User login

Smallpox Vaccination-Associated Myopericarditis

A renewed effort to vaccinate service members fighting the global war on terrorism has brought new diagnostic challenges. Vaccinations not generally given to the public are routinely given to service members when they deploy to various parts of the world. Examples include anthrax, yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, rabies, polio, and smallpox. Every vaccination has potential for adverse effects (AEs), which can range from mild to severe life-threatening complications. These AEs often go unrecognized and untreated because physicians are not routinely screening for vaccination administration.

Background

Smallpox (Variola major) was successfully eradicated in 1977 due to worldwide vaccination efforts.1 However, the threat of bioterrorism has renewed mandatory smallpox vaccinations for high-risk individuals, such as active-duty military personnel.1,2 A notable increase in myopericarditis has been reported with the new generation of smallpox vaccination, ACAM2000.3 We present a case of a 27-year-old healthy male who presented with chest pain and diffuse ST segment elevations consistent with myopericarditis after vaccination with ACAM2000.

Case Presentation

A healthy 27-year-old soldier presented to the emergency department with sudden, new onset, sharp-stabbing, substernal chest pain, which was made worse with lying flat and better with leaning forward. Vital signs were unremarkable. He recently enlisted in the US Army and received the smallpox vaccination about 11 days before as part of a routine predeployment checklist. The patient reported he did not have any viral symptoms, such as fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, shortness of breath, sore throat, rhinorrhea, or sputum production. He also reported having no prior illness for the past 3 months, sick contacts at home or work, or recent travel outside the US. He reported no tobacco use, alcohol use, or illicit drug use. The patient’s family history was negative for significant cardiac disease.

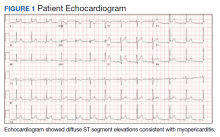

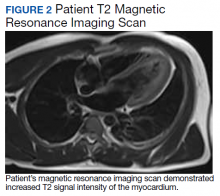

A physical examination was unremarkable. The initial laboratory report showed no leukocytosis, anemia, thrombocytopenia, electrolytes derangement, abnormal kidney function, or abnormal liver function tests. Initial troponin was 0.25 ng/mL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 40 mmol/h and C-reactive protein (CRP) was 120.2 mg/L suggestive of acute inflammation. A urine drug screen was negative. D-dimer was < 0.27. An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed diffuse ST segment elevation (Figure 1). An echocardiogram showed normal left ventricle size, and function with ejection fraction 55 to 60%, normal diastolic dysfunction, and trivial pericardial effusion. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed increased T2 signal intensity of the myocardium suggestive of myopericarditis (Figure 2). A computed tomography (CT) angiogram of the coronary arteries showed no significant stenosis.

The patient was treated with ibuprofen for 2 weeks and colchicine for 3 months, and his symptoms resolved. He followed up with an appointment in the cardiology clinic 1 month later, and his ESR, CRP, and troponin results were negative. A limited echocardiogram showed ejection fraction 60 to 65%, no regional wall motion abnormalities, normal diastolic function, and resolution of the pericardial effusion.

Discussion

Smallpox was a major worldwide cause of mortality; about 30% of those infected died because of smallpox.2,4,5 Due to a worldwide vaccination effort, the World Health Organization declared smallpox was eradicated in 1977.2,4,5 However, despite successful eradication, smallpox is considered a possible bioterrorism target, which prompted a resurgence of mandatory smallpox vaccinations for active-duty personnel.2,5

Dryvax, a freeze-dried calf lymph smallpox vaccine was used extensively from the 1940s to the 1980s but was replaced in 2008 by ACAM2000, a smallpox vaccine cultured in kidney epithelial cells from African green monkeys.3,5 Myopericarditis was rarely associated with the Dryvax, with only 5 cases reported from 1955 to 1986 after millions of doses of vaccines were administered; however, in 230,734 administered ACAM2000 doses, 18 cases of myopericarditis (incidence, 7.8 per 100,000) were reported during a surveillance study in 2002 and 2003.3,5

