User login

New schizophrenia treatment guideline released

The American Psychiatric Association has released a new evidence-based practice guideline for the treatment of schizophrenia.

The guideline focuses on assessment and treatment planning, which are integral to patient-centered care, and includes recommendations regarding pharmacotherapy, with particular focus on clozapine, as well as previously recommended and new psychosocial interventions.

“Our intention was to make recommendations to treat the whole person and take into account their family and other significant people in their lives,” George Keepers, MD, chair of the guideline writing group, said in an interview.

‘State-of-the-art methodology’

Dr. Keepers, professor of psychiatry at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, explained the rigorous process that informs the current guideline, which was “based not solely on expert consensus but was preceded by an evidence-based review of the literature that was then discussed, digested, and distilled into specific recommendations.”

Many current recommendations are “similar to previous recommendations, but there are a few important differences,” he said.

Two experts in schizophrenia who were not involved in guideline authorship praised it for its usefulness and methodology.

Philip D. Harvey, PhD, Leonard M. Miller Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Miami, said in an interview that the guideline “clarified the typical treatment algorithm from first episode to treatment resistance [which is] very clearly laid out for the first time.”

Christoph Correll, MD, professor of psychiatry and molecular medicine, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Hempstead, N.Y., said in an interview that the guideline “followed state-of-the-art methodology.”

First steps

The guideline recommends beginning with assessment of the patient and determination of the treatment plan.

Patients should be “treated with an antipsychotic medication and monitored for effectiveness and side effects.” Even after the patient’s symptoms have improved, antipsychotic treatment should continue.

For patients whose symptoms have improved, treatment should continue with the same antipsychotic and should not be switched.

“The problem we’re addressing in this recommendation is that patients are often treated with an effective medication and then forced, by circumstances or their insurance company, to switch to another that may not be effective for them, resulting in unnecessary relapses of the illness,” said Dr. Keepers.

“ and do what’s in the best interest of the patient,” he said.

“The guideline called out that antipsychotics that are effective and tolerated should be continued, without specifying a duration of treatment, thereby indicating indirectly that there is no clear end of the recommendation for ongoing maintenance treatment in individuals with schizophrenia,” said Dr. Correll.

Clozapine underutilized

The guideline highlights the role of clozapine and recommends its use for patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia and those at risk for suicide. Clozapine is also recommended for patients at “substantial” risk for aggressive behavior, regardless of other treatments.

“Clozapine is underutilized for treatment of schizophrenia in the U.S. and a number of other countries, but it is a really important treatment for patients who don’t respond to other antipsychotic agents,” said Dr. Keepers.

“With this recommendation, we hope that more patients will wind up receiving the medication and benefiting from it,” he added.

In addition, patients should receive treatment with a long-acting injectable antipsychotic “if they prefer such treatment or if they have a history of poor or uncertain adherence” (level of evidence, 2B).

The guideline authors “are recommending long-acting injectable medications for people who want them, not just people with poor prior adherence, which is a critical step,” said Dr. Harvey, director of the division of psychology at the University of Miami.

Managing antipsychotic side effects

The guideline offers recommendations for patients experiencing antipsychotic-induced side effects.

VMAT2s, which represent a “class of drugs that have become available since the last schizophrenia guidelines, are effective in tardive dyskinesia. It is important that patients with tardive dyskinesia have access to these drugs because they do work,” Dr. Keepers said.

Adequate funding needed

Recommended psychosocial interventions include treatment in a specialty care program for patients with schizophrenia who are experiencing a first episode of psychosis, use of cognitive-behavioral therapy for psychosis, psychoeducation, and supported employment services (2B).

“We reviewed very good data showing that patients who receive these services are more likely to be able to be employed and less likely to be rehospitalized or have a relapse,” Dr. Keepers observed.

In addition, patients with schizophrenia should receive assertive community treatment interventions if there is a “history of poor engagement with services leading to frequent relapse or social disruption.”

Family interventions are recommended for patients who have ongoing contact with their families (2B), and patients should also receive interventions “aimed at developing self-management skills and enhancing person-oriented recovery.” They should receive cognitive remediation, social skills training, and supportive psychotherapy.

Dr. Keepers pointed to “major barriers” to providing some of these psychosocial treatments. “They are beyond the scope of someone in an individual private practice situation, so they need to be delivered within the context of treatment programs that are either publicly or privately based,” he said.

“Psychiatrists can and do work closely with community and mental health centers, psychologists, and social workers who can provide these kinds of treatments,” but “many [treatments] require specialized skills and training before they can be offered, and there is a shortage of personnel to deliver them,” he noted.

“Both the national and state governments have not provided adequate funding for treatment of individuals with this condition [schizophrenia],” he added.

Dr. Keepers reports no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Harvey reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Correll disclosed ties to Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Axsome, Gedeon Richter, Gerson Lehrman Group, Indivior, IntraCellular Therapies, Janssen/J&J, LB Pharma, Lundbeck, MedAvante-ProPhase, Medscape, Merck, Mylan, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Pfizer, Recordati, Rovi, Servier, Sumitomo Dainippon, Sunovion, Supernus, Takeda, and Teva. He has received grant support from Janssen and Takeda. He is also a stock option holder of LB Pharma.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The American Psychiatric Association has released a new evidence-based practice guideline for the treatment of schizophrenia.

The guideline focuses on assessment and treatment planning, which are integral to patient-centered care, and includes recommendations regarding pharmacotherapy, with particular focus on clozapine, as well as previously recommended and new psychosocial interventions.

“Our intention was to make recommendations to treat the whole person and take into account their family and other significant people in their lives,” George Keepers, MD, chair of the guideline writing group, said in an interview.

‘State-of-the-art methodology’

Dr. Keepers, professor of psychiatry at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, explained the rigorous process that informs the current guideline, which was “based not solely on expert consensus but was preceded by an evidence-based review of the literature that was then discussed, digested, and distilled into specific recommendations.”

Many current recommendations are “similar to previous recommendations, but there are a few important differences,” he said.

Two experts in schizophrenia who were not involved in guideline authorship praised it for its usefulness and methodology.

Philip D. Harvey, PhD, Leonard M. Miller Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Miami, said in an interview that the guideline “clarified the typical treatment algorithm from first episode to treatment resistance [which is] very clearly laid out for the first time.”

Christoph Correll, MD, professor of psychiatry and molecular medicine, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Hempstead, N.Y., said in an interview that the guideline “followed state-of-the-art methodology.”

First steps

The guideline recommends beginning with assessment of the patient and determination of the treatment plan.

Patients should be “treated with an antipsychotic medication and monitored for effectiveness and side effects.” Even after the patient’s symptoms have improved, antipsychotic treatment should continue.

For patients whose symptoms have improved, treatment should continue with the same antipsychotic and should not be switched.

“The problem we’re addressing in this recommendation is that patients are often treated with an effective medication and then forced, by circumstances or their insurance company, to switch to another that may not be effective for them, resulting in unnecessary relapses of the illness,” said Dr. Keepers.

“ and do what’s in the best interest of the patient,” he said.

“The guideline called out that antipsychotics that are effective and tolerated should be continued, without specifying a duration of treatment, thereby indicating indirectly that there is no clear end of the recommendation for ongoing maintenance treatment in individuals with schizophrenia,” said Dr. Correll.

Clozapine underutilized

The guideline highlights the role of clozapine and recommends its use for patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia and those at risk for suicide. Clozapine is also recommended for patients at “substantial” risk for aggressive behavior, regardless of other treatments.

“Clozapine is underutilized for treatment of schizophrenia in the U.S. and a number of other countries, but it is a really important treatment for patients who don’t respond to other antipsychotic agents,” said Dr. Keepers.

“With this recommendation, we hope that more patients will wind up receiving the medication and benefiting from it,” he added.

In addition, patients should receive treatment with a long-acting injectable antipsychotic “if they prefer such treatment or if they have a history of poor or uncertain adherence” (level of evidence, 2B).

The guideline authors “are recommending long-acting injectable medications for people who want them, not just people with poor prior adherence, which is a critical step,” said Dr. Harvey, director of the division of psychology at the University of Miami.

Managing antipsychotic side effects

The guideline offers recommendations for patients experiencing antipsychotic-induced side effects.

VMAT2s, which represent a “class of drugs that have become available since the last schizophrenia guidelines, are effective in tardive dyskinesia. It is important that patients with tardive dyskinesia have access to these drugs because they do work,” Dr. Keepers said.

