User login

HIV stigma persists globally, according to Harris poll

Four decades into the AIDS epidemic and for some, it’s as if gains in awareness, advances in prevention and treatment, and the concept of undetected equals untransmissable (U=U) never happened. In its place,

Accordingly, findings from a Harris poll conducted Oct. 13-18, 2021, among 5,047 adults (18 and older) residing in Australia, Portugal, the United Kingdom, and the United States, reveal that 88% of those surveyed believe that negative perceptions toward people living with HIV persist even though HIV infection can be effectively managed with antiretroviral therapy (ART). Conversely, three-quarters (76%) are unaware of U=U, and the fact that someone with HIV who is taking effective treatment cannot pass it on to their partner. Two-thirds incorrectly believe that a person living with HIV can pass it onto their baby, even when they are ART adherent.

“The survey made me think of people who work in HIV clinics, and how much of a bubble I think that we in the HIV field live in,” Nneka Nwokolo, MBBS, senior global medical director at ViiV Healthcare, London, and practicing consultant in sexual health and HIV medicine, told this news organization. “I think that we generally feel that everyone knows as much as we do or feels the way that we do.”

Misconceptions abound across the globe

The online survey, which was commissioned by ViiV Healthcare, also highlights that one in five adults do not know that anyone can acquire HIV regardless of lifestyle, thereby perpetuating the stereotype that HIV is a disease that only affects certain populations, such as men who have sex with men (MSM) or transgender women (TGW).

Pervasive stereotypes and stigmatization only serve to magnify preexisting social inequities that affect access to appropriate care. A recent editorial published in the journal AIDS and Behavior underscores that stigma experienced by marginalized populations in particular (for example, Black MSM, TGW) is directly linked to decreased access to and use of effective HIV prevention and treatment services. Additionally, once stigma becomes internalized, it might further affect overall well-being, mental health, and social support.

“One of the most significant consequences of the ongoing stigma is that people are scared to test and then they end up coming to services late [when] they’re really ill,” explained Dr. Nwokolo. “It goes back to the early days when HIV was a death sentence ... it’s still there. I have one patient who to this day hates the fact that he has HIV, that he has to come to the clinic – it’s a reminder of why he hates himself.”

Great strides in testing and advances in treatment might be helping to reframe HIV as a chronic but treatable and preventable disease. Nevertheless, survey findings also revealed that nearly three out of five adults incorrectly believe that a person living with HIV will have a shorter lifespan than someone who is HIV negative, even if they are on effective treatment.

These beliefs are especially true among Dr. Nwokolo’s patient base, most of whom are Africans who’ve immigrated to the United Kingdom from countries that have been devastated by the HIV epidemic. “Those who’ve never tested are reluctant to do so because they are afraid that they will have the same outcome as the people that they know that they’ve left behind,” she said.

HIV stigma in the era of 90-90-90

While there has been progress toward achieving UN AID’s 90-90-90 targets (that is, 90% living with HIV know their status, 90% who know their status are on ART, and 90% of people on ART are virally suppressed), exclusion and isolation – the key hallmarks of stigma – may ultimately be the most important barriers preventing a lofty goal to end the AIDS epidemic by the year 2030.

“Here we are, 40 years in and we are still facing such ignorance, some stigma,” Carl Schmid, MBA, former cochair of the Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS, and executive director of HIV+Policy Institute, told this news organization. “It’s gotten better, but it is really putting a damper on people being tested, getting treated, getting access to PrEP.” Mr. Schmid was not involved in the Harris Poll.

Mr. Schmid also said that, in addition to broader outreach and education as well as dissemination of information about HIV and AIDS from the White House and other government leaders, physician involvement is essential.

“They’re the ones that need to step up. They have to talk about sex with their patients, [but] they don’t do that, especially in the South among certain populations,” he noted.

Data support the unique challenges faced by at-risk individuals living in the southern United States. Not only do Southern states account for roughly half of all new HIV cases annually, but Black MSM and Black women account for the majority of new diagnoses, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data have also demonstrated discrimination and prejudice toward people with HIV persist among many medical professionals in the South (especially those working in rural areas).

But this is not only a Southern problem; a 2018 review of studies in clinicians across the United States published in AIDS Patient Care and STDs linked provider fear of acquiring HIV through occupational exposure to reduced quality of care, refusal of care, and anxiety, especially among providers with limited awareness of PrEP. Discordant attitudes around making a priority to address HIV-related stigma versus other health care needs also reduced overall care delivery and patient experience.

“I think that the first thing that we as HIV clinicians can and should do – and is definitely within our power to do – is to educate our peers about HIV,” Dr. Nwokolo said, “HIV has gone off the radar, but it’s still out there.”

The study was commissioned by Viiv Healthcare. Dr. Nwokolo is an employee of ViiV Healthcare. Mr. Schmid disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Four decades into the AIDS epidemic and for some, it’s as if gains in awareness, advances in prevention and treatment, and the concept of undetected equals untransmissable (U=U) never happened. In its place,

Accordingly, findings from a Harris poll conducted Oct. 13-18, 2021, among 5,047 adults (18 and older) residing in Australia, Portugal, the United Kingdom, and the United States, reveal that 88% of those surveyed believe that negative perceptions toward people living with HIV persist even though HIV infection can be effectively managed with antiretroviral therapy (ART). Conversely, three-quarters (76%) are unaware of U=U, and the fact that someone with HIV who is taking effective treatment cannot pass it on to their partner. Two-thirds incorrectly believe that a person living with HIV can pass it onto their baby, even when they are ART adherent.

“The survey made me think of people who work in HIV clinics, and how much of a bubble I think that we in the HIV field live in,” Nneka Nwokolo, MBBS, senior global medical director at ViiV Healthcare, London, and practicing consultant in sexual health and HIV medicine, told this news organization. “I think that we generally feel that everyone knows as much as we do or feels the way that we do.”

Misconceptions abound across the globe

The online survey, which was commissioned by ViiV Healthcare, also highlights that one in five adults do not know that anyone can acquire HIV regardless of lifestyle, thereby perpetuating the stereotype that HIV is a disease that only affects certain populations, such as men who have sex with men (MSM) or transgender women (TGW).

Pervasive stereotypes and stigmatization only serve to magnify preexisting social inequities that affect access to appropriate care. A recent editorial published in the journal AIDS and Behavior underscores that stigma experienced by marginalized populations in particular (for example, Black MSM, TGW) is directly linked to decreased access to and use of effective HIV prevention and treatment services. Additionally, once stigma becomes internalized, it might further affect overall well-being, mental health, and social support.

“One of the most significant consequences of the ongoing stigma is that people are scared to test and then they end up coming to services late [when] they’re really ill,” explained Dr. Nwokolo. “It goes back to the early days when HIV was a death sentence ... it’s still there. I have one patient who to this day hates the fact that he has HIV, that he has to come to the clinic – it’s a reminder of why he hates himself.”

Great strides in testing and advances in treatment might be helping to reframe HIV as a chronic but treatable and preventable disease. Nevertheless, survey findings also revealed that nearly three out of five adults incorrectly believe that a person living with HIV will have a shorter lifespan than someone who is HIV negative, even if they are on effective treatment.

These beliefs are especially true among Dr. Nwokolo’s patient base, most of whom are Africans who’ve immigrated to the United Kingdom from countries that have been devastated by the HIV epidemic. “Those who’ve never tested are reluctant to do so because they are afraid that they will have the same outcome as the people that they know that they’ve left behind,” she said.

HIV stigma in the era of 90-90-90

While there has been progress toward achieving UN AID’s 90-90-90 targets (that is, 90% living with HIV know their status, 90% who know their status are on ART, and 90% of people on ART are virally suppressed), exclusion and isolation – the key hallmarks of stigma – may ultimately be the most important barriers preventing a lofty goal to end the AIDS epidemic by the year 2030.

“Here we are, 40 years in and we are still facing such ignorance, some stigma,” Carl Schmid, MBA, former cochair of the Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS, and executive director of HIV+Policy Institute, told this news organization. “It’s gotten better, but it is really putting a damper on people being tested, getting treated, getting access to PrEP.” Mr. Schmid was not involved in the Harris Poll.

Mr. Schmid also said that, in addition to broader outreach and education as well as dissemination of information about HIV and AIDS from the White House and other government leaders, physician involvement is essential.

“They’re the ones that need to step up. They have to talk about sex with their patients, [but] they don’t do that, especially in the South among certain populations,” he noted.

