User login

Just Like Rock and Roll, Topical Medications for Psoriasis Are Here to Stay

When I finished my dermatology training in 1986, the only moving parts in the skin that I recall were keratinocytes moving upward from the basal layer of the epidermis until they were desquamated 4 or 5 weeks later and hairs growing within their follicles until they were shed. Now we are learning about countless cytokines, chemokines, interleukins, antibodies, receptors, enzymes, and cell types, as well as their associated pathways, at an endless pace. Every day I am looking in my inbox to sign up for the “Cytokine of the Month” club! Despite the challenges of sorting through what is relevant clinically, it is a very exciting time. Coupled with this myriad of fundamental science is the emergence of newer therapies that are more directly targeting specific disease states and dramatically changing the lives of patients. We see prominent examples of these therapeutic results every day in patients we treat, especially with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Importantly, there also is hope for patients with notoriously refractory skin disorders, such as hidradenitis suppurativa, alopecia areata, and vitiligo, as newer therapies are being thoroughly studied in clinical trials.

Despite the best advances in therapy that we currently have available and those anticipated in the foreseeable future, patients with chronic dermatoses such as psoriasis and atopic dermatitis still require prolonged constant or frequently used intermittent therapies to adequately control their disease. Fortunately, as dermatologists we understand the importance of proper skin care and topical medications as well as how to incorporate them in the management plan. To date, specifically with psoriasis, we have a variety of brand and generic topical corticosteroids, calcipotriene (vitamin D analogue), and tazarotene (retinoid), as well as combination formulations, in our toolbox to help manage localized areas of involvement.1 This includes both patients with more limited psoriasis and those responding favorably to systemic therapy but who still develop some new or persistent areas of localized psoriatic lesions. New data with the brand formulation of calcipotriene–betamethasone dipropionate (Cal-BDP) foam applied once daily shows that after adequate control is achieved, continued application to the affected sites twice weekly is superior to vehicle in preventing relapse of psoriasis.2 A highly cosmetically acceptable Cal-BDP cream incorporating a unique vehicle technology has been US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for once-daily use for plaque psoriasis, overcoming the compatibility difficulties encountered in combining both active ingredients in an aqueous-based formulation and also optimizing the delivery of the active ingredients into the skin. This Cal-BDP cream demonstrated efficacy superior to a brand Cal-BDP suspension, rapid reduction in pruritus, and favorable tolerability and safety.3 Another combination formulation that is FDA approved for plaque psoriasis with once-daily application that has been shown to be effective and safe is halobetasol propionate–tazarotene lotion. This formulation contains lower concentrations of both active ingredients than those normally used in a barrier-friendly polymeric emulsion vehicle, allowing for augmented delivery of both active ingredients into the skin than with the individual agents applied separately and sequentially.4,5 In the best of circumstances, most patients with psoriasis still require use of topical therapy and appreciate its availability. Just like on any menu, it is good to have multiple good options.

What else does this psoriasis management story need? A pipeline! I am happy to tell you that with topical therapy, 2 nonsteroidal agents are under development with completion of phase 2 and phase 3 trials submitted to the FDA to evaluate for approval for psoriasis. They are tapinarof cream, an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist, and roflumilast cream, a phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor. Both of these modes of action involve intracellular pathways that are highly conserved in humans and are ubiquitously present in structural and hematopoietic cells.

Topical application of tapinarof cream once daily has been shown to be effective and safe for plaque psoriasis, is well tolerated with some reports of folliculitis observed that did not typically interfere with use, exhibits a remittive effect in patients achieving clearance on therapy, and is devoid of any systemic safety signals with both short-term and long-term use.6-8 It also is currently under evaluation for atopic dermatitis. Topical roflumilast cream once daily has been shown to be effective and safe for plaque psoriasis as well as intertriginous psoriasis; is well tolerated including negligible rates of skin tolerability reactions such as stinging and burning; and is devoid of systemic safety signals, including those often observed with oral PDE4 inhibitor therapy (apremilast).9,10 In addition, roflumilast has been shown to be more inherently potent in PDE4 inhibition activity than crisaborole and apremilast.11 Roflumilast cream also is being studied for atopic dermatitis and a foam formulation is being evaluated for seborrheic dermatitis. Importantly, both tapinarof and roflumilast are not corticosteroids and are not associated with adverse effects observed with topical corticosteroid therapy, such as atrophy, striae, telangiectasia, and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression. This provides a sense of comfort for clinicians and patients, as potential side effects associated with more prolonged topical corticosteroid therapy are common and lingering concerns.

To summarize, topical therapy for psoriasis is here to stay, just like all the rock and roll we have more access to than ever through expanded modern-day radio access and several music streaming sources, most of which are on demand. Also available to us are some viable current options, including a few newer brand formulations. New nonsteroidal agents with favorable data thus far are on the horizon, providing their own inherent efficacy and safety, which appear to be advantageous thus far. As the late Ric Ocasek of the Cars sang, “Let the good times roll.”

- Lebwohl MG, Van de Kerkhof PCM. Psoriasis. In: Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, et al, eds. Treatment of Skin Disease: Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. 4th ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2014:640-650.

- Lebwohl M, Kircik L, Lacour JP, et al. Twice-weekly topical calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam as proactive management of plaque psoriasis increases time in remission and is well tolerated over 52 weeks (PSO-LONG trial). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1269-1277.

- Wynzora (calcipotriene and betamethasone dipropionate) cream, for topical use. Package insert. EPI Health, LLC; 2020.

- Ramachandran V, Bertus B, Bashyam AM, et al. Treating psoriasis with halobetasol propionate and tazarotene combination: a review of phase II and III clinical trials. Ann Pharmacother. 2020;54:872-878.

- Lebwohl MG, Tanghetti EA, Stein Gold L, et al. Fixed-combination halobetasol propionate and tazarotene in the treatment of psoriasis: narrative review of mechanisms of action and therapeutic benefits. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:1157-1174.

- Bissonnette R, Stein Gold L, Rubenstein DS, et al. Tapinarof in the treatment of psoriasis: a review of the unique mechanism of action of a novel therapeutic aryl hydrocarbon receptor-modulating agent. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1059-1067.

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229.

- Jett JE, McLaughlin M, Lee MS, et al. Tapinarof cream 1% for extensive plaque psoriasis: a maximal use trial on safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics [published online October 28, 2021]. Am J Clin Dermatol. doi:10.100/s40257-021-00641-4

- Lebwohl MG, Papp KA, Stein Gold L, et al. Trial of roflumilast cream for chronic plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:229-239.

- Papp KA, Gooderham M, Droege M, et al. Roflumilast cream improves signs and symptoms of plaque psoriasis: results from a phase 1/2a randomized, controlled study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:734-740.

- Dong C, Virtucio C, Zemska O, et al. Treatment of skin inflammation with benzoxaborole phosphodiesterase inhibitors: selectivity, cellular activity, and effect on cytokines associated with skin inflammation and skin architecture changes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;358:413-422.

When I finished my dermatology training in 1986, the only moving parts in the skin that I recall were keratinocytes moving upward from the basal layer of the epidermis until they were desquamated 4 or 5 weeks later and hairs growing within their follicles until they were shed. Now we are learning about countless cytokines, chemokines, interleukins, antibodies, receptors, enzymes, and cell types, as well as their associated pathways, at an endless pace. Every day I am looking in my inbox to sign up for the “Cytokine of the Month” club! Despite the challenges of sorting through what is relevant clinically, it is a very exciting time. Coupled with this myriad of fundamental science is the emergence of newer therapies that are more directly targeting specific disease states and dramatically changing the lives of patients. We see prominent examples of these therapeutic results every day in patients we treat, especially with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Importantly, there also is hope for patients with notoriously refractory skin disorders, such as hidradenitis suppurativa, alopecia areata, and vitiligo, as newer therapies are being thoroughly studied in clinical trials.

Despite the best advances in therapy that we currently have available and those anticipated in the foreseeable future, patients with chronic dermatoses such as psoriasis and atopic dermatitis still require prolonged constant or frequently used intermittent therapies to adequately control their disease. Fortunately, as dermatologists we understand the importance of proper skin care and topical medications as well as how to incorporate them in the management plan. To date, specifically with psoriasis, we have a variety of brand and generic topical corticosteroids, calcipotriene (vitamin D analogue), and tazarotene (retinoid), as well as combination formulations, in our toolbox to help manage localized areas of involvement.1 This includes both patients with more limited psoriasis and those responding favorably to systemic therapy but who still develop some new or persistent areas of localized psoriatic lesions. New data with the brand formulation of calcipotriene–betamethasone dipropionate (Cal-BDP) foam applied once daily shows that after adequate control is achieved, continued application to the affected sites twice weekly is superior to vehicle in preventing relapse of psoriasis.2 A highly cosmetically acceptable Cal-BDP cream incorporating a unique vehicle technology has been US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for once-daily use for plaque psoriasis, overcoming the compatibility difficulties encountered in combining both active ingredients in an aqueous-based formulation and also optimizing the delivery of the active ingredients into the skin. This Cal-BDP cream demonstrated efficacy superior to a brand Cal-BDP suspension, rapid reduction in pruritus, and favorable tolerability and safety.3 Another combination formulation that is FDA approved for plaque psoriasis with once-daily application that has been shown to be effective and safe is halobetasol propionate–tazarotene lotion. This formulation contains lower concentrations of both active ingredients than those normally used in a barrier-friendly polymeric emulsion vehicle, allowing for augmented delivery of both active ingredients into the skin than with the individual agents applied separately and sequentially.4,5 In the best of circumstances, most patients with psoriasis still require use of topical therapy and appreciate its availability. Just like on any menu, it is good to have multiple good options.

What else does this psoriasis management story need? A pipeline! I am happy to tell you that with topical therapy, 2 nonsteroidal agents are under development with completion of phase 2 and phase 3 trials submitted to the FDA to evaluate for approval for psoriasis. They are tapinarof cream, an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist, and roflumilast cream, a phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor. Both of these modes of action involve intracellular pathways that are highly conserved in humans and are ubiquitously present in structural and hematopoietic cells.

Topical application of tapinarof cream once daily has been shown to be effective and safe for plaque psoriasis, is well tolerated with some reports of folliculitis observed that did not typically interfere with use, exhibits a remittive effect in patients achieving clearance on therapy, and is devoid of any systemic safety signals with both short-term and long-term use.6-8 It also is currently under evaluation for atopic dermatitis. Topical roflumilast cream once daily has been shown to be effective and safe for plaque psoriasis as well as intertriginous psoriasis; is well tolerated including negligible rates of skin tolerability reactions such as stinging and burning; and is devoid of systemic safety signals, including those often observed with oral PDE4 inhibitor therapy (apremilast).9,10 In addition, roflumilast has been shown to be more inherently potent in PDE4 inhibition activity than crisaborole and apremilast.11 Roflumilast cream also is being studied for atopic dermatitis and a foam formulation is being evaluated for seborrheic dermatitis. Importantly, both tapinarof and roflumilast are not corticosteroids and are not associated with adverse effects observed with topical corticosteroid therapy, such as atrophy, striae, telangiectasia, and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression. This provides a sense of comfort for clinicians and patients, as potential side effects associated with more prolonged topical corticosteroid therapy are common and lingering concerns.

To summarize, topical therapy for psoriasis is here to stay, just like all the rock and roll we have more access to than ever through expanded modern-day radio access and several music streaming sources, most of which are on demand. Also available to us are some viable current options, including a few newer brand formulations. New nonsteroidal agents with favorable data thus far are on the horizon, providing their own inherent efficacy and safety, which appear to be advantageous thus far. As the late Ric Ocasek of the Cars sang, “Let the good times roll.”

When I finished my dermatology training in 1986, the only moving parts in the skin that I recall were keratinocytes moving upward from the basal layer of the epidermis until they were desquamated 4 or 5 weeks later and hairs growing within their follicles until they were shed. Now we are learning about countless cytokines, chemokines, interleukins, antibodies, receptors, enzymes, and cell types, as well as their associated pathways, at an endless pace. Every day I am looking in my inbox to sign up for the “Cytokine of the Month” club! Despite the challenges of sorting through what is relevant clinically, it is a very exciting time. Coupled with this myriad of fundamental science is the emergence of newer therapies that are more directly targeting specific disease states and dramatically changing the lives of patients. We see prominent examples of these therapeutic results every day in patients we treat, especially with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Importantly, there also is hope for patients with notoriously refractory skin disorders, such as hidradenitis suppurativa, alopecia areata, and vitiligo, as newer therapies are being thoroughly studied in clinical trials.

Despite the best advances in therapy that we currently have available and those anticipated in the foreseeable future, patients with chronic dermatoses such as psoriasis and atopic dermatitis still require prolonged constant or frequently used intermittent therapies to adequately control their disease. Fortunately, as dermatologists we understand the importance of proper skin care and topical medications as well as how to incorporate them in the management plan. To date, specifically with psoriasis, we have a variety of brand and generic topical corticosteroids, calcipotriene (vitamin D analogue), and tazarotene (retinoid), as well as combination formulations, in our toolbox to help manage localized areas of involvement.1 This includes both patients with more limited psoriasis and those responding favorably to systemic therapy but who still develop some new or persistent areas of localized psoriatic lesions. New data with the brand formulation of calcipotriene–betamethasone dipropionate (Cal-BDP) foam applied once daily shows that after adequate control is achieved, continued application to the affected sites twice weekly is superior to vehicle in preventing relapse of psoriasis.2 A highly cosmetically acceptable Cal-BDP cream incorporating a unique vehicle technology has been US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for once-daily use for plaque psoriasis, overcoming the compatibility difficulties encountered in combining both active ingredients in an aqueous-based formulation and also optimizing the delivery of the active ingredients into the skin. This Cal-BDP cream demonstrated efficacy superior to a brand Cal-BDP suspension, rapid reduction in pruritus, and favorable tolerability and safety.3 Another combination formulation that is FDA approved for plaque psoriasis with once-daily application that has been shown to be effective and safe is halobetasol propionate–tazarotene lotion. This formulation contains lower concentrations of both active ingredients than those normally used in a barrier-friendly polymeric emulsion vehicle, allowing for augmented delivery of both active ingredients into the skin than with the individual agents applied separately and sequentially.4,5 In the best of circumstances, most patients with psoriasis still require use of topical therapy and appreciate its availability. Just like on any menu, it is good to have multiple good options.

