User login

We are all in this together: Lessons learned on a COVID-19 unit

Like most family medicine residencies, our teaching nursing home was struck with a COVID-19 outbreak. Within 10 days, I was the sole physician responsible for 15 patients with varying degrees of illness, quarantined behind the fire doors of a wing of a Memory Support Unit. My daily work there over the course of the next month prompted me to reflect on some of the core principles of family medicine, and health care, that are vital to effective patient care during a pandemic. My experience provided the following reminders:

Work as a team. Gowned, gloved, and masked behind the fire doors, our world shrank to our patients and a 4-person team comprised of a nurse, 2 nursing assistants, and me. For the first time in the 10+ years I’ve worked at that facility, I actually asked for and memorized the names of everyone I was working with that day. Without an intercom or other telecommunications system, it became important for me to be able to call for my team members by name for immediate help. We had to depend on one another to make sure all patients were hydrated and fed, to avert falls whenever possible, to intervene early when dementia-associated behaviors were escalating, and to recognize when patients were crashing.

We also had to depend on each other to ensure that our personal protective equipment remained properly placed, to combat the psychological sense of isolation that quarantine environments engender, and to placate a gnawing undercurrent of unease while working around a potentially deadly pathogen.

Develop clinical routines. Having listened to other medical directors whose nursing homes were affected by the pandemic earlier than we were, and hearing about potentially avoidable complications, we developed clinical routines. This began with identifying any patients with diabetes whose poor appetites while acutely ill could send them into hypoglycemia. We devised a daily clinical report sheet that included vital signs, date of positive COVID-19 test, global clinical status, and advance directives. Unlike the usual mode of working almost in parallel, I began my workday with a “sign-out” from the nurse, then started examining each patient.

Under the strain of this unusual environment and novel circumstances, we communicated more and more often. This allowed us to quickly recognize and communicate emerging changes in the clinical status of a patient by sharing our observations of subtle, nonspecific “sub-threshold” indicators.

Clarify the goals of care. Since most of the patients in the COVID-19 unit were under the long-term care of other attending physicians, it was important for me to understand the wishes of the patient or surrogate decision maker, should life-threatening complications occur. While all affected patients were long-term residents of a memory support unit, some had full-code advance directives. I quickly realized that what was first necessary was to develop rapport and trust with the families who didn’t know me, then discuss goals of care, and finally assure that the advance directives were in congruence with their stated goals. What helped families gain trust in me was knowing that I was seeing their loved one daily, that I was committed to helping the patient survive this infection, and that I was willing to come back to the facility if a crisis occurred—even at night, if necessary.

Appreciate the daily work of team members. One of my greatest worries was dehydration. When elders were acutely ill and eating and drinking poorly, I would assist with feeding and offering liquids. I quickly came to appreciate how complex and subtle this seemingly mundane task can be. Learning the proper pace and portion size, even choosing the right conversation topic and tone, could make the difference between a patient “shutting down” and refusing all nourishment and successfully drinking a 360-cc cup of a high-nutrient shake.

Continue to: In the disrupted routines...

In the disrupted routines and altered physical environments of the COVID-19 unit, the psychological and behavioral complications of dementia intensified for some patients. I observed first-hand the great patience, kindness, and finesse that nurses and nursing assistants display in their efforts to de-escalate and prevent disruptive behaviors.

Empathize with (and appreciate) families. Families tearfully reminded me that they had been suffering from the absence of contact with their loved ones for months; COVID-19 added to that trauma for many of them. They talked about the missed graduations, birthdays, and other precious times together that were lost because of the quarantine.

Families also prevented me from making mistakes. When I ordered nitrofurantoin for a patient with a urinary tract infection, her son called me and respectfully requested I “just check and make sure” it would not cause a problem, given her G6PD deficiency. He prevented me from prescribing an antibiotic contraindicated in that condition.

Bring forward the lessons learned. The COVID-19 outbreak has passed through our nursing home—at least for now. I perceive a subtle shift in how we continue to interact with one another. Behind the masks, we make a little more eye contact; we more often address each other by name; and we acknowledge a greater mutual respect.

The shared experience of COVID-19 has brought us all a little closer together, and in the end, our patients have benefitted.

Like most family medicine residencies, our teaching nursing home was struck with a COVID-19 outbreak. Within 10 days, I was the sole physician responsible for 15 patients with varying degrees of illness, quarantined behind the fire doors of a wing of a Memory Support Unit. My daily work there over the course of the next month prompted me to reflect on some of the core principles of family medicine, and health care, that are vital to effective patient care during a pandemic. My experience provided the following reminders:

Work as a team. Gowned, gloved, and masked behind the fire doors, our world shrank to our patients and a 4-person team comprised of a nurse, 2 nursing assistants, and me. For the first time in the 10+ years I’ve worked at that facility, I actually asked for and memorized the names of everyone I was working with that day. Without an intercom or other telecommunications system, it became important for me to be able to call for my team members by name for immediate help. We had to depend on one another to make sure all patients were hydrated and fed, to avert falls whenever possible, to intervene early when dementia-associated behaviors were escalating, and to recognize when patients were crashing.

We also had to depend on each other to ensure that our personal protective equipment remained properly placed, to combat the psychological sense of isolation that quarantine environments engender, and to placate a gnawing undercurrent of unease while working around a potentially deadly pathogen.

Develop clinical routines. Having listened to other medical directors whose nursing homes were affected by the pandemic earlier than we were, and hearing about potentially avoidable complications, we developed clinical routines. This began with identifying any patients with diabetes whose poor appetites while acutely ill could send them into hypoglycemia. We devised a daily clinical report sheet that included vital signs, date of positive COVID-19 test, global clinical status, and advance directives. Unlike the usual mode of working almost in parallel, I began my workday with a “sign-out” from the nurse, then started examining each patient.

Under the strain of this unusual environment and novel circumstances, we communicated more and more often. This allowed us to quickly recognize and communicate emerging changes in the clinical status of a patient by sharing our observations of subtle, nonspecific “sub-threshold” indicators.

Clarify the goals of care. Since most of the patients in the COVID-19 unit were under the long-term care of other attending physicians, it was important for me to understand the wishes of the patient or surrogate decision maker, should life-threatening complications occur. While all affected patients were long-term residents of a memory support unit, some had full-code advance directives. I quickly realized that what was first necessary was to develop rapport and trust with the families who didn’t know me, then discuss goals of care, and finally assure that the advance directives were in congruence with their stated goals. What helped families gain trust in me was knowing that I was seeing their loved one daily, that I was committed to helping the patient survive this infection, and that I was willing to come back to the facility if a crisis occurred—even at night, if necessary.

Appreciate the daily work of team members. One of my greatest worries was dehydration. When elders were acutely ill and eating and drinking poorly, I would assist with feeding and offering liquids. I quickly came to appreciate how complex and subtle this seemingly mundane task can be. Learning the proper pace and portion size, even choosing the right conversation topic and tone, could make the difference between a patient “shutting down” and refusing all nourishment and successfully drinking a 360-cc cup of a high-nutrient shake.

Continue to: In the disrupted routines...

In the disrupted routines and altered physical environments of the COVID-19 unit, the psychological and behavioral complications of dementia intensified for some patients. I observed first-hand the great patience, kindness, and finesse that nurses and nursing assistants display in their efforts to de-escalate and prevent disruptive behaviors.

Empathize with (and appreciate) families. Families tearfully reminded me that they had been suffering from the absence of contact with their loved ones for months; COVID-19 added to that trauma for many of them. They talked about the missed graduations, birthdays, and other precious times together that were lost because of the quarantine.

Families also prevented me from making mistakes. When I ordered nitrofurantoin for a patient with a urinary tract infection, her son called me and respectfully requested I “just check and make sure” it would not cause a problem, given her G6PD deficiency. He prevented me from prescribing an antibiotic contraindicated in that condition.

Bring forward the lessons learned. The COVID-19 outbreak has passed through our nursing home—at least for now. I perceive a subtle shift in how we continue to interact with one another. Behind the masks, we make a little more eye contact; we more often address each other by name; and we acknowledge a greater mutual respect.

The shared experience of COVID-19 has brought us all a little closer together, and in the end, our patients have benefitted.

Like most family medicine residencies, our teaching nursing home was struck with a COVID-19 outbreak. Within 10 days, I was the sole physician responsible for 15 patients with varying degrees of illness, quarantined behind the fire doors of a wing of a Memory Support Unit. My daily work there over the course of the next month prompted me to reflect on some of the core principles of family medicine, and health care, that are vital to effective patient care during a pandemic. My experience provided the following reminders:

Work as a team. Gowned, gloved, and masked behind the fire doors, our world shrank to our patients and a 4-person team comprised of a nurse, 2 nursing assistants, and me. For the first time in the 10+ years I’ve worked at that facility, I actually asked for and memorized the names of everyone I was working with that day. Without an intercom or other telecommunications system, it became important for me to be able to call for my team members by name for immediate help. We had to depend on one another to make sure all patients were hydrated and fed, to avert falls whenever possible, to intervene early when dementia-associated behaviors were escalating, and to recognize when patients were crashing.

We also had to depend on each other to ensure that our personal protective equipment remained properly placed, to combat the psychological sense of isolation that quarantine environments engender, and to placate a gnawing undercurrent of unease while working around a potentially deadly pathogen.

Develop clinical routines. Having listened to other medical directors whose nursing homes were affected by the pandemic earlier than we were, and hearing about potentially avoidable complications, we developed clinical routines. This began with identifying any patients with diabetes whose poor appetites while acutely ill could send them into hypoglycemia. We devised a daily clinical report sheet that included vital signs, date of positive COVID-19 test, global clinical status, and advance directives. Unlike the usual mode of working almost in parallel, I began my workday with a “sign-out” from the nurse, then started examining each patient.

Under the strain of this unusual environment and novel circumstances, we communicated more and more often. This allowed us to quickly recognize and communicate emerging changes in the clinical status of a patient by sharing our observations of subtle, nonspecific “sub-threshold” indicators.

Clarify the goals of care. Since most of the patients in the COVID-19 unit were under the long-term care of other attending physicians, it was important for me to understand the wishes of the patient or surrogate decision maker, should life-threatening complications occur. While all affected patients were long-term residents of a memory support unit, some had full-code advance directives. I quickly realized that what was first necessary was to develop rapport and trust with the families who didn’t know me, then discuss goals of care, and finally assure that the advance directives were in congruence with their stated goals. What helped families gain trust in me was knowing that I was seeing their loved one daily, that I was committed to helping the patient survive this infection, and that I was willing to come back to the facility if a crisis occurred—even at night, if necessary.

Appreciate the daily work of team members. One of my greatest worries was dehydration. When elders were acutely ill and eating and drinking poorly, I would assist with feeding and offering liquids. I quickly came to appreciate how complex and subtle this seemingly mundane task can be. Learning the proper pace and portion size, even choosing the right conversation topic and tone, could make the difference between a patient “shutting down” and refusing all nourishment and successfully drinking a 360-cc cup of a high-nutrient shake.

Continue to: In the disrupted routines...

In the disrupted routines and altered physical environments of the COVID-19 unit, the psychological and behavioral complications of dementia intensified for some patients. I observed first-hand the great patience, kindness, and finesse that nurses and nursing assistants display in their efforts to de-escalate and prevent disruptive behaviors.

Empathize with (and appreciate) families. Families tearfully reminded me that they had been suffering from the absence of contact with their loved ones for months; COVID-19 added to that trauma for many of them. They talked about the missed graduations, birthdays, and other precious times together that were lost because of the quarantine.

Families also prevented me from making mistakes. When I ordered nitrofurantoin for a patient with a urinary tract infection, her son called me and respectfully requested I “just check and make sure” it would not cause a problem, given her G6PD deficiency. He prevented me from prescribing an antibiotic contraindicated in that condition.

Bring forward the lessons learned. The COVID-19 outbreak has passed through our nursing home—at least for now. I perceive a subtle shift in how we continue to interact with one another. Behind the masks, we make a little more eye contact; we more often address each other by name; and we acknowledge a greater mutual respect.

The shared experience of COVID-19 has brought us all a little closer together, and in the end, our patients have benefitted.

45-year-old man • fever • generalized rash • recent history of calcaneal osteomyelitis • Dx?

THE CASE

A 45-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with a fever and generalized rash. For the previous 2 weeks, he had been treated at a skilled nursing facility with IV vancomycin and cefepime for left calcaneal osteomyelitis. He reported that the rash was pruritic and started 2 days prior to hospital admission.

His past medical history was significant for type 2 diabetes mellitus and polysubstance drug abuse. Medical and travel history were otherwise unremarkable. The patient was taking the following medications at the time of presentation: hydrocodone-acetaminophen, cyclobenzaprine, melatonin, and metformin.

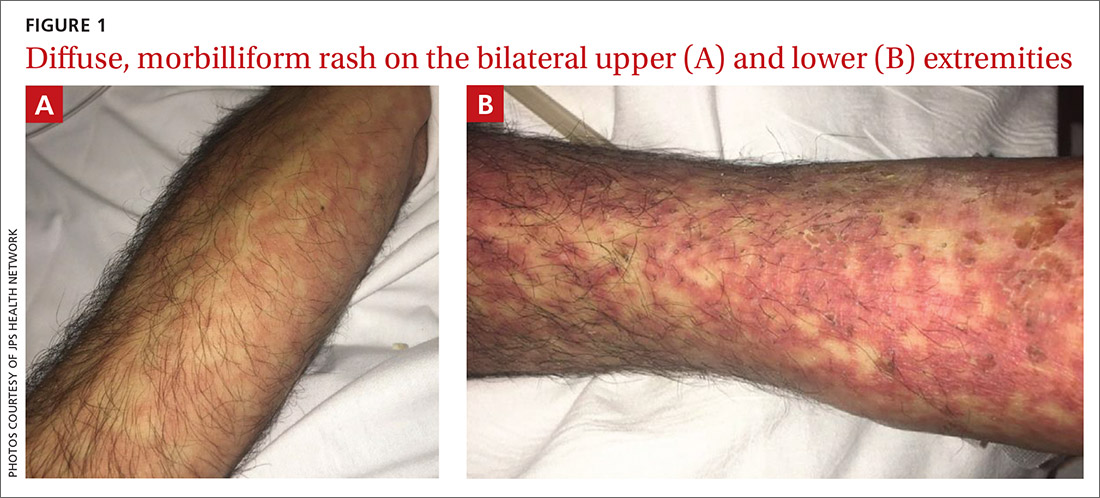

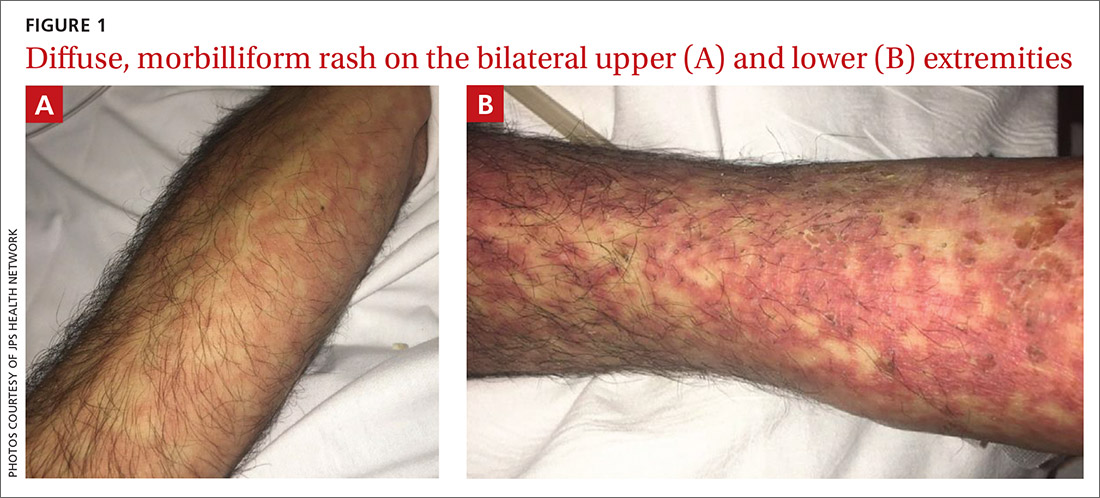

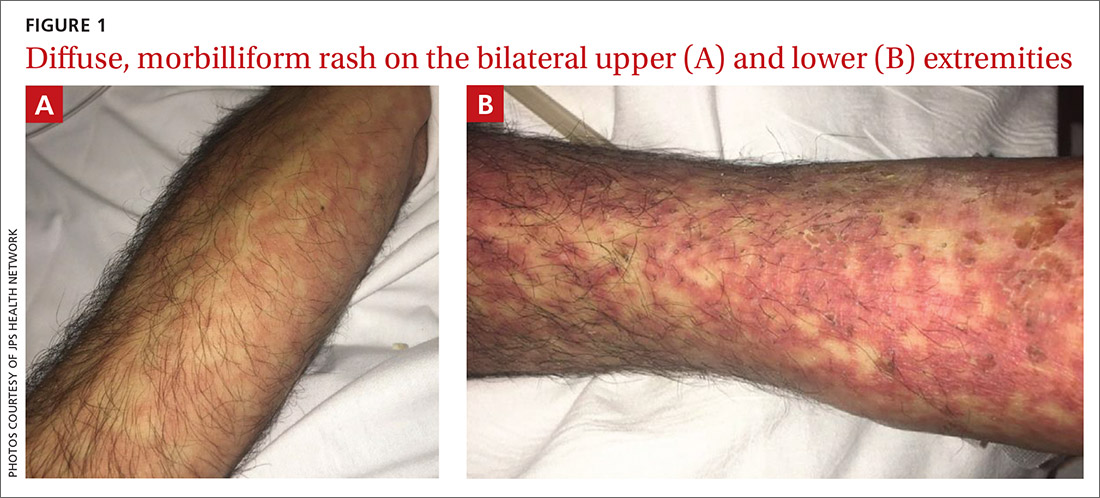

Initial vital signs included a temperature of 102.9°F; respiratory rate, 22 breaths/min; heart rate, 97 beats/min; and blood pressure, 89/50 mm Hg. Physical exam was notable for left anterior cervical and axillary lymphadenopathy. The patient had no facial edema, but he did have a diffuse, morbilliform rash on his bilateral upper and lower extremities, encompassing about 54% of his body surface area (FIGURE 1).