Adequate funding needed

Recommended psychosocial interventions include treatment in a specialty care program for patients with schizophrenia who are experiencing a first episode of psychosis, use of cognitive-behavioral therapy for psychosis, psychoeducation, and supported employment services (2B).

“We reviewed very good data showing that patients who receive these services are more likely to be able to be employed and less likely to be rehospitalized or have a relapse,” Dr. Keepers observed.

In addition, patients with schizophrenia should receive assertive community treatment interventions if there is a “history of poor engagement with services leading to frequent relapse or social disruption.”

Family interventions are recommended for patients who have ongoing contact with their families (2B), and patients should also receive interventions “aimed at developing self-management skills and enhancing person-oriented recovery.” They should receive cognitive remediation, social skills training, and supportive psychotherapy.

Dr. Keepers pointed to “major barriers” to providing some of these psychosocial treatments. “They are beyond the scope of someone in an individual private practice situation, so they need to be delivered within the context of treatment programs that are either publicly or privately based,” he said.

“Psychiatrists can and do work closely with community and mental health centers, psychologists, and social workers who can provide these kinds of treatments,” but “many [treatments] require specialized skills and training before they can be offered, and there is a shortage of personnel to deliver them,” he noted.

“Both the national and state governments have not provided adequate funding for treatment of individuals with this condition [schizophrenia],” he added.

Dr. Keepers reports no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Harvey reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Correll disclosed ties to Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Axsome, Gedeon Richter, Gerson Lehrman Group, Indivior, IntraCellular Therapies, Janssen/J&J, LB Pharma, Lundbeck, MedAvante-ProPhase, Medscape, Merck, Mylan, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Pfizer, Recordati, Rovi, Servier, Sumitomo Dainippon, Sunovion, Supernus, Takeda, and Teva. He has received grant support from Janssen and Takeda. He is also a stock option holder of LB Pharma.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The American Psychiatric Association has released a new evidence-based practice guideline for the treatment of schizophrenia.

The guideline focuses on assessment and treatment planning, which are integral to patient-centered care, and includes recommendations regarding pharmacotherapy, with particular focus on clozapine, as well as previously recommended and new psychosocial interventions.

“Our intention was to make recommendations to treat the whole person and take into account their family and other significant people in their lives,” George Keepers, MD, chair of the guideline writing group, said in an interview.

‘State-of-the-art methodology’

Dr. Keepers, professor of psychiatry at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, explained the rigorous process that informs the current guideline, which was “based not solely on expert consensus but was preceded by an evidence-based review of the literature that was then discussed, digested, and distilled into specific recommendations.”

Many current recommendations are “similar to previous recommendations, but there are a few important differences,” he said.

Two experts in schizophrenia who were not involved in guideline authorship praised it for its usefulness and methodology.

Philip D. Harvey, PhD, Leonard M. Miller Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Miami, said in an interview that the guideline “clarified the typical treatment algorithm from first episode to treatment resistance [which is] very clearly laid out for the first time.”

Christoph Correll, MD, professor of psychiatry and molecular medicine, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Hempstead, N.Y., said in an interview that the guideline “followed state-of-the-art methodology.”

First steps

The guideline recommends beginning with assessment of the patient and determination of the treatment plan.

Patients should be “treated with an antipsychotic medication and monitored for effectiveness and side effects.” Even after the patient’s symptoms have improved, antipsychotic treatment should continue.

For patients whose symptoms have improved, treatment should continue with the same antipsychotic and should not be switched.

“The problem we’re addressing in this recommendation is that patients are often treated with an effective medication and then forced, by circumstances or their insurance company, to switch to another that may not be effective for them, resulting in unnecessary relapses of the illness,” said Dr. Keepers.

“ and do what’s in the best interest of the patient,” he said.

“The guideline called out that antipsychotics that are effective and tolerated should be continued, without specifying a duration of treatment, thereby indicating indirectly that there is no clear end of the recommendation for ongoing maintenance treatment in individuals with schizophrenia,” said Dr. Correll.

Clozapine underutilized

The guideline highlights the role of clozapine and recommends its use for patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia and those at risk for suicide. Clozapine is also recommended for patients at “substantial” risk for aggressive behavior, regardless of other treatments.

“Clozapine is underutilized for treatment of schizophrenia in the U.S. and a number of other countries, but it is a really important treatment for patients who don’t respond to other antipsychotic agents,” said Dr. Keepers.

“With this recommendation, we hope that more patients will wind up receiving the medication and benefiting from it,” he added.

In addition, patients should receive treatment with a long-acting injectable antipsychotic “if they prefer such treatment or if they have a history of poor or uncertain adherence” (level of evidence, 2B).

The guideline authors “are recommending long-acting injectable medications for people who want them, not just people with poor prior adherence, which is a critical step,” said Dr. Harvey, director of the division of psychology at the University of Miami.

Managing antipsychotic side effects

The guideline offers recommendations for patients experiencing antipsychotic-induced side effects.

VMAT2s, which represent a “class of drugs that have become available since the last schizophrenia guidelines, are effective in tardive dyskinesia. It is important that patients with tardive dyskinesia have access to these drugs because they do work,” Dr. Keepers said.

Adequate funding needed

Recommended psychosocial interventions include treatment in a specialty care program for patients with schizophrenia who are experiencing a first episode of psychosis, use of cognitive-behavioral therapy for psychosis, psychoeducation, and supported employment services (2B).

“We reviewed very good data showing that patients who receive these services are more likely to be able to be employed and less likely to be rehospitalized or have a relapse,” Dr. Keepers observed.

In addition, patients with schizophrenia should receive assertive community treatment interventions if there is a “history of poor engagement with services leading to frequent relapse or social disruption.”

Family interventions are recommended for patients who have ongoing contact with their families (2B), and patients should also receive interventions “aimed at developing self-management skills and enhancing person-oriented recovery.” They should receive cognitive remediation, social skills training, and supportive psychotherapy.

Dr. Keepers pointed to “major barriers” to providing some of these psychosocial treatments. “They are beyond the scope of someone in an individual private practice situation, so they need to be delivered within the context of treatment programs that are either publicly or privately based,” he said.

“Psychiatrists can and do work closely with community and mental health centers, psychologists, and social workers who can provide these kinds of treatments,” but “many [treatments] require specialized skills and training before they can be offered, and there is a shortage of personnel to deliver them,” he noted.

“Both the national and state governments have not provided adequate funding for treatment of individuals with this condition [schizophrenia],” he added.

Dr. Keepers reports no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Harvey reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Correll disclosed ties to Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Axsome, Gedeon Richter, Gerson Lehrman Group, Indivior, IntraCellular Therapies, Janssen/J&J, LB Pharma, Lundbeck, MedAvante-ProPhase, Medscape, Merck, Mylan, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Pfizer, Recordati, Rovi, Servier, Sumitomo Dainippon, Sunovion, Supernus, Takeda, and Teva. He has received grant support from Janssen and Takeda. He is also a stock option holder of LB Pharma.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Gene signature may improve prognostication in ovarian cancer

according to a study published in Annals of Oncology.

“Gene expression signature tests for prognosis are available for other cancers, such as breast cancer, and these help with treatment decisions, but no such tests are available for ovarian cancer,” senior investigator Susan J. Ramus, PhD, of Lowy Cancer Research Centre, University of NSW Sydney, commented in an interview.

Dr. Ramus and associates developed and validated their 101-gene expression signature using pretreatment tumor tissue from 3,769 women with high-grade serous ovarian cancer treated on 21 studies.

The investigators found this signature, called OTTA-SPOT (Ovarian Tumor Tissue Analysis Consortium–Stratified Prognosis of Ovarian Tumors), performed well at stratifying women according to overall survival. Median overall survival times ranged from about 2 years for patients in the top quintile of scores to more than 9 years for patients in the bottom quintile.

Moreover, OTTA-SPOT significantly improved prognostication when added to age and stage.

“This tumor test works on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumors, as collected routinely in clinical practice,” Dr. Ramus noted. “Women predicted to have poor survival using current treatments could be included in clinical trials to rapidly get alternative treatment. Many of the genes included in this test are targets of known drugs, so this information could lead to alternative targeted treatments.

“This test is not ready for routine clinical care yet,” she added. “The next step would be to include this signature as part of a clinical trial. If patients predicted to have poor survival are given alternative treatments that improve their survival, then the test could be included in treatment decisions.”

Study details

Dr. Ramus and colleagues began this work by measuring tumor expression of 513 genes selected via meta-analysis. The team then developed a gene expression assay and a prognostic signature for overall survival, which they trained on tumors from 2,702 women in 15 studies and validated on an independent set of tumors from 1,067 women in 6 studies.