What else does this psoriasis management story need? A pipeline! I am happy to tell you that with topical therapy, 2 nonsteroidal agents are under development with completion of phase 2 and phase 3 trials submitted to the FDA to evaluate for approval for psoriasis. They are tapinarof cream, an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist, and roflumilast cream, a phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor. Both of these modes of action involve intracellular pathways that are highly conserved in humans and are ubiquitously present in structural and hematopoietic cells.

Topical application of tapinarof cream once daily has been shown to be effective and safe for plaque psoriasis, is well tolerated with some reports of folliculitis observed that did not typically interfere with use, exhibits a remittive effect in patients achieving clearance on therapy, and is devoid of any systemic safety signals with both short-term and long-term use.6-8 It also is currently under evaluation for atopic dermatitis. Topical roflumilast cream once daily has been shown to be effective and safe for plaque psoriasis as well as intertriginous psoriasis; is well tolerated including negligible rates of skin tolerability reactions such as stinging and burning; and is devoid of systemic safety signals, including those often observed with oral PDE4 inhibitor therapy (apremilast).9,10 In addition, roflumilast has been shown to be more inherently potent in PDE4 inhibition activity than crisaborole and apremilast.11 Roflumilast cream also is being studied for atopic dermatitis and a foam formulation is being evaluated for seborrheic dermatitis. Importantly, both tapinarof and roflumilast are not corticosteroids and are not associated with adverse effects observed with topical corticosteroid therapy, such as atrophy, striae, telangiectasia, and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression. This provides a sense of comfort for clinicians and patients, as potential side effects associated with more prolonged topical corticosteroid therapy are common and lingering concerns.

To summarize, topical therapy for psoriasis is here to stay, just like all the rock and roll we have more access to than ever through expanded modern-day radio access and several music streaming sources, most of which are on demand. Also available to us are some viable current options, including a few newer brand formulations. New nonsteroidal agents with favorable data thus far are on the horizon, providing their own inherent efficacy and safety, which appear to be advantageous thus far. As the late Ric Ocasek of the Cars sang, “Let the good times roll.”

- Lebwohl MG, Van de Kerkhof PCM. Psoriasis. In: Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, et al, eds. Treatment of Skin Disease: Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. 4th ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2014:640-650.

- Lebwohl M, Kircik L, Lacour JP, et al. Twice-weekly topical calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam as proactive management of plaque psoriasis increases time in remission and is well tolerated over 52 weeks (PSO-LONG trial). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1269-1277.

- Wynzora (calcipotriene and betamethasone dipropionate) cream, for topical use. Package insert. EPI Health, LLC; 2020.

- Ramachandran V, Bertus B, Bashyam AM, et al. Treating psoriasis with halobetasol propionate and tazarotene combination: a review of phase II and III clinical trials. Ann Pharmacother. 2020;54:872-878.

- Lebwohl MG, Tanghetti EA, Stein Gold L, et al. Fixed-combination halobetasol propionate and tazarotene in the treatment of psoriasis: narrative review of mechanisms of action and therapeutic benefits. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:1157-1174.

- Bissonnette R, Stein Gold L, Rubenstein DS, et al. Tapinarof in the treatment of psoriasis: a review of the unique mechanism of action of a novel therapeutic aryl hydrocarbon receptor-modulating agent. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1059-1067.

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229.

- Jett JE, McLaughlin M, Lee MS, et al. Tapinarof cream 1% for extensive plaque psoriasis: a maximal use trial on safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics [published online October 28, 2021]. Am J Clin Dermatol. doi:10.100/s40257-021-00641-4

- Lebwohl MG, Papp KA, Stein Gold L, et al. Trial of roflumilast cream for chronic plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:229-239.

- Papp KA, Gooderham M, Droege M, et al. Roflumilast cream improves signs and symptoms of plaque psoriasis: results from a phase 1/2a randomized, controlled study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:734-740.

- Dong C, Virtucio C, Zemska O, et al. Treatment of skin inflammation with benzoxaborole phosphodiesterase inhibitors: selectivity, cellular activity, and effect on cytokines associated with skin inflammation and skin architecture changes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;358:413-422.

- Lebwohl MG, Van de Kerkhof PCM. Psoriasis. In: Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, et al, eds. Treatment of Skin Disease: Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. 4th ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2014:640-650.

- Lebwohl M, Kircik L, Lacour JP, et al. Twice-weekly topical calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam as proactive management of plaque psoriasis increases time in remission and is well tolerated over 52 weeks (PSO-LONG trial). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1269-1277.

- Wynzora (calcipotriene and betamethasone dipropionate) cream, for topical use. Package insert. EPI Health, LLC; 2020.

- Ramachandran V, Bertus B, Bashyam AM, et al. Treating psoriasis with halobetasol propionate and tazarotene combination: a review of phase II and III clinical trials. Ann Pharmacother. 2020;54:872-878.

- Lebwohl MG, Tanghetti EA, Stein Gold L, et al. Fixed-combination halobetasol propionate and tazarotene in the treatment of psoriasis: narrative review of mechanisms of action and therapeutic benefits. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:1157-1174.

- Bissonnette R, Stein Gold L, Rubenstein DS, et al. Tapinarof in the treatment of psoriasis: a review of the unique mechanism of action of a novel therapeutic aryl hydrocarbon receptor-modulating agent. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1059-1067.

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229.

- Jett JE, McLaughlin M, Lee MS, et al. Tapinarof cream 1% for extensive plaque psoriasis: a maximal use trial on safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics [published online October 28, 2021]. Am J Clin Dermatol. doi:10.100/s40257-021-00641-4

- Lebwohl MG, Papp KA, Stein Gold L, et al. Trial of roflumilast cream for chronic plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:229-239.

- Papp KA, Gooderham M, Droege M, et al. Roflumilast cream improves signs and symptoms of plaque psoriasis: results from a phase 1/2a randomized, controlled study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:734-740.

- Dong C, Virtucio C, Zemska O, et al. Treatment of skin inflammation with benzoxaborole phosphodiesterase inhibitors: selectivity, cellular activity, and effect on cytokines associated with skin inflammation and skin architecture changes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;358:413-422.

Adjunctive Use of Halobetasol Propionate–Tazarotene in Biologic-Experienced Patients With Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a common chronic immunologic skin disease that affects approximately 7.4 million adults in the United States1 and more than 100 million individuals worldwide.2 Patients with psoriasis have a potentially heightened risk for cardiometabolic diseases, psychiatric disorders, and psoriatic arthritis,3 as well as impaired quality of life (QOL).4 Psoriasis also is associated with increased health care costs5 and may result in substantial socioeconomic repercussions for affected patients.6,7

Psoriasis treatments focus on relieving symptoms and improving patient QOL. Systemic therapy has been the mainstay of treatment for moderate to severe psoriasis.8 Although topical therapy usually is applied to treat mild symptoms, it also can be used as an adjunct to enhance efficacy of other treatment approaches.9 The National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) recommends a treat-to-target (TTT) strategy for plaque psoriasis, the most common form of psoriasis, with a target response of attaining affected body surface area (BSA) of 1% or lower at 3 months after treatment initiation, allowing for regular assessments of treatment responses.10

Not all patients with moderate to severe psoriasis can achieve a satisfactory response with systemic biologic monotherapy.11 Switching to a new biologic improves responses in some but not all cases12 and could be associated with new safety issues and additional costs. Combinations of biologics with phototherapy, nonbiologic systemic agents, or topical medications were found to be more effective than biologics alone,9,11 though long-term safety studies are needed for biologics combined with other systemic inverventions.11

A lotion containing a fixed combination of halobetasol propionate (HP) 0.01%, a corticosteroid, and tazarotene (TAZ) 0.045%, a retinoid, is indicated for plaque psoriasis in adults.13 Two randomized, controlled, phase 3 trials demonstrated the rapid and sustained efficacy of HP-TAZ in treating moderate to severe plaque psoriasis without any safety concerns.14,15 However, combining HP-TAZ lotion with biologics has not been examined yet, to our knowledge.

This open-label study evaluated the effectiveness and safety of adjunctive HP-TAZ lotion in adult patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who were being treated with biologics in a real-world setting. Potential cost savings with the addition of topical HP-TAZ to ongoing biologics vs switching to a new biologic also were assessed.

Methods

Study Design and Participants—A single-center, institutional review board–approved, open-label study evaluated adjunctive therapy with HP 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion in patients with psoriasis being treated with biologic agents. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and in compliance with Good Clinical Practices. All patients provided written informed consent before enrollment.

Male and nonpregnant female patients (aged ≥18 years)with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis and a BSA of 2% to 10% who were being treated with biologics for at least 24 weeks at baseline were enrolled. Patients were excluded if they had used oral systemic medications for psoriasis (≤4 weeks), other topical antipsoriatic therapies (≤14 days), UVB phototherapy (≤2 weeks), and psoralen plus UVA phototherapy (≤4 weeks) prior to study initiation. Concomitant use of steroid-free topical emollients or low-potency topical steroids and appropriate interventions deemed necessary by the investigator were allowed.

Although participants maintained their prescribed biologics for the duration of the study, HP-TAZ lotion also was applied once daily for 8 weeks, followed by once every other day for an additional 4 weeks. Participants then continued with biologics only for the last 4 weeks of the study.

Study Outcome Measures—Disease severity and treatment efficacy were assessed by affected BSA, Physician Global Assessment (PGA) score, composite BSA×PGA score, and participant-reported Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). The primary end point was the proportion of participants achieving a BSA of 0% to 1% (NPF TTT status) at week 8. Secondary end points included the proportions of participants with BSA of 0% to 1% at weeks 12 and 16; BSA×PGA score at weeks 8, 12, and 16; and improvements in BSA, PGA, and DLQI at weeks 8, 12, and 16.

Adverse events (AEs) that occurred after the signing of the informed consent and for the duration of the participant’s participation were recorded, regardless of causality. Physical examinations were performed at screening; baseline; and weeks 8, 12, and 16 to document any clinically significant abnormalities. Localized skin reactions were assessed for tolerability of the study drug, with any reaction requiring concomitant therapy recorded as an AE.

The likelihood of switching to a new biologic regimen was assessed by the investigator for each participant at baseline and weeks 8, 12, and 16. Participants with unacceptable responses to their treatments (BSA >3%) were reported as likely to be considered for switching biologics by the investigator.

Pharmacoeconomic Evaluation—Potential cost savings were evaluated for the addition of HP-TAZ lotion to ongoing biologics vs switching to a new biologic. Cost comparisons were made in participants for whom the investigator would likely have switched biologics at baseline but not at the end of the study. For maintaining the same biologic with adjunctive topical HP-TAZ, total cost was estimated by adding the cost for 12 weeks (once daily for 8 weeks and once every other day for 4 weeks) of the HP-TAZ lotion to that of 16-week maintenance dosing with the biologic. The projected cost for switching to a new biologic for 16 weeks of treatment was based on both induction and maintenance dosing as recommended in its product label. Prices were obtained from the 2020 average wholesale price specialty pharmacy reports (BioPlus Specialty Pharmacy Services [https://www.bioplusrx.com]).

Data Handling—Enrollment of approximately 25 participants was desired for the study. Data on disease severity and participant-reported outcomes were assessed using descriptive statistics. Adverse events were summarized descriptively by incidence, severity, and relationship to the study drug. All participants with data available at a measured time point were included in the analyses for that time point.

