User login

MRSA decolonization reduces postdischarge infections

Background: MRSA carriers are at higher risk of infection and rehospitalization after hospital discharge. Education regarding hygiene, environmental cleaning, and decolonization of MRSA carriers have been used as possible preventive strategies. Decolonization has been effective in reducing surgical-site infections, recurrent skin infections, and infections in ICU. However, there is sparsity of data on the efficacy of routine decolonization of MRSA carriers after hospital discharge.

Study design: Multicenter, randomized, unblinded controlled trial.

Setting: A total of 17 hospitals and seven nursing homes in Southern California.

Synopsis: The study included 2,121 inpatients hospitalized within the previous 30 days and found to be MRSA carriers. Patients were randomized to education only (1,063) or decolonization plus education (1,058), with both groups followed for 12 months after discharge. Decolonization consisted of 4% rinse-off chlorhexidine for daily bathing or showering, 0.12% chlorhexidine mouthwash twice daily, and 2% nasal mupirocin twice daily. The primary outcome was MRSA infection as defined by the CDC. Secondary outcomes included MRSA infection based on clinical judgment, infection from any cause, and infection-related hospitalization. Per protocol analysis showed that MRSA infection occurred in 9.2% in the education group and 6.3% in the decolonization plus education group, with 30% reduction in the risk of infection (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.51-0.99; number needed to treat to prevent one infection, 30). The decolonization group also had a lower hazard of clinically judged infection from any cause (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.70-0.99) and infection-related hospitalization (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.62-0.93).

Limitations of the study include unblinded intervention, missing of milder infections that might not have required hospitalization, and frequent insufficient documentation in charts for events to be deemed infection according to the CDC criteria.

Bottom line: Decolonization of MRSA carriers post discharge may lower MRSA-related infections and infections more than hygiene education alone.

Citation: Huang SS et al. Decolonization to reduce postdischarge infection risk among MRSA carriers. N Eng J Med. 2019;380:638-50.

Dr. Vedamurthy is a hospitalist at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Background: MRSA carriers are at higher risk of infection and rehospitalization after hospital discharge. Education regarding hygiene, environmental cleaning, and decolonization of MRSA carriers have been used as possible preventive strategies. Decolonization has been effective in reducing surgical-site infections, recurrent skin infections, and infections in ICU. However, there is sparsity of data on the efficacy of routine decolonization of MRSA carriers after hospital discharge.

Study design: Multicenter, randomized, unblinded controlled trial.

Setting: A total of 17 hospitals and seven nursing homes in Southern California.

Synopsis: The study included 2,121 inpatients hospitalized within the previous 30 days and found to be MRSA carriers. Patients were randomized to education only (1,063) or decolonization plus education (1,058), with both groups followed for 12 months after discharge. Decolonization consisted of 4% rinse-off chlorhexidine for daily bathing or showering, 0.12% chlorhexidine mouthwash twice daily, and 2% nasal mupirocin twice daily. The primary outcome was MRSA infection as defined by the CDC. Secondary outcomes included MRSA infection based on clinical judgment, infection from any cause, and infection-related hospitalization. Per protocol analysis showed that MRSA infection occurred in 9.2% in the education group and 6.3% in the decolonization plus education group, with 30% reduction in the risk of infection (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.51-0.99; number needed to treat to prevent one infection, 30). The decolonization group also had a lower hazard of clinically judged infection from any cause (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.70-0.99) and infection-related hospitalization (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.62-0.93).

Limitations of the study include unblinded intervention, missing of milder infections that might not have required hospitalization, and frequent insufficient documentation in charts for events to be deemed infection according to the CDC criteria.

Bottom line: Decolonization of MRSA carriers post discharge may lower MRSA-related infections and infections more than hygiene education alone.

Citation: Huang SS et al. Decolonization to reduce postdischarge infection risk among MRSA carriers. N Eng J Med. 2019;380:638-50.

Dr. Vedamurthy is a hospitalist at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Background: MRSA carriers are at higher risk of infection and rehospitalization after hospital discharge. Education regarding hygiene, environmental cleaning, and decolonization of MRSA carriers have been used as possible preventive strategies. Decolonization has been effective in reducing surgical-site infections, recurrent skin infections, and infections in ICU. However, there is sparsity of data on the efficacy of routine decolonization of MRSA carriers after hospital discharge.

Study design: Multicenter, randomized, unblinded controlled trial.

Setting: A total of 17 hospitals and seven nursing homes in Southern California.

Synopsis: The study included 2,121 inpatients hospitalized within the previous 30 days and found to be MRSA carriers. Patients were randomized to education only (1,063) or decolonization plus education (1,058), with both groups followed for 12 months after discharge. Decolonization consisted of 4% rinse-off chlorhexidine for daily bathing or showering, 0.12% chlorhexidine mouthwash twice daily, and 2% nasal mupirocin twice daily. The primary outcome was MRSA infection as defined by the CDC. Secondary outcomes included MRSA infection based on clinical judgment, infection from any cause, and infection-related hospitalization. Per protocol analysis showed that MRSA infection occurred in 9.2% in the education group and 6.3% in the decolonization plus education group, with 30% reduction in the risk of infection (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.51-0.99; number needed to treat to prevent one infection, 30). The decolonization group also had a lower hazard of clinically judged infection from any cause (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.70-0.99) and infection-related hospitalization (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.62-0.93).

Limitations of the study include unblinded intervention, missing of milder infections that might not have required hospitalization, and frequent insufficient documentation in charts for events to be deemed infection according to the CDC criteria.

Bottom line: Decolonization of MRSA carriers post discharge may lower MRSA-related infections and infections more than hygiene education alone.

Citation: Huang SS et al. Decolonization to reduce postdischarge infection risk among MRSA carriers. N Eng J Med. 2019;380:638-50.

Dr. Vedamurthy is a hospitalist at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Societies offer advice on treating osteoporosis patients during pandemic

Five leading bone health organizations have gotten together to provide new recommendations for managing patients with osteoporosis during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The joint guidance – released by the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research (ASBMR), the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the Endocrine Society, the European Calcified Tissue Society, and the National Osteoporosis Foundation – offered both general and specific recommendations for patients whose osteoporosis treatment plan is either continuing or has been disrupted during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Among the general recommendations are to initiate oral bisphosphonate therapy over either the telephone or through a video visit, with no delays for patients at high risk of fracture. They also noted that, as elective procedures, bone mineral density examinations may need to be postponed.

For patients already on osteoporosis medications – such as oral and IV bisphosphonates, denosumab, estrogen, raloxifene, teriparatide, abaloparatide, and romosozumab – they recommend continuing treatment whenever possible. “There is no evidence that any osteoporosis therapy increases the risk or severity of COVID-19 infection or alters the disease course,” they wrote. They did add, however, that COVID-19 may increase the risk of hypercoagulable complications and so caution should be exercised when treating patients with estrogen or raloxifene.

Separately, in a letter to the editor published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism (doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa254), Ruban Dhaliwal, MD, MPH, of the State University of New York, Syracuse, and coauthors concur in regard to raloxifene. They wrote that, because of the increased risk of thromboembolic events related to COVID-19, “it is best to discontinue raloxifene, which is also associated with such risk.”

The joint statement recognizes current social distancing policies and therefore recommends avoiding standard pretreatment labs prior to IV bisphosphonate and/or denosumab administration if previous labs were normal and the patient’s recent health has been deemed “stable.” Lab evaluation is recommended, however, for patients with fluctuating renal function and for those at higher risk of developing hypocalcemia.

The statement also provides potential alternative methods for delivering parenteral osteoporosis treatments, including off-site clinics, home delivery and administration, self-injection of denosumab and/or romosozumab, and drive-through administration of denosumab and/or romosozumab. They acknowledged the complications surrounding each alternative, including residents of “socioeconomically challenged communities” being unable to reach clinics if public transportation is not available and the “important medicolegal issues” to consider around self-injection.

For all patients whose treatments have been disrupted, the authors recommend frequent reevaluation “with the goal to resume the original osteoporosis treatment plan once circumstances allow.” As for specific recommendations, patients on denosumab who will not be treatable within 7 months of their previous injection should be transitioned to oral bisphosphonate if at all possible. For patients with underlying gastrointestinal disorders, they recommend monthly ibandronate or weekly/monthly risedronate; for patients with chronic renal insufficiency, they recommend an off-label regimen of lower dose oral bisphosphonate.

For patients on teriparatide or abaloparatide who will be unable to receive continued treatment, they recommend a delay in treatment. If that delay goes beyond several months, they recommend a temporary transition to oral bisphosphonate. For patients on romosozumab who will be unable to receive continued treatment, they also recommend a delay in treatment and a temporary transition to oral bisphosphonate. Finally, they expressed confidence that patients on IV bisphosphonates will not be harmed by treatment delays, even those of several months.

“I think we could fall into a trap during this era of the pandemic and fail to address patients’ underlying chronic conditions, even though those comorbidities will end up greatly affecting their overall health,” said incoming ASBMR president Suzanne Jan de Beur, MD, of the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. “As we continue to care for our patients, we need to keep chronic conditions like osteoporosis on the radar screen and not stop diagnosing people at risk or those who present with fractures. Even when we can’t perform full screening tests due to distancing policies, we need to be vigilant for those patients who need treatment and administer the treatments we have available as needed.”

The statement’s authors acknowledged the limitations of their recommendations, noting that “there is a paucity of data to provide clear guidance” and as such they were “based primarily on expert opinion.”

The authors from the five organizations did not disclose any conflicts of interest.

Five leading bone health organizations have gotten together to provide new recommendations for managing patients with osteoporosis during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The joint guidance – released by the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research (ASBMR), the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the Endocrine Society, the European Calcified Tissue Society, and the National Osteoporosis Foundation – offered both general and specific recommendations for patients whose osteoporosis treatment plan is either continuing or has been disrupted during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Among the general recommendations are to initiate oral bisphosphonate therapy over either the telephone or through a video visit, with no delays for patients at high risk of fracture. They also noted that, as elective procedures, bone mineral density examinations may need to be postponed.

For patients already on osteoporosis medications – such as oral and IV bisphosphonates, denosumab, estrogen, raloxifene, teriparatide, abaloparatide, and romosozumab – they recommend continuing treatment whenever possible. “There is no evidence that any osteoporosis therapy increases the risk or severity of COVID-19 infection or alters the disease course,” they wrote. They did add, however, that COVID-19 may increase the risk of hypercoagulable complications and so caution should be exercised when treating patients with estrogen or raloxifene.

Separately, in a letter to the editor published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism (doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa254), Ruban Dhaliwal, MD, MPH, of the State University of New York, Syracuse, and coauthors concur in regard to raloxifene. They wrote that, because of the increased risk of thromboembolic events related to COVID-19, “it is best to discontinue raloxifene, which is also associated with such risk.”

The joint statement recognizes current social distancing policies and therefore recommends avoiding standard pretreatment labs prior to IV bisphosphonate and/or denosumab administration if previous labs were normal and the patient’s recent health has been deemed “stable.” Lab evaluation is recommended, however, for patients with fluctuating renal function and for those at higher risk of developing hypocalcemia.

The statement also provides potential alternative methods for delivering parenteral osteoporosis treatments, including off-site clinics, home delivery and administration, self-injection of denosumab and/or romosozumab, and drive-through administration of denosumab and/or romosozumab. They acknowledged the complications surrounding each alternative, including residents of “socioeconomically challenged communities” being unable to reach clinics if public transportation is not available and the “important medicolegal issues” to consider around self-injection.

For all patients whose treatments have been disrupted, the authors recommend frequent reevaluation “with the goal to resume the original osteoporosis treatment plan once circumstances allow.” As for specific recommendations, patients on denosumab who will not be treatable within 7 months of their previous injection should be transitioned to oral bisphosphonate if at all possible. For patients with underlying gastrointestinal disorders, they recommend monthly ibandronate or weekly/monthly risedronate; for patients with chronic renal insufficiency, they recommend an off-label regimen of lower dose oral bisphosphonate.

For patients on teriparatide or abaloparatide who will be unable to receive continued treatment, they recommend a delay in treatment. If that delay goes beyond several months, they recommend a temporary transition to oral bisphosphonate. For patients on romosozumab who will be unable to receive continued treatment, they also recommend a delay in treatment and a temporary transition to oral bisphosphonate. Finally, they expressed confidence that patients on IV bisphosphonates will not be harmed by treatment delays, even those of several months.

“I think we could fall into a trap during this era of the pandemic and fail to address patients’ underlying chronic conditions, even though those comorbidities will end up greatly affecting their overall health,” said incoming ASBMR president Suzanne Jan de Beur, MD, of the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. “As we continue to care for our patients, we need to keep chronic conditions like osteoporosis on the radar screen and not stop diagnosing people at risk or those who present with fractures. Even when we can’t perform full screening tests due to distancing policies, we need to be vigilant for those patients who need treatment and administer the treatments we have available as needed.”

The statement’s authors acknowledged the limitations of their recommendations, noting that “there is a paucity of data to provide clear guidance” and as such they were “based primarily on expert opinion.”

The authors from the five organizations did not disclose any conflicts of interest.