Myopericarditis presents with a wide variety of symptoms, such as chest pain, palpitations, chills, shortness of breath, and fever.6,7 Mainstay diagnostic criteria include ECG findings consistent with myopericarditis (such as diffuse ST segment elevations) and elevated cardiac biomarkers (elevated troponins).5-7 An echocardiogram can be helpful in diagnosis, as most cases will not have regional wall motion abnormalities (to distinguish against coronary artery disease).5-7 MRI with diffuse enhancement of the myocardium can be helpful in diagnosis.5,6 The gold standard for diagnosis is an endomyocardial biopsy, which carries a significant risk of complications and is not routinely performed to diagnose myopericarditis.5,6 US military smallpox vaccination data showed that the onset of vaccine-associated myopericarditis averaged (SD) 10.4 (3.6) days after vaccination.5

Vaccine-associated myopericarditis treatment is focused on decreasing inflammation.5,6 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are advised for about 2 weeks with cessation of intensive cardiac activities for between 4 and 6 weeks due to risks of congestive heart failure and fatal cardiac arrhythmias.5,6

Conclusions

Since the September 11 attacks, the US needs to be continually prepared for potential terrorism on American soil and abroad. The threat of bioterrorism has renewed efforts to vaccinate or revaccinate American service members deployed to high-risk regions. These vaccinations put them at risk for vaccination-induced complications that can range from mild fever to life-threatening complications.

1. Bruner DI, Butler BS. Smallpox vaccination-associated myopericarditis is more common with the newest smallpox vaccine. J Emerg Med. 2014;46(3):e85-e87. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.06.001

2. Halsell JS, Riddle JR, Atwood JE, et al. Myopericarditis following smallpox vaccination among vaccinia-naive US military personnel. JAMA. 2003;289(24):3283-3289. doi:10.1001/jama.289.24.3283

3. Nalca A, Zumbrun EE. ACAM2000: the new smallpox vaccine for United States Strategic National Stockpile. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2010;4:71-79. doi:10.2147/dddt.s3687

4. Wollenberg A, Engler R. Smallpox, vaccination and adverse reactions to smallpox vaccine. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;4(4):271-275. doi:10.1097/01.all.0000136758.66442.28

5. Cassimatis DC, Atwood JE, Engler RM, Linz PE, Grabenstein JD, Vernalis MN. Smallpox vaccination and myopericarditis: a clinical review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(9):1503-1510. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.053

6. Sharma U, Tak T. A report of 2 cases of myopericarditis after Vaccinia virus (smallpox) immunization. WMJ. 2011;110(6):291-294.

7. Sarkisian SA, Hand G, Rivera VM, Smith M, Miller JA. A case series of smallpox vaccination-associated myopericarditis: effects on safety and readiness of the active duty soldier. Mil Med. 2019;184(1-2):e280-e283. doi:10.1093/milmed/usy159

A renewed effort to vaccinate service members fighting the global war on terrorism has brought new diagnostic challenges. Vaccinations not generally given to the public are routinely given to service members when they deploy to various parts of the world. Examples include anthrax, yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, rabies, polio, and smallpox. Every vaccination has potential for adverse effects (AEs), which can range from mild to severe life-threatening complications. These AEs often go unrecognized and untreated because physicians are not routinely screening for vaccination administration.

Background

Smallpox (Variola major) was successfully eradicated in 1977 due to worldwide vaccination efforts.1 However, the threat of bioterrorism has renewed mandatory smallpox vaccinations for high-risk individuals, such as active-duty military personnel.1,2 A notable increase in myopericarditis has been reported with the new generation of smallpox vaccination, ACAM2000.3 We present a case of a 27-year-old healthy male who presented with chest pain and diffuse ST segment elevations consistent with myopericarditis after vaccination with ACAM2000.