Results

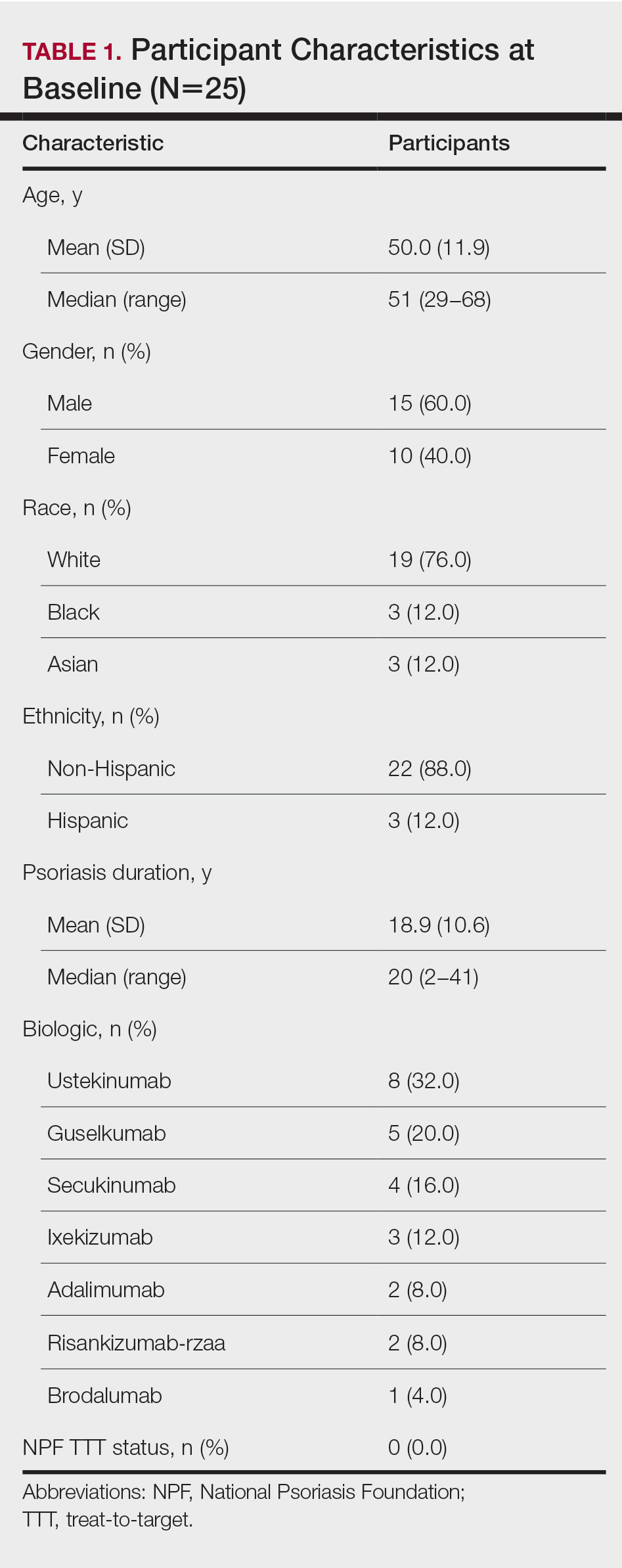

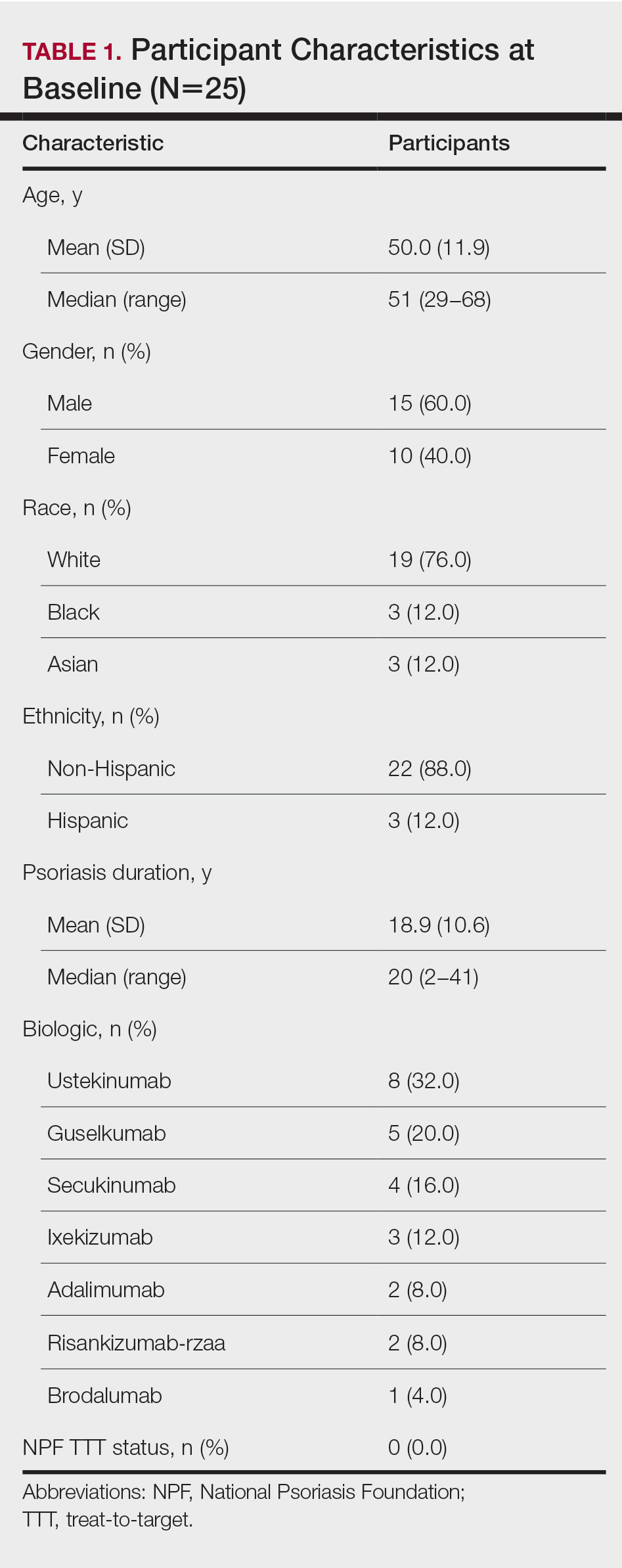

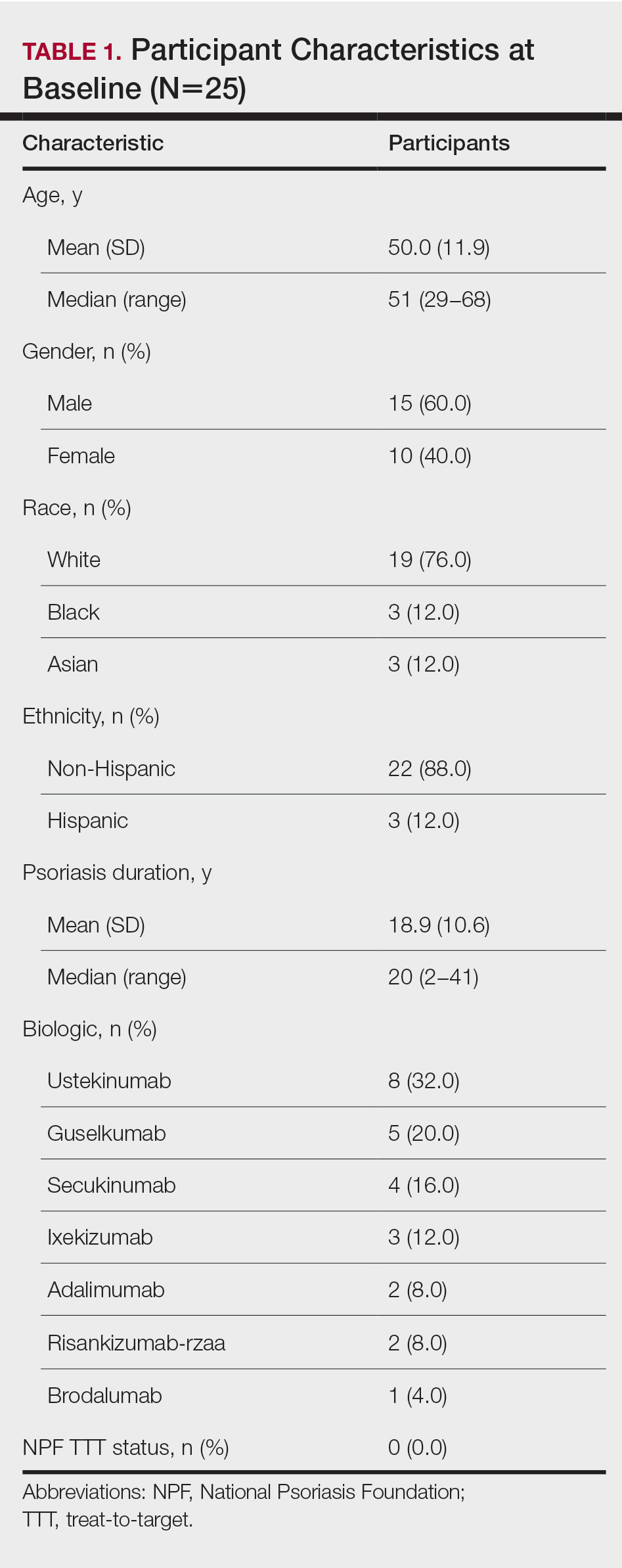

Participant Disposition and Demographics—Twenty-five participants (15 male and 10 female) were included in the study (Table 1). Seven participants discontinued the study for the following reasons: AEs (n=4), patient choice (n=2), and noncompliance (n=1).

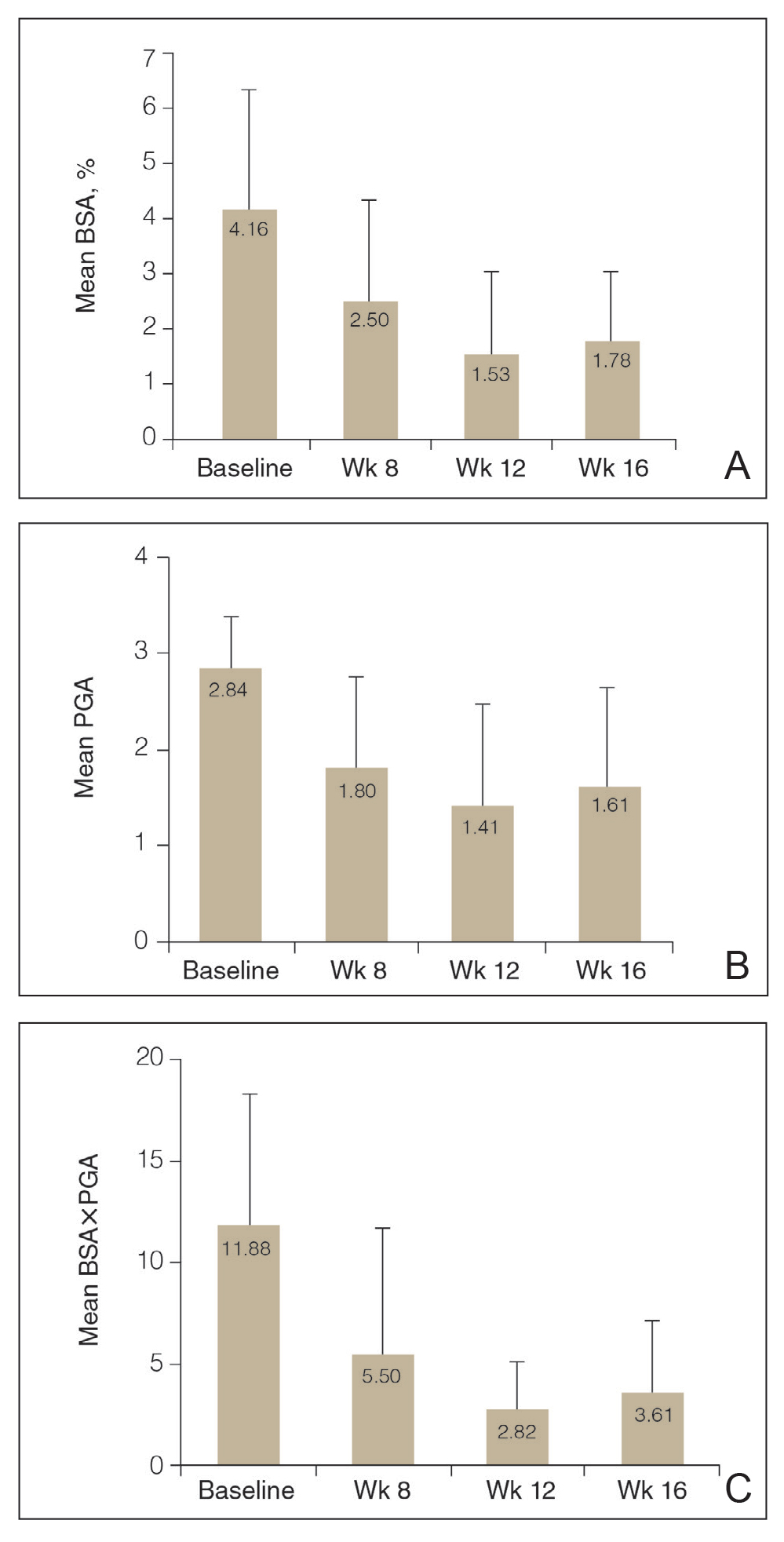

The average age of the participants was 50 years, the majority were White (76.0% [19/25]) andnon-Hispanic (88.0% [22/25]), and the mean duration of chronic plaque psoriasis was 18.9 years (Table 1). Participants had been receiving biologic monotherapy for at least 24 weeks prior to enrollment, most commonly ustekinumab (32.0% [8/25])(Table 1). None had achieved the NPF TTT status with their biologics. At baseline, mean (SD) affected BSA, PGA, BSA×PGA, and participant-reported DLQI were 4.16% (2.04%), 2.84 (0.55), 11.88 (6.39), and 4.00 (4.74), respectively.