Five leading bone health organizations have gotten together to provide new recommendations for managing patients with osteoporosis during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The joint guidance – released by the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research (ASBMR), the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the Endocrine Society, the European Calcified Tissue Society, and the National Osteoporosis Foundation – offered both general and specific recommendations for patients whose osteoporosis treatment plan is either continuing or has been disrupted during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Among the general recommendations are to initiate oral bisphosphonate therapy over either the telephone or through a video visit, with no delays for patients at high risk of fracture. They also noted that, as elective procedures, bone mineral density examinations may need to be postponed.

For patients already on osteoporosis medications – such as oral and IV bisphosphonates, denosumab, estrogen, raloxifene, teriparatide, abaloparatide, and romosozumab – they recommend continuing treatment whenever possible. “There is no evidence that any osteoporosis therapy increases the risk or severity of COVID-19 infection or alters the disease course,” they wrote. They did add, however, that COVID-19 may increase the risk of hypercoagulable complications and so caution should be exercised when treating patients with estrogen or raloxifene.

Separately, in a letter to the editor published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism (doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa254), Ruban Dhaliwal, MD, MPH, of the State University of New York, Syracuse, and coauthors concur in regard to raloxifene. They wrote that, because of the increased risk of thromboembolic events related to COVID-19, “it is best to discontinue raloxifene, which is also associated with such risk.”

The joint statement recognizes current social distancing policies and therefore recommends avoiding standard pretreatment labs prior to IV bisphosphonate and/or denosumab administration if previous labs were normal and the patient’s recent health has been deemed “stable.” Lab evaluation is recommended, however, for patients with fluctuating renal function and for those at higher risk of developing hypocalcemia.

The statement also provides potential alternative methods for delivering parenteral osteoporosis treatments, including off-site clinics, home delivery and administration, self-injection of denosumab and/or romosozumab, and drive-through administration of denosumab and/or romosozumab. They acknowledged the complications surrounding each alternative, including residents of “socioeconomically challenged communities” being unable to reach clinics if public transportation is not available and the “important medicolegal issues” to consider around self-injection.

For all patients whose treatments have been disrupted, the authors recommend frequent reevaluation “with the goal to resume the original osteoporosis treatment plan once circumstances allow.” As for specific recommendations, patients on denosumab who will not be treatable within 7 months of their previous injection should be transitioned to oral bisphosphonate if at all possible. For patients with underlying gastrointestinal disorders, they recommend monthly ibandronate or weekly/monthly risedronate; for patients with chronic renal insufficiency, they recommend an off-label regimen of lower dose oral bisphosphonate.

For patients on teriparatide or abaloparatide who will be unable to receive continued treatment, they recommend a delay in treatment. If that delay goes beyond several months, they recommend a temporary transition to oral bisphosphonate. For patients on romosozumab who will be unable to receive continued treatment, they also recommend a delay in treatment and a temporary transition to oral bisphosphonate. Finally, they expressed confidence that patients on IV bisphosphonates will not be harmed by treatment delays, even those of several months.

“I think we could fall into a trap during this era of the pandemic and fail to address patients’ underlying chronic conditions, even though those comorbidities will end up greatly affecting their overall health,” said incoming ASBMR president Suzanne Jan de Beur, MD, of the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. “As we continue to care for our patients, we need to keep chronic conditions like osteoporosis on the radar screen and not stop diagnosing people at risk or those who present with fractures. Even when we can’t perform full screening tests due to distancing policies, we need to be vigilant for those patients who need treatment and administer the treatments we have available as needed.”

The statement’s authors acknowledged the limitations of their recommendations, noting that “there is a paucity of data to provide clear guidance” and as such they were “based primarily on expert opinion.”

The authors from the five organizations did not disclose any conflicts of interest.

FDA approves Fensolvi for central precocious puberty treatment

Approval was based on results from a multicenter, open-label, single-arm, phase 3 study of 64 children with central precocious puberty, a rare disease described as onset of puberty before age 8 years in girls and before age 9 in boys. The primary study endpoint was achieved, with 87% of children achieving a serum luteinizing-hormone concentration of less than 4 IU/L within 6 months post injection. Sex hormones were suppressed to prepubertal levels, and clinical signs of puberty were halted or reversed.

Adverse events during the study were mostly mild or moderate; none led to withdrawal from the study. The most common adverse events reported were injection-site pain (31%), nasopharyngitis (22%), and fever (17%).

“Children with CPP require treatment for several years and missing treatment or stopping treatment too soon may lead to significant short stature and misalignment between chronological age and physical and emotional development. Fensolvi offers treating physicians and their patients with CPP a safe and effective treatment option that is administered twice a year with a small injection volume that has the potential to improve compliance,” Karen Klein, MD, of Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego, said in the press release.

Approval was based on results from a multicenter, open-label, single-arm, phase 3 study of 64 children with central precocious puberty, a rare disease described as onset of puberty before age 8 years in girls and before age 9 in boys. The primary study endpoint was achieved, with 87% of children achieving a serum luteinizing-hormone concentration of less than 4 IU/L within 6 months post injection. Sex hormones were suppressed to prepubertal levels, and clinical signs of puberty were halted or reversed.

Adverse events during the study were mostly mild or moderate; none led to withdrawal from the study. The most common adverse events reported were injection-site pain (31%), nasopharyngitis (22%), and fever (17%).

“Children with CPP require treatment for several years and missing treatment or stopping treatment too soon may lead to significant short stature and misalignment between chronological age and physical and emotional development. Fensolvi offers treating physicians and their patients with CPP a safe and effective treatment option that is administered twice a year with a small injection volume that has the potential to improve compliance,” Karen Klein, MD, of Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego, said in the press release.

Approval was based on results from a multicenter, open-label, single-arm, phase 3 study of 64 children with central precocious puberty, a rare disease described as onset of puberty before age 8 years in girls and before age 9 in boys. The primary study endpoint was achieved, with 87% of children achieving a serum luteinizing-hormone concentration of less than 4 IU/L within 6 months post injection. Sex hormones were suppressed to prepubertal levels, and clinical signs of puberty were halted or reversed.

Adverse events during the study were mostly mild or moderate; none led to withdrawal from the study. The most common adverse events reported were injection-site pain (31%), nasopharyngitis (22%), and fever (17%).

“Children with CPP require treatment for several years and missing treatment or stopping treatment too soon may lead to significant short stature and misalignment between chronological age and physical and emotional development. Fensolvi offers treating physicians and their patients with CPP a safe and effective treatment option that is administered twice a year with a small injection volume that has the potential to improve compliance,” Karen Klein, MD, of Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego, said in the press release.

FDA approves selpercatinib for lung and thyroid RET tumors

Selpercatinib (Retevmo) becomes the first targeted therapy to be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in patients with cancer who have certain tumors that have an alteration (mutation or fusion) in the RET gene.

The drug is indicated for use in RET-positive tumors found in the following:

- Non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) that has spread in adult patients

- Advanced medullary thyroid cancer (MTC) or MTC that has spread in adult and pediatric patients (older than 12 years) who require systemic therapy

- Thyroid cancer that requires systemic therapy and that has stopped responding to or is not appropriate for radioactive iodine therapy in adult and pediatric (older than 12 years) patients.

Before initiating treatment, a RET gene alteration must be determined via laboratory testing, the FDA emphasized. However, no FDA-approved test is currently available for detecting RET fusions/mutations.

Approval based on responses in open-label trial

This was an accelerated approval based on the overall response rate (ORR) and duration of response (DOR) seen in an open-label clinical trial (the phase 1/2 LIBRETTO-001 study), which involved patients with each of the three types of tumors.

All patients received selpercatinib 160 mg orally twice daily until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity occurred.

For this trial, identification of a RET gene alteration was prospectively determined in plasma or tumor tissue by local laboratories using next-generation sequencing, polymerase chain reaction testing, or fluorescence in situ hybridization, according to Eli Lilly, the company marketing selpercatinib. Immunohistochemistry was not used in the clinical trial.

Efficacy for NSCLC was evaluated in 105 adult patients with RET fusion-positive NSCLC who were previously treated with platinum chemotherapy. The ORR was 64%.

Efficacy was also evaluated in 39 patients with RET fusion-positive NSCLC who had not received any previous treatment. The ORR for these patients was 84%.

For both groups, among patients who responded to treatment, the response lasted more than 6 months.

“In the clinical trial, we observed that the majority of metastatic lung cancer patients experienced clinically meaningful responses when treated with selpercatinib, including responses in difficult-to-treat brain metastases,” LIBRETTO-001 lead investigator Alexander Drilon, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, N.Y., said in an Eli Lilly press release.

“The approval of selpercatinib marks an important milestone in the treatment of NSCLC, making RET-driven cancers now specifically targetable in the same manner as cancers with activating EGFR and ALK alterations, across all lines of therapy,” Dr. Drilon added.

About 1% to 2% of NSCLC tumors are thought to have a RET alteration.

The same trial also included patients with thyroid cancer.

Efficacy for MTC was evaluated in 55 adult and pediatric (older than 12 years) patients with advanced or metastatic RET-mutant MTC who had previously been treated with cabozantinib, vandetanib, or both. The ORR in these patients was 69%.

In addition, selpercatinib was evaluated in 88 patients with advanced or metastatic RET-mutant MTC who had not received prior treatment with cabozantinib or vandetanib. The ORR for these patients was 73%.

The trial also enrolled 19 patients with RET-positive thyroid cancer whose condition was refractory to radioactive iodine (RAI) treatment and who had received another prior systemic treatment. The ORR was 79%. Eight patients had received only RAI. The ORR for these patients was 100%.

In all the cases of thyroid cancer and lung cancer, among the patients who responded to treatment, the response lasted longer than 6 months.

“RET alterations account for the majority of medullary thyroid cancers and a meaningful percentage of other thyroid cancers,” Lori J. Wirth, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center in Boston, noted in the company release.

A fact sheet from Eli Lilly notes that RET mutations are found in about 60% of sporadic MTC cases and in over 90% of familial MTC cases, and that RET fusions are found in approximately 10% to 20% of papillary thyroid cancers.

“For patients living with these cancers, the approval of selpercatinib means they now have a treatment option that selectively and potently inhibits RET,” Dr. Wirth commented. “Based on the published data for this new medicine, as well as my personal experience treating patients, this may be a good treatment option.”

In the LIBRETTO-001 trial, the rate of discontinuations because of adverse reactions (ARs) was 5%, the company reported. The most common ARs, including laboratory abnormalities (≥25%), were increased aspartate aminotransferase level, increased alanine aminotransferase level, increased glucose level, decreased leukocyte count, decreased albumin level, decreased calcium level, dry mouth, diarrhea, increased creatinine level, increased alkaline phosphatase level, hypertension, fatigue, edema, decreased platelet count, increased total cholesterol level, rash, decreased sodium levels, and constipation. The most frequent serious AR (≥2%) was pneumonia.

The FDA warned that selpercatinib can cause hepatotoxicity, elevation in blood pressure, QT prolongation, bleeding, and allergic reactions. It may also be toxic to a fetus or newborn baby so should not be taken by pregnant or breastfeeding women.

Selpercatinib is currently being assessed in two phase 3 confirmatory trials. LIBRETTO-431 will test the drug in previously untreated patients with RET-positive NSCLC. LIBRETTO-531 involves treatment-naive patients with RET-positive MTC.

The company that developed selpercaptinib, Loxo Oncology, was acquired by Eli Lilly last year in an $8 billion takeover. This drug was billed as the most promising asset in that deal, alongside oral BTK inhibitor LOXO-305, according to a report in Pharmaphorum.

Loxo developed Vitrakvi (larotrectinib), the first TRK inhibitor to reach the market, as well as the follow-up drug LOXO-195. Both were acquired by Bayer ahead of the Lilly takeover, that report notes.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Selpercatinib (Retevmo) becomes the first targeted therapy to be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in patients with cancer who have certain tumors that have an alteration (mutation or fusion) in the RET gene.

The drug is indicated for use in RET-positive tumors found in the following:

- Non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) that has spread in adult patients

- Advanced medullary thyroid cancer (MTC) or MTC that has spread in adult and pediatric patients (older than 12 years) who require systemic therapy

- Thyroid cancer that requires systemic therapy and that has stopped responding to or is not appropriate for radioactive iodine therapy in adult and pediatric (older than 12 years) patients.

Before initiating treatment, a RET gene alteration must be determined via laboratory testing, the FDA emphasized. However, no FDA-approved test is currently available for detecting RET fusions/mutations.

Approval based on responses in open-label trial

This was an accelerated approval based on the overall response rate (ORR) and duration of response (DOR) seen in an open-label clinical trial (the phase 1/2 LIBRETTO-001 study), which involved patients with each of the three types of tumors.

All patients received selpercatinib 160 mg orally twice daily until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity occurred.

For this trial, identification of a RET gene alteration was prospectively determined in plasma or tumor tissue by local laboratories using next-generation sequencing, polymerase chain reaction testing, or fluorescence in situ hybridization, according to Eli Lilly, the company marketing selpercatinib. Immunohistochemistry was not used in the clinical trial.

Efficacy for NSCLC was evaluated in 105 adult patients with RET fusion-positive NSCLC who were previously treated with platinum chemotherapy. The ORR was 64%.

Efficacy was also evaluated in 39 patients with RET fusion-positive NSCLC who had not received any previous treatment. The ORR for these patients was 84%.

For both groups, among patients who responded to treatment, the response lasted more than 6 months.

“In the clinical trial, we observed that the majority of metastatic lung cancer patients experienced clinically meaningful responses when treated with selpercatinib, including responses in difficult-to-treat brain metastases,” LIBRETTO-001 lead investigator Alexander Drilon, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, N.Y., said in an Eli Lilly press release.