In analyses adjusted for covariates, expression levels of 276 genes were associated with overall survival. The signature with the best prognostic performance contained 101 genes that were enriched in pathways having treatment implications, such as pathways involved in immune response, mitosis, and homologous recombination repair.

Adding the signature to age and stage alone improved prediction of 2- and 5-year overall survival. The area under the curve increased from 0.61 to 0.69 for 2-year overall survival and from 0.62 to 0.75 for 5-year overall survival (with nonoverlapping 95% confidence intervals for 5-year survival).

Each standard deviation increase in the gene expression score was associated with a more than doubling of the risk of death (hazard ratio, 2.35; P < .001).

The median overall survival by gene expression score quintile was 9.5 years for patients in the first quintile, 5.4 years for patients in the second, 3.8 years for patients in the third, 3.2 years for patients in the fourth, and 2.3 years for patients in the fifth.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute, the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, and the Department of Defense Ovarian Cancer Research Program. Some of the authors disclosed financial relationships with a range of companies. Dr. Ramus disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Millstein J et al. Ann Oncol. 2020 Sep;31(9):1240-50.

according to a study published in Annals of Oncology.

“Gene expression signature tests for prognosis are available for other cancers, such as breast cancer, and these help with treatment decisions, but no such tests are available for ovarian cancer,” senior investigator Susan J. Ramus, PhD, of Lowy Cancer Research Centre, University of NSW Sydney, commented in an interview.

Dr. Ramus and associates developed and validated their 101-gene expression signature using pretreatment tumor tissue from 3,769 women with high-grade serous ovarian cancer treated on 21 studies.

The investigators found this signature, called OTTA-SPOT (Ovarian Tumor Tissue Analysis Consortium–Stratified Prognosis of Ovarian Tumors), performed well at stratifying women according to overall survival. Median overall survival times ranged from about 2 years for patients in the top quintile of scores to more than 9 years for patients in the bottom quintile.

Moreover, OTTA-SPOT significantly improved prognostication when added to age and stage.

“This tumor test works on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumors, as collected routinely in clinical practice,” Dr. Ramus noted. “Women predicted to have poor survival using current treatments could be included in clinical trials to rapidly get alternative treatment. Many of the genes included in this test are targets of known drugs, so this information could lead to alternative targeted treatments.

“This test is not ready for routine clinical care yet,” she added. “The next step would be to include this signature as part of a clinical trial. If patients predicted to have poor survival are given alternative treatments that improve their survival, then the test could be included in treatment decisions.”

Study details

Dr. Ramus and colleagues began this work by measuring tumor expression of 513 genes selected via meta-analysis. The team then developed a gene expression assay and a prognostic signature for overall survival, which they trained on tumors from 2,702 women in 15 studies and validated on an independent set of tumors from 1,067 women in 6 studies.

In analyses adjusted for covariates, expression levels of 276 genes were associated with overall survival. The signature with the best prognostic performance contained 101 genes that were enriched in pathways having treatment implications, such as pathways involved in immune response, mitosis, and homologous recombination repair.

Adding the signature to age and stage alone improved prediction of 2- and 5-year overall survival. The area under the curve increased from 0.61 to 0.69 for 2-year overall survival and from 0.62 to 0.75 for 5-year overall survival (with nonoverlapping 95% confidence intervals for 5-year survival).

Each standard deviation increase in the gene expression score was associated with a more than doubling of the risk of death (hazard ratio, 2.35; P < .001).

The median overall survival by gene expression score quintile was 9.5 years for patients in the first quintile, 5.4 years for patients in the second, 3.8 years for patients in the third, 3.2 years for patients in the fourth, and 2.3 years for patients in the fifth.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute, the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, and the Department of Defense Ovarian Cancer Research Program. Some of the authors disclosed financial relationships with a range of companies. Dr. Ramus disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Millstein J et al. Ann Oncol. 2020 Sep;31(9):1240-50.

according to a study published in Annals of Oncology.

“Gene expression signature tests for prognosis are available for other cancers, such as breast cancer, and these help with treatment decisions, but no such tests are available for ovarian cancer,” senior investigator Susan J. Ramus, PhD, of Lowy Cancer Research Centre, University of NSW Sydney, commented in an interview.

Dr. Ramus and associates developed and validated their 101-gene expression signature using pretreatment tumor tissue from 3,769 women with high-grade serous ovarian cancer treated on 21 studies.

The investigators found this signature, called OTTA-SPOT (Ovarian Tumor Tissue Analysis Consortium–Stratified Prognosis of Ovarian Tumors), performed well at stratifying women according to overall survival. Median overall survival times ranged from about 2 years for patients in the top quintile of scores to more than 9 years for patients in the bottom quintile.

Moreover, OTTA-SPOT significantly improved prognostication when added to age and stage.

“This tumor test works on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumors, as collected routinely in clinical practice,” Dr. Ramus noted. “Women predicted to have poor survival using current treatments could be included in clinical trials to rapidly get alternative treatment. Many of the genes included in this test are targets of known drugs, so this information could lead to alternative targeted treatments.

“This test is not ready for routine clinical care yet,” she added. “The next step would be to include this signature as part of a clinical trial. If patients predicted to have poor survival are given alternative treatments that improve their survival, then the test could be included in treatment decisions.”

Study details

Dr. Ramus and colleagues began this work by measuring tumor expression of 513 genes selected via meta-analysis. The team then developed a gene expression assay and a prognostic signature for overall survival, which they trained on tumors from 2,702 women in 15 studies and validated on an independent set of tumors from 1,067 women in 6 studies.

In analyses adjusted for covariates, expression levels of 276 genes were associated with overall survival. The signature with the best prognostic performance contained 101 genes that were enriched in pathways having treatment implications, such as pathways involved in immune response, mitosis, and homologous recombination repair.

Adding the signature to age and stage alone improved prediction of 2- and 5-year overall survival. The area under the curve increased from 0.61 to 0.69 for 2-year overall survival and from 0.62 to 0.75 for 5-year overall survival (with nonoverlapping 95% confidence intervals for 5-year survival).

Each standard deviation increase in the gene expression score was associated with a more than doubling of the risk of death (hazard ratio, 2.35; P < .001).

The median overall survival by gene expression score quintile was 9.5 years for patients in the first quintile, 5.4 years for patients in the second, 3.8 years for patients in the third, 3.2 years for patients in the fourth, and 2.3 years for patients in the fifth.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute, the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, and the Department of Defense Ovarian Cancer Research Program. Some of the authors disclosed financial relationships with a range of companies. Dr. Ramus disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Millstein J et al. Ann Oncol. 2020 Sep;31(9):1240-50.

