grisham disclosed relationships with Clovis, Regeneron, Mateon, Amgen, Abbvie, OncLive, PRIME, MCM, and Medscape. MDedge News and Medscape are owned by the same parent organization.

Dr. Brown disclosed consulting for Biodesix, Caris, Clovis, Genentech, Invitae, Janssen, Olympus, OncLive, and Tempus.

SOURCE: Gershenson DM et al. SGO 2020, Abstract 42; Grisham RN et al. SGO 2020, Abstract 41.

FROM SGO 2020

Practice During the Pandemic

The first installment of my new column was obsolete on arrival. It referred to walking abroad at midday, with no mention of masks and social distancing. The whole thing was so February 2020.

My last day in the office was in mid-March. Friday the 13th.

, using stored and forwarded images.

What I had in mind was visits by patients in nursing homes or too sick at home to come in. It always bothered me to see very aged and infirm patients brought to the office at great inconvenience and expense for what often turned out to be problems like xerosis or eczema that could have been managed quite well remotely.

The HMO never got back to me, though. There were too many hurdles, mostly bureaucratic rather than medical. Would insurance pay? What about consent? Malpractice? It has been interesting to watch the current crisis sweep away the inertia of such obstacles, including licensure considerations (seeing patients across state lines for cutaneous purposes). People get around to fixing the roof when it pours. Perhaps next time there will be tests, masks, respirators. Perhaps.

Seeing patients remotely has acquainted me with all the technical headaches everyone stuck at home talks and jokes about: Balky transmission (What did you say after, “and then the blood ...”?); patients who can’t figure out how to log on, or start the video, or unmute themselves, and on and on. Picture resolution is not great, as anyone knows from watching TV newscasters interview talking heads stuck in their homes.

I was never all that image-conscious, but my beard has grown fuller and my hair unkempter. Even though I sit at my desk, I do take care to keep my trousers on. Not taking any chances.

Everyone agonizes over what the “new normal” may be. Will people come back to doctors’ offices? Will practices survive economically if many patients don’t return to the office? Stay tuned. For a long time.

Mostly, though, remote visits seem to work. Helped if needed by additional, better-resolution emailed photos, it’s possible to make useful decisions, including which lesions can wait for in-person evaluation, until ...

... Until what? In an effort to keep this column up-to-the-nanosecond, I am writing it as many countries tentatively “open up.” Careful analysis of the knowledge behind this world-wide project shows ... not much. It seems to come down to some educated guesswork about what might work and what the risks might be, which leads to advice that differs widely from state to state and country to country. It’s as if people everywhere just decided that locking everyone down is a real drag, is financially ruinous, has a duration both uncertain and longer than most people and governments think they can handle, so let’s get out there and “be careful,” whatever that is said to mean.

And the risks? Well, more people will get sick and some will die. How many “extra” deaths are ethically acceptable? Thoughtful people are working on that. They’ll get back sometime to those who are still around.

I don’t blame anyone for our staggering ignorance about this terrifying new reality. But absorbing the ignorance in real time is not reassuring.

I have nothing but sympathy for those who are not emeritus, who have practices to sustain and families to feed. I didn’t ask to be born 73 years ago, and take no credit for having done so. So much of what happens to us depends on when and where we were born – two factors for which we deserve absolutely no credit – that it’s a wonder we take such pride in praising ourselves for what we think we accomplish. Having no better choice, we do the best we can.

Meantime, I am in a “high-risk” category. If I were obese, I could try to lose weight. But my risk factor is age, which tends not to decline. Risk-wise, there is just one way to exit my group.

So I don’t expect to get back to the office anytime soon. To paraphrase a comedian who shall remain nameless: I don’t want to live on in the hearts of men. I want to live on in my house.

Dr. Rockoff, who wrote the Dermatology News column “Under My Skin,” is now semiretired, after 40 years of practice in Brookline, Mass. He served on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available online. Write to him at [email protected].

The first installment of my new column was obsolete on arrival. It referred to walking abroad at midday, with no mention of masks and social distancing. The whole thing was so February 2020.

My last day in the office was in mid-March. Friday the 13th.

, using stored and forwarded images.

What I had in mind was visits by patients in nursing homes or too sick at home to come in. It always bothered me to see very aged and infirm patients brought to the office at great inconvenience and expense for what often turned out to be problems like xerosis or eczema that could have been managed quite well remotely.

The HMO never got back to me, though. There were too many hurdles, mostly bureaucratic rather than medical. Would insurance pay? What about consent? Malpractice? It has been interesting to watch the current crisis sweep away the inertia of such obstacles, including licensure considerations (seeing patients across state lines for cutaneous purposes). People get around to fixing the roof when it pours. Perhaps next time there will be tests, masks, respirators. Perhaps.

Seeing patients remotely has acquainted me with all the technical headaches everyone stuck at home talks and jokes about: Balky transmission (What did you say after, “and then the blood ...”?); patients who can’t figure out how to log on, or start the video, or unmute themselves, and on and on. Picture resolution is not great, as anyone knows from watching TV newscasters interview talking heads stuck in their homes.

I was never all that image-conscious, but my beard has grown fuller and my hair unkempter. Even though I sit at my desk, I do take care to keep my trousers on. Not taking any chances.

Everyone agonizes over what the “new normal” may be. Will people come back to doctors’ offices? Will practices survive economically if many patients don’t return to the office? Stay tuned. For a long time.

Mostly, though, remote visits seem to work. Helped if needed by additional, better-resolution emailed photos, it’s possible to make useful decisions, including which lesions can wait for in-person evaluation, until ...

... Until what? In an effort to keep this column up-to-the-nanosecond, I am writing it as many countries tentatively “open up.” Careful analysis of the knowledge behind this world-wide project shows ... not much. It seems to come down to some educated guesswork about what might work and what the risks might be, which leads to advice that differs widely from state to state and country to country. It’s as if people everywhere just decided that locking everyone down is a real drag, is financially ruinous, has a duration both uncertain and longer than most people and governments think they can handle, so let’s get out there and “be careful,” whatever that is said to mean.

And the risks? Well, more people will get sick and some will die. How many “extra” deaths are ethically acceptable? Thoughtful people are working on that. They’ll get back sometime to those who are still around.

I don’t blame anyone for our staggering ignorance about this terrifying new reality. But absorbing the ignorance in real time is not reassuring.