Laboratory studies revealed a white blood cell count of 4.7/mcL, with 3.4% eosinophils and 10.9% monocytes; an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 60 mm/h; and a C-reactive protein level of 1 mg/dL. Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were both elevated (AST: 95 U/L [normal range, 8 - 48 U/L]; ALT: 115 U/L [normal range: 7 - 55 U/L]). A chest x-ray was obtained and showed new lung infiltrates (FIGURE 2).

Linezolid and meropenem were initiated for a presumed health care–associated pneumonia, and a sepsis work-up was initiated.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s rash and pruritus worsened after meropenem was introduced. A hepatitis panel was nonreactive except for prior hepatitis A exposure. Ultrasound of the liver and spleen was normal. Investigation of pneumonia pathogens including Legionella, Streptococcus, Mycoplasma, and Chlamydia psittaci did not reveal any causative agents. A skin biopsy revealed perivascular neutrophilic dermatitis with dyskeratosis.

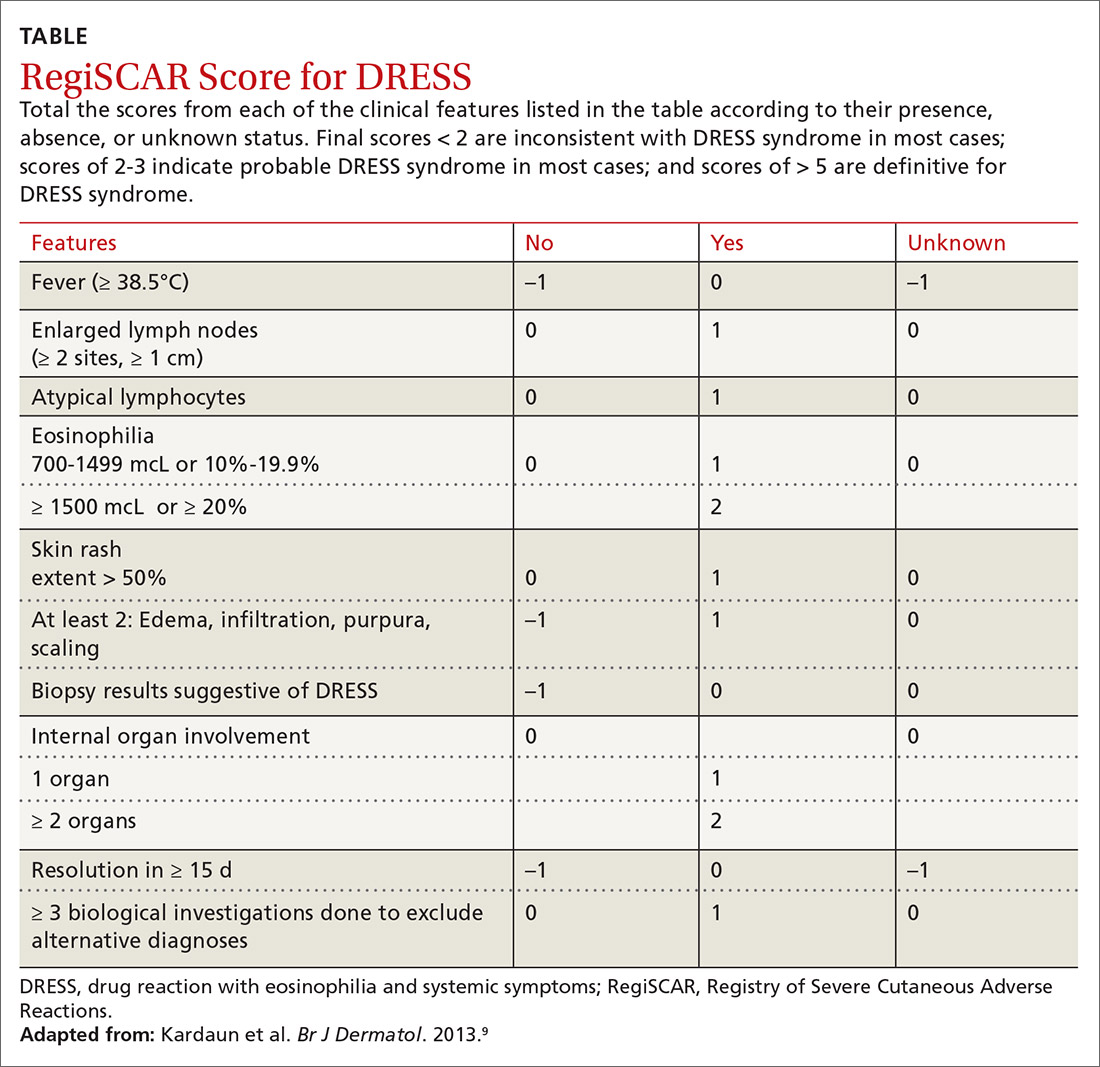

The patient was diagnosed with DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome based on his fever, worsening morbilliform rash, lymphadenopathy, and elevated liver transaminase levels. Although he did not have marked eosinophilia, atypical lymphocytes were present. Serologies for human herpesvirus (HHV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and cytomegalovirus (CMV) were all unremarkable.

Continue to: During discussions...

During discussions with an infectious disease specialist, it was concluded that the patient’s DRESS syndrome was likely secondary to beta-lactam antibiotics. The patient had been receiving cefepime prior to hospitalization. Meropenem was discontinued and aztreonam was started, with continued linezolid. This patient did not have a reactivation of a herpesvirus (HHV-6, HHV-7, EBV, or CMV), which has been previously reported in cases of DRESS syndrome.

DISCUSSION

DRESS syndrome is a challenging diagnosis to make due to the multiplicity of presenting symptoms. Skin rash, lymphadenopathy, hepatic involvement, and hypereosinophilia are characteristic findings.1 Accurate diagnosis reduces fatal disease outcomes, which are estimated to occur in 5%-10% of cases.1,2

Causative agents. DRESS syndrome typically occurs 2 to 6 weeks after the introduction of the causative agent, commonly an aromatic anticonvulsant or antibiotic.3 The incidence of DRESS syndrome in patients using carbamazepine and phenytoin is estimated to be 1 to 5 per 10,000 patients. The incidence of DRESS syndrome in patients using antibiotics is unknown. Frequently, the inducing antibiotic is a beta-lactam, as in this case.4,5

The pathogenesis of DRESS syndrome is not well understood, although there appears to be an immune-mediated reaction that occurs in certain patients after viral reactivation, particularly with herpesviruses. In vitro studies have demonstrated that the culprit drug is able to induce viral reactivation leading to T-lymphocyte response and systemic inflammation, which occurs in multiple organs.6,7 Reported long-term sequelae of DRESS syndrome include immune-mediated diseases such as thyroiditis and type 1 diabetes. In addition, it is hypothesized that there is a genetic predisposition involving human leukocyte antigens that increases the likelihood that individuals will develop DRESS syndrome.5,8

Diagnosis. The

Continue to: Treatment

Treatment is aimed at stopping the causative agent and starting moderate- to high-dose systemic corticosteroids (from 0.5 to 2 mg/kg/d). If symptoms continue to progress, cyclosporine can be used. N-acetylcysteine may also be beneficial due to its ability to neutralize drug metabolites that can stimulate T-cell response.7 There has not been sufficient evidence to suggest that antiviral medication should be initiated.1,7

Our patient was treated with 2 mg/kg/d of prednisone, along with triamcinolone cream, diphenhydramine, and N-acetylcysteine. His rash improved dramatically during his hospital stay and at the subsequent 1-month follow-up was completely resolved.

THE TAKEAWAY

DRESS syndrome should be suspected in patients presenting with fever, rash, lymphadenopathy, pulmonary infiltrates, and liver involvement after initiation of drugs commonly associated with this syndrome. Our case reinforces previous clinical evidence that beta-lactam antibiotics are a common cause of DRESS syndrome; patients taking these medications should be closely monitored. Cross-reactions are frequent, and it is imperative that patients avoid related drugs to prevent recurrence. Although glucocorticoids are the mainstay of treatment, further studies are needed to assess the benefits of N-acetylcysteine.

CORRESPONDENCE

W. Jacob Cobb, MD, JPS Health Network, 1500 South Main Street, Fort Worth, TX, 76104; [email protected]

1. Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review. Am J Med. 2011;124:588-597.

2. Chen Y, Chiu H, Chu C. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: a retrospective study of 60 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1373-1379.

3. Jeung Y-J, Lee J-Y, Oh M-J, et al. Comparison of the causes and clinical features of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2010;2:123–126.

4. Shiohara T, Iijima M, Ikezawa Z, et al. The diagnosis of a DRESS syndrome has been sufficiently established on the basis of typical clinical features and viral reactivations [commentary]. Br J Dermatol. 2006;156:1083-1084.

5. Ben-Said B, Arnaud-Butel S, Rozières A, et al. Allergic delayed drug hypersensitivity is more frequently diagnosed in drug reaction, eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome than in exanthema induced by beta lactam antibiotics. J Dermatol Sci. 2015;80:71-74.

6. Schrijvers R, Gilissen L, Chiriac AM, et al. Pathogenesis and diagnosis of delayed-type drug hypersensitivity reactions, from bedside to bench and back. Clin Transl Allergy. 2015;5:31.

7. Moling O, Tappeiner L, Piccin A, et al. Treatment of DIHS/DRESS syndrome with combined N-acetylcysteine, prednisone and valganciclovir—a hypothesis. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18:CS57-CS62.

8. Cardoso CS, Vieira AM, Oliveira AP. DRESS syndrome: a case report and literature review. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0220113898.

9. Kardaun SH, Sekula P, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an original multisystem adverse drug reaction. Results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1071-1080.

10. Bernard L, Eichenfield L. Drug-associated rashes. In: Zaoutis L, Chiang V, eds. Comprehensive Pediatric Hospital Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2010: 1005-1011.

11. Grover S. Severe cutaneous adverse reactions. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:3-6.

THE CASE

A 45-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with a fever and generalized rash. For the previous 2 weeks, he had been treated at a skilled nursing facility with IV vancomycin and cefepime for left calcaneal osteomyelitis. He reported that the rash was pruritic and started 2 days prior to hospital admission.

His past medical history was significant for type 2 diabetes mellitus and polysubstance drug abuse. Medical and travel history were otherwise unremarkable. The patient was taking the following medications at the time of presentation: hydrocodone-acetaminophen, cyclobenzaprine, melatonin, and metformin.

Initial vital signs included a temperature of 102.9°F; respiratory rate, 22 breaths/min; heart rate, 97 beats/min; and blood pressure, 89/50 mm Hg. Physical exam was notable for left anterior cervical and axillary lymphadenopathy. The patient had no facial edema, but he did have a diffuse, morbilliform rash on his bilateral upper and lower extremities, encompassing about 54% of his body surface area (FIGURE 1).

Laboratory studies revealed a white blood cell count of 4.7/mcL, with 3.4% eosinophils and 10.9% monocytes; an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 60 mm/h; and a C-reactive protein level of 1 mg/dL. Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were both elevated (AST: 95 U/L [normal range, 8 - 48 U/L]; ALT: 115 U/L [normal range: 7 - 55 U/L]). A chest x-ray was obtained and showed new lung infiltrates (FIGURE 2).

Linezolid and meropenem were initiated for a presumed health care–associated pneumonia, and a sepsis work-up was initiated.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s rash and pruritus worsened after meropenem was introduced. A hepatitis panel was nonreactive except for prior hepatitis A exposure. Ultrasound of the liver and spleen was normal. Investigation of pneumonia pathogens including Legionella, Streptococcus, Mycoplasma, and Chlamydia psittaci did not reveal any causative agents. A skin biopsy revealed perivascular neutrophilic dermatitis with dyskeratosis.

The patient was diagnosed with DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome based on his fever, worsening morbilliform rash, lymphadenopathy, and elevated liver transaminase levels. Although he did not have marked eosinophilia, atypical lymphocytes were present. Serologies for human herpesvirus (HHV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and cytomegalovirus (CMV) were all unremarkable.

Continue to: During discussions...

During discussions with an infectious disease specialist, it was concluded that the patient’s DRESS syndrome was likely secondary to beta-lactam antibiotics. The patient had been receiving cefepime prior to hospitalization. Meropenem was discontinued and aztreonam was started, with continued linezolid. This patient did not have a reactivation of a herpesvirus (HHV-6, HHV-7, EBV, or CMV), which has been previously reported in cases of DRESS syndrome.

DISCUSSION

DRESS syndrome is a challenging diagnosis to make due to the multiplicity of presenting symptoms. Skin rash, lymphadenopathy, hepatic involvement, and hypereosinophilia are characteristic findings.1 Accurate diagnosis reduces fatal disease outcomes, which are estimated to occur in 5%-10% of cases.1,2

Causative agents. DRESS syndrome typically occurs 2 to 6 weeks after the introduction of the causative agent, commonly an aromatic anticonvulsant or antibiotic.3 The incidence of DRESS syndrome in patients using carbamazepine and phenytoin is estimated to be 1 to 5 per 10,000 patients. The incidence of DRESS syndrome in patients using antibiotics is unknown. Frequently, the inducing antibiotic is a beta-lactam, as in this case.4,5

The pathogenesis of DRESS syndrome is not well understood, although there appears to be an immune-mediated reaction that occurs in certain patients after viral reactivation, particularly with herpesviruses. In vitro studies have demonstrated that the culprit drug is able to induce viral reactivation leading to T-lymphocyte response and systemic inflammation, which occurs in multiple organs.6,7 Reported long-term sequelae of DRESS syndrome include immune-mediated diseases such as thyroiditis and type 1 diabetes. In addition, it is hypothesized that there is a genetic predisposition involving human leukocyte antigens that increases the likelihood that individuals will develop DRESS syndrome.5,8

Diagnosis. The

Continue to: Treatment

Treatment is aimed at stopping the causative agent and starting moderate- to high-dose systemic corticosteroids (from 0.5 to 2 mg/kg/d). If symptoms continue to progress, cyclosporine can be used. N-acetylcysteine may also be beneficial due to its ability to neutralize drug metabolites that can stimulate T-cell response.7 There has not been sufficient evidence to suggest that antiviral medication should be initiated.1,7

Our patient was treated with 2 mg/kg/d of prednisone, along with triamcinolone cream, diphenhydramine, and N-acetylcysteine. His rash improved dramatically during his hospital stay and at the subsequent 1-month follow-up was completely resolved.