Data support the unique challenges faced by at-risk individuals living in the southern United States. Not only do Southern states account for roughly half of all new HIV cases annually, but Black MSM and Black women account for the majority of new diagnoses, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data have also demonstrated discrimination and prejudice toward people with HIV persist among many medical professionals in the South (especially those working in rural areas).

But this is not only a Southern problem; a 2018 review of studies in clinicians across the United States published in AIDS Patient Care and STDs linked provider fear of acquiring HIV through occupational exposure to reduced quality of care, refusal of care, and anxiety, especially among providers with limited awareness of PrEP. Discordant attitudes around making a priority to address HIV-related stigma versus other health care needs also reduced overall care delivery and patient experience.

“I think that the first thing that we as HIV clinicians can and should do – and is definitely within our power to do – is to educate our peers about HIV,” Dr. Nwokolo said, “HIV has gone off the radar, but it’s still out there.”

The study was commissioned by Viiv Healthcare. Dr. Nwokolo is an employee of ViiV Healthcare. Mr. Schmid disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Four decades into the AIDS epidemic and for some, it’s as if gains in awareness, advances in prevention and treatment, and the concept of undetected equals untransmissable (U=U) never happened. In its place,

Accordingly, findings from a Harris poll conducted Oct. 13-18, 2021, among 5,047 adults (18 and older) residing in Australia, Portugal, the United Kingdom, and the United States, reveal that 88% of those surveyed believe that negative perceptions toward people living with HIV persist even though HIV infection can be effectively managed with antiretroviral therapy (ART). Conversely, three-quarters (76%) are unaware of U=U, and the fact that someone with HIV who is taking effective treatment cannot pass it on to their partner. Two-thirds incorrectly believe that a person living with HIV can pass it onto their baby, even when they are ART adherent.

“The survey made me think of people who work in HIV clinics, and how much of a bubble I think that we in the HIV field live in,” Nneka Nwokolo, MBBS, senior global medical director at ViiV Healthcare, London, and practicing consultant in sexual health and HIV medicine, told this news organization. “I think that we generally feel that everyone knows as much as we do or feels the way that we do.”

Misconceptions abound across the globe

The online survey, which was commissioned by ViiV Healthcare, also highlights that one in five adults do not know that anyone can acquire HIV regardless of lifestyle, thereby perpetuating the stereotype that HIV is a disease that only affects certain populations, such as men who have sex with men (MSM) or transgender women (TGW).

Pervasive stereotypes and stigmatization only serve to magnify preexisting social inequities that affect access to appropriate care. A recent editorial published in the journal AIDS and Behavior underscores that stigma experienced by marginalized populations in particular (for example, Black MSM, TGW) is directly linked to decreased access to and use of effective HIV prevention and treatment services. Additionally, once stigma becomes internalized, it might further affect overall well-being, mental health, and social support.

“One of the most significant consequences of the ongoing stigma is that people are scared to test and then they end up coming to services late [when] they’re really ill,” explained Dr. Nwokolo. “It goes back to the early days when HIV was a death sentence ... it’s still there. I have one patient who to this day hates the fact that he has HIV, that he has to come to the clinic – it’s a reminder of why he hates himself.”

Great strides in testing and advances in treatment might be helping to reframe HIV as a chronic but treatable and preventable disease. Nevertheless, survey findings also revealed that nearly three out of five adults incorrectly believe that a person living with HIV will have a shorter lifespan than someone who is HIV negative, even if they are on effective treatment.

These beliefs are especially true among Dr. Nwokolo’s patient base, most of whom are Africans who’ve immigrated to the United Kingdom from countries that have been devastated by the HIV epidemic. “Those who’ve never tested are reluctant to do so because they are afraid that they will have the same outcome as the people that they know that they’ve left behind,” she said.

HIV stigma in the era of 90-90-90

While there has been progress toward achieving UN AID’s 90-90-90 targets (that is, 90% living with HIV know their status, 90% who know their status are on ART, and 90% of people on ART are virally suppressed), exclusion and isolation – the key hallmarks of stigma – may ultimately be the most important barriers preventing a lofty goal to end the AIDS epidemic by the year 2030.

“Here we are, 40 years in and we are still facing such ignorance, some stigma,” Carl Schmid, MBA, former cochair of the Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS, and executive director of HIV+Policy Institute, told this news organization. “It’s gotten better, but it is really putting a damper on people being tested, getting treated, getting access to PrEP.” Mr. Schmid was not involved in the Harris Poll.

Mr. Schmid also said that, in addition to broader outreach and education as well as dissemination of information about HIV and AIDS from the White House and other government leaders, physician involvement is essential.

“They’re the ones that need to step up. They have to talk about sex with their patients, [but] they don’t do that, especially in the South among certain populations,” he noted.

Data support the unique challenges faced by at-risk individuals living in the southern United States. Not only do Southern states account for roughly half of all new HIV cases annually, but Black MSM and Black women account for the majority of new diagnoses, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data have also demonstrated discrimination and prejudice toward people with HIV persist among many medical professionals in the South (especially those working in rural areas).

But this is not only a Southern problem; a 2018 review of studies in clinicians across the United States published in AIDS Patient Care and STDs linked provider fear of acquiring HIV through occupational exposure to reduced quality of care, refusal of care, and anxiety, especially among providers with limited awareness of PrEP. Discordant attitudes around making a priority to address HIV-related stigma versus other health care needs also reduced overall care delivery and patient experience.

“I think that the first thing that we as HIV clinicians can and should do – and is definitely within our power to do – is to educate our peers about HIV,” Dr. Nwokolo said, “HIV has gone off the radar, but it’s still out there.”

The study was commissioned by Viiv Healthcare. Dr. Nwokolo is an employee of ViiV Healthcare. Mr. Schmid disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Yescarta label updated: Prophylactic steroids to prevent CRS

This is a chimeric antigen receptor T-cell product indicated for use in adult patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL) after two or more lines of systemic therapy.

The product label carries a black box warning that CRS is a potentially fatal complication. With the update, the new labeling advises clinicians to “consider the use of prophylactic corticosteroid in patients after weighing the potential benefits and risks ... to delay the onset and decrease the duration of CRS.”

However, labeling also notes that “prophylactic corticosteroids ... may result in [a] higher grade of neurologic toxicities or prolongation of neurologic toxicities,” another potentially fatal complication noted in the black box warning.

The addition of prophylactic corticosteroids to labeling was based on data from 39 patients with relapsed or refractory LBCL who received dexamethasone 10 mg orally once daily for 3 days starting prior to Yescarta infusion. In this cohort, 31 of the 39 patients (79%) developed CRS, at which point they were managed with tocilizumab and/or corticosteroids. No one developed grade 3 or higher CRS. The median time to CRS onset was 5 days and the median duration was 4 days, according to labeling.

In contrast, in another cohort of 41 patients who were started on tocilizumab and/or corticosteroids only after becoming symptomatic, the overall incidence of CRS was 93% (38/41), with a median onset at 2 days, median duration of 7 days, and two patients who developed grade 3 CRS.

Prophylactic steroids do not compromise the activity of the cell therapy, Kite said in a press release.

“These new data will enable doctors to more easily and confidently manage treatment for patients,” said Frank Neumann, MD, PhD, the company’s global head of clinical development.

Yescarta is currently under review in the United States and Europe for second-line use in relapsed or refractory LBCL, Kite noted.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This is a chimeric antigen receptor T-cell product indicated for use in adult patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL) after two or more lines of systemic therapy.

The product label carries a black box warning that CRS is a potentially fatal complication. With the update, the new labeling advises clinicians to “consider the use of prophylactic corticosteroid in patients after weighing the potential benefits and risks ... to delay the onset and decrease the duration of CRS.”

However, labeling also notes that “prophylactic corticosteroids ... may result in [a] higher grade of neurologic toxicities or prolongation of neurologic toxicities,” another potentially fatal complication noted in the black box warning.

The addition of prophylactic corticosteroids to labeling was based on data from 39 patients with relapsed or refractory LBCL who received dexamethasone 10 mg orally once daily for 3 days starting prior to Yescarta infusion. In this cohort, 31 of the 39 patients (79%) developed CRS, at which point they were managed with tocilizumab and/or corticosteroids. No one developed grade 3 or higher CRS. The median time to CRS onset was 5 days and the median duration was 4 days, according to labeling.

In contrast, in another cohort of 41 patients who were started on tocilizumab and/or corticosteroids only after becoming symptomatic, the overall incidence of CRS was 93% (38/41), with a median onset at 2 days, median duration of 7 days, and two patients who developed grade 3 CRS.