FROM ANNALS OF ONCOLOGY

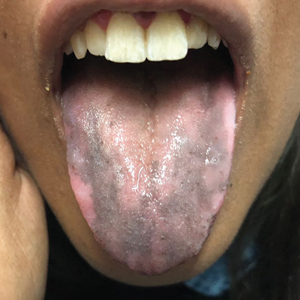

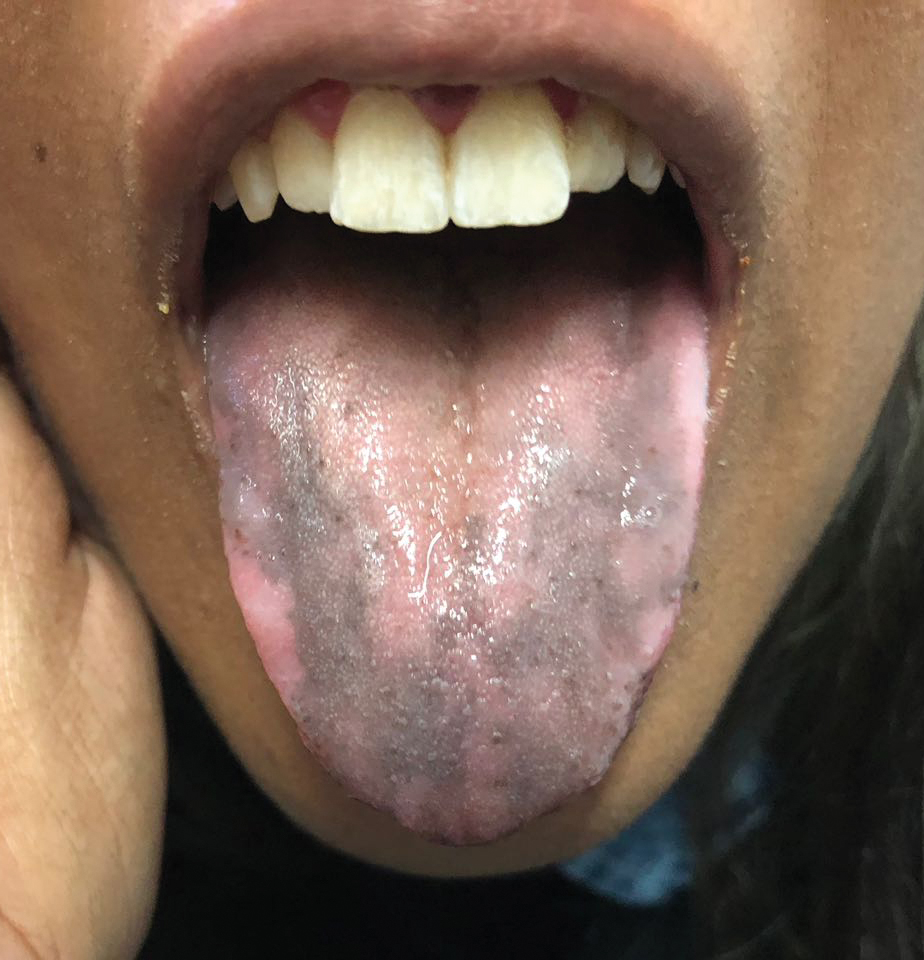

Hyperpigmentation of the Tongue

The Diagnosis: Addison Disease in the Context of Polyglandular Autoimmune Syndrome Type 2

The patient’s hormone levels as well as distinct clinical features led to a diagnosis of Addison disease in the context of polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type 2 (PAS-2). Approximately 50% of PAS-2 cases are familiar, and different modes of inheritance—autosomal recessive, autosomal dominant, and polygenic—have been reported. Women are affected up to 3 times more often than men.1,2 The age of onset ranges from infancy to late adulthood, with most cases occurring in early adulthood. Primary adrenal insufficiency (Addison disease) is the principal manifestation of PAS-2. It appears in approximately 50% of patients, occurring simultaneously with autoimmune thyroid disease or diabetes mellitus in 20% of patients and following them in 30% of patients.1,2 Autoimmune thyroid diseases such as chronic autoimmune thyroiditis and occasionally Graves disease as well as type 1 diabetes mellitus also are common. Polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type 2 with primary adrenal insufficiency and autoimmune thyroid disease was formerly referred to as Schmidt syndrome.3 It must be differentiated from polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type 1, a rare condition that also is referred to as autoimmune polyendocrinopathycandidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy syndrome.1,3 As with any other cause of adrenal insufficiency, the treatment involves hormone replacement therapy up to normal levels and then tapering according to stress levels (ie, surgery or infections that require a dose increase). Our patient was diagnosed according to hormone levels and clinical features and was started on 30 mg daily of hydrocortisone and 50 μg daily of levothyroxine. No improvement in her condition was noted after 6 months of treatment. The patient is still under yearly follow-up, and the mucous hyperpigmentation faded approximately 6 months after hormonal homeostasis was achieved.

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion. It is characterized by multiple hamartomatous polyps in the gastrointestinal tract, mucocutaneous pigmentation, and an increased risk for gastrointestinal and nongastrointestinal cancer. Mucocutaneous pigmented macules most commonly occur on the lips and perioral region, buccal mucosa, and the palms and soles. However, mucocutaneous pigmentation usually occurs during the first 1 to 2 years of life, increases in size and number over the ensuing years, and usually fades after puberty.4

Laugier-Hunziker syndrome is an acquired benign disorder presenting in adults with lentigines on the lips and buccal mucosa. It frequently is accompaniedby longitudinal melanonychia, macular pigmentation of the genitals, and involvement of the palms and soles. The diagnosis of Laugier-Hunziker syndrome is one of exclusion and is made after ruling out other causes of oral and labial hyperpigmentation, including physiologic pigmentation seen in darker-skinned individuals as well as inherited diseases associated with lentiginosis, requiring complete physical examination, endoscopy, and colonscopy.5

A wide variety of drugs and chemicals can lead to diffuse cutaneous hyperpigmentation. Increased production of melanin and/or the deposition of drug complexes or metals in the dermis is responsible for the skin discoloration. Drugs that most often cause hyperpigmentation on mucosal surfaces are hydroxychloroquine, minocycline, nicotine, silver, and some chemotherapy agents. The hyperpigmentation usually resolves with discontinuation of the offending agent, but the course may be prolonged over months to years.6

Changes in the skin and subcutaneous tissue occur in patients with Cushing syndrome. Hyperpigmentation is induced by increased secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone, not cortisol, and occurs most often in patients with the ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone syndrome. Hyperpigmentation may be generalized but is more intense in areas exposed to light (eg, face, neck, dorsal aspects of the hands) or to chronic mild trauma, friction, or pressure (eg, elbows, knees, spine, knuckles). Patchy pigmentation may occur on the inner surface of the lips and the buccal mucosa along the line of dental occlusion. Acanthosis nigricans also can be present in the axillae and around the neck.7

- Ferre EM, Rose SR, Rosenzweig SD, et al. Redefined clinical features and diagnostic criteria in autoimmune polyendocrinopathycandidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy. JCI Insight. 2016;1:E88782.

- Orlova EM, Sozaeva LS, Kareva MA, et al. Expanding the phenotypic and genotypic landscape of autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:3546-3556.

- Ahonen P, Myllärniemi S, Sipilä I, et al. Clinical variation of autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy (APECED) in a series of 68 patients. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1829-1836.

- Utsunomiya J, Gocho H, Miyanaga T, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: its natural course and management. Johns Hopkins Med J. 1975;136:71-82.

- Nayak RS, Kotrashetti VS, Hosmani JV. Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2012;16:245-250.

- Krause W. Drug-induced hyperpigmentation: a systematic review. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:644-651.

- Newell-Price J, Trainer P, Besser M, et al. The diagnosis and differential diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome and pseudo-Cushing’s states. Endocr Rev. 1998;19:647-672.

The Diagnosis: Addison Disease in the Context of Polyglandular Autoimmune Syndrome Type 2

The patient’s hormone levels as well as distinct clinical features led to a diagnosis of Addison disease in the context of polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type 2 (PAS-2). Approximately 50% of PAS-2 cases are familiar, and different modes of inheritance—autosomal recessive, autosomal dominant, and polygenic—have been reported. Women are affected up to 3 times more often than men.1,2 The age of onset ranges from infancy to late adulthood, with most cases occurring in early adulthood. Primary adrenal insufficiency (Addison disease) is the principal manifestation of PAS-2. It appears in approximately 50% of patients, occurring simultaneously with autoimmune thyroid disease or diabetes mellitus in 20% of patients and following them in 30% of patients.1,2 Autoimmune thyroid diseases such as chronic autoimmune thyroiditis and occasionally Graves disease as well as type 1 diabetes mellitus also are common. Polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type 2 with primary adrenal insufficiency and autoimmune thyroid disease was formerly referred to as Schmidt syndrome.3 It must be differentiated from polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type 1, a rare condition that also is referred to as autoimmune polyendocrinopathycandidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy syndrome.1,3 As with any other cause of adrenal insufficiency, the treatment involves hormone replacement therapy up to normal levels and then tapering according to stress levels (ie, surgery or infections that require a dose increase). Our patient was diagnosed according to hormone levels and clinical features and was started on 30 mg daily of hydrocortisone and 50 μg daily of levothyroxine. No improvement in her condition was noted after 6 months of treatment. The patient is still under yearly follow-up, and the mucous hyperpigmentation faded approximately 6 months after hormonal homeostasis was achieved.