THE TAKEAWAY

DRESS syndrome should be suspected in patients presenting with fever, rash, lymphadenopathy, pulmonary infiltrates, and liver involvement after initiation of drugs commonly associated with this syndrome. Our case reinforces previous clinical evidence that beta-lactam antibiotics are a common cause of DRESS syndrome; patients taking these medications should be closely monitored. Cross-reactions are frequent, and it is imperative that patients avoid related drugs to prevent recurrence. Although glucocorticoids are the mainstay of treatment, further studies are needed to assess the benefits of N-acetylcysteine.

CORRESPONDENCE

W. Jacob Cobb, MD, JPS Health Network, 1500 South Main Street, Fort Worth, TX, 76104; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 45-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with a fever and generalized rash. For the previous 2 weeks, he had been treated at a skilled nursing facility with IV vancomycin and cefepime for left calcaneal osteomyelitis. He reported that the rash was pruritic and started 2 days prior to hospital admission.

His past medical history was significant for type 2 diabetes mellitus and polysubstance drug abuse. Medical and travel history were otherwise unremarkable. The patient was taking the following medications at the time of presentation: hydrocodone-acetaminophen, cyclobenzaprine, melatonin, and metformin.

Initial vital signs included a temperature of 102.9°F; respiratory rate, 22 breaths/min; heart rate, 97 beats/min; and blood pressure, 89/50 mm Hg. Physical exam was notable for left anterior cervical and axillary lymphadenopathy. The patient had no facial edema, but he did have a diffuse, morbilliform rash on his bilateral upper and lower extremities, encompassing about 54% of his body surface area (FIGURE 1).

Laboratory studies revealed a white blood cell count of 4.7/mcL, with 3.4% eosinophils and 10.9% monocytes; an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 60 mm/h; and a C-reactive protein level of 1 mg/dL. Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were both elevated (AST: 95 U/L [normal range, 8 - 48 U/L]; ALT: 115 U/L [normal range: 7 - 55 U/L]). A chest x-ray was obtained and showed new lung infiltrates (FIGURE 2).

Linezolid and meropenem were initiated for a presumed health care–associated pneumonia, and a sepsis work-up was initiated.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s rash and pruritus worsened after meropenem was introduced. A hepatitis panel was nonreactive except for prior hepatitis A exposure. Ultrasound of the liver and spleen was normal. Investigation of pneumonia pathogens including Legionella, Streptococcus, Mycoplasma, and Chlamydia psittaci did not reveal any causative agents. A skin biopsy revealed perivascular neutrophilic dermatitis with dyskeratosis.

The patient was diagnosed with DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome based on his fever, worsening morbilliform rash, lymphadenopathy, and elevated liver transaminase levels. Although he did not have marked eosinophilia, atypical lymphocytes were present. Serologies for human herpesvirus (HHV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and cytomegalovirus (CMV) were all unremarkable.

Continue to: During discussions...

During discussions with an infectious disease specialist, it was concluded that the patient’s DRESS syndrome was likely secondary to beta-lactam antibiotics. The patient had been receiving cefepime prior to hospitalization. Meropenem was discontinued and aztreonam was started, with continued linezolid. This patient did not have a reactivation of a herpesvirus (HHV-6, HHV-7, EBV, or CMV), which has been previously reported in cases of DRESS syndrome.

DISCUSSION

DRESS syndrome is a challenging diagnosis to make due to the multiplicity of presenting symptoms. Skin rash, lymphadenopathy, hepatic involvement, and hypereosinophilia are characteristic findings.1 Accurate diagnosis reduces fatal disease outcomes, which are estimated to occur in 5%-10% of cases.1,2

Causative agents. DRESS syndrome typically occurs 2 to 6 weeks after the introduction of the causative agent, commonly an aromatic anticonvulsant or antibiotic.3 The incidence of DRESS syndrome in patients using carbamazepine and phenytoin is estimated to be 1 to 5 per 10,000 patients. The incidence of DRESS syndrome in patients using antibiotics is unknown. Frequently, the inducing antibiotic is a beta-lactam, as in this case.4,5

The pathogenesis of DRESS syndrome is not well understood, although there appears to be an immune-mediated reaction that occurs in certain patients after viral reactivation, particularly with herpesviruses. In vitro studies have demonstrated that the culprit drug is able to induce viral reactivation leading to T-lymphocyte response and systemic inflammation, which occurs in multiple organs.6,7 Reported long-term sequelae of DRESS syndrome include immune-mediated diseases such as thyroiditis and type 1 diabetes. In addition, it is hypothesized that there is a genetic predisposition involving human leukocyte antigens that increases the likelihood that individuals will develop DRESS syndrome.5,8

Diagnosis. The

Continue to: Treatment

Treatment is aimed at stopping the causative agent and starting moderate- to high-dose systemic corticosteroids (from 0.5 to 2 mg/kg/d). If symptoms continue to progress, cyclosporine can be used. N-acetylcysteine may also be beneficial due to its ability to neutralize drug metabolites that can stimulate T-cell response.7 There has not been sufficient evidence to suggest that antiviral medication should be initiated.1,7

Our patient was treated with 2 mg/kg/d of prednisone, along with triamcinolone cream, diphenhydramine, and N-acetylcysteine. His rash improved dramatically during his hospital stay and at the subsequent 1-month follow-up was completely resolved.

THE TAKEAWAY

DRESS syndrome should be suspected in patients presenting with fever, rash, lymphadenopathy, pulmonary infiltrates, and liver involvement after initiation of drugs commonly associated with this syndrome. Our case reinforces previous clinical evidence that beta-lactam antibiotics are a common cause of DRESS syndrome; patients taking these medications should be closely monitored. Cross-reactions are frequent, and it is imperative that patients avoid related drugs to prevent recurrence. Although glucocorticoids are the mainstay of treatment, further studies are needed to assess the benefits of N-acetylcysteine.

CORRESPONDENCE

W. Jacob Cobb, MD, JPS Health Network, 1500 South Main Street, Fort Worth, TX, 76104; [email protected]

1. Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review. Am J Med. 2011;124:588-597.

2. Chen Y, Chiu H, Chu C. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: a retrospective study of 60 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1373-1379.

3. Jeung Y-J, Lee J-Y, Oh M-J, et al. Comparison of the causes and clinical features of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2010;2:123–126.

4. Shiohara T, Iijima M, Ikezawa Z, et al. The diagnosis of a DRESS syndrome has been sufficiently established on the basis of typical clinical features and viral reactivations [commentary]. Br J Dermatol. 2006;156:1083-1084.

5. Ben-Said B, Arnaud-Butel S, Rozières A, et al. Allergic delayed drug hypersensitivity is more frequently diagnosed in drug reaction, eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome than in exanthema induced by beta lactam antibiotics. J Dermatol Sci. 2015;80:71-74.

6. Schrijvers R, Gilissen L, Chiriac AM, et al. Pathogenesis and diagnosis of delayed-type drug hypersensitivity reactions, from bedside to bench and back. Clin Transl Allergy. 2015;5:31.

7. Moling O, Tappeiner L, Piccin A, et al. Treatment of DIHS/DRESS syndrome with combined N-acetylcysteine, prednisone and valganciclovir—a hypothesis. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18:CS57-CS62.

8. Cardoso CS, Vieira AM, Oliveira AP. DRESS syndrome: a case report and literature review. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0220113898.

9. Kardaun SH, Sekula P, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an original multisystem adverse drug reaction. Results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1071-1080.

10. Bernard L, Eichenfield L. Drug-associated rashes. In: Zaoutis L, Chiang V, eds. Comprehensive Pediatric Hospital Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2010: 1005-1011.

11. Grover S. Severe cutaneous adverse reactions. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:3-6.

1. Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review. Am J Med. 2011;124:588-597.

2. Chen Y, Chiu H, Chu C. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: a retrospective study of 60 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1373-1379.

3. Jeung Y-J, Lee J-Y, Oh M-J, et al. Comparison of the causes and clinical features of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2010;2:123–126.

4. Shiohara T, Iijima M, Ikezawa Z, et al. The diagnosis of a DRESS syndrome has been sufficiently established on the basis of typical clinical features and viral reactivations [commentary]. Br J Dermatol. 2006;156:1083-1084.

5. Ben-Said B, Arnaud-Butel S, Rozières A, et al. Allergic delayed drug hypersensitivity is more frequently diagnosed in drug reaction, eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome than in exanthema induced by beta lactam antibiotics. J Dermatol Sci. 2015;80:71-74.

6. Schrijvers R, Gilissen L, Chiriac AM, et al. Pathogenesis and diagnosis of delayed-type drug hypersensitivity reactions, from bedside to bench and back. Clin Transl Allergy. 2015;5:31.

7. Moling O, Tappeiner L, Piccin A, et al. Treatment of DIHS/DRESS syndrome with combined N-acetylcysteine, prednisone and valganciclovir—a hypothesis. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18:CS57-CS62.

8. Cardoso CS, Vieira AM, Oliveira AP. DRESS syndrome: a case report and literature review. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0220113898.

9. Kardaun SH, Sekula P, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an original multisystem adverse drug reaction. Results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1071-1080.

10. Bernard L, Eichenfield L. Drug-associated rashes. In: Zaoutis L, Chiang V, eds. Comprehensive Pediatric Hospital Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2010: 1005-1011.

11. Grover S. Severe cutaneous adverse reactions. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:3-6.

A primary care guide to bipolar depression treatment

Bipolar disorder is a prevalent disorder in the primary care setting.1,2 Primary care providers therefore commonly encounter bipolar depression (BD; a major depressive episode in the context of bipolar disorder), which might be (1) an emerging depressive episode in previously undiagnosed bipolar disorder or (2) a recurrent episode during the course of chronic bipolar illness.3,4

A primary care–based collaborative model has been identified as a potential strategy for effective management of chronic mental health conditions such as bipolar disorder.5,6 However, this collaborative treatment model isn’t widely available; many patients with bipolar disorder are, in fact, treated solely by their primary care provider.

Two years ago in this journal,7 we addressed how to precisely identify an episode of BD and differentiate it from major depressive disorder (MDD; also known as unipolar depression). In this review, in addition to advancing clinical knowledge of BD, we provide:

- an overview of treatment options for BD (in contrast to the treatment of unipolar depression)

- the pharmacotherapeutic know-how to initiate and maintain treatment for uncomplicated episodes of BD.

We do not discuss management of manic, hypomanic, and mixed episodes of bipolar disorder.

How to identify bipolar depression

Understanding the (sometimes) unclear distinction between bipolar I and bipolar II disorders in an individual patient is key to formulating a therapeutic regimen for BD.

Bipolar I disorder consists of manic episodes, alternating (more often than not) with depressive episodes. Bipolar I usually manifests first with a depressive episode.

Bipolar II disorder manifests with depressive episodes and hypomanic episodes (but never manic episodes).

Continue to: Depressive episodes in the bipolar disorders

Depressive episodes in the bipolar disorders. Bipolar depression can be seen in the settings of both bipolar I and II disorders. When a patient presents with a manic episode, a history of depressive episodes is common (although not essential) to diagnose bipolar I; alternatively, a history of hypomania (but no prior mania) and depression is needed to make the diagnosis of bipolar II. The natural history of the bipolar disorders is therefore alternating manic and almost always depressive episodes (bipolar I) and alternating hypomanic and always depressive episodes (bipolar II).8

