User login

Recent-onset bloody nodule

A 45-year-old man presented to the Dermatology Clinic with a 4-month history of a bump on his left upper back. The lesion was tender and had been draining clear fluid and intermittent blood; he denied any preceding trauma. He had been seen both by his primary care physician and by a physician at an urgent care clinic, where he was told to use an antibiotic ointment and benzoyl peroxide daily on the area and advised to seek a dermatology consult should it not resolve. He did not see any improvement from these measures.

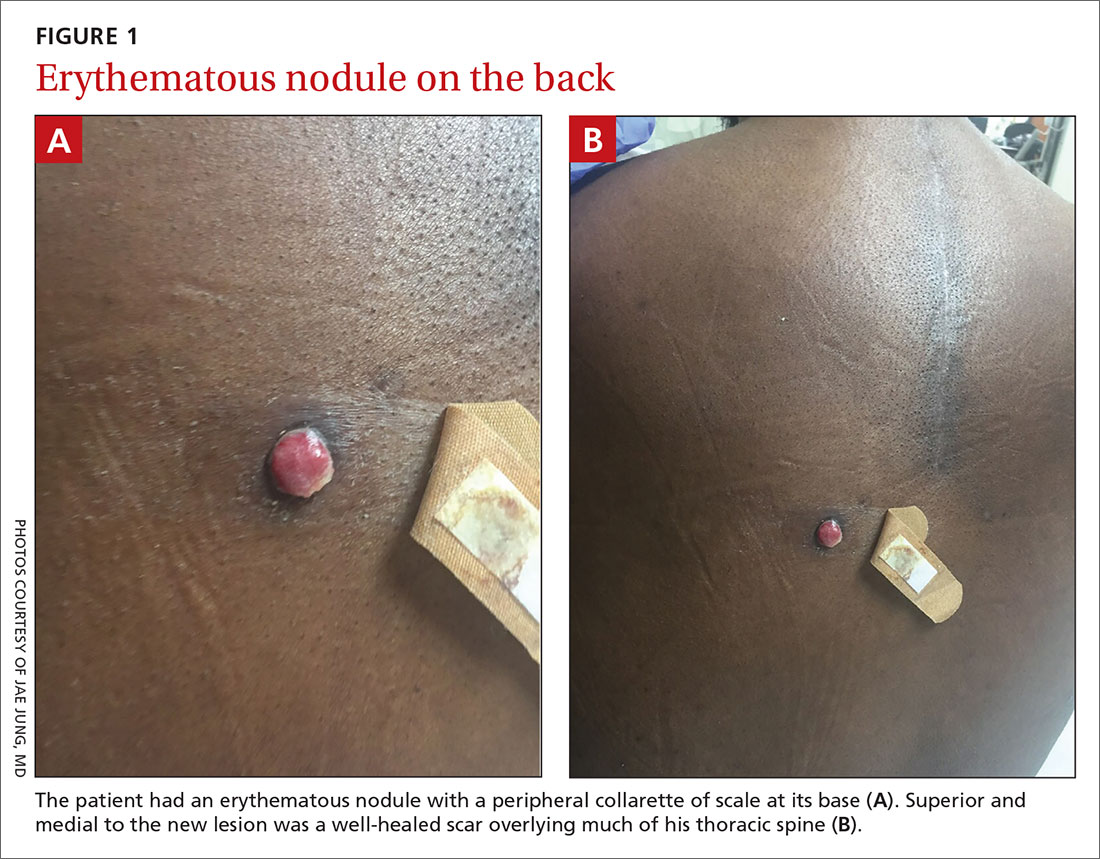

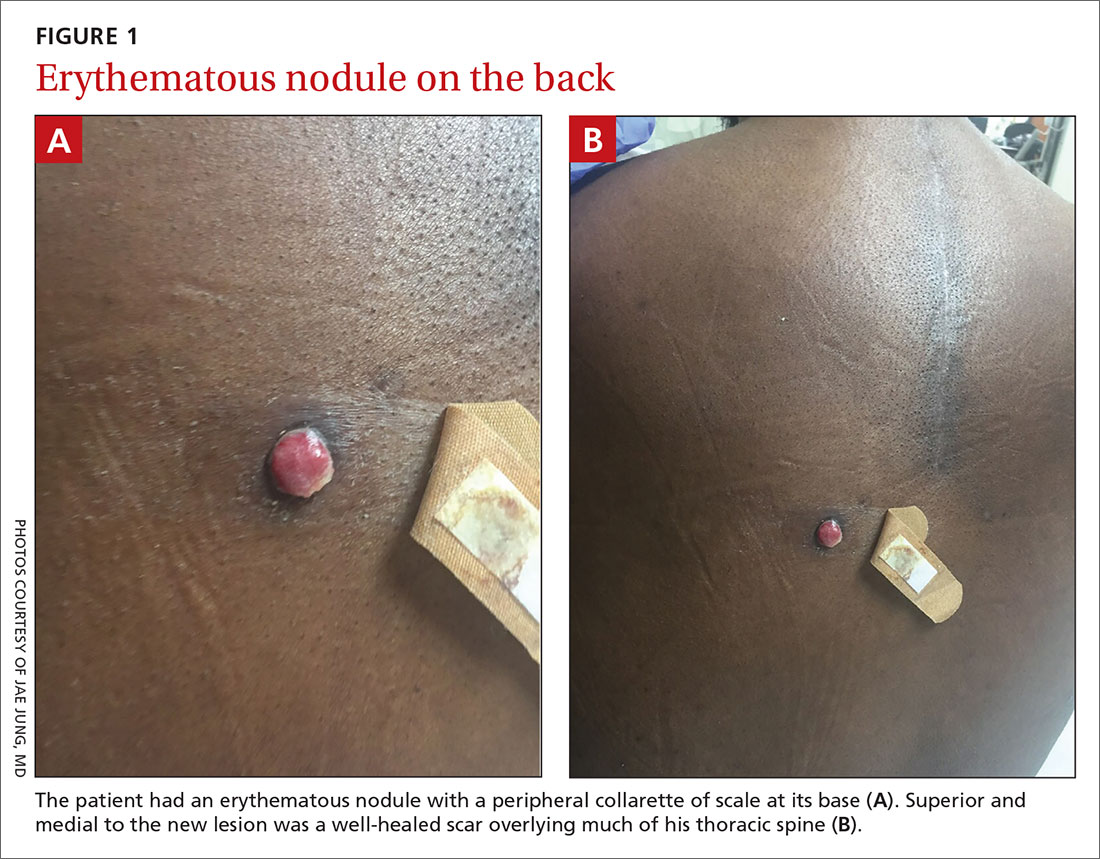

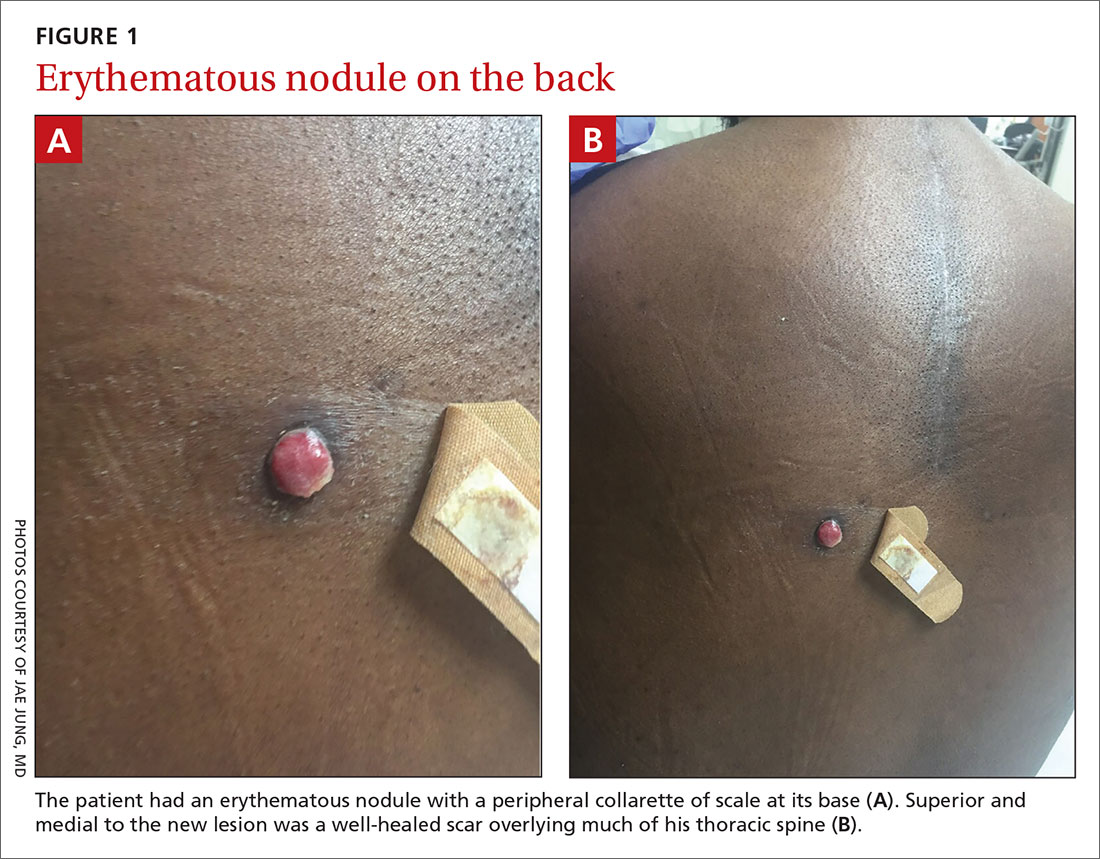

Physical exam revealed a 0.8-cm erythematous nodule with a peripheral collarette of scale at its base. The bandage used to cover the nodule was stained with hemorrhagic crust (FIGURE 1A). Superior and medial to the new lesion was a well-healed scar overlying much of the patient’s thoracic spine (FIGURE 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Metastatic renal cell carcinoma