I have nothing but sympathy for those who are not emeritus, who have practices to sustain and families to feed. I didn’t ask to be born 73 years ago, and take no credit for having done so. So much of what happens to us depends on when and where we were born – two factors for which we deserve absolutely no credit – that it’s a wonder we take such pride in praising ourselves for what we think we accomplish. Having no better choice, we do the best we can.

Meantime, I am in a “high-risk” category. If I were obese, I could try to lose weight. But my risk factor is age, which tends not to decline. Risk-wise, there is just one way to exit my group.

So I don’t expect to get back to the office anytime soon. To paraphrase a comedian who shall remain nameless: I don’t want to live on in the hearts of men. I want to live on in my house.

Dr. Rockoff, who wrote the Dermatology News column “Under My Skin,” is now semiretired, after 40 years of practice in Brookline, Mass. He served on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available online. Write to him at [email protected].

The first installment of my new column was obsolete on arrival. It referred to walking abroad at midday, with no mention of masks and social distancing. The whole thing was so February 2020.

My last day in the office was in mid-March. Friday the 13th.

, using stored and forwarded images.

What I had in mind was visits by patients in nursing homes or too sick at home to come in. It always bothered me to see very aged and infirm patients brought to the office at great inconvenience and expense for what often turned out to be problems like xerosis or eczema that could have been managed quite well remotely.

The HMO never got back to me, though. There were too many hurdles, mostly bureaucratic rather than medical. Would insurance pay? What about consent? Malpractice? It has been interesting to watch the current crisis sweep away the inertia of such obstacles, including licensure considerations (seeing patients across state lines for cutaneous purposes). People get around to fixing the roof when it pours. Perhaps next time there will be tests, masks, respirators. Perhaps.

Seeing patients remotely has acquainted me with all the technical headaches everyone stuck at home talks and jokes about: Balky transmission (What did you say after, “and then the blood ...”?); patients who can’t figure out how to log on, or start the video, or unmute themselves, and on and on. Picture resolution is not great, as anyone knows from watching TV newscasters interview talking heads stuck in their homes.

I was never all that image-conscious, but my beard has grown fuller and my hair unkempter. Even though I sit at my desk, I do take care to keep my trousers on. Not taking any chances.

Everyone agonizes over what the “new normal” may be. Will people come back to doctors’ offices? Will practices survive economically if many patients don’t return to the office? Stay tuned. For a long time.

Mostly, though, remote visits seem to work. Helped if needed by additional, better-resolution emailed photos, it’s possible to make useful decisions, including which lesions can wait for in-person evaluation, until ...

... Until what? In an effort to keep this column up-to-the-nanosecond, I am writing it as many countries tentatively “open up.” Careful analysis of the knowledge behind this world-wide project shows ... not much. It seems to come down to some educated guesswork about what might work and what the risks might be, which leads to advice that differs widely from state to state and country to country. It’s as if people everywhere just decided that locking everyone down is a real drag, is financially ruinous, has a duration both uncertain and longer than most people and governments think they can handle, so let’s get out there and “be careful,” whatever that is said to mean.

And the risks? Well, more people will get sick and some will die. How many “extra” deaths are ethically acceptable? Thoughtful people are working on that. They’ll get back sometime to those who are still around.

I don’t blame anyone for our staggering ignorance about this terrifying new reality. But absorbing the ignorance in real time is not reassuring.

I have nothing but sympathy for those who are not emeritus, who have practices to sustain and families to feed. I didn’t ask to be born 73 years ago, and take no credit for having done so. So much of what happens to us depends on when and where we were born – two factors for which we deserve absolutely no credit – that it’s a wonder we take such pride in praising ourselves for what we think we accomplish. Having no better choice, we do the best we can.

Meantime, I am in a “high-risk” category. If I were obese, I could try to lose weight. But my risk factor is age, which tends not to decline. Risk-wise, there is just one way to exit my group.

So I don’t expect to get back to the office anytime soon. To paraphrase a comedian who shall remain nameless: I don’t want to live on in the hearts of men. I want to live on in my house.

Dr. Rockoff, who wrote the Dermatology News column “Under My Skin,” is now semiretired, after 40 years of practice in Brookline, Mass. He served on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available online. Write to him at [email protected].

Obesity can shift severe COVID-19 to younger age groups

published in The Lancet.

“By itself, obesity seems to be a sufficient risk factor to start seeing younger people landing in the ICU,” said the study’s lead author, David Kass, MD, a professor of cardiology and medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

“In that sense, there’s a simple message: If you’re very, very overweight, don’t think that if you’re 35 you’re that much safer [from severe COVID-19] than your mother or grandparents or others in their 60s or 70s,” Kass told Medscape Medical News.

The findings, which Kass describes as a “2-week snapshot” of 265 patients (58% male) in late March and early April at a handful of university hospitals in the United States reinforces other recent research indicating that obesity is one of the biggest risk factors for severe COVID-19 disease, particularly among younger patients. In addition, a large British study showed that, after adjusting for comorbidities, obesity was a significant factor associated with in-hospital death in COVID-19.

But this new analysis stands out as the only dataset to date that specifically “asks the question relative to age” of whether severe COVID-19 disease correlates to ICU treatment, he said.

The mean age of his study population of ICU patients was 55, Kass said, “and that was young, not what we were expecting.”

“Even with the first 20 patients, we were already seeing younger people and they definitely were heavier, with plenty of patients with a BMI over 35 kg/m2,” he added. “The relationship was pretty tight, pretty quick.”

“Just don’t make the assumption that any of us are too young to be vulnerable if, in fact, this is an aspect of our bodies,” he said.

Steven Heymsfield, MD, past president and a spokesperson for the Obesity Society, agrees with Kass’ conclusions.

“One thing we’ve had on our minds is that the prototype of a person with this disease is older...but now if we get [a patient] who’s symptomatic and 40 and obese, we shouldn’t assume they have some other disease,” Heymsfield told Medscape Medical News.

“We should think of them as a susceptible population.”

Kass and colleagues agree. “Public messaging to younger adults, reducing the threshold for virus testing in obese individuals, and maintaining greater vigilance for this at-risk population should reduce the prevalence of severe COVID-19 disease [among those with obesity],” they state.

“I think it’s a mental adjustment from a health care standpoint, which might hopefully help target the folks who are at higher risk before they get into trouble,” Kass told Medscape Medical News.