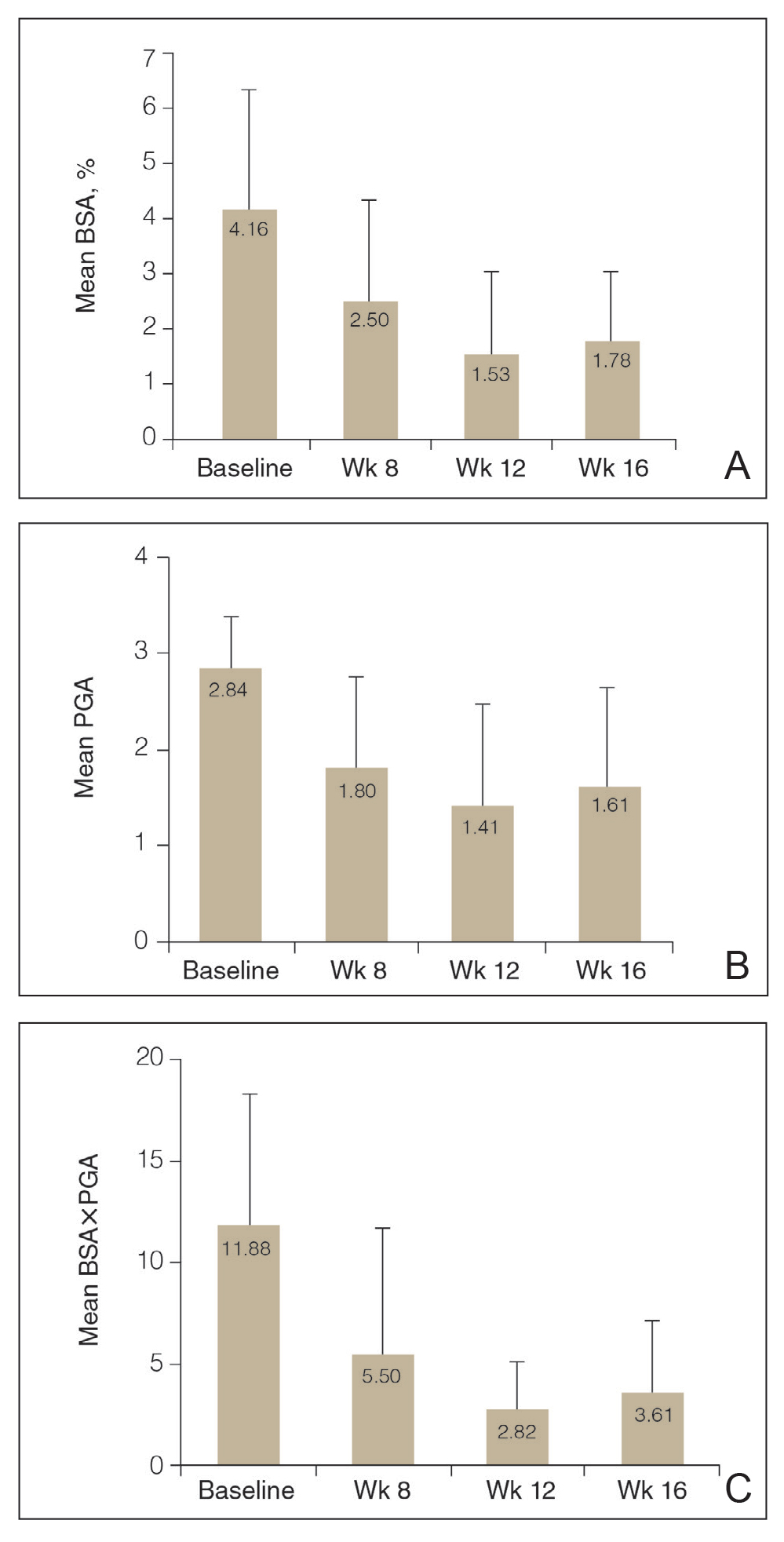

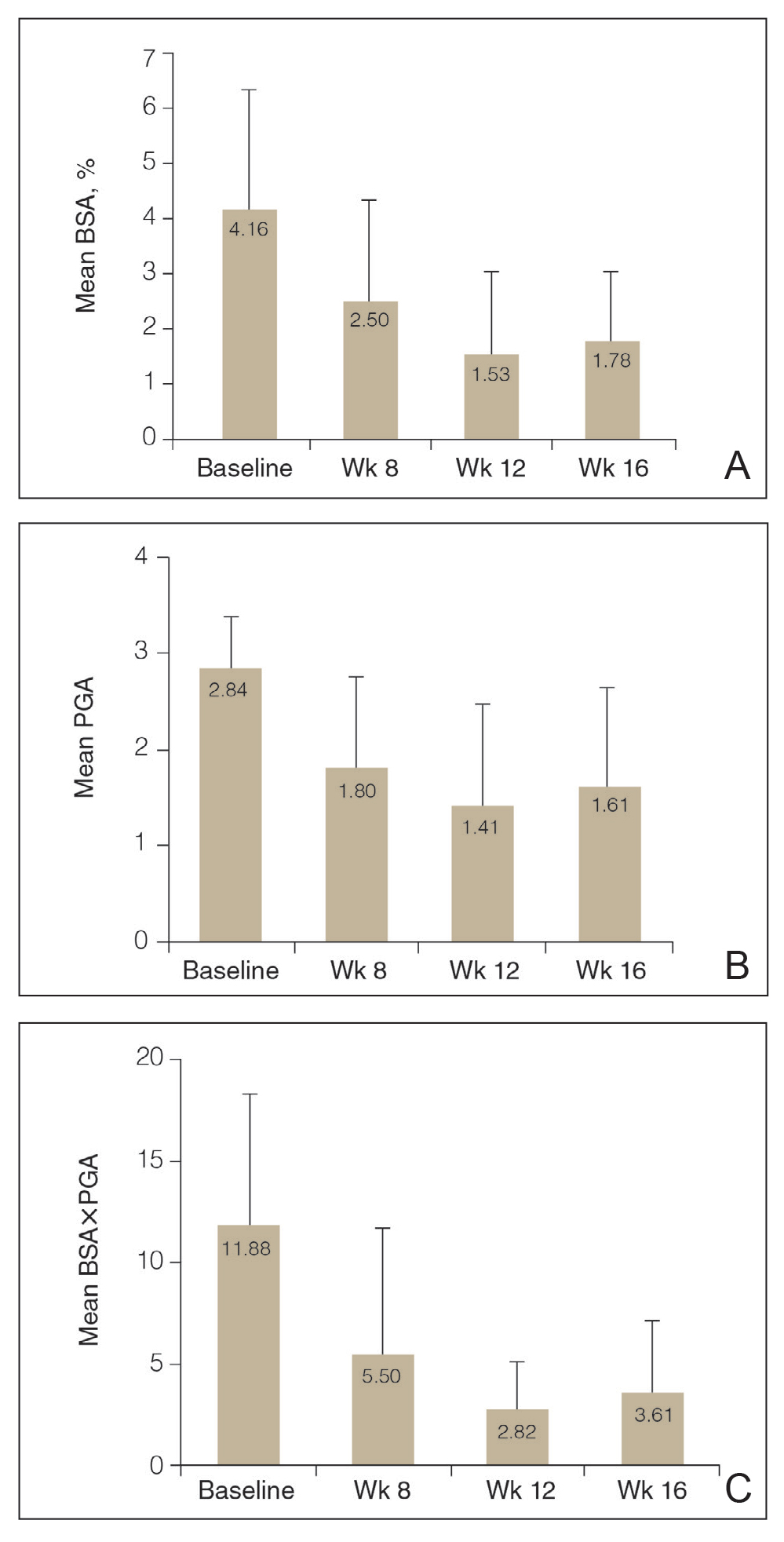

Efficacy Assessment—Application of HP-TAZ lotion in addition to the participants’ existing biologic therapy reduced severity of the disease, as evidenced by the reductions in mean BSA, PGA, and BSA×PGA. After 8 weeks of once-daily concomitant HP-TAZ use with biologic, mean BSA and PGA dropped by approximately 40% and 37%, respectively (Figures 1A and 1B). A greater reduction (54%) was found for mean BSA×PGA (Figure 1C). Disease severity continued to improve when the application schedule for HP-TAZ was changed to once every other day for 4 weeks, as mean BSA, PGA, and BSA×PGA decreased further at week 12. These beneficial effects were sustained during the last 4 weeks of the study after HP-TAZ was discontinued, with reductions of 57%, 43%, and 70% from baseline for mean BSA, PGA, and BSA×PGA, respectively (Figure 1).

The proportion of participants who achieved NPF TTT status increased from 0% at baseline to 20.0% (5/20) at week 8 with once-daily use of HP-TAZ plus biologic for 8 weeks (Figure 2). At week 12, more participants (64.7% [11/17]) achieved the treatment goal after application of HP-TAZ once every other day with biologic for 4 weeks. Most participants maintained NPF TTT status after HP-TAZ was discontinued; at week 16, 50.0% (9/18) attained the NPF treatment goal (Figure 2).

![Proportion of participants achieving National Psoriasis Foundation target-to-treat status (body surface area [BSA] ≤1%) at baseline and weeks 8, 12, and 16 Proportion of participants achieving National Psoriasis Foundation target-to-treat status (body surface area [BSA] ≤1%) at baseline and weeks 8, 12, and 16](https://cdn.mdedge.com/files/s3fs-public/Bagel_0222_2.JPG)

The mean DLQI score decreased from 4.00 at baseline to 2.45 after 8 weeks of concomitant use of once-daily HP-TAZ with biologic, reflecting a 39% score reduction. An additional 4 weeks of adjunctive HP-TAZ applied once every other day with biologic further decreased the DLQI score to 2.18 at week 12. Mean DLQI remained similar (2.33) after another 4 weeks of biologics alone. The proportion of participants reporting a DLQI score of 0 to 1 increased from 40% (10/25) at baseline to 60% (12/20) at week 8 and 76.5% (13/17) at week 12 with adjunctive HP-TAZ lotion use with biologic. At week 16, a DLQI score of 0 to 1 was reported in 61.1% (11/18) of participants after receiving only biologics for 4 weeks.

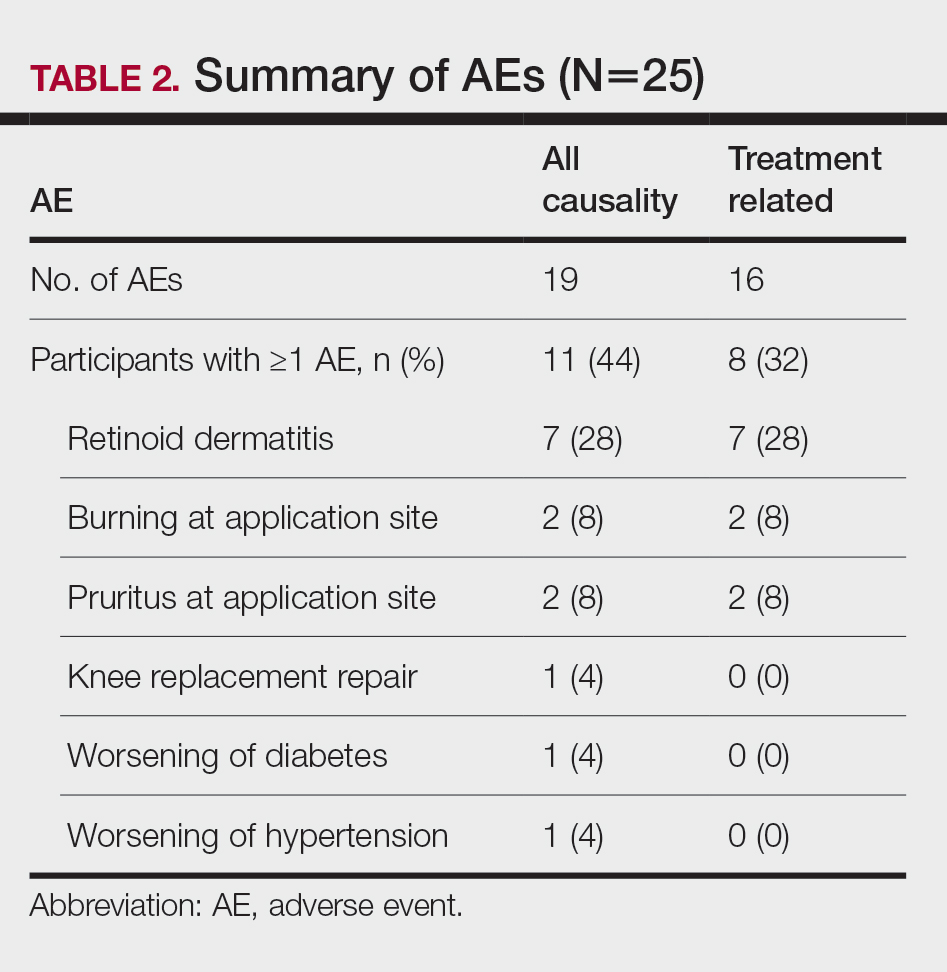

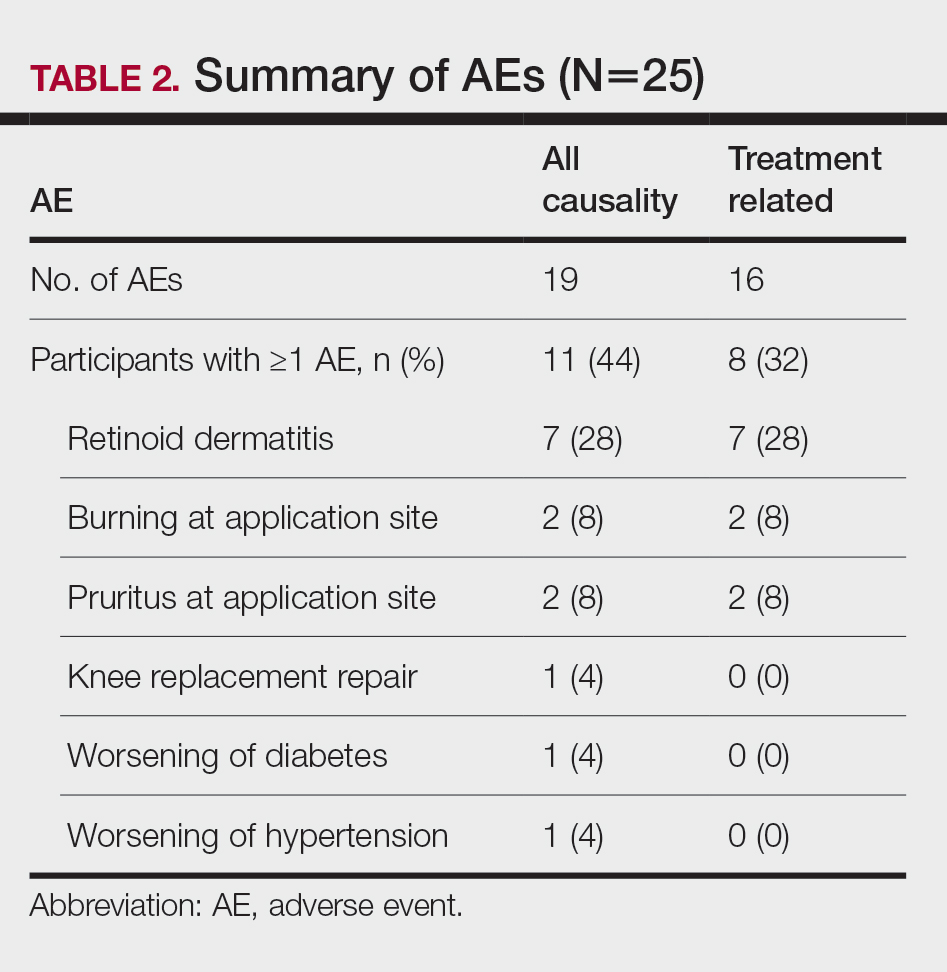

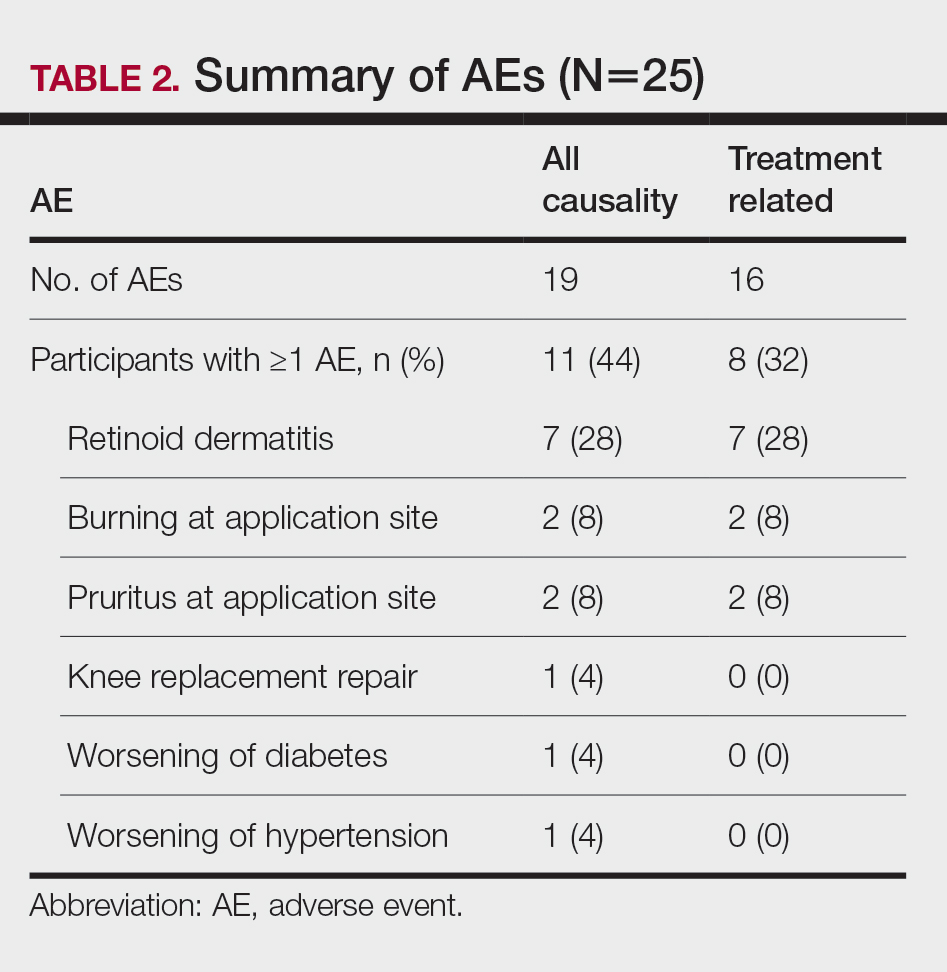

Safety Assessment—A total of 19 AEs were reported in 11 participants during the study; 16 AEs were considered treatment related in 8 participants (Table 2). The most common AEs were retinoid dermatitis (28% [7/25]), burning at the application site (8% [2/25]), and pruritus at the application site (8% [2/25]), all of which were considered related to the treatment. Among all AEs, 12 were mild in severity, and the remaining 7 were moderate. Adverse events led to early study termination in 4 participants, all with retinoid dermatitis as the primary reason.