The nodule initially appeared to be a benign pyogenic granuloma. In fact, a biopsy of the nodule showed a profile similar to that of a pyogenic granuloma and it exhibited granulation tissue. However, further questioning revealed that the patient had a history of metastatic clear cell renal carcinoma. (The scar was from a prior unrelated orthopedic surgery.) Immunohistochemical stains showed positive staining in the cells of interest for PAX8 and CK8, 2 markers for renal cell lineage.

Cutaneous metastasis to the skin is a rare event, representing roughly 2% of all skin tumors.1 Anatomically, lesions tend to appear on the head and neck in men and anterior chest and abdomen in women.2 Eruptions on the back, as seen in our patient, are relatively rare. The primary source of the metastasis also is gender dependent. Melanoma is the most common source overall; but in women, breast cancer represents the large majority of cutaneous metastases3 while in men lung, large intestine, and oral cavity tumors are the most common origin.3 Renal metastases are the fourth most common cause in men.3

The clinical morphology of cutaneous metastases is protean; the most common manifestations are nodules, papules, plaques, tumors, and ulcers.2 Rare manifestations include alopecia plaques, erysipelas, herpes zoster–like eruptions,4 and pyogenic granuloma–like manifestations, as in our case. Pyogenic granuloma–like manifestations have been described in renal cell carcinoma, breast carcinoma, acute myelogenous leukemia,5 and hepatocellular carcinoma.6

Differential includes an array of erythematous nodules

The differential diagnosis of a lesion with the appearance of a pyogenic granuloma is variable.

Pyogenic granulomas tend to arise over a short period of time. They are more common in children and pregnant women. Pyogenic granulomas can manifest anywhere but often are reported on the digits and extremities. Clinical history is important to ensure no history of internal malignancy.

Continue to: Bartonella henselae

Bartonella henselae, known as “cat scratch disease,” also can present as a friable, erythematous nodule reminiscent of a pyogenic granuloma. Patients with bartonella henselae usually are immunocompromised and/or have had close contact with a cat.7

Kaposi sarcoma is a vascular tumor that may manifest as erythematous papules or nodules. Erythematous or violaceous patches or plaques may be present before a nodule arises. Kaposi sarcoma may manifest on the legs of elderly patients or anywhere on immunocompromised patients. Immunohistochemical stains for human herpesvirus-8 can clinch the diagnosis.8

Amelanotic melanoma may be impossible to discern clinically from a pyogenic granuloma. It appears as erythematous, violaceous, or flesh-colored nodules. Histologic evaluation is paramount in the diagnosis.9

Clinical suspicion should prompt a biopsy

The diagnosis of metastatic renal cell carcinoma is made on clinical suspicion and skin biopsy. Dermoscopy is an important tool in the evaluation of primary cutaneous tumors. Due to the rarity of cutaneous metastases, studies on dermoscopic findings in cutaneous metastases are limited to case series. One series showed a vascular dermoscopy pattern in 15 of 17 cases (88%).10

In light of this nonspecific pattern, it’s wise to consider biopsy of a pyogenic granuloma–like lesion or one with a vascular pattern on dermoscopy in any patient with a history of malignancy. Any lesion suspected of being a pyogenic granuloma that does not respond to conservative measures also would warrant a biopsy. Definitive diagnosis is made based upon histologic evaluation.

Continue to: Surgery is the cornerstone of treatment

Surgery is the cornerstone of treatment

Upon diagnosis, immediate referral for further local and systemic control is recommended. Treatment may consist of any combination of surgery, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or radiation.11

In this case, our patient was referred to Oncology for further treatment. Unfortunately, cutaneous metastases portend a very poor prognosis, with approximate survival times of 7.5 months.12

CORRESPONDENCE

M. Tye Haeberle, MD, 3810 Springhurst Boulevard, Ste 200, Louisville, KY 40241; [email protected]

1. Nashan D, Meiss F, Braun-Flaco M, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:567-580.

2. Alcaraz IM, Cerroni LM, Rütten AM, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

3. Lookingbill D, Spangler N, Helm K. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

4. Hussein MR. Skin metastases: a pathologist’s perspective. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:E1-E20.

5. Hager C, Cohen P. Cutaneous lesions of metastatic visceral malignancy mimicking pyogenic granuloma. Cancer Invest. 1999;17:385-390.

6. Kubota Y, Koga T, Nakayama J. Cutaneous metastasis from hepatocellular carcinoma resembling pyogenic granuloma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1999;24:78-80.

7. Anderson BE, Neuman MA. Bartonella spp. as emerging human pathogens. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:203-219.

8. Patel RM, Goldblum JR, Hsi ED. Immunohistochemical detection of human herpes virus-8 latent nuclear antigen-1 is useful in the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:456-460.

9. Wee E, Wolfe R, Mclean C, et al. Clinically amelanotic or hypomelanotic melanoma: anatomic distribution, risk factors, and survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:645-651.

10. Chernoff K, Marghoob A, Lacouture M, et al. Dermoscopic findings in cutaneous metastases. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;4:429-433.

11. Adibi M, Thomas AZ, Borregales LD, et al. Surgical considerations for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2015;33:528-537.

12. Saeed S, Keehm C, Morgan M. Cutaneous metastases: a clinical, pathological and immunohistochemical appraisal. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;31:419-430.

A 45-year-old man presented to the Dermatology Clinic with a 4-month history of a bump on his left upper back. The lesion was tender and had been draining clear fluid and intermittent blood; he denied any preceding trauma. He had been seen both by his primary care physician and by a physician at an urgent care clinic, where he was told to use an antibiotic ointment and benzoyl peroxide daily on the area and advised to seek a dermatology consult should it not resolve. He did not see any improvement from these measures.

Physical exam revealed a 0.8-cm erythematous nodule with a peripheral collarette of scale at its base. The bandage used to cover the nodule was stained with hemorrhagic crust (FIGURE 1A). Superior and medial to the new lesion was a well-healed scar overlying much of the patient’s thoracic spine (FIGURE 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Metastatic renal cell carcinoma

The nodule initially appeared to be a benign pyogenic granuloma. In fact, a biopsy of the nodule showed a profile similar to that of a pyogenic granuloma and it exhibited granulation tissue. However, further questioning revealed that the patient had a history of metastatic clear cell renal carcinoma. (The scar was from a prior unrelated orthopedic surgery.) Immunohistochemical stains showed positive staining in the cells of interest for PAX8 and CK8, 2 markers for renal cell lineage.

Cutaneous metastasis to the skin is a rare event, representing roughly 2% of all skin tumors.1 Anatomically, lesions tend to appear on the head and neck in men and anterior chest and abdomen in women.2 Eruptions on the back, as seen in our patient, are relatively rare. The primary source of the metastasis also is gender dependent. Melanoma is the most common source overall; but in women, breast cancer represents the large majority of cutaneous metastases3 while in men lung, large intestine, and oral cavity tumors are the most common origin.3 Renal metastases are the fourth most common cause in men.3

The clinical morphology of cutaneous metastases is protean; the most common manifestations are nodules, papules, plaques, tumors, and ulcers.2 Rare manifestations include alopecia plaques, erysipelas, herpes zoster–like eruptions,4 and pyogenic granuloma–like manifestations, as in our case. Pyogenic granuloma–like manifestations have been described in renal cell carcinoma, breast carcinoma, acute myelogenous leukemia,5 and hepatocellular carcinoma.6

Differential includes an array of erythematous nodules

The differential diagnosis of a lesion with the appearance of a pyogenic granuloma is variable.

Pyogenic granulomas tend to arise over a short period of time. They are more common in children and pregnant women. Pyogenic granulomas can manifest anywhere but often are reported on the digits and extremities. Clinical history is important to ensure no history of internal malignancy.