Trio of mechanisms explain obesity’s extra COVID-19 risks

Kass and coauthors write that, in analyzing their data, they anticipated similar results to the largest study of 1591 ICU patients from Italy in which only 203 were younger than 51 years. Common comorbidities among those patients included hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes, with similar data reported from China.

When the COVID-19 epidemic accelerated in the United States, older age was also identified as a risk factor. Obesity had not yet been added to this list, Kass noted. But following informal discussions with colleagues in other ICUs around the country, he decided to investigate further as to whether it was an underappreciated risk factor.

Kass and colleagues did a quick evaluation of the link between BMI and age of patients with COVID-19 admitted to ICUs at Johns Hopkins, University of Cincinnati, New York University, University of Washington, Florida Health, and University of Pennsylvania.

The “significant inverse correlation between age and BMI” showed younger ICU patients were more likely to be obese, with no difference by gender.

Median BMI among study participants was 29.3 kg/m2, with only a quarter having a BMI lower than 26 kg/m2 and another 25% having a BMI higher than 34.7 kg/m2.

Kass acknowledged that it wasn’t possible with this simple dataset to account for any other potential confounders, but he told Medscape Medical News that, “while diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and hypertension, for example, can occur with obesity, this is generally less so in younger populations as it takes time for the other comorbidities to develop.”

He said several mechanisms could explain why obesity predisposes patients with COVID-19 to severe disease.

For one, obesity places extra pressure on the diaphragm while lying on the back, restricting breathing.

“Morbid obesity itself is sort of proinflammatory,” he continued.

“Here we’ve got a viral infection where the early reports suggest that cytokine storms and immune mishandling of the virus are why it’s so much more severe than other forms of coronavirus we’ve seen before. So if you have someone with an already underlying proinflammatory state, this could be a reason there’s higher risk.”

Additionally, the angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE-2) receptor to which the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 attaches is expressed in higher amounts in adipose tissue than the lungs, Kass noted.

“This could turn into kind of a viral replication depot,” he explained. “You may well be brewing more virus as a component of obesity.”

Sensitivity needed in public messaging about risks, but test sooner

With an obesity rate of about 40% in the United States, the results are particularly relevant for Americans, Kass and Heymsfield say, noting that the country’s “obesity belt” runs through the South.

Heymsfield, who wasn’t part of the new analysis, notes that public messaging around severe COVID-19 risks to younger adults with obesity is “tricky,” especially because the virus is “still pretty common in nonobese people.”

Kass agrees, noting, “it’s difficult to turn to 40% of the population and say: ‘You guys have to watch it.’ ”

But the mounting research findings necessitate linking obesity with severe COVID-19 disease and perhaps testing patients in this category for the virus sooner before symptoms become severe.

And of note, since shortness of breath is common among people with obesity regardless of illness, similar COVID-19 symptoms might catch these individuals unaware, pointed out Heymsfield, who is also a professor in the Metabolism and Body Composition Lab at Pennington Biomedical Research Center at Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge.

“They may find themselves literally unable to breathe, and the concern would be that they wait much too long to come in” for treatment, he said. Typically, people can deteriorate between day 7 and 10 of the COVID-19 infection.

Individuals with obesity “need to be educated to recognize the serious complications of COVID-19 often appear suddenly, although the virus has sometimes been working its way through the body for a long time,” he concluded.

Kass and Heymsfield have declared no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

published in The Lancet.

“By itself, obesity seems to be a sufficient risk factor to start seeing younger people landing in the ICU,” said the study’s lead author, David Kass, MD, a professor of cardiology and medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

“In that sense, there’s a simple message: If you’re very, very overweight, don’t think that if you’re 35 you’re that much safer [from severe COVID-19] than your mother or grandparents or others in their 60s or 70s,” Kass told Medscape Medical News.

The findings, which Kass describes as a “2-week snapshot” of 265 patients (58% male) in late March and early April at a handful of university hospitals in the United States reinforces other recent research indicating that obesity is one of the biggest risk factors for severe COVID-19 disease, particularly among younger patients. In addition, a large British study showed that, after adjusting for comorbidities, obesity was a significant factor associated with in-hospital death in COVID-19.

But this new analysis stands out as the only dataset to date that specifically “asks the question relative to age” of whether severe COVID-19 disease correlates to ICU treatment, he said.

The mean age of his study population of ICU patients was 55, Kass said, “and that was young, not what we were expecting.”

“Even with the first 20 patients, we were already seeing younger people and they definitely were heavier, with plenty of patients with a BMI over 35 kg/m2,” he added. “The relationship was pretty tight, pretty quick.”

“Just don’t make the assumption that any of us are too young to be vulnerable if, in fact, this is an aspect of our bodies,” he said.

Steven Heymsfield, MD, past president and a spokesperson for the Obesity Society, agrees with Kass’ conclusions.

“One thing we’ve had on our minds is that the prototype of a person with this disease is older...but now if we get [a patient] who’s symptomatic and 40 and obese, we shouldn’t assume they have some other disease,” Heymsfield told Medscape Medical News.

“We should think of them as a susceptible population.”

Kass and colleagues agree. “Public messaging to younger adults, reducing the threshold for virus testing in obese individuals, and maintaining greater vigilance for this at-risk population should reduce the prevalence of severe COVID-19 disease [among those with obesity],” they state.

“I think it’s a mental adjustment from a health care standpoint, which might hopefully help target the folks who are at higher risk before they get into trouble,” Kass told Medscape Medical News.

Trio of mechanisms explain obesity’s extra COVID-19 risks

Kass and coauthors write that, in analyzing their data, they anticipated similar results to the largest study of 1591 ICU patients from Italy in which only 203 were younger than 51 years. Common comorbidities among those patients included hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes, with similar data reported from China.

When the COVID-19 epidemic accelerated in the United States, older age was also identified as a risk factor. Obesity had not yet been added to this list, Kass noted. But following informal discussions with colleagues in other ICUs around the country, he decided to investigate further as to whether it was an underappreciated risk factor.

Kass and colleagues did a quick evaluation of the link between BMI and age of patients with COVID-19 admitted to ICUs at Johns Hopkins, University of Cincinnati, New York University, University of Washington, Florida Health, and University of Pennsylvania.

The “significant inverse correlation between age and BMI” showed younger ICU patients were more likely to be obese, with no difference by gender.

Median BMI among study participants was 29.3 kg/m2, with only a quarter having a BMI lower than 26 kg/m2 and another 25% having a BMI higher than 34.7 kg/m2.