“The approval of selpercatinib marks an important milestone in the treatment of NSCLC, making RET-driven cancers now specifically targetable in the same manner as cancers with activating EGFR and ALK alterations, across all lines of therapy,” Dr. Drilon added.

About 1% to 2% of NSCLC tumors are thought to have a RET alteration.

The same trial also included patients with thyroid cancer.

Efficacy for MTC was evaluated in 55 adult and pediatric (older than 12 years) patients with advanced or metastatic RET-mutant MTC who had previously been treated with cabozantinib, vandetanib, or both. The ORR in these patients was 69%.

In addition, selpercatinib was evaluated in 88 patients with advanced or metastatic RET-mutant MTC who had not received prior treatment with cabozantinib or vandetanib. The ORR for these patients was 73%.

The trial also enrolled 19 patients with RET-positive thyroid cancer whose condition was refractory to radioactive iodine (RAI) treatment and who had received another prior systemic treatment. The ORR was 79%. Eight patients had received only RAI. The ORR for these patients was 100%.

In all the cases of thyroid cancer and lung cancer, among the patients who responded to treatment, the response lasted longer than 6 months.

“RET alterations account for the majority of medullary thyroid cancers and a meaningful percentage of other thyroid cancers,” Lori J. Wirth, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center in Boston, noted in the company release.

A fact sheet from Eli Lilly notes that RET mutations are found in about 60% of sporadic MTC cases and in over 90% of familial MTC cases, and that RET fusions are found in approximately 10% to 20% of papillary thyroid cancers.

“For patients living with these cancers, the approval of selpercatinib means they now have a treatment option that selectively and potently inhibits RET,” Dr. Wirth commented. “Based on the published data for this new medicine, as well as my personal experience treating patients, this may be a good treatment option.”

In the LIBRETTO-001 trial, the rate of discontinuations because of adverse reactions (ARs) was 5%, the company reported. The most common ARs, including laboratory abnormalities (≥25%), were increased aspartate aminotransferase level, increased alanine aminotransferase level, increased glucose level, decreased leukocyte count, decreased albumin level, decreased calcium level, dry mouth, diarrhea, increased creatinine level, increased alkaline phosphatase level, hypertension, fatigue, edema, decreased platelet count, increased total cholesterol level, rash, decreased sodium levels, and constipation. The most frequent serious AR (≥2%) was pneumonia.

The FDA warned that selpercatinib can cause hepatotoxicity, elevation in blood pressure, QT prolongation, bleeding, and allergic reactions. It may also be toxic to a fetus or newborn baby so should not be taken by pregnant or breastfeeding women.

Selpercatinib is currently being assessed in two phase 3 confirmatory trials. LIBRETTO-431 will test the drug in previously untreated patients with RET-positive NSCLC. LIBRETTO-531 involves treatment-naive patients with RET-positive MTC.

The company that developed selpercaptinib, Loxo Oncology, was acquired by Eli Lilly last year in an $8 billion takeover. This drug was billed as the most promising asset in that deal, alongside oral BTK inhibitor LOXO-305, according to a report in Pharmaphorum.

Loxo developed Vitrakvi (larotrectinib), the first TRK inhibitor to reach the market, as well as the follow-up drug LOXO-195. Both were acquired by Bayer ahead of the Lilly takeover, that report notes.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Selpercatinib (Retevmo) becomes the first targeted therapy to be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in patients with cancer who have certain tumors that have an alteration (mutation or fusion) in the RET gene.

The drug is indicated for use in RET-positive tumors found in the following:

- Non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) that has spread in adult patients

- Advanced medullary thyroid cancer (MTC) or MTC that has spread in adult and pediatric patients (older than 12 years) who require systemic therapy

- Thyroid cancer that requires systemic therapy and that has stopped responding to or is not appropriate for radioactive iodine therapy in adult and pediatric (older than 12 years) patients.

Before initiating treatment, a RET gene alteration must be determined via laboratory testing, the FDA emphasized. However, no FDA-approved test is currently available for detecting RET fusions/mutations.

Approval based on responses in open-label trial

This was an accelerated approval based on the overall response rate (ORR) and duration of response (DOR) seen in an open-label clinical trial (the phase 1/2 LIBRETTO-001 study), which involved patients with each of the three types of tumors.

All patients received selpercatinib 160 mg orally twice daily until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity occurred.

For this trial, identification of a RET gene alteration was prospectively determined in plasma or tumor tissue by local laboratories using next-generation sequencing, polymerase chain reaction testing, or fluorescence in situ hybridization, according to Eli Lilly, the company marketing selpercatinib. Immunohistochemistry was not used in the clinical trial.

Efficacy for NSCLC was evaluated in 105 adult patients with RET fusion-positive NSCLC who were previously treated with platinum chemotherapy. The ORR was 64%.

Efficacy was also evaluated in 39 patients with RET fusion-positive NSCLC who had not received any previous treatment. The ORR for these patients was 84%.

For both groups, among patients who responded to treatment, the response lasted more than 6 months.

“In the clinical trial, we observed that the majority of metastatic lung cancer patients experienced clinically meaningful responses when treated with selpercatinib, including responses in difficult-to-treat brain metastases,” LIBRETTO-001 lead investigator Alexander Drilon, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, N.Y., said in an Eli Lilly press release.

“The approval of selpercatinib marks an important milestone in the treatment of NSCLC, making RET-driven cancers now specifically targetable in the same manner as cancers with activating EGFR and ALK alterations, across all lines of therapy,” Dr. Drilon added.

About 1% to 2% of NSCLC tumors are thought to have a RET alteration.

The same trial also included patients with thyroid cancer.

Efficacy for MTC was evaluated in 55 adult and pediatric (older than 12 years) patients with advanced or metastatic RET-mutant MTC who had previously been treated with cabozantinib, vandetanib, or both. The ORR in these patients was 69%.

In addition, selpercatinib was evaluated in 88 patients with advanced or metastatic RET-mutant MTC who had not received prior treatment with cabozantinib or vandetanib. The ORR for these patients was 73%.

The trial also enrolled 19 patients with RET-positive thyroid cancer whose condition was refractory to radioactive iodine (RAI) treatment and who had received another prior systemic treatment. The ORR was 79%. Eight patients had received only RAI. The ORR for these patients was 100%.

In all the cases of thyroid cancer and lung cancer, among the patients who responded to treatment, the response lasted longer than 6 months.

“RET alterations account for the majority of medullary thyroid cancers and a meaningful percentage of other thyroid cancers,” Lori J. Wirth, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center in Boston, noted in the company release.

A fact sheet from Eli Lilly notes that RET mutations are found in about 60% of sporadic MTC cases and in over 90% of familial MTC cases, and that RET fusions are found in approximately 10% to 20% of papillary thyroid cancers.

“For patients living with these cancers, the approval of selpercatinib means they now have a treatment option that selectively and potently inhibits RET,” Dr. Wirth commented. “Based on the published data for this new medicine, as well as my personal experience treating patients, this may be a good treatment option.”

In the LIBRETTO-001 trial, the rate of discontinuations because of adverse reactions (ARs) was 5%, the company reported. The most common ARs, including laboratory abnormalities (≥25%), were increased aspartate aminotransferase level, increased alanine aminotransferase level, increased glucose level, decreased leukocyte count, decreased albumin level, decreased calcium level, dry mouth, diarrhea, increased creatinine level, increased alkaline phosphatase level, hypertension, fatigue, edema, decreased platelet count, increased total cholesterol level, rash, decreased sodium levels, and constipation. The most frequent serious AR (≥2%) was pneumonia.

The FDA warned that selpercatinib can cause hepatotoxicity, elevation in blood pressure, QT prolongation, bleeding, and allergic reactions. It may also be toxic to a fetus or newborn baby so should not be taken by pregnant or breastfeeding women.

Selpercatinib is currently being assessed in two phase 3 confirmatory trials. LIBRETTO-431 will test the drug in previously untreated patients with RET-positive NSCLC. LIBRETTO-531 involves treatment-naive patients with RET-positive MTC.

The company that developed selpercaptinib, Loxo Oncology, was acquired by Eli Lilly last year in an $8 billion takeover. This drug was billed as the most promising asset in that deal, alongside oral BTK inhibitor LOXO-305, according to a report in Pharmaphorum.

Loxo developed Vitrakvi (larotrectinib), the first TRK inhibitor to reach the market, as well as the follow-up drug LOXO-195. Both were acquired by Bayer ahead of the Lilly takeover, that report notes.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

S-ICD ‘noninferior’ to transvenous-lead ICD in head-to-head PRAETORIAN trial

by turning in a “noninferior” performance when it was compared with transvenous-lead devices in a first-of-its-kind head-to-head study.

Patients implanted with the subcutaneous-lead S-ICD (Boston Scientific) defibrillator showed a 4-year risk for inappropriate shocks or device-related complications similar to that seen with standard transvenous-lead implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD) in a randomized comparison.

At the same time, the S-ICD did its job by showing a highly significant three-fourths reduction in risk for lead-related complications, compared with ICDs with standard leads, in the trial with more than 800 patients, called PRAETORIAN.

The study population represented a mix of patients seen in “real-world” practice who have an ICD indication, of whom about two-thirds had ischemic cardiomyopathy, said Reinoud Knops, MD, PhD, Academic Medical Center, Hilversum, the Netherlands. About 80% received the devices for primary prevention.

Knops, the trial’s principal investigator, presented the results online May 8 as one of the Heart Rhythm Society 2020 Scientific Sessions virtual presentations.

“I think the PRAETORIAN trial has really shown now, in a conventional ICD population – the real-world patients that we treat with ICD therapy, the single-chamber ICD cohort – that the S-ICD is a really good alternative option,” he said to reporters during a media briefing.

“The main conclusion is that the S-ICD should be considered in all patients who need an ICD who do not have a pacing indication,” Knops said.

This latter part is critical, because the S-ICD does not provide pacing therapy, including antitachycardia pacing (ATP) and cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), and the trial did not enter patients considered likely to benefit from it. For example, it excluded anyone with bradycardia or treatment-refractory monomorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) and patients considered appropriate for CRT.

In fact, there are a lot reasons clinicians might prefer a transvenous-lead ICD over the S-ICD, observed Anne B. Curtis, MD, University at Buffalo, State University of New York, who is not associated with PRAETORIAN.

A transvenous-lead system might be preferred in older patients, those with heart failure, and those with a lot of comorbidities. “A lot of these patients already have cardiomyopathies, so they’re more likely to develop atrial fibrillation or a need for CRT,” conditions that might make a transvenous-lead system the better choice, Curtis told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

“For a lot of patients, you’re always thinking that you may have a need for that kind of therapy.”

In contrast, younger patients who perhaps have survived cardiac arrest and probably don’t have heart failure, and so may be less likely to benefit from pacing therapy, Curtis said, “are the kind of patient who you would probably lean very strongly toward for an S-ICD rather than a transvenous ICD.”

Remaining patients, those who might be considered candidates for either kind of device, are actually “a fairly limited subset,” she said.

The trial randomized 849 patients in Europe and the United States, from March 2011 to January 2017, who had a class I or IIa indication for an ICD but no bradycardia or need for CRT or ATP, to be implanted with an S-ICD or a transvenous-lead ICD.

The rates of the primary end point, a composite of device-related complications and inappropriate shocks at a median follow-up of 4 years, were comparable, at 15.1% in the S-ICD group and 15.7% for those with transvenous-lead ICDs.

The incidence of device-related complications numerically favored the S-ICD group, and the incidence of inappropriate shocks numerically favored the transvenous-lead group, but neither difference reached significance.

Knops said the PRAETORIAN researchers are seeking addition funding to extend the follow-up to 8 years. “We will get more insight into the durability of the S-ICD when we follow these patients longer,” he told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

The investigator-initiated trial received support from Boston Scientific. Knops discloses receiving consultancy fees and research grants from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Cairdac, and holding stock options from AtaCor Medical.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

by turning in a “noninferior” performance when it was compared with transvenous-lead devices in a first-of-its-kind head-to-head study.

Patients implanted with the subcutaneous-lead S-ICD (Boston Scientific) defibrillator showed a 4-year risk for inappropriate shocks or device-related complications similar to that seen with standard transvenous-lead implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD) in a randomized comparison.

At the same time, the S-ICD did its job by showing a highly significant three-fourths reduction in risk for lead-related complications, compared with ICDs with standard leads, in the trial with more than 800 patients, called PRAETORIAN.

The study population represented a mix of patients seen in “real-world” practice who have an ICD indication, of whom about two-thirds had ischemic cardiomyopathy, said Reinoud Knops, MD, PhD, Academic Medical Center, Hilversum, the Netherlands. About 80% received the devices for primary prevention.

Knops, the trial’s principal investigator, presented the results online May 8 as one of the Heart Rhythm Society 2020 Scientific Sessions virtual presentations.

“I think the PRAETORIAN trial has really shown now, in a conventional ICD population – the real-world patients that we treat with ICD therapy, the single-chamber ICD cohort – that the S-ICD is a really good alternative option,” he said to reporters during a media briefing.

“The main conclusion is that the S-ICD should be considered in all patients who need an ICD who do not have a pacing indication,” Knops said.