Continue to: Bartonella henselae

Bartonella henselae, known as “cat scratch disease,” also can present as a friable, erythematous nodule reminiscent of a pyogenic granuloma. Patients with bartonella henselae usually are immunocompromised and/or have had close contact with a cat.7

Kaposi sarcoma is a vascular tumor that may manifest as erythematous papules or nodules. Erythematous or violaceous patches or plaques may be present before a nodule arises. Kaposi sarcoma may manifest on the legs of elderly patients or anywhere on immunocompromised patients. Immunohistochemical stains for human herpesvirus-8 can clinch the diagnosis.8

Amelanotic melanoma may be impossible to discern clinically from a pyogenic granuloma. It appears as erythematous, violaceous, or flesh-colored nodules. Histologic evaluation is paramount in the diagnosis.9

Clinical suspicion should prompt a biopsy

The diagnosis of metastatic renal cell carcinoma is made on clinical suspicion and skin biopsy. Dermoscopy is an important tool in the evaluation of primary cutaneous tumors. Due to the rarity of cutaneous metastases, studies on dermoscopic findings in cutaneous metastases are limited to case series. One series showed a vascular dermoscopy pattern in 15 of 17 cases (88%).10

In light of this nonspecific pattern, it’s wise to consider biopsy of a pyogenic granuloma–like lesion or one with a vascular pattern on dermoscopy in any patient with a history of malignancy. Any lesion suspected of being a pyogenic granuloma that does not respond to conservative measures also would warrant a biopsy. Definitive diagnosis is made based upon histologic evaluation.

Continue to: Surgery is the cornerstone of treatment

Surgery is the cornerstone of treatment

Upon diagnosis, immediate referral for further local and systemic control is recommended. Treatment may consist of any combination of surgery, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or radiation.11

In this case, our patient was referred to Oncology for further treatment. Unfortunately, cutaneous metastases portend a very poor prognosis, with approximate survival times of 7.5 months.12

CORRESPONDENCE

M. Tye Haeberle, MD, 3810 Springhurst Boulevard, Ste 200, Louisville, KY 40241; [email protected]

A 45-year-old man presented to the Dermatology Clinic with a 4-month history of a bump on his left upper back. The lesion was tender and had been draining clear fluid and intermittent blood; he denied any preceding trauma. He had been seen both by his primary care physician and by a physician at an urgent care clinic, where he was told to use an antibiotic ointment and benzoyl peroxide daily on the area and advised to seek a dermatology consult should it not resolve. He did not see any improvement from these measures.

Physical exam revealed a 0.8-cm erythematous nodule with a peripheral collarette of scale at its base. The bandage used to cover the nodule was stained with hemorrhagic crust (FIGURE 1A). Superior and medial to the new lesion was a well-healed scar overlying much of the patient’s thoracic spine (FIGURE 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Metastatic renal cell carcinoma

The nodule initially appeared to be a benign pyogenic granuloma. In fact, a biopsy of the nodule showed a profile similar to that of a pyogenic granuloma and it exhibited granulation tissue. However, further questioning revealed that the patient had a history of metastatic clear cell renal carcinoma. (The scar was from a prior unrelated orthopedic surgery.) Immunohistochemical stains showed positive staining in the cells of interest for PAX8 and CK8, 2 markers for renal cell lineage.

Cutaneous metastasis to the skin is a rare event, representing roughly 2% of all skin tumors.1 Anatomically, lesions tend to appear on the head and neck in men and anterior chest and abdomen in women.2 Eruptions on the back, as seen in our patient, are relatively rare. The primary source of the metastasis also is gender dependent. Melanoma is the most common source overall; but in women, breast cancer represents the large majority of cutaneous metastases3 while in men lung, large intestine, and oral cavity tumors are the most common origin.3 Renal metastases are the fourth most common cause in men.3

The clinical morphology of cutaneous metastases is protean; the most common manifestations are nodules, papules, plaques, tumors, and ulcers.2 Rare manifestations include alopecia plaques, erysipelas, herpes zoster–like eruptions,4 and pyogenic granuloma–like manifestations, as in our case. Pyogenic granuloma–like manifestations have been described in renal cell carcinoma, breast carcinoma, acute myelogenous leukemia,5 and hepatocellular carcinoma.6

Differential includes an array of erythematous nodules

The differential diagnosis of a lesion with the appearance of a pyogenic granuloma is variable.

Pyogenic granulomas tend to arise over a short period of time. They are more common in children and pregnant women. Pyogenic granulomas can manifest anywhere but often are reported on the digits and extremities. Clinical history is important to ensure no history of internal malignancy.

Continue to: Bartonella henselae

Bartonella henselae, known as “cat scratch disease,” also can present as a friable, erythematous nodule reminiscent of a pyogenic granuloma. Patients with bartonella henselae usually are immunocompromised and/or have had close contact with a cat.7

Kaposi sarcoma is a vascular tumor that may manifest as erythematous papules or nodules. Erythematous or violaceous patches or plaques may be present before a nodule arises. Kaposi sarcoma may manifest on the legs of elderly patients or anywhere on immunocompromised patients. Immunohistochemical stains for human herpesvirus-8 can clinch the diagnosis.8

Amelanotic melanoma may be impossible to discern clinically from a pyogenic granuloma. It appears as erythematous, violaceous, or flesh-colored nodules. Histologic evaluation is paramount in the diagnosis.9

Clinical suspicion should prompt a biopsy

The diagnosis of metastatic renal cell carcinoma is made on clinical suspicion and skin biopsy. Dermoscopy is an important tool in the evaluation of primary cutaneous tumors. Due to the rarity of cutaneous metastases, studies on dermoscopic findings in cutaneous metastases are limited to case series. One series showed a vascular dermoscopy pattern in 15 of 17 cases (88%).10

In light of this nonspecific pattern, it’s wise to consider biopsy of a pyogenic granuloma–like lesion or one with a vascular pattern on dermoscopy in any patient with a history of malignancy. Any lesion suspected of being a pyogenic granuloma that does not respond to conservative measures also would warrant a biopsy. Definitive diagnosis is made based upon histologic evaluation.

Continue to: Surgery is the cornerstone of treatment

Surgery is the cornerstone of treatment

Upon diagnosis, immediate referral for further local and systemic control is recommended. Treatment may consist of any combination of surgery, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or radiation.11

In this case, our patient was referred to Oncology for further treatment. Unfortunately, cutaneous metastases portend a very poor prognosis, with approximate survival times of 7.5 months.12

CORRESPONDENCE

M. Tye Haeberle, MD, 3810 Springhurst Boulevard, Ste 200, Louisville, KY 40241; [email protected]

1. Nashan D, Meiss F, Braun-Flaco M, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:567-580.

2. Alcaraz IM, Cerroni LM, Rütten AM, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

3. Lookingbill D, Spangler N, Helm K. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

4. Hussein MR. Skin metastases: a pathologist’s perspective. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:E1-E20.

5. Hager C, Cohen P. Cutaneous lesions of metastatic visceral malignancy mimicking pyogenic granuloma. Cancer Invest. 1999;17:385-390.

6. Kubota Y, Koga T, Nakayama J. Cutaneous metastasis from hepatocellular carcinoma resembling pyogenic granuloma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1999;24:78-80.

7. Anderson BE, Neuman MA. Bartonella spp. as emerging human pathogens. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:203-219.

8. Patel RM, Goldblum JR, Hsi ED. Immunohistochemical detection of human herpes virus-8 latent nuclear antigen-1 is useful in the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:456-460.

9. Wee E, Wolfe R, Mclean C, et al. Clinically amelanotic or hypomelanotic melanoma: anatomic distribution, risk factors, and survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:645-651.

10. Chernoff K, Marghoob A, Lacouture M, et al. Dermoscopic findings in cutaneous metastases. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;4:429-433.

11. Adibi M, Thomas AZ, Borregales LD, et al. Surgical considerations for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2015;33:528-537.

12. Saeed S, Keehm C, Morgan M. Cutaneous metastases: a clinical, pathological and immunohistochemical appraisal. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;31:419-430.

1. Nashan D, Meiss F, Braun-Flaco M, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:567-580.

2. Alcaraz IM, Cerroni LM, Rütten AM, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

3. Lookingbill D, Spangler N, Helm K. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

4. Hussein MR. Skin metastases: a pathologist’s perspective. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:E1-E20.

5. Hager C, Cohen P. Cutaneous lesions of metastatic visceral malignancy mimicking pyogenic granuloma. Cancer Invest. 1999;17:385-390.

6. Kubota Y, Koga T, Nakayama J. Cutaneous metastasis from hepatocellular carcinoma resembling pyogenic granuloma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1999;24:78-80.

7. Anderson BE, Neuman MA. Bartonella spp. as emerging human pathogens. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:203-219.