Prophylactic steroids do not compromise the activity of the cell therapy, Kite said in a press release.

“These new data will enable doctors to more easily and confidently manage treatment for patients,” said Frank Neumann, MD, PhD, the company’s global head of clinical development.

Yescarta is currently under review in the United States and Europe for second-line use in relapsed or refractory LBCL, Kite noted.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This is a chimeric antigen receptor T-cell product indicated for use in adult patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL) after two or more lines of systemic therapy.

The product label carries a black box warning that CRS is a potentially fatal complication. With the update, the new labeling advises clinicians to “consider the use of prophylactic corticosteroid in patients after weighing the potential benefits and risks ... to delay the onset and decrease the duration of CRS.”

However, labeling also notes that “prophylactic corticosteroids ... may result in [a] higher grade of neurologic toxicities or prolongation of neurologic toxicities,” another potentially fatal complication noted in the black box warning.

The addition of prophylactic corticosteroids to labeling was based on data from 39 patients with relapsed or refractory LBCL who received dexamethasone 10 mg orally once daily for 3 days starting prior to Yescarta infusion. In this cohort, 31 of the 39 patients (79%) developed CRS, at which point they were managed with tocilizumab and/or corticosteroids. No one developed grade 3 or higher CRS. The median time to CRS onset was 5 days and the median duration was 4 days, according to labeling.

In contrast, in another cohort of 41 patients who were started on tocilizumab and/or corticosteroids only after becoming symptomatic, the overall incidence of CRS was 93% (38/41), with a median onset at 2 days, median duration of 7 days, and two patients who developed grade 3 CRS.

Prophylactic steroids do not compromise the activity of the cell therapy, Kite said in a press release.

“These new data will enable doctors to more easily and confidently manage treatment for patients,” said Frank Neumann, MD, PhD, the company’s global head of clinical development.

Yescarta is currently under review in the United States and Europe for second-line use in relapsed or refractory LBCL, Kite noted.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Open-label placebo improves symptoms in pediatric IBS and functional abdominal pain

A spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down – but what if the sugar is the medicine?

Nearly three in four children with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or unexplained abdominal pain reported at least a 30% improvement in discomfort after taking a regimen of sugar water they knew had no medicinal properties.

The findings, published online in JAMA Pediatrics on Jan. 31, 2022, also revealed that participants used significantly less rescue medications when taking the so-called “open-label placebo.” The magnitude of the effect was enough to meet one of the criteria from the Food and Drug Administration to approve drugs to treat IBS, which affects between 10% and 15% of U.S. children.

Although open-label placebo is not ready for clinical use, IBS expert Miranda van Tilburg, PhD, said she is “glad we have evidence” of a strong response in this patient population and that the results “may make clinicians rethink how they introduce treatments.

“By emphasizing their belief that a treatment may work, clinicians can harness the placebo effect,” Dr. van Tilburg, professor of medicine and vice chair of research at Marshall University, Huntington, W.Va., told this news organization.

Study leader Samuel Nurko, MD, MPH, the director of the functional abdominal pain program at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said placebo-controlled trials in patients with IBS and functional abdominal pain consistently show a “very high placebo response.” The question his group set out to answer, he said, was: “Can we get the pain symptoms of these children better by giving them placebo with no deception?”

Between 2015 and 2018, Dr. Nurko and colleagues randomly assigned 30 children and adolescents, aged 8-18 years, with IBS or functional abdominal pain to receive either an open-label inert liquid placebo – consisting of 85% sucrose, citric acid, purified water, and the preservative methyl paraben – twice daily for 3 weeks followed by 3 weeks with no placebo, or to follow the reverse sequence. Roughly half (53%) of the children had functional abdominal pain, and 47% had IBS as defined by Rome III criteria.

Researchers at the three participating clinical sites followed a standardized protocol for explaining the nature of placebo (“like sugar pills without medication”), telling participants that adults with conditions like theirs often benefit from placebo when they receive it as part of blinded, randomized clinical trials. Participants in the study were allowed to use hyoscyamine, an anticholinergic medication, as rescue treatment during the trial.

Dr. Nurko’s team reported that patients had a mean pain score of 39.9 on a 100-point visual analogue scale during the open-label placebo phase of the trial and a mean score of 45 during the control period. That difference was statistically significant (P = .03).

Participants took an average of two hyoscyamine pills during the placebo phase, compared with 3.8 pills during the 3-week period when they did not receive placebo (P < .001).

Nearly three-fourths (73.3%) of children in the study reported that open-label placebo improved their pain by over 30%, thus meeting one of the FDA’s criteria for clinical evaluation of drugs for IBS. Half said the placebo liquid cut their pain by more than 50%.

Dr. Nurko said the findings highlight the need to address “mind-body connections” in the management of gut-brain disorders. Like Dr. van Tilburg, he cautioned that open-label placebo “is not ready for widespread use. Placebo is complicated, and we need to understand the mechanism” underlying its efficacy.

“The idea is eventually we will be able to sort out the exact mechanism and harness it for clinical practice,” he added.

However, Dr. van Tilburg expressed that using placebo therapy to treat children and adolescents with these conditions could send the message that “the pain is not real or all in their heads. Children with chronic pain encounter a lot of stigma, and this kind of treatment may increase the feeling of not being believed. We should be careful to avoid this.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Schwartz family fund, the Foundation for the Science of the Therapeutic Relationship, and the Morgan Family Foundation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down – but what if the sugar is the medicine?

Nearly three in four children with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or unexplained abdominal pain reported at least a 30% improvement in discomfort after taking a regimen of sugar water they knew had no medicinal properties.

The findings, published online in JAMA Pediatrics on Jan. 31, 2022, also revealed that participants used significantly less rescue medications when taking the so-called “open-label placebo.” The magnitude of the effect was enough to meet one of the criteria from the Food and Drug Administration to approve drugs to treat IBS, which affects between 10% and 15% of U.S. children.

Although open-label placebo is not ready for clinical use, IBS expert Miranda van Tilburg, PhD, said she is “glad we have evidence” of a strong response in this patient population and that the results “may make clinicians rethink how they introduce treatments.

“By emphasizing their belief that a treatment may work, clinicians can harness the placebo effect,” Dr. van Tilburg, professor of medicine and vice chair of research at Marshall University, Huntington, W.Va., told this news organization.

Study leader Samuel Nurko, MD, MPH, the director of the functional abdominal pain program at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said placebo-controlled trials in patients with IBS and functional abdominal pain consistently show a “very high placebo response.” The question his group set out to answer, he said, was: “Can we get the pain symptoms of these children better by giving them placebo with no deception?”

Between 2015 and 2018, Dr. Nurko and colleagues randomly assigned 30 children and adolescents, aged 8-18 years, with IBS or functional abdominal pain to receive either an open-label inert liquid placebo – consisting of 85% sucrose, citric acid, purified water, and the preservative methyl paraben – twice daily for 3 weeks followed by 3 weeks with no placebo, or to follow the reverse sequence. Roughly half (53%) of the children had functional abdominal pain, and 47% had IBS as defined by Rome III criteria.

Researchers at the three participating clinical sites followed a standardized protocol for explaining the nature of placebo (“like sugar pills without medication”), telling participants that adults with conditions like theirs often benefit from placebo when they receive it as part of blinded, randomized clinical trials. Participants in the study were allowed to use hyoscyamine, an anticholinergic medication, as rescue treatment during the trial.

Dr. Nurko’s team reported that patients had a mean pain score of 39.9 on a 100-point visual analogue scale during the open-label placebo phase of the trial and a mean score of 45 during the control period. That difference was statistically significant (P = .03).

Participants took an average of two hyoscyamine pills during the placebo phase, compared with 3.8 pills during the 3-week period when they did not receive placebo (P < .001).

Nearly three-fourths (73.3%) of children in the study reported that open-label placebo improved their pain by over 30%, thus meeting one of the FDA’s criteria for clinical evaluation of drugs for IBS. Half said the placebo liquid cut their pain by more than 50%.

Dr. Nurko said the findings highlight the need to address “mind-body connections” in the management of gut-brain disorders. Like Dr. van Tilburg, he cautioned that open-label placebo “is not ready for widespread use. Placebo is complicated, and we need to understand the mechanism” underlying its efficacy.

“The idea is eventually we will be able to sort out the exact mechanism and harness it for clinical practice,” he added.