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion. It is characterized by multiple hamartomatous polyps in the gastrointestinal tract, mucocutaneous pigmentation, and an increased risk for gastrointestinal and nongastrointestinal cancer. Mucocutaneous pigmented macules most commonly occur on the lips and perioral region, buccal mucosa, and the palms and soles. However, mucocutaneous pigmentation usually occurs during the first 1 to 2 years of life, increases in size and number over the ensuing years, and usually fades after puberty.4

Laugier-Hunziker syndrome is an acquired benign disorder presenting in adults with lentigines on the lips and buccal mucosa. It frequently is accompaniedby longitudinal melanonychia, macular pigmentation of the genitals, and involvement of the palms and soles. The diagnosis of Laugier-Hunziker syndrome is one of exclusion and is made after ruling out other causes of oral and labial hyperpigmentation, including physiologic pigmentation seen in darker-skinned individuals as well as inherited diseases associated with lentiginosis, requiring complete physical examination, endoscopy, and colonscopy.5

A wide variety of drugs and chemicals can lead to diffuse cutaneous hyperpigmentation. Increased production of melanin and/or the deposition of drug complexes or metals in the dermis is responsible for the skin discoloration. Drugs that most often cause hyperpigmentation on mucosal surfaces are hydroxychloroquine, minocycline, nicotine, silver, and some chemotherapy agents. The hyperpigmentation usually resolves with discontinuation of the offending agent, but the course may be prolonged over months to years.6

Changes in the skin and subcutaneous tissue occur in patients with Cushing syndrome. Hyperpigmentation is induced by increased secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone, not cortisol, and occurs most often in patients with the ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone syndrome. Hyperpigmentation may be generalized but is more intense in areas exposed to light (eg, face, neck, dorsal aspects of the hands) or to chronic mild trauma, friction, or pressure (eg, elbows, knees, spine, knuckles). Patchy pigmentation may occur on the inner surface of the lips and the buccal mucosa along the line of dental occlusion. Acanthosis nigricans also can be present in the axillae and around the neck.7

The Diagnosis: Addison Disease in the Context of Polyglandular Autoimmune Syndrome Type 2

The patient’s hormone levels as well as distinct clinical features led to a diagnosis of Addison disease in the context of polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type 2 (PAS-2). Approximately 50% of PAS-2 cases are familiar, and different modes of inheritance—autosomal recessive, autosomal dominant, and polygenic—have been reported. Women are affected up to 3 times more often than men.1,2 The age of onset ranges from infancy to late adulthood, with most cases occurring in early adulthood. Primary adrenal insufficiency (Addison disease) is the principal manifestation of PAS-2. It appears in approximately 50% of patients, occurring simultaneously with autoimmune thyroid disease or diabetes mellitus in 20% of patients and following them in 30% of patients.1,2 Autoimmune thyroid diseases such as chronic autoimmune thyroiditis and occasionally Graves disease as well as type 1 diabetes mellitus also are common. Polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type 2 with primary adrenal insufficiency and autoimmune thyroid disease was formerly referred to as Schmidt syndrome.3 It must be differentiated from polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type 1, a rare condition that also is referred to as autoimmune polyendocrinopathycandidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy syndrome.1,3 As with any other cause of adrenal insufficiency, the treatment involves hormone replacement therapy up to normal levels and then tapering according to stress levels (ie, surgery or infections that require a dose increase). Our patient was diagnosed according to hormone levels and clinical features and was started on 30 mg daily of hydrocortisone and 50 μg daily of levothyroxine. No improvement in her condition was noted after 6 months of treatment. The patient is still under yearly follow-up, and the mucous hyperpigmentation faded approximately 6 months after hormonal homeostasis was achieved.

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion. It is characterized by multiple hamartomatous polyps in the gastrointestinal tract, mucocutaneous pigmentation, and an increased risk for gastrointestinal and nongastrointestinal cancer. Mucocutaneous pigmented macules most commonly occur on the lips and perioral region, buccal mucosa, and the palms and soles. However, mucocutaneous pigmentation usually occurs during the first 1 to 2 years of life, increases in size and number over the ensuing years, and usually fades after puberty.4

Laugier-Hunziker syndrome is an acquired benign disorder presenting in adults with lentigines on the lips and buccal mucosa. It frequently is accompaniedby longitudinal melanonychia, macular pigmentation of the genitals, and involvement of the palms and soles. The diagnosis of Laugier-Hunziker syndrome is one of exclusion and is made after ruling out other causes of oral and labial hyperpigmentation, including physiologic pigmentation seen in darker-skinned individuals as well as inherited diseases associated with lentiginosis, requiring complete physical examination, endoscopy, and colonscopy.5

A wide variety of drugs and chemicals can lead to diffuse cutaneous hyperpigmentation. Increased production of melanin and/or the deposition of drug complexes or metals in the dermis is responsible for the skin discoloration. Drugs that most often cause hyperpigmentation on mucosal surfaces are hydroxychloroquine, minocycline, nicotine, silver, and some chemotherapy agents. The hyperpigmentation usually resolves with discontinuation of the offending agent, but the course may be prolonged over months to years.6

Changes in the skin and subcutaneous tissue occur in patients with Cushing syndrome. Hyperpigmentation is induced by increased secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone, not cortisol, and occurs most often in patients with the ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone syndrome. Hyperpigmentation may be generalized but is more intense in areas exposed to light (eg, face, neck, dorsal aspects of the hands) or to chronic mild trauma, friction, or pressure (eg, elbows, knees, spine, knuckles). Patchy pigmentation may occur on the inner surface of the lips and the buccal mucosa along the line of dental occlusion. Acanthosis nigricans also can be present in the axillae and around the neck.7

- Ferre EM, Rose SR, Rosenzweig SD, et al. Redefined clinical features and diagnostic criteria in autoimmune polyendocrinopathycandidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy. JCI Insight. 2016;1:E88782.

- Orlova EM, Sozaeva LS, Kareva MA, et al. Expanding the phenotypic and genotypic landscape of autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:3546-3556.

- Ahonen P, Myllärniemi S, Sipilä I, et al. Clinical variation of autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy (APECED) in a series of 68 patients. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1829-1836.

- Utsunomiya J, Gocho H, Miyanaga T, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: its natural course and management. Johns Hopkins Med J. 1975;136:71-82.

- Nayak RS, Kotrashetti VS, Hosmani JV. Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2012;16:245-250.

- Krause W. Drug-induced hyperpigmentation: a systematic review. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:644-651.

- Newell-Price J, Trainer P, Besser M, et al. The diagnosis and differential diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome and pseudo-Cushing’s states. Endocr Rev. 1998;19:647-672.

- Ferre EM, Rose SR, Rosenzweig SD, et al. Redefined clinical features and diagnostic criteria in autoimmune polyendocrinopathycandidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy. JCI Insight. 2016;1:E88782.

- Orlova EM, Sozaeva LS, Kareva MA, et al. Expanding the phenotypic and genotypic landscape of autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:3546-3556.

- Ahonen P, Myllärniemi S, Sipilä I, et al. Clinical variation of autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy (APECED) in a series of 68 patients. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1829-1836.

- Utsunomiya J, Gocho H, Miyanaga T, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: its natural course and management. Johns Hopkins Med J. 1975;136:71-82.

- Nayak RS, Kotrashetti VS, Hosmani JV. Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2012;16:245-250.

- Krause W. Drug-induced hyperpigmentation: a systematic review. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:644-651.

- Newell-Price J, Trainer P, Besser M, et al. The diagnosis and differential diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome and pseudo-Cushing’s states. Endocr Rev. 1998;19:647-672.

An otherwise healthy 17-year-old adolescent girl from Spain presented with hyperpigmentation on the tongue of several weeks’ duration. She denied licking graphite pencils or pens. Physical examination revealed pigmentation in the palmar creases and a slight generalized tan. The patient denied sun exposure. Neither melanonychia nor genital hyperpigmented lesions were noted. Blood tests showed overt hypothyroidism.

Smallpox Vaccination-Associated Myopericarditis

A renewed effort to vaccinate service members fighting the global war on terrorism has brought new diagnostic challenges. Vaccinations not generally given to the public are routinely given to service members when they deploy to various parts of the world. Examples include anthrax, yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, rabies, polio, and smallpox. Every vaccination has potential for adverse effects (AEs), which can range from mild to severe life-threatening complications. These AEs often go unrecognized and untreated because physicians are not routinely screening for vaccination administration.

Background

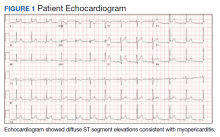

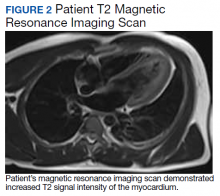

Smallpox (Variola major) was successfully eradicated in 1977 due to worldwide vaccination efforts.1 However, the threat of bioterrorism has renewed mandatory smallpox vaccinations for high-risk individuals, such as active-duty military personnel.1,2 A notable increase in myopericarditis has been reported with the new generation of smallpox vaccination, ACAM2000.3 We present a case of a 27-year-old healthy male who presented with chest pain and diffuse ST segment elevations consistent with myopericarditis after vaccination with ACAM2000.