8. Patel RM, Goldblum JR, Hsi ED. Immunohistochemical detection of human herpes virus-8 latent nuclear antigen-1 is useful in the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:456-460.

9. Wee E, Wolfe R, Mclean C, et al. Clinically amelanotic or hypomelanotic melanoma: anatomic distribution, risk factors, and survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:645-651.

10. Chernoff K, Marghoob A, Lacouture M, et al. Dermoscopic findings in cutaneous metastases. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;4:429-433.

11. Adibi M, Thomas AZ, Borregales LD, et al. Surgical considerations for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2015;33:528-537.

12. Saeed S, Keehm C, Morgan M. Cutaneous metastases: a clinical, pathological and immunohistochemical appraisal. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;31:419-430.

How to responsibly engage with social media during disasters

A few months into the COVID-19 pandemic, social media’s role in the rapid spread of information is undeniable. From the beginning, Chinese ophthalmologist Li Wenliang, MD, first raised the alarm to his classmates through WeChat, a messaging and social media app. Since that time, individuals, groups, organizations, government agencies, and mass media outlets have used social media to share ideas and disseminate information. Individuals check in on loved ones and update others on their own safety. Networks of clinicians discuss patient presentations, new therapeutics, management strategies, and institutional protocols. Multiple organizations including the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the World Health Organization use Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter accounts to provide updates on ongoing efforts and spread public health messaging.

Unfortunately, not all information is trustworthy. Social media outlets have been used to spread misinformation and conspiracy theories, and to promote false treatments. Google, YouTube, and Facebook are now actively trying to reduce the viral spread of misleading information and to block hoaxes. With the increasing amount of news and information consumed and disseminated via social media, clinicians need to critically appraise information presented on those platforms, and to be familiar with how to use them to disseminate informed, effective, and responsible information.

Appraisal of social media content

Traditional scholarly communication exists in many forms and includes observations, anecdotes, perspectives, case reports, and research. Each form involves differing levels of academic rigor and standards of evaluation. Electronic content and online resources pose a unique challenge because there is no standardized method for assessing impact and quality. Proposed scales for evaluation of online resources such as Medical Education Translational Resources: Impact and Quality (METRIQ),1 Academic Life in Emergency Medicine Approved Instructional Resources (AliEM AIR) scoring system,2 and the Social Media Index3 are promising and can be used to guide critical appraisal of social media content.

The same skepticism and critical thinking applied to traditional resources should be applied when evaluating online resources. The scales listed above include questions such as:

- How accurate is the data presented and conclusions drawn?

- Does the content reflect evidence-based medicine?

- Has the content undergone an editorial process?

- Who are the authors and what are their credentials?

- Are there potential biases or conflicts of interest present?

- Have references been cited?

- How does this content affect/change clinical practice?

While these proposed review metrics may not apply to all forms of social media content, clinicians should be discerning when consuming or disseminating online content.

Strategies for effective communication on social media

In addition to appraising social media content, clinicians also should be able to craft effective messages on social media to spread trustworthy content. The CDC offers guidelines and best practices for social media communication4,5 and the WHO has created a framework for effective communications.6 Both organizations recognize social media as a powerful communication tool that has the potential to greatly impact public health efforts.

Some key principles highlighted from these sources include the following:

- Identify an audience and make messages relevant. Taking time to listen to key stakeholders within the target audience (individuals, health care providers, communities, policy-makers, organizations) allows for better understanding of baseline knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs that may drive concerns and ultimately helps to tailor the messaging.

- Make messages accessible. Certain social media platforms are more often utilized for specific target audiences. Verbiage used should take into account the health literacy of the audience. A friendly, professional, conversational tone encourages interaction and dialogue.

- Engage the audience by offering something actionable. Changing behavior is a daunting task that involves multiple steps. Encouraging behavioral changes initially at an individual level has the potential to influence community practices and policies.

- Communication should be timely. It should address current and urgent topics. Keep abreast of the situation as it evolves to ensure messaging stays relevant. Deliver consistent messaging and updates.

- Sources must be credible. It is important to be transparent about expertise and honest about what is known and unknown about the topic.

- Content should be understandable. In addition to using plain language, visual aids and real stories can be used to reinforce messages.

Use social media responsibly

Clinicians have a responsibility to use social media to disseminate credible content, refute misleading content, and create accurate content. When clinicians share health-related information via social media, it should be appraised skeptically and crafted responsibly because that message can have profound implications on public health. Mixed messaging that is contradictory, inconsistent, or unclear can lead to panic and confusion. By recognizing the important role of social media in access to information and as a tool for public health messaging and crisis communication, clinicians have an obligation to consider both the positive and negative impacts as messengers in that space.

Dr. Ren is a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at Children’s National Hospital, Washington. Dr. Simpson is a pediatric emergency medicine attending and medical director of emergency preparedness of Children’s National Hospital. They do not have any disclosures or conflicts of interest. Email Dr. Ren and Dr. Simpson at [email protected].

References

1. AEM Educ Train. 2019;3(4):387-92.

2. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68(6):729-35.

3. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;72(6):696-702.

4. CDC Guide to Writing for Social Media.

5. The Health Communicator’s Social Media Toolkit.

6. WHO Strategic Communications Framework for effective communications.

A few months into the COVID-19 pandemic, social media’s role in the rapid spread of information is undeniable. From the beginning, Chinese ophthalmologist Li Wenliang, MD, first raised the alarm to his classmates through WeChat, a messaging and social media app. Since that time, individuals, groups, organizations, government agencies, and mass media outlets have used social media to share ideas and disseminate information. Individuals check in on loved ones and update others on their own safety. Networks of clinicians discuss patient presentations, new therapeutics, management strategies, and institutional protocols. Multiple organizations including the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the World Health Organization use Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter accounts to provide updates on ongoing efforts and spread public health messaging.

Unfortunately, not all information is trustworthy. Social media outlets have been used to spread misinformation and conspiracy theories, and to promote false treatments. Google, YouTube, and Facebook are now actively trying to reduce the viral spread of misleading information and to block hoaxes. With the increasing amount of news and information consumed and disseminated via social media, clinicians need to critically appraise information presented on those platforms, and to be familiar with how to use them to disseminate informed, effective, and responsible information.

Appraisal of social media content

Traditional scholarly communication exists in many forms and includes observations, anecdotes, perspectives, case reports, and research. Each form involves differing levels of academic rigor and standards of evaluation. Electronic content and online resources pose a unique challenge because there is no standardized method for assessing impact and quality. Proposed scales for evaluation of online resources such as Medical Education Translational Resources: Impact and Quality (METRIQ),1 Academic Life in Emergency Medicine Approved Instructional Resources (AliEM AIR) scoring system,2 and the Social Media Index3 are promising and can be used to guide critical appraisal of social media content.

The same skepticism and critical thinking applied to traditional resources should be applied when evaluating online resources. The scales listed above include questions such as:

- How accurate is the data presented and conclusions drawn?

- Does the content reflect evidence-based medicine?

- Has the content undergone an editorial process?

- Who are the authors and what are their credentials?

- Are there potential biases or conflicts of interest present?

- Have references been cited?

- How does this content affect/change clinical practice?

While these proposed review metrics may not apply to all forms of social media content, clinicians should be discerning when consuming or disseminating online content.

Strategies for effective communication on social media

In addition to appraising social media content, clinicians also should be able to craft effective messages on social media to spread trustworthy content. The CDC offers guidelines and best practices for social media communication4,5 and the WHO has created a framework for effective communications.6 Both organizations recognize social media as a powerful communication tool that has the potential to greatly impact public health efforts.

Some key principles highlighted from these sources include the following:

- Identify an audience and make messages relevant. Taking time to listen to key stakeholders within the target audience (individuals, health care providers, communities, policy-makers, organizations) allows for better understanding of baseline knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs that may drive concerns and ultimately helps to tailor the messaging.

- Make messages accessible. Certain social media platforms are more often utilized for specific target audiences. Verbiage used should take into account the health literacy of the audience. A friendly, professional, conversational tone encourages interaction and dialogue.

- Engage the audience by offering something actionable. Changing behavior is a daunting task that involves multiple steps. Encouraging behavioral changes initially at an individual level has the potential to influence community practices and policies.

- Communication should be timely. It should address current and urgent topics. Keep abreast of the situation as it evolves to ensure messaging stays relevant. Deliver consistent messaging and updates.

- Sources must be credible. It is important to be transparent about expertise and honest about what is known and unknown about the topic.

- Content should be understandable. In addition to using plain language, visual aids and real stories can be used to reinforce messages.

Use social media responsibly

Clinicians have a responsibility to use social media to disseminate credible content, refute misleading content, and create accurate content. When clinicians share health-related information via social media, it should be appraised skeptically and crafted responsibly because that message can have profound implications on public health. Mixed messaging that is contradictory, inconsistent, or unclear can lead to panic and confusion. By recognizing the important role of social media in access to information and as a tool for public health messaging and crisis communication, clinicians have an obligation to consider both the positive and negative impacts as messengers in that space.