Kass acknowledged that it wasn’t possible with this simple dataset to account for any other potential confounders, but he told Medscape Medical News that, “while diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and hypertension, for example, can occur with obesity, this is generally less so in younger populations as it takes time for the other comorbidities to develop.”

He said several mechanisms could explain why obesity predisposes patients with COVID-19 to severe disease.

For one, obesity places extra pressure on the diaphragm while lying on the back, restricting breathing.

“Morbid obesity itself is sort of proinflammatory,” he continued.

“Here we’ve got a viral infection where the early reports suggest that cytokine storms and immune mishandling of the virus are why it’s so much more severe than other forms of coronavirus we’ve seen before. So if you have someone with an already underlying proinflammatory state, this could be a reason there’s higher risk.”

Additionally, the angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE-2) receptor to which the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 attaches is expressed in higher amounts in adipose tissue than the lungs, Kass noted.

“This could turn into kind of a viral replication depot,” he explained. “You may well be brewing more virus as a component of obesity.”

Sensitivity needed in public messaging about risks, but test sooner

With an obesity rate of about 40% in the United States, the results are particularly relevant for Americans, Kass and Heymsfield say, noting that the country’s “obesity belt” runs through the South.

Heymsfield, who wasn’t part of the new analysis, notes that public messaging around severe COVID-19 risks to younger adults with obesity is “tricky,” especially because the virus is “still pretty common in nonobese people.”

Kass agrees, noting, “it’s difficult to turn to 40% of the population and say: ‘You guys have to watch it.’ ”

But the mounting research findings necessitate linking obesity with severe COVID-19 disease and perhaps testing patients in this category for the virus sooner before symptoms become severe.

And of note, since shortness of breath is common among people with obesity regardless of illness, similar COVID-19 symptoms might catch these individuals unaware, pointed out Heymsfield, who is also a professor in the Metabolism and Body Composition Lab at Pennington Biomedical Research Center at Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge.

“They may find themselves literally unable to breathe, and the concern would be that they wait much too long to come in” for treatment, he said. Typically, people can deteriorate between day 7 and 10 of the COVID-19 infection.

Individuals with obesity “need to be educated to recognize the serious complications of COVID-19 often appear suddenly, although the virus has sometimes been working its way through the body for a long time,” he concluded.

Kass and Heymsfield have declared no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

published in The Lancet.

“By itself, obesity seems to be a sufficient risk factor to start seeing younger people landing in the ICU,” said the study’s lead author, David Kass, MD, a professor of cardiology and medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

“In that sense, there’s a simple message: If you’re very, very overweight, don’t think that if you’re 35 you’re that much safer [from severe COVID-19] than your mother or grandparents or others in their 60s or 70s,” Kass told Medscape Medical News.

The findings, which Kass describes as a “2-week snapshot” of 265 patients (58% male) in late March and early April at a handful of university hospitals in the United States reinforces other recent research indicating that obesity is one of the biggest risk factors for severe COVID-19 disease, particularly among younger patients. In addition, a large British study showed that, after adjusting for comorbidities, obesity was a significant factor associated with in-hospital death in COVID-19.

But this new analysis stands out as the only dataset to date that specifically “asks the question relative to age” of whether severe COVID-19 disease correlates to ICU treatment, he said.

The mean age of his study population of ICU patients was 55, Kass said, “and that was young, not what we were expecting.”

“Even with the first 20 patients, we were already seeing younger people and they definitely were heavier, with plenty of patients with a BMI over 35 kg/m2,” he added. “The relationship was pretty tight, pretty quick.”

“Just don’t make the assumption that any of us are too young to be vulnerable if, in fact, this is an aspect of our bodies,” he said.

Steven Heymsfield, MD, past president and a spokesperson for the Obesity Society, agrees with Kass’ conclusions.

“One thing we’ve had on our minds is that the prototype of a person with this disease is older...but now if we get [a patient] who’s symptomatic and 40 and obese, we shouldn’t assume they have some other disease,” Heymsfield told Medscape Medical News.

“We should think of them as a susceptible population.”

Kass and colleagues agree. “Public messaging to younger adults, reducing the threshold for virus testing in obese individuals, and maintaining greater vigilance for this at-risk population should reduce the prevalence of severe COVID-19 disease [among those with obesity],” they state.

“I think it’s a mental adjustment from a health care standpoint, which might hopefully help target the folks who are at higher risk before they get into trouble,” Kass told Medscape Medical News.

Trio of mechanisms explain obesity’s extra COVID-19 risks

Kass and coauthors write that, in analyzing their data, they anticipated similar results to the largest study of 1591 ICU patients from Italy in which only 203 were younger than 51 years. Common comorbidities among those patients included hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes, with similar data reported from China.

When the COVID-19 epidemic accelerated in the United States, older age was also identified as a risk factor. Obesity had not yet been added to this list, Kass noted. But following informal discussions with colleagues in other ICUs around the country, he decided to investigate further as to whether it was an underappreciated risk factor.

Kass and colleagues did a quick evaluation of the link between BMI and age of patients with COVID-19 admitted to ICUs at Johns Hopkins, University of Cincinnati, New York University, University of Washington, Florida Health, and University of Pennsylvania.

The “significant inverse correlation between age and BMI” showed younger ICU patients were more likely to be obese, with no difference by gender.

Median BMI among study participants was 29.3 kg/m2, with only a quarter having a BMI lower than 26 kg/m2 and another 25% having a BMI higher than 34.7 kg/m2.

Kass acknowledged that it wasn’t possible with this simple dataset to account for any other potential confounders, but he told Medscape Medical News that, “while diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and hypertension, for example, can occur with obesity, this is generally less so in younger populations as it takes time for the other comorbidities to develop.”

He said several mechanisms could explain why obesity predisposes patients with COVID-19 to severe disease.

For one, obesity places extra pressure on the diaphragm while lying on the back, restricting breathing.

“Morbid obesity itself is sort of proinflammatory,” he continued.

“Here we’ve got a viral infection where the early reports suggest that cytokine storms and immune mishandling of the virus are why it’s so much more severe than other forms of coronavirus we’ve seen before. So if you have someone with an already underlying proinflammatory state, this could be a reason there’s higher risk.”

Additionally, the angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE-2) receptor to which the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 attaches is expressed in higher amounts in adipose tissue than the lungs, Kass noted.