However, Dr. van Tilburg expressed that using placebo therapy to treat children and adolescents with these conditions could send the message that “the pain is not real or all in their heads. Children with chronic pain encounter a lot of stigma, and this kind of treatment may increase the feeling of not being believed. We should be careful to avoid this.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Schwartz family fund, the Foundation for the Science of the Therapeutic Relationship, and the Morgan Family Foundation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down – but what if the sugar is the medicine?

Nearly three in four children with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or unexplained abdominal pain reported at least a 30% improvement in discomfort after taking a regimen of sugar water they knew had no medicinal properties.

The findings, published online in JAMA Pediatrics on Jan. 31, 2022, also revealed that participants used significantly less rescue medications when taking the so-called “open-label placebo.” The magnitude of the effect was enough to meet one of the criteria from the Food and Drug Administration to approve drugs to treat IBS, which affects between 10% and 15% of U.S. children.

Although open-label placebo is not ready for clinical use, IBS expert Miranda van Tilburg, PhD, said she is “glad we have evidence” of a strong response in this patient population and that the results “may make clinicians rethink how they introduce treatments.

“By emphasizing their belief that a treatment may work, clinicians can harness the placebo effect,” Dr. van Tilburg, professor of medicine and vice chair of research at Marshall University, Huntington, W.Va., told this news organization.

Study leader Samuel Nurko, MD, MPH, the director of the functional abdominal pain program at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said placebo-controlled trials in patients with IBS and functional abdominal pain consistently show a “very high placebo response.” The question his group set out to answer, he said, was: “Can we get the pain symptoms of these children better by giving them placebo with no deception?”

Between 2015 and 2018, Dr. Nurko and colleagues randomly assigned 30 children and adolescents, aged 8-18 years, with IBS or functional abdominal pain to receive either an open-label inert liquid placebo – consisting of 85% sucrose, citric acid, purified water, and the preservative methyl paraben – twice daily for 3 weeks followed by 3 weeks with no placebo, or to follow the reverse sequence. Roughly half (53%) of the children had functional abdominal pain, and 47% had IBS as defined by Rome III criteria.

Researchers at the three participating clinical sites followed a standardized protocol for explaining the nature of placebo (“like sugar pills without medication”), telling participants that adults with conditions like theirs often benefit from placebo when they receive it as part of blinded, randomized clinical trials. Participants in the study were allowed to use hyoscyamine, an anticholinergic medication, as rescue treatment during the trial.

Dr. Nurko’s team reported that patients had a mean pain score of 39.9 on a 100-point visual analogue scale during the open-label placebo phase of the trial and a mean score of 45 during the control period. That difference was statistically significant (P = .03).

Participants took an average of two hyoscyamine pills during the placebo phase, compared with 3.8 pills during the 3-week period when they did not receive placebo (P < .001).

Nearly three-fourths (73.3%) of children in the study reported that open-label placebo improved their pain by over 30%, thus meeting one of the FDA’s criteria for clinical evaluation of drugs for IBS. Half said the placebo liquid cut their pain by more than 50%.

Dr. Nurko said the findings highlight the need to address “mind-body connections” in the management of gut-brain disorders. Like Dr. van Tilburg, he cautioned that open-label placebo “is not ready for widespread use. Placebo is complicated, and we need to understand the mechanism” underlying its efficacy.

“The idea is eventually we will be able to sort out the exact mechanism and harness it for clinical practice,” he added.

However, Dr. van Tilburg expressed that using placebo therapy to treat children and adolescents with these conditions could send the message that “the pain is not real or all in their heads. Children with chronic pain encounter a lot of stigma, and this kind of treatment may increase the feeling of not being believed. We should be careful to avoid this.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Schwartz family fund, the Foundation for the Science of the Therapeutic Relationship, and the Morgan Family Foundation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

“I didn’t want to meet you.” Dispelling myths about palliative care

The names of health care professionals and patients cited within the dialogue text have been changed to protect their privacy.

but over the years I have come to realize that she was right – most people, including many within health care, don’t have a good appreciation of what palliative care is or how it can help patients and health care teams.

A recent national survey about cancer-related health information found that of more than 1,000 surveyed Americans, less than 30% professed any knowledge of palliative care. Of those who had some knowledge of palliative care, around 30% believed palliative care was synonymous with hospice.1 Another 15% believed that a patient would have to give up cancer-directed treatments to receive palliative care.1

It’s not giving up

This persistent belief that palliative care is equivalent to hospice, or is tantamount to “giving up,” is one of the most commonly held myths I encounter in everyday practice.

I knock on the exam door and walk in.

A small, trim woman in her late 50s is sitting in a chair, arms folded across her chest, face drawn in.

“Hi,” I start. “I’m Sarah, the palliative care nurse practitioner who works in this clinic. I work closely with Dr. Smith.”

Dr. Smith is the patient’s oncologist.

“I really didn’t want to meet you,” she says in a quiet voice, her eyes large with concern.

I don’t take it personally. Few patients really want to be in the position of needing to meet the palliative care team.

“I looked up palliative care on Google and saw the word hospice.”

“Yeah,” I say. “I hear that a lot. Well, I can reassure you that this isn’t hospice.

In this clinic, our focus is on your cancer symptoms, your treatment side effects, and your quality of life.”

She looks visibly relieved. “Quality of life,” she echoes. “I need more of that.”

“OK,” I say. “So, tell me what you’re struggling with the most right now.”

That’s how many palliative care visits start. I actually prefer if patients haven’t heard of palliative care because it allows me to frame it for them, rather than having to start by addressing a myth or a prior negative experience. Even when patients haven’t had a negative experience with palliative care per se, typically, if they’ve interacted with palliative care in the past, it’s usually because someone they loved died in a hospital setting and it is the memory of that terrible loss that becomes synonymous with their recollection of palliative care.

Many patients I meet have never seen another outpatient palliative care practitioner – and this makes sense – we are still too few and far between. Most established palliative care teams are hospital based and many patients seen in the community do not have easy access to palliative care teams where they receive oncologic care.2 As an embedded practitioner, I see patients in the same exam rooms and infusion centers where they receive their cancer therapies, so I’m effectively woven into the fabric of their oncology experience. Just being there in the cancer center allows me to be in the right place at the right time for the right patients and their care teams.

More than pain management

Another myth I tend to dispel a lot is that palliative care is just a euphemism for “pain management.” I have seen this less lately, but still occasionally in the chart I’ll see documented in a note, “patient is seeing palliative/pain management,” when a patient is seeing me or one of my colleagues. Unfortunately, when providers have limited or outdated views of what palliative care is or the value it brings to patient-centered cancer care, referrals to palliative care tend to be delayed.3

“I really think Ms. Lopez could benefit from seeing palliative care,” an oncology nurse practitioner says to an oncologist.

I’m standing nearby, about to see another patient in one of the exam rooms in our clinic.

“But I don’t think she’s ready. And besides, she doesn’t have any pain,” he says.

He turns to me quizzically. “What do you think?”

“Tell me about the patient,” I ask, taking a few steps in their direction.

“Well, she’s a 64-year-old woman with metastatic cancer.

She has a really poor appetite and is losing some weight.

Seems a bit down, kind of pessimistic about things.

Her scan showed some new growth, so guess I’m not surprised by that.”

“I might be able to help her with the appetite and the mood changes.

I can at least talk with her and see where she’s at,” I offer.

“Alright,” he says. “We’ll put the palliative referral in.”

He hesitates. “But are you sure you want to see her?

She doesn’t have any pain.” He sounds skeptical.

“Yeah, I mean, it sounds like she has symptoms that are bothering her, so I’d be happy to see her. She sounds completely appropriate for palliative care.”

I hear this assumption a lot – that palliative care is somehow equivalent to pain management and that unless a patient’s pain is severe, it’s not worth referring the patient to palliative care. Don’t get me wrong – we do a lot of pain management, but at its heart, palliative care is an interdisciplinary specialty focused on improving or maintaining quality of life for people with serious illness. Because the goal is so broad, care can take many shapes.4

In addition to pain, palliative care clinicians commonly treat nausea, shortness of breath, constipation or diarrhea, poor appetite, fatigue, anxiety, depression, and insomnia.

Palliative care is more than medical or nursing care

A related misconception about palliative care held by many lay people and health care workers alike is that palliative care is primarily medical or nursing care focused mostly on alleviating physical symptoms such as pain or nausea. This couldn’t be further from the truth.

We’ve been talking for a while.