This latter part is critical, because the S-ICD does not provide pacing therapy, including antitachycardia pacing (ATP) and cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), and the trial did not enter patients considered likely to benefit from it. For example, it excluded anyone with bradycardia or treatment-refractory monomorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) and patients considered appropriate for CRT.

In fact, there are a lot reasons clinicians might prefer a transvenous-lead ICD over the S-ICD, observed Anne B. Curtis, MD, University at Buffalo, State University of New York, who is not associated with PRAETORIAN.

A transvenous-lead system might be preferred in older patients, those with heart failure, and those with a lot of comorbidities. “A lot of these patients already have cardiomyopathies, so they’re more likely to develop atrial fibrillation or a need for CRT,” conditions that might make a transvenous-lead system the better choice, Curtis told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

“For a lot of patients, you’re always thinking that you may have a need for that kind of therapy.”

In contrast, younger patients who perhaps have survived cardiac arrest and probably don’t have heart failure, and so may be less likely to benefit from pacing therapy, Curtis said, “are the kind of patient who you would probably lean very strongly toward for an S-ICD rather than a transvenous ICD.”

Remaining patients, those who might be considered candidates for either kind of device, are actually “a fairly limited subset,” she said.

The trial randomized 849 patients in Europe and the United States, from March 2011 to January 2017, who had a class I or IIa indication for an ICD but no bradycardia or need for CRT or ATP, to be implanted with an S-ICD or a transvenous-lead ICD.

The rates of the primary end point, a composite of device-related complications and inappropriate shocks at a median follow-up of 4 years, were comparable, at 15.1% in the S-ICD group and 15.7% for those with transvenous-lead ICDs.

The incidence of device-related complications numerically favored the S-ICD group, and the incidence of inappropriate shocks numerically favored the transvenous-lead group, but neither difference reached significance.

Knops said the PRAETORIAN researchers are seeking addition funding to extend the follow-up to 8 years. “We will get more insight into the durability of the S-ICD when we follow these patients longer,” he told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

The investigator-initiated trial received support from Boston Scientific. Knops discloses receiving consultancy fees and research grants from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Cairdac, and holding stock options from AtaCor Medical.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

by turning in a “noninferior” performance when it was compared with transvenous-lead devices in a first-of-its-kind head-to-head study.

Patients implanted with the subcutaneous-lead S-ICD (Boston Scientific) defibrillator showed a 4-year risk for inappropriate shocks or device-related complications similar to that seen with standard transvenous-lead implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD) in a randomized comparison.

At the same time, the S-ICD did its job by showing a highly significant three-fourths reduction in risk for lead-related complications, compared with ICDs with standard leads, in the trial with more than 800 patients, called PRAETORIAN.

The study population represented a mix of patients seen in “real-world” practice who have an ICD indication, of whom about two-thirds had ischemic cardiomyopathy, said Reinoud Knops, MD, PhD, Academic Medical Center, Hilversum, the Netherlands. About 80% received the devices for primary prevention.

Knops, the trial’s principal investigator, presented the results online May 8 as one of the Heart Rhythm Society 2020 Scientific Sessions virtual presentations.

“I think the PRAETORIAN trial has really shown now, in a conventional ICD population – the real-world patients that we treat with ICD therapy, the single-chamber ICD cohort – that the S-ICD is a really good alternative option,” he said to reporters during a media briefing.

“The main conclusion is that the S-ICD should be considered in all patients who need an ICD who do not have a pacing indication,” Knops said.

This latter part is critical, because the S-ICD does not provide pacing therapy, including antitachycardia pacing (ATP) and cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), and the trial did not enter patients considered likely to benefit from it. For example, it excluded anyone with bradycardia or treatment-refractory monomorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) and patients considered appropriate for CRT.

In fact, there are a lot reasons clinicians might prefer a transvenous-lead ICD over the S-ICD, observed Anne B. Curtis, MD, University at Buffalo, State University of New York, who is not associated with PRAETORIAN.

A transvenous-lead system might be preferred in older patients, those with heart failure, and those with a lot of comorbidities. “A lot of these patients already have cardiomyopathies, so they’re more likely to develop atrial fibrillation or a need for CRT,” conditions that might make a transvenous-lead system the better choice, Curtis told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

“For a lot of patients, you’re always thinking that you may have a need for that kind of therapy.”

In contrast, younger patients who perhaps have survived cardiac arrest and probably don’t have heart failure, and so may be less likely to benefit from pacing therapy, Curtis said, “are the kind of patient who you would probably lean very strongly toward for an S-ICD rather than a transvenous ICD.”

Remaining patients, those who might be considered candidates for either kind of device, are actually “a fairly limited subset,” she said.

The trial randomized 849 patients in Europe and the United States, from March 2011 to January 2017, who had a class I or IIa indication for an ICD but no bradycardia or need for CRT or ATP, to be implanted with an S-ICD or a transvenous-lead ICD.

The rates of the primary end point, a composite of device-related complications and inappropriate shocks at a median follow-up of 4 years, were comparable, at 15.1% in the S-ICD group and 15.7% for those with transvenous-lead ICDs.

The incidence of device-related complications numerically favored the S-ICD group, and the incidence of inappropriate shocks numerically favored the transvenous-lead group, but neither difference reached significance.

Knops said the PRAETORIAN researchers are seeking addition funding to extend the follow-up to 8 years. “We will get more insight into the durability of the S-ICD when we follow these patients longer,” he told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

The investigator-initiated trial received support from Boston Scientific. Knops discloses receiving consultancy fees and research grants from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Cairdac, and holding stock options from AtaCor Medical.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The many variants of psoriasis

The “heartbreak of psoriasis,” coined by an advertiser in the 1960s, conveyed the notion that this disease was a cosmetic disorder mainly limited to skin involvement. John Updike’s article in the September 1985 issue of The New Yorker, “At War With My Skin,” detailed Mr. Updike’s feelings of isolation and stress related to his condition, helping to reframe the popular concept of psoriasis.1 Updike’s eloquent account describing his struggles to find effective treatment increased public awareness about psoriasis, which in fact affects other body systems as well.

The overall prevalence of psoriasis is 1.5% to 3.1% in the United States and United Kingdom.2,3 More than 6.5 million adults in the United States > 20 years of age are affected.3 The most commonly affected demographic group is non-Hispanic Caucasians.

Our expanding knowledge of pathogenesis

Studies of genetic linkage have identified genes and single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with psoriasis.4 The interaction between environmental triggers and the innate and adaptive immune systems leads to keratinocyte hyperproliferation. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin (IL) 23, and IL-17 are important cytokines associated with psoriatic inflammation.4 There are common pathways of inflammation in both psoriasis and cardiovascular disease resulting in oxidative stress and endothelial cell dysfunction.4 Ninety percent of early-onset psoriasis is associated with human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-Cw6.4 And alterations in the microbiome of the skin may contribute, as reduced microbial diversity has been found in psoriatic lesions.5

Comorbidities are common

Psoriasis is an independent risk factor for diabetes and major adverse cardiovascular events.6 Hypertension, dyslipidemia, inflammatory bowel disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, chronic kidney disease, and lymphoma (particularly cutaneous T-cell lymphoma) are also associated with psoriasis.6 Psoriatic arthritis is frequently encountered with cutaneous psoriasis; however, it is often not recognized until late in the disease course.

There also appears to be an association among psoriasis, dietary factors, and celiac disease.7-9 Positive testing for IgA anti-endomysial antibodies and IgA tissue transglutaminase antibodies should prompt consideration of starting a gluten-free diet, which has been shown to improve psoriatic

The different types of psoriasis

The classic presentation of psoriasis involves stubborn plaques with silvery scale on extensor surfaces such as the elbows and knees. The severity of the disease corresponds with the amount of body surface area affected. While plaque-type psoriasis is the most common form, other patterns exist. Individuals may exhibit 1 dominant pattern or multiple psoriatic variants simultaneously. Most types of psoriasis have 3 characteristic features: erythema, skin thickening, and scales.

Certain history and physical clues can aid in diagnosing psoriasis; these include the Koebner phenomenon, the Auspitz sign, and the Woronoff ring. The Koebner phenomenon refers to the development of psoriatic lesions in an area of trauma (FIGURE 1), frequently resulting in a linear streak-like appearance. The Auspitz sign describes the pinpoint bleeding that may be encountered with the removal of a psoriatic plaque. The Woronoff ring is a pale blanching ring that may surround a psoriatic lesion.

Continue to: Chronic plaque-type psoriasis

Chronic plaque-type psoriasis (Figures 2A and 2B), the most common variant, is characterized by sharply demarcated pink papules and plaques with a silvery scale in a symmetric distribution on the extensor surfaces, scalp, trunk, and lumbosacral areas.