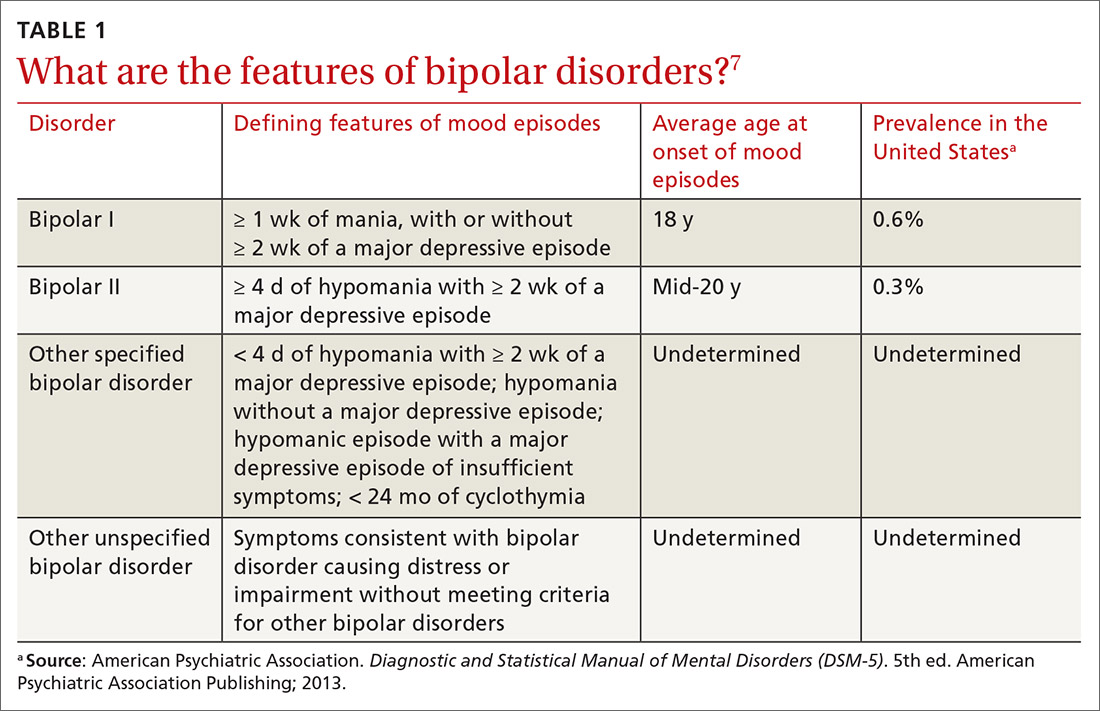

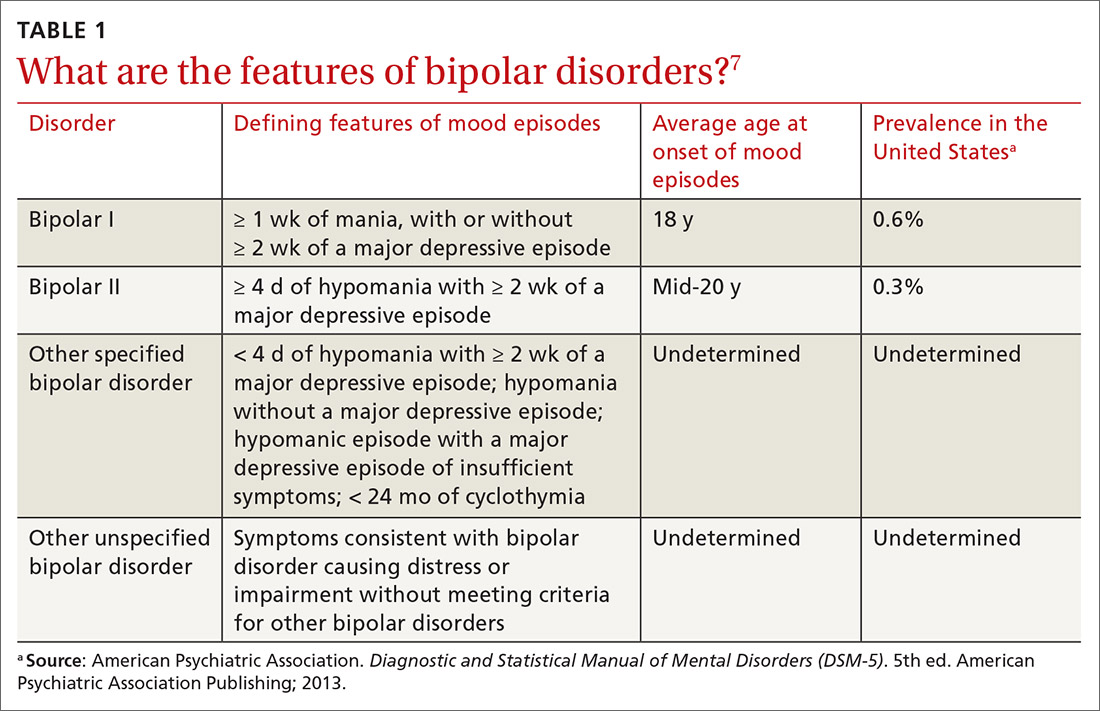

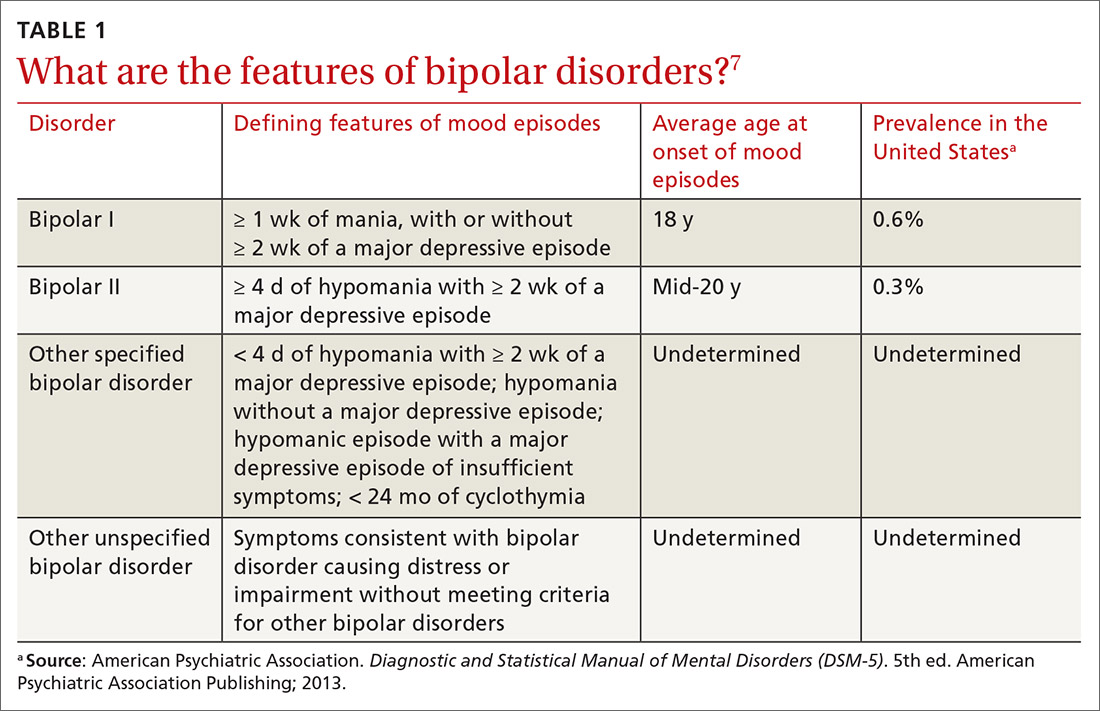

Symptoms of hypomanic episodes are similar to what are seen in manic episodes, but are of shorter duration (≥ 4 days [episodes of mania are at least of 1 week’s duration]), lower intensity (no psychotic symptoms), and not associated with significant functional impairment or hospitalization. Table 17 further describes the differentiating features of bipolar I and bipolar II. A history of an unequivocal manic or hypomanic episode makes the diagnosis of BD relatively easy. However, an unclear history of manic or hypomanic symptoms or episodes frequently leads to misdiagnosis or underdiagnosis of BD.

In both bipolar I and II, it is depressive symptoms and episodes that place the greatest burden on patients across the lifespan: They are the most commonly experienced features of the bipolar disorders9,10 and lead to significant distress and functional impairment11; in fact, patients with bipolar disorder spend 3 (or more) times as long in depressive episodes as in manic or hypomanic episodes.12,13 In addition, subthreshold depressive symptoms occur commonly between major mood episodes.

Failure to identify and adequately treat depressive episodes of the bipolar disorders can have serious consequences: Patients are at risk of a worsening course of illness, alcohol use disorder, substance use disorder, chronic disability, mixed states, rapid cycling of mood episodes, and suicide.

Guidelines for treating bipolar depression

Despite the similarity in presenting symptoms and signs of depressive episodes in bipolar disorders and MDD, treating episodes of BD is significantly different than treating MDD. Antidepressant monotherapy, a mainstay of treatment for MDD, has limited utility in BD (especially depressive episodes of bipolar I) because of its limited efficacy and potential to destabilize mood, lead to rapid cycling, and induce mania or hypomania. Treatment options for BD include pharmacotherapy (the primary modality), psychological intervention (a useful adjunct, described later), and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT; highly worth considering in severe or treatment-resistant cases).

Continue to: For this article...

For this article, we searched PubMed and Google Scholar for guidelines for the management of bipolar disorders in adults that were published between July 2013 (when the US Food and Drug Administration [FDA] approved lurasidone for the treatment of BD) and March 2019. Related guideline-referenced articles and clinical trials were also reviewed.

Our search identified 6 guidelines issued during the search period, developed by the:

- Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD),14

- British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP),15

- Japanese Society of Mood Disorders (JSMD),16

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE),17

- International College of Neuropsychopharmacology (CINP),18 and

- Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists.19

How to manage an episode of bipolar depression

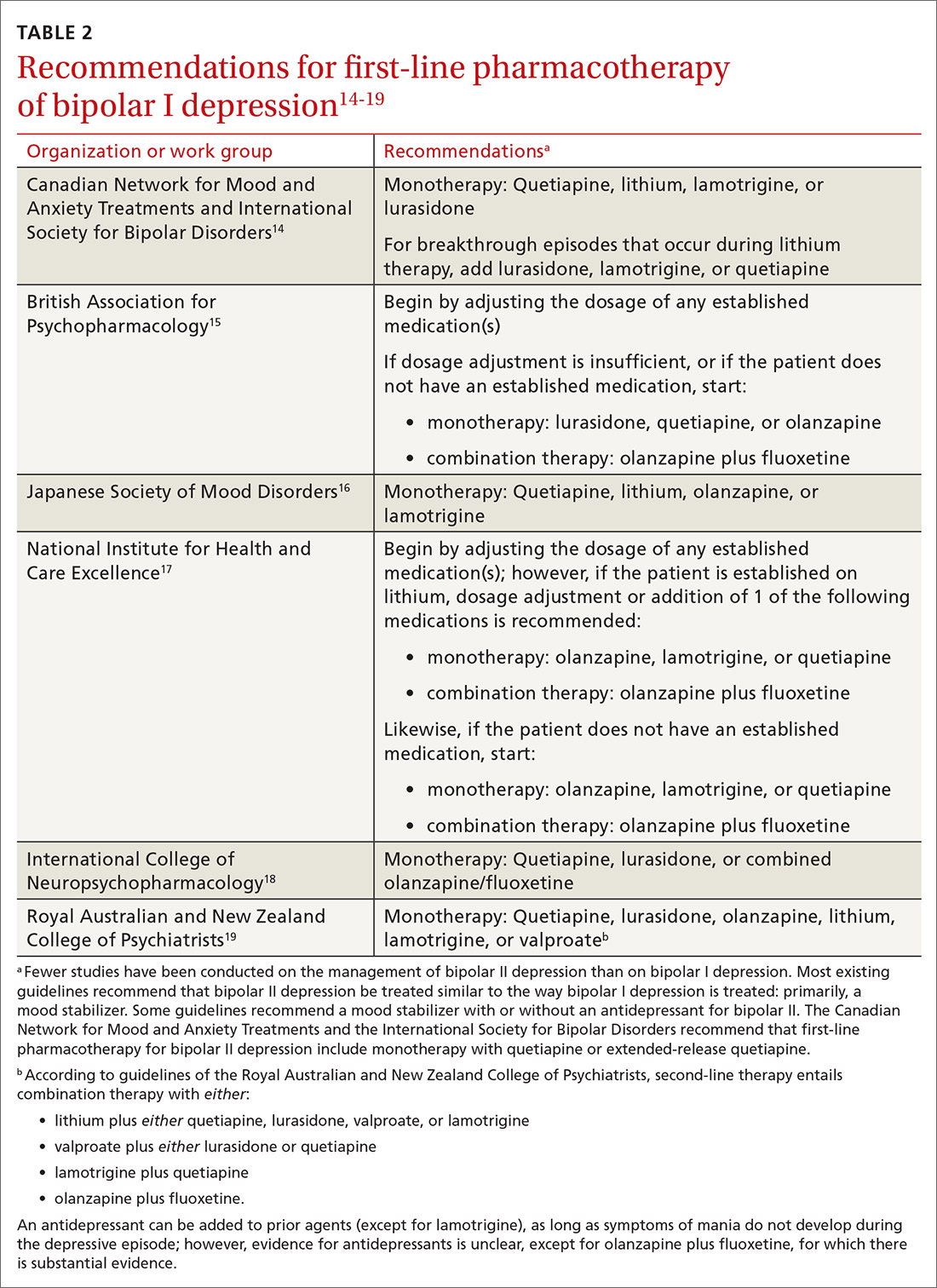

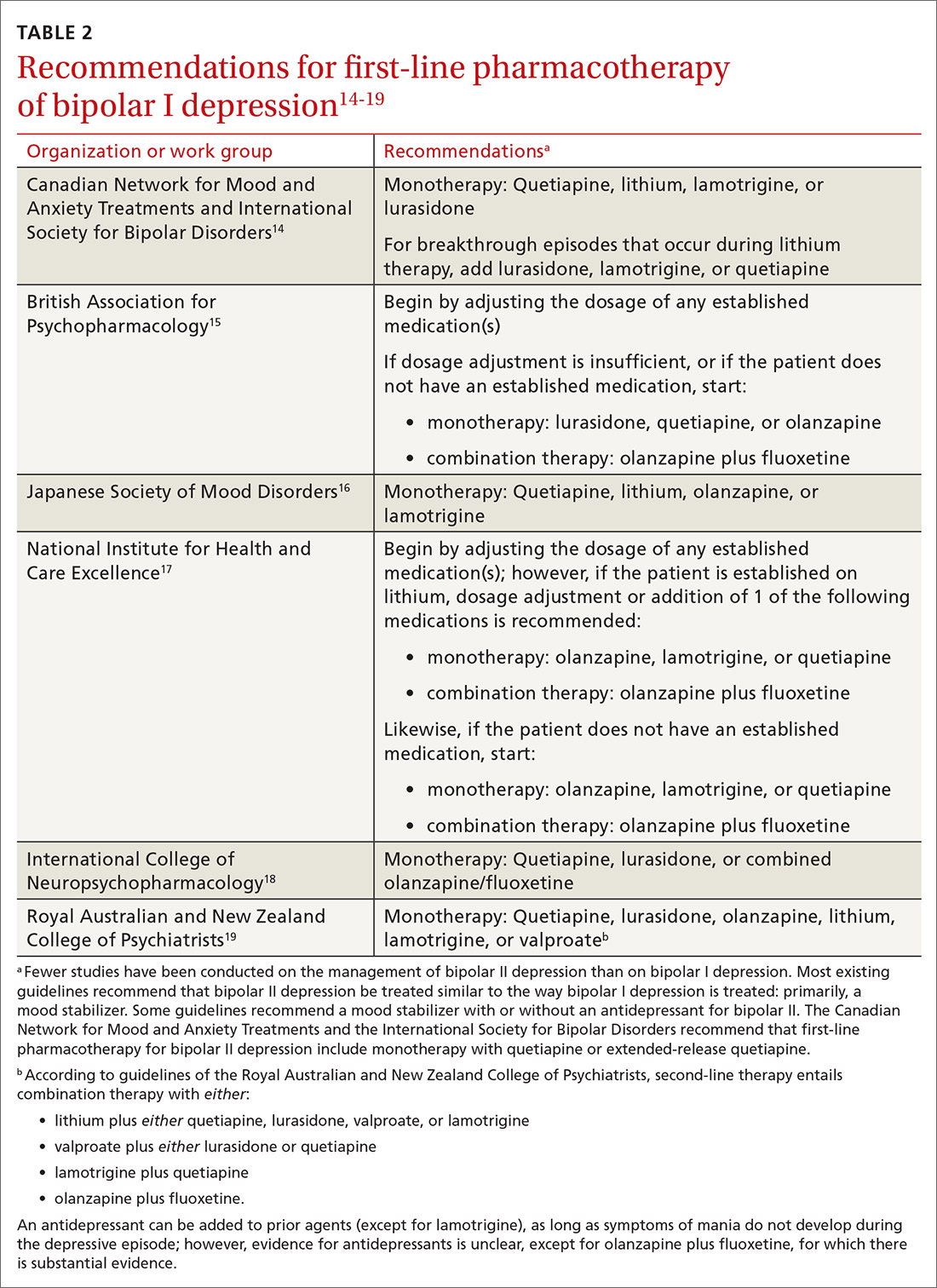

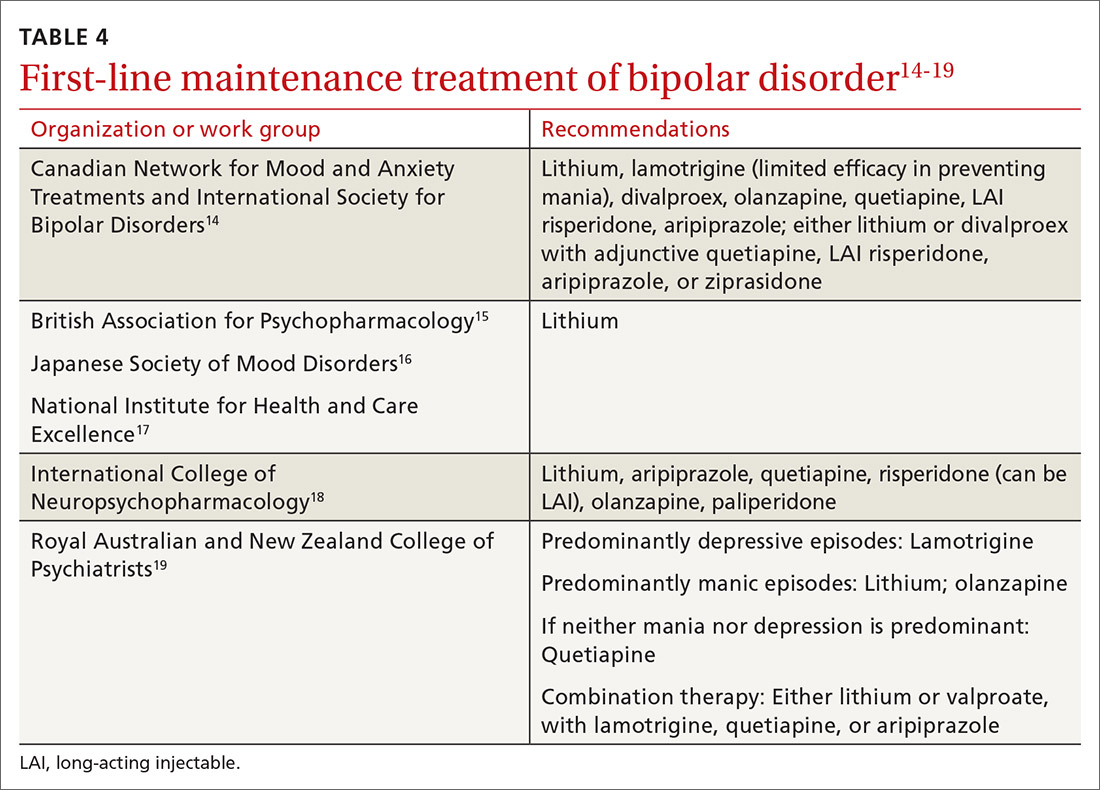

First-line pharmacotherapeutic agents for the management of BD in acute bipolar I are listed and described in Table 2.4-19 Compared to the number of studies and reports on the management of BD in bipolar I, few studies have been conducted that specifically examine the treatment of BD in acute bipolar II. In practice, evidence from the treatment of BD in bipolar I has been extrapolated to the treatment of bipolar II depression. CANMAT–ISBD guidelines recommend quetiapine as the only first-line therapy for BD in bipolar II; JSMD, CINP, and NICE guidelines do not make distinct recommendations for treating BD in bipolar II.