“This could turn into kind of a viral replication depot,” he explained. “You may well be brewing more virus as a component of obesity.”

Sensitivity needed in public messaging about risks, but test sooner

With an obesity rate of about 40% in the United States, the results are particularly relevant for Americans, Kass and Heymsfield say, noting that the country’s “obesity belt” runs through the South.

Heymsfield, who wasn’t part of the new analysis, notes that public messaging around severe COVID-19 risks to younger adults with obesity is “tricky,” especially because the virus is “still pretty common in nonobese people.”

Kass agrees, noting, “it’s difficult to turn to 40% of the population and say: ‘You guys have to watch it.’ ”

But the mounting research findings necessitate linking obesity with severe COVID-19 disease and perhaps testing patients in this category for the virus sooner before symptoms become severe.

And of note, since shortness of breath is common among people with obesity regardless of illness, similar COVID-19 symptoms might catch these individuals unaware, pointed out Heymsfield, who is also a professor in the Metabolism and Body Composition Lab at Pennington Biomedical Research Center at Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge.

“They may find themselves literally unable to breathe, and the concern would be that they wait much too long to come in” for treatment, he said. Typically, people can deteriorate between day 7 and 10 of the COVID-19 infection.

Individuals with obesity “need to be educated to recognize the serious complications of COVID-19 often appear suddenly, although the virus has sometimes been working its way through the body for a long time,” he concluded.

Kass and Heymsfield have declared no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