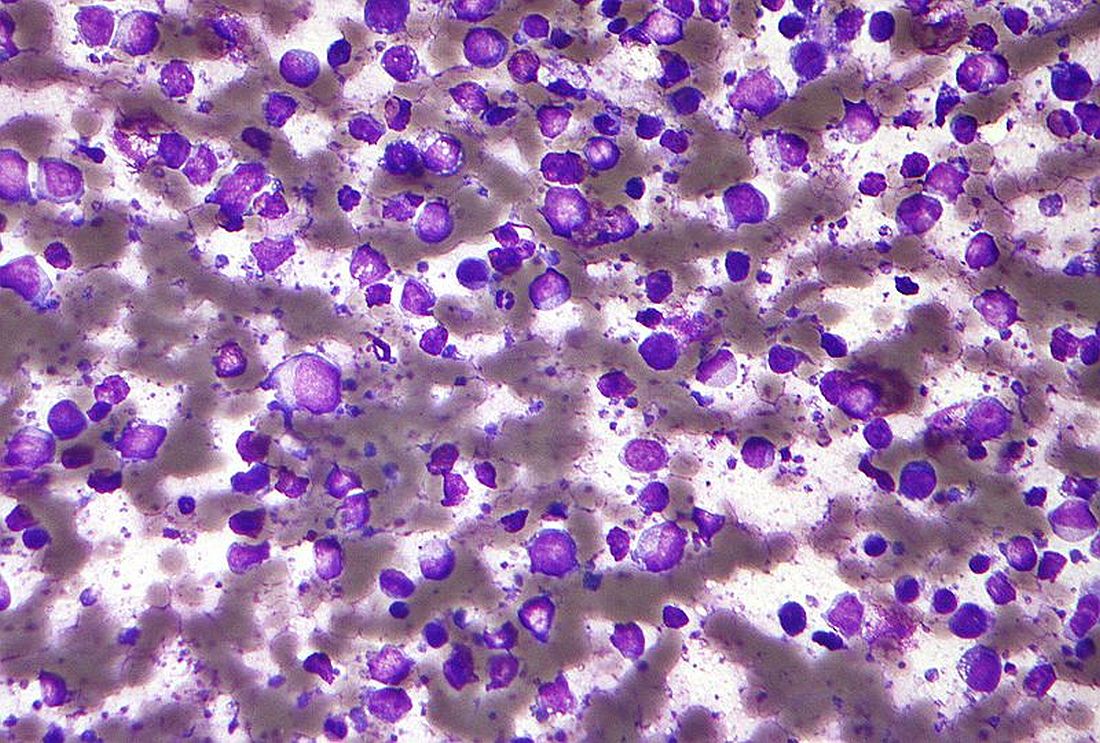

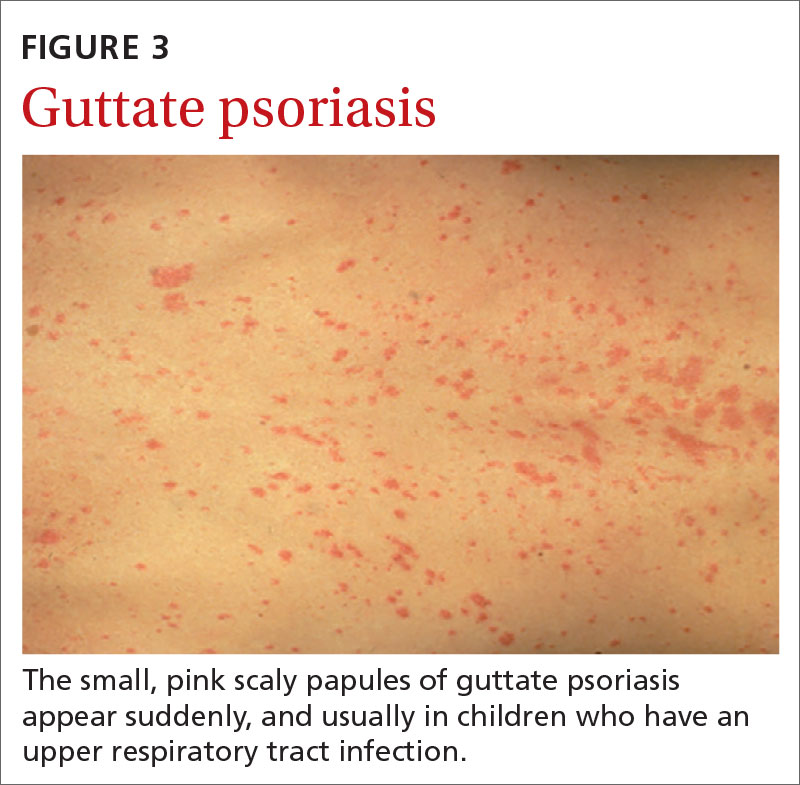

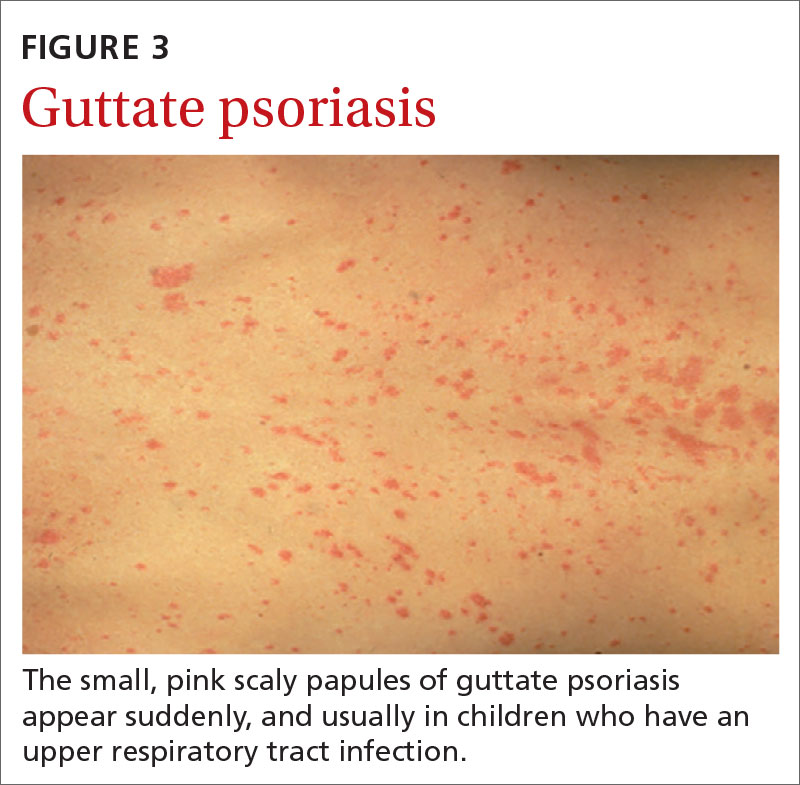

Guttate psoriasis (FIGURE 3) features small (often < 1 cm) pink scaly papules that appear suddenly. It is more commonly seen in children and is usually preceded by an upper respiratory tract infection, often with Streptococcus.10 If strep testing is positive, guttate psoriasis may improve after appropriate antibiotic treatment.

Erythrodermic psoriasis (FIGUREs 4A and 4B) involves at least 75% of the body with erythema and scaling.11 Erythroderma can be caused by many other conditions such as atopic dermatitis, a drug reaction, Sezary syndrome, seborrheic dermatitis, and pityriasis rubra pilaris. Treatments for other conditions in the differential diagnosis can potentially make psoriasis worse. Unfortunately, findings on a skin biopsy are often nonspecific, making careful clinical observation crucial to arriving at an accurate diagnosis.

Pustular psoriasis is characterized by bright erythema and sterile pustules. Pustular psoriasis can be triggered by pregnancy, sudden tapering of corticosteroids, hypocalcemia, and infection. Involvement of the palms and soles with severe desquamation can drastically impact daily functioning and quality of life.