Patients who have BD can present de novo (ie, not taking any medication for bipolar disorder) or with a breakthrough episode while on maintenance medication(s). In either case, monotherapy for BD is preferred, although combinations of medications (Table 214-19) can be more effective in some cases. Treatment guidelines overlap to a high degree, especially in regard to first-line treatments, but there is variation, especially beyond first-line therapeutics.20

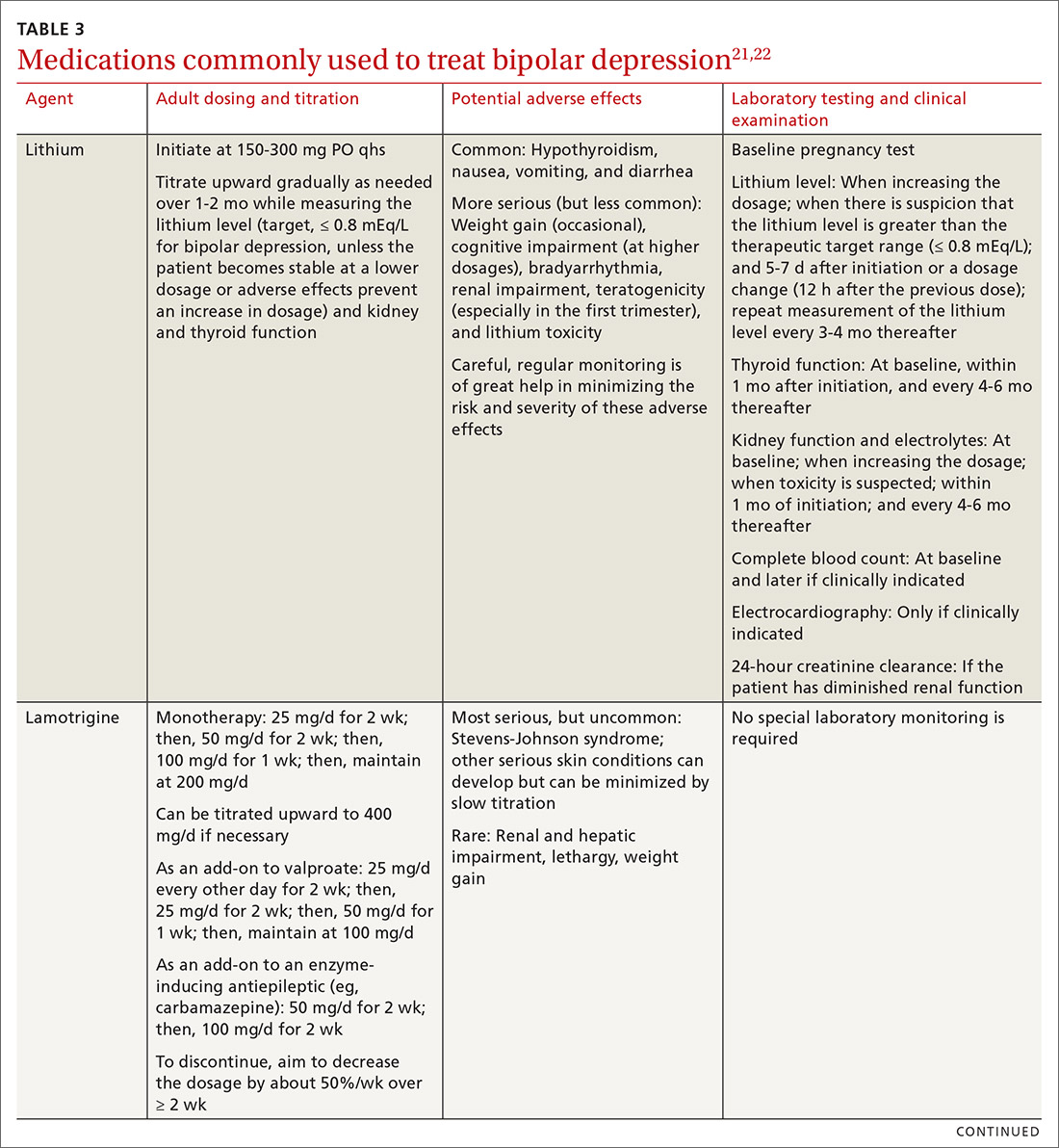

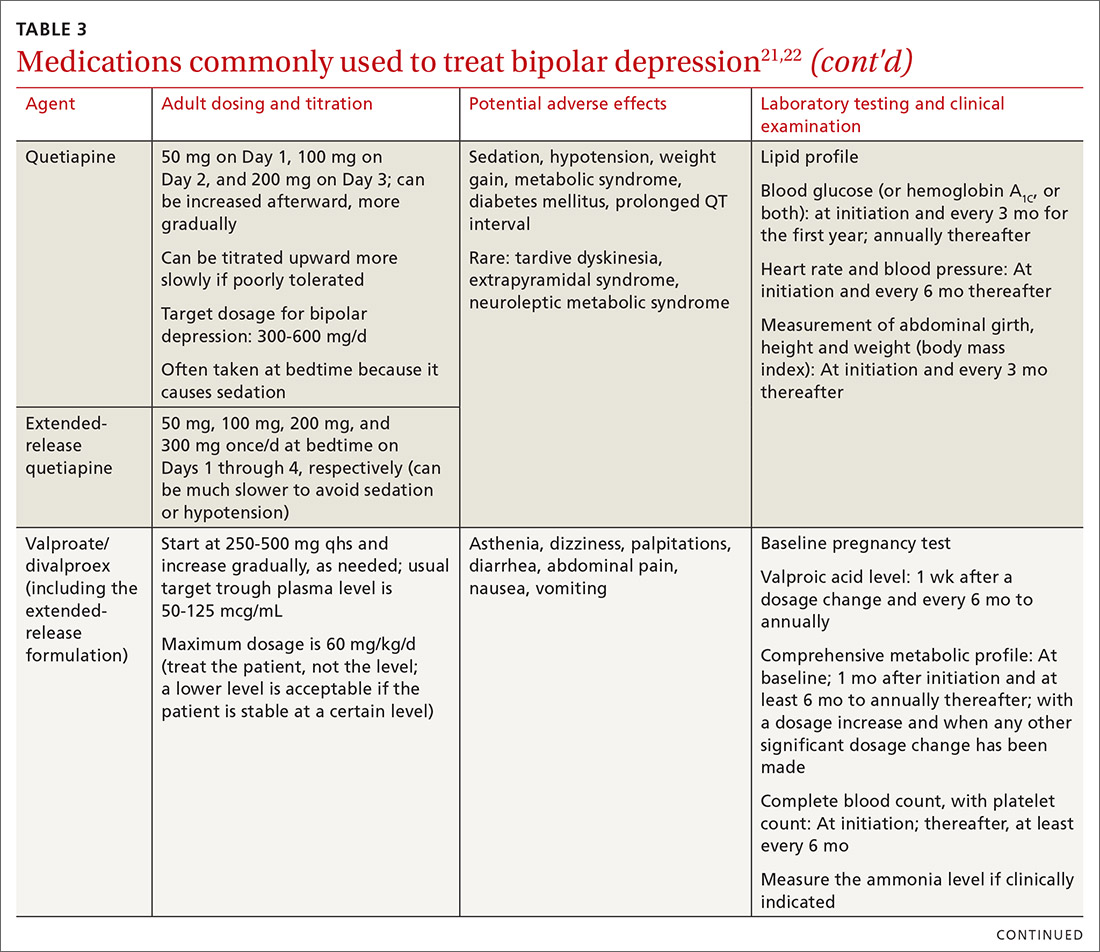

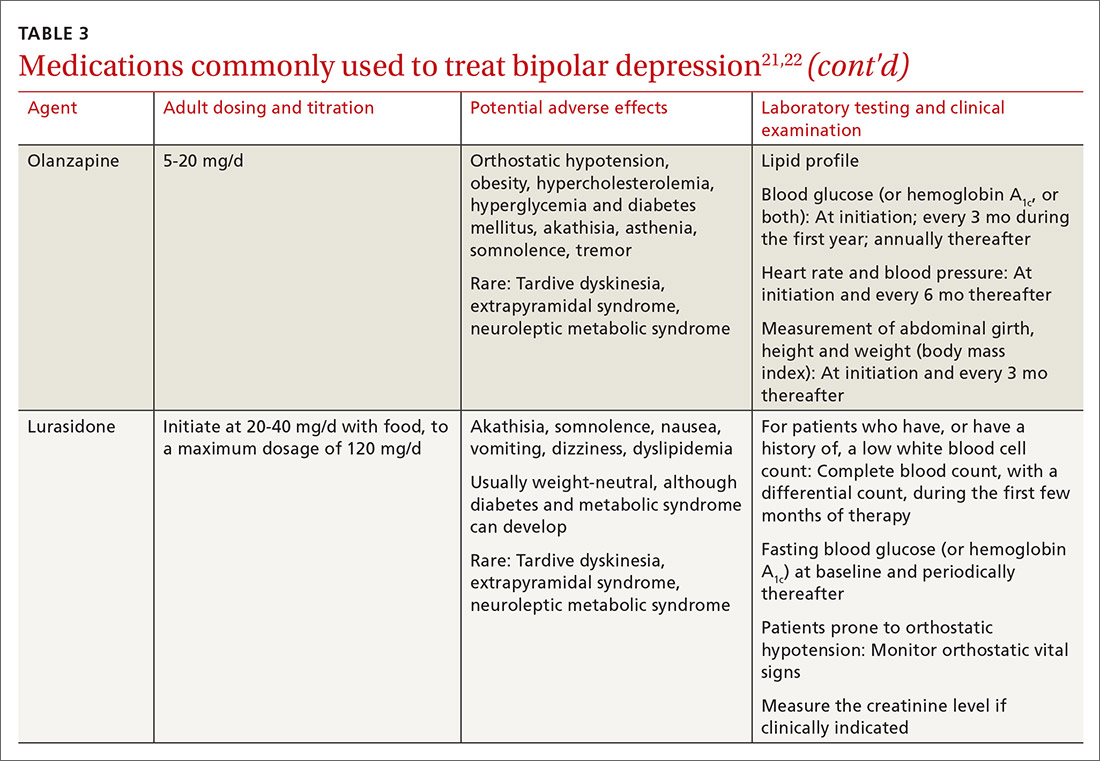

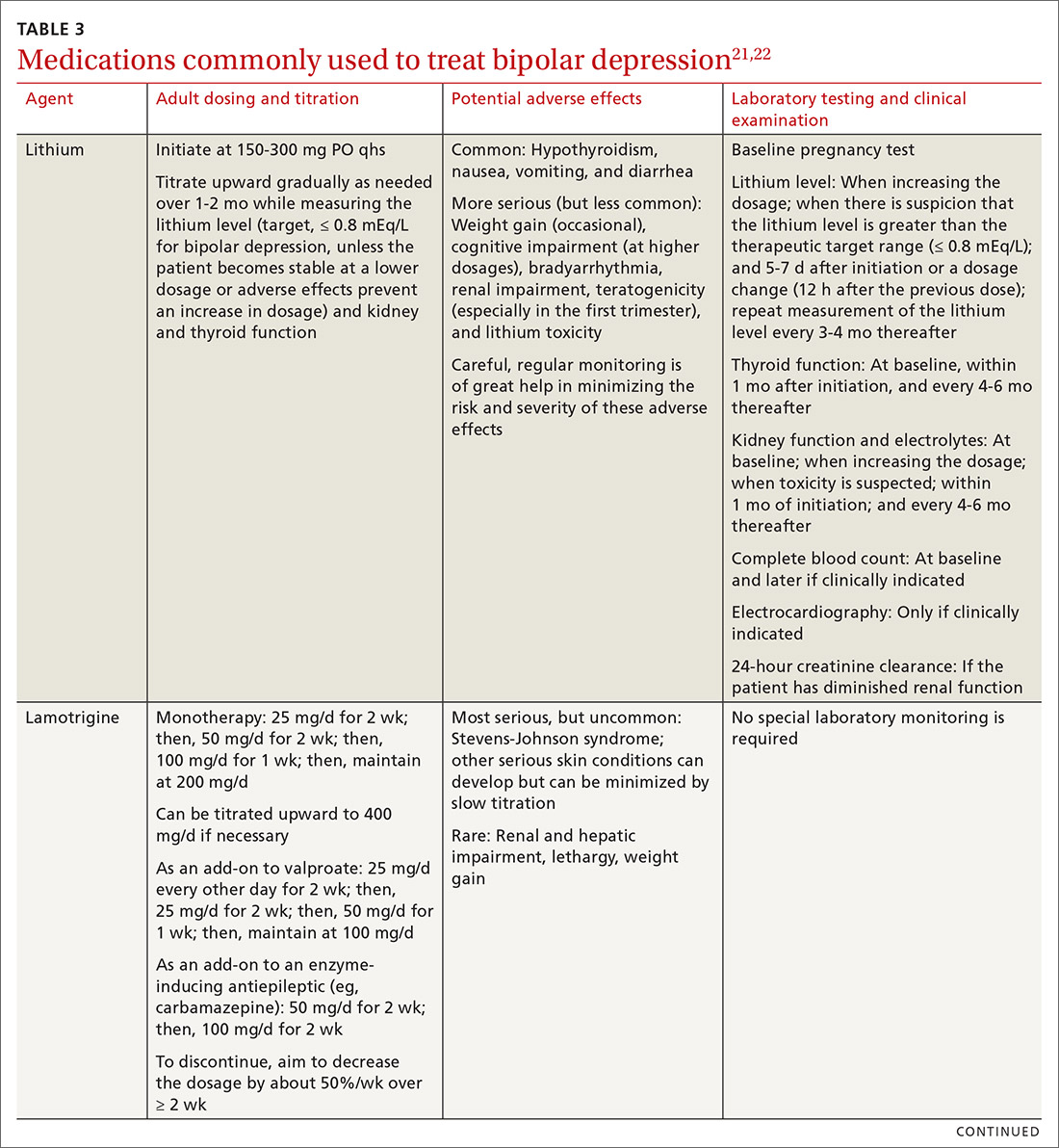

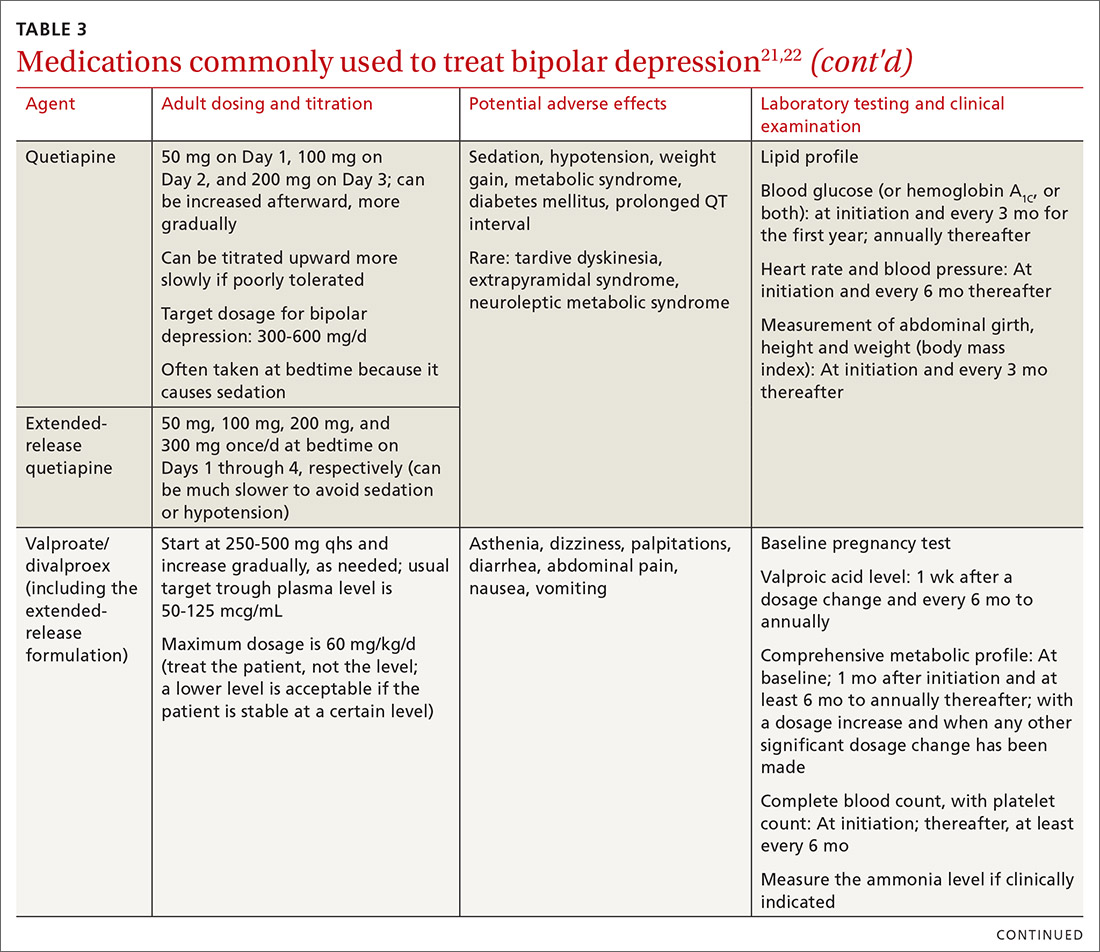

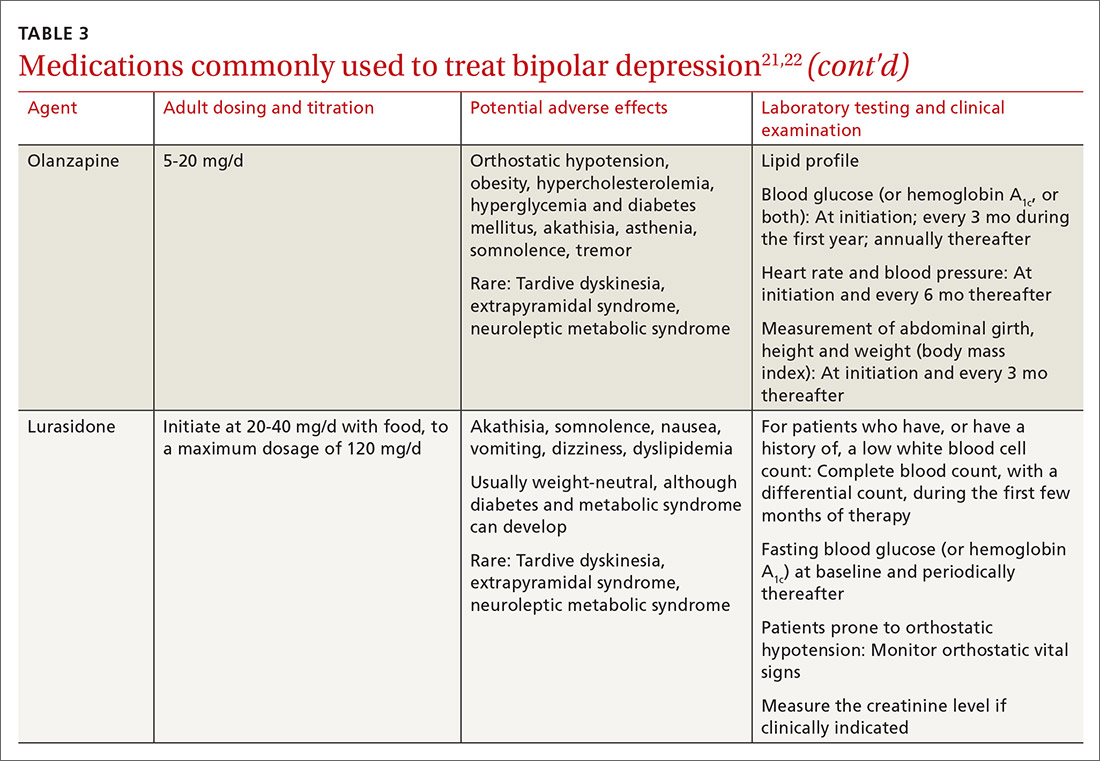

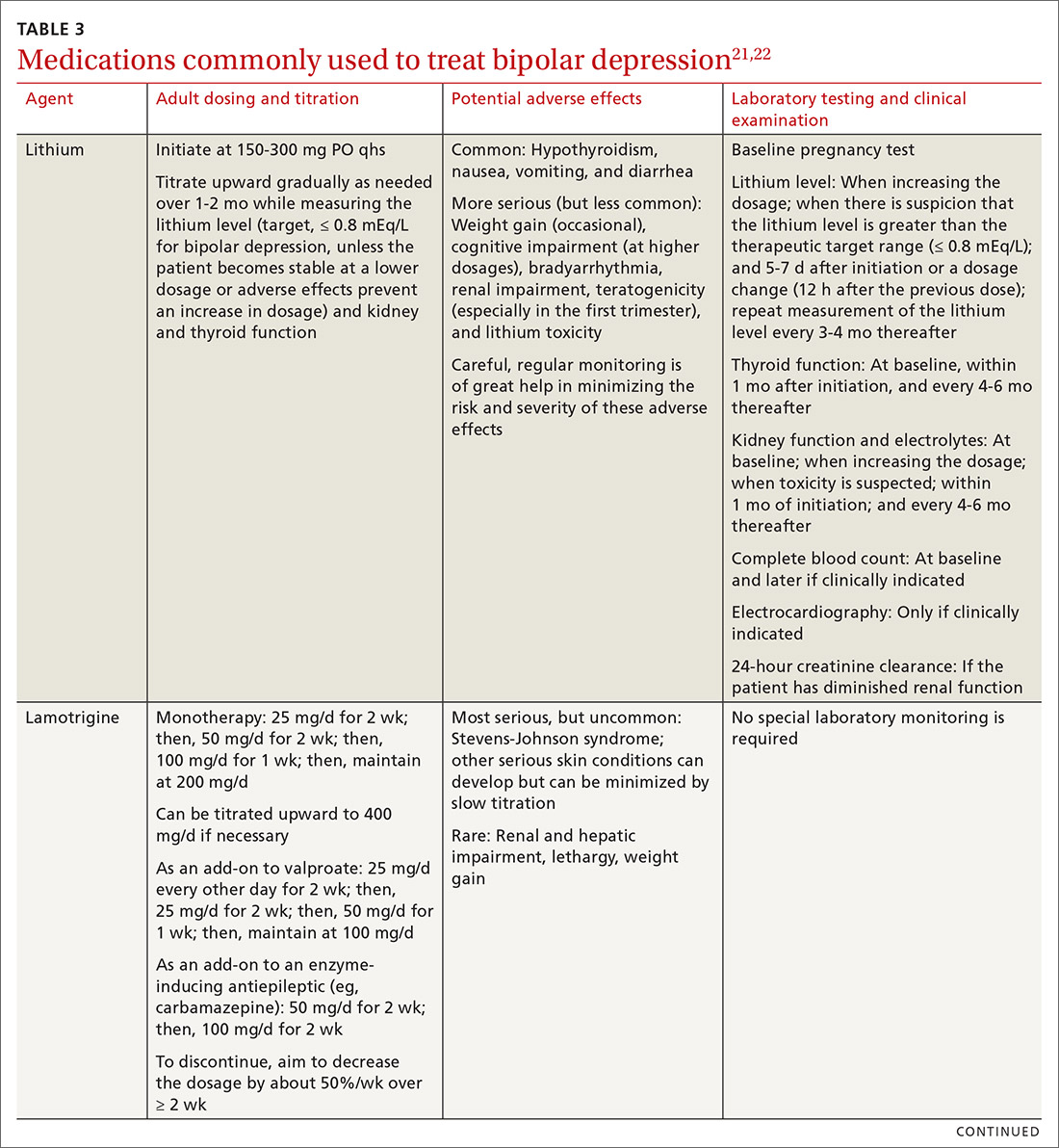

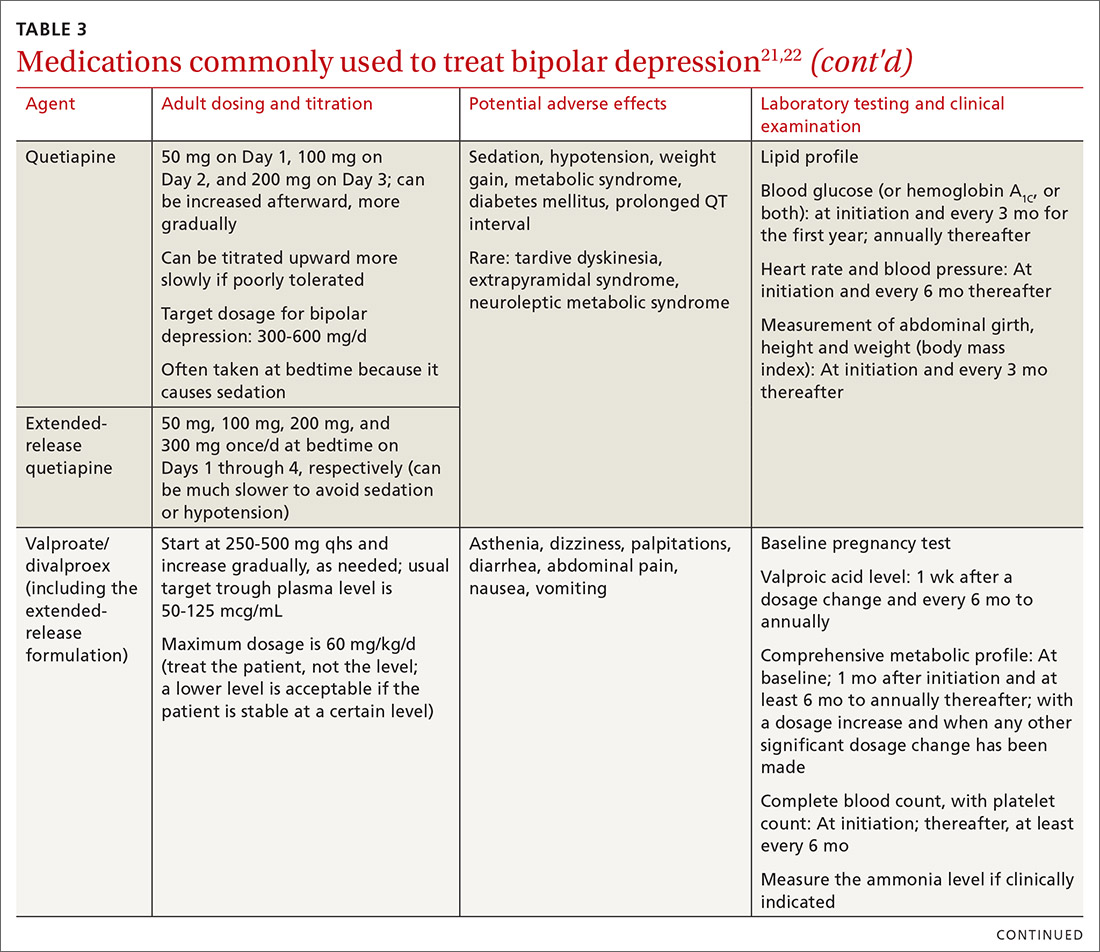

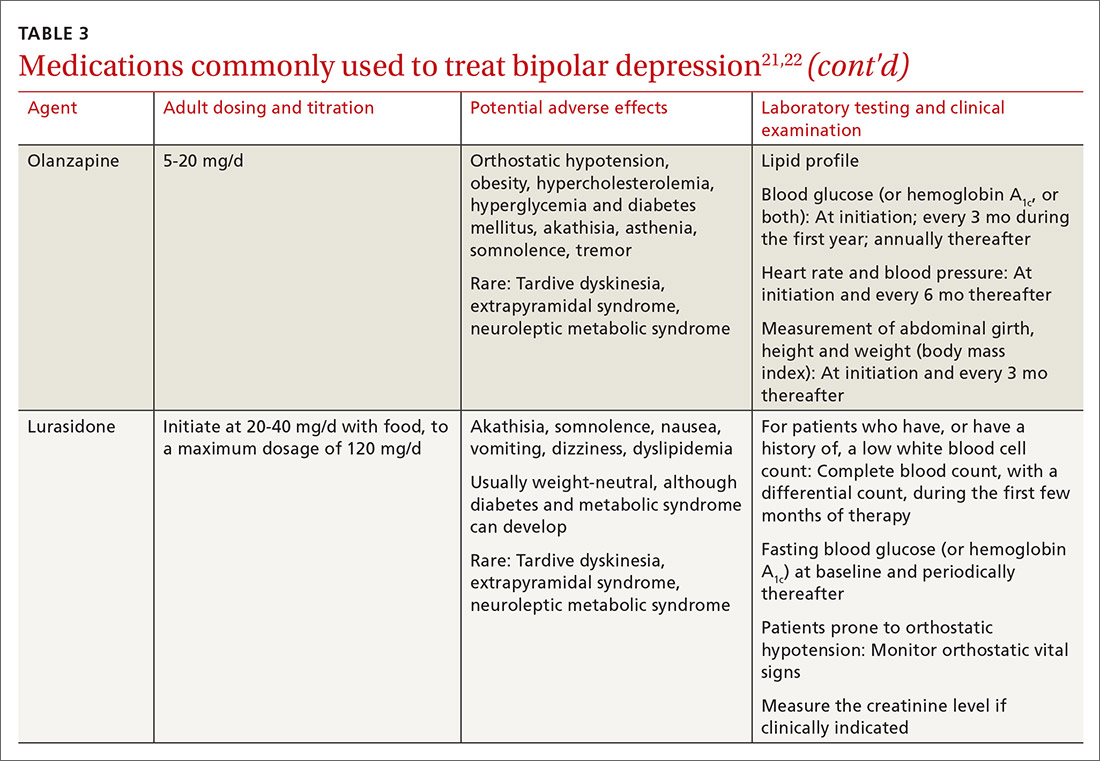

The top recommended medications for BD are lithium, quetiapine, olanzapine, lamotrigine, and combined olanzapine/fluoxetine. FDA-approved agents for treating acute BD specifically include quetiapine, lurasidone, and combined olanzapine/fluoxetine. Guidelines generally recommend a first step of adjusting the dosage of medications in any established regimen before changing or adding other agents. If clinical improvement is not seen using any recommended medications, psychiatric referral is recommended. See Table 321,22 for dosing and titration guidance and highlights of both common and rare but serious adverse effects.

Continue to: Recommendations, best options for acute bipolar depression

Recommendations, best options for acute bipolar depression

Start with lithium, lamotrigine, quetiapine, or lurasidone as the first-line medication at the dosages given in Table 3.21,22 Olanzapine alone, or in combination with fluoxetine, can be used when it has been determined that the medications listed above are ineffective.

Note that lithium requires regular blood monitoring (Table 321,22). However, lithium has the advantage of strong supporting evidence of benefit in all mood episodes of bipolar disorders (depressive, manic, hypomanic), as well as maintenance, prevention of recurrence, and anti-suicidal properties.

Also of note: Lurasidone is much more costly than other recommended medications because it is available only by brand name in the United States; the other agents are available as generics. Consider generic equivalents of the recommended agents when cost is an important factor, in part because of the impact that cost has on medication adherence for some patients.

Last, olanzapine should be used later in the treatment algorithm, unless rapid control of symptoms is needed or other first-line medications are ineffective or not tolerated—given the higher propensity of the drug to produce weight gain and cause metabolic problems, including obesity and hyperglycemia.