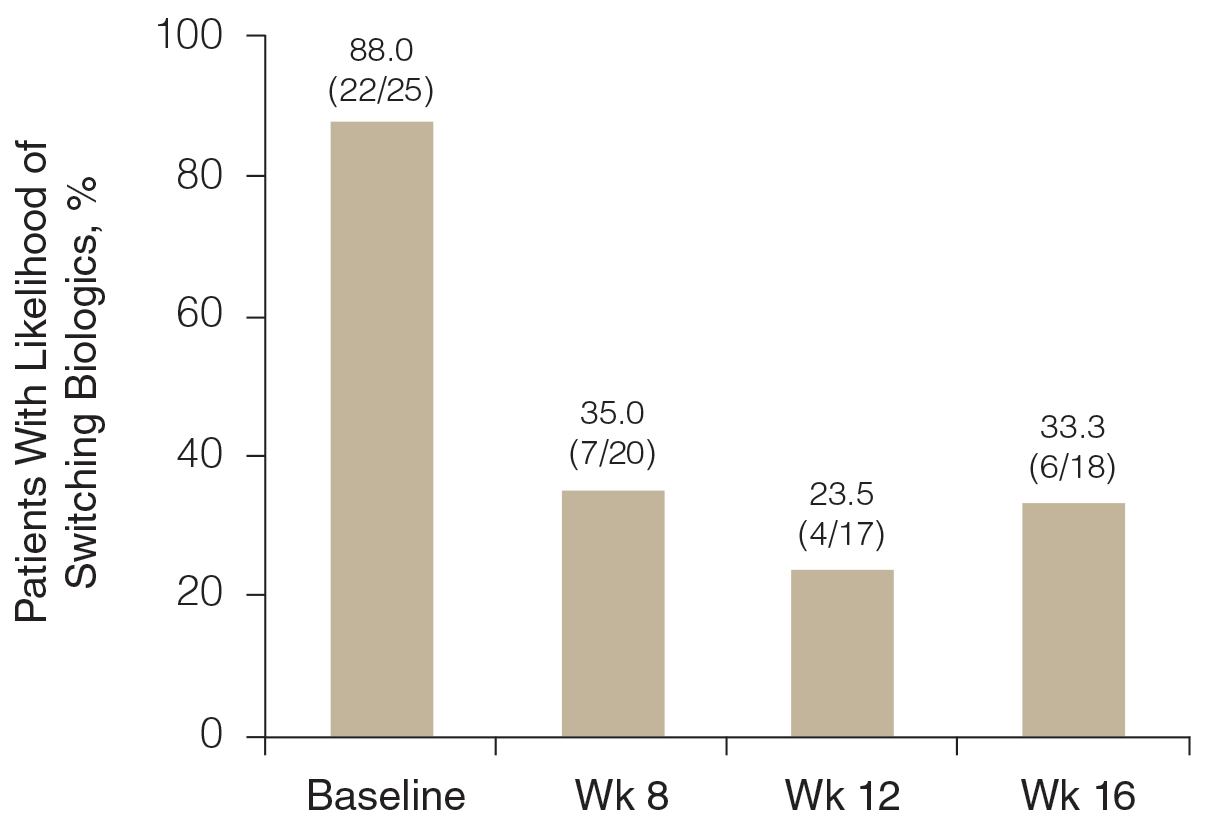

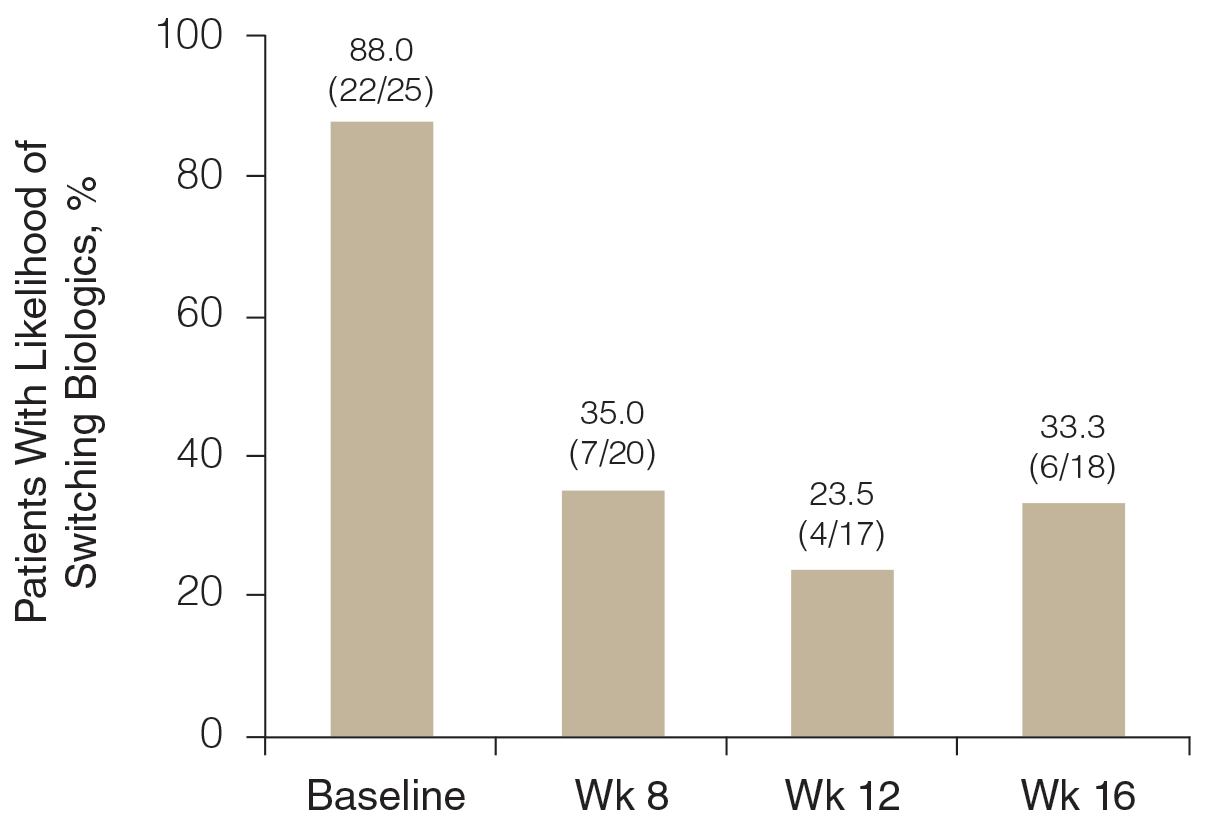

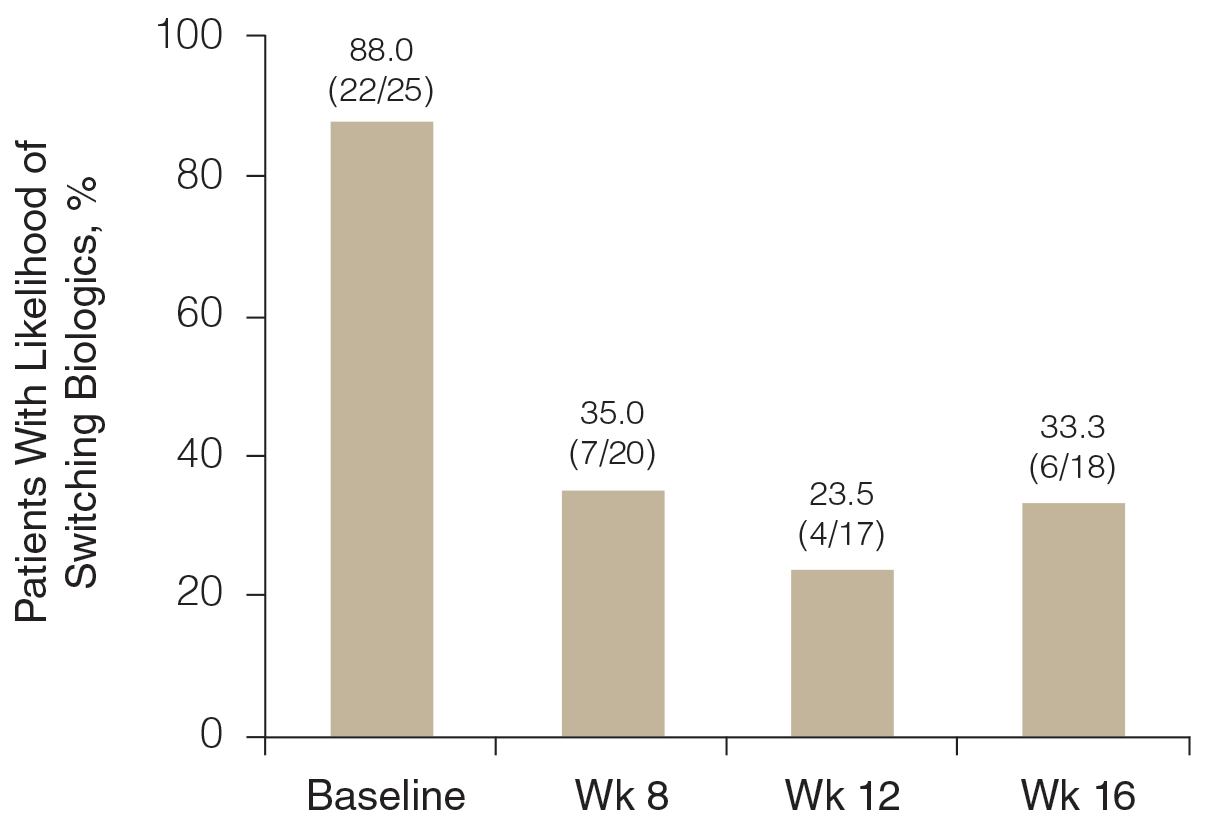

Likelihood of Switching Biologics—At baseline, almost 90% (22/25) of participants were rated as likely to switch biologics by the investigator due to unacceptable responses to their currently prescribed biologics (BSA >3%)(Figure 3). The likelihood was greatly reduced by concomitant HP-TAZ, as the proportion of participants defined as nonresponders to their biologic decreased to 35% (7/20) with 8-week adjunctive application of once-daily HP-TAZ with biologic and further decreased to 23.5% (4/17) with another 4 weeks of adjunctive HP-TAZ applied every other day plus biologic. At week 16, after 4 weeks of biologics alone, the proportion was maintained at 33.3% (6/18).