Case Presentation

A healthy 27-year-old soldier presented to the emergency department with sudden, new onset, sharp-stabbing, substernal chest pain, which was made worse with lying flat and better with leaning forward. Vital signs were unremarkable. He recently enlisted in the US Army and received the smallpox vaccination about 11 days before as part of a routine predeployment checklist. The patient reported he did not have any viral symptoms, such as fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, shortness of breath, sore throat, rhinorrhea, or sputum production. He also reported having no prior illness for the past 3 months, sick contacts at home or work, or recent travel outside the US. He reported no tobacco use, alcohol use, or illicit drug use. The patient’s family history was negative for significant cardiac disease.

A physical examination was unremarkable. The initial laboratory report showed no leukocytosis, anemia, thrombocytopenia, electrolytes derangement, abnormal kidney function, or abnormal liver function tests. Initial troponin was 0.25 ng/mL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 40 mmol/h and C-reactive protein (CRP) was 120.2 mg/L suggestive of acute inflammation. A urine drug screen was negative. D-dimer was < 0.27. An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed diffuse ST segment elevation (Figure 1). An echocardiogram showed normal left ventricle size, and function with ejection fraction 55 to 60%, normal diastolic dysfunction, and trivial pericardial effusion. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed increased T2 signal intensity of the myocardium suggestive of myopericarditis (Figure 2). A computed tomography (CT) angiogram of the coronary arteries showed no significant stenosis.

The patient was treated with ibuprofen for 2 weeks and colchicine for 3 months, and his symptoms resolved. He followed up with an appointment in the cardiology clinic 1 month later, and his ESR, CRP, and troponin results were negative. A limited echocardiogram showed ejection fraction 60 to 65%, no regional wall motion abnormalities, normal diastolic function, and resolution of the pericardial effusion.

Discussion

Smallpox was a major worldwide cause of mortality; about 30% of those infected died because of smallpox.2,4,5 Due to a worldwide vaccination effort, the World Health Organization declared smallpox was eradicated in 1977.2,4,5 However, despite successful eradication, smallpox is considered a possible bioterrorism target, which prompted a resurgence of mandatory smallpox vaccinations for active-duty personnel.2,5

Dryvax, a freeze-dried calf lymph smallpox vaccine was used extensively from the 1940s to the 1980s but was replaced in 2008 by ACAM2000, a smallpox vaccine cultured in kidney epithelial cells from African green monkeys.3,5 Myopericarditis was rarely associated with the Dryvax, with only 5 cases reported from 1955 to 1986 after millions of doses of vaccines were administered; however, in 230,734 administered ACAM2000 doses, 18 cases of myopericarditis (incidence, 7.8 per 100,000) were reported during a surveillance study in 2002 and 2003.3,5

Myopericarditis presents with a wide variety of symptoms, such as chest pain, palpitations, chills, shortness of breath, and fever.6,7 Mainstay diagnostic criteria include ECG findings consistent with myopericarditis (such as diffuse ST segment elevations) and elevated cardiac biomarkers (elevated troponins).5-7 An echocardiogram can be helpful in diagnosis, as most cases will not have regional wall motion abnormalities (to distinguish against coronary artery disease).5-7 MRI with diffuse enhancement of the myocardium can be helpful in diagnosis.5,6 The gold standard for diagnosis is an endomyocardial biopsy, which carries a significant risk of complications and is not routinely performed to diagnose myopericarditis.5,6 US military smallpox vaccination data showed that the onset of vaccine-associated myopericarditis averaged (SD) 10.4 (3.6) days after vaccination.5

Vaccine-associated myopericarditis treatment is focused on decreasing inflammation.5,6 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are advised for about 2 weeks with cessation of intensive cardiac activities for between 4 and 6 weeks due to risks of congestive heart failure and fatal cardiac arrhythmias.5,6

Conclusions

Since the September 11 attacks, the US needs to be continually prepared for potential terrorism on American soil and abroad. The threat of bioterrorism has renewed efforts to vaccinate or revaccinate American service members deployed to high-risk regions. These vaccinations put them at risk for vaccination-induced complications that can range from mild fever to life-threatening complications.

1. Bruner DI, Butler BS. Smallpox vaccination-associated myopericarditis is more common with the newest smallpox vaccine. J Emerg Med. 2014;46(3):e85-e87. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.06.001

2. Halsell JS, Riddle JR, Atwood JE, et al. Myopericarditis following smallpox vaccination among vaccinia-naive US military personnel. JAMA. 2003;289(24):3283-3289. doi:10.1001/jama.289.24.3283

3. Nalca A, Zumbrun EE. ACAM2000: the new smallpox vaccine for United States Strategic National Stockpile. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2010;4:71-79. doi:10.2147/dddt.s3687

4. Wollenberg A, Engler R. Smallpox, vaccination and adverse reactions to smallpox vaccine. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;4(4):271-275. doi:10.1097/01.all.0000136758.66442.28

5. Cassimatis DC, Atwood JE, Engler RM, Linz PE, Grabenstein JD, Vernalis MN. Smallpox vaccination and myopericarditis: a clinical review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(9):1503-1510. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.053

6. Sharma U, Tak T. A report of 2 cases of myopericarditis after Vaccinia virus (smallpox) immunization. WMJ. 2011;110(6):291-294.

7. Sarkisian SA, Hand G, Rivera VM, Smith M, Miller JA. A case series of smallpox vaccination-associated myopericarditis: effects on safety and readiness of the active duty soldier. Mil Med. 2019;184(1-2):e280-e283. doi:10.1093/milmed/usy159

A renewed effort to vaccinate service members fighting the global war on terrorism has brought new diagnostic challenges. Vaccinations not generally given to the public are routinely given to service members when they deploy to various parts of the world. Examples include anthrax, yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, rabies, polio, and smallpox. Every vaccination has potential for adverse effects (AEs), which can range from mild to severe life-threatening complications. These AEs often go unrecognized and untreated because physicians are not routinely screening for vaccination administration.

Background

Smallpox (Variola major) was successfully eradicated in 1977 due to worldwide vaccination efforts.1 However, the threat of bioterrorism has renewed mandatory smallpox vaccinations for high-risk individuals, such as active-duty military personnel.1,2 A notable increase in myopericarditis has been reported with the new generation of smallpox vaccination, ACAM2000.3 We present a case of a 27-year-old healthy male who presented with chest pain and diffuse ST segment elevations consistent with myopericarditis after vaccination with ACAM2000.

Case Presentation

A healthy 27-year-old soldier presented to the emergency department with sudden, new onset, sharp-stabbing, substernal chest pain, which was made worse with lying flat and better with leaning forward. Vital signs were unremarkable. He recently enlisted in the US Army and received the smallpox vaccination about 11 days before as part of a routine predeployment checklist. The patient reported he did not have any viral symptoms, such as fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, shortness of breath, sore throat, rhinorrhea, or sputum production. He also reported having no prior illness for the past 3 months, sick contacts at home or work, or recent travel outside the US. He reported no tobacco use, alcohol use, or illicit drug use. The patient’s family history was negative for significant cardiac disease.

A physical examination was unremarkable. The initial laboratory report showed no leukocytosis, anemia, thrombocytopenia, electrolytes derangement, abnormal kidney function, or abnormal liver function tests. Initial troponin was 0.25 ng/mL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 40 mmol/h and C-reactive protein (CRP) was 120.2 mg/L suggestive of acute inflammation. A urine drug screen was negative. D-dimer was < 0.27. An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed diffuse ST segment elevation (Figure 1). An echocardiogram showed normal left ventricle size, and function with ejection fraction 55 to 60%, normal diastolic dysfunction, and trivial pericardial effusion. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed increased T2 signal intensity of the myocardium suggestive of myopericarditis (Figure 2). A computed tomography (CT) angiogram of the coronary arteries showed no significant stenosis.

The patient was treated with ibuprofen for 2 weeks and colchicine for 3 months, and his symptoms resolved. He followed up with an appointment in the cardiology clinic 1 month later, and his ESR, CRP, and troponin results were negative. A limited echocardiogram showed ejection fraction 60 to 65%, no regional wall motion abnormalities, normal diastolic function, and resolution of the pericardial effusion.