Ms. Lopez tells me about her struggles to maintain her weight while undergoing chemotherapy. She has low-grade nausea that is impacting her ability and desire to eat more and didn’t think that her weight loss was severe enough to warrant taking medication.

We talk about how she may be able to use antinausea medication sparingly to alleviate nausea while also limiting side effects from the medications—which was a big concern for her.

I ask her what else is bothering her.

She tells me that she has always been a strong Catholic and even when life has gotten tough, her faith was never shaken – until now.

She is struggling to understand why she ended up with metastatic cancer at such a relatively young age—why would God do this to her?

She had plans for retirement that have since evaporated in the face of a foreshortened life.

Why did this happen to her of all people? She was completely healthy until her diagnosis.

Her face is wet with tears.

We talk a little about how a diagnosis like this can change so much of a person’s life and identity. I try to validate her experience. She’s clearly suffering from a sense that her life is not what she expected, and she is struggling to integrate how her future looks at this point.

I ask her what conversations with her priest have been like.

At this point you may be wondering where this conversation is going. Why are we talking about Ms. Lopez’s religion? Palliative care is best delivered through high functioning interdisciplinary teams that can include other supportive people in a patient’s life. We work in concert to try to bring comfort to a patient and their family.4 That support network can include nurses, physicians, social workers, and chaplains. In this case, Ms. Lopez had not yet reached out to her priest. She hasn’t had the time or energy to contact her priest given her symptoms.

“Can I contact your priest for you?

Maybe he can visit or call and chat with you?”

She nods and wipes tears away.

“That would be really nice,” she says. “I’d love it if he could pray with me.”

A few hours after the visit, I call Ms. Lopez’s priest.

I ask him to reach out to her and about her request for prayer.

He says he’s been thinking about her and that her presence has been missed at weekly Mass. He thanks me for the call and says he’ll call her tomorrow.

I say my own small prayer for Ms. Lopez and head home, the day’s work completed.

Sarah D'Ambruoso was born and raised in Maine. She completed her undergraduate and graduate nursing education at New York University and UCLA, respectively, and currently works as a palliative care nurse practitioner in an oncology clinic in Los Angeles.

References

1. Cheng BT et al. Patterns of palliative care beliefs among adults in the U.S.: Analysis of a National Cancer Database. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019 Aug 10. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.07.030.

2. Finlay E et al. Filling the gap: Creating an outpatient palliative care program in your institution. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018 May 23. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_200775.

3. Von Roenn JH et al. Barriers and approaches to the successful integration of palliative care and oncology practice. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013 Mar. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0209.

4. Ferrell BR et al. Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2016 Oct 31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.1474.

The names of health care professionals and patients cited within the dialogue text have been changed to protect their privacy.

but over the years I have come to realize that she was right – most people, including many within health care, don’t have a good appreciation of what palliative care is or how it can help patients and health care teams.

A recent national survey about cancer-related health information found that of more than 1,000 surveyed Americans, less than 30% professed any knowledge of palliative care. Of those who had some knowledge of palliative care, around 30% believed palliative care was synonymous with hospice.1 Another 15% believed that a patient would have to give up cancer-directed treatments to receive palliative care.1

It’s not giving up

This persistent belief that palliative care is equivalent to hospice, or is tantamount to “giving up,” is one of the most commonly held myths I encounter in everyday practice.

I knock on the exam door and walk in.

A small, trim woman in her late 50s is sitting in a chair, arms folded across her chest, face drawn in.

“Hi,” I start. “I’m Sarah, the palliative care nurse practitioner who works in this clinic. I work closely with Dr. Smith.”

Dr. Smith is the patient’s oncologist.

“I really didn’t want to meet you,” she says in a quiet voice, her eyes large with concern.

I don’t take it personally. Few patients really want to be in the position of needing to meet the palliative care team.

“I looked up palliative care on Google and saw the word hospice.”

“Yeah,” I say. “I hear that a lot. Well, I can reassure you that this isn’t hospice.

In this clinic, our focus is on your cancer symptoms, your treatment side effects, and your quality of life.”

She looks visibly relieved. “Quality of life,” she echoes. “I need more of that.”

“OK,” I say. “So, tell me what you’re struggling with the most right now.”

That’s how many palliative care visits start. I actually prefer if patients haven’t heard of palliative care because it allows me to frame it for them, rather than having to start by addressing a myth or a prior negative experience. Even when patients haven’t had a negative experience with palliative care per se, typically, if they’ve interacted with palliative care in the past, it’s usually because someone they loved died in a hospital setting and it is the memory of that terrible loss that becomes synonymous with their recollection of palliative care.

Many patients I meet have never seen another outpatient palliative care practitioner – and this makes sense – we are still too few and far between. Most established palliative care teams are hospital based and many patients seen in the community do not have easy access to palliative care teams where they receive oncologic care.2 As an embedded practitioner, I see patients in the same exam rooms and infusion centers where they receive their cancer therapies, so I’m effectively woven into the fabric of their oncology experience. Just being there in the cancer center allows me to be in the right place at the right time for the right patients and their care teams.

More than pain management

Another myth I tend to dispel a lot is that palliative care is just a euphemism for “pain management.” I have seen this less lately, but still occasionally in the chart I’ll see documented in a note, “patient is seeing palliative/pain management,” when a patient is seeing me or one of my colleagues. Unfortunately, when providers have limited or outdated views of what palliative care is or the value it brings to patient-centered cancer care, referrals to palliative care tend to be delayed.3

“I really think Ms. Lopez could benefit from seeing palliative care,” an oncology nurse practitioner says to an oncologist.

I’m standing nearby, about to see another patient in one of the exam rooms in our clinic.

“But I don’t think she’s ready. And besides, she doesn’t have any pain,” he says.

He turns to me quizzically. “What do you think?”

“Tell me about the patient,” I ask, taking a few steps in their direction.

“Well, she’s a 64-year-old woman with metastatic cancer.

She has a really poor appetite and is losing some weight.

Seems a bit down, kind of pessimistic about things.

Her scan showed some new growth, so guess I’m not surprised by that.”

“I might be able to help her with the appetite and the mood changes.

I can at least talk with her and see where she’s at,” I offer.

“Alright,” he says. “We’ll put the palliative referral in.”

He hesitates. “But are you sure you want to see her?

She doesn’t have any pain.” He sounds skeptical.

“Yeah, I mean, it sounds like she has symptoms that are bothering her, so I’d be happy to see her. She sounds completely appropriate for palliative care.”

I hear this assumption a lot – that palliative care is somehow equivalent to pain management and that unless a patient’s pain is severe, it’s not worth referring the patient to palliative care. Don’t get me wrong – we do a lot of pain management, but at its heart, palliative care is an interdisciplinary specialty focused on improving or maintaining quality of life for people with serious illness. Because the goal is so broad, care can take many shapes.4

In addition to pain, palliative care clinicians commonly treat nausea, shortness of breath, constipation or diarrhea, poor appetite, fatigue, anxiety, depression, and insomnia.

Palliative care is more than medical or nursing care

A related misconception about palliative care held by many lay people and health care workers alike is that palliative care is primarily medical or nursing care focused mostly on alleviating physical symptoms such as pain or nausea. This couldn’t be further from the truth.

We’ve been talking for a while.

Ms. Lopez tells me about her struggles to maintain her weight while undergoing chemotherapy. She has low-grade nausea that is impacting her ability and desire to eat more and didn’t think that her weight loss was severe enough to warrant taking medication.

We talk about how she may be able to use antinausea medication sparingly to alleviate nausea while also limiting side effects from the medications—which was a big concern for her.

I ask her what else is bothering her.

She tells me that she has always been a strong Catholic and even when life has gotten tough, her faith was never shaken – until now.

She is struggling to understand why she ended up with metastatic cancer at such a relatively young age—why would God do this to her?

She had plans for retirement that have since evaporated in the face of a foreshortened life.

Why did this happen to her of all people? She was completely healthy until her diagnosis.

Her face is wet with tears.

We talk a little about how a diagnosis like this can change so much of a person’s life and identity. I try to validate her experience. She’s clearly suffering from a sense that her life is not what she expected, and she is struggling to integrate how her future looks at this point.

I ask her what conversations with her priest have been like.

At this point you may be wondering where this conversation is going. Why are we talking about Ms. Lopez’s religion? Palliative care is best delivered through high functioning interdisciplinary teams that can include other supportive people in a patient’s life. We work in concert to try to bring comfort to a patient and their family.4 That support network can include nurses, physicians, social workers, and chaplains. In this case, Ms. Lopez had not yet reached out to her priest. She hasn’t had the time or energy to contact her priest given her symptoms.