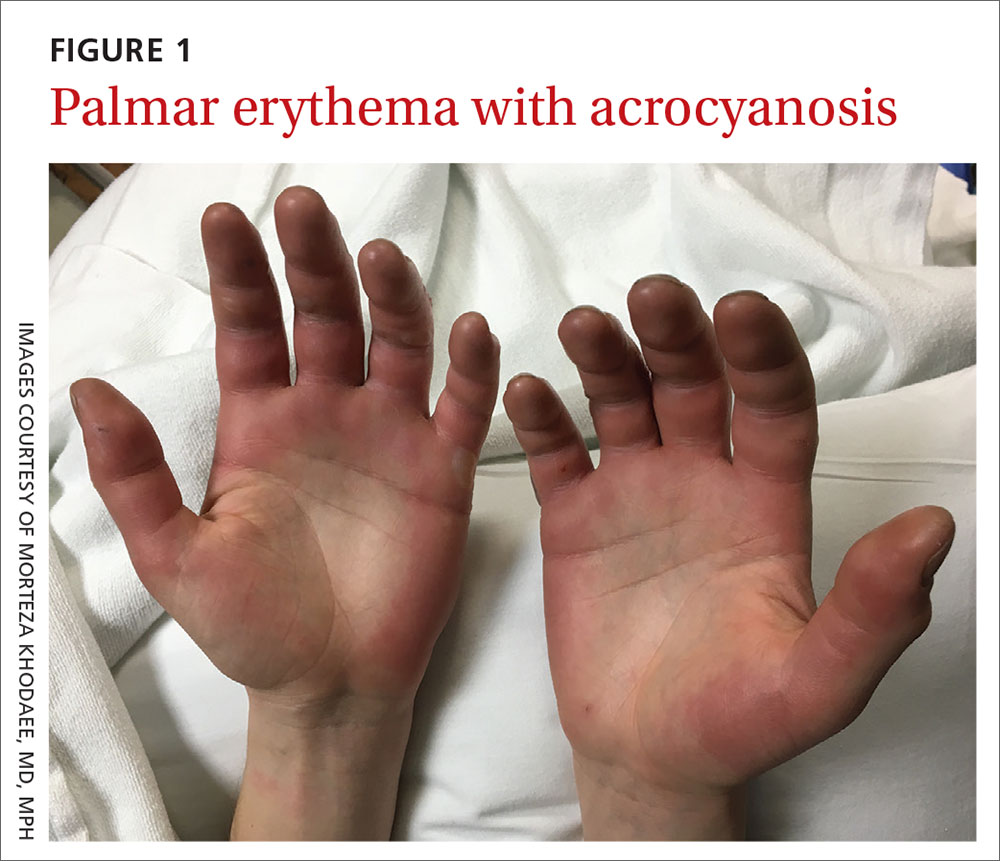

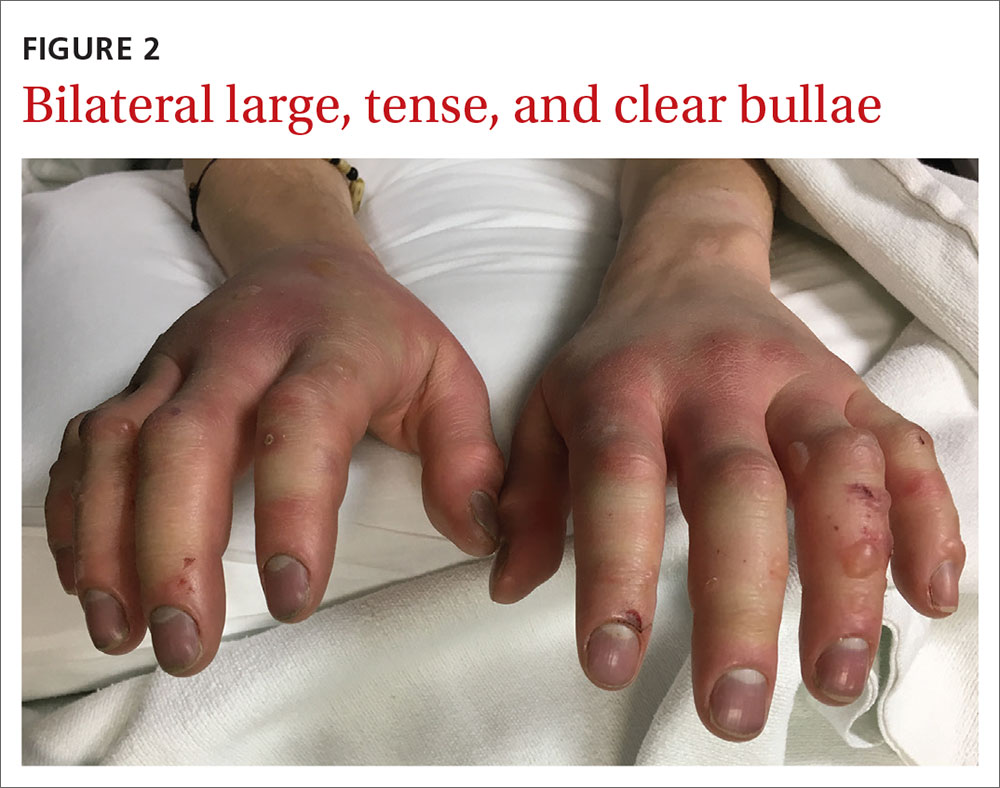

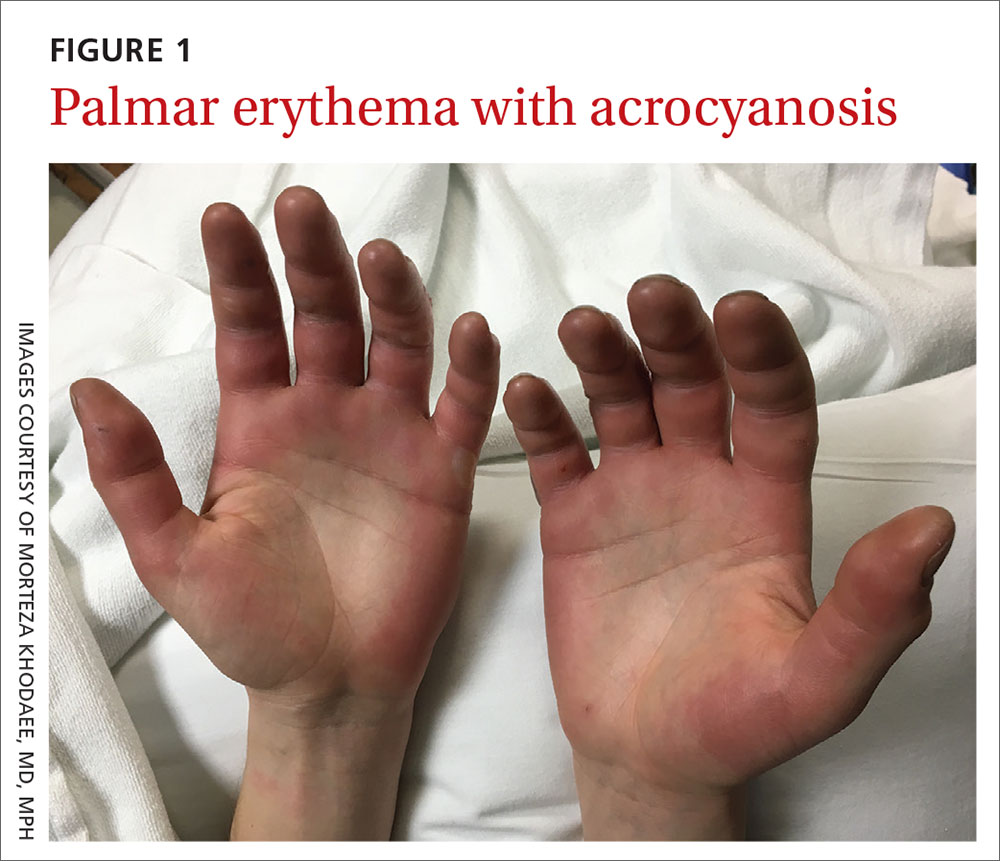

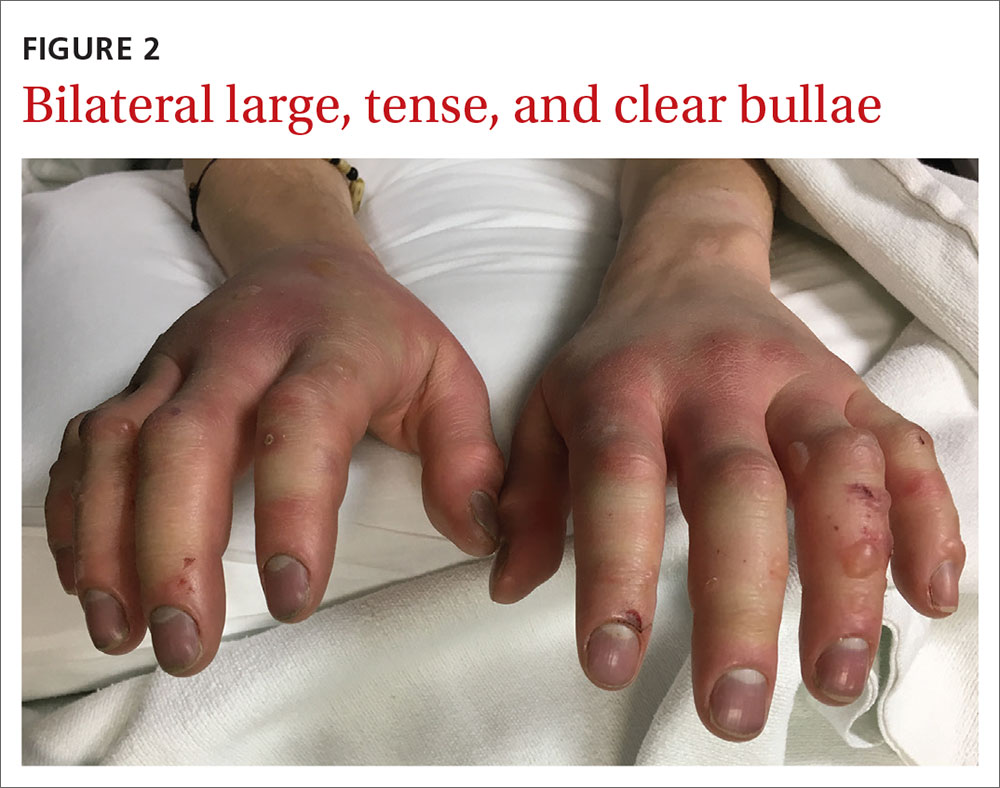

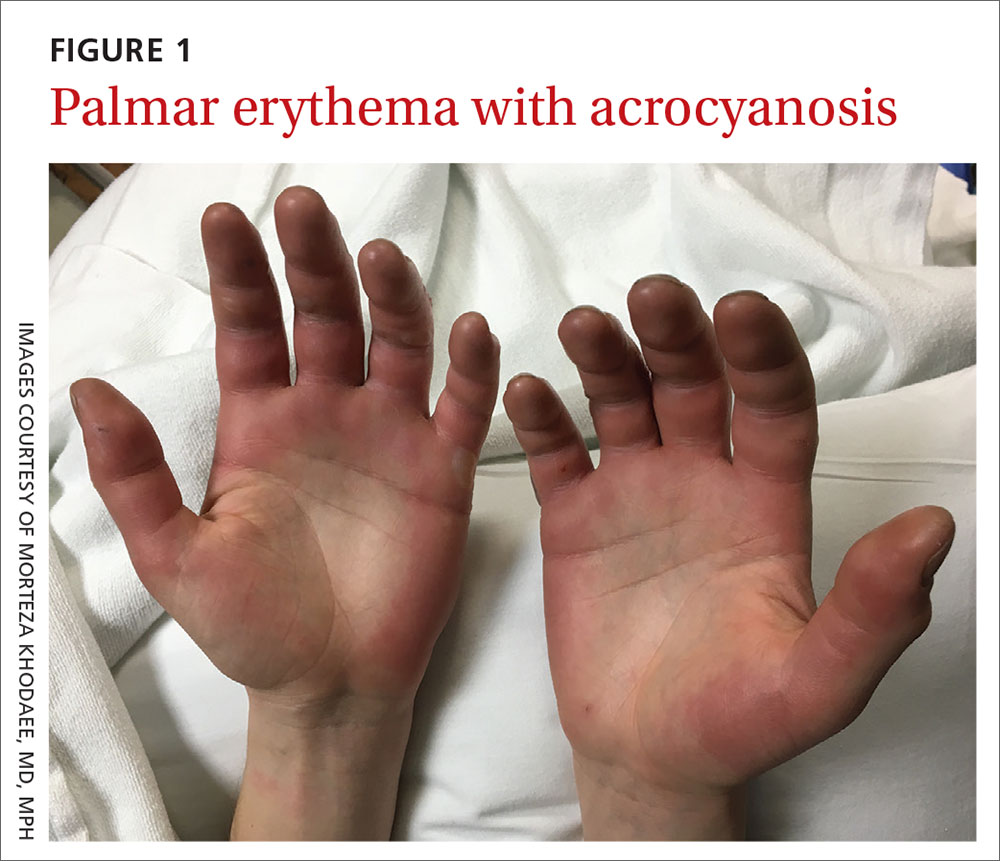

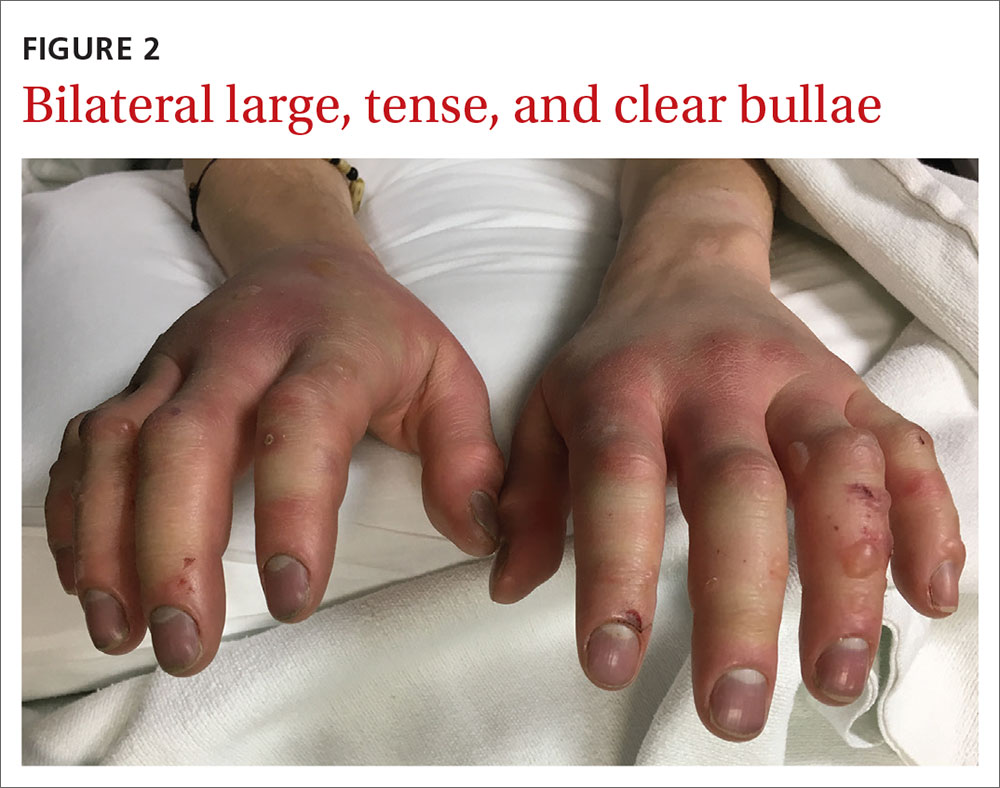

Acute bilateral hand edema and vesiculation

A 27-year-old man presented to the urgent care clinic with acute bilateral hand swelling, blisters, numbness, and pain. History taking revealed that these symptoms developed after he was locked outside of his apartment for 45 minutes in –22°C (–8°F) weather following a night of heavy drinking.

On physical examination, the patient had a temperature of 36.2°C (97.2°F) and a heart rate of 116 beats/min. He had

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Second-degree frostbite

Frostbite is the result of tissue freezing, which generally occurs after prolonged exposure to freezing temperatures (typically –4°C or below).1,2 The majority (~90%) of frostbite injuries occur in the hands and feet; however, frostbite has also been observed in the face, perineum, buttocks, and male genitalia.3

Frostbite is a clinical diagnosis based on a history of sustained exposure to freezing temperatures, paresthesia of affected areas, and typical skin changes. Evidence is lacking regarding the epidemiology of frostbite within the general population.2