Discussion

Smallpox was a major worldwide cause of mortality; about 30% of those infected died because of smallpox.2,4,5 Due to a worldwide vaccination effort, the World Health Organization declared smallpox was eradicated in 1977.2,4,5 However, despite successful eradication, smallpox is considered a possible bioterrorism target, which prompted a resurgence of mandatory smallpox vaccinations for active-duty personnel.2,5

Dryvax, a freeze-dried calf lymph smallpox vaccine was used extensively from the 1940s to the 1980s but was replaced in 2008 by ACAM2000, a smallpox vaccine cultured in kidney epithelial cells from African green monkeys.3,5 Myopericarditis was rarely associated with the Dryvax, with only 5 cases reported from 1955 to 1986 after millions of doses of vaccines were administered; however, in 230,734 administered ACAM2000 doses, 18 cases of myopericarditis (incidence, 7.8 per 100,000) were reported during a surveillance study in 2002 and 2003.3,5

Myopericarditis presents with a wide variety of symptoms, such as chest pain, palpitations, chills, shortness of breath, and fever.6,7 Mainstay diagnostic criteria include ECG findings consistent with myopericarditis (such as diffuse ST segment elevations) and elevated cardiac biomarkers (elevated troponins).5-7 An echocardiogram can be helpful in diagnosis, as most cases will not have regional wall motion abnormalities (to distinguish against coronary artery disease).5-7 MRI with diffuse enhancement of the myocardium can be helpful in diagnosis.5,6 The gold standard for diagnosis is an endomyocardial biopsy, which carries a significant risk of complications and is not routinely performed to diagnose myopericarditis.5,6 US military smallpox vaccination data showed that the onset of vaccine-associated myopericarditis averaged (SD) 10.4 (3.6) days after vaccination.5

Vaccine-associated myopericarditis treatment is focused on decreasing inflammation.5,6 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are advised for about 2 weeks with cessation of intensive cardiac activities for between 4 and 6 weeks due to risks of congestive heart failure and fatal cardiac arrhythmias.5,6

Conclusions

Since the September 11 attacks, the US needs to be continually prepared for potential terrorism on American soil and abroad. The threat of bioterrorism has renewed efforts to vaccinate or revaccinate American service members deployed to high-risk regions. These vaccinations put them at risk for vaccination-induced complications that can range from mild fever to life-threatening complications.

A renewed effort to vaccinate service members fighting the global war on terrorism has brought new diagnostic challenges. Vaccinations not generally given to the public are routinely given to service members when they deploy to various parts of the world. Examples include anthrax, yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, rabies, polio, and smallpox. Every vaccination has potential for adverse effects (AEs), which can range from mild to severe life-threatening complications. These AEs often go unrecognized and untreated because physicians are not routinely screening for vaccination administration.

Background

Smallpox (Variola major) was successfully eradicated in 1977 due to worldwide vaccination efforts.1 However, the threat of bioterrorism has renewed mandatory smallpox vaccinations for high-risk individuals, such as active-duty military personnel.1,2 A notable increase in myopericarditis has been reported with the new generation of smallpox vaccination, ACAM2000.3 We present a case of a 27-year-old healthy male who presented with chest pain and diffuse ST segment elevations consistent with myopericarditis after vaccination with ACAM2000.

Case Presentation

A healthy 27-year-old soldier presented to the emergency department with sudden, new onset, sharp-stabbing, substernal chest pain, which was made worse with lying flat and better with leaning forward. Vital signs were unremarkable. He recently enlisted in the US Army and received the smallpox vaccination about 11 days before as part of a routine predeployment checklist. The patient reported he did not have any viral symptoms, such as fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, shortness of breath, sore throat, rhinorrhea, or sputum production. He also reported having no prior illness for the past 3 months, sick contacts at home or work, or recent travel outside the US. He reported no tobacco use, alcohol use, or illicit drug use. The patient’s family history was negative for significant cardiac disease.

A physical examination was unremarkable. The initial laboratory report showed no leukocytosis, anemia, thrombocytopenia, electrolytes derangement, abnormal kidney function, or abnormal liver function tests. Initial troponin was 0.25 ng/mL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 40 mmol/h and C-reactive protein (CRP) was 120.2 mg/L suggestive of acute inflammation. A urine drug screen was negative. D-dimer was < 0.27. An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed diffuse ST segment elevation (Figure 1). An echocardiogram showed normal left ventricle size, and function with ejection fraction 55 to 60%, normal diastolic dysfunction, and trivial pericardial effusion. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed increased T2 signal intensity of the myocardium suggestive of myopericarditis (Figure 2). A computed tomography (CT) angiogram of the coronary arteries showed no significant stenosis.

The patient was treated with ibuprofen for 2 weeks and colchicine for 3 months, and his symptoms resolved. He followed up with an appointment in the cardiology clinic 1 month later, and his ESR, CRP, and troponin results were negative. A limited echocardiogram showed ejection fraction 60 to 65%, no regional wall motion abnormalities, normal diastolic function, and resolution of the pericardial effusion.

Discussion

Smallpox was a major worldwide cause of mortality; about 30% of those infected died because of smallpox.2,4,5 Due to a worldwide vaccination effort, the World Health Organization declared smallpox was eradicated in 1977.2,4,5 However, despite successful eradication, smallpox is considered a possible bioterrorism target, which prompted a resurgence of mandatory smallpox vaccinations for active-duty personnel.2,5

Dryvax, a freeze-dried calf lymph smallpox vaccine was used extensively from the 1940s to the 1980s but was replaced in 2008 by ACAM2000, a smallpox vaccine cultured in kidney epithelial cells from African green monkeys.3,5 Myopericarditis was rarely associated with the Dryvax, with only 5 cases reported from 1955 to 1986 after millions of doses of vaccines were administered; however, in 230,734 administered ACAM2000 doses, 18 cases of myopericarditis (incidence, 7.8 per 100,000) were reported during a surveillance study in 2002 and 2003.3,5

Myopericarditis presents with a wide variety of symptoms, such as chest pain, palpitations, chills, shortness of breath, and fever.6,7 Mainstay diagnostic criteria include ECG findings consistent with myopericarditis (such as diffuse ST segment elevations) and elevated cardiac biomarkers (elevated troponins).5-7 An echocardiogram can be helpful in diagnosis, as most cases will not have regional wall motion abnormalities (to distinguish against coronary artery disease).5-7 MRI with diffuse enhancement of the myocardium can be helpful in diagnosis.5,6 The gold standard for diagnosis is an endomyocardial biopsy, which carries a significant risk of complications and is not routinely performed to diagnose myopericarditis.5,6 US military smallpox vaccination data showed that the onset of vaccine-associated myopericarditis averaged (SD) 10.4 (3.6) days after vaccination.5

Vaccine-associated myopericarditis treatment is focused on decreasing inflammation.5,6 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are advised for about 2 weeks with cessation of intensive cardiac activities for between 4 and 6 weeks due to risks of congestive heart failure and fatal cardiac arrhythmias.5,6

Conclusions

Since the September 11 attacks, the US needs to be continually prepared for potential terrorism on American soil and abroad. The threat of bioterrorism has renewed efforts to vaccinate or revaccinate American service members deployed to high-risk regions. These vaccinations put them at risk for vaccination-induced complications that can range from mild fever to life-threatening complications.

1. Bruner DI, Butler BS. Smallpox vaccination-associated myopericarditis is more common with the newest smallpox vaccine. J Emerg Med. 2014;46(3):e85-e87. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.06.001

2. Halsell JS, Riddle JR, Atwood JE, et al. Myopericarditis following smallpox vaccination among vaccinia-naive US military personnel. JAMA. 2003;289(24):3283-3289. doi:10.1001/jama.289.24.3283

3. Nalca A, Zumbrun EE. ACAM2000: the new smallpox vaccine for United States Strategic National Stockpile. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2010;4:71-79. doi:10.2147/dddt.s3687

4. Wollenberg A, Engler R. Smallpox, vaccination and adverse reactions to smallpox vaccine. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;4(4):271-275. doi:10.1097/01.all.0000136758.66442.28

5. Cassimatis DC, Atwood JE, Engler RM, Linz PE, Grabenstein JD, Vernalis MN. Smallpox vaccination and myopericarditis: a clinical review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(9):1503-1510. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.053

6. Sharma U, Tak T. A report of 2 cases of myopericarditis after Vaccinia virus (smallpox) immunization. WMJ. 2011;110(6):291-294.