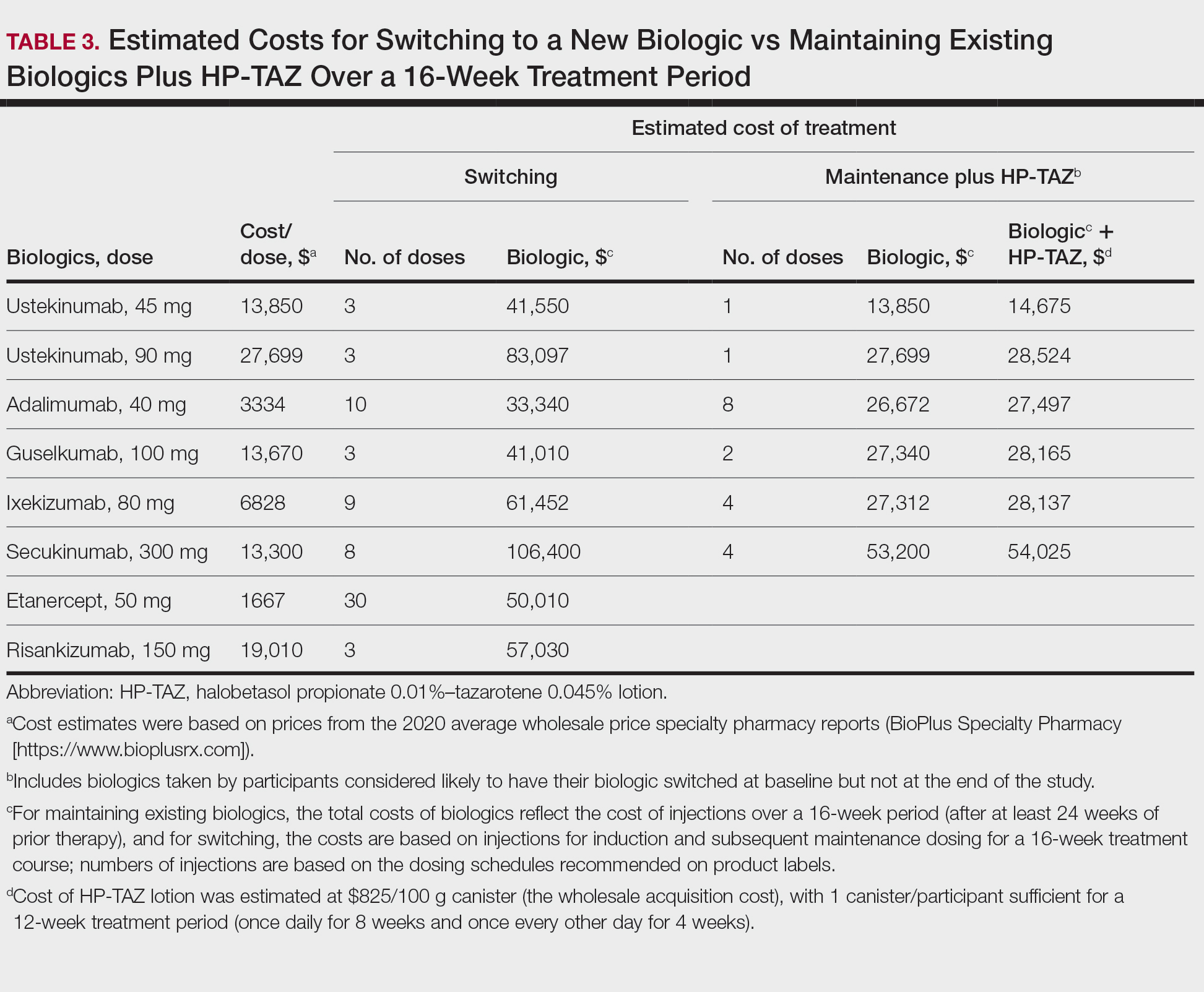

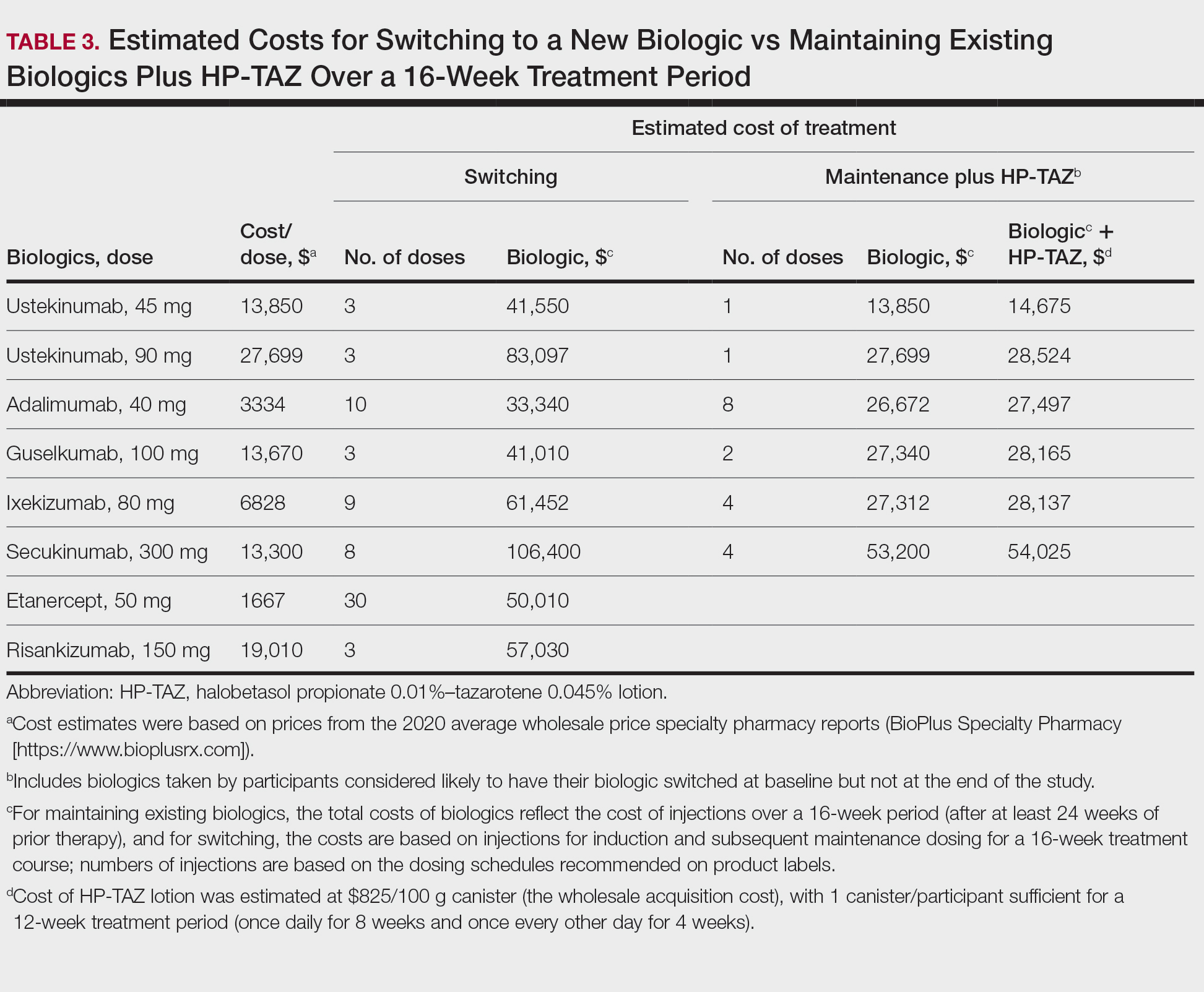

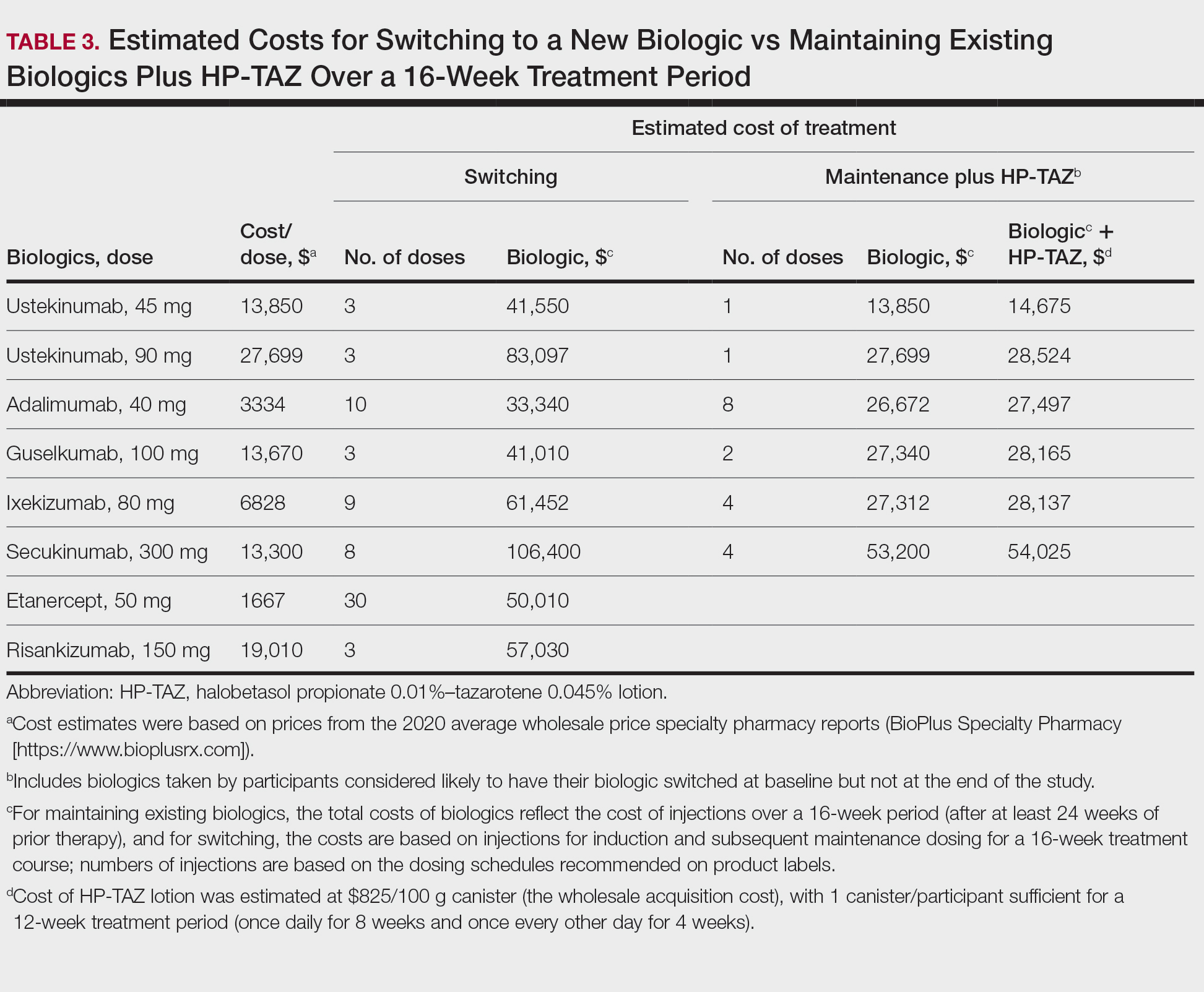

Pharmacoeconomics of Adding Topical HP-TAZ vs Switching Biologics—In the participants whom the investigator reported as likely to switch biologics at baseline, 9 had improvements in disease control such that switching biologics was no longer considered necessary for them at week 16. Potential cost savings with adjunctive therapy of HP-TAZ plus biologic vs switching biologics were therefore evaluated in these 9 participants, who were receiving ustekinumab, adalimumab, guselkumab, ixekizumab, and secukinumab during the study (Table 3). The estimated total cost of 16-week maintenance dosing of biologics plus adjunct HP-TAZ lotion ranged from $14,675 (ustekinumab 45 mg) to $54,025 (secukinumab 300 mg), while switching to other most commonly prescribed biologics for 16 weeks would cost an estimated $33,340 to $106,400 (induction and subsequent maintenance phases)(Table 3). Most biologic plus HP-TAZ combinations were estimated to cost less than $30,000, potentially saving $4816 to $91,725 compared with switching to any of the other 7 biologics (Table 3). The relatively more expensive maintenance combination containing secukinumab plus HP-TAZ ($54,025) appeared to be a less expensive option when compared with switching to ustekinumab (90 mg)($83,097), ixekizumab (80 mg)($61,452), or risankizumab (150 mg)($57,030) as an alternative biologic.

Comment

Adjunctive Use of HP-TAZ Lotion—In the present study, we showed that adjunctive HP-TAZ lotion improved biologic treatment response and reduced disease severity in participants with moderate to severe psoriasis whose symptoms could not be adequately controlled by 24 weeks or more of biologic monotherapy in a real-world setting. Disease activity decreased as evidenced by reductions in all assessed effectiveness variables, including BSA involvement, PGA score, composite BSA×PGA score, and participant-reported DLQI score. Half of the participants achieved NPF TTT status at the end of the study. The treatment was well tolerated with no unexpected safety concerns. Compared with switching to a new biologic, adding topical HP-TAZ to ongoing biologics appeared to be a more cost-effective approach to enhance treatment effects. Our results suggest that adjunctive use of HP-TAZ lotion may be a safe, effective, and economical option for patients with psoriasis who are failing their ongoing biologic monotherapy.

Treat-to-Target Status—The NPF-recommended target response to a treatment for plaque psoriasis is BSA of 1% or lower at 3 months postinitiation.10 Patients in the current study had major psoriasis activity at study entry despite being treated with a biologic for at least 24 weeks, as none had attained NPF TTT status at baseline. Because the time period of prior biologic treatment (at least 24 weeks) is much longer than the 3 months suggested by NPF, we believe that we were observing a true failure of the biologic rather than a slow onset of treatment effects in these patients at the time of enrollment. By week 12, with the addition of HP-TAZ lotion to the biologic, a high rate of participants achieved NPF TTT status (64.7%), with most participants being able to maintain this TTT status at study end after 4 weeks of biologic alone. Most participants also reported no impact of psoriasis on their QOL (DLQI, 0–116; 76.5%) at week 12. Improvements we found in disease control with adjunctive HP-TAZ lotion plus biologic support prior reports showing enhanced responses when a topical medication was added to a biologic.17,18 Reductions in psoriasis activity after 8 weeks of combined biologics plus once-daily HP-TAZ also are consistent with 2 phase 3 RCTs in which a monotherapy of HP-TAZ lotion used once daily for 8 weeks reduced BSA and DLQI.15 Notably, in the current study, disease severity continued to decrease when dosing of HP-TAZ was reduced to once every other day for 4 weeks, and the improvements were maintained even after the adjunct topical therapy was discontinued.

Safety Profile of HP-TAZ Lotion—The overall safety profile in our study also was consistent with that previously reported for HP-TAZ lotion,15,19-21 with no new safety signals observed. The combination treatment was well tolerated, with most reported AEs being mild in severity. Adverse events were mostly related to application-site reactions, the most common being dermatitis (28%), which was likely attributable to the TAZ component of the topical regimen.15

Likelihood of Switching Biologics—Reduced disease activity was reflected by a decrease in the percentage of participants the investigator considered likely to change biologics, which was 88.0% at baseline but only 33.3% at the end of the study. Although switching to a different biologic agent can improve treatment effect,22 it could lead to a substantial increase in health care costs and use of resources compared with no switch.5 We found that switching to one of the other most commonly prescribed biologics could incur $4816 to $91,725 in additional costs in most cases when compared with the combination strategy we evaluated over the 16-week treatment period. Therefore, concomitant use of HP-TAZ lotion with the ongoing biologics would be a potentially more economical alternative for patients to achieve acceptable responses or the NPF TTT goal. Moreover, combination with an adjunctive topical medication could avoid potential risks associated with switching, such as new AEs with new biologic regimens or disease flare during any washout period sometimes adopted for switching biologics.

Study Limitations—Our estimated costs were based on average wholesale prices and did not reflect net prices paid by patients or health plans due to the lack of known discount rates.

Conclusion

In this real-world study, patients with psoriasis that failed to respond to biologic monotherapy had improved disease control and QOL and reported no new safety concerns with adjunctive use of HP-TAZ lotion. Adding HP-TAZ to the ongoing biologics could be a more cost-effective option vs switching biologics for patients whose psoriasis symptoms could not be controlled with biologic monotherapy. Taken together, our results support the use of HP-TAZ lotion as an effective and safe adjunctive topical therapy in combination with biologics for psoriasis treatment.

Acknowledgments—We acknowledge the medical writing assistance provided by Hui Zhang, PhD, and Kathleen Ohleth, PhD, from Precise Publications LLC (Far Hills, New Jersey), which was funded by Ortho Dermatologics.

- Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:512-516.

- Global Report on Psoriasis. World Health Organization; 2016. Accessed January 11, 2022. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/204417

- Takeshita J, Grewal S, Langan SM, et al. Psoriasis and comorbid diseases: epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:377-390.

- Moller AH, Erntoft S, Vinding GR, et al. A systematic literature review to compare quality of life in psoriasis with other chronic diseases using EQ-5D-derived utility values. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2015;6:167-177.

- Feldman SR, Tian H, Wang X, et al. Health care utilization and cost associated with biologic treatment patterns among patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: analyses from a large U.S. claims database. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25:479-488.

- Thomsen SF, Skov L, Dodge R, et al. Socioeconomic costs and health inequalities from psoriasis: a cohort study. Dermatology. 2019;235:372-379.