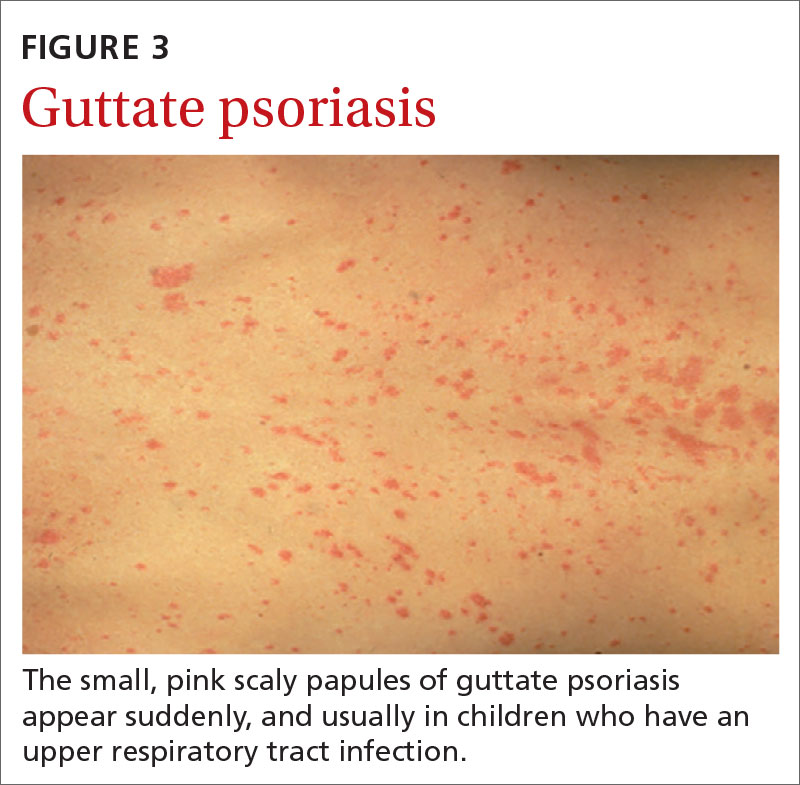

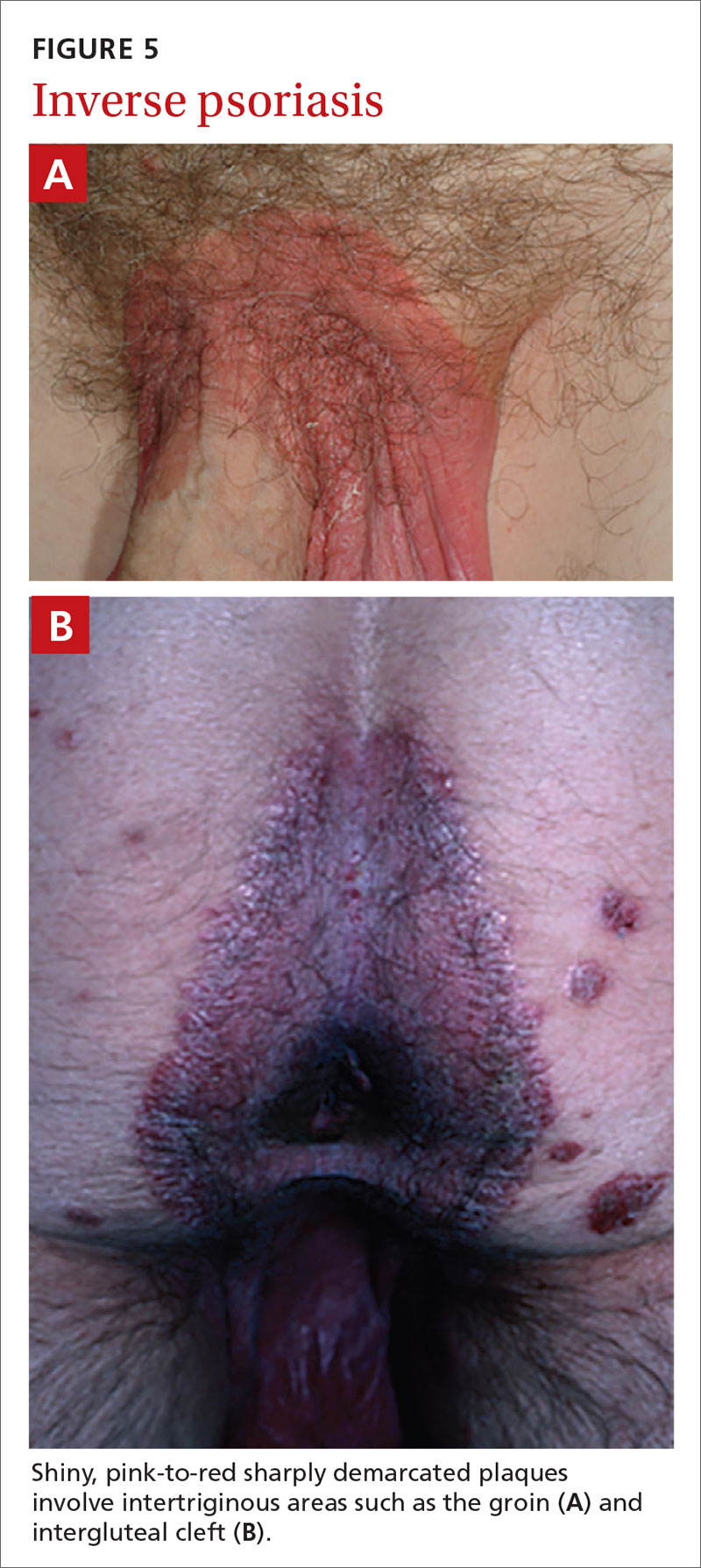

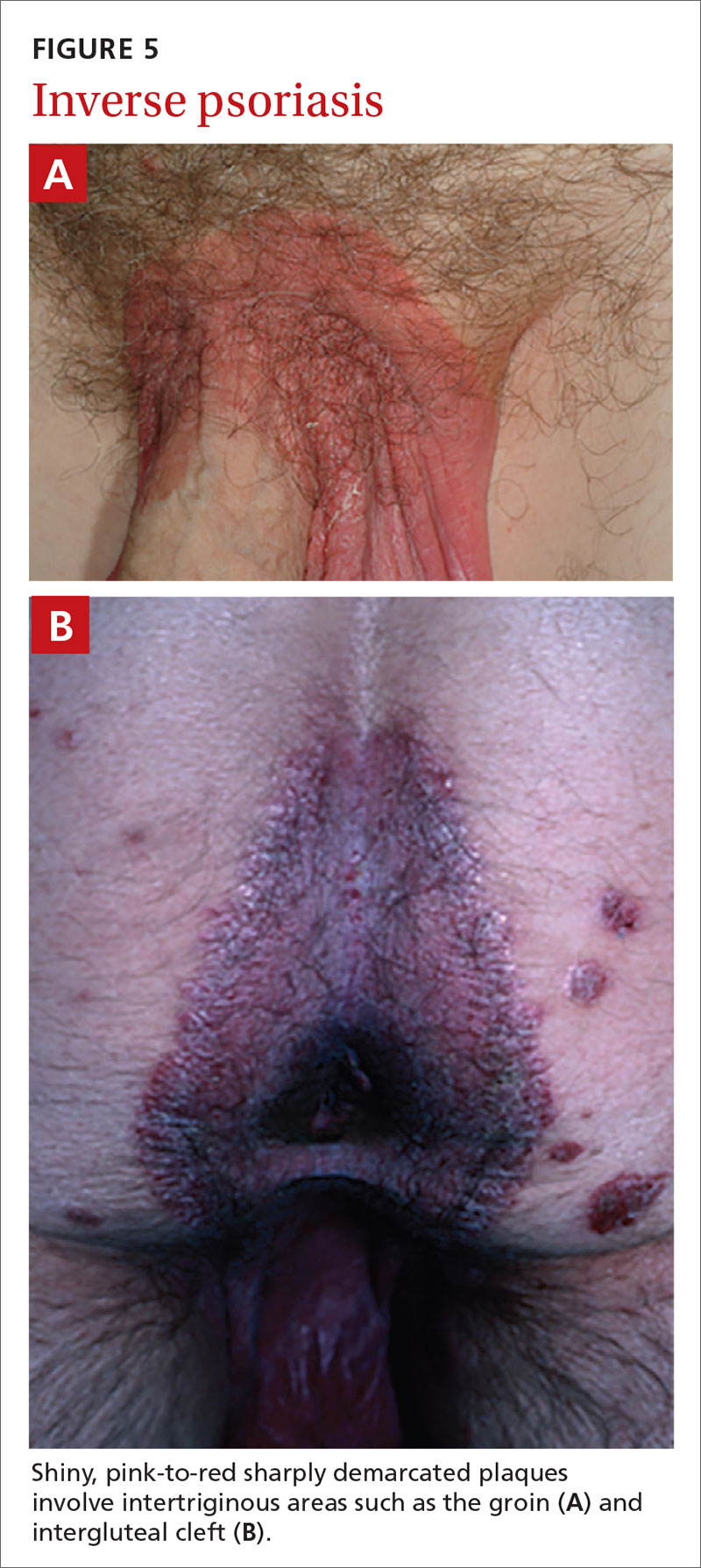

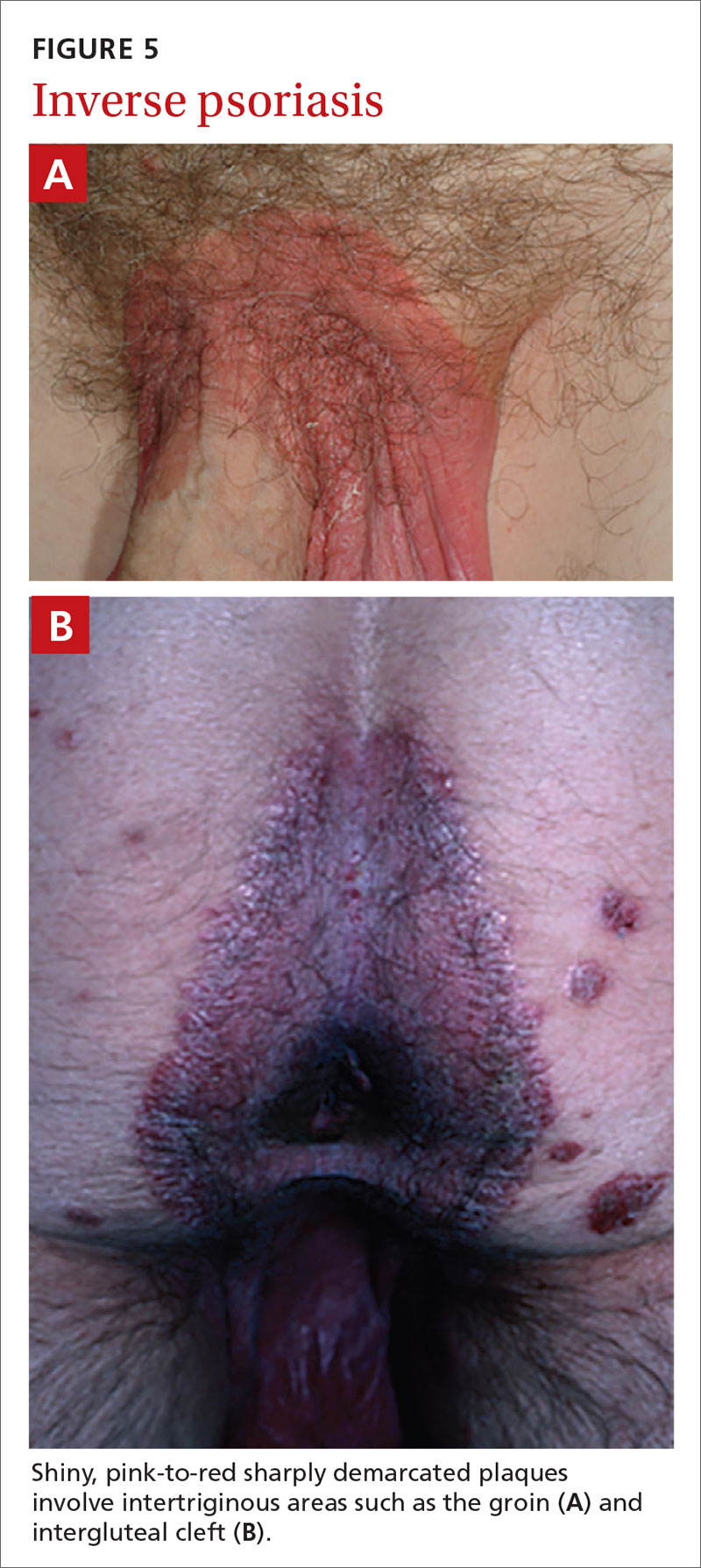

Inverse or flexural psoriasis (FIGUREs 5A and 5B) is characterized by shiny, pink-to-red sharply demarcated plaques involving intertriginous areas, typically the groin, inguinal crease, axilla, inframammary regions, and intergluteal cleft.

Continue to: Geographic tongue

Geographic tongue describes psoriasis of the tongue. The mucosa of the tongue has white plaques with a geographic border. Instead of scale, the moisture on the tongue causes areas of hyperkeratosis that appear white.

Nail psoriasis can manifest as nail pitting (FIGURE 6), oil staining, onycholysis (distal lifting of the nail), and subungual hyperkeratosis. Nail psoriasis is often quite distressing for patients and can be difficult to treat.

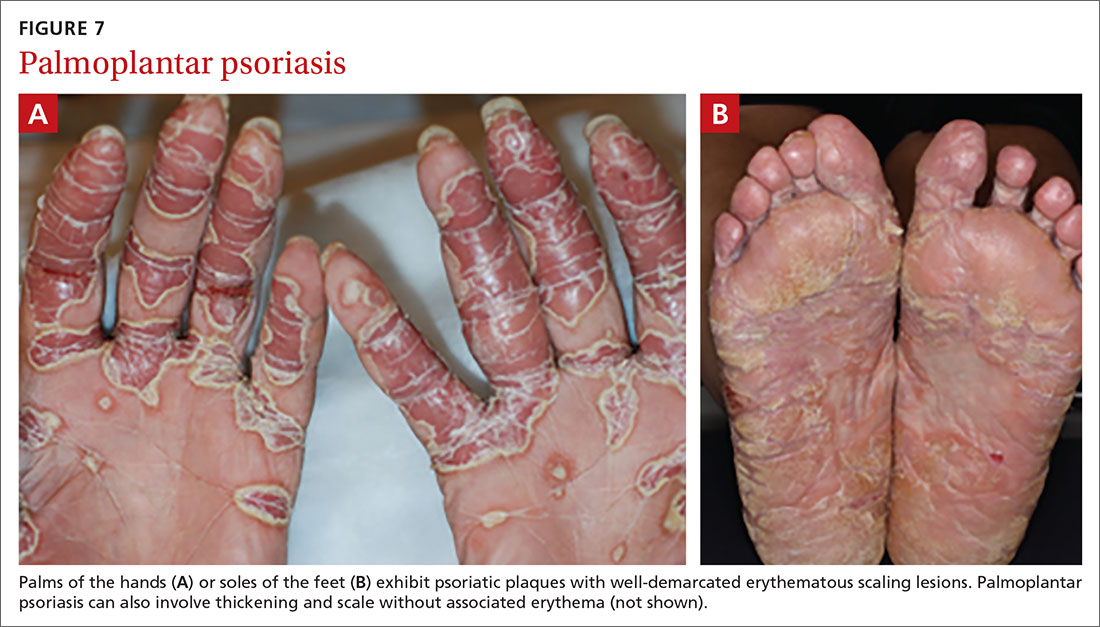

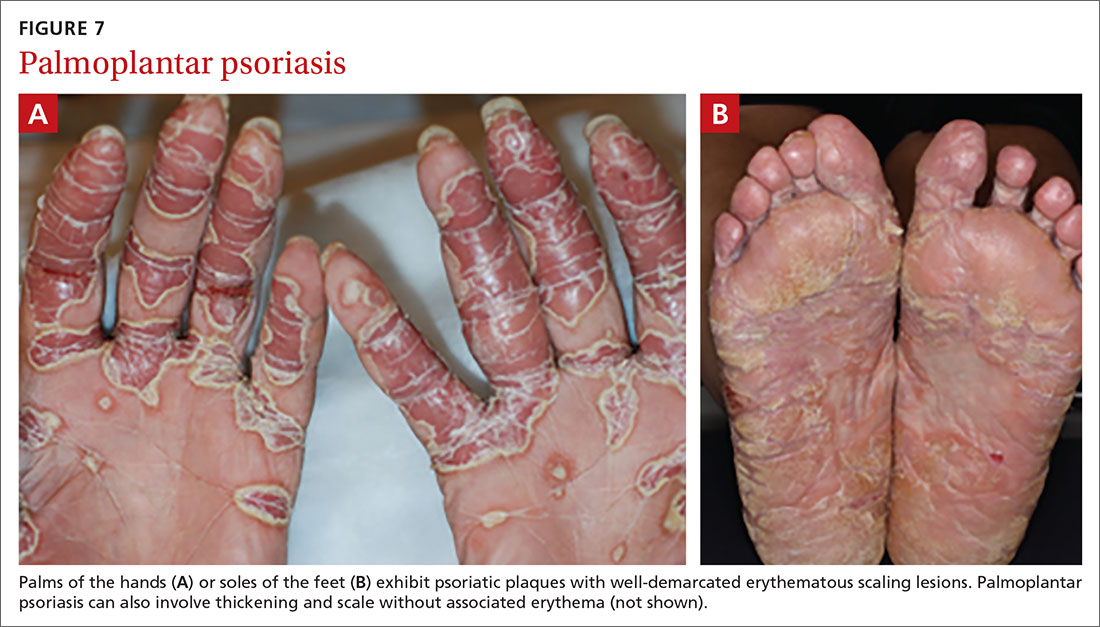

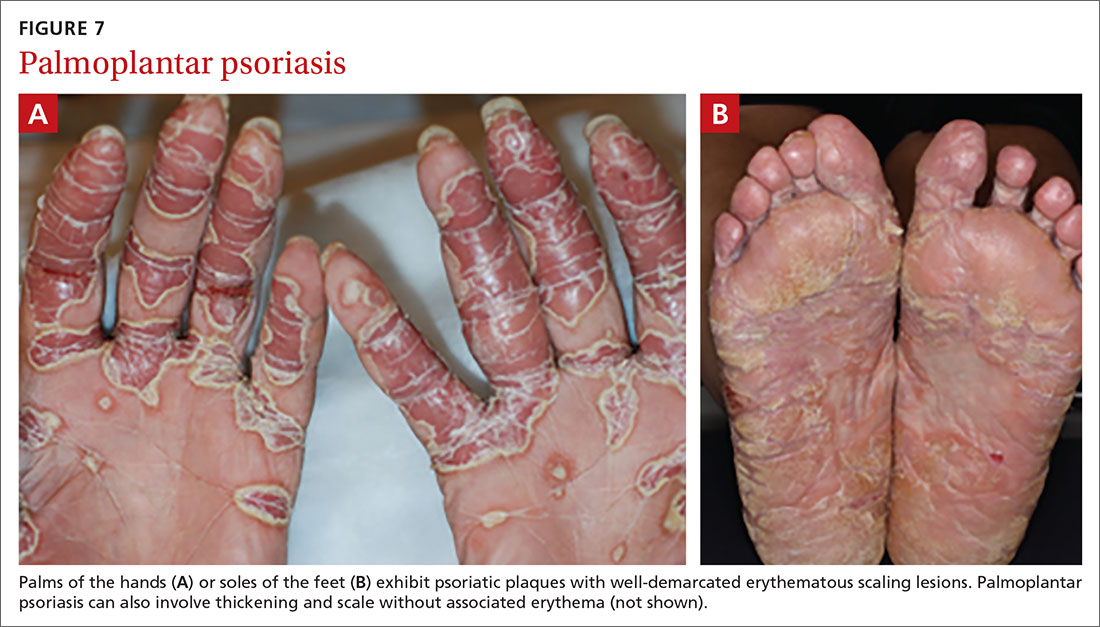

Palmoplantar psoriasis (FIGUREs 7A and 7B) can be painful due to the involvement of the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. Lesions will either be similar to other psoriatic plaques with well-demarcated erythematous scaling lesions or involve thickening and scale without associated erythema.

Psoriatic arthritis can cause significant joint damage and disability. Most affected individuals with psoriatic arthritis have a history of preceding skin disease.12 There are no specific lab tests for psoriasis; radiologic studies can show bulky syndesmophytes, central and marginal erosions, and periostitis. Patterns of joint involvement are variable. Psoriatic arthritis is more likely to affect the distal interphalangeal joints than rheumatoid arthritis and is more likely to affect the metacarpophalangeal joints than osteoarthritis.13

Psoriatic arthritis often progresses insidiously and is commonly described as causing discomfort rather than acute pain. Enthesitis, inflammation at the site where tendons or ligaments insert into the bone, is often present. Joint destruction may lead to the telescoping “opera glass” digit (FIGURE 8).

Continue to: Drug-provoked psoriasis

Drug-provoked psoriasis is divided into 2 groups: drug-induced and drug-aggravated. Drug-induced psoriasis will improve after discontinuation of the causative drug and tends to occur in patients without a personal or family history of psoriasis. Drug-aggravated psoriasis continues to progress after the discontinuation of the offending drug and is more often seen in patients with a history of psoriasis.14 Drugs that most commonly provoke psoriasis are beta-blockers, lithium, and antimalarials.10 Other potentially aggravating agents include antibiotics, digoxin, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.10

Consider these skin disorders in the differential diagnosis

The diagnosis of psoriasis is usually clinical, and a skin biopsy is rarely needed. However, a range of other skin disorders should be kept in mind when considering the differential diagnosis.

Mycosis fungoides is a type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that forms erythematous plaques that may show wrinkling and epidermal atrophy in sun-protected sites. Onset usually occurs among the elderly.

Pityriasis rubra pilaris is characterized by salmon-colored patches that may have small areas of normal skin (“islands of sparing”), hyperkeratotic follicular papules, and hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles.

Seborrheic dermatitis, dandruff of the skin, usually involves the scalp and nasolabial areas and the T-zone of the face.

Continue to: Lichen planus

Lichen planus usually appears slightly more purple than psoriasis and typically involves the mouth, flexural surfaces of the wrists, genitals, and ankles.

Other conditions in the differential include pityriasis lichenoides chronica, which may be identified on skin biopsy. Inverse psoriasis can be difficult to differentiate from candida intertrigo, erythrasma, or tinea cruris.

A potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation can help differentiate psoriasis from candida or tinea. In psoriasis, a KOH test will be negative for fungal elements. Mycology culture on skin scrapings may be performed to rule out fungal infection. Erythrasma may exhibit a coral red appearance under Wood lamp examination.

If a lesion fails to respond to appropriate treatment, a careful drug history and biopsy can help clarify the diagnosis.

Document disease

It’s important to thoroughly document the extent and severity of the psoriasis and to monitor the impact of treatment. The Psoriasis Area and Severity Index is a commonly used method that calculates a score based on the area (extent) of involvement surrounding 4 major anatomical regions (head, upper extremities, trunk, and lower extremities), as well as the degree of erythema, induration, and scaling of lesions. The average redness, thickness, and scaling are graded on a scale of 0 to 4 and the extent of involvement is calculated to form a total numerical score ranging from 0 (no disease) to 72 (maximal disease).