Case Presentation

A healthy 27-year-old soldier presented to the emergency department with sudden, new onset, sharp-stabbing, substernal chest pain, which was made worse with lying flat and better with leaning forward. Vital signs were unremarkable. He recently enlisted in the US Army and received the smallpox vaccination about 11 days before as part of a routine predeployment checklist. The patient reported he did not have any viral symptoms, such as fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, shortness of breath, sore throat, rhinorrhea, or sputum production. He also reported having no prior illness for the past 3 months, sick contacts at home or work, or recent travel outside the US. He reported no tobacco use, alcohol use, or illicit drug use. The patient’s family history was negative for significant cardiac disease.

A physical examination was unremarkable. The initial laboratory report showed no leukocytosis, anemia, thrombocytopenia, electrolytes derangement, abnormal kidney function, or abnormal liver function tests. Initial troponin was 0.25 ng/mL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 40 mmol/h and C-reactive protein (CRP) was 120.2 mg/L suggestive of acute inflammation. A urine drug screen was negative. D-dimer was < 0.27. An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed diffuse ST segment elevation (Figure 1). An echocardiogram showed normal left ventricle size, and function with ejection fraction 55 to 60%, normal diastolic dysfunction, and trivial pericardial effusion. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed increased T2 signal intensity of the myocardium suggestive of myopericarditis (Figure 2). A computed tomography (CT) angiogram of the coronary arteries showed no significant stenosis.

The patient was treated with ibuprofen for 2 weeks and colchicine for 3 months, and his symptoms resolved. He followed up with an appointment in the cardiology clinic 1 month later, and his ESR, CRP, and troponin results were negative. A limited echocardiogram showed ejection fraction 60 to 65%, no regional wall motion abnormalities, normal diastolic function, and resolution of the pericardial effusion.

Discussion

Smallpox was a major worldwide cause of mortality; about 30% of those infected died because of smallpox.2,4,5 Due to a worldwide vaccination effort, the World Health Organization declared smallpox was eradicated in 1977.2,4,5 However, despite successful eradication, smallpox is considered a possible bioterrorism target, which prompted a resurgence of mandatory smallpox vaccinations for active-duty personnel.2,5

Dryvax, a freeze-dried calf lymph smallpox vaccine was used extensively from the 1940s to the 1980s but was replaced in 2008 by ACAM2000, a smallpox vaccine cultured in kidney epithelial cells from African green monkeys.3,5 Myopericarditis was rarely associated with the Dryvax, with only 5 cases reported from 1955 to 1986 after millions of doses of vaccines were administered; however, in 230,734 administered ACAM2000 doses, 18 cases of myopericarditis (incidence, 7.8 per 100,000) were reported during a surveillance study in 2002 and 2003.3,5

Myopericarditis presents with a wide variety of symptoms, such as chest pain, palpitations, chills, shortness of breath, and fever.6,7 Mainstay diagnostic criteria include ECG findings consistent with myopericarditis (such as diffuse ST segment elevations) and elevated cardiac biomarkers (elevated troponins).5-7 An echocardiogram can be helpful in diagnosis, as most cases will not have regional wall motion abnormalities (to distinguish against coronary artery disease).5-7 MRI with diffuse enhancement of the myocardium can be helpful in diagnosis.5,6 The gold standard for diagnosis is an endomyocardial biopsy, which carries a significant risk of complications and is not routinely performed to diagnose myopericarditis.5,6 US military smallpox vaccination data showed that the onset of vaccine-associated myopericarditis averaged (SD) 10.4 (3.6) days after vaccination.5

Vaccine-associated myopericarditis treatment is focused on decreasing inflammation.5,6 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are advised for about 2 weeks with cessation of intensive cardiac activities for between 4 and 6 weeks due to risks of congestive heart failure and fatal cardiac arrhythmias.5,6

Conclusions

Since the September 11 attacks, the US needs to be continually prepared for potential terrorism on American soil and abroad. The threat of bioterrorism has renewed efforts to vaccinate or revaccinate American service members deployed to high-risk regions. These vaccinations put them at risk for vaccination-induced complications that can range from mild fever to life-threatening complications.