“Can I contact your priest for you?

Maybe he can visit or call and chat with you?”

She nods and wipes tears away.

“That would be really nice,” she says. “I’d love it if he could pray with me.”

A few hours after the visit, I call Ms. Lopez’s priest.

I ask him to reach out to her and about her request for prayer.

He says he’s been thinking about her and that her presence has been missed at weekly Mass. He thanks me for the call and says he’ll call her tomorrow.

I say my own small prayer for Ms. Lopez and head home, the day’s work completed.

Sarah D'Ambruoso was born and raised in Maine. She completed her undergraduate and graduate nursing education at New York University and UCLA, respectively, and currently works as a palliative care nurse practitioner in an oncology clinic in Los Angeles.

References

1. Cheng BT et al. Patterns of palliative care beliefs among adults in the U.S.: Analysis of a National Cancer Database. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019 Aug 10. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.07.030.

2. Finlay E et al. Filling the gap: Creating an outpatient palliative care program in your institution. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018 May 23. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_200775.

3. Von Roenn JH et al. Barriers and approaches to the successful integration of palliative care and oncology practice. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013 Mar. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0209.

4. Ferrell BR et al. Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2016 Oct 31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.1474.

The names of health care professionals and patients cited within the dialogue text have been changed to protect their privacy.

but over the years I have come to realize that she was right – most people, including many within health care, don’t have a good appreciation of what palliative care is or how it can help patients and health care teams.

A recent national survey about cancer-related health information found that of more than 1,000 surveyed Americans, less than 30% professed any knowledge of palliative care. Of those who had some knowledge of palliative care, around 30% believed palliative care was synonymous with hospice.1 Another 15% believed that a patient would have to give up cancer-directed treatments to receive palliative care.1

It’s not giving up

This persistent belief that palliative care is equivalent to hospice, or is tantamount to “giving up,” is one of the most commonly held myths I encounter in everyday practice.

I knock on the exam door and walk in.

A small, trim woman in her late 50s is sitting in a chair, arms folded across her chest, face drawn in.

“Hi,” I start. “I’m Sarah, the palliative care nurse practitioner who works in this clinic. I work closely with Dr. Smith.”

Dr. Smith is the patient’s oncologist.

“I really didn’t want to meet you,” she says in a quiet voice, her eyes large with concern.

I don’t take it personally. Few patients really want to be in the position of needing to meet the palliative care team.

“I looked up palliative care on Google and saw the word hospice.”

“Yeah,” I say. “I hear that a lot. Well, I can reassure you that this isn’t hospice.

In this clinic, our focus is on your cancer symptoms, your treatment side effects, and your quality of life.”

She looks visibly relieved. “Quality of life,” she echoes. “I need more of that.”

“OK,” I say. “So, tell me what you’re struggling with the most right now.”

That’s how many palliative care visits start. I actually prefer if patients haven’t heard of palliative care because it allows me to frame it for them, rather than having to start by addressing a myth or a prior negative experience. Even when patients haven’t had a negative experience with palliative care per se, typically, if they’ve interacted with palliative care in the past, it’s usually because someone they loved died in a hospital setting and it is the memory of that terrible loss that becomes synonymous with their recollection of palliative care.

Many patients I meet have never seen another outpatient palliative care practitioner – and this makes sense – we are still too few and far between. Most established palliative care teams are hospital based and many patients seen in the community do not have easy access to palliative care teams where they receive oncologic care.2 As an embedded practitioner, I see patients in the same exam rooms and infusion centers where they receive their cancer therapies, so I’m effectively woven into the fabric of their oncology experience. Just being there in the cancer center allows me to be in the right place at the right time for the right patients and their care teams.

More than pain management

Another myth I tend to dispel a lot is that palliative care is just a euphemism for “pain management.” I have seen this less lately, but still occasionally in the chart I’ll see documented in a note, “patient is seeing palliative/pain management,” when a patient is seeing me or one of my colleagues. Unfortunately, when providers have limited or outdated views of what palliative care is or the value it brings to patient-centered cancer care, referrals to palliative care tend to be delayed.3

“I really think Ms. Lopez could benefit from seeing palliative care,” an oncology nurse practitioner says to an oncologist.

I’m standing nearby, about to see another patient in one of the exam rooms in our clinic.

“But I don’t think she’s ready. And besides, she doesn’t have any pain,” he says.

He turns to me quizzically. “What do you think?”

“Tell me about the patient,” I ask, taking a few steps in their direction.

“Well, she’s a 64-year-old woman with metastatic cancer.

She has a really poor appetite and is losing some weight.

Seems a bit down, kind of pessimistic about things.

Her scan showed some new growth, so guess I’m not surprised by that.”

“I might be able to help her with the appetite and the mood changes.

I can at least talk with her and see where she’s at,” I offer.

“Alright,” he says. “We’ll put the palliative referral in.”

He hesitates. “But are you sure you want to see her?

She doesn’t have any pain.” He sounds skeptical.

“Yeah, I mean, it sounds like she has symptoms that are bothering her, so I’d be happy to see her. She sounds completely appropriate for palliative care.”

I hear this assumption a lot – that palliative care is somehow equivalent to pain management and that unless a patient’s pain is severe, it’s not worth referring the patient to palliative care. Don’t get me wrong – we do a lot of pain management, but at its heart, palliative care is an interdisciplinary specialty focused on improving or maintaining quality of life for people with serious illness. Because the goal is so broad, care can take many shapes.4

In addition to pain, palliative care clinicians commonly treat nausea, shortness of breath, constipation or diarrhea, poor appetite, fatigue, anxiety, depression, and insomnia.

Palliative care is more than medical or nursing care

A related misconception about palliative care held by many lay people and health care workers alike is that palliative care is primarily medical or nursing care focused mostly on alleviating physical symptoms such as pain or nausea. This couldn’t be further from the truth.

We’ve been talking for a while.

Ms. Lopez tells me about her struggles to maintain her weight while undergoing chemotherapy. She has low-grade nausea that is impacting her ability and desire to eat more and didn’t think that her weight loss was severe enough to warrant taking medication.

We talk about how she may be able to use antinausea medication sparingly to alleviate nausea while also limiting side effects from the medications—which was a big concern for her.

I ask her what else is bothering her.

She tells me that she has always been a strong Catholic and even when life has gotten tough, her faith was never shaken – until now.

She is struggling to understand why she ended up with metastatic cancer at such a relatively young age—why would God do this to her?

She had plans for retirement that have since evaporated in the face of a foreshortened life.

Why did this happen to her of all people? She was completely healthy until her diagnosis.

Her face is wet with tears.

We talk a little about how a diagnosis like this can change so much of a person’s life and identity. I try to validate her experience. She’s clearly suffering from a sense that her life is not what she expected, and she is struggling to integrate how her future looks at this point.

I ask her what conversations with her priest have been like.

At this point you may be wondering where this conversation is going. Why are we talking about Ms. Lopez’s religion? Palliative care is best delivered through high functioning interdisciplinary teams that can include other supportive people in a patient’s life. We work in concert to try to bring comfort to a patient and their family.4 That support network can include nurses, physicians, social workers, and chaplains. In this case, Ms. Lopez had not yet reached out to her priest. She hasn’t had the time or energy to contact her priest given her symptoms.

“Can I contact your priest for you?

Maybe he can visit or call and chat with you?”

She nods and wipes tears away.

“That would be really nice,” she says. “I’d love it if he could pray with me.”

A few hours after the visit, I call Ms. Lopez’s priest.

I ask him to reach out to her and about her request for prayer.

He says he’s been thinking about her and that her presence has been missed at weekly Mass. He thanks me for the call and says he’ll call her tomorrow.

I say my own small prayer for Ms. Lopez and head home, the day’s work completed.

Sarah D'Ambruoso was born and raised in Maine. She completed her undergraduate and graduate nursing education at New York University and UCLA, respectively, and currently works as a palliative care nurse practitioner in an oncology clinic in Los Angeles.

References

1. Cheng BT et al. Patterns of palliative care beliefs among adults in the U.S.: Analysis of a National Cancer Database. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019 Aug 10. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.07.030.

2. Finlay E et al. Filling the gap: Creating an outpatient palliative care program in your institution. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018 May 23. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_200775.

3. Von Roenn JH et al. Barriers and approaches to the successful integration of palliative care and oncology practice. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013 Mar. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0209.

4. Ferrell BR et al. Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2016 Oct 31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.1474.