Dr. Ren is a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at Children’s National Hospital, Washington. Dr. Simpson is a pediatric emergency medicine attending and medical director of emergency preparedness of Children’s National Hospital. They do not have any disclosures or conflicts of interest. Email Dr. Ren and Dr. Simpson at [email protected].

References

1. AEM Educ Train. 2019;3(4):387-92.

2. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68(6):729-35.

3. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;72(6):696-702.

4. CDC Guide to Writing for Social Media.

5. The Health Communicator’s Social Media Toolkit.

6. WHO Strategic Communications Framework for effective communications.

A few months into the COVID-19 pandemic, social media’s role in the rapid spread of information is undeniable. From the beginning, Chinese ophthalmologist Li Wenliang, MD, first raised the alarm to his classmates through WeChat, a messaging and social media app. Since that time, individuals, groups, organizations, government agencies, and mass media outlets have used social media to share ideas and disseminate information. Individuals check in on loved ones and update others on their own safety. Networks of clinicians discuss patient presentations, new therapeutics, management strategies, and institutional protocols. Multiple organizations including the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the World Health Organization use Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter accounts to provide updates on ongoing efforts and spread public health messaging.

Unfortunately, not all information is trustworthy. Social media outlets have been used to spread misinformation and conspiracy theories, and to promote false treatments. Google, YouTube, and Facebook are now actively trying to reduce the viral spread of misleading information and to block hoaxes. With the increasing amount of news and information consumed and disseminated via social media, clinicians need to critically appraise information presented on those platforms, and to be familiar with how to use them to disseminate informed, effective, and responsible information.

Appraisal of social media content

Traditional scholarly communication exists in many forms and includes observations, anecdotes, perspectives, case reports, and research. Each form involves differing levels of academic rigor and standards of evaluation. Electronic content and online resources pose a unique challenge because there is no standardized method for assessing impact and quality. Proposed scales for evaluation of online resources such as Medical Education Translational Resources: Impact and Quality (METRIQ),1 Academic Life in Emergency Medicine Approved Instructional Resources (AliEM AIR) scoring system,2 and the Social Media Index3 are promising and can be used to guide critical appraisal of social media content.

The same skepticism and critical thinking applied to traditional resources should be applied when evaluating online resources. The scales listed above include questions such as:

- How accurate is the data presented and conclusions drawn?

- Does the content reflect evidence-based medicine?

- Has the content undergone an editorial process?

- Who are the authors and what are their credentials?

- Are there potential biases or conflicts of interest present?

- Have references been cited?

- How does this content affect/change clinical practice?

While these proposed review metrics may not apply to all forms of social media content, clinicians should be discerning when consuming or disseminating online content.

Strategies for effective communication on social media

In addition to appraising social media content, clinicians also should be able to craft effective messages on social media to spread trustworthy content. The CDC offers guidelines and best practices for social media communication4,5 and the WHO has created a framework for effective communications.6 Both organizations recognize social media as a powerful communication tool that has the potential to greatly impact public health efforts.

Some key principles highlighted from these sources include the following:

- Identify an audience and make messages relevant. Taking time to listen to key stakeholders within the target audience (individuals, health care providers, communities, policy-makers, organizations) allows for better understanding of baseline knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs that may drive concerns and ultimately helps to tailor the messaging.

- Make messages accessible. Certain social media platforms are more often utilized for specific target audiences. Verbiage used should take into account the health literacy of the audience. A friendly, professional, conversational tone encourages interaction and dialogue.

- Engage the audience by offering something actionable. Changing behavior is a daunting task that involves multiple steps. Encouraging behavioral changes initially at an individual level has the potential to influence community practices and policies.

- Communication should be timely. It should address current and urgent topics. Keep abreast of the situation as it evolves to ensure messaging stays relevant. Deliver consistent messaging and updates.

- Sources must be credible. It is important to be transparent about expertise and honest about what is known and unknown about the topic.

- Content should be understandable. In addition to using plain language, visual aids and real stories can be used to reinforce messages.

Use social media responsibly

Clinicians have a responsibility to use social media to disseminate credible content, refute misleading content, and create accurate content. When clinicians share health-related information via social media, it should be appraised skeptically and crafted responsibly because that message can have profound implications on public health. Mixed messaging that is contradictory, inconsistent, or unclear can lead to panic and confusion. By recognizing the important role of social media in access to information and as a tool for public health messaging and crisis communication, clinicians have an obligation to consider both the positive and negative impacts as messengers in that space.

Dr. Ren is a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at Children’s National Hospital, Washington. Dr. Simpson is a pediatric emergency medicine attending and medical director of emergency preparedness of Children’s National Hospital. They do not have any disclosures or conflicts of interest. Email Dr. Ren and Dr. Simpson at [email protected].

References

1. AEM Educ Train. 2019;3(4):387-92.

2. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68(6):729-35.

3. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;72(6):696-702.

4. CDC Guide to Writing for Social Media.

5. The Health Communicator’s Social Media Toolkit.

6. WHO Strategic Communications Framework for effective communications.

Performance of the Veterans Choice Program for Improving Access to Colonoscopy at a Tertiary VA Facility

In April 2014, amid concerns for long wait times for care within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act was signed into law. This included the Veterans Choice Program (VCP), which included a provision for veterans to be referred outside of the VA to the community for care if their nearest VHA facility could not provide the requested care within 30 days of the clinically indicated date.1 Since implementation of the VCP, both media outlets and policy researchers have raised concerns about both the timeliness and quality of care provided through this program.2-4

Specifically for colonoscopy, referral outside of the VA in the pre-VCP era resulted in lower adenoma detection rate (ADR) and decreased adherence to surveillance guidelines when compared with matched VA control colonoscopies, raising concerns about quality assurance.5 Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening and timely colonoscopy is a VA priority; however, the performance of the VCP for colonoscopy timelines and quality has not been examined in detail.

Methods

We identified 3,855 veterans at the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System (VAPHS) who were referred for colonoscopy in the community by using VCP from June 2015 through May 2017, using a query for colonoscopy procedure orders within the VA Corporate Data Warehouse. A total of 190 patients had a colonoscopy completed in the community by utilizing the VCP during this time frame.

At VAPHS, veterans who are referred for colonoscopy are contacted by a scheduler. The scheduler contacts the patient and offers the first available colonoscopy date at VAPHS and schedules the procedure for this date. However, if this date is > 30 days from the procedure order date, the scheduler gives the veteran the option of being contacted by VCP to schedule a colonoscopy within the community (Figure 1). We measured the time interval from the date of the initially scheduled first available colonoscopy at VAPHS to the date the colonoscopy was actually performed through VCP.

Quality assurance also was assessed by checking for the availability of records of colonoscopies performed through the VCP in the VA electronic health record (EHR) system. Colonoscopy procedure reports also were reviewed to assess for documentation of established colonoscopy quality metrics for examinations performed through the VCP. Additionally, we reviewed records scanned into the VA EHR pertaining to the VCP colonoscopy, including pathology information and pre- or postvisit records if available.

Data extraction was initiated in November 2017 to allow for at least 6 months of lead time for outside health records from the community to be received and scanned into the EHR for the veteran at VAPHS. For colonoscopy quality metrics, we chose 3 metrics that are universally documented for all colonoscopy procedures performed at VAPHS: quality of bowel preparation, cecal withdrawal time, and performance of retroflexion in the rectum. Documentation of these quality metrics is recommended in gastroenterology practice guidelinesand/or required by VA national policy.6,7

We separately reviewed a sample of 350 of the 3,855 patients referred for colonoscopy through VCP at VAPHS during the same time period to investigate overall VCP utilization. This sample was representative at a 95% CI with 5% margin of error of the total and sampled from 2 high-volume referral months (October and November 2015) and 3 low-volume months (January, February, and March 2017). Detailed data were collected regarding the colonoscopy scheduling and VCP referral process, including dates of colonoscopy procedure request; scheduling within the VAPHS; scheduling through the VCP; and ultimately if, when, and where (VAPHS vs community) a veteran had a colonoscopy performed. Wait times for colonoscopy procedures performed at the VAPHS and those performed through the VCP were compared.

The institutional review board at VAPHS reviewed and approved this quality improvement study.

Statistical Analysis

For the 190 veterans who had a colonoscopy performed through VCP, a 1-sample Wilcoxon signed rank test was used with a null hypothesis that the median difference in days between first available VAPHS colonoscopy and community colonoscopy dates was 0. For the utilization sample of 350 veterans, an independent samples median test was used to compare the median wait times for colonoscopy procedures performed at the VA and those performed through VCP. IBM SPSS Version 25 was used for all statistical analysis.