The importance of maintenance therapy

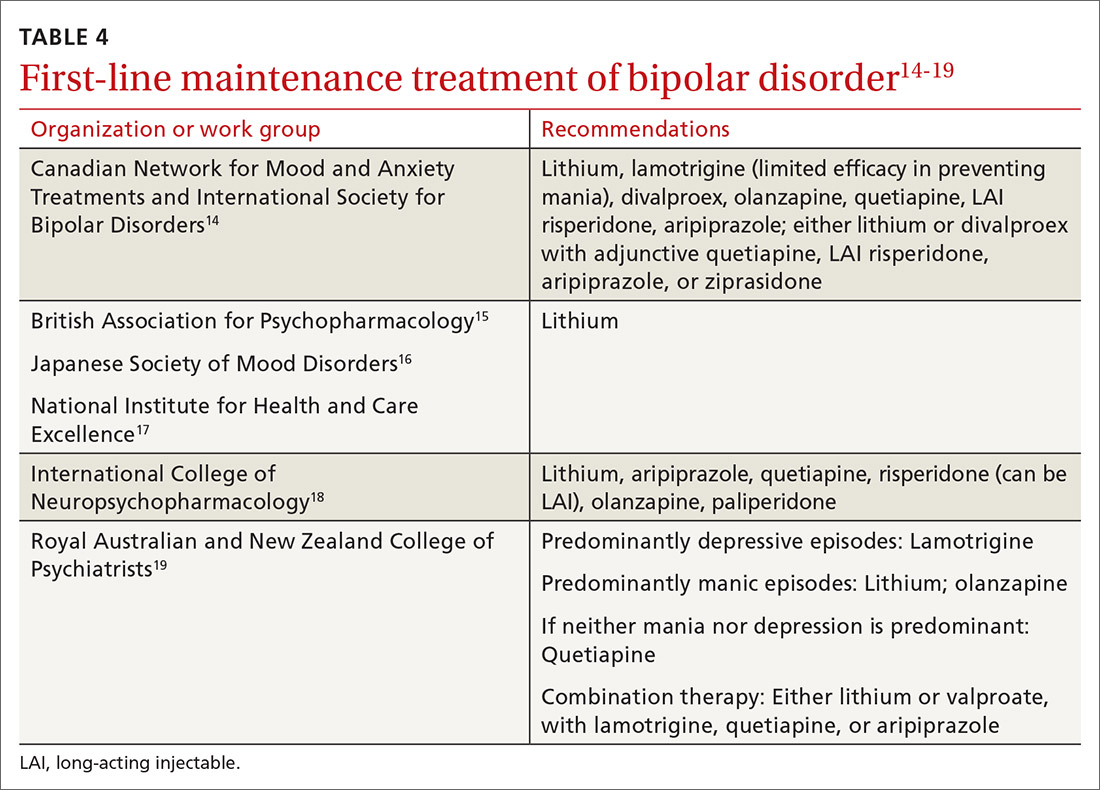

Almost all patients with BD require maintenance treatment to prevent subsequent episodes, reduce residual symptoms, and restore functioning and quality of life. Maintenance therapy is formulated on the basis of efficacy and tolerability in the individual patient.

Continue to: As a general rule...

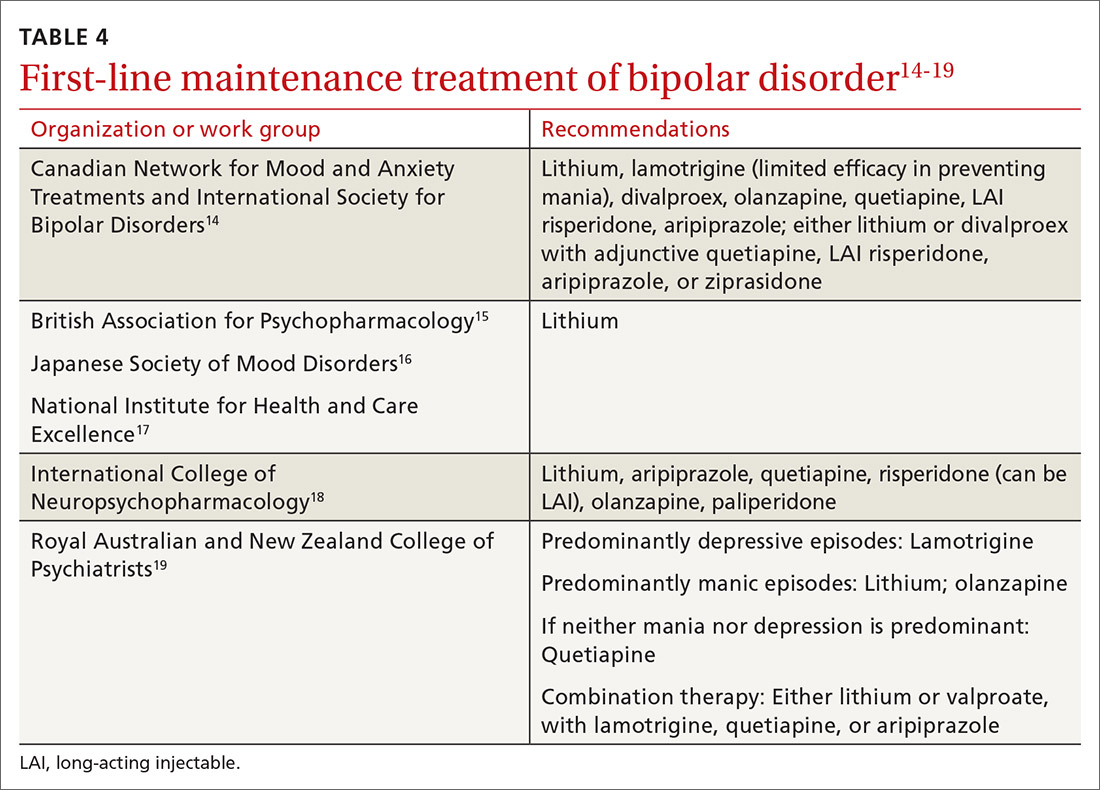

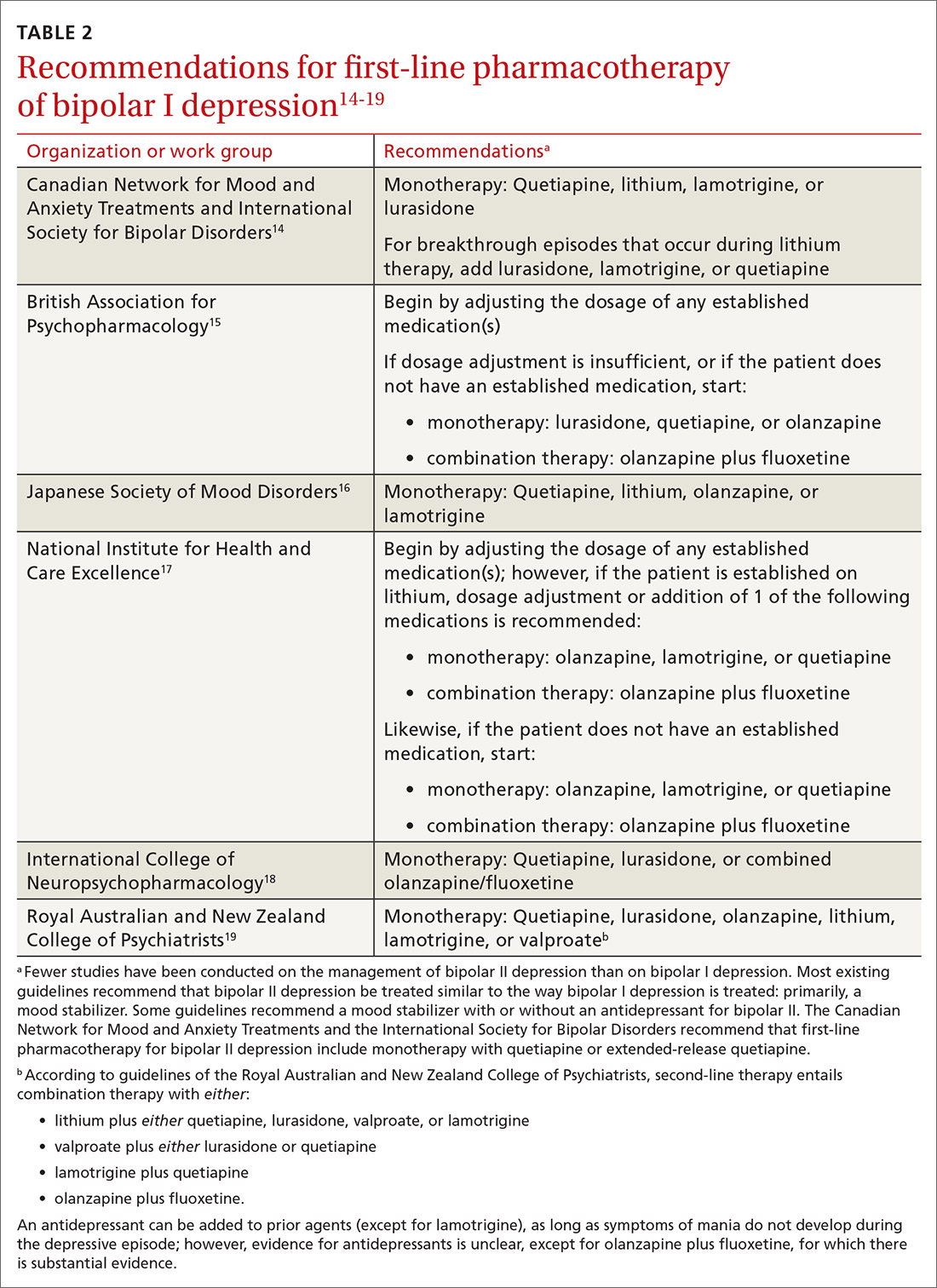

As a general rule, the strongest evidence for preventing recurrent BD episodes favors lithium—and most guidelines therefore support lithium as first-line maintenance therapy. It is important to note, however, that if a medication (or medications) successfully aborted an acute BD episode in a given patient, that agent (or agents) should be continued for maintenance purposes to prevent or minimize future episodes—generally, at the same dosage. First-line pharmacotherapeutic agents for the maintenance of bipolar disorder, and thus to prevent subsequent episodes of BD, are listed in Table 4.14-19

℞ antidepressantsin bipolar depression?

The use of antidepressants to treat BD remains a topic of ongoing deliberation. Antidepressant treatment of BD has historically raised concern for depressive relapse due to ineffectiveness and the ability of antidepressants to increase (1) the frequency of manic and hypomanic episodes23 and (2) mood instability in the form of induction of mixed states or rapid cycling. Among most authorities, the recommendation against using antidepressants for BD in both bipolar I and II is the same; however, limited evidence allows the use of antidepressant monotherapy in select cases of BD episodes in bipolar II,24,25 although not bipolar I.

The consensus in the field is that medications with mood-stabilizing effects should be considered as monotherapy before adding an antidepressant (if an antidepressant is to be added) to treat BD in bipolar II.26 In other words, if an antidepressant is to be used at all, it should be combined with a mood stabilizer or atypical antipsychotic15,27 and should probably not be used long term. The efficacy of antidepressants in treating BD in bipolar II should be assessed periodically at follow-up.

Nonpharmaceutical treatment options

Although pharmacotherapy is the mainstay of treatment of BD, adjunctive psychotherapy can be useful for treating acute BD episodes that occur during the maintenance phase of the disorder. Psychoeducation (ie, education on psychiatric illness and the importance of medication adherence), alone or in combination with interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (IPSRT), family-focused therapy (FFT), and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can add to the overall efficacy of pharmacotherapy by lowering the risk of relapse and enhancing psychosocial functioning.28

IPSRT is supported by what is known as the instability model, which specifies that 3 interconnected pathways trigger recurrences of a bipolar episode: stressful life events, medication nonadherence, and social-rhythm disruption. IPSRT also uses principles of interpersonal psychotherapy that are applied in treating MDD, “arguing that improvement in interpersonal relationships can ameliorate affective symptoms and prevent their return.”29,30

Continue to: FFT

FFT focuses on communication styles between patients and their spouses and families. The goal is to improve relationship functioning. FFT is delivered to the patient and the family.

Attention to social factors. For psychotherapy to provide adequate results as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy, social stressors (eg, homelessness and financial concerns) might also need to be considered and addressed through social services or a social work consult.

NICE guidelines recommend psychological intervention (in particular, with CBT and FFT) for acute BD. CANMAT–ISBD guidelines recommend either adjunctive psychoeducation, CBT, or FFT during the maintenance phase. Again, medication is the mainstay of treatment for BD in bipolar disorders; psychotherapy has an adjunctive role—unlike the approach to treatment of MDD, in which psychotherapy can be used alone in cases of mild, or even moderate, severity.

Referral for specialty care

In the primary care setting, providers might choose to manage BD by initiating first-line pharmacotherapeutic agents or continuing established treatment regimens with necessary dosage adjustments. These patients should be monitored closely until symptoms remit.

However, it is important for the primary care provider to identify patients who need psychiatric referral. Complex presentations, severe symptoms, and poor treatment response might warrant evaluation and management by a psychiatrist. Furthermore, patients with comorbid psychotic features, catatonia, or severely debilitating depression (with or without suicidality) need referral to the emergency department.

Continue to: Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Patients might also need referral to Psychiatry for ECT, which is recommended by CANMAT–ISBD and JSMD guidelines as a second-line option; by the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists as a third-line option; and by BAP for cases that are resistant to conventional treatment, with or without a high risk of suicide; in pregnancy; and in life-threatening situations.15,31,32

Telemedicine. There is a considerable shortage of mental health care professionals.33,34 The fact that nearly all (96%) counties in the United States have an unmet need for prescribers of mental health services (mainly psychiatrists) makes it crucial that primary care physicians be knowledgeable and prepared to manage BD—often with infrequent psychiatry consultation or, even, without psychiatry consultation. For primary care facilities that lack access to psychiatric services, telemedicine can be used as a consultative resource.

Psychiatric consultation using telemedicine technologies has provided significant cost savings for medical centers and decreased the likelihood of hospital admission,35 thereby alleviating health care costs and improving care, as shown in a rural Kansas county study.36 Furthermore, the burden on emergency departments in several states has been significantly reduced with psychiatric consultations via interactive telemedicine technologies.37

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Mark Yassa, BS, provided editing assistance.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nagy Youssef, MD, PhD, Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, Department of Psychiatry and Health Behavior, 997 St. Sebastian Way, Augusta, GA 30912; [email protected].

1. Cerimele JM, Chwastiak LA, Dodson S, et al. The prevalence of bipolar disorder in general primary care samples: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:19-25.

2. Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, Solmi M, et al. How common is bipolar disorder in general primary care attendees? A systematic review and meta-analysis investigating prevalence determined according to structured clinical assessments. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50:631-639.

3. Carta MG, Norcini-Pala A, Moro MF, et al. Does mood disorder questionnaire identify sub-threshold bipolarity? Evidence studying worsening of quality of life. J Affect Disord. 2015;183:173-178.

4. Fonseca-Pedrero E, Ortuno-Sierra J, Paino M, et al. Screening the risk of bipolar spectrum disorders: validity evidence of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire in adolescents and young adults. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. 2016;9:4-12.

5. Reilly S, Planner C, Gask L, et al. Collaborative care approaches for people with severe mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(11):CD009531.

6. Woltmann E, Grogan-Kaylor A, Perron B, et al. Comparative effectiveness of collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions across primary, specialty, and behavioral health care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:790-804.

7. Aquadro E, Youssef NA. Combine these screening tools to detect bipolar depression. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:500-503.

8. Bipolar and related disorders. In: American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2013:123.

9. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The comparative clinical phenotype and long term longitudinal episode course of bipolar I and II: a clinical spectrum or distinct disorders? J Affect Disord. 2013;73:19-32.

10. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:530-537.

11. Simon GE, Bauer MS, Ludman EJ, et al. Mood symptoms, functional impairment, and disability in people with bipolar disorder: specific effects of mania and depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1237-1245.

12. Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Akiskal HS, et al. Residual symptom recovery from major affective episodes in bipolar disorders and rapid episode relapse/recurrence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:386-394.

13. Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Solomon DA, et al. Psychosocial disability and work role function compared across the long-term course of bipolar I, bipolar II and unipolar major depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 2008;108:49-58.

14. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh S, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20:97-170.

15. Goodwin GM, Haddad PM, Ferrier IN, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised third edition recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30:495-553.

16. Kanba S, Kato T, Terao T, et al; Committee for Treatment Guidelines of Mood Disorders, Japanese Society of Mood Disorders, 2012. Guideline for treatment of bipolar disorder by the Japanese Society of Mood Disorders, 2012. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;67:285-300.

17. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Bipolar disorder: assessment and management. Clinical Guideline CG185. September 24, 2014. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg185. Accessed August 17, 2020.

18. Fountoulakis KN, Grunze H, Vieta E, et al. The International College of Neuro-Psychopharmacology (CINP) Treatment Guidelines for Bipolar Disorder in Adults (CINP-BD-2017), Part 3: the clinical guidelines. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;20:180-195.

19. Malhi GS, Outhred T, Morris G, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders: bipolar disorder summary. Med J Aust. 2018;208:219-225.

20. Hammett S, Youssef NA. Systematic review of recent guidelines for pharmacological treatments of bipolar disorders in adults. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2017;29:266-282.

21. Gabbard GO, ed. Gabbard’s Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2014: chap 12-15.

22. National Health Service. Guidelines for the monitoring of antimanic and prophylactic medication in bipolar disorder. NHT policy number MM-G-023. 2009. http://fac.ksu.edu.sa/sites/default/files/bipolar_disorder_guidelines.pdf. Accessed August 17, 2020.

23. Geddes JR, Carney SM, Davies C, et al. Relapse prevention with antidepressant drug treatment in depressive disorders: a systematic review. Lancet. 2003;361:653-661.

24. Amsterdam JD, Lorenzo-Luaces L, Soeller I, et al. Safety and effectiveness of continuation antidepressant versus mood stabilizer monotherapy for relapse-prevention of bipolar II depression: a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, prospective study. J Affect Disord. 2015;185:31-37.

25. Parker G, Tully L, Olley A, et al. SSRIs as mood stabilizers for bipolar II disorder? A proof of concept study. J Affect Disord. 2006;92:205-214.

26. Pacchiarotti I, Bond DJ, Baldessarini RJ, et al. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) Task Force report on antidepressant use in bipolar disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:1249-1262.

27. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists Clinical Practice Guidelines Team for Bipolar Disorder. Australian and New Zealand clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of bipolar disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2004;38:280-305.

28. Chiang K-J, Tsai J-C, Liu D, et al. Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy in patients with bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0176849.

29. de Mello MF, de Jesus Mari J, Bacaltchuk J, et al. A systematic review of research findings on the efficacy of interpersonal therapy for depressive disorders. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;255:75-82.

30. Zhou X, Teng T, Zhang Y, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antidepressants, psychotherapies, and their combination for acute treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:581-601.

31. Daly JJ, Prudic J, Devanand DP, et al. ECT in bipolar and unipolar depression: differences in speed of response. Bipolar Disord. 2001;3:95-104.

32. Medda P, Perugi G, Zanello S, et al. Response to ECT in bipolar I, bipolar II and unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2009;118:55-59.

33. Ellis AR, Konrad TR, Thomas KC, et al. County-level estimates of mental health professional supply in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1315-1322.

34. Thomas KC, Ellis AR, Konrad TR, et al. County-level estimates of mental health professional shortage in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1323-1328.

35. Narasimhan M, Druss BG, Hockenberry JM, et al. Impact of a telepsychiatry program at emergency departments statewide on the quality, utilization, and costs of mental health services. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66:1167-1172.

36. Spaulding R, Belz N, DeLurgio S, et al. Cost savings of telemedicine utilization for child psychiatry in a rural Kansas community. Telemed J E Health. 2010;16:867-871.

37. States leverage telepsychiatry solutions to ease ED crowding, accelerate care. ED Manag. 2015;27:13-17.

Bipolar disorder is a prevalent disorder in the primary care setting.1,2 Primary care providers therefore commonly encounter bipolar depression (BD; a major depressive episode in the context of bipolar disorder), which might be (1) an emerging depressive episode in previously undiagnosed bipolar disorder or (2) a recurrent episode during the course of chronic bipolar illness.3,4

A primary care–based collaborative model has been identified as a potential strategy for effective management of chronic mental health conditions such as bipolar disorder.5,6 However, this collaborative treatment model isn’t widely available; many patients with bipolar disorder are, in fact, treated solely by their primary care provider.

Two years ago in this journal,7 we addressed how to precisely identify an episode of BD and differentiate it from major depressive disorder (MDD; also known as unipolar depression). In this review, in addition to advancing clinical knowledge of BD, we provide:

- an overview of treatment options for BD (in contrast to the treatment of unipolar depression)

- the pharmacotherapeutic know-how to initiate and maintain treatment for uncomplicated episodes of BD.

We do not discuss management of manic, hypomanic, and mixed episodes of bipolar disorder.

How to identify bipolar depression

Understanding the (sometimes) unclear distinction between bipolar I and bipolar II disorders in an individual patient is key to formulating a therapeutic regimen for BD.

Bipolar I disorder consists of manic episodes, alternating (more often than not) with depressive episodes. Bipolar I usually manifests first with a depressive episode.

Bipolar II disorder manifests with depressive episodes and hypomanic episodes (but never manic episodes).

Continue to: Depressive episodes in the bipolar disorders

Depressive episodes in the bipolar disorders. Bipolar depression can be seen in the settings of both bipolar I and II disorders. When a patient presents with a manic episode, a history of depressive episodes is common (although not essential) to diagnose bipolar I; alternatively, a history of hypomania (but no prior mania) and depression is needed to make the diagnosis of bipolar II. The natural history of the bipolar disorders is therefore alternating manic and almost always depressive episodes (bipolar I) and alternating hypomanic and always depressive episodes (bipolar II).8

Symptoms of hypomanic episodes are similar to what are seen in manic episodes, but are of shorter duration (≥ 4 days [episodes of mania are at least of 1 week’s duration]), lower intensity (no psychotic symptoms), and not associated with significant functional impairment or hospitalization. Table 17 further describes the differentiating features of bipolar I and bipolar II. A history of an unequivocal manic or hypomanic episode makes the diagnosis of BD relatively easy. However, an unclear history of manic or hypomanic symptoms or episodes frequently leads to misdiagnosis or underdiagnosis of BD.

In both bipolar I and II, it is depressive symptoms and episodes that place the greatest burden on patients across the lifespan: They are the most commonly experienced features of the bipolar disorders9,10 and lead to significant distress and functional impairment11; in fact, patients with bipolar disorder spend 3 (or more) times as long in depressive episodes as in manic or hypomanic episodes.12,13 In addition, subthreshold depressive symptoms occur commonly between major mood episodes.

Failure to identify and adequately treat depressive episodes of the bipolar disorders can have serious consequences: Patients are at risk of a worsening course of illness, alcohol use disorder, substance use disorder, chronic disability, mixed states, rapid cycling of mood episodes, and suicide.

Guidelines for treating bipolar depression

Despite the similarity in presenting symptoms and signs of depressive episodes in bipolar disorders and MDD, treating episodes of BD is significantly different than treating MDD. Antidepressant monotherapy, a mainstay of treatment for MDD, has limited utility in BD (especially depressive episodes of bipolar I) because of its limited efficacy and potential to destabilize mood, lead to rapid cycling, and induce mania or hypomania. Treatment options for BD include pharmacotherapy (the primary modality), psychological intervention (a useful adjunct, described later), and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT; highly worth considering in severe or treatment-resistant cases).

Continue to: For this article...

For this article, we searched PubMed and Google Scholar for guidelines for the management of bipolar disorders in adults that were published between July 2013 (when the US Food and Drug Administration [FDA] approved lurasidone for the treatment of BD) and March 2019. Related guideline-referenced articles and clinical trials were also reviewed.

Our search identified 6 guidelines issued during the search period, developed by the:

- Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD),14

- British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP),15

- Japanese Society of Mood Disorders (JSMD),16

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE),17

- International College of Neuropsychopharmacology (CINP),18 and

- Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists.19

How to manage an episode of bipolar depression

First-line pharmacotherapeutic agents for the management of BD in acute bipolar I are listed and described in Table 2.4-19 Compared to the number of studies and reports on the management of BD in bipolar I, few studies have been conducted that specifically examine the treatment of BD in acute bipolar II. In practice, evidence from the treatment of BD in bipolar I has been extrapolated to the treatment of bipolar II depression. CANMAT–ISBD guidelines recommend quetiapine as the only first-line therapy for BD in bipolar II; JSMD, CINP, and NICE guidelines do not make distinct recommendations for treating BD in bipolar II.

Patients who have BD can present de novo (ie, not taking any medication for bipolar disorder) or with a breakthrough episode while on maintenance medication(s). In either case, monotherapy for BD is preferred, although combinations of medications (Table 214-19) can be more effective in some cases. Treatment guidelines overlap to a high degree, especially in regard to first-line treatments, but there is variation, especially beyond first-line therapeutics.20

The top recommended medications for BD are lithium, quetiapine, olanzapine, lamotrigine, and combined olanzapine/fluoxetine. FDA-approved agents for treating acute BD specifically include quetiapine, lurasidone, and combined olanzapine/fluoxetine. Guidelines generally recommend a first step of adjusting the dosage of medications in any established regimen before changing or adding other agents. If clinical improvement is not seen using any recommended medications, psychiatric referral is recommended. See Table 321,22 for dosing and titration guidance and highlights of both common and rare but serious adverse effects.

Continue to: Recommendations, best options for acute bipolar depression

Recommendations, best options for acute bipolar depression

Start with lithium, lamotrigine, quetiapine, or lurasidone as the first-line medication at the dosages given in Table 3.21,22 Olanzapine alone, or in combination with fluoxetine, can be used when it has been determined that the medications listed above are ineffective.

Note that lithium requires regular blood monitoring (Table 321,22). However, lithium has the advantage of strong supporting evidence of benefit in all mood episodes of bipolar disorders (depressive, manic, hypomanic), as well as maintenance, prevention of recurrence, and anti-suicidal properties.

Also of note: Lurasidone is much more costly than other recommended medications because it is available only by brand name in the United States; the other agents are available as generics. Consider generic equivalents of the recommended agents when cost is an important factor, in part because of the impact that cost has on medication adherence for some patients.

Last, olanzapine should be used later in the treatment algorithm, unless rapid control of symptoms is needed or other first-line medications are ineffective or not tolerated—given the higher propensity of the drug to produce weight gain and cause metabolic problems, including obesity and hyperglycemia.

The importance of maintenance therapy

Almost all patients with BD require maintenance treatment to prevent subsequent episodes, reduce residual symptoms, and restore functioning and quality of life. Maintenance therapy is formulated on the basis of efficacy and tolerability in the individual patient.

Continue to: As a general rule...

As a general rule, the strongest evidence for preventing recurrent BD episodes favors lithium—and most guidelines therefore support lithium as first-line maintenance therapy. It is important to note, however, that if a medication (or medications) successfully aborted an acute BD episode in a given patient, that agent (or agents) should be continued for maintenance purposes to prevent or minimize future episodes—generally, at the same dosage. First-line pharmacotherapeutic agents for the maintenance of bipolar disorder, and thus to prevent subsequent episodes of BD, are listed in Table 4.14-19

℞ antidepressantsin bipolar depression?

The use of antidepressants to treat BD remains a topic of ongoing deliberation. Antidepressant treatment of BD has historically raised concern for depressive relapse due to ineffectiveness and the ability of antidepressants to increase (1) the frequency of manic and hypomanic episodes23 and (2) mood instability in the form of induction of mixed states or rapid cycling. Among most authorities, the recommendation against using antidepressants for BD in both bipolar I and II is the same; however, limited evidence allows the use of antidepressant monotherapy in select cases of BD episodes in bipolar II,24,25 although not bipolar I.

The consensus in the field is that medications with mood-stabilizing effects should be considered as monotherapy before adding an antidepressant (if an antidepressant is to be added) to treat BD in bipolar II.26 In other words, if an antidepressant is to be used at all, it should be combined with a mood stabilizer or atypical antipsychotic15,27 and should probably not be used long term. The efficacy of antidepressants in treating BD in bipolar II should be assessed periodically at follow-up.

Nonpharmaceutical treatment options

Although pharmacotherapy is the mainstay of treatment of BD, adjunctive psychotherapy can be useful for treating acute BD episodes that occur during the maintenance phase of the disorder. Psychoeducation (ie, education on psychiatric illness and the importance of medication adherence), alone or in combination with interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (IPSRT), family-focused therapy (FFT), and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can add to the overall efficacy of pharmacotherapy by lowering the risk of relapse and enhancing psychosocial functioning.28

IPSRT is supported by what is known as the instability model, which specifies that 3 interconnected pathways trigger recurrences of a bipolar episode: stressful life events, medication nonadherence, and social-rhythm disruption. IPSRT also uses principles of interpersonal psychotherapy that are applied in treating MDD, “arguing that improvement in interpersonal relationships can ameliorate affective symptoms and prevent their return.”29,30

Continue to: FFT

FFT focuses on communication styles between patients and their spouses and families. The goal is to improve relationship functioning. FFT is delivered to the patient and the family.

Attention to social factors. For psychotherapy to provide adequate results as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy, social stressors (eg, homelessness and financial concerns) might also need to be considered and addressed through social services or a social work consult.

NICE guidelines recommend psychological intervention (in particular, with CBT and FFT) for acute BD. CANMAT–ISBD guidelines recommend either adjunctive psychoeducation, CBT, or FFT during the maintenance phase. Again, medication is the mainstay of treatment for BD in bipolar disorders; psychotherapy has an adjunctive role—unlike the approach to treatment of MDD, in which psychotherapy can be used alone in cases of mild, or even moderate, severity.

Referral for specialty care

In the primary care setting, providers might choose to manage BD by initiating first-line pharmacotherapeutic agents or continuing established treatment regimens with necessary dosage adjustments. These patients should be monitored closely until symptoms remit.

However, it is important for the primary care provider to identify patients who need psychiatric referral. Complex presentations, severe symptoms, and poor treatment response might warrant evaluation and management by a psychiatrist. Furthermore, patients with comorbid psychotic features, catatonia, or severely debilitating depression (with or without suicidality) need referral to the emergency department.

Continue to: Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Patients might also need referral to Psychiatry for ECT, which is recommended by CANMAT–ISBD and JSMD guidelines as a second-line option; by the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists as a third-line option; and by BAP for cases that are resistant to conventional treatment, with or without a high risk of suicide; in pregnancy; and in life-threatening situations.15,31,32

Telemedicine. There is a considerable shortage of mental health care professionals.33,34 The fact that nearly all (96%) counties in the United States have an unmet need for prescribers of mental health services (mainly psychiatrists) makes it crucial that primary care physicians be knowledgeable and prepared to manage BD—often with infrequent psychiatry consultation or, even, without psychiatry consultation. For primary care facilities that lack access to psychiatric services, telemedicine can be used as a consultative resource.

Psychiatric consultation using telemedicine technologies has provided significant cost savings for medical centers and decreased the likelihood of hospital admission,35 thereby alleviating health care costs and improving care, as shown in a rural Kansas county study.36 Furthermore, the burden on emergency departments in several states has been significantly reduced with psychiatric consultations via interactive telemedicine technologies.37

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Mark Yassa, BS, provided editing assistance.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nagy Youssef, MD, PhD, Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, Department of Psychiatry and Health Behavior, 997 St. Sebastian Way, Augusta, GA 30912; [email protected].

Bipolar disorder is a prevalent disorder in the primary care setting.1,2 Primary care providers therefore commonly encounter bipolar depression (BD; a major depressive episode in the context of bipolar disorder), which might be (1) an emerging depressive episode in previously undiagnosed bipolar disorder or (2) a recurrent episode during the course of chronic bipolar illness.3,4

A primary care–based collaborative model has been identified as a potential strategy for effective management of chronic mental health conditions such as bipolar disorder.5,6 However, this collaborative treatment model isn’t widely available; many patients with bipolar disorder are, in fact, treated solely by their primary care provider.