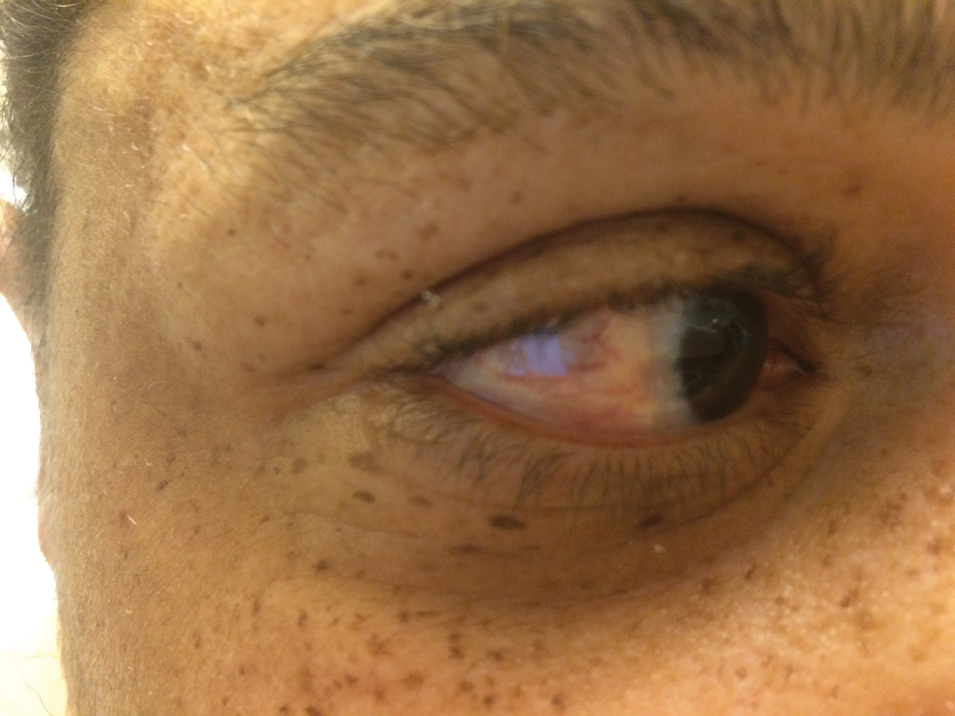

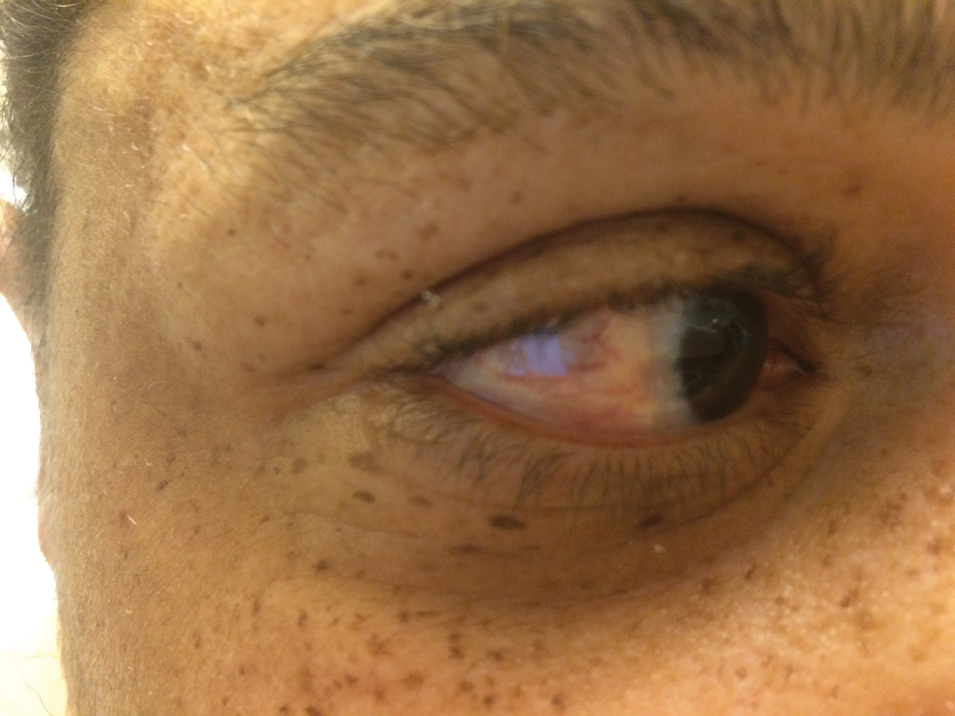

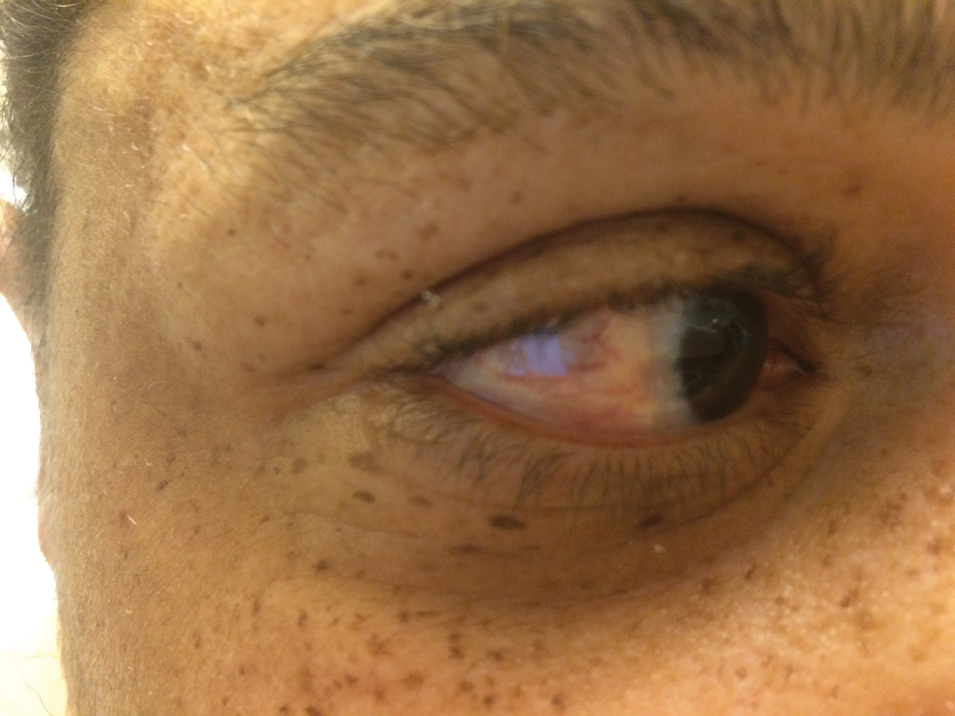

Dryness, conjunctival telangiectasia among ocular symptoms common in rosacea

according to a study recently published in International Ophthalmology.

In the study, investigators compared the right eyes of 76 patients with acne rosacea and 113 age-matched and gender-matched patients without rosacea. The mean age of the patients was 47-48 years, and about 63% were females. Ophthalmologic examinations that included tear breakup time and optical CT-assisted infrared meibography were conducted, and participants were asked to complete the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) questionnaire, which the authors say is widely used to assess aspects of ocular surface diseases.

Compared with controls, significantly more patients with rosacea had itching (35.5% vs. 17.7%), dryness (46.1% vs. 10.6%), hyperemia (10.5% vs. 2.7%), conjunctival telangiectasia (26.3% vs. 1.8%), and meibomitis (52.6% vs. 31%) (P ≤ .05 for all), according to the investigators, from the departments of ophthalmology and dermatology, Dokuz Eylul University, Izmir, Turkey. The most common ocular symptom among those with rosacea was having a foreign body sensation (53.9% vs. 24.8%, P < .001).

Ocular surface problems were also more common among those with rosacea, and OSDI scores were significantly higher among those with rosacea, compared with controls.

Estee Williams, MD, a dermatologist in private practice in New York and assistant clinical professor of dermatology at Mount Sinai Hospital, also in New York, who was not involved with the study, said the results reinforce the need to keep ocular rosacea in mind when examining a patient.

“The study is a reminder that ocular rosacea is, like its facial counterpart, an inflammatory disease that can manifest in many ways; for this reason, it’s often misdiagnosed or missed altogether,” Dr. Williams told this news organization. “This is unfortunate because it is usually easily managed.”