Results

Of the 190 identified colonoscopies completed in the community utilizing VCP, scanned records could not be found for 29 procedures (15.3%) (Table). VCP procedures were performed a median 2 days earlier than the first available VAPHS procedure, but this difference was not statistically significant (P = .62) (Figure 2). Although 52% of colonoscopies occurred sooner through VCP than the initially scheduled VAPHS date, 44% were performed later, and there was wide variability in the difference between these dates, ranging from 49 days sooner to 165 days later.

Pathology results from VCP procedures for which tissue samples were obtained were absent in 11.9% (14 of 118) of procedures. There were no clear follow-up recommendations to referring VA health care providers in the 18% (29 of 161) of available procedure reports. In VCP procedures, documentation of selected quality metrics: bowel preparation, cecal withdrawal time, and rectal retroflexion, were deficient in 27.3%, 70.2%, and 32.9%, respectively (Figure 3).

The utilization dataset sample included 350 veterans who were offered a VCP colonoscopy because the first available VAPHS procedure could not be scheduled for > 30 days. Of these patients, 231 (66%) ultimately had their colonoscopy performed at VAPHS. An additional 26.6% of the patients in the utilization sample were lost in the scheduling process (ie, could not be contacted, cancelled and could not be rescheduled, or were a “no show” their scheduled VAPHS procedure). An unknown number of these patients may have had a procedure outside of the VA, but there are no records to confirm or exclude this possibility. Ultimately, there were only 26 (7.4%) confirmed VCP colonoscopy procedures within the utilization sample (Figure 4). The median actual wait time for colonoscopy was 61 days for VA procedures and 66 days for procedures referred through the VCP, which was not statistically significant (P = .15).

Discussion

This is the first study to evaluate the performance of the VCP for colonoscopy referrals. Consistent with recently reported data in other specialties, colonoscopy referrals through VCP did not lead to more timely procedures overall, although there was wide variation.8 The use of VCP for veteran referral to the community for colonoscopy led to fragmentation of care—with 15% of records for VCP colonoscopies unavailable in the VA EHR 6 months after the procedure. In addition, there were 45 pre- or postprocedure visits in the community, which is not standard practice at VAPHS, and therefore may add to the cost of care for veterans.

Documentation of selected colonoscopy quality metrics were deficient in 27.3% to 70.2% of available VCP procedure reports. Although many veterans were eligible for VCP referral for colonoscopy, only 7.4% had a documented procedure through VCP, and two-thirds of veterans eligible for VCP participation had their colonoscopy performed at the VAPHS, reflecting overall low utilization of the program.

The national average wait time for VCP referrals for multiple specialties was estimated to be 51 days in a 2018 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report, which is similar to our findings.9 The GAO report also concluded that the VCP does not have timeliness standards and notes missed opportunities to develop a mechanism for record transfer between the community and the VA. Our finding of missing colonoscopy procedure and pathology reports within the VA EHR is consistent with this claim. Our analysis revealed that widely accepted quality standards for colonoscopy, those that are required at the VA and monitored for quality assurance at the VAPHS, are not being consistently reported for veterans who undergo procedures in the community. Last, the overall low utilization rate, combined with overall similar wait times for colonoscopies referred through the VCP vs those done at the VA, should lead to reconsideration of offering community care referral to all veterans based solely on static wait time cutoffs.

Limitations

There are several limitations to our analysis. First, all data were extracted via chart review by one author; therefore, some scanned procedure or pathology reports or pre- and postprocedure records may have been missed. Second, these data are representative of a single VA medical center and may not reflect trends nationwide. Third, there are many factors that can influence veteran decision making regarding when and where colonoscopy procedures are performed, which could be related to the VCP community care referral process or independent of this. Finally, colonoscopies performed through the VCP are grouped and may not reflect variability in the performance of community practices that veterans were referred to though the VCP.

Adenoma detection rates (ADR) were not included in the assessment for 2 reasons. First, there was an insufficient number of screening colonoscopies to use for the ADR calculation. Second, a composite non-VA ADR of multiple community endoscopists in different practices would likely be inaccurate and not clinically meaningful. Of note, the VAPHS does calculate and maintain ADR information as a practice for its endoscopists.

Conclusions

Our findings are particularly important as the VA expands access to care in the community through the VA Mission Act, which replaces the VCP but continues to include a static wait time threshold of 28 days for referral to community-based care.10 Especially for colonoscopies with the indication of screening or surveillance, wait times > 28 days are likely not clinically significant. Additionally, this study demonstrates that there also are delays in access to colonoscopy by community-based care providers, and potentially reflects widespread colonoscopy access issues that are not unique to the VA.

Our findings are similar to other published results and reports and raise similar concerns about the pitfalls of veteran referral into the community, including (1) similar wait times for the community and the VA; (2) the risk of fragmented care; (3) unevenquality of care; and (4) low overall utilization of VCP for colonoscopy.11 We agree with the GAO’s recommendations, which include establishing clinically meaningful wait time thresholds, systemic monitoring of the timeliness of care, and additional mechanisms for seamless transfer of complete records of care into the VA system. If a referral is placed for community-based care, this should come with an expectation that the care will be offered and can be delivered sooner than would be possible at the VA. We additionally recommend that standards for reporting quality metrics, including ADR, also be required of community colonoscopy providers contracted to provide care for veterans through the VA Mission Act. Importantly, we recommend that data for comparative wait times and quality metrics for VA and the community should be publicly available for veterans so that they may make more informed choices about where they receive health care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kaneen Allen, PhD, for her administrative assistance and guidance.

1. Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014. 42 USC §1395 (2014).

2. Farmer CM, Hosek SD. Did we improve veterans health care? It’s unclear. https://www.rand.org/blog/2016/05/did-we-improve-veterans-health-care-its-unclear.html. Published May 24, 2016. Accessed April 20, 2020.

3. Farmer CM, Hosek SD, Adamson DM. balancing demand and supply for veterans’ health care: a summary of three RAND assessments conducted under the Veterans Choice Act. Rand Health Q. 2016;6(1):12.

4. Mattocks KM, Mengeling M, Sadler A, Baldor R, Bastian L. The Veterans Choice Act: a qualitative examination of rapid policy implementation in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Med Care. 2017;55(suppl 7)(suppl 1):S71-S75.

5. Bartel MJ, Robertson DJ, Pohl H. Colonoscopy practice for veterans within and outside the Veterans Affairs setting: a matched cohort study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84(2):272-278.

6. Rex DK, Schoenfeld PS, Cohen J, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(1):72-90.

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1015, colorectal cancer screening. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=3068.Published December 30, 2014. Accessed April 12, 2020.

8. Penn M, Bhatnagar S, Kuy S, et al. Comparison of wait times for new patients between the private sector and United States Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(1):e187096.

9. US Government Accountability Office. Veterans Choice Program: improvements needed to address access-related challenges as VA plans consolidation of its community care programs. https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/692271.pdf. Published June 4, 2018. Accessed April 12, 2020.

10. VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks Act of 2018. 38 USC §1703 (2018).

11. Barnett PG, Hong JS, Carey E, Grunwald GK, Joynt Maddox K, Maddox TM. Comparison of accessibility, cost, and quality of elective coronary revascularization between Veterans Affairs and community care hospitals. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(2):133-141.

In April 2014, amid concerns for long wait times for care within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act was signed into law. This included the Veterans Choice Program (VCP), which included a provision for veterans to be referred outside of the VA to the community for care if their nearest VHA facility could not provide the requested care within 30 days of the clinically indicated date.1 Since implementation of the VCP, both media outlets and policy researchers have raised concerns about both the timeliness and quality of care provided through this program.2-4

Specifically for colonoscopy, referral outside of the VA in the pre-VCP era resulted in lower adenoma detection rate (ADR) and decreased adherence to surveillance guidelines when compared with matched VA control colonoscopies, raising concerns about quality assurance.5 Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening and timely colonoscopy is a VA priority; however, the performance of the VCP for colonoscopy timelines and quality has not been examined in detail.

Methods

We identified 3,855 veterans at the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System (VAPHS) who were referred for colonoscopy in the community by using VCP from June 2015 through May 2017, using a query for colonoscopy procedure orders within the VA Corporate Data Warehouse. A total of 190 patients had a colonoscopy completed in the community by utilizing the VCP during this time frame.

At VAPHS, veterans who are referred for colonoscopy are contacted by a scheduler. The scheduler contacts the patient and offers the first available colonoscopy date at VAPHS and schedules the procedure for this date. However, if this date is > 30 days from the procedure order date, the scheduler gives the veteran the option of being contacted by VCP to schedule a colonoscopy within the community (Figure 1). We measured the time interval from the date of the initially scheduled first available colonoscopy at VAPHS to the date the colonoscopy was actually performed through VCP.