A renewed effort to vaccinate service members fighting the global war on terrorism has brought new diagnostic challenges. Vaccinations not generally given to the public are routinely given to service members when they deploy to various parts of the world. Examples include anthrax, yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, rabies, polio, and smallpox. Every vaccination has potential for adverse effects (AEs), which can range from mild to severe life-threatening complications. These AEs often go unrecognized and untreated because physicians are not routinely screening for vaccination administration.

Background

Smallpox (Variola major) was successfully eradicated in 1977 due to worldwide vaccination efforts.1 However, the threat of bioterrorism has renewed mandatory smallpox vaccinations for high-risk individuals, such as active-duty military personnel.1,2 A notable increase in myopericarditis has been reported with the new generation of smallpox vaccination, ACAM2000.3 We present a case of a 27-year-old healthy male who presented with chest pain and diffuse ST segment elevations consistent with myopericarditis after vaccination with ACAM2000.

Case Presentation

A healthy 27-year-old soldier presented to the emergency department with sudden, new onset, sharp-stabbing, substernal chest pain, which was made worse with lying flat and better with leaning forward. Vital signs were unremarkable. He recently enlisted in the US Army and received the smallpox vaccination about 11 days before as part of a routine predeployment checklist. The patient reported he did not have any viral symptoms, such as fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, shortness of breath, sore throat, rhinorrhea, or sputum production. He also reported having no prior illness for the past 3 months, sick contacts at home or work, or recent travel outside the US. He reported no tobacco use, alcohol use, or illicit drug use. The patient’s family history was negative for significant cardiac disease.

A physical examination was unremarkable. The initial laboratory report showed no leukocytosis, anemia, thrombocytopenia, electrolytes derangement, abnormal kidney function, or abnormal liver function tests. Initial troponin was 0.25 ng/mL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 40 mmol/h and C-reactive protein (CRP) was 120.2 mg/L suggestive of acute inflammation. A urine drug screen was negative. D-dimer was < 0.27. An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed diffuse ST segment elevation (Figure 1). An echocardiogram showed normal left ventricle size, and function with ejection fraction 55 to 60%, normal diastolic dysfunction, and trivial pericardial effusion. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed increased T2 signal intensity of the myocardium suggestive of myopericarditis (Figure 2). A computed tomography (CT) angiogram of the coronary arteries showed no significant stenosis.

The patient was treated with ibuprofen for 2 weeks and colchicine for 3 months, and his symptoms resolved. He followed up with an appointment in the cardiology clinic 1 month later, and his ESR, CRP, and troponin results were negative. A limited echocardiogram showed ejection fraction 60 to 65%, no regional wall motion abnormalities, normal diastolic function, and resolution of the pericardial effusion.

Discussion

Smallpox was a major worldwide cause of mortality; about 30% of those infected died because of smallpox.2,4,5 Due to a worldwide vaccination effort, the World Health Organization declared smallpox was eradicated in 1977.2,4,5 However, despite successful eradication, smallpox is considered a possible bioterrorism target, which prompted a resurgence of mandatory smallpox vaccinations for active-duty personnel.2,5

Dryvax, a freeze-dried calf lymph smallpox vaccine was used extensively from the 1940s to the 1980s but was replaced in 2008 by ACAM2000, a smallpox vaccine cultured in kidney epithelial cells from African green monkeys.3,5 Myopericarditis was rarely associated with the Dryvax, with only 5 cases reported from 1955 to 1986 after millions of doses of vaccines were administered; however, in 230,734 administered ACAM2000 doses, 18 cases of myopericarditis (incidence, 7.8 per 100,000) were reported during a surveillance study in 2002 and 2003.3,5