Continue to: Many options in the treatment arsenal

Many options in the treatment arsenal

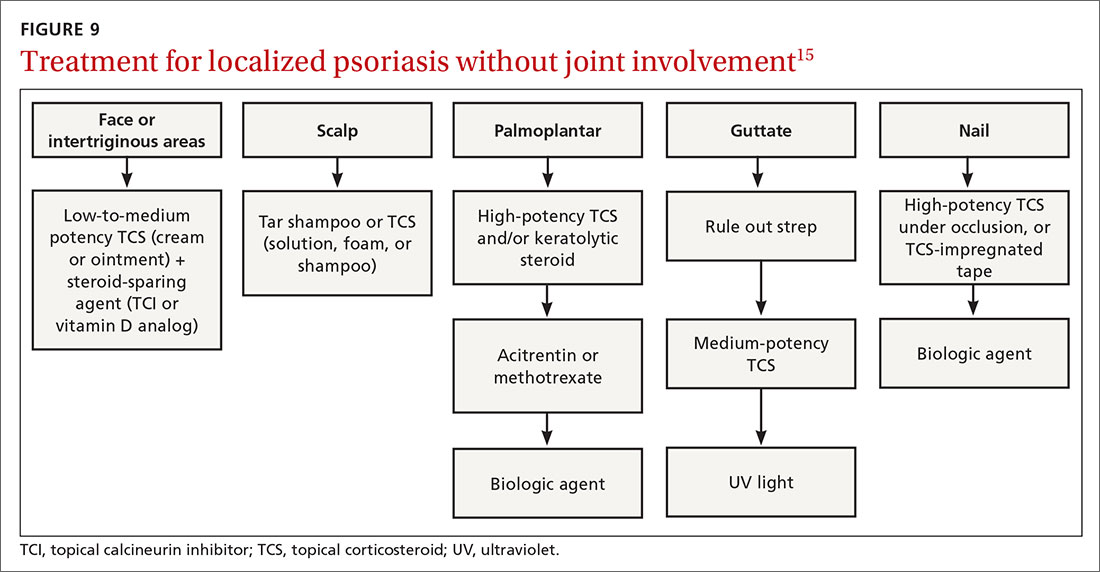

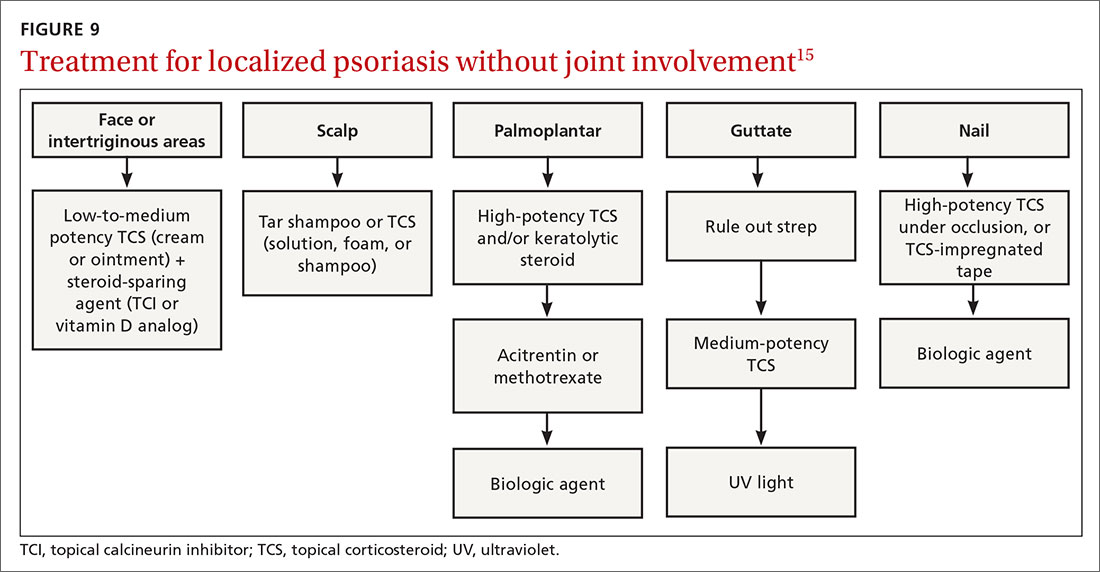

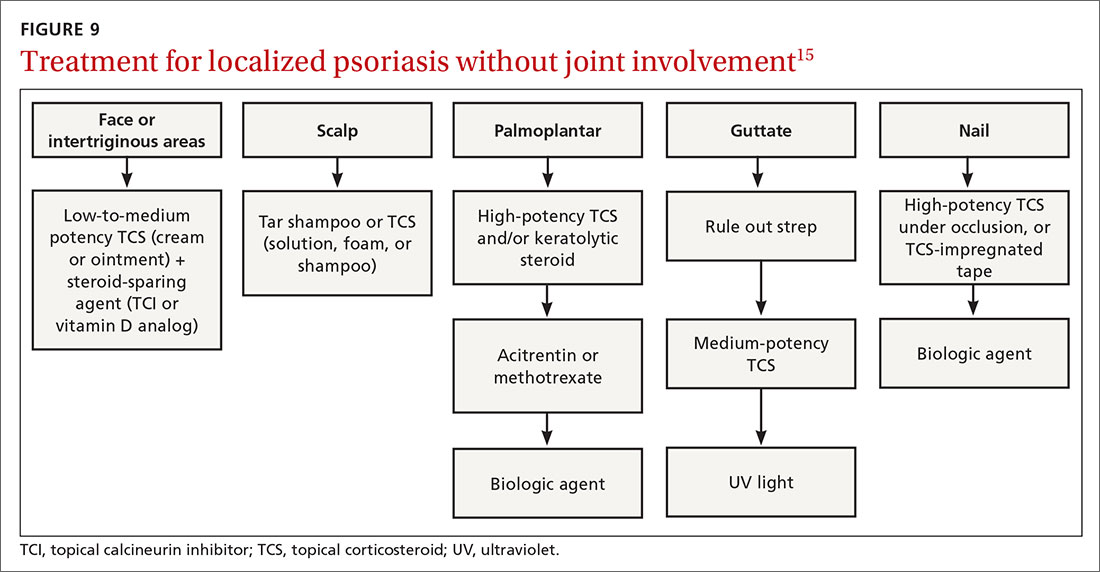

Many treatments can improve psoriasis.9,15-19 Most affected individuals discover that emollients and exposure to natural sunlight can be effective, as are soothing baths (balneotherapy) or topical coal tar application. More persistent disease requires prescription therapy. Individualize therapy according to the severity of disease, location of the lesions, involvement of joints, and comorbidities (FIGURE 9).15

If ≤ 10% of the body surface area is involved, treatment options generally are explored in a stepwise progression from safest and most affordable to more involved therapies as needed: moisturization and avoidance of repetitive trauma, topical corticosteroids (TCS), vitamin D analogs, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and vitamin A creams. Recalcitrant disease will likely require ultraviolet (UV) light treatment or a systemic agent.15

If > 10% of the body surface area is involved, but joints are not involved, consider UV light treatment or a combination of alcitretin and TCS. If the joints are involved, likely initial options would be methotrexate, cyclosporine, or TNF-α inhibitor. Additional options to consider are anti-IL-17 or anti-IL-23 agents.15

If there’s joint involvement. In individuals with mild peripheral arthritis involving fewer than 4 joints without evidence of joint damage on imaging, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are the mainstay of treatment. If the peripheral arthritis persists, or if it is associated with moderate-to-severe erosions or with substantial functional limitations, initiate treatment with a conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drug. If the disease remains active, consider biologic agents.

Case studies

Mild-to-moderate psoriasis

Patient A is a 19-year-old woman presenting for evaluation of a persistently dry, flaking scalp. She has had the itchy scalp for years, as well as several small “patches” across her elbows, legs, knees, and abdomen. Over-the-counter emollients have not helped. The patient also says she has had brittle nails on several of her fingers, which she keeps covered with thick polish.

Continue to: The condition exemplified...

The condition exemplified by Patient A can typically be managed with topical products.

Topical steroids may be classified by different delivery vehicles, active ingredients, and potencies. The National Psoriasis Foundation's Topical Steroids Potency Chart can provide guidance (visit www.psoriasis.org/about-psoriasis/treatments/topicals/steroids/potency-chart and scroll down). Prescribing an appropriate amount is important; the standard 30-g prescription tube is generally required to cover the entire skin surface. Ointments have a greasy consistency (typically a petroleum base), which enhances potency and hydrates the skin. Creams and lotions are easier to rub on and spread. Gels are alcohol based and readily absorbed.16 Solutions, foams, and shampoos are particularly useful to treat psoriasis in hairy areas such as the scalp.

Corticosteroid potency ranges from Class I to Class VII, with the former being the most potent. While TCS products are typically effective with minimal systemic absorption, it is important to counsel patients on the risk of skin atrophy, impaired wound healing, and skin pigmentation changes with chronic use. With nail psoriasis, a potent topical steroid (including flurandrenolide [Cordran] tape) applied to the proximal nail fold has shown benefit.20

Topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs; eg, tacrolimus ointment and pimecrolimus cream) are anti-inflammatory agents often used in conjunction with topical steroids to minimize steroid use and associated adverse effects.15 A possible steroid-sparing regimen includes using a TCI Monday through Friday and a topical steroid on the weekend.

Topical vitamin D analogs (calcipotriene, calcipotriol, calcitriol) inhibit proliferation of keratinocytes and decrease the production of inflammatory mediators.15,17-19,21 Application of a vitamin D analog in combination with a high-potency TCS, systemic treatment, or phototherapy can provide greater efficacy, a more rapid onset of action, and less irritation than can the vitamin D analog used alone.21 If used in combination with UV light, apply topical vitamin D after the light therapy to prevent degradation.

Continue to: UV light therapy

UV light therapy is often used in cases refractory to topical therapy. Patients are typically prescribed 2 to 3 treatments per week with narrowband UVB (311-313 nm), the excimer laser (308 nm), or, less commonly, PUVA (UV treatment with psoralens). Treatment begins with a minimal erythema dose—the lowest dose to achieve minimal erythema of the skin before burning. When that is determined, exposure is increased as needed—depending on the response. If this is impractical or too time-consuming for the patient, an alternative recommendation would be increased exposure to natural sunlight or even use of a tanning booth. However, patients must then be cautioned about the increased risk of skin cancer.

Refractory/severe psoriasis

Patient B is a 35-year-old man with a longstanding history of psoriasis affecting his scalp and nails. Over the past 10 years, psoriatic lesions have also appeared and grown across his lower back, gluteal fold, legs, abdomen, and arms. He is now being evaluated by a rheumatologist for worsening symmetric joint pain that includes his lower back.

Methotrexate has been used to treat psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis since the 1950s. Methotrexate is a competitive inhibitor of dihydrofolate reductase and is typically given as an oral medication dosed once weekly with folic acid supplementation on the other 6 days.17 The most common adverse effects encountered with methotrexate are gastrointestinal upset and oral ulcers; however, routine monitoring for myelosuppression and hepatotoxicity is required.