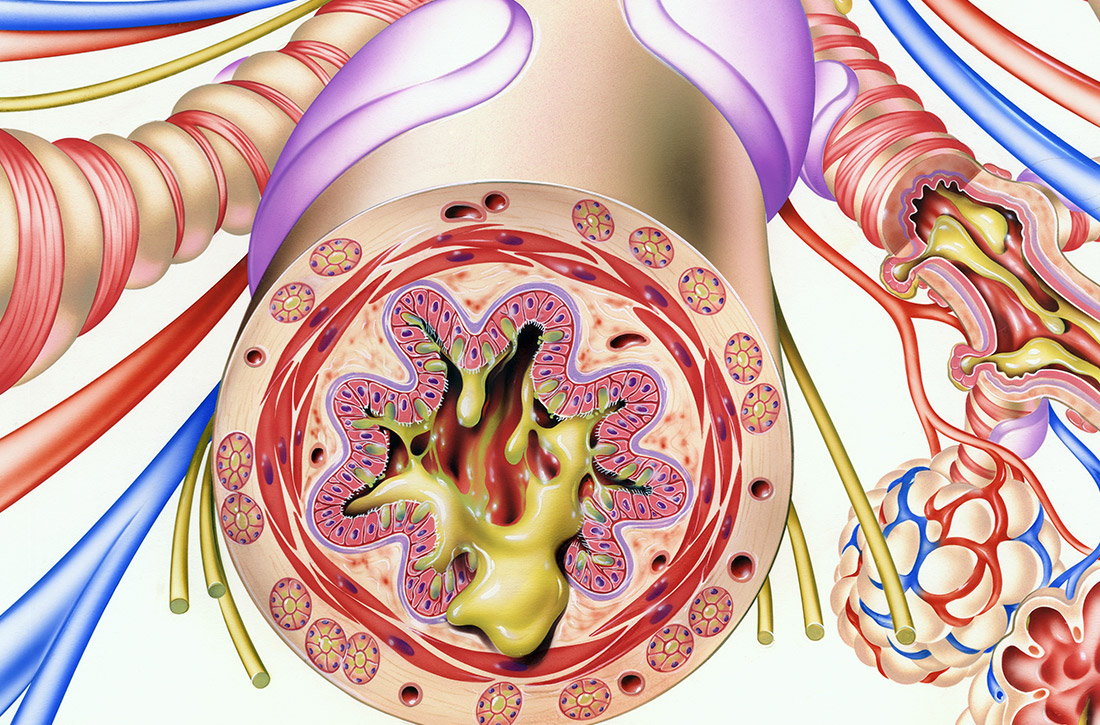

Pathophysiology. Intra- and extracellular ice crystal formation causes fluid and electrolyte disturbances, cell dehydration, lipid denaturation, and subsequent cell death.1 After thawing, progressive tissue ischemia can occur as a result of endothelial damage and dysfunction, intravascular sludging, increased inflammatory markers, an influx of free radicals, and microvascular thrombosis.1

Classification. Traditionally, frostbite has been classified according to a 4-tiered system based on tissue appearance after rewarming.2 First-degree frostbite is characterized by white plaques with surrounding erythema; second degree by edema and clear or cloudy vesicles; third degree by hemorrhagic bullae; and fourth degree by cold and hard tissue that eventually progresses to gangrene.2

A simpler scheme designates frostbite as either superficial (corresponding to first- or second-degree frostbite) or deep (corresponding to third- or fourth-degree frostbite) with presumed muscle and bone involvement.2

Continue to: Risk factors

Risk factors. Frostbite is often associated with risk factors such as alcohol or drug intoxication, vehicular failure or trauma, immobilizing trauma, psychiatric illness, homelessness, Raynaud phenomenon, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, inadequate clothing, previous cold-weather injury, outdoor winter recreation, and the use of certain medications (eg, beta-blockers).1-3 Apart from environmental exposure, frostbite can also occur by direct contact with freezing materials, such as ice packs or industrial refrigerants.3

Differential includes nonfreezing injuries

Frostnip, pernio, and trench foot are other cold-weather injuries distinguished by the absence of tissue freezing.4 Raynaud phenomenon is a condition that is triggered by either cold temperatures or emotional stress.5

Frostnip is characterized by pallor and paresthesia of exposed areas. It may precede frostbite, but it quickly resolves after rewarming.2

Pernio occurs when skin is exposed to damp, cold, nonfreezing environments.6 It results in edematous and inflammatory skin lesions that may be painful, pruritic, violaceous, or erythematous.6 These lesions are typically found over the fingers, toes, nose, ears, buttocks, or thighs.4,6 Pernio may be classified as either primary or secondary disease.5 Primary pernio is considered idiopathic.6 Secondary pernio is thought to be either drug induced or due to underlying autoimmune diseases, such as hepatitis or cryopathy.6

Trench foot develops under similar conditions to pernio but requires exposure to a wet environment for at least 10 to 14 hours.7 It is characterized by foot pain, paresthesia, pruritus, edema, erythema, cyanosis, blisters, and even gangrene if left untreated.7

Continue to: Raynaud phenomenon

Raynaud phenomenon results from transient, acral vasocontraction and manifests as well-demarcated pallor, cyanosis, and then erythema as the affected body part reperfuses.5 Similar to pernio, it can be categorized as either primary or secondary.5 Primary phenomenon is idiopathic. Secondary phenomenon is thought to be a result of autoimmune disease, use of certain medications, occupational vibratory exposure, obstructive vascular disease, or infection

In the absence of a history of exposure to subfreezing temperatures, frostbite can be excluded from the differential diagnosis.

Treatment entails rewarming

The aim of frostbite treatment is to save injured cells and minimize tissue loss.1 This is accomplished through rapid rewarming and—in severe cases—reperfusion techniques.

Tissue should be rewarmed in a 37°C to 39°C water bath with povidone iodine or chlorhexidine added for antiseptic effect.1 All efforts should be made to avoid refreezing or trauma, as this could worsen the initial injury.2 Oral or intravenous hydration may be offered to optimize fluid status.1 Supplemental oxygen may be administered to maintain saturations above 90%.1 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are helpful for analgesia and anti-inflammatory effect, and opioids can be used for breakthrough pain.1 It is recommended that blisters be drained in a sterile fashion and that all affected tissue be covered with topical aloe vera and a loose dressing.1,2,4

Treatment of severe frostbite. Angiography should be performed on all patients with third- or fourth-degree frostbite.3 If imaging shows evidence of vascular occlusion, tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and heparin can be initiated within 24 hours to reduce the risk for amputation.8-10

Continue to: Iloprost is another...

Iloprost is another proposed treatment for severe frostbite. It is a prostacyclin analog that may lower the amputation rate in patients with at least third-degree frostbite.11 Unlike tPA, iloprost may be given to trauma patients, and it can be used more than 24 hours after injury.2

In cases of fourth-degree frostbite that is not successfully reperfused, amputation is delayed until dry gangrene develops. This often takes weeks to months.12