Myopericarditis presents with a wide variety of symptoms, such as chest pain, palpitations, chills, shortness of breath, and fever.6,7 Mainstay diagnostic criteria include ECG findings consistent with myopericarditis (such as diffuse ST segment elevations) and elevated cardiac biomarkers (elevated troponins).5-7 An echocardiogram can be helpful in diagnosis, as most cases will not have regional wall motion abnormalities (to distinguish against coronary artery disease).5-7 MRI with diffuse enhancement of the myocardium can be helpful in diagnosis.5,6 The gold standard for diagnosis is an endomyocardial biopsy, which carries a significant risk of complications and is not routinely performed to diagnose myopericarditis.5,6 US military smallpox vaccination data showed that the onset of vaccine-associated myopericarditis averaged (SD) 10.4 (3.6) days after vaccination.5

Vaccine-associated myopericarditis treatment is focused on decreasing inflammation.5,6 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are advised for about 2 weeks with cessation of intensive cardiac activities for between 4 and 6 weeks due to risks of congestive heart failure and fatal cardiac arrhythmias.5,6

Conclusions

Since the September 11 attacks, the US needs to be continually prepared for potential terrorism on American soil and abroad. The threat of bioterrorism has renewed efforts to vaccinate or revaccinate American service members deployed to high-risk regions. These vaccinations put them at risk for vaccination-induced complications that can range from mild fever to life-threatening complications.

1. Bruner DI, Butler BS. Smallpox vaccination-associated myopericarditis is more common with the newest smallpox vaccine. J Emerg Med. 2014;46(3):e85-e87. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.06.001

2. Halsell JS, Riddle JR, Atwood JE, et al. Myopericarditis following smallpox vaccination among vaccinia-naive US military personnel. JAMA. 2003;289(24):3283-3289. doi:10.1001/jama.289.24.3283

3. Nalca A, Zumbrun EE. ACAM2000: the new smallpox vaccine for United States Strategic National Stockpile. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2010;4:71-79. doi:10.2147/dddt.s3687

4. Wollenberg A, Engler R. Smallpox, vaccination and adverse reactions to smallpox vaccine. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;4(4):271-275. doi:10.1097/01.all.0000136758.66442.28

5. Cassimatis DC, Atwood JE, Engler RM, Linz PE, Grabenstein JD, Vernalis MN. Smallpox vaccination and myopericarditis: a clinical review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(9):1503-1510. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.053

6. Sharma U, Tak T. A report of 2 cases of myopericarditis after Vaccinia virus (smallpox) immunization. WMJ. 2011;110(6):291-294.

7. Sarkisian SA, Hand G, Rivera VM, Smith M, Miller JA. A case series of smallpox vaccination-associated myopericarditis: effects on safety and readiness of the active duty soldier. Mil Med. 2019;184(1-2):e280-e283. doi:10.1093/milmed/usy159

1. Bruner DI, Butler BS. Smallpox vaccination-associated myopericarditis is more common with the newest smallpox vaccine. J Emerg Med. 2014;46(3):e85-e87. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.06.001

2. Halsell JS, Riddle JR, Atwood JE, et al. Myopericarditis following smallpox vaccination among vaccinia-naive US military personnel. JAMA. 2003;289(24):3283-3289. doi:10.1001/jama.289.24.3283

3. Nalca A, Zumbrun EE. ACAM2000: the new smallpox vaccine for United States Strategic National Stockpile. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2010;4:71-79. doi:10.2147/dddt.s3687

4. Wollenberg A, Engler R. Smallpox, vaccination and adverse reactions to smallpox vaccine. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;4(4):271-275. doi:10.1097/01.all.0000136758.66442.28

5. Cassimatis DC, Atwood JE, Engler RM, Linz PE, Grabenstein JD, Vernalis MN. Smallpox vaccination and myopericarditis: a clinical review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(9):1503-1510. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.053

6. Sharma U, Tak T. A report of 2 cases of myopericarditis after Vaccinia virus (smallpox) immunization. WMJ. 2011;110(6):291-294.

7. Sarkisian SA, Hand G, Rivera VM, Smith M, Miller JA. A case series of smallpox vaccination-associated myopericarditis: effects on safety and readiness of the active duty soldier. Mil Med. 2019;184(1-2):e280-e283. doi:10.1093/milmed/usy159