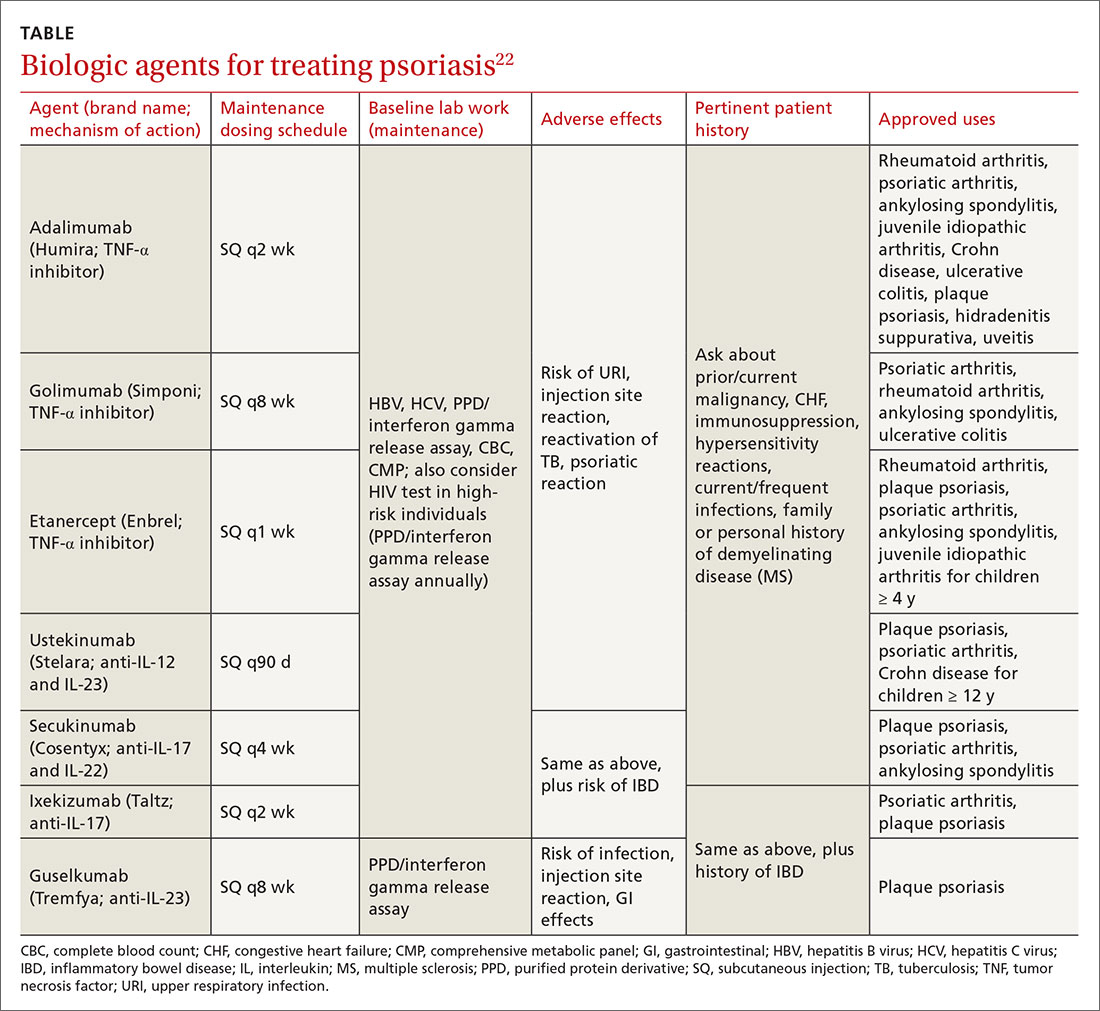

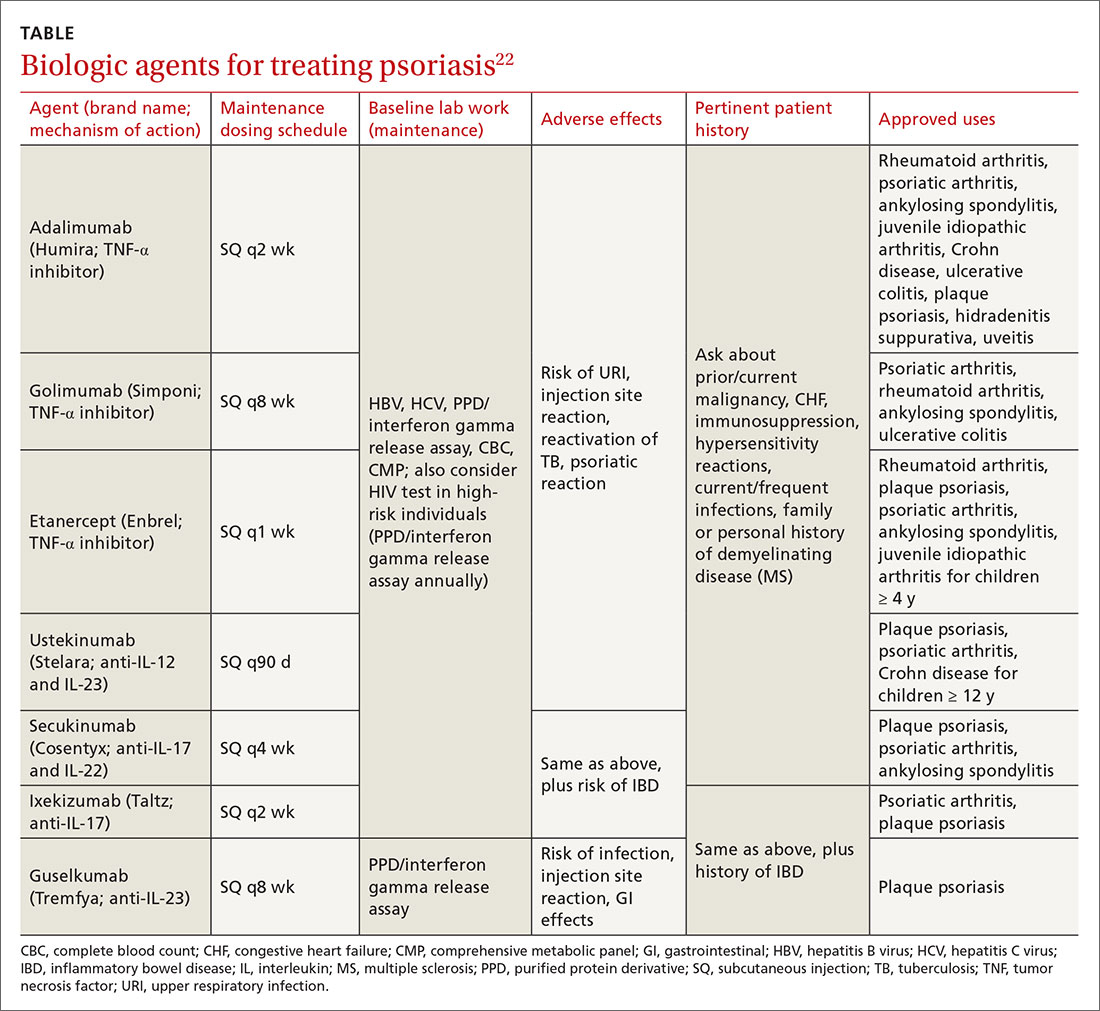

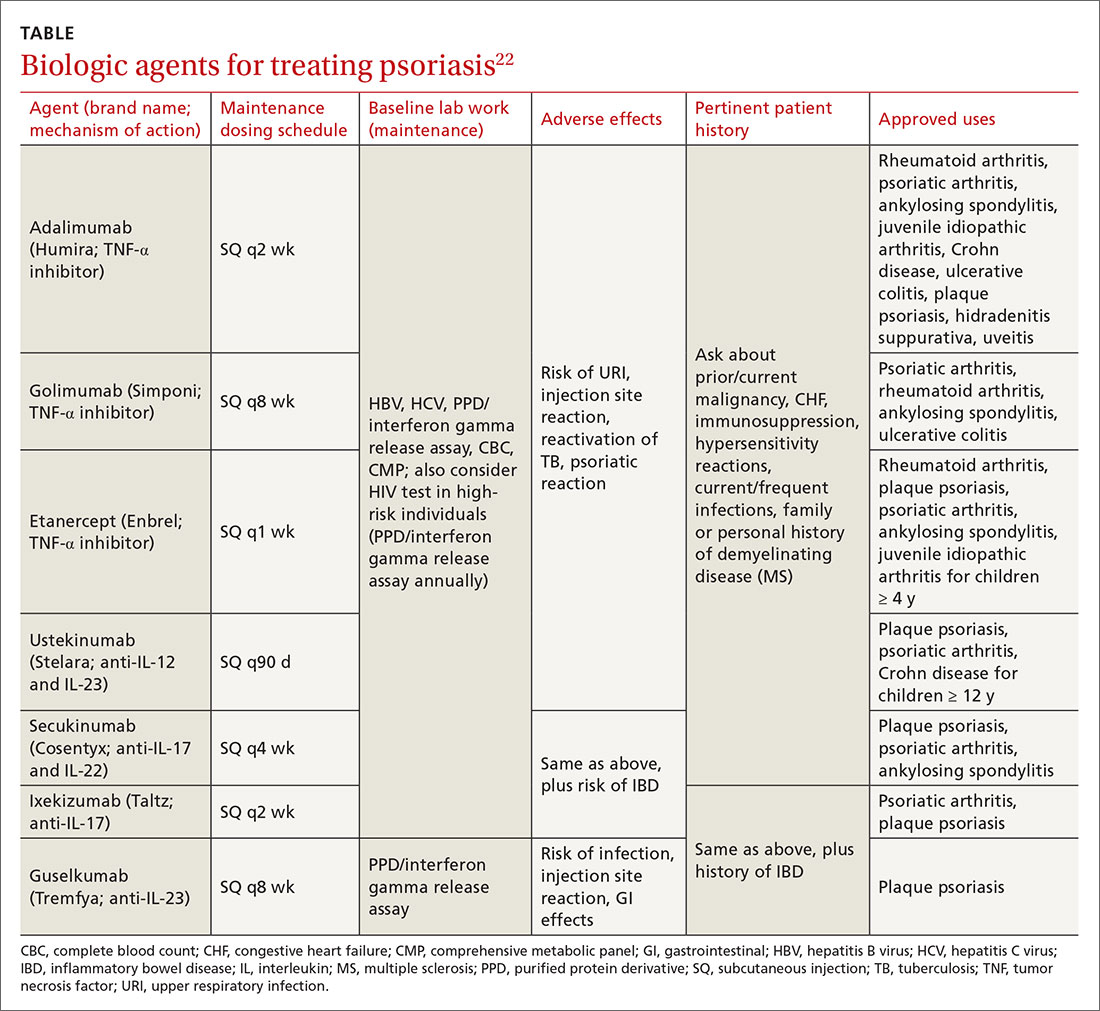

Biologic therapy. When conventional therapies fail, immune-targeted treatment with “biologics” may be initiated. As knowledge of signaling pathways and the immunopathogenesis of psoriasis has increased, so has the number of biologic agents, which are generally well tolerated and effective in managing plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Although their use, which requires monitoring, is handled primarily by specialists, familiarizing yourself with available agents can be helpful (TABLE).22

Nutritional modification and supplementation in treating skin disease still requires further investigation. Fish oil has shown benefit for cutaneous psoriasis in randomized controlled trials.7,8 Oral vitamin D supplementation requires further study, whereas selenium and B12 supplementation have not conferred consistent benefit.7 Given that several studies have demonstrated a relationship between body mass index and psoriatic disease severity, weight loss may be helpful in the management of psoriasis as well as psoriatic arthritis.8

Continue to: Other systemic agents

Other systemic agents—for individuals who cannot tolerate the biologic agents—include acitretin, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and cyclosporine.15,17

Paradoxical psoriatic reactions

When a psoriatic condition develops during biologic drug therapy, it is known as a paradoxical psoriatic reaction. The onset of de novo psoriasis has been documented during TNF-α inhibitor therapy for individuals with underlying rheumatoid arthritis.23 Skin biopsy reveals the same findings as common plaque psoriasis.

Using immunosuppressive Tx? Screen for tuberculosis

Testing to exclude a diagnosis of latent or undiagnosed tuberculosis must be performed prior to initiating immunosuppressive therapy with methotrexate or a biologic agent. Tuberculin skin testing, QuantiFERON-TB gold test, and the T-SPOT.TB test are accepted screening modalities. Discordance between tuberculin skin tests and the interferon gamma release assays in latent TB highlights the need for further study using the available QuantiFERON-TB gold test and the T-SPOT.TB test.24

CORRESPONDENCE

Karl T. Clebak, MD, FAAFP, Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Department of Family and Community Medicine, 500 University Drive, Hershey, PA 17033; [email protected].

1. Jackson R. John Updike on psoriasis. At war with my skin, from the journal of a leper. J Cutan Med Surg. 2000;4:113-115.

2. Gelfand JM, Weinstein R, Porter SB, et al. Prevalence and treatment of psoriasis in the United Kingdom: a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1537-1541.

3. Helmick CG, Lee-Han H, Hirsch SC, et al. Prevalence of psoriasis among adults in the U.S.: 2003-2006 and 2009-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47:37-45.

4. Alexander H, Nestle FO. Pathogenesis and immunotherapy in cutaneous psoriasis: what can rheumatologists learn? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2017;29:71-78.

5. Fahlén A, Engstrand L, Baker BS, et al. Comparison of bacterial microbiota in skin biopsies from normal and psoriatic skin. Arch Dermatol Res. 2012;304:15-22.

6. Takeshita J, Grewal S, Langan SM, et al. Psoriasis and comorbid diseases: epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:377-390.

7. Millsop JW, Bhatia BK, Debbaneh M, et al. Diet and psoriasis, part III: role of nutritional supplements. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:561-569.

8. Debbaneh M, Millsop JW, Bhatia BK, et al. Diet and psoriasis, part I: impact of weight loss interventions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:133-140.

9. Bhatia BK, Millsop JW, Debbaneh M, et al. Diet and psoriasis, part II: celiac disease and role of a gluten-free diet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:350-358.

10. Fry L, Baker BS. Triggering psoriasis: the role of infections and medications. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:606-615.

11. Singh RK, Lee KM, Ucmak D, et al. Erythrodermic psoriasis: pathophysiology and current treatment perspectives. Psoriasis (Aukl). 2016;6:93-104.

12. Garg A, Gladman D. Recognizing psoriatic arthritis in the dermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:733-748.

13. McGonagle D, Hermann KG, Tan AL. Differentiation between osteoarthritis and psoriatic arthritis: implications for pathogenesis and treatment in the biologic therapy era. Rheumatology. 2015;54:29-38.

14. Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ. Drug-provoked psoriasis: is it drug induced or drug aggravated?: understanding pathophysiology and clinical relevance. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:32-38.

15. Kupetsky EA, Keller M. Psoriasis vulgaris: an evidence-based guide for primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:787-801.

16. Helm MF, Farah JB, Carvalho M, et al. Compounded topical medications for diseases of the skin: a long tradition still relevant today. N Am J Med Sci. 2017;10:116-118.

17. Weigle N, McBane S. Psoriasis. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:626-633.

18. Helfrich YR, Sachs DL, Kang S. Topical vitamin D3. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2007:691-695.

19. Lebwohl M, Siskin SB, Epinette W, et al. A multicenter trial of calcipotriene ointment and halobetasol ointment compared with either agent alone for the treatment of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:268-269.