7. Sarkisian SA, Hand G, Rivera VM, Smith M, Miller JA. A case series of smallpox vaccination-associated myopericarditis: effects on safety and readiness of the active duty soldier. Mil Med. 2019;184(1-2):e280-e283. doi:10.1093/milmed/usy159

1. Bruner DI, Butler BS. Smallpox vaccination-associated myopericarditis is more common with the newest smallpox vaccine. J Emerg Med. 2014;46(3):e85-e87. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.06.001

2. Halsell JS, Riddle JR, Atwood JE, et al. Myopericarditis following smallpox vaccination among vaccinia-naive US military personnel. JAMA. 2003;289(24):3283-3289. doi:10.1001/jama.289.24.3283

3. Nalca A, Zumbrun EE. ACAM2000: the new smallpox vaccine for United States Strategic National Stockpile. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2010;4:71-79. doi:10.2147/dddt.s3687

4. Wollenberg A, Engler R. Smallpox, vaccination and adverse reactions to smallpox vaccine. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;4(4):271-275. doi:10.1097/01.all.0000136758.66442.28

5. Cassimatis DC, Atwood JE, Engler RM, Linz PE, Grabenstein JD, Vernalis MN. Smallpox vaccination and myopericarditis: a clinical review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(9):1503-1510. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.053

6. Sharma U, Tak T. A report of 2 cases of myopericarditis after Vaccinia virus (smallpox) immunization. WMJ. 2011;110(6):291-294.

7. Sarkisian SA, Hand G, Rivera VM, Smith M, Miller JA. A case series of smallpox vaccination-associated myopericarditis: effects on safety and readiness of the active duty soldier. Mil Med. 2019;184(1-2):e280-e283. doi:10.1093/milmed/usy159

Mild TBI/Concussion Clinical Tools for Providers Used Within the Department of Defense and Defense Health Agency

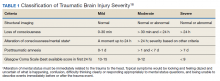

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a major health concern that can cause significant disability as well as economic and social burden. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported a 58% increase in the number of TBI-related emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths from 2006 to 2014.1 In the CDC report, falls and motor vehicle accidents accounted for 52.3% and 20.4%, respectively, of all civilian TBI-related hospitalizations. In 2014, 56,800 TBIs in the US resulted in death. A large proportion of severe TBI survivors continue to experience long-term physical, cognitive, and psychologic disorders and require extensive rehabilitation, which may disrupt relationships and prevent return to work.2 About 37% of people with mild TBI (mTBI) cases and 51% of severe cases were unable to return to previous jobs. A study examining psychosocial burden found that people with a history of TBI reported greater feelings of loneliness compared with individuals without TBI.3

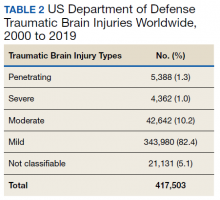

Within the US military, the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center (DVBIC) indicates that > 417,503 service members (SMs) have been diagnosed with TBI since November 2000.4 Of these, 82.4% were classified as having a mTBI, or concussion (Tables 1 and 2). The nature of combat and military training to which SMs are routinely exposed may increase the risk for sustaining a TBI. Specifically, the increased use of improvised explosives devices by enemy combatants in the recent military conflicts (ie, Operation Enduring Freedom, Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation New Dawn) resulted in TBI being recognized as the signature injury of these conflicts and brought attention to the prevalence of concussion within the US military.5,6 In the military, the effects of concussion can decrease individual and unit effectiveness, emphasizing the importance of prompt diagnosis and proper management.7

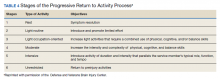

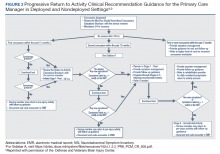

Typically, patients recover from concussion within a few weeks of injury; however, some individuals experience symptoms that persist for months or years. Studies found that early intervention after concussion may aid in expediting recovery, stressing the importance of identifying concussion as promptly as possible.8,9 Active treatment is centered on patient education and symptom management, in addition to a progressive return to activities, as tolerated. Patient education may help validate the symptoms of some patients, as well as help to reattribute the symptoms to benign causes, leading to better outcomes.10 Since TBI is such a relevant health concern within the DoD, it is paramount for practitioners to understand what resources are available in order to identify and initiate treatment expeditiously.

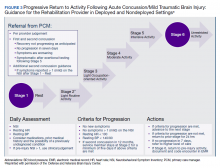

This article focuses on the clinical tools used in evaluating and treating concussion, and best practices treatment guidelines for health care providers (HCPs) who are required to evaluate and treat military populations. While these resources are used for military SMs, they can also be used in veteran and civilian populations. This article showcases 3 DoD clinical tools that assist HCPs in evaluating and treating patients with TBI: (1) the Military Acute Concussion Evaluation 2 (MACE 2); (2) the Progressive Return to Activity (PRA) Clinical Recommendation (CR); and (3) the Concussion Management Tool (CMT). Additional DoD clinical tools and resources are discussed, and resources and links for the practitioner are provided for easy access and reference.

Military Acute Concussion Evaluation 2

Early concussion identification and evaluation are important steps in the treatment process to ensure timely recovery and return to duty for SMs. As such, DVBIC assembled a working group of military and civilian brain injury experts to create an evidence-based clinical practice guideline for the assessment and management of concussion in a military operational setting that could be learned and effectively used by corpsmen and combat medics in the battlefield to screen for a possible concussion.7 This team created the first version of the MACE, a clinical tool that prompted a systematic assessment of concussion related symptoms, neurologic signs, and cognitive deficits. The cognitive assessment portion was based on the standardized assessment of concussion (SAC) that had been reported by McCrea and colleagues in 1998.11 Soon after its creation, field utilization of the MACE for screening of concussion was mandated by the Army through an All Army Action (ALARACT 178/2008) and for all of the Services through the DoD Instruction (DoDI) 6490.11 published in 2014.12

The MACE has been updated several times since the original version. Most recently, the MACE was revised in 2018 to include a vestibular oculomotor assessment section, and red flags that immediately alert the HCP to the need for immediate triage referral and treatment of the patient possibly at a higher echelon of care or with more emergent evaluation.13-15 Additionally, the neurologic examination was expanded to increase clarity and comprehensiveness, including speech and balance testing. Updates made to the tool were intended to provide a more thorough and informative evaluation of the SM with suspected concussion.

This latest version, MACE 2, is designed to be used by any HCP who is treating SMs with a suspected or potential TBI, not just corpsmen and combat medics in theater. The MACE 2 is a comprehensive evaluation within a set of portable pocket cards designed to assist end-users in the proper triage of potentially concussed individuals. The DoD has specified 4 events that require a MACE 2 evaluation: (1) SM was in a vehicle associated with a blast event, collision, or roll over; (2) SM was within 50 meters of a blast; (3) anyone who sustained a direct blow to the head; or (4) when command provides direction (eg, repeated exposures to the events above or in accordance with protocols).12 Sleep deprivation, medications, and pain may affect MACE 2 results, in addition to deployment related stress, chronic stress, high adrenaline sustained over time, and additional comorbidities. This tool is most effective when used as close to the time of injury as possible but also may be used later (after 24 hours of rest) to reevaluate symptoms. The MACE 2 Instructor Guide, a student workbook, HCP training, and Vestibular/Ocular-Motor Screening (VOMS) for Concussion instructions can be found on the DVBIC website (Table 3).

Description

The MACE 2 is a brief multimodal screening tool that assists medics, corpsman, and primary care managers (PCMs) in the assessment and identification of a potential concussion (Figure 1). Embedded in the MACE 2 is the Standardized Assessment of Concussion (SAC), a well-validated sports concussion tool, and the VOMS tool as portions of the 2-part cognitive examination. The entirety of the tool has 5 sections: (1) red flags; (2) acute concussion screening; (3) cognitive examination, part 1; (4) neurologic examination; and (5) cognitive examination, part 2. The end of the MACE 2 includes sections on the scoring, instructions for International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, TBI coding, and next steps following completion of the MACE 2. The latest version of this screening tool impacts TBI care in several noteworthy ways. First, it broadens the scope of users by expanding use to all medically trained personnel, allowing any provider to treat SMs in the field. Second, it combines state-of-the-science advances from the research field and reflects feedback from end-users collected during the development. Last, the MACE 2 is updated as changes in the field occur, and is currently undergoing research to better identify end-user utility and usability.

Screening Tools

• Red Flags. The red flags section aids in identifying potentially serious underlying conditions in patients presenting with Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) between 13 and 15. A positive red flag prompts the practitioner to stop administering the MACE 2 and immediately consult a higher level of care and consider urgent evacuation. While the red flags are completed first, and advancement to later sections of the MACE 2 is dependent upon the absence of red flags, the red flags should be monitored throughout the completion of the MACE 2. Upon completion of patient demographics and red flags, the remaining sections of the MACE 2 are dedicated to acute concussion screening.