- Fowler JF, Duh MS, Rovba L, et al. The impact of psoriasis on health care costs and patient work loss. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:772-780.

- Menter A, Gottlieb A, Feldman SR, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 1. overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:826-850.

- Bagel J, Gold LS. Combining topical psoriasis treatment to enhance systemic and phototherapy: a review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1209-1222.

- Armstrong AW, Siegel MP, Bagel J, et al. From the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: treatment targets for plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:290-298.

- Armstrong AW, Bagel J, Van Voorhees AS, et al. Combining biologic therapies with other systemic treatments in psoriasis: evidence-based, best-practice recommendations from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:432-438.

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072.

- Duobrii. Prescribing information. Bausch Health Companies Inc; 2019.

- Sugarman JL, Weiss J, Tanghetti EA, et al. Safety and efficacy of a fixed combination halobetasol and tazarotene lotion in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a pooled analysis of two phase 3 studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:855-861.

- Gold LS, Lebwohl MG, Sugarman JL, et al. Safety and efficacy of a fixed combination of halobetasol and tazarotene in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results of 2 phase 3 randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:287-293.

- Finlay AY. Current severe psoriasis and the rule of tens. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:861-867.

- Campione E, Mazzotta A, Paterno EJ, et al. Effect of calcipotriol on etanercept partial responder psoriasis vulgaris and psoriatic arthritis patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:288-291.

- Bagel J, Zapata J, Nelson E. A prospective, open-label study evaluating adjunctive calcipotriene 0.005%/betamethasone dipropionate 0.064% foam in psoriasis patients with inadequate response to biologic therapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:845-850.

- Sugarman JL, Gold LS, Lebwohl MG, et al. A phase 2, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, vehicle controlled clinical study to assess the safety and efficacy of a halobetasol/tazarotene fixed combination in the treatment of plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:197-204.

- Lebwohl MG, Sugarman JL, Gold LS, et al. Long-term safety results from a phase 3 open-label study of a fixed combination halobetasol propionate 0.01% and tazarotene 0.045% lotion in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:282-285.

- Bhatia ND, Pariser DM, Kircik L, et al. Safety and efficacy of a halobetasol 0.01%/tazarotene 0.045% fixed combination lotion in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a comparison with halobetasol propionate 0.05% cream. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:15-19.

- Wang TS, Tsai TF. Biologics switch in psoriasis. Immunotherapy. 2019;11:531-541.

Psoriasis is a common chronic immunologic skin disease that affects approximately 7.4 million adults in the United States1 and more than 100 million individuals worldwide.2 Patients with psoriasis have a potentially heightened risk for cardiometabolic diseases, psychiatric disorders, and psoriatic arthritis,3 as well as impaired quality of life (QOL).4 Psoriasis also is associated with increased health care costs5 and may result in substantial socioeconomic repercussions for affected patients.6,7

Psoriasis treatments focus on relieving symptoms and improving patient QOL. Systemic therapy has been the mainstay of treatment for moderate to severe psoriasis.8 Although topical therapy usually is applied to treat mild symptoms, it also can be used as an adjunct to enhance efficacy of other treatment approaches.9 The National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) recommends a treat-to-target (TTT) strategy for plaque psoriasis, the most common form of psoriasis, with a target response of attaining affected body surface area (BSA) of 1% or lower at 3 months after treatment initiation, allowing for regular assessments of treatment responses.10

Not all patients with moderate to severe psoriasis can achieve a satisfactory response with systemic biologic monotherapy.11 Switching to a new biologic improves responses in some but not all cases12 and could be associated with new safety issues and additional costs. Combinations of biologics with phototherapy, nonbiologic systemic agents, or topical medications were found to be more effective than biologics alone,9,11 though long-term safety studies are needed for biologics combined with other systemic inverventions.11

A lotion containing a fixed combination of halobetasol propionate (HP) 0.01%, a corticosteroid, and tazarotene (TAZ) 0.045%, a retinoid, is indicated for plaque psoriasis in adults.13 Two randomized, controlled, phase 3 trials demonstrated the rapid and sustained efficacy of HP-TAZ in treating moderate to severe plaque psoriasis without any safety concerns.14,15 However, combining HP-TAZ lotion with biologics has not been examined yet, to our knowledge.

This open-label study evaluated the effectiveness and safety of adjunctive HP-TAZ lotion in adult patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who were being treated with biologics in a real-world setting. Potential cost savings with the addition of topical HP-TAZ to ongoing biologics vs switching to a new biologic also were assessed.

Methods

Study Design and Participants—A single-center, institutional review board–approved, open-label study evaluated adjunctive therapy with HP 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion in patients with psoriasis being treated with biologic agents. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and in compliance with Good Clinical Practices. All patients provided written informed consent before enrollment.

Male and nonpregnant female patients (aged ≥18 years)with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis and a BSA of 2% to 10% who were being treated with biologics for at least 24 weeks at baseline were enrolled. Patients were excluded if they had used oral systemic medications for psoriasis (≤4 weeks), other topical antipsoriatic therapies (≤14 days), UVB phototherapy (≤2 weeks), and psoralen plus UVA phototherapy (≤4 weeks) prior to study initiation. Concomitant use of steroid-free topical emollients or low-potency topical steroids and appropriate interventions deemed necessary by the investigator were allowed.

Although participants maintained their prescribed biologics for the duration of the study, HP-TAZ lotion also was applied once daily for 8 weeks, followed by once every other day for an additional 4 weeks. Participants then continued with biologics only for the last 4 weeks of the study.

Study Outcome Measures—Disease severity and treatment efficacy were assessed by affected BSA, Physician Global Assessment (PGA) score, composite BSA×PGA score, and participant-reported Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). The primary end point was the proportion of participants achieving a BSA of 0% to 1% (NPF TTT status) at week 8. Secondary end points included the proportions of participants with BSA of 0% to 1% at weeks 12 and 16; BSA×PGA score at weeks 8, 12, and 16; and improvements in BSA, PGA, and DLQI at weeks 8, 12, and 16.

Adverse events (AEs) that occurred after the signing of the informed consent and for the duration of the participant’s participation were recorded, regardless of causality. Physical examinations were performed at screening; baseline; and weeks 8, 12, and 16 to document any clinically significant abnormalities. Localized skin reactions were assessed for tolerability of the study drug, with any reaction requiring concomitant therapy recorded as an AE.

The likelihood of switching to a new biologic regimen was assessed by the investigator for each participant at baseline and weeks 8, 12, and 16. Participants with unacceptable responses to their treatments (BSA >3%) were reported as likely to be considered for switching biologics by the investigator.

Pharmacoeconomic Evaluation—Potential cost savings were evaluated for the addition of HP-TAZ lotion to ongoing biologics vs switching to a new biologic. Cost comparisons were made in participants for whom the investigator would likely have switched biologics at baseline but not at the end of the study. For maintaining the same biologic with adjunctive topical HP-TAZ, total cost was estimated by adding the cost for 12 weeks (once daily for 8 weeks and once every other day for 4 weeks) of the HP-TAZ lotion to that of 16-week maintenance dosing with the biologic. The projected cost for switching to a new biologic for 16 weeks of treatment was based on both induction and maintenance dosing as recommended in its product label. Prices were obtained from the 2020 average wholesale price specialty pharmacy reports (BioPlus Specialty Pharmacy Services [https://www.bioplusrx.com]).

Data Handling—Enrollment of approximately 25 participants was desired for the study. Data on disease severity and participant-reported outcomes were assessed using descriptive statistics. Adverse events were summarized descriptively by incidence, severity, and relationship to the study drug. All participants with data available at a measured time point were included in the analyses for that time point.

Results

Participant Disposition and Demographics—Twenty-five participants (15 male and 10 female) were included in the study (Table 1). Seven participants discontinued the study for the following reasons: AEs (n=4), patient choice (n=2), and noncompliance (n=1).

The average age of the participants was 50 years, the majority were White (76.0% [19/25]) andnon-Hispanic (88.0% [22/25]), and the mean duration of chronic plaque psoriasis was 18.9 years (Table 1). Participants had been receiving biologic monotherapy for at least 24 weeks prior to enrollment, most commonly ustekinumab (32.0% [8/25])(Table 1). None had achieved the NPF TTT status with their biologics. At baseline, mean (SD) affected BSA, PGA, BSA×PGA, and participant-reported DLQI were 4.16% (2.04%), 2.84 (0.55), 11.88 (6.39), and 4.00 (4.74), respectively.

Efficacy Assessment—Application of HP-TAZ lotion in addition to the participants’ existing biologic therapy reduced severity of the disease, as evidenced by the reductions in mean BSA, PGA, and BSA×PGA. After 8 weeks of once-daily concomitant HP-TAZ use with biologic, mean BSA and PGA dropped by approximately 40% and 37%, respectively (Figures 1A and 1B). A greater reduction (54%) was found for mean BSA×PGA (Figure 1C). Disease severity continued to improve when the application schedule for HP-TAZ was changed to once every other day for 4 weeks, as mean BSA, PGA, and BSA×PGA decreased further at week 12. These beneficial effects were sustained during the last 4 weeks of the study after HP-TAZ was discontinued, with reductions of 57%, 43%, and 70% from baseline for mean BSA, PGA, and BSA×PGA, respectively (Figure 1).

The proportion of participants who achieved NPF TTT status increased from 0% at baseline to 20.0% (5/20) at week 8 with once-daily use of HP-TAZ plus biologic for 8 weeks (Figure 2). At week 12, more participants (64.7% [11/17]) achieved the treatment goal after application of HP-TAZ once every other day with biologic for 4 weeks. Most participants maintained NPF TTT status after HP-TAZ was discontinued; at week 16, 50.0% (9/18) attained the NPF treatment goal (Figure 2).

![Proportion of participants achieving National Psoriasis Foundation target-to-treat status (body surface area [BSA] ≤1%) at baseline and weeks 8, 12, and 16 Proportion of participants achieving National Psoriasis Foundation target-to-treat status (body surface area [BSA] ≤1%) at baseline and weeks 8, 12, and 16](https://cdn.mdedge.com/files/s3fs-public/Bagel_0222_2.JPG)

The mean DLQI score decreased from 4.00 at baseline to 2.45 after 8 weeks of concomitant use of once-daily HP-TAZ with biologic, reflecting a 39% score reduction. An additional 4 weeks of adjunctive HP-TAZ applied once every other day with biologic further decreased the DLQI score to 2.18 at week 12. Mean DLQI remained similar (2.33) after another 4 weeks of biologics alone. The proportion of participants reporting a DLQI score of 0 to 1 increased from 40% (10/25) at baseline to 60% (12/20) at week 8 and 76.5% (13/17) at week 12 with adjunctive HP-TAZ lotion use with biologic. At week 16, a DLQI score of 0 to 1 was reported in 61.1% (11/18) of participants after receiving only biologics for 4 weeks.

Safety Assessment—A total of 19 AEs were reported in 11 participants during the study; 16 AEs were considered treatment related in 8 participants (Table 2). The most common AEs were retinoid dermatitis (28% [7/25]), burning at the application site (8% [2/25]), and pruritus at the application site (8% [2/25]), all of which were considered related to the treatment. Among all AEs, 12 were mild in severity, and the remaining 7 were moderate. Adverse events led to early study termination in 4 participants, all with retinoid dermatitis as the primary reason.

Likelihood of Switching Biologics—At baseline, almost 90% (22/25) of participants were rated as likely to switch biologics by the investigator due to unacceptable responses to their currently prescribed biologics (BSA >3%)(Figure 3). The likelihood was greatly reduced by concomitant HP-TAZ, as the proportion of participants defined as nonresponders to their biologic decreased to 35% (7/20) with 8-week adjunctive application of once-daily HP-TAZ with biologic and further decreased to 23.5% (4/17) with another 4 weeks of adjunctive HP-TAZ applied every other day plus biologic. At week 16, after 4 weeks of biologics alone, the proportion was maintained at 33.3% (6/18).

Pharmacoeconomics of Adding Topical HP-TAZ vs Switching Biologics—In the participants whom the investigator reported as likely to switch biologics at baseline, 9 had improvements in disease control such that switching biologics was no longer considered necessary for them at week 16. Potential cost savings with adjunctive therapy of HP-TAZ plus biologic vs switching biologics were therefore evaluated in these 9 participants, who were receiving ustekinumab, adalimumab, guselkumab, ixekizumab, and secukinumab during the study (Table 3). The estimated total cost of 16-week maintenance dosing of biologics plus adjunct HP-TAZ lotion ranged from $14,675 (ustekinumab 45 mg) to $54,025 (secukinumab 300 mg), while switching to other most commonly prescribed biologics for 16 weeks would cost an estimated $33,340 to $106,400 (induction and subsequent maintenance phases)(Table 3). Most biologic plus HP-TAZ combinations were estimated to cost less than $30,000, potentially saving $4816 to $91,725 compared with switching to any of the other 7 biologics (Table 3). The relatively more expensive maintenance combination containing secukinumab plus HP-TAZ ($54,025) appeared to be a less expensive option when compared with switching to ustekinumab (90 mg)($83,097), ixekizumab (80 mg)($61,452), or risankizumab (150 mg)($57,030) as an alternative biologic.

Comment

Adjunctive Use of HP-TAZ Lotion—In the present study, we showed that adjunctive HP-TAZ lotion improved biologic treatment response and reduced disease severity in participants with moderate to severe psoriasis whose symptoms could not be adequately controlled by 24 weeks or more of biologic monotherapy in a real-world setting. Disease activity decreased as evidenced by reductions in all assessed effectiveness variables, including BSA involvement, PGA score, composite BSA×PGA score, and participant-reported DLQI score. Half of the participants achieved NPF TTT status at the end of the study. The treatment was well tolerated with no unexpected safety concerns. Compared with switching to a new biologic, adding topical HP-TAZ to ongoing biologics appeared to be a more cost-effective approach to enhance treatment effects. Our results suggest that adjunctive use of HP-TAZ lotion may be a safe, effective, and economical option for patients with psoriasis who are failing their ongoing biologic monotherapy.