Quality assurance also was assessed by checking for the availability of records of colonoscopies performed through the VCP in the VA electronic health record (EHR) system. Colonoscopy procedure reports also were reviewed to assess for documentation of established colonoscopy quality metrics for examinations performed through the VCP. Additionally, we reviewed records scanned into the VA EHR pertaining to the VCP colonoscopy, including pathology information and pre- or postvisit records if available.

Data extraction was initiated in November 2017 to allow for at least 6 months of lead time for outside health records from the community to be received and scanned into the EHR for the veteran at VAPHS. For colonoscopy quality metrics, we chose 3 metrics that are universally documented for all colonoscopy procedures performed at VAPHS: quality of bowel preparation, cecal withdrawal time, and performance of retroflexion in the rectum. Documentation of these quality metrics is recommended in gastroenterology practice guidelinesand/or required by VA national policy.6,7

We separately reviewed a sample of 350 of the 3,855 patients referred for colonoscopy through VCP at VAPHS during the same time period to investigate overall VCP utilization. This sample was representative at a 95% CI with 5% margin of error of the total and sampled from 2 high-volume referral months (October and November 2015) and 3 low-volume months (January, February, and March 2017). Detailed data were collected regarding the colonoscopy scheduling and VCP referral process, including dates of colonoscopy procedure request; scheduling within the VAPHS; scheduling through the VCP; and ultimately if, when, and where (VAPHS vs community) a veteran had a colonoscopy performed. Wait times for colonoscopy procedures performed at the VAPHS and those performed through the VCP were compared.

The institutional review board at VAPHS reviewed and approved this quality improvement study.

Statistical Analysis

For the 190 veterans who had a colonoscopy performed through VCP, a 1-sample Wilcoxon signed rank test was used with a null hypothesis that the median difference in days between first available VAPHS colonoscopy and community colonoscopy dates was 0. For the utilization sample of 350 veterans, an independent samples median test was used to compare the median wait times for colonoscopy procedures performed at the VA and those performed through VCP. IBM SPSS Version 25 was used for all statistical analysis.

Results

Of the 190 identified colonoscopies completed in the community utilizing VCP, scanned records could not be found for 29 procedures (15.3%) (Table). VCP procedures were performed a median 2 days earlier than the first available VAPHS procedure, but this difference was not statistically significant (P = .62) (Figure 2). Although 52% of colonoscopies occurred sooner through VCP than the initially scheduled VAPHS date, 44% were performed later, and there was wide variability in the difference between these dates, ranging from 49 days sooner to 165 days later.

Pathology results from VCP procedures for which tissue samples were obtained were absent in 11.9% (14 of 118) of procedures. There were no clear follow-up recommendations to referring VA health care providers in the 18% (29 of 161) of available procedure reports. In VCP procedures, documentation of selected quality metrics: bowel preparation, cecal withdrawal time, and rectal retroflexion, were deficient in 27.3%, 70.2%, and 32.9%, respectively (Figure 3).

The utilization dataset sample included 350 veterans who were offered a VCP colonoscopy because the first available VAPHS procedure could not be scheduled for > 30 days. Of these patients, 231 (66%) ultimately had their colonoscopy performed at VAPHS. An additional 26.6% of the patients in the utilization sample were lost in the scheduling process (ie, could not be contacted, cancelled and could not be rescheduled, or were a “no show” their scheduled VAPHS procedure). An unknown number of these patients may have had a procedure outside of the VA, but there are no records to confirm or exclude this possibility. Ultimately, there were only 26 (7.4%) confirmed VCP colonoscopy procedures within the utilization sample (Figure 4). The median actual wait time for colonoscopy was 61 days for VA procedures and 66 days for procedures referred through the VCP, which was not statistically significant (P = .15).

Discussion

This is the first study to evaluate the performance of the VCP for colonoscopy referrals. Consistent with recently reported data in other specialties, colonoscopy referrals through VCP did not lead to more timely procedures overall, although there was wide variation.8 The use of VCP for veteran referral to the community for colonoscopy led to fragmentation of care—with 15% of records for VCP colonoscopies unavailable in the VA EHR 6 months after the procedure. In addition, there were 45 pre- or postprocedure visits in the community, which is not standard practice at VAPHS, and therefore may add to the cost of care for veterans.

Documentation of selected colonoscopy quality metrics were deficient in 27.3% to 70.2% of available VCP procedure reports. Although many veterans were eligible for VCP referral for colonoscopy, only 7.4% had a documented procedure through VCP, and two-thirds of veterans eligible for VCP participation had their colonoscopy performed at the VAPHS, reflecting overall low utilization of the program.

The national average wait time for VCP referrals for multiple specialties was estimated to be 51 days in a 2018 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report, which is similar to our findings.9 The GAO report also concluded that the VCP does not have timeliness standards and notes missed opportunities to develop a mechanism for record transfer between the community and the VA. Our finding of missing colonoscopy procedure and pathology reports within the VA EHR is consistent with this claim. Our analysis revealed that widely accepted quality standards for colonoscopy, those that are required at the VA and monitored for quality assurance at the VAPHS, are not being consistently reported for veterans who undergo procedures in the community. Last, the overall low utilization rate, combined with overall similar wait times for colonoscopies referred through the VCP vs those done at the VA, should lead to reconsideration of offering community care referral to all veterans based solely on static wait time cutoffs.

Limitations

There are several limitations to our analysis. First, all data were extracted via chart review by one author; therefore, some scanned procedure or pathology reports or pre- and postprocedure records may have been missed. Second, these data are representative of a single VA medical center and may not reflect trends nationwide. Third, there are many factors that can influence veteran decision making regarding when and where colonoscopy procedures are performed, which could be related to the VCP community care referral process or independent of this. Finally, colonoscopies performed through the VCP are grouped and may not reflect variability in the performance of community practices that veterans were referred to though the VCP.

Adenoma detection rates (ADR) were not included in the assessment for 2 reasons. First, there was an insufficient number of screening colonoscopies to use for the ADR calculation. Second, a composite non-VA ADR of multiple community endoscopists in different practices would likely be inaccurate and not clinically meaningful. Of note, the VAPHS does calculate and maintain ADR information as a practice for its endoscopists.

Conclusions

Our findings are particularly important as the VA expands access to care in the community through the VA Mission Act, which replaces the VCP but continues to include a static wait time threshold of 28 days for referral to community-based care.10 Especially for colonoscopies with the indication of screening or surveillance, wait times > 28 days are likely not clinically significant. Additionally, this study demonstrates that there also are delays in access to colonoscopy by community-based care providers, and potentially reflects widespread colonoscopy access issues that are not unique to the VA.

Our findings are similar to other published results and reports and raise similar concerns about the pitfalls of veteran referral into the community, including (1) similar wait times for the community and the VA; (2) the risk of fragmented care; (3) unevenquality of care; and (4) low overall utilization of VCP for colonoscopy.11 We agree with the GAO’s recommendations, which include establishing clinically meaningful wait time thresholds, systemic monitoring of the timeliness of care, and additional mechanisms for seamless transfer of complete records of care into the VA system. If a referral is placed for community-based care, this should come with an expectation that the care will be offered and can be delivered sooner than would be possible at the VA. We additionally recommend that standards for reporting quality metrics, including ADR, also be required of community colonoscopy providers contracted to provide care for veterans through the VA Mission Act. Importantly, we recommend that data for comparative wait times and quality metrics for VA and the community should be publicly available for veterans so that they may make more informed choices about where they receive health care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kaneen Allen, PhD, for her administrative assistance and guidance.

In April 2014, amid concerns for long wait times for care within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act was signed into law. This included the Veterans Choice Program (VCP), which included a provision for veterans to be referred outside of the VA to the community for care if their nearest VHA facility could not provide the requested care within 30 days of the clinically indicated date.1 Since implementation of the VCP, both media outlets and policy researchers have raised concerns about both the timeliness and quality of care provided through this program.2-4

Specifically for colonoscopy, referral outside of the VA in the pre-VCP era resulted in lower adenoma detection rate (ADR) and decreased adherence to surveillance guidelines when compared with matched VA control colonoscopies, raising concerns about quality assurance.5 Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening and timely colonoscopy is a VA priority; however, the performance of the VCP for colonoscopy timelines and quality has not been examined in detail.

Methods

We identified 3,855 veterans at the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System (VAPHS) who were referred for colonoscopy in the community by using VCP from June 2015 through May 2017, using a query for colonoscopy procedure orders within the VA Corporate Data Warehouse. A total of 190 patients had a colonoscopy completed in the community by utilizing the VCP during this time frame.

At VAPHS, veterans who are referred for colonoscopy are contacted by a scheduler. The scheduler contacts the patient and offers the first available colonoscopy date at VAPHS and schedules the procedure for this date. However, if this date is > 30 days from the procedure order date, the scheduler gives the veteran the option of being contacted by VCP to schedule a colonoscopy within the community (Figure 1). We measured the time interval from the date of the initially scheduled first available colonoscopy at VAPHS to the date the colonoscopy was actually performed through VCP.