She added that there is a need for more randomized, controlled studies to determine optimal treatments for ocular rosacea, which is underdiagnosed. Part of the reason she believes it is underdiagnosed is that often “ophthalmologists don’t think about ocular rosacea specifically, unless they are given the information that the patient suffers from rosacea. The patient may not be aware that their skin and eye problems are connected.”

The take-home message of the study, Dr. Williams added, is that dermatologists who treat rosacea should be ready to screen their patients with rosacea for ocular symptoms, as well as have a basic understanding of ocular rosacea and know when to refer patients to an ophthalmologist.

“Preservative-free eye drops are usually well tolerated and a good starting point for those cases that are limited to symptoms only,” she said. “However, once a patient has signs of overt inflammation on exam, such as arcades of blood vessels on the eyelid margin or on the white of the eye, prescription medication is usually needed.”

A limitation of the study is that both eyes of patients were not included, said Dr. Williams, noting that ocular rosacea is usually bilateral.

Also asked to comment on the results, Marc Lupin, MD, a dermatologist in Victoria, B.C., and clinical instructor in the department of dermatology and skin science, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, noted that one of the shortcomings of the study is that it did not account for any effect of treatment.

“Were they on treatment for their rosacea either during the study or before the study?” asked Dr. Lupin. “That would affect the ocular findings.” Still, he agreed that the study underlines the need for dermatologists to be aware of the high incidence of ocular rosacea in patients and to appreciate that it can present subtly.

The study authors, Dr. Williams, and Dr. Lupin disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to a study recently published in International Ophthalmology.

In the study, investigators compared the right eyes of 76 patients with acne rosacea and 113 age-matched and gender-matched patients without rosacea. The mean age of the patients was 47-48 years, and about 63% were females. Ophthalmologic examinations that included tear breakup time and optical CT-assisted infrared meibography were conducted, and participants were asked to complete the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) questionnaire, which the authors say is widely used to assess aspects of ocular surface diseases.

Compared with controls, significantly more patients with rosacea had itching (35.5% vs. 17.7%), dryness (46.1% vs. 10.6%), hyperemia (10.5% vs. 2.7%), conjunctival telangiectasia (26.3% vs. 1.8%), and meibomitis (52.6% vs. 31%) (P ≤ .05 for all), according to the investigators, from the departments of ophthalmology and dermatology, Dokuz Eylul University, Izmir, Turkey. The most common ocular symptom among those with rosacea was having a foreign body sensation (53.9% vs. 24.8%, P < .001).

Ocular surface problems were also more common among those with rosacea, and OSDI scores were significantly higher among those with rosacea, compared with controls.

Estee Williams, MD, a dermatologist in private practice in New York and assistant clinical professor of dermatology at Mount Sinai Hospital, also in New York, who was not involved with the study, said the results reinforce the need to keep ocular rosacea in mind when examining a patient.

“The study is a reminder that ocular rosacea is, like its facial counterpart, an inflammatory disease that can manifest in many ways; for this reason, it’s often misdiagnosed or missed altogether,” Dr. Williams told this news organization. “This is unfortunate because it is usually easily managed.”

She added that there is a need for more randomized, controlled studies to determine optimal treatments for ocular rosacea, which is underdiagnosed. Part of the reason she believes it is underdiagnosed is that often “ophthalmologists don’t think about ocular rosacea specifically, unless they are given the information that the patient suffers from rosacea. The patient may not be aware that their skin and eye problems are connected.”

The take-home message of the study, Dr. Williams added, is that dermatologists who treat rosacea should be ready to screen their patients with rosacea for ocular symptoms, as well as have a basic understanding of ocular rosacea and know when to refer patients to an ophthalmologist.

“Preservative-free eye drops are usually well tolerated and a good starting point for those cases that are limited to symptoms only,” she said. “However, once a patient has signs of overt inflammation on exam, such as arcades of blood vessels on the eyelid margin or on the white of the eye, prescription medication is usually needed.”

A limitation of the study is that both eyes of patients were not included, said Dr. Williams, noting that ocular rosacea is usually bilateral.

Also asked to comment on the results, Marc Lupin, MD, a dermatologist in Victoria, B.C., and clinical instructor in the department of dermatology and skin science, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, noted that one of the shortcomings of the study is that it did not account for any effect of treatment.

“Were they on treatment for their rosacea either during the study or before the study?” asked Dr. Lupin. “That would affect the ocular findings.” Still, he agreed that the study underlines the need for dermatologists to be aware of the high incidence of ocular rosacea in patients and to appreciate that it can present subtly.

The study authors, Dr. Williams, and Dr. Lupin disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to a study recently published in International Ophthalmology.

In the study, investigators compared the right eyes of 76 patients with acne rosacea and 113 age-matched and gender-matched patients without rosacea. The mean age of the patients was 47-48 years, and about 63% were females. Ophthalmologic examinations that included tear breakup time and optical CT-assisted infrared meibography were conducted, and participants were asked to complete the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) questionnaire, which the authors say is widely used to assess aspects of ocular surface diseases.

Compared with controls, significantly more patients with rosacea had itching (35.5% vs. 17.7%), dryness (46.1% vs. 10.6%), hyperemia (10.5% vs. 2.7%), conjunctival telangiectasia (26.3% vs. 1.8%), and meibomitis (52.6% vs. 31%) (P ≤ .05 for all), according to the investigators, from the departments of ophthalmology and dermatology, Dokuz Eylul University, Izmir, Turkey. The most common ocular symptom among those with rosacea was having a foreign body sensation (53.9% vs. 24.8%, P < .001).

Ocular surface problems were also more common among those with rosacea, and OSDI scores were significantly higher among those with rosacea, compared with controls.

Estee Williams, MD, a dermatologist in private practice in New York and assistant clinical professor of dermatology at Mount Sinai Hospital, also in New York, who was not involved with the study, said the results reinforce the need to keep ocular rosacea in mind when examining a patient.

“The study is a reminder that ocular rosacea is, like its facial counterpart, an inflammatory disease that can manifest in many ways; for this reason, it’s often misdiagnosed or missed altogether,” Dr. Williams told this news organization. “This is unfortunate because it is usually easily managed.”

She added that there is a need for more randomized, controlled studies to determine optimal treatments for ocular rosacea, which is underdiagnosed. Part of the reason she believes it is underdiagnosed is that often “ophthalmologists don’t think about ocular rosacea specifically, unless they are given the information that the patient suffers from rosacea. The patient may not be aware that their skin and eye problems are connected.”

The take-home message of the study, Dr. Williams added, is that dermatologists who treat rosacea should be ready to screen their patients with rosacea for ocular symptoms, as well as have a basic understanding of ocular rosacea and know when to refer patients to an ophthalmologist.

“Preservative-free eye drops are usually well tolerated and a good starting point for those cases that are limited to symptoms only,” she said. “However, once a patient has signs of overt inflammation on exam, such as arcades of blood vessels on the eyelid margin or on the white of the eye, prescription medication is usually needed.”

A limitation of the study is that both eyes of patients were not included, said Dr. Williams, noting that ocular rosacea is usually bilateral.

Also asked to comment on the results, Marc Lupin, MD, a dermatologist in Victoria, B.C., and clinical instructor in the department of dermatology and skin science, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, noted that one of the shortcomings of the study is that it did not account for any effect of treatment.

“Were they on treatment for their rosacea either during the study or before the study?” asked Dr. Lupin. “That would affect the ocular findings.” Still, he agreed that the study underlines the need for dermatologists to be aware of the high incidence of ocular rosacea in patients and to appreciate that it can present subtly.

The study authors, Dr. Williams, and Dr. Lupin disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM INTERNATIONAL OPTHALMOLOGY

Lipedema: A potentially devastating, often unrecognized disease

” according to C. William Hanke, MD, MPH.

“This disease is well known in Europe, especially in the Netherlands, Germany, and Austria, but in this country, I believe most dermatologists have never heard of it,” Dr. Hanke said at the ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgical Conference.

Clinically, patients with lipedema – also known as “two-body syndrome” – present with a symmetric, bilateral increase in subcutaneous fat, with “cuffs of fat” around the ankles. It usually affects the legs and thighs; the hands and feet are not affected.

“From the waist on up, the body looks like one person, and from the waist on down, it looks like an entirely different person,” said Dr. Hanke, a dermatologist who is program director for the micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology fellowship training program at Ascension St. Vincent Hospital in Indianapolis. “Just think of the difficulty that the person has with their life in terms of buying clothes or social interactions. This is a devastating problem.”