Treat-to-Target Status—The NPF-recommended target response to a treatment for plaque psoriasis is BSA of 1% or lower at 3 months postinitiation.10 Patients in the current study had major psoriasis activity at study entry despite being treated with a biologic for at least 24 weeks, as none had attained NPF TTT status at baseline. Because the time period of prior biologic treatment (at least 24 weeks) is much longer than the 3 months suggested by NPF, we believe that we were observing a true failure of the biologic rather than a slow onset of treatment effects in these patients at the time of enrollment. By week 12, with the addition of HP-TAZ lotion to the biologic, a high rate of participants achieved NPF TTT status (64.7%), with most participants being able to maintain this TTT status at study end after 4 weeks of biologic alone. Most participants also reported no impact of psoriasis on their QOL (DLQI, 0–116; 76.5%) at week 12. Improvements we found in disease control with adjunctive HP-TAZ lotion plus biologic support prior reports showing enhanced responses when a topical medication was added to a biologic.17,18 Reductions in psoriasis activity after 8 weeks of combined biologics plus once-daily HP-TAZ also are consistent with 2 phase 3 RCTs in which a monotherapy of HP-TAZ lotion used once daily for 8 weeks reduced BSA and DLQI.15 Notably, in the current study, disease severity continued to decrease when dosing of HP-TAZ was reduced to once every other day for 4 weeks, and the improvements were maintained even after the adjunct topical therapy was discontinued.

Safety Profile of HP-TAZ Lotion—The overall safety profile in our study also was consistent with that previously reported for HP-TAZ lotion,15,19-21 with no new safety signals observed. The combination treatment was well tolerated, with most reported AEs being mild in severity. Adverse events were mostly related to application-site reactions, the most common being dermatitis (28%), which was likely attributable to the TAZ component of the topical regimen.15

Likelihood of Switching Biologics—Reduced disease activity was reflected by a decrease in the percentage of participants the investigator considered likely to change biologics, which was 88.0% at baseline but only 33.3% at the end of the study. Although switching to a different biologic agent can improve treatment effect,22 it could lead to a substantial increase in health care costs and use of resources compared with no switch.5 We found that switching to one of the other most commonly prescribed biologics could incur $4816 to $91,725 in additional costs in most cases when compared with the combination strategy we evaluated over the 16-week treatment period. Therefore, concomitant use of HP-TAZ lotion with the ongoing biologics would be a potentially more economical alternative for patients to achieve acceptable responses or the NPF TTT goal. Moreover, combination with an adjunctive topical medication could avoid potential risks associated with switching, such as new AEs with new biologic regimens or disease flare during any washout period sometimes adopted for switching biologics.

Study Limitations—Our estimated costs were based on average wholesale prices and did not reflect net prices paid by patients or health plans due to the lack of known discount rates.

Conclusion

In this real-world study, patients with psoriasis that failed to respond to biologic monotherapy had improved disease control and QOL and reported no new safety concerns with adjunctive use of HP-TAZ lotion. Adding HP-TAZ to the ongoing biologics could be a more cost-effective option vs switching biologics for patients whose psoriasis symptoms could not be controlled with biologic monotherapy. Taken together, our results support the use of HP-TAZ lotion as an effective and safe adjunctive topical therapy in combination with biologics for psoriasis treatment.

Acknowledgments—We acknowledge the medical writing assistance provided by Hui Zhang, PhD, and Kathleen Ohleth, PhD, from Precise Publications LLC (Far Hills, New Jersey), which was funded by Ortho Dermatologics.

Psoriasis is a common chronic immunologic skin disease that affects approximately 7.4 million adults in the United States1 and more than 100 million individuals worldwide.2 Patients with psoriasis have a potentially heightened risk for cardiometabolic diseases, psychiatric disorders, and psoriatic arthritis,3 as well as impaired quality of life (QOL).4 Psoriasis also is associated with increased health care costs5 and may result in substantial socioeconomic repercussions for affected patients.6,7

Psoriasis treatments focus on relieving symptoms and improving patient QOL. Systemic therapy has been the mainstay of treatment for moderate to severe psoriasis.8 Although topical therapy usually is applied to treat mild symptoms, it also can be used as an adjunct to enhance efficacy of other treatment approaches.9 The National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) recommends a treat-to-target (TTT) strategy for plaque psoriasis, the most common form of psoriasis, with a target response of attaining affected body surface area (BSA) of 1% or lower at 3 months after treatment initiation, allowing for regular assessments of treatment responses.10

Not all patients with moderate to severe psoriasis can achieve a satisfactory response with systemic biologic monotherapy.11 Switching to a new biologic improves responses in some but not all cases12 and could be associated with new safety issues and additional costs. Combinations of biologics with phototherapy, nonbiologic systemic agents, or topical medications were found to be more effective than biologics alone,9,11 though long-term safety studies are needed for biologics combined with other systemic inverventions.11

A lotion containing a fixed combination of halobetasol propionate (HP) 0.01%, a corticosteroid, and tazarotene (TAZ) 0.045%, a retinoid, is indicated for plaque psoriasis in adults.13 Two randomized, controlled, phase 3 trials demonstrated the rapid and sustained efficacy of HP-TAZ in treating moderate to severe plaque psoriasis without any safety concerns.14,15 However, combining HP-TAZ lotion with biologics has not been examined yet, to our knowledge.

This open-label study evaluated the effectiveness and safety of adjunctive HP-TAZ lotion in adult patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who were being treated with biologics in a real-world setting. Potential cost savings with the addition of topical HP-TAZ to ongoing biologics vs switching to a new biologic also were assessed.

Methods

Study Design and Participants—A single-center, institutional review board–approved, open-label study evaluated adjunctive therapy with HP 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion in patients with psoriasis being treated with biologic agents. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and in compliance with Good Clinical Practices. All patients provided written informed consent before enrollment.

Male and nonpregnant female patients (aged ≥18 years)with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis and a BSA of 2% to 10% who were being treated with biologics for at least 24 weeks at baseline were enrolled. Patients were excluded if they had used oral systemic medications for psoriasis (≤4 weeks), other topical antipsoriatic therapies (≤14 days), UVB phototherapy (≤2 weeks), and psoralen plus UVA phototherapy (≤4 weeks) prior to study initiation. Concomitant use of steroid-free topical emollients or low-potency topical steroids and appropriate interventions deemed necessary by the investigator were allowed.

Although participants maintained their prescribed biologics for the duration of the study, HP-TAZ lotion also was applied once daily for 8 weeks, followed by once every other day for an additional 4 weeks. Participants then continued with biologics only for the last 4 weeks of the study.

Study Outcome Measures—Disease severity and treatment efficacy were assessed by affected BSA, Physician Global Assessment (PGA) score, composite BSA×PGA score, and participant-reported Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). The primary end point was the proportion of participants achieving a BSA of 0% to 1% (NPF TTT status) at week 8. Secondary end points included the proportions of participants with BSA of 0% to 1% at weeks 12 and 16; BSA×PGA score at weeks 8, 12, and 16; and improvements in BSA, PGA, and DLQI at weeks 8, 12, and 16.

Adverse events (AEs) that occurred after the signing of the informed consent and for the duration of the participant’s participation were recorded, regardless of causality. Physical examinations were performed at screening; baseline; and weeks 8, 12, and 16 to document any clinically significant abnormalities. Localized skin reactions were assessed for tolerability of the study drug, with any reaction requiring concomitant therapy recorded as an AE.

The likelihood of switching to a new biologic regimen was assessed by the investigator for each participant at baseline and weeks 8, 12, and 16. Participants with unacceptable responses to their treatments (BSA >3%) were reported as likely to be considered for switching biologics by the investigator.

Pharmacoeconomic Evaluation—Potential cost savings were evaluated for the addition of HP-TAZ lotion to ongoing biologics vs switching to a new biologic. Cost comparisons were made in participants for whom the investigator would likely have switched biologics at baseline but not at the end of the study. For maintaining the same biologic with adjunctive topical HP-TAZ, total cost was estimated by adding the cost for 12 weeks (once daily for 8 weeks and once every other day for 4 weeks) of the HP-TAZ lotion to that of 16-week maintenance dosing with the biologic. The projected cost for switching to a new biologic for 16 weeks of treatment was based on both induction and maintenance dosing as recommended in its product label. Prices were obtained from the 2020 average wholesale price specialty pharmacy reports (BioPlus Specialty Pharmacy Services [https://www.bioplusrx.com]).

Data Handling—Enrollment of approximately 25 participants was desired for the study. Data on disease severity and participant-reported outcomes were assessed using descriptive statistics. Adverse events were summarized descriptively by incidence, severity, and relationship to the study drug. All participants with data available at a measured time point were included in the analyses for that time point.

Results

Participant Disposition and Demographics—Twenty-five participants (15 male and 10 female) were included in the study (Table 1). Seven participants discontinued the study for the following reasons: AEs (n=4), patient choice (n=2), and noncompliance (n=1).

The average age of the participants was 50 years, the majority were White (76.0% [19/25]) andnon-Hispanic (88.0% [22/25]), and the mean duration of chronic plaque psoriasis was 18.9 years (Table 1). Participants had been receiving biologic monotherapy for at least 24 weeks prior to enrollment, most commonly ustekinumab (32.0% [8/25])(Table 1). None had achieved the NPF TTT status with their biologics. At baseline, mean (SD) affected BSA, PGA, BSA×PGA, and participant-reported DLQI were 4.16% (2.04%), 2.84 (0.55), 11.88 (6.39), and 4.00 (4.74), respectively.

Efficacy Assessment—Application of HP-TAZ lotion in addition to the participants’ existing biologic therapy reduced severity of the disease, as evidenced by the reductions in mean BSA, PGA, and BSA×PGA. After 8 weeks of once-daily concomitant HP-TAZ use with biologic, mean BSA and PGA dropped by approximately 40% and 37%, respectively (Figures 1A and 1B). A greater reduction (54%) was found for mean BSA×PGA (Figure 1C). Disease severity continued to improve when the application schedule for HP-TAZ was changed to once every other day for 4 weeks, as mean BSA, PGA, and BSA×PGA decreased further at week 12. These beneficial effects were sustained during the last 4 weeks of the study after HP-TAZ was discontinued, with reductions of 57%, 43%, and 70% from baseline for mean BSA, PGA, and BSA×PGA, respectively (Figure 1).

The proportion of participants who achieved NPF TTT status increased from 0% at baseline to 20.0% (5/20) at week 8 with once-daily use of HP-TAZ plus biologic for 8 weeks (Figure 2). At week 12, more participants (64.7% [11/17]) achieved the treatment goal after application of HP-TAZ once every other day with biologic for 4 weeks. Most participants maintained NPF TTT status after HP-TAZ was discontinued; at week 16, 50.0% (9/18) attained the NPF treatment goal (Figure 2).

![Proportion of participants achieving National Psoriasis Foundation target-to-treat status (body surface area [BSA] ≤1%) at baseline and weeks 8, 12, and 16 Proportion of participants achieving National Psoriasis Foundation target-to-treat status (body surface area [BSA] ≤1%) at baseline and weeks 8, 12, and 16](https://cdn.mdedge.com/files/s3fs-public/Bagel_0222_2.JPG)

The mean DLQI score decreased from 4.00 at baseline to 2.45 after 8 weeks of concomitant use of once-daily HP-TAZ with biologic, reflecting a 39% score reduction. An additional 4 weeks of adjunctive HP-TAZ applied once every other day with biologic further decreased the DLQI score to 2.18 at week 12. Mean DLQI remained similar (2.33) after another 4 weeks of biologics alone. The proportion of participants reporting a DLQI score of 0 to 1 increased from 40% (10/25) at baseline to 60% (12/20) at week 8 and 76.5% (13/17) at week 12 with adjunctive HP-TAZ lotion use with biologic. At week 16, a DLQI score of 0 to 1 was reported in 61.1% (11/18) of participants after receiving only biologics for 4 weeks.

Safety Assessment—A total of 19 AEs were reported in 11 participants during the study; 16 AEs were considered treatment related in 8 participants (Table 2). The most common AEs were retinoid dermatitis (28% [7/25]), burning at the application site (8% [2/25]), and pruritus at the application site (8% [2/25]), all of which were considered related to the treatment. Among all AEs, 12 were mild in severity, and the remaining 7 were moderate. Adverse events led to early study termination in 4 participants, all with retinoid dermatitis as the primary reason.

Likelihood of Switching Biologics—At baseline, almost 90% (22/25) of participants were rated as likely to switch biologics by the investigator due to unacceptable responses to their currently prescribed biologics (BSA >3%)(Figure 3). The likelihood was greatly reduced by concomitant HP-TAZ, as the proportion of participants defined as nonresponders to their biologic decreased to 35% (7/20) with 8-week adjunctive application of once-daily HP-TAZ with biologic and further decreased to 23.5% (4/17) with another 4 weeks of adjunctive HP-TAZ applied every other day plus biologic. At week 16, after 4 weeks of biologics alone, the proportion was maintained at 33.3% (6/18).

Pharmacoeconomics of Adding Topical HP-TAZ vs Switching Biologics—In the participants whom the investigator reported as likely to switch biologics at baseline, 9 had improvements in disease control such that switching biologics was no longer considered necessary for them at week 16. Potential cost savings with adjunctive therapy of HP-TAZ plus biologic vs switching biologics were therefore evaluated in these 9 participants, who were receiving ustekinumab, adalimumab, guselkumab, ixekizumab, and secukinumab during the study (Table 3). The estimated total cost of 16-week maintenance dosing of biologics plus adjunct HP-TAZ lotion ranged from $14,675 (ustekinumab 45 mg) to $54,025 (secukinumab 300 mg), while switching to other most commonly prescribed biologics for 16 weeks would cost an estimated $33,340 to $106,400 (induction and subsequent maintenance phases)(Table 3). Most biologic plus HP-TAZ combinations were estimated to cost less than $30,000, potentially saving $4816 to $91,725 compared with switching to any of the other 7 biologics (Table 3). The relatively more expensive maintenance combination containing secukinumab plus HP-TAZ ($54,025) appeared to be a less expensive option when compared with switching to ustekinumab (90 mg)($83,097), ixekizumab (80 mg)($61,452), or risankizumab (150 mg)($57,030) as an alternative biologic.

Comment

Adjunctive Use of HP-TAZ Lotion—In the present study, we showed that adjunctive HP-TAZ lotion improved biologic treatment response and reduced disease severity in participants with moderate to severe psoriasis whose symptoms could not be adequately controlled by 24 weeks or more of biologic monotherapy in a real-world setting. Disease activity decreased as evidenced by reductions in all assessed effectiveness variables, including BSA involvement, PGA score, composite BSA×PGA score, and participant-reported DLQI score. Half of the participants achieved NPF TTT status at the end of the study. The treatment was well tolerated with no unexpected safety concerns. Compared with switching to a new biologic, adding topical HP-TAZ to ongoing biologics appeared to be a more cost-effective approach to enhance treatment effects. Our results suggest that adjunctive use of HP-TAZ lotion may be a safe, effective, and economical option for patients with psoriasis who are failing their ongoing biologic monotherapy.