Quality assurance also was assessed by checking for the availability of records of colonoscopies performed through the VCP in the VA electronic health record (EHR) system. Colonoscopy procedure reports also were reviewed to assess for documentation of established colonoscopy quality metrics for examinations performed through the VCP. Additionally, we reviewed records scanned into the VA EHR pertaining to the VCP colonoscopy, including pathology information and pre- or postvisit records if available.

Data extraction was initiated in November 2017 to allow for at least 6 months of lead time for outside health records from the community to be received and scanned into the EHR for the veteran at VAPHS. For colonoscopy quality metrics, we chose 3 metrics that are universally documented for all colonoscopy procedures performed at VAPHS: quality of bowel preparation, cecal withdrawal time, and performance of retroflexion in the rectum. Documentation of these quality metrics is recommended in gastroenterology practice guidelinesand/or required by VA national policy.6,7

We separately reviewed a sample of 350 of the 3,855 patients referred for colonoscopy through VCP at VAPHS during the same time period to investigate overall VCP utilization. This sample was representative at a 95% CI with 5% margin of error of the total and sampled from 2 high-volume referral months (October and November 2015) and 3 low-volume months (January, February, and March 2017). Detailed data were collected regarding the colonoscopy scheduling and VCP referral process, including dates of colonoscopy procedure request; scheduling within the VAPHS; scheduling through the VCP; and ultimately if, when, and where (VAPHS vs community) a veteran had a colonoscopy performed. Wait times for colonoscopy procedures performed at the VAPHS and those performed through the VCP were compared.

The institutional review board at VAPHS reviewed and approved this quality improvement study.

Statistical Analysis

For the 190 veterans who had a colonoscopy performed through VCP, a 1-sample Wilcoxon signed rank test was used with a null hypothesis that the median difference in days between first available VAPHS colonoscopy and community colonoscopy dates was 0. For the utilization sample of 350 veterans, an independent samples median test was used to compare the median wait times for colonoscopy procedures performed at the VA and those performed through VCP. IBM SPSS Version 25 was used for all statistical analysis.

Results

Of the 190 identified colonoscopies completed in the community utilizing VCP, scanned records could not be found for 29 procedures (15.3%) (Table). VCP procedures were performed a median 2 days earlier than the first available VAPHS procedure, but this difference was not statistically significant (P = .62) (Figure 2). Although 52% of colonoscopies occurred sooner through VCP than the initially scheduled VAPHS date, 44% were performed later, and there was wide variability in the difference between these dates, ranging from 49 days sooner to 165 days later.

Pathology results from VCP procedures for which tissue samples were obtained were absent in 11.9% (14 of 118) of procedures. There were no clear follow-up recommendations to referring VA health care providers in the 18% (29 of 161) of available procedure reports. In VCP procedures, documentation of selected quality metrics: bowel preparation, cecal withdrawal time, and rectal retroflexion, were deficient in 27.3%, 70.2%, and 32.9%, respectively (Figure 3).

The utilization dataset sample included 350 veterans who were offered a VCP colonoscopy because the first available VAPHS procedure could not be scheduled for > 30 days. Of these patients, 231 (66%) ultimately had their colonoscopy performed at VAPHS. An additional 26.6% of the patients in the utilization sample were lost in the scheduling process (ie, could not be contacted, cancelled and could not be rescheduled, or were a “no show” their scheduled VAPHS procedure). An unknown number of these patients may have had a procedure outside of the VA, but there are no records to confirm or exclude this possibility. Ultimately, there were only 26 (7.4%) confirmed VCP colonoscopy procedures within the utilization sample (Figure 4). The median actual wait time for colonoscopy was 61 days for VA procedures and 66 days for procedures referred through the VCP, which was not statistically significant (P = .15).

Discussion

This is the first study to evaluate the performance of the VCP for colonoscopy referrals. Consistent with recently reported data in other specialties, colonoscopy referrals through VCP did not lead to more timely procedures overall, although there was wide variation.8 The use of VCP for veteran referral to the community for colonoscopy led to fragmentation of care—with 15% of records for VCP colonoscopies unavailable in the VA EHR 6 months after the procedure. In addition, there were 45 pre- or postprocedure visits in the community, which is not standard practice at VAPHS, and therefore may add to the cost of care for veterans.

Documentation of selected colonoscopy quality metrics were deficient in 27.3% to 70.2% of available VCP procedure reports. Although many veterans were eligible for VCP referral for colonoscopy, only 7.4% had a documented procedure through VCP, and two-thirds of veterans eligible for VCP participation had their colonoscopy performed at the VAPHS, reflecting overall low utilization of the program.

The national average wait time for VCP referrals for multiple specialties was estimated to be 51 days in a 2018 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report, which is similar to our findings.9 The GAO report also concluded that the VCP does not have timeliness standards and notes missed opportunities to develop a mechanism for record transfer between the community and the VA. Our finding of missing colonoscopy procedure and pathology reports within the VA EHR is consistent with this claim. Our analysis revealed that widely accepted quality standards for colonoscopy, those that are required at the VA and monitored for quality assurance at the VAPHS, are not being consistently reported for veterans who undergo procedures in the community. Last, the overall low utilization rate, combined with overall similar wait times for colonoscopies referred through the VCP vs those done at the VA, should lead to reconsideration of offering community care referral to all veterans based solely on static wait time cutoffs.

Limitations

There are several limitations to our analysis. First, all data were extracted via chart review by one author; therefore, some scanned procedure or pathology reports or pre- and postprocedure records may have been missed. Second, these data are representative of a single VA medical center and may not reflect trends nationwide. Third, there are many factors that can influence veteran decision making regarding when and where colonoscopy procedures are performed, which could be related to the VCP community care referral process or independent of this. Finally, colonoscopies performed through the VCP are grouped and may not reflect variability in the performance of community practices that veterans were referred to though the VCP.

Adenoma detection rates (ADR) were not included in the assessment for 2 reasons. First, there was an insufficient number of screening colonoscopies to use for the ADR calculation. Second, a composite non-VA ADR of multiple community endoscopists in different practices would likely be inaccurate and not clinically meaningful. Of note, the VAPHS does calculate and maintain ADR information as a practice for its endoscopists.

Conclusions

Our findings are particularly important as the VA expands access to care in the community through the VA Mission Act, which replaces the VCP but continues to include a static wait time threshold of 28 days for referral to community-based care.10 Especially for colonoscopies with the indication of screening or surveillance, wait times > 28 days are likely not clinically significant. Additionally, this study demonstrates that there also are delays in access to colonoscopy by community-based care providers, and potentially reflects widespread colonoscopy access issues that are not unique to the VA.

Our findings are similar to other published results and reports and raise similar concerns about the pitfalls of veteran referral into the community, including (1) similar wait times for the community and the VA; (2) the risk of fragmented care; (3) unevenquality of care; and (4) low overall utilization of VCP for colonoscopy.11 We agree with the GAO’s recommendations, which include establishing clinically meaningful wait time thresholds, systemic monitoring of the timeliness of care, and additional mechanisms for seamless transfer of complete records of care into the VA system. If a referral is placed for community-based care, this should come with an expectation that the care will be offered and can be delivered sooner than would be possible at the VA. We additionally recommend that standards for reporting quality metrics, including ADR, also be required of community colonoscopy providers contracted to provide care for veterans through the VA Mission Act. Importantly, we recommend that data for comparative wait times and quality metrics for VA and the community should be publicly available for veterans so that they may make more informed choices about where they receive health care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kaneen Allen, PhD, for her administrative assistance and guidance.

1. Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014. 42 USC §1395 (2014).

2. Farmer CM, Hosek SD. Did we improve veterans health care? It’s unclear. https://www.rand.org/blog/2016/05/did-we-improve-veterans-health-care-its-unclear.html. Published May 24, 2016. Accessed April 20, 2020.

3. Farmer CM, Hosek SD, Adamson DM. balancing demand and supply for veterans’ health care: a summary of three RAND assessments conducted under the Veterans Choice Act. Rand Health Q. 2016;6(1):12.

4. Mattocks KM, Mengeling M, Sadler A, Baldor R, Bastian L. The Veterans Choice Act: a qualitative examination of rapid policy implementation in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Med Care. 2017;55(suppl 7)(suppl 1):S71-S75.

5. Bartel MJ, Robertson DJ, Pohl H. Colonoscopy practice for veterans within and outside the Veterans Affairs setting: a matched cohort study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84(2):272-278.

6. Rex DK, Schoenfeld PS, Cohen J, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(1):72-90.

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1015, colorectal cancer screening. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=3068.Published December 30, 2014. Accessed April 12, 2020.

8. Penn M, Bhatnagar S, Kuy S, et al. Comparison of wait times for new patients between the private sector and United States Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(1):e187096.